Англо-русский перевод SCANIA

Сконе

American English-Russian dictionary.

Американский Англо-Русский словарь.

2012

1

Scania

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > Scania

2

Scania Buses and Coaches

«Городские и туристические автобусы Scania» (подразделение фирмы «Scania»)

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > Scania Buses and Coaches

3

Scania Driving Academy

авто

курсы по повышению водительского мастерства; консультационный центр по повышению профессионального мастерства водителей грузовиков и автобусов

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > Scania Driving Academy

4

Scania XPI

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > Scania XPI

5

Ecolution by Scania

авто

экологическая концепция фирмы «Scania»

Программа Ecolution by Scania означает появление новой линейки экологически ориентированных продуктов и услуг. Концепция этой программы включает оптимизацию технических характеристик транспортных средств, производство автомобилей, работающих на возобновляемых видах топлива, поддержку водителей, помощь в эффективном использовании транспортного парка, а также специальные программы технического обслуживания.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > Ecolution by Scania

6

commonality

[ˏkɒmə`nælɪtɪ]

1. общность (нужд и т.п.)

Extensive parts commonality facilitates servicing and repairs, and makes trucks with Scania Opticruise familiar to any Scania service technician. — Широкая унификация деталей упрощает проведение технического обслуживания и ремонта и делает грузовые автомобили с системой Scania Opticruise хорошо знакомыми для любого техника по обслуживанию Scania.

3.

дипл.

совпадение или общность (точек зрения)

We don’t have the same commonality of interest …

4.

книжн.

простой люд, простонародье

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > commonality

7

O/D

повышенная передача, ускоряющая передача

Scania Opticruise is available on Scania’s 8-, 12- and 12+2-speed gearboxes, the latter also with overdrive. — Система Scania Opticruise поставляется с 8-, 12- и 12+2-ступенчатыми коробками передач Scania, причем последняя также может быть с ускоряющей передачей.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > O/D

8

overdrive

повышенная передача, ускоряющая передача

Scania Opticruise is available on Scania’s 8-, 12- and 12+2-speed gearboxes, the latter also with overdrive. — Система Scania Opticruise поставляется с 8-, 12- и 12+2-ступенчатыми коробками передач Scania, причем последняя также может быть с ускоряющей передачей.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > overdrive

9

show stopper

1) песня, танец и пр., вызывающие бурные или продолжительные аплодисменты

2) исполнитель, вызывающий восторг публики

3) что-либо удивляющее или очень популярное

Новенький Scania Red Pearl R999 в ходе выставки стал шоу стоппером фирменного стенда «Scania». — The new Scania Red Pearl R999 during the exhibition became a show-stopper of the firm stand «Scania».

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > show stopper

10

show-stopper

1) песня, танец и пр., вызывающие бурные или продолжительные аплодисменты

2) исполнитель, вызывающий восторг публики

3) что-либо удивляющее или очень популярное

Новенький Scania Red Pearl R999 в ходе выставки стал шоу стоппером фирменного стенда «Scania». — The new Scania Red Pearl R999 during the exhibition became a show-stopper of the firm stand «Scania».

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > show-stopper

11

showstopper

1) песня, танец и пр., вызывающие бурные или продолжительные аплодисменты

2) исполнитель, вызывающий восторг публики

3) что-либо удивляющее или очень популярное

Новенький Scania Red Pearl R999 в ходе выставки стал шоу стоппером фирменного стенда «Scania». — The new Scania Red Pearl R999 during the exhibition became a show-stopper of the firm stand «Scania».

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > showstopper

12

close to

близко к

The picture looks very different when you see it close to.

поблизости от

около, почти

Since it was originally unveiled in 1994, close to 150,000 trucks and buses worldwide have been delivered with Scania Opticruise — С момента первого представления в 1994 году во всем мире было произведено около 150.000 грузовиков и автобусов с системой Scania Opticruise

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > close to

13

door storage bin

карман на внутренней поверхности двери для хранения различных вещей

Door storage bins, each with two big bottle holders, optionally with leather armrest and leatherette door panel with embossed Scania Griffin. — Карманы на внутренней поверхности двери для хранения различных вещей с двумя подставками для больших бутылок, а также, по желанию заказчика, кожаный подлокотник и панель двери из искусственной кожи с рельефным изображением эмблемы Scania — головы грифона.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > door storage bin

14

downhill speed

скорость автомобиля на спусках

The Scania Retarder was introduced in 1993, becoming the first auxiliary braking system with automated downhill speed control and with the retarder function integrated in the brake pedal. — Ретардер Scania был впервые представлен в 1993 году, став первой вспомогательной тормозной системой в своем классе с автоматическим управлением скоростью автомобиля на спусках и с функцией ретардера, встроенной в педаль тормоза.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > downhill speed

15

long-haul truck

магистральный грузовик

магистральный тягач

тягач для перевозок на дальние расстояния

This newcomer aims to give Scania a leading position in the world market for construction vehicles, a position Scania currently enjoys for its long-haul trucks.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > long-haul truck

16

extra pressure injection

extra-high pressure injection (

сокр.

XPI)

«впрыск (топлива) под сверхвысоким давлением»

син.

Common Rail

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > extra pressure injection

17

extra-high pressure injection

extra-high pressure injection (

сокр.

XPI)

«впрыск (топлива) под сверхвысоким давлением»

син.

Common Rail

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > extra-high pressure injection

18

heavy construction duties

тяжелая строительная работа

A truck specially designed for heavy construction duties is the latest addition to Scania’s new truck generation.

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > heavy construction duties

19

Lane Guard System

Lane Guard System (LGS)

система безопасного движения по узкой дороге

система слежения за дорожной разметкой

система контроля за разметкой

|| Ответом производителей стала система слежения за дорожной разметкой LGS (Lane Guard System), система предупреждения о нарушении ряда или об уходе с занимаемой полосы. У разных производителей она называется по-своему, но принцип ее работы от этого не меняется. Например, у MAN это LGS, у Mercedes-Benz – Telligent, у Scania – LDW, у DAF Trucks – LDWA, у других производителей – LA (Lane Assist).

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > Lane Guard System

20

LGS

Lane Guard System (LGS)

система безопасного движения по узкой дороге

система слежения за дорожной разметкой

система контроля за разметкой

|| Ответом производителей стала система слежения за дорожной разметкой LGS (Lane Guard System), система предупреждения о нарушении ряда или об уходе с занимаемой полосы. У разных производителей она называется по-своему, но принцип ее работы от этого не меняется. Например, у MAN это LGS, у Mercedes-Benz – Telligent, у Scania – LDW, у DAF Trucks – LDWA, у других производителей – LA (Lane Assist).

Англо-русский универсальный дополнительный практический переводческий словарь И. Мостицкого > LGS

скания

скания (Сконеланд; ; ; ; ) — исторический регион на юге Швеции, состоящий из трёх бывших датских провинций Сконе, Халланда и Блекинге, приблизительно совпадающих с тремя современными ленами: Сконе, Халланд и Блекинге.

скания

(Scania) – марка автомобиля, Швеция.

скания

исторический регион на юге Швеции

И «татра», и сверкающая хромированными дугами на радиаторной решетке «скания» громко сигналили.

Рванувшись к краю дороги, «скания» поднялась по склону футов на пятнадцать и рухнула вниз, завалившись набок.

Сжав руку в кулак, капрал пробил в нем дыру как раз вовремя, чтобы заметить, что «скания» летит прямо в образованную взрывом воронку.

Вглядываясь сквозь покрытое дождевыми каплями стекло, майор Джон Уитерби заметил, как внизу проехали два грузовика «скания».

Многотонный грузовик «скания» мчался, как ей казалось, прямо на нее; металлическая цистерна сверкала под лучами солнца.

Его огромная «скания» неслась по шоссе в сторону Гате.

скания морского дна, с одной стороны, и роста кораллов, с другой.

Скания — исторический регион на юге Швеции , состоящий из трёх бывших датских провинций Сконе , Халланда и Блекинге , приблизительно совпадающих с тремя современными ленами : Сконе , Халланд и Блекинге . До 1658 года входила в состав Дании под названием Восточных провинций. Остров Борнхольм , тогда же отошедший к Швеции, но позднее возвращённый Дании, также иногда включается в состав Скании.

В языковом отношении Скания заметно отличается от остальной Швеции, так как в ней говорят на сканском наречии , более близком к датскому языку , чем к шведскому .

Англо-русский перевод SCANIA

Сконе

American English-Russian dictionary.

Американский Англо-Русский словарь.

2012

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

Ска́—ни·я

Существительное, неодушевлённое, женский род, 1-е склонение (тип склонения 7a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -Сканиj-; окончание: -я.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [ˈskanʲɪɪ̯ə]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- исторический регион на юге Швеции ◆ СКОНЕ Сконе, или Скания, — самый южный район Швеции, граничащий с соседней Данией. Жители Сконе, так же как датчане, любят хорошо поесть и хорошо выпить. Они словоохотливы и говорят с местным акцентом, который … Jean-Paul Labourdette, «Швеция», 2005 г.

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

|

|

Scania’s headquarters in Södertälje |

|

| Formerly | AB Scania-Vabis |

|---|---|

| Type | Subsidiary (Aktiebolag) |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Predecessors |

|

| Founded | 1911; 112 years ago |

| Headquarters |

Södertälje , Sweden |

|

Number of locations |

10 |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

| Services | Financial services |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

|

| Parent | Traton |

| Website | www.scania.com |

Scania AB is a major Swedish manufacturer headquartered in Södertälje, focusing on commercial vehicles—specifically heavy lorries, trucks and buses. It also manufactures diesel engines for heavy vehicles as well as marine and general industrial applications.

Scania was formed in 1911 through the merger of Södertälje-based Vabis and Malmö-based Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania. Since 1912, the company has been re-located again to Södertälje after the merger. Today, Scania has production facilities in Sweden, France, the Netherlands, Thailand, China, India, Argentina, Brazil, Poland, Russia and Finland.[3] In addition, there are assembly plants in ten countries in Africa, Asia and Europe. Scania’s sales and service organisation and finance companies are worldwide. In 2012, the company employed approximately 42,100 people around the world.[3]

Scania was listed on the NASDAQ OMX Stockholm stock exchange from 1996 to 2014.[4][5] The company is a subsidiary of Traton, part of the Volkswagen Group.

Scania’s logo shows a griffin, from the coat of arms of the province of Scania (Swedish: Skåne).[6]

History[edit]

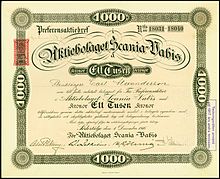

Scania-Vabis share, issued 1916

A vintage Scania truck (L80 successor to the Scania-Vabis L56)

Vabis and Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania[edit]

AB Scania-Vabis was established in 1911 as the result of a merger between Södertälje-based Vabis and Malmö-based Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania. Vagnfabriks Aktiebolaget i Södertelge (Vabis) was established as a railway car manufacturer in 1891, while Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania was established as a bicycle manufacturer in 1900. Both companies had tried their luck at building automobiles, trucks and engines, but with varied success. In 1910, Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania had succeeded in constructing reliable vehicles, while Vabis was at the brink of closing down. An offer from Per Alfred Nordeman, managing director of Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania, to steel manufacturer Surahammars Bruk, owner of Vabis, led to an agreement in November 1910, and in 1911 the merger was a reality.

Development and production of engines and light vehicles were set to Södertälje, while trucks were manufactured in Malmö. The company’s logo was redesigned from Maskinfabriks-aktiebolaget Scania’s original logo with the head of a griffin, the coat of arms of the Swedish region Scania (Skåne), centered on a three-spoke bicycle chainset. Initially the headquarters were located in Malmö, but in 1912 they were moved to Södertälje.[7][8]

First World War and 1920s[edit]

Because there were many inexpensive, imported cars in Sweden at the time, Scania-Vabis decided to build high-class, luxury cars, for instance the type III limousine from 1920 that had a top hat holder in the roof. Prince Carl of Sweden owned a 1913 Scania-Vabis 3S, a type which was fitted with in-car buttons so the passenger could communicate with the driver. Scania-Vabis also built two-seat sports cars (or «sportautomobil»).[9]

For the next few years the company’s profits stagnated, with around a third of their orders coming from abroad.[7] The outbreak of the First World War, however, changed the company, with almost all output being diverted to the Swedish Army. By 1916, Scania-Vabis was making enough profit to invest in redeveloping both of their production facilities.[7]

Following the war, in 1919, Scania decided to focus completely on building trucks, abandoning other outputs including cars and buses.[7] However, they were hurt by the swamping of the market with decommissioned military vehicles from the war, and by 1921 the company was bankrupt.[6]

After some economic difficulties in 1921, new capital came from Stockholms Enskilda Bank owned by the Wallenberg family, and Scania-Vabis became a solid and technically, high standing, company.

- Denmark

Towards the end of 1913, the company established a subsidiary in Denmark. The following year the first Danish-built car, a four-seater Phaeton, was built at the company’s Frederiksberg factory in Copenhagen. In 1914, the factory produced Denmark’s first Scania-Vabis truck, and following this developed a V8 engine, one of the first in the world. In 1921, having sold around 175 trucks, and 75 cars, the Danish operation was closed down.[6]

- Norway

In 1917 an agreement was established with the newly formed Norwegian company Norsk Automobilfabrik A/S about production under license of Scania-Vabis cars and lorries. Production began in 1919, but was ended in 1921 after production of only 77 lorries, mostly built from Swedish produced parts.

1930s and 1940s[edit]

During the Second World War Scania produced a variety of military vehicles for the Swedish Army, including Stridsvagn m/41 light tanks produced under licence.[6]

1950s and 1960s[edit]

During the 1950s, the company expanded its operations into new customer segments, becoming agents for the Willys Jeep and the Volkswagen Beetle, the latter being very profitable for Scania-Vabis. It also started to become a genuine competitor to Volvo with their new L71 Regent truck which was introduced in 1954.[10]

During this period, Scania-Vabis expanded its dealer network and country-wide specialist workshop facilities. By the end of the 1950s, their market-share in Sweden was between 40 and 50%, and was achieving 70% in the heaviest truck sector – helped by the entrepreneurial efforts of their dealers into the haulier market.[10]

Probably their largest impact was in export markets. Before 1950, exports accounted for only 10 percent of production output, but a decade later, exports were now at 50% of output. Beers in the Netherlands became a very important partner. Beers became official importers for Scania-Vabis in the Netherlands, and established a dealer network, along with training programmes for both mechanics and drivers. Beers also offered free twice-yearly overhauls of their customers vehicles, and offered a mobile service throughout the Netherlands with their custom-equipped service trucks. Due to Beers concerted efforts, Scania-Vabis market share in the country remained at a consistent 20% throughout this period. Scania-Vabis were to adopt the business model of Beers in their own overseas sales operations.[10]

The 1960s saw Scania-Vabis expanding its production operations into overseas locations. Until now, all Scania-Vabis production had been carried out solely at Södertälje, but the 1960s saw the need to expand production overseas. Brazil was becoming a notable market for heavy trucks, and was also dependent on inter-urban buses, with particular requirement for Brazil’s mountainous roads which became nigh-on impassable at times.[11] On 2 July 1957, Brazilian subsidiary Scania-Vabis do Brasil S.A. (today known as Scania Latin America Ltda.) was established and started assembling some vehicles themselves in 1958. On 29 May 1959, a new engine plant was inaugurated in the Ipiranga district of São Paulo, and from June 1960, Scania-Vabis do Brasil assembled all vehicles themselves.[12] Scania-Vabis vehicles had already been assembled in Brazil by a local company called Vemag (Veículos e Máquinas Agrícolas S.A.) for several years.[13] Scania-Vabis established its first full manufacturing plant outside Södertälje, by building a new facility in São Bernardo do Campo near São Paulo, which was opened on 8 December 1962, and this was to set the standard for Scania-Vabis international operations.[11][12]

Closer to home, the recently formed European Economic Community (EEC) offered further opportunities. Based on their now strong presence in the Dutch markets, Scania-Vabis constructed a new plant in Zwolle, which was completed in 1964.[11] This new Dutch facility provided Scania-Vabis with a stepping stone into the other five EEC countries, particularly the German and French markets.[11]

In 1966, Scania-Vabis acquired ownership of a then valuable supplier – Be-Ge Karosserifabrik, who were based in Oskarshamn. Be-Ge had been making truck cabs since 1946, and had been supplying cabs not only to Scania-Vabis, but also to their Swedish competitors Volvo. It was normal practice for truck manufacturers to outsource production of cabs to independent bodybuilders, so their acquisition by Scania-Vabis seemed a good move.[11] Be-Ge owner Bror Göthe Persson had also established an additional cab factory at Meppel.[11]

Scania-Vabis continued their expansion of production facilities through acquisitions. In 1967, they acquired Katrineholm based coachwork company Svenska Karosseri Verkstäderna (SKV), and created a new subsidiary, Scania-Bussar. A year later, all bus production, along with R&D was moved to Katrineholm.[11] Further production locations were added at Sibbhult and Falun, and Scania’s employee numbers rose, particularly at Södertälje, which was to help double the town’s population.[11]

Scania-Vabis at some point in their history also manufactured trucks in Botswana, Brazil, South-Korea, Tanzania, the Netherlands, Zimbabwe and the United States.

For some time Daimler-Benz waged a ‘logo war’ with Scania-Vabis, claiming a possible confusion between the Scania-Vabis ‘pedal crank’ design featuring on Scania bicycles around 1900 and the Mercedes ‘three-pointed star’.[citation needed] In 1968, Daimler-Benz won and the Scania-Vabis logo changed to a simple griffin’s head on a white background.

In February 1968, a new range of trucks was launched, and at the same time the company was rebranded as just Scania. In addition to Vabis disappearing from the name and a new logo, all current models received new model designations.[14][15]

1970s and 1980s[edit]

In 1976, the Argentinian industrial complex was launched. A few months later, on 10 September, the first gearbox outside of Sweden was manufactured and finally in December an L111[16] truck became the first Scania made in Argentina. Soon the plant specialised in the production of gearboxes, axles and differentials that equipped both the units produced in Tucumán and those built in Brazil.[17]

Also in Argentina, in 1982 the Series 2 was launched as part of the «Scania Program», consisting of the T-112[18] and R-112[19] trucks with two cab versions and different options in engine and load capacity. In 1983, was launched the K112[20] made in Tucuman (like the rest models) for replace the BR-116.[21]

In mid-1985 Scania entered the US market for the first time (aside from having sold 12,000 diesel engines installed in Mack trucks from 1962 until 1975), starting modestly with a goal of 200 trucks in all of 1987 (121 trucks were sold during calendar year 1986[22]). Scania limited their marketing to New England, where conditions resemble those in Europe more closely.[23]

Many examples of Scania, Vabis and Scania-Vabis commercial and military vehicles can be seen at the Marcus Wallenberg-hallen (the Scania Museum) in Södertälje.

Ownership[edit]

Saab-Scania AB (1969–1995)[edit]

On 1 September 1969, Scania merged with Saab AB, and formed Saab-Scania AB.[14] When Saab-Scania was split in 1995, the name of the truck and bus division changed simply to Scania AB. One year later, Scania AB was introduced on the stock exchange, which resulted in a minor change of name to Scania AB (publ).

Aborted Volvo takeover[edit]

On 7 August 1999, Volvo announced it had agreed to acquire a majority share in Scania. Volvo was to buy the 49.3% stake in Scania that was owned by Investor AB, Scania’s then main shareholder. The acquisition, for US$7.5 billion (60.7 billion SEK), would have created the world’s second-largest manufacturer of heavy trucks, behind DaimlerChrysler. The cash for the deal was to come from the sale of Volvo’s car division to Ford Motor Company in January 1999.[24]

The merger failed, after the European Union disapproved, announcing one company would have almost 100% market share in the Nordic markets.[citation needed]

Aborted MAN takeover[edit]

In September 2006, the German truckmaker MAN AG launched a €10.3bn hostile offer to acquire Scania AB. Scania’s CEO Leif Östling was forced to apologise for comparing the bid of MAN to a «Blitzkrieg». MAN AG later dropped its hostile offer, but in January 2008, MAN increased their voting rights in Scania up to 17%.

Volkswagen Group era[edit]

Scania AB is 100% owned by the German automotive company Volkswagen Group, forming part of its heavy commercial vehicle subsidiary, Traton, along with MAN Truck & Bus, Volkswagen Caminhões e Ônibus and Navistar.

Volkswagen gained ownership of Scania by first buying Volvo’s stake in 2000, after the latter’s aborted takeover attempt, increasing it to 36.4% in the first quarter 2007.[25] It then bought out Investor AB in March 2008, raising its share to 70.94%.[26] The deal was approved by regulatory bodies in July 2008. Scania then became the ninth marque in the Volkswagen Group.[27] By 1 January 2015, Volkswagen controlled 100% of the shares in Scania AB.

Price-fixing fines[edit]

In September 2017, Scania was fined 880 million euros (8.45bn Swedish krona) by the EU for taking part in a 14-year price fixing cartel.[28] The other five members of the cartel – Daimler, DAF, MAN, Iveco and Volvo/Renault – settled with the commission in 2016.[29]

Products[edit]

Trucks and special vehicles[edit]

Scania R 730 LA4x2MNB with the 2009 facelift

Scania develops, manufactures and sells trucks with a gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) of more than 16 tonnes (Class 8), intended for long-distance haulage, regional, and local distribution of goods, as well as construction haulage.

The 1963 forward-control LB76 forged Scania-Vabis’s reputation outside Sweden, being one of the first exhaustively crash-tested truck cabs.

Current[edit]

All current trucks from Scania are part of the PRT-range, but are marketed as different series based on the general cab height.

- L-series – launched in December 2017. It has an even lower cab than the P-series, and is optimised for distribution and other short-haul duties.

- P-series – launched in August 2004, typical applications are regional and local distribution, construction, and various specialised operations associated with locally based transportation and services. P-series trucks have the new P cabs, which are available in several variations: a single-berth sleeper, a spacious day cab, a short cab and a crew cab

-

2021 Scania R450 «Heróis da estrada» («Highway Heros»)- A special edition celebrating 63 years of Scania in the Brazilian market

G-series – launched in September 2007, the series offer an enlarged range of options for operators engaged in national long haul and virtually all types of construction applications. All models have a G cab, and each is available as a tractor or rigid. The G-series truck comes with five cab variants: three sleepers, a day cab and a short cab. There are different axle configurations, and in most cases a choice of chassis height and suspension

- R-series – launched in March 2004, and won the prestigious International Truck of the Year award in 2005 and again in 2010.[30] The range offers various trucks optimised for long haulage. All models have a Scania R cab, and each vehicle is available as a tractor or rigid. There are different axle configurations and a choice of chassis height and suspension. The Scania R 730 is the most powerful variant of the R-series. Its 16.4-litre DC16 Turbo Diesel V8 engine produces 730 PS (540 kW; 720 hp) at 1,900 rpm and 3,500 N⋅m (2,600 lb⋅ft) of torque at 1,000–1,350 rpm.

- S-series – launched in August 2016. It is the highest cab Scania has ever built. It features a completely flat floor and a low bed that is extendable up to 100 cm (about 3.28 feet).

Historical[edit]

- CLb/CLc (1911–27)

- DLa (1911–26)

- ELa (1912–26)

- FLa (1911–24)

- GLa (1914–23)

- 314/324/325 (1925–36)

- 335/345/355 (1931–44)

- L10/F10/L40/F40/L51 Drabant (1944–59)

- L20/L60/L71 Regent (1946–58)

- L75/L76/LB76 (1958–68)

- L55/L56/L66 (1959–68)

- L36 (1964–68)

- 50, 80, 85, 110, 140 (1968–74)

- 81, 86, 111, 141 (1974–81)

- 2-series: 82, 92, 112, 142 (1980–88)

- 3-series: 93, 113, 143 (1987–97)

- 4-series: 94, 114, 124, 144, 164 (1995–2004)

- T-series (2004–05) – former part of the PRT-range

Buses and coaches[edit]

Scania’s bus and coach range has always been concentrated on chassis, intended for use with anything between tourist coaches to city traffic, but ever since the 1950s, when the company was still known as Scania-Vabis, they have manufactured complete buses for their home markets of Sweden and the rest of Scandinavia, and since the 1990s even for major parts of Europe.

Chassis[edit]

Scania-Vabis 3243 bus from 1927.

Scania-Vabis B15V bodied by Helko in Finland in 1949.

Scania-Vabis was involved in bus production from its earliest days, producing mail buses in the 1920s.

|

This section needs expansion with: pre WW2 models. You can help by adding to it. (March 2016) |

In 1946, the company introduced their B-series of bus chassis, with the engine mounted above the front-axle, giving a short front overhang and the door behind the front-axle. The first generation consisted of the B15/B16, the B20/B21/B22 and the B31, primarily divided by weight class, and then by wheelbase. The latter became upgraded in 1948 and renamed 2B20/2B21/2B22 and 3B31. The T31/T32 trolleybus chassis was also available from 1947. In 1950, the next generation was introduced, with the B41/B42, the B61/B62/B63/B64 and later the B83. From then, Scania-Vabis also offered the BF-series chassis, available as BF61/BF62/BF63, which had the engine more conventionally mounted before the front-axle, leaving room for the door on a longer front overhang. From 1954, the B-series came as B51 and B71, and the BF as BF71 and later BF73. In 1959, the B55, B65 and B75, plus the BF75 were introduced, and were from 1963 available as B56, B66 and B76, plus the BF56 and BF76.

Before the rebranding to Scania in 1968, Scania-Vabis had delivered a very limited number of CR76 chassis-frameworks (less actual bodywork) with transversally rear-mounted engine for external bodying, based on the complete bus with the same name. From 1968 it was also delivered as a standard bus chassis known as BR110.[31]

The other chassis models were renamed too, so the Scania-Vabis B56/B76 became the Scania B80/B110 and the BF56/BF76 became BF80/BF110. The numbers in the new model designations were based on the engine displacement (8 and 11-litre), a scheme that Scania used for almost 40 years.

In 1971, a new range of longitudinally mounted rear-engined chassis was launched, with the BR85 and its larger brother, the V8-powered 14-litre BR145, targeted at the coach market. In Brazil, the higher powered version was equipped with the standard 11-litre instead of the V8, known as the BR115. Also the BR111 was launched as the replacement for the BR110, being derived from the CR111 complete bus. In 1976, many of the models were renewed, and designations were upped from 80 and 85 to 86, and from 110 to 111, except the BR145 which was later replaced by the BR116 in 1978.

The BR112 was launched in 1978 as a forerunner to the 2-series, replacing the BR111. The rest of the 2-series were launched in 1981 with the F82/F112 replacing the BF86/BF111 and the S82/S112 replacing the B86/B111, and then in 1982 the K82/K112 replacing the BR86/BR116. The BR112 was then updated to the N112 in 1984, and a tri-axle version of the K112 became available, known as the K112T. In 1985, the K82 and F82 were replaced by the 8.5-litre engined K92 and F92. Front-engined versions were in general discontinued on the European markets in the mid-1980s, but production continued in Brazil.

In 1988, the 3-series was introduced, continuing the main models of the 2-series. In 1990, the new L113 became available, with a longitudinally rear-mounted engine which was inclined 60° to the left, to make a lower height than the K113. The 4-series was launched in 1997, continuing all model characteristics from the 3-series, but with all of them being just modular configurations of the basic chassis. The 8.5-litre engine was replaced by a 9-litre, and the 11-litre was replaced by an 11.7-litre. They were joined by a 10.6-litre engine in 2000.

The current Scania’s bus and coach range has been available since 2006, and is marketed as the K-series, N-series and F-series, based on the engine position.[32]

Current[edit]

- K series – rear-engined (longitudinal mounted) with Euro III – Euro VI compliant engines

- N series – rear-engined (transversal mounted) with Euro III – Euro VI compliant engines

- F series – front-engined with Euro III and Euro V compliant engines

Historical[edit]

- B55/B56/B65/B66/B75/B76/B80/B110

- BF56/BF75/BF76/BF80/BF110

- BR110

- BR85/BR115/BR145

- B86/B111

- BF86/BF111

- BR111

- BR86/BR116

- 2-series: BR112/N112, F82/F92/F112, K82/K92/K112, S82/S112

- 3-series: F93/F113, K93/K113, L113, N113, S113

- 4-series: F94, K94/K114/K124, L94, N94

Complete buses[edit]

Scania-Vabis Capitol (C75) from 1962.

Scania MaxCi (CN113CLL) in Russia.

Scania Touring HD in Poland.

A Scania Metrolink operated by the MSRTC in India.

Scania-Vabis’ first complete bus model was the transversally rear-engined commuter bus Metropol (C50), which was built in the workshop in Södertälje on licence from the Mack C50 in 1953–1954 for customer Stockholms Spårvägar. It was followed in 1955 by the slightly shorter city bus version Capitol (C70/C75/C76), which was manufactured until 1964. In 1959, the front-engined CF-series was introduced with the CF65 and CF75 (later CF66 and CF76). The CF-series was built until 1966.

In 1965, the rear-engined CR76 was introduced as a replacement for the Capitol. It was available in two versions; the CR76M with double doors (2-2-0) for city and suburban traffic, and the CR76L with single doors (1-1-0) for longer distances. Because of Sweden’s switch to right-hand traffic in September 1967 and the need for new buses with doors on the right-hand side, the model sold well. With the rebranding from Scania-Vabis to Scania in 1968, the model was renamed CR110 (CR110M and CR110L). In 1967, the coachwork manufacturer Svenska Karosseri Verkstäderna (SKV) in Katrineholm was acquired, and all production of bus chassis soon moved there too.[15] Together with the rebranding in 1968, Scania re-introduced the front-engined CF range for customers in Sweden as a body-on-chassis product with the newly acquired SKV’s former bodywork model «6000» on standard Scania chassis, but less than 100 were delivered until 1970. The CF110L (BF110 chassis) was the most successful, while a handful of C80L (B80) and C110L (B110) were made.[33]

In 1971, the CR110 was upgraded and became the CR111. With extended sound-proofing for its time, it was marketed as the «silent bus». The same year, Scania also introduced a new range of longitudally rear-engined coaches known as the CR85 and the CR145. While CR85 had the small 8-litre engine, the CR145 was powered by a 14-litre V8 engine. The coaches were built until 1978, but never sold very well. In 1973, one right-hand drive CR145 prototype was built in Sweden, with the finishing touches done by MCW, but it remained the only one of its kind.[34] The CR111 was replaced by the all-new CR112 in 1978. With its angular design, the CR112 was called a «shoebox». As with the BR112 chassis being renamed the N112, the CR112 was renamed the CN112 in 1984, and it was also launched in an articulated version. A North American version of the CN112 was built in around 250 units between 1984 and 1988. The CK112 was launched as a simple coach or intercity bus in 1986, sharing most of the styling with the CN112. With the launch of the 3-series in 1988, both the CN112 and CK112 were upgraded to CN113 and CK113. The CK113 was replaced by the L113-based CL113 in 1991 with new rectangular headlights, but production ended in 1992. Less than 100 units of the CK112/CK113/CL113 were ever built.

The MaxCi (CN113CLL), launched in 1992, was Scania’s first ever low-entry bus, with a low floor between the front and centre doors, and kneeling to make entering even easier. The bodywork was based on the CN113, but with a lowered window line in the front half, and a new front including the headlights from the CL113. In 1996, the aluminium body OmniCity was launched as Scania’s first full low-floor bus, and in 1998 the MaxCi was replaced by the OmniLink, which shared styling with the OmniCity. A step-entrance intercity bus returned with the OmniLine in 2000. In 2007, Scania returned to the complete coach market with the Finnish-built OmniExpress, which in 2011 even replaced the OmniLine, which had gone out of production in 2009.

Scania’s current styling was first seen in 2009, with the launch of the Touring coach, manufactured by Higer Bus in China, and in 2011 the Citywide was launched to replace both the OmniCity and the OmniLink. Scania in India launched their very own Metrolink coach in 2013, built at their plant there. The Interlink was then launched in October 2015 to replace the OmniExpress. The latest addition to Scania’s complete bus models is the Fencer range featuring buses to coaches, the F1 single decker bus was launched in May 2021 initially for the UK market and available in diesel and electric drivetrains.[35][36]

Current[edit]

- Citywide – low-floor and low-entry city bus range

- Fencer – low-floor urban, intercity and coach range

- Interlink – coach and intercity bus range

- Metrolink – coach for India

- Touring – premium coach, manufactured by Higer Bus

Historical[edit]

- Metropol (C50) – rear-engined step-entrance commuter bus

- Capitol (C70/C75/C76) – rear-engined step-entrance city bus

- CF65/CF75/CF66/CF76 – front-engined step-entrance city/intercity bus

- CR76/CR110/CR111 – rear-engined step-entrance city/intercity bus

- C80/C110/CF110 – front-engined step-entrance city/intercity bus

- CR85/CR145 – rear-engined coach

- CR112/CN112/CN113 – rear-engined step-entrance city/intercity bus (rigid/articulated)

- CK112/CK113/CL113 – rear-engined intercity bus

- MaxCi (CN113CLL) – low-entry city bus

- OmniCity – low-floor city bus (rigid/articulated/double-decker)

- OmniExpress – coach and intercity bus range

- OmniLink – low-entry city bus (rigid/articulated)

- OmniLine – intercity bus

Buses through collaborations[edit]

Preserved 1988 Scania Classic on K112 chassis in Norway, belonging to Telemark Bilruter.

In addition to supplying chassis for external bodywork, and their own bodyworks, Scania have also collaborated with some bodywork manufacturers to deliver buses through Scania’s distribution lines, both on a global base and on smaller markets.

In 1969, Scania teamed up with MCW to make the Metro-Scania single-decker for the UK market based on the BR110MH, and since 1971 the BR111MH chassis. In 1973, it was replaced by the Metropolitan double-decker, built on the BR111DH chassis. Production ended in 1978, when the BR111 was replaced by the BR112. East Lancashire Coachbuilders (ELC) launched their low-entry MaxCi in 1993, one year after Scania’s own left-hand drive version. It was followed by the L113-based European in 1995 until 1996. In 2003, ELC was back with both the OmniDekka double-decker and the OmniTown midibus to complement Scania’s own OmniCity.

Since the mid-1990s, Scania started a long-lasting collaboration with Spanish bus builder Irizar to sell their coaches through Scania’s global distribution network. The agreement meant that Scania had exclusive distribution rights for all Irizar coaches in Northern Europe for many years. The most widespread model was the Irizar Century, but later also the Irizar PB was sold as Scania’s premium coach.

In 1985, Scania’s Norwegian distributor and the Finnish bus builder Ajokki announced the Scania Classic,[37] a coach built exclusively for Norway. It was technically based on Ajokki’s own Royal coach model, but received its own styling details. In 1990, when Ajokki had become Carrus, the second generation was launched based on the Vector/Regal models. The third generation from 1995 was also available in Sweden and Finland in limited numbers, and the fourth and last generation from 2001 was built with the same bodywork as the Volvo 9700. Volvo, who had bought Carrus in 1998, put the foot down against any further Scanias with this bodywork from 2002, and since then Scania instead put the «Classic» sticker on all Irizar Century sold in Norway for several years. The collaboration also led to some Norway-exclusive intercity buses; the Scania Cruiser (Ajokki Victor), Scania Universal (Carrus Fifty) and Scania InterClassic (Carrus Vega), but neither of these had special styling, nor as successful as the Classic.

In 2006, Scania and Higer Bus announced the A80, the first coach in the Higer A Series of coaches built on Scania chassis in China. The coaches are generally available in Asia, but the A30 is also available in Europe as an affordable intercity bus or simple coach. Even the A80 is globally available, but under make-up known as the Scania Touring HD, also referred to as the A80T.

Since 2012, Scania and Belgian bus manufacturer Van Hool offer some of their most luxurious coaches from their TX series on Scania K EB chassis, including the Astronef with theatrical floor, the Astromega double-decker and the Altano.[38] Since 2014, also the Exqui.City BRT concept is available on Scania N UA chassis with CNG-powered engines.[39]

Diesel engines[edit]

In addition to bus and truck engines, Scania’s industrial and marine engines are used in generator sets and in earthmoving and agricultural machinery, as well as on board ships and pleasure crafts.

Scania’s involvement with internal combustion engine production dates back to 1897, when engineer Gustav Erickson designed the engine for the company’s first motor car. Over the subsequent years, Scania has grown to be one of the world’s most experienced engine manufacturers, building engines not only for trucks and buses, but also for marine and general industrial applications, which are exported across the globe.[40]

Year in parentheses is first year of application in road vehicles.

Current[edit]

- DC07 I6 6,692 cc (2014) − licensed Cummins ISB 6.7 for buses

- DC09/DI09 I5 9,291 cc (2007)

- DC13/DI13 I6 12,742 cc (2007)

- DC16/DI16 V8 16,353 cc (2010)

Historical[edit]

- D10/DS10 I6 10,261 cc (1958)

- D7 I6 7,167 cc (1959)

- D8/DS8 I6 7,790 cc (1962)

- D11/DN11/DS11/DSC11/DSI11 I6 11,021 cc (1963)

- D5/DS5 I4 5,193 cc (1964)

- DI14/DS14/DSC14/DSI14 V8 14,188 cc (1969)

- DC9/DI9/DN9/DS9/DSC9 I6 8,476 cc (1984)

- DC9 I6 8,974 cc (1996)

- DH12/DI12/DSC12/DSI12/DT12 I6 11,705 cc (1996)

- DC11 I6 10,641 cc (1999)

- DC16 I6 15,607 cc (2000)

- DC9 I5 8,867 cc (2004)

Other products[edit]

- Scania also designs and manufacture clothes especially designed for truckers under the label Scania Truck Gear.[41]

- Scania is featured in Scania Truck Driving Simulator and Euro Truck Simulator 2, both developed by SCS Software.

Production sites[edit]

The table below shows the locations of the current[42] and former production facilities of Scania AB. As Scania is now majority owned by Volkswagen AG, making it part of Volkswagen Group, the table also includes Volkswagen Group references.[43]

Notes: the second column of the table, the ‘factory VIN ID code’, is indicated in the 11th digit of the vehicles’ 17 digit Vehicle Identification Number, and this factory code is only assigned to plants which produce complete vehicles. Component factories which do not produce complete vehicles do not have this factory ID code.

|

This section needs expansion with: factory VIN ID codes, specific detail of current production, former production, dates, coordinates, any former plants. You can help by adding to it. (October 2009) |

| factory name |

factory VIN ID code(s) |

factory WMI code(s) | location (continent, country) |

location (town/city, state/region) |

current motor vehicle production |

former motor vehicle production |

automotive products & components |

year opened |

comments | factory coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angers [43][44] |

9 | VLU | Europe, France |

Angers, Maine- et-Loire, Pays de la Loire |

Scania truck assembly | 1992 | Scania Production Angers S.A.S. factory and assembly line, part of Scania AB | 47°30′4″N 0°30′55″W / 47.50111°N 0.51528°W | ||

| Katrineholm | YS4 | Europe, Sweden |

Katrineholm Municipality, Södermanland County |

Scania bus chassis and body assembly |

Scania-Bussar AB, acquired by Scania-Vabis in 1967 (former Svenska Karosseri Verkstäderna) | 58°59′42.7956″N 16°10′7.914″E / 58.995221000°N 16.16886500°E | ||||

| Lahti | YK900L | Europe, Finland |

Lahti, Päijänne Tavastia |

Scania bus body assembly |

2007 | SOE Busproduction Finland Oy, part of Scania AB since 2014 (former Lahden Autokori) | 60°57′0″N 25°36′3″E / 60.95000°N 25.60083°E | |||

| Luleå [43][45] |

Europe, Sweden |

Luleå Municipality, Norrbotten, Norrbotten County |

Scania truck frame members, Rear axle housings | Ferruform AB factory, part of Scania AB | 65°36′48″N 22°7′45″E / 65.61333°N 22.12917°E | |||||

| Meppel [43][46] |

Europe, Netherlands |

Meppel, Drenthe |

Scania truck components and paint shop | Scania Production Meppel B.V. factory, part of Scania AB | 52°41′25″N 6°10′24″E / 52.69028°N 6.17333°E | |||||

| Oskarshamn [43][47] |

Europe, Sweden |

Oskarshamn Municipality, Kalmar County, Småland |

Scania truck cab production | Scania AB factory | 57°15′24″N 16°25′42″E / 57.25667°N 16.42833°E | |||||

| São Bernardo do Campo[43][48] |

3 | 9BS | South America, Brazil |

São Bernardo do Campo, Greater São Paulo, São Paulo state |

Scania trucks Scania bus chassis |

Engines, gearboxes, components, axles, truck cabs | 1962 | Scania Latin America Ltda., part of Scania AB | 23°42′49″S 46°33′58″W / 23.71361°S 46.56611°W | |

| Słupsk [43][49] |

SZA | Europe, Poland |

Słupsk, Pomeranian Voivodeship |

Scania bus body assembly |

1993 | Scania Production Slupsk S.A factory and assembly line, part of Scania AB | 54°28′42″N 17°0′46″E / 54.47833°N 17.01278°E | |||

| Södertälje [43][50] |

1 2 |

YS2 | Europe, Sweden |

Södertälje, Södertälje Municipality, Södermanland, Stockholm County |

Scania trucks Scania bus chassis |

Components, Engines |

1891 | Scania AB headquarters, R&D and main production plant | 59°10′14″N 17°38′26″E / 59.17056°N 17.64056°E | |

| St Petersburg [43][51] |

X8U | Europe, Russia |

St Petersburg, Northwestern Federal District |

Scania bus body assembly Scania trucks since 2010 |

OOO Scania Peter factory and assembly line, part of Scania AB | 59°53′24″N 30°20′24″E / 59.89000°N 30.34000°E | ||||

| Tucumán [43][52] |

8A3 | South America, Argentina |

San Miguel de Tucumán, Tucumán Province |

Rear axle gears Gearboxes Differentials Drive shafts |

1976[17] | Scania Argentina S.A. factory, part of Scania AB | 26°52′47.5″S 65°7′38″W / 26.879861°S 65.12722°W | |||

| Zwolle [43][53] |

4 5 |

XLE | Europe, Netherlands |

Zwolle, Overijssel |

Scania truck assembly | 1964[54] | Scania Nederland B.V. factory, part of Scania AB | 52°30′46″N 6°3′48″E / 52.51278°N 6.06333°E |

In 2015 Scania opened its first Asian Plant in Bangalore, Karnataka, India. This plant specialises in bus and coach making.

In November 2020 Scania bought truck company Nantong Gaokai based in China’s eastern city of Rugao to start the plan of vehicles production there.[55]

Former production site[edit]

|

This section needs expansion with: factory VIN ID codes, specific detail of current production, former production, dates, coordinates, any former plants. You can help by adding to it. (October 2009) |

| factory name |

factory VIN ID code(s) |

factory WMI code(s) | location (continent, country) |

location (town/city, state/region) |

current motor vehicle production |

former motor vehicle production |

automotive products & components |

year opened |

comments | factory coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silkeborg | Europe, Denmark |

Silkeborg Municipality, Central Denmark Region |

Scania bus body assembly |

1912 | Scania Busser Silkeborg A/S, acquired by Scania AB in 1995 (former Danish Automobile Building), sold to Norwegian-Brazilian joint-venture Vest-Busscar in 2002 and closed down in 2003 |

See also[edit]

- Ainax – holding company created after an attempted acquisition of Scania by Volvo

- Marcus Wallenberg-hallen – Swedish vehicle museum, including Scania vehicles

- List of Volkswagen Group diesel engines – includes all current Scania engines

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Board of Directors». Scania AB. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f «2021 Annual and Sustainability Report» (PDF). Scania AB. pp. III, 63–64. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b «Key figures Scania (2012)». Scania. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ «Scania now a publicly listed company». Scania. 1 April 1996. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ «Scania’s application for delisting approved». Scania. 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d «The history of Scania». TruckerLinks. DK. Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ a b c d «Scania». Autoevolution. SoftNews NET. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012.

- ^ «The history of Scania: 1910 − A new company is born». Scania AB. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ Ekström, Gert (1984). Svenska bilbyggare. Allt om hobby. ISBN 91-85496-22-7.

- ^ a b c «1950 – Growth and new frontiers». Scania. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «1960 – Expanding production». Scania. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- ^ a b «História 1957–1966» (in Portuguese). Scania Latin America. Archived from the original on 17 September 2009.

- ^ Shapiro, Helen (Winter 1991). «Determinants of Firm Entry into the Brazilian Automobile Manufacturing Industry, 1956–1968». The Business History Review. 65 (4, The Automobile Industry): 897. doi:10.2307/3117267. JSTOR 3117267. S2CID 153363903.

- ^ a b Berg, Jørgen Seemann (1995). King of the road i femti år: Norsk Scania AS 1945–1995 (in Norwegian). Oslo, Norway: Norsk Scania AS. p. 85. ISBN 82-993693-0-4.

- ^ a b «Scania buses 100 years – public service on road» (PDF). Scania. April 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2016.

- ^ Dl, Esteban (16 June 2012). «Camión Argentino: Scania L/LT 111». camionargentino.blogspot.com.ar. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b Dl, Esteban (16 February 2012). «Camión Argentino: Scania». camionargentino.blogspot.com.ar. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Camionero, El (2 September 2012). «Camión Argentino: Scania T 112H 4×2». camionargentino.blogspot.com.ar. Archived from the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Dl, Esteban (30 January 2013). «Camión Argentino: Scania R 112H 4×2». camionargentino.blogspot.com.ar. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Camionero, El (30 June 2012). «Camión Argentino: Scania K 112». camionargentino.blogspot.com.ar. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Dl, Esteban (28 May 2012). «Camión Argentino: Scania BR 116». camionargentino.blogspot.com.ar. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Stark, Harry A., ed. (1987). Ward’s Automotive Yearbook 1987. Vol. 49. Detroit, MI: Ward’s Communications, Inc. p. 174. ISBN 0910589007.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ Kerr, John (December 1986). Barden, Paul (ed.). «View: USA». TRUCK. London, UK: FF Publishing Ltd: 30, 34.

- ^ «Volvo buys Scania». Diesel Net. Ecopoint. 7 August 1999. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ «January–March 2007 Interim Report» (PDF). Wolfsburg: Volkswagen. May 2007: 1, 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ «VW CEO hints there will be no merger of Scania and MAN». Thomson Financial. Retrieved 21 March 2008. (registration required)[verification needed]

- ^ «Scania has become the ninth brand in the Volkswagen Group» (Press release). Volkswagen. 1 December 2008. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ^ «VW’s truckmaker Scania fined 880 million euros for price fixing». Reuters. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ «VW’s Scania truck firm fined €880m by EU for price fixing». The Guardian. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ «International Truck and Van of the Year 2005». Transport News Network. 4 August 2005. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ «Scania CR76». Bussnack (in Swedish and Norwegian). 2008. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «Type designation system for buses and coaches, STD4218-2» (PDF). Scania. 11 January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2015.

- ^ «När Scania-Vabis blev Scania 1968» [When Scania-Vabis became Scania]. Bussnack (in Swedish). April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ «MCW Scania CR145 National Express». Flickr. 28 November 2009. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ «Scania’s new Fencer single-deck bus offers multiple alternative fuel options». www.transportengineer.org.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Deakin, Tim (17 May 2021). «Scania Fencer bus range receives global launch in UK market». routeone. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ «Kort historikk om Norsk Scania AS per 2013» [Brief history of Scania in Norway] (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norsk Scania. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ «New luxury coach with theatre floor from Scania». Scania. 28 November 2012. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ «New city travel in great style – Scania Van Hool Exqui.City, gas» (PDF). Scania. 28 October 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ «Scania – Undisturbed pleasure». Kelly’s Truck and Marine Service. Archived from the original on 14 October 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ «Scania Truck Gear». scania.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ «Production units». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k «Production Plants». Volkswagen. 31 December 2008. Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «France, Angers». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Sweden, Luleå». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «The Nederlands, Meppel». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Sweden, Oskarshamn». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Brazil, São Paulo». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Poland, Slupsk». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Sweden, Södertälje». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Russia, St. Petersburg». Scania. 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Argentina, Tucamán». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «The Nederlands, Zwolle». Scania. 2008. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Sweden’s Scania to start making trucks in China after acquisition, Reuters, 24 November 2020

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scania AB.

- Official website

- The Scania Museum – Marcus Wallenberg Hall

Coordinates: 59°10′14″N 17°38′26″E / 59.17056°N 17.64056°E

|

Scania Skåne |

|

|---|---|

|

Historical province |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

|

|

| Coordinates: 55°48′N 13°37′E / 55.800°N 13.617°ECoordinates: 55°48′N 13°37′E / 55.800°N 13.617°E | |

| Country | |

| Land | Götaland |

| County | |

| Largest city | |

| Area

[1] |

|

| • Total | 10,939 km2 (4,224 sq mi) |

| Population

(31 December 2020[2]) |

|

| • Total | 1,389,336 |

| • Density | 130/km2 (330/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Language | Swedish |

| • Dialect | Scanian |

| Culture | |

| • Flower | Oxeye daisy |

| • Animal | Red deer |

| • Bird | Red kite |

| • Fish | Eel |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal codes |

20000–29999 |

| Area codes | 040–046 |

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne[3] (Swedish: [ˈskôːnɛ] (listen), Danish: [ˈskɔːnə]), is the southernmost of the historical provinces (landskap) of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous with Skåne County, created in 1997. Like the other former provinces of Sweden, Scania still features in colloquial speech and in cultural references, and can therefore not be regarded as an archaic concept. Within Scania there are 33 municipalities that are autonomous within the Skåne Regional Council. Scania’s largest city, Malmö, is the third-largest city in Sweden, as well as the fifth-largest in Scandinavia.

To the north, Scania borders the former provinces of Halland and Småland, to the northeast Blekinge, to the east and south the Baltic Sea, and to the west Öresund. Since 2000, a road and railway bridge, the Öresund Bridge,[4] bridges the Sound and connects Scania with Denmark. Scania forms part of the transnational Øresund Region.[5]

From north to south Scania is around 130 km; it covers less than 3% of Sweden’s total area. The population of over 1,320,000[6] represents 13% of the country’s population. With 121 inhabitants per square kilometre (310/sq mi) Scania is the second-most densely populated province of Sweden.

Historically, Scania formed part of the kingdom of Denmark until the signing of the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658.[7] Denmark regained control of the province (1676–1679) during the Scanian War and again briefly in 1711 during the Great Northern War. Scania has been an undisputed part of Sweden since 1720.[8][9]

Name[edit]

Endonym and exonyms[edit]

The endonym used in Swedish and other North Germanic languages is Skåne (formerly spelled Skaane in Danish and Norwegian). The Latinized form Scania is an exonym in English.[3] Sometimes the endonym Skåne is used in English text, such as in tourist information,[10] even sometimes as Skane with the diacritic omitted.[11][12] Scania (as also Dalarna) is one of the few Swedish provinces for which exonyms are widely used in many languages, such as French Scanie, Dutch and German Schonen, Polish Skania, Spanish Escania, Italian Scania, etc. For the province’s modern administrative counterpart, Skåne län, the endonym Skåne is used in English.[13]

In the Alfredian translation of Orosius’s and Wulfstan’s travel accounts, the Old English form Sconeg appears.[14][15] Frankish sources mention a place called Sconaowe; Æthelweard, an Anglo-Saxon historian, wrote about Scani;[16] and in Beowulf’s fictional account, the names Scedenige and Scedeland appear as names for what is a Danish land.[14]

Etymology[edit]

The names Scania and Scandinavia are considered to have the same etymology.[17][18][19][20] The southernmost tip of what is today Sweden was called Scania by the Romans and thought to be an island. The actual etymology of the word remains dubious and has long been a matter of debate among scholars. The name is possibly derived from the Germanic root *Skaðin-awjã, which appears in Old Norse as Skáney [ˈskɑːnˌœy].[21] According to some scholars, the Germanic stem can be reconstructed as *Skaðan- meaning «danger» or «damage» (English scathing, German Schaden, Swedish skada).[22] Skanör in Scania, with its long Falsterbo reef, has the same stem (skan) combined with —ör, which means «sandbanks».

Administration[edit]

The two counties of Scania from 1719 to 1996

Between 1719 and 1996, the province was subdivided in two administrative counties (län), Kristianstad County and Malmöhus County, each under a governor (landshövding) appointed by the central government of Sweden.

When the first local government acts took effect in 1863, each county also got an elected county council (landsting). The counties were further divided into municipalities.

The local government reform of 1952 reduced the number of municipalities, and a second subdivision reform, carried out between 1968 and 1974, established today’s 33 municipalities[23] (Swedish: kommuner) in Scania. The municipalities have municipal governments, similar to city commissions, and are further divided into parishes (församlingar). The parishes are primarily entities of the Church of Sweden, but they also serve as a divisioning measure for the Swedish population registration and other statistical uses.

In 1999, the county council areas were amalgamated, forming Skåne Regional Council (Region Skåne), responsible mainly for public healthcare, public transport and regional planning and culture.

Heraldry[edit]

During the Danish era, the province had no coat of arms. In Sweden, however, every province had been represented by heraldic arms since 1560.[24] When Charles X Gustav of Sweden suddenly died in 1660 a coat of arms had to be created for the newly acquired province, as each province was to be represented by its arms at his royal funeral. After an initiative from Baron Gustaf Bonde, the Lord High Treasurer of Sweden, the coat of arms of the City of Malmö was used as a base for the new provincial arms. The Malmö coat of arms had been granted in 1437, during the Kalmar Union, by Eric of Pomerania and contains a Pomeranian griffin’s head. To distinguish it from the city’s coat of arms the tinctures were changed and the official blazon for the provincial arms is, in English: Or, a griffin’s head erased gules, crowned azure and armed azure, when it should be armed.

The province was divided in two administrative counties 1719–1996. Coats of arms were created for these entities, also using the griffin motif. The new Skåne County, operative from 1 January 1997, got a coat of arms that is the same as the province’s, but with reversed tinctures. When the county arms is shown with a Swedish royal crown, it represents the County Administrative Board, which is the regional presence of central government authority. In 1999 the two county councils (landsting) were amalgamated forming Region Skåne. It is the only one of its kind using a heraldic coat of arms. It is also the same as the province’s and the county’s, but with a golden griffin’s head on a blue shield.[25] The 33 municipalities within the county also have coats of arms.

The Scania Griffin has become a well-known symbol for the province and is also used by commercial enterprises. It is, for instance, included in the logotypes of the automotive manufacturer Scania AB and the airline Malmö Aviation.

Coat of arms[edit]

-

-

Skåne

(1660, revised 1939) -

-

-

History[edit]

Ale’s Stones, a stone ship (burial monument) from c. 500 AD on the coast at Kåseberga, around ten kilometres (6.2 miles) south east of Ystad.

Gerhard von Buhrman’s map of Scania, 1684

Map of Denmark in the Middle Ages, Scania was together with the provinces Blekinge and Halland a part of Denmark

Front page of the latest and current peace treaty between Denmark and Sweden, Swedish version

Scania was first mentioned in written texts in the 9th century. It came under Danish king Harald Bluetooth in the middle of the 10th century. It was then a region that included Blekinge and Halland, situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula and formed the eastern part of the kingdom of Denmark. This geographical position made it the focal point of the frequent Dano-Swedish wars for hundreds of years.

By the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658, all Danish lands east of Øresund were ceded to the Swedish Crown. First placed under a Governor-General, the province was eventually integrated into the kingdom of Sweden. The last Danish attempt to regain its lost provinces failed after the 1710 Battle of Helsingborg.

In 1719, the province was subdivided in two counties and administered in the same way as the rest of Sweden. Scania has since that year been fully integrated in the Swedish nation. In the following summer, July 1720, the last peace treaty between Sweden and Denmark was signed.[26][27]

On 28 November 2017 it was ruled that the Scanian flag would become the official flag of Scania.[28][29]

Politics[edit]

During Sweden’s financial crisis in the early and mid-1990s, Scania, Västra Götaland and Norrbotten were among the hardest hit in the country, with high unemployment rates as a result.[30] In response to the crisis, the County Governors were given a task by the government in September 1996 to co-ordinate various measures in the counties to increase economic growth and employment by bringing in regional actors.[30] The first proposal for regional autonomy and a regional parliament had been introduced by the Social Democratic Party’s local districts in Scania and Västra Götaland already in 1993. When Sweden joined the European Union two years later, the concept «Regions of Europe» came in focus and a more regionalist-friendly approach was adopted in national politics.[31] These factors contributed to the subsequent transformation of Skåne County into one of the first «trial regions» in Sweden in 1999, established as the country’s first «regional experiment».[31]

The relatively strong regional identity in Scania is often referred to in order to explain the general support in the province for the decentralization efforts introduced by the Swedish government.[32] On the basis of large scale interview investigations about Region Skåne in Scania, scholars have found that the prevailing trend among the inhabitants of Scania is to «[look] upon their region with more positive eyes and a firm reliance that it would deliver the goods in terms of increased democracy and constructive results out of economic planning».[33]

Transportation[edit]

The motorway through western Scania, E6, here at motorway service Glumslöv, is the artery of the western part of the province.

All local, regional and inter-regional train services within Scania (2018). In all, 72 stations are served, during day times at least one train per hour and direction. Many stations (especially in the west) have far better service than so. The most busy part is between Hyllie (Malmö) and Lund.

Electrified dual track railroad exists from the border with Denmark at the Øresund Bridge to Malmö and onwards to Lund. The latter part is currently being upgraded to four tracks and expected to enter service in 2023.[34] In Lund, the tracks split into two directions.[35] The dual tracks going towards Gothenburg end at Helsingborg,[36] while the other branch continues beyond the provincial border to neighbouring Småland, close to Killeberg.[37][35] This latter dual track continues to mid-Sweden.[35] There are also a few single track railroads connecting cities like Trelleborg, Ystad and Kristianstad.[35] Just as five Scanian stations are served partly (Hässleholm and Osby) or entirely (Ballingslöv, Hästveda and Killeberg) by Småland local trains, the Scanian Pågatåg trains serve Markaryd in Småland.[38]

There are basically three ticket systems: Skånetrafiken tickets can be purchased for all regional traffic including to Denmark, while the Danish Rejsekort system can only be used at stations served by Øresundståg and equipped with special card readers. Additionally, Swedish national SJ-tickets are available for longer trips to the north.

The E6 motorway is the main artery through the western part of Scania all the way from Trelleborg to the provincial border towards neighbouring Halland. It continues along the Swedish west coast to Gothenburg and most of the way to the Norwegian border. There are also several other motorways, especially around Malmö. Since 2000, the economic focus of the region has changed, with the opening of a road link across the Øresund Bridge to Denmark.[39]

The car ferry service between Helsingborg and Helsingør

has 70 departures in each direction daily as of 2014.[40]

There are three minor airports in Sturup, Ängelholm and Kristianstad. The nearby Copenhagen Airport, which is the largest international airport in the Nordic countries, also serves the province.[41]

Geography and environmental factors[edit]

Land usage in Scania, showing hardwood forests (light green), pinewood forests (dark green), fields (yellow), garden and fruit (orange) and residential areas (red)

Aerial view of Scania near Lund

A typical Beech forest, the Western edge of Karlslund in Northern Landskrona

Unlike some regions of Sweden, the Scanian landscape is generally not mountainous, though a few examples of uncovered cliffs can be found at Hovs Hallar, at Kullaberg, and on the island Hallands Väderö. With the exception of the lake-rich and densely forested northern parts (Göinge), the rolling hills in the north-west (the Bjäre and Kulla peninsulas) and the beech-wood-clad areas extending from the slopes of the horsts, a sizeable portion of Scania’s terrain consists of plains. Its low profile and open landscape distinguish Scania from most other geographical regions of Sweden which consist mainly of waterway-rich, cool, mixed coniferous forests, boreal taiga and alpine tundra.[42] The province has several lakes but there are relatively few compared to Småland, the province directly to the north. Stretching from the north-western to the south-eastern parts of Scania is a belt of deciduous forests following the Linderödsåsen ridge and previously marking the border between Malmöhus County and Kristianstad County. The much denser fir forests — typical of the greater part of Sweden — are only found in the north-eastern Göinge parts of Scania along the border with the forest-dominated province of Småland. While the landscape typically has a slightly sloping profile, in some places, such as north of Malmö, the terrain is almost completely flat.

The narrow lakes with a long north to south extent, which are very common further north, are lacking in Scania. The largest lake, Ivösjön in the north-east, has similarities with the lakes further north, but has a different shape. All other lakes tend to be round, oval or of more complex shape and also lack any specific cardinal direction. Ringsjön, in the middle of the province, is the largest of such lakes.[citation needed]

In the winter, some smaller lakes east of Lund often attract young Eurasian sea eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla).

Typical Scanian coastline, here southern peak of Ven island in Øresund. The yellow colour indicates sand rather than chalk, while white colour at similar cliffs indicates chalk rather than sand

Where the sea meets higher parts of the sloping landscape, cliffs emerge. Such cliffs are white if the soil has a high content of chalk. Good examples of such coastlines exist at the southern side of Ven, between the towns of Helsingborg and Landskrona, and in parts of the south and south-east coasts. In other Swedish provinces, steep coastlines usually reveal primary rock instead.

The two major plains, Söderslätt in the south-west and Österlen in the south-east, consist of highly fertile agricultural land. The yield per unit area is higher than in any other region in Sweden. The Scanian plains are an important resource for Sweden since 25–95% of the total production of various types of cereals come from the region. Almost all Swedish sugar beet comes from Scania; the plant needs a long vegetation period. The same applies also to corn, pea and rape (grown for its oil), although these plants are less imperative in comparison with sugar beets.[43][clarification needed] The soil is among the most fertile in the world.[citation needed]

The Kullaberg Nature Preserve in northwest Scania is home to several rare species including spring vetchling, Lathyrus sphaericus.[44]

Geology and geomorphology[edit]

[T]he present landscape is a mosaic of landforms shaped during widely different ages.

The gross relief of Scania reflects more the preglacial development than the erosion and deposits caused by the Quaternary glaciers.[45] In Swedish the word ås commonly refers to eskers, but major landmarks in Scania, such as Söderåsen, are horsts[46] formed by tectonic inversion along the Sorgenfrei-Tornquist Zone in the late Cretaceous. The Scanian horsts run in a north-west to south-east direction, marking the southwest border of Fennoscandia.[47] Tectonic activity of the Sorgenfrei-Tornquist Zone during the break-up of Pangaea in the Jurassic and Cretaceous epochs led to the formation of hundreds of small volcanoes in central Scania.[48][49] Remnants of the volcanoes are still visible today.[48] Parallel with volcanism a hilly peneplain formed in northeastern Scania due to weathering and erosion of basement rocks.[50][51] The kaolinite formed by this weathering can be observed at Ivö Klack.[51] In the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous a sea level rise led to the complete drowning of Scania. Subsequently, marine sediments buried old surfaces preserving the rocky shores and hilly terrain of the day.[51][52]

In the Paleogene period southern Sweden was at a lower position relative to sea level but was likely still above it as it was covered by sediments.[45][50] Rivers flowing over the South Småland peneplain flowed also across Scania which was at the time covered by thick sediments.[45] As the relative sea level sank and much of Scania lost its sedimentary cover antecedent rivers begun to incise the Söderåsen horst forming valleys.[45] During deglaciation these valleys likely evacuated large amounts of melt-water.[45] The relief of Scania’s south-western landscape was formed by the accumulation of thick Quaternary sediments during the Quaternary glaciations.[47]

Vegetation and vegetation zones[edit]

The vast majority of Scania belongs to the European hardwood vegetation zone, a considerable part of which is now agricultural rather than the original forest. This zone covers Europe west of Poland and north of the Alps, and includes the British Isles, northern and central France and the countries and regions to the south and southeast of the North Sea up to Denmark. A smaller north-eastern part of Scania is part of the pinewood vegetation zone, in which spruce grows naturally. Within the larger part, pine may grow together with birch on sandy soil. The most common tree is beech. Other common trees are willow, oak, ash, alder and elm (which until the 1970s formed a few forests but now is heavily infected by the elm disease). Also rather southern trees like walnut tree, chestnut and hornbeam can be found. In parks horse chestnut, lime and maple are commonly planted as well. Common fruit trees planted in commercial orchards and private gardens include several varieties of apple, pear, cherry and plum; strawberries are commercially cultivated in many locations across the province. Examples of wild berries grown in domesticated form are blackberry, raspberry, cloudberry (in the north-east), blueberry, wild strawberry and loganberry.

National parks[edit]

Three of the 29 National parks of Sweden[53] are situated in Scania.

- Dalby Söderskog[54]

- Stenshuvud[55]

- Söderåsen[56]

Extremes[edit]

- Southernmost point: Smygehuk, Trelleborg Municipality, (55° 20′ N) (also the southernmost point of Sweden)[57]

- Northernmost point: Gränsholmen, Osby Municipality

- Westernmost point: Kulla udd, Höganäs Municipality

- Easternmost point: Nyhult, Bromölla Municipality

- Highest point: Highest peak of Söderåsen, 212 metres

- Lowest spot: Kristianstad, −2.7 metres (also the lowest spot in all of Sweden)

- Largest lake: Ivösjön, 55 km2

- Largest island: Ven, 7.5 km2

Population[edit]

Map of the 33 municipalities of Scania. The western, yellow coloured municipalities, close to Øresund, have much higher population densities than the eastern ones