Как правильно пишется словосочетание «спинномозговая жидкость»

- Как правильно пишется слово «спинномозговой»

- Как правильно пишется слово «жидкость»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: вайма — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «спинномозговая жидкость»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «спинномозговая жидкость»

Предложения со словосочетанием «спинномозговая жидкость»

- Через несколько лет после этого я прошёл начальный курс биомеханической краниосакральной терапии, которая улучшает циркуляцию спинномозговой жидкости.

- Сканирование мозга, как и в предыдущем случае, показало, что основной объём мозга занимали желудочки, заполненные спинномозговой жидкостью.

- Для возникновения боли в голове более ранними и наиболее часто встречающимися являются симптомы, связанные с нарушениями венозного оттока или оттока спинномозговой жидкости из полости черепа.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «спинномозговая жидкость»

- Но когда мы выходим из нашей келейности и с дерзостью начинаем утверждать, что разговор об околоплодной жидкости есть единственный достойный женщины разговор — alors la police intervient et nous dit: halte-la, mesdames et messieurs! respectons la morale et n’embetons pas les passants par des mesquineries inutiles! [тогда вмешивается полиция и говорит нам: стойте-ка, милостивые государыни и милостивые государи! давайте уважать нравственность и не будем досаждать прохожим никчемными пустяками! (франц.)]

- Вероятно, это странное явление можно подвести под самый простой закон переливания жидкости из одного сосуда в другой: что убыло в одном, то прибыло в другом.

- Летят прочь оторванные лапы, белая густая жидкость выступает каплями из пронзенных яйцевидных мягких туловищ.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Сочетаемость слова «жидкость»

- прозрачная жидкость

тёмная жидкость

горячая жидкость - жидкости тела

жидкости организма

жидкость янтарного цвета - количество жидкости

капля жидкости

остатки жидкости - жидкость закипит

жидкость испарится

жидкость зашипела - выпить жидкость

глотнуть обжигающую жидкость

слить жидкость - (полная таблица сочетаемости)

Значение словосочетания «спинномозговая жидкость»

-

Спинномозгова́я жидкость (лат. liquor cerebrospinalis, цереброспина́льная жидкость, ли́квор) — жидкость, постоянно циркулирующая в желудочках головного мозга, ликворопроводящих путях, субарахноидальном (подпаутинном) пространстве головного и спинного мозга. (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «жидкость»

- Слава — жидкость мутного цвета, кисловатого вкуса и… в большом количестве она действует на слабые головы плохо, вызывая у принимающих ее тяжелое опьянение, подобное «пивному». Принимать эту микстуру следует осторожно. Не более одной чайной ложки в год; усиленные дозы вызывают ожирение сердца, опухоли чванства, заносчивости, самомнения, нетерпимости и вообще всякие болезненные уродства.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Смотрите также

Спинномозгова́я жидкость (лат. liquor cerebrospinalis, цереброспина́льная жидкость, ли́квор) — жидкость, постоянно циркулирующая в желудочках головного мозга, ликворопроводящих путях, субарахноидальном (подпаутинном) пространстве головного и спинного мозга.

Все значения словосочетания «спинномозговая жидкость»

-

Через несколько лет после этого я прошёл начальный курс биомеханической краниосакральной терапии, которая улучшает циркуляцию спинномозговой жидкости.

-

Сканирование мозга, как и в предыдущем случае, показало, что основной объём мозга занимали желудочки, заполненные спинномозговой жидкостью.

-

Для возникновения боли в голове более ранними и наиболее часто встречающимися являются симптомы, связанные с нарушениями венозного оттока или оттока спинномозговой жидкости из полости черепа.

- (все предложения)

- плевральная жидкость

- тканевая жидкость

- мозговая жидкость

- отёчная жидкость

- серозная жидкость

- (ещё синонимы…)

- спина

- (ещё ассоциации…)

- спинномозговая жидкость

- спинномозговые нервы

- корешки спинномозговых нервов

- анализ спинномозговой жидкости

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- прозрачная жидкость

- жидкости тела

- количество жидкости

- жидкость закипит

- выпить жидкость

- (полная таблица сочетаемости…)

- Разбор по составу слова «спинномозговой»

- Разбор по составу слова «жидкость»

- Как правильно пишется слово «спинномозговой»

- Как правильно пишется слово «жидкость»

| Cerebrospinal fluid | |

|---|---|

The cerebrospinal fluid circulates in the subarachnoid space around the brain and spinal cord, and in the ventricles of the brain. |

|

Image showing the location of CSF highlighting the brain’s ventricular system |

|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | liquor cerebrospinalis |

| Acronym(s) | CSF |

| MeSH | D002555 |

| TA98 | A14.1.01.203 |

| TA2 | 5388 |

| Anatomical terminology

[edit on Wikidata] |

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

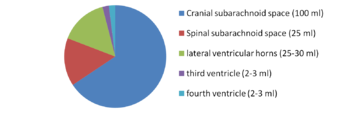

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain, and absorbed in the arachnoid granulations. There is about 125 mL of CSF at any one time, and about 500 mL is generated every day. CSF acts as a shock absorber, cushion or buffer, providing basic mechanical and immunological protection to the brain inside the skull. CSF also serves a vital function in the cerebral autoregulation of cerebral blood flow.

CSF occupies the subarachnoid space (between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater) and the ventricular system around and inside the brain and spinal cord. It fills the ventricles of the brain, cisterns, and sulci, as well as the central canal of the spinal cord. There is also a connection from the subarachnoid space to the bony labyrinth of the inner ear via the perilymphatic duct where the perilymph is continuous with the cerebrospinal fluid. The ependymal cells of the choroid plexus have multiple motile cilia on their apical surfaces that beat to move the CSF through the ventricles.

A sample of CSF can be taken from around the spinal cord via lumbar puncture. This can be used to test the intracranial pressure, as well as indicate diseases including infections of the brain or the surrounding meninges.

Although noted by Hippocrates, it was forgotten for centuries, though later was described in the 18th century by Emanuel Swedenborg. In 1914, Harvey Cushing demonstrated that CSF is secreted by the choroid plexus.

Structure[edit]

Circulation[edit]

MRI showing pulsation of CSF

There is about 125–150 mL of CSF at any one time.[1] This CSF circulates within the ventricular system of the brain. The ventricles are a series of cavities filled with CSF. The majority of CSF is produced from within the two lateral ventricles. From here, CSF passes through the interventricular foramina to the third ventricle, then the cerebral aqueduct to the fourth ventricle. From the fourth ventricle, the fluid passes into the subarachnoid space through four openings – the central canal of the spinal cord, the median aperture, and the two lateral apertures.[1] CSF is present within the subarachnoid space, which covers the brain, spinal cord, and stretches below the end of the spinal cord to the sacrum.[1][2] There is a connection from the subarachnoid space to the bony labyrinth of the inner ear making the cerebrospinal fluid continuous with the perilymph in 93% of people.[3]

CSF moves in a single outward direction from the ventricles, but multidirectionally in the subarachnoid space.[3] Fluid movement is pulsatile, matching the pressure waves generated in blood vessels by the beating of the heart.[3] Some authors dispute this, posing that there is no unidirectional CSF circulation, but cardiac cycle-dependent bi-directional systolic-diastolic to-and-from cranio-spinal CSF movements.[4]

Contents[edit]

CSF is derived from blood plasma and is largely similar to it, except that CSF is nearly protein-free compared with plasma and has some different electrolyte levels. Due to the way it is produced, CSF has a higher chloride level than plasma, and an equivalent sodium level.[2][5]

CSF contains approximately 0.3% plasma proteins, or approximately 15 to 40 mg/dL, depending on sampling site.[6] In general, globular proteins and albumin are in lower concentration in ventricular CSF compared to lumbar or cisternal fluid.[7] This continuous flow into the venous system dilutes the concentration of larger, lipid-insoluble molecules penetrating the brain and CSF.[8] CSF is normally free of red blood cells and at most contains fewer than 5 white blood cells per mm3 (if the white cell count is higher than this it constitutes pleocytosis and can indicate inflammation or infection).[9]

Development[edit]

At around the third week of development, the embryo is a three-layered disc, covered with ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. A tube-like formation develops in the midline, called the notochord. The notochord releases extracellular molecules that affect the transformation of the overlying ectoderm into nervous tissue.[10] The neural tube, forming from the ectoderm, contains CSF prior to the development of the choroid plexuses.[3] The open neuropores of the neural tube close after the first month of development, and CSF pressure gradually increases.[3]

As the brain develops, by the fourth week of embryological development three swellings have formed within the embryo around the canal, near where the head will develop. These swellings represent different components of the central nervous system: the prosencephalon, mesencephalon and rhombencephalon.[10] Subarachnoid spaces are first evident around the 32nd day of development near the rhombencephalon; circulation is visible from the 41st day.[3] At this time, the first choroid plexus can be seen, found in the fourth ventricle, although the time at which they first secrete CSF is not yet known.[3]

The developing forebrain surrounds the neural cord. As the forebrain develops, the neural cord within it becomes a ventricle, ultimately forming the lateral ventricles. Along the inner surface of both ventricles, the ventricular wall remains thin, and a choroid plexus develops, producing and releasing CSF.[10] CSF quickly fills the neural canal.[10] Arachnoid villi are formed around the 35th week of development, with arachnoid granulations noted around the 39th, and continuing developing until 18 months of age.[3]

The subcommissural organ secretes SCO-spondin, which forms Reissner’s fiber within CSF assisting movement through the cerebral aqueduct. It is present in early intrauterine life but disappears during early development.[3]

Physiology[edit]

Function[edit]

CSF serves several purposes:

- Buoyancy: The actual mass of the human brain is about 1400–1500 grams; however, the net weight of the brain suspended in CSF is equivalent to a mass of 25-50 grams.[11][1] The brain therefore exists in neutral buoyancy, which allows the brain to maintain its density without being impaired by its own weight, which would cut off blood supply and kill neurons in the lower sections without CSF.[5]

- Protection: CSF protects the brain tissue from injury when jolted or hit, by providing a fluid buffer that acts as a shock absorber from some forms of mechanical injury.[1][5]

- Prevention of brain ischemia: The prevention of brain ischemia is aided by decreasing the amount of CSF in the limited space inside the skull. This decreases total intracranial pressure and facilitates blood perfusion.[1]

- Homeostasis: CSF allows for regulation of the distribution of substances between cells of the brain,[3] and neuroendocrine factors, to which slight changes can cause problems or damage to the nervous system. For example, high glycine concentration disrupts temperature and blood pressure control, and high CSF pH causes dizziness and syncope.[5]

- Clearing waste: CSF allows for the removal of waste products from the brain,[1] and is critical in the brain’s lymphatic system, called the glymphatic system.[12] Metabolic waste products diffuse rapidly into CSF and are removed into the bloodstream as CSF is absorbed.[13] When this goes awry, CSF can be toxic, such as in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the commonest form of motor neuron disease.[14][15]

Production[edit]

| Substance | CSF | Serum |

|---|---|---|

| Water content (% wt) | 99 | 93 |

| Protein (mg/dL) | 35 | 7000 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 60 | 90 |

| Osmolarity (mOsm/L) | 295 | 295 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138 | 138 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 2.8 | 4.5 |

| Calcium (mEq/L) | 2.1 | 4.8 |

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 2.0–2.5[16] | 1.7 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 119 | 102 |

| pH | 7.33 | 7.41 |

|

Further information: List of reference ranges |

The brain produces roughly 500 mL of cerebrospinal fluid per day,[2] at a rate of about 25 mL an hour.[1] This transcellular fluid is constantly reabsorbed, so that only 125–150 mL is present at any one time.[1]

CSF volume is higher on a mL per kg body weight basis in children compared to adults. Infants have a CSF volume of 4 mL/kg, children have a CSF volume of 3 mL/kg, and adults have a CSF volume of 1.5–2 mL/kg. A high CSF volume is why a larger dose of local anesthetic, on a mL/kg basis, is needed in infants.[citation needed] Additionally, the larger CSF volume may be one reason as to why children have lower rates of postdural puncture headache.[17]

Most (about two-thirds to 80%) of CSF is produced by the choroid plexus.[1][2] The choroid plexus is a network of blood vessels present within sections of the four ventricles of the brain. It is present throughout the ventricular system except for the cerebral aqueduct, and the frontal and occipital horns of the lateral ventricles.[18] CSF is also produced by the single layer of column-shaped ependymal cells which line the ventricles; by the lining surrounding the subarachnoid space; and a small amount directly from the tiny spaces surrounding blood vessels around the brain.[2]

CSF is produced by the choroid plexus in two steps. Firstly, a filtered form of plasma moves from fenestrated capillaries in the choroid plexus into an interstitial space,[1] with movement guided by a difference in pressure between the blood in the capillaries and the interstitial fluid.[3] This fluid then needs to pass through the epithelium cells lining the choroid plexus into the ventricles, an active process requiring the transport of sodium, potassium and chloride that draws water into CSF by creating osmotic pressure.[3] Unlike blood passing from the capillaries into the choroid plexus, the epithelial cells lining the choroid plexus contain tight junctions between cells, which act to prevent most substances flowing freely into CSF.[19] Cilia on the apical surfaces of the ependymal cells beat to help transport the CSF.[20]

Water and carbon dioxide from the interstitial fluid diffuse into the epithelial cells. Within these cells, carbonic anhydrase converts the substances into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions. These are exchanged for sodium and chloride on the cell surface facing the interstitium.[3] Sodium, chloride, bicarbonate and potassium are then actively secreted into the ventricular lumen.[2][3] This creates osmotic pressure and draws water into CSF,[2] facilitated by aquaporins.[3] Chloride, with a negative charge, moves with the positively charged sodium, to maintain electroneutrality.[2] Potassium and bicarbonate are also transported out of CSF.[2] As a result, CSF contains a higher concentration of sodium and chloride than blood plasma, but less potassium, calcium and glucose and protein.[5] Choroid plexuses also secrete growth factors, iodine,[21] vitamins B1, B12, C, folate, beta-2 microglobulin, arginine vasopressin and nitric oxide into CSF.[3] A Na-K-Cl cotransporter and Na/K ATPase found on the surface of the choroid endothelium, appears to play a role in regulating CSF secretion and composition.[3][1]

Orešković and Klarica hypothesise that CSF is not primarily produced by the choroid plexus, but is being permanently produced inside the entire CSF system, as a consequence of water filtration through the capillary walls into the interstitial fluid of the surrounding brain tissue, regulated by AQP-4.[4]

There are circadian variations in CSF secretion, with the mechanisms not fully understood, but potentially relating to differences in the activation of the autonomic nervous system over the course of the day.[3]

Choroid plexus of the lateral ventricle produces CSF from the arterial blood provided by the anterior choroidal artery.[22] In the fourth ventricle, CSF is produced from the arterial blood from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (cerebellopontine angle and the adjacent part of the lateral recess), the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (roof and median opening), and the superior cerebellar artery.[23]

Reabsorption[edit]

CSF returns to the vascular system by entering the dural venous sinuses via arachnoid granulations.[2] These are outpouchings of the arachnoid mater into the venous sinuses around the brain, with valves to ensure one-way drainage.[2] This occurs because of a pressure difference between the arachnoid mater and venous sinuses.[3] CSF has also been seen to drain into lymphatic vessels,[24] particularly those surrounding the nose via drainage along the olfactory nerve through the cribriform plate. The pathway and extent are currently not known,[1] but may involve CSF flow along some cranial nerves and be more prominent in the neonate.[3] CSF turns over at a rate of three to four times a day.[2] CSF has also been seen to be reabsorbed through the sheathes of cranial and spinal nerve sheathes, and through the ependyma.[3]

Regulation[edit]

The composition and rate of CSF generation are influenced by hormones and the content and pressure of blood and CSF.[3] For example, when CSF pressure is higher, there is less of a pressure difference between the capillary blood in choroid plexuses and CSF, decreasing the rate at which fluids move into the choroid plexus and CSF generation.[3] The autonomic nervous system influences choroid plexus CSF secretion, with activation of the sympathetic nervous system decreasing secretion and the parasympathetic nervous system increasing it.[3] Changes in the pH of the blood can affect the activity of carbonic anhydrase, and some drugs (such as furosemide, acting on the Na-Cl cotransporter) have the potential to impact membrane channels.[3]

Clinical significance[edit]

Pressure[edit]

CSF pressure, as measured by lumbar puncture, is 10–18 cmH2O (8–15 mmHg or 1.1–2 kPa) with the patient lying on the side and 20–30 cmH2O (16–24 mmHg or 2.1–3.2 kPa) with the patient sitting up.[25] In newborns, CSF pressure ranges from 8 to 10 cmH2O (4.4–7.3 mmHg or 0.78–0.98 kPa). Most variations are due to coughing or internal compression of jugular veins in the neck. When lying down, the CSF pressure as estimated by lumbar puncture is similar to the intracranial pressure.

Hydrocephalus is an abnormal accumulation of CSF in the ventricles of the brain.[26] Hydrocephalus can occur because of obstruction of the passage of CSF, such as from an infection, injury, mass, or congenital abnormality.[26][27] Hydrocephalus without obstruction associated with normal CSF pressure may also occur.[26] Symptoms can include problems with gait and coordination, urinary incontinence, nausea and vomiting, and progressively impaired cognition.[27] In infants, hydrocephalus can cause an enlarged head, as the bones of the skull have not yet fused, seizures, irritability and drowsiness.[27] A CT scan or MRI scan may reveal enlargement of one or both lateral ventricles, or causative masses or lesions,[26][27] and lumbar puncture may be used to demonstrate and in some circumstances relieve high intracranial pressure.[28] Hydrocephalus is usually treated through the insertion of a shunt, such as a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt, which diverts fluid to another part of the body.[26][27]

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a condition of unknown cause characterized by a rise in CSF pressure. It is associated with headaches, double vision, difficulties seeing, and a swollen optic disc.[26] It can occur in association with the use of vitamin A and tetracycline antibiotics, or without any identifiable cause at all, particularly in younger obese women.[26] Management may include ceasing any known causes, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor such as acetazolamide, repeated drainage via lumbar puncture, or the insertion of a shunt such as a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.[26]

CSF leak[edit]

CSF can leak from the dura as a result of different causes such as physical trauma or a lumbar puncture, or from no known cause when it is termed a spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak.[29] It is usually associated with intracranial hypotension: low CSF pressure.[28] It can cause headaches, made worse by standing, moving and coughing,[28] as the low CSF pressure causes the brain to «sag» downwards and put pressure on its lower structures.[28] If a leak is identified, a beta-2 transferrin test of the leaking fluid, when positive, is highly specific and sensitive for the detection for CSF leakage.[29] Medical imaging such as CT scans and MRI scans can be used to investigate for a presumed CSF leak when no obvious leak is found but low CSF pressure is identified.[30] Caffeine, given either orally or intravenously, often offers symptomatic relief.[30] Treatment of an identified leak may include injection of a person’s blood into the epidural space (an epidural blood patch), spinal surgery, or fibrin glue.[30]

Lumbar puncture[edit]

Vials containing human cerebrospinal fluid

CSF can be tested for the diagnosis of a variety of neurological diseases, usually obtained by a procedure called lumbar puncture.[31] Lumbar puncture is carried out under sterile conditions by inserting a needle into the subarachnoid space, usually between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. CSF is extracted through the needle, and tested.[29] About one third of people experience a headache after lumbar puncture,[29] and pain or discomfort at the needle entry site is common. Rarer complications may include bruising, meningitis or ongoing post lumbar-puncture leakage of CSF.[1]

Testing often includes observing the colour of the fluid, measuring CSF pressure, and counting and identifying white and red blood cells within the fluid; measuring protein and glucose levels; and culturing the fluid.[29][31] The presence of red blood cells and xanthochromia may indicate subarachnoid hemorrhage; whereas central nervous system infections such as meningitis, may be indicated by elevated white blood cell levels.[31] A CSF culture may yield the microorganism that has caused the infection,[29] or PCR may be used to identify a viral cause.[31] Investigations to the total type and nature of proteins reveal point to specific diseases, including multiple sclerosis, paraneoplastic syndromes, systemic lupus erythematosus, neurosarcoidosis, cerebral angiitis;[1] and specific antibodies such as aquaporin-4 may be tested for to assist in the diagnosis of autoimmune conditions.[1] A lumbar puncture that drains CSF may also be used as part of treatment for some conditions, including idiopathic intracranial hypertension and normal pressure hydrocephalus.[1]

Lumbar puncture can also be performed to measure the intracranial pressure, which might be increased in certain types of hydrocephalus. However, a lumbar puncture should never be performed if increased intracranial pressure is suspected due to certain situations such as a tumour, because it can lead to fatal brain herniation.[29]

Anaesthesia and chemotherapy[edit]

Some anaesthetics and chemotherapy are injected intrathecally into the subarachnoid space, where they spread around CSF, meaning substances that cannot cross the blood–brain barrier can still be active throughout the central nervous system.[32][33] Baricity refers to the density of a substance compared to the density of human cerebrospinal fluid and is used in regional anesthesia to determine the manner in which a particular drug will spread in the intrathecal space.[32]

History[edit]

Various comments by ancient physicians have been read as referring to CSF. Hippocrates discussed «water» surrounding the brain when describing congenital hydrocephalus, and Galen referred to «excremental liquid» in the ventricles of the brain, which he believed was purged into the nose. But for some 16 intervening centuries of ongoing anatomical study, CSF remained unmentioned in the literature. This is perhaps because of the prevailing autopsy technique, which involved cutting off the head, thereby removing evidence of CSF before the brain was examined.[34]

The modern rediscovery of CSF is credited to Emanuel Swedenborg. In a manuscript written between 1741 and 1744, unpublished in his lifetime, Swedenborg referred to CSF as «spirituous lymph» secreted from the roof of the fourth ventricle down to the medulla oblongata and spinal cord. This manuscript was eventually published in translation in 1887.[34]

Albrecht von Haller, a Swiss physician and physiologist, made note in his 1747 book on physiology that the «water» in the brain was secreted into the ventricles and absorbed in the veins, and when secreted in excess, could lead to hydrocephalus.[34] François Magendie studied the properties of CSF by vivisection. He discovered the foramen Magendie, the opening in the roof of the fourth ventricle, but mistakenly believed that CSF was secreted by the pia mater.[34]

Thomas Willis (noted as the discoverer of the circle of Willis) made note of the fact that the consistency of CSF is altered in meningitis.[34] In 1869 Gustav Schwalbe proposed that CSF drainage could occur via lymphatic vessels.[1]

In 1891, W. Essex Wynter began treating tubercular meningitis by removing CSF from the subarachnoid space, and Heinrich Quincke began to popularize lumbar puncture, which he advocated for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.[34] In 1912, a neurologist William Mestrezat gave the first accurate description of the chemical composition of CSF.[34] In 1914, Harvey W. Cushing published conclusive evidence that CSF is secreted by the choroid plexus.[34]

Other animals[edit]

During phylogenesis, CSF is present within the neuraxis before it circulates.[3] The CSF of Teleostei fish is contained within the ventricles of the brains, but not in a nonexistent subarachnoid space.[3] In mammals, where a subarachnoid space is present, CSF is present in it.[3] Absorption of CSF is seen in amniotes and more complex species, and as species become progressively more complex, the system of absorption becomes progressively more enhanced, and the role of spinal epidural veins in absorption plays a progressively smaller and smaller role.[3]

The amount of cerebrospinal fluid varies by size and species.[35] In humans and other mammals, cerebrospinal fluid, produced, circulating, and reabsorbed in a similar manner to humans, and with a similar function, turns over at a rate of 3–5 times a day.[35] Problems with CSF circulation leading to hydrocephalus occur in other animals.[35]

See also[edit]

- Neuroglobin

- Pandy’s test

- Reissner’s fiber

- Syrinx (medicine)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Wright BL, Lai JT, Sinclair AJ (August 2012). «Cerebrospinal fluid and lumbar puncture: a practical review». Journal of Neurology. 259 (8): 1530–45. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6413-x. PMID 22278331. S2CID 2563483.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Guyton AC, Hall JE (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 764–7. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Sakka L, Coll G, Chazal J (December 2011). «Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid». European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 128 (6): 309–16. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2011.03.002. PMID 22100360.

- ^ a b Orešković D, Klarica M (2014). «A new look at cerebrospinal fluid movement». Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 11: 16. doi:10.1186/2045-8118-11-16. PMC 4118619. PMID 25089184.

- ^ a b c d e Saladin K (2012). Anatomy and Physiology (6th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 519–20.

- ^ Felgenhauer K (December 1974). «Protein size and cerebrospinal fluid composition». Klinische Wochenschrift. 52 (24): 1158–64. doi:10.1007/BF01466734. PMID 4456012. S2CID 19776406.

- ^ Merril CR, Goldman D, Sedman SA, Ebert MH (March 1981). «Ultrasensitive stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels shows regional variation in cerebrospinal fluid proteins». Science. 211 (4489): 1437–8. Bibcode:1981Sci…211.1437M. doi:10.1126/science.6162199. PMID 6162199.

- ^ Saunders NR, Habgood MD, Dziegielewska KM (January 1999). «Barrier mechanisms in the brain, I. Adult brain». Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 26 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.02986.x. PMID 10027064. S2CID 34773752.

- ^ Jurado R, Walker HK (1990). «Cerebrospinal Fluid». Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. ISBN 978-0409900774. PMID 21250239.

- ^ a b c d Schoenwolf GC, Larsen WJ (2009). «Development of the Brain and Cranial Nerves». Larsen’s human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.[page needed]

- ^ Noback C, Strominger NL, Demarest RJ, Ruggiero DA (2005). The Human Nervous System. Humana Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-58829-040-3.

- ^ Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. (August 2012). «A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β». Science Translational Medicine. 4 (147): 147ra111. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. PMC 3551275. PMID 22896675.

- ^ Ropper, Allan H.; Brown, Robert H. (March 29, 2005). «Chapter 30». Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 530.

- ^ Kwong KC, Gregory JM, Pal S, Chandran S, Mehta AR (2020). «Cerebrospinal fluid cytotoxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review of in vitro studies». Brain Communications. 2 (2): fcaa121. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcaa121. PMC 7566327. PMID 33094283.

- ^ Ng Kee Kwong KC, Mehta AR, Nedergaard M, Chandran S (August 2020). «Defining novel functions for cerebrospinal fluid in ALS pathophysiology». Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 8 (1): 140. doi:10.1186/s40478-020-01018-0. PMC 7439665. PMID 32819425.

- ^ Irani DN (14 April 2018). Cerebrospinal Fluid in Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781416029083. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^

- ^ Young PA (2007). Basic clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7817-5319-7.

- ^ Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 749. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Kishimoto N, Sawamoto K (February 2012). «Planar polarity of ependymal cilia». Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 83 (2): S86-90. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2011.10.007. PMID 22101065.

- ^ Venturi S, Venturi M (2014). «Iodine, PUFAs and Iodolipids in Health and Disease: An Evolutionary Perspective». Human Evolution. 29 (1–3): 185–205.

- ^ Zagórska-Swiezy K, Litwin JA, Gorczyca J, Pityński K, Miodoński AJ (August 2008). «Arterial supply and venous drainage of the choroid plexus of the human lateral ventricle in the prenatal period as revealed by vascular corrosion casts and SEM». Folia Morphologica. 67 (3): 209–13. PMID 18828104.

- ^ Sharifi M, Ciołkowski M, Krajewski P, Ciszek B (August 2005). «The choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle and its arteries». Folia Morphologica. 64 (3): 194–8. PMID 16228955.

- ^ Johnston M (2003). «The importance of lymphatics in cerebrospinal fluid transport». Lymphatic Research and Biology. 1 (1): 41–4, discussion 45. doi:10.1089/15396850360495682. PMID 15624320.

- ^ Agamanolis D (May 2011). «Chapter 14 – Cerebrospinal Fluid :THE NORMAL CSF». Neuropathology. Northeast Ohio Medical University. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH, eds. (2010). Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1220–1. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ a b c d e «Hydrocephalus Fact Sheet». www.ninds.nih.gov. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J (2015). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (19 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 2606–7. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH, eds. (2010). Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1147–8. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ a b c Rosen CL (October 2003). «Meningiomas: the role of preoperative angiography and embolization». Neurosurgical Focus. 15 (4): 1 p following ECP4. doi:10.3171/foc.2003.15.6.8. PMID 15376362.

- ^ a b c d Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA (September 2003). «Cerebrospinal fluid analysis». American Family Physician. 68 (6): 1103–8. PMID 14524396. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ a b Hocking G, Wildsmith JA (October 2004). «Intrathecal drug spread». British Journal of Anaesthesia. 93 (4): 568–78. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh204. PMID 15220175.

- ^ «Intrathecal Chemotherapy for Cancer Treatment | CTCA». CancerCenter.com. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hajdu SI (2003). «A note from history: discovery of the cerebrospinal fluid». Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 33 (3): 334–6. PMID 12956452.

- ^ a b c Reece WO (2013). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-118-68589-1.

External links[edit]

- Circulation of Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) – interactive tool

- Cerebrospinal fluid – course material in neuropathology

- Identification of the Cerebrospinal Fluid System Dynamics

| Cerebrospinal fluid | |

|---|---|

The cerebrospinal fluid circulates in the subarachnoid space around the brain and spinal cord, and in the ventricles of the brain. |

|

Image showing the location of CSF highlighting the brain’s ventricular system |

|

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | liquor cerebrospinalis |

| Acronym(s) | CSF |

| MeSH | D002555 |

| TA98 | A14.1.01.203 |

| TA2 | 5388 |

| Anatomical terminology

[edit on Wikidata] |

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the brain, and absorbed in the arachnoid granulations. There is about 125 mL of CSF at any one time, and about 500 mL is generated every day. CSF acts as a shock absorber, cushion or buffer, providing basic mechanical and immunological protection to the brain inside the skull. CSF also serves a vital function in the cerebral autoregulation of cerebral blood flow.

CSF occupies the subarachnoid space (between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater) and the ventricular system around and inside the brain and spinal cord. It fills the ventricles of the brain, cisterns, and sulci, as well as the central canal of the spinal cord. There is also a connection from the subarachnoid space to the bony labyrinth of the inner ear via the perilymphatic duct where the perilymph is continuous with the cerebrospinal fluid. The ependymal cells of the choroid plexus have multiple motile cilia on their apical surfaces that beat to move the CSF through the ventricles.

A sample of CSF can be taken from around the spinal cord via lumbar puncture. This can be used to test the intracranial pressure, as well as indicate diseases including infections of the brain or the surrounding meninges.

Although noted by Hippocrates, it was forgotten for centuries, though later was described in the 18th century by Emanuel Swedenborg. In 1914, Harvey Cushing demonstrated that CSF is secreted by the choroid plexus.

Structure[edit]

Circulation[edit]

MRI showing pulsation of CSF

There is about 125–150 mL of CSF at any one time.[1] This CSF circulates within the ventricular system of the brain. The ventricles are a series of cavities filled with CSF. The majority of CSF is produced from within the two lateral ventricles. From here, CSF passes through the interventricular foramina to the third ventricle, then the cerebral aqueduct to the fourth ventricle. From the fourth ventricle, the fluid passes into the subarachnoid space through four openings – the central canal of the spinal cord, the median aperture, and the two lateral apertures.[1] CSF is present within the subarachnoid space, which covers the brain, spinal cord, and stretches below the end of the spinal cord to the sacrum.[1][2] There is a connection from the subarachnoid space to the bony labyrinth of the inner ear making the cerebrospinal fluid continuous with the perilymph in 93% of people.[3]

CSF moves in a single outward direction from the ventricles, but multidirectionally in the subarachnoid space.[3] Fluid movement is pulsatile, matching the pressure waves generated in blood vessels by the beating of the heart.[3] Some authors dispute this, posing that there is no unidirectional CSF circulation, but cardiac cycle-dependent bi-directional systolic-diastolic to-and-from cranio-spinal CSF movements.[4]

Contents[edit]

CSF is derived from blood plasma and is largely similar to it, except that CSF is nearly protein-free compared with plasma and has some different electrolyte levels. Due to the way it is produced, CSF has a higher chloride level than plasma, and an equivalent sodium level.[2][5]

CSF contains approximately 0.3% plasma proteins, or approximately 15 to 40 mg/dL, depending on sampling site.[6] In general, globular proteins and albumin are in lower concentration in ventricular CSF compared to lumbar or cisternal fluid.[7] This continuous flow into the venous system dilutes the concentration of larger, lipid-insoluble molecules penetrating the brain and CSF.[8] CSF is normally free of red blood cells and at most contains fewer than 5 white blood cells per mm3 (if the white cell count is higher than this it constitutes pleocytosis and can indicate inflammation or infection).[9]

Development[edit]

At around the third week of development, the embryo is a three-layered disc, covered with ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm. A tube-like formation develops in the midline, called the notochord. The notochord releases extracellular molecules that affect the transformation of the overlying ectoderm into nervous tissue.[10] The neural tube, forming from the ectoderm, contains CSF prior to the development of the choroid plexuses.[3] The open neuropores of the neural tube close after the first month of development, and CSF pressure gradually increases.[3]

As the brain develops, by the fourth week of embryological development three swellings have formed within the embryo around the canal, near where the head will develop. These swellings represent different components of the central nervous system: the prosencephalon, mesencephalon and rhombencephalon.[10] Subarachnoid spaces are first evident around the 32nd day of development near the rhombencephalon; circulation is visible from the 41st day.[3] At this time, the first choroid plexus can be seen, found in the fourth ventricle, although the time at which they first secrete CSF is not yet known.[3]

The developing forebrain surrounds the neural cord. As the forebrain develops, the neural cord within it becomes a ventricle, ultimately forming the lateral ventricles. Along the inner surface of both ventricles, the ventricular wall remains thin, and a choroid plexus develops, producing and releasing CSF.[10] CSF quickly fills the neural canal.[10] Arachnoid villi are formed around the 35th week of development, with arachnoid granulations noted around the 39th, and continuing developing until 18 months of age.[3]

The subcommissural organ secretes SCO-spondin, which forms Reissner’s fiber within CSF assisting movement through the cerebral aqueduct. It is present in early intrauterine life but disappears during early development.[3]

Physiology[edit]

Function[edit]

CSF serves several purposes:

- Buoyancy: The actual mass of the human brain is about 1400–1500 grams; however, the net weight of the brain suspended in CSF is equivalent to a mass of 25-50 grams.[11][1] The brain therefore exists in neutral buoyancy, which allows the brain to maintain its density without being impaired by its own weight, which would cut off blood supply and kill neurons in the lower sections without CSF.[5]

- Protection: CSF protects the brain tissue from injury when jolted or hit, by providing a fluid buffer that acts as a shock absorber from some forms of mechanical injury.[1][5]

- Prevention of brain ischemia: The prevention of brain ischemia is aided by decreasing the amount of CSF in the limited space inside the skull. This decreases total intracranial pressure and facilitates blood perfusion.[1]

- Homeostasis: CSF allows for regulation of the distribution of substances between cells of the brain,[3] and neuroendocrine factors, to which slight changes can cause problems or damage to the nervous system. For example, high glycine concentration disrupts temperature and blood pressure control, and high CSF pH causes dizziness and syncope.[5]

- Clearing waste: CSF allows for the removal of waste products from the brain,[1] and is critical in the brain’s lymphatic system, called the glymphatic system.[12] Metabolic waste products diffuse rapidly into CSF and are removed into the bloodstream as CSF is absorbed.[13] When this goes awry, CSF can be toxic, such as in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the commonest form of motor neuron disease.[14][15]

Production[edit]

| Substance | CSF | Serum |

|---|---|---|

| Water content (% wt) | 99 | 93 |

| Protein (mg/dL) | 35 | 7000 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 60 | 90 |

| Osmolarity (mOsm/L) | 295 | 295 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138 | 138 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 2.8 | 4.5 |

| Calcium (mEq/L) | 2.1 | 4.8 |

| Magnesium (mEq/L) | 2.0–2.5[16] | 1.7 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 119 | 102 |

| pH | 7.33 | 7.41 |

|

Further information: List of reference ranges |

The brain produces roughly 500 mL of cerebrospinal fluid per day,[2] at a rate of about 25 mL an hour.[1] This transcellular fluid is constantly reabsorbed, so that only 125–150 mL is present at any one time.[1]

CSF volume is higher on a mL per kg body weight basis in children compared to adults. Infants have a CSF volume of 4 mL/kg, children have a CSF volume of 3 mL/kg, and adults have a CSF volume of 1.5–2 mL/kg. A high CSF volume is why a larger dose of local anesthetic, on a mL/kg basis, is needed in infants.[citation needed] Additionally, the larger CSF volume may be one reason as to why children have lower rates of postdural puncture headache.[17]

Most (about two-thirds to 80%) of CSF is produced by the choroid plexus.[1][2] The choroid plexus is a network of blood vessels present within sections of the four ventricles of the brain. It is present throughout the ventricular system except for the cerebral aqueduct, and the frontal and occipital horns of the lateral ventricles.[18] CSF is also produced by the single layer of column-shaped ependymal cells which line the ventricles; by the lining surrounding the subarachnoid space; and a small amount directly from the tiny spaces surrounding blood vessels around the brain.[2]

CSF is produced by the choroid plexus in two steps. Firstly, a filtered form of plasma moves from fenestrated capillaries in the choroid plexus into an interstitial space,[1] with movement guided by a difference in pressure between the blood in the capillaries and the interstitial fluid.[3] This fluid then needs to pass through the epithelium cells lining the choroid plexus into the ventricles, an active process requiring the transport of sodium, potassium and chloride that draws water into CSF by creating osmotic pressure.[3] Unlike blood passing from the capillaries into the choroid plexus, the epithelial cells lining the choroid plexus contain tight junctions between cells, which act to prevent most substances flowing freely into CSF.[19] Cilia on the apical surfaces of the ependymal cells beat to help transport the CSF.[20]

Water and carbon dioxide from the interstitial fluid diffuse into the epithelial cells. Within these cells, carbonic anhydrase converts the substances into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions. These are exchanged for sodium and chloride on the cell surface facing the interstitium.[3] Sodium, chloride, bicarbonate and potassium are then actively secreted into the ventricular lumen.[2][3] This creates osmotic pressure and draws water into CSF,[2] facilitated by aquaporins.[3] Chloride, with a negative charge, moves with the positively charged sodium, to maintain electroneutrality.[2] Potassium and bicarbonate are also transported out of CSF.[2] As a result, CSF contains a higher concentration of sodium and chloride than blood plasma, but less potassium, calcium and glucose and protein.[5] Choroid plexuses also secrete growth factors, iodine,[21] vitamins B1, B12, C, folate, beta-2 microglobulin, arginine vasopressin and nitric oxide into CSF.[3] A Na-K-Cl cotransporter and Na/K ATPase found on the surface of the choroid endothelium, appears to play a role in regulating CSF secretion and composition.[3][1]

Orešković and Klarica hypothesise that CSF is not primarily produced by the choroid plexus, but is being permanently produced inside the entire CSF system, as a consequence of water filtration through the capillary walls into the interstitial fluid of the surrounding brain tissue, regulated by AQP-4.[4]

There are circadian variations in CSF secretion, with the mechanisms not fully understood, but potentially relating to differences in the activation of the autonomic nervous system over the course of the day.[3]

Choroid plexus of the lateral ventricle produces CSF from the arterial blood provided by the anterior choroidal artery.[22] In the fourth ventricle, CSF is produced from the arterial blood from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (cerebellopontine angle and the adjacent part of the lateral recess), the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (roof and median opening), and the superior cerebellar artery.[23]

Reabsorption[edit]

CSF returns to the vascular system by entering the dural venous sinuses via arachnoid granulations.[2] These are outpouchings of the arachnoid mater into the venous sinuses around the brain, with valves to ensure one-way drainage.[2] This occurs because of a pressure difference between the arachnoid mater and venous sinuses.[3] CSF has also been seen to drain into lymphatic vessels,[24] particularly those surrounding the nose via drainage along the olfactory nerve through the cribriform plate. The pathway and extent are currently not known,[1] but may involve CSF flow along some cranial nerves and be more prominent in the neonate.[3] CSF turns over at a rate of three to four times a day.[2] CSF has also been seen to be reabsorbed through the sheathes of cranial and spinal nerve sheathes, and through the ependyma.[3]

Regulation[edit]

The composition and rate of CSF generation are influenced by hormones and the content and pressure of blood and CSF.[3] For example, when CSF pressure is higher, there is less of a pressure difference between the capillary blood in choroid plexuses and CSF, decreasing the rate at which fluids move into the choroid plexus and CSF generation.[3] The autonomic nervous system influences choroid plexus CSF secretion, with activation of the sympathetic nervous system decreasing secretion and the parasympathetic nervous system increasing it.[3] Changes in the pH of the blood can affect the activity of carbonic anhydrase, and some drugs (such as furosemide, acting on the Na-Cl cotransporter) have the potential to impact membrane channels.[3]

Clinical significance[edit]

Pressure[edit]

CSF pressure, as measured by lumbar puncture, is 10–18 cmH2O (8–15 mmHg or 1.1–2 kPa) with the patient lying on the side and 20–30 cmH2O (16–24 mmHg or 2.1–3.2 kPa) with the patient sitting up.[25] In newborns, CSF pressure ranges from 8 to 10 cmH2O (4.4–7.3 mmHg or 0.78–0.98 kPa). Most variations are due to coughing or internal compression of jugular veins in the neck. When lying down, the CSF pressure as estimated by lumbar puncture is similar to the intracranial pressure.

Hydrocephalus is an abnormal accumulation of CSF in the ventricles of the brain.[26] Hydrocephalus can occur because of obstruction of the passage of CSF, such as from an infection, injury, mass, or congenital abnormality.[26][27] Hydrocephalus without obstruction associated with normal CSF pressure may also occur.[26] Symptoms can include problems with gait and coordination, urinary incontinence, nausea and vomiting, and progressively impaired cognition.[27] In infants, hydrocephalus can cause an enlarged head, as the bones of the skull have not yet fused, seizures, irritability and drowsiness.[27] A CT scan or MRI scan may reveal enlargement of one or both lateral ventricles, or causative masses or lesions,[26][27] and lumbar puncture may be used to demonstrate and in some circumstances relieve high intracranial pressure.[28] Hydrocephalus is usually treated through the insertion of a shunt, such as a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt, which diverts fluid to another part of the body.[26][27]

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is a condition of unknown cause characterized by a rise in CSF pressure. It is associated with headaches, double vision, difficulties seeing, and a swollen optic disc.[26] It can occur in association with the use of vitamin A and tetracycline antibiotics, or without any identifiable cause at all, particularly in younger obese women.[26] Management may include ceasing any known causes, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor such as acetazolamide, repeated drainage via lumbar puncture, or the insertion of a shunt such as a ventriculoperitoneal shunt.[26]

CSF leak[edit]

CSF can leak from the dura as a result of different causes such as physical trauma or a lumbar puncture, or from no known cause when it is termed a spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leak.[29] It is usually associated with intracranial hypotension: low CSF pressure.[28] It can cause headaches, made worse by standing, moving and coughing,[28] as the low CSF pressure causes the brain to «sag» downwards and put pressure on its lower structures.[28] If a leak is identified, a beta-2 transferrin test of the leaking fluid, when positive, is highly specific and sensitive for the detection for CSF leakage.[29] Medical imaging such as CT scans and MRI scans can be used to investigate for a presumed CSF leak when no obvious leak is found but low CSF pressure is identified.[30] Caffeine, given either orally or intravenously, often offers symptomatic relief.[30] Treatment of an identified leak may include injection of a person’s blood into the epidural space (an epidural blood patch), spinal surgery, or fibrin glue.[30]

Lumbar puncture[edit]

Vials containing human cerebrospinal fluid

CSF can be tested for the diagnosis of a variety of neurological diseases, usually obtained by a procedure called lumbar puncture.[31] Lumbar puncture is carried out under sterile conditions by inserting a needle into the subarachnoid space, usually between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. CSF is extracted through the needle, and tested.[29] About one third of people experience a headache after lumbar puncture,[29] and pain or discomfort at the needle entry site is common. Rarer complications may include bruising, meningitis or ongoing post lumbar-puncture leakage of CSF.[1]

Testing often includes observing the colour of the fluid, measuring CSF pressure, and counting and identifying white and red blood cells within the fluid; measuring protein and glucose levels; and culturing the fluid.[29][31] The presence of red blood cells and xanthochromia may indicate subarachnoid hemorrhage; whereas central nervous system infections such as meningitis, may be indicated by elevated white blood cell levels.[31] A CSF culture may yield the microorganism that has caused the infection,[29] or PCR may be used to identify a viral cause.[31] Investigations to the total type and nature of proteins reveal point to specific diseases, including multiple sclerosis, paraneoplastic syndromes, systemic lupus erythematosus, neurosarcoidosis, cerebral angiitis;[1] and specific antibodies such as aquaporin-4 may be tested for to assist in the diagnosis of autoimmune conditions.[1] A lumbar puncture that drains CSF may also be used as part of treatment for some conditions, including idiopathic intracranial hypertension and normal pressure hydrocephalus.[1]

Lumbar puncture can also be performed to measure the intracranial pressure, which might be increased in certain types of hydrocephalus. However, a lumbar puncture should never be performed if increased intracranial pressure is suspected due to certain situations such as a tumour, because it can lead to fatal brain herniation.[29]

Anaesthesia and chemotherapy[edit]

Some anaesthetics and chemotherapy are injected intrathecally into the subarachnoid space, where they spread around CSF, meaning substances that cannot cross the blood–brain barrier can still be active throughout the central nervous system.[32][33] Baricity refers to the density of a substance compared to the density of human cerebrospinal fluid and is used in regional anesthesia to determine the manner in which a particular drug will spread in the intrathecal space.[32]

History[edit]

Various comments by ancient physicians have been read as referring to CSF. Hippocrates discussed «water» surrounding the brain when describing congenital hydrocephalus, and Galen referred to «excremental liquid» in the ventricles of the brain, which he believed was purged into the nose. But for some 16 intervening centuries of ongoing anatomical study, CSF remained unmentioned in the literature. This is perhaps because of the prevailing autopsy technique, which involved cutting off the head, thereby removing evidence of CSF before the brain was examined.[34]

The modern rediscovery of CSF is credited to Emanuel Swedenborg. In a manuscript written between 1741 and 1744, unpublished in his lifetime, Swedenborg referred to CSF as «spirituous lymph» secreted from the roof of the fourth ventricle down to the medulla oblongata and spinal cord. This manuscript was eventually published in translation in 1887.[34]

Albrecht von Haller, a Swiss physician and physiologist, made note in his 1747 book on physiology that the «water» in the brain was secreted into the ventricles and absorbed in the veins, and when secreted in excess, could lead to hydrocephalus.[34] François Magendie studied the properties of CSF by vivisection. He discovered the foramen Magendie, the opening in the roof of the fourth ventricle, but mistakenly believed that CSF was secreted by the pia mater.[34]

Thomas Willis (noted as the discoverer of the circle of Willis) made note of the fact that the consistency of CSF is altered in meningitis.[34] In 1869 Gustav Schwalbe proposed that CSF drainage could occur via lymphatic vessels.[1]

In 1891, W. Essex Wynter began treating tubercular meningitis by removing CSF from the subarachnoid space, and Heinrich Quincke began to popularize lumbar puncture, which he advocated for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.[34] In 1912, a neurologist William Mestrezat gave the first accurate description of the chemical composition of CSF.[34] In 1914, Harvey W. Cushing published conclusive evidence that CSF is secreted by the choroid plexus.[34]

Other animals[edit]

During phylogenesis, CSF is present within the neuraxis before it circulates.[3] The CSF of Teleostei fish is contained within the ventricles of the brains, but not in a nonexistent subarachnoid space.[3] In mammals, where a subarachnoid space is present, CSF is present in it.[3] Absorption of CSF is seen in amniotes and more complex species, and as species become progressively more complex, the system of absorption becomes progressively more enhanced, and the role of spinal epidural veins in absorption plays a progressively smaller and smaller role.[3]

The amount of cerebrospinal fluid varies by size and species.[35] In humans and other mammals, cerebrospinal fluid, produced, circulating, and reabsorbed in a similar manner to humans, and with a similar function, turns over at a rate of 3–5 times a day.[35] Problems with CSF circulation leading to hydrocephalus occur in other animals.[35]

See also[edit]

- Neuroglobin

- Pandy’s test

- Reissner’s fiber

- Syrinx (medicine)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Wright BL, Lai JT, Sinclair AJ (August 2012). «Cerebrospinal fluid and lumbar puncture: a practical review». Journal of Neurology. 259 (8): 1530–45. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6413-x. PMID 22278331. S2CID 2563483.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Guyton AC, Hall JE (2005). Textbook of medical physiology (11th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 764–7. ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Sakka L, Coll G, Chazal J (December 2011). «Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid». European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 128 (6): 309–16. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2011.03.002. PMID 22100360.

- ^ a b Orešković D, Klarica M (2014). «A new look at cerebrospinal fluid movement». Fluids and Barriers of the CNS. 11: 16. doi:10.1186/2045-8118-11-16. PMC 4118619. PMID 25089184.

- ^ a b c d e Saladin K (2012). Anatomy and Physiology (6th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 519–20.

- ^ Felgenhauer K (December 1974). «Protein size and cerebrospinal fluid composition». Klinische Wochenschrift. 52 (24): 1158–64. doi:10.1007/BF01466734. PMID 4456012. S2CID 19776406.

- ^ Merril CR, Goldman D, Sedman SA, Ebert MH (March 1981). «Ultrasensitive stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels shows regional variation in cerebrospinal fluid proteins». Science. 211 (4489): 1437–8. Bibcode:1981Sci…211.1437M. doi:10.1126/science.6162199. PMID 6162199.

- ^ Saunders NR, Habgood MD, Dziegielewska KM (January 1999). «Barrier mechanisms in the brain, I. Adult brain». Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 26 (1): 11–9. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.02986.x. PMID 10027064. S2CID 34773752.

- ^ Jurado R, Walker HK (1990). «Cerebrospinal Fluid». Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. ISBN 978-0409900774. PMID 21250239.

- ^ a b c d Schoenwolf GC, Larsen WJ (2009). «Development of the Brain and Cranial Nerves». Larsen’s human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.[page needed]

- ^ Noback C, Strominger NL, Demarest RJ, Ruggiero DA (2005). The Human Nervous System. Humana Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-58829-040-3.

- ^ Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. (August 2012). «A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β». Science Translational Medicine. 4 (147): 147ra111. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. PMC 3551275. PMID 22896675.

- ^ Ropper, Allan H.; Brown, Robert H. (March 29, 2005). «Chapter 30». Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 530.

- ^ Kwong KC, Gregory JM, Pal S, Chandran S, Mehta AR (2020). «Cerebrospinal fluid cytotoxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review of in vitro studies». Brain Communications. 2 (2): fcaa121. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcaa121. PMC 7566327. PMID 33094283.

- ^ Ng Kee Kwong KC, Mehta AR, Nedergaard M, Chandran S (August 2020). «Defining novel functions for cerebrospinal fluid in ALS pathophysiology». Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 8 (1): 140. doi:10.1186/s40478-020-01018-0. PMC 7439665. PMID 32819425.

- ^ Irani DN (14 April 2018). Cerebrospinal Fluid in Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781416029083. Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^

- ^ Young PA (2007). Basic clinical neuroscience (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7817-5319-7.

- ^ Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 749. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Kishimoto N, Sawamoto K (February 2012). «Planar polarity of ependymal cilia». Differentiation; Research in Biological Diversity. 83 (2): S86-90. doi:10.1016/j.diff.2011.10.007. PMID 22101065.

- ^ Venturi S, Venturi M (2014). «Iodine, PUFAs and Iodolipids in Health and Disease: An Evolutionary Perspective». Human Evolution. 29 (1–3): 185–205.

- ^ Zagórska-Swiezy K, Litwin JA, Gorczyca J, Pityński K, Miodoński AJ (August 2008). «Arterial supply and venous drainage of the choroid plexus of the human lateral ventricle in the prenatal period as revealed by vascular corrosion casts and SEM». Folia Morphologica. 67 (3): 209–13. PMID 18828104.

- ^ Sharifi M, Ciołkowski M, Krajewski P, Ciszek B (August 2005). «The choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle and its arteries». Folia Morphologica. 64 (3): 194–8. PMID 16228955.

- ^ Johnston M (2003). «The importance of lymphatics in cerebrospinal fluid transport». Lymphatic Research and Biology. 1 (1): 41–4, discussion 45. doi:10.1089/15396850360495682. PMID 15624320.

- ^ Agamanolis D (May 2011). «Chapter 14 – Cerebrospinal Fluid :THE NORMAL CSF». Neuropathology. Northeast Ohio Medical University. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH, eds. (2010). Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1220–1. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ a b c d e «Hydrocephalus Fact Sheet». www.ninds.nih.gov. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J (2015). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (19 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 2606–7. ISBN 978-0-07-180215-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colledge NR, Walker BR, Ralston SH, eds. (2010). Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 1147–8. ISBN 978-0-7020-3084-0.

- ^ a b c Rosen CL (October 2003). «Meningiomas: the role of preoperative angiography and embolization». Neurosurgical Focus. 15 (4): 1 p following ECP4. doi:10.3171/foc.2003.15.6.8. PMID 15376362.

- ^ a b c d Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA (September 2003). «Cerebrospinal fluid analysis». American Family Physician. 68 (6): 1103–8. PMID 14524396. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ a b Hocking G, Wildsmith JA (October 2004). «Intrathecal drug spread». British Journal of Anaesthesia. 93 (4): 568–78. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh204. PMID 15220175.

- ^ «Intrathecal Chemotherapy for Cancer Treatment | CTCA». CancerCenter.com. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hajdu SI (2003). «A note from history: discovery of the cerebrospinal fluid». Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 33 (3): 334–6. PMID 12956452.

- ^ a b c Reece WO (2013). Functional Anatomy and Physiology of Domestic Animals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-118-68589-1.

External links[edit]

- Circulation of Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) – interactive tool

- Cerebrospinal fluid – course material in neuropathology

- Identification of the Cerebrospinal Fluid System Dynamics

Спинномозговая жидкость

- Спинномозговая жидкость

-

цереброспинальная жидкость, ликвор (liquor cerebrospinalis), жидкая среда, циркулирующая в полостях желудочков головного мозга, спинномозгового канала и субарахноидальном (под паутинной оболочкой) пространстве головного и спинного мозга. В образовании С. ж. участвуют сосудистые сплетения, железистые клетки, эпендима и субэпендимальная ткань желудочков головного мозга, паутинная оболочка, глия и др. Отток осуществляется через венозные сплетения мозга, пазухи твёрдой мозговой оболочки, периневральные пространства черепно-мозговых и спинномозговых нервов. С. ж. — своего рода «водяная подушка», предохраняющая от наружных воздействий головной и спинной мозг; она регулирует внутричерепное давление, обеспечивает постоянство внутренней среды; посредством С. ж. осуществляется тканевой обмен в центральной нервной системе. С. ж. здорового человека — бесцветная, прозрачная; её количество у взрослого — 100—150 мл; удельный вес 1,006—1,007; реакция слабощелочная. Давление С. ж. различно на разных уровнях центральной нервной системы и зависит от положения тела (в горизонтальном положении — 100—200 мм вод. cm.). По химическому составу С. ж. сходна с сывороткой крови. Содержит 0—5 клеток в 1мм3 и 0,22—0,33% белка.

С диагностической и лечебной целью производят пункцию (См. Пункция) спинномозгового канала, позволяющую определить величину давления С. ж. и извлечь ее для анализа. При поражениях центральной нервной системы давление и состав (в частности, соотношение содержания белка и клеток) С. ж. изменяются. Давление С. ж. повышается при нарушении её оттока (травмы черепа и позвоночника, опухоли мозга, кровоизлияния и т.д.). При менингите обнаруживаются бактерии. Коллоидные реакции помогают, например, в диагностике сифилиса; биохимические исследования С. ж. (определение сахара, хлоридов, свободных аминокислот, ферментов и др.) — при распознавании нейроинфекций, эпилепсии и др.

Лит.: Шамбуров Д. A., Спинно-мозговая жидкость, М., 1954; Бургман Г. П., Лобкова Т. Н., Исследование спинномозговой жидкости, М., 1968; Макаров А. Ю., Современные биохимические исследования ликвора в неврологии, Л., 1973.

В. Б. Гельфанд.

Большая советская энциклопедия. — М.: Советская энциклопедия.

1969—1978.

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Спинномозговая жидкость» в других словарях:

-

СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ — (ликвор цереброспинальная жидкость), заполняет у позвоночных животных и человека полости спинного и головного мозга. По составу близка к лимфе. Исследование спинномозговой жидкости имеет диагностическое значение при некоторых заболеваниях … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ — СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ, см. ЦЕРЕБРОСПИНАЛЬНАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ … Научно-технический энциклопедический словарь

-

СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ — цереброспинальная жидкость, ликвор (liquor cerebrospinalis), жидкая среда, циркулирующая в полостях желудочков, субарахноидальном пространстве мозга и спинномозговом канале. Образуется в сосудистых сплетениях мозговых желудочков. Колебат.… … Биологический энциклопедический словарь

-

Спинномозговая жидкость — (ликвор, СМЖ) жидкость, циркулирующая в желудочковой системе головного мозга и субарахноидальных пространствах спинного и головного мозга. От остального организма отделена гематоэнцефалическим барьером. По составу молекул и клеток отличается от… … Словарь микробиологии

-

спинномозговая жидкость — (ликвор, цереброспинальная жидкость), заполняет у позвоночных животных и человека полости спинного и головного мозга. По составу близка к лимфе. Исследования спинномозговой жидкости имеют диагностическое значение при некоторых заболеваниях. * * * … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Спинномозговая жидкость — Пульсация ликвора при сердцебиении Спинномозговая жидкость, цереброспинальная жидкость (лат. liquor cerebrospinalis), ликвор жидкость, постоянно циркулирующая в желудочках головного мозга, ликворопроводящ … Википедия

-

Спинномозговая жидкость — I Спинномозговая жидкость см. Цереброспинальная жидкость. II Спинномозговая жидкость (liquor cerebrospinalis) см. Цереброспинальная жидкость … Медицинская энциклопедия

-

СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ — спинномозговая жидкость, цереброспинальная жидкость, ликвор, прозрачная, бесцветная жидкость, заполняющая желудочки головного мозга, спинномозговой канал и подпаутинные пространства спинного и головного мозга. Образуется в основном железистыми… … Ветеринарный энциклопедический словарь

-

спинномозговая жидкость — (liquor cerebrospinalis) см. Цереброспинальная жидкость … Большой медицинский словарь

-

СПИННОМОЗГОВАЯ ЖИДКОСТЬ — (ликвор, цереброспинальная жидкость), заполняет у позвоночных животных и человека полости спинного и головного мозга. По составу близка к лимфе. Иссл. С. ж. имеет диагностич. значение при нек рых заболеваниях … Естествознание. Энциклопедический словарь

Характеристика ликвора

- амортизировать – по сути, мозг практически ничем не прикреплен к костным структурам, поэтому в процессе перемещения человека подвергается нагрузке и трению, их-то и нивелирует ликвор;

- участие в обменных процессах – поскольку нервные ткани самостоятельно неспособны извлекать и доставлять питательные компоненты, а также молекулы кислорода, то за них эту функцию выполняет ликвор.

Циркуляция спинномозговой жидкости происходит постоянно и непрерывно – этим обеспечивается поддержка внутренней среды. В случае химических или функциональных сбоев человек сразу же ощущает ухудшение самочувствие в виде болей, затруднений передвижения, общей интоксикации. По характеру неприятных симптомов врачи судят о возможных причинах и назначают лабораторные исследования мозговой жидкости.

Состав ликвора

Цереброспинальная субстанция производится, в среднем, со скоростью около 0,40-0,45 мл в минуту (у взрослого). Объем, скорость продукции, а самое главное – компонентный состав ЦСЖ непосредственно зависит от метаболической активности и возраста организма. Обычно анализы отражают, что чем старше человек – тем сильнее снижено продуцирование.

Эта субстанция синтезируется из плазменной части крови, однако и субстрат, и продуцент существенно отличаются по ионному и клеточному содержанию. Основные компоненты:

- Белок.

- Глюкоза.

- Катионы: ионы натрия, калия, кальция и магния.

- Анионы: ионы хлора.

- Цитоз (наличие клеток в ликворе).

Повышенное содержание белка и клеточных скоплений указывает на отклонение от нормы, а значит – это состояние, что требует дальнейших анализов и обязательной консультации с лечащим врачом.

.jpg)

Подготовка к обследованию

Подготовка к анализу ликвора заключается в следующем:

- Берутся анализы крови (общий, на свертываемость).

- На предварительной консультации собирается анамнез. Пациенту нужно сообщить врачу данные о перенесенных заболеваниях, наличии хронических недугов, негативных реакциях на медикаменты.

- Сдавать спинномозговую жидкость необходимо натощак – за 12 часов до процедуры запрещается употребление пищи.

Перед обследованием не разрешен прием медикаментов, разжижающих кровь, а также анальгетиков и нестероидных противовоспалительных препаратов.

Анализ и исследования ликвора

Исследование церебрально-спинного пунктата – это метод, который применяют для выявления и диагностики различных расстройств мозговых структур и оболочек, центральной нервной системы. К таким патологиям относится:

- менингит, туберкулезный менингит;

- воспалительные процессы в оболочке;

- опухолевые образования;

- энцефалит;

- сифилис.

Проведение процедуры анализа и исследования СМ жидкости требует забора пробы в качестве пунктата из поясничного отдела спинного мозга. Забор производится через маленький точечный прокол в требуемой области позвоночника.

В полный анализ ЦСЖ входит макроскопическое и микроскопическое исследование, а также цитология, биохимия, бактериоскопия и бактериальный посев на питательную среду.

Ликвор в норме

Ликвор вырабатывается клетками желудочков головного мозга и выполняет ряд важнейших функций

Ликвор, как и кровь у человека, имеет ряд показателей, которые могут быть оценены с помощью лабораторных методов исследования. Спинномозговую жидкость для исследования получают при помощи люмбальной пункции, во время которой можно набрать однократно до 10 мл жидкости без осложнений для пациента.

Оценивают следующие показатели:

- Цвет и прозрачность.

- Спинномозговая жидкость в норме бесцветная, прозрачная и без запаха. На 99% ликвор состоит из воды, на оставшийся 1% приходится сухой остаток.

- Относительная плотность в норме составляет 1,006-1,007.

- Количество белка 0,2-0,33 гл.

- Количество глюкозы 2,8-3,9 ммольл.

- Количество Cl- (хлориды) 120-130 ммольл.

- Кислотность ликвора (рН) в норме 7,28-7,32. Если проницаемость гемато-энцефалического барьера не изменена, то рН спинномозговой жидкости остается в пределах нормы даже при изменении рН крови.

- Количество клеток в 1 мкл ликвора (цитоз) – до 4 клеток.

Цитологическое позволяет определить общее количество клеток в перерасчете на 1 мкл или 1л жидкости, а так же дифференцировать клеточные элементы (лимфоциты, нейтрофилы, в ряде случаев эритроциты и другие клетки). У взрослого человека в 1 л ликвора содержится от 3*106 до 5*106 клеток, а у детей первых трех месяцев жизни их количество достигает 20-25*106 /л.

Содержание лимфоцитов составляет 80-85%, нейтрофилов 3-5%.

Патологии ликвора и их последствия

В первую очередь, безусловно, специалисты обращают внимание на изменение окраски ликвора. Так, при желто-буром либо зеленовато-сером оттенке следует исключить опухолевое новообразование в мозге, реже течение гепатита. Тогда как красноватое окрашивание свидетельствует о возможном кровоизлиянии в желудочках и подпаутинном пространстве. Иногда подобный результат – следствие черепно-мозговой травмы.

Помутнение и присутствие осадка в ликворе – показание для экстренного медицинского вмешательства. Чаще всего замешены болезнетворные микроорганизмы, как причина инфекционного поражения мозга. Повышение же давления ликвора – указание на его чрезмерное скопление в мозговых полостях, к примеру, при сотрясениях и ушибах, переломах черепных костей или давления на ткани опухоли.

Обнаружение глюкозы в ликворе – предвестник или последствие сахарного диабета, энцефалита или даже столбняка. Врач порекомендует дополнительные обследования – магнитно-резонансную томографию, бактериологический посев жидкости, кровь на онкомаркеры, ПЦР-диагностику различных инфекций. Ведь установление точного диагноза способствует оптимальному подбору схемы лечения. При позднем обращении к врачу это функциях спинномозговой жидкости, что усугубляет ситуацию – развиваются метаболические расстройства, парезы и параличи, эпилепсия и деменция, а также летальный исход.

Для недопущения различных осложнений врачи призывают людей заботиться о собственном здоровье, отказаться от вредных привычек, правильно питаться и своевременно проходить профилактические медицинские осмотры.

Текущая версия страницы пока не проверялась опытными участниками и может значительно отличаться от версии, проверенной 6 июня 2015;

проверки требует 1 правка.

Пульсация ликвора при сердцебиении

Спинномозгова́я жидкость, цереброспина́льная жидкость (лат. liquor cerebrospinalis), ли́квор — жидкость, постоянно циркулирующая в желудочках головного мозга, ликворопроводящих путях, субарахноидальном (подпаутинном) пространстве головного и спинного мозга.

Функции[править | править вики-текст]

Предохраняет головной и спинной мозг от механических воздействий, обеспечивает поддержание постоянного внутричерепного давления и водно-электролитного гомеостаза. Поддерживает трофические и обменные процессы между кровью и мозгом, выделение продуктов его метаболизма. Флуктуация ликвора оказывает влияние на вегетативную нервную систему.

Образование[править | править вики-текст]

Основной объём цереброспинальной жидкости образуется путём активной секреции железистыми клетками сосудистых сплетений в желудочках головного мозга. Весомый вклад в формирование ликвора вносит глимфатическая система во время сна. Другим механизмом образования цереброспинальной жидкости является пропотевание плазмы крови через стенки кровеносных сосудов и эпендиму желудочков.

Циркуляция[править | править вики-текст]

Ликвор образуется в мозге: в эпендимальных клетках сосудистого сплетения (50—70 %), вокруг кровеносных сосудов и вдоль желудочковой стенки. Далее цереброспинальная жидкость циркулирует от боковых желудочков в отверстие Монро (межжелудочковое отверстия), затем вдоль третьего желудочка, проходит через Сильвиев водопровод. Затем проходит в четвертый желудочек, через отверстия Мажанди и Лушки выходит в субарахноидальное пространство головного и спинного мозга. Ликвор реабсорбируется в кровь венозных синусов и через грануляции паутинной оболочки.

Показатели ликвора здорового человека[править | править вики-текст]

(на 100—150 мл)

| Показатели | Значения |

|---|---|

| Относительная плотность | 1005—1009 |

| Давление | На территории бывшего СССР и ряде других стран принятая норма 100—200 мм вод. ст. По данным некоторых зарубежных авторов разброс больше: 60-240 мм вод.ст |

| Цвет | Бесцветная |

| Цитоз в 1 мкл | вентрикулярная жидкость 0—1 цистернальная жидкость 0—1 люмбальная жидкость 2—3 |

| Реакция, рН | 7,31—7,33 |

| Общий белок | 0,16—0,33 г/л |

| Глюкоза | 2,78—3,89 ммоль/л |

| Ионы хлора | 120—128 ммоль/л |

См. также[править | править вики-текст]

- Люмбальная пункция