Not to be confused with Slovenia.

|

Slovak Republic Slovenská republika (Slovak) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Nad Tatrou sa blýska (Slovak) (English: «Lightning over the Tatras») |

|

| National seal

|

|

Location of Slovakia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Bratislava 48°09′N 17°07′E / 48.150°N 17.117°E |

| Official languages | Slovak |

| Ethnic groups

(2021)[1] |

|

| Religion

(2021)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Slovak |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

|

• President |

Zuzana Čaputová |

|

• Prime Minister |

Eduard Heger |

|

• Speaker of the National Council |

Boris Kollár |

| Legislature | National Council |

| Establishment history | |

|

• Independence from |

28 October 1918 |

|

• Second Czechoslovak Republic |

30 September 1938 |

|

• Autonomous Land of Slovakia (within Second Czechoslovak Republic) |

23 November 1938 |

|

• Third Czechoslovak Republic |

24 October 1945 |

|

• Fourth Czechoslovak Republic |

1948 |

|

• Czechoslovak Socialist Republic |

11 July 1960 |

|

• Slovak Socialist Republic (within Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, change of unitary Czechoslovak state into a federation) |

1 January 1969 |

|

• Slovak Republic (change of name within established Czech and Slovak Federative Republic) |

1 March 1990 |

|

• Dissolution of |

1 January 1993 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

49,035 km2 (18,933 sq mi) (127th) |

|

• Water (%) |

0.72 (2015)[3] |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 census |

|

|

• Density |

111/km2 (287.5/sq mi) (88th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2019) | low |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 45th |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | d. m. yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +421 |

| ISO 3166 code | SK |

| Internet TLD | .sk and .eu |

Slovakia (;[8][9] Slovak: Slovensko [ˈslɔʋenskɔ] (listen)), officially the Slovak Republic (Slovak: Slovenská republika [ˈslɔʋenskaː ˈrepublika] (

listen)), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the southwest, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia’s mostly mountainous territory spans about 49,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi), with a population of over 5.4 million. The capital and largest city is Bratislava, while the second largest city is Košice.

The Slavs arrived in the territory of present-day Slovakia in the fifth and sixth centuries. In the seventh century, they played a significant role in the creation of Samo’s Empire. In the ninth century, they established the Principality of Nitra, which was later conquered by the Principality of Moravia to establish Great Moravia. In the 10th century, after the dissolution of Great Moravia, the territory was integrated into the Principality of Hungary, which then became the Kingdom of Hungary in 1000.[10] In 1241 and 1242, after the Mongol invasion of Europe, much of the territory was destroyed. The area was recovered largely thanks to Béla IV of Hungary, who also settled Germans, leading them to become an important ethnic group in the area, especially in what are today parts of central and eastern Slovakia.[11]

After World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the state of Czechoslovakia was established. It was the only country in central and eastern Europe to remain a democracy during the interwar period. Nevertheless, local fascist parties gradually came to power in the Slovak lands, and the first Slovak Republic existed during World War II as a partially-recognised client state of Nazi Germany. At the end of World War II, Czechoslovakia was re-established as an independent country. After a coup in 1948, Czechoslovakia came under communist administration, and became a part of the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc. Attempts to liberalise communism in Czechoslovakia culminated in the Prague Spring, which was crushed by the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. In 1989, the Velvet Revolution peacefully ended the Communist rule in Czechoslovakia. Slovakia became an independent state on 1 January 1993 after the peaceful dissolution of Czechoslovakia, sometimes known as the Velvet Divorce.

Slovakia is a developed country with an advanced high-income economy, ranking 45th very high in the Human Development Index. It also performs favourably in measurements of civil liberties, press freedom, internet freedom, democratic governance, and peacefulness. The country maintains a combination of a market economy with a comprehensive social security system, providing citizens with universal health care, free education, and one of the longest paid parental leaves in the OECD.[12] Slovakia is a member of the European Union, the Eurozone, the Schengen Area, the United Nations, NATO, CERN, the OECD, the WTO, the Council of Europe, the Visegrád Group, and the OSCE. Slovakia is also home to eight UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The world’s largest per-capita car producer, Slovakia manufactured a total of 1.1 million cars in 2019, representing 43% of its total industrial output.[13]

Etymology[edit]

Slovakia’s name in theory means the «Land of the Slavs» (Slovensko in Slovak stemming from the older form Sloven/Slovienin). As such, it is a cognate of the words Slovenia and Slavonia. In medieval Latin, German, and even some Slavic sources, the same name has often been used for Slovaks, Slovenes, Slavonians, and Slavs in general. According to one of the theories, a new form of national name formed for the ancestors of the Slovaks between the 13th and 14th century, possibly due to foreign influence; the Czech word Slovák (in medieval sources from 1291 onward).[14] This form slowly replaced the name for the male members of the community, but the female name (Slovenka), reference to the lands inhabited (Slovensko) and the name of the language (slovenčina) all remained the same, with their base in the older form (compare to Slovenian counterparts). Most foreign translations tend to stem from this newer form (Slovakia in English, Slowakei in German, Slovaquie in French, etc.).

In medieval Latin sources, terms Slavus, Slavonia, or Slavorum (and more variants, from as early as 1029)[14] have been used. In German sources, names for the Slovak lands were Windenland or Windische Lande (early 15th century),[15] with the forms «Slovakia» and «Schlowakei» starting to appear in the 16th century.[16] The present Slovak form Slovensko is first attested in the year 1675.[17]

History[edit]

The oldest surviving human artefacts from Slovakia are found near Nové Mesto nad Váhom and are dated at 270,000 BCE, in the Early Paleolithic era. These ancient tools, made by the Clactonian technique, bear witness to the ancient habitation of Slovakia.[18]

Other stone tools from the Middle Paleolithic era (200,000–80,000 BCE) come from the Prévôt (Prepoštská) cave in Bojnice and from other nearby sites.[19] The most important discovery from that era is a Neanderthal cranium (c. 200,000 BCE), discovered near Gánovce, a village in northern Slovakia.

Archaeologists have found prehistoric human skeletons in the region, as well as numerous objects and vestiges of the Gravettian culture, principally in the river valleys of Nitra, Hron, Ipeľ, Váh and as far as the city of Žilina, and near the foot of the Vihorlat, Inovec, and Tribeč mountains, as well as in the Myjava Mountains. The most well-known finds include the oldest female statue made of mammoth bone (22,800 BCE), the famous Venus of Moravany. The statue was found in the 1940s in Moravany nad Váhom near Piešťany. Numerous necklaces made of shells from Cypraca thermophile gastropods of the Tertiary period have come from the sites of Zákovská, Podkovice, Hubina, and Radošina. These findings provide the most ancient evidence of commercial exchanges carried out between the Mediterranean and Central Europe.

Bronze Age[edit]

During the Bronze Age, the geographical territory of modern-day Slovakia went through three stages of development, stretching from 2000 to 800 BCE. Major cultural, economic, and political development can be attributed to the significant growth in production of copper, especially in central Slovakia (for example in Špania Dolina) and northwest Slovakia. Copper became a stable source of prosperity for the local population.

After the disappearance of the Čakany and Velatice cultures, the Lusatian people expanded building of strong and complex fortifications, with the large permanent buildings and administrative centres. Excavations of Lusatian hill forts document the substantial development of trade and agriculture at that period. The richness and diversity of tombs increased considerably. The inhabitants of the area manufactured arms, shields, jewellery, dishes, and statues.

Iron Age[edit]

Hallstatt Period[edit]

The arrival of tribes from Thrace disrupted the people of the Kalenderberg culture, who lived in the hamlets located on the plain (Sereď) and in the hill forts like Molpír, near Smolenice, in the Little Carpathians. During Hallstatt times, monumental burial mounds were erected in western Slovakia, with princely equipment consisting of richly decorated vessels, ornaments and decorations. The burial rites consisted entirely of cremation. Common people were buried in flat urnfield cemeteries.

A special role was given to weaving and the production of textiles. The local power of the «Princes» of the Hallstatt period disappeared in Slovakia during the century before the middle of first millennium BC, after strife between the Scytho-Thracian people and locals, resulting in abandonment of the old hill-forts. Relatively depopulated areas soon caught the interest of emerging Celtic tribes, who advanced from the south towards the north, following the Slovak rivers, peacefully integrating into the remnants of the local population.

La Tène Period[edit]

From around 500 BCE, the territory of modern-day Slovakia was settled by Celts, who built powerful oppida on the sites of modern-day Bratislava and Devín. Biatecs, silver coins with inscriptions in the Latin alphabet, represent the first known use of writing in Slovakia. At the northern regions, remnants of the local population of Lusatian origin, together with Celtic and later Dacian influence, gave rise to the unique Púchov culture, with advanced crafts and iron-working, many hill-forts and fortified settlements of central type with the coinage of the «Velkobysterecky» type (no inscriptions, with a horse on one side and a head on the other). This culture is often connected with the Celtic tribe mentioned in Roman sources as Cotini.

Roman Period[edit]

A Roman inscription at the castle hill of Trenčín (178–179 AD)

From 2 AD, the expanding Roman Empire established and maintained a series of outposts around and just south of the Danube, the largest of which were known as Carnuntum (whose remains are on the main road halfway between Vienna and Bratislava) and Brigetio (present-day Szőny at the Slovak-Hungarian border). Such Roman border settlements were built on the present area of Rusovce, currently a suburb of Bratislava. The military fort was surrounded by a civilian vicus and several farms of the villa rustica type. The name of this settlement was Gerulata. The military fort had an auxiliary cavalry unit, approximately 300 horses strong, modelled after the Cananefates. The remains of Roman buildings have also survived in Stupava, Devín Castle, Bratislava Castle Hill, and the Bratislava-Dúbravka suburb.

Near the northernmost line of the Roman hinterlands, the Limes Romanus, there existed the winter camp of Laugaricio (modern-day Trenčín) where the Auxiliary of Legion II fought and prevailed in a decisive battle over the Germanic Quadi tribe in 179 CE during the Marcomannic Wars. The Kingdom of Vannius, a kingdom founded by the Germanic Suebi tribes of Quadi and Marcomanni, as well as several small Germanic and Celtic tribes, including the Osi and Cotini, existed in western and central Slovakia from 8–6 BCE to 179 CE.

Great invasions from the fourth to seventh centuries[edit]

In the second and third centuries AD, the Huns began to leave the Central Asian steppes. They crossed the Danube in 377 AD and occupied Pannonia, which they used for 75 years as their base for launching looting-raids into Western Europe. However, Attila’s death in 453 brought about the disappearance of the Hunnic empire. In 568, a Turko-Mongol tribal confederacy, the Avars, conducted its invasion into the Middle Danube region. The Avars occupied the lowlands of the Pannonian Plain and established an empire dominating the Carpathian Basin.

In 623, the Slavic population living in the western parts of Pannonia seceded from their empire after a revolution led by Samo, a Frankish merchant.[20] After 626, the Avar power started a gradual decline[21] but its reign lasted to 804.

Slavic states[edit]

The Slavic tribes settled in the territory of present-day Slovakia in the fifth century. Western Slovakia was the centre of Samo’s empire in the seventh century. A Slavic state known as the Principality of Nitra arose in the eighth century and its ruler Pribina had the first known Christian church of the territory of present-day Slovakia consecrated by 828. Together with neighbouring Moravia, the principality formed the core of the Great Moravian Empire from 833. The high point of this Slavonic empire came with the arrival of Saints Cyril and Methodius in 863, during the reign of Duke Rastislav, and the territorial expansion under King Svätopluk I.

Great Moravia (830–before 907)[edit]

Great Moravia arose around 830 when Mojmír I unified the Slavic tribes settled north of the Danube and extended the Moravian supremacy over them.[22] When Mojmír I endeavoured to secede from the supremacy of the king of East Francia in 846, King Louis the German deposed him and assisted Mojmír’s nephew Rastislav (846–870) in acquiring the throne.[23] The new monarch pursued an independent policy: after stopping a Frankish attack in 855, he also sought to weaken the influence of Frankish priests preaching in his realm. Duke Rastislav asked the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send teachers who would interpret Christianity in the Slavic vernacular.

On Rastislav’s request, two brothers, Byzantine officials and missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius came in 863. Cyril developed the first Slavic alphabet and translated the Gospel into the Old Church Slavonic language. Rastislav was also preoccupied with the security and administration of his state. Numerous fortified castles built throughout the country are dated to his reign and some of them (e.g., Dowina, sometimes identified with Devín Castle)[24][25] are also mentioned in connection with Rastislav by Frankish chronicles.[26][27]

During Rastislav’s reign, the Principality of Nitra was given to his nephew Svätopluk as an appanage.[25] The rebellious prince allied himself with the Franks and overthrew his uncle in 870. Similarly to his predecessor, Svätopluk I (871–894) assumed the title of the king (rex). During his reign, the Great Moravian Empire reached its greatest territorial extent, when not only present-day Moravia and Slovakia but also present-day northern and central Hungary, Lower Austria, Bohemia, Silesia, Lusatia, southern Poland and northern Serbia belonged to the empire, but the exact borders of his domains are still disputed by modern authors.[28] Svatopluk also withstood attacks of the Magyar tribes and the Bulgarian Empire, although sometimes it was he who hired the Magyars when waging war against East Francia.[29]

In 880, Pope John VIII set up an independent ecclesiastical province in Great Moravia with Archbishop Methodius as its head. He also named the German cleric Wiching the Bishop of Nitra.

Certain and disputed borders of Great Moravia under Svatopluk I (according to modern historians)

After the death of Prince Svatopluk in 894, his sons Mojmír II (894–906?) and Svatopluk II succeeded him as the Prince of Great Moravia and the Prince of Nitra respectively.[25] However, they started to quarrel for domination of the whole empire. Weakened by an internal conflict as well as by constant warfare with Eastern Francia, Great Moravia lost most of its peripheral territories.

In the meantime, the semi-nomadic Magyar tribes, possibly having suffered defeat from the similarly nomadic Pechenegs, left their territories east of the Carpathian Mountains,[30] invaded the Carpathian Basin and started to occupy the territory gradually around 896.[31] Their armies’ advance may have been promoted by continuous wars among the countries of the region whose rulers still hired them occasionally to intervene in their struggles.[32]

It is not known what happened with both Mojmír II and Svatopluk II because they are not mentioned in written sources after 906. In three battles (4–5 July and 9 August 907) near Bratislava, the Magyars routed Bavarian armies. Some historians put this year as the date of the break-up of the Great Moravian Empire, due to the Hungarian conquest; other historians take the date a little bit earlier (to 902).

Great Moravia left behind a lasting legacy in Central and Eastern Europe. The Glagolitic script and its successor Cyrillic were disseminated to other Slavic countries, charting a new path in their sociocultural development.

Kingdom of Hungary and Austro-Hungarian Empire (1000–1918)[edit]

Following the disintegration of the Great Moravian Empire at the turn of the tenth century, the Hungarians annexed the territory comprising modern Slovakia. After their defeat on the river Lech, the Hungarians abandoned their nomadic ways and settled in the centre of the Carpathian valley, slowly adopting Christianity and began to build a new state — the Hungarian kingdom.[33] Slovaks seemed to play an important role during the development of the realm. as evident by large number of loanwords into Hungarian language, concerning primarily economical, agricultural or metallurgy fields.[34]

In the years 1001–1002 and 1018–1029, Slovakia was part of the Kingdom of Poland, having been conquered by Boleslaus I the Brave.[35] After the territory of Slovakia was returned to Hungary, a semi-autonomous polity continued to exist (or was created in 1048 by king Andrew I) called Duchy of Nitra. Comprising roughly the territory of Principality of Nitra and Bihar principality, they formed what was called a tercia pars regni, third of a kingdom.[36] It used to be ruled by would-be successors to the throne from the house of Arpád. Interestingly, in the Hungarian-Polish chronicle from 13th century, the ruler of said duchy, duke Emeric (son of Stephen I of Hungary), is called «Henricus dux Sclavonie», in essence — duke of Slovakia.[37]

This polity existed up until 1108/1110, after which it was not restored. After this, until the year 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsed, the territory of Slovakia was an integral part of the Hungarian state.[38][39][40] The ethnic composition of Slovakia became more diverse with the arrival of the Carpathian Germans in the 13th century and the Jews in the 14th century.

A significant decline in the population resulted from the invasion of the Mongols in 1241 and the subsequent famine. However, in medieval times the area of Slovakia was characterised by German and Jewish immigration, burgeoning towns, construction of numerous stone castles, and the cultivation of the arts.[41] The arrival of German element sometimes proved a problem for the autochthonous Slovaks (and even Hungarians in the broader Hungary), since they often quickly gained most power in medieval towns, only to later refuse to share it. Breaking of old customs by Germans often resulted in national quarrels. One of which had to be sorted out by the king Louis I. with the proclamation Privilegium pro Slavis (Privilege for Slovaks) in the year 1381. According to this privilege, Slovaks and Germans were to occupy each half of the seats in the city council of Žilina and the mayor should be elected each year, alternating between those nationalities. This would not be the last such case.[42]

In 1465, King Matthias Corvinus founded the Hungarian Kingdom’s third university, in Pressburg (Bratislava), but it was closed in 1490 after his death.[43] Hussites also settled in the region after the Hussite Wars.[44]

Owing to the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into Hungarian territory, Bratislava was designated the new capital of Hungary in 1536, ahead of the fall of the old Hungarian capital of Buda in 1541. It became part of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy, marking the beginning of a new era. The territory comprising modern Slovakia, then known as Upper Hungary, became the place of settlement for nearly two-thirds of the Magyar nobility fleeing the Turks and became far more linguistically and culturally Hungarian than it was before.[44] Partly thanks to old Hussite families and Slovaks studying under Martin Luther, the region then experienced a growth in Protestantism.[44] For a short period in the 17th century, most Slovaks were Lutherans.[44] They defied the Catholic Habsburgs and sought protection from neighbouring Transylvania, a rival continuation of the Magyar state that practised religious tolerance and normally had Ottoman backing. Upper Hungary, modern Slovakia, became the site of frequent wars between Catholics in the west territory and Protestants in the east, as well as against Turks; the frontier was on a constant state of military alert and heavily fortified by castles and citadels often manned by Catholic German and Slovak troops on the Habsburg side. By 1648, Slovakia was not spared the Counter-Reformation, which brought the majority of its population from Lutheranism back to Roman Catholicism. In 1655, the printing press at the Trnava university produced the Jesuit Benedikt Szöllősi’s Cantus Catholici, a Catholic hymnal in Slovak that reaffirmed links to the earlier works of Cyril and Methodius.

The Ottoman wars, the rivalry between Austria and Transylvania, and the frequent insurrections against the Habsburg monarchy inflicted a great deal of devastation, especially in the rural areas.[45] In the Austro-Turkish War (1663–1664) a Turkish army led by the Grand Vizier decimated Slovakia.[44] Even so, Thököly’s kuruc rebels from the Principality of Upper Hungary fought alongside the Turks against the Austrians and Poles at the Battle of Vienna of 1683 led by John III Sobieski. As the Turks withdrew from Hungary in the late 17th century, the importance of the territory composing modern Slovakia decreased, although Pressburg retained its status as the capital of Hungary until 1848 when it was transferred back to Buda.[46]

During the revolution of 1848–49, the Slovaks supported the Austrian Emperor, hoping for independence from the Hungarian part of the Dual Monarchy, but they failed to achieve their aim. Thereafter relations between the nationalities deteriorated (see Magyarisation), culminating in the secession of Slovakia from Hungary after World War I.[47]

Czechoslovakia (1918–1939)[edit]

On 18 October 1918, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Edvard Beneš declared in Washington, D.C. the independence for the territories of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Upper Hungary and Carpathian Ruthenia from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and proclaimed a common state, Czechoslovakia. In 1919, during the chaos following the break-up of Austria-Hungary, Czechoslovakia was formed with numerous Germans, Slovaks, Hungarians and Ruthenians within the newly set borders. The borders were set by the Treaty of Saint Germain and Treaty of Trianon. In the peace following the World War, Czechoslovakia emerged as a sovereign European state. It provided what were at the time rather extensive rights to its minorities.

During the Interwar period, democratic Czechoslovakia was allied with France, and also with Romania and Yugoslavia (Little Entente); however, the Locarno Treaties of 1925 left East European security open. Both Czechs and Slovaks enjoyed a period of relative prosperity. There was progress in not only the development of the country’s economy but also culture and educational opportunities. Yet the Great Depression caused a sharp economic downturn, followed by political disruption and insecurity in Europe.[48]

In the 1930s Czechoslovakia came under continuous pressure from the revisionist governments of Germany, Hungary and Poland who used the aggrieved minorities in the country as a useful vehicle. Revision of the borders was called for, as Czechs constituted only 43% of the population. Eventually, this pressure led to the Munich Agreement of September 1938, which allowed the majority ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland, borderlands of Czechoslovakia, to join with Germany. The remaining minorities stepped up their pressures for autonomy and the State became federalised, with Diets in Slovakia and Ruthenia. The remainder of Czechoslovakia was renamed Czecho-Slovakia and promised a greater degree of Slovak political autonomy. This, however, failed to materialise.[49] Parts of southern and eastern Slovakia were also reclaimed by Hungary at the First Vienna Award of November 1938.

World War II (1939–1945)[edit]

After the Munich Agreement and its Vienna Award, Nazi Germany threatened to annex part of Slovakia and allow the remaining regions to be partitioned by Hungary or Poland unless independence was declared.[citation needed] Thus, Slovakia seceded from Czecho-Slovakia in March 1939 and allied itself, as demanded by Germany, with Hitler’s coalition.[50] Secession had created the first Slovak state in history.[51] The government of the First Slovak Republic, led by Jozef Tiso and Vojtech Tuka, was strongly influenced by Germany and gradually became a puppet regime in many respects.

Meanwhile, the Czechoslovak government-in-exile sought to reverse the Munich Agreement and the subsequent German occupation of Czechoslovakia and to return the Republic to its 1937 boundaries. The government operated from London and it was ultimately considered, by those countries that recognised it, the legitimate government for Czechoslovakia throughout the Second World War.

As part of the Holocaust in Slovakia, 75,000 Jews out of 80,000 who remained on Slovak territory after Hungary had seized southern regions were deported and taken to German death camps.[52][53] Thousands of Jews, Gypsies and other politically undesirable people remained in Slovak forced labour camps in Sereď, Vyhne, and Nováky.[54] Tiso, through the granting of presidential exceptions, allowed between 1,000 and 4,000 people crucial to the war economy to avoid deportations.[55]

Under Tiso’s government and Hungarian occupation, the vast majority of Slovakia’s pre-war Jewish population (between 75,000 and 105,000 individuals including those who perished from the occupied territory) were murdered.[56][57] The Slovak state paid Germany 500 RM per every deported Jew for «retraining and accommodation» (a similar but smaller payment of 30 RM was paid by Croatia).[58]

After it became clear that the Soviet Red Army was going to push the Nazis out of eastern and central Europe, an anti-Nazi resistance movement launched a fierce armed insurrection, known as the Slovak National Uprising, near the end of summer 1944. A bloody German occupation and a guerilla war followed. Germans and their local collaborators completely destroyed 93 villages and massacred thousands of civilians, often hundreds at a time.[59] The territory of Slovakia was liberated by Soviet and Romanian forces by the end of April 1945.

Communist party rule (1948–1989)[edit]

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reconstituted and Jozef Tiso was executed in 1947 for collaboration with the Nazis. More than 80,000 Hungarians[60] and 32,000 Germans[61] were forced to leave Slovakia, in a series of population transfers initiated by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference.[62] Out of about 130,000 Carpathian Germans in Slovakia in 1938, by 1947 only some 20,000 remained.[63][failed verification] The NKVD arrested and deported over 20,000 people to Siberia[64]

As a result of the Yalta Conference, Czechoslovakia came under the influence and later under direct occupation of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact, after a coup in 1948. Eight thousand two hundred and forty people went to forced labour camps in 1948–1953.[65]

In 1968, following the Prague Spring, the country was invaded by the Warsaw Pact forces (People’s Republic of Bulgaria, People’s Republic of Hungary, People’s Republic of Poland, and Soviet Union, with the exception of Socialist Republic of Romania and People’s Socialist Republic of Albania), ending a period of liberalisation under the leadership of Alexander Dubček. 137 Czechoslovak civilians were killed[66] and 500 seriously wounded during the occupation.[67]

In 1969, Czechoslovakia became a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. It became a puppet state of the Soviet Union, but it was never part of the Soviet Union and remained independent to a certain degree.

Borders with the West were protected by the Iron Curtain. About 600 people, men, women, and children, were killed on the Czechoslovak border with Austria and West Germany between 1948 and 1989.[68]

Dissolution of Czechoslovakia (1989–1992)[edit]

The end of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia in 1989, during the peaceful Velvet Revolution, was followed once again by the country’s dissolution, this time into two successor states. The word «socialist» was dropped in the names of the two republics, with the Slovak Socialist Republic renamed as Slovak Republic. On 17 July 1992, Slovakia, led by Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar, declared itself a sovereign state, meaning that its laws took precedence over those of the federal government. Throughout the autumn of 1992, Mečiar and Czech Prime Minister Václav Klaus negotiated the details for disbanding the federation. In November, the federal parliament voted to dissolve the country officially on 31 December 1992.

Slovak Republic (1993–present)[edit]

Slovakia became a member of the European Union in 2004 and signed the Lisbon Treaty in 2007.

The Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic went their separate ways after 1 January 1993, an event sometimes called the Velvet Divorce.[69][70] Slovakia has, nevertheless, remained a close partner with the Czech Republic. Both countries co-operate with Hungary and Poland in the Visegrád Group. Slovakia became a member of NATO on 29 March 2004 and of the European Union on 1 May 2004. On 1 January 2009, Slovakia adopted the Euro as its national currency.[71] In 2019, Zuzana Čaputová became Slovakia’s first female president.[72]

Geography[edit]

Slovakia lies between latitudes 47° and 50° N, and longitudes 16° and 23° E. The Slovak landscape is noted primarily for its mountainous nature, with the Carpathian Mountains extending across most of the northern half of the country. Among these mountain ranges are the high peaks of the Fatra-Tatra Area (including Tatra Mountains, Greater Fatra and Lesser Fatra), Slovak Ore Mountains, Slovak Central Mountains or Beskids. The largest lowland is the fertile Danubian Lowland in the southwest, followed by the Eastern Slovak Lowland in the southeast.[73] Forests cover 41% of Slovak land surface.[74]

Tatra mountains[edit]

The Tatra Mountains, with 29 peaks higher than 2,500 metres (8,202 feet) AMSL, are the highest mountain range in the Carpathian Mountains. The Tatras occupy an area of 750 square kilometres (290 sq mi), of which the greater part 600 square kilometres (232 sq mi) lies in Slovakia. They are divided into several parts.

To the north, close to the Polish border, are the High Tatras which are a popular hiking and skiing destination and home to many scenic lakes and valleys as well as the highest point in Slovakia, the Gerlachovský štít at 2,655 metres (8,711 ft) and the country’s highly symbolic mountain Kriváň. To the west are the Western Tatras with their highest peak of Bystrá at 2,248 metres (7,375 ft) and to the east are the Belianske Tatras, smallest by area.

Separated from the Tatras proper by the valley of the Váh river are the Low Tatras, with their highest peak of Ďumbier at 2,043 metres (6,703 ft).

The Tatra mountain range is represented as one of the three hills on the coat of arms of Slovakia.

National parks[edit]

There are 9 national parks in Slovakia, covering 6.5% of the Slovak land surface.[75]

| Name | Established | Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|

| Tatra National Park | 1949 | 738 |

| Low Tatras National Park | 1978 | 728 |

| Veľká Fatra National Park | 2002 | 404 |

| Slovak Karst National Park | 2002 | 346 |

| Poloniny National Park | 1997 | 298 |

| Malá Fatra National Park | 1988 | 226 |

| Muránska planina National Park | 1998 | 203 |

| Slovak Paradise National Park | 1988 | 197 |

| Pieniny National Park | 1967 | 38 |

Caves[edit]

Slovakia has hundreds of caves and caverns under its mountains, of which 30 are open to the public.[76] Most of the caves have stalagmites rising from the ground and stalactites hanging from above. There are currently five Slovak caves under UNESCO’s World Heritage Site status. They are Dobšiná Ice Cave, Domica, Gombasek Cave, Jasovská Cave and Ochtinská Aragonite Cave. Other caves open to the public include Belianska Cave, Demänovská Cave of Liberty, Demänovská Ice Cave or Bystrianska Cave.

Rivers[edit]

Most of the rivers arise in the Slovak mountains. Some only pass through Slovakia, while others make a natural border with surrounding countries (more than 620 kilometres [390 mi]). For example, the Dunajec (17 kilometres [11 mi]) to the north, the Danube (172 kilometres [107 mi]) to the south or the Morava (119 kilometres [74 mi]) to the West. The total length of the rivers on Slovak territory is 49,774 kilometres (30,928 mi).

The longest river in Slovakia is the Váh (403 kilometres [250 mi]), the shortest is the Čierna voda. Other important and large rivers are the Myjava, the Nitra (197 kilometres [122 mi]), the Orava, the Hron (298 kilometres [185 mi]), the Hornád (193 kilometres [120 mi]), the Slaná (110 kilometres [68 mi]), the Ipeľ (232 kilometres [144 mi], forming the border with Hungary), the Bodrog, the Laborec, the Latorica and the Ondava.

The biggest volume of discharge in Slovak rivers is during spring, when the snow melts from the mountains. The only exception is the Danube, whose discharge is the greatest during summer when the snow melts in the Alps. The Danube is the largest river that flows through Slovakia.[77]

Climate[edit]

The Slovak climate lies between the temperate and continental climate zones with relatively warm summers and cold, cloudy and humid winters. Temperature extremes are between −41 to 40.3 °C (−41.8 to 104.5 °F) although temperatures below −30 °C (−22 °F) are rare. The weather differs from the mountainous north to the plains in the south.

The warmest region is Bratislava and Southern Slovakia where the temperatures may reach 30 °C (86 °F) in summer, occasionally to 39 °C (102 °F) in Hurbanovo. During night, the temperatures drop to 20 °C (68 °F). The daily temperatures in winter average in the range of −5 °C (23 °F) to 10 °C (50 °F). During night it may be freezing, but usually not below −10 °C (14 °F).

In Slovakia, there are four seasons, each season (spring, summer, autumn and winter) lasts three months. The dry continental air brings in the summer heat and winter frosts. In contrast, oceanic air brings rainfalls and reduces summer temperatures. In the lowlands and valleys, there is often fog, especially in winter.

Spring starts with 21 March and is characterised by colder weather with an average daily temperature of 9 °C (48 °F) in the first weeks and about 14 °C (57 °F) in May and 17 °C (63 °F) in June. In Slovakia, the weather and climate in the spring are very unstable.

Summer starts on 22 June and is usually characterised by hot weather with daily temperatures exceeding 30 °C (86 °F). July is the warmest month with temperatures up to about 37 to 40 °C (99 to 104 °F), especially in regions of southern Slovakia — in the urban area of Komárno, Hurbanovo or Štúrovo. Showers or thunderstorms may occur because of the summer monsoon called Medardova kvapka (Medard drop — 40 days of rain). Summer in Northern Slovakia is usually mild with temperatures around 25 °C (77 °F) (less in the mountains).

Autumn in Slovakia starts on 23 September and is mostly characterised by wet weather and wind, although the first weeks can be very warm and sunny. The average temperature in September is around 14 °C (57 °F), in November to 3 °C (37 °F). Late September and early October is a dry and sunny time of year (so-called Indian summer).

Winter starts on 21 December with temperatures around −5 to −10 °C (23 to 14 °F). In December and January, it is usually snowing, these are the coldest months of the year. At lower altitudes, snow does not stay the whole winter, it changes into the thaw and frost. Winters are colder in the mountains, where the snow usually lasts until March or April and the night temperatures fall to −20 °C (−4 °F) and colder.[78]

Biodiversity[edit]

Slovakia signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 19 May 1993, and became a party to the convention on 25 August 1994.[79] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 2 November 1998.[80]

The biodiversity of Slovakia comprises animals (such as annelids, arthropods, molluscs, nematodes and vertebrates), fungi (Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota and Zygomycota), micro-organisms (including Mycetozoa), and plants. The geographical position of Slovakia determines the richness of the diversity of fauna and flora. More than 11,000 plant species have been described throughout its territory, nearly 29,000 animal species and over 1,000 species of protozoa. Endemic biodiversity is also common.[81]

Slovakia is located in the biome of temperate broadleaf and mixed forests and terrestrial ecoregions of Pannonian mixed forests and Carpathian montane conifer forests.[82] As the altitude changes, the vegetation associations and animal communities are forming height levels (oak, beech, spruce, scrub pine, alpine meadows and subsoil). Forests cover 44% of the territory of Slovakia.[83] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.34/10, ranking it 129th globally out of 172 countries.[84] In terms of forest stands, 60% are broadleaf trees and 40% are coniferous trees. The occurrence of animal species is strongly connected to the appropriate types of plant associations and biotopes.[81]

Over 4,000 species of fungi have been recorded from Slovakia.[85][86] Of these, nearly 1,500 are lichen-forming species.[87] Some of these fungi are undoubtedly endemic, but not enough is known to say how many. Of the lichen-forming species, about 40% have been classified as threatened in some way. About 7% are apparently extinct, 9% endangered, 17% vulnerable, and 7% rare. The conservation status of non-lichen-forming fungi in Slovakia is not well documented, but there is a red list for its larger fungi.[88]

Government and politics[edit]

Slovakia is a parliamentary democratic republic with a multi-party system. The last parliamentary elections were held on 29 February 2020 and two rounds of presidential elections took place on 16 and 30 March 2019.

The Slovak head of state and the formal head of the executive is the president (currently Zuzana Čaputová, the first female president), though with very limited powers. The president is elected by direct, popular vote under the two-round system for a five-year term. Most executive power lies with the head of government, the prime minister (currently Eduard Heger),[89] who is usually the leader of the winning party and who needs to form a majority coalition in the parliament. The prime minister is appointed by the president. The remainder of the cabinet is appointed by the president on the recommendation of the prime minister.

Slovak President Zuzana Čaputová with the first lady of the United States Jill Biden at the Grassalkovich Palace in Bratislava, 2022

Slovakia’s highest legislative body is the 150-seat unicameral National Council of the Slovak Republic (Národná rada Slovenskej republiky). Delegates are elected for a four-year term on the basis of proportional representation.

Slovakia’s highest judicial body is the Constitutional Court of Slovakia (Ústavný súd), which rules on constitutional issues. The 13 members of this court are appointed by the president from a slate of candidates nominated by parliament.

The Constitution of the Slovak Republic was ratified 1 September 1992, and became effective 1 January 1993. It was amended in September 1998 to allow direct election of the president and again in February 2001 due to EU admission requirements. The civil law system is based on Austro-Hungarian codes. The legal code was modified to comply with the obligations of Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and to expunge the Marxist–Leninist legal theory. Slovakia accepts the compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction with reservations.

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Zuzana Čaputová | Independent | 15 June 2019 |

| Prime Minister | Eduard Heger | OĽaNO | 1 April 2021 |

| National Council Chairman | Boris Kollár | SR | 21 March 2020 |

Foreign relations[edit]

The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (Slovak: Ministerstvo zahraničných vecí a európskych záležitostí) is responsible for maintaining the Slovak Republic’s external relations and the management of its international diplomatic missions. The ministry’s director is Rastislav Káčer.[90][91] The ministry oversees Slovakia’s affairs with foreign entities, including bilateral relations with individual nations and its representation in international organisations.

Slovakia joined the European Union and NATO in 2004 and the Eurozone in 2009.

Slovakia is a member of the United Nations (since 1993) and participates in its specialised agencies. The country was, on 10 October 2005, elected to a two-year term on the UN Security Council from 2006 to 2007. It is also a member of the Schengen Area, the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the Bucharest Nine (B9) and part of the Visegrád Group (V4: Slovakia, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland).

In 2022, Slovak citizens had visa-free or visa-on-arrival access to 182 countries and territories, putting the Slovak passport at the ninth rank of travel freedom (tied with Lithuanian and Polish) on the Henley Passport Index.[92]

Slovakia maintains diplomatic relations with 134 countries, primarily through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As of December 2013, Slovakia maintained 90 missions abroad, including 64 embassies, seven missions to multilateral organisations, nine consulates-general, one consular office, one Slovak Economic and Cultural Office and eight Slovak Institutes.[93] There are 44 embassies and 35 honorary consulates in Bratislava.

Slovakia and the United States retain strong diplomatic ties and cooperate in the military and law enforcement areas. The U.S. Department of Defense programmes has contributed significantly to Slovak military reforms. Around one million Americans have their roots in Slovakia, and many retain strong cultural and familial ties to the Slovak Republic. President Woodrow Wilson and the United States played a major role in the establishment of the original Czechoslovak state on 28 October 1918.

Military[edit]

Slovak members of UNFICYP peacekeepers patrolling the buffer zone in Cyprus

The president is formally the commander-in-chief of the Slovak armed forces.

Slovakia joined NATO in March 2004.[94] From 2006, the army transformed into a fully professional organisation and compulsory military service was abolished. Slovak armed forces numbered 19,500 uniformed personnel and 4,208 civilians in 2022.[95]

The country has been an active participant in US- and NATO-led military actions and involved in many United Nations peacekeeping military missions: UNPROFOR in the Yugoslavia (1992-1995), UNOMUR in Uganda and Rwanda (1993-1994), UNAMIR in Rwanda (1993-1996), UNTAES in Croatia (1996-1998), UNOMIL in Liberia (1993-1997), MONUA in Angola (1997-1999), SFOR in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1999-2003), OSCE mission in Moldova (1998-2002), OSCE mission in Albania (1999), KFOR in Kosovo (1999-2002), UNGCI in Iraq (2000-2003), UNMEE in Ethiopia and Eritrea (2000-2004), UNMISET in East Timor (2001), EUFOR Concordia in Macedonia (2003), UNAMSIL in Sierra Leone (1999-2005), EU supporting action to African Union in Darfur (2006), Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan (2002-2005), Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq (2003-2007) and UNDOF at the borders of Israel and Syria (1998-2008).[96]

As of 2021, Slovakia has 169 military personnel deployed in Cyprus for UNFICYP United Nations led peace support operations[97][98] and 41 troops deployed in Bosnia and Herzegovina for EUFOR Althea.[99]

Slovak Ground Forces are made up of two active Mechanised infantry brigades. The Air and Air Defence Forces comprise one wing of fighters, one wing of utility helicopters, and one SAM brigade. Training and support forces comprise a National Support Element (Multifunctional Battalion, Transport Battalion, Repair Battalion), a garrison force of the capital city Bratislava, as well as a training battalion, and various logistics and communication and information bases. Miscellaneous forces under the direct command of the General Staff include the 5th Special Forces Regiment.

Human rights[edit]

Human rights in Slovakia are guaranteed by the Constitution of Slovakia from the year 1992 and by multiple international laws signed in Slovakia between 1948 and 2006.[100]

The US State Department in 2017 reported:

The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; however, there were problems in some areas. The most significant human rights issues included incidents of interference with privacy; corruption; widespread discrimination against Roma minority; and security force violence against ethnic and racial minorities government actions and rhetoric did little to discourage. The government investigated reports of abuses by members of the security forces and other government institutions, although some observers questioned the thoroughness of these investigations. Some officials engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. Two former ministers were convicted of corruption during the year.[101]

According to the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC), Romani people in Slovakia «endure racism in the job market, housing and education fields and are often subjected to forced evictions, vigilante intimidation, disproportionate levels of police brutality and more subtle forms of discrimination.»[102]

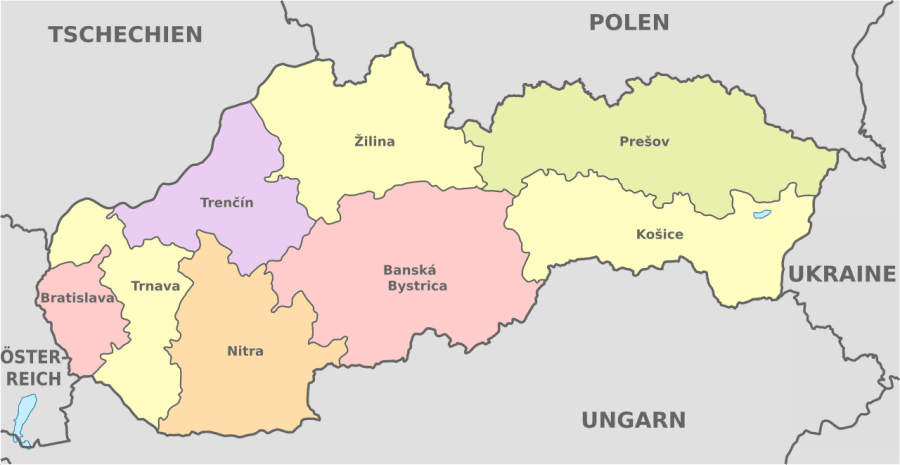

Administrative divisions[edit]

Slovakia is divided into 8 kraje (singular—kraj, usually translated as «region»), each of which is named after its principal city. Regions have enjoyed a certain degree of autonomy since 2002. Their self-governing bodies are referred to as Self-governing (or autonomous) Regions (sg. samosprávny kraj, pl. samosprávne kraje) or Upper-Tier Territorial Units (sg. vyšší územný celok, pl. vyššie územné celky, abbr. VÚC).

The kraje are subdivided into okresy (sg. okres, usually translated as districts). Slovakia currently has 79 districts.

The okresy are further divided into obce (sg. obec, usually translated as «municipality»). There are currently 2,890 municipalities.

In terms of economics and unemployment rate, the western regions are richer than eastern regions. Bratislava is the third-richest region of the European Union by GDP (PPP) per capita (after Hamburg and Luxembourg City); GDP at purchasing power parity is about three times higher than in other Slovak regions.[103][104]

|

Prešov Košice Žilina Banská Bystrica Trenčín Nitra Trnava Bratislava |

|

Economy[edit]

The Slovak economy is a developed, high-income[105] economy, with the GDP per capita equalling 78% of the average of the European Union in 2018.[106] The country has difficulties addressing regional imbalances in wealth and employment.[107] GDP per capita ranges from 188% of EU average in Bratislava to 54% in Eastern Slovakia.[108] Although regional income inequality is high, 90% of citizens own their homes.

The OECD in 2017 reported:

The Slovak Republic continues exhibiting robust economic performance, with strong growth backed by a sound financial sector, low public debt and high international competitiveness drawing on large inward investment.[109]

In 2021, Slovakia was ranked by the International Monetary Fund as the 45th richest country in the world (out of 226 countries and territories), with purchasing power parity per capita GDP of $34,815. The country used to be dubbed the «Tatra Tiger». Slovakia successfully transformed from a centrally planned economy to a market-driven economy. Major privatisations are completed, the banking sector is almost completely in private hands, and foreign investment has risen.

As of 2021, with population only 5 million, Slovakia is the 61st largest economy in the world (out of 216 countries and territories). The Slovak economy is one of the fastest-growing economies in Europe and 3rd-fastest in eurozone (2017). In 2007, 2008 and 2010 (with GDP growth of 10.5%, 6% and 4%, retrospectively). In 2016, more than 86% of Slovak exports went to the European Union, and more than 50% of Slovak imports came from other European Union member states.[110]

The ratio of government debt to GDP in Slovakia reached 49.4% by the end of 2018, far below the OECD average.[111]

Unemployment, peaking at 19% at the end of 1999, decreased to 4.9% in 2019, lowest recorded rate in Slovak history.[112]

Slovakia adopted the Euro currency on 1 January 2009 as the 16th member of the Eurozone. The euro in Slovakia was approved by the European commission on 7 May 2008. The Slovak koruna was revalued on 28 May 2008 to 30.126 for 1 euro,[113] which was also the exchange rate for the euro.[114]

High-rise buildings in Bratislava’s business districts

The Slovak government encourages foreign investment since it is one of the driving forces of the economy. Slovakia is an attractive country for foreign investors mainly because of its low wages, low tax rates, well educated labour force, favourable geographic location in the heart of Central Europe, strong political stability and good international relations reinforced by the country’s accession to the European Union. Some regions, mostly at the east of Slovakia have failed to attract major investment, which has aggravated regional disparities in many economic and social areas. Foreign direct investment inflow grew more than 600% from 2000 and cumulatively reached an all-time high of $17.3 billion in 2006, or around $22,000 per capita by the end of 2008.

Slovakia ranks 45th out of 190 economies in terms of ease of doing business, according to the 2020 World Bank Doing Business Report and 57th out of the 63 countries and territories in terms of competitive economy, according to the 2020 World Competitiveness Yearbook Report.

Industry[edit]

Although Slovakia’s GDP comes mainly from the tertiary (services) sector, the industrial sector also plays an important role within its economy. The main industry sectors are car manufacturing and electrical engineering. Since 2007, Slovakia has been the world’s largest producer of cars per capita,[115] with a total of 1,090,000 cars manufactured in the country in 2018 alone.[116] 275,000 people are employed directly and indirectly

by the automotive industry.[117] There are currently four automobile assembly plants and fifth under construction: Volkswagen’s in Bratislava (models: Volkswagen Up, Volkswagen Touareg, Audi Q7, Audi Q8, Porsche Cayenne, Lamborghini Urus), PSA Peugeot Citroën’s in Trnava (models: Peugeot 208, Citroën C3 Picasso), Kia Motors’ Žilina Plant (models: Kia Cee’d, Kia Sportage, Kia Venga) and Jaguar Land Rover’s in Nitra (model: Land Rover Discovery). Volvo will build electric cars at a new plant in Slovakia, construction is scheduled to begin in 2023, with series production starting in 2026.[118] Hyundai Mobis in Žilina is the largest suppliers for the automotive industry in Slovakia.[119]

From electrical engineering companies, Foxconn has a factory at Nitra for LCD TV manufacturing, Samsung at Galanta for computer monitors and television sets manufacturing. Slovnaft based in Bratislava with 4,000 employees, is an oil refinery with a processing capacity of 5.5 — 6 million tonnes of crude oil, annually. Steel producer U. S. Steel in Košice is the largest employer in the east of Slovakia with 12,000 employees.

A proportional representation of Slovakia’s exports, 2019

ESET is an IT security company from Bratislava with more than 1,000[120] employees worldwide at present. Their branch offices are in the United States, Ireland, United Kingdom, Argentina, the Czech Republic, Singapore and Poland.[121] In recent years, service and high-tech-oriented businesses have prospered in Bratislava. Many global companies, including IBM, Dell, Lenovo, AT&T, SAP, and Accenture, have built outsourcing and service centres here.[122] Reasons for the influx of multi-national corporations include proximity to Western Europe, skilled labour force and the high density of universities and research facilities.[123] Other large companies and employers with headquarters in Bratislava include Amazon, Slovak Telekom, Orange Slovensko, Slovenská sporiteľňa, Tatra banka, Doprastav, Hewlett-Packard Slovakia, Henkel Slovensko, Slovenský plynárenský priemysel, Microsoft Slovakia, Mondelez Slovakia, Whirlpool Slovakia and Zurich Insurance Group Slovakia.

Bratislava’s geographical position in Central Europe has long made Bratislava a crossroads for international trade traffic.[124][125] Various ancient trade routes, such as the Amber Road and the Danube waterway, have crossed territory of present-day Bratislava. Today, Bratislava is a road, railway, waterway and airway hub.[126]

Energy[edit]

In 2012, Slovakia produced a total of 28,393 GWh of electricity while at the same time consumed 28 786 GWh. The slightly higher level of consumption than the capacity of production (- 393 GWh) meant the country was not self-sufficient in energy sourcing. Slovakia imported electricity mainly from the Czech Republic (9,961 GWh — 73.6% of total import) and exported mainly to Hungary (10,231 GWh — 78.2% of total export).

Nuclear energy accounts for 53.8% of total electricity production in Slovakia, followed by 18.1% of thermal power energy, 15.1% by hydro power energy, 2% by solar energy, 9.6% by other sources and the rest 1.4% is imported.[127]

The two nuclear power-plants in Slovakia are in Jaslovské Bohunice and Mochovce, each of them containing two operating reactors. Before the accession of Slovakia to the EU in 2004, the government agreed to turn-off the V1 block of Jaslovské Bohunice power-plant, built-in 1978. After deactivating the last of the two reactors of the V1 block in 2008, Slovakia stopped being self-dependent in energy production.[citation needed] Currently there is another block (V2) with two active reactors in Jaslovské Bohunice. It is scheduled for decommissioning in 2025. Two new reactors are under construction in Mochovce plant. The nuclear power production in Slovakia occasionally draws the attention of Austrian green-energy activists who organise protests and block the borders between the two countries.[citation needed]

Transportation[edit]

There are four main highways D1 to D4 and eight expressways R1 to R8. Many of them are still under construction.

The D1 motorway connects Bratislava to Trnava, Nitra, Trenčín, Žilina and beyond, while the D2 motorway connects it to Prague, Brno and Budapest in the north–south direction. A large part of D4 motorway (an outer bypass), which should ease the pressure on Bratislava’s highway system, is scheduled to open in 2020.[128] The A6 motorway to Vienna connects Slovakia directly to the Austrian motorway system and was opened on 19 November 2007.[129]

Slovakia has three international airports. Bratislava’s M. R. Štefánik Airport is the main and largest international airport. It is located nine kilometres (5+1⁄2 miles) northeast of the city centre. It serves civil and governmental, scheduled and unscheduled domestic and international flights. The current runways support the landing of all common types of aircraft currently used. The airport has enjoyed rapidly growing passenger traffic in recent years; it served 279,028 passengers in 2000 and 2,292,712 in 2018.[130] Košice International Airport is an airport serving Košice. It is the second-largest international airport in Slovakia. The Poprad–Tatry Airport is the third busiest airport, the airport is located 5 km west-northwest of Poprad. It is an airport with one of the highest elevations in Central Europe, at 718 m, which is 150 m higher than Innsbruck Airport in Austria.

Railways of Slovak Republic provides railway transport services on national and international lines.

The Port of Bratislava is one of the two international river ports in Slovakia. The port connects Bratislava to international boat traffic, especially the interconnection from the North Sea to the Black Sea via the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal.

Additionally, tourist boats operate from Bratislava’s passenger port, including routes to Devín, Vienna and elsewhere. The Port of Komárno is the second largest port in Slovakia with an area of over 20 hectares and is located approximately 100 km east of Bratislava. It lies at the confluence of two rivers — the Danube and Váh.

Tourism[edit]

Slovakia features natural landscapes, mountains, caves, medieval castles and towns, folk architecture, spas and ski resorts. More than 5,4 million tourists visited Slovakia in 2017. The most attractive destinations are the capital of Bratislava and the High Tatras.[131] Most visitors come from the Czech Republic (about 26%), Poland (15%) and Germany (11%).[132]

Slovakia contains many castles, most of which are in ruins. The best known castles include Bojnice Castle (often used as a filming location), Spiš Castle, (on the UNESCO list), Orava Castle, Bratislava Castle, and the ruins of Devín Castle. Čachtice Castle was once the home of the world’s most prolific female serial killer, the ‘Bloody Lady’, Elizabeth Báthory.

Slovakia’s position in Europe and the country’s past (part of the Kingdom of Hungary, the Habsburg monarchy and Czechoslovakia) made many cities and towns similar to the cities in the Czech Republic (such as Prague), Austria (such as Salzburg) or Hungary (such as Budapest). A historical centre with at least one square has been preserved in many towns. Large historical centres can be found in Bratislava, Trenčín, Košice, Banská Štiavnica, Levoča, and Trnava. Historical centres have been going through a restoration in recent years.

Historical churches can be found in virtually every village and town in Slovakia. Most of them are built in the Baroque style, but there are also many examples of Romanesque and Gothic architecture, for example Banská Bystrica, Bardejov and Spišská Kapitula. The Basilica of St. James in Levoča with the tallest wood-carved altar in the world and the Church of the Holy Spirit in Žehra with medieval frescos are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The St. Martin’s Concathedral in Bratislava served as the coronation church for the Kingdom of Hungary. The oldest sacral buildings in Slovakia stem from the Great Moravian period in the ninth century.

Cable cars at Jasná in the Tatra Mountains.

Very precious structures are the complete wooden churches of northern and northern-eastern Slovakia. Most were built from the 15th century onwards by Catholics, Lutherans and members of eastern-rite churches.

Tourism is one of the main sectors of the Slovakia’s economy, although still underserved. It is based on domestic tourism, as most of the tourists are the Slovak nationals and residents travelling for leisure within the country. Bratislava and the High and Low Tatras are the busiest tourist stops. Other popular tourist destinations are the cities and towns of Košice, Banská Štiavnica, or Bardejov, and numerous national parks, such as Pieniny National Park Malá and Veľká Fatra National Parks, Poloniny National Park, or Slovak Paradise National Park, among others.

There are many castles located throughout the country. Among the tourists, some of the most popular are Bojnice Castle, Spiš Castle, Stará Ľubovňa Castle, Krásna Hôrka Castle, Orava Castle (where many scenes of Nosferatu were filmed), Trenčín Castle, and Bratislava Castle, and also castles in ruins, such as Beckov Castle, Devín Castle, Šariš Castle, Považie Castle, and Strečno Castle (where Dragonheart was filmed).

Caves open to the public are mainly located in Northern Slovakia. Driny is the only cave located in Western Slovakia that is open to the public. Dobšiná Ice Cave, Demänovská Ice Cave, Demänovská Cave of Liberty, Belianska Cave, or Domica Cave are among the most popular tourist stops. Ochtinská Aragonite Cave, located in Central Slovakia, is one of only three aragonite caves in the world. There are thousands of caves located in Slovakia, thirteen of which are open to the public.

Slovakia is also known for its numerous spas. Piešťany is the biggest and busiest spa town in the country, attracting many visitors from the Gulf countries, mostly the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain. Bardejov, Trenčianske Teplice, Turčianske Teplice, and Rajecké Teplice are other major spa towns. Some well-known minor spa towns and villages are Štós, Číž, Dudince, Kováčová, Nimnica, Smrdáky, Lúčky, and Vyšné Ružbachy, among others.

Typical souvenirs from Slovakia are dolls dressed in folk costumes, ceramic objects, crystal glass, carved wooden figures, črpáks (wooden pitchers), fujaras (a folk instrument on the UNESCO list) and valaškas (a decorated folk hatchet) and above all products made from corn husks and wire, notably human figures. Souvenirs can be bought in the shops run by the state organisation ÚĽUV (Ústredie ľudovej umeleckej výroby—Centre of Folk Art Production). Dielo shop chain sells works of Slovak artists and craftsmen. These shops are mostly found in towns and cities.

Prices of imported products are generally the same as in the neighbouring countries, whereas prices of local products and services, especially food, are usually lower.

Science[edit]

The Slovak Academy of Sciences has been the most important scientific and research institution in the country since 1953. Slovaks have made notable scientific and technical contributions during history. Slovakia is currently in the negotiation process of becoming a member of the European Space Agency. Observer status was granted in 2010, when Slovakia signed the General Agreement on Cooperation[133] in which information about ongoing education programmes was shared and Slovakia was invited to various negotiations of the ESA. In 2015, Slovakia signed the European Cooperating State Agreement based on which Slovakia committed to the finance entrance programme named PECS (Plan for the European Cooperating States) which serves as preparation for full membership. Slovak research and development organisations can apply for funding of projects regarding space technologies advancement. Full membership of Slovakia in the ESA is expected in 2020 after signing the ESA Convention. Slovakia will be obliged to set state budget inclusive ESA funding. Slovakia was ranked 33rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2021.[134]

Demographics[edit]

|

Largest cities or towns in Slovakia Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky – 31 December 2020 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

Bratislava  Košice |

1 | Bratislava | Bratislava | 475,503 | 11 | Prievidza | Trenčín | 45,017 |  Prešov  Žilina |

| 2 | Košice | Košice | 229,040 | 12 | Zvolen | Banská Bystrica | 40,637 | ||

| 3 | Prešov | Prešov | 84,824 | 13 | Považská Bystrica | Trenčín | 38,641 | ||

| 4 | Žilina | Žilina | 82,656 | 14 | Nové Zámky | Nitra | 37,791 | ||

| 5 | Nitra | Nitra | 78,489 | 15 | Michalovce | Košice | 36,704 | ||

| 6 | Banská Bystrica | Banská Bystrica | 76 018 | 16 | Spišská Nová Ves | Košice | 35,431 | ||

| 7 | Trnava | Trnava | 63,803 | 17 | Komárno | Nitra | 32,967 | ||

| 8 | Trenčín | Trenčín | 54,740 | 18 | Levice | Nitra | 31,974 | ||

| 9 | Martin | Žilina | 52,520 | 19 | Humenné | Prešov | 31,359 | ||

| 10 | Poprad | Prešov | 49,855 | 20 | Bardejov | Prešov | 30,840 |

Population density in Slovakia. The two biggest cities are clearly visible, Bratislava in the far west and Košice in the east.

The population is over 5.4 million and consists mostly of Slovaks. The average population density is 110 inhabitants per km2.[135] According to the 2021 census, the majority of the inhabitants of Slovakia are Slovaks (83.82%). Hungarians are the largest ethnic minority (7.75%). Other ethnic groups include Roma (1.23%),[136] Czechs (0.53%), Rusyns (0.44%) and others or unspecified (6.1%).[137]

In 2018 the median age of the Slovak population was 41 years.[138]

The largest waves of Slovak emigration occurred in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 1990 US census, 1.8 million people self-identified as having Slovak ancestry.[139][needs update]

Languages[edit]

The official language is Slovak, a member of the Slavic language family. Hungarian is widely spoken in the southern regions, and Rusyn is used in some parts of the Northeast. Minority languages hold co-official status in the municipalities in which the size of the minority population meets the legal threshold of 15% in two consecutive censuses.[140]

Slovakia is ranked among the top EU countries regarding the knowledge of foreign languages. In 2007, 68% of the population aged from 25 to 64 years claimed to speak two or more foreign languages, finishing second highest in the European Union. The best known foreign language in Slovakia is Czech. Eurostat report also shows that 98.3% of Slovak students in the upper secondary education take on two foreign languages, ranking highly over the average 60.1% in the European Union.[141] According to a Eurobarometer survey from 2012, 26% of the population have knowledge of English at a conversational level, followed by German (22%) and Russian (17%).[142]

The deaf community uses the Slovak Sign Language. Even though spoken Czech and Slovak are similar, the Slovak Sign language is not particularly close to Czech Sign Language.[citation needed]

Religion[edit]

Basilica of St. James in Levoča

The Slovak constitution guarantees freedom of religion. In 2021, 55.8% of population identified themselves as Roman Catholics, 5.3% as Lutherans, 1.6% as Calvinists, 4% as Greek Catholics, 0.9% as Orthodox, 23.8% identified themselves as atheists or non-religious, and 6.5% did not answer the question about their belief.[143] In 2004, about one third of the church members regularly attended church services.[144] The Slovak Greek Catholic Church is an Eastern rite sui iuris Catholic Church. Before World War II, an estimated 90,000 Jews lived in Slovakia (1.6% of the population), but most were murdered during the Holocaust. After further reductions due to postwar emigration and assimilation, only about 2,300 Jews remain today (0.04% of the population).[145]

There are 18 state-registered religions in Slovakia, of which 16 are Christian, one is Jewish, and one is the Baháʼí Faith.[146] In 2016, a two-thirds majority of the Slovak parliament passed a new bill that would obstruct Islam and other religious organisations from becoming state-recognised religions by doubling the minimum followers threshold from 25,000 to 50,000; however, Slovakia’s then-president Andrej Kiska vetoed the bill.[146] In 2010, there were an estimated 5,000 Muslims in Slovakia representing less than 0.1% of the country’s population.[147] Slovakia is the only member state of the European Union to not have any mosques.[148]

Education[edit]

The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks Slovak secondary education the 30th in the world (placing it just below the United States and just above Spain).[149]

Education in Slovakia is compulsory from age 6 to 16. The education system consists of elementary school which is divided into two parts, the first grade (age 6–10) and the second grade (age 10–15) which is finished by taking nationwide testing called Monitor, in Slovak and math. Parents may apply for social assistance for a child that is studying on an elementary school or a high-school. If approved, the state provides basic study necessities for the child. Schools provide books to all their students with usual exceptions of books for studying a foreign language and books which require taking notes in them, which are mostly present in the first grade of elementary school.

After finishing elementary school, students are obliged to take one year in high school.

After finishing high school, students can go to university and are highly encouraged to do so. Slovakia has a wide range of universities. The biggest university is Comenius University, established in 1919. Although it’s not the first university ever established on Slovak territory, it’s the oldest university that is still running. Most universities in Slovakia are public funded, where anyone can apply. Every citizen has a right to free education in public schools.

Slovakia has several privately funded universities, however public universities consistently score better in the ranking than their private counterparts. Universities have different criteria for accepting students. Anyone can apply to any number of universities.

Culture[edit]

Folk tradition[edit]

Folk tradition has rooted strongly in Slovakia and is reflected in literature, music, dance and architecture. The prime example is the Slovak national anthem, «Nad Tatrou sa blýska», which is based on a melody from the «Kopala studienku» folk song.

The manifestation of Slovak folklore culture is the «Východná» Folklore Festival. It is the oldest and largest nationwide festival with international participation,[150] which takes place in Východná annually. Slovakia is usually represented by many groups but mainly by SĽUK (Slovenský ľudový umelecký kolektív—Slovak folk art collective). SĽUK is the largest Slovak folk art group, trying to preserve the folklore tradition.

An example of wooden folk architecture in Slovakia can be seen in the well-preserved village of Vlkolínec which has been the UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993.[151] The Prešov Region preserves the world’s most remarkable folk wooden churches. Most of them are protected by Slovak law as cultural heritage, but some of them are on the UNESCO list too, in Bodružal, Hervartov, Ladomirová and Ruská Bystrá.

The best known Slovak hero, found in many folk mythologies, is Juraj Jánošík (1688–1713) (the Slovak equivalent of Robin Hood). The legend says he was taking from the rich and giving to the poor. Jánošík’s life was depicted in a list of literary works and many movies throughout the 20th century. One of the most popular is a film Jánošík directed by Martin Frič in 1935.[152]

Art[edit]

Main altar in the Basilica of St. James, crafted by Master Paul of Levoča, 1517. It is the tallest wooden altar in the world.

Visual art in Slovakia is represented through painting, drawing, printmaking, illustration, arts and crafts, sculpture, photography or conceptual art. The Slovak National Gallery founded in 1948, is the biggest network of galleries in Slovakia. Two displays in Bratislava are situated in Esterházy Palace (Esterházyho palác) and the Water Barracks (Vodné kasárne), adjacent one to another. They are located on the Danube riverfront in the Old Town.[153][154]

The Bratislava City Gallery, founded in 1961 is the second biggest Slovak gallery of its kind. It stores about 35,000 pieces of Slovak international art and offers permanent displays in Pálffy Palace and Mirbach Palace, located in the Old Town. Danubiana Art Museum, one of the youngest art museums in Europe, is situated near Čunovo waterworks (part of Gabčíkovo Waterworks). Other major galleries include: Andy Warhol Museum of Modern Art (Warhol’s parents were from Miková), East Slovak Gallery, Ernest Zmeták Art Gallery, Zvolen Castle.

Literature[edit]

Christian topics include poem Proglas as a foreword to the four Gospels, partial translations of the Bible into Old Church Slavonic, Zakon sudnyj ljudem.

Medieval literature, in the period from the 11th to the 15th centuries, was written in Latin, Czech and Slovakised Czech. Lyric (prayers, songs and formulas) was still controlled by the Church, while epic was concentrated on legends. Authors from this period include Johannes de Thurocz, author of the Chronica Hungarorum and Maurus, both of them Hungarians.[155] The worldly literature also emerged and chronicles were written in this period.

Two leading persons codified Slovak. The first was Anton Bernolák, whose concept was based on the western Slovak dialect in 1787. It was the codification of the first-ever literary language of Slovaks. The second was Ľudovít Štúr, whose formation of the Slovak took principles from the central Slovak dialect in 1843.

Slovakia is also known for its polyhistors, of whom include Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Matej Bel, Ján Kollár, and its political revolutionaries and reformists, such Milan Rastislav Štefánik and Alexander Dubček.

Cuisine[edit]

Traditional Slovak cuisine is based mainly on pork, poultry (chicken is the most widely eaten, followed by duck, goose, and turkey), flour, potatoes, cabbage, and milk products. It is relatively closely related to Hungarian, Czech, Polish and Austrian cuisine. On the east it is also influenced by Ukrainian, including Lemko and Rusyn. In comparison with other European countries, «game meat» is more accessible in Slovakia due to vast resources of forest and because hunting is relatively popular.[156] Boar, rabbit, and venison are generally available throughout the year. Lamb and goat are eaten but are not widely popular.[citation needed]

The traditional Slovak meals are bryndzové halušky, bryndzové pirohy and other meals with potato dough and bryndza. Bryndza is a salty cheese made of sheep milk, characterised by a strong taste and aroma. Bryndzové halušky especially is considered a national dish, and is very commonly found on the menu of traditional Slovak restaurants.

A typical soup is a sauerkraut soup («kapustnica»). A blood sausage called «krvavnica», made from any parts of a butchered pig is also a specific Slovak meal.

Wine is enjoyed throughout Slovakia. Slovak wine comes predominantly from the southern areas along the Danube and its tributaries; the northern half of the country is too cold and mountainous to grow grapevines. Traditionally, white wine was more popular than red or rosé (except in some regions), and sweet wine more popular than dry, but in recent years tastes seem to be changing.[157] Beer (mainly of the pilsener style, though dark lagers are also consumed) is also popular.

Sport[edit]

Sporting activities are practised widely in Slovakia, many of them on a professional level. Ice hockey and football have traditionally been regarded as the most popular sports in Slovakia, though tennis, handball, basketball, volleyball, whitewater slalom, cycling, alpine skiing, biathlon and athletics are also popular.[citation needed]

One of the most popular team sports in Slovakia is ice hockey. Slovakia became a member of the IIHF on 2 February 1993[158] and since then has won 4 medals in Ice Hockey World Championships, consisting of 1 gold, 2 silver and 1 bronze. The most recent success was a silver medal at the 2012 IIHF World Championship in Helsinki. The Slovak national hockey team made eight appearances in the Olympic games, finishing fourth in the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver and third with bronze medal at the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. The country has 8,280 registered players and is ranked seventh in the IIHF World Ranking at present. The Slovak hockey teams HC Slovan Bratislava and HC Lev Poprad participated in the Kontinental Hockey League.[159]

Slovakia hosted the 2011 IIHF World Championship, where Finland won the gold medal and 2019 IIHF World Championship, where Finland also won the gold medal. Both competitions took place in Bratislava and Košice.[citation needed]

Football stadium Tehelné pole in Bratislava. Football is the most popular sport in Slovakia.

Football is the most popular sport in Slovakia, with over 400,000 registered players. Since 1993, the Slovak national football team has qualified for the FIFA World Cup once, in 2010. They progressed to the last 16, where they were defeated by the Netherlands. The most notable result was the 3–2 victory over Italy. In 2016, the Slovak national football team qualified for the UEFA Euro 2016 tournament, under head coach Ján Kozák. This helped the team reach its best-ever position of 14th in the FIFA World Rankings.[citation needed]