Всего найдено: 38

Скажите, пожалуйста, как писать «восточный фронт», «западный фронт» и проч. подобное — со строчной или с заглавной? Или тут есть разница, в контексте какой войны, например? Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Пишутся с прописной буквы сочетания типа Северный фронт, когда они указывают на крупные оперативно-стратегические объединения войск вооруженных сил государства в условиях континентальных военных действий или на места, районы военных действий и расположение действующих войск во время войны. Например: Столь же поспешно эвакуировался штаб Северного фронта. . По-видимому, обозначение территории не воспринимается как название, когда речь идет о непродолжительных военных операциях, поэтому корректно написание со строчной в таком контексте: Петр и на этот раз утешал себя и свое правительство надеждой, что неудача на юге укрепит другую сторону, северный фронт, несравненно более важный .

Здравствуйте! Допустим ли вариант использования предлога «из» с существительным «континентов»? Пример: Товары из разных континентов. Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нет, это ошибка. Со словом континент используется предлог с (и противоположный ему на): товары с разных континентов.

«томские ученые» прилагательное, образованное от имени собственного, пишется с прописной буквы?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Прилагательные, образованные от названий городов, стран, континентов и т. п. пишутся с маленькой буквы: томские, российские, европейские ученые.

Можно ли сказать: Эта продукция достаточно универсальна и создана объединить людей и континенты. Или сказать «создана объединить» будет стилистически неверно?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Лучше: создана, чтобы объединить.

Подскажите расстановку знаков препинания в предложении Привлекавшие участников со всех континентов, экспозиции сохраняли вполне читаемую толерантность к соотечественникам. если оборот стоит перед определяемвм словом — запятая не нужна, но возможно здесь она уместна?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Запятая после континентов уместна, если причастный оборот имеет дополнительное обстоятельственное значение («хотя экспозиции привлекали участников со всех континентов»). Но предложение стилистически небезупречно, оборот сохраняли читаемую толерантность неудачен. Предложение лучше переформулировать.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Лучше, конечно, добавить родовое слово ракета: сменит легендарную ракету «Сатана», которую так боялись…

Если это невозможно, следует использовать форму мужского рода: сменит легендарного «Сатану», которого так боялись…

Здравствуйте! У меня такой вопрос. Вот предложение: Русский язык изучают более ста восьмидесяти миллионов человек на всех континентах планеты. Каким членом предложения является числительное в данном случае.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Сочетание более ста восьмидесяти миллионов человек является подлежащим.

Добрый день, уважаемая Грамота! Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно писать: восточная Украина или Восточная Украина. И почему. Спасибо!

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно: Восточная Украина. В полном академическом справочнике «Правила русской орфографии и пунктуации» под ред. В. В. Лопатина (М., 2006 и более поздние издания) сформулировано следующее правило: «Названия частей государств и континентов, носящие терминологический характер, пишутся с прописной буквы, напр.: Европейская Россия, Западная Белоруссия, Правобережная Украина…».

Скажите, пожалуйста, как пишется индийский субконтинент — с прописной или строчной?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректное написание: Индийский субконтинент.

Добрый день. Воспользовавшись строкой «Поиск вопроса» я нашла такой противоречивый ответ на мой вопрос: Вопрос № 211146

….

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Правильно с маленькой буквы: _европейский континент, африканский континент, американский континент, европейские страны, азиатские страны, африканские страны, Скандинавские страны_.

Так с какой же все-таки буквы писать «Скандинавские страны» — отвечаете «с маленькой», а пишете с прописной….

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Действительно, словарная фиксация такова: европейские страны (по общему правилу), но Скандинавские страны.

Здравствуйте! Подскажите пожалуйста, с какой буквы — прописной или строчной — пишутся официальные названия спортивных соревнований?

Например: — Чемпионат мира по футболу, Кубок Европы по водному поло

А также с какой буквы — прописной или строчной — надо писать словосочетания чемпионат мира и Кубок мира?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Слово чемпионат пишется строчными: чемпионат мира по футболу, чемпионат Европы, чемпионат России. Слово Кубок пишется с большой буквы как первое слово в названии спортивных соревнований: Кубок Европы по водному поло, Кубок мира, Кубок России. Но: Межконтинентальный кубок.

Уважаемая Грамота! Сейчас повсеместно говорят и пишут: Европейский континент. Но ведь нет такого континента — есть континент Евразия! Объясните, пожалуйста, насколько правомерно употребление словосочетания Европейский континент в средствах массовой информации, допустимо ли это или нужно все-таки исправлять?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Нужно править. Вероятно, эта ошибка вызвана смешением понятий «часть света» и «континент». Часть света Европа существует, а континента Европа нет, есть континент Евразия. Но корректно сочетание континентальная Европа (для обозначения той части Европы, которая находится на континенте и в которую не входят островные государства, такие как Великобритания, Ирландия и др.).

Уважаемые коллеги, помогите, пожалуйста, разрешить спор. При редактировании пособия по географии нами было внесено исправление в сочетание Зарубежная Европа (с прописной) на зарубежная Европа (з — строчная). Это вызвало возмущение географов, настаивающих на написании слова «зарубежная» (Европа, Азия) с прописной. Все наше филологическое естестество против этого. Помогите, пожалуйста, убедить оппонентов или подтверите их правоту. Заранее благодарим

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Вы правы. Есть правило: названия частей государств и континентов, носящие терминологический характер, пишутся с прописной буквы: Западная Европа, Средняя Азия, Центральная Америка. Но нет оснований для написания с прописной слова зарубежный в сочетании зарубежная Европа: это не терминологическое понятие, а некое наше условное обозначение всех европейских стран, кроме России.

В Континентальную хоккейную лигу вступил словацкий хоккейный клуб «Лев» (ныне уже имеет чешскую приписку). Хоккейными журналистами и болельщиками стало использоваться два варианта склонения названия данного клуба: первый — как русского слова (например: «Льва», «Львом»; «СКА вырвал победу у «Льва»»), второй — как слова иностранного, игнорируя его похожесть с русским и совпадение в значении (например, «Ле́ва», «Ле́вом»; «И, кстати, если там, в «Леве», что в попрадском, что затем в пражском»).

Какой из этих вариантов склонения верный?

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Это название корректно склонять без выпадения гласного: «Лева», «Леву» и т. д. Склонение без выпадения гласного как раз и указывает на то, что это название не русское.

Добрый день! Подскажите, пожалуйста, как пишется сочетание двух слов «умеренно негативный»? В два слова или через дефис? Поспорили с коллегами, я настаиваю на раздельном написании, поскольк умеренно — наречие, а негативный — прилагательное. Заранее спасибо за ответ! С уважением, Елена.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка

Корректно раздельное написание. Ср.:

умеренно влажный

умеренно динамический

умеренно жаркий

умеренно консервативный

умеренно континентальный

умеренно левый

умеренно либеральный

Страницы: 2 3 последняя

Генеральная Ассамблея

Генеральная Ассамблея является главным совещательным, директивным и представительным органом Организации Объединенных Наций, cостоящим из 193 государств-членов. Генеральная Ассамблея является единственным органом Организации Объединенных Наций, в котором представлены все 193 ее члена. В сентябре каждого года представители всех государств-членов собираются в зале Генеральной Ассамблеи в Нью-Йорке для участия в ежегодной сессии Генеральной Ассамблеи и общих прениях. Решения по важным вопросам, таким как рекомендации в отношении мира и безопасности, выборы новых членов и бюджетные вопросы, принимаются большинством в две трети голосов государств-членов; решения по другим вопросам принимаются простым большинством голосов. Каждый год Генеральная Ассамблея избирает своего Председателя на новую сессию.

Совет Безопасности

Согласно Уставу, Совет Безопасности несет главную ответственность за поддержание международного мира и безопасности. Совет Безопасности состоит из 15 членов (5 постоянных членов с правом вето и 10 непостоянных членов, которые избираются Генеральной Ассамблеей на двухлетний срок). Каждый член Совета Безопасности имеет один голос. В соответствии с Уставом, государства-члены соглашаются подчиняться решениям Совета Безопасности и выполнять их. Совет Безопасности играет ведущую роль в определении наличия угрозы миру или акта агрессии. Он призывает стороны в споре урегулировать его мирным путем, и рекомендует методы урегулирования или условия урегулирования. В некоторых случаях Совет Безопасности может прибегать к санкциям или даже санкционировать применение силы в целях поддержания или восстановления международного мира и безопасности. Члены Совета Безопасности по очереди выполняют обязанности Председателя в течение месяца.

- Программа на месяц

- Вспомогательные органы

Экономический и Социальный Совет

Экономический и Социальный Совет является основным органом, занимающимся координацией, проведением обзора политики и разработкой рекомендаций по решению экономических, социальных и экологических вопросов. Совет также занимается осуществлением согласованных на международном уровне целей в области развития. Совет является центральным механизмом системы ООН и специализированных учреждений, отвечающим за работу в экономической, социальной и экологической сферах, а также координирущим и направляющим работу вспомогательных органов и экспертных групп. 54 члена Совета избираются Генеральной Ассамблеей сроком на три года. ЭКОСОС является центральной платформой для рассмотрения и обсуждения вопросов устойчивого развития.

Совет по Опеке

Совет по Опеке был учрежден в 1945 году Уставом ООН, глава XIII, в качестве одного из главных органов Организации Объединенных Наций, на который была возложена задача по наблюдению за управлением подопечными территориями, подпадающими под систему опеки. К 1994 году все подопечные территории достигли самоуправления или независимости либо в качестве самостоятельных государств, либо посредством объединения с соседними независимыми странами. Совет по Опеке приостановил свою работу 1 ноября 1994 года. Своей резолюцией, принятой 25 мая 1994 года, Совет внес в свои правила процедуры поправки, предусматривающие отмену обязательства о проведении ежегодных заседаний, и согласился собираться по мере необходимости — по своему решению или решению своего Председателя, либо по просьбе большинства своих членов, Генеральной Ассамблеи или Совета Безопасности.

Международный Суд

Международный Суд является главным судебным органом Организации Объединенных Наций. Международный Суд находится во Дворце мира в Гааге (Нидерланды). Это единственный из шести главных органов ООН, который находится не в Нью-Йорке. Суд выполняет две основные задачи: разрешение в соответствии с международным правом юридических споров, переданных ему на рассмотрение государствами, и вынесение консультативных заключений по юридическим вопросам, запрашиваемых должным образом на то уполномоченными органами и специализированными учреждениями ООН.

Секретариат

Секретариат — это международный персонал, работающий в учреждениях по всему миру и выполняющий разнообразную повседневную работу Организации. Он обслуживает и другие главные органы ООН и осуществляет принятые ими программы и политические установки. Во главе Секретариата стоит Генеральный секретарь, который назначается Генеральной Ассамблеей по рекомендации Совета Безопасности сроком на 5 лет с возможностью переизбрания на новый срок. Сотрудников ООН принимают на работу на международной и местной основе, они заняты во всех местах службы ООН, а также в миротворческих операциях. Служение делу мира в жестоких условиях действительности — занятие чрезвычайно опасное. С момента основания Организации Объединенных Наций на этой службе погибли сотни храбрых мужчин и женщин.

| Conseil de l’Europe | |

Logo |

|

Flag |

|

|

|

| Abbreviation |

CoE |

|---|---|

| Formation | Treaty of London |

| Type | Regional intergovernmental organisation |

| Headquarters | Palace of Europe, Strasbourg, France |

| Location |

|

|

Membership |

|

|

Official languages |

English, French[1] |

|

Secretary General |

Marija Pejčinović Burić |

|

Deputy Secretary General |

Bjørn Berge |

|

President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe |

Tiny Kox |

|

Chair of the Committee of Ministers |

Þórdís Kolbrún R. Gylfadóttir |

|

President of the Congress |

Leendert Verbeek |

| Website | www.coe.int |

The Council of Europe (CoE; French: Conseil de l’Europe, CdE) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe.[2] Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a population of approximately 675 million; it operates with an annual budget of approximately 500 million euros.[3]

The organisation is distinct from the European Union (EU), although it is sometimes confused with it, partly because the EU has adopted the original European flag, created for the Council of Europe in 1955,[4] as well as the European anthem.[5] No country has ever joined the EU without first belonging to the Council of Europe.[6] The Council of Europe is an official United Nations Observer.[7]

Being an international organisation, the Council of Europe cannot make laws,[8] but it does have the ability to push for the enforcement of select international agreements reached by member states on various topics.[9] The best-known body of the Council of Europe is the European Court of Human Rights, which functions on the basis of the European Convention on Human Rights.[10]

The council’s two statutory bodies are the Committee of Ministers, which comprises the foreign ministers of each member state, and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), which is composed of members of the national parliaments of each member state.[11] The Commissioner for Human Rights is an institution within the Council of Europe, mandated to promote awareness of and respect for human rights within the member states. The secretary general presides over the secretariat of the organisation. Other major CoE bodies include the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare (EDQM) and the European Audiovisual Observatory.[12]

The headquarters of the Council of Europe, as well as its Court of Human Rights, are situated in Strasbourg, France. English and French are its two official languages. The Committee of Ministers, the PACE, and the Congress of the Council of Europe also use German and Italian for some of their work.[13]

History[edit]

Founding[edit]

The European Council is one of the oldest and the largest European organisation with 46 members states.[14] The primary aim of creating the council was to create a common democratic and legal parameters for its members states.[15]

In a speech in 1929, French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand floated the idea of an organisation which would gather European nations together in a «federal union» to resolve common problems.[16] But it was Britain’s wartime leader Sir Winston Churchill who first publicly suggested the creation of a «Council of Europe» in a BBC radio broadcast on 21 March 1943,[17] while the Second World War was still raging. In his own words,[18] he tried to «peer through the mists of the future to the end of the war», and think about how to re-build and maintain peace on a shattered continent. Given that Europe had been at the origin of two world wars, the creation of such a body would be, he suggested, «a stupendous business». He returned to the idea during a well-known speech at the University of Zurich on 19 September 1946,[19][20] throwing the full weight of his considerable post-war prestige behind it. But there were many other statesmen and politicians across the continent, many of them members of the European Movement, who were quietly working towards the creation of the council. Some regarded it as a guarantee that the horrors of war could never again be visited on the continent, others came to see it as a «club of democracies», built around a set of common values that could stand as a bulwark against totalitarian states belonging to the Eastern Bloc. Others again saw it as a nascent «United States of Europe», the resonant phrase that Churchill had reached for at Zurich in 1946.

The future structure of the Council of Europe was discussed at the Congress of Europe which brought together several hundred leading politicians, government representatives and members of civil society in The Hague, Netherlands, in 1948.[15] Responding to the conclusions of the Congress of Europe, the Consultative Council of the Treaty of Brussels convened a Committee for the Study of European Unity, which met eight times from November 1948 to January 1949 to draw up the blueprint of a new broad-based European organisation.[21] There were two competing schools of thought: some favoured a classical international organisation with representatives of governments, while others preferred a political forum with parliamentarians. Both approaches were finally combined through the creation of a Committee of Ministers (in which governments were represented) and a Consultative Assembly (in which parliaments were represented), the two main bodies mentioned in the Statute of the Council of Europe. This dual intergovernmental and inter-parliamentary structure was later copied for the European Communities, NATO and OSCE.[22]

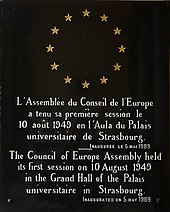

The Council of Europe was signed into existence on 5 May 1949 by the Treaty of London, the organisation’s founding Statute which set out the three basic values that should guide its work: democracy, human rights and the rule of law.[23] It was signed in London on that day by ten states: Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom, though Turkey and Greece joined three months later. On 10 August 1949, 100 members of the council’s Consultative Assembly, parliamentarians drawn from the twelve member nations, met in Strasbourg for its first plenary session, held over 18 sittings and lasting nearly a month. They debated how to reconcile and reconstruct a continent still reeling from war, yet already facing a new East–West divide, launched the concept of a trans-national court to protect the basic human rights of every citizen, and took the first steps in a process that would eventually lead to the creation of the European Union.[24]

In August 1949, Paul-Henri Spaak resigned as Belgium’s foreign minister in order to be elected as the first president of the assembly. Behind the scenes, he too had been quietly working towards the creation of the council, and played a key role in steering its early work. However, in December 1951, after nearly three years in the role, Spaak resigned in disappointment after the Assembly rejected proposals for a «European political authority».[25] Convinced that the Council of Europe was never going to be in a position to achieve his long-term goal of a unified Europe,[26] he soon tried again in a new and more promising format, based this time on economic integration, becoming one of the founders of the European Union.[27]

Early years[edit]

There was huge enthusiasm for the Council of Europe in its early years, as its pioneers set about drafting what was to become the European Convention on Human Rights, a charter of individual rights which – it was hoped – no member government could ever again violate. They drew, in part, on the tenets of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed only a few months earlier in Paris. But crucially, where the Universal Declaration was essentially aspirational, the European Convention from the beginning featured an enforcement mechanism — an international Court — which was to adjudicate on alleged violations of its articles and hold governments to account, a dramatic leap forward for international justice. Today, this is the European Court of Human Rights, whose rulings are binding on 47 European nations, the most far-reaching system of international justice anywhere in the world.

One of the council’s first acts was to welcome West Germany into its fold on 2 May 1951,[28] setting a pattern of post-war reconciliation that was to become a hallmark of the council, and beginning a long process of «enlargement» which was to see the organisation grow from its original ten founding member states to the 47 nations that make up the Council of Europe today.[29] Iceland had already joined in 1950, followed in 1956 by Austria, Cyprus in 1961, Switzerland in 1963 and Malta in 1965.

Historic speeches at the Council of Europe[edit]

In 2018, an archive of all speeches made to the PACE by heads of state or government since the Council of Europe’s creation in 1949 appeared online, the fruit of a two-year project entitled «Voices of Europe».[30] At the time of its launch,[31] the archive comprised 263 speeches delivered over a 70-year period by some 216 presidents, prime ministers, monarchs and religious leaders from 45 countries – though it continues to expand, as new speeches are added every few months.

Some very early speeches by individuals considered to be «founding figures» of the European institutions, even if they were not heads of state or government at the time, are also included (such as Sir Winston Churchill or Robert Schuman). Addresses by eight monarchs appear in the list (such as King Juan Carlos I of Spain, King Albert II of Belgium and Grand Duke Henri of Luxembourg) as well as the speeches given by religious figures (such as Pope John Paul II, and Pope Francis) and several leaders from countries in the Middle East and North Africa (such as Shimon Peres, Yasser Arafat, Hosni Mubarak, Léopold Sédar Senghor or King Hussein of Jordan).

The full text of the speeches is given in both English and French, regardless of the original language used. The archive is searchable by country, by name, and chronologically.[32]

Aims and achievement[edit]

Article 1(a) of the Statute states that «The aim of the Council of Europe is to achieve a greater unity between its members for the purpose of safeguarding and realising the ideals and principles which are their common heritage and facilitating their economic and social progress.»[33] Membership is open to all European states who seek harmony, cooperation, good governance and human rights, accepting the principle of the rule of law and are able and willing to guarantee democracy, fundamental human rights and freedoms.

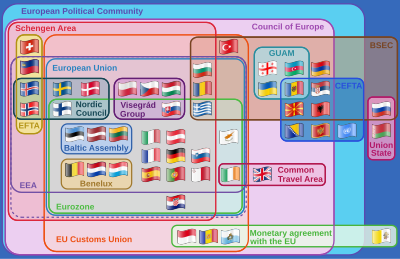

Whereas the member states of the European Union transfer part of their national legislative and executive powers to the European Commission and the European Parliament, Council of Europe member states maintain their sovereignty but commit themselves through conventions/treaties (international law) and co-operate on the basis of common values and common political decisions. Those conventions and decisions are developed by the member states working together at the Council of Europe. Both organisations function as concentric circles around the common foundations for European co-operation and harmony, with the Council of Europe being the geographically wider circle. The European Union could be seen as the smaller circle with a much higher level of integration through the transfer of powers from the national to the EU level. «The Council of Europe and the European Union: different roles, shared values.»[34] Council of Europe conventions/treaties are also open for signature to non-member states, thus facilitating equal co-operation with countries outside Europe.

The Council of Europe’s most famous achievement is the European Convention on Human Rights, which was adopted in 1950 following a report by the PACE, and followed on from the United Nations ‘Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ (UDHR).[35] The Convention created the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. The Court supervises compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights and thus functions as the highest European court. It is to this court that Europeans can bring cases if they believe that a member country has violated their fundamental rights and freedoms.

The various activities and achievements of the Council of Europe can be found in detail on its official website. The Council of Europe works in the following areas:

- Protection of the rule of law and fostering legal co-operation through some 200 conventions and other treaties,[36] including such leading instruments as the Convention on Cybercrime, the Convention on the Prevention of Terrorism, Conventions against Corruption and Organised Crime,[37][38][39] the Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings, and the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine.[36]

- CODEXTER, designed to co-ordinate counter-terrorism measures

- The European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ)

- Protection of human rights, notably through:

- the European Convention on Human Rights

- the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture

- the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance

- the Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings[40]

- the Convention for the protection of individuals with regard to automatic processing of personal data

- the Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse[36]

- The Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence.[41]

- social rights under the European Social Charter

- European Charter of Local Self-Government guaranteeing the political, administrative and financial independence of local authorities.

- linguistic rights under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages

- minority rights under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities

- Media freedom under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Convention on Transfrontier Television

- Protection of democracy through parliamentary scrutiny and election monitoring by its Parliamentary Assembly as well as assistance in democratic reforms, in particular by the Venice Commission.

- Promotion of cultural co-operation and diversity under the Council of Europe’s Cultural Convention of 1954 and several conventions on the protection of cultural heritage as well as through its Centre for Modern Languages in Graz, Austria, and its North-South Centre in Lisbon, Portugal.

- Promotion of the right to education under Article 2 of the first Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights and several conventions on the recognition of university studies and diplomas (see also Bologna Process and Lisbon Recognition Convention).

- Promotion of fair sport through the Anti-Doping Convention[42]

- Promotion of European youth exchanges and co-operation through European Youth Centres in Strasbourg and Budapest, Hungary.

- Promotion of the quality of medicines throughout Europe by the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and its European Pharmacopoeia.

- Support for intercultural integration through the Intercultural Cities (ICC) program. This program offers information and advice for local authorities on the integration of minorities and the prevention of discrimination.[43]

Institutions[edit]

The institutions of the Council of Europe are:

- The Secretary General, who is elected for a term of five years by the PACE and heads the Secretariat of the Council of Europe. Thorbjørn Jagland, the former Prime Minister of Norway, was elected Secretary General of the Council of Europe on 29 September 2009.[44] In June 2014, he became the first Secretary General to be re-elected, commencing his second term in office on 1 October 2014.[45]

- The Committee of Ministers, comprising the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of all 47 member states who are represented by their Permanent Representatives and Ambassadors accredited to the Council of Europe.[46] Committee of Ministers’ presidencies are held in alphabetical order for six months following the English alphabet: Turkey 11/2010-05/2011, Ukraine 05/2011-11/2011, the United Kingdom 11/2011-05/2012, Albania 05/2012-11/2012, Andorra 11/2012-05/2013, Armenia 05/2013-11/2013, Austria 11/2013-05/2014, and so on.[47]

- The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), which comprises national parliamentarians from all member states.[48] Adopting resolutions and recommendations to governments, the Assembly holds a dialogue with its governmental counterpart, the Committee of Ministers, and is often regarded as the «motor» of the organisation. The national parliamentary delegations to the Assembly must reflect the political spectrum of their national parliament, i.e. comprise government and opposition parties. The Assembly appoints members as rapporteurs with the mandate to prepare parliamentary reports on specific subjects. The British MP Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe was rapporteur for the drafting of the European Convention on Human Rights.[49] Dick Marty’s reports on secret CIA detentions and rendition flights in Europe became quite famous in 2006 and 2007. Other Assembly reports were instrumental in, for example, the abolition of the death penalty in Europe, highlighting the political and human rights situation in Chechnya, identifying who was responsible for disappeared persons in Belarus, chronicling threats to freedom of expression in the media and many other subjects.[50]

- The Congress of the Council of Europe (Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of Europe), which was created in 1994 and comprises political representatives from local and regional authorities in all member states. The most influential instruments of the Council of Europe in this field are the European Charter of Local Self-Government of 1985 and the European Outline Convention on Transfrontier Co-operation between Territorial Communities or Authorities of 1980.[51][52]

- The European Court of Human Rights, created under the European Convention on Human Rights of 1950, is composed of a judge from each member state elected for a single, non-renewable term of nine years by the PACE and is headed by the elected president of the court.[53] The current president of the court is Guido Raimondi from Italy. Under the recent Protocol No. 14 to the European Convention on Human Rights, the Court’s case-processing was reformed and streamlined. Ratification of Protocol No. 14 was delayed by Russia for a number of years, but won support to be passed in January 2010.[54]

- The Commissioner for Human Rights is elected by the PACE for a non-renewable term of six years since the creation of this position in 1999. Since April 2018, this position has been held by Dunja Mijatović from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[55]

- The Conference of INGOs.[56] NGOs can participate in the INGOs Conference of the Council of Europe. Since the [Resolution (2003)8] adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 19 November 2003, they are given a «participatory status».[57]

- The Joint Council on Youth of the Council of Europe.[58] The European Steering Committee (CDEJ) on Youth and the Advisory Council on Youth (CCJ) of the Council of Europe form together the Joint Council on Youth (CMJ). The CDEJ brings together representatives of ministries or bodies responsible for youth matters from the 50 States Parties to the European Cultural Convention. The CDEJ fosters co-operation between governments in the youth sector and provides a framework for comparing national youth policies, exchanging best practices and drafting standard-setting texts.[59] The Advisory Council on Youth comprises 30 representatives of non-governmental youth organisations and networks. It provides opinions and input from youth NGOs on all youth sector activities and ensures that young people are involved in the council’s other activities.[60]

- Information Offices of the Council of Europe in many member states.

The CoE system also includes a number of semi-autonomous structures known as «Partial Agreements», some of which are also open to non-member states:

- The Council of Europe Development Bank in Paris

- The European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines with its European Pharmacopoeia

- The European Audiovisual Observatory

- The European Support Fund Eurimages for the co-production and distribution of films.[61]

- The Enlarged Partial Agreement on Cultural Routes, which awards the certification «Cultural Route of the Council of Europe» to transnational networks promoting European heritage and intercultural dialogue (Luxembourg)

- The Pompidou Group – Cooperation Group to Combat Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking in Drugs.[62]

- The European Commission for Democracy through Law, better known as the Venice Commission

- The Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO)

- The European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement (EUR-OPA) which is a platform for co-operation between European and Southern Mediterranean countries in the field of major natural and technological disasters.[63]

- The Enlarged Partial Agreement on Sport, which is open to accession by states and sport associations.[64]

- The North-South Centre of the Council of Europe in Lisbon (Portugal)

- The Centre for Modern Languages is in Graz (Austria)

Headquarters and buildings[edit]

Council of Europe’s Agora building

The seat of the Council of Europe is in Strasbourg, France. First meetings were held in Strasbourg’s University Palace in 1949,[65] but the Council of Europe soon moved into its own buildings. The Council of Europe’s eight main buildings are situated in the Quartier européen, an area in the northeast of Strasbourg spread over the three districts of Le Wacken, La Robertsau and Quartier de l’Orangerie, where are also located the four buildings of the seat of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, the Arte headquarters and the seat of the International Institute of Human Rights.[66]

Building in the area started in 1949 with the predecessor of the Palais de l’Europe, the House of Europe (demolished in 1977), and came to a provisional end in 2007 with the opening of the New General Office Building, later named «Agora», in 2008.[67] The Palais de l’Europe (Palace of Europe) and the Art Nouveau Villa Schutzenberger (seat of the European Audiovisual Observatory) are in the Orangerie district, and the European Court of Human Rights, the EDQM and the Agora Building are in the Robertsau district. The Agora building has been voted «best international business center real estate project of 2007» on 13 March 2008, at the MIPIM 2008.[68] The European Youth Centre is located in the Wacken district.

Besides its headquarters in Strasbourg, the Council of Europe is also present in other cities and countries. The Council of Europe Development Bank has its seat in Paris, the North-South Centre of the Council of Europe is established in Lisbon, Portugal, and the Centre for Modern Languages is in Graz, Austria. There are European Youth Centres in Budapest, Hungary, and in Strasbourg. The European Wergeland Centre, a new Resource Centre on education for intercultural dialogue, human rights and democratic citizenship, operated in cooperation with the Norwegian Government, opened in Oslo, Norway, in February 2009.[69]

The Council of Europe has external offices all over the European continent and beyond. There are four ‘Programme Offices’, namely in Ankara, Podgorica, Skopje, Venice. There are also ‘Council of Europe Offices’ in Baku, Belgrade, Chisinau, Kyiv, Paris, Pristina, Sarajevo, Tbilisi, Tirana, and Yerevan. Bucharest has a Council of Europe Office on Cybercrime. There are also Council of Europe Offices in non-European capital cities like Rabat and Tunis.[70]

Additionally, there are 4 «Council of Europe Liaison Offices», this includes:

- Council of Europe Liaison Office in Brussels: The office is in charge of liaison with the European Union

- Council of Europe Office in Geneva: Permanent Delegation of the Council of Europe to the United Nations Office and other international organisations in Geneva

- Council of Europe Office in Vienna: The office is in charge of liaison with the OSCE, United Nations Office, and other international organisations in Vienna

- Council of Europe Office in Warsaw: The office is in charge of liaison with other international organisations and institutions in Warsaw, in particular the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR)[71]

Member states, observers, partners[edit]

Eligibility[edit]

There are two main criteria for membership: geographic (Article 4 of the Council of Europe Statute specifies that membership is open to any «European» State) and political (Article 3 of the Statute states applying for membership must accept democratic values—»Every member of the Council of Europe must accept the principles of the rule of law and the enjoyment by all persons within its jurisdiction of human rights and fundamental freedoms, and collaborate sincerely and effectively in the realisation of the aim of the Council as specified in Chapter I»).[72][73]

Since «Europe» is not defined in international law, the definition of «Europe» has been a question that has recurred during the CoE’s history. Turkey was admitted in 1950, although it is a transcontinental state that lies mostly in Asia, with a smaller portion in Europe.[73] In 1994, the PACE adopted Recommendation 1247, which said that admission to the CoE should be «in principle open only to states whose national territory lies wholly or partly in Europe»; later, however, the Assembly extended eligibility to apply and be admitted to Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.[73]

Member states and observers[edit]

The Council of Europe was founded on 5 May 1949 by Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom.[74] Greece and Turkey joined 3 months later.[75][76][77][78] Iceland[79][80] West Germany and Saarland Protectorate joined the Council of Europe as associate members in 1950. West Germany became a full member in 1951, and the Saar withdrew its application after it joined West Germany following the 1955 Saar Statute referendum.[81][82] Joining later were Austria (1956), Cyprus (1961), Switzerland (1963), Malta (1965), and Portugal (1976).[73] Spain joined in 1977, two years after the death of its dictator Francisco Franco and the Spanish transition to democracy.[83] Next to join were Liechtenstein (1978), San Marino (1988) and Finland (1989).[73] After the fall of Communism with the Revolutions of 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union, the post-Soviet states in Europe that began democratization joined: Hungary (1990), Poland (1991), Bulgaria (1992), Estonia (1993), Lithuania (1993), Slovenia (1993), the Czech Republic (1993), Slovakia (1993), Romania (1993), Latvia (1995), Moldova (1995), Albania (1995), Ukraine (1995), the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (1995) (later renamed North Macedonia), Russia (1996, expelled 2022), Croatia (1996), Georgia (1999), Armenia (2001), Azerbaijan (2001), Bosnia and Herzegovina (2002) and Serbia and Montenegro (later Serbia) (2003).[73] Also joining were the small Western European nations of Andorra (1994) and Monaco (2004).[73] The Council now has 46 member states, with Montenegro (2007) being the latest to join.[84]

Although most Council members are predominantly Christian in heritage, there are three Muslim-majority member states: Turkey, Albania, and Azerbaijan.[73]

The CoE has granted some countries a status that allows them to participate in CoE activities without being full members. There are three types of nonmember status: associate member, special guest and observer.[73] Associate member status is no longer used.[73] «Special guest» status was used as a transitional status for post-Soviet countries that wished to join the council after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and is no longer commonly used.[73] «Observer» status is for non-European nations who accept democracy, rule of law, and human rights, and wish to participate in Council initiatives.[73] The United States became an observer state in 1995.[85] Currently, Canada, the Holy See, Japan, Mexico, and the United States are observer states, while Israel is an observer to the PACE.[84]

Withdrawal, suspension, and expulsion[edit]

The Statute of the Council of Europe provides for the voluntary suspension, involuntary suspension, and exclusion of members.[86] Article 8 of the Statute provides that any member who has «seriously violated» Article 3 may be suspended from its rights of representation, and that the Committee of Ministers may request that such a member withdraw from the Council under Article 7. (The Statute does not define the «serious violation» phrase.[86] Under Article 8 of the Statute, if a member state fails to withdraw upon request, the Committee may terminate its membership, in consultation with the PACE.[86]

The Council suspended Greece in 1967, after a military coup d’état, and the Greek junta withdrew from the CoE.[86] Greece was readmitted to the council in 1974.[87]

Suspension and exclusion of Russia[edit]

Russia became a member of the Council of Europe in 1996. In 2014, after Russia invaded and annexed Crimea from Ukraine and supported separatists in eastern Ukraine, precipitating a bloody conflict, the Council stripped Russia of its voting rights in the PACE.[88] In response, Russia began to boycott the Assembly in 2016, and beginning in 2017 refused to pay its annual membership dues of 32.6 million euros (US$37.1 million) to the Council[88][89] placing the institution under financial strain.[90]

Russia claimed that its suspension by the council was unfair, and demanded the restoration of voting rights.[91] Russia had threatened to withdraw from the Council unless its voting rights were restored in time for the election of a new secretary general.[88] European Council secretary-general Thorbjørn Jagland organized a special committee to find a compromise with Russia in early 2018, a move that was criticized as giving in to alleged Russian pressure by Council members and academic observers, especially if voting sanctions were lifted.[90][91][92] In June 2019, the Council voted (on a 118–62 vote, with 10 abstentions) to restore Russia’s voting rights in the council.[88][93] Opponents of lifting the suspension included Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries, such as Poland and the Baltic states, who argued that readmission amounted to normalizing Russia’s malign activity.[88] Supporters of restoring Russia’s council rights included France and Germany,[94] which argued that a Russian withdrawal from the council would be harmful because it would deprive Russian citizens of their ability to initiate cases in the European Court of Human Rights.[88]

On 3 March 2022, after Russia launched a full-scale military invasion of Ukraine, the council suspended Russia for violations of the council’s statute and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The suspension blocked Russia from participation in the council’s ministerial council, the PACE, and the Council of the Baltic Sea States, but still left Russia obligated to follow the ECHR.[94][95][96] On 15 March 2022, hours before the vote to expel the country, Russia initiated a voluntary withdrawal procedure from the council. The Russian delegation planned to deliver its formal withdrawal on 31 December 2022, and announced its intent to denounce the ECHR. However, on the same day, the council’s Committee of Ministers decided Russia’s membership in the council would be terminated immediately, and determined that Russia had been excluded from the Council instead under its exclusion mechanism rather than the withdrawal mechanism.[97] After being excluded from the Council of Europe, Russia’s former president and prime minister Dmitry Medvedev endorsed restoring the death penalty in Russia.[98][99]

Co-operation[edit]

Non-member states[edit]

The Council of Europe works mainly through international treaties, usually called conventions in its system. By drafting conventions or international treaties, common legal standards are set for its member states. However, several conventions have also been opened for signature to non-member states. Important examples are the Convention on Cybercrime (signed for example, by Canada, Japan, South Africa and the United States), the Lisbon Recognition Convention on the recognition of study periods and degrees (signed for example, by Australia, Belarus, Canada, the Holy See, Israel, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, New Zealand and the United States), the Anti-doping Convention (signed, for example, by Australia, Belarus, Canada and Tunisia) and the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (signed for example, by Burkina Faso, Morocco, Tunisia and Senegal as well as the European Community). Non-member states also participate in several partial agreements, such as the Venice Commission, the Group of States Against Corruption (GRECO), the European Pharmacopoeia Commission and the North-South Centre.[100]

Invitations to sign and ratify relevant conventions of the Council of Europe on a case-by-case basis are sent to three groups of non-member entities:[101]

- Non-European states: Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Bahamas, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, South Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mauritius, Morocco, New Zealand, Panama, Peru, Philippines, Senegal, South Africa, Syria, Tajikistan, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Uruguay, Venezuela and the observers Canada, Israel, Japan, Mexico, United States.

- European states: Kosovo, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Russia and the observer Vatican City.

- the European Community and later the European Union after its legal personality was established by the ratification of the EU’s Lisbon Treaty.

European Union[edit]

A clickable Euler diagram[file] showing the relationships between various multinational European organisations and agreements

- v

- t

- e

The Council of Europe is not to be confused with the Council of the European Union (the «Council of Ministers») or the European Council. These belong to the European Union, which is separate from the Council of Europe, although they have shared the same European flag and anthem since the 1980s since they both work for European integration.[102] Nor is the Council of Europe to be confused with the European Union itself.

The Council of Europe is an entirely separate body[103] from the European Union. It is not controlled by it.

Cooperation between the European Union and the Council of Europe has recently been reinforced, notably on culture and education as well as on the international enforcement of justice and Human Rights.[104]

The European Union is expected to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights (the convention). There are also concerns about consistency in case law – the European Court of Justice (the EU’s court in Luxembourg) is treating the convention as part of the legal system of all EU member states in order to prevent conflict between its judgements and those of the European Court of Human Rights (the court in Strasbourg interpreting the convention). Protocol No. 14 of the convention is designed to allow the EU to accede to it and the EU Treaty of Lisbon contains a protocol binding the EU to join. The EU would thus be subject to its human rights law and external monitoring as its member states currently are.[105][106]

Schools of Political Studies[edit]

The Council of Europe Schools of political studies were established to train future generations of political, economic, social and cultural leaders in countries in transition. With the participation of national and international experts, they run annual series of seminars and conferences on topics such as European integration, democracy, human rights, the rule of law and globalisation. The first School of Political Studies was created in Moscow in 1992. Since then, 20 other schools have been set up along the same lines and now form an Association;[107] a genuine network now covering the whole of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, as well as some countries in the Southern Mediterranean region. The Council of Europe Schools of political studies is part of the Education Department which is part of the Directorate of Democratic Participation within the Directorate General of Democracy («DGII») of the Council of Europe.[108]

United Nations[edit]

The beginning of co-operation between the CoE and the UN started with the agreement signed by the Secretariats of these institutions on 15 December 1951. On 17 October 1989, the General Assembly of the United Nations approved a resolution on granting observer status to the Council of Europe which was proposed by several member states of the CoE.[109] Currently, the Council of Europe holds observer status with the United Nations and is regularly represented in the UN General Assembly. It has organised the regional UN conferences against racism and on women and co-operates with the United Nations at many levels, in particular in the areas of human rights, minorities, migration and counter-terrorism. In November 2016, the UN General Assembly adopted by consensus Resolution (A/Res/71/17) on Cooperation between the United Nations and the Council of Europe whereby it acknowledged the contribution of Council of Europe to the protection and strengthening of human rights and fundamental freedoms, democracy and the rule of law, welcomed the ongoing co-operation in a variety of fields.

Non-governmental organisations[edit]

Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) can participate in the INGOs Conference of the Council of Europe and become observers to inter-governmental committees of experts. The Council of Europe drafted the European Convention on the Recognition of the Legal Personality of International Non-Governmental Organisations in 1986, which sets the legal basis for the existence and work of NGOs in Europe. Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to freedom of association, which is also a fundamental norm for NGOs. The rules for consultative status for INGOs appended to the resolution (93)38 «On relation between the Council of Europe and non-governmental organisations», adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 18 October 1993 at the 500th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies.

On 19 November 2003, the Committee of Ministers changed the consultative status into a participatory status, «considering that it is indispensable that the rules governing the relations between the Council of Europe and NGOs evolve to reflect the active participation of international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) in the Organisation’s policy and work programme».[110]

Others[edit]

On 30 May 2018, the Council of Europe signed a memorandum of understanding with the European football confederation UEFA.[111]

The Council of Europe also signed an agreement with FIFA in which the two agreed to strengthen future cooperation in areas of common interests. The deal which included cooperation between member states in the sport of football and safety and security at football matches was finalized in October 2018.[112]

Characteristics[edit]

Privileges and immunities[edit]

The General Agreement on Privileges and Immunities of the Council of Europe grants the organisation certain privileges and immunities.[113]

The working conditions of staff are governed by the council’s staff regulations, which are public.[114] Salaries and emoluments paid by the Council of Europe to its officials are tax-exempt on the basis of Article 18 of the General Agreement on Privileges and Immunities of the Council of Europe.[113]

Symbol and anthem[edit]

The Council of Europe created, and has since 1955 used as its official symbol, the European Flag with 12 golden stars arranged in a circle on a blue background.

Its musical anthem since 1972, the «European anthem», is based on the «Ode to Joy» theme from Ludwig van Beethoven’s ninth symphony.

On 5 May 1964, the 15th anniversary of its founding, the Council of Europe established 5 May as Europe Day.[115]

The wide private and public use of the European Flag is encouraged to symbolise a European dimension. To avoid confusion with the European Union which subsequently adopted the same flag in the 1980s, as well as other European institutions, the Council of Europe often uses a modified version with a lower-case «e» surrounding the stars which are referred to as the «Council of Europe Logo».[115][116]

Criticism and controversies[edit]

The Council of Europe has been accused of not having any meaningful purpose, being superfluous in its aims to other pan-European bodies, including the European Union and OSCE.[117][118] In 2013 The Economist agreed, saying that the «Council of Europe’s credibility is on the line».[119] Both Human Rights Watch and the European Stability Initiative have called on the Council of Europe to undertake concrete actions to show that it is willing and able to return to its «original mission to protect and ensure human rights».[120]

In October 2022, a new and different Pan-European meeting of 44 states was held, as the «inaugural summit of the European Political Community», a new forum largely organized by French President Emmanuel Macron. The Council of Europe, sidelined, reportedly was «perplexed» with this development, with a spokesperson stating «In the field of human rights, democracy and the rule of law, such a pan-European community already exists: it is the Council of Europe.»[121] A feature of the new forum is that Russia and Belarus are deliberately excluded,[121] but that does not immediately explain the need for a different entity, Russia is no longer a member of the Council of Europe and Belarus only participates partially, as a non-member.

«Caviar diplomacy» scandal[edit]

After Azerbaijan joined the CoE in 2001, both the Council and its Parliamentary Assembly were criticized for having a weak response to election rigging and human rights violations in Azerbaijan.[122] The Human Rights Watch criticized the Council of Europe in 2014 for allowing Azerbaijan to assume the six-month rotating chairmanship of the council’s Committee of Ministers, writing that the Azeri government’s repression of human rights defenders, dissidents, and journalists «shows sheer contempt for its commitments to the Council of Europe».[123] An internal inquiry was set up in 2017 amid allegations of bribery by Azerbajian government officials and criticism of «caviar diplomacy at the Council.[124][125] A 219-page report was issued in 2018 after a ten-month investigation.[122] It concluded that several members of the Parliamentary Assembly broke CoE ethical rules and were «strongly suspected» of corruption; it strongly criticized former Parliamentary Assembly president Pedro Agramunt and suggested that he had engaged in «corruptive activities» before his resignation under pressure in 2017.[122] The inquiry also named Italian member Luca Volontè as a suspect in «activities of a corruptive nature».[122] Volontè was investigated by Italian police and accused by Italian prosecutors in 2017 of receiving over 2.39 million euros in bribes in exchange for working for Azerbaijan in the parliamentary assembly, and that in 2013 he played a key role in orchestrating the defeat of a highly critical report on the abuse of political prisoners in Azerbaijan.[124][125][126] In 2021, Volontè was convicted of accepting bribes from Azerbaijani officials to water down critiques of the nation’s human rights record, and he was sentenced by a court in Milan to four years in prison.[127]

See also[edit]

- CAHDI

- Common European Framework of Reference for Languages

- Conference of Specialised Ministers

- Council of Europe Archives

- The Europe Prize

- European Anti-fraud Office

- Film Award of the Council of Europe

- Moneyval

- International organisations in Europe, and co-ordinated organisations

- List of Council of Europe treaties

- List of linguistic rights in European constitutions

- North–South Centre of the Council of Europe

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c Transcontinental country straddling both Europe and Asia.

- ^ Depending on varying geographic definitions, some member states or portions thereof may be considered transcontinental or Eurasian (Armenia, Azerbaijan,[a] Cyprus, Georgia[a] and Turkey[a]), or belonging to the Americas (Dutch Caribbean, French Guiana, and Greenland), Oceania (French Polynesia), and Africa (Canary Islands, Ceuta, Mayotte, Melilla, and Réunion)

References[edit]

- ^ «Did you know?». Retrieved 1 November 2022.

English and French are the official languages of the Council of Europe.

- ^ «Profile: The Council of Europe». BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022.

- ^ Council of Europe, Budget, Retrieved: 21 April 2016

- ^ «The European flag — The Council of Europe in brief». The Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 20 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ «The European anthem — The Council of Europe in brief». The Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ «Do not get confused — The Council of Europe in brief». The Council of Europe. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ «Intergovernmental Organizations». United Nations. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018.

- ^ «European Commission – what it does | European Union». european-union.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «The role of the Council in international agreements». www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «The European Court of Human Rights — Council of Europe Office in Georgia — publi.coe.int». Council of Europe Office in Georgia. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Structure — The Council of Europe in brief — publi.coe.int». The Council of Europe in brief. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare — European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare — EDQM». European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & HealthCare. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Headquarters and offices — The Council of Europe in brief — publi.coe.int». The Council of Europe in brief. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «About the Council of Europe — Council of Europe Office in Yerevan — publi.coe.int». Council of Europe Office in Yerevan. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ a b «History — Language policy — publi.coe.int». Language policy. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Lumni | Enseignement — Discours d’Aristide Briand devant la SDN du 7 septembre 1929» [Lumni | Teaching — Speech by Aristide Briand to the SDN on September 7, 1929]. Fresques.ina.fr. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «National Address». International Churchill Society. 21 March 1943.

- ^ «Post-War Councils on World Problems: A FOUR YEAR PLAN FOR ENGLAND by WINSTON CHURCHILL, Prime Minister of Great Britain, broadcast from London over BBC, March 21, 1943».

- ^ «Winston Churchill and the Council of Europe». Council of Europe: Archiving and Documentary Resources. Council of Europe. 6 April 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2013., including audio extracts

- ^ «European Navigator (ENA)». Retrieved 4 April 2011. Including full transcript

- ^ Robertson, A. H. (1954). «The Council of Europe, 1949-1953: II». The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 3 (3): 404–420. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/3.3.404. ISSN 0020-5893. JSTOR 755483.

- ^ NATO. «Relations with the OSCE». NATO. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «About the Council of Europe». training.itcilo.org. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Parliamentary Assembly — No Hate Speech Youth Campaign — publi.coe.int». No Hate Speech Youth Campaign. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Spaak (11 December 1951). «Speeches made to the Parliamentary Assembly (1949–2018)». Assembly.coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Sandro Guerrieri, «From the Hague Congress to the Council of Europe: hopes, achievements and disappointments in the parliamentary way to European integration (1948–51).» Parliaments, Estates and Representation 34#2 (2014): 216-227.

- ^ «European Commission: Paul–Henri Spaak: a European visionary and talented persuader» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2016.

- ^ «Accession of Germany to the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, 2 May 1951) — CVCE Website». Cvce.eu. 2 May 1951. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ The Council of Europe in brief (5 May 1949). «Our member States». Coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «Speeches made to the Parliamentary Assembly (by Country)». Assembly.coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «All speeches by heads of state and government to PACE since 1949 online». Assembly.coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «Discours prononcés devant l’Assemblée parlementaire (1949–2018) — par pays» [Speeches delivered to the Parliamentary Assembly (1949–2018) – by country]. Assembly.coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «Statute of the Council of Europe». conventions.coe.int. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ «The Council of Europe and the European Union». www.coe.int.

- ^ «Universal Declaration of Human Rights». www.un.org.

- ^ a b c «Full list». Treaty Office. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ «Full list (Details of Treaty No.173)». Treaty Office. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ «Details of Treaty No.198: Council of Europe Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime and on the Financing of Terrorism». Treaty Office. Council of Europe.

- ^ «Details of Treaty No.174: Civil Law Convention on Corruption». Treaty Office. Council of Europe.

- ^ «Microsoft Word — Convention 197 Trafficking E.doc» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008.

- ^ «Details of Treaty No.210: Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence». Treaty Office. Council of Europe.

- ^ «Details of Treaty No.135: Anti-Doping Convention». Treaty Office. Council of Europe.

- ^ «2019 ICC Brochure». Council of Europe. 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ regjeringen.no (25 June 2014). «Thorbjørn Jagland». Government.no. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ «Jagland re-elected head of Council of Europe». POLITICO. 25 June 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ «History, Role, and Activities of the Council of Europe: Facts, Figures and Information Sources — GlobaLex». www.nyulawglobal.org. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Chairmanship». Committee of Ministers. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ «How it works». website-pace.net. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ «The establishment of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights — The first organisations and cooperative ventures in post-war Europe — CVCE Website». www.cvce.eu. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «PACE website». assembly.coe.int. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «In brief». Congress

of Local and Regional Authorities. Retrieved 13 December 2017. - ^ «History». Congress

of Local and Regional Authorities. Retrieved 13 December 2017. - ^ «European Court of Human Rights». International Justice Resource Center. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Full list (Chart of signatures and ratifications of Treaty 194)». Treaty Office. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ «Biography — Commissioner for Human Rights». Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ «Home». Coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «A word from the President on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Conference of INGOs of the Council of Europe». rm.coe.int. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017.

- ^ «About us». Coe.int. 14 February 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «European Steering Committee for Youth — Youth — publi.coe.int». Youth. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «About us — Youth — publi.coe.int». Youth. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ s.r.o, Appio Digital. «Eurimages — co-production, distribution and exhibition support | DOKweb». dokweb.net. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Home — Pompidou Group — publi.coe.int». Pompidou Group. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement — European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement — publi.coe.int». European and Mediterranean Major Hazards Agreement. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Enlarged Partial Agreement on Sport». Council of Europe.

- ^ Robertson, A. H. (1954). «The Council of Europe, 1949-1953: I». The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 3 (2): 235–255. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/3.2.235. ISSN 0020-5893. JSTOR 755535.

- ^ McManus, David (17 September 2008). «New General Building of Council of Europe». e-architect. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Inauguration of the Agora Building» (PDF) (Press release) (in French). Council of Europe. 30 January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008.

- ^ «2008 List of MIPIM winners».

- ^ «European Wergeland Centre». Archived from the original on 18 April 2009.

- ^ «List of external offices». Office of the Directorate General of Programmes. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ «List of external offices». Office of the Directorate General of Programmes. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ «Statute of the Council of Europe, London, 5.V.1949». Council of Europe.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Benoît-Rohmer, Florence; Klebes, Heinrich (June 2005). «Council of Europe law: Towards a pan-European legal area» (PDF). Council of Europe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- ^ «Statute of the Council of Europe is signed in London». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

On 5 May 1949, at St James’s Palace, London, the Foreign Ministers of Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom signed the Treaty establishing the Council of Europe.

- ^ «Turkey joins». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ «Turkey – Member state». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ «Turkey». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019. and Greece

- ^ «Greece – Member state». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

Greece and Turkey became the 11th and 12th member State of the Council of Europe on 9 August 1949.

- ^ «Iceland joins». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019..

- ^ «Iceland – Member state». Council of Europe. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

Iceland became the 13th member State of the Council of Europe on 7 March 1950.

- ^ «13 July 1950: Federal Republic of Germany joins the Council of Europe». Council of Europe.

- ^ Lansing Warren (3 May 1951), «Council of Europe Raises Bonn To the Status of a Full Member», The New York Times.

- ^ Carlos Lopez (2010), «Franco’s Spain and the Council of Europe», Archived 11 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Centre virtuel de la connaissance sur l’Europe.

- ^ a b 46 «Member States», Council of Europe.

- ^ «United States // Observer», Council of Europe.

- ^ a b c d Kanstantsin Dzehtsiarou & Donal K. Coffey, Suspension and expulsion of members of the Council of Europe: difficult decisions in troubled times, International & Comparative Law Quarterly, Vol. 68, Issue 2 (2019).

- ^ Vasilopoulou, Sofia. (2018) The party politics of Euroscepticism in times of crisis: The case of Greece. Politics, 38. DOI: 10.1177/0263395718770599.

- ^ a b c d e f Steven Erlanger, Council of Europe Restores Russia’s Voting Rights, New York Times (June 25, 2019).

- ^ Russia cancels payment to Council of Europe after claiming its delegates are being persecuted over Crimea, The Independent. 30 June 2017

- ^ a b «Russia withholds payments to the Council of Europe». Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b Buckley, Neil (26 November 2017). «Russia tests Council of Europe in push to regain vote». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ «A Classic Dilemma: Russia’s Threat to Withdraw from the Council of Europe». Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Weise, Zia (17 May 2019). «Council of Europe restores Russia’s voting rights». POLITICO. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ^ a b Steven Erlanger, The Council of Europe suspends Russia for its attack on Ukraine., New York Times (March 3, 2022).

- ^ Pooja Mehta, Russia withdraws from Council of Europe, JURIST (March 12, 2022).

- ^ «Council of Europe suspends Russia’s rights of representation». COE. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ «The Russian Federation is excluded from the Council of Europe» (Press release). Council of Europe. 16 March 2022.

- ^ «Russia Quits Europe’s Rule of Law Body, Sparking Questions Over Death Penalty». The Moscow Times. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Nilsen, Thomas. «Dmitry Medvedev vows to reintroduce death penalty». The Independent Barents Observer. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ «Full list — Treaty Office — publi.coe.int». Treaty Office. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «CoE Conventions». Conventions.coe.int. 31 December 1998. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ «The Council of Europe and the European Union — Portal — publi.coe.int». Portal. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ «Council of the European Union». European Union. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ «The Council of Europe and the European Union sign an agreement to foster mutual cooperation». Council of Europe. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ Juncker, Jean-Claude (2006). «Council of Europe – European Union: «A sole ambition for the European continent»» (PDF). Council of Europe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ «Draft treaty modifying the treaty on the European Union and the treaty establishing the European community» (PDF). Open Europe. 24 July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ «Home». Schoolsofpoliticalstudies.eu. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «Schools of Political Studies». Coe.int. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «The Council of Europe’s Relations with the United Nations». www.coe.int. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ «COUNCIL OF EUROPE COMMITTEE OF MINISTERS Resolution Res(2003)8 Participatory status for international non-governmental organisations with the Council of Europe (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 19 November 2003 at the 861st meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies)». wcd.coe.int. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ «UEFA and the Council of Europe sign Memorandum of Understanding». UEFA. 30 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ «Council of Europe and FIFA ink landmark deal on cooperation in shared areas». TASS (in Russian). Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ a b General Agreement on Privileges and Immunities of the Council of Europe, Council of Europe

- ^ Resolutions on the Council of Europe Staff Regulations, Council of Europe

- ^ a b «Flag, anthem and logo: the Council of Europe’s symbols». Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ «Logo of the Council of Europe». Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ «What is the Council of Europe?». BBC News. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Morgan, Sam (26 April 2017). «The Brief: Council of Europe in hunt for relevance». Euractiv.com. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ «Azerbaijan and the Council of Europe». The Economist. 23 March 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ European Stability Initiative. «What the 2014 Havel Prize says about the Council of Europe – and what should happen now». No. 29 September 2014. ESI web. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b Lorne Cook; Karel Janicek; Sylvie Corbet (6 October 2022). «Europe holds 44-leader summit, leaves Russia in the cold». Associated Press. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d «Council of Europe members suspected of corruption, inquiry reveals». The Guardian. 22 April 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (29 September 2014). «Azerbaijan: Government Repression Tarnishes Chairmanship Council of Europe’s Leadership Should Take Action». Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b Jennifer Rankin, Council of Europe urged to investigate Azerbaijan bribery allegations, The Guardian, 1 February 2017.

- ^ a b Matthew Valencia (19 June 2020). «Heaping on the Caviar Diplomacy». The Economist. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gabanelli, Milena. «Il Consiglio d’Europa e il caso Azerbaijan tra regali e milioni» [The Council of Europe and the Azerbaijan case between gifts and millions]. Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Zdravko Ljubas, Italian Court Sentences Former Council of Europe MP for Bribery, Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (January 14, 2021).

Further reading[edit]

- Dedman, Martin (2006). The Origins and Development of the European Union 1945–1995. doi:10.4324/9780203131817. ISBN 9780203131817.

- Dinan, Desmond. Europe Recast: A History of European Union (2nd ed. 2004). excerpt Archived 21 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine; the excerpt covers the historiography

- Gillingham, John. Coal, Steel, and the Rebirth of Europe, 1945–1955: The Germans and French from Ruhr Conflict to Economic Community (Cambridge UP, 2004).

- Guerrieri, Sandro (2014). «From the Hague Congress to the Council of Europe: Hopes, achievements and disappointments in the parliamentary way to European integration (1948–51)». Parliaments, Estates and Representation. 34 (2): 216–227. doi:10.1080/02606755.2014.952133. S2CID 142610321.

- Kopf, Susanne. Debating the European Union Transnationally: Wikipedians’ Construction of the EU on a Wikipedia Talk Page (2001–2015). (PhD dissertation Lancaster University, 2018)online.

- Moravcsik, Andrew. The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht (Cornell UP, 1998). ISBN 9780801435096. OCLC 925023272.

- Stone, Dan. Goodbye to All That?: The Story of Europe Since 1945 (Oxford UP, 2014).

- Urwin, Derek W. (2014). The Community of Europe. doi:10.4324/9781315843650. ISBN 9781315843650.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- General Agreement on Privileges and Immunities of the Council of Europe, Paris, 2 September 1949

| Conseil de l’Europe | |

Logo |

|

Flag |

|

|

|

| Abbreviation |

CoE |

|---|---|

| Formation | Treaty of London |

| Type | Regional intergovernmental organisation |

| Headquarters | Palace of Europe, Strasbourg, France |

| Location |

|

|

Membership |

|

|

Official languages |

English, French[1] |

|

Secretary General |

Marija Pejčinović Burić |

|

Deputy Secretary General |

Bjørn Berge |

|

President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe |

Tiny Kox |

|

Chair of the Committee of Ministers |

Þórdís Kolbrún R. Gylfadóttir |

|

President of the Congress |

Leendert Verbeek |

| Website | www.coe.int |

The Council of Europe (CoE; French: Conseil de l’Europe, CdE) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Europe.[2] Founded in 1949, it has 46 member states, with a population of approximately 675 million; it operates with an annual budget of approximately 500 million euros.[3]

The organisation is distinct from the European Union (EU), although it is sometimes confused with it, partly because the EU has adopted the original European flag, created for the Council of Europe in 1955,[4] as well as the European anthem.[5] No country has ever joined the EU without first belonging to the Council of Europe.[6] The Council of Europe is an official United Nations Observer.[7]

Being an international organisation, the Council of Europe cannot make laws,[8] but it does have the ability to push for the enforcement of select international agreements reached by member states on various topics.[9] The best-known body of the Council of Europe is the European Court of Human Rights, which functions on the basis of the European Convention on Human Rights.[10]