Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher, LG, OM, DStJ, PC, FRS, HonFRSC (née Roberts; 13 October 1925 – 8 April 2013), was a British politician and stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime minister and the longest-serving British prime minister of the 20th century. As prime minister, she implemented economic policies that became known as Thatcherism. A Soviet journalist dubbed her the «Iron Lady«, a nickname that became associated with her uncompromising politics and leadership style.

|

The Right Honourable The Baroness Thatcher LG OM DStJ PC FRS HonFRSC |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

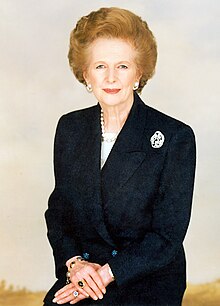

Studio portrait, c. 1995–96 |

|||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||

| In office 4 May 1979 – 28 November 1990 |

|||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||

| Deputy | Geoffrey Howe (1989–90) | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | James Callaghan | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | John Major | ||||||||||||

| Leader of the Opposition | |||||||||||||

| In office 11 February 1975 – 4 May 1979 |

|||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister |

|

||||||||||||

| Deputy | William Whitelaw | ||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | James Callaghan | ||||||||||||

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |||||||||||||

| In office 11 February 1975 – 28 November 1990 |

|||||||||||||

| Deputy | The Viscount Whitelaw | ||||||||||||

| Chairman |

See list

|

||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | John Major | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||

| Born |

Margaret Hilda Roberts 13 October 1925 |

||||||||||||

| Died | 8 April 2013 (aged 87) London, England |

||||||||||||

| Resting place | Royal Hospital Chelsea 51°29′21″N 0°09′22″W / 51.489057°N 0.156195°W |

||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Sir Denis Thatcher, 1st Bt (m. ; died ) |

||||||||||||

| Children |

|

||||||||||||

| Parent |

|

||||||||||||

| Education | Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ School | ||||||||||||

| Alma mater |

|

||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||

| Awards | List of honours | ||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||

| Website | Foundation | ||||||||||||

Thatcher studied chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford, and worked briefly as a research chemist, before becoming a barrister. She was elected Member of Parliament for Finchley in 1959. Edward Heath appointed her Secretary of State for Education and Science in his 1970–1974 government. In 1975, she defeated Heath in the Conservative Party leadership election to become Leader of the Opposition, the first woman to lead a major political party in the United Kingdom.

On becoming prime minister after winning the 1979 general election, Thatcher introduced a series of economic policies intended to reverse high inflation and Britain’s struggles in the wake of the Winter of Discontent and an oncoming recession.[nb 1] Her political philosophy and economic policies emphasised deregulation (particularly of the financial sector), the privatisation of state-owned companies, and reducing the power and influence of trade unions. Her popularity in her first years in office waned amid recession and rising unemployment. Victory in the 1982 Falklands War and the recovering economy brought a resurgence of support, resulting in her landslide re-election in 1983. She survived an assassination attempt by the Provisional IRA in the 1984 Brighton hotel bombing and achieved a political victory against the National Union of Mineworkers in the 1984–85 miners’ strike.

Thatcher was re-elected for a third term with another landslide in 1987, but her subsequent support for the Community Charge (also known as the «poll tax») was widely unpopular, and her increasingly Eurosceptic views on the European Community were not shared by others in her cabinet. She resigned as prime minister and party leader in 1990, after a challenge was launched to her leadership, and was succeeded by John Major, the Chancellor of the Exchequer.[nb 2] After retiring from the Commons in 1992, she was given a life peerage as Baroness Thatcher (of Kesteven in the County of Lincolnshire) which entitled her to sit in the House of Lords. In 2013, she died of a stroke at the Ritz Hotel, London, at the age of 87.

A polarising figure in British politics, Thatcher is nonetheless viewed favourably in historical rankings and public opinion of British prime ministers. Her tenure constituted a realignment towards neoliberal policies in Britain, with the complicated legacy attributed to Thatcherism debated into the 21st century.

Early life and education

2009 photograph of her father’s former shop[4]

Margaret and her elder sister were raised in the bottom of two flats on North Parade.[3]

Family and childhood (1925–1943)

Margaret Hilda Roberts was born on 13 October 1925, in Grantham, Lincolnshire.[6] Her parents were Alfred Roberts (1892–1970), from Northamptonshire, and Beatrice Ethel Stephenson (1888–1960), from Lincolnshire.[6][7] Her father’s maternal grandmother, Catherine Sullivan, was born in County Kerry, Ireland.[8]

Roberts spent her childhood in Grantham, where her father owned a tobacconist’s and a grocery shop. In 1938, before the Second World War, the Roberts family briefly gave sanctuary to a teenage Jewish girl who had escaped Nazi Germany. With her pen-friending elder sister Muriel, Margaret saved pocket money to help pay for the teenager’s journey.[9]

Alfred was an alderman and a Methodist local preacher.[10] He brought up his daughter as a strict Wesleyan Methodist,[11] attending the Finkin Street Methodist Church,[12] but Margaret was more sceptical; the future scientist told a friend that she could not believe in angels, having calculated that they needed a breastbone 6 feet (1.8 m) long to support wings.[13] Alfred came from a Liberal family but stood (as was then customary in local government) as an Independent. He served as Mayor of Grantham in 1945–46 and lost his position as alderman in 1952 after the Labour Party won its first majority on Grantham Council in 1950.[10]

1938 portrait, aged 12–13

Roberts attended Huntingtower Road Primary School and won a scholarship to Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ School, a grammar school.[6][14] Her school reports showed hard work and continual improvement; her extracurricular activities included the piano, field hockey, poetry recitals, swimming and walking.[15] She was head girl in 1942–43,[16] and outside school, while the Second World War was ongoing, she voluntarily worked as a fire watcher in the local ARP service.[17] Other students thought of Roberts as the «star scientist», although mistaken advice regarding cleaning ink from parquetry almost caused chlorine gas poisoning. In her upper sixth year Roberts was accepted for a scholarship to study chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford, a women’s college, starting in 1944. After another candidate withdrew, Roberts entered Oxford in October 1943.[18][13]

Oxford (1943–1947)

Roberts arrived at Oxford in 1943 and graduated in 1947 with a second-class degree in chemistry, after specialising in X-ray crystallography under the supervision of Dorothy Hodgkin.[19] Her dissertation was on the structure of the antibiotic gramicidin.[20] She also received the degree of Master of Arts in 1950 (as an Oxford BA, she was entitled to the degree 21 terms after her matriculation).[21] Roberts did not only study chemistry as she intended to be a chemist only for a short period of time,[22] already thinking about law and politics.[23] She was reportedly prouder of becoming the first prime minister with a science degree than becoming the first female prime minister.[24] While prime minister she attempted to preserve Somerville as a women’s college.[25] Twice a week outside study she worked in a local forces canteen.[26]

During her time at Oxford, Roberts was noted for her isolated and serious attitude.[13] Her first boyfriend, Tony Bray (1926–2014), recalled that she was «very thoughtful and a very good conversationalist. That’s probably what interested me. She was good at general subjects».[13][27] Roberts’s enthusiasm for politics as a girl made him think of her as «unusual» and her parents as «slightly austere» and «very proper».[13][27]

Roberts became President of the Oxford University Conservative Association in 1946.[28] She was influenced at university by political works such as Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom (1944),[29] which condemned economic intervention by government as a precursor to an authoritarian state.[30]

Post-Oxford career (1947–1951)

After graduating, Roberts moved to Colchester in Essex to work as a research chemist for BX Plastics.[31] In 1948 she applied for a job at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), but was rejected after the personnel department assessed her as «headstrong, obstinate and dangerously self-opinionated».[32] Jon Agar in Notes and Records argues that her understanding of modern scientific research later impacted her views as prime minister.[33]

Roberts joined the local Conservative Association and attended the party conference at Llandudno, Wales, in 1948, as a representative of the University Graduate Conservative Association.[34] Meanwhile, she became a high-ranking affiliate of the Vermin Club,[35][36] a group of grassroots Conservatives formed in response to a derogatory comment made by Aneurin Bevan.[36] One of her Oxford friends was also a friend of the Chair of the Dartford Conservative Association in Kent, who were looking for candidates.[34] Officials of the association were so impressed by her that they asked her to apply, even though she was not on the party’s approved list; she was selected in January 1950 (aged 24) and added to the approved list post ante.[37]

At a dinner following her formal adoption as Conservative candidate for Dartford in February 1949 she met divorcé Denis Thatcher, a successful and wealthy businessman, who drove her to her Essex train.[38] After their first meeting she described him to Muriel as «not a very attractive creature – very reserved but quite nice».[13] In preparation for the election Roberts moved to Dartford, where she supported herself by working as a research chemist for J. Lyons and Co. in Hammersmith, part of a team developing emulsifiers for ice cream.[39] She married at Wesley’s Chapel and her children were baptised there,[40] but she and her husband began attending Church of England services and would later convert to Anglicanism.[41][42]

Early political career

In the 1950 and 1951 general elections, Roberts was the Conservative candidate for the Labour seat of Dartford. The local party selected her as its candidate because, though not a dynamic public speaker, Roberts was well-prepared and fearless in her answers. A prospective candidate, Bill Deedes, recalled: «Once she opened her mouth, the rest of us began to look rather second-rate.»[24] She attracted media attention as the youngest and the only female candidate;[43] in 1950, she was the youngest Conservative candidate in the country.[44] She lost on both occasions to Norman Dodds, but reduced the Labour majority by 6,000, and then a further 1,000.[45] During the campaigns, she was supported by her parents and by future husband Denis Thatcher, whom she married in December 1951.[45][46] Denis funded his wife’s studies for the bar;[47] she qualified as a barrister in 1953 and specialised in taxation.[48] Later that same year their twins Carol and Mark were born, delivered prematurely by Caesarean section.[49]

Member of Parliament (1959–1970)

In 1954, Thatcher was defeated when she sought selection to be the Conservative Party candidate for the Orpington by-election of January 1955. She chose not to stand as a candidate in the 1955 general election, in later years stating: «I really just felt the twins were […] only two, I really felt that it was too soon. I couldn’t do that.»[50] Afterwards, Thatcher began looking for a Conservative safe seat and was selected as the candidate for Finchley in April 1958 (narrowly beating Ian Montagu Fraser). She was elected as MP for the seat after a hard campaign in the 1959 election.[51][52] Benefiting from her fortunate result in a lottery for backbenchers to propose new legislation,[24] Thatcher’s maiden speech was, unusually, in support of her private member’s bill, the Public Bodies (Admission to Meetings) Act 1960, requiring local authorities to hold their council meetings in public; the bill was successful and became law.[53][54] In 1961 she went against the Conservative Party’s official position by voting for the restoration of birching as a judicial corporal punishment.[55]

On the frontbenches

Thatcher’s talent and drive caused her to be mentioned as a future prime minister in her early 20s[24] although she herself was more pessimistic, stating as late as 1970: «There will not be a woman prime minister in my lifetime – the male population is too prejudiced.»[56] In October 1961 she was promoted to the frontbench as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry for Pensions by Harold Macmillan.[57] Thatcher was the youngest woman in history to receive such a post, and among the first MPs elected in 1959 to be promoted.[58] After the Conservatives lost the 1964 election, she became spokeswoman on Housing and Land, in which position she advocated her party’s policy of giving tenants the Right to Buy their council houses.[59] She moved to the Shadow Treasury team in 1966 and, as Treasury spokeswoman, opposed Labour’s mandatory price and income controls, arguing they would unintentionally produce effects that would distort the economy.[59]

Jim Prior suggested Thatcher as a Shadow Cabinet member after the Conservatives’ 1966 defeat, but party leader Edward Heath and Chief Whip William Whitelaw eventually chose Mervyn Pike as the Conservative Shadow Cabinet’s sole woman member.[58] At the 1966 Conservative Party conference, Thatcher criticised the high-tax policies of the Labour government as being steps «not only towards Socialism, but towards Communism», arguing that lower taxes served as an incentive to hard work.[59] Thatcher was one of the few Conservative MPs to support Leo Abse’s bill to decriminalise male homosexuality.[60] She voted in favour of David Steel’s bill to legalise abortion,[61][62] as well as a ban on hare coursing.[63] She supported the retention of capital punishment[64] and voted against the relaxation of divorce laws.[65][66]

In the Shadow Cabinet

In 1967, the United States Embassy chose Thatcher to take part in the International Visitor Leadership Program (then called the Foreign Leader Program), a professional exchange programme that allowed her to spend about six weeks visiting various US cities and political figures as well as institutions such as the International Monetary Fund. Although she was not yet a Shadow Cabinet member, the embassy reportedly described her to the State Department as a possible future prime minister. The description helped Thatcher meet with prominent people during a busy itinerary focused on economic issues, including Paul Samuelson, Walt Rostow, Pierre-Paul Schweitzer and Nelson Rockefeller. Following the visit, Heath appointed Thatcher to the Shadow Cabinet[58] as Fuel and Power spokeswoman.[67] Before the 1970 general election, she was promoted to Shadow Transport spokeswoman and later to Education.[68]

In 1968, Enoch Powell delivered his «Rivers of Blood» speech in which he strongly criticised Commonwealth immigration to the United Kingdom and the then-proposed Race Relations Bill. When Heath telephoned Thatcher to inform her that he would sack Powell from the Shadow Cabinet, she recalled that she «really thought that it was better to let things cool down for the present rather than heighten the crisis». She believed that his main points about Commonwealth immigration were correct and that the selected quotations from his speech had been taken out of context.[69] In a 1991 interview for Today, Thatcher stated that she thought Powell had «made a valid argument, if in sometimes regrettable terms».[70]

Around this time, she gave her first Commons speech as a shadow transport minister and highlighted the need for investment in British Rail. She argued: «[…] if we build bigger and better roads, they would soon be saturated with more vehicles and we would be no nearer solving the problem.»[71] Thatcher made her first visit to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1969 as the Opposition Transport spokeswoman, and in October delivered a speech celebrating her ten years in Parliament. In early 1970, she told The Finchley Press that she would like to see a «reversal of the permissive society».[72]

Education Secretary (1970–1974)

Thatcher abolished free milk for children aged 7–11 (pictured) in 1971 as her predecessor had done for older children in 1968.

The Conservative Party, led by Edward Heath, won the 1970 general election, and Thatcher was appointed to the Cabinet as Secretary of State for Education and Science. Thatcher caused controversy when, after only a few days in office, she withdrew Labour’s Circular 10/65 which attempted to force comprehensivisation, without going through a consultation process. She was highly criticised for the speed at which she carried this out.[73] Consequently, she drafted her own new policy (Circular 10/70), which ensured that local authorities were not forced to go comprehensive. Her new policy was not meant to stop the development of new comprehensives; she said: «We shall […] expect plans to be based on educational considerations rather than on the comprehensive principle.»[74]

Thatcher supported Lord Rothschild’s 1971 proposal for market forces to affect government funding of research. Although many scientists opposed the proposal, her research background probably made her sceptical of their claim that outsiders should not interfere with funding.[23] The department evaluated proposals for more local education authorities to close grammar schools and to adopt comprehensive secondary education. Although Thatcher was committed to a tiered secondary modern-grammar school system of education and attempted to preserve grammar schools,[75] during her tenure as education secretary she turned down only 326 of 3,612 proposals (roughly 9 per cent)[76] for schools to become comprehensives; the proportion of pupils attending comprehensive schools consequently rose from 32 per cent to 62 per cent.[77] Nevertheless, she managed to save 94 grammar schools.[74]

During her first months in office she attracted public attention due to the government’s attempts to cut spending. She gave priority to academic needs in schools,[75] while administering public expenditure cuts on the state education system, resulting in the abolition of free milk for schoolchildren aged seven to eleven.[78] She held that few children would suffer if schools were charged for milk but agreed to provide younger children with 0.3 imperial pints (0.17 l) daily for nutritional purposes.[78] She also argued that she was simply carrying on with what the Labour government had started since they had stopped giving free milk to secondary schools.[79] Milk would still be provided to those children that required it on medical grounds, and schools could still sell milk.[79] The aftermath of the milk row hardened her determination; she told the editor-proprietor Harold Creighton of The Spectator: «Don’t underestimate me, I saw how they broke Keith [Joseph], but they won’t break me.»[80]

Cabinet papers later revealed that she opposed the policy but had been forced into it by the Treasury.[81] Her decision provoked a storm of protest from Labour and the press,[82] leading to her being notoriously nicknamed «Margaret Thatcher, Milk Snatcher».[78][83] She reportedly considered leaving politics in the aftermath and later wrote in her autobiography: «I learned a valuable lesson. I had incurred the maximum of political odium for the minimum of political benefit.»[84]

Leader of the Opposition (1975–1979)

| External audio |

|---|

| 1975 speech to the US National Press Club |

|

Thatcher in late 1975 |

| National Press Club Luncheon Speakers: Margaret Thatcher (Speech).[85] (Starts at 7:39, finishes at 28:33.)[86] |

The Heath government continued to experience difficulties with oil embargoes and union demands for wage increases in 1973, subsequently losing the February 1974 general election.[82] Labour formed a minority government and went on to win a narrow majority in the October 1974 general election. Heath’s leadership of the Conservative Party looked increasingly in doubt. Thatcher was not initially seen as the obvious replacement, but she eventually became the main challenger, promising a fresh start.[87] Her main support came from the parliamentary 1922 Committee[87] and The Spectator,[88] but Thatcher’s time in office gave her the reputation of a pragmatist rather than that of an ideologue.[24] She defeated Heath on the first ballot and he resigned the leadership.[89] In the second ballot she defeated Whitelaw, Heath’s preferred successor. Thatcher’s election had a polarising effect on the party; her support was stronger among MPs on the right, and also among those from southern England, and those who had not attended public schools or Oxbridge.[90]

Thatcher became Conservative Party leader and Leader of the Opposition on 11 February 1975;[91] she appointed Whitelaw as her deputy. Heath was never reconciled to Thatcher’s leadership of the party.[92]

Television critic Clive James, writing in The Observer prior to her election as Conservative Party leader, compared her voice of 1973 to «a cat sliding down a blackboard».[nb 3] Thatcher had already begun to work on her presentation on the advice of Gordon Reece, a former television producer. By chance, Reece met the actor Laurence Olivier, who arranged lessons with the National Theatre’s voice coach.[94][95][nb 4]

Thatcher began attending lunches regularly at the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), a think tank founded by Hayekian poultry magnate Antony Fisher; she had been visiting the IEA and reading its publications since the early 1960s. There she was influenced by the ideas of Ralph Harris and Arthur Seldon, and became the face of the ideological movement opposing the British welfare state. Keynesian economics, they believed, was weakening Britain. The institute’s pamphlets proposed less government, lower taxes, and more freedom for business and consumers.[98]

Thatcher intended to promote neoliberal economic ideas at home and abroad. Despite setting the direction of her foreign policy for a Conservative government, Thatcher was distressed by her repeated failure to shine in the House of Commons. Consequently, Thatcher decided that as «her voice was carrying little weight at home», she would «be heard in the wider world».[99] Thatcher undertook visits across the Atlantic, establishing an international profile and promoting her economic and foreign policies. She toured the United States in 1975 and met President Gerald Ford,[100] visiting again in 1977, when she met President Jimmy Carter.[101] Among other foreign trips, she met Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi during a visit to Iran in 1978.[102] Thatcher chose to travel without being accompanied by her shadow foreign secretary, Reginald Maudling, in an attempt to make a bolder personal impact.[101]

In domestic affairs, Thatcher opposed Scottish devolution (home rule) and the creation of a Scottish Assembly. She instructed Conservative MPs to vote against the Scotland and Wales Bill in December 1976, which was successfully defeated, and then when new Bills were proposed she supported amending the legislation to allow the English to vote in the 1979 referendum on Scottish devolution.[103]

Britain’s economy during the 1970s was so weak that then Foreign Secretary James Callaghan warned his fellow Labour Cabinet members in 1974 of the possibility of «a breakdown of democracy», telling them: «If I were a young man, I would emigrate.»[104] In mid-1978, the economy began to recover, and opinion polls showed Labour in the lead, with a general election being expected later that year and a Labour win a serious possibility. Now prime minister, Callaghan surprised many by announcing on 7 September that there would be no general election that year, and he would wait until 1979 before going to the polls. Thatcher reacted to this by branding the Labour government «chickens», and Liberal Party leader David Steel joined in, criticising Labour for «running scared».[105]

The Labour government then faced fresh public unease about the direction of the country and a damaging series of strikes during the winter of 1978–79, dubbed the «Winter of Discontent». The Conservatives attacked the Labour government’s unemployment record, using advertising with the slogan «Labour Isn’t Working». A general election was called after the Callaghan ministry lost a motion of no confidence in early 1979. The Conservatives won a 44-seat majority in the House of Commons, and Thatcher became the first female British prime minister.[106]

«The ‘Iron Lady‘«

| External video |

|---|

| 1976 speech to Finchley Conservatives |

| Speech to Finchley Conservatives (admits to being an «Iron Lady») (Speech) – via the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.[107] |

I stand before you tonight in my Red Star chiffon evening gown, my face softly made up and my fair hair gently waved, the Iron Lady of the Western world.[107]

— Thatcher embracing her Soviet nickname in 1976

In 1976, Thatcher gave her «Britain Awake» foreign policy speech which lambasted the Soviet Union, saying it was «bent on world dominance».[108] The Soviet Army journal Red Star reported her stance in a piece headlined «Iron Lady Raises Fears»,[109] alluding to her remarks on the Iron Curtain.[108] The Sunday Times covered the Red Star article the next day,[110] and Thatcher embraced the epithet a week later; in a speech to Finchley Conservatives she likened it to the Duke of Wellington’s nickname «The Iron Duke».[107] The «Iron» metaphor followed her throughout ever since,[111] and would become a generic sobriquet for other strong-willed female politicians.[112]

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1979–1990)

| External video |

|---|

| 1979 remarks on becoming prime minister |

|

Thatcher arriving at 10 Downing Street |

| Remarks on becoming Prime Minister (St Francis’s prayer) (Speech) – via the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.[113] |

Thatcher became prime minister on 4 May 1979. Arriving at Downing Street she said, paraphrasing the Prayer of Saint Francis:

Where there is discord, may we bring harmony;

Where there is error, may we bring truth;

Where there is doubt, may we bring faith;

And where there is despair, may we bring hope.[113]

In office throughout the 1980s, Thatcher was frequently referred to as the most powerful woman in the world.[114][115][116]

Domestic affairs

Minorities

Thatcher was Opposition leader and prime minister at a time of increased racial tension in Britain. On the local elections of 1977, The Economist commented: «The Tory tide swamped the smaller parties—specifically the National Front [NF], which suffered a clear decline from last year.»[117][118] Her standing in the polls had risen by 11% after a 1978 interview for World in Action in which she said «the British character has done so much for democracy, for law and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in», as well as «in many ways [minorities] add to the richness and variety of this country. The moment the minority threatens to become a big one, people get frightened».[119][120] In the 1979 general election, the Conservatives had attracted votes from the NF, whose support almost collapsed.[121] In a July 1979 meeting with Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington and Home Secretary William Whitelaw, Thatcher objected to the number of Asian immigrants, in the context of limiting the total of Vietnamese boat people allowed to settle in the UK to fewer than 10,000 over two years.[122]

The Queen

As prime minister, Thatcher met weekly with Queen Elizabeth II to discuss government business, and their relationship came under scrutiny.[123] Campbell (2011a, p. 464) states:

One question that continued to fascinate the public about the phenomenon of a woman Prime Minister was how she got on with the Queen. The answer is that their relations were punctiliously correct, but there was little love lost on either side. As two women of very similar age – Mrs Thatcher was six months older – occupying parallel positions at the top of the social pyramid, one the head of government, the other head of state, they were bound to be in some sense rivals. Mrs Thatcher’s attitude to the Queen was ambivalent. On the one hand she had an almost mystical reverence for the institution of the monarchy […] Yet at the same time she was trying to modernise the country and sweep away many of the values and practices which the monarchy perpetuated.

Michael Shea, the Queen’s press secretary, in 1986 leaked stories of a deep rift to The Sunday Times. He said that she felt Thatcher’s policies were «uncaring, confrontational and socially divisive».[124] Thatcher later wrote: «I always found the Queen’s attitude towards the work of the Government absolutely correct […] stories of clashes between ‘two powerful women’ were just too good not to make up.»[125]

Economy and taxation

| Economic growth and public spending % change in real terms: 1979/80 to 1989/90 |

|

|---|---|

| Economic growth (GDP) | +23.3 |

| Total government spending | +12.9 |

| Law and order | +53.3 |

| Employment and training | +33.3 |

| NHS | +31.8 |

| Social security | +31.8 |

| Education | +13.7 |

| Defence | +9.2 |

| Environment | +7.9 |

| Transport | −5.8 |

| Trade and industry | −38.2 |

| Housing | −67.0 |

Thatcher’s economic policy was influenced by monetarist thinking and economists such as Milton Friedman and Alan Walters.[126] Together with her first chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, she lowered direct taxes on income and increased indirect taxes.[127] She increased interest rates to slow the growth of the money supply, and thereby lower inflation;[126] introduced cash limits on public spending and reduced expenditure on social services such as education and housing.[127] Cuts to higher education led to Thatcher being the first Oxonian post-war prime minister without an honorary doctorate from Oxford University, after a 738–319 vote of the governing assembly and a student petition.[128]

Some Heathite Conservatives in the Cabinet, the so-called «wets», expressed doubt over Thatcher’s policies.[129] The 1981 England riots resulted in the British media discussing the need for a policy U-turn. At the 1980 Conservative Party conference, Thatcher addressed the issue directly, with a speech written by the playwright Ronald Millar,[130] that notably included the following lines:

To those waiting with bated breath for that favourite media catchphrase, the «U» turn, I have only one thing to say. «You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning.»[131]

Thatcher’s job approval rating fell to 23% by December 1980, lower than recorded for any previous prime minister.[132] As the recession of the early 1980s deepened, she increased taxes,[133] despite concerns expressed in a March 1981 statement signed by 364 leading economists,[134] which argued there was «no basis in economic theory […] for the Government’s belief that by deflating demand they will bring inflation permanently under control», adding that «present policies will deepen the depression, erode the industrial base of our economy and threaten its social and political stability».[135]

By 1982, the UK began to experience signs of economic recovery;[136] inflation was down to 8.6% from a high of 18%, but unemployment was over 3 million for the first time since the 1930s.[137] By 1983, overall economic growth was stronger, and inflation and mortgage rates had fallen to their lowest levels in 13 years, although manufacturing employment as a share of total employment fell to just over 30%,[138] with total unemployment remaining high, peaking at 3.3 million in 1984.[139]

During the 1982 Conservative Party Conference, Thatcher said: «We have done more to roll back the frontiers of socialism than any previous Conservative Government.»[140] She said at the Party Conference the following year that the British people had completely rejected state socialism and understood «the state has no source of money other than money which people earn themselves […] There is no such thing as public money; there is only taxpayers’ money.»[141]

By 1987, unemployment was falling, the economy was stable and strong, and inflation was low. Opinion polls showed a comfortable Conservative lead, and local council election results had also been successful, prompting Thatcher to call a general election for 11 June that year, despite the deadline for an election still being 12 months away. The election saw Thatcher re-elected for a third successive term.[142]

Thatcher had been firmly opposed to British membership of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM, a precursor to European Economic and Monetary Union), believing that it would constrain the British economy,[143] despite the urging of both Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson and Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe;[144] in October 1990 she was persuaded by John Major, Lawson’s successor as Chancellor, to join the ERM at what proved to be too high a rate.[145]

Thatcher reformed local government taxes by replacing domestic rates (a tax based on the nominal rental value of a home) with the Community Charge (or poll tax) in which the same amount was charged to each adult resident.[146] The new tax was introduced in Scotland in 1989 and in England and Wales the following year,[147] and proved to be among the most unpopular policies of her premiership.[146] Public disquiet culminated in a 70,000 to 200,000-strong[148] demonstration in London in March 1990; the demonstration around Trafalgar Square deteriorated into riots, leaving 113 people injured and 340 under arrest.[149] The Community Charge was abolished in 1991 by her successor, John Major.[149] It has since transpired that Thatcher herself had failed to register for the tax, and was threatened with financial penalties if she did not return her form.[150]

Industrial relations

Thatcher believed that the trade unions were harmful to both ordinary trade unionists and the public.[151] She was committed to reducing the power of the unions, whose leadership she accused of undermining parliamentary democracy and economic performance through strike action.[152] Several unions launched strikes in response to legislation introduced to limit their power, but resistance eventually collapsed.[153] Only 39% of union members voted Labour in the 1983 general election.[154] According to the BBC’s political correspondent in 2004, Thatcher «managed to destroy the power of the trade unions for almost a generation».[155] The miners’ strike of 1984–85 was the biggest and most devastating confrontation between the unions and the Thatcher government.[156]

Pro-strike rally in London, 1984

In March 1984, the National Coal Board (NCB) proposed to close 20 of the 174 state-owned mines and cut 20,000 jobs out of 187,000.[157][158][159] Two-thirds of the country’s miners, led by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) under Arthur Scargill, downed tools in protest.[157][160][161] However, Scargill refused to hold a ballot on the strike,[162] having previously lost three ballots on a national strike (in January and October 1982, and March 1983).[163] This led to the strike being declared illegal by the High Court of Justice.[164][165]

Thatcher refused to meet the union’s demands and compared the miners’ dispute to the Falklands War, declaring in a speech in 1984: «We had to fight the enemy without in the Falklands. We always have to be aware of the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight and more dangerous to liberty.»[166] Thatcher’s opponents misrepresented her words as indicating contempt for the working class and have been employed in criticism of her ever since.[167]

After a year out on strike in March 1985, the NUM leadership conceded without a deal. The cost to the economy was estimated to be at least £1.5 billion, and the strike was blamed for much of the pound’s fall against the US dollar.[168] Thatcher reflected on the end of the strike in her statement that «if anyone has won» it was «the miners who stayed at work» and all those «that have kept Britain going».[169]

The government closed 25 unprofitable coal mines in 1985, and by 1992 a total of 97 mines had been closed;[159] those that remained were privatised in 1994.[170] The resulting closure of 150 coal mines, some of which were not losing money, resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of jobs and had the effect of devastating entire communities.[159] Strikes had helped bring down Heath’s government, and Thatcher was determined to succeed where he had failed. Her strategy of preparing fuel stocks, appointing hardliner Ian MacGregor as NCB leader, and ensuring that police were adequately trained and equipped with riot gear contributed to her triumph over the striking miners.[171]

The number of stoppages across the UK peaked at 4,583 in 1979, when more than 29 million working days had been lost. In 1984, the year of the miners’ strike, there were 1,221, resulting in the loss of more than 27 million working days. Stoppages then fell steadily throughout the rest of Thatcher’s premiership; in 1990, there were 630 and fewer than 2 million working days lost, and they continued to fall thereafter.[172] Thatcher’s tenure also witnessed a sharp decline in trade union density, with the percentage of workers belonging to a trade union falling from 57.3% in 1979 to 49.5% in 1985.[173] In 1979 up until Thatcher’s final year in office, trade union membership also fell, from 13.5 million in 1979 to fewer than 10 million.[174]

Privatisation

The policy of privatisation has been called «a crucial ingredient of Thatcherism».[175] After the 1983 election the sale of state utilities accelerated;[176] more than £29 billion was raised from the sale of nationalised industries, and another £18 billion from the sale of council houses.[177] The process of privatisation, especially the preparation of nationalised industries for privatisation, was associated with marked improvements in performance, particularly in terms of labour productivity.[178]

Some of the privatised industries, including gas, water, and electricity, were natural monopolies for which privatisation involved little increase in competition. The privatised industries that demonstrated improvement sometimes did so while still under state ownership. British Steel Corporation had made great gains in profitability while still a nationalised industry under the government-appointed MacGregor chairmanship, which faced down trade-union opposition to close plants and halve the workforce.[179] Regulation was also significantly expanded to compensate for the loss of direct government control, with the foundation of regulatory bodies such as Oftel (1984), Ofgas (1986), and the National Rivers Authority (1989).[180] There was no clear pattern to the degree of competition, regulation, and performance among the privatised industries.[178]

In most cases, privatisation benefited consumers in terms of lower prices and improved efficiency, but results overall have been mixed.[181] Not all privatised companies have had successful share price trajectories in the longer term.[182] A 2010 review by the IEA states: «[I]t does seem to be the case that once competition and/or effective regulation was introduced, performance improved markedly […] But I hasten to emphasise again that the literature is not unanimous.»[183]

Thatcher always resisted privatising British Rail and was said to have told Transport Secretary Nicholas Ridley: «Railway privatisation will be the Waterloo of this government. Please never mention the railways to me again.» Shortly before her resignation in 1990, she accepted the arguments for privatisation, which her successor John Major implemented in 1994.[184]

The privatisation of public assets was combined with financial deregulation to fuel economic growth. Chancellor Geoffrey Howe abolished the UK’s exchange controls in 1979,[185] which allowed more capital to be invested in foreign markets, and the Big Bang of 1986 removed many restrictions on the London Stock Exchange.[185]

Northern Ireland

Visiting Northern Ireland in 1982

In 1980 and 1981, Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) prisoners in Northern Ireland’s Maze Prison carried out hunger strikes to regain the status of political prisoners that had been removed in 1976 by the preceding Labour government.[186] Bobby Sands began the 1981 strike, saying that he would fast until death unless prison inmates won concessions over their living conditions.[186] Thatcher refused to countenance a return to political status for the prisoners, having declared «Crime is crime is crime; it is not political».[186] Nevertheless, the British government privately contacted republican leaders in a bid to bring the hunger strikes to an end.[187] After the deaths of Sands and nine others, the strike ended. Some rights were restored to paramilitary prisoners, but not official recognition of political status.[188] Violence in Northern Ireland escalated significantly during the hunger strikes.[189]

Thatcher narrowly escaped injury in an IRA assassination attempt at a Brighton hotel early in the morning on 12 October 1984.[190] Five people were killed, including the wife of minister John Wakeham. Thatcher was staying at the hotel to prepare for the Conservative Party conference, which she insisted should open as scheduled the following day.[190] She delivered her speech as planned,[191] though rewritten from her original draft,[192] in a move that was widely supported across the political spectrum and enhanced her popularity with the public.[193]

On 6 November 1981, Thatcher and Taoiseach (Irish prime minister) Garret FitzGerald had established the Anglo-Irish Inter-Governmental Council, a forum for meetings between the two governments.[188] On 15 November 1985, Thatcher and FitzGerald signed the Hillsborough Anglo-Irish Agreement, which marked the first time a British government had given the Republic of Ireland an advisory role in the governance of Northern Ireland. In protest, the Ulster Says No movement led by Ian Paisley attracted 100,000 to a rally in Belfast,[194] Ian Gow, later assassinated by the PIRA, resigned as Minister of State in the HM Treasury,[195][196] and all 15 Unionist MPs resigned their parliamentary seats; only one was not returned in the subsequent by-elections on 23 January 1986.[197]

Environment

Thatcher supported an active climate protection policy; she was instrumental in the passing of the Environmental Protection Act 1990,[198] the founding of the Hadley Centre for Climate Research and Prediction,[199] the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,[200] and the ratification of the Montreal Protocol on preserving the ozone.[201]

Thatcher helped to put climate change, acid rain and general pollution in the British mainstream in the late 1980s,[200][202] calling for a global treaty on climate change in 1989.[203] Her speeches included one to the Royal Society in 1988,[204] followed by another to the UN General Assembly in 1989.

Foreign affairs

Thatcher appointed Lord Carrington, an ennobled member of the party and former Secretary of State for Defence, to run the Foreign Office in 1979.[205] Although considered a «wet», he avoided domestic affairs and got along well with Thatcher. One issue was what to do with Rhodesia, where the white-minority had determined to rule the prosperous, black-majority breakaway colony in the face of overwhelming international criticism. With the 1975 Portuguese collapse in the continent, South Africa (which had been Rhodesia’s chief supporter) realised that their ally was a liability; black rule was inevitable, and the Thatcher government brokered a peaceful solution to end the Rhodesian Bush War in December 1979 via the Lancaster House Agreement. The conference at Lancaster House was attended by Rhodesian prime minister Ian Smith, as well as by the key black leaders: Muzorewa, Mugabe, Nkomo and Tongogara. The result was the new Zimbabwean nation under black rule in 1980.[206]

Cold War

Thatcher’s first foreign-policy crisis came with the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. She condemned the invasion, said it showed the bankruptcy of a détente policy and helped convince some British athletes to boycott the 1980 Moscow Olympics. She gave weak support to US president Jimmy Carter who tried to punish the USSR with economic sanctions. Britain’s economic situation was precarious, and most of NATO was reluctant to cut trade ties.[207] Thatcher nevertheless gave the go-ahead for Whitehall to approve MI6 (along with the SAS) to undertake «disruptive action» in Afghanistan.[208] As well working with the CIA in Operation Cyclone, they also supplied weapons, training and intelligence to the mujaheddin.[209]

The Financial Times reported in 2011 that her government had secretly supplied Iraq under Saddam Hussein with «non-lethal» military equipment since 1981.[210][211]

Having withdrawn formal recognition from the Pol Pot regime in 1979,[212] the Thatcher government backed the Khmer Rouge keeping their UN seat after they were ousted from power in Cambodia by the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. Although Thatcher denied it at the time,[213] it was revealed in 1991 that, while not directly training any Khmer Rouge,[214] from 1983 the Special Air Service (SAS) was sent to secretly train «the armed forces of the Cambodian non-communist resistance» that remained loyal to Prince Norodom Sihanouk and his former prime minister Son Sann in the fight against the Vietnamese-backed puppet regime.[215][216]

Thatcher was one of the first Western leaders to respond warmly to reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Following Reagan–Gorbachev summit meetings and reforms enacted by Gorbachev in the USSR, she declared in November 1988 that «We’re not in a Cold War now», but rather in a «new relationship much wider than the Cold War ever was».[217] She went on a state visit to the Soviet Union in 1984 and met with Gorbachev and Council of Ministers chairman Nikolai Ryzhkov.[218]

Ties with the US

Despite opposite personalities, Thatcher bonded quickly with US president Ronald Reagan.[nb 5] She gave strong support to the Reagan administration’s Cold War policies based on their shared distrust of communism.[153] A sharp disagreement came in 1983 when Reagan did not consult with her on the invasion of Grenada.[219][220]

During her first year as prime minister she supported NATO’s decision to deploy US nuclear cruise and Pershing II missiles in Western Europe,[153] permitting the US to station more than 160 cruise missiles at RAF Greenham Common, starting in November 1983 and triggering mass protests by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.[153] She bought the Trident nuclear missile submarine system from the US to replace Polaris, tripling the UK’s nuclear forces[221] at an eventual cost of more than £12 billion (at 1996–97 prices).[222] Thatcher’s preference for defence ties with the US was demonstrated in the Westland affair of 1985–86, when she acted with colleagues to allow the struggling helicopter manufacturer Westland to refuse a takeover offer from the Italian firm Agusta in favour of the management’s preferred option, a link with Sikorsky Aircraft. Defence Secretary Michael Heseltine, who had supported the Agusta deal, resigned from the government in protest.[223]

In April 1986 she permitted US F-111s to use Royal Air Force bases for the bombing of Libya in retaliation for the alleged Libyan bombing of a Berlin discothèque,[224] citing the right of self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter.[225][nb 6] Polls suggested that fewer than one in three British citizens approved of her decision.[227]

Thatcher was in the US on a state visit when Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August 1990.[228] During her talks with President George H. W. Bush, who succeeded Reagan in 1989, she recommended intervention,[228] and put pressure on Bush to deploy troops in the Middle East to drive the Iraqi Army out of Kuwait.[229] Bush was apprehensive about the plan, prompting Thatcher to remark to him during a telephone conversation: «This was no time to go wobbly!»[230][231] Thatcher’s government supplied military forces to the international coalition in the build-up to the Gulf War, but she had resigned by the time hostilities began on 17 January 1991.[232][233] She applauded the coalition victory on the backbenches, while warning that «the victories of peace will take longer than the battles of war».[234] It was disclosed in 2017 that Thatcher had suggested threatening Saddam with chemical weapons after the invasion of Kuwait.[235][236]

Crisis in the South Atlantic

On 2 April 1982, the ruling military junta in Argentina ordered the invasion of the British possessions of the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, triggering the Falklands War.[237] The subsequent crisis was «a defining moment of [Thatcher’s] premiership».[238] At the suggestion of Harold Macmillan and Robert Armstrong,[238] she set up and chaired a small War Cabinet (formally called ODSA, Overseas and Defence committee, South Atlantic) to oversee the conduct of the war,[239] which by 5–6 April had authorised and dispatched a naval task force to retake the islands.[240] Argentina surrendered on 14 June and Operation Corporate was hailed a success, notwithstanding the deaths of 255 British servicemen and 3 Falkland Islanders. Argentine fatalities totalled 649, half of them after the nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror torpedoed and sank the cruiser ARA General Belgrano on 2 May.[241]

Thatcher was criticised for the neglect of the Falklands’ defence that led to the war, and especially by Labour MP Tam Dalyell in Parliament for the decision to torpedo the General Belgrano, but overall she was considered a competent and committed war leader.[242] The «Falklands factor», an economic recovery beginning early in 1982, and a bitterly divided opposition all contributed to Thatcher’s second election victory in 1983.[243] Thatcher frequently referred after the war to the «Falklands spirit»;[244] Hastings & Jenkins (1983, p. 329) suggests that this reflected her preference for the streamlined decision-making of her War Cabinet over the painstaking deal-making of peacetime cabinet government.

Negotiating Hong Kong

In September 1982 she visited China to discuss with Deng Xiaoping the sovereignty of Hong Kong after 1997. China was the first communist state Thatcher had visited as prime minister, and she was the first British prime minister to visit China. Throughout their meeting, she sought the PRC’s agreement to a continued British presence in the territory. Deng insisted that the PRC’s sovereignty over Hong Kong was non-negotiable but stated his willingness to settle the sovereignty issue with the British government through formal negotiations. Both governments promised to maintain Hong Kong’s stability and prosperity.[245] After the two-year negotiations, Thatcher conceded to the PRC government and signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration in Beijing in 1984, agreeing to hand over Hong Kong’s sovereignty in 1997.[246]

Apartheid in South Africa

Despite saying that she was in favour of «peaceful negotiations» to end apartheid,[247][248] Thatcher opposed sanctions imposed on South Africa by the Commonwealth and the European Economic Community (EEC).[249] She attempted to preserve trade with South Africa while persuading its government to abandon apartheid. This included «[c]asting herself as President Botha’s candid friend», and inviting him to visit the UK in 1984,[250] in spite of the «inevitable demonstrations» against his government.[251] Alan Merrydew of the Canadian broadcaster BCTV News asked Thatcher what her response was «to a reported ANC statement that they will target British firms in South Africa?» to which she later replied: «[…] when the ANC says that they will target British companies […] This shows what a typical terrorist organisation it is. I fought terrorism all my life and if more people fought it, and we were all more successful, we should not have it and I hope that everyone in this hall will think it is right to go on fighting terrorism.»[252] During his visit to Britain five months after his release from prison, Nelson Mandela praised Thatcher: «She is an enemy of apartheid […] We have much to thank her for.»[250]

Europe

| External video |

|---|

| 1988 speech to the College of Europe |

| Speech to the College of Europe (‘The Bruges Speech’) (Speech) – via the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.[253] |

Thatcher and her party supported British membership of the EEC in the 1975 national referendum[254] and the Single European Act of 1986, and obtained the UK rebate on contributions,[255] but she believed that the role of the organisation should be limited to ensuring free trade and effective competition, and feared that the EEC approach was at odds with her views on smaller government and deregulation.[256] Believing that the single market would result in political integration,[255] Thatcher’s opposition to further European integration became more pronounced during her premiership and particularly after her third government in 1987.[257] In her Bruges speech in 1988, Thatcher outlined her opposition to proposals from the EEC,[253] forerunner of the European Union, for a federal structure and increased centralisation of decision-making:

We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels.[256]

Sharing the concerns of French president François Mitterrand,[258] Thatcher was initially opposed to German reunification,[nb 7] telling Gorbachev that it «would lead to a change to postwar borders, and we cannot allow that because such a development would undermine the stability of the whole international situation and could endanger our security». She expressed concern that a united Germany would align itself more closely with the Soviet Union and move away from NATO.[260]

In March 1990, Thatcher held a Chequers seminar on the subject of German reunification that was attended by members of her cabinet and historians such as Norman Stone, George Urban, Timothy Garton Ash and Gordon A. Craig. During the seminar, Thatcher described «what Urban called ‘saloon bar clichés’ about the German character, including ‘angst, aggressiveness, assertiveness, bullying, egotism, inferiority complex [and] sentimentality‘«. Those present were shocked to hear Thatcher’s utterances and «appalled» at how she was «apparently unaware» about the post-war German collective guilt and Germans’ attempts to work through their past.[261] The words of the meeting were leaked by her foreign-policy advisor Charles Powell and, subsequently, her comments were met with fierce backlash and controversy.[262]

During the same month, German chancellor Helmut Kohl reassured Thatcher that he would keep her «informed of all his intentions about unification»,[263] and that he was prepared to disclose «matters which even his cabinet would not know».[263]

Challenges to leadership and resignation

During her premiership Thatcher had the second-lowest average approval rating (40%) of any post-war prime minister. Since Nigel Lawson’s resignation as Chancellor in October 1989,[264] polls consistently showed that she was less popular than her party.[265] A self-described conviction politician, Thatcher always insisted that she did not care about her poll ratings and pointed instead to her unbeaten election record.[266]

In December 1989, Thatcher was challenged for the leadership of the Conservative Party by the little-known backbench MP Sir Anthony Meyer.[267] Of the 374 Conservative MPs eligible to vote, 314 voted for Thatcher and 33 for Meyer. Her supporters in the party viewed the result as a success and rejected suggestions that there was discontent within the party.[267]

Opinion polls in September 1990 reported that Labour had established a 14% lead over the Conservatives,[268] and by November, the Conservatives had been trailing Labour for 18 months.[265] These ratings, together with Thatcher’s combative personality and tendency to override collegiate opinion, contributed to further discontent within her party.[269]

In July 1989, Thatcher removed Geoffrey Howe as foreign secretary after he and Lawson had forced her to agree to a plan for Britain to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). Britain joined the ERM in October 1990.

On 1 November 1990, Howe, by then the last remaining member of Thatcher’s original 1979 cabinet, resigned as deputy prime minister, ostensibly over her open hostility to moves towards European monetary union.[268][270] In his resignation speech on 13 November, which was instrumental in Thatcher’s downfall,[271] Howe attacked Thatcher’s openly dismissive attitude to the government’s proposal for a new European currency competing against existing currencies (a «hard ECU»):

How on earth are the Chancellor and the Governor of the Bank of England, commending the hard ECU as they strive to, to be taken as serious participants in the debate against that kind of background noise? I believe that both the Chancellor and the Governor are cricketing enthusiasts, so I hope that there is no monopoly of cricketing metaphors. It is rather like sending your opening batsmen to the crease only for them to find, the moment the first balls are bowled, that their bats have been broken before the game by the team captain.[272][273]

On 14 November, Michael Heseltine mounted a challenge for the leadership of the Conservative Party.[274][275] Opinion polls had indicated that he would give the Conservatives a national lead over Labour.[276] Although Thatcher led on the first ballot with the votes of 204 Conservative MPs (54.8%) to 152 votes (40.9%) for Heseltine, with 16 abstentions, she was four votes short of the required 15% majority. A second ballot was therefore necessary.[277] Thatcher initially declared her intention to «fight on and fight to win» the second ballot, but consultation with her cabinet persuaded her to withdraw.[269][278] After holding an audience with the Queen, calling other world leaders, and making one final Commons speech,[279] on 28 November she left Downing Street in tears. She reportedly regarded her ousting as a betrayal.[280] Her resignation was a shock to many outside Britain, with such foreign observers as Henry Kissinger and Gorbachev expressing private consternation.[281]

Thatcher was replaced as head of government and party leader by Chancellor John Major, whose lead over Heseltine in the second ballot was sufficient for Heseltine to drop out. Major oversaw an upturn in Conservative support in the 17 months leading to the 1992 general election, and led the party to a fourth successive victory on 9 April 1992.[282] Thatcher had lobbied for Major in the leadership contest against Heseltine, but her support for him waned in later years.[283]

Later life

Return to backbenches (1990–1992)

Thatcher returned to the backbenches as a constituency parliamentarian after leaving the premiership.[284] Her domestic approval rating recovered after her resignation, though public opinion remained divided on whether her government had been good for the country.[264][285] Aged 66, she retired from the House of Commons at the 1992 general election, saying that leaving the Commons would allow her more freedom to speak her mind.[286]

Post-Commons (1992–2003)

On leaving the Commons, Thatcher became the first former British prime minister to set up a foundation;[287] the British wing of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation was dissolved in 2005 due to financial difficulties.[288] She wrote two volumes of memoirs, The Downing Street Years (1993) and The Path to Power (1995). In 1991, she and her husband Denis moved to a house in Chester Square, a residential garden square in central London’s Belgravia district.[289]

Thatcher was hired by the tobacco company Philip Morris as a «geopolitical consultant» in July 1992, for $250,000 per year and an annual contribution of $250,000 to her foundation.[290] Thatcher earned $50,000 for each speech she delivered.[291]

Thatcher became an advocate of Croatian and Slovenian independence.[292] Commenting on the Yugoslav Wars, in a 1991 interview for Croatian Radiotelevision, she was critical of Western governments for not recognising the breakaway republics of Croatia and Slovenia as independent and for not supplying them with arms after the Serbian-led Yugoslav Army attacked.[293]

In August 1992 she called for NATO to stop the Serbian assault on Goražde and Sarajevo, to end ethnic cleansing during the Bosnian War, comparing the situation in Bosnia–Herzegovina to «the barbarities of Hitler’s and Stalin’s».[294]

She made a series of speeches in the Lords criticising the Maastricht Treaty,[286] describing it as «a treaty too far» and stated: «I could never have signed this treaty.»[295] She cited A. V. Dicey when arguing that, as all three main parties were in favour of the treaty, the people should have their say in a referendum.[296]

Thatcher served as honorary chancellor of the College of William & Mary in Virginia from 1993 to 2000,[297] while also serving as chancellor of the private University of Buckingham from 1992 to 1998,[298][299] a university she had formally opened in 1976 as the former education secretary.[299]

After Tony Blair’s election as Labour Party leader in 1994, Thatcher praised Blair as «probably the most formidable Labour leader since Hugh Gaitskell», adding: «I see a lot of socialism behind their front bench, but not in Mr Blair. I think he genuinely has moved.»[300] Blair responded in kind: «She was a thoroughly determined person, and that is an admirable quality.»[301]

In 1998, Thatcher called for the release of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet when Spain had him arrested and sought to try him for human rights violations. She cited the help he gave Britain during the Falklands War.[302] In 1999, she visited him while he was under house arrest near London.[303] Pinochet was released in March 2000 on medical grounds by Home Secretary Jack Straw.[304]

At the 2001 general election, Thatcher supported the Conservative campaign, as she had done in 1992 and 1997, and in the Conservative leadership election following its defeat, she endorsed Iain Duncan Smith over Kenneth Clarke.[305] In 2002 she encouraged George W. Bush to aggressively tackle the «unfinished business» of Iraq under Saddam Hussein,[306] and praised Blair for his «strong, bold leadership» in standing with Bush in the Iraq War.[307]

She broached the same subject in her Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World, which was published in April 2002 and dedicated to Ronald Reagan, writing that there would be no peace in the Middle East until Saddam was toppled. Her book also said that Israel must trade land for peace and that the European Union (EU) was a «fundamentally unreformable», «classic utopian project, a monument to the vanity of intellectuals, a programme whose inevitable destiny is failure».[308] She argued that Britain should renegotiate its terms of membership or else leave the EU and join the North American Free Trade Area.[309]

Following several small strokes she was advised by her doctors not to engage in further public speaking.[310] In March 2002 she announced that, on doctors’ advice, she would cancel all planned speaking engagements and accept no more.[311]

Being Prime Minister is a lonely job. In a sense, it ought to be: you cannot lead from the crowd. But with Denis there I was never alone. What a man. What a husband. What a friend.

Thatcher (1993, p. 23)

On 26 June 2003, Thatcher’s husband Sir Denis died aged 88;[312] he was cremated on 3 July at Mortlake Crematorium in London.[313]

Final years (2003–2013)

Arriving for the funeral of President Reagan in 2004

On 11 June 2004, Thatcher (against doctors’ orders) attended the state funeral service for Ronald Reagan.[314] She delivered her eulogy via videotape; in view of her health, the message had been pre-recorded several months earlier.[315][316] Thatcher flew to California with the Reagan entourage, and attended the memorial service and interment ceremony for the president at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.[317]

In 2005, Thatcher criticised how Blair had decided to invade Iraq two years previously. Although she still supported the intervention to topple Saddam Hussein, she said that (as a scientist) she would always look for «facts, evidence and proof» before committing the armed forces.[233] She celebrated her 80th birthday on 13 October at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Hyde Park, London; guests included the Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh, Princess Alexandra and Tony Blair.[318] Geoffrey Howe, Baron Howe of Aberavon, was also in attendance and said of his former leader: «Her real triumph was to have transformed not just one party but two, so that when Labour did eventually return, the great bulk of Thatcherism was accepted as irreversible.»[319]

Thatcher (left) at a Washington memorial service on the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks

In 2006, Thatcher attended the official Washington, D.C., memorial service to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on the US. She was a guest of Vice President Dick Cheney and met Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice during her visit.[320] In February 2007 Thatcher became the first living British prime minister to be honoured with a statue in the Houses of Parliament. The bronze statue stood opposite that of her political hero, Winston Churchill,[321] and was unveiled on 21 February 2007 with Thatcher in attendance; she remarked in the Members’ Lobby of the Commons: «I might have preferred iron – but bronze will do […] It won’t rust.»[321]

Thatcher was a public supporter of the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism and the resulting Prague Process, and sent a public letter of support to its preceding conference.[322]

After collapsing at a House of Lords dinner, Thatcher, suffering low blood pressure,[323] was admitted to St Thomas’ Hospital in central London on 7 March 2008 for tests. In 2009 she was hospitalised again when she fell and broke her arm.[324] Thatcher returned to 10 Downing Street in late November 2009 for the unveiling of an official portrait by artist Richard Stone,[325] an unusual honour for a living former prime minister. Stone was previously commissioned to paint portraits of the Queen and Queen Mother.[325]

On 4 July 2011, Thatcher was to attend a ceremony for the unveiling of a 10 ft (3.0 m) statue to Ronald Reagan, outside the US Embassy in London, but was unable to attend due to her frail health.[326] She last attended a sitting of the House of Lords on 19 July 2010,[327] and on 30 July 2011 it was announced that her office in the Lords had been closed.[328] Earlier that month, Thatcher was named the most competent prime minister of the past 30 years in an Ipsos MORI poll.[329]

Thatcher’s daughter Carol first revealed that her mother had dementia in 2005,[330] saying «Mum doesn’t read much any more because of her memory loss». In her 2008 memoir, Carol wrote that her mother «could hardly remember the beginning of a sentence by the time she got to the end».[330] She later recounted how she was first struck by her mother’s dementia when, in conversation, Thatcher confused the Falklands and Yugoslav conflicts; she recalled the pain of needing to tell her mother repeatedly that her husband Denis was dead.[331]

Death and funeral (2013)

Thatcher died on 8 April 2013, at the age of 87, after suffering a stroke. She had been staying at a suite in the Ritz Hotel in London since December 2012 after having difficulty with stairs at her Chester Square home in Belgravia.[332] Her death certificate listed the primary causes of death as a «cerebrovascular accident» and «repeated transient ischaemic attack»;[333] secondary causes were listed as a «carcinoma of the bladder» and dementia.[333]

Reactions to the news of Thatcher’s death were mixed across the UK, ranging from tributes lauding her as Britain’s greatest-ever peacetime prime minister to public celebrations of her death and expressions of hatred and personalised vitriol.[334]

Details of Thatcher’s funeral had been agreed with her in advance.[335] She received a ceremonial funeral, including full military honours, with a church service at St Paul’s Cathedral on 17 April.[336][337]

Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh attended her funeral,[338] marking only the second and final time in the Queen’s reign that she attended the funeral of any of her former prime ministers, after that of Churchill, who received a state funeral in 1965.[339]

After the service at St Paul’s, Thatcher’s body was cremated at Mortlake, where her husband had been cremated. On 28 September, a service for Thatcher was held in the All Saints Chapel of the Royal Hospital Chelsea’s Margaret Thatcher Infirmary. In a private ceremony, Thatcher’s ashes were interred in the hospital’s grounds, next to her husband’s.[340][341]

Legacy

Political impact

Thatcherism represented a systematic and decisive overhaul of the post-war consensus, whereby the major political parties largely agreed on the central themes of Keynesianism, the welfare state, nationalised industry, and close regulation of the economy, and high taxes. Thatcher generally supported the welfare state while proposing to rid it of abuses.[nb 8]

She promised in 1982 that the highly popular National Health Service was «safe in our hands».[342] At first, she ignored the question of privatising nationalised industries; heavily influenced by right-wing think tanks, and especially by Sir Keith Joseph,[343] Thatcher broadened her attack. Thatcherism came to refer to her policies as well as aspects of her ethical outlook and personal style, including moral absolutism, nationalism, liberal individualism, and an uncompromising approach to achieving political goals.[344][345][nb 9]

Thatcher defined her own political philosophy, in a major and controversial break with the one-nation conservatism[346] of her predecessor Edward Heath, in a 1987 interview published in Woman’s Own magazine:

I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand «I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with it!» or «I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!» «I am homeless, the Government must house me!» and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour and life is a reciprocal business and people have got the entitlements too much in mind without the obligations.[347]

Overview

The number of adults owning shares rose from 7 per cent to 25 per cent during her tenure, and more than a million families bought their council houses, giving an increase from 55 per cent to 67 per cent in owner-occupiers from 1979 to 1990. The houses were sold at a discount of 33–55 per cent, leading to large profits for some new owners. Personal wealth rose by 80 per cent in real terms during the 1980s, mainly due to rising house prices and increased earnings. Shares in the privatised utilities were sold below their market value to ensure quick and wide sales, rather than maximise national income.[348][349]

The «Thatcher years» were also marked by periods of high unemployment and social unrest,[350][351] and many critics on the left of the political spectrum fault her economic policies for the unemployment level; many of the areas affected by mass unemployment as well as her monetarist economic policies remained blighted for decades, by such social problems as drug abuse and family breakdown.[352] Unemployment did not fall below its May 1979 level during her tenure,[353] only falling below its April 1979 level in 1990.[354] The long-term effects of her policies on manufacturing remain contentious.[355][356]

Speaking in Scotland in 2009, Thatcher insisted she had no regrets and was right to introduce the poll tax and withdraw subsidies from «outdated industries, whose markets were in terminal decline», subsidies that created «the culture of dependency, which had done such damage to Britain».[357] Political economist Susan Strange termed the neoliberal financial growth model «casino capitalism», reflecting her view that speculation and financial trading were becoming more important to the economy than industry.[358]

Critics on the left describe her as divisive[359] and say she condoned greed and selfishness.[350] Leading Welsh politician Rhodri Morgan,[360] among others,[361] characterised Thatcher as a «Marmite» figure. Journalist Michael White, writing in the aftermath of the 2007–08 financial crisis, challenged the view that her reforms were still a net benefit.[362] Others consider her approach to have been «a mixed bag»[363][364] and «[a] Curate’s egg».[365]

Thatcher did «little to advance the political cause of women» either within her party or the government.[366] Some British feminists regarded her as «an enemy».[367] June Purvis of Women’s History Review says that, although Thatcher had struggled laboriously against the sexist prejudices of her day to rise to the top, she made no effort to ease the path for other women.[368] Thatcher did not regard women’s rights as requiring particular attention as she did not, especially during her premiership, consider that women were being deprived of their rights. She had once suggested the shortlisting of women by default for all public appointments yet had also proposed that those with young children ought to leave the workforce.[369]

Thatcher’s stance on immigration in the late 1970s was perceived as part of a rising racist public discourse,[370] which Martin Barker terms «new racism».[371] In opposition, Thatcher believed that the National Front (NF) was winning over large numbers of Conservative voters with warnings against floods of immigrants. Her strategy was to undermine the NF narrative by acknowledging that many of their voters had serious concerns in need of addressing. In 1978 she criticised Labour’s immigration policy to attract voters away from the NF to the Conservatives.[372] Her rhetoric was followed by an increase in Conservative support at the expense of the NF. Critics on the left accused her of pandering to racism.[373][nb 10]

Many Thatcherite policies had an influence on the Labour Party,[377][378] which returned to power in 1997 under Tony Blair. Blair rebranded the party «New Labour» in 1994 with the aim of increasing its appeal beyond its traditional supporters,[379] and to attract those who had supported Thatcher, such as the «Essex man».[380] Thatcher is said to have regarded the «New Labour» rebranding as her greatest achievement.[381] In contrast to Blair, the Conservative Party under William Hague attempted to distance himself and the party from Thatcher’s economic policies in an attempt to gain public approval.[382]

Shortly after Thatcher’s death in 2013, Scottish first minister Alex Salmond argued that her policies had the «unintended consequence» of encouraging Scottish devolution.[383] Lord Foulkes of Cumnock agreed on Scotland Tonight that she had provided «the impetus» for devolution.[384] Writing for The Scotsman in 1997, Thatcher argued against devolution on the basis that it would eventually lead to Scottish independence.[385]

Reputation

Margaret Thatcher was not merely the first woman and the longest-serving Prime Minister of modern times, but the most admired, most hated, most idolised and most vilified public figure of the second half of the twentieth century. To some she was the saviour of her country who […] created a vigorous enterprise economy which twenty years later was still outperforming the more regulated economies of the Continent. To others, she was a narrow ideologue whose hard-faced policies legitimised greed, deliberately increased inequality […] and destroyed the nation’s sense of solidarity and civic pride. There is no reconciling these views: yet both are true.[nb 11]

Biographer John Campbell (2011b, p. 499)

Thatcher’s tenure of 11 years and 209 days as British prime minister was the longest since Lord Salisbury (13 years and 252 days, in three spells) and the longest continuous period in office since Lord Liverpool (14 years and 305 days).[386][387]

Having led the Conservative Party to victory in three consecutive general elections, twice in a landslide, she ranks among the most popular party leaders in British history in terms of votes cast for the winning party; over 40 million ballots were cast in total for the party under her leadership.[388][389][390] Her electoral successes were dubbed a «historic hat trick» by the British press in 1987.[391]