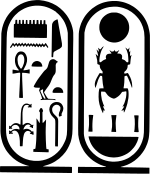

1) Чтобы прочесть имя фараона, надо разобраться с тем, как вообще записываются имена царей и фараонов. Из сравнения с титулами и с именами богов мы видим, что имена царей и фараонов заключены в овал с вертикальной чертой. Это так называемый картуш (так его назвал по-французски дешифровщик египетской письменности Жан-Франсуа Шампольон). Часть, предшествующая картушу, — это титул, и здесь он легко находится: «сын Ра». Ра — это, очевидно, имя Бога Солнца, верховного божества египетского пантеона.

2) Из сравнения записи имени бога Ра и записи титула «сын Ра» можно заключить, что основным элементом записи этого имени является кружок с точкой, по-видимому изображающий солнечный диск. Однако в записи имени бога присутствуют еще два элемента: штрих под диском и сидящая фигура. Подобная фигура сопровождает все имена богов, кроме Анубиса, для которого фигура имеет голову собаки (известно, что Анубис, бог подземного царства, у египтян изображался с головой шакала). По-видимому, такая фигура является смысловой подсказкой, своеобразной «иконкой», а не читаемым знаком, так как имена богов не содержат одинаковых звуков ни в начале, ни в конце. Шампольон назвал такие знаки «детерминативами», то есть определителями. Своего рода определителем имени фараона является и картуш.

3) Вертикальная черта при знаке солнца Ра встречается еще один раз — в имени Амон-Ра; еще в нескольких случаях диск используется без черты. Можно предположить, что черта сопровождает диск только в именах богов (но не фараонов). С другой стороны, три вертикальных черты встречаются в титуле «владелец корон»; это наводит на мысль, что три черты передают множественность, однако здесь нет возможности проверить эту гипотезу.

4) Первая часть заданного имени встречается в имени Амон-Ра с чтением [imen] (условно: перо — шахматная доска — волна). Дальше надо найти чтения трех знаков: полудиска, цыпленка и знака типа жезла с петлей1. Цыпленок встречается дважды в имени Хеопса [khufu], откуда можно вывести, что он передает звук [u]. Полудиск встречается в имени Птах, где, по-видимому, передает звук [t]. Знак жезла встречается в титуле «дающий жизнь» [diānkh] из двух знаков, что позволяет предположить, что звуковое значение данного знака [ānkh]. Это предположение подтверждается записью имени Панки, где квадратик соответствует [p] (ср. Птах, Анубис), а два знака пера (или камыша) передают долгое [ī] (ср. Анубис, Амон-Ра).

Прочтение знаков в картуше дает /imen-t-u-t-ānkh/. Кажется, задание 1 выполнено (хотя это не похоже ни на какое из известных имен фараонов).

5) Попробуем выполнить задание 2. Для записи хорошей подсказкой должно послужить последнее имя фараона Хахепер-Ра. Оно записано всего тремя знаками, однако начинается со знака Ра [rā]. Может быть, читать надо в обратном порядке? Но до сих пор всё непротиворечиво читалось слева направо. Возможно, обратный порядок используется только в именах фараонов? Попробуем прочесть с конца. Тогда первый знак — жук — должен иметь чтение [khep(e)r] — это следует из имени бога Хепри. Второй же знак, видимо, [khā]. В обратном чтении это дает /khep(e)r-khā-rā/, что не соответствует данному в условии прочтению. Очевидно, обычный порядок записи слева направо нарушается лишь вынесением на первое место знака для Ра. Это наблюдение подтверждается записью имени Хефрена /rā-khā-f/. Можно предположить, что имена фараонов, содержащие имя бога Ра, требуют инверсии — вынесения знака Ра на «почетное» первое место.

6) Однако знак для Ра имеется и в имени Эхнатон [akhenitenrā], но ему предшествует группа знаков, которые, по-видимому, читаются [iten] (ср. [imen] в Амон-Ра). То есть имя Эхнатон записано /iten-rā-akhen/. Почему же здесь Ра не на первом месте? По-видимому, в данном случае имя верховного бога, требующее почетного первого места, не просто Ра, а Итен-Ра, то есть Атон-Ра2.

7) Теперь можем записать имя Менхепер-Ра, используя знаки в картуше в следующем порядке: /rā-m-n-kheper/, то есть диск — шахматная доска — волна — жук, что дает в транскрипции [menkheperrā].

1 Знак анх (анкх) представляет собой оберег, изображая пояс, завязанный узлом; его вариантом предположительно является и картуш, заключающий имена фараонов.

2 Действительно, фараон Эхнатон как раз и известен как учредитель культа единого бога Атона-Ра, чье имя и включено в состав его собственного имени (прежнее его имя Аменхотеп IV; Эхнатон буквально «дух, угодный Атону’). Этот культ сменил предшествующий культ многих богов, возглавляемых верховным богом Амоном-Ра, другим воплощением Ра. Вернул культ Амона-Ра фараон Тутанхамон.

Golden funerary mask of Tutankhamun.

Tutankhamun (alternately spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon), Egyptian twt-ˁnḫ-ı͗mn; 1341 BCE – 1323 BCE) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled c.1333 BCE – 1323 BCE in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. His original name, Tutankhaten, means «Living Image of Aten», while Tutankhamun means «Living Image of Amun». In hieroglyphs the name Tutankhamun was typically written Amen-tut-ankh, because of a scribal custom that placed a divine name at the beginning of a phrase to show appropriate reverence.[1] He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters. He was likely the 18th dynasty king ‘Rathotis’ who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years — a figure which conforms with Flavius Josephus’s version of Manetho’s Epitome.[2]

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun’s nearly intact tomb received worldwide press coverage. It sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun’s burial mask remains the popular symbol. Exhibits of artifacts from his tomb have toured the world. In February 2010, the results of DNA tests confirmed that Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten (mummy KV55) and his sister/wife (mummy KV35YL), whose name is unknown but whose remains are positively identified as «The Younger Lady» mummy found in KV35.[3]

Life

Tutankhamun was born in 1341 BCE, the son of Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV) and one of his sisters.[4] As a prince he was known as Tutankhaten.[5] He ascended to the throne in 1333 BCE, at the age of nine, taking the reign name of Tutankhaten.

When he became king, he married his half sister, Ankhesenepatan, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun. They had two daughters, both stillborn.[3]

Reign

Given his age, the king must have had very powerful advisers, presumably including General Horemheb, the Vizier Ay, and Maya the «Overseer of the Treasury». Horemheb records that the king appointed him lord of the land as hereditary prince to maintain law. He also noted his ability to calm the young king when his temper flared.[6]

Domestic policy

In his third regnal year, Tutankhamun reversed several changes made during his father’s reign. He ended the worship of the god, Aten and restored the god Amun to supremacy. The ban on the cult of Amun was lifted and traditional privileges were restored to its priesthood. The capital was moved back to Thebes and the city of Akhenaten abandoned.[7] This is also when he changed his name to Tutankhamun.

As part of his restoration, the king initiated building projects, in particular at Thebes and Karnak, where he dedicated a temple to Amun. Many monuments were erected, and an inscription on his tomb door declares the king had «spent his life in fashioning the images of the gods». The traditional festivals were now celebrated again, including those related to the Apis Bull, Horemakhet and Opet. His restoration stela says:

Foreign policy

The country was economically weak and in turmoil following the reign of Akhenaten. Diplomatic relations with other kingdoms had been neglected, and Tutankhamun sought to restore them, in particular with the Mitanni. Evidence of his success is suggested by the gifts from various countries found in his tomb. Despite his efforts for improved relations, battles with Nubians and Asiatics were recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes. His tomb contained body armour and folding stools appropriate for military campaigns. However, given his youth and physical disabilities, which seemed to require the use of a cane in order to walk, historians speculate that he did not take part personally in these battles.[3][8]

Health and appearance

Tutankhamun was slight of build, and was roughly 170 centimetres tall. He had large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, although it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathological. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten often featured such an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality. The research also showed that the Tutankhamun had «a slightly cleft palate»[9] and possibly a mild case of scoliosis.

Cause of death

There are no surviving records of Tutankhamun’s final days. The cause of Tutankhamun’s death has been the subject of considerable debate with several major studies being conducted in an effort to find the answer.

Although there is some speculation that Tutankhamun was assassinated, the general consensus is that his death was accidental. A CT scan taken in 2005 shows that he badly broke his leg shortly before his death and that it became infected. DNA analysis, conducted in 2010 showed the presence of malaria in his system. It is believed that these two conditions, combined, led to his death.[10]

Product of incest

According to an article in the September 2010 issue of National Geographic, King Tut was the product of incest and as such, suffered from several genetic defects which contributed to his early death.[11] For years, scientists have tried to unravel ancient clues as to why the boy king of Egypt, who reigned for 10 years, died at the age of 19. Several theories have been put forth. As stated above, one was that he was killed by a blow to the head. Another put the blame on a broken leg. As recently as June 2010, German scientists said they believe there is evidence he died of sickle cell disease.

The research was conducted by archaeologists, radiologists, and geneticists who started performing CT scans on Tutankhamun five years ago and found that he was not killed by a blow to the head, as previously though. That same team began doing DNA research on Tut’s mummy, as well as the mummified remains of other members of his family, in 2008. DNA finally put to rest questions about Tut’s lineage, proving that his father was Akhenaten and that his mother was not one of Akhenaten’s known wives. His mother was one of Akhenaten’s five sisters, although it is not known which one. New CT images discovered congenital flaws, which are more common among the children of incest. Siblings are more likely to pass on twin copies of harmful genes, which is why children of incest more commonly manifest genetic defects.[12] It is suspected he also had a partially cleft palate, another congenital defect.[13]

The team was able to establish with a probability of better than 99.99 percent that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[14] The DNA of the so-called Younger Lady (KV35YL), found lying beside Queen Tiye in the alcove of KV35, matched that of the boy king. Her DNA proved that, like Akhenaten, she was the daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye; thus, Tut’s parents were brother & sister.[15] Queen Tiye held much political influence at court and acted as an adviser to her son after the death of her husband. There has been speculation that her eldest son Prince Tuthmose was in fact Moses who led the Israelites into the Promised Land.[16]

While the data are still incomplete, the study suggests that one of the mummified fetuses found in Tut’s tomb is the daughter of Tutankhamun himself, and the other fetus is probably his child as well. So far only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained.[17] One of them, KV21A, may well be the infants’ mother and thus, Tutankhamun’s wife, Ankhesenamun. It is known from history that she was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and thus likely her husband’s half sister. Another consequence of inbreeding can be children whose genetic defects do not allow them to be brought to term.

The research team consisted of Egyptian scientists Yehia Gad and Somaia Ismail from the National Research Center in Cairo. The CT scans were conducted under the direction of Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem of the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University. Three international experts served as consultants: Carsten Pusch of the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany; Albert Zink of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman in Bolzano, Italy[18]; and Paul Gostner of the Central Hospital Bolzano.[19]

As stated above, the team discovered DNA from several strains of a parasite proving he was infected with the most severe strain of malaria several times in his short life. Malaria can trigger circulatory shock or cause a fatal immune response in the body, either of which can lead to death. And while Tut did suffer from a bone disease which was crippling, it would not have been fatal. “Perhaps he struggled against others [congenital flaws] until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load,” wrote Zahi Hawass, archeologist and head of Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity involved in the research.

Tomb

Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was small relative to his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, so that his mummy was buried in a tomb intended for someone else. This would preserve the observance of the customary seventy days between death and burial.[20]

King Tutankhamun still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. November 4, 2007, 85 years to the day after Carter’s discovery, the 19-year-old pharaoh went on display in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus to a climate-controlled glass box. The case was designed to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.[21]

Discovery of tomb

Tutankhamun seems to have faded from public consciousness in Ancient Egypt within a short time after his death, and he remained virtually unknown until the 1920s. His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the initial burial. Eventually the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some huts for workers were built over the tomb entrance, clearly not knowing what lay beneath. When at the end of the twentieth dynasty the Valley of the Kings burials were systematically dismantled, the burial of Tutankhamun was overlooked, presumably because knowledge of it had been lost and his name may have been forgotten.

Exhibitions

Relics from Tutankhamun’s tomb are among the most traveled artifacts in the world. They have been to many countries, but probably the best-known exhibition tour was The Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, which ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from March 30 until September 30, 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors came to see the exhibition, some queuing for up to eight hours and it was the most popular exhibition in the Museum’s history. The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the USA, USSR, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from November 17, 1976, through April 15, 1979. More than eight million attended.

In 2004, the tour of Tutankhamun funerary objects entitled «Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter» made up of fifty artifacts from Tutenkhamun’s tomb and seventy funerary goods from other 18th Dynasty tombs began in Basle, Switzerland, went to Bonn Germany, the second leg of the tour, and from there toured the United States. The exhibition returned to Europe and to London. The European tour was organised by the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), and the Egyptian Museum in cooperation with the Antikenmuseum Basel and Sammlung Ludwig. Deutsche Telekom sponsored the Bonn exhibition.[22]

In 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched the U.S. tour of the Tutenkahamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects this time called «Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs». It was expected to draw more than three million people.[23]

The exhibition started in Los Angeles, California, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Chicago and Philadelphia. The exhibition then moved to London[24] before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. Subsequent events have propelled an encore of the exhibition in the United States, beginning with the Dallas Museum of Art in October 2008 which hosted the exhibition until May 2009.[25] The tour will continued to other U.S. cities.[26] After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, to be followed the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.[27]

The exhibition includes eighty exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessors in the Eighteenth dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun’s burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun’s tomb. The exhibition does not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972-1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has determined that the mask is too fragile to withstand travel and will never again leave the country.[28]

A separate exhibition called «Tutankhamun and the World of the Pharaohs» began at the Ethnological Museum in Vienna from March 9 to September 28, 2008 showing a further 140 treasures from the tomb. This exhibition continued to Atlanta and the Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Curse

For many years, rumors of a «Curse of the Pharaohs» (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had first entered the tomb. However, a recent study of journals and death records indicates no statistical difference between the age of death of those who entered the tomb and those on the expedition who did not. Indeed, most lived past seventy.

Significance

Tutankhamun was nine years old when he became pharaoh and reigned for approximately ten years. In historical terms, Tutankhamun’s significance stems from his rejection of the radical religious innovations introduced by his predecessor and father, Akhenaten.[29] Secondly, his tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered by Carter almost completely intact — the most complete ancient Egyptian royal tomb ever found. As Tutankhamun began his reign at such an early age, his vizier and eventual successor Ay was probably making most of the important political decisions during Tutankhamun’s reign.

Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped as a god and honored with a cult-like following in his own lifetime.[30] A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Ra and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by wrongdoing. Temples of his cult were built as far away as in Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king, indicative of the universality of his cult.[31]

In popular culture

If Tutankhamun is the world’s best known pharaoh, it is partly because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most-exhibited. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter’s The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, «The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt’s kings has become in death the most renowned.» As a side effect, the interest in this tomb and its alleged «curse» led to horror movies featuring a vengeful mummy.

Film and television

- We Want Our Mummy, a 1939 film by the Three Stooges. In it, the slapstick comedy trio explore the tomb of the midget King Rutentuten (pronounced «rootin’-tootin'») and his Queen, Hotsy Totsy. A decade later, they were crooked used-chariot salesmen in Mummy’s Dummies, in which they ultimately assist a different King Rootentootin (Vernon Dent) with a toothache.

- King Tut, played by Victor Buono, was a villain on the Batman TV series which aired from 1966 to 1968. Mild-mannered Egyptologist William Omaha McElroy, after suffering a concussion, came to believe he was the reincarnation of Tutankhamun. His response to this knowledge was to embark upon a crime spree that required him to fight against the «Caped Crusaders», Batman and Robin.

- The Discovery Kids animated series Tutenstein stars a fictional mummy based on Tutankhamun, named Tutankhensetamun and nicknamed Tutenstein in his afterlife. He is depicted as a lazy and spoiled 10-year-old mummy boy who must guard a magical artifact called the Scepter of Was from the evil Egyptian god of Set.

- La Reine Soleil (2007 animated film by Philippe Leclerc), features Akhenaten, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun), Akhesa (Ankhesenepaten, later Ankhesenamun), Nefertiti, and Horemheb in a complex struggle pitting the priests of Amun against Akhenaten’s intolerant monotheism.

- The first episode of the 2005 BBC series Egypt: Rediscovering a Lost World focuses on the life and death of Tutankhamun and the serendipitous discover of his tomb.

Other

- «King Tut», a whimsical 1978 song by (American comedian) «Steve Martin and the Toot Uncommons» (a backup group consisting of members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band).

- The mummy of Tutankhamun is depicted as a villain in Raj Comics’s Nagraj, a Hindi superhero comicbook. In this series, his mask is the source of his power.

- The video game Sphinx and the Cursed Mummy features a fictional representation of Prince Tutankhamun. Tutankhamun is the victim of an unnamed magical ritual which results in almost instantaneous mummification and extraction of what appears to be his «life force». In the instruction manual, the Mummy is described as young, inexperienced and naive.

Names

At the reintroduction of traditional religious practice, Tutankaten’s name changed. It is transliterated as twt-ˁnḫ-ỉmn ḥq3-ỉwnw-šmˁ, and often realized as Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, meaning «Living image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis». On his ascension to the throne, Tutankhamun took a praenomen. This is translated as nb-ḫprw-rˁ, and realized as Nebkheperure, meaning «Lord of the forms of Ra». The name Nibhurrereya in the Amarna letters may be a variation of this praenomen.

References

- ↑ Zauzich, Karl-Theodor (1992). Hieroglyphs Without Mystery. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9780292798045. http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/books/zauhie.html.

- ↑ «Manetho’s King List». http://www.phouka.com/pharaoh/egypt/history/KLManetho.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hawass, Zahi et al. «Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family» The Journal of the American Medical Association, February 17, 2010. Vol 303, No. 7 p.638-647

- ↑ Hawass, Zahi et al. «Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family» The Journal of the American Medical Association p.640-641

- ↑ Jacobus van Dijk. «The Death of Meketaten» (PDF). http://history.memphis.edu/murnane/Van%20Dijk.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Booth p. 86-87

- ↑ Erik Hornung, Akhenaten and the Religion of Light, Translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0801487250

- ↑ Booth p. 129-130

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian (March 8, 2005). «King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show». National Geographic News. p. 2. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/03/0308_050308_kingtutmurder.html. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- ↑ Roberts, Michelle (2010-02-16). «‘Malaria’ killed King Tutankhamun». BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8516425.stm. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1251731/King-Tutankhamuns-incestuous-family-revealed.html

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/8

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/5

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/7

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1251731/King-Tutankhamuns-incestuous-family-revealed.html

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/9

- ↑ http://www.eurac.edu/en/research/institutes/iceman/pages/default.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/3

- ↑ «The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendour in the New Kingdom«, Zahi Hawass, p. 61, American University in Cairo Press, 2004, ISBN 9774248368

- ↑ Michael McCarthy (2007-10-05). «3,000 years old: the face of Tutankhamun». London: The Independent. http://news.independent.co.uk/sci_tech/article3129650.ece.

- ↑ «Al-Ahram Weekly | Heritage | Under Tut’s spell». Weekly.ahram.org.eg. http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2004/716/he1.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑

«King Tut exhibition. Tutankhamun & the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Treasures from the Valley of the Kings». Arts and Exhibitions International. http://www.kingtut.org/exhibition.htm. Retrieved 2006-08-05. - ↑ Return of the King (Times Online)[dead link]

- ↑ «Dallas Museum of Art Website». Dallasmuseumofart.org. http://dallasmuseumofart.org/Dallas_Museum_of_Art/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Associated Press, «Tut Exhibit to Return to US Next Year»

- ↑ «Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs | King Tut Returns to San Francisco, June 27, 2009–March 28, 2010». Famsf.org. http://www.famsf.org/tut/. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Jenny Booth (2005-01-06). «CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle». London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article409075.ece?token=null&offset=12.

- ↑ Aude Gros de Beler, Tutankhamun, foreword Aly Maher Sayed, Moliere, ISBN 2-84790-210-4

- ↑ «Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology», Editor Donald B. Redford, p. 85, Berkley, ISBN 0-425-19096-x

- ↑ «The Boy Behind the Mask», Charlotte Booth, p. 120, Oneworld, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

Further reading

- Andritsos, John. Social Studies of ancient Egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006

- Booth, Charlotte. The Boy Behind the Mask«, Oneworld, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

- Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story. Putnam Adult, April 13, 1998, ISBN 0425166899 (paperback)/ISBN 0-399-14383-1 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding)

- Carter, Howard and Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Courier Dover Publications, June 1, 1977, ISBN 0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discovery and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamun: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover) /ISBN 0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback)

- Edwards, I.E.S., Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976, ISBN 0-345-27349-4 (paperback)/ISBN 0-670-72723-7 (hardcover)

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: the CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Haag, Michael. The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty. London 2005. ISBN 1-84353-554-8.

- Hoving, Thomas. The search for Tutankhamun: The untold story of adventure and intrigue surrounding the greatest modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, October 15, 1978, ISBN 0-671-24305-5 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of interesting anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb

- James, T. G. H. Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, September 1, 2000, ISBN 1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects

- Neubert, Otto. Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings. London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972, ISBN 583-12141-1 (paperback) First hand account of the discovery of the Tomb

- Reeeves, C. Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, November 1, 1990, ISBN 0-500-05058-9 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-500-27810-5 (paperback) Fully covers the complete contents of his tomb

- Rossi, Renzo. Tutankhamun. Cincinnati (Ohio) 2007 ISBN 978-0-7153-2763-0,

External links

- Grim secrets of Pharaoh’s city BBC News

- Tutankhamun and the Age of the Golden Pharaohs website

- The Independent, October 20, 2007: «A 3,000-year-old mystery is finally solved: Tutankhamun died in a hunting accident». See also video at The-Maker.net

- British Museum Tutankhamun highlight

- King Tut: Ancient Egypt Unveiled — slideshow by Life magazine

Golden funerary mask of Tutankhamun.

Tutankhamun (alternately spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon), Egyptian twt-ˁnḫ-ı͗mn; 1341 BCE – 1323 BCE) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled c.1333 BCE – 1323 BCE in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. His original name, Tutankhaten, means «Living Image of Aten», while Tutankhamun means «Living Image of Amun». In hieroglyphs the name Tutankhamun was typically written Amen-tut-ankh, because of a scribal custom that placed a divine name at the beginning of a phrase to show appropriate reverence.[1] He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters. He was likely the 18th dynasty king ‘Rathotis’ who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years — a figure which conforms with Flavius Josephus’s version of Manetho’s Epitome.[2]

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter of Tutankhamun’s nearly intact tomb received worldwide press coverage. It sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun’s burial mask remains the popular symbol. Exhibits of artifacts from his tomb have toured the world. In February 2010, the results of DNA tests confirmed that Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten (mummy KV55) and his sister/wife (mummy KV35YL), whose name is unknown but whose remains are positively identified as «The Younger Lady» mummy found in KV35.[3]

Life

Tutankhamun was born in 1341 BCE, the son of Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV) and one of his sisters.[4] As a prince he was known as Tutankhaten.[5] He ascended to the throne in 1333 BCE, at the age of nine, taking the reign name of Tutankhaten.

When he became king, he married his half sister, Ankhesenepatan, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun. They had two daughters, both stillborn.[3]

Reign

Given his age, the king must have had very powerful advisers, presumably including General Horemheb, the Vizier Ay, and Maya the «Overseer of the Treasury». Horemheb records that the king appointed him lord of the land as hereditary prince to maintain law. He also noted his ability to calm the young king when his temper flared.[6]

Domestic policy

In his third regnal year, Tutankhamun reversed several changes made during his father’s reign. He ended the worship of the god, Aten and restored the god Amun to supremacy. The ban on the cult of Amun was lifted and traditional privileges were restored to its priesthood. The capital was moved back to Thebes and the city of Akhenaten abandoned.[7] This is also when he changed his name to Tutankhamun.

As part of his restoration, the king initiated building projects, in particular at Thebes and Karnak, where he dedicated a temple to Amun. Many monuments were erected, and an inscription on his tomb door declares the king had «spent his life in fashioning the images of the gods». The traditional festivals were now celebrated again, including those related to the Apis Bull, Horemakhet and Opet. His restoration stela says:

Foreign policy

The country was economically weak and in turmoil following the reign of Akhenaten. Diplomatic relations with other kingdoms had been neglected, and Tutankhamun sought to restore them, in particular with the Mitanni. Evidence of his success is suggested by the gifts from various countries found in his tomb. Despite his efforts for improved relations, battles with Nubians and Asiatics were recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes. His tomb contained body armour and folding stools appropriate for military campaigns. However, given his youth and physical disabilities, which seemed to require the use of a cane in order to walk, historians speculate that he did not take part personally in these battles.[3][8]

Health and appearance

Tutankhamun was slight of build, and was roughly 170 centimetres tall. He had large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, although it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathological. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten often featured such an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality. The research also showed that the Tutankhamun had «a slightly cleft palate»[9] and possibly a mild case of scoliosis.

Cause of death

There are no surviving records of Tutankhamun’s final days. The cause of Tutankhamun’s death has been the subject of considerable debate with several major studies being conducted in an effort to find the answer.

Although there is some speculation that Tutankhamun was assassinated, the general consensus is that his death was accidental. A CT scan taken in 2005 shows that he badly broke his leg shortly before his death and that it became infected. DNA analysis, conducted in 2010 showed the presence of malaria in his system. It is believed that these two conditions, combined, led to his death.[10]

Product of incest

According to an article in the September 2010 issue of National Geographic, King Tut was the product of incest and as such, suffered from several genetic defects which contributed to his early death.[11] For years, scientists have tried to unravel ancient clues as to why the boy king of Egypt, who reigned for 10 years, died at the age of 19. Several theories have been put forth. As stated above, one was that he was killed by a blow to the head. Another put the blame on a broken leg. As recently as June 2010, German scientists said they believe there is evidence he died of sickle cell disease.

The research was conducted by archaeologists, radiologists, and geneticists who started performing CT scans on Tutankhamun five years ago and found that he was not killed by a blow to the head, as previously though. That same team began doing DNA research on Tut’s mummy, as well as the mummified remains of other members of his family, in 2008. DNA finally put to rest questions about Tut’s lineage, proving that his father was Akhenaten and that his mother was not one of Akhenaten’s known wives. His mother was one of Akhenaten’s five sisters, although it is not known which one. New CT images discovered congenital flaws, which are more common among the children of incest. Siblings are more likely to pass on twin copies of harmful genes, which is why children of incest more commonly manifest genetic defects.[12] It is suspected he also had a partially cleft palate, another congenital defect.[13]

The team was able to establish with a probability of better than 99.99 percent that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[14] The DNA of the so-called Younger Lady (KV35YL), found lying beside Queen Tiye in the alcove of KV35, matched that of the boy king. Her DNA proved that, like Akhenaten, she was the daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye; thus, Tut’s parents were brother & sister.[15] Queen Tiye held much political influence at court and acted as an adviser to her son after the death of her husband. There has been speculation that her eldest son Prince Tuthmose was in fact Moses who led the Israelites into the Promised Land.[16]

While the data are still incomplete, the study suggests that one of the mummified fetuses found in Tut’s tomb is the daughter of Tutankhamun himself, and the other fetus is probably his child as well. So far only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained.[17] One of them, KV21A, may well be the infants’ mother and thus, Tutankhamun’s wife, Ankhesenamun. It is known from history that she was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and thus likely her husband’s half sister. Another consequence of inbreeding can be children whose genetic defects do not allow them to be brought to term.

The research team consisted of Egyptian scientists Yehia Gad and Somaia Ismail from the National Research Center in Cairo. The CT scans were conducted under the direction of Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem of the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University. Three international experts served as consultants: Carsten Pusch of the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany; Albert Zink of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman in Bolzano, Italy[18]; and Paul Gostner of the Central Hospital Bolzano.[19]

As stated above, the team discovered DNA from several strains of a parasite proving he was infected with the most severe strain of malaria several times in his short life. Malaria can trigger circulatory shock or cause a fatal immune response in the body, either of which can lead to death. And while Tut did suffer from a bone disease which was crippling, it would not have been fatal. “Perhaps he struggled against others [congenital flaws] until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load,” wrote Zahi Hawass, archeologist and head of Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity involved in the research.

Tomb

Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was small relative to his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, so that his mummy was buried in a tomb intended for someone else. This would preserve the observance of the customary seventy days between death and burial.[20]

King Tutankhamun still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. November 4, 2007, 85 years to the day after Carter’s discovery, the 19-year-old pharaoh went on display in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus to a climate-controlled glass box. The case was designed to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.[21]

Discovery of tomb

Tutankhamun seems to have faded from public consciousness in Ancient Egypt within a short time after his death, and he remained virtually unknown until the 1920s. His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the initial burial. Eventually the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some huts for workers were built over the tomb entrance, clearly not knowing what lay beneath. When at the end of the twentieth dynasty the Valley of the Kings burials were systematically dismantled, the burial of Tutankhamun was overlooked, presumably because knowledge of it had been lost and his name may have been forgotten.

Exhibitions

Relics from Tutankhamun’s tomb are among the most traveled artifacts in the world. They have been to many countries, but probably the best-known exhibition tour was The Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, which ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from March 30 until September 30, 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors came to see the exhibition, some queuing for up to eight hours and it was the most popular exhibition in the Museum’s history. The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the USA, USSR, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from November 17, 1976, through April 15, 1979. More than eight million attended.

In 2004, the tour of Tutankhamun funerary objects entitled «Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter» made up of fifty artifacts from Tutenkhamun’s tomb and seventy funerary goods from other 18th Dynasty tombs began in Basle, Switzerland, went to Bonn Germany, the second leg of the tour, and from there toured the United States. The exhibition returned to Europe and to London. The European tour was organised by the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), and the Egyptian Museum in cooperation with the Antikenmuseum Basel and Sammlung Ludwig. Deutsche Telekom sponsored the Bonn exhibition.[22]

In 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched the U.S. tour of the Tutenkahamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects this time called «Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs». It was expected to draw more than three million people.[23]

The exhibition started in Los Angeles, California, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Chicago and Philadelphia. The exhibition then moved to London[24] before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. Subsequent events have propelled an encore of the exhibition in the United States, beginning with the Dallas Museum of Art in October 2008 which hosted the exhibition until May 2009.[25] The tour will continued to other U.S. cities.[26] After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, to be followed the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.[27]

The exhibition includes eighty exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun’s immediate predecessors in the Eighteenth dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun’s burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun’s tomb. The exhibition does not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972-1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has determined that the mask is too fragile to withstand travel and will never again leave the country.[28]

A separate exhibition called «Tutankhamun and the World of the Pharaohs» began at the Ethnological Museum in Vienna from March 9 to September 28, 2008 showing a further 140 treasures from the tomb. This exhibition continued to Atlanta and the Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Curse

For many years, rumors of a «Curse of the Pharaohs» (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had first entered the tomb. However, a recent study of journals and death records indicates no statistical difference between the age of death of those who entered the tomb and those on the expedition who did not. Indeed, most lived past seventy.

Significance

Tutankhamun was nine years old when he became pharaoh and reigned for approximately ten years. In historical terms, Tutankhamun’s significance stems from his rejection of the radical religious innovations introduced by his predecessor and father, Akhenaten.[29] Secondly, his tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered by Carter almost completely intact — the most complete ancient Egyptian royal tomb ever found. As Tutankhamun began his reign at such an early age, his vizier and eventual successor Ay was probably making most of the important political decisions during Tutankhamun’s reign.

Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped as a god and honored with a cult-like following in his own lifetime.[30] A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Ra and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by wrongdoing. Temples of his cult were built as far away as in Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king, indicative of the universality of his cult.[31]

In popular culture

If Tutankhamun is the world’s best known pharaoh, it is partly because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most-exhibited. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter’s The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, «The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt’s kings has become in death the most renowned.» As a side effect, the interest in this tomb and its alleged «curse» led to horror movies featuring a vengeful mummy.

Film and television

- We Want Our Mummy, a 1939 film by the Three Stooges. In it, the slapstick comedy trio explore the tomb of the midget King Rutentuten (pronounced «rootin’-tootin'») and his Queen, Hotsy Totsy. A decade later, they were crooked used-chariot salesmen in Mummy’s Dummies, in which they ultimately assist a different King Rootentootin (Vernon Dent) with a toothache.

- King Tut, played by Victor Buono, was a villain on the Batman TV series which aired from 1966 to 1968. Mild-mannered Egyptologist William Omaha McElroy, after suffering a concussion, came to believe he was the reincarnation of Tutankhamun. His response to this knowledge was to embark upon a crime spree that required him to fight against the «Caped Crusaders», Batman and Robin.

- The Discovery Kids animated series Tutenstein stars a fictional mummy based on Tutankhamun, named Tutankhensetamun and nicknamed Tutenstein in his afterlife. He is depicted as a lazy and spoiled 10-year-old mummy boy who must guard a magical artifact called the Scepter of Was from the evil Egyptian god of Set.

- La Reine Soleil (2007 animated film by Philippe Leclerc), features Akhenaten, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun), Akhesa (Ankhesenepaten, later Ankhesenamun), Nefertiti, and Horemheb in a complex struggle pitting the priests of Amun against Akhenaten’s intolerant monotheism.

- The first episode of the 2005 BBC series Egypt: Rediscovering a Lost World focuses on the life and death of Tutankhamun and the serendipitous discover of his tomb.

Other

- «King Tut», a whimsical 1978 song by (American comedian) «Steve Martin and the Toot Uncommons» (a backup group consisting of members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band).

- The mummy of Tutankhamun is depicted as a villain in Raj Comics’s Nagraj, a Hindi superhero comicbook. In this series, his mask is the source of his power.

- The video game Sphinx and the Cursed Mummy features a fictional representation of Prince Tutankhamun. Tutankhamun is the victim of an unnamed magical ritual which results in almost instantaneous mummification and extraction of what appears to be his «life force». In the instruction manual, the Mummy is described as young, inexperienced and naive.

Names

At the reintroduction of traditional religious practice, Tutankaten’s name changed. It is transliterated as twt-ˁnḫ-ỉmn ḥq3-ỉwnw-šmˁ, and often realized as Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, meaning «Living image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis». On his ascension to the throne, Tutankhamun took a praenomen. This is translated as nb-ḫprw-rˁ, and realized as Nebkheperure, meaning «Lord of the forms of Ra». The name Nibhurrereya in the Amarna letters may be a variation of this praenomen.

References

- ↑ Zauzich, Karl-Theodor (1992). Hieroglyphs Without Mystery. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9780292798045. http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/books/zauhie.html.

- ↑ «Manetho’s King List». http://www.phouka.com/pharaoh/egypt/history/KLManetho.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hawass, Zahi et al. «Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family» The Journal of the American Medical Association, February 17, 2010. Vol 303, No. 7 p.638-647

- ↑ Hawass, Zahi et al. «Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family» The Journal of the American Medical Association p.640-641

- ↑ Jacobus van Dijk. «The Death of Meketaten» (PDF). http://history.memphis.edu/murnane/Van%20Dijk.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ Booth p. 86-87

- ↑ Erik Hornung, Akhenaten and the Religion of Light, Translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0801487250

- ↑ Booth p. 129-130

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian (March 8, 2005). «King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show». National Geographic News. p. 2. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/03/0308_050308_kingtutmurder.html. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

- ↑ Roberts, Michelle (2010-02-16). «‘Malaria’ killed King Tutankhamun». BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8516425.stm. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1251731/King-Tutankhamuns-incestuous-family-revealed.html

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/8

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/5

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/7

- ↑ http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1251731/King-Tutankhamuns-incestuous-family-revealed.html

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/9

- ↑ http://www.eurac.edu/en/research/institutes/iceman/pages/default.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1

- ↑ http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text/3

- ↑ «The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendour in the New Kingdom«, Zahi Hawass, p. 61, American University in Cairo Press, 2004, ISBN 9774248368

- ↑ Michael McCarthy (2007-10-05). «3,000 years old: the face of Tutankhamun». London: The Independent. http://news.independent.co.uk/sci_tech/article3129650.ece.

- ↑ «Al-Ahram Weekly | Heritage | Under Tut’s spell». Weekly.ahram.org.eg. http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2004/716/he1.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑

«King Tut exhibition. Tutankhamun & the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Treasures from the Valley of the Kings». Arts and Exhibitions International. http://www.kingtut.org/exhibition.htm. Retrieved 2006-08-05. - ↑ Return of the King (Times Online)[dead link]

- ↑ «Dallas Museum of Art Website». Dallasmuseumofart.org. http://dallasmuseumofart.org/Dallas_Museum_of_Art/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Associated Press, «Tut Exhibit to Return to US Next Year»

- ↑ «Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs | King Tut Returns to San Francisco, June 27, 2009–March 28, 2010». Famsf.org. http://www.famsf.org/tut/. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ↑ Jenny Booth (2005-01-06). «CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle». London: The Times. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article409075.ece?token=null&offset=12.

- ↑ Aude Gros de Beler, Tutankhamun, foreword Aly Maher Sayed, Moliere, ISBN 2-84790-210-4

- ↑ «Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology», Editor Donald B. Redford, p. 85, Berkley, ISBN 0-425-19096-x

- ↑ «The Boy Behind the Mask», Charlotte Booth, p. 120, Oneworld, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

Further reading

- Andritsos, John. Social Studies of ancient Egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006

- Booth, Charlotte. The Boy Behind the Mask«, Oneworld, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

- Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story. Putnam Adult, April 13, 1998, ISBN 0425166899 (paperback)/ISBN 0-399-14383-1 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding)

- Carter, Howard and Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Courier Dover Publications, June 1, 1977, ISBN 0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discovery and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamun: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover) /ISBN 0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback)

- Edwards, I.E.S., Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976, ISBN 0-345-27349-4 (paperback)/ISBN 0-670-72723-7 (hardcover)

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: the CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Haag, Michael. The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty. London 2005. ISBN 1-84353-554-8.

- Hoving, Thomas. The search for Tutankhamun: The untold story of adventure and intrigue surrounding the greatest modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, October 15, 1978, ISBN 0-671-24305-5 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of interesting anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb

- James, T. G. H. Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, September 1, 2000, ISBN 1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects

- Neubert, Otto. Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings. London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972, ISBN 583-12141-1 (paperback) First hand account of the discovery of the Tomb

- Reeeves, C. Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, November 1, 1990, ISBN 0-500-05058-9 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-500-27810-5 (paperback) Fully covers the complete contents of his tomb

- Rossi, Renzo. Tutankhamun. Cincinnati (Ohio) 2007 ISBN 978-0-7153-2763-0,

External links

- Grim secrets of Pharaoh’s city BBC News

- Tutankhamun and the Age of the Golden Pharaohs website

- The Independent, October 20, 2007: «A 3,000-year-old mystery is finally solved: Tutankhamun died in a hunting accident». See also video at The-Maker.net

- British Museum Tutankhamun highlight

- King Tut: Ancient Egypt Unveiled — slideshow by Life magazine

Новый взгляд на древнюю историю Египта и символы маски Тутанхамона

Об авторе: Ткачёв Александр – родился в 1957 году, к.э.н. (защищался в МГУ на кафедре Гавриила Попова), последние 10 лет работал в ОАО «НК»Роснефть», сейчас на пенсии. В 2014 г. издал книгу «Тайны древней истории».

Памяти Говарда Картера (9 мая 1874 г.- 2 марта 1939 г.)

Открытие гробницы Тутанхамона в «Долине царей» возле города Фивы (современный Луксор) — результат длительных поисков английского археолога Говарда Картера (Howard Carter). Вскрытие могилы произошло 26 ноября 1922 года и этот факт был признан крупнейшим открытием в области древней археологии. С тех пор ученые — египтологи выдвинули ряд гипотез по поводу происхождения фараона Тутанхамона и времени его правления. Об этих гипотезах можно прочитать в интернете, но я не буду на них останавливаться, поскольку новые исторические и этимологические данные не подтверждают ни одной из них.

Кем же был столь пышно похороненный фараон Египта? Чтобы разобраться в этом нужны были дополнительные данные по древней истории Египта. Такие данные появились в результате частичной расшифровки текстов древних еврейских рукописей, сделанных мной в 2007 году.

Оказалось, что ряд древних египетских символов, относящихся к иероглифическому письму не могут быть прочитаны с помощью открытий, сделанных французским ученым Франсуа Шампольоном (Jean Francois Champollion 1790-1832), или с помощью теории среднеегипетской грамматики английского лингвиста Алана Гардинера (Alan Henderson Gardiner 1879-1963). Большая часть иероглифов, на которых были сделаны надписи в могилах Луксора, относятся к периоду истории Египта до 1500 года до н.э., их древние значения были уже утеряны ко времени исследований Гардинера и Шампольона.

Что же дают новые исследования древних египетских иероглифов? Расшифровывая с помощью «Розетского камня» картуши Птолемея и Клеопатры, Франсуа Шампольон установил, что египетские символы могут означать буквы. В частности, изображение ястреба обозначало букву «А», а изображение льва — букву «Л». В древних же картушах писались не буквы, а родовые знаки фамилий древних царей.

Символика картуша

До сих пор было неизвестно зачем надписи делались в картушах. Согласно новых исследований древний картуш был брачным символом соединения двух царских родов. «Овал» картуша означал женщину, вступавшую в брак, «палка» означала мужчину, вступавшего в брак. Веревка, которая на древних изображениях связывала «палку» и «овал», показывала их «связывание» брачными узами. В «овале» картуша иероглифами записывалось родовое происхождение мужчины и женщины. Эта запись была очень важна, поскольку родовое происхождение царской четы указывало на их место в «табеле о рангах» царей Египта.

Из тайнописей еврейских рукописей удалось выяснить, что самым древним и самым знатным правящим родом в древности был род фараонов с фамилией Ра (Солнцевы). Род имел свою символику в виде солнца. Мальчики рода носили на короне изображение змеи-кобры с солнцем на голове. Вторым по значению после рода Ра шел род царей Кара, он обозначался символом в виде черного жука, которого в Египте времен Птолемеев называли скарабеем, а в глубокой древности называли «Кара». Третьим по положению в «табеле о рангах» древних правителей Египта был род Мата, он изображался в картуше символом из трех сплетенных в пучок женских кос и на вид напоминал букву «М». Ошибочно этот иероглиф был прочтен учеными как Маат. Род Мата (Маат) шел по материнской линии от первой царицы Египта, и пока точно не установлено как передавалась эта фамилия. Построение родовых символов в картуше показывало из какого рода вышел царь Египта и каково было его положение в иерархии египетских царей.

Фараон – глава царей Египта

Ко времени завоевания греками Египта слово фараон означало титул местных царей, но до 1500 года до н.э. слово фараон означало высшее родовое положение правителя династии Ра (Солнцевых). Сегодня считают, что этимология слова «фараон» означает «дом Ра», на самом деле слово «фараон» является словосочетанием древнего слогового языка, описанного кратко в тайнописях еврейских рукописей. В этом слове три отдельных слоговых слова, которые читаются следующим образом:

Фа-фамилия

Ра- Солнцев

Он- первый

В древнем Египте фараоном считался только главный правитель — первенец рода Ра (Солнцевых). Трон фараона, правителя всей империи династии Солнцевых(Ра), после смерти отца мог занять только первый сын фараона, что, собственно, и было записано в названии титула. Остальные дети фараона, коих было очень много, фамилию Ра (Солнцев) и титул «фараон» не наследовали. Они образовывали династии рангом пониже и назывались царями. Так образовывались роды царей: Кара, Мата, Горов, Амонов, Атонов и т.д. Мальчики, родившиеся четвертыми или пятыми в семье, могли вообще не получить титула и были в прислуге у старших или занимали военные должности при дворе фараона. Их родословная часто не записывалась.

Считают, что фараоны древнего Египта были язычниками и солнцепоклонниками и от того так много изображений солнца в могильниках царей. На самом деле древней верой империи Солнцевых был монотеизм, получивший свое более позднее отражение в Иудаизме и Исламе.

Примерно за 1200 лет до прихода греков на север Африки с исторической сцены исчез основной правитель рода Ра – фараон. Его титул стали присваивать цари других родовых династий, родственных и не родственных роду Ра. Многочисленные войны и революции смешали роды, монотеисты египтяне превратились в идолопоклонников, а слово фараон превратилось просто в титул. На земле появились новые царские династии. Одну из таких династий назвали Хан, что на древнем слоговом языке означало «Небо». Мальчик, первым получивший такую фамилию, стал фактически основателем династии китайских императоров.

Династии правителей Хан и Амон

В картушах Египта династия Хан обозначалась иероглифом в виде креста с надутым над крестом шаром. Ученые прочли этот иероглиф как «Анх», допустив маленькую неточность в порядке записи букв. В верхнем Египте после гибели основной династии Ра (Солнцевых) возникла новая династия потомков фараонов Ра и носила она фамилию Амон Ра или Амонов (Барановых по-русски). Пока неизвестно в какое время началась война рода Хан против рода Амонов, предположительно это 2000-1500 лет до н.э. Однако, известно, что род Хан захватил земли Верхнего и Нижнего Египта. В качестве послевоенного примирения решили царя из рода Хан женить на царице из рода Амон. Такой политический прием перемирия на уровне биологического союза родовой знати часто применялся в древности. Обычно военный правитель завоевателей брал в жены дочь царя завоеванной территории. Мальчика, родившегося от такого брака, назвали Тут, а его двойная царская фамилия была записана как Хан-Амон. Но так мы пишем двойные фамилии сегодня. В древности никаких знаков препинания не было, вот и получилось «Тутханамон», учитывая ошибку ученых с иероглифом «Анх» сегодня пишут «Тутанхамон».

По двойной фамилии фараона видно, что «Тут Хан — Амон» (Туанхамон) – потомок двух крупных царских родов: рода «Амон» — прямого потомка рода Ра и китайского рода Хан. Символом рода Ра была змея – кобра с солнцем на голове, в древности ее носили только мужчины рода Ра, но со временем эта традиция была нарушена и символ стали изображать и на коронах женщин. Символ рода Хан был придуман позднее, и это было изображение коршуна, которое Франсуа Шампольон, кстати, принял за изображение ястреба. На маске Тут Хан-Амона (Тутанхамона) эти два родовых знака изображены вместе на царской короне. В данном случае змея, как символ рода Ра, досталась в корону от матери из рода Амонов, а коршун, как символ рода Хан, изображал род отца мальчика с фамилией Хан (Небо). Золото, из которого сделана маска символизирует солнце, а вот синяя лазурь соответствует небу и родовой фамилии царя Хан (Небо). С точки зрения современных понятий, Тут Хан-Амон (Тутанхамон) — это принц полукровка, потомок царицы черной расы, дочери правителя Верхнего Египта из рода Амон и древнего китайского царя из рода Хан.

Новые данные истории древнего Египта

Как было отмечено ранее, из исследований древнего слогового языка, описанного в еврейских рукописях, выяснилось, что фамилия Хан означала «Небо». Со временем это значение фамилии было утеряно, и фамилия превратилась в титул. Древняя история Китая, шла примерно по тому же сценарию, что и древняя история Египта. Со временем от основной китайской династии Хань, «откололась» очень крупная родовая династия Цинь и множество мелких родовых династий. Однако, китайские императоры все это время продолжали называть себя «царями неба», а китайская империя получила название «поднебесной». При этом уже никто не помнил причину такого названия. Ученые ошибочно записали иероглиф «Хан» как «Анх», а поскольку символов неба в могилах Египта найдено было очень много решили, что «Анх» — это символ вечной жизни или бессмертия.

Такая же ошибка произошла и с иероглифом Мата. Этот иероглиф, изображаемый плетью с тремя косами, ошибочно назвали Маат.

Ошибка вышла и с титулом «фараон». Титул стали применять в своих записях даже греки в период колонизации Африки, его первоначальное значение было утеряно. Только благодаря расшифровкам тайнописи еврейских рукописей удалось установить, что это был глава империи царей рода Ра(Солнцевых).

Когда Говард Картер открыл миру великолепную золотую маску Тутанхамона, он записал в своем дневнике: «Все, что мы знаем об этом человеке, так это то, что он жил и умер…». Теперь мы знаем немного больше: потомок двух царских династий, символы которых змея и коршун, изображенные на маске, был правителем земли Верхнего Египта. Этой территорией правил род Амон Ра, но в ходе войны государство было захвачено китайским родом Хан. В результате межродового брака и перемирия между двумя царскими родами возник новый род — Хан-Амон. Этот род правил Верхним Египтом примерно за 1500 лет до н.э. Могила царя этого рода по имени Тут и фамилии Хан-Амон и была найден Говардом Картером.

Александр Ткачёв.

Тутанхамо́н (Тутанхато́н) — фараон Древнего Египта из XVIII династии Нового царства, правивший приблизительно в 1332—1323 годах до н. э. Его обнаруженная Говардом Картером в 1922 году практически нетронутая гробница KV62 в Долине Царей стала сенсацией и возродила интерес публики к Древнему Египту.

Фараон и его золотая погребальная маска (ныне выставлена в Каирском египетском музее) с тех пор остаются популярными символами[1], а «мистические» смерти участников экспедиции 1922 года привели к возникновению понятия «проклятие фараонов».

Происхождение

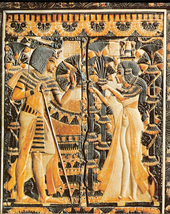

Тутанхамон и его жена Анхесенамон. Фрагмент спинки золотого трона, XIV век до н. э.

Точных данных, в которых указано происхождение Тутанхамона, не найдено. Подтверждением существования царевича до его коронации служит камень из Гермополя с надписью: «возлюбленный сын фараона от его плоти Тутанхатон»[2]. Египтологи выдвинули две версии его происхождения:

- он был сыном фараона Эхнатона[3];

- отцом Тутанхамона был фараон Сменхкара, зять, брат или сын Эхнатона.

17 февраля 2010 года Захи Хавасс и министр культуры Египта Фарук Хосни обнародовали результаты исследований, которые проходили в 2007—2009 годах и заключались в комбинированном ДНК-анализе, а также радиологическом исследовании мумий[4]. Исследователи пришли к выводу, что Тутанхамон был сыном мумии из гробницы KV55 (предположительно, Эхнатона) и неидентифицированной принцессы («младшей дамы») из гробницы KV35[5]. Гаплотип не обнародован, однако управляющий директор швейцарской компании iGENEA Роман Шольц заявил, что по данным, показанным каналом Discovery, им удалось определить 16 маркеров из Y-хромосомы[6], после чего ими было выдвинуто предположение, что Тутанхамон принадлежал к Y-хромосомной гаплогруппе R1b1a2[7][8].

В том же 2010 году российский египтолог А. О. Большаков усомнился в результатах исследований Хавасса[9]. По его мнению, данные эпиграфики показывают, что среди детей Эхнатона мальчик Тутанхамон не изображается, хотя даже маленькие дочери изображены в качестве участниц культов Атона наравне с отцом. Также Большаков поддержал гипотезу, защищавшуюся Ю. Я. Перепёлкиным, о том, что мумия из KV55 — это Сменхкара.

В поздних документах своего правления Тутанхамон называет отцом своего деда Аменхотепа III, что объясняется сменой политического и религиозного вектора[2].

Имя

|

|

|

|

Слева: Расшифровка иероглифов имени Тутанхамона (на англ.) |

В детстве получил имя Тутанхатон (егип. twt-anx-itn — «Живое воплощение Атона»), что в иероглифической записи выглядит так:

После смерти Эхнатона и тенденции на восстановление прежнего пантеона на второй год своего правления Тутанхатон изменил своё имя на Тутанхамон (егип. twt-anx-imn HqA-iwnw-šmA Тутанхамон Хекаиунушема — «Живое воплощение Амона, властитель южного Иуну»). Его супруга царица Анхесенпаатон («Живёт она для Атона») соответственно изменила своё имя на Анхесенамон («Живёт она для Амона»)[2]. Иероглифически его имя записывалось как Амон-тут-анкх, где божественное имя в знак благоговения ставилось первым[10]. С восшествием на трон Тутанхамон принял тронное имя Небхепрура (егип. Nb-ḫprw-Rˁ — «живое воплощение Ра»), под которым фигурирует в Амарнском архиве.

Семья

Тутанхамон был женат на Анхесенамон (предположительно мумия KV21A), третьей дочери Эхнатона и Нефертити. В этом союзе были две мертворождённые дочери[en], найденные в гробнице Тутанхамона[12][13].

В конце 1996 года на мемфисском некрополе Саккары французская экспедиция под руководством Алена Зиви обнаружила гробницу кормилицы Тутанхамона по имени Майя. Согласно надписям и рисункам в гробнице, работы над усыпальницей продолжались и после смерти Тутанхамона[14][15].

XVIII династия

Серым цветом выделены представители XVII династии.

Правление

Вступление на престол

После смерти Эхнатона власть перешла к Сменхкаре, а с его скоропостижной смертью — к некой царице, взявшей тронное имя Анкхетхеперура, возлюбленная Ваенра (=Эхнатоном) Нефернефруатон. Ею могла быть Нефертити, либо Меритатон (вдова Сменхкары)[16], либо даже Нефернефруатон-ташерит (четвёртая дочь Эхнатона и Нефертити). Личность Нефернефруатон иногда объединяют с безымянной царицей из хеттских источников, где она называется Дахамунцу[15]; либо же письма Дахамунцу исходили от вдовствующей Анхесенамон десятилетием позже[17]. Нефернефруатон могла оставаться регентшей при малолетнем Тутанхамоне[15].

Вступил на престол в возрасте около 10 лет[2].

В новой столице Амарне археологами не найдено предметов с именем фараона Тутанхатона или его тронных имён (Хорово имя, Имя по Небти). Это свидетельствует о том, что малолетний фараон начал своё правление после возвращения к прежнему культу со своим новым именем Тутанхамон[15].

Внутренняя политика

Деревянный бюст мальчика-фараона из его гробницы

Религиозная реставрация

Из текста большой стелы, воздвигнутой от его имени в Карнаке, известно, что первые три года после вступления на престол Тутанхамон продолжал пребывать вместе с двором в Ахетатоне. На втором году правления[2] Тутанхатон и его супруга изменили имена в честь Амона, чей культ восстанавливался после упадка культа Атона. Одно из второстепенных имён фараона провозглашало его «Удовлетворяющим богов»[18]. Тутанхамон легитимизировал своё правление, назвав себя прямым наследником фараона Аменхотепа III (своего деда), а Эхнатона провозгласил отступником[2].

При Тутанхамоне велось усиленное восстановление заброшенных во время правления Эхнатона святилищ прежних богов[2], не только в Египте, но и в Куше — например, храмы в Каве (Гемпаатоне) и в Фарасе. Но впоследствии Хоремхеб уничтожал картуши Тутанхамона, заменяя их на свои, и захватил памятники его правления.

Также он даровал привилегии жрецам, певцам и служителям храмов, распорядился изготавливать церемониальные лодки из лучшего ливанского кедра, покрывать их золотом (Стела Реставрации)[2]. Юный Тутанхамон оставался марионеткой в руках придворных чиновников и жрецов традиционного культа. Регентом при малолетнем фараоне был Эйе (брат бабки Тутанхамона — Тии)[19].

Покинув Ахетатон, двор Тутанхамона не вернулся в Фивы (божество-покровитель Амон), а обосновался в Мемфисе[19] (божество-покровитель Птах). Тутанхамон периодически посещал южную столицу. Например, он участвовал там в главном городском празднестве Амона. Восстановив культ Амона и всех прочих старых богов, Тутанхамон не подвергал гонениям культ Атона. Храм Солнца ещё в 9-м году царствования Тутанхамона владел виноградниками. Изображения Солнца и Эхнатона сохранились нетронутыми, а в своих надписях Тутанхамон величает себя иногда «сыном Атона».

Строительство

Ввиду избрания фараоном Мемфиса своей фактической столицей, в некрополе Саккара были сооружены многочисленные гробницы вельмож, среди которых выделяются усыпальницы военачальника Хоремхеба, казначея и архитектора Майа (англ.), известные своей изящной рельефной декорировкой. В Фивах хорошо сохранилась гробница вельможи Аменхотепа Хеви, который был в это время царским наместником Нубии («Царским сыном Куша»).

Помимо реставрационных работ во многих святилищах по приказу Тутанхамона была завершена отделка процессионной колоннады Аменхотепа III в Луксорском храме, построен небольшой храм Хорона в Гизе; в Нубии — достроен гигантский храмовый комплекс Аменхотепа III в Солебе, возведён храм Амона в Кава и святилище самого обожествленного Тутанхамона в Фарасе. Заупокойный храм царя, украшенный красивейшими полихромными песчаниковыми колоссами, находился в Фивах неподалёку от Мединет Абу; позже храм был узурпирован преемниками фараона — Эйе и Хоремхебом (последний включал Тутанхамона в список еретиков, преданных забвению).

Внешняя политика

Тутанхамон поражает врагов на колеснице (ок. 1327 года до н. э.) Роспись по дереву, Каирский музей

Возможно, в правление Тутанхамона военачальник Хоремхеб, будущий фараон, одержал победу в Сирии, в связи с чем в Карнаке изобразили прибытие царского судна с сирийцем в клетке. Возможно, в это же царствование велись успешные военные действия в Нубии. От имени Тутанхамона утверждали, что он обогащал храмы из своей военной добычи. Из надписи в гробнице наместника Нубии Аменхотепа (сокращенно Хаи) известно, что несколько сирийских племён регулярно выплачивали дань. Поступали подати и из Нубии.

Правление Тутанхамона не отличилось ничем значительным, помимо отказа от атонизма. Обнаруживший гробницу Тутанхамона археолог Говард Картер заявил:

При нынешнем состоянии наших знаний мы можем с уверенностью сказать только одно: единственным примечательным событием его жизни было то, что он умер и был похоронен.

Смерть Тутанхамона

![Некоторые из 130 тростей Тутанхамона. Либо фараон не мог ходить без них, либо они служили аксессуаром, как другим правителям XVIII династии[20]](https://wiki2.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ee/By_ovedc_-_Egyptian_Museum_%28Cairo%29_-_202.jpg/im244-337px-By_ovedc_-_Egyptian_Museum_%28Cairo%29_-_202.jpg)

Некоторые из 130 тростей Тутанхамона. Либо фараон не мог ходить без них, либо они служили аксессуаром, как другим правителям XVIII династии[20]

Тутанхамон скончался на 19-м году жизни и был упокоен в своей гробнице KV62 в Долине Царей.

Существует несколько версий смерти фараона Тутанхамона:

- Тутанхамон мог быть убит по приказу регента Эйе, ставшего после новым фараоном;

- Исследования 2005 года выдвинули предположение о смерти Тутанхамона в результате травмы. 8 марта 2005 года египтолог Захи Хавасс огласил результаты компьютерной томографии Тутанхамона, которые не обнаружили следов черепно-мозговой травмы (прореха в черепе, очевидно, появилась в результате мумификации). Были опровергнуты также результаты предыдущих рентгеновских исследований тела фараона, приписывающих ему тяжёлую степень сколиоза;

- Исследования 2010 года свидетельствуют, что Тутанхамон умер «от тяжёлой осложнённой формы малярии, возбудители которой обнаружены в его теле в ходе ДНК-анализов». Этот вывод подтверждает и наличие в гробнице Тутанхамона лекарственных снадобий для лечения малярии[4].

- Причиной травмы послужило падение с колесницы во время охоты, поскольку смерть Тутанхамона совпадает с разгаром охотничьего сезона в Египте. Время смерти установлено по надетому на мумию венку из цветущих васильков и ромашек. Время их цветения выпадает на март-апрель, а поскольку процесс мумификации длился 70 дней, то смерть должна была наступить в декабре-январе[21].

- Медицинские работники (патологоанатомы-криминалисты) Скотленд-Ярда, осмотрев череп мумии, пришли к выводу, что человека убили чем-то похожим на топор[источник не указан 1645 дней].

17 февраля 2010 года Захи Хавасс и министр культуры Египта Фарук Хосни обнародовали результаты ДНК-исследований 2007—2009 годов, согласно которым члены семьи Тутанхамона страдали генетическими заболеваниями[22]. В частности, некоторые её представители, в том числе и Тутанхамон, страдали болезнью Кёлера (некроз костей стоп, вызванный нарушением кровоснабжения). В то же время синдрома Марфана, гинекомастии и других генетических отклонений, которые могли спровоцировать «женские» очертания фигур у правителей той эпохи, обнаружены не были[4]. Среди других недугов фараона также имелись расщепление нёба («волчья пасть» — врожденное незаращение твёрдого нёба и верхней челюсти) и косолапость[23].

Смерть Тутанхамона, не оставившего законного наследника, привела к сложностям в престолонаследии[2]. Сведения о периоде после смерти Тутанхамона дискуссионны и сложны для детального восстановления[15]. Имеется предположение, что некоторое время вдовствующая Анхесенамон, не обладая правами на единоличное правление и не имея подходящего по статусу жениха, пыталась заключить брак с хеттским принцем Заннанзой (см. Дахамунцу). Принц погиб на границе Египта, след царицы теряется в истории[2][17]. Официальным правителем после Тутанхамона стал Эйе, затем власть перешла к бывшему военачальнику Хоремхебу. Никто из них не оставил после себя наследников, что положило конец XVIII династии.

Гробница

Гробница KV62

В глазах историков Тутанхамон оставался малоизвестным второстепенным фараоном вплоть до начала XX века. Более того, даже высказывались сомнения в реальности его существования. Поэтому открытие гробницы Тутанхамона считается одним из величайших событий в истории археологии.

Скорее всего, при жизни Эхнатона для царевича Тутанхатона возле Амарны строилась усыпальница, работы над которой прекратились с возвращением к старым порядкам. Для Тутанхамона начали готовить новую гробницу в Фивах, но не успели завершить все работы к дню его смерти. Его гробницу (KV62) в Долине царей обнаружил английский археолог Говард Картер в 1922 году. Она оказалась почти нетронутой расхитителями (найдены следы двух проникновений древних грабителей, которым, очевидно, помешали совершить преступление), что прославило этого фараона в наши дни. Гробница уступает в размерах по сравнению с прочими гробницами XVIII династии, поскольку не предназначалась для захоронения Тутанхамона, — её спешно обустроили, когда молодой фараон умер[19].

В ней, среди погребальных принадлежностей и утвари, обнаружено множество произведений искусства той эпохи — различные предметы быта (позолоченная колесница, кресла, кровать, светильники), драгоценные украшения, одежда, письменные принадлежности и даже пучок волос его бабушки Тии.

Все артефакты гробницы Тутанхамона из собрания музеев Египта предстанут в единой экспозиции строящегося Большого египетского музея в Гизе[24][25].

Легенда о «проклятии фараона»