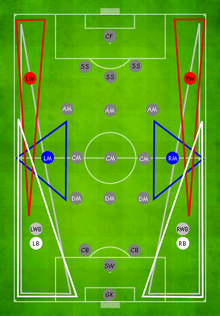

The midfield positions highlighted in relation to other positions in association football

A midfielder is an outfield position in association football.[1] Midfielders may play an exclusively right back role, breaking up attacks, and are in that case known as defensive midfielders. As central midfielders often go across boundaries, with mobility and passing ability, they are often referred to as deep-lying midfielders, play-makers, box-to-box midfielders, or holding midfielders. There are also attacking midfielders with limited defensive assignments.

The size of midfield units on a team and their assigned roles depend on what formation is used; the unit of these players on the pitch is commonly referred to as the midfield.[2] Its name derives from the fact that midfield units typically make up the in-between units to the defensive units and forward units of a formation.

Managers frequently assign one or more midfielders to disrupt the opposing team’s attacks, while others may be tasked with creating goals, or have equal responsibilities between attack and defence. Midfielders are the players who typically travel the greatest distance during a match. Midfielders arguably have the most possession during a game, and thus they are some of the fittest players on the pitch.[3] Midfielders are often assigned the task of assisting forwards to create scoring chances.

Central midfielder[edit]

Central or centre midfielders are players whose role is divided mostly equally between attacking and defensive duties to control the play in and around the centre of the pitch. These players will try to pass the ball to the team’s attacking midfielders and forwards and may also help their team’s attacks by making runs into the opposition’s penalty area and attempting shots on goal themselves. They also provide secondary support to attackers, both in and out of possession.

When the opposing team has the ball, a central midfielder may drop back to protect the goal or move forward and press the opposition ball-carrier to recover the ball. A centre midfielder defending their goal will move in front of their centre-backs to block long shots by the opposition and possibly track opposition midfielders making runs towards the goal.

The 4–3–3 and 4–5–1 formations each use three central midfielders. The 4−4−2 formation may use two central midfielders,[4] and in the 4–2–3–1 formation one of the two deeper midfielders may be a central midfielder. Prominent central midfielders are known for their ability of pacing the game when their team is in possession of the ball, by dictating the tempo of play from the centre of the pitch.

Box-to-box midfielder[edit]

A hardworking box-to-box midfielder, Steven Gerrard has been lauded for his effectiveness both offensively and defensively;[5] and his ability to make late runs from behind into the penalty area.[6]

The term box-to-box midfielder refers to central midfielders who are hard-working and who have good all-round abilities, which makes them skilled at both defending and attacking.[7] These players can therefore track back to their own box to make tackles and block shots and also carry the ball forward or run to the opponents’ box to try to score.[8] Beginning in the mid-2000s, the change of trends and the decline of the standard 4–4–2 formation (in many cases making way for the 4–2–3–1 and 4–3–3 formations) imposed restrictions on the typical box-to-box midfielders of the 1980s and 1990s, as teams’ two midfield roles were now often divided into «holders» or «creators», with a third variation upon the role being described as that of a «carrier» or «surger».[9] Some notable examples of box-to-box midfielders are Lothar Matthäus, Clarence Seedorf, Bastian Schweinsteiger, Steven Gerrard, Johan Neeskens, Sócrates, Yaya Touré, Park Ji-sung, Patrick Vieira, Frank Lampard, Bryan Robson and Roy Keane.[10]

Mezzala[edit]

In Italian football, the term mezzala (literally «half-winger» in Italian) is used to describe the position of the one or two central midfielders who play on either side of a holding midfielder and/or playmaker. The term was initially applied to the role of an inside forward in the WM and Metodo formations in Italian, but later described a specific type of central midfielder. The mezzala is often a quick and hard-working attack-minded midfielder, with good skills and noted offensive capabilities, as well as a tendency to make overlapping attacking runs, but also a player who participates in the defensive aspect of the game, and who can give width to a team by drifting out wide; as such, the term can be applied to several different roles. In English, the term has come to be seen as a variant of the box-to-box midfielder role.[11][12][13][14]

Wide midfielder[edit]

A wide midfielder, David Beckham was lauded for his range of passing, vision, crossing ability and bending free-kicks, which enabled him to create chances for teammates or score goals.[15][17]

Left and right midfielders have a role balanced between attack and defence whilst they play a lot of crosses in the box for forwards.They are positioned closer to the touchlines of the pitch. They may be asked to cross the ball into the opponents’ penalty area to make scoring chances for their teammates, and when defending they may put pressure on opponents who are trying to cross.[18]

Common modern formations that include left and right midfielders are the 4−4−2, the 4−4−1−1, the 4–2–3–1 and the 4−5−1 formations.[19] Jonathan Wilson describes the development of the 4−4−2 formation: «…the winger became a wide midfielder, a shuttler, somebody who might be expected to cross a ball but was also meant to put in a defensive shift.»[20] Two notable examples of wide midfielders are David Beckham and Ryan Giggs.[21]

In Italian football, the role of the wide midfielder is known as tornante di centrocampo or simply tornante («returning»); it originated from the role of an outside forward, and came to be known as such as it often required players in this position to track back and assist the back-line with defensive duties, in addition to aiding the midfield and attacking.[22][23]

Wing-half[edit]

The historic position of wing-half (not to be confused with mezzala) was given to midfielders (half-backs) who played near the side of the pitch. It became obsolete as wide players with defensive duties have tended to become more a part of the defence as full-backs.[24][25]

Defensive midfielder[edit]

Defensive midfielders are midfield players who focus on protecting their team’s goal. These players may defend a zone in front of their team’s defence, or man mark specific opposition attackers.[26][27][28] Defensive midfielders may also move to the full-back or centre-back positions if those players move forward to join in an attack.[29][30]

Sergio Busquets described his attitude: «The coach knows that I am an obedient player who likes to help out and if I have to run to the wing to cover someone’s position, great.»[30] A good defensive midfielder needs good positional awareness, anticipation of opponent’s play, marking, tackling, interceptions, passing and great stamina and strength (for their tackling). In South American football, this role is known as a volante de marca, while in Mexico it is known as volante de contención. In Portugal, it is instead known as trinco.[31]

Holding midfielder[edit]

Yaya Touré, pictured playing for the Ivory Coast in 2012, was a versatile holding midfielder; although his playing style initially led him to be described by pundits as a «carrier», due to his ability to carry the ball and transition from defence to attack, he later adapted to more of a playmaking role.

A holding or deep-lying midfielder stays close to their team’s defence, while other midfielders may move forward to attack.[32] The holding midfielder may also have responsibilities when their team has the ball. This player will make mostly short and simple passes to more attacking members of their team but may try some more difficult passes depending on the team’s strategy. Marcelo Bielsa is considered as a pioneer for the use of a holding midfielder in defence.[9] This position may be seen in the 4–2–3–1 and 4–4–2 diamond formations.[33]

Initially, a defensive midfielder, or «destroyer», and a playmaker, or «creator», were often fielded alongside each other as a team’s two holding central midfielders. The destroyer was usually responsible for making tackles, regaining possession, and distributing the ball to the creator, while the creator was responsible for retaining possession and keeping the ball moving, often with long passes out to the flanks, in the manner of a more old-fashioned deep-lying playmaker or regista (see below). Early examples of a destroyer are Obdulio Varela, Nobby Stiles, Herbert Wimmer, Marco Tardelli, while later examples include Claude Makélélé, Lee Carsley and Javier Mascherano, although several of these players also possessed qualities of other types of midfielders, and were therefore not confined to a single role. Early examples of a creator would be Gérson, Glenn Hoddle, and Sunday Oliseh, while more recent examples are Xabi Alonso and Michael Carrick.

The latest and third type of holding midfielder developed as a box-to-box midfielder, or «carrier» or «surger», neither entirely destructive nor creative, who is capable of winning back possession and subsequently advancing from deeper positions either by distributing the ball to a teammate and making late runs into the box, or by carrying the ball themself; recent examples of this type of player are Clarence Seedorf and Bastian Schweinsteiger, while Sami Khedira and Fernandinho are destroyers with carrying tendencies, Luka Modrić is a carrier with several qualities of the regista, and Yaya Touré was a carrier who became a playmaker, in later part of his career, after losing his stamina.[9]

Deep-lying playmaker (Strolling 10)[edit]

Italian deep-lying playmaker Andrea Pirlo executing a pass for Juventus. Pirlo is often regarded as one of the best deep-lying playmakers of all time.

A deep-lying playmaker is a holding midfielder who specializes in ball skills such as passing, rather than defensive skills like tackling.[35] When this player has the ball, they may attempt longer or more complex passes than other holding players. They may try to set the tempo of their team’s play, retain possession, or build plays through short exchanges, or they may try to pass the ball long to a centre forward or winger, or even pass short to a teammate in the hole, the area between the opponents’ defenders and midfielders.[35][36][37] In Italy, the deep-lying playmaker is known as a regista,[38] whereas in Brazil, it is known as a «meia-armador».[39] In Italy, the role of the regista developed from the centre half-back or centromediano metodista position in Vittorio Pozzo’s metodo system (a precursor of the central or holding midfield position in the 2–3–2–3 formation), as the metodista‘s responsibilities were not entirely defensive but also creative; as such, the metodista was not solely tasked with breaking down possession, but also with starting attacking plays after winning back the ball.[40]

Writer Jonathan Wilson instead described Xabi Alonso’s holding midfield role as that of a «creator», a player who was responsible for retaining possession in the manner of a more old-fashioned deep-lying playmaker or regista, noting that: «although capable of making tackles, [Alonso] focused on keeping the ball moving, occasionally raking long passes out to the flanks to change the angle of attack.»[9]

Centre-half[edit]

The historic central half-back position gradually retreated from the midfield line to provide increased protection to the back line against centre-forwards – that dedicated defensive role in the centre is still commonly referred to as a «centre-half» as a legacy of its origins.[41] In Italian football jargon, this position was known as the centromediano metodista or metodista, as it became an increasingly important role in Vittorio Pozzo’s metodo system, although this term was later also applied to describe players who operated in a central holding-midfielder role, but who also had creative responsibilities in addition to defensive duties.[40]

Attacking midfielder[edit]

An attacking midfielder is a midfield player who is positioned in an advanced midfield position, usually between central midfield and the team’s forwards, and who has a primarily offensive role.[42]

Some attacking midfielders are called trequartista or fantasista (Italian: three-quarter specialist, i.e. a creative playmaker between the forwards and the midfield), who are usually mobile, creative and highly skilful players, known for their deft touch, technical ability, dribbling skills, vision, ability to shoot from long range, and passing prowess.

However, not all attacking midfielders are trequartistas – some attacking midfielders are very vertical and are essentially auxiliary attackers who serve to link-up play, hold up the ball, or provide the final pass, i.e. secondary strikers.[43] As with any attacking player, the role of the attacking midfielder involves being able to create space for attack.[44]

According to positioning along the field, attacking midfield may be divided into left, right and central attacking midfield roles but most importantly they are a striker behind the forwards. A central attacking midfielder may be referred to as a playmaker, or number 10 (due to the association of the number 10 shirt with this position).[45][46]

Advanced playmaker[edit]

These players typically serve as the offensive pivot of the team, and are sometimes said to be «playing in the hole», although this term can also be used as deep-lying forward. The attacking midfielder is an important position that requires the player to possess superior technical abilities in terms of passing and dribbling, as well as, perhaps more importantly, the ability to read the opposing defence to deliver defence-splitting passes to the striker.

This specialist midfielder’s main role is to create good shooting and goal-scoring opportunities using superior vision, control, and technical skill, by making crosses, through balls, and headed knockdowns to teammates. They may try to set up shooting opportunities for themselves by dribbling or performing a give-and-go with a teammate. Attacking midfielders may also make runs into the opponents’ penalty area to shoot from another teammate’s pass.[2]

Where a creative attacking midfielder, i.e. an Advanced playmaker, is regularly utilized, they are commonly the team’s star player, and often wear the number 10 shirt. As such, a team is often constructed so as to allow their attacking midfielder to roam free and create as the situation demands. One such popular formation is the 4–4–2 «diamond» (or 4–1–2–1–2), in which defined attacking and defensive midfielders replace the more traditional pair of central midfielders. Known as the «fantasista» or «trequartista» in Italy,[43] in Spain, the offensive playmaker is known as the «Mediapunta, in Brazil, the offensive playmaker is known as the «meia atacante«,[39] whereas in Argentina and Uruguay, it is known as the «enganche«.[47] Some examples of the advanced playmaker would be Zico, Francesco Totti, Kevin De Bruyne, Martin Ødegaard and Juan Riquelme.

There are also some examples of more flexible advanced playmakers, such as Zinedine Zidane, Andrés Iniesta, David Silva, and Nécib. These players could control the tempo of the game in deeper areas of the pitch while also being able to push forward and play line-breaking through balls.[48][49][50][51][52]

Mesut Özil can be considered as a classic 10 who adopted a slightly more direct approach and specialised in playing the final ball.

False attacking midfielder[edit]

The false attacking midfielder description has been used in Italian football to describe a player who is seemingly playing as an attacking midfielder in a 4–3–1–2 formation, but who eventually drops deeper into midfield, drawing opposing players out of position and creating space to be exploited by teammates making attacking runs; the false-attacking midfielder will eventually sit in a central midfield role and function as a deep-lying playmaker. The false-attacking midfielder is therefore usually a creative and tactically intelligent player with good vision, technique, movement, passing ability, and striking ability from distance. They should also be a hard-working player, who is able to read the game and help the team defensively.[53] Wayne Rooney has been deployed in a similar role, on occasion; seemingly positioned as a number 10 behind the main striker, he would often drop even deeper into midfield to help his team retrieve possession and start attacks.[54]

«False 10» or «central winger»[edit]

The «false 10» or «central winger»[55] is a type of midfielder, which differs from the false-attacking midfielder. Much like the «false 9», their specificity lies in the fact that, although they seemingly play as an attacking midfielder on paper, unlike a traditional playmaker who stays behind the striker in the centre of the pitch, the false 10’s goal is to move out of position and drift wide when in possession of the ball to help both the wingers and fullbacks to overload the flanks. This means two problems for the opposing midfielders: either they let the false 10 drift wide, and their presence, along with both the winger and the fullback, creates a three-on-two player advantage out wide; or they follow the false 10, but leave space in the centre of the pitch for wingers or onrushing midfielders to exploit. False 10s are usually traditional wingers who are told to play in the centre of the pitch, and their natural way of playing makes them drift wide and look to provide deliveries into the box for teammates. On occasion, the false-10 can also function in a different manner alongside a false-9, usually in a 4–6–0 formation, disguised as either a 4–3–3 or 4–2–3–1 formation. When other forwards or false-9s drop deep and draw defenders away from the false-10s, creating space in the middle of the pitch, the false-10 will then also surprise defenders by exploiting this space and moving out of position once again, often undertaking offensive dribbling runs forward towards goal, or running on to passes from false-9s, which in turn enables them to create goalscoring opportunities or go for goal themselves.[56]

Winger[edit]

«Right winger» redirects here. For the political position, see Right-wing politics.

Players in the bold positions can be referred to as wingers.

In modern football, the terms winger or wide player refer to a non-defender who plays on the left or right sides of the pitch. These terms can apply to left or right midfielders, left or right attacking midfielders, or left or right forwards.[18] Left or right-sided defenders such as wing-backs or full-backs are generally not called wingers.

In the 2−3−5 formation popular in the late 19th century wingers remained mostly near the touchlines of the pitch, and were expected to cross the ball for the team’s inside and centre forwards.[57] Traditionally, wingers were purely attacking players and were not expected to track back and defend. This began to change in the 1960s. In the 1966 World Cup, England manager Alf Ramsey did not select wingers from the quarter-final onwards. This team was known as the «Wingless Wonders» and led to the modern 4–4–2 formation.[58][59]

This has led to most modern wide players having a more demanding role in the sense that they are expected to provide defensive cover for their full-backs and track back to repossess the ball, as well as provide skillful crosses for centre forwards and strikers.[60] Some forwards are able to operate as wingers behind a lone striker. In a three-man midfield, specialist wingers are sometimes deployed down the flanks alongside the central midfielder or playmaker.

Even more demanding is the role of wing-back, where the wide player is expected to provide both defence and attack.[61] As the role of winger can be classed as a forward or a midfielder, this role instead blurs the divide between defender and midfielder. Italian manager Antonio Conte has been known to use wide midfielders or wingers who act as wing-backs in his trademark 3–5–2 and 3–4–3 formations, for example; these players are expected both to push up and provide width in attack as well as track back and assist their team defensively.[62]

On occasion, the role of a winger can also be occupied by a different type of player. For example, certain managers have been known to use a «wide target man» on the wing, namely a large and physical player who usually plays as a centre-forward, and who will attempt to win aerial challenges and hold up the ball on the flank, or drag full-backs out of position; Romelu Lukaku, for example, has been used in this role on occasion.[63] Another example is Mario Mandžukić under manager Massimiliano Allegri at Juventus during the 2016–17 season; normally a striker, he was instead used on the left flank, and was required to win aerial duels, hold up the ball, and create space, as well as being tasked with pressing opposing players.[64]

Wingers are indicated in red, while the «wide men» (who play to the flanks of the central midfielders) are indicated in blue.

Today, a winger is usually an attacking midfielder who is stationed in a wide position near the touchlines.[60] Wingers such as Stanley Matthews or Jimmy Johnstone used to be classified as outside forwards in traditional W-shaped formations, and were formally known as «Outside Right» or «Outside Left», but as tactics evolved through the last 40 years, wingers have dropped to deeper field positions and are now usually classified as part of the midfield, usually in 4–4–2 or 4–5–1 formations (but while the team is on the attack, they tend to resemble 4–2–4/2–4–4 and 4–3–3 formations respectively).

The responsibilities of the winger include:

- Providing a «wide presence» as a passing option on the flank.

- To beat the opposing full-back either with skill or with speed.

- To read passes from the midfield that give them a clear crossing opportunity, when going wide, or that give them a clear scoring opportunity, when cutting inside towards goal.

- To double up on the opposition winger, particularly when they are being «double-marked» by both the team’s full back and winger.

The prototypical winger is fast, tricky and enjoys ‘hugging’ the touchline, that is, running downfield close to the touchline and delivering crosses. However, players with different attributes can thrive on the wing as well. Some wingers prefer to cut infield (as opposed to staying wide) and pose a threat as playmakers by playing diagonal passes to forwards or taking a shot at goal. Even players who are not considered quick, have been successfully fielded as wingers at club and international level for their ability to create play from the flank. Occasionally wingers are given a free role to roam across the front line and are relieved of defensive responsibilities.

The typical abilities of wingers include:

- Technical skill to beat a full-back in a one-to-one situation.

- Pace, to beat the full-back one-on-one.

- Crossing ability when out wide.

- Good off-the-ball ability when judging a pass from the midfield or from fellow attackers.

- Good passing ability and composure, to retain possession while in opposition territory.

- The modern winger should also be comfortable on either wing so as to adapt to quick tactical changes required by the coach.

Although wingers are a familiar part of football, the use of wingers is by no means universal. There are many successful football teams who operate without wingers. A famous example is Carlo Ancelotti’s late 2000s Milan, who typically play in a narrow midfield diamond formation or in a Christmas tree formation (4–3–2–1), relying on full-backs to provide the necessary width down the wings.

Inverted winger[edit]

USWNT midfielder Megan Rapinoe (left) has been deployed as an inverted winger throughout her career.

An inverted winger is a modern tactical development of the traditional winger position. Most wingers are assigned to either side of the field based on their footedness, with right-footed players on the right and left-footed players on the left.[65] This assumes that assigning a player to their natural side ensures a more powerful cross as well as greater ball-protection along the touch-lines. However, when the position is inverted and a winger instead plays inside-out on the opposite flank (i.e., a right-footed player as a left inverted winger), they effectively become supporting strikers and primarily assume a role in the attack.[66]

As opposed to traditionally pulling the opponent’s full-back out and down the flanks before crossing the ball in near the by-line, positioning a winger on the opposite side of the field allows the player to cut-in around the 18-yard box, either threading passes between defenders or shooting on goal using the dominant foot.[67] This offensive tactic has found popularity in the modern game due to the fact that it gives traditional wingers increased mobility as playmakers and goalscorers,[68] such as the left-footed right winger Domenico Berardi of Sassuolo who achieved 30 career goals faster than any player in the past half-century of Serie A football.[69] Not only are inverted wingers able to push full-backs onto their weak sides, but they are also able to spread and force the other team to defend deeper as forwards and wing-backs route towards the goal, ultimately creating more scoring opportunities.[70]

Although naturally left-footed Arjen Robben (left, 11) has often been deployed as an inverted winger on the right flank throughout his career, which allows him to cut inside and shoot on goal with his stronger foot.

Other midfielders within this tactical archetype include Lionel Messi[71] and Eden Hazard,[72] as well as Megan Rapinoe of the USWNT.[73] Clubs such as Real Madrid often choose to play their wingers on the «wrong» flank for this reason; former Real Madrid coach José Mourinho often played Ángel Di María on the right and Cristiano Ronaldo on the left.[74][75][76] Former Bayern Munich manager Jupp Heynckes often played the left-footed Arjen Robben on the right and the right-footed Franck Ribéry on the left.[77][78] One of the foremost practitioners of playing from either flank was German winger Jürgen Grabowski, whose flexibility helped Germany to third place in the 1970 World Cup, and the world title in 1974.

A description that has been used in the media to label a variation upon the inverted winger position is that of an «attacking», «false», or «goalscoring winger», as exemplified by Cristiano Ronaldo’s role on the left flank during his time at Real Madrid in particular. This label has been used to describe an offensive-minded inverted winger, who will seemingly operate out wide on paper, but who instead will be given the freedom to make unmarked runs into more advanced central areas inside the penalty area to get on the end of passes and crosses and score goals, effectively functioning as a striker.[79][80][81][82][83] This role is somewhat comparable to what is known as the raumdeuter role in German football jargon (literally «space interpreter»), as exemplified by Thomas Müller, namely an attacking-minded wide player, who will move into central areas to find spaces from which they can receive passes and score or assist goals.[63][84]

False winger[edit]

The «false winger» or «seven-and-a-half» is a label which has been used to describe a type of player who normally plays centrally, but who instead is deployed out wide on paper; during the course of a match, however, they will move inside and operate in the centre of the pitch to drag defenders out of position, congest the midfield and give their team a numerical advantage in this area, so that they can dominate possession in the middle of the pitch and create chances for the forwards; this position also leaves space for full-backs to make overlapping attacking runs up the flank. Samir Nasri, who has been deployed in this role, once described it as that of a «non-axial playmaker».[85][86][87][88][89][90][91]

See also[edit]

Association football portal

- Association football positions

- Association football tactics

- Defender (association football)

- Forward (association football)

- Goalkeeper (association football)

References[edit]

- ^

«Positions guide: Central midfield». London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2013. - ^ a b «Football / Soccer Positions». Keanu salah. Expert Football. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Di Salvo, V. (6 October 2005). «Performance characteristics according to playing position in elite soccer». International Journal of Sports Medicine. 28 (3): 222–227. doi:10.1055/s-2006-924294. PMID 17024626.

- ^ «Formations guide». BBC Sport. September 2005. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ «Steven Gerrard completes decade at Liverpool». The Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Bull, JJ (30 March 2020). «Retro Premier League review: Why 2008/09 was Steven Gerrard’s peak season». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ «Box to box Bowyer». London: BBC Sport. 29 April 2002. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Cox, Michael (4 June 2014). «In praise of the box-to-box midfielder». ESPN FC. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Jonathan (18 December 2013). «The Question: what does the changing role of holding midfielders tell us?». The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ The Best Box-to-Box Midfielders of All-Time

- ^ Tallarita, Andrea (4 September 2018). «Just what is a mezzala?». Football Italia. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ «Understanding roles in Football Manager (and real life) (part 2)». Medium. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «English translation of ‘mezzala’«. Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Walker-Roberts, James (25 February 2018). «How Antonio Conte got the best from Paul Pogba at Juventus». Sky Sports. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Kings of the free-kick». FIFA. Retrieved 20 December 2014

- ^ «England – Who’s Who: David Beckham». ESPN FC. 3 September 2002. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b «Wide midfielder». BBC Sport. September 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ «Formations guide». London: BBC Sport. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (24 March 2010). «The Question: Why are so many wingers playing on the ‘wrong’ wings?». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Daniel (18 February 2010). «Milan wrong to play David Beckham in central midfield says Sir Alex Ferguson». The Guardian. England. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ «Genoa: Top 11 All Time» (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ «tornante». La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ «Old football formations explained — Classic soccer tactics & strategies». Football Bible. n.d. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ «Football Glossary, Letter W». Football Bible. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ Cox, Michael (20 January 2013). «Manchester United nullified Gareth Bale but forgot about Aaron Lennon». The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (16 July 2010). «The final analysis, part three: brilliant Busquets». zonalmarking.net. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Cox, Michael (10 February 2013). «How Manchester United nullified threat of Everton’s Marouane Fellaini». The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (3 March 2010). «Analysing Brazil’s fluid system at close quarters». zonalmarking.net. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ a b Lowe, Sid (27 May 2011). «Sergio Busquets: Barcelona’s best supporting actor sets the stage». The Guardian. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ «50 Best Defensive Midfielders in World Football History». Bleacher Report. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ F., Edward (28 January 2014). «On Going Beyond Holding Midfielders». Cartilage Free Captain. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (29 January 2010). «Teams of the Decade #11: Valencia 2001-04». zonalmarking.net. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (2013). Inverting the Pyramid. Nation Books. ISBN 9781568589633.

- ^ a b Cox, Michael (19 March 2012). «Paul Scholes, Xavi and Andrea Pirlo revive the deep-lying playmaker». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ Goldblatt, David (2009). The Football Book. Dorling Kindersley. p. 48. ISBN 978-1405337380.

- ^ Dunmore, Thomas (2013). Soccer for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-51066-7.

- ^ «The Regista And the Evolution Of The Playmaker». 5 July 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b «Playmaker». MTV. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b Radogna, Fiorenzo (20 December 2018). «Mezzo secolo senza Vittorio Pozzo, il mitico (e discusso) c.t. che cambiò il calcio italiano: Ritiri e regista». Il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). p. 8. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (20 September 2011). «The Question: Did Herbert Chapman really invent the W-M formation?». The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ «Positions in football». talkfootball.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ a b «The Number 10». RobertoMancini.com. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Michalak, Joakim. «Identifying football players who create and generate space». Uppsala University Publications. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (18 August 2010). «The Question: What is a playmaker’s role in the modern game?». TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (26 March 2010). «How the 2000s changed tactics #2: Classic Number 10s struggle». ZonalMarking.net. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ «Tactics: the changing role of the playmaker». Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Ciaran Kelly (7 December 2011). «Zinedine Zidane: The Flawed Genius». Back Page Football. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Bandini, Paolo (3 May 2017). «Year Zero: The making of Zinedine Zidane (Juventus, 1996/97)». FourFourTwo. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Vincenzi, Massimo (4 December 2000). «Zidane vede il Pallone d’oro ma Sheva è il suo scudiero». La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ «More to come from Louisa Necib». Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (in French). 14 July 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Jason Cowley (18 June 2006). «Lonesome Riquelme is the go-to man». The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ James Horncastle. «Horncastle: Riccardo Montolivo straddles both sides of the Germany/Italy divide». The Score. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (20 December 2011). «The football tactical trends of 2011». the Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ «Introducing…the central winger?». zonalmarking.net. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ «The False-10». Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (2013). «It’s a Simple Game». Football League 125. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Galvin, Robert. «Sir Alf Ramsey». National Football Museum. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ «Chelsea prayers fly to the wings». FIFA. 5 March 2006. Archived from the original on 7 November 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- ^ a b «Positions guide: Wide midfield». London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ «Positions guide: Wing-back». London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Debono, Matt (17 July 2019). «The issues with Antonio Conte’s 3-5-2 system». Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b «Understanding roles in Football Manager (and real life) (part 1)». Medium. 13 May 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Homewood, Brian (10 May 2017). «Versatile Mandzukic becomes Juve’s secret weapon». Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Barve, Abhijeet (28 February 2013). «Football Jargon for dummies Part 2- Inverted Wingers». Football Paradise. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Johnathan (2013). Inverting The Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics. New York, NY: Nation Books. pp. 373, 377. ISBN 978-1568587387.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (24 March 2010). «The Question: Why are so many wingers playing on the ‘wrong’ wings?». The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Singh, Amit (21 June 2012). «Positional Analysis: What Has Happened To All The Wingers?». Just-Football.com.

- ^ Newman, Blair (8 September 2015). «The young players who could rejuvenate Antonio Conte’s Italy at Euro 2016». The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Goodman, Mike L. (6 June 2014). «How to Watch the World Cup Like a True Soccer Nerd». Grantland. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Reng, Ronald (27 May 2011). «Lionel Messi». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Silvestri, Stefano (15 August 2016). «Diego Costa fa felice Conte: il Chelsea batte il West Ham all’89’» (in Italian). Eurosport. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ «11 Questions with Megan Rapinoe» (Interview). www.ussoccer.com. 22 September 2009.

- ^ Al-Hendy, Mohamed (17 May 2012). «Real Madrid: Tactical Review of the 2011-12 Season Under Jose Mourinho». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Tighe, Sam (21 November 2012). «Breaking Down the 10 Most Popular Formations in World Football». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Richards, Alex (30 July 2013). «The 15 Best Wingers in World Football». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Koch, Ben (1 February 2011). «Tactics Tuesday: Natural vs. Inverted Wingers». Fútbol for Gringos. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ «Robbery, Aubameyang and Mkhitaryan and the Bundesliga’s Top 10 telepathic understandings». Bundesliga. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Dunne, Robbie (14 March 2018). «Cristiano Ronaldo evolving into an effective striker for Real Madrid». ESPN FC. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ MOLINARO, JOHN. «RONALDO VS. MESSI: THE CASE FOR RONALDO AS WORLD’S BEST PLAYER». Sportsnet. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Driscoll, Jon (2 August 2018). «Cristiano Ronaldo’s rise at Real Madrid». Football Italia. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Goodman, Mike (8 March 2016). «Are Real Madrid ready for life without Cristiano Ronaldo?». ESPN FC. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Laurence, Martin (11 February 2013). «Bale and Ronaldo comparisons not so ridiculous». ESPN FC. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Thomas Müller: the most under-appreciated player in world football». bundesliga.com. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Cox, Michael (6 August 2013). «Roberto Soldado perfectly anchors AVB’s ‘vertical’ football». ESPN FC. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Cox, Michael (18 November 2016). «Man United must play Paul Pogba in best position to get the most from him». ESPN FC. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Baldi, Ryan (1 July 2016). «Man United, meet Miki: The one-man arsenal who’ll revitalise your attack». FourFourTwo. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Davis, Toby (22 March 2015). «ANALYSIS-Soccer-Van Gaal’s tactical wits edge battle of the bosses». Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Murray, Andrew (16 August 2016). «The long read: Guardiola’s 16-point blueprint for dominance — his methods, management and tactics». FourFourTwo. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Ndiyo, David (3 August 2017). «Julian Weigl: The Modern Day Regista». Medium. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ McNicholas, James (1 July 2015). «The Tactical Evolution of Arsenal Midfielder Santi Cazorla». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

External links[edit]

Media related to Association football midfielders at Wikimedia Commons

[[Category:Association football player non-biographical articles]

The midfield positions highlighted in relation to other positions in association football

A midfielder is an outfield position in association football.[1] Midfielders may play an exclusively right back role, breaking up attacks, and are in that case known as defensive midfielders. As central midfielders often go across boundaries, with mobility and passing ability, they are often referred to as deep-lying midfielders, play-makers, box-to-box midfielders, or holding midfielders. There are also attacking midfielders with limited defensive assignments.

The size of midfield units on a team and their assigned roles depend on what formation is used; the unit of these players on the pitch is commonly referred to as the midfield.[2] Its name derives from the fact that midfield units typically make up the in-between units to the defensive units and forward units of a formation.

Managers frequently assign one or more midfielders to disrupt the opposing team’s attacks, while others may be tasked with creating goals, or have equal responsibilities between attack and defence. Midfielders are the players who typically travel the greatest distance during a match. Midfielders arguably have the most possession during a game, and thus they are some of the fittest players on the pitch.[3] Midfielders are often assigned the task of assisting forwards to create scoring chances.

Central midfielder[edit]

Central or centre midfielders are players whose role is divided mostly equally between attacking and defensive duties to control the play in and around the centre of the pitch. These players will try to pass the ball to the team’s attacking midfielders and forwards and may also help their team’s attacks by making runs into the opposition’s penalty area and attempting shots on goal themselves. They also provide secondary support to attackers, both in and out of possession.

When the opposing team has the ball, a central midfielder may drop back to protect the goal or move forward and press the opposition ball-carrier to recover the ball. A centre midfielder defending their goal will move in front of their centre-backs to block long shots by the opposition and possibly track opposition midfielders making runs towards the goal.

The 4–3–3 and 4–5–1 formations each use three central midfielders. The 4−4−2 formation may use two central midfielders,[4] and in the 4–2–3–1 formation one of the two deeper midfielders may be a central midfielder. Prominent central midfielders are known for their ability of pacing the game when their team is in possession of the ball, by dictating the tempo of play from the centre of the pitch.

Box-to-box midfielder[edit]

A hardworking box-to-box midfielder, Steven Gerrard has been lauded for his effectiveness both offensively and defensively;[5] and his ability to make late runs from behind into the penalty area.[6]

The term box-to-box midfielder refers to central midfielders who are hard-working and who have good all-round abilities, which makes them skilled at both defending and attacking.[7] These players can therefore track back to their own box to make tackles and block shots and also carry the ball forward or run to the opponents’ box to try to score.[8] Beginning in the mid-2000s, the change of trends and the decline of the standard 4–4–2 formation (in many cases making way for the 4–2–3–1 and 4–3–3 formations) imposed restrictions on the typical box-to-box midfielders of the 1980s and 1990s, as teams’ two midfield roles were now often divided into «holders» or «creators», with a third variation upon the role being described as that of a «carrier» or «surger».[9] Some notable examples of box-to-box midfielders are Lothar Matthäus, Clarence Seedorf, Bastian Schweinsteiger, Steven Gerrard, Johan Neeskens, Sócrates, Yaya Touré, Park Ji-sung, Patrick Vieira, Frank Lampard, Bryan Robson and Roy Keane.[10]

Mezzala[edit]

In Italian football, the term mezzala (literally «half-winger» in Italian) is used to describe the position of the one or two central midfielders who play on either side of a holding midfielder and/or playmaker. The term was initially applied to the role of an inside forward in the WM and Metodo formations in Italian, but later described a specific type of central midfielder. The mezzala is often a quick and hard-working attack-minded midfielder, with good skills and noted offensive capabilities, as well as a tendency to make overlapping attacking runs, but also a player who participates in the defensive aspect of the game, and who can give width to a team by drifting out wide; as such, the term can be applied to several different roles. In English, the term has come to be seen as a variant of the box-to-box midfielder role.[11][12][13][14]

Wide midfielder[edit]

A wide midfielder, David Beckham was lauded for his range of passing, vision, crossing ability and bending free-kicks, which enabled him to create chances for teammates or score goals.[15][17]

Left and right midfielders have a role balanced between attack and defence whilst they play a lot of crosses in the box for forwards.They are positioned closer to the touchlines of the pitch. They may be asked to cross the ball into the opponents’ penalty area to make scoring chances for their teammates, and when defending they may put pressure on opponents who are trying to cross.[18]

Common modern formations that include left and right midfielders are the 4−4−2, the 4−4−1−1, the 4–2–3–1 and the 4−5−1 formations.[19] Jonathan Wilson describes the development of the 4−4−2 formation: «…the winger became a wide midfielder, a shuttler, somebody who might be expected to cross a ball but was also meant to put in a defensive shift.»[20] Two notable examples of wide midfielders are David Beckham and Ryan Giggs.[21]

In Italian football, the role of the wide midfielder is known as tornante di centrocampo or simply tornante («returning»); it originated from the role of an outside forward, and came to be known as such as it often required players in this position to track back and assist the back-line with defensive duties, in addition to aiding the midfield and attacking.[22][23]

Wing-half[edit]

The historic position of wing-half (not to be confused with mezzala) was given to midfielders (half-backs) who played near the side of the pitch. It became obsolete as wide players with defensive duties have tended to become more a part of the defence as full-backs.[24][25]

Defensive midfielder[edit]

Defensive midfielders are midfield players who focus on protecting their team’s goal. These players may defend a zone in front of their team’s defence, or man mark specific opposition attackers.[26][27][28] Defensive midfielders may also move to the full-back or centre-back positions if those players move forward to join in an attack.[29][30]

Sergio Busquets described his attitude: «The coach knows that I am an obedient player who likes to help out and if I have to run to the wing to cover someone’s position, great.»[30] A good defensive midfielder needs good positional awareness, anticipation of opponent’s play, marking, tackling, interceptions, passing and great stamina and strength (for their tackling). In South American football, this role is known as a volante de marca, while in Mexico it is known as volante de contención. In Portugal, it is instead known as trinco.[31]

Holding midfielder[edit]

Yaya Touré, pictured playing for the Ivory Coast in 2012, was a versatile holding midfielder; although his playing style initially led him to be described by pundits as a «carrier», due to his ability to carry the ball and transition from defence to attack, he later adapted to more of a playmaking role.

A holding or deep-lying midfielder stays close to their team’s defence, while other midfielders may move forward to attack.[32] The holding midfielder may also have responsibilities when their team has the ball. This player will make mostly short and simple passes to more attacking members of their team but may try some more difficult passes depending on the team’s strategy. Marcelo Bielsa is considered as a pioneer for the use of a holding midfielder in defence.[9] This position may be seen in the 4–2–3–1 and 4–4–2 diamond formations.[33]

Initially, a defensive midfielder, or «destroyer», and a playmaker, or «creator», were often fielded alongside each other as a team’s two holding central midfielders. The destroyer was usually responsible for making tackles, regaining possession, and distributing the ball to the creator, while the creator was responsible for retaining possession and keeping the ball moving, often with long passes out to the flanks, in the manner of a more old-fashioned deep-lying playmaker or regista (see below). Early examples of a destroyer are Obdulio Varela, Nobby Stiles, Herbert Wimmer, Marco Tardelli, while later examples include Claude Makélélé, Lee Carsley and Javier Mascherano, although several of these players also possessed qualities of other types of midfielders, and were therefore not confined to a single role. Early examples of a creator would be Gérson, Glenn Hoddle, and Sunday Oliseh, while more recent examples are Xabi Alonso and Michael Carrick.

The latest and third type of holding midfielder developed as a box-to-box midfielder, or «carrier» or «surger», neither entirely destructive nor creative, who is capable of winning back possession and subsequently advancing from deeper positions either by distributing the ball to a teammate and making late runs into the box, or by carrying the ball themself; recent examples of this type of player are Clarence Seedorf and Bastian Schweinsteiger, while Sami Khedira and Fernandinho are destroyers with carrying tendencies, Luka Modrić is a carrier with several qualities of the regista, and Yaya Touré was a carrier who became a playmaker, in later part of his career, after losing his stamina.[9]

Deep-lying playmaker (Strolling 10)[edit]

Italian deep-lying playmaker Andrea Pirlo executing a pass for Juventus. Pirlo is often regarded as one of the best deep-lying playmakers of all time.

A deep-lying playmaker is a holding midfielder who specializes in ball skills such as passing, rather than defensive skills like tackling.[35] When this player has the ball, they may attempt longer or more complex passes than other holding players. They may try to set the tempo of their team’s play, retain possession, or build plays through short exchanges, or they may try to pass the ball long to a centre forward or winger, or even pass short to a teammate in the hole, the area between the opponents’ defenders and midfielders.[35][36][37] In Italy, the deep-lying playmaker is known as a regista,[38] whereas in Brazil, it is known as a «meia-armador».[39] In Italy, the role of the regista developed from the centre half-back or centromediano metodista position in Vittorio Pozzo’s metodo system (a precursor of the central or holding midfield position in the 2–3–2–3 formation), as the metodista‘s responsibilities were not entirely defensive but also creative; as such, the metodista was not solely tasked with breaking down possession, but also with starting attacking plays after winning back the ball.[40]

Writer Jonathan Wilson instead described Xabi Alonso’s holding midfield role as that of a «creator», a player who was responsible for retaining possession in the manner of a more old-fashioned deep-lying playmaker or regista, noting that: «although capable of making tackles, [Alonso] focused on keeping the ball moving, occasionally raking long passes out to the flanks to change the angle of attack.»[9]

Centre-half[edit]

The historic central half-back position gradually retreated from the midfield line to provide increased protection to the back line against centre-forwards – that dedicated defensive role in the centre is still commonly referred to as a «centre-half» as a legacy of its origins.[41] In Italian football jargon, this position was known as the centromediano metodista or metodista, as it became an increasingly important role in Vittorio Pozzo’s metodo system, although this term was later also applied to describe players who operated in a central holding-midfielder role, but who also had creative responsibilities in addition to defensive duties.[40]

Attacking midfielder[edit]

An attacking midfielder is a midfield player who is positioned in an advanced midfield position, usually between central midfield and the team’s forwards, and who has a primarily offensive role.[42]

Some attacking midfielders are called trequartista or fantasista (Italian: three-quarter specialist, i.e. a creative playmaker between the forwards and the midfield), who are usually mobile, creative and highly skilful players, known for their deft touch, technical ability, dribbling skills, vision, ability to shoot from long range, and passing prowess.

However, not all attacking midfielders are trequartistas – some attacking midfielders are very vertical and are essentially auxiliary attackers who serve to link-up play, hold up the ball, or provide the final pass, i.e. secondary strikers.[43] As with any attacking player, the role of the attacking midfielder involves being able to create space for attack.[44]

According to positioning along the field, attacking midfield may be divided into left, right and central attacking midfield roles but most importantly they are a striker behind the forwards. A central attacking midfielder may be referred to as a playmaker, or number 10 (due to the association of the number 10 shirt with this position).[45][46]

Advanced playmaker[edit]

These players typically serve as the offensive pivot of the team, and are sometimes said to be «playing in the hole», although this term can also be used as deep-lying forward. The attacking midfielder is an important position that requires the player to possess superior technical abilities in terms of passing and dribbling, as well as, perhaps more importantly, the ability to read the opposing defence to deliver defence-splitting passes to the striker.

This specialist midfielder’s main role is to create good shooting and goal-scoring opportunities using superior vision, control, and technical skill, by making crosses, through balls, and headed knockdowns to teammates. They may try to set up shooting opportunities for themselves by dribbling or performing a give-and-go with a teammate. Attacking midfielders may also make runs into the opponents’ penalty area to shoot from another teammate’s pass.[2]

Where a creative attacking midfielder, i.e. an Advanced playmaker, is regularly utilized, they are commonly the team’s star player, and often wear the number 10 shirt. As such, a team is often constructed so as to allow their attacking midfielder to roam free and create as the situation demands. One such popular formation is the 4–4–2 «diamond» (or 4–1–2–1–2), in which defined attacking and defensive midfielders replace the more traditional pair of central midfielders. Known as the «fantasista» or «trequartista» in Italy,[43] in Spain, the offensive playmaker is known as the «Mediapunta, in Brazil, the offensive playmaker is known as the «meia atacante«,[39] whereas in Argentina and Uruguay, it is known as the «enganche«.[47] Some examples of the advanced playmaker would be Zico, Francesco Totti, Kevin De Bruyne, Martin Ødegaard and Juan Riquelme.

There are also some examples of more flexible advanced playmakers, such as Zinedine Zidane, Andrés Iniesta, David Silva, and Nécib. These players could control the tempo of the game in deeper areas of the pitch while also being able to push forward and play line-breaking through balls.[48][49][50][51][52]

Mesut Özil can be considered as a classic 10 who adopted a slightly more direct approach and specialised in playing the final ball.

False attacking midfielder[edit]

The false attacking midfielder description has been used in Italian football to describe a player who is seemingly playing as an attacking midfielder in a 4–3–1–2 formation, but who eventually drops deeper into midfield, drawing opposing players out of position and creating space to be exploited by teammates making attacking runs; the false-attacking midfielder will eventually sit in a central midfield role and function as a deep-lying playmaker. The false-attacking midfielder is therefore usually a creative and tactically intelligent player with good vision, technique, movement, passing ability, and striking ability from distance. They should also be a hard-working player, who is able to read the game and help the team defensively.[53] Wayne Rooney has been deployed in a similar role, on occasion; seemingly positioned as a number 10 behind the main striker, he would often drop even deeper into midfield to help his team retrieve possession and start attacks.[54]

«False 10» or «central winger»[edit]

The «false 10» or «central winger»[55] is a type of midfielder, which differs from the false-attacking midfielder. Much like the «false 9», their specificity lies in the fact that, although they seemingly play as an attacking midfielder on paper, unlike a traditional playmaker who stays behind the striker in the centre of the pitch, the false 10’s goal is to move out of position and drift wide when in possession of the ball to help both the wingers and fullbacks to overload the flanks. This means two problems for the opposing midfielders: either they let the false 10 drift wide, and their presence, along with both the winger and the fullback, creates a three-on-two player advantage out wide; or they follow the false 10, but leave space in the centre of the pitch for wingers or onrushing midfielders to exploit. False 10s are usually traditional wingers who are told to play in the centre of the pitch, and their natural way of playing makes them drift wide and look to provide deliveries into the box for teammates. On occasion, the false-10 can also function in a different manner alongside a false-9, usually in a 4–6–0 formation, disguised as either a 4–3–3 or 4–2–3–1 formation. When other forwards or false-9s drop deep and draw defenders away from the false-10s, creating space in the middle of the pitch, the false-10 will then also surprise defenders by exploiting this space and moving out of position once again, often undertaking offensive dribbling runs forward towards goal, or running on to passes from false-9s, which in turn enables them to create goalscoring opportunities or go for goal themselves.[56]

Winger[edit]

«Right winger» redirects here. For the political position, see Right-wing politics.

Players in the bold positions can be referred to as wingers.

In modern football, the terms winger or wide player refer to a non-defender who plays on the left or right sides of the pitch. These terms can apply to left or right midfielders, left or right attacking midfielders, or left or right forwards.[18] Left or right-sided defenders such as wing-backs or full-backs are generally not called wingers.

In the 2−3−5 formation popular in the late 19th century wingers remained mostly near the touchlines of the pitch, and were expected to cross the ball for the team’s inside and centre forwards.[57] Traditionally, wingers were purely attacking players and were not expected to track back and defend. This began to change in the 1960s. In the 1966 World Cup, England manager Alf Ramsey did not select wingers from the quarter-final onwards. This team was known as the «Wingless Wonders» and led to the modern 4–4–2 formation.[58][59]

This has led to most modern wide players having a more demanding role in the sense that they are expected to provide defensive cover for their full-backs and track back to repossess the ball, as well as provide skillful crosses for centre forwards and strikers.[60] Some forwards are able to operate as wingers behind a lone striker. In a three-man midfield, specialist wingers are sometimes deployed down the flanks alongside the central midfielder or playmaker.

Even more demanding is the role of wing-back, where the wide player is expected to provide both defence and attack.[61] As the role of winger can be classed as a forward or a midfielder, this role instead blurs the divide between defender and midfielder. Italian manager Antonio Conte has been known to use wide midfielders or wingers who act as wing-backs in his trademark 3–5–2 and 3–4–3 formations, for example; these players are expected both to push up and provide width in attack as well as track back and assist their team defensively.[62]

On occasion, the role of a winger can also be occupied by a different type of player. For example, certain managers have been known to use a «wide target man» on the wing, namely a large and physical player who usually plays as a centre-forward, and who will attempt to win aerial challenges and hold up the ball on the flank, or drag full-backs out of position; Romelu Lukaku, for example, has been used in this role on occasion.[63] Another example is Mario Mandžukić under manager Massimiliano Allegri at Juventus during the 2016–17 season; normally a striker, he was instead used on the left flank, and was required to win aerial duels, hold up the ball, and create space, as well as being tasked with pressing opposing players.[64]

Wingers are indicated in red, while the «wide men» (who play to the flanks of the central midfielders) are indicated in blue.

Today, a winger is usually an attacking midfielder who is stationed in a wide position near the touchlines.[60] Wingers such as Stanley Matthews or Jimmy Johnstone used to be classified as outside forwards in traditional W-shaped formations, and were formally known as «Outside Right» or «Outside Left», but as tactics evolved through the last 40 years, wingers have dropped to deeper field positions and are now usually classified as part of the midfield, usually in 4–4–2 or 4–5–1 formations (but while the team is on the attack, they tend to resemble 4–2–4/2–4–4 and 4–3–3 formations respectively).

The responsibilities of the winger include:

- Providing a «wide presence» as a passing option on the flank.

- To beat the opposing full-back either with skill or with speed.

- To read passes from the midfield that give them a clear crossing opportunity, when going wide, or that give them a clear scoring opportunity, when cutting inside towards goal.

- To double up on the opposition winger, particularly when they are being «double-marked» by both the team’s full back and winger.

The prototypical winger is fast, tricky and enjoys ‘hugging’ the touchline, that is, running downfield close to the touchline and delivering crosses. However, players with different attributes can thrive on the wing as well. Some wingers prefer to cut infield (as opposed to staying wide) and pose a threat as playmakers by playing diagonal passes to forwards or taking a shot at goal. Even players who are not considered quick, have been successfully fielded as wingers at club and international level for their ability to create play from the flank. Occasionally wingers are given a free role to roam across the front line and are relieved of defensive responsibilities.

The typical abilities of wingers include:

- Technical skill to beat a full-back in a one-to-one situation.

- Pace, to beat the full-back one-on-one.

- Crossing ability when out wide.

- Good off-the-ball ability when judging a pass from the midfield or from fellow attackers.

- Good passing ability and composure, to retain possession while in opposition territory.

- The modern winger should also be comfortable on either wing so as to adapt to quick tactical changes required by the coach.

Although wingers are a familiar part of football, the use of wingers is by no means universal. There are many successful football teams who operate without wingers. A famous example is Carlo Ancelotti’s late 2000s Milan, who typically play in a narrow midfield diamond formation or in a Christmas tree formation (4–3–2–1), relying on full-backs to provide the necessary width down the wings.

Inverted winger[edit]

USWNT midfielder Megan Rapinoe (left) has been deployed as an inverted winger throughout her career.

An inverted winger is a modern tactical development of the traditional winger position. Most wingers are assigned to either side of the field based on their footedness, with right-footed players on the right and left-footed players on the left.[65] This assumes that assigning a player to their natural side ensures a more powerful cross as well as greater ball-protection along the touch-lines. However, when the position is inverted and a winger instead plays inside-out on the opposite flank (i.e., a right-footed player as a left inverted winger), they effectively become supporting strikers and primarily assume a role in the attack.[66]

As opposed to traditionally pulling the opponent’s full-back out and down the flanks before crossing the ball in near the by-line, positioning a winger on the opposite side of the field allows the player to cut-in around the 18-yard box, either threading passes between defenders or shooting on goal using the dominant foot.[67] This offensive tactic has found popularity in the modern game due to the fact that it gives traditional wingers increased mobility as playmakers and goalscorers,[68] such as the left-footed right winger Domenico Berardi of Sassuolo who achieved 30 career goals faster than any player in the past half-century of Serie A football.[69] Not only are inverted wingers able to push full-backs onto their weak sides, but they are also able to spread and force the other team to defend deeper as forwards and wing-backs route towards the goal, ultimately creating more scoring opportunities.[70]

Although naturally left-footed Arjen Robben (left, 11) has often been deployed as an inverted winger on the right flank throughout his career, which allows him to cut inside and shoot on goal with his stronger foot.

Other midfielders within this tactical archetype include Lionel Messi[71] and Eden Hazard,[72] as well as Megan Rapinoe of the USWNT.[73] Clubs such as Real Madrid often choose to play their wingers on the «wrong» flank for this reason; former Real Madrid coach José Mourinho often played Ángel Di María on the right and Cristiano Ronaldo on the left.[74][75][76] Former Bayern Munich manager Jupp Heynckes often played the left-footed Arjen Robben on the right and the right-footed Franck Ribéry on the left.[77][78] One of the foremost practitioners of playing from either flank was German winger Jürgen Grabowski, whose flexibility helped Germany to third place in the 1970 World Cup, and the world title in 1974.

A description that has been used in the media to label a variation upon the inverted winger position is that of an «attacking», «false», or «goalscoring winger», as exemplified by Cristiano Ronaldo’s role on the left flank during his time at Real Madrid in particular. This label has been used to describe an offensive-minded inverted winger, who will seemingly operate out wide on paper, but who instead will be given the freedom to make unmarked runs into more advanced central areas inside the penalty area to get on the end of passes and crosses and score goals, effectively functioning as a striker.[79][80][81][82][83] This role is somewhat comparable to what is known as the raumdeuter role in German football jargon (literally «space interpreter»), as exemplified by Thomas Müller, namely an attacking-minded wide player, who will move into central areas to find spaces from which they can receive passes and score or assist goals.[63][84]

False winger[edit]

The «false winger» or «seven-and-a-half» is a label which has been used to describe a type of player who normally plays centrally, but who instead is deployed out wide on paper; during the course of a match, however, they will move inside and operate in the centre of the pitch to drag defenders out of position, congest the midfield and give their team a numerical advantage in this area, so that they can dominate possession in the middle of the pitch and create chances for the forwards; this position also leaves space for full-backs to make overlapping attacking runs up the flank. Samir Nasri, who has been deployed in this role, once described it as that of a «non-axial playmaker».[85][86][87][88][89][90][91]

See also[edit]

Association football portal

- Association football positions

- Association football tactics

- Defender (association football)

- Forward (association football)

- Goalkeeper (association football)

References[edit]

- ^

«Positions guide: Central midfield». London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 27 August 2013. - ^ a b «Football / Soccer Positions». Keanu salah. Expert Football. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Di Salvo, V. (6 October 2005). «Performance characteristics according to playing position in elite soccer». International Journal of Sports Medicine. 28 (3): 222–227. doi:10.1055/s-2006-924294. PMID 17024626.

- ^ «Formations guide». BBC Sport. September 2005. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ «Steven Gerrard completes decade at Liverpool». The Times. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Bull, JJ (30 March 2020). «Retro Premier League review: Why 2008/09 was Steven Gerrard’s peak season». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ «Box to box Bowyer». London: BBC Sport. 29 April 2002. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Cox, Michael (4 June 2014). «In praise of the box-to-box midfielder». ESPN FC. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Jonathan (18 December 2013). «The Question: what does the changing role of holding midfielders tell us?». The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ The Best Box-to-Box Midfielders of All-Time

- ^ Tallarita, Andrea (4 September 2018). «Just what is a mezzala?». Football Italia. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ «Understanding roles in Football Manager (and real life) (part 2)». Medium. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «English translation of ‘mezzala’«. Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Walker-Roberts, James (25 February 2018). «How Antonio Conte got the best from Paul Pogba at Juventus». Sky Sports. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Kings of the free-kick». FIFA. Retrieved 20 December 2014

- ^ «England – Who’s Who: David Beckham». ESPN FC. 3 September 2002. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b «Wide midfielder». BBC Sport. September 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ «Formations guide». London: BBC Sport. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (24 March 2010). «The Question: Why are so many wingers playing on the ‘wrong’ wings?». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Daniel (18 February 2010). «Milan wrong to play David Beckham in central midfield says Sir Alex Ferguson». The Guardian. England. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ «Genoa: Top 11 All Time» (in Italian). Storie di Calcio. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ «tornante». La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ «Old football formations explained — Classic soccer tactics & strategies». Football Bible. n.d. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ «Football Glossary, Letter W». Football Bible. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ^ Cox, Michael (20 January 2013). «Manchester United nullified Gareth Bale but forgot about Aaron Lennon». The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (16 July 2010). «The final analysis, part three: brilliant Busquets». zonalmarking.net. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Cox, Michael (10 February 2013). «How Manchester United nullified threat of Everton’s Marouane Fellaini». The Guardian. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (3 March 2010). «Analysing Brazil’s fluid system at close quarters». zonalmarking.net. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ a b Lowe, Sid (27 May 2011). «Sergio Busquets: Barcelona’s best supporting actor sets the stage». The Guardian. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ «50 Best Defensive Midfielders in World Football History». Bleacher Report. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ F., Edward (28 January 2014). «On Going Beyond Holding Midfielders». Cartilage Free Captain. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (29 January 2010). «Teams of the Decade #11: Valencia 2001-04». zonalmarking.net. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (2013). Inverting the Pyramid. Nation Books. ISBN 9781568589633.

- ^ a b Cox, Michael (19 March 2012). «Paul Scholes, Xavi and Andrea Pirlo revive the deep-lying playmaker». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ^ Goldblatt, David (2009). The Football Book. Dorling Kindersley. p. 48. ISBN 978-1405337380.

- ^ Dunmore, Thomas (2013). Soccer for Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-51066-7.

- ^ «The Regista And the Evolution Of The Playmaker». 5 July 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b «Playmaker». MTV. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b Radogna, Fiorenzo (20 December 2018). «Mezzo secolo senza Vittorio Pozzo, il mitico (e discusso) c.t. che cambiò il calcio italiano: Ritiri e regista». Il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). p. 8. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (20 September 2011). «The Question: Did Herbert Chapman really invent the W-M formation?». The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ «Positions in football». talkfootball.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ a b «The Number 10». RobertoMancini.com. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ Michalak, Joakim. «Identifying football players who create and generate space». Uppsala University Publications. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (18 August 2010). «The Question: What is a playmaker’s role in the modern game?». TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Cox, Michael (26 March 2010). «How the 2000s changed tactics #2: Classic Number 10s struggle». ZonalMarking.net. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ «Tactics: the changing role of the playmaker». Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Ciaran Kelly (7 December 2011). «Zinedine Zidane: The Flawed Genius». Back Page Football. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Bandini, Paolo (3 May 2017). «Year Zero: The making of Zinedine Zidane (Juventus, 1996/97)». FourFourTwo. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Vincenzi, Massimo (4 December 2000). «Zidane vede il Pallone d’oro ma Sheva è il suo scudiero». La Repubblica (in Italian). Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ «More to come from Louisa Necib». Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (in French). 14 July 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ Jason Cowley (18 June 2006). «Lonesome Riquelme is the go-to man». The Guardian. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ James Horncastle. «Horncastle: Riccardo Montolivo straddles both sides of the Germany/Italy divide». The Score. Archived from the original on 20 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (20 December 2011). «The football tactical trends of 2011». the Guardian. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ «Introducing…the central winger?». zonalmarking.net. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ «The False-10». Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (2013). «It’s a Simple Game». Football League 125. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Galvin, Robert. «Sir Alf Ramsey». National Football Museum. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ «Chelsea prayers fly to the wings». FIFA. 5 March 2006. Archived from the original on 7 November 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- ^ a b «Positions guide: Wide midfield». London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ «Positions guide: Wing-back». London: BBC Sport. 1 September 2005. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- ^ Debono, Matt (17 July 2019). «The issues with Antonio Conte’s 3-5-2 system». Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b «Understanding roles in Football Manager (and real life) (part 1)». Medium. 13 May 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Homewood, Brian (10 May 2017). «Versatile Mandzukic becomes Juve’s secret weapon». Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Barve, Abhijeet (28 February 2013). «Football Jargon for dummies Part 2- Inverted Wingers». Football Paradise. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Johnathan (2013). Inverting The Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics. New York, NY: Nation Books. pp. 373, 377. ISBN 978-1568587387.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (24 March 2010). «The Question: Why are so many wingers playing on the ‘wrong’ wings?». The Guardian. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Singh, Amit (21 June 2012). «Positional Analysis: What Has Happened To All The Wingers?». Just-Football.com.

- ^ Newman, Blair (8 September 2015). «The young players who could rejuvenate Antonio Conte’s Italy at Euro 2016». The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Goodman, Mike L. (6 June 2014). «How to Watch the World Cup Like a True Soccer Nerd». Grantland. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Reng, Ronald (27 May 2011). «Lionel Messi». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Silvestri, Stefano (15 August 2016). «Diego Costa fa felice Conte: il Chelsea batte il West Ham all’89’» (in Italian). Eurosport. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ «11 Questions with Megan Rapinoe» (Interview). www.ussoccer.com. 22 September 2009.

- ^ Al-Hendy, Mohamed (17 May 2012). «Real Madrid: Tactical Review of the 2011-12 Season Under Jose Mourinho». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Tighe, Sam (21 November 2012). «Breaking Down the 10 Most Popular Formations in World Football». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Richards, Alex (30 July 2013). «The 15 Best Wingers in World Football». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Koch, Ben (1 February 2011). «Tactics Tuesday: Natural vs. Inverted Wingers». Fútbol for Gringos. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ «Robbery, Aubameyang and Mkhitaryan and the Bundesliga’s Top 10 telepathic understandings». Bundesliga. Retrieved 15 April 2020.