Whitesnake (в переводе с англ. — «белая змея») — британская, затем американская рок-группа, играющая хард-рок с блюзовыми элементами, созданная в 1978 году Дэвидом Ковердэйлом, бывшим вокалистом Deep Purple.

История

1977—1984

Hammersmith Odeon, 1981 год

Гитаристы Whitesnake Берни Марсден и Мики Муди. 1981 год

Дэвид Ковердейл основал Whitesnake в конце 1977 года в Северном Йоркшире, Англия. Основу его группы составили музыканты аккомпанирующего состава под названием The White Snake Band.

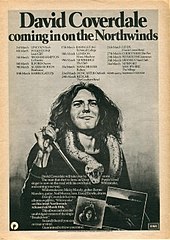

Официально группа создана в январе 1978 года Дэвидом Ковердэйлом, бывшим вокалистом Deep Purple. В связи с тем, что Дэвид Ковердэйл был связан контрактом, запрещающим ему участие в группах, он был вынужден с момента распада Deep Purple выпускать сольные альбомы с аккомпанирующим составом, т. н. David Coverdale’s Whitesnake. С ним он выпустил два альбома — White Snake (1977) и Northwinds (1978), продюсером которых стал небезызвестный Роджер Гловер.

В создании группы, наряду с Ковердэйлом, участвовали Берни Марсден — гитара, Мики Муди — гитара, Нил Маррей — бас, Дэйв Даул — барабаны и Брайан Джонстон — клавишные. Впрочем, Джонстон вскоре был заменен на Пита Соллея (экс-Procol Harum). Они записали 7-дюймовый EP Snakebite (1978). Продюсером всех альбомов, начиная с дебютного и до 1984 года был Мартин Бёрч, продюсировавший последние альбомы Deep Purple с участием Ковердэйла. Параллельно работе с Whitesnake, Бёрч также продюсировал альбомы Rainbow (сольного проекта бывшего коллеги Ковердейла по Deep Purple Ричи Блэкмора), Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden и других.

В 1979 году вышел второй альбом — Lovehunter. Обложка альбома была несколько эротического содержания, поэтому в некоторых случаях пластинка продавалась в специальных коричневых пакетах. В данный период сформировался «золотой состав» Whitesnake — Марсден, Муди, Ковердэйл, Лорд, Пейс, Маррей. В 1980 году был выпущен ещё один альбом — Ready an’ Willing, принёсший группе хит «Fool For Your Lovin’» (изначально написанный для Би Би Кинга, а впоследствии переделанный и исполняемый и по сей день). Концертный альбом Live…In the Heart of the City[en], записанный в период 1978—1980 годов, получил 5-ую строчку в британском чарте[1].

В 1981 году группа записала альбом Come An’ Get It, который поднялся до 2 позиции в чартах Великобритании. Хит «Don’t Break My Heart Again» попал Top 20, а хит «Would I Lie to You» — в Top 40. Альбом провалился в США. В 1982 году Ковердейл взял отпуск, чтобы ухаживать за больной дочерью, и решил приостановить деятельность Whitesnake.

Во время записи Saints & Sinners уходит Марсден, а вскоре приходит конец и «золотому составу» — группу также покидают Пейс и Маррей.

1984—1991

После некоторой паузы «Белая Змея» оживает вновь. Теперь в группе играют: спешно рекрутированный на запись недописанных партий Марсдена гитарист Мел Гэлли, игравший ранее с Гленном Хьюзом в Trapeze, басист-виртуоз и друг Джона Лорда Колин Ходжкинсон и экс-барабанщик Rainbow Кози Пауэлл. В этом составе группа записывает альбом Slide It In, в котором уже чувствуется желание Ковердэйла перевести группу на коммерческие рельсы.

После записи альбома группу покидают Муди и Ходжкинсон. Вместо них в группу приходят гитарист Thin Lizzy Джон Сайкс и вернувшийся Нил Маррей. В 1987 году группа выпускает очень успешный альбом 1987 (также известный как просто Whitesnake), который завоевал трансатлантическую аудиторию и стал восьмикратно платиновым. Данный альбом отличает от предшественников отсутствие блюзового звучания — группа полностью уклоняется в хард-н-хэви. Два года спустя группа выпускает вместе со Стивом Ваем альбом Slip of the Tongue, уже не имевший прежнего успеха. В 1990 году Whitesnake выступают хедлайнерами на фестивале «Monsters of Rock» в Донингтоне[2], но вскоре группа распадается, так как Ковердэйл решил взять творческую паузу.

1994 — наши дни

В 1994 году Дэвид Ковердэйл с гитаристом Адрианом Ванденбергом воссоздают группу. В 1997 году записывается альбом Restless Heart, который Ковердэйл изначально планировал в качестве сольной работы (отсюда непохожесть по звучанию на предыдущие работы). Затем Дэвид снова распускает группу и собирает её вновь в 2002 году, но с новым составом (из «ветеранов» группы в этот состав попал только барабанщик Томми Олдридж).

Whitesnake live 2003

В начале 2006 года вышел концертный DVD Live… In the Still of the Night[en], записанный в 2004 году в Лондоне в легендарном зале Hammersmith Odeon. А в конце 2006 года вышел двойной концертный альбом — Live… in the Shadow of the Blues[en]. В марте того же года мир увидел перепевку хита «Is This Love» в исполнении певца Томаса Андерса, бывшего солиста легендарной группы Modern Talking.

В 2008 году вышел новый студийный альбом группы Good to Be Bad, получивший положительные отзывы критиков.

В начале 2010 года Whitesnake сообщили о том, что группа не будет гастролировать на протяжении всего 2010 года, потому что музыканты работают над несколькими проектами, главный из которых — сочинение и запись нового студийного альбома. В феврале 2010 года группа подписала контракт с лейблом «Frontiers Records». 18 июня 2010 года во время работы над альбомом Whitesnake покидают барабанщик Крис Фрэйзер и басист Юрайя Даффи. В августе 2010 года на смену Юрайе Даффи группа ангажировала басиста Майкла Дэвина. В сентябре 2010 года группу покидает клавишник Тимоти Друри — по официальной версии, «чтобы заняться сольной карьерой».

В 2011 году на лейбле «Frontiers» вышел новый студийный альбом Whitesnake — Forevermore («Навеки»).

В конце февраля 2015 года на официальном сайте группы было объявлено о выходе нового альбома «The Purple Album», целиком состоящего из песен Deep Purple, периода, когда вокалистом был Дэвид Ковердэйл. Также был представлен клип на песню «Stormbringer».

Дискография

Студийные записи

- 1978 — Snakebite (EP)

- 1978 — Trouble

- 1979 — Lovehunter

- 1980 — Ready an’ Willing

- 1981 — Come an’ Get It

- 1982 — Saints and Sinners

- 1984 — Slide It In

- 1987 — 1987

- 1989 — Slip of the Tongue

- 1997 — Restless Heart

- 2008 — Good to Be Bad

- 2011 — Forevermore[3]

- 2015 — The Purple Album[4]

- 2019 — Flesh & Blood

Концертные альбомы

- 1980 — Live at Hammersmith (1978)

- 1980 — Live … In the Heart of the City (1980)

- 1990 — Live at Donington (1990)

- 1998 — Starkers in Tokyo (1997)

- 2006 — Live… In the Shadow of the Blues (2004)

- 2013 — Made in Japan (2011)

Составы

| Время | Состав | Альбомы |

|---|---|---|

| David Coverdale’s Whitesnake (январь—март 1978) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (март—июль 1978) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (август 1978 — июль 1979) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (июль 1979 — март 1982) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (сентябрь 1982 — ноя/дек 1983) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1984) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1984) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1985—1987) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1987—1988) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1988—1989) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1989—1991) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1994) |

|

|

| David Coverdale’s Whitesnake (1997) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (1997—1998) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (декабрь 2002 — апрель 2005) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (май 2005 — ноябрь 2007) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (ноябрь 2007 — июнь 2010) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (июль 2010 — январь 2013) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (январь 2013—2014) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (2014—2015) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (2015—2021) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (2021) |

|

|

| Whitesnake (ноябрь 2021 — настоящее время) |

|

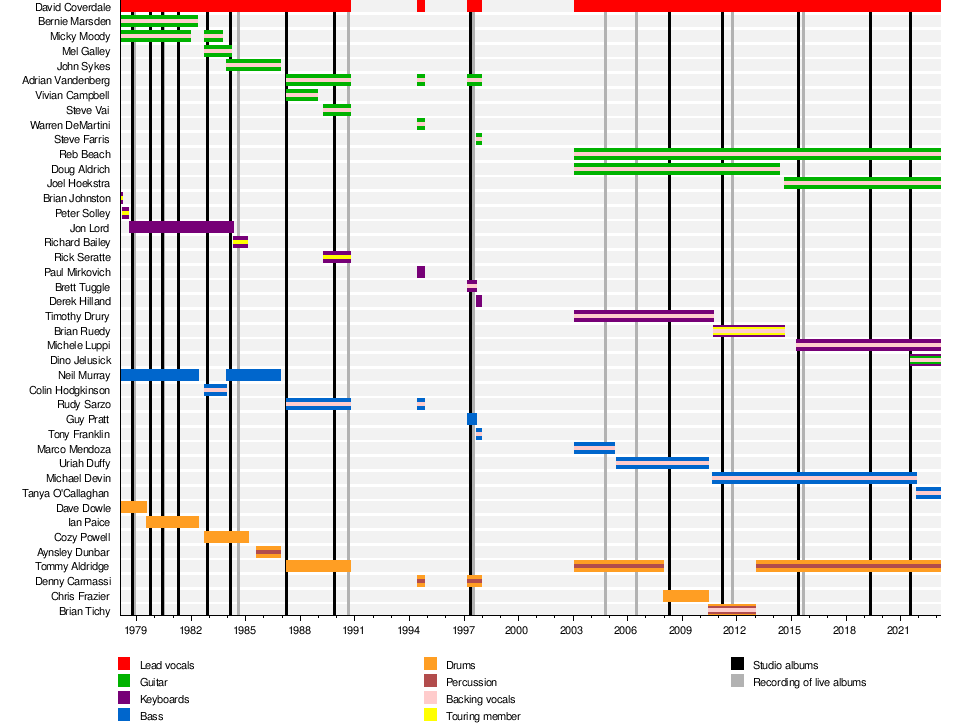

Временная шкала

Примечания

Ссылки

Эта страница в последний раз была отредактирована 11 октября 2022 в 20:00.

Как только страница обновилась в Википедии она обновляется в Вики 2.

Обычно почти сразу, изредка в течении часа.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dino Jelusick, Reb Beach, Tommy Aldridge, Tanya O’Callaghan, Michele Luppi and David Coverdale

Whitesnake performing in 1980 (first), 1983 (second), 2003 (third), 2016 (fourth), and 2022 (fifth)

Whitesnake are a British-American hard rock band originally from Middlesbrough. Formed in 1978, the group originally consisted of vocalist David Coverdale, guitarists Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden, bassist Neil Murray, drummer Dave Dowle and keyboardist Brian Johnston. The current lineup of the band includes Coverdale, drummer Tommy Aldridge (from 1987 to 1990, 2003 to 2007, and since 2013), guitarists Reb Beach and Joel Hoekstra (since 2003 and 2014, respectively), keyboardists Michele Luppi (since 2015) and Dino Jelusick (since 2021) and bassist Tanya O’Callaghan (also since 2021).

History[edit]

1978–1986[edit]

Following the release and promotion of his debut solo album White Snake in 1977, vocalist David Coverdale formed the band of the same name the following February,[1] with the initial lineup including guitarists and backing vocalists Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden, bassist Neil Murray, drummer Dave «Duck» Dowle and touring keyboardist Brian Johnston.[2] After their first few shows, the group replaced Johnston with Peter Solley (although he was still credited as a «special guest», rather than a full member)[3] and recorded their debut EP Snakebite.[4] By August, Solley had also been replaced by Jon Lord, Coverdale’s former bandmate in Deep Purple, in time for the recording of their debut album Trouble.[4] Dowle was replaced in July 1979 after the recording of Lovehunter by Ian Paice, another Deep Purple alumnus.[5] After Ready an’ Willing and Come an’ Get It, Whitesnake were placed on hiatus by Coverdale in early 1982, during which time Marsden, Murray and Paice all left the band for other projects.[1][6]

Coverdale reformed the group in October 1982, with Moody and Lord joined by new guitarist Mel Galley, bassist Colin Hodgkinson and drummer Cozy Powell.[1] After the recording of Slide It In, Moody and Hodgkinson left in December 1983, with John Sykes and the returning Neil Murray taking their places.[7] Both new members featured on the US reissue of the album, which featured re-recorded tracks.[8] A few dates into the subsequent tour, Galley broke his arm and was forced to leave the band, who completed the shows as a five-piece.[9] Lord also left in April to rejoin his former bandmates in reforming Deep Purple.[10] Whitesnake subsequently continued performing as a four-piece, adding Richard Bailey as a touring keyboardist throughout the rest of the year.[11] After two Rock in Rio performances in January 1985, Powell then left to form Emerson, Lake & Powell.[12] A few months later, the band started recording their self-titled album with new drummer Aynsley Dunbar and session keyboardist Don Airey.[13]

1987–1997[edit]

After it was completed the previous year, Whitesnake was released in 1987.[14] Shortly before its release, Coverdale put together an all-new lineup which included former Dio guitarist Vivian Campbell, former Vandenberg guitarist Adrian Vandenberg, and former Ozzy Osbourne bassist and drummer Rudy Sarzo and Tommy Aldridge.[14] After the end of the album’s touring cycle, Campbell left the band.[15] He was replaced the next April by Steve Vai, formerly of David Lee Roth’s solo band.[16] Vai performed all guitars on the group’s next album Slip of the Tongue, after Vandenberg suffered a wrist injury that prevented him from playing.[17] For the album’s touring cycle, Rick Seratte joined on live keyboards.[18] At the end of the tour in September 1990, Coverdale chose to disband Whitesnake.[19]

In 1994, Coverdale revived Whitesnake following the breakup of Coverdale•Page, touring between June and October in promotion of Greatest Hits.[20] The band’s lineup included returning members Vandenberg and Sarzo, in addition to Ratt guitarist Warren DeMartini, former Coverdale•Page touring drummer Denny Carmassi, and backup keyboardist Paul Mirkovich.[21] At the end of the run, the group’s contract with Geffen Records expired and they disbanded again.[21] A second reformation followed in 1997, when Coverdale, Vandenberg and Carmassi reunited alongside former Coverdale•Page touring members Guy Pratt (bass) and Brett Tuggle (keyboards) for Restless Heart.[22] The album was initially intended to be a Coverdale solo release, however due to pressure from his new label EMI Records it was branded a Whitesnake album.[23] The tour, which ran from September to December 1997, featured Vandenberg and Carmassi, plus guitarist Steve Farris, bassist Tony Franklin and keyboardist Derek Hilland.[22]

2003 onwards[edit]

After a five-year break, it was announced in December 2002 that Whitesnake would reformed for a tour the following year, with drummer Tommy Aldridge returning alongside new members Doug Aldrich and Reb Beach on guitars, Marco Mendoza on bass, and Timothy Drury on keyboards.[24] In April 2005, Mendoza left to pursue «other musical avenues»,[25] with Uriah Duffy taking his place the following month.[26] In December 2007, it was also announced that Aldridge had departed, with Chris Frazier having taken his place to record drums for Good to Be Bad, the first Whitesnake studio album since 1997.[27] Both Frazier and Duffy had left by June 2010, with Brian Tichy and Michael Devin taking their places, respectively.[28][29] Drury left to pursue a solo career in September,[30] with his place taken on the Forevermore touring cycle by Brian Ruedy.[31] After two years of touring, Tichy left in January 2013 and was replaced by Aldridge a few weeks later.[32][33] Aldrich later left in May 2014, citing a desire to start a solo career.[34]

Aldrich’s place in the band was taken by Night Ranger guitarist Joel Hoekstra in August 2014.[35] The following year saw the release of The Purple Album, a collection of recordings of tracks from Coverdale’s time in Deep Purple.[36] Shortly after the album’s release, Michele Luppi was enlisted as Whitesnake’s new keyboardist.[37] Flesh & Blood followed in 2019.[38] In July 2021, Whitesnake recruited Dino Jelusick for their 2022 farewell tour, turning Whitesnake into a septet for the first time.[39] Later that November, Michael Devin parted ways with the band.[40] He was replaced by Tanya O’Callaghan.[41]

Members[edit]

Current members[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

David Coverdale |

[1][19][20][21][22][24] |

lead vocals | all Whitesnake releases |

|

|

Tommy Aldridge |

[14][42][19][24][27][33] |

|

|

|

|

Reb Beach | 2003–present[24] |

|

|

|

|

Joel Hoekstra | 2014–present[35] |

|

|

|

|

Michele Luppi | 2015–present[37] |

|

|

|

|

Dino Jelusick[39] | 2021–present |

|

none |

|

|

Tanya O’Callaghan[41] |

|

Former members[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Micky Moody |

[2][7] |

|

all Whitesnake releases from Snakebite (1978) to Slide It In (1984) |

|

|

Neil Murray |

[2][1][6][7] |

|

|

|

|

Bernie Marsden | 1978–1982[2][1][6] |

|

all Whitesnake releases from Snakebite (1978) to Saints & Sinners (1982) |

| Dave «Duck» Dowle | 1978–1979[2][5] | drums | all Whitesnake releases from Snakebite (1978) to Live at Hammersmith (1980) | |

|

|

Jon Lord | 1978–1984 (died 2012)[4][10] | keyboards |

|

|

|

Ian Paice | 1979–1982[5][1][6] | drums | all Whitesnake releases from Ready an’ Willing (1980) to Saints & Sinners (1982) |

|

|

Mel Galley | 1982–1984 (died 2008)[1][9] |

|

|

|

|

Cozy Powell | 1982–1985 (died 1998)[1][12] | drums |

|

|

|

Colin Hodgkinson | 1982–1983[1][7] |

|

|

|

|

John Sykes | 1983–1986[7] |

|

|

|

|

Aynsley Dunbar | 1985–1986[13] |

|

Whitesnake (1987) |

|

|

Adrian Vandenberg |

[14][19][21][22] |

|

|

|

|

Rudy Sarzo |

[14][21] |

|

|

|

|

Vivian Campbell | 1987–1988[14][15] |

|

«Give Me All Your Love» (single version) (1988) |

|

|

Steve Vai | 1989–1990[16][19] |

|

|

| Denny Carmassi |

[21][22] |

|

|

|

|

|

Warren DeMartini | 1994[21] |

|

none |

|

|

Paul Mirkovich | keyboards | ||

|

|

Brett Tuggle | 1997 (died 2022)[22] |

|

Restless Heart (1997) |

|

|

Guy Pratt[22] | 1997 | bass | |

|

|

Steve Farris[22] |

|

none | |

|

|

Tony Franklin[22] |

|

||

|

|

Derek Hilland[22] | keyboards | The Purple Album (2015) | |

|

|

Doug Aldrich | 2003–2014[24][34] |

|

|

|

|

Timothy Drury | 2003–2010[24][30] |

|

|

|

|

Marco Mendoza | 2003–2005[24][25] |

|

|

|

|

Uriah Duffy | 2005–2010[26][28] |

|

|

|

|

Chris Frazier | 2007–2010[28] | drums |

|

|

|

Brian Tichy | 2010–2013[28][32] |

|

|

|

|

Michael Devin | 2010–2021[29][40] |

|

|

Session/touring musicians[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brian Johnston[2] | 1978 |

|

Johnston was the keyboardist for Whitesnake’s first few shows, but was not credited as a full band member.[2] | |

| Peter Solley[3] | Solley replaced Johnston and performed on Snakebite, but was still credited as a «special guest» performer.[4][3] | |||

| Richard Bailey | 1984–1985[11] | Following the departure of Jon Lord in April 1984, Whitesnake enlisted Richard Bailey to take his place on tour.[11] | ||

| Rick Seratte | 1989–1990[18] | In the absence of a full-time keyboardist, Seratte performed on the tour promoting 1989’s Slip of the Tongue.[18] | ||

| Brian Ruedy | 2011–2013[31] |

|

Following the departure of Timothy Drury in September 2010, Ruedy performed on the Forevermore tour.[31] |

Session musicians[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bill Cuomo |

|

keyboards |

[44] |

|

|

|

Don Airey |

|

[44] |

|

| Tommy Funderburk |

|

backing vocals |

|

|

| Dann Huff | 1985–1986 | guitar | «Here I Go Again» (single version) (1987) | |

|

|

Mark Andes | bass | ||

| Claude Gaudette | 1988–1989 | keyboards | Slip of the Tongue (1989) | |

|

|

Glenn Hughes | backing vocals | ||

|

|

Richard Page | |||

| Beth Anderson | 1997 | Restless Heart (1997) | ||

| Maxine Waters | ||||

| Elk Thunder | harmonica | |||

| Chris Whitemyer | percussion | |||

| Jasper Coverdale | 2010 | backing vocals | Forevermore (2011) | |

|

|

Derek Sherinian | 2020 | keyboards | Sherinian performed on remixed versions of Slip of the Tongue and Restless Heart.[45][46] |

| Chritopher Collier | 2021 |

|

Restless Heart (1997) (2021 remix) |

Timeline[edit]

Lineups[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barton, Geoff (1 October 2018). «Whitesnake: «The Coverdale I recall was a vain, preposterous oaf»«. Louder. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g «40 Years Ago Today – Whitesnake’s First Show». Whitesnake. 3 March 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Thelen, Christopher (31 July 1999). «Whitesnake: Snakebite». Daily Vault. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Rivadavia, Eduardo (3 March 2016). «The Day Whitesnake Played Their First Concert». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 19, August 1979». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 25, July 1982». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 29, July 1984». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (30 January 2014). «30 Years Ago: Whitesnake Release ‘Slide It In’«. Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b Daniels, Neil (4 July 2008). «Obituary: Mel Galley». The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Jon Lord Biografie» (PDF). Ear Music. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 30, December 1984». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Correspondent Reports: More News» (PDF). Eurotipsheet. Vol. 2, no. 11. 18 March 1985. p. 20. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 32, February 1986». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Kielty, Martin (7 April 2017). «30 Years Ago: David Coverdale Returns From The Abyss With ‘Whitesnake’«. Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Compact Data: Short Cuts» (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 768. Los Angeles, California: Radio & Records, Inc. 16 December 1988. p. 40. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Compact Data» (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 784. Los Angeles, California: Radio & Records, Inc. 14 April 1989. p. 50. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (18 November 2014). «How Whitesnake’s ‘Slip of the Tongue’ Marked the End of an Era». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Carlson, Taylor (11 August 2015). «Whitesnake Live at Donington 1990 — Great Concert Derailed by Terrible Video Quality». ZRock’R Magazine. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Chirazi, Steffan (25 March 2011). «The Growing Pains Of Whitesnake’s David Coverdale». Classic Rock. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b «That’s Sho-Biz: Sho-Talk» (PDF). Gavin Report. No. 2012. San Francisco, California: United Newspapers. 8 July 1994. p. 9. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reesman, Bryan (13 April 2010). «It’s good to be… Whitesnake». Goldmine. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 50, February 1998». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ «With a Whisper David Coverdale Goes Into the Light». The Pure Rock Shop. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Whitesnake 2003 Lineup Confirmed!». Blabbermouth.net. 15 December 2002. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Part Ways With Bassist Marco Mendoza, Seek Replacement». Blabbermouth.net. 12 April 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announce New Bassist». Blabbermouth.net. 12 May 2005. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announces New Drummer». Blabbermouth.net. 27 December 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d «Whitesnake Parts Ways With Duffy, Frazier; New Drummer Announced». Blabbermouth.net. 18 June 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announces New Bassist». Blabbermouth.net. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Keyboardist Quits To Pursue ‘Solo’ Career». Blabbermouth.net. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b c «Whitesnake Announces New Touring Keyboardist». Blabbermouth.net. 20 March 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Drummer Brian Tichy Quits Whitesnake». Blabbermouth.net. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Drummer Tommy Aldridge Rejoins Whitesnake». Blabbermouth.net. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Guitarist Doug Aldrich Quits Whitesnake». Blabbermouth.net. 9 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Recruits Night Ranger Guitarist Joel Hoekstra». Blabbermouth.net. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Monger, James Christopher. «The Purple Album — Whitesnake: Songs, Reviews, Credits». AllMusic. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announces New Keyboardist». Blabbermouth.net. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ «Whitesnake Release New Album, ‘Flesh & Blood’«. Guitar World. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Welcomes Trans-Siberian Orchetra Singer Dino Jelusick». Blabbermouth.net. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Parts Ways With Longtime Bassist Michael Devin». Blabbermouth.net. 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ a b «Welcome Our New Bass Player!». Whitesnake Official Website. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Dana. «DRUMMER TOMMY ALDRIDGE BACK IN WHITESNAKE». Eddie Trunk. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ a b Blabbermouth (2022-05-02). «WHITESNAKE’s DINO JELUSICK Will Be ‘Singing A Lot’ On Upcoming Tour». BLABBERMOUTH.NET. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ a b Whitesnake liner notes – EMI

- ^ Sherinian, Derek [@@DerekSherinian] (17 April 2020). «I am proud to be featured on the new Whitesnake compilation «The Rock Album»! I re-recorded the keys on the albums «Slip Of The Tongue» and «Restless Heart», which many songs are on this release- a LOT of Hammond B3! Thank you DC for the opportunity!» (Tweet). Retrieved 23 November 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Wilkening, Matthew (19 June 2020). «David Coverdale Is Hearing Whitesnake in a Whole New Way». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

External links[edit]

- Whitesnake official website

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dino Jelusick, Reb Beach, Tommy Aldridge, Tanya O’Callaghan, Michele Luppi and David Coverdale

Whitesnake performing in 1980 (first), 1983 (second), 2003 (third), 2016 (fourth), and 2022 (fifth)

Whitesnake are a British-American hard rock band originally from Middlesbrough. Formed in 1978, the group originally consisted of vocalist David Coverdale, guitarists Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden, bassist Neil Murray, drummer Dave Dowle and keyboardist Brian Johnston. The current lineup of the band includes Coverdale, drummer Tommy Aldridge (from 1987 to 1990, 2003 to 2007, and since 2013), guitarists Reb Beach and Joel Hoekstra (since 2003 and 2014, respectively), keyboardists Michele Luppi (since 2015) and Dino Jelusick (since 2021) and bassist Tanya O’Callaghan (also since 2021).

History[edit]

1978–1986[edit]

Following the release and promotion of his debut solo album White Snake in 1977, vocalist David Coverdale formed the band of the same name the following February,[1] with the initial lineup including guitarists and backing vocalists Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden, bassist Neil Murray, drummer Dave «Duck» Dowle and touring keyboardist Brian Johnston.[2] After their first few shows, the group replaced Johnston with Peter Solley (although he was still credited as a «special guest», rather than a full member)[3] and recorded their debut EP Snakebite.[4] By August, Solley had also been replaced by Jon Lord, Coverdale’s former bandmate in Deep Purple, in time for the recording of their debut album Trouble.[4] Dowle was replaced in July 1979 after the recording of Lovehunter by Ian Paice, another Deep Purple alumnus.[5] After Ready an’ Willing and Come an’ Get It, Whitesnake were placed on hiatus by Coverdale in early 1982, during which time Marsden, Murray and Paice all left the band for other projects.[1][6]

Coverdale reformed the group in October 1982, with Moody and Lord joined by new guitarist Mel Galley, bassist Colin Hodgkinson and drummer Cozy Powell.[1] After the recording of Slide It In, Moody and Hodgkinson left in December 1983, with John Sykes and the returning Neil Murray taking their places.[7] Both new members featured on the US reissue of the album, which featured re-recorded tracks.[8] A few dates into the subsequent tour, Galley broke his arm and was forced to leave the band, who completed the shows as a five-piece.[9] Lord also left in April to rejoin his former bandmates in reforming Deep Purple.[10] Whitesnake subsequently continued performing as a four-piece, adding Richard Bailey as a touring keyboardist throughout the rest of the year.[11] After two Rock in Rio performances in January 1985, Powell then left to form Emerson, Lake & Powell.[12] A few months later, the band started recording their self-titled album with new drummer Aynsley Dunbar and session keyboardist Don Airey.[13]

1987–1997[edit]

After it was completed the previous year, Whitesnake was released in 1987.[14] Shortly before its release, Coverdale put together an all-new lineup which included former Dio guitarist Vivian Campbell, former Vandenberg guitarist Adrian Vandenberg, and former Ozzy Osbourne bassist and drummer Rudy Sarzo and Tommy Aldridge.[14] After the end of the album’s touring cycle, Campbell left the band.[15] He was replaced the next April by Steve Vai, formerly of David Lee Roth’s solo band.[16] Vai performed all guitars on the group’s next album Slip of the Tongue, after Vandenberg suffered a wrist injury that prevented him from playing.[17] For the album’s touring cycle, Rick Seratte joined on live keyboards.[18] At the end of the tour in September 1990, Coverdale chose to disband Whitesnake.[19]

In 1994, Coverdale revived Whitesnake following the breakup of Coverdale•Page, touring between June and October in promotion of Greatest Hits.[20] The band’s lineup included returning members Vandenberg and Sarzo, in addition to Ratt guitarist Warren DeMartini, former Coverdale•Page touring drummer Denny Carmassi, and backup keyboardist Paul Mirkovich.[21] At the end of the run, the group’s contract with Geffen Records expired and they disbanded again.[21] A second reformation followed in 1997, when Coverdale, Vandenberg and Carmassi reunited alongside former Coverdale•Page touring members Guy Pratt (bass) and Brett Tuggle (keyboards) for Restless Heart.[22] The album was initially intended to be a Coverdale solo release, however due to pressure from his new label EMI Records it was branded a Whitesnake album.[23] The tour, which ran from September to December 1997, featured Vandenberg and Carmassi, plus guitarist Steve Farris, bassist Tony Franklin and keyboardist Derek Hilland.[22]

2003 onwards[edit]

After a five-year break, it was announced in December 2002 that Whitesnake would reformed for a tour the following year, with drummer Tommy Aldridge returning alongside new members Doug Aldrich and Reb Beach on guitars, Marco Mendoza on bass, and Timothy Drury on keyboards.[24] In April 2005, Mendoza left to pursue «other musical avenues»,[25] with Uriah Duffy taking his place the following month.[26] In December 2007, it was also announced that Aldridge had departed, with Chris Frazier having taken his place to record drums for Good to Be Bad, the first Whitesnake studio album since 1997.[27] Both Frazier and Duffy had left by June 2010, with Brian Tichy and Michael Devin taking their places, respectively.[28][29] Drury left to pursue a solo career in September,[30] with his place taken on the Forevermore touring cycle by Brian Ruedy.[31] After two years of touring, Tichy left in January 2013 and was replaced by Aldridge a few weeks later.[32][33] Aldrich later left in May 2014, citing a desire to start a solo career.[34]

Aldrich’s place in the band was taken by Night Ranger guitarist Joel Hoekstra in August 2014.[35] The following year saw the release of The Purple Album, a collection of recordings of tracks from Coverdale’s time in Deep Purple.[36] Shortly after the album’s release, Michele Luppi was enlisted as Whitesnake’s new keyboardist.[37] Flesh & Blood followed in 2019.[38] In July 2021, Whitesnake recruited Dino Jelusick for their 2022 farewell tour, turning Whitesnake into a septet for the first time.[39] Later that November, Michael Devin parted ways with the band.[40] He was replaced by Tanya O’Callaghan.[41]

Members[edit]

Current members[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

David Coverdale |

[1][19][20][21][22][24] |

lead vocals | all Whitesnake releases |

|

|

Tommy Aldridge |

[14][42][19][24][27][33] |

|

|

|

|

Reb Beach | 2003–present[24] |

|

|

|

|

Joel Hoekstra | 2014–present[35] |

|

|

|

|

Michele Luppi | 2015–present[37] |

|

|

|

|

Dino Jelusick[39] | 2021–present |

|

none |

|

|

Tanya O’Callaghan[41] |

|

Former members[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Micky Moody |

[2][7] |

|

all Whitesnake releases from Snakebite (1978) to Slide It In (1984) |

|

|

Neil Murray |

[2][1][6][7] |

|

|

|

|

Bernie Marsden | 1978–1982[2][1][6] |

|

all Whitesnake releases from Snakebite (1978) to Saints & Sinners (1982) |

| Dave «Duck» Dowle | 1978–1979[2][5] | drums | all Whitesnake releases from Snakebite (1978) to Live at Hammersmith (1980) | |

|

|

Jon Lord | 1978–1984 (died 2012)[4][10] | keyboards |

|

|

|

Ian Paice | 1979–1982[5][1][6] | drums | all Whitesnake releases from Ready an’ Willing (1980) to Saints & Sinners (1982) |

|

|

Mel Galley | 1982–1984 (died 2008)[1][9] |

|

|

|

|

Cozy Powell | 1982–1985 (died 1998)[1][12] | drums |

|

|

|

Colin Hodgkinson | 1982–1983[1][7] |

|

|

|

|

John Sykes | 1983–1986[7] |

|

|

|

|

Aynsley Dunbar | 1985–1986[13] |

|

Whitesnake (1987) |

|

|

Adrian Vandenberg |

[14][19][21][22] |

|

|

|

|

Rudy Sarzo |

[14][21] |

|

|

|

|

Vivian Campbell | 1987–1988[14][15] |

|

«Give Me All Your Love» (single version) (1988) |

|

|

Steve Vai | 1989–1990[16][19] |

|

|

| Denny Carmassi |

[21][22] |

|

|

|

|

|

Warren DeMartini | 1994[21] |

|

none |

|

|

Paul Mirkovich | keyboards | ||

|

|

Brett Tuggle | 1997 (died 2022)[22] |

|

Restless Heart (1997) |

|

|

Guy Pratt[22] | 1997 | bass | |

|

|

Steve Farris[22] |

|

none | |

|

|

Tony Franklin[22] |

|

||

|

|

Derek Hilland[22] | keyboards | The Purple Album (2015) | |

|

|

Doug Aldrich | 2003–2014[24][34] |

|

|

|

|

Timothy Drury | 2003–2010[24][30] |

|

|

|

|

Marco Mendoza | 2003–2005[24][25] |

|

|

|

|

Uriah Duffy | 2005–2010[26][28] |

|

|

|

|

Chris Frazier | 2007–2010[28] | drums |

|

|

|

Brian Tichy | 2010–2013[28][32] |

|

|

|

|

Michael Devin | 2010–2021[29][40] |

|

|

Session/touring musicians[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brian Johnston[2] | 1978 |

|

Johnston was the keyboardist for Whitesnake’s first few shows, but was not credited as a full band member.[2] | |

| Peter Solley[3] | Solley replaced Johnston and performed on Snakebite, but was still credited as a «special guest» performer.[4][3] | |||

| Richard Bailey | 1984–1985[11] | Following the departure of Jon Lord in April 1984, Whitesnake enlisted Richard Bailey to take his place on tour.[11] | ||

| Rick Seratte | 1989–1990[18] | In the absence of a full-time keyboardist, Seratte performed on the tour promoting 1989’s Slip of the Tongue.[18] | ||

| Brian Ruedy | 2011–2013[31] |

|

Following the departure of Timothy Drury in September 2010, Ruedy performed on the Forevermore tour.[31] |

Session musicians[edit]

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bill Cuomo |

|

keyboards |

[44] |

|

|

|

Don Airey |

|

[44] |

|

| Tommy Funderburk |

|

backing vocals |

|

|

| Dann Huff | 1985–1986 | guitar | «Here I Go Again» (single version) (1987) | |

|

|

Mark Andes | bass | ||

| Claude Gaudette | 1988–1989 | keyboards | Slip of the Tongue (1989) | |

|

|

Glenn Hughes | backing vocals | ||

|

|

Richard Page | |||

| Beth Anderson | 1997 | Restless Heart (1997) | ||

| Maxine Waters | ||||

| Elk Thunder | harmonica | |||

| Chris Whitemyer | percussion | |||

| Jasper Coverdale | 2010 | backing vocals | Forevermore (2011) | |

|

|

Derek Sherinian | 2020 | keyboards | Sherinian performed on remixed versions of Slip of the Tongue and Restless Heart.[45][46] |

| Chritopher Collier | 2021 |

|

Restless Heart (1997) (2021 remix) |

Timeline[edit]

Lineups[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Barton, Geoff (1 October 2018). «Whitesnake: «The Coverdale I recall was a vain, preposterous oaf»«. Louder. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g «40 Years Ago Today – Whitesnake’s First Show». Whitesnake. 3 March 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Thelen, Christopher (31 July 1999). «Whitesnake: Snakebite». Daily Vault. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Rivadavia, Eduardo (3 March 2016). «The Day Whitesnake Played Their First Concert». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 19, August 1979». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 25, July 1982». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 29, July 1984». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (30 January 2014). «30 Years Ago: Whitesnake Release ‘Slide It In’«. Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b Daniels, Neil (4 July 2008). «Obituary: Mel Galley». The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Jon Lord Biografie» (PDF). Ear Music. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 30, December 1984». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Correspondent Reports: More News» (PDF). Eurotipsheet. Vol. 2, no. 11. 18 March 1985. p. 20. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 32, February 1986». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Kielty, Martin (7 April 2017). «30 Years Ago: David Coverdale Returns From The Abyss With ‘Whitesnake’«. Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Compact Data: Short Cuts» (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 768. Los Angeles, California: Radio & Records, Inc. 16 December 1988. p. 40. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Compact Data» (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 784. Los Angeles, California: Radio & Records, Inc. 14 April 1989. p. 50. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (18 November 2014). «How Whitesnake’s ‘Slip of the Tongue’ Marked the End of an Era». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Carlson, Taylor (11 August 2015). «Whitesnake Live at Donington 1990 — Great Concert Derailed by Terrible Video Quality». ZRock’R Magazine. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Chirazi, Steffan (25 March 2011). «The Growing Pains Of Whitesnake’s David Coverdale». Classic Rock. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b «That’s Sho-Biz: Sho-Talk» (PDF). Gavin Report. No. 2012. San Francisco, California: United Newspapers. 8 July 1994. p. 9. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reesman, Bryan (13 April 2010). «It’s good to be… Whitesnake». Goldmine. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «DPAS Magazine Archive: Issue 50, February 1998». Deep Purple Appreciation Society. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ «With a Whisper David Coverdale Goes Into the Light». The Pure Rock Shop. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Whitesnake 2003 Lineup Confirmed!». Blabbermouth.net. 15 December 2002. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Part Ways With Bassist Marco Mendoza, Seek Replacement». Blabbermouth.net. 12 April 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announce New Bassist». Blabbermouth.net. 12 May 2005. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announces New Drummer». Blabbermouth.net. 27 December 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d «Whitesnake Parts Ways With Duffy, Frazier; New Drummer Announced». Blabbermouth.net. 18 June 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announces New Bassist». Blabbermouth.net. 20 August 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Keyboardist Quits To Pursue ‘Solo’ Career». Blabbermouth.net. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b c «Whitesnake Announces New Touring Keyboardist». Blabbermouth.net. 20 March 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Drummer Brian Tichy Quits Whitesnake». Blabbermouth.net. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Drummer Tommy Aldridge Rejoins Whitesnake». Blabbermouth.net. 25 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b «Guitarist Doug Aldrich Quits Whitesnake». Blabbermouth.net. 9 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Recruits Night Ranger Guitarist Joel Hoekstra». Blabbermouth.net. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Monger, James Christopher. «The Purple Album — Whitesnake: Songs, Reviews, Credits». AllMusic. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Announces New Keyboardist». Blabbermouth.net. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ «Whitesnake Release New Album, ‘Flesh & Blood’«. Guitar World. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Welcomes Trans-Siberian Orchetra Singer Dino Jelusick». Blabbermouth.net. 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ a b «Whitesnake Parts Ways With Longtime Bassist Michael Devin». Blabbermouth.net. 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ a b «Welcome Our New Bass Player!». Whitesnake Official Website. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Dana. «DRUMMER TOMMY ALDRIDGE BACK IN WHITESNAKE». Eddie Trunk. Retrieved 2023-02-12.

- ^ a b Blabbermouth (2022-05-02). «WHITESNAKE’s DINO JELUSICK Will Be ‘Singing A Lot’ On Upcoming Tour». BLABBERMOUTH.NET. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ a b Whitesnake liner notes – EMI

- ^ Sherinian, Derek [@@DerekSherinian] (17 April 2020). «I am proud to be featured on the new Whitesnake compilation «The Rock Album»! I re-recorded the keys on the albums «Slip Of The Tongue» and «Restless Heart», which many songs are on this release- a LOT of Hammond B3! Thank you DC for the opportunity!» (Tweet). Retrieved 23 November 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Wilkening, Matthew (19 June 2020). «David Coverdale Is Hearing Whitesnake in a Whole New Way». Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

External links[edit]

- Whitesnake official website

Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с английского на русский

Хотите общаться в чатах с собеседниками со всего мира, понимать, о чем поет Билли Айлиш, читать английские сайты на русском? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет ваш текст с английского на русский и еще на 20+ языков.

Точный перевод с транскрипцией

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом с английского на русский, а для слов и фраз смотрите английскую транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов с примерами употребления в разных контекстах. Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим перевод с английского на русский и с русского на английский.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One бесплатно переводит онлайн с английского на азербайджанский, арабский, греческий, иврит, испанский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, татарский, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, украинский, финский, французский, эстонский и японский.

|

Whitesnake |

|

|---|---|

Whitesnake performing in Helsinki, 2022 |

|

| Background information | |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres |

|

| Years active |

|

| Spinoffs |

|

| Spinoff of | Deep Purple |

| Members |

|

| Past members | List of Whitesnake members |

| Website | whitesnake.com |

Whitesnake are an English hard rock band formed in London in 1978. The group was originally put together as the backing band for singer David Coverdale, who had recently left Deep Purple. Though the band quickly developed into their own entity, Coverdale is the only constant member throughout their history.

Whitesnake enjoyed much success in the UK, Europe and Japan through their early years. Their albums Ready an’ Willing, Come an’ Get It and Saints & Sinners all reached the top ten on the UK Albums Chart. By the mid-1980s, however, Coverdale had set his sights on breaking through in North America, where Whitesnake remained largely unknown. With the backing of American label Geffen Records, Whitesnake released Slide It In in 1984, followed by an eponymous album in 1987, which became their biggest success to date, selling over eight million copies in the US and spawning the hit singles «Here I Go Again» and «Is This Love».

Whitesnake also adopted a more contemporary look, akin to the Los Angeles glam metal scene. After releasing Slip of the Tongue in 1989, Coverdale decided to put Whitesnake on hold to take a break from the music industry. Aside from a few short-lived reunions in the 1990s, Whitesnake remained mostly inactive until 2003, when Coverdale put together a new line-up to celebrate the band’s 25th anniversary. Since then Whitesnake have released four more studio albums and toured extensively around the world.

Whitesnake’s early sound has been characterized by critics as blues rock, but by the mid-1980s the band slowly began moving toward a more commercially accessible hard rock style. Topics such as love and sex are common in Whitesnake’s lyrics, which have been criticized for their excessive use of sexual innuendos and double entendres. Whitesnake have been nominated for several awards during their career, including Best British Group at the 1988 Brit Awards. They have also been featured on lists of the greatest hard rock bands of all time by several media outlets,[1][2] while their songs and albums have appeared on many «best of» lists by outlets, such as VH1 and Rolling Stone.[3][4][5]

History

Formation, Snakebite and Trouble (1976–1978)

In March 1976, singer David Coverdale left the English hard rock group Deep Purple. He had joined the band three years prior and recorded three successful albums with them. After leaving Deep Purple, Coverdale released his solo album White Snake in May 1977.[6] His second solo album Northwinds was released in March 1978.[7] Both combined elements of blues, soul and funk, as Coverdale had wanted to distance himself from the hard rock sound synonymous with Deep Purple.[8] Both records featured former Snafu guitarist Micky Moody, whom Coverdale had known since the late 1960s.[9]

As Coverdale began assembling a backing band in London, Moody was the first to join.[10][11] Among the other early candidates for the group were drummers Dave Holland and Cozy Powell, as well as guitarist Mel Galley.[12] The decision to recruit a second guitarist was made at Moody’s suggestion. Bernie Marsden, formerly of UFO and Paice Ashton Lord, agreed to join.[11][13] Through Marsden, they were also able to recruit bassist Neil Murray, as the two had played together in Cozy Powell’s Hammer.[14] The band’s initial line-up was rounded out by drummer Dave «Duck» Dowle and keyboardist Brian Johnson, who had played together in Streetwalkers.[15]

A newspaper advert for Whitesnake’s first UK tour, promoting Coverdale’s second solo album Northwinds

The band, dubbed David Coverdale’s Whitesnake, played their first show at Lincoln Technical College on 3 March 1978.[17][18] Their live debut had originally been scheduled for 23 February at the Sky Bird Club in Nottingham, but the show was cancelled.[18][19] Coverdale had originally wanted the group to be simply called Whitesnake, but was forced to use his own name as it still carried some clout as the former lead singer of Deep Purple.[20][21][22] In a 2009 interview with Metro, Coverdale jokingly stated that the name «Whitesnake» was a euphemism for his penis: «If I had been from Africa it would have been Blacksnake». In fact, it came from the song of the same name found on his first solo album.[23]

After completing a small UK club tour, the band adjourned to a rehearsal place in London’s West End to begin writing new songs.[11] They soon caught the attention of EMI International’s Robbie Dennis, who wanted to sign the group. According to Bernie Marsden, however, his higher-ups were not ready to commit to a full album. Thus, the band entered London’s Central Recorders Studio in April 1978 to record an EP.[24] By this point, original keyboardist Brian Johnston had been replaced by Pete Solley.[21] Martin Birch, who had worked with Coverdale during his time in Deep Purple, was chosen to produce.[19]

The resulting record, Snakebite, was released in June 1978.[21] In Europe, the EP was combined with four tracks from Coverdale’s album Northwinds to make up a full-length album.[21] Snakebite also contained a slowed down cover of Bobby Bland’s «Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City», which had originally been used by the band to audition bass players. While the song was only included because the group were short on songs, the track would later become a popular live staple at Whitesnake concerts, with Coverdale calling it «the national anthem of the Whitesnake choir», referring to the band’s audience.[16][25] When Snakebite reached number 61 on the UK Singles Chart,[26] the band were duly signed to EMI proper.[27]

In July 1978, the band (now known simply as Whitesnake) entered Central Recorders in London to begin work on their first proper studio album with Martin Birch again producing. The recording and mixing only took ten days.[28] Towards the end of the sessions, Pete Solley’s keyboard parts were completely replaced by Coverdale’s former Deep Purple bandmate Jon Lord, who agreed to join Whitesnake after much coaxing from Coverdale.[29][30] Colin Towns and Tony Ashton were also approached, having previously played with fellow Deep Purple offshoots the Ian Gillan Band and Paice Ashton Lord, respectively.[28] Whitesnake’s debut album Trouble was released in October 1978,[21] and it reached number 50 on the UK Albums Chart.[31]

In a retrospective review for AllMusic, Eduardo Rivadavia stated: «A few unexpected oddities throw the album off-balance here and there, […] but all things considered, it is easy to understand why Trouble turned out to be the first step in a long, and very successful career.»[32] The release of Trouble was followed by an 18-date UK tour, beginning on 26 October 1978.[33] The final show at the Hammersmith Odeon in London was recorded and released in Japan as Live at Hammersmith.[34] According to Coverdale, this was done to appease Japanese promoters who allegedly refused to book Whitesnake without some kind of a live recording.[35]

Lovehunter and Ready an’ Willing (1979–1980)

Whitesnake began their first continental European tour on 9 February 1979 in Germany.[33] They then began recording their second album in April 1979 at Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire, where Coverdale had previously worked with Deep Purple. Martin Birch returned to produce and the band employed the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio to record.[36] Bernie Marsden later described the resulting record as a «transition album», where the band really began to «blossom» and find their footing.[37] Before the album’s release though, drummer Dave «Duck» Dowle was replaced by Ian Paice, Coverdale and Lord’s former Deep Purple bandmate.[38] There is some contention as to the nature of Dowle’s departure. Coverdale maintains that Dowle’s performance on the album was lacking and that he was «unable to take constructive criticism», which ultimately led to his firing.[38][39]

Bernie Marsden, meanwhile, asserted that Dowle left because he didn’t like being at Clearwell Castle and away from his family.[39] The idea of Paice re-recording Dowle’s drum parts was considered, but ultimately rejected by the band’s management allegedly due to cost.[40] Paice’s addition also spurred speculation from the British music press about Coverdale mounting a Deep Purple reunion, something he denied.[38] Coverdale later remarked how Paice joining the band felt like «truly the beginning of Whitesnake», where all the members were «performing at [their] absolute best» and «inspiring the best out of each other».[41] Lovehunter, Whitesnake’s second album, was released in October 1979,[39] and it reached number 29 on the UK Albums Chart.[42]

Sounds gave the record a positive review,[36] while AllMusic’s Eduardo Rivadavia was more mixed, commending many of the songs, but criticizing the band’s studio performance as «strangely tame».[43] The album’s cover art, depicting a naked woman straddling a giant serpent, caused some controversy when the record was released. Whitesnake had already received criticism from the British music press for their alleged sexist lyrics. The cover art for Lovehunter, done by artist Chris Achilleos, was reportedly commissioned to «just piss [the critics] off even more».[36][41] In North America, a sticker was placed on the cover to hide the woman’s buttocks, while in Argentina the cover art was modified so that the woman wore a chain-mail bikini.[39] Nevertheless, Whitesnake began a supporting tour for Lovehunter on 11 October 1979 in the UK, followed by dates in Europe.[44]

After completing the supporting tour for Lovehunter, Whitesnake promptly started work on their third album at Ridge Farm Studios, with Martin Birch once again producing.[38] The resulting record, Ready an’ Willing, was released on 31 May 1980,[45] and it reached number six on the UK Albums Chart.[46] It also became the band’s first album to chart in the US, where it reached number 90 on the Billboard 200 chart.[47] Its success was helped by the lead single «Fool for Your Loving», which reached number 13 and number 53 in the UK and the US, respectively.[48][49] Geoff Barton, writing for Sounds, gave Ready an’ Willing a positive review, awarding it four stars out of five.[38] Eduardo Rivadavia of AllMusic commended the band’s growing consistency, but still described the production as «flat».[50] Micky Moody and Bernie Marsden later named Ready an’ Willing their favourite Whitesnake album.[51]

In the UK, the record would later be certified gold by the British Phonographic Industry for sales of over 100,000 copies.[52] In support of the album, Whitesnake toured the US for the first time supporting Jethro Tull. Later that year, they supported AC/DC in Europe.[53] With the benefit of a hit single, Whitesnake’s audience in the UK began to grow.[41] Thus, the band recorded and released the double live album Live… in the Heart of the City. The record combined new material recorded in June 1980 at the Hammersmith Odeon with the previously released Live at Hammersmith album.[35] Live… in the Heart of the City proved to be an even bigger success than Ready an’ Willing, reaching number five in the UK.[54] It would later go platinum, with sales of over 300,000 copies.[55] In North America, the album was released as a single record version, excluding the live material from 1978.[56]

Come an’ Get It and Saints & Sinners (1981–1982)

In early 1981, Whitsnake began recording their fourth studio album with producer Martin Birch at Ringo Starr’s Startling Studios in Ascot, Berkshire. After the success of Ready an’ Willing and Live… in the Heart of the City, Whitesnake were riding high with the atmosphere in the studio being described by Coverdale as «great» and «positive». The resulting record, Come an’ Get It, was released on 6 April 1981.[57] Charting in seven countries, it gave the group their highest ever UK chart position at number two.[58] That same year, the album was certified gold.[59] The single «Don’t Break My Heart Again» also charted at number seventeen in the UK.[60] Circus magazine gave the album a positive review, which proclaimed: «[Whitesnake] has made its claim to rock history with Come an’ Get It, which even stands ahead of classic hard rock in the Free mold.»[61]

Coverdale later named the record his favorite album of the band’s early years, stating: «Even though we had some great songs on each album, I don’t feel that we came as close as we did on [Come an’ Get It], as far as consistency is concerned.[57] Whitesnake kicked off the supporting tour for Come an’ Get It on 14 April 1981 in Germany.[62] During the tour, the band played five nights at the Hammersmith Odeon and eight dates in Japan.[62][63] They also played the US in July, supporting Judas Priest with Iron Maiden.[62] At the 1981 Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington, Whitesnake were direct support for headliners AC/DC.[57] The supporting tour for Come an’ Get It lasted approximately five months.[64]

Whitesnake in 1981. From left to right: Micky Moody, Ian Paice, Bernie Marsden, David Coverdale, Jon Lord and Neil Murray

In late 1981, Coverdale retreated to a small villa in southern Portugal to begin writing the band’s next album. After returning to England, he and the rest of Whitesnake gathered at Nomis Studios in London to start rehearsals. However, as Coverdale would later explain: «There wasn’t that ‘spark’ that was usually in attendance. It felt more of an effort to be there.»[64] Micky Moody later stated that by the end of 1981, the band had become tired, partially from «too many late nights, too much partying».[65] In an effort to lift their collective spirits, Whitesnake returned to Clearwell Castle in Gloucestershire, where they had recorded Lovehunter. Though morale still remained low, the band were able to record the basic tracks for the new album. Guy Bidmead replaced producer Martin Birch, who was reportedly too ill to work at the time (Birch did eventually return when recording moved to Britannia Row.[64]). This exacerbated the band’s ever worsening mental state.[66]

To make matters worse, the band were experiencing financial troubles with Moody recalling: «We weren’t making nowhere near the kind of money we should have been making. Whitesnake always seemed to be in debt, and I thought ‘What is this?, we’re playing in some of the biggest places and we’re still being told we’re in debt, where is all the money going?’.»[65] Eventually, Moody became fed up with the band’s situation and left Whitesnake in December 1981.[65] The remaining band members blamed the group’s management company Seabreeze, headed by Deep Purple’s former manager John Coletta, for their financial state.[22][25][67]

According to Bernie Marsden, the band set up a meeting to fire Coletta, but Coverdale failed to show. Instead, Marsden, Neil Murray and Ian Paice were informed that Whitesnake had been put on hold and that they were fired.[67] Marsden later remarked that «David [Coverdale] decided he would be king of Whitesnake».[25] Coverdale asserted that he elected to put the band on hold when his daughter contracted bacterial meningitis.[64][68] He claimed that this gave him courage to cut ties with Coletta. Coverdale ended up buying himself out of his contracts, which reportedly cost him over a million dollars.[25][68] As for the firing of Marsden, Murray and Paice, Coverdale felt they lacked the needed enthusiasm to keep working in Whitesnake.[25][67] Coverdale later stated that it was «a business decision, not personal».[64]

«I thought [David Coverdale] was a star frontman, a star singer, I felt he had a mediocre band and just average songs. My job was to make them a commercial rock band for the United States.»

—John Kalodner on his role working with Whitesnake.[69]

After waiting for his daughter to recupurate and severing ties with the band’s management, record companies and publishers, Coverdale began putting Whitesnake back together. Micky Moody and Jon Lord agreed to return, while guitarist Mel Galley, bassist Colin Hodgkinson and drummer Cozy Powell were brought in as new recruits.[25][64] Coverdale completed the band’s new album with Martin Birch in October 1982 at Battery Studios in London.[66] Saints & Sinners was released on 15 November 1982.[64] It reached number nine in the UK and charted in eight additional countries.[70] In the UK, the record was certified silver.[71]

Chas de Whalley, writing for Kerrang!, gave the album a lukewarm review. Save for two tracks («Crying in the Rain» and «Here I Go Again»), he characterized the rest of the record as generally mediocre.[72] Conversely, AllMusic’s Eduardo Rivadavia, in a retrospective review, hailed Saints & Sinners as Whitesnake’s «best album yet».[73] By the time the record was released, Coverdale had signed a new recording contract with American label Geffen Records, who would handle all of Whitesnake’s future releases in North America. In Europe, the band remained with Liberty (a subsidiary of EMI), while in Japan, they signed with Sony.[74][75]

A&R executive John Kalodner, who had been a long-time fan of Coverdale’s, convinced David Geffen to sign the band.[74] Meeting Geffen and Kalodner had a major impact on Coverdale and his future vision for Whitesnake. He explained: «I’d been surrounded by a mentality if you make five pounds profit let’s go to the pub. Whereas David Geffen said to me ‘If you can make five dollars profit, why not 50? If 50, why not 500? Why not 50,000, why not five million?'» Coverdale soon set his sights on breaking through in North America with Kalodner advising him.[68][76] Meanwhile, Whitesnake began a supporting for Saints & Sinners on 10 December 1982 in the UK.[66][77]

Slide It In (1983–1984)

Whitesnake toured across Europe and Japan in early 1983,[66] before starting rehearsals for their next album at Jon Lord’s house in Oxfordshire.[78] Coverdale began steering Whitesnake’s music more towards hard rock, which was emphasized by the additions of Mel Galley and Cozy Powell, whose past projects included Trapeze and Rainbow, respectively.[65][79] Majority of Whitesnake’s next album was co-written by Coverdale and Galley, while Micky Moody contributed to only one song.[80] Whitesnake began recording their sixth album at Musicland Studios in Munich with producer Eddie Kramer, who had come recommended by John Kalodner.[78][81]

In August 1983, Whitesnake headlined the Monsters of Rock festival at Castle Donington, England. The show was filmed and later released as the band’s first long-form video, titled Whitesnake Commandos. The band also premiered the new single «Guilty of Love», which was released to coincide with the festival. The entire album had originally been slated for release three weeks prior to the Donington show, but failed to meet the deadline. The band were having problems adapting to Eddie Kramer’s style of producing, particularly his method of mixing the record. Eventually things came to a head and Kramer was let go. Coverdale then rehired Martin Birch to complete the album.[78] A new release date for the record was set for mid-November with a supporting tour scheduled to start in December.[82]

However, as Whitesnake finished up a European tour in October, Micky Moody left the group. He later attributed his departure to a growing dissatisfaction working in the band, particularly with Coverdale. Moody remarked: «Me and David weren’t friends and co-writers anymore. […] David was a guy who five, six years earlier was my best friend. Now he acted as if I wasn’t there.»[65] Moody also felt uncomfortable with the level of influence he felt John Kalodner was having on the band.[83] Colin Hodgkinson was also let go in late 1983, only to be replaced by his predecessor Neil Murray. Coverdale later explained the decision to rehire Murray by simply stating: «I’d missed his playing».[78] Towards the end of 1983, Jon Lord also informed Coverdale of his intention to leave the band, but Coverdale convinced him to stay until the supporting tour for their next album was over.[84] With the line-up changes and the troubled production of the album, both the record and its accompanying tour were delayed until early 1984.[85]

According to Coverdale, John Kalodner had convinced him that in order for the band to achieve their full potential, they needed a «guitar hero» that could match Coverdale as a frontman.[86] Therefore, to replace Moody, Coverdale initially looked to Michael Schenker and Adrian Vandenberg. Schenker claims he turned down the offer to join Whitesnake, while Coverdale insists he decided to pass on Schenker.[68][87] Vandenberg declined the offer to join as well, due to the success he was having at the time with his own band.[68][88] Coverdale then approached Thin Lizzy guitarist John Sykes, who he met when Whitesnake and Thin Lizzy played some of the same festivals in Europe.[89] Sykes was initially reluctant to join, wanting to continue working with Thin Lizzy frontman Phil Lynott, but after several more offers he accepted.[90] John Sykes and Neil Murray were officially confirmed as members of Whitesnake in January 1984.[91][92]

Slide It In, Whitesnake’s sixth studio album, was released on 30 January 1984.[93] On the UK Albums Chart, it reached number nine.[94] The album’s highest chart position was in Finland, where it reached number four.[95] Slide It In received mixed reviews from critics, with the production being a common complaint.[96][97] Dave Dickson, writing for Kerrang!, called the record «the best thing Whitesnake have yet commited to vinyl»,[98] while Record Mirror‘s Jim Reid was highly critical of the lyrical content.[99] AllMusic’s Eduardo Rivadavia, in a retrospective review, called Slide It In «an even greater triumph» than the band’s previous works,[100] whereas Garry Bushell of Sounds gave the album a particularly scathing review, in which he likened Coverdale’s voice to that of a «dying dog».[25][97]

Whitesnake’s new line-up made their live debut in Dublin on 17 February 1984.[101] During a tour stop in Germany, Mel Galley broke his arm leaping on top of a parked car. He sustained nerve damage, leaving him unable to play guitar. As a result, Galley was forced to leave Whitesnake.[97][102][103] By April 1984, a reunion of Deep Purple’s Mark II line-up had become imminent, which led to Jon Lord also leaving. He played his final show with Whitesnake on 16 April 1984.[97] That same day, Geffen Records released Slide It In in North America.[104] Kalodner had been unimpressed by Martin Birch’s work on the album and had demanded a complete remix for the American market. Though initially reluctant, Coverdale agreed after a trip to Geffen’s offices in Los Angeles, where he came to the conclusion that Whitesnake’s studio approach had become «dated» by American standards. Keith Olsen was brought on board to remix Slide It In, while John Sykes and Neil Murray were tasked with re-recording Micky Moody and Colin Hodgkinson’s parts, respectively.[105] The remixed version of Slide It In reached number 40 on the Billboard 200 chart.[106]

By 1986, the album had sold over 500,000 copies in the US.[107] Critical reception was also positive, with Pete Bishop of The Pittsburg Press calling the album «muscular, melodic and musical all together».[108] With the band now left as a four-piece (with Richard Bailey providing keyboards off-stage),[109] Whitesnake supported Dio for several show in the US, after which they toured Japan as a part of the Super Rock ’84 festival.[110][111] Later that year, Whitesnake embarked on a six week North American tour supporting Quiet Riot.[112] To further the band’s reach in America, Whitesnake shot two music videos for the singles «Slow an’ Easy» and «Love Ain’t No Stranger», respectively.[113] Both songs reached the Top Tracks chart in the US.[114][115] In an effort to take America more seriously, Coverdale also relocated to the US.[116]

Whitesnake (1985–1988)

A&R executive John Kalodner asked Coverdale to re-record «Here I Go Again» for the band’s eponymous album, believing the song had the potential to become a number one hit.[25] Ultimately, «Here I Go Again» would reach number one on the Billboard Hot 100.[117]

The supporting tour for Slide It In came to an end in January 1985, when Whitesnake played two shows at the Rock in Rio festival in Brazil.[118] After the tour ended, Cozy Powell parted ways with the band. According to Coverdale, his relationship with Powell had deteriorated increasingly over the course of the tour. After the final show, Coverdale flew to Los Angeles to inform Geffen Records he was letting the rest of the band go. Coverdale was persuaded to keep Sykes involved (as Geffen felt they formed a «strong image together»), while also changing his mind about Murray. Powell, however, was fired.[119] According to Murray, Powell’s departure was the result of financial disputes.[120] Coverdale would later state that Powell didn’t feel like the offer he got for his involvement was «appropriate».[121]

Coverdale and Sykes retreated to the South of France in early 1985 to begin writing the band’s next album. The sessions proved fruitful and they were joined by Murray, who helped with the arrangements.[118] The new material saw Whitesnake moving further away from their bluesier roots in favour of a more American hard rock sound.[122][123] John Kalodner also convinced Coverdale to re-record two songs from the Saints & Sinners album, «Here I Go Again» and «Crying in the Rain», which he thought had great potential with better production and arranging.[124]

With new material ready, the band then began searching for a new drummer. A reported sixty drummers auditioned for the group, with prolific session drummer Aynsley Dunbar eventually being chosen. Former Ozzy Osbourne drummer Tommy Aldridge was also offered the spot, but an equally satisfactory agreement couldn’t be reached.[119] Drummer Carmine Appice claimed to have turned down the position due to commitments with his own band King Kobra. Appice would later join Sykes in Blue Murder.[125]

The band began tracking their new record at Little Mountain Sound Studios in Vancouver with producer Mike Stone.[126] By early 1986, much of the album had been recorded.[118] When it came time for Coverdale to record his vocals though, he noticed his voice was unusually nasal and off-pitch. After consulting several specialists, it was revealed that Coverdale had contracted a severe sinus infection. After receiving some antibiotics, Coverdale flew to Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas to resume recording. However, the infection resurfaced which caused Coverdale’s septum to collapse. He required surgery, followed by a six month rehabilitation period.[119]

Sykes has disputed this, claiming that Coverdale was just suffering from nerves and that he used «every excuse possible» not to record his vocals.[127] After recovering from surgery, Coverdale, by his own account, did develop a «mental block» that prevented him from singing.[128] Following some failed sessions with Ron Nevison, Coverdale was finally able to record his vocals with producer Keith Olsen.[119] By late 1986, production on the record was mostly finished. Keyboards were provided by Don Airey and Bill Cuomo, while Adrian Vandenberg was brought in to do some guitar overdubs.[118] Additional guitar parts were also provided by Dann Huff.[129]

David Coverdale performing with Whitesnake in 1987

By the time the album was finished, Coverdale was the sole remaining member of Whitesnake. «It was a band in disarray…» observed keyboardist Don Airey. «David was four million dollars in debt; didn’t know if he was coming or going.»[130] Coverdale has claimed that Sykes and Mike Stone were fired after they began conspiring against him by booking studio time and making decisions without his involvement.[119] Stone allegedly suggested bringing in someone else to record Coverdale’s vocals while he was recovering from surgery.[131] Sykes has denied this, instead claiming that he and other members were systematically fired as soon as they finished recording their parts.[127]

Murray and Dunbar had stopped receiving their wages in April 1986, at which point Dunbar immediately left Whitesnake. Murray was still officially a member of the group until January 1987, when he heard Coverdale was putting together a new line-up.[132][133] With the help of John Kalodner, Coverdale recruited Adrian Vandenberg and Tommy Aldridge, as well as guitarist Vivian Campbell (formerly of Dio) and bassist Rudy Sarzo (formerly of Quiet Riot).[68][134][135] This new line-up would appear in all the promotional materials for the forthcoming album.[136] Whitesnake also adopted a new look, akin to glam metal bands of the time, in order to appeal more to American audiences. When asked about the band’s makeover, Coverdale responded: «I’m competing with people like Jon Bon Jovi. I’ve gotta look the part.»[137]

Whitesnake (titled 1987 in Europe and Serpens Albus in Japan) was released on 30 March 1987 in Europe and 7 April in North America.[138][139] It peaked at number eight in the UK, while in the US it reached number two on the Billboard 200 chart.[140][141] In total, the record charted in 14 countries and quickly became the most commercially successful of the band’s career, selling over eight million copies in the US alone.[107] Its success also boosted Slide It In‘s sales to over two million copies in the US.[107] The singles «Here I Go Again» and «Is This Love» reached number one and two, respectively, on the Billboard Hot 100.[117][142]

In the UK, both reached number nine.[143][144] The record’s success was helped by the heavy airplay Whitesnake received on MTV, courtesy of a trilogy of music videos featuring Coverdale’s future wife and actress Tawny Kitaen.[137] The album was generally well received by critics, though reviews in the UK were less favourable, with Coverdale being accused of «selling out» to America, which he strongly denied.[109] Rolling Stone‘s J. D. Considine praised the band’s ability to present old ideas in new and interesting ways, while AllMusic’s Steve Huey, in a retrospective review, touted the album as the band’s best.[145][146]

The new Whitesnake lineup made their live debut following the record’s release at the Texxas Jam festival in June 1987.[137] They then toured the US supporting Mötley Crüe on their Girls, Girls, Girls Tour.[88] Beginning on 30 October 1987,[147] Whitesnake embarked on a headlining arena tour, which was temporarily interrupted in April 1988, when Coverdale had a herniated disc removed from his lower back.[88][148][149] At the 1988 Brit Awards, the band were nominated for Best British Group, while the album Whitesnake was nominated for Favorite Pop/Rock Album at the American Music Awards.[150][151] When the supporting tour for Whitesnake ended in August 1988,[152]

Coverdale informed the rest of the band that the next album would be written by him and Adrian Vandenberg, who had established a fruitful working relationship.[136] After approximately a month of writing, the band regrouped at Lake Tahoe for three weeks of rehearsals.[153] In December 1988, Vivian Campbell parted ways with the band. The official reason given was «musical differences».[154] However, Campbell later revealed that his departure was partially due to a falling out between his wife and Tawny Kitaen. This resulted in Campbell’s wife being barred from the band’s tour. In addition to this, Vandenberg had made it known that he wanted to be the sole guitarist in Whitesnake, which also played into Campbell’s departure.[136][155]

Slip of the Tongue (1989–1990)

Whitesnake started recording their eighth album in January 1989.[156] Bruce Fairbairn was initially chosen to produce, but was forced to drop out due to scheduling conflicts. The band then hired both Keith Olsen and Mike Clink to produce the record.[157] Coverdale later explained the decision to hire two producers, citing pressure to follow-up the band’s previous record. He stated: «I brought them both in… Just that decision alone tells me I was in fear of failing…»[158] During the recording process, Adrian Vandenberg sustained an injury to his wrists while performing some playing exercises. Despite consulting a doctor and significant rest, the injury persisted, leaving Vandenberg unable to play the guitar properly.[153] It wasn’t until 2003 that he learned the injury was the result of nerve damage sustained in a 1980 car accident.[88]

Vandenberg’s injury caused significant delays to the album, which had originally been slated for release in June–July 1989.[159] Ultimately, Coverdale was forced to find another guitar player to finish the record.[158] He opted to recruit former Frank Zappa and David Lee Roth guitarist Steve Vai, who he had seen in the 1986 film Crossroads a few years earlier.[158] According to Coverdale, he had originally wanted to recruit Vai back then, but John Sykes ultimately rejected the idea.[68] Vai officially joined Whitesnake in March 1989.[160] Vandenberg, meanwhile, was given time to recuperate while Vai recorded the album.[153] Vandenberg is still minimally featured on the finished record.[158]