Зубная формула

Зубная

формула –

это графическое отображение зубов в

челюстях.

Одной

из самых старых является «угловая

система».

Формула

записывается в четырех квадратах,

разграниченных горизонтальной и

вертикальной линиями.

В

этой формуле горизонтальная

линия указывает на принадлежность

зубов к верхней или нижней челюсти, а

вертикальная

– на

принадлежность зубов к правой или левой

стороне.

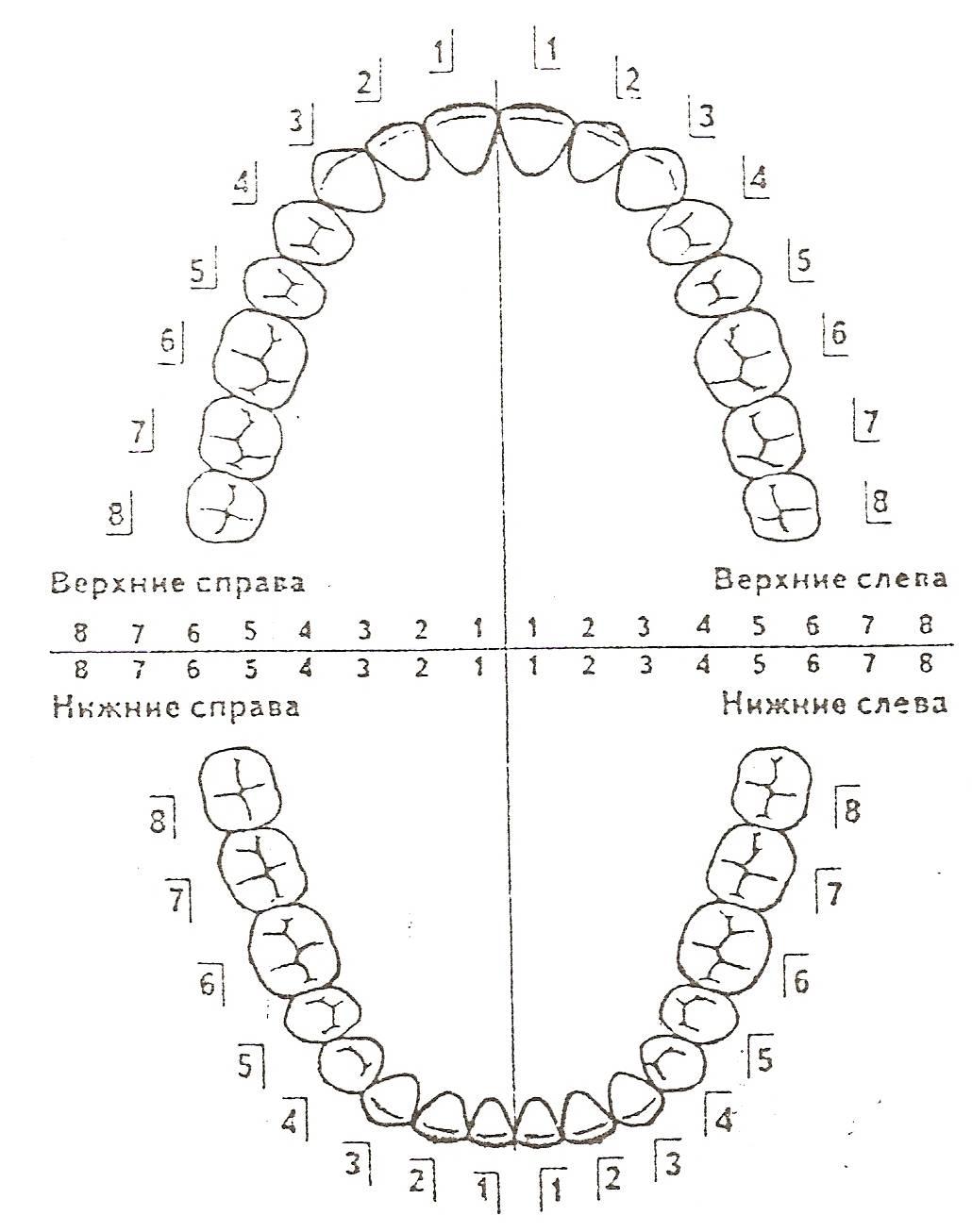

При

этом постоянные зубы принято обозначать

арабскими цифрами:

8

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

8

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

| 1 2

3 4 5 6 7 8

А молочные

(временные) – римскими:

V

IV III II I | I II III IV V

V

IV III II I | I II III IV V

В

настоящее время в Республике Беларусь

применяется двузначная международная

формула.

Её

сущность состоит в обозначении каждого

двузначным

числом,

в котором первая цифра обозначает

квадрант ряда, а вторая – позицию,

занимаемую в нем зубом.

НОМЕР

КВАДРАНТА

1

квадрант |

2 квадрант

4

квадрант |

3 квадрант

ФОРМУЛА

ЗУБОВ

ЧАСТНАЯ

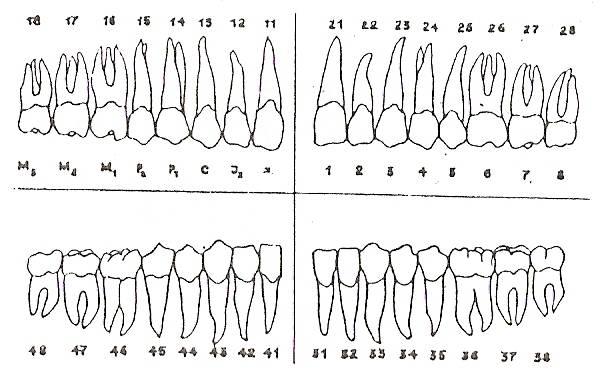

АНАТОМИЯ ЗУБОВ ВЕРХНЕЙ И НИЖНЕЙ ЧЕЛЮСТИ

ЦЕНТРАЛЬНЫЕ

РЕЗЦЫ ВЕРХНЕЙ ЧЕЛЮСТИ

РЕЗЦЫ

Посередине

зубных дуг расположено 8

резцов –

поэтому их называют передними

зубами.

В

каждой половине зубного ряда имеется

по 2 резца:

-

медиальный

(центральный) и -

латеральный

(боковой),

занимающие I

и II

позиции.

Характерными

особенностями строения резцов является:

-

одиночный

корень и -

уплощенная

в вестибуло-лингвальном направлении

коронка, заканчивающаяся на окклюзионной

поверхности режущим краем.

Центральные

резцы верхней челюсти больше боковых,

а центральные резцы нижней челюсти,

наоборот меньше боковых. Коронки резцов

верхней челюсти наклонены в губном

направлении, что обусловливает отклонение

корней в небную сторону. Резцы нижней

челюсти расположены почти вертикально.

Правый

1|,

11.

Левый

|1,

21.

Сроки

прорезывания – 6-8 лет.

Общая

длина 23,0 мм

Высота

коронки – 10,5 мм.

Длина

корня 12,5 мм.

Из

группы резцов самые

крупные.

Зуб

имеет долотообразную форму, коронка

уплощена в вестибулярно-оральном

направлении.

Вестибулярная

поверхность

слегка выпуклая, по средней линии

имеется продольный валик. Вестибулярные

и небные поверхности сходясь, образуют

режущий край, который у недавно

прорезавшихся

зубов имеет 3 бугорка (из которых

медиальный

выше), однако,

с возрастом бугорки стираются.

Небная

поверхность

уже губной, слегка вогнута, имеет форму

треугольника. На небной поверхности

(на медиальном и дистальном краях)

имеются боковые валики, которые сходясь

у шейки образуют бугорок.

Контактная

поверхность

– медиальная и латеральная имеют вид

треугольника, с основанием в области

шейки и вершиной у режущего края.

Медиальная

поверхность длиннее, переходит в режущий

край почти под прямым углом.

Корень

– один, прямой, слабо уплощен в

медиодистальном направлении. Латеральная

поверхность корня более выпуклая, с

неглубокой продольной бороздой. Корень

отклонен латерально от вертикальной

оси.

Признаки

принадлежности корня выражены хорошо.

Полость

зуба –

соответствует внешней форме зуба.

Признак

корня, угла и кривизны коронки выражены.

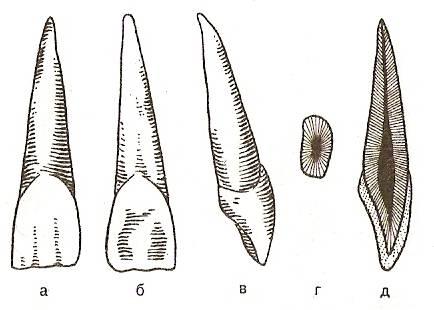

а

– вестибулярная поверхность; б – небная

поверхность; в – боковая поверхность;

г – поперечный срез; д – продольный

срез.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Зубы различаются не только по размеру, но и по форме. Каждому виду соответствует название и цифра. Стоматологи чаще используют буквенно-цифровую или цифровую нумерацию зубов для их обозначения, нежели названия. Это удобнее, и позволяет врачам лучше понимать друг друга. Такое обозначение называется зубной формулой.

Зачем стоматологи решили нумеровать зубы

Зубная формула призвана облегчить понимание того, о каком конкретно костном образовании идёт речь во время лечения или при изучении амбулаторной карты пациента. Стоматологические процедуры редко проводятся в одиночку, поэтому врачам нужно кратко, но максимально понятно сообщать друг другу, где требуется лечение.

Иногда пациент вынужден сменить врача. Тогда новый специалист по амбулаторной карте больного должен понять, какие именно костные образования требуют лечения, над какими уже была произведена работа, а каким нужно уделить повышенное внимание. В этом помогает нумерация.

Каждый зуб у человека отличается от другого размерами, конфигурацией и функциями. Некоторые помогают откусывать и отрывать пищу, другие предназначены для жевания. Для точного определения каждого зуба в стоматологии введена система их нумерации.

Все о строении зуба

Начинается она с середины челюсти и идёт симметрично вправо и влево. Первую пару передних резцов обозначают единицей (1), а вторую двойкой (2). Ими человек откусывает пищу.

Далее расположены клыки под номером 3. Ими люди отрывают куски от особенно твёрдой и плотной пищи. Функцию пережёвывания выполняют премоляры, которые расположены после клыков и обозначаются как 4. Для более тщательного пережёвывания челюсть человека снабжена мощными костными образованиями, которые называются моляры (6, 7). Последней парой выступают зубы мудрости, их номер 8. Они вырастают не у всех людей, а многие их удаляют, так как лечить их считается нецелесообразным.

Зубы мудрости считаются учёными рудиментами, так как их смысл был в перетирании сырой и очень плотной пищи. Современные люди не питаются таким образом, мы готовим еду множеством различных способов, что облегчает её пережёвывание.

Перетирать пищу нам уже не нужно. Из-за этого с ходом эволюции челюсть человека стала уже и часто не вмещает в себя весь набор зубов. Последней паре моляров некуда расти, их прорезывание затрудняется, доставляет боль и дискомфорт.

Во многих случаях зубы мудрости удаляют даже здоровыми. Они чаще всего подвержены разрушению, их тяжело лечить и нахождение их во рту человека в современном мире почти не имеет смысла. Иногда эти зубы не вырастают совсем, и это тоже вариант нормы.

Поэтому не нужно беспокоиться, если стоматолог не указал в зубной формуле последнюю пару или сказал о наличии 28 зубов. Этого набора вполне достаточно для жизни в современном обществе.

Для удобства челюсти человека разделили на сегменты двумя линиями: горизонтальной между челюстями и вертикальной через середину лица. Отсчёт начинается с правого верхнего сегмента и движется по ходу стрелки часов.

Получается, что костные образования из первого сегмента будут десятками, второго (сверху слева) двадцатками. В третьей части (снизу слева) находятся тридцатки, а в четвёртой (снизу справа) сороковки. Полное название будет содержать номер сегмента и номер зубной пары.

Для нумерации у детей применяют 5 – 8 десятки, так как помимо ряда молочных зубов, у них есть зачатки постоянных с номерами 10, 20, 30 и 40 соответственно.

Типы зубных формул

Хотя схема зубов в норме у всех одинакова, существует 4 основные формулы. Каждую из них используют разные специалисты, поэтому все они по-своему удобны. Типы зубных формул различаются как для взрослых, так и для детей.

По всему миру нет единой системы нумерации костных образований во рту, хотя многие из них считаются международными.

В первую очередь это связано с различиями в методиках лечения зубов, подходах к терапии и наличием специалистов разного уровня и направления в каждой конкретной стране.

Универсальная зубная формула

Это одна из самых популярных систем обозначения зубов. Её второе название «буквенно-цифровая нумерация». Зубы обозначены прописными буквами согласно латинским названиям:

- I – резцы (4 верхнечелюстных + 4 нижнечелюстных = 8);

- C – клыки (2 на верхней челюсти + 2 на нижней = 4);

- P – премоляры (4 наверху+4 внизу = 8);

- M – моляры (от 8 до 12 при наличии или отсутствии зубов мудрости).

Эффективные способы лечения фиссур на зубах

Для детской нумерации используются строчные буквы. Количество зубов в ряду фиксируется арабскими цифрами. При абсолютной норме универсальная формула будет записана так:

Расшифровка: резцов 2 пары, клыков 1 пара, 2 пары премоляров, моляров 3 пары, всего 32 единицы. Если количество зубов не соответствует в норме, цифры меняются в соответствии с тем количеством, которое имеется.

Формула Зигмонти-Палмера

Система квадратно-цифровой нумерации или формула Зигмонти-Палмера используется с 1876г. И остаётся востребованной поныне, особенно у хирургов челюстно-лицевого профиля и среди ортодонтов.

По этой формуле зубам присваиваются номера с 1 по 8, а челюсти делятся на четыре сектора: верхние два и нижние два. Границы проходят посередине горизонтально и вертикально. Получается, что каждая цифра принадлежит четырём зубам: по одному в каждом секторе. Схематично при полной норме это выглядит так:

| 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

Каждому числу соответствует свой вид зуба:

- Центральные резцы.

- Боковые резцы.

- Клыки.

- Первые премоляры.

- Вторые премоляры.

- Первые моляры.

- Вторые моляры.

- Зубы мудрости (третьи моляры).

Для нумерации у детей используются римские цифры. Моляры в этом случае обозначения не имеют.

Система Виола

Этот вид зубной формулы наиболее современный, дата принятия схемы Международной ассоциацией зубных врачей – 1971 г. Система Виола признана и рекомендована ВОЗ (Всемирной ассоциацией здравоохранения).

Данный подход к нумерации расположения зубов удобен тем, что каждому костному образованию в челюсти присвоен уникальный номер. Второе название этой формулы – «двухцифровая система».

Такой термин возник из-за нумерации костных образований, которая состоит из двух частей, причём вторая из них из формулы Зигмонда-Палмера. Начальная же цифра представляет собой число, обозначающее квадрант, к которому принадлежит зуб:

- Левый верхний.

- Правый верхний.

- Правый нижний.

- Левый нижний.

Получается, что верхнечелюстной правый центральный резец будет иметь номер 21, где двойка означает квадрант, в котором расположен зуб, а единица вид костного образования. Области считаются от врача к пациенту, а не наоборот.

Детская формула содержит цифры 5 – 8 соответственно.

Система Виола получила международное признание и широкую известность благодаря отсутствию в нумерации сложных формул и буквенных обозначений.

Все существующие методы определения индекса гигиены полости рта

Её считают самой удобной, так как она позволяет легко прочитать и понять информацию о костных образованиях пациента, а также передавать её факсу, телефону, электронной почте и пр.

Но из-за различий в методиках лечения и наличия или отсутствия специалистов определённого рода, формула Виола не стала универсальной. Врачам некоторых специальностей удобнее использовать другие системы нумерации зубов.

Теория Хадерупа

В основе обозначения расположения зубов по этой схеме лежит система нумерации Зигмонди-Палмера. Но по теории Хадерупа перед числом в квадрантах ставится знак «+» или «-». Это помогает правильно определить, на какой из челюстей находится зуб: на верхней («+») или на нижней («-»).

Второе число – это порядковый номер по формуле Зигмонди-Палмера с 1 по 8. От квадранта зависит, будет знак «+» или «-» стоять до цифры или после. Если костное образование находится слева, то знак ставится перед номером. Если справа, то сначала пишется цифровое обозначение, а затем «+» или «-».

При использовании формулы Хадерупа в детской стоматологии, используют арабскую нумерацию с 1 до 5, а перед ними ставят 0. То есть формула правого бокового переднего резца верхней челюсти будет записана как 02+.

Запомнить все варианты обозначения расположения зубов несложно и доступно человеку без специального образования. Знать их необходимо для того, чтобы лучше понимать, о каком конкретно костном образовании говорят врачи. Это поможет вовремя отреагировать, если вдруг врач перепутает нужный зуб со здоровым.

20 января 2019

Зубная формула. Полезная шпаргалка

Доброе воскресное утро друзья. Немного полезного контента. Обязательно нажимайте на флажок и сохраняйте эту шпаргалку, однажды она вам точно пригодится.

Что такое зубная формула?

Это некий международный стандарт обозначения каждого зуба с помощью номера. Это необходимо для быстрой коммуникации между врачами и в идеале пациентами.

Чтобы не говорить – нижний левый боковой предпоследний зуб, легче сказать – зуб 37.

Получая план лечения в клинике вы видите такую логику: Наименование услуги/номер зуба/количество/стоимость.

И если в клинике доктор вроде бы все понятно объяснил, то переступив порог дома и открыв план в голове каша. Непонятно что надо делать и зачем. Что за номера зубов, как в них разобраться?

Есть 2 схемы которые очень быстро и легко вы запомните на всю жизнь и в беседе со стоматологом получите восхищенный комплимент от доктора.

Логика нумерации зубов

Каждый зуб имеет две цифры (шифр). Первая цифра это сегмент (право/лево/верх/низ) и вторая цифра номер зуба в сегменте.

Как понять какой сегмент?

Мы смотрим на человека vis-a-vis (лицом друг к другу) и проводим окружность по часовой стрелке начиная с его верхней губы справа (не ваша правая рука, не путайте). Это первый сегмент.

Далее линия идет на верхнюю губу слева — это второй сегмент.

Линия спускается на нижнюю губу слева и это третий сегмент.

Заканчивается на нижней губе справа — это четвертый сегмент.

Если спроецировать это не на губы, а на зубы, то получите схему 1 номер , где красными римскими цифрами обозначены сегменты.

С сегментами надеюсь разобрались.

Нумерация зубов в сегменте

Если провести центральную линию от носа до подбородка разделяя лицо вдоль пополам, то эта линия пройдет между центральными зубами верхней и нижней челюсти.

Именно центральный зуб каждый в своем сегменте носит номер 1.

От него нумерация идет до 8-ого зуба во всех 4-х сегментах.

Что получаем в итоге.

Правая верхняя 6-ка – это первый сегмент зуб номер 6 или в цифрах — 16.

А нижний левый клык — 33.

Разобрались? Точно? Обращайтесь за консультацией стоматолога в клинику TopSmile

Прочитайте больше полезных статей добавленных недавно:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age.[1] That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology (that is, the relationship between the shape and form of the tooth in question and its inferred function) of the teeth of an animal.[2]

Animals whose teeth are all of the same type, such as most non-mammalian vertebrates, are said to have homodont dentition, whereas those whose teeth differ morphologically are said to have heterodont dentition. The dentition of animals with two successions of teeth (deciduous, permanent) is referred to as diphyodont, while the dentition of animals with only one set of teeth throughout life is monophyodont. The dentition of animals in which the teeth are continuously discarded and replaced throughout life is termed polyphyodont.[2] The dentition of animals in which the teeth are set in sockets in the jawbones is termed thecodont.

Overview[edit]

The evolutionary origin of the vertebrate dentition remains contentious. Current theories suggest either an «outside-in» or «inside-out» evolutionary origin to teeth, with the dentition arising from odontodes on the skin surface moving into the mouth, or vice versa.[3] Despite this debate, it is accepted that vertebrate teeth are homologous to the dermal denticles found on the skin of basal Gnathostomes (i.e. Chondrichtyans).[4] Since the origin of teeth some 450 mya, the vertebrate dentition has diversified within the reptiles, amphibians, and fish: however most of these groups continue to possess a long row of pointed or sharp-sided, undifferentiated teeth (homodont) that are completely replaceable. The mammalian pattern is significantly different. The teeth in the upper and lower jaws in mammals have evolved a close-fitting relationship such that they operate together as a unit. «They ‘occlude’, that is, the chewing surfaces of the teeth are so constructed that the upper and lower teeth are able to fit precisely together, cutting, crushing, grinding or tearing the food caught between.»[5]

All mammals except the monotremes, the xenarthrans, the pangolins, and the cetaceans[citation needed] have up to four distinct types of teeth, with a maximum number for each. These are the incisor (cutting), the canine, the premolar, and the molar (grinding). The incisors occupy the front of the tooth row in both upper and lower jaws. They are normally flat, chisel-shaped teeth that meet in an edge-to-edge bite. Their function is cutting, slicing, or gnawing food into manageable pieces that fit into the mouth for further chewing. The canines are immediately behind the incisors. In many mammals, the canines are pointed, tusk-shaped teeth, projecting beyond the level of the other teeth. In carnivores, they are primarily offensive weapons for bringing down prey. In other mammals such as some primates, they are used to split open hard-surfaced food. In humans, the canine teeth are the main components in occlusal function and articulation. The mandibular teeth function against the maxillary teeth in a particular movement that is harmonious to the shape of the occluding surfaces. This creates the incising and grinding functions. The teeth must mesh together the way gears mesh in a transmission. If the interdigitation of the opposing cusps and incisal edges are not directed properly the teeth will wear abnormally (attrition), break away irregular crystalline enamel structures from the surface (abrasion), or fracture larger pieces (abfraction). This is a three-dimensional movement of the mandible in relation to the maxilla. There are three points of guidance: the two posterior points provided by the temporomandibular joints and the anterior component provided by the incisors and canines. The incisors mostly control the vertical opening of the chewing cycle when the muscles of mastication move the jaw forwards and backwards (protrusion/retrusion). The canines come into function guiding the vertical movement when the chewing is side to side (lateral). The canines alone can cause the other teeth to separate at the extreme end of the cycle (cuspid guided function) or all the posterior teeth can continue to stay in contact (group function). The entire range of this movement is the envelope of mastacatory function. The initial movement inside this envelope is directed by the shape of the teeth in contact and the Glenoid Fossa/Condyle shape. The outer extremities of this envelope are limited by muscles, ligaments and the articular disc of the TMJ. Without the guidance of anterior incisors and canines, this envelope of function can be destructive to the remaining teeth resulting in periodontal trauma from occlusion seen as wear, fracture or tooth loosening and loss. The premolars and molars are at the back of the mouth. Depending on the particular mammal and its diet, these two kinds of teeth prepare pieces of food to be swallowed by grinding, shearing, or crushing. The specialised teeth—incisors, canines, premolars, and molars—are found in the same order in every mammal.[6] In many mammals, the infants have a set of teeth that fall out and are replaced by adult teeth. These are called deciduous teeth, primary teeth, baby teeth or milk teeth.[7][8] Animals that have two sets of teeth, one followed by the other, are said to be diphyodont. Normally the dental formula for milk teeth is the same as for adult teeth except that the molars are missing.

Dental formula[edit]

Because every mammal’s teeth are specialised for different functions, many mammal groups have lost the teeth that are not needed in their adaptation. Tooth form has also undergone evolutionary modification as a result of natural selection for specialised feeding or other adaptations. Over time, different mammal groups have evolved distinct dental features, both in the number and type of teeth and in the shape and size of the chewing surface.[9]

The number of teeth of each type is written as a dental formula for one side of the mouth, or quadrant, with the upper and lower teeth shown on separate rows. The number of teeth in a mouth is twice that listed, as there are two sides. In each set, incisors (I) are indicated first, canines (C) second, premolars (P) third, and finally molars (M), giving I:C:P:M.[9][10] So for example, the formula 2.1.2.3 for upper teeth indicates 2 incisors, 1 canine, 2 premolars, and 3 molars on one side of the upper mouth. The deciduous dental formula is notated in lowercase lettering preceded by the letter d: for example: di:dc:dp.[10]

An animal’s dentition for either deciduous or permanent teeth can thus be expressed as a dental formula, written in the form of a fraction, which can be written as I.C.P.MI.C.P.M, or I.C.P.M / I.C.P.M.[10][11] For example, the following formulae show the deciduous and usual permanent dentition of all catarrhine primates, including humans:

- Deciduous:

[7] This can also be written as di2.dc1.dm2di2.dc1.dm2. Superscript and subscript denote upper and lower jaw, i.e. do not indicate mathematical operations; the numbers are the count of the teeth of each type. The dashes (-) in the formula are likewise not mathematical operators, but spacers, meaning «to»: for instance the human formula is 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 meaning that people may have 2 or 3 molars on each side of each jaw. ‘d’ denotes deciduous teeth (i.e. milk or baby teeth); lower case also indicates temporary teeth. Another annotation is 2.1.0.22.1.0.2, if the fact that it pertains to deciduous teeth is clearly stated, per examples found in some texts such as The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution[10]

- Permanent:

[7] This can also be written as 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. When the upper and lower dental formulae are the same, some texts write the formula without a fraction (in this case, 2.1.2.3), on the implicit assumption that the reader will realise it must apply to both upper and lower quadrants. This is seen, for example, throughout The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution.

The greatest number of teeth in any known placental land mammal[specify] was 48, with a formula of 3.1.5.33.1.5.3.[9] However, no living placental mammal has this number. In extant placental mammals, the maximum dental formula is 3.1.4.33.1.4.3 for pigs. Mammalian tooth counts are usually identical in the upper and lower jaws, but not always. For example, the aye-aye has a formula of 1.0.1.31.0.0.3, demonstrating the need for both upper and lower quadrant counts.[10]

Tooth naming discrepancies[edit]

Teeth are numbered starting at 1 in each group. Thus the human teeth are I1, I2, C1, P3, P4, M1, M2, and M3.[12] (See next paragraph for premolar naming etymology.) In humans, the third molar is known as the wisdom tooth, whether or not it has erupted.[13]

Regarding premolars, there is disagreement regarding whether the third type of deciduous tooth is a premolar (the general consensus among mammalogists) or a molar (commonly held among human anatomists).[8] There is thus some discrepancy between nomenclature in zoology and in dentistry. This is because the terms of human dentistry, which have generally prevailed over time, have not included mammalian dental evolutionary theory. There were originally four premolars in each quadrant of early mammalian jaws. However, all living primates have lost at least the first premolar. «Hence most of the prosimians and platyrrhines have three premolars. Some genera have also lost more than one. A second premolar has been lost in all catarrhines. The remaining permanent premolars are then properly identified as P2, P3 and P4 or P3 and P4; however, traditional dentistry refers to them as P1 and P2».[7]

Dental eruption sequence[edit]

The order in which teeth emerge through the gums is known as the dental eruption sequence. Rapidly developing anthropoid primates such as macaques, chimpanzees, and australopithecines have an eruption sequence of M1 I1 I2 M2 P3 P4 C M3, whereas anatomically modern humans have the sequence M1 I1 I2 C P3 P4 M2 M3. The later that tooth emergence begins, the earlier the anterior teeth (I1–P4) appear in the sequence.[12]

Dental formulae examples[edit]

| Species | Dental formula | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Non placental | Non-placental mammals such as marsupials (e.g., opossums) can have more teeth than placentals. | |

| Bilby | 5.1.3.43.1.3.4[15] | |

| Kangaroo | 3.1.2.41.0.2.4[16] | |

| Musky rat-kangaroo | 3.1.1.42.0.1.4[17] | |

| Rest of Potoroidae | 3.1.1.41.0.1.4[17] | The marsupial family Potoroidae includes the bettongs, potoroos, and two of the rat-kangaroos. All are rabbit-sized, brown, jumping marsupials and resemble a large rodent or a very small wallaby. |

| Tasmanian devil | 4.1.2.43.1.2.4 [18] | |

| Opossum | 5.1.3.44.1.3.4 [19] | |

| Placental | Some examples of dental formulae for placental mammals. | |

| Apes | 2.1.2.32.1.2.3 | All apes (excluding 20–23% of humans) and Old World monkeys share this formula, sometimes known as the cercopithecoid dental formula.[13] |

| Armadillo | 0.0.7.10.0.7.1[20] | |

| Aye-aye | 1.0.1.31.0.0.3[21] | A prosimian. The aye-aye’s deciduous dental formula (dI:dC:dM) is 2.1.22.1.2.[10] |

| Badger | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] | |

| Big brown bat | 2.1.1.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Red bat, hoary bat, Seminole bat, Mexican free-tailed bat | 1.1.2.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Camel | 1.1.3.33.1.2.3[23] | |

| Cat (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.2.0[24] | |

| Cat (permanent) | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[11] | The last upper premolar and first lower molar of the cat, since it is a carnivore, are called carnassials and are used to slice meat and skin. |

| Cow | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[25] | The cow has no upper incisors or canines, the rostral portion of the upper jaw forming a dental pad. The lower canine is incisiform, giving the appearance of a 4th incisor. |

| Dog (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.3.0[24] | |

| Dog (permanent) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Eared Seal | 3.1.4.1-32.1.4.1[26] | |

| Eulemur | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the large Malagasy or ‘true’ lemurs belong.[27] Ruffed lemurs (genus Varecia),[28] dwarf lemurs (genus Mirza),[29] and mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) also have this dental formula, but the mouse lemurs have a dental comb.[30] |

| Euoticus | 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the needle-clawed bushbabies (or galagos) belong. Specialised morphology for gummivory includes procumbent dental comb and caniniform upper anterior premolars.[27] |

| Fox (red) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Guinea pig | 1.0.1.31.0.1.3[31] | |

| Hedgehog | 3.1.3.32.1.2.3[22] | |

| Horse (deciduous) | 3.0.3.03.0.3.0[32][33] | |

| Horse (permanent) | 3.0-1.3-4.33.0-1.3.3 | Permanent dentition varies from 36 to 42, depending on the presence or absence of canines and the number of premolars.[34] The first premolar (wolf tooth) may be absent or rudimentary,[32][33] and is mostly present only in the upper (maxillary) jaw.[33] The canines are small and spade-shaped, and usually present only in males.[34] Canines appear in 20–25% of females and are usually smaller than in males.[33][35] |

| Human (deciduous teeth) | 2.1.2.02.1.2.0 | |

| Human (permanent teeth) | 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 | Wisdom teeth are congenitally absent in 20–23% of the human population; the proportion of agenesis of wisdom teeth varies considerably among human populations, ranging from a near 0% incidence rate among Aboriginal Tasmanians to near 100% among Indigenous Mexicans.[36] |

| Indri | See comment | A prosimian. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Proponents of both formulae agree there are 30 teeth and that there are only four teeth in the dental comb.[37] |

| Lepilemur | 0.1.3.32.1.3.3 | A prosimian. The upper incisors are lost in the adult, but are present in the deciduous dentition.[38] |

| Lion | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[39] | |

| Mole | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Mouse | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | Plains pocket mouse (Perognathus flavescens) have dental formula of 1.0.1.31.0.1.3.[40] |

| New World monkeys | See comment | All New World monkeys have a dentition formula of 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 or 2.1.3.22.1.3.2.[13] |

| Pantodonta | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[41] | Extinct suborder of early eutherians. |

| Pig (deciduous) | 3.1.4.03.1.4.0[24] | |

| Pig (permanent) | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Rabbit | 2.0.3.31.0.2.3[11] | |

| Raccoon | 3.1.4.23.1.4.2 | |

| Rat | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Sheep (deciduous) | 0.0.3.04.0.3.0[24] | |

| Sheep (permanent) | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[19] | |

| Shrew | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3[22] | |

| Sifakas | See comment | Prosimians. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Possess dental comb comprising four teeth.[42] |

| Slender loris Slow loris |

2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimians. Lower incisors and canines form a dental comb; upper anterior dentition is peg-like and short.[43][44] |

| Squirrel | 1.0.2.31.0.1.3[22] | |

| Tarsiers | 2.1.3.31.1.3.3 | Prosimians.[45] |

| Tiger | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[46] | |

| Vole (field) | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Weasel | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] |

Dentition use in archaeology[edit]

Dentition, or the study of teeth, is an important area of study for archaeologists, especially those specializing in the study of older remains.[47][48][49] Dentition affords many advantages over studying the rest of the skeleton itself (osteometry). The structure and arrangement of teeth is constant and, although it is inherited, does not undergo extensive change during environmental change, dietary specializations, or alterations in use patterns. The rest of the skeleton is much more likely to exhibit change because of adaptation. Teeth also preserve better than bone, and so the sample of teeth available to archaeologists is much more extensive and therefore more representative.

Dentition is particularly useful in tracking ancient populations’ movements, because there are differences in the shapes of incisors, the number of grooves on molars, presence/absence of wisdom teeth, and extra cusps on particular teeth. These differences can not only be associated with different populations across space, but also change over time so that the study of the characteristics of teeth could say which population one is dealing with, and at what point in that population’s history they are.

Dinosaurs[edit]

A dinosaur’s dentition included all the teeth in its jawbones, which consist of the dentary, maxillary, and in some cases the premaxillary bones. The maxilla is the main bone of the upper jaw. The premaxilla is a smaller bone forming the anterior of the animal’s upper jaw. The dentary is the main bone that forms the lower jaw (mandible). The predentary is a smaller bone that forms the anterior end of the lower jaw in ornithischian dinosaurs; it is always edentulous and supported a horny beak.

Unlike modern lizards, dinosaur teeth grew individually in the sockets of the jawbones, which are known as the alveoli. This thecodont dentition is also present in crocodilians and mammals, but is not found among the non-archosaur reptiles, which instead have acrodont or pleurodont dentition.[50] Teeth that were lost were replaced by teeth below the roots in each tooth socket. Occlusion refers to the closing of the dinosaur’s mouth, where the teeth from the upper and lower parts of the jaw meet. If the occlusion causes teeth from the maxillary or premaxillary bones to cover the teeth of the dentary and predentary, the dinosaur is said to have an overbite, the most common condition in this group. The opposite condition is considered to be an underbite, which is rare in theropod dinosaurs.

The majority of dinosaurs had teeth that were similarly shaped throughout their jaws but varied in size. Dinosaur tooth shapes included cylindrical, peg-like, teardrop-shaped, leaf-like, diamond-shaped and blade-like. A dinosaur that has a variety of tooth shapes is said to have heterodont dentition. An example of this are dinosaurs of the group Heterodontosauridae and the enigmatic early dinosaur, Eoraptor. While most dinosaurs had a single row of teeth on each side of their jaws, others had dental batteries where teeth in the cheek region were fused together to form compound teeth. Individually these teeth were not suitable for grinding food, but when joined together with other teeth they would form a large surface area for the mechanical digestion of tough plant materials. This type of dental strategy is observed in ornithopod and ceratopsian dinosaurs as well as the duck-billed hadrosaurs, which had more than one hundred teeth in each dental battery. The teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs, called ziphodont, were typically blade-like or cone-shaped, curved, with serrated edges. This dentition was adapted for grasping and cutting through flesh. In some cases, as observed in the railroad-spike-sized teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex, the teeth were designed to puncture and crush bone. Some dinosaurs had procumbent teeth, which projected forward in the mouth.[51]

See also[edit]

- Deciduous teeth

- Dental notation

- Dentistry

- Dentition analysis

- Odontometrics

- Permanent teeth

- Phalangeal formula

- Teething

- Tooth eruption

Dentition discussions in other articles[edit]

Some articles have helpful discussions on dentition, which will be listed as identified.

- Lemur

Citations[edit]

- ^ Angus Stevenson, ed. (2007), «Dentition definition», Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, vol. 1: A–M (6th ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 646, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ^ a b Martin (1983), p. 103

- ^ Fraser, G. J.; et al. (2010). «The odontode explosion: The origin of tooth-like structures in vertebrates». BioEssays. 32 (9): 808–817. doi:10.1002/bies.200900151. PMC 3034446. PMID 20730948.

- ^ Martin et al. (2016) Sox2+ progenitors in sharks link taste development with the evolution of regenerative teeth from denticles, PNAS

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–131

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 132–135

- ^ a b c d Swindler (2002), p. 11

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 135

- ^ a b c Weiss & Mann (1985), p. 134

- ^ a b c d e f Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139

- ^ a b c Martin (1983), p. 102

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139. See section on dental eruption sequence, where numbering used is per this text.

- ^ a b c Marvin Harris (1988), Culture, People, Nature: An Introduction to General Anthropology (5th ed.), New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-042697-2

- ^ Unless otherwise stated, the formulae can be assumed to be for adult, or permanent dentition.

- ^ Johnson, Ken A. (n.d.). ««Fauna of Australia»» (PDF). Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia

- ^ «Kangaroo». www.1902encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b Andrew W. Claridge; John H. Seebeck; Randy Rose (2007), Bettongs, Potoroos and the Musky Rat-kangaroo, Csiro Publishing, ISBN 978-0-643-09341-6

- ^ University Of Edinburgh Natural History Collection, archived from the original on 2012-03-01

- ^ a b c d Dental formulae of mammal skulls of North America, Wildwood Tracking, archived from the original on 2011-04-14

- ^ Freeman, Patricia W.; Genoways, Hugh H. (December 1998), «Recent northern records of the Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypodidae) in Nebraska», The Southwestern Naturalist, 43 (4): 491–504, JSTOR 30054089, archived from the original on 2011-06-11

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), pp. 134, 139

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «The Skulls». Chunnie’s British Mammal Skulls. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Bravo, P. Walter (2016-08-27). «Camelidae». veteriankey.com. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula for both Bactrian and dromedary camels is incisors (I) 1/3, canines (C) 1/1, premolars (P) 3/2, molars (M) 3/3.

- ^ a b c d «Dental formulae». www.provet.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Using Dentition to Age Cattle». fsis.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Myers, Phil (2000). ««Otariidae»«. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula is 3/2, 1/1, 4/4, 1-3/1 = 34-38.

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 177

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 550

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 340

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 335

- ^ Noonan, Denise. «The Guinea Pig (Cavia porcellus)» (PDF). ANZCCART. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-04.

- ^ a b Pence (2002), p. 7

- ^ a b c d Cirelli

- ^ a b Ultimate Ungulates

- ^ Regarding horse dentition, Pence (2002, p. 7) gives erroneous upper and lower figures of 40 to 44 for the dental range. It is not possible to arrive at this range from the figures she provides. The figures from Cirelli and Ultimate Ungulates are more reliable, although there is a self-evident error for Cirelli’s calculation of the upper female range of 40, which is not possible from the figures he provides. One can only arrive at an upper figure of 38 without canines, which for females Cirelli shows as 0/0. It appears canines do sometimes appear in females, hence the sentence in Ultimate Ungulates that canines are «usually present only in males». However, Pence’s and Cirelli’s references are clearly otherwise useful, hence the inclusion, but with the caveat of this footnote.

- ^ Rozkovcová, E.; Marková, M.; Dolejší, J. (1999). «Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin». Sborník Lékařský. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 267

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 300

- ^ «Dental Formula». www.geocities.ws. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens)». www.nsrl.ttu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth David (2006). «Cimolesta». The Beginning of the Age of Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 94–118. ISBN 978-0-8018-8472-6.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 438

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 309

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 371

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 520

- ^ Emily, Peter P.; Eisner, Edward R. (2021-06-16). Zoo and Wild Animal Dentistry. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 319. ISBN 978-1119545811.

- ^ Towle, Ian; Irish, Joel D.; Groote, Isabelle De (2017). «Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi» (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (1): 184–192. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23250. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 28542710.

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–135

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005). The utility of dental formulae in species identification is indicated throughout this dictionary. Dental formulae are noted for many species, both extant and extinct, and where unknown (in some extinct species) this is noted.

- ^ «Palaeos Vertebrates > Bones > Teeth: Tooth Implantation». Palaeos: Life through Deep Time. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Martin, A. J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. 560 pp. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

General references[edit]

- Adovasio, J. M.; Pedler, David (2005), «The peopling of North America», in Pauketat, Timothy R.; Loren, Diana DiPaolo (eds.), North American Archaeology, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 35–36, ISBN 978-0-631-23184-4

- Cirelli, Al, Equine Dentition (PDF), Nevada: University of Nevada, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Mai, Larry L.; Young Owl, Marcus; Kersting, M. Patricia (2005), The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution, Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66486-8

- Martin, E. A. (1983), Macmillan Dictionary of Life Sciences (2nd revised ed.), London: Macmillan Press, ISBN 978-0-333-34867-3

- Pence, Patricia (2002), Equine Dentistry: A Practical Guide, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 978-0-683-30403-9

- Swindler, Daris R. (2002), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates (PDF), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6

- Ultimate Ungulates, Family Equidae: Horses, asses, and zebras, Ultimate Unqulate.com, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Weiss, M. L.; Mann, A. E. (1985), Human Biology and Behaviour: An Anthropological Perspective (4th ed.), Boston: Little Brown, ISBN 978-0-673-39013-4

Further reading[edit]

- Daris R. Swindler (2002), «Chapter 1: Introduction (pp. 1–11) and Chapter 2: Dental anatomy (pp. 12–20).» (PDF), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6 See also preview pages in Google books

- Feldhamer, George A.; Lee C. Drickhamer; Stephen H. Vessey; Joseph F. Merritt; Carey Krajewski (2007), «4: Evolution and Dental Characteristics», Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 48–67, ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9, retrieved 7 June 2010 (link provided to title page to give reader choice of scrolling straight to relevant chapter or perusing other material).

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dentition.

- Colorado State’s Dental Anatomy Page

- For image of skulls and more information on dental formula of mammals.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age.[1] That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology (that is, the relationship between the shape and form of the tooth in question and its inferred function) of the teeth of an animal.[2]

Animals whose teeth are all of the same type, such as most non-mammalian vertebrates, are said to have homodont dentition, whereas those whose teeth differ morphologically are said to have heterodont dentition. The dentition of animals with two successions of teeth (deciduous, permanent) is referred to as diphyodont, while the dentition of animals with only one set of teeth throughout life is monophyodont. The dentition of animals in which the teeth are continuously discarded and replaced throughout life is termed polyphyodont.[2] The dentition of animals in which the teeth are set in sockets in the jawbones is termed thecodont.

Overview[edit]

The evolutionary origin of the vertebrate dentition remains contentious. Current theories suggest either an «outside-in» or «inside-out» evolutionary origin to teeth, with the dentition arising from odontodes on the skin surface moving into the mouth, or vice versa.[3] Despite this debate, it is accepted that vertebrate teeth are homologous to the dermal denticles found on the skin of basal Gnathostomes (i.e. Chondrichtyans).[4] Since the origin of teeth some 450 mya, the vertebrate dentition has diversified within the reptiles, amphibians, and fish: however most of these groups continue to possess a long row of pointed or sharp-sided, undifferentiated teeth (homodont) that are completely replaceable. The mammalian pattern is significantly different. The teeth in the upper and lower jaws in mammals have evolved a close-fitting relationship such that they operate together as a unit. «They ‘occlude’, that is, the chewing surfaces of the teeth are so constructed that the upper and lower teeth are able to fit precisely together, cutting, crushing, grinding or tearing the food caught between.»[5]

All mammals except the monotremes, the xenarthrans, the pangolins, and the cetaceans[citation needed] have up to four distinct types of teeth, with a maximum number for each. These are the incisor (cutting), the canine, the premolar, and the molar (grinding). The incisors occupy the front of the tooth row in both upper and lower jaws. They are normally flat, chisel-shaped teeth that meet in an edge-to-edge bite. Their function is cutting, slicing, or gnawing food into manageable pieces that fit into the mouth for further chewing. The canines are immediately behind the incisors. In many mammals, the canines are pointed, tusk-shaped teeth, projecting beyond the level of the other teeth. In carnivores, they are primarily offensive weapons for bringing down prey. In other mammals such as some primates, they are used to split open hard-surfaced food. In humans, the canine teeth are the main components in occlusal function and articulation. The mandibular teeth function against the maxillary teeth in a particular movement that is harmonious to the shape of the occluding surfaces. This creates the incising and grinding functions. The teeth must mesh together the way gears mesh in a transmission. If the interdigitation of the opposing cusps and incisal edges are not directed properly the teeth will wear abnormally (attrition), break away irregular crystalline enamel structures from the surface (abrasion), or fracture larger pieces (abfraction). This is a three-dimensional movement of the mandible in relation to the maxilla. There are three points of guidance: the two posterior points provided by the temporomandibular joints and the anterior component provided by the incisors and canines. The incisors mostly control the vertical opening of the chewing cycle when the muscles of mastication move the jaw forwards and backwards (protrusion/retrusion). The canines come into function guiding the vertical movement when the chewing is side to side (lateral). The canines alone can cause the other teeth to separate at the extreme end of the cycle (cuspid guided function) or all the posterior teeth can continue to stay in contact (group function). The entire range of this movement is the envelope of mastacatory function. The initial movement inside this envelope is directed by the shape of the teeth in contact and the Glenoid Fossa/Condyle shape. The outer extremities of this envelope are limited by muscles, ligaments and the articular disc of the TMJ. Without the guidance of anterior incisors and canines, this envelope of function can be destructive to the remaining teeth resulting in periodontal trauma from occlusion seen as wear, fracture or tooth loosening and loss. The premolars and molars are at the back of the mouth. Depending on the particular mammal and its diet, these two kinds of teeth prepare pieces of food to be swallowed by grinding, shearing, or crushing. The specialised teeth—incisors, canines, premolars, and molars—are found in the same order in every mammal.[6] In many mammals, the infants have a set of teeth that fall out and are replaced by adult teeth. These are called deciduous teeth, primary teeth, baby teeth or milk teeth.[7][8] Animals that have two sets of teeth, one followed by the other, are said to be diphyodont. Normally the dental formula for milk teeth is the same as for adult teeth except that the molars are missing.

Dental formula[edit]

Because every mammal’s teeth are specialised for different functions, many mammal groups have lost the teeth that are not needed in their adaptation. Tooth form has also undergone evolutionary modification as a result of natural selection for specialised feeding or other adaptations. Over time, different mammal groups have evolved distinct dental features, both in the number and type of teeth and in the shape and size of the chewing surface.[9]

The number of teeth of each type is written as a dental formula for one side of the mouth, or quadrant, with the upper and lower teeth shown on separate rows. The number of teeth in a mouth is twice that listed, as there are two sides. In each set, incisors (I) are indicated first, canines (C) second, premolars (P) third, and finally molars (M), giving I:C:P:M.[9][10] So for example, the formula 2.1.2.3 for upper teeth indicates 2 incisors, 1 canine, 2 premolars, and 3 molars on one side of the upper mouth. The deciduous dental formula is notated in lowercase lettering preceded by the letter d: for example: di:dc:dp.[10]

An animal’s dentition for either deciduous or permanent teeth can thus be expressed as a dental formula, written in the form of a fraction, which can be written as I.C.P.MI.C.P.M, or I.C.P.M / I.C.P.M.[10][11] For example, the following formulae show the deciduous and usual permanent dentition of all catarrhine primates, including humans:

- Deciduous:

[7] This can also be written as di2.dc1.dm2di2.dc1.dm2. Superscript and subscript denote upper and lower jaw, i.e. do not indicate mathematical operations; the numbers are the count of the teeth of each type. The dashes (-) in the formula are likewise not mathematical operators, but spacers, meaning «to»: for instance the human formula is 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 meaning that people may have 2 or 3 molars on each side of each jaw. ‘d’ denotes deciduous teeth (i.e. milk or baby teeth); lower case also indicates temporary teeth. Another annotation is 2.1.0.22.1.0.2, if the fact that it pertains to deciduous teeth is clearly stated, per examples found in some texts such as The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution[10]

- Permanent:

[7] This can also be written as 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. When the upper and lower dental formulae are the same, some texts write the formula without a fraction (in this case, 2.1.2.3), on the implicit assumption that the reader will realise it must apply to both upper and lower quadrants. This is seen, for example, throughout The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution.

The greatest number of teeth in any known placental land mammal[specify] was 48, with a formula of 3.1.5.33.1.5.3.[9] However, no living placental mammal has this number. In extant placental mammals, the maximum dental formula is 3.1.4.33.1.4.3 for pigs. Mammalian tooth counts are usually identical in the upper and lower jaws, but not always. For example, the aye-aye has a formula of 1.0.1.31.0.0.3, demonstrating the need for both upper and lower quadrant counts.[10]

Tooth naming discrepancies[edit]

Teeth are numbered starting at 1 in each group. Thus the human teeth are I1, I2, C1, P3, P4, M1, M2, and M3.[12] (See next paragraph for premolar naming etymology.) In humans, the third molar is known as the wisdom tooth, whether or not it has erupted.[13]

Regarding premolars, there is disagreement regarding whether the third type of deciduous tooth is a premolar (the general consensus among mammalogists) or a molar (commonly held among human anatomists).[8] There is thus some discrepancy between nomenclature in zoology and in dentistry. This is because the terms of human dentistry, which have generally prevailed over time, have not included mammalian dental evolutionary theory. There were originally four premolars in each quadrant of early mammalian jaws. However, all living primates have lost at least the first premolar. «Hence most of the prosimians and platyrrhines have three premolars. Some genera have also lost more than one. A second premolar has been lost in all catarrhines. The remaining permanent premolars are then properly identified as P2, P3 and P4 or P3 and P4; however, traditional dentistry refers to them as P1 and P2».[7]

Dental eruption sequence[edit]

The order in which teeth emerge through the gums is known as the dental eruption sequence. Rapidly developing anthropoid primates such as macaques, chimpanzees, and australopithecines have an eruption sequence of M1 I1 I2 M2 P3 P4 C M3, whereas anatomically modern humans have the sequence M1 I1 I2 C P3 P4 M2 M3. The later that tooth emergence begins, the earlier the anterior teeth (I1–P4) appear in the sequence.[12]

Dental formulae examples[edit]

| Species | Dental formula | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Non placental | Non-placental mammals such as marsupials (e.g., opossums) can have more teeth than placentals. | |

| Bilby | 5.1.3.43.1.3.4[15] | |

| Kangaroo | 3.1.2.41.0.2.4[16] | |

| Musky rat-kangaroo | 3.1.1.42.0.1.4[17] | |

| Rest of Potoroidae | 3.1.1.41.0.1.4[17] | The marsupial family Potoroidae includes the bettongs, potoroos, and two of the rat-kangaroos. All are rabbit-sized, brown, jumping marsupials and resemble a large rodent or a very small wallaby. |

| Tasmanian devil | 4.1.2.43.1.2.4 [18] | |

| Opossum | 5.1.3.44.1.3.4 [19] | |

| Placental | Some examples of dental formulae for placental mammals. | |

| Apes | 2.1.2.32.1.2.3 | All apes (excluding 20–23% of humans) and Old World monkeys share this formula, sometimes known as the cercopithecoid dental formula.[13] |

| Armadillo | 0.0.7.10.0.7.1[20] | |

| Aye-aye | 1.0.1.31.0.0.3[21] | A prosimian. The aye-aye’s deciduous dental formula (dI:dC:dM) is 2.1.22.1.2.[10] |

| Badger | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] | |

| Big brown bat | 2.1.1.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Red bat, hoary bat, Seminole bat, Mexican free-tailed bat | 1.1.2.33.1.2.3[19] | |

| Camel | 1.1.3.33.1.2.3[23] | |

| Cat (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.2.0[24] | |

| Cat (permanent) | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[11] | The last upper premolar and first lower molar of the cat, since it is a carnivore, are called carnassials and are used to slice meat and skin. |

| Cow | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[25] | The cow has no upper incisors or canines, the rostral portion of the upper jaw forming a dental pad. The lower canine is incisiform, giving the appearance of a 4th incisor. |

| Dog (deciduous) | 3.1.3.03.1.3.0[24] | |

| Dog (permanent) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Eared Seal | 3.1.4.1-32.1.4.1[26] | |

| Eulemur | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the large Malagasy or ‘true’ lemurs belong.[27] Ruffed lemurs (genus Varecia),[28] dwarf lemurs (genus Mirza),[29] and mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) also have this dental formula, but the mouse lemurs have a dental comb.[30] |

| Euoticus | 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimian genus to which the needle-clawed bushbabies (or galagos) belong. Specialised morphology for gummivory includes procumbent dental comb and caniniform upper anterior premolars.[27] |

| Fox (red) | 3.1.4.23.1.4.3[22] | |

| Guinea pig | 1.0.1.31.0.1.3[31] | |

| Hedgehog | 3.1.3.32.1.2.3[22] | |

| Horse (deciduous) | 3.0.3.03.0.3.0[32][33] | |

| Horse (permanent) | 3.0-1.3-4.33.0-1.3.3 | Permanent dentition varies from 36 to 42, depending on the presence or absence of canines and the number of premolars.[34] The first premolar (wolf tooth) may be absent or rudimentary,[32][33] and is mostly present only in the upper (maxillary) jaw.[33] The canines are small and spade-shaped, and usually present only in males.[34] Canines appear in 20–25% of females and are usually smaller than in males.[33][35] |

| Human (deciduous teeth) | 2.1.2.02.1.2.0 | |

| Human (permanent teeth) | 2.1.2.2-32.1.2.2-3 | Wisdom teeth are congenitally absent in 20–23% of the human population; the proportion of agenesis of wisdom teeth varies considerably among human populations, ranging from a near 0% incidence rate among Aboriginal Tasmanians to near 100% among Indigenous Mexicans.[36] |

| Indri | See comment | A prosimian. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Proponents of both formulae agree there are 30 teeth and that there are only four teeth in the dental comb.[37] |

| Lepilemur | 0.1.3.32.1.3.3 | A prosimian. The upper incisors are lost in the adult, but are present in the deciduous dentition.[38] |

| Lion | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[39] | |

| Mole | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Mouse | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | Plains pocket mouse (Perognathus flavescens) have dental formula of 1.0.1.31.0.1.3.[40] |

| New World monkeys | See comment | All New World monkeys have a dentition formula of 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 or 2.1.3.22.1.3.2.[13] |

| Pantodonta | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[41] | Extinct suborder of early eutherians. |

| Pig (deciduous) | 3.1.4.03.1.4.0[24] | |

| Pig (permanent) | 3.1.4.33.1.4.3[22] | |

| Rabbit | 2.0.3.31.0.2.3[11] | |

| Raccoon | 3.1.4.23.1.4.2 | |

| Rat | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Sheep (deciduous) | 0.0.3.04.0.3.0[24] | |

| Sheep (permanent) | 0.0.3.33.1.3.3[19] | |

| Shrew | 3.1.3.33.1.3.3[22] | |

| Sifakas | See comment | Prosimians. Dental formula disputed. Either 2.1.2.32.0.2.3 or 2.1.2.31.1.2.3. Possess dental comb comprising four teeth.[42] |

| Slender loris Slow loris |

2.1.3.32.1.3.3 | Prosimians. Lower incisors and canines form a dental comb; upper anterior dentition is peg-like and short.[43][44] |

| Squirrel | 1.0.2.31.0.1.3[22] | |

| Tarsiers | 2.1.3.31.1.3.3 | Prosimians.[45] |

| Tiger | 3.1.3.13.1.2.1[46] | |

| Vole (field) | 1.0.0.31.0.0.3[22] | |

| Weasel | 3.1.3.13.1.3.2[22] |

Dentition use in archaeology[edit]

Dentition, or the study of teeth, is an important area of study for archaeologists, especially those specializing in the study of older remains.[47][48][49] Dentition affords many advantages over studying the rest of the skeleton itself (osteometry). The structure and arrangement of teeth is constant and, although it is inherited, does not undergo extensive change during environmental change, dietary specializations, or alterations in use patterns. The rest of the skeleton is much more likely to exhibit change because of adaptation. Teeth also preserve better than bone, and so the sample of teeth available to archaeologists is much more extensive and therefore more representative.

Dentition is particularly useful in tracking ancient populations’ movements, because there are differences in the shapes of incisors, the number of grooves on molars, presence/absence of wisdom teeth, and extra cusps on particular teeth. These differences can not only be associated with different populations across space, but also change over time so that the study of the characteristics of teeth could say which population one is dealing with, and at what point in that population’s history they are.

Dinosaurs[edit]

A dinosaur’s dentition included all the teeth in its jawbones, which consist of the dentary, maxillary, and in some cases the premaxillary bones. The maxilla is the main bone of the upper jaw. The premaxilla is a smaller bone forming the anterior of the animal’s upper jaw. The dentary is the main bone that forms the lower jaw (mandible). The predentary is a smaller bone that forms the anterior end of the lower jaw in ornithischian dinosaurs; it is always edentulous and supported a horny beak.

Unlike modern lizards, dinosaur teeth grew individually in the sockets of the jawbones, which are known as the alveoli. This thecodont dentition is also present in crocodilians and mammals, but is not found among the non-archosaur reptiles, which instead have acrodont or pleurodont dentition.[50] Teeth that were lost were replaced by teeth below the roots in each tooth socket. Occlusion refers to the closing of the dinosaur’s mouth, where the teeth from the upper and lower parts of the jaw meet. If the occlusion causes teeth from the maxillary or premaxillary bones to cover the teeth of the dentary and predentary, the dinosaur is said to have an overbite, the most common condition in this group. The opposite condition is considered to be an underbite, which is rare in theropod dinosaurs.

The majority of dinosaurs had teeth that were similarly shaped throughout their jaws but varied in size. Dinosaur tooth shapes included cylindrical, peg-like, teardrop-shaped, leaf-like, diamond-shaped and blade-like. A dinosaur that has a variety of tooth shapes is said to have heterodont dentition. An example of this are dinosaurs of the group Heterodontosauridae and the enigmatic early dinosaur, Eoraptor. While most dinosaurs had a single row of teeth on each side of their jaws, others had dental batteries where teeth in the cheek region were fused together to form compound teeth. Individually these teeth were not suitable for grinding food, but when joined together with other teeth they would form a large surface area for the mechanical digestion of tough plant materials. This type of dental strategy is observed in ornithopod and ceratopsian dinosaurs as well as the duck-billed hadrosaurs, which had more than one hundred teeth in each dental battery. The teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs, called ziphodont, were typically blade-like or cone-shaped, curved, with serrated edges. This dentition was adapted for grasping and cutting through flesh. In some cases, as observed in the railroad-spike-sized teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex, the teeth were designed to puncture and crush bone. Some dinosaurs had procumbent teeth, which projected forward in the mouth.[51]

See also[edit]

- Deciduous teeth

- Dental notation

- Dentistry

- Dentition analysis

- Odontometrics

- Permanent teeth

- Phalangeal formula

- Teething

- Tooth eruption

Dentition discussions in other articles[edit]

Some articles have helpful discussions on dentition, which will be listed as identified.

- Lemur

Citations[edit]

- ^ Angus Stevenson, ed. (2007), «Dentition definition», Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, vol. 1: A–M (6th ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 646, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ^ a b Martin (1983), p. 103

- ^ Fraser, G. J.; et al. (2010). «The odontode explosion: The origin of tooth-like structures in vertebrates». BioEssays. 32 (9): 808–817. doi:10.1002/bies.200900151. PMC 3034446. PMID 20730948.

- ^ Martin et al. (2016) Sox2+ progenitors in sharks link taste development with the evolution of regenerative teeth from denticles, PNAS

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–131

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 132–135

- ^ a b c d Swindler (2002), p. 11

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 135

- ^ a b c Weiss & Mann (1985), p. 134

- ^ a b c d e f Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139

- ^ a b c Martin (1983), p. 102

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 139. See section on dental eruption sequence, where numbering used is per this text.

- ^ a b c Marvin Harris (1988), Culture, People, Nature: An Introduction to General Anthropology (5th ed.), New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-042697-2

- ^ Unless otherwise stated, the formulae can be assumed to be for adult, or permanent dentition.

- ^ Johnson, Ken A. (n.d.). ««Fauna of Australia»» (PDF). Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

Fauna of Australia Volume 1b — Mammalia

- ^ «Kangaroo». www.1902encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b Andrew W. Claridge; John H. Seebeck; Randy Rose (2007), Bettongs, Potoroos and the Musky Rat-kangaroo, Csiro Publishing, ISBN 978-0-643-09341-6

- ^ University Of Edinburgh Natural History Collection, archived from the original on 2012-03-01

- ^ a b c d Dental formulae of mammal skulls of North America, Wildwood Tracking, archived from the original on 2011-04-14

- ^ Freeman, Patricia W.; Genoways, Hugh H. (December 1998), «Recent northern records of the Nine-banded Armadillo (Dasypodidae) in Nebraska», The Southwestern Naturalist, 43 (4): 491–504, JSTOR 30054089, archived from the original on 2011-06-11

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), pp. 134, 139

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l «The Skulls». Chunnie’s British Mammal Skulls. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Bravo, P. Walter (2016-08-27). «Camelidae». veteriankey.com. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula for both Bactrian and dromedary camels is incisors (I) 1/3, canines (C) 1/1, premolars (P) 3/2, molars (M) 3/3.

- ^ a b c d «Dental formulae». www.provet.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Using Dentition to Age Cattle». fsis.usda.gov. Archived from the original on 2008-09-16. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- ^ Myers, Phil (2000). ««Otariidae»«. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

The dental formula is 3/2, 1/1, 4/4, 1-3/1 = 34-38.

- ^ a b Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 177

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 550

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 340

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 335

- ^ Noonan, Denise. «The Guinea Pig (Cavia porcellus)» (PDF). ANZCCART. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-04.

- ^ a b Pence (2002), p. 7

- ^ a b c d Cirelli

- ^ a b Ultimate Ungulates

- ^ Regarding horse dentition, Pence (2002, p. 7) gives erroneous upper and lower figures of 40 to 44 for the dental range. It is not possible to arrive at this range from the figures she provides. The figures from Cirelli and Ultimate Ungulates are more reliable, although there is a self-evident error for Cirelli’s calculation of the upper female range of 40, which is not possible from the figures he provides. One can only arrive at an upper figure of 38 without canines, which for females Cirelli shows as 0/0. It appears canines do sometimes appear in females, hence the sentence in Ultimate Ungulates that canines are «usually present only in males». However, Pence’s and Cirelli’s references are clearly otherwise useful, hence the inclusion, but with the caveat of this footnote.

- ^ Rozkovcová, E.; Marková, M.; Dolejší, J. (1999). «Studies on agenesis of third molars amongst populations of different origin». Sborník Lékařský. 100 (2): 71–84. PMID 11220165.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 267

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 300

- ^ «Dental Formula». www.geocities.ws. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ «Plains Pocket Mouse (Perognathus flavescens)». www.nsrl.ttu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Rose, Kenneth David (2006). «Cimolesta». The Beginning of the Age of Mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 94–118. ISBN 978-0-8018-8472-6.

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 438

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 309

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 371

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005), p. 520

- ^ Emily, Peter P.; Eisner, Edward R. (2021-06-16). Zoo and Wild Animal Dentistry. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 319. ISBN 978-1119545811.

- ^ Towle, Ian; Irish, Joel D.; Groote, Isabelle De (2017). «Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi» (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (1): 184–192. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23250. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 28542710.

- ^ Weiss & Mann (1985), pp. 130–135

- ^ Mai, Young Owl & Kersting (2005). The utility of dental formulae in species identification is indicated throughout this dictionary. Dental formulae are noted for many species, both extant and extinct, and where unknown (in some extinct species) this is noted.

- ^ «Palaeos Vertebrates > Bones > Teeth: Tooth Implantation». Palaeos: Life through Deep Time. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Martin, A. J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. 560 pp. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

General references[edit]

- Adovasio, J. M.; Pedler, David (2005), «The peopling of North America», in Pauketat, Timothy R.; Loren, Diana DiPaolo (eds.), North American Archaeology, Blackwell Publishing, pp. 35–36, ISBN 978-0-631-23184-4

- Cirelli, Al, Equine Dentition (PDF), Nevada: University of Nevada, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Mai, Larry L.; Young Owl, Marcus; Kersting, M. Patricia (2005), The Cambridge Dictionary of Human Biology and Evolution, Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66486-8

- Martin, E. A. (1983), Macmillan Dictionary of Life Sciences (2nd revised ed.), London: Macmillan Press, ISBN 978-0-333-34867-3

- Pence, Patricia (2002), Equine Dentistry: A Practical Guide, Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, ISBN 978-0-683-30403-9

- Swindler, Daris R. (2002), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates (PDF), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6

- Ultimate Ungulates, Family Equidae: Horses, asses, and zebras, Ultimate Unqulate.com, retrieved 7 June 2010

- Weiss, M. L.; Mann, A. E. (1985), Human Biology and Behaviour: An Anthropological Perspective (4th ed.), Boston: Little Brown, ISBN 978-0-673-39013-4

Further reading[edit]

- Daris R. Swindler (2002), «Chapter 1: Introduction (pp. 1–11) and Chapter 2: Dental anatomy (pp. 12–20).» (PDF), Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-65289-6 See also preview pages in Google books

- Feldhamer, George A.; Lee C. Drickhamer; Stephen H. Vessey; Joseph F. Merritt; Carey Krajewski (2007), «4: Evolution and Dental Characteristics», Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 48–67, ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9, retrieved 7 June 2010 (link provided to title page to give reader choice of scrolling straight to relevant chapter or perusing other material).

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dentition.

- Colorado State’s Dental Anatomy Page

- For image of skulls and more information on dental formula of mammals.

Большинству пациентов на приеме у дантиста давно стали привычны сложные стоматологические термины. Мост, винир, пломба, премоляр – эти слова практически не вызывают затруднений для понимания, когда врач диагностирует проблему и назначает лечение.

Чаще всего больных сбивает с толку непонятная нумерация. К примеру, говоря о зубах мудрости, стоматолог может объяснить пациенту, что в лечении нуждаются нижние «восьмерки». При этом у каждого зуба есть собственное числовое обозначение, которое может отражать его тип и точное местоположение в ротовой полости.

За все существование стоматологии как науки было изобретено несколько классификаций зубов, которые называются зубными формулами. В зависимости от выбранного способа нумерации каждому зубу присваивается определенный номер. В некоторых системах зубы обозначаются сочетанием букв, цифр и даже символов, что позволяет изобразить зубной ряд в виде точной схемы.

Зачем нужна нумерация зубов в стоматологии ↑

Задача системы нумерации зубов — оптимизировать диагностику полости рта пациента и максимально конкретно внести полученную информацию в его амбулаторную карту.

По каким же принципам нумеруются зубы? Прежде всего, исходя из особенностей строения челюсти человека.

Каждый человеческий зуб имеет строго индивидуальную конфигурацию, обусловленную выполняемыми им каждодневными задачами. Одни зубы предназначены для откусывания пищи, а другие — для ее пережевывания.

Постоянные зубы человека

- С целью их безошибочного обозначения, так, чтобы сразу стало понятно, о каком конкретном зубе идет речь, и была придумана система нумерации.

- Нумерация начинается с середины зубного ряда по направлению влево и вправо от него.

- Два передних зуба или резца, задачей которых является откусывание пищи, обозначаются номером 1, а идущие следом за ними номером 2.

Клыки, размещающиеся после передних резцов, предназначены для того чтобы откусывать и отрывать особенно твердую пищу и имеют порядковый номер 3.

Попадая в ротовую полость, откушенные кусочки пищи пережевываются идущими следом за клыками жевательными зубами. Они имеют название премоляры и обозначаются цифрами 4 и 5.

А для наиболее эффективного измельчения и пережевывания пищи существуют большие жевательные зубы или моляры, рабочая поверхность которых имеет характерные бугорки. Их порядковый номер — 6, 7 и 8, называемые зубами мудрости.

Нумерация зубов

Конечно, нумерация сильно облегчает их обозначение. Но как узнать в какой части челюсти находится заданный зуб: в верхней челюсти или нижней, слева или справа? Для этого человеческую челюсть визуально поделили на четыре части или сегмента.

Отсчет зубов по сегментам производится с правой стороны верхнего ряда по часовой стрелке. Таким образом, зубы находящиеся в первом сегменте (верхний ряд справа) будут называться десятками, а во втором сегменте (верхний ряд слева) — двадцатками.

На нижнем левом ряду находятся тридцатки, а в правом — сороковые. Называя обследуемый зуб, его порядковый номер добавляют к номеру сегмента, в котором он расположен. И таким образом, получается, что у каждого зуба есть свой индивидуальный номер.

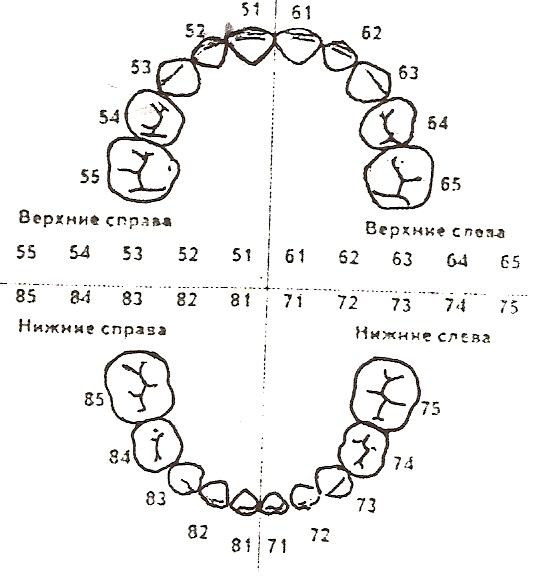

Зубная формула

Несколько иным методом нумеруют зубы в детской стоматологии, что связанно с особенностями анатомии детской челюсти. Прорезывание молочных зубов, происходящее в возрасте от 4 до 6 месяцев, совпадает со временем начала формирования зачатков постоянных зубов.

Если ребенку пятилетнего возраста сделать рентгеновский снимок челюсти, на нем будут визуализироваться и молочные, и постоянные зубы.

А так как последние уже имеют свою нумерацию с 11 по 48, то для счета молочных используют следующие десятки.

Нумерация молочных зубов

В верхнем ряду справа будут находиться пятидесятые зубы, а слева — шестидесятые. Нижний левый ряд занимают семидесятые, а правый — восьмидесятые. Так что теперь, зная особенности счета молочных зубов, родители уже не будут так удивляться заявлению врача о требующем лечения 72-ом зубе.

Видео: зубы человека

Основные системы ↑

На сегодняшний день существует несколько основных систем нумерации.

- Квадратно-цифровая система Зигмонди-Палмера.

- Система Хадерупа.

- Международная двухцифровая система Виола.

- Универсальная цифровая буквенная система.

Каждая из них по своему удобна и имеет свои особенности исчисления постоянных и молочных зубов.

Квадратно-цифровая система Зигмонди-Палмера

Система Зигмонди-Палмера или, как ее еще называют, квадратно-цифровая система была принята в 1876 году и до сих пор используется для обозначения зубов у детей и взрослых.

Для счета постоянных зубов используют арабские цифры от 1 до 8, а для молочных — римские от I до V. Само исчисление начинается с середины челюсти.

Формула записи постоянных зубов по системе Зигмонди-Палмера

Формула записи молочных зубов по системе Зигмонди-Палмера

Стандартная квадратно-цифровая система Зигмонди-Палмера чаще всего используется врачами-ортодонтами и челюстно-лицевыми хирургами.

Система Хадерупа

Система Хадерупа отличается использованием знаков «+» и «-» для обозначения верхнего и нижнего ряда зубов соответственно. А вычисление зубов по системе производится при помощи совмещения арабских чисел с данными знаками.

Формула записи постоянных зубов по системе Хадерупа

Молочные зубы обозначают арабскими цифрами от 1 до 5 с добавлением знака «0» и, по аналогии с постоянными зубами, знаками «+» и «-».

Формула записи молочных зубов по системе Хадерупа

Международная двухцифровая система Виола

Двухцифровая система Виола, принятая Международной ассоциацией стоматологов в 1971 году получила широкое распространение в стоматологической практике.

Суть данной системы заключается в делении верхней и нижней челюсти пациента на четыре сегмента (по два на каждую челюсть) по 8 зубов. Причем у взрослых нумерация сегментов исчисляется цифрами с 1 до 4, а у детей — с 5 до 8.

Формула записи постоянных зубов по системе Виола

Формула записи молочных зубов по системе Виола

При необходимости назвать тот или иной зуб его обозначают двузначным числом, где первая цифра является номером сегмента, в котором он располагается, а вторая обозначает его порядковый номер.

С чем связано широкое распространение международной двухцифровой системы Виола? Прежде всего, с отсутствием букв и сложных формул, способствующим удобству ее использования и позволяющие быстро и точно передавать информацию о пациенте по телефону, факсу, электронной почте и т. д.

Универсальная цифровая буквенная система

Принятая американской ассоциацией стоматологов (ADA), универсальная буквенно-цифровая система отличается наличием своего буквенного обозначения, которое зависит от назначения зуба (резцы, клыки, моляры), а также цифрового обозначения его последовательности в зубном ряду.

Так, буквой I обозначают резцы (по два на каждый сегмент, а всего 8), С — клыки (по одному на каждый сегмент, а всего 4), P — это премоляры, число которых составляет 8 единиц, и моляры, обозначенные буквой M, число которых при наличии зубов мудрости составляет 12 единиц.

Формула записи постоянных зубов по универсальной буквенно-цифровой системе

Формула записи молочных зубов по универсальной буквенно-цифровой системе

- Также системой допускается исчисление зубов по сегментам с обозначением зубов, выполняющих одну и ту же функцию одним порядковым номером.

- При этом, как и в системе Виола, используют число сегмента, в котором он находится, в результате чего каждый зуб приобретает свой двузначный порядковый номер.

- Что касается молочных зубов, то, помимо использования буквенной формулы, их могут исчислять, начиная с правого верхнего зуба по часовой стрелке, используя при этом латинские буквы от A до K.

Нумерация в рисунках, схемах и фото ↑

С целью визуального восприятия стоматологических систем исчисления зубов ниже представлены тематические рисунки и схемы.

Квадратно-цифровая система Зигмонди-Палмера

Система Хадерупа

Международная двухцифровая система Виола