| Radian | |

|---|---|

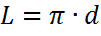

An arc of a circle with the same length as the radius of that circle subtends an angle of 1 radian. The circumference subtends an angle of 2π radians. |

|

| General information | |

| Unit system | SI |

| Unit of | angle |

| Symbol | rad |

| Conversions | |

| 1 rad in … | … is equal to … |

| milliradians | 1000 mrad |

| turns | 1/2π turn |

| degrees | 180/π° ≈ 57.296° |

| gradians | 200/πg ≈ 63.662g |

The radian, denoted by the symbol rad, is the unit of angle in the International System of Units (SI) and is the standard unit of angular measure used in many areas of mathematics. The unit was formerly an SI supplementary unit (before that category was abolished in 1995).[1] The radian is defined in the SI as being a dimensionless unit, with 1 rad = 1.[2] Its symbol is accordingly often omitted, especially in mathematical writing.

Definition

One radian is defined as the angle subtended from the center of a circle which intercepts an arc equal in length to the radius of the circle.[3] More generally, the magnitude in radians of a subtended angle is equal to the ratio of the arc length to the radius of the circle; that is,

The rotation angle (360°) corresponding to one complete revolution is the length of the circumference divided by the radius, which is

The relation 2π rad = 360° can be derived using the formula for arc length,

Unit symbol

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures[4] and International Organization for Standardization[5] specify rad as the symbol for the radian. Alternative symbols that were in use in 1909 are c (the superscript letter c, for «circular measure»), the letter r, or a superscript R,[6] but these variants are infrequently used, as they may be mistaken for a degree symbol (°) or a radius (r). Hence an angle of 1.2 radians would be written today as 1.2 rad; archaic notations could include 1.2 r, 1.2rad, 1.2c, or 1.2R.

In mathematical writing, the symbol «rad» is often omitted. When quantifying an angle in the absence of any symbol, radians are assumed, and when degrees are meant, the degree sign ° is used.

Dimensional analysis

Plane angle is defined as θ = s/r, where θ is the subtended angle in radians, s is arc length, and r is radius. One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, hence 1 radian = 1 m/m.[7] However, rad is only to be used to express angles, not to express ratios of lengths in general.[4] A similar calculation using the area of a circular sector θ = 2A/r2 gives 1 radian as 1 m2/m2.[8] The key fact is that the radian is a dimensionless unit equal to 1. In SI 2019, the radian is defined accordingly as 1 rad = 1.[9] It is a long-established practice in mathematics and across all areas of science to make use of rad = 1.[10][11] In 1993 the American Association of Physics Teachers Metric Committee specified that the radian should explicitly appear in quantities only when different numerical values would be obtained when other angle measures were used, such as in the quantities of angle measure (rad), angular speed (rad/s), angular acceleration (rad/s2), and torsional stiffness (N⋅m/rad), and not in the quantities of torque (N⋅m) and angular momentum (kg⋅m2/s).[12]

Giacomo Prando says «the current state of affairs leads inevitably to ghostly appearances and disappearances of the radian in the dimensional analysis of physical equations.»[13] For example, an object hanging by a string from a pulley will rise or drop by y = rθ centimeters, where r is the radius of the pulley in centimeters and θ is the angle the pulley turns in radians. When multiplying r by θ the unit of radians disappears from the result. Similarly in the formula for the angular velocity of a rolling wheel, ω = v/r, radians appear in the units of ω but not on the right hand side.[14] Anthony French calls this phenomenon «a perennial problem in the teaching of mechanics».[15] Oberhofer says that the typical advice of ignoring radians during dimensional analysis and adding or removing radians in units according to convention and contextual knowledge is «pedagogically unsatisfying».[16]

At least a dozen scientists between 1936 and 2022 have made proposals to treat the radian as a base unit of measure defining its own dimension of «angle».[17][18][19] Quincey’s review of proposals outlines two classes of proposal. The first option changes the unit of a radius to meters per radian, but this is incompatible with dimensional analysis for the area of a circle, πr2. The other option is to introduce a dimensional constant. According to Quincey this approach is «logically rigorous» compared to SI, but requires «the modification of many familiar mathematical and physical equations».[20]

In particular, Quincey identifies Torrens’ proposal to introduce a constant η equal to 1 inverse radian (1 rad−1) in a fashion similar to the introduction of the constant ε0.[20][a] With this change the formula for the angle subtended at the center of a circle, s = rθ, is modified to become s = ηrθ, and the Taylor series for the sine of an angle θ becomes:[19][21]

The capitalized function Sin is the «complete» function that takes an argument with a dimension of angle and is independent of the units expressed,[21] while sinrad is the traditional function on pure numbers which assumes its argument is in radians.[22]

SI can be considered relative to this framework as a natural unit system where the equation η = 1 is assumed to hold, or similarly, 1 rad = 1. This radian convention allows the omission of η in mathematical formulas.[24]

A dimensional constant for angle is «rather strange» and the difficulty of modifying equations to add the dimensional constant is likely to preclude widespread use.[19] Defining radian as a base unit may be useful for software, where the disadvantage of longer equations is minimal.[25] For example, the Boost units library defines angle units with a plane_angle dimension,[26] and Mathematica’s unit system similarly considers angles to have an angle dimension.[27][28]

Conversions

| Turns | Radians | Degrees | Gradians |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 turn | 0 rad | 0° | 0g |

| 1/24 turn | π/12 rad | 15° | 16+2/3g |

| 1/16 turn | π/8 rad | 22.5° | 25g |

| 1/12 turn | π/6 rad | 30° | 33+1/3g |

| 1/10 turn | π/5 rad | 36° | 40g |

| 1/8 turn | π/4 rad | 45° | 50g |

| 1/2π turn | 1 rad | c. 57.3° | c. 63.7g |

| 1/6 turn | π/3 rad | 60° | 66+2/3g |

| 1/5 turn | 2π/5 rad | 72° | 80g |

| 1/4 turn | π/2 rad | 90° | 100g |

| 1/3 turn | 2π/3 rad | 120° | 133+1/3g |

| 2/5 turn | 4π/5 rad | 144° | 160g |

| 1/2 turn | π rad | 180° | 200g |

| 3/4 turn | 3π/2 rad | 270° | 300g |

| 1 turn | 2π rad | 360° | 400g |

Between degrees

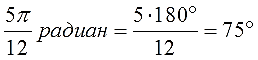

As stated, one radian is equal to

For example:

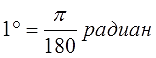

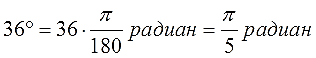

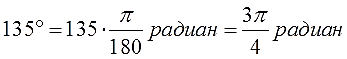

Conversely, to convert from degrees to radians, multiply by

For example:

Radians can be converted to turns (one turn is the angle corresponding to a revolution) by dividing the number of radians by 2π.

Between gradians

Usage

Mathematics

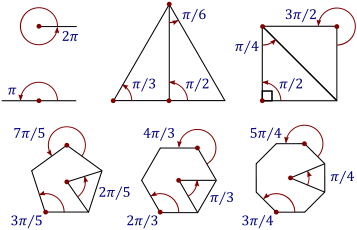

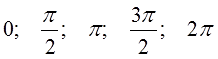

Some common angles, measured in radians. All the large polygons in this diagram are regular polygons.

In calculus and most other branches of mathematics beyond practical geometry, angles are measured in radians. This is because radians have a mathematical naturalness that leads to a more elegant formulation of some important results.

Results in analysis involving trigonometric functions can be elegantly stated when the functions’ arguments are expressed in radians. For example, the use of radians leads to the simple limit formula

which is the basis of many other identities in mathematics, including

Because of these and other properties, the trigonometric functions appear in solutions to mathematical problems that are not obviously related to the functions’ geometrical meanings (for example, the solutions to the differential equation

The trigonometric functions also have simple and elegant series expansions when radians are used. For example, when x is in radians, the Taylor series for sin x becomes:

If x were expressed in degrees, then the series would contain messy factors involving powers of π/180: if x is the number of degrees, the number of radians is y = πx / 180, so

In a similar spirit, mathematically important relationships between the sine and cosine functions and the exponential function (see, for example, Euler’s formula) can be elegantly stated, when the functions’ arguments are in radians (and messy otherwise).

Physics

The radian is widely used in physics when angular measurements are required. For example, angular velocity is typically expressed in the unit radian per second (rad/s). One revolution per second corresponds to 2π radians per second.

Similarly, the unit used for angular acceleration is often radian per second per second (rad/s2).

For the purpose of dimensional analysis, the units of angular velocity and angular acceleration are s−1 and s−2 respectively.

Likewise, the phase difference of two waves can also be expressed using the radian as the unit. For example, if the phase difference of two waves is (n⋅2π) radians with n is an integer, they are considered to be in phase, whilst if the phase difference of two waves is (n⋅2π + π) with n an integer, they are considered to be in antiphase.

Prefixes and variants

Metric prefixes for submultiples are used with radians. A milliradian (mrad) is a thousandth of a radian (0.001 rad), i.e. 1 rad = 103 mrad. There are 2π × 1000 milliradians (≈ 6283.185 mrad) in a circle. So a milliradian is just under 1/6283 of the angle subtended by a full circle. This unit of angular measurement of a circle is in common use by telescopic sight manufacturers using (stadiametric) rangefinding in reticles. The divergence of laser beams is also usually measured in milliradians.

The angular mil is an approximation of the milliradian used by NATO and other military organizations in gunnery and targeting. Each angular mil represents 1/6400 of a circle and is 15/8% or 1.875% smaller than the milliradian. For the small angles typically found in targeting work, the convenience of using the number 6400 in calculation outweighs the small mathematical errors it introduces. In the past, other gunnery systems have used different approximations to 1/2000π; for example Sweden used the 1/6300 streck and the USSR used 1/6000. Being based on the milliradian, the NATO mil subtends roughly 1 m at a range of 1000 m (at such small angles, the curvature is negligible).

Prefixes smaller than milli- are useful in measuring extremely small angles. Microradians (μrad, 10−6 rad) and nanoradians (nrad, 10−9 rad) are used in astronomy, and can also be used to measure the beam quality of lasers with ultra-low divergence. More common is the arc second, which is π/648,000 rad (around 4.8481 microradians).

History

Pre-20th century

The idea of measuring angles by the length of the arc was in use by mathematicians quite early. For example, al-Kashi (c. 1400) used so-called diameter parts as units, where one diameter part was 1/60 radian. They also used sexagesimal subunits of the diameter part.[29] Newton in 1672 spoke of «the angular quantity of a body’s circular motion», but used it only as a relative measure to develop an astronomical algorithm.[30]

The concept of the radian measure is normally credited to Roger Cotes, who died in 1716. By 1722, his cousin Robert Smith had collected and published Cotes’ mathematical writings in a book, Harmonia mensurarum.[31] In a chapter of editorial comments, Smith gave what is probably the first published calculation of one radian in degrees, citing a note of Cotes that has not survived. Smith described the radian in everything but name, and recognized its naturalness as a unit of angular measure.[32][33]

In 1765, Leonhard Euler implicitly adopted the radian as a unit of angle.[30] Specifically, Euler defined angular velocity as «The angular speed in rotational motion is the speed of that point, the distance of which from the axis of gyration is expressed by one.»[34] Euler was probably the first to adopt this convention, referred to as the radian convention, which gives the simple formula for angular velocity ω = v/r. As discussed in § Dimensional analysis, the radian convention has been widely adopted, and other conventions have the drawback of requiring a dimensional constant, for example ω = v/(ηr).[24]

Prior to the term radian becoming widespread, the unit was commonly called circular measure of an angle.[35] The term radian first appeared in print on 5 June 1873, in examination questions set by James Thomson (brother of Lord Kelvin) at Queen’s College, Belfast. He had used the term as early as 1871, while in 1869, Thomas Muir, then of the University of St Andrews, vacillated between the terms rad, radial, and radian. In 1874, after a consultation with James Thomson, Muir adopted radian.[36][37][38] The name radian was not universally adopted for some time after this. Longmans’ School Trigonometry still called the radian circular measure when published in 1890.[39]

As a SI unit

As Paul Quincey et al. writes, «the status of angles within the International System of Units (SI) has long been a source of controversy and confusion.»[40] In 1960, the CGPM established the SI and the radian was classified as a «supplementary unit» along with the steradian. This special class was officially regarded «either as base units or as derived units», as the CGPM could not reach a decision on whether the radian was a base unit or a derived unit.[41] Richard Nelson writes «This ambiguity [in the classification of the supplemental units] prompted a spirited discussion over their proper interpretation.»[42] In May 1980 the Consultative Committee for Units (CCU) considered a proposal for making radians an SI base unit, using a constant α0 = 1 rad,[43][24] but turned it down to avoid an upheaval to current practice.[24]

In October 1980 the CGPM decided that supplementary units were dimensionless derived units for which the CGPM allowed the freedom of using them or not using them in expressions for SI derived units,[42] on the basis that «[no formalism] exists which is at the same time coherent and convenient and in which the quantities plane angle and solid angle might be considered as base quantities» and that «[the possibility of treating the radian and steradian as SI base units] compromises the internal coherence of the SI based on only seven base units».[44] In 1995 the CGPM eliminated the class of supplementary units and defined the radian and the steradian as «dimensionless derived units, the names and symbols of which may, but need not, be used in expressions for other SI derived units, as is convenient».[45] Mikhail Kalinin writing in 2019 has criticized the 1980 CGPM decision as «unfounded» and says that the 1995 CGPM decision used inconsistent arguments and introduced «numerous discrepancies, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the wordings of the SI».[46]

At the 2013 meeting of the CCU, Peter Mohr gave a presentation on alleged inconsistencies arising from defining the radian as a dimensionless unit rather than a base unit. CCU President Ian M. Mills declared this to be a «formidable problem» and the CCU Working Group on Angles and Dimensionless Quantities in the SI was established.[47] The CCU met most recently in 2021, but did not reach a consensus. A small number of members argued strongly that the radian should be a base unit, but the majority felt the status quo was acceptable or that the change would cause more problems than it would solve. A task group was established to «review the historical use of SI supplementary units and consider whether reintroduction would be of benefit», among other activities.[48][49]

See also

- Angular frequency

- Minute and second of arc

- Steradian, a higher-dimensional analog of the radian which measures solid angle

- Trigonometry

Notes

References

- ^ «Resolution 8 of the CGPM at its 20th Meeting (1995)». Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: «The CGPM decided to interpret the supplementary units in the SI, namely the radian and the steradian, as dimensionless derived units.»

- ^ Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Charles B. Jr. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, p. APP-4, LCCN 76087042

- ^ a b c International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151.

- ^ «ISO 80000-3:2006 Quantities and Units — Space and Time».

- ^ Hall, Arthur Graham; Frink, Fred Goodrich (January 1909). «Chapter VII. The General Angle [55] Signs and Limitations in Value. Exercise XV.». Written at Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Trigonometry. Vol. Part I: Plane Trigonometry. New York, USA: Henry Holt and Company / Norwood Press / J. S. Cushing Co. — Berwick & Smith Co., Norwood, Massachusetts, USA. p. 73. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: «One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r«

- ^ Quincey 2016, p. 844: «Also, as alluded to in Mohr & Phillips 2015, the radian can be defined in terms of the area A of a sector (A = 1/2 θ r2), in which case it has the units m2⋅m−2.»

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: «One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, thus 1 rad = 1.»

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Bridgman, Percy Williams (1922). Dimensional analysis. New Haven : Yale University Press.

Angular amplitude of swing […] No dimensions.

- ^ Aubrecht, Gordon J.; French, Anthony P.; Iona, Mario; Welch, Daniel W. (February 1993). «The radian—That troublesome unit». The Physics Teacher. 31 (2): 84–87. Bibcode:1993PhTea..31…84A. doi:10.1119/1.2343667.

- ^ Prando, Giacomo (August 2020). «A spectral unit». Nature Physics. 16 (8): 888. Bibcode:2020NatPh..16..888P. doi:10.1038/s41567-020-0997-3. S2CID 225445454.

- ^ Leonard, William J. (1999). Minds-on Physics: Advanced topics in mechanics. Kendall Hunt. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7872-5412-4.

- ^ French, Anthony P. (May 1992). «What happens to the ‘radians’? (comment)». The Physics Teacher. 30 (5): 260–261. doi:10.1119/1.2343535.

- ^ Oberhofer, E. S. (March 1992). «What happens to the ‘radians’?». The Physics Teacher. 30 (3): 170–171. Bibcode:1992PhTea..30..170O. doi:10.1119/1.2343500.

- ^ Brinsmade 1936; Romain 1962; Eder 1982; Torrens 1986; Brownstein 1997; Lévy-Leblond 1998; Foster 2010; Mills 2016; Quincey 2021; Leonard 2021; Mohr et al. 2022

- ^ Mohr & Phillips 2015.

- ^ a b c d Quincey, Paul; Brown, Richard J C (1 June 2016). «Implications of adopting plane angle as a base quantity in the SI». Metrologia. 53 (3): 998–1002. arXiv:1604.02373. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..998Q. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/3/998. S2CID 119294905.

- ^ a b Quincey 2016.

- ^ a b Torrens 1986.

- ^ Mohr et al. 2022, p. 6.

- ^ Mohr et al. 2022, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d Quincey 2021.

- ^ Quincey, Paul; Brown, Richard J C (1 August 2017). «A clearer approach for defining unit systems». Metrologia. 54 (4): 454–460. arXiv:1705.03765. Bibcode:2017Metro..54..454Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/aa7160. S2CID 119418270.

- ^ Schabel, Matthias C.; Watanabe, Steven. «Boost.Units FAQ – 1.79.0». www.boost.org. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

Angles are treated as units

- ^ Mohr et al. 2022, p. 3.

- ^ «UnityDimensions—Wolfram Language Documentation». reference.wolfram.com. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Luckey, Paul (1953) [Translation of 1424 book]. Siggel, A. (ed.). Der Lehrbrief über den kreisumfang von Gamshid b. Mas’ud al-Kasi [Treatise on the Circumference of al-Kashi]. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. p. 40.

- ^ a b Roche, John J. (21 December 1998). The Mathematics of Measurement: A Critical History. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-387-91581-4.

- ^ O’Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (February 2005). «Biography of Roger Cotes». The MacTutor History of Mathematics. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ Cotes, Roger (1722). «Editoris notæ ad Harmoniam mensurarum». In Smith, Robert (ed.). Harmonia mensurarum (in Latin). Cambridge, England. pp. 94–95.

In Canone Logarithmico exhibetur Systema quoddam menfurarum numeralium, quæ Logarithmi dicuntur: atque hujus systematis Modulus is est Logarithmus, qui metitur Rationem Modularem in Corol. 6. definitam. Similiter in Canone Trigonometrico finuum & tangentium, exhibetur Systema quoddam menfurarum numeralium, quæ Gradus appellantur: atque hujus systematis Modulus is est Numerus Graduum, qui metitur Angulum Modularem modo definitun, hoc est, qui continetur in arcu Radio æquali. Eft autem hic Numerus ad Gradus 180 ut Circuli Radius ad Semicircuinferentiam, hoc eft ut 1 ad 3.141592653589 &c. Unde Modulus Canonis Trigonometrici prodibit 57.2957795130 &c. Cujus Reciprocus eft 0.0174532925 &c. Hujus moduli subsidio (quem in chartula quadam Auctoris manu descriptum inveni) commodissime computabis mensuras angulares, queinadmodum oftendam in Nota III.

[In the Logarithmic Canon there is presented a certain system of numerical measures called Logarithms: and the Modulus of this system is the Logarithm, which measures the Modular Ratio as defined in Corollary 6. Similarly, in the Trigonometrical Canon of sines and tangents, there is presented a certain system of numerical measures called Degrees: and the Modulus of this system is the Number of Degrees which measures the Modular Angle defined in the manner defined, that is, which is contained in an equal Radius arc. Now this Number is equal to 180 Degrees as the Radius of a Circle to the Semicircumference, this is as 1 to 3.141592653589 &c. Hence the Modulus of the Trigonometric Canon will be 57.2957795130 &c. Whose Reciprocal is 0.0174532925 &c. With the help of this modulus (which I found described in a note in the hand of the Author) you will most conveniently calculate the angular measures, as mentioned in Note III.] - ^ Gowing, Ronald (27 June 2002). Roger Cotes — Natural Philosopher. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52649-4.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard. Theoria Motus Corporum Solidorum seu Rigidorum [Theory of the motion of solid or rigid bodies] (PDF) (in Latin). Translated by Bruce, Ian. Definition 6, paragraph 316.

- ^ Isaac Todhunter, Plane Trigonometry: For the Use of Colleges and Schools, p. 10, Cambridge and London: MacMillan, 1864 OCLC 500022958

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1929). History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 2. Dover Publications. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-486-67766-4.

- ^

- Muir, Thos. (1910). «The Term «Radian» in Trigonometry». Nature. 83 (2110): 156. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..156M. doi:10.1038/083156a0. S2CID 3958702.

- Thomson, James (1910). «The Term «Radian» in Trigonometry». Nature. 83 (2112): 217. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..217T. doi:10.1038/083217c0. S2CID 3980250.

- Muir, Thos. (1910). «The Term «Radian» in Trigonometry». Nature. 83 (2120): 459–460. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..459M. doi:10.1038/083459d0. S2CID 3971449.

- ^ Miller, Jeff (Nov 23, 2009). «Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics». Retrieved Sep 30, 2011.

- ^ Frederick Sparks, Longmans’ School Trigonometry, p. 6, London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1890 OCLC 877238863 (1891 edition)

- ^ Quincey, Paul; Mohr, Peter J; Phillips, William D (1 August 2019). «Angles are inherently neither length ratios nor dimensionless». Metrologia. 56 (4): 043001. arXiv:1909.08389. Bibcode:2019Metro..56d3001Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ab27d7. S2CID 198428043.

- ^ Le Système international d’unités (PDF) (in French), 1970, p. 12,

Pour quelques unités du Système International, la Conférence Générale n’a pas ou n’a pas encore décidé s’il s’agit d’unités de base ou bien d’unités dérivées.

[For some units of the SI, the CGPM still hasn’t yet decided whether they are base units or derived units.] - ^ a b Nelson, Robert A. (March 1984). «The supplementary units». The Physics Teacher. 22 (3): 188–193. Bibcode:1984PhTea..22..188N. doi:10.1119/1.2341516.

- ^ Report of the 7th meeting (PDF) (in French), Consultative Committee for Units, May 1980, pp. 6–7

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, pp. 174–175.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 179.

- ^ Kalinin, Mikhail I (1 December 2019). «On the status of plane and solid angles in the International System of Units (SI)». Metrologia. 56 (6): 065009. arXiv:1810.12057. Bibcode:2019Metro..56f5009K. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ab3fbf. S2CID 53627142.

- ^ Consultative Committee for Units (11–12 June 2013). Report of the 21st meeting to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (Report). pp. 18–20.

- ^ Consultative Committee for Units (21–23 September 2021). Report of the 25th meeting to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (Report). pp. 16–17.

- ^ «CCU Task Group on angle and dimensionless quantities in the SI Brochure (CCU-TG-ADQSIB)». BIPM. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (20 May 2019), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (9th ed.), ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0, archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2021

- Brinsmade, J. B. (December 1936). «Plane and Solid Angles. Their Pedagogic Value When Introduced Explicitly». American Journal of Physics. 4 (4): 175–179. Bibcode:1936AmJPh…4..175B. doi:10.1119/1.1999110.

- Romain, Jacques E. (July 1962). «Angle as a fourth fundamental quantity». Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards Section B. 66B (3): 97. doi:10.6028/jres.066B.012.

- Eder, W E (January 1982). «A Viewpoint on the Quantity «Plane Angle»«. Metrologia. 18 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:1982Metro..18….1E. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/18/1/002. S2CID 250750831.

- Torrens, A B (1 January 1986). «On Angles and Angular Quantities». Metrologia. 22 (1): 1–7. Bibcode:1986Metro..22….1T. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/22/1/002. S2CID 250801509.

- Brownstein, K. R. (July 1997). «Angles—Let’s treat them squarely». American Journal of Physics. 65 (7): 605–614. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..605B. doi:10.1119/1.18616.

- Lévy-Leblond, Jean-Marc (September 1998). «Dimensional angles and universal constants». American Journal of Physics. 66 (9): 814–815. Bibcode:1998AmJPh..66..814L. doi:10.1119/1.18964.

- Foster, Marcus P (1 December 2010). «The next 50 years of the SI: a review of the opportunities for the e-Science age». Metrologia. 47 (6): R41–R51. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/47/6/R01. S2CID 117711734.

- Mohr, Peter J; Phillips, William D (1 February 2015). «Dimensionless units in the SI». Metrologia. 52 (1): 40–47. arXiv:1409.2794. Bibcode:2015Metro..52…40M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/52/1/40.

- Quincey, Paul (1 April 2016). «The range of options for handling plane angle and solid angle within a system of units». Metrologia. 53 (2): 840–845. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..840Q. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/2/840. S2CID 125438811.

- Mills, Ian (1 June 2016). «On the units radian and cycle for the quantity plane angle». Metrologia. 53 (3): 991–997. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..991M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/3/991. S2CID 126032642.

- Quincey, Paul (1 October 2021). «Angles in the SI: a detailed proposal for solving the problem». Metrologia. 58 (5): 053002. arXiv:2108.05704. Bibcode:2021Metro..58e3002Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ac023f. S2CID 236547235.

- Leonard, B P (1 October 2021). «Proposal for the dimensionally consistent treatment of angle and solid angle by the International System of Units (SI)». Metrologia. 58 (5): 052001. Bibcode:2021Metro..58e2001L. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/abe0fc. S2CID 234036217.

- Mohr, Peter J; Shirley, Eric L; Phillips, William D; Trott, Michael (23 June 2022). «On the dimension of angles and their units». Metrologia. 59 (5): 053001. arXiv:2203.12392. Bibcode:2022Metro..59e3001M. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ac7bc2.

External links

Look up radian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Media related to Radian at Wikimedia Commons

| Radian | |

|---|---|

An arc of a circle with the same length as the radius of that circle subtends an angle of 1 radian. The circumference subtends an angle of 2π radians. |

|

| General information | |

| Unit system | SI |

| Unit of | angle |

| Symbol | rad |

| Conversions | |

| 1 rad in … | … is equal to … |

| milliradians | 1000 mrad |

| turns | 1/2π turn |

| degrees | 180/π° ≈ 57.296° |

| gradians | 200/πg ≈ 63.662g |

The radian, denoted by the symbol rad, is the unit of angle in the International System of Units (SI) and is the standard unit of angular measure used in many areas of mathematics. The unit was formerly an SI supplementary unit (before that category was abolished in 1995).[1] The radian is defined in the SI as being a dimensionless unit, with 1 rad = 1.[2] Its symbol is accordingly often omitted, especially in mathematical writing.

Definition

One radian is defined as the angle subtended from the center of a circle which intercepts an arc equal in length to the radius of the circle.[3] More generally, the magnitude in radians of a subtended angle is equal to the ratio of the arc length to the radius of the circle; that is,

The rotation angle (360°) corresponding to one complete revolution is the length of the circumference divided by the radius, which is

The relation 2π rad = 360° can be derived using the formula for arc length,

Unit symbol

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures[4] and International Organization for Standardization[5] specify rad as the symbol for the radian. Alternative symbols that were in use in 1909 are c (the superscript letter c, for «circular measure»), the letter r, or a superscript R,[6] but these variants are infrequently used, as they may be mistaken for a degree symbol (°) or a radius (r). Hence an angle of 1.2 radians would be written today as 1.2 rad; archaic notations could include 1.2 r, 1.2rad, 1.2c, or 1.2R.

In mathematical writing, the symbol «rad» is often omitted. When quantifying an angle in the absence of any symbol, radians are assumed, and when degrees are meant, the degree sign ° is used.

Dimensional analysis

Plane angle is defined as θ = s/r, where θ is the subtended angle in radians, s is arc length, and r is radius. One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, hence 1 radian = 1 m/m.[7] However, rad is only to be used to express angles, not to express ratios of lengths in general.[4] A similar calculation using the area of a circular sector θ = 2A/r2 gives 1 radian as 1 m2/m2.[8] The key fact is that the radian is a dimensionless unit equal to 1. In SI 2019, the radian is defined accordingly as 1 rad = 1.[9] It is a long-established practice in mathematics and across all areas of science to make use of rad = 1.[10][11] In 1993 the American Association of Physics Teachers Metric Committee specified that the radian should explicitly appear in quantities only when different numerical values would be obtained when other angle measures were used, such as in the quantities of angle measure (rad), angular speed (rad/s), angular acceleration (rad/s2), and torsional stiffness (N⋅m/rad), and not in the quantities of torque (N⋅m) and angular momentum (kg⋅m2/s).[12]

Giacomo Prando says «the current state of affairs leads inevitably to ghostly appearances and disappearances of the radian in the dimensional analysis of physical equations.»[13] For example, an object hanging by a string from a pulley will rise or drop by y = rθ centimeters, where r is the radius of the pulley in centimeters and θ is the angle the pulley turns in radians. When multiplying r by θ the unit of radians disappears from the result. Similarly in the formula for the angular velocity of a rolling wheel, ω = v/r, radians appear in the units of ω but not on the right hand side.[14] Anthony French calls this phenomenon «a perennial problem in the teaching of mechanics».[15] Oberhofer says that the typical advice of ignoring radians during dimensional analysis and adding or removing radians in units according to convention and contextual knowledge is «pedagogically unsatisfying».[16]

At least a dozen scientists between 1936 and 2022 have made proposals to treat the radian as a base unit of measure defining its own dimension of «angle».[17][18][19] Quincey’s review of proposals outlines two classes of proposal. The first option changes the unit of a radius to meters per radian, but this is incompatible with dimensional analysis for the area of a circle, πr2. The other option is to introduce a dimensional constant. According to Quincey this approach is «logically rigorous» compared to SI, but requires «the modification of many familiar mathematical and physical equations».[20]

In particular, Quincey identifies Torrens’ proposal to introduce a constant η equal to 1 inverse radian (1 rad−1) in a fashion similar to the introduction of the constant ε0.[20][a] With this change the formula for the angle subtended at the center of a circle, s = rθ, is modified to become s = ηrθ, and the Taylor series for the sine of an angle θ becomes:[19][21]

The capitalized function Sin is the «complete» function that takes an argument with a dimension of angle and is independent of the units expressed,[21] while sinrad is the traditional function on pure numbers which assumes its argument is in radians.[22]

SI can be considered relative to this framework as a natural unit system where the equation η = 1 is assumed to hold, or similarly, 1 rad = 1. This radian convention allows the omission of η in mathematical formulas.[24]

A dimensional constant for angle is «rather strange» and the difficulty of modifying equations to add the dimensional constant is likely to preclude widespread use.[19] Defining radian as a base unit may be useful for software, where the disadvantage of longer equations is minimal.[25] For example, the Boost units library defines angle units with a plane_angle dimension,[26] and Mathematica’s unit system similarly considers angles to have an angle dimension.[27][28]

Conversions

| Turns | Radians | Degrees | Gradians |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 turn | 0 rad | 0° | 0g |

| 1/24 turn | π/12 rad | 15° | 16+2/3g |

| 1/16 turn | π/8 rad | 22.5° | 25g |

| 1/12 turn | π/6 rad | 30° | 33+1/3g |

| 1/10 turn | π/5 rad | 36° | 40g |

| 1/8 turn | π/4 rad | 45° | 50g |

| 1/2π turn | 1 rad | c. 57.3° | c. 63.7g |

| 1/6 turn | π/3 rad | 60° | 66+2/3g |

| 1/5 turn | 2π/5 rad | 72° | 80g |

| 1/4 turn | π/2 rad | 90° | 100g |

| 1/3 turn | 2π/3 rad | 120° | 133+1/3g |

| 2/5 turn | 4π/5 rad | 144° | 160g |

| 1/2 turn | π rad | 180° | 200g |

| 3/4 turn | 3π/2 rad | 270° | 300g |

| 1 turn | 2π rad | 360° | 400g |

Between degrees

As stated, one radian is equal to

For example:

Conversely, to convert from degrees to radians, multiply by

For example:

Radians can be converted to turns (one turn is the angle corresponding to a revolution) by dividing the number of radians by 2π.

Between gradians

Usage

Mathematics

Some common angles, measured in radians. All the large polygons in this diagram are regular polygons.

In calculus and most other branches of mathematics beyond practical geometry, angles are measured in radians. This is because radians have a mathematical naturalness that leads to a more elegant formulation of some important results.

Results in analysis involving trigonometric functions can be elegantly stated when the functions’ arguments are expressed in radians. For example, the use of radians leads to the simple limit formula

which is the basis of many other identities in mathematics, including

Because of these and other properties, the trigonometric functions appear in solutions to mathematical problems that are not obviously related to the functions’ geometrical meanings (for example, the solutions to the differential equation

The trigonometric functions also have simple and elegant series expansions when radians are used. For example, when x is in radians, the Taylor series for sin x becomes:

If x were expressed in degrees, then the series would contain messy factors involving powers of π/180: if x is the number of degrees, the number of radians is y = πx / 180, so

In a similar spirit, mathematically important relationships between the sine and cosine functions and the exponential function (see, for example, Euler’s formula) can be elegantly stated, when the functions’ arguments are in radians (and messy otherwise).

Physics

The radian is widely used in physics when angular measurements are required. For example, angular velocity is typically expressed in the unit radian per second (rad/s). One revolution per second corresponds to 2π radians per second.

Similarly, the unit used for angular acceleration is often radian per second per second (rad/s2).

For the purpose of dimensional analysis, the units of angular velocity and angular acceleration are s−1 and s−2 respectively.

Likewise, the phase difference of two waves can also be expressed using the radian as the unit. For example, if the phase difference of two waves is (n⋅2π) radians with n is an integer, they are considered to be in phase, whilst if the phase difference of two waves is (n⋅2π + π) with n an integer, they are considered to be in antiphase.

Prefixes and variants

Metric prefixes for submultiples are used with radians. A milliradian (mrad) is a thousandth of a radian (0.001 rad), i.e. 1 rad = 103 mrad. There are 2π × 1000 milliradians (≈ 6283.185 mrad) in a circle. So a milliradian is just under 1/6283 of the angle subtended by a full circle. This unit of angular measurement of a circle is in common use by telescopic sight manufacturers using (stadiametric) rangefinding in reticles. The divergence of laser beams is also usually measured in milliradians.

The angular mil is an approximation of the milliradian used by NATO and other military organizations in gunnery and targeting. Each angular mil represents 1/6400 of a circle and is 15/8% or 1.875% smaller than the milliradian. For the small angles typically found in targeting work, the convenience of using the number 6400 in calculation outweighs the small mathematical errors it introduces. In the past, other gunnery systems have used different approximations to 1/2000π; for example Sweden used the 1/6300 streck and the USSR used 1/6000. Being based on the milliradian, the NATO mil subtends roughly 1 m at a range of 1000 m (at such small angles, the curvature is negligible).

Prefixes smaller than milli- are useful in measuring extremely small angles. Microradians (μrad, 10−6 rad) and nanoradians (nrad, 10−9 rad) are used in astronomy, and can also be used to measure the beam quality of lasers with ultra-low divergence. More common is the arc second, which is π/648,000 rad (around 4.8481 microradians).

History

Pre-20th century

The idea of measuring angles by the length of the arc was in use by mathematicians quite early. For example, al-Kashi (c. 1400) used so-called diameter parts as units, where one diameter part was 1/60 radian. They also used sexagesimal subunits of the diameter part.[29] Newton in 1672 spoke of «the angular quantity of a body’s circular motion», but used it only as a relative measure to develop an astronomical algorithm.[30]

The concept of the radian measure is normally credited to Roger Cotes, who died in 1716. By 1722, his cousin Robert Smith had collected and published Cotes’ mathematical writings in a book, Harmonia mensurarum.[31] In a chapter of editorial comments, Smith gave what is probably the first published calculation of one radian in degrees, citing a note of Cotes that has not survived. Smith described the radian in everything but name, and recognized its naturalness as a unit of angular measure.[32][33]

In 1765, Leonhard Euler implicitly adopted the radian as a unit of angle.[30] Specifically, Euler defined angular velocity as «The angular speed in rotational motion is the speed of that point, the distance of which from the axis of gyration is expressed by one.»[34] Euler was probably the first to adopt this convention, referred to as the radian convention, which gives the simple formula for angular velocity ω = v/r. As discussed in § Dimensional analysis, the radian convention has been widely adopted, and other conventions have the drawback of requiring a dimensional constant, for example ω = v/(ηr).[24]

Prior to the term radian becoming widespread, the unit was commonly called circular measure of an angle.[35] The term radian first appeared in print on 5 June 1873, in examination questions set by James Thomson (brother of Lord Kelvin) at Queen’s College, Belfast. He had used the term as early as 1871, while in 1869, Thomas Muir, then of the University of St Andrews, vacillated between the terms rad, radial, and radian. In 1874, after a consultation with James Thomson, Muir adopted radian.[36][37][38] The name radian was not universally adopted for some time after this. Longmans’ School Trigonometry still called the radian circular measure when published in 1890.[39]

As a SI unit

As Paul Quincey et al. writes, «the status of angles within the International System of Units (SI) has long been a source of controversy and confusion.»[40] In 1960, the CGPM established the SI and the radian was classified as a «supplementary unit» along with the steradian. This special class was officially regarded «either as base units or as derived units», as the CGPM could not reach a decision on whether the radian was a base unit or a derived unit.[41] Richard Nelson writes «This ambiguity [in the classification of the supplemental units] prompted a spirited discussion over their proper interpretation.»[42] In May 1980 the Consultative Committee for Units (CCU) considered a proposal for making radians an SI base unit, using a constant α0 = 1 rad,[43][24] but turned it down to avoid an upheaval to current practice.[24]

In October 1980 the CGPM decided that supplementary units were dimensionless derived units for which the CGPM allowed the freedom of using them or not using them in expressions for SI derived units,[42] on the basis that «[no formalism] exists which is at the same time coherent and convenient and in which the quantities plane angle and solid angle might be considered as base quantities» and that «[the possibility of treating the radian and steradian as SI base units] compromises the internal coherence of the SI based on only seven base units».[44] In 1995 the CGPM eliminated the class of supplementary units and defined the radian and the steradian as «dimensionless derived units, the names and symbols of which may, but need not, be used in expressions for other SI derived units, as is convenient».[45] Mikhail Kalinin writing in 2019 has criticized the 1980 CGPM decision as «unfounded» and says that the 1995 CGPM decision used inconsistent arguments and introduced «numerous discrepancies, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the wordings of the SI».[46]

At the 2013 meeting of the CCU, Peter Mohr gave a presentation on alleged inconsistencies arising from defining the radian as a dimensionless unit rather than a base unit. CCU President Ian M. Mills declared this to be a «formidable problem» and the CCU Working Group on Angles and Dimensionless Quantities in the SI was established.[47] The CCU met most recently in 2021, but did not reach a consensus. A small number of members argued strongly that the radian should be a base unit, but the majority felt the status quo was acceptable or that the change would cause more problems than it would solve. A task group was established to «review the historical use of SI supplementary units and consider whether reintroduction would be of benefit», among other activities.[48][49]

See also

- Angular frequency

- Minute and second of arc

- Steradian, a higher-dimensional analog of the radian which measures solid angle

- Trigonometry

Notes

References

- ^ «Resolution 8 of the CGPM at its 20th Meeting (1995)». Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: «The CGPM decided to interpret the supplementary units in the SI, namely the radian and the steradian, as dimensionless derived units.»

- ^ Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Charles B. Jr. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, p. APP-4, LCCN 76087042

- ^ a b c International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151.

- ^ «ISO 80000-3:2006 Quantities and Units — Space and Time».

- ^ Hall, Arthur Graham; Frink, Fred Goodrich (January 1909). «Chapter VII. The General Angle [55] Signs and Limitations in Value. Exercise XV.». Written at Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Trigonometry. Vol. Part I: Plane Trigonometry. New York, USA: Henry Holt and Company / Norwood Press / J. S. Cushing Co. — Berwick & Smith Co., Norwood, Massachusetts, USA. p. 73. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: «One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r«

- ^ Quincey 2016, p. 844: «Also, as alluded to in Mohr & Phillips 2015, the radian can be defined in terms of the area A of a sector (A = 1/2 θ r2), in which case it has the units m2⋅m−2.»

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 151: «One radian corresponds to the angle for which s = r, thus 1 rad = 1.»

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Bridgman, Percy Williams (1922). Dimensional analysis. New Haven : Yale University Press.

Angular amplitude of swing […] No dimensions.

- ^ Aubrecht, Gordon J.; French, Anthony P.; Iona, Mario; Welch, Daniel W. (February 1993). «The radian—That troublesome unit». The Physics Teacher. 31 (2): 84–87. Bibcode:1993PhTea..31…84A. doi:10.1119/1.2343667.

- ^ Prando, Giacomo (August 2020). «A spectral unit». Nature Physics. 16 (8): 888. Bibcode:2020NatPh..16..888P. doi:10.1038/s41567-020-0997-3. S2CID 225445454.

- ^ Leonard, William J. (1999). Minds-on Physics: Advanced topics in mechanics. Kendall Hunt. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-7872-5412-4.

- ^ French, Anthony P. (May 1992). «What happens to the ‘radians’? (comment)». The Physics Teacher. 30 (5): 260–261. doi:10.1119/1.2343535.

- ^ Oberhofer, E. S. (March 1992). «What happens to the ‘radians’?». The Physics Teacher. 30 (3): 170–171. Bibcode:1992PhTea..30..170O. doi:10.1119/1.2343500.

- ^ Brinsmade 1936; Romain 1962; Eder 1982; Torrens 1986; Brownstein 1997; Lévy-Leblond 1998; Foster 2010; Mills 2016; Quincey 2021; Leonard 2021; Mohr et al. 2022

- ^ Mohr & Phillips 2015.

- ^ a b c d Quincey, Paul; Brown, Richard J C (1 June 2016). «Implications of adopting plane angle as a base quantity in the SI». Metrologia. 53 (3): 998–1002. arXiv:1604.02373. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..998Q. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/3/998. S2CID 119294905.

- ^ a b Quincey 2016.

- ^ a b Torrens 1986.

- ^ Mohr et al. 2022, p. 6.

- ^ Mohr et al. 2022, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d Quincey 2021.

- ^ Quincey, Paul; Brown, Richard J C (1 August 2017). «A clearer approach for defining unit systems». Metrologia. 54 (4): 454–460. arXiv:1705.03765. Bibcode:2017Metro..54..454Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/aa7160. S2CID 119418270.

- ^ Schabel, Matthias C.; Watanabe, Steven. «Boost.Units FAQ – 1.79.0». www.boost.org. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

Angles are treated as units

- ^ Mohr et al. 2022, p. 3.

- ^ «UnityDimensions—Wolfram Language Documentation». reference.wolfram.com. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Luckey, Paul (1953) [Translation of 1424 book]. Siggel, A. (ed.). Der Lehrbrief über den kreisumfang von Gamshid b. Mas’ud al-Kasi [Treatise on the Circumference of al-Kashi]. Berlin: Akademie Verlag. p. 40.

- ^ a b Roche, John J. (21 December 1998). The Mathematics of Measurement: A Critical History. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-387-91581-4.

- ^ O’Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (February 2005). «Biography of Roger Cotes». The MacTutor History of Mathematics. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ Cotes, Roger (1722). «Editoris notæ ad Harmoniam mensurarum». In Smith, Robert (ed.). Harmonia mensurarum (in Latin). Cambridge, England. pp. 94–95.

In Canone Logarithmico exhibetur Systema quoddam menfurarum numeralium, quæ Logarithmi dicuntur: atque hujus systematis Modulus is est Logarithmus, qui metitur Rationem Modularem in Corol. 6. definitam. Similiter in Canone Trigonometrico finuum & tangentium, exhibetur Systema quoddam menfurarum numeralium, quæ Gradus appellantur: atque hujus systematis Modulus is est Numerus Graduum, qui metitur Angulum Modularem modo definitun, hoc est, qui continetur in arcu Radio æquali. Eft autem hic Numerus ad Gradus 180 ut Circuli Radius ad Semicircuinferentiam, hoc eft ut 1 ad 3.141592653589 &c. Unde Modulus Canonis Trigonometrici prodibit 57.2957795130 &c. Cujus Reciprocus eft 0.0174532925 &c. Hujus moduli subsidio (quem in chartula quadam Auctoris manu descriptum inveni) commodissime computabis mensuras angulares, queinadmodum oftendam in Nota III.

[In the Logarithmic Canon there is presented a certain system of numerical measures called Logarithms: and the Modulus of this system is the Logarithm, which measures the Modular Ratio as defined in Corollary 6. Similarly, in the Trigonometrical Canon of sines and tangents, there is presented a certain system of numerical measures called Degrees: and the Modulus of this system is the Number of Degrees which measures the Modular Angle defined in the manner defined, that is, which is contained in an equal Radius arc. Now this Number is equal to 180 Degrees as the Radius of a Circle to the Semicircumference, this is as 1 to 3.141592653589 &c. Hence the Modulus of the Trigonometric Canon will be 57.2957795130 &c. Whose Reciprocal is 0.0174532925 &c. With the help of this modulus (which I found described in a note in the hand of the Author) you will most conveniently calculate the angular measures, as mentioned in Note III.] - ^ Gowing, Ronald (27 June 2002). Roger Cotes — Natural Philosopher. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52649-4.

- ^ Euler, Leonhard. Theoria Motus Corporum Solidorum seu Rigidorum [Theory of the motion of solid or rigid bodies] (PDF) (in Latin). Translated by Bruce, Ian. Definition 6, paragraph 316.

- ^ Isaac Todhunter, Plane Trigonometry: For the Use of Colleges and Schools, p. 10, Cambridge and London: MacMillan, 1864 OCLC 500022958

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1929). History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 2. Dover Publications. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-486-67766-4.

- ^

- Muir, Thos. (1910). «The Term «Radian» in Trigonometry». Nature. 83 (2110): 156. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..156M. doi:10.1038/083156a0. S2CID 3958702.

- Thomson, James (1910). «The Term «Radian» in Trigonometry». Nature. 83 (2112): 217. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..217T. doi:10.1038/083217c0. S2CID 3980250.

- Muir, Thos. (1910). «The Term «Radian» in Trigonometry». Nature. 83 (2120): 459–460. Bibcode:1910Natur..83..459M. doi:10.1038/083459d0. S2CID 3971449.

- ^ Miller, Jeff (Nov 23, 2009). «Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics». Retrieved Sep 30, 2011.

- ^ Frederick Sparks, Longmans’ School Trigonometry, p. 6, London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1890 OCLC 877238863 (1891 edition)

- ^ Quincey, Paul; Mohr, Peter J; Phillips, William D (1 August 2019). «Angles are inherently neither length ratios nor dimensionless». Metrologia. 56 (4): 043001. arXiv:1909.08389. Bibcode:2019Metro..56d3001Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ab27d7. S2CID 198428043.

- ^ Le Système international d’unités (PDF) (in French), 1970, p. 12,

Pour quelques unités du Système International, la Conférence Générale n’a pas ou n’a pas encore décidé s’il s’agit d’unités de base ou bien d’unités dérivées.

[For some units of the SI, the CGPM still hasn’t yet decided whether they are base units or derived units.] - ^ a b Nelson, Robert A. (March 1984). «The supplementary units». The Physics Teacher. 22 (3): 188–193. Bibcode:1984PhTea..22..188N. doi:10.1119/1.2341516.

- ^ Report of the 7th meeting (PDF) (in French), Consultative Committee for Units, May 1980, pp. 6–7

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, pp. 174–175.

- ^ International Bureau of Weights and Measures 2019, p. 179.

- ^ Kalinin, Mikhail I (1 December 2019). «On the status of plane and solid angles in the International System of Units (SI)». Metrologia. 56 (6): 065009. arXiv:1810.12057. Bibcode:2019Metro..56f5009K. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ab3fbf. S2CID 53627142.

- ^ Consultative Committee for Units (11–12 June 2013). Report of the 21st meeting to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (Report). pp. 18–20.

- ^ Consultative Committee for Units (21–23 September 2021). Report of the 25th meeting to the International Committee for Weights and Measures (Report). pp. 16–17.

- ^ «CCU Task Group on angle and dimensionless quantities in the SI Brochure (CCU-TG-ADQSIB)». BIPM. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (20 May 2019), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (9th ed.), ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0, archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2021

- Brinsmade, J. B. (December 1936). «Plane and Solid Angles. Their Pedagogic Value When Introduced Explicitly». American Journal of Physics. 4 (4): 175–179. Bibcode:1936AmJPh…4..175B. doi:10.1119/1.1999110.

- Romain, Jacques E. (July 1962). «Angle as a fourth fundamental quantity». Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards Section B. 66B (3): 97. doi:10.6028/jres.066B.012.

- Eder, W E (January 1982). «A Viewpoint on the Quantity «Plane Angle»«. Metrologia. 18 (1): 1–12. Bibcode:1982Metro..18….1E. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/18/1/002. S2CID 250750831.

- Torrens, A B (1 January 1986). «On Angles and Angular Quantities». Metrologia. 22 (1): 1–7. Bibcode:1986Metro..22….1T. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/22/1/002. S2CID 250801509.

- Brownstein, K. R. (July 1997). «Angles—Let’s treat them squarely». American Journal of Physics. 65 (7): 605–614. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..605B. doi:10.1119/1.18616.

- Lévy-Leblond, Jean-Marc (September 1998). «Dimensional angles and universal constants». American Journal of Physics. 66 (9): 814–815. Bibcode:1998AmJPh..66..814L. doi:10.1119/1.18964.

- Foster, Marcus P (1 December 2010). «The next 50 years of the SI: a review of the opportunities for the e-Science age». Metrologia. 47 (6): R41–R51. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/47/6/R01. S2CID 117711734.

- Mohr, Peter J; Phillips, William D (1 February 2015). «Dimensionless units in the SI». Metrologia. 52 (1): 40–47. arXiv:1409.2794. Bibcode:2015Metro..52…40M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/52/1/40.

- Quincey, Paul (1 April 2016). «The range of options for handling plane angle and solid angle within a system of units». Metrologia. 53 (2): 840–845. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..840Q. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/2/840. S2CID 125438811.

- Mills, Ian (1 June 2016). «On the units radian and cycle for the quantity plane angle». Metrologia. 53 (3): 991–997. Bibcode:2016Metro..53..991M. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/53/3/991. S2CID 126032642.

- Quincey, Paul (1 October 2021). «Angles in the SI: a detailed proposal for solving the problem». Metrologia. 58 (5): 053002. arXiv:2108.05704. Bibcode:2021Metro..58e3002Q. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ac023f. S2CID 236547235.

- Leonard, B P (1 October 2021). «Proposal for the dimensionally consistent treatment of angle and solid angle by the International System of Units (SI)». Metrologia. 58 (5): 052001. Bibcode:2021Metro..58e2001L. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/abe0fc. S2CID 234036217.

- Mohr, Peter J; Shirley, Eric L; Phillips, William D; Trott, Michael (23 June 2022). «On the dimension of angles and their units». Metrologia. 59 (5): 053001. arXiv:2203.12392. Bibcode:2022Metro..59e3001M. doi:10.1088/1681-7575/ac7bc2.

External links

Look up radian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Media related to Radian at Wikimedia Commons

Углы в математике (а также в тригонометрии и физике) высчитываются и измеряются в градусах или в радианах. Важно понимать и определять связь между этими единицами измерения, и переводить их из одной в другую. Понимание и определение этой связи позволяет оперировать углами и перевести градусы в радианы, а также осуществить перевод из радиан в градусы с помощью специальной тригонометрической формулы — формулы перевода градусов в радианы. В данной статье мы разберемся, зачем все это нужно конвертировать (и что делать с конвертируемым), выведем формулу для перевода градусов в радианы и обратно — из радианов в градусы, а также разберем несколько примеров из практики по конвертации.

Связь между градусами и радианами

Что такое радиан? Радиан вместе с градусом является выражением угловой меры: это величина, которая используется для измерения плоских углов. Поэтому, когда говорят о таблице градусов и радиан, то имеют в виду таблицу, в которой представлены соответствия угловых градусов радианам (что позволяет вам не находить и не считать самостоятельно на калькуляторе, к примеру).

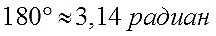

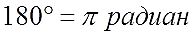

Как перевести радианы в градусы — есть формула? Для нахождения связи между градусами и радианами, необходимо узнать, сколько будет градусная и ридианная (радиальная) мера какого-либо угла (и для этого нам не нужно пользоваться каким-либо переводчиком онлайн). Например, возьмем центральный угол, который опирается на диаметр окружности радиуса r. Чтобы вычислить радианную меру этого угла, необходимо рассчитать определенные данные: длину дуги разделить на длину радиуса окружности. Рассматриваемому углу соответствует длина дуги, равная половине длины окружности π·r. Разделим длину дуги на радиус и получим радианную меру угла: π·rr=π рад.

Итак, рассматриваемый угол равен π радиан. С другой стороны, это развернутый угол, равный 180°. Следовательно, 180°=π рад.

Связь между радианами и градусами выражается следующей полной формулой

π радиан =180°

Формулы перевода из градусов в радианы и наоборот

Как перевести градусы в радианы не более, чем за минуту? Что делать с координатами в градусах, если нужны в радианах? Из содержания формулы, полученной выше, можно вывести другие формулы для перевода углов из радианов в градусы и обратно из градусов в радианы (взаимно преобразовывать и пересчитывать).

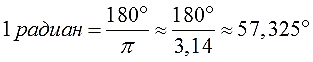

Как онлайн найти градусную меру угла и сделать пересчет? Выразим 1 радиан в градусах. Для этого разделим левую и правую части радиуса на пи.

1 рад=180π° — град. мера угла в 1 радиан равна 180π.

Также можно выразить один градус в радианах. Чему равен 1 радиан и во что он будет переходить? Вот простой расчет.

1°=π180рад

Можно произвести приблизительные вычисления величин угла в радианах и наоборот. Для этого возьмем значения числа π с точностью до десятитысячных и подставим в полученные формулы.

1 рад=180π°=1803,1416°=57,2956°

Значит, в одном радиане примерно 57 градусов

1°=π180рад=3,1416180рад=0,0175 рад

Один градус содержит 0,0175 радиана.

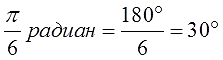

По какой формуле перевести радианы в градусы?

x рад=х·180π°

Чтобы перевести угол из радианов в градусы, нужно значение угла в радианах умножить на 180 и разделить на пи.

Примеры перевода градусов в радианы и радианов в градусы

Рассмотрим пример, как перевести градусы в радианы по формуле.

Конечно, в интернете это все может считаться за секунду, но у самостоятельного подсчета другие преимущества.

Пусть α=3,2 рад. Нужно узнать градусную меру этого угла.

Применим формулу перехода от радианов к градусам и получим:

3,2 рад=3,2·180π°≈3,2·1803,14°≈5763,14°≈183,4°

Аналогично можно получить формулу перевода в радианы из градусов.

y°=y·π180рад

Переведем 47 градусов в радианы.

Согласно формуле, умножим 47 на пи и разделим на 180.

47°≈47·3,14180≈0,82 рад

Преподаватель математики и информатики. Кафедра бизнес-информатики Российского университета транспорта

А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

радиа́н, -а, р. мн. -ов, счетн. ф. -иа́н (ед. измер.)

Рядом по алфавиту:

раджастха́нский , (от Раджастха́н, штат в Индии)

раджастха́нцы , и раджаста́нцы, -ев, ед. -а́нец, -а́нца, тв. -а́нцем (народ)

раджпу́тский

раджпу́ты , -ов, ед. -пу́т, -а (каста-сословие, ист.)

Радзиви́лловская ле́топись

радзиви́лловский , (от Радзиви́ллы, княжеский род)

ра́ди , предлог

радиа́льно расходя́щийся

радиа́льно-кольцево́й

радиа́льно-лучи́стый

радиа́льно-осево́й

радиа́льно-поршнево́й

радиа́льно-сверли́льный

радиа́льность , -и

радиа́льный

радиа́н , -а, р. мн. -ов, счетн. ф. -иа́н (ед. измер.)

радиа́нный

радиа́нт , -а (астр.)

радиа́тор , -а

радиа́тор-охлади́тель , радиа́тора-охлади́теля

радиа́торный

радиацио́нно безопа́сный

радиацио́нно опа́сный

радиацио́нно сто́йкий

радиацио́нно усто́йчивый

радиацио́нно-авари́йный

радиацио́нно-защи́тный

радиацио́нно-медици́нский

радиацио́нно-терми́ческий

радиацио́нно-физи́ческий

радиацио́нно-хими́ческий

О словаре

Сайт создан на основе «Русского орфографического словаря», составленного Институтом русского языка имени В. В. Виноградова РАН. Объем второго издания, исправленного и дополненного, составляет около 180 тысяч слов, и существенно превосходит все предшествующие орфографические словари. Он является нормативным справочником, отражающим с возможной полнотой лексику русского языка начала 21 века и регламентирующим ее правописание.

Радиан

Радиан ‒ угол, соответствующий дуге, длина которой равна её радиусу.

Окружность любого радиуса можно разбить только на шесть радиан.

Для того чтобы найти общую длину данной окружности необходимо либо сложить все длины всех радиан друг с другом, либо умножить длину одного радиана на шесть.

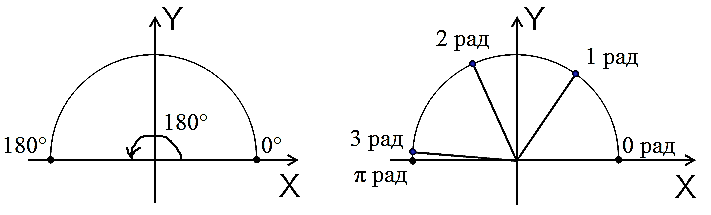

Формула нахождения общей длины окружности:

или

где

‒ общая длина окружности;

‒ количество радиан;

‒ радиан.

Для того чтобы найти общее количество радиан, которое может вместить в себя данная окружность необходимо общую длину данной окружности разделить на длину её радиуса.

Формула нахождения общего количества радиан окружности:

где

‒ общее количество радиан;

‒ радиус.

Для того чтобы найти длину радиуса данной окружности необходимо общую длину данной окружности поделить на общее количество радиан.

Формула нахождения длины радиуса окружности:

Задача №1

Найдите общую длину окружности, если её

Решение:

подставим значения, посчитаем

Ответ:

Задача №2

Найдите общую длину окружности, если её

Задача №3

Найдите общую длину окружности, если её

Задача №4

Найдите общую длину окружности, если её

Задача №5

Найдите общую длину окружности, если её

Задача №1

Найдите общее количество радиан окружности, если её а

Решение:

подставим значения, посчитаем

Ответ:

Задача №2

Найдите общее количество радиан окружности, если её а

Задача №3

Найдите общее количество радиан окружности, если её а

Задача №4

Найдите общее количество радиан окружности, если её а

Задача №5

Найдите общее количество радиан окружности, если её а

Задача №1

Найдите длину радиуса окружности, если её а

Решение:

подставим значения, посчитаем

Ответ:

Задача №2

Найдите длину радиуса окружности, если её а

Задача №3

Найдите длину радиуса окружности, если её а

Задача №4

Найдите длину радиуса окружности, если её а

Задача №5

Найдите длину радиуса окружности, если её а

Полезно? Поделись с другими:

Если Вы являетесь автором этой работы и хотите отредактировать, либо удалить ее с сайта — свяжитесь, пожалуйста, с нами.

Материал из Циклопедии

Радиан (в математике и физике) — это единица измерения плоскостных углов, принятая в Международной системе единиц СИ.

Один радиан — это плоскостной угол, образованный двумя радиусами, так, что длина дуги между ними точно равна радиусу окружности. То есть, измерение угла в радианах показывает во сколько раз длина дуги окружности, опирающейся на этот угол, отличается от его радиуса.

Радиан является безразмерной единицей измерения и имеет обозначение рад (международное — rad), но, как правило, при написании это обозначение не пишется. При измерении углов в градусах используют обозначения °, для того чтобы отличить их от радианов.

[править] Пояснение

Полная длина окружности равна 2πr, где r — радиус окружности. Поэтому полный круг является углом в 2π≈6,28319 радиан. Преобразование радианов в градусы и наоборот осуществляется следующим образом:

- 2π рад = 360°,

- 1 рад = 360°/(2π) = 180°/π ≈ 57,29578°.

- 360° = 2π рад,

- 1° = 2π/360 рад = π/180 рад.

[править] Свойства

Широкое применение радианов в математическом анализе обусловлено тем, что выражения с тригонометрическими функциями, аргументы которых измеряются в радианах, приобретают максимально простой вид (без числовых коэффициентов). Например, используя радианы, получим простое тождество

- [math]lim_{hrightarrow 0}frac{sin h}{h}=1,[/math]

что лежит в основе многих элегантных формул в математике.

При малых углах синус и тангенс угла, выраженного в радианах, равен самому углу, что удобно при приближенных вычислениях.

Косинус малого угла, выраженного в радианах, приблизительно равен:

- [math]cos(x) approx 1 — frac{x^2}{2}[/math]

[править] Размерность

Радиан есть безразмерной единицей измерения. То есть числовое значение угла, измеренного в радианах, лишено размерности. Это легко видеть из самого определения радиана, как отношения длины окружности к радиусу. Согласно рекомендациям Международного бюро мер и весов радиан интерпретируется как единица с размерностью 1 = м·м−1 (м/м, то есть метр на метр — числитель и знаменатель возможно сократить, то есть оно не имеет размерности).

Иначе, безразмерность радиана можно видеть по выражению ряда Тейлора для тригонометрической функции sin(x):

- [math]sin(x) = x — frac{x^3}{3!} + frac{x^5}{5!}-cdots.[/math]

Если бы x имел размерность, тогда эта сумма была бы лишена смысла — линейное слагаемое x нельзя было бы добавить к кубическому x3/3!, как величины разных размерностей. Итак, x должен быть безразмерным.

[править] См. также

- Стерадиан

Угол может измеряться следующими величинами:

- Градусами (и соответствующими ему величинами: угловыми минутами и секундами);

- Радианами.

Градусная мера угла

Если взять развернутый угол (это два прямых угла) и поделить его на 180 частей, то одна такая часть будет называться одним градусом. Для того, чтобы измерить градусную меру угла, необходимо посчитать, сколько раз 1 градус входит в данный угол. Полученное число и будет ответом.

Если угол таков, что его нельзя измерить целым числом, либо же он меньше единичного угла, то используют такие меры измерения как угловые минуты и секунды.

Если градус поделить на 60 частей, то одной такой частью будет минута. В свою же очередь, если минуту разделить на те же 60 частей, то полученным числом будет 1 секунда.

Радианная мера угла

Радианом называют угол, образованный дугой окружности длинной равной радиусу этой окружности.

Длина окружности равна:

l=2⋅π⋅rl=2cdotpicdot r,

где rr — радиус этой окружности.

Тогда, разделив на радиус, получаем, что полный угол в радианах равен:

lr=2⋅π⋅rr=2⋅π радианfrac{l}{r}=frac{2cdotpicdot r}{r}=2cdotpitext{ радиан}

В градусах этот же угол равен, как известно, 360∘360^{circ}.

Отсюда находим связь между радианами и градусами:

2⋅π радиан=360∘2cdotpitext{ радиан}=360^{circ}

Это та главная формула, которая нужна, чтобы переводить градусы в радианы и наоборот.

Один радиан равен:

1 радиан=360∘2⋅π≈57.3∘1text{ радиан}=frac{360^{circ}}{2cdotpi}approx57.3^{circ}

Один радиан в минутах:

1 радиан=360∘2⋅π⋅60≈3438′1text{ радиан}=frac{360^{circ}}{2cdotpi}cdot60approx3438′

Один радиан в секундах:

1 радиан=360∘2⋅π⋅60⋅60≈206280′′1text{ радиан}=frac{360^{circ}}{2cdotpi}cdot60cdot60approx206280»

Перевод градусов в радианы

Если по условию известна градусная мера угла, то чтобы перевести ее в радианную, нужно сделать следующие действия: умножить ее на πpi и разделить на 180.

y радиан=π180⋅xytext{ радиан}=frac{pi}{180}cdot x

xx — значение угла в градусах;

yy — значение того же угла в радианах.

Переведите 45 градусов в радианную меру измерения. Ответ округлите до десятой доли.

Решение

45∘=π180⋅45 радиан≈0.8 радиан45^{circ}=frac{pi}{180}cdot 45text{ радиан}approx0.8text{ радиан}

Ответ

0.8 радиан0.8text{ радиан}

Земля совершила треть от половины оборота вокруг Солнца. На какой угол в радианах она повернулась?

Решение

Найдем сначала этот угол в градусах. Полный угол составляет 360∘360^circ. Половина от полного оборота это 180∘180^{circ}. Нам же нужна треть этого угла, то есть:

180∘3=60∘frac{180^circ}{3}=60^circ

Земля отклонилась на угол 60∘60^circ от своего начального положения. Переведем теперь этот угол в радианы:

60∘=π180⋅60 радиан≈1 радиан60^circ=frac{pi}{180}cdot 60text{ радиан}approx1text{ радиан}

Решение

1 радиан1text{ радиан}

Перевод радиан в градусы

Чтобы перевести радианы в градусы, нужно умножить угол в радианах на 180 и разделить на πpi.

y∘=180π⋅xy^{circ}=frac{180}{pi}cdot x

xx — значение угла в радианах;

yy — значение того же угла в градусах.

Переведите 3 радиана в градусную меру угла.

Решение

3 радиана=180π⋅3≈172∘3text{ радиана}=frac{180}{pi}cdot3approx172^circ

Ответ

172∘172^circ

Ищете, где можно заказать задачу по математике недорого? Обратитесь к нашим экспертам в данной области!

Тест по теме «Перевод градусов в радианы и наоборот»

В прошлый раз мы с вами ответили на первый вопрос, касаемый работы с углами. А именно — как отсчитываются углы. Рассмотрели положительные и отрицательные углы, а также углы, большие 360 градусов. И на круге углы порисовали.)

В этом же уроке настал черёд ответить на второй вопрос, связанный с измерением углов. Здесь мы разберёмся с загадочными радианами и особенно — с пресловутым числом «пи», которое будет мозолить нам глаза на протяжении всего дальнейшего изучения тригонометрии. Поймём, что это за число, откуда оно берётся и как с ним работать. И задания порешаем, само собой. Стандартные и не очень…)

Разберёмся? Ну сколько же можно бояться числа «пи», в конце-то концов!)

Итак, в чём же измеряются углы в математике? Начнём с привычного и знакомого. С градусов.

Что такое один градус? Градусная мера угла.

К градусам вы уже попривыкли. Геометрию изучаете, да и в жизни постоянно сталкиваетесь. Например, «повернул на 90 градусов».) Короче, градус — штука простая и понятная.

Вы и вправду так думаете? Тогда сможете сказать мне, что такое градус? Нет, гуглить и потрошить Википедию не надо. Ну как, слабо с ходу? Вот так-то…

Начнём издалека. С древнейших времён. А именно — с двух очагов древних цивилизаций Вавилона и Египта.)

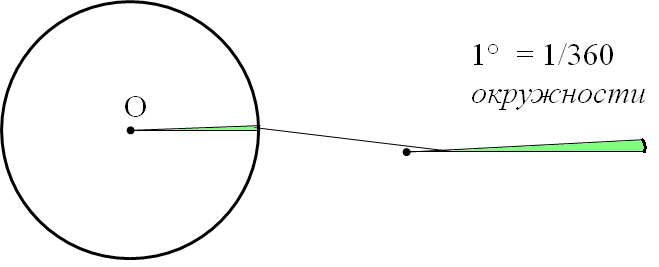

Градус — это 1/360 часть окружности. И всё!

Смотрим картинку:

Придумали градусы в Древнем Вавилоне.) Как? Очень просто! Просто взяли да разбили окружность на 360 равных кусочков. Почему именно на 360? А не на 100 или на 1000? Вроде бы, число 100 поровнее, чем 360… Вопрос хороший.

Основная версия — астрономическая. Ведь число 360 очень близко к числу дней в году! А для наблюдений за Солнцем, Луной и звёздами это было оч-чень удобно.)

Кроме того, в астрономии (а также строительстве, землемерии и прочих смежных областях) очень удобно делить окружность на равные части. А теперь давайте прикинем чисто математически, на какие числа делится нацело 100 и на какие — 360? И в каком из вариантов этих делителей нацело больше? А людям такое деление очень удобно, да…)

Что такое число «пи»? Как оно возникло?

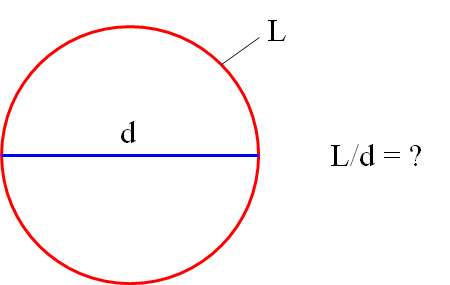

А теперь переместимся из Древнего Вавилона в Древний Египет. Примерно в то же самое время там разгадывали другую загадку. Не менее интересную, чем вопрос, на сколько частей бить окружность. А именно — во сколько раз длина окружности больше её диаметра? Или по-другому: чему равна длина окружности с диаметром, равным единице?

И так измеряли и сяк… Каждый раз получалось чуть-чуть больше трёх. Но как-то коряво получалось, неровно…

Но они, египтяне, ни в чём не виноваты. После них математики всех мастей продолжали мучиться аж до 18 века! Пока в 1767 году окончательно не доказали, что, как бы мелко ни нарезать окружность на равные кусочки, из таких кусочков сложить точно длину диаметра нельзя. Принципиально нельзя. Только лишь примерно.

Нет, конечно же, во сколько раз длина окружности больше её диаметра установили давным-давно. Но, опять же, примерно… В 3,141592653… раза.

Это число — и есть число «пи» собственной персоной.) Да уж… Корявое так корявое… После запятой — бесконечное число цифр безо всякого порядка, безо всякой логики. В математике такие числа называются иррациональными. И на сегодняшний день доказательство факта иррациональности числа «пи» занимает аж десять (!) лекций на 4-м курсе мехмата МГУ… Этот факт, кстати, и означает, что из одинаковых кусочков окружности её диаметр точно не сложить. Никак. И никогда…

Конечно, рациональные приближения числа «пи» известны людям ещё со времён Архимеда. Например:

22/7 = 3,14285714…

377/120 = 3,14166667…

355/113 = 3,14159292…

Сейчас, в век суперкомпьютеров, погоня за десятичными знаками числа «пи» не стихает, и на сегодняшний день человечеству известно уже два квадриллиона (!) знаков этого числа…

Но нам для практического применения такая сверхточность совершенно не требуется. Чаще всего достаточно запомнить всего лишь две цифры после запятой.

Запоминаем:

Вот и всё. Раз уж нам ясно, что длина окружности больше её диаметра в «пи» раз, то можно записать (и запомнить) точную формулу для длины окружности:

Здесь L — длина окружности, а d — её диаметр.

В геометрии всяко пригодится.)

Для общего развития скажу, что число «пи» сидит не только в геометрии или тригонометрии. Оно возникает в самых различных разделах высшей математики. В интегралах, например. Или в теории вероятностей. Или в теории комплексных чисел, а также рядов. Само по себе возникает, хотим мы того или нет… Поступите в ВУЗ — убедитесь лично.)

Ну а теперь снова вернёмся к старым добрым градусам. Как мы помним, один градус — это 1/360 часть окружности. С исторической и практической точек зрения людям такое деление на 360 равных частей оказалось очень даже удобно, но…

Как выяснилось гораздо позже Древнего Вавилона, градусы удобны далеко не всем. Например, высшей математике они ой как неудобны! Высшая математика — дама серьёзная. По законам природы устроена. И она справедливо заявляет: «Сегодня вы на 360 частей круг разбили, завтра — на 100 разобьёте, послезавтра — на 250… А мне что делать? Каждый раз под ваши хотелки подстраиваться?»

Против природы не попрёшь… Пришлось прислушаться и уступить. И ввести новую меру угла, не зависящую от наших хотелок. )

Итак, знакомьтесь — радиан!

Что такое один радиан? Радианная мера угла.

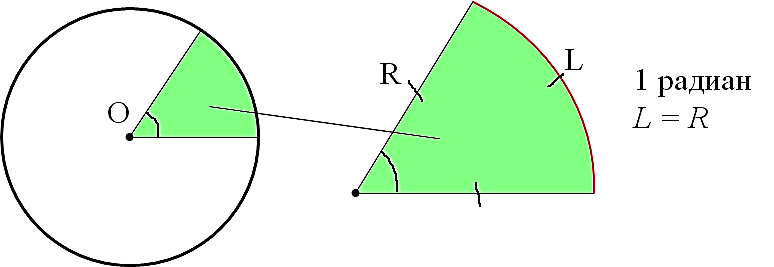

В основе определения радиана — та же самая окружность. Угол в 1 радиан — это угол, который отсекает от окружности дугу, длина которой (L) равна радиусу окружности (R). И всё!

Смотрим картинку:

Причём величина угла в один радиан не зависит от радиуса окружности! Никак. Можно нарисовать очень большую окружность, можно очень маленькую. Но угол, отсекающий от окружности дугу, равную радиусу, никогда не изменит своей величины и будет составлять ровно один радиан. Всегда. Это важно.)

Запоминаем:

Угол в один радиан — это угол, вырезающий из окружности дугу, равную радиусу окружности. Величина угла в 1 радиан не зависит от радиуса окружности.

Кстати говоря, градусная мера угла тоже не зависит от радиуса окружности. Большая окружность, маленькая — углу в один градус без разницы. Но градус — это величина, искусственно придуманная людьми для их личного удобства! Древними вавилонянами, если мы помним.) 1/360 часть окружности. Так уж сложилось чисто исторически. А если бы по каким-то причинам договорились на 100 частей разбить окружность? Или на 200? Кто знает, что тогда называлось бы градусом сегодня… Вот на сколько частей разобьём окружность, такой «градус» и получим. А вот радиан — штука универсальная!) К способу разбиения окружности никак не привязан. Строго дуга, равная радиусу! И чем больше радиус, тем больше (по длине) будет и соответствующая вырезаемая дуга. И наоборот. Но сама величина угла в один радиан не меняется. И разбиение окружности (любой!) радианами — всегда одинаковое. И сейчас мы в этом лично убедимся.)

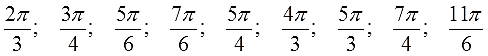

Как переводить радианы в градусы и обратно?

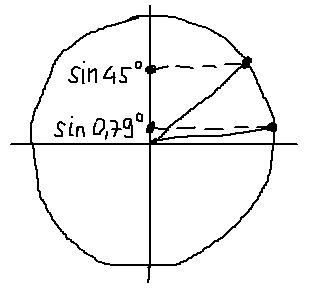

К этому моменту вам уже должно быть интуитивно понятно, что один радиан существенно больше одного градуса. Всё-таки непонятно? Тогда смотрим снова на картинку:

Будем считать, что малюсенький красный угол имеет величину примерно один градус. Совсем крохотный уголок, почти и нет его… А большой зелёный угол — примерно один радиан! Чувствуете разницу?) Конечно же, один радиан сильно больше одного градуса…

А вот теперь начинается самое интересное! Вопрос: а во сколько раз один радиан больше одного градуса? Или сколько градусов в одном радиане? Сейчас выясним!)

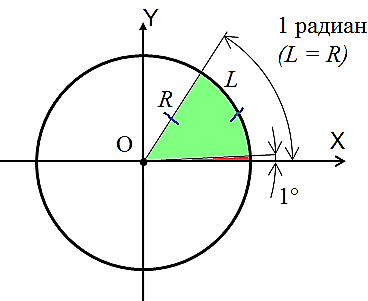

Смотрим на очередные картинки:

На картинке слева изображён полукруг. Обычный развёрнутый угол величиной 180°. А вот на картинке справа — тот же самый полукруг, но нарезанный радианами! Видно, что в 180° помещается примерно три с хвостиком радиана.

Вопрос на засыпку: как вы думаете, чему равен этот хвостик?)

Да! Он равен 0,141592653… Привет, число «пи», вот мы про тебя и вспомнили!)

Стало быть, в 180° укладывается 3,141592653… радиан. Понятное дело, что каждый раз писать такое длинное число неудобно, поэтому пишут приближённо:

Или точно:

Вот и всё. Вот и весь секрет тотального присутствия числа «пи» в тригонометрии. Эту простую формулку надо знать железно. Уловили?)