Текущая версия страницы пока не проверялась опытными участниками и может значительно отличаться от версии, проверенной 23 апреля 2021 года; проверки требует 101 правка.

Напиток кофе содержит психоактивное вещество кофеин

Психоактивные вещества́ (ПАВ) — вещества (или смеси нескольких веществ), влияющие на функции центральной нервной системы и приводящие к изменению психического состояния[1], вплоть до изменённого состояния сознания[2]. Используются в медицине и в рекреационных целях.

Психоактивные вещества, влияющие на высшие психические функции и используемые при лечении психических расстройств, называют психофармакологическими веществами.

- Термин психотропные вещества́, или психотро́пы (от др.-греч. — «поворотный, изменяющий»), в самом широком смысле обозначает то же, что и термин «психоактивные вещества», под которым понимаются как психофармакологические средства, используемые в психиатрии, так и наркотические вещества, например психостимуляторы, галлюциногены, опиоиды[3].

В контексте международного контроля над оборотом наркотических средств термин «психотропное» применяется к веществам, перечисленным в Международной конвенции о психотропных веществах 1971 года[3].

- Нейротро́пные сре́дства — обширная группа лекарственных средств, оказывающих качественное воздействие на центральную и периферическую нервную систему. Они могут угнетать или стимулировать передачу нервного возбуждения, понижать или повышать чувствительность нервных окончаний в периферических нервах, воздействовать на разные типы рецепторов, синапсов.

Виды психоактивных веществ[править | править код]

По происхождению психоактивные вещества делятся на:

- растительные;

- полусинтетические (синтезируемые на основе растительного сырья);

- синтетические.

Классификация психоактивных веществ может проводиться по их химическому строению, по эффекту их воздействия на нервную систему человека, а также по механизму воздействия на организм. Существуют и комбинированные классификации.

Некоторые психоактивные вещества растительного происхождения[править | править код]

|

|

Эта статья или раздел описывает ситуацию применительно лишь к одному региону, возможно, нарушая при этом правило о взвешенности изложения. Вы можете помочь Википедии, добавив информацию для других стран и регионов. |

| Запрещенные в Российской Федерации | Разрешенные в Российской Федерации |

|

|

Некоторые растения, вещества и препараты, вызывающие психотропные эффекты, имеют различный юридический статус в разных странах, например алкоголь, кат, конопля и др.

По фармакологическим свойствам[править | править код]

(наиболее известные вещества)

Лекарственные средства для лечения заболеваний нервной системы

Комбинированные классификации психоактивных веществ[править | править код]

Приведённые ниже круги Эйлера представляют собой попытку в наглядном виде представить в пересекающихся группах и подгруппах наиболее распространённые психоактивные средства, с использованием и синтезом классификаций, основанных как на их клиническом эффекте, так и на химическом строении[8][9][10][11].

Психомоторные

Легенда

- Базовые группы

- Синий: Стимулирующие центральную нервную систему вещества.

- Красный: Депрессанты (успокоительные средства).

- Зелёный: Галлюциногены.

- Розовый: Нейролептики.

- Вторичные группы

- Голубой: Пересечение стимулирующих (Синий) и психоделических галлюциногенов (Зелёный) — Психоделики со стимулирующим эффектом.

- Жёлтый: Пересечение депрессантов (Красный) и диссоциативных галлюциногенов (Зелёный) — Диссоциотивы с успокаивающим эффектом.

- Светло-фиолетовый: Пересечение стимулирующих (Синий) и нейролептиков (Розовый) — Антидепрессанты без седативного эффекта.

- Кремово-красный: Пересечение депрессантов (Красный) и нейролептиков (Розовый) — Антидепрессанты и антипсихотики с седативным эффектом.

- Третичные группы

- Пурпурный: Пересечение стимулирующих (Синий) и депрессантов (Красный) — Пример: никотин.

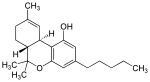

- Белый: Пересечение стимулирующих, депрессантов и галлюциногенов — Пример: ТГК.

- Дымно-голубой: Пересечение стимулирующих, психоделических галлюциногенов и нейролептиков — Пример: эмпатогены-энтактогены.

- Персиковый: Пересечение депрессантов, диссоциативных галлюциногенов и нейролептиков.

- Четвертичные группы

- Светло-розовый: Центр заключает в себя пересечение всех четырёх секций (стимулирующие, нейролептики, депрессанты, галлюциногены) — Пример — Марихуана, содержащая и ТГК и каннабидиол.

Классификации по силе воздействия на психику[править | править код]

Чем меньшее количество вещества необходимо принять для того, чтобы полностью ощутить его действие, тем более сильным, более психоактивным оно является. Для ЛСД, например, активная доза равна 100 микрограммам, в то время как для этанола доза измеряется десятками граммов. Таким образом, психоактивность ЛСД в десятки тысяч раз выше, чем психоактивность этанола. В зависимости от особенностей метаболизма индивида вещество может почти не действовать или делать это гораздо сильнее (гиперчувствительность). Принято измерять дозу в граммах вещества на килограмм веса.

Деление по силе зависимости неоднозначно. Лидерами по данному показателю среди веществ считаются героин, кокаин и никотин, а также алкоголь. Из классов веществ выделяют опиаты и стимуляторы как вызывающие сильную зависимость. Сильную зависимость могут также вызывать барбитураты.

Кофе и чай, содержащие пурины, оказывают слабый стимулирующий эффект[4]. Под «лёгкими наркотиками» обычно подразумевают вещества с низкой аддиктивностью и отсутствием нейротоксичности, такие как ЛСД, марихуана и некоторые другие.

Механизм действия[править | править код]

Психоактивные вещества оказывают разнообразное влияние на ЦНС на разных уровнях её функционирования: молекулярном, синаптическом, клеточном, системном. В целом любое такое влияние сопровождается изменением обмена веществ на том уровне, на котором происходит это влияние.

Психоактивные вещества могут попадать в организм самыми разными путями. Распространённые способы:

- перорально, при глотании — через пищеварительную систему,

- парентерально — инъекционно внутримышечно или внутривенно,

- через слизистые, в том числе интраназально — через носоглотку, путём вдыхания измельчённого вещества,

- через лёгкие — путём курения или вдыхания паров.

Психоактивное вещество проходит сложный путь в организме, и в зависимости от строения, способа использования, состояния выводящих систем, может перерабатываться организмом в производные с разной активностью. Попадая в кровь, проходя через гематоэнцефалический барьер, вещество воздействует на передачу нейронами нервных импульсов. Воздействуя на баланс нейромедиаторов разного влияния (активирующие и тормозные) в мозге, препараты изменяют таким образом работу всей нервной системы.

Толерантность[править | править код]

Чем выше толерантность к употребляемому веществу, тем большие дозы необходимы для получения ожидаемого эффекта. Обычно толерантность вырабатывается при приёме веществ, активность которых со временем снижается. Толерантность быстро формируется к кофеину и опиатам. Чем чаще и в большем количестве употребляются вещества — тем быстрее возрастает толерантность.

Своеобразной толерантностью обладают классические психоделики (ЛСД, псилоцибин, мескалин) — при приёме ЛСД толерантность возрастает очень быстро, буквально через несколько часов после начала действия, но полностью исчезает приблизительно за неделю. Более того, для психоделиков характерна кросстолерантность.

Отмечают, что у некоторых веществ, например, у сальвинорина, природного диссоциатива, содержащегося в мексиканском шалфее Salvia divinorum, может отмечаться обратная толерантность, то есть при длительном употреблении для достижения одного и того же эффекта требуется меньшее количество вещества.

Формирование зависимости и синдрома отмены[править | править код]

Обычно формирование зависимости связывают со злоупотреблением ПАВ, его систематическим применением. Действие веществ на человека очень индивидуально, но среди распространённых веществ быстрее всего зависимость формируется при приёме героина, никотина. Также некоторые психостимуляторы, например кокаин и амфетамин, вызывают психическую (но не физическую) зависимость.

Физическая зависимость формируется, когда организм привыкает к регулярному поступлению участвующих в метаболизме веществ извне и снижает их эндогенную выработку. При прекращении поступления вещества в организм в нём возникает обусловленная физиологическими процессами потребность в этом веществе. Физическая зависимость от психической отличается тем, что в результате замещения собственных нейромедиаторов экзогенными снижается их продукция в организме[12] (либо количество рецепторов к ним).

Механизм формирования зависимости может быть связан как с самим веществом, так и с его метаболитами. Например героин путём удаления ацетил групп метаболизируется в морфин, воздействующий на опиоидные рецепторы. Алкоголь воздействует на нервную систему, напрямую соединяясь с рецепторами ГАМК[13]. Никотин и амфетамин стимулируют выброс эндогенного адреналина[источник не указан 3220 дней].

Психическая зависимость связывается в основном с приятными ощущениями от приёма веществ, что стимулирует человека к повторению опыта их употребления. Зависимость может формироваться и при употреблении веществ, не вызывающих приятных ощущений. Например NMDA-антагонисты, которые вызывают распад сознания (в трип-репортах сообщается даже о переживаниях смерти под их действием); переживания и визуальные эффекты от психоделиков часто не могут быть описаны как приятные, тем не менее, при частом употреблении эти вещества могут вызывать разрыв с реальностью, связанный с эскапистским характером психоделического опыта и формирование психической зависимости.

Психоактивные вещества и соответствующие мишени[править | править код]

См. также[править | править код]

Примечания[править | править код]

- ↑ Психоактивное вещество // Cловарь по естественным наукам. Глоссарий.ру

- ↑ Каплан Г. И., Сэдок Б.Дж. Клиническая психиатрия: В 2 т. Т. 1. М., 1994. С. 148.

- ↑ 1 2 World Health Organization. Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms published by the World Health Organization (англ.). — [Словарь терминов, связанных с алкоголем и психоактивными веществами, опубликованный Всемирной организацией здравоохранения]. Дата обращения: 3 апреля 2019. Архивировано 4 июля 2004 года.

- ↑ 1 2 3 Перечень веществ и запрещённых методов к Конвенции против применения допинга (ETS № 135)

- ↑ с 2018 года запрещено добавление в баночные алкогольные коктейли в РФ

- ↑ Психиатрия и психофармакотерапия — Клинико-фармакологические эффекты антидепрессантов (недоступная ссылка). Дата обращения: 16 сентября 2006. Архивировано 8 ноября 2006 года.

- ↑ Регистр лекарственных средств России — Энциклопедия лекарств — Нейрометаболические стимуляторы (недоступная ссылка). Дата обращения: 16 сентября 2006. Архивировано 2 октября 2003 года.

- ↑ McKim, William A. Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5th Edition) (англ.). — Prentice Hall, 2002. — P. 400. — ISBN 0-13-048118-1.

- ↑ Information on Drugs of Abuse. Commonly Abused Drug Chart. Дата обращения: 27 декабря 2005.

- ↑ Stafford, Peter. Psychedelics Encycloedia (англ.). — 1992. — ISBN 0914171518.

- ↑ Kent, James. Psychedelic Information Theory — Shamanism in the Age of Reason. Retrieved on July 5, 2007.

- ↑ Наука и жизнь: Выпуски 5—8 (недоступная ссылка) Изд-во Академии наук СССР, 2004 стр. 103.

Психическая зависимость сменяется физической. Организм постепенно перестает вырабатывать нужные ферменты.

- ↑ Почему алкоголь вызывает головокружение? (недоступная ссылка). Дата обращения: 23 октября 2006. Архивировано 30 сентября 2007 года.

Литература[править | править код]

- «Лекарственные средства» М. Д. Машковского

- «ЛСД — мой трудный ребёнок», Хоффман А.

- PiHKAL: «Фенэтиламины, которые я знал и любил», Шульгин А.

- TiHKAL: «Триптамины, которые я знал и любил», Шульгин А.

- От ЛСД к виртуальной реальности. Тимоти Лири

- Дмитриева Т. Б., Игонин А. Л., Клименко Т. Б., Пищикова Л. Е., Кулагина Н. Е., Сравнительная характеристика основных групп психоактивных веществ // Наркология № 5, 2002

Ссылки[править | править код]

- «Психоактивные вещества» // ВОЗ (рус.)

- Lycaeum — База психоактивных веществ и растений (англ.)

- Центр исследований психоактивных веществ

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical, psychoactive agent or psychotropic drug is a chemical substance that changes functions of the nervous system, and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, or behavior.[1]

These substances may be used medically, recreationally, for spiritual reasons — for example, to alter one’s consciousness (as with entheogens for ritual, spiritual or shamanic purposes), or for research.

Some categories of psychoactive drugs may be prescribed by physicians[2] and other healthcare practitioners because of their therapeutic value.

Examples of medication categories that may contain potentially beneficial psychoactive drugs include, but are not limited to:

- Anesthetics

- Analgesics

- Anticonvulsants

- Anti-Parkinson’s medications

- Medications used to treat Neuropsychiatric Disorders (Antidepressants, Anxiolytics, Antipsychotics and Stimulant Medications.)

Some psychoactive substances may be used in detoxification and rehabilitation programs for people who may have become dependent upon, or addicted to, other mind or mood altering substances. Drug rehabilitation attempts to reduce addiction through a combination of psychotherapy, support groups, and sometimes — psychoactive substances.

Psychoactive substances often bring various changes in consciousness and mood that the user may find rewarding and pleasant (e.g., euphoria or a sense of relaxation) or advantageous in an objectively observable or measurable way (e.g. increased alertness). Substances which are rewarding, and thus positively reinforcing, have the potential to induce a state of addiction – compulsive drug use despite negative consequences. In addition, sustained use of some substances may produce physical or psychological dependence, or both, associated with somatic or psychological-emotional withdrawal states respectively.

Psychoactive drug misuse, dependence, and addiction have resulted in legal measures and moral debate. Governmental controls on manufacture, supply, and prescription attempt to reduce problematic medical drug use. Ethical concerns have also been raised about over-use of these drugs clinically, and about their marketing by manufacturers. Popular campaigns to decriminalize[3] or legalize the recreational use of certain drugs (e.g. cannabis) are also ongoing.

History[edit]

Alcohol is a widely used and abused psychoactive drug. The global alcoholic drinks market was expected to exceed $1 trillion in 2013.[4] Beer is the third-most popular drink overall, after water and tea.[5]

Psychoactive drug use can be traced to prehistory. There is archaeological evidence of the use of psychoactive substances, mostly plants, dating back at least 10,000 years, and historical evidence of cultural use over the past 5,000 years.[6] The chewing of coca leaves, for example, dates back over 8,000 years ago in Peruvian society.[7][8]

Medicinal use is one important facet of psychoactive drug usage. However, some have postulated that the urge to alter one’s consciousness is as primary as the drive to satiate thirst, hunger, or sexual desire.[9] Supporters of this belief contend that the history of drug use, and even children’s desire for spinning, swinging, or sliding indicate that the drive to alter one’s state of mind is universal.[10]

One of the first people to articulate this point of view, set aside from a medicinal context, was American author Fitz Hugh Ludlow (1836–1870) in his book The Hasheesh Eater (1857):

[D]rugs are able to bring humans into the neighborhood of divine experience and can thus carry us up from our personal fate and the everyday circumstances of our life into a higher form of reality. It is, however, necessary to understand precisely what is meant by the use of drugs. We do not mean the purely physical craving…That of which we speak is something much higher, namely the knowledge of the possibility of the soul to enter into a lighter being, and to catch a glimpse of deeper insights and more magnificent visions of the beauty, truth, and the divine than we are normally able to spy through the cracks in our prison cell. But there are not many drugs which have the power of stilling such craving. The entire catalog, at least to the extent that research has thus far written it, may include only opium, hashish, and in rarer cases alcohol, which has enlightening effects only upon very particular characters.[11]

During the 20th century, many governments across the world initially responded to the use of recreational drugs by banning them, and making their use, supply, or trade a criminal offense. A notable example of this was Prohibition in the United States, where alcohol was made illegal for 13 years. However, many governments, government officials, and persons in law enforcement have concluded that illicit drug use cannot be sufficiently stopped through criminalization. Organizations such as Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) have come to such a conclusion, believing:

[T]he existing drug policies have failed in their intended goals of addressing the problems of crime, drug abuse, addiction, juvenile drug use, stopping the flow of illegal drugs into this country and the internal sale and use of illegal drugs. By fighting a war on drugs the government has increased the problems of society and made them far worse. A system of regulation rather than prohibition is a less harmful, more ethical and a more effective public policy.[12][failed verification]

In some countries, there has been a move toward harm reduction by health services, where the use of illicit drugs is neither condoned nor promoted, but services and support are provided to ensure users have adequate factual information readily available, and that the negative effects of their use be minimized. Such is the case of the Portuguese drug policy of decriminalization, which achieved its primary goal of reducing the adverse health effects of drug abuse.[13]

Purposes[edit]

Psychoactive substances are used by humans for a number of different purposes, and these uses vary widely between cultures. Some substances may have controlled or illegal uses, some may have shamanic purposes, and others are used medicinally. Other examples include social drinking, nootropic, or sleep aids. Caffeine is the world’s most widely consumed psychoactive substance, but unlike many others, it is legal and unregulated in nearly all jurisdictions. In North America, 90% of adults consume caffeine daily.[14]

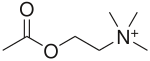

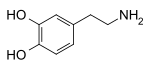

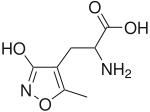

Psychoactive drugs are divided into different groups according to their pharmacological effects. Commonly used psychoactive drugs and groups are listed below:

- Anxiolytics. Used to reduce symptoms of anxiety and panic.

-

- Example: benzodiazepines such as Xanax and Valium, barbiturates

- Empathogen–entactogens

-

- Example: MDMA (ecstasy), MDA, 6-APB, AMT

- Stimulants (colloquially referred to as «uppers»). This category comprises substances that increase wakefulness and productivity, stimulate the mind, and may cause euphoria, but do not affect vision.

-

- Examples: amphetamine, caffeine, cocaine, nicotine, modafinil

- Depressants (colloquially referred to as «downers»), including sedatives, hypnotics, and opioids. This category includes all of the calmative, sleep-inducing, anesthetizing substances, which sometimes induce perceptual changes, such as dream images, and often evoke feelings of euphoria.

-

- Examples: Ethanol (alcohol), opioids such as morphine, fentanyl, and codeine, cannabis, barbiturates, benzodiazepines.

- Hallucinogens, including psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. This category encompasses all substances that produce distinct alterations in perception, sensation of space and time, and emotional states[15]

-

- Examples: psilocybin, LSD, DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine)/ayahuasca, mescaline, Salvia divinorum, Nitrous oxide, and Scopolamine

Uses[edit]

Anesthesia[edit]

General anesthetics are a class of psychoactive drug used on people to block physical pain and other sensations. Most anesthetics induce unconsciousness, allowing the person to undergo medical procedures like surgery, without the feelings of physical pain or emotional trauma.[16] To induce unconsciousness, anesthetics affect the GABA and NMDA systems. For example, propofol is a GABA agonist,[17] and ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist.[18]

Pain management[edit]

Psychoactive drugs are often prescribed to manage pain. The subjective experience of pain is primarily regulated by endogenous opioid peptides. Thus, pain can often be managed using psychoactives that operate on this neurotransmitter system, also known as opioid receptor agonists. This class of drugs can be highly addictive, and includes opiate narcotics, like morphine and codeine.[19] NSAIDs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, are also analgesics. These agents also reduce eicosanoid-mediated inflammation by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase.

Mental disorders[edit]

Psychiatric medications are psychoactive drugs prescribed for the management of mental and emotional disorders, or to aid in overcoming challenging behavior.[20] There are six major classes of psychiatric medications:

- Antidepressants treat disorders such as clinical depression, dysthymia, anxiety, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder.[21]

- Stimulants, used to treat disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, and for weight reduction.

- Antipsychotics, used to treat psychotic symptoms, such as those associated with schizophrenia or severe mania, or as adjuncts to relieve clinical depression.

- Mood stabilizers, used to treat bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

- Anxiolytics, used to treat anxiety disorders.

- Depressants, used as hypnotics, sedatives, and anesthetics, depending upon dosage.

In addition, several psychoactive substances are currently employed to treat various addictions. These include acamprosate or naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism, or methadone or buprenorphine maintenance therapy in the case of opioid addiction.[22]

Exposure to psychoactive drugs can cause changes to the brain that counteract or augment some of their effects; these changes may be beneficial or harmful. However, there is a significant amount of evidence that the relapse rate of mental disorders negatively corresponds with the length of properly followed treatment regimens (that is, relapse rate substantially declines over time), and to a much greater degree than placebo.[23]

Recreation[edit]

Many psychoactive substances are used for their mood and perception altering effects, including those with accepted uses in medicine and psychiatry. Examples of psychoactive substances include caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, LSD, nicotine and cannabis.[24] Classes of drugs frequently used recreationally include:

- Stimulants, which activate the central nervous system. These are used recreationally for their euphoric effects.

- Hallucinogens (psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants), which induce perceptual and cognitive alterations.

- Hypnotics, which depress the central nervous system.

- Opioid analgesics, which also depress the central nervous system. These are used recreationally because of their euphoric effects.

- Inhalants, in the forms of gas aerosols, or solvents, which are inhaled as a vapor because of their stupefying effects. Many inhalants also fall into the above categories (such as nitrous oxide which is also an analgesic).

In some modern and ancient cultures, drug usage is seen as a status symbol. Recreational drugs are seen as status symbols in settings such as at nightclubs and parties.[25] For example, in ancient Egypt, gods were commonly pictured holding hallucinogenic plants.[26]

Because there is controversy about regulation of recreational drugs, there is an ongoing debate about drug prohibition. Critics of prohibition believe that regulation of recreational drug use is a violation of personal autonomy and freedom.[27] In the United States, critics have noted that prohibition or regulation of recreational and spiritual drug use might be unconstitutional, and causing more harm than is prevented.[28]

Some people who take psychoactive drugs experience drug or substance induced psychosis. A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis by Murrie et al. found that the pooled proportion of transition from substance-induced psychosis to schizophrenia was 25% (95% CI 18%–35%), compared with 36% (95% CI 30%–43%) for brief, atypical and not otherwise specified psychoses.[29] Type of substance was the primary predictor of transition from drug-induced psychosis to schizophrenia, with highest rates associated with cannabis (6 studies, 34%, CI 25%–46%), hallucinogens (3 studies, 26%, CI 14%–43%) and amphetamines (5 studies, 22%, CI 14%–34%). Lower rates were reported for opioid (12%), alcohol (10%) and sedative (9%) induced psychoses. Transition rates were slightly lower in older cohorts but were not affected by sex, country of the study, hospital or community location, urban or rural setting, diagnostic methods, or duration of follow-up.[29]

Ritual and spiritual[edit]

Timothy Leary was a leading proponent of spiritual hallucinogen use.

Certain psychoactives, particularly hallucinogens, have been used for religious purposes since prehistoric times. Native Americans have used peyote cacti containing mescaline for religious ceremonies for as long as 5700 years.[30] The muscimol-containing Amanita muscaria mushroom was used for ritual purposes throughout prehistoric Europe.[31]

The use of entheogens for religious purposes resurfaced in the West during the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 70s. Under the leadership of Timothy Leary, new spiritual and intention-based movements began to use LSD and other hallucinogens as tools to access deeper inner exploration. In the United States, the use of peyote for ritual purposes is protected only for members of the Native American Church, which is allowed to cultivate and distribute peyote. However, the genuine religious use of peyote, regardless of one’s personal ancestry, is protected in Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Oregon.[32]

Military[edit]

Psychoactive drugs have been used in military applications as non-lethal weapons.

Both military and civilian American intelligence officials are known to have used psychoactive drugs while interrogating captives apprehended in its «war on terror». In July 2012 Jason Leopold and Jeffrey Kaye, psychologists and human rights workers, had a Freedom of Information Act request fulfilled that confirmed that the use of psychoactive drugs during interrogation was a long-standing

practice.[33][34] Captives and former captives had been reporting medical staff collaborating with interrogators to drug captives with powerful psychoactive drugs prior to interrogation since the very first captives release.[35][36]

In May 2003 recently released Pakistani captive Sha Mohammed Alikhel described the routine use of psychoactive drugs. He said that Jihan Wali, a captive kept in a nearby cell, was rendered catatonic through the use of these drugs.[citation needed]

Additionally, militaries worldwide have used or are using various psychoactive drugs to improve performance of soldiers by suppressing hunger, increasing the ability to sustain effort without food, increasing and lengthening wakefulness and concentration, suppressing fear, reducing empathy, and improving reflexes and memory-recall among other things.[37][38]

The first documented case of a soldier overdosing on methamphetamine during combat, was the Finnish corporal Aimo Koivunen, a soldier who fought in the Winter War and the Continuation War.[39][40]

Route of administration[edit]

Psychoactive drugs are administered via oral ingestion as a tablet, capsule, powder, liquid, and beverage; via injection by subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intravenous route; via rectum by suppository and enema; and via inhalation by smoking, vaporizing, and snorting. The efficiency of each method of administration varies from drug to drug.[41]

The psychiatric drugs fluoxetine, quetiapine, and lorazepam are ingested orally in tablet or capsule form. Alcohol and caffeine are ingested in beverage form; nicotine and cannabis are smoked or vaporized; peyote and psilocybin mushrooms are ingested in botanical form or dried; and crystalline drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine are usually inhaled or snorted.

Determinants of effects[edit]

The theory of dosage, set, and setting is a useful model in dealing with the effects of psychoactive substances, especially in a controlled therapeutic setting as well as in recreational use. Dr. Timothy Leary, based on his own experiences and systematic observations on psychedelics, developed this theory along with his colleagues Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) in the 1960s.[42]

- Dosage

The first factor, dosage, has been a truism since ancient times, or at least since Paracelsus who said, «Dose makes the poison.» Some compounds are beneficial or pleasurable when consumed in small amounts, but harmful, deadly, or evoke discomfort in higher doses.

- Set

The set is the internal attitudes and constitution of the person, including their expectations, wishes, fears, and sensitivity to the drug. This factor is especially important for the hallucinogens, which have the ability to make conscious experiences out of the unconscious. In traditional cultures, set is shaped primarily by the worldview, health and genetic characteristics that all the members of the culture share.

- Setting

The third aspect is setting, which pertains to the surroundings, the place, and the time in which the experiences transpire.

This theory clearly states that the effects are equally the result of chemical, pharmacological, psychological, and physical influences. The model that Timothy Leary proposed applied to the psychedelics, although it also applies to other psychoactives.[43]

Effects[edit]

Illustration of the major elements of neurotransmission. Depending on its method of action, a psychoactive substance may block the receptors on the post-synaptic neuron (dendrite), or block reuptake or affect neurotransmitter synthesis in the pre-synaptic neuron (axon).

Psychoactive drugs operate by temporarily affecting a person’s neurochemistry, which in turn causes changes in a person’s mood, cognition, perception and behavior. There are many ways in which psychoactive drugs can affect the brain. Each drug has a specific action on one or more neurotransmitter or neuroreceptor in the brain.

Drugs that increase activity in particular neurotransmitter systems are called agonists. They act by increasing the synthesis of one or more neurotransmitters, by reducing its reuptake from the synapses, or by mimicking the action by binding directly to the postsynaptic receptor. Drugs that reduce neurotransmitter activity are called antagonists, and operate by interfering with synthesis or blocking postsynaptic receptors so that neurotransmitters cannot bind to them.[44]

Exposure to a psychoactive substance can cause changes in the structure and functioning of neurons, as the nervous system tries to re-establish the homeostasis disrupted by the presence of the drug (see also, neuroplasticity). Exposure to antagonists for a particular neurotransmitter can increase the number of receptors for that neurotransmitter or the receptors themselves may become more responsive to neurotransmitters; this is called sensitization. Conversely, overstimulation of receptors for a particular neurotransmitter may cause a decrease in both number and sensitivity of these receptors, a process called desensitization or tolerance. Sensitization and desensitization are more likely to occur with long-term exposure, although they may occur after only a single exposure. These processes are thought to play a role in drug dependence and addiction.[45] Physical dependence on antidepressants or anxiolytics may result in worse depression or anxiety, respectively, as withdrawal symptoms. Unfortunately, because clinical depression (also called major depressive disorder) is often referred to simply as depression, antidepressants are often requested by and prescribed for patients who are depressed, but not clinically depressed.

Affected neurotransmitter systems[edit]

The following is a brief table of notable drugs and their primary neurotransmitter, receptor or method of action. Many drugs act on more than one transmitter or receptor in the brain.[46]

| Neurotransmitter/receptor | Classification | Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Acetylcholine |

Cholinergics (acetylcholine receptor agonists) | arecoline, nicotine, piracetam |

| Muscarinic antagonists (acetylcholine receptor antagonists) | scopolamine, benzatropine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, trihexiphenidyl, doxylamine, atropine, quetiapine, olanzapine, most tricyclics | |

| Nicotinic antagonists (acetylcholine receptor antagonists) | memantine, bupropion | |

|

Adenosine |

Adenosine receptor antagonists[47] | caffeine, theobromine, theophylline |

|

Dopamine |

Dopamine reuptake inhibitors | cocaine, bupropion, methylphenidate, St John’s wort, and certain TAAR1 agonists like amphetamine, phenethylamine, and methamphetamine |

| Dopamine releasing agents | Cavendish bananas,[48] TAAR1 agonists like amphetamine, phenethylamine, and methamphetamine | |

| Dopamine agonists | pramipexole, Ropinirole, L-DOPA (prodrug), memantine | |

| Dopamine antagonists | haloperidol, droperidol, many antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) | |

| Dopamine partial agonists | LSD, aripiprazole | |

|

gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) |

GABA reuptake inhibitors | tiagabine, St John’s wort, vigabatrin, deramciclane |

| GABAA receptor agonists | ethanol, niacin,[49] barbiturates, diazepam, clonazepam, lorazepam, temazepam, alprazolam and other benzodiazepines, zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon and other nonbenzodiazepines, muscimol, phenibut | |

| GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators | ||

| GABA receptor antagonists | thujone, bicuculline | |

| GABAA receptor negative allosteric modulators | ||

|

Norepinephrine |

Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | St John’s wort,[50] most non-SSRI antidepressants such as amoxapine, atomoxetine, bupropion, venlafaxine, quetiapine, the tricyclics, methylphenidate, SNRIs such as duloxetine, venlafaxine, cocaine, tramadol, and certain TAAR1 agonists like amphetamine, phenethylamine, methamphetamine. |

| Norepinephrine releasing agents | ephedrine, PPA, pseudoephedrine, amphetamine, phenethylamine, methamphetamine | |

| Adrenergic agonists | clonidine, guanfacine, phenylephrine | |

| Adrenergic antagonists | carvedilol, metoprolol, mianserin, prazosin, propranolol, trazodone, yohimbine, olanzapine | |

|

Serotonin |

Serotonin receptor agonists | triptans (e.g. sumatriptan, eletriptan), psychedelics (e.g. lysergic acid diethylamide, psilocybin, mescaline), ergolines (e.g. lisuride, bromocriptine) |

| Serotonin reuptake inhibitors | most antidepressants including St John’s wort, tricyclics such as imipramine, SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram), SNRIs (e.g. duloxetine, venlafaxine) | |

| Serotonin releasing agents | fenfluramine, MDMA (ecstasy), tryptamine | |

| Serotonin receptor antagonists | ritanserin, mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone, cyproheptadine, memantine, atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) | |

|

AMPA receptor |

AMPA receptor positive allosteric modulators | aniracetam, CX717, piracetam |

| AMPA receptor antagonists | kynurenic acid, NBQX, topiramate | |

|

Cannabinoid |

Cannabinoid receptor agonists | JWH-018 |

| Cannabinoid receptor partial agonists | Anandamide, THC, cannabidiol, cannabinol | |

| Cannabinoid receptor inverse agonists | Rimonabant | |

| Anandamide reuptake inhibitors | LY 2183240, VDM 11, AM 404 | |

| FAAH enzyme inhibitors | MAFP, URB597, N-Arachidonylglycine | |

|

NMDA receptor |

NMDA receptor antagonists | ethanol, ketamine, deschloroketamine, 2-Fluorodeschloroketamine, PCP, DXM, Nitrous Oxide, memantine |

|

GHB receptor |

GHB receptor agonists | GHB, T-HCA |

| Sigma receptor | Sigma-1 receptor agonists | cocaine, DMT, DXM, fluvoxamine, ibogaine, opipramol, PCP, methamphetamine |

| Sigma-2 receptor agonists | methamphetamine | |

| Opioid receptor | μ-opioid receptor agonists | Narcotic opioids (e.g. codeine, morphine, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, heroin, fentanyl) |

| μ-opioid receptor partial agonists | buprenorphine | |

| μ-opioid receptor inverse agonists | naloxone | |

| μ-opioid receptor antagonists | naltrexone | |

| κ-opioid receptor agonists | salvinorin A, butorphanol, nalbuphine, pentazocine, ibogaine[51] | |

| κ-opioid receptor antagonists | buprenorphine | |

|

Histamine receptor |

H1 receptor antagonists | diphenhydramine, doxylamine, mirtazapine, mianserin, quetiapine, olanzapine, meclozine, most tricyclics |

| H3 receptor antagonists | pitolisant | |

| Indirect histamine receptor agonists | modafinil[52] | |

|

Monoamine oxidase |

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | phenelzine, iproniazid, tranylcypromine, selegiline, rasagiline, moclobemide, isocarboxazid, Linezolid, benmoxin, St John’s wort, coffee,[53] garlic[54] |

|

Melatonin receptor |

Melatonin receptor agonists | agomelatine, melatonin, ramelteon, tasimelteon |

|

Imidazoline receptor |

Imidazoline receptor agonists | apraclonidine, clonidine, moxonidine, rilmenidine |

| Orexin receptor | Inderict Orexin receptor agonists | modafinil[55] |

| Orexin receptor antagonists | SB-334,867, SB-408,124, TCS-OX2-29, suvorexant |

Addiction and dependence[edit]

| Addiction and dependence glossary[56][57][58][59] |

|---|

|

|

Comparison of the perceived harm for various psychoactive drugs from a poll among medical psychiatrists specialized in addiction treatment (David Nutt et al. 2007)[60]

Psychoactive drugs are often associated with addiction or drug dependence. Dependence can be divided into two types: psychological dependence, by which a user experiences negative psychological or emotional withdrawal symptoms (e.g., depression) and physical dependence, by which a user must use a drug to avoid physically uncomfortable or even medically harmful physical withdrawal symptoms.[61] Drugs that are both rewarding and reinforcing are addictive; these properties of a drug are mediated through activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, particularly the nucleus accumbens. Not all addictive drugs are associated with physical dependence, e.g., amphetamine, and not all drugs that produce physical dependence are addictive drugs, e.g., caffeine.

Many professionals, self-help groups, and businesses specialize in drug rehabilitation, with varying degrees of success, and many parents attempt to influence the actions and choices of their children regarding psychoactives.[62]

Common forms of rehabilitation include psychotherapy, support groups and pharmacotherapy, which uses psychoactive substances to reduce cravings and physiological withdrawal symptoms while a user is going through detox. Methadone, itself an opioid and a psychoactive substance, is a common treatment for heroin addiction, as is another opioid, buprenorphine. Recent research on addiction has shown some promise in using psychedelics such as ibogaine to treat and even cure drug addictions, although this has yet to become a widely accepted practice.[63][64]

Legality[edit]

Historical image of legal heroin bottle

The legality of psychoactive drugs has been controversial through most of recent history; the Second Opium War and Prohibition are two historical examples of legal controversy surrounding psychoactive drugs. However, in recent years, the most influential document regarding the legality of psychoactive drugs is the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, an international treaty signed in 1961 as an Act of the United Nations. Signed by 73 nations including the United States, the USSR, Pakistan, India, and the United Kingdom, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs established Schedules for the legality of each drug and laid out an international agreement to fight addiction to recreational drugs by combatting the sale, trafficking, and use of scheduled drugs.[65] All countries that signed the treaty passed laws to implement these rules within their borders. However, some countries that signed the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, such as the Netherlands, are more lenient with their enforcement of these laws.[66]

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has authority over all drugs, including psychoactive drugs. The FDA regulates which psychoactive drugs are over the counter and which are only available with a prescription.[67] However, certain psychoactive drugs, like alcohol, tobacco, and drugs listed in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs are subject to criminal laws. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 regulates the recreational drugs outlined in the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[68] Alcohol is regulated by state governments, but the federal National Minimum Drinking Age Act penalizes states for not following a national drinking age.[69] Tobacco is also regulated by all fifty state governments.[70] Most people accept such restrictions and prohibitions of certain drugs, especially the «hard» drugs, which are illegal in most countries.[71][72][73]

In the medical context, psychoactive drugs as a treatment for illness is widespread and generally accepted. Little controversy exists concerning over the counter psychoactive medications in antiemetics and antitussives. Psychoactive drugs are commonly prescribed to patients with psychiatric disorders. However, certain critics[who?] believe that certain prescription psychoactives, such as antidepressants and stimulants, are overprescribed and threaten patients’ judgement and autonomy.[74][75]

Effect on animals[edit]

A number of animals consume different psychoactive plants, animals, berries and even fermented fruit, becoming intoxicated, such as cats after consuming catnip. Traditional legends of sacred plants often contain references to animals that introduced humankind to their use.[76] Animals and psychoactive plants appear to have co-evolved, possibly explaining why these chemicals and their receptors exist within the nervous system.[77]

Widely used psychoactive drugs[edit]

This is a list of commonly used drugs that contain psychoactive ingredients. Please note that the following lists contains legal and illegal drugs (based on the country’s laws).

- Alcohol

- Benzodiazepines

- Caffeine

- Cannabis

- Cocaine

- Heroin

- LSD

- Methamphetamine

- Ecstasy

- Nicotine

- Opioids

- Psilocybin mushrooms

See also[edit]

- Contact high

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Demand reduction

- Designer drug

- Drug

- Drug addiction

- Drug checking

- Drug rehabilitation

- Hamilton’s Pharmacopeia

- Hard and soft drugs

- Harm reduction

- Neuropsychopharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Poly drug use

- Project MKULTRA

- Psychedelic plants

- Psychoactive fish

- Recreational drug use

- Responsible drug use

- Self-medication

References[edit]

- ^ «CHAPTER 1 Alcohol and Other Drugs». The Public Health Bush Book: Facts & approaches to three key public health issues. ISBN 0-7245-3361-3. Archived from the original on 2015-03-28.

- ^ Levine, Robert J. (1991). «Medicalization of Psychoactive Substance Use and the Doctor-Patient Relationship». The Milbank Quarterly. 69 (4): 623–640. doi:10.2307/3350230. ISSN 0887-378X.

- ^ Zhang, Mona. «Missouri’s marijuana legalization campaign is splitting the weed world». POLITICO. Retrieved 2023-01-25.

- ^ «Will Your Retirement Home Have A Liquor License?». Forbes. 26 December 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian’s Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 0-415-31121-7. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Merlin, M.D (2003). «Archaeological Evidence for the Tradition of Psychoactive Plant Use in the Old World». Economic Botany. 57 (3): 295–323. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0295:AEFTTO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 30297486.

- ^ Early Holocene coca chewing in northern Peru Volume: 84 Number: 326 Page: 939–953

- ^ «Coca leaves first chewed 8,000 years ago, says research». BBC News. December 2, 2010. Archived from the original on May 23, 2014.

- ^ Siegel, Ronald K (2005). Intoxication: The Universal Drive for Mind-Altering Substances. Park Street Press, Rochester, Vermont. ISBN 1-59477-069-7.

- ^ Weil, Andrew (2004). The Natural Mind: A Revolutionary Approach to the Drug Problem (Revised ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 15. ISBN 0-618-46513-8.

- ^ The Hashish Eater (1857) pg. 181

- ^ «LEAP’s Mission Statement». Law Enforcement Against Prohibition. Archived from the original on 2008-09-13. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ «5 Years After: Portugal’s Drug Decriminalization Policy Shows Positive Results». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2013-08-15. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ Lovett, Richard (24 September 2005). «Coffee: The demon drink?» (fee required). New Scientist (2518). Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Bersani FS, Corazza O, Simonato P, Mylokosta A, Levari E, Lovaste R, Schifano F; Corazza; Simonato; Mylokosta; Levari; Lovaste; Schifano (2013). «Drops of madness? Recreational misuse of tropicamide collyrium; early warning alerts from Russia and Italy». General Hospital Psychiatry. 35 (5): 571–3. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.013. PMID 23706777.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Medline Plus. Anesthesia. Archived 2016-07-04 at the Wayback Machine Accessed on July 16, 2007.

- ^ Li X, Pearce RA; Pearce (2000). «Effects of halothane on GABA(A) receptor kinetics: evidence for slowed agonist unbinding». The Journal of Neuroscience. 20 (3): 899–907. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-00899.2000. PMC 6774186. PMID 10648694.

- ^ Harrison NL, Simmonds MA; Simmonds (1985). «Quantitative studies on some antagonists of N-methyl D-aspartate in slices of rat cerebral cortex». British Journal of Pharmacology. 84 (2): 381–91. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb12922.x. PMC 1987274. PMID 2858237.

- ^ Quiding H, Lundqvist G, Boréus LO, Bondesson U, Ohrvik J; Lundqvist; Boréus; Bondesson; Ohrvik (1993). «Analgesic effect and plasma concentrations of codeine and morphine after two dose levels of codeine following oral surgery». European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 44 (4): 319–23. doi:10.1007/BF00316466. PMID 8513842. S2CID 37268044.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matson, Johnny L.; Neal, Daniene (2009). «Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: An overview». Research in Developmental Disabilities. 30 (3): 572–86. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.007. PMID 18845418.

- ^ Schatzberg AF (2000). «New indications for antidepressants». The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (11): 9–17. PMID 10926050.

- ^ Swift RM (2016). «Pharmacotherapy of Substance Use, Craving, and Acute Abstinence Syndromes». In Sher KJ (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders. Oxford University Press. pp. 601–603, 606. ISBN 9780199381708. Archived from the original on 2018-05-09.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Robert M. A. (2001). «Clinical importance of long-term antidepressant treatment». The British Journal of Psychiatry. 179 (42): S4–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.179.42.s4. PMID 11532820.

- ^ Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence Archived 2006-10-03 at the Wayback Machine by the World Health Organization. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ Anderson TL (1998). «Drug identity change processes, race, and gender. III. Macrolevel opportunity concepts». Substance Use & Misuse. 33 (14): 2721–35. doi:10.3109/10826089809059347. PMID 9869440.

- ^ Bertol E, Fineschi V, Karch SB, Mari F, Riezzo I; Fineschi; Karch; Mari; Riezzo (2004). «Nymphaea cults in ancient Egypt and the New World: a lesson in empirical pharmacology». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 97 (2): 84–5. doi:10.1177/014107680409700214. PMC 1079300. PMID 14749409.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayry M (2004). «Prescribing cannabis: freedom, autonomy, and values». Journal of Medical Ethics. 30 (4): 333–6. doi:10.1136/jme.2002.001347. PMC 1733898. PMID 15289511.

- ^ Barnett, Randy E. «The Presumption of Liberty and the Public Interest: Medical Marijuana and Fundamental Rights» Archived 2007-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ a b Murrie, Benjamin; Lappin, Julia; Large, Matthew; Sara, Grant (16 October 2019). «Transition of Substance-Induced, Brief, and Atypical Psychoses to Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis». Schizophrenia Bulletin. 46 (3): 505–516. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbz102. PMC 7147575. PMID 31618428.

- ^ El-Seedi HR, De Smet PA, Beck O, Possnert G, Bruhn JG; De Smet; Beck; Possnert; Bruhn (2005). «Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas». Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 101 (1–3): 238–42. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022. PMID 15990261.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vetulani J (2001). «Drug addiction. Part I. Psychoactive substances in the past and presence». Polish Journal of Pharmacology. 53 (3): 201–14. PMID 11785921.

- ^ Bullis RK (1990). «Swallowing the scroll: legal implications of the recent Supreme Court peyote cases». Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 22 (3): 325–32. doi:10.1080/02791072.1990.10472556. PMID 2286866.

- ^

Jason Leopold, Jeffrey Kaye (2011-07-11). «EXCLUSIVE: DoD Report Reveals Some Detainees Interrogated While Drugged, Others «Chemically Restrained»«. Truthout. Archived from the original on 2020-03-28.Truthout obtained a copy of the report — «Investigation of Allegations of the Use of Mind-Altering Drugs to Facilitate Interrogations of Detainees» — prepared by the DoD’s deputy inspector general for intelligence in September 2009, under a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request we filed nearly two years ago.

- ^

Robert Beckhusen (2012-07-11). «U.S. Injected Gitmo Detainees With ‘Mind Altering’ Drugs». Wired magazine. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2012-07-14.That’s according to a recently declassified report (.pdf) from the Pentagon’s inspector general, obtained by Truthout’s Jeffrey Kaye and Jason Leopold after a Freedom of Information Act Request. In it, the inspector general concludes that ‘certain detainees, diagnosed as having serious mental health conditions being treated with psychoactive medications on a continuing basis, were interrogated.’ The report does not conclude, though, that anti-psychotic drugs were used specifically for interrogation purposes.

- ^

Haroon Rashid (2003-05-23). «Pakistani relives Guantanamo ordeal». BBC News. Archived from the original on 2012-10-31. Retrieved 2009-01-09.Mr Shah alleged that the Americans had given him injections and tablets prior to interrogations. «They used to tell me I was mad,» the 23-year-old told the BBC in his native village in Dir district near the Afghan border. I was given injections at least four or five times as well as different tablets. I don’t know what they were meant for.»

- ^

«People the law forgot». The Guardian. 2003-12-03. Archived from the original on 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2012-07-14.The biggest damage is to my brain. My physical and mental state isn’t right. I’m a changed person. I don’t laugh or enjoy myself much.

- ^ Stoker, Liam (14 April 2013). «Analysis Creating Supermen: battlefield performance enhancing drugs». Army Technology. Verdict Media Limited. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Kamienski, Lukasz (2016-04-08). «The Drugs That Built a Super Soldier». The Atlantic. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ «Aimo Allan Koivunen». www.sotapolku.fi (in Finnish). 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Rantanen, Miska (28 May 2002). «Finland: History: Amphetamine Overdose In Heat Of Combat». www.mapinc.org. Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration. CDER Data Standards Manual Archived 2006-01-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on May 15, 2007.

- ^ Timothy Leary; Ralph Metzner; Richard Alpert. The Psychedelic Experience. New York: University Books. 1964

- ^ Ratsch, Christian (May 5, 2005). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants. Park Street Press. p. 944. ISBN 0-89281-978-2.

- ^ Seligma, Martin E.P. (1984). «4». Abnormal Psychology. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-94459-X.

- ^ «University of Texas, Addiction Science Research and Education Center». Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ Lüscher C, Ungless MA; Ungless (2006). «The mechanistic classification of addictive drugs». PLOS Medicine. 3 (11): e437. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030437. PMC 1635740. PMID 17105338.

- ^ Ford, Marsha. Clinical Toxicology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001. Chapter 36 – Caffeine and Related Nonprescription Sympathomimetics. ISBN 0-7216-5485-1[page needed]

- ^ Kanazawa, Kazuki; Sakakibara, Hiroyuki (2000). «High Content of Dopamine, a Strong Antioxidant, in Cavendish Banana». Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (3): 844–8. doi:10.1021/jf9909860. PMID 10725161.

- ^ «Supplements Accelerate Benzodiazepine Withdrawal: A Case Report and Biochemical Rationale». Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2016-07-31.[full citation needed]

- ^ Di Carlo, Giulia; Borrelli, Francesca; Ernst, Edzard; Izzo, Angelo A. (2001). «St John’s wort: Prozac from the plant kingdom». Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 22 (6): 292–7. doi:10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01716-8. PMID 11395157.

- ^ Glick, Stanley D; Maisonneuve, Isabelle M (1998). «Mechanisms of Antiaddictive Actions of Ibogainea». Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 844 (1): 214–26. Bibcode:1998NYASA.844..214G. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08237.x. PMID 9668680. S2CID 11416176.

- ^ Ishizuka, Tomoko; Sakamoto, Yasuhiko; Sakurai, Toshimi; Yamatodani, Atsushi (2003-03-20). «Modafinil increases histamine release in the anterior hypothalamus of rats». Neuroscience Letters. 339 (2): 143–146. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00006-5. ISSN 0304-3940. PMID 12614915. S2CID 42291148.

- ^ Herraiz, Tomas; Chaparro, Carolina (2006). «Human monoamine oxidase enzyme inhibition by coffee and β-carbolines norharman and harman isolated from coffee». Life Sciences. 78 (8): 795–802. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.05.074. PMID 16139309.

- ^ Dhingra, Dinesh; Kumar, Vaibhav (2008). «Evidences for the involvement of monoaminergic and GABAergic systems in antidepressant-like activity of garlic extract in mice». Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 40 (4): 175–9. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.43165. PMC 2792615. PMID 20040952.

- ^ Gerrard, Paul; Malcolm, Robert (June 2007). «Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research». Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (3): 349–364. ISSN 1176-6328. PMC 2654794. PMID 19300566.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). «Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders». In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ Nestler EJ (December 2013). «Cellular basis of memory for addiction». Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. … A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal’s sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement … Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41. … Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ «Glossary of Terms». Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). «Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction». New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). «Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse». The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ Johnson, B (2003). «Psychological Addiction, Physical Addiction, Addictive Character, and Addictive Personality Disorder: A Nosology of Addictive Disorders». Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis. 11 (1): 135–60. OCLC 208052223.

- ^ Hops, Hyman; Tildesley, Elizabeth; Lichtenstein, Edward; Ary, Dennis; Sherman, Linda (2009). «Parent-Adolescent Problem-Solving Interactions and Drug Use». The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 16 (3–4): 239–58. doi:10.3109/00952999009001586. PMID 2288323.

- ^ «Psychedelics Could Treat Addiction Says Vancouver Official». 2006-08-09. Archived from the original on December 2, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ «Ibogaine research to treat alcohol and drug addiction». Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. Archived 2008-05-10 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ MacCoun, R; Reuter, P (1997). «Interpreting Dutch Cannabis Policy: Reasoning by Analogy in the Legalization Debate». Science. 278 (5335): 47–52. doi:10.1126/science.278.5335.47. PMID 9311925.

- ^ History of the Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved at FDA’s website Archived 2009-01-19 at the Wayback Machine on June 23, 2007.

- ^ United States Controlled Substances Act of 1970. Retrieved from the DEA’s website Archived 2009-05-08 at the Wayback Machine on June 20, 2007.

- ^ Title 23 of the United States Code, Highways. Archived 2007-06-14 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ Taxadmin.org. State Excise Tax Rates on Cigarettes. Archived 2009-11-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ «What’s your poison?». Caffeine. Archived from the original on July 26, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ^ Griffiths, RR (1995). Psychopharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 2002. ISBN 0-7817-0166-X.

- ^ Edwards, Griffith (2005). Matters of Substance: Drugs—and Why Everyone’s a User. Thomas Dunne Books. p. 352. ISBN 0-312-33883-X.

- ^ Dworkin, Ronald. Artificial Happiness. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006. pp.2–6. ISBN 0-7867-1933-8

- ^ Manninen, B A (2006). «Medicating the mind: A Kantian analysis of overprescribing psychoactive drugs». Journal of Medical Ethics. 32 (2): 100–5. doi:10.1136/jme.2005.013540. PMC 2563334. PMID 16446415.

- ^ Samorini, Giorgio (2002). Animals And Psychedelics: The Natural World & The Instinct To Alter Consciousness. Park Street Press. ISBN 0-89281-986-3.

- ^ Albert, David Bruce, Jr. (1993). «Event Horizons of the Psyche». Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved February 2, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

- Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence by the WHO

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical, psychoactive agent or psychotropic drug is a chemical substance that changes functions of the nervous system, and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition, or behavior.[1]

These substances may be used medically, recreationally, for spiritual reasons — for example, to alter one’s consciousness (as with entheogens for ritual, spiritual or shamanic purposes), or for research.

Some categories of psychoactive drugs may be prescribed by physicians[2] and other healthcare practitioners because of their therapeutic value.

Examples of medication categories that may contain potentially beneficial psychoactive drugs include, but are not limited to:

- Anesthetics

- Analgesics

- Anticonvulsants

- Anti-Parkinson’s medications

- Medications used to treat Neuropsychiatric Disorders (Antidepressants, Anxiolytics, Antipsychotics and Stimulant Medications.)

Some psychoactive substances may be used in detoxification and rehabilitation programs for people who may have become dependent upon, or addicted to, other mind or mood altering substances. Drug rehabilitation attempts to reduce addiction through a combination of psychotherapy, support groups, and sometimes — psychoactive substances.

Psychoactive substances often bring various changes in consciousness and mood that the user may find rewarding and pleasant (e.g., euphoria or a sense of relaxation) or advantageous in an objectively observable or measurable way (e.g. increased alertness). Substances which are rewarding, and thus positively reinforcing, have the potential to induce a state of addiction – compulsive drug use despite negative consequences. In addition, sustained use of some substances may produce physical or psychological dependence, or both, associated with somatic or psychological-emotional withdrawal states respectively.

Psychoactive drug misuse, dependence, and addiction have resulted in legal measures and moral debate. Governmental controls on manufacture, supply, and prescription attempt to reduce problematic medical drug use. Ethical concerns have also been raised about over-use of these drugs clinically, and about their marketing by manufacturers. Popular campaigns to decriminalize[3] or legalize the recreational use of certain drugs (e.g. cannabis) are also ongoing.

History[edit]

Alcohol is a widely used and abused psychoactive drug. The global alcoholic drinks market was expected to exceed $1 trillion in 2013.[4] Beer is the third-most popular drink overall, after water and tea.[5]

Psychoactive drug use can be traced to prehistory. There is archaeological evidence of the use of psychoactive substances, mostly plants, dating back at least 10,000 years, and historical evidence of cultural use over the past 5,000 years.[6] The chewing of coca leaves, for example, dates back over 8,000 years ago in Peruvian society.[7][8]

Medicinal use is one important facet of psychoactive drug usage. However, some have postulated that the urge to alter one’s consciousness is as primary as the drive to satiate thirst, hunger, or sexual desire.[9] Supporters of this belief contend that the history of drug use, and even children’s desire for spinning, swinging, or sliding indicate that the drive to alter one’s state of mind is universal.[10]

One of the first people to articulate this point of view, set aside from a medicinal context, was American author Fitz Hugh Ludlow (1836–1870) in his book The Hasheesh Eater (1857):

[D]rugs are able to bring humans into the neighborhood of divine experience and can thus carry us up from our personal fate and the everyday circumstances of our life into a higher form of reality. It is, however, necessary to understand precisely what is meant by the use of drugs. We do not mean the purely physical craving…That of which we speak is something much higher, namely the knowledge of the possibility of the soul to enter into a lighter being, and to catch a glimpse of deeper insights and more magnificent visions of the beauty, truth, and the divine than we are normally able to spy through the cracks in our prison cell. But there are not many drugs which have the power of stilling such craving. The entire catalog, at least to the extent that research has thus far written it, may include only opium, hashish, and in rarer cases alcohol, which has enlightening effects only upon very particular characters.[11]

During the 20th century, many governments across the world initially responded to the use of recreational drugs by banning them, and making their use, supply, or trade a criminal offense. A notable example of this was Prohibition in the United States, where alcohol was made illegal for 13 years. However, many governments, government officials, and persons in law enforcement have concluded that illicit drug use cannot be sufficiently stopped through criminalization. Organizations such as Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP) have come to such a conclusion, believing:

[T]he existing drug policies have failed in their intended goals of addressing the problems of crime, drug abuse, addiction, juvenile drug use, stopping the flow of illegal drugs into this country and the internal sale and use of illegal drugs. By fighting a war on drugs the government has increased the problems of society and made them far worse. A system of regulation rather than prohibition is a less harmful, more ethical and a more effective public policy.[12][failed verification]

In some countries, there has been a move toward harm reduction by health services, where the use of illicit drugs is neither condoned nor promoted, but services and support are provided to ensure users have adequate factual information readily available, and that the negative effects of their use be minimized. Such is the case of the Portuguese drug policy of decriminalization, which achieved its primary goal of reducing the adverse health effects of drug abuse.[13]

Purposes[edit]

Psychoactive substances are used by humans for a number of different purposes, and these uses vary widely between cultures. Some substances may have controlled or illegal uses, some may have shamanic purposes, and others are used medicinally. Other examples include social drinking, nootropic, or sleep aids. Caffeine is the world’s most widely consumed psychoactive substance, but unlike many others, it is legal and unregulated in nearly all jurisdictions. In North America, 90% of adults consume caffeine daily.[14]

Psychoactive drugs are divided into different groups according to their pharmacological effects. Commonly used psychoactive drugs and groups are listed below:

- Anxiolytics. Used to reduce symptoms of anxiety and panic.

-

- Example: benzodiazepines such as Xanax and Valium, barbiturates

- Empathogen–entactogens

-

- Example: MDMA (ecstasy), MDA, 6-APB, AMT

- Stimulants (colloquially referred to as «uppers»). This category comprises substances that increase wakefulness and productivity, stimulate the mind, and may cause euphoria, but do not affect vision.

-

- Examples: amphetamine, caffeine, cocaine, nicotine, modafinil

- Depressants (colloquially referred to as «downers»), including sedatives, hypnotics, and opioids. This category includes all of the calmative, sleep-inducing, anesthetizing substances, which sometimes induce perceptual changes, such as dream images, and often evoke feelings of euphoria.

-

- Examples: Ethanol (alcohol), opioids such as morphine, fentanyl, and codeine, cannabis, barbiturates, benzodiazepines.

- Hallucinogens, including psychedelics, dissociatives, and deliriants. This category encompasses all substances that produce distinct alterations in perception, sensation of space and time, and emotional states[15]

-

- Examples: psilocybin, LSD, DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine)/ayahuasca, mescaline, Salvia divinorum, Nitrous oxide, and Scopolamine

Uses[edit]

Anesthesia[edit]

General anesthetics are a class of psychoactive drug used on people to block physical pain and other sensations. Most anesthetics induce unconsciousness, allowing the person to undergo medical procedures like surgery, without the feelings of physical pain or emotional trauma.[16] To induce unconsciousness, anesthetics affect the GABA and NMDA systems. For example, propofol is a GABA agonist,[17] and ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist.[18]

Pain management[edit]

Psychoactive drugs are often prescribed to manage pain. The subjective experience of pain is primarily regulated by endogenous opioid peptides. Thus, pain can often be managed using psychoactives that operate on this neurotransmitter system, also known as opioid receptor agonists. This class of drugs can be highly addictive, and includes opiate narcotics, like morphine and codeine.[19] NSAIDs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, are also analgesics. These agents also reduce eicosanoid-mediated inflammation by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase.

Mental disorders[edit]

Psychiatric medications are psychoactive drugs prescribed for the management of mental and emotional disorders, or to aid in overcoming challenging behavior.[20] There are six major classes of psychiatric medications:

- Antidepressants treat disorders such as clinical depression, dysthymia, anxiety, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder.[21]

- Stimulants, used to treat disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and narcolepsy, and for weight reduction.

- Antipsychotics, used to treat psychotic symptoms, such as those associated with schizophrenia or severe mania, or as adjuncts to relieve clinical depression.

- Mood stabilizers, used to treat bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder.

- Anxiolytics, used to treat anxiety disorders.

- Depressants, used as hypnotics, sedatives, and anesthetics, depending upon dosage.

In addition, several psychoactive substances are currently employed to treat various addictions. These include acamprosate or naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism, or methadone or buprenorphine maintenance therapy in the case of opioid addiction.[22]

Exposure to psychoactive drugs can cause changes to the brain that counteract or augment some of their effects; these changes may be beneficial or harmful. However, there is a significant amount of evidence that the relapse rate of mental disorders negatively corresponds with the length of properly followed treatment regimens (that is, relapse rate substantially declines over time), and to a much greater degree than placebo.[23]

Recreation[edit]

Many psychoactive substances are used for their mood and perception altering effects, including those with accepted uses in medicine and psychiatry. Examples of psychoactive substances include caffeine, alcohol, cocaine, LSD, nicotine and cannabis.[24] Classes of drugs frequently used recreationally include:

- Stimulants, which activate the central nervous system. These are used recreationally for their euphoric effects.

- Hallucinogens (psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants), which induce perceptual and cognitive alterations.

- Hypnotics, which depress the central nervous system.

- Opioid analgesics, which also depress the central nervous system. These are used recreationally because of their euphoric effects.

- Inhalants, in the forms of gas aerosols, or solvents, which are inhaled as a vapor because of their stupefying effects. Many inhalants also fall into the above categories (such as nitrous oxide which is also an analgesic).

In some modern and ancient cultures, drug usage is seen as a status symbol. Recreational drugs are seen as status symbols in settings such as at nightclubs and parties.[25] For example, in ancient Egypt, gods were commonly pictured holding hallucinogenic plants.[26]

Because there is controversy about regulation of recreational drugs, there is an ongoing debate about drug prohibition. Critics of prohibition believe that regulation of recreational drug use is a violation of personal autonomy and freedom.[27] In the United States, critics have noted that prohibition or regulation of recreational and spiritual drug use might be unconstitutional, and causing more harm than is prevented.[28]

Some people who take psychoactive drugs experience drug or substance induced psychosis. A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis by Murrie et al. found that the pooled proportion of transition from substance-induced psychosis to schizophrenia was 25% (95% CI 18%–35%), compared with 36% (95% CI 30%–43%) for brief, atypical and not otherwise specified psychoses.[29] Type of substance was the primary predictor of transition from drug-induced psychosis to schizophrenia, with highest rates associated with cannabis (6 studies, 34%, CI 25%–46%), hallucinogens (3 studies, 26%, CI 14%–43%) and amphetamines (5 studies, 22%, CI 14%–34%). Lower rates were reported for opioid (12%), alcohol (10%) and sedative (9%) induced psychoses. Transition rates were slightly lower in older cohorts but were not affected by sex, country of the study, hospital or community location, urban or rural setting, diagnostic methods, or duration of follow-up.[29]

Ritual and spiritual[edit]

Timothy Leary was a leading proponent of spiritual hallucinogen use.

Certain psychoactives, particularly hallucinogens, have been used for religious purposes since prehistoric times. Native Americans have used peyote cacti containing mescaline for religious ceremonies for as long as 5700 years.[30] The muscimol-containing Amanita muscaria mushroom was used for ritual purposes throughout prehistoric Europe.[31]

The use of entheogens for religious purposes resurfaced in the West during the counterculture movements of the 1960s and 70s. Under the leadership of Timothy Leary, new spiritual and intention-based movements began to use LSD and other hallucinogens as tools to access deeper inner exploration. In the United States, the use of peyote for ritual purposes is protected only for members of the Native American Church, which is allowed to cultivate and distribute peyote. However, the genuine religious use of peyote, regardless of one’s personal ancestry, is protected in Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Oregon.[32]

Military[edit]

Psychoactive drugs have been used in military applications as non-lethal weapons.

Both military and civilian American intelligence officials are known to have used psychoactive drugs while interrogating captives apprehended in its «war on terror». In July 2012 Jason Leopold and Jeffrey Kaye, psychologists and human rights workers, had a Freedom of Information Act request fulfilled that confirmed that the use of psychoactive drugs during interrogation was a long-standing

practice.[33][34] Captives and former captives had been reporting medical staff collaborating with interrogators to drug captives with powerful psychoactive drugs prior to interrogation since the very first captives release.[35][36]

In May 2003 recently released Pakistani captive Sha Mohammed Alikhel described the routine use of psychoactive drugs. He said that Jihan Wali, a captive kept in a nearby cell, was rendered catatonic through the use of these drugs.[citation needed]

Additionally, militaries worldwide have used or are using various psychoactive drugs to improve performance of soldiers by suppressing hunger, increasing the ability to sustain effort without food, increasing and lengthening wakefulness and concentration, suppressing fear, reducing empathy, and improving reflexes and memory-recall among other things.[37][38]

The first documented case of a soldier overdosing on methamphetamine during combat, was the Finnish corporal Aimo Koivunen, a soldier who fought in the Winter War and the Continuation War.[39][40]

Route of administration[edit]

Psychoactive drugs are administered via oral ingestion as a tablet, capsule, powder, liquid, and beverage; via injection by subcutaneous, intramuscular, and intravenous route; via rectum by suppository and enema; and via inhalation by smoking, vaporizing, and snorting. The efficiency of each method of administration varies from drug to drug.[41]