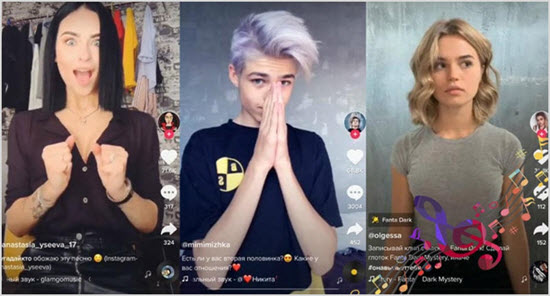

Данным приложением пользуются в основном школьники и подростки, ведь средний возраст активных аккаунтов – 14 лет.

TikTok устанавливается на мобильные устройства, но возможна инсталляция и на компьютер. По сути основная идея соц. сети – это обмен короткими видео смешного характера.

Появился на рынке этот продукт в 2016 году и мгновенно стал популярен.

Приложение разработано в Китае компанией ByteDance, которая появилась за 4 года до этого. Интересно то, что сейчас приложение в Китае заблокировано, пользоваться им нельзя, но есть альтернативные варианты.

Почему приложение называется ТикТок

TikTok, в большей мере, был создан для коротких видеороликов, длина которых не превышает 15 секунд. Но часто видео достигают только 4-5 секунд.

Автор контента совершает действия, которые интересны другим пользователям, и которые хочется повторять.

К примеру, он может открывать рот под звуки топовой песни, петь сам, прыгать или кривляться. Присутствуют различные музыкальные эффекты, что добавляет ролику интереса.

Тик Ток очень популярен у русскоязычной аудитории, поэтому многим интересно не только то, как появилась эта платформа в Китае и как стала популярной в России, но и то, как правильно пишется и переводится название мобильного приложения.

Владельцем Тик тока считается стартап из Китая Bytedance, основал который 36-летний предприниматель Чжан Имин.

Изначально парень занимался работой над искусственным интеллектом и планировал поставлять инновационные продукты только для китайского рынка. Но со временем он понял перспективу Тик Тока и решил заняться этим направлением.

Именно Чжан Имин и придумал название, которое есть на слуху даже у людей старшего поколения, которые не пользуются мобильными гаджетами.

Название социальной сути переводится с английского языка. Tik Tok – это графическое и звуковое обозначение хода часового механизма.

Мы можем вспомнить и русское междометие «тик-так», которое означает тоже и довольно схожее по своему звучанию.

Объяснения выбора такого названия нет. Но эксперты думают, что такое обозначение социальной сути было использовано из-за основы контента – коротких видео, которые по длительности не могут превышать 15 секунд.

Пользователи должны уложиться в этот короткий временной промежуток, успеть заинтересовать и вызывать реакцию зрителя.

Понятно, что тут есть аналогия со стуканьем часов: эти равные и короткие промежутки служат отчетом. Нельзя сказать, что в название сервиса вкладывали глубокий смысл.

Но в это и есть его преимущество. Оно быстро запоминается, вызывает ассоциации.

На русском языке пользователи обычно пишут название Тик Ток. Но на латинице правильно будет написать именно TikTok без разделения пробелом.

Именно такое название является общепринятым, по таком виду его ищут в поисковых системах жители других стран. Интересно то, что и на немецком языке название будет аналогичным английскому.

Как переводится Тик Ток на китайский

Сервис на китайских просторах интернета закрыт. Но перевод его был идентичным, что и в английском, ведь именно из этого языка и была заимствована фраза для китайской платформы.

Сейчас в Китае аналогом приложения выступает Douyin, которое использует более 600 миллионов пользователей, что составляет 80 процентов населения, имеющего возможность выхода в интернет.

По-китайски приложение называется 抖音. Работает оно по такому же принципу, что и ТикТок, но на других платформах.

Правила написания слова ТикТок или Тик Ток

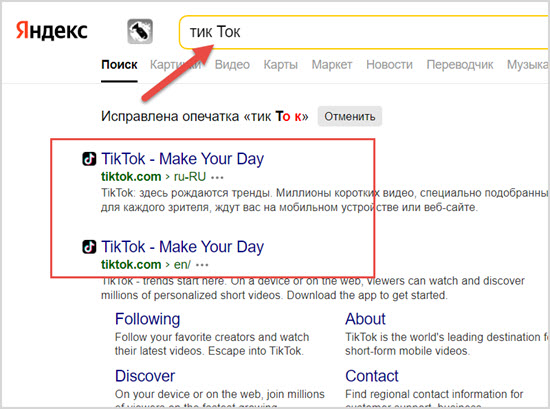

Интересно то, что названия поисковые системы могут воспринимать по-разному, но для обычного пользователя, не особенно знакомого с нюансами компьютерной грамотности, это слова идентичные.

Но, как утверждают эксперты, в русском языке иностранные названия пишутся ровно так же, что в оригинале, но адаптированными на наш язык буквами.

Правильно получается писать именно ТикТок без пробела – это соответствует оригинальному названию платформы, созданной в Китае.

Как реагируют поисковые системы

ТикТок набирает популярностью во всем мире. Понятно дело, что называние соц сети, каждый пишет, как ему вздумается. Но алгоритмы поисковых систем научились понимать эти разногласия и автоматически адаптируются к запросам пользователей.

То есть, вбивая в поиск Яндекса или Гула слово «тик То к» или «Тик Ток» вы в любом случае попадаете на оригинальную версию страницы и сможете скачать приложение на свой мобильный телефон.

Но если вы хотите писать правильно, то в оригинале это будет именно TikTok. В транскрипции на русской язык следует писать ТикТок без пробела.

Мнения тиктокеров

Единого мнения насчет правильного написания называния китайского гиганта у тиктокеров нет. В основном они пишут без пробела на русском языке. Хотя встречаются различные версии.

ТикТок – популярное приложение, родом из Китая. Сейчас нет разницы как именно вы напишите название (слитно или раздельно, на русском или на английском языке).

В любом случае система будет воспринимать запросы релевантными меду собой и даст вам возможность скачать приложение.

Социалка отличается простотой интерфейса, что дает возможность разобраться в ней любому школьнику, разнообразием контента, ведь тут присутствуют и развлекательные ролики и познавательные.

Если вы хотите скачать приложение для творческого развития, то это именно то, что нужно.

Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | ТикТо́к | — |

| Р. | ТикТо́ка | — |

| Д. | ТикТо́ку | — |

| В. | ТикТо́к | — |

| Тв. | ТикТо́ком | — |

| Пр. | ТикТо́ке | — |

Тик—То́к

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 3a по классификации А. А. Зализняка); формы мн. ч. не используются.

Корень: -ТикТок-.

Произношение[править]

- МФА: [tʲɪˈktok]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- неол. название международной компании — оператора популярной социальной сети и одноименного мобильного приложения для обмена короткими видео продолжительностью от пятнадцати секунд до одной минуты ◆ Мировой судья участка № 422 Таганского района Москвы во вторник признал «ТикТок» (TikTok Pte.Ltd) виновным в совершении административного правонарушения, предусмотренного ч. 2 ст. 13.41 КоАП РФ. То есть за нарушение порядка ограничения доступа к информации, доступ к которой подлежит ограничению в соответствии с законодательством РФ. Иван Егоров, «Штрафной клип», Столичный суд оштрафовал соцсеть „ТикТок“ на 2,6 млн рублей // «Российская газета», № 73 (8424), 6 апреля 2021 г.

Синонимы[править]

- ?

Антонимы[править]

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- социальная сеть

Гипонимы[править]

- ?

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология[править]

От самоназвания TikTok, далее от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

Библиография[править]

- Словарь перемен 2017—2018 / Сост. М. Вишневецкая. — М. : Три квадрата, 2022. — С. 164. — ISBN 978-5-94607-256-4.

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

TikTok Pte. Ltd.

|

|

Screenshot of TikTok.com |

|

| Developer(s) | ByteDance |

|---|---|

| Initial release | September 2016; 6 years ago |

| Stable release |

26.4.1 |

| Operating system |

|

| Predecessor | musical.ly |

| Available in | 40 languages[1] |

|

List of languages

|

|

| Type | Video sharing |

| License | Proprietary software with Terms of Use |

| Website | tiktok.com douyin.com |

| Douyin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 抖音 | |||||

| Literal meaning | «Vibrating sound» | |||||

|

TikTok, deployed[2] in China as Douyin (Chinese: 抖音; pinyin: Dǒuyīn), is a short-form video hosting service owned by the Chinese company ByteDance.[3] It hosts user-submitted videos, which can range in duration from 15 seconds to 10 minutes.[4]

TikTok is a entirely separate,[2] internationalized version of Douyin, which was released in the Chinese market in September 2016.[5] It launched in 2017 for iOS and Android in most markets outside of mainland China; however, it became available worldwide only after merging with another Chinese social media service, Musical.ly, on 2 August 2018.

TikTok and Douyin have almost the same user interface but no access to each other’s content.[2] Their servers are each based in the market where the respective app is available.[6] The two products are similar, but their features are not identical. Douyin includes an in-video search feature that can search by people’s faces for more videos of them, along with other features such as buying, booking hotels, and making geo-tagged reviews.[7]

Since their launches, TikTok and Douyin have gained global popularity.[8][9] In October 2020, TikTok surpassed 2 billion mobile downloads worldwide.[10][11][12] Morning Consult named TikTok the third-fastest growing brand of 2020, after Zoom and Peacock.[13] Cloudflare ranked TikTok the most popular website of 2021, surpassing google.com.[14]

TikTok has been subject to criticism over psychological effects such as addiction, as well as controversies regarding inappropriate content, misinformation, censorship, moderation, and user privacy.

History

Evolution

Douyin was launched by ByteDance in Beijing, China in September 2016, originally under the name A.me, before rebranding to Douyin (抖音) in December 2016.[15][16] ByteDance planned on Douyin expanding overseas. The founder of ByteDance, Zhang Yiming, stated that «China is home to only one-fifth of Internet users globally. If we don’t expand on a global scale, we are bound to lose to peers eyeing the four-fifths. So, going global is a must.»[17] Douyin was developed in 200 days and within a year had 100 million users, with more than one billion videos viewed every day.[18][19]

The app was launched as TikTok in the international market in September 2017.[20] On 23 January 2018, the TikTok app ranked first among free application downloads on app stores in Thailand and other countries.[21]

TikTok has been downloaded more than 130 million times in the United States and has reached 2 billion downloads worldwide,[22][23] according to data from mobile research firm Sensor Tower (those numbers exclude Android users in China).[24]

In the United States, celebrities, including Jimmy Fallon and Tony Hawk, began using the app in 2018.[25][26] Other celebrities, including Jennifer Lopez, Jessica Alba, Will Smith, and Justin Bieber joined TikTok as well and many other celebrities have followed.[27]

In January 2019, TikTok platform combines short video and traditional e-commerce, producing an innovative business model. Creators were allowed to add the product from shops in merchandise windows could be embedded into their videos.[28]

On 3 September 2019, TikTok and the U.S. National Football League (NFL) announced a multi-year partnership.[29] The agreement occurred just two days before the NFL’s 100th season kick-off at Soldier Field, where TikTok hosted activities for fans in honor of the deal. The partnership entails the launch of an official NFL TikTok account, which is to bring about new marketing opportunities such as sponsored videos and hashtag challenges. In July 2020, TikTok, excluding Douyin, reported close to 800 million monthly active users worldwide after less than four years of existence.[30]

In May 2021, TikTok appointed Shou Zi Chew as their new CEO[31] who assumed the position from interim CEO Vanessa Pappas, following the resignation of Kevin A. Mayer on 27 August 2020.[32][33][34] On 3 August 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to ban TikTok in the United States on 15 September if negotiations for the company to be bought by Microsoft or a different «very American» company failed.[35] On 6 August, Trump signed two executive orders banning U.S. «transactions» with TikTok and WeChat to its respective parent companies ByteDance and Tencent, set to take effect 45 days after the signing.[36] A planned ban of the app on 20 September 2020[37][38] was postponed by a week and then blocked by a federal judge.[39][40][41][42] President Biden revoked the ban in a new executive order in June 2021.[43] The app has been banned by the government of India since June 2020 along with 223 other Chinese apps in view of privacy concerns.[44] Pakistan banned TikTok citing «immoral» and «indecent» videos on 9 October 2020 but reversed its ban ten days later.[45][46][47] In March 2021, a Pakistani court ordered a new TikTok ban due to complaints over «indecent» content.

In September 2021, TikTok reported that it had reached 1 billion users.[48] In 2021, TikTok earned $4 billion in advertising revenue.[49]

In October 2022, TikTok was reported to be planning an expansion into the ecommerce market in the US, following the launch of TikTok Shop in the United Kingdom. The company posted job listings for staff for a series of order fulfillment centers in the US and is reportedly planning to start the new live shopping business before the end of the year.[50]

Musical.ly merger

On 9 November 2017, TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, spent nearly $1 billion to purchase musical.ly, a startup headquartered in Shanghai with an overseas office in Santa Monica, California, U.S.[51][52] Musical.ly was a social media video platform that allowed users to create short lip-sync and comedy videos, initially released in August 2014. It was well known, especially to the younger audience. Looking forward to leveraging the U.S. digital platform’s young user base, TikTok merged with musical.ly on 2 August 2018 to create a larger video community, with existing accounts and data consolidated into one app, keeping the title TikTok.[53] This ended musical.ly and made TikTok a worldwide app, excluding China, since China already has Douyin.[52][54][55]

Expansion in other markets

As of 2018, TikTok was available in more than 150 markets, and in 75 languages.[56][57] TikTok was downloaded more than 104 million times on Apple’s App Store during the full first half of 2018, according to data provided to CNBC by Sensor Tower.[58]

After merging with musical.ly in August, downloads increased and TikTok became the most downloaded app in the U.S. in October 2018, which musical.ly had done once before.[59][60] In February 2019, TikTok, together with Douyin, hit one billion downloads globally, excluding Android installs in China.[61] In 2019, media outlets cited TikTok as the 7th-most-downloaded mobile app of the decade, from 2010 to 2019.[62] It was also the most-downloaded app on Apple’s App Store in 2018 and 2019, surpassing Facebook, YouTube and Instagram.[63][64] In September 2020, a deal was confirmed between ByteDance and Oracle in which the latter will serve as a partner to provide cloud hosting.[65][66] Walmart intends to invest in TikTok.[67] This deal would stall in 2021 as newly elected President Biden’s Justice Department put a hold on the previous U.S. ban under President Trump.[68][69][70] In November 2020, TikTok signed a licensing deal with Sony Music.[71] In December 2020, Warner Music Group signed a licensing deal with TikTok.[72][73][74] In April 2021, Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism partnered with TikTok to promote tourism.[75] It came following the January 2021 winter campaign, initiated through a partnership between the UAE Government Media Office partnered and TikTok to promote the country’s tourism.[76]

Since 2014, the first non-gaming apps[77] with more than 3 billion downloads were Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger; all of these apps belong to Meta. TikTok was the first non-Facebook app to reach that figure. App market research firm Sensor Tower reported that although TikTok had been banned in India, its largest market, in June 2020, downloads in the rest of the world continue to increase, reaching 3 billion downloads in 2021.[78]

Features

The TikTok mobile app allows users to create short videos, which often feature music in the background and can be sped up, slowed down, or edited with a filter.[79] They can also add their own sound on top of the background music. To create a music video with the app, users can choose background music from a wide variety of music genres, edit with a filter and record a 15-second video with speed adjustments before uploading it to share with others on TikTok or other social platforms.[80] They can also film short lip-sync videos to popular songs.

The «For You» page on TikTok is a feed of videos that are recommended to users based on their activity on the app. Content is generated by TikTok’s artificial intelligence (AI) depending on the content a user liked, interacted with, or searched. This is in contrast to other social networks’ algorithms basing such content off of the user’s relationships with other users and what they liked or interacted with.[81]

The app’s «react» feature allows users to film their reaction to a specific video, over which it is placed in a small window that is movable around the screen.[82] Its «duet» feature allows users to film a video aside from another video.[83] The «duet» feature was another trademark of musical.ly. The duet feature is also only able to be used if both parties adjust the privacy settings.[84]

Videos that users do not want to post yet can be stored in their «drafts.» The user is allowed to see their «drafts» and post when they find it fitting.[85]

The app allows users to set their accounts as «private.» When first downloading the app, the user’s account is public by default. The user can change to private in their settings. Private content remains visible to TikTok but is blocked from TikTok users who the account holder has not authorized to view their content.[86] Users can choose whether any other user, or only their «friends,» may interact with them through the app via comments, messages, or «react» or «duet» videos.[82] Users also can set specific videos to either «public,» «friends only,» or «private» regardless if the account is private or not.[86]

Users can also send their friends videos, emojis, and messages with direct messaging. TikTok has also included a feature to create a video based on the user’s comments. Influencers often use the «live» feature. This feature is only available for those who have at least 1,000 followers and are over 16 years old. If over 18, the user’s followers can send virtual «gifts» that can be later exchanged for money.[87][88]

One of the newest features as of 2020 is the «Virtual Items» of «Small Gestures» feature. This is based on China’s big practice of social gifting. Since this feature was added, many beauty companies and brands created a TikTok account to participate in and advertise this feature. With COVID-19 lockdown in the United States, social gifting has grown in popularity. According to a TikTok representative, the campaign was launched as a result of the lockdown, «to build a sense of support and encouragement with the TikTok community during these tough times.»[89]

TikTok announced a «family safety mode» in February 2020 for parents to be able to control their children’s digital well-being. There is a screen time management option, restricted mode, and can put a limit on direct messages.[90][91]

The app expanded its parental controls feature called «Family Pairing» in September 2020 to provide parents and guardians with educational resources to understand what children on TikTok are exposed to. Content for the feature was created in partnership with online safety nonprofit, Internet Matters.[92]

In October 2021, TikTok launched a test feature that allows users to directly tip certain creators. Accounts of users that are of age, have at least 100,000 followers and agree to the terms can activate a «Tip» button on their profile, which allows followers to tip any amount, starting from $1.[93]

In December 2021, TikTok started beta-testing Live Studio, a streaming software that would let users broadcast applications open on their computers, including games. The software also launched with support for mobile and PC streaming.[94] However, a few days later, users on Twitter discovered that the software allegedly uses code from the open-source OBS Studio. OBS made a statement saying that, under the GNU GPL version 2, TikTok has to make the code of Live Studio publicly available if it wants to use any code from OBS.[95]

In May 2022, TikTok announced TikTok Pulse, an ad revenue-sharing program. It covers the «top 4% of all videos on TikTok» and is only available to creators with more than 100,000 followers. If an eligible creator’s video reaches the top 4%, they will receive a 50% share of the revenue from ads displayed with the video.[96]

Content and usage

Demographics

TikTok tends to appeal to younger users, as 41% of its users are between the ages of 16 and 24. These individuals are considered Generation Z or Gen Z and this audience is part of the generation that grew up in a world filled with internet.[81] Since they grew up surrounded by the internet, social media has become a part of their daily life. Among these TikTok users, 90% say they use the app daily.[97] TikTok’s geographical use has shown that 43% of new users are from India.[98] As of the first quarter of 2022, there were over 100 million monthly active users in the United States and 23 million in the UK. The average user, daily, was spending 1 hour and 25 minutes on the app and opening TikTok 17 times.[99]

Viral trends

A variety of trends have risen within TikTok, including memes, lip-synced songs, and comedy videos. Duets, a feature that allows users to add their own video to an existing video with the original content’s audio, have sparked many of these trends.

Trends are shown on TikTok’s explore page or the page with the search logo. The page enlists the trending hashtags and challenges among the app. Some include #posechallenge, #filterswitch, #dontjudgemechallenge, #homedecor, #hitormiss, #bottlecapchallenge and more. In June 2019, the company introduced the hashtag #EduTok which received 37 billion views. Following this development, the company initiated partnerships with edtech startups to create educational content on the platform.[100]

The app has spawned numerous viral trends, Internet celebrities, and music trends around the world.[101] Many stars got their start on musical.ly, which merged with TikTok on 2 August 2018. These users include Loren Gray, Baby Ariel, Kristen Hancher, Zach King, Lisa and Lena, Jacob Sartorius, and many others. Loren Gray remained the most-followed individual on TikTok until Charli D’Amelio surpassed her on 25 March 2020. Gray’s was the first TikTok account to reach 40 million followers on the platform. She was surpassed with 41.3 million followers. D’Amelio was the first to ever reach 50, 60, and 70 million followers. Charli D’Amelio remained the most-followed individual on the platform until she was surpassed by Khaby Lame on June 23, 2022. Other creators rose to fame after the platform merged with musical.ly on 2 August 2018.[102]

One notable TikTok trend is the «hit or miss» meme, which began from a snippet of iLOVEFRiDAY’s song «Mia Khalifa.» The song has been used in over four million TikTok videos and helped introduce the app to a larger Western audience.[103][104] TikTok also played a major part in making «Old Town Road» by Lil Nas X one of the biggest songs of 2019 and the longest-running number-one song in the history of the US Billboard Hot 100.[105][106][107]

TikTok has allowed many music artists to gain a wider audience, often including foreign fans. For example, despite never having toured in Asia, the band Fitz and the Tantrums developed a large following in South Korea following the widespread popularity of their 2016 song «HandClap» on the platform.[108] «Any Song» by R&B and rap artist Zico became number one on the Korean music charts due to the popularity of the #anysongchallenge, where users dance to the choreography of the song.[109] The platform has also launched many songs that failed to garner initial commercial success into sleeper hits, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.[110][111] However, it has received some criticism for not paying royalties to artists whose music is used on the platform.[104] In 2020, more than 176 different songs surpassed one billion video views on TikTok.[112]

In June 2020, TikTok users and K-pop fans «claimed to have registered potentially hundreds of thousands of tickets» for President Trump’s campaign rally in Tulsa through communication on TikTok,[113] contributing to «rows of empty seats»[114] at the event. Later, in October 2020, an organization called TikTok for Biden was created to support then-presidential candidate Joe Biden.[115] After the election, the organization was renamed to Gen-Z for Change.[116][117]

TikTok has banned Holocaust denial, but other conspiracy theories have become popular on the platform, such as Pizzagate and QAnon (two conspiracy theories popular among the U.S. alt-right) whose hashtags reached almost 80 million views and 50 million views respectively by June 2020.[118] The platform has also been used to spread misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic, such as clips from Plandemic.[118] TikTok removed some of these videos and has generally added links to accurate COVID-19 information on videos with tags related to the pandemic.[119]

On 10 August 2020, Emily Jacobssen wrote and sang «Ode To Remy,» a song praising the protagonist from Pixar’s 2007 computer-animated film named Ratatouille. The song rose to popularity when musician Daniel Mertzlufft composed a backing track to the song. In response, began creating a «crowdsourced» project called Ratatouille The Musical. Since Mertzlufft’s video, many new elements including costume design, additional songs, and a playbill have been created.[120] On 1 January 2021, a full one-hour virtual presentation of Ratatouille the Musical premiered on the TodayTix. It starred Titus Burgess as Remy, Wayne Brady as Django, Adam Lambert as Emile, Chamberlin as Gusteau, Andrew Barth Feldman as Linguini, Ashley Park as Colette, Priscilla Lopez as Mabel, Mary Testa as Skinner, and André De Shields as Ego.

Another TikTok usage that corresponds with engagement and bonds people in society is the use of «challenges.» These could be on any related topic such as dances or cooking certain meals. People see other people doing something that is trending and then it continues to spread until it is a viral trend that connects people from all over.[121]

While TikTok has primarily been used for entertainment purposes, TikTok may soon have another use, that of a job resource with the idea that prospective employment seekers would send in videos rather than traditional resumes. The form would most likely be a job search add-on. TikTok has had favorable results in the past with people using the site to find jobs and may be expanding that need, especially in the newer generations.[122]

Alt TikTok

Around mid-2020, some of the users on the platform started to differentiate between the «alt», «elite»,»deep», or «floptok» side of TikTok, seen as having more alternative and queer users, and the «straight» side of TikTok, seen as the mainstream.[123] Hyperpop music, including artists like 100 Gecs, became widely used on Alt TikTok, complementing the bright and colourful «Indie Kid» aesthetic.[124] Alt TikTok was also accompanied by memes with surrealist or supernatural themes (sometimes being described as cursed), such as videos with heavy saturation and humanoid animals.[125] One of the popular videos from Alt TikTok, gaining 18 million likes, shows a llama dancing to a cover of a song from a Russian commercial by the cereal brand Miel Pops, later becoming a viral audio.[126][127] Some Alt TikTok users personified brands and products in what some referred to as Retail TikTok.[125]

Profile picture cults

Another popular trend on TikTok is a large number of users putting the same image as their profile picture, known as a profile picture cult or a TikTok cult. Popular examples include «The Step Chickens» (started by the user @chunkysdead),[128] «The Hamster Cult» and the «Lana Del Rey Cult«.[129]

Influencer marketing

TikTok has provided a platform for users to create content not only for fun but also for money. As the platform has grown significantly over the past few years, it has allowed companies to advertise and rapidly reach their intended demographic through influencer marketing.[130] The platform’s AI algorithm also contributes to the influencer marketing potential, as it picks out content according to the user’s preference.[131] Sponsored content is not as prevalent on the platform as it is on other social media apps, but brands and influencers still can make as much as they would if not more in comparison to other platforms.[131] Influencers on the platform who earn money through engagement, such as likes and comments, are referred to as «meme machines.»[130]

In 2021, The New York Times reported that viral TikTok videos by young people relating the emotional impact of books on them, tagged with the label «BookTok,» significantly drove sales of literature. Publishers were increasingly using the platform as a venue for influencer marketing.[132]

In 2022, NBC News reported in a television segment that some TikTok and YouTube influencers were being given free and discounted cosmetic surgeries in order for them to advertise the surgeries to users of the platforms.[133]

Use by businesses

In October 2020, the e-commerce platform Shopify added TikTok to its portfolio of social media platforms, allowing online merchants to sell their products directly to consumers on TikTok.[134]

Some small businesses have used TikTok to advertise and to reach an audience wider than the geographical region they would normally serve. The viral response to many small business TikTok videos has been attributed to TikTok’s algorithm, which shows content that viewers at large are drawn to, but which they are unlikely to actively search for (such as videos on unconventional types of businesses, like beekeeping and logging).[135]

In 2020, digital media companies such as Group Nine Media and Global used TikTok increasingly, focusing on tactics such as brokering partnerships with TikTok influencers and developing branded content campaigns.[136] Notable collaborations between larger brands and top TikTok influencers have included Chipotle’s partnership with David Dobrik in May 2019[137] and Dunkin’ Donuts’ partnership with Charli D’Amelio in September 2020.[138]

Collab houses

Popular TikTok users have lived collectively in collab houses, predominantly in the Los Angeles area.[139]

Bans and attempted bans

Asia

As of January 2023, Tiktok is reportedly banned in several Asian countries including Afghanistan,[140] Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh,[141][142] India,[143][144][145] Iran,[146] Pakistan,[147] and Syria. The app was previously banned temporarily in Indonesia[148] and Jordan,[149] though both have been lifted since.

United States

On 6 August 2020, then U.S. President Donald Trump signed an order[150][151] which would ban TikTok transactions in 45 days if it was not sold by ByteDance. Trump also signed a similar order against the WeChat application owned by the Chinese multinational company Tencent.[152][38]

On 14 August 2020, Trump issued another order[153][154] giving ByteDance 90 days to sell or spin off its U.S. TikTok business.[155] In the order, Trump said that there is «credible evidence» that leads him to believe that ByteDance «might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States.»[156] Donald Trump was concerned about TikTok being a threat because TikTok’s parent company was rumored to be taking United States user data and reporting it back to Chinese operations through the company ByteDance.[157] As of 2021, there is still the fear that TikTok is not protecting the privacy of its users and may be giving their data away.[158]

TikTok considered selling the American portion of its business and held talks with companies including Microsoft, Walmart, and Oracle.[159]

On 18 September, TikTok filed a lawsuit, TikTok v. Trump. On 23 September 2020, TikTok filed a request for a preliminary injunction to prevent the app from being banned by the Trump administration.[160] U.S. judge Carl J. Nichols temporarily blocked the Trump administration order that would effectively ban TikTok from being downloaded in U.S. app stores starting midnight on 27 September 2020. Nichols allowed the app to remain available in the U.S. app stores but declined to block the additional Commerce Department restrictions that could have a larger impact on TikTok’s operations in the U.S. These restrictions were set to take place on 12 November 2020.[161]

Three TikTok influencers filed a lawsuit, Marland v. Trump.[162] On 30 October, Pennsylvania judge Wendy Beetlestone ruled against the Commerce Department, blocking them from restricting TikTok.[162] On 12 November, the Commerce Department stated that it would obey the Pennsylvania ruling and that it would not try to enforce the restrictions against TikTok that had been scheduled for 12 November.[162]

The Commerce Department appealed the original ruling in TikTok v. Trump. On 7 December, Washington D.C. district court judge Carl J. Nichols issued a preliminary injunction against the Commerce Department, preventing them from imposing restrictions on TikTok.[163][164][165]

In June 2021, new president Joe Biden signed an executive order revoking the Trump administration ban on TikTok, and instead ordered the Secretary of Commerce to investigate the app to determine if it poses a threat to U.S. national security.[166]

In June 2022, reports emerged that ByteDance employees in China could access US data and repeatedly accessed the private information of TikTok users,[167][168][169] TikTok employees were cited saying that «everything is seen in China,» while one director claimed a Beijing-based engineer referred to as a «Master Admin» has «access to everything.»[167][170][171]

Following the reports, TikTok announced that 100% of its US user traffic is now being routed to Oracle Cloud, along with their intention to delete all US user data from their own data centers.[168][170] This deal stems from the talks with Oracle instigated in September 2020 in the midst of Trump’s threat to ban TikTok in the US.[172][173][171]

In June 2022, FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr called for Google and Apple to remove TikTok from their app stores, citing national security concerns, saying TikTok «harvests swaths of sensitive data that new reports show are being accessed in Beijing.»[174][167]

However, back in March 2022, Bytedance and Oracle negotiated Oracle to take over TikTok’s US data storage. After BuzzFeed said China-based employees may have access to US private data, TikTok responded that all US private data are being stored in Oracle’s servers.[175] In June 2022, TikTok said that it was moving all of the data produced by its American users through servers controlled by Oracle and it will not expose the personal information of Americans to the Chinese government.[176]

In October 2022, a Forbes report claimed that the ByteDance team planned to surveil individual American citizens for undisclosed reasons. TikTok denied these claims in a series of tweets, saying that this report lacked «both rigor and journalistic integrity.»[177][178]

In November 2022, Christopher A. Wray, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, told U.S. lawmakers that «the Chinese government could use [TikTok] to control data collection on millions of users or control the recommendation algorithm, which could be used for influence operations.»[179]

In December 2022, Senator Marco Rubio and representatives Mike Gallagher and Raja Krishnamoorthi introduced the Averting the National Threat of Internet Surveillance, Oppressive Censorship and Influence, and Algorithmic Learning by the Chinese Communist Party Act (ANTI-SOCIAL CCP Act), which would prohibit Chinese- and Russian-owned social networks from doing business in the United States.[180][181] That month, Senator Josh Hawley also introduced a separate measure, the No TikTok on Government Devices Act (S. 3455), to ban federal employees from using TikTok on all government devices.[182] On December 15, Hawley’s measure was unanimously passed by the U.S. Senate.[183] On December 27, the Chief Administrative Officer of the United States House of Representatives banned TikTok from all devices managed by the House of Representatives.[184]

Controversies

Addiction concerns

There are concerns that some users may find it hard to stop using TikTok.[185] In April 2018, an addiction-reduction feature was added to Douyin.[185] This encouraged users to take a break every 90 minutes.[185] Later in 2018, the feature was rolled out to the TikTok app. TikTok uses some top influencers such as Gabe Erwin, Alan Chikin Chow, James Henry, and Cosette Rinab to encourage viewers to stop using the app and take a break.[186]

Many were also concerned with the app affecting users’ attention spans due to the short-form nature of the content. This is a concern as many of TikTok’s audience are younger children, whose brains are still developing.[187] TikTok executives and representatives have noted and made aware to advertisers on the platform that users have poor attention spans. With a large amount of video content, nearly 50% of users find it stressful to watch a video longer than a minute and a third of users watch videos at double speed.[99]

In June 2022, TikTok introduced the ability to set a maximum uninterrupted screen time allowance, after which the app blocks off the ability to navigate the feed. The block only lifts after the app is exited and left unused for a set period of time. Additionally, the app features a dashboard with statistics on how often the app is opened, how much time is spent browsing it and when the browsing occurs.[188]

Content concerns

Some countries have shown concerns regarding the content on TikTok, as their cultures view it as obscene, immoral, vulgar, and encouraging pornography. There have been temporary blocks and warnings issued by countries including Indonesia,[189] Bangladesh,[190] India,[191] and Pakistan[192][193] over the content concerns. In 2018, Douyin was reprimanded by Chinese media watchdogs for showing «unacceptable» content.[194]

On 27 July 2020, Egypt sentenced five women to two years in prison over TikTok videos. One of the women had encouraged other women to try and earn money on the platform, another woman was sent to prison for dancing. The court also imposed a fine of 300,000 Egyptian pounds (UK£14,600) on each defendant.[195]

Concerns have been voiced regarding content relating to, and the promotion and spreading of, hateful words and far-right extremism, such as anti-semitism, racism, and xenophobia. Some videos were shown to expressly deny the existence of the Holocaust and told viewers to take up arms and fight in the name of white supremacy and the swastika.[196] As TikTok has gained popularity among young children,[197] and the popularity of extremist and hateful content is growing, calls for tighter restrictions on their flexible boundaries have been made. TikTok has since released tougher parental controls to filter out inappropriate content and to ensure they can provide sufficient protection and security.[198]

A viral TikTok trend known as «devious licks» involves students vandalizing or stealing school property and posting videos of the action on the platform. The trend has led to increasing school vandalism and subsequent measures taken by some schools to prevent damage. Some students have been arrested for participating in the trend.[199][200] TikTok has taken measures to remove and prevent access to content displaying the trend.[201]

The Wall Street Journal has reported that doctors experienced a surge in reported cases of tics, tied to an increasing number of TikTok videos from content creators with Tourette syndrome. Doctors suggested that the cause may be a social one as users who consumed content showcasing various tics would sometimes develop tics of their own.[202]

In March 2022, the Washington Post reported that Facebook owner Meta Platforms had paid Targeted Victory—a consulting firm backed by supporters of the U.S. Republican Party—to coordinate lobbying and media campaigns against TikTok to portray it as «a danger to American children and society», primarily to counter criticism of Facebook’s own services. This included op-eds and letters to the editor in regional publications, the amplification of «dubious local news stories citing TikTok as the origin of dangerous teen trends» (such as the aforementioned «devious licks», and an alleged «Slap a Teacher» challenge), including those whose initial development actually began on Facebook, and the similar promotion of «proactive coverage» of Facebook corporate initiatives.[203]

In Malaysia, TikTok are used by some users to perform hate speech against race and religion especially mentioning 13 May incident after election. TikTok respond by turn down video with content that violated its community guidelines.[204]

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita filed lawsuits against TikTok, alleging that the platform exposed inappropriate content to minors. The complaint also alleges that TikTok «intentionally falsely reports the frequency of sexual content, nudity, and mature/suggestive themes» on their platform which made the app’s «12-plus» age ratings on the Apple and Google app stores deceptive.[205][206]

Appropriation from Black content creators

Numerous examples of White TikTokers appropriating what was initially created by Black TikTokers have been noted on the platform. In June 2021, The New York Times published an investigation into the practice as part of the Hulu documentary, Who Gets to be an Influencer?[207] In July 2021, after Megan Thee Stallion released her song «Thot Shit,» Black content creators refused to make dances to it as they normally would, in protest of the inequity to Black creators due to White TikTokers mimicking them.[208]

Misinformation

In January 2020, left-leaning media watchdog Media Matters for America said that TikTok hosted misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic despite a recent policy against misinformation.[209] In April 2020, the government of India asked TikTok to remove users posting misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[210] There were also multiple conspiracy theories that the government is involved with the spread of the pandemic.[211] As a response to this, TikTok launched a feature to report content for misinformation.[212] It reported that in the second half of 2020, over 340,000 videos in the U.S. about election misinformation and 50,000 videos of COVID-19 misinformation were removed.[213]

To combat misinformation in the 2022 midterm election in the US, TikTok announced a midterms Elections Center available in-app to users in 40 different languages. TikTok partnered with the National Association of Secretaries of State to give accurate local information to users.[214]

In September 2022, NewsGuard Technologies reported that among the TikTok searches it had conducted and analyzed from the U.S., 19.4% surfaced misinformation such as questionable or harmful content about COVID-19 vaccines, homemade remedies, the 2020 US elections, the war in Ukraine, the Robb Elementary School shooting, and abortion. NewsGuard suggested that in contrast, results from Google were of higher quality.[215] Mashable’s own test from Australia found innocuous results after searching for «getting my COVID vaccine» but suggestions such as «climate change is a myth» after typing in «climate change».[213]

Content censorship and moderation by the platform

TikTok’s censorship policy has been criticized as non-transparent.[216] Criticism of leaders such as Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Mahatma Gandhi[217] and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan[218] has been suppressed by the platform, as well as information relating to the Xinjiang internment camps and the Uyghur genocide.[219][220] Internal documents have revealed that moderators suppress posts created by users deemed «too ugly, poor, or disabled» for the platform, and censor political speech on livestreams.[221][222][223] TikTok moderators have also blocked content that could be perceived as positive towards LGBT people.[218][224]

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

TikTok is the 10th most popular app in Russia.[225] After a new set of Russian fake news laws was installed in March 2022, the company announced a series of restrictions on Russian and non-Russian posts and livestreams.[226][227] Tracking Exposed, a user data rights group, learned of what was likely a technical glitch that became exploited by pro-Russia posters. It stated that although this and other loopholes were patched by TikTok before the end of March, the initial failure to correctly implement the restrictions, in addition to the effects from Kremlin’s ‘fake news’ laws, contributed to the formation of a «splinternet … dominated by pro-war content» in Russia.[228][225] TikTok said that it had removed 204 accounts for swaying public opinion about the war while obscuring their origins and that its fact checkers had removed 41,191 videos for violating its misinformation policies.[229][230]

ISIL propaganda

In October 2019, TikTok removed about two dozen accounts that were responsible for posting ISIL propaganda on the app.[231][232]

User privacy concerns

Privacy concerns have also been brought up regarding the app.[233][234] In its privacy policy, TikTok lists that it collects usage information, IP addresses, a user’s mobile carrier, unique device identifiers, keystroke patterns, and location data, among other data.[235][236] Web developers Talal Haj Bakry and Tommy Mysk said that allowing videos and other content to be shared by the app’s users through HTTP puts the users’ data privacy at risk.[237]

In January 2020, Check Point Research discovered a security flaw in TikTok which could have allowed hackers access to user accounts using SMS.[238] In February, Reddit CEO Steve Huffman criticised the app, calling it «spyware,» and stating «I look at that app as so fundamentally parasitic, that it’s always listening, the fingerprinting technology they use is truly terrifying, and I could not bring myself to install an app like that on my phone.»[239][240] Responding to Huffman’s comments, TikTok stated, «These are baseless accusations made without a shred of evidence.»[235] Wells Fargo banned the app from its devices due to privacy and security concerns.[241]

In May 2020, the Dutch Data Protection Authority announced an investigation into TikTok in relation to privacy protections for children.[242][243] In June 2020, the European Data Protection Board announced that it would assemble a task force to examine TikTok’s user privacy and security practices.[244]

In August 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that TikTok tracked Android user data, including MAC addresses and IMEIs, with a tactic in violation of Google’s policies.[245][246] The report sparked calls in the U.S. Senate for the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to launch an investigation.[247]

In June 2021, TikTok updated its privacy policy to include a collection of biometric data, including «faceprints and voiceprints.»[248] Some experts reacted by calling the terms of collection and data use «vague» and «highly problematic.»[249] The same month, CNBC reported that former employees had stated that «the boundaries between TikTok and ByteDance were so blurry as to be almost non-existent» and that «ByteDance employees are able to access U.S. user data» on TikTok.[250]

In October 2021, following the Facebook Files and controversies about social media ethics, a bipartisan group of lawmakers also pressed TikTok, YouTube, and Snapchat on questions of data privacy and moderation for age-appropriate content. The New York Times reported, «Lawmakers also hammered [head of U.S. policy at TikTok] Mr. Beckerman about whether TikTok’s Chinese ownership could expose consumer data to Beijing,» stating that «Critics have long argued that the company would be obligated to turn Americans’ data over to the Chinese government if asked.»[251] TikTok told U.S. lawmakers it does not give information to China’s government. TikTok’s representative stated that TikTok’s data is stored in the U.S. with backups in Singapore. According to the company’s representative, TikTok had ‘no affiliation’ with the subsidiary Beijing ByteDance Technology, in which the Chinese government has a minority stake and board seat.[252]

In June 2022, BuzzFeed News reported that leaked audio recordings of internal TikTok meetings revealed that certain China-based employees of the company maintain full access to overseas data.[253][254]

In August 2022, Software engineer and security researcher Felix Krause found that the TikTok software contained keylogger functionality.[255]

In September 2022, during testimony to the Senate Homeland Security Committee, TikTok’s COO stated that the company could not commit to stopping data transfers from US users to China. The COO reacted to concerns of the company’s handling of user data by stating that TikTok does not operate in China, though the company does have an office there.[256]

Additionally, in November 2022, TikTok’s head of privacy for Europe, Elaine Fox, confirmed that some of its workers, including the workers in China, have access to the user info of accounts from the UK and European Union. According to Fox, this «privacy policy» was «based on a demonstrated need to do their job.»[257]

U.S. COPPA fines

On 27 February 2019, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fined ByteDance U.S.$5.7 million for collecting information from minors under the age of 13 in violation of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act.[258] ByteDance responded by adding a kids-only mode to TikTok which blocks the upload of videos, the building of user profiles, direct messaging, and commenting on others’ videos, while still allowing the viewing and recording of content.[259] In May 2020, an advocacy group filed a complaint with the FTC saying that TikTok had violated the terms of the February 2019 consent decree, which sparked subsequent Congressional calls for a renewed FTC investigation.[260][261][262][263] In July 2020, it was reported that the FTC and the United States Department of Justice had initiated investigations.[264]

UK Information Commissioner’s Office investigation

In February 2019, the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office launched an investigation of TikTok following the fine ByteDance received from the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Speaking to a parliamentary committee, Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham said that the investigation focuses on the issues of private data collection, the kind of videos collected and shared by children online, as well as the platform’s open messaging system which allows any adult to message any child. She noted that the company was potentially violating the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which requires the company to provide different services and different protections for children.[265]

On 22 January 2021, the Italian Data Protection Authority ordered the blocking of the use of the data of users whose age has not been established on the social network.[266][267] The order was issued after the death of a 10-year-old Sicilian girl, which occurred after the execution of a challenge shared by users of the platform that involved attempting to choke the user with a belt around the neck. The block is set to remain in place until 15 February, when it will be re-evaluated.[268][needs update]

Ireland Data Protection Commission

In September 2021, the Ireland Data Protection Commissioner opened investigations into TikTok concerning the protection of minors’ data and transfers of personal data to China.[269][270]

Texas Attorney General investigation

In February 2022, the incumbent Texas Attorney General, Ken Paxton, initiated an investigation into TikTok for alleged violations of children’s privacy and facilitation of human trafficking.[271][272] Paxton claimed that the Texas Department of Public Safety gathered several pieces of content showing the attempted recruitment of teenagers to smuggle people or goods across the Mexico–United States border. He claimed the evidence may prove the company’s involvement in «human smuggling, sex trafficking and drug trafficking.» The company claimed that no illegal activity of any kind is supported on the platform.[273]

Journalist spying scandal

In December 2022, TikTok confirmed that journalists’ data was accessed by employees of its parent company. It previously denied using location information to track U.S. users.[274]

TikTok parent company ByteDance fired four employees who improperly accessed the personal data of two journalists on the platform, a TikTok spokesman ByteDance confirmed to CNN. As ByteDance employees investigated potential employee leaks to the media, they accessed the TikTok user data of two journalists, according to the company. Personal data obtained from journalists’ accounts included IP addresses, which can be used to track location. The disclosure could further intensify the scrutiny TikTok faces in the U.S. over national security concerns, given its ties to China.[275]

“The public trust that we have spent huge efforts building is going to be significantly undermined by the misconduct of a few individuals. … I believe this situation will serve as a lesson to us all,» Rubo Liang told Forbes after the incident.[276]

Cyberbullying

As with other platforms,[277] journalists in several countries have raised privacy concerns about the app because it is popular with children and has the potential to be used by sexual predators.[277][278][279][280]

Several users have reported endemic cyberbullying on TikTok,[281][282] including racism[283] and ableism.[284][285][286] In December 2019, following a report by German digital rights group Netzpolitik.org, TikTok admitted that it had suppressed videos by disabled users as well as LGBTQ+ users in a purported effort to limit cyberbullying.[287][221] TikTok’s moderators were also told to suppress users with «abnormal body shape,» «ugly facial looks,» «too many wrinkles,» or in «slums, rural fields» and «dilapidated housing» to prevent bullying.[288]

In 2021, the platform revealed that it will be introducing a feature that will prevent teenagers from receiving notifications past their bedtime. The company will no longer send push notifications after 9 PM to users aged between 13 and 15. For 16 to 17 year olds, notifications will not be sent after 10 PM.[289]

Microtransactions

TikTok has received criticism for enabling children to purchase coins which they can send to other users.[290]

Impact on mental health

In February 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported that «Mental-health professionals around the country are growing increasingly concerned about the effects on teen girls of posting sexualized TikTok videos.»[291] In March 2022, a coalition of U.S. state attorneys general launched an investigation into TikTok’s effect on children’s mental health.[292]

In April 2022, NBC News reported that surgeons were giving influencers on the platform discounted or free cosmetic surgeries in order to advertise the procedures to their audiences. They also reported that facilities that offered these surgeries were also posting about them on TikTok. TikTok has banned the advertising of cosmetic surgeries on the platform but cosmetic surgeons are still able to reach large audiences using unpaid photo and video posts. NBC reported that videos using the hashtags ‘#plasticsurgery’ and ‘#lipfiller’ had amassed a combined 26 billion views on the platform.[293]

In December 2022 it was reported that a cosmetic surgery procedure known as buccal fat removal was going viral on the platform. The procedure involves surgically removing fat from the cheeks in order to give the face a slimmer and more chiseled appearance. Videos using hashtags related to buccal fat removal had collectively amassed over 180 million views. Some TikTok users criticised the trend for promoting an unobtainable beauty standard.[294][295][296]

Medication shortages

In November 2022, Australia’s medical regulatory agency, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) reported that there was a global shortage of the diabetes medication Ozempic. Ozempic is a brand of semaglutide used by patients with Type-2 diabetes to regulate blood glucose, with weight loss as side effect. According to the TGA, the rise in demand was caused by an increase in off-label prescription of the drug for weight loss purposes. Off-label prescription is the prescription of a drug for purposes other than what it was approved for.[297] In December 2022, after the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) listed Ozempic as being in shortage in the United States as well, it was reported that huge increase in demand for off-label prescriptions of the medicine was caused by a weight loss trend on TikTok, where videos about the drug had exceeded 360 million views.[298][299][300] Wegovy, a drug with a higher dosage of semaglutide that has been specifically approved for use in treating obesity, also became popular on the platform after Elon Musk credited it for helping him lose weight.[301][302]

Workplace conditions

Several former employees of the company have claimed of poor workplace conditions, including the start of the workweek on Sunday to cooperate with Chinese timezones and excessive workload. Employees claimed they averaged 85 hours of meetings per week and would frequently stay up all night in order to complete tasks. Some employees claimed the workplace’s schedule operated similarly to the 996 schedule. The company has a stated policy of working from 10 AM to 7 PM five days per week (63 hours per week), but employees noted that it was encouraged for employees to work after hours. One female worker complained that the company did not allow her adequate time to change her feminine hygiene product because of back-to-back meetings. Another employee noted that working at the company caused her to seek marriage therapy and lose an unhealthy amount of weight.[303] In response to the allegations, the company noted that they were committed to allowing employees «support and flexibility.»[304][305]

Syrian refugee child begging

TikTok raised the minimum age for livestreaming from 16 to 18 after a BBC News investigation found hundreds of accounts going live from Syrian refugee camps, with children begging for donations through digital gifts.[306]

Privacy settings

Users of TikTok under the age of 18 will have their accounts set to private by default, meaning that only people they have given permission to follow them can watch their videos. The modification is a component of a larger set of policies intended to promote better levels of user.[307]

Legal issues

Tencent lawsuits

Tencent’s WeChat platform has been accused of blocking Douyin’s videos.[308][309] In April 2018, Douyin sued Tencent and accused it of spreading false and damaging information on its WeChat platform, demanding CN¥1 million in compensation and an apology. In June 2018, Tencent filed a lawsuit against Toutiao and Douyin in a Beijing court, alleging they had repeatedly defamed Tencent with negative news and damaged its reputation, seeking a nominal sum of CN¥1 in compensation and a public apology.[310] In response, Toutiao filed a complaint the following day against Tencent for allegedly unfair competition and asking for CN¥90 million in economic losses.[311]

Data transfer class action lawsuit

In November 2019, a class action lawsuit was filed in California that alleged that TikTok transferred personally identifiable information of U.S. persons to servers located in China owned by Tencent and Alibaba.[312][313][314] The lawsuit also accused ByteDance, TikTok’s parent company, of taking user content without their permission. The plaintiff of the lawsuit, college student Misty Hong, downloaded the app but said she never created an account. She realized a few months later that TikTok has created an account for her using her information (such as biometrics) and made a summary of her information. The lawsuit also alleged that information was sent to Chinese tech giant Baidu.[315] In July 2020, twenty lawsuits against TikTok were merged into a single class action lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois.[316] In February 2021, TikTok agreed to pay $92 million to settle the class action lawsuit.[317]

Voice actor lawsuit

In May 2021, Canadian voice actor Bev Standing filed a lawsuit against TikTok over the use of her voice in the text-to-speech feature without her permission. The lawsuit was filed in the Southern District of New York. TikTok declined to comment. Standing believes that TikTok used recordings she made for the Chinese government-run Institute of Acoustics.[318] The voice used in the feature was subsequently changed.[319]

Market Information Research Foundation lawsuit

In June 2021, the Netherlands-based Market Information Research Foundation (SOMI) filed a €1.4 billion lawsuit on behalf of Dutch parents against TikTok, alleging that the app gathers data on children without adequate permission.[320]

Blackout Challenge lawsuits

Multiple lawsuits have been filed against TikTok, accusing the platform of hosting content that led to the death of at least seven children.[321] The lawsuits claim that children died after attempting the Blackout Challenge — a TikTok trend that involves strangling someone or themselves until they black out (passing out). TikTok stated that search queries for the challenge do not show any results, linking instead to protective resources, while the parents of two of the deceased argued that the content showed up on their children’s TikTok feeds, without them searching for it.[322]

See also

- List of most-followed TikTok accounts

- List of most-liked TikTok videos

- Musical.ly

- Timeline of social media

References

- ^ «TikTok — Make Your Day». iTunes. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Lin, Pellaeon (22 March 2021). «TikTok vs Douyin: A Security and Privacy Analysis». Citizen Lab. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (8 October 2020). «U.S. Appeals Injunction Against TikTok Ban». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (1 July 2021). «TikTok is rolling out longer videos to everyone». The Verge. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ «TikTok, WeChat and the growing digital divide between the US and China». TechCrunch. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ «Forget The Trade War. TikTok Is China’s Most Important Export Right Now». BuzzFeed News. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Niewenhuis, Lucas (25 September 2019). «The difference between TikTok and Douyin». SupChina. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ «50 TikTok Stats That Will Blow Your Mind [Updated 2020]». Influencer Marketing Hub. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ RouteBot (21 March 2020). «Top 10 Countries with the Largest Number of TikTok Users». routenote.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (29 April 2020). «TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads». The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ «2020年春季报告:抖音用户规模达5.18亿人次,女性用户占比57%» (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Ahmad, Asif Shahzad, Jibran (11 March 2021). «Pakistan to block social media app TikTok over ‘indecency’ complaint». Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ «The Fastest Growing Brands of 2020». Morning Consult. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ «TikTok surpasses Google as most popular website of the year, new data suggests». NBC News. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ «The App That Launched a Thousand Memes | Sixth Tone». Sixth Tone. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ «Is Douyin the Right Social Video Platform for Luxury Brands? | Jing Daily». Jing Daily. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ «TIKTOK’S RISE TO GLOBAL MARKETS 1». Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Graziani, Thomas (30 July 2018). «How Douyin became China’s top short-video App in 500 days». WalktheChat. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ «8 Lessons from the rise of Douyin (Tik Tok) · TechNode». TechNode. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ «Tik Tok, a Global Music Video Platform and Social Network, Launches in Indonesia». Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ «Tik Tok, Global Short Video Community launched in Thailand with the latest AI feature, GAGA Dance Machine The very first short video app with a new function based on AI technology». thailand.shafaqna.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (29 April 2020). «TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads». The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Doyle, Brandon (6 October 2020). «TikTok Statistics — Everything You Need to Know [Sept 2020 Update]». Wallaroo Media. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Yurieff, Kaya (21 November 2018). «TikTok is the latest social network sensation». Cnn.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (15 November 2018). «TikTok surges past 6M downloads in the US as celebrities join the app». The Verge. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (20 November 2018). «TikTok App Nears 80 Million U.S. Downloads After Phasing Out Musical.ly, Lands Jimmy Fallon as Fan». Variety. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ «A-Rod & J.Lo, Reese Witherspoon and the Rest of the A-List Celebs You Should Be Following on TikTok». PEOPLE.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Yuan, Lin; Xia, Hao; Ye, Qiang (16 August 2022). «The effect of advertising strategies on a short video platform: evidence from TikTok». Industrial Management & Data Systems. 122 (8): 1956–1974. doi:10.1108/IMDS-12-2021-0754. ISSN 0263-5577. S2CID 251508287.

- ^ «The NFL joins TikTok in multi-year partnership». TechCrunch. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ «50 TikTok Stats That Will Blow Your Mind in 2020 [UPDATED ]». Influencer Marketing Hub. 11 January 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ «TikTok Names ByteDance CFO Shou Zi Chew as New CEO». NDTV Gadgets 360. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ «TikTok CEO Kevin Mayer quits after 4 months». Fortune (magazine). Bloomberg News. 27 August 2020. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (18 May 2020). «In surprise move, a top Disney executive will run TikTok». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ «Australian appointed interim chief executive of TikTok». ABC News. 28 August 2020. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Adi (3 August 2020). «Trump threatens that TikTok will «close down» on September 15th unless an American company buys it». The Verge. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Singh, Maanvi (6 August 2020). «Trump bans US transactions with Chinese-owned TikTok and WeChat». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 December 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ «Commerce Department Prohibits WeChat and TikTok Transactions to Protect the National Security of the United States». U.S. Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ a b Arbel, Tali (6 August 2020). «Trump bans dealings with Chinese owners of TikTok, WeChat». Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Fung, Brian. «Trump says he has approved a deal for TikTok». CNN. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Wells, Andrew Restuccia, John D. McKinnon and Georgia (20 September 2020). «Trump Signs Off on TikTok Deal With Oracle, Walmart». Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020 – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ Swanson, Ana; McCabe, David; Griffith, Erin (19 September 2020). «Trump Approves Deal Between Oracle and TikTok». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ TikTok ban: Judge rules app won’t be blocked in the US, for now Archived 2 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine; CNN by way of MSN; published 28 September 2020; accessed 7 February 2021

- ^ McKinnon, John; Leary, Alex (9 June 2021). «Trump’s TikTok, WeChat Actions Targeting China Revoked by Biden». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Doval, Pankaj (30 June 2020). «TikTok, UC Browser among 59 Chinese apps blocked as threat to sovereignty». The Times of India. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020.

- ^ Charles Riley. «Pakistan reverses TikTok ban after 10 days». CNN. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Kastrenakes, Jacob (9 October 2020). «Pakistan bans TikTok for «immoral» and «indecent» videos». The Verge. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ «Pakistan bans TikTok for allowing ‘immoral and indecent’ content». Android Police. 9 October 2020. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Lyons, Kim (27 September 2021). «TikTok says it has passed 1 billion users». The Verge. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ «The all-conquering quaver». The Economist. 9 July 2022.

- ^ Belanger, Ashley (12 October 2022). «TikTok wants to be Amazon, plans US fullfillment centers and poaches staff». ArsTechnica. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Lin, Liza; Winkler, Rolfe (9 November 2017). «Social-Media App Musical.ly Is Acquired for as Much as $1 Billion». wsj.com. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b «Social video app Musical.ly acquired for up to $1 billion». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ Lee, Dami (2 August 2018). «The popular Musical.ly app has been rebranded as TikTok». Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ «Musical.ly Is Going Away: Users to Be Shifted to Bytedance’s TikTok Video App». msn.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Kundu, Kishalaya (2 August 2018). «Musical.ly App To Be Shut Down, Users Will Be Migrated to TikTok». Beebom. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ «Chinese video sharing app boasts 500 mln monthly active users». Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ «Why China’s Viral Video App Douyin is No Good for Luxury | Jing Daily». Jing Daily. 13 June 2018. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ Chen, Qian (19 September 2018). «The biggest trend in Chinese social media is dying, and another has already taken its place». CNBC. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ «Tik Tok, a Global Music Video Platform and Social Network, Launches in Indonesia-PR Newswire APAC». en.prnasia.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ «How Douyin became China’s top short-video App in 500 days – WalktheChat». WalktheChat. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ «TikTok Pte. Ltd». Sensortower. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Rayome, Alison DeNisco. «Facebook was the most-downloaded app of the decade». CNET. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Chen, Qian (18 September 2018). «The biggest trend in Chinese social media is dying, and another has already taken its place». CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ «TikTok surpassed Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat & YouTube in downloads last month». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ Novet, Jordan (13 September 2020). «Oracle stock surges after it confirms deal with TikTok-owner ByteDance». CNBC. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

Shares of Oracle surged Monday morning after it confirmed it has been chosen to serve as TikTok owner ByteDance’s “trusted technology provider” in the U.S.

- ^ Kharpal, Arjun (25 September 2020). «Here’s where things stand with the messy TikTok deal». CNBC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Corkery, Michael (23 September 2020). «Beyond TikTok, Walmart Looks to Transform». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

Walmart’s planned investment in TikTok is being called “transformative.”

- ^ Allyn, Bobby (10 February 2021). «Biden Administration Pauses Trump’s TikTok Ban, Backs Off Pressure To Sell App». NPR. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ «TikTok Sale to Oracle, Walmart Is Shelved as Biden Reviews Security». Wall Street Journal. 10 February 2021. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ «ByteDance is walking away from its TikTok deal with Oracle now that Trump isn’t in office, report says». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ «TikTok signs deal with Sony Music to expand music library». finance.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ «Warner Music Group inks licensing deal with TikTok». Music Business Worldwide. 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ «Warner Music signs with TikTok as more record companies jump on social media bandwagon». themusicnetwork.com. 7 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ «Warner Music Group: Modernized And Ready To Play In The New Streaming World». seekingalpha.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ «The Department of Culture and Tourism — Abu Dhabi Partners with TikTok for Destination Promotion». Department of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ^ «The UAE Government Media Office and TikTok bring people together to discover the UAE’s hidden gems in World’s Coolest Winter». Campaign Middle East. 14 January 2021. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Cowley, Ric (12 August 2020). «Subway Surfers has surpassed three billion downloads». pocketgamer.biz. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ «TikTok Becomes the First Non-Facebook Mobile App to Reach 3 Billion Downloads Globally». sensortower.com. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- ^ «How to Use TikTok: Tips for New Users». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ Matsakis, Louise (6 March 2019). «How to Use TikTok: Tips for New Users». Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ a b Cervi, Laura (3 April 2021). «Tik Tok and generation Z». Theatre, Dance and Performance Training. 12 (2): 198–204. doi:10.1080/19443927.2021.1915617. ISSN 1944-3927. S2CID 236323384.

- ^ a b «TikTok adds video reactions to its newly-merged app». TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ «Tik Tok lets you duet with yourself, a pal, or a celebrity». The Nation. 22 May 2018. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Weir, Melanie. «How to duet on TikTok and record a video alongside someone else’s». Business Insider. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Liao, Christina. «How to make and find drafts on TikTok using your iPhone or Android». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ a b «It’s time to pay serious attention to TikTok». TechCrunch. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ Delfino, Devon. «How to ‘go live’ on TikTok and livestream video to your followers». Business Insider. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ «How To Go Live & Stream on TikTok». Tech Junkie. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ «TikTok’s social gifting campaign attracts beauty brands». Glossy. 7 May 2020. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ «Introducing Family Safety Mode and Screentime Management in Feed». TikTok. 16 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.