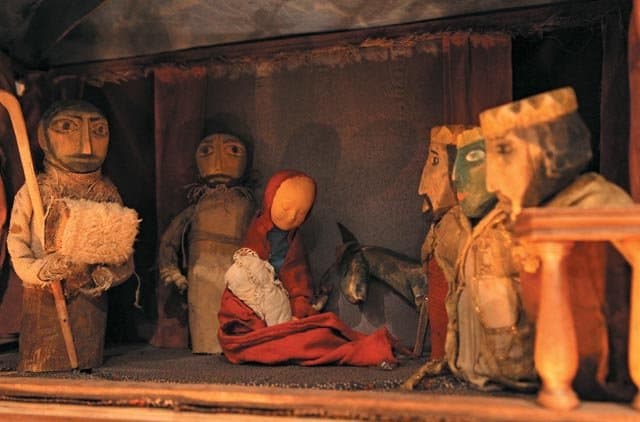

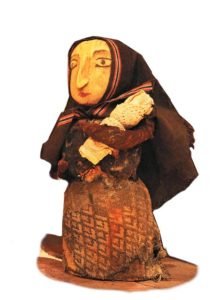

Detail of an elaborate Neapolitan presepio in Rome

In the Christian tradition, a nativity scene (also known as a manger scene, crib, crèche ( or ), or in Italian presepio or presepe, or Bethlehem) is the special exhibition, particularly during the Christmas season, of art objects representing the birth of Jesus.[1][2] While the term «nativity scene» may be used of any representation of the very common subject of the Nativity of Jesus in art, it has a more specialized sense referring to seasonal displays, either using model figures in a setting or reenactments called «living nativity scenes» (tableau vivant) in which real humans and animals participate. Nativity scenes exhibit figures representing the infant Jesus, his mother, Mary, and her husband, Joseph.

Other characters from the nativity story, such as shepherds, sheep, and angels may be displayed near the manger in a barn (or cave) intended to accommodate farm animals, as described in the Gospel of Luke. A donkey and an ox are typically depicted in the scene, and the Magi and their camels, described in the Gospel of Matthew, are also included. Many also include a representation of the Star of Bethlehem. Several cultures add other characters and objects that may or may not be Biblical.

Saint Francis of Assisi

is credited with creating the first live nativity scene in 1223 in order to cultivate the worship of Christ. He himself had recently been inspired by his visit to the Holy Land, where he’d been shown Jesus’s traditional birthplace. The scene’s popularity inspired communities throughout Christian countries to stage similar exhibitions.

Distinctive nativity scenes and traditions have been created around the world, and are displayed during the Christmas season in churches, homes, shopping malls, and other venues, and occasionally on public lands and in public buildings. Nativity scenes have not escaped controversy, and in the United States of America their inclusion on public lands or in public buildings has provoked court challenges.

Birth of Jesus[edit]

Moravian paper nativity scene from Třebíč, 1885

At Church and College of São Lourenço or Church of the Crickets or Major Seminary of the Cathedral of Porto, Portugal, 2007

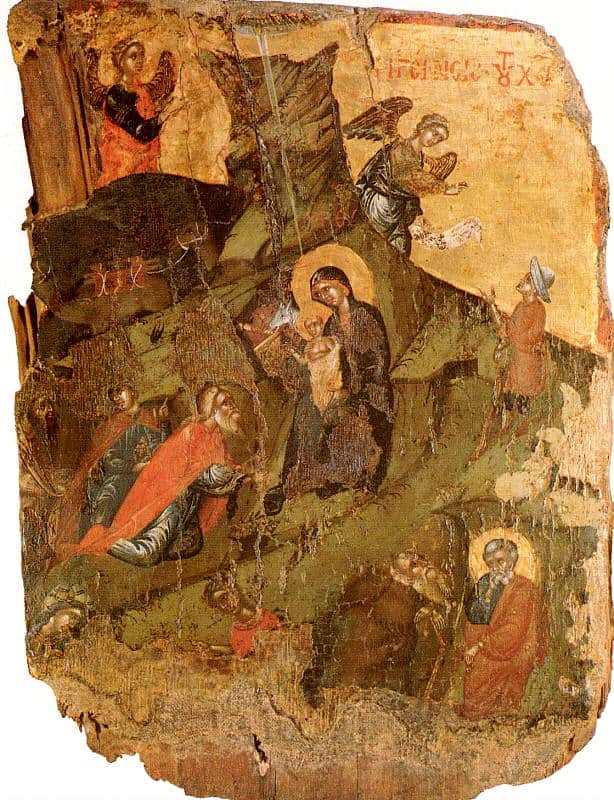

A nativity scene takes its inspiration from the accounts of the birth of Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.[3][4] Luke’s narrative describes an angel announcing the birth of Jesus to shepherds who then visit the humble site where Jesus is found lying in a manger, a trough for cattle feed.(Luke 2:8-20) Matthew’s narrative tells of «wise men» (Greek: μαγοι, romanized: magoi ) who follow a star to the house where Jesus dwelt, and indicates that the Magi found Jesus some time later, less than two years after his birth, rather than on the exact day (Mat. 2:1-23). Matthew’s account does not mention the angels and shepherds, while Luke’s narrative is silent on the Magi and the star. The Magi and the angels are often displayed in a nativity scene with the Holy Family and the shepherds (Luke 2:7, 12, 17).

Origins and early history[edit]

St. Francis at Greccio by Giotto, 1295

The earliest nativity scene has been found in the early Christian catacomb of Saint Valentine.[5] It traces to A.D. 380.[6]

Saint Francis of Assisi, who is now commemorated on the calendars of the Catholic, Lutheran and Anglican liturgical calendars, is credited with creating the first live nativity scene[7][8][9][10] in 1223 at Greccio, central Italy,[8][11] in an attempt to place the emphasis of Christmas upon the worship of Christ rather than upon «material things».[12][13] The nativity scene created by Saint Francis,[7] is described by Saint Bonaventure in his Life of Saint Francis of Assisi written around 1260.[14] Staged in a cave near Greccio, Saint Francis’ nativity scene was a living one[8] with humans and animals cast in the Biblical roles.[15] Pope Honorius III gave his blessing to the exhibit.[16]

Such reenactment exhibitions became hugely popular and spread throughout Christendom.[15] Within a hundred years every Catholic church in Italy was expected to have a nativity scene at Christmastime.[11] Eventually, statues replaced human and animal participants, and static scenes grew to elaborate affairs with richly robed figurines placed in intricate landscape settings.[15] Charles III, King of the Two Sicilies, collected such elaborate scenes, and his enthusiasm encouraged others to do the same.[11]

The scene’s popularity inspired much imitation throughout Christian countries, and in the early modern period sculpted cribs, often exported from Italy, were set up in many Christian churches and homes.[17] These elaborate scenes reached their artistic apogee in the Papal State, in Emilia, in the Kingdom of Naples and in Genoa. By the end of the 19th century nativity scenes became widely popular in many Christian denominations, and many versions in various sizes and made of various materials, such as terracotta, paper, wood, wax, and ivory, were marketed, often with a backdrop setting of a stable.[1]

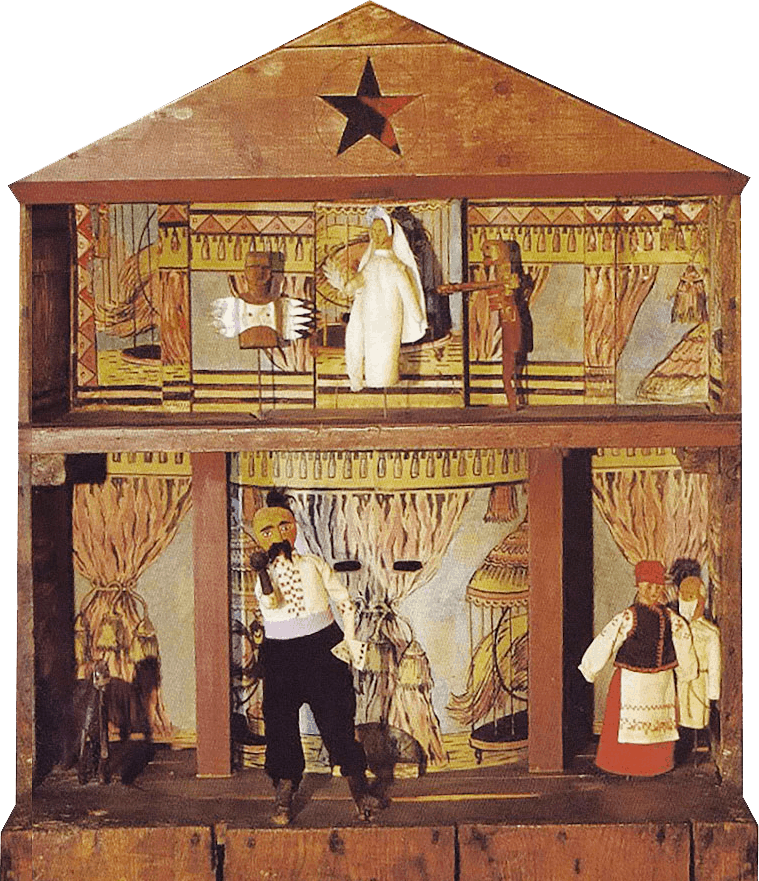

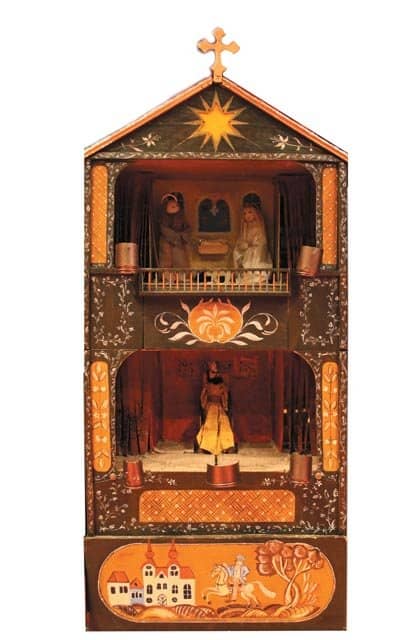

Different traditions of nativity scenes emerged in different countries. Hand-painted santons are popular in Provence. In southern Germany, Austria and Trentino-Alto Adige, the wooden figurines are handcut. Colorful szopki are typical in Poland.

A tradition in England involved baking a mince pie in the shape of a manger which would hold the Christ child until dinnertime, when the pie was eaten. When the Puritans banned Christmas celebrations in the 17th century, they also passed specific legislation to outlaw such pies, calling them «idolaterie in crust».[11]

Distinctive nativity scenes and traditions have been created around the world and are displayed during the Christmas season in churches, homes, shopping malls, and other venues, and occasionally on public lands and in public buildings. The Vatican has displayed a scene in St. Peter’s Square near its Christmas tree since 1982 and the Pope has for many years blessed the mangers of children assembled in St. Peter’s Square for a special ceremony.[18][citation needed] In the United States, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City annually displays a Neapolitan Baroque nativity scene before a 20 feet (6.1 m) blue spruce.[19]

Nativity scenes have not escaped controversy. A life-sized scene in the United Kingdom featuring waxwork celebrities provoked outrage in 2004,[20] and, in Spain, a city council forbade the exhibition of a traditional toilet humor character[21] in a public nativity scene. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) claimed in 2014 that animals in living displays lacked proper care and suffered abuse.[22] In the United States, nativity scenes on public lands and in public buildings have provoked court challenges, and the prankish theft of ceramic or plastic nativity figurines from outdoor displays has become commonplace.[23]

Components[edit]

Static nativity scenes[edit]

Outdoor nativity scene of life-sized figurines in Barcelona (2009)

Static nativity scenes may be erected indoors or outdoors during the Christmas season, and are composed of figurines depicting the infant Jesus resting in a manger, Mary, and Joseph. Other figures in the scene may include angels, shepherds, and various animals. The figures may be made of any material,[8][24] and arranged in a stable or grotto. The Magi may also appear, and are sometimes not placed in the scene until the week following Christmas to account for their travel time to Bethlehem.[25] While most home nativity scenes are packed away at Christmas or shortly thereafter, nativity scenes in churches usually remain on display until the feast of the Baptism of the Lord.[8]

The nativity scene may not accurately reflect gospel events. With no basis in the gospels, for example, the shepherds, the Magi, and the ox and ass may be displayed together at the manger. The art form can be traced back to eighteenth-century Naples, Italy. Neapolitan nativity scenes do not represent Palestine at the time of Jesus but the life of the Naples of 1700, during the Bourbon period. Families competed with each other to produce the most elegant and elaborate scenes and so, next to the Child Jesus, to the Holy Family and the shepherds, were placed ladies and gentlemen of the nobility, representatives of the bourgeoisie of the time, vendors with their banks and miniatures of cheese, bread, sheep, pigs, ducks or geese, and typical figures of the time like gypsy predicting the future, people playing cards, housewives doing shopping, dogs, cats and chickens.[26]

Peruvian crucifix with nativity scene at its base, c.1960

Regional variants on the standard nativity scene are many. The putz of Pennsylvania Dutch Americans evolved into elaborate decorative Christmas villages in the twentieth century. In Colombia, the pesebre may feature a town and its surrounding countryside with shepherds and animals. Mary and Joseph are often depicted as rural Boyacá people with Mary clad in a countrywoman’s shawl and fedora hat, and Joseph garbed in a poncho. The infant Jesus is depicted as European with Italianate features. Visitors bringing gifts to the Christ child are depicted as Colombian natives.[27] After World War I, large, lighted manger scenes in churches and public buildings grew in popularity, and, by the 1950s, many companies were selling lawn ornaments of non-fading, long-lasting, weather resistant materials telling the nativity story.[28]

Living nativity scenes[edit]

Living nativity in Sicily, which also contains a mock rural 19th-century village

Exhibitions similar to the scene staged by St. Francis at Greccio became an annual event throughout Christendom.[10] Abuses and exaggerations in the presentation of mystery plays during the Middle Ages, however, forced the church to prohibit performances during the 15th century.[8] The plays survived outside church walls, and 300 years after the prohibition, German immigrants brought simple forms of the nativity play to America. Some features of the dramas became part of both Catholic and Protestant Christmas services with children often taking the parts of characters in the nativity story. Nativity plays and pageants, culminating in living nativity scenes, eventually entered public schools. Such exhibitions have been challenged on the grounds of separation of church and state.[8]

Living nativity in Bascara

In some countries, the nativity scene took to the streets with human performers costumed as Joseph and Mary traveling from house to house seeking shelter and being told by the houses’ occupants to move on. The couple’s journey culminated in an outdoor tableau vivant at a designated place with the shepherds and the Magi then traveling the streets in parade fashion looking for the Christ child.[28]

Living nativity scenes are not without their problems. In the United States in 2008, for example, vandals destroyed all eight scenes and backdrops at a drive-through living nativity scene in Georgia. About 120 of the church’s 500 members were involved in the construction of the scenes or playing roles in the production. The damage was estimated at more than US$2,000.[29]

In southern Italy, living nativity scenes (presepe vivente) are extremely popular. They may be elaborate affairs, featuring not only the classic nativity scene but also a mock rural 19th-century village, complete with artisans in traditional costumes working at their trades. These attract many visitors and have been televised on RAI. In 2010, the old city of Matera in Basilicata hosted the world’s largest living nativity scene of the time, which was performed in the historic center, Sassi.[30]

Animals in nativity scenes[edit]

The ox, the ass, and the infant Jesus in one of the earliest depictions of the nativity, (Ancient Roman Christian sarcophagus, 4th century)

Christmas crib parish Church St. James in Ebing, Germany

A donkey (or ass) and an ox typically appear in nativity scenes. Besides the necessity of animals for a manger, this is an allusion to the Book of Isaiah: «the ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib; but Israel doth not know, my people doth not consider» (Isaiah 1:3). The Gospels do not mention an ox and donkey[31] Another source for the tradition may be the extracanonical text, the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew of the 7th century. (The translation in this text of Habakkuk 3:2 is not taken from the Septuagint.):[32][33]

«And on the third day after the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, Mary went out of the cave, and, entering a stable, placed the child in a manger, and an ox and an ass adored him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by the prophet Isaiah, «The ox knows his owner, and the ass his master’s crib.» Therefore, the animals, the ox and the ass, with him in their midst incessantly adored him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Habakkuk the prophet, saying, «Between two animals you are made manifest.»[31]

The ox traditionally represents patience, the nation of Israel, and Old Testament sacrificial worship while the ass represents humility, readiness to serve, and the Gentiles.[34]

The ox and the ass, as well as other animals, became a part of nativity scene tradition. In a 1415, Corpus Christi celebration, the Ordo paginarum notes that Jesus was lying between an ox and an ass.[35] Other animals introduced to nativity scenes include elephants and camels.[25]

By the 1970s, churches and community organizations increasingly included animals in nativity pageants.[28] Since then, automobile-accessible «drive-through» scenes with sheep and donkeys have become popular.[36]

Traditions[edit]

Australia[edit]

Nativity Scene at St. Elizabeth’s, Dandenong North. Creator and Artist Wilson Fernandez

Christmas is celebrated by Australians in a number of ways. In Australia, it’s summer season and is very hot during Christmas time.

During the Christmas time, locals and visitors visit places around their towns and suburbs to view the outdoor and indoor displays. All over the towns, the places are lit with colorful and modern spectacular lighting displays. The displays of nativity scenes with Aussie featured native animals like kangaroos and koalas are also evident.[citation needed]

In Melbourne, a traditional and authentic nativity Scene is on display at St. Elizabeth’s Parish, Dandenong North. This annual Australian Nativity Scene creator and artist Wilson Fernandez has been building and creating the traditional nativity scenes since 2004 at St. Elizabeth’s Parish.[37]

To mark this special event, Most Reverend Denis Hart Archbishop of Melbourne celebrated the Vigil Mass and blessed the nativity scene on Saturday, 14 December 2013.[38]

Canada[edit]

Bethlehem Live is an all-volunteer living nativity produced by Gateway Christian Community Church in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The production includes a reconstruction of the ancient town of Bethlehem and seven individual vignettes. There is also an annual, highly publicized nativity scene at the St. Patrick’s Basilica, Ottawa in Ottawa, Ontario.[39][40]

Czech Republic[edit]

Part of the Krýza’s crèche – a castle

The Czech Republic, and the cultures represented in its predecessors i.e. Czechoslovakia and the lands of former Bohemia, have a long tradition regarding betlémy (literally «Bethlehems»), crèches. The tradition of home nativity scenes is often traced to the 1782 ban of church and institutional crèches by emperor Joseph II, officially responding to public disturbances and the resulting «loss of dignity» of such displays.[41][42] As this followed the Edict of Toleration proclaimed the previous year, it reduced State support of the Catholic church in this multi-confessional land.[43][44]

Třebechovice pod Orebem[edit]

The Museum of Nativity Scenes in Třebechovice pod Orebem has over 400 examples dated from the 18th until early 20th century, including the Probošt’s mechanical Christmas crib, so called Třebechovice’s Bethlehem.

The issue of cost arose, and paper-cut crèches, «the crèche of the poor», became one major expression,[45] as well as wood-carved ones, some of them complex and detailed. Many major Czech artists, sculptors and illustrators have as a significant part of their legacy the crèches that they created.

The following people are known for creating Czech paper crèches:

- Mikoláš Aleš (1852–1913), painter famed for his murals of the National Theatre

- Josef Wenig (1885–1939), illustrator, theatre decorator and playwright

- Josef Lada (1887–1957), known for his work in The Good Soldier Švejk

- Marie Fischerová-Kvěchová (1892–1984), illustrator of a large number of children books

Krýza’s crèche[edit]

Tomáš Krýza (1838–1918) built in a period of over 60 years a nativity scene covering 60 m2 (length 17 m, size and height 2 m) which contains 1,398 figures of humans and animals, of which 133 are moveable. It is on display in southern Bohemian town Jindřichův Hradec. It figures as the largest mechanical nativity scene in the world in the Guinness Book of World Records.[46]

Gingerbread crèches[edit]

Gingerbread nativity scenes and cribs in the church of St. Matthew in Šárka (Prague 6 Dejvice) have around 200 figures and houses, the tradition dates from since 1972; every year new ones are baked and after holidays eaten.[citation needed]

France (Santons)[edit]

A santon (Provençal: «little saint») is a small hand-painted, terracotta nativity scene figurine produced in the Provence region of southeastern France.[47] In a traditional Provençal crèche, the santons represent various characters from Provençal village life such as the scissors grinder, the fishwife, and the chestnut seller.[47] The figurines were first created during the French Revolution when churches were forcibly closed and large nativity scenes prohibited.[48] Today, their production is a family affair passed from parents to children.[49] During the Christmas season, santon makers gather in Marseille and other locales in southeastern France to display and sell their wares.[48]

Italy and the Vatican[edit]

In 1982, Pope John Paul II inaugurated the annual tradition of placing a nativity scene on display in the Vatican City in the Piazza San Pietro before the Christmas Tree.[50]

In 2006, the nativity scene featured seventeen new figures of spruce on loan to the Vatican from sculptors and wood sawyers of the town of Tesero, Italy in the Italian Alps.[51] The figures included peasants, a flutist, a bagpipe player and a shepherd named Titaoca.[51] Twelve nativity scenes created before 1800 from Tesero were put on display in the Vatican audience hall.[51]

The Vatican nativity scene for 2007 placed the birth of Jesus in Joseph’s house, based upon an interpretation of the Gospel of Matthew. Mary was shown with the newborn infant Jesus in a room in Joseph’s house. To the left of the room was Joseph’s workshop while to the right was a busy inn—a comment on materialism versus spirituality.[52] The Vatican’s written description of the diorama said, «The scene for this year’s Nativity recalls the painting style of the Flemish School of the 1500s.»[53] The scene was unveiled on December 24 and remained in place until February 2, 2008, for The Feast of the Presentation of the Lord.[54] Ten new figures were exhibited with seven on loan from the town of Tesero and three—a baker, a woman, and a child—donated to the Vatican.[54] The decision for the atypical setting was believed to be part of a crackdown on fanciful scenes erected in various cities around Italy. In Naples, Italy, for example, Elvis Presley and Prime Minister of Italy Silvio Berlusconi, were depicted among the shepherds and angels worshipping at the manger.

In 2008, the Province of Trento, Italy, provided sculpted wooden figures and animals as well as utensils to create depictions of daily life.[55] The scene featured seventeen figures[55] with nine depicting the Holy Family, the Magi, and the shepherds.[56] The nine figures were originally donated by Saint Vincent Pallotti for the nativity at Rome’s Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle in 1842[55] and eventually found their way to the Vatican. They are dressed anew each year for the scene.[56] The 2008 scene was set in Bethlehem with a fountain and a hearth representing regeneration and light.[57] The same year, the Paul VI Audience Hall exhibited a nativity designed by Mexican artists.[55]

Since 1968, the Pope has officiated at a special ceremony in St. Peter’s Square on Gaudete Sunday that involves blessing hundreds of mangers and Babies Jesus for the children of Rome.[16] In 1978, 50,000 schoolchildren attended the ceremony.[16]

Philippines (Belén)[edit]

In the majority-Catholic Philippines, miniature, full-scale, or giant dioramas or tableaus of the nativity scene are known as Belén (from the Spanish name for Bethlehem). They were introduced by the Spanish since the 16th century. They are an ubiquitous and iconic Christmas symbol in the Philippines, on par with the parol (Christmas lanterns depicting the Star of Bethlehem) which are often incorporated into the scene as the source of illumination. Both the Belén and the parol were the traditional Christmas decorations in Filipino homes before Americans introduced the Christmas tree.[58][59][60][61][62] Most churches in the Philippines also transform their altars into a Belén at Christmas. They are also found in schools (which also hold nativity plays), government buildings, commercial establishments, and in public spaces.[63][64][65]

The city of Tarlac holds an annual competition of giant Belén in a festival known as «Belenismo sa Tarlac».[66][67][68]

Poland[edit]

Szopka are traditional Polish nativity scenes dating to 19th century Kraków, Poland.[69] Its cultural significance has landed it on the UNESCO cultural heritage list. Their modern construction incorporates elements of Kraków’s historic architecture including Gothic spires, Renaissance facades, and Baroque domes,[69] and utilizes everyday materials such as colored tinfoils, cardboard, and wood.[70] Some are mechanized.[71] Prizes are awarded for the most elaborately designed and decorated pieces[69] in an annual competition held in Kraków’s main square beside the statue of Adam Mickiewicz.[71] Some of the best are then displayed in Kraków’s Museum of History.[72] Szopka were traditionally carried from door-to-door in the nativity plays (Jasełka) by performing groups.[73]

A similar tradition, called «betlehemezés» and involving schoolchildren carrying portable folk-art nativity scenes door-to-door, chanting traditional texts, is part of Hungarian folk culture, and has enjoyed a renaissance in recent years. An example of such a portable wooden nativity scene is on display at the Nativity Museum in Bethlehem.

United States[edit]

White House nativity scene, 2008

Perhaps the best known nativity scene in America is the Neapolitan Baroque Crèche displayed annually in the Medieval Sculpture Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Its backdrop is a 1763 choir screen from the Cathedral of Valladolid and a twenty-foot blue spruce decorated with a host of 18th-century angels. The nativity figures are placed at the tree’s base. The crèche was the gift of Loretta Hines Howard in 1964, and the choir screen was the gift of The William Randolph Hearst Foundation in 1956.[74] Both this presepio and the one displayed in Pittsburgh originated from the collection of Eugenio Catello.

A life-size nativity scene has been displayed annually at Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah for several decades as part of the large outdoor Christmas displays sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Each holiday season, from Light Up Night in November through Epiphany in January, the Pittsburgh Crèche is on display in downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Pittsburgh Creche is the world’s only authorized replica of the Vatican’s Christmas crèche, on display in St. Peter’s Square in Rome.[75] Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art also displays a Neapolitan presepio. The presepio was handcrafted between 1700 and 1830, and re-creates the nativity within a panorama of 18th-century Italian village life. More than 100 human and angelic figures, along with animals, accessories, and architectural elements, cover 250 square feet and create a depiction of the nativity as seen through the eyes of Neapolitan artisans and collectors.[76]

The Radio City Christmas Spectacular, an annual musical holiday stage show presented at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, features a Living Nativity segment with live animals.[77][78]

In 2005, President of the United States of America, George W. Bush and his wife, First Lady of the United States, Laura Bush displayed an 18th-century Italian presepio. The presepio was donated to the White House in the last decades of the 20th century.[79]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh annually display Neapolitan Baroque nativity scenes which both originated from the collection of Eugenio Catello.

On her Christmas Day 2007 television show, Martha Stewart exhibited the nativity scene she made in pottery classes at the Alderson Federal Prison Camp in Alderson, West Virginia while serving a 2005 sentence. She remarked, «Even though every inmate was only allowed to do one a month, and I was only there for five months, I begged because I said I was an expert potter—ceramicist actually—and could I please make the entire nativity scene.»[80] She supplemented her nativity figurines on the show with tiny artificial palm trees imported from Germany.[80]

Associations and notable collections[edit]

The Universalis Foederatio Praesepistica, World association of Friends of Cribs was founded in 1952, counting today 20 national associations dedicated to this subject. The Central office is in Austria.[81]

In the United States and Canada Friends of the Creche has over 200 members, with a major conference every two years.[82] FotC maintains a list of permanent exhibits of nativity scenes in the United States and a list of permanent exhibits of nativity scenes in other parts of the world.

The Bavarian National Museum displays a notable collection of nativity scenes from the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries.

Every year in Lanciano, Abruzzo (Italy), a nativity scene exhibition (called in Italian «Riscopriamo il presepe») takes place at Auditorium Diocleziano, usually until the 6th of January. An average of one hundred nativity scenes are shown, coming from every region of Italy. There are also many nativity scenes made by local kindergarten, primary, secondary and high school. The event is organised by Associazione Amici di Lancianovecchia[83]

Museums dedicated specifically to paper nativity scenes exist in Pečky (Czech Republic).[84]

A static outdoor nativity scene in the United States, (Christkindlmarket, Chicago, Illinois)

Controversies[edit]

United States[edit]

Nativity scenes have been involved in controversies and lawsuits surrounding the principle of accommodationism.[85]

In 1969, the American Civil Liberties Union (representing three clergymen, an atheist, and a leader of the American Ethical Society), tried to block the construction of a nativity scene on The Ellipse in Washington, D.C.[86] When the ACLU claimed the government sponsorship of a distinctly Christian symbol violated separation of church and state,[86] the sponsors of the fifty-year-old Christmas celebration, Pageant of Peace, who had an exclusive permit from the Interior Department for all events on the Ellipse, responded that the nativity scene was a reminder of America’s spiritual heritage.[86] The United States Court of Appeals ruled on December 12, 1969, that the crèche be allowed that year.[86] The case continued until September 26, 1973, when the court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs[86] and found the involvement of the Interior Department and the National Park Service in the Pageant of Peace amounted to government support for religion.[86] The court opined that the nativity scene should be dropped from the pageant or the government end its participation in the event in order to avoid «excessive entanglements» between government and religion.[86] In 1973, the nativity scene was not displayed.[86]

A nativity scene inside an American home.

Nativity scenes are permitted on public lands in the United States as long as equal time is given to non-religious symbols.

In 1985, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ACLU v. Scarsdale, New York that nativity scenes on public lands violate separation of church and state statutes unless they comply with «The Reindeer Rule»—a regulation calling for equal opportunity for non-religious symbols, such as reindeer.[87] This principle was further clarified in 1989, when Pittsburgh attorney Roslyn Litman argued, and the Supreme Court in County of Allegheny v. ACLU ruled,[88] that a crèche placed on the grand staircase of the Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh, PA violated the Establishment Clause, because the «principal or primary effect» of the display was to advance religion.

In 1994, at Christmas, the Park Board of San Jose, California, removed a statue of the infant Jesus from Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park and replaced it with a statue of the plumed Aztec god, Quetzalcoatl, commissioned with US$500,000 of public funds. In response, protestors staged a living nativity scene in the park.[87]

In 2006, a lawsuit by the Alliance Defense Fund, a Christian legal organization in the United States, was brought against the state of Washington when it permitted a public display of a holiday tree and a menorah but not a nativity scene. Because of the lawsuit, the decision was made to permit a nativity scene to be displayed in the rotunda of the state Capitol, in Olympia, as long as other symbols of the season were included.[89]

In 2013, Gov. Rick Perry signed into Texas law the Merry Christmas bill which would allow school districts in Texas to display nativity scenes.

Baby Jesus theft[edit]

In the United States, nativity figurines are sometimes stolen from outdoor public and private displays during the Christmas season[90] in an act that is generally called Baby Jesus theft. The thefts are usually pranks with figurines recovered within a few hours or days of their disappearances.[91] Some have been damaged beyond repair or defaced with profanity, antisemitic epithets, or Satanic symbols.[92][93] It is unclear if Baby Jesus theft is on the rise as United States federal law enforcement officials do not track such theft.[91] Some communities protect outdoor nativity scenes with surveillance cameras or GPS devices concealed within the figurines.[92]

United Kingdom[edit]

In December 2004, Madame Tussaud’s London, England, United Kingdom nativity scene featured waxwork models of soccer star David Beckham and his wife Victoria Beckham as Joseph and Mary, and Kylie Minogue as the Angel.[94] Tony Blair, George W. Bush, and the Duke of Edinburgh were cast as the Magi while actors Hugh Grant, Samuel L. Jackson, and comedian Graham Norton were cast as shepherds.[95] The celebrities were chosen for the roles by 300 people who visited the Madame Tussaud’s in October 2004 and voted on the display. The Archbishop of Canterbury (Rowan Williams) was not impressed, and a Vatican spokesperson said the display was in very poor taste. Other officials reacted angrily, with one noting it was «a nativity stunt too far».[95] «We’re sorry if we have offended people,» said Diane Moon, a spokesperson for the museum. She said the display was intended in the spirit of fun.[96]

The scene was damaged in protest by James Anstice, a member of the Jesus Fellowship Church, who pushed over one of the figures and knocked the head off another. He was later ordered to pay £100 in compensation.[97]

Spain[edit]

There is a regional tradition in the Catalonia region where an additional figure is added to the nativity scene: the Caganer. It depicts a person defecating. In 2005, the Barcelona city council provoked a public outcry by commissioning a nativity scene which did not include a Caganer.[98]

Electronic nativity scene of Begonte

Since 1972 an electronic nativity scene in Begonte (Lugo, Spain), is visited by around 40,000 Galicians every year. The scene represents the day and night, the rain and snow, the culture and the works of the countryside way of life that has kept changing in recent decades. The scene reproduces the houses of the region and the almost unknown environment of the rural Galicia from mid twentieth century.

A particular feature of the nativity scene of Begonte is that its figures are animated electronically, and has impressed visitors by the movement of its figures.

It was declared of Galician tourist interest in 2014. For the last fifty years the nativity scene of Begonte opens its physical doors from the first Saturday of December to the last Saturday of January. It can also be watched virtually at any time, in Spanish, Galician and English, www.belendebegonte.es/belenvirtual on a website.

Gallery[edit]

-

Christmas crib on the Saint Peter’s square, Vatican

-

Living nativity at St. Wojciech Church, Wyszków, Poland, 2006

-

Christmas crib inside the Saint Peter’s Basilica, Vatican

-

Nativity scene in Buchach, Ukraine

-

Nativity scene in Buenos Aires (1924)

-

Christmas crib

-

Crib family with shepherds at the crib exhibition in Bamberg 2015

-

Abstract nativity display in a home.

-

Christmas crib outside a Catholic church Goa, India

-

Christmas crib and tree display in House Mumbai, India.

See also[edit]

- Weihnachtsberg — a traditional Christmas mountain scene that combines the nativity scene with mining motifs

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Introduction to Christmas Season». General Board of Discipleship (GBOD). The United Methodist Church. 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

Christmas is a season of praise and thanksgiving for the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ, which begins with Christmas Eve (December 24 after sundown) or Day and continues through the Day of Epiphany. The name Christmas comes from the season’s first service, the Christ Mass. Epiphany comes from the Greek word epiphania, which means «manifestation.» New Year’s Eve or Day is often celebrated in the United Methodist tradition with a Covenant Renewal Service. In addition to acts and services of worship for the Christmas Season on the following pages, see The Great Thanksgivings and the scripture readings for the Christmas Season in the lectionary…. Signs of the season include a Chrismon tree, a nativity scene (include the magi on the Day of Epiphany), a Christmas star, angels, poinsettias, and roses.

- ^ Berliner, R. The Origins of the Creche. Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 30 (1946), p. 251.

- ^ Brown, Raymond E.. The Birth of the Messiah. Doubleday, 1997.

- ^ Vermes, Geza. The Nativity: History and Legend. Penguin, 2006

- ^ Osborne, John (31 May 2020). Rome in the Eighth Century: A History in Art. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-108-87372-7.

- ^ Tuleja, Thaddeus F. (1999). Curious Customs: The Stories Behind More Than 300 Popular American Rituals. BBS Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-1-57866-070-4.

Francis Weiser (1952) says that the first known depiction of the nativity scene, found in the catacombs of Rome , dates from A.D. 380.

- ^ a b Matheson, Lister M. (2012). Icons of the Middle Ages: Rulers, Writers, Rebels, and Saints. ABC-CLIO. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-313-34080-2.

He was responsible for staging the first living Nativity scene or creche, in Christian history; and he was also Christianity’s first stigmatic. He shares the honor of being patron saint of Italy with Saint Catherine of Siena. His feast day is celbrated on October 4, the day of his death; many churches, including the Anglican, Lutheran, and Episcopal churches, commemorate this with the blessing of the animals.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dues, Greg.Catholic Customs and Traditions: A Popular Guide Twenty-Third Publications, 2000.

- ^ Thomas, George F.. Vitality of the Christian Tradition. Ayer Co. Publishing, 1944.

- ^ a b «#MyLivingNativity». Upper Room Books. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Kevin Orlin. Why Do Catholics Do That? Random House, Inc., 1994.

- ^ Mazar, Peter and Evelyn Grala. To Crown the Year: Decorating the Church Through the Year. Liturgy Training, 1995. ISBN 1-56854-041-8

- ^ Federer, William J.. There Really is a Santa Claus: The History of Saint Nicholas & Christmas Holiday Traditions. Amerisearch, Inc., 2003. p. 37.

- ^ St. Bonaventure. «The Life of St. Francis of Assisi». e-Catholic 2000. Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b c Santino, Jack. All Around the Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life. University of Illinois Press, 1995. ISBN 0-252-06516-6.

- ^ a b c Christmas in Italy. World Book Encyclopedia, Inc., 1996, 1979.

- ^ Orsini, Joseph E. (2000). Italian Family Cooking. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-24225-1.

In later centuries the Nativity scenes became beautiful works of art in wooden sculptures and ceramic figures. The most remarkable ones were created in southern Italy, especially in Naples, Calabria, and Sicily, Today, in most Christian homes the Presepio, Creche, or Nativity Scene is in a special place of honor reserved for it beneath the Christmas tree. In both Italy and in Italian parishes…the Nativity Scenes is placed, significantly, right in front of the main altar of the church, and Christmas trees adorn the spaces behind or on the side of the altar.

- ^ «Pope blesses Nativity scene statues, calls them signs of God’s love». TheCatholicSpirit.com. 2019-12-17. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2020-01-06.

- ^ «Met Museum Celebrates Christmas andHanukkah at Main Building and Cloisters | the Metropolitan Museum of Art». Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2016-12-21.

- ^ «Celebrity wax Nativity scene vandalized». Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ «BBC News — A traditional Nativity scene, Catalan-style». BBC News. 23 December 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ «PETA mistakenly targets nativity scene — US news — Weird news — Animal weirdness — NBC News». msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ Burke, Jennifer (2021-11-30). «Christmas creches help Catholics enter into Nativity story». Catholic Courier. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ a b Tangerman, Elmer John. The Big Book of Whittling and Woodcarving. Courier Dover Publications, 1989. ISBN 0-486-26171-9.

- ^ «Neapolitan Crib: The crib and 1700s Naples.» Archived 2013-12-20 at Wikiwix. CitiesItaly.com. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ Duncan, Ronald J. The Ceramics of Ráquira, Colombia: Gender, Work, and Economic Change. University Press of Florida, 1998. ISBN 0-8130-1615-0.

- ^ a b c Collins, Ace. Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Zondervan, 2003. ISBN 0-310-24880-9.

- ^ Mehta, Hemant. «Would You Help Restore a Nativity Scene?» Archived 2009-02-09 at the Wayback Machine. The Friendly Atheist, December 13, 2008.

- ^ «Most people in a nativity scene: Welton Baptist Church sets world record». worldrecordacademy.com. 4 December 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b Hobgood-Oster, Laura. Holy Dogs and Asses: Animals in the Christian Tradition. University of Illinois Press, 2008. ISBN 0-252-03213-6.

- ^ Gill, John (1748–63). John Gill’s Exposition of the Bible. Archived from the original on 2010-08-21.

- ^ Saxon, Elizabeth (2006). The Eucharist in Romanesque France: iconography and theology. Boydell Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-84383-256-0. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ Webber, F.R.. Church Symbolism. Kessinger Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-7661-4009-1.

- ^ King, Pamela M.. The York Mystery Cycle and the Worship of the City. DS Brewer, 2006.

ISBN 1-84384-098-7. - ^ «California Nativity: Drive Thru & Living Nativities in California» Archived 2009-01-27 at the Wayback Machine. BeachCalifornia.com. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- ^ «Australian Nativity Scene Homepage». Australian Nativity Scene Homepage. Archived from the original on 2015-12-23. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ^ «Kairos, Volume 25 Issue 23». www.cam.org.au. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- ^ «Doing the time-warp». CBC News. 12 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011.

- ^ «Business-Class Web Hosting by (mt) Media Temple». Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ «From Nutshells to Life‑size Statues» (PDF). Bridge Publishing House. December 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Velinger, Jan (December 7, 2005). «Czech Nativity scenes». Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ «Edict of Toleration (2 January 1782): Emperor Joseph II» (PDF). New Hartford, New York: New Hartford Central School District. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ «The Eighteenth Century». LITURGIE &CETERA. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Osborne (2004). «Paper Crèches». Archived from the original on 2014-12-31. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ «Krýza Nativity Scene». Jindřichův Hradec Museum. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ a b Porter, Darwin, and Danforth Prince and Cheryl A. Pientka. France for Dummies. For Dummies, 2007. ISBN 0-470-08581-9.

- ^ a b Williams, Nicola. Lonely Planet: Provence and the Côte D’Azur. Lonely Planet, 2007. ISBN 1-74104-236-4.

- ^ «Christmas in France». World Book, Inc., 1995. ISBN 0-7166-0876-6.

- ^ Murphy, Bruce and Alessandra de Rosa. Italy for Dummies. For Dummies, 2007. ISBN 0-470-06932-5.

- ^ a b c Wooden, Cindy. «No Room at the Inn? Vatican Nativity Scene Gets More Figures». Catholic Online International News, December 18, 2007.

- ^ «Vatican Nativity Scene Trades Manger for St. Joseph’s House». Catholic News Agency.

- ^ Glatz, Carol. «Vatican Nativity Scene Places Christ’s Birth in Edifice in Bethlehem». Catholic News Service, December 26, 2007.

- ^ a b Glatz, Carol. «Vatican Nativity Scene». Catholic Online, December 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Bunson, Matthew E.. Catholic Almanac 2009. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, 2008. ISBN 1-59276-441-X.

- ^ a b De Cristofaro, Maria, and Sebastian Rotella. «Vatican, Rome Go Head-to-Head with Nativities» Archived 2008-12-27 at the Wayback Machine. Los Angeles Times, December 24, 2008.

- ^ CNS, Vatican Nativity scene unveiled Archived 2009-05-14 at Wikiwix, December 24, 2008.

- ^ Bondoc, Joshua (22 December 2021). «Christmas in our isles, a long enduring feast (First published 1978, TV Times magazine)». PhilStar Global. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Ferrolino, Mark Louis F. (15 December 2017). «A Christmas like no other». BusinessWorld. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Macairan, Evelyn (19 December 2010). «‘Belen most important Christmas decor’«. PhilStar Global. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Gonzalez, Joaquin Jay (2009). Filipino American Faith in Action: Immigration, Religion, and Civic Engagement. NYU Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780814732977.

- ^ Laquian, Eleanor R. «Christmas Belen tradition brings Baby Jesus to Vancouver homes». CanadianFilipino.net. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Dice, Elizabeth A. (2009). Christmas and Hanukkah. Infobase Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 9781438119717.

- ^ Bowler, Gerry (2012). The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 9781551996073.

- ^ Llamas, Cora (20 December 2021). «The Philippines Has the Longest Christmas Season in the World». Christianity Today. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Moaje, Marita (15 November 2021). «‘Belenismo’ continues tradition of bringing hope, inspiration». Philippine News Agency. Republic of the Philippines. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Concepcion, Pocholo (15 November 2017). «Bringing back the ‘belen’«. Lifestyle.Inq. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Dayrit, Christine (16 December 2018). «Belenismo: A spectacle of hope». PhilStar Global. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Deck-Partyka, Alicja. Poland: A Unique Country and Its People. AuthorHouse, 2006. ISBN 1-4259-1838-7.

- ^ Salter, Mark, and Jonathan Bousfield. Poland. Penguin Putnam, 2002.

- ^ a b Wilson, Neil. Poland. Lonely Planet, 2005. ISBN 1-74059-522-X.

- ^ Johnstone, Sarah. Europe on a Shoestring. Lonely Planet, 2007. ISBN 1-74104-591-6.

- ^ Silverman, Deborah Anders. Polish-American Folklore. University of Illinois Press, 2000. ISBN 0-252-02569-5

- ^ Special Exhibitions Archived 2009-12-04 at the Wayback Machine Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Albrecht Powell. «Pittsurgh Creche — Pittsburgh Nativity Scene». About. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ «Carnegie Museum of Art». Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ «Living nativity scene in Radio City Christmas Spectacular». YouTube. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10.

- ^ «Arrival of live animals that appear in Radio City Christmas Spectacular’s living nativity scene». YouTube. Archived from the original on 2017-03-09.

- ^ Walters, Gary. «Ask the White House» Archived 2017-07-12 at the Wayback Machine. 2005.

- ^ a b «Martha Built Nativity Scene in Prison». Huffington Post, December 25, 2007.

- ^ «Universalis Foederatio Praesepistica». Archived from the original on 2013-12-02.

- ^ «Friends of the Creche». Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ «Riscopriamo il presepe 2014» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-19.

- ^ «Papírové betlémy». Papirove-betlemy.sweb.cz. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Sherrill, Roland A.. Religion and the Life of the Nation. University of Illinois Press. 1990. p. 165.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Menendez, Albert J.. Christmas in the White House. The Westminster Press, 1983.

- ^ a b Comfort, David. Just Say Noel: A History of Christmas from the Nativity to the Nineties. Simon and Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-684-80057-8.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (8 October 2016). «Roslyn Litman, Antitrust Lawyer and Civil Liberties Advocate, Dies at 88». New York Times.

- ^ «Nonbelievers’ sign at Capitol counters Nativity» Archived 2012-01-22 at the Wayback Machine. Seattle Times. December 2, 2008.

- ^ Cloud, Olivia M. Joy to the World: Inspirational Christmas Messages from America’s Preachers Archived 2016-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. Simon and Schuster, 2006. ISBN 1-4165-4000-8. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ a b Nasaw, Daniel.»Thefts of Baby Jesus Figurines Sweep US» Archived 2013-09-05 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. January 1, 2009. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ a b «Communities Protect Baby Jesus Statues With Hidden Cameras, GPS» Archived 2008-12-14 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press. December 10, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ Lee, Don.»Suspect Arrested in Baby Jesus Theft» Archived 2008-12-28 at the Wayback Machine Lovely County Citizen, Eureka Springs, Arkansas. December 22, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ «Madame Tussaud’s Celebrity Nativity Scene» Archived 2011-05-26 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ^ a b «Posh and Beckham in Wax Nativity» Archived 2006-03-30 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, December 8, 2004. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ «Celebrity Nativity Scene Draws Ire in UK» Archived 2008-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. Red Orbit, December 9, 2004.

- ^ «Becks waxworks vandal discharged- BBC News» Archived 2007-01-25 at the Wayback Machine Retr. 8/1/2017

- ^ «Els pessebres més polèmics de Sant Jaume». Betevé (in Catalan). 2018-11-26. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

External links[edit]

Media related to Nativity scenes at Wikimedia Commons

- A selected English bibliography – 2013 of the Friends of the Creche. Also links to bibliographies in other languages

- The Mermaid in Mexican Folk Creches. An article portraying how pagan elements have become part of this Christian art form.

- links to national associations Universalis Foederatio Praesepistica The International Association of Friends of the Creche

- Discover the Christmas Cribs and Santons of Provence on Notreprovence.fr (English)

- The Living Nativity by Larry Peacock

Detail of an elaborate Neapolitan presepio in Rome

In the Christian tradition, a nativity scene (also known as a manger scene, crib, crèche ( or ), or in Italian presepio or presepe, or Bethlehem) is the special exhibition, particularly during the Christmas season, of art objects representing the birth of Jesus.[1][2] While the term «nativity scene» may be used of any representation of the very common subject of the Nativity of Jesus in art, it has a more specialized sense referring to seasonal displays, either using model figures in a setting or reenactments called «living nativity scenes» (tableau vivant) in which real humans and animals participate. Nativity scenes exhibit figures representing the infant Jesus, his mother, Mary, and her husband, Joseph.

Other characters from the nativity story, such as shepherds, sheep, and angels may be displayed near the manger in a barn (or cave) intended to accommodate farm animals, as described in the Gospel of Luke. A donkey and an ox are typically depicted in the scene, and the Magi and their camels, described in the Gospel of Matthew, are also included. Many also include a representation of the Star of Bethlehem. Several cultures add other characters and objects that may or may not be Biblical.

Saint Francis of Assisi

is credited with creating the first live nativity scene in 1223 in order to cultivate the worship of Christ. He himself had recently been inspired by his visit to the Holy Land, where he’d been shown Jesus’s traditional birthplace. The scene’s popularity inspired communities throughout Christian countries to stage similar exhibitions.

Distinctive nativity scenes and traditions have been created around the world, and are displayed during the Christmas season in churches, homes, shopping malls, and other venues, and occasionally on public lands and in public buildings. Nativity scenes have not escaped controversy, and in the United States of America their inclusion on public lands or in public buildings has provoked court challenges.

Birth of Jesus[edit]

Moravian paper nativity scene from Třebíč, 1885

At Church and College of São Lourenço or Church of the Crickets or Major Seminary of the Cathedral of Porto, Portugal, 2007

A nativity scene takes its inspiration from the accounts of the birth of Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.[3][4] Luke’s narrative describes an angel announcing the birth of Jesus to shepherds who then visit the humble site where Jesus is found lying in a manger, a trough for cattle feed.(Luke 2:8-20) Matthew’s narrative tells of «wise men» (Greek: μαγοι, romanized: magoi ) who follow a star to the house where Jesus dwelt, and indicates that the Magi found Jesus some time later, less than two years after his birth, rather than on the exact day (Mat. 2:1-23). Matthew’s account does not mention the angels and shepherds, while Luke’s narrative is silent on the Magi and the star. The Magi and the angels are often displayed in a nativity scene with the Holy Family and the shepherds (Luke 2:7, 12, 17).

Origins and early history[edit]

St. Francis at Greccio by Giotto, 1295

The earliest nativity scene has been found in the early Christian catacomb of Saint Valentine.[5] It traces to A.D. 380.[6]

Saint Francis of Assisi, who is now commemorated on the calendars of the Catholic, Lutheran and Anglican liturgical calendars, is credited with creating the first live nativity scene[7][8][9][10] in 1223 at Greccio, central Italy,[8][11] in an attempt to place the emphasis of Christmas upon the worship of Christ rather than upon «material things».[12][13] The nativity scene created by Saint Francis,[7] is described by Saint Bonaventure in his Life of Saint Francis of Assisi written around 1260.[14] Staged in a cave near Greccio, Saint Francis’ nativity scene was a living one[8] with humans and animals cast in the Biblical roles.[15] Pope Honorius III gave his blessing to the exhibit.[16]

Such reenactment exhibitions became hugely popular and spread throughout Christendom.[15] Within a hundred years every Catholic church in Italy was expected to have a nativity scene at Christmastime.[11] Eventually, statues replaced human and animal participants, and static scenes grew to elaborate affairs with richly robed figurines placed in intricate landscape settings.[15] Charles III, King of the Two Sicilies, collected such elaborate scenes, and his enthusiasm encouraged others to do the same.[11]

The scene’s popularity inspired much imitation throughout Christian countries, and in the early modern period sculpted cribs, often exported from Italy, were set up in many Christian churches and homes.[17] These elaborate scenes reached their artistic apogee in the Papal State, in Emilia, in the Kingdom of Naples and in Genoa. By the end of the 19th century nativity scenes became widely popular in many Christian denominations, and many versions in various sizes and made of various materials, such as terracotta, paper, wood, wax, and ivory, were marketed, often with a backdrop setting of a stable.[1]

Different traditions of nativity scenes emerged in different countries. Hand-painted santons are popular in Provence. In southern Germany, Austria and Trentino-Alto Adige, the wooden figurines are handcut. Colorful szopki are typical in Poland.

A tradition in England involved baking a mince pie in the shape of a manger which would hold the Christ child until dinnertime, when the pie was eaten. When the Puritans banned Christmas celebrations in the 17th century, they also passed specific legislation to outlaw such pies, calling them «idolaterie in crust».[11]

Distinctive nativity scenes and traditions have been created around the world and are displayed during the Christmas season in churches, homes, shopping malls, and other venues, and occasionally on public lands and in public buildings. The Vatican has displayed a scene in St. Peter’s Square near its Christmas tree since 1982 and the Pope has for many years blessed the mangers of children assembled in St. Peter’s Square for a special ceremony.[18][citation needed] In the United States, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City annually displays a Neapolitan Baroque nativity scene before a 20 feet (6.1 m) blue spruce.[19]

Nativity scenes have not escaped controversy. A life-sized scene in the United Kingdom featuring waxwork celebrities provoked outrage in 2004,[20] and, in Spain, a city council forbade the exhibition of a traditional toilet humor character[21] in a public nativity scene. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) claimed in 2014 that animals in living displays lacked proper care and suffered abuse.[22] In the United States, nativity scenes on public lands and in public buildings have provoked court challenges, and the prankish theft of ceramic or plastic nativity figurines from outdoor displays has become commonplace.[23]

Components[edit]

Static nativity scenes[edit]

Outdoor nativity scene of life-sized figurines in Barcelona (2009)

Static nativity scenes may be erected indoors or outdoors during the Christmas season, and are composed of figurines depicting the infant Jesus resting in a manger, Mary, and Joseph. Other figures in the scene may include angels, shepherds, and various animals. The figures may be made of any material,[8][24] and arranged in a stable or grotto. The Magi may also appear, and are sometimes not placed in the scene until the week following Christmas to account for their travel time to Bethlehem.[25] While most home nativity scenes are packed away at Christmas or shortly thereafter, nativity scenes in churches usually remain on display until the feast of the Baptism of the Lord.[8]

The nativity scene may not accurately reflect gospel events. With no basis in the gospels, for example, the shepherds, the Magi, and the ox and ass may be displayed together at the manger. The art form can be traced back to eighteenth-century Naples, Italy. Neapolitan nativity scenes do not represent Palestine at the time of Jesus but the life of the Naples of 1700, during the Bourbon period. Families competed with each other to produce the most elegant and elaborate scenes and so, next to the Child Jesus, to the Holy Family and the shepherds, were placed ladies and gentlemen of the nobility, representatives of the bourgeoisie of the time, vendors with their banks and miniatures of cheese, bread, sheep, pigs, ducks or geese, and typical figures of the time like gypsy predicting the future, people playing cards, housewives doing shopping, dogs, cats and chickens.[26]

Peruvian crucifix with nativity scene at its base, c.1960

Regional variants on the standard nativity scene are many. The putz of Pennsylvania Dutch Americans evolved into elaborate decorative Christmas villages in the twentieth century. In Colombia, the pesebre may feature a town and its surrounding countryside with shepherds and animals. Mary and Joseph are often depicted as rural Boyacá people with Mary clad in a countrywoman’s shawl and fedora hat, and Joseph garbed in a poncho. The infant Jesus is depicted as European with Italianate features. Visitors bringing gifts to the Christ child are depicted as Colombian natives.[27] After World War I, large, lighted manger scenes in churches and public buildings grew in popularity, and, by the 1950s, many companies were selling lawn ornaments of non-fading, long-lasting, weather resistant materials telling the nativity story.[28]

Living nativity scenes[edit]

Living nativity in Sicily, which also contains a mock rural 19th-century village

Exhibitions similar to the scene staged by St. Francis at Greccio became an annual event throughout Christendom.[10] Abuses and exaggerations in the presentation of mystery plays during the Middle Ages, however, forced the church to prohibit performances during the 15th century.[8] The plays survived outside church walls, and 300 years after the prohibition, German immigrants brought simple forms of the nativity play to America. Some features of the dramas became part of both Catholic and Protestant Christmas services with children often taking the parts of characters in the nativity story. Nativity plays and pageants, culminating in living nativity scenes, eventually entered public schools. Such exhibitions have been challenged on the grounds of separation of church and state.[8]

Living nativity in Bascara

In some countries, the nativity scene took to the streets with human performers costumed as Joseph and Mary traveling from house to house seeking shelter and being told by the houses’ occupants to move on. The couple’s journey culminated in an outdoor tableau vivant at a designated place with the shepherds and the Magi then traveling the streets in parade fashion looking for the Christ child.[28]

Living nativity scenes are not without their problems. In the United States in 2008, for example, vandals destroyed all eight scenes and backdrops at a drive-through living nativity scene in Georgia. About 120 of the church’s 500 members were involved in the construction of the scenes or playing roles in the production. The damage was estimated at more than US$2,000.[29]

In southern Italy, living nativity scenes (presepe vivente) are extremely popular. They may be elaborate affairs, featuring not only the classic nativity scene but also a mock rural 19th-century village, complete with artisans in traditional costumes working at their trades. These attract many visitors and have been televised on RAI. In 2010, the old city of Matera in Basilicata hosted the world’s largest living nativity scene of the time, which was performed in the historic center, Sassi.[30]

Animals in nativity scenes[edit]

The ox, the ass, and the infant Jesus in one of the earliest depictions of the nativity, (Ancient Roman Christian sarcophagus, 4th century)

Christmas crib parish Church St. James in Ebing, Germany

A donkey (or ass) and an ox typically appear in nativity scenes. Besides the necessity of animals for a manger, this is an allusion to the Book of Isaiah: «the ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib; but Israel doth not know, my people doth not consider» (Isaiah 1:3). The Gospels do not mention an ox and donkey[31] Another source for the tradition may be the extracanonical text, the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew of the 7th century. (The translation in this text of Habakkuk 3:2 is not taken from the Septuagint.):[32][33]

«And on the third day after the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, Mary went out of the cave, and, entering a stable, placed the child in a manger, and an ox and an ass adored him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by the prophet Isaiah, «The ox knows his owner, and the ass his master’s crib.» Therefore, the animals, the ox and the ass, with him in their midst incessantly adored him. Then was fulfilled that which was said by Habakkuk the prophet, saying, «Between two animals you are made manifest.»[31]

The ox traditionally represents patience, the nation of Israel, and Old Testament sacrificial worship while the ass represents humility, readiness to serve, and the Gentiles.[34]

The ox and the ass, as well as other animals, became a part of nativity scene tradition. In a 1415, Corpus Christi celebration, the Ordo paginarum notes that Jesus was lying between an ox and an ass.[35] Other animals introduced to nativity scenes include elephants and camels.[25]

By the 1970s, churches and community organizations increasingly included animals in nativity pageants.[28] Since then, automobile-accessible «drive-through» scenes with sheep and donkeys have become popular.[36]

Traditions[edit]

Australia[edit]

Nativity Scene at St. Elizabeth’s, Dandenong North. Creator and Artist Wilson Fernandez

Christmas is celebrated by Australians in a number of ways. In Australia, it’s summer season and is very hot during Christmas time.

During the Christmas time, locals and visitors visit places around their towns and suburbs to view the outdoor and indoor displays. All over the towns, the places are lit with colorful and modern spectacular lighting displays. The displays of nativity scenes with Aussie featured native animals like kangaroos and koalas are also evident.[citation needed]

In Melbourne, a traditional and authentic nativity Scene is on display at St. Elizabeth’s Parish, Dandenong North. This annual Australian Nativity Scene creator and artist Wilson Fernandez has been building and creating the traditional nativity scenes since 2004 at St. Elizabeth’s Parish.[37]

To mark this special event, Most Reverend Denis Hart Archbishop of Melbourne celebrated the Vigil Mass and blessed the nativity scene on Saturday, 14 December 2013.[38]

Canada[edit]

Bethlehem Live is an all-volunteer living nativity produced by Gateway Christian Community Church in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The production includes a reconstruction of the ancient town of Bethlehem and seven individual vignettes. There is also an annual, highly publicized nativity scene at the St. Patrick’s Basilica, Ottawa in Ottawa, Ontario.[39][40]

Czech Republic[edit]

Part of the Krýza’s crèche – a castle

The Czech Republic, and the cultures represented in its predecessors i.e. Czechoslovakia and the lands of former Bohemia, have a long tradition regarding betlémy (literally «Bethlehems»), crèches. The tradition of home nativity scenes is often traced to the 1782 ban of church and institutional crèches by emperor Joseph II, officially responding to public disturbances and the resulting «loss of dignity» of such displays.[41][42] As this followed the Edict of Toleration proclaimed the previous year, it reduced State support of the Catholic church in this multi-confessional land.[43][44]

Třebechovice pod Orebem[edit]

The Museum of Nativity Scenes in Třebechovice pod Orebem has over 400 examples dated from the 18th until early 20th century, including the Probošt’s mechanical Christmas crib, so called Třebechovice’s Bethlehem.

The issue of cost arose, and paper-cut crèches, «the crèche of the poor», became one major expression,[45] as well as wood-carved ones, some of them complex and detailed. Many major Czech artists, sculptors and illustrators have as a significant part of their legacy the crèches that they created.

The following people are known for creating Czech paper crèches:

- Mikoláš Aleš (1852–1913), painter famed for his murals of the National Theatre

- Josef Wenig (1885–1939), illustrator, theatre decorator and playwright

- Josef Lada (1887–1957), known for his work in The Good Soldier Švejk

- Marie Fischerová-Kvěchová (1892–1984), illustrator of a large number of children books

Krýza’s crèche[edit]

Tomáš Krýza (1838–1918) built in a period of over 60 years a nativity scene covering 60 m2 (length 17 m, size and height 2 m) which contains 1,398 figures of humans and animals, of which 133 are moveable. It is on display in southern Bohemian town Jindřichův Hradec. It figures as the largest mechanical nativity scene in the world in the Guinness Book of World Records.[46]

Gingerbread crèches[edit]

Gingerbread nativity scenes and cribs in the church of St. Matthew in Šárka (Prague 6 Dejvice) have around 200 figures and houses, the tradition dates from since 1972; every year new ones are baked and after holidays eaten.[citation needed]

France (Santons)[edit]

A santon (Provençal: «little saint») is a small hand-painted, terracotta nativity scene figurine produced in the Provence region of southeastern France.[47] In a traditional Provençal crèche, the santons represent various characters from Provençal village life such as the scissors grinder, the fishwife, and the chestnut seller.[47] The figurines were first created during the French Revolution when churches were forcibly closed and large nativity scenes prohibited.[48] Today, their production is a family affair passed from parents to children.[49] During the Christmas season, santon makers gather in Marseille and other locales in southeastern France to display and sell their wares.[48]

Italy and the Vatican[edit]

In 1982, Pope John Paul II inaugurated the annual tradition of placing a nativity scene on display in the Vatican City in the Piazza San Pietro before the Christmas Tree.[50]

In 2006, the nativity scene featured seventeen new figures of spruce on loan to the Vatican from sculptors and wood sawyers of the town of Tesero, Italy in the Italian Alps.[51] The figures included peasants, a flutist, a bagpipe player and a shepherd named Titaoca.[51] Twelve nativity scenes created before 1800 from Tesero were put on display in the Vatican audience hall.[51]

The Vatican nativity scene for 2007 placed the birth of Jesus in Joseph’s house, based upon an interpretation of the Gospel of Matthew. Mary was shown with the newborn infant Jesus in a room in Joseph’s house. To the left of the room was Joseph’s workshop while to the right was a busy inn—a comment on materialism versus spirituality.[52] The Vatican’s written description of the diorama said, «The scene for this year’s Nativity recalls the painting style of the Flemish School of the 1500s.»[53] The scene was unveiled on December 24 and remained in place until February 2, 2008, for The Feast of the Presentation of the Lord.[54] Ten new figures were exhibited with seven on loan from the town of Tesero and three—a baker, a woman, and a child—donated to the Vatican.[54] The decision for the atypical setting was believed to be part of a crackdown on fanciful scenes erected in various cities around Italy. In Naples, Italy, for example, Elvis Presley and Prime Minister of Italy Silvio Berlusconi, were depicted among the shepherds and angels worshipping at the manger.

In 2008, the Province of Trento, Italy, provided sculpted wooden figures and animals as well as utensils to create depictions of daily life.[55] The scene featured seventeen figures[55] with nine depicting the Holy Family, the Magi, and the shepherds.[56] The nine figures were originally donated by Saint Vincent Pallotti for the nativity at Rome’s Church of Sant’Andrea della Valle in 1842[55] and eventually found their way to the Vatican. They are dressed anew each year for the scene.[56] The 2008 scene was set in Bethlehem with a fountain and a hearth representing regeneration and light.[57] The same year, the Paul VI Audience Hall exhibited a nativity designed by Mexican artists.[55]

Since 1968, the Pope has officiated at a special ceremony in St. Peter’s Square on Gaudete Sunday that involves blessing hundreds of mangers and Babies Jesus for the children of Rome.[16] In 1978, 50,000 schoolchildren attended the ceremony.[16]

Philippines (Belén)[edit]

In the majority-Catholic Philippines, miniature, full-scale, or giant dioramas or tableaus of the nativity scene are known as Belén (from the Spanish name for Bethlehem). They were introduced by the Spanish since the 16th century. They are an ubiquitous and iconic Christmas symbol in the Philippines, on par with the parol (Christmas lanterns depicting the Star of Bethlehem) which are often incorporated into the scene as the source of illumination. Both the Belén and the parol were the traditional Christmas decorations in Filipino homes before Americans introduced the Christmas tree.[58][59][60][61][62] Most churches in the Philippines also transform their altars into a Belén at Christmas. They are also found in schools (which also hold nativity plays), government buildings, commercial establishments, and in public spaces.[63][64][65]

The city of Tarlac holds an annual competition of giant Belén in a festival known as «Belenismo sa Tarlac».[66][67][68]

Poland[edit]

Szopka are traditional Polish nativity scenes dating to 19th century Kraków, Poland.[69] Its cultural significance has landed it on the UNESCO cultural heritage list. Their modern construction incorporates elements of Kraków’s historic architecture including Gothic spires, Renaissance facades, and Baroque domes,[69] and utilizes everyday materials such as colored tinfoils, cardboard, and wood.[70] Some are mechanized.[71] Prizes are awarded for the most elaborately designed and decorated pieces[69] in an annual competition held in Kraków’s main square beside the statue of Adam Mickiewicz.[71] Some of the best are then displayed in Kraków’s Museum of History.[72] Szopka were traditionally carried from door-to-door in the nativity plays (Jasełka) by performing groups.[73]

A similar tradition, called «betlehemezés» and involving schoolchildren carrying portable folk-art nativity scenes door-to-door, chanting traditional texts, is part of Hungarian folk culture, and has enjoyed a renaissance in recent years. An example of such a portable wooden nativity scene is on display at the Nativity Museum in Bethlehem.

United States[edit]

White House nativity scene, 2008

Perhaps the best known nativity scene in America is the Neapolitan Baroque Crèche displayed annually in the Medieval Sculpture Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Its backdrop is a 1763 choir screen from the Cathedral of Valladolid and a twenty-foot blue spruce decorated with a host of 18th-century angels. The nativity figures are placed at the tree’s base. The crèche was the gift of Loretta Hines Howard in 1964, and the choir screen was the gift of The William Randolph Hearst Foundation in 1956.[74] Both this presepio and the one displayed in Pittsburgh originated from the collection of Eugenio Catello.

A life-size nativity scene has been displayed annually at Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah for several decades as part of the large outdoor Christmas displays sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Each holiday season, from Light Up Night in November through Epiphany in January, the Pittsburgh Crèche is on display in downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Pittsburgh Creche is the world’s only authorized replica of the Vatican’s Christmas crèche, on display in St. Peter’s Square in Rome.[75] Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art also displays a Neapolitan presepio. The presepio was handcrafted between 1700 and 1830, and re-creates the nativity within a panorama of 18th-century Italian village life. More than 100 human and angelic figures, along with animals, accessories, and architectural elements, cover 250 square feet and create a depiction of the nativity as seen through the eyes of Neapolitan artisans and collectors.[76]

The Radio City Christmas Spectacular, an annual musical holiday stage show presented at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, features a Living Nativity segment with live animals.[77][78]

In 2005, President of the United States of America, George W. Bush and his wife, First Lady of the United States, Laura Bush displayed an 18th-century Italian presepio. The presepio was donated to the White House in the last decades of the 20th century.[79]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh annually display Neapolitan Baroque nativity scenes which both originated from the collection of Eugenio Catello.

On her Christmas Day 2007 television show, Martha Stewart exhibited the nativity scene she made in pottery classes at the Alderson Federal Prison Camp in Alderson, West Virginia while serving a 2005 sentence. She remarked, «Even though every inmate was only allowed to do one a month, and I was only there for five months, I begged because I said I was an expert potter—ceramicist actually—and could I please make the entire nativity scene.»[80] She supplemented her nativity figurines on the show with tiny artificial palm trees imported from Germany.[80]

Associations and notable collections[edit]

The Universalis Foederatio Praesepistica, World association of Friends of Cribs was founded in 1952, counting today 20 national associations dedicated to this subject. The Central office is in Austria.[81]

In the United States and Canada Friends of the Creche has over 200 members, with a major conference every two years.[82] FotC maintains a list of permanent exhibits of nativity scenes in the United States and a list of permanent exhibits of nativity scenes in other parts of the world.

The Bavarian National Museum displays a notable collection of nativity scenes from the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries.

Every year in Lanciano, Abruzzo (Italy), a nativity scene exhibition (called in Italian «Riscopriamo il presepe») takes place at Auditorium Diocleziano, usually until the 6th of January. An average of one hundred nativity scenes are shown, coming from every region of Italy. There are also many nativity scenes made by local kindergarten, primary, secondary and high school. The event is organised by Associazione Amici di Lancianovecchia[83]

Museums dedicated specifically to paper nativity scenes exist in Pečky (Czech Republic).[84]

A static outdoor nativity scene in the United States, (Christkindlmarket, Chicago, Illinois)

Controversies[edit]

United States[edit]

Nativity scenes have been involved in controversies and lawsuits surrounding the principle of accommodationism.[85]

In 1969, the American Civil Liberties Union (representing three clergymen, an atheist, and a leader of the American Ethical Society), tried to block the construction of a nativity scene on The Ellipse in Washington, D.C.[86] When the ACLU claimed the government sponsorship of a distinctly Christian symbol violated separation of church and state,[86] the sponsors of the fifty-year-old Christmas celebration, Pageant of Peace, who had an exclusive permit from the Interior Department for all events on the Ellipse, responded that the nativity scene was a reminder of America’s spiritual heritage.[86] The United States Court of Appeals ruled on December 12, 1969, that the crèche be allowed that year.[86] The case continued until September 26, 1973, when the court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs[86] and found the involvement of the Interior Department and the National Park Service in the Pageant of Peace amounted to government support for religion.[86] The court opined that the nativity scene should be dropped from the pageant or the government end its participation in the event in order to avoid «excessive entanglements» between government and religion.[86] In 1973, the nativity scene was not displayed.[86]

A nativity scene inside an American home.

Nativity scenes are permitted on public lands in the United States as long as equal time is given to non-religious symbols.

In 1985, the United States Supreme Court ruled in ACLU v. Scarsdale, New York that nativity scenes on public lands violate separation of church and state statutes unless they comply with «The Reindeer Rule»—a regulation calling for equal opportunity for non-religious symbols, such as reindeer.[87] This principle was further clarified in 1989, when Pittsburgh attorney Roslyn Litman argued, and the Supreme Court in County of Allegheny v. ACLU ruled,[88] that a crèche placed on the grand staircase of the Allegheny County Courthouse in Pittsburgh, PA violated the Establishment Clause, because the «principal or primary effect» of the display was to advance religion.

In 1994, at Christmas, the Park Board of San Jose, California, removed a statue of the infant Jesus from Plaza de Cesar Chavez Park and replaced it with a statue of the plumed Aztec god, Quetzalcoatl, commissioned with US$500,000 of public funds. In response, protestors staged a living nativity scene in the park.[87]