А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

румы́нский, (к румы́ны и Румы́ния)

Рядом по алфавиту:

руло́нчик , -а

руль , руля́

ру́лька , -и, р. мн. ру́лек

румб , -а (деление компаса)

ру́мба , -ы (танец)

ру́мбовый

румели́йский , (от Руме́лия, ист.)

ру́мпель , -я

ру́мпельный

румы́нка , -и, р. мн. -нок

румы́но-болга́рский

румы́но-венге́рский

румы́но-молда́вский

румы́но-росси́йский

румы́но-сове́тский

румы́нский , (к румы́ны и Румы́ния)

румы́нско-ру́сский

румы́ны , -ы́н, ед. румы́н, -а

румя́на , -я́н

румя́невший , (от румя́неть)

румя́ненный , кр. ф. -ен, -ена (от румя́нить)

румя́ненький

румя́неть , -ею, -еет (становиться румяным)

румя́нец , -нца, тв. -нцем

румя́нивший(ся) , (от румя́нить(ся)

румя́нить , -ню, -нит (кого, что)

румя́ниться , -нюсь, -нится

румя́нка , -и, р. мн. -нок

румя́нный , (от румя́на)

румя́ность , -и

румянощёкий

Как написать слово «румынский» правильно? Где поставить ударение, сколько в слове ударных и безударных гласных и согласных букв? Как проверить слово «румынский»?

румы́нский

Правильное написание — румынский, ударение падает на букву: ы, безударными гласными являются: у, и.

Выделим согласные буквы — румынский, к согласным относятся: р, м, н, с, к, й, звонкие согласные: р, м, н, й, глухие согласные: с, к.

Количество букв и слогов:

- букв — 9,

- слогов — 3,

- гласных — 3,

- согласных — 6.

Формы слова: румы́нский (к румы́ны и Румы́ния).

Румынский язык (на рум. limba română/român) относится к романским языкам и насчитывает около 24 млн. носителей в Румынии, Молдавии и Украине. В румынском языке сохраняется ряд особенностей латинского языка, включая падежи существительных, которые уже давно были утрачены другими романскими языками. Румынский язык содержит много слов, заимствованных из славянских языков соседних стран, а также из французского, древнеславянского, немецкого, греческого и турецкого языков.

Первые письменные памятники румынского языка появились в XVI в. и представляют собой, преимущественно, религиозные тексты и другие документы. Самый древний текст на румынском языке датируется 1521 г. – это письмо боярина Някшу из Кымпулунга градоначальнику Брашова. Письмо написано криллическим шрифтом, похожим на древнеславянский, который использовался в Валахии и Молдавии до 1859 г.

С конца XVI в. для письма на румынском языке в Трансильвании использовался вариант латинского алфавита с венгерскими особенностями. В конце XVIII в. была принята система правописания на основе итальянского языка.

Кириллическое письмо использовалось в Молдавской ССР до 1989 г., когда его заменил румынский вариант латинского алфавита.

Древнерумынский алфавит

Этот вариант латинского алфавита использовался в период перехода от кириллического шрифта к латинскому. В настоящее время он всё еще используется, главным образом, в церковных текстах.

Кириллический алфавит румынского языка (1600-1860 гг.)

Примечания

Некоторые буквы имели особую форму, которая использовалась в начале слова:

| Начальная форма | Ѻѻ | Єє | Оу` оу` | Оу Ȣ | Ѩѩ | Ѥѥ |

| Обычная форма | Оо | Ее | ОУ Оу | У Ȣ | ІА | ІЕ |

Буквы Ѯ, Ψ, Ѳ и Ѵ использовались в греческих заимствованиях.

Современный алфавит румынского языка

| A a | Ă ă | Â â | B b | C c | D d | E e | F f | G g | H h | I i | Î î | J j | K k |

| a | ă | â | be | ce | de | e | ef | ge | has | i | î | jî | ca |

| L l | M m | N n | O o | P p | R r | S s | Ș ș | T t | Ț ț | U u | V v | X x | Z z |

| el | em | en | o | pe | er | es | șî | te | țî | u | ve | ics | zet |

Буквы Q (chiu), W (dublu ve) и Y (i grec) используются, главным образом, в иностранных заимствованных словах.

Фонетическая транскрипция румынского языка

Гласные, дифтонги и трифтонги

Согласные

Примечания

- c= [ ʧ ] перед i или e, но [ k ] в любой другой позиции

- g= [ ʤ ] перед i или e, но [ g ] в любой другой позиции

- ch= [ k ] перед i или e

- gh= [ g ] перед i или e

- i= [ i ̯] перед гласными, но [ i ] в любой другой позиции. Когда буква i стоит в конце многосложного слова, она не произносится, но смягчает предыдущую согласную. Например, vorbiţi (вы говорите) = [vorbitsʲ]. Исключение составляют слова, которые заканчиваются на согласный + r + i, а также инфинитивные формы глаголов, напр. «a vorbi» (говорить).

Для передачи полного звука [ i ] в конце слова используется диграф «ii», напр. «copii» (дети) = [ kopi ].

iii в конце слова произносится [ iji ], напр. «copiii» (эти дети) = [ kopiji ]. - u= [ u̯ ] перед гласными, но [ u ] в любой другой позиции

- k, q, w и y употребляются только в заимствованных словах

Здесь Вы найдете слово написание на румынском языке. Надеемся, это поможет Вам улучшить свой румынский язык.

Вот как будет написание по-румынски:

Написание на всех языках

Другие слова рядом со словом написание

Цитирование

«Написание по-румынски.» In Different Languages, https://www.indifferentlanguages.com/ru/%D1%81%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BE/%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5/%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D1%80%D1%83%D0%BC%D1%8B%D0%BD%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8.

Копировать

Скопировано

Посмотрите другие переводы русских слов на румынский язык:

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — румынский

Ударение и произношение — рум`ынский

Значение слова -прил. 1) Относящийся к Румынии, румынам, связанный с ними. 2) Свойственный румынам, характерный для них и для Румынии. 3) Принадлежащий Румынии, румынам. 4) Созданный, выведенный и т.п. в Румынии или румынами.

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — ЗУБЧАТЫЙ ?

Слово состоит из букв:

Р,

У,

М,

Ы,

Н,

С,

К,

И,

Й,

Похожие слова:

румпель

румпельный

румын

Румыния

румынка

румя

румян

румяна

румянами

румяная

Рифма к слову румынский

вздвиженский, энский, здржинский, протодиаконский, сперанский, каменский, оболенский, партизанский, болконский, копенгагенский, успенский, илагинский, христианский, екатерининский, волконский, эльхингенский, берлинский, женский, венский, македонский, отрадненский, драгунский, смоленский, жилинский, бородинский, апшеронский, уланский, неаполитанский, энгиенский, сардинский, шевардинский, поэтический, купеческий, панический, эгоистический, кутузовский, корчевский, виртембергский, голландский, георгиевский, августовский, московский, педантический, княжеский, героический, комический, фурштадский, ольденбургский, павлоградский, козловский, ребяческий, дипломатический, персидский, киевский, раевский, пржебышевский, семеновский, дружеский, сангвинический, понятовский, политический, кавалергардский, логический, стратегический, адский, человеческий, шведский, электрический, иронический, измайловский, энергический, физический, чарторижский, господский, нелогический, трагический, католический, исторический, фантастический, платовский, петербургский, робкий, ловкий, дикий, низкий, узкий, негромкий, одинокий, бойкий, звонкий, тонкий, крепкий, глубокий, великий, гладкий, жаркий, сладкий, жалкий, легкий, скользкий, пылкий, неловкий, невысокий, резкий, высокий, жестокий, близкий, некий, далекий, редкий, яркий, неробкий, широкий, громкий, дерзкий, краснорожий, удовольствий, георгий, препятствий, рыжий, похожий, строгий, орудий, приветствий, жребий, отлогий, бедствий, свежий, действий, происшествий, условий, сергий, пологий, божий, проезжий, религий, сословий, хорунжий, самолюбий, непохожий, дивизий, кривоногий, толсторожий, муругий, последствий, приезжий

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

| Romanian | |

|---|---|

| Daco-Romanian | |

| limba română[1] | |

| Pronunciation | [roˈmɨnə] |

| Native to | Romania, Moldova |

| Region | Central Europe, Southeastern Europe, and Eastern Europe |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

Native speakers |

23.6–24 million (2016)[2]

|

|

Language family |

Indo-European

|

|

Early forms |

Old Latin

|

| Dialects |

|

|

Writing system |

|

| Official status | |

|

Official language in |

|

|

Recognised minority |

|

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ro |

| ISO 639-2 | rum (B) ron (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | ron |

| Glottolog | roma1327 |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAD-c (varieties: 51-AAD-ca to -ck) |

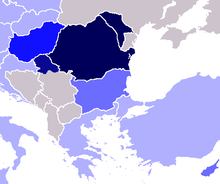

Blue: region where Romanian is the dominant language. Cyan: areas with a notable minority of Romanian speakers. |

|

Distribution of the Romanian language in Romania, Moldova and surroundings |

|

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. |

A Romanian speaker (with a Transylvanian accent), recorded in Romania

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: limba română [ˈlimba roˈmɨnə] (listen), or românește, lit. ‘in Romanian’) is the official and main language of Romania and the Republic of Moldova. As a minority language it is spoken by stable communities in the countries surrounding Romania (Bulgaria, Hungary, Serbia, and Ukraine), and by the large Romanian diaspora. In total, it is spoken by 28–29 million people as an L1+L2 language, of whom c. 24 million are native speakers. In Europe, Romanian is rated as a medium level language, occupying the 10th position among 37 official languages.[4]

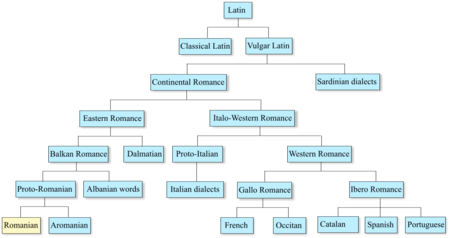

Romanian is part of the Eastern Romance sub-branch of Romance languages, a linguistic group that evolved from several dialects of Vulgar Latin which separated from the Western Romance languages in the course of the period from the 5th to the 8th centuries.[5] To distinguish it within the Eastern Romance languages, in comparative linguistics it is called Daco-Romanian as opposed to its closest relatives, Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian. Romanian is also known as Moldovan in Moldova, although the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled in 2013 that «the official language of Moldova is Romanian».[nb 1]

Overview[edit]

The history of the Romanian language started in the Roman provinces north of the Jireček Line in Classical antiquity, over a large area . Between the 6th and 8th century, following the accumulated tendencies inherited from the vernacular spoken in this large area and, to a much smaller degree, the influences from native dialects, and in the context of a lessened power of the Roman central authority the language evolved into Common Romanian. This proto-language then came into close contact with the Slavic languages and subsequently divided into Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, Istro-Romanian, and Daco-Romanian.[6][7] Due to limited attestation between the 6th and 16th century, entire stages from its history are re-constructed by researchers, often with proposed relative chronologies and loose limits.[8]

As a separate entity, starting from the 12th or 13th century, Romanian was superseded[citation needed] in official documents and religious texts by Old Church Slavonic, a language that had a similar role to Medieval Latin in Western Europe. The oldest dated text in Romanian is a letter written in 1521 with Cyrillic letters, and until late 18th century, including during the development of printing, the same alphabet was used. The period after 1780, starting with the writing of its first grammar books, represents the modern age of the language — a phase when the Latin alphabet became official, the literary language was standardized, and a large number of words from Modern Latin and other Romance languages entered the lexis.

In the process of language evolution from less than 2500 attested words from Late Antiquity to a lexicon of over 150,000 words in its contemporary form,[9] Romanian showed a high degree of lexical permeability, reflecting contact with Thraco-Dacian, Slavic languages (including Old Slavic, Serbian, Bulgarian, Ukrainian, and Russian), Greek, Hungarian, German, Turkish, and to languages that served as cultural models during and after the Age of Enlightenment, in particular French.[10] This lexical permeability is continuing today with the introduction of English words.[11]

Yet while the overall lexis was enriched with foreign words and internal constructs, in accordance with the history and development of the society and the diversification in semantic fields, the fundamental lexicon — the core vocabulary used in every day conversation — remains governed by inherited elements from the Latin spoken in the Roman provinces bordering Danube, without which no coherent sentence can be made.[12]

History[edit]

Common Romanian[edit]

Romanian descended from the Vulgar Latin spoken in the Roman provinces of Southeastern Europe.[13] Roman inscriptions show that Latin was primarily used to the north of the so-called Jireček Line (a hypothetical boundary between the predominantly Latin- and Greek-speaking territories of the Balkan Peninsula in the Roman Empire).

Most scholars agree that two major dialects developed from Common Romanian by the 10th century.[13] Daco-Romanian (the official language of Romania and Moldova) and Istro-Romanian (a language spoken by no more than 2,000 people in Istria) descended from the northern dialect.[13] Two other languages, Aromanian and Megleno-Romanian, developed from the southern version of Common Romanian.[13] These two languages are now spoken in lands to the south of the Jireček Line.[14]

Of the features that individualize Common Romanian, inherited from Latin or subsequently developed, of particular importance are:[15]

- appearance of the ă vowel;

- growth of the plural inflectional ending -uri for the neuter gender;

- analytic present conditional (ex: Daco-Romanian aș cânta);

- analytic future with an auxiliary derived from Latin volo (ex: Aromanian va s-cântu);

- enclisis of the definite article (ex. Istro-Romanian câre – cârele);

- nominal declension with two case forms in the singular feminine.

Old Romanian[edit]

Neacșu’s letter is the oldest surviving document written in Old Romanian

The oldest extant document written in Romanian remains Neacșu’s letter (1521) and was written using the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, which was used until the late 19th century. The letter is oldest testimony of Romanian epistolary style and uses a prevalent lexis of Romanic origin.[16]

In Palia de la Orăștie (1582), first known translation from the Bible in Romanian, stands written «we printed … in the Romanian language … The Five Books of Moses … and we gift them to you Romanian brothers «[17]

The use of the denomination Romanian (română) for the language and use of the demonym Romanians (Români) for speakers of this language predates the foundation of the modern Romanian state. Romanians always used the general term rumân/român or regional terms like ardeleni (or ungureni), moldoveni or munteni to designate themselves. Both the name of rumână or rumâniască for the Romanian language and the self-designation rumân/român are attested as early as the 16th century, by various foreign travelers into the Carpathian Romance-speaking space,[18] as well as in other historical documents written in Romanian at that time such as Cronicile Țării Moldovei [ro] (The Chronicles of the land of Moldova) by Grigore Ureche.

An attested reference to Romanian comes from a Latin title of an oath made in 1485 by the Moldavian Prince Stephen the Great to the Polish King Casimir, in which it is reported that «Haec Inscriptio ex Valachico in Latinam versa est sed Rex Ruthenica Lingua scriptam accepta»—»This Inscription was translated from Valachian (Romanian) into Latin, but the King has received it written in the Ruthenian language (Slavic)».[19][20]

In 1534, Tranquillo Andronico notes: «Valachi nunc se Romanos vocant» («The Wallachians are now calling themselves Romans»).[21] Francesco della Valle [it] writes in 1532 that Romanians «are calling themselves Romans in their own language», and he subsequently quotes the expression: «Sti Rominest?» for «Știi Românește?» («Do you know Romanian?»).[22]

The Transylvanian Saxon Johann Lebel writes in 1542 that «‘Vlachi’ call themselves ‘Romuini‘«.[23]

The Polish chronicler Stanislaw Orzechowski (Orichovius) notes in 1554 that «In their language they call themselves Romini from the Romans, while we call them Wallachians from the Italians».[24]

The Croatian prelate and diplomat Antun Vrančić recorded in 1570 that «Vlachs in Transylvania, Moldavia and Wallachia designate themselves as ‘Romans‘«.[25]

Pierre Lescalopier writes in 1574 that those who live in Moldavia, Wallachia and the vast part of Transylvania, «consider themselves as true descendants of the Romans and call their language romanechte, which is Roman».[26]

After travelling through Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania Ferrante Capecci accounts in 1575 that the vallachian population of these regions call themselves romanesci (românești).[27]

In Letopisețul Țării Moldovei (17th century), the Moldavian chronicler Grigore Ureche wrote: «In Transylvania there live not only Hungarians, but also very many Saxons, and Romanians everywhere around, so much so that the country is inhabited more by Romanians than by Hungarians.»[28]

Miron Costin, in his De neamul moldovenilor (1687), while noting that Moldavians, Wallachians, and the Romanians living in the Kingdom of Hungary have the same origin, says that although people of Moldavia call themselves Moldavians, they name their language Romanian (românește) instead of Moldavian (moldovenește).[29]

The Transylvanian Hungarian Martin Szentiványi in 1699 quotes the following: «Si noi sentem Rumeni» («We too are Romanians») and «Noi sentem di sange Rumena» («We are of Romanian blood»).[30] Notably, Szentiványi used Italian-based spellings to try to write the Romanian words.

Dimitrie Cantemir, in his Descriptio Moldaviae (Berlin, 1714), points out that the inhabitants of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania spoke the same language. He notes, however, some differences in accent and vocabulary.[31]

Cantemir’s work provides one of the earliest histories of the language, in which he notes, like Ureche before him, the evolution from Latin and notices the Greek and Polish borrowings. Additionally, he introduces the idea that some words must have had Dacian roots. Cantemir also notes that while the idea of a Latin origin of the language was prevalent in his time, other scholars considered it to have derived from Italian.

The slow process of Romanian establishing itself as an official language, used in the public sphere, in literature and ecclesiastically, began in the late 15th century and ended in the early decades of the 18th century, by which time Romanian had begun to be regularly used by the Church. The oldest Romanian texts of a literary nature are religious manuscripts (Codicele Voronețean, Psaltirea Scheiană), translations of essential Christian texts. These are considered either propagandistic results of confessional rivalries, for instance between Lutheranism and Calvinism, or as initiatives by Romanian monks stationed at Peri Monastery in Maramureș to distance themselves from the influence of the Mukacheve eparchy in Ukraine.[32]

Modern Romanian[edit]

The modern age of Romanian starts in 1780 with the printing in Vienna of a very important grammar book[15] titled Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae. The author of the book, Samuil Micu-Klein, and the revisor, Gheorghe Șincai, both members of the Transylvanian School, chose to use Latin as the language of the text and presented the phonetical and grammatical features of Romanian in comparison to its ancestor.[33] The Modern age of Romanian language can be further divided into three phases: pre-modern or modernizing between 1780 and 1830, modern phase between 1831 and 1880, and contemporary from 1880 onwards.

Pre-modern period[edit]

Beginning with the printing in 1780 of Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae, the pre-modern phase was characterized by the publishing of school textbooks, appearance of first normative works in Romanian, numerous translations, and the beginning of a conscious stage of re-latinization of the language.[15] Notable contributions, besides that of the Transylvanian School, are the activities of Gheorghe Lazăr, founder of the first Romanian school, and Ion Heliade Rădulescu. The end of this period is marked by the first printing of magazines and newspapers in Romanian, in particular Curierul Românesc and Albina Românească.[34]

Modern period[edit]

Starting from 1831 and lasting until 1880 the modern phase is characterized by the development of literary styles: scientific, administrative, and belletristic. It quickly reached a high point with the printing of Dacia Literară, a journal founded by Mihail Kogălniceanu and representing a literary society, which together with other publications like Propășirea and Gazeta de Transilvania spread the ideas of Romantic nationalism and later contributed to the formation of other societies that took part in the Revolutions of 1848. Their members and those that shared their views are collectively known in Romania as pașoptiști – literally meaning «of ’48» – a name that was extended to the literature and writers around this time such as Vasile Alecsandri, Grigore Alexandrescu, Nicolae Bălcescu, Timotei Cipariu.[35]

Between 1830 and 1860 «transitional alphabet»s were used, adding Latin letters to the Romanian Cyrillic alphabet. In 1860 the Latin alphabet became official.[36][citation needed][by whom?]

Following the unification of Moldavia and Wallachia further studies on the language were made, culminating with the founding of Societatea Literară Română on 1 April 1866 on the initiative of C. A. Rosetti, an academic society that had the purpose of standardizing the orthography, formalizing the grammar and (via a dictionary) vocabulary of the language, and promoting literary and scientific publications. This institution later became the Romanian Academy.[37]

Contemporary period[edit]

The third phase of the modern age of Romanian language, starting from 1880 and continuing to this day, is characterized by the prevalence of the supradialectal form of the language, standardized with the express contribution of the school system and Romanian Academy, bringing a close to the process of literary language modernization and development of literary styles.[11] It is distinguished by the activity of Romanian literature classics in its early decades: Mihai Eminescu, Ion Luca Caragiale, Ion Creangă.[38]

The current orthography, with minor reforms to this day and using Latin letters, was fully implemented in 1881, regulated by the Romanian Academy on a fundamentally phonological principle, with few morpho-syntactic exceptions.[39]

Modern history of Romanian in Bessarabia[edit]

The first Romanian grammar was published in Vienna in 1780.[40] Following the annexation of Bessarabia by Russia in 1812, Moldavian was established as an official language in the governmental institutions of Bessarabia, used along with Russian,[41]

The publishing works established by Archbishop Gavril Bănulescu-Bodoni were able to produce books and liturgical works in Moldavian between 1815 and 1820.[42]

Bessarabia during the 1812–1918 era witnessed the gradual development of bilingualism. Russian continued to develop as the official language of privilege, whereas Romanian remained the principal vernacular.[citation needed]

The period from 1905 to 1917 was one of increasing linguistic conflict, with the re-awakening of Romanian national consciousness.[citation needed] In 1905 and 1906, the Bessarabian zemstva asked for the re-introduction of Romanian in schools as a «compulsory language», and the «liberty to teach in the mother language (Romanian language)». At the same time, Romanian-language newspapers and journals began to appear, such as Basarabia (1906), Viața Basarabiei (1907), Moldovanul (1907), Luminătorul (1908), Cuvînt moldovenesc (1913), Glasul Basarabiei (1913). From 1913, the synod permitted that «the churches in Bessarabia use the Romanian language». Romanian finally became the official language with the Constitution of 1923.

Historical grammar[edit]

Romanian has preserved a part of the Latin declension, but whereas Latin had six cases, from a morphological viewpoint, Romanian has only three: the nominative/accusative, genitive/dative, and marginally the vocative. Romanian nouns also preserve the neuter gender, although instead of functioning as a separate gender with its own forms in adjectives, the Romanian neuter became a mixture of masculine and feminine. The verb morphology of Romanian has shown the same move towards a compound perfect and future tense as the other Romance languages. Compared with the other Romance languages, during its evolution, Romanian simplified the original Latin tense system.[43]

Geographic distribution[edit]

| Country | Speakers (%) |

Speakers (native) |

Country Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | |||

| World | 0.33% | 23,623,890 | 7,035,000,000 |

| official: | |||

| Countries where Romanian is an official language | |||

| Romania | 90.65% | 17,263,561[44] | 19,043,767 |

| Moldova 2 | 82.1% | 2,184,065 | 2,681,735 |

| Transnistria (Moldova)3 | 33.0% | 156,600 | 475,665 |

| Vojvodina (Serbia) | 1.32% | 29,512 | 1,931,809 |

| minority regional co-official language: | |||

| Ukraine 5 | 0.8% | 327,703 | 48,457,000 |

| not official: | |||

| Other neighboring European states (except for CIS where Romanian is not official) | |||

| Hungary | 0.14% | 13,886[45] | 9,937,628 |

| Central Serbia | 0.4% | 35,330 | 7,186,862 |

| Bulgaria | 0.06% | 4,575[46][full citation needed] | 7,364,570 |

| 114,050,000 | |||

| CIS | |||

| not official: | |||

| Russia 1 | 0.06% | 92,675[47] | 142,856,536 |

| Kazakhstan 1 | 0.1% | 14,666 | 14,953,126 |

| Asia | |||

| Israel | 1.11% | ~82,300[48] | 7,412,200 |

| UAE | 0.1% | 5,000[citation needed] | 4,106,427 |

| Singapore | 0.02% | 1,400[citation needed] | 5,535,000 |

| Japan | 0.002% | 2,185[citation needed] | 126,659,683 |

| South Korea | 0.0006% | 300[citation needed] | 50,004,441 |

| China | 0.0008% | 12,000[citation needed] | 1,376,049,000 |

| The Americas | |||

| not official: | |||

| United States | 0.049% | 154,625[49] | 315,091,138 |

| Canada | 0.0289% | 100,610[50] | 34,767,250 |

| Argentina | 0.03% | 13,000[citation needed] | 40,117,096 |

| Venezuela | 0.036% | 10,000[citation needed] | 27,150,095 |

| Brazil | 0.002% | 4,000[citation needed] | 190,732,694 |

| Oceania | |||

| not official: | |||

| Australia | 0.09% | 12,251[51] | 21,507,717 |

| New Zealand | 0.08% | 3,100[citation needed] | 4,027,947 |

| Africa | |||

| not official: | |||

| South Africa | 0.007% | 3,000[citation needed] | 44,819,778 |

|

1 Many are Moldavians who were deported |

Romanian is spoken mostly in Central, South-Eastern, and Eastern Europe, although speakers of the language can be found all over the world, mostly due to emigration of Romanian nationals and the return of immigrants to Romania back to their original countries. Romanian speakers account for 0.5% of the world’s population,[53] and 4% of the Romance-speaking population of the world.[54]

Romanian is the single official and national language in Romania and Moldova, although it shares the official status at regional level with other languages in the Moldovan autonomies of Gagauzia and Transnistria. Romanian is also an official language of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina in Serbia along with five other languages. Romanian minorities are encountered in Serbia (Timok Valley), Ukraine (Chernivtsi and Odessa oblasts), and Hungary (Gyula). Large immigrant communities are found in Italy, Spain, France, and Portugal.

In 1995, the largest Romanian-speaking community in the Middle East was found in Israel, where Romanian was spoken by 5% of the population.[55][56] Romanian is also spoken as a second language by people from Arabic-speaking countries who have studied in Romania. It is estimated that almost half a million Middle Eastern Arabs studied in Romania during the 1980s.[57] Small Romanian-speaking communities are to be found in Kazakhstan and Russia. Romanian is also spoken within communities of Romanian and Moldovan immigrants in the United States, Canada and Australia, although they do not make up a large homogeneous community statewide.

Legal status[edit]

In Romania[edit]

According to the Constitution of Romania of 1991, as revised in 2003, Romanian is the official language of the Republic.[58]

Romania mandates the use of Romanian in official government publications, public education and legal contracts. Advertisements as well as other public messages must bear a translation of foreign words,[59] while trade signs and logos shall be written predominantly in Romanian.[60]

The Romanian Language Institute (Institutul Limbii Române), established by the Ministry of Education of Romania, promotes Romanian and supports people willing to study the language, working together with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Department for Romanians Abroad.[61]

Since 2013, the Romanian Language Day is celebrated on every 31 August.[62][63]

In Moldova[edit]

Romanian is the official language of the Republic of Moldova. The 1991 Declaration of Independence names the official language Romanian.[64][65] The Constitution of Moldova names the state language of the country Moldovan. In December 2013, a decision of the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled that the Declaration of Independence takes precedence over the Constitution and the state language should be called Romanian.[66]

Scholars agree that Moldovan and Romanian are the same language, with the glottonym «Moldovan» used in certain political contexts.[67] It has been the sole official language since the adoption of the Law on State Language of the Moldavian SSR in 1989.[68] This law mandates the use of Moldovan in all the political, economic, cultural and social spheres, as well as asserting the existence of a «linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity».[69] It is also used in schools, mass media, education and in the colloquial speech and writing. Outside the political arena the language is most often called «Romanian». In the breakaway territory of Transnistria, it is co-official with Ukrainian and Russian.

In the 2014 census, out of the 2,804,801 people living in Moldova, 24% (652,394) stated Romanian as their most common language, whereas 56% stated Moldovan. While in the urban centers speakers are split evenly between the two names (with the capital Chișinău showing a strong preference for the name «Romanian», i.e. 3:2), in the countryside hardly a quarter of Romanian/Moldovan speakers indicated Romanian as their native language.[70] Unofficial results of this census first showed a stronger preference for the name Romanian, however the initial reports were later dismissed by the Institute for Statistics, which led to speculations in the media regarding the forgery of the census results.[71]

In Serbia[edit]

Vojvodina[edit]

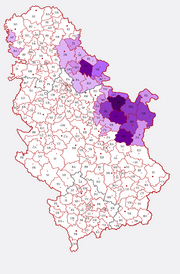

Official usage of Romanian language in Vojvodina, Serbia

Romanian language in entire Serbia (see also Romanians in Serbia), census 2002

|

1–5% 5–10% 10–15% |

15–25% 25–35% over 35% |

The Constitution of the Republic of Serbia determines that in the regions of the Republic of Serbia inhabited by national minorities, their own languages and scripts shall be officially used as well, in the manner established by law.[72]

The Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina determines that, together with the Serbian language and the Cyrillic script, and the Latin script as stipulated by the law, the Croat, Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian and Rusyn languages and their scripts, as well as languages and scripts of other nationalities, shall simultaneously be officially used in the work of the bodies of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, in the manner established by the law.[73][74] The bodies of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina are: the Assembly, the Executive Council and the provincial administrative bodies.

The Romanian language and script are officially used in eight municipalities: Alibunar, Bela Crkva (Romanian: Biserica Albă), Žitište (Zitiște), Zrenjanin (Zrenianin), Kovačica (Kovăcița), Kovin (Cuvin), Plandište (Plandiște) and Sečanj. In the municipality of Vršac (Vârșeț), Romanian is official only in the villages of Vojvodinci (Voivodinț), Markovac (Marcovăț), Straža (Straja), Mali Žam (Jamu Mic), Malo Središte (Srediștea Mică), Mesić (Mesici), Jablanka, Sočica (Sălcița), Ritiševo (Râtișor), Orešac (Oreșaț) and Kuštilj (Coștei).[75]

In the 2002 Census, the last carried out in Serbia, 1.5% of Vojvodinians stated Romanian as their native language.

Timok Valley[edit]

The Vlachs of Serbia are considered to speak Romanian as well.[76]

Regional language status in Ukraine[edit]

In parts of Ukraine where Romanians constitute a significant share of the local population (districts in Chernivtsi, Odessa and Zakarpattia oblasts) Romanian is taught in schools as a primary language and there are Romanian-language newspapers, TV, and radio broadcasting.[77][78]

The University of Chernivtsi in western Ukraine trains teachers for Romanian schools in the fields of Romanian philology, mathematics and physics.[79]

In Hertsa Raion of Ukraine as well as in other villages of Chernivtsi Oblast and Zakarpattia Oblast, Romanian has been declared a «regional language» alongside Ukrainian as per the 2012 legislation on languages in Ukraine.

In other countries and organizations[edit]

Romanian is an official or administrative language in various communities and organisations, such as the Latin Union and the European Union. Romanian is also one of the five languages in which religious services are performed in the autonomous monastic state of Mount Athos, spoken in the monastic communities of Prodromos and Lakkoskiti. In the unrecognised state of Transnistria, Moldovan is one of the official languages. However, unlike all other dialects of Romanian, this variety of Moldovan is written in Cyrillic script.

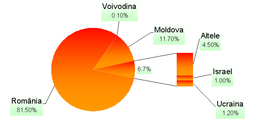

Distribution of first-language native Romanian speakers by country—Voivodina is an autonomous province of northern Serbia bordering Romania, while Altele means «Other»

As a second and foreign language[edit]

Romanian is taught in some areas that have Romanian minority communities, such as Vojvodina in Serbia, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Hungary. The Romanian Cultural Institute (ICR) has since 1992 organised summer courses in Romanian for language teachers.[80] There are also non-Romanians who study Romanian as a foreign language, for example the Nicolae Bălcescu High-school in Gyula, Hungary.

Romanian is taught as a foreign language in tertiary institutions, mostly in European countries such as Germany, France and Italy, and the Netherlands, as well as in the United States. Overall, it is taught as a foreign language in 43 countries around the world.[81]

Romanian as secondary or foreign language in Central and Eastern Europe

Native

Above 3%

1–3%

Under 1%

N/A

Popular culture[edit]

Romanian has become popular in other countries through movies and songs performed in the Romanian language. Examples of Romanian acts that had a great success in non-Romanophone countries are the bands O-Zone (with their No. 1 single Dragostea Din Tei/Numa Numa across the world in 2003–2004), Akcent (popular in the Netherlands, Poland and other European countries), Activ (successful in some Eastern European countries), DJ Project (popular as clubbing music) SunStroke Project (known by viral video «Epic sax guy») and Alexandra Stan (worldwide no.1 hit with «Mr. Saxobeat») and Inna as well as high-rated movies like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days, The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, 12:08 East of Bucharest or California Dreamin’ (all of them with awards at the Cannes Film Festival).

Also some artists wrote songs dedicated to the Romanian language. The multi-platinum pop trio O-Zone (originally from Moldova) released a song called «Nu mă las de limba noastră» («I won’t forsake our language»). The final verse of this song, «Eu nu mă las de limba noastră, de limba noastră cea română», is translated in English as «I won’t forsake our language, our Romanian language». Also, the Moldovan musicians Doina and Ion Aldea Teodorovici performed a song called «The Romanian language».

Dialects[edit]

Romanian is also called Daco-Romanian in comparative linguistics to distinguish from the other dialects of Common Romanian: Aromanian, Megleno-Romanian, and Istro-Romanian. The origin of the term «Daco-Romanian» can be traced back to the first printed book of Romanian grammar in 1780,[40] by Samuil Micu and Gheorghe Șincai. There, the Romanian dialect spoken north of the Danube is called lingua Daco-Romana to emphasize its origin and its area of use, which includes the former Roman province of Dacia, although it is spoken also south of the Danube, in Dobruja, the Timok Valley and northern Bulgaria.

This article deals with the Romanian (i.e. Daco-Romanian) language, and thus only its dialectal variations are discussed here. The differences between the regional varieties are small, limited to regular phonetic changes, few grammar aspects, and lexical particularities. There is a single written and spoken standard (literary) Romanian language used by all speakers, regardless of region. Like most natural languages, Romanian dialects are part of a dialect continuum. The dialects of Romanian are also referred to as ‘sub-dialects’ and are distinguished primarily by phonetic differences. Romanians themselves speak of the differences as ‘accents’ or ‘speeches’ (in Romanian: accent or grai).[82]

Depending on the criteria used for classifying these dialects, fewer or more are found, ranging from 2 to 20, although the most widespread approaches give a number of five dialects. These are grouped into two main types, southern and northern, further divided as follows:

- The southern type has only one member:

- the Wallachian dialect, spoken in the southern part of Romania, in the historical regions of Muntenia, Oltenia and the southern part of Northern Dobruja, but also extending in the southern parts of Transylvania.

- The northern type consists of several dialects:

- the Moldavian dialect, spoken in the historical region of Moldavia, now split among Romania, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine (Bukovina and Bessarabia), as well as northern part of Northern Dobruja;

- the Banat dialect, spoken in the historical region of Banat, including parts of Serbia;

- a group of finely divided and transition-like Transylvanian varieties, among which two are most often distinguished, those of Crișana and Maramureș.

Over the last century, however, regional accents have been weakened due to mass communication and greater mobility.

Some argots and speech forms have also arisen from the Romanian language. Examples are the Gumuțeasca, spoken in Mărgău,[83][84] and the Totoiana, an inverted «version» of Romanian spoken in Totoi.[85][86][87]

Classification[edit]

Romance language[edit]

Romanian language in the Romance language family

Romanian is a Romance language, belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family, having much in common with languages such as Italian, Spanish, French and Portuguese.[88]

Compared with the other Romance languages, the closest relative of Romanian is Italian.[88] Romanian has had a greater share of foreign influence than some other Romance languages such as Italian in terms of vocabulary and other aspects. A study conducted by Mario Pei in 1949 which analyzed the degree of differentiation of languages from their parental language (in the case of Romance languages to Latin comparing phonology, inflection, discourse, syntax, vocabulary, and intonation) produced the following percentages (the higher the percentage, the greater the distance from Latin):[89]

- Sardinian: 8%

- Italian: 12%

- Spanish: 20%

- Romanian: 23.5%

- Occitan: 25%

- Portuguese: 31%

- French: 44%

The lexical similarity of Romanian with Italian has been estimated at 77%, followed by French at 75%, Sardinian 74%, Catalan 73%, Portuguese and Rhaeto-Romance 72%, Spanish 71%.[90]

The Romanian vocabulary became predominantly influenced by French and, to a lesser extent, Italian in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[91]

Balkan language area[edit]

While most of Romanian grammar and morphology are based on Latin, there are some features that are shared only with other languages of the Balkans and not found in other Romance languages. The shared features of Romanian and the other languages of the Balkan language area (Bulgarian, Macedonian, Albanian, Greek, and Serbo-Croatian) include a suffixed definite article, the syncretism of genitive and dative case and the formation of the future and the alternation of infinitive with subjunctive constructions.[92][93] According to a well-established scholarly theory, most Balkanisms could be traced back to the development of the Balkan Romance languages; these features were adopted by other languages due to language shift.[94]

Slavic influence[edit]

Slavic influence on Romanian is especially noticeable in its vocabulary, with words of Slavic origin constituting about 10–15% of modern Romanian lexicon,[95][96] and with further influences in its phonetics, morphology and syntax. The greater part of its Slavic vocabulary comes from Old Church Slavonic,[97][98] which was the official written language of Wallachia and Moldavia from the 14th to the 18th century (although not understood by most people), as well as the liturgical language of the Romanian Orthodox Church.[99][100] As a result, much Romanian vocabulary dealing with religion, ritual, and hierarchy is Slavic.[101][99] The number of high-frequency Slavic-derived words is also believed to indicate contact or cohabitation with South Slavic tribes from around the 6th century, though it is disputed where this took place (see Origin of the Romanians).[99] Words borrowed in this way tend to be more vernacular (compare sfârși, «to end», with săvârși, «to commit»).[101] The extent of this borrowing is such that some scholars once mistakenly viewed Romanian as a Slavic language.[102][103][104] It has also been argued that Slavic borrowing was a key factor in the development of [ɨ] (î and â) as a separate phoneme.[105]

Other influences[edit]

Even before the 19th century, Romanian came in contact with several other languages. Notable examples of lexical borrowings include:

- German: cartof < Kartoffel «potato», bere < Bier «beer», șurub < Schraube «screw», turn < Turm «tower», ramă < Rahmen «frame», muștiuc < Mundstück «mouth piece», bormașină < Bohrmaschine «drilling machine», cremșnit < Kremschnitte «cream slice», șvaițer < Schweizer «Swiss cheese», șlep < Schleppkahn «barge», șpriț < Spritzer «wine with soda water», abțibild < Abziehbild «decal picture», șnițel < (Wiener) Schnitzel «a battered cutlet», șmecher < Schmecker «taster (not interested in buying)», șuncă < dialectal Schunke (Schinken) «ham», punct < Punkt «point», maistru < Meister «master», rundă < Runde «round».

Furthermore, during the Habsburg and, later on, Austrian rule of Banat, Transylvania, and Bukovina, a large number of words were borrowed from Austrian High German, in particular in fields such as the military, administration, social welfare, economy, etc.[106] Subsequently, German terms have been taken out of science and technics, like: șină < Schiene «rail», știft < Stift «peg», liță < Litze «braid», șindrilă < Schindel «shingle», ștanță < Stanze «punch», șaibă < Scheibe «washer», ștangă < Stange «crossbar», țiglă < Ziegel «tile», șmirghel < Schmirgelpapier «emery paper»;

- Greek: folos < ófelos «use», buzunar < buzunára «pocket», proaspăt < prósfatos «fresh», cutie < cution «box», portocale < portokalia «oranges». While Latin borrowed words of Greek origin, Romanian obtained Greek loanwords on its own. Greek entered Romanian through the apoikiai (colonies) and emporia (trade stations) founded in and around Dobruja, through the presence of Byzantine Empire in north of the Danube, through Bulgarian during Bulgarian Empires that converted Romanians to Orthodox Christianity, and after the Greek Civil War, when thousands of Greeks fled Greece.

- Hungarian: a cheltui < költeni «to spend», a făgădui < fogadni «to promise», a mântui < menteni «to save», oraș < város «city»;

- Turkish: papuc < pabuç «slipper», ciorbă < çorba «wholemeal soup, sour soup», bacșiș < bahşiş «tip» (ultimately from Persian baksheesh);

- Additionally, the Romani language has provided a series of slang words to Romanian such as: mișto «good, beautiful, cool» < mišto,[107] gagică «girlie, girlfriend» < gadji, a hali «to devour» < halo, mandea «yours truly» < mande, a mangli «to pilfer» < manglo.

French, Italian, and English loanwords[edit]

Since the 19th century, many literary or learned words were borrowed from the other Romance languages, especially from French and Italian (for example: birou «desk, office», avion «airplane», exploata «exploit»). It was estimated that about 38% of words in Romanian are of French and/or Italian origin (in many cases both languages); and adding this to Romanian’s native stock, about 75%–85% of Romanian words can be traced to Latin. The use of these Romanianized French and Italian learned loans has tended to increase at the expense of Slavic loanwords, many of which have become rare or fallen out of use. As second or third languages, French and Italian themselves are better known in Romania than in Romania’s neighbors. Along with the switch to the Latin alphabet in Moldova, the re-latinization of the vocabulary has tended to reinforce the Latin character of the language.

In the process of lexical modernization, much of the native Latin stock have acquired doublets from other Romance languages, thus forming a further and more modern and literary lexical layer. Typically, the native word is a noun and the learned loan is an adjective. Some examples of doublets:

In the 20th century, an increasing number of English words have been borrowed (such as: gem < jam; interviu < interview; meci < match; manager < manager; fotbal < football; sandviș < sandwich; bișniță < business; chec < cake; veceu < WC; tramvai < tramway). These words are assigned grammatical gender in Romanian and handled according to Romanian rules; thus «the manager» is managerul. Some borrowings, for example in the computer field, appear to have awkward (perhaps contrived and ludicrous) ‘Romanisation,’ such as cookie-uri which is the plural of the Internet term cookie.

Lexis[edit]

Romanian’s core lexicon (2,581 words); Marius Sala, VRLR (1988)

A statistical analysis sorting Romanian words by etymological source carried out by Macrea (1961)[97] based on the DLRM[108] (49,649 words) showed the following makeup:[98]

- 43% recent Romance loans (mainly French: 38.42%, Latin: 2.39%, Italian: 1.72%)

- 20% inherited Latin

- 11.5% Slavic (Old Church Slavonic: 7.98%, Bulgarian: 1.78%, Bulgarian-Serbian: 1.51%)

- 8.31% Unknown/unclear origin

- 3.62% Turkish

- 2.40% Modern Greek

- 2.17% Hungarian

- 1.77% German (including Austrian High German)[106]

- 2.24% Onomatopoeic

If the analysis is restricted to a core vocabulary of 2,500 frequent, semantically rich and productive words, then the Latin inheritance comes first, followed by Romance and classical Latin neologisms, whereas the Slavic borrowings come third.

Romanian has a lexical similarity of 77% with Italian, 75% with French, 74% with Sardinian, 73% with Catalan, 72% with Portuguese and Rheto-Romance, 71% with Spanish.[109]

- ^ German-based influence and English loanwords

| Romanian according to word origin[95][110] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Romance and Latin | 78% | |

| Slavic | 14% | |

| Germanic[a] | 2.54% | |

| Greek | 1.7% | |

| Others | 5.49% |

Although they are rarely used nowadays, the Romanian calendar used to have the traditional Romanian month names, unique to the language.[111]

The longest word in Romanian is pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcaniconioză, with 44 letters,[112] but the longest one admitted by the Dicționarul explicativ al limbii române («Explanatory Dictionary of the Romanian Language», DEX) is electroglotospectrografie, with 25 letters.[113][114]

Grammar[edit]

Romanian nouns are characterized by gender (feminine, masculine, and neuter), and declined by number (singular and plural) and case (nominative/accusative, dative/genitive and vocative). The articles, as well as most adjectives and pronouns, agree in gender, number and case with the noun they modify.

Romanian is the only Romance language where definite articles are enclitic: that is, attached to the end of the noun (as in Scandinavian, Bulgarian and Albanian), instead of in front (proclitic).[115] They were formed, as in other Romance languages, from the Latin demonstrative pronouns.

As in all Romance languages, Romanian verbs are highly inflected for person, number, tense, mood, and voice. The usual word order in sentences is subject–verb–object (SVO). Romanian has four verbal conjugations which further split into ten conjugation patterns. Verbs can be put in five moods that are inflected for the person (indicative, conditional/optative, imperative, subjunctive, and presumptive) and four impersonal moods (infinitive, gerund, supine, and participle).

Phonology[edit]

Romanian has seven vowels: /i/, /ɨ/, /u/, /e/, /ə/, /o/ and /a/. Additionally, /ø/ and /y/ may appear in some borrowed words. Arguably, the diphthongs /e̯a/ and /o̯a/ are also part of the phoneme set. There are twenty-two consonants. The two approximants /j/ and /w/ can appear before or after any vowel, creating a large number of glide-vowel sequences which are, strictly speaking, not diphthongs.

In final positions after consonants, a short /i/ can be deleted, surfacing only as the palatalization of the preceding consonant (e.g., [mʲ]). Similarly, a deleted /u/ may prompt labialization of a preceding consonant, though this has ceased to carry any morphological meaning.

Phonetic changes[edit]

Owing to its isolation from the other Romance languages, the phonetic evolution of Romanian was quite different, but the language does share a few changes with Italian, such as [kl] → [kj] (Lat. clarus → Rom. chiar, Ital. chiaro, Lat. clamare → Rom. chemare, Ital. chiamare) and [ɡl] → [ɡj] (Lat. *glacia (glacies) → Rom. gheață, Ital. ghiaccia, ghiaccio, Lat. *ungla (ungula) → Rom. unghie, Ital. unghia), although this did not go as far as it did in Italian with other similar clusters (Rom. place, Ital. piace); another similarity with Italian is the change from [ke] or [ki] to [tʃe] or [tʃi] (Lat. pax, pacem → Rom. and Ital. pace, Lat. dulcem → Rom. dulce, Ital. dolce, Lat. circus → Rom. cerc, Ital. circo) and [ɡe] or [ɡi] to [dʒe] or [dʒi] (Lat. gelu → Rom. ger, Ital. gelo, Lat. marginem → Rom. and Ital. margine, Lat. gemere → Rom. geme (gemere), Ital. gemere). There are also a few changes shared with Dalmatian, such as /ɡn/ (probably phonetically [ŋn]) → [mn] (Lat. cognatus → Rom. cumnat, Dalm. comnut) and /ks/ → [ps] in some situations (Lat. coxa → Rom. coapsă, Dalm. copsa).

Among the notable phonetic changes are:

- diphthongization of e and o → ea and oa, before ă (or e as well, in the case of o) in the next syllable:

-

- Lat. cera → Rom. ceară (wax)

- Lat. sole → Rom. soare (sun)

- iotation [e] → [ie] in the beginning of the word

-

- Lat. herba → Rom. iarbă (grass, herb)

- velar [k ɡ] → labial [p b m] before alveolar consonants and [w] (e.g. ngu → mb):

-

- Lat. octo → Rom. opt (eight)

- Lat. lingua → Rom. limbă (tongue, language)

- Lat. signum → Rom. semn (sign)

- Lat. coxa → Rom. coapsă (thigh)

- rhotacism [l] → [r] between vowels

-

- Lat. caelum → Rom. cer (sky)

- Alveolars [d t] assibilated to [(d)z] [ts] when before short [e] or long [iː]

-

- Lat. deus → Rom. zeu (god)

- Lat. tenem → Rom. ține (hold)

Romanian has entirely lost Latin /kw/ (qu), turning it either into /p/ (Lat. quattuor → Rom. patru, «four»; cf. It. quattro) or /k/ (Lat. quando → Rom. când, «when»; Lat. quale → Rom. care, «which»). In fact, in modern re-borrowings, while isolated cases of /kw/ exist, as in cuaternar «quaternary», it usually takes the German-like form /kv/, as in acvatic, «aquatic». Notably, it also failed to develop the palatalised sounds /ɲ/ and /ʎ/, which exist at least historically in all other major Romance languages, and even in neighbouring non-Romance languages such as Serbian and Hungarian. However, the other Eastern Romance languages kept these sounds, so it’s likely old Romanian had them as well.

Writing system[edit]

The first written record about a Romance language spoken in the Middle Ages in the Balkans is from 587. A Vlach muleteer accompanying the Byzantine army noticed that the load was falling from one of the animals and shouted to a companion Torna, torna, fratre! (meaning «Return, return, brother!»). Theophanes Confessor recorded it as part of a 6th-century military expedition by Comentiolus and Priscus against the Avars and Slovenes.[116]

The oldest surviving written text in Romanian is a letter from late June 1521,[117] in which Neacșu of Câmpulung wrote to the mayor of Brașov about an imminent attack of the Turks. It was written using the Cyrillic alphabet, like most early Romanian writings. The earliest surviving writing in Latin script was a late 16th-century Transylvanian text which was written with the Hungarian alphabet conventions.

In the 18th century, Transylvanian scholars noted the Latin origin of Romanian and adapted the Latin alphabet to the Romanian language, using some orthographic rules from Italian, recognized as Romanian’s closest relative. The Cyrillic alphabet remained in (gradually decreasing) use until 1860, when Romanian writing was first officially regulated.

In the Soviet Republic of Moldova, the Russian-derived Moldovan Cyrillic alphabet was used until 1989, when the Romanian Latin alphabet was introduced; in the breakaway territory of Transnistria the Cyrillic alphabet remains in use.[118]

Romanian alphabet[edit]

The Romanian alphabet is as follows:

-

Capital letters A Ă Â B C D E F G H I Î J K L M N O P Q R S Ș T Ț U V W X Y Z Lower case letters a ă â b c d e f g h i î j k l m n o p q r s ș t ț u v w x y z Phonemes /a/ /ə/ /ɨ/ /b/ /k/,

/t͡ʃ//d/ /e/,

/e̯/,

/je//f/ /ɡ/,

/d͡ʒ//h/,

mute/i/,

/j/,

/ʲ//ɨ/ /ʒ/ /k/ /l/ /m/ /n/ /o/,

/o̯//p/ /k/ /r/ /s/ /ʃ/ /t/ /t͡s/ /u/,

/w//v/ /v/,

/w/,

/u//ks/,

/ɡz//j/,

/i//z/

K, Q, W and Y, not part of the native alphabet, were officially introduced in the Romanian alphabet in 1982 and are mostly used to write loanwords like kilogram, quasar, watt, and yoga.

The Romanian alphabet is based on the Latin script with five additional letters Ă, Â, Î, Ș, Ț. Formerly, there were as many as 12 additional letters, but some of them were abolished in subsequent reforms. Also, until the early 20th century, a breve marker was used, which survives only in ă.

Today the Romanian alphabet is largely phonemic. However, the letters â and î both represent the same close central unrounded vowel /ɨ/. Â is used only inside words; î is used at the beginning or the end of non-compound words and in the middle of compound words. Another exception from a completely phonetic writing system is the fact that vowels and their respective semivowels are not distinguished in writing. In dictionaries the distinction is marked by separating the entry word into syllables for words containing a hiatus.

Stressed vowels also are not marked in writing, except very rarely in cases where by misplacing the stress a word might change its meaning and if the meaning is not obvious from the context. For example, trei copíi means «three children» while trei cópii means «three copies».

Pronunciation[edit]

A close shot of some keys with Romanian characters on the keyboard of a laptop

- h is not silent like in other Romance languages such as Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Catalan and French, but represents the phoneme /h/, except in the digraphs ch /k/ and gh /g/ (see below)

- j represents /ʒ/, as in French, Catalan or Portuguese (the sound spelled with s in the English words «vision, pleasure, treasure»).

- There are two letters with a comma below, Ș and Ț, which represent the sounds /ʃ/ and /t͡s/. However, the allographs with a cedilla instead of a comma, Ş and Ţ, became widespread when pre-Unicode and early Unicode character sets did not include the standard form.

- A final orthographical i after a consonant often represents the palatalization of the consonant[citation needed] (e.g., lup /lup/ «wolf» vs. lupi /lupʲ/ «wolves») – it is not pronounced like Italian lupi (which also means «wolves»), and is an example of the Slavic influence on Romanian[citation needed].

- ă represents the schwa, /ə/.

- î and â both represent the sound /ɨ/. In rapid speech (for example in the name of the country) the â sound may sound similar to a casual listener to the short schwa sound ă (in fact, Aromanian does merge the two, writing them ã) but careful speakers will distinguish the sound. The nearest equivalent is the vowel in the last syllable of the word Beatles for some English speakers or the second syllable of the word «rhythm». It is also roughly equivalent to European Portuguese /ɨ/, the Polish y or the Russian ы.

- The letter e generally represents the mid front unrounded vowel [e], somewhat like in the English word set. However, the letter e is pronounced as [je] ([j] sounds like ‘y’ in ‘you’) when it is the first letter of any form of the verb a fi «to be», or of a personal pronoun, for instance este /jeste/ «is» and el /jel/ «he».[119][120] This addition of the semivowel /j/ does not occur in more recent loans and their derivatives, such as eră «era», electric «electric» etc. Some words (such as iepure «hare», formerly spelled epure) are now written with the initial i to indicate the semivowel.

- x represents either the phoneme sequence /ks/ as in expresie = expression, or /ɡz/ as in exemplu = example, as in English.

- As in Italian, the letters c and g represent the affricates /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ before i and e, and /k/ and /ɡ/ elsewhere. When /k/ and /ɡ/ are followed by vowels /e/ and /i/ (or their corresponding semivowels or the final /ʲ/) the digraphs ch and gh are used instead of c and g, as shown in the table below. Unlike Italian, however, Romanian uses ce- and ge- to write /t͡ʃ/ and /d͡ʒ/ before a central vowel instead of ci- and gi-.

| Group | Phoneme | Pronunciation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| ce, ci | /tʃ/ | ch in chest, cheek | cerc (circle), ceașcă (cup), cercel (earring), cină (dinner), ciocan (hammer) |

| che, chi | /k/ | k in kettle, kiss | cheie (key), chelner (waiter), chioșc (kiosk), chitară (guitar), ureche (ear) |

| ge, gi | /dʒ/ | j in jelly, jigsaw | ger (frost), gimnast (gymnast), gem (jam), girafă (giraffe), geantă (bag) |

| ghe, ghi | /ɡ/ | g in get, give | ghețar (glacier), ghid (guide), ghindă (acorn), ghidon (handle bar), stingher (lonely) |

Punctuation and capitalization[edit]

Uses of punctuation peculiar to Romanian are:

- The quotation marks use the Polish format in the format „quote «inside» quote”, that is, „. . .” for a normal quotation, and double angle symbols for a quotation inside a quotation.

- Proper quotations which span multiple paragraphs do not start each paragraph with the quotation marks; one single pair of quotation marks is always used, regardless of how many paragraphs are quoted.

- Dialogues are identified with quotation dashes.

- The Oxford comma before «and» is considered incorrect («red, yellow and blue» is the proper format).

- Punctuation signs which follow a text in parentheses always follow the final bracket.

- In titles, only the first letter of the first word is capitalized, the rest of the title using sentence capitalization (with all its rules: proper names are capitalized as usual, etc.).

- Names of months and days are not capitalized (ianuarie «January», joi «Thursday»).

- Adjectives derived from proper names are not capitalized (Germania «Germany», but german «German»).

Academy spelling recommendations[edit]

In 1993, new spelling rules were proposed by the Romanian Academy. In 2000, the Moldovan Academy recommended adopting the same spelling rules,[121] and in 2010 the Academy launched a schedule for the transition to the new rules that was intended to be completed by publications in 2011.[122]

On 17 October 2016, Minister of Education Corina Fusu signed Order No. 872, adopting the revised spelling rules as recommended by the Moldovan Academy of Sciences, coming into force on the day of signing (due to be completed within two school years). From this day, the spelling as used by institutions subordinated to the ministry of education is in line with the Romanian Academy’s 1993 recommendation. This order, however, has no application to other government institutions and neither has Law 3462 of 1989 (which provided for the means of transliterating of Cyrillic to Latin) been amended to reflect these changes; thus, these institutions, along with most Moldovans, prefer to use the spelling adopted in 1989 (when the language with Latin script became official).

Examples of Romanian text[edit]

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

- (Universal Declaration of Human Rights)

The sentence in contemporary Romanian. Words inherited directly from Latin are highlighted:

- Toate ființele umane se nasc libere și egale în demnitate și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu rațiune și conștiință și trebuie să se comporte unele față de altele în spiritul fraternității.

The same sentence, with French and Italian loanwords highlighted instead:

- Toate ființele umane se nasc libere și egale în demnitate și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu rațiune și conștiință și trebuie să se comporte unele față de altele în spiritul fraternității.

The sentence rewritten to exclude French and Italian loanwords. Slavic loanwords are highlighted:

- Toate ființele omenești se nasc slobode și deopotrivă în destoinicie și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu înțelegere și cuget și trebuie să se poarte unele față de altele în duh de frățietate.

The sentence rewritten to exclude all loanwords. The meaning is somewhat compromised due to the paucity of native vocabulary:

- Toate ființele omenești se nasc nesupuse și asemenea în prețuire și în drepturi. Ele sunt înzestrate cu înțelegere și cuget și se cuvine să se poarte unele față de altele după firea frăției.

See also[edit]

- Albanian–Romanian linguistic relationship

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- Romanian lexis

- Romanianization

- Moldovan language

- BABEL Speech Corpus

- Controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity in Moldova

- Moldova–Romania relations

Notes[edit]

- ^ The constitution of the Republic of Moldova refers to the country’s language as Moldovan, whilst the 1991 Declaration of Independence names the official language Romanian. In December 2013, an official decision of the Constitutional Court of Moldova ruled that the Declaration of Independence takes precedence over the Constitution and that the state language is therefore Romanian, not ‘Moldovan’. «Moldovan court rules official language is ‘Romanian,’ replacing Soviet-flavored ‘Moldovan'»

References[edit]

- ^ лимба ромынэ (in Moldovan Cyrillic; solely applied to a moderate extent nowadays in Moldova)

- ^ Romanian at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ^ «Româna» [Romania]. Union Latine (in Romanian).

- ^ Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 1

- ^ «Istoria limbii române» («History of the Romanian Language»), II, Academia Română, Bucharest, 1969

- ^ Sala, Marius (2012). De la Latină la Română] [From Latin to Romanian]. Editura Pro Universitaria. p. 13. ISBN 978-606-647-435-1.

- ^ Brâncuș, Grigore (2005). Introducere în istoria limbii române] [Introduction to the History of Romanian Language]. Editura Fundaţiei România de Mâine. p. 16. ISBN 973-725-219-5.

- ^ Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, pages 3 and 4

- ^ Sala, Marius (2012). De la Latină la Română] [From Latin to Romanian]. Editura Pro Universitaria. p. 44. ISBN 978-606-647-435-1.

- ^ Schulte, Kim (2009). «Loanwords in Romanian». In Haspelmath, Martin; Tadmor, Uri (eds.). Loanwords in the World’s Languages: A Comparative Handbook. De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 231–250. ISBN 978-3-11-021843-5.

- ^ a b Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 5

- ^ Sala, Marius (2012). De la Latină la Română] [From Latin to Romanian]. Editura Pro Universitaria. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-606-647-435-1.

- ^ a b c d Petrucci 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Andreose & Renzi 2013, p. 287.

- ^ a b c Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 4

- ^ Romanian letter-writing: a cultural-rhetorical perspective

- ^ «scoasem … pre limbă românească 5 cărți ale lui Moisi prorocul … și le dăruim voo fraților rumâni» Pamfil, V. (1968) Palia de la Orǎstie 1581-1582 : text, facsimile, indice. Bucureşti. (p.1-11)

- ^ Ștefan Pascu, Documente străine despre români, ed. Arhivelor statului, București 1992, ISBN 973-95711-2-3

- ^ Dahmen, Wolfgang (2008). «Externe Sprachgeschichte des Rumänischen». In Ernst, Gerhard; Gleßgen, Martin-Dietrich; Schmitt, Christian; Schweickard, Wolfgang (eds.). Romanische Sprachgeschichte: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Geschichte der romanischen Sprachen (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 738. ISBN 978-3-11-014694-3.

- ^ Tomescu, Mircea (1968). Istoria cărții românești de la începuturi până la 1918 (in Romanian). București: Editura Științifică. p. 40.

- ^ Tranquillo Andronico în Endre Veress, Fontes rerum transylvanicarum: Erdélyi történelmi források, Történettudományi Intézet, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, Budapest, 1914, S. 204

- ^ «… si dimandano in lingua loro Romei…se alcuno dimanda se sano parlare in la lingua valacca, dicono a questo in questo modo: Sti Rominest ? Che vol dire: Sai tu Romano ?» Claudiu Isopescu, «Notizie intorno ai romeni nella letteratura geografica italiana del Cinquecento», Bulletin de la Section Historique, XVI, 1929, pp. 1–90

- ^ «Ex Vlachi Valachi, Romanenses Italiani,/Quorum reliquae Romanensi lingua utuntur…/Solo Romanos nomine, sine re, repraesentantes. Ideirco vulgariter Romuini sunt appelanti.» Ioannes Lebelius, De opido Thalmus, Carmen Istoricum, Cibinii, 1779, pp. 11–12

- ^ «qui eorum lingua Romini ab Romanis, nostra Walachi, ab Italis appellantur». St. Orichovius, «Annales polonici ab excessu Sigismundi», in I. Dlugossus, Historiae polonicae vol. XII, col 1555

- ^ «Valacchi, qui se Romanos nominant …» «Gens quae ear terras (Transsylvaniam, Moldaviam et Transalpinam) nostra aetate incolit, Valacchi sunt, eaque a Romania ducit originem, tametsi nomine longe alieno…» «De situ Transsylvaniae, Moldaviae et Transaplinae», in Monumenta Hungariae Historica, Scriptores; II, Pesta, 1857, p. 120

- ^ «Tout ce pays: la Wallachie, la Moldavie et la plus part de la Transylvanie, a esté peuplé des colonies romaines du temps de Trajan l’empereur … Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c’est-à-dire romain». «Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l’an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople», in: Paul Cernovodeanu, Studii și materiale de istorie medievală, IV, 1960, p. 444

- ^ «Anzi essi si chiamano romanesci, e vogliono molti che erano mandati quì quei che erano dannati a cavar metalli». Maria Holban, Călători străini despre Țările Române, Bucharest: Editura Stiințifică, 1970, vol. II, pp. 158–161

- ^ «În ţara Ardealului nu lăcuiescu numai unguri, ce şi saşi peste samă de mulţi şi români peste tot locul, de mai multu-i ţara lăţită de români decât de unguri.» Grigore Ureche, Letopisețul Țării Moldovei, pp. 133–134

- ^ Constantiniu, Florin, O istorie sinceră a poporului român [An honest history of the Romanian people], Univers Enciclopedic, Bucharest, 1997, ISBN 97-3924-307-X, p. 175

- ^ «Valachos … dicunt enim communi modo loquendi: Sie noi sentem Rumeni: etiam nos sumus Romani. Item: Noi sentem di sange Rumena: Nos sumus de sanguine Romano». Martinus Szent-Ivany, «Dissertatio Paralimpomenica rerum memorabilium Hungariae», Tyrnaviae, 1699, p. 39

- ^ From Descriptio Moldaviae: «Valachiae et Transylvaniae incolis eadem est cum Moldavis lingua, pronunciatio tamen rudior, ut dziur, Vlachus proferet zur, jur, per z polonicum sive j gallicum; Dumnedzeu, Deus, val. Dumnezeu: akmu, nunc, val. akuma, aczela hic, val: ahela.»

- ^ Munteanu, Eugen. «Dinamica istorică a cultivării instituţionalizate a limbii române». Revista română., în Iași, vol. IV, no. 4 (34), December 2003, p. 6 (I), no. 1 (35), March 2004, p. 7 (II); no. 2, June 2004, p. 6 (III); no. 3, October 2004, p. 6 (IV); no. 4 (38), December 2004, p. 6 (V). Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ N. Felecan — Considerations on the First Books of Romanian Grammar

- ^ Michael J. F. Suarez; H. R. Woudhuysen (24 October 2013). The Book: A Global History. OUP Oxford. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-0-19-166875-3. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Sala, Marius (2012). De la Latină la Română] [From Latin to Romanian]. Editura Pro Universitaria. p. 159. ISBN 978-606-647-435-1.

- ^ Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela (ed.); Maiden, Martin (consultant ed.): The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, p. 5

- ^ History of Romanian Academy

- ^ Sala, Marius (2012). De la Latină la Română] [From Latin to Romanian]. Editura Pro Universitaria. p. 160. ISBN 978-606-647-435-1.

- ^ Pană Dindelegan, Gabriela, The Grammar of Romanian, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-964492-6, page 5

- ^ a b Micu, Samuil; Șincai, Gheorghe (1780). Elementa linguae daco-romanae sive valachicae (in Latin). Vienna.

- ^ (in Russian)Charter for the organization of the Bessarabian Oblast, 29 April 1818, in «Печатается по изданию: Полное собрание законов Российской империи. Собрание первое.», Vol 35. 1818, Sankt Petersburg, 1830, pg. 222–227. Available online at hrono.info

- ^ King, Charles (2000). The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 08-1799-792-X.

- ^ D’hulst, Yves; Coene, Martine; Avram, Larisa (2004). «Syncretic and Analytic Tenses in Romanian: The Balkan Setting of Romance». In Mišeska Tomić, Olga (ed.). Balkan Syntax and Semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 355. doi:10.1075/la.67.18dhu. ISBN 978-90-272-2790-4.

general absence of consecutio temporum.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Hungarian Census 2011» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ Ethnologue.com

- ^ 2010 Russia Census Archived 22 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Perepis 2010

- ^ «Jews, by Country of Origin(1) and Age». CBS, Statistical Abstract of Israel 2013. Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Bureau, US Census. «Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over: 2009-2013». Census.gov. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (2 August 2017). «Mother Tongue (263), Single and Multiple Mother Tongue Responses (3), Age (7) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 2016 Census — 100% Data». www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. «Redirect to Census data page». www.abs.gov.au.

- ^ RDSCJ.ro Archived 22 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Latin Union – Languages and cultures online 2005». Dtil.unilat.org. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People». MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

- ^ According to the 1993 Statistical Abstract of Israel there were 250,000 Romanian speakers in Israel, of a population of 5,548,523 in 1995 (census).

- ^ «Reports of about 300,000 Jews that left the country after WW2». Eurojewcong.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Laslau, Andi (27 April 2005). «Arabii din Romania, radiografie completa». Evz.ro (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Constitution of Romania». Cdep.ro. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Legea «Pruteanu»: 500/2004 – Law on the Protection of the Romanian Language

- ^ Art. 27 (3), Legea nr. 26/1990 privind Registrul Comerțului

- ^ «Ministry of Education of Romania». Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2006.

- ^ «31 august — Ziua Limbii Române». Agerpres (in Romanian). 31 August 2020.

- ^ «De ce este sărbătorită Ziua Limbii Române la 31 august». Historia (in Romanian). 31 August 2020.

- ^ «Declarația de independența a Republicii Moldova, Moldova Suverană» (in Romanian). Moldova-suverana.md. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ «A Field Guide to the Main Languages of Europe – Spot that language and how to tell them apart» (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ «Moldovan Court Rules Official Language is ‘Romanian’, Replacing Soviet-Flavored ‘Moldovan’«. Fox News. Associated Press. 25 March 2015.

- ^ «Marian Lupu: Româna și moldoveneasca sunt aceeași limbă». Realitatea .NET. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of Languages. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 518. ISBN 07-4753-117-X.

- ^ Legea cu privire la functionarea limbilor vorbite pe teritoriul RSS Moldovenesti Nr.3465-XI din 01.09.89 Vestile nr.9/217, 1989 Archived 19 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine (Law regarding the usage of languages spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova): «Moldavian RSS supports the desire of the Moldavian that live across the borders of the Republic, and – considering the existing Moldo-Romanian linguistic identity – of the Romanians that live on the territory of the USSR, of doing their studies and satisfying their cultural needs in their maternal language.»

- ^ National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova: Census 2014

- ^ «Biroul Național de Statistică, acuzat că a falsificat rezultatele recensământului». Independent (in Romanian). 29 March 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Official Gazette of Republic of Serbia, No.1/90

- ^ Article 24, «The Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina», published in the Official Gazette of AP Vojvodina No.20/2014

- ^ «Official Use of Languages and Scripts in the AP Vojvodina». Provincial Secretariat for Education, Regulations, Administration and National Minorities – National Communities. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Provincial Secretariat for Regulations, Administration and National Minorities: «Official use of the Romanian language in the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina (APV)»

- ^ Sorescu-Marinković, Annemarie; Huțanu, Monica (2018). «Non-Dominant Varieties of Romanian in Serbia: Between Pluricentricity and Division». In Muhr, Rudolf; Meisnitzer, Benjamin (eds.). Pluricentric Languages and Non-Dominant Varieties Worldwide: New Pluricentric Languages – Old Problems. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Verlag. pp. 233–246. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_5795 – via DAIS — Digital Archive of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

- ^

- «Регіональний портрет України. 2003 р. Чернівецька область». Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2006.

- «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ «Internetový časopis človek a spoločnosť». www.clovekaspolocnost.sk. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009.

- ^ Kramar Andriy. «University of Chernivtsi». Chnu.cv.ua. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ «Cursuri de perfecționare» Archived 25 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Ziua, 19 August 2005

- ^ «Data concerning the teaching of the Romanian language abroad» Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Romanian Language Institute.

- ^ Delyusto, Maryna (2016). «Mul’tilingval’nyy atlas mezhdurech’ya Dnestra i Dunaya: Istochniki i priyemy sozdaniya» Мультилингвальный атлас междуречья Днестра и Дуная:источники и приемы создания [Multi-Lingual Atlas of Dialects Spread Between the Danube and the Dniester Rivers: Sources and Tools of Creation]. Journal of Danubian Studies and Research (in Russian). 6 (1): 362–369.