| Sheffield | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Clockwise from top left: The Cholera Monument, Modern buildings in the city centre, Meadowhall shopping centre, Sheffield Town Hall, Peace Gardens, Skyline of both Central Sheffield and Sheffield City Centre and Sheffield Cathedral |

|

|

Sheffield Location within South Yorkshire |

|

| Area | 122.5 km2 (47.3 sq mi) |

| Population | 556,500 (2021 census) |

| • Density | 4,543/km2 (11,770/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Sheffielder |

| OS grid reference | SK355875 |

| Metropolitan borough |

|

| Metropolitan county |

|

| Region |

|

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Areas of the city (2011 census BUASD) |

List

|

| Post town | SHEFFIELD |

| Postcode district | S1-S17, S20, S35 |

| Dialling code | 0114 |

| Police | South Yorkshire |

| Fire | South Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| UK Parliament |

|

| Website | www.sheffield.gov.uk |

53°22′51″N 01°28′13″W / 53.38083°N 1.47028°WCoordinates: 53°22′51″N 01°28′13″W / 53.38083°N 1.47028°W |

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its southern suburbs were transferred from Derbyshire to the city council. It is the largest settlement in South Yorkshire.[1][2][3]

The city is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines and the valleys of the River Don with its four tributaries: the Loxley, the Porter Brook, the Rivelin and the Sheaf. Sixty-one per cent of Sheffield’s entire area is green space and a third of the city lies within the Peak District national park.[4] There are more than 250 parks, woodlands and gardens in the city,[4] which is estimated to contain around 4.5 million trees.[5] The city is 29 miles (47 km) south of Leeds, 32 miles (51 km) east of Manchester, and 33 miles (53 km) north of Nottingham.

Sheffield played a crucial role in the Industrial Revolution, with many significant inventions and technologies having developed in the city. In the 19th century, the city saw a huge expansion of its traditional cutlery trade, when stainless steel and crucible steel were developed locally, fuelling an almost tenfold increase in the population. Sheffield received its municipal charter in 1843, becoming the City of Sheffield in 1893. International competition in iron and steel caused a decline in these industries in the 1970s and 1980s, coinciding with the collapse of coal mining in the area. The Yorkshire ridings became counties in their own right in 1889, the West Riding of Yorkshire county was disbanded in 1974. The city then became part of the county of South Yorkshire; this has been made up of separately-governed unitary authorities since 1986. The 21st century has seen extensive redevelopment in Sheffield, consistent with other British cities. Sheffield’s gross value added (GVA) has increased by 60% since 1997, standing at £11.3 billion in 2015. The economy has experienced steady growth, averaging around 5% annually, which is greater than that of the broader region of Yorkshire and the Humber.[6]

Sheffield had a population of 556,500 at the 2021 census, making it the second largest city in the Yorkshire and the Humber region. The Sheffield Built-up Area, of which the Sheffield sub-division is the largest part, had a population of 685,369 also including the town of Rotherham. The district borough, governed from the city, had a population of 556,521 at the mid-2019 estimate, making it the 4th most populous district in England. It is one of eleven British cities that make up the Core Cities Group.[7] In 2011, the unparished area had a population of 490,070.[8]

The city has a long sporting heritage and is home both to the world’s oldest football club, Sheffield F.C.,[9] and the world’s oldest football ground, Sandygate. Matches between the two professional clubs, Sheffield United and Sheffield Wednesday, are known as the Steel City derby. The city is also home to the World Snooker Championship and the Sheffield Steelers, the UK’s first professional ice hockey team.

Etymology[edit]

The name, Sheffield, has its origins in Old English and derives from the name of a principal river in the city, the River Sheaf. This name, in turn, is a corruption of shed or sheth, which refers to a divide or separation.[10][11] The second half of the name Sheffield refers to a field, or forest clearing.[12] Combining the two words, it is believed that the name refers to an Anglo-Saxon settlement in a clearing by the confluence of the River Don and River Sheaf.[13]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The area now occupied by the City of Sheffield is believed to have been inhabited since at least the late Upper Paleolithic, about 12,800 years ago.[14] The earliest evidence of human occupation in the Sheffield area was found at Creswell Crags to the east of the city. In the Iron Age the area became the southernmost territory of the Pennine tribe called the Brigantes. It is this tribe who are thought to have constructed several hill forts in and around Sheffield.[15]

Following the departure of the Romans, the Sheffield area may have been the southern part of the Brittonic kingdom of Elmet, with the rivers Sheaf and Don forming part of the boundary between this kingdom and the kingdom of Mercia.[16] Gradually, Anglian settlers pushed west from the kingdom of Deira. A Britonnic presence within the Sheffield area is evidenced by two settlements called Wales and Waleswood close to Sheffield.[17] The settlements that grew and merged to form Sheffield, however, date from the second half of the first millennium, and are of Anglo-Saxon and Danish origin.[15] In Anglo-Saxon times, the Sheffield area straddled the border between the kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that Eanred of Northumbria submitted to Egbert of Wessex at the hamlet of Dore (now a suburb of Sheffield) in 829,[18] a key event in the unification of the kingdom of England under the House of Wessex.[19]

After the Norman conquest of England, Sheffield Castle was built to protect the local settlements, and a small town developed that is the nucleus of the modern city.[20] By 1296, a market had been established at what is now known as Castle Square,[21] and Sheffield subsequently grew into a small market town. In the 14th century, Sheffield was already noted for the production of knives, as mentioned in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales,[22] and by the early 1600s it had become the main centre of cutlery manufacture in England outside London, overseen by the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire.[23] From 1570 to 1584, Mary, Queen of Scots, was imprisoned in Sheffield Castle and Sheffield Manor.[24]

Industrial Revolution[edit]

Sheffield in the 19th century. The dominance of industry in the city is evident.

Sheffield was targeted heavily by the Luftwaffe during WW2, owing to the city’s industrial importance. The bombing campaign became known as the Sheffield Blitz.

During the 1740s, a form of the crucible steel process was discovered that allowed the manufacture of a better quality of steel than had previously been possible.[25] In about the same period, a technique was developed for fusing a thin sheet of silver onto a copper ingot to produce silver plating, which became widely known as Sheffield plate.[26] These innovations spurred Sheffield’s growth as an industrial town,[27] but the loss of some important export markets led to a recession in the late 18th and early 19th century. The resulting poor conditions culminated in a cholera epidemic that killed 402 people in 1832.[15] The population of the town grew rapidly throughout the 19th century; increasing from 60,095 in 1801 to 451,195 by 1901.[15] The Sheffield and Rotherham railway was constructed in 1838, connecting the two towns. The town was incorporated as a borough in 1842, and was granted city status by letters patent in 1893.[28][29] The influx of people also led to demand for better water supplies, and a number of new reservoirs were constructed on the outskirts of the town.

The collapse of the dam wall of one of these reservoirs in 1864 resulted in the Great Sheffield Flood, which killed 270 people and devastated large parts of the town.[30] The growing population led to the construction of many back-to-back dwellings that, along with severe pollution from the factories, inspired George Orwell in 1937 to write: «Sheffield, I suppose, could justly claim to be called the ugliest town in the Old World».[31]

The Women of Steel statue commemorates the women of Sheffield who worked in the city’s steel industry during the First and Second World Wars.

Blitz[edit]

The Great Depression hit the city in the 1930s, but as international tensions increased and the Second World War became imminent; Sheffield’s steel factories were set to work manufacturing weapons and ammunition for the war effort. As a result, the city became a target for bombing raids, the heaviest of which occurred on the nights of 12 and 15 December 1940, now known as the Sheffield Blitz. The city was partially protected by barrage balloons managed from RAF Norton.[32] More than 660 people died and many buildings were destroyed or left badly damaged, including the Marples Hotel, which was hit directly by a 500lb bomb, killing over 70 people.[33]

Post-Second World War[edit]

Park Hill flats, an example of 1950s and 1960s council housing estates in Sheffield

In the 1950s and 1960s, many of the city’s slums were demolished, and replaced with housing schemes such as the Park Hill flats. Large parts of the city centre were also cleared to make way for a new system of roads.[15] In February 1962, the city was devastated by the Great Sheffield Gale; winds of up to 97 mph (156 km/h) killed four people and damaged 150,000 houses, more than two-thirds of the city’s housing stock at the time.[34] Increased automation and competition from abroad resulted in the closure of many steel mills. The 1980s saw the worst of this run-down of Sheffield’s industries, along with those of many other areas of the UK.[35] The building of the Meadowhall Centre on the site of a former steelworks in 1990 was a mixed blessing, creating much-needed jobs but hastening the decline of the city centre. Attempts to regenerate the city were kick-started when the city hosted the 1991 World Student Games, which saw the construction of new sporting facilities such as the Sheffield Arena, Don Valley Stadium and the Ponds Forge complex.[15]

21st century[edit]

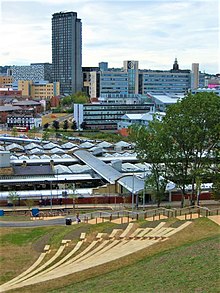

Sheffield city centre in 2007.

Sheffield is changing rapidly as new projects regenerate some of the more run-down parts of the city. One such, the Heart of the City Project, has initiated a number of public works in the city centre: the Peace Gardens were renovated in 1998, the Millennium Galleries opened in April 2001, the Winter Gardens were opened in May 2003, and a public space to link these two areas, the Millennium Square, was opened in May 2006. Additional developments included the remodelling of Sheaf Square, in front of the refurbished railway station. The square contains «The Cutting Edge», a sculpture designed by Si Applied Ltd[36] and made from Sheffield steel.

Sheffield was particularly hard hit during the 2007 United Kingdom floods and the 2010 ‘Big Freeze’. Many landmark buildings such as Meadowhall and the Hillsborough Stadium flooded due to being close to rivers that flow through the city. In 2010, 5,000 properties in Sheffield were identified as still being at risk of flooding. In 2012 the city narrowly escaped another flood, despite extensive work by the Environment Agency to clear local river channels since the 2007 event. In 2014 Sheffield Council’s cabinet approved plans to further reduce the possibility of flooding by adopting plans to increase water catchment on tributaries of the River Don.[37][38][39] Another flood hit the city in 2019, resulting in shoppers being contained in Meadowhall Shopping Centre.[40][41]

Between 2014 and 2018, there were disputes between the city council and residents over the fate of the city’s 36,000 highway trees. Around 4,000 highway trees have since been felled as part of the ‘Streets Ahead’ Private Finance Initiative (PFI) contract signed in 2012 by the city council, Amey plc and the Department for Transport to maintain the city streets.[42] The tree fellings have resulted in many arrests of residents and other protesters across the city even though most felled trees in the city have been replanted, including those historically felled and not previously replanted.[43] The protests eventually stopped in 2018 after the council paused the tree felling programme as part of a new approach developed by the council for the maintenance of street trees in the city.[44] In May 2022, Sheffield was named a «Tree City of the World» in recognition of its work to sustainably manage and maintain urban forests and trees.[45]

Governance[edit]

[edit]

The Council Chamber at Sheffield Town Hall

Sheffield is governed at the local level by Sheffield City Council and is led by Councillor Terry Fox (Assumed office

19 May 2021). It consists of 84 councillors elected to represent 28 wards: three councillors per ward. Following the 2019 local elections, the distribution of council seats is Labour 49, Liberal Democrats 26, the Green Party 8 and UKIP 1. The city also has a Lord Mayor; though now simply a ceremonial position, in the past the office carried considerable authority, with executive powers over the finances and affairs of the city council. The position of Lord Mayor is elected on an annual basis.

For much of its history the council was controlled by the Labour Party, and was noted for its leftist sympathies; during the 1980s, when Sheffield City Council was led by David Blunkett, the area gained the epithet the «Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire».[46] However, the Liberal Democrats controlled the Council between 1999 and 2001 and took control again from 2008 to 2011.

The majority of council-owned facilities are operated by independent charitable trusts. Sheffield International Venues runs many of the city’s sporting and leisure facilities, including Sheffield Arena and the English Institute of Sport. Museums Sheffield and the Sheffield Industrial Museums Trust take care of galleries and museums owned by the council.[47][48]

Combined authority[edit]

The city of Sheffield is part of the wider South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority, headed by mayor Oliver Coppard since 2022. The combined authority covers the former 1974–1986 South Yorkshire County Council area which functions either went to local or regional authorities.

In 2004, as part of the Moving Forward: The Northern Way document,[49] city regions were created in a collaboration with the three northern regional development agencies. These became independent Local Enterprise Partnerships in 2011.

The area’s partnership retains the Sheffield City Region name, covering the South Yorkshire authorities, as well as Bolsover District, Borough of Chesterfield, Derbyshire Dales, North East Derbyshire and Bassetlaw District. In 2014, the Sheffield City Region Combined authority was formed by the South Yorkshire local authorities with the other councils as non-constituent members and the partnership integrated with the authority structure. In September 2020, the authority changed to its current name.[50]

Parliamentary Representation[edit]

The city returns five members of parliament to the House of Commons, with a sixth, the Member of Parliament for Penistone and Stocksbridge representing parts of Sheffield and Barnsley.[51] The former Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg was an MP for Sheffield, representing Sheffield Hallam from 2005 until he was unseated 2017, when the seat returned a Labour MP for the first time in its history.[52]

Geography[edit]

Sheffield is located at 53°22′59″N 1°27′57″W / 53.38297°N 1.4659°W. It lies directly beside Rotherham, from which it is separated largely by the M1 motorway. Although Barnsley Metropolitan Borough also borders Sheffield to the north, the town itself is a few miles further away. The southern and western borders of the city are shared with Derbyshire; in the first half of the 20th century Sheffield extended its borders south into Derbyshire, annexing a number of villages,[53] including Totley, Dore and the area now known as Mosborough Townships.

Sheffield is a geographically diverse city.[54] It nestles in the eastern foothills of the Pennines,[55] between the main upland range and Peak District National Park to the west, and the lower-lying South Yorkshire Coalfield to the east. It lies at the confluence of five rivers: Don, Sheaf, Rivelin, Loxley and Porter. As such, much of the city is built on hillsides with views into the city centre or out to the countryside. Blake Street, in the S6 postcode area, is the third steepest residential street in England, with a gradient of 16.6°.[56] The highest point in the City of Sheffield is 548 m (1,798 ft) near High Stones and Margery Hill.[57] The city’s lowest point is just 29 m (95 ft) above sea level near Blackburn Meadows. However, 79% of the housing in the city is between 100 and 200 m (330 and 660 ft) above sea level.[58] This variation of altitudes across Sheffield has led to frequent claims, particularly among locals, that the city was built on Seven Hills. As this claim is disputed, it likely originated as a joke referencing the Seven Hills of Rome.[59][60]

Gleadless Valley, demonstrating the hilly terrain within the city

Estimated to contain around 4.5 million trees,[5] Sheffield has more trees per person than any other city in Europe and is considered to be one of the greenest cities in England and the UK,[61][62] which was further reinforced when it won the 2005 Entente Florale competition. With more than 250 parks, woodlands and gardens, it has over 170 woodlands (covering 10.91 sq mi or 28.3 km2), 78 public parks (covering 7.07 sq mi or 18.3 km2) and 10 public gardens. Added to the 52.0 sq mi (134.7 km2) of national park and 4.20 sq mi (10.9 km2) of water this means that 61% of the city is greenspace. Despite this, about 64% of Sheffield householders live further than 300 m (328 yd) from their nearest greenspace, although access is better in less affluent neighbourhoods across the city.[4][63] Sheffield also has a very wide variety of habitat, comparing favourably with any city in the United Kingdom: urban, parkland and woodland, agricultural and arable land, moors, meadows and freshwater-based habitats. There are six areas within the city that are designated as sites of special scientific interest.[64]

The present city boundaries were set in 1974 (with slight modification in 1994), when the former county borough of Sheffield merged with Stocksbridge Urban District and two parishes from the Wortley Rural District.[4] This area includes a significant part of the countryside surrounding the main urban region. Roughly a third of Sheffield lies in the Peak District National Park. No other English city had parts of a national park within its boundary,[65] until the creation in March 2010 of the South Downs National Park, part of which lies within Brighton and Hove.

Climate[edit]

According to the Köppen classification, Sheffield generally has an oceanic climate (Cfb) like the rest of the United Kingdom. The uplands of the Pennines to the west can create a cool, gloomy and wet environment, but they also provide shelter from the prevailing westerly winds, casting a «rain shadow» across the area.[66] Between 1971 and 2000 Sheffield averaged 824.7 mm (32.47 in) of rain per year; December was the wettest month with 91.9 mm (3.62 in) and July the driest with 51.0 mm (2.01 in). July was also the hottest month, with an average maximum temperature of 20.8 °C (69.4 °F). The highest temperature ever recorded in the city of Sheffield was 39.4 °C (102.9 °F), on 19 July 2022.[67] The average minimum temperature in January and February was 1.6 °C (34.9 °F),[68] though the lowest temperatures recorded in these months can be between −10 and −15 °C (14 and 5 °F), although since 1960, the temperature has never fallen below −9.2 °C (15.4 °F),[69] suggesting that urbanisation around the Weston Park site during the second half of the 20th century may prevent temperatures below −10 °C (14 °F) occurring.

The coldest temperature to be recorded was −8.2 °C (17.2 °F) in 2010.[70] (Note: The official Weston Park Weather Station statistics, which can also be viewed at Sheffield Central Library, has the temperature at −8.7 °C (16.3 °F), recorded on 20 December, and states that to be the lowest December temperature since 1981.) The coldest temperature ever recorded in the city of Sheffield at Weston Park, since records began in 1882, is −14.6 °C (5.7 °F), registered in February 1895.[71] The lowest daytime maximum temperature in the city since records began is −5.6 °C (21.9 °F), also recorded in February 1895.[citation needed] More recently, −4.4 °C (24.1 °F) was recorded as a daytime maximum at Weston Park, on 20 December 2010 (from the Weston Park Weather Station statistics, which also can be viewed at Sheffield Central Library.) On average, through the winter months of December to March, there are 67 days during which ground frost occurs.[66]

| Climate data for Sheffield Cdl, elevation: 131 m (430 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1882–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

28.9 (84.0) |

30.7 (87.3) |

39.4 (102.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.7 (45.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.3 (45.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

12.6 (54.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.9 (44.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.3 (8.1) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 75.7 (2.98) |

67.0 (2.64) |

59.5 (2.34) |

58.8 (2.31) |

54.5 (2.15) |

75.1 (2.96) |

62.2 (2.45) |

65.1 (2.56) |

63.5 (2.50) |

78.7 (3.10) |

84.7 (3.33) |

86.9 (3.42) |

831.6 (32.74) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.2 | 11.5 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 13.7 | 133.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 50.1 | 76.8 | 121.0 | 153.2 | 198.2 | 181.0 | 180.7 | 181.3 | 138.2 | 97.0 | 59.4 | 48.3 | 1,485.2 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source 1: Met Office[72] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI,[73][74] WeatherAtlas[75] and Meteo Climat[76] |

The Weston Park Weather station, established in 1882, is one of the longest running weather stations in the United Kingdom. It has recorded weather for more than 125 years, and a 2008 report showed that the climate of Sheffield is warming faster than it has at any time during this period, with 1990 and 2006 being the hottest years on record.[77] In collaboration with the Stockholm Environment Institute, Sheffield developed a carbon footprint (based on 2004–05 consumption figures) of 5,798,361 tonnes per year. This compares to the UK’s total carbon footprint of 698,568,010 tonnes per year. The factors with the greatest impact are housing (34%), transport (25%), consumer (11%), private services (9%), public services (8%), food (8%) and capital investment (5%).[78] Sheffield City Council has signed up to the 10:10 campaign.[79]

Green belt[edit]

Sheffield is within a green belt region that extends into the wider surrounding counties, and is in place to reduce urban sprawl, prevent the towns and areas in the Sheffield built-up area conurbation from further convergence, protect the identity of outlying communities, encourage brownfield reuse, and preserve nearby countryside. This is achieved by restricting inappropriate development within the designated areas, and imposing stricter conditions on permitted building.[80][81] The main urban area and larger villages of the borough are exempt from the green belt area, but surrounding smaller villages, hamlets and rural areas are ‘washed over’ with the designation. A subsidiary aim of the green belt is to encourage recreation and leisure interests,[80] with many rural landscape features and facilities included.

Subdivisions[edit]

Sheffield is made up of many suburbs and neighbourhoods, many of which developed from villages or hamlets that were absorbed into Sheffield as the city grew.[15] These historical areas are largely ignored by the modern administrative and political divisions of the city; instead it is divided into 28 electoral wards, with each ward generally covering 4–6 areas.[82] These electoral wards are grouped into six parliamentary constituencies. Sheffield is largely unparished, but Bradfield and Ecclesfield have parish councils, and Stocksbridge has a town council.[83]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 60,095 | — |

| 1821 | 84,540 | +40.7% |

| 1841 | 134,599 | +59.2% |

| 1861 | 219,634 | +63.2% |

| 1881 | 335,953 | +53.0% |

| 1901 | 451,195 | +34.3% |

| 1921 | 543,336 | +20.4% |

| 1941 | 569,884 | +4.9% |

| 1951 | 577,050 | +1.3% |

| 1961 | 574,915 | −0.4% |

| 1971 | 572,794 | −0.4% |

| 1981 | 530,844 | −7.3% |

| 1991 | 528,708 | −0.4% |

| 2001 | 513,234 | −2.9% |

| 2011 | 551,800 | +7.5% |

| 2019 | 584,028 | +5.8% |

| [84] |

Population of Sheffield from 1700 to 2011. The exponential population growth during the 19th century and the subsequent plateauing during the 20th century are evident.

The United Kingdom Census 2001 reported a resident population for Sheffield of 513,234, a 2% decline from the 1991 census.[85] The city is part of the wider Sheffield urban area, which had a population of 640,720.[86] In 2011 the racial composition of Sheffield’s population was 84% White (81% White British, 0.5% White Irish, 0.1% Romani or Irish Traveller, 2.3% Other White), 2.4% of mixed race (1.0% White and Black Caribbean, 0.2% White and Black African, 0.6% White and Asian, 0.6% Other Mixed), 8% Asian (1.1% Indian, 4% Pakistani, 0.6% Bangladeshi, 1.3% Chinese, 1.0% Other Asian), 3.6% Black (2.1% African, 1% Caribbean, 0.5% Other Black), 1.5% Arab and 0.7% of other ethnic heritage.[87][failed verification] In terms of religion, 53% of the population are Christian, 6% are Muslim, 0.6% are Hindu, 0.4% are Buddhist, 0.2% are Sikh, 0.1% are Jewish, 0.4% belong to another religion, 31% have no religion and 7% did not state their religion.[88] The largest quinary group is 20- to 24-year-olds (9%) because of the large university student population.[89]

The Industrial Revolution served as a catalyst for considerable population growth and demographic change in Sheffield. Large numbers of people were driven to the city as the cutlery and steel industries flourished. The population continued to grow until the mid-20th century, at which point, due to industrial decline, the population began to contract. However, by the early 21st century, the population had begun to grow once again.

The population of Sheffield peaked in 1951 at 577,050, and has since declined steadily. However, the mid-2007 population estimate was 530,300, representing an increase of about 17,000 residents since 2001.[90]

Although a city, Sheffield is informally known as «the largest village in England»,[91][92][93] because of a combination of topographical isolation and demographic stability.[91] It is relatively geographically isolated, being cut off from other places by a ring of hills.[94][95] Local folklore insists that, like Rome, Sheffield was built «on seven hills».[95] The land surrounding Sheffield was unsuitable for industrial use,[91] and now includes several protected green belt areas.[96] These topographical factors have served to restrict urban spread,[96] resulting in a relatively stable population size and a low degree of mobility.

Economy[edit]

| Labour profile | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total employee jobs | 255,700 | |

| Full-time | 168,000 | 65.7% |

| Part-time | 87,700 | 34.3% |

| Manufact. & Construct. | 40,300 | 15.7% |

| Manufacturing | 31,800 | 12.4% |

| Construction | 8,500 | 3.3% |

| Services | 214,900 | 84.1% |

| Distribution, hotels & restaurants | 58,800 | 23.0% |

| Transport & communications | 14,200 | 5.5% |

| Finance, IT, other business activities | 51,800 | 20.2% |

| Public admin, education & health | 77,500 | 30.3% |

| Other services | 12,700 | 5.0% |

| Tourism-related | 18,400 | 7.2% |

After many years of decline, the Sheffield economy is going through a strong revival. The 2004 Barclays Bank Financial Planning study[97] revealed that, in 2003, the Sheffield district of Hallam was the highest ranking area outside London for overall wealth, the proportion of people earning over £60,000 a year standing at almost 12%. A survey by Knight Frank[98] revealed that Sheffield was the fastest-growing city outside London for office and residential space and rents during the second half of 2004. This can be seen in a surge of redevelopments, including the City Lofts Tower and accompanying St Paul’s Place, Velocity Living and the Moor redevelopment,[99] the forthcoming NRQ and the Winter Gardens, Peace Gardens, Millennium Galleries and many projects completed under the Sheffield One redevelopment agency. The Sheffield economy grew from £5.6 billion in 1997 (1997 GVA)[100] to £9.2 billion in 2007 (2007 GVA).[101]

The «UK Cities Monitor 2008» placed Sheffield among the top ten «best cities to locate a business today», the city occupying third and fourth places respectively for best office location and best new call centre location. The same report places Sheffield in third place regarding «greenest reputation» and second in terms of the availability of financial incentives.[102]

Heavy industries and metallurgy[edit]

Sheffield has an international reputation for metallurgy and steel-making.[103] The earliest official record of cutlery production, for which Sheffield is particularly well known, is from 1297 when a tax return for ‘Robert the Cutler’ was submitted.[104] A key reason for Sheffield’s success in the production of cutlery lies in its geographic makeup. The abundance of streams in the area provided water power and the geological formations in the Hope Valley, in particular, provided sufficient grit stones for grinding wheels.[104] In the 17th century, the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire, which oversaw the booming cutlery industry in the area and remains to this day, was established and focused on markets outside the Sheffield area, leading to the gradual establishment of Sheffield as a respected producer of cutlery.[104] this gradually developed from a national reputation into an international one.[104]

Playing a crucial role in the Industrial Revolution, the city became an industrial powerhouse in the 18th century, and was dubbed «Steel City».[105] Many innovations in these fields have been made in Sheffield, for example Benjamin Huntsman discovered the crucible technique in the 1740s at his workshop in Handsworth.[106] This process was rendered obsolete in 1856 by Henry Bessemer’s invention of the Bessemer converter. Thomas Boulsover invented Sheffield Plate (silver-plated copper) in the early 18th century.

Stainless steel was invented by Harry Brearley in 1912, bringing affordable cutlery to the masses.[105][107] The work of F. B. Pickering and T. Gladman throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s was fundamental to the development of modern high-strength low-alloy steels.[108] Further innovations continue, with new advanced manufacturing technologies and techniques being developed on the Advanced Manufacturing Park, situated just over the boundary in the borough of Rotherham, by Sheffield’s universities and other independent research organisations.[109] Organisations located on the AMP include the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC, a research partnership between the Boeing Company and the University of Sheffield), Castings Technology International (CTI), The Welding Institute (TWI),[110] Rolls-Royce plc and McLaren Automotive.

Forgemasters steel works in Sheffield. The site was formerly run by Vickers Limited which was founded in Sheffield in 1828 and became one of the most prominent engineering companies in the world.

Forgemasters, founded in 1805, is the sole remaining independent steel works in the world and dominates the north-east of Sheffield around the Lower Don Valley.[111] The firm has a global reputation for producing the largest and most complex steel forgings and castings and is certified to produce critical nuclear components, with recent projects including the Royal Navy’s Astute-class submarines.[112] The firm also has the capacity for pouring the largest single ingot (570 tonnes) in Europe and is currently in the process of expanding its capabilities.[113] In July 2021 Forgemasters was bought outright by the UK Ministry of Defence for £2.56 million, with the intention of investing a further £400 million over the next decade.[114] The decision was based on the important role Forgemasters plays in the construction of the UK nuclear submarine fleet as well other vessels for the Royal Navy.[114]

While iron and steel have long been the main industries of Sheffield, coal mining has also been a major industry, particularly in the outlying areas, and the Palace of Westminster in London was built using limestone from quarries in the nearby village of Anston.

Public sector[edit]

Sheffield has a large public sector workforce, numbering 77,500 workers. During the period 1995 – 2008 (a period of growth for the city and many others in the UK), the number of jobs in the city increased by 22% and 50% of these were in the public sector.[115] Major public sector employers include the National Health Service, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield Hallam University, and numerous government departments and agencies including the Home Office (Visas & Immigration), Department for Education & Department for Business, Innovation & Skills. Recently developed offices in St Paul’s Place and Riverside Exchange play host to the aforementioned government departments.

Sheffield City Council, which is also a major public sector employer in the city, employs over 8,000 people, spread across four different sections (known as portfolios). Sheffield City Council is also the Local Education Authority (LEA) and as such manages all states schools and their associated staff. As part of its mandate to provide public services, Sheffield City Council maintains contracts with three private contractors — Amey, Veolia & Capita (contract ending in 2020). Together, these contractors provide additional employment in the city.

Leisure and retail[edit]

City Centre[edit]

A view of Sheffield City Centre. Some of the major shopping precincts can be seen in the left and centre of the image.

The Moor shopping precinct

Sheffield is a major retail centre, and is home to many High Street and department stores as well as designer boutiques.[116] The main shopping areas in the city centre are on The Moor precinct, Fargate, Orchard Square and the Devonshire Quarter. Department stores in the city centre include Marks and Spencer and Atkinsons. Sheffield’s main market was once Castle Market, built above the remains of the castle. This has since been demolished.[117] Sheffield Moor Market opened in 2013 and became the main destination for fresh produce. The market has 196 stalls and includes local and organic produce, as well as international fusion cuisine such as Russian, Jamaican and Thai.[118] In March 2021 it was announced that the Sheffield branch of John Lewis would close due to falling sales and a move to online shopping, which had increased because of the COVID-19 pandemic. John Lewis received £3 million of public funding from Sheffield City Council in 2020 to keep the local store open.[119] The local Debenhams branches are expected to re-open ofter the lifting of the 2021 COVID-19 lockdown restrictions, but only to clear existing stock, after which it is expected the stores will close.[120][121]

With the decline in high street shopping around the UK, efforts have been made to rejuvenate Sheffield City Centre and improve the retail and leisure offering. Major developments include Leopold Square, The Moor, St Paul’s Place (a mixed use development) and the Heart of the City I & II projects. In March 2022 Sheffield City Council announced that a new leisure hub would be constructed at the southern end of Fargate. The £300,000 hub will feature cafes, shops and large screen TVs for sports events.[122] The development is also related to other efforts to rejuvenate the Fargate area, such as a new mixed-use events and coworking hub at 20-26 Fargate, also overseen by Sheffield City Council.[123]

Shopping centres[edit]

Meadowhall shopping centre, located to the north of Sheffield close to the boundary with Rotherham and next to the M1 motorway, is a major regional shopping destination and currently ranked eleventh largest in the UK with a floorspace of 1,500,000 sq ft (140,000 m2). Attracting over 30 million visitors a year (up from 19 million in its first year), the centre hosts 270 shops, 37 restaurants and a cinema.[124][125] Many nationally renowned brands have a presence at the centre including Marks & Spencer, Hugo Boss and Jaeger. The centre is connected to the city centre by rail, Supertram and bus services.[124] Prior to the opening of Meadowhall, the site was occupied for East Hecla (steel) works, a major employer in the north-east of the city. The opening of Meadowhall in 1990 marked the beginning of major rejuvenation in the Lower Don Valley as the steel industry contracted. In a 2010 survey of forecast expenditure at retail centres in the United Kingdom, Meadowhall was ranked 12th and Sheffield City Centre 19th.[126]

To the south of Meadowhall shopping centre is Meadowhall Retail Park, a 190,500 sq ft (17,700 m2) retail park with 13 retail and food units.[127] Next to the retail park is the Sheffield IKEA store, opened in 2017. The opening ceremony was attended by dignitaries including the Swedish Ambassador to the UK.[128] The Sheffield store was the 20th opened in the UK and led to the creation of 480 new local jobs.

The second largest shopping centre in Sheffield is Crystal Peaks, located in the south-east of the city, alongside Drakehouse Retail Park. Both the shopping centre and the retail park opened in 1988 and now attract around 11 million visitors a year.[129] In total there are 101 retailers (including eateries) at Crystal Peaks and Drakehouse, including a range high street brands. Crystal Peaks also includes a travel interchange which serves as the hub for bus travel in the east and south-east of Sheffield.

Suburbs[edit]

Little Kelham in the Kelham Island Quarter

Beyond the city centre there are numerous other leisure and shopping areas. To the south-west of the city centre is Ecclesall Road, a major thoroughfare connecting the south-western suburbs to the city centre and lined with bars, restaurants and cafes, as well as housing.[130] The area has a large student community owing to the presence of the Sheffield Hallam University Collegiate Campus adjacent to Ecclesall Road. The leisure section of the road is approximately 1.6 mi (2.5 km) long, with the south-western end becoming Ecclesall Road South and a predominantly

residential area. Another popular shopping and leisure area is London Road, to the south of the city centre. The road is famous for its multicultural community which has led to an abundance of international cuisines being served at restaurants along the road. To the west of the city centre is Broomhill, a student-centric neighbourhood which also caters for school students as well local university students and NHS staff. To the north-west of the city centre are Hillsborough, a large retail and sports hub, and Stocksbridge Fox Valley, a modern leisure and retail centre built on a brownfield industrial site.[131]

In the late 2010s and early 2020s several new developments began to the north of the city centre in the Kelham Island Quarter, an increasingly popular mixed-use development. The area has become known for its independent cafes, restaurants and pubs and has seen significant residential development in recent years.

Tourism[edit]

Tourism plays a major role in the city’s economy on account of numerous attractions — namely the Peak District, sports events (in particular, the Snooker World Championships) and musical festivals (such as Tramlines). In 2019, the tourism industry in Sheffield was valued at £1.36 billion and supported 15,000 jobs.[132]

In 2012, Sheffield City Region Enterprise Zone was launched to promote development in a number of sites in Sheffield and across the wider region. In March 2014 additional sites were added to the zone.[133]

Transport[edit]

Cars, coaches and cycling[edit]

Aerial view of Park Square, where the Sheffield Parkway meets the Sheffield Inner Ring Road

Motorways near the city are the M1 and M18.[134] Sheffield Parkway connects the city centre to the motorways. The M1 skirts the city’s north-east and crossing Tinsley Viaduct near Rotherham. The M18 branches from the M1 close to Sheffield, linking the city with Doncaster and ending at Goole.

The A57 and A61 roads are the major trunk roads through Sheffield.[134] These run east–west and north–south respectively, crossing in the city centre, from where the other major roads generally radiate spoke-like. An inner ring road, mostly constructed in the 1970s and extended in 2007 to form a complete ring,[135] allows traffic to avoid the city centre, and an outer ring road runs to the east, south-east and north, nearer the edge of the city, but does not serve the western side of Sheffield.[134]

Sheffield Interchange is the city’s bus main hub; other bus stations are at Halfway, Hillsborough and Meadowhall. After deregulation in 1986,[136] there were multiple new service providers. Current providers are First South Yorkshire, Stagecoach Yorkshire, TM Travel, Hulleys of Baslow and Sheffield Community Transport. First South Yorkshire, is the largest bus operator.[137][138] There is also the Bus Rapid Transit North route between Sheffield and Maltby via Rotherham. It was planned as two routes: the Northern route to Rotherham via Meadowhall and Templeborough, and the southern route via the developing employment centre and Waverley.[139] The northern route opened in September 2016; it involved an 800m Tinsley Road Link to be built between Meadowhall and the A6178 road.[140] Yorkshire Terrier, Andrews and the parent company Yorkshire Traction formerly operated in the city and were taken-over by Stagecoach Sheffield.[141] Stagecoach Group also operates the Supertram and has an integrated ticketing system with buses and tram.[142]

Coach services running through Sheffield are operated by National Express and to a lesser extent Megabus and Flixbus. National Express services call at Sheffield Interchange, Meadowhall Interchange and Meadowhead Bus Stop. Megabus and Flixbus services only call at Meadowhall. National Express services 564, 560, 350, 320, 310 and 240 call at Sheffield, as do others on a less frequent basis.[143] The 560/564 service is a direct connection to London Victoria Coach Station via Chesterfield and Milton Keynes, operating 12 times a day in both directions. The 350 and 240 services connect Sheffield to Manchester Airport and Heathrow/Gatwick Airports respectively.[144] Two Megabus services, the M12 and M20, call at Sheffield en route to London from Newcastle upon Tyne and Inverness respectively.[145]

Although hilly, Sheffield is compact and has few major trunk roads, therefore cycling in Sheffield is a popular method of transport. It is on the Trans-Pennine Trail, a National Cycle Network route running from West to East from Southport in Merseyside to Hornsea in the East Riding of Yorkshire and North to South from Leeds in West Yorkshire to Chesterfield in Derbyshire.[146] There are many cycle routes going along country paths in the woods surrounding the city, and an increasing number of cycle lanes in the city itself.

Trams, trains and tramtrains[edit]

Train services in Sheffield are operated by East Midlands Railway, CrossCountry, TransPennine Express and Northern. Major railway routes through Sheffield station include the Midland Main Line (to London via the East Midlands), the Cross Country Route (which runs between eastern Scotland and south-west England) and the lines linking Liverpool and Manchester with Hull and East Anglia.[147] With the redevelopment of London St Pancras completed, Sheffield has a direct connection to continental Europe, via the East Midlands Railway, to St Pancras and the Eurostar to France and Belgium.[148] East Midlands Railway also operates three premium trains: the Master Cutler, the Sheffield Continental and the South Yorkshireman.

High Speed 2 is planned to serve a city centre station in Sheffield as a spur from the main HS2 line. Proposals for the HS2 station’s location have been considered, including: Sheffield station, Sheffield Victoria (on the location of the former station of the same name) and Meadowhall Interchange. It is scheduled to be operational by 2033. There will be four trains an hour serving the station, with journey times to London and Birmingham reduced to 1 hour 19 minutes and 48 minutes respectively.[149] In November 2021, the UK government published the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands in which it announced HS2’s eastern spur route (between the East Midlands and Leeds) had been cancelled, which had been planned to include Sheffield. The document announced upgrades to the Midland Mainline, with HS2 trains able to run on this upgraded and electrified route.[150]

There are several local rail routes running along the city’s valleys and beyond, connecting it with other parts of South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire and Derbyshire. These local routes include the Penistone Line, the Dearne Valley Line, the Hope Valley Line and the Hallam Line. As well as the main stations of Sheffield and Meadowhall, there are five suburban stations at Chapeltown, Darnall, Woodhouse and Dore & Totley.[151] As part of improvements to rail services along the Hope Valley Line between Sheffield and Manchester, a new platform, station facilities and track are being built at Dore & Totley Station with the expanded station due to open in 2023.[152]

The Sheffield Supertram (not derived from the previous tramways), opened in 1994 and is operated by Stagecoach. The opening was shortly after the similar Metrolink scheme in Greater Manchester. The Supertram network consists of 37 mi (60 km) of track and four lines (with all lines running via the city centre): from Halfway to Malin Bridge (Blue Line), from Meadowhall to Middlewood (Yellow Line), from Meadowhall to Herdings Park (Purple Line),[153] and the from Cathedral to Rotherham Parkgate (Black Line). The system contains both on-street and segregated running, depending upon the section and line. The Black Line opened in 2018,[154] with tram-trains; these are trams that are able to share a line with conventional heavy rail trains between Sheffield and Rotherham.

Canal[edit]

The Sheffield & South Yorkshire Navigation (S&SY) is a system of navigable inland waterways (canals and canalised rivers) in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.[155] Chiefly based on the River Don, it runs for a length of 43 mi (69 km) and has 29 locks. It connects Sheffield, Rotherham and Doncaster with the River Trent at Keadby and (via the New Junction Canal) the Aire & Calder Navigation.[156] The terminus of the canal is at Victoria Quays, a redevelopment mixed-used area adjacent to Park Square in Sheffield City Centre.

Air[edit]

The closest airports are in Leeds Bradford, Humberside, East Midlands (within an hour’s drive of the city), Manchester (hourly direct service by South TransPennine).

Due to the topographical nature of the city, Sheffield was not served by its own airport. In 1997, Sheffield City Airport was opened on land close to the M1 and the Sheffield Parkway. The airport was operated on STOLPORT model similar to London City Airport and operated a limited range of short range business focused flights to destinations in the British Isles and the Netherlands. The airport fell into decline with the growth of low cost airlines in the late 1990s and the last scheduled flight took place in 2002. The airport closed and lost its CAA license in 2008. Following the closure of Sheffield City Airport (also known as Robin Hood Airport) in 2008,[157] the closest international airport to Sheffield is Doncaster Sheffield Airport which located 18 mi (29 km) from the city centre and closed on 4 November 2022. It opened on 28 April 2005 on the former RAF Finningley site and is served mainly by charter and budget airlines, with about one million passengers a year.[158] A link road, called the Great Yorkshire Way, connects Doncaster Sheffield Airport to the M18 motorway, reducing the journey time from Sheffield city centre from 40 to 25 minutes.[159]

Education[edit]

Within the city of Sheffield there are two universities, 141 primary schools and 28 secondary schools.[160]

Museums[edit]

Sheffield’s museums are managed by two distinct organisations. Museums Sheffield manages the Weston Park Museum (a Grade II*listed Building), Millennium Galleries and Graves Art Gallery.[161] These museums constitute the oldest extant museums in the city, with Graves Art Gallery and Weston Park Museum being gifted to the city by industrialist philanthropists in the 19th and 20th centuries. The Millennium Galleries, being established in the early 2000s, is one of the newest museums and constitutes part of the Heart of the City development, connecting directly to the Winter Garden and Millennium Square. All three museums host a broad range of exhibits which reflect Sheffield’s history and numerous other themes, including exhibitions on loan from other major galleries and museums.

Sheffield Industrial Museums Trust manages the museums dedicated to Sheffield’s industrial heritage of which there are three.[162] Kelham Island Museum (located just to the North of the city centre) is located on the site of a 19th-century iron foundry and showcases the city’s history of steel manufacturing and includes a range of important historical artifacts, including a preserved Bessemer Converter (which won an Engineering Heritage Award in 2004 from the Institution of Mechanical Engineers), munitions and mechanical components from WW2 aircraft (Including a crankshaft from a Spitfire which, during the early stages of the war, could only be produced in Sheffield) and a fully functional 12,000 horsepower steam engine dating to the 19th century.[163] The museum is an Anchor Point for the ERIH, The European Route of Industrial Heritage. Abbeydale Industrial Hamlet (in the south of the city) is a Grade I Listed building and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[164] Shepherd Wheel (in the south-East of the city) is a former water-powered grinding workshop, Grade II listed and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[165] Also there are Sheffield Archives.

In August 2022 the Yorkshire Natural History Museum opened on Holme Lane in Sheffield. Many of the exhibits come from the collection of James Hogg and feature a collection of Jurassic marine life, such as ammonites, belemnites, plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, many of which were collected from the Lias of the Yorkshire Coast. The museum has Europe’s first publicly accessible fossil preparation and conservation laboratory with ultrasonic preparation facilities, an acid preparation laboratory, 3D scanning, CT scanning and 3D printing.[166][167] On the opening day palaeontologist Dean Lomax exmined one of the fossils on display and declared it to be the oldest example of a vertebrate embryo found in Britain and the oldest complete ichthyosaur embryo ever found in Britain.[168]

Universities, colleges and UTCs[edit]

The city’s universities are the University of Sheffield and Sheffield Hallam University. The two combined bring about 60,000 students to the city every year.[169] The University of Sheffield is the city’s oldest university. It was established in 1897 as University College Sheffield and gained university status in 1905. Its history traces back to Sheffield Medical School found in 1828, Firth College in 1879 and Sheffield Technical School in 1884. The university is one of the original red brick universities and is a member of the Russell Group.

Sheffield Hallam University (SHU) is a university on two sites in Sheffield. City Campus is located in the city centre, close to Sheffield railway station, and Collegiate Crescent Campus is about 2 mi (3.2 km) away, adjacent to Ecclesall Road in south-west Sheffield. Sheffield Hallam University’s history goes back to 1843 with the establishment of the Sheffield School of Design. During the 1960s several independent colleges (including the School of Design) joined to become Sheffield Polytechnic (Sheffield City Polytechnic from 1976) and was finally renamed Sheffield Hallam University in 1992.

Sheffield has three main further education providers: The Sheffield College, Longley Park Sixth Form and Chapeltown Academy. The Sheffield College is organised on a federal basis and was originally created from the merger of six colleges around the city: Sheffield City (formerly Castle),[170] Olive Grove and Eyre Street near the city centre, Hillsborough and Fir Vale, serving the north of the city and Peaks to the south.[171]

Launched by the coalition government in 2010, the University Technical College program was designed to foster greater interest in STEM subjects amongst students aged 14 to 18. Sheffield currently hosts two UTCs, UTC Sheffield City Centre and UTC Sheffield Olympic Legacy Park. All UTCs, including those in Sheffield, are sponsored by the Baker Dearing Educational Trust,[172] established by Lord Baker. The two UTCs in Sheffield are also sponsored and supported by Sheffield Hallam University. Whilst the UTCs are equivalent to regular secondary schools and sixth forms, their governance structure and curriculum are different, owing to their status as free schools and focusing on STEM, as opposed to a broader curriculum.

Secondary, primary and nursery[edit]

There are 137 primary schools, 26 secondary schools – of which 10 have sixth forms: (High Storrs, King Ecgberts, King Edward VII, Silverdale, Meadowhead, Tapton, Notre Dame Catholic High and All Saints Catholic High[173]) – and a sixth-form college, Longley Park Sixth Form.[174] The city’s five independent private schools include Birkdale School and the Sheffield High School.[175] There are also 12 special schools and a number of Integrated Resource Units in mainstream schools which are, along with all other schools, managed by Sheffield City Council.[176] All schools are non-selective, mixed sex schools (apart from Sheffield High School which is an all-girls school).[176]

The Early Years Education and Childcare Service of Sheffield City Council manages 32 nurseries and children’s centres in the city.[176]

Religion[edit]

Wolseley Road Mosque, which is one of the tallest religious establishments in Sheffield and dominates part of the skyline of the city

Sheffield is home to a centre of multicultural events, institutions, and places of worship. Some of the city’s most notable buildings include its main Church of England Diocese of Sheffield’s cathedral on Church Street and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Hallam’s cathedral on Norfolk Row.

The city also has other churches including St Vincent’s Church, St Matthew’s Church, St Paul’s Church, St Paul’s Church and Centre, Victoria Hall and Christ Church. Other places of worship include the Madina Mosque, Sheffield & District Reform Jewish Congregation and Wilson Road Synagogue.

Sport[edit]

Teams[edit]

Football codes[edit]

Sheffield has a long sporting heritage. In 1857 a collective of cricketers formed the world’s first-ever official football club, Sheffield FC,[177] and the world’s second-ever, Hallam FC, who also play at the world’s oldest football ground[178] in the suburb of Crosspool. Sheffield and Hallam are today Sheffield’s two major non-league sides, although Sheffield now play just outside the city in nearby Dronfield, Derbyshire. Sheffield and Hallam contest what has become known as the Sheffield derby. By 1860 there were 15 football clubs in Sheffield, with the first ever amateur league and cup competitions taking place in the city.[179]

Sheffield is best known for its two professional football teams, Sheffield United, nicknamed The Blades, and Sheffield Wednesday, nicknamed The Owls. United, who play at Bramall Lane south of the city centre, compete in the Football League Championship and Wednesday, who play at Hillsborough in the north-west of the city, compete in the Football League One. The two clubs contest the Steel City Derby, which is considered by many to be one of the most fierce football rivalries in English Football.[180]

In the pre-war era, both Wednesday and United enjoyed large amounts of success and found themselves two of the country’s top clubs; Sheffield Wednesday have been champions of the Football League four times – in 1902–03, 1903–04, 1928–29 and 1929–30, whilst Sheffield United have won it once, in 1897–98. During the 1970s and early 1980s the two sides fell from grace, with Wednesday finding themselves in the Third Division by the mid-70s and United as far as the Fourth Division in 1981. Wednesday once again became one of England’s high-flying clubs following promotion back to the First Division in 1984, winning the League Cup in 1991, competing in the UEFA Cup in 1992–93, and reaching the final of both the League Cup and FA Cup in the same season.

United and Wednesday were both founding members of the Premier League in 1992, but The Blades were relegated in 1994. The Owls remained until 2000. Both clubs had gone into decline in the 21st century, Wednesday twice relegated to League One and United suffering the same fate in 2011, despite a brief spell in the Premier League in 2006–07. United was promoted to the Premier League in 2019 under manager, and Sheffield United Fan, Chris Wilder. Despite being written off by most football pundits, and declared favourites for relegation from the Premier League, United exceeded expectations and finished in the top half of the table in the 2019–20 season. In the 2020-2021 season, United sat at the bottom of the Premier League table by the conclusion of the season and were relegated.

Sheffield was the site of the deadliest sports venue disaster in the United Kingdom, the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, when 97 Liverpool supporters were killed in a stampede and crush during an FA Cup semi-final at the venue.

Rotherham United, who play in the Championship, did play their home games in the city between 2008 and 2012, having moved to play at Sheffield’s Don Valley Stadium in 2008 following a dispute with their previous landlord at their traditional home ground of Millmoor, Rotherham. However, in July 2012, the club moved to the new 12,000 seat New York Stadium in Rotherham. There are also facilities for golf, climbing and bowling, as well as a newly inaugurated national ice-skating arena (IceSheffield).

Sheffield Eagles RLFC are the city’s professional rugby league team and play their matches at Sheffield Olympic Legacy Stadium. They currently play in the second tier of the professional league, the Championship and won back to back titles in 2012 and 2013. Their most successful moment came in 1998, when, against all the odds they defeated Wigan in the Challenge Cup final, despite being huge underdogs. The team then hit troubled times before reforming in 2003. Since then they have played their rugby in the Championship (second tier). In 2011, they made the playoffs finishing in fifth place. They made the Grand Final, by defeating Leigh, who were huge favourites in a playoff semi final. In the final, they were comprehensively beaten by Featherstone Rovers. Sheffield also put in a bid to be a host city for the 2013 Rugby League World Cup, but their bid was unsuccessful.

Sheffield Giants are an American football team who play in the BAFA National Leagues Premier Division, the highest level of British American Football.

Ice Hockey and roller derby[edit]

Sheffield is home to the Sheffield Steelers professional ice hockey team who play out of the 9.300 seater Sheffield Arena and are known as one of the top teams in the UK, regularly selling out the arena. They have the 28th highest average attendance rating in Europe, and the highest in the UK. They play in the 10 team professional Elite Ice Hockey League. Sheffield is also home to the semi-professional ice hockey team Sheffield Steeldogs who play in the NIHL.

The Sheffield Ice Hockey Academy also are based in Sheffield, and play out of IceSheffield, competing in the EIHA Junior North Leagues and have had one player, Liam Kirk, become the first born and trained British player to be drafted into the NHL, when he was drafted in the NHL Entry Draft 189th overall in 2018 by the Arizona Coyotes. The National Hockey League’s Stanley Cup was made in Sheffield in 1892. Sheffield is also home to the Sheffield Steel Rollergirls, a roller derby team.

Facilities and events[edit]

English Institute of Sport, Sheffield

Ponds Forge (bottom left) with Sheffield City Centre behind and Park Square in the bottom right

Many of Sheffield’s sporting facilities were built for the World Student Games, which the city hosted in 1991, including Sheffield Arena and the Ponds Forge international diving and swimming complex. Ponds Forge is also the home of Sheffield City Swimming Club, a local swimming club competing in the Speedo league. The former Don Valley International Athletics Stadium, once the largest athletics stadium in the UK, was also constructed for the Universiade games.[181]

Following the closure and demolition of Don Valley Stadium in 2013, The Sheffield Olympic Legacy Park was established and constructed on the same site, adjacent to the English Institute for Sport. The park is designed to a collaborative project with input from numerous stakeholders including both universities in Sheffield, the English Institute of Sport Sheffield, the NHS and private medical companies.[182] A key part of this collaboration is Sheffield Hallam University’s £14 million Advanced Well-being Research Centre (AWRC), which was established along similar lines to the University of Sheffield’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre’s (AMRC’s).[182] The site also includes teaching facilities, a stadium and research & innovation facilities.[182]

The Sheffield Ski Village was the largest artificial ski resort in Europe, before being destroyed in a series of suspected arson attacks in 2012 and 2013. The city also has six indoor climbing centres and is home to a significant community of professional climbers, including Britain’s most successful competitive climber Shauna Coxsey. Sheffield was the UK’s first National City of Sport and is now home to the English Institute of Sport – Sheffield, where British athletes trained for the 2012 Olympics.[183]

Sheffield also has close ties with snooker, with the city’s Crucible Theatre being the venue for the World Snooker Championships.[184] The English Institute of Sport hosts most of the top fencing competitions each year, including the National Championships for Seniors, Juniors (U20’s) and Cadets (U17’s) as well as the 2011 Senior European Fencing Championships. The English squash open is also held in the city every year. The International Open and World Matchplay Championship bowls tournaments have both been held at Ponds Forge.[185] The city also hosts the Sheffield Tigers rugby union, Sheffield Sharks, American Football team the Sheffield Giants, basketball, Sheffield University Bankers hockey, Sheffield Steelers ice hockey and Sheffield Tigers speedway teams. Sheffield also has many golf courses all around the city.

Sheffield was selected as a candidate host city by the Football Association (FA) as part of the English 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup bid on 16 December 2009.[186]

Hillsborough Stadium was chosen as the proposed venue for matches in Sheffield.[187] The bid failed.

Sheffield hosted the finish of Stage 2 of the 2014 Tour de France. Within the City limits and located just 4 km (2.5 mi) from the finish, was the ninth and final climb of the stage, the Category 4 Côte de Jenkin Road. The one point in the King of the Mountains competition was claimed by Chris Froome of Team Sky. The climb was just 0.8 km (0.5 mi) long at an average gradient of 10.8%. The stage was won by the eventual overall winner, Vincenzo Nibali of Astana Pro Team.[188]

IceSheffield, an Ice Rink with 2 Olympic sized rinks, was opened in May 2003, and is home to the Sheffield Steeldogs, Sheffield Ice Hockey Academy, and Sutton Sting amongst other teams. It is the host to the yearly EIHA Conference Tournament, EIHA Nationals, and Sheffield Junior Tournament.

The Sheffield Half Marathon is held annually.[189] It has thousands of participants every year.

Culture and attractions[edit]

Sheffield made the shortlist for the first city to be designated UK City of Culture, but in July 2010 it was announced that Derry had been selected.[190]

Attractions[edit]

The Sheffield Walk of Fame in the City Centre honours famous Sheffield residents past and present in a similar way to the Hollywood version.[191] Sheffield also had its own Ferris Wheel known as the Wheel of Sheffield, located atop Fargate shopping precinct. The Wheel was dismantled in October 2010 and moved to London’s Hyde Park.[192] Heeley City Farm and Graves Park are home to Sheffield’s two farm animal collections, both of which are fully open to the public.[193][194] Sheffield also has its own zoo; the Tropical Butterfly House, Wildlife & Falconry Centre.[195]

There are about 1,100 listed buildings in Sheffield (including the whole of the Sheffield postal district).[196] Of these, only five are Grade I listed. Sixty-seven are Grade II*, but the overwhelming majority are listed as Grade II.[197] Compared to other English cities, Sheffield has few buildings with the highest Grade I listing: Liverpool, for example, has 26 Grade I listed buildings. This situation led the noted architecture historian Nikolaus Pevsner, writing in 1959, to comment that the city was «architecturally a miserable disappointment», with no pre-19th-century buildings of any distinction.[198] By contrast, in November 2007, Sheffield’s Peace and Winter Gardens beat London’s South Bank to gain the Royal Institute of British Architects’ Academy of Urbanism «Great Place» Award, as an «outstanding example of how cities can be improved, to make urban spaces as attractive and accessible as possible».[199] In the summer of 2016 a public art event across the city occurred called the Herd of Sheffield which raised £410,000 for the Sheffield Children’s Hospital.[200]

Music and dance[edit]

A number of major music acts, including Joe Cocker, Ace, Def Leppard, Paul Carrack, Arctic Monkeys, Bring Me the Horizon, Rolo Tomassi, While She Sleeps, Pulp and Moloko, hail from the city.[201][202][203][204] Indie band The Long Blondes originated from the city,[205] as part of what the NME dubbed the New Yorkshire scene.[206]

Sheffield has been home to several well-known bands and musicians, with a notably large number of synthpop and other electronic bands originating from the city.[207] These include The Human League, Heaven 17, ABC, Thompson Twins and the more industrially inclined Cabaret Voltaire and Clock DVA. This electronic tradition has continued: techno label Warp Records was a central pillar of the Yorkshire Bleeps and Bass scene of the early 1990s, and has gone on to become one of the UK’s oldest and best-loved dance music labels. More recently, other popular genres of electronic music such as bassline house have originated in the city.[208] Sheffield was once home to a number of historically important nightclubs in the early dance music scene of the 1980s and 1990s, Gatecrasher One was one of the most popular clubs in the North of England until its destruction by fire on 18 June 2007.[209]

In 1999 the National Centre for Popular Music, a museum dedicated to the subject of popular music, was opened in the city.[210] It was not as successful as was hoped, however, and later evolved to become a live music venue; then in February 2005, the unusual steel-covered building became the students’ union for Sheffield Hallam University.[211] Live music venues in the city include the Harley Hotel, Leadmill, Maggie Mays, West Street Live, the Boardwalk, Dove & Rainbow, The Greystones, The Casbah, The Cremorne, Corporation, New Barrack Tavern, The Broadfield Hotel, Redstone bar and nightclub, the City Hall, the University of Sheffield Students’ Union, the Studio Theatre at the Crucible Theatre, the O2 Academy Sheffield and The Grapes.[212][213][214][215][216][217]

The city is home to several local orchestras and choirs, such as the Sheffield Symphony Orchestra, the Sheffield Philharmonic Orchestra, the Sheffield Chamber Orchestra, the City of Sheffield Youth Orchestra, the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus and the Chorus UK community choir.[218][219][220][221] It is also home to Music in the Round, a charitable organisation that exists to promote chamber music. It describes itself as the largest promoter of chamber music outside London.

Sheffield has a thriving folk music, song and dance community. Singing and music sessions occur weekly in many pubs around the city and it also hosts the annual Sheffield Sessions Festival.[222] The University of Sheffield runs a number of courses and research projects dedicated to folk culture.[223]

The tradition of singing carols in pubs around Christmas is still kept alive in the city. The Sheffield Carols, as they are known locally, predate modern carols by over a century and are sung with alternative words and verses.[224] Although there is a core of carols that are sung at most venues, each particular place has its own mini-tradition. The repertoire at two nearby places can vary widely, and woe betide those who try to strike up a ‘foreign’ carol. Some are unaccompanied, some have a piano or organ, there is a flip chart with the words on in one place, a string quartet (quintet, sextet, septet) accompanies the singing at another, some encourage soloists, others stick to audience participation, a brass band plays at certain events, the choir takes the lead at another.[225] It is thought this tradition is now unique in Britain.

The city is home to thirteen morris dance teams – thought to be one of the highest concentration of sides in the country. Nearly all forms of the dance are represented in the city, including Cotswold (Five Rivers Morris,[226] Pecsaetan Morris,[227] Harthill Morris,[228] Lord Conyer’s Morris Men,[229] Sheffield City Morris,[230] William Morris[231]), border (Boggart’s Breakfast[232]), North West (Yorkshire Chandelier,[233] Silkstone Greens,[234] Lizzie Dripping[235]), rapper (Sheffield Steel Rapper[236]) and Yorkshire Longsword.

Festivals[edit]

Sheffield hosts a number of festivals, the Grin Up North Sheffield Comedy Festival,[237] the Sensoria Music & Film Festival and the Tramlines Festival. The Tramlines Festival was launched as an annual music festival in 2009,[238] it is held at Hillsborough Park (the main stage) and at venues throughout Sheffield City Centre, and features local and national artists.[239]

Theatres[edit]

Sheffield has two large theatres, the Lyceum Theatre and the Crucible Theatre, which together with the smaller Studio Theatre make up the largest theatre complex outside London, located in Tudor Square.[240] The Crucible Theatre, a grade II listed building, is the home (since 1977) of the World Snooker Championships, which sees most of Tudor Square and the adjoining Winter Garden used for side events, and hosts many well-known stage productions throughout the year from local, national and international performance groups. The theatre was awarded the Barclays ‘Theatre of the Year Award’ in 2001. Between 2007 and 2009, the theatre underwent a £15 million refurbishment during which time major internal and external improvements were carried out. The Lyceum, which opened in 1897, serves as a venue for touring West End productions and operas by Opera North, as well as locally produced shows. Sheffield also has the Montgomery Theatre, a small 420 seater theatre located a short distance from Tudor Square, opposite the town hall on Surrey Street.[241] There are also a large number of smaller amateur theatres scattered throughout the city.

Greenspace[edit]

Sheffield Winter Gardens & St Paul’s Tower

Sheffield has a reputed 4.5 million trees[5] and is considered to be one of the greenest cities in England and the UK.[242][62] There are many parks and woods throughout the city and beyond. Containing more than 250 parks, woodlands and gardens, there are around 78 public parks and 10 public gardens in Sheffield,[4] including 83 managed parks (13 ‘City’ Parks, 20 ‘District’ Parks and 50 ‘Local’ Parks) located throughout the city.[243] Included in the city parks category are 3 of Sheffield’s 6 public gardens (the Sheffield Botanical Gardens, the Peace Gardens and Hillsborough Walled Gardens, with the Sheffield Winter Gardens, Beauchief Gardens and Lynwood Gardens being the separate entities).

The Sheffield Botanical Gardens are on a 19-acre site located to the south-west of the city centre and date back to 1836. The site includes a large, Grade II listed, Victorian era glasshouse. The Peace Gardens, neighboured next to the Town Hall and forming part of the Heart of the City project, occupy a 0.67 hectares (1.7 acres) site in the centre of the city. The site is dominated by its water features, principal among which is the Goodwin Fountain. Made up of 89 individual jets of water, this fountain lies at the corner of the quarter-circle shaped Peace Gardens and is named after Stuart Goodwin, a notable Sheffield industrialist. Since their redevelopment in 1998, the Peace gardens have received a number of regional and national accolades.[244] Hillsborough Walled Garden is located in Hillsborough Park, to the north-west of the city centre. The gardens date back to 1779 and have been dedicated to the victims of the Hillsborough Disaster since the redevelopment of the gardens in the early 1990s.[245] The Winter Garden, lying within the Heart of the City, is a large wood framed, glass skinned greenhouse housing some 2,500 plants from around the world.[246]

Also within the city there are a number of nature reserves which when combined occupy 1,600 acres (6.5 km2) of land.[247] There are also 170 woodland areas within the city, 80 of which are classed as ancient.[247]

The south-west boundary of the city overlaps with the Peak District National Park, the first national park in England (est. 1951).[248] As a consequence, several communities actually reside within both entities. The Peak District is home to many notable, natural, features and also man-made features such as Chatsworth House, the setting for the BBC series Pride and Prejudice.[249]

Sheffield City Council has created a new chain of parks spanning the hillside behind Sheffield Station. The park, known as Sheaf Valley Park, has an open-air amphitheatre and will include an arboretum.[250] The site was once home to a medieval deer park, latterly owned by the Duke of Norfolk.[250]

Entertainment[edit]

Valley Centertainment, Sheffield

Millennium Square, Sheffield.

Valley Centertainment, located in the Don Valley, is the main out of town leisure complex in Sheffield. It opened in the 1990s and was built on land previously occupied by steel mills across the road from what is now Sheffield Arena. It is anchored by a 20 screen Cineworld complex which is the largest in the chain and contains the only IMAX screens and 4DX screen in Sheffield.[251] Other features of the complex include a bowling alley, several chain restaurants, an indoor play area as well as indoor laser tag.

Sheffield has five other cinema complexes, four of which are in the city centre and a one at Meadowhall — Odeon Sheffield, situated on Arundel Gate in the city centre, The Light, located on The Moor and opened in 2017 as part of the regeneration project, and Vue, located within Meadowhall Shopping Centre, are the three other mainstream cinemas in the city. The Showroom, an independent cinema showing non-mainstream productions, is located in Sheaf Square, close to Sheffield station. In 2002 the Showroom was voted as the best Independent cinema in the country by Guardian readers.[252] A Curzon Cinemas complex is based in the former Sheffield Banking Company building, located just off Arundel Gate. The cinema features 4K resolution projectors and was opened in January 2015.[253][254] In 2020 a drive-in cinema opened at the Don Valley Bowl.[255]