«The Tea Set» and «The T-Set» redirect here. For tea service, see tea set. For the Dutch band, see Tee-Set. For other uses, see T Set (disambiguation).

|

Pink Floyd |

|

|---|---|

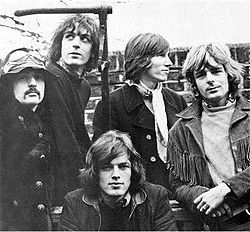

Pink Floyd in January 1968. Clockwise from bottom: David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Syd Barrett, Roger Waters and Richard Wright. |

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres |

|

| Years active |

|

| Labels |

|

| Spinoffs | Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets |

| Members |

|

| Past members |

|

| Website | pinkfloyd.com |

Pink Floyd are an English rock band formed in London in 1965. Gaining an early following as one of the first British psychedelic groups, they were distinguished by their extended compositions, sonic experimentation, philosophical lyrics and elaborate live shows. They became a leading band of the progressive rock genre, cited by some as the greatest progressive rock band of all time.

Pink Floyd were founded in 1965 by Syd Barrett (guitar, lead vocals), Nick Mason (drums), Roger Waters (bass guitar, vocals), and Richard Wright (keyboards, vocals). Under Barrett’s leadership, they released two charting singles and the successful debut album The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967). The guitarist and vocalist David Gilmour joined in December 1967; Barrett left in April 1968 due to deteriorating mental health. Waters became the primary lyricist and thematic leader, devising the concepts behind Pink Floyd’s most successful albums, The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975), Animals (1977) and The Wall (1979). The musical film based on The Wall, Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982), won two BAFTA Awards. Pink Floyd also composed several film scores.

Following personal tensions, Wright left Pink Floyd in 1979, followed by Waters in 1985. Gilmour and Mason continued as Pink Floyd, rejoined later by Wright. They produced the albums A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987) and The Division Bell (1994), backed by major tours, before entering a long hiatus. In 2005, all but Barrett reunited for a performance at the global awareness event Live 8. Barrett died in 2006, and Wright in 2008. The last Pink Floyd studio album, The Endless River (2014), was based on unreleased material from the Division Bell recording sessions. In 2022, Gilmour and Mason reformed Pink Floyd to release the song «Hey, Hey, Rise Up!» in protest of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

By 2013, Pink Floyd had sold more than 250 million records worldwide, making them one of the best-selling music artists of all time. The Dark Side of the Moon and The Wall were inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame,[1] and these albums and Wish You Were Here are among the best-selling albums of all time. Four Pink Floyd albums topped the US Billboard 200, and five topped the UK Albums Chart. Pink Floyd’s hit singles include «See Emily Play» (1967), «Money» (1973), «Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2» (1979), «Not Now John» (1983), «On the Turning Away» (1987) and «High Hopes» (1994). They were inducted into the US Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. In 2008, Pink Floyd were awarded the Polar Music Prize in Sweden for their contribution to modern music.

History

1963–1965: Formation

Preceding the band

Roger Waters and Nick Mason met while studying architecture at the London Polytechnic at Regent Street.[2] They first played music together in a group formed by fellow students Keith Noble and Clive Metcalfe,[3] with Noble’s sister Sheilagh. Richard Wright, a fellow architecture student,[nb 1] joined later that year, and the group became a sextet, Sigma 6. Waters played lead guitar, Mason drums, and Wright rhythm guitar, later moving to keyboards.[5] The band performed at private functions and rehearsed in a tearoom in the basement of the Regent Street Polytechnic. They performed songs by the Searchers and material written by their manager and songwriter, fellow student Ken Chapman.[6]

In September 1963, Waters and Mason moved into a flat at 39 Stanhope Gardens near Crouch End in London, owned by Mike Leonard, a part-time tutor at the nearby Hornsey College of Art and the Regent Street Polytechnic.[7][nb 2] Mason moved out after the 1964 academic year, and guitarist Bob Klose moved in during September 1964, prompting Waters’s switch to bass.[8][nb 3] Sigma 6 went through several names, including the Meggadeaths, the Abdabs and the Screaming Abdabs, Leonard’s Lodgers, and the Spectrum Five, before settling on the Tea Set.[9][nb 4] In 1964, as Metcalfe and Noble left to form their own band, guitarist Syd Barrett joined Klose and Waters at Stanhope Gardens.[13] Barrett, two years younger, had moved to London in 1962 to study at the Camberwell College of Arts.[14] Waters and Barrett were childhood friends; Waters had often visited Barrett and watched him play guitar at Barrett’s mother’s house.[15] Mason said about Barrett: «In a period when everyone was being cool in a very adolescent, self-conscious way, Syd was unfashionably outgoing; my enduring memory of our first encounter is the fact that he bothered to come up and introduce himself to me.»[16]

Noble and Metcalfe left the Tea Set in late 1963, and Klose introduced the band to singer Chris Dennis, a technician with the Royal Air Force (RAF).[17] In December 1964, they secured their first recording time, at a studio in West Hampstead, through one of Wright’s friends, who let them use some down time free. Wright, who was taking a break from his studies, did not participate in the session.[18][nb 5] When the RAF assigned Dennis a post in Bahrain in early 1965, Barrett became the band’s frontman.[19][nb 6] Later that year, they became the resident band at the Countdown Club near Kensington High Street in London, where from late night until early morning they played three sets of 90 minutes each. During this period, spurred by the group’s need to extend their sets to minimise song repetition, the band realised that «songs could be extended with lengthy solos», wrote Mason.[20] After pressure from his parents and advice from his college tutors, Klose quit the band in mid-1965 and Barrett took over lead guitar.[21]

1965–1967: Early years

Pink Floyd

The group rebranded in late 1965, first referring to themselves as the Pink Floyd Sound. They would later be referred to as the Pink Floyd and later simply Pink Floyd. Barrett created the name on the spur of the moment when he discovered that another band, also called the Tea Set, were to perform at one of their gigs.[22] The name is derived from the given names of two blues musicians whose Piedmont blues records Barrett had in his collection, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.[23] By 1966, the group’s repertoire consisted mainly of rhythm and blues songs, and they had begun to receive paid bookings, including a performance at the Marquee Club in December 1966, where Peter Jenner, a lecturer at the London School of Economics, noticed them. Jenner was impressed by the sonic effects Barrett and Wright created and, with his business partner and friend Andrew King, became their manager.[24] The pair had little experience in the music industry and used King’s inheritance to set up Blackhill Enterprises, purchasing about £1,000 (equivalent to £19,800 in 2021[25]) worth of new instruments and equipment for the band.[nb 7] It was around this time that Jenner suggested they drop the «Sound» part of their band name, thus becoming Pink Floyd.[27] Under Jenner and King’s guidance, the group became part of London’s underground music scene, playing at venues including All Saints Hall and the Marquee.[28] While performing at the Countdown Club, the band had experimented with long instrumental excursions, and they began to expand them with rudimentary but effective light shows, projected by coloured slides and domestic lights.[29] Jenner and King’s social connections helped gain the band prominent coverage in the Financial Times and an article in the Sunday Times which stated: «At the launching of the new magazine IT the other night a pop group called the Pink Floyd played throbbing music while a series of bizarre coloured shapes flashed on a huge screen behind them … apparently very psychedelic.»[30]

In 1966, the band strengthened their business relationship with Blackhill Enterprises, becoming equal partners with Jenner and King and the band members each holding a one-sixth share.[27] By late 1966, their set included fewer R&B standards and more Barrett originals, many of which would be included on their first album.[31] While they had significantly increased the frequency of their performances, the band were still not widely accepted. Following a performance at a Catholic youth club, the owner refused to pay them, claiming that their performance was not music.[32] When their management filed suit in a small claims court against the owner of the youth organisation, a local magistrate upheld the owner’s decision. The band was much better received at the UFO Club in London, where they began to build a fan base.[33] Barrett’s performances were enthusiastic, «leaping around … madness … improvisation … [inspired] to get past his limitations and into areas that were … very interesting. Which none of the others could do», wrote biographer Nicholas Schaffner.[34]

Signing with EMI

In 1967, Pink Floyd began to attract the attention of the music industry.[35][nb 8] While in negotiations with record companies, IT co-founder and UFO club manager Joe Boyd and Pink Floyd’s booking agent Bryan Morrison arranged and funded a recording session at Sound Techniques in Kensington.[37] Three days later, Pink Floyd signed with EMI, receiving a £5,000 advance (equivalent to £96,500 in 2021[25]). EMI released the band’s first single, «Arnold Layne», with the B-side «Candy and a Currant Bun», on 10 March 1967 on its Columbia label.[38][nb 9] Both tracks were recorded on 29 January 1967.[39][nb 10] «Arnold Layne»‘s references to cross-dressing led to a ban by several radio stations; however, creative manipulation by the retailers who supplied sales figures to the music business meant that the single reached number 20 in the UK.[41]

EMI-Columbia released Pink Floyd’s second single, «See Emily Play», on 16 June 1967. It fared slightly better than «Arnold Layne», peaking at number 6 in the UK.[42] The band performed on the BBC’s Look of the Week, where Waters and Barrett, erudite and engaging, faced tough questioning from Hans Keller.[43] They appeared on the BBC’s Top of the Pops, a popular programme that controversially required artists to mime their singing and playing.[44] Though Pink Floyd returned for two more performances, by the third, Barrett had begun to unravel, and around this time the band first noticed significant changes in his behaviour.[45] By early 1967, he was regularly using LSD, and Mason described him as «completely distanced from everything going on».[46]

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

Morrison and EMI producer Norman Smith negotiated Pink Floyd’s first recording contract. As part of the deal, the band agreed to record their first album at EMI Studios in London.[47][nb 11] Mason recalled that the sessions were trouble-free. Smith disagreed, stating that Barrett was unresponsive to his suggestions and constructive criticism.[49] EMI-Columbia released The Piper at the Gates of Dawn in August 1967. The album reached number six, spending 14 weeks on the UK charts.[50] One month later, it was released under the Tower Records label.[51] Pink Floyd continued to draw large crowds at the UFO Club; however, Barrett’s mental breakdown was by then causing serious concern. The group initially hoped that his erratic behaviour would be a passing phase, but some were less optimistic, including Jenner and his assistant, June Child, who commented: «I found [Barrett] in the dressing room and he was so … gone. Roger Waters and I got him on his feet, [and] we got him out to the stage … The band started to play and Syd just stood there. He had his guitar around his neck and his arms just hanging down».[52]

Forced to cancel Pink Floyd’s appearance at the prestigious National Jazz and Blues Festival, as well as several other shows, King informed the music press that Barrett was suffering from nervous exhaustion.[53] Waters arranged a meeting with psychiatrist R. D. Laing, and though Waters personally drove Barrett to the appointment, Barrett refused to come out of the car.[54] A stay in Formentera with Sam Hutt, a doctor well established in the underground music scene, led to no visible improvement. The band followed a few concert dates in Europe during September with their first tour of the US in October.[55][nb 12] As the US tour went on, Barrett’s condition grew steadily worse.[57] During appearances on the Dick Clark and Pat Boone shows in November, Barrett confounded his hosts by giving terse answers to questions (or not responding at all) and staring into space. He refused to move his lips when it came time to mime «See Emily Play» on Boone’s show. After these embarrassing episodes, King ended their US visit and immediately sent them home to London.[58][nb 13] Soon after their return, they supported Jimi Hendrix during a tour of England; however, Barrett’s depression worsened as the tour continued.[60][nb 14]

1967–1978: Transition and international success

1967: Replacement of Barrett by Gilmour

In December 1967, reaching a crisis point with Barrett, Pink Floyd added guitarist David Gilmour as the fifth member.[63][nb 15] Gilmour already knew Barrett, having studied with him at Cambridge Tech in the early 1960s.[15] The two had performed at lunchtimes together with guitars and harmonicas, and later hitch-hiked and busked their way around the south of France.[65] In 1965, while a member of Joker’s Wild, Gilmour had watched the Tea Set.[66]

Morrison’s assistant, Steve O’Rourke, set Gilmour up in a room at O’Rourke’s house with a salary of £30 per week (equivalent to £600 in 2021[25]). In January 1968, Blackhill Enterprises announced Gilmour as the band’s newest member, intending to continue with Barrett as a nonperforming songwriter.[67] According to Jenner, the group planned that Gilmour would «cover for [Barrett’s] eccentricities». When this proved unworkable, it was decided that Barrett would just write material.[68][nb 16] In an expression of his frustration, Barrett, who was expected to write additional hit singles to follow up «Arnold Layne» and «See Emily Play», instead introduced «Have You Got It Yet?» to the band, intentionally changing the structure on each performance so as to make the song impossible to follow and learn.[63] In a January 1968 photoshoot of Pink Floyd, the photographs show Barrett looking detached from the others, staring into the distance.[70]

Working with Barrett eventually proved too difficult, and matters came to a conclusion in January while en route to a performance in Southampton when a band member asked if they should collect Barrett. According to Gilmour, the answer was «Nah, let’s not bother», signalling the end of Barrett’s tenure with Pink Floyd.[71][nb 17] Waters later said, «He was our friend, but most of the time we now wanted to strangle him.»[73] In early March 1968, Pink Floyd met with business partners Jenner and King to discuss the band’s future; Barrett agreed to leave.[74]

Jenner and King believed Barrett was the creative genius of the band, and decided to represent him and end their relationship with Pink Floyd.[75] Morrison sold his business to NEMS Enterprises, and O’Rourke became the band’s personal manager.[76] Blackhill announced Barrett’s departure on 6 April 1968.[77][nb 18] After Barrett’s departure, the burden of lyrical composition and creative direction fell mostly on Waters.[79] Initially, Gilmour mimed to Barrett’s voice on the group’s European TV appearances; however, while playing on the university circuit, they avoided Barrett songs in favour of Waters and Wright material such as «It Would Be So Nice» and «Careful with That Axe, Eugene».[80]

A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

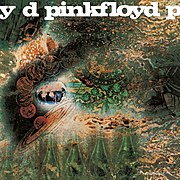

The psychedelic artwork for A Saucerful of Secrets was the first of many Pink Floyd covers designed by Hipgnosis.

In 1968, Pink Floyd returned to Abbey Road Studios to complete their second album, A Saucerful of Secrets, which they had begun in 1967 under Barrett’s leadership. The album included Barrett’s final contribution to their discography, «Jugband Blues». Waters developed his own songwriting, contributing «Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun», «Let There Be More Light», and «Corporal Clegg». Wright composed «See-Saw» and «Remember a Day». Norman Smith encouraged them to self-produce their music, and they recorded demos of new material at their houses. With Smith’s instruction at Abbey Road, they learned how to use the recording studio to realise their artistic vision. However, Smith remained unconvinced by their music, and when Mason struggled to perform his drum part on «Remember a Day», Smith stepped in as his replacement.[81] Wright recalled Smith’s attitude about the sessions, «Norman gave up on the second album … he was forever saying things like, ‘You can’t do twenty minutes of this ridiculous noise‘«.[82] As neither Waters nor Mason could read music, to illustrate the structure of the album’s title track, they invented their own system of notation. Gilmour later described their method as looking «like an architectural diagram».[83]

Released in June 1968, the album featured a psychedelic cover designed by Storm Thorgerson and Aubrey Powell of Hipgnosis. The first of several Pink Floyd album covers designed by Hipgnosis, it was the second time that EMI permitted one of their groups to contract designers for an album jacket.[84] The release reached number nine, spending 11 weeks on the UK chart.[50] Record Mirror gave the album an overall favourable review, but urged listeners to «forget it as background music to a party».[83] John Peel described a live performance of the title track as «like a religious experience», while NME described the song as «long and boring … [with] little to warrant its monotonous direction».[82][nb 19] On the day after the album’s UK release, Pink Floyd performed at the first ever free concert in Hyde Park.[86] In July 1968, they returned to the US for a second visit. Accompanied by the Soft Machine and the Who, it marked Pink Floyd’s first major tour.[87] That December, they released «Point Me at the Sky»; no more successful than the two singles they had released since «See Emily Play», it was their last single until «Money» in 1973.[88]

Ummagumma (1969), Atom Heart Mother (1970) and Meddle (1971)

Pink Floyd in 1971, following Barrett’s departure. From left to right: Waters, Mason, Gilmour, Wright.

Ummagumma represented a departure from Pink Floyd’s previous work. Released as a double-LP on EMI’s Harvest label, the first two sides contained live performances recorded at Manchester College of Commerce and Mothers, a club in Birmingham. The second LP contained a single experimental contribution from each band member.[89] Ummagumma was released in November 1969 and received positive reviews.[90] It reached number five, spending 21 weeks on the UK chart.[50]

In October 1970, Pink Floyd released Atom Heart Mother.[91][nb 20] An early version premièred in England in mid January, but disagreements over the mix prompted the hiring of Ron Geesin to work out the sound problems. Geesin worked to improve the score, but with little creative input from the band, production was troublesome. Geesin eventually completed the project with the aid of John Alldis, who was the director of the choir hired to perform on the record. Smith earned an executive producer credit, and the album marked his final official contribution to the band’s discography. Gilmour said it was «A neat way of saying that he didn’t … do anything».[93] Waters was critical of Atom Heart Mother, claiming that he would prefer if it were «thrown into the dustbin and never listened to by anyone ever again».[94] Gilmour once described it as «a load of rubbish», stating: «I think we were scraping the barrel a bit at that period.»[94] Pink Floyd’s first number-one album, Atom Heart Mother was hugely successful in Britain, spending 18 weeks on the UK chart.[50] It premièred at the Bath Festival on 27 June 1970.[95]

Pink Floyd toured extensively across America and Europe in 1970.[96][nb 21] In 1971, Pink Floyd took second place in a reader’s poll, in Melody Maker, and for the first time were making a profit. Mason and Wright became fathers and bought homes in London while Gilmour, still single, moved to a 19th-century farm in Essex. Waters installed a home recording studio at his house in Islington in a converted toolshed at the back of his garden.[97]

In January 1971, upon their return from touring Atom Heart Mother, Pink Floyd began working on new material.[98] Lacking a central theme, they attempted several unproductive experiments; engineer John Leckie described the sessions as often beginning in the afternoon and ending early the next morning, «during which time nothing would get [accomplished]. There was no record company contact whatsoever, except when their label manager would show up now and again with a couple of bottles of wine and a couple of joints».[99] The band spent long periods working on basic sounds, or a guitar riff. They also spent several days at Air Studios, attempting to create music using a variety of household objects, a project which would be revisited between The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here.[100]

Meddle was released in October 1971, and reached number three, spending 82 weeks on the UK chart.[50] It marks a transition between the Barrett-led group of the late 1960s and the emerging Pink Floyd;[101] Jean-Charles Costa of Rolling Stone wrote that «not only confirms lead guitarist David Gilmour’s emergence as a real shaping force with the group, it states forcefully and accurately that the group is well into the growth track again».[102][nb 22][nb 23] NME called it «an exceptionally good album», singling out «Echoes» as the «Zenith which the Floyd have been striving for».[106] However, Melody Maker’s Michael Watts found it underwhelming, calling the album «a soundtrack to a non-existent movie», and shrugging off Pink Floyd as «so much sound and fury, signifying nothing».[107]

The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

The iconic artwork for The Dark Side of the Moon was designed by Hipgnosis and George Hardie.

Pink Floyd recorded The Dark Side of the Moon between May 1972 and January 1973 with EMI staff engineer Alan Parsons at Abbey Road. The title is an allusion to lunacy rather than astronomy.[108] The band had composed and refined the material while touring the UK, Japan, North America, and Europe.[109] Producer Chris Thomas assisted Parsons.[110] Hipgnosis designed the packaging, which included George Hardie’s iconic refracting prism design on the cover.[111] Thorgerson’s cover features a beam of white light, representing unity, passing through a prism, which represents society. The refracted beam of coloured light symbolises unity diffracted, leaving an absence of unity.[112] Waters is the sole author of the lyrics.[113]

Pink Floyd performing on their early 1973 US tour, shortly before the release of The Dark Side of the Moon

Released in March 1973, the LP became an instant chart success in the UK and throughout Western Europe, earning an enthusiastic response from critics.[114] Each member of Pink Floyd except Wright boycotted the press release of The Dark Side of the Moon because a quadraphonic mix had not yet been completed, and they felt presenting the album through a poor-quality stereo PA system was insufficient.[115] Melody Maker‘s Roy Hollingworth described side one as «utterly confused … [and] difficult to follow», but praised side two, writing: «The songs, the sounds … [and] the rhythms were solid … [the] saxophone hit the air, the band rocked and rolled».[116] Rolling Stone‘s Loyd Grossman described it as «a fine album with a textural and conceptual richness that not only invites, but demands involvement.»[117]

Throughout March 1973, The Dark Side of the Moon featured as part of Pink Floyd’s US tour.[118] The album is one of the most commercially successful rock albums of all time. A US number-one, it remained on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart for more than fourteen years during the 1970s and 1980s, selling more than 45 million copies worldwide.[119] In Britain, it reached number two, spending 364 weeks on the UK chart.[50] The Dark Side of the Moon is the world’s third best-selling album, and the twenty-first best-selling album of all time in the US.[120][121] The success of the album brought enormous wealth to the members of Pink Floyd. Waters and Wright bought large country houses while Mason became a collector of expensive cars.[122] Disenchanted with their US record company, Capitol Records, Pink Floyd and O’Rourke negotiated a new contract with Columbia Records, who gave them a reported advance of $1,000,000 (US$5,494,602 in 2021 dollars).[123] In Europe, they continued to be represented by Harvest Records.[124]

Wish You Were Here (1975)

After a tour of the UK performing Dark Side, Pink Floyd returned to the studio in January 1975 and began work on their ninth studio album, Wish You Were Here.[125] Parsons declined an offer to continue working with them, becoming successful in his own right with the Alan Parsons Project, and so the band turned to Brian Humphries.[126] Initially, they found it difficult to compose new material; the success of The Dark Side of the Moon had left Pink Floyd physically and emotionally drained. Wright later described these early sessions as «falling within a difficult period» and Waters found them «tortuous».[127] Gilmour was more interested in improving the band’s existing material. Mason’s failing marriage left him in a general malaise and with a sense of apathy, both of which interfered with his drumming.[127]

Despite the lack of creative direction, Waters began to visualise a new concept after several weeks.[127] During 1974, Pink Floyd had sketched out three original compositions and had performed them at a series of concerts in Europe.[128] These compositions became the starting point for a new album whose opening four-note guitar phrase, composed purely by chance by Gilmour, reminded Waters of Barrett.[129] The songs provided a fitting summary of the rise and fall of their former bandmate.[130] Waters commented: «Because I wanted to get as close as possible to what I felt … [that] indefinable, inevitable melancholy about the disappearance of Syd.»[131]

While Pink Floyd were working on the album, Barrett made an impromptu visit to the studio. Thorgerson recalled that he «sat round and talked for a bit, but he wasn’t really there».[132] He had changed significantly in appearance, so much so that the band did not initially recognise him. Waters was reportedly deeply upset by the experience.[133][nb 24] Most of Wish You Were Here premiered on 5 July 1975, at an open-air music festival at Knebworth. Released in September, it reached number one in both the UK and the US.[135]

Animals (1977)

Battersea Power Station is featured in the cover image for Animals.

In 1975, Pink Floyd bought a three-storey group of church halls at 35 Britannia Row in Islington and began converting them into a recording studio and storage space.[136] In 1976, they recorded their tenth album, Animals, in their newly finished 24-track studio.[137] The album concept originated with Waters, loosely based on George Orwell’s political fable Animal Farm. The lyrics describe different classes of society as dogs, pigs, and sheep.[138][nb 25] Hipgnosis received credit for the packaging; however, Waters designed the final concept, choosing an image of the ageing Battersea Power Station, over which they superimposed an image of a pig.[140][nb 26]

The division of royalties was a source of conflict between band members, who earned royalties on a per-song basis. Although Gilmour was largely responsible for «Dogs», which took up almost the entire first side of the album, he received less than Waters, who contributed the much shorter two-part «Pigs on the Wing».[143] Wright commented: «It was partly my fault because I didn’t push my material … but Dave did have something to offer, and only managed to get a couple of things on there.»[144] Mason recalled: «Roger was in full flow with the ideas, but he was really keeping Dave down, and frustrating him deliberately.»[144][nb 27] Gilmour, distracted by the birth of his first child, contributed little else toward the album. Similarly, neither Mason nor Wright contributed much toward Animals; Wright had marital problems, and his relationship with Waters was also suffering.[146] Animals was the first Pink Floyd album with no writing credit for Wright, who said: «This was when Roger really started to believe that he was the sole writer for the band … that it was only because of him that [we] were still going … when he started to develop his ego trips, the person he would have his conflicts with would be me.»[146]

Released in January 1977, Animals reached number two in the UK and number three in the US.[147] NME described it as «one of the most extreme, relentless, harrowing and downright iconoclastic hunks of music», and Melody Maker‘s Karl Dallas called it «[an] uncomfortable taste of reality in a medium that has become in recent years, increasingly soporific».[148]

Pink Floyd performed much of Animals during their «In the Flesh» tour. It was their first experience playing large stadiums, whose size caused unease in the band.[149] Waters began arriving at each venue alone, departing immediately after the performance. On one occasion, Wright flew back to England, threatening to quit.[150] At the Montreal Olympic Stadium, a group of noisy and enthusiastic fans in the front row of the audience irritated Waters so much that he spat at one of them.[151][nb 28] The end of the tour marked a low point for Gilmour, who felt that the band achieved the success they had sought, with nothing left for them to accomplish.[152]

1978–1985: Waters-led era

The Wall (1979)

In July 1978, amid a financial crisis caused by negligent investments, Waters presented two ideas for Pink Floyd’s next album. The first was a 90-minute demo with the working title Bricks in the Wall; the other later became Waters’s first solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking. Although both Mason and Gilmour were initially cautious, they chose the former.[153][nb 29] Bob Ezrin co-produced and wrote a forty-page script for the new album.[155] Ezrin based the story on the central figure of Pink—a gestalt character inspired by Waters’s childhood experiences, the most notable of which was the death of his father in World War II. This first metaphorical brick led to more problems; Pink would become drug-addled and depressed by the music industry, eventually transforming into a megalomaniac, a development inspired partly by the decline of Syd Barrett. At the end of the album, the increasingly fascist audience would watch as Pink tore down the wall, once again becoming a regular and caring person.[156][nb 30]

During the recording of The Wall, the band became dissatisfied with Wright’s lack of contribution and fired him.[159] Gilmour said that Wright was dismissed as he «hadn’t contributed anything of any value whatsoever to the album—he did very, very little».[160] According to Mason, Wright would sit in on the sessions «without doing anything, just ‘being a producer‘«.[161] Waters said the band agreed that Wright would either have to «have a long battle» or agree to «leave quietly» after the album was finished; Wright accepted the ultimatum and left.[162][nb 31]

The Wall was supported by Pink Floyd’s first single since «Money», «Another Brick in the Wall (Part II)», which topped the charts in the US and the UK.[165] The Wall was released on 30 November 1979 and topped the Billboard chart in the US for 15 weeks, reaching number three in the UK.[166] It is tied for sixth most certified album by RIAA, with 23 million certified units sold in the US.[167] The cover, with a stark brick wall and band name, was the first Pink Floyd album cover since The Piper at the Gates of Dawn not designed by Hipgnosis.[168]

Gerald Scarfe produced a series of animations for the Wall tour. He also commissioned the construction of large inflatable puppets representing characters from the storyline, including the «Mother», the «Ex-wife» and the «Schoolmaster». Pink Floyd used the puppets during their performances.[169] Relationships within the band reached an all-time low; their four Winnebagos parked in a circle, the doors facing away from the centre. Waters used his own vehicle to arrive at the venue and stayed in different hotels from the rest of the band. Wright returned as a paid musician, making him the only band member to profit from the tour, which lost about $600,000 (US$1,788,360 in 2021 dollars[123]).[170]

The Wall was adapted into a film, Pink Floyd – The Wall. The film was conceived as a combination of live concert footage and animated scenes; however, the concert footage proved impractical to film. Alan Parker agreed to direct and took a different approach. The animated sequences remained, but scenes were acted by actors with no dialogue. Waters was screentested but quickly discarded, and they asked Bob Geldof to accept the role of Pink. Geldof was initially dismissive, condemning The Wall‘s storyline as «bollocks».[171] Eventually won over by the prospect of participation in a significant film and receiving a large payment for his work, Geldof agreed.[172][nb 32] Screened at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1982, Pink Floyd – The Wall premièred in the UK in July 1982.[173][nb 33]

The Final Cut (1983)

In 1982, Waters suggested a project with the working title Spare Bricks, originally conceived as the soundtrack album for Pink Floyd – The Wall. With the onset of the Falklands War, Waters changed direction and began writing new material. He saw Margaret Thatcher’s response to the invasion of the Falklands as jingoistic and unnecessary, and dedicated the album to his late father. Immediately arguments arose between Waters and Gilmour, who felt that the album should include all new material, rather than recycle songs passed over for The Wall. Waters felt that Gilmour had contributed little to the band’s lyrical repertoire.[174] Michael Kamen, a contributor to the orchestral arrangements of The Wall, mediated between the two, also performing the role traditionally occupied by the then-absent Wright.[175][nb 34] The tension within the band grew. Waters and Gilmour worked independently; however, Gilmour began to feel the strain, sometimes barely maintaining his composure. After a final confrontation, Gilmour’s name disappeared from the credit list, reflecting what Waters felt was his lack of songwriting contributions.[177][nb 35]

Though Mason’s musical contributions were minimal, he stayed busy recording sound effects for an experimental Holophonic system to be used on the album. With marital problems of his own, he remained a distant figure. Pink Floyd did not use Thorgerson for the cover design, Waters choosing to design the cover himself.[178][nb 36] Released in March 1983, The Final Cut went straight to number one in the UK and number six in the US.[179] Waters wrote all the lyrics, as well as all the music on the album.[180] Gilmour did not have any material ready for the album and asked Waters to delay the recording until he could write some songs, but Waters refused.[181] Gilmour later commented: «I’m certainly guilty at times of being lazy … but he wasn’t right about wanting to put some duff tracks on The Final Cut.»[181][nb 37] Rolling Stone gave the album five stars, with Kurt Loder calling it «a superlative achievement … art rock’s crowning masterpiece».[183][nb 38] Loder viewed The Final Cut as «essentially a Roger Waters solo album».[185]

Waters’s departure and legal battles

Gilmour recorded his second solo album, About Face, in 1984, and used it to express his feelings about a variety of topics, from the murder of John Lennon to his relationship with Waters. He later stated that he used the album to distance himself from Pink Floyd. Soon afterwards, Waters began touring his first solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking (1984).[186] Wright formed Zee with Dave Harris and recorded Identity, which went almost unnoticed upon its release.[187][nb 39] Mason released his second solo album, Profiles, in August 1985.[188]

Gilmour, Mason, Waters and O’Rourke met for dinner in 1984 to discuss their future. Mason and Gilmour left the restaurant thinking that Pink Floyd could continue after Waters had finished The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, noting that they had had several hiatuses before; however, Waters left believing that Mason and Gilmour had accepted that Pink Floyd were finished. Mason said that Waters later saw the meeting as «duplicity rather than diplomacy», and wrote in his memoir: «Clearly, our communication skills were still troublingly nonexistent. We left the restaurant with diametrically opposed views of what had been decided.»[189]

Following the release of The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, Waters publicly insisted that Pink Floyd would not reunite. He contacted O’Rourke to discuss settling future royalty payments. O’Rourke felt obliged to inform Mason and Gilmour, which angered Waters, who wanted to dismiss him as the band’s manager. He terminated his management contract with O’Rourke and employed Peter Rudge to manage his affairs.[188][nb 40] Waters wrote to EMI and Columbia announcing he had left the band, and asked them to release him from his contractual obligations. Gilmour believed that Waters left to hasten the demise of Pink Floyd. Waters later stated that, by not making new albums, Pink Floyd would be in breach of contract—which would suggest that royalty payments would be suspended—and that the other band members had forced him from the group by threatening to sue him. He went to the High Court in an effort to dissolve the band and prevent the use of the Pink Floyd name, declaring Pink Floyd «a spent force creatively».[191]

When Waters’s lawyers discovered that the partnership had never been formally confirmed, Waters returned to the High Court in an attempt to obtain a veto over further use of the band’s name. Gilmour responded with a press release affirming that Pink Floyd would continue to exist.[192] The sides reached an out-of-court agreement, finalised on Gilmour’s houseboat, the Astoria, on Christmas Eve 1987.[193] In 2013, Waters said he regretted the lawsuit and had failed to appreciate that the Pink Floyd name had commercial value independent of the band members.[194]

1985–present: Gilmour-led era

A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

The Astoria recording studio

In 1986, Gilmour began recruiting musicians for what would become Pink Floyd’s first album without Waters, A Momentary Lapse of Reason.[195][nb 41] There were legal obstacles to Wright’s re-admittance to the band, but after a meeting in Hampstead, Pink Floyd invited Wright to participate in the coming sessions.[196] Gilmour later stated that Wright’s presence «would make us stronger legally and musically», and Pink Floyd employed him with weekly earnings of $11,000.[197]

Recording sessions began on Gilmour’s houseboat, the Astoria, moored along the River Thames.[198][nb 42] The group found it difficult to work without Waters’s creative direction;[200] to write lyrics, Gilmour worked with several songwriters, including Eric Stewart and Roger McGough, eventually choosing Anthony Moore.[201] Wright and Mason were out of practice; Gilmour said they had been «destroyed» by Waters, and their contributions were minimal.[202]

A Momentary Lapse of Reason was released in September 1987. Storm Thorgerson, whose creative input was absent from The Wall and The Final Cut, designed the album cover.[203] To drive home that Waters had left the band, they included a group photograph on the inside cover, the first since Meddle.[204][nb 43] The album went straight to number three in the UK and the US.[206] Waters commented: «I think it’s facile, but a quite clever forgery … The songs are poor in general … [and] Gilmour’s lyrics are third-rate.»[207] Although Gilmour initially viewed the album as a return to the band’s top form, Wright disagreed, stating: «Roger’s criticisms are fair. It’s not a band album at all.»[208] Q described it as essentially a Gilmour solo album.[209]

Waters attempted to subvert the Momentary Lapse of Reason tour by contacting promoters in the US and threatening to sue if they used the Pink Floyd name. Gilmour and Mason funded the start-up costs with Mason using his Ferrari 250 GTO as collateral.[210] Early rehearsals for the tour were chaotic, with Mason and Wright out of practice. Realising he had taken on too much work, Gilmour asked Ezrin to assist them. As Pink Floyd toured North America, Waters’s Radio K.A.O.S. tour was on occasion, close by, in much smaller venues. Waters issued a writ for copyright fees for Pink Floyd’s use of the flying pig. Pink Floyd responded by attaching a large set of male genitalia to its underside to distinguish it from Waters’s design.[211] The parties reached a legal agreement on 23 December; Mason and Gilmour retained the right to use the Pink Floyd name in perpetuity and Waters received exclusive rights to, among other things, The Wall.[212]

The Division Bell (1994)

The album artwork for The Division Bell, designed by Storm Thorgerson, was intended to represent the absence of Barrett and Waters from the band.

For several years, Pink Floyd had busied themselves with personal pursuits, such as filming and competing in the La Carrera Panamericana and recording a soundtrack for a film based on the event.[213][nb 44] In January 1993, they began working on a new album, The Division Bell, in Britannia Row Studios, where Gilmour, Mason and Wright worked collaboratively, improvising material. After about two weeks, they had enough ideas to begin creating songs. Ezrin returned to co-produce the album and production moved to the Astoria, where the band worked from February to May 1993.[215]

Contractually, Wright was not a member of the band, and said «It came close to a point where I wasn’t going to do the album».[216] However, he earned five co-writing credits, his first on a Pink Floyd album since 1975’s Wish You Were Here.[216] Gilmour’s future wife, the novelist Polly Samson, is also credited; she helped Gilmour write tracks including «High Hopes», a collaborative arrangement which, though initially tense, «pulled the whole album together», according to Ezrin.[217] They hired Michael Kamen to arrange the orchestral parts; Dick Parry and Chris Thomas also returned.[218] The writer Douglas Adams provided the album title and Thorgerson the cover artwork.[219][nb 45] Thorgerson drew inspiration from the Moai monoliths of Easter Island; two opposing faces forming an implied third face about which he commented: «the absent face—the ghost of Pink Floyd’s past, Syd and Roger».[221] To avoid competing against other album releases, as had happened with A Momentary Lapse, Pink Floyd set a deadline of April 1994, at which point they would resume touring.[222] The Division Bell reached number 1 in the UK and the US,[121] and spent 51 weeks on the UK chart.[50]

Pink Floyd spent more than two weeks rehearsing in a hangar at Norton Air Force Base in San Bernardino, California, before opening on 29 March 1994, in Miami, with an almost identical road crew to that used for their Momentary Lapse of Reason tour.[223] They played a variety of Pink Floyd favourites, and later changed their setlist to include The Dark Side of the Moon in its entirety.[224][nb 46] The tour, Pink Floyd’s last, ended on 29 October 1994.[225][nb 47] Mason published a memoir, Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd, in 2004.[227]

2005—2006: Live 8 reunion

Waters (right) rejoined his former bandmates at Live 8 in Hyde Park, London on 2 July 2005

On 2 July 2005, Waters, Gilmour, Mason, and Wright performed together as Pink Floyd at Live 8, a benefit concert raising awareness about poverty, in Hyde Park, London.[228] It was their first performance together in more than 24 years.[228] The reunion was arranged by the Live 8 organiser, Bob Geldof. After Gilmour declined, Geldof asked Mason, who contacted Waters. About two weeks later, Waters called Gilmour, their first conversation in two years, and the next day Gilmour agreed. In a statement to the press, the band stressed the unimportance of their problems in the context of the Live 8 event.[115]

The group planned their setlist at the Connaught hotel in London, followed by three days of rehearsals at Black Island Studios.[115] The sessions were problematic, with disagreements over the style and pace of the songs they were practising; the running order was decided on the eve of the event.[229] At the beginning of their performance of «Wish You Were Here», Waters told the audience: «[It is] quite emotional, standing up here with these three guys after all these years, standing to be counted with the rest of you … We’re doing this for everyone who’s not here, and particularly of course for Syd.»[230] At the end, Gilmour thanked the audience and started to walk off the stage. Waters called him back, and the band shared a hug. Images of the hug were a favourite among Sunday newspapers after Live 8.[231][nb 48] Waters said of their almost 20 years of animosity: «I don’t think any of us came out of the years from 1985 with any credit … It was a bad, negative time, and I regret my part in that negativity.»[233]

Though Pink Floyd turned down a contract worth £136 million for a final tour, Waters did not rule out more performances, suggesting it ought to be for a charity event only.[231] However, Gilmour told the Associated Press that a reunion would not happen: «The [Live 8] rehearsals convinced me it wasn’t something I wanted to be doing a lot of … There have been all sorts of farewell moments in people’s lives and careers which they have then rescinded, but I think I can fairly categorically say that there won’t be a tour or an album again that I take part in. It isn’t to do with animosity or anything like that. It’s just … I’ve been there, I’ve done it.»[234]

In February 2006, Gilmour was interviewed for the Italian newspaper La Repubblica, which announced that Pink Floyd had officially disbanded.[235] Gilmour said that Pink Floyd were «over», citing his advancing age and his preference for working alone.[235] He and Waters repeatedly said that they had no plans to reunite.[236][237][nb 49]

2006—2008: Deaths of Barrett and Wright

Barrett died on 7 July 2006, at his home in Cambridge, aged 60.[239] His funeral was held at Cambridge Crematorium on 18 July 2006. No Pink Floyd members attended. Wright said: «The band are very naturally upset and sad to hear of Syd Barrett’s death. Syd was the guiding light of the early band line-up and leaves a legacy which continues to inspire.»[239] Although Barrett had faded into obscurity over the decades, the national press praised him for his contributions to music.[240][nb 50] On 10 May 2007, Waters, Gilmour, Wright, and Mason performed at the Barrett tribute concert «Madcap’s Last Laugh» at the Barbican Centre in London. Gilmour, Wright, and Mason performed the Barrett compositions «Bike» and «Arnold Layne», and Waters performed a solo version of his song «Flickering Flame».[242]

Wright died of an undisclosed form of cancer on 15 September 2008, aged 65.[243] His former bandmates paid tributes to his life and work; Gilmour said that Wright’s contributions were often overlooked, and that his «soulful voice and playing were vital, magical components of our most recognised Pink Floyd sound».[244] A week after Wright’s death, Gilmour performed «Remember a Day» from A Saucerful of Secrets, written and originally sung by Wright, in tribute to him on BBC Two’s Later… with Jools Holland.[245] The keyboardist Keith Emerson released a statement praising Wright as the «backbone» of Pink Floyd.[246]

2010—2011: Further performances and rereleases

In March 2010, Pink Floyd went to the High Court of Justice to prevent EMI selling individual tracks online, arguing that their 1999 contract «prohibits the sale of albums in any configuration other than the original». The judge ruled in their favour, which the Guardian described as a «triumph for artistic integrity» and a «vindication of the album as a creative format».[247] In January 2011, Pink Floyd signed a new five-year contract with EMI that permitted the sale of single downloads.[248]

On 10 July 2010, Waters and Gilmour performed together at a charity event for the Hoping Foundation. The event, which raised money for Palestinian children, took place at Kidlington Hall in Oxfordshire, England, with an audience of approximately 200.[249] In return for Waters’s appearance at the event, Gilmour performed «Comfortably Numb» at Waters’s performance of The Wall[250][nb 51] at the London O2 Arena on 12 May 2011, singing the choruses and playing the two guitar solos. Mason also joined, playing tambourine for «Outside the Wall» with Gilmour on mandolin.[nb 52]

On 26 September 2011, Pink Floyd and EMI launched an exhaustive re-release campaign under the title Why Pink Floyd…?, reissuing the back catalogue in newly remastered versions, including «Experience» and «Immersion» multi-disc multi-format editions. The albums were remastered by James Guthrie, co-producer of The Wall.[253] In November 2015, Pink Floyd released a limited edition EP, 1965: Their First Recordings, comprising six songs recorded prior to The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.[254]

The Endless River (2014) and Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets

In November 2013, Gilmour and Mason revisited recordings made with Wright during the Division Bell sessions to create a new Pink Floyd album. They recruited session musicians to help record new parts and «generally harness studio technology».[255] Waters was not involved.[256] Mason described the album as a tribute to Wright: «I think this record is a good way of recognising a lot of what he does and how his playing was at the heart of the Pink Floyd sound. Listening back to the sessions, it really brought home to me what a special player he was.»[257]

The Endless River was released on 7 November 2014, the second Pink Floyd album distributed by Parlophone following the release of the 20th anniversary editions of The Division Bell earlier in 2014.[258] Though it received mixed reviews,[259] it became the most pre-ordered album of all time on Amazon UK[260] and debuted at number one in several countries.[261][262] The vinyl edition was the fastest-selling UK vinyl release of 2014 and the fastest-selling since 1997.[263] Gilmour said The Endless River would be Pink Floyd’s last album, saying: «I think we have successfully commandeered the best of what there is … It’s a shame, but this is the end.»[264] There was no supporting tour, as Gilmour felt it was impossible without Wright.[265][266] In 2015, Gilmour reiterated that Pink Floyd were «done» and that to reunite without Wright would be wrong.[267]

In November 2016, Pink Floyd released a box set, The Early Years 1965–1972, comprising outtakes, live recordings, remixes, and films from their early career.[268] It was followed in December 2019 by The Later Years, compiling Pink Floyd’s work after Waters’s departure. The set includes a remixed version of A Momentary Lapse of Reason with more contributions by Wright and Mason, and an expanded reissue of the live album Delicate Sound of Thunder.[269] In November 2020, the reissue of Delicate Sound of Thunder was given a standalone release on multiple formats.[270] Pink Floyd’s Live at Knebworth 1990 performance, previously released as part of the Later Years box set, was released on CD and vinyl on 30 April.[271]

In 2018, Mason formed a new band, Nick Mason’s Saucerful of Secrets, to perform Pink Floyd’s early material. The band includes Gary Kemp of Spandau Ballet and the longtime Pink Floyd collaborator Guy Pratt.[272] They toured Europe in September 2018[273] and North America in 2019.[274] Waters joined the band at the New York Beacon Theatre to perform vocals for «Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun».[275]

Mason said in 2018 that, while he remained close to Gilmour and Waters, the two remained «at loggerheads».[276] A remixed version of Animals was delayed until 2022 after Gilmour and Waters could not agree on the liner notes.[277] In a public statement, Waters accused Gilmour of attempting to steal credit and complained that Gilmour would not allow him to use Pink Floyd’s website and social media channels.[277] Rolling Stone noted that the pair seemed «to have hit yet another low point in their relationship».[277]

«Hey, Hey, Rise Up!» (2022)

Andriy Khlyvnyuk, whose vocals are featured in «Hey, Hey, Rise Up!»

In March 2022, Gilmour and Mason reunited as Pink Floyd, alongside bassist Guy Pratt and keyboardist Nitin Sawhney, to record the single «Hey, Hey, Rise Up!», protesting Russian’s invasion of Ukraine that February. It features vocals by the BoomBox singer Andriy Khlyvnyuk, taken from an Instagram video of Khlyvnyuk singing the 1914 Ukrainian anthem «Oh, the Red Viburnum in the Meadow» a cappella in Kyiv. Gilmour described Khlyvnyuk’s performance as «a powerful moment that made me want to put it to music».[278]

«Hey, Hey, Rise Up!» was released on 8 April, with proceeds going to Ukrainian Humanitarian Relief. Gilmour said the war had inspired him to release new music as Pink Floyd as he felt it was important to raise awareness in support of Ukraine.[278] Pink Floyd had already removed music from streaming services in Russia and Belarus. Their work with Waters remained, leading to speculation that Waters had blocked its removal; Gilmour said only that «I was disappointed … Read into that what you will.»[278] He said «Hey, Hey, Rise Up!» was a «one-off for charity» and that Pink Floyd had no plans to reform.[279]

Band members

- Syd Barrett – lead and rhythm guitars, vocals (1965–1968) (died 2006[280])

- David Gilmour – lead and rhythm guitars, vocals, bass, keyboards, synthesisers (1967–present)

- Roger Waters – bass, vocals, rhythm guitar, synthesisers (1965–1985)

- Richard Wright – keyboards, piano, organ, synthesisers, vocals (1965–1979, 1987–2008) (touring/session member 1979–1981 and 1986–1990) (died 2008[281])

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion (1965–present)

Musicianship

Genres

Considered one of the UK’s first psychedelic music groups, Pink Floyd began their career at the vanguard of London’s underground music scene,[282][nb 53] appearing at UFO Club and its successor Middle Earth. According to Rolling Stone: «By 1967, they had developed an unmistakably psychedelic sound, performing long, loud suitelike compositions that touched on hard rock, blues, country, folk, and electronic music.»[285] Released in 1968, the song «Careful with That Axe, Eugene» helped galvanise their reputation as an art rock group.[80] Other genres attributed to the band are space rock,[286] experimental rock,[287] acid rock,[288][289][290] proto-prog,[291] experimental pop (while under Barrett),[292] psychedelic pop,[293] and psychedelic rock.[294] O’Neill Surber comments on the music of Pink Floyd:

Rarely will you find Floyd dishing up catchy hooks, tunes short enough for air-play, or predictable three-chord blues progressions; and never will you find them spending much time on the usual pop album of romance, partying, or self-hype. Their sonic universe is expansive, intense, and challenging … Where most other bands neatly fit the songs to the music, the two forming a sort of autonomous and seamless whole complete with memorable hooks, Pink Floyd tends to set lyrics within a broader soundscape that often seems to have a life of its own … Pink Floyd employs extended, stand-alone instrumentals which are never mere vehicles for showing off virtuoso but are planned and integral parts of the performance.[295]

During the late 1960s, the press labelled Pink Floyd’s music psychedelic pop,[296] progressive pop[297] and progressive rock;[298] they gained a following as a psychedelic pop group.[296][299][300] In 1968, Wright said: «It’s hard to see why we were cast as the first British psychedelic group. We never saw ourselves that way … we realised that we were, after all, only playing for fun … tied to no particular form of music, we could do whatever we wanted … the emphasis … [is] firmly on spontaneity and improvisation.»[301] Waters said later: «There wasn’t anything ‘grand’ about it. We were laughable. We were useless. We couldn’t play at all so we had to do something stupid and ‘experimental’ … Syd was a genius, but I wouldn’t want to go back to playing ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ for hours and hours.»[302] Unconstrained by conventional pop formats, Pink Floyd were innovators of progressive rock during the 1970s and ambient music during the 1980s.[303]

Gilmour’s guitar work

«While Waters was Floyd’s lyricist and conceptualist, Gilmour was the band’s voice and its main instrumental focus.»[304]

—Alan di Perna, in Guitar World, May 2006

Rolling Stone critic Alan di Perna praised Gilmour’s guitar work as integral to Pink Floyd’s sound,[304] and described him as the most important guitarist of the 1970s, «the missing link between Hendrix and Van Halen».[305] Rolling Stone named him the 14th greatest guitarist of all time.[305] In 2006, Gilmour said of his technique: «[My] fingers make a distinctive sound … [they] aren’t very fast, but I think I am instantly recognisable … The way I play melodies is connected to things like Hank Marvin and the Shadows.»[306] Gilmour’s ability to use fewer notes than most to express himself without sacrificing strength or beauty drew a favourable comparison to jazz trumpeter Miles Davis.[307]

In 2006, Guitar World writer Jimmy Brown described Gilmour’s guitar style as «characterised by simple, huge-sounding riffs; gutsy, well-paced solos; and rich, ambient chordal textures.»[307] According to Brown, Gilmour’s solos on «Money», «Time» and «Comfortably Numb» «cut through the mix like a laser beam through fog.»[307] Brown described the «Time» solo as «a masterpiece of phrasing and motivic development … Gilmour paces himself throughout and builds upon his initial idea by leaping into the upper register with gut-wrenching one-and-one-half-step ‘over bends’, soulful triplet arpeggios and a typically impeccable bar vibrato.»[308] Brown described Gilmour’s phrasing as intuitive and perhaps his best asset as a lead guitarist. Gilmour explained how he achieved his signature tone: «I usually use a fuzz box, a delay and a bright EQ setting … [to get] singing sustain … you need to play loud—at or near the feedback threshold. It’s just so much more fun to play … when bent notes slice right through you like a razor blade.»[307]

Sonic experimentation

Throughout their career, Pink Floyd experimented with their sound. Their second single, «See Emily Play» premiered at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in London, on 12 May 1967. During the performance, the group first used an early quadraphonic device called an Azimuth Co-ordinator.[309] The device enabled the controller, usually Wright, to manipulate the band’s amplified sound, combined with recorded tapes, projecting the sounds 270 degrees around a venue, achieving a sonic swirling effect.[310] In 1972, they purchased a custom-built PA which featured an upgraded four-channel, 360-degree system.[311]

Waters experimented with the VCS 3 synthesiser on Pink Floyd pieces such as «On the Run», «Welcome to the Machine», and «In the Flesh?».[312] He used a binson echorec 2 delay effect on his bass-guitar track for «One of These Days».[313]

Pink Floyd used innovative sound effects and state of the art audio recording technology during the recording of The Final Cut. Mason’s contributions to the album were almost entirely limited to work with the experimental Holophonic system, an audio processing technique used to simulate a three-dimensional effect. The system used a conventional stereo tape to produce an effect that seemed to move the sound around the listener’s head when they were wearing headphones. The process enabled an engineer to simulate moving the sound to behind, above or beside the listener’s ears.[314]

Film scores

Pink Floyd also composed several film scores, starting in 1968, with The Committee.[315] In 1969, they recorded the score for Barbet Schroeder’s film More. The soundtrack proved beneficial: not only did it pay well but, along with A Saucerful of Secrets, the material they created became part of their live shows for some time thereafter.[316] While composing the soundtrack for director Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Zabriskie Point, the band stayed at a luxury hotel in Rome for almost a month. Waters claimed that, without Antonioni’s constant changes to the music, they would have completed the work in less than a week. Eventually he used only three of their recordings. One of the pieces turned down by Antonioni, called «The Violent Sequence», later became «Us and Them», included on 1973’s The Dark Side of the Moon.[317] In 1971, the band again worked with Schroeder on the film La Vallée, for which they released a soundtrack album called Obscured by Clouds. They composed the material in about a week at the Château d’Hérouville near Paris, and upon its release, it became Pink Floyd’s first album to break into the top 50 on the US Billboard chart.[318]

Live performances

A live performance of The Dark Side of the Moon at Earls Court, shortly after its release in 1973: (l–r) Gilmour, Mason, Dick Parry, Waters

Regarded as pioneers of live music performance and renowned for their lavish stage shows, Pink Floyd also set high standards in sound quality, making use of innovative sound effects and quadraphonic speaker systems.[319] From their earliest days, they employed visual effects to accompany their psychedelic music while performing at venues such as the UFO Club in London.[33] Their slide-and-light show was one of the first in British rock, and it helped them become popular among London’s underground.[285]

To celebrate the launch of the London Free School’s magazine International Times in 1966, they performed in front of 2,000 people at the opening of the Roundhouse, attended by celebrities including Paul McCartney and Marianne Faithfull.[320] In mid-1966, road manager Peter Wynne-Willson joined their road crew, and updated the band’s lighting rig with some innovative ideas including the use of polarisers, mirrors and stretched condoms.[321] After their record deal with EMI, Pink Floyd purchased a Ford Transit van, then considered extravagant band transportation.[322] On 29 April 1967, they headlined an all-night event called The 14 Hour Technicolour Dream at the Alexandra Palace, London. Pink Floyd arrived at the festival at around three o’clock in the morning after a long journey by van and ferry from the Netherlands, taking the stage just as the sun was beginning to rise.[323][nb 54] In July 1969, precipitated by their space-related music and lyrics, they took part in the live BBC television coverage of the Apollo 11 moon landing, performing an instrumental piece which they called «Moonhead».[325]

In November 1974, they employed for the first time the large circular screen that would become a staple of their live shows.[326] In 1977, they employed the use of a large inflatable floating pig named «Algie». Filled with helium and propane, Algie, while floating above the audience, would explode with a loud noise during the In the Flesh Tour.[327] The behaviour of the audience during the tour, as well as the large size of the venues, proved a strong influence on their concept album The Wall. The subsequent The Wall Tour featured a 40 feet (12 m) high wall, built from cardboard bricks, constructed between the band and the audience. They projected animations onto the wall, while gaps allowed the audience to view various scenes from the story. They commissioned the creation of several giant inflatables to represent characters from the story.[328] One striking feature of the tour was the performance of «Comfortably Numb». While Waters sang his opening verse, in darkness, Gilmour waited for his cue on top of the wall. When it came, bright blue and white lights would suddenly reveal him. Gilmour stood on a flightcase on castors, an insecure setup supported from behind by a technician. A large hydraulic platform supported both Gilmour and the tech.[329]

During the Division Bell Tour, an unknown person using the name Publius posted a message on an internet newsgroup inviting fans to solve a riddle supposedly concealed in the new album. White lights in front of the stage at the Pink Floyd concert in East Rutherford spelled out the words Enigma Publius. During a televised concert at Earls Court on 20 October 1994, someone projected the word «enigma» in large letters on to the backdrop of the stage. Mason later acknowledged that their record company had instigated the Publius Enigma mystery, rather than the band.[224]

Lyrical themes

Marked by Waters’s philosophical lyrics, Rolling Stone described Pink Floyd as «purveyors of a distinctively dark vision».[288] Author Jere O’Neill Surber wrote: «their interests are truth and illusion, life and death, time and space, causality and chance, compassion and indifference.»[330] Waters identified empathy as a central theme in the lyrics of Pink Floyd.[331] Author George Reisch described Meddle‘s psychedelic opus, «Echoes», as «built around the core idea of genuine communication, sympathy, and collaboration with others.»[332] Despite having been labelled «the gloomiest man in rock», author Deena Weinstein described Waters as an existentialist, dismissing the unfavourable moniker as the result of misinterpretation by music critics.[333]

Disillusionment, absence, and non-being

Waters’s lyrics to Wish You Were Here‘s «Have a Cigar» deal with a perceived lack of sincerity on the part of music industry representatives.[334] The song illustrates a dysfunctional dynamic between the band and a record label executive who congratulates the group on their current sales success, implying that they are on the same team while revealing that he erroneously believes «Pink» is the name of one of the band members.[335] According to author David Detmer, the album’s lyrics deal with the «dehumanising aspects of the world of commerce», a situation the artist must endure to reach their audience.[336]

Absence as a lyrical theme is common in the music of Pink Floyd. Examples include the absence of Barrett after 1968, and that of Waters’s father, who died during the Second World War. Waters’s lyrics also explored unrealised political goals and unsuccessful endeavours. Their film score, Obscured by Clouds, dealt with the loss of youthful exuberance that sometimes comes with ageing.[337] Longtime Pink Floyd album cover designer, Storm Thorgerson, described the lyrics of Wish You Were Here: «The idea of presence withheld, of the ways that people pretend to be present while their minds are really elsewhere, and the devices and motivations employed psychologically by people to suppress the full force of their presence, eventually boiled down to a single theme, absence: The absence of a person, the absence of a feeling.»[338][nb 55] Waters commented: «it’s about none of us really being there … [it] should have been called Wish We Were Here«.[339]

O’Neill Surber explored the lyrics of Pink Floyd and declared the issue of non-being a common theme in their music.[330][nb 56] Waters invoked non-being or non-existence in The Wall, with the lyrics to «Comfortably Numb»: «I caught a fleeting glimpse, out of the corner of my eye. I turned to look, but it was gone, I cannot put my finger on it now, the child is grown, the dream is gone.»[337] Barrett referred to non-being in his final contribution to the band’s catalogue, «Jugband Blues»: «I’m most obliged to you for making it clear that I’m not here.»[337]

Exploitation and oppression

Author Patrick Croskery described Animals as a unique blend of the «powerful sounds and suggestive themes» of Dark Side with The Wall‘s portrayal of artistic alienation.[341] He drew a parallel between the album’s political themes and that of Orwell’s Animal Farm.[341] Animals begins with a thought experiment, which asks: «If you didn’t care what happened to me. And I didn’t care for you», then develops a beast fable based on anthropomorphised characters using music to reflect the individual states of mind of each. The lyrics ultimately paint a picture of dystopia, the inevitable result of a world devoid of empathy and compassion, answering the question posed in the opening lines.[342]

The album’s characters include the «Dogs», representing fervent capitalists, the «Pigs», symbolising political corruption, and the «Sheep», who represent the exploited.[343] Croskery described the «Sheep» as being in a «state of delusion created by a misleading cultural identity», a false consciousness.[344] The «Dog», in his tireless pursuit of self-interest and success, ends up depressed and alone with no one to trust, utterly lacking emotional satisfaction after a life of exploitation.[345] Waters used Mary Whitehouse as an example of a «Pig»; being someone who in his estimation, used the power of the government to impose her values on society.[346] At the album’s conclusion, Waters returns to empathy with the lyrical statement: «You know that I care what happens to you. And I know that you care for me too.»[347] However, he also acknowledges that the «Pigs» are a continuing threat and reveals that he is a «Dog» who requires shelter, suggesting the need for a balance between state, commerce and community, versus an ongoing battle between them.[348]

Alienation, war, and insanity

When I say, «I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon» … what I mean [is] … If you feel that you’re the only one … that you seem crazy [because] you think everything is crazy, you’re not alone.[349]

—Waters, quoted in Harris, 2005

O’Neill Surber compared the lyrics of Dark Side of the Moon‘s «Brain Damage» with Karl Marx‘s theory of self-alienation; «there’s someone in my head, but it’s not me.»[350][nb 57] The lyrics to Wish You Were Here‘s «Welcome to the Machine» suggest what Marx called the alienation of the thing; the song’s protagonist preoccupied with material possessions to the point that he becomes estranged from himself and others.[350] Allusions to the alienation of man’s species being can be found in Animals; the «Dog» reduced to living instinctively as a non-human.[351] The «Dogs» become alienated from themselves to the extent that they justify their lack of integrity as a «necessary and defensible» position in «a cutthroat world with no room for empathy or moral principle» wrote Detmer.[352] Alienation from others is a consistent theme in the lyrics of Pink Floyd, and it is a core element of The Wall.[350]

War, viewed as the most severe consequence of the manifestation of alienation from others, is also a core element of The Wall, and a recurring theme in the band’s music.[353] Waters’s father died in combat during the Second World War, and his lyrics often alluded to the cost of war, including those from «Corporal Clegg» (1968), «Free Four» (1972), «Us and Them» (1973), «When the Tigers Broke Free» and «The Fletcher Memorial Home» from The Final Cut (1983), an album dedicated to his late father and subtitled A Requiem for the Postwar Dream.[354] The themes and composition of The Wall express Waters’s upbringing in an English society depleted of men after the Second World War, a condition that negatively affected his personal relationships with women.[355]

Waters’s lyrics to The Dark Side of the Moon dealt with the pressures of modern life and how those pressures can sometimes cause insanity.[356] He viewed the album’s explication of mental illness as illuminating a universal condition.[357] However, Waters also wanted the album to communicate positivity, calling it «an exhortation … to embrace the positive and reject the negative.»[358] Reisch described The Wall as «less about the experience of madness than the habits, institutions, and social structures that create or cause madness.»[359] The Wall‘s protagonist, Pink, is unable to deal with the circumstances of his life, and overcome by feelings of guilt, slowly closes himself off from the outside world inside a barrier of his own making. After he completes his estrangement from the world, Pink realises that he is «crazy, over the rainbow».[360] He then considers the possibility that his condition may be his own fault: «have I been guilty all this time?»[360] Realising his greatest fear, Pink believes that he has let everyone down, his overbearing mother wisely choosing to smother him, the teachers rightly criticising his poetic aspirations, and his wife justified in leaving him. He then stands trial for «showing feelings of an almost human nature», further exacerbating his alienation of species being.[361] As with the writings of philosopher Michel Foucault, Waters’s lyrics suggest Pink’s insanity is a product of modern life, the elements of which, «custom, codependancies, and psychopathologies», contribute to his angst, according to Reisch.[362]

Legacy

Pink Floyd are one of the most commercially successful and influential rock bands of all time.[363] They have sold more than 250 million records worldwide, including 75 million certified units in the United States, and 37.9 million albums sold in the US since 1993.[364] The Sunday Times Rich List, Music Millionaires 2013 (UK), ranked Waters at number 12 with an estimated fortune of £150 million, Gilmour at number 27 with £85 million and Mason at number 37 with £50 million.[365]

In 2003, Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list included The Dark Side of the Moon at number 43,[366] The Wall at number 87,[367] Wish You Were Here at number 209,[368] and The Piper at the Gates of Dawn at number 347.[369] In 2004, on their 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list, Rolling Stone included «Comfortably Numb» at number 314, «Wish You Were Here» at number 316, and «Another Brick in the Wall, Part 2» at number 375.[370]

In 2004, MSNBC ranked Pink Floyd number 8 on their list of «The 10 Best Rock Bands Ever».[371] In the same year, Q named Pink Floyd as the biggest band of all time according to «a points system that measured sales of their biggest album, the scale of their biggest headlining show and the total number of weeks spent on the UK album chart».[372] Rolling Stone ranked them number 51 on their list of «The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time».[373] VH1 ranked them number 18 in the list of the «100 Greatest Artists of All Time».[374] Colin Larkin ranked Pink Floyd number 3 in his list of the ‘Top 50 Artists of All Time’, a ranking based on the cumulative votes for each artist’s albums included in his All Time Top 1000 Albums.[375] In 2008, the head rock and pop critic of The Guardian, Alexis Petridis, wrote that the band occupy a unique place in progressive rock, stating, «Thirty years on, prog is still persona non grata […] Only Pink Floyd—never really a prog band, their penchant for long songs and ‘concepts’ notwithstanding—are permitted into the 100 best album lists.»[376] The writer Eric Olsen has called Pink Floyd «the most eccentric and experimental multi-platinum band of the album rock era».[377]

Pink Floyd have won several awards. In 1981 audio engineer James Guthrie won the Grammy Award for «Best Engineered Non-Classical Album» for The Wall, and Roger Waters won the British Academy of Film and Television Arts award for «Best Original Song Written for a Film» in 1983 for «Another Brick in the Wall» from The Wall film.[378] In 1995, Pink Floyd won the Grammy for «Best Rock Instrumental Performance» for «Marooned».[379] In 2008, Pink Floyd were awarded the Swedish Polar Music Prize for their contribution to modern music.[380] They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996, the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005, and the Hit Parade Hall of Fame in 2010.[381]

Pink Floyd have influenced numerous artists. David Bowie called Barrett a significant inspiration, and the Edge of U2 bought his first delay pedal after hearing the opening guitar chords to «Dogs» from Animals.[382] Other bands and artists who cite them as an influence include Queen, Radiohead, Steven Wilson, Marillion, Queensrÿche, Nine Inch Nails, the Orb and the Smashing Pumpkins.[383] Pink Floyd were an influence on the neo-progressive rock subgenre which emerged in the 1980s.[384] The English rock band Mostly Autumn «fuse the music of Genesis and Pink Floyd» in their sound.[385]

Pink Floyd were admirers of the Monty Python comedy group, and helped finance their 1975 film Monty Python and the Holy Grail.[386] In 2016, Pink Floyd became the second band (after the Beatles) to feature on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail.[387] In May 2017, to mark the 50th anniversary of Pink Floyd’s first single, an audio-visual exhibition, Their Mortal Remains, opened at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.[388] The exhibition featured analysis of cover art, conceptual props from the stage shows, and photographs from Mason’s personal archive.[389][390] Due to its success, it was extended for two weeks beyond its planned closing date of 1 October.[391]

Discography

Studio albums

- The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967)

- A Saucerful of Secrets (1968)

- More (1969)

- Ummagumma (1969)

- Atom Heart Mother (1970)

- Meddle (1971)

- Obscured by Clouds (1972)

- The Dark Side of the Moon (1973)

- Wish You Were Here (1975)

- Animals (1977)

- The Wall (1979)

- The Final Cut (1983)

- A Momentary Lapse of Reason (1987)

- The Division Bell (1994)

- The Endless River (2014)

Concert tours

- Pink Floyd World Tour (1968)

- The Man and The Journey Tour (1969)

- Atom Heart Mother World Tour (1970–71)

- Meddle Tour (1971)

- Dark Side of the Moon Tour (1972–73)

- French Summer Tour (1974)

- British Winter Tour (1974)

- Wish You Were Here Tour (1975)

- In the Flesh Tour (1977)

- The Wall Tour (1980–81)

- A Momentary Lapse of Reason Tour (1987–89)

- The Division Bell Tour (1994)

Notes

- ^ Wright studied architecture until 1963, when he began studying music at London’s Royal College of Music.[4]