Слово «оксфорд»

Слово состоит из 7 букв, начинается на гласную, заканчивается на согласную, первая буква — «о», вторая буква — «к», третья буква — «с», четвёртая буква — «ф», пятая буква — «о», шестая буква — «р», последняя буква — «д».

- Синонимы к слову

- Написание слова наоборот

- Написание слова в транслите

- Написание слова шрифтом Брайля

- Передача слова на азбуке Морзе

- Произношение слова на дактильной азбуке

- Фразы со слова

- Остальные слова из 7 букв

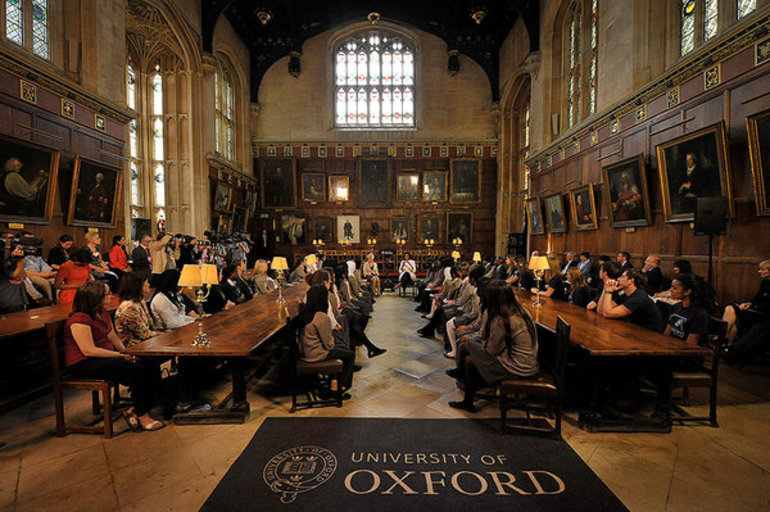

Ислам vs Атеизм Оксфордские дебаты:»Объясняет ли Ислам реальность лучше,чем атеизм?»

ОКСФОРДСКИЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ обзор. Колледжи Оксфордского Университета

Ужасы общежития Оксфорда / Вся правда про общагу Оксфордского Университета

КАК ПОСТУПИТЬ В ОКСФОРД И ВЫИГРАТЬ СТИПЕНДИЮ. Моя история

Непутевые заметки. Великобритания: Оксфорд и места Гарри Поттера. Выпуск от 29.10.2017

Один день ученика Оксфорда / дом моей host family, Kaplan International

Синонимы к слову «оксфорд»

Какие близкие по смыслу слова и фразы, а также похожие выражения существуют. Как можно написать по-другому или сказать другими словами.

Фразы

- + аттестат зрелости −

- + диплом юриста −

- + завершает обучение −

- + изучать математику −

- + изучать право −

- + королевский адвокат −

- + лига плюща −

- + магистр гуманитарных наук −

- + магистр делового администрирования −

- + молодые джентльмены −

- + палата общин −

- + пасхальные каникулы −

- + подготовительная школа −

- + последний семестр −

- + поступить в университет −

- + преподобный мистер −

- + пресвитерианская церковь −

- + светский сезон −

- + сдать экзамен −

- + степень бакалавра искусств −

- + сын сэра −

- + теологический факультет −

- + университетский колледж −

- + частные школы −

Ваш синоним добавлен!

Написание слова «оксфорд» наоборот

Как это слово пишется в обратной последовательности.

дрофско 😀

Написание слова «оксфорд» в транслите

Как это слово пишется в транслитерации.

в армянской🇦🇲 ոկսֆորդ

в греческой🇬🇷 οξφορδ

в грузинской🇬🇪 ოკსფორდ

в еврейской🇮🇱 וכספורד

в латинской🇬🇧 oksford

Как это слово пишется в пьюникоде — Punycode, ACE-последовательность IDN

xn--d1allbkev

Как это слово пишется в английской Qwerty-раскладке клавиатуры.

jrcajhl

Написание слова «оксфорд» шрифтом Брайля

Как это слово пишется рельефно-точечным тактильным шрифтом.

⠕⠅⠎⠋⠕⠗⠙

Передача слова «оксфорд» на азбуке Морзе

Как это слово передаётся на морзянке.

– – – – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ ⋅ – ⋅ – – – ⋅ – ⋅ – ⋅ ⋅

Произношение слова «оксфорд» на дактильной азбуке

Как это слово произносится на ручной азбуке глухонемых (но не на языке жестов).

Передача слова «оксфорд» семафорной азбукой

Как это слово передаётся флажковой сигнализацией.

Фразы со слова «оксфорд»

Какие фразы начинаются с этого слова.

- оксфорд — кембридж

Ваша фраза добавлена!

Остальные слова из 7 букв

Какие ещё слова состоят из такого же количества букв.

- аа-лава

- ааленец

- ааронов

- аахенец

- аба-ван

- аба-вуа

- абадзех

- абазгия

- абазины

- абакост

- абакумы

- абандон

- абацист

- аббатов

- абгаллу

- абдалов

- абдерит

- абдомен

- абдулла

- абевега

- абелева

- абелево

- абессив

- абиетин

×

Здравствуйте!

У вас есть вопрос или вам нужна помощь?

Спасибо, ваш вопрос принят.

Ответ на него появится на сайте в ближайшее время.

Народный словарь великого и могучего живого великорусского языка.

Онлайн-словарь слов и выражений русского языка. Ассоциации к словам, синонимы слов, сочетаемость фраз. Морфологический разбор: склонение существительных и прилагательных, а также спряжение глаголов. Морфемный разбор по составу словоформ.

По всем вопросам просьба обращаться в письмошную.

Морфемный разбор слова:

Однокоренные слова к слову:

существительное

Мои примеры

Словосочетания

Примеры

Oxford University

He went up to Oxford.

Он поступил в Оксфордский университет.

A single to Oxford, please.

Один билет до Оксфорда, пожалуйста.

Sarah came down from Oxford in 1966.

Сара закончила Оксфорд в 1966 году.

Oxford is an ancient seat of learning

Did he graduate at Oxford or Cambridge?

Он окончил университет в Оксфорде или Кембридже?

Oxford bags

«оксфордские мешки» (свободные, мешковатые брюки, популярные в 20х-50х годах у студентов Оксфорда)

Oxford Circus

Оксфорд-Серкус, Оксфордская площадь

Oxford junior encyclopaedia

Оксфордский энциклопедический словарь для юношества

I came back from Oxford in ten days.

Через десять дней я вернулся из Оксфорда.

Secret files reveal an Oxford spy ring.

Секретные файлы разоблачают оксфордскую шпионскую сеть.

It is eleven miles from Oxford to Witney.

От Оксфорда до Уитни одиннадцать миль.

We decided to break our journey in Oxford.

Мы решили ненадолго прервать наше путешествие в Оксфорде.

Hulme was a student at Oxford in the 1960s.

В шестидесятых годах Халм учился в Оксфорде.

We could drive over to Oxford this afternoon.

Мы могли бы сегодня днём заехать в Оксфорд.

He was a bright, brisk lad, fresh from Oxford.

Это был весёлый, живой молодой человек, совсем недавно окончивший Оксфорд.

On the M40, there are lane closures near Oxford.

На трассе M40, в районе Оксфорда, частично перекрыто движение.

The Oxford crew won by three and a half lengths.

Команда гребцов Оксфорда выиграла гонки с преимуществом в три с половиной корпуса.

The Cherwell joins the Thames just below Oxford.

Черуэлл впадает в Темзу чуть ниже Оксфорда.

Sheila enjoyed her years as a student in Oxford.

Шейле очень понравились годы учёбы, проведённые в Оксфорде.

The whole idea of going to Oxford intimidated me.

Сама мысль о поездке в Оксфорд пугала меня.

He has come down from Oxford with a history degree.

Он только что окончил Оксфорд с дипломом историка.

I bumped into her quite by chance in Oxford Street.

Я совершенно случайно столкнулся с ней на Оксфорд-Стрит.

Он только что окончил Оксфорд с дипломом историка.

There are only two old colours in the new Oxford team.

В новой оксфордской команде есть только два «старика».

Students from all over the world come to study at Oxford.

Студенты со всего мира приезжают учиться в Оксфорд.

It was a pity he mured himself up in his college at Oxford.

Жаль, что он заточил себя в своём колледже в Оксфорде.

Примеры, ожидающие перевода

Judith studied classics at Oxford.

. an Oxford don who’s definitely a pernickety old chap.

It is a professional service based at our offices in Oxford.

Источник

Преимущества обучения

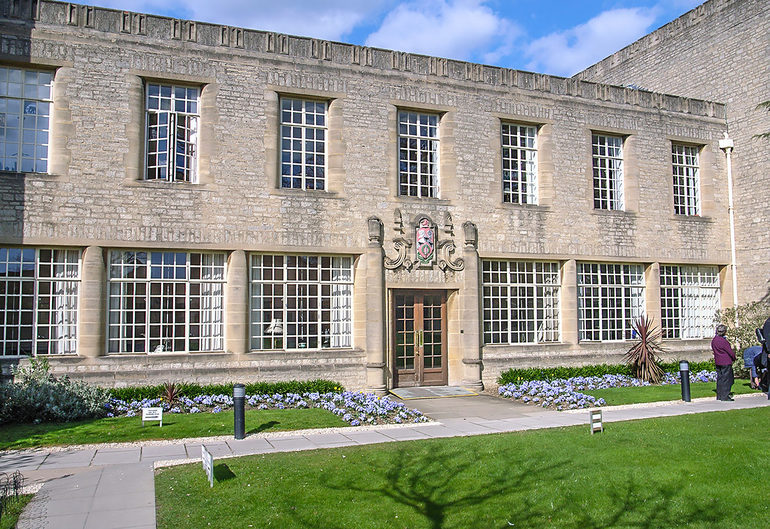

Прежде чем рассказать об уникальном университете Великобритании, да и, пожалуй, всего мира, важно узнать, где находится Оксфорд. Вуз расположен в живописном городе с одноименным названием, который является центром графства Оксфордшир, всего в 90 км от Лондона.

Невозможно перечислить все преимущества получения образования в Оксфордском университете. Вот лишь некоторые из них:

Все эти интересные факты об Оксфордском университете ежегодно привлекают в него сотни тысяч выпускников лучших школ мира. Кроме того, люди, окончившие вуз, будут востребованы на рынке труда в любой развитой стране мира.

Краткая история создания

В 1074 году церковью святого Георгия был основан колледж светских законов. Именно с этого момента началась многовековая история Оксфорда. На протяжении последующих 12 столетий колледж служил магнитом для различных религиозных центров.

В 1167 году король Англии Генрих отозвал из Франции всех обучавшихся там студентов, запретив им в дальнейшем возвращаться на чужбину. Из-за этого первым учащимся не оставалось ничего, кроме как продолжить обучение в Оксфорде.

Согласно одной из знаменитых университетских легенд, основателем величайшего вуза мира был Альфред Великий, любивший вести с монахами ученые беседы. Легенда называет 872 год в качестве примерной даты основания университета, однако официальных подтверждений этому нет.

В XIII—XIV вв. история Оксфордского университета разворачивалась стремительно. В XIII столетии была заложена основа для последующей системы колледжей (первоначально их было 10, в наши дни их количество достигло 38). На их территории студенты и получали образование.

Самыми старинными колледжами являются Баллиол и Мертон. Оба были основаны в 1264 году. Несмотря на почтенный возраст, эти колледжи и по сей день продолжают свою работу, посвященную обучению и организации жизни студентов внутри вуза.

В XIV веке университет стал средоточием научных и образовательных ресурсов Великобритании, а также неизменным центром научных, теологических и идеологических диспутов.

Именно в эту золотую эпоху развития в нем появилась должность канцлера (руководителя учебного заведения). Эта ответственная и почетная должность в Оксфорде никогда не прекращала своего существования на протяжении всей многовековой истории учебного заведения.

Кроме того, сотрудники вуза, как и его студенты и преподаватели, получили неприкосновенность при столкновениях с городскими властями. Им была предоставлена солидная скидка на оплату проживания в кампусе. Для студентов и преподавателей действовали бессрочные скидки на учебники, канцелярские товары и продукты питания.

Интересным можно считать тот факт, что до 1878 года право на обучение в Оксфорде имели исключительно мужчины.

Структура и факультеты

Университет представляет собой систему колледжей, каждый из которых является центром самоуправления. Он выполняет административные функции, в которым относятся составление графиков лекций, экзаменов и практических занятий, принятие экзаменов у студентов и предоставление учащимся аудиторий и лабораторий, присуждение научных степеней. В сферу компетенции колледжа входят:

Предоставление жилья студентам подразумевает одну комнату на одного человека. В настоящий момент в Оксфорде работает 38 колледжей. Среди них:

Также в инфраструктуру Оксфорда входят несколько сотен библиотек, часовня, театр, кабинеты для музицирования, хор, множество музеев, ботанический сад, издательство, спортивные клубы, зоны для отдыха, парки, столовые и общежития. Всего в Оксфордском университете функционируют 13 факультетов:

На каждом из них осуществляется обучение по нескольким направлениям. Поступив в Оксфорд, можно изучать не только клиническую, но и молекулярную медицину.

Правила подачи заявки

Учащимся Оксфорда может стать любой человек. Но прежде чем начать учебу, необходимо будет выдержать вступительные испытания (в зависимости от выбранной для изучения профессии), о которых подробно рассказано на онлайн-портале UCAS. Это общий для всех высших учебных заведений Объединенного Королевства портал. Заявка на обучение подается там же.

Также необходимо сдать тест на знание английского языка. Русскоязычным абитуриентам достаточно успешно пройти квалификацию A-Level либо IB (International Baccalaureate), чтобы учиться бесплатно. Кроме того, допустимо прохождение американских систем тестирования SAT и ACT. Проходные баллы по тестам:

В декабре после завершения приема и обработки тестов будет составлен список абитуриентов, приглашенных на интервью. Также есть возможность пройти его по Skype или телефону.

На официальном сайте Оксфордского университета существует программа-калькулятор, которая поможет рассчитать точную стоимость обучения в долларах. Затем русский абитуриент может перевести ее в рубли по текущему курсу.

Если же поступить на бюджет не удалось, то важно знать, сколько стоит обучение в Оксфорде в 2019 году. Следует помнить, что цена зависит от выбранной специальности и типа обучения (бакалавриат или магистратура).

Стоимость отличается в зависимости от факультета и варьируется от 6500 до 16 000 фунтов стерлингов в год. Плата за проживание и обслуживание составляет около 8000, за материальное обеспечение — 5—6 тысяч. Итого получается в среднем не менее 21 500 фунтов стерлингов в год.

Для студентов из России возможно получение стипендии от благотворительного фонда Hill. Ее сумма полностью покрывает стоимость обучения в Оксфордском университете. Но соискатель должен иметь степень, полученную в российском высшем учебном заведении. Для этого нужно много и упорно учиться.

Помимо этого, своим студентам Оксфорд предлагает альтернативного гида, насчитывающего больше 100 возможностей получения дополнительного финансирования. Там же предоставлены и инструкции по заполнению заявок на получение грантов и порядок их присуждения.

Обучение в Оксфорде предоставляет выпускникам огромные возможности в плане построения карьеры и самореализации, поэтому в вуз хотят попасть десятки тысяч абитуриентов. Следует добавить, что дети многих отечественных знаменитостей и их друзья выбирают этот университет, поскольку он стал модным среди российской элиты.

Источник

Значение слова оксфорд

оксфорд в словаре кроссвордиста

оксфорд

Энциклопедический словарь, 1998 г.

ОКСФОРД (Oxford) город в Великобритании, в Англии, на р. Темза, административный центр графства Оксфордшир. 123 тыс. жителей (1991). Автомобилестроение, полиграфическая промышленность. Университет (c 12 в.). Музей Ашмола. Впервые упоминается в 912. Позднероманский собор (основан в 12 в.), романские и готические церкви (13-15 вв.), готические, классицистические, неоготические ансамбли университетских колледжей (14-19 вв.).

Большая Советская Энциклопедия

(Oxford), город в Великобритании, в Англии, на р. Темза. Админмстративный центр графства Оксфордшир. 108,6 тыс. жителей (1971). Важный транспортный узел и торговый центр. В пригороде О. ≈ Коули ≈ крупные предприятия автостроения (фирма «Бритиш Лейленд мотор корпорейшен», БЛМК), на которых работает 3/4 всех занятых в промышленности О. Имеются электротехническая и др. отрасли промышленности; значительная полиграфическая промышленность.

Возник как поселение, по-видимому, в 8 в. Впервые в письменных источниках упоминается под 912. Большое значение имел как крепость. Во 2-й половине 12 в. в О. был основан университет ≈ старейший в Великобритании и один из старейших в Европе (см. Оксфордский университет ). С 1541 ≈ местопребывание английского епископа. Во время гражданской войны 1642√1646 О. ≈ опорный пункт Карла I и его сторонников.

В О., изобилующем садами, хорошо сохранилась средневековая планировка, носящая (благодаря прямоугольным дворам колледжей) регулярный характер; позднероманский собор (основное строительство в 12 в.), романские и готические церкви, классицистические театр Шелдона (1664≈69, архитектор К. Рен) и библиотека Рэдклиффа. Среди колледжей преобладают позднеготические здания «украшенного» и «перпендикулярного» стиля с классицистическими (архитектор К. Рен и др.) и неоготическими (архитектор А. Баттерфилд, А. Уотерхаус и др.) достройками. Растущая с 1920-х гг. промышленная зона строго отграничена от университетской; современные здания органически сочетаются со старой застройкой. Музей Ашмола (археологические и художественные коллекции университета).

Википедия

Тауншипбыл назван в честь округа Оксфорд в штате Мэн.

Оксфорд — вид ткани, традиционно используемой для пошива мужских сорочек ( рубашек ). Выполняется ткацким переплетением рогожка .

На данный момент существует огромное количество совершенно разных тканей, которые распространяются под торговой маркой «Оксфорд». Их не следует путать с классической тканью данного типа.

Ткань Оксфорд (Oxford) делится на несколько видов в зависимости от толщины нитки, лежащей в основе полотна: 210den, 240den, 300den, 420den, 600den. Для изготовления чехлов-тентов для автомобилей, мотоциклов, скутеров, квадроциклов, снегоходов, гидроциклов, применяется ткань 240-300den при стояночном хранении. Для транспортировки техники используется более плотный полиэстер 600den, во избежание разрыва чехла при перевозке.

«Оксфорд» :

— город на юго-западе штата Огайо, США.

Примеры употребления слова оксфорд в литературе.

Когда Стиль появился в Оксфорде, Аддисон был там важной фигурой, а сам он не слишком выделился.

Шотландии, бранится на Темзе с барочником и готов полуночничать с молодыми друзьями, нагрянувшими из Оксфорда.

Роджер Бэкон был учеником Гроссетеста, учился сначала в Оксфорде, затем в Париже, изучал основы всех тогдашних научных дисциплин: математики, медицины, права, теологии, философии.

Мы возвращаемся в Оксфорд, ему предоставили там докторантскую стипендию.

Вот так, покинув Оксфорд, Замарашка обосновался в Лондоне, официально сменив фамилию на Грайс.

Той же осенью праведное негодование Замарашки проследовало вместе с ним в Оксфорд.

Действительно, Тарл Кабот, соответствующий описанию, вырос в Бристоле, учился в Оксфорде и небольшом новоанглийском колледже, упоминаемом в первой книге.

Однако посольство Лямблии нажало на Форин Оффис, и профессора все же пригласили на Всемирный конгресс кибернетики в Оксфорде.

Как бы то ни было, никаких точных данных о том, что пьеса действительно исполнялась в Кембридже и Оксфорде, нет, и само упоминание знаменитых университетов на титульном листе первого кварто свидетельствует лишь о том, что автор пьесы, Уильям Потрясающий Копьем, связан с ними обоими.

Он тут у нас на время, из Оксфорда, по лендлизу, что ли, и он такой жуткий старый самодовольный притворяшка, а волосы у него торчат дикой белой копной.

Источник: библиотека Максима Мошкова

Транслитерация: oksford

Задом наперед читается как: дрофско

Оксфорд состоит из 7 букв

Источник

Как правильно пишется слово «оксфордский»

Источник: Орфографический академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база 2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: студенчество — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Синонимы к слову «оксфордский»

Предложения со словом «оксфордский»

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «оксфордский»

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Предложения со словом «оксфордский»

Оксфордский словарь английского языка определяет его как английский язык, которому благоволит королева, то есть стадартный вариант языка, соответствующий нормам употребления.

В нём проснулись итонский ученик и оксфордский студент – ба!

Оксфордский институт интернета на протяжении последнего десятилетия стал для меня уютным домом, позволив обзавестись разнообразными связями.

Синонимы к слову «оксфордский»

Карта слов и выражений русского языка

Онлайн-тезаурус с возможностью поиска ассоциаций, синонимов, контекстных связей и примеров предложений к словам и выражениям русского языка.

Справочная информация по склонению имён существительных и прилагательных, спряжению глаголов, а также морфемному строению слов.

Сайт оснащён мощной системой поиска с поддержкой русской морфологии.

Источник

Преимущества обучения

Прежде чем рассказать об уникальном университете Великобритании, да и, пожалуй, всего мира, важно узнать, где находится Оксфорд. Вуз расположен в живописном городе с одноименным названием, который является центром графства Оксфордшир, всего в 90 км от Лондона.

Невозможно перечислить все преимущества получения образования в Оксфордском университете. Вот лишь некоторые из них:

Все эти интересные факты об Оксфордском университете ежегодно привлекают в него сотни тысяч выпускников лучших школ мира. Кроме того, люди, окончившие вуз, будут востребованы на рынке труда в любой развитой стране мира.

Краткая история создания

В 1074 году церковью святого Георгия был основан колледж светских законов. Именно с этого момента началась многовековая история Оксфорда. На протяжении последующих 12 столетий колледж служил магнитом для различных религиозных центров.

В 1167 году король Англии Генрих отозвал из Франции всех обучавшихся там студентов, запретив им в дальнейшем возвращаться на чужбину. Из-за этого первым учащимся не оставалось ничего, кроме как продолжить обучение в Оксфорде.

Согласно одной из знаменитых университетских легенд, основателем величайшего вуза мира был Альфред Великий, любивший вести с монахами ученые беседы. Легенда называет 872 год в качестве примерной даты основания университета, однако официальных подтверждений этому нет.

В XIII—XIV вв. история Оксфордского университета разворачивалась стремительно. В XIII столетии была заложена основа для последующей системы колледжей (первоначально их было 10, в наши дни их количество достигло 38). На их территории студенты и получали образование.

Самыми старинными колледжами являются Баллиол и Мертон. Оба были основаны в 1264 году. Несмотря на почтенный возраст, эти колледжи и по сей день продолжают свою работу, посвященную обучению и организации жизни студентов внутри вуза.

В XIV веке университет стал средоточием научных и образовательных ресурсов Великобритании, а также неизменным центром научных, теологических и идеологических диспутов.

Именно в эту золотую эпоху развития в нем появилась должность канцлера (руководителя учебного заведения). Эта ответственная и почетная должность в Оксфорде никогда не прекращала своего существования на протяжении всей многовековой истории учебного заведения.

Кроме того, сотрудники вуза, как и его студенты и преподаватели, получили неприкосновенность при столкновениях с городскими властями. Им была предоставлена солидная скидка на оплату проживания в кампусе. Для студентов и преподавателей действовали бессрочные скидки на учебники, канцелярские товары и продукты питания.

Интересным можно считать тот факт, что до 1878 года право на обучение в Оксфорде имели исключительно мужчины.

Структура и факультеты

Университет представляет собой систему колледжей, каждый из которых является центром самоуправления. Он выполняет административные функции, в которым относятся составление графиков лекций, экзаменов и практических занятий, принятие экзаменов у студентов и предоставление учащимся аудиторий и лабораторий, присуждение научных степеней. В сферу компетенции колледжа входят:

Предоставление жилья студентам подразумевает одну комнату на одного человека. В настоящий момент в Оксфорде работает 38 колледжей. Среди них:

Также в инфраструктуру Оксфорда входят несколько сотен библиотек, часовня, театр, кабинеты для музицирования, хор, множество музеев, ботанический сад, издательство, спортивные клубы, зоны для отдыха, парки, столовые и общежития. Всего в Оксфордском университете функционируют 13 факультетов:

На каждом из них осуществляется обучение по нескольким направлениям. Поступив в Оксфорд, можно изучать не только клиническую, но и молекулярную медицину.

Правила подачи заявки

Учащимся Оксфорда может стать любой человек. Но прежде чем начать учебу, необходимо будет выдержать вступительные испытания (в зависимости от выбранной для изучения профессии), о которых подробно рассказано на онлайн-портале UCAS. Это общий для всех высших учебных заведений Объединенного Королевства портал. Заявка на обучение подается там же.

Также необходимо сдать тест на знание английского языка. Русскоязычным абитуриентам достаточно успешно пройти квалификацию A-Level либо IB (International Baccalaureate), чтобы учиться бесплатно. Кроме того, допустимо прохождение американских систем тестирования SAT и ACT. Проходные баллы по тестам:

В декабре после завершения приема и обработки тестов будет составлен список абитуриентов, приглашенных на интервью. Также есть возможность пройти его по Skype или телефону.

На официальном сайте Оксфордского университета существует программа-калькулятор, которая поможет рассчитать точную стоимость обучения в долларах. Затем русский абитуриент может перевести ее в рубли по текущему курсу.

Если же поступить на бюджет не удалось, то важно знать, сколько стоит обучение в Оксфорде в 2019 году. Следует помнить, что цена зависит от выбранной специальности и типа обучения (бакалавриат или магистратура).

Стоимость отличается в зависимости от факультета и варьируется от 6500 до 16 000 фунтов стерлингов в год. Плата за проживание и обслуживание составляет около 8000, за материальное обеспечение — 5—6 тысяч. Итого получается в среднем не менее 21 500 фунтов стерлингов в год.

Для студентов из России возможно получение стипендии от благотворительного фонда Hill. Ее сумма полностью покрывает стоимость обучения в Оксфордском университете. Но соискатель должен иметь степень, полученную в российском высшем учебном заведении. Для этого нужно много и упорно учиться.

Помимо этого, своим студентам Оксфорд предлагает альтернативного гида, насчитывающего больше 100 возможностей получения дополнительного финансирования. Там же предоставлены и инструкции по заполнению заявок на получение грантов и порядок их присуждения.

Обучение в Оксфорде предоставляет выпускникам огромные возможности в плане построения карьеры и самореализации, поэтому в вуз хотят попасть десятки тысяч абитуриентов. Следует добавить, что дети многих отечественных знаменитостей и их друзья выбирают этот университет, поскольку он стал модным среди российской элиты.

Источник

Теперь вы знаете какие однокоренные слова подходят к слову Как правильно пишется оксфорд, а так же какой у него корень, приставка, суффикс и окончание. Вы можете дополнить список однокоренных слов к слову «Как правильно пишется оксфорд», предложив свой вариант в комментариях ниже, а также выразить свое несогласие проведенным с морфемным разбором.

Значение слова «Оксфорд»

-

О́ксфорд (англ. Oxford — «воловий брод», «бычий брод», произносится [ˈɒksfəd]) — город в Великобритании, столица графства Оксфордшир. Оксфорд известен благодаря старейшему в англоязычных странах и одному из старейших в Европе высших учебных заведений — Оксфордскому университету. Оксфордский университет — это уникальное и историческое учреждение. О точной дате его создания не известно, однако, в той или иной форме обучение в Оксфорде существовало уже в 1096 году. А с 1167 г., когда Генрих II объявил о запрете английским студентам поступать в Парижский университет, обучение стало быстро развиваться. Все ведущие рейтинги учебных заведений Великобритании называют этот университет лучшим в стране; кроме того, он дал миру около 50 Нобелевских лауреатов.

Оксфорд стоит на берегу Темзы. Примечательно, что протекающий через город участок реки длиною в 10 миль принято называть The Isis. В 2015 году население составляло 159 574 человек, из них около 30 000 — студенты университета.

Источник: Википедия

-

О́ксфорд

1. город в Великобритании

Источник: Викисловарь

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: пошехонский — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «Оксфорд»

Синонимы к слову «оксфорд»

Предложения со словом «оксфорд»

- Оксфорд славится своими тайными сообществами, ну а это было самым тайным среди всех.

- Системы объединяются в группы (юра входит в состав мезозоя) и делятся на отделы (нижняя, средняя и верхняя юра), ярусы (верхняя юра – на келловей, оксфорд, кимеридж и титон), а далее на зоны (Cardioceras cordatum).

- Оксфорд играл очень небольшую роль.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словом «Оксфорд»

- — Что там делать? Я сам знаком был с Матеем, да и с Геймом, — ну, а все, кажется бы, в Оксфорд лучше; а, Софья? Право, лучше. А по какой части хочешь ты идти?

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Понятия со словом «Оксфорд»

-

Оксфорд (англ. oxford) — вид ткани, традиционно используемой для пошива мужских сорочек (рубашек). Выполняется ткацким переплетением рогожка.

-

«Оксфорд — Кембридж» (англ. The Boat Race, буквально — «Лодочная гонка») — лодочная регата по Темзе между командами лодочных клубов Оксфордского и Кембриджского университетов.

- (все понятия)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

-

Оксфорд славится своими тайными сообществами, ну а это было самым тайным среди всех.

-

Системы объединяются в группы (юра входит в состав мезозоя) и делятся на отделы (нижняя, средняя и верхняя юра), ярусы (верхняя юра – на келловей, оксфорд, кимеридж и титон), а далее на зоны (Cardioceras cordatum).

-

Оксфорд играл очень небольшую роль.

- (все предложения)

- степень бакалавра искусств

- Лига плюща

- завершает обучение

- член парламента

- аттестат зрелости

- (ещё синонимы…)

- университет

- (ещё ассоциации…)

Разбор слова «оксфорд»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «оксфорд» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «оксфорд» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «оксфорд».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «оксфорд» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «оксфорд»

- 3 Синонимы слова «оксфорд»

- 4 Значение слова «оксфорд»

- 5 Как правильно пишется слово «оксфорд»

- 6 Ассоциации к слову «оксфорд»

Слоги в слове «оксфорд» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 2

По слогам: о-ксфорд

По правилам школьной программы слово «оксфорд» можно поделить на слоги разными способами. Допускается вариативность, то есть все варианты правильные. Например, такой:

ок-сфорд

По программе института слоги выделяются на основе восходящей звучности:

о-ксфорд

Ниже перечислены виды слогов и объяснено деление с учётом программы института и школ с углублённым изучением русского языка.

к примыкает к этому слогу, а не к предыдущему, так как не является сонорной (непарной звонкой согласной)

Как перенести слово «оксфорд»

ок—сфорд

окс—форд

Синонимы слова «оксфорд»

Значение слова «оксфорд»

О́ксфорд (англ. Oxford — «воловий брод», «бычий брод», произносится [ˈɒksfəd]) — город в Великобритании, столица графства Оксфордшир. Оксфорд известен благодаря старейшему в англоязычных странах и одному из старейших в Европе высших учебных заведений — Оксфордскому университету. Оксфордский университет — это уникальное и историческое учреждение. О точной дате его создания не известно, однако, в той или иной форме обучение в Оксфорде существовало уже в 1096 году. А с 1167 г., когда Генрих II объявил о запрете английским студентам поступать в Парижский университет, обучение стало быстро развиваться. Все ведущие рейтинги учебных заведений Великобритании называют этот университет лучшим в стране; кроме того, он дал миру около 50 Нобелевских лауреатов. (Википедия)

Как правильно пишется слово «оксфорд»

Правописание слова «оксфорд»

Орфография слова «оксфорд»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «оксфорд» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Ассоциации к слову «оксфорд»

-

Кембридж

-

Стрит

-

Колледж

-

Бакалавр

-

Выпускник

-

Стипендия

-

Темза

-

Миссисипи

-

Эдинбург

-

Магдалина

-

Баронет

-

Дублин

-

Винчестер

-

Манчестер

-

Учёба

-

Диплом

-

Лондон

-

Богословие

-

Каникулы

-

Преподаватель

-

Магдалена

-

Вира

-

Университет

-

Великобритания

-

Шекспир

-

Паб

-

Поступление

-

Графство

-

Кола

-

Ливерпуль

-

Студент

-

Таймс

-

Огайо

-

Латынь

-

Лекция

-

Англия

-

Сити

-

Стефана

-

Лейпциг

-

Копенгаген

-

Лира

-

Бат

-

Беркли

-

Мэн

-

Уэльс

-

Экзамен

-

Обучение

-

Рукопись

-

Манускрипт

-

Авторство

-

Образование

-

Граф

-

Клайв

-

Брюссель

-

Уорд

-

Философия

-

Вильям

-

Профессор

-

Графа

-

Аспирантура

-

Эдуарда

-

Парламент

-

Пэр

-

Фаворит

-

Шпиль

-

Произношение

-

Преподавание

-

Астрономия

-

Словесность

-

Льюис

-

Руперт

-

Шелли

-

Йорк

-

Декан

-

Семинар

-

Магистр

-

Уолтер

-

Герберт

-

Матильда

-

Кафедра

-

Эдвард

-

Филолог

-

Олимп

-

Университетский

-

Докторский

-

Лондонский

-

Гребной

-

Рукописный

-

Студенческий

-

Привилегированный

-

Британский

-

Престижный

-

Английский

-

Нобелевский

-

Учиться

-

Преподавать

-

Обучаться

-

Окончить

-

Воспитываться

-

Изучать

|

Oxford |

|

|---|---|

|

City and non-metropolitan district |

|

From top left to bottom right: Oxford skyline panorama from St Mary’s Church; Radcliffe Camera; High Street from above looking east; University College, main quadrangle; High Street by night; Natural History Museum and Pitt Rivers Museum |

|

|

Coat of arms of Oxford |

|

| Nickname:

«the City of Dreaming Spires» |

|

| Motto:

«Fortis est veritas» «The truth is strong» |

|

Shown within Oxfordshire |

|

|

Oxford Location within England Oxford Location within the United Kingdom Oxford Location within Europe |

|

| Coordinates: 51°45′7″N 1°15′28″W / 51.75194°N 1.25778°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | South East England |

| Ceremonial county | Oxfordshire |

| Admin HQ | Oxford City Centre |

| Founded | 8th century |

| City status | 1542 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Governing body | Oxford City Council |

| • Sheriff of Oxford | Dick Wolff[2] |

| • Executive | Labour |

| • MPs | Anneliese Dodds (Labour Co-op, Oxford East) Layla Moran (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West and Abingdon) |

| Area | |

| • City and non-metropolitan district | 17.60 sq mi (45.59 km2) |

| Population

(2021) |

|

| • City and non-metropolitan district | 162,100[1] |

| • Density | 8,500/sq mi (3,270/km2) |

| • Metro | 244,000 |

| • Ethnicity (2011)[3] | 63.6% White British 1.6% White Irish 12.5% Other White 12.5% British Asian 4.0% Mixed Race 4.6% Black 1.4% Other |

| Demonym | Oxonian |

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode |

OX1, OX2, OX3, OX4 |

| Area code | 01865 |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-OXF |

| ONS code | 38UC (ONS) E07000178 (GSS) |

| OS grid reference | SP513061 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| Fire & Rescue | Oxfordshire |

| Website | www.oxford.gov.uk |

|

Oxford ()[4][5] is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. It had a population of 162,100 at the 2021 census.[1] It is 56 miles (90 km) north-west of London, 64 miles (103 km) south-east of Birmingham and 61 miles (98 km) north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the University of Oxford, the oldest university in the English-speaking world;[6] it has buildings in every style of English architecture since late Anglo-Saxon. Oxford’s industries include motor manufacturing, education, publishing, information technology and science.

History[edit]

The history of Oxford in England dates back to its original settlement in the Saxon period. Originally of strategic significance due to its controlling location on the upper reaches of the River Thames at its junction with the River Cherwell, the town grew in national importance during the early Norman period, and in the late 12th century became home to the fledgling University of Oxford.[7] The city was besieged during The Anarchy in 1142.[8]

The university rose to dominate the town. A heavily ecclesiastical town, Oxford was greatly affected by the changes of the English Reformation, emerging as the seat of a bishopric and a full-fledged city. During the English Civil War, Oxford housed the court of Charles I and stood at the heart of national affairs.[9]

The city began to grow industrially during the 19th century, and had an industrial boom in the early 20th century, with major printing and car-manufacturing industries. These declined, along with other British heavy industry, in the 1970s and 1980s, leaving behind a city which had developed far beyond the university town of the past.[10]

Geography[edit]

Physical[edit]

Location[edit]

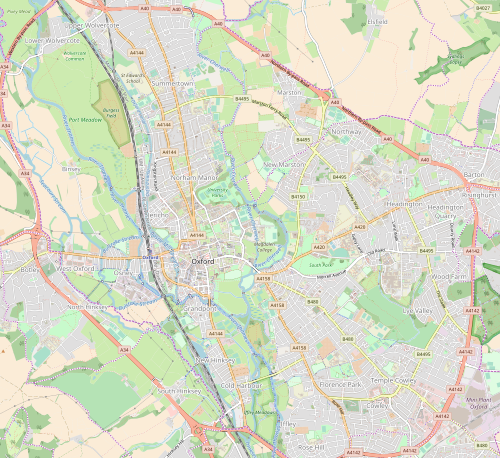

Oxford’s latitude and longitude are 51°45′07″N 1°15′28″W / 51.75194°N 1.25778°WCoordinates: 51°45′07″N 1°15′28″W / 51.75194°N 1.25778°W or grid reference SP513061 (at Carfax Tower, which is usually considered the centre). Oxford is 24 miles (39 km) north-west of Reading, 26 miles (42 km) north-east of Swindon, 36 miles (58 km) east of Cheltenham, 43 miles (69 km) east of Gloucester, 29 miles (47 km) south-west of Milton Keynes, 38 miles (61 km) south-east of Evesham, 43 miles (69 km) south of Rugby and 51 miles (82 km) west-north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames (also sometimes known as the Isis locally, supposedly from the Latinised name Thamesis) run through Oxford and meet south of the city centre. These rivers and their flood plains constrain the size of the city centre.

Climate[edit]

Wellington Square, the name of which has become synonymous with the university’s central administration

Oxford has a maritime temperate climate (Köppen: Cfb). Precipitation is uniformly distributed throughout the year and is provided mostly by weather systems that arrive from the Atlantic. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Oxford was −17.8 °C (0.0 °F) on 24 December 1860. The highest temperature ever recorded in Oxford is 38.1 °C (101 °F) on 19 July 2022.[11] The average conditions below are from the Radcliffe Meteorological Station. It boasts the longest series of temperature and rainfall records for one site in Britain. These records are continuous from January 1815. Irregular observations of rainfall, cloud and temperature exist from 1767.[12]

The driest year on record was 1788, with 336.7 mm (13.26 in) of rainfall. Whereas, the wettest year was 2012, with 979.5 mm (38.56 in). The wettest month on record was September 1774, with a total fall of 223.9 mm (8.81 in). The warmest month on record is July 1983, with an average of 21.1 °C (70 °F) and the coldest is January 1963, with an average of −3.0 °C (27 °F). The warmest year on record is 2014, with an average of 11.8 °C (53 °F) and the coldest is 1879, with a mean temperature of 7.7 °C (46 °F). The sunniest month on record is May 2020, with 331.7 hours and December 1890 is the least sunny, with 5.0 hours. The greatest one-day rainfall occurred on 10 July 1968, with a total of 87.9 mm (3.46 in). The greatest known snow depth was 61.0 cm (24.0 in) in February 1888.[13]

| Climate data for Oxford (RMS),[a] elevation: 200 ft (61 m), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1815–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

35.1 (95.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.4 (41.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.6 (2.1) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59.6 (2.35) |

46.8 (1.84) |

43.2 (1.70) |

48.7 (1.92) |

56.9 (2.24) |

49.7 (1.96) |

52.5 (2.07) |

61.7 (2.43) |

51.9 (2.04) |

73.2 (2.88) |

71.5 (2.81) |

66.1 (2.60) |

681.6 (26.83) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.1 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 117.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.4 | 81.9 | 118.2 | 165.6 | 200.3 | 197.1 | 212.0 | 193.3 | 145.3 | 110.2 | 70.8 | 57.6 | 1,615.5 |

| Source 1: Met Office[14] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: University of Oxford[15] |

- ^ Weather station is located 0.7 miles (1.1 km) from the Oxford city centre.

Districts[edit]

The city centre[edit]

The city centre is relatively small, and is centred on Carfax, a crossroads which forms the junction of Cornmarket Street (pedestrianised), Queen Street (mainly pedestrianised), St Aldate’s and the High Street («the High»; blocked for through traffic). Cornmarket Street and Queen Street are home to Oxford’s chain stores, as well as a small number of independent retailers, one of the longest established of which was Boswell’s, founded in 1738.[16] The store closed in 2020.[17] St Aldate’s has few shops but several local government buildings, including the town hall, the city police station and local council offices. The High (the word street is traditionally omitted) is the longest of the four streets and has a number of independent and high-end chain stores, but mostly university and college buildings. The historic buildings mean the area is regularly used by film and TV crews.

Suburbs[edit]

Aside from the city centre, there are several suburbs and neighbourhoods within the borders of the city of Oxford, including:

- Barton

- Blackbird Leys

- Cowley

- Temple Cowley

- Iffley

- Littlemore

- Rose Hill

- Cutteslowe

- Headington

- New Marston

- Jericho

- North Oxford

- Park Town

- Norham Manor

- Walton Manor

- Osney

- Risinghurst

- Summertown

- Sunnymead

- Waterways

- Wolvercote

Green belt[edit]

Oxford is at the centre of the Oxford Green Belt, which is an environmental and planning policy that regulates the rural space in Oxfordshire surrounding the city which aims to prevent urban sprawl and minimize convergence with nearby settlements.[18] The policy has been blamed for the large rise in house prices in Oxford, making it the least affordable city in the United Kingdom outside of London, with estate agents calling for brownfield land inside the green belt to be released for new housing.[19][20][21] The vast majority of the area covered is outside of the city, but there are some green spaces within that which are covered by the designation such as much of the Thames and river Cherwell flood-meadows, and the village of Binsey, along with several smaller portions on the fringes. Other landscape features and places of interest covered include Cutteslowe Park and the mini railway attraction, the University Parks, Hogacre Common Eco Park, numerous sports grounds, Aston’s Eyot, St Margaret’s Church and well, and Wolvercote Common and community orchard.[22]

Economy[edit]

Oxford’s economy includes manufacturing, publishing and science-based industries as well as education, research and tourism.

Car production[edit]

Oxford has been an important centre of motor manufacturing since Morris Motors was established in the city in 1910. The principal production site for Mini cars, owned by BMW since 2000, is in the Oxford suburb of Cowley. The plant, which survived the turbulent years of British Leyland in the 1970s and was threatened with closure in the early 1990s, also produced cars under the Austin and Rover brands following the demise of the Morris brand in 1984, although the last Morris-badged car was produced there in 1982.

Publishing[edit]

Oxford University Press, a department of the University of Oxford, is based in the city, although it no longer operates its own paper mill and printing house. The city is also home to the UK operations of Wiley-Blackwell, Elsevier and several smaller publishing houses.

Science and technology[edit]

The presence of the university has given rise to many science and technology based businesses, including Oxford Instruments, Research Machines and Sophos. The university established Isis Innovation in 1987 to promote technology transfer. The Oxford Science Park was established in 1990, and the Begbroke Science Park, owned by the university, lies north of the city. Oxford increasingly has a reputation for being a centre of digital innovation, as epitomized by Digital Oxford.[23] Several startups including Passle,[24] Brainomix,[25] Labstep,[26] and more, are based in Oxford.

Education[edit]

The presence of the university has also led to Oxford becoming a centre for the education industry. Companies often draw their teaching staff from the pool of Oxford University students and graduates, and, especially for EFL education, use their Oxford location as a selling point.[27]

Tourism[edit]

The University Church of St Mary the Virgin

Carfax Tower at Carfax, the junction of the High Street, Queen Street, Cornmarket and St Aldate’s streets at what is considered by many to be the centre of the city

Oxford has numerous major tourist attractions, many belonging to the university and colleges. As well as several famous institutions, the town centre is home to Carfax Tower and the University Church of St Mary the Virgin, both of which offer views over the spires of the city. Many tourists shop at the historic Covered Market. In the summer, punting on the Thames/Isis and the Cherwell is a common practice. As well as being a major draw for tourists (9.1 million in 2008, similar in 2009),[28] Oxford city centre has many shops, several theatres and an ice rink.

Retail[edit]

Night view of High Street with Christmas lights – one of Oxford’s main streets

There are two small shopping malls in the city centre: the Clarendon Centre[29] and the Westgate Centre.[30] The Westgate Centre is named for the original West Gate in the city wall, and is at the west end of Queen Street. A major redevelopment and expansion to 750,000 sq ft (70,000 m2), with a new 230,000 sq ft (21,000 m2) John Lewis department store and a number of new homes, was completed in October 2017. Blackwell’s Bookshop is a bookshop which claims the largest single room devoted to book sales in the whole of Europe, the Norrington Room (10,000 sq ft).[31]

Brewing[edit]

There is a long history of brewing in Oxford. Several of the colleges had private breweries, one of which, at Brasenose, survived until 1889. In the 16th century brewing and malting appear to have been the most popular trades in the city. There were breweries in Brewer Street and Paradise Street, near the Castle Mill Stream. The rapid expansion of Oxford and the development of its railway links after the 1840s facilitated expansion of the brewing trade.[32] As well as expanding the market for Oxford’s brewers, railways enabled brewers further from the city to compete for a share of its market.[32] By 1874 there were nine breweries in Oxford and 13 brewers’ agents in Oxford shipping beer in from elsewhere.[32] The nine breweries were: Flowers & Co in Cowley Road, Hall’s St Giles Brewery, Hall’s Swan Brewery (see below), Hanley’s City Brewery in Queen Street, Le Mills’s Brewery in St. Ebbes, Morrell’s Lion Brewery in St Thomas Street (see below), Simonds’s Brewery in Queen Street, Weaving’s Eagle Brewery (by 1869 the Eagle Steam Brewery) in Park End Street and Wootten and Cole’s St. Clement’s Brewery.[32]

The Swan’s Nest Brewery, later the Swan Brewery, was established by the early 18th century in Paradise Street, and in 1795 was acquired by William Hall.[33] The brewery became known as Hall’s Oxford Brewery, which acquired other local breweries. Hall’s Brewery was acquired by Samuel Allsopp & Sons in 1926, after which it ceased brewing in Oxford.[34] Morrell’s was founded in 1743 by Richard Tawney. He formed a partnership in 1782 with Mark and James Morrell, who eventually became the owners.[35] After an acrimonious family dispute this much-loved brewery was closed in 1998,[36] the beer brand names being taken over by the Thomas Hardy Burtonwood brewery,[37] while the 132 tied pubs were bought by Michael Cannon, owner of the American hamburger chain Fuddruckers, through a new company, Morrells of Oxford.[38] The new owners sold most of the pubs on to Greene King in 2002.[39] The Lion Brewery was converted into luxury apartments in 2002.[40] Oxford’s first legal distillery, the Oxford Artisan Distillery, was established in 2017 in historic farm buildings at the top of South Park.[41]

Bellfounding[edit]

The Taylor family of Loughborough had a bell-foundry in Oxford between 1786 and 1854.[42]

Buildings[edit]

- Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

- The Headington Shark

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Botanic Garden

- Sheldonian Theatre

- St. Mary the Virgin Church

- Radcliffe Camera

- Radcliffe Observatory

- Oxford Oratory

- Malmaison Hotel, in a converted prison in part of the medieval Oxford Castle

Parks and nature walks[edit]

Oxford is a very green city, with several parks and nature walks within the ring road, as well as several sites just outside the ring road. In total, 28 nature reserves exist within or just outside Oxford ring road, including:

- University Parks

- Mesopotamia

- Rock Edge Nature Reserve

- Lye Valley

- South Park

- C. S. Lewis Nature Reserve

- Shotover Nature Reserve

- Port Meadow

- Cutteslowe Park

Demography[edit]

Population pyramid of Oxford in 2020

Ethnicity[edit]

| Ethnic Group | 1991[43] | 2001[44] | 2011[45] | 2021[46] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 99,935 | 90.8% | 116,948 | 87.1% | 117,957 | 77.7% | 120,509 | 70.7% |

| White: British | – | – | 103,041 | 76.8% | 96,633 | 63.6% | 86,672 | 53.5% |

| White: Irish | – | – | 2,898 | 2,431 | 2,351 | |||

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | – | – | 92 | 62 | ||

| White: Roma | – | – | – | – | – | – | 501 | |

| White: Other | – | – | 11,009 | 8.2% | 18,801 | 12.4% | 24,975 | 15.4% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 5,808 | 5.3% | 8,931 | 6.7% | 18,827 | 12.4% | 24,991 | 15.4% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 1,560 | 1.4% | 2,323 | 1.7% | 4,449 | 2.9% | 6,005 | 3.7% |

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 2042 | 1.9% | 2,625 | 2.0% | 4,825 | 3.2% | 6,619 | 4.1% |

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 510 | 0.5% | 878 | 0.7% | 1,791 | 1.2% | 2,025 | 1.3% |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 859 | 0.8% | 2,460 | 1.8% | 3,559 | 2.3% | 4,479 | 2.8% |

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | 837 | 0.8% | 645 | 0.5% | 4,203 | 2.8% | 5,863 | 3.6% |

| Black or Black British: Total | 3,055 | 2.8% | 3,368 | 2.5% | 7,028 | 4.6% | 7,535 | 4.7% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | 1745 | 1,664 | 1,874 | 1,629 | ||||

| Black or Black British: African | 593 | 1,408 | 4,456 | 5,060 | ||||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | 717 | 296 | 698 | 846 | ||||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | 3,239 | 2.4% | 6,035 | 4% | 9,005 | 5.6% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | 1,030 | 1,721 | 1,916 | |||

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | 380 | 703 | 1,072 | |||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | 974 | 2,008 | 3,197 | |||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | 855 | 1,603 | 2,820 | |||

| Other: Total | 1,305 | 1.2% | 1,762 | 1.3% | 2,059 | 1.4% | 5,948 | 3.7% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | 922 | 0.6% | 1,449 | 0.9% |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 1,305 | 1.2% | 1,762 | 1.3% | 1,137 | 0.7% | 4,499 | 2.8% |

| Total | 110,103 | 100% | 134,248 | 100% | 151,906 | 100% | 162,040 | 100% |

Religion[edit]

| Religion | 2001[47] | 2011[48] | 2021[49] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| No religion | 32,075 | 23.9 | 50,274 | 33.1 | 63,201 | 39.0 |

| Christian | 81,100 | 60.4 | 72,924 | 48.0 | 61,750 | 38.1 |

| Religion not stated | 11,725 | 8.7 | 12,611 | 8.3 | 16,110 | 9.9 |

| Muslim | 5,165 | 3.8 | 10,320 | 6.8 | 14,093 | 8.7 |

| Hindu | 1,041 | 0.8 | 2,044 | 1.3 | 2,523 | 1.6 |

| Other religion | 656 | 0.5 | 796 | 0.5 | 1,447 | 0.9 |

| Buddhism | 1,080 | 0.8 | 1,431 | 0.9 | 1,195 | 0.7 |

| Jewish | 1,091 | 0.8 | 1,072 | 0.7 | 1,120 | 0.7 |

| Sikh | 315 | 0.2 | 434 | 0.3 | 599 | 0.4 |

| Total | 134,248 | 100.00% | 151,906 | 100.00% | 162,040 | 100.0% |

Transport[edit]

Air[edit]

In addition to the larger airports in the region, Oxford is served by nearby Oxford Airport, in Kidlington. The airport is also home to CAE Oxford Aviation Academy and Airways Aviation[50] airline pilot flight training centres, and several private jet companies. The airport is also home to Airbus Helicopters UK headquarters.[51]

Rail–airport links[edit]

Direct trains run from Oxford station to London Paddington where there is an interchange with the Heathrow Express train links serving Heathrow Airport. Passengers can change at Reading for connecting trains to Gatwick Airport. Some CrossCountry trains run direct services to Birmingham International, as well as to Southampton Airport Parkway further afield.

Buses[edit]

Bus services in Oxford and its suburbs are run by the Oxford Bus Company and Stagecoach Oxfordshire as well as other operators including Arriva Shires & Essex and Thames Travel. Oxford has one of the largest urban park and ride networks in the United Kingdom. Its five sites, at Pear Tree, Redbridge, Seacourt, Thornhill, Water Eaton and Oxford Parkway have a combined capacity of 4,930 car parking spaces,[52] served by 20 Oxford Bus Company double decker buses with a combined capacity of 1,695 seats.[53] Hybrid buses began to be used in Oxford in 2010, and their usage has been expanded.[54] In 2014 Oxford Bus introduced a fleet of 20 new buses with flywheel energy storage on the services it operates under contract for Oxford Brookes University.[55] Most buses in the city now use a smartcard to pay for journeys[56] and have free WiFi installed.[57][58][59]

Coach[edit]

The Oxford to London coach route offers a frequent coach service to London. The Oxford Tube is operated by Stagecoach Oxfordshire and the Oxford Bus Company runs the Airline services to Heathrow and Gatwick airports. There is a bus station at Gloucester Green, used mainly by the London and airport buses, National Express coaches and other long-distance buses including route X5 to Milton Keynes and Cambridge and Stagecoach Gold routes S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S8 and S9.

Cycling[edit]

Among British cities, Oxford has the second highest percentage of people cycling to work.[60]

Rail[edit]

Oxford railway station is half a mile (about 1 km) west of the city centre. The station is served by CrossCountry services to Bournemouth and Manchester Piccadilly; Great Western Railway (who manage the station) services to London Paddington, Banbury and Hereford; and Chiltern Railways services to London Marylebone. Oxford has had three main railway stations. The first was opened at Grandpont in 1844,[61] but this was a terminus, inconvenient for routes to the north;[62] it was replaced by the present station on Park End Street in 1852 with the opening of the Birmingham route.[63] Another terminus, at Rewley Road, was opened in 1851 to serve the Bletchley route;[64] this station closed in 1951.[65] There have also been a number of local railway stations, all of which are now closed. A fourth station, Oxford Parkway, is just outside the city, at the park and ride site near Kidlington. The present railway station opened in 1852.

Oxford is the junction for a short branch line to Bicester, a remnant of the former Varsity line to Cambridge. This Oxford–Bicester line was upgraded to 100 mph (161 km/h) running during an 18-month closure in 2014/2015 – and is scheduled to be extended to form the planned East West Rail line to Milton Keynes.[66] East West Rail is proposed to continue through Bletchley (for Milton Keynes Central) to Bedford,[67] Cambridge,[68] and ultimately Ipswich and Norwich,[69] thus providing alternative route to East Anglia without needing to travel via, and connect between, the London mainline terminals.

Chiltern Railways operates from Oxford to London Marylebone via Bicester Village, having sponsored the building of about 400 metres of new track between Bicester Village and the Chiltern Main Line southwards in 2014. The route serves High Wycombe and London Marylebone, avoiding London Paddington and Didcot Parkway.

In 1844, the Great Western Railway linked Oxford with London Paddington via Didcot and Reading;[70][71] in 1851, the London & North Western Railway opened its own route from Oxford to London Euston, via Bicester, Bletchley and Watford;[72] and in 1864 a third route, also to Paddington, running via Thame, High Wycombe and Maidenhead, was provided;[73] this was shortened in 1906 by the opening of a direct route between High Wycombe and London Paddington by way of Denham.[74] The distance from Oxford to London was 78 miles (125.5 km) via Bletchley; 63.5 miles (102.2 km) via Didcot and Reading; 63.25 miles (101.8 km) via Thame and Maidenhead;[75] and 55.75 miles (89.7 km) via Denham.[74]

Only the original (Didcot) route is still in use for its full length, portions of the others remain. There were also routes to the north and west. The line to Banbury was opened in 1850,[62] and was extended to Birmingham Snow Hill in 1852;[63] a route to Worcester opened in 1853.[76] A branch to Witney was opened in 1862,[77] which was extended to Fairford in 1873.[78] The line to Witney and Fairford closed in 1962, but the others remain open.

River and canal[edit]

Oxford was historically an important port on the River Thames, with this section of the river being called the Isis; the Oxford-Burcot Commission in the 17th century attempted to improve navigation to Oxford.[79] Iffley Lock and Osney Lock lie within the bounds of the city. In the 18th century the Oxford Canal was built to connect Oxford with the Midlands.[80] Commercial traffic has given way to recreational use of the river and canal. Oxford was the original base of Salters Steamers (founded in 1858), which was a leading racing-boatbuilder that played an important role in popularising pleasure boating on the Upper Thames. The firm runs a regular service from Folly Bridge downstream to Abingdon and beyond.

Roads[edit]

Oxford’s central location on several transport routes means that it has long been a crossroads city with many coaching inns, although road traffic is now strongly discouraged from using the city centre. The Oxford Ring Road or A4142 (southern part) surrounds the city centre and close suburbs Marston, Iffley, Cowley and Headington; it consists of the A34 to the west, a 330-yard section of the A44, the A40 north and north-east, A4142/A423 to the east. It is a dual carriageway, except for a 330-yard section of the A40 where two residential service roads adjoin, and was completed in 1966.

A roads[edit]

The main roads to/from Oxford are:

- A34 – a trunk route connecting the North and Midlands to the port of Southampton. It leaves J9 of the M40 north of Oxford, passes west of Oxford to Newbury and Winchester to the south and joins the M3 12.7 miles (20.4 km) north of Southampton. Since the completion of the Newbury bypass in 1998, this section of the A34 has been an entirely grade separated dual carriageway. Historically the A34 led to Bicester, Banbury, Stratford-upon-Avon, Birmingham and Manchester, but since the completion of the M40 it disappears at J9 and re-emerges 50 miles (80 km) north at Solihull.

- A40 – leading east dualled to J8 of the M40 motorway, then an alternative route to High Wycombe and London; leading west part-dualled to Witney then bisecting Cheltenham, Gloucester, Monmouth, Abergavenny, passing Brecon, Llandovery, Carmarthen and Haverfordwest to reach Fishguard.

- A44 – which begins in Oxford, leading past Evesham to Worcester, Hereford and Aberystwyth.

- A420 – which also begins in Oxford and leads to Bristol passing Swindon and Chippenham.

Zero Emission Zone[edit]

On 28 February 2022 a zero-emission pilot area became operational in Oxford City Centre. Zero emission vehicles can be used without incurring a charge but all petrol and diesel vehicles (including hybrids) incur a daily charge if they are driven in the zone between 7am and 7pm.[81]

A consultation on the introduction of a wider Zero Emission Zone is expected in the future, at a date to be confirmed.

Bus gates[edit]

Oxford has eight bus gates, short sections of road where only buses and other authorised vehicles can pass.[82]

Six further bus gates are currently proposed. A council-led consultation on the traffic filters ended on 13 October 2022. In a decision made on 29 November 2022, Oxfordshire County Council cabinet approved the introduction on a trial basis, for a minimum period of six months.[83] The trial will begin after improvement works to Oxford railway station are complete, which is expected to be by Christmas 2023.[84] The additional bus gates have been controversial; Oxford University and Oxford Bus Company support the proposals but more than 3,700 people have signed an online petition opposing the new traffic filters for Marston Ferry Road and Hollow Way, and hotelier Jeremy Mogford has argued they would be a mistake.[85][86] In November 2022, Mogford announced that his hospitality group The Oxford Collection had joined up with Oxford Business Action Group (OBAG), Oxford High Street Association (OHSA), ROX (Backing Oxford Business), Reconnecting Oxford, Jericho Traders, and Summertown traders to launch a legal challenge to the new bus gates.[87]

Motorway[edit]

The city is served by the M40 motorway, which connects London to Birmingham. The M40 approached Oxford in 1974, leading from London to Waterstock, where the A40 continued to Oxford. When the M40 extension to Birmingham was completed in January 1991, it curved sharply north, and a mile of the old motorway became a spur. The M40 comes no closer than 6 miles (9.7 km) away from the city centre, curving to the east of Otmoor. The M40 meets the A34 to the north of Oxford.

Education[edit]

Schools[edit]

Universities and colleges[edit]

Scrollable image. Aerial panorama of the university.

There are two universities in Oxford, the University of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University, as well as the specialist further and higher education institution Ruskin College that is an Affiliate of the University of Oxford. The Islamic Azad University also has a campus near Oxford. The University of Oxford is the oldest university in the English-speaking world,[88] and one of the most prestigious higher education institutions of the world, averaging nine applications to every available place, and attracting 40% of its academic staff and 17% of undergraduates from overseas.[89] In September 2016, it was ranked as the world’s number one university, according to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[90] Oxford is renowned for its tutorial-based method of teaching.

The Bodleian Library[edit]

The University of Oxford maintains the largest university library system in the United Kingdom,[91] and, with over 11 million volumes housed on 120 miles (190 km) of shelving, the Bodleian group is the second-largest library in the United Kingdom, after the British Library. The Bodleian Library is a legal deposit library, which means that it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the United Kingdom. As such, its collection is growing at a rate of over three miles (five kilometres) of shelving every year.[92]

Media[edit]

As well as the BBC national radio stations, Oxford and the surrounding area has several local stations, including BBC Radio Oxford, Heart South, Destiny 105, Jack FM, Jack 2 Hits and Jack 3 & Chill, along with Oxide: Oxford Student Radio[93] (which went on terrestrial radio at 87.7 MHz FM in late May 2005). A local TV station, Six TV: The Oxford Channel, was also available[94] but closed in April 2009; a service operated by That’s TV, originally called That’s Oxford (now That’s Oxfordshire), took to the airwaves in 2015.[95][96] The city is home to a BBC Television newsroom which produces an opt-out from the main South Today programme broadcast from Southampton.

Local papers include The Oxford Times (compact; weekly), its sister papers the Oxford Mail (tabloid; daily) and the Oxford Star (tabloid; free and delivered), and Oxford Journal (tabloid; weekly free pick-up). Oxford is also home to several advertising agencies. Daily Information (known locally as Daily Info) is an events and advertising news sheet which has been published since 1964 and now provides a connected website. Nightshift is a monthly local free magazine that has covered the Oxford music scene since 1991.[97]

Culture[edit]

Museums and galleries[edit]

Oxford is home to many museums, galleries, and collections, most of which are free of admission charges and are major tourist attractions. The majority are departments of the University of Oxford. The first of these to be established was the Ashmolean Museum, the world’s first university museum,[98] and the oldest museum in the UK.[99] Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house a cabinet of curiosities given to the University of Oxford in 1677. The museum reopened in 2009 after a major redevelopment. It holds significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Turner, and Picasso, as well as treasures such as the Scorpion Macehead, the Parian Marble and the Alfred Jewel. It also contains «The Messiah», a pristine Stradivarius violin, regarded by some as one of the finest examples in existence.[100]

The University Museum of Natural History holds the university’s zoological, entomological and geological specimens. It is housed in a large neo-Gothic building on Parks Road, in the university’s Science Area.[101] Among its collection are the skeletons of a Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, and the most complete remains of a dodo found anywhere in the world. It also hosts the Simonyi Professorship of the Public Understanding of Science, currently held by Marcus du Sautoy. Adjoining the Museum of Natural History is the Pitt Rivers Museum, founded in 1884, which displays the university’s archaeological and anthropological collections, currently holding over 500,000 items. It recently built a new research annexe; its staff have been involved with the teaching of anthropology at Oxford since its foundation, when as part of his donation General Augustus Pitt Rivers stipulated that the university establish a lectureship in anthropology.[102]

The Museum of the History of Science is housed on Broad Street in the world’s oldest-surviving purpose-built museum building.[103] It contains 15,000 artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century, representing almost all aspects of the history of science. In the university’s Faculty of Music on St Aldate’s is the Bate Collection of Musical Instruments, a collection mostly of instruments from Western classical music, from the medieval period onwards. Christ Church Picture Gallery holds a collection of over 200 old master paintings. The university also has an archive at the Oxford University Press Museum.[104] Other museums and galleries in Oxford include Modern Art Oxford, the Museum of Oxford, the Oxford Castle, Science Oxford and The Story Museum.[105]

Art[edit]

Art galleries in Oxford include the Ashmolean Museum, the Christ Church Picture Gallery, and Modern Art Oxford. William Turner (aka «Turner of Oxford», 1789–1862), was a watercolourist who painted landscapes in the Oxford area. The Oxford Art Society was established in 1891. The later watercolourist and draughtsman Ken Messer (1931–2018) has been dubbed «The Oxford Artist» by some, with his architectural paintings around the city.[106] In 2018, The Oxford Art Book featured many contemporary local artists and their depictions of Oxford scenes.[107] The annual Oxfordshire Artweeks is well-represented by artists in Oxford itself.[108]

Music[edit]

Holywell Music Room is said to be the oldest purpose-built music room in Europe, and hence Britain’s first concert hall.[109] Tradition has it that George Frideric Handel performed there, though there is little evidence.[110] Joseph Haydn was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University in 1791, an event commemorated by three concerts of his music at the Sheldonian Theatre, directed by the composer and from which his Symphony No. 92 earned the nickname of the «Oxford» Symphony.[111] Victorian composer Sir John Stainer was organist at Magdalen College and later Professor of Music at the university, and is buried in Holywell Cemetery.[112]

Oxford, and its surrounding towns and villages, have produced many successful bands and musicians in the field of popular music. The most notable Oxford act is Radiohead, who all met at nearby Abingdon School, though other well known local bands include Supergrass, Ride, Mr Big, Swervedriver, Lab 4, Talulah Gosh, the Candyskins, Medal, the Egg, Unbelievable Truth, Hurricane No. 1, Crackout, Goldrush and more recently, Young Knives, Foals, Glass Animals, Dive Dive and Stornoway. These and many other bands from over 30 years of the Oxford music scene’s history feature in the documentary film Anyone Can Play Guitar?. In 1997, Oxford played host to Radio 1’s Sound City, with acts such as Travis, Bentley Rhythm Ace, Embrace, Spiritualized and DJ Shadow playing in various venues around the city including Oxford Brookes University.[113] It is also home to several brass bands, notably the City of Oxford Silver Band, founded in 1887.

Theatres and cinemas[edit]

- Burton Taylor Studio, Gloucester Street

- New Theatre, George Street

- Odeon Cinema, George Street

- Odeon Cinema, Magdalen Street

- Curzon Cinema, Westgate, Bonn Square

- Old Fire Station Theatre, George Street

- O’Reilly Theatre, Blackhall Road

- Oxford Playhouse, Beaumont Street

- Pegasus Theatre,[114] Magdalen Road

- Phoenix Picturehouse, Walton Street

- Ultimate Picture Palace, Cowley Road

- Vue Cinema, Grenoble Road

- The North Wall Arts Centre, South Parade

- Creation Theatre Company

Literature and film[edit]

{{{annotations}}}

«Dreaming spires» of Oxford University viewed from South Park in the snow

Well-known Oxford-based authors include:

- Brian Aldiss (1925–2017), science fiction novelist, lived in Oxford.[115]

- Vera Brittain (1893–1970), undergraduate at Somerville.

- John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (1875–1940), attended Brasenose College, best known for The Thirty-nine Steps.

- A.S. Byatt (born 1936), Booker Prize winner, undergraduate at Somerville.

- Lewis Carroll (real name Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), (1832–1898), author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was a student and Mathematical Lecturer of Christ Church.

- Susan Cooper (born 1935), undergraduate at Somerville, best known for her The Dark Is Rising sequence.

- Sir William Davenant (1606–1668), poet and playwright.[116]

- Colin Dexter (1930–2017), wrote and set his Inspector Morse detective novels in Oxford.[115]

- John Donaldson (ca.1921–1989), a poet resident in Oxford in later life.

- Siobhan Dowd (1960–2007), Oxford resident, undergraduate at Lady Margaret Hall.

- Victoria Glendinning (born 1937), undergraduate at Somerville.

- Kenneth Grahame (1859–1932), educated at St Edward’s School, wrote The Wind in the Willows.

- Michael Innes (J. I. M. Stewart) (1906–1994), Scottish novelist and academic, Student of Christ Church

- P. D. James (1920–2014), born and died in Oxford; wrote about Adam Dalgliesh

- C. S. Lewis (1898–1963), student at University College and Fellow of Magdalen.

- T. E. Lawrence (1888–1935), «Lawrence of Arabia», Oxford resident, undergraduate at Jesus, postgraduate at Magdalen.

- Iris Murdoch (1919–1999), undergraduate at Somerville and fellow of St Anne’s.

- Carola Oman (1897–1978), novelist and biographer, born and brought up in the city.

- Iain Pears (born 1955), undergraduate at Wadham and Oxford resident, wrote An Instance of the Fingerpost.

- Philip Pullman (born 1946), undergraduate at Exeter, teacher and resident in the city.

- Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), undergraduate at Somerville, wrote about Lord Peter Wimsey.

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973), undergraduate at Exeter and later professor of English at Merton

- John Wain (1925–1994), undergraduate at St John’s and later Professor of Poetry at Oxford University 1973–78.

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), 19th-century poet and author who attended Oxford from 1874 to 1878.[117]

- Athol Williams (born 1970), South African poet, postgraduate at Hertford and Regent’s Park from 2015 to 2020.

- Charles Williams (1886–1945), editor at Oxford University Press.

Oxford appears in the following works:[citation needed]

- the poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis by Matthew Arnold.[118] Thyrsis includes the lines: «And that sweet city with her dreaming spires, She needs not June for beauty’s heightening,…»

- The Scarlet Pimpernel

- «Harry Potter» (all the films to date)

- The Chronicles of the Imaginarium Geographica by James A. Owen

- Jude the Obscure (1895) by Thomas Hardy (in which Oxford is thinly disguised as «Christminster»)[119]

- Zuleika Dobson (1911) by Max Beerbohm

- Gaudy Night (1935) by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Brideshead Revisited (1945) by Evelyn Waugh

- A Question of Upbringing (1951 ) by Anthony Powell

- Alice in Wonderland (1951 ) by Walt Disney

- Second Generation (1964) by Raymond Williams

- Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) by Steven Spielberg

- Inspector Morse (1987–2000)

- Where the Rivers Meet (1988) trilogy set in Oxford by John Wain

- All Souls (1989) by Javier Marías

- The Children of Men (1992) by P. D. James

- Doomsday Book (1992) by Connie Willis

- His Dark Materials trilogy (1995 onwards) by Philip Pullman

- Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)

- The Saint (1997)

- 102 Dalmatians (2000)

- Endymion Spring (2006) by Matthew Skelton

- Lewis (2006–15)

- The Oxford Murders (2008)

- Mr. Nice (1996), autobiography of Howard Marks, subsequently a 2010 film

- A Discovery of Witches (2011) by Deborah Harkness

- X-Men: First Class (2011)

- Endeavour (2012 onwards)

- The Reluctant Cannibals (2013) by Ian Flitcroft

- Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (2018)

Sport[edit]

Football[edit]

The city’s leading football club, Oxford United, are currently in League One, the third tier of league football, though they enjoyed some success in the past in the upper reaches of the league. They were elected to the Football League in 1962, reached the Third Division after three years and the Second Division after six, and most notably reached the First Division in 1985 – 23 years after joining the Football League. They spent three seasons in the top flight, winning the Football League Cup a year after promotion. The 18 years that followed relegation in 1988 saw their fortunes decline gradually, though a brief respite in 1996 saw them win promotion to the new (post Premier League) Division One in 1996 and stay there for three years. They were relegated to the Football Conference in 2006, staying there for four seasons before returning to the Football League in 2010.

They play at the Kassam Stadium (named after former chairman Firoz Kassam), which is near the Blackbird Leys housing estate and has been their home since relocation from the Manor Ground in 2001. The club’s notable former managers include Ian Greaves, Jim Smith, Maurice Evans, Brian Horton, Ramon Diaz and Denis Smith. Notable former players include John Aldridge, Ray Houghton, Tommy Caton, Matt Elliott, Dean Saunders and Dean Whitehead. Oxford City F.C. is a semi-professional football club, separate from Oxford United. It plays in the Conference South, the sixth tier, two levels below the Football League in the pyramid. Oxford City Nomads F.C. was a semi-professional football club who ground-shared with Oxford City and played in the Hellenic league.

Rowing[edit]