Всего найдено: 6

Как писать названия государств или территорий периода начала прошлого века типа: Кубанская народная республика, Литовско-Белорусская советская социалистическая республика и т. п.? Вроде бы они уже столетие как не существуют, и надо писать всё со строчной кроме первого слова, но с другой стороны есть аналоги типа Украинская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Болгарская Народная Республика, которых тоже уже нет, только не столетие, а пару десятилетий.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Непростой вопрос. С одной стороны, в исторических (не существующих в настоящее время) названиях государств с большой буквы пишутся первое слово и входящие в состав названия имена собственные: Французское королевство, Неаполитанское королевство, Королевство обеих Сицилий; Римская империя, Византийская империя, Российская империя; Новгородская республика, Венецианская республика; Древнерусское государство, Великое государство Ляо и т. д.

С другой стороны, в названии Союз Советских Социалистических Республик все слова пишутся с большой буквы, хотя этого государства тоже уже не существует. Сохраняются прописные буквы и в названиях союзных республик, в исторических названиях стран соцлагеря: Польская Народная Республика, Народная Республика Болгария и т. д.

Историческая дистанция, безусловно, является здесь одним из ключевых факторов. Должно пройти какое-то время (не два–три десятилетия, а гораздо больше), для того чтобы появились основания писать Союз советских социалистических республик по аналогии с Российская империя.

Историческая дистанция вроде бы позволяет писать в приведенных Вами названиях государственных образований с большой буквы только первое слово (эти образования существовали непродолжительное время и исчезли уже почти 100 лет назад). Но, с другой стороны, прописная буква в каждом слове названия подчеркивает тот факт, что эти сочетания в свое время были официальными названиями государств (или претендовали на такой статус). Если автору текста важно обратить на это внимания читателя, он вправе оставить прописные буквы (даже несмотря на то, что таких государственных образований давно уже нет на карте).

Интересуют прописные в выражении: Римская республика (а также в частях этого периода — Ранняя республика, Средняя… и Поздняя…).

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Справочник Д. Э. Розенталя «Прописная или строчная?» фиксирует: Римская республика. Сочетания этих слов с определениями Ранняя, Поздняя в словарях не отмечены, но по аналогии с зафиксированным в указанном справочнике Ранняя Римская империя корректно: Ранняя Римская республика, Поздняя Римская республика.

Здравствуйте! Ранее в ответах на вопросы №№ 186741, 190772 и 247771 Вы указали, что второе слово в названии Российская Империя пишется со строчной буквы. Пожалуйста, объясните такое написание. Согласно правилам, приведённым здесь же на сайте, «§ 100. Пишутся с прописной буквы индивидуальные названия aстрономических и географических объектов (в том числе и названия государств и их административно-политических частей), улиц, зданий. Если эти названия составлены из двух или нескольких слов, то с прописной буквы пишутся все слова, кроме служебных слов и родовых названий». В данном случае Империя не родовое название, а имя собственное, так же как и Российская Федерация. Почему же во втором случае второе слово считается частью имени собственного и пишется с прописной буквы (Федерация), а в первом — родовым названием и пишется со строчной (империя)???

На чём это основано и не является ли претенциозным пережитком недавнего прошлого?

Спасибо! С уважением,

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

С прописной буквы пишутся все слова (кроме служебных) в официальных названиях существующих государств и государственных объединений. Государства Российская империя в настоящее время не существует, это исторический термин, поэтому с прописной пишется только первое слово. Ср.: Королевство Испания, Соединенное Королевство (официальные названия современных государств), но: Французское королевство, Неаполитанское королевство (исторические названия); Республика Кипр, Итальянская Республика, но: Венецианская республика, Новгородская республика. Правильно: Российская империя (а также Римская империя, Османская империя, Британская империя и т. п.).

Римская империя или римская империя… пишется ли в этом случае Римская с большой буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Римская империя.

Восточная Римская Империя — все слова с прописных. Правильно? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

С прописных — первые два: _Восточная Римская империя_.

Восточная Римская империя или Восточная римская империя?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: _Восточная Римская империя_.

Смотреть что такое РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ в других словарях:

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ

Римская империя (Roman empire), в строгом смысле, период, когда рим. гос-во и его заморские пров. управлялись императором, т.е. со времен Августа (27 г. до н.э.) и до 476 г. н.э. В 375 г. н.э. Р.и. разделилась на Восточную и Западную. Однако часто термин «Р.и.» относят к владениям Рима как в респ., так и имперский периоды. Рим начал набирать силу в эпоху Тарквиниев (6 в. до н.э.), он покорил этрусков, сабинов, самнитов и греч. поселенцев, а к сер. 3 в. до н.э. уже господствовал над всей Италией. Конфликты с Карфагеном в Зап. Средиземноморье и с эллинистическим миром на В. закончились победой римлян в Пунических войнах, что позволило им установить господство над Сицилией (241 до н.э.), Испанией (201), Сев. Африкой (146), а победив в Македонских войнах, они захватили Македонию, Грецию и часть М. Азии. Помпей и Цезарь завоевали земли в М. Азии, Сирию и Галлию от Рейна до Атлантики, а после сражения у м. Акций (31) был присоединен еще и Египет. Император Август намеревался консолидировать империю в естеств. границах, но в 43 г. н.э. Клавдий вторгся на Британские о-ва, а Траян в 106 г. захватил Дакию (оставлена в 270 г.) и на короткое время Месопотамию (114-117). Единство огромной империи поддерживалось благодаря надежной связи между ее отдельными частями и внутр. стабильности, обеспечиваемой армией (римский легион). Флоты охраняли мор. пути, а сеть римских дорог, построенных для быстрой переброски воинских отрядов, способствовала развитию торговли и гос. почтовой системы, облегчала общение жителей империи между собой. Целостность Р.и. обеспечивали также единое законодательство и общий язык (лат. на 3. и греч. на В.). Процветавшие рим. города имели надежные системы водоснабжения и канализации. Влияние Рима распространялось до Индии, терр. совр. России, Юго-Вост. Азии и — по Великому Шелковому пути» — до Китая. С этими терр. были также налажены и торг, связи. В успехах Р.и. крылись и причины ее падения: на огромных пространствах обострилась борьба за власть, привлеченные богатством империи, начали вторгаться полчища варваров. В 410 г. вестготы разграбили Рим, в 455 г. вандалы захватили Карфаген, в 476 г. был низложен Ро-мул Августул, последний западнорим. император. (Византийская) империя просуществовала до 1453 г. Клас-сич. описание крушения Р.и. дано в кн. Гиббона «История упадка и разрушения Римской империи» (1776-81)…. смотреть

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ

величайшее и значительнейшее рабовладельч. государство античности. Историч. истоком Р. и. явился располож. в области Лаций г. Рим, основанный п… смотреть

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ

1) Орфографическая запись слова: римская империя2) Ударение в слове: Р`имская имп`ерия3) Деление слова на слоги (перенос слова): римская империя4) Фоне… смотреть

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ

Roman Empire, территория Старого Света, завоеванная и контролировавшаяся Римом с 27г. до н.э., когда Октавиан взял власть в стране, став, по сути дела,… смотреть

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ

Ударение в слове: Р`имская имп`ерияУдарение падает на буквы: и,еБезударные гласные в слове: Р`имская имп`ерия

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ

Начальная форма — Римская империя, единственное число, женский род, именительный падеж, неодушевленное

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ В I В. Н. Э

Императоры и сенат

Начавшийся еще во времена Августа процесс изменения состава правящего класса продолжался и при его преемниках. К середине I в. потомки старой знати составляли ничтожное меньшинство (около 1/10 общего числа сенаторов). Остальные сенаторы разбогатели и достигли высокого положения уже при империи. Это были выходцы из италийской знати, выслужившиеся императорские чиновники, иногда даже сыновья богатых воль ноотпущенников. Попадали в сенат, хотя еще в небольшом числе, уроженцы Нарбонекой Галлии и Испании, а затем и наиболее знатные и богатые представители общин. Великой Гайлий.

Крупнейшие рабовладельцы и землевладельцы Италии все еще не могли прииириться с потерей политической власти и поступиться своими исключительными правами и привилегиями. Среди них процветал культ республики и «последних республиканцев» — Брута и Кассия. Но по существу о республике всерьез они уже не мечтали, а хотели лишь видеть у власти принцепса, избранного сенатом и от него зависящего.

Представители этой группы сенаторов стремились к подавлению всех подданных, будь то рабы, плебс или провинциалы, путем прямого насилия. Они были недовольны тем, что знать провинций получила право высказывать одобрение или порицание уходившему в отставку провинциальному наместнику, которого в соответствии с этим император награждал или предавал суду. Когда в сенат были допущены галлы, это вызвало среди оппозиции негодование и насмешки. Еще больше эта группа негодовала на богатых и влиятельных вольноотпущенников, требуя, чтобы был издан закон, разрешающий патрону вернуть в рабство вольноотпущенника, показавшегося ему «неблагодарным».

Особенно беспощадной суровости требовала эта сенаторская группировка по отношению к рабам. В 61 г. префект Рима Педаний Секунд был убит своим рабом. По восстановленному Августом закону все 400 человек его городской фамилии подлежали смертной казни. В народе, возмущенном этой жестокостью, началось волнение. Вопрос был поставлен на обсуждение в сенате. С речью выступил потомок «тираноубийцы» Кассия — Гай Касснй. Он считал, что закон должен быть исполнен, так как только непрерывным страхом можно держать в узде разноплеменных рабов. Речь Кассия убедила сенаторов, и рабы Секунда были казнены.

Те сенаторы, которые лишь недавно вошли в состав высшего сословия, готовы были безоговорочно поддерживать сильную императорскую власть и приветствовали борьбу со старосенатской знатью. К этой группе примыкали и представители других сословий,, которые делали карьеру на императорской службе: всадники, императорские вольноотпущенники. Самую значительную роль среди них играл префект преторианцев. Должность эта впервые получила решающее значение уже при первом преемнике Августа. Тогдашний начальник преторианцев Сеян собрал разрозненные преторианские части в один лагерь. В этом лагере и происходило фактическое провозглашение императоров, хотя формально их утверждал сенат.

Из числа всадников выходило большинство военных командиров. Все большее влияние приобретали прокураторы, ведавшие в провинциях императорскими землями, возраставшими в результате конфискаций имущества осужденных. Возросла роль императорских вольноотпущенников. Формально они занимали различные должности в личной канцелярии императора. Наиболее важными были должности в ведомствах, занимавшихся финансовой отчетностью, прошениями, поступавшими на имя императора, и ответами на эти прошения. Но постепенно грань между императорским хозяйством и государственной администрацией все более стиралась, и главы ведомств фактически стали управлять большинством государственных дел. Император Нерон уже посылал своих вольноотпущенников ревизовать дела даже сенатских провинций, а отправившись в Грецию, поручил управление Римом своему отпущеннику Гелию.

Между всеми этими группировками шла непрерывная борьба. Оппозиция сената проявлялась в самой различной форме — от анонимных памфлетов и сатирических песенок против императоров до заговоров на их жизнь. Наиболее ярким представителем сенатской оппозиции императорскому режиму был крупнейший римский историк Корнелий Тацит (ок. 55—120), писавший спустя несколько десятилетий после смерти последнего представителя первой императорской династии Рима, известной в исторической традиции под именем Юлиев-Клавдиев (поскольку сменивший Августа Тиберий и последующие принцепсы принадлежали по-рождению или усыновление к этим родам). Знакомство Тацита с официальными источниками и закулисными интригами того времени и его огромный писательский талант позволили ему мастерски обрисовать образы тиранов на престоле Римской империи. Их посмертному бесславию немало способствовал и современник Тацита — Светоний Транквилл (около 70—160), написавший биографию двенадцати цезарей, начиная с Юлия Цезаря. Он тщательно собрал все слухи и сплетни, ходившие в сенатской среде, и включил их в свою книгу. В результате императоры династии Юлиев-Клавдиев остались в веках образцами безудержного самовластия, кровожадной, бессмысленной жестокости, чудовищного разврата.

Тиберия (14—37) обвиняли в надменности, двуличии и жестокости. Говорили, что по его тайному приказу был отравлен его племянник Германик, пользовавшийся большой популярностью в сенатских кругах. Особенную ненависть вызывал всесильный, но затем обвиненный в заговоре и казненный префект преторианцев Сеян. Его влиянию приписывали жестокие репрессии, которыми Тиберий отвечал на рост сенатской оппозиции, начавшей проявляться еще в конце правления Августа. В борьбе с этой оппозицией император охотно принимал всевозможные доносы, между прочим и от рабов, что особенно возмущало знать. Грозным орудием стал и так называемый «закон об оскорблении величества римского народа», некогда направленный против врагов республики, а со времен Тиберия применявшийся для осуждения действительных и мнимых врагов императора. На семьдесят восьмом году жизни Тиберий был задушен в своем дворце на острове Капреях (Капри) префектом преторианцев Макроном.

Новый император, Гай Цезарь (37—41), прозванный Калигулой (уменьшительное от «калига» — солдатский сапог; так называли его солдаты, среди которых он провел детство), не только не прекратил борьбы с аристократией, но даже усилил ее. Сенатские историки описывали его как безумца, требовавшего божеских почестей, казнившего невинных людей исключительно из кровожадности, жалевшего, что у всего народа не одна шея, которую можно было бы перерубить одним ударом. Он так увлекался скачками,писали они, что собирался сделать консулом своего любимого коня. Когда Калигула был убит трибуном преторианцев Кассием Хереей, сенат собирался провозгласить восстановление республики, но эта беспомощная попытка была быстро пресечена преторианцами, провозгласившими императором дядю Калигулы, брата Германика — Клавдия.

Вскоре после убийства Калигулы по наущению группы сенаторов наместник Далмации Скрибониан призвал солдат восстать за республику. Однако среди солдат лозунг республики не был популярен. После недолгих колебаний легионарии перебили командиров, подстрекавших их к мятежу, и заявили о своей преданности Клавдию.

Хотя, по сообщениям все тех же просенатских источников, Клавдия даже в собственной семье считали чудаком, он достаточно ясно понимал некоторые из стоявших перед ним задач, в частности вопрос об урегулировании взаимоотношений с аристократией провинций. Но это отнюдь не способствовало его популярности в сенате, куда он долгое время являлся только в сопровождении вооруженной стражи. Его обвиняли в том, что он всецело подчиняется своим вольноотпущенникам и женам. Последняя из них, властная и честолюбивая дочь Германика — Агриппина уговорила императора усыновить и объявить наследником ее сына от первого брака—Нерона, а затем отравила Клавдия. Семнадцатилетний Нерон был доставлен матерью в лагерь преторианцев и провозглашен императором.

Образ Нерона (54—68), которого сенат ненавидел, а христиане считали своим . первым гонителем и чуть ли не антихристом, рисовался особенно черными красками. Правда, первые пять лет его правления, когда он находился под влиянием своего воспитателя—знаменитого философа Сенеки, сенат был им доволен. Он отстранил вольноотпущенников Клавдия, не принимал доносов от рабов, не вмешивался в управлен» сенатскими провинциями. Но затем согласие былр снова нарушено. Сенека был отстранен. Снова под руководством префекта преторианцев Тигеллина начались преследования и казни сенаторов. Они ответили на это новым заговором. Теперь заговорщики даже на словах не выступали за республику, стремясь заменить Нерона своим ставленником Пизоном. Это был человек знатнейшего рода, но совершенно ничтожный, что было на руку выдвинувшей его клике. К заговору примкнули многие, между прочим и молодой поэт Лукан, который прославился республиканской по духу поэмой «Фарсалии»; возможно, что участником заговора был и Сенека. Заговор был раскрыт по доносу раба одного из участников. Это дало правительству повод расправиться и с остальными недовольными.

Нерон покровительствовал грекам и выходцам из восточных провинций, что возмущало римскую знать. Ее негодование вызывало его пристрастие к поэзии и музыке, которое дошло до того, что он публично выступал на сцене и участвовал в Греции в состязаниях актеров и музыкантов. Когда в Риме произошел длившийся целую неделю пожар, знать распустила слух, что Нерон приказал поджечь город, чтобы, глядя на пожар, воспеть гибель Трои. С этим пожаром связывают и первое преследование христиан, которых Нерон обвинил в поджоге, чтобы отвести от себя подозрение. Колоссальные средства расходовались Нероном на постройку нового дворца, так называемого «Золотого дома»., на роскошные празднества и раздачи народу Казна была пуста, провинции, особенно западные, переобременены налогами. Правление Нерона закончилось тем, что против него восстали наместники Галлии и Испании. Когда даже преторианцы покинули его и сенат объявил его низложенным, он бежал из Рима и покончил с собой со словами: «Какой великий артист погибает!»… смотреть

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ ВО ВТОРОЙ ПОЛОВИНЕ IV В

Междоусобия преемников Константида

Движение агонистиков и религиозные распри на Востоке показывают, что достигнутая напряжением всех сил видимая стабилизация империи при Диоклетиане и Константине была крайне непрочной. С совершенной очевидностью это выявилось при преемниках Константина. Константин завещал империю трем сыновьям — Константину, Константу, Констанцию и двум племянникам. Последние сразу же после его смерти были перебиты вместе с другими родственниками Константина во время вспыхнувшего в Константинополе военного мятежа, вызванного происками Констанция, который стремился избавиться от возможных соперников. Констант, отняв у своего брата Константина придунайские области, 13 лет правил Западом и погиб в борьбе с объявившим себя императором военачальником Магненцпем. Констанцию удалось разбить Магненция и снова воссоединить империю под своей властью.

Констанций и Юлиан, Воины с «варварами»

При Констанции опять усиливается натиск «варваров». Франки и аламаны, еще не умевшие брать города, захватывали сельские местности Галлии и размещались здесь со своими семьями. Население, истощенное непомерными налогами и в значительной мере разбежавшееся по лесам и болотам, и даже солдаты, оборванные и голодные, почти не оказывали им сопротивления. На Дунае наступали сарматы. Одно из сарматских племен, покоренное другим племенем, восстало против своих поработителей. Те просили помощи Констанция, который, будучи верен римскому принципу поддерживать господ против рабов, в помощи не отказал и был втянут в неудачную для него войну. В это же время на Востоке началась война с Персией из-за Армении и месопотамских областей. В этих сложных условиях Констанций сделал цезарем Востока одного из своих уцелевших во время константинопольской резни двоюродных братьев — Галла, которого, однако, вскоре казнил. После этого он возвел в звание цезаря брата Галла — Юлиана и отправил его очищать Галлию от «варваров». Многие считали, что подозрительный, ревнивый к своей власти Констанций послал молодого цезаря, последнего из рода Констанция Хлора, в Галлию в расчете на то, что он оттуда не вернется: так Мало дал он ему войска и таким бдительным надзором стеснил его действия.

В Галлии новый цезарь неожиданно достиг значительных успехов. Добившись большой популярности среди солдат заботами об их нуждах, он одержал над франками и аламанами ряд побед, из которых особенно знаменита победа при Аргенторатс (Страсбург), когда в плен был взят вождь франков Хнодомар. Юлиан трижды переходил Рейн. В провинциях он, несмотря на ограниченность своей власти, старался улучшить положение мелких и средних землевладельцев, снизив и более равномерно распределив налоги, отстраивая разрушенные города. Все это, конечно, создавало ему популярность и среди куриалов Востока.

Кое-кто из языческой партии Востока, встречавшийся с Юлианом в Афинах и Эфесе, где он оканчивал образование, знал, что воспитанный в христианской вере Юлиан втайне придерживается неоплатонизма и поклоняется Солнцу. Это делало нового цезаря желанным кандидатом на императорский трон в глазах довольно значительной части населения восточных провинций. В правление Констанция язычники терпели гонения. Многие храмы были закрыты, их имущество отобрано в казну. Обширные земли храмов Каппадокии и Коммагены были выделены в особые округа и обогащали управлявших ими придворных. Конфискация собственности богатых городских храмов, которой распоряжались курии, еще более ослабила платежеспособность последних. Свою ненависть ко всей системе домината куриалы переносили на христианство и, мечтая о возвращении прежних порядков и прежней религии, с надеждой смотрели на Юлиана.

Между тем Констанций, терпя поражение от персов, приказал Юлиану отослать к ному часть войска. Солдаты, в большинстве местные уроженцы из провинциалов и «варваров», отказались покидать родину и семьи и, подняв мятеж, провозгласили августом Юлиана. Западные провинции признали его без сопротивления. Готовясь к неизбежной войне с Констанцией, Юлиан рассылал письма городским куриям, принимал делегации городов, обещая им помощь и удовлетворяя их просьбы. Столкновение с Констанцием было предотвращено смертью последнего, и Юлиан стал правителем всей империи (361—363 гг.).

Политика Юлиана

Прибыв на Восток, Юлиан открыто заявил о своем разрыве с христианством, лишил клир всех привилегии и приказал восстановить языческие храмы и языческий культ. Стремясь привлечь на свою сторону бедноту, он организовывал больницы и убежища для нищих, проводил большие раздачи, старался дать стройную организацию языческому жречеству. Рассчитывая, что внутренние распри ослабят христиан, он вернул из ссылки «еретиков» всех толков и устроил собор представителей всех учений и сект, наслаждаясь их взаимной грызней. Прямому преследованию христиане при Юлиане не подвергались, но он удалил их с высших должностей и запретил им преподавание в школах. Превосходно зная священное писание, он выступал с его опровержением. Антихристианская политика Юлиана сочеталась с попыткой воскресить городские курии. Он приказал разыскивать и возвращать в курии всех незаконно пользовавшихся привилегиями или скрывавшихся куриалов, возвращал городам их земли, оказывал им щедрую помощь, сократил придворную челядь, чтобы уменьшить тяжесть шедших на ее содержание налогов.

Однако мероприятия Юлиана не встретили широкой поддержки, так как не только христиане, высшие чиновники и придворные, но и богатые куриалы были ими недовольны. Среди богачей Антиохии вызвал негодование закон о максимальной цене на муку. Чтобы поддержать этот закон, Юлиан приказал на свой счет привезти дешевое зерно из Египта, но богатые купцы раскупили и спрятали его, что повело к голоду и волнениям плебса. Не удалось возродить и не имевший уже реальной базы языческий культ во всем его былом великолепии. Недолгое правление Юлиана закончилось большим походом против Персии. Военные операции вначале протекали довольно успешно, так как Юлиан в армии был очень популярен за борьбу со злоупотреблениями командиров. Но заведя свое войско далеко вглубь пустынной вражеской территории, Юлиан погиб в бою.

Преемник Юлиана Иовиан (363—364) должен был отдать персам пять областей Месопотамии, чтобы получить возможность вернуться в империю с остатками войска, сильно пострадавшего от жары, голода и жажды. Христиане ликовали по случаю гибели «отступника». Неудача Юлиана показала, что сословие куриалов и язычество окончательно отжили свой век. Она показала также всю невозможность возрождения римской военной мощи, к чему стремился Юлиан. После его смерти становится все более очевидным, что империя уже не может обходиться без помощи «варваров» ни во внешних, ни в междоусобных войнах…. смотреть

РИМСКАЯ ИМПЕРИЯ ВО ВТОРОЙ ПОЛОВИНЕ I В. И ВО II В. Н. Э

Столетие, протекшее со времени победы Веспасиана, обычно характеризуется как период наивысшего развития римского рабовладельческого общества, как период укрепления империи и ее наибольшего территориального расширения. Однако если рабовладельческий строй достиг теперь предельного развития, то к концу периода он уже явно начинает клониться к своему упадку.

Римская империя — орган господства Средиземноморья

Одним из наиболее характерных явлений этого периода была дальнейшая «романизация» провинций, развитие их экономики, возрастание роли провинциалов в жизни империи, числа провинциальных сенаторов, всадников, военных.

К концу II в. более 40% сенаторов были уроженцами провинций, и уже в начале этого столетия представители знати восточных провинций заняли в сенате такое же место, как и знать провинций западных. Постепенно число уроженцев Малой Азии, Сирии, а затем и Африки начинает превышать число сенаторов из Испании и Нарбонской Галлии, а к началу III в. они составляют подавляющее большинство провинциальных сенаторов. Сменявшие друг Друга императоры при всех своих индивидуальных особенностях в общем продолжали одну политическую линию, продиктованную общим ходом исторического развития Римской империи: они поддерживали провинциальные города и провинциальную знать, пытаясь в то же время предотвратить прогрессирующий упадок Италии; они стремились также укрепить боеспособность армии, сберечь те слои населения, которые могли поставлять солдат в легионы и вспомогательные части, они принимали всевозможные меры к тому, чтобы не допустить новых восстаний в провинциях и восстаний рабов. Многие из этих императоров были людьми, весьма типичными для своего времени. Первый из них — Флавий Веспасиан (69—79), основатель новой династии Флавиев, был сыном небогатого гражданина сабинского города Реате. Пройдя обязательную лестницу военных и гражданских должностей, он стал сенатором. Продвигаясь по этому пути, ему случалось наталкиваться на недоброжелательство старой аристократии, искать протекции у вольноотпущенников Клавдия. Подобный путь проделали и многие другие уроженцы италийских городов, которые заменили в сенате старую римскую аристократию.

Для новой знати Веспасиан был своим человеком. Став императором, он пополнил ряды всадников и сенаторов самыми богатыми и знатными гражданами городов Италии и западных провинций. При нем все города Испании и многие города других западных провинций получили права латинского гражданства. Отсюда же теперь стали набирать большое число легионариев. Напротив, восточные провинции не пользовались при Веспасиане такими преимуществами. Более того, некоторые города этих провинций были лишены прежних привилегий. Некоторые зависимые царства (Коммагена, часть Киликии) были присоединены к империи. На Востоке не стихало глухое недовольство; несколько самозванцев, выдававших себя за Нерона, нашли там многочисленных сторонников. Отчасти это вызывалось податями, которыми Веспасиан, заставший казну пустой, переобременял провинции. Ему пришлось столкнуться с оппозицией и в сенате. Невидимому, главной причиной недовольства было желание Веспасиана передать власть своему сыну Титу, а в случае его бездетности — второму сыну, Домициану. Последний был особенно непопулярен в сенате, но главное, часть сенаторов была против наследственной монархии, считая, что принцепс должен избираться сенатом. Однако Веспасиан одержал верх, и после смерти первого Флавия императором стал Тит, вскоре умерший (79—81), а затем к власти пришел Домициан (81—96).

В правление Домициана, особенно к концу его, сенатская оппозиция вновь крайне усилилась. Была даже попытка поднять мятеж, во главе которого стал наместник Верхней Германии Антоний Сатурнин, постаравшийся привлечь на свою сторону солдат. Однако Домициан, повысивший солдатам жалованье на 1/3 и даровавший значительные привилегии ветеранам, был популярен в армии, и мятеж был легко подавлен. Результатом явились новые преследования сенаторов, казни и конфискации. Домициан, именовавший себя «богом» и «господином», изгонял из сената неугодных ему лиц.

В войнах с возникшим на территории Дакии племенным союзом, во главе которого стал Децебал, римляне потерпели несколько поражений. Домициану пришлось заключить с даками мир на условиях выплаты субсидни зерном и деньгами и присылки римских ремесленников. Все это усиливало недовольство знати. Особенно враждебно относились к Домициану провинциальные наместники, поставленные им под строжайший контроль. Было раскрыто несколько заговоров, что повело к новым репрессиям и новому росту недовольства. Наконец, Домициан был убит своими отпущенниками. Сенат объявил ненавистного ему Домициана врагом римского народа, его статуи были низвергнуты, память проклята.

Императором сенат провозгласил Нерву, представителя старой сенатской знати. С него начинается так называемая династия Антонинов (по имени одного из ее представителей— Антонина Пия). При этой династии осуществилась наиболее приемлемая для сената форма монархии. Власть передавалась не сыну или ближайшему родственнику императора, а лицу, которое он усыновлял с одобрения сената. Начиная с Нервы, каждый принценс его династии, принимая класть, давал клятву не казнить и не лишать имущества сенатора без приговора сената и не принимать доносов об оскорблении его особы. Только при соблюдении императором этого условия сенат был обязан ему верностью. Знать Италии и провинций была этим вполне удовлетворена.

Траян (98—117), уроженец Испании, усыновленный Первой, был первым провинциалом среди императоров. Этот факт весьма показателен для того положения, которое заняли западные провинции в Римской империи. Траян считался энергичным администратором и хорошим полководцем. В двух войнах он разбил Децсбала и обратил Дакию в провинцию. В 106 г. из Набатейского царства была образована провинция Аравия. Успешна была сначала и война Траппа с Парфией, в ходе которой он подчинил Армению, взял Селевкию и Ктесифон. Однако тяжелые условия похода, безуспешная длительная осада города Атры, а главное — общее восстание, начавшееся в тылу, в покоренных местностях, а также восстание иудеев в Киренаике вынудили его прекратить войну. Он умер в Киликии на обратном пути в Италию. Его преемник Адриан (117—138), тоже уроженец Испании, бывший в момент смерти Траяна наместником Сирии, немедленно отказался от всех восточных завоеваний Траяна (кроме Аравии), которые империя не могла удержать. Все свое внимание он обратил на оборону границ. В этот период отмечается интенсивное строительство укреплений — валов, рвов и башен, опоясавших почти все границы империи. Большую часть времени Адриан проводил в объездах провинций и инспектировании войск. Он стремился как можно больше развивать городскую жизнь, украшая старые и основывая новые города. Во многих колониях и муниципиях он избирался на должность эдила или дуумвира и как таковой жертвовал значительные суммы в городские кассы, а также зерно для раздачи горожанам. К тому времени городская жизнь провинций достигает наивысшего подъема. Город, античный полис, хотя и пользовавшийся лишь номинальной автономией, был наиболее выгодной формой организации для рабовладельцев. Рознь между знатью Рима и провинций сгладилась. Для новых условий показательна карьера одного из известнейших полководцев Траяна—Лузия Квиета. Он был вождем одного из мавретанских племен и поступил на римскую службу командиром конного отряда мавров. В дакийских войнах он выдвинулся, попал в сонат и стал консулом. Достаточно сравнить его карьеру с судьбой его соплеменника Такфарината, бежавшего из римской армии и поднявшего восстание при Тиберии, чтобы понять, как изменилось положение провинций в системе империи и какие возможности открылись перед провинциальной знатью.

Преемник Адриана — Антонин Пий (138—161) сенатской историографией изображался как идеальный, кроткий правитель, уважавший сенат, как защитник провинций и миролюбец. Однако его правление отнюдь не было так прекрасно и спокойно, как его рисовали. Уже при нем появились предвестники Кризиса, который вскоре охватил всю империю.

Симптомы кризиса становятся еще более явными при следующем императоре — Марке Аврелии (161—180). Сам он был также весьма характерной фигурой. Он был не только превосходно образован, но являлся последним крупным представителем стоической школы. Сохранилось сочинение Марка Аврелия «К самому себе». Оно поражает беспросветным пессимизмом и безнадежностью, которыми проникнута каждая глава.

Последним императором династии Антонинов был сын Марка Аврелия — Коммод (180—192). События, ознаменовавшие его правление, показали, что «век Антонинов», который имперская знать называла «золотым», пришел к концу.

Новая знать и усиление императорской власти

Новая италийская и провинциальная знать окончательно отказалась от республиканских идеалов, так как поняла, что ее интересы, что ее интересы может защитить лишь сильная императорская власть. Идеал республики заменяется идеалом «хорошего императора». Одним из известнейших проповедников этого идеала был ритор и философ-киник Дион из Прусы в Вифинии, прозванный Хрисостомом (Златоустом). Изгнанный Домицианом, он снова вошел в милость при Нерве и Траяне и развивал взгляды на монархию, популярные среди сенаторского сословия, а также муниципальной знати Италии и провинций. Хороший монарх, согласно этим взглядам, находится под особым покровительством Зевса, врага и гонителя тиранов. Он должен быть милостивым и справедливым, отцом граждан, другом «лучших людей», слугой общества. «Хорошим» считался тот принцепс, который держал в повиновении рабов и народ, не переобременял провинции налогами в пользу армии, поддерживал дисциплину среди солдат, а главное, давал возможность состоятельным людям спокойно пользоваться их имуществом. Плиний Младший в панегирике Траяну, который он, согласно обычаю, произнес в благодарность за назначение его консулом, особенно подчеркивал, что Траян не стремился завладеть всей землей империи и что он вернул частным лицам многое из того, что захватили его предшественники. На таких условиях знать была согласна отказаться от активного участия в политической жизни.

Монархическая власть императоров все более крепла. Когда Веспасиан захватил власть, сенат декретировал ему все права, которыми пользовались его предшественники. Он получил право единолично ведать внешней политикой, предлагать кандидатов на любые должности, издавать любые распоряжения, имевшие силу закона. Все большее значение в ущерб сенату приобретал «совет друзей» принцепса. Уже Домициан стал назначать римских всадников в ведомства по императорской переписке, прошениям на имя императора и т. д. Со времени Адриана это стало правилом, что подняло значение императорской бюрократии. Еще более укрепил ее переход сбора налогов от откупщиков к императорским чиновникам. Особенно большое значение приобрел префект анноны, ведавший сбором натуральных поставок, предназначавшихся для нужд армии и раздач плебсу. Многочисленные уполномоченные фиска и префекта анноны вместе с администрацией императорских земель составляли основное ядро все растущей императорской бюрократии, вербовавшейся из всадников, императорских отпущенников и даже рабов. Постепенно среди нее образуется известная иерархия должностей с соответствовавшими им окладами.

Большое значение имело начало кодификации права при Адриане. По поручению Адриана юристы собрали выдержки из преторских эдиктов в один, так называемый «вечный», эдикт, утвержденный затем сенатом. После этого преторы утратили законодательную власть, дальнейшее развитие права стало делом только императора и состоявших при нем юрисконсультов. Усилился контроль императорских чиновников и наместников над городами, провинциями, отдельными гражданами. Во второй половине II в. был издан специальный закон против тех, кто своими словами или действиями «смутит душу простого и суеверного народа». К официальному надзору прибавлялся неофициальный. Уже Адриан широко использовал тайных соглядатаев, так называемых фрументариев.

Восхваление императоров было обязательным. Города, коллегии, воинские части посвящали им статуи и пышные надписи. Умершие «хорошие» императоры объявлялись богами, в честь которых строились храмы. Статуй и хвалебных надписей удостаивались не только императоры, но и члены их семьи, наместники, командиры, чиновники, наконец просто богатые люди, избиравшиеся патронами городов и коллегий. Всякий занимавший более или менее видное положение требовал лести и угодливости от тех, кто стоял ниже его. Такова была «свобода», царившая, по мнению приверженцев Антонинов, в «золотой век» их правления.

Армия во второй половине I в. и во II в. н.э.

Начиная со времени правления Веспасиана, благодаря распространению римского гражданства, еще более значительна», чем Раньше, часть солдат стала вербоваться из провинции.

Италики служили главным образом в преторианских когортах и, пройдя здесь римскую военную школу, назначались центурионами в провинциальные войска. Введенная Клавдием практика дарования римского гражданства ветеранам всиомогательных частей способствовала дальнейшей романизации провинций и усиливала преданность солдат Риму. Учтя опыт восстания Цивилиса, правительство не оставляло вспомогательных частей в тех провинциях, в которых они были набраны, а формировало их из солдат различных племен. Различие между легионами и вспомогательными частями постепенно стиралось.

Набор провинциалов в армию привел к изменению ее социального состава. Если армия I в. н. э., состоявшая из италиков, включала преимущественно бедняков, рассчитывавших обогатиться на службе, то теперь в солдаты шли провинциалы, пользовавшиеся известным благосостоянием, привлеченные надеждой сделать карьеру и получить римское гражданство и различные привилегии, став ветеранами. Ветераны, приобретая землю и рабов, играли видную роль в городах или селах, где они селились после отставки. Здесь они организовывали коллегии, которым нередко принадлежала инициатива в демонстрациях преданности Риму и императору. Часто ветераны получали земли около лагеря своего легиона, где образовывались поселения торговцев и ремесленников, а также семей солдат, которые узаконивали эти семьи после своей отставки. Лагерные поселения постепенно превращались в города. Армия была важным фактором в жизни провинций. Солдаты строили дороги, каналы, водопроводы, общественные здания. Но вместе с тем содержание огромной, примерно четырехсоттысячной, армии ложилось тяжелым бременем на население провинций. Основная масса налогов и поставок шла в ее пользу, население вынуждено было исполнять ряд работ для армии, брать солдат на постой. Солдаты нередко притесняли жителей, отбирали у них имущество Выделение земель ветеранам ускоряло распад общины, разоряло крестьянство. В самой армии противоречия между солдатами и командирами продолжали существовать. Высшие должности были попрежнему доступны лишь всадникам и сенаторам. Несмотря на правительственный контроль, командиры брали взятки с солдат и притесняли их. В результате случаи дезертирства и перехода на сторону противника были нередки. Состоянием армии отчасти объясняется стремление Флавиев и Антонинов избегать войн. Другой важнейшей причиной, определявшей их внешнюю политику, было положение в провинциях…. смотреть

|

Roman Empire

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 BC–AD 395 (unified)[2] AD 395–476/480 (Western) AD 395–1453 (Eastern) |

||||||||||

|

Vexillum Imperial aquila |

||||||||||

![The Roman Empire in AD 117 at its greatest extent, at the time of Trajan's death (with its vassals in pink)[3][b]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/00/Roman_Empire_Trajan_117AD.png/250px-Roman_Empire_Trajan_117AD.png)

The Roman Empire in AD 117 at its greatest extent, at the time of Trajan’s death (with its vassals in pink)[3][b] |

||||||||||

The Roman Empire from the rise of the city-state of Rome to the fall of the Western Roman Empire |

||||||||||

| Capital |

|

|||||||||

| Official languages | Latin | |||||||||

| Common languages | Regional languages | |||||||||

| Religion |

|

|||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Roman | |||||||||

| Government | Semi-elective absolute monarchy (de facto) | |||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||

|

• 27 BC – AD 14 |

Augustus (first) | |||||||||

|

• 98–117 |

Trajan | |||||||||

|

• 138–161 |

Antoninus Pius | |||||||||

|

• 270–275 |

Aurelian | |||||||||

|

• 284–305 |

Diocletian | |||||||||

|

• 306–337 |

Constantine I | |||||||||

|

• 379–395 |

Theodosius I[d] | |||||||||

|

• 474–480 |

Julius Nepos[e] | |||||||||

|

• 475–476 |

Romulus Augustus | |||||||||

|

• 527–565 |

Justinian I | |||||||||

|

• 610–641 |

Heraclius | |||||||||

|

• 780–797 |

Constantine VI[f] | |||||||||

|

• 976–1025 |

Basil II | |||||||||

|

• 1143–1180 |

Manuel I | |||||||||

|

• 1449–1453 |

Constantine XI[g] | |||||||||

| Historical era | Classical era to Late Middle Ages | |||||||||

|

• War of Actium |

32–30 BC | |||||||||

|

• Empire established |

30–2 BC | |||||||||

|

• Octavian named augustus |

16 January 27 BC | |||||||||

|

• Constantinople |

11 May 330 | |||||||||

|

• Final East-West divide |

17 January 395 | |||||||||

|

• Deposition of Romulus Augustus |

4 September 476 | |||||||||

|

• Murder of Julius Nepos |

9 May 480 | |||||||||

|

• Fourth Crusade |

12 April 1204 | |||||||||

|

• Reconquest of Constantinople |

25 July 1261 | |||||||||

|

• Fall of Constantinople |

29 May 1453 | |||||||||

|

• Fall of Trebizond |

15 August 1461 | |||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||

| 25 BC[6] | 2,750,000 km2 (1,060,000 sq mi) | |||||||||

| AD 117[6][7] | 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi) | |||||||||

| AD 390[6] | 3,400,000 km2 (1,300,000 sq mi) | |||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||

|

• 25 BC[8] |

56,800,000 | |||||||||

| Currency | sestertius,[h] aureus, solidus, nomisma | |||||||||

|

The Roman Empire (Latin: Imperium Romanum [ɪmˈpɛri.ũː roːˈmaːnũː]; Greek: Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, translit. Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterranean Sea in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, and was ruled by emperors. From the accession of Caesar Augustus as the first Roman emperor to the military anarchy of the 3rd century, it was a Principate with Italia as the metropole of its provinces and the city of Rome as its sole capital. The Empire was later ruled by multiple emperors who shared control over the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. The city of Rome remained the nominal capital of both parts until AD 476 when the imperial insignia were sent to Constantinople following the capture of the Western capital of Ravenna by the Germanic barbarians.[dubious – discuss] The adoption of Christianity as the state church of the Roman Empire in AD 380 and the fall of the Western Roman Empire to Germanic kings conventionally marks the end of classical antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. Because of these events, along with the gradual Hellenization of the Eastern Roman Empire, historians distinguish the medieval Roman Empire that remained in the Eastern provinces as the Byzantine Empire.

The predecessor state of the Roman Empire, the Roman Republic, became severely destabilized in civil wars and political conflicts. In the middle of the 1st century BC, Julius Caesar was appointed as dictator perpetuo («dictator in perpetuity»), and then assassinated in 44 BC. Civil wars and proscriptions continued, eventually culminating in the victory of Octavian over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The following year, Octavian conquered the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt, ending the Hellenistic period that had begun with the 4th century BC conquests of Alexander the Great. Octavian’s power became unassailable and the Roman Senate granted him overarching power and the new title of Augustus, making him the first Roman emperor. The vast Roman territories were organized in senatorial and imperial provinces except Italy, which continued to serve as a metropole.

The first two centuries of the Roman Empire saw a period of unprecedented stability and prosperity known as the Pax Romana (lit. ‘Roman Peace’). Rome reached its greatest territorial expanse during the reign of Trajan (AD 98–117); a period of increasing trouble and decline began with the reign of Commodus (177–192). In the 3rd century, the Empire underwent a crisis that threatened its existence, as the Gallic and Palmyrene Empires broke away from the Roman state, and a series of short-lived emperors, often from the legions, led the Empire. It was reunified under Aurelian (r. 270–275). To stabilize it, Diocletian set up two different imperial courts in the Greek East and Latin West in 286; Christians rose to positions of power in the 4th century following the Edict of Milan of 313. Shortly after, the Migration Period, involving large invasions by Germanic peoples and by the Huns of Attila, led to the decline of the Western Roman Empire. With the fall of Ravenna to the Germanic Herulians and the deposition of Romulus Augustus in AD 476 by Odoacer, the Western Roman Empire finally collapsed; the Eastern Roman emperor Zeno formally abolished it in AD 480. The Eastern Roman Empire survived for another millennium, until Constantinople fell in 1453 to the Ottoman Turks under Mehmed II.[i]

Due to the Roman Empire’s vast extent and long endurance, the institutions and culture of Rome had a profound and lasting influence on the development of language, religion, art, architecture, literature, philosophy, law, and forms of government in the territory it governed. The Latin language of the Romans evolved into the Romance languages of the medieval and modern world, while Medieval Greek became the language of the Eastern Roman Empire. The Empire’s adoption of Christianity led to the formation of medieval Christendom. Roman and Greek art had a profound impact on the Italian Renaissance. Rome’s architectural tradition served as the basis for Romanesque, Renaissance and Neoclassical architecture, and also had a strong influence on Islamic architecture. The rediscovery of Greek and Roman science and technology (which also formed the basis for Islamic science) in Medieval Europe led to the Scientific Renaissance and Scientific Revolution. The corpus of Roman law has its descendants in many modern legal systems of the world, such as the Napoleonic Code of France, while Rome’s republican institutions have left an enduring legacy, influencing the Italian city-state republics of the medieval period, as well as the early United States and other modern democratic republics.

History

Transition from Republic to Empire

Rome had begun expanding shortly after the founding of the Roman Republic in the 6th century BC, though it did not expand outside the Italian peninsula until the 3rd century BC. Then, it was an «empire» (i.e., a great power) long before it had an emperor.[10] The Republic was not a nation-state in the modern sense, but a network of towns left to rule themselves (though with varying degrees of independence from the Roman Senate) and provinces administered by military commanders. It was ruled, not by emperors, but by annually elected magistrates (Roman consuls above all) in conjunction with the Senate.[11] For various reasons, the 1st century BC was a time of political and military upheaval, which ultimately led to rule by emperors.[12][13][14] The consuls’ military power rested in the Roman legal concept of imperium, which literally means «command» (though typically in a military sense).[15] Occasionally, successful consuls were given the honorary title imperator (commander), and this is the origin of the word emperor (and empire) since this title (among others) was always bestowed to the early emperors upon their accession.[16]

Rome suffered a long series of internal conflicts, conspiracies, and civil wars from the late second century BC onward, while greatly extending its power beyond Italy. This was the period of the Crisis of the Roman Republic. Towards the end of this era, in 44 BC, Julius Caesar was briefly perpetual dictator before being assassinated. The faction of his assassins was driven from Rome and defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC by an army led by Mark Antony and Caesar’s adopted son Octavian. Antony and Octavian’s division of the Roman world between themselves did not last and Octavian’s forces defeated those of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. In 27 BC the Senate and People of Rome made Octavian princeps («first citizen») with proconsular imperium, thus beginning the Principate (the first epoch of Roman imperial history, usually dated from 27 BC to 284 AD), and gave him the title Augustus («the venerated»). Though the old constitutional machinery remained in place, Augustus came to predominate it. Although the republic stood in name, contemporaries of Augustus knew it was just a veil and that Augustus had all meaningful authority in Rome.[17] Since his rule ended a century of civil wars and began an unprecedented period of peace and prosperity, he was so loved that he came to hold the power of a monarch de facto if not de jure. During the years of his rule, a new constitutional order emerged (in part organically and in part by design), so that, upon his death, this new constitutional order operated as before when Tiberius was accepted as the new emperor.

In 117 AD, under the rule of Trajan, the Roman Empire, at its farthest extent, dominated much of the Mediterranean Basin, spanning three continents.

The Pax Romana

The 200 years that began with Augustus’s rule is traditionally regarded as the Pax Romana («Roman Peace»). During this period, the cohesion of the empire was furthered by a degree of social stability and economic prosperity that Rome had never before experienced. Uprisings in the provinces were infrequent but put down «mercilessly and swiftly» when they occurred.[18] The success of Augustus in establishing principles of dynastic succession was limited by his outliving a number of talented potential heirs. The Julio-Claudian dynasty lasted for four more emperors—Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, and Nero—before it yielded in 69 AD to the strife-torn Year of the Four Emperors, from which Vespasian emerged as victor. Vespasian became the founder of the brief Flavian dynasty, to be followed by the Nerva–Antonine dynasty which produced the «Five Good Emperors»: Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and the philosophically-inclined Marcus Aurelius.

Fall in the West and survival in the East

The Barbarian Invasions consisted of the movement of (mainly) ancient Germanic peoples into Roman territory. Even though northern invasions took place throughout the life of the Empire, this period officially began in the 4th century and lasted for many centuries, during which the western territory was under the dominion of foreign northern rulers, a notable one being Charlemagne. Historically, this event marked the transition between classical antiquity and the Middle Ages.

In the view of the Greek historian Dio Cassius, a contemporary observer, the accession of the emperor Commodus in 180 AD marked the descent «from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron»[19]—a famous comment which has led some historians, notably Edward Gibbon, to take Commodus’ reign as the beginning of the decline of the Roman Empire.[20][21]

In 212 AD, during the reign of Caracalla, Roman citizenship was granted to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. But despite this gesture of universality, the Severan dynasty was tumultuous—an emperor’s reign was ended routinely by his murder or execution—and, following its collapse, the Roman Empire was engulfed by the Crisis of the Third Century, a period of invasions, civil strife, economic disorder, and plague.[22]

In defining historical epochs, this crisis is sometimes viewed as marking the transition from Classical Antiquity to Late Antiquity. Aurelian (r. 270–275) brought the empire back from the brink and stabilized it. Diocletian completed the work of fully restoring the empire, but declined the role of princeps and became the first emperor to be addressed regularly as domine («master» or «lord»).[23] Diocletian’s reign also brought the empire’s most concerted effort against the perceived threat of Christianity, the «Great Persecution».

Diocletian divided the empire into four regions, each ruled by a separate emperor, the Tetrarchy.[24] Confident that he fixed the disorders that were plaguing Rome, he abdicated along with his co-emperor, and the Tetrarchy soon collapsed. Order was eventually restored by Constantine the Great, who became the first emperor to convert to Christianity, and who established Constantinople as the new capital of the Eastern Empire. During the decades of the Constantinian and Valentinian dynasties, the empire was divided along an east–west axis, with dual power centres in Constantinople and Rome. The reign of Julian, who under the influence of his adviser Mardonius attempted to restore Classical Roman and Hellenistic religion, only briefly interrupted the succession of Christian emperors. Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule over both East and West, died in 395 AD after making Christianity the official religion of the empire.[25]

The Roman Empire by 476, noting western and eastern divisions

The Western Roman Empire began to disintegrate in the early 5th century as Germanic migrations and invasions overwhelmed the capacity of the empire to assimilate the migrants and fight off the invaders. The Romans were successful in fighting off all invaders, most famously Attila,[26] although the empire had assimilated so many Germanic peoples of dubious loyalty to Rome that the empire started to dismember itself.[27] Most chronologies place the end of the Western Roman Empire in 476, when Romulus Augustulus was forced to abdicate to the Germanic warlord Odoacer.[28][29][30]

By placing himself under the rule of the Eastern Emperor, rather than naming a puppet emperor of his own, Odoacer ended the Western Empire. He did this by declaring Zeno sole emperor, and placing himself as his nominal subordinate. In reality, Italy was now ruled by Odoacer alone.[28][29][31] The Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire by later historians, continued to exist until the reign of Constantine XI Palaiologos. The last Roman emperor died in battle on 29 May 1453 against Mehmed II «the Conqueror» and his Ottoman forces in the final stages of the siege of Constantinople. Mehmed II would himself also claim the title of caesar or Kayser-i Rum in an attempt to claim a connection to the Roman Empire.[32]

Geography and demography

The Roman Empire was one of the largest in history, with contiguous territories throughout Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.[33] The Latin phrase imperium sine fine («empire without end»[34]) expressed the ideology that neither time nor space limited the Empire. In Virgil’s epic poem the Aeneid, limitless empire is said to be granted to the Romans by their supreme deity Jupiter.[35] This claim of universal dominion was renewed and perpetuated when the Empire came under Christian rule in the 4th century.[j] In addition to annexing large regions in their quest for empire-building, the Romans were also very large sculptors of their environment who directly altered their geography. For instance, entire forests were cut down to provide enough wood resources for an expanding empire.[37]

The cities of the Roman world in the Imperial Period.[38]

In reality, Roman expansion was mostly accomplished under the Republic, though parts of northern Europe were conquered in the 1st century AD, when Roman control in Europe, Africa, and Asia was strengthened. During the reign of Augustus, a «global map of the known world» was displayed for the first time in public at Rome, coinciding with the composition of the most comprehensive work on political geography that survives from antiquity, the Geography of the Pontic Greek writer Strabo.[39] When Augustus died, the commemorative account of his achievements (Res Gestae) prominently featured the geographical cataloguing of peoples and places within the Empire.[40] Geography, the census, and the meticulous keeping of written records were central concerns of Roman Imperial administration.[41]

The Empire reached its largest expanse under Trajan (r. 98–117),[42] encompassing an area of 5 million square kilometres.[6][7] The traditional population estimate of 55–60 million inhabitants[43] accounted for between one-sixth and one-fourth of the world’s total population[44] and made it the largest population of any unified political entity in the West until the mid-19th century.[45] Recent demographic studies have argued for a population peak ranging from 70 million to more than 100 million.[46] Each of the three largest cities in the Empire – Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch – was almost twice the size of any European city at the beginning of the 17th century.[47]

As the historian Christopher Kelly has described it:

Then the empire stretched from Hadrian’s Wall in drizzle-soaked northern England to the sun-baked banks of the Euphrates in Syria; from the great Rhine–Danube river system, which snaked across the fertile, flat lands of Europe from the Low Countries to the Black Sea, to the rich plains of the North African coast and the luxuriant gash of the Nile Valley in Egypt. The empire completely circled the Mediterranean … referred to by its conquerors as mare nostrum—’our sea’.[43]

Trajan’s successor Hadrian adopted a policy of maintaining rather than expanding the empire. Borders (fines) were marked, and the frontiers (limites) patrolled.[42] The most heavily fortified borders were the most unstable.[13] Hadrian’s Wall, which separated the Roman world from what was perceived as an ever-present barbarian threat, is the primary surviving monument of this effort.[48]

Languages

The language of the Romans was Latin, which Virgil emphasized as a source of Roman unity and tradition.[49] Until the time of Alexander Severus (r. 222–235), the birth certificates and wills of Roman citizens had to be written in Latin.[50] Latin was the language of the law courts in the West and of the military throughout the Empire,[51] but was not imposed officially on peoples brought under Roman rule.[52] This policy contrasts with that of Alexander the Great, who aimed to impose Greek throughout his empire as the official language.[53] As a consequence of Alexander’s conquests, Koine Greek had become the shared language around the eastern Mediterranean and into Asia Minor.[54] The «linguistic frontier» dividing the Latin West and the Greek East passed through the Balkan peninsula.[55]

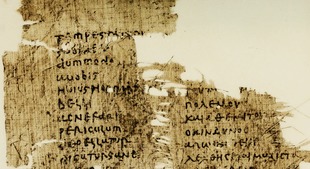

A 5th-century papyrus showing a parallel Latin-Greek text of a speech by Cicero[56]

Romans who received an elite education studied Greek as a literary language, and most men of the governing classes could speak Greek.[57] The Julio-Claudian emperors encouraged high standards of correct Latin (Latinitas), a linguistic movement identified in modern terms as Classical Latin, and favoured Latin for conducting official business.[58] Claudius tried to limit the use of Greek, and on occasion revoked the citizenship of those who lacked Latin, but even in the Senate he drew on his own bilingualism in communicating with Greek-speaking ambassadors.[58] Suetonius quotes him as referring to «our two languages».[59]

In the Eastern empire, laws and official documents were regularly translated into Greek from Latin.[60] The everyday interpenetration of the two languages is indicated by bilingual inscriptions, which sometimes even switch back and forth between Greek and Latin.[61] After all freeborn inhabitants of the empire were universally enfranchised in 212 AD, a great number of Roman citizens would have lacked Latin, though Latin remained a marker of «Romanness.»[62]

Among other reforms, the emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305) sought to renew the authority of Latin, and the Greek expression hē kratousa dialektos attests to the continuing status of Latin as «the language of power.»[63] In the early 6th century, the emperor Justinian engaged in a quixotic effort to reassert the status of Latin as the language of law, even though in his time Latin no longer held any currency as a living language in the East.[64]

Local languages and linguistic legacy

References to interpreters indicate the continuing use of local languages other than Greek and Latin, particularly in Egypt, where Coptic predominated, and in military settings along the Rhine and Danube. Roman jurists also show a concern for local languages such as Punic, Gaulish, and Aramaic in assuring the correct understanding and application of laws and oaths.[65] In the province of Africa, Libyco-Berber and Punic were used in inscriptions and for legends on coins during the time of Tiberius (1st century AD). Libyco-Berber and Punic inscriptions appear on public buildings into the 2nd century, some bilingual with Latin.[66] In Syria, Palmyrene soldiers even used their dialect of Aramaic for inscriptions, in a striking exception to the rule that Latin was the language of the military.[67]

The Babatha Archive is a suggestive example of multilingualism in the Empire. These papyri, named for a Jewish woman in the province of Arabia and dating from 93 to 132 AD, mostly employ Aramaic, the local language, written in Greek characters with Semitic and Latin influences; a petition to the Roman governor, however, was written in Greek.[68]

The dominance of Latin among the literate elite may obscure the continuity of spoken languages, since all cultures within the Roman Empire were predominantly oral.[66] In the West, Latin, referred to in its spoken form as Vulgar Latin, gradually replaced Celtic and Italic languages that were related to it by a shared Indo-European origin. Commonalities in syntax and vocabulary facilitated the adoption of Latin.[69][70]

After the decentralization of political power in late antiquity, Latin developed locally into branches that became the Romance languages, such as Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Catalan and Romanian, and a large number of minor languages and dialects. Today, more than 900 million people are native speakers worldwide.[71] As an international language of learning and literature, Latin itself continued as an active medium of expression for diplomacy and for intellectual developments identified with Renaissance humanism up to the 17th century, and for law and the Roman Catholic Church to the present.[72]

Although Greek continued as the language of the Byzantine Empire, linguistic distribution in the East was more complex. A Greek-speaking majority lived in the Greek peninsula and islands, western Anatolia, major cities, and some coastal areas.[74] Like Greek and Latin, the Thracian language was of Indo-European origin, as were several now-extinct languages in Anatolia attested by Imperial-era inscriptions.[74][66] Albanian is often seen as the descendant of Illyrian, although this hypothesis has been challenged by some linguists, who maintain that it derives from Dacian or Thracian.[75] (Illyrian, Dacian, and Thracian, however, may have formed a subgroup or a Sprachbund; see Thraco-Illyrian.) Various Afroasiatic languages—primarily Coptic in Egypt, and Aramaic in Syria and Mesopotamia—were never replaced by Greek. The international use of Greek, however, was one factor enabling the spread of Christianity, as indicated for example by the use of Greek for the Epistles of Paul.[74]

Several references to Gaulish in late antiquity may indicate that it continued to be spoken. In the second century AD there was an explicit recognition of its usage in some legal manners,[76] soothsaying[77] and pharmacology.[78] Sulpicius Severus, writing in the 5th century AD in Gallia Aquitania, noted bilingualism with Gaulish as the first language.[77] The survival of the Galatian dialect in Anatolia akin to that spoken by the Treveri near Trier was attested by Jerome (331–420), who had first-hand knowledge.[79] Much of historical linguistics scholarship postulates that Gaulish was indeed still spoken as late as the mid to late 6th century in France.[80] Despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture, the Gaulish language is held to have survived and had coexisted with spoken Latin during the centuries of Roman rule of Gaul.[80] The last reference to Galatian was made by Cyril of Scythopolis, claiming that an evil spirit had possessed a monk and rendered him able to speak only in Galatian,[k] while the last reference to Gaulish in France was made by Gregory of Tours between 560 and 575, noting that a shrine in Auvergne which «is called Vasso Galatae in the Gallic tongue» was destroyed and burnt to the ground.[82][80] After the long period of bilingualism, the emergent Gallo-Romance languages including French were shaped by Gaulish in a number of ways; in the case of French these include loanwords and calques (including oui,[83] the word for «yes»),[84][83] sound changes,[85] and influences in conjugation and word order.[84][83][86]

Proto-Basque language or Aquitanian survived the Roman conquest, and evolved with Latin loans to present day Basque language.[87] Recent discoveries as the hand of Irulegi shows that this language was also written during the Roman conquest,[88] but only proper names are known from the Roman Empire times.

Society

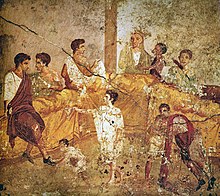

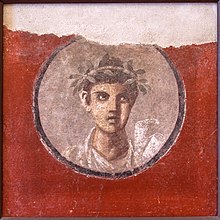

A multigenerational banquet depicted on a wall painting from Pompeii (1st century AD)

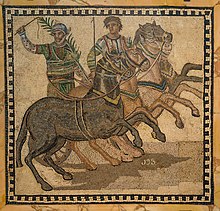

The Roman Empire was remarkably multicultural, with «a rather astonishing cohesive capacity» to create a sense of shared identity while encompassing diverse peoples within its political system over a long span of time.[89] The Roman attention to creating public monuments and communal spaces open to all—such as forums, amphitheatres, racetracks and baths—helped foster a sense of «Romanness».[90]

Roman society had multiple, overlapping social hierarchies that modern concepts of «class» in English may not represent accurately.[91] The two decades of civil war from which Augustus rose to sole power left traditional society in Rome in a state of confusion and upheaval,[92] but did not effect an immediate redistribution of wealth and social power. From the perspective of the lower classes, a peak was merely added to the social pyramid.[93] Personal relationships—patronage, friendship (amicitia), family, marriage—continued to influence the workings of politics and government, as they had in the Republic.[94] By the time of Nero, however, it was not unusual to find a former slave who was richer than a freeborn citizen, or an equestrian who exercised greater power than a senator.[95]

The blurring or diffusion of the Republic’s more rigid hierarchies led to increased social mobility under the Empire,[96] both upward and downward, to an extent that exceeded that of all other well-documented ancient societies.[97] Women, freedmen, and slaves had opportunities to profit and exercise influence in ways previously less available to them.[98] Social life in the Empire, particularly for those whose personal resources were limited, was further fostered by a proliferation of voluntary associations and confraternities (collegia and sodalitates) formed for various purposes: professional and trade guilds, veterans’ groups, religious sodalities, drinking and dining clubs,[99] performing arts troupes,[100] and burial societies.[101]

Legal status

According to the jurist Gaius, the essential distinction in the Roman «law of persons» was that all human beings were either free (liberi) or slaves (servi).[102] The legal status of free persons might be further defined by their citizenship. Most citizens held limited rights (such as the ius Latinum, «Latin right»), but were entitled to legal protections and privileges not enjoyed by those who lacked citizenship. Free people not considered citizens, but living within the Roman world, held status as peregrini, non-Romans.[103] In 212 AD, by means of the edict known as the Constitutio Antoniniana, the emperor Caracalla extended citizenship to all freeborn inhabitants of the empire. This legal egalitarianism would have required a far-reaching revision of existing laws that had distinguished between citizens and non-citizens.[104]

Women in Roman law

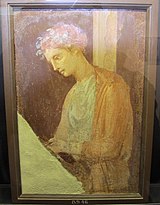

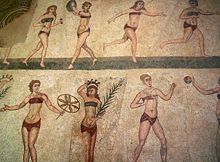

Dressing of a priestess or bride, Roman fresco from Herculaneum, Italy (30–40 AD)

Freeborn Roman women were considered citizens throughout the Republic and Empire, but did not vote, hold political office, or serve in the military. A mother’s citizen status determined that of her children, as indicated by the phrase ex duobus civibus Romanis natos («children born of two Roman citizens»).[l] A Roman woman kept her own family name (nomen) for life. Children most often took the father’s name, but in the Imperial period sometimes made their mother’s name part of theirs, or even used it instead.[107]

The archaic form of manus marriage in which the woman had been subject to her husband’s authority was largely abandoned by the Imperial era, and a married woman retained ownership of any property she brought into the marriage. Technically she remained under her father’s legal authority, even though she moved into her husband’s home, but when her father died she became legally emancipated.[108] This arrangement was one of the factors in the degree of independence Roman women enjoyed relative to those of many other ancient cultures and up to the modern period:[109] although she had to answer to her father in legal matters, she was free of his direct scrutiny in her daily life,[110] and her husband had no legal power over her.[111] Although it was a point of pride to be a «one-man woman» (univira) who had married only once, there was little stigma attached to divorce, nor to speedy remarriage after the loss of a husband through death or divorce.[112]

Girls had equal inheritance rights with boys if their father died without leaving a will.[113] A Roman mother’s right to own property and to dispose of it as she saw fit, including setting the terms of her own will, gave her enormous influence over her sons even when they were adults.[114]

As part of the Augustan programme to restore traditional morality and social order, moral legislation attempted to regulate the conduct of men and women as a means of promoting «family values». Adultery, which had been a private family matter under the Republic, was criminalized,[115] and defined broadly as an illicit sex act (stuprum) that occurred between a male citizen and a married woman, or between a married woman and any man other than her husband. That is, a double standard was in place: a married woman could have sex only with her husband, but a married man did not commit adultery if he had sex with a prostitute, slave, or person of marginalized status.[116] Childbearing was encouraged by the state: a woman who had given birth to three children was granted symbolic honours and greater legal freedom (the ius trium liberorum).

Because of their legal status as citizens and the degree to which they could become emancipated, women could own property, enter contracts, and engage in business,[117] including shipping, manufacturing, and lending money. Inscriptions throughout the Empire honour women as benefactors in funding public works, an indication they could acquire and dispose of considerable fortunes; for instance, the Arch of the Sergii was funded by Salvia Postuma, a female member of the family honoured, and the largest building in the forum at Pompeii was funded by Eumachia, a priestess of Venus.[118]

Slaves and the law

At the time of Augustus, as many as 35% of the people in Italy were slaves,[119] making Rome one of five historical «slave societies» in which slaves constituted at least a fifth of the population and played a major role in the economy.[m][119] Slavery was a complex institution that supported traditional Roman social structures as well as contributing economic utility.[120] In urban settings, slaves might be professionals such as teachers, physicians, chefs, and accountants, in addition to the majority of slaves who provided trained or unskilled labour in households or workplaces. Agriculture and industry, such as milling and mining, relied on the exploitation of slaves. Outside Italy, slaves made up on average an estimated 10 to 20% of the population, sparse in Roman Egypt but more concentrated in some Greek areas. Expanding Roman ownership of arable land and industries would have affected preexisting practices of slavery in the provinces.[121]

Although the institution of slavery has often been regarded as waning in the 3rd and 4th centuries, it remained an integral part of Roman society until the 5th century. Slavery ceased gradually in the 6th and 7th centuries along with the decline of urban centres in the West and the disintegration of the complex Imperial economy that had created the demand for it.[122]

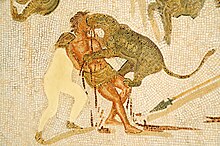

Slave holding writing tablets for his master (relief from a 4th-century sarcophagus)

Laws pertaining to slavery were «extremely intricate».[123] Under Roman law, slaves were considered property and had no legal personhood. They could be subjected to forms of corporal punishment not normally exercised on citizens, sexual exploitation, torture, and summary execution. A slave could not as a matter of law be raped since rape could be committed only against people who were free; a slave’s rapist had to be prosecuted by the owner for property damage under the Aquilian Law.[124] Slaves had no right to the form of legal marriage called conubium, but their unions were sometimes recognized, and if both were freed they could marry.[125]

Following the Servile Wars of the Republic, legislation under Augustus and his successors shows a driving concern for controlling the threat of rebellions through limiting the size of work groups, and for hunting down fugitive slaves.[126]

Technically, a slave could not own property,[127] but a slave who conducted business might be given access to an individual account or fund (peculium) that he could use as if it were his own. The terms of this account varied depending on the degree of trust and co-operation between owner and slave: a slave with an aptitude for business could be given considerable leeway to generate profit and might be allowed to bequeath the peculium he managed to other slaves of his household.[128] Within a household or workplace, a hierarchy of slaves might exist, with one slave in effect acting as the master of other slaves.[129]

Over time slaves gained increased legal protection, including the right to file complaints against their masters. A bill of sale might contain a clause stipulating that the slave could not be employed for prostitution, as prostitutes in ancient Rome were often slaves.[130] The burgeoning trade in eunuch slaves in the late 1st century AD prompted legislation that prohibited the castration of a slave against his will «for lust or gain.»[131]

Roman slavery was not based on race.[132] Slaves were drawn from all over Europe and the Mediterranean, including Gaul, Hispania, Germany, Britannia, the Balkans, Greece… Generally, slaves in Italy were indigenous Italians,[133] with a minority of foreigners (including both slaves and freedmen) born outside of Italy estimated at 5% of the total in the capital at its peak, where their number was largest. Those from outside of Europe were predominantly of Greek descent, while the Jewish ones never fully assimilated into Roman society, remaining an identifiable minority. These slaves (especially the foreigners) had higher mortality rates and lower birth rates than natives, and were sometimes even subjected to mass expulsions.[134] The average recorded age at death for the slaves of the city of Rome was extraordinarily low: seventeen and a half years (17.2 for males; 17.9 for females).[135]

During the period of republican expansionism when slavery had become pervasive, war captives were a main source of slaves. The range of ethnicities among slaves to some extent reflected that of the armies Rome defeated in war, and the conquest of Greece brought a number of highly skilled and educated slaves into Rome. Slaves were also traded in markets and sometimes sold by pirates. Infant abandonment and self-enslavement among the poor were other sources.[136] Vernae, by contrast, were «homegrown» slaves born to female slaves within the urban household or on a country estate or farm. Although they had no special legal status, an owner who mistreated or failed to care for his vernae faced social disapproval, as they were considered part of his familia, the family household, and in some cases might actually be the children of free males in the family.[137]

Talented slaves with a knack for business might accumulate a large enough peculium to justify their freedom, or be manumitted for services rendered. Manumission had become frequent enough that in 2 BC a law (Lex Fufia Caninia) limited the number of slaves an owner was allowed to free in his will.[138]

Freedmen

Cinerary urn for the freedman Tiberius Claudius Chryseros and two women, probably his wife and daughter

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become citizens. After manumission, a slave who had belonged to a Roman citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote.[139] A slave who had acquired libertas was a libertus («freed person,» feminine liberta) in relation to his former master, who then became his patron (patronus): the two parties continued to have customary and legal obligations to each other. As a social class generally, freed slaves were libertini, though later writers used the terms libertus and libertinus interchangeably.[140][141]