Англо-русский перевод TOTTENHAM

г. Тоттенем

Тоттенем

English-Russian dictionary Tiger.

Англо-Русский словарь Tiger.

2012

Tottenham

«То́ттенхэм Хо́тспур» — английский профессиональный футбольный клуб из Тоттенема, боро Харинги на севере Лондона. Выступает в Премьер-лиге, высшем дивизионе в системе футбольных лиг Англии. Основан в 1882 году. Прозвище клуба — «шпоры» (англ. Spurs). Домашние матчи проводит на одноимённом стадионе. Wikipedia

Премьер-Лига, 36-й тур

Всем добрый вечерочек! Ливерпуль-Тоттенхэм. Конечно, точный счет здесь угадать не представляется возможным, так как может быть как лютый тм в виде нулей или одного гола, так и тб с кучей голов. Я, как поклонник красивого футбола, буду думать, что здесь второй вариант) 2:1, 3:2 вот какие варианты я рассматриваю на данный матч. Ливерпуль в… читать полностью

+3

4 дня назад

русский

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

украинский

китайский

английский

Синонимы

арабский

немецкий

английский

испанский

французский

иврит

итальянский

японский

голландский

польский

португальский

румынский

русский

шведский

турецкий

украинский

китайский

украинский

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать грубую лексику.

На основании Вашего запроса эти примеры могут содержать разговорную лексику.

Он рассказал, как тебя арестовали на Тоттенхэм Корт Роад.

He told me about your arrest in the Tottenham Court Road.

Ровно. Тоттенхэм Корт Роуд, 10:30.

Гарднер подписан контракт с «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» Джорджа Грэма в январе 2000 года за £ 1 млн.

Gardner signed for George Graham’s Tottenham Hotspur in January 2000 for a £1 million fee.

Северолондонское дерби — играется командами Арсенал и Тоттенхэм Хотспур.

North London derby — between Arsenal and Tottenham Hotspur.

Среди его любимых видов спорта — гольф, теннис, футбол (он поклонник футбольного клуба Тоттенхэм Хотспур).

Among his favourite sports are golf, tennis, football and is a fan of Tottenham Hotspur football club.

Послом УЕФА на финал Лиги чемпионов 2011 года стал бывший нападающий «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» Гари Линекер.

UEFA’s ambassador for the 2011 Champions League Final was the former Tottenham Hotspur forward Gary Lineker.

На Тоттенхэм Корт Роуд. Северная линия, у выхода на платформу.

Today, Tottenham Court Road tube, northern line, northbound platform.

Тоттенхэм Хотспур победил «Челси» со счетом 2-1 в дополнительное время, завоевав свой первый трофей за 9 лет.

Tottenham Hotspur defeated Chelsea 2-1, after extra time, winning their first trophy in nine years.

28 июля 2000 года «Тоттенхэм» продал Крауча в клуб Чемпионшипа «Куинз Парк Рейнджерс» за 60000 фунтов.

On 28 July 2000, Tottenham sold Crouch to First Division club Queens Park Rangers for £60,000.

Стайлз был включён в состав сборной Англии на Чемпионат Европы 1968 года, но роль «сдерживающего» полузащитника перешла к Алану Маллери из «Тоттенхэм Хотспур».

Stiles was selected for the England squad which contested the 1968 European Championships, but the holding role in midfield had been taken by Tottenham Hotspur’s Alan Mullery.

В 2008 году Халси был назначен главным арбитром финального матча Кубка Футбольной лиги, в котором сыграли «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» и «Челси».

In 2008 Halsey was appointed to referee the League Cup final between Tottenham Hotspur and Chelsea.

Полноценно Филип дебютировал за «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» в матче против «Ливерпуля» в первый день сезона 2004/05, и сыграл еще три игры в премьер-лиге.

A full-back, he made his debut for Tottenham Hotspur against Liverpool on the first day of the 2004-05 season, and went on to make three appearances in the Premier League.

Главный тренер «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» Гарри Реднапп назвал футбольное поле «позором» после поражения в полуфинале от «Портсмута».

The then Tottenham Hotspur boss, Harry Redknapp labelled it a «disgrace» after his side’s semi-final defeat to Portsmouth.

В июне 2007 года Лили выступила с Psychotic Dance Company на карнавале Тоттенхэм (Tottenham Carnival).

In June 2007, she performed with the Psychotic Dance Company at the Tottenham Carnival.

«Тоттенхэм» и «Манчестер Сити» одержали победу и вышли в финал.

Tottenham and Manchester City were victorious and reached the Final.

Позже он был подписан на контракт с Академией «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» в 2011 году после испытания, которое включало его забивание двух мячей в одном матче.

Later he was signed to a contract by the Tottenham Hotspur Academy in 2011 following a trial which included him scoring two goals in a single match.

В ноябре 1975 года Армстронг переехал в Англию, подписав контракт с «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» на сумму 25 тысяч фунтов стерлингов.

In November 1975, Armstrong moved to England, signing with Tottenham Hotspur for a fee of £25,000.

29 сентября 2010 года, в ходе визита в клуб главы скаутского отдела Тоттенхэм Хотспур Яна Брумфилда, он похвалил Ипа за его огромный потенциал.

On 29 September 2010, during Tottenham Hotspur’s chief scout Ian Broomfield’s visit to South China, he praised Yapp for his enormous potential.

Он был уволен из «Ньюкасла» в мае 1975 года и перешёл в «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» в том же месяце.

He was sacked by Newcastle in May 1975 and joined Tottenham Hotspur as coach the same month.

Он играл за футбольный клуб «Спрингфилд», базирующийся в Кингсбери, Лондон, прежде чем подписать контракт с «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» в подростковом возрасте.

He played for Springfield Football Club based in Kingsbury, London before signing for Tottenham Hotspur as a teenager.

Результатов: 112. Точных совпадений: 68. Затраченное время: 160 мс

Documents

Корпоративные решения

Спряжение

Синонимы

Корректор

Справка и о нас

Индекс слова: 1-300, 301-600, 601-900

Индекс выражения: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

Индекс фразы: 1-400, 401-800, 801-1200

- Страна

- Англия

- Город

- Лондон

- Полное название

- Tottenham Hotspur Football Club

- Прозвища

- Шпоры, спёрс, лилейно-белые

- Дата основания

- 05.09.1882

- Год основания

- 1882

- Стадион

- Уайт Харт Лэйн

- Президент

- Леви Дэниел

- Капитан

-

Льорис Уго - Главный тренер

- Конте Антонио

- Официальный сайт

- http://www.tottenhamhotspur.com/

- Основные цвета

- белый, синий

- Предыдущие названия

- 1882 — 1884 — «Хотспур»

1885 — н.в. «Тоттенхэм Хотспур»

История

Клуб был создан в 1882 году сообществом мальчиков из крикетного клуба «Хотспур» и мальчиков местной грамматической школы. Новую команду назвали ФК «Хотспур». Переименование в «Тоттенхэм Хотспур» состоялось в 1884. Три года спустя, «шпоры» сыграли своё первое северо-лондонское дерби против «Арсенала», но матч был прерван уже через пятнадцать минут из-за якобы наступившей темноты. К тому моменту «Тоттенхэм» обыгрывал своего соперника со счётом 2:1.

Профессиональный статус клуб получил в 1885 году, но не мог пробиться в профессиональную футбольную лигу до 1908 года. При этом «шпоры» умудрились стать первой (и пока последней) любительской командой, которой удалось завоевать Кубок Англии в 1901 году.

«Тоттенхэм» начали воспринимать в качестве большого клуба в 1958 году, когда команду возглавил Билл Никольсон. Первый же матч под началом этого специалиста «шпоры» выиграли со счётом 10:4. А за 16 лет работы в клубе Никольсон выиграл восемь серьёзных трофеев, включая золотой дубль (победу в чемпионате и Кубке Англии) в 1961 году и успех 1963 года, когда «Тоттенхэму» удалось стать первой британской командой, завоевавшей европейский трофей, которым стал Кубок Обладателей Кубков.

В дальнейшем чемпионство ускользало от «шпор», а после ухода Никольсона команда и вовсе умудрилась вылететь во второй дивизион, где провела один год в сезоне 1977/78. В целом «Тоттенхэм» всегда был остроатакующей командой, порой потрясающей зрителей своим футболом. Среди ярчайших футболистов «шпор» нужно выделить Оссье Ардилеса, Гленна Ходдла, Пола Гаскойна и Гари Линекера.

С момента образования премьер-лиги «Тоттенхэм» является стабильным её участником, сыграв немалую роль в подъеме уровня чемпионата. С игроками вроде Юргена Клинсманна и Илие Димитреску «шпоры» забивали множество голов, однако очки при этом команде доставались с огромным трудом. Лишь в 1998 году лондонцы были близки к вылету из элиты, а болельщики смогли вздохнуть с облегчением, когда команду возглавил легенда злейшего соперника «Арсенала» – Джордж Грэм.

Он быстро завоевал доверие фанатов, сумев выиграть Кубок Лиги в первом же сезоне. Причём трофей стал первым для «шпор» с момента образования премьер-лиги. Но только Мартин Йол, взявший борозды правления в 2004-м, начал строительство команды на длительное время. Голландский специалист сделал ставку на молодёжь, и «шпоры» начали поступательное движение наверх. Два года подряд в сезонах 2005/06 и 2006/07 «Тоттенхэм» был близок к попаданию в Лигу чемпионов, но оба раза финишировал пятым.

Неудачный старт в сезоне 2007/08 спровоцировал уход Йола, а его сменщик Хуанде Рамос сумел повторить достижение Грэма, также сходу выиграв Кубок Лиги. Правда по итогам сезона клуб занял только одиннадцатое место, а вскоре полетела и голова Рамоса. Занявший его место Харри Реднапп за полтора годы работы сумел вывести «Тоттенхэм» в Лигу чемпионов, что случилось впервые в его истории.

Дебют в Лиге чемпионов оказался для «шпор» более чем удачным. Команда пробилась в 1/4 финала, где, правда, ничего не смогла противопоставить грозному мадридскому «Реалу». «Тоттенхэм» должен был играть в ЛЧ и в следующем сезоне, но из-за победы «Челси» «шпоры» остались лишь с Лигой Европы. Перед стартом нового сезона команду возглавил Андре Виллаш-Боаш. Команда топталась на месте, не сумев сделать шаг вперед.

Летом 2013 года «Тоттенхэм» продал «Реалу» своего лидера Гарета Бэйла за невероятные сто миллионов евро. На эти деньги «шпоры» купили целый ряд футболистов, но только Кристиана Эриксена можно было в полной мере назвать усилением. По итогам сезона Виллаш-Боаш был отправлен в отставку. Его сменщик Тим Шервуд надолго не задержался в клубе, и в мае 2014 года было объявлено о подписании контракта с Маурисио Почеттино, который весьма удачно тренировал «Саутгемптон».

Награды и достижения

Чемпион Англии (2): 1950/51, 1960/61

Серебряный призёр чемпионата Англии (4): 1921/22, 1951/52, 1956/57, 1962/63

Обладатель Кубка Англии (8): 1901, 1921, 1961, 1962, 1967, 1981, 1982, 1991

Обладатель Кубка английской лиги (4): 1971, 1973, 1999, 2008

Обладатель Суперкубка Англии (7): 1921, 1952, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1982, 1992

Победитель Кубка УЕФА (2): 1972, 1984

Победитель Кубка обладателей Кубков: 1963

Подробная информация о фамилии Тоттенхэм, а именно ее происхождение, история образования, суть фамилии, значение, перевод и склонение. Какая история происхождения фамилии Тоттенхэм? Откуда родом фамилия Тоттенхэм? Какой национальности человек с фамилией Тоттенхэм? Как правильно пишется фамилия Тоттенхэм? Верный перевод фамилии Тоттенхэм на английский язык и склонение по падежам. Полную характеристику фамилии Тоттенхэм и ее суть вы можете прочитать онлайн в этой статье совершенно бесплатно без регистрации.

Происхождение фамилии Тоттенхэм

Большинство фамилий, в том числе и фамилия Тоттенхэм, произошло от отчеств (по крестильному или мирскому имени одного из предков), прозвищ (по роду деятельности, месту происхождения или какой-то другой особенности предка) или других родовых имён.

История фамилии Тоттенхэм

В различных общественных слоях фамилии появились в разное время. История фамилии Тоттенхэм насчитывает несколько сотен лет. Первое упоминание фамилии Тоттенхэм встречается в XVIII—XIX веках, именно в это время на руси стали распространяться фамилии у служащих людей и у купечества. Поначалу только самое богатое — «именитое купечество» — удостаивалось чести получить фамилию Тоттенхэм. В это время начинают называться многочисленные боярские и дворянские роды. Именно на этот временной промежуток приходится появление знатных фамильных названий. Фамилия Тоттенхэм наследуется из поколения в поколение по мужской линии (или по женской).

Суть фамилии Тоттенхэм по буквам

Фамилия Тоттенхэм состоит из 9 букв. Фамилии из девяти букв – признак склонности к «экономии энергии» или, проще говоря – к лени. Таким людям больше всего подходит образ жизни кошки или кота. Чтобы «ни забот, ни хлопот», только возможность нежить свое тело, когда и сколько хочется, а так же наличие полной уверенности в том, что для удовлетворения насущных потребностей не придется делать «лишних движений». Проанализировав значение каждой буквы в фамилии Тоттенхэм можно понять ее суть и скрытое значение.

Значение фамилии Тоттенхэм

Фамилия является основным элементом, связывающим человека со вселенной и окружающим миром. Она определяет его судьбу, основные черты характера и наиболее значимые события. Внутри фамилии Тоттенхэм скрывается опыт, накопленный предыдущими поколениями и предками. По нумерологии фамилии Тоттенхэм можно определить жизненный путь рода, семейное благополучие, достоинства, недостатки и характер носителя фамилии. Число фамилии Тоттенхэм в нумерологии — 3. Люди с фамилией Тоттенхэм — творческие натуры, увлеченные собственными идеями. Они стремятся развивать свой внутренний мир, и нацелены на успешное завершение начатого дела. Обладатели фамилии Тоттенхэм не терпят разгильдяйства и строго придерживаются установленных сроков. Они великолепно владеют разговорной речью и обладают талантом увещевания. Как правило, таким личностям не страшны небольшие трудности: они успешно преодолевают их без особых усилий.

С масштабными проблемами дела обстоят хуже, а потому носители фамилии Тоттенхэм активно пользуются помощью ближайших соратников. Они умело адаптируются в новом коллективе и легко заводят полезные знакомства. Это люди с оптимистическими взглядами на жизнь: в каждой ситуации они находят позитивную сторону и извлекают нужные уроки. С ними приятно работать: все возложенные обязанности будут выполнены в соответствии с запланированными сроками.

На жизненном человека с фамилией Тоттенхэм встретится немалое количество проблем. Судьба не слишком благосклонна к этим людям, а потому посылает массу испытаний. Носителям фамилии Тоттенхэм следует приготовиться к суровой борьбе, которая может привести как к успеху, так и поражению. Это прирожденные бойцы, способные совершать невероятные поступки. Там, где другие видят проблемы, обладатели фамилии Тоттенхэм находят новые возможности.

Построить семью с фамилией Тоттенхэм легко, преданные семьянины, влюбленные в свою половину и родных детей. Практически все, что делают носители фамилии Тоттенхэм – ради семьи. Они способны принести родному дому материальное благополучие и защиту от всевозможных проблем. Все, что они требуют взамен – спокойную атмосферу, уют и тепло домашнего очага. Носители фамилии Тоттенхэм не способны на измену и сохраняют верность выбранному человеку на протяжении всей своей жизни. Сторонние связи любимой половины простить не смогут, и будут помнить об этом событии все последующие годы.

Сильный характер позволяет носителям фамилии Тоттенхэм выбирать для себя сложные профессии. К ним относится бизнес, банковское дело и маркетинг. При хороших физических данных они могут добиться значительных успехов в профессиональном спорте.

Общительность, умение наладить контакт с новыми людьми, деловая активность и стремление к достижению поставленной цели. Также к достоинствам фамилии Тоттенхэм можно отнести честность и принципиальность. Такие люди не поддерживают смутные проекты и стараются заработать на жизнь честным путем. Они являются верными деловыми партнерами и не оставят своего напарника один на один с проблемой. Это прирожденные оптимисты, шагающие по жизни с высоко поднятой головой.

Как правильно пишется фамилия Тоттенхэм

В русском языке грамотным написанием этой фамилии является — Тоттенхэм. В английском языке фамилия Тоттенхэм может иметь следующий вариант написания — Tottenhem.

Склонение фамилии Тоттенхэм по падежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Фамилия |

| Именительный | Кто? | Тоттенхэм |

| Родительный | Нет Кого? | Тоттенхэм |

| Дательный | Рад Кому? | Тоттенхэм |

| Винительный | Вижу Кого? | Тоттенхэм |

| Творительный | Доволен Кем? | Тоттенхэм |

| Предложный | Думаю О ком? | Тоттенхэм |

Видео про фамилию Тоттенхэм

Вы согласны с описанием фамилии Тоттенхэм, ее происхождением, историей образования, значением и изложенной сутью? Какую информацию о фамилии Тоттенхэм вы еще знаете? С какими известными и успешными людьми с фамилией Тоттенхэм вы знакомы? Будем рады обсудить фамилию Тоттенхэм более подробно с посетителями нашего сайта в комментариях.

Если вы нашли ошибку в описании фамилии, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

«THFC» redirects here. For a different football club in London with the same initials, see Tower Hamlets F.C.

|

|||

| Full name | Tottenham Hotspur Football Club | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Lilywhites | ||

| Short name | Spurs | ||

| Founded | 5 September 1882; 140 years ago, as Hotspur F.C. | ||

| Ground | Tottenham Hotspur Stadium | ||

| Capacity | 62,850[1] | ||

| Owner | ENIC International Ltd. (85.55%) | ||

| Chairman | Daniel Levy | ||

| Head coach | Antonio Conte | ||

| League | Premier League | ||

| 2021–22 | Premier League, 4th of 20 | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

|||

Tottenham Hotspur Football Club, commonly referred to as Tottenham ()[2][3] or Spurs, is a professional football club based in Tottenham, London, England. It competes in the Premier League, the top flight of English football. The team has played its home matches in the 62,850-capacity Tottenham Hotspur Stadium since April 2019, replacing their former home of White Hart Lane, which had been demolished to make way for the new stadium on the same site.

Founded in 1882, Tottenham’s emblem is a cockerel standing upon a football, with the Latin motto Audere est Facere («to dare is to do»). The club has traditionally worn white shirts and navy blue shorts home kit since the 1898–99 season. Their training ground is on Hotspur Way in Bulls Cross, Enfield. After its inception, Tottenham won the FA Cup for the first time in 1901, the only non-League club to do so since the formation of the Football League in 1888. Tottenham were the first club in the 20th century to achieve the League and FA Cup Double, winning both competitions in the 1960–61 season. After successfully defending the FA Cup in 1962, in 1963 they became the first British club to win a UEFA club competition – the European Cup Winners’ Cup.[4] They were also the inaugural winners of the UEFA Cup in 1972, becoming the first British club to win two different major European trophies. They collected at least one major trophy in each of the six decades from the 1950s to 2000s, an achievement only matched by Manchester United.[5][6]

In domestic football, Spurs have won two league titles, eight FA Cups, four League Cups, and seven FA Community Shields. In European football, they have won one European Cup Winners’ Cup and two UEFA Cups. Tottenham were also runners-up in the 2018–19 UEFA Champions League. They have a long-standing rivalry with nearby club Arsenal, with whom they contest the North London derby. Tottenham is owned by ENIC Group, which purchased the club in 2001. The club was estimated to be worth £1.67 billion ($2.3 billion) in 2021, and it was the ninth highest-earning football club in the world, with an annual revenue of £390.9 million in 2020.[7][8]

History

Formation and early years (1882–1908)

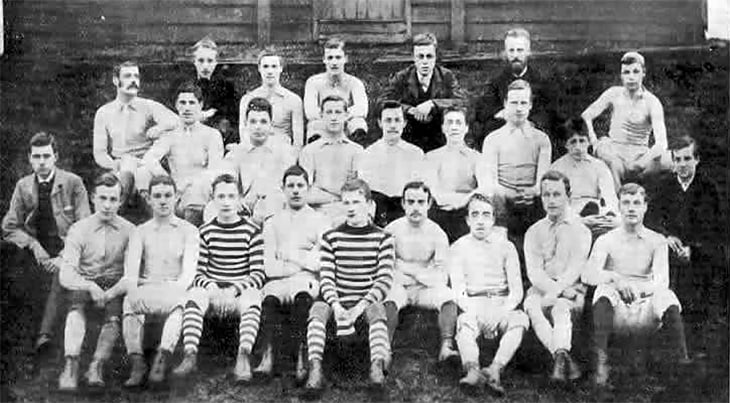

Spurs’ first and second teams in 1885. Club president John Ripsher top row second right, team captain Jack Jull middle row fourth left, Bobby Buckle bottom row second left.

Originally named Hotspur Football Club, the club was formed on 5 September 1882 by a group of schoolboys led by Bobby Buckle. They were members of the Hotspur Cricket Club and the football club was formed to play sports during the winter months.[9] A year later the boys sought help with the club from John Ripsher, the Bible class teacher at All Hallows Church, who became the first president of the club and its treasurer. Ripsher helped and supported the boys through the club’s formative years, reorganised and found premises for the club.[10][11][12] In April 1884 the club was renamed «Tottenham Hotspur Football Club» to avoid confusion with another London club named Hotspur, whose post had been mistakenly delivered to North London.[13][14] Nicknames for the club include «Spurs» and «the Lilywhites».[15]

Initially, the north London side played games between themselves and friendly matches against other local clubs. The first recorded match took place on 30 September 1882 against a local team named the Radicals, which Hotspur lost 2–0.[16] The team entered their first cup competition in the London Association Cup, and won 5–2 in their first competitive match on 17 October 1885 against a company’s works team called St Albans.[17] The club’s fixtures began to attract the interest of the local community and attendances at its home matches increased. In 1892, they played for the first time in a league, the short-lived Southern Alliance.[18]

The club turned professional on 20 December 1895 and, in the summer of 1896, was admitted to Division One of the Southern League (the third tier at the time). On 2 March 1898, the club also became a limited company, the Tottenham Hotspur Football and Athletic Company.[18] Soon after, Frank Brettell became the first ever manager of Spurs, and he signed John Cameron, who took over as player-manager when Brettell left a year later. Cameron would have a significant impact on Spurs, helping the club win its first trophy, the Southern League title in the 1899–1900 season.[19] The following year Spurs won the 1901 FA Cup by beating Sheffield United 3–1 in a replay of the final, after the first game ended in a 2–2 draw. In doing so they became the only non-League club to achieve the feat since the formation of The Football League in 1888.[20]

Early decades in the Football League (1908–1958)

In 1908, the club was elected into the Football League Second Division and won promotion to the First Division in their first season, finishing runners-up. In 1912, Peter McWilliam became manager; Tottenham finished bottom of the league at the end of the 1914–15 season when football was suspended due to the First World War. Spurs were relegated to the Second Division on the resumption of league football after the war, but quickly returned to the First Division as Second Division champions of the 1919–20 season.[21]

On 23 April 1921, McWilliam guided Spurs to their second FA Cup win, beating Wolverhampton Wanderers 1–0 in the Cup Final. Spurs finished second to Liverpool in the league in 1922, but would finish mid-table in the next five seasons. Spurs were relegated in the 1927–28 season after McWilliam left. For most of the 1930s and 40s, Spurs languished in the Second Division, apart from a brief return to the top flight in the 1933–34 and 1934–35 seasons.[22]

Former Spurs player Arthur Rowe became manager in 1949. Rowe developed a style of play, known as «push and run», that proved to be successful in his early years as manager. He took the team back to the First Division after finishing top of the Second Division in the 1949–50 season.[23] In his second season in charge, Tottenham won their first ever top-tier league championship title when they finished top of the First Division for the 1950–51 season.[24][25] Rowe resigned in April 1955 due to a stress-induced illness from managing the club.[26][27] Before he left, he signed one of Spurs’ most celebrated players, Danny Blanchflower, who won the FWA Footballer of the Year twice while at Tottenham.[28]

Bill Nicholson and the glory years (1958–1974)

Bill Nicholson took over as manager in October 1958. He became the club’s most successful manager, guiding the team to major trophy success three seasons in a row in the early 1960s: the Double in 1961, the FA Cup in 1962 and the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1963.[29] Nicholson signed Dave Mackay and John White in 1959, two influential players of the Double-winning team, and Jimmy Greaves in 1961, the most prolific goal-scorer in the history of the top tier of English football.[30][31]

The 1960–61 season started with a run of 11 wins, followed by a draw and another four wins, at that time the best ever start by any club in the top flight of English football.[32] The title was won on 17 April 1961 when they beat the eventual runner-up Sheffield Wednesday at home 2–1, with three more games still to play.[33] The Double was achieved when Spurs won 2–0 against Leicester City in the final of the 1960–61 FA Cup. It was the first Double of the 20th century, and the first since Aston Villa achieved the feat in 1897.[34] The next year Spurs won their consecutive FA Cup after beating Burnley in the 1962 FA Cup Final.[35]

On 15 May 1963, Tottenham became the first British team to win a European trophy by winning the 1962–63 European Cup Winners’ Cup when they beat Atlético Madrid 5–1 in the final.[36] Spurs also became the first British team to win two different European trophies when they won the 1971–72 UEFA Cup with a rebuilt team that included Martin Chivers, Pat Jennings, and Steve Perryman.[37] They had also won the FA Cup in 1967,[38] two League Cups (in 1971 and 1973), as well as a second place league finish (1962–63) and runners-up to the 1973–74 UEFA Cup. In total, Nicholson won eight major trophies in his 16 years at the club as manager.[29]

Burkinshaw to Venables (1974–1992)

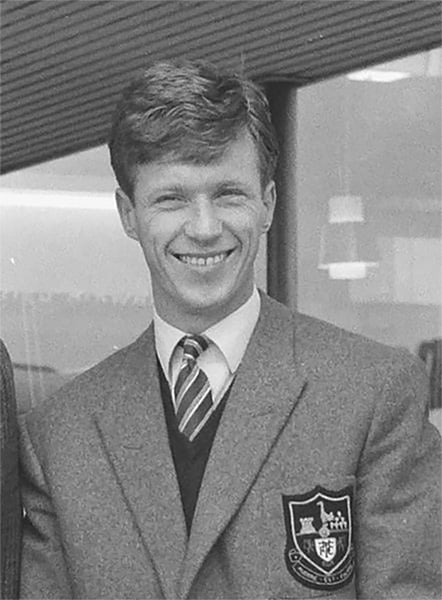

Spurs went into a period of decline after the successes of the early 1970s, and Nicholson resigned after a poor start to the 1974–75 season.[39] The team was then relegated at the end of the 1976–77 season with Keith Burkinshaw as manager. Burkinshaw quickly returned the club to the top flight, building a team that included Glenn Hoddle, as well as two Argentinians, Osvaldo Ardiles and Ricardo Villa, which was unusual as players from outside the British Isles were rare at that time.[40] The team that Burkinshaw rebuilt went on to win the FA Cup in 1981 and 1982[41] and the UEFA Cup in 1984.[42]

The 1980s was a period of change that began with a new phase of redevelopment at White Hart Lane, as well as a change of directors. Irving Scholar took over the club and moved it in a more commercial direction, the beginning of the transformation of English football clubs into commercial enterprises.[43][44] Debt at the club would again lead to a change in the boardroom, and Terry Venables teamed up with businessman Alan Sugar in June 1991 to take control of Tottenham Hotspur plc.[45][46][47] Venables, who had become manager in 1987, signed players such as Paul Gascoigne and Gary Lineker. Under Venables, Spurs won the 1990–91 FA Cup, making them the first club to win eight FA Cups.[48]

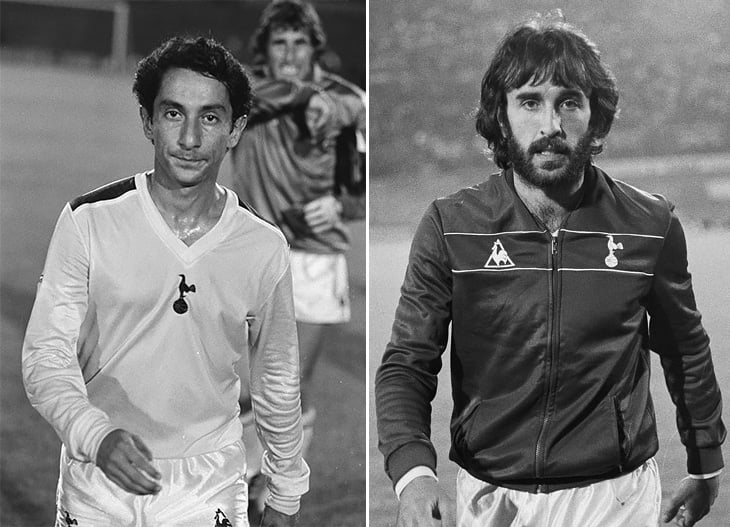

Premier League football (1992–present)

Tottenham was one of the five clubs that pushed for the founding of the Premier League, created with the approval of The Football Association, replacing the Football League First Division as the highest division of English football.[49] Despite a succession of managers and players such as Teddy Sheringham, Jürgen Klinsmann and David Ginola, for a long period in the Premier League until the late 2000s, Spurs finished mid-table most seasons with few trophies won. They won the League Cup in 1999 under George Graham, and again in 2008 under Juande Ramos. Performance improved under Harry Redknapp with players such as Gareth Bale and Luka Modrić, and the club finished in the top five in the early 2010s.[50][51]

In February 2001, Sugar sold his shareholding in Spurs to ENIC Sports plc, run by Joe Lewis and Daniel Levy, and stepped down as chairman.[52] Lewis and Levy would eventually own 85% of the club, with Levy responsible for the running of the club.[53][54] They appointed Mauricio Pochettino as head coach, who was in the role between 2014 and 2019.[55] Under Pochettino, Spurs finished second in the 2016–17 season, their highest league finish since the 1962–63 season, and advanced to the UEFA Champions League final in 2019, the club’s first UEFA Champions League final, ultimately losing the final to eventual champions Liverpool 2–0.[56][57][58] Pochettino was subsequently sacked after a poor start to the 2019–20 season, in November 2019, and was replaced by José Mourinho.[59] Mourinho’s tenure, however, lasted only 17 months; he was sacked in April 2021 to be replaced by interim head coach Ryan Mason for the remainder of the 2020–21 season.[60][61] Nuno Espírito Santo was appointed the new manager for 2021–22 season on 30 June 2021[62] but was sacked after just 4 months in charge,[63] and replaced by Antonio Conte.[64] During the 21-22 season, Conte guided Spurs to fourth, back to a Champions League place for the first time in two seasons.[65]

Stadiums

Early grounds

Spurs played their early matches on public land at the Park Lane end of Tottenham Marshes, where they had to mark out and prepare their own pitch.[9] Occasionally fights broke out on the marshes in disputes with other teams over the use of the ground.[66] The first Spurs game reported by the local press took place on Tottenham Marshes on 6 October 1883 against Brownlow Rovers, which Spurs won 9–0.[67] It was at this ground that, in 1887, Spurs first played the team that would later become their arch rivals, Arsenal (then known as Royal Arsenal), leading 2–1 until the match was called off due to poor light after the away team arrived late.[68]

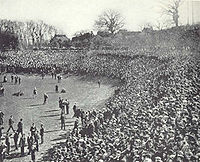

Northumberland Park, 28 January 1899, Spurs vs Newton Heath (later renamed Manchester United)

As they played on public parkland, the club could not charge admission fees and, while the number of spectators grew to a few thousand, it yielded no gate receipts. In 1888, the club rented a pitch between numbers 69 and 75 Northumberland Park[69] at a cost of £17 per annum, where spectators were charged 3d a game, raised to 6d for cup ties.[70] The first game at the Park was played on 13 October 1888, a reserve match that yielded gate receipts of 17 shillings. The first stand with just over 100 seats and changing rooms underneath was built at the ground for the 1894–95 season at a cost of £60. However, the stand was blown down a few weeks later and had to be repaired.[71] In April 1898, 14,000 fans turned up to watch Spurs play Woolwich Arsenal. Spectators climbed on the roof of the refreshment stand for a better view of the match. The stand collapsed, causing a few injuries. As Northumberland Park could no longer cope with the larger crowds, Spurs were forced to look for a larger ground and moved to the White Hart Lane site in 1899.[72]

White Hart Lane

First game at White Hart Lane, Spurs vs Notts County for the official opening on 4 September 1899

The White Hart Lane ground was built on an unused plant nursery owned by the Charrington Brewery and located behind a public house named the White Hart on Tottenham High Road (the road White Hart Lane actually lies a few hundred yards north of the main entrance). The ground was initially leased from Charringtons, and the stands they used at Northumberland Park were moved here, giving shelter for 2,500 spectators.[73] Notts County were the first visitors to ‘the Lane’ in a friendly watched by 5,000 people and yielding £115 in receipts; Spurs won 4–1.[74] Queens Park Rangers became the first competitive visitors to the ground and 11,000 people saw them lose 1–0 to Tottenham. In 1905, Tottenham raised enough money to buy the freehold to the land, as well as land at the northern (Paxton Road) end.[73]

Since 1909, Tottenham have displayed the statue of a cockerel, first made in bronze by a former player.

After Spurs were admitted to the Football League, the club started to build a new stadium, with stands designed by Archibald Leitch being constructed over the next two and a half decades. The West Stand was added in 1909, the East Stand was also covered this year and extended further two years later. The profits from the 1921 FA Cup win were used to build a covered terrace at the Paxton Road end and the Park Lane end was built at a cost of over £3,000 some two years later. This increased the stadium’s capacity to around 58,000, with room for 40,000 under cover. The East Stand (Worcester Avenue) was finished in 1934 and this increased capacity to around 80,000 spectators and cost £60,000.[73]

Aerial image of White Hart Lane. Redevelopment of this stadium began in early 1980s and completed in the late 1990s.

Starting in the early 1980s, the stadium underwent another major phase of redevelopment. The West Stand was replaced by an expensive new structure in 1982, and the East Stand was renovated in 1988. In 1992, following the Taylor Report’s recommendation that Premier League clubs eliminate standing areas, the lower terraces of the south and east stand were converted to seating, with the North Stand becoming all-seater the following season. The South Stand redevelopment was completed in March 1995 and included the first giant Sony Jumbotron TV screen for live game coverage and away match screenings.[75] In the 1997–98 season the Paxton Road stand received a new upper tier and a second Jumbotron screen.[75] Minor amendments to the seating configuration were made in 2006, bringing the capacity of the stadium to 36,310.[73]

By the turn of the millennium, the capacity of White Hart Lane had become lower than other major Premier League clubs. Talks began over the future of the ground with a number of schemes considered, such as increasing the stadium capacity through redevelopment of the current site, or using of the 2012 London Olympic Stadium in Stratford.[76][77] Eventually the club settled on the Northumberland Development Project, whereby a new stadium would be built on a larger piece of land that incorporated the existing site. In 2016, the northeast corner of the stadium was removed to facilitate the construction of the new stadium. As this reduced the stadium capacity below that required for European games, Tottenham Hotspur played every European home game in 2016–17 at Wembley Stadium.[78] Domestic fixtures of the 2016–17 season continued to be played at the Lane, but demolition of the rest of the stadium started the day after the last game of the season,[79] and White Hart Lane was completely demolished by the end of July 2017.[80]

Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

In October 2008, the club announced a plan to build a new stadium immediately to the north of the existing White Hart Lane stadium, with the southern half of the new stadium’s pitch overlapping the northern part of the Lane.[81] This proposal would become the Northumberland Development Project. The club submitted a planning application in October 2009 but, following critical reactions to the plan, it was withdrawn in favour of a substantially revised planning application for the stadium and other associated developments. The new plan was resubmitted and approved by Haringey Council in September 2010,[82] and an agreement for the Northumberland Development Project was signed on 20 September 2011.[83]

After a long delay over the compulsory purchase order of local businesses located on land to the north of the stadium and a legal challenge against the order,[84][85] resolved in early 2015,[86] planning application for another new design was approved by Haringey Council on 17 December 2015.[87] Construction started in 2016,[88] and the new stadium was scheduled to open during the 2018–19 season.[89][90] While it was under construction, all Tottenham home games in the 2017–18 season as well as all but five in 2018–19 were played at Wembley Stadium.[91] After two successful test events, Tottenham Hotspur officially moved into the new ground on 3 April 2019[92] with a Premier League match against Crystal Palace which Spurs won 2–0.[93] The new stadium is called Tottenham Hotspur Stadium while a naming-rights agreement is reached.[94]

Training grounds

An early training ground used by Tottenham was located at Brookfield Lane in Cheshunt, Hertfordshire. The club bought the 11-acre ground used by Cheshunt F.C. in 1952 for £35,000.[95][96] It had three pitches, including a small stadium with a small stand used for matches by the junior team.[97] The ground was later sold for over 4 million,[98] and the club moved the training ground to the Spurs Lodge on Luxborough Lane, Chigwell in Essex, opened in September 1996 by Tony Blair.[99] The training ground and press centre in Chigwell were used until 2014.[100]

In 2007, Tottenham bought a site at Bulls Cross in Enfield, a few miles south of their former ground in Cheshunt. A new training ground was constructed at the site for £45 million, which opened in 2012.[101] The 77-acre site has 15 grass pitches and one-and-a-half artificial pitches, as well as a covered artificial pitch in the main building.[102][103] The main building on Hotspur Way also has hydrotherapy and swimming pools, gyms, medical facilities, dining and rest areas for players as well as classrooms for academy and schoolboy players. A 45-bedroom players lodge with catering, treatment, rest and rehabilitation facilities was later added at Myddleton Farm next to the training site in 2018.[104][105] The lodge is mainly used by Tottenham’s first team and Academy players, but it has also been used by national football teams – the first visitors to use the facilities at the site were the Brazilian team in preparation for the 2018 FIFA World Cup.[106]

Crest

Between 1956 and 2006, the club crest featured a heraldic shield, displaying a number of local landmarks and associations.

This crest is from the 2017–18 season which is when the club reintroduced the shield. This was also of similar design of what was introduced in the 1950s before the change to the 1956 shield.

Since the 1921 FA Cup Final the Tottenham Hotspur crest has featured a cockerel. Harry Hotspur, after whom the club is named, was said to have been given the nickname Hotspur as he dug in his spurs to make his horse go faster as he charged in battles,[107] and spurs are also associated with fighting cocks.[108] The club used spurs as a symbol in 1900, which then evolved into a fighting cock.[107] A former player named William James Scott made a bronze cast of a cockerel standing on a football at a cost of £35 (equivalent to £3,880 in 2021), and this 9-foot-6-inch (2.90 m) figure was then placed on top of the West Stand the end of the 1909–10 season.[107] Since then the cockerel and ball emblem has become a part of the club’s identity.[109] The club badge on the shirt used in 1921 featured a cockerel within a shield, but it was changed to a cockerel sitting on a ball in the late 1960s.[108]

Between 1956 and 2006 Spurs used a faux heraldic shield featuring a number of local landmarks and associations. The castle is Bruce Castle, 400 yards from the ground and the trees are the Seven Sisters. The arms featured the Latin motto Audere Est Facere (to dare is to do).[66]

In 1983, to overcome unauthorised «pirate» merchandising, the club’s badge was altered by adding the two red heraldic lions to flank the shield (which came from the arms of the Northumberland family, of which Harry Hotspur was a member), as well as the motto scroll. This device appeared on Spurs’ playing kits for three seasons 1996–99.

In 2006, in order to rebrand and modernise the club’s image, the club badge and coat of arms were replaced by a professionally designed logo/emblem.[110] This revamp displayed a sleeker and more elegant cockerel standing on an old-time football. The club claimed that they dropped their club name and would be using the rebranded logo only on playing kits.[111] In November 2013, Tottenham forced non-league club Fleet Spurs to change their badge because its new design was «too similar» to the Tottenham crest.[112]

In 2017, Spurs added a shield around the cockerel logo on the shirts similar to the 1950s badge, but with the cockerel of modern design.[113] The shield was however removed the following season.

Kit

The first Tottenham kit recorded in 1883 included a navy blue shirt with a letter H on a scarlet shield on the left breast, and white breeches.[114] In 1884 or 1885, the club changed to a «quartered» kit similar to Blackburn Rovers after watching them win in the 1884 FA Cup Final.[115] After they moved to Northumberland Park in 1888, they returned to the navy blue shirts for the 1889–90 season. Their kit changed again to red shirt and blue shorts in 1890, and for a time the team were known as ‘the Tottenham Reds’.[116] Five years later in 1895, the year they became a professional club, they switched to a chocolate and gold striped kit.[66]

In the 1898–99 season, their final year at Northumberland Park, the club switched colours to white shirts and blue shorts, same colour choice as that for Preston North End.[117] White and navy blue have remained as the club’s basic colours ever since, with the white shirts giving the team the nickname «The Lilywhites».[118] In 1921, the year they won the FA Cup, the cockerel badge was added to the shirt for the final. A club crest has featured on the shirt since, and Spurs became the first major club to have its club crest on the players shirt on every match apart from the war years.[119] In 1939 numbers first appeared on shirt backs.[66]

In the early days, the team played in kits sold by local outfitters. An early supplier of Spurs’ jerseys recorded was a firm on Seven Sisters Road, HR Brookes.[70] In the 1920s, Bukta produced the jerseys for the club. From the mid-1930s onwards, Umbro was the supplier for forty years. In 1959, the V-neck shirt replaced the collared shirts of the past, and then in 1963, the crew neck shirt appeared (the style has fluctuated since).[120] In 1961, Bill Nicholson sent Spurs players out to play in white instead of navy shorts for their European campaign, starting a tradition which continues to this day in European competitions.[121]

In 1977, a deal was signed with Admiral to supply the team their kits. Although Umbro kits in generic colours had been sold to football fans since 1959, it was with the Admiral deal that the market for replica shirts started to take off.[122] Admiral changed the plain colours of earlier strips to shirts with more elaborate designs, which included manufacturer’s logos, stripes down the arms and trims on the edges.[122] Admiral was replaced by Le Coq Sportif in the summer of 1980.[123] In 1985, Spurs entered into a business partnership with Hummel, who then supplied the strips.[124] However, the attempt by Tottenham to expand the business side of the club failed, and in 1991, they returned to Umbro.[125] In 1991, the club was the first to wear long-cut shorts, an innovation at a time when football kits all featured shorts cut well above the knee.[66] Umbro was followed by Pony in 1995, Adidas in 1999, Kappa in 2002,[66][126] and a five-year deal with Puma in 2006.[127] In March 2011, Under Armour announced a five-year deal to supply Spurs with shirts and other apparel from the start of 2012–13,[128][129] with the home, away and the third kits revealed in July and August 2012.[130][131] The shirts incorporate technology that can monitor the players’ heart rate and temperature and send the biometric data to the coaching staff.[132] In June 2017, it was announced that Nike would be their new kits supplier, with the 2017–18 kit released on 30 June, featuring the Spurs’ crest encased in a shield, paying homage to Spurs’ 1960–61 season, where they became the first post-war-club to win both the Football League First Division and the FA Cup.[133] In October 2018, Nike agreed a 15-year deal reportedly worth £30 million a year with the club to supply their kits until 2033.[134]

Shirt sponsorship in English football was first adopted by the non-league club Kettering Town F.C. in 1976 despite it being banned by the FA.[135] FA soon lifted the ban, and this practice spread to the major clubs when sponsored shirts were allowed on non-televised games in 1979, and then on televised games as well in 1983.[132][136] In December 1983, after the club was floated on the London Stock Exchange, Holsten became the first commercial sponsor logo to appear on a Spurs shirt.[137] When Thomson was chosen as kit sponsor in 2002 some Tottenham fans were unhappy as the shirt-front logo was red, the colour of their closest rivals, Arsenal.[138] In 2006, Tottenham secured a £34 million sponsorship deal with internet casino group Mansion.com.[139] In July 2010, Spurs announced a two-year shirt sponsorship contract with software infrastructure company Autonomy said to be worth £20 million.[140] A month later they unveiled a £5 million deal with leading specialist bank and asset management firm Investec as shirt sponsor for the Champions League and domestic cup competitions for the next two years.[141][142] Since 2014, AIA has been the main shirt sponsor, initially in a deal worth over £16 million annually,[143][144] increased to a reported £40 to £45 million per year in 2019 in an eight-year deal that lasts until 2027.[145][146]

|

1883–84: First kit |

1884–86 |

1889–90 |

1890–96 |

1896–98 |

Kit suppliers and shirt sponsors

| Period | Kit manufacturer[66] | Shirt sponsor (chest)[66] | Shirt sponsor (sleeve) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1907–11 | HR Brookes | None | None |

| 1921–30 | Bukta | ||

| 1935–77 | Umbro | ||

| 1977–80 | Admiral | ||

| 1980–83 | Le Coq Sportif | ||

| 1983–85 | Holsten | ||

| 1985–91 | Hummel | ||

| 1991–95 | Umbro | ||

| 1995–99 | Pony | Hewlett-Packard | |

| 1999–2002 | Adidas | Holsten | |

| 2002–06 | Kappa | Thomson Holidays | |

| 2006–10 | Puma | Mansion.com Casino & Poker | |

| 2010–11 | Autonomy Corporation1[147] | ||

| 2011–12 | Aurasma12[66] | ||

| 2012–13 | Under Armour | ||

| 2013–14 | HP3[148] | ||

| 2014–17 | AIA[143] | ||

| 2017–2021 | Nike[149] | ||

| 2021–present | Cinch[150] |

1 Only appeared in the Premier League. Investec Bank appeared in the Champions League, FA Cup, League Cup and Europa League.[142][151]

2 Aurasma is a subsidiary of the Autonomy Corporation.

3 Hewlett-Packard is the parent company of the Autonomy Corporation and only appeared in the Premier League. AIA appeared in the FA Cup, League Cup and Europa League.[152]

Ownership

Tottenham Hotspur F.C. became a limited company, the Tottenham Hotspur Football and Athletic Company Ltd, on 2 March 1898 so as to raise funds for the club and limit the personal liability of its members. 8,000 shares were issued at £1 each, although only 1,558 shares were taken up in the first year.[153] 4,892 shares were sold in total by 1905.[154] A few families held significant shares; they included the Wale family, who had association with the club since the 1930s,[155] as well as the Richardson and the Bearman families. From 1943 to 1984, members of these families were chairmen of Tottenham Hotspur F.C. after Charles Robert who had been chairman since 1898 died.[156]

In the early 1980s, cost overruns in the construction of a new West Stand together with the cost of rebuilding the team in previous years led to accumulating debts. In November 1982, a fan of the club Irving Scholar bought 25% of Tottenham for £600,000, and together with Paul Bobroff gained control of the club.[47] In order to bring in funds, Scholar floated Tottenham Hotspur plc, which wholly owns the football club, on the London Stock Exchange in 1983, the first European sports club to be listed in a stock market, and became the first sports company to go public.[43][154] Fans and institutions alike can now freely buy and trade shares in the company; a court ruling in 1935 involving the club (Berry and Stewart v Tottenham Hotspur FC Ltd) had previously established a precedent in company law that the directors of a company can refuse the transfer of shares from a shareholder to another person.[157] The share issue was successful with 3.8 million shares quickly sold.[158] However, ill-judged business decisions under Scholar led to financial difficulties,[153] and in June 1991 Terry Venables teamed up with businessman Alan Sugar to buy the club, initially as equal partner with each investing £3.25 million. Sugar increased his stake to £8 million by December 1991 and became the dominant partner with effective control of the club. In May 1993, Venables was sacked from the board after a dispute.[159] By 2000, Sugar began to consider selling the club,[160] and in February 2001, he sold the major part of his shareholding to ENIC International Ltd.[161]

The majority shareholder, ENIC International Ltd, is an investment company established by the British billionaire Joe Lewis. Daniel Levy, Lewis’s partner at ENIC, is Executive Chairman of the club. They first acquired 29.9% share of the club in 1991, of which 27% was bought from Sugar for £22 million.[161] Shareholding by ENIC increased over the decade through the purchase of the remaining 12% holding of Alan Sugar in 2007 for £25m,[162][163] and the 9.9% stake belonging to Stelios Haji-Ioannou through Hodram Inc. in 2009. On 21 August 2009 the club reported that they had issued a further 30 million shares to fund the initial development costs of the new stadium project, and that 27.8 million of these new shares had been purchased by ENIC.[164] The Annual Report for 2010 indicated that ENIC had acquired 76% of all Ordinary Shares and also held 97% of all convertible redeemable preference shares, equivalent to a holding of 85% of share capital.[165] The remaining shares are held by over 30,000 individuals.[166] Between 2001 and 2011 shares in Tottenham Hotspur F.C. were listed on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM index). Following an announcement at the 2011 AGM, in January 2012 Tottenham Hotspur confirmed that the club had delisted its shares from the stock market, taking it into private ownership.[167]

Support

Tottenham has a large fan base in the United Kingdom, drawn largely from North London and the Home counties. The attendance figures for its home matches, however, have fluctuated over the years. Five times between 1950 and 1962, Tottenham had the highest average attendance in England.[168][169] Tottenham was 9th in average attendances for the 2008–09 Premier League season, and 11th for all Premier League seasons.[170] In the 2017–18 season when Tottenham used Wembley as its home ground, it had the second highest attendance in the Premier League.[171][172] It also holds the record for attendance in the Premier League, with 83,222 attending the North London derby on 10 February 2018.[173] Historical supporters of the club have included such figures as philosopher A.J. Ayer.[174][175] There are many official supporters’ clubs located around the world,[176] while an independent supporters club, the Tottenham Hotspur Supporters’ Trust, is officially recognised by the club as the representative body for Spurs supporters.[177][178]

Historically, the club had a significant Jewish following from the Jewish communities in east and north London, with around a third of its supporters estimated to be Jewish in the 1930s.[179] Due to this early support, all three chairmen of the club since 1984 have been Jewish businessmen with prior history of supporting the club.[179] The club no longer has a greater Jewish contingent among its fans than other major London clubs (Jewish supporters are estimated to form at most 5% of its fanbase), though it is nevertheless still identified as a Jewish club by rival fans.[180] Antisemitic chants directed at the club and its supporters by rival fans have been heard since the 1960s, with words such as «Yids» or «Yiddos» used against Tottenham supporters.[179][181][182] In response to the abusive chants, Tottenham supporters, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, began to chant back the insults and adopt the «Yids» or «Yid Army» identity starting from around the late 1970s or early 1980s.[183] Some fans view adopting «Yid» as a badge of pride, helping defuse its power as an insult.[184] The use of «Yid» as a self-identification, however, has been controversial; some argued that the word is offensive and its use by Spurs fans «legitimis[es] references to Jews in football»,[185] and that such racist abuse should be stamped out in football.[186] Both the World Jewish Congress and the Board of Deputies of British Jews have denounced the use of the word by fans.[187] Others, such as former Prime Minister David Cameron, argued that its use by the Spurs fans is not motivated by hate as it is not used pejoratively, and therefore cannot be considered hate speech.[188] Attempts to prosecute Tottenham fans who chanted the words have failed, as the Crown Prosecution Service considered that the words as used by Tottenham fans could not be judged legally «threatening, abusive or insulting».[189]

Fan culture

There are a number of songs associated with the club and frequently sung by Spurs fans, such as «Glory Glory Tottenham Hotspur». The song originated in 1961 after Spurs completed the Double in 1960–61, and the club entered the European Cup for the first time. Their first opponents were Górnik Zabrze, the Polish champions, and after a hard-fought match Spurs suffered a 4–2 reverse. Tottenham’s tough tackling prompted the Polish press to write that «they were no angels». These comments incensed a group of three fans and for the return match at White Hart Lane they dressed as angels wearing white sheets fashioned into togas, sandals, false beards and carrying placards bearing biblical-type slogans. The angels were allowed on the perimeter of the pitch and their fervour whipped up the home fans who responded with a rendition of «Glory Glory Hallelujah», which is still sung on terraces at White Hart Lane and other football grounds.[190] The Lilywhites also responded to the atmosphere to win the tie 8–1. Then manager of Spurs, Bill Nicholson, wrote in his autobiography:

A new sound was heard in English football in the 1961–62 season. It was the hymn Glory, Glory Hallelujah being sung by 60,000 fans at White Hart Lane in our European Cup matches. I don’t know how it started or who started it, but it took over the ground like a religious feeling.

— Bill Nicholson[191]

There had been a number of incidents of hooliganism involving Spurs fans, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s. Significant events include the rioting by Spurs fans in Rotterdam at the 1974 UEFA Cup Final against Feyenoord, and again during the 1983–84 UEFA Cup matches against Feyenoord in Rotterdam and Anderlecht in Brussels.[192] Although fan violence has since abated, the occasional incidence of hooliganism continues to be reported.[193][194]

Rivalries

Tottenham supporters have rivalries with several clubs, mainly within the London area. The fiercest of these is with north London rivals Arsenal. The rivalry began in 1913 when Arsenal moved from the Manor Ground, Plumstead to Arsenal Stadium, Highbury, and this rivalry intensified in 1919 when Arsenal were unexpectedly promoted to the First Division, taking a place that Tottenham believed should have been theirs.[195]

Tottenham also share notable rivalries with fellow London clubs Chelsea and West Ham United.[196] The rivalry with Chelsea is secondary in importance to the one with Arsenal[196] and began when Tottenham beat Chelsea in the 1967 FA Cup Final, the first ever all-London final.[197] West Ham fans view Tottenham as a bitter rival, although the animosity is not reciprocated to the same extent by Tottenham fans.[198]

The club through its Community Programme has, since 2006, been working with Haringey Council and the Metropolitan Housing Trust and the local community on developing sports facilities and social programmes which have also been financially supported by Barclays Spaces for Sport and the Football Foundation.[199][200] The Tottenham Hotspur Foundation received high-level political support from the prime minister when it was launched at 10 Downing Street in February 2007.[201]

In March 2007 the club announced a partnership with the charity SOS Children’s Villages UK.[202] Player fines will go towards this charity’s children’s village in Rustenburg, South Africa with the funds being used to cover the running costs as well as in support of a variety of community development projects in and around Rustenburg. In the financial year 2006–07, Tottenham topped a league of Premier League charitable donations when viewed both in overall terms[203] and as a percentage of turnover by giving £4,545,889, including a one-off contribution of £4.5 million over four years, to set up the Tottenham Hotspur Foundation.[204] This compared to donations of £9,763 in 2005–06.[205]

The football club is one of the highest profile participants in the 10:10 project which encourages individuals, businesses and organisations to take action on environmental issues. They joined in 2009 in a commitment to reducing their carbon footprint. To do this they upgraded their lights to more efficient models, they turned down their heating dials and took less short-haul flights among a host of other things.[206] After working with 10:10 for one year, they reported that they had reduced their carbon emissions by 14%.[206]

In contrast, they have successfully sought the reduction of section 106 planning obligations connected to the redevelopment of the stadium in the Northumberland Development Project. Initially the development would incorporate 50% affordable housing, but this requirement was later waived, and a payment of £16m for community infrastructure was reduced to £0.5m.[207] This is controversial in an area which has suffered high levels of deprivation as Spurs had bought up properties for redevelopment, removing existing jobs and businesses for property development but not creating enough new jobs for the area.[208] The club however argued that the project, when completed, would support 3,500 jobs and inject an estimated £293 million into the local economy annually,[209] and that it would serve as the catalyst for a wider 20-year regeneration programme for the Tottenham area.[210][211] In other developments in North Tottenham, the club has built 256 affordable homes and a 400-pupil primary school.[212][213]

Tottenham Hotspur Women

Tottenham’s women’s team was founded in 1985 as Broxbourne Ladies. They started using the Tottenham Hotspur name for the 1991–92 season and played in the London and South East Women’s Regional Football League (then fourth tier of the game). They won promotion after topping the league in 2007–08. In the 2016–17 season they won the FA Women’s Premier League Southern Division and a subsequent playoff, gaining promotion to the FA Women’s Super League 2.[214]

On 1 May 2019 Tottenham Hotspur Ladies won promotion to the FA Women’s Super League with a 1–1 draw at Aston Villa, which confirmed they would finish second in the Championship.[215] Tottenham Hotspur Ladies changed their name to Tottenham Hotspur Women in the 2019–20 season.[216]

Tottenham Hotspur Women announced the signing of Cho So-hyun on 29 January 2021. With her Korean men’s counterpart Son Heung-min already at the club it gave Spurs the rare distinction of having both the men’s and women’s Korean National Team captains at one club.[217]

Honours

Sources:Tottenham Hotspur – History[218]

Domestic

Leagues

- First Division / Premier League (Tier 1)[219]

- Winners (2): 1950–51, 1960–61

- Second Division / Championship (Tier 2)[219]

- Winners (2): 1919–20, 1949–50

Cups

- FA Cup

- Winners (8): 1900–01, 1920–21, 1960–61, 1961–62, 1966–67, 1980–81, 1981–82, 1990–91

- League Cup / EFL Cup

- Winners (4): 1970–71, 1972–73, 1998–99, 2007–08

- FA Charity Shield / FA Community Shield

- Winners (7): 1921, 1951, 1961, 1962, 1967, 1981, 1991

- Sheriff of London Charity Shield

- Winners (1): 1902

European

- UEFA Cup Winners’ Cup

- Winners (1): 1962–63

- UEFA Cup / UEFA Europa League

- Winners (2): 1971–72, 1983–84

Statistics and records

Chart of Tottenham’s performance since joining the Football League in 1908

Steve Perryman holds the appearance record for Spurs, having played 854 games for the club between 1969 and 1986, of which 655 were league matches.[220][221] Jimmy Greaves holds the club goal scoring record with 268 goals scored.

Tottenham’s record league win is 9–0 against Bristol Rovers in the Second Division on 22 October 1977.[222][223] The club’s record cup victory came on 3 February 1960 with a 13–2 win over Crewe Alexandra in the FA Cup.[224] Spurs’ biggest top-flight victory came against Wigan Athletic on 22 November 2009, when they won 9–1 with Jermain Defoe scoring five goals.[223][225] The club’s record defeat is an 8–0 loss to 1. FC Köln in the Intertoto Cup on 22 July 1995.[226]

The record home attendance at White Hart Lane was 75,038 on 5 March 1938 in a cup tie against Sunderland.[227] The highest recorded home attendances were at their temporary home, Wembley Stadium, due to its higher capacity – 85,512 spectators were present on 2 November 2016 for the 2016–17 UEFA Champions League game against Bayer Leverkusen,[228] while 83,222 attended the North London derby against Arsenal on 10 February 2018 which is the highest attendance recorded for any Premier League game.[229]

The club is ranked No. 18 by UEFA with a club coefficient of 79.0 points as of November 2022.[230]

Players

Current squad

- As of 31 January 2023[231]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Youth Academy

Management and support staff

| Role | Name[243][244] |

|---|---|

| Manager | |

| Assistant head coach | |

| First-team coach | |

| Fitness coach | |

| Fitness coach | |

| Analytics coach | |

| Set pieces coach | |

| Goalkeeping coach | |

| Club ambassadors |

|

| Academy manager | |

| Performance director | |

| Head of player development (U-17 to U-23) | |

| Head scout | |

| Assistant head scout | |

| Senior scout | |

| European scout | |

| Head of medicine and sports science | |

| Head physiotherapist | |

| Nutritionist | |

| Head of kit and equipment |

Directors

| Role | Name[251][252] |

|---|---|

| Executive chairman | Daniel Levy |

| Operations and finance director | Matthew Collecott |

| Executive director | Donna-Maria Cullen |

| Chief commercial officer | Todd Kline[253] |

| Director of football administration and governance | Rebecca Caplehorn |

| Managing director of football | Fabio Paratici[254] |

| Non-executive director | Jonathan Turner |

Managers and players

Managers and head coaches in club’s history

-

- Listed according to when they became managers for Tottenham Hotspur:[156]

-

- (C) – Caretaker

- (I) – Interim

- (FTC) – First team coach

Club hall of fame

The following players are noted as «greats» for their contributions to the club or have been inducted into the club’s Hall of Fame:[255][256][257] The most recent additions to the club’s Hall of Fame are Steve Perryman and Jimmy Greaves on 20 April 2016.[258]

Player of the Year

- As voted by members and season ticket holders (calendar year until 2005–06 season)[259]

Affiliated clubs

References

- ^ «Local: Information for local residents and businesses». Tottenham Hotspur F.C. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180, retrieved 30 June 2018

- ^ Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521152532, retrieved 30 June 2018

- ^ «Tottenham legend Nicholson dies». BBC Sport. 23 October 2004. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Delaney, Miguel (11 March 2017). «Christian Eriksen says Tottenham are determined to end their nine-year silverware drought». The Independent. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ «Manchester United football club honours». 11v11.com. AFS Enterprises. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ «The Business of Soccer — Full List». Forbes. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ «Deloitte Football Money League 2021». Deloitte. 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b Cloake & Fisher 2016, Chapter 1: A crowd walked across the muddy fields to watch the Hotspur play.

- ^ The Tottenham & Edmonton Herald 1921, p. 5.

- ^ «John Ripsher». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 24 September 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Spencer, Nicholas (24 September 2007). «Why Tottenham Hotspur owe it all to a pauper». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «History: Year by year». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur Club History & Football Trophies». Aford Awards. 17 July 2015. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Nilsson, Leonard Jägerskiöld (2018). World Football Club Crests: The Design, Meaning and Symbolism of World Football’s Most Famous Club Badges. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4729-5424-4.

- ^ «Potted History». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 8 November 2004. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur – Complete History». TOPSPURS.COM. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b Welch 2015, Chapter 3: Moneyball.

- ^ The Tottenham & Edmonton Herald 1921, p. 28.

- ^ Holmes, Logan (27 April 2013). «Tottenham Won Their First FA Cup Final on 27th April 1901». Spurs HQ. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Peter McWilliam: The Tottenham Boss Who Created Legends». A Halftime Report. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Welch 2015, Chapter 8: Spurs Shot Themselves in the Foot.

- ^ Drury, Reg (11 November 1993). «Obituary: Arthur Rowe». The Independent. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Scott Murray (21 January 2011). «The Joy of Six: Newly promoted success stories». The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Karel Stokkermans (17 June 2018). «English Energy and Nordic Nonsense». RSSSF. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Welch 2015, Chapter 11: One of the Good Guys.

- ^ Harris, Tim (10 November 2009). «Arthur Rowe». Players: 250 Men, Women and Animals Who Created Modern Sport. Vintage Digital. ISBN 9781409086918. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ «Danny Blanchflower – Captain, leader, All-Time Great». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 10 February 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b «The Bill Nicholson years – glory, glory – 1960–1974». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 25 October 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy (28 February 2017). «Special report: Jimmy Greaves pays tribute to Cristiano Ronaldo as Portuguese closes in on his magical mark». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Welch 2015, Chapter 12: Going Up, Up, Up.

- ^ Smith, Adam (14 December 2017). «Manchester City smash all-time Football League record with win at Swansea». Sky Sports. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Welch 2015, Chapter 13: What’s the Story, Eternal Glory?.

- ^ «1961 – Spurs’ double year». BBC Sport. 10 May 2001. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «The Cup Final 1962». British Pathé. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «It was 50 years ago today – our historic win in Europe…» Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Goodwin 1988, p. 48.

- ^ «Kinnear, Robertson, England and Mullery: 1967 FA Cup Heroes on Playing Chelsea at Wembley». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 19 April 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Goodwin 2003, pp. 150–154.

- ^ Viner, Brian (1 June 2006). «Ricky Villa: ‘I recognise I am a little part of English football history’«. The Independent. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Top 50 FA Cup goals: ‘And still Ricky Villa». BBC Sport. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Parry, Richard (22 October 2015). «Anderlecht vs Tottenham: Remembering Spurs’ 1984 Uefa Cup winners». London Evening Standard. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b «100 Owners: Number 81 – Irving Scholar (Tottenham Hotspur & Nottingham Forest)». Twohundredpercent. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (18 October 2013). The Association Game: A History of British Football. Routledge. p. 342. ISBN 9781317870081. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Football: Turbulent times at Tottenham Hotspur». The Independent. 14 June 1993. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Profile: Sir Alan Sugar». BBC. 31 July 2007. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b Horrie, Chris (31 July 1999). «They saw an open goal, and directors scored a million». The Independent. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «FA Cup winners list: Full record of finals and results from history». The Daily Telegraph. 27 May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Rodrigues, Jason (2 February 2012). «Premier League football at 20: 1992, the start of a whole new ball game». The Guardian. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy (5 May 2010). «Manchester City v Tottenham Hotspur: Harry Redknapp secures place in the history books». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Donovan 2017, pp. 160, 163.

- ^ Hughes, Simon (16 February 2001). «The crestfallen cockerels». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Ruthven, Hunter (22 April 2016). «Tottenham Hotspur share sales see football club valued at £426m». Real Business. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Bains, Raj (27 April 2017). «Daniel Levy has divided Tottenham fans, but now he’s overseeing something special at Spurs». FourFourTwo. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Mauricio Pochettino: Tottenham appoint Southampton boss». BBC. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Bysouth, Alex (21 May 2017). «Hull City 1–7 Tottenham Hotspur». BBC Sport. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Johnston, Neil (9 May 2019). «Ajax 2–3 Tottenham (3–3 on aggregate – Spurs win on away goals) Lucas Moura scores dramatic winner». BBC Sport. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ «Liverpool beat Spurs 2–0 to win Champions League final in Madrid». BBC Sport. 1 June 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur: José Mourinho named new manager of Spurs». The Guardian. 20 November 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ Percy, John; Wallace, Sam (19 April 2021). «Exclusive: Mourinho tenure comes to an end as chairman Daniel Levy takes drastic action over club’s disappointing second half to the season». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ McNulty, Phil (25 April 2021). «Manchester City 1-0 Tottenham Hotspur». BBC Sport. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Christenson, Marcus (30 June 2021). «Tottenham appoint Nuno Espírito Santo as manager on two-year deal». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ «Club Announcement». Tottenham Hotspur F.C. 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- ^ «Antonio Conte: Tottenham appoint former Chelsea boss as new manager». BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ «Norwich v Spurs, 2021/22 | Premier League». www.premierleague.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «Historical Kits – Tottenham Hotspur». historicalkits.co.uk. Historic Football Kits. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ The Tottenham & Edmonton Herald 1921, p. 6.

- ^ Holmes, Logan. «A Month in the Illustrious History of Spurs: November». topspurs.com. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ^ «Tottenham hotspur FC». Tottenham Hotspur. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ a b Cloake & Fisher 2016, Chapter 2: Enclosure Changed the Game Forever.

- ^ The Tottenham & Edmonton Herald 1921, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Cloake, Martin (13 May 2017). White Hart Lane has seen Diego Maradona and Johan Cruyff, but after 118 years Tottenham have outgrown it. The Independent. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d «History of White Hart Lane». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Spurs v Notts County 1899». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 3 August 2004. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b «Stadium History». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 7 July 2004. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ «Proposed New East Stand Redevelopment for Tottenham Hotspur Football Club» (PDF). Spurs Since 1882. June 2001. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Ley, John (1 October 2010). «Tottenham interested in making London 2012 Olympic Stadium their new ground». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur to play Champions League matches at Wembley». The Guardian. 28 May 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Molloy, Mark (15 May 2017). «Tottenham waste no time as White Hart Lane demolition work begins». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Jones, Adam (31 July 2017). «Historic update on Spurs new stadium site as last visual remnants of White Hart Lane disappear». Football London. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham reveal new ground plan». BBC Sport. 30 October 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ «Stadium Plans». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham sign planning agreement to build new stadium». BBC. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Collomosse, Tom (3 June 2014). «Tottenham baffled by Government’s delay to stadium go-ahead». London Evening Standard. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Morby, Aaron (12 July 2014). «Pickles gives final nod to £400m Spurs stadium plan». Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Riach, James (13 March 2015). «Spurs’ new stadium can proceed after Archway owners opt not to appeal». The Guardian. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Stadium Update». Tottenham Hotspur Football Club. 17 December 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham’s new stadium: the changing face of White Hart Lane – in pictures». The Guardian. 14 May 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur stadium dispute firm in court challenge». BBC News online. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Aarons, Ed (26 October 2018). «Tottenham confirm they will not play in new stadium until 2019». The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Lyall (28 April 2017). «Tottenham confirm move to Wembley for 2017/18 season». Sky Sports. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Rosser, Jack (3 April 2019). «Tottenham stadium opening ceremony Live: Spurs officially unveil 62,062 capacity venue». Evening Standard. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Burrows, Ben (17 March 2019). «Tottenham new stadium: Spurs confirm Crystal Palace as first fixture at new home». The Independent. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Collomosse, Tom (27 February 2018). «New Tottenham stadium will be called the ‘Tottenham Hotspur Stadium’ if club starts season without naming-rights deal». London Evening Standard. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Davies 1972, Chapter 1 – The First Day.

- ^ «Cheshunt FC Club History». Cheshunt F.C. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ «Spurs Ground – Cheshunt». BBC. 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Randall, Jeff (10 November 1991). «How they won their Spurs». The Sunday Times Magazine. pp. 34–44.

- ^ Binns, Daniel (24 February 2014). «CHIGWELL: Questions raised over Spurs training ground move». East London & West Sussex Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ O’Brien, Zoie (24 February 2014). «Tottenham Hotspur Football Club has confirmed that it is leaving Spurs Lodge this month». East London & West Sussex Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Collomosse, Tom (2 December 2014). «Tottenham await green light on multi-million pound ‘player lodge’«. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ «Hotspur Way». Tottenham Hotspur F.C. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur FC Training Centre Enfield». KSS. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Hytner, David (18 October 2018). «Tottenham reaping rewards of Pochettino’s vision, on and off the pitch». The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Peat, Charlie (27 January 2015). «Tottenham Hotspur’s 45-room players’ lodge plans approved». Enfield Independent. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ «Inside Tottenham Hotspur’s training ground hotel being used for the first time by Brazil’s World Cup squad». talkSport. 29 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Donald Insall Associates (September 2015). «Northumberland Development Project». Haringey Council. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b The Stadium Tour Experience. Vision Sports Publishing Ltd. pp. 32–33.

- ^ James Dart (31 August 2005). «The most unlikely football bet to come off». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ «Tottenham unveil new club badge». BBC. 19 January 2006. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur unveils modernised club badge». Campaign. 25 January 2006. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur force Fleet Spurs badge redesign». BBC News. 14 November 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ «Nike Tottenham Hotspur 17-18 Home Kit Released». Footy Headlines. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Burney & Evans 2018, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Burney & Evans 2018, p. 22.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Burney & Evans 2018, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Burney & Evans 2018, p. 26.

- ^ «Tottenham Hotspur». Premier Skill English. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Burney & Evans 2018, pp. 28–29.