|

Queen |

|

|---|---|

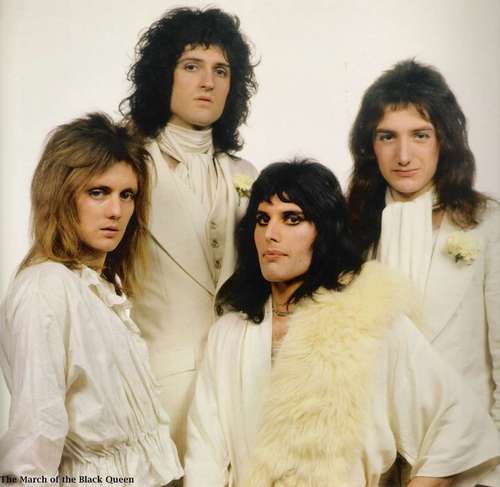

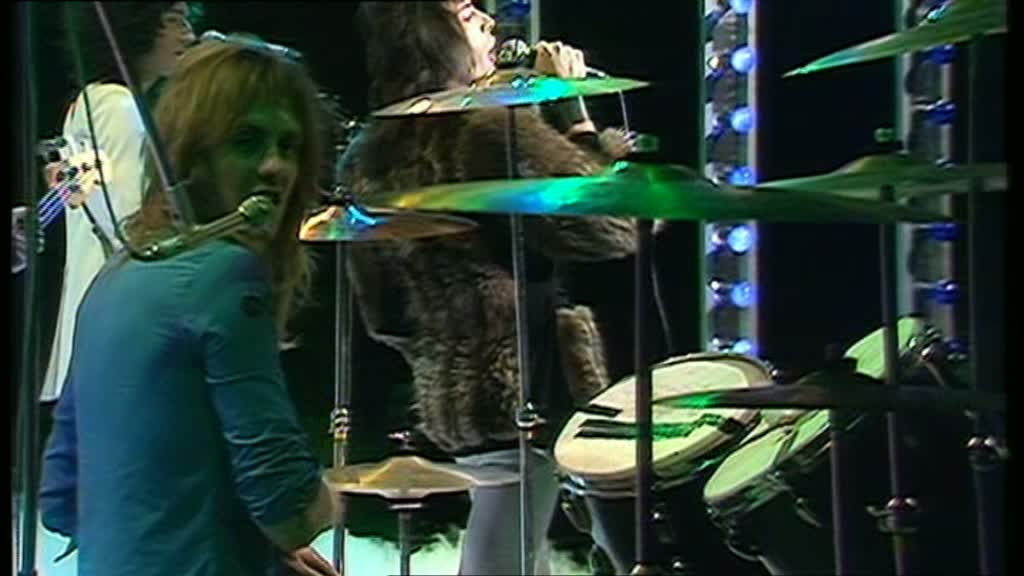

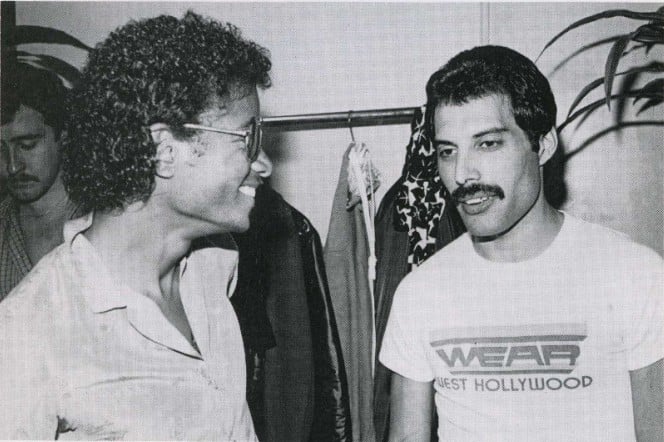

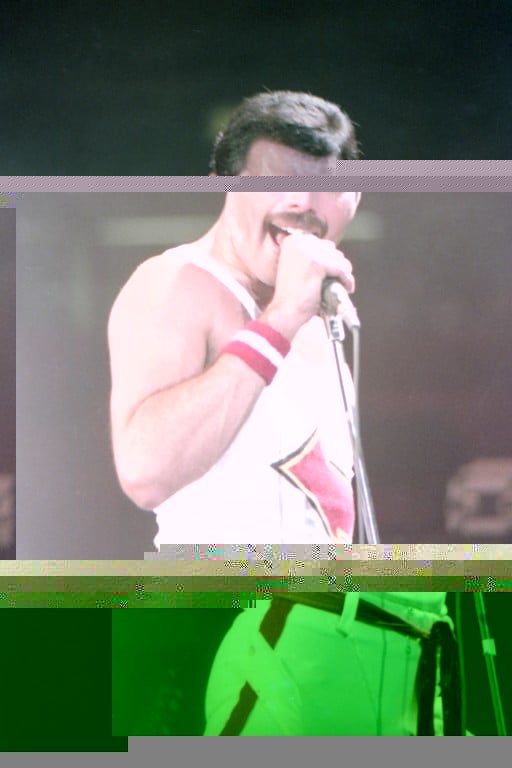

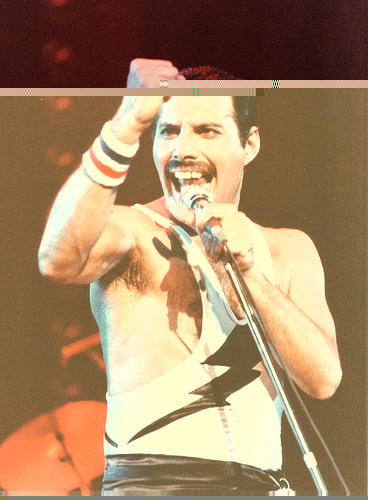

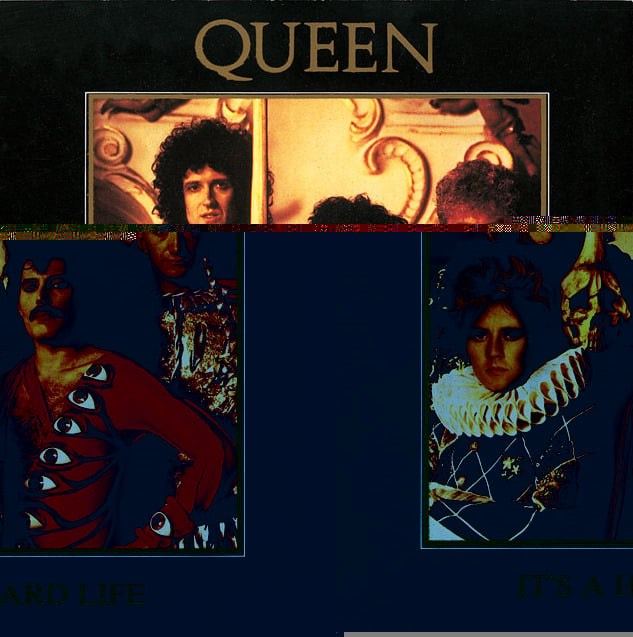

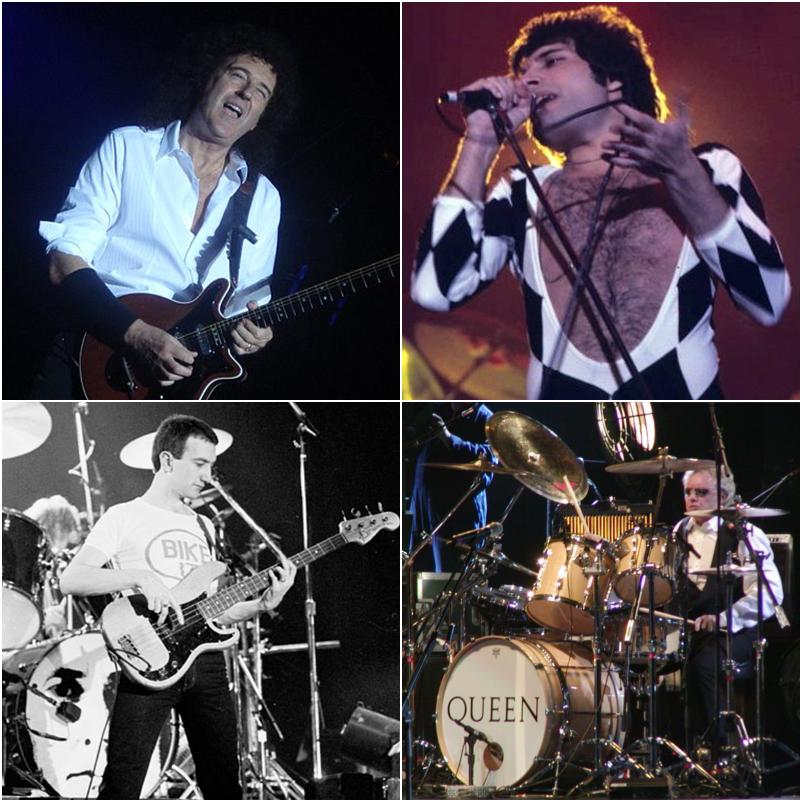

Clockwise from top left: Brian May, Freddie Mercury, Roger Taylor, John Deacon |

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres | Rock |

| Years active | 1970–present |

| Labels |

|

| Spinoffs |

|

| Spinoff of | Smile |

| Members |

|

| Past members |

|

| Website | queenonline.com |

Queen are a British rock band formed in London in 1970 by Freddie Mercury (lead vocals, piano), Brian May (guitar, vocals) and Roger Taylor (drums, vocals), later joined by John Deacon (bass). Their earliest works were influenced by progressive rock, hard rock and heavy metal, but the band gradually ventured into more conventional and radio-friendly works by incorporating further styles, such as arena rock and pop rock.

Before forming Queen, May and Taylor had played together in the band Smile. Mercury was a fan of Smile and encouraged them to experiment with more elaborate stage and recording techniques. He joined in 1970 and suggested the name «Queen». Deacon was recruited in February 1971, before the band released their eponymous debut album in 1973. Queen first charted in the UK with their second album, Queen II, in 1974. Sheer Heart Attack later that year and A Night at the Opera in 1975 brought them international success. The latter featured «Bohemian Rhapsody», which stayed at number one in the UK for nine weeks and helped popularise the music video format.

The band’s 1977 album News of the World contained «We Will Rock You» and «We Are the Champions», which have become anthems at sporting events. By the early 1980s, Queen were one of the biggest stadium rock bands in the world. «Another One Bites the Dust» from The Game (1980) became their best-selling single, while their 1981 compilation album Greatest Hits is the best-selling album in the UK and is certified nine times platinum in the US. Their performance at the 1985 Live Aid concert is ranked among the greatest in rock history by various publications. In August 1986, Mercury gave his last performance with Queen at Knebworth, England.

Though he kept his condition private, Mercury was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987. The band released two more albums, The Miracle in 1989 and Innuendo in 1991. On 23 November 1991, Mercury publicly revealed that he had AIDS, and the next day died of bronchopneumonia, a complication of AIDS. One more album was released featuring Mercury’s vocal, 1995’s Made in Heaven. John Deacon retired in 1997, while May and Taylor continued to make sporadic appearances together. Since 2004 they have toured as «Queen +», with vocalists Paul Rodgers and Adam Lambert.

Queen have been a global presence in popular culture for more than half a century. Estimates of their record sales range from 250 million to 300 million, making them one of the world’s best-selling music artists. In 1990, Queen received the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music. They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001, and with each member having composed hit singles all four were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003. In 2005 they received the Ivor Novello Award for Outstanding Song Collection from the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers, and Authors, and in 2018 they were presented the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

History

1968–1971: Foundations

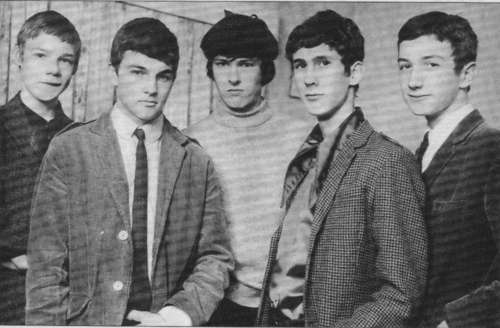

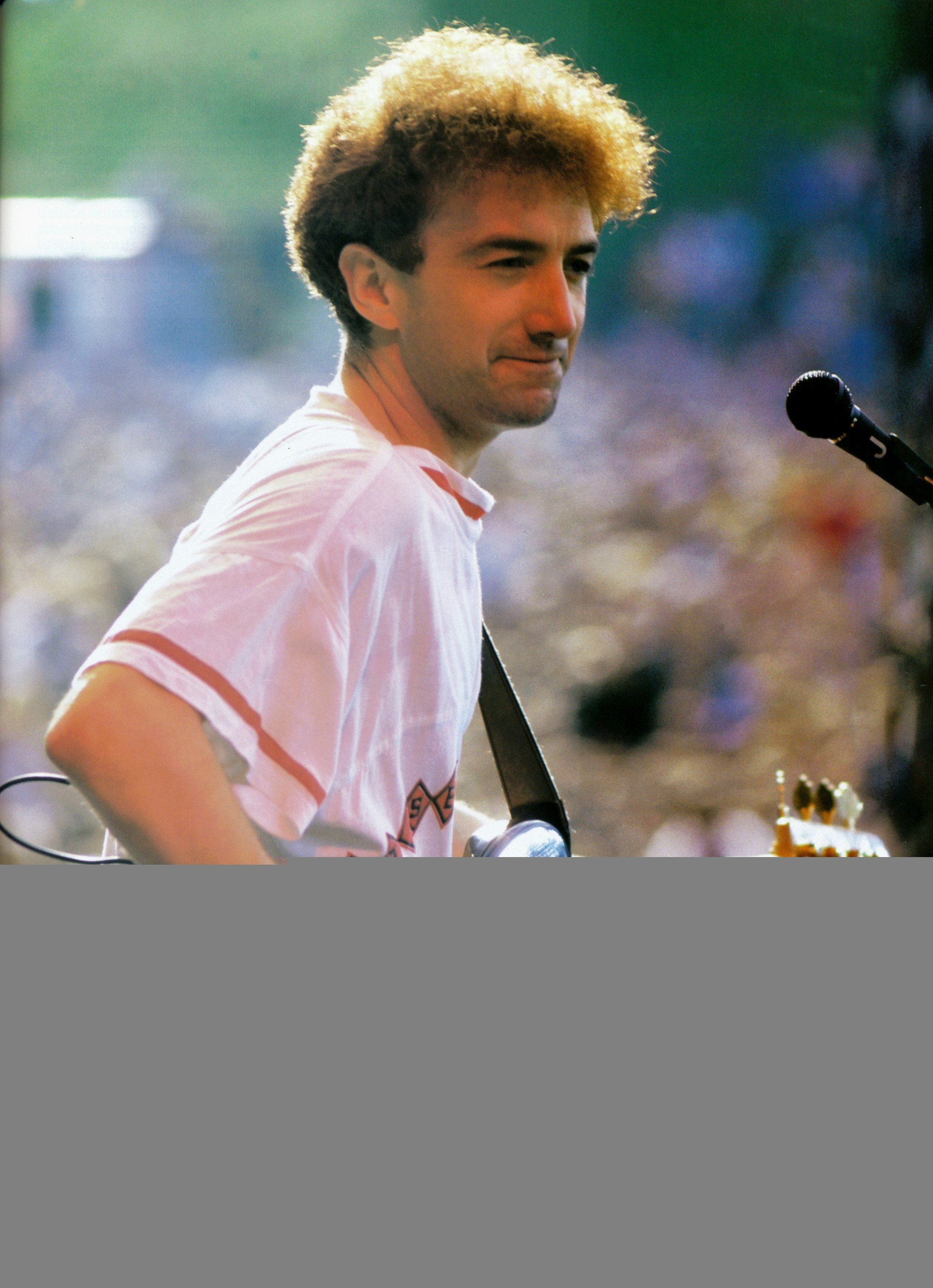

Queen in 1970. Left to right; Mike Grose, Roger Taylor, Freddie Mercury and Brian May

The founding members of Queen met in West London during the late 1960s. Guitarist Brian May had built his own guitar with his father in 1963, and formed the group 1984 (named after Orwell’s novel) the following year with singer Tim Staffell.[1] May left the group in early 1968 to focus on his degree in Physics and Infrared Astronomy at Imperial College and find a group that could write original material.[2] He formed the group Smile with Staffell (now playing bass) and keyboardist Chris Smith.[3] To complete the line-up, May placed an advertisement on a college notice board for a «Mitch Mitchell/Ginger Baker type» drummer; Roger Taylor, a young dental student, auditioned and got the job.[4] Smith left the group in early 1969, immediately before a gig at the Royal Albert Hall with Free and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band.[5]

While attending Ealing Art College in west London, Staffell became friends with fellow student Freddie Bulsara, who was from Zanzibar and of Indian Parsi descent.[6][7] Bulsara had studied fashion design for a year before switching to graphic art and design,[8] and soon became a keen fan of Smile. He asked if he could join the group as lead singer, but May felt Staffell would not give up that role.[9] He also ran a stall in Kensington Market with Taylor.[10]

In 1970, Staffell quit Smile, feeling his interests in soul and R&B clashed with the group’s hard rock sound and being fed up with the lack of success. He formed the group Humpy Bong with former Bee Gees drummer Colin Petersen.[11] The remaining members accepted Bulsara as lead singer, and recruited Taylor’s friend Mike Grose as bassist. The four played their first gig at a fundraising event in Truro on 27 June 1970.[12] Bulsara suggested the group should be renamed to «Queen». The others were uncertain at first, but he said, «it’s wonderful, dear, people will love it».[12] At the same time, he decided to change his surname to Mercury, inspired by the line «Mother Mercury, look what they’ve done to me» in the song «My Fairy King».[13] The group played their first London gig on 18 July.[14] The early set consisted of material that would later appear on the first two albums, along with various rock and roll covers, such as Cliff Richard and the Shadows’ «Please Don’t Tease». They attracted the attention of producer John Anthony, who was interested in the group’s sound but thought they had the wrong bass player.[13] After three live gigs, Mike Grose decided not to continue with the band and was replaced by Barry Mitchell (ex Crushed Butler) on bass guitar. Mitchell played thirteen gigs with Queen between August 1970 to January 1971. [15] In turn, Barry Mitchell left in January 1971 and was replaced by Doug Bogie for two live gigs.[16]

1971–1974: Queen and Queen II

In February 1971, John Deacon joined Queen. In addition to being an experienced bassist, his quiet demeanour complemented the band, and he was skilled in electronics.[17] On 2 July, Queen played their first show with the classic line-up of Mercury, May, Taylor and Deacon at a Surrey college outside London.[18] May called Terry Yeadon, an engineer at Pye Studios where Smile had recorded, to see if he knew anywhere where Queen could go. Yeadon had since moved to De Lane Lea Studios’ new premises in Wembley, and they needed a group to test out the equipment and recording rooms. He tried asking the Kinks but couldn’t get hold of them. Therefore, he told Queen they could record some demos in exchange for the studio’s acoustic tests.[19] They recorded five of their own songs, «Liar», «Keep Yourself Alive», «Great King Rat», «The Night Comes Down» and «Jesus». During the recording, John Anthony visited the band with Roy Thomas Baker. The two were taken with «Keep Yourself Alive» and began promoting the band to several record companies.[20]

Queen guitar (right, next to a Rolling Stones guitar) at the Cavern Club in Liverpool, marking a 31 October 1970 Queen concert at the venue

Promoter Ken Testi managed to attract the interest of Charisma Records, who offered Queen an advance of around £25,000, but the group turned them down as they realised the label would promote Genesis as a priority. Testi then entered discussions with Trident Studios’ Norman Sheffield, who offered the band a management deal under Neptune Productions, a subsidiary of Trident, to manage the band and enable them to use their facilities, whilst the management searched for a deal. This suited both parties, as Trident were expanding into management, and under the deal, Queen were able to make use of the hi-tech recording facilities used by signed musicians.[21] Taylor later described these early off-peak studio hours as «gold dust».[22]

Queen began 1972 with a gig at Bedford College, London where only six people turned up. After a few more shows, they stopped live performances for eight months to work on the album with Anthony and Baker.[21] During the sessions at Trident, they saw David Bowie with the Spiders From Mars live and realised they needed to make an impact with the album, otherwise they would be left behind.[23] Co-producers Anthony and Baker initially clashed with the band (May in particular) on the direction of the album, bringing the band’s inexperience in the studio to bear.[24] The band’s fighting centered around their efforts to integrate technical perfection with the reality of live performances, leading to what Baker referred to as «kitchen sink overproduction».[25] The resulting album was a mix of heavy metal and progressive rock.[24] The group were unhappy with the re-recording of «The Night Comes Down», so the finished album uses the De Lane Lea demo. Another track, «Mad the Swine» was dropped from the running order after the band and Baker could not agree on a mix.[26] Mike Stone created the final mix for «Keep Yourself Alive», and he would go on to work on several other Queen albums.[27] By January 1972, the band finished recording their debut album, but had yet to secure a record contract.[24] In order to attract record company interest, Trident booked a «showcase» gig on 6 November at The Pheasantry, followed by a show at the Marquee Club on 20 December.[28]

Queen promoted the unreleased album in February 1973 on BBC Radio 1, still unsigned. The following month, Trident managed to strike a deal with EMI Records. «Keep Yourself Alive» was released as a single on 6 July, with the album Queen appearing a week later. The front cover showed a shot of Mercury live on stage taken by Taylor’s friend Douglass Puddifoot. Deacon was credited as «Deacon John» while Taylor used his full name, Roger Meddows-Taylor.[29] The album was received well by critics; Gordon Fletcher of Rolling Stone called it «superb»,[30] and Chicago’s Daily Herald called it an «above-average debut».[31] However, it drew little mainstream attention, and «Keep Yourself Alive» sold poorly. Retrospectively, it is cited as the album’s highlight, and in 2008 Rolling Stone ranked it 31st in the «100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time», describing it as «an entire album’s worth of riffs crammed into a single song».[32] The album was certified gold in the UK and the US.[33][34]

A sample of «The March of the Black Queen» from Queen II (1974). The band’s earlier songs (such as this) leaned more towards progressive rock and heavy metal compared to their later work.

The group began to record their second album, Queen II in August 1973. Now able to use regular studio time, they decided to make full use of the facilities available. May created a multi-layer guitar introduction «Procession», while Mercury wrote «The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke» based on the painting of the same name by Richard Dadd.[35] The group spent the remainder of the year touring the UK, supporting Mott The Hoople, and began to attract an audience.[36] The tour ended with two shows at the Hammersmith Odeon on 14 December, playing to 7,000 people.[37]

In January 1974, Queen played the Sunbury Pop Festival in Australia. They arrived late, and were jeered and taunted by the audience who expected to see home grown acts.[38] Before leaving, Mercury announced, «when we come back to Australia, Queen will be the biggest band in the world!»[39][40] Queen II was released in March, and features Mick Rock’s iconic Dietrich-inspired image of the band on the cover.[41] This image would later be used as the basis for «Bohemian Rhapsody» music video production.[42][43] The album reached number five on the British album chart and became the first Queen album to chart in the UK. The Mercury-written lead single «Seven Seas of Rhye» reached number 10 in the UK, giving the band their first hit.[44] The album featured a ‘layered’ sound which would become their signature, and features long complex instrumental passages, fantasy-themed lyrics, and instrumental virtuosity.[45][46] Aside from its only single, the album also included the song «The March of the Black Queen», a six-minute epic which lacks a chorus.[47] Critical reaction was mixed; the Winnipeg Free Press, while praising the band’s debut album, described Queen II as an «over-produced monstrosity».[48] AllMusic has described the album as a favourite among the band’s hardcore fans,[49] and it is the first of three Queen albums to feature in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[50] The group ended their early 1974 UK tour with a show at the Rainbow Theatre on 31 March. Mercury chose to a wear a Zandra Rhodes-designed tunic for the gig, changing into a slashed black top midway through the show.[51]

1974–1976: Sheer Heart Attack to A Night at the Opera

In May 1974, a month into the band’s first US tour opening for Mott the Hoople, May collapsed and was diagnosed with hepatitis, forcing the cancellation of their remaining dates.[45] While recuperating, May was initially absent when the band started work on their third album, but he returned midway through the recording process.[52] Released in 1974, Sheer Heart Attack reached number two in the UK,[53] sold well throughout Europe, and went gold in the US.[34] It gave the band their first real experience of international success, and was a hit on both sides of the Atlantic.[54] The album experimented with a variety of musical genres, including British music hall, heavy metal, ballads, ragtime, and Caribbean. May’s «Now I’m Here» documented the group’s curtailed American tour, and «Brighton Rock» served as a vehicle for his regular on-stage solo guitar spot. Deacon wrote his first song for the group, «Misfire», while the live favourite «Stone Cold Crazy» was credited to the whole band. Mercury wrote the closing number, «In the Lap of the Gods», with the intention that the audience could sing along to the chorus when played live. This would be repeated later on, more successfully, in songs such as «We Are the Champions.[55]

The single «Killer Queen» was written by Mercury about a high-class prostitute.[56] It reached number two on the British charts,[33] and became their first US hit, reaching number 12 on the Billboard Hot 100.[57] The song was partly recorded at Rockfield Studios in Wales.[58] With Mercury playing the grand piano, it combines camp, vaudeville, and British music hall with May’s guitar. «Now I’m Here» was released as the second single, reached number eleven.[59] In 2006, Classic Rock ranked Sheer Heart Attack number 28 in «The 100 Greatest British Rock Albums Ever»,[60] and in 2007, Mojo ranked it No.88 in «The 100 Records That Changed the World».[61] It is also the second of three Queen albums to feature in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[50]

In January 1975, Queen left for a world tour with an upgraded light show. They toured the US as headliners, and played in Canada for the first time.[62] Several dates were cancelled after Mercury contracted laryngitis.[63] The band then toured Japan from mid-April to the beginning of May. They were greeted by thousands of screaming fans, and played eight times in seven cities.[64][65] Despite the success, Queen were still tied to the original Trident deal and wages. They were all living in relative poverty in bedsits, while Deacon was refused money for a deposit on a house. EMI contacted lawyer Jim Beach, who tried to find a way of extracting them from their contract. Trident complained that they had invested £200,000 in Queen and wanted their money back first.[66] In August, after an acrimonious split with Trident, the band negotiated themselves out of their contract and searched for new management.[67] One of the options they considered was an offer from Led Zeppelin’s manager, Peter Grant, who wanted them to sign with Led Zeppelin’s own production company, Swan Song Records. The band were concerned about being a lower priority than Zeppelin and Bad Company (also signed to Swan Song) and instead contacted Elton John’s manager, John Reid, who accepted the position.[67][68] Reid’s first instruction to the band was «I’ll take care of the business; you make the best record you can».[69]

Queen started work on their fourth album A Night at the Opera, taking its name from the popular Marx Brothers movie. At the time, it was the most expensive album ever produced, costing £40,000 and using three different studios.[70] Like its predecessor, the album features diverse musical styles and experimentation with stereo sound. Mercury wrote the opening song «Death on Two Legs», a savage dig at perceived wrongdoers (and later dedicated to Trident in concert)[71][62] and the camp vaudeville «Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon» and «Seaside Rendezvous».[71] May’s «The Prophet’s Song» was an eight-minute epic; the middle section is a canon, with simple phrases layered to create a full-choral sound. The Mercury penned ballad, «Love of My Life», featured a harp and overdubbed vocal harmonies.[72]

He knew exactly what he was doing. It was Freddie’s baby. We just helped him bring it to life. We realized we’d look odd trying to mime such a hugely complex thing on TV. It had to be presented in some other way.

—Brian May on Mercury writing «Bohemian Rhapsody» and the groundbreaking music video.[73]

The best-known song on the album, «Bohemian Rhapsody», originated from pieces of music that Mercury had written at Ealing College. Mercury played a run-through of the track on piano in his flat to Baker, stopping suddenly to announce, «This is where the opera section comes in».[74] When the rest of the band started recording the song they were unsure as to how it would be pieced together. After recording the backing track, Baker left a 30-second section of tape to add the operatic vocals. Reportedly, 180 overdubs were used, to the extent that the original tape wore thin.[74] EMI initially refused to release the single, thinking it too long, and demanded a radio edit which Queen refused. Mercury’s close friend and advisor, Capital London radio DJ Kenny Everett, played a pivotal role in giving the single exposure.[75] He was given a promotional copy on the condition he didn’t play it, but ended up doing so fourteen times over a single weekend.[76] Capital’s switchboard was overwhelmed with callers inquiring when the song would be released.[75] With EMI forced to release «Bohemian Rhapsody» due to public demand, the single reached number one in the UK for nine weeks.[33][77] It is the third-best-selling single of all time in the UK, surpassed only by Band Aid’s «Do They Know It’s Christmas?» and Elton John’s «Candle in the Wind 1997», and is the best-selling commercial single (i.e. not for-charity) in the UK. It also reached number nine in the US (a 1992 re-release reached number two on the Billboard Hot 100 for five weeks).[57] It is the only single ever to sell a million copies on two separate occasions,[78] and became the Christmas number one twice in the UK, the only single ever to do so. It has also been voted the greatest song of all time in three different polls.[79][80][81]

«Bohemian Rhapsody» was promoted with a music video directed by Bruce Gowers, who had already shot several of Queen’s live concerts. The group wanted a video so they could avoid appearing on the BBC’s Top of the Pops, which would clash with tour dates, and it would have looked strange miming to such a complex song.[82] Filmed at Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, the video cost £3,500, five times the typical promotional budget, and was shot in three hours. The operatic section featured a reprise of the Queen II cover, with the band member’s heads animated.[77][83] On the impact of the «Bohemian Rhapsody» promotional video, Rolling Stone states: «Its influence cannot be overstated, practically inventing the music video seven years before MTV went on the air.»[84] Ranking it number 31 on their list of the 50 key events in rock music history, The Guardian stated it «ensured videos would henceforth be a mandatory tool in the marketing of music».[85] Radio broadcaster Tommy Vance states, «It became the first record to be pushed into the forefront by virtue of a video. Queen were certainly the first band to create a ‘concept’ video. The video captured the musical imagery perfectly. You cannot hear that music without seeing the visuals in your mind’s eye.»[87]

A Night at the Opera was very successful in the UK,[33] and went triple platinum in the United States.[34] The British public voted it the 13th-greatest album of all time in a 2004 Channel 4 poll.[88] It has also ranked highly in international polls; in a worldwide Guinness poll, it was voted the 19th-greatest of all time,[89] while an ABC poll saw the Australian public vote it the 28th-greatest of all time.[90] A Night at the Opera has frequently appeared in «greatest albums» lists reflecting the opinions of critics. Among other accolades, it was ranked number 16 in Q magazine’s «The 50 Best British Albums Ever» in 2004, and number 11 in Rolling Stone’s «The 100 Greatest Albums of All Time» as featured in their Mexican edition in 2004.[91] It was also placed at number 230 on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of «The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time» in 2003.[92] A Night at the Opera is the third and final Queen album to be featured in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[50] The second single from the album was Deacon’s «You’re My Best Friend», which peaked at number sixteen on the US Billboard Hot 100,[57] and went on to become a worldwide top-ten hit.[78] The band’s A Night at the Opera Tour began in November 1975, and covered Europe, the United States, Japan, and Australia.[93] On 24 December, Queen played a special concert at the Hammersmith Odeon which was broadcast live on the BBC show The Old Grey Whistle Test, with the audio being later broadcast on BBC Radio 1. It became one of the band’s most popular bootleg recordings for decades before being officially released in 2015.[94]

1976–1979: A Day at the Races to Live Killers

By 1976, Queen were back in the studio recording A Day at the Races, which is often regarded as a sequel album to A Night at the Opera.[95][96] It again borrowed the name of a Marx Brothers movie, and its cover was similar to that of A Night at the Opera, a variation on the same Queen logo.[97] The most recognisable of the Marx Brothers, Groucho Marx, invited Queen to visit him in his Los Angeles home in March 1977; there the band thanked him in person, and performed «’39» a cappella.[98] Baker did not return to produce the album; instead the band self-produced with assistance from Mike Stone, who performed several of the backing vocals.[99] The major hit on the album was «Somebody to Love», a gospel-inspired song in which Mercury, May, and Taylor multi-tracked their voices to create a gospel choir.[100] The song went to number two in the UK,[33] and number thirteen in the US.[57] The album also featured one of the band’s heaviest songs, May’s «Tie Your Mother Down», which became a staple of their live shows.[101][102] Musically, A Day at the Races was by both fans’ and critics’ standards a strong effort, reaching number one in the UK and Japan, and number five in the US.[33][97]

Queen played a landmark gig on 18 September 1976, a free concert in Hyde Park, London, organised by the entrepreneur Richard Branson.[103] It set an attendance record at the park, with 150,000 people confirmed in the audience.[103][104] Queen were late arriving onstage and ran out of time to play an encore; the police informed Mercury that he would be arrested if he attempted to go on stage again.[96] May enjoyed the gig particularly, as he had been to see previous concerts at the park, such as the first one organised by Blackhill Enterprises in 1968, featuring Pink Floyd.[105]

On 1 December 1976, Queen were the intended guests on London’s early evening Today programme, but they pulled out at the last-minute, which saw their late replacement on the show, EMI labelmate the Sex Pistols, give their infamous expletive-strewn interview with Bill Grundy.[106][107] During the A Day at the Races Tour in 1977, Queen performed sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden, New York, in February, supported by Thin Lizzy, and Mercury and Taylor socialised with that group’s leader Phil Lynott.[108] They then performed a series of concerts at Earls Court, London, in June. The concerts commemorated the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II, and saw the band use a lighting rig in the shape of a crown for the first time, which cost the group £50,000.[109][110][111]

The band’s sixth studio album News of the World was released in 1977, which has gone four times platinum in the United States, and twice in the UK.[34] The album contained many songs tailor-made for live performance, including two of rock’s most recognisable anthems, «We Will Rock You» and the rock ballad «We Are the Champions», both of which became enduring international sports anthems, and the latter reached number four in the US.[57][112] Queen commenced the News of the World Tour in November 1977, and Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times called this concert tour the band’s «most spectacularly staged and finely honed show».[113] During the tour they sold out another two shows at MSG, and in 1978 they received the Madison Square Garden Gold Ticket Award for passing more than 100,000 unit ticket sales at the venue.[114]

Queen in New Haven, Connecticut in November 1977

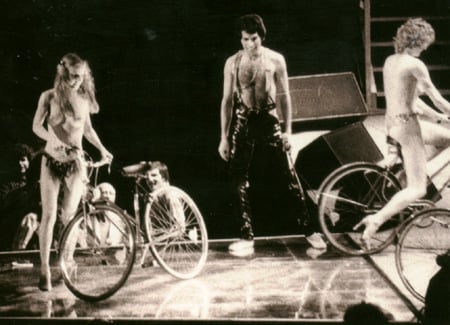

In 1978, Queen released Jazz, which reached number two in the UK and number six on the Billboard 200 in the US.[115] The album included the hit singles «Fat Bottomed Girls» and «Bicycle Race» on a double-sided record. Critical reviews of the album in the years since its release have been more favourable than initial reviews.[116][117] Another notable track from Jazz, «Don’t Stop Me Now», provides another example of the band’s exuberant vocal harmonies.[118]

In 1978, Queen toured the US and Canada, and spent much of 1979 touring in Europe and Japan.[119] They released their first live album, Live Killers, in 1979; it went platinum twice in the US.[120] Queen also released the very successful single «Crazy Little Thing Called Love», a rockabilly inspired song done in the style of Elvis Presley.[121][122] The song made the top 10 in many countries, topped the Australian ARIA Charts for seven consecutive weeks, and was the band’s first number one single in the United States where it topped the Billboard Hot 100 for four weeks.[57][123] Having written the song on guitar and played rhythm on the record, Mercury played rhythm guitar while performing the song live, which was the first time he ever played guitar in concert.[122] On 26 December 1979, Queen played the opening night at the Concert for the People of Kampuchea in London, having accepted a request by the event’s organiser, Paul McCartney.[122] The concert was the last date of their Crazy Tour of London.[124]

1980–1982: The Game, Hot Space and stadium tours

Queen began their 1980s career with The Game. It featured the singles «Crazy Little Thing Called Love» and «Another One Bites the Dust», both of which reached number one in the US.[57] After attending a Queen concert in Los Angeles, Michael Jackson suggested to Mercury backstage that «Another One Bites the Dust» be released as a single, and in October 1980 it spent three weeks at number one.[125] The album topped the Billboard 200 for five weeks,[126] and sold over four million copies in the US.[34] It was also the first appearance of a synthesiser on a Queen album. Heretofore, their albums featured a distinctive «No Synthesisers!» sleeve note. The note is widely assumed to reflect an anti-synth, pro-«hard»-rock stance by the band,[127] but was later revealed by producer Roy Thomas Baker to be an attempt to clarify that those albums’ multi-layered solos were created with guitars, not synths, as record company executives kept assuming at the time.[128] In September 1980, Queen performed three sold-out shows at Madison Square Garden.[43] In 1980, Queen also released the soundtrack they had recorded for Flash Gordon.[130] At the 1981 American Music Awards in January, «Another One Bites the Dust» won the award for Favorite Pop/Rock Single, and Queen were nominated for Favorite Pop/Rock Band, Duo, or Group.[131]

Queen with Argentine footballer Diego Maradona (middle) during the South American part of The Game Tour

In February 1981, Queen travelled to South America as part of The Game Tour, and became the first major rock band to play significant shows in Latin America. Tom Pinnock in the March 1981 issue of Melody Maker wrote,

Queen chalked up a major international «first» by becoming the band to do for popular music in South America what The Beatles did for North America 17 years ago. Half a million Argentinians and Brazilians, starved of appearances of top British or American bands at their peak, gave Queen a heroic welcome which changed the course of pop history in this uncharted territory of the world rock map. The ecstatic young people saw eight Queen concerts at giant stadia, while many more millions saw the shows on TV and heard the radio broadcasts live.[132]

The tour included five shows in Argentina, one of which drew the largest single concert crowd in Argentine history with an audience of 300,000 in Buenos Aires[133] and two concerts at the Morumbi Stadium in São Paulo, Brazil, where they played to more than 131,000 people in the first night (then the largest paying audience for a single band anywhere in the world)[134] and more than 120,000 people the following night.[135] A region then largely ruled by military dictatorships, the band were greeted with scenes of fan-fever, and the promoter of their first shows at the Vélez Sarsfield Stadium in Buenos Aires was moved to say: «For music in Argentina, this has been a case of before the war and after the war. Queen have liberated this country, musically speaking.»[132] The group’s second show at the Vélez Sarsfield Stadium was broadcast on national television and watched by over 30 million. Backstage, the group were introduced to footballer Diego Maradona.[136]

Topping the charts in Brazil and Argentina, the ballad «Love of My Life» stole the show in South American concerts. Mercury would stop singing and would then conduct the audience as they took over, with Lesley-Ann Jones writing «the fans knew the song by heart. Their English was word-perfect.»[137] Later that year Queen performed for more than 150,000 fans on 9 October at Monterrey (Estadio Universitario) and 17 and 18 at Puebla (Estadio Zaragoza), Mexico.[138] Though the gigs were successful, they were marred by a lack of planning and suitable facilities, with audiences throwing projectiles on stage. Mercury finished the final gig saying, «Adios, amigos, you motherfuckers!»[139] On 24 and 25 November. Queen played two sell out nights at the Montreal Forum, Quebec, Canada.[140] One of Mercury’s most notable performances of The Game‘s final track, «Save Me», took place in Montreal, and the concert is recorded in the live album, Queen Rock Montreal.[141]

Queen worked with David Bowie on the 1981 single «Under Pressure». The first-time collaboration with another artist was spontaneous, as Bowie happened to drop by the studio while Queen were recording. Mercury and Bowie recorded their vocals on the track separately to each other, each coming up with individual ideas. The song topped the UK charts.[142] In October, Queen released their first compilation album, titled Greatest Hits, which showcased the group’s highlights from 1974 to 1981.[143] The best-selling album in UK chart history, it is the only album to sell over seven million copies in the UK.[144] As of July 2022, it has spent over 1000 weeks in the UK Album Chart.[145][146] According to The Telegraph, approximately one in three families in the UK own a copy.[147] The album is certified nine times platinum in the US.[34] As of August 2022, it has spent over 500 weeks on the US Billboard 200.[148] Greatest Hits has sold over 25 million copies worldwide.[149]

We moved out to Munich to isolate ourselves from normal life so we could focus on the music. We all ended up in a place that was rather unhealthy. A difficult period. We weren’t getting along together. We all had different agendas. It was a difficult time for me, personally – some dark moments.

— May on the recording of Hot Space during a difficult period for the band.[150]

In 1982, the band released the album Hot Space, a departure from their trademark seventies sound, this time being a mixture of pop rock, dance, disco, funk, and R&B.[151] Most of the album was recorded in Munich during the most turbulent period in the band’s history.[152] While Mercury and Deacon enjoyed the new soul and funk influences, Taylor and May were less favourable, and were critical of the influence Mercury’s personal manager Paul Prenter had on him.[153] According to Mack, Queen’s producer, Prenter loathed rock music and was in Mercury’s ear throughout the Hot Space sessions.[154] May was also scathing of Prenter—Mercury’s manager from 1977 to 1984—for being dismissive of the importance of radio stations and their vital connection between the artist and the community, and for denying them access to Mercury.[155] May states, «this guy, in the course of one tour, told every record station to fuck off».[154] Queen roadie Peter Hince wrote «None of the band cared for him [Prenter], apart from Freddie», with Hince regarding Mercury’s favouring of Prenter as an act of «misguided loyalty».[154] During the Munich sessions, Mercury spent time with Mack and his family, becoming godfather to Mack’s first child.[156] Q magazine would list Hot Space as one of the top fifteen albums where great rock acts lost the plot.[157] Though the album confused some fans with the change of musical direction, it still reached number 4 in the UK.[158]

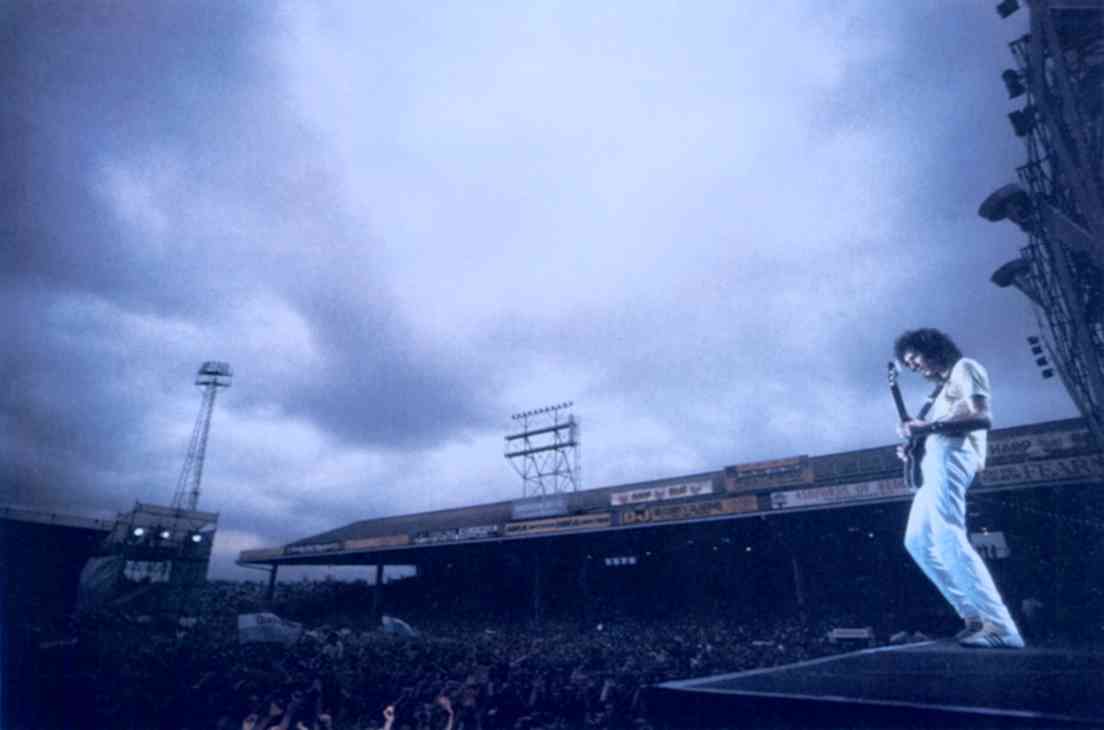

Queen toured to promote Hot Space, but found some audience unreceptive to the new material. At a gig in Frankfurt, Mercury told some people heckling the new material, «If you don’t want to listen to it, go home!»[159] Former Mott The Hoople keyboardist Morgan Fisher joined as an additional touring member.[160] Shows were planned at Arsenal Stadium and Old Trafford, but these were cancelled as Pope John Paul II was touring Britain, leading to a lack of available outdoor facilities such as toilets. The gigs were moved to the Milton Keynes Bowl and Elland Road, Leeds instead. The Milton Keynes concert was filmed by Tyne Tees Television and later released on DVD.[158] On 14 and 15 September 1982, the band performed their last two gigs in the US with Mercury on lead vocals, playing at The Forum in Inglewood, California.[161] Fisher was replaced as touring keyboardist by Fred Mandel for the North American shows.[162] The band stopped touring North America after their Hot Space Tour, as their success there had waned, although they would perform on American television for the only time during the eighth-season premiere of Saturday Night Live on 25 September of the same year;[163] it became the final public performance of the band in North America before the death of their frontman. Their fall in popularity in the US has been partially attributed to a homophobia:[164] «At some shows on the band’s 1980 American tour, fans tossed disposable razor blades onstage: They didn’t like this identity of Mercury—what they perceived as a brazenly gay rock & roll hero—and they wanted him to shed it.»[165] The group finished the year with a Japanese tour.[166]

1983–1984: The Works

After the Hot Space Tour concluded with a concert at Seibu Lions Stadium in Tokorozawa, Japan in November 1982, Queen decided they would take a significant amount of time off. May later said at that point, «we hated each other for a while».[166] The band reconvened nine months later to begin recording a new album at the Record Plant Studios, Los Angeles and Musicland Studios, Munich.[167] Several members of the band also explored side projects and solo work. Taylor released his second solo album, Strange Frontier. May released the mini-album Star Fleet Project, collaborating with Eddie Van Halen.[168] Queen left Elektra Records, their label in the US, Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, and signed onto EMI/Capitol Records.[154]

Queen on stage in Frankfurt on 26 September 1984.

In February 1984, Queen released their eleventh studio album, The Works. Hit singles included «Radio Ga Ga», which makes a nostalgic defence of the radio format, «Hammer to Fall» and «I Want to Break Free».[169][170] Rolling Stone hailed the album as «the Led Zeppelin II of the eighties.»[154] In the UK The Works went triple platinum and remained in the albums chart for two years.[171] The album failed to do well in the US, where, in addition to issues with their new record label Capitol Records (who had recently severed ties with their independent promotions teams due to a government report on payola),[154] the cross-dressing video for «I Want to Break Free», a spoof of the British soap opera Coronation Street, proved controversial and was banned by MTV.[172] The concept of the video came from Roger Taylor via a suggestion from his girlfriend.[154] He told Q magazine: «We had done some really serious, epic videos in the past, and we just thought we’d have some fun. We wanted people to know that we didn’t take ourselves too seriously, that we could still laugh at ourselves.»[173] Director of the video David Mallet said Mercury was reluctant to do it, commmeting «it was a hell of a job to get him out of the dressing room».[154]

That year, Queen began The Works Tour, the first tour to feature keyboardist Spike Edney as an extra live musician. The tour featured nine sold-out dates in October in Bophuthatswana, South Africa, at the arena in Sun City.[174][175] Upon returning to England, they were the subject of outrage, having played in South Africa during the height of apartheid and in violation of worldwide divestment efforts and a United Nations cultural boycott. The band responded to the critics by stating that they were playing music for fans in South Africa, and they also stressed that the concerts were played before integrated audiences.[176] Queen donated to a school for the deaf and blind as a philanthropic gesture but were fined by the British Musicians’ Union and placed on the United Nations’ blacklisted artists.[177] In 2021, Taylor voiced his regret for the decision to perform at Sun City, stating that «We went with the best intentions, but I still think it was kind of a mistake.»[178]

1985–1986: Live Aid, A Kind of Magic and tours

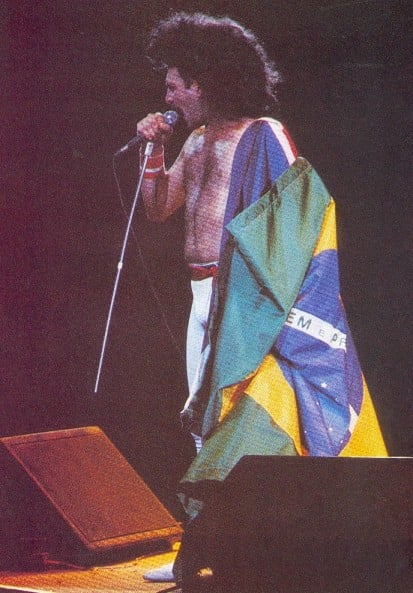

In January 1985, Queen headlined two nights of the first Rock in Rio festival at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and played in front of over 300,000 people each night.[179] The Boston Globe described it as a «mesmerising performance».[180] Highlights from both nights were released on VHS as Queen: Live in Rio, which was broadcast on MTV in the US.[180][181] In April and May 1985, Queen completed the Works Tour with sold-out shows in Australia and Japan.[182]

Queen were absolutely the best band of the day … they just went and smashed one hit after another … it was the perfect stage for Freddie: the whole world.

—Bob Geldof, on Queen’s performance at Live Aid.[183]

At Live Aid, held at Wembley on 13 July 1985, in front of the biggest-ever TV audience of an estimated 1.9 billion, Queen performed some of their greatest hits. Many of the sold-out stadium audience of 72,000 people clapped, sang, and swayed in unison.[184][185] The show’s organisers, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure; other musicians such as Elton John and Cliff Richard; and journalists writing for the BBC, CNN, Rolling Stone, MTV, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph, among others, described Queen as the highlight.[186][187][188] Interviewed backstage, Roger Waters stated: «Everybody’s been buzzing about Queen that I’ve run into. They had everybody completely spellbound.»[189] An industry poll in 2005 ranked it the greatest rock performance of all time.[186][190] Mercury’s powerful, sustained note—»Aaaaaay-o»—during the call-and-response a cappella segment came to be known as «The Note Heard Round the World».[191][192] The band were revitalised by the response to Live Aid—a «shot in the arm» Roger Taylor called it—and the ensuing increase in record sales.[193] In 1986 Mercury commented: «From our perspective, the fact that Live Aid happened when it did was really lucky. It came out of nowhere to save us. For sure that was a turning point. Maybe you could say that in the history of Queen, it was a really special moment.»[194]

Queen ended 1985 by releasing the single «One Vision» and a limited-edition boxed set of Queen albums, The Complete Works. The package included the 1984 Christmas single «Thank God It’s Christmas» and previously unreleased material.[196] In early 1986, Queen recorded the album A Kind of Magic, containing several reworkings of songs written for the fantasy action film Highlander.[197] The album was successful in the UK, Germany and several other countries, producing a string of hits including «A Kind of Magic», «Friends Will Be Friends», «Princes of the Universe» and «Who Wants to Live Forever»; the latter featuring an orchestra conducted by Michael Kamen. The album was less successful in North America, reaching 46 in the US, and was described by biographer Mark Blake as «a so-so album» and «a somewhat uneven listening experience».[198]

In mid-1986, Queen went on the Magic Tour, their final tour with Mercury.[199] They once again hired Spike Edney.[200][201] Queen began the tour at the Råsunda Stadium in Stockholm, Sweden, and later performed a concert at Slane Castle, Ireland, in front of an audience of 95,000, which broke the venue’s attendance record.[202] The band also played behind the Iron Curtain when they performed to a crowd of 80,000 at the Népstadion in Budapest (released in the concert film Hungarian Rhapsody: Queen Live in Budapest), in what was one of the biggest rock concerts ever held in Eastern Europe.[203] More than one million people saw Queen on the tour—400,000 in the UK alone, a record at the time.[175] The Magic Tour’s highlight was at Wembley Stadium and resulted in the live double album Queen at Wembley, released on CD and as a live concert VHS/DVD, which has gone five times platinum in the US and four times platinum in the UK.[34][204] Queen could not book Wembley for a third night, but played at Knebworth Park on 9 August. The show sold out within two hours and over 120,000 fans packed the park for what was Queen’s final performance with Mercury.[205][206] Roadie Peter Hince states, «At Knebworth, I somehow felt it was going to be the last for all of us», while Brian May recalled Mercury saying «I’m not going to be doing this forever. This is probably the last time.»[154]

1988–1992: The Miracle, Innuendo and Mercury’s final years

There was all that time when we knew Freddie was on the way out, we kept our heads down.

—Brian May[207]

After fans noticed Mercury’s increasingly gaunt appearance in 1988, the media reported that Mercury was seriously ill, with AIDS frequently mentioned as a likely illness. Mercury denied this, insisting he was merely «exhausted» and too busy to provide interviews; he was now 42 years old and had been involved in music for nearly two decades.[208] Mercury had in fact been diagnosed as HIV positive in 1987, but did not make his illness public, with only his inner circle of colleagues and friends aware of his condition.[207]

After working on various solo projects during 1988 (including Mercury’s collaboration with Montserrat Caballé, Barcelona), the band released The Miracle in 1989. The album continued the direction of A Kind of Magic, using a pop-rock sound mixed with a few heavy numbers. It spawned the hit singles «I Want It All»—which became an anti-apartheid anthem in South Africa—»Scandal», and «The Miracle».[209][210] The Miracle also began a change in direction of Queen’s songwriting philosophy. Beforehand, nearly all songs had been written by and credited to a single member. With The Miracle, their songwriting became more collaborative, and they vowed to credit the final product only to Queen as a group.[211]

In 1990, Queen ended their contract with Capitol and signed with Hollywood Records; through the deal, Disney acquired the North American distribution rights to Queen’s catalogue for $10 million, and remains the group’s music catalogue owner and distributor in the United States and Canada.[212][213] In February that year, Mercury made what would prove to be his final public appearance when he joined the rest of Queen onstage at the Dominion Theatre in London to collect the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music.[214]

Their fourteenth studio album, Innuendo, was released in early 1991 with «Innuendo» and other charting singles released later in the year. The music video for «The Show Must Go On» featured archive footage of Queen’s performances between 1981 and 1989, and along with the manner of the song’s lyrics, fuelled reports that Mercury was dying.[215][216] Mercury was increasingly ill and could barely walk when the band recorded «The Show Must Go On» in 1990. Because of this, May had concerns about whether he was physically capable of singing it, but May recalled that he «completely killed it».[217] The rest of the band were ready to record when Mercury felt able to come into the studio, for an hour or two at a time. May says of Mercury: «He just kept saying. ‘Write me more. Write me stuff. I want to just sing this and do it and when I am gone you can finish it off.’ He had no fear, really.»[195] The band’s second-greatest hits compilation, Greatest Hits II, followed in October 1991; it is the tenth best-selling album in the UK,[218] the seventh best-selling album in Germany,[219] is certified Diamond in France where it is one of the best-selling albums,[220] and has sold 16 million copies worldwide.[221][222]

Following Mercury’s death on 24 November 1991, his tribute concert was held at the original Wembley Stadium in London on 20 April 1992, the same venue where Queen performed at Live Aid in July 1985

On 23 November 1991, in a prepared statement made on his deathbed, Mercury confirmed that he had AIDS.[223] Within 24 hours of the statement, he died of bronchial pneumonia, which was brought on as a complication of the disease.[224] His funeral service on 27 November in Kensal Green, West London was private, and held in accordance with the Zoroastrian religious faith of his family.[225][226]

«Bohemian Rhapsody» was re-released as a single shortly after Mercury’s death, with «These Are the Days of Our Lives» as the double A-side. The music video for the latter contains Mercury’s final scenes in front of the camera. Ron Hart of Rolling Stone wrote, «the conga-driven synth ballad «These Are the Days of Our Lives» is Innuendo‘s most significant single, given that its video marked the last time his fans were able to see the singer alive.»[227] The video was recorded on 30 May 1991 (which proved to be Mercury’s final work with Queen).[228] The single went to number one in the UK, remaining there for five weeks—the only recording to top the Christmas chart twice and the only one to be number one in four different years (1975, 1976, 1991, and 1992).[229] Initial proceeds from the single—approximately £1,000,000—were donated to the Terrence Higgins Trust, an AIDS charity.[230]

Queen’s popularity was stimulated in North America when «Bohemian Rhapsody» was featured in the 1992 comedy film Wayne’s World.[231] Its inclusion helped the song reach number two on the Billboard Hot 100 for five weeks in 1992 (including its 1976 chart run, it remained in the Hot 100 for a combined 41 weeks),[231] and won the band an MTV Award at the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards.[232] The compilation album Classic Queen also reached number four on the Billboard 200, and is certified three times platinum in the US.[34][231] Wayne’s World footage was used to make a new music video for «Bohemian Rhapsody», with which the band and management were delighted.[233]

On 20 April 1992, The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert was held at London’s Wembley Stadium to a crowd of 72,000.[234] Performers, including Def Leppard, Robert Plant, Tony Iommi, Roger Daltrey, Guns N’ Roses, Elton John, David Bowie, George Michael, Annie Lennox, Seal, Extreme, and Metallica performed various Queen songs along with the three remaining Queen members (and Spike Edney.) The concert is listed in the Guinness Book of Records as «The largest rock star benefit concert»,[235] as it was televised to over 1.2 billion viewers worldwide,[175] and raised over £20,000,000 for AIDS charities.[230]

1995–2003: Made in Heaven to 46664 Concert

Queen’s last album with Mercury, titled Made in Heaven, was released in 1995, four years after his death.[236] Featuring tracks such as «Too Much Love Will Kill You» and «Heaven for Everyone», it was constructed from Mercury’s final recordings in 1991, material left over from their previous studio albums and re-worked material from May, Taylor, and Mercury’s solo albums. The album also featured the song «Mother Love», the last vocal recording Mercury made, which he completed using a drum machine, over which May, Taylor and Deacon later added the instrumental track.[237] After completing the penultimate verse, Mercury had told the band he «wasn’t feeling that great» and stated, «I will finish it when I come back, next time». Mercury never returned to the studio afterwards, leaving May to record the final verse of the song.[195] Both stages of recording, before and after Mercury’s death, were completed at the band’s studio in Montreux, Switzerland.[238] The album reached number one in the UK following its release, their ninth number one album, and sold 20 million copies worldwide.[239][240] On 25 November 1996, a statue of Mercury was unveiled in Montreux overlooking Lake Geneva, almost five years to the day since his death.[238][241]

You guys should go out and play again. It must be like having a Ferrari in the garage waiting for a driver.

—Elton John, on Queen being without a lead singer since the death of Freddie Mercury.[242]

In 1997, Queen returned to the studio to record «No-One but You (Only the Good Die Young)», a song dedicated to Mercury and all those who die too soon.[243] It was released as a bonus track on the Queen Rocks compilation album later that year, and features in Greatest Hits III.[244] In January 1997, Queen performed «The Show Must Go On» live with Elton John and the Béjart Ballet in Paris on a night Mercury was remembered, and it marked the last performance and public appearance of John Deacon, who chose to retire.[245] The Paris concert was only the second time Queen had played live since Mercury’s death, prompting Elton John to urge them to perform again.[242] Brian May and Roger Taylor performed together at several award ceremonies and charity concerts, sharing vocals with various guest singers. During this time, they were billed as Queen + followed by the guest singer’s name. In 1998, the duo appeared at Luciano Pavarotti’s benefit concert with May performing «Too Much Love Will Kill You» with Pavarotti, later playing «Radio Ga Ga», «We Will Rock You», and «We Are the Champions» with Zucchero. They again attended and performed at Pavarotti’s benefit concert in Modena, Italy in May 2003.[246] Several of the guest singers recorded new versions of Queen’s hits under the Queen + name, such as Robbie Williams providing vocals for «We Are the Champions» for the soundtrack of A Knight’s Tale (2001).[247]

In November 1999, Greatest Hits III was released. This featured, among others, «Queen + Wyclef Jean» on a rap version of «Another One Bites the Dust». A live version of «Somebody to Love» by George Michael and a live version of «The Show Must Go On» with Elton John were also featured in the album.[248] By this point, Queen’s vast amount of record sales made them the second-bestselling artist in the UK of all time, behind the Beatles.[240] In November 2000, the band released the box set, The Platinum Collection. It is certified seven times platinum in the UK and five times platinum in the US.[249][250] On 18 October 2002, Queen were awarded the 2,207th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, for their work in the music industry, which is located at 6358 Hollywood Blvd.[251] On 29 November 2003, May and Taylor performed at the 46664 Concert hosted by Nelson Mandela at Green Point Stadium, Cape Town, to raise awareness of the spread of HIV/AIDS in South Africa.[252] A new song, «Invincible Hope», featuring Mandela’s speech and credited to Queen + Nelson Mandela, was performed during the concert and later released on the 46664: One Year On EP.[253] During that period May and Taylor spent time at Mandela’s home, discussing how Africa’s problems might be approached, and two years later the band were made ambassadors for the 46664 cause.[252]

2004–2009: Queen + Paul Rodgers

At the end of 2004, May and Taylor announced that they would reunite and return to touring in 2005 with Paul Rodgers (founder and former lead singer of Free and Bad Company). Brian May’s website also stated that Rodgers would be «featured with» Queen as «Queen + Paul Rodgers», not replacing Mercury. Deacon, who was retired, did not participate.[254] In November 2004, Queen were among the inaugural inductees into the UK Music Hall of Fame, and the award ceremony was the first event at which Rodgers joined May and Taylor as vocalist.[252]

Between 2005 and 2006, Queen + Paul Rodgers embarked on a world tour, which was the first time Queen toured since their last tour with Freddie Mercury in 1986.[255] Taylor said: «We never thought we would tour again, Paul came along by chance and we seemed to have a chemistry. Paul is just such a great singer. He’s not trying to be Freddie.»[255] The first leg was in Europe, the second in Japan, and the third in the US in 2006.[256] Queen received the inaugural VH1 Rock Honors at the Mandalay Bay Events Center in Las Vegas, Nevada, on 25 May 2006.[257] Foo Fighters paid homage, performing «Tie Your Mother Down» to open the ceremony before being joined on stage by May, Taylor, and Rodgers, who played a selection of Queen hits.[258]

On 15 August 2006, May confirmed through his website and fan club that Queen + Paul Rodgers would begin producing their first studio album beginning in October, to be recorded at a «secret location».[259] Queen + Paul Rodgers performed at the Nelson Mandela 90th Birthday Tribute held in Hyde Park, London on 27 June 2008, to commemorate Mandela’s ninetieth birthday, and again promote awareness of the HIV/AIDS pandemic.[260] The first Queen + Paul Rodgers album, titled The Cosmos Rocks, was released in Europe on 12 September 2008 and in the United States on 28 October 2008.[239] Following the release of the album, the band again went on a tour through Europe, opening on Kharkiv’s Freedom Square in front of 350,000 Ukrainian fans.[261] The Kharkiv concert was later released on DVD.[261] The tour then moved to Russia, and the band performed two sold-out shows at the Moscow Arena.[262] Having completed the first leg of its extensive European tour, which saw the band play 15 sold-out dates across nine countries, the UK leg of the tour sold out within 90 minutes of going on sale and included three London dates, the first of which was the O2 Arena on 13 October.[263] The last leg of the tour took place in South America, and included a sold-out concert at José Amalfitani Stadium, Buenos Aires.[262]

Queen and Paul Rodgers officially split up without animosity on 12 May 2009.[264] Rodgers stated: «My arrangement with [Queen] was similar to my arrangement with Jimmy [Page] in The Firm in that it was never meant to be a permanent arrangement».[264] Rodgers did not rule out the possibility of working with Queen again.[265][266]

2009–2011: Departure from EMI, 40th anniversary

On 20 May 2009, May and Taylor performed «We Are the Champions» live on the season finale of American Idol with winner Kris Allen and runner-up Adam Lambert providing a vocal duet.[267] In mid-2009, after the split of Queen + Paul Rodgers, the Queen online website announced a new greatest hits compilation named Absolute Greatest. The album was released on 16 November and peaked at number 3 in the official UK Chart.[268] The album contains 20 of Queen’s biggest hits spanning their entire career and was released in four different formats: single disc, double disc (with commentary), double disc with feature book, and a vinyl record. Before its release, Queen ran an online competition to guess the track listing as a promotion for the album.[269] On 30 October 2009, May wrote a fanclub letter on his website stating that Queen had no intentions to tour in 2010 but that there was a possibility of a performance.[270] On 15 November 2009, May and Taylor performed «Bohemian Rhapsody» live on the British TV show The X Factor alongside the finalists.[271]

Many of you will have read bits and pieces on the internet about Queen changing record companies and so I wanted to confirm to you that the band have signed a new contract with Universal Music … we would like to thank the EMI team for all their hard work over the years, the many successes and the fond memories, and of course we look forward to continuing to work with EMI Music Publishing who take care of our songwriting affairs. Next year we start working with our new record company to celebrate Queen’s 40th anniversary and we will be announcing full details of the plans over the next 3 months. As Brian has already said Queen’s next moves will involve ‘studio work, computers and live work.

—Jim Beach, Queen’s Manager, on the change of record label.[272]

On 7 May 2010, May and Taylor announced that they were quitting their record label, EMI, after almost 40 years.[273] On 20 August 2010, Queen’s manager Jim Beach put out a Newsletter stating that the band had signed a new contract with Universal Music.[272] During an interview for HARDtalk on the BBC on 22 September, May confirmed that the band’s new deal was with Island Records, a subsidiary of Universal Music Group.[274][275] Hollywood Records remained as the group’s label in the United States and Canada, however. As such, for the first time since the late 1980s, Queen’s catalogue now has the same distributor worldwide, as Universal distributes for both the Island and Hollywood labels (for a time in the late 1980s, Queen was on EMI-owned Capitol Records in the US).[276]

On 14 March 2011, which marked the band’s 40th anniversary, Queen’s first five albums were re-released in the UK and some other territories as remastered deluxe editions (the US versions were released on 17 May).[277] The second five albums of Queen’s back catalogue were released worldwide on 27 June, with the exception of the US and Canada (27 September).[278][279] The final five were released in the UK on 5 September.[280]

In May 2011, Jane’s Addiction vocalist Perry Farrell noted that Queen are currently scouting their once former and current live bassist Chris Chaney to join the band. Farrell stated: «I have to keep Chris away from Queen, who want him and they’re not gonna get him unless we’re not doing anything. Then they can have him.»[281] In the same month, Paul Rodgers stated he may tour with Queen again in the near future.[282] At the 2011 Broadcast Music, Incorporated (BMI) Awards held in London on 4 October, Queen received the BMI Icon Award in recognition for their airplay success in the US.[283][284] At the 2011 MTV Europe Music Awards on 6 November, Queen received the Global Icon Award, which Katy Perry presented to Brian May.[285] Queen closed the awards ceremony, with Adam Lambert on vocals, performing «The Show Must Go On», «We Will Rock You» and «We Are the Champions».[285] The collaboration garnered a positive response from both fans and critics, resulting in speculation about future projects together.[286]

2011–present: Queen + Adam Lambert, Queen Forever

On 25 and 26 April, May and Taylor appeared on the eleventh series of American Idol at the Nokia Theatre, Los Angeles, performing a Queen medley with the six finalists on the first show, and the following day performed «Somebody to Love» with the ‘Queen Extravaganza’ band.[287] Queen were scheduled to headline Sonisphere at Knebworth on 7 July 2012 with Adam Lambert[288] before the festival was cancelled.[289] Queen’s final concert with Freddie Mercury was in Knebworth in 1986. Brian May commented, «It’s a worthy challenge for us, and I’m sure Adam would meet with Freddie’s approval.»[286] Queen expressed disappointment at the cancellation and released a statement to the effect that they were looking to find another venue.[290] Queen + Adam Lambert played two shows at the Hammersmith Apollo, London on 11 and 12 July 2012.[291][292] Both shows sold out within 24 hours of tickets going on open sale.[293] A third London date was scheduled for 14 July.[294] On 30 June, Queen + Lambert performed in Kyiv, Ukraine at a joint concert with Elton John for the Elena Pinchuk ANTIAIDS Foundation.[295] Queen also performed with Lambert on 3 July 2012 at Moscow’s Olympic Stadium,[296][297] and on 7 July 2012 at the Municipal Stadium in Wroclaw, Poland.[298]

Queen performing with Adam Lambert during their 2017 tour

On 12 August 2012, Queen performed at the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.[299] The performance at London’s Olympic Stadium opened with a special remastered video clip of Mercury on stage performing his call and response routine during their 1986 concert at Wembley Stadium.[300] Following this, May performed part of the «Brighton Rock» solo before being joined by Taylor and solo artist Jessie J for a performance of «We Will Rock You».[300][301]

On 20 September 2013, Queen + Adam Lambert performed at the iHeartRadio Music Festival at the MGM Grand Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas.[302] Queen + Adam Lambert toured North America in Summer 2014[303][304] and Australia and New Zealand in August/September 2014.[305] In an interview with Rolling Stone, May and Taylor said that although the tour with Lambert is a limited thing, they are open to him becoming an official member, and cutting new material with him.[306]

In November 2014 Queen released a new album Queen Forever.[307] The album is largely a compilation of previously-released material but features three new Queen tracks featuring vocals from Mercury with backing added by the surviving members of Queen. One new track, «There Must Be More to Life Than This», is a duet between Mercury and Michael Jackson.[308] Queen + Adam Lambert performed in the shadow of Big Ben in Central Hall, Westminster, central London at the Big Ben New Year concert on New Year’s Eve 2014 and New Year’s Day 2015.[309]

In 2016, the group embarked across Europe and Asia on the Queen + Adam Lambert 2016 Summer Festival Tour. This included closing the Isle of Wight Festival in England on 12 June where they performed «Who Wants to Live Forever» as a tribute to the victims of the mass shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida earlier that day.[310] On 12 September they performed at the Yarkon Park in Tel Aviv, Israel for the first time in front of 58,000 people.[311] As part of the Queen + Adam Lambert Tour 2017–2018, the band toured North America in the summer of 2017, toured Europe in late 2017, before playing dates in Australia and New Zealand in February and March 2018.[312] On 24 February 2019, Queen + Adam Lambert opened the 91st Academy Awards ceremony held at the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood, Los Angeles.[313] In July 2019 they embarked on the North American leg of The Rhapsody Tour, with the dates sold out in April.[314] They toured Japan and South Korea in January 2020 followed by Australia and New Zealand the following month.[315][316][317] On 16 February the band reprised their Live Aid set for the first time in 35 years at the Fire Fight Australia concert at ANZ Stadium in Sydney to raise money for the 2019–20 Australian bushfire crisis.[318]

Because Queen were not able to tour due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they released a live album with Adam Lambert on 2 October 2020. The 20-plus song collection, titled Live Around the World, contains personally selected highlights by the band members from over 200 shows throughout their history. It marked their first live album with Lambert who, as of 2020, has played 218 shows with the band.[319] On 31 December 2020, Queen performed on the Japanese New Year’s Eve television special Kōhaku with composer Yoshiki and vocalist Sarah Brightman.[320] In 2021 Queen received the Japan Gold Disc Award for the fourth time (having previously won it in 2005, 2019 and 2020) as the most popular Western act in Japan.[321]

On 4 June 2022, Queen + Adam Lambert opened the Platinum Party at the Palace outside Buckingham Palace to mark the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee.[322] Performing a three-song set, they opened with «We Will Rock You» which had been introduced in a comedy segment where Queen Elizabeth II and Paddington Bear tapped their tea cups to the beat of the song.[323][324]

A previously unheard Queen song with Mercury’s vocals, «Face It Alone», recorded over thirty years ago and originally thought «unsalvageable» by May and Taylor, was released on 13 October 2022; five more songs — «You Know You Belong to Me», «When Love Breaks Up», «Dog With a Bone», «Water», and «I Guess We’re Falling Out» — were released on 18 November 2022 as part of The Miracle Collector’s Edition box set.[325]

Music style and influences

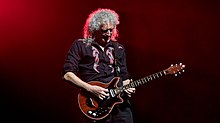

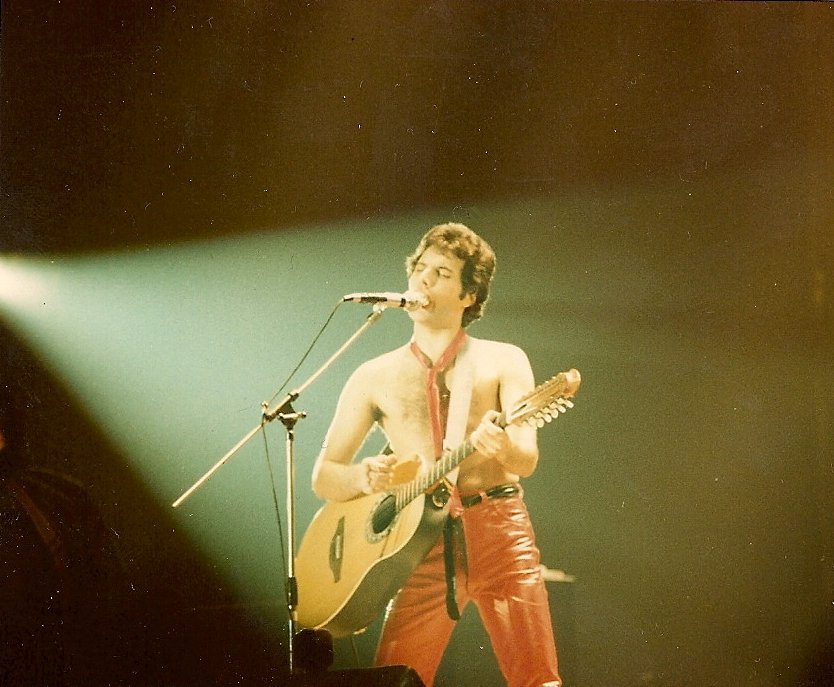

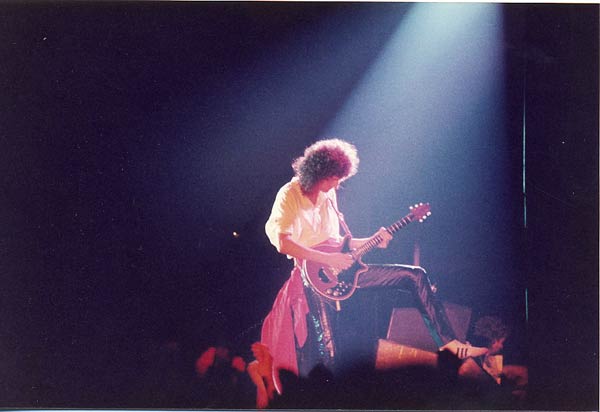

Brian May playing his custom-made Red Special at the O2 Arena in London in 2017. He has used this guitar almost exclusively since the band’s advent in the early 1970s.

Queen drew artistic influence from British rock acts of the 1960s and early 1970s, such as the Beatles, the Kinks, Cream, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, the Who, Black Sabbath, Slade, Deep Purple, David Bowie, Genesis and Yes,[326] with Mercury also inspired by the rock and roll singers Little Richard,[327] Elvis Presley[328] and the gospel singer Aretha Franklin.[329] On the Beatles, Brian May stated they «built our bible as far as musical composition, arrangement and production went. The White Album is a complete catalogue of how you should use a studio to build songs.»[330] Mercury said, «John Lennon was larger than life, and an absolute genius. Even at a very early stage when they were the Beatles, I always preferred John Lennon’s things. I don’t know why. He just had that magic.»[328] May and Mercury were influenced by Jimi Hendrix, with Mercury saying «he really had everything any rock ‘n’ roll star should have»,[331] and May saying «Jimi is, of course, my number one. And I’ve always said that […] I never stop learning from Jimi.»[332] Mercury’s thesis for his Ealing College degree was on Hendrix, and Mercury and Taylor closed their Kensington Market stall on 18 September 1970 to commemorate his death.[333]

At their outset in the early 1970s, Queen’s music has been characterised as «Led Zeppelin meets Yes» due to its combination of «acoustic/electric guitar extremes and fantasy-inspired multi-part song epics».[334] Although Mercury stated Robert Plant as his favourite singer and Led Zeppelin as «the greatest» rock band, he also said Queen «have more in common with Liza Minnelli than Led Zeppelin. We’re more in the showbiz tradition than the rock’n’roll tradition».[328] In his book on Essential Hard Rock and Heavy Metal, Eddie Trunk described Queen as «a hard rock band at the core but one with a high level of majesty and theatricality that delivered a little something for everyone», as well as observing that the band «sounded British».[335] Rob Halford of Judas Priest commented, «It’s rare that you struggle to label a band. If you’re a heavy metal band you’re meant to look and sound like a heavy metal band but you can’t really call Queen anything. They could be a pop band one day or the band that wrote ‘Bicycle Race’ the next and a full-blown metal band the next. In terms of the depth of the musical landscape that they covered, it was very similar to some extent to the Beatles.»[336] While stating they were influenced by various artists and genres, Joe Bosso of Guitar World magazine writes, «Queen seemed to occupy their own lane.»[337]

Queen composed music that drew inspiration from many different genres of music, often with a tongue-in-cheek attitude.[338] The music styles and genres they have been associated with include progressive rock (also known as symphonic rock),[339] art rock,[46][340] glam rock,[341] arena rock,[339] heavy metal,[339] operatic pop,[339] pop rock,[339] psychedelic rock,[342] baroque pop,[343] and rockabilly.[343] Queen also wrote songs that were inspired by diverse musical styles which are not typically associated with rock groups, such as opera,[344] music hall,[344] folk music,[345] gospel,[346] ragtime,[347] and dance/disco.[348] Their 1980 single «Another One Bites the Dust» became a major hit single in the funk rock genre.[349] Several Queen songs were written with audience participation in mind, such as «We Will Rock You» and «We Are the Champions».[350] Similarly, «Radio Ga Ga» became a live favourite because it would have «crowds clapping like they were at a Nuremberg rally».[351]

A sample of «We Will Rock You». The stamping and clapping effects were created by the band overdubbing sounds of themselves stamping and clapping many times, and adding delay effects to create a sound that seemed many people were participating.

In 1963, the teenage Brian May and his father custom-built his signature guitar Red Special, which was purposely designed to feedback.[352][353] May has used Vox AC30 amplifiers almost exclusively since a meeting with his long-time hero Rory Gallagher at a gig in London during the late 1960s/early 1970s.[354] He also uses a sixpence as a plectrum to get the sound he wants.[355] Sonic experimentation figured heavily in Queen’s songs. A distinctive characteristic of Queen’s music are the vocal harmonies which are usually composed of the voices of May, Mercury, and Taylor best heard on the studio albums A Night at the Opera and A Day at the Races. Some of the ground work for the development of this sound is attributed to the producer Roy Thomas Baker and engineer Mike Stone.[356][357] Besides vocal harmonies, Queen were also known for multi-tracking voices to imitate the sound of a large choir through overdubs. For instance, according to Brian May, there are over 180 vocal overdubs in «Bohemian Rhapsody».[358] The band’s vocal structures have been compared with the Beach Boys.[340][359]

Media

Logo

Queen logo (without the crest)

Having studied graphic design in art college, Mercury also designed Queen’s logo, called the Queen crest, shortly before the release of the band’s first album.[360] The logo combines the zodiac signs of all four members: two lions for Leo (Deacon and Taylor), a crab for Cancer (May), and two fairies for Virgo (Mercury).[360] The lions embrace a stylised letter Q, the crab rests atop the letter with flames rising directly above it, and the fairies are each sheltering below a lion.[360] There is also a crown inside the Q and the whole logo is over-shadowed by an enormous phoenix. The whole symbol bears a passing resemblance to the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, particularly with the lion supporters.[360] The original logo, as found on the reverse-side of the cover of the band’s first album, was a simple line drawing. Later sleeves bore more intricate-coloured versions of the logo.[360][361]

Music videos

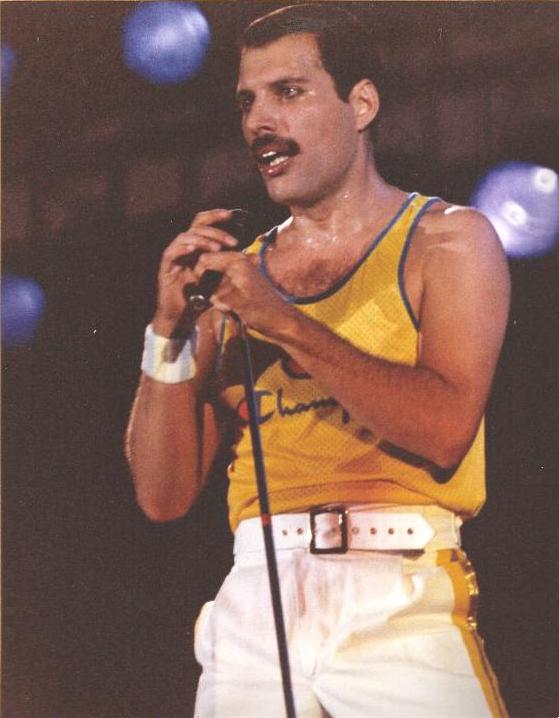

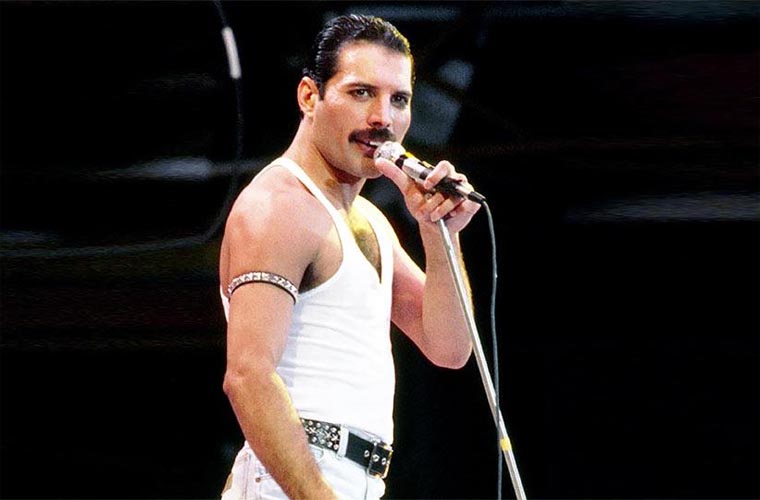

Mercury performing in a Harlequin outfit. He appeared in a half black, half white version in the music video for «We Are the Champions».

Directed by Bruce Gowers, the groundbreaking «Bohemian Rhapsody» promotional video sees the band adopt a «decadent ‘glam’ sensibility».[362] Replicating Mick Rock’s photograph of the band from the cover of Queen II—which itself was inspired by a photo of actress Marlene Dietrich from Shanghai Express (1932)—the video opens with «Queen standing in diamond formation, heads tilted back like Easter Island statues» in near darkness as they sing the a cappella part.[362]

One of the industry’s leading music video directors, David Mallet, directed a number of their subsequent videos. Some of their later videos use footage from classic films: «Under Pressure» incorporates 1920s silent films, Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin and F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu; the 1984 video for «Radio Ga Ga» includes footage from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927); «Calling All Girls» was a homage to George Lucas’s THX 1138;[363] and the 1995 video «Heaven for Everyone» shows footage from Georges Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Voyage (1904).[364] The first part of Mallet’s music video for «I Want to Break Free» spoofed the popular long-running British soap opera Coronation Street.[365]

The music video for «Innuendo» combines stop motion animation with rotoscoping and band members appear as illustrations and images taken from earlier Queen music videos on a cinema screen akin to the dystopian film Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984).[366] The music videos for «Flash» (from Flash Gordon) and «Princes of the Universe» (from Highlander) are themed on the films the band recorded soundtracks for, with the latter featuring Mercury briefly re-enact the sword-fighting scene with the titular character.[367] Queen also appeared in conventional music videos. «We Will Rock You» was filmed outdoors in Roger Taylor’s back garden during a cold day in early January 1977.[368] Filmed at the New London Theatre later that year, the music video for «We Are the Champions» features the band—with Mercury in a trademark Harlequin outfit—performing in front of an enthusiastic crowd who wave Queen scarves in a manner similar to English football fans.[368] The last music video of the group while Mercury was alive, «These Are the Days of Our Lives», was filmed in black-and-white to hide the full extent of his illness.[369]

Musical theatre

In May 2002, a musical or «rock theatrical» based on the songs of Queen, titled We Will Rock You, opened at the Dominion Theatre in London’s West End.[370] The musical was written by British comedian and author Ben Elton in collaboration with Brian May and Roger Taylor, and produced by Robert De Niro. It has since been staged in many cities around the world.[370] The launch of the musical coincided with Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee. As part of the Jubilee celebrations, Brian May performed a guitar solo of «God Save the Queen»,[371] as featured on Queen’s A Night at the Opera, from the roof of Buckingham Palace. The recording of this performance was used as video for the song on the 30th Anniversary DVD edition of A Night at the Opera.[372][373] Following the Las Vegas premiere on 8 September 2004, Queen were inducted into the Hollywood RockWalk in Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles.[374]

We Will Rock You musical in Tokyo, Japan, November 2006

The original London production was scheduled to close on Saturday, 7 October 2006, at the Dominion Theatre, but due to public demand, the show ran until May 2014.[375] We Will Rock You has become the longest running musical ever to run at this prime London theatre, overtaking the previous record holder, the musical Grease.[376] Brian May stated in 2008 that they were considering writing a sequel to We Will Rock You.[377] The musical toured around the UK in 2009, playing at Manchester Palace Theatre, Sunderland Empire, Birmingham Hippodrome, Bristol Hippodrome, and Edinburgh Playhouse.[378]

Sean Bovim created «Queen at the Ballet», a tribute to Mercury, which uses Queen’s music as a soundtrack for the show’s dancers, who interpret the stories behind tracks such as «Bohemian Rhapsody», «Radio Ga Ga», and «Killer Queen».[379] Queen’s music also appears in the Off-Broadway production Power Balladz, most notably the song «We Are the Champions», with the show’s two performers believing the song was «the apex of artistic achievement in its day».[380]

Software and digital releases

In conjunction with Electronic Arts, Queen released the computer game Queen: The eYe in 1998.[381] The game received mixed reviews. Several reviewers described the fight sequences as frustrating, due to unresponsive controls and confusing camera angles.[382][383] PC Zone found the game’s graphics unimpressive,[382] although PC PowerPlay considered them «absolutely stunning».[383] The extremely long development time resulted in graphic elements that already seemed outdated by the time of release.[384]

Under the supervision of May and Taylor, numerous restoration projects have been under way involving Queen’s lengthy audio and video catalogue. DVD releases of their 1986 Wembley concert (titled Live at Wembley Stadium), 1982 Milton Keynes concert (Queen on Fire – Live at the Bowl), and two Greatest Video Hits (Volumes 1 and 2, spanning the 1970s and 1980s) have seen the band’s music remixed into 5.1 and DTS surround sound. So far, only two of the band’s albums, A Night at the Opera and The Game, have been fully remixed into high-resolution multichannel surround on DVD-Audio. A Night at the Opera was re-released with some revised 5.1 mixes and accompanying videos in 2005 for the 30th anniversary of the album’s original release (CD+DVD-Video set). In 2007, a Blu-ray edition of Queen’s previously released concerts, Queen Rock Montreal & Live Aid, was released, marking their first project in 1080p HD.[385]

Queen have been featured multiple times in the Guitar Hero franchise: a cover of «Killer Queen» in the original Guitar Hero, «We Are The Champions», «Fat Bottomed Girls», and the Paul Rodgers collaboration «C-lebrity» in a track pack for Guitar Hero World Tour, «Under Pressure» with David Bowie in Guitar Hero 5,[386] «I Want It All» in Guitar Hero: Van Halen,[387] «Stone Cold Crazy» in Guitar Hero: Metallica,[388] and «Bohemian Rhapsody» in Guitar Hero: Warriors of Rock.[389] On 13 October 2009, Brian May revealed there was «talk» going on «behind the scenes» about a dedicated Queen Rock Band game.[390]

Queen have also been featured multiple times in the Rock Band franchise: a track pack of 10 songs which are compatible with Rock Band, Rock Band 2, and Rock Band 3 (three of those are also compatible with Lego Rock Band). Their hit «Bohemian Rhapsody» was featured in Rock Band 3 with full harmony and keys support.