Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| м. | ж. | ||

| Им. | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вичи |

| Р. | Ростропо́вича | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вичей |

| Д. | Ростропо́вичу | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вичам |

| В. | Ростропо́вича | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вичей |

| Тв. | Ростропо́вичем | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вичами |

| Пр. | Ростропо́виче | Ростропо́вич | Ростропо́вичах |

Ро—стро—по́—вич

Существительное, одушевлённое. Имя собственное (фамилия).

Непроизводное.

Корень: -Ростропович-.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [rəstrɐˈpovʲɪt͡ɕ]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- польская фамилия белорусского происхождения ◆ Есть люди, наделённые даром превращать в праздник каждую проведённую рядом с ними минуту. Мстислав Ростропович и Галина Вишневская ― из их числа. С. З. Спивакова, «Не всё», 2002 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Слухи о том, что коллекцию русского искусства, которую знаменитые музыканты Мстислав Ростропович и Галина Вишневская собирали во время своей вынужденной эмиграции, хочет целиком приобрести некий русский покупатель, появились накануне. Татьяна Маркина, Майя Стравинская, «Продано без молотка», Алишер Усманов купил коллекцию Ростроповича—Вишневской до аукциона // «Коммерсантъ», № 169, стр. 1, 18 сентября 2007 г.

Синонимы[править]

- —

Антонимы[править]

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- фамилия

Гипонимы[править]

- —

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

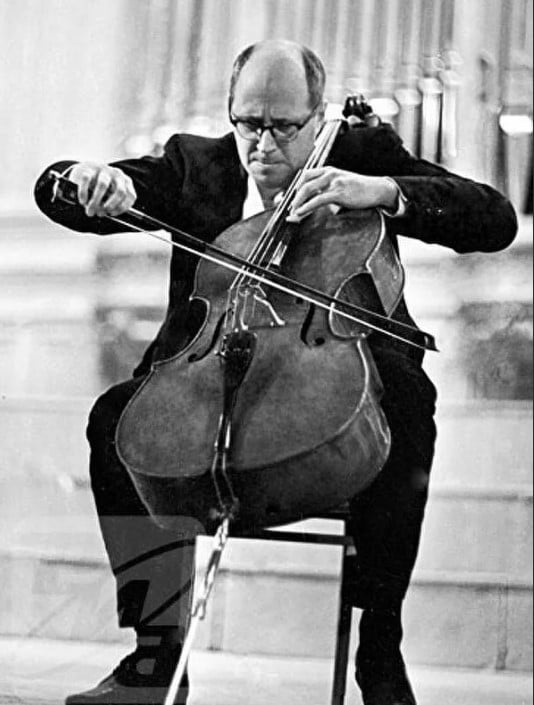

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich[a] (27 March 1927 – 27 April 2007) was a Russian cellist and conductor. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well known for both inspiring and commissioning new works, which enlarged the cello repertoire more than any cellist before or since. He inspired and premiered over 100 pieces,[citation needed] forming long-standing friendships and artistic partnerships with composers including Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Henri Dutilleux, Witold Lutosławski, Olivier Messiaen, Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Alfred Schnittke, Norbert Moret, Andreas Makris, Leonard Bernstein, Aram Khachaturian and Benjamin Britten.

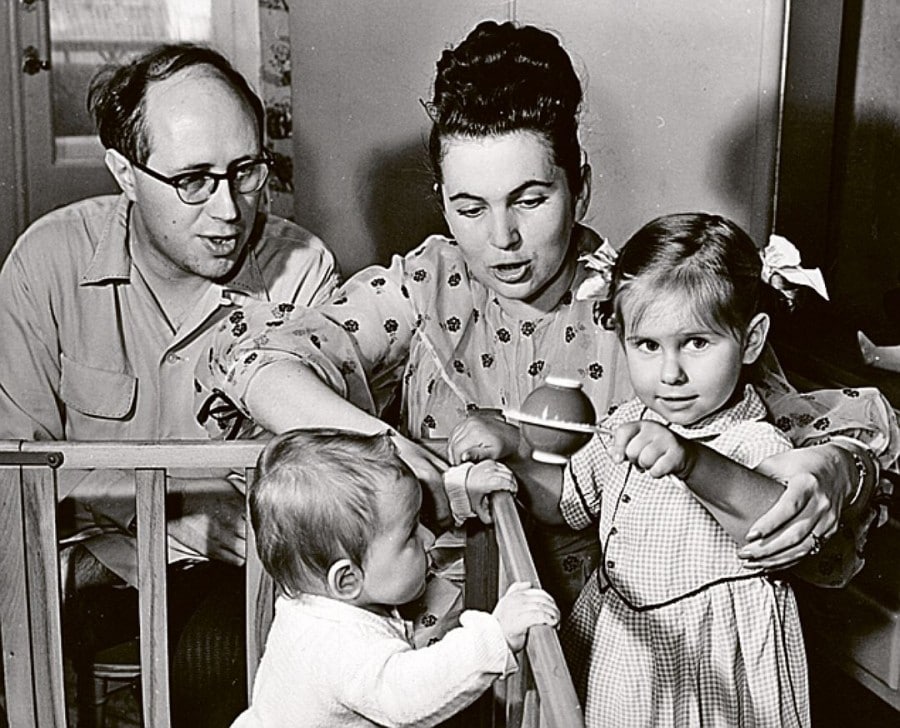

Rostropovich was internationally recognized as a staunch advocate of human rights, and was awarded the 1974 Award of the International League of Human Rights. He was married to the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya and had two daughters, Olga and Elena Rostropovich.

Early years[edit]

House in Baku, where Rostropovich was born

Mstislav Rostropovich was born in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR, to parents who had moved from Orenburg: Leopold Vitoldovich Rostropovich [ru], a renowned cellist and former student of Pablo Casals,[1] and Sofiya Nikolaevna Fedotova-Rostropovich, a talented pianist. Mstislav’s father, Leopold (1892–1942), was born in Voronezh to Witold Rostropowicz [ru], a composer of Polish noble descent, and Matilda Rostropovich (née Pule) of Belarusian descent. The Polish part of his family bore the Bogoria coat of arms, which was located at the family palace in Skotniki.[citation needed]

Mstislav’s mother, Sofiya, of Russian descent,[2] was the daughter of musicians.[3] Her elder sister, Nadezhda, married cellist Semyon Kozolupov, who was thus Rostropovich’s uncle by marriage.[4]

Rostropovich grew up in Baku and spent his youth there. During World War II his family moved back to Orenburg and then in 1943 to Moscow.[5]

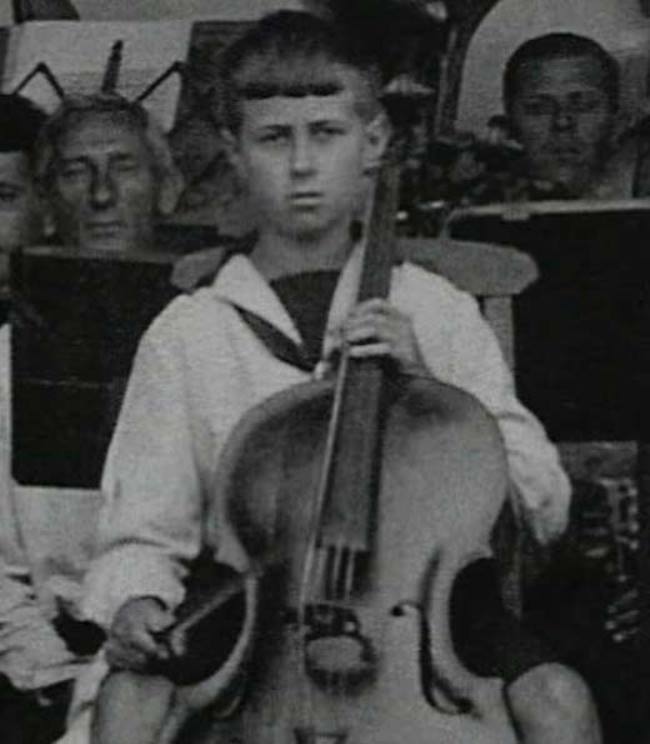

At the age of four, Rostropovich learned the piano with his mother. He began the cello at the age of 10 with his father. In 1943, at the age of 16, he entered the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied cello with his uncle Semyon Kozolupov, and piano, conducting and composition with Vissarion Shebalin. His teachers also included Dmitri Shostakovich. In 1945, he came to prominence as a cellist when he won the gold medal in the Soviet Union’s first ever competition for young musicians.[1] He graduated from the Conservatory in 1948, and became professor of cello there in 1956.

First concerts[edit]

Rostropovich gave his first cello concert in 1942. He won first prize at the international Music Awards of Prague and Budapest in 1947, 1949 and 1950. In 1950, at the age of 23 he was awarded what was then considered the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, the Stalin Prize.[6] At that time, Rostropovich was already well known in his country and while actively pursuing his solo career, he taught at the Leningrad (Saint-Petersburg) Conservatory and the Moscow Conservatory.

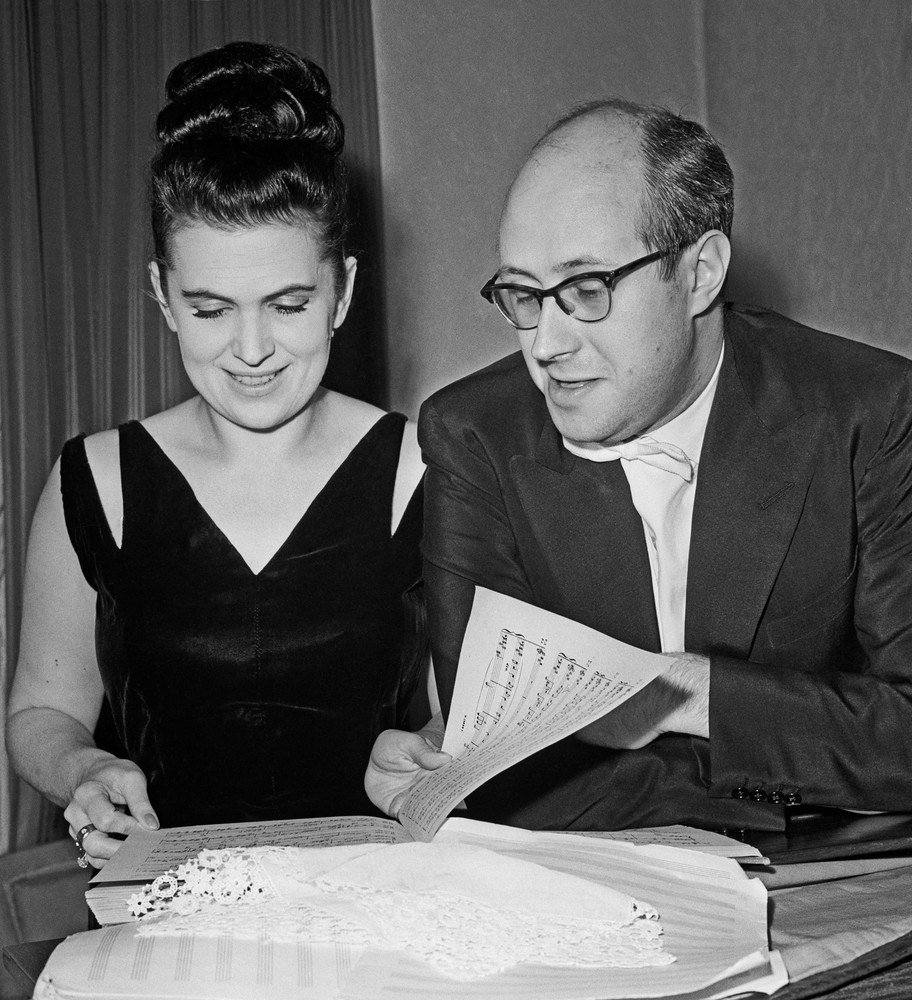

In 1955, he married Galina Vishnevskaya, a leading soprano at the Bolshoi Theatre.[7]

Rostropovich had working relationships with Soviet composers of the era. In 1949 Sergei Prokofiev wrote his Cello Sonata in C, Op. 119, for the 22-year-old Rostropovich, who gave the first performance in 1950, with Sviatoslav Richter. Prokofiev also dedicated his Symphony-Concerto to him; this was premiered in 1952. Rostropovich and Dmitry Kabalevsky completed Prokofiev’s Cello Concertino after the composer’s death. Dmitri Shostakovich wrote both his first and second cello concertos for Rostropovich, who also gave their first performances.[citation needed]

Mstislav Rostropovich and Benjamin Britten in 1964

His international career started in 1963 in the Conservatoire of Liège (with Kirill Kondrashin) and in 1964 in West Germany.[citation needed]

Rostropovich went on several tours in Western Europe and met several composers, including Benjamin Britten, who dedicated his Cello Sonata, three Solo Suites, and his Cello Symphony to Rostropovich. Rostropovich gave their first performances, and the two had an obviously special affinity – Rostropovich’s family described him as «always smiling» when discussing «Ben», and on his death bed he was said to have expressed no fear as he and Britten would, he believed, be reunited in Heaven.[8]

Britten was also renowned as a pianist and together they recorded, among other works, Schubert’s Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A minor. His daughter claimed that this recording moved her father to tears of joy even on his deathbed.[citation needed]

Rostropovich also had a long-standing artistic partnership with Henri Dutilleux (Tout un monde lointain… for cello and orchestra, Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher for solo cello), Witold Lutosławski (Cello Concerto, Sacher-Variation for solo cello), Krzysztof Penderecki (cello concerto n°2, Largo for cello and orchestra, Per Slava for solo cello, sextet for piano, clarinet, horn, violin, viola and cello), Luciano Berio (Ritorno degli snovidenia for cello and thirty instruments, Les mots sont allés… for solo cello) as well as Olivier Messiaen (Concert à quatre for piano, cello, oboe, flute and orchestra).[citation needed]

Rostropovich took private lessons in conducting with Leo Ginzburg,[9] and first conducted in public in Gorky in November 1962, performing the four entractes from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and Shostakovich’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death with Vishnevskaya singing.[10]

In 1967, at the invitation of the Bolshoi Theatre’s director Mikhail Chulaki, he conducted Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin at the Bolshoi, thus letting forth his passion for both the role of conductor and the opera.[11]

August 1968 proms[edit]

Rostropovich played at The Proms on the night of 21 August 1968. He played with the Soviet State Symphony Orchestra – it was the orchestra’s debut performance at the Proms. The programme featured Czech composer Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor and took place on the same day that the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia to end Alexander Dubček’s Prague Spring.[12] After the performance, which had been preceded by heckling and demonstrations, the orchestra and soloist were cheered by the Proms audience.[13] Rostropovich stood and held aloft the conductor’s score of the Dvořák as a gesture of solidarity for the composer’s homeland and the city of Prague.[citation needed]

Exile[edit]

Rostropovich fought for art without borders, freedom of speech, and democratic values, resulting in harassment from the Soviet regime. An early example was in 1948, when he was a student at the Moscow Conservatory. In response to the 10 February 1948 decree on so-called ‘formalist’ composers, his teacher Dmitri Shostakovich was dismissed from his professorships in Leningrad and Moscow; the 21-year-old Rostropovich quit the conservatory, dropping out in protest.[14] Rostropovich also smuggled to the West the manuscript of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13, emphasizing Soviet indifference to the Babi Yar massacre.[15]

In 1970, Rostropovich sheltered Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who otherwise would have had nowhere to go, in his own home. His friendship with Solzhenitsyn and his support for dissidents led to official disgrace in the early 1970s. As a result, Rostropovich was restricted from foreign touring,[16] as was his wife, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, and his appearances performing in Moscow were curtailed, as increasingly were his appearances in such major cities as Leningrad and Kiev.[17]

Rostropovich left the Soviet Union in 1974 with his wife and children and settled in the United States. He was banned from touring his homeland with foreign orchestras and, in 1977, the Soviet leadership instructed musicians from the Soviet bloc not to take part in an international competition he had organised.[18] In 1978, Rostropovich was deprived of his Soviet citizenship because of his public opposition to the Soviet Union’s restriction of cultural freedom. He would not return to the Soviet Union until 1990.[6]

Further career[edit]

On December 17, 1988, Rostropovich gave a special concert at Barbican Hall in London, after postponing a trip to India for the Armenian Earthquake relief program. The event was part of an effort called Musicians for Armenia, which was expected to raise more than $450,000 from donations worldwide, including gifts from musicians, concert proceeds and film and recording rights. Prince Charles and the Princess of Wales attended the concert in the sold-out 2,026-seat concert hall.[19]

On February 7, 1989, a cello concert was organized by the Armenian Relief Society and the Volunteers Technical Assistance (VTA) for the victims of the Spitak Earthquake. At the concert, Rostropovich played his favorite cello repertoire, including Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor; Haydn’s cello concerti in C and D; Prokofiev’s Symphony-Concerto; the two cello concerti of Shostakovich, and others. The evening with Rostropovich raised awareness and helped hundreds of earthquake victims put food on their table. The concert was held at the Kennedy Center and over 2,300 were in attendance.[20]

Galina Vishnevskaya and Mstislav Rostropovich with their daughters at home, 1 February 1959

Mstislav Rostropovich, 18 September 1959

Mstislav Rostropovich, chief conductor of U.S. National Symphony Orchestra, greets the audience in Bolshoi Hall of the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, 13 February 1990

Mstislav Rostropovich and his fans in Moscow

From 1977 until 1994, he was music director and conductor of the U.S. National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C. while still performing with some of the most famous musicians such as Martha Argerich, Sviatoslav Richter and Vladimir Horowitz.[21] He was also the director and founder of the Mstislav Rostropovich Baku International Festival and was a regular performer at the Aldeburgh Festival in the UK.[22]

His impromptu performance during the fall of the Berlin Wall as events unfolded was reported throughout the world.[23] His Soviet citizenship was restored in 1990. When, in August 1991, news footage was broadcast of tanks in the streets of Moscow, Rostropovich responded with a characteristically brave, impetuous and patriotic gesture: he bought a plane ticket to Japan on a flight that stopped at Moscow, talked his way out of the airport and went to join Boris Yeltsin in the hope that his fame might make some difference to the chance of tanks moving in.[24]

Rostropovich supported Yeltsin during the 1993 constitutional crisis and conducted the National Symphony Orchestra in Red Square at the height of the crackdown.[25]

In 1993, he was instrumental in the foundation of the Kronberg Academy and was a patron until his death. He commissioned Rodion Shchedrin to compose the opera Lolita and conducted its premiere in 1994 at the Royal Swedish Opera. Rostropovich received many international awards, including the French Legion of Honor and honorary doctorates from many international universities. He was an activist, fighting for freedom of expression in art and politics. An ambassador for the UNESCO, he supported many educational and cultural projects.[26] Rostropovich performed several times in Madrid and was a close friend of Queen Sofía of Spain.

With wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, he founded the Rostropovich-Vishnevskaya Foundation, a publicly supported non-profit 501(c)(3) organization based in Washington, D.C., in 1991 to improve the health and future of children in the former Soviet Union. The Rostropovich Home Museum opened on 4 March 2002, in Baku.[27] The couple visited Azerbaijan occasionally. Rostropovich also presented cello master classes at the Azerbaijan State Conservatory. Together they formed a valuable art collection. In September 2007, when it was slated to be sold at auction by Sotheby’s in London and dispersed, Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov stepped forward and negotiated the purchase of all 450 lots in order to keep the collection together and bring it to Russia as a memorial to the great cellist’s memory. Christie’s reported that the buyer paid a «substantially higher» sum than the £20 million pre-sale estimate[28]

In 2006, he was featured in Alexander Sokurov’s documentary Elegy of a life: Rostropovich, Vishnevskaya.[29]

Later life[edit]

Rostropovich’s health declined in 2006, with the Chicago Tribune reporting rumours of unspecified surgery in Geneva and later treatment for what was reported as an aggravated ulcer. Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Rostropovich to discuss details of a celebration the Kremlin was planning for 27 March 2007, Rostropovich’s 80th birthday. Rostropovich attended the celebration but was reportedly in frail health.

Though Rostropovich’s last home was in Paris, he maintained residences in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, London, Lausanne, and Jordanville, New York. Rostropovich was admitted to a Paris hospital at the end of January 2007, but then decided to fly to Moscow, where he had been receiving care.[30] On 6 February 2007 the 79-year-old Rostropovich was admitted to a hospital in Moscow. «He is just feeling unwell», Natalya Dolezhale, Rostropovich’s secretary in Moscow, said.[This quote needs a citation]

Asked if there was serious cause for concern about his health she said: «No, right now there is no cause whatsoever.» She refused to specify the nature of his illness. The Kremlin said that President Putin had visited the musician on Monday in the hospital, which prompted speculation that he was in a serious condition. Dolezhale said the visit was to discuss arrangements for marking Rostropovich’s 80th birthday. On 27 March 2007, Putin issued a statement praising Rostropovich.[31]

He re-entered the Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Centre on 7 April 2007, where he was treated for intestinal cancer. He died on 27 April, aged 80.[23][32][33]

On 28 April, Rostropovich’s body lay in an open coffin at the Moscow Conservatory,[34] where he once studied as a teenager, and was then moved to the Church of Christ the Saviour. Thousands of mourners, including Putin, bade farewell. Spain’s Queen Sofia, French first lady Bernadette Chirac and President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan, where Rostropovich was born, as well as Naina Yeltsina, the widow of Boris Yeltsin, were among those in attendance at the funeral on 29 April. Rostropovich was then buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery, the same cemetery where his friend Boris Yeltsin had been buried four days earlier.[35]

Stature[edit]

Rostropovich was a huge influence on the younger generation of cellists. Many have openly acknowledged their debt to his example. In the Daily Telegraph, Julian Lloyd Webber called him «probably the greatest cellist of all time.»[36]

Rostropovich either commissioned or was the recipient of compositions by many composers including Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Benjamin Britten, Henri Dutilleux, Olivier Messiaen, André Jolivet, Witold Lutosławski, Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Schnittke, Aram Khachaturian, Astor Piazzolla, Andreas Makris, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arthur Bliss, Colin Matthews and Lopes Graça. His commissions of new works enlarged the cello repertoire more than any previous cellist: he gave the premiere of 117 compositions.[citation needed]

Rostropovich is also well known for his interpretations of standard repertoire works, including Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor.

Between 1997 and 2001 he was intimately involved in the development and testing of the BACH.Bow,[37] a curved bow designed by the cellist Michael Bach. In 2001 he invited Michael Bach for a presentation of his BACH.Bow to Paris (7th Concours de violoncelle Rostropovitch).[38] In July 2011, the city of Moscow announced plans to erect a statue of Rostropovich in a central square,[39] and the statue was unveiled in March 2012.[40]

He was also a notably generous spirit. Seiji Ozawa relates an anecdote: on hearing of the death of the baby daughter of his friend the sumo wrestler Chiyonofuji, Rostropovich flew unannounced to Tokyo, took a 1+1⁄2-hour cab ride to Chiyonofuji’s house and played his Bach sarabande outside, as his gesture of sympathy—then got back in the taxi and returned to the airport to fly back to Europe.

Rostropovich is included in the Russian-American Chamber of Fame of Congress of Russian Americans, which is dedicated to Russian immigrants who made outstanding contributions to American science or culture.[41]

Plaque on building where Azerbaijani and Russian cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich lived in Baku

Awards and recognition[edit]

Rostropovich received about 50 awards during his life, including:

Russian Federation and USSR[edit]

- Order of Merit for the Fatherland;

- 1st class (24 February 2007) – for outstanding contribution to world music and many years of creative activity

- 2nd class (25 March 1997) – for services to the state and the great personal contribution to the world of music

- Medal Defender of a Free Russia (2 February 1993) – for courage and dedication shown during the defence of democracy and constitutional order of 19–21 August 1991

- Jubilee Medal «60 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945»

- Medal «For Valiant Labor. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin»

- Medal «For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945»

- Medal «For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945»

- Medal «For the Development of Virgin Lands»

- Medal «In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow»

- People’s Artist of the USSR

- People’s Artist of the RSFSR (1964)

- Honoured Artist of the RSFSR (1955)

- State Prize of the Russian Federation (1995)

- Lenin Prize (1964)

- Stalin Prize (1951)

- Commemorative Medal for the 850th anniversary of Moscow

Other governmental awards[edit]

- Praemium Imperiale (1993)

- Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class (2001)[42]

- Heydar Aliyev Order (Azerbaijan, 2007)

- Order «Independence» (Azerbaijan, 3 March 2002)[43]

- Order of «Glory» (Azerbaijan, 1998)

- Order de Mayo (Argentina, 1991)

- Order of Freedom (Argentina, 1994)

- Commander of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Argentina, 1994)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, 1989)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary (2003)

- Order of Francisco de Miranda (Venezuela, 1979)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2001)

- Commander of the Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

- Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog (Denmark, 1983)

- Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain, 1985)

- Commander of the Order of Charles III (Spain, 2004)

- Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (31 August 1984)[44]

- Grand Officer of the National Order of the Cedar (Lebanon, 1997)

- Grand Officer of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (Lithuania, 24 November 1995)

- January 13 Commemorative Medal (Lithuania, 10 June 1992)

- Commander of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (1999; previously Knight, 1982)

- Commander of the Order of Adolphe of Nassau (Luxembourg, 1991)

- Commander of the Order of Saint-Charles (Monaco, 1989)

- Commander of the Order of Cultural Merit (Monaco, November 1999)[45]

- Commander of the Order of the Dutch Lion (Netherlands, 1989)

- Commander of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (1997)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint James of the Sword (Portugal)

- Order «For merits in the sphere of culture» (Romania, 2004)

- Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands awarded him the rare Medal for Art and Science (Dutch: «Eremedaille voor Kunst en Wetenschap») of the House-Order of Orange.

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (USA, 1987)

- Kennedy Center Honoree (USA, 1992)

- Knight of the Order of Brilliant Star (Taiwan, 1977)

- Knight of the Order of the Lion of Finland

- Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France, 1998; previously Commander, 1987, and Officer, 1981)

- Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France, 1975)

- Order of Arts and Letters (Sweden) (1984)

- National Order «For Merit» (Ecuador, 1993)

- Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star (2nd class) (Japan, 2003)

- Sharaf Order (Order of Honor) of the Republic of Azerbaijan

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1987)

Honorary citizenships[edit]

- Citizen of honor of Orenburg, Russia (1993)

- Citizen of honor of Vilnius, Lithuania (2000)

Honorary degrees[edit]

- Honorary Doctorate, University of British Columbia (1984)

- Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (L.H.D.), Northern Illinois University (1989)

- Laurea ad honorem at the University of Bologna in Political Science (2006)

Competitive awards[edit]

- Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance (1984): Mstislav Rostropovich & Rudolf Serkin for Brahms: Sonata for Cello and Piano in E Minor, Op. 38 and Sonata in F, Op. 99

Other awards[edit]

- Polar Music Prize (1995)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society (1970)

- Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (1976)

- Sonning Award (1981; Denmark)

- Prince of Asturias Award (in the concord category), 1997 (jointly with Yehudi Menuhin)

- Konex Decoration granted by the Konex Foundation of Argentina in 2002.

- Wolf Prize in Arts (2004)

- Sanford Medal (Yale University)[46]

- Honorary Membership of the Royal Academy of Music, London.[47]

- Gold UNESCO Mozart Medal (2007)[48]

- Roosevelt Institute’s Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Speech (1992)[49]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Russian: Мстислав Леопольдович Ростропович, pronounced [rəstrɐˈpovʲɪtɕ]

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Mstislav Rostropovich biography». Sony Classical. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Афанасьева, Ольга (11 July 2018). Mstislav Rostropovich. ISBN 9785457717503.

- ^ «Софья Николаевна Федотова-Ростропович».

- ^ Elizabeth Wilson, Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ «Mstislav Rostropovich: Obituary». The Times. London. 28 April 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ a b «Mirė maestro M.Rostropovičius» (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos rytas. 28 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ «Biography of Mstislav Rostropovitch». UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ John Bridcut, Galina Vishnevskaya, Elena and Olga Rostropovich, Seiji Ozawa, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Natalia Gutman, and Mischa Maisky (13 December 2011). Rostropovich: The Genius of the Cello (Television). BBC Four.

- ^ Wilson: p. 34

- ^ Wilson: p. 188

- ^ Wilson: pp. 287–289.

- ^ «For One Night Only – The Prom of Peace». BBC Radio 4. 1 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Wilson: pp. 292–293

- ^ Wilson: p. 45

- ^ «Mstislav Rostropovich, 80; Russian cello virtuoso, iconic political figure — Los Angeles Times». www.latimes.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020.

- ^ Wilson: p. 320

- ^ Wilson: p. 329

- ^ «12 May 1977*, 958-A». wordpress.com. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ «A Concert in London For Quake Survivors». The New York Times. 19 December 1988.

- ^ «Armenian Relief Society Was at the Center of Earthquake Relief Efforts». Asbarez.com. 6 December 2018.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (27 April 2007). «National Symphony Orchestra». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Rostropovich remembered – Britten-Pears Foundation, Undated.Retrieved on 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b «Russian maestro Rostropovich dies». BBC News. 27 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Wilson: p. 345

- ^ Steven Erlanger (27 September 1993). «Isolated Foes of Yeltsin Are Sad but Still Defiant». The New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ «UNESCO Celebrity Advocates: Mstislav Rostropovitch». UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Gulnar Aydamirova (Summer 2003). «Rostropovich The Home Museum». Azerbaijan International. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ News.BBC.co.uk, 17 September 2007.

- ^ Variety.com Archived 2010-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Allan Kozinn (27 April 2007). «Mstislav Rostropovich, Cellist and Conductor, Dies». The New York Times.

- ^ «Russian President Marks World-renowned Musician’s 80th Birthday». VOA News. 27 March 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ «Russian Conductor, Composer, Cellist Rostropovich Dies». Voice of America News. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ «Russian cellist Rostropovish ‘seriously ill’«. Contactmusic. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ «Russian Musician Rostropovich Honored Before Burial». VOA News. 28 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ «Russian farewell to Rostropovich». BBC News. 29 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Julian Lloyd Webber (28 April 2007). «The greatest cellist of all time». The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ «BACH.Bogen». Atelier BACH.Bogen. 6 October 2001. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Presentation of the BACH.Bogen®». Cello.org. 6 October 2001. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Rostropovich statue set to be unveiled in Moscow for cellist’s 85th anniversary». The Strad. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ «Putin Praises Cellist Rostropovich at Monument Opening». The Moscow Times. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ «Hall of Fame». russian-americans.org. 20 June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ «Reply to a parliamentary question» (PDF) (in German). p. 1447. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ «M. L. Rostropoviçin «İstiqlal»ordeni ilə təltif edilməsi haqqında AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI PREZİDENTİNİN FƏRMANI» [Order of the President of Azerbaijan Republic on awarding M. L. Rostropovich with Istiglal Order of Azerbaijan Republic]. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ «Onorificenze: parametri di ricerca» (in Italian). Italian Presidency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Sovereign Ordonnance n° 14.274 of 18 Nov. 1999 : promotions or nominations

- ^ Leading clarinetist to receive Sanford Medal Archived 2012-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Rostropovich:The Honors & Awards». Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ «Death of master Russian cellist and UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador mourned». 27 April 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ «Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Awards – Roosevelt Institute». rooseveltinstitute.org. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Wilson, Elizabeth, Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. London: Faber & Faber, 2007. ISBN 978-0-571-22051-9

Further reading[edit]

- Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya. Russia, Music, and Liberty. Conversations with Claude Samuel, Amadeus Press, Portland (1995), ISBN 0-931340-76-4

- Rostrospektive. Zum Leben und Werk von Mstislaw Rostropowitsch. On the Life and Achievement of Mstislav Rostropovich, Alexander Ivashkin and Josef Oehrlein, Internationale Kammermusik-Akademie Kronberg, Schweinfurt: Maier (1997), ISBN 3-926300-30-2

- Inside the Recording Studio. Working with Callas, Rostropovich, Domingo, and the Classical Elite, Peter Andry, with Robin Stringer and Tony Locantro, The Scarecrow Press, Lanham MD (2008). ISBN 978-0-8108-6026-1

External links[edit]

- Rostropovich Vishnevskaya Foundation

- Home-museum of Leopold and Mstislav Rostropovich

- Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Conductor, Humanitarian Cellist Arash Amini shares his personal experiences with Slava, a feature from the Bloomingdale School of Music (October 2007)

- «Why the cello is a hero», interview with The Daily Telegraph

- Interview by Tim Janof

- Famous People: Then and Now article and interview at Azerbaijan International (Winter 1999)

- Intellectual Responsibility. When Silence Is Not Golden: Conversations with Mstislav Rostropovich, another Azerbaijan International interview (Summer 2005)

- Hearing Mstislav Rostropovich Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine survey of Rostropovich recordings, by Jens F. Laurson (WETA, May 4, 2007)

- 1987 Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- The first Prague Spring International Cello Competition in 1950 in photographs, documents and reminiscences Archived 2011-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- National Symphony Orchestra Pays Homage to Rostropovich, WQXR Live Broadcast, Spring for Music Festival, Carnegie Hall, New York (May 11, 2013)

- Interview with Mstislav Rostropovich by Bruce Duffie, April 30, 2004

- Playing Brahms

- Conference in Brescia, june 4, 2003 ed. by Carlo Bianchi

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Richard Goode and Richard Stoltzman |

Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance 1984 |

Succeeded by

Juilliard String Quartet |

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich[a] (27 March 1927 – 27 April 2007) was a Russian cellist and conductor. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was well known for both inspiring and commissioning new works, which enlarged the cello repertoire more than any cellist before or since. He inspired and premiered over 100 pieces,[citation needed] forming long-standing friendships and artistic partnerships with composers including Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Henri Dutilleux, Witold Lutosławski, Olivier Messiaen, Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Alfred Schnittke, Norbert Moret, Andreas Makris, Leonard Bernstein, Aram Khachaturian and Benjamin Britten.

Rostropovich was internationally recognized as a staunch advocate of human rights, and was awarded the 1974 Award of the International League of Human Rights. He was married to the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya and had two daughters, Olga and Elena Rostropovich.

Early years[edit]

House in Baku, where Rostropovich was born

Mstislav Rostropovich was born in Baku, Azerbaijan SSR, to parents who had moved from Orenburg: Leopold Vitoldovich Rostropovich [ru], a renowned cellist and former student of Pablo Casals,[1] and Sofiya Nikolaevna Fedotova-Rostropovich, a talented pianist. Mstislav’s father, Leopold (1892–1942), was born in Voronezh to Witold Rostropowicz [ru], a composer of Polish noble descent, and Matilda Rostropovich (née Pule) of Belarusian descent. The Polish part of his family bore the Bogoria coat of arms, which was located at the family palace in Skotniki.[citation needed]

Mstislav’s mother, Sofiya, of Russian descent,[2] was the daughter of musicians.[3] Her elder sister, Nadezhda, married cellist Semyon Kozolupov, who was thus Rostropovich’s uncle by marriage.[4]

Rostropovich grew up in Baku and spent his youth there. During World War II his family moved back to Orenburg and then in 1943 to Moscow.[5]

At the age of four, Rostropovich learned the piano with his mother. He began the cello at the age of 10 with his father. In 1943, at the age of 16, he entered the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied cello with his uncle Semyon Kozolupov, and piano, conducting and composition with Vissarion Shebalin. His teachers also included Dmitri Shostakovich. In 1945, he came to prominence as a cellist when he won the gold medal in the Soviet Union’s first ever competition for young musicians.[1] He graduated from the Conservatory in 1948, and became professor of cello there in 1956.

First concerts[edit]

Rostropovich gave his first cello concert in 1942. He won first prize at the international Music Awards of Prague and Budapest in 1947, 1949 and 1950. In 1950, at the age of 23 he was awarded what was then considered the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, the Stalin Prize.[6] At that time, Rostropovich was already well known in his country and while actively pursuing his solo career, he taught at the Leningrad (Saint-Petersburg) Conservatory and the Moscow Conservatory.

In 1955, he married Galina Vishnevskaya, a leading soprano at the Bolshoi Theatre.[7]

Rostropovich had working relationships with Soviet composers of the era. In 1949 Sergei Prokofiev wrote his Cello Sonata in C, Op. 119, for the 22-year-old Rostropovich, who gave the first performance in 1950, with Sviatoslav Richter. Prokofiev also dedicated his Symphony-Concerto to him; this was premiered in 1952. Rostropovich and Dmitry Kabalevsky completed Prokofiev’s Cello Concertino after the composer’s death. Dmitri Shostakovich wrote both his first and second cello concertos for Rostropovich, who also gave their first performances.[citation needed]

Mstislav Rostropovich and Benjamin Britten in 1964

His international career started in 1963 in the Conservatoire of Liège (with Kirill Kondrashin) and in 1964 in West Germany.[citation needed]

Rostropovich went on several tours in Western Europe and met several composers, including Benjamin Britten, who dedicated his Cello Sonata, three Solo Suites, and his Cello Symphony to Rostropovich. Rostropovich gave their first performances, and the two had an obviously special affinity – Rostropovich’s family described him as «always smiling» when discussing «Ben», and on his death bed he was said to have expressed no fear as he and Britten would, he believed, be reunited in Heaven.[8]

Britten was also renowned as a pianist and together they recorded, among other works, Schubert’s Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A minor. His daughter claimed that this recording moved her father to tears of joy even on his deathbed.[citation needed]

Rostropovich also had a long-standing artistic partnership with Henri Dutilleux (Tout un monde lointain… for cello and orchestra, Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher for solo cello), Witold Lutosławski (Cello Concerto, Sacher-Variation for solo cello), Krzysztof Penderecki (cello concerto n°2, Largo for cello and orchestra, Per Slava for solo cello, sextet for piano, clarinet, horn, violin, viola and cello), Luciano Berio (Ritorno degli snovidenia for cello and thirty instruments, Les mots sont allés… for solo cello) as well as Olivier Messiaen (Concert à quatre for piano, cello, oboe, flute and orchestra).[citation needed]

Rostropovich took private lessons in conducting with Leo Ginzburg,[9] and first conducted in public in Gorky in November 1962, performing the four entractes from Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and Shostakovich’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death with Vishnevskaya singing.[10]

In 1967, at the invitation of the Bolshoi Theatre’s director Mikhail Chulaki, he conducted Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin at the Bolshoi, thus letting forth his passion for both the role of conductor and the opera.[11]

August 1968 proms[edit]

Rostropovich played at The Proms on the night of 21 August 1968. He played with the Soviet State Symphony Orchestra – it was the orchestra’s debut performance at the Proms. The programme featured Czech composer Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor and took place on the same day that the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia to end Alexander Dubček’s Prague Spring.[12] After the performance, which had been preceded by heckling and demonstrations, the orchestra and soloist were cheered by the Proms audience.[13] Rostropovich stood and held aloft the conductor’s score of the Dvořák as a gesture of solidarity for the composer’s homeland and the city of Prague.[citation needed]

Exile[edit]

Rostropovich fought for art without borders, freedom of speech, and democratic values, resulting in harassment from the Soviet regime. An early example was in 1948, when he was a student at the Moscow Conservatory. In response to the 10 February 1948 decree on so-called ‘formalist’ composers, his teacher Dmitri Shostakovich was dismissed from his professorships in Leningrad and Moscow; the 21-year-old Rostropovich quit the conservatory, dropping out in protest.[14] Rostropovich also smuggled to the West the manuscript of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 13, emphasizing Soviet indifference to the Babi Yar massacre.[15]

In 1970, Rostropovich sheltered Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who otherwise would have had nowhere to go, in his own home. His friendship with Solzhenitsyn and his support for dissidents led to official disgrace in the early 1970s. As a result, Rostropovich was restricted from foreign touring,[16] as was his wife, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, and his appearances performing in Moscow were curtailed, as increasingly were his appearances in such major cities as Leningrad and Kiev.[17]

Rostropovich left the Soviet Union in 1974 with his wife and children and settled in the United States. He was banned from touring his homeland with foreign orchestras and, in 1977, the Soviet leadership instructed musicians from the Soviet bloc not to take part in an international competition he had organised.[18] In 1978, Rostropovich was deprived of his Soviet citizenship because of his public opposition to the Soviet Union’s restriction of cultural freedom. He would not return to the Soviet Union until 1990.[6]

Further career[edit]

On December 17, 1988, Rostropovich gave a special concert at Barbican Hall in London, after postponing a trip to India for the Armenian Earthquake relief program. The event was part of an effort called Musicians for Armenia, which was expected to raise more than $450,000 from donations worldwide, including gifts from musicians, concert proceeds and film and recording rights. Prince Charles and the Princess of Wales attended the concert in the sold-out 2,026-seat concert hall.[19]

On February 7, 1989, a cello concert was organized by the Armenian Relief Society and the Volunteers Technical Assistance (VTA) for the victims of the Spitak Earthquake. At the concert, Rostropovich played his favorite cello repertoire, including Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor; Haydn’s cello concerti in C and D; Prokofiev’s Symphony-Concerto; the two cello concerti of Shostakovich, and others. The evening with Rostropovich raised awareness and helped hundreds of earthquake victims put food on their table. The concert was held at the Kennedy Center and over 2,300 were in attendance.[20]

Galina Vishnevskaya and Mstislav Rostropovich with their daughters at home, 1 February 1959

Mstislav Rostropovich, 18 September 1959

Mstislav Rostropovich, chief conductor of U.S. National Symphony Orchestra, greets the audience in Bolshoi Hall of the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, 13 February 1990

Mstislav Rostropovich and his fans in Moscow

From 1977 until 1994, he was music director and conductor of the U.S. National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C. while still performing with some of the most famous musicians such as Martha Argerich, Sviatoslav Richter and Vladimir Horowitz.[21] He was also the director and founder of the Mstislav Rostropovich Baku International Festival and was a regular performer at the Aldeburgh Festival in the UK.[22]

His impromptu performance during the fall of the Berlin Wall as events unfolded was reported throughout the world.[23] His Soviet citizenship was restored in 1990. When, in August 1991, news footage was broadcast of tanks in the streets of Moscow, Rostropovich responded with a characteristically brave, impetuous and patriotic gesture: he bought a plane ticket to Japan on a flight that stopped at Moscow, talked his way out of the airport and went to join Boris Yeltsin in the hope that his fame might make some difference to the chance of tanks moving in.[24]

Rostropovich supported Yeltsin during the 1993 constitutional crisis and conducted the National Symphony Orchestra in Red Square at the height of the crackdown.[25]

In 1993, he was instrumental in the foundation of the Kronberg Academy and was a patron until his death. He commissioned Rodion Shchedrin to compose the opera Lolita and conducted its premiere in 1994 at the Royal Swedish Opera. Rostropovich received many international awards, including the French Legion of Honor and honorary doctorates from many international universities. He was an activist, fighting for freedom of expression in art and politics. An ambassador for the UNESCO, he supported many educational and cultural projects.[26] Rostropovich performed several times in Madrid and was a close friend of Queen Sofía of Spain.

With wife, Galina Vishnevskaya, he founded the Rostropovich-Vishnevskaya Foundation, a publicly supported non-profit 501(c)(3) organization based in Washington, D.C., in 1991 to improve the health and future of children in the former Soviet Union. The Rostropovich Home Museum opened on 4 March 2002, in Baku.[27] The couple visited Azerbaijan occasionally. Rostropovich also presented cello master classes at the Azerbaijan State Conservatory. Together they formed a valuable art collection. In September 2007, when it was slated to be sold at auction by Sotheby’s in London and dispersed, Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov stepped forward and negotiated the purchase of all 450 lots in order to keep the collection together and bring it to Russia as a memorial to the great cellist’s memory. Christie’s reported that the buyer paid a «substantially higher» sum than the £20 million pre-sale estimate[28]

In 2006, he was featured in Alexander Sokurov’s documentary Elegy of a life: Rostropovich, Vishnevskaya.[29]

Later life[edit]

Rostropovich’s health declined in 2006, with the Chicago Tribune reporting rumours of unspecified surgery in Geneva and later treatment for what was reported as an aggravated ulcer. Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Rostropovich to discuss details of a celebration the Kremlin was planning for 27 March 2007, Rostropovich’s 80th birthday. Rostropovich attended the celebration but was reportedly in frail health.

Though Rostropovich’s last home was in Paris, he maintained residences in Moscow, Saint Petersburg, London, Lausanne, and Jordanville, New York. Rostropovich was admitted to a Paris hospital at the end of January 2007, but then decided to fly to Moscow, where he had been receiving care.[30] On 6 February 2007 the 79-year-old Rostropovich was admitted to a hospital in Moscow. «He is just feeling unwell», Natalya Dolezhale, Rostropovich’s secretary in Moscow, said.[This quote needs a citation]

Asked if there was serious cause for concern about his health she said: «No, right now there is no cause whatsoever.» She refused to specify the nature of his illness. The Kremlin said that President Putin had visited the musician on Monday in the hospital, which prompted speculation that he was in a serious condition. Dolezhale said the visit was to discuss arrangements for marking Rostropovich’s 80th birthday. On 27 March 2007, Putin issued a statement praising Rostropovich.[31]

He re-entered the Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Centre on 7 April 2007, where he was treated for intestinal cancer. He died on 27 April, aged 80.[23][32][33]

On 28 April, Rostropovich’s body lay in an open coffin at the Moscow Conservatory,[34] where he once studied as a teenager, and was then moved to the Church of Christ the Saviour. Thousands of mourners, including Putin, bade farewell. Spain’s Queen Sofia, French first lady Bernadette Chirac and President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan, where Rostropovich was born, as well as Naina Yeltsina, the widow of Boris Yeltsin, were among those in attendance at the funeral on 29 April. Rostropovich was then buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery, the same cemetery where his friend Boris Yeltsin had been buried four days earlier.[35]

Stature[edit]

Rostropovich was a huge influence on the younger generation of cellists. Many have openly acknowledged their debt to his example. In the Daily Telegraph, Julian Lloyd Webber called him «probably the greatest cellist of all time.»[36]

Rostropovich either commissioned or was the recipient of compositions by many composers including Dmitri Shostakovich, Sergei Prokofiev, Benjamin Britten, Henri Dutilleux, Olivier Messiaen, André Jolivet, Witold Lutosławski, Luciano Berio, Krzysztof Penderecki, Leonard Bernstein, Alfred Schnittke, Aram Khachaturian, Astor Piazzolla, Andreas Makris, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arthur Bliss, Colin Matthews and Lopes Graça. His commissions of new works enlarged the cello repertoire more than any previous cellist: he gave the premiere of 117 compositions.[citation needed]

Rostropovich is also well known for his interpretations of standard repertoire works, including Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor.

Between 1997 and 2001 he was intimately involved in the development and testing of the BACH.Bow,[37] a curved bow designed by the cellist Michael Bach. In 2001 he invited Michael Bach for a presentation of his BACH.Bow to Paris (7th Concours de violoncelle Rostropovitch).[38] In July 2011, the city of Moscow announced plans to erect a statue of Rostropovich in a central square,[39] and the statue was unveiled in March 2012.[40]

He was also a notably generous spirit. Seiji Ozawa relates an anecdote: on hearing of the death of the baby daughter of his friend the sumo wrestler Chiyonofuji, Rostropovich flew unannounced to Tokyo, took a 1+1⁄2-hour cab ride to Chiyonofuji’s house and played his Bach sarabande outside, as his gesture of sympathy—then got back in the taxi and returned to the airport to fly back to Europe.

Rostropovich is included in the Russian-American Chamber of Fame of Congress of Russian Americans, which is dedicated to Russian immigrants who made outstanding contributions to American science or culture.[41]

Plaque on building where Azerbaijani and Russian cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich lived in Baku

Awards and recognition[edit]

Rostropovich received about 50 awards during his life, including:

Russian Federation and USSR[edit]

- Order of Merit for the Fatherland;

- 1st class (24 February 2007) – for outstanding contribution to world music and many years of creative activity

- 2nd class (25 March 1997) – for services to the state and the great personal contribution to the world of music

- Medal Defender of a Free Russia (2 February 1993) – for courage and dedication shown during the defence of democracy and constitutional order of 19–21 August 1991

- Jubilee Medal «60 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945»

- Medal «For Valiant Labor. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin»

- Medal «For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945»

- Medal «For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941-1945»

- Medal «For the Development of Virgin Lands»

- Medal «In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow»

- People’s Artist of the USSR

- People’s Artist of the RSFSR (1964)

- Honoured Artist of the RSFSR (1955)

- State Prize of the Russian Federation (1995)

- Lenin Prize (1964)

- Stalin Prize (1951)

- Commemorative Medal for the 850th anniversary of Moscow

Other governmental awards[edit]

- Praemium Imperiale (1993)

- Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, 1st class (2001)[42]

- Heydar Aliyev Order (Azerbaijan, 2007)

- Order «Independence» (Azerbaijan, 3 March 2002)[43]

- Order of «Glory» (Azerbaijan, 1998)

- Order de Mayo (Argentina, 1991)

- Order of Freedom (Argentina, 1994)

- Commander of the Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Argentina, 1994)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium, 1989)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Hungary (2003)

- Order of Francisco de Miranda (Venezuela, 1979)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2001)

- Commander of the Order of the Phoenix (Greece)

- Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog (Denmark, 1983)

- Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic (Spain, 1985)

- Commander of the Order of Charles III (Spain, 2004)

- Grand Officer of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (31 August 1984)[44]

- Grand Officer of the National Order of the Cedar (Lebanon, 1997)

- Grand Officer of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas (Lithuania, 24 November 1995)

- January 13 Commemorative Medal (Lithuania, 10 June 1992)

- Commander of the Order of Merit of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (1999; previously Knight, 1982)

- Commander of the Order of Adolphe of Nassau (Luxembourg, 1991)

- Commander of the Order of Saint-Charles (Monaco, 1989)

- Commander of the Order of Cultural Merit (Monaco, November 1999)[45]

- Commander of the Order of the Dutch Lion (Netherlands, 1989)

- Commander of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland (1997)

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Saint James of the Sword (Portugal)

- Order «For merits in the sphere of culture» (Romania, 2004)

- Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands awarded him the rare Medal for Art and Science (Dutch: «Eremedaille voor Kunst en Wetenschap») of the House-Order of Orange.

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (USA, 1987)

- Kennedy Center Honoree (USA, 1992)

- Knight of the Order of Brilliant Star (Taiwan, 1977)

- Knight of the Order of the Lion of Finland

- Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France, 1998; previously Commander, 1987, and Officer, 1981)

- Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters (France, 1975)

- Order of Arts and Letters (Sweden) (1984)

- National Order «For Merit» (Ecuador, 1993)

- Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star (2nd class) (Japan, 2003)

- Sharaf Order (Order of Honor) of the Republic of Azerbaijan

- Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (1987)

Honorary citizenships[edit]

- Citizen of honor of Orenburg, Russia (1993)

- Citizen of honor of Vilnius, Lithuania (2000)

Honorary degrees[edit]

- Honorary Doctorate, University of British Columbia (1984)

- Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters (L.H.D.), Northern Illinois University (1989)

- Laurea ad honorem at the University of Bologna in Political Science (2006)

Competitive awards[edit]

- Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance (1984): Mstislav Rostropovich & Rudolf Serkin for Brahms: Sonata for Cello and Piano in E Minor, Op. 38 and Sonata in F, Op. 99

Other awards[edit]

- Polar Music Prize (1995)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society (1970)

- Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (1976)

- Sonning Award (1981; Denmark)

- Prince of Asturias Award (in the concord category), 1997 (jointly with Yehudi Menuhin)

- Konex Decoration granted by the Konex Foundation of Argentina in 2002.

- Wolf Prize in Arts (2004)

- Sanford Medal (Yale University)[46]

- Honorary Membership of the Royal Academy of Music, London.[47]

- Gold UNESCO Mozart Medal (2007)[48]

- Roosevelt Institute’s Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Speech (1992)[49]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Russian: Мстислав Леопольдович Ростропович, pronounced [rəstrɐˈpovʲɪtɕ]

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Mstislav Rostropovich biography». Sony Classical. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Афанасьева, Ольга (11 July 2018). Mstislav Rostropovich. ISBN 9785457717503.

- ^ «Софья Николаевна Федотова-Ростропович».

- ^ Elizabeth Wilson, Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ «Mstislav Rostropovich: Obituary». The Times. London. 28 April 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ^ a b «Mirė maestro M.Rostropovičius» (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos rytas. 28 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ «Biography of Mstislav Rostropovitch». UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ John Bridcut, Galina Vishnevskaya, Elena and Olga Rostropovich, Seiji Ozawa, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Natalia Gutman, and Mischa Maisky (13 December 2011). Rostropovich: The Genius of the Cello (Television). BBC Four.

- ^ Wilson: p. 34

- ^ Wilson: p. 188

- ^ Wilson: pp. 287–289.

- ^ «For One Night Only – The Prom of Peace». BBC Radio 4. 1 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ Wilson: pp. 292–293

- ^ Wilson: p. 45

- ^ «Mstislav Rostropovich, 80; Russian cello virtuoso, iconic political figure — Los Angeles Times». www.latimes.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020.

- ^ Wilson: p. 320

- ^ Wilson: p. 329

- ^ «12 May 1977*, 958-A». wordpress.com. 5 July 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ «A Concert in London For Quake Survivors». The New York Times. 19 December 1988.

- ^ «Armenian Relief Society Was at the Center of Earthquake Relief Efforts». Asbarez.com. 6 December 2018.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (27 April 2007). «National Symphony Orchestra». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Rostropovich remembered – Britten-Pears Foundation, Undated.Retrieved on 2007-07-31.

- ^ a b «Russian maestro Rostropovich dies». BBC News. 27 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Wilson: p. 345

- ^ Steven Erlanger (27 September 1993). «Isolated Foes of Yeltsin Are Sad but Still Defiant». The New York Times. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ «UNESCO Celebrity Advocates: Mstislav Rostropovitch». UNESCO. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Gulnar Aydamirova (Summer 2003). «Rostropovich The Home Museum». Azerbaijan International. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ News.BBC.co.uk, 17 September 2007.

- ^ Variety.com Archived 2010-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Allan Kozinn (27 April 2007). «Mstislav Rostropovich, Cellist and Conductor, Dies». The New York Times.

- ^ «Russian President Marks World-renowned Musician’s 80th Birthday». VOA News. 27 March 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ «Russian Conductor, Composer, Cellist Rostropovich Dies». Voice of America News. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ «Russian cellist Rostropovish ‘seriously ill’«. Contactmusic. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ «Russian Musician Rostropovich Honored Before Burial». VOA News. 28 April 2007. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ «Russian farewell to Rostropovich». BBC News. 29 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ Julian Lloyd Webber (28 April 2007). «The greatest cellist of all time». The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ^ «BACH.Bogen». Atelier BACH.Bogen. 6 October 2001. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Presentation of the BACH.Bogen®». Cello.org. 6 October 2001. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ «Rostropovich statue set to be unveiled in Moscow for cellist’s 85th anniversary». The Strad. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ «Putin Praises Cellist Rostropovich at Monument Opening». The Moscow Times. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ «Hall of Fame». russian-americans.org. 20 June 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ «Reply to a parliamentary question» (PDF) (in German). p. 1447. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ «M. L. Rostropoviçin «İstiqlal»ordeni ilə təltif edilməsi haqqında AZƏRBAYCAN RESPUBLİKASI PREZİDENTİNİN FƏRMANI» [Order of the President of Azerbaijan Republic on awarding M. L. Rostropovich with Istiglal Order of Azerbaijan Republic]. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ «Onorificenze: parametri di ricerca» (in Italian). Italian Presidency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Sovereign Ordonnance n° 14.274 of 18 Nov. 1999 : promotions or nominations

- ^ Leading clarinetist to receive Sanford Medal Archived 2012-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Rostropovich:The Honors & Awards». Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ «Death of master Russian cellist and UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador mourned». 27 April 2007. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ «Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Awards – Roosevelt Institute». rooseveltinstitute.org. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Wilson, Elizabeth, Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Teacher, Legend. London: Faber & Faber, 2007. ISBN 978-0-571-22051-9

Further reading[edit]

- Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya. Russia, Music, and Liberty. Conversations with Claude Samuel, Amadeus Press, Portland (1995), ISBN 0-931340-76-4

- Rostrospektive. Zum Leben und Werk von Mstislaw Rostropowitsch. On the Life and Achievement of Mstislav Rostropovich, Alexander Ivashkin and Josef Oehrlein, Internationale Kammermusik-Akademie Kronberg, Schweinfurt: Maier (1997), ISBN 3-926300-30-2

- Inside the Recording Studio. Working with Callas, Rostropovich, Domingo, and the Classical Elite, Peter Andry, with Robin Stringer and Tony Locantro, The Scarecrow Press, Lanham MD (2008). ISBN 978-0-8108-6026-1

External links[edit]

- Rostropovich Vishnevskaya Foundation

- Home-museum of Leopold and Mstislav Rostropovich

- Mstislav Rostropovich: Cellist, Conductor, Humanitarian Cellist Arash Amini shares his personal experiences with Slava, a feature from the Bloomingdale School of Music (October 2007)

- «Why the cello is a hero», interview with The Daily Telegraph

- Interview by Tim Janof

- Famous People: Then and Now article and interview at Azerbaijan International (Winter 1999)

- Intellectual Responsibility. When Silence Is Not Golden: Conversations with Mstislav Rostropovich, another Azerbaijan International interview (Summer 2005)

- Hearing Mstislav Rostropovich Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine survey of Rostropovich recordings, by Jens F. Laurson (WETA, May 4, 2007)

- 1987 Presidential Medal of Freedom Recipients Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- The first Prague Spring International Cello Competition in 1950 in photographs, documents and reminiscences Archived 2011-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- National Symphony Orchestra Pays Homage to Rostropovich, WQXR Live Broadcast, Spring for Music Festival, Carnegie Hall, New York (May 11, 2013)

- Interview with Mstislav Rostropovich by Bruce Duffie, April 30, 2004

- Playing Brahms

- Conference in Brescia, june 4, 2003 ed. by Carlo Bianchi

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by

Richard Goode and Richard Stoltzman |

Grammy Award for Best Chamber Music Performance 1984 |

Succeeded by

Juilliard String Quartet |

Подробная информация о фамилии Ростропович, а именно ее происхождение, история образования, суть фамилии, значение, перевод и склонение. Какая история происхождения фамилии Ростропович? Откуда родом фамилия Ростропович? Какой национальности человек с фамилией Ростропович? Как правильно пишется фамилия Ростропович? Верный перевод фамилии Ростропович на английский язык и склонение по падежам. Полную характеристику фамилии Ростропович и ее суть вы можете прочитать онлайн в этой статье совершенно бесплатно без регистрации.

Происхождение фамилии Ростропович

Большинство фамилий, в том числе и фамилия Ростропович, произошло от отчеств (по крестильному или мирскому имени одного из предков), прозвищ (по роду деятельности, месту происхождения или какой-то другой особенности предка) или других родовых имён.

История фамилии Ростропович

В различных общественных слоях фамилии появились в разное время. История фамилии Ростропович насчитывает долгую историю. Впервые фамилия Ростропович встречается в летописях духовенства с середины XVIII века. Обычно они образовались от названий приходов и церквей или имени отца. Некоторые священнослужители приобретали фамилии при выпуске из семинарии, при этом лучшим ученикам давались фамилии наиболее благозвучные и несшие сугубо положительный смысл, как например Ростропович. Фамилия Ростропович наследуется из поколения в поколение по мужской линии (или по женской).

Суть фамилии Ростропович по буквам

Фамилия Ростропович состоит из 11 букв. Проанализировав значение каждой буквы в фамилии Ростропович можно понять ее суть и скрытое значение.

Значение фамилии Ростропович

Фамилия является основным элементом, связывающим человека со вселенной и окружающим миром. Она определяет его судьбу, основные черты характера и наиболее значимые события. Внутри фамилии Ростропович скрывается опыт, накопленный предыдущими поколениями и предками. По нумерологии фамилии Ростропович можно определить жизненный путь рода, семейное благополучие, достоинства, недостатки и характер носителя фамилии. Число фамилии Ростропович в нумерологии — 7. Представители фамилии Ростропович достаточно образованные люди, наделенные врожденной интуицией. Они обожают загадки, паззлы, сложные задания и нестандартные ситуации. Носители фамилии с цифрой 7 великолепно чувствуют своих собеседников и могут находить нужные в данные момент слова.

Они являются интеллектуально развитыми людьми с непреодолимой жаждой новых знаний. Их влечет все сложное, неизведанное и загадочное. Порой, люди с фамилией Ростропович наполняют свою жизнь мистикой и с головой уходят в изучение оккультных наук.

В обычной жизни людей с фамилией Ростропович считают чудаками: они могут с головой погружаться в свой внутренний мир и не замечать окружающих событий. Именно эти люди разрабатывают сложные изобретения, необычные машины или альтернативные источники получения энергии. Носители фамилии Ростропович проходят сложный жизненный путь, посвященный высоким целям. Они годами набивают шишки, ищут верное направление и следуют внутренним идеалам. С окружающими людьми их отношения складываются по двум сценариям: носителей фамилии Ростропович либо принимают в коллектив, либо сразу же сторонятся и определяют в дальний угол. При этом самих представителей фамилии Ростропович эти процессы совершенно не волнуют. Они являются добрыми людьми, а потому не могут пройти мимо чужого горя и несправедливости. Этим активно пользуются новоявленные религиозные секты, мошенники и обычные попрошайки.

Носители фамилии Ростропович требуют особых семейных отношений. Они будут счастливы только со своим соратником или человеком, который разделяет их высокие взгляды. Семью создают в достаточно зрелом возрасте и долго выбирают кандидата. Не терпят насмешек и ежедневных требований и часто закрываются в своей комнате для работы.

Решение бытовых проблем возлагают на своего спутника жизни, а свободное время тратят на работу, которая и является единственным хобби. Детей признают и уважают, но при этом не проявляют особой любви или нежности.

Обладатели фамилии Ростропович – потенциальные ученые, мыслители и философы. Они обожают точные науки, сложные теории и неразрешимые задачи. Это прирожденные детективы, эксперты по криминалистике, сотрудники диагностических лабораторий. Способность сострадать позволяет им выбирать для себя профессию медицинского работника.

К ним относится целеустремленность, работоспособность, усидчивость и упрямство в хорошем смысле слова.

Как правильно пишется фамилия Ростропович

В русском языке грамотным написанием этой фамилии является — Ростропович. В английском языке фамилия Ростропович может иметь следующий вариант написания — Rostropovich.

Склонение фамилии Ростропович по падежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Фамилия |

| Именительный | Кто? | Ростропович |

| Родительный | Нет Кого? | Ростроповича |

| Дательный | Рад Кому? | Ростроповичу |

| Винительный | Вижу Кого? | Ростроповича |

| Творительный | Доволен Кем? | Ростроповичем |

| Предложный | Думаю О ком? | Ростроповиче |

Видео про фамилию Ростропович

Вы согласны с описанием фамилии Ростропович, ее происхождением, историей образования, значением и изложенной сутью? Какую информацию о фамилии Ростропович вы еще знаете? С какими известными и успешными людьми с фамилией Ростропович вы знакомы? Будем рады обсудить фамилию Ростропович более подробно с посетителями нашего сайта в комментариях.

Фамилия Ростропович

Ростропович – женская или мужская русская, сербская, хорватская, еврейская, польская или белорусская фамилия. К самым характерным белорусским фамилиям относятся фамилии на -ович/-евич. Такие фамилии охватывают до 17 % (приблизительно 1 700 000 человек) белорусской популяции, и по распространённости наименований на -ович/-евич среди славян белорусы уступают только хорватам и сербам.

Национальность

Белорусская, русская, еврейская, сербская, хорватская, польская.

Происхождение фамилии с суффиксами -ович/-евич

Как возникла и откуда произошла фамилия Ростропович? Ростропович – белорусская, реже русская фамильная модель от отчеств, образованных из имён, прозвищ в полной либо уменьшительной конфигурациях. Например, Андрей → Андреевич, Юрий → Юревич, уменьшительно Исаак → Сакович, Станислав → Стасевич.

Суффикс -ович/-евич по причине своего обширного применения в личных именованиях шляхты ВКЛ, начал рассматриваться как дворянский и, являясь белорусским по происхождению, твёрдо вошёл в польскую антропонимическую традицию, полностью вытеснив в Польше из обихода исконный польскоязычный аналог -овиц/-евиц. В свою очередь данный тип фамилий, под влиянием польского языка, сменил древнерусское ударение, как в русских отчествах, на предпоследний слог. Многие фамилии на -ович/-евич, деятелей польской культуры, являются безусловно белорусскими по происхождению, так как образованы от православных имён: Генрик Сенкевич (от имени Сенька (← Семён), при католическом аналоге Шимкевич «Шимко»), Ярослав Ивашкевич (от уменьшительного имени Ивашка (← Иван), при католической форме Янушкевич), Адам Мицкевич (Митька — уменьшительное от Дмитрий, в католической традиции такого имени нет).

Так как первоначально фамилии на -ович/-евич считались по сути отчествами, большая часть их основ (вплоть до 80%) берёт начало от крестильных имён в полной либо уменьшительной формах. Только лишь фонд данных имён несколько более архаичен, по сопоставлению с фамилиями прочих типов, то что указывает об их более древнем происхождении.

Значение и история возникновения фамилии с суффиксами -ович/-евич:

- От крестильных православных и католических имён.

Например, уменьшительно Юрий → Юшкевич, Павел → Павлович, Якуб → Якубович и т.п. - От языческих имён.

Например, Ждан → Жданович, Кунец → Кунцевич и т.п. - От прозвищ.

Например, короткий → Короткевич, гуля (шар на белорусском, возможно прозвище полного человека) → Гулевич и т.п. - От вида деятельности.

Например, войт (деревенский староста) → Войтович, коваль (кузнец) → Ковалевич, хотько (хотеть, желать) → Хацкевич и т.п.

История

Исторически сложилось, что фамилии на -ович/-евич распространены по территории Белоруссии неравномерно. Основной их ареал охватывает Минскую и Гродненскую область, северо-восток Брестской, юго-запад Витебской, область вокруг Осипович в Могилёвской, и территорию на запад от Мозыря в Гомельской. Здесь к фамилиям это типа принадлежит до 40 % населения, с максимальной концентрацией носителей на стыке Минской, Брестской и Гродненской областей.

Склонение

Женская фамилия Ростропович не склоняется (женский род). К примеру: Тамаре Ростропович, Екатерину Ростропович, Татьяне Ростропович и т.д.

Мужская фамилия Ростропович склоняется.

| Склонение фамилии Ростропович по падежам (мужской род) | |

|---|---|

| Именительный падеж (кто?) | Ростропович |

| Родительный падеж (кого?) | Ростроповича |

| Дательный падеж (кому?) | Ростроповичу |

| Винительный падеж (кого?) | Ростроповича |

| Творительный падеж (кем?) | Ростроповичом |

| Предложный падеж (о ком?) | Ростроповиче |

Обратите внимание, что в творительном падеже после шипящего согласного «ч» под ударением пишется буква «о» в окончании – Ростроповичом, а не ошибочно – Ростроповичём.

Транслитерация

Транслитерация (транслит) – перевод кириллических знаков в латинские.

Написание фамилии Ростропович латиницей:

- Rostropovich – фамилия латинскими буквами;

- ROSTROPOVICH – ГОСТ Р 52535.1-2006 (для авиабилетов, билетов, бронирования и т.п.);

- ROSTROPOVICH – ИКАО (для загранпаспорта, паспорта, водительского удостоверения и т.п.).

В последнем варианте замещение русских букв на латинские производится в соответствии с рекомендованным ИКАО (Международной организацией гражданской авиации) международным стандартом (Doc 9303, часть 1).

Ударение

Ударение в фамилии Ростропович не регламентируется правилами русского языка. Точно ответить затруднительно. Лучше уточнить произношение у носителя фамилии.

Другие фамилии

Возможно вас заинтересует информация о других фамилиях:

Мстислав Ростропович — биография

Мстислав Ростропович – известный виолончелист, пианист, композитор, дирижер, педагог, общественный деятель. В 1951 году удостоен Сталинской премии 2-й степени, в 1964 году получил Ленинскую премию, в 1966-м стал Народным артистом СССР. В 1991 году получил Государственную премию РСФСР им.Глинки, спустя пять лет музыканту вручили Государственную премию РФ. Пять раз становился обладателем премии Грэмми. Муж Галины Вишневской, Народной артистки СССР.

Имя Мстислава Ростроповича известно всем, не знает его только очень ленивый и ограниченный человек. Его обожал весь мир, он добился признания президентов и королей, а о том, сколько поклонниц мечтало хотя бы прикоснуться к своему кумиру, можно не говорить. Мировую известность Ростроповичу принес его незаурядный талант музыканта. Он часто говорил, что этим «кусочком солнца» с ним поделился Прокофьев. Кроме невероятных способностей, Мстислав имел потрясающую харизму, легкий характер и авантюризм. Его называли «русским гением», «славой Америки», английская королева Елизавета посвятила Ростроповича в рыцари, и если верить легенде, сняла перед ним свою шляпку, чего не делала никогда.

Детство

Родился будущий музыкант с мировым именем 27 марта 1927 года в Баку. Его родители – профессиональные музыканты. Отец – виолончелист Леопольд Ростропович, мама – пианистка София Ростропович. Родители мальчика ранее жили в Оренбурге, переехать в Баку им предложил азербайджанский композитор Узеир Гаджибеков. Родня Мстислава по отцовской линии тоже имела прямое отношение к музыке. Дед – пианист и композитор Витольд Ростропович, бабушка – пианистка Софья Федотова.

В четыре года мальчик уже осилил рояль, сам сочинял незамысловатые мелодии и подбирал песенки. Когда Мстиславу исполнилось восемь лет, он уже прилично играл на виолончели. Первые уроки музыки давал ему отец, с другими преподавателями мальчик просто не хотел заниматься.

В 1932-м Ростроповичи переехали в Москву. В семь лет Мстислава уже отвели в музыкальную школу имени Гнесиных, там работал преподавателем его отец. Леопольд Ростропович часто менял место работы, переходил из одной музыкальной школы в другую. Следом за ним переходил и Мстислав. В 1937 году отец и сын оказались в музыкальной школе Свердловского района столицы. Именно там состоялся первый в биографии прославленного музыканта концерт. Двенадцатилетний мальчик вышел на сцену вместе с симфоническим оркестром, и сыграл главную партию Концерта Камиля Сен-Санса.

После окончания музыкальной школы Мстислав продолжил обучаться музыке. Он стал студентом училища при столичной консерватории имени Чайковского. Ростропович мечтал создавать музыку, но его мечты перечеркнула война. Семья в полном составе эвакуировалась в город Чкалов (нынешний Оренбург). В 1941 году Мстислав поступил в железнодорожную школу и музыкальное училище, то, где работал преподавателем его папа. Именно в то время подросток начал разрабатывать свои первые концерты.

Спустя немного времени Мстислава приняли на службу в оперный театр. Там и родились его первые произведения для виолончели и фортепиано, которые он написал под непосредственным руководством Михаила Чулаки. Уже в следующем, 1942 году, подросток принял участие в отчетном концерте. Его представили, как композитора и исполнителя собственных произведений. Выступление юного музыканта прошло с невероятным успехом. Он получил высокую оценку критиков, публики, журналистов, которые восторженно отзывались о его музыкальном вкусе, чувстве гармонии и невероятном таланте.

Еще через год, в 1943-м, Ростроповичи вернулись из эвакуации в столицу. Мстислав продолжил обучение в том же училище. Благодаря своему старанию и трудолюбию, Ростропович вместо второго курса оказался на пятом.

В 1946 году Мстиславу вручили красный диплом училища, он приобрел сразу две специальности, виолончелиста и композитора. Далее была аспирантура, после окончания которой, Ростропович преподавал в консерваториях Москвы и Ленинграда. Общий стаж его педагогической деятельности – 26 лет, за которые он воспитал множество известных музыкантов. Среди них Наталья Шаховская, Иван Монигетти, Давид Герингас, Наталья Гутман.

Музыка

К концу 40-х годов музыкант давал концерты в самых разных городах. Ему аплодировали Москва, Киев, Минск. Мстислав стал участником многих международных конкурсов, откуда непременно возвращался победителем. Его популярность росла день ото дня. Этому способствовали и гастроли за рубежом, принесшие молодому дарованию международное признание и успех.

Музыкант уже тогда мог гордиться достигнутым, но этого ему казалось мало, он стремился к постоянному совершенствованию. В одном из своих интервью Ростропович сказал, что в те годы у него был период, когда очень хотелось играть хорошо. Мстислав занимался изучением партитур, анализировал трактовки партий виолончели другими композиторами, слушал, как их исполняют другие музыканты.

В 1955 году на фестивале «Пражская весна» Ростропович встретил оперную певицу Галину Вишневскую. Позже они много раз выходили на сцену вместе – Ростропович аккомпанировал, Галина пела. Есть в творческой биографии виолончелиста и сотрудничество с такими выдающимися музыкантами, как Святослав Рихтер и Давид Ойстрах. В 1957-м Мстислав Леопольдович первый раз попробовал себя в качестве дирижера. Тогда в Большом театре ставили «Евгения Онегина». Постановка прошла с аншлагом, и еще больше прославила Мстислава Ростроповича.

С ростом славы и популярности, росла и востребованность музыканта. Мстислав так энергично воплощал свои задумки в жизнь, что ему было мало времени в сутках. Он занимался педагогической деятельностью, постоянно гастролировал, давал концерты, сочинял собственную музыку. У него имелась собственная точка зрения на все происходящее в мире музыки, он следил также за общественно-политической ситуацией в СССР. Если Ростроповича что-то волновало, он никогда не молчал, смело и открыто высказывал свою точку зрения, даже тогда, когда его мнение шло вразрез с мнением окружающих.

В 1989-м, когда разрушили Берлинскую стену, Ростропович мгновенно умчался в Германию с собственной виолончелью, и на руинах исполнил сюиту Баха. Мстислав ненавидел гонения в любом их виде, поэтому страстно отстаивал Иосифа Бродского, Анну Ахматову, Александра Солженицына. Когда над Солженицыным сгустились тучи, он предоставил ему свою дачу. Естественно, что такое поведение композитора очень не нравилось правительству страны, стало причиной давления на него.

После того, как в 1972 году Мстислав Леопольдович подписал обращение к Верховному совету СССР об амнистии и отмене смертной казни, он потерял работу в Большом театре. Потом вышел запрет на гастрольную деятельность за рубежом. Но и этого мало, ни Ростропович, ни Вишневская, больше не выступали со столичными театрами, их просто перестали звать.

С большим трудом композитор выхлопотал выездную визу, забрал семью, и отправился в Соединенные Штаты. Спустя четыре года Мстислав и Галина лишились советского гражданства, их признали антипатриотами. Для Ростроповича наступили не самые легкие времена, он почти не выходил на сцену. Однако этот период длился недолго, постепенно жизнь наладилась, он выступал с концертами, стал художественным руководителем Вашингтонского симфонического оркестра.