| В Википедии есть статья «Самарканд». |

Содержание

- 1 Русский

- 1.1 Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

- 1.2 Произношение

- 1.3 Семантические свойства

- 1.3.1 Значение

- 1.3.2 Синонимы

- 1.3.3 Антонимы

- 1.3.4 Гиперонимы

- 1.3.5 Гипонимы

- 1.4 Родственные слова

- 1.5 Этимология

- 1.6 Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- 1.7 Перевод

- 1.8 Библиография

Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | Самарка́нд | Самарка́нды |

| Р. | Самарка́нда | Самарка́ндов |

| Д. | Самарка́нду | Самарка́ндам |

| В. | Самарка́нд | Самарка́нды |

| Тв. | Самарка́ндом | Самарка́ндами |

| Пр. | Самарка́нде | Самарка́ндах |

Самарка́нд

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Имя собственное, топоним.

Корень: -Самарканд-.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [səmɐrˈkant]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- город в Узбекистане ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

|

Samarkand Uzbek: Samarqand / Самарқанд Самарканд |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

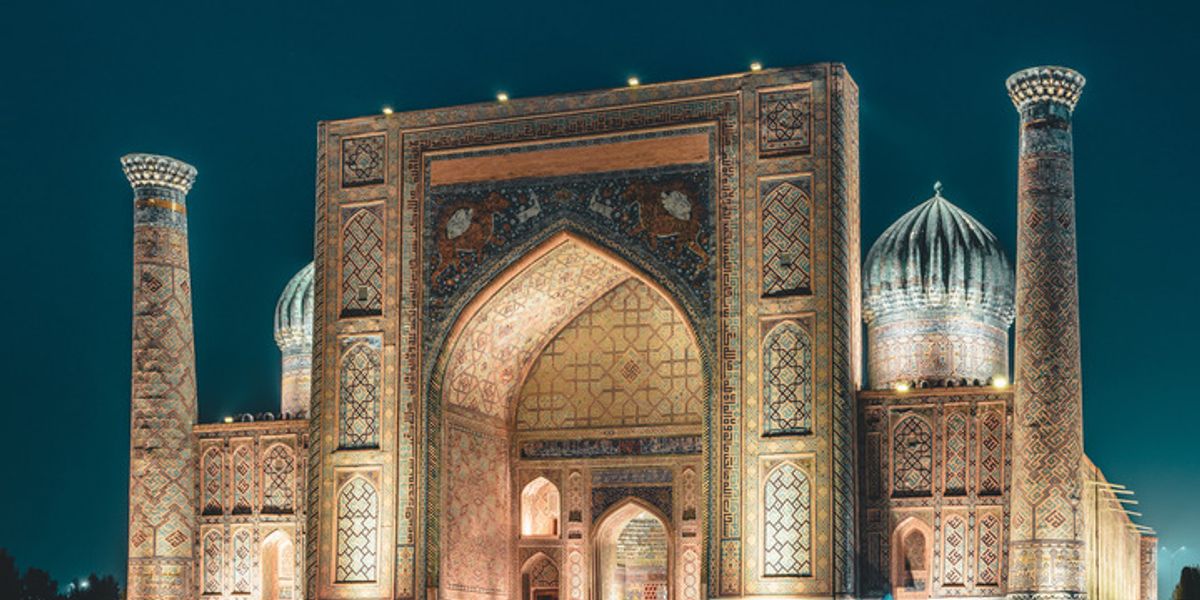

Clockwise from the top: |

|

|

Seal |

|

|

Samarkand Location in Uzbekistan Samarkand Samarkand (West and Central Asia) Samarkand Samarkand (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 39°39′17″N 66°58′33″E / 39.65472°N 66.97583°ECoordinates: 39°39′17″N 66°58′33″E / 39.65472°N 66.97583°E | |

| Country | |

| Vilayat | Samarkand Vilayat |

| Settled | 8th century BCE |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Administration |

| • Body | Hakim (Mayor) |

| Area | |

| • City | 120 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 705 m (2,313 ft) |

| Population

(1 January 2019) |

|

| • City | 513,572[1] |

| • Metro | 950,000 |

| Demonym | Samarkandian / Samarkandi |

| Time zone | UTC+5 |

| Postal code |

140100 |

| Website | samarkand.uz |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 603 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

| Area | 1,123 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,369 ha |

Samarkand (; Uzbek: Самарқанд, Samarqand, pronounced [samarqand, –qant]; Tajik: Самарқанд; Persian: سمرقند; Sogdian: *smā́rkąθ, 𐼑𐼍𐼀𐼘𐼋𐼎𐼌𐼆, 𐼼𐼺𐼰𐽀𐼸𐼻𐼹𐼳 smʾrknδH), also known as Samarqand, is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. There is evidence of human activity in the area of the city from the late Paleolithic Era. Though there is no direct evidence of when Samarkand was founded, several theories propose that it was founded between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Prospering from its location on the Silk Road between China, Persia and Europe, at times Samarkand was one of the largest[2] cities of Central Asia.[3] Most of the inhabitants of this city are native speakers of Tajik dialect of Persian language. This city is one of the historical centers of the Tajik people in Central Asia, which in the past was one of the important cities of the great empires of Greater Iran.[4][5]

By the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, it was the capital of the Sogdian satrapy. The city was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE, when it was known as Markanda, which was rendered in Greek as Μαράκανδα.[6] The city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic rulers until it was conquered by the Mongols under Genghis Khan in 1220. Today, Samarkand is the capital of Samarqand Region and a district-level city, that includes the urban-type settlements Kimyogarlar, Farxod and Xishrav.[7] With 551,700 inhabitants (2021),[8] it is the second-largest city of Uzbekistan.[citation needed]

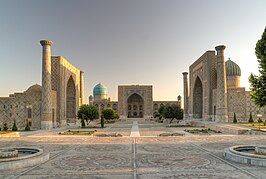

The city is noted as a centre of Islamic scholarly study and the birthplace of the Timurid Renaissance. In the 14th century, Timur (Tamerlane) made it the capital of his empire and the site of his mausoleum, the Gur-e Amir. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, rebuilt during the Soviet era, remains one of the city’s most notable landmarks. Samarkand’s Registan square was the city’s ancient centre and is bounded by three monumental religious buildings. The city has carefully preserved the traditions of ancient crafts: embroidery, goldwork, silk weaving, copper engraving, ceramics, wood carving, and wood painting.[9] In 2001, UNESCO added the city to its World Heritage List as Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures.

Modern Samarkand is divided into two parts: the old city, and the new city, which was developed during the days of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. The old city includes historical monuments, shops, and old private houses; the new city includes administrative buildings along with cultural centres and educational institutions.[10] On September 15–16, 2022, the city hosted the 2022 SCO summit.

Etymology[edit]

The name comes from Sogdian samar «stone, rock» and kand «fort, town.»[11] In this respect, Samarkand shares the same meaning as the name of the Uzbek capital Tashkent, with tash- being the Turkic term for «stone» and -kent the Turkic analogue of kand.[citation needed]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Along with Bukhara,[12] Samarkand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, prospering from its location on the trade route between China and Europe. There is no direct evidence of when it was founded. Researchers at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand date the city’s founding to the 8th–7th centuries BCE.

Archaeological excavations conducted within the city limits (Syob and midtown) as well as suburban areas (Hojamazgil, Sazag’on) unearthed 40,000-year-old evidence of human activity, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. A group of Mesolithic (12th–7th millennia BCE) archaeological sites were discovered in the suburbs of Sazag’on-1, Zamichatosh, and Okhalik. The Syob and Darg’om canals, supplying the city and its suburbs with water, appeared around the 7th–5th centuries BCE (early Iron Age).

From its earliest days, Samarkand was one of the main centres of Sogdian civilization. By the time of the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia, the city had become the capital of the Sogdian satrapy.

Hellenistic period[edit]

Ancient city walls of Samarkand, 4th century BCE

Alexander the Great conquered Samarkand in 329 BCE. The city was known as Maracanda by the Greeks.[13] Written sources offer small clues as to the subsequent system of government;[14] they mention one Orepius who became ruler «not from ancestors, but as a gift of Alexander.»[15]

While Samarkand suffered significant damage during Alexander’s initial conquest, the city recovered rapidly and flourished under the new Hellenic influence. There were also major new construction techniques; oblong bricks were replaced with square ones and superior methods of masonry and plastering were introduced.[16]

Alexander’s conquests introduced classical Greek culture into Central Asia; for a time, Greek aesthetics heavily influenced local artisans. This Hellenistic legacy continued as the city became part of various successor states in the centuries following Alexander’s death, i.e. the Seleucid Empire, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and Kushan Empire (even though the Kushana themselves originated in Central Asia). After the Kushan state lost control of Sogdia during the 3rd century CE, Samarkand went into decline as a centre of economic, cultural, and political power. It did not significantly revive until the 5th century.

Sassanian era[edit]

Samarkand was conquered by the Persian Sassanians c. 260 CE. Under Sassanian rule, the region became an essential site for Manichaeism and facilitated the dissemination of the religion throughout Central Asia.[17]

Hephtalites and Turkic Khaganate era[edit]

In AD 350–375 Samarkand was conquered by the nomadic tribes of Xionites, the origin of which remains controversial.[18]

The resettlement of nomadic groups to Samarkand confirms archaeological material from the 4th century. The culture of nomads from the Middle Syrdarya basin is spreading in the region.[19] In 457-509 Samarkand was part of the Kidarite state.[20]

After the Hephtalites («White Huns») conquered Samarkand, they controlled it until the Göktürks, in an alliance with the Sassanid Persians, won it at the Battle of Bukhara, c. 560 CE.[citation needed]

In the middle of the 6th century, a Turkic state was formed in Altai, founded by the Ashina dynasty. The new state formation was named the Turkic Khaganate after the people of the Turks, which were headed by the ruler — the Khagan. In 557-561, the Hephthalites empire was defeated by the joint actions of the Turks and Sassanids, which led to the establishment of a common border between the two empires.[23]

In the early Middle Ages, Samarkand was surrounded by four rows of defensive walls and had four gates.[24]

An ancient Turkic burial with a horse was investigated on the territory of Samarkand. It dates back to the 6th century.[25]

During the period of the ruler of the Western Turkic Kaganate, Tong Yabghu Qaghan (618-630), family relations were established with the ruler of Samarkand — Tong Yabghu Qaghan gave him his daughter.[26]

Some parts of Samarkand have been Christians since the 4th century. In the 5th century, a Nestorian chair was established in Samarkand. At the beginning of the 8th century, it was transformed into a Nestorian metropolitanate.[27] Discussions and polemics arose between the Sogdian followers of Christianity and Manichaeism, reflected in the documents.[28]

Early Islamic era[edit]

The armies of the Umayyad Caliphate under Qutayba ibn Muslim captured the city from the Turks c. 710 CE.[17]

During this period, Samarkand was a diverse religious community and was home to a number of religions, including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, Judaism, and Nestorian Christianity, with most of the population following Zoroastrianism.[30]

Qutayba generally did not settle Arabs in Central Asia; he forced the local rulers to pay him tribute but largely left them to their own devices. Samarkand was the major exception to this policy: Qutayba established an Arab garrison and Arab governmental administration in the city, its Zoroastrian fire temples were razed, and a mosque was built.[31] Much of the city’s population converted to Islam.[32]

As a long-term result, Samarkand developed into a center of Islamic and Arabic learning.[31]

Abbasid gold dinar minted in AH 248–252 / AD 862–866 Samarkand

At the end of the 740s, a movement of those dissatisfied with the power of the Umayyads emerged in the Arab Caliphate, led by the Abbasid commander Abu Muslim, who, after the victory of the uprising, became the governor of Khorasan and Maverannahr (750-755). He chose Samarkand as his residence. His name is associated with the construction of a multi-kilometer defensive wall around the city and the palace.[33]

Legend has it that during Abbasid rule,[34] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas in 751, which led to the foundation of the first paper mill in the Islamic world at Samarkand. The invention then spread to the rest of the Islamic world and thence to Europe.[citation needed]

Abbasid control of Samarkand soon dissipated and was replaced with that of the Samanids (875–999), though the Samanids were still nominal vassals of the Caliph during their control of Samarkand. Under Samanid rule the city became a capital of the Samanid dynasty and an even more important node of numerous trade routes. The Samanids were overthrown by the Karakhanids around 999. Over the next 200 years, Samarkand would be ruled by a succession of Turkic tribes, including the Seljuqs and the Khwarazmshahs.[35]

The 10th-century Persian author Istakhri, who travelled in Transoxiana, provides a vivid description of the natural riches of the region he calls «Smarkandian Sogd»:

I know no place in it or in Samarkand itself where if one ascends some elevated ground one does not see greenery and a pleasant place, and nowhere near it are mountains lacking in trees or a dusty steppe… Samakandian Sogd… [extends] eight days travel through unbroken greenery and gardens… . The greenery of the trees and sown land extends along both sides of the river [Sogd]… and beyond these fields is pasture for flocks. Every town and settlement has a fortress… It is the most fruitful of all the countries of Allah; in it are the best trees and fruits, in every home are gardens, cisterns and flowing water.

Karakhanid (Ilek-Khanid) period (11th–12th centuries)[edit]

Shah-i Zinda memorial complex, 11th–15th centuries

After the fall of the Samanids state in the year 999, it was replaced by the Qarakhanid State, where the Turkic Qarakhanid dynasty ruled.[36] After the state of the Qarakhanids split into two parts, Samarkand became a part of the West Karakhanid Kaganate and in 1040–1212 was its capital.[36] The founder of the Western Qarakhanid Kaganate was Ibrahim Tamgach Khan (1040–1068).[36] For the first time, he built a madrasah in Samarkand with state funds and supported the development of culture in the region. During his reign, a public hospital (bemoristan) and a madrasah were established in Samarkand, where medicine was also taught.

The memorial complex Shah-i-Zinda was founded by the rulers of the Karakhanid dynasty in the 11th century.[37]

The most striking monument of the Qarakhanid era in Samarkand was the palace of Ibrahim ibn Hussein (1178–1202), which was built in the citadel in the 12th century. During the excavations, fragments of monumental painting were discovered. On the eastern wall, a Turkic warrior was depicted, dressed in a yellow caftan and holding a bow. Horses, hunting dogs, birds and periodlike women were also depicted here.[38]

Mongol period[edit]

Ruins of Afrasiab – ancient Samarkand destroyed by Genghis Khan.

The Mongols conquered Samarkand in 1220. Juvaini writes that Genghis killed all who took refuge in the citadel and the mosque, pillaged the city completely, and conscripted 30,000 young men along with 30,000 craftsmen. Samarkand suffered at least one other Mongol sack by Khan Baraq to get treasure he needed to pay an army. It remained part of the Chagatai Khanate (one of four Mongol successor realms) until 1370.

The Travels of Marco Polo, where Polo records his journey along the Silk Road in the late 13th century, describes Samarkand as «a very large and splendid city…»[39]

The Yenisei area had a community of weavers of Chinese origin, and Samarkand and Outer Mongolia both had artisans of Chinese origin, as reported by Changchun.[40] After Genghis Khan conquered Central Asia, foreigners were chosen as governmental administrators; Chinese and Qara-Khitays (Khitans) were appointed as co-managers of gardens and fields in Samarkand, which Muslims were not permitted to manage on their own.[41][42] The khanate allowed the establishment of Christian bishoprics (see below).

Timur’s rule (1370–1405)[edit]

Shakhi Zinda mausoleums in Samarkand

Bibi-Khanym Friday Mosque, 1399–1404

Ibn Battuta, who visited in 1333, called Samarkand «one of the greatest and finest of cities, and most perfect of them in beauty.» He also noted that the orchards were supplied water via norias.[43]

In 1365, a revolt against Chagatai Mongol control occurred in Samarkand.[44] In 1370, the conqueror Timur (Tamerlane), the founder and ruler of the Timurid Empire, made Samarkand his capital. Over the next 35 years, he rebuilt most of the city and populated it with great artisans and craftsmen from across the empire. Timur gained a reputation as a patron of the arts, and Samarkand grew to become the centre of the region of Transoxiana. Timur’s commitment to the arts is evident in how, in contrast with the ruthlessness he showed his enemies, he demonstrated mercy toward those with special artistic abilities. The lives of artists, craftsmen, and architects were spared so that they could improve and beautify Timur’s capital.[citation needed]

Timur was also directly involved in construction projects, and his visions often exceeded the technical abilities of his workers. The city was in a state of constant construction, and Timur would often order buildings to be done and redone quickly if he was unsatisfied with the results.[45] By his orders, Samarkand could be reached only by roads; deep ditches were dug, and walls 8 km (5 mi) in circumference separated the city from its surrounding neighbors.[46] At this time, the city had a population of about 150,000.[47]

Henry III’s ambassador Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo, who was stationed at Samarkand between 1403 and 1406, attested to the never-ending construction that went on in the city. «The Mosque which Timur had built seemed to us the noblest of all those we visited in the city of Samarkand. «[48]

Ulugbek’s period (1409–1449)[edit]

Ulugbek’s madrasa in Samarkand, Uzbekistan

In 1417–1420, Timur’s grandson Ulugbek built a madrasah in Samarkand, which became the first building in the architectural ensemble of Registan. Ulugbek invited a large number of astronomers and mathematicians of the Islamic world to this madrasah. Under Ulugbek Samarkand became one of the world centers of medieval science. Here, in the first half of the 15th century, a whole scientific school arose around Ulugbek, uniting prominent astronomers and mathematicians — Giyasiddin Jamshid Kashi, Kazizade Rumi, al-Kushchi. Ulugbek’s main interest in science was astronomy. In 1428, the construction of the Ulugbek observatory was completed. Her main instrument was the wall quadrant, which had no equal in the world.[49]

16th–18th centuries[edit]

The Registan and its three madrasahs. From left to right: Ulugh Beg Madrasah, Tilya-Kori Madrasah and Sher-Dor Madrasah.

In 1500, nomadic Uzbek warriors took control of Samarkand.[47] The Shaybanids emerged as the city’s leaders at or about this time. In 1501, Samarkand was finally taken by Muhammad Shaybani from the Uzbek dynasty of Shaybanids, and the city became part of the newly formed “Bukhara Khanate”. Samarkand was chosen as the capital of this state, in which Muhammad Shaybani Khan was crowned. In Samarkand, Muhammad Shaybani Khan ordered to build a large madrasah, where he later took part in scientific and religious disputes. The first dated news about the Shaybani Khan madrasah dates back to 1504 (it was completely destroyed during the years of Soviet power). Muhammad Salikh wrote that Sheibani Khan built a madrasah in Samarkand to perpetuate the memory of his brother Mahmud Sultan.[50]

Fazlallah ibn Ruzbihan[who?] in «Mikhmon-namei Bukhara» expresses his admiration for the majestic building of the madrasah, its gilded roof, high hujras, spacious courtyard and quotes a verse praising the madrasah.[51] Zayn ad-din Vasifi, who visited the Sheibani-khan madrasah several years later, wrote in his memoirs that the veranda, hall and courtyard of the madrassah are spacious and magnificent.[50]

Abdulatif Khan, the son of Mirzo Ulugbek’s grandson Kuchkunji Khan, who ruled in Samarkand in 1540–1551, was considered an expert in the history of Maverannahr and the Shibanid dynasty. He patronized poets and scientists. Abdulatif Khan himself wrote poetry under the literary pseudonym Khush.[52]

During the reign of the Ashtarkhanid Imam Quli Khan (1611–1642) famous architectural masterpieces were built in Samarkand. In 1612–1656, the governor of Samarkand, Yalangtush Bahadur, built a cathedral mosque, Tillya-Kari madrasah and Sherdor madrasah.[citation needed]

After an assault by the Afshar Shahanshah Nader Shah, the city was abandoned in the early 1720s.[53] From 1599 to 1756, Samarkand was ruled by the Ashtrakhanid branch of the Khanate of Bukhara.

-

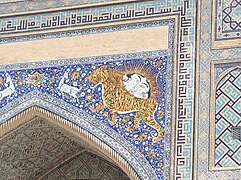

Ulugh Beg Madrasah

-

Sher-Dor Madrasah

-

Tilya Kori Madrasah

-

Ulugh Beg Madrasah courtyard

-

Tiger on the Sher-Dor Madrasah iwan

Second half of the 18th–19th centuries[edit]

Khazrat Hizr mosque, 1854

From 1756 to 1868, it was ruled by the Manghud Emirs of Bukhara.[54] The revival of the city began during the reign of the founder of the Uzbek dynasty, the Mangyts, Muhammad Rakhim (1756–1758), who became famous for his strong-willed qualities and military art. Muhammad Rakhimbiy made some attempts to revive Samarkand.[55]

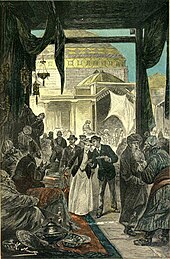

Russian Empire period[edit]

The city came under imperial Russian rule after the citadel had been taken by a force under Colonel Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman in 1868. Shortly thereafter the small Russian garrison of 500 men were themselves besieged. The assault, which was led by Abdul Malik Tura, the rebellious elder son of the Bukharan Emir, as well as Baba Beg of Shahrisabz and Jura Beg of Kitab, was repelled with heavy losses. General Alexander Konstantinovich Abramov became the first Governor of the Military Okrug, which the Russians established along the course of the Zeravshan River with Samarkand as the administrative centre. The Russian section of the city was built after this point, largely west of the old city.

In 1886, the city became the capital of the newly-formed Samarkand Oblast of Russian Turkestan and regained even more importance when the Trans-Caspian railway reached it in 1888.

Soviet period[edit]

Samarkand, by Richard-Karl Karlovitch Zommer

Samarkand was the capital of the Uzbek SSR from 1925 to 1930, before being replaced by Tashkent. During World War II, after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, a number of Samarkand’s citizens were sent to Smolensk to fight the enemy. Many were taken captive or killed by the Nazis.[56][57] Additionally, thousands of refugees from the occupied western regions of the USSR fled to the city, and it served as one of the main hubs for the fleeing civilians in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and the Soviet Union as a whole.[citation needed]

The scientific study of the history of Samarkand begins after the conquest of Samarkand by the Russian Empire in 1868. The first studies of the history of Samarkand belong to N. Veselovsky, V. Bartold and V. Vyatkin. In the Soviet period, the generalization of materials on the history of Samarkand was reflected in the two-volume History of Samarkand edited by the academician of Uzbekistan Ibraghim Muminov.[58]

On the initiative of Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR I. Muminov and with the support of Sharaf Rashidov, the 2500th anniversary of Samarkand was widely celebrated in 1970. In this regard, a monument to Mirzo Ulugbek was opened, the Museum of the History of Samarkand was founded, and a two-volume history of Samarkand was prepared and published.[59][60]

After Uzbekistan gained independence, several monographs were published on the ancient and medieval history of Samarkand.[61][62]

Geography[edit]

Samarkand from space in September 2013.[63]

Samarkand is located in southeastern Uzbekistan, in the Zarefshan River valley, 135 km from Qarshi. Road M37 connects Samarkand to Bukhara, 240 km away. Road M39 connects it to Tashkent, 270 km away. The Tajikistan border is about 35 km from Samarkand; the Tajik capital Dushanbe is 210k m away from Samarkand. Road M39 connects Samarkand to Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, which is 340 km away.

Climate[edit]

Samarkand has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa) that closely borders on a semi-arid climate (BSk) with hot, dry summers and relatively wet, variable winters that alternate periods of warm weather with periods of cold weather. July and August are the hottest months of the year, with temperatures reaching and exceeding 40 °C (104 °F). Precipitation is sparse from December through April. January 2008 was particularly cold; the temperature dropped to −22 °C (−8 °F).[64]

| Climate data for Samarkand (1981–2010, extremes 1936–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.5 (103.1) |

41.4 (106.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

41.0 (105.8) |

38.6 (101.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.5 (88.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

42.4 (108.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−22 (−8) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

−25.4 (−13.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.2 (1.62) |

46.2 (1.82) |

68.8 (2.71) |

60.5 (2.38) |

36.3 (1.43) |

6.1 (0.24) |

3.7 (0.15) |

1.2 (0.05) |

3.5 (0.14) |

16.8 (0.66) |

33.9 (1.33) |

47.0 (1.85) |

365.2 (14.38) |

| Average precipitation days | 14 | 14 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 101 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 7 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 6 | 28 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 74 | 70 | 63 | 54 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 47 | 59 | 68 | 74 | 59 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | −2 (28) |

−1 (30) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

9 (48) |

9 (48) |

10 (50) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

4 (39) |

2 (36) |

−1 (30) |

4 (40) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.9 | 130.9 | 169.3 | 219.3 | 315.9 | 376.8 | 397.7 | 362.3 | 310.1 | 234.3 | 173.3 | 130.3 | 2,953.1 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Source 1: Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of Uzbekistan[65] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV),[66] Time and Date (dewpoints, 1985–2015),[67] 理科年表 (mean temperatures/humidity/snow days 1981–2010, record low and record high temperatures),[68] NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[69] |

People[edit]

According to official reports, a majority of Samarkand’s inhabitants are Uzbeks, while many sources refer to the city as majority Tajik,[70][71][72][73] up to 70 percent of the city’s population.[74] Tajiks are especially concentrated in the eastern part of the city, where the main architectural landmarks are.

According to various independent sources, Tajiks are Samarkand’s majority ethnic group. Ethnic Uzbeks are the second-largest group[75] and are most concentrated in the west of Samarkand. Exact demographic figures are difficult to obtain since some people in Uzbekistan identify as «Uzbek» even though they speak Tajiki as their first language, often because they are registered as Uzbeks by the central government despite their Tajiki language and identity. As explained by Paul Bergne:

During the census of 1926 a significant part of the Tajik population was registered as Uzbek. Thus, for example, in the 1920 census in Samarkand city the Tajiks were recorded as numbering 44,758 and the Uzbeks only 3301. According to the 1926 census, the number of Uzbeks was recorded as 43,364 and the Tajiks as only 10,716. In a series of kishlaks [villages] in the Khojand Okrug, whose population was registered as Tajik in 1920 e.g. in Asht, Kalacha, Akjar i Tajik and others, in the 1926 census they were registered as Uzbeks. Similar facts can be adduced also with regard to Ferghana, Samarkand, and especially the Bukhara oblasts.[75]

Samarkand is also home to large ethnic communities of «Iranis» (the old, Persian-speaking, Shia population of Merv city and oasis, deported en masse to this area in the late 18th century), Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Armenians, Azeris, Tatars, Koreans, Poles, and Germans, all of whom live primarily in the centre and western neighborhoods of the city. These peoples have emigrated to Samarkand since the end of the 19th century, especially during the Soviet Era; by and large, they speak the Russian language.

In the extreme west and southwest of Samarkand is a population of Central Asian Arabs, who mostly speak Uzbek; only a small portion of the older generation speaks Central Asian Arabic. In eastern Samarkand there was once a large mahallah of Bukharian (Central Asian) Jews, but starting in the 1970s, hundreds of thousands of Jews left Uzbekistan for Israel, United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe. Only a few Jewish families are left in Samarkand today.

Also in the eastern part of Samarkand there are several quarters where Central Asian «Gypsies»[76] (Lyuli, Djugi, Parya, and other groups) live. These peoples began to arrive in Samarkand several centuries ago from what are now India and Pakistan. They mainly speak a dialect of the Tajik language, as well as their own languages, most notably Parya.

Language[edit]

Greeting in two languages: Uzbek (Latin) and Tajik (Cyrillic) at the entrance to one of the mahallahs (Bo’zi) of Samarkand

The state and official language in Samarkand, as in all Uzbekistan, is the Uzbek language. Uzbek is one of the Turkic languages and the mother tongue of Uzbeks, Turkmens, Samarkandian Iranians, and most Samarkandian Arabs living in Samarkand.

As in the rest of Uzbekistan, the Russian language is the de facto second official language in Samarkand, and about 5% of signs and inscriptions in Samarkand are in this language. Russians, Belarusians, Poles, Germans, Koreans, the majority of Ukrainians, the majority of Armenians, Greeks, some Tatars, and some Azerbaijanis in Samarkand speak Russian. Several Russian-language newspapers are published in Samarkand, the most popular of which is «Samarkandskiy vestnik» (Russian: Самаркандский вестник — Samarkand Herald). The Samarkandian TV channel STV conducts some broadcasts in Russian.

De facto, the most common native language in Samarkand is Tajik, which is a dialect or variant of the Persian language. Samarkand was one of the cities in which the Persian language developed. Many classical Persian poets and writers lived in or visited Samarkand over the millennia, the most famous being Abulqasem Ferdowsi, Omar Khayyam, Abdurahman Jami, Abu Abdullah Rudaki, Suzani Samarqandi, and Kamal Khujandi.

While the official stance is that Uzbek is the most common language in Samarkand, some data indicate that only about 30% of residents speak it as a native tongue. For the other 70%, Tajik is the native tongue, with Uzbek the second language and Russian the third. However, as no population census has been taken in Uzbekistan since 1989, there are no accurate data on this matter. Despite Tajik being the second most common language in Samarkand, it does not enjoy the status of an official or regional language.[74][77][71][78][72][79][73][80] Only one newspaper in Samarkand is published in Tajik, in the Cyrillic Tajik alphabet: «Ovozi Samarqand» (Tajik: Овози Самарқанд — Voice of Samarkand). Local Samarkandian STV and «Samarqand» TV channels offer some broadcasts in Tajik, as does one regional radio station.

In addition to Uzbek, Tajik, and Russian, native languages spoken in Samarkand include Ukrainian, Armenian, Azerbaijani, Tatar, Crimean Tatar, Arabic (for a very small percentage of Samarkandian Arabs), and others.

Modern Samarkand is a vibrant city, and in 2019 the city hosted the first Samarkand Half Marathon.[81] In 2022 this also included a full marathon for the first time.

Religion[edit]

Islam[edit]

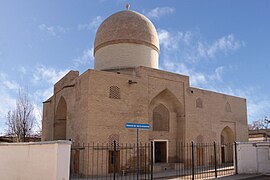

Downtown with Bibi-Khanym Mosque in 1990s

Islam entered Samarkand in the 8th century, during the invasion of the Arabs in Central Asia (Umayyad Caliphate). Before that, almost all inhabitants of Samarqand were Zoroastrians, and many Nestorians and Buddhists also lived in the city. From that point forward, throughout the reigns of many Muslim governing powers, numerous mosques, madrasahs, minarets, shrines, and mausoleums were built in the city. Many have been preserved. For example, there is the Shrine of Imam Bukhari, an Islamic scholar who authored the hadith collection known as Sahih al-Bukhari, which Sunni Muslims regard as one of the most authentic (sahih) hadith collections. His other books included Al-Adab al-Mufrad. Samarkand is also home to the Shrine of Imam Maturidi, the founder of Maturidism and the Mausoleum of the Prophet Daniel, who is revered in Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

Most inhabitants of Samarkand are Muslim, primarily Sunni (mostly Hanafi) and Sufi. Approximately 80-85% of Muslims in the city are Sunni, comprising almost all Tajiks, Uzbeks, and Samarqandian Arabs living therein. Samarqand’s best-known Islamic sacred lineages are the descendants of Sufi leaders

such as Khodja Akhror Wali (1404–1490) and Makhdumi A’zam (1461–1542), the descendants of Sayyid Ata (first half of 14th c.) and Mirakoni Xojas (Sayyids from Mirakon, a village in Iran).[82]

The liberal policy of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev opened up new opportunities for the expression of the religious identity. In Samarkand, since 2018, there has been an increase in the number of women wearing the hijab.[83]

Shia Muslims[edit]

The Samarqand Vilayat is one of the two regions of Uzbekistan (along with Bukhara Vilayat) that is home to a large number of Shiites. The total population of the Samarqand Vilayat is more than 3,720,000 people (2019).

There are no exact data on the number of Shiites in the city of Samarkand, but the city has several Shiite mosques and madrasas. The largest of these are the Punjabi Mosque, the Punjabi Madrassah, and the Mausoleum of Mourad Avliya. Every year, the Shiites of Samarkand celebrate Ashura, as well as other memorable Shiite dates and holidays.

Shiites in Samarkand are mostly Samarqandian Iranians, who call themselves Irani. Their ancestors began to arrive Samarkand in the 18th century. Some migrated there

in search of a better life, others were sold as slaves there by Turkmen captors, and others were soldiers who were posted to Samarkand. Mostly they came from Khorasan, Mashhad, Sabzevar, Nishapur, and Merv; and secondarily from Iranian Azerbaijan, Zanjan, Tabriz, and Ardabil. Samarkandian Shiites also include Azerbaijanis, as well as small numbers of Tajiks and Uzbeks.

While there are no official data on the total number of Shiites in Uzbekistan, they are estimated to be «several hundred thousand.» According to WikiLeaks, in 2007–2008, the US Ambassador for International Religious Freedom held a series of meetings with Sunni mullahs and Shiite imams in Uzbekistan. During one of the talks, the imam of the Shiite mosque in Bukhara said that about 300,000 Shiites live in the Bukhara Vliayat and 1 million in the Samarqand Vilayat. The Ambassador slightly doubted the authenticity of these figures, emphasizing in his report that data on the numbers of religious and ethnic minorities provided by the government of Uzbekistan were considered a very «delicate topic» due to their potential to provoke interethnic and interreligious conflicts. All the ambassadors of the ambassador tried to emphasize that traditional Islam, especially Sufism and Sunnism, in the regions of Bukhara and Samarqand is characterized by great religious tolerance toward other religions and sects, including Shiism.[84][85][86]

Christianity[edit]

Christianity was introduced to Samarkand when it was part of Soghdiana, long before the penetration of Islam into Central Asia. The city then became one of the centers of Nestorianism in Central Asia.[87] The majority of the population were then Zoroastrians, but since Samarkand was the crossroads of trade routes among China, Persia, and Europe, it was religiously tolerant. Under the Umayyad Caliphate, Zoroastrians and Nestorians were persecuted by the Arab conquerors; the survivors fled to other places or converted to Islam. Several Nestorian temples were built in Samarkand, but they have not survived. Their remains were found by archeologists at the ancient site of Afrasiyab and on the outskirts of Samarkand.

In the three decades of 1329–1359, the Samarkand eparchy of the Roman Catholic Church served several thousand Catholics who lived in the city. According to Marco Polo and Johann Elemosina, a descendant of Chaghatai Khan, the founder of the Chaghatai dynasty, Eljigidey, converted to Christianity and was baptized. With the assistance of Eljigidey, the Catholic Church of St. John the Baptist was built in Samarkand. After a while, however, Islam completely supplanted Catholicism.

Christianity reappeared in Samarkand several centuries later, from the mid-19th century onward, after the city was seized by the Russian Empire. Russian Orthodoxy was introduced to Samarkand in 1868, and several churches and temples were built. In the early 20th century several more Orthodox cathedrals, churches, and temples were built, most of which were demolished while Samarkand was part of the USSR.

In present time, Christianity is the second-largest religious group in Samarkand with the predominant form is the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). More than 5% of Samarkand residents are Orthodox, mostly Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, and also some Koreans and Greeks. Samarkand is the center of the Samarkand branch (which includes the Samarkand, Qashqadarya, and Surkhandarya provinces of Uzbekistan) of the Uzbekistan and Tashkent eparchy of the Central Asian Metropolitan District of the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The city has several active Orthodox churches: Cathedral of St. Alexiy Moscowskiy, Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin, and Church of St. George the Victorious. There are also a number of inactive Orthodox churches and temples, for example that of Church of St. George Pobedonosets.[88][89]

There are also a few tens of thousands of Catholics in Samarkand, mostly Poles, Germans, and some Ukrainians. In the center of Samarkand is St. John the Baptist Catholic Church, which was built at the beginning of the 20th century. Samarkand is part of the Apostolic Administration of Uzbekistan.[90]

The third largest Christian sect in Samarkand is the Armenian Apostolic Church, followed by a few tens of thousands of Armenian Samarkandians. Armenian Christians began emigrating to Samarkand at the end of the 19th century, this flow increasing especially in the Soviet era.[91] In the west of Samarkand is the Armenian Church Surb Astvatsatsin.[92]

Samarkand also has several thousand Protestants, including Lutherans, Baptists, Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Adventists, and members of the Korean Presbyterian church. These Christian movements appeared in Samarkand mainly after the independence of Uzbekistan in 1991.[93]

Main sights[edit]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Bibi Khanym Mosque |

|

| Official name | Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures |

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (ii), (iv) |

| Reference | 603bis |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

| Area | 1,123 ha |

| Coordinates | 39°39′38″N 66°58′46″E / 39.66056°N 66.97944°E |

Ensembles[edit]

Mausoleums and shrines[edit]

Mausoleums[edit]

Holy shrines and mausoleums[edit]

Other complexes[edit]

Madrasas[edit]

Mosques[edit]

Silk Road Samarkand (Eternal city)[edit]

Silk Road Samarkand is a modern multiplex which is set to open in early 2022 in eastern Samarkand. The complex covers 260 hectares and includes world-class business and medical hotels, eateries, recreational facilities, park grounds, an ethnographic corner and a large congress hall for hosting international events.[94]

Eternal city situated in Silk Road Samarkand complex. This site which occupies 17 hectares accurately recreates the spirit of the ancient city backed up by the history and traditions of Uzbek lands and Uzbek people for the guests of the Silk Road Samarkand. The narrow streets here house multiple shops of artists, artisans, and craftsmen. The pavilions of the Eternal City were inspired by real houses and picturesque squares described in ancient books. This is where you can plunge into a beautiful oriental fairy tale: with turquoise domes, mosaics on palaces, and high minarets that pierce the sky.

Visitors to the Eternal City can taste national dishes from different eras and regions of the country and also see authentic street performances. The Eternal City showcases a unique mix of Parthian, Hellenistic, and Islamic cultures so that the guests could imagine the versatile heritage of bygone centuries in full splendor. The project was inspired and designed by Bobur Ismoilov, a famous modern artist.[95]

Ornate dome in Eternal city Samarkand

Architecture[edit]

Building the Great Mosque of Samarkand. Illustration by Bihzad for the Zafar-Nameh. Text copied in Herat in 1467–68 and illuminated the late 1480s. John Work Garret Collection, Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Timur initiated the building of Bibi Khanum after his 1398–1399 campaign in India. Bibi Khanum originally had about 450 marble columns, which were hauled there and set up with the help of 95 elephants that Timur had brought back from Hindustan. Artisans and stonemasons from India designed the mosque’s dome, giving it its distinctive appearance amongst the other buildings. An 1897 earthquake destroyed the columns, which were not entirely restored in the subsequent reconstruction.[45]

The best-known landmark of Samarkand is the mausoleum known as Gur-i Amir. It exhibits the influences of many cultures, past civilizations, neighboring peoples, and religions, especially those of Islam. Despite the devastation wrought by Mongols to Samarkand’s pre-Timurid Islamic architecture, under Timur these architectural styles were revived, recreated, and restored. The blueprint and layout of the mosque itself, with their precise measurements, demonstrate the Islamic passion for geometry. The entrance to the Gur-i Amir is decorated with Arabic calligraphy and inscriptions, the latter a common feature in Islamic architecture. Timur’s meticulous attention to detail is especially obvious inside the mausoleum: the tiled walls are a marvelous example of mosaic faience, an Iranian technique in which each tile is cut, colored, and fit into place individually.[45] The tiles of the Gur-i Amir were also arranged so that they spell out religious words such as «Muhammad» and «Allah.»[45]

The ornamentation of the Gur-i Amir’s walls includes floral and vegetal motifs, which signify gardens; the floor tiles feature uninterrupted floral patterns. In Islam, gardens are symbols of paradise, and as such, they were depicted on the walls of tombs and grown in Samarkand itself.[45] Samarkand boasted two major gardens, the New Garden and the Garden of Heart’s Delight, which became the central areas of entertainment for ambassadors and important guests. In 1218, a friend of Genghis Khan named Yelü Chucai reported that Samarkand was the most beautiful city of all, as «it was surrounded by numerous gardens. Every household had a garden, and all the gardens were well designed, with canals and water fountains that supplied water to round or square-shaped ponds. The landscape included rows of willows and cypress trees, and peach and plum orchards were shoulder to shoulder.»[96] Persian carpets with floral patterns have also been found in some Timurid buildings.[97]

The elements of traditional Islamic architecture can be seen in traditional mud-brick Uzbek houses that are built around central courtyards with gardens.[98] Most of these houses have painted wooden ceilings and walls. By contrast, houses in the west of the city are chiefly European-style homes built in the 19th and 20th centuries.[98]

Turko-Mongol influence is also apparent in Samarkand’s architecture. It is believed that the melon-shaped domes of the mausoleums were designed to echo yurts or gers, traditional Mongol tents in which the bodies of the dead were displayed before burial or other disposition. Timur built his tents from more-durable materials, such as bricks and wood, but their purposes remained largely unchanged.[45] The chamber in which Timur’s own body was laid included «tugs», poles whose tops were hung with a circular arrangement of horse or yak tail hairs. These banners symbolized an ancient Turkic tradition of sacrificing horses, which were valuable commodities, to honor the dead.[45] Tugs were also a type of cavalry standard used by many nomads, up to the time of the Ottoman Turks.

Colors of buildings in Samarkand also have significant meanings. The dominant architectural color is blue, which Timur used to convey a broad range of concepts. For example, the shades of blue in the Gur-i Amir are colors of mourning; in that era, blue was the color of mourning in Central Asia, as it still is in various cultures today. Blue was also considered the color that could ward off «the evil eye» in Central Asia; this notion is evidenced by in the number of blue-painted doors in and around the city. Furthermore, blue represented water, a particularly rare resource in the Middle East and Central Asia; walls painted blue symbolized the wealth of the city.

Gold also has a strong presence in the city. Timur’s fascination with vaulting explains the excessive use of gold in the Gur-i Amir, as well as the use of embroidered gold fabric in both the city and his buildings. The Mongols had great interests in Chinese- and Persian-style golden silk textiles, as well as nasij[99] woven in Iran and Transoxiana. Mongol leaders like Ögedei Khan built textile workshops in their cities to be able to produce gold fabrics themselves.

Suburbs[edit]

Samarkand’s recent expansion led to it having suburbs, including: Gulyakandoz, Superfosfatnyy, Bukharishlak, Ulugbek, Ravanak, Kattakishlak, Registan, Zebiniso, Kaftarkhona, Uzbankinty.[100]

Transport[edit]

Local[edit]

Samarkand has a strong public-transport system. From Soviet times up through today, municipal buses and taxis (GAZ-21, GAZ-24, GAZ-3102, VAZ-2101, VAZ-2106 and VAZ-2107) have operated in Samarkand. Buses, mostly SamAuto and Isuzu buses, are the most common and popular mode of transport in the city. Taxis, which are mostly Chevrolets and Daewoo sedans, are usually yellow in color. Since 2017, there have also been several Samarkandian tram lines, mostly Vario LF.S Czech trams. From the Soviet Era up until 2005, Samarkandians also got around via trolleybus. Finally, Samarkand has the so-called «Marshrutka,» which are Daewoo Damas and GAZelle minibuses.

-

Many yellow taxis on the streets of Samarkand

-

Taxi and tram on Rudaki Street in Samarkand

-

Tram in Samarkand

-

Beruni and Rudaki Streets in Samarkand

-

Taxi and bus on Mirzo Ulughbek Avenue in Samarkand

Until 1950, the main forms of transport in Samarkand were carriages and «arabas» with horses and donkeys. However, the city had a steam tram in 1924–1930, and there were more-modern trams in 1947–1973.

-

«Araba» and donkey in Samarkand in 1890

-

Samarkand railway station in 1890

-

«Araba» in Samarkand in 1964

-

«Araba» in Samarkand in 1964

Air transport[edit]

In the north of the city is Samarkand International Airport, which was opened in the 1930s, under the Soviets. As of spring 2019, Samarkand International Airport has flights to Tashkent, Nukus, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Kazan, Istanbul, and Dushanbe; charter flights to other cities are also available.

Railway[edit]

Modern Samarkand is an important railway center of Uzbekistan; all national east–west railway routes pass through the city. The most important and longest of these is Tashkent–Kungrad. High-speed Tashkent–Samarkand high-speed rail line trains run between Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara. Samarkand also has international railway connections: Saratov–Samarkand, Moscow–Samarkand, and Nur-Sultan–Samarkand.

-

Samarkand railway station

-

Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train in Samarkand railway station

-

In Samarkand railway station

-

Afrasiyab (Talgo 250) high-speed train

In 1879–1891, the Russian Empire built the Trans-Caspian Railway to facilitate its expansion into Central Asia. The railway originated in Krasnovodsk (now Turkmenbashi) on the Caspian Sea coast. Its terminus was originally Samarkand, whose station first opened in May 1888. However, a decade later, the railway was extended eastward to Tashkent and Andijan, and its name was changed to Central Asian Railways. Nonetheless, Samarkand remained one of the largest and most important stations of the Uzbekistan SSR and Soviet Central Asia.

International relations[edit]

Twin towns – sister cities[edit]

Samarkand is twinned with:[101]

Agra, India

Balkh, Afghanistan

Banda Aceh, Indonesia

Cusco, Peru

Jūrmala, Latvia

Kairouan, Tunisia

Khujand, Tajikistan

Krasnoyarsk, Russia

Lahore, Pakistan

Liège, Belgium

Mary, Turkmenistan

Merv, Turkmenistan

Mexico City, Mexico

New Delhi, India

Nishapur, Iran

Plovdiv, Bulgaria

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Samara, Russia

Xi’an, China

Friendly cities[edit]

Samarkand has friendly relations with:[101][102]

Antalya, Turkey

Babruysk, Belarus

Bremen, Germany

Eskişehir, Turkey

Florence, Italy

Gyeongju, South Korea

Istanbul, Turkey

İzmir, Turkey

Lyon, France

Lviv, Ukraine

Valencia, Spain

Gallery[edit]

See also[edit]

- Samarkand Airport

Citations[edit]

- ^ «THE STATE COMMITTEE OF THE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN ON STATISTICS». Archived from the original on 2020-04-29. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ Varadarajan, Tunku (24 October 2009). «Metropolitan Glory». The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Guidebook of history of Samarkand», ISBN 978-9943-01-139-7

- ^ D.I. Kertzer/D. Arel, Census and identity Archived 2022-11-17 at the Wayback Machine, p. ۱۸۷, Cambridge University Press, 2001

- ^ NikTalab, Poopak (2019). From the Alleyways of Samarkand to the Mediterranean Coast (The Evolution of the World of Child and Adolescent Literature). Tehran, Iran: Faradid publishing. pp. 18–27. ISBN 9786226606622.

- ^ «History of Samarkand». Sezamtravel. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ «Classification system of territorial units of the Republic of Uzbekistan» (in Uzbek and Russian). The State Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan on statistics. July 2020.

- ^ «Urban and rural population by district» (in Uzbek). Samarkand regional department of statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-02-13.

- ^ Энциклопедия туризма Кирилла и Мефодия. 2008.

- ^ «History of Samarkand». www.advantour.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- ^ Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites (2nd ed.). London: McFarland. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

Samarkand City, southeastern Uzbekistan. The city here was already named Marakanda, when captured by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE. Its own name derives from the Sogdian words samar, «stone, rock», and kand, «fort, town».

- ^ Vladimir Babak, Demian Vaisman, Aryeh Wasserman, Political organization in Central Asia and Azerbaijan: sources and documents, p. 374

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1972 reprint) p. 1657

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Road: two thousand years in the heart of Asia. London.

- ^ Shichkina, G.V. (1994). «Ancient Samarkand: capital of Soghd». Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 83.

- ^ Shichkina, G.V. (1994). «Ancient Samarkand: capital of Soghd». Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 8: 86.

- ^ a b Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California. p. 319.

- ^ Grenet Frantz, Regional interaction in Central Asia and northwest India in the Kidarite and Hephtalites periods in Indo-Iranian languages and peoples. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Oxford university press, 2003. Р.219-220

- ^ Buryakov Y.F. Iz istorii arkheologicheskikh rabot v zonakh oroshayemogo zemledeliya Uzbekistana // Arkheologicheskiye raboty na novostroykakh Uzbekistana. Tashkent, 1990. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Etienne de la Vaissiere, Sogdian traders. A history. Translated by James Ward. Brill. Leiden. Boston, 2005, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (2004). «Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole». Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. B.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, AD 250 to 750. Vol. 3. Unesco, 1996. p. 332

- ^ Belenitskiy A.M., Bentovich I.B., Bolshakov O.G. Srednevekovyy gorod Sredney Azii. L., 1973.

- ^

Sprishevskiy V.I. Pogrebeniye s konem serediny I tysyacheletiya n.e., obnaruzhennoye okolo observatorii Ulugbeka. // Tr. Muzeya istorii narodov Uzbekistana. T.1.- Tashkent, 1951. - ^ Klyashtornyy S. G., Savinov D. G., Stepnyye imperii drevney Yevrazii. Sankt-Peterburg: Filologicheskiy fakul’tet SPbGU, 2005 god, s. 97

- ^ Masson M.Ye., Proiskhozhdeniye dvukh nestorianskikh namogilnykh galek Sredney Azii // Obshchestvennyye nauki v Uzbekistane, 1978, №10, p. 53.

- ^ Sims-Wlliams Nicholas, A Christian sogdian polemic against the manichaens // Religious themes and texts of pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia. Edited by Carlo G. Cereti, Mauro Maggi and Elio Provasi. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2003, pp. 399–407

- ^ Tadjikistan : au pays des fleuves d’or. Paris: Musée Guimet. 2021. p. 152. ISBN 978-9461616272.

- ^ Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California.

- ^ a b Wellhausen, J. (1927). Weir, Margaret Graham (ed.). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. University of Calcutta. pp. 437–438. ISBN 9780415209045. Archived from the original on 2019-04-21. Retrieved 2019-05-04.

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (1999). Life Along the Silk Road. California: University of California Press. p. 33.

- ^ Bartold V. V., Abu Muslim//Akademik V. V. Bartol’d. Sochineniya. Tom VII. Moskva: Nauka, 1971

- ^ Quraishi, Silim «A survey of the development of papermaking in Islamic Countries», Bookbinder, 1989 (3): 29–36.

- ^ Dumper, Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. California. p. 320.

- ^ a b c Kochnev B. D., Numizmaticheskaya istoriya Karakhanidskogo kaganata (991—1209 gg.). Moskva «Sofiya», 2006

- ^ Nemtseva, N.B., Shvab, IU. Ansambl Shah-i Zinda: istoriko-arkhitektymyi ocherk. Tashent: 1979.

- ^ Karev, Yury. Qarakhanid wall paintings in the citadel of Samarqand: First report and preliminary observations in Muqarnas 22 (2005): 45-84.

- ^ «Samarkand Travel Guide». Caravanistan. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ Jacques Gernet (31 May 1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 377–. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7. Archived from the original on 15 June 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ E.J.W. Gibb memorial series. 1928. p. 451.

- ^ E. Bretschneider (1888). «The Travels of Ch’ang Ch’un to the West, 1220–1223 recorded by his disciple Li Chi Ch’ang». Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources. Barnes & Noble. pp. 37–108. Archived from the original on 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2018-04-26.

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 143. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed, p. 204

- ^ a b c d e f g Marefat, Roya (Summer 1992). «The Heavenly City of Samarkand». The Wilson Quarterly. 16 (3): 33–38. JSTOR 40258334.

- ^ Wood, Frances (2002). The Silk Roads: two thousand ears in the heart of Asia. Berkeley. pp. 136–7.

- ^ a b Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer, p. 1657

- ^ Le Strange, Guy (trans) (1928). Clavijo: Embassy to Tamburlaine 1403–1406. London. p. 280.

- ^ «Ulugh Beg — Biography». Maths History.

- ^ a b Mukminova R. G., K istorii agrarnykh otnosheniy v Uzbekistane XVI veke. Po materialam «Vakf-name». Tashkent. Nauka. 1966

- ^ Fazlallakh ibn Ruzbikhan Isfakhani. Mikhman-name-yi Bukhara (Zapiski bukharskogo gostya). M. Vostochnaya literatura. 1976, p. 3

- ^ B.V. Norik. Rol’ shibanidskikh praviteley v literaturnoy zhizni Maverannakhra XVI veka. Sankt-Peterburg: Rakhmat-name, 2008. p. 233.

- ^ Britannica. 15th Ed, p. 204

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazetteer. p. 1657

- ^ Materialy po istorii Sredney i Tsentral’noy Azii X—XIX veka. Tashkent: Fan, 1988, рр. 270—271

- ^ «Советское Поле Славы». www.soldat.ru. Archived from the original on April 13, 2020.

- ^ Rustam Qobil (2017-05-09). «Why were 101 Uzbeks killed in the Netherlands in 1942?». BBC. Archived from the original on 2020-03-30. Retrieved 2017-05-09.

- ^ Montgomery David. Samarkand taarikhi (History of Samarkand) by I.M.Muminov, The American historical review, volume 81, no.8 (October 1976), pp. 914–915

- ^ Istoriya Samarkanda v dvukh tomakh. Pod redaktsiyey I. Muminova. Tashkent, 1970

- ^ Montgomery David, Review of Samarkand taarikhi by I. M. Muminov et al. // The American historical review, volume 81, no. 4 (October 1976)

- ^ Shirinov T.SH., Isamiddinov M.KH. Arkheologiya drevnego Samarkanda. Tashkent, 2007

- ^ Malikov A.M. Istoriya Samarkanda (s drevnikh vremen do serediny XIV veka). Tom. 1. Tashkent: Paradigma, 2017.

- ^ «Samarkand, Uzbekistan». Earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-09-17. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- ^ Samarkand.info. «Weather in Samarkand». Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ^

«Average monthly data about air temperature and precipitation in 13 regional centers of the Republic of Uzbekistan over period from 1981 to 2010». Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of the Republic of Uzbekistan (Uzhydromet). Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019. - ^ «Samarkand, Uzbekistan – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast». Weather Atlas. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ «Climate & Weather Averages in Samarkand». Time and Date. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^

«Weather and Climate-The Climate of Samarkand» (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Archived from the original on December 6, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2019. - ^ «Samarkand Climate Normals 1961–1990». National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin; Djalili, Mohammad-Reza; Grare, Frederic (2013). Tajikistan: The Trials of Independence. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-10490-9 p. 78, «Bukhara and Samarkand, inhabited by a marked Tajik majority (…)»

- ^ a b Lena Jonson (1976) «Tajikistan in the New Central Asia», I.B.Tauris, p. 108: «According to official Uzbek statistics there are slightly over 1 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan or about 3% of the population. The unofficial figure is over 6 million Tajiks. They are concentrated in the Sukhandarya, Samarqand and Bukhara regions.»

- ^ a b «Узбекистан: Таджикский язык подавляется». catoday.org — ИА «Озодагон». Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ a b «Таджики – иранцы Востока? Рецензия книги от Камолиддина Абдуллаева». «ASIA-Plus» Media Group / Tajikistan — news.tj. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ a b Richard Foltz (1996). «The Tajiks of Uzbekistan». Central Asian Survey. 15 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1080/02634939608400946.

- ^ a b Paul Bergne: The Birth of Tajikistan. National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. International Library of Central Asia Studies. I.B. Tauris. 2007. Pg. 106

- ^ Marushiakova; Popov, Vesselin (January 2014). Migrations and Identities of Central Asian ‘Gypsies’. Asia Pacific Sociological Association (APSA) Conference «Transforming Societies: Conestations and Convergences in Asia and the Pacific». doi:10.1057/ces.2008.3. S2CID 154689140. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ^ Karl Cordell, «Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe», Routledge, 1998. p. 201: «Consequently, the number of citizens who regard themselves as Tajiks is difficult to determine. Tajikis within and outside of the republic, Samarkand State University (SamGU) academic and international commentators suggest that there may be between six and seven million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30% of the republic’s 22 million population, rather than the official figure of 4.7%(Foltz 1996;213; Carlisle 1995:88).

- ^ Richard Foltz. A History of the Tajiks. Iranians of the East. London: I.B. Tauris, 2019

- ^ «Статус таджикского языка в Узбекистане». Лингвомания.info — lingvomania.info. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ «Есть ли шансы на выживание таджикского языка в Узбекистане — эксперты». «Биржевой лидер» — pfori-forex.org. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ^ Samarkand Half Marathon.

- ^ Malikov Azim, Sacred lineages of Samarqand: history and identity in Anthropology of the Middle East, Volume 15, Issue 1, Summer 2020, р.36

- ^ Malikov A. and Djuraeva D. 2021. Women, Islam, and politics in Samarkand (1991–2021), International Journal of Modern Anthropology. 2 (16): 561

- ^ «Шииты в Узбекистане». www.islamsng.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ «Ташкент озабочен делами шиитов». www.dn.kz. Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ «Узбекистан: Иранцы-шииты сталкиваются c проблемами с правоохранительными органами». catoday.org. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ Dickens, Mark «Nestorian Christianity in Central Asia. p. 17

- ^ В. А. Нильсен. У истоков современного градостроительства Узбекистана (ΧΙΧ — начало ΧΧ веков). —Ташкент: Издательство литературы и искусства имени Гафура Гуляма, 1988. 208 с.

- ^ Голенберг В. А. «Старинные храмы туркестанского края». Ташкент 2011 год

- ^ Католичество в Узбекистане. Ташкент, 1990.

- ^ Armenians. Ethnic atlas of Uzbekistan, 2000.

- ^ Назарьян Р.Г. Армяне Самарканда. Москва. 2007

- ^ Бабина Ю. Ё. Новые христианские течения и страны мира. Фолкв, 1995.

- ^ «Silk Road Samarkand Tourist Complex». www.advantour.com. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ «Eternal City». www.silkroad-samarkand.com. Retrieved 2023-01-20.

- ^ Liu, Xinru (2010). The Silk Road in world history. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516174-8.

- ^ Cohn-Wiener, Ernst (June 1935). «An Unknown Timurid Building». The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 66 (387): 272–273+277. JSTOR 866154.

- ^ a b «Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures». UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- ^ «Textiles in «The world of Kubilai Khan» @ Metropolitan Museum, New York». Alain.R.Truong. 25 December 2010. Archived from the original on 2019-11-18. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ^ «Superfosfatnyy · Uzbekistan». Superfosfatnyy · Uzbekistan.

- ^ a b «Самарканд и Валенсия станут городами-побратимами». podrobno.uz (in Russian). Podrobno.uz. 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- ^ «Внешнеэкономическое сотрудничество». bobruisk.by (in Russian). Babruysk. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

General and cited references[edit]

- Azim Malikov, «Cult of saints and shrines in the Samarqand province of Uzbekistan». International Journal of Modern Anthropology. No. 4. 2010, pp. 116–123.

- Azim Malikov, «The politics of memory in Samarkand in post-Soviet period». International Journal of Modern Anthropology. (2018) Vol. 2. Issue No. 11. pp. 127–145.

- Azim Malikov, «Sacred lineages of Samarqand: history and identity». Anthropology of the Middle East, Volume 15, Issue 1, Summer 2020, рp. 34–49.

- Alexander Morrison, Russian Rule in Samarkand 1868–1910: A Comparison with British India (Oxford, OUP, 2008) (Oxford Historical Monographs).

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samarkand.

- Forbes, Andrew, & Henley, David: Timur’s Legacy: The Architecture of Bukhara and Samarkand (CPA Media).

- Samarkand – Silk Road Seattle Project, University of Washington

- The history of Samarkand, according to Columbia University’s Encyclopædia Iranica (archived 11 March 2007)

- Samarkand – Crossroad of Cultures, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Bealby, John Thomas (1911). «Samarkand (city)» . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). pp. 112–113.

- GCatholic – former Latin Catholic bishopric

- Samarkand: Photos, History, Sights, Useful information for travelers

- About Samarkand in Uzbekistan Latest (archived 18 August 2018)

- Tilla-Kori Madrasa was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List

|

Samarkand Uzbek: Samarqand / Самарқанд Самарканд |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

Clockwise from the top: |

|

|

Seal |

|

|

Samarkand Location in Uzbekistan Samarkand Samarkand (West and Central Asia) Samarkand Samarkand (Asia) |

|

| Coordinates: 39°39′17″N 66°58′33″E / 39.65472°N 66.97583°ECoordinates: 39°39′17″N 66°58′33″E / 39.65472°N 66.97583°E | |

| Country | |

| Vilayat | Samarkand Vilayat |

| Settled | 8th century BCE |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Administration |

| • Body | Hakim (Mayor) |

| Area | |

| • City | 120 km2 (50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 705 m (2,313 ft) |

| Population

(1 January 2019) |

|

| • City | 513,572[1] |

| • Metro | 950,000 |

| Demonym | Samarkandian / Samarkandi |

| Time zone | UTC+5 |

| Postal code |

140100 |

| Website | samarkand.uz |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 603 |

| Inscription | 2001 (25th Session) |

| Area | 1,123 ha |

| Buffer zone | 1,369 ha |

Samarkand (; Uzbek: Самарқанд, Samarqand, pronounced [samarqand, –qant]; Tajik: Самарқанд; Persian: سمرقند; Sogdian: *smā́rkąθ, 𐼑𐼍𐼀𐼘𐼋𐼎𐼌𐼆, 𐼼𐼺𐼰𐽀𐼸𐼻𐼹𐼳 smʾrknδH), also known as Samarqand, is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central Asia. There is evidence of human activity in the area of the city from the late Paleolithic Era. Though there is no direct evidence of when Samarkand was founded, several theories propose that it was founded between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Prospering from its location on the Silk Road between China, Persia and Europe, at times Samarkand was one of the largest[2] cities of Central Asia.[3] Most of the inhabitants of this city are native speakers of Tajik dialect of Persian language. This city is one of the historical centers of the Tajik people in Central Asia, which in the past was one of the important cities of the great empires of Greater Iran.[4][5]

By the time of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, it was the capital of the Sogdian satrapy. The city was conquered by Alexander the Great in 329 BCE, when it was known as Markanda, which was rendered in Greek as Μαράκανδα.[6] The city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic rulers until it was conquered by the Mongols under Genghis Khan in 1220. Today, Samarkand is the capital of Samarqand Region and a district-level city, that includes the urban-type settlements Kimyogarlar, Farxod and Xishrav.[7] With 551,700 inhabitants (2021),[8] it is the second-largest city of Uzbekistan.[citation needed]

The city is noted as a centre of Islamic scholarly study and the birthplace of the Timurid Renaissance. In the 14th century, Timur (Tamerlane) made it the capital of his empire and the site of his mausoleum, the Gur-e Amir. The Bibi-Khanym Mosque, rebuilt during the Soviet era, remains one of the city’s most notable landmarks. Samarkand’s Registan square was the city’s ancient centre and is bounded by three monumental religious buildings. The city has carefully preserved the traditions of ancient crafts: embroidery, goldwork, silk weaving, copper engraving, ceramics, wood carving, and wood painting.[9] In 2001, UNESCO added the city to its World Heritage List as Samarkand – Crossroads of Cultures.

Modern Samarkand is divided into two parts: the old city, and the new city, which was developed during the days of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. The old city includes historical monuments, shops, and old private houses; the new city includes administrative buildings along with cultural centres and educational institutions.[10] On September 15–16, 2022, the city hosted the 2022 SCO summit.

Etymology[edit]

The name comes from Sogdian samar «stone, rock» and kand «fort, town.»[11] In this respect, Samarkand shares the same meaning as the name of the Uzbek capital Tashkent, with tash- being the Turkic term for «stone» and -kent the Turkic analogue of kand.[citation needed]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Along with Bukhara,[12] Samarkand is one of the oldest inhabited cities in Central Asia, prospering from its location on the trade route between China and Europe. There is no direct evidence of when it was founded. Researchers at the Institute of Archaeology of Samarkand date the city’s founding to the 8th–7th centuries BCE.

Archaeological excavations conducted within the city limits (Syob and midtown) as well as suburban areas (Hojamazgil, Sazag’on) unearthed 40,000-year-old evidence of human activity, dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. A group of Mesolithic (12th–7th millennia BCE) archaeological sites were discovered in the suburbs of Sazag’on-1, Zamichatosh, and Okhalik. The Syob and Darg’om canals, supplying the city and its suburbs with water, appeared around the 7th–5th centuries BCE (early Iron Age).

From its earliest days, Samarkand was one of the main centres of Sogdian civilization. By the time of the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia, the city had become the capital of the Sogdian satrapy.

Hellenistic period[edit]

Ancient city walls of Samarkand, 4th century BCE

Alexander the Great conquered Samarkand in 329 BCE. The city was known as Maracanda by the Greeks.[13] Written sources offer small clues as to the subsequent system of government;[14] they mention one Orepius who became ruler «not from ancestors, but as a gift of Alexander.»[15]

While Samarkand suffered significant damage during Alexander’s initial conquest, the city recovered rapidly and flourished under the new Hellenic influence. There were also major new construction techniques; oblong bricks were replaced with square ones and superior methods of masonry and plastering were introduced.[16]

Alexander’s conquests introduced classical Greek culture into Central Asia; for a time, Greek aesthetics heavily influenced local artisans. This Hellenistic legacy continued as the city became part of various successor states in the centuries following Alexander’s death, i.e. the Seleucid Empire, Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and Kushan Empire (even though the Kushana themselves originated in Central Asia). After the Kushan state lost control of Sogdia during the 3rd century CE, Samarkand went into decline as a centre of economic, cultural, and political power. It did not significantly revive until the 5th century.

Sassanian era[edit]

Samarkand was conquered by the Persian Sassanians c. 260 CE. Under Sassanian rule, the region became an essential site for Manichaeism and facilitated the dissemination of the religion throughout Central Asia.[17]

Hephtalites and Turkic Khaganate era[edit]

In AD 350–375 Samarkand was conquered by the nomadic tribes of Xionites, the origin of which remains controversial.[18]

The resettlement of nomadic groups to Samarkand confirms archaeological material from the 4th century. The culture of nomads from the Middle Syrdarya basin is spreading in the region.[19] In 457-509 Samarkand was part of the Kidarite state.[20]

After the Hephtalites («White Huns») conquered Samarkand, they controlled it until the Göktürks, in an alliance with the Sassanid Persians, won it at the Battle of Bukhara, c. 560 CE.[citation needed]

In the middle of the 6th century, a Turkic state was formed in Altai, founded by the Ashina dynasty. The new state formation was named the Turkic Khaganate after the people of the Turks, which were headed by the ruler — the Khagan. In 557-561, the Hephthalites empire was defeated by the joint actions of the Turks and Sassanids, which led to the establishment of a common border between the two empires.[23]

In the early Middle Ages, Samarkand was surrounded by four rows of defensive walls and had four gates.[24]

An ancient Turkic burial with a horse was investigated on the territory of Samarkand. It dates back to the 6th century.[25]

During the period of the ruler of the Western Turkic Kaganate, Tong Yabghu Qaghan (618-630), family relations were established with the ruler of Samarkand — Tong Yabghu Qaghan gave him his daughter.[26]

Some parts of Samarkand have been Christians since the 4th century. In the 5th century, a Nestorian chair was established in Samarkand. At the beginning of the 8th century, it was transformed into a Nestorian metropolitanate.[27] Discussions and polemics arose between the Sogdian followers of Christianity and Manichaeism, reflected in the documents.[28]

Early Islamic era[edit]

The armies of the Umayyad Caliphate under Qutayba ibn Muslim captured the city from the Turks c. 710 CE.[17]

During this period, Samarkand was a diverse religious community and was home to a number of religions, including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Manichaeism, Judaism, and Nestorian Christianity, with most of the population following Zoroastrianism.[30]

Qutayba generally did not settle Arabs in Central Asia; he forced the local rulers to pay him tribute but largely left them to their own devices. Samarkand was the major exception to this policy: Qutayba established an Arab garrison and Arab governmental administration in the city, its Zoroastrian fire temples were razed, and a mosque was built.[31] Much of the city’s population converted to Islam.[32]

As a long-term result, Samarkand developed into a center of Islamic and Arabic learning.[31]

Abbasid gold dinar minted in AH 248–252 / AD 862–866 Samarkand

At the end of the 740s, a movement of those dissatisfied with the power of the Umayyads emerged in the Arab Caliphate, led by the Abbasid commander Abu Muslim, who, after the victory of the uprising, became the governor of Khorasan and Maverannahr (750-755). He chose Samarkand as his residence. His name is associated with the construction of a multi-kilometer defensive wall around the city and the palace.[33]

Legend has it that during Abbasid rule,[34] the secret of papermaking was obtained from two Chinese prisoners from the Battle of Talas in 751, which led to the foundation of the first paper mill in the Islamic world at Samarkand. The invention then spread to the rest of the Islamic world and thence to Europe.[citation needed]

Abbasid control of Samarkand soon dissipated and was replaced with that of the Samanids (875–999), though the Samanids were still nominal vassals of the Caliph during their control of Samarkand. Under Samanid rule the city became a capital of the Samanid dynasty and an even more important node of numerous trade routes. The Samanids were overthrown by the Karakhanids around 999. Over the next 200 years, Samarkand would be ruled by a succession of Turkic tribes, including the Seljuqs and the Khwarazmshahs.[35]

The 10th-century Persian author Istakhri, who travelled in Transoxiana, provides a vivid description of the natural riches of the region he calls «Smarkandian Sogd»:

I know no place in it or in Samarkand itself where if one ascends some elevated ground one does not see greenery and a pleasant place, and nowhere near it are mountains lacking in trees or a dusty steppe… Samakandian Sogd… [extends] eight days travel through unbroken greenery and gardens… . The greenery of the trees and sown land extends along both sides of the river [Sogd]… and beyond these fields is pasture for flocks. Every town and settlement has a fortress… It is the most fruitful of all the countries of Allah; in it are the best trees and fruits, in every home are gardens, cisterns and flowing water.

Karakhanid (Ilek-Khanid) period (11th–12th centuries)[edit]

Shah-i Zinda memorial complex, 11th–15th centuries