Whitney Elizabeth Houston (August 9, 1963 – February 11, 2012) was an American singer and actress. Nicknamed «The Voice», she is one of the bestselling music artists of all time, with over 200 million records sold worldwide.[1] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked her second on their list of the greatest singers of all time.[2] Houston influenced many singers in popular music, and was known for her powerful, soulful vocals and vocal improvisation skills.[3][4] She is the only artist to have had seven consecutive number-one singles on the Billboard Hot 100, from «Saving All My Love for You» in 1985 to «Where Do Broken Hearts Go» in 1988. Houston also enhanced her popularity upon entering the movie industry. Throughout her career and posthumously, she has received numerous accolades, including two Emmy Awards, six Grammy Awards, 16 Billboard Music Awards, and 28 Guinness World Records. Houston has also been inducted into the Grammy, Rhythm and Blues Music, and Rock and Roll halls of fame.

|

Whitney Houston |

|

|---|---|

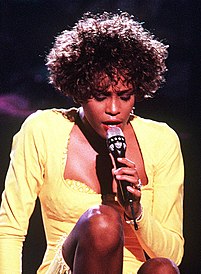

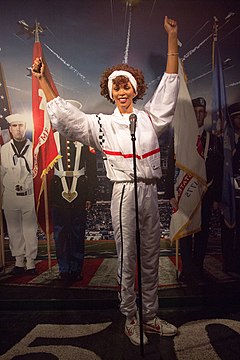

Houston singing «Greatest Love of All» at the Welcome Home Heroes concert in 1991 |

|

| Born |

Whitney Elizabeth Houston August 9, 1963 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | February 11, 2012 (aged 48)

Beverly Hills, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Fairview Cemetery,Westfield, New Jersey |

| Education | Mount Saint Dominic Academy |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1977–2012 |

| Spouse |

Bobby Brown (m. 1992; div. 2007) |

| Children | Bobbi Kristina Brown |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards |

|

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Labels |

|

| Website | whitneyhouston.com |

| Signature | |

|

Houston began singing in church as a child and became a background vocalist while in high school. She was one of the first black women to appear on the cover of Seventeen after becoming a teen model in 1981. With the guidance of Arista Records chairman Clive Davis, Houston signed to the label at age 19. Her first two studio albums, Whitney Houston (1985) and Whitney (1987), both peaked at number one on the Billboard 200 and are among the best-selling albums of all time. Houston’s third studio album, I’m Your Baby Tonight (1990), yielded two Billboard Hot 100 number-one singles: «I’m Your Baby Tonight» and «All the Man That I Need».

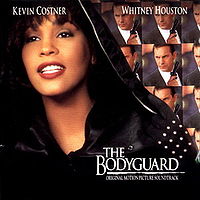

Houston made her acting debut with the romantic thriller film The Bodyguard (1992), which became the tenth highest-grossing film to that date despite receiving poor reviews for its screenplay and lead performances. She recorded six songs for the film’s soundtrack, including «I Will Always Love You» which won the Grammy Award for Record of the Year and became the best-selling physical single by a woman in music history. The soundtrack for The Bodyguard won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year and remains the bestselling soundtrack album of all time. Houston went on to star and record soundtracks for Waiting to Exhale (1995) and The Preacher’s Wife (1996). Houston produced the latter’s soundtrack, which became the bestselling gospel album of all time. As a film producer, she produced multicultural movies, including Cinderella (1997), and series, including The Princess Diaries and The Cheetah Girls.

Houston’s first studio album in eight years, My Love Is Your Love (1998), sold millions and spawned several hit singles, including «Heartbreak Hotel», «It’s Not Right but It’s Okay» and «My Love Is Your Love». Following the success, she renewed her contract with Arista for $100 million, one of the biggest recording deals of all time.[5] However, her personal problems began to overshadow her career. Her 2002 studio album, Just Whitney, received mixed reviews. Her drug use and a tumultuous marriage to singer Bobby Brown received widespread media coverage. After a six-year break from recording, Houston returned to the top of the Billboard 200 chart with her final studio album, I Look to You (2009). On February 11, 2012, Houston accidentally drowned in a bathtub at the Beverly Hilton hotel in Beverly Hills, with heart disease and cocaine use as contributing factors. News of her death coincided with the 2012 Grammy Awards (which took place the day following her death), and was covered internationally.

An official biopic movie of Houston, titled I Wanna Dance with Somebody, was released in theaters on December 23, 2022.

Life and career

1963–1984: Early life, family and career beginnings

Whitney Elizabeth Houston was born on August 9, 1963, in Newark, New Jersey.[6] Her mother, Emily «Cissy» Houston (née Drinkard), was a gospel singer who was part of The Drinkard Singers and who later joined the Gospelaires, a popular session vocal group whose name eventually changed to The Sweet Inspirations.[7][8] Cissy recorded several albums with the group on their own, in addition to singing background for musicians such as Aretha Franklin, Jimi Hendrix and Elvis Presley,[9] and earned a Grammy Award nomination for the song, «Sweet Inspiration».[10] Her father, John Russell Houston Jr., was an ex-Army serviceman, a Newark city administrator who worked for then-Newark mayor Kenneth A. Gibson and a manager of the Sweet Inspirations. Her elder brother, Michael, was a songwriter, and her elder maternal half-brother is former basketball player and singer Gary Garland.[11][12] She also had an elder paternal half-brother, John III.[13] Both of Houston’s parents were African-American. On her mother’s side, it is alleged that Houston had Dutch and Native American ancestry.[14] Through her mother, Houston was a first cousin of singers Dionne and Dee Dee Warwick as well as a distant cousin of opera singer Leontyne Price. Through her father, she is a great-great-granddaughter of Jeremiah Burke Sanderson, an American abolitionist and advocate for the civil and educational rights of black Americans. Her godmother was singer Darlene Love[15] and Franklin was considered an «honorary aunt».[16][17] Devastated by the events of the 1967 Newark riots, Whitney’s family eventually relocated to a middle-class area in East Orange, New Jersey.[18] Her parents later divorced.[19] Houston was raised a Baptist but admitted to being exposed to the Pentecostal church as well. Houston began singing in the church choir at the New Hope Baptist Church in Newark at age five, where she also learned to play the piano.[20] By age eleven, she began performing as a soloist for the junior gospel choir, performing the hymn, «Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah».[21] Houston would be taught how to sing throughout her adolescence by her mother Cissy.[22] After attending Franklin Elementary School (now the Whitney E. Houston Academy of Creative and Performing Arts), Houston was transferred to an all-girls Catholic school, Mount Saint Dominic Academy at nearby Caldwell, in her sixth grade year where she eventually graduated from in 1981 at 17.[23]

On February 18, 1978, a fourteen-year-old Houston made her non-church performance debut at Manhattan’s Town Hall singing the Broadway standard, «Tomorrow» from the musical, Annie, receiving her first standing ovation. Later that year, Houston sang background on mother Cissy’s solo album, Think It Over, with the title track later reaching the top 5 of the Billboard disco chart. The album’s producer Michael Zager recorded her lead vocal on his disco song, «Life’s a Party», with the album of the same name released later in 1978.[24] Throughout her childhood and early career, Houston was influenced by her mother, cousins Dionne and Dee Dee and singers such as Aretha Franklin, Chaka Khan, Gladys Knight and Roberta Flack.[25] During this period, Houston sang background for her mother on the cabaret club circuit in New York City. Houston contributed backing vocals for Khan and Lou Rawls on their respective albums, Naughty and Shades of Blue.[26]

In the same year, Houston met Robyn Crawford while both worked as counselors at a youth summer camp in East Orange. The two became fast friends and Houston later described Crawford as the «sister [she] never had».[27][28] Along with being best friends, Crawford would become a roommate and executive assistant.[29][28][30] Following Houston’s rise to fame, rumors began speculating that Houston and Crawford were lovers, which the two denied to the press during a 1987 interview for Time magazine.[28] In 2019, seven years after Houston’s death, Crawford admitted that their early relationship included sexual activity but stopped before Houston signed a recording deal.[31]

Houston became a fashion model after she was discovered by a photographer who filmed her and her mother during a performance for the United Negro College Fund at Carnegie Hall. She became one of the first women of color to appear on the cover of a fashion magazine when she appeared on the cover of Seventeen.[32] She would also appear inside other magazines such as Glamour, Cosmopolitan and Young Miss and a TV commercial for the Canada Dry soft drink. Her looks and girl-next-door charm made her one of the most sought-after teen models.[26] Houston was offered record deals around this time, first by Michael Zager in 1979, Luther Vandross in 1980 and Bruce Lundvall in 1981.[24][33] The offers, however, were turned down by her mother because Cissy wanted Houston to finish school.[24] Around the same time, Houston recorded Paul Jabara’s «Eternal Love», which was shelved for nearly two years before it was placed on Jabara’s 1983 album, Paul Jabara & Friends, released that January.[34] Houston recalled recording the song at just 16 years old. The quiet storm R&B ballad was later covered by fellow singer Stephanie Mills. In February 1982, Houston signed with Tara Productions and hired Gene Harvey as her manager with Daniel Gittleman and Seymour Flics as co-managers. With them, Houston furthered her recording career by working with producers Michael Beinhorn, Bill Laswell and Martin Bisi on an album they were spearheading called One Down, which was credited to the group Material. For that project, she contributed the ballad «Memories», a cover of a song by Hugh Hopper of Soft Machine. Robert Christgau of The Village Voice called her contribution «one of the most gorgeous ballads you’ve ever heard».[35]

In February 1983, Gerry Griffith, an A&R representative from Arista Records, saw Houston performing with her mother at the Sweetwaters nightclub in Manhattan. He convinced Arista head Clive Davis to make time to see her perform. Davis was impressed and immediately offered a worldwide record deal, which Houston eventually signed on April 10, 1983; since she was only nineteen, her parents also signed for her. Two weeks later, Houston made her national television debut alongside Davis on The Merv Griffin Show, which later aired that June.[36] She performed «Home», a song from the musical The Wiz.[37] Houston did not begin work on an album immediately.[38] The label wanted to make sure no other label signed her away and Davis wanted to ensure he had the right material and producers for her debut album. Some producers passed on the project because of prior commitments.[39] Houston first recorded a duet with Teddy Pendergrass, «Hold Me», which appeared on his gold album, Love Language.[40] The single was released in 1984 and gave Houston her first taste of success, becoming a Top 5 R&B hit.[41] It would also appear on her debut album in 1985.

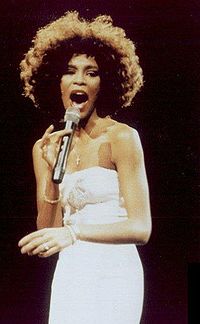

1985–1986: Whitney Houston and rise to international prominence

With production from Michael Masser, Kashif, Jermaine Jackson and Narada Michael Walden, Houston’s debut album Whitney Houston was released on Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1985.[42] Rolling Stone magazine praised Houston, calling her «one of the most exciting new voices in years» while The New York Times called the album «an impressive, musically conservative showcase for an exceptional vocal talent».[43][44] Arista Records promoted Houston’s album with three different singles from the album in the United States, the United Kingdom and other European countries. In the UK, the dance-funk song «Someone for Me», which failed to chart, was the first single while «All at Once» was in such European countries as the Netherlands and Belgium, where the song reached the top five on the singles charts, respectively.[45]

In the US, the soulful ballad «You Give Good Love» was chosen as the lead single from Houston’s debut to establish her in the black marketplace.[46] Outside the US, the song failed to get enough attention to become a hit, but in the US, it gave the album its first major hit as it peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot 100 chart and number one on the Hot Black Singles chart.[39] As a result, the album began to sell strongly and Houston continued promotion by touring nightclubs in the US. She also began performing on late-night television talk shows, which were not usually accessible to non-established black acts. The jazzy ballad «Saving All My Love for You» was released next and it would become Houston’s first number one single in both the US and the UK. By then, she was an opening act for singer Jeffrey Osborne on his nationwide tour.[47] The funk-oriented «Thinking About You» was released as the promo single only to R&B-oriented radio stations and dance clubs all over the country, resulting in the song reaching number 10 on the Hot Black Singles chart and number 24 on the Hot Dance Club Play chart in December 1985.

Houston’s success also translated to television where, in addition to performing on several late night talk shows such as The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and Late Night with David Letterman, Houston also became a video star thanks to early videos for «You Give Good Love» and «Saving All My Love for You» being heavily played on BET and VH1 stations. During this period, Houston and Arista struggled to get these videos submitted to MTV. At the time, MTV had received harsh criticism for not playing enough videos by black, Latino and other racial minorities while favoring white acts.[47] In an interview with MTV years later, Houston explained the difficulties she and Arista faced on trying to bring «You Give Good Love» on the channel but was rebuffed because it was «too R&B» for their playlist.[48] Eventually, Houston’s video for «Saving All My Love» was featured in light rotation after the song had become a huge pop hit, with Houston stating that the channel «had no choice but to play [the video]…I love it when they have no choice».[48] By the time Houston’s third US single, «How Will I Know», was released, the colorful video clip, directed by Brian Grant, was immediately added to MTV’s playlist, instantly gaining heavy rotation on the channel after just a couple weeks and introducing Houston to the MTV audience.[49] The song itself became Houston’s second consecutive number one pop hit on the Billboard Hot 100, where it stayed for two weeks, also topping the Hot Black and Hot AC chart and peaking at number three on the dance charts. Following the successful airing of «How Will I Know» on MTV, Houston became a regular presence on the channel as it slowly began changing its programming from rock to a more pop-R&B-dance hybrid playlist, along with artists such as Madonna and Janet Jackson.

On the week of March 8, 1986, a year after its initial release, Whitney Houston topped the Billboard 200 albums chart and stayed there for 14 non-consecutive weeks.[50] The final single, «Greatest Love of All» (a cover of «The Greatest Love of All», originally recorded by George Benson in 1977), became Houston’s biggest hit yet; the single peaked at number one and remained there for three weeks, making Houston’s debut the first album by a woman to yield three number-one hits. Houston ended 1986 as the top artist of the year while her debut album topped the Billboard Year-End chart, making her the first woman to earn that distinction.[50] At the time, the album was the bestselling debut album by a solo artist.[51] The album would later be certified 14× platinum for sales of 14 million units alone in the United States, while selling over 22 million copies worldwide.[52][53][54] In July 1986, Houston launched her first world tour, The Greatest Love World Tour, where she performed mainly in North America, Europe, Australia and Japan. The tour lasted into December, ending in Hawaii.

At the 1986 Grammy Awards, Houston was nominated for three awards, including Album of the Year.[55] She was not eligible for the Best New Artist category because of her previous hit R&B duet recording with Teddy Pendergrass in 1984.[56] She won her first Grammy Award for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for «Saving All My Love for You».[57] Houston’s performance of the song during the Grammy telecast later earned her an Emmy Award for Outstanding Individual Performance in a Variety or Music Program.[58]

Houston won seven American Music Awards in total in 1986 and 1987 and an MTV Video Music Award.[59][60] The album’s popularity would also carry over to the 1987 Grammy Awards, when «Greatest Love of All» would receive a Record of the Year nomination. Houston’s debut album is listed as one of Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time and on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s Definitive 200 list.[61][62] Houston’s grand entrance into the music industry is considered one of the 25 musical milestones of the last 25 years, according to USA Today.[63] Following Houston’s success, doors were opened for other African-American women such as Janet Jackson and Anita Baker.[64][65]

1987–1991: Whitney, I’m Your Baby Tonight and «The Star-Spangled Banner»

Houston’s second album, Whitney, was released in June 1987. The album again featured production from Masser, Kashif and Walden as well as Jellybean Benitez. Many critics complained that the material was too similar to her previous album. Rolling Stone said, «the narrow channel through which this talent has been directed is frustrating».[66] Still, the album enjoyed commercial success. Houston became the first woman in music history to debut at number one on the Billboard 200 albums chart and the first artist to enter the albums chart at number one in both the US and UK, while also hitting number one or top ten in dozens of other countries around the world.[67][68]

The album’s first single, «I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)», was also a massive hit worldwide, peaking at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and topping the singles chart in 17 countries, including Australia, Germany and the UK. Her next three singles, «Didn’t We Almost Have It All», «So Emotional» and «Where Do Broken Hearts Go», all peaked at number one on the US pop chart, giving Houston a record total of seven consecutive number one hits; the previous record of six consecutive number one hits had been shared by the Beatles and the Bee Gees.[67][68] Houston became the first woman to generate four number-one singles from one album. Whitney has been certified Diamond in the US for shipments of over ten million copies[69] and has sold a total of 20 million copies worldwide.[70]

At the 30th Grammy Awards in 1988, Houston was nominated for three awards, including Album of the Year. She won her second Grammy for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for «I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)».[71][72] Houston also won two American Music Awards in 1988 and 1989, respectively and a Soul Train Music Award.[73][74][75] Following the release of the album, Houston embarked on the Moment of Truth World Tour, which was one of the ten highest-grossing concert tours of 1987 and the highest-grossing tour by a female artist, topping tours by both Madonna and Tina Turner.[76][77] The success of the tours during 1986–87 and her two studio albums ranked Houston No. 8 for the highest-earning entertainers list according to Forbes.[78] She was the highest-earning African-American woman overall, highest-earning musician and the third highest entertainer after Bill Cosby and Eddie Murphy.[78]

Houston was a supporter of Nelson Mandela and the anti-apartheid movement. During her modeling days, she refused to work with agencies who did business with the then-apartheid South Africa.[79][80] On June 11, 1988, during the European leg of her tour, Houston joined other musicians to perform a set at Wembley Stadium in London to celebrate a then-imprisoned Nelson Mandela’s 70th birthday.[79] Over 72,000 people attended Wembley Stadium and over a billion people tuned in worldwide as the rock concert raised over $1 million for charities while bringing awareness to apartheid.[81] Houston then flew back to the US for a concert at Madison Square Garden in New York City in August. The show was a benefit concert that raised a quarter of a million dollars for the United Negro College Fund.[82] In the same year, she recorded a song for NBC’s coverage of the 1988 Summer Olympics, «One Moment in Time», which became a Top 5 hit in the US, while reaching number one in the UK and Germany.[83][84][85] With her world tour continuing overseas, Houston was still one of the top 20 highest-earning entertainers for 1987–88 according to Forbes.[86][87]

In 1989, Houston formed The Whitney Houston Foundation For Children, a nonprofit organization that has raised funds for the needs of children around the world. The organization cares for homelessness, children with cancer or AIDS and other issues of self-empowerment.[88]

With the success of her first two albums, Houston became an international crossover superstar, appealing to all demographics. However, some black critics believed she was «selling out».[89] They felt her singing on record lacked the soul that was present during her live concerts.[90] At the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards, when Houston’s name was called out for a nomination, a few in the audience jeered.[91][92] Houston defended herself against the criticism, stating, «If you’re gonna have a long career, there’s a certain way to do it and I did it that way. I’m not ashamed of it.»[90]

Houston took a more urban direction with her third studio album, I’m Your Baby Tonight, released in November 1990. She produced and chose producers for this album and as a result, it featured production and collaborations with L.A. Reid and Babyface, Luther Vandross and Stevie Wonder. The album showed Houston’s versatility on a new batch of tough rhythmic grooves, soulful ballads and up-tempo dance tracks. Reviews were mixed. Rolling Stone felt it was her «best and most integrated album».[93] while Entertainment Weekly, at the time thought Houston’s shift towards an urban direction was «superficial».[94]

I’m Your Baby Tonight contained several hits: the first two singles, «I’m Your Baby Tonight» and «All the Man That I Need» peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart; «Miracle» peaked at number nine; «My Name Is Not Susan» peaked in the top twenty; «I Belong to You» reached the top ten of the US R&B chart and garnered Houston a Grammy nomination; and the sixth single, the Stevie Wonder duet «We Didn’t Know», reached the R&B top twenty. A bonus track from the album’s Japanese edition, «Higher Love», was remixed by Norwegian DJ and record producer Kygo and released posthumously in 2019 to commercial success. It topped the US Dance Club Songs chart and peaked at number two in the UK, becoming Houston’s highest-charting single in the country since 1999.[95] I’m Your Baby Tonight peaked at number three on the Billboard 200 and went on to be certified 4× platinum in the US while selling 10 million total worldwide.[96]

During the Persian Gulf War, on January 27, 1991, Houston performed «The Star-Spangled Banner», the US national anthem, at Super Bowl XXV at Tampa Stadium.[97] Houston’s vocals were pre-recorded, prompting criticism.[98][99][100][101] Dan Klores, a spokesman for Houston, said: «This is not a Milli Vanilli thing. She sang live, but the microphone was turned off. It was a technical decision, partially based on the noise factor. This is standard procedure at these events.»[102] Nevertheless, a commercial single and video of the performance reached the Top 20 on the US Hot 100, giving Houston the biggest chart hit for a performance of the national anthem (José Feliciano’s version reached No. 50 in November 1968).[103][104]

Houston donated her share of the proceeds to the American Red Cross Gulf Crisis Fund and was named to the Red Cross Board of Governors.[97][105][106] Her rendition was critically acclaimed and is considered the benchmark for singers;[101][107] VH1 listed the performance as one of the greatest moments that rocked TV.[108] Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the single was rereleased, with all profits going towards the firefighters and victims of the attacks. It peaked at No. 6 in the Hot 100 and was certified platinum.[109]

Later in 1991, Houston put together her Welcome Home Heroes concert with HBO for the soldiers fighting in the Persian Gulf War and their families. The free concert took place at Naval Station Norfolk in Norfolk, Virginia in front of 3,500 servicemen and women. HBO descrambled the concert so that it was free for everyone to watch.[110] The show gave HBO its highest ratings ever.[111]

1992–1994: Marriage, motherhood and The Bodyguard

Throughout the 1980s, Houston was romantically linked to musician Jermaine Jackson,[112] American football star Randall Cunningham and actor Eddie Murphy.[92]

She then met R&B singer Bobby Brown at the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards. After a three-year courtship, the two were married on July 18, 1992.[113] Brown would go on to have several run-ins with the law for drunken driving, drug possession and battery, including some jail time.[114][115][116] On March 4, 1993, Houston gave birth to their daughter Bobbi Kristina Brown (March 4, 1993 – July 26, 2015),[117] the couple’s only child. Houston revealed in a 1993 interview with Barbara Walters that she had a miscarriage during the filming of The Bodyguard.[118]

With the massive commercial success of her music, film offers poured in, including offers to work with Robert De Niro, Quincy Jones and Spike Lee, but Houston never felt the time was right.[92] Her first film role was in The Bodyguard, released in 1992. Houston played a star who is stalked by a crazed fan and hires a bodyguard (played by Kevin Costner) to protect her. Houston’s mainstream appeal allowed audiences to look past the interracial nature of her character’s relationship with Costner’s character.[119] However, controversy arose as some felt Houston’s face had been intentionally left out of the film’s advertising to hide the film’s interracial relationship. In a 1993 interview with Rolling Stone, Houston remarked that «people know who Whitney Houston is – I’m black. You can’t hide that fact.»[25]

Houston received a Razzie Award nomination for Worst Actress. The Washington Post remarked that Houston was «doing nothing more than playing [herself]», but added that she came out «largely unscathed if that is possible in so cockamamie an undertaking».[120] The New York Times stated that she lacked chemistry with Costner.[121] Despite the film’s mixed reviews, it was hugely successful at the box office, grossing more than $121 million in the U.S. and $410 million worldwide, making it one of the top 100 grossing films in film history at its time of release, though it later fell out of the top 100 because of rising ticket prices since the time the film was released.[122] It remains in the top forty of most successful rated-R films in box office history.[123] Despite the Razzie, however, Houston was nominated for the NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Actress in the film, losing the award to Angela Bassett for her role as Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It and also received several MTV Movie Award nominations, winning Best Song from a Movie for «I Will Always Love You» and was nominated for Best Breakthrough Performance.

The film’s soundtrack also enjoyed success. Houston co-executive produced[124] The Bodyguard: Original Soundtrack Album and recorded six songs for the album.[125] Rolling Stone described it as «nothing more than pleasant, tasteful and urbane».[126] The soundtrack’s lead single was «I Will Always Love You», written and originally recorded by Dolly Parton in 1974. Houston’s version was highly acclaimed by critics, regarding it as her «signature song» or «iconic performance». Rolling Stone and USA Today called her rendition a tour-de-force.[127][128] The single peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 for a then-record-breaking 14 weeks, number one on the R&B chart for a then-record-breaking 11 weeks and number one on the Adult Contemporary charts for five weeks.[129] The single was certified Diamond by the RIAA, making Houston’s first Diamond single, the third female artist who had a Diamond single,[130] and becoming the bestselling single by a woman in the U.S.[131][132][133][134] The song was a global success, topping the charts in almost all countries. With 20 million copies sold it became the best-selling single of all time by a female solo artist.[135][136] Houston won the Grammy Award for Record of the Year in 1994 for «I Will Always Love You».[137]

The soundtrack topped the Billboard 200 chart and remained there for 20 non-consecutive weeks, the longest tenure by any Arista album on the chart in the Nielsen SoundScan era (tied for tenth overall by any label) and became one of the fastest selling albums ever.[138] During Christmas week of 1992, the soundtrack sold over a million copies within a week, becoming the first album to achieve that feat under Nielsen SoundScan system.[139][140] With the follow-up singles «I’m Every Woman», a Chaka Khan cover, and «I Have Nothing» both reaching the top five, Houston became the first woman to ever have three singles in the Top 11 simultaneously.[141][142][143] The album was certified 18× platinum in the US alone,[144] with worldwide sales of 45 million copies.[145]

The album became the bestselling soundtrack album of all time.[146] Houston won the 1994 Grammy Award for Album of the Year for the soundtrack, becoming only the second African American woman to win in that category after Natalie Cole’s Unforgettable… with Love album.[147] In addition, she won a record eight American Music Awards at that year’s ceremony including the Award of Merit,[148] 11 Billboard Music Awards, 3 Soul Train Music Awards in 1993–94 including Sammy Davis, Jr. Award as Entertainer of the Year,[149] 5 NAACP Image Awards including Entertainer of the Year,[150][151][152] a record 5 World Music Awards,[153] and a BRIT award.[154]

Following the success of The Bodyguard, Houston embarked on another expansive global tour (The Bodyguard World Tour) in 1993–94. Her concerts, movie and recording grosses made her the third highest-earning female entertainer of 1993–94, just behind Oprah Winfrey and Barbra Streisand according to Forbes.[155] Houston placed in the top five of Entertainment Weekly‘s annual «Entertainer of the Year» ranking[156] and was labeled by Premiere magazine as one of the 100 most powerful people in Hollywood.[157]

In October 1994, Houston attended and performed at a state dinner in the White House honoring newly elected South African president Nelson Mandela.[158][159] At the end of her world tour, Houston performed three concerts in South Africa to honor President Mandela, playing to over 200,000 people; this made her the first major musician to visit the newly unified and apartheid free nation following Mandela’s winning election.[160] Portions of Whitney: The Concert for a New South Africa were broadcast live on HBO with funds of the concerts being donated to various charities in South Africa. The event was considered the nation’s «biggest media event since the inauguration of Nelson Mandela».[161]

1995–1997: Waiting to Exhale, The Preacher’s Wife and Cinderella

In 1995, Houston starred alongside Angela Bassett, Loretta Devine and Lela Rochon in her second film, Waiting to Exhale, a motion picture about four African-American women struggling with relationships. Houston played the lead character Savannah Jackson, a TV producer in love with a married man. She chose the role because she saw the film as «a breakthrough for the image of black women because it presents them both as professionals and as caring mothers».[162] After opening at number one and grossing $67 million in the US at the box office and $81 million worldwide,[163] it proved that a movie primarily targeting a black audience can cross over to success, while paving the way for other all-black movies such as How Stella Got Her Groove Back and the Tyler Perry movies that became popular in the 2000s.[164][165][166] The film is also notable for its portrayal of black women as strong middle class citizens rather than as stereotypes.[167] The reviews were mainly positive for the ensemble cast. The New York Times said: «Ms. Houston has shed the defensive hauteur that made her portrayal of a pop star in ‘The Bodyguard’ seem so distant.»[168] Houston was nominated for an NAACP Image Award for «Outstanding Actress in a Motion Picture», but lost to her co-star Bassett.[169]

The film’s accompanying soundtrack, Waiting to Exhale: Original Soundtrack Album, was written and produced by Babyface. Though he originally wanted Houston to record the entire album, she declined. Instead, she «wanted it to be an album of women with vocal distinction» and thus gathered several African-American female artists for the soundtrack, to go along with the film’s message about strong women.[162] Consequently, the album featured a range of contemporary R&B female recording artists along with Houston, such as Mary J. Blige, Brandy, Toni Braxton, Aretha Franklin and Patti LaBelle. Houston’s «Exhale (Shoop Shoop)» became just the third single in music history to debut at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 after Michael Jackson’s «You Are Not Alone» and Mariah Carey’s «Fantasy».[170]

It also would spend a record eleven weeks at the No. 2 spot and eight weeks on top of the R&B charts, her second most successful single on that chart after «I Will Always Love You». «Count On Me», a duet with CeCe Winans, hit the U.S. Top 10; and Houston’s third contribution, «Why Does It Hurt So Bad», made the Top 30. The album was certified 7× Platinum in the United States, denoting shipments of seven million copies.[170] The soundtrack received strong reviews; as Entertainment Weekly stated: «the album goes down easy, just as you’d expect from a package framed by Whitney Houston tracks … the soundtrack waits to exhale, hovering in sensuous suspense»[171] and has since ranked it as one of the 100 Best Movie Soundtracks.[172] Later that year, Houston’s children’s charity organization was awarded a VH1 Honor for all the charitable work.[173]

In 1996, Houston starred in the holiday comedy The Preacher’s Wife, with Denzel Washington. She plays the gospel-singing wife of a pastor (Courtney B. Vance). It was largely an updated remake of the 1948 film The Bishop’s Wife, which starred Loretta Young, David Niven and Cary Grant. Houston earned $10 million for the role, making her one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood at the time and the highest-earning African-American actress in Hollywood.[174] The movie, with its all African-American cast, was a moderate success, earning about $50 million at the U.S. box offices.[175] The movie gave Houston her strongest reviews so far. The San Francisco Chronicle said Houston «is rather angelic herself, displaying a divine talent for being virtuous and flirtatious at the same time» and she «exudes gentle yet spirited warmth, especially when praising the Lord in her gorgeous singing voice».[176] Houston was again nominated for an NAACP Image Award and won for Outstanding Actress in a Motion Picture.[177]

Houston recorded and co-produced, with Mervyn Warren, the film’s accompanying gospel soundtrack. The Preacher’s Wife: Original Soundtrack Album included six gospel songs with Georgia Mass Choir that were recorded at the Great Star Rising Baptist Church in Atlanta. Houston also duetted with gospel legend Shirley Caesar. The album sold six million copies worldwide and scored hit singles with «I Believe in You and Me» and «Step by Step», becoming the largest selling gospel album of all time.[178] The album received mainly positive reviews. She won Favorite Adult Contemporary Artist at the 1997 American Music Awards for The Preacher’s Wife soundtrack.

In December 1996, a spokesperson for Houston confirmed that she had suffered a miscarriage.[179]

In 1997, Houston’s production company changed its name to BrownHouse Productions and was joined by Debra Martin Chase. Their goal was «to show aspects of the lives of African-Americans that have not been brought to the screen before» while improving how African-Americans are portrayed in film and television.[180] Their first project was a made-for-television remake of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella. In addition to co-producing, Houston starred in the film as the Fairy Godmother along with Brandy, Jason Alexander, Whoopi Goldberg and Bernadette Peters. Houston was initially offered the role of Cinderella in 1993, but other projects intervened.[181] The film is notable for its multi-racial cast and non-stereotypical message.[182] An estimated 60 million viewers tuned into the special giving ABC its highest TV ratings in 16 years.[183] The movie received seven Emmy nominations including Outstanding Variety, Musical or Comedy, while winning Outstanding Art Direction in a Variety, Musical or Comedy Special.

Houston and Chase then obtained the rights to the story of Dorothy Dandridge. Houston was to play Dandridge, the first African-American actress to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress. Houston wanted the story told with dignity and honor.[180] However, Halle Berry also had rights to the project and got her version going first.[184] Later that year, Houston paid tribute to her idols, such as Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross and Dionne Warwick, by performing their hits during the three-night HBO Concert Classic Whitney: Live from Washington, D.C.. The special raised over $300,000 for the Children’s Defense Fund.[185] Houston received the Quincy Jones Award for outstanding career achievements in the field of entertainment at the 12th Soul Train Music Awards.[186][187]

1998–2000: My Love Is Your Love and Whitney: The Greatest Hits

After spending much of the early and mid-1990s working on motion pictures and their soundtrack albums, Houston’s first studio album in eight years, the critically acclaimed My Love Is Your Love, was released in November 1998. Though originally slated to be a greatest hits album with a handful of new songs, recording sessions were so fruitful that a new full-length studio album was released. Recorded and mixed in only six weeks, it featured production from Rodney Jerkins, Wyclef Jean and Missy Elliott. The album debuted at number thirteen, its peak position, on the Billboard 200 chart.[188] It had a funkier and edgier sound than past releases and saw Houston handling urban dance, hip hop, mid-tempo R&B, reggae, torch songs and ballads all with great dexterity.[189]

From late 1998 to early 2000, the album spawned several hit singles: «When You Believe» (US No. 15, UK No. 4), a duet with Mariah Carey for 1998’s The Prince of Egypt soundtrack, which also became an international hit as it peaked in the Top 10 in several countries and won an Academy Award for Best Original Song;[190] «Heartbreak Hotel» (US No. 2, UK No. 25) featured Faith Evans and Kelly Price, received a 1999 MTV VMA nomination for Best R&B Video,[191] and number one on the US R&B chart for seven weeks; «It’s Not Right but It’s Okay» (US No. 4, UK No. 3) won Houston her sixth Grammy Award for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance;[192] «My Love Is Your Love» (US No. 4, UK No. 2) with 3 million copies sold worldwide;[193] and «I Learned from the Best» (US No. 27, UK No. 19).[194][195] These singles became international hits as well and all the singles, except «When You Believe», became number one hits on the Billboard Hot Dance/Club Play chart. The album sold four million copies in America, making it certified 4× platinum and a total of eleven million copies worldwide.[52]

The album gave Houston some of her strongest reviews ever. Rolling Stone said Houston was singing «with a bite in her voice»[196] and The Village Voice called it «Whitney’s sharpest and most satisfying so far».[197] In 1999, Houston participated in VH-1’s Divas Live ’99, alongside Brandy, Mary J. Blige, Tina Turner and Cher. The same year, Houston hit the road with her 70 date My Love Is Your Love World Tour. While the European leg of the tour was Europe’s highest grossing arena tour of the year,[198] Houston canceled «a string of dates [during the] summer citing throat problems and a ‘bronchitis situation'».[199] In November 1999, Houston was named Top-selling R&B Female Artist of the Century with certified US sales of 51 million copies at the time and The Bodyguard Soundtrack was named the Top-selling Soundtrack Album of the Century by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[200] She also won The Artist of the Decade, Female award for extraordinary artistic contributions during the 1990s at the 14th Soul Train Music Awards and an MTV Europe Music Award for Best R&B.[201][202][203][204][205]

In May 2000, Whitney: The Greatest Hits was released worldwide. The double disc set peaked at number five in the United States, reaching number one in the United Kingdom.[195][206] In addition, the album reached the Top 10 in many other countries.[207] While ballad songs were left unchanged, the album features house/club remixes of many of Houston’s up-tempo hits. Included on the album were four new songs: «Could I Have This Kiss Forever» (a duet with Enrique Iglesias), «Same Script, Different Cast» (a duet with Deborah Cox), «If I Told You That» (a duet with George Michael) and «Fine» and three hits that had never appeared on a Houston album: «One Moment in Time», «The Star-Spangled Banner» and «If You Say My Eyes Are Beautiful», a duet with Jermaine Jackson from his 1986 Precious Moments album.[208] Along with the album, an accompanying VHS and DVD was released featuring the music videos to Houston’s greatest hits, as well as several hard-to-find live performances including her 1983 debut on The Merv Griffin Show and interviews.[209] The greatest hits album was certified 5× platinum in the US, with worldwide sales of 10 million.[210][211]

2000–2008: Just Whitney and personal struggles

Houston outside the Capitol Hill, Washington, D.C. on October 16, 2000

Though Houston was seen as a «good girl» with a perfect image in the 1980s and early 1990s, her behavior had changed by 1999 and 2000. She was often hours late for interviews, photo shoots and rehearsals, she canceled concerts and talk-show appearances and there were reports of erratic behavior.[212][213] Missed performances and weight loss led to rumors about Houston using drugs with her husband. On January 11, 2000, while traveling with Brown, airport security guards discovered half an ounce of marijuana in Houston’s handbag at Keahole-Kona International Airport in Hawaii, but she departed before authorities could arrive.[214][215] Charges against her were later dropped,[216] but rumors of drug usage by Houston and Brown would continue to surface. Two months later, Clive Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; Houston had been scheduled to perform at the event, but was a no-show.[217]

Shortly thereafter, Houston was scheduled to perform at the Academy Awards, but was fired from the event by musical director and longtime friend Burt Bacharach. Her publicist cited throat problems as the reason for the cancellation. In his book The Big Show: High Times and Dirty Dealings Backstage at the Academy Awards, author Steve Pond revealed that «Houston’s voice was shaky, she seemed distracted and jittery and her attitude was casual, almost defiant»; though she was supposed to perform «Over the Rainbow», she would sing a different song during rehearsals.[218] Houston later admitted she had been fired.[219]

In May 2000, Houston’s longtime executive assistant and friend, Robyn Crawford, resigned from Houston’s management company.[217] In 2019, Crawford said she had left after Houston declined to seek help for her drug dependency.[220][30] The following month, Rolling Stone published a story stating that Cissy Houston and others had held a July 1999 intervention in which they unsuccessfully attempted to persuade Whitney to obtain drug treatment.[217]

In August 2001, Houston signed one of the biggest record deals in music history, with Arista/BMG. She renewed her contract for $100 million to release six new albums, for which she would also earn royalties.[221][222][223] She later made an appearance on Michael Jackson: 30th Anniversary Special, where her extremely thin frame further spurred rumors of drug use. Her publicist stated, «Whitney has been under stress due to family matters and when she is under stress she doesn’t eat.»[224] In a 2009 interview with Oprah Winfrey, Houston acknowledged that drug use had been the reason for her weight loss.[225] She canceled a second performance scheduled for the following night.[226] Within weeks, Houston’s rendition of «The Star-Spangled Banner» was re-released after the September 11 attacks, with the proceeds donated to the New York Firefighters 9/11 Disaster Relief Fund and the New York Fraternal Order of Police.[227] It reached No. 6 on the US Hot 100, topping its previous position.[194]

In 2002, Houston became embroiled in a legal dispute with John Houston Enterprise. Although the company was started by her father to manage her career, it was actually run by company president Kevin Skinner. Skinner filed a breach of contract lawsuit and sued for $100 million (but lost), stating that Houston owed the company previously unpaid compensation for helping to negotiate her $100 million contract with Arista Records and for sorting out legal matters.[228] Houston stated that her 81-year-old father had nothing to do with the lawsuit. Although Skinner tried to claim otherwise, John Houston never appeared in court.[229] Houston’s father later died in February 2003.[230] The lawsuit was dismissed on April 5, 2004, and Skinner was awarded nothing.[231]

Also in 2002, Houston gave an interview with Diane Sawyer to promote her then-upcoming album. During the primetime special, she spoke about her drug use and marriage, among other topics. Addressing the ongoing drug rumors, she said, «First of all, let’s get one thing straight. Crack is cheap. I make too much money to ever smoke crack. Let’s get that straight. Okay? We don’t do crack. We don’t do that. Crack is wack.»[219] The «crack is wack» line was drawn from a mural that Keith Haring painted in 1986 on the handball court at 128th Street and Second Avenue in Manhattan.[232] Houston did, however, admit to using alcohol, marijuana, cocaine and pills; she also acknowledged that her mother had urged her to seek help regarding her drug use. She also denied having an eating disorder and that her very thin appearance was connected to drug use. She further stated that Bobby Brown had never hit her, but acknowledged that she had hit him.[219]

In December 2002, Houston released her fifth studio album, Just Whitney. The album included productions from then-husband Bobby Brown, as well as Missy Elliott and Babyface, and marked the first time that Houston did not produce with Clive Davis, as Davis had been released by top management at BMG. Upon its release, Just Whitney received mixed reviews.[233] The album debuted at number 9 on the Billboard 200 chart and it had the highest first week sales of any album Houston had ever released.[234] The four singles released from the album did not fare well on the Billboard Hot 100, but became dance chart hits. Just Whitney was certified platinum in the United States and sold about two million worldwide.[235][236]

In late 2003, Houston released her first Christmas album One Wish: The Holiday Album, with a collection of traditional holiday songs. Houston produced the album with Mervyn Warren and Gordon Chambers. A single titled «One Wish (for Christmas)» reached the Top 20 on the Adult Contemporary chart and the album was certified gold in the US.[237]

In December 2003, Brown was charged with battery following an altercation during which he threatened to beat Houston and then assaulted her. Police reported that Houston had visible injuries to her face.[116]

Having always been a touring artist, Houston spent most of 2004 touring and performing in Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Russia. In September 2004, she gave a surprise performance at the World Music Awards in a tribute to long-time friend Clive Davis. After the show, Davis and Houston announced plans to go into the studio to work on her new album.[238]

In early 2004, Brown starred in his own reality TV program, Being Bobby Brown, on Bravo. The show provided a view of the domestic goings-on in the Brown household. Houston was a prominent figure throughout the show, receiving as much screen time as Brown. The series aired in 2005 and featured Houston in unflattering moments. Years later, The Guardian opined that through her participation in the show, Houston had lost «the last remnants of her dignity».[42] The Hollywood Reporter said that the show was «undoubtedly the most disgusting and execrable series ever to ooze its way onto television».[239] Despite the perceived train-wreck nature of the show, the series gave Bravo its highest ratings in its time slot and continued Houston’s successful forays into film and television.[240] The show was not renewed for a second season after Houston said that she would no longer appear in it and Brown and Bravo could not come to an agreement for another season.[241]

2009–2012: Return and I Look to You

Houston gave her first interview in seven years in September 2009, appearing on Oprah Winfrey’s season premiere. The interview was billed as «the most anticipated music interview of the decade».[242] Houston admitted on the show to having used drugs with Brown during their marriage; she said Brown had «laced marijuana with rock cocaine».[243] She told Winfrey that before The Bodyguard her drug use was light, that she used drugs more heavily after the film’s success and the birth of her daughter and that by 1996 «[doing drugs] was an everyday thing … I wasn’t happy by that point in time. I was losing myself.»[244]

Houston told Winfrey that she had attended a 30-day rehabilitation program.[245] Houston also acknowledged to Oprah that her drug use had continued after rehabilitation and that at one point, her mother obtained a court order and the assistance of law enforcement to press her into receiving further drug treatment.[246] (In her 2013 book, Remembering Whitney: My Story of Love, Loss and the Night the Music Stopped, Cissy Houston described the scene she encountered at Whitney Houston’s house in 2005 as follows: «Somebody had spray-painted the walls and door with big glaring eyes and strange faces. Evil eyes, staring out like a threat… In another room, there was a big, framed photo of [Whitney] – but someone had cut [her] head out. It was beyond disturbing, seeing my daughter’s face cut out like that.» This visit led Cissy to return with law enforcement and perform an intervention.[247]) Houston also told Winfrey that Brown had been emotionally abusive during their marriage and had even spat on her on one occasion.[248] When Winfrey asked Houston if she was drug-free, Houston responded, «‘Yes, ma’am. I mean, you know, don’t think I don’t have desires for it.'»[249]

Houston released her new album, I Look to You, in August 2009.[250] The album’s first two singles were the title track «I Look to You» and «Million Dollar Bill». The album entered the Billboard 200 at No. 1, with Houston’s best opening week sales of 305,000 copies, marking Houston’s first number one album since The Bodyguard and Houston’s first studio album to reach number one since 1987’s Whitney. Houston also appeared on European television programs to promote the album. She performed the song «I Look to You» on the German television show Wetten, dass..?. Houston appeared as a guest mentor on The X Factor in the United Kingdom. She performed «Million Dollar Bill» on the following day’s results show, completing the song even as a strap in the back of her dress popped open two seconds into the performance. She later commented that she «sang [herself] out of [her] clothes». The performance was poorly received by the British media and was described as «weird» and «ungracious».[251]

Despite this reception, «Million Dollar Bill» jumped to its peak from 14 to number 5 (her first UK top 5 for over a decade). Three weeks after its release, I Look to You went gold. Houston appeared on the Italian version of The X Factor, where she performed «Million Dollar Bill» to excellent reviews.[252] In November, Houston performed «I Didn’t Know My Own Strength» at the 2009 American Music Awards in Los Angeles, California. Two days later, Houston performed «Million Dollar Bill» and «I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)» on the Dancing with the Stars season 9 finale.

Houston later embarked on a world tour, entitled the Nothing but Love World Tour. It was her first world tour in over ten years and was announced as a triumphant comeback. However, some poor reviews and rescheduled concerts brought negative media attention.[253][254] Houston canceled some concerts because of illness and received widespread negative reviews from fans who were disappointed in the quality of her voice and performance. Some fans reportedly walked out of her concerts.[255]

In January 2010, Houston was nominated for two NAACP Image Awards, one for Best Female Artist and one for Best Music Video. She won the award for Best Music Video for her single «I Look to You».[256] On January 16, she received The BET Honors Award for Entertainer citing her lifetime achievements spanning over 25 years in the industry.[257] Houston also performed the song «I Look to You» on the 2011 BET Celebration of Gospel, with gospel–jazz singer Kim Burrell, held at the Staples Center, Los Angeles. The performance aired on January 30, 2011.[258]

In May 2011, Houston enrolled in a rehabilitation center again, citing drug and alcohol problems. A representative for Houston said that the outpatient treatment was a part of Houston’s «longstanding recovery process».[259] In September 2011, The Hollywood Reporter announced that Houston would produce and star alongside Jordin Sparks and Mike Epps in the remake of the 1976 film Sparkle. In the film, Houston portrays Sparks’s «not-so encouraging» mother. Houston is also credited as an executive producer of the film. Debra Martin Chase, producer of Sparkle, stated that Houston deserved the title considering she had been there from the beginning in 2001, when Houston obtained Sparkle production rights. R&B singer Aaliyah – originally tapped to star as Sparkle – died in a 2001 plane crash. Her death derailed production, which would have begun in 2002.[260][261][262]

Houston’s remake of Sparkle was filmed in late 2011 over two months[263] and was released by TriStar Pictures.[264] On May 21, 2012, «Celebrate», the last song Houston recorded with Sparks, premiered at RyanSeacrest.com. It was made available for digital download on iTunes on June 5. The song was featured on the Sparkle: Music from the Motion Picture soundtrack as the first official single.[265] The movie was released on August 17, 2012, in the United States.

Death and funeral

Houston reportedly appeared «disheveled»[266][267][268] and «erratic»[266][269] in the days before her death. On February 9, 2012, Houston visited singers Brandy and Monica, together with Clive Davis, at their rehearsals for Davis’s pre-Grammy Awards party at The Beverly Hilton in Beverly Hills.[270][271] That same day, she made her last public performance when she joined Kelly Price on stage in Hollywood, California, and sang «Jesus Loves Me».[272][273]

Two days later, on February 11, Houston was found unconscious in Suite 434 at the Beverly Hilton, submerged in the bathtub.[274][275] Beverly Hills paramedics arrived about 3:30 pm, found Houston unresponsive, and performed CPR. Houston was pronounced dead at 3:55 pm PST.[276][277] The cause of death was not immediately known;[6][276] local police said there were «no obvious signs of criminal intent».[278]

Flowers near the Beverly Hilton Hotel

An invitation-only memorial service was held for Houston on February 18, 2012, at the New Hope Baptist Church in Newark, New Jersey. The service was scheduled for two hours, but lasted four.[279] Among those who performed at the funeral were Stevie Wonder (rewritten version of «Ribbon in the Sky» and «Love’s in Need of Love Today»), CeCe Winans («Don’t Cry» and «Jesus Loves Me»), Alicia Keys («Send Me an Angel»), Kim Burrell (rewritten version of «A Change Is Gonna Come») and R. Kelly («I Look to You»).[280][281]

The performances were interspersed with hymns by the church choir and remarks by Clive Davis, Houston’s record producer; Kevin Costner; Rickey Minor, her music director; Dionne Warwick, her cousin; and Ray Watson, her security guard for the past 11 years. Aretha Franklin was listed on the program, and was expected to sing, but was unable to attend the service.[280][281] Bobby Brown departed shortly after the service began.[282] Houston was buried on February 19, 2012, in Fairview Cemetery, in Westfield, New Jersey, next to her father, John Russell Houston, who had died in 2003.[283]

On March 22, 2012, the Los Angeles County Coroner’s Office reported that Houston’s death was caused by drowning and the «effects of atherosclerotic heart disease and cocaine use».[284][285] The office said the amount of cocaine found in Houston’s body indicated that she used the substance shortly before her death.[286] Toxicology results revealed additional drugs in her system: diphenhydramine (Benadryl), alprazolam (Xanax), cannabis, and cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril).[287] The manner of death was listed as an «accident».[288]

Reaction

Pre-Grammy party

The February 11, 2012, Clive Davis pre-Grammy party that Houston had been expected to attend, which featured many of the biggest names in music and film, went on as scheduled – although it was quickly turned into a tribute to Houston. Davis spoke about Houston’s death at the evening’s start:

By now you have all learned of the unspeakably tragic news of our beloved Whitney’s passing. I don’t have to mask my emotion in front of a room full of so many dear friends. I am personally devastated by the loss of someone who has meant so much to me for so many years. Whitney was so full of life. She was so looking forward to tonight even though she wasn’t scheduled to perform. Whitney was a beautiful person and a talent beyond compare. She graced this stage with her regal presence and gave so many memorable performances here over the years. Simply put, Whitney would have wanted the music to go on and her family asked that we carry on.[289]

Tony Bennett spoke of Houston’s death before performing at Davis’s party. He said, «First, it was Michael Jackson, then Amy Winehouse, now, the magnificent Whitney Houston.» Bennett sang «How Do You Keep the Music Playing?» and said of Houston: «When I first heard her, I called Clive Davis and said, ‘You finally found the greatest singer I’ve ever heard in my life.‘«[290]

Some celebrities opposed Davis’s decision to continue with the party while a police investigation was being conducted in Houston’s hotel room and her body was still in the building. Chaka Khan, in an interview with CNN’s Piers Morgan on February 13, 2012, shared that she felt the party should have been canceled, saying: «I thought that was complete insanity. And knowing Whitney I don’t believe that she would have said ‘the show must go on.’ She’s the kind of woman that would’ve said ‘Stop everything! Un-unh. I’m not going to be there.'»[291]

Sharon Osbourne condemned the Davis party, declaring: «I think it was disgraceful that the party went on. I don’t want to be in a hotel room when there’s someone you admire who’s tragically lost their life four floors up. I’m not interested in being in that environment and I think when you grieve someone, you do it privately, you do it with people who understand you. I thought it was so wrong.»[292]

Further reaction and tributes

Many other celebrities released statements responding to Houston’s death. Darlene Love, Houston’s godmother, hearing the news of her death, said, «It felt like I had been struck by a lightning bolt in my gut.»[293] Dolly Parton, whose song «I Will Always Love You» was covered by Houston, said, «I will always be grateful and in awe of the wonderful performance she did on my song and I can truly say from the bottom of my heart, ‘Whitney, I will always love you. You will be missed.‘» Aretha Franklin said, «It’s so stunning and unbelievable. I couldn’t believe what I was reading coming across the TV screen.»[294] Others paying tribute included Mariah Carey, Quincy Jones, and Oprah Winfrey.[295][296]

Moments after news of her death emerged, CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News all broke from their regularly scheduled programming to dedicate time to non-stop coverage of Houston’s death. All three featured live interviews with people who had known Houston, including those that had worked with her, along with some of her peers in the music industry. Saturday Night Live displayed a photo of a smiling Houston, alongside Molly Shannon, from her 1996 appearance.[297][298] MTV and VH1 interrupted their regularly scheduled programming on Sunday, February 12, to air many of Houston’s classic videos, with MTV often airing news segments in between and featuring various reactions from fans and celebrities.

The first full hour after the news of Houston’s death broke saw 2,481,652 tweets and retweets on Twitter alone, equating to a rate of more than a thousand tweets every second.[299]

Houston’s former husband, Bobby Brown, was reported to be «in and out of crying fits» after receiving the news. He did not cancel a scheduled performance, and within hours of his ex-wife’s sudden death, an audience in Mississippi watched as Brown blew kisses skyward, tearfully saying: «I love you, Whitney.»[300]

Ken Ehrlich, executive producer of the 54th Grammy Awards, announced that Jennifer Hudson would perform a tribute to Houston at the February 12, 2012, ceremony. He said, «Event organizers believed Hudson – an Academy Award-winning actress and Grammy Award-winning artist – could perform a respectful musical tribute to Houston.» Ehrlich went on to say, «It’s too fresh in everyone’s memory to do more at this time, but we would be remiss if we didn’t recognize Whitney’s remarkable contribution to music fans in general and in particular her close ties with the Grammy telecast and her Grammy wins and nominations over the years.»[301] At the start of the awards ceremony, footage of Houston performing «I Will Always Love You» from the 1994 Grammys was shown following a prayer read by host LL Cool J. Later in the program, following a montage of photos of musicians who died in 2011 with Houston singing «Saving All My Love for You» at the 1986 Grammys, Hudson paid tribute to Houston and the other artists by performing «I Will Always Love You».[302][303] The tribute was partially credited for the Grammys telecast getting its second highest ratings in history.[304]

Houston was honored with various tributes at the 43rd NAACP Image Awards, held on February 17. An image montage of Houston and important black figures who died in 2011 was followed by video footage from the 1994 ceremony, which depicted her accepting two Image Awards for outstanding female artist and entertainer of the year. Following the video tribute, Yolanda Adams delivered a rendition of «I Love the Lord» from The Preacher’s Wife Soundtrack. In the finale of the ceremony, Kirk Franklin and the Family started their performance with «The Greatest Love of All».[305]

The 2012 Brit Awards, which took place at the O2 Arena in London on February 21, also paid tribute to Houston by playing a 30-second video montage of her music videos with a snippet of «One Moment in Time» as the background music in the ceremony’s first segment.[306] New Jersey Governor Chris Christie said that all New Jersey state flags would be flown at half-staff on Tuesday, February 21, to honor Houston.[307] Houston was also featured, alongside other recently deceased figures from the film industry, in the In Memoriam montage at the 84th Academy Awards on February 26, 2012.[308][309]

In June 2012, the year’s McDonald’s Gospelfest in Newark was dedicated as a tribute to Houston.[310]

Houston topped the list of Google searches in 2012, both globally and in the United States, according to Google’s Annual Zeitgeist most-popular searches list.[311]

On May 17, 2017, Bebe Rexha released a single titled «The Way I Are (Dance with Somebody)» from her two-part album All Your Fault.[312] The song mentions Houston’s name in the opening lyrics, «I’m sorry, I’m not the most pretty, I’ll never ever sing like Whitney», before going on to sample some of Houston’s lyrics from «I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)» in the chorus.[313] The song was in part made as a tribute to Whitney Houston’s life.[314][315]

Posthumous sales

According to representatives from Houston record label, Houston sold 3.7 million albums and 4.3 million singles worldwide in the first ten months of the year she died.[316] With just 24 hours passing between news of Houston’s death and Nielsen SoundScan tabulating the weekly album charts, Whitney: The Greatest Hits climbed into the Top 10 with 64,000 copies sold; it was a 10,419 percent gain compared to the previous week.[317] 43 of the top 100 most-downloaded tracks on iTunes were Houston songs, including «I Will Always Love You» from The Bodyguard at number one. Two other Houston classics, «I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me)» and «Greatest Love of All», were in the top 10.[318] As fans of Houston rushed to rediscover the singer’s music, single digital track sales of the artist’s music rose to more than 887,000 paid song downloads in 24 hours in the US alone.[319]

The single «I Will Always Love You» returned to the Billboard Hot 100 after almost twenty years, peaking at number three and becoming a posthumous top-ten single for Houston, the first one since 2001. Two other Houston songs also jumped back on the Hot 100: «I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me)» at 25 and «Greatest Love of All» at 36.[320] Her death on February 11 ignited an incredible drive to her YouTube and Vevo pages. She went from 868,000 views in the week prior to her death to 40,200,000 views in the week following her death, a 45-fold increase.[321]

On February 29, 2012, Houston became the first and only female act to ever place three albums in the Top Ten of the US Billboard 200 Album Chart all at the same time, with Whitney: The Greatest Hits at number 2, The Bodyguard at number 6 and Whitney Houston at number 9.[322] On March 7, 2012, Houston claimed two more additional feats on the US Billboard charts: she became the first and only female act to place nine albums within the top 100[323] (with Whitney: The Greatest Hits at number 2, The Bodyguard at number 5, Whitney Houston at number 10, I Look to You at number 13, Triple Feature at number 21, My Love Is Your Love at number 31, I’m Your Baby Tonight at number 32, Just Whitney at number 50 and The Preacher’s Wife at number 80);[324][325] in addition, other Houston albums were also on the US Billboard Top 200 Album Chart at this time. Houston also became the second female act, after Adele, to place two albums in the top five of the US Billboard Top 200, with Whitney: The Greatest Hits at number 2 and The Bodyguard at number 5.

Posthumous releases

Houston’s first posthumous greatest hits album, I Will Always Love You: The Best of Whitney Houston, was released on November 13, 2012, by RCA Records. It features the remastered versions of her number-one hits, an unreleased song titled «Never Give Up» and a duet version of «I Look to You» with R. Kelly.[326] The album won two NAACP Image Awards for ‘Outstanding Album’ and ‘Outstanding Song’ («I Look to You»). It was certified Gold by the RIAA in 2020.[327] In October 2021, the album was reissued on vinyl and included Houston’s first posthumous hit, «Higher Love». Since its release, it has spent more than 100 weeks on the Billboard 200, making it one of the longest-charting compilations in chart history,[328] the fourth by a woman after H.E.R., Madonna and Carrie Underwood.

Houston’s posthumous live album, Her Greatest Performances (2014), was a US R&B number-one[329] and received positive reviews by music critics.[330][331] In 2017, the 25th anniversary reissue of The Bodyguard (soundtrack)—I Wish You Love: More from The Bodyguard—was released by Legacy Recordings.[332] It includes film versions, remixes and live performances of Houston’s Bodyguard songs.[332]

In 2019, Houston and Kygo’s version of «Higher Love» was released as a single.[333] The record became a worldwide hit. It peaked at number two in the UK Singles Chart[95] and reached the top ten in several countries.[334][335][336] «Higher Love» was nominated at the 2020 Billboard Music Awards for «Top Dance/Electronic Song of the Year»,[337] the 2020 iHeartRadio Music Awards for «Dance Song of the Year» and «Best Remix».[338] It was certified multi-platinum in the United States,[339] Australia,[340] Canada,[341] Poland[342] and the United Kingdom.[343] The song was also a platinum hit in Denmark,[344] Switzerland,[345] and Belgium.[346]

On December 16, 2022, RCA released the soundtrack album to Houston’s featured film biopic, titled, I Wanna Dance with Somebody (The Movie: Whitney New, Classic and Reimagined), to every digital download platform all over the world.[347] The soundtrack includes reimagined remixes of some of Houston’s classics and several newly discovered songs such as Houston’s cover of CeCe Winans’ «Don’t Cry» (labeled as «Don’t Cry for Me» on Houston’s soundtrack) at the Commitment to Life AIDS benefit concert in Los Angeles in January 1994, remixed by house producer Sam Feldt.[347]

Artistry

Houston’s vocal ability earned her the nickname «the Voice».

Houston possessed a spinto soprano vocal range,[348][349][350] and was referred to as «The Voice» in reference to her vocal talent.[351] Jon Pareles of The New York Times stated Houston «always had a great big voice, a technical marvel from its velvety depths to its ballistic middle register to its ringing and airy heights».[352] In 2023, Rolling Stone ranked Houston as the second greatest singer of all time, stating, «The standard-bearer for R&B vocals, Whitney Houston possessed a soprano that was as powerful as it was tender. Take her cover of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You,” which became one of the defining singles of the 1990s; it opens with her gently brooding, her unaccompanied voice sounding like it’s turning over the idea of leaving her lover behind with the lightest touch. By the end, it’s transformed into a showcase for her limber, muscular upper register; she sings the title phrase with equal parts bone-deep feeling and technical perfection, turning the conflicted emotions at the song’s heart into a jumping-off point for her life’s next step.»[2]

Matthew Perpetua of Rolling Stone also acknowledged Houston’s vocal prowess, enumerating ten performances, including «How Will I Know» at the 1986 MTV VMAs and «The Star-Spangled Banner» at the 1991 Super Bowl. «Whitney Houston was blessed with an astonishing vocal range and extraordinary technical skill, but what truly made her a great singer was her ability to connect with a song and drive home its drama and emotion with incredible precision», he stated. «She was a brilliant performer and her live shows often eclipsed her studio recordings.»[353] According to Newsweek, Houston had a four-octave range.[354]

Elysa Gardner of the Los Angeles Times in her review for The Preacher’s Wife Soundtrack highly praised Houston’s vocal ability, commenting, «She is first and foremost a pop diva – at that, the best one we have. No other female pop star – not Mariah Carey, not Celine Dion, not Barbra Streisand – quite rivals Houston in her exquisite vocal fluidity and purity of tone and her ability to infuse a lyric with mesmerizing melodrama.»[355]

Singer Faith Evans stated: «Whitney wasn’t just a singer with a beautiful voice. She was a true musician. Her voice was an instrument and she knew how to use it. With the same complexity as someone who has mastered the violin or the piano, Whitney mastered the use of her voice. From every run to every crescendo—she was in tune with what she could do with her voice and it’s not something simple for a singer—even a very talented one—to achieve. Whitney is ‘the Voice’ because she worked for it. This is someone who was singing backup for her mom when she was 14 years old at nightclubs across the country. This is someone who sang backup for Chaka Khan when she was only 17. She had years and years of honing her craft on stage and in the studio before she ever got signed to a record label. Coming from a family of singers and surrounded by music; she pretty much had a formal education in music, just like someone who might attend a performing arts high school or major in voice in college.»[356]

Jon Caramanica of The New York Times commented, «Her voice was clean and strong, with barely any grit, well suited to the songs of love and aspiration. [ … ] Hers was a voice of triumph and achievement and it made for any number of stunning, time-stopping vocal performances.»[3] Mariah Carey stated, «She [Whitney] has a really rich, strong mid-belt that very few people have. She sounds really good, really strong.»[357] While in her review of I Look to You, music critic Ann Powers of the Los Angeles Times writes, «[Houston’s voice] stands like monuments upon the landscape of 20th century pop, defining the architecture of their times, sheltering the dreams of millions and inspiring the climbing careers of countless imitators», adding «When she was at her best, nothing could match her huge, clean, cool mezzo-soprano.»[350]

Lauren Everitt from BBC News commented on melisma used in Houston’s recording and its influence. «An early ‘I’ in Whitney Houston’s ‘I Will Always Love You’ takes nearly six seconds to sing. In those seconds the former gospel singer-turned-pop star packs a series of different notes into the single syllable», stated Everitt. «The technique is repeated throughout the song, most pronouncedly on every ‘I’ and ‘you’. The vocal technique is called melisma and it has inspired a host of imitators. Other artists may have used it before Houston, but it was her rendition of Dolly Parton’s love song that pushed the technique into the mainstream in the 90s. [ … ] But perhaps what Houston nailed best was moderation.» Everitt said that «[i]n a climate of reality shows ripe with ‘oversinging,’ it’s easy to appreciate Houston’s ability to save melisma for just the right moment.»[358]

Houston’s vocal stylings have had a significant impact on the music industry. According to Linda Lister in Divafication: The Deification of Modern Female Pop Stars, she has been called the «Queen of Pop» for her influence during the 1990s, commercially rivaling Mariah Carey and Celine Dion.[359] Stephen Holden from The New York Times, in his review of Houston’s Radio City Music Hall concert on July 20, 1993, praised her attitude as a singer, writing, «Whitney Houston is one of the few contemporary pop stars of whom it might be said: the voice suffices. While almost every performer whose albums sell in the millions calls upon an entertainer’s bag of tricks, from telling jokes to dancing to circus pyrotechnics, Ms. Houston would rather just stand there and sing.» With regard to her singing style, he added: «Her [Houston’s] stylistic trademarks – shivery melismas that ripple up in the middle of a song, twirling embellishments at the ends of phrases that suggest an almost breathless exhilaration – infuse her interpretations with flashes of musical and emotional lightning.»[360]

Houston struggled with vocal problems in her later years. Gary Catona, a voice coach who began working with Houston in 2005, stated: «‘When I first started working with her in 2005, she had lost 99.9 percent of her voice … She could barely speak, let alone sing. Her lifestyle choices had made her almost completely hoarse.'»[361] After Houston’s death, Catona asserted that Houston’s voice reached «‘about 75 to 80 percent'» of its former capacity after he had worked with her.[362] However, during the world tour that followed the release of I Look to You, «YouTube videos surfaced, showing [Houston’s] voice cracking, seemingly unable to hold the notes she was known for».[362]

Regarding the musical style, Houston’s vocal performances incorporated a wide variety of genres, including R&B, pop, rock,[363] soul, gospel, funk,[364] dance, Latin pop,[365] disco,[366] house,[367] hip hop soul,[368] new jack swing,[369] opera,[370] and Christmas. The lyrical themes in her recordings are mainly about love, social, religious and feminism.[371] The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame stated: «Her sound expanded through collaborations with a wide array of artists, including Stevie Wonder, Luther Vandross, Babyface, Missy Elliott, Bobby Brown, and Mariah Carey.»[363] While AllMusic commented that, «Houston was able to handle big adult contemporary ballads, effervescent, stylish dance-pop and slick urban contemporary soul with equal dexterity».[372]

Legacy

Houston has been regarded as one of the greatest vocalists of all time and a cultural icon.[373][374][375] She is also recognized as one of the most influential R&B artists in history.[376][377] Black female artists, such as Janet Jackson and Anita Baker, were successful in popular music partly because Houston paved the way.[378][64][379] Baker commented that «Because of what Whitney and Sade did, there was an opening for me … For radio stations, black women singers aren’t taboo anymore.»[380]

AllMusic noted her contribution to the success of black artists on the pop scene.[372] The New York Times stated that «Houston was a major catalyst for a movement within black music that recognized the continuity of soul, pop, jazz and gospel vocal traditions».[381] Richard Corliss of Time magazine commented on her initial success breaking various barriers: