|

William Shakespeare |

|

|---|---|

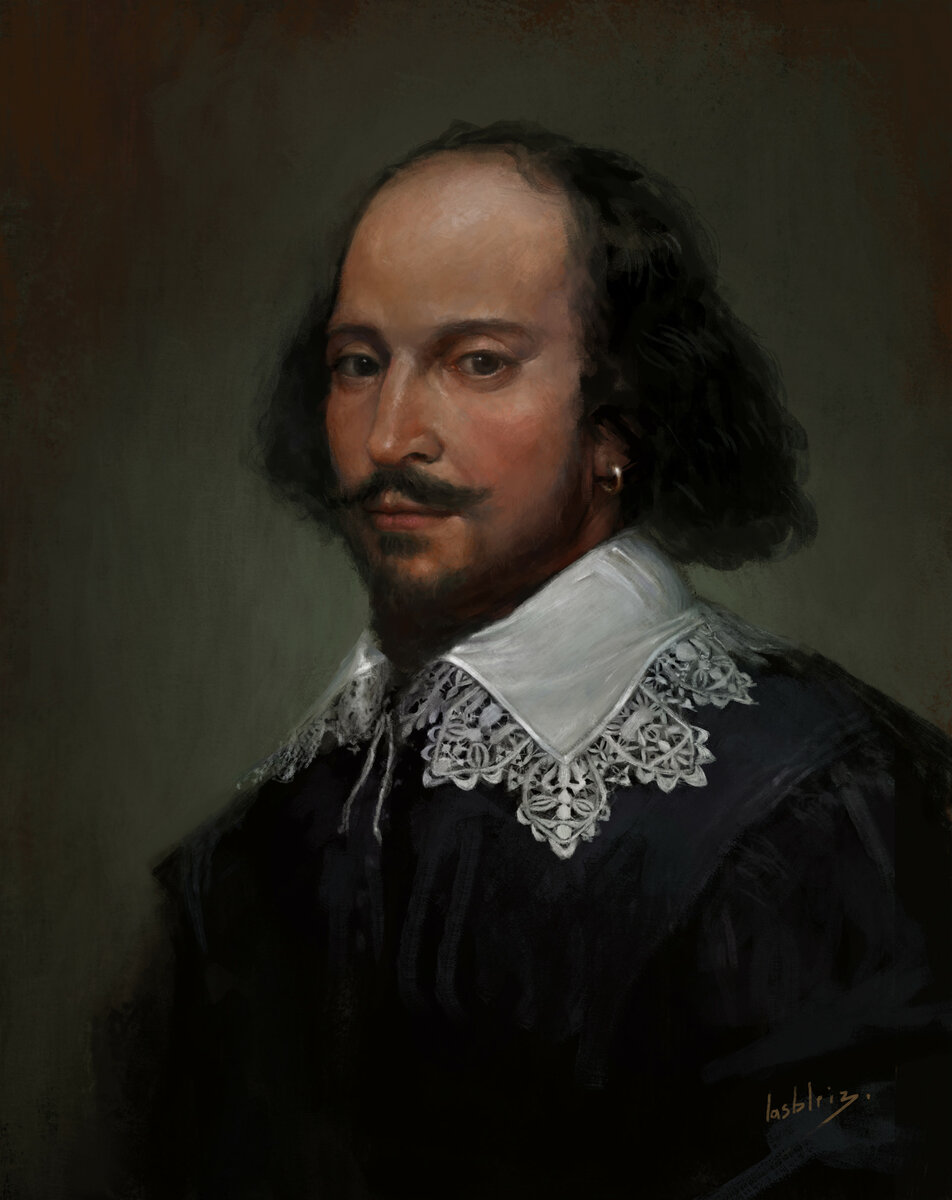

The Chandos portrait (held by the National Portrait Gallery, London) |

|

| Born |

Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Baptised | 26 April 1564 |

| Died | 23 April 1616 (aged 52)[a]

Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Resting place | Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | c. 1585–1613 |

| Era |

|

| Movement | English Renaissance |

| Spouse |

Anne Hathaway (m. 1582) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

William Shakespeare (bapt. 26 April[b] 1564 – 23 April 1616)[c] was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s pre-eminent dramatist.[2][3][4] He is often called England’s national poet and the «Bard of Avon» (or simply «the Bard»).[5][d] His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays,[e] 154 sonnets, three long narrative poems, and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[7] He remains arguably the most influential writer in the English language, and his works continue to be studied and reinterpreted.

Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Sometime between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, later known as the King’s Men. At age 49 (around 1613), he appears to have retired to Stratford, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive; this has stimulated considerable speculation about such matters as his physical appearance, his sexuality, his religious beliefs and whether the works attributed to him were written by others.[8][9][10]

Shakespeare produced most of his known works between 1589 and 1613.[11][12][f] His early plays were primarily comedies and histories and are regarded as some of the best works produced in these genres. He then wrote mainly tragedies until 1608, among them Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth, all considered to be among the finest works in the English language.[2][3][4] In the last phase of his life, he wrote tragicomedies (also known as romances) and collaborated with other playwrights.

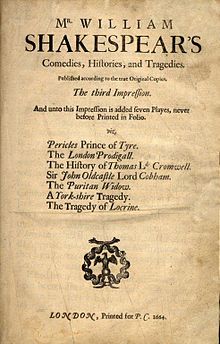

Many of Shakespeare’s plays were published in editions of varying quality and accuracy in his lifetime. However, in 1623, John Heminges and Henry Condell, two fellow actors and friends of Shakespeare’s, published a more definitive text known as the First Folio, a posthumous collected edition of Shakespeare’s dramatic works that included all but two of his plays.[13] Its Preface was a prescient poem by Ben Jonson, a former rival of Shakespeare, that hailed Shakespeare with the now famous epithet: «not of an age, but for all time».[13]

Life

Early life

Shakespeare was the son of John Shakespeare, an alderman and a successful glover (glove-maker) originally from Snitterfield in Warwickshire, and Mary Arden, the daughter of an affluent landowning family.[14] He was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, where he was baptised on 26 April 1564. His date of birth is unknown, but is traditionally observed on 23 April, Saint George’s Day.[15] This date, which can be traced to William Oldys and George Steevens, has proved appealing to biographers because Shakespeare died on the same date in 1616.[16][17] He was the third of eight children, and the eldest surviving son.[18]

Although no attendance records for the period survive, most biographers agree that Shakespeare was probably educated at the King’s New School in Stratford,[19][20][21] a free school chartered in 1553,[22] about a quarter-mile (400 m) from his home. Grammar schools varied in quality during the Elizabethan era, but grammar school curricula were largely similar: the basic Latin text was standardised by royal decree,[23][24] and the school would have provided an intensive education in grammar based upon Latin classical authors.[25]

At the age of 18, Shakespeare married 26-year-old Anne Hathaway. The consistory court of the Diocese of Worcester issued a marriage licence on 27 November 1582. The next day, two of Hathaway’s neighbours posted bonds guaranteeing that no lawful claims impeded the marriage.[26] The ceremony may have been arranged in some haste since the Worcester chancellor allowed the marriage banns to be read once instead of the usual three times,[27][28] and six months after the marriage Anne gave birth to a daughter, Susanna, baptised 26 May 1583.[29] Twins, son Hamnet and daughter Judith, followed almost two years later and were baptised 2 February 1585.[30] Hamnet died of unknown causes at the age of 11 and was buried 11 August 1596.[31]

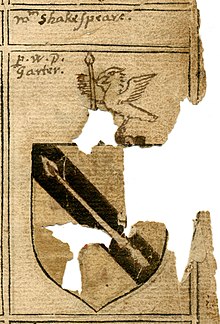

Shakespeare’s coat of arms, from the 1602 book The book of coates and creasts. Promptuarium armorum. It features spears as a pun on the family name.[g]

After the birth of the twins, Shakespeare left few historical traces until he is mentioned as part of the London theatre scene in 1592. The exception is the appearance of his name in the «complaints bill» of a law case before the Queen’s Bench court at Westminster dated Michaelmas Term 1588 and 9 October 1589.[32] Scholars refer to the years between 1585 and 1592 as Shakespeare’s «lost years».[33] Biographers attempting to account for this period have reported many apocryphal stories. Nicholas Rowe, Shakespeare’s first biographer, recounted a Stratford legend that Shakespeare fled the town for London to escape prosecution for deer poaching in the estate of local squire Thomas Lucy. Shakespeare is also supposed to have taken his revenge on Lucy by writing a scurrilous ballad about him.[34][35] Another 18th-century story has Shakespeare starting his theatrical career minding the horses of theatre patrons in London.[36] John Aubrey reported that Shakespeare had been a country schoolmaster.[37] Some 20th-century scholars suggested that Shakespeare may have been employed as a schoolmaster by Alexander Hoghton of Lancashire, a Catholic landowner who named a certain «William Shakeshafte» in his will.[38][39] Little evidence substantiates such stories other than hearsay collected after his death, and Shakeshafte was a common name in the Lancashire area.[40][41]

London and theatrical career

It is not known definitively when Shakespeare began writing, but contemporary allusions and records of performances show that several of his plays were on the London stage by 1592.[42] By then, he was sufficiently known in London to be attacked in print by the playwright Robert Greene in his Groats-Worth of Wit:

… there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.[43]

Scholars differ on the exact meaning of Greene’s words,[43][44] but most agree that Greene was accusing Shakespeare of reaching above his rank in trying to match such university-educated writers as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, and Greene himself (the so-called «University Wits»).[45] The italicised phrase parodying the line «Oh, tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide» from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 3, along with the pun «Shake-scene», clearly identify Shakespeare as Greene’s target. As used here, Johannes Factotum («Jack of all trades») refers to a second-rate tinkerer with the work of others, rather than the more common «universal genius».[43][46]

Greene’s attack is the earliest surviving mention of Shakespeare’s work in the theatre. Biographers suggest that his career may have begun any time from the mid-1580s to just before Greene’s remarks.[47][48][49] After 1594, Shakespeare’s plays were performed only by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a company owned by a group of players, including Shakespeare, that soon became the leading playing company in London.[50] After the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, the company was awarded a royal patent by the new King James I, and changed its name to the King’s Men.[51]

«All the world’s a stage,

and all the men and women merely players:

they have their exits and their entrances;

and one man in his time plays many parts …»

—As You Like It, Act II, Scene 7, 139–142[52]

In 1599, a partnership of members of the company built their own theatre on the south bank of the River Thames, which they named the Globe. In 1608, the partnership also took over the Blackfriars indoor theatre. Extant records of Shakespeare’s property purchases and investments indicate that his association with the company made him a wealthy man,[53] and in 1597, he bought the second-largest house in Stratford, New Place, and in 1605, invested in a share of the parish tithes in Stratford.[54]

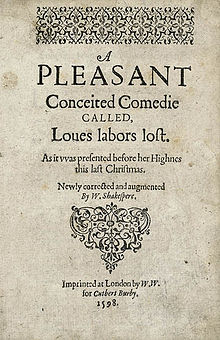

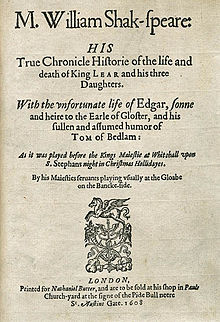

Some of Shakespeare’s plays were published in quarto editions, beginning in 1594, and by 1598, his name had become a selling point and began to appear on the title pages.[55][56][57] Shakespeare continued to act in his own and other plays after his success as a playwright. The 1616 edition of Ben Jonson’s Works names him on the cast lists for Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Sejanus His Fall (1603).[58] The absence of his name from the 1605 cast list for Jonson’s Volpone is taken by some scholars as a sign that his acting career was nearing its end.[47] The First Folio of 1623, however, lists Shakespeare as one of «the Principal Actors in all these Plays», some of which were first staged after Volpone, although one cannot know for certain which roles he played.[59] In 1610, John Davies of Hereford wrote that «good Will» played «kingly» roles.[60] In 1709, Rowe passed down a tradition that Shakespeare played the ghost of Hamlet’s father.[35] Later traditions maintain that he also played Adam in As You Like It, and the Chorus in Henry V,[61][62] though scholars doubt the sources of that information.[63]

Throughout his career, Shakespeare divided his time between London and Stratford. In 1596, the year before he bought New Place as his family home in Stratford, Shakespeare was living in the parish of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate, north of the River Thames.[64][65] He moved across the river to Southwark by 1599, the same year his company constructed the Globe Theatre there.[64][66] By 1604, he had moved north of the river again, to an area north of St Paul’s Cathedral with many fine houses. There, he rented rooms from a French Huguenot named Christopher Mountjoy, a maker of women’s wigs and other headgear.[67][68]

Later years and death

Nicholas Rowe was the first biographer to record the tradition, repeated by Samuel Johnson, that Shakespeare retired to Stratford «some years before his death».[69][70] He was still working as an actor in London in 1608; in an answer to the sharers’ petition in 1635, Cuthbert Burbage stated that after purchasing the lease of the Blackfriars Theatre in 1608 from Henry Evans, the King’s Men «placed men players» there, «which were Heminges, Condell, Shakespeare, etc.».[71] However, it is perhaps relevant that the bubonic plague raged in London throughout 1609.[72][73] The London public playhouses were repeatedly closed during extended outbreaks of the plague (a total of over 60 months closure between May 1603 and February 1610),[74] which meant there was often no acting work. Retirement from all work was uncommon at that time.[75] Shakespeare continued to visit London during the years 1611–1614.[69] In 1612, he was called as a witness in Bellott v Mountjoy, a court case concerning the marriage settlement of Mountjoy’s daughter, Mary.[76][77] In March 1613, he bought a gatehouse in the former Blackfriars priory;[78] and from November 1614, he was in London for several weeks with his son-in-law, John Hall.[79] After 1610, Shakespeare wrote fewer plays, and none are attributed to him after 1613.[80] His last three plays were collaborations, probably with John Fletcher,[81] who succeeded him as the house playwright of the King’s Men. He retired in 1613, before the Globe Theatre burned down during the performance of Henry VIII on 29 June.[80]

Shakespeare died on 23 April 1616, at the age of 52.[h] He died within a month of signing his will, a document which he begins by describing himself as being in «perfect health». No extant contemporary source explains how or why he died. Half a century later, John Ward, the vicar of Stratford, wrote in his notebook: «Shakespeare, Drayton, and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting and, it seems, drank too hard, for Shakespeare died of a fever there contracted»,[82][83] not an impossible scenario since Shakespeare knew Jonson and Drayton. Of the tributes from fellow authors, one refers to his relatively sudden death: «We wondered, Shakespeare, that thou went’st so soon / From the world’s stage to the grave’s tiring room.»[84][i]

He was survived by his wife and two daughters. Susanna had married a physician, John Hall, in 1607,[85] and Judith had married Thomas Quiney, a vintner, two months before Shakespeare’s death.[86] Shakespeare signed his last will and testament on 25 March 1616; the following day, his new son-in-law, Thomas Quiney was found guilty of fathering an illegitimate son by Margaret Wheeler, who had died during childbirth. Thomas was ordered by the church court to do public penance, which would have caused much shame and embarrassment for the Shakespeare family.[86]

Shakespeare bequeathed the bulk of his large estate to his elder daughter Susanna[87] under stipulations that she pass it down intact to «the first son of her body».[88] The Quineys had three children, all of whom died without marrying.[89][90] The Halls had one child, Elizabeth, who married twice but died without children in 1670, ending Shakespeare’s direct line.[91][92] Shakespeare’s will scarcely mentions his wife, Anne, who was probably entitled to one-third of his estate automatically.[j] He did make a point, however, of leaving her «my second best bed», a bequest that has led to much speculation.[94][95][96] Some scholars see the bequest as an insult to Anne, whereas others believe that the second-best bed would have been the matrimonial bed and therefore rich in significance.[97]

Shakespeare’s grave, next to those of Anne Shakespeare, his wife, and Thomas Nash, the husband of his granddaughter

Shakespeare was buried in the chancel of the Holy Trinity Church two days after his death.[98][99] The epitaph carved into the stone slab covering his grave includes a curse against moving his bones, which was carefully avoided during restoration of the church in 2008:[100]

|

Good frend for Iesvs sake forbeare, |

Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear, |

Some time before 1623, a funerary monument was erected in his memory on the north wall, with a half-effigy of him in the act of writing. Its plaque compares him to Nestor, Socrates, and Virgil.[102] In 1623, in conjunction with the publication of the First Folio, the Droeshout engraving was published.[103] Shakespeare has been commemorated in many statues and memorials around the world, including funeral monuments in Southwark Cathedral and Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey.[104][105]

Plays

Procession of Characters from Shakespeare’s Plays by an unknown 19th-century artist

Most playwrights of the period typically collaborated with others at some point, as critics agree Shakespeare did, mostly early and late in his career.[106]

The first recorded works of Shakespeare are Richard III and the three parts of Henry VI, written in the early 1590s during a vogue for historical drama. Shakespeare’s plays are difficult to date precisely, however,[107][108] and studies of the texts suggest that Titus Andronicus, The Comedy of Errors, The Taming of the Shrew, and The Two Gentlemen of Verona may also belong to Shakespeare’s earliest period.[109][107] His first histories, which draw heavily on the 1587 edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland,[110] dramatise the destructive results of weak or corrupt rule and have been interpreted as a justification for the origins of the Tudor dynasty.[111] The early plays were influenced by the works of other Elizabethan dramatists, especially Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe, by the traditions of medieval drama, and by the plays of Seneca.[112][113][114] The Comedy of Errors was also based on classical models, but no source for The Taming of the Shrew has been found, though it is related to a separate play of the same name and may have derived from a folk story.[115][116] Like The Two Gentlemen of Verona, in which two friends appear to approve of rape,[117][118][119] the Shrew‘s story of the taming of a woman’s independent spirit by a man sometimes troubles modern critics, directors, and audiences.[120]

Shakespeare’s early classical and Italianate comedies, containing tight double plots and precise comic sequences, give way in the mid-1590s to the romantic atmosphere of his most acclaimed comedies.[121] A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a witty mixture of romance, fairy magic, and comic lowlife scenes.[122] Shakespeare’s next comedy, the equally romantic Merchant of Venice, contains a portrayal of the vengeful Jewish moneylender Shylock, which reflects dominant Elizabethan views but may appear derogatory to modern audiences.[123][124] The wit and wordplay of Much Ado About Nothing,[125] the charming rural setting of As You Like It, and the lively merrymaking of Twelfth Night complete Shakespeare’s sequence of great comedies.[126] After the lyrical Richard II, written almost entirely in verse, Shakespeare introduced prose comedy into the histories of the late 1590s, Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and Henry V. His characters become more complex and tender as he switches deftly between comic and serious scenes, prose and poetry, and achieves the narrative variety of his mature work.[127][128][129] This period begins and ends with two tragedies: Romeo and Juliet, the famous romantic tragedy of sexually charged adolescence, love, and death;[130][131] and Julius Caesar— based on Sir Thomas North’s 1579 translation of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives—which introduced a new kind of drama.[132][133] According to Shakespearean scholar James Shapiro, in Julius Caesar, «the various strands of politics, character, inwardness, contemporary events, even Shakespeare’s own reflections on the act of writing, began to infuse each other».[134]

In the early 17th century, Shakespeare wrote the so-called «problem plays» Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida, and All’s Well That Ends Well and a number of his best known tragedies.[135][136] Many critics believe that Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies represent the peak of his art. The titular hero of one of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedies, Hamlet, has probably been discussed more than any other Shakespearean character, especially for his famous soliloquy which begins «To be or not to be; that is the question».[137] Unlike the introverted Hamlet, whose fatal flaw is hesitation, the heroes of the tragedies that followed, Othello and King Lear, are undone by hasty errors of judgement.[138] The plots of Shakespeare’s tragedies often hinge on such fatal errors or flaws, which overturn order and destroy the hero and those he loves.[139] In Othello, the villain Iago stokes Othello’s sexual jealousy to the point where he murders the innocent wife who loves him.[140][141] In King Lear, the old king commits the tragic error of giving up his powers, initiating the events which lead to the torture and blinding of the Earl of Gloucester and the murder of Lear’s youngest daughter Cordelia. According to the critic Frank Kermode, «the play…offers neither its good characters nor its audience any relief from its cruelty».[142][143][144] In Macbeth, the shortest and most compressed of Shakespeare’s tragedies,[145] uncontrollable ambition incites Macbeth and his wife, Lady Macbeth, to murder the rightful king and usurp the throne until their own guilt destroys them in turn.[146] In this play, Shakespeare adds a supernatural element to the tragic structure. His last major tragedies, Antony and Cleopatra and Coriolanus, contain some of Shakespeare’s finest poetry and were considered his most successful tragedies by the poet and critic T. S. Eliot.[147][148][149]

In his final period, Shakespeare turned to romance or tragicomedy and completed three more major plays: Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, and The Tempest, as well as the collaboration, Pericles, Prince of Tyre. Less bleak than the tragedies, these four plays are graver in tone than the comedies of the 1590s, but they end with reconciliation and the forgiveness of potentially tragic errors.[150] Some commentators have seen this change in mood as evidence of a more serene view of life on Shakespeare’s part, but it may merely reflect the theatrical fashion of the day.[151][152][153] Shakespeare collaborated on two further surviving plays, Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen, probably with John Fletcher.[154]

Performances

It is not clear for which companies Shakespeare wrote his early plays. The title page of the 1594 edition of Titus Andronicus reveals that the play had been acted by three different troupes.[155] After the plagues of 1592–93, Shakespeare’s plays were performed by his own company at The Theatre and the Curtain in Shoreditch, north of the Thames.[156] Londoners flocked there to see the first part of Henry IV, Leonard Digges recording, «Let but Falstaff come, Hal, Poins, the rest … and you scarce shall have a room».[157] When the company found themselves in dispute with their landlord, they pulled The Theatre down and used the timbers to construct the Globe Theatre, the first playhouse built by actors for actors, on the south bank of the Thames at Southwark.[158][159] The Globe opened in autumn 1599, with Julius Caesar one of the first plays staged. Most of Shakespeare’s greatest post-1599 plays were written for the Globe, including Hamlet, Othello, and King Lear.[158][160][161]

After the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were renamed the King’s Men in 1603, they entered a special relationship with the new King James. Although the performance records are patchy, the King’s Men performed seven of Shakespeare’s plays at court between 1 November 1604, and 31 October 1605, including two performances of The Merchant of Venice.[62] After 1608, they performed at the indoor Blackfriars Theatre during the winter and the Globe during the summer.[162] The indoor setting, combined with the Jacobean fashion for lavishly staged masques, allowed Shakespeare to introduce more elaborate stage devices. In Cymbeline, for example, Jupiter descends «in thunder and lightning, sitting upon an eagle: he throws a thunderbolt. The ghosts fall on their knees.»[163][164]

The actors in Shakespeare’s company included the famous Richard Burbage, William Kempe, Henry Condell and John Heminges. Burbage played the leading role in the first performances of many of Shakespeare’s plays, including Richard III, Hamlet, Othello, and King Lear.[165] The popular comic actor Will Kempe played the servant Peter in Romeo and Juliet and Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, among other characters.[166][167] He was replaced around 1600 by Robert Armin, who played roles such as Touchstone in As You Like It and the fool in King Lear.[168] In 1613, Sir Henry Wotton recorded that Henry VIII «was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and ceremony».[169] On 29 June, however, a cannon set fire to the thatch of the Globe and burned the theatre to the ground, an event which pinpoints the date of a Shakespeare play with rare precision.[169]

Textual sources

In 1623, John Heminges and Henry Condell, two of Shakespeare’s friends from the King’s Men, published the First Folio, a collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays. It contained 36 texts, including 18 printed for the first time.[170] Many of the plays had already appeared in quarto versions—flimsy books made from sheets of paper folded twice to make four leaves.[171] No evidence suggests that Shakespeare approved these editions, which the First Folio describes as «stol’n and surreptitious copies».[172] Nor did Shakespeare plan or expect his works to survive in any form at all; those works likely would have faded into oblivion but for his friends’ spontaneous idea, after his death, to create and publish the First Folio.[173]

Alfred Pollard termed some of the pre-1623 versions as «bad quartos» because of their adapted, paraphrased or garbled texts, which may in places have been reconstructed from memory.[171][172][174] Where several versions of a play survive, each differs from the other. The differences may stem from copying or printing errors, from notes by actors or audience members, or from Shakespeare’s own papers.[175][176] In some cases, for example, Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida, and Othello, Shakespeare could have revised the texts between the quarto and folio editions. In the case of King Lear, however, while most modern editions do conflate them, the 1623 folio version is so different from the 1608 quarto that the Oxford Shakespeare prints them both, arguing that they cannot be conflated without confusion.[177]

Poems

In 1593 and 1594, when the theatres were closed because of plague, Shakespeare published two narrative poems on sexual themes, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece. He dedicated them to Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. In Venus and Adonis, an innocent Adonis rejects the sexual advances of Venus; while in The Rape of Lucrece, the virtuous wife Lucrece is raped by the lustful Tarquin.[178] Influenced by Ovid’s Metamorphoses,[179] the poems show the guilt and moral confusion that result from uncontrolled lust.[180] Both proved popular and were often reprinted during Shakespeare’s lifetime. A third narrative poem, A Lover’s Complaint, in which a young woman laments her seduction by a persuasive suitor, was printed in the first edition of the Sonnets in 1609. Most scholars now accept that Shakespeare wrote A Lover’s Complaint. Critics consider that its fine qualities are marred by leaden effects.[181][182][183] The Phoenix and the Turtle, printed in Robert Chester’s 1601 Love’s Martyr, mourns the deaths of the legendary phoenix and his lover, the faithful turtle dove. In 1599, two early drafts of sonnets 138 and 144 appeared in The Passionate Pilgrim, published under Shakespeare’s name but without his permission.[181][183][184]

Sonnets

Title page from 1609 edition of Shake-Speares Sonnets

Published in 1609, the Sonnets were the last of Shakespeare’s non-dramatic works to be printed. Scholars are not certain when each of the 154 sonnets was composed, but evidence suggests that Shakespeare wrote sonnets throughout his career for a private readership.[185][186] Even before the two unauthorised sonnets appeared in The Passionate Pilgrim in 1599, Francis Meres had referred in 1598 to Shakespeare’s «sugred Sonnets among his private friends».[187] Few analysts believe that the published collection follows Shakespeare’s intended sequence.[188] He seems to have planned two contrasting series: one about uncontrollable lust for a married woman of dark complexion (the «dark lady»), and one about conflicted love for a fair young man (the «fair youth»). It remains unclear if these figures represent real individuals, or if the authorial «I» who addresses them represents Shakespeare himself, though Wordsworth believed that with the sonnets «Shakespeare unlocked his heart».[187][186]

«Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate …»

—Lines from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18.[189]

The 1609 edition was dedicated to a «Mr. W.H.», credited as «the only begetter» of the poems. It is not known whether this was written by Shakespeare himself or by the publisher, Thomas Thorpe, whose initials appear at the foot of the dedication page; nor is it known who Mr. W.H. was, despite numerous theories, or whether Shakespeare even authorised the publication.[190] Critics praise the Sonnets as a profound meditation on the nature of love, sexual passion, procreation, death, and time.[191]

Style

Shakespeare’s first plays were written in the conventional style of the day. He wrote them in a stylised language that does not always spring naturally from the needs of the characters or the drama.[192] The poetry depends on extended, sometimes elaborate metaphors and conceits, and the language is often rhetorical—written for actors to declaim rather than speak. The grand speeches in Titus Andronicus, in the view of some critics, often hold up the action, for example; and the verse in The Two Gentlemen of Verona has been described as stilted.[193][194]

Pity by William Blake, 1795, Tate Britain, is an illustration of two similes in Macbeth:

«And pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim, hors’d

Upon the sightless couriers of the air.»[195]

However, Shakespeare soon began to adapt the traditional styles to his own purposes. The opening soliloquy of Richard III has its roots in the self-declaration of Vice in medieval drama. At the same time, Richard’s vivid self-awareness looks forward to the soliloquies of Shakespeare’s mature plays.[196][197] No single play marks a change from the traditional to the freer style. Shakespeare combined the two throughout his career, with Romeo and Juliet perhaps the best example of the mixing of the styles.[198] By the time of Romeo and Juliet, Richard II, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the mid-1590s, Shakespeare had begun to write a more natural poetry. He increasingly tuned his metaphors and images to the needs of the drama itself.

Shakespeare’s standard poetic form was blank verse, composed in iambic pentameter. In practice, this meant that his verse was usually unrhymed and consisted of ten syllables to a line, spoken with a stress on every second syllable. The blank verse of his early plays is quite different from that of his later ones. It is often beautiful, but its sentences tend to start, pause, and finish at the end of lines, with the risk of monotony.[199] Once Shakespeare mastered traditional blank verse, he began to interrupt and vary its flow. This technique releases the new power and flexibility of the poetry in plays such as Julius Caesar and Hamlet. Shakespeare uses it, for example, to convey the turmoil in Hamlet’s mind:[200]

Sir, in my heart there was a kind of fighting

That would not let me sleep. Methought I lay

Worse than the mutines in the bilboes. Rashly—

And prais’d be rashness for it—let us know

Our indiscretion sometimes serves us well …— Hamlet, Act 5, Scene 2, 4–8[200]

After Hamlet, Shakespeare varied his poetic style further, particularly in the more emotional passages of the late tragedies. The literary critic A. C. Bradley described this style as «more concentrated, rapid, varied, and, in construction, less regular, not seldom twisted or elliptical».[201] In the last phase of his career, Shakespeare adopted many techniques to achieve these effects. These included run-on lines, irregular pauses and stops, and extreme variations in sentence structure and length.[202] In Macbeth, for example, the language darts from one unrelated metaphor or simile to another: «was the hope drunk/ Wherein you dressed yourself?» (1.7.35–38); «… pity, like a naked new-born babe/ Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim, hors’d/ Upon the sightless couriers of the air …» (1.7.21–25). The listener is challenged to complete the sense.[202] The late romances, with their shifts in time and surprising turns of plot, inspired a last poetic style in which long and short sentences are set against one another, clauses are piled up, subject and object are reversed, and words are omitted, creating an effect of spontaneity.[203]

Shakespeare combined poetic genius with a practical sense of the theatre.[204] Like all playwrights of the time, he dramatised stories from sources such as Plutarch and Holinshed.[205] He reshaped each plot to create several centres of interest and to show as many sides of a narrative to the audience as possible. This strength of design ensures that a Shakespeare play can survive translation, cutting, and wide interpretation without loss to its core drama.[206] As Shakespeare’s mastery grew, he gave his characters clearer and more varied motivations and distinctive patterns of speech. He preserved aspects of his earlier style in the later plays, however. In Shakespeare’s late romances, he deliberately returned to a more artificial style, which emphasised the illusion of theatre.[207][208]

Influence

Shakespeare’s work has made a significant and lasting impression on later theatre and literature. In particular, he expanded the dramatic potential of characterisation, plot, language, and genre.[209] Until Romeo and Juliet, for example, romance had not been viewed as a worthy topic for tragedy.[210] Soliloquies had been used mainly to convey information about characters or events, but Shakespeare used them to explore characters’ minds.[211] His work heavily influenced later poetry. The Romantic poets attempted to revive Shakespearean verse drama, though with little success. Critic George Steiner described all English verse dramas from Coleridge to Tennyson as «feeble variations on Shakespearean themes.»[212] John Milton, considered by many to be the most important English poet after Shakespeare, wrote in tribute: «Thou in our wonder and astonishment/ Has built thyself a live-long monument.»[213]

Shakespeare influenced novelists such as Thomas Hardy, William Faulkner, and Charles Dickens. The American novelist Herman Melville’s soliloquies owe much to Shakespeare; his Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick is a classic tragic hero, inspired by King Lear.[214] Scholars have identified 20,000 pieces of music linked to Shakespeare’s works. These include three operas by Giuseppe Verdi, Macbeth, Otello and Falstaff, whose critical standing compares with that of the source plays.[215] Shakespeare has also inspired many painters, including the Romantics and the Pre-Raphaelites. The Swiss Romantic artist Henry Fuseli, a friend of William Blake, even translated Macbeth into German.[216] The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud drew on Shakespearean psychology, in particular, that of Hamlet, for his theories of human nature.[217] Shakespeare has been a rich source for filmmakers; Akira Kurosawa adapted Macbeth and King Lear as Throne of Blood and Ran, respectively. Other examples of Shakespeare on film include Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet and Al Pacino’s documentary Looking For Richard.[218] Orson Welles, a lifelong lover of Shakespeare, directed and starred in films of Macbeth and Othello, and Chimes at Midnight, in which he plays John Falstaff, which Welles himself called his best work.[219]

In Shakespeare’s day, English grammar, spelling, and pronunciation were less standardised than they are now,[220] and his use of language helped shape modern English.[221] Samuel Johnson quoted him more often than any other author in his A Dictionary of the English Language, the first serious work of its type.[222] Expressions such as «with bated breath» (Merchant of Venice) and «a foregone conclusion» (Othello) have found their way into everyday English speech.[223][224]

Shakespeare’s influence extends far beyond his native England and the English language. His reception in Germany was particularly significant; as early as the 18th century Shakespeare was widely translated and popularised in Germany, and gradually became a «classic of the German Weimar era;» Christoph Martin Wieland was the first to produce complete translations of Shakespeare’s plays in any language.[225][226] Actor and theatre director Simon Callow writes, «this master, this titan, this genius, so profoundly British and so effortlessly universal, each different culture – German, Italian, Russian – was obliged to respond to the Shakespearean example; for the most part, they embraced it, and him, with joyous abandon, as the possibilities of language and character in action that he celebrated liberated writers across the continent. Some of the most deeply affecting productions of Shakespeare have been non-English, and non-European. He is that unique writer: he has something for everyone.»[227]

According to Guinness World Records, Shakespeare remains the world’s best-selling playwright, with sales of his plays and poetry believed to have achieved in excess of four billion copies in the almost 400 years since his death. He is also the third most translated author in history.[228]

Critical reputation

«He was not of an age, but for all time.»

—Ben Jonson[229]

Shakespeare was not revered in his lifetime, but he received a large amount of praise.[230][231] In 1598, the cleric and author Francis Meres singled him out from a group of English playwrights as «the most excellent» in both comedy and tragedy.[232][233] The authors of the Parnassus plays at St John’s College, Cambridge, numbered him with Chaucer, Gower, and Spenser.[234] In the First Folio, Ben Jonson called Shakespeare the «Soul of the age, the applause, delight, the wonder of our stage», although he had remarked elsewhere that «Shakespeare wanted art» (lacked skill).[229]

Between the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the end of the 17th century, classical ideas were in vogue. As a result, critics of the time mostly rated Shakespeare below John Fletcher and Ben Jonson.[235] Thomas Rymer, for example, condemned Shakespeare for mixing the comic with the tragic. Nevertheless, poet and critic John Dryden rated Shakespeare highly, saying of Jonson, «I admire him, but I love Shakespeare».[236] He also famously remarked that Shakespeare «was naturally learned; he needed not the spectacles of books to read nature; he looked inwards, and found her there.»[237] For several decades, Rymer’s view held sway. But during the 18th century, critics began to respond to Shakespeare on his own terms and, like Dryden, to acclaim what they termed his natural genius. A series of scholarly editions of his work, notably those of Samuel Johnson in 1765 and Edmond Malone in 1790, added to his growing reputation.[238][239] By 1800, he was firmly enshrined as the national poet.[240] In the 18th and 19th centuries, his reputation also spread abroad. Among those who championed him were the writers Voltaire, Goethe, Stendhal, and Victor Hugo.[241][l]

A garlanded statue of William Shakespeare in Lincoln Park, Chicago, typical of many created in the 19th and early 20th centuries

During the Romantic era, Shakespeare was praised by the poet and literary philosopher Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and the critic August Wilhelm Schlegel translated his plays in the spirit of German Romanticism.[243] In the 19th century, critical admiration for Shakespeare’s genius often bordered on adulation.[244] «This King Shakespeare,» the essayist Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1840, «does not he shine, in crowned sovereignty, over us all, as the noblest, gentlest, yet strongest of rallying signs; indestructible».[245] The Victorians produced his plays as lavish spectacles on a grand scale.[246] The playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw mocked the cult of Shakespeare worship as «bardolatry», claiming that the new naturalism of Ibsen’s plays had made Shakespeare obsolete.[247]

The modernist revolution in the arts during the early 20th century, far from discarding Shakespeare, eagerly enlisted his work in the service of the avant-garde. The Expressionists in Germany and the Futurists in Moscow mounted productions of his plays. Marxist playwright and director Bertolt Brecht devised an epic theatre under the influence of Shakespeare. The poet and critic T. S. Eliot argued against Shaw that Shakespeare’s «primitiveness» in fact made him truly modern.[248] Eliot, along with G. Wilson Knight and the school of New Criticism, led a movement towards a closer reading of Shakespeare’s imagery. In the 1950s, a wave of new critical approaches replaced modernism and paved the way for post-modern studies of Shakespeare.[249] By the 1980s, Shakespeare studies were open to movements such as structuralism, feminism, New Historicism, African-American studies, and queer studies.[250][251] Comparing Shakespeare’s accomplishments to those of leading figures in philosophy and theology, Harold Bloom wrote, «Shakespeare was larger than Plato and than St. Augustine. He encloses us because we see with his fundamental perceptions.»[252]

Works

Classification of the plays

Shakespeare’s works include the 36 plays printed in the First Folio of 1623, listed according to their folio classification as comedies, histories, and tragedies.[253] Two plays not included in the First Folio, The Two Noble Kinsmen and Pericles, Prince of Tyre, are now accepted as part of the canon, with today’s scholars agreeing that Shakespeare made major contributions to the writing of both.[254][255] No Shakespearean poems were included in the First Folio.

In the late 19th century, Edward Dowden classified four of the late comedies as romances, and though many scholars prefer to call them tragicomedies, Dowden’s term is often used.[256][257] In 1896, Frederick S. Boas coined the term «problem plays» to describe four plays: All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida, and Hamlet.[258] «Dramas as singular in theme and temper cannot be strictly called comedies or tragedies», he wrote. «We may, therefore, borrow a convenient phrase from the theatre of today and class them together as Shakespeare’s problem plays.»[259] The term, much debated and sometimes applied to other plays, remains in use, though Hamlet is definitively classed as a tragedy.[260][261][262]

Speculation

Around 230 years after Shakespeare’s death, doubts began to be expressed about the authorship of the works attributed to him.[263] Proposed alternative candidates include Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, and Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.[264] Several «group theories» have also been proposed.[265] All but a few Shakespeare scholars and literary historians consider it a fringe theory, with only a small minority of academics who believe that there is reason to question the traditional attribution,[266] but interest in the subject, particularly the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship, continues into the 21st century.[267][268][269]

Religion

Shakespeare conformed to the official state religion,[m] but his private views on religion have been the subject of debate. Shakespeare’s will uses a Protestant formula, and he was a confirmed member of the Church of England, where he was married, his children were baptised, and where he is buried. Some scholars claim that members of Shakespeare’s family were Catholics, at a time when practising Catholicism in England was against the law.[271] Shakespeare’s mother, Mary Arden, certainly came from a pious Catholic family. The strongest evidence might be a Catholic statement of faith signed by his father, John Shakespeare, found in 1757 in the rafters of his former house in Henley Street. However, the document is now lost and scholars differ as to its authenticity.[272][273] In 1591, the authorities reported that John Shakespeare had missed church «for fear of process for debt», a common Catholic excuse.[274][275][276] In 1606, the name of William’s daughter Susanna appears on a list of those who failed to attend Easter communion in Stratford.[274][275][276] Other authors argue that there is a lack of evidence about Shakespeare’s religious beliefs. Scholars find evidence both for and against Shakespeare’s Catholicism, Protestantism, or lack of belief in his plays, but the truth may be impossible to prove.[277][278]

Sexuality

Few details of Shakespeare’s sexuality are known. At 18, he married 26-year-old Anne Hathaway, who was pregnant. Susanna, the first of their three children, was born six months later on 26 May 1583. Over the centuries, some readers have posited that Shakespeare’s sonnets are autobiographical,[279] and point to them as evidence of his love for a young man. Others read the same passages as the expression of intense friendship rather than romantic love.[280][281][282] The 26 so-called «Dark Lady» sonnets, addressed to a married woman, are taken as evidence of heterosexual liaisons.[283]

Portraiture

No written contemporary description of Shakespeare’s physical appearance survives, and no evidence suggests that he ever commissioned a portrait, so the Droeshout engraving, which Ben Jonson approved of as a good likeness,[284] and his Stratford monument provide perhaps the best evidence of his appearance. From the 18th century, the desire for authentic Shakespeare portraits fuelled claims that various surviving pictures depicted Shakespeare. That demand also led to the production of several fake portraits, as well as misattributions, repaintings, and relabelling of portraits of other people.[285]

See also

- Outline of William Shakespeare

- English Renaissance theatre

- Spelling of Shakespeare’s name

- World Shakespeare Bibliography

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ His monument states that he was in his 53rd year at death, i.e. 52 years old.

- ^ The concept that Shakespeare was born on 23 April, contrary to belief, is a tradition, and not a fact; see the section on Shakespeare’s life below.

- ^ Dates follow the Julian calendar, used in England throughout Shakespeare’s lifespan, but with the start of the year adjusted to 1 January (see Old Style and New Style dates). Under the Gregorian calendar, adopted in Catholic countries in 1582, Shakespeare died on 3 May.[1]

- ^ The «national cult» of Shakespeare, and the «bard» identification, dates from September 1769, when the actor David Garrick organised a week-long carnival at Stratford to mark the town council awarding him the freedom of the town. In addition to presenting the town with a statue of Shakespeare, Garrick composed a doggerel verse, lampooned in the London newspapers, naming the banks of the Avon as the birthplace of the «matchless Bard».[6]

- ^ The exact figures are unknown. See Shakespeare’s collaborations and Shakespeare Apocrypha for further details.

- ^ Individual play dates and precise writing span are unknown. See Chronology of Shakespeare’s plays for further details.

- ^ The crest is a silver falcon supporting a spear, while the motto is Non Sanz Droict (French for «not without right»). This motto is still used by Warwickshire County Council, in reference to Shakespeare.

- ^ Inscribed in Latin on his funerary monument: AETATIS 53 DIE 23 APR (In his 53rd year he died 23 April).

- ^ Verse by James Mabbe printed in the First Folio.[84]

- ^ Charles Knight, 1842, in his notes on Twelfth Night.[93]

- ^ In the scribal abbreviations ye for the (3rd line) and yt for that (3rd and 4th lines) the letter y represents th: see thorn.

- ^ Grady cites Voltaire’s Philosophical Letters (1733); Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1795); Stendhal’s two-part pamphlet Racine et Shakespeare (1823–25); and Victor Hugo’s prefaces to Cromwell (1827) and William Shakespeare (1864).[242]

- ^ For example, A.L. Rowse, the 20th-century Shakespeare scholar, was emphatic: «He died, as he had lived, a conforming member of the Church of England. His will made that perfectly clear—in facts, puts it beyond dispute, for it uses the Protestant formula.»[270]

References

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. xv.

- ^ a b Greenblatt 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b Bevington 2002, pp. 1–3.

- ^ a b Wells 1997, p. 399.

- ^ Dobson 1992, pp. 185–186.

- ^ McIntyre 1999, pp. 412–432.

- ^ Craig 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, pp. xvii–xviii.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, pp. 41, 66, 397–398, 402, 409.

- ^ Taylor 1990, pp. 145, 210–223, 261–265.

- ^ Chambers 1930a, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Taylor 1987, pp. 109–134.

- ^ a b Greenblatt & Abrams 2012, p. 1168.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 14–22.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 24, 296.

- ^ Honan 1998, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ Baldwin 1944, p. 464.

- ^ Baldwin 1944, pp. 179–180, 183.

- ^ Cressy 1975, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Baldwin 1944, p. 117.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 84.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 93.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 94.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 224.

- ^ Bate 2008, p. 314.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 95.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 97–108.

- ^ a b Rowe 1709.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Honigmann 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, p. xvii.

- ^ Honigmann 1999, pp. 95–117.

- ^ Wood 2003, pp. 97–109.

- ^ Chambers 1930a, pp. 287, 292.

- ^ a b c Greenblatt 2005, p. 213.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 153.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 176.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 151–153.

- ^ a b Wells 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Chambers 1930a, p. 59.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 184.

- ^ Chambers 1923, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, p. 666.

- ^ Chambers 1930b, pp. 67–71.

- ^ Bentley 1961, p. 36.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 188.

- ^ Kastan 1999, p. 37.

- ^ Knutson 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Adams 1923, p. 275.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 200.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 357.

- ^ a b Wells et al. 2005, p. xxii.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b Hales 1904, pp. 401–402.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 121.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 325.

- ^ Greenblatt 2005, p. 405.

- ^ a b Ackroyd 2006, p. 476.

- ^ Wood 1806, pp. ix–x, lxxii.

- ^ Smith 1964, p. 558.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 477.

- ^ Barroll 1991, pp. 179–182.

- ^ Bate 2008, pp. 354–355.

- ^ Honan 1998, pp. 382–383.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 326.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 462–464.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 272–274.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 387.

- ^ a b Schoenbaum 1987, p. 279.

- ^ Honan 1998, pp. 375–378.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 78.

- ^ Rowse 1963, p. 453.

- ^ a b Kinney 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 287.

- ^ a b Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 292–294.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 304.

- ^ Honan 1998, pp. 395–396.

- ^ Chambers 1930b, pp. 8, 11, 104.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 296.

- ^ Chambers 1930b, pp. 7, 9, 13.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 289, 318–319.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 275.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 483.

- ^ Frye 2005, p. 16.

- ^ Greenblatt 2005, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 301–303.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 306–307.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, p. xviii.

- ^ BBC News 2008.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 306.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 308–310.

- ^ Cooper 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Westminster Abbey n.d.

- ^ Southwark Cathedral n.d.

- ^ Thomson 2003, p. 49.

- ^ a b Frye 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 166.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Dutton & Howard 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Ribner 2005, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Frye 2005, p. 105.

- ^ Ribner 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Bednarz 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 136.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 166.

- ^ Frye 2005, p. 91.

- ^ Honan 1998, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Werner 2001, pp. 96–100.

- ^ Friedman 2006, p. 159.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 235.

- ^ Wood 2003, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Wood 2003, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 258.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 359.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 362–383.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, p. 150.

- ^ Gibbons 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 356.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 161.

- ^ Honan 1998, p. 206.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 353, 358.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, p. 151.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 85.

- ^ Muir 2005, pp. 12–16.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 94.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 86.

- ^ Bradley 1991, pp. 40, 48.

- ^ Bradley 1991, pp. 42, 169, 195.

- ^ Greenblatt 2005, p. 304.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 226.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 423.

- ^ Kermode 2004, pp. 141–142.

- ^ McDonald 2006, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 306.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 444.

- ^ McDonald 2006, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Eliot 1934, p. 59.

- ^ Dowden 1881, p. 57.

- ^ Dowden 1881, p. 60.

- ^ Frye 2005, p. 123.

- ^ McDonald 2006, p. 15.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, pp. 1247, 1279.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, p. xx.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, p. xxi.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, p. 16.

- ^ a b Foakes 1990, p. 6.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, pp. 125–131.

- ^ Nagler 1958, p. 7.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Foakes 1990, p. 33.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 454.

- ^ Holland 2000, p. xli.

- ^ Ringler 1997, p. 127.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 210.

- ^ Chambers 1930a, p. 341.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, pp. 247–249.

- ^ a b Wells et al. 2005, p. 1247.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, p. xxxvii.

- ^ a b Wells et al. 2005, p. xxxiv.

- ^ a b Pollard 1909, p. xi.

- ^ Mays & Swanson 2016.

- ^ Maguire 1996, p. 28.

- ^ Bowers 1955, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, pp. xxxiv–xxxv.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, pp. 909, 1153.

- ^ Roe 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Frye 2005, p. 288.

- ^ Roe 2006, pp. 3, 21.

- ^ a b Roe 2006, p. 1.

- ^ Jackson 2004, pp. 267–294.

- ^ a b Honan 1998, p. 289.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 327.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 178.

- ^ a b Schoenbaum 1987, p. 180.

- ^ a b Honan 1998, p. 180.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 268.

- ^ Mowat & Werstine n.d.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Wood 2003, p. 177.

- ^ Clemen 2005a, p. 150.

- ^ Frye 2005, pp. 105, 177.

- ^ Clemen 2005b, p. 29.

- ^ de Sélincourt 1909, p. 174.

- ^ Brooke 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Bradbrook 2004, p. 195.

- ^ Clemen 2005b, p. 63.

- ^ Frye 2005, p. 185.

- ^ a b Wright 2004, p. 868.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 91.

- ^ a b McDonald 2006, pp. 42–46.

- ^ McDonald 2006, pp. 36, 39, 75.

- ^ Gibbons 1993, p. 4.

- ^ Gibbons 1993, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Gibbons 1993, pp. 1–7, 15.

- ^ McDonald 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Meagher 2003, p. 358.

- ^ Chambers 1944, p. 35.

- ^ Levenson 2000, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Clemen 1987, p. 179.

- ^ Steiner 1996, p. 145.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (6 January 2023). «On Shakespeare. 1630 by John Milton». Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Bryant 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Gross 2003, pp. 641–642.

- ^ Paraisz 2006, p. 130.

- ^ Bloom 1995, p. 346.

- ^ Lane, Anthony (25 November 1996). «TIGHTS! CAMERA! ACTION!». The New Yorker.

- ^ BBC Arena. The Orson Welles Story BBC Two/BBC Four. 01:51:46-01:52:16. Broadcast 18 May 1982. Retrieved 30 January 2023

- ^ Cercignani 1981.

- ^ Crystal 2001, pp. 55–65, 74.

- ^ Wain 1975, p. 194.

- ^ Johnson 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Crystal 2001, p. 63.

- ^ «How Shakespeare was turned into a German». DW.com. 22 April 2016.

- ^ «Unser Shakespeare: Germans’ mad obsession with the Bard». The Local Germany. 22 April 2016.

- ^ «Simon Callow: What the Dickens? Well, William Shakespeare was the greatest after all…» The Independent. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ «William Shakespeare:Ten startling Great Bard-themed world records». Guinness World Records. 23 April 2014.

- ^ a b Jonson 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Dominik 1988, p. 9.

- ^ Grady 2001b, p. 267.

- ^ Grady 2001b, p. 265.

- ^ Greer 1986, p. 9.

- ^ Grady 2001b, p. 266.

- ^ Grady 2001b, p. 269.

- ^ Dryden 1889, p. 71.

- ^ «John Dryden (1631-1700). Shakespeare. Beaumont and Fletcher. Ben Jonson. Vol. III. Seventeenth Century. Henry Craik, ed. 1916. English Prose». www.bartleby.com. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Grady 2001b, pp. 270–272.

- ^ Levin 1986, p. 217.

- ^ Grady 2001b, p. 270.

- ^ Grady 2001b, pp. 272–74.

- ^ Grady 2001b, pp. 272–274.

- ^ Levin 1986, p. 223.

- ^ Sawyer 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Carlyle 1841, p. 161.

- ^ Schoch 2002, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Grady 2001b, p. 276.

- ^ Grady 2001a, pp. 22–26.

- ^ Grady 2001a, p. 24.

- ^ Grady 2001a, p. 29.

- ^ Drakakis 1985, pp. 16–17, 23–25.

- ^ Bloom 2008, p. xii.

- ^ Boyce 1996, pp. 91, 193, 513..

- ^ Kathman 2003, p. 629.

- ^ Boyce 1996, p. 91.

- ^ Edwards 1958, pp. 1–10.

- ^ Snyder & Curren-Aquino 2007.

- ^ Schanzer 1963, pp. 1–10.

- ^ Boas 1896, p. 345.

- ^ Schanzer 1963, p. 1.

- ^ Bloom 1999, pp. 325–380.

- ^ Berry 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Shapiro 2010, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Gibson 2005, pp. 48, 72, 124.

- ^ McMichael & Glenn 1962, p. 56.

- ^ The New York Times 2007.

- ^ Kathman 2003, pp. 620, 625–626.

- ^ Love 2002, pp. 194–209.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1991, pp. 430–440.

- ^ Rowse 1988, p. 240.

- ^ Pritchard 1979, p. 3.

- ^ Wood 2003, pp. 75–78.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Wood 2003, p. 78.

- ^ a b Ackroyd 2006, p. 416.

- ^ a b Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 41–42, 286.

- ^ Wilson 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Shapiro 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Lee 1900, p. 55.

- ^ Casey 1998.

- ^ Pequigney 1985.

- ^ Evans 1996, p. 132.

- ^ Fort 1927, pp. 406–414.

- ^ Cooper 2006, pp. 48, 57.

- ^ Schoenbaum 1981, p. 190.

Sources

- Ackroyd, Peter (2006). Shakespeare: The Biography. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-7493-8655-9.

- Adams, Joseph Quincy (1923). A Life of William Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1935264.

- Baldwin, T.W. (1944). William Shakspere’s Small Latine & Lesse Greek. Vol. 1. Urbana, Ill: University of Illinois Press. OCLC 359037.

- Barroll, Leeds (1991). Politics, Plague, and Shakespeare’s Theater: The Stuart Years. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-2479-3.

- Bate, Jonathan (2008). The Soul of the Age. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-91482-1.

- «Bard’s ‘cursed’ tomb is revamped». BBC News. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- Bednarz, James P. (2004). «Marlowe and the English literary scene». In Cheney, Patrick Gerard (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–105. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521820340. ISBN 978-0-511-99905-5 – via Cambridge Core.

- Bentley, G.E. (1961). Shakespeare: A Biographical Handbook. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25042-2. OCLC 356416.

- Berry, Ralph (2005). Changing Styles in Shakespeare. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35316-8.

- Bevington, David (2002). Shakespeare. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22719-9.

- Bloom, Harold (1995). The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1-57322-514-4.

- Bloom, Harold (1999). Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. New York: Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1-57322-751-3.

- Bloom, Harold (2008). Heims, Neil (ed.). King Lear. Bloom’s Shakespeare Through the Ages. Bloom’s Literary Criticism. ISBN 978-0-7910-9574-4.

- Boas, Frederick S. (1896). Shakspere and His Predecessors. The University series. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. hdl:2027/uc1.32106001899191. OL 20577303M.

- Bowers, Fredson (1955). On Editing Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Dramatists. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. OCLC 2993883.

- Boyce, Charles (1996). Dictionary of Shakespeare. Ware, Herts, UK: Wordsworth. ISBN 978-1-85326-372-9.

- Bradbrook, M.C. (2004). «Shakespeare’s Recollection of Marlowe». In Edwards, Philip; Ewbank, Inga-Stina; Hunter, G.K. (eds.). Shakespeare’s Styles: Essays in Honour of Kenneth Muir. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–204. ISBN 978-0-521-61694-2.

- Bradley, A.C. (1991). Shakespearean Tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear and Macbeth. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-053019-3.

- Brooke, Nicholas (2004). «Language and Speaker in Macbeth». In Edwards, Philip; Ewbank, Inga-Stina; Hunter, G.K. (eds.). Shakespeare’s Styles: Essays in Honour of Kenneth Muir. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–78. ISBN 978-0-521-61694-2.

- Bryant, John (1998). «Moby-Dick as Revolution». In Levine, Robert Steven (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Herman Melville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–90. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521554772. ISBN 978-1-139-00037-6 – via Cambridge Core.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1841). On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History. London: James Fraser. hdl:2027/hvd.hnlmmi. OCLC 17473532. OL 13561584M.

- Casey, Charles (1998). «Was Shakespeare gay? Sonnet 20 and the politics of pedagogy». College Literature. 25 (3): 35–51. JSTOR 25112402.

- Cercignani, Fausto (1981). Shakespeare’s Works and Elizabethan Pronunciation. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811937-1.

- Chambers, E.K. (1923). The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811511-3. OCLC 336379.

- Chambers, E.K. (1930a). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811774-2. OCLC 353406.

- Chambers, E.K. (1930b). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811774-2. OCLC 353406.

- Chambers, E.K. (1944). Shakespearean Gleanings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8492-0506-4. OCLC 2364570.

- Clemen, Wolfgang (1987). Shakespeare’s Soliloquies. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35277-2.

- Clemen, Wolfgang (2005a). Shakespeare’s Dramatic Art: Collected Essays. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35278-9.

- Clemen, Wolfgang (2005b). Shakespeare’s Imagery. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35280-2.

- Cooper, Tarnya (2006). Searching for Shakespeare. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11611-3.

- Craig, Leon Harold (2003). Of Philosophers and Kings: Political Philosophy in Shakespeare’s Macbeth and King Lear. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8605-1.

- Cressy, David (1975). Education in Tudor and Stuart England. New York: St Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-7131-5817-5. OCLC 2148260.

- Crystal, David (2001). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40179-1.

- Dobson, Michael (1992). The Making of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660–1769. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818323-5.

- Dominik, Mark (1988). Shakespeare–Middleton Collaborations. Beaverton, OR: Alioth Press. ISBN 978-0-945088-01-1.

- Dowden, Edward (1881). Shakspere. New York: D. Appleton & Company. OCLC 8164385. OL 6461529M.

- Drakakis, John (1985). «Introduction». In Drakakis, John (ed.). Alternative Shakespeares. New York: Methuen. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-0-416-36860-4.

- Dryden, John (1889). Arnold, Thomas (ed.). Dryden: An Essay of Dramatic Poesy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. hdl:2027/umn.31951t00074232s. ISBN 978-81-7156-323-4. OCLC 7847292. OL 23752217M.

- Dutton, Richard; Howard, Jean E. (2003). A Companion to Shakespeare’s Works: The Histories. Vol. II. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22633-8.

- Edwards, Phillip (1958). Shakespeare’s Romances: 1900–1957. Shakespeare Survey. Vol. 11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521064244.001. ISBN 978-1-139-05291-7 – via Cambridge Core.

- Eliot, T.S. (1934). Elizabethan Essays. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-15-629051-7. OCLC 9738219.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Vol. 26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22225-9.

- Foakes, R.A. (1990). «Playhouses and players». In Braunmuller, A.R.; Hattaway, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to English Renaissance Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–52. ISBN 978-0-521-38662-3.

- Fort, J.A. (October 1927). «The Story Contained in the Second Series of Shakespeare’s Sonnets». The Review of English Studies. Original Series. III (12): 406–414. doi:10.1093/res/os-III.12.406. ISSN 0034-6551 – via Oxford Journals.

- Friedman, Michael D. (2006). «‘I’m not a feminist director but…’: Recent Feminist Productions of The Taming of the Shrew«. In Nelsen, Paul; Schlueter, June (eds.). Acts of Criticism: Performance Matters in Shakespeare and his Contemporaries. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 159–174. ISBN 978-0-8386-4059-3.

- Frye, Roland Mushat (2005). The Art of the Dramatist. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35289-5.

- Gibbons, Brian (1993). Shakespeare and Multiplicity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511553103. ISBN 978-0-511-55310-3 – via Cambridge Core.

- Gibson, H.N. (2005). The Shakespeare Claimants: A Critical Survey of the Four Principal Theories Concerning the Authorship of the Shakespearean Plays. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35290-1.

- Grady, Hugh (2001a). «Modernity, Modernism and Postmodernism in the Twentieth Century’s Shakespeare». In Bristol, Michael; McLuskie, Kathleen (eds.). Shakespeare and Modern Theatre: The Performance of Modernity. New York: Routledge. pp. 20–35. ISBN 978-0-415-21984-6.

- Grady, Hugh (2001b). «Shakespeare criticism, 1600–1900». In de Grazia, Margreta; Wells, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 265–278. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521650941.017. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2005). Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-0098-9.

- Greenblatt, Stephen; Abrams, Meyer Howard, eds. (2012). Sixteenth/Early Seventeenth Century. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Vol. 2. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-91250-0.

- Greer, Germaine (1986). Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-287538-9.

- Hales, John W. (26 March 1904). «London Residences of Shakespeare». The Athenaeum. No. 3987. London: John C. Francis. pp. 401–402.

- Holland, Peter, ed. (2000). Cymbeline. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-071472-2.

- Honan, Park (1998). Shakespeare: A Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811792-6.

- Honigmann, E.A.J. (1999). Shakespeare: The ‘Lost Years’ (Revised ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5425-9.

- Jackson, MacDonald P. (2004). Zimmerman, Susan (ed.). «A Lover’s Complaint revisited». Shakespeare Studies. XXXII. ISSN 0582-9399 – via The Free Library.

- Johnson, Samuel (2002) [first published 1755]. Lynch, Jack (ed.). Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary: Selections from the 1755 Work that Defined the English Language. Delray Beach, FL: Levenger Press. ISBN 978-1-84354-296-4.

- Jonson, Ben (1996) [first published 1623]. «To the memory of my beloued, The AVTHOR MR. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE: AND what he hath left vs». In Hinman, Charlton (ed.). The First Folio of Shakespeare (2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-03985-6.

- Kastan, David Scott (1999). Shakespeare After Theory. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-90112-3.

- Kermode, Frank (2004). The Age of Shakespeare. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84881-3.

- Kinney, Arthur F., ed. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956610-5.

- Knutson, Roslyn (2001). Playing Companies and Commerce in Shakespeare’s Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486043. ISBN 978-0-511-48604-3 – via Cambridge Core.

- Lee, Sidney (1900). Shakespeare’s Life and Work. London: Smith, Elder & Co. OL 21113614M.

- Levenson, Jill L., ed. (2000). Romeo and Juliet. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-281496-8.

- Levin, Harry (1986). «Critical Approaches to Shakespeare from 1660 to 1904». In Wells, Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31841-9.

- Love, Harold (2002). Attributing Authorship: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511483165. ISBN 978-0-511-48316-5 – via Cambridge Core.

- Maguire, Laurie E. (1996). Shakespearean Suspect Texts: The ‘Bad’ Quartos and Their Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511553134. ISBN 978-0-511-55313-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Mays, Andrea; Swanson, James (20 April 2016). «Shakespeare Died a Nobody, and then Got Famous by Accident». New York Post. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- McDonald, Russ (2006). Shakespeare’s Late Style. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511483783. ISBN 978-0-511-48378-3 – via Cambridge Core.

- McIntyre, Ian (1999). Garrick. Harmondsworth, England: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-14-028323-5.

- McMichael, George; Glenn, Edgar M. (1962). Shakespeare and his Rivals: A Casebook on the Authorship Controversy. New York: Odyssey Press. OCLC 2113359.

- Meagher, John C. (2003). Pursuing Shakespeare’s Dramaturgy: Some Contexts, Resources, and Strategies in his Playmaking. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3993-1.

- Mowat, Barbara; Werstine, Paul (n.d.). «Sonnet 18». Folger Digital Texts. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Muir, Kenneth (2005). Shakespeare’s Tragic Sequence. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35325-0.

- Nagler, A.M. (1958). Shakespeare’s Stage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02689-4.

- «Did He or Didn’t He? That Is the Question». The New York Times. 22 April 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- Paraisz, Júlia (2006). «The Author, the Editor and the Translator: William Shakespeare, Alexander Chalmers and Sándor Petofi or the Nature of a Romantic Edition». Editing Shakespeare. Shakespeare Survey. Vol. 59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–135. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521868386.010. ISBN 978-1-139-05271-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Pequigney, Joseph (1985). Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-65563-5.

- Pollard, Alfred W. (1909). Shakespeare Quartos and Folios: A Study in the Bibliography of Shakespeare’s Plays, 1594–1685. London: Methuen. OCLC 46308204.

- Pritchard, Arnold (1979). Catholic Loyalism in Elizabethan England. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1345-4.

- Ribner, Irving (2005). The English History Play in the Age of Shakespeare. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35314-4.

- Ringler, William, Jr. (1997). «Shakespeare and His Actors: Some Remarks on King Lear». In Ogden, James; Scouten, Arthur Hawley (eds.). In Lear from Study to Stage: Essays in Criticism. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 123–134. ISBN 978-0-8386-3690-9.

- Roe, John, ed. (2006). The Poems: Venus and Adonis, The Rape of Lucrece, The Phoenix and the Turtle, The Passionate Pilgrim, A Lover’s Complaint. The New Cambridge Shakespeare (2nd revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85551-8.

- Rowe, Nicholas (1997) [first published 1709]. Gray, Terry A. (ed.). Some Account of the Life &c of Mr. William Shakespear. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- Rowse, A.L. (1963). William Shakespeare; A Biography. New York: Harper & Row. OL 21462232M.

- Rowse, A.L. (1988). Shakespeare: the Man. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-44354-5.

- Sawyer, Robert (2003). Victorian Appropriations of Shakespeare. New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3970-2.

- Schanzer, Ernest (1963). The Problem Plays of Shakespeare. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-415-35305-2. OCLC 2378165.

- Schoch, Richard W. (2002). «Pictorial Shakespeare». In Wells, Stanley; Stanton, Sarah (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–75. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521792959.004. ISBN 978-0-511-99957-4 – via Cambridge Core.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1981). William Shakespeare: Records and Images. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-520234-2.

- de Sélincourt, Basil (1909). William Blake. The library of art. London: Duckworth & co. hdl:2027/mdp.39015066033914. OL 26411508M.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1987). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (Revised ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505161-2.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1991). Shakespeare’s Lives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-818618-2.

- Shapiro, James (2005). 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-21480-8.

- Shapiro, James (2010). Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-4162-2.

- Smith, Irwin (1964). Shakespeare’s Blackfriars Playhouse. New York: New York University Press.

- Snyder, Susan; Curren-Aquino, Deborah, eds. (2007). The Winter’s Tale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22158-0.

- «Shakespeare Memorial». Southwark Cathedral. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Steiner, George (1996). The Death of Tragedy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06916-7.

- Taylor, Gary (1987). William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-812914-1.

- Taylor, Gary (1990). Reinventing Shakespeare: A Cultural History from the Restoration to the Present. London: Hogarth Press. ISBN 978-0-7012-0888-2.

- Wain, John (1975). Samuel Johnson. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-61671-8.

- Wells, Stanley; Taylor, Gary; Jowett, John; Montgomery, William, eds. (2005). The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926717-0.

- Wells, Stanley (1997). Shakespeare: A Life in Drama. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31562-2.

- Wells, Stanley (2006). Shakespeare & Co. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 978-0-375-42494-6.

- Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen, eds. (2003). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Gross, John (2003). «Shakespeare’s Influence». In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Kathman, David (2003). «The Question of Authorship». In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: an Oxford Guide. Oxford Guides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 620–632. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Thomson, Peter (2003). «Conventions of Playwriting». In Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena Cowen (eds.). Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

- Werner, Sarah (2001). Shakespeare and Feminist Performance. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22729-2.

- «Visiting the Abbey». Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Wilson, Richard (2004). Secret Shakespeare: Studies in Theatre, Religion and Resistance. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7024-2.

- Wood, Manley, ed. (1806). The Plays of William Shakespeare with Notes of Various Commentators. Vol. I. London: George Kearsley.

- Wood, Michael (2003). Shakespeare. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09264-2.

- Wright, George T. (2004). «The Play of Phrase and Line». In McDonald, Russ (ed.). Shakespeare: An Anthology of Criticism and Theory, 1945–2000. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-23488-3.

External links

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 11 April 2008, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Digital editions

- William Shakespeare’s plays on Bookwise

- Works by William Shakespeare in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Internet Shakespeare Editions

- The Folger Shakespeare

- Open Source Shakespeare complete works, with search engine and concordance

- The Shakespeare Quartos Archive

- Works by William Shakespeare at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Shakespeare at Internet Archive

- Works by William Shakespeare at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Exhibitions

- Shakespeare Documented an online exhibition documenting Shakespeare in his own time

- Shakespeare’s Will from The National Archives

- Discovering Literature: Shakespeare at the British Library

- The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

- William Shakespeare at the British Library

- Benjamin Blom Drama Collection: Shakespeare Materials at the Harry Ransom Center

- Legacy and criticism

- Records on Shakespeare’s Theatre Legacy from the UK Parliamentary Collections

- Winston Churchill & Shakespeare – UK Parliament Living Heritage

- Other links

- Works by William Shakespeare set to music: free scores in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

|

William Shakespeare |

|

|---|---|

The Chandos portrait (held by the National Portrait Gallery, London) |

|

| Born |

Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Baptised | 26 April 1564 |

| Died | 23 April 1616 (aged 52)[a]

Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Resting place | Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | c. 1585–1613 |

| Era |

|

| Movement | English Renaissance |

| Spouse |

Anne Hathaway (m. 1582) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |