-

1

Nürnberg

Allgemeines Lexikon > Nürnberg

-

2

Nürnberg

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Nürnberg

-

3

Nürnberg

Deutsch-Polnisch Wörterbuch neuer > Nürnberg

-

4

Nürnberg

БНРС > Nürnberg

-

5

Nürnberg

Deutsch-russische wörterbuch der kunst > Nürnberg

-

6

Nürnberg

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > Nürnberg

-

7

Nürnberg

n

Нюрнберг

город на юго-востоке Германии (земля Бавария) на р. Пегниц и канале Рейн-Майн-Дунай; 494.000 жителей; упоминается с середины 11 в.; машиностроение, электротехническая, легкая, пищевая промышленность, производство игрушек; проводятся ярмарки (в частности, ярмарка игрушек); старинный центр города в значительной мере восстановлен после разрушений 2-й мировой войны; замок, позднеготические церкви, ратуша; многочисленные музеи (Германский национальный музей); университет, другие вузы; родина художника Альбрехта Дюрера

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der regionalen Studien > Nürnberg

-

8

Nürnberg

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > Nürnberg

-

9

Nürnberg

Современный немецко-русский словарь общей лексики > Nürnberg

-

10

Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg AG

(MAN AG)

«Maшиненфабрик Аугсбург-Нюрнберг АГ»

немецкий машиностроительный концерн, основан в 1898 г.; производит двигатели, автомобили (MAN), паровые турбины, компрессоры и др. оборудование; штаб-квартира в Мюнхене

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der regionalen Studien > Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg AG

-

11

Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg

f

Университет им. Фридриха и Александра гг. Эрланген и Нюрнберг

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg

-

12

Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg

Универсальный немецко-русский словарь > Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg

-

13

Dürerhaus in Nürnberg

Дом-музей Дюрера в Нюрнберге

расположен в доме, где жил немецкий живописец и график Альбрехт Дюрер (1471-1528); коллекция графики и живописи, а также пресс, с помощью которого художник делал гравюры

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der regionalen Studien > Dürerhaus in Nürnberg

-

14

Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nürnberg

Германский национальный музей в Нюрнберге

основан в 1852 немецкими историками, исследователями старины; музей представляет развитие немецкой культуры и искусства различных направлений с ранних времен до 20 в.; крупнейшее собрание включает: гравюры на меди, монеты, медали, скульптуры, собрания произведений живописи, а также библиотеку и архив; в коллекции музея есть хирургические, астрономические инструменты, оружие, домашняя утварь, мебель, одежда и украшения; к числу его сокровищ принадлежат: Золотое Евангелие из Эхтернаха, бургундские часы, произведения Дюрера, Кранаха

Deutsch-Russisch Wörterbuch der regionalen Studien > Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nürnberg

-

15

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

«Нюрнбергские майстерзингеры»

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

-

16

Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg AG

«Машиненфабрик Аугсбург-Нюрнберг АГ»

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg AG

-

17

Augsburg

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Augsburg

-

18

Erlangen

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Erlangen

-

19

MAN AG München

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > MAN AG München

-

20

Sachs Hans

Германия. Лингвострановедческий словарь > Sachs Hans

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

См. также в других словарях:

-

Nürnberg — (hierzu der Stadtplan mit Registerblatt), zweite Haupt und bedeutendste Handelsstadt des Königreichs Bayern, ehemalige deutsche Reichsstadt, jetzt unmittelbare Stadt, liegt im Regbez. Mittelfranken, 296–352 m ü. M., in flacher, gut angebauter… … Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon

-

Nürnberg — Nürnberg, 1) Landgericht im baierischen Kreise Mittelfranken; 31/6 QM., 16,000 Ew.; 2) Stadt darin, zweite Haupt aber erste Handelsstadt des Königreichs Baiern; Sitz eines Kreis u. Stadtgerichts, eines Handelsappellationsgerichts, der… … Pierer’s Universal-Lexikon

-

Nürnberg — [Wichtig (Rating 3200 5600)] Bsp.: • Nürnberg ist nahe meinem Zuhause … Deutsch Wörterbuch

-

Nürnberg — Nürnberg, die ehemalige freie Reichsstadt, berühmt als der Schauplatz so mancher interessanten Begebenheit unserer Geschichte, die Mutter wichtiger Erfindungen, voll von Denkmälern deutscher Kunst und Sitte, gehört seit 1806 zu Baiern und zählt… … Damen Conversations Lexikon

-

Nürnberg — Nürnberg, Hauptstadt des bayer. Kreises Mittelfranken, in sandiger aber durch Kunst fruchtbar gemachter Ebene, an der Pegnitz, dem Ludwigskanale, im Centrum der bayer. Eisenbahnen, alterthümlich gebaute Stadt, mit vielen Denkmälern der alten… … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

-

Nürnberg — m DEFINICIJA grad u Bavarskoj, J Njemačka, 449.900 stan., snažno kulturno središte, 1930 ih mjesto održavanja godišnjih kongresa nacističke stranke … Hrvatski jezični portal

-

Nürnberg — Wappen Deutschlandkarte … Deutsch Wikipedia

-

Nürnberg — /nyuurddn berddk /, n. German name of Nuremberg. * * * I also known as Nuremberg City (pop., 2002 est.: city, 491,307; metro. area, 1,018,211), Bavaria, southern Germany, on the Pegnitz River. It grew up around a castle in the 11th century, and… … Universalium

-

Nürnberg — Frankenmetropole; Lebkuchenstadt (umgangssprachlich); Meistersingerstadt (umgangssprachlich) * * * Nụ̈rn|berg: Stadt in Mittelfranken. * * * Nụ̈rnberg, 1) kreisfreie Stadt in Mittelfranken, mit 486 600 Einwohnern … Universal-Lexikon

-

Nürnberg — 1. Es hat einer zu Nürnberg so nahe zum Himmel als zu Rohm, vnd auch so nahe zur Hölle. – Lehmann, 365, 9. 2. Es hengen die von Nürnberg keinen, sie haben jhn denn. – Petri, II, 252. »Du aber must wissen, dass die Herren von Nürnberg keinen… … Deutsches Sprichwörter-Lexikon

-

Nürnberg — Die alte blühende Reichsstadt mit ihrer Weltgeltung vor allem im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert wird in vielen Redensarten genannt, wenn auch meist nicht ohne Spott. Von allem möglichen, was schlecht und unerlaubt war, hieß es schon im 16. Jahrhundert:… … Das Wörterbuch der Idiome

|

Nuremberg Nürnberg |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

Nuremberg skyline, Nuremberg Castle, Pegnitz River, Nuremberg Opera House, Frauenkirche, view from Nuremberg Castle |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

|

Location of Nuremberg |

|

|

Nuremberg Nuremberg |

|

| Coordinates: 49°27′14″N 11°04′39″E / 49.45389°N 11.07750°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Middle Franconia |

| District | Urban district |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–26) | Marcus König[1] (CSU) |

| Area | |

| • City | 186.46 km2 (71.99 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 302 m (991 ft) |

| Population

(2021-12-31)[2] |

|

| • City | 510,632 |

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,353,032 |

| • Metro | 3,557,648 |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes |

90000-90491 |

| Dialling codes | 0911, 09122, 09129 |

| Vehicle registration | N |

| Website | nuernberg.de |

Nuremberg ( NURE-əm-burg; German: Nürnberg [ˈnʏʁnbɛʁk] (listen); in the local East Franconian dialect: Nämberch [ˈnɛmbɛrç]) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest city in Germany. On the Pegnitz River (from its confluence with the Rednitz in Fürth onwards: Regnitz, a tributary of the River Main) and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it lies in the Bavarian administrative region of Middle Franconia, and is the largest city and the unofficial capital of Franconia. Nuremberg forms with the neighbouring cities of Fürth, Erlangen and Schwabach a continuous conurbation with a total population of 800,376 (2019), which is the heart of the urban area region with around 1.4 million inhabitants,[3] while the larger Nuremberg Metropolitan Region has approximately 3.6 million inhabitants. The city lies about 170 kilometres (110 mi) north of Munich. It is the largest city in the East Franconian dialect area (colloquially: «Franconian»; German: Fränkisch).

There are many institutions of higher education in the city, including the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg). With 39,780 students in 2017, it is Bavaria’s third-largest and Germany’s 11th-largest university, with campuses in Erlangen and Nuremberg and a university hospital in Erlangen (Universitätsklinikum Erlangen). Technische Hochschule Nürnberg Georg Simon Ohm and Hochschule für Musik Nürnberg are also located within the city. The Nuremberg exhibition centre (Messe Nürnberg) is one of the biggest convention center companies in Germany and operates worldwide. Nuremberg Airport (Flughafen Nürnberg «Albrecht Dürer») is the second-busiest airport in Bavaria after Munich Airport, and the tenth-busiest airport of the country.

Nuremberg Castle, with its many towers, is one of Europe’s largest castles. Staatstheater Nürnberg is one of the five Bavarian state theatres,[a] showing operas, operettas, musicals, and ballets (main venue: Nuremberg Opera House), plays (main venue: Schauspielhaus Nürnberg), as well as concerts (main venue: Meistersingerhalle). Its orchestra, the Staatsphilharmonie Nürnberg, is Bavaria’s second-largest opera orchestra after the Bavarian State Opera’s Bavarian State Orchestra in Munich. Nuremberg is the birthplace of Albrecht Dürer and Johann Pachelbel. 1. FC Nürnberg is the most famous football club of the city and one of the most successful football clubs in Germany. Nuremberg was one of the host cities of the 2006 FIFA World Cup.

History[edit]

Middle Ages[edit]

Old fortifications of Nuremberg

The first documentary mention of the city, in 1050, mentions Nuremberg as the location of an Imperial castle between the East Franks and the Bavarian March of the Nordgau.[4] From 1050 to 1572 the city expanded and rose dramatically in importance due to its location on key trade-routes. King Conrad III (reigning as King of Germany from 1137 to 1152) established the Burgraviate of Nuremberg, with the first burgraves coming from the Austrian House of Raab. With the extinction of their male line around 1189, the last Raabs count’s son-in-law, Frederick I from the House of Hohenzollern, inherited the burgraviate in 1193.

From the late 12th century to the Interregnum (1254–1573), however, the power of the burgraves diminished as the Hohenstaufen emperors transferred most non-military powers to a castellan, with the city administration and the municipal courts handed over to an Imperial mayor (German: Reichsschultheiß) from 1173/74.[5][6] The strained relations between the burgraves and the castellans, with gradual transferral of powers to the latter in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, finally broke out into open enmity, which greatly influenced the history of the city.[6]

The city and particularly Nuremberg Castle would become one of the most frequent sites of the Imperial Diet (after Regensburg and Frankfurt), the Diets of Nuremberg from 1211 to 1543, after the first Nuremberg diet elected Frederick II as emperor. Because of the many Diets of Nuremberg, the city became an important routine place of the administration of the Empire during this time and a somewhat ‘unofficial capital’ of the Empire.[citation needed] In 1219 Emperor Frederick II granted the Großen Freiheitsbrief (‘Great Letter of Freedom’), including town rights, Imperial immediacy (Reichsfreiheit), the privilege to mint coins, and an independent customs policy — almost wholly removing the city from the purview of the burgraves.[5][6] Nuremberg soon became, with Augsburg, one of the two great trade-centers on the route from Italy to Northern Europe.

In 1298, the Jews of the town were falsely accused of having desecrated the host, and 698 of them were killed in one of the many Rintfleisch massacres. Behind the massacre of 1298 was also the desire to combine the northern and southern parts of the city,[7] which were divided by the Pegnitz. The Jews of the German lands suffered many massacres during the plague pandemic of the mid-14th century.

In 1349, Nuremberg’s Jews suffered a pogrom.[8] They were burned at the stake or expelled, and a marketplace was built over the former Jewish quarter.[9] The plague returned to the city in 1405, 1435, 1437, 1482, 1494, 1520, and 1534.[10]

The largest growth of Nuremberg occurred in the 14th century. Charles IV’s Golden Bull of 1356, naming Nuremberg as the city where newly elected kings of Germany must hold their first Imperial Diet, made Nuremberg one of the three most important cities of the Empire.[5] Charles was the patron of the Frauenkirche, built between 1352 and 1362 (the architect was likely Peter Parler), where the Imperial court worshipped during its stays in Nuremberg. The royal and Imperial connection grew stronger in 1423 when the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg granted the Imperial regalia to be kept permanently in Nuremberg, where they remained until 1796, when the advance of French troops required their removal to Regensburg and thence to Vienna.[5]

In 1349 the members of the guilds unsuccessfully rebelled against the patricians in a Handwerkeraufstand (‘Craftsmen’s Uprising’), supported by merchants and some by councillors, leading to a ban on any self-organisation of the artisans in the city, abolishing the guilds that were customary elsewhere in Europe; the unions were then dissolved, and the oligarchs remained in power while Nuremberg was a free city (until the early-19th century).[5][6] Charles IV conferred upon the city the right to conclude alliances independently, thereby placing it upon a politically equal footing with the princes of the Empire.[6] Frequent fights took place with the burgraves – without, however, inflicting lasting damage upon the city. After fire destroyed the castle in 1420 during a feud between Frederick IV (from 1417 Margrave of Brandenburg) and the duke of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, the city purchased the ruins and the forest belonging to the castle (1427), resulting in the city’s total sovereignty within its borders.

Through these and other acquisitions the city accumulated considerable territory.[6] The Hussite Wars (1419–1434), a recurrence of the Black Death in 1437, and the First Margrave War (1449–1450) led to a severe fall in population in the mid-15th century.[6] Siding with Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria-Munich, in the Landshut War of Succession of 1503–1505 led the city to gain substantial territory, resulting in lands of 25 sq mi (64.7 km2), making it one of the largest Imperial city.[6]

During the Middle Ages, Nuremberg fostered a rich, varied, and influential literary culture.[11]

Early modern age[edit]

The cultural flowering of Nuremberg in the 15th and 16th centuries made it the centre of the German Renaissance. In 1525 Nuremberg accepted the Protestant Reformation, and in 1532 the Nuremberg Religious Peace was signed[by whom?] there, preventing war between Lutherans and Catholics[6][12] for 15 years.[citation needed] During the Princes’ 1552 revolution against Charles V, Nuremberg tried to purchase its neutrality, but Margrave Albert Alcibiades, one of the leaders of the revolt, attacked the city without a declaration of war and dictated a disadvantageous peace.[6] At the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, the possessions of the Protestants were confirmed by the Emperor, their religious privileges extended and their independence from the Bishop of Bamberg affirmed, while the 1520s’ secularisation of the monasteries was also approved.[6] Families like the Tucher, Imhoff or Haller run trading businesses across Europe, similar to the Fugger and Welser families from Augsburg, although on a slightly smaller scale.

Wolffscher Bau of the old city hall

The state of affairs in the early 16th century, increased trade routes elsewhere and the ossification of the social hierarchy and legal structures contributed to the decline in trade.[6] During the Thirty Years’ War, frequent quartering of Imperial, Swedish and League soldiers, the financial costs of the war and the cessation of trade caused irreparable damage to the city and a near-halving of the population.[6] In 1632, the city, occupied by the forces of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, was besieged by the army of Imperial general Albrecht von Wallenstein. The city declined after the war and recovered its importance only in the 19th century, when it grew as an industrial centre. Even after the Thirty Years’ War, however, there was a late flowering of architecture and culture – secular Baroque architecture is exemplified in the layout of the civic gardens built outside the city walls, and in the Protestant city’s rebuilding of St. Egidien church, destroyed by fire at the beginning of the 18th century, considered a significant contribution to the baroque church architecture of Middle Franconia.[5]

After the Thirty Years’ War, Nuremberg attempted to remain detached from external affairs, but contributions were demanded for the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years’ War and restrictions of imports and exports deprived the city of many markets for its manufactures.[6] The Bavarian elector, Charles Theodore, appropriated part of the land obtained by the city during the Landshut War of Succession, to which Bavaria had maintained its claim; Prussia also claimed part of the territory. Realising its weakness, the city asked to be incorporated into Prussia but Frederick William II refused, fearing to offend Austria, Russia and France.[6] At the Imperial diet in 1803, the independence of Nuremberg was affirmed, but on the signing of the Confederation of the Rhine on 12 July 1806, it was agreed to hand the city over to Bavaria from 8 September, with Bavaria guaranteeing the amortisation of the city’s 12.5 million guilder public debt.[6]

After the Napoleonic Wars[edit]

Old town of Nuremberg in the 19th century

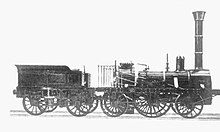

The British-built Adler was the locomotive of the first German Railway between Nuremberg and Fürth.

After the fall of Napoleon, the city’s trade and commerce revived; the skill of its inhabitants together with its favourable situation soon made the city prosperous, particularly after its public debt had been acknowledged as a part of the Bavarian national debt. Having been incorporated into a Catholic country, the city was compelled to refrain from further discrimination against Catholics, who had been excluded from the rights of citizenship. Catholic services had been celebrated in the city by the priests of the Teutonic Order, often under great difficulties. After their possessions had been confiscated by the Bavarian government in 1806, they were given the Frauenkirche on the Market in 1809; in 1810 the first Catholic parish was established, which in 1818 numbered 1,010 souls.[6]

In 1817, the city was incorporated into the district of Rezatkreis (named for the river Franconian Rezat), which was renamed to Middle Franconia (German: Mittelfranken) on 1 January 1838.[6] The first German railway, the Bavarian Ludwigsbahn, from Nuremberg to nearby Fürth, was opened in 1835. The establishment of railways and the incorporation of Bavaria into Zollverein (the 19th-century German Customs Union), commerce and industry opened the way to greater prosperity.[6] In 1852, there were 53,638 inhabitants: 46,441 Protestants and 6,616 Catholics. It subsequently grew to become the more important industrial city of Southern Germany, one of the most prosperous towns of southern Germany, but after the Austro-Prussian War it was given to Prussia as part of their telegraph stations they had to give up. In 1905, its population, including several incorporated suburbs, was 291,351: 86,943 Catholics, 196,913 Protestants, 3,738 Jews and 3,766 members of other creeds.[6]

Nazi era[edit]

Nuremberg held great significance during the Nazi Germany era. Because of the city’s relevance to the Holy Roman Empire and its position in the centre of Germany, the Nazi Party chose the city to be the site of huge Nazi Party conventions – the Nuremberg rallies. The rallies were held in 1927, 1929 and annually from 1933 through 1938. After Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 the Nuremberg rallies became huge Nazi propaganda events, a centre of Nazi ideals. The 1934 rally was filmed by Leni Riefenstahl, and made into a propaganda film called Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will).

At the 1935 rally, Hitler specifically ordered the Reichstag to convene at Nuremberg to pass the Nuremberg Laws which revoked German citizenship for all Jews and other non-Aryans. A number of premises were constructed solely for these assemblies, some of which were not finished. Today many examples of Nazi architecture can still be seen in the city. The city was also the home of the Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, the publisher of Der Stürmer.

Map of city centre with air raid destruction

Bombed-out Nuremberg, 1945

During the Second World War, Nuremberg was the headquarters of Wehrkreis (military district) XIII, and an important site for military production, including aircraft, submarines and tank engines. A subcamp of Flossenbürg concentration camp was located here, and extensively used slave labour.[13]

On 2 January 1945, the medieval city centre was systematically bombed by the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Forces and about ninety percent of it was destroyed in only one hour, with 1,800 residents killed and roughly 100,000 displaced. In February 1945, additional attacks followed. In total, about 6,000 Nuremberg residents are estimated to have been killed in air raids.

Nuremberg was a heavily fortified city that was captured in a fierce battle lasting from 17 to 21 April 1945 by the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, 42nd Infantry Division and 45th Infantry Division, which fought house-to-house and street-by-street against determined German resistance, causing further urban devastation to the already bombed and shelled buildings.[14] Despite this intense degree of destruction, the city was rebuilt after the war and was to some extent restored to its pre-war appearance, including the reconstruction of some of its medieval buildings.[15] Much of this reconstructive work and conservation was done by the organisation ‘Old Town Friends Nuremberg’. However, over half of the historic look of the center, and especially the northeastern half of the old Imperial Free City was not restored.

Nuremberg trials[edit]

Defendants in the dock at the Nuremberg trials

Between 1945 and 1946, German officials involved in war crimes and crimes against humanity were brought before an international tribunal in the Nuremberg trials. The Soviet Union had wanted these trials to take place in Berlin. However, Nuremberg was chosen as the site for the trials for specific reasons:

- The city had been the location of the Nazi Party’s Nuremberg rallies and the laws stripping Jews of their citizenship were passed there. There was symbolic value in making it the place of Nazi demise.

- The Palace of Justice was spacious and largely undamaged (one of the few that had remained largely intact despite extensive Allied bombing of Germany). The already large courtroom was reasonably easily expanded by the removal of the wall at the end opposite the bench, thereby incorporating the adjoining room. A large prison was also part of the complex.

- As a compromise, it was agreed that Berlin would become the permanent seat of the International Military Tribunal and that the first trial (several were planned) would take place in Nuremberg. Due to the Cold War, subsequent trials never took place.

Following the trials, in October 1946, many prominent German Nazi politicians and military leaders were executed in Nuremberg.

The same courtroom in Nuremberg was the venue of the Nuremberg Military Tribunals, organized by the United States as occupying power in the area.

Geography[edit]

Several old villages now belong to the city, for example Grossgründlach, Kraftshof, Thon, and Neunhof in the north-west; Ziegelstein in the northeast, Altenfurt and Fischbach in the south-east; and Katzwang, Kornburg in the south. Langwasser is a modern suburb.

Climate[edit]

Nuremberg has an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb) with a certain humid continental influence (Dfb), categorized in the latter by the 0 °C isotherm.[16] The city’s climate is influenced by its inland position and higher altitude. Winters are changeable, with either mild or cold weather: the average temperature is around −3 °C (27 °F) to 4 °C (39 °F), while summers are generally warm, mostly around 13 °C (55 °F) at night to 25 °C (77 °F) in the afternoon. Precipitation is evenly spread throughout the year, although February and April tend to be a bit drier whereas July tends to have more rainfall.[17]

| Climate data for Nuremberg (~5km of the downtown), 1981–2010 normals, elevation: 314 m, extremes 1955-2013 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

35.1 (95.2) |

38.6 (101.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

38.6 (101.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

0.9 (33.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−30.2 (−22.4) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

3.1 (37.6) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−12.7 (9.1) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−30.2 (−22.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.7 (1.64) |

36.6 (1.44) |

47.0 (1.85) |

39.8 (1.57) |

60.8 (2.39) |

66.1 (2.60) |

80.4 (3.17) |

63.5 (2.50) |

49.6 (1.95) |

52.6 (2.07) |

47.4 (1.87) |

51.4 (2.02) |

636.8 (25.07) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 58.2 | 87.2 | 116.8 | 175.0 | 216.0 | 217.9 | 234.7 | 219.9 | 161.2 | 114.4 | 57.2 | 43.2 | 1,701.6 |

| Source: DWD[17][18] |

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1397 | 5,626 | — |

| 1449 | 18,420 | +227.4% |

| 1485 | 36,000 | +95.4% |

| 1500 | 38,000 | +5.6% |

| 1622 | 40,250 | +5.9% |

| 1700 | 35,000 | −13.0% |

| 1750 | 30,000 | −14.3% |

| 1810 | 28,544 | −4.9% |

| 1825 | 33,018 | +15.7% |

| 1830 | 39,870 | +20.8% |

| 1840 | 46,824 | +17.4% |

| 1855 | 56,398 | +20.4% |

| 1864 | 70,492 | +25.0% |

| 1875 | 91,018 | +29.1% |

| 1900 | 261,081 | +186.8% |

| 1910 | 333,142 | +27.6% |

| 1920 | 364,093 | +9.3% |

| 1930 | 416,700 | +14.4% |

| 1940 | 429,400 | +3.0% |

| 1945 | 286,833 | −33.2% |

| 1950 | 362,459 | +26.4% |

| 1960 | 458,401 | +26.5% |

| 1970 | 478,181 | +4.3% |

| 1980 | 484,405 | +1.3% |

| 1990 | 493,692 | +1.9% |

| 2000 | 488,400 | −1.1% |

| 2005 | 499,237 | +2.2% |

| 2010 | 505,664 | +1.3% |

| 2015 | 509,975 | +0.9% |

| 2019 | 518,370 | +1.6% |

Nuremberg has been a destination for immigrants. 39.5% of the residents had an immigrant background in 2010 (counted with MigraPro).[19]

| Rank | Nationality | Population (31.12.2019)[20] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17,408 | |

| 2 | 14,903 | |

| 3 | 12,145 | |

| 4 | 7,232 | |

| 5 | 6,670 | |

| 6 | 5,893 | |

| 7 | 5,801 | |

| 8 | 4,745 | |

| 9 | 4,710 | |

| 10 | 4,201 | |

| 11 | 3,617 | |

| 12 | 3,137 | |

| 13 | 3,027 | |

| 14 | 2,456 | |

| 15 | 2,142 |

Economy[edit]

Nuremberg for many people is still associated with its traditional gingerbread (Lebkuchen) products, sausages, and handmade toys. Pocket watches — Nuremberg eggs — were made here in the 16th century by Peter Henlein. Only one of the districts in the 1797-1801 sample was early industrial; the economic structure of the region around Nuremberg was dominated by metal and glass manufacturing, reflected by a share of nearly 50% handicrafts and workers.[21] In the 19th century Nuremberg became the «industrial heart» of Bavaria with companies such as Siemens and MAN establishing a strong base in the city. Nuremberg is still an important industrial centre with a strong standing in the markets of Central and Eastern Europe. Items manufactured in the area include electrical equipment, mechanical and optical products, motor vehicles, writing and drawing paraphernalia, stationery products and printed materials.

The city is also strong in the fields of automation, energy and medical technology. Siemens is still the largest industrial employer in the Nuremberg region but a good third of German market research agencies are also located in the city.

The Nuremberg International Toy Fair, held at the city’s exhibition centre is the largest of its kind in the world.[22]

Tourism[edit]

Nuremberg is Bavaria’s second largest city after Munich, and a popular tourist destination for foreigners and Germans alike. It was a leading city 500 years ago, but 90% of the town was destroyed in 1945 during the war. After World War II, many medieval-style areas of the town were rebuilt.

Attractions[edit]

Beyond its main attractions of the Imperial Castle, St. Lorenz Church, and Nazi Trial grounds, there are 54 different museums for arts and culture, history, science and technology, family and children, and more niche categories,[23] where visitors can see the world’s oldest globe (built in 1492), a 500-year-old Madonna, and Renaissance-era German art.[24] There are several types of tours offered in the city, including historic tours, those that are Nazi-focused, underground and night tours, walking tours, sightseeing buses, self guided tours, and an old town tour on a mini train. Nuremberg also offers several parks and green areas, as well as indoor activities such as bowling, rock wall climbing, escape rooms, cart racing, and mini golf, theaters and cinemas, pools and thermal spas. There are also six nearby amusement parks.[23] The city’s tourism board sells the Nurnberg Card which allows for free use of public transportation and free entry to all museums and attractions in Nuremberg for a two-day period.[23]

Culinary tourism[edit]

Nuremberg is also a destination for food lovers. Culinary tourists can taste the city’s famous lebkuchen, gingerbread, local beer, and Nürnberger Rostbratwürstchen, or Nuremberg sausages. There are hundreds of restaurants for all tastes, including traditional franconian restaurants and beer gardens. Also offers 17 vegan and vegetarian restaurants, seven fully organic restaurants. Nuremberg also boasts a two Michelin Star rated restaurant, Essigbrätlein.[23]

Pedestrian zones[edit]

Like many European cities, Nuremberg offers a pedestrian-only zone covering a large portion of the old town, which is a main destination for shopping and specialty retail,[25] including year-round Christmas stores where tourists and locals alike can purchase Christmas ornaments, gifts, decorations, and additions to their toy Christmas villages. The Craftsmen’s Courtyard, or Handwerkerhof, is another tourist shopping destination in the style of a medieval village. It houses several local family-run businesses which sell handcrafted items from glass, wood, leather, pottery, and precious metals. The Handwerkerhof is also home to traditional German restaurants and beer gardens.[26]

The Pedestrian zones of Nuremberg host festivals and markets throughout the year, most well known being Christkindlesmarkt, Germany’s largest Christmas market and the gingerbread capital of the world. Visitors to the Christmas market can peruse the hundreds of stalls and purchase local wood crafts, nutcrackers, smokers, and prune people, while sampling Christmas sweets and traditional Glühwein.[27]

Hospitality[edit]

In 2017, Nuremberg saw a total of 3.3 million overnight stays, a record for the town, and is expected to have surpassed that in 2018, with more growth in tourism anticipated in the coming years.[28] There are over 175 registered places of accommodation in Nuremberg, ranging from hostels to luxury hotels, bed and breakfasts, to multi-hundred room properties.[23] As of 19 April 2019, Nuremberg had 306 Airbnb listings.[29]

Culture[edit]

Nuremberg was an early centre of humanism, science, printing, and mechanical invention. The city contributed much to the science of astronomy. In 1471 Johannes Mueller of Königsberg (Bavaria), later called Regiomontanus, built an astronomical observatory in Nuremberg and published many important astronomical charts.

In 1515, Albrecht Dürer, a native of Nuremberg, created woodcuts of the first maps of the stars of the northern and southern hemispheres, producing the first printed star charts, which had been ordered by Johannes Stabius. Around 1515 Dürer also published the «Stabiussche Weltkarte», the first perspective drawing of the terrestrial globe.[30]

Printers and publishers have a long history in Nuremberg. Many of these publishers worked with well-known artists of the day to produce books that could also be considered works of art. In 1470 Anton Koberger opened Europe’s first print shop in Nuremberg. In 1493, he published the Nuremberg Chronicles, also known as the World Chronicles (Schedelsche Weltchronik), an illustrated history of the world from the creation to the present day. It was written in the local Franconian dialect by Hartmann Schedel and had illustrations by Michael Wohlgemuth, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, and Albrecht Dürer. Others furthered geographical knowledge and travel by map making. Notable among these was navigator and geographer Martin Behaim, who made the first world globe.

Sculptors such as Veit Stoss, Adam Kraft and Peter Vischer are also associated with Nuremberg.

Composed of prosperous artisans, the guilds of the Meistersingers flourished here. Richard Wagner made their most famous member, Hans Sachs, the hero of his opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Baroque composer Johann Pachelbel was born here and was organist of St. Sebaldus Church.

The academy of fine arts situated in Nuremberg is the oldest art academy in central Europe and looks back to a tradition of 350 years of artistic education.

Nuremberg is also famous for its Christkindlesmarkt (Christmas market), which draws well over a million shoppers each year. The market is famous for its handmade ornaments and delicacies.

Museums[edit]

- Germanisches Nationalmuseum

- House of Albrecht Dürer

- Kunsthalle Nürnberg

- Kunstverein Nürnberg

- Neues Museum Nürnberg (Modern Art Museum)

- Nuremberg Toy Museum

- Nuremberg Transport Museum

Performing arts[edit]

The Nuremberg State Theatre

The Nuremberg State Theatre, founded in 1906, is dedicated to all types of opera, ballet and stage theatre. During the season 2009/2010, the theatre presented 651 performances for an audience of 240,000 persons.[31] The State Philharmonic Nuremberg (Staatsphilharmonie Nürnberg) is the orchestra of the State Theatre. Its name was changed in 2011 from its previous name: The Nuremberg Philharmonic (Nürnberger Philharmoniker). It is the second-largest opera orchestra in Bavaria.[32] Besides opera performances, it also presents its own subscription concert series in the Meistersingerhalle. Christof Perick was the principal conductor of the orchestra between 2006 and 2011. Marcus Bosch heads the orchestra since September 2011.

The Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra (Nürnberger Symphoniker) performs around 100 concerts a year to a combined annual audience of more than 180,000.[33] The regular subscription concert series are mostly performed in the Meistersingerhalle but other venues are used as well, including the new concert hall of the Kongresshalle and the Serenadenhof. Alexander Shelley has been the principal conductor of the orchestra since 2009.

The Nuremberg International Chamber Music Festival (Internationales Kammermusikfestival Nürnberg) takes place in early September each year, and in 2011 celebrated its tenth anniversary. Concerts take place around the city; opening and closing events are held in the medieval Burg. The Bardentreffen, an annual folk festival in Nuremberg, has been deemed the largest world music festival in Germany and takes place since 1976. 2014 the Bardentreffen starred 368 artists from 31 nations.[34]

Cuisine[edit]

Nuremberg is known for Nürnberger Bratwurst, which is shorter and thinner than other bratwurst sausages.

Another Nuremberg speciality is Nürnberger Lebkuchen, a kind of gingerbread eaten mainly around Christmas time.

Education[edit]

Nuremberg offers 51 public and 6 private elementary schools in nearly all of its districts. Secondary education is offered at 23 Mittelschulen, 12 Realschulen, and 17 Gymnasien (state, city, church, and privately owned). There are also several other providers of secondary education such as Berufsschule, Berufsfachschule, Wirtschaftsschule etc.[35]

Higher education[edit]

Nuremberg hosts the joint university Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, two Fachhochschulen (Technische Hochschule Nürnberg and Evangelische Hochschule Nürnberg), a pure art academy (Akademie der Bildenden Künste Nürnberg, the first art academy in the German-speaking world) in addition to the design faculty at the TH and a music conservatoire (Hochschule für Musik Nürnberg).[36] There are also private schools such as the Akademie Deutsche POP Nürnberg offering higher education.[37]

Main sights[edit]

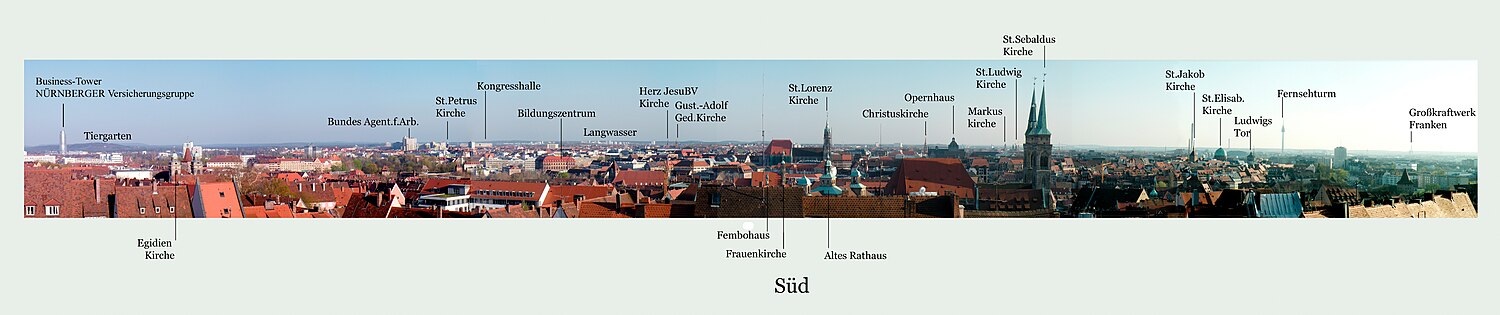

Nuremberg, seen from the castle

- Nuremberg Castle: the three castles that tower over the city including central burgraves’ castle, with Free Reich’s buildings to the east, the Imperial castle to the west.

- Heilig-Geist-Spital. In the centre of the city, on the bank of the river Pegnitz, stands the Hospital of the Holy Spirit. Founded in 1332, this is one of the largest hospitals of the Middle Ages. Lepers were kept here at some distance from the other patients. It now houses elderly persons and a restaurant.

- The Hauptmarkt, dominated by the front of the unique Gothic Frauenkirche (Our Lady’s Church), provides a picturesque setting for the famous Christmas market. A main attraction on the square is the Gothic Schöner Brunnen (Beautiful Fountain) which was erected around 1385 but subsequently replaced with a replica (the original fountain is kept in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum). The unchanged Renaissance bridge Fleischbrücke crosses the Pegnitz nearby.

- The Gothic Lorenzkirche (St. Laurence church) dominates the southern part of the walled city and is one of the most important buildings in Nuremberg. The main body was built around 1270–1350.

- The even earlier and equally impressive Sebalduskirche is St. Lorenz’s counterpart in the northern part of the old city.

- The church of the former Katharinenkloster is preserved as a ruin, the charterhouse (Kartause) is integrated into the building of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum and the choir of the former Franziskanerkirche is part of a modern building.

- Other churches located inside the city walls are: St. Laurence’s, Saint Clare’s, Saint Martha’s, Saint James the Greater’s, Saint Giles’s, and Saint Elisabeth’s.

- The Germanisches Nationalmuseum is Germany’s largest museum of cultural history, among its exhibits are works of famous painters such as Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

- The Neues Museum Nürnberg is a museum for modern and contemporary art.

- The Walburga Chapel and the Romanesque Doppelkapelle (Chapel with two floors) are part of Nuremberg Castle.

- The Johannisfriedhof is a medieval cemetery, containing many old graves (Albrecht Dürer, Willibald Pirckheimer, and others). The Rochusfriedhof or the Wöhrder Kirchhof are near the Old Town.

- The Chain Bridge (Kettensteg), the first chain bridge on the European continent.

- The Tiergarten Nürnberg is a zoo stretching over more than 60 hectares (148 acres) in the Nuremberg Reichswald (or Nürnberger Reichswald) forest.

- There is also a medieval market just inside the city walls, selling handcrafted goods.

- The German National Railways Museum (in German) (an Anchor Point of ERIH, The European Route of Industrial Heritage) is located in Nuremberg.

- The Nuremberg Ring (now welded within an iron fence of Schöner Brunnen) is said to bring good luck to those that spin it.

- The Nazi party rally grounds with the documentation-center.

|

Pilatushaus and Nuremberg Castle |

|

|

Politics[edit]

Nuremberg is represented in the Bundestag by two constituencies; Nuremberg North and Nuremberg South. Since 2002, both constituencies have been held by the CSU.

At local level, Nuremberg has historically been left-leaning in the conservative state of Bavaria — since the end of World War II, the city has mainly elected SPD mayors with the exception of Ludwig Scholz (elected 1996, served until 2002) and Marcus König (elected 2020). From 1957 to 1987, the position of Chief Mayor (Oberbürgermeister) was continuously held by Andreas Urschlechter (SPD) for 30 years.

Mayor[edit]

Results of the second round of the 2020 mayoral election.

The current mayor of Nuremberg is Marcus König of the Christian Social Union (CSU) since 2020. The most recent mayoral election was held on 15 March 2020, with a runoff held on 29 March, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Marcus König | Christian Social Union | 66,521 | 36.5 | 103,865 | 52.2 | |

| Thorsten Brehm | Social Democratic Party | 63,742 | 34.9 | 95,237 | 47.8 | |

| Verena Osgyan | Alliance 90/The Greens | 27,535 | 15.1 | |||

| Roland Hübscher | Alternative for Germany | 7,696 | 4.2 | |||

| Titus Schüller | The Left | 4,631 | 2.5 | |||

| Florian Betz | Pirate Party/Die PARTEI | 2,153 | 1.2 | |||

| Christian Rechholz | Ecological Democratic Party | 2,029 | 1.1 | |||

| Ümit Sormaz | Free Democratic Party | 1,905 | 1.0 | |||

| Marion Padua | Left List Nuremberg | 1,469 | 0.8 | |||

| Fridrich Luft | Citizens’ Initiative A (BIA) | 869 | 0.5 | |||

| Philipp Schramm | The Good Ones (Guten) | 637 | 0.4 | |||

| Valid votes | 182,493 | 99.6 | 199,102 | 99.2 | ||

| Invalid votes | 790 | 0.4 | 1,626 | 0.81 | ||

| Total | 183,283 | 100.0 | 200,728 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 390,547 | 47.1 | 388,998 | 51.6 | ||

| Source: City of Nuremberg (1st round, 2nd round) |

City council[edit]

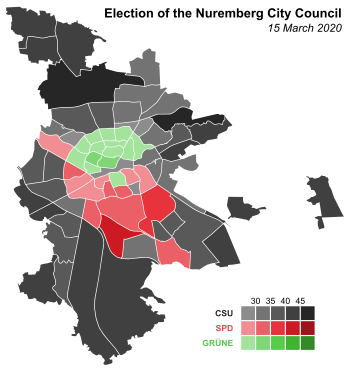

Results of the 2020 city council election.

The Nuremberg city council governs the city alongside the Mayor. The most recent city council election was held on 15 March 2020, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Social Union (CSU) | 3,584,755 | 31.3 | 22 | |||

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 2,943,118 | 25.7 | 18 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 2,283,988 | 20.0 | 14 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 650,369 | 5.7 | New | 4 | New | |

| The Left (Die Linke) | 449,463 | 3.9 | New | 3 | New | |

| Free Voters of Bavaria (FW) | 324,475 | 2.8 | 2 | ±0 | ||

| Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) | 265,079 | 2.3 | 2 | ±0 | ||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 241,329 | 2.1 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Die PARTEI/Pirate Party (PARTEI/Piraten) | 194,693 | 1.7 | New | 1 | ±0 | |

| Socio-Cultural Freedom, Participation and Sustainability (Politbande) | 190,710 | 1.7 | New | 1 | New | |

| Left List Nuremberg | 151,992 | 1.3 | 1 | |||

| The Good Ones (Guten) | 95,862 | 0.8 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Citizens’ Initiative A (BIA) | 62,374 | 0.6 | 0 | |||

| Valid votes | 178,999 | 97.7 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 4,124 | 2.3 | ||||

| Total | 183,123 | 100.0 | 70 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 389,547 | 47.0 | ||||

| Source: City of Nuremberg |

Transport[edit]

The city’s location next to numerous highways, railways, and a waterway has contributed to its rising importance for trade with Eastern Europe.

Railways[edit]

An U-Bahn station in Nuremberg.

Nürnberg Hauptbahnhof is a stop for IC and ICE trains on the German long-distance railway network. The Nuremberg–Ingolstadt–Munich high-speed line with 300 km/h (186 mph) operation opened 28 May 2006, and was fully integrated into the rail schedule on 10 December 2006. Travel times to Munich have been reduced to as little as one hour. The Nuremberg–Erfurt high-speed railway opened in December 2017.

City and regional transport[edit]

An automatic U-Bahn train on the line U3

The Nuremberg tramway network was opened in 1881. As of 2008, it extends a total length of 36 km (22 mi), has six lines, and carried 39.152 million passengers annually. The first segment of the Nuremberg U-Bahn metro system was opened in 1972. Nuremberg’s trams, buses and U-Bahn are operated by the Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft Nürnberg (VAG; Nuremberg Transport Corporation), a member of the Verkehrsverbund Großraum Nürnberg (VGN; Greater Nuremberg Transport Network).

There is also a Nuremberg S-Bahn suburban metro railway and a regional train network, both centred on Nürnberg Hauptbahnhof. Since 2008, Nuremberg has had the first U-Bahn in Germany (U2/U21 and U3) that works without a driver. It also was the first subway system worldwide in which both driver-operated trains and computer-controlled trains shared tracks.

|

|

|

|

|

|

S-, U-Bahn and Tramway network |

|

|

Motorways[edit]

Nuremberg is located at the junction of several important Autobahn routes. The A3 (Netherlands–Frankfurt–Würzburg–Vienna) passes in a south-easterly direction along the north-east of the city. The A9 (Berlin–Munich) passes in a north–south direction on the east of the city. The A6 (France–Saarbrücken–Prague) passes in an east–west direction to the south of the city. Finally, the A73 begins in the south-east of Nuremberg and travels north-west through the city before continuing towards Fürth and Bamberg.

Airport[edit]

Nuremberg Airport has flights to major German cities and many European destinations. The largest operators are currently Eurowings and TUI fly Deutschland, while the low-cost Ryanair and Wizz Air companies connect the city to various European centres. A significant amount of the airport’s traffic flies to and from mainly touristic destinations during the peak winter season. The airport (Flughafen) is the terminus of Nuremberg U-Bahn Line 2; until 2021, it was the only airport in Germany served by a U-Bahn subway system. Stuttgart Airport is also now served by its U-Bahn network, with the line U6 terminating there.

Canals[edit]

Nuremberg is an important port on the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal.

Sport[edit]

Football[edit]

1. FC Nürnberg, known locally as Der Club (English: «The Club»), was founded in 1900 and currently plays in the 2.Bundesliga. The official colours of the association are red and white, but the traditional colours are red and black. They won their first regional title in the Southern German championship in 1916 closely followed by their first national title in 1920. Besides the eleven regional championships they won the German championship for a total of nine times. With this they held the record for the most German championship titles until 1986 when the current record holder FC Bayern München surpassed them. The current chairmen are Nils Rossow and Dieter Hecking. They play in Max-Morlock-Stadion which was refurbished for the 2006 FIFA World Cup and accommodates 50,000 spectators.

- German Champion: 1920, 1921, 1924, 1925, 1927, 1936, 1948, 1961, 1968

- German Cup: 1935, 1939, 1962, 2007

TuS Bar Kochba is a league that was founded in 1913 as a social-sport club for the Jewish community in Nürnberg. Established as the «Jewish Gymnastics and Sports Club Nuremberg», the league was dissolved by the Nazi party in 1939. It was reformed in 1966.[38] The club plays in the senior A-league of the Bavarian Football Association.[39]

Basketball[edit]

The SELLBYTEL Baskets Nürnberg played in the Basketball Bundesliga from 2005 to 2007. Since then, teams from Nuremberg have attempted to return to Germany’s elite league. The recently founded Nürnberg Falcons BC have already established themselves as one of the main teams in Germany’s second division ProA and aim to take on the heritage of the SELLBYTEL Baskets Nürnberg. The Falcons play their home games at the KIA Metropol Arena.

Ice Hockey[edit]

The Nürnberg Ice Tigers play in the country’s premier league, the Deutsche Eishockey Liga. They’ve been runner-up in 1999 and 2007. The Ice Tigers play their home games at the Arena Nürnberger Versicherung.

International relations[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Nuremberg is twinned with:[40]

- Nice, France, since 1954

- Kraków, Poland, since 1979

- Skopje, North Macedonia, since 1982

- San Carlos, Nicaragua, since 1985

- Glasgow, Scotland, since 1985

- Prague, Czech Republic, since 1990

- Kharkiv, Ukraine, since 1990

- Hadera, Israel, since 1995

- Shenzhen, China, since 1997

- Antalya, Turkey, since 1997

- Atlanta, United States, since 1998

- Kavala, Greece, since 1999

- Córdoba, Spain, since 2010

Cooperation[edit]

Nuremberg also cooperates with:

- Venice, Italy; since 1954 a twin town, relations renewed in 1999 as a cooperation agreement[41]

Associated cities[edit]

Twin towns/sister cities and associated cities of Nuremberg

Nuremberg maintains friendly relations with:[42]

- Klausen, Italy, since 1970

- Gera, Germany, since 1988, renewed 1997

- Kalkudah, Sri Lanka, since 2005

- Bar, Montenegro, since 2006

- Brașov, Romania, since 2006

- Changping, China, since 2006

- Montan, Italy, since 2012

- Nablus, Palestine, since 2015

Notable people[edit]

Hans Sachs, wood engraving

Maria Sibylla Merian, 1679

Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg

- The arts

- Michael Wolgemut (1434–1519), painter and printmaker[43]

- Hans Folz (c. 1437–1513), author and poet

- Veit Stoss (c. 1450–1533), Renaissance sculptor, mostly in wood[44]

- Peter Vischer the Elder (c. 1455–1529), sculptor[45]

- Adam Kraft (c. 1460–1509), stone sculptor, master builder and architect[46]

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), painter, engraver, printmaker and theorist of the German Renaissance[47]

- Hans Leonhard Schäufelein (c. 1480–1540), artist, painter and designer of woodcuts[48]

- Augustin Hirschvogel (1503–1553), artist, mathematician and cartographer

- Michael Sigismund Frank (1770–1847), Catholic artist, rediscovered glass-painting[49]

- Lorenz Ritter (1832–1921), painter and etcher[50]

- Philipp Rupprecht (1900–1975), cartoonist of anti-Semitic caricatures

- Hermann Kesten (1900–1996), novelist and dramatist

- Eliyahu Koren (1907–2001), master typographer, graphic artist and designer

- Hermann Zapf (1918–2015), typographer and calligrapher

- Peter Angermann (born 1945), painter[51]

- Christoph Dreher (born 1952), filmmaker, musician and scriptwriter

- Katy Garretson (born 1963), American TV director and producer

- Martina Schradi (born 1972), author, cartoonist and psychologist

- Music

- Conrad Paumann (c. 1410–1473), organist, lutenist and composer

- Hans Sachs (1494–1576), Meistersinger, poet, playwright, and shoemaker[52]

- Sebald Heyden (1499–1561), musicologist, cantor, theologian and hymn-writer

- Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706), composer, organist, and teacher[53]

- Hugo Distler (1908–1942), organist, choral conductor, teacher and composer

- Martha Mödl (1912–2001), Wagner soprano/mezzo-soprano

- Chaya Arbel (1921–2007), Israeli classical composer[54]

- Siegfried Jerusalem (born 1940), operatic tenor

- Kevin Coyne (1944–2004), English musician, singer, composer, film-maker, and writer

- Rudi Mahall (born 1966), contemporary jazz bass clarinet player

- Acting

- Margarete Haagen (1889–1966), actress

- Wolfgang Preiss (1910–2002), actor

- Heinz Bernard (1923–1994), British actor and director and theatre manager[55]

- Annette Carell (1926–1967), American actress

- Sandra Bullock (born 1964), American actress, producer, and philanthropist

- Tom Beck (born 1978), actor, singer, and entrepreneur

- Science and business

- Anton Koberger (c. 1440–1513), goldsmith, printer and publisher[56]

- Katerina Lemmel (1466–1533), patrician businesswoman and Birgittine nun

- Peter Henlein (1485–1542), locksmith and clockmaker, invented the world’s first watch

- Kunz Lochner (1510–1567), plate armourer, blacksmith and silversmith

- Joachim Camerarius the Younger (1534–1598), physician, botanist and zoologist[57]

- Kaspar Uttenhofer (1588–1621), astronomer, author

- Johann Christoph Volkamer (1644–1720), merchant, manufacturer and botanist

- Maria Sybilla Merian (1647–1717), naturalist and scientific illustrator

- Johann Philipp von Wurzelbauer (1651–1725), astronomer

- John Miller (1715–c. 1792), engraver and botanist active in London[58]

- Johann Kaspar Hechtel (1771–1799), brass factory owner, non-fiction writer and designer of parlour games

- Ernst von Bibra (1806–1878), scientist, naturalist and author

- Friedrich Sigmund Merkel (1845–1919), anatomist and histopathologist

- Johann Sigmund Schuckert (1846–1895), electrical engineer, pioneer of the electrical industry

- Siegfried Bettmann (1868–1951), bicycle, motorcycle and car manufacturer

- Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach (1871–1952). paleontologist

- Ulrich Rück (1882–1962), collector of musical instruments, chemist and dealer in pianos

- Karl Bechert (1901–1981), theoretical physicist in atomic physics and politician

- Peter Owen (1927–2016), British publisher, founded Peter Owen Publishers[59]

- Manfred M. Fischer (born 1947), Austrian-German regional scientist and academic

- Public thinking and public service

- St. Sebaldus of Nuremberg (11th century), the patron saint of Nuremberg

- Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor (1368–1437), King of Hungary, Croatia, Germany, Bohemia and Italy; Holy Roman emperor from 1433 until 1437[60]

- Frederick I, Elector of Brandenburg (1371–1440), the last Burgrave of Nuremberg in 1397–1427

- Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia (1361–1419), King of Bohemia and German King[61]

- Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514), physician, humanist, historian and cartographer[62]

- Caritas Pirckheimer (1467–1532), Abbess at the time of the Reformation[63]

- Johannes Pfefferkorn (1469–1523), Catholic theologian and convert from Judaism[64]

- Willibald Pirckheimer (1470–1530), Renaissance humanist, lawyer and author

- Franz Schmidt (1555–1634), executioner and diarist

- Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (1804–1872), philosopher and anthropologist[65]

- Gottlieb Christoph Adolf von Harless (1806–1879), Lutheran theologian[66]

- Helene von Forster (1859–1923), women’s rights activist and author

- Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein (1870–1948), general

- August Engelhardt (1875–1919), founded a sect of sun worshipers in German New Guinea

- Johanna Hellman (1889–1982), German-Swedish surgeon

- Lucie Adelsberger (1895–1971), Jewish physician, imprisoned at Auschwitz and Ravensbrück

- Karl Holz (1895–1945), Nazi Party politician

- Käte Strobel (1907–1996), politician, Federal Minister of Healthcare (1966-1969), Federal Minister of Youth, Family and Health (1969-1972)

- Ronald Grierson (1921–2014), British banker, businessman, government advisor and British Army officer

- Werner Heubeck CBE (1923–2009), Luftwaffe PoW and a British transport executive

- Arnold Hans Weiss (1924–2010), U.S. Army intelligence officer, helped find Hitler’s will

- Günther Beckstein (born 1943), politician, Minister President of Bavaria (2007-2008)

- Robert Kurz (1943–2012), Marxist philosopher, social critic and journalist

- Thomas Händel (born 1953), politician and Member of the European Parliament

- Ulrich Maly (born 1960), politician, Mayor of Nuremberg (2002-2020)

- Markus Söder (born 1967), politician, Minister President of Bavaria since 2018

- Ines Eichmüller (born 1980), politician, former national spokesperson for the Green Youth

- Sport

- Heinrich Stuhlfauth (1896–1966), soccer-player

- Hans Nüsslein (1910–1991), tennis player and coach

- Olga Jensch-Jordan (1913–2000), springboard diver

- Max Morlock (1925–1994), soccer-player

- Günther Meier (1941–2020), amateur boxer, bronze medalist at the 1968 Summer Olympics

- Norbert Schramm (born 1960), figure skater

- Alex Wright (born 1975), British-German professional wrestler

- Deniz Aytekin (born 1978), soccer-referee

- Hannah Stockbauer (born 1982), swimmer, bronze medalist at the 2004 Summer Olympics

- Florian Just (born 1982), pair skater

- Absolute Andy (born 1983), professional wrestler

- Maximilian Müller (born 1987), field hockey player, gold medalist at the 2008 and 2012 Summer Olympics

- Nicole Vaidišová (born 1989), Czech tennis player

- Dominik Eberle (born 1996), American football player

See also[edit]

- List of mayors of Nuremberg

- Norisring Racetrack, where Pedro Rodriguez died in 1971

- Nuremberg Architecture Prize

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Bavarian state theatres in Munich: Bavarian State Opera, Bayerisches Staatsschauspiel, and Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz; in Nuremberg: Staatstheater Nürnberg; in Augsburg: Staatstheater Augsburg

References[edit]

- ^ Liste der Oberbürgermeister in den kreisfreien Städten, Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, accessed 19 July 2021.

- ^ «Tabelle 12411-003r Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes: Gemeinden, Stichtag» (in German). Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik. June 2022.

- ^ Region Nürnberg on hey.bayern

- ^ Compare: (in German) Nürnberg, Reichsstadt: Politische und soziale Entwicklung (Political and Social Development of the Imperial City of Nuremberg), Historisches Lexikon Bayerns: «Nürnberg ist erstmals 1050 als Reichsburg inmitten eines großen Reichsgutkomplexes schriftlich bezeugt. […] Die Stadt Nürnberg entstand um die Wende zum 11. Jahrhundert in Anlehnung an eine 1050 erstmals erwähnte Reichsburg inmitten eines ausgedehnten Reichsgutkomplexes in Ostfranken und dem bayerischen Nordgau.» [The first written attestation of Nuremberg occurs in 1050 as an Imperial castle in the middle of an extensive complex of Imperial property. […] The city of Nuremberg originated about the turn of the 11th century inconnection with an Imperial castle (first mentioned in 1050) in the centre of an expansive complex of Imperial property in East Franconia and in the Bavarian Nordgau.]

- ^ a b c d e f (in German) Nürnberg, Reichsstadt: Politische und soziale Entwicklung (Political and Social Development of the Imperial City of Nuremberg), Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Nuremberg». Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ «Image Gallery of the Coins of Nürnberg». www.medievalcoinage.com. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ «Black Death». JewishEncyclopedia.com

- ^ Cities and People: A Social and Architectural History, Mark Girouard, Yale University Press, 1985, p.69

- ^ Jerry Stannard, Katherine E. Stannard, Richard Kay (1999). Herbs and herbalism in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-86078-774-5

- ^

Sobecki, Sebastian (2016). Nuremberg. Europe: A Literary History, 1348-1418, ed. David Wallace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 566–581. ISBN 978-0-19-873535-9. - ^ Henry Eyster Jacobs; John Augustus William Haas (1899). The Lutheran Cyclopedia. Scribner. p. 351. ISBN 9780790550565.

- ^ Keeffe, Christine O. «Concentration Camps List». Tartanplace.com. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Stanton, Shelby, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division, 1939–1946, Stackpole Books (Revised Edition 2006), p. 90, 129, 135

- ^ Neil Gregor, Haunted City. Nuremberg and the Nazi Past (New Haven, 2008)

- ^ «Nuremberg, Germany Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)». Weatherbase. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b «Ausgabe der Klimadaten: Monatswerte». Dwd.de. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ «German climate normals 1981-2010» (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ «Amt für Stadtforschung und Statistik für Nürnberg und Fürth: Menschen mit Migrationshintergrund in Nürnberg» (PDF). Destatis.de. November 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ «Bevölkerungsstand». Stadtforschung und Statistik für Nürnberg und Fürth. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Baten, Joerg (2000). «Economic development and the distribution of nutritional resources in Bavaria, 1797–1839: An anthropometric study». Journal of Income Distribution. 9: 89–106. doi:10.1016/S0926-6437(99)00014-1.

- ^ «10 Reasons for visiting». Spielwarenmesse Nürnberg. 6 February 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e «Home». Tourismus Nürnberg. 21 March 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ «Germany: Frankfurt and Nürnberg — Video — Rick Steves’ Europe». www.ricksteves.com. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Monheim, Rolf (January 1992). «Town and transport planning and the development of retail trade in metropolitan areas of West Germany». Landscape and Urban Planning. 22 (2–4): 121–136. doi:10.1016/0169-2046(92)90017-t.

- ^ «Craftmen’s Courtyard in Nuremberg – a friendly welcome awaits you!». www.christkindlesmarkt.de (in German). Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ «European Christmas TV Special | Rick Steves’ Europe». www.ricksteves.com. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ «Record results for tourism in 2017: Overnight stays in Nuremberg exceed all expectations». Tourismus Nürnberg. 2 April 2019. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ «Vacation Rentals, Homes, Experiences & Places». Airbnb. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Waetzoldt, Wilhelm (1935). Dürer und seine Zeit. Vienna: Phaedon. pp. 306–309.

- ^ «Audience of the Staatstheater (Mehr Besucher im Staatstheater Nürnberg)» (in German). Mittelbayerische.de. 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ «Die Staatsphilharmonie Nürnberg» (in German). Staatstheater-nuernberg.de. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ «Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra, audience and concerts stats» (in German). 2011. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ ««Krieg und Frieden» – Pippo Pollina eröffnet Bardentreffen». Frankenfernsehen.tv. 2 August 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Schulreferat, Stadt Nürnberg (20 August 2015). «Schulen in Nürnberg». nuernberg.de. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ Stadt Nürnberg (1 May 2016). «Nürnberg in Zahlen» (PDF). nuernberg.de. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ «Deutsche Pop Nürnberg». 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ «Die Chronik des TuS Bar Kochba». nordbayern.de (in German). Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «TuS Bar Kochba Nürnberg e.V.» www.tusbarkochba.de. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ «Partnerstädte». nuernberg.de (in German). Nuremberg Office for International Relations. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ «Norimberga – Germania». comune.venezia.it (in Italian). Venezia. 29 June 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ «Befreundete Kommunen». nuernberg.de (in German). Nuremberg Office for International Relations. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ «Wohlgemuth, Michael» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Stoss, Veit» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Vischer» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Krafft, Adam» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Dürer, Albrecht» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 08 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: «Hans_Leonhard_Schäufelin». Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: «Michael_Sigismund_Frank». Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- ^ «Ritter, Paul» . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- ^ «Biography of Peter Angermann». Biographies.net. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ «Sachs, Hans» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 08 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Pachelbel, Johann» . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- ^ «Chaya Arbel». Jwa.org. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ «OBITUARIES: Heinz Bernard». The Independent. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: «Anthony_Koberger». Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

- ^ «Camerarius, Joachim (botanist)» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 05 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Miller, John» . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 37. 1894. pp. 412–414.

- ^ «Peter Owen dies – The Bookseller». www.thebookseller.com.

- ^ «Sigismund» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Wenceslaus» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: «Hartmann_Schedel». Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. 1912.

- ^ «Caritas Pirckheimer». Home.infionline.net. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: «Johannes_Pfefferkorn». Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. 1911.

- ^ «Feuerbach, Ludwig Andreas» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ «Harless, Gottlieb Christoph Adolf von» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911.

Bibliography[edit]

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuremberg.

Nuremberg travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Nuremberg» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- English website of the city

- KUNSTNÜRNBERG – Online – Magazine for Contemporary Art and History of Art in Nuremberg and Franconia

- 49 digitised objects on Nuremberg in The European Library

|

Nuremberg Nürnberg |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

Nuremberg skyline, Nuremberg Castle, Pegnitz River, Nuremberg Opera House, Frauenkirche, view from Nuremberg Castle |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

|

Location of Nuremberg |

|

|

Nuremberg Nuremberg |

|

| Coordinates: 49°27′14″N 11°04′39″E / 49.45389°N 11.07750°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Middle Franconia |

| District | Urban district |

| Government | |

| • Lord mayor (2020–26) | Marcus König[1] (CSU) |

| Area | |

| • City | 186.46 km2 (71.99 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 302 m (991 ft) |

| Population

(2021-12-31)[2] |

|

| • City | 510,632 |

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,353,032 |

| • Metro | 3,557,648 |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes |

90000-90491 |

| Dialling codes | 0911, 09122, 09129 |

| Vehicle registration | N |

| Website | nuernberg.de |

Nuremberg ( NURE-əm-burg; German: Nürnberg [ˈnʏʁnbɛʁk] (listen); in the local East Franconian dialect: Nämberch [ˈnɛmbɛrç]) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest city in Germany. On the Pegnitz River (from its confluence with the Rednitz in Fürth onwards: Regnitz, a tributary of the River Main) and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it lies in the Bavarian administrative region of Middle Franconia, and is the largest city and the unofficial capital of Franconia. Nuremberg forms with the neighbouring cities of Fürth, Erlangen and Schwabach a continuous conurbation with a total population of 800,376 (2019), which is the heart of the urban area region with around 1.4 million inhabitants,[3] while the larger Nuremberg Metropolitan Region has approximately 3.6 million inhabitants. The city lies about 170 kilometres (110 mi) north of Munich. It is the largest city in the East Franconian dialect area (colloquially: «Franconian»; German: Fränkisch).

There are many institutions of higher education in the city, including the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg). With 39,780 students in 2017, it is Bavaria’s third-largest and Germany’s 11th-largest university, with campuses in Erlangen and Nuremberg and a university hospital in Erlangen (Universitätsklinikum Erlangen). Technische Hochschule Nürnberg Georg Simon Ohm and Hochschule für Musik Nürnberg are also located within the city. The Nuremberg exhibition centre (Messe Nürnberg) is one of the biggest convention center companies in Germany and operates worldwide. Nuremberg Airport (Flughafen Nürnberg «Albrecht Dürer») is the second-busiest airport in Bavaria after Munich Airport, and the tenth-busiest airport of the country.

Nuremberg Castle, with its many towers, is one of Europe’s largest castles. Staatstheater Nürnberg is one of the five Bavarian state theatres,[a] showing operas, operettas, musicals, and ballets (main venue: Nuremberg Opera House), plays (main venue: Schauspielhaus Nürnberg), as well as concerts (main venue: Meistersingerhalle). Its orchestra, the Staatsphilharmonie Nürnberg, is Bavaria’s second-largest opera orchestra after the Bavarian State Opera’s Bavarian State Orchestra in Munich. Nuremberg is the birthplace of Albrecht Dürer and Johann Pachelbel. 1. FC Nürnberg is the most famous football club of the city and one of the most successful football clubs in Germany. Nuremberg was one of the host cities of the 2006 FIFA World Cup.

History[edit]

Middle Ages[edit]

Old fortifications of Nuremberg

The first documentary mention of the city, in 1050, mentions Nuremberg as the location of an Imperial castle between the East Franks and the Bavarian March of the Nordgau.[4] From 1050 to 1572 the city expanded and rose dramatically in importance due to its location on key trade-routes. King Conrad III (reigning as King of Germany from 1137 to 1152) established the Burgraviate of Nuremberg, with the first burgraves coming from the Austrian House of Raab. With the extinction of their male line around 1189, the last Raabs count’s son-in-law, Frederick I from the House of Hohenzollern, inherited the burgraviate in 1193.

From the late 12th century to the Interregnum (1254–1573), however, the power of the burgraves diminished as the Hohenstaufen emperors transferred most non-military powers to a castellan, with the city administration and the municipal courts handed over to an Imperial mayor (German: Reichsschultheiß) from 1173/74.[5][6] The strained relations between the burgraves and the castellans, with gradual transferral of powers to the latter in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, finally broke out into open enmity, which greatly influenced the history of the city.[6]

The city and particularly Nuremberg Castle would become one of the most frequent sites of the Imperial Diet (after Regensburg and Frankfurt), the Diets of Nuremberg from 1211 to 1543, after the first Nuremberg diet elected Frederick II as emperor. Because of the many Diets of Nuremberg, the city became an important routine place of the administration of the Empire during this time and a somewhat ‘unofficial capital’ of the Empire.[citation needed] In 1219 Emperor Frederick II granted the Großen Freiheitsbrief (‘Great Letter of Freedom’), including town rights, Imperial immediacy (Reichsfreiheit), the privilege to mint coins, and an independent customs policy — almost wholly removing the city from the purview of the burgraves.[5][6] Nuremberg soon became, with Augsburg, one of the two great trade-centers on the route from Italy to Northern Europe.

In 1298, the Jews of the town were falsely accused of having desecrated the host, and 698 of them were killed in one of the many Rintfleisch massacres. Behind the massacre of 1298 was also the desire to combine the northern and southern parts of the city,[7] which were divided by the Pegnitz. The Jews of the German lands suffered many massacres during the plague pandemic of the mid-14th century.

In 1349, Nuremberg’s Jews suffered a pogrom.[8] They were burned at the stake or expelled, and a marketplace was built over the former Jewish quarter.[9] The plague returned to the city in 1405, 1435, 1437, 1482, 1494, 1520, and 1534.[10]

The largest growth of Nuremberg occurred in the 14th century. Charles IV’s Golden Bull of 1356, naming Nuremberg as the city where newly elected kings of Germany must hold their first Imperial Diet, made Nuremberg one of the three most important cities of the Empire.[5] Charles was the patron of the Frauenkirche, built between 1352 and 1362 (the architect was likely Peter Parler), where the Imperial court worshipped during its stays in Nuremberg. The royal and Imperial connection grew stronger in 1423 when the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg granted the Imperial regalia to be kept permanently in Nuremberg, where they remained until 1796, when the advance of French troops required their removal to Regensburg and thence to Vienna.[5]

In 1349 the members of the guilds unsuccessfully rebelled against the patricians in a Handwerkeraufstand (‘Craftsmen’s Uprising’), supported by merchants and some by councillors, leading to a ban on any self-organisation of the artisans in the city, abolishing the guilds that were customary elsewhere in Europe; the unions were then dissolved, and the oligarchs remained in power while Nuremberg was a free city (until the early-19th century).[5][6] Charles IV conferred upon the city the right to conclude alliances independently, thereby placing it upon a politically equal footing with the princes of the Empire.[6] Frequent fights took place with the burgraves – without, however, inflicting lasting damage upon the city. After fire destroyed the castle in 1420 during a feud between Frederick IV (from 1417 Margrave of Brandenburg) and the duke of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, the city purchased the ruins and the forest belonging to the castle (1427), resulting in the city’s total sovereignty within its borders.

Through these and other acquisitions the city accumulated considerable territory.[6] The Hussite Wars (1419–1434), a recurrence of the Black Death in 1437, and the First Margrave War (1449–1450) led to a severe fall in population in the mid-15th century.[6] Siding with Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria-Munich, in the Landshut War of Succession of 1503–1505 led the city to gain substantial territory, resulting in lands of 25 sq mi (64.7 km2), making it one of the largest Imperial city.[6]

During the Middle Ages, Nuremberg fostered a rich, varied, and influential literary culture.[11]

Early modern age[edit]

The cultural flowering of Nuremberg in the 15th and 16th centuries made it the centre of the German Renaissance. In 1525 Nuremberg accepted the Protestant Reformation, and in 1532 the Nuremberg Religious Peace was signed[by whom?] there, preventing war between Lutherans and Catholics[6][12] for 15 years.[citation needed] During the Princes’ 1552 revolution against Charles V, Nuremberg tried to purchase its neutrality, but Margrave Albert Alcibiades, one of the leaders of the revolt, attacked the city without a declaration of war and dictated a disadvantageous peace.[6] At the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, the possessions of the Protestants were confirmed by the Emperor, their religious privileges extended and their independence from the Bishop of Bamberg affirmed, while the 1520s’ secularisation of the monasteries was also approved.[6] Families like the Tucher, Imhoff or Haller run trading businesses across Europe, similar to the Fugger and Welser families from Augsburg, although on a slightly smaller scale.

Wolffscher Bau of the old city hall