|

Okinawa Prefecture 沖縄県 |

|

|---|---|

|

Prefecture |

|

| Native transcription(s) | |

| • Japanese | Okinawa-ken |

Tourists on traditional buffalo carts arrive at Yubu Island in Taketomi Town, Yaeyama District, Okinawa Prefecture |

|

|

Flag Symbol |

|

| Anthem: 沖縄県民の歌 (Okinawa kenmin no uta) | |

|

|

| Coordinates: 26°30′N 128°0′E / 26.500°N 128.000°ECoordinates: 26°30′N 128°0′E / 26.500°N 128.000°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kyushu |

| Island | Okinawa, Daitō, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Senkaku |

| Capital | Naha |

| Subdivisions | Districts: 5, Municipalities: 41 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Denny Tamaki |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,281 km2 (881 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 44th |

| Population

(May 1, 2020) |

|

| • Total | 1,466,870 |

| • Rank | 29th |

| • Density | 640/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | JP-47 |

| Website | www.pref.okinawa.lg.jp |

| Symbols of Japan | |

| Bird | Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) |

| Fish | Banana fish (Pterocaesio diagramma, «takasago», «gurukun») |

| Flower | Deego (Erythrina variegata) |

| Tree | Pinus luchuensis («ryūkyūmatsu») |

Okinawa Prefecture (沖縄県, Japanese: Okinawa-ken) is a prefecture of Japan.[1] Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan and has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city, with other major cities including Okinawa, Uruma, and Urasoe.[2] Okinawa Prefecture encompasses two thirds of the Ryukyu Islands, including the Okinawa, Daitō and Sakishima groups, extending 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) southwest from the Satsunan Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture to Taiwan (Hualien and Yilan Counties). Okinawa Prefecture’s largest island, Okinawa Island, is the home to a majority of Okinawa’s population. Okinawa’s indigenous ethnic group are the Ryukyuan people, who also live in the Amami Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture.

Okinawa was ruled by the Ryukyu Kingdom from 1429 and unofficially annexed by Japan after the Invasion of Ryukyu in 1609. Okinawa was officially founded in 1879 by the Empire of Japan after seven years as the Ryukyu Domain, the last domain of the Han system. Okinawa was occupied by the United States during the Allied occupation of Japan after World War II and was governed by the Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands from 1945 to 1950 and Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands from 1950 until the prefecture was returned to Japan in 1972. Okinawa comprises just 0.6 percent of Japan’s total land mass, but about 26,000 (75%) of United States Forces Japan personnel are assigned to the prefecture; the continued U.S. military presence in Okinawa is controversial.[3][4]

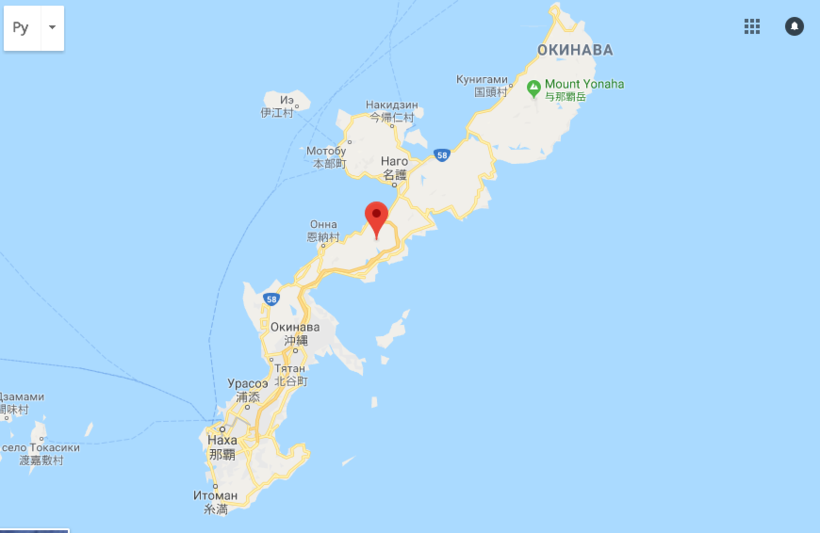

Nago, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan

History[edit]

Okinawa Prefecture occupies the southern half of the island chain lying between Kyushu and Taiwan.

The oldest evidence of human existence on the Ryukyu Islands is from the Stone Age and was discovered in Naha[5] and Yaeyama.[6] Some human bone fragments though to be from from the Paleolithic era were unearthed from a site in Naha, but the artifact was lost in transportation before it was examined.[5] Japanese Jōmon influences are dominant on the Okinawa Islands, although clay vessels on the Sakishima Islands have a commonality with those in Taiwan.[note 1]

The first mention of the word Ryukyu was written in the Book of Sui.[note 2] Okinawa was the Japanese word identifying the islands, first seen in the biography of Jianzhen, written in 779.[note 3] Agricultural societies begun in the 8th century slowly developed until the 12th century.[note 4][13][14] Since the islands are located at the eastern perimeter of the East China Sea relatively close to Japan, China and Southeast Asia, the Ryukyu Kingdom became a prosperous trading nation. Also during this period, many Gusukus, similar to castles, were constructed. The Ryukyu Kingdom entered into the Imperial Chinese tributary system under the Ming dynasty beginning in the 15th century, which established economic relations between the two nations.

In 1609, the Shimazu clan, which controlled the region that is now Kagoshima Prefecture, invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom. The Ryukyu Kingdom was obliged to agree to form a suzerain-vassal relationship with the Satsuma and the Tokugawa shogunate, while maintaining its previous role within the Chinese tributary system; Ryukyuan sovereignty was maintained since complete annexation would have created a conflict with China. The Satsuma clan earned considerable profits from trade with China during a period in which foreign trade was heavily restricted by the shogunate. Although Satsuma maintained strong influence over the islands, the Ryukyu Kingdom maintained a considerable degree of domestic political freedom for over two hundred years.

Four years after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government, through military incursions, officially annexed the kingdom and renamed it Ryukyu han. At the time, the Qing dynasty asserted a nominal suzerainty over the islands. Ryukyu han became Okinawa Prefecture of Japan in 1879, even though all other hans had become prefectures of Japan in 1872. In 1912, Okinawans first obtained the right to vote for representatives to the National Diet (国会) which had been established in 1890.[15]

1945–1965[edit]

Near the end of World War II, in 1945, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps launched an invasion of Okinawa with 185,000 troops. They were faced with fanatical resistance from the Japanese defenders. A third of Okinawa’s civilian population were killed during the ensuing fighting.[16] The dead, of all nationalities, are commemorated at the Cornerstone of Peace.

After the end of World War II, the United States set up the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands administration, which ruled Okinawa for 27 years. During this «trusteeship rule», the United States established numerous military bases on the Ryukyu islands. The Ryukyu independence movement was an Okinawan movement that clamored against U.S. rule.

Continued U.S. military buildup[edit]

During the Korean War, B-29 Superfortresses flew bombing missions over Korea from Kadena Air Base on Okinawa. The military buildup on the island during the Cold War increased a division between local inhabitants and the American military. Under the 1952 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence.

During the mid-1950s, the U.S. seized land from Okinawans to build new bases or expand currently existing ones. According to the Melvin Price Report, by 1955, the military had displaced 250,000 residents.[17]

Secret U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons[edit]

Since 1960, the U.S. and Japan have maintained an agreement that allows the U.S. to secretly bring nuclear weapons into Japanese ports.[18][19][20] The Japanese people tended to oppose the introduction of nuclear arms into Japanese territory[21] and the Japanese government’s assertion of Japan’s non-nuclear policy and a statement of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles reflected this popular opposition. Most of the weapons were alleged to be stored in ammunition bunkers at Kadena Air Base.[22] Between 1954 and 1972, 19 different types of nuclear weapons were deployed in Okinawa, but with fewer than around 1,000 warheads at any one time.[23] In fall 1960, U.S. commandos in Green Light Teams secret training missions carried small nuclear weapons on the east coast of Okinawa Island.[24]

1965–1972 (Vietnam War)[edit]

Between 1965 and 1972, Okinawa was a key staging point for United States in its military operations directed towards North Vietnam. Along with Guam, it presented a geographically strategic launch pad for covert bombing missions over Cambodia and Laos.[25] Anti-Vietnam War sentiment became linked politically to the movement for reversion of Okinawa to Japan. In 1965, the U.S. military bases, earlier viewed as paternal post war protection, were increasingly seen as aggressive. The Vietnam War highlighted the differences between United States and Okinawa but showed a commonality between the islands and mainland Japan.[26]

As controversy grew regarding the alleged placement of nuclear weapons on Okinawa, fears intensified over the escalation of the Vietnam War. Okinawa was perceived by some inside Japan as a potential target for China, should the communist government feel threatened by United States.[27] American military secrecy blocked any local reporting on what was actually occurring at bases such as Kadena Air Base. As information leaked out, and images of air strikes were published, the local population began to fear the potential for retaliation.[26]

Political leaders such as Makoto Oda, a major figure in the Beheiren movement (Foundation of Citizens for Peace in Vietnam), believed that the return of Okinawa to Japan would lead to the removal of U.S. forces ending Japan’s involvement in Vietnam.[28] In a speech delivered in 1967 Oda was critical of Prime Minister Eisaku Satō’s unilateral support of America’s war in Vietnam claiming «Realistically we are all guilty of complicity in the Vietnam War».[28] The Beheiren became a more visible anti-war movement on Okinawa as the American involvement in Vietnam intensified. The movement employed tactics ranging from demonstrations to handing leaflets to soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines directly, warning of the implications for a third World War.[29]

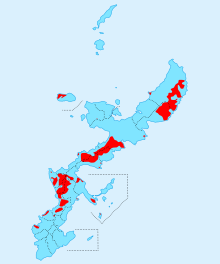

Map of US Military Bases in Okinawa in 1969

The U.S. military bases on Okinawa became a focal point for anti-Vietnam War sentiment. By 1969, over 50,000 American military personnel were stationed on Okinawa.[30] United States Department of Defense began referring to Okinawa as the «Keystone of the Pacific». This slogan was imprinted on local U.S. military license plates.[31]

In 1969, chemicals leaked from the U.S. storage depot at Chibana in central Okinawa, under Operation Red Hat. Evacuations of residents took place over a wide area for two months. Even two years later, government investigators found that Okinawans and the environment near the leak were still suffering because of the depot.[32]

On May 15, 1972, the U.S. government handed over the islands to Japanese administration.[33]

1973–2006[edit]

The 1995 rape of a 12-year-old girl by U.S. servicemen triggered large protests in Okinawa. Reports by the local media of accidents and crimes committed by U.S. servicemen have reduced the local population’s support for the U.S. military bases. A strong emotional response has emerged from certain incidents. As a result, the media has drawn renewed interest in the Ryukyu independence movement.

Documents declassified in 1997 proved that both tactical and strategic weapons have been maintained in Okinawa.[32][34] In 1999 and 2002, the Japan Times and the Okinawa Times reported speculation that not all weapons were removed from Okinawa.[35][36] On October 25, 2005, after a decade of negotiations, the governments of the U.S. and Japan officially agreed to move Marine Corps Air Station Futenma from its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan to the more northerly and remote Camp Schwab in Nago by building a heliport with a shorter runway, partly on Camp Schwab land and partly running into the sea.[16] The move is partly an attempt to relieve tensions between the people of Okinawa and the Marine Corps.

Okinawa prefecture constitutes 0.6% of Japan’s land surface,[16] yet as of 2006, 75% of all USFJ bases were located on Okinawa, and U.S. military bases occupied 18% of the main island.[37]

U.S. military facilities in Okinawa

2007–present[edit]

According to a 2007 Okinawa Times poll, 85% of Okinawans opposed the presence of the U.S. military,[38] because of noise pollution from military drills, the risk of aircraft accidents,[note 5] environmental degradation,[39] and crowding from the number of personnel there,[40] although 73% percent of Japanese citizens appreciated the mutual security treaty with the U.S. and the presence of the USFJ.[41] In another poll conducted by The Asahi Shimbun in May 2010, 43% of the Okinawan population wanted the complete closure of the U.S. bases, 42% wanted reduction, and 11% wanted to maintain status quo.[42] Okinawan feelings about the U.S. military are complex, and some of the resentment towards the U.S. bases is directed towards the government in Tokyo, perceived as being insensitive to Okinawan needs and using Okinawa to house bases not desired elsewhere in Japan.

In early 2008, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a young girl of 14 by a Marine on Okinawa. The U.S. military imposed a temporary 24-hour curfew on military personnel and their families to ease the anger of local residents.[43] Some cited statistics that the crime rate of military personnel is consistently less than that of the general Okinawan population.[44] However, some criticized the statistics as unreliable, since violence against women is under-reported.[45] Between 1972 and 2009, U.S. servicemen committed 5,634 criminal offenses, including 25 murders, 385 burglaries, 25 arsons, 127 rapes, 306 assaults and 2,827 thefts.[46] Yet, per Marine Corps Installations Pacific data, U.S. service members are convicted of far fewer crimes than local Okinawans.[47]

In 2009, a new Japanese government came to power and froze the U.S. forces relocation plan but in April 2010 indicated their interest in resolving the issue by proposing a modified plan.[48] A study done in 2010 found that the prolonged exposure to aircraft noise around the Kadena Air Base and other military bases cause health issues such as a disrupted sleep pattern, high blood pressure, weakening of the immune system in children, and a loss of hearing.[49]

In 2011, it was reported that the U.S. military—contrary to repeated denials by The Pentagon—had kept tens of thousands of barrels of Agent Orange on the island. The Japanese and American governments have angered some U.S. veterans, who believe they were poisoned by Agent Orange while serving on the island, by characterizing their statements regarding Agent Orange as «dubious», and ignoring their requests for compensation. Reports that more than a third of the barrels developed leaks have led Okinawans to ask for environmental investigations, but as of 2012 both Tokyo and Washington refused such action.[50] Jon Mitchell has reported concern that the U.S. used American Marines as chemical-agent guinea pigs.[51]

On September 30, 2018, Denny Tamaki was elected as the next governor of Okinawa prefecture, after a campaign focused on sharply reducing the U.S. military presence on the island.[52]

Marine Corps Air Station Futenma relocation[edit]

In 2006, some 8,000 U.S. Marines were removed from the island and relocated to Guam.[53] The move to Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz is expected to be completed in 2023. Japan paid for a majority of the cost to construct the new base.[54][55] The U.S. still maintains Air Force, Marine, Navy, and Army military installations on the islands. These bases include Kadena Air Base, Camp Foster, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, Camp Hansen, Camp Schwab, Torii Station, Camp Kinser, and Camp Gonsalves. The area of 14 U.S. bases are 233 square kilometres (90 sq mi), occupying 18% of the main island. Okinawa hosts about two-thirds of the 50,000 American forces in Japan although the islands account for less than one percent of total lands in Japan.[37]

Suburbs have grown towards and now surround two historic major bases, Futenma and Kadena. A sizeable portion of the land used by the U.S. military is Camp Gonsalves in the north of the island.[56] On December 21, 2016, 10,000 acres of Camp Gonslaves were returned to Japan.[57] On June 25, 2018, Okinawa residents held a protest demonstration at sea against scheduled land reclamation work for the relocation of a U.S. military base within Japan’s southernmost island prefecture. A protest gathered hundreds of people.[58]

Since the early 2000s, Okinawans have opposed the presence of American troops helipads in the Takae zone of the Yanbaru forest near Higashi and Kunigami.[59] This opposition grew in July 2016 after the construction of six new helipads.[60][61]

Geography[edit]

Major islands[edit]

The islands of Okinawa Prefecture

The islands comprising the prefecture are the southern two thirds of the archipelago of the Ryūkyū Islands (琉球諸島, Ryūkyū-shotō). Okinawa’s inhabited islands are typically divided into three geographical archipelagos. From northeast to southwest:

- Okinawa Islands (沖縄, ʔucinā)

- Iejima (ʔiijima)

- Kume-jima (kumijima)

- Okinawa Island (ʔuhuji)

- Kerama Islands (kirama)

- Miyako Islands (myāku)

- Miyako-jima

- Yaeyama Islands (’ēma)

- Iriomote Island (ʔiriʔumuti)

- Ishigaki Island (ʔishigaci)

- Yonaguni (’yunaguni)

- Senkaku Islands (ʔiyukubajima)

- Daitō Islands (ʔuhuʔagarijima)

- Minamidaitōjima (fēʔuhuʔagarijima)

- Kitadaitōjima (nishiʔuhuʔagarijima)

- Okidaitōjima (ʔuciʔuhuʔagarijima)

Natural parks[edit]

Approximately 36% percent of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as natural parks, namely the Iriomote-Ishigaki, Kerama Shotō, and Yambaru National Parks; Okinawa Kaigan and Okinawa Senseki Quasi-National Parks; and Irabu, Kumejima, Tarama, and Tonaki Prefectural Natural Parks.[62]

Ecology[edit]

The dugong is an endangered marine mammal related to the manatee.[63] Iriomote is home to one of the world’s rarest and most endangered cat species, the Iriomote cat. The region is also home to at least one endemic pit viper, Trimeresurus elegans. The islands of Okinawa are surrounded by some of the most abundant coral reefs found in the world.[64][65] The world’s largest colony of rare blue coral is found off of Ishigaki Island.[66] The sea turtles return yearly to the southern islands of Okinawa to lay their eggs. The summer months carry warnings to swimmers regarding venomous jellyfish and other dangerous sea creatures.

Okinawa is a major producer of sugar cane, pineapple, papaya, and other tropical fruit, and the Southeast Botanical Gardens represent tropical plant species.

Arch at an Okinawan Castle ruin.

Geology[edit]

The island is largely composed of coral, and rainwater filtering through that coral has given the island many caves, which played an important role in the Battle of Okinawa. Gyokusendo[67] is an extensive limestone cave in the southern part of Okinawa’s main island.

Climate[edit]

The island experiences temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F) for most of the year. The climate of the islands ranges from humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) in the north, such as Okinawa Island, to tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south such as Iriomote Island. Snowfall is unheard of at sea level. However, on January 24, 2016, sleet was reported in Nago for the first time on record.[68]

Municipalities[edit]

Cities[edit]

Map of Okinawa Prefecture

City Town Village

Eleven cities are located within the Okinawa Prefecture:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Map | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Okinawan[69] | other languages [script]

(name in brackets) |

||||

| Kana | Rōmaji | ||||||

| 宜野湾市 | じのーん | Jinōn | 19.51 | 94,405 | |||

| 石垣市 | いしがち | ʔIshigaci | Isïgaksï, Ishanagzï (Yaeyama) | 229 | 47,562 | ||

| 糸満市 | いちゅまん | ʔIcuman | 46.63 | 59,605 | |||

| 宮古島市 | なーく、みゃーく | Nāku, Myāku | Myaaku (Miyakoan) | 204.54 | 54,908 | ||

| 名護市 | なぐ | Nagu | Naguu [ナグー] (Kunigami) | 210.37 | 61,659 | ||

| 那覇市 | な |

Nafa | 39.98 | 317,405 | |||

| 南城市 | Fēgusiku | 49.69 | 41,305 | ||||

| 沖縄市 | うちなー | ʔUcinā | 49 | 138,431 | |||

| 豊見城市 | Timigusiku | 19.6 | 61,613 | ||||

| 浦添市 | うら |

ʔUrasī | 19.09 | 113,992 | |||

| うるま市 | うるま | ʔUruma | 86 | 118,330 |

Towns and villages[edit]

These are the towns and villages in each district:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | District | Type | Map | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Okinawan[69] | other languages [script]

(name in brackets) |

||||||

| Kana | Rōmaji | ||||||||

| 粟国村 | あぐに | ʔAguni | 7.63 | 772 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 北谷町 | ちゃたん | Catan | 13.62 | 28,578 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 宜野座村 | じぬざ | Jinuza | 31.28 | 5,544 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 南風原町 | Fēbaru | 10.72 | 37,874 | Shimajiri District | Town | ||||

| 東村 | Figashi | Agaarijimaa [アガーリジマー]

(Kunigami) |

81.79 | 1,683 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 伊江村 | いい | ʔIi | Ii [イー] (Kunigami) | 22.75 | 4,192 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 伊平屋村 | いひゃ、後地 | ʔIhya, Kushijī | 21.72 | 1,214 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 伊是名村 | いじな、前地 | ʔIjina, Mējī | 15.42 | 1,518 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 嘉手納町 | か |

Kadinā | 15.04 | 13,671 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 金武町 | ちん | Cin | Chin [チン] (Kunigami) | 37.57 | 11,259 | Kunigami District | Town | ||

| 北大東村 | うふあがりじま | ʔUhuʔagarijima | 13.1 | 615 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 北中城村 | にしなかーぐ |

Nishinakāgusiku | 11.53 | 16,040 | Nakagami District | Village | |||

| 久米島町 | くみじま | Kumijima | 63.5 | 7,647 | Shimajiri District | Town | |||

| 国頭村 | くんじゃん | Kunjan | Kunzan (Kunigami) | 194.8 | 4,908 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 南大東村 | Hwēʔuhuʔagarijima | 30.57 | 1,418 | Shimajiri District | Village | ||||

| 本部町 | む |

Mutubu | Mutubu (Kunigami) | 54.3 | 13,441 | Kunigami District | Town | ||

| 中城村 | なかーぐ |

Nakāgusiku | 15.46 | 20,030 | Nakagami District | Village | |||

| 今帰仁村 | なちじん | Nacijin | Nachizin (Kunigami) | 39.87 | 9,529 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 西原町 | にしばる | Nishibaru | 15.84 | 34,463 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 大宜味村 | ’Ujimi | Uujimii (Kunigami) | 63.12 | 3,024 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 恩納村 | うんな | ʔUnna | Unna (Kunigami) | 50.77 | 10,443 | Kunigami District | Village | ||

| 多良間村 | たらま | Tarama | Tarama (Miyakoan) | 21.91 | 1,194 | Miyako District | Village | ||

| 竹富町 | だき |

Dakidun | Teedun (Yaeyama) | 334.02 | 4,050 | Yaeyama District | Town | ||

| 渡嘉敷村 | Tukashici | 19.18 | 697 | Shimajiri District | Village | ||||

| 渡名喜村 | Tunaci | 3.74 | 406 | Shimajiri District | Village | ||||

| 八重瀬町 | え゙ー |

’Ēsi | 26.9 | 29,488 | Shimajiri District | Town | |||

| 読谷村 | ’Yuntan | 35.17 | 40,517 | Nakagami District | Village | ||||

| 与那原町 | ’Yunabaru | 5.18 | 18,410 | Shimajiri District | Town | ||||

| 与那国町 | ’Yunaguni | Dunan, Juni (Yonaguni)

Yunoon (Yaeyama) |

28.95 | 2,048 | Yaeyama District | Town | |||

| 座間味村 | ざまみ | Zamami | 16.74 | 924 | Shimajiri District | Village |

Town mergers[edit]

Demography[edit]

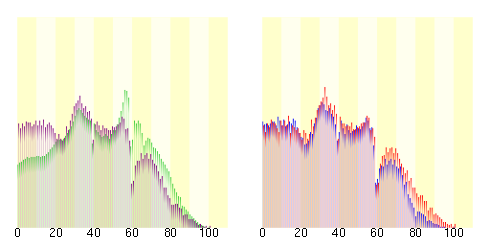

Okinawa prefecture population pyramid in 2020

Ethnic groups[edit]

The indigenous Ryukyuan people make up the majority of Okinawa Prefecture’s population and are also the main ethnic group of the Amami Islands to the north. Large Okinawan diaspora communities persist in places such as South America[70] and Hawaii.[71] With the introduction of American military bases, there are an increasing number of half-American children in Okinawa, including prefecture governor Denny Tamaki.[72] The prefecture also has a sizable minority of Yamato people from mainland Japan; exact population numbers are difficult to establish, as the Japanese government does not officially recognise Ryukyuans as a distinct ethnic group from Yamatos.

The overall ethnic identity of Okinawa residents is rather split. According to a telephone poll conducted by Lim John Chuan-tiong, an associate professor with the University of the Ryukyus, 40.6% of respondents identified as “沖縄人 (Okinawan)”, 21.3% identified as “日本人 (Japanese)” and 36.5% identified as both.

Population[edit]

Per Japanese census data,[74][75] Okinawa prefecture has had continuous positive population growth since 1960.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1873 | 166,789 | — |

| 1920 | 572,000 | +242.9% |

| 1930 | 578,000 | +1.0% |

| 1940 | 575,000 | −0.5% |

| 1950 | 915,000 | +59.1% |

| 1960 | 883,000 | −3.5% |

| 1970 | 945,000 | +7.0% |

| 1980 | 1,107,000 | +17.1% |

| 1990 | 1,222,000 | +10.4% |

| 2000 | 1,318,220 | +7.9% |

| 2010 | 1,392,818 | +5.7% |

| 2020 | 1,457,162 | +4.6% |

Language and culture[edit]

Having been a separate nation until 1879, Okinawan language and culture differ in many ways from those of mainland Japan.

Language[edit]

There remain six Ryukyuan languages which, although related, are incomprehensible to speakers of Japanese. One of the Ryukyuan languages is spoken in Kagoshima Prefecture, rather than in Okinawa Prefecture. These languages are in decline as the younger generation of Okinawans uses Standard Japanese. Mainland Japanese and some Okinawans generally perceive the Ryukyuan languages as «dialects». Standard Japanese is almost always used in formal situations. In informal situations, de facto everyday language among Okinawans under age 60 is Okinawa-accented mainland Japanese («Okinawan Japanese»), which is often mistaken by non-Okinawans as the Okinawan language proper. The actual traditional Okinawan language is still used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music and folk dance. There is a radio-news program in the language as well.[76]

Religion[edit]

Okinawans have traditionally followed Ryukyuan religious beliefs, generally characterized by ancestor worship and the respecting of relationships between the living, the dead, and the gods and spirits of the natural world.[77]

Culture[edit]

Okinawan culture bears traces of its various trading partners. One can find Chinese, Thai and Austronesian influences in the island’s customs. Perhaps Okinawa’s most famous cultural export is karate, probably a product of the close ties with and influence of China on Okinawan culture. Karate is thought to be a synthesis of Chinese kung fu with traditional Okinawan martial arts.

A traditional Okinawan product that owes its existence to Okinawa’s trading history is awamori—an Okinawan distilled spirit made from indica rice imported from Thailand.

Other prominent examples of Okinawan culture include the sanshin—a three-stringed Okinawan instrument, closely related to the Chinese sanxian, and ancestor of the Japanese shamisen, somewhat similar to a banjo. Its body is often bound with snakeskin (from pythons, imported from elsewhere in Asia, rather than from Okinawa’s venomous Trimeresurus flavoviridis, which are too small for this purpose). Okinawan culture also features the eisa dance, a traditional drumming dance. A traditional craft, the fabric named bingata, is made in workshops on the main island and elsewhere.[78]

The Okinawan diet consists of low-fat, low-salt foods, such as whole fruits and vegetables, legumes, tofu, and seaweed. Okinawans are particularly well known for consuming purple potatoes, also known as Okinawan sweet potatoes.[79] Okinawans are known for their longevity. This particular island is a so-called Blue Zone, an area where the people live longer than most others elsewhere in the world. Five times as many Okinawans live to be 100 as in the rest of Japan, and Japanese are already the longest-lived ethnic group globally.[80] As of 2002 there were 34.7 centenarians for every 100,000 inhabitants, which is the highest ratio worldwide.[81]: 131–132 Possible explanations are diet, low-stress lifestyle, caring community, activity, and spirituality of the inhabitants of the island.[81][page needed]

A cultural feature of the Okinawans is the forming of moais. A moai is a community social gathering and groups that come together to provide financial and emotional support through emotional bonding, advice giving, and social funding. This provides a sense of security for the community members and as mentioned in the Blue Zone studies, may be a contributing factor to the longevity of its people.[82]

Two Okinawan writers have received the Akutagawa Prize: Eiki Matayoshi in 1995 for The Pig’s Retribution (豚の報い, Buta no mukui) and Shun Medoruma in 1997 for A Drop of Water (Suiteki). The prize was also won by Okinawans in 1967 by Tatsuhiro Oshiro for Cocktail Party (Kakuteru Pāti) and in 1971 by Mineo Higashi for Okinawan Boy (Okinawa no Shōnen).[83][84]

Karate[edit]

Karate originated in Okinawa. Over time, it developed into several styles and sub-styles. On Okinawa, the three main styles are considered to be Shōrin-ryū, Gōjū-ryū and Uechi-ryū. Internationally, the various styles and sub-styles include Matsubayashi-ryū, Wadō-ryū, Isshin-ryū, Shōrinkan, Shotokan, Shitō-ryū, Shōrinjiryū Kenkōkan, Shorinjiryu Koshinkai, and Shōrinji-ryū.

Architecture[edit]

Despite widespread destruction during World War II, there are many remains of a unique type of castle or fortress known as gusuku; the most significant are inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu).[85] In addition, twenty-three Ryukyuan architectural complexes and forty historic sites have been designated for protection by the national government.[86] Shuri Castle in Naha is an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Whereas most homes in Japan are made from wood and allow free-flow of air to combat humidity, typical modern homes in Okinawa are made from concrete with barred windows to protect from flying plant debris and to withstand regular typhoons. Roofs are designed with strong winds in mind, in which each tile is cemented on and not merely layered as seen with many homes in Japan.[citation needed] The Nakamura House (ja:中村家住宅 (沖縄県)) is an original 18th century farmhouse in Kitanakagusuki. Many roofs also display a lion-dog statue, called a shisa, which is said to protect the home from danger. Roofs are typically red in color and are inspired by Chinese design.[87]

Education[edit]

The public schools in Okinawa are overseen by the Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. The agency directly operates several public high schools[88] including Okinawa Shogaku High School. The U.S. Department of Defense Dependents Schools operates 13 schools total in Okinawa. Seven of these schools are located on Kadena Air Base.

Okinawa has many types of private schools. Some of them are cram schools, also known as juku. Others, such as Nova, solely teach language. There are 10 colleges/universities in Okinawa, including the University of the Ryukyus, the only national university in the prefecture, and the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, a new international research institute. Okinawa’s American military bases also host the Asian Division of the University of Maryland University College.

Sports[edit]

- Association football

- FC Ryukyu (Naha)

- Basketball

- Ryukyu Golden Kings (Naha)

- Handball

- Ryukyu Corazon[89] (Naha)

- Baseball

Announced on July 18, 2019, BASE Okinawa Baseball Club will be forming the first-ever professional baseball team on Okinawa, the Ryukyu Blue Oceans. The team is expected to be fully organized by January 2020 and intends on joining the Nippon Professional Baseball league.[90]

In addition, various baseball teams from Japan hold training during the winter in Okinawa prefecture as it is the warmest prefecture of Japan with no snow and higher temperatures than other prefectures.

- SoftBank Hawks

- Yokohama BayStars

- Chunichi Dragons

- Yakult Swallows

- Golf

There are numerous golf courses in the prefecture, and there was formerly a professional tournament called the Okinawa Open.

Transportation[edit]

Air transportation[edit]

- Aguni Airport

- Hateruma Airport

- Iejima Airport

- New Ishigaki Airport

- Kerama Airport

- Kitadaito Airport

- Kumejima Airport

- Minami-Daito Airport

- Miyako Airport

- Naha Airport

- Shimojishima Airport

- Tarama Airport

- Yonaguni Airport

Highways[edit]

Rail[edit]

- Okinawa Urban Monorail

Ports[edit]

The major ports of Okinawa include:

- Naha Port[91]

- Port of Unten[92]

- Port of Kinwan[93]

- Nakagusukuwan Port[94]

- Hirara Port[95]

- Port of Ishigaki[96]

Economy[edit]

The 34 U.S. military installations on Okinawa are financially supported by the U.S. and Japan.[97] The bases provide jobs for Okinawans, both directly and indirectly; In 2011, the U.S. military employed over 9,800 Japanese workers in Okinawa.[97] As of 2012 the bases accounted for up to 5% of the economy.[98] However, Koji Taira argued in 1997 that because the U.S. bases occupy around 20% of Okinawa’s land, they impose a deadweight loss of 15% on the Okinawan economy.[99] The Tokyo government also pays the prefectural government around ¥10 billion per year[97] in compensation for the American presence, including, for instance, rent paid by the Japanese government to the Okinawans on whose land American bases are situated.[100] A 2005 report by the U.S. Forces Japan Okinawa Area Field Office estimated that in 2003 the combined U.S. and Japanese base-related spending contributed $1.9 billion to the local economy.[101] On January 13, 2015, In response to the citizens electing governor Takeshi Onaga, the national government announced that Okinawa’s funding will be cut, due to the governor’s stance on removing the US military bases from Okinawa, which the national government does not want happening.[102][103]

The Okinawa Convention and Visitors Bureau is exploring the possibility of using facilities on the military bases for large-scale meetings, incentives, conferencing, exhibitions events.[104]

United States military installations[edit]

- United States Marine Corps

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- Camp Foster

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma

- Camp Kinser

- Camp Courtney

- Camp McTureous

- Camp Hansen

- Camp Schwab

- Camp Gonsalves (Jungle Warfare Training Center)

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- United States Air Force

- Kadena Air Base

- Okuma Beach Resort

- United States Navy

- Camp Lester (Camp Kuwae)[citation needed]

- Camp Shields

- Naval Facility White Beach

- United States Army

- Torii Station

- Fort Buckner

- Naha Military Port

Notable people[edit]

- Aisa Senda, singer, actress and TV presenter in Taiwan

- Awich, rapper, singer and songwriter

- Beni Japanese pop and R&B singer

- Byron Fija Okinawan language practitioner and activist

- Chikako Yamashiro filmmaker and video artist

- Chōjun Miyagi founder of Gōjū-ryū, «hard/soft» style of Okinawan Karate.

- Daichi Miura Japanese pop singer, dancer and choreographer.

- Merle Dandridge Japanese American actress and singer

- Eisaku Satō Japanese politician and the 61st, 62nd and 63rd Prime Minister of Japan.

- Gackt Japanese pop rock singer-songwriter, actor, author

- Gichin Funakoshi led the efforts to propagate Okinawa karate to the Japanese mainland and beyond to the World.

- Robert Griffin III, American football quarterback, Heisman Trophy winner

- Hearts Grow Japanese band

- Isamu Chō officer in the Imperial Japanese Army known for his support of ultranationalist politics and involvement in a number of attempted military and right-wing coup d’états in pre-World War II Japan.

- Jin Matsuda, singer, member of INI (Japanese boy group), a former contestant on Produce 101 Japan (season 2)

- Matayoshi Eiki Okinawan novel writer, winner of Akutagawa prize

- Mitsuru Ushijima general at the Battle of Okinawa

- Namie Amuro Japanese R&B, hip hop and pop singer

- Noriyuki Sugasawa basketball player

- Orange Range Japanese rock band

- Ōta Minoru admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II

- Rimi Natsukawa (夏川 りみ Natsukawa Rimi), Japanese women pop singers

- Rino Nakasone Razalan professional dancer and choreographer.

- Dave Roberts, Major League Baseball player and manager

- Saori Minami Japanese kayōkyoku pop singer

- Ben Shepherd Bassist of the band Soundgarden

- Sho Yonashiro, singer, member of JO1, a former contestant on Produce 101 Japan

- Stereopony Japanese all-female pop rock band

- Takuji Iwasaki meteorologist, biologist, ethnologist historian.

- Tamlyn Tomita actress and singer

- Tina Tamashiro, Fashion Model and Actress

- Uechi Kanbun founder of Uechi-ryū, one of the primary karate styles of Okinawa.

- Yabu Kentsū prominent teacher of Shōrin-ryū karate in Okinawa from the 1910s until the 1930s, and was among the first people to demonstrate karate in Hawaii.

- Yoshitaka Funakoshi made significant and innovative contributions to Okinawan karate leading to the style known as Shotokan.

- Yui Aragaki actress, singer, and model

- Yuken Teruya interdisciplinary artist

- Yukie Nakama singer, musician and actress

See also[edit]

- Okinawa Prefectural Assembly

- Names of Okinawa

Notes[edit]

- ^ Naoichi Kokubu at the 1943 excavation of Enzan shell mound in Taipei city noted the clay pottery on Yaeyama island resembled the red coloring of those found in Taiwan,[6][7][8] while Hiroe Takamiya disapproved it by discussing the unique Yaeyama style stone axe independent from Chinese influence.[6][9]

- ^ Though the name Ryukyu appears in the Book of Sui, it is not defined clearly if it refers to the Okinawa island, the islands east of the Sea of China except Japan, or Taiwan.[10]

- ^ Kanjun Higashionna introduces that Jianzhen’s biography notes Ryūkyū, however he argues that the location could have been Taiwan actually, reasoned that it was not accessible in five days’ voyage from mainland China to Okinawa island in the 8th century.[11]

- ^ Masahide Takemoto suggested in his 1972 paper that the 10th century sites he excavated were formed on hillsides suited to agriculture, where remains of Chinese celadonware were also excavated as signs of the beginning of the Gusuku period or centralized governing system.[12]

- ^ One in 1959 killed 17 people.

References[edit]

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). «Okinawa-shi» in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 746–747, p. 746, at Google Books

- ^ Nussbaum, «Naha» in p. 686, p. 686, at Google Books

- ^ Inoue, Masamichi S. (2017), Okinawa and the U.S. Military: Identity Making in the Age of Globalization, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-51114-8, archived from the original on February 17, 2017, retrieved February 12, 2017

- ^ «U.S. civilian arrested in fresh Okinawa DUI case; man injured». The Japan Times. June 26, 2016. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

Under a decades-old security alliance, Okinawa hosts about 26,000 U.S. service personnel, more than half the total Washington keeps in all of Japan, in addition to base workers and family members.

- ^ a b Oda, Shizuo (March 2003). «Yamashitachō dai-1 dōketsu shutsudo no kyūsekki ni tsuite (山下町第1洞穴出土の旧石器について)» [Paleolithic Artifacts Excavated from Cave No.1, Yamashitachō Site]. Nantō Kōko [南島考古] (in Japanese) (22): 1–19. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c Taneishi, Yū (2008). Tsukuba-daigaku shūzō no Taiwan Taipei-shi Enzan kaizuka shūshū masei sekifu-rui ni tsuite [筑波大学収蔵の台湾台北市円山貝塚収集磨製石斧類について] [Polished stone axes from the Enzan shell mound in Taipei, Taiwan; from among the collection at Tsukuba University]. Senshigaku/Kōkogaku kenkyū [先史学・考古学研究] (in Japanese). Tsukuba University. p. 86. ISBN 9784886216717. OCLC 747328754. Retrieved February 12, 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kokubu, Naoichi (1943). «Yūken sekifu, yūdan sekifu oyobi kokutō bunka» [Shouldered and stepped stone axes with black pottery civilization]. Taiwan Bunka Ronsō (in Japanese) (1).

- ^ Kanaseki, Takeo; Kokubu, Naoichi (1979). Taiwan Kōkoshi [Archaeology of Taiwan]. Hosei University Press. pp. 121–179. OCLC 10917186.

- ^ «Yaeyama-gata sekifu no kisoteki kenkyū (3)» [Basic studies on Yaeyama type stone axe]. Nantō Kōko [南島考古] (in Japanese) (15): 1–30. 1995.

- ^ The Dongyi. The Book of Sui. Vol. 81. 607.

- ^ Higashionna, Kanjun (東恩納 寬惇) (1957). Ryūkyū no rekishi [The History of Ryūkyū]. Nihon rekishi shinsho (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shibundō. p. 13. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ^ Takemoto, Masahide (1972). Shinzato, Keiji (ed.). «Kōkogaku no shomondai to sono genjō» [Challenges in Archaeology and the Present Condition]. Rekishi-hen. Okinawa bunka ronsō (in Japanese). 1. OCLC 20843495.

- ^ Takemoto, Masahide (1972). «Okinawa ni okeru genshi shakai no shūmatsu-ki (沖縄における原始社会の終末期)». Nantō shiron : Tomimura Shin’en kyōju kanreki kinen ronbunshu (富村真演教授還暦記念論文集) [The Terminal Stage of the Primitive Society in Okinawa]. Ryūkyū Daigaku Shigakkai. OCLC 703826209.

- ^ Asato (1990). Kōkogaku kara mita Ryūkyū-shi [History of Ryūkyū Seen from Archeological Principles] (in Japanese). Vol. 1. pp. 69–70.

- ^ Steve Rabson, «Meiji Assimilation Policy in Okinawa: Promotion, Resistance, and «Reconstruction» in New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan (Helen Hardacre, ed.). Brill, 1997. p. 642.

- ^ a b c «No home where the dugong roam». The Economist. October 27, 2005. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006.

some of the bloodiest campaigns anywhere in the second world war were fought in Okinawa, and a third of the civilian population died.

- ^ Special Subcommittee of the Armed Services Committee, House of Representatives (1955). «The Melvin Price Report». via Ryukyu-Okinawa History and Culture Website. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Wampler, Robert A. (May 14, 1997). The National Security Archive, The Gelman Library (ed.). «Revelations in Newly Released Documents about U.S. Nuclear Weapons and Okinawa Fuel; NHK Documentary». George Washington University. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ «Memorandum, Ambassador Brown to Secretary Rogers, 4/29/69, Subject: NSC Meeting April 30 — Policy Toward Japan: Briefing Memorandum (Secret), with attached». April 30, 1969: 1. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ «NSSM 5 — Japan, Table of Contents and Part III: Okinawa Reversion (Secret)». 1969: 22. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ «Memorandum of Conversation, Nixon/Sato, 11/19/69 (Top Secret/Sensitive)». November 19, 1969: 2. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ Journal, The Asia Pacific. ««Herbicide Stockpile» at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa: 1971 U.S. Army report on Agent Orange | The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus». apjjf.org. Archived from the original on August 16, 2020. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ Norris, Robert S.; Arkin, William M.; Burr, William (November 1999). «Where They Were» (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 55 (6): 26–35. doi:10.2968/055006011. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2013.

- ^ Annie Jacobsen, «Surprise, Kill, Vanish: The Secret History of CIA Paramilitary Armies, Operators, and Assassins,» (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2019), p. 102

- ^ John Morrocco. Rain of Fire. (United States: Boston Publishing Company), pg 14

- ^ a b Trumbull, Robert (August 1, 1965). «OKINAWA B-52’S ANGER JAPANESE: Bombing of Vietnam From Island Stirs Public Outcry». The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Mori, Kyozo, Two Ends of a Telescope Japanese and American Views of Okinawa, Japan Quarterly, 15:1 (1968:Jan./Mar.) p.17

- ^ a b Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 120

- ^ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 123

- ^ Christopher T. Sanders (2000) America’s Overseas Garrisons the Leasehold Empire Oxford University Press PG 164

- ^ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press Pg 88

- ^ a b Rabson, Steve. «Okinawa’s Henoko was a ‘Storage Location’ for Nuclear Weapons: Published Accounts». The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. 11 (1(6)). Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2012.

- ^ States, United (1973). Reversion to Japan of the Ryukyu and Daito Islands, official text. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ Chan, John (March 24, 2010). «Japanese government reveals secret nuclear agreement with the US». World Socialist Web Site. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Johnston, Eric (May 15, 2002). «Nuclear pact ensured smooth Okinawa reversion». The Japan Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011.

- ^ 疑惑が晴れるのはいつか(in Japanese), Okinawa Times, May 16, 1999

- ^ a b 沖縄に所在する在日米軍施設・区域 Archived October 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese), Japan Ministry of Defense

- ^ 語り継ぎたい「沖縄戦」. Okinawa Times (in Japanese). May 13, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Impact on the Lives of the Okinawan People (Incidents, Accidents and Environmental Issues) Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Okinawa Prefectural Government

- ^ 沖縄・米兵による女性への性犯罪(Rapes and murders by the U.S. military personnel 1945–2000) Archived January 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese), 基地・軍隊を許さない行動する女たちの会

- ^ 自衛隊・防衛問題に関する世論調査 Archived October 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, The Cabinet Office of Japan

- ^ «普天間移設首相方針、県民76%反対 朝日新聞世論調査». Asahi.com. May 23, 2010. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (February 28, 2008). «Rice says sorry for US troop behaviour on Okinawa as crimes shake alliance with Japan». The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ Hassett, Michael (February 26, 2008). «U.S. military crime: SOFA so good?The stats offer some surprises in wake of the latest Okinawa rape claim». The Japan Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008.

- ^ «Okinawa: Effects of long-term US Military presence» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ Hearst, David (March 11, 2011). «Second battle of Okinawa looms as China’s naval ambition grows». The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ^ «米国海兵隊: 品位と名誉の精神» (PDF). Marine Corps Installations Pacific Ethos Data. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2016.

- ^ Pomfret, John (April 24, 2010). «Japan moves to settle dispute with U.S. over Okinawa base relocation». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Cox, Rupert (December 1, 2010). «The Sound of Freedom: US Military Aircraft Noise in Okinawa, Japan». Anthropology News. 51 (9): 13–14. doi:10.1111/j.1556-3502.2010.51913.x. ISSN 1556-3502. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ Jon Mitchell, «Agent Orange on Okinawa – The Smoking Gun: U.S. army report, photographs show 25,000 barrels on island in early ’70s» Archived January 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol 11, Issue 1, No. 6, January 14, 2012.

- ^ Jon Mitchell, «Were U.S marines used as guinea pigs on Okinawa?» Archived February 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol 10, Issue 51, No. 2, December 17, 2012.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (September 30, 2018). «Opponent of U.S. Military bases wins Okinawa gubernatorial election». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 17, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ Steven Donald Smith (April 26, 2006). «Eight Thousand U.S. Marines to Move From Okinawa to Guam». American Forces Press Service. DOD. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ «U.S., Japan unveil revised plan for Okinawa». Reuters. April 27, 2012. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ «A closer look at U.S. Futenma base’s ‘relocation’ issue». Japan Press Weekly. November 1, 2009. Archived from the original on November 13, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, Jon (August 19, 2012). «Rumbles in the jungle». The Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (December 21, 2016). «U.S. Returns 10,000 Acres of Okinawan Training Area to Japan». U.S. Department of Defense. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ «Protest held in Okinawa against landfill for U.S. base transfer». Kyodo News. June 25, 2018. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ «Takae’s Story». Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ «Tensions between protesters and riot police mount over construction of U.S. Marine Corps helipads in Takae». Ryukyu Shimpo. July 12, 2016. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ Mie, Ayako (July 22, 2016). «Okinawa protests erupt as U.S. Helipad construction resumes». The Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ 自然公園都道府県別面積総括 [General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- ^ «Lawsuit Seeks to Halt Construction of U.S. Military Airstrip in Japan That Would Destroy Habitat of Endangered Okinawa Dugongs». Center for Biological Diversity. July 31, 2014. Archived from the original on August 3, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ «Establishing World-Class Coral Reef Ecosystem Monitoring in Okinawa». Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University. September 5, 2013. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ «Coral Reefs». Okinawa Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on March 2, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Obura, D.; Fenner, D.; Hoeksema, B.; Devantier, L.; Sheppard, C. (2008). «Heliopora coerulea«. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T133193A3624060. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T133193A3624060.en. Retrieved November 11, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Gyokusendo Cave». Japan-guide.com. May 29, 2013. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ «沖縄本島で観測史上初のみぞれ 名護». The Asahi Shimbun Company. January 25, 2016. Archived from the original on February 27, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ a b Okinawago jiten (in Japanese). Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyūjo, 国立国語研究所. Tōkyō: Zaimushō Insatsukyoku. March 30, 2001. p. 549. ISBN 4-17-149000-6. OCLC 47773506.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Aug 2015, Mina Otsuka / 18. «Immigration—Missing Link in Japanese History: Why Are There So Many Okinawan Immigrants? – Part 1». Discover Nikkei. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ «Center for Okinawan Studies». Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Rich, Motoko (September 25, 2018). «A Marine’s Son Takes On U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 7, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Jinsui, Japan: Statistics Bureau (総務省 統計局), 2003, archived from the original on May 19, 2006, retrieved June 4, 2006

- ^ «Okinawa 1995-2020 population statistics». Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ «Okinawa 1920-2000 population statistics». Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^

おきなわBBtv★沖縄の方言ニュース★沖縄の「今」を沖縄の「言葉」で!ラジオ沖縄で好評放送中の「方言ニュース」をブロードバンドでお届けします。 Archived January 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Okinawabbtv.com. Retrieved on August 16, 2013. - ^ Okinawa Prefectural reserve cultural assets center (2006). «陶磁器から古の神事(祭祀・儀式)を考える». Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ Trimillos, Ricardo D. (2009). «Review of Drumming Out a Message: Eisa and the Okinawan Diaspora». Asian Music. 40 (2): 161–165. doi:10.1353/amu.0.0035. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 25652439. S2CID 191601292. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Earth, Down to (November 11, 2011). «The Okinawan Sweet Potato: A Purple Powerhouse of Nutrition». Down to Earth Organic and Natural. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ National Geographic magazine, June 1993

- ^ a b Santrock, John W. A (2002). Topical Approach to Life-Span Development (4 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ «Okinawa’s Longevity Lessons». Blue Zones. Admin. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ «Okinawa Writers Excel in Literature». The Okinawa Times. Okinawa Times. July 21, 2000. Archived from the original on August 23, 2000. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ 芥川賞受賞者一覧 (in Japanese). Bungeishunju Ltd. 2009. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ «Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu». UNESCO. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ «Database of National Cultural Properties: 国宝・重要文化財 (建造物): 沖縄県» (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- ^ «The Chinese and Japanese Influence In Ryukyuan Architecture — Okinawa Prefecture». Google Arts & Culture. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ «沖縄県内の高等学校». Okinawa Prefectural Board Of Education. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

- ^ «Ryukyu Corazon». Ryukyu Corazon. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- ^ «Ryukyu Blue Oceans: Okinawa’s first-ever pro baseball team». Ryukyu Shimpo — Okinawa, Japanese newspaper, local news. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2019.

- ^ Naha port Archived March 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Nahaport.jp. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ^ (in Japanese) 運天港 Archived July 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Pref.okinawa.jp. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ^ (in Japanese) 金武湾港 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Pref.okinawa.jp. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ^ 沖縄総合事務局 那覇港湾・空港整備事務所 中城湾港出張所 Archived May 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Dc.ogb.go.jp. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ^ 平良港湾事務所 Archived May 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Dc.ogb.go.jp. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ^ «石垣市建設部港湾課». Archived from the original on January 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Nessen, Stephen (January 4, 2011). «Okinawa U.S. Marine Base Angers Residents And Governor». HuffPost. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ Hongo, Jun. (May 16, 2012) Economic reliance on bases won’t last, trends suggest Archived May 30, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The Japan Times. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ^ Taira, Koji (1997). ‘The Okinawan Charade’ Archived October 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Japan Policy Research Institute, Working Paper No. 28

- ^ The Okinawa Solution. Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. G2mil.com. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ^ Johnston, Eric (March 28, 2006). «Okinawa base issue not cut and dried with locals». The Japan Times Online. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ Reynolds, Isabel; Takahashi, Maiko (January 13, 2015). «Japan cuts Okinawa budget after election of Anti-base governor». Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on April 27, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- ^ «Gov’t cuts budget for Okinawa economic development». January 15, 2015. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ «Okinawa looks to offer more unique venues». TTGmice. September 6, 2012. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

External links[edit]

Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Okinawa.

- Okinawa Prefectural Government Washington DC Office

- Official Okinawa Prefecture website (in Japanese)

- Official Okinawa Prefecture website

- Ryukyu Cultural Archives

- Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum

Geographic data related to Okinawa Prefecture at OpenStreetMap

|

Okinawa Prefecture 沖縄県 |

|

|---|---|

|

Prefecture |

|

| Native transcription(s) | |

| • Japanese | Okinawa-ken |

Tourists on traditional buffalo carts arrive at Yubu Island in Taketomi Town, Yaeyama District, Okinawa Prefecture |

|

|

Flag Symbol |

|

| Anthem: 沖縄県民の歌 (Okinawa kenmin no uta) | |

|

|

| Coordinates: 26°30′N 128°0′E / 26.500°N 128.000°ECoordinates: 26°30′N 128°0′E / 26.500°N 128.000°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kyushu |

| Island | Okinawa, Daitō, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Senkaku |

| Capital | Naha |

| Subdivisions | Districts: 5, Municipalities: 41 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Denny Tamaki |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,281 km2 (881 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 44th |

| Population

(May 1, 2020) |

|

| • Total | 1,466,870 |

| • Rank | 29th |

| • Density | 640/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | JP-47 |

| Website | www.pref.okinawa.lg.jp |

| Symbols of Japan | |

| Bird | Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) |

| Fish | Banana fish (Pterocaesio diagramma, «takasago», «gurukun») |

| Flower | Deego (Erythrina variegata) |

| Tree | Pinus luchuensis («ryūkyūmatsu») |

Okinawa Prefecture (沖縄県, Japanese: Okinawa-ken) is a prefecture of Japan.[1] Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan and has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city, with other major cities including Okinawa, Uruma, and Urasoe.[2] Okinawa Prefecture encompasses two thirds of the Ryukyu Islands, including the Okinawa, Daitō and Sakishima groups, extending 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) southwest from the Satsunan Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture to Taiwan (Hualien and Yilan Counties). Okinawa Prefecture’s largest island, Okinawa Island, is the home to a majority of Okinawa’s population. Okinawa’s indigenous ethnic group are the Ryukyuan people, who also live in the Amami Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture.

Okinawa was ruled by the Ryukyu Kingdom from 1429 and unofficially annexed by Japan after the Invasion of Ryukyu in 1609. Okinawa was officially founded in 1879 by the Empire of Japan after seven years as the Ryukyu Domain, the last domain of the Han system. Okinawa was occupied by the United States during the Allied occupation of Japan after World War II and was governed by the Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands from 1945 to 1950 and Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands from 1950 until the prefecture was returned to Japan in 1972. Okinawa comprises just 0.6 percent of Japan’s total land mass, but about 26,000 (75%) of United States Forces Japan personnel are assigned to the prefecture; the continued U.S. military presence in Okinawa is controversial.[3][4]

Nago, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan

History[edit]

Okinawa Prefecture occupies the southern half of the island chain lying between Kyushu and Taiwan.

The oldest evidence of human existence on the Ryukyu Islands is from the Stone Age and was discovered in Naha[5] and Yaeyama.[6] Some human bone fragments though to be from from the Paleolithic era were unearthed from a site in Naha, but the artifact was lost in transportation before it was examined.[5] Japanese Jōmon influences are dominant on the Okinawa Islands, although clay vessels on the Sakishima Islands have a commonality with those in Taiwan.[note 1]

The first mention of the word Ryukyu was written in the Book of Sui.[note 2] Okinawa was the Japanese word identifying the islands, first seen in the biography of Jianzhen, written in 779.[note 3] Agricultural societies begun in the 8th century slowly developed until the 12th century.[note 4][13][14] Since the islands are located at the eastern perimeter of the East China Sea relatively close to Japan, China and Southeast Asia, the Ryukyu Kingdom became a prosperous trading nation. Also during this period, many Gusukus, similar to castles, were constructed. The Ryukyu Kingdom entered into the Imperial Chinese tributary system under the Ming dynasty beginning in the 15th century, which established economic relations between the two nations.

In 1609, the Shimazu clan, which controlled the region that is now Kagoshima Prefecture, invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom. The Ryukyu Kingdom was obliged to agree to form a suzerain-vassal relationship with the Satsuma and the Tokugawa shogunate, while maintaining its previous role within the Chinese tributary system; Ryukyuan sovereignty was maintained since complete annexation would have created a conflict with China. The Satsuma clan earned considerable profits from trade with China during a period in which foreign trade was heavily restricted by the shogunate. Although Satsuma maintained strong influence over the islands, the Ryukyu Kingdom maintained a considerable degree of domestic political freedom for over two hundred years.

Four years after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government, through military incursions, officially annexed the kingdom and renamed it Ryukyu han. At the time, the Qing dynasty asserted a nominal suzerainty over the islands. Ryukyu han became Okinawa Prefecture of Japan in 1879, even though all other hans had become prefectures of Japan in 1872. In 1912, Okinawans first obtained the right to vote for representatives to the National Diet (国会) which had been established in 1890.[15]

1945–1965[edit]

Near the end of World War II, in 1945, the U.S. Army and Marine Corps launched an invasion of Okinawa with 185,000 troops. They were faced with fanatical resistance from the Japanese defenders. A third of Okinawa’s civilian population were killed during the ensuing fighting.[16] The dead, of all nationalities, are commemorated at the Cornerstone of Peace.

After the end of World War II, the United States set up the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands administration, which ruled Okinawa for 27 years. During this «trusteeship rule», the United States established numerous military bases on the Ryukyu islands. The Ryukyu independence movement was an Okinawan movement that clamored against U.S. rule.

Continued U.S. military buildup[edit]

During the Korean War, B-29 Superfortresses flew bombing missions over Korea from Kadena Air Base on Okinawa. The military buildup on the island during the Cold War increased a division between local inhabitants and the American military. Under the 1952 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence.

During the mid-1950s, the U.S. seized land from Okinawans to build new bases or expand currently existing ones. According to the Melvin Price Report, by 1955, the military had displaced 250,000 residents.[17]

Secret U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons[edit]

Since 1960, the U.S. and Japan have maintained an agreement that allows the U.S. to secretly bring nuclear weapons into Japanese ports.[18][19][20] The Japanese people tended to oppose the introduction of nuclear arms into Japanese territory[21] and the Japanese government’s assertion of Japan’s non-nuclear policy and a statement of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles reflected this popular opposition. Most of the weapons were alleged to be stored in ammunition bunkers at Kadena Air Base.[22] Between 1954 and 1972, 19 different types of nuclear weapons were deployed in Okinawa, but with fewer than around 1,000 warheads at any one time.[23] In fall 1960, U.S. commandos in Green Light Teams secret training missions carried small nuclear weapons on the east coast of Okinawa Island.[24]

1965–1972 (Vietnam War)[edit]

Between 1965 and 1972, Okinawa was a key staging point for United States in its military operations directed towards North Vietnam. Along with Guam, it presented a geographically strategic launch pad for covert bombing missions over Cambodia and Laos.[25] Anti-Vietnam War sentiment became linked politically to the movement for reversion of Okinawa to Japan. In 1965, the U.S. military bases, earlier viewed as paternal post war protection, were increasingly seen as aggressive. The Vietnam War highlighted the differences between United States and Okinawa but showed a commonality between the islands and mainland Japan.[26]

As controversy grew regarding the alleged placement of nuclear weapons on Okinawa, fears intensified over the escalation of the Vietnam War. Okinawa was perceived by some inside Japan as a potential target for China, should the communist government feel threatened by United States.[27] American military secrecy blocked any local reporting on what was actually occurring at bases such as Kadena Air Base. As information leaked out, and images of air strikes were published, the local population began to fear the potential for retaliation.[26]

Political leaders such as Makoto Oda, a major figure in the Beheiren movement (Foundation of Citizens for Peace in Vietnam), believed that the return of Okinawa to Japan would lead to the removal of U.S. forces ending Japan’s involvement in Vietnam.[28] In a speech delivered in 1967 Oda was critical of Prime Minister Eisaku Satō’s unilateral support of America’s war in Vietnam claiming «Realistically we are all guilty of complicity in the Vietnam War».[28] The Beheiren became a more visible anti-war movement on Okinawa as the American involvement in Vietnam intensified. The movement employed tactics ranging from demonstrations to handing leaflets to soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines directly, warning of the implications for a third World War.[29]

Map of US Military Bases in Okinawa in 1969

The U.S. military bases on Okinawa became a focal point for anti-Vietnam War sentiment. By 1969, over 50,000 American military personnel were stationed on Okinawa.[30] United States Department of Defense began referring to Okinawa as the «Keystone of the Pacific». This slogan was imprinted on local U.S. military license plates.[31]

In 1969, chemicals leaked from the U.S. storage depot at Chibana in central Okinawa, under Operation Red Hat. Evacuations of residents took place over a wide area for two months. Even two years later, government investigators found that Okinawans and the environment near the leak were still suffering because of the depot.[32]

On May 15, 1972, the U.S. government handed over the islands to Japanese administration.[33]

1973–2006[edit]

The 1995 rape of a 12-year-old girl by U.S. servicemen triggered large protests in Okinawa. Reports by the local media of accidents and crimes committed by U.S. servicemen have reduced the local population’s support for the U.S. military bases. A strong emotional response has emerged from certain incidents. As a result, the media has drawn renewed interest in the Ryukyu independence movement.

Documents declassified in 1997 proved that both tactical and strategic weapons have been maintained in Okinawa.[32][34] In 1999 and 2002, the Japan Times and the Okinawa Times reported speculation that not all weapons were removed from Okinawa.[35][36] On October 25, 2005, after a decade of negotiations, the governments of the U.S. and Japan officially agreed to move Marine Corps Air Station Futenma from its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan to the more northerly and remote Camp Schwab in Nago by building a heliport with a shorter runway, partly on Camp Schwab land and partly running into the sea.[16] The move is partly an attempt to relieve tensions between the people of Okinawa and the Marine Corps.

Okinawa prefecture constitutes 0.6% of Japan’s land surface,[16] yet as of 2006, 75% of all USFJ bases were located on Okinawa, and U.S. military bases occupied 18% of the main island.[37]

U.S. military facilities in Okinawa

2007–present[edit]

According to a 2007 Okinawa Times poll, 85% of Okinawans opposed the presence of the U.S. military,[38] because of noise pollution from military drills, the risk of aircraft accidents,[note 5] environmental degradation,[39] and crowding from the number of personnel there,[40] although 73% percent of Japanese citizens appreciated the mutual security treaty with the U.S. and the presence of the USFJ.[41] In another poll conducted by The Asahi Shimbun in May 2010, 43% of the Okinawan population wanted the complete closure of the U.S. bases, 42% wanted reduction, and 11% wanted to maintain status quo.[42] Okinawan feelings about the U.S. military are complex, and some of the resentment towards the U.S. bases is directed towards the government in Tokyo, perceived as being insensitive to Okinawan needs and using Okinawa to house bases not desired elsewhere in Japan.

In early 2008, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a young girl of 14 by a Marine on Okinawa. The U.S. military imposed a temporary 24-hour curfew on military personnel and their families to ease the anger of local residents.[43] Some cited statistics that the crime rate of military personnel is consistently less than that of the general Okinawan population.[44] However, some criticized the statistics as unreliable, since violence against women is under-reported.[45] Between 1972 and 2009, U.S. servicemen committed 5,634 criminal offenses, including 25 murders, 385 burglaries, 25 arsons, 127 rapes, 306 assaults and 2,827 thefts.[46] Yet, per Marine Corps Installations Pacific data, U.S. service members are convicted of far fewer crimes than local Okinawans.[47]

In 2009, a new Japanese government came to power and froze the U.S. forces relocation plan but in April 2010 indicated their interest in resolving the issue by proposing a modified plan.[48] A study done in 2010 found that the prolonged exposure to aircraft noise around the Kadena Air Base and other military bases cause health issues such as a disrupted sleep pattern, high blood pressure, weakening of the immune system in children, and a loss of hearing.[49]

In 2011, it was reported that the U.S. military—contrary to repeated denials by The Pentagon—had kept tens of thousands of barrels of Agent Orange on the island. The Japanese and American governments have angered some U.S. veterans, who believe they were poisoned by Agent Orange while serving on the island, by characterizing their statements regarding Agent Orange as «dubious», and ignoring their requests for compensation. Reports that more than a third of the barrels developed leaks have led Okinawans to ask for environmental investigations, but as of 2012 both Tokyo and Washington refused such action.[50] Jon Mitchell has reported concern that the U.S. used American Marines as chemical-agent guinea pigs.[51]

On September 30, 2018, Denny Tamaki was elected as the next governor of Okinawa prefecture, after a campaign focused on sharply reducing the U.S. military presence on the island.[52]

Marine Corps Air Station Futenma relocation[edit]

In 2006, some 8,000 U.S. Marines were removed from the island and relocated to Guam.[53] The move to Marine Corps Base Camp Blaz is expected to be completed in 2023. Japan paid for a majority of the cost to construct the new base.[54][55] The U.S. still maintains Air Force, Marine, Navy, and Army military installations on the islands. These bases include Kadena Air Base, Camp Foster, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, Camp Hansen, Camp Schwab, Torii Station, Camp Kinser, and Camp Gonsalves. The area of 14 U.S. bases are 233 square kilometres (90 sq mi), occupying 18% of the main island. Okinawa hosts about two-thirds of the 50,000 American forces in Japan although the islands account for less than one percent of total lands in Japan.[37]

Suburbs have grown towards and now surround two historic major bases, Futenma and Kadena. A sizeable portion of the land used by the U.S. military is Camp Gonsalves in the north of the island.[56] On December 21, 2016, 10,000 acres of Camp Gonslaves were returned to Japan.[57] On June 25, 2018, Okinawa residents held a protest demonstration at sea against scheduled land reclamation work for the relocation of a U.S. military base within Japan’s southernmost island prefecture. A protest gathered hundreds of people.[58]

Since the early 2000s, Okinawans have opposed the presence of American troops helipads in the Takae zone of the Yanbaru forest near Higashi and Kunigami.[59] This opposition grew in July 2016 after the construction of six new helipads.[60][61]

Geography[edit]

Major islands[edit]

The islands of Okinawa Prefecture

The islands comprising the prefecture are the southern two thirds of the archipelago of the Ryūkyū Islands (琉球諸島, Ryūkyū-shotō). Okinawa’s inhabited islands are typically divided into three geographical archipelagos. From northeast to southwest:

- Okinawa Islands (沖縄, ʔucinā)

- Iejima (ʔiijima)

- Kume-jima (kumijima)

- Okinawa Island (ʔuhuji)

- Kerama Islands (kirama)

- Miyako Islands (myāku)

- Miyako-jima

- Yaeyama Islands (’ēma)

- Iriomote Island (ʔiriʔumuti)

- Ishigaki Island (ʔishigaci)

- Yonaguni (’yunaguni)

- Senkaku Islands (ʔiyukubajima)

- Daitō Islands (ʔuhuʔagarijima)

- Minamidaitōjima (fēʔuhuʔagarijima)

- Kitadaitōjima (nishiʔuhuʔagarijima)

- Okidaitōjima (ʔuciʔuhuʔagarijima)

Natural parks[edit]

Approximately 36% percent of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as natural parks, namely the Iriomote-Ishigaki, Kerama Shotō, and Yambaru National Parks; Okinawa Kaigan and Okinawa Senseki Quasi-National Parks; and Irabu, Kumejima, Tarama, and Tonaki Prefectural Natural Parks.[62]

Ecology[edit]

The dugong is an endangered marine mammal related to the manatee.[63] Iriomote is home to one of the world’s rarest and most endangered cat species, the Iriomote cat. The region is also home to at least one endemic pit viper, Trimeresurus elegans. The islands of Okinawa are surrounded by some of the most abundant coral reefs found in the world.[64][65] The world’s largest colony of rare blue coral is found off of Ishigaki Island.[66] The sea turtles return yearly to the southern islands of Okinawa to lay their eggs. The summer months carry warnings to swimmers regarding venomous jellyfish and other dangerous sea creatures.

Okinawa is a major producer of sugar cane, pineapple, papaya, and other tropical fruit, and the Southeast Botanical Gardens represent tropical plant species.

Arch at an Okinawan Castle ruin.

Geology[edit]

The island is largely composed of coral, and rainwater filtering through that coral has given the island many caves, which played an important role in the Battle of Okinawa. Gyokusendo[67] is an extensive limestone cave in the southern part of Okinawa’s main island.

Climate[edit]

The island experiences temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F) for most of the year. The climate of the islands ranges from humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) in the north, such as Okinawa Island, to tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south such as Iriomote Island. Snowfall is unheard of at sea level. However, on January 24, 2016, sleet was reported in Nago for the first time on record.[68]

Municipalities[edit]

Cities[edit]

Map of Okinawa Prefecture

City Town Village

Eleven cities are located within the Okinawa Prefecture:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Map | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Okinawan[69] | other languages [script]

(name in brackets) |

||||

| Kana | Rōmaji | ||||||

| 宜野湾市 | じのーん | Jinōn | 19.51 | 94,405 | |||

| 石垣市 | いしがち | ʔIshigaci | Isïgaksï, Ishanagzï (Yaeyama) | 229 | 47,562 | ||

| 糸満市 | いちゅまん | ʔIcuman | 46.63 | 59,605 | |||

| 宮古島市 | なーく、みゃーく | Nāku, Myāku | Myaaku (Miyakoan) | 204.54 | 54,908 | ||

| 名護市 | なぐ | Nagu | Naguu [ナグー] (Kunigami) | 210.37 | 61,659 | ||

| 那覇市 | な |

Nafa | 39.98 | 317,405 | |||

| 南城市 | Fēgusiku | 49.69 | 41,305 | ||||

| 沖縄市 | うちなー | ʔUcinā | 49 | 138,431 | |||

| 豊見城市 | Timigusiku | 19.6 | 61,613 | ||||

| 浦添市 | うら |

ʔUrasī | 19.09 | 113,992 | |||

| うるま市 | うるま | ʔUruma | 86 | 118,330 |

Towns and villages[edit]

These are the towns and villages in each district:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | District | Type | Map | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | Okinawan[69] | other languages [script]

(name in brackets) |

||||||

| Kana | Rōmaji | ||||||||

| 粟国村 | あぐに | ʔAguni | 7.63 | 772 | Shimajiri District | Village | |||

| 北谷町 | ちゃたん | Catan | 13.62 | 28,578 | Nakagami District | Town | |||

| 宜野座村 | じぬざ | Jinuza | 31.28 | 5,544 | Kunigami District | Village | |||

| 南風原町 | Fēbaru | 10.72 | 37,874 | Shimajiri District | Town | ||||