Рембрандт

- Рембрандт

-

(2 м)

Орфографический словарь русского языка.

2006.

Смотреть что такое «Рембрандт» в других словарях:

-

Рембрандт — Рембрандт … Википедия

-

РЕМБРАНДТ — (полн. Рембрандт Харменс ван Рейн, Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn) (15 июля 1606, Лейден 4 октября 1669, Амстердам), голландский живописец, рисовальщик, офортист. Новаторское искусство Рембрандта отличается демократизмом, жизненностью образов.… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

рембрандт — Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606 1669), гол. живописец, рисовальщик, офортист. Шляпа в стиле Рембрандта. Цилиндры, шляпы обыкновенные и совершенно необыкновенные, своей циркуляцией, производят головокружащую рябь большого муравейника. Все это… … Исторический словарь галлицизмов русского языка

-

РЕМБРАНДТ — Харменс ван Рейн (Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn) (1606 69), голландский живописец, график. Сочетая глубокую психологическую характеристику с исключительным мастерством живописи, основанной на эффектах светотени, писал портреты, в том числе… … Современная энциклопедия

-

Рембрандт — ван Рейн (Rembrandt van Rijn) Великий голландскийживописец и гравер, сын мельника Гармена Герритса и Нелтье Виллемсдохтерван Рейн, род. 15 июля 1606 г. в Лейдене. Во время появления Р. на светдела его отца находились в цветущем положении, что… … Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Ефрона

-

Рембрандт — Харменс ван Рейн (Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn) (15.7.1606, Лейден, 4.10.1669, Амстердам), голландский живописец, рисовальщик и офортист. Искусство Р. отличается необычайной жизненностью и глубокой человечностью образов. Сочетая… … Большая советская энциклопедия

-

Рембрандт — Харменс ван Рейн (rembrandt harmensz van Rijn) (1606, Лейден – 1669, Амстердам), выдающийся голландский живописец, рисовальщик, гравёр. Сын зажиточного лейденского мельника. Закончил латинскую школу, некоторое время учился в Лейденском… … Художественная энциклопедия

-

Рембрандт — Харменс ван Рейн (Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn) 1606, Лейден 1669, Амстердам. Голландский живописец, рисовальщик, офортист. Родился в семье зажиточного владельца мельницы. После окончания латинской школы и недолгого пребывания в Лейденском… … Европейское искусство: Живопись. Скульптура. Графика: Энциклопедия

-

РЕМБРАНДТ — (Харменс ван Рейн Р. (1606 1669) голландский художник) Бурная кружка с трехгорным Рембрандтом! Спертость предгрозья тебя не испортила. Ночью быть буре. Виденья, обратно! Память, труби отступленье к портерной! П922 (I,219); Уже светает. Шумят сады … Собственное имя в русской поэзии XX века: словарь личных имён

-

РЕМБРАНДТ — (Rembrandt), собств. в а н Р е й н, Харменс Рембрандт (1606–69), голл. живописец и график, значит. часть творчества к–рого была посвящена библ. тематике. Род. в Лейдене, в семье владельца мельницы. Учился в местном ун–те, а также у лейденских и… … Библиологический словарь

-

Рембрандт, Харменс ван Рейн — Рембрандт Автопортрет (около 1661), Кенвуд хаус, Лондон Имя при рождении: Рембрандт Харменс ван Рейн Дата рождения: 15 июля 1606 … Википедия

|

Rembrandt |

|

|---|---|

Rembrandt as depicted in his 1659 Self-Portrait with Beret and Turned-Up Collar (now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.) |

|

| Born |

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn 15 July 1606[1] Leiden, Dutch Republic |

| Died | 4 October 1669 (aged 63)

Amsterdam, Dutch Republic |

| Education | Jacob van Swanenburg Pieter Lastman |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking, drawing |

| Notable work | Self-portraits The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) Belshazzar’s Feast (1635) The Night Watch (1642) Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild (1662) The Hundred Guilder Print (etching, c. 1647–1649) |

| Movement | Dutch Golden Age Baroque |

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (,[2] Dutch: [ˈrɛmbrɑnt ˈɦɑrmə(n)ˌsoːɱ vɑn ˈrɛin] (listen); 15 July 1606[1] – 4 October 1669), usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media,[3] he is generally considered one of the greatest visual artists in the history of art and the most important in Dutch art history.[4] It is estimated Rembrandt produced a total of about three hundred paintings, three hundred etchings and two thousand drawings.

Unlike most Dutch masters of the 17th century, Rembrandt’s works depict a wide range of styles and subject matter, from portraits and self-portraits to landscapes, genre scenes, allegorical and historical scenes, biblical and mythological themes and animal studies. His contributions to art came in a period of great wealth and cultural achievement that historians call the Dutch Golden Age, when Dutch art (especially Dutch painting), whilst antithetical to the Baroque style that dominated Europe, was prolific and innovative. This era gave rise to important new genres. Like many artists of the Dutch Golden Age, such as Jan Vermeer, Rembrandt was an avid art collector and dealer.

Rembrandt never went abroad but was considerably influenced by the work of the Italian masters and Netherlandish artists who had studied in Italy, like Pieter Lastman, the Utrecht Caravaggists, Flemish Baroque, and Peter Paul Rubens. After he achieved youthful success as a portrait painter, Rembrandt’s later years were marked by personal tragedy and financial hardships. Yet his etchings and paintings were popular throughout his lifetime, his reputation as an artist remained high,[5] and for twenty years he taught many important Dutch painters.[6]

Rembrandt’s portraits of his contemporaries, self-portraits and illustrations of scenes from the Bible are regarded as his greatest creative triumphs. His self-portraits form an intimate autobiography.[4] Rembrandt’s foremost contribution in the history of printmaking was his transformation of the etching process from a relatively new reproductive technique into an art form.[7][8] His reputation as the greatest etcher in the history of the medium was established in his lifetime. Few of his paintings left the Dutch Republic while he lived but his prints were circulated throughout Europe, and his wider reputation was initially based on them alone.

In his works, he exhibited knowledge of classical iconography. A depiction of a biblical scene was informed by Rembrandt’s knowledge of the specific text, his assimilation of classical composition, and his observations of Amsterdam’s Jewish population.[9] Because of his empathy for the human condition, he has been called «one of the great prophets of civilization».[10] The French sculptor Auguste Rodin said, «Compare me with Rembrandt! What sacrilege! With Rembrandt, the colossus of Art! We should prostrate ourselves before Rembrandt and never compare anyone with him!»[11]

Early life and education[edit]

Rembrandt[a] Harmenszoon van Rijn was born on 15 July 1606 in Leiden,[1] in the Dutch Republic, now the Netherlands. He was the ninth child born to Harmen Gerritszoon van Rijn and Neeltgen Willemsdochter van Zuijtbrouck.[13] His family was quite well-to-do; his father was a miller and his mother was a baker’s daughter. Religion is a central theme in Rembrandt’s works and the religiously fraught period in which he lived makes his faith a matter of interest. His mother was Catholic, and his father belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church. While his work reveals deep Christian faith, there is no evidence that Rembrandt formally belonged to any church. Five of his children were christened in Dutch Reformed churches in Amsterdam: four in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) and one, Titus, in the Zuiderkerk (Southern Church).[14]

As a boy, he attended a Latin school. At the age of 13, he was enrolled at the University of Leiden, although according to a contemporary he had a greater inclination towards painting; he was soon apprenticed to a Leiden history painter, Jacob van Swanenburg, with whom he spent three years.[15] After a brief but important apprenticeship of six months with the painter Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam, Rembrandt stayed a few months with Jacob Pynas and then started his own workshop, though Simon van Leeuwen claimed that Joris van Schooten taught Rembrandt in Leiden.[15][16] Unlike many of his contemporaries who traveled to Italy as part of their artistic training, Rembrandt never left the Dutch Republic during his lifetime.[17][18]

Career[edit]

In 1624 or 1625, Rembrandt opened a studio in Leiden, which he shared with friend and colleague Jan Lievens. In 1627, Rembrandt began to accept students, which included Gerrit Dou in 1628.[19]

In 1629, Rembrandt was discovered by the statesman Constantijn Huygens who procured for Rembrandt important commissions from the court of The Hague. As a result of this connection, Prince Frederik Hendrik continued to purchase paintings from Rembrandt until 1646.[20]

At the end of 1631, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam, a city rapidly expanding as the business and trade capital. He began to practice as a professional portraitist for the first time, with great success. He initially stayed with an art dealer, Hendrick van Uylenburgh, and in 1634, married Hendrick’s cousin, Saskia van Uylenburgh.[21][22] Saskia came from a respected family: her father Rombertus van Uylenburgh had been a lawyer and a burgomaster (mayor) of Leeuwarden. The couple married in the local church of St. Annaparochie without the presence of Rembrandt’s relatives.[23] In the same year, Rembrandt became a citizen of Amsterdam and a member of the local guild of painters. He also acquired a number of students, among them Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck.[24]

In 1635, Rembrandt and Saskia rented a fashionable lodging with a view of the river.[25] In 1639 they moved to a large and recently modernized house in the upscale ‘Breestraat’ with artists and art dealers; Nicolaes Pickenoy was his neighbor.

The mortgage to finance the 13,000 guilder purchase would be a cause for later financial difficulties.[b][24] The neighborhood sheltered many immigrants and was becoming the Jewish quarter. It was there that Rembrandt frequently sought his Jewish neighbors to model for his Old Testament scenes.[28]

Although they were by now affluent, the couple suffered several personal setbacks; their son Rumbartus died two months after his birth in 1635 and their daughter Cornelia died at just three weeks of age in 1638. In 1640, they had a second daughter, also named Cornelia, who died after living barely over a month. Only their fourth child, Titus, who was born in 1641, survived into adulthood. Saskia died in 1642, probably from tuberculosis. Rembrandt’s drawings of her on her sick and death bed are among his most moving works.[29][30]

During Saskia’s illness, Geertje Dircx was hired as Titus’ caretaker and dry nurse; at some time she also became Rembrandt’s lover. In 1649 she left and charged Rembrandt with breach of promise (a euphemism for seduction under [breached] promise to marry) and be awarded alimony.[24] Rembrandt tried to settle the matter amicably but she pawned the ring he had given her that once belonged to Saskia to maintain her livelihood. The court particularly stated that Rembrandt had to pay a maintenance allowance, provided that Titus remained her only heir and she sold none of Rembrandt’s possessions.[31] In 1650 Rembrandt paid for her trip to have her committed to an asylum or poorhouse at Gouda.[32] Five years later he didn’t support her release. In August 1656 Geertje was listed as one of Rembrandt’s seven major creditors.

In early 1649 Rembrandt began a relationship with the much younger Hendrickje Stoffels, who had initially been his maid. She may have been the cause that Geertje left. In July 1654 she was pregnant, and received a summons from the Reformed Church to answer the charge «that she had committed the acts of a whore with Rembrandt the painter». She admitted and was banned from receiving communion. Rembrandt was not summoned to appear for the Church council; he seems not to have been a (very active) member.[33] In October they had a daughter, Cornelia but Rembrandt had not married Hendrickje. Had he remarried he would have lost access to a trust set up for Titus in Saskia’s will.[29]

Insolvency[edit]

Rembrandt moved to Rozengracht 184, Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Rembrandt lived beyond his means, buying art, prints and rarities. In January 1653 the sale of the property formally closed but Rembrandt still had to pay half of the mortgage. The creditors began to insist on installments but Rembrandt refused and asked for a postponement. The house needed carpentry work and Rembrandt borrowed money from Jan Six among others.[34] In 1655 the 14-years-old Titus made a will, making his father sole heir, shutting out his mother’s family.[35] After a notorious year with plague, (art) business dropped and Rembrandt applied for a high court arrangement (cessio bonorum). In 1656 he declared his insolvency, taking stock and voluntarily surrendered his goods.[36] Meanwhile, he had donated the house to his son.[37] The authorities and his creditors were generally accommodating to him, giving him plenty of time to pay his debts. In November 1657 an auction was organized to sell his paintings and a large number of etching plates, drawings (some by Raphael, Mantegna and Giorgione).[c] Rembrandt was allowed to keep all his tools including his etching press as a mean of income.[38]

The sale list with 363 items gives a good insight into Rembrandt’s collections, which, apart from Old Master paintings and drawings, included statues and busts of the Roman emperors and Greek philosophers, books (a bible), armor (helmets, bows and arrows), porcelain, among many objects from Asia, a collections of natural history (two lion skins, a bird-of-paradise), and minerals.[39] The prices realized in the sale were disappointing.[40] In February 1658 Rembrandt’ house was sold at a (foreclosure) auction and the family quickly moved to more modest accommodation at Rozengracht;[41] Hendrickje complained at the authorities as she left an oak cupboard.[42] Early December 1660 the sale of the house was closed but the money went to Titus’ guardian.[43] Two weeks later Hendrickje and Titus set up a dummy corporation as art dealers, so Rembrandt, who had board and lodging, could continue to produce.[44][45]

In 1661, the new business was contracted to complete work for the newly built city hall. The resulting work, The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis, was rejected by the mayors and returned to the painter within a few weeks; the surviving fragment (in Stockholm) is only a quarter of the original work.[46] In 1662 he was still fulfilling major commissions for portraits and finished the Staalmeesters.[47] Around this time Rembrandt took on his last apprentice, Aert de Gelder. It is problematic how wealthy Rembrandt was and he overestimated the value of his art collection.[48] Anyhow, half was earmarked for Titus’ inheritance.[49]

In March 1663 Hendrickje was sick and Titus was allowed to act. Isaac van Hertsbeeck, Rembrandt’s main creditor, went to the High Court to contest that Titus had to be paid first.[50] He lost more than once and had to pay the money he had already received to Titus in 1665 who was by then declared of age.[51][52] Rembrandt was working on the Jewish Bride and his three final self-portraits but fell into rent arrears.[53] Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany visited Rembrandt twice and travelled back to Florence with one of the self-portraits.[54]

Rembrandt outlived both Hendrickje and Titus, who died in September 1668, leaving a pregnant widow behind. Rembrandt died on Friday 4 October 1669; he was buried four days later in a rented grave in the Westerkerk. Supposedly as a rich man as the heirs paid in burial taxes a substantial amount of money, f 15.[55] Cornelia (1654-1684), his illegitimate child, moved to Batavia in 1670 with an obscure painter and the inheritance of her mother.[56] His only grandchild, Titia (1669-1715), inherited a considerable sum from Titus.[57] According to Bob Wessels: With more than 20 legal conflicts and disputes, in all areas of life and business, Rembrandt also led a turbulent legal and financial life.[58]

Works[edit]

Rembrandt only Winterlandscape 1646

In a letter to Huygens, Rembrandt offered the only surviving explanation of what he sought to achieve through his art, writing that, «the greatest and most natural movement», translated from de meeste en de natuurlijkste beweegelijkheid. The word «beweegelijkheid» translates to «emotion» or «motive». Whether this refers to objectives, material, or something else, is not known but critics have drawn particular attention to the way Rembrandt seamlessly melded the earthly and spiritual.[59]

Earlier 20th century connoisseurs claimed Rembrandt had produced well over 600 paintings,[60] nearly 400 etchings and 2,000 drawings.[61] More recent scholarship, from the 1960s to the present day (led by the Rembrandt Research Project), often controversially, has winnowed his oeuvre to nearer 300 paintings.[d] His prints, traditionally all called etchings, although many are produced in whole or part by engraving and sometimes drypoint, have a much more stable total of slightly under 300.[e] It is likely Rembrandt made many more drawings in his lifetime than 2,000 but those extant are more rare than presumed.[f] Two experts claim that the number of drawings whose autograph status can be regarded as effectively «certain» is no higher than about 75, although this is disputed. The list was to be unveiled at a scholarly meeting in February 2010.[64]

At one time, approximately 90 paintings were counted as Rembrandt self-portraits but it is now known that he had his students copy his own self-portraits as part of their training. Modern scholarship has reduced the autograph count to over forty paintings, as well as a few drawings and thirty-one etchings, which include many of the most remarkable images of the group.[65] Some show him posing in quasi-historical fancy dress, or pulling faces at himself. His oil paintings trace the progress from an uncertain young man, through the dapper and very successful portrait-painter of the 1630s, to the troubled but massively powerful portraits of his old age. Together they give a remarkably clear picture of the man, his appearance and his psychological make-up, as revealed by his richly weathered face.[g]

In his portraits and self-portraits, he angles the sitter’s face in such a way that the ridge of the nose nearly always forms the line of demarcation between brightly illuminated and shadowy areas. A Rembrandt face is a face partially eclipsed; and the nose, bright and obvious, thrusting into the riddle of halftones, serves to focus the viewer’s attention upon, and to dramatize, the division between a flood of light—an overwhelming clarity—and a brooding duskiness.[66]

In a number of biblical works, including The Raising of the Cross, Joseph Telling His Dreams, and The Stoning of Saint Stephen, Rembrandt painted himself as a character in the crowd. Durham suggests that this was because the Bible was for Rembrandt «a kind of diary, an account of moments in his own life».[67]

Among the more prominent characteristics of Rembrandt’s work are his use of chiaroscuro, the theatrical employment of light and shadow derived from Caravaggio, or, more likely, from the Dutch Caravaggisti but adapted for very personal means.[68] Also notable are his dramatic and lively presentation of subjects, devoid of the rigid formality that his contemporaries often displayed, and a deeply felt compassion for mankind, irrespective of wealth and age. His immediate family—his wife Saskia, his son Titus and his common-law wife Hendrickje—often figured prominently in his paintings, many of which had mythical, biblical or historical themes.

Periods, themes and styles[edit]

Portrait of Haesje Jacobsdr. van Cleyburg (1634) completed during the height of his commercial success

Rembrandt van Rijn — Self-Portrait in a Flat Cap (1642) Royal Collection

Self Portrait (1658), now housed in the Frick Collection in New York City, has been described as «the calmest and grandest of all his portraits»[70]

Throughout his career, Rembrandt took as his primary subjects the themes of portraiture, landscape and narrative painting. For the last, he was especially praised by his contemporaries, who extolled him as a masterly interpreter of biblical stories for his skill in representing emotions and attention to detail.[71] Stylistically, his paintings progressed from the early «smooth» manner, characterized by fine technique in the portrayal of illusionistic form, to the late «rough» treatment of richly variegated paint surfaces, which allowed for an illusionism of form suggested by the tactile quality of the paint itself.[72]

A parallel development may be seen in Rembrandt’s skill as a printmaker. In the etchings of his maturity, particularly from the late 1640s onward, the freedom and breadth of his drawings and paintings found expression in the print medium as well. The works encompass a wide range of subject matter and technique, sometimes leaving large areas of white paper to suggest space, at other times employing complex webs of line to produce rich dark tones.[73]

Lastman’s influence on Rembrandt was most prominent during his period in Leiden from 1625 to 1631.[74] Paintings were rather small but rich in details (for example, in costumes and jewelry). Religious and allegorical themes were favored, as were tronies.[74] In 1626 Rembrandt produced his first etchings, the wide dissemination of which would largely account for his international fame.[74] In 1629 he completed Judas Repentant, Returning the Pieces of Silver and The Artist in His Studio, works that evidence his interest in the handling of light and variety of paint application, and constitute the first major progress in his development as a painter.[75]

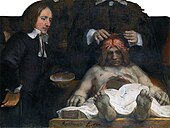

During his early years in Amsterdam (1632–1636), Rembrandt began to paint dramatic biblical and mythological scenes in high contrast and of large format (The Blinding of Samson, 1636, Belshazzar’s Feast, c. 1635 Danaë, 1636 but reworked later), seeking to emulate the baroque style of Rubens.[76] With the occasional help of assistants in Uylenburgh’s workshop, he painted numerous portrait commissions both small (Jacob de Gheyn III) and large (Portrait of the Shipbuilder Jan Rijcksen and his Wife, 1633, Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632).[77]

By the late 1630s, Rembrandt had produced a few paintings and many etchings of landscapes. Often these landscapes highlighted natural drama, featuring uprooted trees and ominous skies (Cottages before a Stormy Sky, c. 1641; The Three Trees, 1643). From 1640 his work became less exuberant and more sober in tone, possibly reflecting personal tragedy. Biblical scenes were now derived more often from the New Testament than the Old Testament, as had been the case before. In 1642 he painted The Night Watch, the most substantial of the important group portrait commissions which he received in this period, and through which he sought to find solutions to compositional and narrative problems that had been attempted in previous works.[78]

In the decade following the Night Watch, Rembrandt’s paintings varied greatly in size, subject, and style. The previous tendency to create dramatic effects primarily by strong contrasts of light and shadow gave way to the use of frontal lighting and larger and more saturated areas of color. Simultaneously, figures came to be placed parallel to the picture plane. These changes can be seen as a move toward a classical mode of composition and, considering the more expressive use of brushwork as well, may indicate a familiarity with Venetian art (Susanna and the Elders, 1637–47).[79]

At the same time, there was a marked decrease in painted works in favor of etchings and drawings of landscapes.[80] In these graphic works natural drama eventually made way for quiet Dutch rural scenes.

In the 1650s, Rembrandt’s style changed again. Colors became richer and brush strokes more pronounced. With these changes, Rembrandt distanced himself from earlier work and current fashion, which increasingly inclined toward fine, detailed works. His use of light becomes more jagged and harsh, and shine becomes almost nonexistent. His singular approach to paint application may have been suggested in part by familiarity with the work of Titian, and could be seen in the context of the then current discussion of ‘finish’ and surface quality of paintings. Contemporary accounts sometimes remark disapprovingly of the coarseness of Rembrandt’s brushwork, and the artist himself was said to have dissuaded visitors from looking too closely at his paintings.[81] The tactile manipulation of paint may hearken to medieval procedures, when mimetic effects of rendering informed a painting’s surface. The result is a richly varied handling of paint, deeply layered and often apparently haphazard, which suggests form and space in both an illusory and highly individual manner.[82]

In later years, biblical themes were often depicted but emphasis shifted from dramatic group scenes to intimate portrait-like figures (James the Apostle, 1661). In his last years, Rembrandt painted his most deeply reflective self-portraits (from 1652 to 1669 he painted fifteen), and several moving images of both men and women (The Jewish Bride, c. 1666)—in love, in life, and before God.[83][84]

Graphic works[edit]

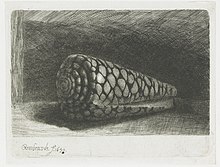

The Shell is the only still life Rembrandt ever etched.

Rembrandt produced etchings for most of his career, from 1626 to 1660, when he was forced to sell his printing-press and practically abandoned etching. Only the troubled year of 1649 produced no dated work.[85] He took easily to etching and, though he learned to use a burin and partly engraved many plates, the freedom of etching technique was fundamental to his work. He was very closely involved in the whole process of printmaking, and must have printed at least early examples of his etchings himself. At first he used a style based on drawing but soon moved to one based on painting, using a mass of lines and numerous bitings with the acid to achieve different strengths of line. Towards the end of the 1630s, he reacted against this manner and moved to a simpler style, with fewer bitings.[86] He worked on the so-called Hundred Guilder Print in stages throughout the 1640s, and it was the «critical work in the middle of his career», from which his final etching style began to emerge.[87]

Although the print only survives in two states, the first very rare, evidence of much reworking can be seen underneath the final print and many drawings survive for elements of it.[88]

In the mature works of the 1650s, Rembrandt was more ready to improvise on the plate and large prints typically survive in several states, up to eleven, often radically changed. He now used hatching to create his dark areas, which often take up much of the plate. He also experimented with the effects of printing on different kinds of paper, including Japanese paper, which he used frequently, and on vellum. He began to use «surface tone,» leaving a thin film of ink on parts of the plate instead of wiping it completely clean to print each impression. He made more use of drypoint, exploiting, especially in landscapes, the rich fuzzy burr that this technique gives to the first few impressions.[89]

His prints have similar subjects to his paintings, although the 27 self-portraits are relatively more common, and portraits of other people less so. There are forty-six landscapes, mostly small, which largely set the course for the graphic treatment of landscape until the end of the 19th century. One third of his etchings are of religious subjects, many treated with a homely simplicity, whilst others are his most monumental prints. A few erotic, or just obscene, compositions have no equivalent in his paintings.[90] He owned, until forced to sell it, a magnificent collection of prints by other artists, and many borrowings and influences in his work can be traced to artists as diverse as Mantegna, Raphael, Hercules Seghers, and Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione.

Drawings by Rembrandt and his pupils/followers have been extensively studied by many artists and scholars[h] through the centuries. His original draughtsmanship has been described as an individualistic art style that was very similar to East Asian old masters, most notably Chinese masters:[97] a «combination of formal clarity and calligraphic vitality in the movement of pen or brush that is closer to Chinese painting in technique and feeling than to anything in European art before the twentieth century».[98]

Asian inspiration[edit]

Self-Portrait with Raised Sabre (c. 1934)

Rembrandt was interested in Mughal miniatures, especially around the 1650s. He drew versions of some 23 Mughal paintings, and may have owned an album of them. These miniatures include paintings of Shah Jahan, Akbar, Jahangir and Dara Shikoh and may have influenced the costumes and other aspects of his works.[99][100][101][102]

The Night Watch[edit]

Rembrandt painted The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq between 1640 and 1642, which became his most famous work.[103] This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by 1781 the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of 18 musketeers stepping from a gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. For Théophile Thoré it was the prettiest painting in the world.

The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of the civic militia. Rembrandt departed from convention, which ordered that such genre pieces should be stately and formal, rather a line-up than an action scene. Instead he showed the militia readying themselves to embark on a mission, though the exact nature of the mission or event is a matter of ongoing debate.

Contrary to what is often said, the work was hailed as a success from the beginning. Parts of the canvas were cut off (approximately 20% from the left hand side was removed) to make the painting fit its new position when it was moved to Amsterdam town hall in 1715. In 1817 this large painting was moved to the Trippenhuis. Since 1885 the painting is on display at the Rijksmuseum.[i] In 1940 the painting was moved to Kasteel Radboud; in 1941 to a bunker near Heemskerk; in 1942 to St Pietersberg; in June 1945 it was shipped back to Amsterdam.

Expert assessments[edit]

In 1968, the Rembrandt Research Project began under the sponsorship of the Netherlands Organization for the Advancement of Scientific Research; it was initially expected to last a highly optimistic ten years. Art historians teamed up with experts from other fields to reassess the authenticity of works attributed to Rembrandt, using all methods available, including state-of-the-art technical diagnostics, and to compile a complete new catalogue raisonné of his paintings. As a result of their findings, many paintings that were previously attributed to Rembrandt have been removed from their list, although others have been added back.[105] Many of those removed are now thought to be the work of his students.

One example of activity is The Polish Rider, now housed in the Frick Collection in New York City. Rembrandt’s authorship had been questioned by at least one scholar, Alfred von Wurzbach, at the beginning of the twentieth century but for many decades later most scholars, including the foremost authority writing in English, Julius S. Held, agreed that it was indeed by the master. In the 1980s, however, Dr. Josua Bruyn of the Foundation Rembrandt Research Project cautiously and tentatively attributed the painting to one of Rembrandt’s closest and most talented pupils, Willem Drost, about whom little is known. But Bruyn’s remained a minority opinion, the suggestion of Drost’s authorship is now generally rejected, and the Frick itself never changed its own attribution, the label still reading «Rembrandt» and not «attributed to» or «school of». More recent opinion has shifted even more decisively in favor of the Frick; In his 1999 book Rembrandt’s Eyes, Simon Schama and the Rembrandt Project scholar Ernst van de Wetering (Melbourne Symposium, 1997) both argued for attribution to the master. Those few scholars who still question Rembrandt’s authorship feel that the execution is uneven, and favour different attributions for different parts of the work.[106]

A similar issue was raised by Schama concerning the verification of titles associated with the subject matter depicted in Rembrandt’s works. For example, the exact subject being portrayed in Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, recently retitled by curators at the Metropolitan Museum, has been directly challenged by Schama applying the scholarship of Paul Crenshaw.[107] Schama presents a substantial argument that it was the famous ancient Greek painter Apelles who is depicted in contemplation by Rembrandt and not Aristotle.[108]

Another painting, Pilate Washing His Hands, is also of questionable attribution. Critical opinion of this picture has varied since 1905, when Wilhelm von Bode described it as «a somewhat abnormal work» by Rembrandt. Scholars have since dated the painting to the 1660s and assigned it to an anonymous pupil, possibly Aert de Gelder. The composition bears superficial resemblance to mature works by Rembrandt but lacks the master’s command of illumination and modeling.[109]

The attribution and re-attribution work is ongoing. In 2005 four oil paintings previously attributed to Rembrandt’s students were reclassified as the work of Rembrandt himself: Study of an Old Man in Profile and Study of an Old Man with a Beard from a US private collection, Study of a Weeping Woman, owned by the Detroit Institute of Arts, and Portrait of an Elderly Woman in a White Bonnet, painted in 1640.[110] The Old Man Sitting in a Chair is a further example: in 2014, Professor Ernst van de Wetering offered his view to The Guardian that the demotion of the 1652 painting Old Man Sitting in a Chair «was a vast mistake…it is a most important painting. The painting needs to be seen in terms of Rembrandt’s experimentation». This was highlighted much earlier by Nigel Konstam who studied Rembrandt throughout his career.[111]

Rembrandt’s own studio practice is a major factor in the difficulty of attribution, since, like many masters before him, he encouraged his students to copy his paintings, sometimes finishing or retouching them to be sold as originals, and sometimes selling them as authorized copies. Additionally, his style proved easy enough for his most talented students to emulate. Further complicating matters is the uneven quality of some of Rembrandt’s own work, and his frequent stylistic evolutions and experiments.[112] As well, there were later imitations of his work, and restorations which so seriously damaged the original works that they are no longer recognizable.[113] It is highly likely that there will never be universal agreement as to what does and what does not constitute a genuine Rembrandt.

Painting materials[edit]

Technical investigation of Rembrandt’s paintings in the possession of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister[114] and in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Kassel)[115] was conducted by Hermann Kühn in 1977. The pigment analyses of some thirty paintings have shown that Rembrandt’s palette consisted of the following pigments: lead white, various ochres, Vandyke brown, bone black, charcoal black, lamp black, vermilion, madder lake, azurite, ultramarine, yellow lake and lead-tin-yellow. One painting (Saskia van Uylenburgh as Flora)[116] reportedly contains gamboge. Rembrandt very rarely used pure blue or green colors, the most pronounced exception being Belshazzar’s Feast[117][118] in the National Gallery in London. The book by Bomford[117] describes more recent technical investigations and pigment analyses of Rembrandt’s paintings predominantly in the National Gallery in London. The entire array of pigments employed by Rembrandt can be found at ColourLex.[119] The best source for technical information on Rembrandt’s paintings on the web is the Rembrandt Database containing all works of Rembrandt with detailed investigative reports, infrared and radiography images and other scientific details.[120]

Name and signature[edit]

«Rembrandt» is a modification of the spelling of the artist’s first name that he introduced in 1633. «Harmenszoon» indicates that his father’s name is Harmen. «van Rijn» indicates that his family lived near the Rhine.[121]

Rembrandt’s earliest signatures (c. 1625) consisted of an initial «R», or the monogram «RH» (for Rembrant Harmenszoon), and starting in 1629, «RHL» (the «L» stood, presumably, for Leiden). In 1632, he used this monogram early in the year, then added his family name to it, «RHL-van Rijn» but replaced this form in that same year and began using his first name alone with its original spelling, «Rembrant». In 1633 he added a «d», and maintained this form consistently from then on, proving that this minor change had a meaning for him (whatever it might have been). This change is purely visual; it does not change the way his name is pronounced. Curiously enough, despite the large number of paintings and etchings signed with this modified first name, most of the documents that mentioned him during his lifetime retained the original «Rembrant» spelling. (Note: the rough chronology of signature forms above applies to the paintings, and to a lesser degree to the etchings; from 1632, presumably, there is only one etching signed «RHL-v. Rijn,» the large-format «Raising of Lazarus,» B 73).[122] His practice of signing his work with his first name, later followed by Vincent van Gogh, was probably inspired by Raphael, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo who, then as now, were referred to by their first names alone.[123]

Workshop[edit]

Rembrandt ran a large workshop and had many pupils. The list of Rembrandt pupils from his period in Leiden as well as his time in Amsterdam is quite long, mostly because his influence on painters around him was so great that it is difficult to tell whether someone worked for him in his studio or just copied his style for patrons eager to acquire a Rembrandt. A partial list should include[124] Ferdinand Bol,

Adriaen Brouwer,

Gerrit Dou,

Willem Drost,

Heiman Dullaart,

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout,

Carel Fabritius,

Govert Flinck,

Hendrick Fromantiou,

Aert de Gelder,

Samuel Dirksz van Hoogstraten,

Abraham Janssens,

Godfrey Kneller,

Philip de Koninck,

Jacob Levecq,

Nicolaes Maes,

Jürgen Ovens,

Christopher Paudiß,

Willem de Poorter,

Jan Victors, and

Willem van der Vliet.

Museum collections[edit]

The most notable collections of Rembrandt’s work are at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, including The Night Watch and The Jewish Bride, the Mauritshuis in The Hague, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the National Gallery in London, Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, The Louvre, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, and Schloss Wilhelmshöhe in Kassel. The Royal Castle in Warsaw displays two paintings by Rembrandt.[125]

Notable collections of Rembrandt’s paintings in the United States are housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Frick Collection in New York City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.[126]

The Rembrandt House Museum in central Amsterdam in the house he bought at the height of his success, has furnishings that are mostly not original but period pieces comparable to those Rembrandt might have had, and paintings reflecting Rembrandt’s use of the house for art dealing. His printmaking studio has been set up with a printing press, where replica prints are printed. The museum has a few Rembrandt paintings, many loaned but an important collection of his prints, a good selection of which are on rotating display. All major print rooms have large collections of Rembrandt prints, although as some exist in only a single impression, no collection is complete. The degree to which these collections are displayed to the public, or can easily be viewed by them in the print room, varies greatly.

Influence and recognition[edit]

In 1775, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, then 25-years-old, wrote in a letter that «I live wholly with Rembrandt» («…ich zeichne, künstle p. Und lebe ganz mit Rembrandt.»). At the age of 81 (1831), Goethe wrote the essay «Rembrandt der Denker» («Rembrandt the Thinker»), published in his posthumous collection.[127][128]

[…] I maintain that it did not occur to Protogenes, Apelles or Parrhasius, nor could it occur to them were they return to earth that (I am amazed simply to report this) a youth, a Dutchman, a beardless miller, could bring together so much in one human figure and express what is universal. All honor to thee, my Rembrandt! To have carried Illium, indeed all Asia, to Italy is a lesser achievement than to have brought the laurels of Greece and Italy to Holland, the achievement of a Dutchman who has seldom ventured outside the walls of his native city…

— Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem, possibly the earliest known notable Rembrandt connoisseur and critic, 1629. Excerpt from the manuscript Autobiography of Constantijn Huygens (Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag), originally published in Oud Holland (1891), translated from the Dutch.[129]

Rembrandt is one of the most famous[130][131] and the best expertly researched visual artists in history.[132][133] His life and art have long attracted the attention of interdisciplinary scholarship such as art history, socio-political history,[134] cultural history,[135] education, humanities, philosophy and aesthetics,[136] psychology, sociology, literary studies,[137] anatomy,[138] medicine,[139] religious studies,[j][140] theology,[141] Jewish studies,[142] Oriental studies (Asian studies),[143] global studies,[144] and art market research.[145] He has been the subject of a vast amount of literature in genres of both fiction and nonfiction. Research and scholarship related to Rembrandt is an academic field in its own right with many notable connoisseurs and scholars[146] and has been very dynamic since the Dutch Golden Age.[132][147][133]

According to art historian and Rembrandt scholar Stephanie Dickey:

[Rembrandt] earned international renown as a painter, printmaker, teacher, and art collector while never leaving the Dutch Republic. In his home city of Leiden and in Amsterdam, where he worked for nearly forty years, he mentored generations of other painters and produced a body of work that has never ceased to attract admiration, critique, and interpretation. (…) Rembrandt’s art is a key component in any study of the Dutch Golden Age, and his membership in the canon of artistic genius is well established but he is also a figure whose significance transcends specialist interest. Literary critics have pondered «Rembrandt» as a «cultural text»; novelists, playwrights, and filmmakers have romanticized his life, and in popular culture, his name has become synonymous with excellence for products and services, ranging from toothpaste to self-help advice.[133]

Francisco Goya, often considered to be among the last of the Old Masters, said, «I have had three masters: Nature, Velázquez, and Rembrandt.» («Yo no he tenido otros maestros que la Naturaleza, Velázquez y Rembrandt.»)[148][149][150] In the history of the reception and interpretation of Rembrandt’s art, it was the significant Rembrandt-inspired ‘revivals’ or ‘rediscoveries’ in 18th–19th century France,[151][152] Germany,[153][154][155] and Britain[156][157][158][159] that decisively helped in establishing his lasting fame in subsequent centuries.[160] When a critic referred to Auguste Rodin’s busts in the same vein as Rembrandt’s portraits, the French sculptor responded: «Compare me with Rembrandt? What sacrilege! With Rembrandt, the colossus of Art! What are you thinking of, my friend! We should prostrate ourselves before Rembrandt and never compare anyone with him!”[11] Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo (1885), «Rembrandt goes so deep into the mysterious that he says things for which there are no words in any language. It is with justice that they call Rembrandt—magician—that’s no easy occupation.»[161]

Rembrandt and the Jewish world[edit]

The Jewish Bride (c. 1665–1669), now housed at Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. Vincent van Gogh’s wrote in 1885, «I should be happy to give 10 years of my life if I could go on sitting here in front of this picture (The Jewish Bride) fortnight, with only a crust of dry bread for food.» In a letter to his brother Theo, Vincent wrote, «What an intimate, what an infinitely sympathetic picture it is.»[162]

Although Rembrandt was not Jewish, he had a considerable influence on many modern Jewish artists, writers and scholars (art critics and art historians in particular).[163][164] The German-Jewish painter Max Liebermann said, «Whenever I see a Frans Hals, I feel like painting; whenever I see a Rembrandt, I feel like giving up.»[165] Marc Chagall wrote in 1922, «Neither Imperial Russia, nor the Russia of the Soviets needs me. They don’t understand me. I am a stranger to them,» and he added, «I’m certain Rembrandt loves me.»[166]

Rembrandt regarded the Bible as the greatest Book in the world and held it in reverent affection all his life, in affluence and poverty, in success and failure. He never wearied in his devotion to biblical themes as subjects for his paintings and other graphic presentations, and in these portrayals he was the first to have the courage to use the Jews of his environment as models for the heroes of the sacred narratives.

— Franz Landsberger, a German Jewish émigré to America, the author of Rembrandt, the Jews, and the Bible (1946)[167][168]

Criticism of Rembrandt[edit]

Rembrandt Memorial Marker in the Westerkerk section of Amsterdam

Rembrandt has also been one of the most controversial (visual) artists in history.[132][169] Several of Rembrandt’s notable critics include Constantijn Huygens, Joachim von Sandrart,[170] Andries Pels (who called Rembrandt «the first heretic in the art of painting»),[171] Samuel van Hoogstraten, Arnold Houbraken,[170] Filippo Baldinucci,[170] Gerard de Lairesse, Roger de Piles, John Ruskin,[172] and Eugène Fromentin.[169]

By 1875 Rembrandt was already a powerful figure, projecting from historical past into the present with such a strength that he could not be simply overlooked or passed by. The great shadow of the old master required a decided attitude. A late Romantic painter and critic, like Fromentin was, if he happened not to like some of Rembrandt’s pictures, he felt obliged to justify his feeling. The greatness of the dramatic old master was for artists of about 1875 not a matter for doubt. ‘Either I am wrong’, Fromentin wrote from Holland ‘or everybody else is wrong’. When Fromentin realized his inability to like some of the works by Rembrandt he formulated the following comments: ‘I even do not dare to write down such a blasphemy; I would get ridiculed if this is disclosed’. Only about twenty-five years earlier another French Romantic master Eugène Delacroix, when expressing his admiration for Rembrandt, has written in his Journal a very different statement: ‘… perhaps one day we will discover that Rembrandt is a much greater painter than Raphael. It is a blasphemy which would make hair raise on the heads of all the academic painters’. In 1851 the blasphemy was to put Rembrandt above Raphael. In 1875 the blasphemy was not to admire everything Rembrandt had ever produced. Between these two dates, the appreciation of Rembrandt reached its turning point and since that time he was never deprived of the high rank in the art world.

In popular culture[edit]

The Rembrandt statue in Leiden

[…] One thing that really surprises me is the extent to which Rembrandt exists as a phenomenon in pop culture. You have this musical group call [sic] the Rembrandts, who wrote the theme song to Friends—»I’ll Be There For You». There are Rembrandt restaurants, Rembrandt hotels, art supplies and other things that are more obvious. But then there’s Rembrandt toothpaste. Why on Earth would somebody name a toothpaste after this artist who’s known for his really dark tonalities? It doesn’t make a lot of sense. But I think it’s because his name has become synonymous with quality. It’s even a verb—there’s a term in underworld slang, ‘to be Rembrandted,’ which means to be framed for a crime. And people in the cinema world use it to mean pictorial effects that are overdone. He’s just everywhere, and people who don’t know anything, who wouldn’t recognize a Rembrandt painting if they tripped over it, you say the name Rembrandt and they already know that this is a great artist. He’s become a synonym for greatness.

— Rembrandt scholar, Stephanie Dickey, in an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, December 2006[131]

While shooting The Warrens of Virginia (1915), Cecil B. DeMille had experimented with lighting instruments borrowed from a Los Angeles opera house. When business partner Sam Goldwyn saw a scene in which only half an actor’s face was illuminated, he feared the exhibitors would pay only half the price for the picture. DeMille remonstrated that it was Rembrandt lighting. «Sam’s reply was jubilant with relief,» recalled DeMille. «For Rembrandt lighting the exhibitors would pay double!»[173]

Works about Rembrandt[edit]

Literary works (e.g. poetry and fiction)[edit]

- To the Picture of Rembrandt, a Russian-language poem by Mikhail Lermontov, 1830

- Gaspard de la nuit: Fantaisies à la manière de Rembrandt et de Callot, a series of French-language poems by Aloysius Bertrand, 1842

- Picture This, a novel by Joseph Heller, 1988

- Moi, la Putain de Rembrandt, a French-language novel by Sylvie Matton, 1998

- Van Rijn, a novel by Sarah Emily Miano, 2006

- I Am Rembrandt’s Daughter, a novel by Lynn Cullen, 2007

- The Rembrandt Affair, a novel by Daniel Silva, 2011

- The Anatomy Lesson, a novel by Nina Siegal, 2014

- Rembrandt’s Mirror, a novel by Kim Devereux, 2015

Films[edit]

- The Stolen Rembrandt, a 1914 film directed by Leo D. Maloney and J. P. McGowan

- The Tragedy of a Great / Die Tragödie eines Großen, a 1920 film directed by Arthur Günsburg

- The Missing Rembrandt, a 1932 film directed by Leslie S. Hiscott

- Rembrandt, a 1936 film directed by Alexander Korda

- Rembrandt, a 1940 film

- Rembrandt in de schuilkelder / Rembrandt in the Bunker, a 1941 film directed by Gerard Rutten

- Rembrandt, a 1942 film directed by Hans Steinhoff

- Rembrandt: A Self-Portrait, a 1954 documentary film by Morrie Roizman

- Rembrandt, schilder van de mens / Rembrandt, Painter of Man, a 1957 film directed by Bert Haanstra

- Rembrandt fecit 1669, a 1977 film directed by Jos Stelling

- Rembrandt: The Public Eye and the Private Gaze, a 1992 documentary film by Simon Schama

- Rembrandt, a 1999 film directed by Charles Matton

- Rembrandt: Fathers & Sons [it], a 1999 film directed by David Devine

- Stealing Rembrandt, a 2003 film directed by Jannik Johansen and Anders Thomas Jensen

- Simon Schama’s Power of Art: Rembrandt, a 2006 BBC documentary film series by Simon Schama

- Nightwatching, a 2007 film directed by Peter Greenaway

- Rembrandt’s J’Accuse, a 2008 documentary film by Peter Greenaway

- Rembrandt en ik [nl], a 2011 film directed by Marleen Gorris

- Schama on Rembrandt: Masterpieces of the Late Years, a 2014 documentary film by Simon Schama

- Rembrandt: From the National Gallery, London and Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, a 2014 documentary film by Exhibition on Screen

Selected works[edit]

The evangelist Matthew and the Angel (1661)

- The Stoning of Saint Stephen (1625) – Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon

- Andromeda Chained to the Rocks (1630) – Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Jacob de Gheyn III (1632) – Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

- Philosopher in Meditation (1632) – The Louvre, Paris

- The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) – Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Artemisia (1634) – oil on canvas, 142 × 152 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Descent from the Cross (1634) – oil on canvas, 158 × 117 cm, looted from the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), Germany in 1806, currently Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- Belshazzar’s Feast (1635) – National Gallery, London

- The Prodigal Son in the Tavern (c. 1635) – oil on canvas, 161 × 131 cm Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

- Danaë (1636 – c. 1643) – Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

- The Scholar at the Lectern (1641) – Royal Castle in Warsaw, Warsaw

- The Girl in a Picture Frame (1641) – Royal Castle, Warsaw

- The Night Watch, formally The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq (1642) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Christ Healing the Sick (etching c. 1643, also known as the Hundred Guilder Print), nicknamed for the huge sum paid for it

- Boaz and Ruth (1643) aka The Old Rabbi or Old Man – Woburn Abbey/Gemaldegalerie, Berlin

- The Mill (1645/48) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Old Man with a Gold Chain («Old Man with a Black Hat and Gorget«) (c. 1631) Art Institute of Chicago

- Susanna and the Elders (1647) – oil on panel, 76 × 91 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Head of Christ (c. 1648–56) – The Philadelphia Museum of Art[174]

- Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer (1653) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Bathsheba at Her Bath (1654) – The Louvre, Paris

- Christ Presented to the People (Ecce Homo) (1655) – Drypoint, Birmingham Museum of Art

- Selfportrait (1658) – Frick Collection, New York

- The Three Crosses (1660) Etching, fourth state

- Ahasuerus and Haman at the Feast of Esther (1660) – Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis (1661) – Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Claudius Civilis led a Dutch revolt against the Romans) (most of the cut up painting is lost, only the central part still exists)

- Portrait of Dirck van Os (1662) – Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska

- Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild (Dutch De Staalmeesters, 1662) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- The Jewish Bride (1665) – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Haman before Esther (1665) – National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest[175]

- The Entombment Sketch (c. 1639, reworked c. 1654) – oil on oak panel, Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, Glasgow

- Saul and David (c. 1660–1665) – Mauritshuis, The Hague

- Portrait of an Old Man (1645) – Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon

- Pallas Athena (c.1657) – Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon

Exhibitions[edit]

- Sept–Oct 1898: Rembrandt Tentoonstelling (Rembrandt Exhibition), Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.[176]

- Jan–Feb 1899: Rembrandt Tentoonstelling (Rembrandt Exhibition), Royal Academy, London, England.[176]

- 21 April 2011 – 18 July 2011: Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus, Musée du Louvre.[177]

- 16 September 2013 – 14 November 2013: Rembrandt: The Consummate Etcher, Syracuse University Art Galleries.[178]

- 19 May 2014 – 27 June 2014: From Rembrandt to Rosenquist: Works on Paper from the NAC’s Permanent Collection, National Arts Club.[179]

- 19 October 2014 – 4 January 2015: Rembrandt, Rubens, Gainsborough and the Golden Age of Painting in Europe, Jule Collins Smith Museum of Art.[180]

- 15 October 2014 – 18 January 2015: Rembrandt: The Late Works, The National Gallery, London.[181]

- 12 February 2015 – 17 May 2015: Late Rembrandt, The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.[182]

- 16 September 2018 – 6 January 2019: Rembrandt – Painter as Printmaker, Denver Art Museum, Denver.[183]

- 24 Aug 2019 – 1 December 2019: Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Kingston, Ontario.[184]

- 4 October 2019 – 2 February 2020: Rembrandt’s Light, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.[185]

- 18 February 2020 – 30 August 2020: Rembrandt and Amsterdam portraiture, 1590–1670 , Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.[186]

- 10 August 2020 – 1 November 2020: Young Rembrandt, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.[187]

Paintings[edit]

Self-portraits[edit]

-

-

Self-Portrait with Velvet Beret and Furred Mantle (1634)

-

-

-

Self-portrait (1655) an oil on walnut portrait cut down in size at. Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

-

-

-

Self-portrait (1669)

Other paintings[edit]

-

Bust of an old man with a fur hat, (1630), a painting of Rembrandt’s father

-

-

-

-

-

Portrait of Aeltje Uylenburgh (1632) at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston

-

-

Portrait of Saskia van Uylenburgh (c. 1633–34)

-

-

Susanna (1636)

-

-

Danaë (c. 1636-43) at Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

An Old Man in Red (c. 1652–54)

-

-

-

-

-

-

Woman in a Doorway (1657–1658)

-

-

-

-

-

-

Drawings and etchings[edit]

- Rembrandt drawings at the Albertina

-

Self-portrait, c. 1628–29, pen and brush and ink on paper

-

Self-portrait in a cap, with eyes wide open, 1630, etching and burin

-

An elephant, 1637, drawing in black chalk on paper, Albertina, Austria

-

Christ and the woman taken in adultery, c. 1639–41, drawing in ink, Louvre

-

The Windmill, 1641, etching

-

-

Two Old Men in Conversation /Two Jews in Discussion, Walking, year unknown, black chalk and brown ink on paper, Teylers Museum

-

A child being taught to walk (c. 1635). David Hockney said: «I think it’s the greatest drawing ever done… It’s a magnificent drawing, magnificent.»[94]

-

A young woman sleeping (c. 1654). Shows Rembrandt’s calligraphic-style draughtsmanship.[97][98]

Notes[edit]

- ^ This version of his first name, «Rembrandt» with a «d,» first appeared in his signatures in 1633. Until then, he had signed with a combination of initials or monograms. In late 1632, he began signing solely with his first name, «Rembrant». He added the «d» in the following year and stuck to this spelling for the rest of his life. Although scholars can only speculate, this change must have had a meaning for Rembrandt, which is generally interpreted as his wanting to be known by his first name like the great figures of the Italian Renaissance: Leonardo, Raphael etc., who did not sign with their last names, if at all.[12]

- ^ Rembrandt promised the owner — a woman with mental problems — to pay a quarter of the purchase price within a year;[26] the rest within five to six years. For some reason the purchase was not registered at the town hall and had to be renewed in 1653.[27]

- ^ Jan van de Capelle bought 500 of the drawings/prints by Lucas van Leyden, Hercules Seghers and Goltzius among others.

- ^ Useful totals of the figures from various different oeuvre catalogues, often divided into classes along the lines of: «very likely authentic», «possibly authentic» and «unlikely to be authentic» are given at the Online Rembrandt catalogue[62]

- ^ Two hundred years ago Bartsch listed 375. More recent catalogues have added three (two in unique impressions) and excluded enough to reach totals as follows: Schwartz, p. 6, 289; Münz 1952, 279; Boon 1963, 287 Print Council of America – but Schwartz’s total quoted does not tally with the book.

- ^ It is not possible to give a total, as a new wave of scholarship on Rembrandt drawings is still in progress – analysis of the Berlin collection for an exhibition in 2006/7 has produced a probable drop from 130 sheets there to about 60. Codart.nl[63] The British Museum is due to publish a new catalogue after a similar exercise.

- ^ While the popular interpretation is that these paintings represent a personal and introspective journey, it is possible that they were painted to satisfy a market for self-portraits by prominent artists. Van de Wetering, p. 290.

- ^ Such as Otto Benesch,[91][92][93] David Hockney,[94] Nigel Konstam, Jakob Rosenberg, Gary Schwartz, and Seymour Slive.[95][96]

- ^ The Rijksmuseum has a smaller copy of what is thought to be the full original composition.

- ^ It is important to note that Rembrandt’s religious affiliation was uncertain. There is little evidence that Rembrandt formally belonged to any Christian denomination.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Or possibly 1607 as on 10 June 1634 he himself claimed to be 26 years old. See Is the Rembrandt Year being celebrated one year too soon? One year too late? Archived 21 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine and (in Dutch) J. de Jong, Rembrandts geboortejaar een jaar te vroeg gevierd Archived 18 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine for sources concerning Rembrandt’s birth year, especially supporting 1607. However, most sources continue to use 1606.

- ^ «Rembrandt» Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ See: list of drawings, prints (etchings), and paintings by Rembrandt.

- ^ a b Gombrich, p. 420.

- ^ Gombrich, p. 427.

- ^ Clark 1969, pp. 203

- ^ Robert Fucci (2020) Rembrandt and the Business of Prints

- ^ https://www.parkwestgallery.com/how-rembrandt-van-rijn-changed-etching-forever/

- ^ Clark 1969, pp. 203–204

- ^ Clark 1969, pp. 205

- ^ a b Rodin, Auguste: Art: Conversations with Paul Gsell. Translated from the French by Jacques de Caso and Patricia B. Sanders. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984) ISBN 0-520-03819-3, p. 85. Originally published as Auguste Rodin, L’Art: Entretiens réunis par Paul Gsell (Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1911). Auguste Rodin: «Me comparer à Rembrandt, quel sacrilège! À Rembrandt, le colosse de l’Art! Y pensez-vous, mon ami! Rembrandt, prosternons-nous et ne mettons jamais personne à côté de lui!” (original in French)

- ^ «Rembrandt Signature Files». www.rembrandt-signature-file.com. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016.

- ^ Bull, et al., p. 28.

- ^ «Doopregisters, Zoek» (in Dutch). Stadsarchief.amsterdam.nl. 3 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b (in Dutch) Rembrandt biography in De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (1718) by Arnold Houbraken, courtesy of the Digital library for Dutch literature

- ^ Joris van Schooten as teacher of Rembrandt and Lievens Archived 26 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Simon van Leeuwen’s Korte besgryving van het Lugdunum Batavorum nu Leyden, Leiden, 1672

- ^ Rembrandt biography Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, nationalgallery.org.uk

- ^ Erhardt, Michelle A., and Amy M. Morris. 2012. Mary Magdalene, Iconographic Studies from the Middle Ages to the Baroque Archived 8 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Boston : Brill. p. 252. ISBN 978-90-04-23195-5.

- ^ Slive has a comprehensive biography, pp. 55ff.

- ^ Slive, pp. 60, 65

- ^ Slive, pp. 60–61

- ^ «Netherlands, Noord-Holland Province, Church Records, 1553–1909 Image Netherlands, Noord-Holland Province, Church Records, 1553–1909; pal:/MM9.3.1/TH-1971-31164-16374-68». Familysearch.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Registration of the banns of Rembrandt and Saskia, kept at the Amsterdam City Archives

- ^ a b c Bull, et al., p. 28

- ^ P. Schatborn, 2017, ‘Rembrandt van Rijn, Bedroom with Saskia in Bed, Amsterdam, c. 1638’, in J. Turner (ed.), Drawings by Rembrandt and his School in the Rijksmuseum, online coll. cat. Amsterdam: hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.28131 (accessed 21 February 2023 21:58:38).

- ^ Vijftien strekkende meter: Nieuwe onderzoeksmogelijkheden in het archief van … edited by Wim van Anrooij, Paul Hoftijzer, p. 18-23

- ^ J.F. Backer (1919) Rembrandt’s boedelafstand. DBNL

- ^ Adams, p. 660

- ^ a b Slive, p. 71

- ^ P. Schatborn, 2017, ‘Rembrandt van Rijn, Bedroom with Saskia in Bed, Amsterdam, c. 1638’, in J. Turner (ed.), Drawings by Rembrandt and his School in the Rijksmuseum, online coll. cat. Amsterdam: hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.28131 (accessed 21 February 2023 21:58:38).

- ^ Crenshaw, Paul (2006). Rembrandt’s bankruptcy: the artist, his patrons, and the art market in seventeenth-century Nederlands. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 9780521858250. OCLC 902528433.

- ^ Driessen, pp. 151–57

- ^ Slive, p. 82

- ^ https://voetnoot.org/tag/rembrandt/

- ^ Broos, B. (1999) Das Leben Rembrandts van Rijn (1606-1669). In: Rembrandt Selbstbildnisse, p. 79.

- ^ M. Bosman (2019) Rembrandts plan. De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement

- ^ J.F. Backer (1919) Rembrandt’s boedelafstand. DBNL

- ^ J.F. Backer (1919) Rembrandt’s boedelafstand. DBNL

- ^ Schwartz (1984), p. 288-291

- ^ Slive, p. 84

- ^ Voorstudies van Misset met plattegrond van de Roomolengang tussen Rozengracht 184-192Rozengracht 146-222

- ^ A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings IV: Self-Portraits edited by Ernst van de Wetering, p. 342

- ^ Kwijtscheldingen, archiefnummer 5061, inventarisnummer 2170

- ^ Clark, 1974 p. 105

- ^ De geldzaken van Rembrandt

- ^ Clark 1974, pp. 60–61

- ^ Bull, et al., p. 29.

- ^ M. Bosman (2019) Rembrandts plan. De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement

- ^ Jan Veth (1906) Rembrandt’s verwarde zaken DBNL

- ^ Ruysscher, D. D., & ‘T Veld, C. I. (2021). Rembrandt’s insolvency: The artist as legal actor, Oud Holland–Journal for Art of the Low Countries, 134(1), 9–24. Archived 7 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hof van Holland, Zeeland en West-Friesland by Maria-Charlotte le Bailly, p. 97

- ^ Wexuan, Li. «Review of: ‘Rembrandts plan: De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement», Oud Holland Reviews, April 2020.

- ^ Whitewashing Rembrandt, part 2

- ^ Clark 1978, p. 34

- ^ Burial register of the Westerkerk with record of Rembrandt’s burial, kept at the Amsterdam City Archives

- ^ https://www.vondel.humanities.uva.nl/ecartico/persons/8528

- ^ Dudok van Heel, S.A.C. (1987) Dossier Rembrandt, p. 86-88

- ^ Bob Wessels (2021) ‘Rembrandt’s Money. The legal and financial life of an artist-entrepreneur in 17th century Holland’.

- ^ Hughes, p. 6

- ^ «A Web Catalogue of Rembrandt Paintings». 28 July 2012. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012.

- ^ «Institute Member Login – Institute for the Study of Western Civilization». Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ «A Web Catalogue of Rembrandt Paintings». Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ «Rembrandt, der Zeichner». Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- ^ «Schwartzlist 301 – Blog entry by the Rembrandt scholar Gary Schwartz». Garyschwartzarthistorian.nl. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ White and Buvelot 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Taylor, Michael (2007).Rembrandt’s Nose: Of Flesh & Spirit in the Master’s Portraits Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 21, D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc., New York ISBN 978-1-933045-44-3′

- ^ Durham, p. 60.

- ^ Bull, et al., pp. 11–13.

- ^ Clough, p. 23

- ^ Clark 1978, p. 28

- ^ van der Wetering, p. 268.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 160, 190.

- ^ Ackley, p. 14.

- ^ a b c van de Wetering, p. 284.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 285.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 287.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 286.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 288.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 163–65.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. 289.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 155–65.

- ^ van de Wetering, pp. 157–58, 190.

- ^ «In Rembrandt’s (late) great portraits we feel face to face with real people, we sense their warmth, their need for sympathy and also their loneliness and suffering. Those keen and steady eyes that we know so well from Rembrandt’s self-portraits must have been able to look straight into the human heart.» Gombrich, p. 423.

- ^ «It (The Jewish Bride) is a picture of grown-up love, a marvelous amalgam of richness, tenderness, and trust… the heads which, in their truth, have a spiritual glow that painters influenced by the classical tradition could never achieve.» Clark, p. 206.

- ^ Schwartz, 1994, pp. 8–12

- ^ White 1969, pp. 5–6

- ^ White 1969, p. 6

- ^ White 1969, pp. 6, 9–10

- ^ White, 1969 pp. 6–7

- ^ See Schwartz, 1994, where the works are divided by subject, following Bartsch.

- ^ Benesch, Otto: The Drawings of Rembrandt: First Complete Edition in Six Volumes. (London: Phaidon, 1954–57)

- ^ Benesch, Otto: Rembrandt as a Draughtsman: An Essay with 115 Illustrations. (London: Phaidon Press, 1960)

- ^ Benesch, Otto: The Drawings of Rembrandt. A Critical and Chronological Catalogue [2nd ed., 6 vols.]. (London: Phaidon, 1973)

- ^ a b Lewis, Tim (16 November 2014). «David Hockney: ‘When I’m working, I feel like Picasso, I feel I’m 30’«. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

David Hockney (2014): «There’s a drawing by Rembrandt, I think it’s the greatest drawing ever done. It’s in the British Museum and it’s of a family teaching a child to walk, so it’s a universal thing, everybody has experienced this or seen it happen. Everybody. I used to print out Rembrandt drawings big and give them to people and say: ‘If you find a better drawing send it to me. But if you find a better one it will be by Goya or Michelangelo perhaps.’ But I don’t think there is one actually. It’s a magnificent drawing, magnificent.»

- ^ Slive, Seymour: The Drawings of Rembrandt: A New Study. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009)

- ^ Silve, Seymour: The Drawings of Rembrandt. (London: Thames & Hudson, 2019)

- ^ a b Mendelowitz, Daniel Marcus: Drawing. (New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc., 1967), p. 305. As Mendelowitz (1967) noted: «Probably no one has combined to as great a degree as Rembrandt a disciplined exposition of what his eye saw and a love of line as a beautiful thing in itself. His «Winter Landscape» displays the virtuosity of performance of an Oriental master, yet unlike the Oriental calligraphy, it is not based on an established convention of brush performance. It is as personal as handwriting.»

- ^ a b Sullivan, Michael: The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art. (Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989), p. 91

- ^ Schrader, Stephanie; et al. (eds.): Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. (Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018) ISBN 978-1-60606-552-5

- ^ «Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India (catalogue)» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ «In Paintings: Rembrandt & his Mughal India Inspiration». 3 September 2017. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ Ganz, James (2013). Rembrandt’s Century. San Francisco, CA: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-7913-5224-4.

- ^ Beliën, H & P. Knevel (2006) Langs Rembrandts roem, p. 92-121

- ^ John Russell (1 December 1985). «Art View; In Search of the Real Thing». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ «The Rembrandt Research Project: Past, Present, Future» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ See «Further Battles for the ‘Lisowczyk’ (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt» Zdzislaw Zygulski, Jr., Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 21, No. 41 (2000), pp. 197–205. Also New York Times story Archived 8 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. There is a book on the subject:Responses to Rembrandt; Who painted the Polish Rider? by Anthony Bailey (New York, 1993)

- ^ Schama, Simon (1999). Rembrandt’s Eyes. Knopf, p. 720.

- ^ Schama, pp 582–591.

- ^ «Rembrandt Pilate Washing His Hands Oil Painting Reproduction». Outpost Art. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ «Entertainment | Lost Rembrandt works discovered». BBC News. 23 September 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ Brown, Mark (23 May 2014), «Rembrandt expert urges National Gallery to rethink demoted painting», The Guardian, archived from the original on 21 September 2016, retrieved 21 December 2015

- ^ «…Rembrandt was not always the perfectly consistent, logical Dutchman he was originally anticipated to be.» Ackley, p. 13.

- ^ van de Wetering, p. x.

- ^ Kühn, Hermann. ‘Untersuchungen zu den Pigmenten und Malgründen Rembrandts, durchgeführt an den Gemälden der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden'(Examination of pigments and grounds used by Rembrandt, analysis carried out on paintings in the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden), Maltechnik/Restauro, issue 4 (1977): 223–233

- ^ Kühn, Hermann. ‘Untersuchungen zu den Pigmenten und Malgründen Rembrandts, durchgeführt an den Gemälden der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Kassel’ (Examination of pigments and grounds used by Rembrandt, analysis carried out on paintings in the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Kassel), Maltechnik/Restauro, volume 82 (1976): 25–33

- ^ Rembrandt, Saskia as Flora Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, ColourLex

- ^ a b Bomford, D. et al., Art in the making: Rembrandt, New edition, Yale University Press, 2006

- ^ Rembrandt, Belshazzar’s Feast, Pigment analysis Archived 7 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine at ColourLex

- ^ «Resources Rembrandt». ColourLex. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ «The Rembrandt Database». Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Russell. Rembrandt. Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2009. ISBN 978-1-61228-760-7. p. 13.

- ^ Chronology of his signatures (pdf) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine with examples. Source: www.rembrandt-signature-file.com

- ^ Slive, p. 60

- ^ Rembrandt pupils (under Leraar van) in the RKD

- ^ «The Lanckoroński Collection – Rembrandt’s Paintings». zamek-krolewski.pl. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

The works of art which Karolina Lanckorońska gave to the Royal Castle in 1994 was one of the most invaluable gift’s made in the museum’s history.

- ^ Clark 1974, pp. 147–50. See the catalogue in Further reading for the location of all accepted Rembrandts

- ^ Münz, Ludwig: Die Kunst Rembrandts und Goethes Sehen. (Leipzig: Verlag Heinrich Keller, 1934)

- ^ Van den Boogert, B.; et al.: Goethe en Rembrandt. Tekeningen uit Weimar. Uit de grafische bestanden van de Kunstsammlungen zu Weimar, aangevuld met werken uit het Goethe-Nationalmuseum. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1999)

- ^ Binstock, Benjamin: Vermeer’s Family Secrets: Genius, Discovery, and the Unknown Apprentice. (New York, NY: Routledge, 2009), p. 330

- ^ *Golahny, Amy (2001), ‘The Use and Misuse of Rembrandt: An Overview of Popular Reception Archived 8 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine,’. Dutch Crossing: Journal of Low Countries Studies 25(2): 305–322

- Solman, Paul (21 June 2004). «Rembrandt’s Journey». PBS.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

Paul Solman (2004): «[Rembrandt] The most famous brand name in western art. In America alone it graces toothpaste, bracelet charms, restaurant and bars, counter-tops and of course the town of Rembrandt, Iowa just halfway around the world from the Rembrandt Hotel in Bangkok, Thailand.»

- Valiunas, Algis (25 December 2006). «Looking at Rembrandt». The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

Algis Valiunas (2006): «Alongside Leonardo and Michelangelo, Rembrandt is one of the three most famous artists ever, with whom the public is on a first-name basis; and the name Rembrandt has lent the cachet of greatness and the grace of familiarity to sell everything from kitchen countertops to whitening toothpaste to fancy hotels in Bangkok and Knightsbridge.»

- Solman, Paul (21 June 2004). «Rembrandt’s Journey». PBS.org. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ a b Crawford, Amy (12 December 2006). «An Interview with Stephanie Dickey, author of «Rembrandt at 400»«. Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Slive, Seymour: Rembrandt and his Critics, 1630–1730. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1953)

- ^ a b c Franits, Wayne (ed.): The Ashgate Research Companion to Dutch Art of the Seventeenth Century. (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2016)

- ^ *Negri, Antonio: The Savage Anomaly: The Power of Spinoza’s Metaphysics and Politics. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991).

- Ahmad, Iftikhar (2008), ‘Art in Social Studies: Exploring the World and Ourselves with Rembrandt,’. The Journal of Aesthetic Education 42(2): 19–37

- Molyneux, John (5 July 2019). «The Dialectics of Art». Rebelnews.ie (2019). Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Bab, Julius: Rembrandt und Spinoza. Ein Doppelbildnis im deutsch-jüdischen Raum. (Berlin: Philo-Verlag, 1934)

- Valentiner, Wilhelm R.: Rembrandt and Spinoza: A Study of the Spiritual Conflicts in Seventeenth-Century Holland. (London: Phaidon Press, 1957)

- Streiff, Bruno: Le Peintre et le Philosophe ou Rembrandt et Spinoza à Amsterdam. (Paris: Éditions Complicités, 2002) ISBN 978-2-910721-34-3

- ^ *Simmel, Georg: Rembrandt: Ein kunstphilodophischer Versuch. (Leipzig: K. Wolff Verlag, 1916)

- Simmel, Georg: Rembrandt: An Essay in the Philosophy of Art. Translated and edited by Alan Scott and Helmut Staubmann. (New York: Routledge, 2005)