| RoboCop | |

|---|---|

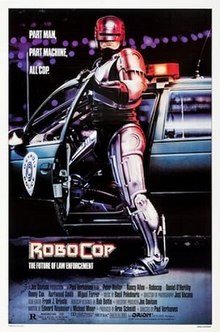

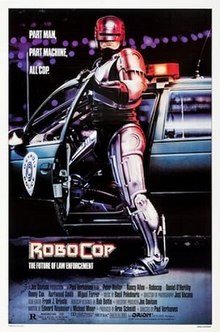

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Paul Verhoeven |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Arne Schmidt |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Jost Vacano |

| Edited by | Frank J. Urioste |

| Music by | Basil Poledouris |

|

Production |

Orion Pictures |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

|

Release date |

|

|

Running time |

102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $13.7 million |

| Box office | $53.4 million |

RoboCop is a 1987 American science fiction action film directed by Paul Verhoeven and written by Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner. The film stars Peter Weller, Nancy Allen, Daniel O’Herlihy, Ronny Cox, Kurtwood Smith, and Miguel Ferrer. Set in a crime-ridden Detroit, in the near future, RoboCop centers on police officer Alex Murphy (Weller) who is murdered by a gang of criminals and subsequently revived by the megacorporation Omni Consumer Products as the cyborg law enforcer RoboCop. Unaware of his former life, RoboCop executes a brutal campaign against crime while coming to terms with the lingering fragments of his humanity.

The film was conceived by Neumeier while working on the set of Blade Runner (1982), and he developed the idea further with Miner. Their script was purchased in early 1985 by producer Jon Davison on behalf of Orion Pictures. Finding a director proved difficult; Verhoeven dismissed the script twice because he did not understand its satirical content until convinced of it by his wife. Filming took place between August and October 1986, mainly in Dallas, Texas. Rob Bottin led the special-effects team in creating practical effects, violent gore, and the RoboCop costume.

Verhoeven emphasized violence throughout the film, making it so outlandish it became comical. Even so, censorship boards believed it was too extreme, and several scenes were shortened or modified to secure an acceptable theatrical rating. Despite predicted difficulties in marketing the film, particularly because of its title, the film was expected to perform well based on pre-release critic screenings and positive word of mouth. RoboCop was a financial success upon its release in July 1987, earning $53.4 million. Reviews praised the film as a clever action film with deeper philosophical messages and satire but were more conflicted over the extreme violence throughout. The film was nominated for several awards, and won an Academy Award as well as numerous Saturn Awards.

Since its release, RoboCop has been critically reevaluated and it has been hailed as one of the best films of the 1980s and one of the greatest science fiction and action films ever made. The film has been lauded for its depiction of a robot affected by the loss of humanity in contrast to the stoic and emotionless robotic characters of that era. The film has continued to be analyzed for themes such as the nature of humanity, personal identity, corporate greed, and corruption, and is seen as a rebuke of the Reaganomics policies of its era. The success of RoboCop created a franchise comprising the sequels RoboCop 2 (1990) and RoboCop 3 (1993), children’s animated series, multiple live-action television shows, video games, comic books, toys, clothing, and other merchandise. A remake was released in 2014. A direct sequel to the original 1987 film, tentatively titled RoboCop Returns, is in development as of 2020; it ignores other entries in the series.

Plot[edit]

In a near-future dystopia, Detroit is on the brink of societal and financial collapse. Overwhelmed by crime and dwindling resources, the city grants the mega-corporation Omni Consumer Products (OCP) control over the Detroit Police Department. OCP Senior President Dick Jones demonstrates ED-209, a law enforcement droid designed to supplant the police. ED-209 malfunctions and brutally kills an executive, allowing ambitious junior executive Bob Morton to introduce the Chairman («The Old Man») to his own project: RoboCop. Meanwhile, officer Alex Murphy is transferred to the Metro West precinct. Murphy and his new partner, Anne Lewis, pursue notorious criminal Clarence Boddicker and his gang—Emil Antonowsky, Leon Nash, Joe Cox and Steve Minh. The gang ambushes and tortures Murphy until Boddicker fatally shoots him. Morton has Murphy’s corpse converted into RoboCop, a powerful and heavily armored cyborg with no memory of his former life. RoboCop is programmed with three prime directives: serve the public trust, protect the innocent, and uphold the law. A fourth prime directive, Directive 4, is classified.

RoboCop is assigned to Metro West and hailed by the media for his brutally efficient campaign against crime. Lewis suspects he is Murphy, recognizing the unique way he holsters his gun, a trick Murphy learned to impress his son. During maintenance, RoboCop experiences a nightmare of Murphy’s death. He leaves the station and encounters Lewis, who addresses him as Murphy. While on patrol, RoboCop arrests Emil, who recognizes Murphy’s mannerisms, furthering RoboCop’s recall. RoboCop then uses the police database to identify Emil’s associates and review Murphy’s police record. RoboCop recalls further memories while exploring Murphy’s former home, his wife and son having moved away following his death. Elsewhere, Jones gets Boddicker to murder Morton, in revenge for Morton’s attempt to usurp his position at OCP. RoboCop tracks down the Boddicker gang and a shootout occurs. He brutally assaults Boddicker, who confesses to working for Jones. RoboCop attempts to kill Boddicker until his programming directs him to uphold the law. He attempts to arrest Jones at OCP Tower, but Directive 4 is activated—a failsafe measure to neutralize RoboCop when acting against an OCP executive. Jones admits his culpability in Morton’s death and releases an ED-209 to destroy RoboCop. Although he escapes, RoboCop is assaulted by the police force on OCP’s order and is badly damaged. Lewis helps RoboCop escape to an abandoned steel mill to repair himself.

Angered by OCP’s underfunding and short-staffing, the police force goes on strike, and Detroit descends into chaos as riots break out throughout the city. Jones frees Boddicker and his remaining gang, arming them with high-powered weaponry to destroy RoboCop. At the steel mill, Boddicker’s men are quickly eliminated, but Lewis is badly injured and RoboCop becomes trapped under steel girders. Even so, he kills Boddicker by stabbing him in the throat with his data spike. RoboCop confronts Jones at OCP Tower during a board meeting, revealing the truth behind Morton’s murder. Jones, in order to escape, takes the Old Man hostage but is promptly fired from OCP, nullifying Directive 4 and allowing RoboCop to shoot him, causing Jones to crash through a window to his death. The Old Man compliments RoboCop’s shooting and asks his name; RoboCop replies, «Murphy».

Cast[edit]

- Peter Weller as Officer Alex Murphy / RoboCop: A Detroit police officer murdered in the line of duty and revived as a cyborg[1]

- Nancy Allen as Officer Anne Lewis: A tough and loyal police officer[2]

- Daniel O’Herlihy as «The Old Man»: The chief executive of OCP[3]

- Ronny Cox as Dick Jones: The Senior President of OCP[4]

- Kurtwood Smith as Clarence Boddicker: A crime lord in league with Dick Jones[1]

- Miguel Ferrer as Bob Morton: An ambitious OCP junior executive responsible for the «RoboCop» project[1][5]

In addition to the main cast, RoboCop features Paul McCrane as Emil Antonowsky, Ray Wise as Leon Nash, Jesse D. Goins as Joe Cox, and Calvin Jung as Steve Minh, who are members of Boddicker’s gang. The cast also includes Robert DoQui as Sergeant Warren Reed,[6][7] Michael Gregory as Lieutenant Hedgecock, Felton Perry as OCP Employee Donald Johnson, Kevin Page as OCP Junior Executive Mr. Kinney—who is shot to death by ED-209—and Lee de Broux as cocaine warehouse owner Sal.[6][7][8]

Mario Machado and Leeza Gibbons portray, respectively, news hosts Casey Wong and Jess Perkins,[6][7] and television show host Bixby Snyder is played by S. D. Nemeth.[6][9] Angie Bollings and Jason Levine appear as Murphy’s wife and son, respectively.[6] RoboCop director Paul Verhoeven makes a cameo appearance as Dancing Nightclub Patron,[10][11] producer Jon Davison provides the voice of ED-209,[5] and director John Landis appears in an in-film advert.[6] Smith’s partner Joan Pirkle appears as Dick Jones’s Secretary.[10]

Production[edit]

Conception and writing[edit]

RoboCop was conceived in the early 1980s by Universal Pictures junior story executive and aspiring screenwriter Edward Neumeier.[a] A fan of robot-themed science fiction films such as Star Wars, as well as action films, Neumeier had developed an interest in mature comic books while researching them for potential adaptation.[12][15][16] The 1982 science fiction film Blade Runner was filming on the Warner Bros. lot behind Neumeier’s office, and he unofficially joined the production to learn about filmmaking.[12][14][15] His work there gave him the idea for RoboCop; he said, «I had this vision of a far-distant, Blade Runner–type world where there was an all-mechanical cop coming to a sense of real human intelligence».[12][14] He spent the next few nights writing a 40-page outline.[12]

While researching story submissions for Universal, Neumeier came across a student video by aspiring director Michael Miner.[10][13][14] The pair met and discussed their similar concepts: Neumeier’s RoboCop and Miner’s robot-themed rock music video. In a 2014 interview, Miner said he also had an idea called SuperCop.[10][12][14] The pair formed a working partnership and spent about two months discussing the idea, plus two to three months writing together at night and over weekends, outside their regular jobs.[b] Their collaboration was initially difficult because they did not know each other well and had to learn how to constructively criticize each other.[18]

Neumeier was influenced to kill off his main character early on by the psychological horror film Psycho (1960), whose heroine was killed in the first act. Inspired by comic books and his personal experience with corporate culture, Neumeier wanted to satirize 1980s business culture, noting the increasing aggression of American financial services in response to growing Japanese influence and that a popular book on Wall Street was The Book of Five Rings, a 17th-century text discussing how to kill more effectively. He also believed that Detroit’s declining automobile industry was due to increased bureaucracy. ED-209’s malfunction in the OCP boardroom was based on Neumeier’s office daydreams about a robot bursting into a meeting and killing everyone.[12][16][19] Miner described the film as «comic relief for a cynical time» during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, when economist «Milton Friedman and the Chicago Boys ransacked the world, enabled by Reagan and the Central Intelligence Agency. So when you have this cop who works for a corporation that insists ‘I own you,’ and he still does the right thing—that’s the core of the film.» The in-film media breaks were Neumeier’s and Miner’s idea. A spec script was completed by December 1984.[10]

Development[edit]

Director Paul Verhoeven (pictured in 2016). He rejected the RoboCop script twice before taking to its underlying story about a character losing their identity.

The first draft of the script, titled RoboCop: The Future of Law Enforcement, was given to industry friends and associates in early 1985.[c] A month later, the pair had two offers: one from Atlantic Releasing[17] and one from director Jonathan Kaplan and producer Jon Davison with Orion Pictures.[13][20] An experienced producer of exploitation and B films, such as the parody film Airplane! (1980), Davison said he was drawn to the script’s satire.[12][13][20] He showed Neumeier and Miner films—including Madigan (1968), Dirty Harry (1971), and Mad Max 2 (1981)—to demonstrate the tone he wanted. After Orion greenlit the project, Neumeier and Miner began a second draft.[21]

Davison produced the film via his Tobor Pictures company.[22][23] Neumeier and Miner were paid a few thousand dollars for the script rights and $25,000 between them for the rewrite. The pair were entitled to 8% of the producer profits once released.[17][24] Davison’s contacts with puppeteers, animators, and practical effects designers were essential to Verhoeven, who had no prior experience with them.[13] The producers discussed changing the Detroit setting, but Neumeier insisted on its importance because of its failing motor car industry.[12] The connection between Clarence Boddicker and Dick Jones was added at Orion’s suggestion.[12]

Kaplan left to direct Project X (1987), and finding his replacement took six months. Many prospects declined because of the film’s title.[d] The role was offered to David Cronenberg, Alex Cox, and Monte Hellman; Hellman joined as second unit director.[17][25][28] Miner petitioned to direct, but Orion refused to trust a $7 million project to an untested director.[12][29] Miner declined the second unit director position in order to direct Deadly Weapon (1989);[12][21] Orion executive Barbara Boyle suggested Paul Verhoeven—who had received acclaim for his work on Soldier of Orange (1977) and his only English-language film Flesh+Blood (1985)—for director.[12][13][21] Verhoeven looked at the first page and rejected the script as awful, stalling the project.[10][13][21] Boyle sent Verhoeven another copy, suggesting he pay attention to the subtext.[12] Verhoeven was still uninterested until his wife Martine read it and encouraged him to give it a chance, saying he had missed the «soul» of the story about someone losing their identity.[10] Unfluent in English, Verhoeven admitted the satire did not make sense to him.[10] The scene that gained his attention was RoboCop returning to Murphy’s abandoned home and experiencing lingering memories of his former life.[1][10]

Davison, Neumeier, and Verhoeven discussed the project at Culver Studios’ Mansion House.[12] Verhoeven wanted to direct it as a serious film; and to explain the tone they wanted, Neumeier gave him comic books, including 2000 AD, featuring the character Judge Dredd.[12][21] Neumeier and Miner wrote a third draft based on Verhoeven’s requests, working through injuries and late nights; this 92-page revision included a subplot involving a romantic affair between Murphy and Lewis.[11][12][21] After reading it, Verhoeven admitted he was wrong and returned to the second draft, looking for a comic book tone.[12][21][30]

Casting[edit]

Around 6–8 months were spent searching for an actor to portray Alex Murphy / RoboCop.[13][26] Arnold Schwarzenegger,[13] Michael Ironside,[31] Rutger Hauer, Tom Berenger, Armand Assante,[25] Keith Carradine, and James Remar were considered.[21] Orion favored Schwarzenegger, the star of their recent success, The Terminator (1984),[25] but he and other actors were considered too physically imposing to be believable in the RoboCop costume. It was thought that Schwarzenegger would look like the Michelin Man or Pillsbury Doughboy.[13][26][31] Others were reluctant because their face would be largely concealed by a helmet.[26] Davison said that Weller was the only person who wanted to be in the film.[26] The low salary he commanded was in his favor, as was his good body control from martial arts training and marathon running, and his fan base in the science fiction genre, following his performance in The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984). Verhoeven said he hired him because «his chin was very good.»[29][25][26] Weller spent months working with mime Moni Yakim, developing a fluid movement style, with a stiff ending, while wearing an American football uniform to approximate the finished costume.[10][32] Weller said working with Verhoeven was his main reason for choosing the role over appearing in King Kong Lives (1986).[15][33]

Stephanie Zimbalist was cast as Murphy’s partner Anne Lewis but dropped out because of contractual obligations to Remington Steele, which had been canceled in 1986, but was revived because of its popularity.[e] Her replacement, Nancy Allen, thought the film’s title was terrible but found the script engrossing. Allen was known for her long blonde hair, but Verhoeven wanted it cut short so the character was not sexualized. Her hair was cut shorter eight times before the desired look was achieved.[37] Allen undertook police academy training for her role, and sought advice from her police lieutenant father.[37] Verhoeven encouraged her to act masculine and gain more weight; she accomplished the latter by quitting smoking.[11]

Kurtwood Smith (Boddicker) auditioned for both Boddicker and Jones. He was known mainly for television work and had not experienced film success. He saw RoboCop as a B film with potential.[10] The character was scripted to wear glasses so that he would look like Nazi party member Heinrich Himmler. Smith was unaware of this and interpreted it as the character portraying an intelligent and militaristic front to conceal being a «sneering, smirking drug kingpin».[10] Ironside was offered the role but did not want to be involved with another special effects-laden film or portray a «psychopath» character after working on Extreme Prejudice (1987).[25][31][38] Robert Picardo also auditioned for the role.[39]

Ronny Cox had been stereotyped as playing generally nice characters and said this left the impression that he could not play more masculine roles.[40] Because of this, Verhoeven cast him as the villainous Dick Jones.[41] Cox said that playing a villain was «about a gazillion times more fun than playing the good guys.»[42] Jones, he said, has absolutely no compassion, he is an «evil [son of a bitch]».[40] Miguel Ferrer was unsure if the film would be successful, but he was desperate for work and would have taken any offer.[15] The Old Man was based on MCA Inc. CEO Lew Wasserman, whom Neumeier considered to be a powerful and intimidating individual.[12] Television host Bixby Snyder was written as an Americanized and more extreme version of British comedian Benny Hill.[10] Radio personality Howard Stern was offered an unspecified role but turned it down because he believed the idea was stupid, though he later praised the finished film.[43]

Filming[edit]

Dallas City Hall appears as the exterior of OCP’s headquarters. Matte paintings were used to make it appear taller.

Principal photography began on August 6, 1986, on an $11 million budget.[44][45] Jost Vacano served as cinematographer, having previously worked with Verhoeven on Soldier of Orange.[22][45] Verhoeven wanted Blade Runner production designer Lawrence G. Paull, but Davison said he could afford either a great production designer or a great RoboCop costume, not both.[37][12] William Sandell was hired.[46] Monte Hellman directed several action scenes.[47]

Filming took place almost entirely on location in Dallas,[10][45][48] with additional shooting on sets in Las Colinas, and in Pittsburgh.[8][45][49] Verhoeven wanted a modern filming location that looked like it was from the near future.[45] Detroit was dismissed because it had many low, featureless, and visually uninteresting buildings.[26][45] Neumeier said it was also a trade union town, making it more expensive to film there.[50] Detroit does make a brief appearance in stock footage shown during the film’s opening.[16] Chicago was dismissed for aesthetic reasons, New York City for high costs, and California because, according to Davison, Orion wanted to distance themselves from the project.[26][45] Dallas was chosen over Houston because it offered modern buildings as well as older, less-maintained areas where they could use explosives.[45] The filming schedule in Dallas was nine weeks, but it soon became clear it was going to take longer. Based on filmed footage, Orion approved extending the schedule and increasing the budget to $13.1 million.[32][44][51] The weather during filming fluctuated: the Dallas summer was often 90 °F (32 °C) to 115 °F (46 °C);[26][37][52] the weather in Pittsburgh was frigid.[10]

RoboCop’s costume was not finished until some time into filming. This did not impact the filming schedule, but it denied Weller the month of costume rehearsal he had expected.[f] Weller was immediately frustrated with the costume because it was too cumbersome for him to move as he had practiced; he spent hours trying to adapt.[10][25][53] He also struggled to see through the thin helmet visor and interact or grab objects while wearing the gloves.[53][54] He fell out with Verhoeven and was eventually fired, with Lance Henriksen considered as a replacement; but because the costume was built for Weller, he was encouraged to mend his relationship with Verhoeven.[25] Yakim helped Weller develop a slower, more deliberate movement style.[15] Weller’s experience in the costume was worsened by warm weather, which caused him to sweat off up to 3 lb (1.4 kg) per day.[26][32] Verhoeven began taking prescription medication to cope with stress-induced insomnia, which left him filming scenes while intoxicated.[55]

Verhoeven often choreographed scenes alongside the actors before filming.[56][57] Even so, improvisation was encouraged because he believed it could create interesting results. Smith improvised some of his character’s quirks, such as sticking his gum on a secretary’s desk and spitting blood onto the police station counter. He recounted saying «‘What if I spat blood on the desk?’… [Verhoeven] got this little smile on his face, and we did it.»[10] Neumeier was on set throughout filming and was occasionally inspired to write additional scenes, including a New Year’s Eve party, after noticing some party-hat props; and a news story about the Strategic Defense Initiative platform misfiring.[10][12][21] Verhoeven found Neumeier’s presence invaluable because they could discuss how to adapt the script or location to make a scene work.[45]

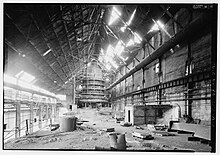

A steel mill in Pennsylvania served as the site of RoboCop’s and Clarence Boddicker’s final battle.

Verhoeven gained a reputation for verbal aggression and unsociable behavior on set, although Smith said that Verhoeven never yelled at the actors but was too engrossed in filming to be sociable.[10] Cox and Allen both spoke fondly of Verhoeven.[37][58] Weller spent his time between filming with the actors who played his enemies, including Smith, Ray Wise, and Calvin Jung, who maintained healthy lifestyles that supported Weller in his training for the New York City Marathon.[15]

Many locations in and around Dallas were used in the production. An office in Renaissance Tower was used for the interior of OCP, and the exterior is the Dallas City Hall (modified with matte paintings to look taller).[g] The OCP elevator was that of the Plaza of the Americas.[48][60] The Detroit police station is a combination of Crozier Tech High School (exterior) and the Sons of Hermann hall (interior), with the city hall being the Dallas Municipal Building.[60] Scenes of Boddicker’s gang blowing up storefronts were filmed in the Deep Ellum neighborhood. One explosion was larger than anticipated; and actors can be seen moving out of the way, Smith having to remove his coat because it was on fire and the actors involved receiving an additional $400 stunt pay.[10][45] The Shell gas station that explodes was located in the Arts District,[48][60] where locals unaware of the filming made calls to the fire department.[1] The scene was scripted for flames to modify the sign to read «hell»; Davison approved it but it does not appear in the film. Miner called it a disappointing omission.[10]

The nightclub was filmed at the former Starck Club. Verhoeven was filmed while demonstrating how the clubbers should dance and used the footage in the film.[10][11] Other Dallas locations include César Chávez Boulevard, the Reunion Arena,[60] and The Crescent car park.[50] The final battle between RoboCop and Boddicker’s gang was filmed at a steel mill in Monessen, outside Pittsburgh.[h] Filming concluded in late October 1986.[64]

Post production[edit]

An additional $600,000 budget increase was approved by Orion for post-production and the music score, raising the budget to $13.7 million.[i][j]

Frank J. Urioste served as the film’s editor.[65] Several pick-up shots were filmed during this phase, including Murphy’s death, RoboCop removing his helmet, and shots of his leg holster.[66] After the OCP boardroom scene in which RoboCop calls himself Murphy, a further scene revealed Lewis was alive in a hospital, before finally showing RoboCop on patrol. The latter scene was said to lessen the triumphant feeling of the former and was removed.[67][68] Verhoeven wanted the in-film media breaks to abruptly interrupt the narrative and unsettle the viewer. He was influenced by Piet Mondrian’s art that featured stark black lines separating colored squares.[10] Peter Conn directed many of the media breaks, except «TJ Lazer», which was directed by Neumeier.[69]

RoboCop‘s violent content made it difficult to receive a desired theatrical R rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). An R rating restricted a film to those over 17 unless accompanied by an adult. RoboCop initially received the restrictive X rating, meaning the film could be seen only by those over 17.[10][25][70] Although some reports suggest it was refused an R-rating eleven times, Verhoeven said the number was actually eight.[10][25] The MPAA took issue with several scenes, including Murphy’s death and ED-209 shooting an executive.[51][65] The violent scenes were shortened and media breaks were added to help lighten the mood although Verhoeven recalled how one reviewer was confused by their jarring appearance in the film and complained the projectionist had used the wrong film reel.[25][10]

The MPAA also objected to a scene of a mutated Emil being disintegrated by Boddicker’s car; but Verhoeven, Davison, and Orion refused to remove it because it consistently received the biggest laughs during test screenings.[13][71] Verhoeven made the violence comical and surreal, and believed the cuts made the scenes appear more, not less, violent.[10][25] He remarked that his young children laughed at the X-rated cut, and audiences laughed less at the R-rated version.[10][51] Verhoeven said people «love seeing violence and horrible things.»[51] The complete version of RoboCop runs for 103 minutes.[72]

Basil Poledouris provided the film score, having worked previously with Verhoeven on Flesh+Blood.[5] The score combines synthesizers and orchestral music, reflecting RoboCop’s cyborg nature. The music was performed by the Sinfonia of London.[73][74]

Special effects and design[edit]

Special effects[edit]

Actor Paul McCrane as Emil Antonowsky. McCrane wore a prosthesis over his upper body to give the appearance of his skin melting. His death was the highest-rated scene by test audiences.[71]

The special effects team was led by Rob Bottin, and included Phil Tippett, Stephan Dupuis, Bart Mixon, and Craig Davies, among others.[k]

The effects were excessively violent, because Verhoeven believed that made scenes funnier.[10][25] He likened the brutality of Murphy’s death to the crucifixion of Jesus, which was an efficient way to gain sympathy for Murphy.[10][65][71] The scene was filmed at an abandoned auto assembly plant in Long Beach, California, on a raised stage that allowed operators to control the effects from below.[77] To show Murphy being dismantled by gunfire, prosthetic arms were cast in alginate and filled with tubing that could pump artificial blood and compressed air. Weller’s left hand was attached to his shoulders by velcro and controlled by three operators; it was manufactured to explode in a controllable way so it could be easily put back together for repeat shots.[77] The right arm was jerked away from Weller’s body by a monofilament wire.[19][77] A detailed, articulated replica of Weller’s upper body was used to depict Boddicker shooting Murphy through the head.[71][77][78] A mold was made of Weller’s face using foam latex that was baked to make it rubbery and flesh-like, and placed over a fiberglass skull containing a blood squib and explosive charge. The articulated head was controlled by four puppeteers and had details of sweat and blood. A fan motor attached to the body made it vibrate as if shaking in fear. The charge in the skull was connected to the trigger of Smith’s gun by wire to synchronize the effect.[79]

Emil’s melting mutation was inspired by the 1977 science fiction film The Incredible Melting Man.[80] Bottin designed and constructed Emil’s prosthetics, creating a foam latex headpiece and matching gloves that gave the appearance of Emil’s skin melting «off his bones like marshmallow sauce».[80][81] A second piece depicting further degradation was applied over the first. Dupuis painted each piece differently to emphasize Emil’s advancing degradation. The prosthetics were applied to an articulated dummy to show Emil being struck by Boddicker’s car. The head was loosened so it would fly off; by chance, it rolled onto the car’s hood. The effect was completed with Emil’s liquified body (raw chicken, soup, and gravy) washing over the windscreen.[81] The same dummy stands in for RoboCop when he is crushed by steel beams (painted wood).[81] Verhoeven wanted RoboCop to kill Boddicker by stabbing him in the eye, but it was believed the effort to create the effect would be wasted out of censorship concerns.[82]

Dick Jones’s fatal fall is shown by a stop-motion puppet of Cox animated by Rocco Gioffre. The limited development time meant Gioffre used a foam rubber puppet with an aluminum skeleton, instead of a higher-quality articulated version. It was composited against Mark Sullivan’s matte painting of the street below.[82][83] ED-209’s murder of OCP executive Kevin Page was filmed over three days. Page’s body was covered in 200 squibs, but Verhoeven was unhappy with the result and brought Page back months later to re-shoot it in a studio-built recreation of the board room. Page was covered in over 200 squibs, as well as plastic bags filled with spaghetti squash and fake blood. Page described being in intense pain, as each squib detonation felt like being punched.[8] In the cocaine warehouse scene, Boddicker’s stuntman was thrown through real glass panes rigged with detonating cord to shatter microseconds before he hit.[84] Gelatin capsules filled with sawdust and a sparkling compound were fired from an air gun at RoboCop to create the appearance of ricocheting bullets.[85]

RoboCop[edit]

Bottin was tasked with designing the RoboCop costume.[10][13][86] He researched the Star Wars character C-3PO, looking at its stiff costume, which made movement difficult.[86] Bottin was also influenced by robot designs in Metropolis (1927) and The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951),[16][65] as well as several comic book superheroes.[87][88] He developed around 50 different designs based on feedback from Verhoeven, who pushed for a more machine-like character,[87][89] finally landing on a sleek aesthetic inspired by the work of Japanese illustrator Hajime Sorayama.[90] Verhoeven admitted he had unrealistic expectations after reading Japanese science fiction manga; and it took him too long to realize it, which contributed to the costumes delay.[10]

The scope of the RoboCop costume was unprecedented, and both design and construction exceeded cost and schedule.[26][45][78] It took six months to build, using flexible foam latex, semi- and completely rigid polyurethane, as well as a fiberglass helmet.[26][87][91] Moving sections were joined with aluminum and ball bearings.[91] The entirety of the costume is supported by an internal harness of hooks, allowing for sustained movement during action-heavy scenes.[78] Seven costumes were made, including a fireproof version and costumes to convey sustained damage.[92] Reports on their weight varies from 25 to 80 lb (11 to 36 kg).[l] RoboCop’s gun, the Auto-9, is a Beretta 93R with an extended barrel and larger grip. It was modified to fire blank bullets, and vents were cut into the side to allow for multi-directional muzzle flashes with every three-shot burst.[96]

ED-209[edit]

To budget for ED-209’s development, Tippett developed preliminary sketches, and hired Davies to design the full-scale model, which was constructed with the help of Paula Lucchesi.[75] Verhoeven wanted ED-209 to look mean and believed Davies’ early designs lacked a «killer» aesthetic. Davies was influenced by killer whales and a United States Air Force LTV A-7 Corsair II. He approached the design with modern American aesthetics and corporate design policy that he believed prioritized looks over functionality, including excessive and impractical components. He did not add eyes, opining that they would make ED-209 more sympathetic.[97] The fully-articulated fiberglass model took four months to build, cost $25,000, stood 7 ft (2.1 m) tall, and weighed 300 to 500 lb (140 to 230 kg).[98][99][100] The 100-hour work weeks took their toll, and Davies made ED-209’s feet minimal in detail, as he did not think they would be shown on camera.[101] The model was later used on promotional tours.[99][100][102]

Davies spent another four months building two 12 in (30 cm) miniature replicas for stop motion animation.[103] The two small models allowed scenes to be animated and filmed more efficiently, which saved time in completing the 55 shots needed in three months.[103] Tippett was the lead ED-209 animator, with Randal M. Dutra and Harry Walton assisting.[13][100][104] Tippett conceived ED-209’s movement as «unanimal»-like as if it was constantly about to fall over before catching itself.[100] To complete the character, the droid was given the roar of a leopard. Davison provided a temporary voiceover for ED-209’s speaking voice, which was retained in the film.[105]

Other effects and design[edit]

RoboCop contains seven matte effects painted mainly by Gioffre. Each matte was painted on masonite. Gioffre supervised on-site filming to mask the camera where the matte is inserted. He recounted having to crawl out from a 5-story high ledge to get the right shot of the Plaza of the Americas.[106] The burnished steel RoboCop logo was developed using special photographic effects that supervisor Peter Kuran based on a black-and-white sketch from Orion. Kuran created a scaled-up matte version and backlit it. A second pass was made with a sheet of aluminum behind it to create reflective detail.[64] RoboCop’s vision was created using hundreds of ink lines on acetate composited over existing footage. Several attempts had to be made to get the line thickness right; at first, the lines would appear too thick or too thin.[107] Assuming thermographic photography would be expensive, Kuran replicated thermal vision using actors in body stockings painted with thermal colors and filmed the scene with a polarized lens filter.[108] RoboCop’s mechanical recharging chair was designed and built by John Zabrucky of Modern Props.[109] The OCP boardroom model of Delta City was made under the supervision of art director Gayle Simon.[110]

The police cars are 1986 Ford Taurus models painted black.[49] The Taurus was chosen because of its new, futuristic, aerodynamic styling for the era, as it was the first production year for that vehicle. The vehicle was intended to feature a customized interior that would show graphical displays for mug shots, fingerprints, and other related information, but the concept was considered too ambitious.[13][64] The 6000 SUX driven by Boddicker, among others, is an Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme modified by Gene Winfield based on a design by Chip Foose. Two working cars were made, alongside a third, non-functional one that was used when the vehicle was shown to explode.[111] The 6000 SUX commercial features a plasticine dinosaur animated by Don Waller and blocked by Steve Chiodo.[111]

Release[edit]

Context[edit]

Industry experts were optimistic about the theatrical summer of 1987 (June–September).[112] The season focused on genre films—science fiction, horror, and fantasy—that were proven to generate revenue if not industry respect.[113] Other films—such as Roxanne, Full Metal Jacket, and The Untouchables—were targeted at older audiences (those aged over 25), who had been ignored in recent years by films targeted at teenagers.[114][115] The action-comedy Beverly Hills Cop II was predicted to dominate the theaters,[112] but many other films were expected to perform well, including the action adventure Ishtar, comedy films Harry and the Hendersons, Who’s That Girl, Spaceballs, the action film Predator, and sequels such as Superman IV: The Quest for Peace and the latest James Bond film, The Living Daylights.[112][115]

Along with the musical La Bamba, RoboCop was predicted to be a sleeper hit,[12][116] having received positive feedback before release, including both a positive industry screening (which was considered a rarity) and multiple pre-release screenings that demonstrated the studio’s confidence in the film.[117][118]

Marketing[edit]

The RoboCop logo used in the film

Marketing the film was considered difficult.[119] Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Jack Mathews described RoboCop as a «terrible title for a movie that anyone would expect an adult to enjoy». Orion head of marketing Charles Glenn said it had a «certain liability … it sounds like ‘Robby the Robot’ or Gobots or something else. It’s nothing like that.»[119] The campaign began three months before the film’s release; 5,000 adult-oriented and family-friendly trailers were sent to theaters. Orion promotions director Jan Kean said children and adults responded positively to the RoboCop character.[119] Miguel Ferrer recalled a theater audience unfavorably laughing at the trailer, which he found disheartening.[120] Models and actors in fiberglass RoboCop costumes made appearances in cities throughout North America. The character appeared at a motor racing event in Florida, a laser show in Boston, a subway in New York City, and children could take their picture with him at the Sherman Oaks Galleria in Los Angeles.[119]

An incomplete version of the unrated film was screened early for critics, which was unconventional for an action film. Glenn reasoned that critics who favored Verhoeven’s earlier work would appreciate RoboCop. The feedback was generally positive, providing quotes for promotional material and making it one of the best-reviewed films of the year up to that point.[119] The week before release saw the introduction of television adverts and limited theatrical screenings for the public.[119] The film was released in the United Kingdom without cuts; the BBFC stated that the comic excess of the violence, and the clear line between the hero and villains justified it.[121]

Box office[edit]

RoboCop began a wide North American release on July 17, 1987.[122][123] During its opening weekend, the film exceeded expectations by earning $8 million from 1,580 theaters—an average of $5,068 per theater.[124][125] It was the weekend’s number-one film, ahead of a re-release of the 1937 animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs ($7.5 million) and the horror sequel Jaws: The Revenge ($7.2 million), both of which were also in their first week of release.[124][126] RoboCop retained the number-one position in its second weekend with an additional gross of $6.3 million, ahead of Snow White ($6.05 million) and the debuting comedy Summer School ($6 million).[127][128] In its third weekend, RoboCop was the fourth-highest-grossing film with a gross of $4.7 million, behind La Bamba ($5.2 million) and the debuts of the horror film The Lost Boys ($5.2 million) and The Living Daylights ($11.1 million).[129]

RoboCop never regained the number one spot but remained in the top ten for six weeks in total.[122][123] By the end of its theatrical run, the film had grossed about $53.4 million, becoming a modest success.[25][122][123][m] This figure made it the year’s fourteenth highest-grossing film, behind Crocodile Dundee ($53.6 million), La Bamba ($54.2 million), comedy film and Dragnet ($57.4 million).[130] Figures are not available for the film’s performance outside North America.[122][123]

Due in part to higher ticket prices and an extra week of the theatrical summer,[114] 1987 set a record of $1.6 billion in box-office gross, just exceeding the previous record of $1.58 billion record set in 1984. Unlike that earlier summer, which featured multiple blockbusters, such as Ghostbusters and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, the summer of 1987 delivered only one: Beverly Hills Cop II. Even so, more films, including RoboCop, had performed modestly well, earning a collective total of $274 million—a 50% increase over 1986.[131][115] The average audience age continued to increase, as teen-oriented films—such as RoboCop and Beverly Hills Cop II—suffered a 22% drop in performance against similar 1986 films. Adult-oriented films saw a 39% increase in revenue.[131] RoboCop was one of the summer’s surprise successes and contributed to Orion’s improving fortunes.[21][132]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Variety‘s review highlighted Nancy Allen (pictured in 1984) for providing the only human warmth in RoboCop.

RoboCop opened to generally positive reviews.[25][51] Audience polls by CinemaScore reported that moviegoers gave the film an averaged letter grade of «A−».[133]

Critics noticed influences in the film from the action of The Terminator (1984) and Aliens (1986), and the narratives of Frankenstein (1931), Repo Man (1984), and the television series Miami Vice.[134][135][136] RoboCop built a distinct, futuristic vision for Detroit, wrote two reviewers, as Blade Runner had done for Los Angeles.[134][116] Multiple critics struggled to identify the film’s genre, writing that it combined social satire and philosophy with elements of action, science fiction, thrillers, Westerns, slapstick comedy, romance, snuff films, superhero comics, and camp, without being derivative.[n]

Some publications found Verhoeven’s direction to be smart and darkly comic, offering sharp social satire that, The Washington Post suggested, would have been just a simple action film in another director’s hands.[136][140][141] Others, such as Dave Kehr and the Chicago Reader, believed the film was over-directed with Verhoeven’s European filmmaking style lacking rhythm, tension, and momentum. The Chicago Reader wrote that Verhoeven’s typical adeptness at portraying the «sleazily psychological» through physicality failed to properly use RoboCop’s «Aryan blandness».[139][142] The Washington Post and Roger Ebert both praised Weller’s performance and his ability to elicit sympathy and convey chivalry and vulnerability while mostly concealed beneath a bulky costume. Weller offered a certain beauty and grace, wrote The Washington Post, that added a mythic quality and made his murder even more horrible.[136][137] In contrast, Weller «hardly registered» behind the mask for the Chicago Reader.[139] Variety highlighted Nancy Allen as providing the only human warmth in the film, and Kurtwood Smith as a well-cast «sicko sadist».[143]

Many reviewers discussed the film’s violent content.[o] The violence was so excessive for Ebert and the Los Angeles Times that it became deliberately comical, with Ebert writing that ED-209 killing an executive subverted audience expectations of a seemingly serious and straightforward science-fiction film. The Los Angeles Times believed the violent scenes succeeded in creating experiences of sadism and poignancy simultaneously.[137][141] Other reviewers were more critical, including Kehr and Walter Goodman, who believed RoboCop‘s satire and critiques of corporate corruption were excuses to indulge in violent visuals.[142][144] The Chicago Reader found the violence had a «brooding, agonized quality … as if Verhoeven were both appalled and fascinated» by it, and The Christian Science Monitor said critical praise for the «nasty» film demonstrated a preference for «style over substance».[139][140]

Kehr and The Washington Post said the satire of corporations and interchangeable use of corporate executives and street-level criminals was the film’s most successful effort, depicting their unchecked greed and callous disregard alongside witty criticisms of subjects such as game shows and military culture.[136][142] Some reviewers appreciated the film’s adaptation of a classic narrative about a tragic hero seeking revenge and redemption, with the Los Angeles Times writing that the typical cliché revenge story is transformed by making the protagonist a machine that keeps succumbing to humanity, emotion, and idealism. The Los Angeles Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer considered RoboCop’s victory to be satisfying because it offered a fable about a decent hero fighting back against corruption, villains, and the theft of his humanity, with morality and technology on his side.[134][135][141] The Washington Post agreed that the film’s «heart» is the story of Murphy regaining his humanity, saying «with all our flesh-and-blood heroes failing us—from brokers to ballplayers—we need a man of mettle, a real straight shooter who doesn’t fool around with Phi Beta Kappas and never puts anything up his nose. What this world needs is ‘RoboCop’.»[136]

Accolades[edit]

RoboCop won the Special Achievement for Best Sound Editing (Stephen Flick and John Pospisil) at the 60th Academy Awards. The film received two other nominations: Best Film Editing for Frank J. Urioste (losing to Gabriella Cristiani for the drama film The Last Emperor) and Best Sound for Michael J. Kohut, Carlos Delarios, Aaron Rochin, and Robert Wald (losing to Bill Rowe and Ivan Sharrock for The Last Emperor).[145] A comedy routine at the event featured the RoboCop character rescuing presenter Pee-wee Herman from ED-209.[146][147] At the 42nd British Academy Film Awards, RoboCop received two nominations: Best Makeup and Hair for Carla Palmer (losing to Fabrizio Sforza for The Last Emperor); and Best Special Visual Effects for Bottin, Tippett, Kuran, and Gioffre (losing to George Gibbs, Richard Williams, Ken Ralston, and Edward Jones for the 1988 fantasy film Who Framed Roger Rabbit).[148] At the 15th Saturn Awards, RoboCop was the most-nominated film. It won awards for Best Science Fiction Film, Best Director for Verhoeven, Best Writing for Neumeier and Miner, Best Make-up for Bottin and Dupuis, and Best Special Effects for Kuran, Tippett, Bottin, and Gioffre. It received a further three nominations, including for Best Actor (Weller) and Best Actress (Allen).[149][150]

Post-release[edit]

Home media[edit]

RoboCop was released on VHS in early 1988, priced at $89.98;[151][152][153] it made an estimated $24 million in sales.[13][p] Orion promoted the film by having former United States President Richard Nixon shake hands with a RoboCop-costumed actor. Nixon was paid $25,000, which he donated to Boys Club of America.[25] The film was a popular rental, peaking at number 1 in mid-March 1988.[154][155] Demand for rentals outstripped supply, as estimates suggested there was one VHS copy of a film per 100 households, making it difficult to find new releases such as Dirty Dancing, Predator, and Platoon; the longest waiting list was for RoboCop.[156] RoboCop was also released in S-VHS in 1988, one of the earliest films to adopt the format. Priced at $39.98, it was offered as a free incentive when buying branded S-VCR players.[151]

The extended violent content removed from the U.S. theatrical release was restored on a Criterion collection LaserDisc that included audio commentary by Verhoeven, Neumeier, and Davison.[13][157] The uncut version of the film has since been made available on other home media releases.[13] It was released on DVD by Criterion in September 1998.[158][159] In June 2004, the DVD version was released in a trilogy boxset that included RoboCop 2 (1990) and RoboCop 3 (1993). This edition included featurettes about the making of the film and the RoboCop design.[158] A 20th-anniversary edition was released in August 2007, which included both the theatrical and uncut versions of the film, as well as previous extras and new featurettes on the special effects and villains.[158]

The scheduled Blu-ray disc debut in 2006 by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment was canceled only days before release. Reviews indicated that the video quality was very poor. A new version was released in 2007 by Fox Home Entertainment without any extra features.[160][161][162] Reviews indicated that the visual quality had improved, but it retained issues in that images were perceived as grainy or too dark.[162][163] The trilogy was released as a Blu-ray disc boxset in October 2010.[164][165]

The film was restored in 4K resolution from the original camera negative by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in 2013 for MGM’s 90th anniversary the following year.[166] The new restoration was approved by Verhoeven, Neumeier, and Davison;[167] it was subsequently released on Blu-ray in January 2014.[168] In 2019, a two-disc limited edition Blu-ray set was released by Arrow Video, which included collectible items (a poster and cards), new commentaries by film historians and fans, deleted scenes, new featurettes with Allen and casting director Julie Selzer, and the theatrical, extended, and television cuts of the film.[169][170] Arrow re-released the set on Ultra HD Blu-ray (UHD) in 2022, which included the uncut version scenes being re-scanned from the negative to match the quality of the theatrical cut scans; the UHD release additionally features Dolby Vision HDR picture grading and Dolby Atmos audio.[171][172]

Other media[edit]

RoboCop was considered easier to merchandise than other R-rated films.[119] Despite its violent content, film merchandise was targeted at a younger audience. Merchandise included cap guns, comic books, other assorted toys,[q] theme park rides, novels,[65] and the RoboCop Ultra Police action figures (released alongside the 1988 animated series adaptation RoboCop).[93] By the time of the film’s release, Marvel Comics had published a black-and-white comic book adaptation of the film, without the violence and adult language;[119][173] a video game was in development; and negotiations were underway to release T-shirts, other video games, and RoboCop dolls by Christmas. The film’s poster was reportedly more popular than the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue;[119] and its novelization, written by Ed Naha, was in its second printing by July.[119][174] Since its release, RoboCop has continued to be merchandised, with collectible action figures, clothing, and crockery.[r] A 2014 book, RoboCop: The Definitive History, details the making of the RoboCop franchise.[178][179][180]

The story of RoboCop has been continued in comics, initially by Marvel Comics. The adaptation of the film was reprinted in color to promote an ongoing series that ran for 23 issues between 1987 and 1992, when the rights were transferred to Dark Horse Comics. Dark Horse released multiple miniseries, including RoboCop Versus The Terminator (1992), which pitted RoboCop against the machinations of Skynet and its Terminators from The Terminator franchise.[32][173] The story was well-received and was followed by other series, including Prime Suspect (1992), Roulette (1994), and Mortal Coils (1996).[32] The RoboCop series was continued by other publishers: Avatar Press (2003), Dynamite Entertainment (2010), and Boom! Studios (2013).[32][173]

Several games based on, or inspired by, the film have been released. A 1988 side-scroller of the same name was released for arcades in 1988, and ported to other platforms, such as the ZX Spectrum and Game Boy.[93][181] RoboCop Versus The Terminator, an adaptation of the comic of the same name, was released in 1994. RoboCop, a 2003 first-person shooter, was poorly received, resulting in the shuttering of developer Titus Interactive.[32]

Thematic analysis[edit]

Corporate power[edit]

President Ronald Reagan addressing the nation in 1981 on tax reduction. RoboCop satirizes Reagan’s political policies, espousing limited regulation, trickle-down economics, and a pro-business agenda.

A central theme in RoboCop is the power of corporations. Those depicted in the film are corrupt and greedy, privatizing public services and gentrifying the entirety of Detroit.[13][182] A self-described hippie who grew up during the Watergate scandal and Vietnam War, Miner was critical of the pro-business policies of President Reagan and believed Detroit to be a city destroyed by American corporations.[10][13][65] The Detroit presented in the film is described by various authors as one beset by rape, crime, and «Reaganomics gone awry», where gentrification is equivalent to crime and unfettered capitalism of Reagan-era politics results in corporations conducting literal war as the police become a profit-driven entity.[136][65][139] Miner said that out-of-control crime was a particularly Republican or right-wing fear, but RoboCop puts the blame for drugs and crime on advancing technology and the privatization of public services, such as hospitals, prisons and the police.[13] The criticism of Reagan-era policies was in the script but Verhoeven did not personally understand urban politics such as privatizing prisons.[15][51] Weller said that trickle-down economics espoused by Reagan were «bullshit» and did not work fast enough for those in need.[15]

Michael Robertson described the media breaks throughout the film as direct criticisms of neoliberal Reagan policies. He focused on OCP’s claim that it has private ownership over RoboCop, despite making use of Murphy’s corpse. The Old Man was based on Reagan, and the corporation policies emphasize greed and profit over individual rights. The police are deliberately underfunded and the creation of RoboCop is done with the aim of supplanting the police with a more efficient force. Jones openly admits that it does not matter if ED-209 works, because they have contracts to provide spare parts for years. He plots with Boddicker to corrupt the workers brought in to build Delta City with drugs and prostitution.[183] Davison believed the film is politically liberal but the violence made it «fascism for liberals».[65] It also demonstrates a pro-labor union stance: the police chief, believing in the essential nature of their service, refuses to strike but the underfunded, understaffed and under-assault police eventually do so. OCP sees the strike merely as an opportunity to develop more robots.[184]

[edit]

Vince Mancini describes the 1980s as a period in which cinematic heroes were unambiguously good, as depicted in films that promoted suburban living, materialism, and unambiguous villains, such as Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Back to the Future (1985).[13] Some films of the decade send the message that authority is good and to be trusted, but RoboCop demonstrates that those in authority are flawed, and that Detroit has been carved up by greed, capitalism, and cheap foreign labor.[13] Weller described RoboCop as an evolution of strait-laced heroes of the 1940s—such as Gary Cooper and Jimmy Stewart—who lived life honorably, with modern audiences now cheering a maimed police officer taking brutal revenge.[51]

Susan Jeffords considers RoboCop to be among the many «hard body» films of the decade that portray perfect, strong, masculine physiques who must protect the «soft bodies»: the ineffectual and the weak. RoboCop portrays strength by eliminating crime and redeeming the city through violence. Bullets ricochet harmlessly off RoboCop’s armor; and even attempts to attack his crotch, a typical weak point, only hurt the attacker, demonstrating the uncompromising strength and masculinity needed to eliminate crime.[185] Darian Leader argues that it requires the addition of something unnatural to a biological body to be truly masculine. RoboCop’s body incorporates technology, a symbolic addition that makes him more than an average man.[186]

Humanity and death[edit]

Another central theme is the question of what humanity is, and how much of Murphy is left in RoboCop.[136][137] Neumeier wanted to leave audiences asking «what’s left» of Murphy, and he described the character’s journey as one of coping with his transformation.[83] As an officer, Murphy works for a corporation that insists it owns individuals based on waivers and can do with Murphy’s remains as it wishes. Even so, Murphy does the right thing and fights against the demands of his corporate masters.[10] Despite his inhuman appearance, RoboCop has a soul, experiences real human fears, and has a core consciousness that makes him more than a machine.[65] In contrast, Brooks Landon argues that Murphy is dead and, while he recalls memories of Murphy’s life, RoboCop is not and can never be Murphy and regain enough of his humanity to rejoin his family.[187] Dale Bradley posits that RoboCop is a machine who mistakenly thinks it is Murphy because of its composite parts and only believes it has a human spirit within.[188] An alternative view is that RoboCop’s personality is a new construct informed partially by fragments of Murphy’s own personality.[189] Slavoj Žižek describes Murphy as a man between life and death, who is by all measure deceased and simultaneously reanimated with mechanical parts. As he regains his humanity, he transforms from a state of being programmed by others to his former state as a being of desire. Žižek calls this return of the living dead a fundamental fantasy of the masses, the desire to avoid death and take revenge against the living.[190]

Murphy’s death is prolonged and violent so that the audience can see RoboCop as imbued with the humanity taken from him by the inhumane actions of Boddicker’s gang and OCP.[51] Verhoeven considered it important to acknowledge the inherent darkness of humanity to avoid inevitable mutual destruction. He was affected by his childhood experiences during World War II and the inhuman actions he witnessed. He believed the concept of the immaculate hero died following the war and subsequent heroes had a dark side that they had to overcome.[51] Describing the difference between making films in Europe and America, Verhoeven said that a European RoboCop would explore the spiritual and psychological problems of RoboCop’s condition, where the American version focuses on revenge.[51] He also incorporated Christian mythology into the film: Murphy’s brutal death is referred to as the crucifixion of Jesus before his resurrection as RoboCop, an American Jesus who walks on water at the steel mill and wields a handgun.[10][65] Verhoeven asserted he had no belief in the resurrection of Jesus but «[he] can see the value of that idea, the purity of that idea. So from an artistic point of view, it’s absolutely true».[10][65] The scene of RoboCop returning to Murphy’s home is described as like finding the Garden of Eden or a paradise.[1][10]

Brooks Landon describes the film as typical of the cyberpunk genre, because it does not treat RoboCop as better or worse than average humans, simply different and asks the audience to consider him as a new lifeform.[51][187] The film does not treat this technological advance as necessarily negative, just an inevitable result of a progression that will change one’s life and one’s understanding of what it means to be human.[187] In this way, the RoboCop character is the embodiment of the struggle of humanity in giving itself over to technology.[12] The central cast are not given romantic interests or overt sexual desires. Paul Sammon described the scene of RoboCop shooting bottles of baby food as a symbol of the relationship he and Lewis can never have.[13][81] Taylor concurred but believed the confrontation between Morton and Jones in the OCP bathroom was sexualized.[65]

Legacy[edit]

Cultural influence[edit]

RoboCop is considered a groundbreaking entry in the science fiction genre.[65] Unlike many protagonists at the time, the film’s central character is not a robotic-like human who is stoic and invincible, but a human-like robot who is openly affected by his lost humanity.[65] In a 2013 interview, following Detroit’s real-life bankruptcy and being labeled as the most dangerous place in America, Neumeier spoke about the prescience of the film. He said, «We are now living in the world that I was proposing in RoboCop … how big corporations will take care of us and … how they won’t.»[185][191] Verhoeven described RoboCop as a film ahead of its time, which could not be improved with digital effects.[192] Weller said the filming experience as among the worst of his life, mainly because of the RoboCop costume.[193] Verhoeven also considered filming RoboCop as a miserable experience, in part due to the difficulties with special effects and things going wrong.[194] In contrast, Ferrer described it as the best summer of his life.[120]

The film’s impact was not limited to North America: Neumeier recalled finding unlicensed RoboCop dolls on sale near the Colosseum in Rome.[12] He has stated that many robotics labs use a «Robo-» prefix for projects in reference to the film, and he was hired as a United States Air Force consultant for futuristic concepts directly because of his involvement in RoboCop.[19] In the years immediately following its release, Verhoeven parlayed his success into directing the science fiction film Total Recall (1990)—featuring Cox—and the erotic thriller Basic Instinct (1992).[5][7] He also worked with Neumeier on the science fiction film Starship Troopers (1997).[5] In 2020, The Guardian‘s Scott Tobias wrote that with hindsight RoboCop formed the beginning of Verhoeven’s unofficial science fiction action film trilogy about authoritarian governance, followed by Total Recall and Starship Troopers.[195] Previously typecast as moral characters, Cox credited RoboCop with changing his image and—along with the Beverly Hills Cop films—boosting his film career to make him one of the decade’s most iconic villains.[40][42][196]

The RoboCop, ED-209, and Clarence Boddicker characters are considered iconic.[s] Dialogue, including RoboCop’s «Dead or alive, you’re coming with me,» ED-209’s «You have 20 seconds to comply,» and television host Bixby Snyder’s «I’d buy that for a dollar», are similarly considered iconic and among the film’s most recognizable.[t] The film has been referred to in a variety of media, from television (including Family Guy,[209] It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia,[210] Red Dwarf,[211] South Park,[212] and The Simpsons[213][214]) to films (including Hot Shots! Part Deux[215] and Ready Player One[216]) and video games (Deus Ex[217] and its prequel Deus Ex: Human Revolution[218]). Doom Eternal (2020) creative director Hugo Martin also cited it as an inspiration.[219] RoboCop (voiced by Weller) appears as a playable character in the fighting game Mortal Kombat 11 (2019).[220] The character also served as a design inspiration for the Nintendo Power Glove (1989),[221] and appeared in advertisements for KFC in 2019 (again voiced by Weller),[222] and Direct Line in 2020, alongside the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Bumblebee.[223]

The crowdfunded making-of documentary RoboDoc: The Creation of RoboCop is set to be released in early 2023.[224] Its filmmakers began raising funds on Kickstarter in 2015 and concluded filming in 2021.[225][226] The documentary covers the technical production of the first three RoboCop films and features interviews with many of the cast and crew involved.[227] Weller initially declined to participate,[228] but was ultimiately interviewed for the documentary.[226]

For the film’s 30th anniversary in 2017, Weller attended a screening by Alamo Drafthouse Cinema at Dallas City Hall, because it was in his home town and he considered it a homage to the city.[33][48] A RoboCop statue is to be erected in Detroit. First proposed in 2011, $70,000 was crowdfunded for its construction. The idea for the 10 ft (3.0 m) statue had Weller’s backing and the approval of RoboCop rights-holder Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). As of 2022, the statue was completed and awaiting installation at an undisclosed location.[u]

Modern reception[edit]

RoboCop has been named one of the best science-fiction and action films of all time,[v] and among the best films of the 1980s.[w] On review aggregator, Rotten Tomatoes, it holds a 91% approval rating, based on 76 reviews, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The website summarizes the reviews with: «While over-the-top and gory, RoboCop is also a surprisingly smart sci-fi flick that uses ultraviolence to disguise its satire of American culture.»[248] The film has a score of 70 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 17 reviews, indicating «generally favorable reviews».[249] Rotten Tomatoes also listed the film at number 139 on its list of 200 essential movies to watch, and one of 300 essential movies.[250][251] In the 2000s, The New York Times listed it as one of the 1,000 Best Movies Ever,[252] and Empire listed the film at number 404 on its list of the 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[253]

Filmmakers have spoken of their appreciation for RoboCop or cited it as an inspiration in their own careers, including Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck,[254] Neill Blomkamp,[24] Leigh Whannell,[255] as well as Ken Russell, who called it the best science fiction film since Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).[256] During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, it was among the action films director James Gunn recommended people watch.[257]

Sequels and adaptations[edit]

By November 1987, Orion had greenlit development of a sequel targeting a PG rating that would allow children to see the film unaccompanied by adults,[258][259][260] and tying into the 12-episode animated series RoboCop, which was released by Marvel Productions in 1988.[32][65] Neumeier and Miner began writing the film but were fired after refusing to work through the 1988 writers strike, and were replaced by Frank Miller, whose second draft was made into RoboCop 2, and his first draft became the second sequel RoboCop 3.[12][261] Weller reprised his role in the Irvin Kershner–directed first sequel,[262] which was released to mixed reviews and was estimated to have lost the studio money.[263][264]

RoboCop 3, directed by Fred Dekker, was targeted mainly at younger audiences, who were driving merchandise sales. Robert John Burke replaced Weller in the title role, and Allen returned as Anne Lewis for the third and final time in the series.[32][37][65] The film was a critical and financial failure.[265] A live-action television series, RoboCop, was released the same year, but also fared poorly critically and was cancelled after 22 episodes. Starring Richard Eden as RoboCop, the series was notable for involving Neumeier and Miner, and using aspects of their original RoboCop 2 ideas.[32][65][93] A second animated series followed in 1998, RoboCop: Alpha Commando.[32][65] Page Fletcher was featured as RoboCop in the four-part live-action miniseries RoboCop: Prime Directives (2001). The series is set 10 years after the events of the first film and ignores the events of the sequels.[32][65] After years of experiencing financial difficulties, Orion—and the rights to RoboCop—were purchased by MGM in the late 1990s.[32][266][267]

A 2014 reboot of the 1987 original, also called RoboCop, was directed by José Padilha and features Joel Kinnaman in the title role. The film received mixed reviews but was a financial success.[12][24][268] Verhoeven said that he «should be dead» before a reboot was attempted, and Allen believed an «iconic» film should not be remade.[37] RoboCop Returns, a direct sequel to RoboCop that ignores the series’ other films, is in development. The film is set to be directed by Abe Forsythe, who is rewriting a script written by Neumeier, Miner, and Justin Rhodes.[266][269][270] In 2020, Ed Neumeier revealed to MovieHole that a RoboCop prequel TV series is in development, which will focus on a young Dick Jones and the rise of Omni Consumer Products.[271]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[12][13][14][15]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[10][12][14][17]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[12][15][17][20]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[12][21][25][26][27]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[11][34][35][36]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[10][25][26][53]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[1][48][59][60][61]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[19][45][62][63]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[13][21][44][51]

- ^ The 1987 budget of $13.7 million is equivalent to $32.7 million in 2021.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[13][54][75][76]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[26][93][94][95]

- ^ The 1987 box office gross of $53.4 million is equivalent to $127 million in 2021.

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[116][135][137][138][139]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[134][141][140][142][144]

- ^ The 1988 VHS cost of $89.98 is equivalent to $206.00 in 2021. The VHS sales generated an estimated $24 million, equivalent to $55 million in 2021

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[25][51][65][119]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[175][176][177][178]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[197][198][199][200][201][202][203][204]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[205][206][207][208]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[25][229][230][231][232]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[233][234][235][236][237][238][239][192][240][241]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[242][243][244][245][246][247] Several publications have listed it as one of the greatest action films of all time:[192][240][241]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Gallagher, Danny (July 11, 2017). «RoboCop, The Movie That Blew Up Dallas Filmmaking, Turns 30″. Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Burke-Block, Candace (July 7, 1987). «Actress’s Role In RoboCop Will Again Surprise». Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ «Oscar Nominee Dan O’Herlihy Dies». BBC News. February 19, 2005. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Miska, Brad (September 9, 2020). «MGM Developing RoboCop Prequel Series Focusing On Villainous Omni VP Dick Jones». Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Brew, Simon (October 22, 2013). «RoboCop: Where Are They Now?». Den of Geek. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f «RoboCop (1987)». British Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Robertson, Chris Chan (September 30, 2017). «RoboCop: What Does The Cast Look Like Now?». Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c Parker, Ryan (July 14, 2017). «RoboCop Actor’s X-Rated Death Wasn’t Gory Enough For Paul Verhoeven». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ Iaquinta, Chris (May 10, 2012). «OCD: RoboCop’s Bixby Snyder». IGN. Archived from the original on June 13, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Abrams, Simon (February 12, 2014). «RoboCop: The Oral History». Esquire. Archived from the original on August 21, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Cohen, Ivan (February 14, 2014). «26 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About The Original RoboCop«. Vulture. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Tobias, Scott (February 13, 2014). «RoboCop Writer Ed Neumeier Discusses The Film’s Origins». The Dissolve. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Mancini, Vince (July 20, 2017). «RoboCop At 30 — An Island Of Dark Satire In A Decade Of Cheerleading». Uproxx. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Goldberg 1988, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Setchfield, Nick (March 14, 2012). «The Making Of RoboCop – Extended Cut». SFX. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Sammon 1987, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Mathews, Jack (September 1, 1987). «The Word Is Out: Good Writing Still Pays Off : Summer Box-office Hits Sparkled On Paper Before They Sparkled On The Screen». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Goldberg 1988, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d «Technology Issue Extra – How Not to Afford a Flying Car». Vice. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 1988, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Goldberg 1988, p. 25.

- ^ a b NiderostD 1987, p. 58.

- ^ Drake 1987, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Fleming, Mike Jr. (July 11, 2018). «Neill Blomkamp To Direct New RoboCop For MGM; Justin Rhodes Rewriting Sequel Script By Creators Ed Neumeier & Michael Miner». Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Lyttleton, Oliver (July 17, 2012). «5 Things You Might Not Know About Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop,’ Released 25 Years Ago Today». IndieWire. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Warren 1987, p. 19.

- ^ Robey, Tim (February 7, 2014). «RoboCop: The Bloody Birth Of The Original Film». The Dissolve. Archived from the original on September 4, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (September 20, 2000). «Alex Cox». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Goldberg 1988, pp. 23, 25.

- ^ NiderostB 1987, pp. 36, 38.

- ^ a b c De Semlyen, Phil (May 16, 2016). «’80s Heroes: Michael Ironside». Empire. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Hawker, Tim (February 6, 2014). «The History Of RoboCop«. IGN. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ a b «Peter Weller Explains How He ‘Bullsh—ted’ His Way Into RoboCop«. Entertainment Weekly. September 5, 2017. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ Bobbin, Jay (January 1, 1987). «Remington Steele Back For Round 2″. Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Bark, Ed (August 12, 1986). «Brosnan A Series Star Caught In TV’s Trap». Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Jacobs, Alexandra (November 24, 2003). «Actress Roles Over 40? ‘It’s A Big Fat Zero’«. The New York Observer. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Spry, Jeff (February 14, 2014). «Exclusive: RoboCop’s Nancy Allen On The Original’s Epic Cast Chemistry, The Remake, And Verhoeven Vs. Kershner». Syfy. Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Kaye, Don (December 7, 2020). «How Total Recall Brought a Memorable Villain to Life». Den of Geek. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Pockross, Adam (June 1, 2020). «Total Recall At 30: Cohaagen, Benny & Johnny Cab Recall Paul Verhoeven’s Mind-Bending Masterpiece». Syfy Wire. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c Mills, Nancy (August 18, 1987). «Recognizing The Assets Of Recognition». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Pockross, Adam (June 24, 2020). «Ronny Cox Only Played ‘Boy Scout Nice-Guys’ Until Paul Verhoeven Turned Him Bad». Syfy. Archived from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Harris, Will (July 5, 2012). «Deliverance’s Ronny Cox On Robocop, Total Recall, And The Glory Of Cop Rock». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (February 9, 2017). «The Lost Roles Of Howard Stern». Vulture. Archived from the original on August 19, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c «RoboCop (1987)». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gallagher, Danny (July 11, 2017). «Director Paul Verhoeven On RoboCop, The Bit Of ‘American Nonsense’ That Changed His Career». Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ Goodman, Walter (July 17, 1987). «Film: RoboCop,’ Police Drama With Peter Weller». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Keith (November 10, 1999). «Monte Hellman». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Wilonsky, Robert (September 8, 2017). «Robocop,’ Now 30, Is Still The Most Dallas Movie Ever Made, Despite Being Set In Detroit». The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ a b Viladas, Pilar (November 1, 1987). «Design In The Movies : Good Guys Don’t Live In White Boxes : In Today’s Movies, Modern Design Signifies Ambition, Money, Power—and Now Evil». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ a b Bates 1987, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m McKenna, Christine (July 18, 1987). «Verhoeven Makes Good With Violence». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ NiderostC 1987, p. 46.

- ^ a b c NiderostC 1987, p. 48.

- ^ a b NiderostD 1987, p. 61.

- ^ Collis, Clark (August 14, 2006). «RoboCop: Collector’s Edition». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Bates 1987, pp. 17, 20.

- ^ NiderostD 1987, p. 60.

- ^ Bates 1987, p. 20.

- ^ NiderostD 1987, p. 59.