парсифаль

-

1

Парсифаль

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Парсифаль

См. также в других словарях:

-

ПАРСИФАЛЬ — (фр. Parcifal, нем. Parzifal) 1. герой стихотворного рыцарского романа Вольфрама фон Эшенбаха «Парцифаль» (1198 1210). В истории П. использованы сюжеты из артуровских легенд о рыцарях Круглого стола и незаконченное сочинение французского… … Литературные герои

-

Парсифаль (опера) — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Парсифаль (значения). Опера Парсифаль Parsifal … Википедия

-

Парсифаль (значения) — Парцифаль: Парцифаль рыцарь, герой средневекогого куртуазного эпоса. Парсифаль опера Рихарда Вагнера … Википедия

-

Парсифаль — Парцифаль (фр. Perceval, нем. Parzival, англ. Percyvelle), также известный как Персифаль герой куртуазного эпоса, образующего одну из ветвей сказания о короле Артуре и его рыцарях и входящего в цикл романов Круглого стола. Содержание 1 … Википедия

-

ПАРСИФАЛЬ — (в средневековом нем. эпосе доблестный рыцарь христианин) Так иногда в банально пестрой зале, Где вальс звенит, волнуя и моля, Зову мечтой я звуки Парсифаля, И Тень, и Смерть над маской короля… (здесь: об опере Р. Вагнера) Анн906 (103.1) … Собственное имя в русской поэзии XX века: словарь личных имён

-

Мёдль, Марта — Марта Мёдль Martha Mödl Основная информация Дата рождения 22 марта 1912(19 … Википедия

-

Лондон, Джордж (певец) — Джордж Лондон George London Основная информация Имя при рождении George Burnstein … Википедия

-

Вагнер Рихард — (1813 1883), немецкий композитор, дирижёр, музыкальный писатель. Реформатор оперного искусства. В опере драме осуществил синтез философско поэтического и музыкального начал. В произведении это нашло выражение в развитой системе лейтмотивов,… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Вагнеровский фестиваль: история и современность — Вагнеровский (или Байройтский) фестиваль (Bayreuther Festspiele) старейший музыкальный фестиваль Европы, который проходит в баварском городе Байройт (Bayreuth) в Германии. Фестиваль был основан немецким композитором Рихардом Вагнером в 1876 году … Энциклопедия ньюсмейкеров

-

ГРААЛЬ — [лат. Gradalis; франц., нем. Graal, Gral], один из символов средневек. куртуазной лит ры, распространенный во Франции, в Германии и в Англии. Существуют 3 основные версии о внешнем виде Г.: камень, некая драгоценная реликвия или чаша из агата или … Православная энциклопедия

-

Вагнер Вильгельм Рихард — Вагнер (Wagner) Вильгельм Рихард (22.5.1813, Лейпциг, ≈ 13.2.1883, Венеция), немецкий композитор, дирижёр, музыкальный писатель и театральный деятель. Родился в чиновничьей семье. Раннему интересу В. к искусству способствовал его отчим, актёр Л.… … Большая советская энциклопедия

Parsifal (WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner’s own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem Parzival of the Minnesänger Wolfram von Eschenbach, recounting the story of the Arthurian knight Parzival (Percival) and his quest for the Holy Grail.

| Parsifal | |

|---|---|

| Music drama by Richard Wagner | |

Amalie Materna, Emil Scaria and Hermann Winkelmann in the first production of the Bühnenweihfestspiel at the Bayreuth Festival |

|

| Librettist | Richard Wagner |

| Language | German |

| Based on | Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach |

| Premiere |

26 July 1882 Bayreuth Festspielhaus |

Wagner conceived the work in April 1857, but did not finish it until 25 years later. In composing it he took advantage of the particular acoustics of his newly built Bayreuth Festspielhaus. Parsifal was first produced at the second Bayreuth Festival in 1882. The Bayreuth Festival maintained a monopoly on Parsifal productions until 1903, when the opera was performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

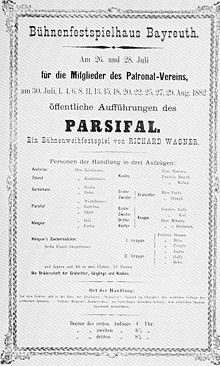

Wagner described Parsifal not as an opera, but as Ein Bühnenweihfestspiel (a festival play for the consecration of the stage).[1] At Bayreuth a tradition has arisen that audiences do not applaud at the end of the first act.

Wagner’s spelling of Parsifal instead of the Parzival he had used up to 1877 is informed by one of the theories about the name Percival, according to which it is of Persian origin, Parsi (or Parseh) Fal meaning «pure (or poor) fool».[2][3][4][5]

CompositionEdit

Drawing for a libretto cover page (undated)

Wagner read von Eschenbach’s poem Parzival while taking the waters at Marienbad in 1845.[6] After encountering Arthur Schopenhauer’s writings in 1854,[7] Wagner became interested in Asian philosophies, especially Buddhism. Out of this interest came Die Sieger (The Victors, 1856), a sketch Wagner wrote for an opera based on a story from the life of Buddha.[8] The themes which were later explored in Parsifal of self-renunciation, reincarnation, compassion, and even exclusive social groups (castes in Die Sieger, the Knights of the Grail in Parsifal) were first introduced in Die Sieger.[9]

According to his autobiography Mein Leben, Wagner conceived Parsifal on Good Friday morning, April 1857, in the Asyl (German: «Asylum»), the small cottage on Otto Wesendonck’s estate in the Zürich suburb of Enge, which Wesendonck – a wealthy silk merchant and generous patron of the arts – had placed at Wagner’s disposal, through the good offices of his wife Mathilde Wesendonck.[10] The composer and his wife Minna had moved into the cottage on 28 April:[11]

… on Good Friday I awoke to find the sun shining brightly for the first time in this house: the little garden was radiant with green, the birds sang, and at last I could sit on the roof and enjoy the long-yearned-for peace with its message of promise. Full of this sentiment, I suddenly remembered that the day was Good Friday, and I called to mind the significance this omen had already once assumed for me when I was reading Wolfram’s Parzival. Since the sojourn in Marienbad [in the summer of 1845], where I had conceived Die Meistersinger and Lohengrin, I had never occupied myself again with that poem; now its noble possibilities struck me with overwhelming force, and out of my thoughts about Good Friday I rapidly conceived a whole drama, of which I made a rough sketch with a few dashes of the pen, dividing the whole into three acts.

However, as his second wife Cosima Wagner later reported on 22 April 1879, this account had been colored by a certain amount of poetic licence:[12]

R[ichard] today recalled the impression which inspired his «Good Friday Music»; he laughs, saying he had thought to himself, «In fact it is all as far-fetched as my love affairs, for it was not a Good Friday at all – just a pleasant mood in Nature which made me think, ‘This is how a Good Friday ought to be’ ».

The work may indeed have been conceived at Wesendonck’s cottage in the last week of April 1857, but Good Friday that year fell on 10 April, when the Wagners were still living at Zeltweg 13 in Zürich.[13] If the prose sketch which Wagner mentions in Mein Leben was accurately dated (and most of Wagner’s surviving papers are dated), it could settle the issue once and for all, but unfortunately it has not survived.

Wagner did not resume work on Parsifal for eight years, during which time he completed Tristan und Isolde and began Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Then, between 27 and 30 August 1865, he took up Parsifal again and made a prose draft of the work; this contains a fairly brief outline of the plot and a considerable amount of detailed commentary on the characters and themes of the drama.[14] But once again the work was dropped and set aside for another eleven and a half years. During this time most of Wagner’s creative energy was devoted to the Ring cycle, which was finally completed in 1874 and given its first full performance at Bayreuth in August 1876. Only when this gargantuan task had been accomplished did Wagner find the time to concentrate on Parsifal. By 23 February 1877 he had completed a second and more extensive prose draft of the work, and by 19 April of the same year he had transformed this into a verse libretto (or «poem», as Wagner liked to call his libretti).[15]

In September 1877 he began the music by making two complete drafts of the score from beginning to end. The first of these (known in German as the Gesamtentwurf and in English as either the preliminary draft or the first complete draft) was made in pencil on three staves, one for the voices and two for the instruments. The second complete draft (Orchesterskizze, orchestral draft, short score or particell) was made in ink and on at least three, but sometimes as many as five, staves. This draft was much more detailed than the first and contained a considerable degree of instrumental elaboration.[16]

The second draft was begun on 25 September 1877, just a few days after the first; at this point in his career Wagner liked to work on both drafts simultaneously, switching back and forth between the two so as not to allow too much time to elapse between his initial setting of the text and the final elaboration of the music. The Gesamtentwurf of Act 3 was completed on 16 April 1879 and the Orchesterskizze on the 26th of the same month.[17]

The full score (Partiturerstschrift) was the final stage in the compositional process. It was made in ink and consisted of a fair copy of the entire opera, with all the voices and instruments properly notated according to standard practice. Wagner composed Parsifal one act at a time, completing the Gesamtentwurf and Orchesterskizze of each act before beginning the Gesamtentwurf of the next act; but because the Orchesterskizze already embodied all the compositional details of the full score, the actual drafting of the Partiturerstschrift was regarded by Wagner as little more than a routine task which could be done whenever he found the time. The prelude of Act 1 was scored in August 1878. The rest of the opera was scored between August 1879 and 13 January 1882.[18]

Poster for the premiere production of Parsifal, 1882

Performance historyEdit

The premiereEdit

On 12 November 1880, Wagner conducted a private performance of the prelude for his patron Ludwig II of Bavaria at the Court Theatre in Munich.[19] The premiere of the entire work was given in the Bayreuth Festspielhaus on 26 July 1882 under the baton of the Jewish-German conductor Hermann Levi. Stage designs were by Max Brückner and Paul von Joukowsky, who took their lead from Wagner himself. The Grail hall was based on the interior of Siena Cathedral which Wagner had visited in 1880, while Klingsor’s magic garden was modelled on those at the Palazzo Rufolo in Ravello.[20] In July and August 1882 sixteen performances of the work were given in Bayreuth conducted by Levi and Franz Fischer. The production boasted an orchestra of 107, a chorus of 135 and 23 soloists (with the main parts being double cast).[21] At the last of these performances, Wagner took the baton from Levi and conducted the final scene of Act 3 from the orchestral interlude to the end.[22]

At the first performances of Parsifal, problems with the moving scenery (the Wandeldekoration[23][24]) during the transition from Scene 1 to Scene 2 in Act 1 meant that Wagner’s existing orchestral interlude finished before Parsifal and Gurnemanz arrived at the Hall of the Grail. Engelbert Humperdinck, who was assisting the production, provided a few extra bars of music to cover this gap.[25] In subsequent years this problem was solved and Humperdinck’s additions were not used.

Ban outside BayreuthEdit

Scene design for the controversial 1903 production at the Metropolitan Opera: Gurnemanz leads Parsifal to Monsalvat (Act 1)

For the first twenty years of its existence, the only staged performances of Parsifal took place in the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, the venue for which Wagner conceived the work (except eight private performances for Ludwig II at Munich in 1884 and 1885). Wagner had two reasons for wanting to keep Parsifal exclusively for the Bayreuth stage. First, he wanted to prevent it from degenerating into ‘mere amusement’ for an opera-going public. Only at Bayreuth could his last work be presented in the way envisaged by him—a tradition maintained by his wife, Cosima, long after his death. Second, he thought that the opera would provide an income for his family after his death if Bayreuth had the monopoly on its performance.

The Bayreuth authorities allowed unstaged performances to take place in various countries after Wagner’s death (London in 1884, New York City in 1886, and Amsterdam in 1894) but they maintained an embargo on stage performances outside Bayreuth. On 24 December 1903, after receiving a court ruling that performances in the United States could not be prevented by Bayreuth, the New York Metropolitan Opera staged the complete opera, using many Bayreuth-trained singers. Cosima barred anyone involved in the New York production from working at Bayreuth in future performances. Unauthorized stage performances were also undertaken in Amsterdam in 1905, 1906 and 1908. There was a performance in Buenos Aires, in the Teatro Coliseo, on June 20, 1913, under Gino Marinuzzi.

Bayreuth lifted its monopoly on Parsifal on 1 January 1914 in the Teatro Comunale di Bologna in Bologna with Giuseppe Borgatti. Some opera houses began their performances at midnight between 31 December 1913 and 1 January.[26] The first authorized performance was staged at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona: it began at 10:30pm Barcelona time, which was an hour behind Bayreuth. Such was the demand for Parsifal that it was presented in more than 50 European opera houses between 1 January and 1 August 1914.[27]

ApplauseEdit

At Bayreuth performances audiences do not applaud at the end of the first act. This tradition is the result of a misunderstanding arising from Wagner’s desire at the premiere to maintain the serious mood of the opera. After much applause following the first and second acts, Wagner spoke to the audience and said that the cast would take no curtain calls until the end of the performance. This confused the audience, who remained silent at the end of the opera until Wagner addressed them again, saying that he did not mean that they could not applaud. After the performance Wagner complained, «Now I don’t know. Did the audience like it or not?»[28] At subsequent performances some believed that Wagner had wanted no applause until the very end, and there was silence after the first two acts. Eventually it became a Bayreuth tradition that no applause would be heard after the first act, but this was certainly not Wagner’s idea. In fact, during the first Bayreuth performances, Wagner himself cried «Bravo!» as the Flowermaidens made their exit in the second act, only to be hissed by other members of the audience.[28] At some theatres other than Bayreuth, applause and curtain calls are normal practice after every act. Program notes until 2013 at the Metropolitan Opera in New York asked the audience not to applaud after Act 1.[29]

Post-war performancesEdit

Parsifal is one of the Wagner operas regularly presented at the Bayreuth Festival to this day. Among the more significant post-war productions was that directed in 1951 by Wieland Wagner, the composer’s grandson. At the first Bayreuth Festival after World War II he presented a radical move away from literal representation of the Hall of the Grail or the Flowermaiden’s bower. Instead, lighting effects and the bare minimum of scenery were used to complement Wagner’s music. This production was heavily influenced by the ideas of the Swiss stage designer Adolphe Appia. The reaction to this production was extreme: Ernest Newman, Richard Wagner’s biographer described it as «not only the best Parsifal I have ever seen and heard, but one of the three or four most moving spiritual experiences of my life».[30] Others were appalled that Wagner’s stage directions were being flouted. The conductor of the 1951 production, Hans Knappertsbusch, on being asked how he could conduct such a disgraceful travesty, declared that right up until the dress rehearsal he imagined that the stage decorations were still to come.[31] Knappertsbusch was particularly upset by the omission of the dove that appears over Parsifal’s head at the end of the opera, which he claimed inspired him to give better performances. To placate his conductor Wieland arranged to reinstate the dove, which descended on a string. What Knappertsbusch did not realise was that Wieland had made the length of the string long enough for the conductor to see the dove, but not for the audience.[32] Wieland continued to modify and refine his Bayreuth production of Parsifal until his death in 1966. Martha Mödl created a «complex, tortured Kundry in Wieland Wagner’s revolutionary production of Parsifal during the festival’s first postwar season», and would remain the company’s exclusive Kundry for the remainder of the decade.[33][34]

RolesEdit

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 26 July 1882 Conductor: Hermann Levi[35] |

Met premiere cast, 24 December 1903 Conductor: Alfred Hertz[36] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parsifal | tenor | Hermann Winkelmann | Alois Burgstaller |

| Kundry | soprano or mezzo-soprano |

Amalie Materna | Milka Ternina |

| Gurnemanz, a veteran Knight of the Grail | bass | Emil Scaria | Robert Blass |

| Amfortas, ruler of the Grail kingdom | baritone | Theodor Reichmann | Anton van Rooy |

| Klingsor, a magician | bass-baritone | Karl Hill | Otto Goritz |

| Titurel, Amfortas’ father | bass | August Kindermann | Marcel Journet |

| Two Grail Knights | tenor, bass |

Anton Fuchs Eugen Stumpf |

Julius Bayer Adolph Mühlmann |

| Four Esquires | soprano, alto, two tenors |

Hermine Galfy Mathilde Keil Max Mikorey Adolf von Hübbenet |

Katherine Moran Paula Braendle Albert Reiss Willy Harden |

| Six Flowermaidens | three sopranos, three contraltos or six sopranos |

Pauline Horson Johanna Meta Carrie Pringle Johanna André Hermine Galfy Luise Belce |

Isabelle Bouton Ernesta Delsarta Miss Förnsen Elsa Harris Lillian Heidelbach Marcia Van Dresser |

| Voice from Above, Eine Stimme | contralto | Sophie Dompierre | Louise Homer |

| Knights of the Grail, boys, Flowermaidens |

SynopsisEdit

Act 1Edit

Prelude to Act 1

Musical introduction to the work with a duration of c. 12–16 minutes.

Scene 1Edit

Gurnemanz and the squires, Act 1, Scene 1, in the 1903 performance of the work in New York

In a forest near the seat of the Grail and its Knights, Gurnemanz, elder Knight of the Grail, wakes his young squires and leads them in morning prayer («He! Ho! Waldhüter ihr»). He sees Amfortas, King of the Grail Knights, and his entourage approaching. Amfortas has been injured by his own Holy Spear, and the wound will not heal. Gurnemanz asks the lead Knight for news of the King’s health. The Knight says the King has suffered during the night and is going early to bathe in the holy lake. The squires ask Gurnemanz to explain how the King’s injury can be healed, but he evades their question and a wild woman – Kundry – bursts in. She gives Gurnemanz a vial of balsam, brought from Arabia, to ease the King’s pain and then collapses, exhausted.

Amfortas arrives, borne on a stretcher by Knights of the Grail. He calls out for the knight Gawain, whose attempt at relieving the King’s pain had failed. He is told that Gawain has left again, seeking a better remedy. Raising himself somewhat, the King says that going off without leave («Ohn’ Urlaub?») is the sort of impulsiveness which led him into Klingsor’s realm and to his downfall. He accepts the potion from Gurnemanz and tries to thank Kundry, but she answers abruptly that thanks will not help and urges him onward to his bath.

The procession leaves. The squires eye Kundry with mistrust and question her. After a brief retort, she falls silent. Gurnemanz tells them Kundry has often helped the Grail Knights but that she comes and goes unpredictably. When he asks directly why she does not stay to help, she answers that she never helps. The squires think she is a witch and sneer that if she does so much, why will she not find the Holy Spear for them? Gurnemanz reveals that this deed is destined for someone else. He says Amfortas was given guardianship of the Spear, but lost it as he was seduced by an irresistibly attractive woman in Klingsor’s domain. Klingsor grabbed the Spear and stabbed Amfortas. The wound causes Amfortas both suffering and shame, and will never heal on its own.

Gurnemanz singing «Titurel, der fromme Held», excerpt from a 1942 recording

Squires returning from the King’s bath tell Gurnemanz that the balsam has eased the King’s suffering. Gurnemanz’s own squires ask how it is that he knew Klingsor. He solemnly tells them how both the Holy Spear, which pierced the side of the Redeemer on the Cross, and the Holy Grail, which caught the flowing blood, had come to Monsalvat to be guarded by the Knights of the Grail under the rule of Titurel, father of Amfortas («Titurel, der fromme Held»). Klingsor had yearned to become one of the Knights but, unable to stifle sinful desires in his mind, resorted to self-mutilation, for which offense Titurel refused to allow him to join the Order. Klingsor then set himself up in opposition to the Knights, learning dark arts, claiming the valley domain to the south of the mountainous realm of the Grail and filling it with beautiful Flowermaidens to seduce and enthrall wayward Grail Knights. It was here that Amfortas lost the Holy Spear, kept by Klingsor as he schemes to get hold of the Grail. Gurnemanz tells how Amfortas later had a holy vision which told him to wait for a «pure fool, enlightened by compassion» («Durch Mitleid wissend, der reine Tor») who will finally heal the wound.

At this moment, cries are heard from the Knights: a flying swan has been shot, and a young man is brought forth, a bow in his hand and a quiver of matching arrows. Gurnemanz speaks sternly to the lad, saying this is a holy place. He asks him outright if he shot the swan, and the lad boasts that if it flies, he can hit it («Im Fluge treff’ ich, was fliegt!») Gurnemanz tells him that the swan is a holy animal, and asks what harm the swan had done him, and shows the youth its lifeless body. Now remorseful, the young man breaks his bow and casts it aside. Gurnemanz asks him why he is here, who his father is, how he found this place and, lastly, his name. To each question the lad replies that he doesn’t know the answer. The elder Knight sends his squires away to help the King and now asks the boy to tell what he does know. The young man says he has a mother, Herzeleide (literally meaning Heart’s Sorrow) and that he made the bow himself. Kundry has been listening and now tells them that this boy’s father was Gamuret, a Knight killed in battle, and also how the lad’s mother had forbidden her son to use a sword, fearing that he would meet the same fate as his father. The youth now recalls that upon seeing Knights pass through his forest, he had left his home and mother to follow them. Kundry laughs and tells the young man that, as she rode by, she saw Herzeleide die of grief. Hearing this, the lad first lunges at Kundry but then collapses in grief. Kundry herself is now weary for sleep, but cries out that she must not sleep and wishes that she might never again waken. She disappears into the undergrowth.

Gurnemanz knows that the Grail draws only the pure of heart to Monsalvat and invites the boy to observe the Grail rite in the hope that perhaps he might be the pure fool of the prophecy revealed to Amfortas. The youth does not know what the Grail is, but remarks that as they approach the ascending mountain path leading through rocky walls to the Castle of the Grail it seems to him he scarcely moves, yet feels as if he had already traveled far. Gurnemanz answers him mysteriously that here time becomes space («Zum Raum wird hier die Zeit»).

Orchestral interlude – Verwandlungsmusik (Transformation music)

Scene 2Edit

Paul von Joukowsky: Design for the Hall of the Grail (second scenes of acts 1 and 3), 1882

Parsifal and Gurnemanz arrive at the Sanctuary of the Grail inside the Castle, where its Knights are just assembling to receive Holy Communion («Zum letzten Liebesmahle»). A procession of squires brings the Holy Grail itself in a reliquary to the centre of the hall, while another procession brings Amfortas on his litter to perform the ritual. The voice of the retired king Titurel then resounds from a vaulted nook in the background, as if from a tomb, telling his son Amfortas to uncover the Grail and serve his kingly office («Mein Sohn Amfortas, bist du am Amt?»). Only through the life-giving power of the sacred chalice and the Saviour’s blood contained therein may Titurel himself, now aged and very feeble, live on. Upon hearing his father’s pleas to reveal the Grail, Amfortas is overcome with shame and suffering («Wehvolles Erbe, dem ich verfallen»). He, the chosen guardian of the holiest of relics, has succumbed to sin and lost the Holy Spear, suffering an ever-bleeding wound in the process, a wound inflicted by that very selfsame Spear whose protection had been bestowed upon him, a wound condemning his existence to one of unending torment. Declaring himself unworthy of his kingship, Amfortas cries out for forgiveness («Erbarmen! Erbarmen!»), begging the Saviour to end his anguish and give him the only grace capable of putting an end to his misery, the peace of death, but hears only again the same promise once given to him repeated by the Knights and squires: he will one day be redeemed by a pure fool.

On hearing Amfortas’ cry of pain, Parsifal appears to suffer with him, clutching convulsively at his heart. The Knights and Titurel urge Amfortas to reveal the Grail («Enthüllet den Gral!»), and he finally does. The dark hall is illuminated by its radiant light and the Knights eat. Gurnemanz motions to Parsifal to participate, but he seems entranced and does not. Amfortas also does not share in taking communion and, as the ceremony ends, again collapses in agony and is carried away. Slowly all the Knights and squires disappear, leaving Parsifal and Gurnemanz alone. Gurnemanz asks the youth if he has understood what he has seen. As Parsifal is unable to answer the question, Gurnemanz dismisses him as just a fool after all and angrily sends him out with a warning to leave the swans in the Grail Kingdom alone. A voice from high above repeats the promise: «The pure fool, made knowing by compassion».

Act 2Edit

Prelude to Act 2 — Klingsors Zauberschloss (Klingsor’s Magic Castle)

Musical introduction of c. 2–3 minutes.

Scene 1Edit

Klingsor’s castle and enchanted garden. Klingsor conjures up Kundry, waking her from her sleep. He calls her by many names: First Sorceress (Urteufelin), Hell’s Rose (Höllenrose), Herodias, Gundryggia and, lastly, Kundry. She is now transformed into an incredibly alluring woman, as when she once seduced Amfortas. She mocks Klingsor’s mutilated condition by sarcastically inquiring if he is chaste («Ha ha! Bist du keusch?»), but she cannot resist his power. Klingsor observes that Parsifal is approaching and summons his enchanted knights to fight the youth. Klingsor watches as Parsifal overcomes his knights, and they flee. Klingsor wishes destruction on their whole kin. Seeing the young man stray into his Flowermaiden garden Klingsor calls to Kundry to seek the boy out and seduce him, but when he turns, he sees that Kundry has already left on her mission.

Scene 2Edit

Scene from Parsifal from the Victrola book of the opera, 1917

The triumphant youth finds himself in a wondrous garden, surrounded by beautiful and seductive Flowermaidens. They call to him and entwine themselves about him while chiding him for wounding their lovers («Komm, komm, holder Knabe!»). They soon fight and bicker among themselves to win his devotion, to the point that he is about to flee, but a different voice suddenly calls out «Parsifal!». He now recalls this name is what his mother called him when she appeared in his dreams. The Flowermaidens back away from him and call him a fool as they leave him and Kundry alone.

Parsifal wonders if the Garden is a dream and asks how it is that Kundry knows his name. Kundry tells him she learned it from his mother («Ich sah das Kind an seiner Mutter Brust»), who had loved him and tried to shield him from his father’s fate, the mother he had abandoned and who had finally died of grief. She reveals many parts of Parsifal’s history to him and he is stricken with remorse, blaming himself for his mother’s death. He thinks himself very stupid to have forgotten her. Kundry says this realization is a first sign of understanding and that, with a kiss, she can help him understand his mother’s love. As they kiss Parsifal suddenly recoils in pain and cries out Amfortas’ name: he feels the wounded king’s pain burning in his own side and now understands Amfortas’ passion during the Grail Ceremony («Amfortas! Die Wunde! Die Wunde!»). Filled with this compassion, Parsifal rejects Kundry’s advances.

Furious that her ploy has failed, Kundry tells Parsifal that if he can feel compassion for Amfortas, then he should also be able to feel it for her. She has been cursed for centuries, unable to rest, because she saw Christ on the cross and laughed at His pains. Now she can never weep, only jeer diabolically, and she is enslaved to Klingsor. Parsifal rejects her again but then asks her to lead him to Amfortas. She begs him to stay with her for just one hour, and then she will take him to Amfortas. When he still refuses, she curses him to wander without ever finding the Kingdom of the Grail, and finally calls on her master Klingsor to help her.

Klingsor appears on the castle rampart and hurls the Spear at Parsifal to destroy him, but it miraculously stops in midair, above his head. Parsifal seizes the Spear in his hand and makes with it the sign of the Cross, banishing Klingsor’s magic. The whole castle with Klingsor suddenly sinks as if by an earthquake and the enchanted garden withers. As Parsifal leaves, he tells Kundry that she knows where she can find him.

Act 3Edit

Prelude to Act 3 — Parsifals Irrfahrt (Parsifal’s Wandering)

Musical introduction of c. 4–6 minutes.

Scene 1Edit

The scene is the same as that of the opening of the opera, in the domain of the Grail, but many years later. Gurnemanz is now aged and bent, living alone as a hermit. It is Good Friday. He hears moaning near his hut and finds Kundry lying unconscious in the brush, similarly as he had many years before («Sie! Wieder da!»). He revives her using water from the Holy Spring, but she will only speak the word «serve» («Dienen»). Gurnemanz wonders if there is any higher significance to her reappearance on this special day. Looking into the forest, he sees a figure approaching, armed and in full armour. The stranger wears a helmet and the hermit cannot see who he is. Gurnemanz admonishes him firmly for being armed on a hallowed ground of the Kingdom of the Grail and all the more so on a day when the Saviour himself, bereft of all arms, had offered his own blood as a sacrifice to redeem the fallen world, but gets no response. Finally, the apparition removes the helmet and Gurnemanz recognizes the lad who shot the swan; to his amazement the Knight also bears the Holy Spear.

Parsifal tells of his desire to bring healing to Amfortas («Zu ihm, des tiefe Klagen»). He relates his seemingly unending arduous wandering, how he strayed again and again, unable to find a way back to the Grail. He was forced to resist and fight countless enemies to guard the Spear, suffering all manner of harms in the process, but has never desecrated the relic by wielding it in battle, preserving the purity of its holiness. Gurnemanz tells Parsifal that the evil curse preventing him from finding the right path has now been lifted, since he finds himself in the Grail’s domain. However, in his absence Amfortas has never unveiled the Grail, and lack of its sustaining powers has caused the death of Titurel. Parsifal is overcome with pity, blaming himself for this state of affairs, and almost faints with exhaustion. Gurnemanz tells him that today is the day of Titurel’s funeral, and that Parsifal has a great duty to perform. Kundry washes Parsifal’s feet and Gurnemanz anoints him with water from the Holy Spring, recognizing him as the pure fool, now enlightened by compassion and freed from guilt, and proclaims him the foretold new King of the Knights of the Grail.

Parsifal looks about and comments on the beauty of the meadow. Gurnemanz explains that today is Good Friday, when all the world is renewed. Kundry silently weeps with remorse and is baptised by Parsifal, who gently kisses her on the forehead and tells her to believe in the Redeemer. Tolling bells are heard in the distance. Gurnemanz says «Midday: the hour has come. My lord, permit your servant to guide you!» («Mittag: – Die Stund ist da: gestatte Herr, dass dich dein Knecht geleite») – and all three set off for the castle of the Grail. A dark orchestral interlude leads into the solemn gathering of the Knights.

Orchestral interlude – Verwandlungsmusik (Transformation music) – Titurels Totenfeier (Titurel’s Funeral March)

Scene 2Edit

Within the Castle of the Grail, Titurel’s funeral is to take place. Mourning processions of Knights bring the deceased Titurel in a coffin and the Grail in its shrine, as well as Amfortas on his litter, to the Grail hall («Geleiten wir im bergenden Schrein»). Expected to perform the ritual, Amfortas begs his deceased father, whose demise he acknowledges as his further guilt, to plead by the Redeemer to grant him the unique mercy of death, which alone would finally deliver him from all his pain. («Mein Vater! Hochgesegneter der Helden!»). The Knights desperately urge Amfortas to keep his promise and at least once more, for the very last time uncover the Grail again, but Amfortas, in a frenzy, says he will never again show the Grail, as doing so would just prolong his unbearable torment. Instead, he commands the Knights to kill him and end with his suffering also the shame he has brought on the brotherhood. At this moment, Parsifal appears and declares only one weapon can help here: only the same Spear that inflicted the wound can now close it («Nur eine Waffe taugt»). He touches Amfortas’ side with the Holy Spear and both heals the wound and absolves him from sin. Extolling the virtue of compassion that made a pure fool knowing, Parsifal replaces Amfortas in his kingly office and orders to unveil the Grail. As the Grail glows ever brighter with light and a white dove descends from the top of the dome and hovers over Parsifal’s head, all Knights praise the miracle of salvation («Höchsten Heiles Wunder!») and proclaim the redemption of the Redeemer («Erlösung dem Erlöser!»). Kundry, also at the very last released from her curse and redeemed, slowly sinks lifeless to the ground with her gaze resting on Parsifal, who raises the Grail in blessing over the worshipping Knighthood.

ReactionsEdit

Since Parsifal could initially only be seen at the Bayreuth Festival, the first presentation in 1882 was attended by many notable figures. Reaction was varied. Some thought that Parsifal marked a weakening of Wagner’s abilities, many others saw the work as a crowning achievement. The famous critic and Wagner’s theoretical opponent Eduard Hanslick gave his opinion that «The Third act may be counted the most unified and the most atmospheric. It is not the richest musically,» going on to note «And Wagner’s creative powers? For a man of his age and his method they are astounding … [but] It would be foolishness to declare that Wagner’s fantasy, and specifically his musical invention, has retained the freshness and facility of yore. One cannot help but discern sterility and prosaicism, together with increasing longwindedness.»[37]

On the other hand, the conductor Felix Weingartner found that: «The Flowermaidens’ costumes showed extraordinary lack of taste, but the singing was incomparable… When the curtain had been rung down on the final scene and we were walking down the hill, I seemed to hear the words of Goethe ‘and you can say you were present’. The Parsifal performances of 1882 were artistic events of supreme interest and it is my pride and joy that I participated in them.»[38] Many contemporary composers shared Weingartner’s opinion. Hugo Wolf was a student at the time of the 1882 Festival, yet still managed to find money for tickets to see Parsifal twice. He emerged overwhelmed: «Colossal – Wagner’s most inspired, sublimest creation.» He reiterated this view in a postcard from Bayreuth in 1883: «Parsifal is without doubt by far the most beautiful and sublime work in the whole field of Art.»[39] Gustav Mahler was also present in 1883 and he wrote to a friend; «I can hardly describe my present state to you. When I came out of the Festspielhaus, completely spellbound, I understood that the greatest and most painful revelation had just been made to me, and that I would carry it unspoiled for the rest of my life.»[40] Max Reger simply noted that «When I first heard Parsifal at Bayreuth I was fifteen. I cried for two weeks and then became a musician.» Alban Berg described Parsifal in 1909 as «magnificent, overwhelming,»[41] and Jean Sibelius, visiting the Festival in 1894 said: «Nothing in the world has made so overwhelming an impression on me. All my innermost heart-strings throbbed… I cannot begin to tell you how Parsifal has transported me. Everything I do seems so cold and feeble by its side. That is really something.»[42] Claude Debussy thought the characters and plot ludicrous, but nevertheless in 1903 wrote that musically it was: «Incomparable and bewildering, splendid and strong. Parsifal is one of the loveliest monuments of sound ever raised to the serene glory of music.»[43] He was later to write to Ernest Chausson that he had deleted a scene he had just written for his own opera Pelléas et Melisande because he had discovered in the music for it «the ghost of old Klingsor, alias R. Wagner».[44]

However, some notable guests of the Festival took a more acerbic view of the experience. Mark Twain visited Bayreuth in 1891: «I was not able to detect in the vocal parts of Parsifal anything that might with confidence be called rhythm or tune or melody… Singing! It does seem the wrong name to apply to it… In Parsifal there is a hermit named Gurnemanz who stands on the stage in one spot and practices by the hour, while first one and then another of the cast endures what he can of it and then retires to die.»[45] Performance standards may have contributed to such reactions; George Bernard Shaw, a committed Wagnerite, commented in 1894 that: «The opening performance of Parsifal this season was, from the purely musical point of view, as far as the principal singers were concerned, simply an abomination. The bass howled, the tenor bawled, the baritone sang flat and the soprano, when she condescended to sing at all and did not merely shout her words, screamed…»[46]

During a break from composing The Rite of Spring, Igor Stravinsky also traveled to the Bayreuth Festival at the invitation of Sergei Diaghilev to see the work. Stravinsky was repulsed by the «quasi-religious atmosphere» of the festival. Stravinsky’s repulsion is speculated to be due to his agnosticism, of which he recanted later in life.[47]

Interpretation and influenceEdit

Wagner’s last work, Parsifal has been both influential and controversial. The use of Christian symbols in Parsifal (the Grail, the Spear, references to the Redeemer) together with its restriction to Bayreuth for almost 30 years sometimes led to performances being regarded almost as a religious rite. However, Wagner never actually refers to Jesus Christ by name in the opera, only to «The Redeemer». In his essay «Religion and Art», Wagner described the use of Christian imagery thus:[48]

When religion becomes artificial, art has a duty to rescue it. Art can show that the symbols which religions would have us believe literally true are actually figurative. Art can idealize those symbols, and so reveal the profound truths they contain.

The critic Eduard Hanslick objected to the religious air surrounding Parsifal even at the premiere: «The question of whether Parsifal should really be withheld from all theatres and limited to… Bayreuth was naturally on all tongues… I must state here that the church scenes in Parsifal did not make the offensive impression on me that others and I had been led to expect from reading the libretto. They are religious situations – but for all their earnest dignity they are not in the style of the church, but completely in the style of the opera. Parsifal is an opera, call it a ‘stage festival’ or ‘consecrational stage festival’ if you will.»[49]

SchopenhauerEdit

Wagner had been greatly impressed with his reading of Arthur Schopenhauer in 1854, and this deeply affected his thoughts and practice on music and art. Most writers (e.g. Bryan Magee) see Parsifal as Wagner’s last great espousal of Schopenhauerian philosophy.[50] Parsifal can heal Amfortas and redeem Kundry because he shows compassion, which Schopenhauer saw as the highest form of human morality. Moreover, he displays compassion in the face of sexual temptation (Act 3, scene 2). Schopenhauerian philosophy also suggests that the only escape from the ever-present temptations of human life is through negation of the Will, and overcoming sexual temptation is in particular a strong form of negation of the Will. When viewed in this light, Parsifal, with its emphasis on Mitleid («compassion») is a natural follow-on to Tristan und Isolde, where Schopenhauer’s influence is perhaps more obvious, with its focus on Sehnen («yearning»). Indeed, Wagner originally considered including Parsifal as a character in Act 3 of Tristan, but later rejected the idea.[51]

NietzscheEdit

Friedrich Nietzsche, who was originally one of Wagner’s champions, chose to use Parsifal as the grounds for his breach with Wagner;[52] an extended critique of Parsifal opens the third essay («What Is the Meaning of Ascetic Ideals?») of On the Genealogy of Morality. In Nietzsche contra Wagner he wrote:[53]

Parsifal is a work of perfidy, of vindictiveness, of a secret attempt to poison the presuppositions of life – a bad work. The preaching of chastity remains an incitement to anti-nature: I despise everyone who does not experience Parsifal as an attempted assassination of basic ethics.

Despite this attack on the subject matter, he also admitted that the music was sublime: «Moreover, apart from all irrelevant questions (as to what the use of this music can or ought to be) and on purely aesthetic grounds; has Wagner ever done anything better?» (Letter to Peter Gast, 1887).[54]

Racism debateEdit

Some writers see in the opera a promotion of racism or anti-semitism.[55][page needed][56][page needed] One line of argument suggests that Parsifal was written in support of the ideas of the French diplomat and racial theorist Count Arthur de Gobineau, expressed most extensively in his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races. Parsifal is proposed as the «pure-blooded» (i.e. Aryan) hero who overcomes Klingsor, who is perceived as a Jewish stereotype, particularly since he opposes the quasi-Christian Knights of the Grail. Such claims remain heavily debated, since there is nothing explicit in the libretto to support them.[17][57][page needed][58] Wagner never mentions such ideas in his many writings, and Cosima Wagner’s diaries, which relate in great detail Wagner’s thoughts over the last 14 years of his life (including the period covering the composition and first performance of Parsifal) never mention any such intention.[50] Having met Gobineau for the first time very briefly in 1876, it was nonetheless only in 1880 that Wagner read Gobineau’s essay.[59] However, the libretto for Parsifal had already been completed by 1877, and the original drafts of the story even date back to 1857. Despite this chronological evidence, Gobineau is sometimes cited as a major inspiration for Parsifal.[60][61]

The related question of whether the opera contains a specifically anti-Semitic message is also debated.[62] Some of Wagner’s contemporaries and commentators (e.g. Hans von Wolzogen and Ernest Newman) who analysed Parsifal at length, make no mention of any anti-Semitic interpretations.[63][page needed][64] However the critics Paul Lindau and Max Nordbeck, present at the world premiere, noted in their reviews how the work accorded with Wagner’s anti-Jewish sentiments.[65] More recent commentators continue to highlight the perceived anti-Semitic nature of the opera,[66] and find correspondences with anti-Semitic passages found in Wagner’s writings and articles of the period.

German stamp showing Parsifal with the Grail, November 1933

The conductor of the premiere was Hermann Levi, the court conductor at the Munich Opera. Since King Ludwig was sponsoring the production, much of the orchestra was drawn from the ranks of the Munich Opera, including the conductor. Wagner objected to Parsifal being conducted by a Jew (Levi’s father was in fact a rabbi). Wagner first suggested that Levi should convert to Christianity, which Levi declined to do.[67] Wagner then wrote to King Ludwig that he had decided to accept Levi despite the fact that (he alleged) he had received complaints that «of all pieces, this most Christian of works» should be conducted by a Jew. When the King expressed his satisfaction at this, replying that «human beings are basically all brothers», Wagner wrote to the King that he «regard[ed] the Jewish race as the born enemy of pure humanity and everything noble about it».[68] Seventy-one years later, the Jewish bass-baritone George London performed in the role of Amfortas at Neu Bayreuth, causing some controversy.[69]

It has been claimed that Parsifal was denounced as being «ideologically unacceptable» in Nazi Germany,[70] and that the Nazis placed a de facto ban on Parsifal.[71][72] In fact there were 26 performances at the Bayreuth Festival between 1934 and 1939[73] and 23 performances at the Deutsche Oper Berlin between 1939 and 1942.[74] However Parsifal was not performed at the Bayreuth Festival during World War II.[72]

MusicEdit

Margaret Matzenauer as Kundry. She made her unexpected debut in the role in 1912 at the New York Met.

LeitmotifsEdit

A leitmotif is a recurring musical theme within a particular piece of music, associated with a particular character, object, event or emotion. Wagner is the composer most often associated with leitmotifs, and Parsifal makes liberal use of them.[75] Wagner did not specifically identify or name leitmotifs in the score of Parsifal (any more than he did in any other of his scores), although his wife Cosima mentions statements he made about some of them in her diary.[76] However, Wagner’s followers (notably Hans von Wolzogen whose guide to Parsifal was published in 1882) named, wrote about and made references to these motifs, and they were highlighted in piano arrangements of the score.[77][78] Wagner’s own reaction to such naming of motifs in the score was one of disgust: «In the end people believe that such nonsense happens by my suggestion.»[79]

The opening prelude introduces two important leitmotifs, generally referred to as the Communion theme and the theme of the Grail. These two, and Parsifal’s own motif, are repeated during the course of the opera. Other characters, especially Klingsor, Amfortas, and «The Voice», which sings the so-called Tormotif («Fool’s motive»), have their own particular leitmotifs. Wagner uses the Dresden amen to represent the Grail, this motif being a sequence of notes he would have known since his childhood in Dresden.

ChromaticismEdit

Many music theorists have used Parsifal to explore difficulties in analyzing the chromaticism of late 19th century music. Theorists such as David Lewin and Richard Cohn have explored the importance of certain pitches and harmonic progressions both in structuring and symbolizing the work.[80][81] The unusual harmonic progressions in the leitmotifs which structure the piece, as well as the heavy chromaticism of Act 2, make it a difficult work to parse musically.

Notable excerptsEdit

As is common in mature Wagner operas, Parsifal was composed such that each act was a continuous flow of music; hence there are no free-standing arias in the work. However, a number of orchestral excerpts from the opera were arranged by Wagner himself, and remain in the concert repertory. The prelude to Act 1 is frequently performed either alone or in conjunction with an arrangement of the «Good Friday» music which accompanies the second half of Act 3, Scene 1. Kundry’s long solo in Act 2 («Ich sah das Kind«) is occasionally performed in concert, as is Amfortas’ lament from Act 1 («Wehvolles Erbe«).

InstrumentationEdit

The score for Parsifal calls for three flutes, three oboes, one English horn, three clarinets in B-flat and A, one bass clarinet in B-flat and A, three bassoons, one contrabassoon; four horns in F, three trumpets in F, three trombones, one tuba, 6 onstage trumpets in F, 6 onstage trombones; a percussion section that includes four timpani (requiring two players), tenor drums, 4 onstage church bells, one onstage thunder machine; two harps and strings. Parsifal is one of only two works by Wagner in which he used the contrabassoon. (The other is the Symphony in C.)

The bells that draw the knights to the Grail ceremony at Monsalvat in acts 1 and 3 have often proved problematic to stage. For the earlier performances of Parsifal in Bayreuth, Wagner had the Parsifal bell, a piano frame with four strings, constructed as a substitute for church bells. For the first performances, the bells were combined with tam-tam and gongs. However, the bell was used with the tuba, four tam-tams tuned to the pitch of the four chime notes and another tam-tam on which a roll is executed by using a drumstick. In modern-day performances, the Parsifal bell has been replaced with tubular bells or synthesizers to produce the desired notes. The thunder machine is used in the moment of the destruction of Klingsor’s castle.

RecordingsEdit

Parsifal was expressly composed for the stage at Bayreuth and many of the most famous recordings of the opera come from live performances on that stage. In the pre-LP era, Karl Muck conducted excerpts from the opera at Bayreuth. These are still considered some of the best performances of the opera on disc. They also contain the only sound evidence of the bells constructed for the work’s premiere, which were melted down for scrap during World War II.

Hans Knappertsbusch was the conductor most closely associated with Parsifal at Bayreuth in the post-war years, and the performances under his baton in 1951 marked the re-opening of the Bayreuth Festival after World War II. These historic performances were recorded and are available on the Teldec label in mono sound. Knappertsbusch recorded the opera again for Philips in 1962 in stereo, and this release is often considered to be the classic Parsifal recording.[82][page needed] There are also many «unofficial» live recordings from Bayreuth, capturing virtually every Parsifal cast ever conducted by Knappertsbusch. Pierre Boulez (1971) and James Levine (1985) have also made recordings of the opera at Bayreuth that were released on Deutsche Grammophon and Philips. The Boulez recording is one of the fastest on record, and the Levine one of the slowest.

Amongst other recordings, those conducted by Georg Solti, James Levine (with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra), Herbert von Karajan, and Daniel Barenboim (the latter two both conducting the Berlin Philharmonic) have been widely praised.[83][page needed] The Karajan recording was voted «Record of the Year» in the 1981 Gramophone Awards. Also highly regarded is a recording of Parsifal under the baton of Rafael Kubelík originally made for Deutsche Grammophon, now reissued on Arts & Archives.

On the 14 December 2013 broadcast of BBC Radio 3’s CD Review – Building a Library, music critic David Nice surveyed recordings of Parsifal and recommended the recording by the Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Rafael Kubelik (conductor), as the best available choice.[84]

Filmed versionsEdit

In addition to a number of staged performances available on DVD, Parsifal was adapted for the screen by Daniel Mangrané in 1951 and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg in 1982. There is also a 1998 documentary directed by Tony Palmer titled: Parsifal – The Search for the Grail. It was recorded in various European theaters, including the Mariinsky Theatre, the Ravello Festival in Siena, and the Bayreuth Festival. It contains extracts from Palmer’s stage production of Parsifal starring Plácido Domingo, Violeta Urmana, Matti Salminen, Nikolai Putilin [ru], and Anna Netrebko. In also includes interviews with Domingo, Wolfgang Wagner, writers Robert Gutman and Karen Armstrong. The film exists in two versions: (1) a complete version running 116 minutes and officially approved by Domingo, and (2) an 88-minute version, with cuts of passages regarded by the German distributor as being too «political», «uncomfortable», and «irrelevant».[85]

See alsoEdit

- Gesamtkunstwerk

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «Parsifal Synopsis». Seattle Opera House. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014. (Section What is a Stage-Consecrating Festival-Play, Anyway?)

- ^ Joseph Görres, «Einleitung», p. vi, in: Lohengrin, ein altteutsches Gedicht, nach der Abschrift des Vaticanischen Manuscriptes by Ferdinand Gloeckle. Mohr und Zimmer, Heidelberg 1813.

- ^ Richard Wagner, Das braune Buch. Tagebuchaufzeichnungen 1865 bis 1882, ed. Joachim Bergfeld, Atlantis Verlag, Zürich and Freiburg im Breisgau 1975, p. 52

- ^ Danielle Buschinger, Renate Ullrich, Das Mittelalter Richard Wagners, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8260-3078-9, p. 140.

- ^ Unger, Max (1932-08-01). «The Persian Origins of ‘Parsifal’ and ‘Tristan’«. The Musical Times. 73 (1074): 703–705. doi:10.2307/917595. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 917595.

The correct spelling of Parzival is Parsi-wal. … the word means Persian flower.

Unger draws on the abstract of a book by Friedrich von Suhtscheck [de] which was never published. - ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983), p. 141

- ^ On the Will in Nature, «Sinology,» Footnote listing books on Buddhism s:On the Will in Nature#SINOLOGY

- ^ Millington (1992), p. 147

- ^ Everett, Derrick. «Prose Sketch for Die Sieger«. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983), p. 270

- ^ Wagner, Richard. Mein Leben vol II. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ Wagner, Cosima (1980) Cosima Wagner’s Diaries tr. Skelton, Geoffrey. Collins. ISBN 0-00-216189-3

- ^ Millington (1992), pp. 135–136

- ^ Beckett (1981), p. 13

- ^ Beckett (1981), p. 22

- ^ Millington (1992), pp. 147 f.

- ^ a b Gregor-Dellin (1983), pp. 477 ff.

- ^ Millington (1992), p. 307

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983), p. 485

- ^ Beckett (1981), pp. 90 f.

- ^ Carnegy (2006), pp. 107–118

- ^ Spencer (2000), p. 270

- ^ Heinz-Hermann Meyer. «Wandeldekoration», Lexikon der Filmbegriffe, ISSN 1610-420X Kiel, Germany, 2012, citing the dissertation by Pascal Lecocq.

- ^ Pascal Lecocq (1987). «La Wandeldekoration». Revue d’Histoire du Théâtre (in French) (156): 359–383. ISSN 0035-2373.

- ^ Spencer (2000), pp. 268 ff.

- ^ Beckett (1981), pp. 93–95

- ^ Beckett (1981), p. 94

- ^ a b Gregor-Dellin (1983), p. 506

- ^ «Pondering the Mysteries of Parsifal» by Fred Plotkin, WQXR, 2 March 2013.

- ^ Spotts (1994), p. 212

- ^ Carnegy (2006), pp. 288–290

- ^ Kluge, Andreas (1992). «Parsifal 1951». Wagner: Parsifal (Media notes). Teldec. 9031-76047-2.

- ^ Erik Eriksson. «Martha Mödl». AllMusic. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Shengold (2012)

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). «Parsifal, 26 July 1882″. L’Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ Parsifal, 24 December 1903, Met performance details

- ^ Hartford (1980), pp. 126 f.

- ^ Hartford (1980), p. 131

- ^ Hartford (1980), pp. 176 f.

- ^ Hartford (1980), p. 178

- ^ Hartford (1980), p. 180

- ^ Hartford (1980), p. 193

- ^ Beckett (1981), p. 108

- ^ Cited in Fauser (2008), p. 225

- ^ Hartford (1980), p. 151

- ^ Hartford (1980), p. 167

- ^ Igor Stravinsky, by Michael Oliver, Phaidon Press, 1995, pp. 57–58

- ^ Wagner, Richard. «Religion and Art». The Wagner Library. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ^ Hartford (1980), pp. 127 f.

- ^ a b Magee (2002), pp. 371–380

- ^ Dokumente zur Entstehung und ersten Aufführung des Bühnenweihfestspiels Parsifal by Richard Wagner, Martin Geck, Egon Voss. Reviewed by Richard Evidon in Notes, 2nd series, vol. 28, no. 4 (June 1972), pp. 685 ff.

- ^ Beckett (1981), pp. 113–120

- ^ Nietzsche, Friedrich. Nietzsche contra Wagner. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ Wikisource:Selected Letters of Friedrich Nietzsche#Nietzsche To Peter Gast – January, 1887

- ^ Gutman (1990)

- ^ Weiner (1997)

- ^ Borchmeyer, Dieter (2003). Drama and the World of Richard Wagner, Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11497-8

- ^ Everett, Derrick. «Parsifal and race». Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ Gutman (1990), p. 406

- ^ Adorno, Theodor (1952). In Search of Wagner. Verso, ISBN 1-84467-500-9, pbk.[page needed]

- ^ Deathridge, John (2007). «Strange love; or, How we learned to stop worrying and love Wagner’s Parsifal«. In Julie Brown (ed.). Western Music and Race. Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–83. ISBN 978-0-521-83887-0..

- ^ Deathridge (2008), pp. 166–169

- ^ Hans von Wolzogen, Thematic guide through the music of Parsifal: with a preface upon the legendary material of the Wagnerian drama, Schirmer, 1904.

- ^ Ernest Newman, A study of Wagner, Dobell, 1899. p. 352–365.

- ^ Rose (1992), pp. 168 f

- ^ E.g. Zelinsky (1982), passim, Rose (1992), pp. 135, 158–169 and Weiner (1997), passim.

- ^ Newman (1976), IV 635

- ^ Deathridge (2008), p. 163

- ^ Of Gods and Demons by Nora London, volume 9 of the «Great Voices» series, published by Baskerville Publishers, p. 37.

- ^ Spotts (1994), p. 166

- ^ Everett, Derrick. «The 1939 Ban on Parsifal«. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Spotts (1994), p. 192

- ^ Bayreuth Festival: Aufführungen sortiert nach Inszenierungen, retrieved on 2 April 2017

- ^ Deathridge (2008), pp. 173–174

- ^ Everett, Derrick. «Introduction to the Music of Parsifal«. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ Thorau (2009), pp. 136–139

- ^ Cosima Wagner’s Diaries, tr. Geoffrey Skelton. Collins, 1980. Entries for 11 August, 5 December 1877.

- ^ Wagner, Richard. «Parsifal». Schirmer Inc, New York. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- ^ Cosima Wagner’s diary, 1 August 1881.[full citation needed]

- ^ David Lewin, «Amfortas’ Prayer to Titurel and the Role of D in Parsifal: The Tonal Spaces of the Drama and the Enharmonic Cb/B,» in Studies in Music with Text (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 183–200.

- ^ Cohn (1996).

- ^ Holloway, Robin (1982) Opera on Record, Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-090910-2

- ^ Blyth, Alan (1992), Opera on CD Kyle Cathie Ltd, ISBN 1-85626-056-9

- ^ Nice, David. «Wagner 200 Building a Library: Parsifal«. CD Review. BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ «Parsifal – The Search for the Grail». Presto Classical Limited. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

SourcesEdit

- Beckett, Lucy (1981). Richard Wagner: Parsifal. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29662-5.

- Carnegy, Patrick (2006). Wagner and the Art of the Theatre. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10695-5.

- Cohn, Richard (1996). «Maximally smooth cycles, hexatonic systems, and the analysis of Late-Romantic triadic progressions». Music Analysis. 15 (1): 9–40. doi:10.2307/854168. JSTOR 854168.

- Deathridge, John (2008). Wagner: Beyond Good and Evil. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25453-4.

- Fauser, Annegret (2008). «Wagnerism». In Thomas S. Grey (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Wagner. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–234. ISBN 978-0-521-64439-6.

- Gregor-Dellin, Martin (1983). Richard Wagner: His Life, His Work, His Century. William Collins. ISBN 0-00-216669-0.

- Gutman, Robert (1990) [1968]. Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind and His Music. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-677615-4.

- Hartford, Robert (1980). Bayreuth: The Early Years. Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-02865-3.

- Magee, Bryan (2002). The Tristan Chord. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-7189-X. (UK title: Wagner and Philosophy, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-029519-4)

- Millington, Barry, ed. (1992). The Wagner Compendium: a Guide to Wagner’s Life and Music. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-02-871359-1.

- Newman, Ernest (1976). The Life of Richard Wagner. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29149-6.

- Rose, Paul Lawrence (1992). Wagner: Race and Revolution. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06745-3.

- Shengold, David (2012). «Martha Mödl: ‘Portrait of a Legend’«. Opera News. 77 (5).

- Spencer, Stewart (2000). Wagner Remembered. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19653-5.

- Spotts, Frederic (1994). Bayreuth: a History of the Wagner Festival. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05777-6.

- Thorau, Christian (2009). «Guides for Wagnerites: leitmotifs and Wagnerian listening». In Thomas S. Grey (ed.). Wagner and His World. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 133–150. ISBN 978-0-691-14366-8.

- Weiner, Marc A. (1997). Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9792-0.

- Zelinsky, Hartmut (1982). «Rettung ins Ungenaue: zu M. Gregor-Dellins Wagner-Biographie». In Heinz-Klaus Metzger; Rainer Riehn (eds.). Richard Wagner: Parsifal. Musik-Konzepte. Vol. 25. Munich: Text & Kritik. pp. 74–115.

Further readingEdit

- Burbidge, Peter; Sutton, Richard, eds. (1979). The Wagner Companion. Faber and Faber Ltd., London. ISBN 0-571-11450-4.

- Konrad, Ulrich (2020). «Through compassion, knowing: the pure fool». In Ulrich Konrad (ed.). Richard Wagner: Parsifal. Autograph Score. Facsimile. Commentary. Documenta musicologica. Vol. II, 55. Kassel: Bärenreiter. pp. I–X. ISBN 978-3-7618-2418-4.

- Magee, Bryan (1997). The Philosophy of Schopenhauer. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-823722-7.

- Melitz, Leo (2001). The Opera Goer’s Complete Guide. London: Best Books. ISBN 0-7222-6262-0.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1989). On the Genealogy of Morals. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-72462-1.

- Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-21762-0.

- Vernon, David (2021). Disturbing the Universe: Wagner’s Musikdrama. Edinburgh: Candle Row Press. ISBN 978-1527299245.

External linksEdit

- Parsifal: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Complete vocal score of Parsifal

- Complete German and English libretti and Wagner’s own stage descriptions, excerpts of the score, rwagner.net

- English libretto

- Parsifal on TV: Met and Festspielhaus by Alunno Marco, mediamusic-journal.com, 26 March 2013

- Monsalvat, Derrick Everett’s extensive website on all aspects of Parsifal

- Essay by Rolf May, a theosophical view of Parsifal, from Sunrise, 1992/1993

- Programme notes for Parsifal Archived 2020-07-16 at the Wayback Machine by Luke Berryman

- Wagner Operas. A comprehensive website featuring photographs of productions, recordings, librettos, and sound files.

- Summary of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival

- Parsifal on Stage: a PDF by Katherine R. Syer

- Richard Wagner – Parsifal, gallery of historic postcards with visual motives from Richard Wagner’s operas

- Reviews of Parsifal on record, by Geoffrey Riggs

- List of all Parsifal conductors at Bayreuth

- Parsifal Suite, constructed by Andrew Gourlay, published by Schott Music

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Perceval (Peredur) | |

|---|---|

| Matter of Britain character | |

Parsifal by Rogelio de Egusquiza (1910) |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Title | Sir |

| Occupation | Knight of the Round Table |

| Family | Various depending on version, including Pellinore, Lamorak, Aglovale, Tor, his sister, Feirefiz |

| Children | Lohengrin in Parzival |

| Religion | Christian |

| Nationality | Welsh |

Percival (, also written Perceval, Parzival, Parsifal), alternatively called Peredur (Welsh pronunciation: [pɛˈrɛdɨr]), is a figure in the legend of King Arthur, often appearing as one of the Knights of the Round Table. First mentioned by the French author Chrétien de Troyes in the tale Perceval, the Story of the Grail, he is best known for being the original hero in the quest for the Grail, before being replaced in later literature by Galahad.

Etymology and origin[edit]

The earliest reference to Perceval is found in Chrétien de Troyes’s first Arthurian romance Erec et Enide, where, as «Percevaus li Galois» (Percevaus of Wales), he appears in a list of Arthur’s knights.[1] In another of Chrétien’s romances, Cligés, Perceval is a «renowned vassal» who is defeated by the knight Cligés in a tournament.[2] He then becomes the eponymous protagonist of Chrétien’s final romance, Perceval, the Story of the Grail.[3]

In the Welsh romance Peredur son of Efrawg, the corresponding figure goes by the name Peredur. The name «Peredur» may derive from Welsh par (spear) and dur (hard, steel).[4] It is generally accepted that Peredur was a well-established figure before he became the hero of Peredur son of Efrawg.[5] However, the earliest Welsh Arthurian text, Culhwch and Olwen, does not mention Peredur in any of its extended catalogues of famous and less famous warriors. Peredur does appear in the romance Geraint and Enid, which includes «Peredur son of Efrawg» in a list of warriors accompanying Geraint. A comparable list in the last pages of The Dream of Rhonabwy refers to a Peredur Paladr Hir («of the Long Spear-Shaft»), whom Peter Bartrum identifies as the same figure.[6] Peredur may derive in part from the sixth-century Coeling chieftain Peredur son of Eliffer. The Peredur of Welsh romance differs from the Coeling chieftain if only in that his father is called Efrawg, rather than Eliffer, and there is no sign of a brother called Gwrgi. Efrawg, on the other hand, is not an ordinary personal name, but the historical Welsh name for the city of York (Latin Eburacum, modern Welsh Efrog).[6] This may represent an epithet that denoted a local association, possibly pointing to Eliffer’s son as the prototype, but which came to be understood and used as a patronymic in the Welsh Arthurian tales.[6]

Scholars disagree as to the exact relationship between Peredur and Percival. Arthur Groos and Norris J. Lacy argue that it is most likely that the use of the name Peredur in Peredur son of Efrawg «represent[s] an attempt to adapt the name [Perceval] to Welsh onomastic traditions»,[7] as the Welsh romance appears to depend on Chrétien de Troyes, at least partially, as a source, and as the name Peredur is attested for unrelated characters in Historia Regum Britanniae and Roman de Brut.[8] Rachel Bromwich, however, regards the name Perceval as a loose French approximation of the Welsh name Peredur.[9] Roger Sherman Loomis attempted to derive both Perceval and Peredur from the Welsh Pryderi, a mythological figure in the Four Branches of the Mabinogi,[10] a derivation that Groos and Lacy find «now seems even less likely».[8]

In all of his appearances, Chrétien de Troyes identifies Perceval as «the Welshman» (li Galois), indicating that, even if he does not originate in Celtic tradition, he alludes to it.[3] Groos and Lacy argue that, «even though there may have been a pre-existing ‘Perceval prototype,’ Chrétien was primarily responsible […] for the creation of [one of] the most fascinating, complex, and productive characters in Arthurian fiction».[11]

In some French texts, the name «Perceval» is derived from either Old French per ce val (through this valley) or perce val (pierce the valley).[12] These etymologies are not found in Chrétien de Troyes, however.[13] Perlesvaus etymologizes the name (there: Pellesvax) as meaning «He Who Has Lost The Vales», referring to the loss of land by his father, while also saying Perceval called himself Par-lui-fet (made by himself).[14] Wolfram von Eschenbach’s German Parzival provides the meaning «right through the middle» for the name (there: Parzival).[14] Richard Wagner followed a discredited etymology proposed by journalist and historian Joseph Görres that the name derived from Arabic fal parsi (pure fool) when choosing the spelling «Parsifal» for the figure in his opera.[15]

Arthurian legend[edit]

Peredur[edit]

In a large series of episodes, Peredur son of Efrawg tells the story of Peredur’s education as a knight. It begins with his birth and secluded upbringing as a naive boy by his widowed mother. When he meets a group of knights, he joins them on their way to King Arthur’s court. Once there, he is ridiculed by Cei and sets out on further adventures, promising to avenge Cei’s insults to himself and those who defended him. While travelling he meets two of his uncles. The first, who is analogous to the Gornemant of Perceval, trains him in arms and warns him not to ask the significance of what he sees. The second uncle is analogous to Chrétien’s Fisher King, but what Peredur sees being carried before him in his uncle’s castle is not the Holy Grail (Old French graal), but a salver containing a man’s severed head. The text agrees with the French poem in listing a bleeding lance among the items which are carried in procession. The young knight does not ask about significance of these items and proceeds to further adventure, including a stay with the Nine Witches and the encounter with the woman who was to be his true love, Angharad. Peredur returns to Arthur’s court, but soon embarks on another series of adventures that do not correspond to material in Perceval. Eventually, the hero learns the severed head at his uncle’s court belonged to his cousin, who had been killed by the Witches. Peredur avenges his family and is celebrated as a hero.

Several elements in the story, such as the severed head on a salver, a hunt for a unicorn, the witches, and a magical board of gwyddbwyll, have all been described as Celtic ingredients that are not otherwise present in Chrétien’s story.[16] Goetinck sees in Peredur a variant on the Celtic theme of the sovereignty goddess, who personifies the country and has to be won sexually by the rightful king or heir to secure peace and prosperity for the kingdom. N. Petrovskaia has recently suggested an alternative interpretation, linking the figure of the Empress with Empress Matilda.[17]

Perceval[edit]

Chrétien de Troyes wrote the first story of Perceval as the main character, the unfinished Perceval, the Story of the Grail, in the late 12th century. Other famous accounts of his adventures include Wolfram’s Parzival and the now-lost Perceval attributed to Robert de Boron.

There are many versions of Perceval’s birth. In Robert de Boron’s account, he is of noble birth, and his father is variably stated to be either Alain le Gros, King Pellinore, or another worthy knight. His mother is usually unnamed, but plays a significant role in the stories. His sister is sometimes the bearer of the Holy Grail, but not originally; she is sometimes named Dindrane. In the tales in which he is Pellinore’s son, his brothers include Aglovale, Lamorak and Dornar, as well as a half-brother named Tor by his father’s affair with a peasant woman. After the death of his father, Perceval’s mother takes him to the forest, where she raises him ignorant of the ways of men until he is 15. Eventually, a group of knights passes through the forest and Perceval is struck by their heroic bearing. Wanting to be a knight himself, he travels to King Arthur’s court. In some versions, his mother faints in shock upon seeing her son leave. After proving his worthiness as a warrior, he is knighted and invited to join the Knights of the Round Table.

In Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval, the character is already connected to the Grail. He meets the crippled Fisher King and sees a grail, not yet identified as «holy», but he fails to ask the question that would heal the injured king. Upon learning of his mistake, Perceval vows to find the Grail castle again and fulfill his quest. The story breaks off soon after, to be continued in a number of different ways by various authors, such as in Perlesvaus and Sir Perceval of Galles. In the later accounts of Arthurian prose cycles, and consequently Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, the true Grail hero is Galahad, the son of Lancelot, but, though his role in the romances is diminished, Percival remains a major character and is one of only two knights (the other is Bors) who accompany Galahad to the Grail castle and complete the quest with him.

In early versions, Perceval’s sweetheart is Blanchefleur and he becomes the King of Carbonek after healing the Fisher King. In later versions, he is a virgin who dies after achieving the Grail. In Wolfram’s version, Perceval’s son is Lohengrin, the Knight of the Swan.

Modern culture[edit]

His story has been featured in many modern works, including Wagner’s influential and controversial 1882 opera Parsifal.

- Daniel Mangrané’s The Evil Forest (Spanish: Parsifal) is a free re-telling in Spain during the barbarian invasions, with Gustavo Rojo as the titular character. It features some music by Wagner.[18]

- Richard Monaco’s 1977 book Parsival: Or, a Knight’s Tale is a re-telling of the Percival legend.[19]

- Éric Rohmer’s 1978 film Perceval le Gallois is an eccentrically staged interpretation of Chrétien’s original poem.[20]

- John Boorman’s 1981 film Excalibur is a retelling of Le Morte d’Arthur in which Percival (Perceval) is given a leading role.

- The 1991 film The Fisher King written by Richard LaGravenese is, in ways, a modern retelling in which the parallels shift between characters, who themselves discuss the legend.

- In the comic series based on the cartoon Gargoyles, Peredur fab Ragnal (Percival’s Welsh name) achieves the Holy Grail and becomes the Fisher King. To honour his mentor Arthur, he establishes a secret order who will guide the world to greater prosperity and progress, which eventually becomes the Illuminati. Part of achieving the Grail is the bestowal of immense longevity upon Peredur and his wife, Fleur, along with certain other members of the order being granted longer lifespans. He is still alive and even appears young by 1996, when his organisation comes into conflict with the re-awakened Arthur and the other characters of the Gargoyles story.[21]

- He is the protagonist of the 2000 book Parzival: The Quest of the Grail Knight by Katherine Paterson, based on Wolfram’s Parzival.

- The 2003 novel Clothar the Frank by Jack Whyte portrays Perceval as an ally of Lancelot in his travels to Camelot.

- He appears in the French comedy TV series Kaamelott as a main character, portrayed as a clueless yet loyal knight of the Round Table.

- In the BBC television series Merlin,[22] Percival is a large, strong commoner. After helping to free Camelot from the occupation of Morgana, Morgause, and their immortal army (which is supplied by a grail-like goblet called the Cup of Life), he is knighted along with Lancelot, Elyan and Gwaine, against the common practice that knights are only of noble birth. He is also one of the few Round Table knights to survive Arthur’s death.[23]

- In Philip Reeve’s Here Lies Arthur, he appears as Peredur, son of Peredur Long-knife, who is raised as a woman by his mother, who had already lost many sons and her husband to war. He befriends the main character, Gwyna/Gwyn. He is one of the few major characters to survive to the end and travels with Gwen (in a male disguise) as ‘Peri’, his childhood shortened name as a woman, playing a harp to Gwen’s stories.

- The main character of Ernest Cline’s 2011 novel Ready Player One (and its film adaptation) names his virtual reality avatar «Parzival» as a reference to Percival and to his role in Arthurian legend.

- Percival appears in Season 5 of the American TV series Once Upon A Time. He is one of King Arthur’s knights, who dances with Regina at the ball when she visits Camelot. Percival, however, recognises her as the Evil Queen and tries to kill her, but he is killed by Prince Charming first.

- Patricia A. McKillip’s 2016 novel Kingfisher includes many elements of the story of Percival and the Fisher King. Young Pierce (Percival meaning «pierce the valley»), after a chance meeting with knights, leaves his mother, who has sheltered him from the world and travels to become a knight.

- In the 2017 television series Knightfall, Percival (rendered as «Parsifal») appears as a young peasant farmer who joins the Knights Templar as a novice knight.

- In the 2020 television series Cursed, Billy Jenkins plays a boy, nicknamed squirrel, who is Percival.

- In the 2018 film High Life, Rob Pattinson’s character is described as being similar to Percival in the Arthurian legend.

- The 2022 novella Spear by Nicola Griffith is a retelling of the story of Percival. The protagonist Peretur disguises herself as a man and hopes to become a knight.

References[edit]

- ^ Erec, vv. 1506, 1526.

- ^ Cligés vv. 4774, 4828.

- ^ a b Gross & Lacy 2002, p. 2.

- ^ The Mabinogion 2007, p. 245.

- ^ Groos & Lacy 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Koch, «Peredur fab Efrawg», pp. 1437–8.

- ^ Groos & Lacy 2002, p. 3.

- ^ a b Groos & Lacy 2002, p. 35.

- ^ Bromwich 1961, p. 490.

- ^ Loomis 1949, pp. 346–352.

- ^ Groos & Lacy 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Gross & Lacy 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Müller 1999, p. 246.

- ^ a b Groos & Lacy 2002, p. 4.