Как гитарист, специализирующийся на рок-музыке, я постоянно работаю, стараясь написать отличный гитарный рифф. Как мне кажется, в современной музыке такое понятие, как гитарный рифф ушло на второй план и несколько потеряло в своей индивидуальности. Вот некоторые советы начинающим гитаристам, как написать отличный гитарный рифф.

Когда я говорил о потере индивидуальности, я не шутил. Нет, серьезно, как давно вы слышали отличный запоминающийся рифф? Наверное, мало кто сможет возразить, если я скажу, что хороший и интересный рифф – важнейший ингридиент при работе над любой рок или метал-песней. Ниже я не расскажу, что нужно сделать, чтобы рифф стал интересным, но дам некоторые советы начинающим гитаристам, которые помогут писать более качественные гитарные партии.

Не используйте только пауэр-аккорды

У большинства гитаристов есть своего рода “мозоль” при сочинении риффов – использование только “паэур-аккордов”. Сотни и тысячи гитаристов ставят указательный и безымянный пальцы на ладах в виде таких аккордов и “елозят” по всему грифу словно зомби.

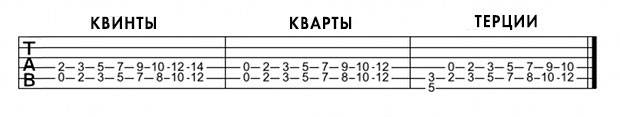

Конечно, такие аккорды звучат мощно. Вместе с тем, такой подход к делу говорит о недостатке знаний и музыкальности (читай, музыкального образования). Мои риффы стали намного разнообразнее, когда я осознал, что пауэр-аккорды не более, чем интервал – квинта. Поняв это, я начал чаще размышлять над использованием и других интервалов. Так мне открылось знание того, что можно активно применять терции и кварты для написания риффов.

Сочиняя гитарный рифф, стоит уменьшить количество квинтовых аккордов до минимума, только если наличие таких трезвучий не будет крайне необходимым. Ну а чтобы легче понять, о чем я говорю, приведу небольшой пример в помощь.

Придумывайте гитарный рифф с учетом всех инструментов

Сочиняя новый рифф, я всегда думаю о том, как он будет звучать в контексте полного набора музыкальных инструментов рок-группы. Оглядываясь на весь коллектив, можно понять, что квинтовые аккорды далеко не всегда звучат идеально, что автоматически возвращает нас к предыдущему совету.

Зачастую, записав в студии даблтрек электрогитары с дисторшн, чья партия целиком и полностью состоит из квинтовых аккордов, можно заметить, что партия бас-гитары, играющая те же ноты начинает портить песню, появляется какая-то музыкальная “каша”. Почему бы не попробовать играть рифф квартами, пока бас-гитара играет основные звуки аккордов? Такой подход даст свой результат: бас задаст тон аккорда, а музыка не будет напоминать кашу.

Бас-гитара не должна повторять партию ритм-гитары

Партия баса, нота в ноту повторяющая партию ритм-гитары, является крайне распространенной проблемой гитаристов. Вспомним предыдущий совет: даблтрек гитары с квинтовыми аккордами и басом приведет к образованию каши. Возникает вопрос: если бас играет все то же, что и ритм-гитара, то зачем он нужен? Попробуйте разделить партии баса и электрогитары, экспериментируйте с ритмами и динамикой.

С другой стороны, не стоит воспринимать данный совет, как некое нерушимое правило. Бывают моменты, когда всем инструментам просто-таки необходимо сыграть вместе одинаковые партии.

Подумайте, какие звуки нужны в аккорде

Игра полноценных аккордов через примочку или отличный усилитель с невероятно мощным перегрузом звучит несколько грязновато. Стоит попробовать разделить аккорды, отбросить лишние звуки из них.

К примеру, возьмем аккорд Ля-минор (Am), который состоит из звуков Ля, До и Ми. Эти ноты, сыгранные вместе, да еще и с перегрузом, могут не давать той самой мощи аккорда. Как насчет того, чтобы отбросить звук Ми наверху, оставив только Ля и До? Аккорд не изменится, но станет мощнее.

В то же самое время, стоит поэкспериментировать с разными звуками аккордов. Возвращаясь к нашему Ля-минору: что если оставить Ля и Ми, До и Ми и т.д.? Эксперименты и контекст песни помогут определиться с выбором.

Придайте гитарным риффам больше музыкальности

Многие наверняка знают, что один и тот же аккорд можно взять совершенно в разных позициях. Это значительно упрощает жизнь музыкантам, так как отпадает необходимость в скачках по всему грифу между двумя разными аккордами. Плюс ко всему, это может помочь разнообразить музыку.

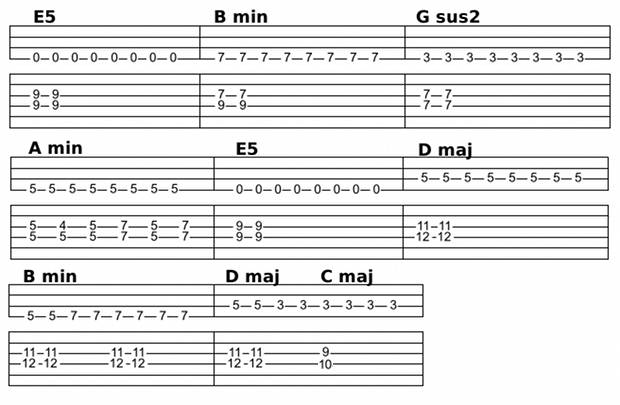

Я уже говорил, что гитарный рифф должен писаться с учетом остальных инструментов музыкальной группы. Если бас играет ноту Ми, которая звучит очень низко, то стоит перенести партию гитары выше. Стоит экспериментировать с разными позициями одних и тех же аккордов, чтобы добиться максимальной музыкальности гитарных партий. Посмотрим на простом примере.

На изображении выше показаны совмещенные партии баса и ритм-гитары. Партия гитары постоянно находится выше, чтобы не мешать звучанию баса. Низкий звук баса вместе с низким звучанием гитарного аккорда – не всегда лучшее решение. Перенеся партию выше, мы расширили музыкальность нашего примера.

Как видите, написать отличный гитарный рифф не так-то просто. Надеемся, что эти советы начинающим музыкантам в значительной степени помогут вам повысить качество собственных риффов, а значит и сделают музыку более интересной.

Guitar strum Play (help·info): pattern created by subtracting the second and fifth (of eight) eighth notes from a pattern of straight eighth notes.

In music performances, rhythm guitar is a technique and role that performs a combination of two functions: to provide all or part of the rhythmic pulse in conjunction with other instruments from the rhythm section (e.g., drum kit, bass guitar); and to provide all or part of the harmony, i.e. the chords from a song’s chord progression, where a chord is a group of notes played together. Therefore, the basic technique of rhythm guitar is to hold down a series of chords with the fretting hand while strumming or fingerpicking rhythmically with the other hand. More developed rhythm techniques include arpeggios, damping, riffs, chord solos, and complex strums.

In ensembles or bands playing within the acoustic, country, blues, rock or metal genres (among others), a guitarist playing the rhythm part of a composition plays the role of supporting the melodic lines and improvised solos played on the lead instrument or instruments, be they strings, wind, brass, keyboard or even percussion instruments, or simply the human voice, in the sense of playing steadily throughout the piece, whereas lead instruments and singers switch between carrying the main or countermelody and falling silent. In big band music, the guitarist is considered part of the rhythm section, alongside bass and drums.

In some musical situations, such as a solo singer-guitarist, the guitar accompaniment provides all the rhythmic drive; in large ensembles it may be only a small part (perhaps one element in a polyrhythm). Likewise, rhythm guitar can supply all of the harmonic input to a singer-guitarist or small band, but in ensembles that have other harmony instruments (such as keyboards) or vocal harmonists, its harmonic input will be less important.

In the most commercially available and consumed genres, electric guitars tend to dominate their acoustic cousins in both the recording studio and live venues. However the acoustic guitar remains a popular choice in country, western and especially bluegrass music, and almost exclusively in folk music.

Rock and pop[edit]

Rock and pop rhythms[edit]

Most rhythms in rock and blues are based on 4/4 time with a backbeat; however, many variations are possible. A backbeat is a syncopated accentuation on the «off» beat. In a simple 4/4 rhythm these are beats 2 and 4.[2] Emphasized back beat, a feature of some African styles, defined rhythm and blues recordings in the late 1940s and so became one of the defining characteristics of rock and roll and much of contemporary popular music.

Rock and pop harmony[edit]

Harmonically, in rock music, the most common way to construct chord progressions is to play major and minor «triads», each comprising a root, third and fifth note of a given scale. An example of a major triad is C major, which contains the notes C, E and G. An example of a minor triad is the A minor chord, which includes the notes A, C and E. Interspersed are some four-note chords, which include the root, third and fifth, as well as a sixth, seventh or ninth note of the scale. The most common chord with four different notes is the dominant seventh chord, which include a root, a major third above the root, a perfect fifth above the root and a flattened seventh. In the key of C major, the dominant seventh chord is a G7, which consists of the notes G, B, D and F.

Three-chord progressions are common in earlier pop and rock, using various combinations of the I, IV and V chords, with the twelve-bar blues particularly common. A four chord progression popular in the 1950s is I-vi-ii-V, which in the key of C major is the chords C major, a minor, d minor and G7. Minor and modal chord progressions such as I-bVII-bVI (in the key of E, the chords E major, D major, C major) feature in popular music.

A power chord in E for guitar. This contains the notes E, B (a fifth above) and an E an octave higher.

In heavy metal music, rhythm guitarists often play power chords, which feature a root note and a fifth above, or with an octave doubling the root. There actually is no third of the chord. Power chords are usually played with distortion.

Arpeggios[edit]

One departure from the basic strummed chord technique is to play arpeggios, i.e. to play individual notes in a chord separately. If this is rapidly done enough, listeners will still hear the sequence as harmony rather than melody. Arpeggiation is often used in folk, country, and heavy metal, sometimes in imitation of older banjo technique. It is also prominent in 1960s pop, such as The Animals’ «House of the Rising Sun», and jangle pop from the 1980s onwards. Rhythm guitarists who use arpeggio often favor semi-acoustic guitars and twelve string guitars to get bright, undistorted «jangly» sound.

The Soukous band TPOK Jazz additionally featured the unique role of mi-solo, (meaning «half solo») guitarist, playing arpeggio patterns and filling a role «between» the lead and rhythm guitars.[3]

Riffs[edit]

In some cases, the chord progression is implied with a simplified sequence of two or three notes, sometimes called a «riff». That sequence is repeated throughout the composition. In heavy metal music, this is typically expanded to more complex sequences comprising a combination of chords, single notes and palm muting. The rhythm guitar part in compositions performed by more technically oriented bands often include riffs employing complex lead guitar techniques. In some genres, especially metal, the audio signal from the rhythm guitar’s output is often subsequently heavily distorted by overdriving the guitar’s amplifier to create a thicker, «crunchier» sound for the palm-muted rhythms.

Interaction with other guitarists[edit]

In bands with two or more guitarists, the guitarists may exchange or even duplicate roles for various songs or several sections within a song. In those with a single guitarist, the guitarist may play lead and rhythm at numerous times or simultaneously, by overlaying the rhythm sequence with a lead line.

Crossover with keyboards[edit]

The availability of electronic effects units such as delay pedals and reverb units enables electric guitarists to play arpeggios and take over some of the role of a synthesizer player in performing sustained «pads». Those serve as sonic backgrounds in modern pop. Creating a pad sound differs from usual rhythm guitar roles in that it is not rhythmic. Some bands have a synthesizer performer play pads. In bands without a synth player, a guitarist can take over this role.

Replacing lead guitar[edit]

Some rhythm techniques cross over into lead guitar playing. In guitar-bass-and-drums power trios guitarists must double up between rhythm and lead. For instance Jimi Hendrix combined full chords with solo licks, double stops and arpeggios. In the 2010s, «looping pedals» are used to record a chord sequence or riff over which musicians can then play the lead line, simulating the sound achieved by having two guitarists.

Equipment[edit]

Rhythm guitarists usually aim to generate a stronger rhythmic and chordal sound, in contrast to the lead guitarists’ goal of producing a sustained, high-pitched melody line that listeners can hear over the top of the band. As a result, rhythm and lead players may use different guitars and amplifiers. Rhythm guitarists may employ an electric acoustic guitar or a humbucker-equipped electric guitar for a richer and fatter output. Also, rhythm guitarists may use strings of a larger gauge than those used by lead guitarists. However, while these may be practices, they are not necessarily the rule and are subject to the style of the song and the preference of the individual guitarist.

While rhythm guitarists in metal bands use distortion effects, they tend to use less of the modulation effects such as flangers used by lead guitar players. Whereas the lead guitarist in a metal band is trying to make the solo tone more prominent, and thus uses a range of colorful effects, the rhythm guitarist is typically trying to provide a thick, solid supporting sound that blends in with the overall sound of the group. In alternative rock and post punk bands, however, where the band is trying to create an ambient soundscape rather than an aggressive Motörhead-style «Wall of Sound», the rhythm guitarist may use flanging and delay effects to create a shimmering background.

Jazz[edit]

Rhythm guitar has been especially important in the development of jazz. The guitar took over the role previously occupied by the banjo to provide rhythmic chordal accompaniment.

Early jazz guitarists like Freddie Green tended to emphasize the percussive quality of the instrument. The ability to keep a steady rhythm while playing through complicated chord patterns made the guitar invaluable to many rhythm sections. Jazz guitarists are expected to have deep knowledge of harmony.

Jazz harmony[edit]

Jazz guitarists use their knowledge of harmony and jazz theory to create jazz chord «voicings», which emphasize the 3rd and 7th notes of the chord. Unlike pop and rock guitarists, who typically include the root of a chord (even, with many open chords and barre chords, doubling the root), jazz guitarists typically omit the root. Some more sophisticated chord voicings also include the 9th, 11th, and 13th notes of the chord. A typical jazz voicing for the chord G7 would be the individual notes B, E, F, and A. This voicing uses the 3rd (the note B), the 7th (the note F), along with the 6th (the note E) and the 9th (the note A).

In some modern jazz styles, dominant 7th chords in a tune may contain altered 9ths (either flattened by a semitone, which is called a «flat 9th», or sharpened by a semitone, which is called a «sharp 9th»); 11ths (sharpened by a semitone, which is called a «sharp 11th»); 13ths (typically flattened by a semitone, which is called a «flat 13th»).

Jazz guitarists need to learn about a range of different chords, including major 7th, major 6th, minor 7th, minor/major 7th, dominant 7th, diminished, half-diminished, and augmented chords. As well, they need to learn about chord transformations (e.g., altered chords, such as «alt dominant chords» described above), chord substitutions, and re-harmonization techniques. Some jazz guitarists use their knowledge of jazz scales and chords to provide a walking bass-style accompaniment.

Jazz guitarists learn to perform these chords over the range of different chord progressions used in jazz, such as the II-V-I progression, the jazz-style blues progression, the minor jazz-style blues form, the «rhythm changes» progression, and the variety of chord progressions used in jazz ballads, and jazz standards. Guitarists may also learn to use the chord types, strumming styles, and effects pedals (e.g., chorus effect or fuzzbox) used in 1970s-era jazz-Latin, jazz-funk, and jazz-rock fusion music.

Big band rhythm[edit]

In jazz big bands, popular during the 1930s and 1940s, the guitarist is considered an integral part of the rhythm section (guitar, drums and bass). They usually played a regular four chords to the bar, although an amount of harmonic improvisation is possible. Freddie Green, guitarist in the Count Basie orchestra, was a noted exponent of this style. The harmonies are often minimal; for instance, the root note is often omitted on the assumption that it will be supplied by the bassist.

Small group comping[edit]

When jazz guitarists play chords underneath a song’s melody or another musician’s solo improvisations, it is called comping, short for accompanying. The accompanying style in most jazz styles differs from the way chordal instruments accompany in many popular styles of music. In many popular styles of music, such as rock and pop, the rhythm guitarist usually performs the chords in rhythmic fashion which sets out the beat or groove of a tune. In contrast, in many modern jazz styles within smaller, the guitarist plays much more sparsely, intermingling periodic chords and delicate voicings into pauses in the melody or solo, and using periods of silence. Jazz guitarists commonly use a wide variety of inversions when comping, rather than only using standard voicings.[4]

Gypsy pumping[edit]

Gypsy jazz is acoustic music, usually played without a drummer. Rhythm guitar in gypsy jazz uses a special form of strumming known as «la pompe», i.e. «the pump». This form of percussive rhythm is similar to the «boom-chick» in bluegrass styles; it is what gives the music its fast swinging feeling. The strumming hand, which never touches the top of the guitar, must make a quick up-down strum followed by a down strum. The up-down part of la pompe must be done extremely fast, regardless of the tempo of the music. It is very similar to a grace note in classical music, albeit the fact that an entire chord is used. This pattern is usually played in unison by two or more guitarists in the rhythm section.

Jazz chord soloing[edit]

Jazz guitar soloists are not limited to playing single notes by their instrument. This allows them to create «chord solos» by adding the song’s melody on top of the chord voicings. Wes Montgomery was noted for playing successive choruses in single notes, octaves and finally a chord solo. This technique differs from chord-melody soloing in that it is not intended to be used unaccompanied

Funk[edit]

Funk utilized the same extended chords found in bebop jazz, such as minor chords with added sevenths and elevenths, or dominant seventh chords with altered ninths. However, unlike bebop jazz, with its complex, rapid-fire chord changes, funk virtually abandoned chord changes, creating static single chord vamps with little harmonic movement, but with a complex and driving rhythmic feel. Some have jazz backgrounds. The chords used in funk songs typically imply a dorian or mixolydian mode, as opposed to the major or natural minor tonalities of most popular music. Melodic content was derived by mixing these modes with the blues scale.

In funk bands, guitarists typically play in a percussive style, often using the wah-wah sound effect and muting the notes in their riffs to create a percussive sound. Guitarists Ernie Isley of The Isley Brothers and Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic were notably influenced by Jimi Hendrix’s improvised solos. Eddie Hazel, who worked with George Clinton, is a notable guitar soloist in funk. Ernie Isley was tutored at an early age by Jimi Hendrix himself, when he was a part of The Isley Brothers backing band and lived in the attic temporarily at the Isleys’ household. Jimmy Nolen and Phelps Collins are famous funk rhythm guitarists who both worked with James Brown.

Reggae[edit]

The guitar in reggae usually plays the chords on beats two and four, a musical figure known as skank or the ‘bang’. It has a very dampened, short and scratchy chop sound, almost like a percussion instrument. Sometimes a double chop is used when the guitar still plays the off beats, but also plays the following 16th or 8th beat on the up-stroke. Depending on the amount of swing or groove, this next secondary stab is often the 16th note sounding closer to an 8th placement in the rhythm. An example is the intro to «Stir It Up» by The Wailers. Artist and producer Derrick Harriott says, «What happened was the musical thing was real widespread, but only among a certain sort of people. It was always a down-town thing, but more than just hearing the music. The equipment was so powerful and the vibe so strong that we feel it.»[9] Reggae chords are typically played without overdrive or distortion.

See also[edit]

- List of rhythm guitarists

- Flamenco guitar

- Steel guitar

- John Lennon

References[edit]

- ^ Traum, Happy (1974). Fingerpicking Styles For Guitar, p.12. Oak Publications. ISBN 0-8256-0005-7. Hardcover (2005): ISBN 0-8256-0343-9.

- ^ «Backbeat». Grove Music Online. 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ^ «TPOK Jazz, members band members, guitarists, history». kenyapage.net.

- ^ «jazz guitar — advanced chords/inversions». eden.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011.

- ^ Natter, Frank (2006). The Total Acoustic Guitarist, p.126. ISBN 9780739038512.

- ^ Marshall, Wolf (2008). Stuff! Good Guitar Players Should Know, p. 138. ISBN 1-4234-3008-5.

- ^ Snyder, Jerry (1999). Jerry Snyder’s Guitar School, p.28. ISBN 0-7390-0260-0.

- ^ a b c Peretz, Jeff (2003). Zen and the Art of Guitar: A Path to Guitar Mastery, p.37. Alfred Music. ISBN 9780739028179.

- ^ Bradley, Lloyd. This Is Reggae Music:The Story Of Jamaica’s Music. New York:Grove Press, 2001

External links[edit]

- Multimedia Rhythm Guitar Lessons

- Jazz Guitar Rhythms

Guitar strum Play (help·info): pattern created by subtracting the second and fifth (of eight) eighth notes from a pattern of straight eighth notes.

In music performances, rhythm guitar is a technique and role that performs a combination of two functions: to provide all or part of the rhythmic pulse in conjunction with other instruments from the rhythm section (e.g., drum kit, bass guitar); and to provide all or part of the harmony, i.e. the chords from a song’s chord progression, where a chord is a group of notes played together. Therefore, the basic technique of rhythm guitar is to hold down a series of chords with the fretting hand while strumming or fingerpicking rhythmically with the other hand. More developed rhythm techniques include arpeggios, damping, riffs, chord solos, and complex strums.

In ensembles or bands playing within the acoustic, country, blues, rock or metal genres (among others), a guitarist playing the rhythm part of a composition plays the role of supporting the melodic lines and improvised solos played on the lead instrument or instruments, be they strings, wind, brass, keyboard or even percussion instruments, or simply the human voice, in the sense of playing steadily throughout the piece, whereas lead instruments and singers switch between carrying the main or countermelody and falling silent. In big band music, the guitarist is considered part of the rhythm section, alongside bass and drums.

In some musical situations, such as a solo singer-guitarist, the guitar accompaniment provides all the rhythmic drive; in large ensembles it may be only a small part (perhaps one element in a polyrhythm). Likewise, rhythm guitar can supply all of the harmonic input to a singer-guitarist or small band, but in ensembles that have other harmony instruments (such as keyboards) or vocal harmonists, its harmonic input will be less important.

In the most commercially available and consumed genres, electric guitars tend to dominate their acoustic cousins in both the recording studio and live venues. However the acoustic guitar remains a popular choice in country, western and especially bluegrass music, and almost exclusively in folk music.

Rock and pop[edit]

Rock and pop rhythms[edit]

Most rhythms in rock and blues are based on 4/4 time with a backbeat; however, many variations are possible. A backbeat is a syncopated accentuation on the «off» beat. In a simple 4/4 rhythm these are beats 2 and 4.[2] Emphasized back beat, a feature of some African styles, defined rhythm and blues recordings in the late 1940s and so became one of the defining characteristics of rock and roll and much of contemporary popular music.

Rock and pop harmony[edit]

Harmonically, in rock music, the most common way to construct chord progressions is to play major and minor «triads», each comprising a root, third and fifth note of a given scale. An example of a major triad is C major, which contains the notes C, E and G. An example of a minor triad is the A minor chord, which includes the notes A, C and E. Interspersed are some four-note chords, which include the root, third and fifth, as well as a sixth, seventh or ninth note of the scale. The most common chord with four different notes is the dominant seventh chord, which include a root, a major third above the root, a perfect fifth above the root and a flattened seventh. In the key of C major, the dominant seventh chord is a G7, which consists of the notes G, B, D and F.

Three-chord progressions are common in earlier pop and rock, using various combinations of the I, IV and V chords, with the twelve-bar blues particularly common. A four chord progression popular in the 1950s is I-vi-ii-V, which in the key of C major is the chords C major, a minor, d minor and G7. Minor and modal chord progressions such as I-bVII-bVI (in the key of E, the chords E major, D major, C major) feature in popular music.

A power chord in E for guitar. This contains the notes E, B (a fifth above) and an E an octave higher.

In heavy metal music, rhythm guitarists often play power chords, which feature a root note and a fifth above, or with an octave doubling the root. There actually is no third of the chord. Power chords are usually played with distortion.

Arpeggios[edit]

One departure from the basic strummed chord technique is to play arpeggios, i.e. to play individual notes in a chord separately. If this is rapidly done enough, listeners will still hear the sequence as harmony rather than melody. Arpeggiation is often used in folk, country, and heavy metal, sometimes in imitation of older banjo technique. It is also prominent in 1960s pop, such as The Animals’ «House of the Rising Sun», and jangle pop from the 1980s onwards. Rhythm guitarists who use arpeggio often favor semi-acoustic guitars and twelve string guitars to get bright, undistorted «jangly» sound.

The Soukous band TPOK Jazz additionally featured the unique role of mi-solo, (meaning «half solo») guitarist, playing arpeggio patterns and filling a role «between» the lead and rhythm guitars.[3]

Riffs[edit]

In some cases, the chord progression is implied with a simplified sequence of two or three notes, sometimes called a «riff». That sequence is repeated throughout the composition. In heavy metal music, this is typically expanded to more complex sequences comprising a combination of chords, single notes and palm muting. The rhythm guitar part in compositions performed by more technically oriented bands often include riffs employing complex lead guitar techniques. In some genres, especially metal, the audio signal from the rhythm guitar’s output is often subsequently heavily distorted by overdriving the guitar’s amplifier to create a thicker, «crunchier» sound for the palm-muted rhythms.

Interaction with other guitarists[edit]

In bands with two or more guitarists, the guitarists may exchange or even duplicate roles for various songs or several sections within a song. In those with a single guitarist, the guitarist may play lead and rhythm at numerous times or simultaneously, by overlaying the rhythm sequence with a lead line.

Crossover with keyboards[edit]

The availability of electronic effects units such as delay pedals and reverb units enables electric guitarists to play arpeggios and take over some of the role of a synthesizer player in performing sustained «pads». Those serve as sonic backgrounds in modern pop. Creating a pad sound differs from usual rhythm guitar roles in that it is not rhythmic. Some bands have a synthesizer performer play pads. In bands without a synth player, a guitarist can take over this role.

Replacing lead guitar[edit]

Some rhythm techniques cross over into lead guitar playing. In guitar-bass-and-drums power trios guitarists must double up between rhythm and lead. For instance Jimi Hendrix combined full chords with solo licks, double stops and arpeggios. In the 2010s, «looping pedals» are used to record a chord sequence or riff over which musicians can then play the lead line, simulating the sound achieved by having two guitarists.

Equipment[edit]

Rhythm guitarists usually aim to generate a stronger rhythmic and chordal sound, in contrast to the lead guitarists’ goal of producing a sustained, high-pitched melody line that listeners can hear over the top of the band. As a result, rhythm and lead players may use different guitars and amplifiers. Rhythm guitarists may employ an electric acoustic guitar or a humbucker-equipped electric guitar for a richer and fatter output. Also, rhythm guitarists may use strings of a larger gauge than those used by lead guitarists. However, while these may be practices, they are not necessarily the rule and are subject to the style of the song and the preference of the individual guitarist.

While rhythm guitarists in metal bands use distortion effects, they tend to use less of the modulation effects such as flangers used by lead guitar players. Whereas the lead guitarist in a metal band is trying to make the solo tone more prominent, and thus uses a range of colorful effects, the rhythm guitarist is typically trying to provide a thick, solid supporting sound that blends in with the overall sound of the group. In alternative rock and post punk bands, however, where the band is trying to create an ambient soundscape rather than an aggressive Motörhead-style «Wall of Sound», the rhythm guitarist may use flanging and delay effects to create a shimmering background.

Jazz[edit]

Rhythm guitar has been especially important in the development of jazz. The guitar took over the role previously occupied by the banjo to provide rhythmic chordal accompaniment.

Early jazz guitarists like Freddie Green tended to emphasize the percussive quality of the instrument. The ability to keep a steady rhythm while playing through complicated chord patterns made the guitar invaluable to many rhythm sections. Jazz guitarists are expected to have deep knowledge of harmony.

Jazz harmony[edit]

Jazz guitarists use their knowledge of harmony and jazz theory to create jazz chord «voicings», which emphasize the 3rd and 7th notes of the chord. Unlike pop and rock guitarists, who typically include the root of a chord (even, with many open chords and barre chords, doubling the root), jazz guitarists typically omit the root. Some more sophisticated chord voicings also include the 9th, 11th, and 13th notes of the chord. A typical jazz voicing for the chord G7 would be the individual notes B, E, F, and A. This voicing uses the 3rd (the note B), the 7th (the note F), along with the 6th (the note E) and the 9th (the note A).

In some modern jazz styles, dominant 7th chords in a tune may contain altered 9ths (either flattened by a semitone, which is called a «flat 9th», or sharpened by a semitone, which is called a «sharp 9th»); 11ths (sharpened by a semitone, which is called a «sharp 11th»); 13ths (typically flattened by a semitone, which is called a «flat 13th»).

Jazz guitarists need to learn about a range of different chords, including major 7th, major 6th, minor 7th, minor/major 7th, dominant 7th, diminished, half-diminished, and augmented chords. As well, they need to learn about chord transformations (e.g., altered chords, such as «alt dominant chords» described above), chord substitutions, and re-harmonization techniques. Some jazz guitarists use their knowledge of jazz scales and chords to provide a walking bass-style accompaniment.

Jazz guitarists learn to perform these chords over the range of different chord progressions used in jazz, such as the II-V-I progression, the jazz-style blues progression, the minor jazz-style blues form, the «rhythm changes» progression, and the variety of chord progressions used in jazz ballads, and jazz standards. Guitarists may also learn to use the chord types, strumming styles, and effects pedals (e.g., chorus effect or fuzzbox) used in 1970s-era jazz-Latin, jazz-funk, and jazz-rock fusion music.

Big band rhythm[edit]

In jazz big bands, popular during the 1930s and 1940s, the guitarist is considered an integral part of the rhythm section (guitar, drums and bass). They usually played a regular four chords to the bar, although an amount of harmonic improvisation is possible. Freddie Green, guitarist in the Count Basie orchestra, was a noted exponent of this style. The harmonies are often minimal; for instance, the root note is often omitted on the assumption that it will be supplied by the bassist.

Small group comping[edit]

When jazz guitarists play chords underneath a song’s melody or another musician’s solo improvisations, it is called comping, short for accompanying. The accompanying style in most jazz styles differs from the way chordal instruments accompany in many popular styles of music. In many popular styles of music, such as rock and pop, the rhythm guitarist usually performs the chords in rhythmic fashion which sets out the beat or groove of a tune. In contrast, in many modern jazz styles within smaller, the guitarist plays much more sparsely, intermingling periodic chords and delicate voicings into pauses in the melody or solo, and using periods of silence. Jazz guitarists commonly use a wide variety of inversions when comping, rather than only using standard voicings.[4]

Gypsy pumping[edit]

Gypsy jazz is acoustic music, usually played without a drummer. Rhythm guitar in gypsy jazz uses a special form of strumming known as «la pompe», i.e. «the pump». This form of percussive rhythm is similar to the «boom-chick» in bluegrass styles; it is what gives the music its fast swinging feeling. The strumming hand, which never touches the top of the guitar, must make a quick up-down strum followed by a down strum. The up-down part of la pompe must be done extremely fast, regardless of the tempo of the music. It is very similar to a grace note in classical music, albeit the fact that an entire chord is used. This pattern is usually played in unison by two or more guitarists in the rhythm section.

Jazz chord soloing[edit]

Jazz guitar soloists are not limited to playing single notes by their instrument. This allows them to create «chord solos» by adding the song’s melody on top of the chord voicings. Wes Montgomery was noted for playing successive choruses in single notes, octaves and finally a chord solo. This technique differs from chord-melody soloing in that it is not intended to be used unaccompanied

Funk[edit]

Funk utilized the same extended chords found in bebop jazz, such as minor chords with added sevenths and elevenths, or dominant seventh chords with altered ninths. However, unlike bebop jazz, with its complex, rapid-fire chord changes, funk virtually abandoned chord changes, creating static single chord vamps with little harmonic movement, but with a complex and driving rhythmic feel. Some have jazz backgrounds. The chords used in funk songs typically imply a dorian or mixolydian mode, as opposed to the major or natural minor tonalities of most popular music. Melodic content was derived by mixing these modes with the blues scale.

In funk bands, guitarists typically play in a percussive style, often using the wah-wah sound effect and muting the notes in their riffs to create a percussive sound. Guitarists Ernie Isley of The Isley Brothers and Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic were notably influenced by Jimi Hendrix’s improvised solos. Eddie Hazel, who worked with George Clinton, is a notable guitar soloist in funk. Ernie Isley was tutored at an early age by Jimi Hendrix himself, when he was a part of The Isley Brothers backing band and lived in the attic temporarily at the Isleys’ household. Jimmy Nolen and Phelps Collins are famous funk rhythm guitarists who both worked with James Brown.

Reggae[edit]

The guitar in reggae usually plays the chords on beats two and four, a musical figure known as skank or the ‘bang’. It has a very dampened, short and scratchy chop sound, almost like a percussion instrument. Sometimes a double chop is used when the guitar still plays the off beats, but also plays the following 16th or 8th beat on the up-stroke. Depending on the amount of swing or groove, this next secondary stab is often the 16th note sounding closer to an 8th placement in the rhythm. An example is the intro to «Stir It Up» by The Wailers. Artist and producer Derrick Harriott says, «What happened was the musical thing was real widespread, but only among a certain sort of people. It was always a down-town thing, but more than just hearing the music. The equipment was so powerful and the vibe so strong that we feel it.»[9] Reggae chords are typically played without overdrive or distortion.

See also[edit]

- List of rhythm guitarists

- Flamenco guitar

- Steel guitar

- John Lennon

References[edit]

- ^ Traum, Happy (1974). Fingerpicking Styles For Guitar, p.12. Oak Publications. ISBN 0-8256-0005-7. Hardcover (2005): ISBN 0-8256-0343-9.

- ^ «Backbeat». Grove Music Online. 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ^ «TPOK Jazz, members band members, guitarists, history». kenyapage.net.

- ^ «jazz guitar — advanced chords/inversions». eden.rutgers.edu. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011.

- ^ Natter, Frank (2006). The Total Acoustic Guitarist, p.126. ISBN 9780739038512.

- ^ Marshall, Wolf (2008). Stuff! Good Guitar Players Should Know, p. 138. ISBN 1-4234-3008-5.

- ^ Snyder, Jerry (1999). Jerry Snyder’s Guitar School, p.28. ISBN 0-7390-0260-0.

- ^ a b c Peretz, Jeff (2003). Zen and the Art of Guitar: A Path to Guitar Mastery, p.37. Alfred Music. ISBN 9780739028179.

- ^ Bradley, Lloyd. This Is Reggae Music:The Story Of Jamaica’s Music. New York:Grove Press, 2001

External links[edit]

- Multimedia Rhythm Guitar Lessons

- Jazz Guitar Rhythms

Download Article

Download Article

The guitar riff is the lifeblood of rock music. It provides the song with a rhythmic theme, and gives listeners something catchy and memorable to draw them in. Writing a solid rock riff requires creativity, originality and a dash of technical understanding, but with the right references it’s something that any musician can eventually master.

-

1

Determine what sort of riff you want to write. Consider your musical goals and think about the kind of riff you aim to create. Are you in a melodic rock band, or would you rather craft a heavy, thrashing metal riff? Musical styles are diverse and often overlapping, so don’t be afraid to get totally original.

- A riff can be almost anything. Some of the most memorable rock and metal riffs of all time are simply repetitions of one bar, like «Sweet Child of Mine» by Guns ‘n’ Roses, or they can be elaborate runs that last for four or more bars, such as AC/DC’s «Highway to Hell» or «She-Wolf» by Megadeth. You should feel no constraints when setting out to compose a rock guitar riff.

-

2

Listen to your favorite riffs for inspiration. Sit down with some of your music and play through your favorite riffs and lines. Note what stands out to you about their rhythm, composition and sound. These will become the stylistic techniques you will use to start inventing your own riffs.

- Listen to lots of different guitarists and study their approach to riff-writing. Bands like Black Sabbath that are known for the structural strength and catchiness of their riffs often employed simple methodologies, yet their writing styles distilled into a one-of-a-kind, instantly identifiable sound.

Advertisement

-

3

Zone in on your sound. It will help to have an idea what type of sound you’re going for so that you can utilize the right tuning and playing methods once you actually start writing. Narrow down your desired sound to heavy or playful, uptempo or slow and grinding, melodious or chugging. It may also be worth thinking about how your idea for a riff might sound in a style you wouldn’t ordinarily choose.

- Rock and metal riffs for guitar are generally written using the Natural Minor or Harmonic Minor scale, although other scales can be used. Try to make something of a «storyline» out of the notes on the scale; just a simple little piece of music that you think sounds good (try playing through the scale a few times and see if inspiration strikes.)[1]

- Classic metal tuning was often played in standard ‘D’ or ‘E,’ while heavier forms of music like death and sludge metal make use of a «drop» (lower) tuning.[2]

- Rock and metal riffs for guitar are generally written using the Natural Minor or Harmonic Minor scale, although other scales can be used. Try to make something of a «storyline» out of the notes on the scale; just a simple little piece of music that you think sounds good (try playing through the scale a few times and see if inspiration strikes.)[1]

-

4

Start composing the riff mentally. Begin laying the groundwork for the riff musically in your head. Hum your riff out loud or else play around on the guitar until you lock into something concrete. You’ll work on the details later; this is your first opportunity to hear how the notes come together and can clue you in to what guitar tone might work best for playing the riff. Let your creativity flow and take the riff where it will. Make minor adjustments as you go and watch your riff take shape.[3]

- Run through different scales and get a sense of how the notes sound. There are often very simple yet structurally-solid riffs just waiting to be picked out of basic scales—think of scales as a kind of «database» of raw sounds.

- Humming along with your riff is one form of «audiation,» or mental listening, and can be an invaluable skill in helping you keep track of the music you’re composing.

Advertisement

-

1

Play around with the riff. Now that you’ve got a direction for your riff, grab your guitar and give it an initial trial run. Play around with the basic melody you’ve thought up to lay the foundation for the notes of the riff. Try to faithfully capture the sound you conceived of in your head. Hearing it played out loud will give you a better idea of what works about it and what doesn’t.

- If you find yourself stuck or your riff sounds lifeless, try adding stylistic embellishments, such as hammer-ons, palm-muting and pinch harmonics. These are invaluable and often-used tools of metal songwriting and can be useful in adding depth to an otherwise bland riff.[4]

- You could also improvise a little, the way jazz musicians play freely based around a theme. Take your riff and play it four or five times, making slight departures from the chosen sequence of notes each time. You may end up with something more original that you like better.

- If you find yourself stuck or your riff sounds lifeless, try adding stylistic embellishments, such as hammer-ons, palm-muting and pinch harmonics. These are invaluable and often-used tools of metal songwriting and can be useful in adding depth to an otherwise bland riff.[4]

-

2

Choose the right structure. Tailor your riff to be measured in a particular number of bars (note: a bar is a segment of time that corresponds with a particular number of beats). Play through the bars at varying speeds or make slight alterations to the final bar of the riff to try out new rhythmic structures and give the riff a rounded sound.[5]

- Most traditional rock-inspired riffs are played in a «3+1» bar structure, with one bar repeated three times and a minor variation on the last bar, for four bars total. Because of its universal application, the 3+1 bar structure could make a great starting place if you’re having trouble coming up with anything.[6]

- Most traditional rock-inspired riffs are played in a «3+1» bar structure, with one bar repeated three times and a minor variation on the last bar, for four bars total. Because of its universal application, the 3+1 bar structure could make a great starting place if you’re having trouble coming up with anything.[6]

-

3

Get technical. If you’re familiar with writing tablature, put your riff down on paper. This way you can neatly see it laid out and arranged visually to begin committing it to memory. Make any necessary notes about tuning or progression that will enable the riff to evolve.[7]

- If you don’t know how to write tabs, it can be a priceless skill to learn. The basic principles of tablature are easy to pick up and become indispensable when you begin writing more complex pieces of music.

-

4

Refine your sound. Listen to how closely your riff matches up with your original idea for it. What sounds right, and what could work better? Music, like any art, is never a finished process. You shouldn’t hesitate to continue making changes to your riff even after you’ve written tabs for it and sounded it out a few times.

- Note how your riff’s notes and chords come together musically. The riff you’re writing should have its own natural rhythm and sound, so if something sounds off, this is the right time to hammer out the particulars of your chord progression, picking style, etc.

Advertisement

-

1

Practice the riff. It’s now time to actually play your riff. Run through it over and over and get familiar with how it feels to play, trying to make every note and chord sound perfect. It can be very rewarding to hear music you’ve written played aloud.

- Make the riff yours. Anybody can pick up a guitar and play; strive to create something with your special stamp on it, and practice it until nobody can play it like you.

-

2

Record yourself. If you have the means, make an audio recording of the riff to preserve it and show off your work. The simplest way to make an audio recording is by using your smart phone’s recording app (using your smart phone also gives you the option of taking a video so that you can spot any mistakes in your playing). For a more sophisticated touch, most computers and some amplifiers come equipped with basic audio recording software, and you can use this to archive your riff or even expand and add other layers to it to create a fleshed-out song.

- Home recording typically only requires a basic microphone and a program like GarageBand or Fruity Loops, which are both free to download.[8]

[9]

- Alternatively, if you have an old tape recorder lying around, you could record yourself the old fashioned way—the way your favorite players used to do.

- Home recording typically only requires a basic microphone and a program like GarageBand or Fruity Loops, which are both free to download.[8]

-

3

Make the riff part of a larger sound. Envision the riff as part of a completed song, and think about how it works when played along with a band. If you happen to be part of a band, demo the riff for your bandmates and figure out how to incorporate it into your music. Take cues from the style you’ve created to formulate new riffs and begin developing your own unique style.[10]

- Remember that the riff serves as a kind of «theme» for the song; it is not a song in itself. To take your songwriting abilities to the next level, start composing riffs for the bigger picture goal of fitting them to individual songs.[11]

- Remember that the riff serves as a kind of «theme» for the song; it is not a song in itself. To take your songwriting abilities to the next level, start composing riffs for the bigger picture goal of fitting them to individual songs.[11]

Advertisement

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

-

Have fun! Creating music is a passionate endeavor. Enjoy yourself and make sure it comes from the heart.

-

It’s always a good idea to know something about music theory. You don’t have to be an expert, just understand some basics; i.e., how chords are structured, how scales are structured, how scales and chords interact, etc. Visit sites like musictheory.net and try out some of the lessons. They’ll give you a handy primer on music and music theory.

-

Listen to all the seminal bands that came before you, and listen to how they structure their songs and riffs. Studying is essential to any discipline.

Show More Tips

Thanks for submitting a tip for review!

Advertisement

-

Make sure your riff doesn’t sound too much like someone else’s, whether it’s a well-known song or not. Even if you didn’t intend to rip off an artist, excessive similarities could be misconstrued as plagiarism.

Advertisement

Things You’ll Need

- Guitar (and amp)

- Pen and paper

- Creativity

- Tunes for inspiration

- Recording software (optional)

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

The best way to write a riff is to start playing around on the guitar or humming to find musical patterns you like. You can combine these patterns into longer melodies for a more complex riff, but keep in mind that a riff can be whatever you like, as long as it provides a rhythmic theme to your song. When you’re composing your riff, try to measure it in a particular number of bars to establish a consistent rhythm. If you’re unsure of where to start, try the traditional «3+1» bar structure, in which one bar repeats three times and the last bar is a minor variation. To learn how to implement your riff in a completed song, keep reading!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 146,686 times.

Did this article help you?

Download Article

Download Article

The guitar riff is the lifeblood of rock music. It provides the song with a rhythmic theme, and gives listeners something catchy and memorable to draw them in. Writing a solid rock riff requires creativity, originality and a dash of technical understanding, but with the right references it’s something that any musician can eventually master.

-

1

Determine what sort of riff you want to write. Consider your musical goals and think about the kind of riff you aim to create. Are you in a melodic rock band, or would you rather craft a heavy, thrashing metal riff? Musical styles are diverse and often overlapping, so don’t be afraid to get totally original.

- A riff can be almost anything. Some of the most memorable rock and metal riffs of all time are simply repetitions of one bar, like «Sweet Child of Mine» by Guns ‘n’ Roses, or they can be elaborate runs that last for four or more bars, such as AC/DC’s «Highway to Hell» or «She-Wolf» by Megadeth. You should feel no constraints when setting out to compose a rock guitar riff.

-

2

Listen to your favorite riffs for inspiration. Sit down with some of your music and play through your favorite riffs and lines. Note what stands out to you about their rhythm, composition and sound. These will become the stylistic techniques you will use to start inventing your own riffs.

- Listen to lots of different guitarists and study their approach to riff-writing. Bands like Black Sabbath that are known for the structural strength and catchiness of their riffs often employed simple methodologies, yet their writing styles distilled into a one-of-a-kind, instantly identifiable sound.

Advertisement

-

3

Zone in on your sound. It will help to have an idea what type of sound you’re going for so that you can utilize the right tuning and playing methods once you actually start writing. Narrow down your desired sound to heavy or playful, uptempo or slow and grinding, melodious or chugging. It may also be worth thinking about how your idea for a riff might sound in a style you wouldn’t ordinarily choose.

- Rock and metal riffs for guitar are generally written using the Natural Minor or Harmonic Minor scale, although other scales can be used. Try to make something of a «storyline» out of the notes on the scale; just a simple little piece of music that you think sounds good (try playing through the scale a few times and see if inspiration strikes.)[1]

- Classic metal tuning was often played in standard ‘D’ or ‘E,’ while heavier forms of music like death and sludge metal make use of a «drop» (lower) tuning.[2]

- Rock and metal riffs for guitar are generally written using the Natural Minor or Harmonic Minor scale, although other scales can be used. Try to make something of a «storyline» out of the notes on the scale; just a simple little piece of music that you think sounds good (try playing through the scale a few times and see if inspiration strikes.)[1]

-

4

Start composing the riff mentally. Begin laying the groundwork for the riff musically in your head. Hum your riff out loud or else play around on the guitar until you lock into something concrete. You’ll work on the details later; this is your first opportunity to hear how the notes come together and can clue you in to what guitar tone might work best for playing the riff. Let your creativity flow and take the riff where it will. Make minor adjustments as you go and watch your riff take shape.[3]

- Run through different scales and get a sense of how the notes sound. There are often very simple yet structurally-solid riffs just waiting to be picked out of basic scales—think of scales as a kind of «database» of raw sounds.

- Humming along with your riff is one form of «audiation,» or mental listening, and can be an invaluable skill in helping you keep track of the music you’re composing.

Advertisement

-

1

Play around with the riff. Now that you’ve got a direction for your riff, grab your guitar and give it an initial trial run. Play around with the basic melody you’ve thought up to lay the foundation for the notes of the riff. Try to faithfully capture the sound you conceived of in your head. Hearing it played out loud will give you a better idea of what works about it and what doesn’t.

- If you find yourself stuck or your riff sounds lifeless, try adding stylistic embellishments, such as hammer-ons, palm-muting and pinch harmonics. These are invaluable and often-used tools of metal songwriting and can be useful in adding depth to an otherwise bland riff.[4]

- You could also improvise a little, the way jazz musicians play freely based around a theme. Take your riff and play it four or five times, making slight departures from the chosen sequence of notes each time. You may end up with something more original that you like better.

- If you find yourself stuck or your riff sounds lifeless, try adding stylistic embellishments, such as hammer-ons, palm-muting and pinch harmonics. These are invaluable and often-used tools of metal songwriting and can be useful in adding depth to an otherwise bland riff.[4]

-

2

Choose the right structure. Tailor your riff to be measured in a particular number of bars (note: a bar is a segment of time that corresponds with a particular number of beats). Play through the bars at varying speeds or make slight alterations to the final bar of the riff to try out new rhythmic structures and give the riff a rounded sound.[5]

- Most traditional rock-inspired riffs are played in a «3+1» bar structure, with one bar repeated three times and a minor variation on the last bar, for four bars total. Because of its universal application, the 3+1 bar structure could make a great starting place if you’re having trouble coming up with anything.[6]

- Most traditional rock-inspired riffs are played in a «3+1» bar structure, with one bar repeated three times and a minor variation on the last bar, for four bars total. Because of its universal application, the 3+1 bar structure could make a great starting place if you’re having trouble coming up with anything.[6]

-

3

Get technical. If you’re familiar with writing tablature, put your riff down on paper. This way you can neatly see it laid out and arranged visually to begin committing it to memory. Make any necessary notes about tuning or progression that will enable the riff to evolve.[7]

- If you don’t know how to write tabs, it can be a priceless skill to learn. The basic principles of tablature are easy to pick up and become indispensable when you begin writing more complex pieces of music.

-

4

Refine your sound. Listen to how closely your riff matches up with your original idea for it. What sounds right, and what could work better? Music, like any art, is never a finished process. You shouldn’t hesitate to continue making changes to your riff even after you’ve written tabs for it and sounded it out a few times.

- Note how your riff’s notes and chords come together musically. The riff you’re writing should have its own natural rhythm and sound, so if something sounds off, this is the right time to hammer out the particulars of your chord progression, picking style, etc.

Advertisement

-

1

Practice the riff. It’s now time to actually play your riff. Run through it over and over and get familiar with how it feels to play, trying to make every note and chord sound perfect. It can be very rewarding to hear music you’ve written played aloud.

- Make the riff yours. Anybody can pick up a guitar and play; strive to create something with your special stamp on it, and practice it until nobody can play it like you.

-

2

Record yourself. If you have the means, make an audio recording of the riff to preserve it and show off your work. The simplest way to make an audio recording is by using your smart phone’s recording app (using your smart phone also gives you the option of taking a video so that you can spot any mistakes in your playing). For a more sophisticated touch, most computers and some amplifiers come equipped with basic audio recording software, and you can use this to archive your riff or even expand and add other layers to it to create a fleshed-out song.

- Home recording typically only requires a basic microphone and a program like GarageBand or Fruity Loops, which are both free to download.[8]

[9]

- Alternatively, if you have an old tape recorder lying around, you could record yourself the old fashioned way—the way your favorite players used to do.

- Home recording typically only requires a basic microphone and a program like GarageBand or Fruity Loops, which are both free to download.[8]

-

3

Make the riff part of a larger sound. Envision the riff as part of a completed song, and think about how it works when played along with a band. If you happen to be part of a band, demo the riff for your bandmates and figure out how to incorporate it into your music. Take cues from the style you’ve created to formulate new riffs and begin developing your own unique style.[10]

- Remember that the riff serves as a kind of «theme» for the song; it is not a song in itself. To take your songwriting abilities to the next level, start composing riffs for the bigger picture goal of fitting them to individual songs.[11]

- Remember that the riff serves as a kind of «theme» for the song; it is not a song in itself. To take your songwriting abilities to the next level, start composing riffs for the bigger picture goal of fitting them to individual songs.[11]

Advertisement

Ask a Question

200 characters left

Include your email address to get a message when this question is answered.

Submit

Advertisement

-

Have fun! Creating music is a passionate endeavor. Enjoy yourself and make sure it comes from the heart.

-

It’s always a good idea to know something about music theory. You don’t have to be an expert, just understand some basics; i.e., how chords are structured, how scales are structured, how scales and chords interact, etc. Visit sites like musictheory.net and try out some of the lessons. They’ll give you a handy primer on music and music theory.

-

Listen to all the seminal bands that came before you, and listen to how they structure their songs and riffs. Studying is essential to any discipline.

Show More Tips

Thanks for submitting a tip for review!

Advertisement

-

Make sure your riff doesn’t sound too much like someone else’s, whether it’s a well-known song or not. Even if you didn’t intend to rip off an artist, excessive similarities could be misconstrued as plagiarism.

Advertisement

Things You’ll Need

- Guitar (and amp)

- Pen and paper

- Creativity

- Tunes for inspiration

- Recording software (optional)

References

About This Article

Article SummaryX

The best way to write a riff is to start playing around on the guitar or humming to find musical patterns you like. You can combine these patterns into longer melodies for a more complex riff, but keep in mind that a riff can be whatever you like, as long as it provides a rhythmic theme to your song. When you’re composing your riff, try to measure it in a particular number of bars to establish a consistent rhythm. If you’re unsure of where to start, try the traditional «3+1» bar structure, in which one bar repeats three times and the last bar is a minor variation. To learn how to implement your riff in a completed song, keep reading!

Did this summary help you?

Thanks to all authors for creating a page that has been read 146,686 times.

Did this article help you?

Как правильно пишется слово «ритм-гитара»

ритм-гита́ра

ритм-гита́ра, -ы

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: донник — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Синонимы к слову «ритм-гитара»

Предложения со словом «ритм-гитара»

- Сначала мне дали в руки ритм-гитару, но когда послушали, как у меня получается играть на басу, даже это никто не стал обсуждать.

- Повсюду расставлена техника для съёмки, которая идёт в полном разгаре: девушка томно стонет, стоя на четвереньках под светом прожекторов, проминая собою кровать, закидывает голову, эротично закусывает губы; парень позади неё, подстраиваясь к темпу барабанов и рифа ритм-гитары, ловит от всего происходящего кайф.

- Музыка потекла и приобрела объём после вступления ритм-гитары – мои медиатор прошёлся по знакомым струнам.

- (все предложения)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

-

Сначала мне дали в руки ритм-гитару, но когда послушали, как у меня получается играть на басу, даже это никто не стал обсуждать.

-

Повсюду расставлена техника для съёмки, которая идёт в полном разгаре: девушка томно стонет, стоя на четвереньках под светом прожекторов, проминая собою кровать, закидывает голову, эротично закусывает губы; парень позади неё, подстраиваясь к темпу барабанов и рифа ритм-гитары, ловит от всего происходящего кайф.

-

Музыка потекла и приобрела объём после вступления ритм-гитары – мои медиатор прошёлся по знакомым струнам.

- (все предложения)

- бас-гитара

- аккордеон

- металлофон

- мандолина

- корнет-а-пистон

- (ещё синонимы…)

Давненько в этой рубрике не было новых постов. Ну да ничего страшного, еще наверстаем упущенное. В этом посте мы поговорим о записи ритм-гитары в домашних условиях, ведь с сегодняшним уровнем развития цифровых технологий можно добиться весьма неплохого звука. О том, как это сделать, смотрите под катом:

Бас, ударные и ритм-гитара — основа ритм-секции в большинстве роковых и около-роковых (да и не только) жанров. Однако, если бас-гитару и ударные можно записать с использованием виртуальных инструментов (VSTi), то ритм-гитара такой подход не приемлет. Возможно, в будущем появятся достойные гитарные синтезаторы, но сейчас таких не существует, звук очень неинтересный и совершенно «мертвый». Поэтому первое, что нам понадобится для записи классной дорожки ритм-гитары — это, собственно, сама гитара.

Чистый звук

Для начала запишем наш драйвовый рокерский рифф без какой-либо обработки, напрямик с гитары. Такой подход в настоящее время применяется и в студиях, для последующего реампинга. Необходимо записать несколько дублей, позже станет понятно, зачем.

Вот так звучит чистый звук гитары без всякого усиления и обработки:

Можно взглянуть на саму звуковую волну:

«Грелка»

В звуковом тракте, применяющемся для записи электрогитары, довольно много компонентов. В этой статье мы не будем рассматривать все варианты трактов, ограничимся основными устройствами — и первым после гитары устройством у нас идет так называемая грелка — обычно это примочка, слегка подгружающая звук, например, педаль овердрайва с маленьким гейном. В качестве грелки я предпочитаю использовать вот такой плагин:

Как видно из картинки, ручка гейна практически на нуле, что дает совсем чуть-чуть подгруженный, подогретый звук, который уже и идет на усилитель.

После обработки грелкой звук принимает вот такой вид:

Если присмотреться к картинке, можно заметить, что по сравнению с чистым звуком сгладились острые пики — это и есть нужный нам результат работы грелки.

Усилитель

«Сердце» гитарного звука — это, конечно же, усилитель. Еще совсем недавно цифровые усилители не могли тягаться с «железными» усилками, однако в наше время ситуация улучшилась — есть множество самых разных вариантов цифровых усилителей, в том числе имеются и очень достойные бесплатные плагины. Для тяжелого звука я предпочитаю использовать вот такой усилитель:

Обратите внимание на положение ручек и переключателей — используется «перегруженный» канал B в режиме Low Gain с прибранным басом. Перегруженный канал используется как раз для получения перегруза (в этот раз отдельные примочки использовать не будем, дабы не загромождать пост). Режим Low Gain, который как раз и выбран в этом случае, используется как раз для ритм-гитар — при небольшом перегрузе гитара остается читаемой, а вместе с подходящей ритм-секцией весь микс будет звучать сочно и тяжело. Для ритм-гитары режим High Gain практически не используется, иначе получается не гитарный звук, а песок и жужжание, предназначение High Gain — это соло-гитара, одиночным высоким нотам сильный перегруз дает нужную певучесть и сустейн. Ну а бас убран исключительно для того, чтобы правильно усадить гитару в микс, потому как эти частоты пересекаются с частотами бочки и бас-гитары.

Сейчас звук усилителя звучит ужасно, но не пугайтесь — без кабинета любой усилитель звучит ужасно)

Кстати, даже по картинке видно, насколько изменился звук после усилителя:

Кабинет

Кабинет — это, собственно, и есть последний элемент тракта между гитарой и слушателем, динамик, грубо говоря. Моделирующих кабинетов сейчас довольно мало, и все они платные, насколько я знаю. Но здесь нас выручат импульсные симуляторы кабинетов — они хоть и гораздо менее гибкие в настройке, но звук выдают честный. Самый популярный импульсный кабсим, который здесь и используется:

У этого плагина есть два варианта — моно и стерео, сейчас нас интересует режим моно. Здесь я использовал импульс легендарного маршалловского V30 — классика не стареет)

Вот теперь уже совсем похоже на настоящий гитарный звук. Картинка:

Дабл-трек в миксе

Вот мы и подобрались к главной хитрости при записи ритм-гитары — к дабл-треку. Именно для него мы записывали несколько дублей.

Суть метода такова — создается два трека ритм-гитары с отдельными звуковыми трактами, и в миксе эти треки разводятся до упора влево и вправо. Таким образом создается стереопанорама, к тому же освобождается место в середине трека под другие инструменты.

Важный момент — в этих двух треках нужно использовать именно два разных дубля, не один и тот же. Наши уши одинаковый дубль распознают даже если он обработан иначе, и в итоге никакой стереопанорамы не получится, весь звук сожмется в середине. К тому же в таком случае возможны всякие нежелательные фазовые искажения.

Дубли следует играть как можно более точно, чтобы не нарушать целостности звука. Так выглядит даблтрек:

Отмечу так же, что существует еще и квадро-трек (его еще называют квадрапл), по названию ясно, что в нем используются не две гитары, а четыре. Такой способ гораздо сложнее в настройке и предъявляет серьезные требования к гитаристу, поскольку ему нужно очень точно попасть в свою же игру как минимум четыре раза. Квадро-трек используется в основном тогда, когда нужна так называемая «стена звука», в других случаях его использование не целесообразно.

Теперь «усадим» ритм-гитару в микс и послушаем, что получилось:

Совсем другое дело, не правда ли?)

Для тех, кто дочитал до этого места и не потерял интереса к теме, предлагаю послушать, как менялся звук гитары по мере добавления устройств в звуковой тракт:

Напоследок еще раз отмечу, что данный тракт — минимальный, в записи на студии используются более длинные цепочки эффектов. Впрочем, о тонкостях мы поговорим позже, в специальной серии статей, где будет рассказана и показана запись трека с нуля.