А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

ша́баш, -а, тв. -ем (субботний отдых; сборище ведьм)

Рядом по алфавиту:

чушь , -и

чу́ющий(ся)

чу́янный , кр. ф. чу́ян, -а, прич.

чу́ять(ся) , чу́ю, чу́ет(ся)

чхать , чха́ю, чха́ет (сниж. к чиха́ть)

чхнуть , чхну, чхнёт (сниж. к чихну́ть)

ч-ш , и ч-ш-ш, неизм.

чьё , чьего́

чья , чьей

ЧЭЗ , нескл., с. (сокр.: частотное электромагнитное зондирование)

чэнду́ский , (от Чэнду́)

ша , нескл., с. (название буквы)

ша , межд.

шабази́т , -а

шабала́ , -ы́

ша́баш , -а, тв. -ем (субботний отдых; сборище ведьм)

шаба́ш , неизм. (кончено, довольно) (сниж.)

шаба́шить , -шу, -шит (сниж.)

шаба́шка , -и, р. мн. -шек (сниж.)

шаба́шник , -а (сниж.)

шаба́шничать , -аю, -ает (сниж.)

шаба́шнический , (сниж.)

шаба́шничество , -а

шаба́шный , (сниж.)

Ша́ббат , -а

шабда́р , -а

ша́бер , -а (инструмент)

шабёр , шабра́ (сосед)

шабли́ , нескл., с.

шабло́н , -а

шаблониза́ция , -и

- ша́баш, -а, тв. -ем (субботний отдых; сборище ведьм)

- шаба́ш, неизм. (кончено, довольно) (сниж.)

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я обязательно научусь отличать широко распространённые слова от узкоспециальных.

Насколько понятно значение слова рейдерство:

Ассоциации к слову «шабаш»

Синонимы к слову «шабаш»

Предложения со словом «шабаш»

- Полуночные шабаши ведьмы проводили в старой хижине, целиком построенной из сучьев и грунта и стоявшей посреди реки, будто огромная бобровая плотина.

- Все лучшие инстинкты были подавлены, лишь только пробудившиеся от спячки массы вырвались на свободу. Это был настоящий шабаш толпы.

- Во время шабаша никто из посторонних не должен даже случайно заглянуть сюда.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «шабаш»

- — Я тебе покажу, подлец, спокойно… У!.. стракулист поганый!.. Думаешь, я на тебя суда не найду? Не-ет, найду!.. Последнюю рубаху просужу, а тебя добуду… Спокойно!.. Да я… А-ах, Владимир Петрович, Владимир Петрович!.. Где у тебя крест-то?.. Ведь ты всю семью по миру пустил… всех… Теперь ведь глаз нельзя никуда показать… срам!.. Старуху и ту по миру пустил… Хуже ты разбойника и душегубца, потому что тот хоть разом живота решит и шабаш, а ты… а-ах, Владимир Петрович, Владимир Петрович!

- — Савоська обнаковенно пирует, — говорил рыжий пристанский мужик в кожаных вачегах, — а ты его погляди, когда он в работе… Супротив него, кажись, ни единому сплавщику не сплыть; чистенько плавает. И народ не томит напрасной работой, а ежели слово сказал — шабаш, как ножом отрезал. Под бойцами ни единой барки не убил… Другой и хороший сплавщик, а как к бойцу барка подходит — в ем уж духу и не стало. Как петух, кричит-кричит, руками махает, а, глядишь, барка блина и съела о боец.

- — Я тебе вот что скажу, барин: как теперь станет весна али осень, вода будет ледяная — шабаш! Как поробил твой Заяц в выработке, пришел в балаган да лег, а встать и невмоготу. Другой раз недели с две Заяц без работы лежит, потому ноги, как деревянные.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение слова «шабаш»

-

ША́БАШ, -а и ШАБА́Ш, -а́, м. 1. (ша́баш). Субботний отдых, предписываемый еврейской религией. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова ШАБАШ

ша́баш

Правильное ударение в этом слове падает на 1-й слог. На букву а

Посмотреть все слова на букву Ш

Ответ:

Правильное написание слова — шабаш

Ударение и произношение — шаб`аш

Значение слова -В иудаизме:|субботний отдых

Выберите, на какой слог падает ударение в слове — МУСОРОПРОВОД?

или

Слово состоит из букв:

Ш,

А,

Б,

А,

Ш,

Похожие слова:

бесшабашно

бесшабашной

бесшабашность

бесшабашною

бесшабашный

зашабашили

зашабашить

пошабашить

шабаша

шабашащий

Рифма к слову шабаш

ваш, наш, таш

Толкование слова. Правильное произношение слова. Значение слова.

Автор Аннита Рудкова На чтение 8 мин. Просмотров 15 Опубликовано 17.12.2021

шабаш, -а, тв.

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

Орфографический словарь

шабаш, -а, тв. -ем (субботнийотдыхсборищеведьм)

шабашнеизм. (конченодовольно) (сниж.)

Большой толковый словарь

ШАБАШ, -а; м. [от др.-евр. sabbath — суббота] В народных поверьях: ночное сборище ведьм, колдунов и т.п., сопровождающееся диким разгулом. Ш. на Лысой горе./Разг. О диком разгуле. Поднять, устроить ш.Ш. пьяного веселья.

ШАБАШ.Разг.I. —ам. Конец работы или перерыв. Объявить ш.Нигде — никого. Видать, ш.II.межд. Команда полного окончания работы или объявление перерыва. Ш., ребята! суши вёсла.Ш.! по домам пора.III.в функц. сказ.1. Хватит, довольно, пора кончать. Ш.! больше не курю.Ш., сколько можно сердиться.2. Гибель, конец. Ш. моему покою.Ш. холостяцкой жизни!

Управление в русском языке

искомое слово отсутствует

Русское словесное ударение

шабаш, -а, -ем (у иудеев: субботнийотдых; в нар. поверьях : сборище ведьм)

шабаш,межд.в знач. сказ.(кончено, довольно)

Словарь имён собственных

искомое слово отсутствует

Словарь синонимов

Синонимы: краткий справочник

искомое слово отсутствует

Словарь антонимов

искомое слово отсутствует

Словарь методических терминов

искомое слово отсутствует

Словарь русских имён

искомое слово отсутствует

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

Большинство ошибок в русском языке связаны с незнанием значения слова или неправильной трактовкой. А это так важно! Всегда нужно знать, что слово значит, чтобы не попасть в некрасивую ситуацию, за которую может быть стыдно. Как правильно: шАбаш или шабАш?

Как поставить ударение в слове: шАбаш или шабАш?

В этом слове допускаются оба варианта.

Какое правило применяется?

Как уже сказано выше, нужно обращать внимание на значение слова. Особенно, если их два. Такое слово называется многозначным. Именно от толкования и зависит ударение.

Итак, если ударение падает на первый слог – «шАбаш», то оно означает шумное мероприятие. Если на второй – «шабАш», – то означает, что все сделано и закончено.

Это слово – яркий пример прямой зависимости ударения от значения.

Как запомнить, где ударение?

ШАбаш был веселый

В городах и селах.

Примеры предложений

- Очередной субботний шАбаш был посвящен преддверию отпуска.

- Я сказал: «ШабАш», – и ушел спать в свою комнату.

Неправильное ударение

будет тогда, когда слово будет употреблено в неверном значении.

Если вы затрудняетесь, воспользуйтесь толковым словарем.

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

Ударение в слове шабаш

Слово шабаш может употребляться в 2-х разных значениях:

I. шаба́ш

— кончено, довольно

В указанном выше варианте ударение падает на слог с последней буквой А — шабАш.

II. ша́баш

— субботний отдых; шумное сборище

В данном слове ударение должно быть поставлено на слог с первой буквой А — шАбаш.

А вы знаете, как правильно ставить ударение в слове ?

Примеры предложений, как пишется шабаш

Чего-то мне вроде не хватает, какая-то чесотка на меня нападет, — не усну, и шабаш

– Шабаш, – сказал он затем. – Устал до смерти.

Зато когда сцапали – шабаш, брат!

– Ребята, шабаш! На сегодня хватит! – предложил Кестер. – Достаточно заработали за один день! Нельзя испытывать бога. Возьмем «Карла» и поедем тренироваться. Гонки на носу.

Штаны не застегну — и шабаш

На данной странице размещена информация о том, на какой слог правильно ставить ударение в слове шабаш. Слово «шабаш» может употребляться в разных значениях, в зависимости от которых ударение может падать на разные слоги. В слове шаба́ш, кончено, довольно, ударение ставят на слог с последней буквой А. В слове ша́баш, субботний отдых; шумное сборище, ударение следует ставить на слог с первой буквой А. Надеемся, что теперь у вас не возникнет вопросов, как пишется слово шабаш, куда ставить ударение, какое ударение, или где должно стоять ударение в слове шабаш, чтобы грамотно его произносить.

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

Лингвистическая помощь: Как правильно — шАбаш или шабАш?

Слово «ша́баш» с ударением на первый слог означает «сборище ведьм».

Слово с ударением на второй слог «шаба́ш» имеет два значения:

1) междометие «довольно»;

2) конец.

Следует отметить, что в словаре это междометие сопровождается пометой «сниж.». Это означает, что оно относится к просторечно-разговорному языку.

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

шабаш

- шабаш

- 1. ша́баш, -а, -ем (у иудеев: субботнийотдых; в нар. поверьях : сборище ведьм)

2. шаба́ш, межд.; в знач. сказ.(кончено, довольно)

Русское словесное ударение. — М.: ЭНАС.

.

Синонимы

Смотреть что такое «шабаш» в других словарях:

-

ШАБАШ — муж., евр., шабаш, суббота, праздник, день молитвы; | отдых, конец работе, время свободное от дела, пора роздыха. Утренний, вечерний шабаш. Работать на один шабаш, более зимой, все светлое время. Дать шабаша, уволить с работы. Шабаш, миряне,… … Толковый словарь Даля

-

шабаш — и шабаш. В знач. «субботний отдых, праздник, предписываемый иудаизмом; в суеверных поверьях ночное сборище колдунов, ведьм, сопровождаемое диким разгулом» шабаш, род. шабаша. Соблюдать шабаш. Ведьмы шабаш справляют. В знач. «окончание работы,… … Словарь трудностей произношения и ударения в современном русском языке

-

шабаш — шабаша, м. [др. евр. покой]. 1. (шабаш). Субботний отдых, предписываемый еврейской религией. 2. (шабаш). В средневековых поверьях ночное собрание ведьм, сопровождавшееся диким разгулом. «Будь я с предрассудками, я порешил бы, что это черти и… … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

шабаш — См. конец, довольно да и шабаш… Словарь русских синонимов и сходных по смыслу выражений. под. ред. Н. Абрамова, М.: Русские словари, 1999. шабаш гульбище, гульба, разгулье, разгул, праздник, отдых, кутеж, свистопляска, сборище, попойка, оргия;… … Словарь синонимов

-

«ШАБАШ» — (Ship your oars) команда, подающаяся на гребных шлюпках для одновременного прекращения гребли и уборки весел внутрь шлюпки всеми гребцами. По этой команде гребцы, подложив локтевые сгибы ближайших к борту рук под валек, резким нажимом кистей… … Морской словарь

-

ШАБАШ — (евр. schabat покой). 1) Еврейский праздник субботы. 2) у рабочих окончание работы, отдых, время, свободное от работы хозяину. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. ШАБАШ еврейск. schabat, араб. sebt.… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

ШАБАШ — (End of a day s work) окончание работы; работать на один шабаш работать без отдыха несколько часов подряд. Работать на два шабаша иметь в промежутке между работами отдых. Самойлов К. И. Морской словарь. М. Л.: Государственное Военно морское… … Морской словарь

-

ШАБАШ — (от др. евр. шаббат суббота) ..1) субботний отдых, праздник, предписываемый иудаизмом2)] В средневековых поверьях ночное сборище ведьм3) (С ударением на 2 м слоге) окончание работы (в просторечии) … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

Шабаш — I ш абаш м. Субботний отдых, когда нельзя работать (в иудаизме). II ш абаш м. 1. Ночное сборище ведьм, сопровождающееся диким разгулом (в поверьях эпохи Средневековья). 2. перен. Неистовый разгул. III шаб аш м. разг. Переры … Современный толковый словарь русского языка Ефремовой

-

Шабаш — I ш абаш м. Субботний отдых, когда нельзя работать (в иудаизме). II ш абаш м. 1. Ночное сборище ведьм, сопровождающееся диким разгулом (в поверьях эпохи Средневековья). 2. перен. Неистовый разгул. III шаб аш м. разг. Переры … Современный толковый словарь русского языка Ефремовой

-

Шабаш — I ш абаш м. Субботний отдых, когда нельзя работать (в иудаизме). II ш абаш м. 1. Ночное сборище ведьм, сопровождающееся диким разгулом (в поверьях эпохи Средневековья). 2. перен. Неистовый разгул. III шаб аш м. разг. Переры … Современный толковый словарь русского языка Ефремовой

Книги

- ШАБАШ ВЕДЬМ, Василий Заботин. Так вот сложилась моя писательская жизнь, что я вынужден окончательно легализоваться в своем писательском псевдониме: отныне я буду Василий Заботин-Лапшин… В этомнебольшом вопросе я не… Подробнее Купить за 516 грн (только Украина)

- ШАБАШ ВЕДЬМ, Василий Заботин. Так вот сложилась моя писательская жизнь, что я вынужден окончательно легализоваться в своем писательском псевдониме: отныне я буду Василий Заботин-Лапшин… В этом небольшом вопросе я – не… Подробнее Купить за 459 руб

- Шабаш, Наталья Валентинова. И вот еще один маленький мирок, по которому неприкаянно бродят Принц-демон, скрываясь от ведьм, и юная ведьмочка, прячущая лицо под капюшоном и набирающая к зачету положенное число пакостей.… Подробнее Купить за 200 руб электронная книга

Другие книги по запросу «шабаш»

Правильное ударение в слове «шабаш»

- Словарь ударений

- Ш

- шабаш

Ударение в слове «шабаш»

Ударение в слове может падать на разные слоги. Место ударения зависит от значения слова.

ша́баш

Собрание ведьм, ритуал. Ударение падает на 1-й слог (с буквой а).

шаба́ш

В значении довольно. Ударение падает на 2-й слог (с буквой а).

Ударение в слове «шабаш» ик нему приведены согласно данным русского орфографического словаря Российской академии наук под редакцией В.В. Лопатина, нового толково-словообразовательного словаря русского языка автора Т.Ф. Ефремовой, русского словесного ударения автора М.В. Зарвы, большого толкового словаря правильной русской речи автора Л.И. Скворцова.

Разбор слова «Шабаш»

На чтение 1 мин.

Значение слова «Шабаш»

— субботний отдых, предписываемый иудаизмом (мужской)

— ночное сборище ведьм, сопровождающееся диким разгулом (в средневековых поверьях) (мужской)

— окончание работы в какое-либо урочное время (мужской, разговорно-сниженное)

Содержание

- Транскрипция слова

- MFA Международная транскрипция

- Цветовая схема слова

Транскрипция слова

[ша́баш]

MFA Международная транскрипция

[ˈʂabəʂ]

| ш | [ш] | согласный, глухой парный, твердый непарный |

| а | [́а] | гласный, ударный |

| б | [б] | согласный, звонкий парный, твердый парный |

| а | [а] | гласный, безударный |

| ш | [ш] | согласный, глухой парный, твердый непарный |

Букв: 5 Звуков: 5

Цветовая схема слова

шабаш

Как правильно пишется «Шабаш»

Как правильно перенести «Шабаш»

ша́—баш

Часть речи

Часть речи слова «шабаш» — Имя существительное

Морфологические признаки.

шабаш (именительный падеж, единственного числа)

Постоянные признаки:

- нарицательное

- неодушевлённое

- мужской

- 2-e склонение

Непостоянные признаки:

- именительный падеж

- единственного числа

Может относится к разным членам предложения.

Склонение слова «Шабаш»

| Падеж | Единственное число | Множественное число |

|---|---|---|

| Именительный Кто? Что? |

ша́баш | ша́баши |

| Родительный Кого? Чего? |

ша́баша | ша́башей |

| Дательный Кому? Чему? |

ша́башу | ша́башам |

| Винительный (неод.) Кого? Что? |

ша́баш | ша́баши |

| Творительный Кем? Чем? |

ша́башем | ша́башами |

| Предложный О ком? О чём? |

ша́баше | ша́башах |

Разбор по составу слова «Шабаш»

Состав слова «шабаш»:

корень — [шабаш]

Проверьте свои знания русского языка

Категория: Русский язык

Русский язык

Тест на тему “Орфограмма”

1 / 5

Как нужно подчеркивать место, где можно совершить ошибку?

Одной чертой

Двумя чертами

Волнистой линией

Двумя волнистыми линиями

2 / 5

Какая орфограмма наблюдается в слове «жизнь»?

Большая буква в начале предложения

Правописание сочетаний «жи-ши», «ча-ща», «чу-щу»

Правописание мягкого знака

Правописание сочетаний «чк-чн»

3 / 5

Укажите неверное утверждение.

Орфограмма с греческого переводится как «правильно писать»

Орфографическая зоркость – это умение видеть слово, в котором есть орфограмма

Наличие большого количества орфограмм способствовало появлению такой науки, как орфография

Условие, по которому пишется та, а не другая буква, подчеркивается волнистой линией

4 / 5

Какая орфограмма наблюдается в слове «сердце»?

Проверяемые безударные гласные в корне слова

Непроверяемые безударные гласные в корне слова

Имена собственные

Непроизносимые согласные в корне слова

5 / 5

Что такое орфограмма?

Раздел языкознания

Иностранный язык

Место в слове, где можно допустить ошибку, написав неправильную букву

Начальная буква в слове

Синонимы к слову «шабаш»

Ассоциации к слову «шабаш»

Предложения со словом «шабаш»

- Полуночные шабаши ведьмы проводили в старой хижине, целиком построенной из сучьев и грунта и стоявшей посреди реки, будто огромная бобровая плотина.

Крис Колфер, Страна Сказок. За гранью сказки, 2015

- Так что американским фашистам можно устраивать шабаш дважды, можно 30 апреля, а можно скажем 11—12 апреля.

Аркадий Велюров, Пепелацы летят на Луну. Большой космический обман США. Часть 10

- На кремлёвском троне начинается шабаш бывших секретарей обкомов.

Вадим Кирпичев, Путин против либерального болота. Как сохранить Россию, 2014

Русский

ша́баш I

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | ша́баш | ша́баши |

| Р. | ша́баша | ша́башей |

| Д. | ша́башу | ша́башам |

| В. | ша́баш | ша́баши |

| Тв. | ша́башем | ша́башами |

| Пр. | ша́баше | ша́башах |

ша́—баш

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 4a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Производное: ??.

Корень: -шабаш-.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [ˈʂabəʂ], мн. ч. [ˈʂabəʂɨ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- религ. в иудаизме: субботний отдых, когда нельзя работать ◆ Шабаш первоначально означал, видимо, наступление субботы. Пока не сгустились сумерки, ты мог неутомимо предаваться любому делу, но в то мгновение, когда тебя заставала первая звезда, ты должен был бросить исполняемую работу. Л. А. Левицкий, Дневник, 1994 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Перед субботой ― шабаш. Здесь сутки начинаются с вечера и кончаются следующим вечером, поэтому с вечера пятницы всё закрывается до вечера субботы: работать нельзя (Бог не велит) до восхода первой звезды. Е. Я. Весник, «Дарю, что помню», 1997 г. [НКРЯ]

Синонимы

- ?

Антонимы

- ?

Гиперонимы

- субботний отдых

Гипонимы

- ?

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

|

Библиография

- Зализняк А. А. шабаш // Грамматический словарь русского языка. — Изд. 5-е, испр. — М. : АСТ Пресс, 2008.

- шабаш // Научно-информационный «Орфографический академический ресурс „Академос“» Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. orfo.ruslang.ru

- Ефремова Т. Ф. шабаш // Современный толковый словарь русского языка. — М. : Русский язык, 2000.

ша́баш II

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | ша́баш | ша́баши |

| Р. | ша́баша | ша́башей |

| Д. | ша́башу | ша́башам |

| В. | ша́баш | ша́баши |

| Тв. | ша́башем | ша́башами |

| Пр. | ша́баше | ша́башах |

ша́—баш

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 4a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Производное: ??.

Корень: -шабаш-.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [ˈʂabəʂ], мн. ч. [ˈʂabəʂɨ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- мифол. в поверьях эпохи Средневековья: ночное сборище ведьм, сопровождающееся диким разгулом ◆ А потом кто-то донёс отцу Доминику, что донна та ведьма и еретичка и летает по ночам на шабаш, где совокупляется с дьяволом. Наталья Александрова, «Последний ученик да Винчи», 2010 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ В 1670-х, когда было модно избавиться от соседки, обозвав её ведьмой, в городе перешёптывались, что здесь собираются колдуньи, перед тем как лететь на шабаш на гору Блокулла. Григорий Гольденцвайг, «Стокгольм», 2011 г. [НКРЯ]

- перен. неистовый разгул ◆ Говорили мне, например, что ночью по субботам полмиллиона работников и работниц, с их детьми, разливаются как море по всему городу, наиболее группируясь в иных кварталах, и всю ночь до пяти часов празднуют шабаш, то есть наедаются и напиваются, как скоты, за всю неделю. Ф. М. Достоевский, «Зимние заметки о летних впечатлениях», 1863 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Вон у соседки-беженки Нюрки (нелёгкая её забери) пьянки каждый день в дому, шабаш. Кирилл Тахтамышев, «Айкара», 2002 г. [НКРЯ]

- перен. специально организованное или спровоцированное политическое, идеологическое публичное мероприятие ◆ — Нет, во всенародных шабашах я не участвую. Леонид Филатов, И. Шевцов, «Сукины дети», 1992 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Слышал, что в Петропавловске состоялся шабаш наших последышей коричнерубашечников, на котором раздавались речи, сводившиеся к тому, что отечественные витязи жидоморства доделают дело, которое начал, но не довёл до конца Адольф и его банда. Л. А. Левицкий, Дневник, 1994 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Это был шабаш зла, торжество всяческой гнусности, когда люди (по крайней мере, часть из них) даже стремились прослыть мерзавцами, ища упоения в ужасе, внушаемом ими окружающим. Д. С. Лихачёв, Воспоминания, 1995 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Иван Петрович, наверное, в могиле перевернулся, какой шабаш вокруг его имени устроили коммунисты от науки. Николай Амосов, «Голоса времён», 1999 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Начался настоящий шабаш по уничтожению «врагов» советского искусства. В. С. Давыдов, «Театр моей мечты», 2004 г. [НКРЯ]

Синонимы

- ?

- ?

- ?

Антонимы

- ?

- ?

- ?

Гиперонимы

- сборище

- разгул

- мероприятие

Гипонимы

- ?

- ?

- ?

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| в поверьях эпохи Средневековья: ночное сборище ведьм, сопровождающееся диким разгулом | |

|

| неистовый разгул | |

|

| специально организованное или спровоцированное политическое, идеологическое публичное мероприятие | |

Библиография

- Зализняк А. А. шабаш // Грамматический словарь русского языка. — Изд. 5-е, испр. — М. : АСТ Пресс, 2008.

- шабаш // Научно-информационный «Орфографический академический ресурс „Академос“» Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. orfo.ruslang.ru

- Ефремова Т. Ф. шабаш // Современный толковый словарь русского языка. — М. : Русский язык, 2000.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

шаба́ш I

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | шаба́ш | шабаши́ |

| Р. | шабаша́ | шабаше́й |

| Д. | шабашу́ | шабаша́м |

| В. | шаба́ш | шабаши́ |

| Тв. | шабашо́м | шабаша́ми |

| Пр. | шабаше́ | шабаша́х |

ша—ба́ш

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 4b по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -шабаш-.

Произношение

- МФА: [ʂɐˈbaʂ]

омофоны: шабашь

Семантические свойства

Значение

- разг. перерыв в работе; окончание работы в какое-либо урочное время ◆ Он не ограничивался десятичасовым рабочим днём, который был установлен для каторжан, и каждый день задерживал как перед обедом, так и перед шабашем на полчаса, а то и больше, выгоняя ежедневно до двенадцати часов. П. Рассказов, «Записки заключённого», 1920 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Здесь светло маячили многотрудный отдых, шабаш: веселье, «швабода» от всех и всего в промытом до голубых слёз, тонком стакане северного прохладного лета. Владимир Скрипкин, «Тинга» // «Октябрь», 2002 г. [НКРЯ]

Синонимы

- ?

Антонимы

- ?

Гиперонимы

- перерыв; окончание

Гипонимы

- ?

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

Библиография

- Зализняк А. А. шабаш // Грамматический словарь русского языка. — Изд. 5-е, испр. — М. : АСТ Пресс, 2008.

- шабаш // Научно-информационный «Орфографический академический ресурс „Академос“» Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. orfo.ruslang.ru

- Ефремова Т. Ф. шабаш // Современный толковый словарь русского языка. — М. : Русский язык, 2000.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

шаба́ш II

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

ша—ба́ш

Междометие, также предикатив; неизменяемое.

Производное: ??.

Корень: -шабаш-.

Произношение

- МФА: [ʂɐˈbaʂ]

омофоны: шабашь

Семантические свойства

Значение

- разг. возглас, выражающий категорическое требование прекратить что-либо и соответствующий по значению словам: довольно!, кончено!, баста! ◆ — Шабаш, мужики! Хорошо поработали. Б. А. Можаев, «Падение лесного короля», 1975 г. [НКРЯ]

- предик., разг. употребляется в качестве обозначения окончания, завершения чего-либо: конец ◆ Сейчас ещё пару слов скажет председательствующий собрания, председатель подкомитета городского законодательно собрания. Закроет торжественную часть ― и шабаш. Можно позволить себе холодного пивка, а заодно уж нужно прояснить некоторые деловые моменты. А. Б. Троицкий, «Удар из прошлого», 2000 г. [НКРЯ]

Синонимы

- баста, довольно, хватит, стоп

- ?

Антонимы

- ?

- ?

Гиперонимы

- ?

- ?

Гипонимы

- ?

- ?

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| возглас, выражающий категорическое требование прекратить что-либо и соответствующий по значению словам: довольно!, кончено!, баста! | |

|

| употребляется в качестве обозначения окончания, завершения чего-либо: конец | |

Библиография

- Зализняк А. А. шабаш // Грамматический словарь русского языка. — Изд. 5-е, испр. — М. : АСТ Пресс, 2008.

- шабаш // Научно-информационный «Орфографический академический ресурс „Академос“» Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова РАН. orfo.ruslang.ru

- Ефремова Т. Ф. шабаш // Современный толковый словарь русского языка. — М. : Русский язык, 2000.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

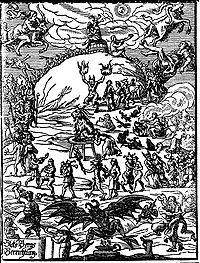

Sixteenth-century Swiss representation of Sabbath gathering from the chronicles of Johann Jakob Wick. Note Devil seated on serpent-enlaced throne, witch performing the osculum infame upon a demon and another being aided by a demon to summon a storm from her cauldron, while others carouse and prepare magic potions

A Witches’ Sabbath is a purported gathering of those believed to practice witchcraft and other rituals. The phrase became popular in the 20th century.

Emergence as a Popular Phrase in the 20th century[edit]

Prior to the late 19th century, it is difficult to locate any English use of the term sabbath to denote a supposed gathering of witches. The phrase is used by Henry Charles Lea in his History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages (1888).[1] Writing in 1900, German historian Joseph Hansen who was a correspondent and a German translator of Lea’s work, frequently uses the shorthand phrase hexensabbat to interpret medieval trial records, though any consistently recurring term is noticeably rare in the copious Latin sources Hansen also provides (see more on various Latin synonyms, below).[2]

Index of a 1574 printing of Malleus Maleficarum

Notably, the most infamous and influential work of witch-phobia, Malleus Maleficarum (1486) does not contain the word sabbath (sabbatum).

Lea and Hansen’s influence may have led to a much broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, use of the term by German historians also seems to have been relatively rare. A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s (Kinder und HausMärchen, Deutsche Mythologie) seems to contain no mention of hexensabbat or any other form of the term sabbat relative to fairies or magical acts.[3] The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, WG Soldan also doesn’t seem to use the term in his history (1843).

A French connection[edit]

In contrast to German and English counterparts, French writers (including Francophone authors writing in Latin) used the term more frequently, albeit still relatively rare. There would seem to possibly be deep roots to inquisitorial persecution of the Waldensians. In 1124, the term inzabbatos is used to describe the Waldensians in Northern Spain.[4] In 1438 and 1460, seemingly related terms synagogam and synagogue of Sathan are used to describe Waldensians by inquisitors in France. These terms could be a reference to Revelation 2:9. («I know the blasphemy of them which say they are Jews and are not, but are the synagogue of Satan.»)[5][6] Writing in Latin in 1458, Francophone author Nicolas Jacquier applies synagogam fasciniorum to what he considers a gathering of witches.[7]

About 150 years later, near the peak of the witch-phobia and the persecutions which led to the execution of an estimated 40,000-100,000 persons,[8][9] with roughly 80% being women,[10][11] the Francophone writers still seem to be the main ones using these related terms, although still infrequently and sporadically in most cases. Lambert Daneau uses sabbatha one time (1581) as Synagogas quas Satanica sabbatha.[12] Nicholas Remi uses the term occasionally as well as synagoga (1588). Jean Bodin uses the term three times (1580) and, across the channel, the Englishman Reginald Scot (1585) writing a book in opposition to witch-phobia, uses the term but only once in quoting Bodin. (The Puritan Richard Baxter writing much later (1691) also uses the term only once in the exact same way–quoting Bodin. Other witch-phobic English Puritans who were Baxter’s contemporaries, like Increase and Cotton Mather (1684, 1689, 1692), did not use the term, perhaps because they were Sabbatarians.)

In 1611, Jacques Fontaine uses sabat five times writing in French and in a way that would seem to correspond with modern usage. The following year (1612), Pierre de Lancre seems to use the term more frequently than anyone before.[13]

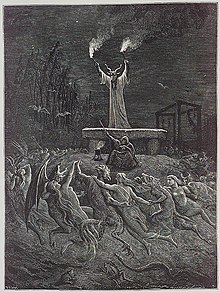

Witches’ Sabbath — Johannes Praetorius: Blockes-Berges Verrichtung, Leipzig, 1668.

In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published «Blockes-Berges Verrichtung», with the subtitle «Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1. Maij in Sanct-Walpurgis Nachte anstellen sollen».[14] As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a «Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches’ journey and magic sabbaths».

Writing more than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, another French writer Lamothe-Langon (whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s) uses the term in (presumably) translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources.

A term favored by recent translators[edit]

Despite the infrequency of the use of the word sabbath to denote any such gatherings in the historical record, it became increasingly popular during the 20th century.

Cautio Criminalis[edit]

In a 2003 translation of Friedrich Spee’s Cautio Criminalis (1631) the word sabbaths is listed in the index with a large number of entries.[15] However, unlike some of Spee’s contemporaries in France (mentioned above), who occasionally, if rarely, use the term sabbatha, Friedrich Spee does not ever use words derived from sabbatha or synagoga. Spee was German-speaking, and like his contemporaries, wrote in Latin. Conventibus is the word Spee uses most frequently to denote a gathering of witches, whether supposed or real, physical or spectral, as seen in the first paragraph of question one of his book.[16] This is the same word from which English words convention, convent, and coven are derived. Cautio Criminalis (1631) was written as a passionate innocence project. As a Jesuit, Spee was often in a position of witnessing the torture of those accused of witchcraft.

Malleus Maleficarum[edit]

In a 2009 translation of Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (1486), the word sabbath does not occur. A line describing a supposed gathering and using concionem is accurately translated as an assembly. But in the accompanying footnote, the translator seems to apologize for the lack of both the term sabbath and a general scarcity of other gatherings that would seem to fit the bill for what he refers to as a «black sabbath».[17]

Fine art[edit]

The phrase is also popular in recent translations of the titles of artworks, including:

- The Witches’ Sabbath by Hans Baldung (1510)

- Witches’ Sabbath by Frans Francken (1606)

- Witches’ Sabbath in Roman Ruins by Jacob van Swanenburgh (1608)

- As a recent translation from the original Spanish El aquelarre to the English title Witches’ Sabbath (1798) and Witches’ Sabbath or The Great He-Goat (1823) both works by Francisco Goya

- Muse of the Night (Witches’ Sabbath) by Luis Ricardo Falero (1880)

Disputed accuracy of the accounts of gatherings[edit]

Modern researchers have been unable to find any corroboration with the notion that physical gatherings of practitioners of witchcraft occurred.[18] In his study «The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat», the historian Scott E. Hendrix presents a two-fold explanation for why these stories were so commonly told in spite of the fact that sabbats likely never actually occurred. First, belief in the real power of witchcraft grew during the late medieval and early-modern Europe as a doctrinal view in opposition to the canon Episcopi gained ground in certain communities. This fueled a paranoia among certain religious authorities that there was a vast underground conspiracy of witches determined to overthrow Christianity. Women beyond child-bearing years provided an easy target and were scapegoated and blamed for famines, plague, warfare, and other problems.[18] Having prurient and orgiastic elements helped ensure that these stories would be relayed to others.[19]

Ritual elements[edit]

Bristol University’s Ronald Hutton has encapsulated the witches’ sabbath as an essentially modern construction, saying:

[The concepts] represent a combination of three older mythical components, all of which are active at night: (1) A procession of female spirits, often joined by privileged human beings and often led by a supernatural woman; (2) A lone spectral huntsman, regarded as demonic, accursed, or otherworldly; (3) A procession of the human dead, normally thought to be wandering to expiate their sins, often noisy and tumultuous, and usually consisting of those who had died prematurely and violently. The first of these has pre-Christian origins, and probably contributed directly to the formulation of the concept of the witches’ sabbath. The other two seem to be medieval in their inception, with the third to be directly related to growing speculation about the fate of the dead in the 11th and 12th centuries.»[20]

The book Compendium Maleficarum (1608) by Francesco Maria Guazzo illustrates a typical witch-phobic view of gathering of witches as «the attendants riding flying goats, trampling the cross, and being re-baptised in the name of the Devil while giving their clothes to him, kissing his behind, and dancing back to back forming a round.»

In effect, the sabbat acted as an effective ‘advertising’ gimmick, causing knowledge of what these authorities believed to be the very real threat of witchcraft to be spread more rapidly across the continent.[18] That also meant that stories of the sabbat promoted the hunting, prosecution, and execution of supposed witches.

The descriptions of Sabbats were made or published by priests, jurists and judges who never took part in these gatherings, or were transcribed during the process of the witchcraft trials.[21] That these testimonies reflect actual events is for most of the accounts considered doubtful. Norman Cohn argued that they were determined largely by the expectations of the interrogators and free association on the part of the accused, and reflect only popular imagination of the times, influenced by ignorance, fear, and religious intolerance towards minority groups.[22]

Some of the existing accounts of the Sabbat were given when the person recounting them was being tortured,[23] and so motivated to agree with suggestions put to them.

Christopher F. Black claimed that the Roman Inquisition’s sparse employment of torture allowed accused witches to not feel pressured into mass accusation. This in turn means there were fewer alleged groups of witches in Italy and places under inquisitorial influence. Because the Sabbath is a gathering of collective witch groups, the lack of mass accusation means Italian popular culture was less inclined to believe in the existence of Black Sabbath. The Inquisition itself also held a skeptical view toward the legitimacy of Sabbath Assemblies.[24]

Many of the diabolical elements of the Witches’ Sabbath stereotype, such as the eating of babies, poisoning of wells, desecration of hosts or kissing of the devil’s anus, were also made about heretical Christian sects, lepers, Muslims, and Jews.[25] The term is the same as the normal English word «Sabbath» (itself a transliteration of Hebrew «Shabbat», the seventh day, on which the Creator rested after creation of the world), referring to the witches’ equivalent to the Christian day of rest; a more common term was «synagogue» or «synagogue of Satan»[26] possibly reflecting anti-Jewish sentiment, although the acts attributed to witches bear little resemblance to the Sabbath in Christianity or Jewish Shabbat customs. The Errores Gazariorum (Errors of the Cathars), which mentions the Sabbat, while not discussing the actual behavior of the Cathars, is named after them, in an attempt to link these stories to an heretical Christian group.[27]

More recently, scholars such as Emma Wilby have argued that although the more diabolical elements of the witches’ sabbath stereotype were invented by inquisitors, the witchcraft suspects themselves may have encouraged these ideas to circulate by drawing on popular beliefs and experiences around liturgical misrule, cursing rites, magical conjuration and confraternal gatherings to flesh-out their descriptions of the sabbath during interrogations.[28]

Christian missionaries’ attitude to African cults was not much different in principle to their attitude to the Witches’ Sabbath in Europe; some accounts viewed them as a kind of Witches’ Sabbath, but they are not.[29] Some African communities believe in witchcraft, but as in the European witch trials, people they believe to be «witches» are condemned rather than embraced.

Possible connections to real groups[edit]

Other historians, including Carlo Ginzburg, Éva Pócs, Bengt Ankarloo and Gustav Henningsen hold that these testimonies can give insights into the belief systems of the accused. Ginzburg famously discovered records of a group of individuals in northern Italy, calling themselves benandanti, who believed that they went out of their bodies in spirit and fought amongst the clouds against evil spirits to secure prosperity for their villages, or congregated at large feasts presided over by a goddess, where she taught them magic and performed divinations.[25] Ginzburg links these beliefs with similar testimonies recorded across Europe, from the armiers of the Pyrenees, from the followers of Signora Oriente in fourteenth century Milan and the followers of Richella and ‘the wise Sibillia’ in fifteenth century northern Italy, and much further afield, from Livonian werewolves, Dalmatian kresniki, Hungarian táltos, Romanian căluşari and Ossetian burkudzauta. In many testimonies these meetings were described as out-of-body, rather than physical, occurrences.[25]

Role of topically-applied hallucinogens[edit]

«Flying ointment» ingredient black henbane Hyoscyamus niger (family: Solanaceae)

Magic ointments…produced effects which the subjects themselves believed in, even stating that they had intercourse with evil spirits, had been at the Sabbat and danced on the Brocken with their lovers…The peculiar hallucinations evoked by the drug had been so powerfully transmitted from the subconscious mind to consciousness that mentally uncultivated persons…believed them to be reality.[30]

Carlo Ginzburg’s researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as Apuleius,

is the use of unguents conferring the power of «flight» and «shape-shifting.»[31] Recipes for such «flying ointments» have survived from early modern times[when?], permitting not only an assessment of their likely pharmacological effects – based on their various plant (and to a lesser extent animal) ingredients – but also the actual recreation of and experimentation with such fat or oil-based preparations.[32] Ginzburg makes brief reference to the use of entheogens in European witchcraft at the end of his analysis of the Witches Sabbath, mentioning only the fungi Claviceps purpurea and Amanita muscaria by name, and stating about the «flying ointment» on page 303 of ‘Ecstasies…’ :

In the Sabbath the judges more and more frequently saw the accounts of real, physical events. For a long time the only dissenting voices were those of the people who, referring back to the Canon episcopi, saw witches and sorcerers as the victims of demonic illusion. In the sixteenth century scientists like Cardano or Della Porta formulated a different opinion : animal metamorphoses, flights, apparitions of the devil were the effect of malnutrition or the use of hallucinogenic substances contained in vegetable concoctions or ointments…But no form of privation, no substance, no ecstatic technique can, by itself, cause the recurrence of such complex experiences…the deliberate use of psychotropic or hallucinogenic substances, while not explaining the ecstasies of the followers of the nocturnal goddess, the werewolf, and so on, would place them in a not exclusively mythical dimension.

– in short, a substrate of shamanic myth could, when catalysed by a drug experience (or simple starvation), give rise to a ‘journey to the Sabbath’, not of the body, but of the mind. Ergot and the Fly Agaric mushroom, while hallucinogenic,[33] were not among the ingredients listed in recipes for the flying ointment. The active ingredients in such unguents were primarily, not fungi, but plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae, most commonly Atropa belladonna (Deadly Nightshade) and Hyoscyamus niger (Henbane), belonging to the tropane alkaloid-rich tribe Hyoscyameae.[34] Other tropane-containing, nightshade ingredients included the Mandrake Mandragora officinarum, Scopolia carniolica and Datura stramonium, the Thornapple.[35]

The alkaloids Atropine, Hyoscyamine and Scopolamine present in these Solanaceous plants are not only potent and highly toxic hallucinogens, but are also fat-soluble and capable of being absorbed through unbroken human skin.[36]

See also[edit]

- Akelarre – Basque for Witches’ Sabbath

- Aradia – Character in the Gospel of the Witches

- Bald Mountain (folklore) – Witchcraft location in Slavic mythology

- Blockula – Devil’s secret island in Swedish legend

- Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath – 1989 book by Carlo Ginzburg

- Flying ointment – Hallucinogenic salve used in the practice of witchcraft

- Isobel Gowdie – Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Auldearn near Nairn during 1662

- Märet Jonsdotter – Swedish witch

- Alice Kyteler – Hiberno-Norman noblewoman accused of witchcraft

- Shabbat Chazon — Sabbath of Vision, aka «Black Sabbath»

- Sorginak – Supernatural being in Basque mythology

- Witch-hunt – Search for witchcraft or subversive activity

References[edit]

- ^ American historian GL Burr does not seem to use the term in his essay «The Literature of Witchcraft» presented to the American Historical Association in 1890.

- ^ Joseph Hansen Zauberwahn (1900) also see companion volume of sources Quellen (1901)

- ^ Grimm, Kinder und HausMärchen (1843 ed, 2nd Volume)

- ^ Phillipus van Limborch, History of Inquisition (1692), English translation (1816) p. 88, original Latin here

- ^ Hansen, Quellen (1901) p.186

- ^ The verse in Revelation is pointed to by Wolfgang Behringer, Witches and Witch-Hunts(2004) p.60

- ^ Nicolaus Jacquier Flagellum (printed 1581) p. 40

- ^ Alison Rowlands, Witchcraft Narratives in Germany, Rothenburg,1561-1652 (Manchester, 2003), 10.

- ^ «…the fear of a monstrous conspiracy of Devil-worshipping witches was fairly recent, and indeed modern scholarship has confirmed that massive witch hunts occurred almost exclusively in the early modern period, reaching their peak intensity during the century 1570-1670.» Benjamin G. Kohl and H.C. Erik Midelfort, editors, On Witchcraft An Abridged Translation of Johann Weyer’s De praestigiis daemonun. Translation by John Shea (North Carolina, 1998) xvi.

- ^ Per Scarre & Callow (2001),»Records suggest that in Europe, as a whole, about 80 per cent of trial defendants were women, though the ratio of women to men charged with the offence varied from place to place, and often, too, in one place over time.»

- ^ «Menopausal and post-menopausal women were disproportionally represented amongst the victims of the witch craze—and their over-representation is the more striking when we recall how rare women over fifty must have been in the population as a whole.» Lyndal Roper Witch Craze (2004)p. 160

- ^ Daneau’s work is included with Jacquier in 1581 printing, link above. See p. 242.

- ^ Pierre de Lancre p. 74

- ^ Johannes Praetorius Blockes-Berges Verrichtung (1900)

- ^ Translation by Marcus Hellyer,(UVA Press, 2003)p.232.

- ^ Available here and also see p.398.

- ^ «It is sometimes argued that the Malleus was of minor influence in the spread of the conception of sorcery as a satanic cult because the black sabbath, which formed a major element in later notions of sorcery, receives little emphasis. Yet, here the black sabbath clearly is mentioned…» —footnote 74, Christopher S. Mackay, The Hammer of Witches, A Complete Translation of Malleus Maleficarum p. 283 fn. 74. The original work with the line Mackay refers to is page 208 as found here.

- ^ a b c Hendrix, Scott E. (December 2011). «The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat» (PDF). Anthropology. 11 (2): 41–58.

- ^ Garrett, Julia M. (2013). «Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England». Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 13 (1): 34. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0002. S2CID 141076116.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (3 July 2014). «The Wild Hunt and the Witches’ Sabbath». Folklore. 125 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2014.896968. hdl:1983/f84bddca-c4a6-4091-b9a4-28a1f1bd5361. S2CID 53371957.

- ^ Glass, Justine (1965). Witchcraft: The Sixth Sense. North Hollywood, California: Wilshire Book Company. p. 100.

- ^ Cohn, Norman (1975). Europe’s inner demons : an enquiry inspired by the great witch-hunt. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465021314.

- ^ Marnef, Guido (1997). «Between Religion and Magic: An Analysis of Witchcraft Trials in the Spanish Netherlands, Seventeenth Century». In Schäfer, Peter; Kippenberg, Hans Gerhard (eds.). Envisioning Magic: A Princeton Seminar and Symposium. Brill. pp. 235–54. ISBN 978-90-04-10777-9. p. 252

- ^ Black, Christopher F. (2009). The Italian inquisition. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300117066.

- ^ a b c Rosenthal, Carlo Ginzburg; translated by Raymond (1991). Ecstasies deciphering the witches’ Sabbath (1st American ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0394581637.

- ^ Kieckhefer, Richard (1976). European witch trials : their foundations in popular and learned culture, 1300–1500. London: Routledge & K. Paul. ISBN 978-0710083142.

- ^ Peters, Edward (2001). «Sorcerer and Witch». In Jolly, Karen Louise; Raudvere, Catharina; et al. (eds.). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 233–37. ISBN 978-0-485-89003-7.

- ^ Wilby, Emma. Invoking the Akelarre: Voices of the Accused in the Basque Witch-Craze 1609-14. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1845199999

- ^ Park, Robert E., «Review of Life in a Haitian Valley,» American Journal of Sociology Vol. 43, No. 2 (Sep., 1937), pp. 346–348.

- ^ Lewin, Louis Phantastica, Narcotic and Stimulating Drugs : Their Use and Abuse. Translated from the second German edition by P.H.A. Wirth, pub. New York : E.P. Dutton. Original German edition 1924.

- ^ Harner, Michael J., Hallucinogens and Shamanism, pub. Oxford University Press 1973, reprinted U.S.A.1978 Chapter 8 : pps. 125–150 : The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft.

- ^ Hansen, Harold A. The Witch’s Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0913300473

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans; Hofmann, Albert (1979). The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens (2nd ed.). Springfield Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. pps. 261-4.

- ^ Hunziker, Armando T. The Genera of Solanaceae A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.G., Ruggell, Liechtenstein 2001. ISBN 3-904144-77-4.

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans; Albert Hofmann (1979). Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-056089-7.

- ^ Sollmann, Torald, A Manual of Pharmacology and Its Applications to Therapeutics and Toxicology. 8th edition. Pub. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia and London 1957.

Further reading[edit]

- Harner, Michael (1973). Hallucinogens and Shamanism. – See the chapter «The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft»

- Michelet, Jules (1862). Satanism and Witchcraft: The Classic Study of Medieval Superstition. ISBN 978-0-8065-0059-1. The first modern attempt to outline the details of the medieval Witches’ Sabbath.

- Summers, Montague (1926). The History of Witchcraft. Chapter IV, The Sabbat has detailed description of Witches’ Sabbath, with complete citations of sources.

- Robbins, Rossell Hope, ed. (1959). «Sabbat». The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. Crown. pp. 414–424. See also the extensive topic bibliography to the primary literature on pg. 560.

- Musgrave, James Brent and James Houran. (1999). «The Witches’ Sabbat in Legend and Literature.» Lore and Language 17, no. 1-2. pg 157–174.

- Wilby, Emma. (2013) «Burchard’s Strigae, the Witches’ Sabbath, and Shamnistic Cannibalism in Early Modern Europe.» Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 8, no.1: 18–49.

- Wilby, Emma (2019). Invoking the Akelarre: Voices of the Accused in the Basque Witch-Craze 1609-14. ISBN 978-1845199999.

- Sharpe, James. (2013) «In Search of the English Sabbat: Popular Conceptions of Witches’ Meetings in Early Modern England. Journal of Early Modern Studies. 2: 161–183.

- Hutton, Ronald. (2014) «The Wild Hunt and the Witches’ Sabbath.» Folklore. 125, no. 2: 161–178.

- Roper, Lyndal. (2004) Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. —See Part II: Fantasy Chapter 5: Sabbaths

- Thompson, R.L. (1929) The History of the Devil- The Horned God of the West- Magic and Worship.

- Murray, Margaret A. (1962)The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

- Black, Christopher F. (2009) The Italian Inquisition. (New Haven: Yale University Press). See Chapter 9- The World of Witchcraft, Superstition and Magic

- Ankarloo, Bengt and Gustav Henningsen. (1990) Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries (Oxford: Clarendon Press). see the following essays- pg 121 Ginzburg, Carlo «Deciphering the Sabbath,» pg 139 Muchembled, Robert «Satanic Myths and Cultural Reality,» pg 161 Rowland, Robert. «Fantastically and Devilishe Person’s: European Witch-Beliefs in Comparative Perspective,» pg 191 Henningsen, Gustav «‘The Ladies from outside’: An Archaic Pattern of Witches’ Sabbath.»

- Wilby, Emma. (2005) Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic visionary traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press)

- Garrett, Julia M. (2013) «Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England,» Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 13, no. 1. pg 32–72.

- Roper, Lyndal. (2006) «Witchcraft and the Western Imagination,» Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6, no. 16. pg 117–141.

Sixteenth-century Swiss representation of Sabbath gathering from the chronicles of Johann Jakob Wick. Note Devil seated on serpent-enlaced throne, witch performing the osculum infame upon a demon and another being aided by a demon to summon a storm from her cauldron, while others carouse and prepare magic potions

A Witches’ Sabbath is a purported gathering of those believed to practice witchcraft and other rituals. The phrase became popular in the 20th century.

Emergence as a Popular Phrase in the 20th century[edit]

Prior to the late 19th century, it is difficult to locate any English use of the term sabbath to denote a supposed gathering of witches. The phrase is used by Henry Charles Lea in his History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages (1888).[1] Writing in 1900, German historian Joseph Hansen who was a correspondent and a German translator of Lea’s work, frequently uses the shorthand phrase hexensabbat to interpret medieval trial records, though any consistently recurring term is noticeably rare in the copious Latin sources Hansen also provides (see more on various Latin synonyms, below).[2]

Index of a 1574 printing of Malleus Maleficarum

Notably, the most infamous and influential work of witch-phobia, Malleus Maleficarum (1486) does not contain the word sabbath (sabbatum).

Lea and Hansen’s influence may have led to a much broader use of the shorthand phrase, including in English. Prior to Hansen, use of the term by German historians also seems to have been relatively rare. A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s (Kinder und HausMärchen, Deutsche Mythologie) seems to contain no mention of hexensabbat or any other form of the term sabbat relative to fairies or magical acts.[3] The contemporary of Grimm and early historian of witchcraft, WG Soldan also doesn’t seem to use the term in his history (1843).

A French connection[edit]

In contrast to German and English counterparts, French writers (including Francophone authors writing in Latin) used the term more frequently, albeit still relatively rare. There would seem to possibly be deep roots to inquisitorial persecution of the Waldensians. In 1124, the term inzabbatos is used to describe the Waldensians in Northern Spain.[4] In 1438 and 1460, seemingly related terms synagogam and synagogue of Sathan are used to describe Waldensians by inquisitors in France. These terms could be a reference to Revelation 2:9. («I know the blasphemy of them which say they are Jews and are not, but are the synagogue of Satan.»)[5][6] Writing in Latin in 1458, Francophone author Nicolas Jacquier applies synagogam fasciniorum to what he considers a gathering of witches.[7]

About 150 years later, near the peak of the witch-phobia and the persecutions which led to the execution of an estimated 40,000-100,000 persons,[8][9] with roughly 80% being women,[10][11] the Francophone writers still seem to be the main ones using these related terms, although still infrequently and sporadically in most cases. Lambert Daneau uses sabbatha one time (1581) as Synagogas quas Satanica sabbatha.[12] Nicholas Remi uses the term occasionally as well as synagoga (1588). Jean Bodin uses the term three times (1580) and, across the channel, the Englishman Reginald Scot (1585) writing a book in opposition to witch-phobia, uses the term but only once in quoting Bodin. (The Puritan Richard Baxter writing much later (1691) also uses the term only once in the exact same way–quoting Bodin. Other witch-phobic English Puritans who were Baxter’s contemporaries, like Increase and Cotton Mather (1684, 1689, 1692), did not use the term, perhaps because they were Sabbatarians.)

In 1611, Jacques Fontaine uses sabat five times writing in French and in a way that would seem to correspond with modern usage. The following year (1612), Pierre de Lancre seems to use the term more frequently than anyone before.[13]

Witches’ Sabbath — Johannes Praetorius: Blockes-Berges Verrichtung, Leipzig, 1668.

In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published «Blockes-Berges Verrichtung», with the subtitle «Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1. Maij in Sanct-Walpurgis Nachte anstellen sollen».[14] As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a «Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches’ journey and magic sabbaths».

Writing more than two hundred years after Pierre de Lancre, another French writer Lamothe-Langon (whose character and scholarship was questioned in the 1970s) uses the term in (presumably) translating into French a handful of documents from the inquisition in Southern France. Joseph Hansen cited Lamothe-Langon as one of many sources.

A term favored by recent translators[edit]

Despite the infrequency of the use of the word sabbath to denote any such gatherings in the historical record, it became increasingly popular during the 20th century.

Cautio Criminalis[edit]

In a 2003 translation of Friedrich Spee’s Cautio Criminalis (1631) the word sabbaths is listed in the index with a large number of entries.[15] However, unlike some of Spee’s contemporaries in France (mentioned above), who occasionally, if rarely, use the term sabbatha, Friedrich Spee does not ever use words derived from sabbatha or synagoga. Spee was German-speaking, and like his contemporaries, wrote in Latin. Conventibus is the word Spee uses most frequently to denote a gathering of witches, whether supposed or real, physical or spectral, as seen in the first paragraph of question one of his book.[16] This is the same word from which English words convention, convent, and coven are derived. Cautio Criminalis (1631) was written as a passionate innocence project. As a Jesuit, Spee was often in a position of witnessing the torture of those accused of witchcraft.

Malleus Maleficarum[edit]

In a 2009 translation of Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (1486), the word sabbath does not occur. A line describing a supposed gathering and using concionem is accurately translated as an assembly. But in the accompanying footnote, the translator seems to apologize for the lack of both the term sabbath and a general scarcity of other gatherings that would seem to fit the bill for what he refers to as a «black sabbath».[17]

Fine art[edit]

The phrase is also popular in recent translations of the titles of artworks, including:

- The Witches’ Sabbath by Hans Baldung (1510)

- Witches’ Sabbath by Frans Francken (1606)

- Witches’ Sabbath in Roman Ruins by Jacob van Swanenburgh (1608)

- As a recent translation from the original Spanish El aquelarre to the English title Witches’ Sabbath (1798) and Witches’ Sabbath or The Great He-Goat (1823) both works by Francisco Goya

- Muse of the Night (Witches’ Sabbath) by Luis Ricardo Falero (1880)

Disputed accuracy of the accounts of gatherings[edit]

Modern researchers have been unable to find any corroboration with the notion that physical gatherings of practitioners of witchcraft occurred.[18] In his study «The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat», the historian Scott E. Hendrix presents a two-fold explanation for why these stories were so commonly told in spite of the fact that sabbats likely never actually occurred. First, belief in the real power of witchcraft grew during the late medieval and early-modern Europe as a doctrinal view in opposition to the canon Episcopi gained ground in certain communities. This fueled a paranoia among certain religious authorities that there was a vast underground conspiracy of witches determined to overthrow Christianity. Women beyond child-bearing years provided an easy target and were scapegoated and blamed for famines, plague, warfare, and other problems.[18] Having prurient and orgiastic elements helped ensure that these stories would be relayed to others.[19]

Ritual elements[edit]

Bristol University’s Ronald Hutton has encapsulated the witches’ sabbath as an essentially modern construction, saying:

[The concepts] represent a combination of three older mythical components, all of which are active at night: (1) A procession of female spirits, often joined by privileged human beings and often led by a supernatural woman; (2) A lone spectral huntsman, regarded as demonic, accursed, or otherworldly; (3) A procession of the human dead, normally thought to be wandering to expiate their sins, often noisy and tumultuous, and usually consisting of those who had died prematurely and violently. The first of these has pre-Christian origins, and probably contributed directly to the formulation of the concept of the witches’ sabbath. The other two seem to be medieval in their inception, with the third to be directly related to growing speculation about the fate of the dead in the 11th and 12th centuries.»[20]

The book Compendium Maleficarum (1608) by Francesco Maria Guazzo illustrates a typical witch-phobic view of gathering of witches as «the attendants riding flying goats, trampling the cross, and being re-baptised in the name of the Devil while giving their clothes to him, kissing his behind, and dancing back to back forming a round.»

In effect, the sabbat acted as an effective ‘advertising’ gimmick, causing knowledge of what these authorities believed to be the very real threat of witchcraft to be spread more rapidly across the continent.[18] That also meant that stories of the sabbat promoted the hunting, prosecution, and execution of supposed witches.

The descriptions of Sabbats were made or published by priests, jurists and judges who never took part in these gatherings, or were transcribed during the process of the witchcraft trials.[21] That these testimonies reflect actual events is for most of the accounts considered doubtful. Norman Cohn argued that they were determined largely by the expectations of the interrogators and free association on the part of the accused, and reflect only popular imagination of the times, influenced by ignorance, fear, and religious intolerance towards minority groups.[22]

Some of the existing accounts of the Sabbat were given when the person recounting them was being tortured,[23] and so motivated to agree with suggestions put to them.

Christopher F. Black claimed that the Roman Inquisition’s sparse employment of torture allowed accused witches to not feel pressured into mass accusation. This in turn means there were fewer alleged groups of witches in Italy and places under inquisitorial influence. Because the Sabbath is a gathering of collective witch groups, the lack of mass accusation means Italian popular culture was less inclined to believe in the existence of Black Sabbath. The Inquisition itself also held a skeptical view toward the legitimacy of Sabbath Assemblies.[24]

Many of the diabolical elements of the Witches’ Sabbath stereotype, such as the eating of babies, poisoning of wells, desecration of hosts or kissing of the devil’s anus, were also made about heretical Christian sects, lepers, Muslims, and Jews.[25] The term is the same as the normal English word «Sabbath» (itself a transliteration of Hebrew «Shabbat», the seventh day, on which the Creator rested after creation of the world), referring to the witches’ equivalent to the Christian day of rest; a more common term was «synagogue» or «synagogue of Satan»[26] possibly reflecting anti-Jewish sentiment, although the acts attributed to witches bear little resemblance to the Sabbath in Christianity or Jewish Shabbat customs. The Errores Gazariorum (Errors of the Cathars), which mentions the Sabbat, while not discussing the actual behavior of the Cathars, is named after them, in an attempt to link these stories to an heretical Christian group.[27]

More recently, scholars such as Emma Wilby have argued that although the more diabolical elements of the witches’ sabbath stereotype were invented by inquisitors, the witchcraft suspects themselves may have encouraged these ideas to circulate by drawing on popular beliefs and experiences around liturgical misrule, cursing rites, magical conjuration and confraternal gatherings to flesh-out their descriptions of the sabbath during interrogations.[28]

Christian missionaries’ attitude to African cults was not much different in principle to their attitude to the Witches’ Sabbath in Europe; some accounts viewed them as a kind of Witches’ Sabbath, but they are not.[29] Some African communities believe in witchcraft, but as in the European witch trials, people they believe to be «witches» are condemned rather than embraced.

Possible connections to real groups[edit]

Other historians, including Carlo Ginzburg, Éva Pócs, Bengt Ankarloo and Gustav Henningsen hold that these testimonies can give insights into the belief systems of the accused. Ginzburg famously discovered records of a group of individuals in northern Italy, calling themselves benandanti, who believed that they went out of their bodies in spirit and fought amongst the clouds against evil spirits to secure prosperity for their villages, or congregated at large feasts presided over by a goddess, where she taught them magic and performed divinations.[25] Ginzburg links these beliefs with similar testimonies recorded across Europe, from the armiers of the Pyrenees, from the followers of Signora Oriente in fourteenth century Milan and the followers of Richella and ‘the wise Sibillia’ in fifteenth century northern Italy, and much further afield, from Livonian werewolves, Dalmatian kresniki, Hungarian táltos, Romanian căluşari and Ossetian burkudzauta. In many testimonies these meetings were described as out-of-body, rather than physical, occurrences.[25]

Role of topically-applied hallucinogens[edit]

«Flying ointment» ingredient black henbane Hyoscyamus niger (family: Solanaceae)

Magic ointments…produced effects which the subjects themselves believed in, even stating that they had intercourse with evil spirits, had been at the Sabbat and danced on the Brocken with their lovers…The peculiar hallucinations evoked by the drug had been so powerfully transmitted from the subconscious mind to consciousness that mentally uncultivated persons…believed them to be reality.[30]

Carlo Ginzburg’s researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as Apuleius,

is the use of unguents conferring the power of «flight» and «shape-shifting.»[31] Recipes for such «flying ointments» have survived from early modern times[when?], permitting not only an assessment of their likely pharmacological effects – based on their various plant (and to a lesser extent animal) ingredients – but also the actual recreation of and experimentation with such fat or oil-based preparations.[32] Ginzburg makes brief reference to the use of entheogens in European witchcraft at the end of his analysis of the Witches Sabbath, mentioning only the fungi Claviceps purpurea and Amanita muscaria by name, and stating about the «flying ointment» on page 303 of ‘Ecstasies…’ :

In the Sabbath the judges more and more frequently saw the accounts of real, physical events. For a long time the only dissenting voices were those of the people who, referring back to the Canon episcopi, saw witches and sorcerers as the victims of demonic illusion. In the sixteenth century scientists like Cardano or Della Porta formulated a different opinion : animal metamorphoses, flights, apparitions of the devil were the effect of malnutrition or the use of hallucinogenic substances contained in vegetable concoctions or ointments…But no form of privation, no substance, no ecstatic technique can, by itself, cause the recurrence of such complex experiences…the deliberate use of psychotropic or hallucinogenic substances, while not explaining the ecstasies of the followers of the nocturnal goddess, the werewolf, and so on, would place them in a not exclusively mythical dimension.

– in short, a substrate of shamanic myth could, when catalysed by a drug experience (or simple starvation), give rise to a ‘journey to the Sabbath’, not of the body, but of the mind. Ergot and the Fly Agaric mushroom, while hallucinogenic,[33] were not among the ingredients listed in recipes for the flying ointment. The active ingredients in such unguents were primarily, not fungi, but plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae, most commonly Atropa belladonna (Deadly Nightshade) and Hyoscyamus niger (Henbane), belonging to the tropane alkaloid-rich tribe Hyoscyameae.[34] Other tropane-containing, nightshade ingredients included the Mandrake Mandragora officinarum, Scopolia carniolica and Datura stramonium, the Thornapple.[35]

The alkaloids Atropine, Hyoscyamine and Scopolamine present in these Solanaceous plants are not only potent and highly toxic hallucinogens, but are also fat-soluble and capable of being absorbed through unbroken human skin.[36]

See also[edit]

- Akelarre – Basque for Witches’ Sabbath

- Aradia – Character in the Gospel of the Witches

- Bald Mountain (folklore) – Witchcraft location in Slavic mythology

- Blockula – Devil’s secret island in Swedish legend

- Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches’ Sabbath – 1989 book by Carlo Ginzburg

- Flying ointment – Hallucinogenic salve used in the practice of witchcraft

- Isobel Gowdie – Scottish woman who confessed to witchcraft at Auldearn near Nairn during 1662

- Märet Jonsdotter – Swedish witch

- Alice Kyteler – Hiberno-Norman noblewoman accused of witchcraft

- Shabbat Chazon — Sabbath of Vision, aka «Black Sabbath»

- Sorginak – Supernatural being in Basque mythology

- Witch-hunt – Search for witchcraft or subversive activity

References[edit]

- ^ American historian GL Burr does not seem to use the term in his essay «The Literature of Witchcraft» presented to the American Historical Association in 1890.

- ^ Joseph Hansen Zauberwahn (1900) also see companion volume of sources Quellen (1901)

- ^ Grimm, Kinder und HausMärchen (1843 ed, 2nd Volume)

- ^ Phillipus van Limborch, History of Inquisition (1692), English translation (1816) p. 88, original Latin here

- ^ Hansen, Quellen (1901) p.186

- ^ The verse in Revelation is pointed to by Wolfgang Behringer, Witches and Witch-Hunts(2004) p.60

- ^ Nicolaus Jacquier Flagellum (printed 1581) p. 40

- ^ Alison Rowlands, Witchcraft Narratives in Germany, Rothenburg,1561-1652 (Manchester, 2003), 10.

- ^ «…the fear of a monstrous conspiracy of Devil-worshipping witches was fairly recent, and indeed modern scholarship has confirmed that massive witch hunts occurred almost exclusively in the early modern period, reaching their peak intensity during the century 1570-1670.» Benjamin G. Kohl and H.C. Erik Midelfort, editors, On Witchcraft An Abridged Translation of Johann Weyer’s De praestigiis daemonun. Translation by John Shea (North Carolina, 1998) xvi.

- ^ Per Scarre & Callow (2001),»Records suggest that in Europe, as a whole, about 80 per cent of trial defendants were women, though the ratio of women to men charged with the offence varied from place to place, and often, too, in one place over time.»

- ^ «Menopausal and post-menopausal women were disproportionally represented amongst the victims of the witch craze—and their over-representation is the more striking when we recall how rare women over fifty must have been in the population as a whole.» Lyndal Roper Witch Craze (2004)p. 160

- ^ Daneau’s work is included with Jacquier in 1581 printing, link above. See p. 242.

- ^ Pierre de Lancre p. 74

- ^ Johannes Praetorius Blockes-Berges Verrichtung (1900)

- ^ Translation by Marcus Hellyer,(UVA Press, 2003)p.232.

- ^ Available here and also see p.398.

- ^ «It is sometimes argued that the Malleus was of minor influence in the spread of the conception of sorcery as a satanic cult because the black sabbath, which formed a major element in later notions of sorcery, receives little emphasis. Yet, here the black sabbath clearly is mentioned…» —footnote 74, Christopher S. Mackay, The Hammer of Witches, A Complete Translation of Malleus Maleficarum p. 283 fn. 74. The original work with the line Mackay refers to is page 208 as found here.

- ^ a b c Hendrix, Scott E. (December 2011). «The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat» (PDF). Anthropology. 11 (2): 41–58.

- ^ Garrett, Julia M. (2013). «Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England». Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 13 (1): 34. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0002. S2CID 141076116.

- ^ Hutton, Ronald (3 July 2014). «The Wild Hunt and the Witches’ Sabbath». Folklore. 125 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2014.896968. hdl:1983/f84bddca-c4a6-4091-b9a4-28a1f1bd5361. S2CID 53371957.

- ^ Glass, Justine (1965). Witchcraft: The Sixth Sense. North Hollywood, California: Wilshire Book Company. p. 100.

- ^ Cohn, Norman (1975). Europe’s inner demons : an enquiry inspired by the great witch-hunt. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465021314.

- ^ Marnef, Guido (1997). «Between Religion and Magic: An Analysis of Witchcraft Trials in the Spanish Netherlands, Seventeenth Century». In Schäfer, Peter; Kippenberg, Hans Gerhard (eds.). Envisioning Magic: A Princeton Seminar and Symposium. Brill. pp. 235–54. ISBN 978-90-04-10777-9. p. 252

- ^ Black, Christopher F. (2009). The Italian inquisition. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300117066.

- ^ a b c Rosenthal, Carlo Ginzburg; translated by Raymond (1991). Ecstasies deciphering the witches’ Sabbath (1st American ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0394581637.

- ^ Kieckhefer, Richard (1976). European witch trials : their foundations in popular and learned culture, 1300–1500. London: Routledge & K. Paul. ISBN 978-0710083142.

- ^ Peters, Edward (2001). «Sorcerer and Witch». In Jolly, Karen Louise; Raudvere, Catharina; et al. (eds.). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 233–37. ISBN 978-0-485-89003-7.

- ^ Wilby, Emma. Invoking the Akelarre: Voices of the Accused in the Basque Witch-Craze 1609-14. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1845199999

- ^ Park, Robert E., «Review of Life in a Haitian Valley,» American Journal of Sociology Vol. 43, No. 2 (Sep., 1937), pp. 346–348.

- ^ Lewin, Louis Phantastica, Narcotic and Stimulating Drugs : Their Use and Abuse. Translated from the second German edition by P.H.A. Wirth, pub. New York : E.P. Dutton. Original German edition 1924.

- ^ Harner, Michael J., Hallucinogens and Shamanism, pub. Oxford University Press 1973, reprinted U.S.A.1978 Chapter 8 : pps. 125–150 : The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft.

- ^ Hansen, Harold A. The Witch’s Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0913300473

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans; Hofmann, Albert (1979). The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens (2nd ed.). Springfield Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. pps. 261-4.

- ^ Hunziker, Armando T. The Genera of Solanaceae A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.G., Ruggell, Liechtenstein 2001. ISBN 3-904144-77-4.

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans; Albert Hofmann (1979). Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-056089-7.

- ^ Sollmann, Torald, A Manual of Pharmacology and Its Applications to Therapeutics and Toxicology. 8th edition. Pub. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia and London 1957.

Further reading[edit]

- Harner, Michael (1973). Hallucinogens and Shamanism. – See the chapter «The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft»

- Michelet, Jules (1862). Satanism and Witchcraft: The Classic Study of Medieval Superstition. ISBN 978-0-8065-0059-1. The first modern attempt to outline the details of the medieval Witches’ Sabbath.

- Summers, Montague (1926). The History of Witchcraft. Chapter IV, The Sabbat has detailed description of Witches’ Sabbath, with complete citations of sources.

- Robbins, Rossell Hope, ed. (1959). «Sabbat». The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. Crown. pp. 414–424. See also the extensive topic bibliography to the primary literature on pg. 560.

- Musgrave, James Brent and James Houran. (1999). «The Witches’ Sabbat in Legend and Literature.» Lore and Language 17, no. 1-2. pg 157–174.