|

Johnny Depp |

|

|---|---|

Depp in 2020 |

|

| Born |

John Christopher Depp II June 9, 1963 (age 59) Owensboro, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1984–present |

| Works |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Partner(s) | Sherilyn Fenn (1985–1988) Winona Ryder (1989–1993) Kate Moss (1994–1998) Vanessa Paradis (1998–2012) |

| Children | 2, including Lily-Rose |

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Labels |

|

| Member of |

|

| Formerly of |

|

| Signature | |

|

John Christopher Depp II (born June 9, 1963) is an American actor and musician. He is the recipient of multiple accolades, including a Golden Globe Award and a Screen Actors Guild Award, in addition to nominations for three Academy Awards and two BAFTA awards.

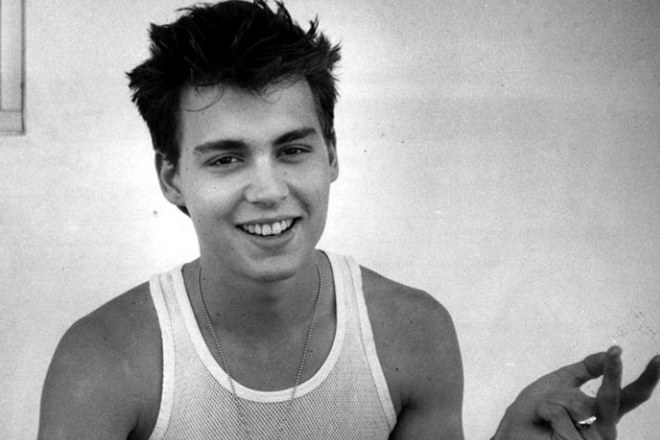

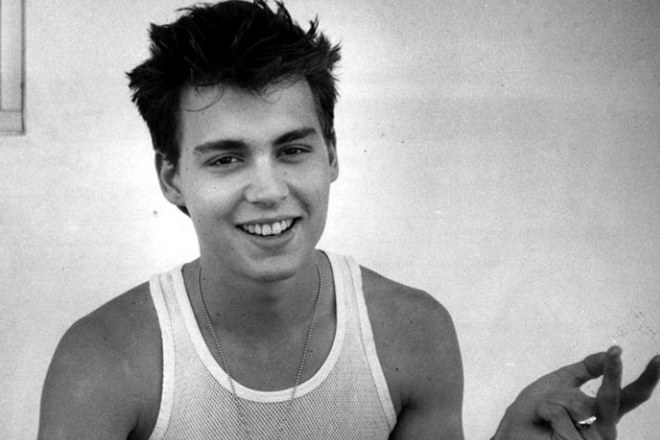

Depp made his feature film debut in the horror film A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and appeared in Platoon (1986), before rising to prominence as a teen idol on the television series 21 Jump Street (1987–1990). In the 1990s, Depp acted mostly in independent films with auteur directors, often playing eccentric characters. These included Cry-Baby (1990), What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993), Benny and Joon (1993), Dead Man (1995), Donnie Brasco (1997), and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998). Depp also began his longtime collaboration with director Tim Burton, portraying the leads in the films Edward Scissorhands (1990), Ed Wood (1994), and Sleepy Hollow (1999).

In the 2000s, Depp became one of the most commercially successful film stars by playing Captain Jack Sparrow in the Walt Disney swashbuckler film series Pirates of the Caribbean (2003–2017). He also received critical praise for Chocolat (2000), Finding Neverland (2004) and Public Enemies (2009), while also continuing his commercially successful collaboration with Tim Burton with the films Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), where he portrayed Willy Wonka, Corpse Bride (2005), Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007), and Alice in Wonderland (2010).

In 2012, Depp was one of the world’s biggest film stars,[1][2] and was listed by the Guinness World Records as the world’s highest-paid actor, with earnings of US$75 million in a year.[3] During the 2010s, Depp began producing films through his company Infinitum Nihil. He also received critical praise for Black Mass (2015) and formed the rock supergroup Hollywood Vampires with Alice Cooper and Joe Perry, before starring as Gellert Grindelwald in the Wizarding World films Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016) and Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald (2018).

Between 1998 and 2012, Depp was in a relationship with French singer Vanessa Paradis and together they had two children, including actress Lily-Rose Depp. From 2015 to 2017, Depp was married to actress Amber Heard. Their divorce drew much media attention, as both alleged abuse against each other. In 2018, Depp unsuccessfully sued the publishers of British tabloid The Sun for defamation under English law; a judge ruled the publication labelling him a «wife beater» was «substantially true». Depp later successfully sued Heard in a 2022 trial in Virginia; a seven-member jury ruled that Heard’s allegations of «sexual violence» and «domestic abuse» were false and defamed Depp under American law.[4][5]

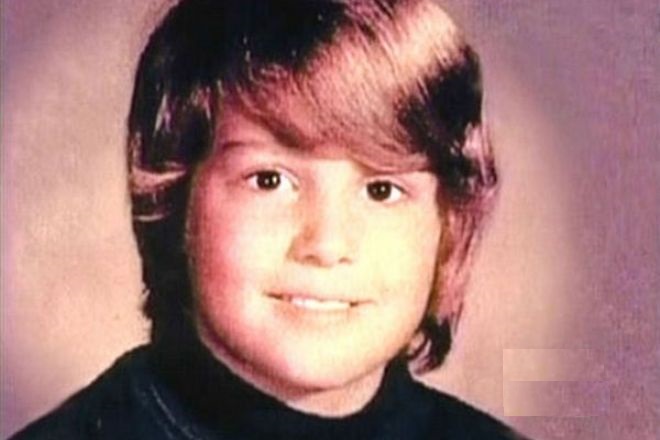

Early life

John Christopher Depp II was born on June 9, 1963, in Owensboro, Kentucky,[6][7][8] the youngest of four children of waitress Betty Sue Depp (née Wells; later Palmer)[9] and civil engineer John Christopher Depp.[10][11] Depp’s family moved frequently during his childhood, eventually settling in Miramar, Florida, in 1970.[12] His parents divorced in 1978 when he was 15,[12][13] and his mother later married Robert Palmer, whom Depp has called «an inspiration».[14][15]

Depp’s mother gave him a guitar when he was 12, and he began playing in various bands.[12] He dropped out of Miramar High School at 16 in 1979 to become a rock musician. He attempted to go back to school two weeks later, but the principal told him to follow his dream of being a musician.[12] In 1980, Depp began playing in a band called The Kids. After modest local success in Florida, the band moved to Los Angeles in pursuit of a record deal, changing its name to Six Gun Method. In addition to the band, Depp worked a variety of odd jobs, such as in telemarketing. In December 1983, Depp married makeup artist Lori Anne Allison,[7] the sister of his band’s bassist and singer. The Kids split up before signing a record deal in 1984, and Depp began collaborating with the band Rock City Angels.[16] He co-wrote their song «Mary», which appeared on their debut Geffen Records album Young Man’s Blues.[17] Depp and Allison divorced in 1985.[7]

Depp is of primarily English descent, with some French, German, and Irish ancestry.[18] His surname comes from a French Huguenot immigrant, Pierre Dieppe, who settled in Virginia around 1700. In interviews in 2002 and 2011, Depp claimed to have Native American ancestry, saying: «I guess I have some Native American somewhere down the line. My great-grandmother was quite a bit of Native American. She grew up Cherokee or maybe Creek Indian. Makes sense in terms of coming from Kentucky, which is rife with Cherokee and Creek Indian».[19] Depp’s claims came under scrutiny when Indian Country Today wrote that Depp had never inquired about his heritage or been recognized as a member of the Cherokee Nation.[20] This led to criticism from the Native American community, as Depp has no documented Native ancestry,[20] and Native community leaders consider him «a non-Indian»[20][21] and a pretendian.[22][23][24] Depp’s choice to portray Tonto, a Native American character, in The Lone Ranger was criticized,[20][21] along with his choice to name his rock band «Tonto’s Giant Nuts».[25][26][27][28] During the promotion for The Lone Ranger, Depp was formally adopted as an honorary son by LaDonna Harris, a member of the Comanche Nation, making him an honorary member of her family but not a member of any tribe.[29][30] Depp’s Comanche name given at the adoption was «Mah Woo May», which means shape shifter.[31] Critical response to his claims from the Native community increased after this, including satirical portrayals of Depp by Native comedians.[26][27][28] An ad featuring Depp and Native American imagery, by Dior for the fragrance «Sauvage», was pulled in 2019 after being accused of cultural appropriation and racism.[32][33][34][35][29]

Career

1984–1989: Early roles and 21 Jump Street

Depp moved to Los Angeles with his band when he was 20. After the band split up, Depp’s then-wife Lori Ann Allison introduced him to actor Nicolas Cage.[12] After they became drinking buddies, Cage advised him to pursue acting.[36] Depp had been interested in acting since reading a biography of James Dean and watching Rebel Without a Cause.[37] Cage helped Depp get an audition with Wes Craven for A Nightmare on Elm Street; Depp, who had no acting experience, said he «ended up acting by accident».[38][39] Thanks in part to his catching the eye of Craven’s daughter,[38] Depp landed the role of the main character’s boyfriend, one of Freddy Krueger’s victims.[12]

Though Depp said he «didn’t have any desire to be an actor», he continued to be cast in films,[39] making enough to cover some bills that his musical career left unpaid.[38] After a starring role in the 1985 comedy Private Resort, Depp was cast in the lead role of the 1986 skating drama Thrashin’ by the film’s director, but its producer overrode the decision.[40][41] Instead, Depp appeared in a minor supporting role as a Vietnamese-speaking private in Oliver Stone’s 1986 Vietnam War drama Platoon. He became a teen idol during the late 1980s, when he starred as an undercover police officer in a high school operation in the Fox television series 21 Jump Street, which premiered in 1987.[12] He accepted this role to work with actor Frederic Forrest, who inspired him. Despite his success, Depp felt that the series «forced [him] into the role of product».[42]

1990–2002: Independent films and first collaborations with Tim Burton

Disillusioned by his experiences as a teen idol in 21 Jump Street, Depp began taking roles he found more interesting, rather than those he thought would succeed at the box office.[42][43] His first film release in 1990 was John Waters’s Cry-Baby, a musical comedy set in the 1950s. Although not a box-office success upon its release,[44] over the years it has gained cult classic status.[45] Also in 1990, Depp played the title character in Tim Burton’s romantic fantasy film Edward Scissorhands opposite Dianne Wiest and Winona Ryder. The film was a commercial and critical success with a domestic gross of $53 million.[46] In preparation for the role, Depp watched many Charlie Chaplin films to study how to create sympathy without dialogue.[47] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone praised Depp’s performance, writing that he «artfully expresses the fierce longing in gentle Edward; it’s a terrific performance»,[48] while Rita Kempley of The Washington Post wrote that he «brings the eloquence of the silent era to this part of few words, saying it all through bright black eyes and the tremulous care with which he holds his horror-movie hands».[49] Depp earned his first Golden Globe nomination for the film. Owing to this role, a species of extinct arthropod with prominent claws was named after Depp as Kootenichela deppi (chela is Latin for claws or scissors).

Depp had no film releases in the next two years, except a brief cameo in Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991), the sixth installment in the A Nightmare on Elm Street franchise. He appeared in three films in 1993. In the romantic comedy Benny and Joon, he played an eccentric and illiterate silent film fan who befriends a mentally ill woman and her brother; it became a sleeper hit. Janet Maslin of The New York Times wrote that Depp «may look nothing like Buster Keaton, but there are times when he genuinely seems to become the Great Stone Face, bringing Keaton’s mannerisms sweetly and magically to life».[50] Depp received a second Golden Globe nomination for the performance. His second film of 1993 was Lasse Hallström’s What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, a drama about a dysfunctional family co-starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Juliette Lewis. It did not perform well commercially, but received positive notices from critics.[51] Although most of the reviews focused on DiCaprio, who was nominated for an Academy Award for his performance, Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote that «Depp manages to command center screen with a greatly affable, appealing characterization».[52] Depp’s last 1993 release was Emir Kusturica’s surrealist comedy-drama Arizona Dream, which opened to positive reviews and won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

In 1994, Depp reunited with Burton, playing the title role in Ed Wood, a biographical film about one of history’s most inept film directors. Depp later said that he was depressed about films and filmmaking at the time, but that «within 10 minutes of hearing about the project, I was committed».[53] He found that the role gave him a «chance to stretch out and have some fun» and that working with Martin Landau, who played Bela Lugosi, «rejuvenated my love for acting».[53] Although it did not earn back its production costs, Ed Wood received a positive reception from critics, with Maslin writing that Depp had «proved himself as an established, certified great actor» and «captured all the can-do optimism that kept Ed Wood going, thanks to an extremely funny ability to look at the silver lining of any cloud».[54] Depp was nominated for a third time for a Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe for his performance.

The next year, Depp starred in three films. He played opposite Marlon Brando in the box-office hit Don Juan DeMarco, as a man who believes he is Don Juan, the world’s greatest lover. He starred in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, a Western shot entirely in black-and-white; it was not a commercial success and had mixed critical reviews. And in the financial and critical failure Nick of Time, Depp played an accountant who is told to kill a politician to save his kidnapped daughter.

In 1997, Depp and Al Pacino starred in the crime drama Donnie Brasco, directed by Mike Newell. Depp played Joseph D. Pistone, an undercover FBI agent who assumes the name Donnie Brasco to infiltrate the Mafia in New York City. To prepare, Depp spent time with Pistone, on whose memoirs the film was based. Donnie Brasco was a commercial and critical success, and is considered one of Depp’s finest performances.[55][56] Also in 1997, Depp debuted as a director and screenwriter with The Brave. He starred in it as a poor Native American man who accepts a proposal from a wealthy man, played by Marlon Brando, to appear in a snuff film in exchange for money for his family. It premiered at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival to generally negative reviews.[57] Variety called it «a turgid and unbelievable neo-western»,[58] and Time Out wrote that «besides the implausibilities, the direction has two fatal flaws: it’s both tediously slow and hugely narcissistic as the camera focuses repeatedly on Depp’s bandana’d head and rippling torso».[59] Due to the reviews, Depp did not release The Brave in the U.S.[60][61]

Depp was a fan and friend of writer Hunter S. Thompson, and played his alter ego Raoul Duke in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), Terry Gilliam’s film adaptation of Thompson’s pseudo-biographical novel of the same name.[a] It was a box-office failure[64] and polarized critics.[65] Later that year, Depp made a brief cameo in Mika Kaurismäki’s L.A. Without a Map (1998).

Depp appeared in three films in 1999. The first was the sci-fi thriller The Astronaut’s Wife, co-starring Charlize Theron, which was not a commercial or critical success. The second, Roman Polanski’s The Ninth Gate, starred Depp as a seller of old books who becomes entangled in a mystery. It was moderately more successful with audiences but received mixed reviews. The third was Burton’s adaptation of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, where Depp played Ichabod Crane opposite Christina Ricci and Christopher Walken. For his performance, Depp took inspiration from Angela Lansbury, Roddy McDowall and Basil Rathbone, saying he «always thought of Ichabod as a very delicate, fragile person who was maybe a little too in touch with his feminine side, like a frightened little girl».[66][67] Sleepy Hollow was a commercial and critical success.

Depp’s first film release of the new millennium was British-French drama The Man Who Cried (2000), directed by Sally Potter and starring him as a Roma horseman opposite Christina Ricci, Cate Blanchett, and John Turturro. It was not a critical success. Depp also had a supporting role in Julian Schnabel’s critically acclaimed Before Night Falls (2000). His final film of 2000 was Hallström’s critically and commercially successful Chocolat, in which he played a Roma man and the love interest of the main character, Juliette Binoche. Depp’s next roles were both based on historical persons. In Blow (2001), he starred as cocaine smuggler George Jung, who was part of the Medellín Cartel in the 1980s. The film underperformed at the box office[68] and received mixed reviews.[69][70] In the comic book adaptation From Hell (2001), Depp portrayed inspector Frederick Abberline, who investigated the Jack the Ripper murders in the 1880s London. The film also received mixed reviews[71] but was a moderate commercial success.[72]

2003–2011: Pirates of the Caribbean, commercial and critical success

In 2003, Depp starred in the Walt Disney Pictures adventure film Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, which was a major box office success.[43] He earned widespread acclaim for his comic performance as pirate Captain Jack Sparrow, and received Academy Award, Golden Globe and BAFTA nominations and won a Screen Actor’s Guild Award for Best Actor as well as an MTV Movie Award. Depp has said that Sparrow is «definitely a big part of me»,[73] and that he modeled the character after The Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards[74] and cartoon skunk Pepé Le Pew.[75] Studio executives had at first been ambivalent about Depp’s portrayal,[76] but the character became popular with audiences.[43] In his other film release in 2003, Robert Rodriguez’ action film Once Upon a Time in Mexico, Depp played a corrupt CIA agent. A moderate box-office success,[77] it received average to good reviews, with Depp’s performance in particular receiving praise.[78][79]

Depp next starred as an author with writer’s block in the thriller Secret Window (2004), based on a short story by Stephen King. It was a moderate commercial success but received mixed reviews.[80][81] Released around the same time, the British-Australian independent film The Libertine (2004) saw Depp portray the seventeenth-century poet and rake, the Earl of Rochester. It had only limited release, and received mainly negative reviews. Depp’s third film of 2004, Finding Neverland, was more positively received by the critics, and earned him his second Academy Award nomination as well as Golden Globe, BAFTA, and SAG nominations for his performance as Scottish author J. M. Barrie. Depp also made a brief cameo appearance in the French film Happily Ever After (2004), and founded his own film production company, Infinitum Nihil, under Warner Bros. Pictures.[82]

Depp continued his box-office success with a starring role as Willy Wonka in Tim Burton’s adaptation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005). It also had a positive critical reception,[83][84] with Depp being nominated again for the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Comedy or Musical.[74][85] Chocolate Factory was followed by another Burton project, stop-motion animation Corpse Bride (2005), in which Depp voiced the main character, Victor Van Dort.[86] Depp reprised the role of Jack Sparrow in the Pirates sequels Dead Man’s Chest (2006) and At World’s End (2007), both of which were major box office successes.[87] He also voiced the character in the video game Pirates of the Caribbean: The Legend of Jack Sparrow.[88] According to a survey taken by Fandango, Depp in the role of Jack Sparrow was the main reason for many cinema-goers to see a Pirates film.[89]

In 2007, Depp collaborated with Burton for their sixth film together, this time playing murderous barber Sweeney Todd in the musical Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007). Depp cited Peter Lorre’s performance in Mad Love (1935), in which Lorre played a «creepy but sympathetic» surgeon, as his main influence for the role.[90] Sweeney Todd was the first film in which Depp had been required to sing. Instead of hiring a qualified vocal coach, he prepared for the role by recording demos with his old bandmate Bruce Witkin. The film was a commercial and critical success. Entertainment Weekly‘s Chris Nashawaty stated that «Depp’s soaring voice makes you wonder what other tricks he’s been hiding … Watching Depp’s barber wield his razors … it’s hard not to be reminded of Edward Scissorhands frantically shaping hedges into animal topiaries 18 years ago … and all of the twisted beauty we would’ve missed out on had [Burton and Depp] never met».[91] Depp won the Golden Globe for Best Musical or Comedy Actor for the role, and was nominated for the third time for an Academy Award.

In 2009, Depp portrayed real-life gangster John Dillinger in Michael Mann’s 1930s crime film Public Enemies.[92] It was commercially successful[93] and gained moderately positive reviews.[94][95] Roger Ebert stated in his review that «This Johnny Depp performance is something else. For once an actor playing a gangster does not seem to base his performance on movies he has seen. He starts cold. He plays Dillinger as a fact».[96] Depp’s second film of 2009, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, reunited him with director Terry Gilliam. Depp, Jude Law, and Colin Farrell each played the character initially portrayed by their friend Heath Ledger, who had died before the film was completed. All three actors gave their salaries to Ledger’s daughter, Matilda.[97]

Depp began the 2010s with another collaboration with Tim Burton, Alice in Wonderland (2010), in which he played the Mad Hatter opposite Helena Bonham Carter, Anne Hathaway and Alan Rickman. Despite mixed reviews, it earned US$1.025 billion in the box office, thus becoming the second-highest-grossing film of 2010[98] and one of the highest-grossing films of all time.[99] Depp’s second film release of 2010 was the romantic thriller The Tourist, in which he starred opposite Angelina Jolie. It was commercially successful, although panned by critics.[100] Regardless, he received Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy Golden Globe nominations for both films.

Depp’s first 2011 film release was the animated film Rango, in which he voiced the title character, a lizard. It was a major critical and commercial success.[101][102] His second film of the year, the fourth installment in the Pirates series, On Stranger Tides, was again a box office hit,[87] becoming the third-highest-grossing film of 2011.[103] Later in 2011, Depp released the first two projects co-produced by his company, Infinitum Nihil. The first was a film adaptation of the novel The Rum Diary by Hunter S. Thompson and starred Depp.[104] It failed to bring back its production costs[105][106] and received mixed reviews.[107][108] The company’s second undertaking, Martin Scorsese’s Hugo (2011), garnered major critical acclaim and several awards nominations, but similarly did not perform well in the box office. In 2011, Depp also made a brief cameo in the Adam Sandler film Jack and Jill.

2012–2020: Career setbacks

By 2012, Depp was one of the world’s biggest film stars,[1][2] and was listed by the Guinness World Records as the world’s highest-paid actor, with earnings of US$75 million.[3] That year, he and his 21 Jump Street co-stars Peter DeLuise and Holly Robinson reprised their roles in cameo appearances in the series’ feature film adaptation.[109] Depp also starred in and co-produced his eighth film with Tim Burton, Dark Shadows (2012), alongside Helena Bonham Carter, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Eva Green.[110] The film was based on a 1960s Gothic television soap opera of the same name, which had been one of his favorites as a child. The film’s poor reception in the United States brought Depp’s star appeal into question.[111]

After Infinitum Nihil’s agreement with WB expired in 2011, Depp signed a multi-year first-look deal with Walt Disney Studios.[82] The first film made in the collaboration was The Lone Ranger (2013), in which Depp starred as Tonto. Depp’s casting as a Native American brought accusations of whitewashing, and the film was not well received by the public or the critics,[112] causing Disney to take a US$190 million loss.[113][114][115][116] Following a brief cameo in the independent film Lucky Them (2013), Depp starred as an AI-studying scientist in the sci-fi thriller Transcendence (2014), which was yet another commercial failure,[117][118] and earned mainly negative reviews.[113][119][120] His other roles in 2014 were a minor supporting part as The Wolf in the film adaptation of Into the Woods, and a more substantial appearance as eccentric French-Canadian ex-detective in Kevin Smith’s horror-comedy Tusk, in which he was credited by the character’s name, Guy LaPointe.

In 2015, Depp appeared in two films produced by Infinitum Nihil. The first was comedy-thriller Mortdecai, in which he acted opposite Gwyneth Paltrow. The film was a critical and commercial failure and brought both stars Golden Raspberry nominations.[113][121][122][123] The second film, Black Mass (2015), in which he played Boston crime boss Whitey Bulger, was better received.[124][125] Critics from The Hollywood Reporter and Variety called it one of Depp’s best performances to date,[126][127] and the role earned Depp his third nomination for the Best Actor SAG award.[128] However, the film failed to bring back its production costs.[113] Depp also made a cameo appearance in the critically panned London Fields, starring his then-wife Amber Heard, which was to be released in 2015, but its general release was delayed by litigation until 2018.[129][130] In addition to his work in films in 2015, French luxury fashion house Dior signed Depp as the face of their men’s fragrance, Sauvage,[131] and he was inducted as a Disney Legend.[132]

Depp’s first film release in 2016 was Yoga Hosers, a sequel to Tusk (2014), in which Depp appeared with his daughter, Lily-Rose Depp. Next, he played businessman and presidential candidate Donald Trump in a Funny or Die satire entitled Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal: The Movie, released during the run-up to the US presidential election. He earned praise for the role, with a headline from The A.V. Club declaring, «Who knew Donald Trump was the comeback role Johnny Depp needed?»[133] It was also announced that Depp had been cast in a new franchise role as Dr. Jack Griffin/The Invisible Man in Universal Studios’s planned shared film universe entitled the Dark Universe, a rebooted version of their classic Universal Monsters franchise.[134] Depp reprised the role of the Mad Hatter in Tim Burton’s Alice Through the Looking Glass (2016), the sequel to Alice in Wonderland. In contrast to the first film’s success, the sequel lost Disney approximately US$70 million.[135][113] It also gained Depp two Golden Raspberry nominations. Depp had also been secretly cast to play dark wizard Gellert Grindelwald in a cameo appearance in Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016), the first installment of the Fantastic Beasts franchise. His name was not mentioned in the promotional materials and his cameo was only revealed at the end of the film.[136][137]

In 2017, Depp appeared alongside other actors and filmmakers in The Black Ghiandola, a short film made by a terminally ill teenager through the non-profit Make a Film Foundation.[138][139][140] He also reprised his role as Captain Jack Sparrow in the fifth installment of the Pirates series, Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017). In the US, it did not perform as well as previous installments,[141] and Depp was nominated for two Golden Raspberry Awards for worst actor and for worst screen combo with «his worn-out drunk routine».[142] However, the film had a good box office return internationally, especially in China, Japan and Russia.[143] Depp’s last film release in 2017 was the Agatha Christie adaptation Murder on the Orient Express, in which he was part of an ensemble cast led by director-star Kenneth Branagh.

In 2018, Depp voiced the title character Sherlock Gnomes in the animated movie Gnomeo & Juliet: Sherlock Gnomes. Although moderately commercially successful, it was critically panned[144][145] and earned Depp two Golden Raspberry nominations, one for his acting and another for his «fast-fading film career».[146] Depp then starred in two independent films, both produced by him and his company, Infinitum Nihil. The first was City of Lies, in which he starred as Russell Poole, an LAPD detective who attempts to solve the murders of rappers Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G. It was set for release in September 2018, but was pulled from the release schedule after a crew member sued Depp for assault.[147] The second film was the comedy-drama Richard Says Goodbye, in which Depp played a professor with terminal cancer. It premiered at the Zurich Film Festival in October 2018.[148] Depp’s last film release of 2018 was Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald, in which he reprised his role as Grindelwald. Depp’s casting received criticism from fans of the series due to the domestic violence allegations against him.[149][150]

Depp also experienced other career setbacks around this time, as Disney confirmed that they would not be casting him in new Pirates installments[151] and he was reported to no longer be attached to Universal’s Dark Universe franchise.[152][153] Depp’s next films were the independent dramas Waiting for the Barbarians (2019), based on a novel by J.M. Coetzee, and Minamata (2020), in which he portrayed photographer W. Eugene Smith and which premiered at the 2020 Berlin International Film Festival.[154] In November 2020, Depp resigned from his role as Grindelwald in the Fantastic Beasts franchise at the request of its production company, Warner Bros., after he lost his UK libel case against The Sun, which had accused him of being a domestic abuser.[155][156][157] He was replaced by Mads Mikkelsen.[158] Soon after, The Hollywood Reporter called Depp «persona non-grata» in the film industry.[159]

2021–present: Multiple European film awards and upcoming projects

In March 2021, City of Lies, which was originally scheduled for 2018, was released in theaters and streaming services.[160][161] The same month, an online petition to bring Depp back to the Pirates franchise, begun four months earlier, reached its goal of 500,000 signatures.[162] His Pirates co-star Kevin McNally also expressed support for Depp returning to the role.[163] In July 2021, Andrew Levitas, the director of Minamata (2020), accused MGM of trying to bury the film due to Depp’s involvement,[164][165][166] with Depp claiming he is being boycotted by the Hollywood industry and calling his changed reputation an «absurdity of media mathematics».[167] Minamata was released in the UK and Ireland in August 2021,[168] and in North America in December 2021.[169] The film received positive reviews,[170] with multiple publications praising Depp’s performance as his best in years.[171][172][173][174][175] Depp also continues as the face of Dior’s men’s fragrance, Sauvage.[176][177]

Depp received multiple honorary awards at numerous European film festivals, including at the Camerimage festival in Poland,[178] the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic,[179] and the San Sebastián International Film Festival in Spain,[180] where Depp was awarded the Donostia Award.[181] These awards were controversial, with various domestic violence charities criticizing the festivals.[182][183] The organisers of the ceremonies released statements defending their decision to award Depp,[184][185][186] with the San Sebastian Film Festival stating that «he has not been charged by any authority in any jurisdiction, nor convicted of any form of violence against women».[187]

In September 2021, Depp described himself as a victim of cancel culture.[188] The same month, he launched IN.2, a London-based sister company to his production company, Infinitum Nihil, and announced that IN.2 and the Spanish production company A Contracorriente Films were starting a new development fund for TV and film projects.[189]

On February 15, 2022, Depp received the Serbian Gold Medal of Merit from President Aleksandar Vučić for «outstanding merits in public and cultural activities, especially in the field of film art and the promotion of the Republic of Serbia in the world».[190][191] Minamata and animated series Puffins were shot in the country.[192]

As of May 2022, Depp has been cast as King Louis XV in French actor-director Maïwenn’s period film Jeanne Du Barry, which is to begin filming in the summer.[193] The previously titled Jeanne du Barry is now titled La Favorite and will tell the story of Madame du Barry, an impoverished seamstress who rises through the ranks of Louis XV’s court to become his official mistress. Netflix will co-finance and stream the French period drama. This will be the first film for Depp where he acts in French.[194]

In August 2022, Depp is set to direct Modigliani, a film about Amedeo Modigliani, which he will co-produce alongside Al Pacino and Barry Navidi.[195] The film is based on a play by Dennis McIntyre, which was previously adapted for the 2004 film of the same name, from a screenplay by Jerzy and Mary Kromolowski.[195] Principal photography will commence in 2023.[195] He made a surprise cameo appearance at the 2022 MTV Video Music Awards.[196]

Other ventures

In 2004, Depp founded film production company Infinitum Nihil to develop projects where he will serve as actor or producer.[82] He serves as its CEO, while his sister, Christi Dembrowski, serves as president.[82][197] The company’s first two film releases were The Rum Diary (2011) and Hugo (2011).[198]

Depp co-owned the nightclub The Viper Room in Los Angeles from 1993 to 2003,[199] and he was also part owner of the restaurant-bar Man Ray in Paris for a short period of time.[200] Depp and Douglas Brinkley edited folk singer Woody Guthrie’s novel House of Earth,[201] which was published in 2013.[202]

Music

Prior to his acting career, Depp was a guitarist, and has later featured on songs by Oasis, Shane MacGowan, Iggy Pop, Vanessa Paradis, Aerosmith, Marilyn Manson, and The New Basement Tapes, among others. He also performed with Manson at the Revolver Golden Gods Awards in 2012.[203] Depp played guitar on the soundtrack of his films Chocolat and Once Upon a Time in Mexico, and has appeared in music videos for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, The Lemonheads, Avril Lavigne and Paul McCartney. In the 1990s, he was also a member of P, a musical group featuring Butthole Surfers singer Gibby Haynes, Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea and Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones.

In 2015, Depp formed the supergroup Hollywood Vampires with Alice Cooper and Joe Perry; the band also includes Bruce Witkin, his friend from his 1980s band, The Kids. Hollywood Vampires released their self-titled debut studio album in September 2015. It featured eleven classic rock covers, as well as three original songs (all co-written by Depp).[204] The band made their live debut at The Roxy in Los Angeles in September 2015,[205] and has since done two world tours in 2016[206] and 2018.[207][208] Their second studio album, Rise, was released in June 2019 and consists mostly of original material, including songs written by Depp. The album also features a cover version of David Bowie’s «Heroes», sung by Depp.[209]

In 2020, Depp released a cover of John Lennon’s «Isolation» with guitarist Jeff Beck, and stated that they would be releasing more music together in the future.[210] Beginning in May 2022, Depp joined Beck onstage for a number of concerts in the United Kingdom, where Beck announced they had recorded an album together.[211] Their joint record, titled 18, was released on July 15, 2022. Depp also accompanied Beck on his European tour, which began in June.[212]

Art

In July 2022, artwork made by Depp sold out in less than a day since it debuted in the UK-based art retailer Castle Fine Art gallery in London’s Covent Garden. The art house hosted the actor’s «Friends & Heroes» collection, which was described as paintings of people «who have inspired him as a person». Among the art pieces, the names include actors Al Pacino and Elizabeth Taylor and musicians Bob Dylan and Keith Richards. Depp made for nearly $4 million dollars and sold 780 prints through the art house’s 37 galleries. Ahead of the sale, Depp expressed his desire to display his art publicly and stated, «I’ve always used art to express my feelings and to reflect on those who matter most to me, like my family, friends and people I admire.» He added, «My paintings surround my life, but I kept them to myself and limited myself. No one should ever limit themselves.»[213] All 780 pieces sold within hours, with framed individual images going for £3,950 and the complete portfolio of four images selling for £14,950. «This world-first release proved to be our fastest-selling collection to date, with all titles selling out in just hours,» the gallery announced on Instagram. Speaking on behalf of fine art publishers, Washington Green Glyn Washington described Depp as a «true creative, with an extraordinary eye for detail and nuance».[214][215]

Reception and public image

In the 1990s, Depp was seen as a new type of male film star that rejected the norms of that role.[216][217] After becoming a teen idol in 21 Jump Street,[218] he publicly protested against the image, and with his subsequent film and public relations choices began to cultivate a new public persona.[216][217] The Sydney Morning Herald characterized Depp in the 1990s as the «bad boy of Hollywood»;[219] Depp’s chain smoking,[219] recreational drug use and drinking habits were generally documented during this time.[220] According to The Guardian journalist Hadley Freeman in 2020:

«Along with Phoenix and Keanu Reeves, he was part of a holy trinity of grunge heart-throbs. They were the opposite of the Beverly Hills, 90210 boys, or Brad Pitt and DiCaprio, because they seemed embarrassed by their looks, even resentful of them. …This uninterest in their own prettiness made them seem edgy, even while their prettiness softened that edge. They signified not just a different kind of celebrity, but a different kind of masculinity: desirable but gentle, manly but girlish. Depp in particular was the cool pinup it was safe to like, and the safe pinup it was cool to like. We fans understood that there was more to Depp, Phoenix and Reeves than handsomeness. They were artistic—they had bands!—and they thought really big thoughts, which they would ramble on about confusingly in interviews. If we dated them, we understood that our role would be to understand their souls.»[216]

Similarly, film scholar Anna Everett has described Depp’s 1990s films and public persona as «anti-macho» and «gender-bending», going against the conventions of a Hollywood leading man.[217] After 21 Jump Street, Depp chose to work in independent films, often taking on quirky roles that sometimes even completely obscured his looks, such as Edward Scissorhands.[216][217] Critics often described Depp’s characters as «iconic loners»[43] or «gentle outsiders».[217] According to Depp, his onetime agent, Tracey Jacobs of United Talent Agency (UTA), had to take «a lot of heat over the years» for his role choices; Depp characterized higher-ups at UTA as thinking, «Jesus Christ! When does he do a movie where he kisses the girl? When does he get to pull a gun out and shoot somebody? When does he get to be a [fucking] man for a change? When is he finally going to do a blockbuster?»[221] Depp also cultivated the image of a bad boy. According to Everett, his «rule-breaking» roles matched with the «much publicized rebelliousness, unconventionality, and volatility ascribed to Depp’s own personal life throughout the decade. From reports of his repeated confrontations with the police, trashing of a hotel room, chain smoking, drinking, and drug use, to his multiple engagements to such glamorous women as supermodel Kate Moss and Hollywood starlet Winona Ryder and others, we clearly see a perfect fit between his non-conformist star image and his repertoire of outsider characters».[217]

After a decade of appearing mainly in independent films with varying commercial success, Depp became one of the biggest box-office draws in the 2000s with his role as Captain Jack Sparrow in Walt Disney Studios’ Pirates of the Caribbean franchise.[222] The five films in the series have earned US$4.5 billion as of 2021. In addition to the Pirates franchise, Depp also made further four films with Tim Burton that were major successes, with one, Alice in Wonderland (2010), becoming the biggest commercial hit of Depp’s career and one of the highest-grossing films in history (as of 2021).[223]

According to film scholar Murray Pomerance, Depp’s collaboration with Disney «can be seen to purport and herald a new era for Johnny Depp, one in which he is, finally, as though long-promised and long-expected, the proud proprietor of a much-accepted career; not only a star but a middle-class hero».[222] In 2003, the same year as the first film in the Pirates series was released, Depp was named «World’s Sexiest Man» by People; he would receive the title again in 2009.[222] During the decade and into the 2010s, Depp was one of the biggest and most popular film stars in the world[1][2] and was named by public vote as «Favorite Male Movie Star» at the People’s Choice Awards every year for 2005 through 2012. In 2012, Depp became the highest-paid actor in the American film industry, earning as high as $75 million per film,[3] and as of 2020, is the tenth highest-grossing actor worldwide, with his films having grossed over US$3.7 billion at the United States box office and over US$10 billion worldwide.[224] Although a mainstream favorite with the audiences, critics’ views on Depp changed in the 2000s, becoming more negative as he was seen to conform more to the Hollywood ideal.[222] Regardless, Depp continued to eschew more traditional leading-man roles until towards the end of the 2000s, when he starred as John Dillinger in Public Enemies (2009).[222]

In the 2010s, Depp’s films were less successful, with many big-budget studio films such as Dark Shadows (2012), The Lone Ranger (2013), and Alice Through the Looking Glass (2016) which underperformed at the box office.[113][111][116][117] Depp also received negative publicity due to allegations of domestic violence, substance abuse, poor on-set behavior and the loss of his US$650 million fortune.[225][226][227][228][216] After losing a highly publicized libel trial against the publishers of The Sun, Depp was asked to resign from Warner Bros.’ Fantastic Beasts franchise.[155] Many publications alleged that Depp would struggle to find further work in major studio productions in the future.[159][216][229]

Personal life

Relationships

Depp and makeup artist Lori Anne Allison were married from 1983 until 1985.[230] In the late 1980s, he was engaged to actresses Jennifer Grey and Sherilyn Fenn.[216] In 1990, he proposed to his Edward Scissorhands co-star Winona Ryder, who he began dating the year prior when she was 17 and he was 26.[231][232] They ended their relationship in 1993;[231] Depp later had the «Winona Forever» tattoo on his right arm changed to «Wino Forever».[216]

Between 1994 and 1998, he was in a relationship with English model Kate Moss.[233] Following his breakup from Moss, Depp began a relationship with French actress and singer Vanessa Paradis, whom he met while filming The Ninth Gate in France in 1998. They have two children, daughter Lily-Rose Melody Depp (born 1999) and a son, Jack (born 2002).[234] Depp stated that having children has given him a «real foundation, a real strong place to stand in life, in work, in everything …You cannot plan the kind of deep love that results in children. Fatherhood was not a conscious decision. It was part of the wonderful ride I was on. It was destiny. All the math finally worked».[73] Depp and Paradis announced that they had separated in June 2012.[235]

Amber Heard

Following the end of his relationship with Vanessa Paradis, Depp began dating actress Amber Heard, with whom he had co-starred in The Rum Diary (2011).[236] Depp and Heard were married in a civil ceremony in February 2015.[237][238][239] Heard filed for divorce in May 2016 and obtained a temporary restraining order against Depp, alleging in her court declaration that he had been verbally and physically abusive throughout their relationship, usually while under the influence of drugs or alcohol.[240][241][242][228] Depp denied these claims and alleged that she was «attempting to secure a premature financial resolution».[243][240][244] A settlement was reached in August 2016,[245] and the divorce was finalized in January 2017.[246] Heard dismissed the restraining order, and they issued a joint statement saying that their «relationship was intensely passionate and at times volatile, but always bound by love. Neither party has made false accusations for financial gain. There was never any intent of physical or emotional harm».[245] Depp paid Heard a divorce settlement of US$7 million, which she pledged to donate[247] to the ACLU[248] and the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA).[249][250]

Legal issues

Depp v News Group Newspapers Ltd

In 2018,[251] Depp brought a libel lawsuit in the UK against News Group Newspapers (NGN), publishers of The Sun, over an April 2018 article titled «GONE POTTY How Can J K Rowling be «genuinely happy» casting wife beater Johnny Depp in the new Fantastic Beasts film?».[252][253][254] The case had a highly publicized trial in July 2020, with both Depp and Heard testifying for several days.[255] In November 2020, the High Court of Justice ruled that 12 of the 14 incidents of violence claimed by Heard were «substantially true».[253][254] The court rejected Depp’s claim of a hoax[256] and accepted that the allegations Heard had made against Depp had damaged her career and activism.[253][254] Following the verdict, Depp resigned from the Fantastic Beasts franchise, after being asked to do so by its production company, Warner Bros.[157]

Depp appealed the verdict, with his lawyers accusing Heard of not following through on the charity pledge, and that the pledge had significantly influenced the judge’s view of Heard.[257] In response, Heard’s legal team stated that she had not donated the full amount yet due to the lawsuits against her by Depp.[258] Depp’s appeal to overturn the verdict was rejected by the Court of Appeal in March 2021.[259] The Court of Appeal did not find the argument that the charity pledge influenced the outcome convincing, as the judge in the trial had reached their verdict by evaluating the evidence related to the 14 alleged incidents of violence; the issue of the donation was not part of it, but a comment made after the verdict had already been reached.[260]

Depp v. Heard

In February 2019, Depp sued Heard for defamation over a December 2018 op-ed for The Washington Post.[261][262][263] The lawsuit ultimately resulting in Depp alleging that the op-ed contained three defamatory statements: first, its headline, «Amber Heard: I spoke up against sexual violence — and faced our culture’s wrath. That has to change»; second, Heard’s writing: «Then two years ago, I became a public figure representing domestic abuse, and I felt the full force of our culture’s wrath for women who speak out»; and third, Heard’s writing: «I had the rare vantage point of seeing, in real time, how institutions protect men accused of abuse.»[4][264] Depp alleged that he had been the one who was abused by Heard, that her allegations constituted a hoax against him, and that as a consequence, Disney had declined to cast him in future projects.[261][263]

Heard countersued Depp in August 2020, alleging that he had coordinated «a harassment campaign via Twitter and [by] orchestrating online petitions in an effort to get her fired from Aquaman and L’Oreal».[265][266] Ultimately, Heard’s counter-suit went to trial over three allegations that Depp that defamed her through statements made by his then-lawyer, Adam Waldman, published in the Daily Mail in April 2020: first, Waldman stated that «Heard and her friends in the media used fake sexual violence allegations as both sword and shield», publicizing a «sexual violence hoax» against Depp; second, Waldman stated that in one incident at a penthouse, «Amber and her friends spilled a little wine and roughed the place up, got their stories straight under the direction of a lawyer and publicist, and then placed a second call to 911» as a «hoax» against Depp; third, Waldman stated that there had been an «abuse hoax» by Heard against Depp.[4][5]

In October 2020, the judge in the case dismissed Depp’s lawyer Adam Waldman after he leaked confidential information covered by a protective order to the media.[159][267] Following the verdict in Depp’s lawsuit against The Sun the next month, Heard’s lawyers filed to have the defamation suit dismissed, but judge Penny Azcarate ruled against it because Heard had not been a defendant in the UK case.[268] In August 2021, a New York judge ruled that the ACLU must disclose documents related to Heard’s charity pledge to the organization.[269][270]

The Depp-Heard trial took place in Fairfax County, Virginia from April 11, 2022, to June 1, 2022.[271] In their verdict, the jury found that all three statements from Heard’s op-ed were false, defamed Depp, and made with actual malice, so the jury awarded Depp $10 million in compensatory damages and $5 million in punitive damages from Heard.[4][5] The punitive damages were reduced to $350,000 due to a limit imposed by Virginia state law.[272] For Heard’s counter-suit, the jury found that Waldman’s first and third statements to the Daily Mail were not defamatory, while finding that Waldman’s second statement to the Daily Mail was false, defamatory and made with actual malice.[5] As a result, Heard was awarded $2 million in compensatory damages and zero in punitive damages from Depp.[4]

Depp reacted to the result of the trial by declaring that the «jury gave me my life back. I am truly humbled.»[273] Depp also stated that he was «overwhelmed by the outpouring of love and the colossal support and kindness from around the world.» He continued: «I hope that my quest to have the truth be told will have helped others, men or women, who have found themselves in my situation, and that those supporting them never give up.»[274] Depp also highlighted «the noble work of the Judge, the jurors, the court staff and the Sheriffs who have sacrificed their own time to get to this point», and praised his «diligent and unwavering legal team» for «an extraordinary job».[275]

After Heard appealed the verdict, Heard in December 2022 settled the case against Depp, while maintaining that the settlement was «not an act of concession»; meanwhile Depp’s lawyers stated that the «jury’s unanimous decision and the resulting judgement in Mr. Depp’s favor against Ms. Heard remain fully in place», and that the settlement would result in $1 million being paid to Depp, which «Depp is pledging and will donate to charities».[276][277]

Other legal issues

Depp was arrested in Vancouver in 1989 for assaulting a security guard after the police were called to end a loud party at his hotel room.[278] He was also arrested in New York City in 1994 after causing significant damage to his room at The Mark Hotel, where he was staying with Kate Moss, his girlfriend. The charges were dropped against him after he agreed to pay US$9,767 in damages.[279]

Depp was arrested again in 1999 for brawling with paparazi, when the photographers tried to take his picture. He allegedly threatened them with a wooden plank when they approached him outside Mirabelle restaurant in central London early on Sunday morning.[280]

In 2012, UC Irvine medical professor Robin Eckert sued Depp and three security firms, Premier Group International, Damian Executive Production Inc. and Staff Pro Inc.[281], claiming to have been roughed up by his bodyguards at a concert in Los Angeles in 2011. During the incident, she was allegedly hand-cuffed and dragged 40 feet across the floor, resulting in injuries including a dislocated elbow. Depp’s attorneys contended that Eckert provoked the alleged assault and therefore «consented to any assault and battery».[282] Ekert’s court papers stated that Depp, despite being his security guards’ direct manager, did nothing to stop the attack.[283] Before the case went to trial, Depp settled with Eckert for an undisclosed sum, according to TMZ.[284]

In April 2015, Depp’s then-wife Amber Heard breached Australia’s biosecurity laws when she failed to declare their two dogs to the customs when they flew to Queensland, where he was working on a film.[285][286] Heard pleaded guilty to falsifying quarantine documents, stating that she had made a mistake due to sleep deprivation.[287] She was placed on a $1,000 one-month good behavior bond for producing a false document;[288] Heard and Depp also released a video in which they apologized for their behavior and urged people to adhere to the biosecurity laws.[288] The Guardian called the case the «highest profile criminal quarantine case» in Australian history.[288]

In March 2016, Depp cut ties with his management company, The Management Group (TMG), and sued them in January 2017 for allegedly improperly managing his money and leaving him over $40 million in debt.[289][290] TMG stated that Depp was responsible for his own fiscal mismanagement and countersued him for unpaid fees.[289][291] In a related suit, Depp also sued his lawyers, Bloom Hergott, in January 2017.[292] Both lawsuits were settled, the former in 2018 and the latter in 2019.[292][293][289]

In 2018, two of Depp’s former bodyguards sued him for unpaid fees and unsafe working conditions.[294] The suit was settled in 2019.[295]

Also in 2018, Depp was sued for allegedly hitting and verbally insulting a crew member while under the influence of alcohol on the set of City of Lies.[296] A lawyer for Depp told the media that «Depp never touched the [crew member], as over a dozen witnesses present will attest»; meanwhile Depp’s legal team entered a court filing that did not admit that Depp hit the crew member, but stated that the crew member «provoked» the incident with «unlawful and wrongful conduct», causing Depp and film director Brad Furman to fear for their safety.[297] A film script supervisor submitted a court declaration that Depp did not hit the crew member, and only scolded him.[298] Before the lawsuit went to trial, a tentative settlement regarding the dismissal of the lawsuit was reached between Depp and the crew member in July 2022.[298]

Alcohol and drug use

Depp has struggled with alcoholism and addiction for much of his life. He has stated that he began using drugs by taking his mother’s «nerve pills» at the age of 11, was smoking at age 12 and by the age of 14 had used «every kind of drugs there were».[299][300] In a 1997 interview, Depp acknowledged past abuse of alcohol during the filming of What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? (1993).[299] In a 2008 interview, Depp stated that he had «poisoned» himself with alcohol «for years».[299] In 2013, Depp declared that he had stopped drinking alcohol, adding that he «pretty much got everything [he] could get out of it»; Depp also said, «I investigated wine and spirits thoroughly, and they certainly investigated me as well, and we found out that we got along beautifully, but maybe too well».[301] Regarding his breakup with longtime partner Vanessa Paradis, Depp said that he «definitely wasn’t going to rely on the drink to ease things or cushion the blow or cushion the situation …[because] that could have been fatal».[301]

According to his ex-wife, Amber Heard, Depp «plunged into the depths of paranoia and violence after binging on drugs and alcohol» during their relationship between 2013 and 2016.[228][302][245] In a 2018 Rolling Stone profile of Depp, reporter Stephen Rodrick wrote that he had used hashish in his presence and described him as «alternately hilarious, sly and incoherent»; Depp also said that the allegation made by his former business managers that he had spent US$30,000 per month on wine was «insulting» because he had spent «far more» than that amount.[225] During his 2020 libel trial, Depp admitted to having been addicted to Roxicodone and alcohol as well as using other substances such as MDMA and cocaine during his relationship with Heard.[303][304][305][306]

Political views

In November 2016, Depp joined the campaign Imprisoned for Art to call for the release of Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Sentsov, who was being held in custody in Russia.[307]

At the Glastonbury Festival 2017, Depp, criticizing President Donald Trump, asked: «When was the last time an actor assassinated a president? I want to clarify: I’m not an actor. I lie for a living. However, it’s been a while and maybe it’s time». He added, «I’m not insinuating anything». The comment was interpreted as a reference to John Wilkes Booth, the actor who assassinated Abraham Lincoln. Shawn Holtzclaw of the Secret Service told CNN they were aware of Depp’s comment, but that «[f]or security reasons, we cannot discuss specifically nor in general terms the means and methods of how we perform our protective responsibilities».[308][309] Depp apologized shortly afterward, saying the remark «did not come out as intended, and I intended no malice».[310]

Filmography and accolades

Discography

| Year | Song | Artist | Album | Credits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | «That Woman’s Got Me Drinking» | Shane MacGowan and The Popes | The Snake | Guitar |

| 1995 | All tracks | P | P | Guitar, bass |

| «Fade Away» | Oasis | The Help Album | Guitar | |

| 1997 | «Fade In-Out» | Be Here Now | ||

| 1999 | «Hollywood Affair» | Iggy Pop | «Corruption» (B-side) | Featured performer |

| 2000 | «St. Germain» | Vanessa Paradis | Bliss | Co-writer |

| «Bliss» | ||||

| «Firmaman» | Guitar | |||

| «Minor Swing» | Rachel Portman | Chocolat (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | Guitar | |

| «They’re Red Hot» | ||||

| «Caravan» | ||||

| 2003 | «Sand’s Theme» | Various artists | Once Upon A Time In Mexico (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | Composer |

| 2007 | «No Place Like London» | Various artists | Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street: The Motion Picture Soundtrack | Performer |

| «My Friends» | ||||

| «Pirelli’s Miracle Elixir» | ||||

| «Pretty Women» | ||||

| «Epiphany» | ||||

| «A Little Priest» | ||||

| «Johanna (Reprise)» | ||||

| «By the Sea» | ||||

| «Final Scene» | ||||

| 2008 | «Too Close to the Sun» | Glenn Tilbrook and The Fluffers | Pandemonium Ensues | Guitar |

| 2010 | «I Put a Spell on You» | Shane MacGowan and Friends | — | Guitar |

| «Unloveable» | Babybird | Ex-Maniac | Guitar | |

| 2011 | «Kemp in the Village» | Christopher Young | The Rum Diary (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | Performer, co-writer |

| «The Mermaid Song» (instrumental) | Piano | |||

| «Ballade de Melody Nelson» | Lulu Gainsbourg | From Gainsbourg to Lulu | Co-lead vocals, guitar, bass, drums | |

| «The Jesus Stag Night Club» | Babybird | The Pleasures of Self Destruction | Guitar | |

| 2012 | «Freedom Fighter» | Aerosmith | Music from Another Dimension! | Background vocals |

| «You’re So Vain» | Marilyn Manson | Born Villain | Guitar, drums, production | |

| «Street Runners» | Jup & Rob Jackson | Collective Bargaining | Featured performer | |

| «Little Lion Man» | Various artists | West of Memphis: Voices of Justice | Performer | |

| «Damien Echols Death Row Letter Year 16» | ||||

| 2013 | «The Mermaid» | Various artists | Son of Rogues Gallery: Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs & Chanteys | Guitar, drums |

| «The Brooklyn Shuffle» | Steve Hunter | The Manhattan Blues Project | Guitar | |

| «New Year» | Vanessa Paradis | Love Songs | Co-writer | |

| «Poor Paddy on the Railway» | Various artists | The Lone Ranger: Wanted (Music Inspired by the Film) | Guitar | |

| «Sweet Betsy from Pike» | Arrangement | |||

| 2014 | «Kansas City» | The New Basement Tapes | Lost on the River: The New Basement Tapes | Guitar |

| «Hello, Little Girl» | Various artists | Into the Woods (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | Performer | |

| 2015 | All tracks | Hollywood Vampires | Hollywood Vampires | Guitar, keyboards, backing vocals, co-writer, sound design |

| «21+» | Butch Walker | Afraid of Ghosts | Guitar | |

| 2019 | All tracks | Hollywood Vampires | Rise | Guitar, keyboards, backing vocals, co-writer, sound design |

| 2022 | All tracks | Jeff Beck & Johnny Depp | 18 | Vocals, acoustic guitar, rhythm guitar, bass, drums, backing vocals, co-writer |

See also

- List of people from Kentucky

- List of actors with Academy Award nominations

- List of actors with two or more Academy Award nominations in acting categories

- Jack Sparrow

Notes

- ^ Depp accompanied Thompson as his road manager on one of the author’s last book tours.[62] In 2006, he contributed a foreword to Gonzo: Photographs by Hunter S. Thompson, a posthumous collection of photographs of and by Thompson, and in 2008 narrated the documentary film Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson. Following Thompson’s suicide in 2005, Depp paid for most of his memorial event in his hometown of Aspen, Colorado. Following Thompson’s wishes, fireworks were set off and his ashes were shot from a cannon.[63]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Labrecque, Jeff (June 8, 2012). «Tom Cruise, Johnny Depp, and the state of the modern Movie Star». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c «Johnny Depp May Now Be The Biggest Movie Star Of All Time». NBC4 Washington. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ a b c Erenza, Jen (September 14, 2011). «Justin Bieber, Miranda Cosgrove, & Lady Gaga Are Welcomed Into 2012 Guinness World Records». RyanSeacrest.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Hennessy, Joan (June 1, 2022). «Jurors mostly side with Depp in defamation case against Heard». Courthouse News. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Rico, R.J. (June 1, 2022). «Explainer: Each count the Depp-Heard jurors considered». Associated Press. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ «Monitor». Entertainment Weekly. No. 1263. June 14, 2013. p. 40.

- ^ a b c «Celebrity Central: Johnny Depp». People. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (July 6, 2020). «7 Things You Need to Know About Johnny Depp’s U.K. Trial». Variety. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

…over the case brought by John Christopher Depp II against Rupert Murdoch’s News Group Newspapers…

- ^ Ng, Philiana (May 25, 2016). «Johnny Depp’s Mother Dies After Long Illness». Etonline.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- ^ Blitz & Krasniewicz 2007, p. 1.

- ^ The Genealogist Archived June 26, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, «Richard T. Oren Depp (1879–1912); m. Effie America Palmore. 9th gen. Oren Larimore Depp; m. Violet Grinstead. 10th gen. John Christopher Depp; m. Betty Sue Wells. 11th gen John Christopher Depp II (Johnny Depp), b. 9 June 1963, Owensboro. See Warder Harrison, «Screen Star, Johnny Depp, Has Many Relatives in Ky.», Kentucky Explorer (Jackson, Ky), July–August 1997, 38–39. 247 Barren Co.»

- ^ a b c d e f g Stated on Inside the Actors Studio, 2002

- ^ Smith, Kyle (December 13, 1999). «Keeping His Head». People. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ Hiscock, John (June 25, 2009). «Johnny Depp interview for Public Enemies». The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on January 29, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Alexander, Bryan (February 16, 2016). «Johnny Depp’s Grammy song is a toast to his late stepfather». USA TODAY. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- ^ «Sleaze Roxx». ROCK CITY ANGELS. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ «Rock City Angels – Mary». YouTube. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ Robb, Brian J. (2006). Johnny Depp: A Modern Rebel. Plexus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85965-385-5.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (May 8, 2011). «Johnny Depp on ‘The Lone Ranger’«. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d «Disney Exploiting Confusion About Whether Depp Has Indian Blood». June 17, 2013. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Toensing, Gale Courney (June 11, 2013). «Sonny Skyhawk on Johnny Depp, Disney, Indian Stereotypes and White Film Indians». Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

Yet [Disney] has the gall and audacity to knowingly cast a non-Native person in the role of an established Native character. … American Indians in Film and Television’s argument is not so much with Johnny Depp, a charlatan at his best, as it is with the machinations of Disney proper. The controversy that will haunt this endeavor and ultimately cause its demise at the box office is the behind-the-scenes concerted effort and forced manipulation by Disney to attempt to sell Johnny Depp as an American Indian. American Indians, as assimilated and mainstream as they may be today, remain adamantly resistant to anyone who falsely claims to be one of theirs.

- ^ Mouallem, Omar (May 22, 2019). «‘Billionaires, Bombers, and Bellydancers’: How the First Arab American Movie Star Foretold a Century of Muslim Misrepresentation». The Ringer. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

Though not a ‘pretendian’ to the degree of Iron Eyes Cody, the Sicilian American impostor of ‘Keep America Beautiful’ fame, or Johnny Depp for that matter, Lackteen appropriated Native American culture.

- ^ Murray, John (April 20, 2018). «APTN Investigates: Cowboys and Pretendians». Aboriginal Peoples Television Network. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Jago, Robert (February 1, 2021). «Criminalizing ‘Pretendians’ is not the answer; we need to give First Nations control over grants». National Post. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- ^ «Is ‘Tonto’s Giant Nuts’ a Good Name for Johnny Depp’s Band?». Indian Country Today Media Network. May 22, 2013. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ a b ICTMN Staff (June 12, 2013). «Tito Ybarra Greets Indian Country as ‘Phat Johnny Depp’«. Indian Country Today Media Network. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Keene, Adrienne (December 3, 2012). «Native Video Round-Up: Johnny Depp, Identity, and Poetry». Native Appropriations. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Bogado, Aura (November 25, 2013). «Five Things to Celebrate About Indian Country (Humor)». ColorLines. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Moore, Nohemi M. (May 15, 2022). «Johnny Depp’s History of Racism and Broken Promises to Native Americans». Eight Tribes. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

While promoting The Lone Ranger, Depp was made an honorary son by LaDonna Harris, a member of the Comanche Nation. Although now an honorary member of his family, he is not a member of any tribe.

- ^ Gornstein, Leslie (May 23, 2012). «Why Can Johnny Depp Play Tonto, but Ashton Kutcher and Sacha Baron Cohen Get Slammed?». E! Online. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Johnny Depp made honorary member of Comanche nation». The Guardian. May 23, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ Singh, Maanvi (August 30, 2019). «Dior perfume ad featuring Johnny Depp criticized over Native American tropes – Video for ‘Sauvage’ fragrance has been called ‘deeply offensive and racist’ and the fashion brand has removed it from social media». The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ «Dior pulls ad for Sauvage perfume amid criticism over Indigenous imagery». CBC News. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ «Dior Is Accused of Racism and Cultural Appropriation Over New Native American-Themed Sauvage Ad». The WOW Report. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ «Dior Deletes Johnny Depp Sauvage Ad Amidst Backlash for Native American Depiction». Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ Blitz & Krasniewicz 2007, pp. 16–17.

- ^ «Hooked on Dean, says Johnny Depp». bbc.co.uk.

- ^ a b c Blitz & Krasniewicz 2007, p. 17.

- ^ a b «Johnny Depp reveals the legendary thespian who encouraged him to pursue acting». Marca. April 20, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ Winters, David (2003) [1986]. Thrashin’ (Commentary track). MGM Home Video.

- ^ Tyner, Adam (August 5, 1993). «Thrashin’«. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

something that (the) cast found so astonishing that they apparently called Depp’s girlfriend in the middle of the commentary to find out if it is actually true.

- ^ a b «It’s a pirates life for Johnny Depp». Sify. Reuters. July 4, 2006. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c d «Interview: Johnny Depp». MoviesOnline. Archived from the original on July 5, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Cry-Baby at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Booth, Michael (September 16, 2010). ««Cry-Baby» Depp makes the girls swoon». The Denver Post. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Edward Scissorhands at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ «Tim Burton’s latest film». Entertainment Weekly. December 14, 1990. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ «Edward Scissorhands». Rolling Stone. December 14, 1990. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ «‘Edward Scissorhands’«. The Washington Post. December 14, 1990. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 16, 1993). «He’s His Sister’s Keeper, and What a Job That Is». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ «What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 2, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (December 6, 1993). «What’s Eating Gilbert Grape Review». Variety. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2008.

- ^ a b Arnold, Gary (October 2, 1994). «Depp sees promise in cult filmmaker Ed Wood’s story». The Washington Times.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (September 23, 1994). «Film Festival Review; Ode to a Director Who Dared to Be Dreadful». The New York Times.

- ^ Lyttelton, Oliver (June 9, 2012). «The Essentials: The 5 Best Johnny Depp Performances». IndieWire. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Ehrlich, David (September 16, 2015). «15 Best and Worst Johnny Depp Roles: From Scissorhands to Sparrow». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ «The Brave (1997)». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Cheshire, Godfrey (May 25, 1997). «The Brave». Variety. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ «The Brave». Time Out. February 9, 2006. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Free, Erin (May 27, 2016). «Movies You Might Not Have Seen: The Brave (1997)». filmink.com.au. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ «The Sad, Strange Journey of Johnny Depp’s ‘The Brave’«. Los Angeles Times. May 19, 1997. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ «Depp was ray for thompson book tour». ContactMusic. July 3, 2006. Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ «Thompson’s ashes fired into sky». BBC News Entertainment. August 21, 2005. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ «Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas«. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- ^ Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Burton & Salisbury 2006, pp. 177–178.

- ^ «Johnny Depp on playing Ichabod Crane in Sleepy Hollow«. Entertainment Weekly. May 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- ^ «Blow (2001)». The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ «Blow (2001)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ «Blow Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ «From Hell Reviews». Metacritic. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ «From Hell (2010)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ a b «Johnny Depp Finds Himself, And Success, As Captain Jack Sparrow». ABC. Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2006.

- ^ a b Howell, Peter (June 23, 2006). «Depp thoughts; Reluctant superstar Johnny Depp returns in a Pirates of the Caribbean sequel, but vows success won’t stop him from making movies his way». Toronto Star. p. C.01. Archived from the original on March 24, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Sean (June 26, 2006). «A Pirate’s Life». Newsweek. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Derschowitz, Jessica (November 30, 2010). «Johnny Depp: Disney Hated My Jack Sparrow». CBS News. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ «Once Upon a Time in Mexico». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ «Once upon a Time in Mexico (2003)». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ «Once Upon a Time in Mexico». Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 16, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ «Secret Window (2004)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ «Secret Window Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Marc Graser; Dave McNary (July 12, 2013). «Johnny Depp Moves Production Company to Disney (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ «Charlie and the Chocolate Factory». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ^ «Charlie and the Chocolate Factory». Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved May 17, 2008.

- ^ «Charlie and the Chocolate Factory». Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ^ Papamichael, Stella (October 21, 2005). «Corpse Bride (2005)». BBC. Archived from the original on April 14, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ a b «Depp’s Pirates Plunders Record $132M». ABC News. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ^ «Round Up: PAX, Depp In Pirates Game, KumaWar». Gamasutra. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2006.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (July 10, 2006). «Crazy for Johnny, or Captain Jack?». USA Today. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Gold, Sylviane (November 4, 2007). «Demon Barber, Meat Pies and All, Sings on Screen». The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (April 4, 2008). «Johnny Depp and Tim Burton: A DVD Report Card». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Walker-Mitchell, Donna (July 24, 2009). «Smooth criminal». The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ «Worldwide Box Office Grosses». Boxofficeguru.com. March 28, 2010. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ «Public Enemies». Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ^ «Public Enemies reviews». Metacritic. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. «Public Enemies». Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Salter, Jessica (August 18, 2008). «Heath Ledger’s daughter given wages of stars in Terry Gilliam’s Dr Parnassus». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on May 13, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ^ «2010 Yearly Box Office Results». Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (May 13, 2012). «The Avengers Storms the Billion Dollar Club — In Just 19 DaysP» Archived January 16, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Time.

- ^ «The Tourist (2010)». Box Office Mojo. March 10, 2011. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ Semigran, Aly (July 6, 2011). «Riding high off the success of ‘Rango,’ Paramount Pictures to launch in-house animation division». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Scott, A.O (March 3, 2011). «There’s a New Sheriff in Town, and He’s a Rootin’-Tootin’ Reptile». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ «WORLDWIDE GROSSES». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (November 10, 2011). «The Rum Diary – review». The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 28, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ «The Rum Diary (2011)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Kaufman, Amy (October 27, 2011). «Movie Projector: ‘Puss in Boots’ to stomp on competition». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ «The Rum Diary (2011)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ «The Rum Diary Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ Rosen, Christopher (March 19, 2012). «Johnny Depp ’21 Jump Street’ Cameo: Inside The Star’s Appearance In Big Screen Reboot». moviefone.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ Kit, Borys (September 25, 2008). «Depp to play Tonto, Mad Hatter in upcoming films». Reuters. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.