For other uses, see Stasis.

| Ministerium für Staatssicherheit | |

Seal |

|

Stasi Museum in East Berlin |

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 8 February 1950 |

| Dissolved | 13 January 1990[1] |

| Type | Secret police |

| Headquarters | Lichtenberg, East Berlin |

| Motto | Schild und Schwert der Partei |

| Employees |

|

| Agency executives |

|

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the Stasi (German: [ˈʃtaːziː] (listen)),[n 1] was the state security service of East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi’s function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maintaining state authority, i.e., the «Sword and Shield of the Party» (Schild und Schwert der Partei). This was accomplished primarily through the use of a network of civilian informants. This organization contributed to the arrest of approximately 250,000 people in East Germany.[3] The Stasi also conducted espionage and other clandestine operations abroad through its subordinate foreign intelligence service, the Office of Reconnaissance, or Head Office A (German: Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung). They also maintained contacts and occasionally cooperated with West German terrorists.[4]

The Stasi was headquartered in East Berlin, with an extensive complex in Berlin-Lichtenberg and several smaller facilities throughout the city. Erich Mielke was the Stasi’s longest-serving chief, in power for 32 of the 40 years of the GDR’s existence. The HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung), under Markus Wolf, gained a reputation as one of the most effective intelligence agencies of the Cold War.[5]

After German reunification, numerous officials were prosecuted for their crimes and the surveillance files that the Stasi had maintained on millions of East Germans were unclassified so that all citizens could inspect their personal file on request. The files were maintained by the Stasi Records Agency until June 2021, when they became part of the German Federal Archives.

Creation[edit]

The Stasi was founded on 8 February 1950.[6] Wilhelm Zaisser was the first Minister of State Security of the GDR, and Erich Mielke was his deputy. Zaisser tried to depose SED General Secretary Walter Ulbricht after the June 1953 uprising,[7] but was instead removed by Ulbricht and replaced with Ernst Wollweber thereafter. Following the June 1953 uprising, the Politbüro decided to downgrade the apparatus to a State Secretariat and incorporate it under the Ministry of the Interior under the leadership of Willi Stoph. The Minister of State Security simultaneously became a State Secretary of State Security. The Stasi held this status until November 1955, when it was restored to a ministry.[8][9] Wollweber resigned in 1957 after clashes with Ulbricht and Erich Honecker, and was succeeded by his deputy, Erich Mielke.

In 1957, Markus Wolf became head of the Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung (HVA) (Main Reconnaissance Administration), the foreign intelligence section of the Stasi. As intelligence chief, Wolf achieved great success in penetrating the government, political and business circles of West Germany with spies. The most influential case was that of Günter Guillaume, which led to the downfall of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt in May 1974. In 1986, Wolf retired and was succeeded by Werner Grossmann.

Relationship with Soviet Intelligence Services[edit]

Although Mielke’s Stasi was superficially granted independence in 1957, the KGB continued to maintain liaison officers in all eight main Stasi directorates at the Stasi headquarters and in each of the fifteen district headquarters around the GDR. The Stasi had also been invited by the KGB to establish operational bases in Moscow and Leningrad to monitor visiting East German tourists. Due to their close ties with Soviet intelligence services, Mielke referred to the Stasi officers as «Chekists». In 1978, Mielke formally granted KGB officers in East Germany the same rights and powers that they enjoyed in the Soviet Union.[10]

Operations[edit]

Personnel and recruitment[edit]

Between 1950 and 1989, the Stasi employed a total of 274,000 people in an effort to root out the class enemy.[11][12][13] In 1989, the Stasi employed 91,015 people full-time, including 2,000 fully employed unofficial collaborators, 13,073 soldiers and 2,232 officers of GDR army,[14] along with 173,081 unofficial informants inside GDR[15] and 1,553 informants in West Germany.[16]

Regular commissioned Stasi officers were recruited from conscripts who had been honourably discharged from their 18 months’ compulsory military service, had been members of the SED, had had a high level of participation in the Party’s youth wing’s activities and had been Stasi informers during their service in the Military. The candidates would then have to be recommended by their military unit political officers and Stasi agents, the local chiefs of the District (Bezirk) Stasi and Volkspolizei office, of the district in which they were permanently resident, and the District Secretary of the SED. These candidates were then made to sit through several tests and exams, which identified their intellectual capacity to be an officer, and their political reliability. University graduates who had completed their military service did not need to take these tests and exams. They then attended a two-year officer training programme at the Stasi college (Hochschule) in Potsdam. Less mentally and academically endowed candidates were made ordinary technicians and attended a one-year technology-intensive course for non-commissioned officers.

By 1995, some 174,000 inoffizielle Mitarbeiter (IMs) Stasi informants had been identified, almost 2.5% of East Germany’s population between the ages of 18 and 60.[11] 10,000 IMs were under 18 years of age.[11] From the volume of material destroyed in the final days of the regime, the office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records (BStU) believes that there could have been as many as 500,000 informers.[11] A former Stasi colonel who served in the counterintelligence directorate estimated that the figure could be as high as 2 million if occasional informants were included.[11] There is significant debate about how many IMs were actually employed.

Infiltration[edit]

The main entrance to the Stasi headquarters in Berlin

Full-time officers were posted to all major industrial plants (the extent of any surveillance largely depended on how valuable a product was to the economy)[12] and one tenant in every apartment building was designated as a watchdog reporting to an area representative of the Volkspolizei (Vopo). Spies reported every relative or friend who stayed the night at another’s apartment. Tiny holes were drilled in apartment and hotel room walls through which Stasi agents filmed citizens with special video cameras. Schools, universities, and hospitals were extensively infiltrated,[17] as were organizations, such as computer clubs where teenagers exchanged Western video games.[18]

The Stasi had formal categorizations of each type of informant, and had official guidelines on how to extract information from, and control, those with whom they came into contact.[19] The roles of informants ranged from those already in some way involved in state security (such as the police and the armed services) to those in the dissident movements (such as in the arts and the Protestant Church).[20] Information gathered about the latter groups was frequently used to divide or discredit members.[21] Informants were made to feel important, given material or social incentives, and were imbued with a sense of adventure, and only around 7.7%, according to official figures, were coerced into cooperating. A significant proportion of those informing were members of the SED. Use of some form of blackmail was not uncommon.[20] A large number of Stasi informants were tram conductors, janitors, doctors, nurses and teachers. Mielke believed that the best informants were those whose jobs entailed frequent contact with the public.[22]

The Stasi’s ranks swelled considerably after Eastern Bloc countries signed the 1975 Helsinki accords, which GDR leader Erich Honecker viewed as a grave threat to his regime because they contained language binding signatories to respect «human and basic rights, including freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and conviction».[23] The number of IMs peaked at around 180,000 in that year, having slowly risen from 20,000 to 30,000 in the early 1950s, and reaching 100,000 for the first time in 1968, in response to Ostpolitik and protests worldwide.[24] The Stasi also acted as a proxy for KGB to conduct activities in other Eastern Bloc countries, such as Poland, where the Soviets were despised.[25]

The Stasi infiltrated almost every aspect of GDR life. In the mid-1980s, a network of IMs began growing in both German states. By the time that East Germany collapsed in 1989, the Stasi employed 91,015 employees and 173,081 informants.[26] About one out of every 63 East Germans collaborated with the Stasi. By at least one estimate, the Stasi maintained greater surveillance over its own people than any secret police force in history.[27] The Stasi employed one secret policeman for every 166 East Germans. By comparison, the Gestapo deployed one secret policeman per 2,000 people. As ubiquitous as this was, the ratios swelled when informers were factored in: counting part-time informers, the Stasi had one agent per 6.5 people. This comparison led Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal to call the Stasi even more oppressive than the Gestapo.[28] Stasi agents infiltrated and undermined West Germany’s government and spy agencies.[citation needed]

In some cases, spouses even spied on each other. A high-profile example of this was peace activist Vera Lengsfeld, whose husband, Knud Wollenberger, was a Stasi informant.[22]

Zersetzung (Decomposition)[edit]

The Stasi perfected the technique of psychological harassment of perceived enemies known as Zersetzung (pronounced [ʦɛɐ̯ˈzɛtsʊŋ]) – a term borrowed from chemistry which literally means «decomposition».

…the Stasi often used a method which was really diabolic. It was called Zersetzung, and it’s described in another guideline. The word is difficult to translate because it means originally «biodegradation». But actually, it’s a quite accurate description. The goal was to destroy secretly the self-confidence of people, for example by damaging their reputation, by organizing failures in their work, and by destroying their personal relationships. Considering this, East Germany was a very modern dictatorship. The Stasi didn’t try to arrest every dissident. It preferred to paralyze them, and it could do so because it had access to so much personal information and to so many institutions.

—Hubertus Knabe, German historian[29]

By the 1970s, the Stasi had decided that the methods of overt persecution that had been employed up to that time, such as arrest and torture, were too crude and obvious. Such forms of oppression were drawing significant international condemnation. It was realised that psychological harassment was far less likely to be recognised for what it was, so its victims, and their supporters, were less likely to be provoked into active resistance, given that they would often not be aware of the source of their problems, or even its exact nature. International condemnation could also be avoided. Zersetzung was designed to side-track and «switch off» perceived enemies so that they would lose the will to continue any «inappropriate» activities.[n 2] Anyone who was judged to display politically, culturally, or religiously incorrect attitudes could be viewed as a «hostile-negative»[30] force and targeted with Zersetzung methods. For this reason members of the Church, writers, artists, and members of youth sub-cultures were often the victims. Zersetzung methods were applied and further developed in a «creative and differentiated»[31] manner based upon the specific person being targeted i.e. they were tailored based upon the target’s psychology and life situation.[32]

Tactics employed under Zersetzung usually involved the disruption of the victim’s private or family life. This often included psychological attacks, such as breaking into their home and subtly manipulating the contents, in a form of gaslighting i.e. moving furniture around, altering the timing of an alarm, removing pictures from walls, or replacing one variety of tea with another etc. Other practices included property damage, sabotage of cars, travel bans, career sabotage, administering purposely incorrect medical treatment, smear campaigns which could include sending falsified, compromising photos or documents to the victim’s family, denunciation, provocation, psychological warfare, psychological subversion, wiretapping, bugging, mysterious phone calls or unnecessary deliveries, even including sending a vibrator to a target’s wife. Increasing degrees of unemployment and social isolation could and frequently did occur due to the negative psychological, physical, and social ramifications of being targeted.[33] Usually, victims had no idea that the Stasi were responsible. Many thought that they were losing their minds, and mental breakdowns and suicide were sometimes the result. There is on-going debate as to the extent, if at all, that weaponised directed energy devices, such as X-ray transmitters, were also used against victims.[34]

One great advantage of the harassment perpetrated under Zersetzung was that its relatively subtle nature meant that it was able to be plausibly denied, including in diplomatic circles. This was important given that the GDR was trying to improve its international standing during the 1970s and 80s, especially in conjunction with the Ostpolitik of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt massively improving relations between the two German states. For these political and operational reasons Zersetzung became the primary method of repression in the GDR.[n 3]

International operations[edit]

After German reunification, revelations of the Stasi’s international activities were publicized, such as its military training of the West German Red Army Faction.[35]

Examples[edit]

- Stasi experts helped train the secret police organization of Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia.[36][37]

- Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba was particularly interested in receiving training from the Stasi. Stasi instructors worked in Cuba and Cuban communists received training in East Germany.[38] Stasi chief Markus Wolf described how he modelled the Cuban system based on the East German one.[39]

- Stasi officers helped in initial training and indoctrination of Egyptian State Security organizations under the Nasser regime from 1957 to 58 onwards. This was discontinued by Anwar Sadat in 1976.

- The Stasi’s experts worked to help create secret police forces in the People’s Republic of Angola, the People’s Republic of Mozambique, and the People’s Republic of Yemen (South Yemen).[37]

- The Stasi organized and extensively trained Syrian intelligence services under the regime of Hafez al-Assad and Ba’ath Party from 1966 onwards and especially from 1973.[40]

- Stasi experts helped to set up Idi Amin’s secret police.[37][41]

- Stasi experts helped the President of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, to set up his secret police. When Nkrumah was ousted by a military coup, Stasi Major Jürgen Rogalla was imprisoned.[37][42]

- The Stasi sent agents to the West as sleeper agents. For instance, sleeper agent Günter Guillaume became a senior aide to social democratic chancellor Willy Brandt, and reported about his politics and private life.[43]

- The Stasi operated at least one brothel. Agents were used against both men and women working in Western governments. «Entrapment» was used against married men and homosexuals.[44]

- Martin Schlaff – According to the German parliament’s investigations, the Austrian billionaire’s Stasi codename was «Landgraf» and registration number «3886-86». He made money by supplying embargoed goods to East Germany.[45]

- Sokratis Kokkalis – Stasi documents suggest that the Greek businessman was a Stasi agent, whose operations included delivering Western technological secrets and bribing Greek officials to buy outdated East German telecom equipment.[46]

- Red Army Faction (Baader-Meinhof Group) – The terrorist organization which killed dozens of West Germans and others received financial and logistical support from the Stasi, as well as shelter and new identities.[47][4][5]

- The Stasi ordered a campaign in which cemeteries and other Jewish sites in West Germany were smeared with swastikas and other Nazi symbols. Funds were channelled to a small West German group for it to defend Adolf Eichmann.[48]

- The Stasi channelled large amounts of money to Neo-Nazi groups in West, with the purpose of discrediting the West.[49][4]

- The Stasi allowed the wanted West German Neo-Nazi Odfried Hepp to hide in East Germany and then provided him with a new identity so that he could live in the Middle East.[4]

- The Stasi worked in a campaign to create extensive material and propaganda against Israel.[48]

- Murder of Benno Ohnesorg – A Stasi informant in the West Berlin police, Karl-Heinz Kurras, fatally shot an unarmed demonstrator, which stirred a whole movement of Marxist radicalism, protest, and terrorist violence.[50] The Economist describes it as «the gunshot that hoaxed a generation».[51][52] The surviving Stasi Records contain no evidence that Kurras was acting under their orders when he shot Ohnesorg.[53][54]

- Operation Infektion—The Stasi helped the KGB to spread HIV/AIDS disinformation that the United States had created the disease. Millions of people around the world still believe these claims.[55][56]

- Sandoz chemical spill—The KGB reportedly[by whom?] ordered the Stasi to sabotage the chemical factory to distract attention from the Chernobyl disaster six months earlier in Ukraine.[57][58][59]

- Investigators have found evidence of a death squad that carried out a number of assassinations (including assassination of Swedish journalist Cats Falck) on orders from the East German government from 1976 to 1987. Attempts to prosecute members failed.[60][61][62]

- The Stasi attempted to assassinate Wolfgang Welsch, a famous critic of the regime. Stasi collaborator Peter Haack (Stasi codename «Alfons») befriended Welsch and then fed him hamburgers poisoned with thallium. It took weeks for doctors to find out why Welsch had suddenly lost his hair.[63]

- Documents in the Stasi archives state that the KGB ordered Bulgarian agents to assassinate Pope John Paul II, who was known for his criticism of human rights in the Eastern Bloc, and the Stasi was asked to help with covering up traces.[64]

- A special unit of the Stasi assisted Romanian intelligence in kidnapping Romanian dissident Oliviu Beldeanu from West Germany.[65]

- The Stasi in 1972 made plans to assist the Ministry of Public Security (Vietnam) in improving its intelligence work during the Vietnam War.[66]

- In 1975, the Stasi recorded a conversation between senior West German CDU politicians Helmut Kohl and Kurt Biedenkopf. It was then «leaked» to Stern magazine as a transcript recorded by American intelligence. The magazine then claimed that Americans were wiretapping West Germans and the public believed the story.[67]

Fall of the Soviet Union[edit]

Recruitment of informants became increasingly difficult towards unification, and after 1986 there was a negative turnover rate of IMs. This had a significant impact on the Stasi’s ability to survey the populace in a period of growing unrest, and knowledge of the Stasi’s activities became more widespread.[68] Stasi had been tasked during this period with preventing the country’s economic difficulties becoming a political problem, through suppression of the very worst problems the state faced, but it failed to do so.[12]

On 7 November 1989, in response to the rapidly changing political and social situation in the GDR in late 1989, Erich Mielke resigned. On 17 November 1989, the Council of Ministers (Ministerrat der DDR) renamed the Stasi the Office for National Security (Amt für Nationale Sicherheit – AfNS), which was headed by Generalleutnant Wolfgang Schwanitz. On 8 December 1989, GDR Prime Minister Hans Modrow directed the dissolution of the AfNS, which was confirmed by a decision of the Ministerrat on 14 December 1989.

As part of this decision, the Ministerrat originally called for the evolution of the AfNS into two separate organizations: a new foreign intelligence service (Nachrichtendienst der DDR) and an «Office for the Protection of the Constitution of the GDR» (Verfassungsschutz der DDR), along the lines of the West German Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, however, the public reaction was extremely negative, and under pressure from the «Round Table» (Runder Tisch), the government dropped the creation of the Verfassungsschutz der DDR and directed the immediate dissolution of the AfNS on 13 January 1990. Certain functions of the AfNS reasonably related to law enforcement were handed over to the GDR Ministry of Internal Affairs. The same ministry also took guardianship of remaining AfNS facilities.

When the parliament of Germany investigated public funds that disappeared after the Fall of the Berlin Wall, it found out that East Germany had transferred large amounts of money to Martin Schlaff through accounts in Vaduz, the capital of Liechtenstein, in return for goods «under Western embargo».

Moreover, high-ranking Stasi officers continued their post-GDR careers in management positions in Schlaff’s group of companies. For example, in 1990, Herbert Kohler, Stasi commander in Dresden, transferred 170 million marks to Schlaff for «harddisks» and months later went to work for him.[45][69]

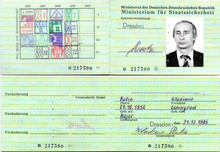

The investigations concluded that «Schlaff’s empire of companies played a crucial role» in the Stasi attempts to secure the financial future of Stasi agents and keep the intelligence network alive.[45] Stern magazine noted that KGB officer (and future Russian President) Vladimir Putin worked with his Stasi colleagues in Dresden in 1989.[69]

Recovery of Stasi files[edit]

During the Peaceful Revolution of 1989, Stasi offices and prisons throughout the country were occupied by citizens, but not before the Stasi destroyed a number of documents (approximately 5%)[70] consisting of, by one calculation, 1 billion sheets of paper.[71]

Storming the Stasi headquarters[edit]

Citizens protesting and entering the Stasi building in Berlin; the sign accuses the Stasi and SED of being Nazi-like dictators (1990)

With the fall of the GDR, the Stasi was dissolved. Stasi employees began to destroy the extensive files and documents they held, either by hand or by using incineration or shredders. When these activities became known, a protest began in front of the Stasi headquarters.[72] The evening of 15 January 1990 saw a large crowd form outside the gates calling for a stop to the destruction of sensitive files. The building contained vast records of personal files, many of which would form important evidence in convicting those who had committed crimes for the Stasi. The protesters continued to grow in number until they were able to overcome the police and gain entry into the complex. Once inside, specific targets of the protesters’ anger were portraits of Erich Honecker and Erich Mielke, which were torn down, trampled upon or burnt. Some Stasi employees were thrown out of upper floor windows and beaten after falling to the streets below, but there were no deaths or serious injuries. Among the protesters were former Stasi collaborators seeking to destroy incriminating documents.[citation needed]

Stasi file controversy[edit]

With German reunification on 3 October 1990, a new government agency was founded, called the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic (German: Der Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik), officially abbreviated «BStU».[73] There was a debate about what should happen to the files, whether they should be opened to the people or kept sealed.

Those who opposed opening the files cited privacy as a reason.[citation needed] They felt that the information in the files would lead to negative feelings about former Stasi members, and, in turn, cause violence. Pastor Rainer Eppelmann, who became Minister of Defense and Disarmament after March 1990, felt that new political freedoms for former Stasi members would be jeopardized by acts of revenge. Prime Minister Lothar de Maizière even went so far as to predict murder. They also argued against the use of the files to capture former Stasi members and prosecute them, arguing that not all former members were criminals and should not be punished solely for being a member. There were also some who believed that everyone was guilty of something. Peter-Michael Diestel, the Minister of Interior, opined that these files could not be used to determine innocence and guilt, claiming that «there were only two types of individuals who were truly innocent in this system, the newborn and the alcoholic». Others, such as West German Interior Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, believed in putting the Stasi past behind them and working on German reunification.

But why did the Stasi collect all this information in its archives? The main purpose was to control the society. In nearly every speech, the Stasi minister gave the order to find out who is who, which meant who thinks what. He didn’t want to wait until somebody tried to act against the regime. He wanted to know in advance what people were thinking and planning. The East Germans knew, of course, that they were surrounded by informers, in a totalitarian regime that created mistrust and a state of widespread fear, the most important tools to oppress people in any dictatorship.

—Hubertus Knabe, German historian[29]

Those on the other side of the debate argued that everyone should have the right to see their own file, and that the files should be opened to investigate former Stasi members and prosecute them, as well as prevent them from holding office. Opening the files would also help clear up some of the rumors circulating at the time. Some believed that politicians involved with the Stasi should be investigated.

The fate of the files was finally decided under the Unification Treaty between the GDR and West Germany. This treaty took the Volkskammer law further and allowed more access and greater use of the files. Along with the decision to keep the files in a central location in the East, they also decided who could see and use the files, allowing people to see their own files.

In 1992, following a declassification ruling by the German government, the Stasi files were opened, leading people to gain access to their files. Timothy Garton Ash, an English historian, after reading his file, wrote The File: A Personal History.[74]

Between 1991 and 2011, around 2.75 million individuals, mostly GDR citizens, requested to see their own files.[75] The ruling also gave people the ability to make duplicates of their documents. Another significant question was how the media could use and benefit from the documents. It was decided that the media could obtain files as long as they were depersonalized and did not contain information about individuals under the age of 18 or former Stasi members. This ruling not only granted file access to the media, but also to schools.

Tracking down former Stasi informers with recovered files[edit]

Some groups within the former Stasi community used threats of violence to scare off Stasi hunters, who were actively tracking down ex-members. Though these hunters succeeded in identifying many ex-Stasi, charges could not be brought against anyone merely for being a registered Stasi member. The person in question had to have participated in an illegal act. Among the high-profile individuals arrested and tried were Erich Mielke, Third Minister of State Security of the GDR, and Erich Honecker, GDR head of state. Mielke was sentenced to six years prison for the 1931 murder of two policemen. Honecker was charged with authorizing the killing of would-be escapees along the east–west border and Berlin Wall. During his trial, he underwent cancer treatment. Nearing death, Honecker was allowed to spend his final years a free man. He died in Chile in May 1994.

Reassembling destroyed files[edit]

Reassembling the destroyed files has been relatively easy due to the amount of archives and the failure of shredding machines (in some cases, «shredding» meant tearing pages in two by hand, making the documents easily recoverable). In 1995, the BStU began reassembling the shredded documents; 13 years later, the three dozen archivists commissioned to the projects had reassembled only 327 bags. Computer-assisted data recovery is now being used to reassemble the remaining 16,000 bags – representing approximately 45 million pages. It is estimated that the task may require 30 million dollars to complete.[76]

The CIA acquired some Stasi records during the looting of the Stasi’s archives. Germany asked for their return and received some in April 2000.[77] See also Rosenholz files.

Museums[edit]

Part of the former Stasi compound in Berlin, with «Haus 1» in the centre

There are a number of memorial sites and museums relating to the Stasi in former Stasi prisons and administration buildings. In addition, offices of the Stasi Records Agency in Berlin, Dresden, Erfurt, Frankfurt-an-der-Oder and Halle (Saale) all have permanent and changing exhibitions relating to the activities of the Stasi in their region.[78]

Berlin[edit]

- Stasi Museum (Berlin) — This is located at Ruschestraße 103, in «Haus 1» on the former Stasi headquarters compound. The office of Erich Mielke, the head of the Stasi, was in this building and it has been preserved along with a number of other rooms. The building was occupied by protesters on 15 January 1990. On 7 November 1990, a Research Centre and Memorial was opened, which now called the Stasi Museum.[79]

- Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial — A memorial to repression during both the Soviet occupation and GDR era in a former prison that was used by both regimes. The building was a Soviet prison from 1946, and from 1951 until 1989 it was a Stasi remand centre. It officially closed on 3 October 1990, the day of German reunification. The museum and memorial site opened in 1994. It is in Alt-Hohenschönhausen, in Lichtenberg in north-east Berlin.[80]

Erfurt[edit]

Memorial and Education Centre Andreasstraße — a museum in Erfurt which is housed in a former Stasi remand prison. From 1952 until 1989, over 5000 political prisoners were held on remand and interrogated in the Andreasstrasse prison, which was one of 17 Stasi remand prisons in the GDR.[81][82] On 4 December 1989, local citizens occupied the prison and the neighbouring Stasi district headquarters to stop the mass destruction of Stasi files. It was the first time East Germans had undertaken such resistance against the Stasi and it instigated the take over of Stasi buildings throughout the country.[83]

Dresden[edit]

Cells in Bautzner Strasse Memorial, Dresden

Gedenkstätte Bautzner Straße Dresden [de] (The Bautzner Strasse Memorial in Dresden) — A Stasi remand prison and the Stasi’s regional head office in Dresden. It was used as a prison by the Soviet occupying forces from 1945 to 1953, and from 1953 to 1989 by the Stasi. The Stasi held and interrogated between 12,000 and 15,000 people during the time they used the prison. The building was originally a 19th-century paper mill. It was converted into a block of flats in 1933 before being confiscated by the Soviet army in 1945. The Stasi prison and offices were occupied by local citizens on 5 December 1989, during a wave of such takeovers across the country. The museum and memorial site was opened to the public in 1994.[84]

Frankfurt-an-der-Oder[edit]

Remembrance and Documentation Centre for «Victims of political tyranny» [de] — A memorial and museum at Collegienstraße 10 in Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, in a building that was used as a detention centre by the Gestapo, the Soviet occupying forces and the Stasi. The building was the Stasi district offices and a remand prison from 1950 until 1969, after which the Volkspolizei used the prison. From 1950 to 1952 it was an execution site where 12 people sentenced to death were executed. The prison closed in 1990. It has been a cultural centre and a memorial to the victims of political tyranny since June 1994, managed by the Museum Viadrina.[85][86]

Gera[edit]

Gedenkstätte Amthordurchgang [de], a memorial and ‘centre of encounter’ in Gera in a former remand prison, originally opened in 1874, that was used by the Gestapo from 1933 to 1945, the Soviet occupying forces from 1945 to 1949, and from 1952 to 1989 by the Stasi. The building was also the district offices of the Stasi administration. Between 1952 and 1989 over 2,800 people were held in the prison on political grounds. The memorial site opened with the official name «Die Gedenk- und Begegnungsstätte im Torhaus der politischen Haftanstalt von 1933 bis 1945 und 1945 bis 1989» in November 2005.[87][88]

Halle (Saale)[edit]

The Roter Ochse (Red Ox) is a museum and memorial site at the prison at Am Kirchtor 20, Halle (Saale). Part of the prison, built 1842, was used by the Stasi from 1950 until 1989, during with time over 9,000 political prisoners were held in the prison. From 1954 it was mainly used for women prisoners. The name «Roter Ochse» is the informal name of the prison, possibly originating in the 19th century from the colour of the external walls. It still operates as a prison for young people. Since 1996, the building which was used as an interrogation centre by the Stasi and an execution site by the Nazis has been a museum and memorial centre for victims of political persecution.[89]

Leipzig[edit]

Entrance to the «Runde Ecke» museum, Leipzig, 2009

- Gedenkstätte Museum in der „Runden Ecke“ [de] (Memorial Museum in the «Round Corner») — The former Stasi district headquarters on am Dittrichring is now a museum focusing on the history and activities of the organisation. It is named after the curved shape of the front of the building. The Stasi used the building from 1950 until 1989. On the evening of 4 December 1989, it was occupied by protesters in order to stop the destruction of Stasi files. There has been a permanent exhibition on the site since 1990. The building also houses the Leipzig branch of the Stasi Records Agency, which holds about 10 km of files on its shelves.[90]

- Lübschützer Teiche Stasi Bunker — The Stasi Bunker Museum is in Machern, a village about 30 km from Leipzig. It is managed by the Runde Ecke Museum administration. The bunker was built from 1968 to 1972, as a fallout shelter for the staff of the Stasi’s Leipzig administration in case of a nuclear attack. It could accommodate about 120 people. The bunker, which was disguised as a holiday resort on 5.2 hectares of land, was only discovered in December in 1989. «The emergency command centre was a secretly-created complex, designed to maintain the Stasi leadership’s hold on power, even in exceptional circumstances.» The whole grounds are classified as a historic monument and are open to the public on the last weekend of every month, and for pre-arranged group tours at other times.[91]

- GDR Execution site — The execution site at Alfred-Kästner-Straße in south Leipzig, was the central site in East Germany where the death penalty was carried out from 1960 until 1981. It remains in its original condition. The management of the «Runde Ecke» Museum opens the site once a year on «Museum night» and on special state-wide days when historic buildings and sites that are not normally accessible to the public are opened.[92]

Magdeburg[edit]

Gedenkstätte Moritzplatz Magdeburg [de] — The memorial site at Moritzplatz in Magdeburg is a museum on the site of a former prison, built from 1873 to 1876, that was used by the Soviet administration from 1945 to 1949 and the Stasi from 1958 until 1989 to hold political prisoners. Between 1950 and 1958 the Stasi shared another prison with the civil police. The prison at Moritzplatz was used by the Volkspolizei from 1952 until 1958. Between 1945 and 1989, more than 10,000 political prisoners were held in the prison. The memorial site and museum was founded in December 1990.[93]

Potsdam[edit]

Façade of the Memorial Site, Lindenstrasse, Potsdam

- Gedenkstätte Lindenstraße [de] The memorial site and museum at Lindenstraße 54/55 in Potsdam, examines political persecution in the Nazi, Soviet occupation and GDR eras. The original building was built 1733-1737 as a baroque palace; it became a court and prison in 1820. From 1933, the Nazi regime held political prisoners there, many of whom were arrested for racial reasons, for example Jews who refused to wear the yellow star on their clothing.[94]

The Soviet administration took over the prison in 1945, also using it as a prison for holding political prisoners on remand. The Stasi then used it as a remand prison, mainly for political prisoners from 1952 until 1989. Over 6,000 people were held in the prison by the Stasi during that time. On 27 October 1989, the prison freed all political prisoners due to a nationwide amnesty. On 5 December 1989, the Stasi Headquarters in Potsdam and the Lindenstrasse Prison were occupied by protesters. From January 1990 the building was used as offices for various citizens initiatives and new political groups, such as the Neue Forum. The building was opened to the public from 20 January 1990 and people were taken on tours of the site. It officially became a Memorial site in 1995.[94]

Rostock[edit]

- Documentation Centre and Memorial site, former Stasi remand prison, Rostock [de] — The memorial site is in a former Stasi remand prison at Hermanstrasse 34b. It is on what was part of a Stasi compound in Rostock, where its district headquarters were also located. Most of the site is now used by the Rostock county court and the University of Rostock. The complex was built 1958–1960. The remand prison was used by the Stasi from 1960 until 1989. About 4,900 people were held in the prison during that time, most of them were political prisoners.[95] Most of prisoners were released after an amnesty issued on 27 October 1989. The Stasi prison in the Rostock compound was occupied by protesters on 4 December 1989 following a wave of such occupation across East Germany starting in Erfurt on the same day.[96]

The prison closed in the early 1990s. The state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern took ownership of it in 1998, and the memorial site and museum were established in 1999. An extensive restoration of the site began in December 2018.[97]

Stasi officers after the reunification[edit]

Recruitment by Russian companies[edit]

Former Stasi agent Matthias Warnig (codename «Arthur») is currently the head of Nord Stream.[98]

Investigations have revealed that some key Gazprom Germania managers are former Stasi agents.[99][100]

Lobbying[edit]

Former Stasi officers continue to be politically active via the Gesellschaft zur Rechtlichen und Humanitären Unterstützung (GRH, Society for Legal and Humanitarian Support). Former high-ranking officers and employees of the Stasi, including the last Stasi director, Wolfgang Schwanitz, make up the majority of the organization’s members, and it receives support from the German Communist Party, among others.

The impetus for the establishment of the GRH was provided by the criminal charges filed against the Stasi in the early 1990s. The GRH, decrying the charges as «victor’s justice», called for them to be dropped. Today the group provides an alternative if a somewhat utopian voice in the public debate on the GDR’s legacy. It calls for the closure of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial and can be a vocal presence at memorial services and public events. In March 2006 in Berlin, GRH members disrupted a museum event; a political scandal ensued when the Berlin Senator (Minister) of Culture refused to confront them.[101]

Behind the scenes, the GRH also lobbies people and institutions promoting opposing viewpoints. For example, in March 2006, the Berlin Senator for Education received a letter from a GRH member and former Stasi officer attacking the Museum for promoting «falsehoods, anti-communist agitation and psychological terror against minors».[102] Similar letters have also been received by schools organizing field trips to the museum.[103]

Stasi agents[edit]

- Christel Boom

- Gabriele Gast

- Günter Guillaume

- Karl-Heinz Kurras

- Lilli Pöttrich

- Rainer Rupp

- Hans Sommer

- Werner Teske

Alleged informants[edit]

- Vic Allen, University of Leeds professor.[104]

- Helmut Aris, co-founder of the Association of Jewish Communities in the GDR.[105]

- Horst Bartel, Marxist–Leninist historian.[106]

- Almuth Beck, SED/PDS politician.[107]

- Jutta Braband, civil rights activist and PDS politician.[108]

- Siegfried Brietzke, three-time gold medal-winning Olympic rower.[109]

- Georg Buschner, football coach at FC Carl Zeiss Jena and the East Germany national football team. Buschner was listed as an informant under the codename Georg.

- Harald Czudaj, bobsledder.[110]

- Richard Clements, adviser to Neil Kinnock.[104]

- 18 of the 72 players (every fourth player) who played at least once for football team Dynamo Dresden between 1972 and 1989 were listed as unofficial collaborators (IM).[111][112] This included players such as Ulf Kirsten, who was listed under the codename «Knut Krüger».[113]

- Gwyneth Edwards[114]

- Horst Faas, journalist.

- Uta Felgner, hotel manager.[115]

- Eduard Geyer, former football coach at Dynamo Dresden[116] Eduard Geyer was listed as an informant for more than ten years under the codeame «Jahn».[117]

- Horst Giese, actor.[118]

- Paul Gratzik, communist writer.[119]

- Gerhart Hass, Marxist historian.[120]

- Brigitte Heinrich, Alliance 90/The Greens politician.[121]

- Anetta Kahane, journalist, activist and founder of the Amadeu Antonio Foundation.[122][123]

- Heinz Kahlau, socialist writer.[124]

- Heinz Kamnitzer, Marxist–Leninist academic.[125]

- Sokratis Kokkalis[126][127][128]

- Karl-Heinz Kurras, policeman and shooter of Benno Ohnesorg.

- Christa Luft, left-wing politician.[129]

- Lothar de Maizière, last prime minister of East Germany.[130]

- Thomas Nord, Left Party politician.[131]

- Helga M. Novak, writer.[132]

- Robin Pearson (Lecturer at the University of Hull)[133]

- Aleksander Radler, Lutheran theologian.[134]

- Bernd Runge, CEO of Phillips de Pury auction house[135]

- Martin Schlaff, billionaire businessman.[136]

- Holm Singer[137]

- Ingo Steuer, figure skater and now trainer[138]

- Barbara Thalheim, popular singer and songwriter.[139]

- Christa Wolf, socialist writer.[140]

See also[edit]

- Barkas (van manufacturer)

- Deutschland 83, Deutschland 86 and Deutschland 89

- Edgar Braun, a former Stasi officer

- Felix Dzerzhinsky Guards Regiment

- The Lives of Others, movie centered on the Stasi

- SED (Socialist Unity Party of Germany)

- Stasi Records Agency

- Stasiland

- Weissensee, TV series

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ An abbreviation of Staatssicherheit.

- ^ ‘The MfS dictionary summarised the goal of operational decomposition as ‘splitting up, paralysing, disorganising and isolating hostile-negative forces in order, thorough preventive action, to foil, considerably reduce or stop completely hostile-negative actions and their consequences or, in a varying degree, to win them back both politically and ideologically.’ Dennis, Mike (2003). «Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition». The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 112. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ ‘In the age of detente, the Stasi’s main method of combating subversive activity was ‘operational decomposition’ (operative Zersetzung) which was the central element in what Hubertus Knabe has called a system of ‘quiet repression’ (lautlose Unterdrukung). This was not a new departure as ‘dirty tricks’ had been widely used in the 1950s and 1960s. The distinctive feature was the primacy of operational decomposition over other methods of repression in a system to which historians have attached labels such as post-totalitarianism and modern dictatorship.’ Dennis, Mike (2003). «Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition». The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 112. ISBN 0582414229.

References[edit]

- ^ Vilasi, Antonella Colonna (9 March 2015). The History of the Stasi. AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781504937054.

- ^ Hinsey, Ellen (2010). «Eternal Return: Berlin Journal, 1989–2009». New England Review. 31 (1): 124–134. JSTOR 25699473.

- ^ East Germany’s inescapable Hohenschönhausen prison, Deutsche Welle, 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Blumenau, Bernhard (2018). «Unholy Alliance: The Connection between the East German Stasi and the Right-Wing Terrorist Odfried Hepp». Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 43: 47–68. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2018.1471969.

- ^ a b Blumenau, Bernhard (2014). The United Nations and Terrorism: Germany, Multilateralism, and Antiterrorism Efforts in the 1970s. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-137-39196-4.

- ^ Glees, Anthony (1996). Reinventing Germany: German political development since 1945. Berg. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-85973-185-7.

- ^ Grieder, Peter (1999). The East German Leadership, 1946-73: Conflict and Crisis. pp. 53–85. ISBN 9780719054983.

- ^ Gieseke, Jens (2014). The History of the Stasi: East Germany’s Secret Police, 1945-1990 (1st ed.). Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-78238-254-6.

- ^ Ghouas, Nessim (2004). The Conditions, Means and Methods of the MfS in the GDR; An Analysis of the Post and Telephone Control (1st ed.). Göttingen: Cuvillier Verlag. p. 80. ISBN 3-89873-988-0.

- ^ Koehler 2000, p. 74

- ^ a b c d e Koehler 2000, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b c Fulbrook 2005, pp. 228

- ^ «Political prisoners in the German Democratic Republic». Political prisoners in the German Democratic Republic | Communist Crimes. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Gieseke 2001, pp. 86–87

- ^ Müller-Enbergs 1993, p. 55

- ^ Gieseke 2001, p. 58

- ^ Koehler 2000, p. 9

- ^ Gießler, Denis (21 November 2018). «Video Games in East Germany: The Stasi Played Along». Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ Fulbrook 2005, p. 241

- ^ a b Fulbrook 2005, pp. 242–243

- ^ Fulbrook 2005, pp. 245

- ^ a b Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- ^ Koehler 2000, p. 142

- ^ Fulbrook 2005, pp. 240

- ^ Koehler 2000, p. 76

- ^ Gieseke 2001, p. 54

- ^ Computers to solve stasi puzzle-BBC, Friday 25 May 2007.

- ^ «Stasi». The New York Times.

- ^ a b Hubertus Knabe: The dark secrets of a surveillance state, TED Salon, Berlin, 2014

- ^ Dennis, Mike (2003). «Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition». The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 112. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ Dennis, Mike (2003). «Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition». The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 114. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ Dennis, Mike (2003). «Monitor and firefighter». The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. pp. 109–115. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ Dennis, Mike (2003). «Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition». The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 115. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ Grashoff, Udo. «Zersetzung (GDR) in Global Encyclopaedia of Informality, Volume 2: Understanding Social and Cultural Complexity«. jstor.org. UCL Press: 452–455. JSTOR j.ctt20krxgs.13. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Kinzer, Steven (28 March 1991). «Spy Charges Widen in Germany’s East». The New York Times.

- ^ A brave woman seeks justice and historical recognition for past wrongs. 27 September 2007. The Economist.

- ^ a b c d THE FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE-GATHERING OF THE MfS’ HAUPTVERWALTUNG AUFKLÄRUNG. Jérôme Mellon. 16 October 2001.

- ^ Seduced by Secrets: Inside the Stasi’s Spy-Tech World. Kristie Macrakis. P. 166–171.

- ^ The Culture of Conflict in Modern Cuba. Nicholas A. Robins. P. 45.

- ^ Rafiq Hariri and the Fate of Lebanon (2009). Marwān Iskandar. P. 201.

- ^ Gareth M. Winrow. The Foreign Policy of the GDR in Africa, p. 141

- ^ Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police (1999). John O. Koehler.

- ^ Craig R. Whitney (12 April 1995). «Gunter Guillaume, 68, Is Dead; Spy Caused Willy Brandt’s Fall». The New York Times.

- ^ Where Have All His Spies Gone?. New York Times. 12 August 1990

- ^ a b c «The Schlaff Saga / Laundered funds & ‘business’ ties to the Stasi». Haaretz. 7 September 2010.

- ^ Olympiakos soccer chief was ‘spy for Stasi’ Archived 26 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. The Independent. 24 February 2002.

- ^ Koehler (1999), The Stasi, pages 387-401.

- ^ a b E. Germany Ran Antisemitic Campaign in West in ’60s Archived 20 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Washington Post, 28 February 1993.

- ^ Neo-Nazism: a threat to Europe? Jillian Becker, Institute for European Defence & Strategic Studies. P. 16.

- ^ Blumenau, Bernhard (2014). The United Nations and Terrorism: Germany, Multilateralism, and Antiterrorism Efforts in the 1970s. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-137-39196-4.

- ^ The Truth about the Gunshot that Changed Germany. Spiegel Online. 28 May 2009.

- ^ The gunshot that hoaxed a generation. The Economist. 28 May 2009.

- ^ Kulish, Nicholas (26 May 2009). «East German Stasi Spy Killed Protester, Ohnesorg, in 1967». The New York Times.

- ^ «Karl-Heinz Kurras: Erschoss er Benno Ohnesorg? Gab Mielke den Schießbefehl?». 23 May 2009.

- ^ Koehler, John O. (1999) Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police ISBN 0-8133-3409-8.

- ^ Operation INFEKTION — Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign. Thomas Boghardt. 2009.

- ^ «KGB ordered Swiss explosion to distract attention from Chernobyl.» United Press International. 27 November 2000.

- ^ Stasi accused of Swiss disaster Archived 21 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Irish Times. 23 November 2000.

- ^ Sehnsucht Natur: Ökologisierung des Denkens (2009). Johannes Straubinger.

- ^ Hall, Thomas (25 September 2003). «Svensk tv-reporter mördades av DDR» (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. Archived from the original on 16 December 2004.

- ^ Svensson, Leif (26 September 2003). «Misstänkt mördare från DDR gripen» (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter/Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå. Archived from the original on 16 December 2004.

- ^ «Misstänkte DDR-mördaren släppt» (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter/Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå. 17 December 2003. Archived from the original on 17 December 2004.

- ^ Seduced by Secrets: Inside the Stasi’s Spy-Tech World. Kristie Macrakis. P. 176.

- ^ «Stasi Files Implicate KGB in Pope Shooting». Deutsche Welle.

- ^ The Kremlin’s Killing Ways—A long tradition continues. 28 November 2006. National Review.

- ^ «Stasi Aid and the Modernization of the Vietnamese Secret Police». 20 August 2014.

- ^ Stasi: Shield and Sword of the Party (2008). John C. Schmeidel. P. 138.

- ^ Fulbrook 2005, pp. 242

- ^ a b A tale of gazoviki, money and greed Archived 28 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Stern magazine, 13 September 2007

- ^ «Piecing Together the Dark Legacy of East Germany’s Secret Police». Wired. 18 January 2008.

- ^ Murphy, Cullen (17 January 2012). God’s Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-09156-0. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ The Stasi Headquarters now a museum open to the public.

- ^ Functions of the BStU Archived 9 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, from the English version of the official BStU website

- ^ The File, Information about «The File»

- ^ Pidd, Helen (13 March 2011). «Germans piece together millions of lives spied on by Stasi». The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Wired: «Piecing Together the Dark Legacy of East Germany’s Secret Police»

- ^ «Stasi files return to Germany». BBC News. 5 April 2000. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ Stasi Records Agency. History of the Records. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Stasi Museum Berlin. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen. History. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Wüstenberg, Jenny (2017). Civil Society and Memory in Postwar Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1071-7746-8.

- ^ Stiftung Ettersberg. Andreasstrasse. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ How ordinary people smashed the Stasi in The Local.de, 4 December 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2019

- ^ The Bautzner Straße Memorial in Dresden website. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Rost, Susanne (25 May 2002) Frankfurt (Oder) baut sein altes Gefängnis zum Kulturzentrum um / Gedenkstättenbeirat entsetzt Der einstige Hinrichtungsraum wird ein Café Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Museum Viadrina. Gedenk- und Dokumentationsstätte „Opfer politischer Gewaltherrschaft“. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Torhaus Gera Archived 24 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Geschichtsverbund Thüringen Arbeitsgemeinschaft zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur. Gedenkstätte Amthordurchgang Gera e.V. Archived 18 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 18 August 1990

- ^ Stiftung Gedenkstätten Sachsen-Anhalt. Gedenkstätte Roter Ochse Halle (Saale). Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Runde Ecke Leipzig (in English). Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Runde Ecke Leipzig. Stasi Bunker Museum. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Runde Ecke Leipzig. Execution site. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Gedenkstätte Moritzplatz Magdeburg. Zur Geschicte der Gedenkstätte. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ a b Stiftung Gedenkstaette Lindenstrasse. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ DDR Museum. Dokumentations- und Gedenkstätte in der ehemaligen U-Haft der Stasi in Rostock, 14 October 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Vilasi, Antonella Colonna (2015). The History of the Stasi. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse.

- ^ BBL-MV. Sanierung einer Dokumentations- und Gedenkstätte in Rostock[permanent dead link], 3 December 2018.Retrieved 18 August 2019

- ^ Nord Stream, Matthias Warnig (codename «Arthur») and the Gazprom Lobby Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 114

- ^ Gazprom’s Loyalists in Berlin and Brussels. Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 100. 26 May 2009

- ^ «Police investigate Gazprom executive’s Stasi past». 7 May 2008.

- ^ Berliner Morgenpost 16 March 2006. Stasi_Offiziere_leugnen_den_Terror(subscription required)

- ^ Backmann, Christa (25 March 2006). «Stasi-Anhänger schreiben an Bildungssenator Böger» [Stasi supporters write to Education Senator Böger]. Berliner Morgenpost. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ Schomaker, Gilbert. Die Welt, 26 March 2006. Ehemalige Stasi-Kader schreiben Schulen an

- ^ a b «I regret nothing, says Stasi spy». BBC. 20 September 1999.

- ^ Bernd-Rainer Barth; Jan Wielgohs. «Aris, Helmut * 11.5.1908, † 22.11.1987 Präsident des Verbandes der Jüdischen Gemeinden». Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur: Biographische Datenbanken. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ^ Lothar Mertens (2006). Lexikon der DDR-Historiker. Biographien und Bibliographien zu den Geschichtswissenschaftlern aus der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. K. G. Saur, München. p. 114. ISBN 3-598-11673-X.

- ^ «Mandatsentzug läßt Beck kalt: «Ich bin ein Schlachtroß»«. Rhein-Zeitung. 29 April 1999. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ «Neues Maueropfer». Die SED-Nachfolgepartei PDS nutzt den Freitod eines Genossen für den Versuch, die Stasi-Debatte abzuwürgen. Die SED-Nachfolgepartei PDS nutzt den Freitod eines Genossen für den Versuch, die Stasi-Debatte abzuwürgen. Vol. 9/1992. Der Spiegel (online). 24 February 1992.

- ^ «Perfektes Dopen mit der Stasi» [Perfect doping with the Stasi]. Tagesschau (in German). 3 August 2013.

- ^ February 11, 1992 New York Times article on Czudaj’s espionage involvement. — accessed 12 April 2008.

- ^ «H-Soz-u-Kult / Mielke, Macht und Meisterschaft». hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de.

- ^ Pleil, Ingolf (11 June 2018). «Was der Geheimdienst der DDR mit dem Sport zu tun hatte». Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten (in German). Hannover: Verlagsgesellschaft Madsack GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Jörg Winterfeldt (22 March 2000). «Mielkes Rächer unbestraft». Die Welt. welt.de. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ «Spying Who’s Who». BBC. 22 September 1999.

- ^ Uwe Müller (22 November 2009). «Das Stasi-Geheimnis der Hotelchefin Uta Felgner». WeltN24 GmbH, Berlin.

- ^ «Cottbus-Trainer Geyer horchte Kirsten und Sammer aus». Spiegel (in German). Hamburg: DER SPIEGEL GmbH & Co. KG. 27 August 2000. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ «Dynamo-Vereinslegenden treten als Ehrenspielführer zurück — wegen Ede Geyer». Spiegel (in German). Hamburg: DER SPIEGEL GmbH & Co. KG. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ I Was DEFA’s Goebbels. Die Zeit, 12 March 2003.

- ^ «Vaterlandsverräter». Film homepage. IT WORKS! Medien GmbH. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ Martin Sabrow: Das Diktat des Konsenses: Geschichtswissenschaft in der DDR 1949–1969. Oldenbourg, München 2001, ISBN 3-486-56559-1, pp. 172-173.

- ^ Strafjustiz und DDR-Unrecht: Dokumentation (in German). Klaus Marxen, Gerhard Werle (eds.). Berlin; New York: De Gruyter. 2000. pp. 19–20. ISBN 3110161346.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rogalla, Thomas. «Eine Stasi-Debatte, die nicht beendet wurde». Berliner Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Müller, Uwe (25 September 2007). «DDR: Birthler-Behörde ließ Stasi-Spitzel einladen — WELT». DIE WELT. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ «Heinz Kahlau ist tot». Dichter und Drehbuchautor …. Er zählte zu den bekanntesten Lyrikern der DDR: Heinz Kahlau ist im Alter von 81 Jahren an Herzschwäche gestorben. Berühmt wurde der Autor unter anderem durch seine Liebesgedichte — doch er verfasste auch kritische Verse. Der Spiegel (online). 9 April 2012.

- ^ Bernd-Rainer Barth. «Kamnitzer, Heinz * 10.5.1917, † 21.5.2001 Präsident des PEN-Zentrums DDR». Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur: Biographische Datenbanken. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ «Olympiakos soccer chief was ‘spy for Stasi’«. The Independent. 24 February 2002. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022.

- ^ «Socrates Kokkalis and the STASI». cryptome.org.

- ^ «Stasi spy claims hit Greek magnate». BBC News. 20 February 2002.

- ^ Helmut Müller-Enbergs. «Luft, Christa geb. geb. Hecht * 22.02.1938 Stellv. Vorsitzende des Ministerrats u. Ministerin für Wirtschaft». Wer war wer in der DDR?. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin & Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ «Biography: Lothar de Maizière — Biographies — Chronik der Wende». www.chronikderwende.de. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ «Stellungnahme Homepage» [Opinion Homepage] (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ^ «Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung».

- ^ «Respected lecturer’s double life». BBC News. 20 September 1999.

- ^ «Wie ein Jenaer Stasi-Spitzel Menschen verriet, die ihm eigentlich vertrauen» (in German). Thueringer Allgemeine. 27 October 2014.

- ^ Reyburn, Scott (26 January 2009). «Former Stasi Agent Bernd Runge Gets Phillips Top Job (Update1)». Bloomberg.

- ^ «The Schlaff Saga / Laundered funds & ‘business’ ties to the Stasi». Haaretz. 7 September 2010.

- ^ Palmer, Carolyn (25 March 2008). «E.German Stasi informant wins battle to conceal past». Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ «Court Decision Paves Olympics Way for Stasi-linked Coach — Germany — DW — 06.02.2006». Deutsche Welle.

- ^ Klaus Schroeder (16 July 1999). «Projektgruppe moralische Entsorgung: Linke Gesinnungswächter denunzieren die Gauck-Behörde». Frankfurter Allgemeine (Feuilleton section).

- ^ Christa Wolf obituary, The Telegraph, 2 December 2011.

General bibliography[edit]

- Blumenau, Bernhard. «Unholy Alliance: The Connection between the East German Stasi and the Right-Wing Terrorist Odfried Hepp». Studies in Conflict & Terrorism (2 May 2018): 1–22. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2018.1471969.

- Gary Bruce: The Firm: The Inside Story of Stasi, The Oxford Oral History Series; Oxford University Press, Oxford 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-539205-0.

- De La Motte and John Green, Stasi State or Socialist Paradise? The German Democratic Republic and What became of it, Artery Publications. 2015.

- Funder, Anna (2003). Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall. London: Granta. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-86207-655-6. OCLC 55891480.

- Fulbrook, Mary (2005). The People’s State: East German Society from Hitler to Honecker. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-14424-6.

- Gieseke, Jens (2014). The History of the Stasi: East Germany’s Secret Police 1945–1990. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-254-6. Translation of 2001 book.

- Harding, Luke (2011). Mafia State. London: Guardian Books. ISBN 978-0-85265-247-3.

- Koehler, John O. (2000). Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-3744-9.

- Macrakis, Kristie (2008). Seduced by Secrets: Inside the Stasi’s Spy-Tech World. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88747-2.

- Pickard, Ralph (2007). STASI Decorations and Memorabilia, A Collector’s Guide. Frontline Historical Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9797199-0-5.

- Pickard, Ralph (2012). Stasi Decorations and Memorabilia Volume II. Frontline Historical Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9797199-2-9.

External links[edit]

- Germany’s Records of Repression on YouTube on Al Jazeera English

- Knabe, Hubertus (2014). «The dark secrets of a surveillance state». TED Salon. Berlin.

- Stasi Mediathek Behörde des Bundesbeauftragten für die Stasi-Unterlagen Archive with records from the Stasi Records Agency (in German)

- Witness account by a former political prisoner in the Stasi Prison system.

For other uses, see Stasis.

| Ministerium für Staatssicherheit | |

Seal |

|

Stasi Museum in East Berlin |

|

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 8 February 1950 |

| Dissolved | 13 January 1990[1] |

| Type | Secret police |

| Headquarters | Lichtenberg, East Berlin |

| Motto | Schild und Schwert der Partei |

| Employees |

|

| Agency executives |

|

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the Stasi (German: [ˈʃtaːziː] (listen)),[n 1] was the state security service of East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi’s function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maintaining state authority, i.e., the «Sword and Shield of the Party» (Schild und Schwert der Partei). This was accomplished primarily through the use of a network of civilian informants. This organization contributed to the arrest of approximately 250,000 people in East Germany.[3] The Stasi also conducted espionage and other clandestine operations abroad through its subordinate foreign intelligence service, the Office of Reconnaissance, or Head Office A (German: Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung). They also maintained contacts and occasionally cooperated with West German terrorists.[4]

The Stasi was headquartered in East Berlin, with an extensive complex in Berlin-Lichtenberg and several smaller facilities throughout the city. Erich Mielke was the Stasi’s longest-serving chief, in power for 32 of the 40 years of the GDR’s existence. The HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung), under Markus Wolf, gained a reputation as one of the most effective intelligence agencies of the Cold War.[5]

After German reunification, numerous officials were prosecuted for their crimes and the surveillance files that the Stasi had maintained on millions of East Germans were unclassified so that all citizens could inspect their personal file on request. The files were maintained by the Stasi Records Agency until June 2021, when they became part of the German Federal Archives.

Creation[edit]

The Stasi was founded on 8 February 1950.[6] Wilhelm Zaisser was the first Minister of State Security of the GDR, and Erich Mielke was his deputy. Zaisser tried to depose SED General Secretary Walter Ulbricht after the June 1953 uprising,[7] but was instead removed by Ulbricht and replaced with Ernst Wollweber thereafter. Following the June 1953 uprising, the Politbüro decided to downgrade the apparatus to a State Secretariat and incorporate it under the Ministry of the Interior under the leadership of Willi Stoph. The Minister of State Security simultaneously became a State Secretary of State Security. The Stasi held this status until November 1955, when it was restored to a ministry.[8][9] Wollweber resigned in 1957 after clashes with Ulbricht and Erich Honecker, and was succeeded by his deputy, Erich Mielke.

In 1957, Markus Wolf became head of the Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung (HVA) (Main Reconnaissance Administration), the foreign intelligence section of the Stasi. As intelligence chief, Wolf achieved great success in penetrating the government, political and business circles of West Germany with spies. The most influential case was that of Günter Guillaume, which led to the downfall of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt in May 1974. In 1986, Wolf retired and was succeeded by Werner Grossmann.

Relationship with Soviet Intelligence Services[edit]

Although Mielke’s Stasi was superficially granted independence in 1957, the KGB continued to maintain liaison officers in all eight main Stasi directorates at the Stasi headquarters and in each of the fifteen district headquarters around the GDR. The Stasi had also been invited by the KGB to establish operational bases in Moscow and Leningrad to monitor visiting East German tourists. Due to their close ties with Soviet intelligence services, Mielke referred to the Stasi officers as «Chekists». In 1978, Mielke formally granted KGB officers in East Germany the same rights and powers that they enjoyed in the Soviet Union.[10]

Operations[edit]

Personnel and recruitment[edit]

Between 1950 and 1989, the Stasi employed a total of 274,000 people in an effort to root out the class enemy.[11][12][13] In 1989, the Stasi employed 91,015 people full-time, including 2,000 fully employed unofficial collaborators, 13,073 soldiers and 2,232 officers of GDR army,[14] along with 173,081 unofficial informants inside GDR[15] and 1,553 informants in West Germany.[16]

Regular commissioned Stasi officers were recruited from conscripts who had been honourably discharged from their 18 months’ compulsory military service, had been members of the SED, had had a high level of participation in the Party’s youth wing’s activities and had been Stasi informers during their service in the Military. The candidates would then have to be recommended by their military unit political officers and Stasi agents, the local chiefs of the District (Bezirk) Stasi and Volkspolizei office, of the district in which they were permanently resident, and the District Secretary of the SED. These candidates were then made to sit through several tests and exams, which identified their intellectual capacity to be an officer, and their political reliability. University graduates who had completed their military service did not need to take these tests and exams. They then attended a two-year officer training programme at the Stasi college (Hochschule) in Potsdam. Less mentally and academically endowed candidates were made ordinary technicians and attended a one-year technology-intensive course for non-commissioned officers.

By 1995, some 174,000 inoffizielle Mitarbeiter (IMs) Stasi informants had been identified, almost 2.5% of East Germany’s population between the ages of 18 and 60.[11] 10,000 IMs were under 18 years of age.[11] From the volume of material destroyed in the final days of the regime, the office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records (BStU) believes that there could have been as many as 500,000 informers.[11] A former Stasi colonel who served in the counterintelligence directorate estimated that the figure could be as high as 2 million if occasional informants were included.[11] There is significant debate about how many IMs were actually employed.

Infiltration[edit]

The main entrance to the Stasi headquarters in Berlin

Full-time officers were posted to all major industrial plants (the extent of any surveillance largely depended on how valuable a product was to the economy)[12] and one tenant in every apartment building was designated as a watchdog reporting to an area representative of the Volkspolizei (Vopo). Spies reported every relative or friend who stayed the night at another’s apartment. Tiny holes were drilled in apartment and hotel room walls through which Stasi agents filmed citizens with special video cameras. Schools, universities, and hospitals were extensively infiltrated,[17] as were organizations, such as computer clubs where teenagers exchanged Western video games.[18]

The Stasi had formal categorizations of each type of informant, and had official guidelines on how to extract information from, and control, those with whom they came into contact.[19] The roles of informants ranged from those already in some way involved in state security (such as the police and the armed services) to those in the dissident movements (such as in the arts and the Protestant Church).[20] Information gathered about the latter groups was frequently used to divide or discredit members.[21] Informants were made to feel important, given material or social incentives, and were imbued with a sense of adventure, and only around 7.7%, according to official figures, were coerced into cooperating. A significant proportion of those informing were members of the SED. Use of some form of blackmail was not uncommon.[20] A large number of Stasi informants were tram conductors, janitors, doctors, nurses and teachers. Mielke believed that the best informants were those whose jobs entailed frequent contact with the public.[22]

The Stasi’s ranks swelled considerably after Eastern Bloc countries signed the 1975 Helsinki accords, which GDR leader Erich Honecker viewed as a grave threat to his regime because they contained language binding signatories to respect «human and basic rights, including freedom of thought, conscience, religion, and conviction».[23] The number of IMs peaked at around 180,000 in that year, having slowly risen from 20,000 to 30,000 in the early 1950s, and reaching 100,000 for the first time in 1968, in response to Ostpolitik and protests worldwide.[24] The Stasi also acted as a proxy for KGB to conduct activities in other Eastern Bloc countries, such as Poland, where the Soviets were despised.[25]

The Stasi infiltrated almost every aspect of GDR life. In the mid-1980s, a network of IMs began growing in both German states. By the time that East Germany collapsed in 1989, the Stasi employed 91,015 employees and 173,081 informants.[26] About one out of every 63 East Germans collaborated with the Stasi. By at least one estimate, the Stasi maintained greater surveillance over its own people than any secret police force in history.[27] The Stasi employed one secret policeman for every 166 East Germans. By comparison, the Gestapo deployed one secret policeman per 2,000 people. As ubiquitous as this was, the ratios swelled when informers were factored in: counting part-time informers, the Stasi had one agent per 6.5 people. This comparison led Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal to call the Stasi even more oppressive than the Gestapo.[28] Stasi agents infiltrated and undermined West Germany’s government and spy agencies.[citation needed]

In some cases, spouses even spied on each other. A high-profile example of this was peace activist Vera Lengsfeld, whose husband, Knud Wollenberger, was a Stasi informant.[22]

Zersetzung (Decomposition)[edit]

The Stasi perfected the technique of psychological harassment of perceived enemies known as Zersetzung (pronounced [ʦɛɐ̯ˈzɛtsʊŋ]) – a term borrowed from chemistry which literally means «decomposition».

…the Stasi often used a method which was really diabolic. It was called Zersetzung, and it’s described in another guideline. The word is difficult to translate because it means originally «biodegradation». But actually, it’s a quite accurate description. The goal was to destroy secretly the self-confidence of people, for example by damaging their reputation, by organizing failures in their work, and by destroying their personal relationships. Considering this, East Germany was a very modern dictatorship. The Stasi didn’t try to arrest every dissident. It preferred to paralyze them, and it could do so because it had access to so much personal information and to so many institutions.

—Hubertus Knabe, German historian[29]

By the 1970s, the Stasi had decided that the methods of overt persecution that had been employed up to that time, such as arrest and torture, were too crude and obvious. Such forms of oppression were drawing significant international condemnation. It was realised that psychological harassment was far less likely to be recognised for what it was, so its victims, and their supporters, were less likely to be provoked into active resistance, given that they would often not be aware of the source of their problems, or even its exact nature. International condemnation could also be avoided. Zersetzung was designed to side-track and «switch off» perceived enemies so that they would lose the will to continue any «inappropriate» activities.[n 2] Anyone who was judged to display politically, culturally, or religiously incorrect attitudes could be viewed as a «hostile-negative»[30] force and targeted with Zersetzung methods. For this reason members of the Church, writers, artists, and members of youth sub-cultures were often the victims. Zersetzung methods were applied and further developed in a «creative and differentiated»[31] manner based upon the specific person being targeted i.e. they were tailored based upon the target’s psychology and life situation.[32]

Tactics employed under Zersetzung usually involved the disruption of the victim’s private or family life. This often included psychological attacks, such as breaking into their home and subtly manipulating the contents, in a form of gaslighting i.e. moving furniture around, altering the timing of an alarm, removing pictures from walls, or replacing one variety of tea with another etc. Other practices included property damage, sabotage of cars, travel bans, career sabotage, administering purposely incorrect medical treatment, smear campaigns which could include sending falsified, compromising photos or documents to the victim’s family, denunciation, provocation, psychological warfare, psychological subversion, wiretapping, bugging, mysterious phone calls or unnecessary deliveries, even including sending a vibrator to a target’s wife. Increasing degrees of unemployment and social isolation could and frequently did occur due to the negative psychological, physical, and social ramifications of being targeted.[33] Usually, victims had no idea that the Stasi were responsible. Many thought that they were losing their minds, and mental breakdowns and suicide were sometimes the result. There is on-going debate as to the extent, if at all, that weaponised directed energy devices, such as X-ray transmitters, were also used against victims.[34]

One great advantage of the harassment perpetrated under Zersetzung was that its relatively subtle nature meant that it was able to be plausibly denied, including in diplomatic circles. This was important given that the GDR was trying to improve its international standing during the 1970s and 80s, especially in conjunction with the Ostpolitik of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt massively improving relations between the two German states. For these political and operational reasons Zersetzung became the primary method of repression in the GDR.[n 3]

International operations[edit]

After German reunification, revelations of the Stasi’s international activities were publicized, such as its military training of the West German Red Army Faction.[35]

Examples[edit]

- Stasi experts helped train the secret police organization of Mengistu Haile Mariam in Ethiopia.[36][37]

- Fidel Castro’s regime in Cuba was particularly interested in receiving training from the Stasi. Stasi instructors worked in Cuba and Cuban communists received training in East Germany.[38] Stasi chief Markus Wolf described how he modelled the Cuban system based on the East German one.[39]

- Stasi officers helped in initial training and indoctrination of Egyptian State Security organizations under the Nasser regime from 1957 to 58 onwards. This was discontinued by Anwar Sadat in 1976.

- The Stasi’s experts worked to help create secret police forces in the People’s Republic of Angola, the People’s Republic of Mozambique, and the People’s Republic of Yemen (South Yemen).[37]

- The Stasi organized and extensively trained Syrian intelligence services under the regime of Hafez al-Assad and Ba’ath Party from 1966 onwards and especially from 1973.[40]

- Stasi experts helped to set up Idi Amin’s secret police.[37][41]

- Stasi experts helped the President of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, to set up his secret police. When Nkrumah was ousted by a military coup, Stasi Major Jürgen Rogalla was imprisoned.[37][42]