Женевские конвенции и Дополнительные протоколы к ним составляют ядро международного гуманитарного права — отрасли международного права, которая регулирует ведение вооруженных конфликтов и стремится ограничить их последствия. Они, в частности, защищают людей, которые не принимают участия в военных действиях (гражданских лиц, врачей и медсестер, гуманитарных работников), или тех, кто перестал принимать участие в военных действиях, например, раненых, больных и потерпевших кораблекрушение солдат, а также военнопленных.

Конвенции и Протоколы призывают принимать меры к тому, чтобы предотвратить любые нарушения права или положить им конец. В них содержатся строгие нормы относительно так называемых «серьезных нарушений». Лиц, ответственных за серьезные нарушения, следует разыскивать, судить или выдавать другой стране вне зависимости от их гражданства.

Женевские конвенции 1949 г.

Первая Женевская конвенция защищает раненых и больных солдат во время войны на суше

Эта Конвенция является четвертым переработанным вариантом Женевской конвенции о раненых и больных; предыдущие были приняты в 1864, 1906 и 1929 гг. В Конвенции 64 статьи, которые предусматривают защиту раненых и больных, а также медицинского и духовного персонала, медицинских формирований и санитарно-транспортных средств. Конвенция также признает отличительные эмблемы. В двух приложениях к Конвенции содержатся проект соглашения о санитарных зонах и форма удостоверения личности для медицинского и духовного персонала.

Вторая Женевская конвенция защищает раненых, больных и потерпевших кораблекрушение военнослужащих во время войны на море

Эта Конвенция заменила Гаагскую конвенцию 1907 г. о применении принципов Женевской конвенции к морской войне. По своей структуре и содержанию она во многом повторяет положения Первой Женевской конвенции. В ней 63 статьи, специально предназначенные для применения к войне на море. К примеру, она защищает госпитальные суда. В единственном приложении содержится форма удостоверения личности для медицинского и духовного персонала.

Третья Женевская конвенция применяется к военнопленным

Эта конвенция заменила Конвенцию о военнопленных 1929 г. В ней 143 статьи, тогда как в Конвенции 1929 г. было всего лишь 97. Был расширен перечень категорий лиц, имеющих право на статус военнопленных, в соответствии с Конвенциями I и II. Получили более четкое определение условия и места содержания в плену, в частности, в том, что касается труда военнопленных, их финансовых средств, получаемой ими гуманитарной помощи и возбуждаемого против них судебного преследования. Конвенция устанавливает тот принцип, что военнопленные должны быть без промедления освобождены и репатриированы после окончания активных военных действий. К Конвенции имеется пять приложений, содержащих различные типовые соглашения, правила, удостоверение личности и образцы карточек.

Четвертая Женевская конвенция предоставляет защиту гражданским лицам, в том числе на оккупированной территории

Женевские конвенции, принятые до 1949 г., касались только комбатантов, но не гражданских лиц. События Второй мировой войны показали, сколь катастрофичны последствия того, что не существует конвенции для защиты гражданских лиц во время войны. В Конвенции, принятой в 1949 г., учтен опыт Второй мировой войны.

Конвенция состоит из 159 статей. В ней содержится короткий раздел, относящийся к общей защите населения от определенных последствий войны, но не касающийся ведения военных действий как такового, — оно будет позже рассмотрено в Дополнительных протоколах 1977 г.

Основная часть положений Конвенции касается статуса лиц, пользующихся защитой, и обращения с ними, различия между положением иностранцев на территории одной из сторон в конфликте и положением гражданских лиц на оккупированной территории. Она проясняет обязательства оккупирующей державы по отношению к гражданскому населению и содержит подробные положения о гуманитарной помощи, оказываемой населению оккупированной территории. В ней также предусмотрены конкретные нормы об обращении с интернированными гражданскими лицами.

Три приложения к Конвенции содержат проект соглашения о санитарных зонах, проект правил, касающихся гуманитарной помощи, и формы карточек.

Общая статья 3

Статья 3, общая для всех четырех Женевских конвенций, стала настоящим прорывом, поскольку она впервые предусматривала нормы, относящиеся к ситуациям немеждународных вооруженных конфликтов.

Существует много типов подобных конфликтов. Среди них традиционные гражданские войны, внутренние вооруженные конфликты, которые захватывают территорию других государств, или внутренние конфликты, в которые, помимо правительства, вмешиваются третьи государства или многонациональные силы.

Общая статья 3 устанавливает основополагающие нормы, отступление от которых недопустимо. Она напоминает мини-конвенцию в рамках Конвенций, поскольку содержит главные нормы Женевских конвенций в сжатом виде и делает их применимыми к конфликтам немеждународного характера:

- Она требует гуманного обращения со всеми лицами, находящимися в руках неприятеля, без какого-либо неблагоприятного различия. Она особо запрещает убийство, нанесение увечий, пытки, жестокое, оскорбительное и унижающее обращение, взятие заложников и отсутствие надлежащего судебного разбирательства.

- Она требует, чтобы раненых, больных и потерпевших кораблекрушение подбирали и оказывали им помощь.

- Она дает МККК право предлагать свои услуги сторонам в конфликте.

- Она призывает стороны в конфликте ввести в действие все или часть положений Женевских конвенций путем специальных соглашений.

- Она признает, что применение этих норм не затрагивает юридического статуса сторон в конфликте.

Учитывая, что сегодня большинство вооруженных конфликтов носят немеждународный характер, применение общей статьи 3 имеет огромное значение. Необходимо полное ее соблюдение.

Когда применяются Женевские конвенции?

Женевские конвенции вступили в силу 21 октября 1950 г.

С каждым новым десятилетием все больше государств ратифицировали Конвенции: в течение 1950-х гг. их ратифицировали 74 государства, в 1960-х – 48 государств, в 1970-х гг. – 20 государств, и еще 20 государств – в 1980-х гг. В начале 1990-х гг., в основном, после распада Советского Союза, Чехословакии и бывшей Югославии, Конвенции ратифицировали 26 стран.

После 2000 г. Конвенции были ратифицированы еще семью странами, таким образом, общее число их участников составило 194, и Женевские конвенции теперь применяются всеми государствами мира.

Дополнительные протоколы к Женевским конвенциям

В течение двух десятилетий после принятия Женевских конвенций в мире наблюдалось увеличение числа немеждународных вооруженных конфликтов и национально-освободительных войн. В ответ на это в 1977 г. были приняты два Дополнительных протокола к четырем Женевским конвенциям 1949 г. Они усиливают защиту жертв международных (Протокол I) и немеждународных (Протокол II) вооруженных конфликтов и налагают ограничения на средства и методы ведения войны. Протокол II стал первым в истории международным документом, посвященным исключительно ситуациям немеждународных вооруженных конфликтов.

В 2007 г. был принят третий Дополнительный протокол , который учредил дополнительную эмблему, красный кристалл, обладающую тем же международным статусом, что и эмблемы красного креста и красного полумесяца.

- Дополнительный протокол I – международные конфликты

- Дополнительный протокол II — немеждународные конфликты

- Дополнительный протокол III – дополнительная отличительная эмблема

Женевские конвенции

- Женевские конвенции

-

Жен’евские конв’енции

Русский орфографический словарь. / Российская академия наук. Ин-т рус. яз. им. В. В. Виноградова. — М.: «Азбуковник».

.

1999.

Смотреть что такое «Женевские конвенции» в других словарях:

-

Женевские конвенции — шесть международных соглашений, регламентирующих правила вексельного и чекового обращения, заключенные на конференциях в Женеве в 1930 и 1931 гг. Женевские конвенции обеспечили унификацию правил применения векселей и чеков, упростив их… … Финансовый словарь

-

ЖЕНЕВСКИЕ КОНВЕНЦИИ — международные соглашения (всего их шесть), регламентирующие правила вексельного и чекового обращения, порядок использования векселей и чеков в платежном обороте, заключенные на конференциях в Женеве в 1930 и 1931 гг. Конвенции обеспечили… … Экономический словарь

-

ЖЕНЕВСКИЕ КОНВЕНЦИИ — 1949 международные конвенции о защите жертв войны, подписанные 12.8.1949: 1) об улучшении участи раненых и больных в действующих армиях;2) об улучшении участи раненых, больных и лиц, потерпевших кораблекрушение, из состава вооруженных сил на… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ЖЕНЕВСКИЕ КОНВЕНЦИИ — 1949, международные конвенции о защите жертв войны, подписанные 12 августа 1949: 1) об улучшении участи раненых и больных в действующих армиях; 2) об улучшении участи раненых, больных и лиц, потерпевших кораблекрушение, из состава вооруженных сил … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Женевские конвенции — (Geneva Conventions), ряд подписанных в разные годы междунар. соглашений о более гуманном отношении к жертвам войны. Первая Ж.к. (1864) стала прямым рез том деятельности швейцарца Анри Дюнана, основателя междунар. об ва Красного Креста. Она… … Всемирная история

-

Женевские конвенции — Оригинальный документ. Женевские конвенции ряд международных соглашений, заключенных на конференциях в Женеве (Швейцария). Жен … Википедия

-

Женевские конвенции о защите жертв войны (1949) — Женевские конвенции от 12 августа 1949 года международно правовые соглашения о защите жертв войны. Являются основой международного гуманитарного права. Конвенции приняты 12 августа 1949 года на Дипломатической конференции и вступили в силу… … Википедия

-

ЖЕНЕВСКИЕ КОНВЕНЦИИ О ЗАЩИТЕ ЖЕРТВ ВОЙНЫ 1949 г И ДОПОЛНИТЕЛЬНЫЕ ПРОТОКОЛЫ К НИМ 1977 г — ЖЕНЕВСКИЕ КОНВЕНЦИИ О ЗАЩИТЕ ЖЕРТВ ВОЙНЫ 1949 г. И ДОПОЛНИТЕЛЬНЫЕ ПРОТОКОЛЫ К НИМ 1977 г. наиболее важные международные многосторонние соглашения в области законов и обычаев войны, направленные на защиту жертв вооруженных конфликтов. Участниками… … Юридическая энциклопедия

-

Женевские конвенции 1949 о защите жертв войны — Женевские конвенции от 12 августа 1949 года международно правовые соглашения о защите жертв войны. Конвенции приняты 12 августа 1949 года на Дипломатической конференцим и вступили в силу 21 октября 1950. Конвенция (I) об улучшении участи раненых… … Википедия

-

Женевские Конвенции 1949 — многосторонние международные соглашения о защите жертв войны: 1) Об улучшении участи раненых и больных в действующих армиях. Обязывает участников конвенции подбирать на поле боя и оказывать помощь раненым и больным неприятеля, запрещает… … Словарь черезвычайных ситуаций

-

Женевские конвенции по морскому праву — (англ. Geneva connentions on sea law) подписанные в 29.04.1958 г. по итогам Конференции ООН по морскому праву конвенции, отразившие многовековую историю развития морского права как преимущественно обычного права и в договорном порядке закрепившие … Энциклопедия права

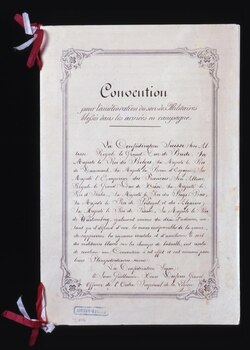

A facsimile of the signature-and-seals page of the 1864 Geneva Convention, that established humane rules of war.

The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term Geneva Convention usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners, civilians and military personnel, established protections for the wounded and sick, and provided protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone.[1]

The Geneva Convention defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with reservations, by 196 countries.[1] The Geneva Conventions concern only prisoners and non-combatants in war. They do not address the use of weapons of war, which are addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which concern conventional weapons, and the Geneva Protocol, which concerns biological and chemical warfare.

History[edit]

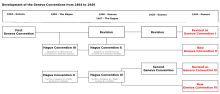

The progression of the Geneva Conventions from 1864 to 1949.

The Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, A Memory of Solferino, in 1862, on the horrors of war.[2] His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

- A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

- A government treaty recognizing the neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. On 22 August 1864, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field». Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:[3][4]

For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became co recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.[5][6]

On 20 October 1868 the first unsuccessful attempt to expand the 1864 treaty was undertaken. With the ‘Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War’ an attempt was initiated to clarify some rules of the 1864 convention and to extend them to maritime warfare. The Articles were signed but were only ratified by the Netherlands and the United States of America.[7] The Netherlands later withdrew their ratification.[8] The protection of the victims of maritime warfare would later be realized by the third Hague Convention of 1899 and the tenth Hague Convention of 1907.[9]

In 1906 thirty-five states attended a conference convened by the Swiss government. On 6 July 1906 it resulted in the adoption of the «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field», which improved and supplemented, for the first time, the 1864 convention.[10] It remained in force until 1970 when Costa Rica acceded to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.[11]

The 1929 conference yielded two conventions that were signed on 27 July 1929. One, the «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field», was the third version to replace the original convention of 1864.[9][12] The other was adopted after experiences in World War I had shown the deficiencies in the protection of prisoners of war under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The «Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» was not to replace these earlier conventions signed at The Hague, rather it supplemented them.[13][14]

Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior Geneva and Hague Conventions. It yielded four distinct conventions:

- The First Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field» was the fourth update of the original 1864 convention and replaced the 1929 convention on the same subject matter.[15]

- The Second Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea» replaced the Hague Convention (X) of 1907.[16] It was the first Geneva Convention on the protection of the victims of maritime warfare and mimicked the structure and provisions of the First Geneva Convention.[9]

- The Third Geneva Convention «relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» replaced the 1929 Geneva Convention that dealt with prisoners of war.[17]

- In addition to these three conventions, the conference also added a new elaborate Fourth Geneva Convention «relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War». It was the first Geneva Convention not to deal with combatants, rather it had the protection of civilians as its subject matter. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had already contained some provisions on the protection of civilians and occupied territory. Article 154 specifically provides that the Fourth Geneva Convention is supplementary to these provisions in the Hague Conventions.[18]

The third protocol emblem, also known as the Red Crystal

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. The nature of armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality:[19] on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric. Modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

[edit]

The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949. Commentary (The Commentaries) is a series of four volumes of books published between 1952 and 1958 and containing commentaries to each of the four Geneva Conventions. The series was edited by Jean Pictet who was the vice-president of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The Commentaries are often relied upon to provide authoritative interpretation of the articles.[20]

Contents[edit]

Parties to Geneva Conventions and Protocols

|

Parties to GC I–IV and P I–III |

Parties to GC I–IV and P I–II |

|

Parties to GC I–IV and P I and III |

Parties to GC I–IV and P I |

|

Parties to GC I–IV and P III |

Parties to GC I–IV and no P |

The Geneva Conventions are rules that apply only in times of armed conflict and seek to protect people who are not or are no longer taking part in hostilities; these include the sick and wounded of armed forces on the field, wounded, sick, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea, prisoners of war, and civilians. The first convention dealt with the treatment of wounded and sick armed forces in the field.[21]

The second convention dealt with the sick, wounded, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea.[22][23] The third convention dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war during times of conflict.[24] The fourth convention dealt with the treatment of civilians and their protection during wartime.[25]

During the negotiations for the 1949 conventions, Britain and France successfully removed language from early drafts that they saw as unfavorable to their colonial rule.[26]

Conventions[edit]

In international law and diplomacy the term convention refers to an international agreement, or treaty.

- The First Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field» (first adopted in 1864,[27] revised in 1906,[28] 1929[29] and finally 1949);[30]

- The Second Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea» (first adopted in 1949, successor of the Hague Convention (X) 1907);[31]

- The Third Geneva Convention «relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» (first adopted in 1929,[32] last revision in 1949);[33]

- The Fourth Geneva Convention «relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War» (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the Hague Convention (II) of 1899 and Hague Convention (IV) 1907).[34]

With two Geneva Conventions revised and adopted, and the second and fourth added, in 1949 the whole set is referred to as the «Geneva Conventions of 1949» or simply the «Geneva Conventions». Usually only the Geneva Conventions of 1949 are referred to as First, Second, Third or Fourth Geneva Convention. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in whole or with reservations, by 196 countries.[1]

Protocols[edit]

The 1949 conventions have been modified with three amendment protocols:

- Protocol I (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts[35]

- Protocol II (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts[36]

- Protocol III (2005) relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem[37]

Application[edit]

The Geneva Conventions apply at times of war and armed conflict to governments who have ratified its terms. The details of applicability are spelled out in Common Articles 2 and 3.

Common Article 2 relating to international armed conflicts[edit]

This article states that the Geneva Conventions apply to all the cases of international conflict, where at least one of the warring nations have ratified the Conventions. Primarily:

- The Conventions apply to all cases of declared war between signatory nations. This is the original sense of applicability, which predates the 1949 version.

- The Conventions apply to all cases of armed conflict between two or more signatory nations. This language was added in 1949 to accommodate situations that have all the characteristics of war without the existence of a formal declaration of war, such as a police action.[23]

- The Conventions apply to a signatory nation even if the opposing nation is not a signatory, but only if the opposing nation «accepts and applies the provisions» of the Conventions.[23]

Article 1 of Protocol I further clarifies that armed conflict against colonial domination and foreign occupation also qualifies as an international conflict.

When the criteria of international conflict have been met, the full protections of the Conventions are considered to apply.

Common Article 3 relating to non-international armed conflict[edit]

This article states that the certain minimum rules of war apply to armed conflicts «not of an international character.»[38] The International Committee of the Red Cross has explained that this language describes armed conflicts «where at least one Party is not a State.»[39]

The interpretation of the term armed conflict and therefore the applicability of this article is a matter of debate.[23] For example, it would apply to conflicts between the Government and rebel forces, or between two rebel forces, or to other conflicts that have all the characteristics of war, whether carried out within the confines of one country or not.[40]

There are two criteria to distinguish non-international armed conflicts from lower forms of violence. The level of violence has to be of certain intensity, for example when the state cannot contain the situation with regular police forces. Also, involved non-state groups need to have a certain level of organization, like a military command structure.[41]

The other Geneva Conventions are not applicable in this situation but only the provisions contained within Article 3,[23] and additionally within the language of Protocol II. The rationale for the limitation is to avoid conflict with the rights of Sovereign States that were not part of the treaties. When the provisions of this article apply, it states that:[42]

Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria. To this end, the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the above-mentioned persons:

- violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

- taking of hostages;

- outrages upon dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; and

- the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

- The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.

On February 7, 2002, President Bush adopted the view that Common Article 3 did not protect al Qaeda prisoners because the United States-al Qaeda conflict was not «not of an international character.»[43] The Supreme Court of the United States invalidated the Bush Administration view of Common Article 3, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, by ruling that Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions applies to detainees in the «War on Terror», and that the Guantanamo military commission process used to try these suspects was in violation of U.S. and international law.[44] In response to Hamdan, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which President Bush signed into law on October 17, 2006. Like the Military Commissions Act of 2006, its successor the Military Commissions Act of 2009 explicitly forbids the invocation of the Geneva Conventions «as a basis for a private right of action.»[45]

Enforcement[edit]

Protecting powers[edit]

The term protecting power has a specific meaning under these Conventions. A protecting power is a state that is not taking part in the armed conflict, but that has agreed to look after the interests of a state that is a party to the conflict. The protecting power is a mediator enabling the flow of communication between the parties to the conflict. The protecting power also monitors implementation of these Conventions, such as by visiting the zone of conflict and prisoners of war. The protecting power must act as an advocate for prisoners, the wounded, and civilians.

Grave breaches[edit]

Not all violations of the treaty are treated equally. The most serious crimes are termed grave breaches and provide a legal definition of a war crime. Grave breaches of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions include the following acts if committed against a person protected by the convention:

- willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, including biological experiments

- willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health

- compelling a protected person to serve in the armed forces of a hostile power

- willfully depriving a protected person of the right to a fair trial if accused of a war crime.

Also considered grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention are the following:

- taking of hostages

- extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly

- unlawful deportation, transfer, or confinement.[46]

Nations who are party to these treaties must enact and enforce legislation penalizing any of these crimes. Nations are also obligated to search for persons alleged to commit these crimes, or persons having ordered them to be committed, and to bring them to trial regardless of their nationality and regardless of the place where the crimes took place.[47]

The principle of universal jurisdiction also applies to the enforcement of grave breaches when the United Nations Security Council asserts its authority and jurisdiction from the UN Charter to apply universal jurisdiction. The UNSC did this when they established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to investigate and/or prosecute alleged violations.

Right to a fair trial when no crime is alleged[edit]

Soldiers, as prisoners of war, will not receive a trial unless the allegation of a war crime has been made. According to article 43 of the 1949 Conventions, soldiers are employed for the purpose of serving in war; engaging in armed conflict is legitimate, and does not constitute a grave breach.[48] Should a soldier be arrested by belligerent forces, they are to be considered «lawful combatants» and afforded the protectorate status of a prisoner of war (POW) until the cessation of the conflict.[49] Human rights law applies to any incarcerated individual, including the right to a fair trial.[50]

Charges may only be brought against an enemy POW after a fair trial, but the initial crime being accused must be an explicit violation of the accords, more severe than simply fighting against the captor in battle.[50] No trial will otherwise be afforded to a captured soldier, as deemed by human rights law. This element of the convention has been confused during past incidents of detainment of US soldiers by North Vietnam, where the regime attempted to try all imprisoned soldiers in court for committing grave breaches, on the incorrect assumption that their sole existence as enemies of the state violated international law.[50]

Legacy[edit]

Although warfare has changed dramatically since the Geneva Conventions of 1949, they are still considered the cornerstone of contemporary international humanitarian law.[51] They protect combatants who find themselves hors de combat, and they protect civilians caught up in the zone of war. These treaties came into play for all recent international armed conflicts, including the War in Afghanistan,[52] the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion of Chechnya (1994–2017),[53] and the Russo-Georgian War. The Geneva Conventions also protect those affected by non-international armed conflicts such as the Syrian civil war.[dubious – discuss]

The lines between combatants and civilians have blurred when the actors are not exclusively High Contracting Parties (HCP).[54] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, an HCP often is faced with a non-state actor,[55] as argued by General Wesley Clark in 2007.[56] Examples of such conflict include the Sri Lankan Civil War, the Sudanese Civil War, and the Colombian Armed Conflict, as well as most military engagements of the US since 2000.

Some scholars hold that Common Article 3 deals with these situations, supplemented by Protocol II (1977).[dubious – discuss] These set out minimum legal standards that must be followed for internal conflicts. International tribunals, particularly the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), have clarified international law in this area.[57] In the 1999 Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic judgement, the ICTY ruled that grave breaches apply not only to international conflicts, but also to internal armed conflict.[dubious – discuss] Further, those provisions are considered customary international law.

Controversy has arisen over the US designation of irregular opponents as «unlawful enemy combatants» (see also unlawful combatant), especially in the SCOTUS judgments over the Guantanamo Bay detention camp brig facility Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and Rasul v. Bush,[58] and later Boumediene v. Bush. President George W. Bush, aided by Attorneys-General John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales and General Keith B. Alexander, claimed the power, as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, to determine that any person, including an American citizen, who is suspected of being a member, agent, or associate of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or possibly any other terrorist organization, is an «enemy combatant» who can be detained in U.S. military custody until hostilities end, pursuant to the international law of war.[59][60][61]

The application of the Geneva Conventions in the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present) has been troublesome[vague] because some of the personnel who engaged in combat against the Ukrainians were not identified by insignia, although they did wear military-style fatigues.[62] The types of comportment qualified as acts of perfidy under jus in bello doctrine are listed in Articles 37 through 39 of the Geneva Convention; the prohibition of fake insignia is listed at Article 39.2, but the law is silent on the complete absence of insignia. The status of POWs captured in this circumstance remains a question.

Educational institutions and organizations including Harvard University,[63][64] the International Committee of the Red Cross,[65] and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute use the Geneva Convention as a primary text investigating torture and warfare.[66]

New challenges[edit]

Artificial intelligence and autonomous weapon systems, such as military robots and cyber-weapons, are creating challenges in the creation, interpretation and application of the laws of armed conflict. The complexity of these new challenges, as well as the speed in which they are developed, complicates the application of the Conventions, which have not been updated in a long time.[67][68] Adding to this challenge is the very slow speed of the procedure of developing new treaties to deal with new forms of warfare, and determining agreed-upon interpretations to existing ones, meaning that by the time a decision can be made, armed conflict may have already evolved in a way that makes the changes obsolete.

See also[edit]

- Attacks on humanitarian workers

- Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons

- Customary international humanitarian law

- Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict

- Geneva Conference (disambiguation)

- Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights

- German Prisoners of War in the United States

- Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 – traditional rules on fighting wars

- Human rights

- Human shield

- International Committee of the Red Cross

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- International humanitarian law

- Laws of war

- Lieber Code General Order 100

- Nuremberg Principles

- Reprisals

- Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project

- Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868

- Targeted killing

People[edit]

- Ian Fishback

Notes[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Matthew Evangelista and Nina Tannenwald (eds.). 2017. Do the Geneva Conventions Matter? Oxford University Press.

- Giovanni Mantilla, «Conforming Instrumentalists: Why the USA and the United Kingdom Joined the 1949 Geneva Conventions,» European Journal of International Law, Volume 28, Issue 2, May 2017, Pages 483–511.

- Helen Kinsella, «The image before the weapon : a critical history of the distinction between combatant and civilian» Cornell University Press.

- Boyd van Dijk (2022). Preparing for War: The Making of the Geneva Conventions. Oxford University Press.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «State Parties / Signatories: Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949». International Humanitarian Law. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ Dunant, Henry (December 2015). A Memory of Solferino. English version, full text online.

- ^ «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 22 August 1864». Geneva, Switzerland: International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Roxburgh, Ronald (1920). International Law: A Treatise. London: Longmans, Green and co. p. 707. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Abrams, Irwin (2001). The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates: An Illustrated Biographical History, 1901–2001. US: Science History Publications. ISBN 9780881353884. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ The story of an idea, film on the creation of the Red Cross, Red Crescent Movement and the Geneva Conventions

- ^ ICRC. «Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War. Geneva, 20 October 1868 – State Parties». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Dutch Government (20 April 1900). «Kamerstukken II 1899/00, nr. 3 (Memorie van Toelichting)» (PDF) (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Fleck, Dietrich (2013). The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-19-872928-0.

- ^ Fleck, Dietrich (2013). The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 22 and 322. ISBN 978-0-19-872928-0.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 6 July 1906». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 27 July 1929». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Fleck, Dietrich (2013). The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-19-872928-0.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The undersigned Plenipotentiaries of the Governments represented at the Diplomatic Conference held at Geneva from April 21 to August 12, 1949, for the purpose of revising the Geneva Convention for the Relief of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field of July 27, 1929 […]

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The undersigned Plenipotentiaries of the Governments represented at the Diplomatic Conference held at Geneva from April 21 to August 12, 1949, for the purpose of revising the Xth Hague Convention of October 18, 1907 for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention of 1906 […]

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The undersigned Plenipotentiaries of the Governments represented at the Diplomatic Conference held at Geneva from April 21 to August 12, 1949, for the purpose of revising the Convention concluded at Geneva on July 27, 1929, relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War […]

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

In the relations between the Powers who are bound by the Hague Conventions respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, whether that of July 29, 1899, or that of October 18, 1907, and who are parties to the present Convention, this last Convention shall be supplementary to Sections II and III of the Regulations annexed to the above-mentioned Conventions of The Hague.

- ^ Kolb, Robert (2009). Ius in bello. Basel: Helbing Lichtenhahn. ISBN 978-2-8027-2848-1.

- ^ For example by the U.S. Supreme Court, see Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, Opinion of the Court, U.S. Supreme Court, 548 U.S. ___ (2006), Slip Opinion, p. 68, available at supremecourt.gov

- ^ Sperry, C. (1906). «The Revision of the Geneva Convention, 1906». Proceedings of the American Political Science Association. 3: 33–57. doi:10.2307/3038537. JSTOR 3038537.

- ^ Yingling, Raymund (1952). «The Geneva Conventions of 1949». The American Journal of International Law. 46 (3): 393–427. doi:10.2307/2194498. JSTOR 2194498. S2CID 146828573.

- ^ a b c d e Pictet, Jean (1958). Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: Commentary. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ «The Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» (PDF). The American Journal of International Law. 47 (4): 119–177. 1953. doi:10.2307/2213912. JSTOR 2213912. S2CID 154281279. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2021.

- ^ Bugnion, Francios (2000). «The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: From the 1949 Diplomatic Conference to the Dawn of the New Millennium». International Affairs. 76 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.00118. JSTOR 2626195. S2CID 143727870.

- ^ Elkins, Caroline (2022). Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 486–488. ISBN 978-0-593-32008-2.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 22 August 1864». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 6 July 1906». International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 27 July 1929». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ treaties.un.org: «Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflicts (Protocol I)»

- ^ treaties.un.org: «Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the protection of victims of non-international armed conflicts (Protocol II)», consulted July 2014

- ^ «Protocol additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the adoption of an additional distinctive emblem (Protocol III)», consulted July 2014

- ^ «Article 3—Conflicts Not of an International Character». icrc.org. ICRC. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ ICRC (2016). «2016 Commentary on the Geneva Convention». ICRC. p. 393.

- ^ ICRC (8 March 2016). «The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols».

- ^ ICRC (2008). «How is the Term «Armed Conflict» Defined in International Humanitarian Law?» (PDF). Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- ^ «Article 3 of Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field: Conflicts not of an international character. Geneva, 12 August 1949». International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Bush, George. «Humane Treatment of Taliban and al Qaeda Detainees» (PDF). Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ Michael Isikoff and Stuart Taylor Jr. (July 17, 2006), «The Gitmo Fallout: The fight over the Hamdan ruling heats up – as fears about its reach escalate». Archived May 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Newsweek

- ^ 10 U.S.C. § 948a(e)

- ^ How «grave breaches» are defined in the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols, International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ^ «Practice Relating to Rule 157. Jurisdiction over War Crimes». International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

Article 49 of the 1949 Geneva Convention I, Article 50 of the 1949 Geneva Convention II, Article 129 of the 1949 Geneva Convention III and Article 146 of the 1949 Geneva Convention IV provide: The High Contracting Parties undertake to enact any legislation necessary to provide effective penal sanctions for persons committing, or ordering to be committed, any of the grave breaches of the present Convention defined in the following Article. Each High Contracting Party shall be under the obligation to search for persons alleged to have committed, or to have ordered to be committed [grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions], and shall bring such persons, regardless of their nationality, before its own courts. It may also, if it prefers, and in accordance with the provisions of its own legislation, hand such persons over for trial to another High Contracting Party concerned, provided such High Contracting Party has made out a prima facie case.

- ^ «Treaties, States parties, and Commentaries — Additional Protocol (I) to the Geneva Conventions, 1977 — 43 — Armed forces». ihl-databases.icrc.org. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ III, John B. Bellinger; Padmanabhan, Vijay M. (2011). «Detention Operations in Contemporary Conflicts: Four Challenges for The Geneva Conventions and Other Existing Law». The American Journal of International Law. 105 (2): 201–243. doi:10.5305/amerjintelaw.105.2.0201. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 10.5305/amerjintelaw.105.2.0201. S2CID 229170590.

- ^ a b c Prisoner of war : rights & obligations under the Geneva Convention. HathiTrust. DoD GEN35 B. American Forces Information Service, Dept. of Defense. 1987. hdl:2027/uiug.30112000632791. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ «The Geneva Conventions Today». International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ See U.S. Supreme Court decision, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

- ^ Abresch, William (2005). «A Human Rights Law of Internal Armed Conflict: The European Court of Human Rights in Chechnya» (PDF). European Journal of International Law. 16 (4): 741–767. doi:10.1093/ejil/chi139.

- ^ «Sixty years of the Geneva Conventions and the decades ahead». International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ «Meisels, T: «COMBATANTS – LAWFUL AND UNLAWFUL» (2007 Law and Philosophy, v26 pp.31–65)» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Clark, Wesley K.; Raustiala, Kal (8 August 2007). «Opinion | Why Terrorists Aren’t Soldiers». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ «The Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic – Case No. IT-94-1-A». International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Sliedregt, Elies van; Gill, Terry D. (19 July 2005). «Guantánamo Bay: A Reflection On The Legal Status And Rights Of ‘Unlawful Enemy Combatants’«. Utrecht Law Review. 1 (1): 28–54. doi:10.18352/ulr.2. ISSN 1871-515X.

- ^ JK Elsea: «Presidential Authority to Detain ‘Enemy Combatants'» (2002) Archived 23 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, for Congressional Research Service

- ^ presidency.ucsb.edu: «Press Briefing by White House Counsel Judge Alberto Gonzales, DoD General Counsel William Haynes, DoD Deputy General Counsel Daniel Dell’Orto and Army Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence General Keith Alexander June 22, 2004» Archived 18 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, consulted July 2014

- ^ Gonzales, Alberto R. (30 November 2001). «Martial Justice, Full and Fair». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Faith, Ryan (10 March 2014). «The Russian Soldier Captured in Crimea May Not Be Russian, a Soldier, or Captured». Vice News. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ «Training vs. Torture». President and Fellows of Harvard College.

- ^ Khouri, Rami. «International Law, Torture and Accountability». Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ «Advanced Seminar in International Humanitarian Law for University Lecturers». International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ^ McManus, Shani (13 July 2015). «Responding to terror explored». South Florida Sun-Sentinel.

- ^ Peace and, Security (13 August 2019). «Amidst new challenges, Geneva Conventions mark 70 years of ‘limiting brutality’ during war». United Nations News. United Nations. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Ray, Amit (4 July 2018). Compassionate Superintelligence AI 5.0: AI with Blockchain, Bmi, Drone, Iot, and Biometric Technologies. Compassionate AI Lab, Inner Light Publishers. ISBN 978-9382123446.

External links[edit]

Works related to Geneva Convention at Wikisource

The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Texts and commentaries of 1949 Conventions & Additional Protocols

- The Geneva Conventions: the core of international humanitarian law, ICRC

- Rules of war (in a nutshell)—video

- Commentaries:

- GCI: Commentary

- GCII: Commentary

- GCIII: Commentary

- GCIV: Commentary

A facsimile of the signature-and-seals page of the 1864 Geneva Convention, that established humane rules of war.

The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term Geneva Convention usually denotes the agreements of 1949, negotiated in the aftermath of the Second World War (1939–1945), which updated the terms of the two 1929 treaties and added two new conventions. The Geneva Conventions extensively define the basic rights of wartime prisoners, civilians and military personnel, established protections for the wounded and sick, and provided protections for the civilians in and around a war-zone.[1]

The Geneva Convention defines the rights and protections afforded to non-combatants. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in their entirety or with reservations, by 196 countries.[1] The Geneva Conventions concern only prisoners and non-combatants in war. They do not address the use of weapons of war, which are addressed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, which concern conventional weapons, and the Geneva Protocol, which concerns biological and chemical warfare.

History[edit]

The progression of the Geneva Conventions from 1864 to 1949.

The Swiss businessman Henry Dunant went to visit wounded soldiers after the Battle of Solferino in 1859. He was shocked by the lack of facilities, personnel, and medical aid available to help these soldiers. As a result, he published his book, A Memory of Solferino, in 1862, on the horrors of war.[2] His wartime experiences inspired Dunant to propose:

- A permanent relief agency for humanitarian aid in times of war

- A government treaty recognizing the neutrality of the agency and allowing it to provide aid in a war zone

The former proposal led to the establishment of the Red Cross in Geneva. The latter led to the 1864 Geneva Convention, the first codified international treaty that covered the sick and wounded soldiers on the battlefield. On 22 August 1864, the Swiss government invited the governments of all European countries, as well as the United States, Brazil, and Mexico, to attend an official diplomatic conference. Sixteen countries sent a total of twenty-six delegates to Geneva. On 22 August 1864, the conference adopted the first Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field». Representatives of 12 states and kingdoms signed the convention:[3][4]

For both of these accomplishments, Henry Dunant became co recipient of the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.[5][6]

On 20 October 1868 the first unsuccessful attempt to expand the 1864 treaty was undertaken. With the ‘Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War’ an attempt was initiated to clarify some rules of the 1864 convention and to extend them to maritime warfare. The Articles were signed but were only ratified by the Netherlands and the United States of America.[7] The Netherlands later withdrew their ratification.[8] The protection of the victims of maritime warfare would later be realized by the third Hague Convention of 1899 and the tenth Hague Convention of 1907.[9]

In 1906 thirty-five states attended a conference convened by the Swiss government. On 6 July 1906 it resulted in the adoption of the «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field», which improved and supplemented, for the first time, the 1864 convention.[10] It remained in force until 1970 when Costa Rica acceded to the 1949 Geneva Conventions.[11]

The 1929 conference yielded two conventions that were signed on 27 July 1929. One, the «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field», was the third version to replace the original convention of 1864.[9][12] The other was adopted after experiences in World War I had shown the deficiencies in the protection of prisoners of war under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The «Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» was not to replace these earlier conventions signed at The Hague, rather it supplemented them.[13][14]

Inspired by the wave of humanitarian and pacifistic enthusiasm following World War II and the outrage towards the war crimes disclosed by the Nuremberg Trials, a series of conferences were held in 1949 reaffirming, expanding and updating the prior Geneva and Hague Conventions. It yielded four distinct conventions:

- The First Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field» was the fourth update of the original 1864 convention and replaced the 1929 convention on the same subject matter.[15]

- The Second Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea» replaced the Hague Convention (X) of 1907.[16] It was the first Geneva Convention on the protection of the victims of maritime warfare and mimicked the structure and provisions of the First Geneva Convention.[9]

- The Third Geneva Convention «relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» replaced the 1929 Geneva Convention that dealt with prisoners of war.[17]

- In addition to these three conventions, the conference also added a new elaborate Fourth Geneva Convention «relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War». It was the first Geneva Convention not to deal with combatants, rather it had the protection of civilians as its subject matter. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions had already contained some provisions on the protection of civilians and occupied territory. Article 154 specifically provides that the Fourth Geneva Convention is supplementary to these provisions in the Hague Conventions.[18]

The third protocol emblem, also known as the Red Crystal

Despite the length of these documents, they were found over time to be incomplete. The nature of armed conflicts had changed with the beginning of the Cold War era, leading many to believe that the 1949 Geneva Conventions were addressing a largely extinct reality:[19] on the one hand, most armed conflicts had become internal, or civil wars, while on the other, most wars had become increasingly asymmetric. Modern armed conflicts were inflicting an increasingly higher toll on civilians, which brought the need to provide civilian persons and objects with tangible protections in time of combat, bringing a much needed update to the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

In light of these developments, two Protocols were adopted in 1977 that extended the terms of the 1949 Conventions with additional protections. In 2005, a third brief Protocol was added establishing an additional protective sign for medical services, the Red Crystal, as an alternative to the ubiquitous Red Cross and Red Crescent emblems, for those countries that find them objectionable.

[edit]

The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949. Commentary (The Commentaries) is a series of four volumes of books published between 1952 and 1958 and containing commentaries to each of the four Geneva Conventions. The series was edited by Jean Pictet who was the vice-president of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The Commentaries are often relied upon to provide authoritative interpretation of the articles.[20]

Contents[edit]

Parties to Geneva Conventions and Protocols

|

Parties to GC I–IV and P I–III |

Parties to GC I–IV and P I–II |

|

Parties to GC I–IV and P I and III |

Parties to GC I–IV and P I |

|

Parties to GC I–IV and P III |

Parties to GC I–IV and no P |

The Geneva Conventions are rules that apply only in times of armed conflict and seek to protect people who are not or are no longer taking part in hostilities; these include the sick and wounded of armed forces on the field, wounded, sick, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea, prisoners of war, and civilians. The first convention dealt with the treatment of wounded and sick armed forces in the field.[21]

The second convention dealt with the sick, wounded, and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea.[22][23] The third convention dealt with the treatment of prisoners of war during times of conflict.[24] The fourth convention dealt with the treatment of civilians and their protection during wartime.[25]

During the negotiations for the 1949 conventions, Britain and France successfully removed language from early drafts that they saw as unfavorable to their colonial rule.[26]

Conventions[edit]

In international law and diplomacy the term convention refers to an international agreement, or treaty.

- The First Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field» (first adopted in 1864,[27] revised in 1906,[28] 1929[29] and finally 1949);[30]

- The Second Geneva Convention «for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea» (first adopted in 1949, successor of the Hague Convention (X) 1907);[31]

- The Third Geneva Convention «relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» (first adopted in 1929,[32] last revision in 1949);[33]

- The Fourth Geneva Convention «relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War» (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the Hague Convention (II) of 1899 and Hague Convention (IV) 1907).[34]

With two Geneva Conventions revised and adopted, and the second and fourth added, in 1949 the whole set is referred to as the «Geneva Conventions of 1949» or simply the «Geneva Conventions». Usually only the Geneva Conventions of 1949 are referred to as First, Second, Third or Fourth Geneva Convention. The treaties of 1949 were ratified, in whole or with reservations, by 196 countries.[1]

Protocols[edit]

The 1949 conventions have been modified with three amendment protocols:

- Protocol I (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts[35]

- Protocol II (1977) relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts[36]

- Protocol III (2005) relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem[37]

Application[edit]

The Geneva Conventions apply at times of war and armed conflict to governments who have ratified its terms. The details of applicability are spelled out in Common Articles 2 and 3.

Common Article 2 relating to international armed conflicts[edit]

This article states that the Geneva Conventions apply to all the cases of international conflict, where at least one of the warring nations have ratified the Conventions. Primarily:

- The Conventions apply to all cases of declared war between signatory nations. This is the original sense of applicability, which predates the 1949 version.

- The Conventions apply to all cases of armed conflict between two or more signatory nations. This language was added in 1949 to accommodate situations that have all the characteristics of war without the existence of a formal declaration of war, such as a police action.[23]

- The Conventions apply to a signatory nation even if the opposing nation is not a signatory, but only if the opposing nation «accepts and applies the provisions» of the Conventions.[23]

Article 1 of Protocol I further clarifies that armed conflict against colonial domination and foreign occupation also qualifies as an international conflict.

When the criteria of international conflict have been met, the full protections of the Conventions are considered to apply.

Common Article 3 relating to non-international armed conflict[edit]

This article states that the certain minimum rules of war apply to armed conflicts «not of an international character.»[38] The International Committee of the Red Cross has explained that this language describes armed conflicts «where at least one Party is not a State.»[39]

The interpretation of the term armed conflict and therefore the applicability of this article is a matter of debate.[23] For example, it would apply to conflicts between the Government and rebel forces, or between two rebel forces, or to other conflicts that have all the characteristics of war, whether carried out within the confines of one country or not.[40]

There are two criteria to distinguish non-international armed conflicts from lower forms of violence. The level of violence has to be of certain intensity, for example when the state cannot contain the situation with regular police forces. Also, involved non-state groups need to have a certain level of organization, like a military command structure.[41]

The other Geneva Conventions are not applicable in this situation but only the provisions contained within Article 3,[23] and additionally within the language of Protocol II. The rationale for the limitation is to avoid conflict with the rights of Sovereign States that were not part of the treaties. When the provisions of this article apply, it states that:[42]

Persons taking no active part in the hostilities, including members of armed forces who have laid down their arms and those placed hors de combat by sickness, wounds, detention, or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated humanely, without any adverse distinction founded on race, colour, religion or faith, sex, birth or wealth, or any other similar criteria. To this end, the following acts are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever with respect to the above-mentioned persons:

- violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

- taking of hostages;

- outrages upon dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment; and

- the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

- The wounded and sick shall be collected and cared for.

On February 7, 2002, President Bush adopted the view that Common Article 3 did not protect al Qaeda prisoners because the United States-al Qaeda conflict was not «not of an international character.»[43] The Supreme Court of the United States invalidated the Bush Administration view of Common Article 3, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, by ruling that Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions applies to detainees in the «War on Terror», and that the Guantanamo military commission process used to try these suspects was in violation of U.S. and international law.[44] In response to Hamdan, Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which President Bush signed into law on October 17, 2006. Like the Military Commissions Act of 2006, its successor the Military Commissions Act of 2009 explicitly forbids the invocation of the Geneva Conventions «as a basis for a private right of action.»[45]

Enforcement[edit]

Protecting powers[edit]

The term protecting power has a specific meaning under these Conventions. A protecting power is a state that is not taking part in the armed conflict, but that has agreed to look after the interests of a state that is a party to the conflict. The protecting power is a mediator enabling the flow of communication between the parties to the conflict. The protecting power also monitors implementation of these Conventions, such as by visiting the zone of conflict and prisoners of war. The protecting power must act as an advocate for prisoners, the wounded, and civilians.

Grave breaches[edit]

Not all violations of the treaty are treated equally. The most serious crimes are termed grave breaches and provide a legal definition of a war crime. Grave breaches of the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions include the following acts if committed against a person protected by the convention:

- willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment, including biological experiments

- willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health

- compelling a protected person to serve in the armed forces of a hostile power

- willfully depriving a protected person of the right to a fair trial if accused of a war crime.

Also considered grave breaches of the Fourth Geneva Convention are the following:

- taking of hostages

- extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly

- unlawful deportation, transfer, or confinement.[46]

Nations who are party to these treaties must enact and enforce legislation penalizing any of these crimes. Nations are also obligated to search for persons alleged to commit these crimes, or persons having ordered them to be committed, and to bring them to trial regardless of their nationality and regardless of the place where the crimes took place.[47]

The principle of universal jurisdiction also applies to the enforcement of grave breaches when the United Nations Security Council asserts its authority and jurisdiction from the UN Charter to apply universal jurisdiction. The UNSC did this when they established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to investigate and/or prosecute alleged violations.

Right to a fair trial when no crime is alleged[edit]

Soldiers, as prisoners of war, will not receive a trial unless the allegation of a war crime has been made. According to article 43 of the 1949 Conventions, soldiers are employed for the purpose of serving in war; engaging in armed conflict is legitimate, and does not constitute a grave breach.[48] Should a soldier be arrested by belligerent forces, they are to be considered «lawful combatants» and afforded the protectorate status of a prisoner of war (POW) until the cessation of the conflict.[49] Human rights law applies to any incarcerated individual, including the right to a fair trial.[50]

Charges may only be brought against an enemy POW after a fair trial, but the initial crime being accused must be an explicit violation of the accords, more severe than simply fighting against the captor in battle.[50] No trial will otherwise be afforded to a captured soldier, as deemed by human rights law. This element of the convention has been confused during past incidents of detainment of US soldiers by North Vietnam, where the regime attempted to try all imprisoned soldiers in court for committing grave breaches, on the incorrect assumption that their sole existence as enemies of the state violated international law.[50]

Legacy[edit]

Although warfare has changed dramatically since the Geneva Conventions of 1949, they are still considered the cornerstone of contemporary international humanitarian law.[51] They protect combatants who find themselves hors de combat, and they protect civilians caught up in the zone of war. These treaties came into play for all recent international armed conflicts, including the War in Afghanistan,[52] the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion of Chechnya (1994–2017),[53] and the Russo-Georgian War. The Geneva Conventions also protect those affected by non-international armed conflicts such as the Syrian civil war.[dubious – discuss]

The lines between combatants and civilians have blurred when the actors are not exclusively High Contracting Parties (HCP).[54] Since the fall of the Soviet Union, an HCP often is faced with a non-state actor,[55] as argued by General Wesley Clark in 2007.[56] Examples of such conflict include the Sri Lankan Civil War, the Sudanese Civil War, and the Colombian Armed Conflict, as well as most military engagements of the US since 2000.

Some scholars hold that Common Article 3 deals with these situations, supplemented by Protocol II (1977).[dubious – discuss] These set out minimum legal standards that must be followed for internal conflicts. International tribunals, particularly the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), have clarified international law in this area.[57] In the 1999 Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic judgement, the ICTY ruled that grave breaches apply not only to international conflicts, but also to internal armed conflict.[dubious – discuss] Further, those provisions are considered customary international law.

Controversy has arisen over the US designation of irregular opponents as «unlawful enemy combatants» (see also unlawful combatant), especially in the SCOTUS judgments over the Guantanamo Bay detention camp brig facility Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and Rasul v. Bush,[58] and later Boumediene v. Bush. President George W. Bush, aided by Attorneys-General John Ashcroft and Alberto Gonzales and General Keith B. Alexander, claimed the power, as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, to determine that any person, including an American citizen, who is suspected of being a member, agent, or associate of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or possibly any other terrorist organization, is an «enemy combatant» who can be detained in U.S. military custody until hostilities end, pursuant to the international law of war.[59][60][61]

The application of the Geneva Conventions in the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present) has been troublesome[vague] because some of the personnel who engaged in combat against the Ukrainians were not identified by insignia, although they did wear military-style fatigues.[62] The types of comportment qualified as acts of perfidy under jus in bello doctrine are listed in Articles 37 through 39 of the Geneva Convention; the prohibition of fake insignia is listed at Article 39.2, but the law is silent on the complete absence of insignia. The status of POWs captured in this circumstance remains a question.

Educational institutions and organizations including Harvard University,[63][64] the International Committee of the Red Cross,[65] and the Rohr Jewish Learning Institute use the Geneva Convention as a primary text investigating torture and warfare.[66]

New challenges[edit]

Artificial intelligence and autonomous weapon systems, such as military robots and cyber-weapons, are creating challenges in the creation, interpretation and application of the laws of armed conflict. The complexity of these new challenges, as well as the speed in which they are developed, complicates the application of the Conventions, which have not been updated in a long time.[67][68] Adding to this challenge is the very slow speed of the procedure of developing new treaties to deal with new forms of warfare, and determining agreed-upon interpretations to existing ones, meaning that by the time a decision can be made, armed conflict may have already evolved in a way that makes the changes obsolete.

See also[edit]

- Attacks on humanitarian workers

- Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons

- Customary international humanitarian law

- Declaration on the Protection of Women and Children in Emergency and Armed Conflict

- Geneva Conference (disambiguation)

- Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights

- German Prisoners of War in the United States

- Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 – traditional rules on fighting wars

- Human rights

- Human shield

- International Committee of the Red Cross

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- International humanitarian law

- Laws of war

- Lieber Code General Order 100

- Nuremberg Principles

- Reprisals

- Rule of Law in Armed Conflicts Project

- Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868

- Targeted killing

People[edit]

- Ian Fishback

Notes[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Matthew Evangelista and Nina Tannenwald (eds.). 2017. Do the Geneva Conventions Matter? Oxford University Press.

- Giovanni Mantilla, «Conforming Instrumentalists: Why the USA and the United Kingdom Joined the 1949 Geneva Conventions,» European Journal of International Law, Volume 28, Issue 2, May 2017, Pages 483–511.

- Helen Kinsella, «The image before the weapon : a critical history of the distinction between combatant and civilian» Cornell University Press.

- Boyd van Dijk (2022). Preparing for War: The Making of the Geneva Conventions. Oxford University Press.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «State Parties / Signatories: Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949». International Humanitarian Law. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- ^ Dunant, Henry (December 2015). A Memory of Solferino. English version, full text online.

- ^ «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 22 August 1864». Geneva, Switzerland: International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Roxburgh, Ronald (1920). International Law: A Treatise. London: Longmans, Green and co. p. 707. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Abrams, Irwin (2001). The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates: An Illustrated Biographical History, 1901–2001. US: Science History Publications. ISBN 9780881353884. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ The story of an idea, film on the creation of the Red Cross, Red Crescent Movement and the Geneva Conventions

- ^ ICRC. «Additional Articles relating to the Condition of the Wounded in War. Geneva, 20 October 1868 – State Parties». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Dutch Government (20 April 1900). «Kamerstukken II 1899/00, nr. 3 (Memorie van Toelichting)» (PDF) (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Fleck, Dietrich (2013). The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-19-872928-0.

- ^ Fleck, Dietrich (2013). The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 22 and 322. ISBN 978-0-19-872928-0.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 6 July 1906». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 27 July 1929». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Fleck, Dietrich (2013). The Handbook of International Humanitarian Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-19-872928-0.

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The undersigned Plenipotentiaries of the Governments represented at the Diplomatic Conference held at Geneva from April 21 to August 12, 1949, for the purpose of revising the Geneva Convention for the Relief of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field of July 27, 1929 […]

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The undersigned Plenipotentiaries of the Governments represented at the Diplomatic Conference held at Geneva from April 21 to August 12, 1949, for the purpose of revising the Xth Hague Convention of October 18, 1907 for the Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention of 1906 […]

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The undersigned Plenipotentiaries of the Governments represented at the Diplomatic Conference held at Geneva from April 21 to August 12, 1949, for the purpose of revising the Convention concluded at Geneva on July 27, 1929, relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War […]

- ^ ICRC. «Convention (IV) relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949». Retrieved 5 March 2017.

In the relations between the Powers who are bound by the Hague Conventions respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, whether that of July 29, 1899, or that of October 18, 1907, and who are parties to the present Convention, this last Convention shall be supplementary to Sections II and III of the Regulations annexed to the above-mentioned Conventions of The Hague.

- ^ Kolb, Robert (2009). Ius in bello. Basel: Helbing Lichtenhahn. ISBN 978-2-8027-2848-1.

- ^ For example by the U.S. Supreme Court, see Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, Opinion of the Court, U.S. Supreme Court, 548 U.S. ___ (2006), Slip Opinion, p. 68, available at supremecourt.gov

- ^ Sperry, C. (1906). «The Revision of the Geneva Convention, 1906». Proceedings of the American Political Science Association. 3: 33–57. doi:10.2307/3038537. JSTOR 3038537.

- ^ Yingling, Raymund (1952). «The Geneva Conventions of 1949». The American Journal of International Law. 46 (3): 393–427. doi:10.2307/2194498. JSTOR 2194498. S2CID 146828573.

- ^ a b c d e Pictet, Jean (1958). Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: Commentary. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ «The Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War» (PDF). The American Journal of International Law. 47 (4): 119–177. 1953. doi:10.2307/2213912. JSTOR 2213912. S2CID 154281279. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2021.