B = {9,14,28}

B = {3,9,14},

A = B

B = {1,2,3},

A B = {9,14}

B = {1,2,3},

A — B = {9,14}

B = {1,2,3},

A ∆ B = {1,2,9,14}

B = {1,2,3},

A ⊖ B = {1,2,9,14}

принадлежит

Как записываются множества и подмножества?

Если каждый элемент множества Б является элементом множества А, то множество Б называется подмножеством А. Обозначается: Б ⊂ А. Пример. Сколько существует подмножеств множества А={1, 2, 3}.

Что является множеством и подмножеством?

В математике изучают не только те или иные множества, но и отношения, взаимосвязи между ними (в частности: равенство множеств, включение). Определение 5: Множество В является подмножеством множества А, если каждый элемент множества В является также элементом множества А.

Как обозначают подмножества?

Подмножества Если множество A состоит из элементов, принадлежащих некоторому другому множеству E, то A называют подмножеством или частью множества E. Для обозначения этого используют специальный символ subset , и запись A subset E означает, что «A является подмножеством E».

Что такое подмножество примеры?

Примеры подмножеств: Множество людей является подмножеством приматов, живущих на Земле. Множество квадратов является подмножеством прямоугольников. Множество полосатых летающих слонов – как пустое множество — является подмножеством чего угодно: приматов, чисел, прямоугольников.

Сколько подмножеств в множестве из n элементов?

Теорема 2.1.1. Число подмножеств конечного множества, состоящего из n элементов, равно 2 n . Доказательство. Множество, состоящее из одного элемента a, имеет два (т.

Как найти разность двух множеств?

Можно пользоваться терминами «уменьшаемое», «вычитаемое». Чтобы составить множество-разность надо записать множество, содержащее все элементы множества-уменьшаемого, которые не содержатся в множестве-вычитаемом, т. е. из множества-вычитаемого изъять все элементы, входящие в множество-вычитаемое.

Что такое подмножество в математике 5 класс?

Например: А= {1;2;3;4;5;6;7}. Числа связанные с данным множеством, называются подмножеством множества А. В= {2;4;6} Обозначается : B A. Читается: множество B является подмножеством множества A.

Что такое подмножество 7 класс?

Подмножество может содержать все элементы множества, а может не содержать ни одного (пустое множество; обозначается знаком ∅). Некоторые элементы множества могут принадлежать одновременно разным подмножествам (пример 5.3). Для наглядной геометрической иллюстрации множеств и отношений между ними используют круги Эйлера.

Что называют пересечением?

Пересечением множеств A и B является множество их общих элементов, т. е. всех элементов, принадлежащих и множеству A, и множеству B. Пересечение множеств обозначается: A ∩ B .

Как доказать что множество ограниченно?

Множество X называется ограниченным сверху, если существует действительное число a такое, что x≤a для всех x∈X. Всякое число, обладающее этим свойством, называется верхней гранью множества X.

Что является пересечением двух множеств?

Пересечением множеств A и B является множество их общих элементов, т. е. всех элементов, принадлежащих и множеству A, и множеству B. Пересечение множеств обозначается: A ∩ B .

Чему равна мощность множества?

мощность множества всех k-элементных подмножеств множества N равна Ckn = n! k!(

Какое множество называют универсальным?

Универса́льное мно́жество — в математике множество, содержащее все объекты и все множества. … В аксиоматике фон Неймана — Бернайса — Гёделя существует универсальный класс — класс всех множеств, но множеством он не является. Класс всех множеств является классом объектов категории Set.

Как определить разность?

Чтобы найти разность, надо от уменьшаемого отнять вычитаемое.

Как найти пересечение двух множеств?

Для того чтобы составить пересечение двух числовых множеств, надо последовательно брать элементы первого множества и проверять, принадлежат ли они второму множеству, те из них, которые принадлежат, и будут составлять пересечение.

Что такое соотношение между множествами?

В математике часто используется для обозначения какой-либо связи между предметами или понятиями термин «отношение». Примеры отношений: отношение равенства между двумя или несколькими переменными, фигурами.

Что понимают подмножеством?

Подмножества Под множеством понимают объединение в одно целое объектов, связанных между собой неким свойством. Термин «множество» в математике не всегда обозначает большое количество предметов, оно может состоять и из одного элемента и вообще не содержать элементов, тогда его называют пустым и обозначают Ж.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

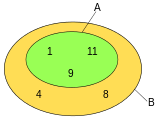

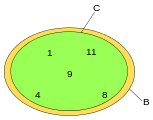

Euler diagram showing

A is a subset of B, A ⊆ B, and conversely B is a superset of A, B ⊇ A.

In mathematics, set A is a subset of a set B if all elements of A are also elements of B; B is then a superset of A. It is possible for A and B to be equal; if they are unequal, then A is a proper subset of B. The relationship of one set being a subset of another is called inclusion (or sometimes containment). A is a subset of B may also be expressed as B includes (or contains) A or A is included (or contained) in B. A k-subset is a subset with k elements.

The subset relation defines a partial order on sets. In fact, the subsets of a given set form a Boolean algebra under the subset relation, in which the join and meet are given by intersection and union, and the subset relation itself is the Boolean inclusion relation.

Definition[edit]

If A and B are sets and every element of A is also an element of B, then:

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B (i.e. there exists at least one element of B which is not an element of A), then:

The empty set, written

When quantified,

We can prove the statement

Let sets A and B be given. To prove that

- suppose that a is a particular but arbitrarily chosen element of A

- show that a is an element of B.

The validity of this technique can be seen as a consequence of Universal generalization: the technique shows

The set of all subsets of

![{displaystyle [A]^{k}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0fe283baada639c7008fb3a8612464d214ee1e5d)

Properties[edit]

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their intersection is equal to A.

- Formally:

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their union is equal to B.

- Formally:

- A finite set A is a subset of B, if and only if the cardinality of their intersection is equal to the cardinality of A.

- Formally:

⊂ and ⊃ symbols[edit]

Some authors use the symbols

Other authors prefer to use the symbols

Examples of subsets[edit]

- The set A = {1, 2} is a proper subset of B = {1, 2, 3}, thus both expressions

and

are true.

- The set D = {1, 2, 3} is a subset (but not a proper subset) of E = {1, 2, 3}, thus

is true, and

is not true (false).

- Any set is a subset of itself, but not a proper subset. (

is true, and

is false for any set X.)

- The set {x: x is a prime number greater than 10} is a proper subset of {x: x is an odd number greater than 10}

- The set of natural numbers is a proper subset of the set of rational numbers; likewise, the set of points in a line segment is a proper subset of the set of points in a line. These are two examples in which both the subset and the whole set are infinite, and the subset has the same cardinality (the concept that corresponds to size, that is, the number of elements, of a finite set) as the whole; such cases can run counter to one’s initial intuition.

- The set of rational numbers is a proper subset of the set of real numbers. In this example, both sets are infinite, but the latter set has a larger cardinality (or power) than the former set.

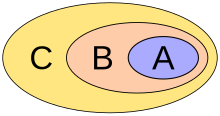

Another example in an Euler diagram:

-

A is a proper subset of B.

-

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B.

Other properties of inclusion[edit]

Inclusion is the canonical partial order, in the sense that every partially ordered set

![[n]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a26847bfc29bbeb4d6ef62ac3fd076378c0fd1db)

![{displaystyle [a]subseteq [b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86c0b0cba950301eacc0a11b017b876d2460a33f)

For the power set

See also[edit]

- Convex subset

- Inclusion order

- Region

- Subset sum problem

- Subsumptive containment

- Total subset

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Rosen, Kenneth H. (2012). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ Epp, Susanna S. (2011). Discrete Mathematics with Applications (Fourth ed.). p. 337. ISBN 978-0-495-39132-6.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- ^ Subsets and Proper Subsets (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23, retrieved 2012-09-07

Bibliography[edit]

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

External links[edit]

Media related to Subsets at Wikimedia Commons

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». MathWorld.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Euler diagram showing

A is a subset of B, A ⊆ B, and conversely B is a superset of A, B ⊇ A.

In mathematics, set A is a subset of a set B if all elements of A are also elements of B; B is then a superset of A. It is possible for A and B to be equal; if they are unequal, then A is a proper subset of B. The relationship of one set being a subset of another is called inclusion (or sometimes containment). A is a subset of B may also be expressed as B includes (or contains) A or A is included (or contained) in B. A k-subset is a subset with k elements.

The subset relation defines a partial order on sets. In fact, the subsets of a given set form a Boolean algebra under the subset relation, in which the join and meet are given by intersection and union, and the subset relation itself is the Boolean inclusion relation.

Definition[edit]

If A and B are sets and every element of A is also an element of B, then:

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B (i.e. there exists at least one element of B which is not an element of A), then:

The empty set, written

When quantified,

We can prove the statement

Let sets A and B be given. To prove that

- suppose that a is a particular but arbitrarily chosen element of A

- show that a is an element of B.

The validity of this technique can be seen as a consequence of Universal generalization: the technique shows

The set of all subsets of

![{displaystyle [A]^{k}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0fe283baada639c7008fb3a8612464d214ee1e5d)

Properties[edit]

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their intersection is equal to A.

- Formally:

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their union is equal to B.

- Formally:

- A finite set A is a subset of B, if and only if the cardinality of their intersection is equal to the cardinality of A.

- Formally:

⊂ and ⊃ symbols[edit]

Some authors use the symbols

Other authors prefer to use the symbols

Examples of subsets[edit]

- The set A = {1, 2} is a proper subset of B = {1, 2, 3}, thus both expressions

and

are true.

- The set D = {1, 2, 3} is a subset (but not a proper subset) of E = {1, 2, 3}, thus

is true, and

is not true (false).

- Any set is a subset of itself, but not a proper subset. (

is true, and

is false for any set X.)

- The set {x: x is a prime number greater than 10} is a proper subset of {x: x is an odd number greater than 10}

- The set of natural numbers is a proper subset of the set of rational numbers; likewise, the set of points in a line segment is a proper subset of the set of points in a line. These are two examples in which both the subset and the whole set are infinite, and the subset has the same cardinality (the concept that corresponds to size, that is, the number of elements, of a finite set) as the whole; such cases can run counter to one’s initial intuition.

- The set of rational numbers is a proper subset of the set of real numbers. In this example, both sets are infinite, but the latter set has a larger cardinality (or power) than the former set.

Another example in an Euler diagram:

-

A is a proper subset of B.

-

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B.

Other properties of inclusion[edit]

Inclusion is the canonical partial order, in the sense that every partially ordered set

![[n]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a26847bfc29bbeb4d6ef62ac3fd076378c0fd1db)

![{displaystyle [a]subseteq [b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86c0b0cba950301eacc0a11b017b876d2460a33f)

For the power set

See also[edit]

- Convex subset

- Inclusion order

- Region

- Subset sum problem

- Subsumptive containment

- Total subset

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Rosen, Kenneth H. (2012). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ Epp, Susanna S. (2011). Discrete Mathematics with Applications (Fourth ed.). p. 337. ISBN 978-0-495-39132-6.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- ^ Subsets and Proper Subsets (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23, retrieved 2012-09-07

Bibliography[edit]

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

External links[edit]

Media related to Subsets at Wikimedia Commons

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». MathWorld.

Из элементов множества можно составлять различные подмножества.

Например, из множества

X=⊲,∨,⊗

можно составить такие подмножества:

Подмножеством множествa (X) называется любое множество (Y), каждый элемент которого является элементом множества (X).

называют знаком включения.

На рисунке фигура (B) полностью находится в фигуре (A).

На математическом языке записывают:

B⊂A

.

Обрати внимание!

Не путай знак принадлежности

∈

и знак включения

⊂

!

Правильно писать следует

3∈−1,0,1,2,3,4

(число (3) является элементом множества

−1,0,1,2,3,4

),

В этом случае в левой части находится число, а не множество.

Источники:

Рис. 1. Подмножество, © ЯКласс.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Euler diagram showing

A is a subset of B, A ⊆ B, and conversely B is a superset of A, B ⊇ A.

In mathematics, set A is a subset of a set B if all elements of A are also elements of B; B is then a superset of A. It is possible for A and B to be equal; if they are unequal, then A is a proper subset of B. The relationship of one set being a subset of another is called inclusion (or sometimes containment). A is a subset of B may also be expressed as B includes (or contains) A or A is included (or contained) in B. A k-subset is a subset with k elements.

The subset relation defines a partial order on sets. In fact, the subsets of a given set form a Boolean algebra under the subset relation, in which the join and meet are given by intersection and union, and the subset relation itself is the Boolean inclusion relation.

Definition[edit]

If A and B are sets and every element of A is also an element of B, then:

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B (i.e. there exists at least one element of B which is not an element of A), then:

The empty set, written

When quantified,

We can prove the statement

Let sets A and B be given. To prove that

- suppose that a is a particular but arbitrarily chosen element of A

- show that a is an element of B.

The validity of this technique can be seen as a consequence of Universal generalization: the technique shows

The set of all subsets of

![{displaystyle [A]^{k}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0fe283baada639c7008fb3a8612464d214ee1e5d)

Properties[edit]

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their intersection is equal to A.

- Formally:

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their union is equal to B.

- Formally:

- A finite set A is a subset of B, if and only if the cardinality of their intersection is equal to the cardinality of A.

- Formally:

⊂ and ⊃ symbols[edit]

Some authors use the symbols

Other authors prefer to use the symbols

Examples of subsets[edit]

- The set A = {1, 2} is a proper subset of B = {1, 2, 3}, thus both expressions

and

are true.

- The set D = {1, 2, 3} is a subset (but not a proper subset) of E = {1, 2, 3}, thus

is true, and

is not true (false).

- Any set is a subset of itself, but not a proper subset. (

is true, and

is false for any set X.)

- The set {x: x is a prime number greater than 10} is a proper subset of {x: x is an odd number greater than 10}

- The set of natural numbers is a proper subset of the set of rational numbers; likewise, the set of points in a line segment is a proper subset of the set of points in a line. These are two examples in which both the subset and the whole set are infinite, and the subset has the same cardinality (the concept that corresponds to size, that is, the number of elements, of a finite set) as the whole; such cases can run counter to one’s initial intuition.

- The set of rational numbers is a proper subset of the set of real numbers. In this example, both sets are infinite, but the latter set has a larger cardinality (or power) than the former set.

Another example in an Euler diagram:

-

A is a proper subset of B.

-

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B.

Other properties of inclusion[edit]

Inclusion is the canonical partial order, in the sense that every partially ordered set

![[n]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a26847bfc29bbeb4d6ef62ac3fd076378c0fd1db)

![{displaystyle [a]subseteq [b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86c0b0cba950301eacc0a11b017b876d2460a33f)

For the power set

See also[edit]

- Convex subset

- Inclusion order

- Region

- Subset sum problem

- Subsumptive containment

- Total subset

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Rosen, Kenneth H. (2012). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ Epp, Susanna S. (2011). Discrete Mathematics with Applications (Fourth ed.). p. 337. ISBN 978-0-495-39132-6.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- ^ Subsets and Proper Subsets (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23, retrieved 2012-09-07

Bibliography[edit]

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

External links[edit]

Media related to Subsets at Wikimedia Commons

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». MathWorld.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Euler diagram showing

A is a subset of B, A ⊆ B, and conversely B is a superset of A, B ⊇ A.

In mathematics, set A is a subset of a set B if all elements of A are also elements of B; B is then a superset of A. It is possible for A and B to be equal; if they are unequal, then A is a proper subset of B. The relationship of one set being a subset of another is called inclusion (or sometimes containment). A is a subset of B may also be expressed as B includes (or contains) A or A is included (or contained) in B. A k-subset is a subset with k elements.

The subset relation defines a partial order on sets. In fact, the subsets of a given set form a Boolean algebra under the subset relation, in which the join and meet are given by intersection and union, and the subset relation itself is the Boolean inclusion relation.

Definition[edit]

If A and B are sets and every element of A is also an element of B, then:

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B (i.e. there exists at least one element of B which is not an element of A), then:

The empty set, written

When quantified,

We can prove the statement

Let sets A and B be given. To prove that

- suppose that a is a particular but arbitrarily chosen element of A

- show that a is an element of B.

The validity of this technique can be seen as a consequence of Universal generalization: the technique shows

The set of all subsets of

![{displaystyle [A]^{k}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0fe283baada639c7008fb3a8612464d214ee1e5d)

Properties[edit]

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their intersection is equal to A.

- Formally:

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their union is equal to B.

- Formally:

- A finite set A is a subset of B, if and only if the cardinality of their intersection is equal to the cardinality of A.

- Formally:

⊂ and ⊃ symbols[edit]

Some authors use the symbols

Other authors prefer to use the symbols

Examples of subsets[edit]

- The set A = {1, 2} is a proper subset of B = {1, 2, 3}, thus both expressions

and

are true.

- The set D = {1, 2, 3} is a subset (but not a proper subset) of E = {1, 2, 3}, thus

is true, and

is not true (false).

- Any set is a subset of itself, but not a proper subset. (

is true, and

is false for any set X.)

- The set {x: x is a prime number greater than 10} is a proper subset of {x: x is an odd number greater than 10}

- The set of natural numbers is a proper subset of the set of rational numbers; likewise, the set of points in a line segment is a proper subset of the set of points in a line. These are two examples in which both the subset and the whole set are infinite, and the subset has the same cardinality (the concept that corresponds to size, that is, the number of elements, of a finite set) as the whole; such cases can run counter to one’s initial intuition.

- The set of rational numbers is a proper subset of the set of real numbers. In this example, both sets are infinite, but the latter set has a larger cardinality (or power) than the former set.

Another example in an Euler diagram:

-

A is a proper subset of B.

-

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B.

Other properties of inclusion[edit]

Inclusion is the canonical partial order, in the sense that every partially ordered set

![[n]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a26847bfc29bbeb4d6ef62ac3fd076378c0fd1db)

![{displaystyle [a]subseteq [b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86c0b0cba950301eacc0a11b017b876d2460a33f)

For the power set

See also[edit]

- Convex subset

- Inclusion order

- Region

- Subset sum problem

- Subsumptive containment

- Total subset

References[edit]

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

- ^ Rosen, Kenneth H. (2012). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ Epp, Susanna S. (2011). Discrete Mathematics with Applications (Fourth ed.). p. 337. ISBN 978-0-495-39132-6.

- ^ Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- ^ Subsets and Proper Subsets (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23, retrieved 2012-09-07

Bibliography[edit]

- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

External links[edit]

Media related to Subsets at Wikimedia Commons

- Weisstein, Eric W. «Subset». MathWorld.