английский

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

украинский

китайский

русский

Синонимы

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

украинский

китайский

украинский

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

кракен

Кракена

Kraken

Кракене

кракеном

Prospective juror number 17, the defendant is a kraken.

Возможный присяжный номер 17, подсудимый — кракен.

We don’t want the kraken to catch us.

Как бы нас Кракен не настиг.

You were born to kill the Kraken.

Ты родился, чтобы убить Чудище.

You are born to kill the Kraken.

Ты родился, чтобы убить Чудище.

If the Kraken falls Hades will be weak enough for you to strike a deathly blow.

Если Кракен падет, Аид будет достаточно слаб, чтобы ты нанес смертельный удар.

You thought the Kraken would bring you their prayers.

Ты думал, что Кракен принесет тебе их молитвы.

Kraken tells Baron Strucker that there are three arriving.

Кракен говорит барону Штрукеру, что есть три человека.

If the Kraken can be killed, the Stygian witches would know how.

Если Чудище и можно убить, то как это сделать знают Стигийские Ведьмы.

You heard the witches’ prophecy, you won’t defeat the Kraken, …much less Hades.

Ты слышал пророчество ведьм, тебе не победить Чудище… тем более Аида.

Do you know what the Kraken is?

Ты знаешь, что такое Кракен?

I thought maybe it’s a Kraken. Jenkins says it’s a Grendel.

Я думал, что там может быть Кракен, а Дженкинс говорит, что Грендель.

Some say he sleeps in caves like a beast, slumbers deep like the Kraken.

Говорят, он спит в пещере, как зверь. Дремлет, как Кракен.

A trading-focused bitcoin service provider, Kraken appeals to bitcoin traders as you can leverage andeven short on the platform.

Торговые ориентированный поставщик Bitcoin услуг, Кракен обращается к Bitcoin трейдеров, как вы можете использовать и даже короткие на платформе.

Disco Ball 10 Bewitched Censer Bond: Peaceful Kraken Bond: The Ghost of the Dawn

Диско-шар 10 Ведьмовское кадило Пакт: Мирный кракен Пакт: Призрак Рассвета

The Kraken, a beast so terrifying it was said to devour men and ships and whales, and so enormous it could be mistaken for an island.

Кракен. Животное настолько жуткое, что считалось, будто он способен пожирать корабли и китов, и настолько огромное, что его можно было принять за остров.

As I’ve stated before on numerous occasions, the only sea creature I would even consider being eaten by is the Kraken, because the last words I would hear are:

Как я уже частенько замечал ранее, единственное морское существо, которым я хотел бы быть съеден, является Кракен, потому что последними словами, которые я услышал бы были:

When the war is won, the Lion shall rule the land, the Kraken shall rule the sea… and our child

Когда мы победим, лев будет править землями, кракен — морями… а наше дитя в один прекрасный

Slumbers deep like the kraken.

Take that, you scurvy Kraken.

The Kraken fears no weapon.

Результатов: 97. Точных совпадений: 97. Затраченное время: 55 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Звуко буквенный разбор слова: чем отличаются звуки и буквы?

Прежде чем перейти к выполнению фонетического разбора с примерами обращаем ваше внимание, что буквы и звуки в словах — это не всегда одно и тоже.

Буквы — это письмена, графические символы, с помощью которых передается содержание текста или конспектируется разговор. Буквы используются для визуальной передачи смысла, мы воспримем их глазами. Буквы можно прочесть. Когда вы читаете буквы вслух, то образуете звуки — слоги — слова.

Список всех букв — это просто алфавит

Почти каждый школьник знает сколько букв в русском алфавите. Правильно, всего их 33. Русскую азбуку называют кириллицей. Буквы алфавита располагаются в определенной последовательности:

Алфавит русского языка:

| Аа | «а» | Бб | «бэ» | Вв | «вэ» | Гг | «гэ» |

| Дд | «дэ» | Ее | «е» | Ёё | «йо» | Жж | «жэ» |

| Зз | «зэ» | Ии | «и» | Йй | «й» | Кк | «ка» |

| Лл | «эл» | Мм | «эм» | Нн | «эн» | Оо | «о» |

| Пп | «пэ» | Рр | «эр» | Сс | «эс» | Тт | «тэ» |

| Уу | «у» | Фф | «эф» | Хх | «ха» | Цц | «цэ» |

| Чч | «чэ» | Шш | «ша» | Щщ | «ща» | ъ | «т.з.» |

| Ыы | «ы» | ь | «м.з.» | Ээ | «э» | Юю | «йу» |

| Яя | «йа» |

Всего в русском алфавите используется:

- 21 буква для обозначения согласных;

- 10 букв — гласных;

- и две: ь (мягкий знак) и ъ (твёрдый знак), которые указывают на свойства, но сами по себе не определяют какие-либо звуковые единицы.

Звуки — это фрагменты голосовой речи. Вы можете их услышать и произнести. Между собой они разделяются на гласные и согласные. При фонетическом разборе слова вы анализируете именно их.

Звуки в фразах вы зачастую проговариваете не так, как записываете на письме. Кроме того, в слове может использоваться больше букв, чем звуков. К примеру, «детский» — буквы «Т» и «С» сливаются в одну фонему [ц]. И наоборот, количество звуков в слове «чернеют» большее, так как буква «Ю» в данном случае произносится как [йу].

Что такое фонетический разбор?

Звучащую речь мы воспринимаем на слух. Под фонетическим разбором слова имеется ввиду характеристика звукового состава. В школьной программе такой разбор чаще называют «звуко буквенный» анализ. Итак, при фонетическом разборе вы просто описываете свойства звуков, их характеристики в зависимости от окружения и слоговую структуру фразы, объединенной общим словесным ударением.

Фонетическая транскрипция

Для звуко-буквенного разбора применяют специальную транскрипцию в квадратных скобках. К примеру, правильно пишется:

- чёрный -> [ч’о́рный’]

- яблоко -> [йа́блака]

- якорь -> [йа́кар’]

- ёлка -> [йо́лка]

- солнце -> [со́нцэ]

В схеме фонетического разбора используются особые символы. Благодаря этому можно корректно обозначить и отличить буквенную запись (орфографию) и звуковое определение букв (фонемы).

- фонетически разбираемое слово заключается квадратные скобки – [ ];

- мягкий согласный обозначается знаком транскрипции [’] — апострофом;

- ударный [´] — ударением;

- в сложных словоформах из нескольких корней применяется знак второстепенного ударения [`] — гравис (в школьной программе не практикуется);

- буквы алфавита Ю, Я, Е, Ё, Ь и Ъ в транскрипции НИКОГДА не используются (в учебной программе);

- для удвоенных согласных применяется [:] — знак долготы произнесения звука.

Ниже приводятся подробные правила для орфоэпического, буквенного и фонетического и разбора слов с примерами онлайн, в соответствии с общешкольными нормами современного русского языка. У профессиональных лингвистов транскрипция фонетических характеристик отличается акцентами и другими символами с дополнительными акустическими признаками гласных и согласных фонем.

Как сделать фонетический разбор слова?

Провести буквенный анализ вам поможет следующая схема:

- Выпишите необходимое слово и произнесите его несколько раз вслух.

- Посчитайте сколько в нем гласных и согласных букв.

- Обозначьте ударный слог. (Ударение при помощи интенсивности (энергии) выделяет в речи определенную фонему из ряда однородных звуковых единиц.)

- Разделите фонетическое слово по слогам и укажите их общее количество. Помните, что слогораздел в отличается от правил переноса. Общее число слогов всегда совпадает с количеством гласных букв.

- В транскрипции разберите слово по звукам.

- Напишите буквы из фразы в столбик.

- Напротив каждой буквы квадратных скобках [ ] укажите ее звуковое определение (как она слышатся). Помните, что звуки в словах не всегда тождественны буквам. Буквы «ь» и «ъ» не представляют никаких звуков. Буквы «е», «ё», «ю», «я», «и» могут обозначать сразу 2 звука.

- Проанализируйте каждую фонему по отдельности и обозначьте ее свойства через запятую:

- для гласного указываем в характеристике: звук гласный; ударный или безударный;

- в характеристиках согласных указываем: звук согласный; твёрдый или мягкий, звонкий или глухой, сонорный, парный/непарный по твердости-мягкости и звонкости-глухости.

- В конце фонетического разбора слова подведите черту и посчитайте общее количество букв и звуков.

Данная схема практикуется в школьной программе.

Пример фонетического разбора слова

Вот образец фонетического разбора по составу для слова «явление» → [йивл’э′н’ийэ]. В данном примере 4 гласных буквы и 3 согласных. Здесь всего 4 слога: я-вле′-ни-е. Ударение падает на второй.

Звуковая характеристика букв:

я [й] — согл., непарный мягкий, непарный звонкий, сонорный [и] — гласн., безударныйв [в] — согл., парный твердый, парный зв.л [л’] — согл., парный мягк., непарн. зв., сонорныйе [э′] — гласн., ударныйн [н’] — согласн., парный мягк., непарн. зв., сонорный и [и] — гласн., безударный [й] — согл., непарн. мягк., непарн. зв., сонорный [э] — гласн., безударный________________________Всего в слове явление – 7 букв, 9 звуков. Первая буква «Я» и последняя «Е» обозначают по два звука.

Теперь вы знаете как сделать звуко-буквенный анализ самостоятельно. Далее даётся классификация звуковых единиц русского языка, их взаимосвязи и правила транскрипции при звукобуквенном разборе.

Фонетика и звуки в русском языке

Какие бывают звуки?

Все звуковые единицы делятся на гласные и согласные. Гласные звуки, в свою очередь, бывают ударными и безударными. Согласный звук в русских словах бывает: твердым — мягким, звонким — глухим, шипящим, сонорным.

— Сколько в русской живой речи звуков?

Правильный ответ 42.

Делая фонетический разбор онлайн, вы обнаружите, что в словообразовании участвуют 36 согласных звуков и 6 гласных. У многих возникает резонный вопрос, почему существует такая странная несогласованность? Почему разнится общее число звуков и букв как по гласным, так и по согласным?

Всё это легко объяснимо. Ряд букв при участии в словообразовании могут обозначать сразу 2 звука. Например, пары по мягкости-твердости:

- [б] — бодрый и [б’] — белка;

- или [д]-[д’]: домашний — делать.

А некоторые не обладают парой, к примеру [ч’] всегда будет мягким. Сомневаетесь, попытайтесь сказать его твёрдо и убедитесь в невозможности этого: ручей, пачка, ложечка, чёрным, Чегевара, мальчик, крольчонок, черемуха, пчёлы. Благодаря такому практичному решению наш алфавит не достиг безразмерных масштабов, а звуко-единицы оптимально дополняются, сливаясь друг с другом.

Гласные звуки в словах русского языка

Гласные звуки в отличии от согласных мелодичные, они свободно как бы нараспев вытекают из гортани, без преград и напряжения связок. Чем громче вы пытаетесь произнести гласный, тем шире вам придется раскрыть рот. И наоборот, чем громче вы стремитесь выговорить согласный, тем энергичнее будете смыкать ротовую полость. Это самое яркое артикуляционное различие между этими классами фонем.

Ударение в любых словоформах может падать только на гласный звук, но также существуют и безударные гласные.

— Сколько гласных звуков в русской фонетике?

В русской речи используется меньше гласных фонем, чем букв. Ударных звуков всего шесть: [а], [и], [о], [э], [у], [ы]. А букв, напомним, десять: а, е, ё, и, о, у, ы, э, я, ю. Гласные буквы Е, Ё, Ю, Я не являются «чистыми» звуками и в транскрипции не используются. Нередко при буквенном разборе слов на перечисленные буквы падает ударение.

Фонетика: характеристика ударных гласных

Главная фонематическая особенность русской речи — четкое произнесение гласных фонем в ударных слогах. Ударные слоги в русской фонетике отличаются силой выдоха, увеличенной продолжительностью звучания и произносятся неискаженно. Поскольку они произносятся отчетливо и выразительно, звуковой анализ слогов с ударными гласными фонемами проводить значительно проще. Положение, в котором звук не подвергается изменениям и сохранят основной вид, называется сильной позицией. Такую позицию может занимать только ударный звук и слог. Безударные же фонемы и слоги пребывают в слабой позиции.

- Гласный в ударном слоге всегда находится в сильной позиции, то есть произносится более отчётливо, с наибольшей силой и продолжительностью.

- Гласный в безударном положении находится в слабой позиции, то есть произносится с меньшей силой и не столь отчётливо.

В русском языке неизменяемые фонетические свойства сохраняет лишь одна фонема «У»: кукуруза, дощечку, учусь, улов, — во всех положениях она произносятся отчётливо как [у]. Это означает, что гласная «У» не подвергается качественной редукции. Внимание: на письме фонема [у] может обозначатся и другой буквой «Ю»: мюсли [м’у´сл’и], ключ [кл’у´ч’] и тд.

Разбор по звукам ударных гласных

Гласная фонема [о] встречается только в сильной позиции (под ударением). В таких случаях «О» не подвергается редукции: котик [ко´т’ик], колокольчик [калако´л’ч’ык], молоко [малако´], восемь [во´с’им’], поисковая [паиско´вайа], говор [го´вар], осень [о´с’ин’].

Исключение из правила сильной позиции для «О», когда безударная [о] произносится тоже отчётливо, представляют лишь некоторые иноязычные слова: какао [кака’о], патио [па’тио], радио [ра’дио], боа [боа’] и ряд служебных единиц, к примеру, союз но.

Звук [о] в письменности можно отразить другой буквой«ё» – [о]: тёрн [т’о´рн], костёр [кас’т’о´р]. Выполнить разбор по звукам оставшихся четырёх гласных в позиции под ударением так же не представит сложностей.

Безударные гласные буквы и звуки в словах русского языка

Сделать правильный звуко разбор и точно определить характеристику гласного можно лишь после постановки ударения в слове. Не забывайте так же о существовании в нашем языке омонимии: за’мок — замо’к и об изменении фонетических качеств в зависимости от контекста (падеж, число):

- Я дома [йа до‘ма].

- Новые дома [но’выэ дама’].

В безударном положении гласный видоизменяется, то есть, произносится иначе, чем записывается:

- горы — гора = [го‘ры] — [гара’];

- он — онлайн = [о‘н] — [анла’йн]

- свидетельница = [св’ид’э‘т’ил’н’ица].

Подобные изменения гласных в безударных слогах называются редукцией. Количественной, когда изменяется длительность звучания. И качественной редукцией, когда меняется характеристика изначального звука.

Одна и та же безударная гласная буква может менять фонетическую характеристику в зависимости от положения:

- в первую очередь относительно ударного слога;

- в абсолютном начале или конце слова;

- в неприкрытых слогах (состоят только из одного гласного);

- од влиянием соседних знаков (ь, ъ) и согласного.

Так, различается 1-ая степень редукции. Ей подвергаются:

- гласные в первом предударном слоге;

- неприкрытый слог в самом начале;

- повторяющиеся гласные.

Примечание: Чтобы сделать звукобуквенный анализ первый предударный слог определяют исходя не с «головы» фонетического слова, а по отношению к ударному слогу: первый слева от него. Он в принципе может быть единственным предударным: не-зде-шний [н’из’д’э´шн’ий].

(неприкрытый слог)+(2-3 предударный слог)+ 1-й предударный слог ← Ударный слог → заударный слог (+2/3 заударный слог)

- впе-ре-ди [фп’ир’ид’и´];

- е-сте-стве-нно [йис’т’э´с’т’в’ин:а];

Любые другие предударные слоги и все заударные слоги при звуко разборе относятся к редукции 2-й степени. Ее так же называют «слабая позиция второй степени».

- поцеловать [па-цы-ла-ва´т’];

- моделировать [ма-ды-л’и´-ра-ват’];

- ласточка [ла´-ста-ч’ка];

- керосиновый [к’и-ра-с’и´-на-вый].

Редукция гласных в слабой позиции так же различается по ступеням: вторая, третья (после твердых и мягких соглас., — это за пределами учебной программы): учиться [уч’и´ц:а], оцепенеть [ацып’ин’э´т’], надежда [над’э´жда]. При буквенном анализе совсем незначительно проявятся редукция у гласного в слабой позиции в конечном открытом слоге (= в абсолютном конце слова):

- чашечка;

- богиня;

- с песнями;

- перемена.

Звуко буквенный разбор: йотированные звуки

Фонетически буквы Е — [йэ], Ё — [йо], Ю — [йу], Я — [йа] зачастую обозначают сразу два звука. Вы заметили, что во всех обозначенных случаях дополнительной фонемой выступает «Й»? Именно поэтому данные гласные называют йотированными. Значение букв Е, Ё, Ю, Я определяется их позиционным положением.

При фонетическом разборе гласные е, ё, ю, я образуют 2 звука:

◊ Ё — [йо], Ю — [йу], Е — [йэ], Я — [йа] в случаях, когда находятся:

- В начале слова «Ё» и «Ю» всегда:

- — ёжиться [йо´жыц:а], ёлочный [йо´лач’ный], ёжик [йо´жык], ёмкость [йо´мкаст’];

- — ювелир [йув’ил’и´р], юла [йула´], юбка [йу´пка], Юпитер [йуп’и´т’ир], юркость [йу´ркас’т’];

- в начале слова «Е» и «Я» только под ударением*:

- — ель [йэ´л’], езжу [йэ´ж:у], егерь [йэ´г’ир’], евнух [йэ´внух];

- — яхта [йа´хта], якорь [йа´кар’], яки [йа´ки], яблоко [йа´блака];

- (*чтобы выполнить звуко буквенный разбор безударных гласных «Е» и «Я» используется другая фонетическая транскрипция, см. ниже);

- в положении сразу после гласного «Ё» и «Ю» всегда. А вот «Е» и «Я» в ударных и в безударных слогах, кроме случаев, когда указанные буквы располагаются за гласным в 1-м предударном слоге или в 1-м, 2-м заударном слоге в середине слов. Фонетический разбор онлайн и примеры по указным случаям:

- — приёмник [пр’ийо´мн’ик], поёт [пайо´т], клюёт [кл’уйо´т];

- —аюрведа [айур’в’э´да], поют [пайу´т], тают [та´йут], каюта [кайу´та],

- после разделительного твердого «Ъ» знака «Ё» и «Ю» — всегда, а«Е» и «Я» только под ударением или в абсолютном конце слова: — объём [аб йо´м], съёмка [сйо´мка], адъютант [адйу‘та´нт]

- после разделительного мягкого «Ь» знака «Ё» и «Ю» — всегда, а «Е» и «Я» под ударением или в абсолютном конце слова: — интервью [интырв’йу´], деревья [д’ир’э´в’йа], друзья [друз’йа´], братья [бра´т’йа], обезьяна [аб’из’йа´на], вьюга [в’йу´га], семья [с’эм’йа´]

Как видите, в фонематической системе русского языка ударения имеют решающее значение. Наибольшей редукции подвергаются гласные в безударных слогах. Продолжим звука буквенный разбор оставшихся йотированных и посмотрим как они еще могут менять характеристики в зависимости от окружения в словах.

◊ Безударные гласные «Е» и «Я» обозначают два звука и в фонетической транскрипции и записываются как [ЙИ]:

- в самом начале слова:

- — единение [йид’ин’э´н’и’йэ], еловый [йило´вый], ежевика [йижив’и´ка], его [йивo´], егоза [йигаза´], Енисей [йин’ис’э´й], Египет [йиг’и´п’ит];

- — январский [йинва´рский], ядро [йидро´], язвить [йиз’в’и´т’], ярлык [йирлы´к], Япония [йипо´н’ийа], ягнёнок [йигн’о´нак];

- (Исключения представляют лишь редкие иноязычные словоформы и имена: европеоидная [йэврап’ио´иднайа], Евгений [йэ]вге´ний, европеец [йэврап’э´йиц], епархия [йэ]па´рхия и тп).

- сразу после гласного в 1-м предударном слоге или в 1-м, 2-м заударном слоге, кроме расположения в абсолютном конце слова.

- своевременно [свайивр’э´м’ина], поезда [пайизда´], поедим [пайид’и´м], наезжать [найиж:а´т’], бельгиец [б’ил’г’и´йиц], учащиеся [уч’а´щ’ийис’а], предложениями [пр’идлажэ´н’ийим’и], суета [суйита´],

- лаять [ла´йит’], маятник [ма´йитн’ик], заяц [за´йиц], пояс [по´йис], заявить [зайив’и´т’], проявлю [прайив’л’у´]

- после разделительного твердого «Ъ» или мягкого «Ь» знака: — пьянит [п’йин’и´т], изъявить [изйив’и´т’], объявление [абйи вл’э´н’ийэ], съедобный [сйидо´бный].

Примечание: Для петербургской фонологической школы характерно «эканье», а для московской «иканье». Раньше йотрованный «Ё» произносили с более акцентированным «йэ». Со сменой столиц, выполняя звуко-буквенный разбор, придерживаются московских норм в орфоэпии.

Некоторые люди в беглой речи произносят гласный «Я» одинаково в слогах с сильной и слабой позицией. Такое произношение считается диалектом и не является литературным. Запомните, гласный «я» под ударением и без ударения озвучивается по-разному: ярмарка [йа´рмарка], но яйцо [йийцо´].

Важно:

Буква «И» после мягкого знака «Ь» тоже представляет 2 звука — [ЙИ] при звуко буквенном анализе. (Данное правило актуально для слогов как в сильной, так и в слабой позиции). Проведем образец звукобуквенного онлайн разбора: — соловьи [салав’йи´], на курьих ножках [на ку´р’йи’х’ но´шках], кроличьи [кро´л’ич’йи], нет семьи [с’им’йи´], судьи [су´д’йи], ничьи [н’ич’йи´], ручьи [руч’йи´], лисьи [ли´с’йи]. Но: Гласная «О» после мягкого знака «Ь» транскрибируется как апостроф мягкости [’] предшествующего согласного и [О], хотя при произнесении фонемы может слышаться йотированность: бульон [бул’о´н], павильон [пав’ил’о´н], аналогично: почтальон, шампиньон, шиньон, компаньон, медальон, батальон, гильотина, карманьола, миньон и прочие.

Фонетический разбор слов, когда гласные «Ю» «Е» «Ё» «Я» образуют 1 звук

По правилам фонетики русского языка при определенном положении в словах обозначенные буквы дают один звук, когда:

- звуковые единицы «Ё» «Ю» «Е» находятся в под ударением после непарного согласного по твердости: ж, ш, ц. Тогда они обозначают фонемы:

- ё — [о],

- е — [э],

- ю — [у].

Примеры онлайн разбора по звукам: жёлтый [жо´лтый], шёлк [шо´лк], целый [цэ´лый], рецепт [р’ицэ´пт], жемчуг [жэ´мч’ук], шесть [шэ´ст’], шершень [шэ´ршэн’], парашют [парашу´т];

- Буквы «Я» «Ю» «Е» «Ё» и «И» обозначают мягкость предшествующего согласного [’]. Исключение только для: [ж], [ш], [ц]. В таких случаях в ударной позиции они образуют один гласный звук:

- ё – [о]: путёвка [пут’о´фка], лёгкий [л’о´хк’ий], опёнок [ап’о´нак], актёр [акт’о´р], ребёнок [р’иб’о´нак];

- е – [э]: тюлень [т’ул’э´н’], зеркало [з’э´ркала], умнее [умн’э´йэ], конвейер [канв’э´йир];

- я – [а]: котята [кат’а´та], мягко [м’а´хка], клятва [кл’а´тва], взял [вз’а´л], тюфяк [т’у ф’а´к], лебяжий [л’иб’а´жый];

- ю – [у]: клюв [кл’у´ф], людям [л’у´д’ам ], шлюз [шл’у´с], тюль [т’у´л’], костюм [кас’т’у´м].

- Примечание: в заимствованных из других языков словах ударная гласная «Е» не всегда сигнализирует о мягкости предыдущего согласного. Данное позиционное смягчение перестало быть обязательной нормой в русской фонетике лишь в XX веке. В таких случаях, когда вы делаете фонетический разбор по составу, такой гласный звук транскрибируется как [э] без предшествующего апострофа мягкости: отель [атэ´л’], бретелька [бр’итэ´л’ка], тест [тэ´ст], теннис [тэ´н:ис], кафе [кафэ´], пюре [п’урэ´], амбре [амбрэ´], дельта [дэ´л’та], тендер [тэ´ндэр], шедевр [шэдэ´вр], планшет [планшэ´т].

- Внимание! После мягких согласных в предударных слогах гласные «Е» и «Я» подвергаются качественной редукции и трансформируются в звук [и] (искл. для [ц], [ж], [ш]). Примеры фонетического разбора слов с подобными фонемами: — зерно [з’ирно´], земля [з’имл’а´], весёлый [в’ис’о´лый], звенит [з’в’ин’и´т], лесной [л’исно´й], метелица [м’ит’е´л’ица], перо [п’иро´], принесла [пр’ин’исла´], вязать [в’иза´т’], лягать [л’ига´т’], пятёрка [п’ит’о´рка]

Фонетический разбор: согласные звуки русского языка

Согласных в русском языке абсолютное большинство. При выговаривании согласного звука поток воздуха встречает препятствия. Их образуют органы артикуляции: зубы, язык, нёбо, колебания голосовых связок, губы. За счет этого в голосе возникает шум, шипение, свист или звонкость.

Сколько согласных звуков в русской речи?

В алфавите для их обозначения используется 21 буква. Однако, выполняя звуко буквенный анализ, вы обнаружите, что в русской фонетике согласных звуков больше, а именно — 36.

Звуко-буквенный разбор: какими бывают согласные звуки?

В нашем языке согласные бывают:

- твердые — мягкие и образуют соответствующие пары:

- [б] — [б’]: банан — белка,

- [в] — [в’]: высота — вьюн,

- [г] — [г’]: город — герцог,

- [д] — [д’]: дача — дельфин,

- [з] — [з’]: звон — зефир,

- [к] — [к’]: конфета — кенгуру,

- [л] — [л’]: лодка — люкс,

- [м] — [м’]: магия — мечты,

- [н] — [н’]: новый — нектар,

- [п] — [п’]: пальма— пёсик,

- [р] — [р’]: ромашка — ряд,

- [с] — [с’]: сувенир — сюрприз,

- [т] — [т’]: тучка — тюльпан,

- [ф] — [ф’]: флаг — февраль,

- [х] — [х’]: хорек — хищник.

- Определенные согласные не обладают парой по твердости-мягкости. К непарным относятся:

- звуки [ж], [ц], [ш] — всегда твердые (жизнь, цикл, мышь);

- [ч’], [щ’] и [й’] — всегда мягкие (дочка, чаще, твоей).

- Звуки [ж], [ч’], [ш], [щ’] в нашем языке называются шипящими.

Согласный может быть звонким — глухим, а так же сонорным и шумным.

Определить звонкость-глухость или сонорность согласного можно по степени шума-голоса. Данные характеристики будут варьироваться в зависимости от способа образования и участия органов артикуляции.

- Сонорные (л, м, н, р, й) — самые звонкие фонемы, в них слышится максимум голоса и немного шумов: лев, рай, ноль.

- Если при произношении слова во время звуко разбора образуется и голос, и шум — значит перед вами звонкий согласный (г, б, з и тд.): завод, блюдо, жизнь.

- При произнесении глухих согласных (п, с, т и прочих) голосовые связки не напрягаются, издаётся только шум: стопка, фишка, костюм, цирк, зашить.

Примечание: В фонетике у согласных звуковых единиц также существует деление по характеру образования: смычка (б, п, д, т) — щель (ж, ш, з, с) и способу артикуляции: губно-губные (б, п, м), губно-зубные (ф, в), переднеязычные (т, д, з, с, ц, ж, ш, щ, ч, н, л, р), среднеязычный (й), заднеязычные (к, г, х). Названия даны исходя из органов артикуляции, которые участвуют в звукообразовании.

Подсказка: Если вы только начинаете практиковаться в фонетическом разборе слов, попробуйте прижать к ушам ладони и произнести фонему. Если вам удалось услышать голос, значит исследуемый звук — звонкий согласный, если же слышится шум, — то глухой.

Подсказка: Для ассоциативной связи запомните фразы: «Ой, мы же не забывали друга.» — в данном предложении содержится абсолютно весь комплект звонких согласных (без учета пар мягкость-твердость). «Степка, хочешь поесть щец? – Фи!» — аналогично, указанные реплики содержат набор всех глухих согласных.

Позиционные изменения согласных звуков в русском языке

Согласный звук так же как и гласный подвергается изменениям. Одна и та же буква фонетически может обозначать разный звук, в зависимости от занимаемой позиции. В потоке речи происходит уподобление звучания одного согласного под артикуляцию располагающегося рядом согласного. Данное воздействие облегчает произношение и называется в фонетике ассимиляцией.

Позиционное оглушение/озвончение

В определённом положении для согласных действует фонетический закон ассимиляции по глухости-звонкости. Звонкий парный согласный сменяется на глухой:

- в абсолютном конце фонетического слова: но ж [но´ш], снег [с’н’э´к], огород [агаро´т], клуб [клу´п];

- перед глухими согласными: незабудка [н’изабу´тка], обхватить [апхват’и´т’], вторник [фто´рн’ик], трубка [трупка].

- делая звуко буквенный разбор онлайн, вы заметите, что глухой парный согласный, стоящий перед звонким (кроме [й’], [в] — [в’], [л] — [л’], [м] — [м’], [н] — [н’], [р] — [р’]) тоже озвончается, то есть заменяется на свою звонкую пару: сдача [зда´ч’а], косьба [каз’ба´], молотьба [малад’ба´], просьба [про´з’ба], отгадать [адгада´т’].

В русской фонетике глухой шумный согласный не сочетается с последующим звонким шумным, кроме звуков [в] — [в’]: взбитыми сливками. В данном случае одинаково допустима транскрипция как фонемы [з], так и [с].

При разборе по звукам слов: итого, сегодня, сегодняшний и тп, буква «Г» замещается на фонему [в].

По правилам звуко буквенного анализа в окончаниях «-ого», «-его» имён прилагательных, причастий и местоимений согласный «Г» транскрибируется как звук [в]: красного [кра´снава], синего [с’и´н’ива], белого [б’э´лава], острого, полного, прежнего, того, этого, кого.

Если после ассимиляции образуются два однотипных согласных, происходит их слияние. В школьной программе по фонетике этот процесс называется стяжение согласных: отделить [ад:’ил’и´т’] → буквы «Т» и «Д» редуцируются в звуки [д’д’], бесшумный [б’иш:у´мный].

При разборе по составу у ряда слов в звукобуквенном анализе наблюдается диссимиляция — процесс обратный уподоблению. В этом случае изменяется общий признак у двух стоящих рядом согласных: сочетание «ГК» звучит как [хк] (вместо стандартного [кк]): лёгкий [л’о′х’к’ий], мягкий [м’а′х’к’ий].

Мягкие согласные в русском языке

В схеме фонетического разбора для обозначения мягкости согласных используется апостроф [’].

- Смягчение парных твердых согласных происходит перед «Ь»;

- мягкость согласного звука в слоге на письме поможет определить последующая за ним гласная буква (е, ё, и, ю, я);

- [щ’], [ч’] и [й] по умолчанию только мягкие;

- всегда смягчается звук [н] перед мягкими согласными «З», «С», «Д», «Т»: претензия [пр’итэн’з’ийа], рецензия [р’ицеэн’з’ийа], пенсия [пэн’с’ийа], ве[н’з’]ель, лице́[н’з’]ия, ка[н’д’]идат, ба[н’д’]ит, и[н’д’]ивид, бло[н’д’]ин, стипе[н’д’]ия, ба[н’т’]ик, ви[н’т’]ик, зо[н’т’]ик, ве[н’т’]илъ, а[н’т’]ичный, ко[н’т’]екст, ремо[н’т’]ировать;

- буквы «Н», «К», «Р» при фонетических разборах по составу могут смягчаться перед мягкими звуками [ч’], [щ’]: стаканчик [стака′н’ч’ик], сменщик [см’э′н’щ’ик], пончик [по′н’ч’ик], каменщик [кам’э′н’щ’ик], бульварщина [бул’ва′р’щ’ина], борщ [бо′р’щ’];

- часто звуки [з], [с], [р], [н] перед мягким согласным претерпевают ассимиляцию по твердости-мягкости: стенка [с’т’э′нка], жизнь [жыз’н’], здесь [з’д’эс’];

- чтобы корректно выполнить звуко буквенный разбор, учитывайте слова исключения, когда согласный [р] перед мягкими зубными и губными, а так же перед [ч’], [щ’] произносится твердо: артель, кормить, корнет, самоварчик;

Примечание: буква «Ь» после согласного непарного по твердости/мягкости в некоторых словоформах выполняет только грамматическую функцию и не накладывает фонетическую нагрузку: учиться, ночь, мышь, рожь и тд. В таких словах при буквенном анализе в квадратных скобках напротив буквы «Ь» ставится [-] прочерк.

Позиционные изменения парных звонких-глухих перед шипящими согласными и их транскрипция при звукобуквенном разборе

Чтобы определить количество звуков в слове необходимо учитывать их позиционные изменения. Парные звонкие-глухие: [д-т] или [з-с] перед шипящими (ж, ш, щ, ч) фонетически заменяются шипящим согласным.

- Буквенный разбор и примеры слов с шипящими звуками: приезжий [пр’ийэ´жжий], восшествие [вашшэ´ств’ийэ], изжелта [и´жжэлта], сжалиться [жжа´л’иц:а].

Явление, когда две разных буквы произносятся как одна, называется полной ассимиляцией по всем признакам. Выполняя звуко-буквенный разбор слова, один из повторяющихся звуков вы должны обозначать в транскрипции символом долготы [:].

- Буквосочетания с шипящим «сж» – «зж», произносятся как двойной твердый согласный [ж:], а «сш» – «зш» — как [ш:]: сжали, сшить, без шины, влезший.

- Сочетания «зж», «жж» внутри корня при звукобуквенном разборе записывается в транскрипции как долгий согласный [ж:]: езжу, визжу, позже, вожжи, дрожжи, жженка.

- Сочетания «сч», «зч» на стыке корня и суффикса/приставки произносятся как долгий мягкий [щ’:]: счет [щ’:о´т], переписчик, заказчик.

- На стыке предлога со следующим словом на месте «сч», «зч» транскрибируется как [щ’ч’]: без числа [б’эщ’ ч’исла´], с чем-то [щ’ч’э′мта].

- При звуко буквенном разборе сочетания «тч», «дч» на стыке морфем определяют как двойной мягкий [ч’:]: лётчик [л’о´ч’:ик], молодчик [мало´ч’:ик], отчёт [ач’:о´т].

Шпаргалка по уподоблению согласных звуков по месту образования

- сч → [щ’:]: счастье [щ’:а´с’т’йэ], песчаник [п’ищ’:а´н’ик], разносчик [разно´щ’:ик], брусчатый, расчёты, исчерпать, расчистить;

- зч → [щ’:]: резчик [р’э´щ’:ик], грузчик [гру´щ’:ик], рассказчик [раска´щ’:ик];

- жч → [щ’:]: перебежчик [п’ир’ибе´ щ’:ик], мужчина [мущ’:и´на];

- шч → [щ’:]: веснушчатый [в’исну′щ’:итый];

- стч → [щ’:]: жёстче [жо´щ’:э], хлёстче, оснастчик;

- здч → [щ’:]: объездчик [абйэ´щ’:ик], бороздчатый [баро´щ’:итый];

- сщ → [щ’:]: расщепить [ращ’:ип’и′т’], расщедрился [ращ’:э′др’илс’а];

- тщ → [ч’щ’]: отщепить [ач’щ’ип’и′т’], отщёлкивать [ач’щ’о´лк’иват’], тщетно [ч’щ’этна], тщательно [ч’щ’ат’эл’на];

- тч → [ч’:]: отчет [ач’:о′т], отчизна [ач’:и′зна], реснитчатый [р’ис’н’и′ч’:и′тый];

- дч → [ч’:]: подчёркивать [пач’:о′рк’иват’], падчерица [пач’:ир’ица];

- сж → [ж:]: сжать [ж:а´т’];

- зж → [ж:]: изжить [иж:ы´т’], розжиг [ро´ж:ык], уезжать [уйиж:а´т’];

- сш → [ш:]: принёсший [пр’ин’о′ш:ый], расшитый [раш:ы´тый];

- зш → [ш:]: низший [н’иш:ы′й]

- чт → [шт], в словоформах с «что» и его производными, делая звуко буквенный анализ, пишем [шт]: чтобы [што′бы], не за что [н’э′ зашта], что-нибудь [што н’ибут’], кое-что;

- чт → [ч’т] в остальных случаях буквенного разбора: мечтатель [м’ич’та´т’ил’], почта [по´ч’та], предпочтение [пр’итпач’т’э´н’ийэ] и тп;

- чн → [шн] в словах-исключениях: конечно [кан’э´шна′], скучно [ску´шна′], булочная, прачечная, яичница, пустячный, скворечник, девичник, горчичник, тряпочный, а так же в женских отчествах, оканчивающихся на «-ична»: Ильинична, Никитична, Кузьминична и т. п.;

- чн → [ч’н] — буквенный анализ для всех остальных вариантов: сказочный [ска´зач’ный], дачный [да´ч’ный], земляничный [з’им’л’ин’и´ч’ный], очнуться, облачный, солнечный и пр.;

- !жд → на месте буквенного сочетания «жд» допустимо двоякое произношение и транскрипция [щ’] либо [шт’] в слове дождь и в образованных от него словоформах: дождливый, дождевой.

Непроизносимые согласные звуки в словах русского языка

Во время произношения целого фонетического слова с цепочкой из множества различных согласных букв может утрачиваться тот, либо иной звук. Вследствие этого в орфограммах слов находятся буквы, лишенные звукового значения, так называемые непроизносимые согласные. Чтобы правильно выполнить фонетический разбор онлайн, непроизносимый согласный не отображают в транскрипции. Число звуков в подобных фонетических словах будет меньшее, чем букв.

В русской фонетике к числу непроизносимых согласных относятся:

- «Т» — в сочетаниях:

- стн → [сн]: местный [м’э´сный], тростник [трас’н’и´к]. По аналогии можно выполнить фонетический разбор слов лестница, честный, известный, радостный, грустный, участник, вестник, ненастный, яростный и прочих;

- стл → [сл]: счастливый [щ’:асл’и´вый’], счастливчик, совестливый, хвастливый (слова-исключения: костлявый и постлать, в них буква «Т» произносится);

- нтск → [нск]: гигантский [г’ига´нск’ий], агентский, президентский;

- стьс → [с:]: шестьсот [шэс:о´т], взъесться [взйэ´с:а], клясться [кл’а´с:а];

- стс → [с:]: туристский [тур’и´с:к’ий], максималистский [макс’имал’и´с:к’ий], расистский [рас’и´с:к’ий], бестселлер, пропагандистский, экспрессионистский, индуистский, карьеристский;

- нтг → [нг]: рентген [р’энг’э´н];

- «–тся», «–ться» → [ц:] в глагольных окончаниях: улыбаться [улыба´ц:а], мыться [мы´ц:а], смотрится, сгодится, поклониться, бриться, годится;

- тс → [ц] у прилагательных в сочетаниях на стыке корня и суффикса: детский [д’э´цк’ий], братский [бра´цкий];

- тс → [ц:] / [цс]: спортсмен [спарц:м’э´н], отсылать [ацсыла´т’];

- тц → [ц:] на стыке морфем при фонетическом разборе онлайн записывается как долгий «цц»: братца [бра´ц:а], отцепить [ац:ып’и´т’], к отцу [к ац:у´];

- «Д» — при разборе по звукам в следующих буквосочетаниях:

- здн → [зн]: поздний [по´з’н’ий], звёздный [з’в’о´зный], праздник [пра′з’н’ик], безвозмездный [б’извазм’э′зный];

- ндш → [нш]: мундштук [муншту´к], ландшафт [ланша´фт];

- ндск → [нск]: голландский [гала´нск’ий], таиландский [таила´нск’ий], нормандский [нарма´нск’ий];

- здц → [сц]: под уздцы [пад усцы´];

- ндц → [нц]: голландцы [гала´нцы];

- рдц → [рц]: сердце [с’э´рцэ], сердцевина [с’ирцыв’и´на];

- рдч → [рч’]: сердчишко [с’эрч’и´шка];

- дц → [ц:] на стыке морфем, реже в корнях, произносятся и при звуко разборе слова записывается как двойной [ц]: подцепить [пац:ып’и´т’], двадцать [два´ц:ыт’];

- дс → [ц]: заводской [завацко´й], родство [рацтво´], средство [ср’э´цтва], Кисловодск [к’иславо´цк];

- «Л» — в сочетаниях:

- лнц → [нц]: солнце [со´нцэ], солнцестояние;

- «В» — в сочетаниях:

- вств → [ств] буквенный разбор слов: здравствуйте [здра´ствуйт’э], чувство [ч’у´ства], чувственность [ч’у´ств’инас’т’], баловство [баластво´], девственный [д’э´ств’ин:ый].

Примечание: В некоторых словах русского языка при скоплении согласных звуков «стк», «нтк», «здк», «ндк» выпадение фонемы [т] не допускается: поездка [пайэ´стка], невестка, машинистка, повестка, лаборантка, студентка, пациентка, громоздкий, ирландка, шотландка.

- Две идентичные буквы сразу после ударного гласного при буквенном разборе транскрибируется как одиночный звук и символ долготы [:]: класс, ванна, масса, группа, программа.

- Удвоенные согласные в предударных слогах обозначаются в транскрипции и произносится как один звук: тоннель [танэ´л’], терраса, аппарат.

Если вы затрудняетесь выполнить фонетический разбор слова онлайн по обозначенным правилам или у вас получился неоднозначный анализ исследуемого слова, воспользуйтесь помощью словаря-справочника. Литературные нормы орфоэпии регламентируются изданием: «Русское литературное произношение и ударение. Словарь – справочник». М. 1959 г.

Использованная литература:

- Литневская Е.И. Русский язык: краткий теоретический курс для школьников. – МГУ, М.: 2000

- Панов М.В. Русская фонетика. – Просвещение, М.: 1967

- Бешенкова Е.В., Иванова О.Е. Правила русской орфографии с комментариями.

- Учебное пособие. – «Институт повышения квалификации работников образования», Тамбов: 2012

- Розенталь Д.Э., Джанджакова Е.В., Кабанова Н.П. Справочник по правописанию, произношению, литературному редактированию. Русское литературное произношение.– М.: ЧеРо, 1999

Теперь вы знаете как разобрать слово по звукам, сделать звуко буквенный анализ каждого слога и определить их количество. Описанные правила объясняют законы фонетики в формате школьной программы. Они помогут вам фонетически охарактеризовать любую букву.

Содержание

- 1 Русский

- 1.1 Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

- 1.2 Произношение

- 1.3 Семантические свойства

- 1.3.1 Значение

- 1.3.2 Синонимы

- 1.3.3 Антонимы

- 1.3.4 Гиперонимы

- 1.3.5 Гипонимы

- 1.4 Родственные слова

- 1.5 Этимология

- 1.6 Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- 1.7 Перевод

- 1.8 Библиография

Русский[править]

| В Викиданных есть лексема кракен (L120466). |

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | кра́кен | кра́кены |

| Р. | кра́кена | кра́кенов |

| Д. | кра́кену | кра́кенам |

| В. | кра́кена | кра́кенов |

| Тв. | кра́кеном | кра́кенами |

| Пр. | кра́кене | кра́кенах |

кра́—кен

Существительное, одушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -кракен-.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: ед. ч. [ˈkrakʲɪn], мн. ч. [ˈkrakʲɪnɨ]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мифол. мифическое морское чудовище гигантских размеров, известное по описаниям исландских моряков ◆ Челюсти кашалота перекусили туловище кракена пополам, тяжелый клюв в последний раз воткнулся в изуродованную китовую пасть. Илья Бояшов, «Путь Мури», 2007 г. [НКРЯ]

Синонимы[править]

- —

Антонимы[править]

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- чудовище

Гипонимы[править]

- —

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

|

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

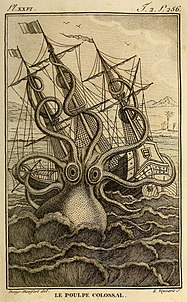

Kraken, an unconfirmed cephalopod.[a] Engraving by W. H. Lizars, in Hamilton, Robert (1839). Naturalist’s Library. Adapted «from Denys Montford» [sic.][3]

The kraken ()[7] is a legendary sea monster of enormous size said to appear off the coasts of Norway.

Kraken, the subject of sailors’ superstitions and mythos, was first described in the modern era in a travelogue by Francesco Negri in 1700. This description was followed in 1734 by an account from Dano-Norwegian missionary and explorer Hans Egede, who described the kraken in detail and equated it with the hafgufa of medieval lore.

However, the first description of the creature is usually credited to the Norwegian bishop Pontoppidan (1753). Pontoppidan was the first to describe the kraken as an octopus (polypus) of tremendous size,[b] and wrote that it had a reputation for pulling down ships. The French malacologist Denys-Montfort, of the 19th century, is also known for his pioneering inquiries into the existence of gigantic octopuses.

The great man-killing octopus entered French fiction when novelist Victor Hugo (1866) introduced the pieuvre octopus of Guernsey lore, which he identified with the kraken of legend. This led to Jules Verne’s depiction of the kraken, although Verne did not distinguish between squid and octopus.

The legend of the Kraken may have originated from sightings of giant squid, which may grow to 12–15 m (40–50 feet) in length.

Linnaeus may have indirectly written about the kraken. Linnaeus wrote about the Microcosmus genus (an animal with various other organisms or growths attached to it, comprising a colony). Subsequent authors have referred to Linnaeus’s writing, and the writings of Bartholin’s cetus called hafgufa, and Paullini’s monstrous marinum as «krakens».[c]

That said, the claim that Linnaeus used the word «kraken» in the margin of a later edition of Systema Naturae has not been confirmed.

Etymology[edit]

The English word «kraken» (in the sense of sea monster) derives from Norwegian kraken or krakjen, which are the definite forms of krake.[7]

According to a Norwegian dictionary, krake, in the sense of «malformed or crooked tree» originates from Old Norse kraki,[8] meaning «pole, stake».[9] And krake in the sense of «sea monster» or «octopus» may share the same etymology.[8] Swedish krake for «sea monster» is also traced to krake meaning «pole».[10]

However Finnur Jónsson remarked that the krake also signified a grapnel (dregg) or anchor, which readily conjured up the image of a cephalopod. He also explained the synonym of krake, namely horv, was an alternative form of harv ‘harrow’ and conjectured that this name was suggested by the inkfish’s action of seeming to plow the sea.[11]

Shetlandic krekin for «whale», a taboo word, is listed as etymologically related.[10][12]

Some of the synonyms of krake given by Erik Pontoppidan were, in Danish:[d] søe-krake, kraxe, horv,[13] krabbe, søe-horv, anker-trold.[14][e][f]

The form krabbe also suggests an etymological root cognate with the German verb krabbeln, ‘to crawl’.[24]

First descriptions[edit]

Two monsters, the ferocious toothed «swine whale», and the horned, flashy-eyed «bearded whale» on Olaus’s map, given specific names by Gesner.[25][26] The «bearded» is possibly a kraken.[27][g] Olaus Magnus, Carta marina (1539)

The first description of the krake as «sciu-crak» was given by Italian writer Negri in Viaggio settentrionale (Padua, 1700), a travelogue about Scandinavia.[29][30] The book describes the sciu-crak as a massive «fish» which was many-horned or many-armed. The author also distinguished this from a sea-serpent.[31]

The kraken was described as a many-headed and clawed creature by Egede (1741)[1729], who stated it was equivalent to the Icelanders’ hafgufa,[32] but the latter is commonly treated as a fabulous whale.[33] Erik Pontoppidan (1753) who popularized the kraken to the world noted that it was multiple-armed according to lore, and conjectured it to be a giant sea-crab, starfish or a polypus (octopus).[34] Still, the bishop is considered to have been instrumental in sparking interest for the kraken in the English-speaking world,[35] as well as becoming regarded as the authority on sea-serpents and krakens.[36]

Although it has been stated that the kraken (Norwegian: krake) was «described for the first time by that name» in the writings of Erik Pontoppidan, bishop of Bergen, in his Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie «The First Attempt at [a] Natural History of Norway» (1752–53),[37] a German source qualified Pontoppidan to be the first source on kraken available to be read in the German language.[38] A description of the kraken had been anticipated by Hans Egede.[39]

Denys-Montfort (1801) published on two giants, the «colossal octopus» with the enduring image of it attacking a ship, and the «kraken octopod», deemed to be the largest organism in zoology. Denys-Montfort matched his «colossal» with Pliny’s tale of the giant polypus that attacked ships-wrecked people, while making correspondence between his kraken and Pliny’s monster called the arbor marina.[h] Finnur Jónsson (1920) also favored identifying the kraken as an inkfish (squid/octopus) on etymological grounds.

Egede[edit]

The krake (English: kraken) was described by Hans Egede in his Det gamle Grønlands nye perlustration (1729; Ger. t. 1730; tr. Description of Greenland , 1745),[40] drawing from the «fables» of his native region, the Nordlandene len [no] of Norway, then under Danish rule.[42][43]

According to his Norwegian informants, the kraken’s body measured many miles in length, and when it surfaced it seemed to cover the whole sea, and «having many heads and a number of claws». With its claws it captured its prey, which included ships, men, fish, and animals, carrying its victims back into the depths.[43]

Egede conjectured that the krake was equitable to the monster that the Icelanders call hafgufa, but as he has not obtained anything related to him through an informant, he had difficuty describing the latter.[32][i]

According to the lore of Norwegian fishermen, they can mount upon the fish-attracting kraken as if it were a sand-bank (Fiske-Grund ‘fishing shoal’), but if they ever had the misfortune to capture the kraken, getting it entangled on their hooks, the only way to avoid destruction was to pronounce its name to make it go back to its depths.[45][46] Egede also wrote that the krake fell under the general category of «sea spectre» (Danish: søe-trold og [søe]-spøgelse),[48] adding that «the Draw» (Danish: Drauen, definite form) was another being within that sea spectre classification.[19][46][j]

Hafgufa[edit]

Egede also made the aforementioned identification of krake as being the same as the hafgufa of the Icelanders,[15][32] though he seemed to have obtained the information indirectly from medieval Norwegian work, the Speculum Regale (or King’s Mirror, c. 1250).[k][51][52][39][15]

Later David Crantz [de] in Historie von Grönland (History of Greenland, 1765) also reported kraken and the hafgufa to be synonymous.[53][54]

An English translator of the King’s Mirror in 1917 opted to translate hafgufa as kraken.[55]

And the hafgufa [l]from the 13th-century Old Norse work[56][57][m] continues to be identified with the kraken in some scholarly writings,[59][15] and if this equivalence were allowed, the kraken-hafgufa’s range would extend, at least legendarily, to waters approaching Helluland (Baffin Island, Canada), as described in Örvar-Odds saga.[60][n]

- Contrary opinion

The description of the hafgufa in the King’s Mirror suggests a garbled eyewitness account of what was actually a whale, at least to some opinion.[61] Halldór Hermannsson [sv] also reads the work as describing the hafgufa as a type of whale.[33]

Finnur Jónsson (1920) having arrived at the opinion that the kraken probably represented an inkfish (squid/octopus), as discussed earlier, expressed his skepticism towards the standing notion that the kraken originated from the hafgufa.[11]

Pontoppidan[edit]

Erik Pontoppidan’s Det første Forsøg paa Norges naturlige Historie (1752, actually volume 2, 1753)[62] made several claims regarding kraken, including the notion that the creature was sometimes mistaken for a group of small islands with fish swimming in-between,[63] Norwegian fishermen often took the risk of trying to fish over kraken, since the catch was so plentiful[64] (hence the saying «You must have fished on Kraken»[65]).

However, there was also the danger to seamen of being engulfed by the whirlpool when it submerged,[66][24] and this whirlpool was compared to Norway’s famed Moskstraumen often known as «the Maelstrom».[67][68]

Pontoppidan also described the destructive potential of the giant beast: «it is said that if [the creature’s arms] were to lay hold of the largest man-of-war, they would pull it down to the bottom».[69][66][24][70]

Kraken purportedly exclusively fed for several months, then spent the following few months emptying its excrement, and the thickened clouded water attracted fish.[71] Later Henry Lee commented that the supposed excreta may have been the discharge of ink by a cephalopod.[72]

Taxonomic identifications[edit]

Pontoppidan wrote of a possible specimen of the krake, «perhaps a young and careless one», which washed ashore and died at Alstahaug in 1680.[70][68][17] He observed that it had long «arms», and guessed that it must have been crawling like a snail/slug with the use of these «arms», but got lodged in the landscape during the process.[73][74] 20th century malacologist Paul Bartsch conjectured this to have been a giant squid,[75] as did literary scholar Finnur Jónsson.[76]

However, what Pontoppidan actually stated regarding what creatures he regarded as candidates for the kraken is quite complicated.

Pontoppidan did tentatively identify the kraken to be a sort of giant crab, stating that the alias krabben best describes its characteristics.[16][77][68][o]

Gorgonocephalus eucnemis.[83] «Shetland Argus», according to Bell; possibly Linnaeus’s caput medusa[e] also;[84][85] this a more far-ranging species.[85]

However, further down in his writing, compares the creature to some creature(s) from Pliny, Book IX, Ch. 4: the sea-monster called arbor, with tree-branch like multiple arms,[p] complicated by the fact that Pontoppidan adds another of Pliny’s creature called rota with eight arms, and conflates them into one organism.[86][87] Pontoppidan is suggesting this is an ancient example of kraken, as a modern commentator analyzes.[88]

Pontoppidan then declared the kraken to be a type of polypus (=octopus)[91] or «starfish», particularly the kind Gesner called Stella Arborescens, later identifiable as one of the northerly ophiurids[92] or possibly more specifically as one of the Gorgonocephalids or even the genus Gorgonocephalus (though no longer regarded as family/genus under order Ophiurida, but under Phrynophiurida in current taxonomy).[96][99]

This ancient arbor (admixed rota and thus made eight-armed) seems an octopus at first blush[100] but with additional data, the ophiurid starfish now appears bishop’s preferential choice.[101]

The ophiurid starfish seems further fortified when he notes that «starfish» called «Medusa’s heads» (caput medusæ; pl. capita medusæ) are considered to be «the young of the great sea-krake» by local lore. Pontoppidan ventured the ‘young krakens’ may rather be the eggs (ova) of the starfish.[102] Pontopiddan was satisfied that «Medusa’s heads» was the same as the foregoing starfish (Stella arborensis of old),[103] but «Medusa’s heads» were something found ashore aplenty across Norway according to von Bergen, who thought it absurd these could be young «Kraken» since that would mean the seas would be full of (the adults).[104][105] The «Medusa’s heads» appear to be a Gorgonocephalid, with Gorgonocephalus spp. being tentatively suggested.[106][q]

[110][112]

In the end though, Pontoppidan again appears ambivalent, stating «Polype, or Star-fish [belongs to] the whole genus of Kors-Trold [‘cross troll’], .. some that are much larger, .. even the very largest.. of the ocean», and concluding that «this Krake must be of the Polypus kind».[113] By «this Krake» here, he apparently meant in particular the giant polypus octopus of Carteia from Pliny, Book IX, Ch. 30 (though he only used the general nickname «ozaena» ‘stinkard’ for the octopus kind).[87][114][r]

Denys-Montfort[edit]

In 1802, the French malacologist Pierre Denys-Montfort recognized the existence of two «species» of giant octopuses in Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques, an encyclopedic description of mollusks.[4]

The «colossal giant» was supposedly the same as Pliny’s «monstrous polypus»,[115][116] which was a man-killer which ripped apart (Latin: distrahit) shipwrecked people and divers.[119][120] Montfort accompanied his publication with an engraving representing the giant octopus poised to destroy a three-masted ship.[4][121]

Whereas the «kraken octopus», was the most gigantic animal on the planet in the writer’s estimation, dwarfing Pliny’s «colossal octopus»/»monstrous polypus»,[122][123] and identified here as the aforementioned Pliny’s monster, called the arbor marinus.[124]

Montfort also listed additional wondrous fauna as identifiable with the kraken.[125]

[126] There was Paullini’s monstrum marinum glossed as a sea crab (German: Seekrabbe),[127] which a later biologist has suggested to be one of the Hyas spp.[128] It was also described as resembling Gesner’s Cancer heracleoticus crab alleged to appear off the Finnish coast.[127][123] von Bergen’s «bellua marina omnium vastissima» (meaning ‘vastest-of-all sea-beast’), namely the trolwal (‘ogre whale’, ‘troll whale’) of Northern Europe, and the Teufelwal (‘devil whale’) of the Germans follow in the list.[129][126]

Angola octopus, pictured in St. Malo[edit]

It is in his chapter on the «colossal octopus» that Montfort provides the contemporary eyewitness example of a group of sailors who encounter the giant off the coast of Angola, who afterwards deposited a pictorial commemoration of the event as a votive offering at St. Thomas’s chapel in Saint-Malo, France.[130] Based on that picture, Montfort drew a «colossal octopus» attacking a ship, and included the engraving in his book.[5][6] However, an English author recapitulating Montfort’s account of it attaches an illustration of it, which was captioned: «The Kraken supposed a sepia or cuttlefish», while attributing Montfort.[131]

Hamilton’s book was not alone in recontextualizing Montfort’s ship-assaulting colossal octopus as a kraken, for instance, the piece on the «kraken» by American zoologist Packard.[132]

The Frenchman Montfort used the obsolete scientific name Sepia octopodia but called it a pouple,[133] which means «octopus» to this day; meanwhile the English-speaking naturalists had developed the convention of calling the octopus «eight-armed cuttle-fish», as did Packard[2] and Hamilton,[3] even though modern-day speakers are probably unfamiliar with that name.

Warship Ville de Paris[edit]

The Niagara sighting. 60-metre (200 ft) creature allegedly seen afloat in 1813, depicted as octopus by a naturalist

Having accepted as fact that a colossal octopus was capable of dragging a ship down, Montfort made a more daring hypothesis. He attempted to blame colossal octopuses for the loss of ten warships under British control in 1782, including six captured French men-of-war. The disaster began with the distress signal fired by the captured ship of the line Ville de Paris which was then swallowed up by parting waves, and the other ships coming to aid shared the same fate. He proposed, by process of elimination, that such an event could only be accounted for as the work of many octopuses.[134][135][136]

But it has been pointed out the sinkings have simply been explained by the presence of a storm,[121] and Montfort’s involving octopuses as complicit has been characterized as «reckless falsity».[136]

It has also been noted that Montfort once quipped to a friend, DeFrance: «If my entangled ship is accepted, I will make my ‘colossal poulpe’ overthrow a whole fleet».[137][138][2]

Niagara[edit]

The ship Niagara on course from Lisbon to New York in 1813 logged a sighting of a marine animal spotted afloat at sea. It was claimed to be 60 m (200 feet) in length, covered in shells, and had many birds alighted upon it.

Samuel Latham Mitchill reported this, and referencing Montfort’s kraken, reproduced an illustration of it as an octopus.[139]

Linnaeus’s microcosmus[edit]

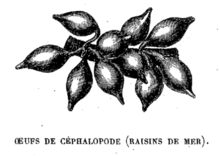

Sea-grapes, or cephalopod eggs

The famous Swedish 18th century naturalist Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae (1735) described a fabulous genus Microcosmus a «body covered with various heterogeneous [other bits]» (Latin: Corpus variis heterogeneis tectum).[128][140][141][s]

Linnaeus cited four sources under Microcosmus, namely:[t][128][143] Thomas Bartholin’s cetus (≈whale) type hafgufa;[145] Paullin’s monstrum marinum aforementioned;[127] and Francesco Redi’s giant tunicate (Ascidia[128]) in Italian and Latin.[146][147]

According to the Swedish zoologist Lovén, the common name kraken was added to the 6th edition of Systema Naturae (1748),[128] which was a Latin version augmented with Swedish names[148] (in blackletter), but such Swedish text is wanting on this particular entry, e.g. in the copy held by NCSU.[142] It is true that the 7th edition of 1748, which adds German vernacular names,[148] identifies the Microcosmus as «sea-grape» (German: Meertrauben), referring to a cluster of cephalopod eggs.[149][150][u][v]

Also, the Frenchman Louis Figuier in 1860 misstated that Linnaeus included in his classification a cephalopod called «Sepia microcosmus«[w] in his first edition of Systema Naturae (1735).[154] Figuier’s mistake has been pointed out, and Linnaeus never represented the kraken as such a cephalopod.[155] Nevertheless, the error has been perpetuated by even modern-day writers.[157]

Linnaeus in English[edit]

Thomas Pennant, an Englishman, had written of Sepia octopodia as «eight-armed cuttlefish» (we call it octopus today), and documented reported cases in the Indian isles where specimen grow to 2 fathoms [3.7 m; 12 ft] wide, «and each arms 9 fathoms [16 m; 54 ft] long».[2][1] This was added as a species Sepia octopusa [sic.] by William Turton in his English version of Linnaeus’s System of Nature, together with the account of the 9-fathom-long (16 m; 54 ft) armed octopuses.[2][158]

The trail stemming from Linnaeus, eventually leading to such pieces on the kraken written in English by the naturalist James Wilson for the Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1818 sparked an awareness of the kraken among 19th century English, hence Tennyson’s poem, «The Kraken».[59]

Iconography[edit]

«Kraken of the imagination». John Gibson, 1887.[159]

As to the iconography, Denys-Montfort’s engraving of the «colossal octopus» is often shown, though this differs from the kraken according to the French malacologist,[5] and commentators are found characterizing the ship attack representing the «kraken octopod».[2][160]

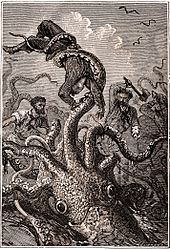

And after Denys-Monfort’s illustration, various publishers produced similar illustrations depicting the kraken attacking a ship.[3][159]

Whereas the kraken was described by Egede as having «many Heads and a Number of Claws», the creature is also depicted to have spikes or horns, at least in illustrations of creatures which commentators have conjectured to be krakens. The «bearded whale» shown on an early map (pictured above) is conjectured to be a kraken perhaps (cf. §Olaus Magnus below). Also, there was an alleged two-headed and horned monster that beached ashore in Dingle, Co. Kerry, Ireland, thought to be a giant cephalopod, of which there was a picture/painting made by the discoverer.[161] He made a travelling show of his work on canvas, as introduced in a book on the kraken.[162]

Olaus Magnus[edit]

Monster «M». Carta marina (1539), detail.

Giant lobster attacking ship. Lee, Henry (1884), p. 58, after Olaus Magnus (1555), Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus.

«Kraken is represented as a Crayfish or Lobster»[163]

Giant fish encountered by St. Brendan. «Insula Fortunata» marked near it.[164]

While Swedish writer Olaus Magnus did not use the term kraken, various sea-monsters were illustrated on his famous map, the Carta marina (1539). Modern writers have since tried to interpret various sea creatures illustrated as a portrayal of the kraken.

Olaus gives description of a whale with two elongated teeth («like a boar’s or elephant’s tusk») to protect its huge eyes, which «sprouts horns», and although these are as hard as horn, they can be made supple also.[165][28] But the tusked form was named «swine-whale» (German: Schweinwal), and the horned form «bearded whale» (German: Bart-wal) by Swiss naturalist Gesner, who observed it possessed a «starry beard» around the upper and lower jaws.[166][26] At least one writer has suggested this might represent the kraken of Norwegian lore.[27]

Another work commented less discerningly that Olaus’s map is «replete with imagery of krakens and other monsters».[15]

Ashton’s Curious Creatures (1890) drew significantly from Olaus’s work[167] and even quoted the Swede’s description of the horned whale.[168] But he identified the kraken as a cephalopod and devoted much space on Pliny’s and Olaus’s descriptions of the giant «polypus»,[169] noting that Olaus had represented the kraken-polypus as a crayfish or lobster in his illustrations, [170] and reproducing the images from both Olaus’s book[171][165][28] and his map.[172][173] In Olaus book, the giant lobster illustration is uncaptioned, but appears right above the words «De Polypis (on the octopus)», which is the chapter heading.[165] Hery Lee was also of the opinion that the multi-legged lobster was a misrepresentation of a reported cephalopod attack on a ship.[174]

The legend in Olaus’s map fails to clarify on the lobster-like monster «M»,[x] depicted off the island of Iona.[y][176] However, the associated writing called the Auslegung adds that this section of the map extends from Ireland to the «Insula Fortunata».[177] This «Fortunate Island» was a destination on St. Brendan’s Voyage, one of whose adventures was the landing of the crew on an island-sized monstrous, as depicted in a 17th century engraving (cf. figure right);[179] and this monstrous fish, according to Bartholin was the aforementioned hafgufa,[145] which has already been discussed above as one of the creatures of lore equated with kraken.

Giant squid[edit]

The piece of squid recovered by the French ship Alecton in 1861, discussed by Henry Lee in his chapter on the «Kraken»,[180] would later be identified as a giant squid, Architeuthis by A. E. Verrill.[181]

After a specimen of the giant squid, Architeuthis, was discovered by Rev. Moses Harvey and published in science by Professor A. E. Verrill, commentators have remarked on this cephalopod as possibly explaining the legendary kraken.[182][183][184]

Paleo-cephalopod[edit]

An ancient, giant cephalopod resembling the legendary kraken has been proposed as responsible for the deaths of ichthyosaurs during the Triassic Period.[185] This theory has met with severe criticism.[186]

Literary influences[edit]

The French novelist Victor Hugo’s Les Travailleurs de la mer (1866, «Toilers of the Sea») discusses the man-eating octopus, the kraken of legend, called pieuvre by the locals of the Channel Islands (in the Guernsey dialect, etc.).[187][188][z] Hugo’s octopus later influenced Jules Verne’s depiction of the kraken in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,[190] though Verne also drew on the real-life encounter the French ship Alecton had with what was probably a giant squid.[191] It has been noted that Verne indiscriminately interchanged kraken with calmar (squid) and poulpe (octopus).[192]

In the English-speaking world, examples in fine literature are Alfred Tennyson’s 1830 irregular sonnet The Kraken,[193] references in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick (Chapter 59 «Squid»),[194]

In popular culture[edit]

Although fictional and the subject of myth, the legend of the Kraken continues to the present day, with numerous references in film, literature, television, and other popular culture topics.[195]

Examples include: John Wyndham’s novel The Kraken Wakes (1953), the Kraken of Marvel Comics, the 1981 film Clash of the Titans and its 2010 remake of the same name, and the Seattle Kraken professional ice hockey team. Krakens also appear in video games such as Sea of Thieves, God of War II and Return of the Obra Dinn. The kraken was also featured in two of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, primarily in the 2006 film, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, as the pet of the fearsome Davy Jones, the main antagonist of the film. The kraken also makes an appearance in the film’s sequel, At World’s End.

See also[edit]

- Akkorokamui

- Cetus

- Cthulhu

- Globster

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Caption: «The Kraken, supposed a sepia or cuttlefish from Denys Montford» [sic.]». Sepia was formerly the genus that octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish (cephalopods) were all assigned to. Thus «eight-armed cuttle-fish» became the standardized name for «octopus».[1][2]

- ^ He vacillated between polypus and «star fish» however.

- ^ Denys-Montfort’s footnote identified his kraken with Paullini’s monstrum marinum also, leading Samuel Latham Mitchill to comment that «Linnaeus considered the Kraken as a real existence», publishing it under Microcosmus.

- ^ Pontoppidan of course wrote in Danish, the standard literary language for Norwegians at the time, though words like krake were presumably taken down from the mouths of the native Norwegian populace.

- ^ With definite article suffixed forms such as Kraxen or Krabben[15] appearing in the English translation.[16]

- ^ Pontopoppidan’s «Soe-draulen, Soe-trolden, Sea-mischief» has been frequently requoted,[17][18] but these terms can be deferred to Egede’s explanation (discussed further, below) that employs søe-trold as a general classification, under which krake and the søe-drau fall.[19] The word drau as a variant of draug was recognized by Pontoppidan as meaning ‘spøgelse ghost, spectre’,[20] and the latter form draug is defined more specifically as a being associated with sea or water in modern Norwegian dictionaries.[21] The «Sea-mischief» appears in the English translation[22] but is absent in the original.[23]

- ^ The two are changing forms of just one beast, which has both tusks and protrusible horns to protect its large eyes, according to Olaus’s book.[28]

- ^ And other fabulous-seeming creatures, such as monstrum marinum, bellua marina omnium vastissima, etc.

- ^ Machan quoted Egede’s text proper regarding some sort of «Bæst«[15] or «forfærdelige Hav-Dyr [terrible sea-animal]» witnessed in the Colonies (Greenland),[19] but ignored the footnote which tells much on the krake. Ruickbie quoted Egede’s footnote, but decided to place it under his entry for «Hafgufa».[44]

- ^ Reference to the sea spectre («phantom») was added in the English margin header: «A Norway Tale of Kraken, a pretended phantom»,[49] but that reference is wanting in the Danish original. It was already noted that the original wording localizes the legend specifically to Nordlandene len [no], not Norway altogether.

- ^ Speculum Regale Islandicum after Thormodus Torfæus, as elocuted by Egede. The Speculum contains a detailed digression about whales and seals in the seas around Iceland and Greenland,[50] where one finds description of the hafgufa.

- ^ Described as the largest of the sea monsters, inhabiting the Greenland Sea

- ^ Bushnell speaks of Icelandic literature (in the 13th century) also, but strictly speaking, Örvar-Odds saga contains the mention of hafgufa and lyngbakr[58] only in the later recension, dated to the late 14th century.

- ^ Mouritsen & Styrbæk (2018) (book on inkfish) distinguishes the whale lyngbakr with the monster hafgufa.

- ^ Cf. kraken aka «the crab-fish» (Swedish: Krabbfisken) described by Swedish magnate Jacob Wallenberg [sv] in Min son på galejan («My son on the galley», 1781):

Kraken, also called the crab-fish, which is not that huge, for heads and tails counted, he is reckoned not to overtake the length of our Öland off Kalmar [i.e., 85 mi or 137 kilometres] … He stays at the sea floor, constantly surrounded by innumerable small fishes, who serve as his food and are fed by him in return: for his meal, (if I remember correctly what E. Pontoppidan writes,) lasts no longer than three months, and another three are then needed to digest it. His excrements nurture in the following an army of lesser fish, and for this reason, fishermen plumb after his resting place … Gradually, Kraken ascends to the surface, and when he is at ten to twelve fathoms [18 to 22 m; 60 to 72 ft] below, the boats had better move out of his vicinity, as he will shortly thereafter burst up, like a floating island, gushing out currnts like at Trollhättan [Trollhätteströmmar], his dreadful nostrils and making an ever-expanding ring of whirlpool, reaching many miles around. Could one doubt that this is the Leviathan of Job?[78][79]

- ^ This is called arbor marinus by Denys-Montfort, and equated with his kraken octopus, as discussed below.

- ^ Actually there is even the species «Gorgon’s head» Astrocladus euryale, whose old name was Asterias euryale,[107] which Blumenbach claimed was one of the species that Scandinavian naturalists considered kraken’s children.[108] But A. euryale inhabits South African waters. Blumenbach also named Euryale verrucosum, old name of Astrocladus exiguus[109] which occur in the Pacific.

- ^ The ozaena nickname as literally ‘stinkard’ for the octopus on account of its reek is given in the side-by-sidy translation by Gerhardt. The polypus of Carteia tract, is thus given, but the Latin quoted by Pontoppidan «»Namque et afflatu terribli canes agebat..» is blanked Gerhardt and only given in modern English, «were pitted against something uncanny, for by its awful breath it tormented the dogs, which it now scourged with the ends of its tentacles».. because it represents an interpolation by Pliny.

- ^ Lovén gave the text as tegmen ex heterogeneis compilatis,[128] but this reading occurs in the Latin-Swedish 6th edition of 1748.[142] Whereas the 2nd edition has «testa» instead of «tegmen».[143]

- ^ Lóven indicates that these sources appeared in print in the second edition of SN, but as a piece of marginalia, he notes these sources were also given in Linnaeus’s 1733 lectures.[128] The lecture was preserved in the Notes taken by Mennander, held by the Royal Library, Stockholm.[144]

- ^ «Meer=Trauben» already appeared in the 1740 Latin-German edition.[141] The 9th edition of 1956, which is said to be the same as the 6th edition,[148] also leaves a blanc instead of adding the French vernacular name.[151]

- ^ An illustration of sea-grapes (French: raisins de mer) appears on Moquin-Tandon (1865), p. 309.

- ^ As noted previously, Sepia genus represents cuttlefish in modern taxonomy, Linnaeus’s genus Sepia was essentially «cephalopods», and his Sepia octopodia was the common octopus.[152][153]

- ^ However, elsewhere on the map, the giant lobster is called a lobster (Medieval Latin: gambarus > Latin: cammarus > Ancient Greek: κάμμαρος) in the legend; this is the one shown struggling with a one-horned beast.[175]

- ^ Iona is of course associated with the Irish saints, Columcille and St. Brendan.

- ^ Hugo also produced an ink and wash sketch of the octopus.[189]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Pennant, Thomas (1777). «Sepia». British ZoologyIV: Crustacea. Mollusca. Testacea. Benjamin White. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c d e f g Packard, A. S. (March 1872). «Kraken». The Connecticut School Journal. 2 (3): 78–79. JSTOR 44648937.

- ^ a b c Hamilton (1839). Plate XXX, p. 326a.

- ^ a b c Denys-Montfort (1801), p. 256, Pl. XXVI.

- ^ a b c Lee (1875), pp. 100–103.

- ^ a b Nigg (2014), p. 147: «The hand-colored woodcut is a reproduction of art in the Church of St. Malo in France».

- ^ a b «kraken». Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. V (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. 1933. p. 754.

Norw. kraken, krakjen, the -n, being the suffixed definite article

= A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (1901), V: 754 - ^ a b «kraken». Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka.

- ^ Cleasby & Vigfusson (1874), An Icelandic-English Dictionary, s.v. «https://books.google.com/books?id=ne9fAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA354&q=kraki+kraki» ‘[Dan. krage], a pole, stake’

- ^ a b «krake». Svenska Akademiens ordbok (in Swedish).

- ^ a b Finnur Jónsson (1920), pp. 113–114.

- ^ Jakobsen, Jakob (1921), «krekin, krechin», Etymologisk ordbog over det norrøne sprog på Shetland, Prior, p. 431; Cited in Collingwood, W. G. (1910). Review, Antiquary 46: 157

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), p. xvi(?)

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), p. 340.

- ^ a b c d e f Machan, Tim William (2020). «Ch. 5. Narrative, Memory, Meaning /§Kraken». Northern memories and the English Middle Ages. David Matthews, Anke Bernau, James Paz. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-5261-4537-6.

- ^ a b Pontoppidan (1755), p. 210.

- ^ a b Metropolitana (1845), p. 256.

- ^ W[ilson] (1818), p. 647.

- ^ a b c Egede (1741), p. 49.

- ^ Knudsen, Knud (1862). Er Norsk det samme som Dansk?. Christiania: Steenske Bogtrykkeri. p. 41).

- ^ «draug». Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1755), p. 214.

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a), pp. 346–347: Danish: .. krake, hvilken nongle Søe-fokl ogsaa kalde Søe-Draulen, det er Søe-Trolden

- ^ a b c [Anonymous] (1849). (Review) New Books: An Essay on the credibility of the Kraken. The Nautical Magazine 18(5): 272–276.

- ^ Olaus Magnus (1887) [1539], Brenner, Oscar [in German] (ed.), «Die ächte Karte des Olaus Magnus vom Jahre 1539 nach dem Exemplar de Münchener Staatsbibliothek», Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-selskabet i Christiania, Trykt hos Brøgger & Christie, p. 7,

monstra duo marina maxima vnum dentibus truculentum, alterum cornibus et visu flammeo horrendum / Cuius oculi circumferentia XVI vel XX pedum mensuram continet

- ^ a b Gesner, Conrad (1670). Fisch-Buch. Gesnerus redivivus auctus & emendatus, oder: Allgemeines Thier-Buch 4. Frankfurt-am-Main: Wilhelm Serlin. pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b Nigg, Joseph (2014). «The Kraken». Sea Monsters: A Voyage around the World’s Most Beguiling Map. David Matthews, Anke Bernau, James Paz. University of Chicago Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-226-92518-9.

- ^ a b c Olaus Magnus (1998). Foote, Peter (ed.). Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus: Romæ 1555 [Description of the Northern Peoples : Rome 1555]. Fisher, Peter;, Higgens, Humphrey (trr.). Hakluyt Society. p. 1092. ISBN 0-904180-43-3.

- ^ Eberhart, George M. (2002). «Kraken». Mysterious Creatures: A Guide to Cryptozoology. ABC-CLIO. p. 282ff. ISBN 1-57607-283-5.

- ^ Beck, Thor Jensen (1934), Northern Antiquities in French Learning and Literature (1755-1855): A Study in Preromantic Ideas, vol. 2, Columbia university, p. 199, ISBN 5-02-002481-3,

Before Pontoppidan , the same » Krake » had been taken very seriously by the Italian traveler , Francesco Negri

- ^ Negri, Francesco (1701) [1700], Viaggio settentrionale (in Italian), Forli, pp. 184–185,

Sciu-crak è chiamato un pesce di smisurata grandezza, di figura piana , rotonda , con molte corna o braccia alle sue estremità

- ^ a b c Egede (1741). p. 48: «Det 3die Monstrum, kaldet Havgufa som det allerforunderligte, veed Autor ikke ret at beskrive» p. 49: » af dennem kaldes Kraken, og er uden Tvil den self jamm; som Islænderne kalde Havgufa»; Egede (1745). p. 86: «The third monster, named Hafgufa.. the Author does not well know ow to describe.. he never had any relation of it.» p. 87: «Kracken.. no doubt the same that the Islanders call Hafgufa«

- ^ a b Halldór Hermannsson (1938), p. 11: Speculum regiae of the 13th century describes a monstrous whale which it calls hafgufa… The whale as an island was, of course, known from the Saga of St. Brandan, but there it was called Jaskonius».

- ^ Pontoppidan (1753a) (Danish); Pontoppidan (1755) (English); vid. infra.

- ^ Bushnell (2019), p. 56: «Nineteenth-century English interest in the Kraken stems from Linnaeus’s discussion of the creature in the first edition of Systema Naturae (1735) and most famously from Natural History of Norway (1752-3) by the Bishop.. Pontoppidan (translated into English soon after)».

- ^ Oudemans (1892), p. 414.

- ^ Anderson, Rasmus B. (1896). Kra’ken. Johnson’s Universal Cyclopædia. Vol. 5 (new ed.). D. Appletons. p. 26.

- ^ Müller (1802), p. 594: «Der norwegische Bischoff Pontoppidan ist der erster, welcher uns einer umständliche und deutsche Nachricht von diesem Seethier gegeben hat».

- ^ a b Kongelige nordiske oldskrift-selskab, ed. (1845). Grönlands historiske Mindesmaerker. Vol. 3. Brünnich. p. 371, note 52).

- ^ Pilling, James Constantine (1885). Proof-sheets of a Bibliography of the Languages of the North American Indians. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnology: Miscellaneous publications 2. U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 226–227.

- ^ Egede (1741), p. 49 (footnote).

- ^ The marginal header in the original is «Fabel om Kraken i Nordlandene«[41] which refers specifically to the len of Nordland under Danish rule; this is not just modern Norway’s Nordland county, but includes the counties that lies farther north. Egede was born in Harstad, in Nordland (len) during his life, but the town is now part of Troms og Finnmark, Norway.