Во французском языке все красиво, в том числе и прописные буквы. Писать на французском – это целое искусство. В современных школах, к сожалению, очень мало внимания уделяют почерку.Не зная как пишутся французские буквы, порой очень сложно разобрать текст написанный от руки, а иногда и вовсе загадка, некоторые буквы совсем не похожи на печатные. В основе французской письменности лежит латинский алфавит и диакритические знаки.

В мире современных гаджетов все больше людей предпочитают печатать, нежели писать. А очень зря, теряются очень много навыков, когда совсем перестаем брать в руки ручку чтобы начиркать хотя бы пару строк…

Если Вы все же решитесь написать письмо Пэр Ноэлю, взяв в руки ручку, а не смартфон, наша статья пригодится ;).

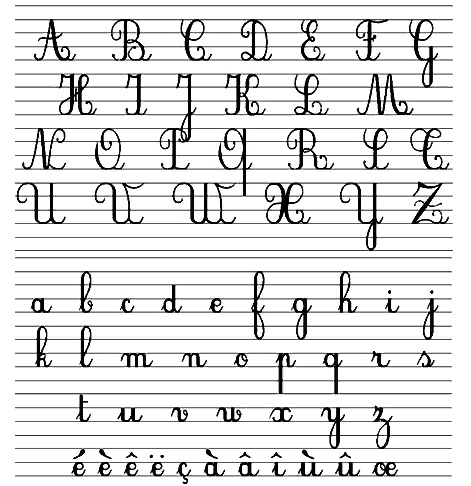

Обратите ниже внимание на написание букв с диакритическими знаками.

Рейтинг 4,6 на основе 29 голосов

Французский алфавит для детей можно легко усвоить вместе с малышом. Ведь дети любят что-то новое, а главное интересное, а ещё лучше если вместе с мамой и папой … Ниже есть несколько вариантов для изучения французского алфавита, выбирайте какой Вам больше понравиться и подходит по темпераменту.

Содержание

- Пишем буквы прописью!

- Графические символы, которые надо знать

- Учим алфавит вместе с малышом!

- Несколько способов выучить алфавит

Пишем буквы прописью!

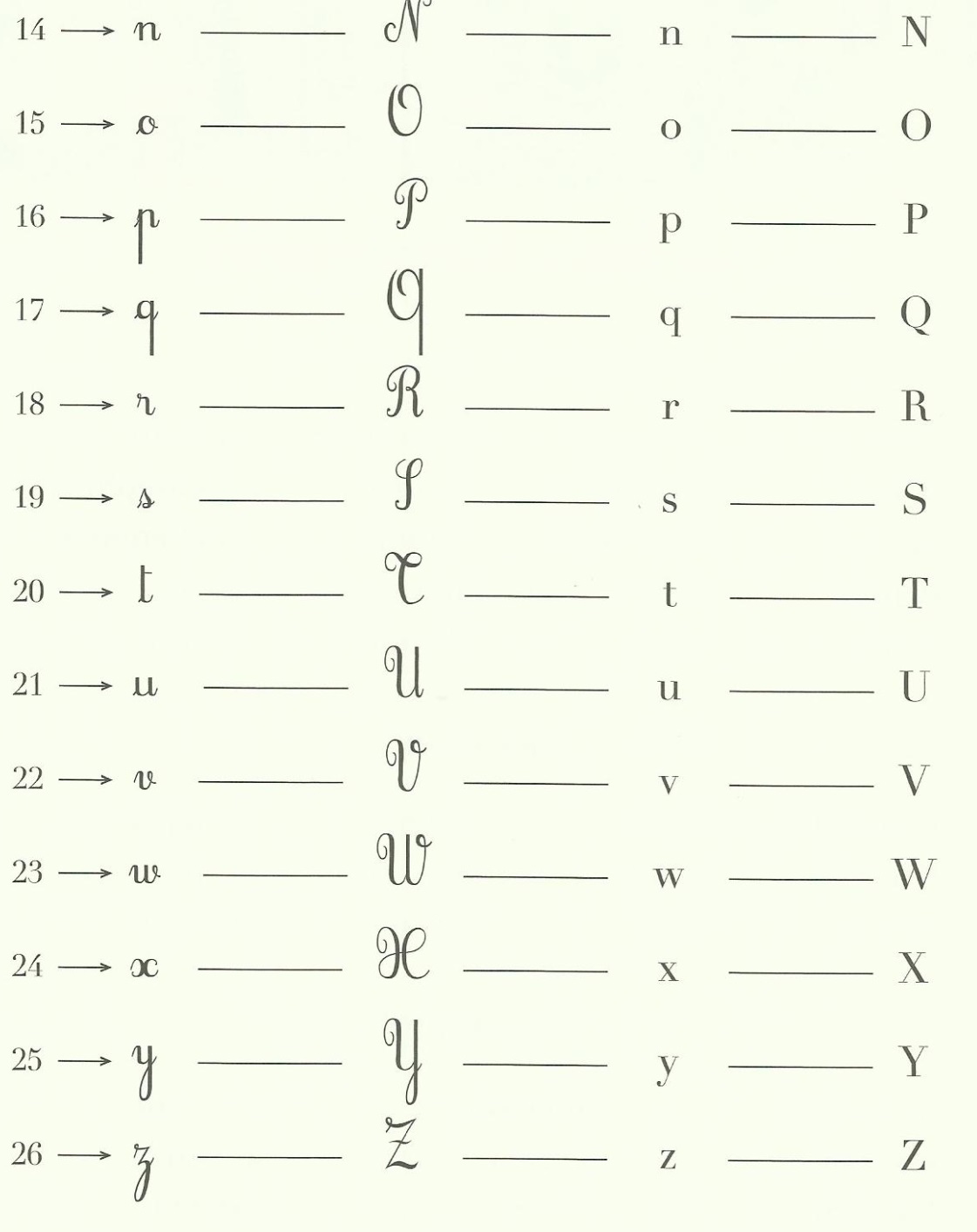

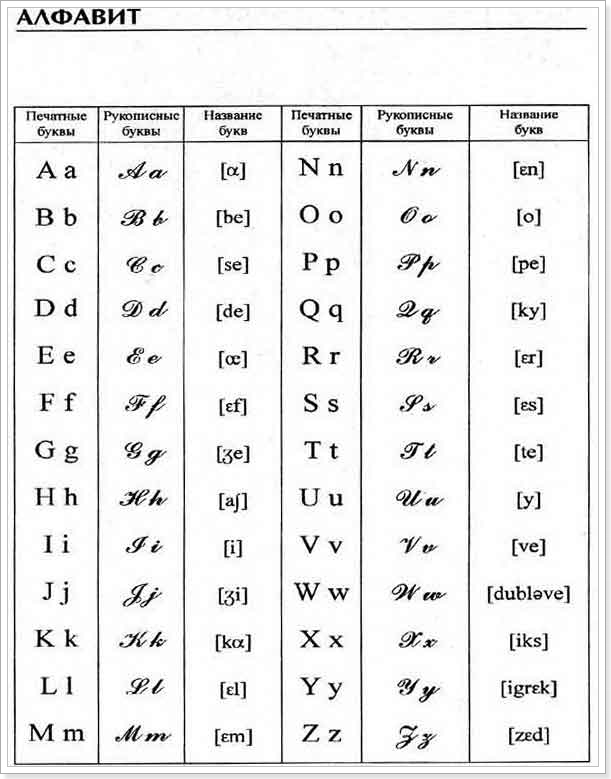

Если вы хотите узнать, как писать прописные французские буквы, то вот они, перед вами. Таблица разделена на колонки: первая с печатными буквами, вторая с прописными и третья с русской транскрипцией этих букв.

Друзья, если вы хотите научиться красиво выводить французские буквы на письме, то потренируйтесь на листке бумаги, стараясь писать буквы так, как в нашей таблице.

Графические символы, которые надо знать

Мы уже рассматривали более подробно все графические символы французского языка. Но раз сегодня мы говорим об алфавите, то стоит вкратце их напомнить.

- Accent aigu: é. Употребляется только с буквой e и означает закрытый звук [e]: enchanté

- Accent grave: à, è, ù: là, frère, où

- Accent circonflexe: â, ê, î, ô, û: âme, être, plaît, clôturer, dû

- Cédille: ç: français

- Tréma: ë, ï, ü, ÿ: Citroën, maïs

Друзья, помните о том, что если не соблюдать все эти графические символы на письме, то это считается орфографической ошибкой. Следовательно, в диктанте, в сочинении или другой письменной работе за это снимают баллы, и ваша оценка будет ниже.

Также, не забудьте про так называемые лигатуры: æ, œ. Впрочем, они нередко заменяются на две буквы: ae (или фонетическую запись é), oe.

Буквы k, w и лигатура æ (довольно редкая) используются только в иностранных словах (kilo —килограмм, wagon — вагон, nævus — бородавка), а также в именах собственных.

Учим алфавит вместе с малышом!

Друзья, если вы решили, что вашему ребенку пора заняться французским языком, то с чего начать, как не с алфавита?

Для детей дошкольного возраста прекрасно подойдут учебно-развлекательные видео и песенки на французском языке про буквы. Слушая песенку, ваш малыш и вы сами можете подпевать диктору, таким образом, осваивая алфавит и первые слова на французском языке.

Мы хотим предложить вам несколько вариантов, которые помогут вашему ребенку быстро выучить французский алфавит.

Здесь очень милый котенок поможет ребенку выучить буквы и повторить их за ним или вместе с ним. Включайте видео вашему малышу столько, сколько нужно! И да, у котенка прекрасное произношение!

Такие видео для детей можно как смотреть, так и просто слушать, изучая французский алфавит и язык в целом. Будьте рядом с вашим ребенком, чтобы в любой момент прийти ему на помощь и объяснить то, чего он не понял или не расслышал.

Несколько способов выучить алфавит

Если вы взрослый человек, то для вас выучить французский алфавит не составит особого труда: достаточно несколько раз прослушать его и повторить вслед за диктором, и voilà – вы его уже знаете! Главное – потренировать правильное произношение.

А вот с малышом дело обстоит иначе, ему потребуется ваша помощь и терпение.

- Во-первых, вы можете использовать те видео по алфавиту, которые мы предложили; найдите и другие ролики по теме алфавита.

- Во-вторых, сделайте процесс изучения букв французского языка креативным: нарисуйте каждую букву на отдельном листе бумаги. Рисуйте вместе с вашим малышом, сделайте каждую букву цветной, узорчатой и красочной.

- В-третьих, к каждой букве нарисуйте или подберите подходящую картинку, например: a – abeille, b – bâteau и т.д.

Теперь, повторив несколько раз алфавит целиком, показывайте ребенку каждую букву отдельно, а он пусть ее произносит. Через пять-шесть таких занятий ваш малыш полностью освоит французский алфавит и сможет рассказать его легко, свободно и без запинки!

Желаем вам удачи, друзья и до новых встреч!

Прописные буквы французского языка

На чтение 3 мин Просмотров 5.6к.

Французский алфавит состоит из 26 букв и относится к латинской группе. Алфавит похож с английским в написании, но сильно отличается в произношении.

Часто учебники и пособия дают только напечатанные буквы. Однако в дальнейшем мы сталкиваемся даже чаще с прописным вариантом, поэтому мы предлагаем и французский алфавит прописной. Прописные буквы, конечно, в зависят от почерка или пособия, но основа, позволяющая отличить одну букву от другой, всегда одинакова.

Французский алфавит прописной

| Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Gg | Hh | Ii | Jj | Kk | Ll | Mm |

| Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Vv | Ww | Xx | Yy | Zz |

Во французском языке целый ряд букв не имеет звукового эквивалента. Так, буква <е >[e] не произносится: 1) в конце слов, например: base [ba:z] база; vue [vy] вид; 2) в тех случаях, когда опущение < е> не влечёт за собой столкновения трёх согласных, например: la fenêtre [lafnetr] окно.

В конце слов не произносятся, за редкими исключениями, буквы b, d, g, p, s, t, x, z, например: lait [le] молоко; accord [akɔ:r] аккорд; loup [lu] волк.

Отметим! Также не произносится ent – окончание 3-го лица множественного числа глаголов, например: ils lisent [il li:z] они читают.

французский алфавит прописной вторая часть

Связывание звуков (liaison)

Во французском языке в произношении связываются только слова, тесно связанные по смыслу. Главные случаи связывания следующие:

- артикль связывается с последующим существительным или прилагательным: les élèves [leselev], les hommes [lezɔm];

- прилагательное с последующим существительным mon ami [mõnami];

- числительное с последующим прилагательным или существительным: deux animaux [dø:zanimo];

- наречие с последующим прилагательным или наречием: très utile [trezytil];

- личное местоимение с последующим глаголом или местоимением en и y: nous arrivons [nuzarivõ]; jʼen ai [ӡãne]; nous y venons [nuzivnõ];

- глагол с последующим личным местоимением или местоимениями en и y: vas-y [vazi];

- предлог с его дополнением: sans abri [sãzabri];

- союз quand с последующим словом: quand il viendra [kãtilvjĕdra];

- глаголы être и avoir с последующим словом: il est ici [iletisi]; ils ont appris [ilzõtãpri];

- слова, входящие в состав сложных слов: mot-à-mot [mɔtamɔ]; de temps en temps [dɔtazãtã].

При связывании звук переходит s в z, d — в t, f – в v.

Союз et никогда не связывается с последующим словом. Также не делается связывание с начальным h тех слов, которые в словаре отмечены звёздочкой, например: trois harengs [trwa arã].

Онлайн карточки французского алфавита

Шпаргалка для красивого письма на французском (рукописная латиница французского языка):

Источник: https://bebris.ru/2012/11/16/французский-алфавит-прописной/

Источник: http://irgol.ru/pismennye-bukvy-frantsuzskogo-alfav/

17 комментариев

-

А как правильно рукописно написать Œ (из слов CŒUR, SŒUR) или допустимо написать их по раздельности (oe)?

-

Лучше вместе. Пишите «е» сразу же без пробелов за «о»

-

Y-a-t-il en français comtemporaine la lettre æ? Ex.on peut voir parfois le mot præsident…

-

@Анатолий

В современном французском лигатура æ пишется в некоторых словах, пришедших из латыни. Президента не встречала ни разу, а вот слово президиум пишется с лигатурой — præsidium.

Из распространенных еще можно упомянуть curriculum vitæ — «резюме», nævus — «родимое пятно», tædium vitæ — «пресыщение жизнью, депрессия», intuitu personæ — «учитывая, о ком идет речь»… -

а как произносить число 9 и 12

-

-

Будет ли ошибкой писать «z» не так, как написано на картинке, а, например, как в английском? Или обязательно она должна походить на русскую «з»?

-

не будет. Пишите, как удобно )

-

-

а что озночают те буквы которые в синем написанны

-

@ Аноним

Это буквы с диакритическими знаками (аксанами, …). -

Скажите, а если посмотреть в советских учебниках, то письменные буквы здесь и там будут различаться? Потому что, когда я смотрела английские письменные буквы они различались. И скажите, а французы сейчас используют письменные буквы или нет?

-

@ Аноним

Вроде одинаковые. Используют. -

Здравствуйте! Мы в школе писали по французски буквы с наклоном в право, а у Вас в примере «французский алфавит, прописные буквы» все буквы написаны прямо, без наклона! Скажите как сейчас учат письму в институте, наклоняют буквы? СПАСИБО!

-

@ Евгения

Здравствуйте! Не могу ответить, т.к. не обучаю письму. Думаю, в принципе, наклон не имеет никакого значения. -

некоторые французы думают,что с наклоном писать очень трудно

то как нас учили в школе писать , отличается о того как пишут французы -

СПАСИБО БОЛЬШОЕ, НЕДАВНО БЫЛ ДИКТАНТ ПО НАПИСАНИЮ БУКВ В АЛФАВИТЕ, БЛАГОДАРЯ ВАМ, ПЯТЬ

-

Здравствуйте, а английский и должен выглядеть поххоже как французский?

Просто в школе говорят что они не похожи.

Оставить комментарий

Французский алфавит для детей можно легко усвоить вместе с малышом. Ведь дети любят что-то новое, а главное интересное, а ещё лучше если вместе с мамой и папой … Ниже есть несколько вариантов для изучения французского алфавита, выбирайте какой Вам больше понравиться и подходит по темпераменту.

Содержание

- Пишем буквы прописью!

- Графические символы, которые надо знать

- Учим алфавит вместе с малышом!

- Несколько способов выучить алфавит

Пишем буквы прописью!

Если вы хотите узнать, как писать прописные французские буквы, то вот они, перед вами. Таблица разделена на колонки: первая с печатными буквами, вторая с прописными и третья с русской транскрипцией этих букв.

Друзья, если вы хотите научиться красиво выводить французские буквы на письме, то потренируйтесь на листке бумаги, стараясь писать буквы так, как в нашей таблице.

Графические символы, которые надо знать

Мы уже рассматривали более подробно все графические символы французского языка. Но раз сегодня мы говорим об алфавите, то стоит вкратце их напомнить.

- Accent aigu: é. Употребляется только с буквой e и означает закрытый звук [e]: enchanté

- Accent grave: à, è, ù: là, frère, où

- Accent circonflexe: â, ê, î, ô, û: âme, être, plaît, clôturer, dû

- Cédille: ç: français

- Tréma: ë, ï, ü, ÿ: Citroën, maïs

Друзья, помните о том, что если не соблюдать все эти графические символы на письме, то это считается орфографической ошибкой. Следовательно, в диктанте, в сочинении или другой письменной работе за это снимают баллы, и ваша оценка будет ниже.

Также, не забудьте про так называемые лигатуры: æ, œ. Впрочем, они нередко заменяются на две буквы: ae (или фонетическую запись é), oe.

Буквы k, w и лигатура æ (довольно редкая) используются только в иностранных словах (kilo —килограмм, wagon — вагон, nævus — бородавка), а также в именах собственных.

Учим алфавит вместе с малышом!

Друзья, если вы решили, что вашему ребенку пора заняться французским языком, то с чего начать, как не с алфавита?

Для детей дошкольного возраста прекрасно подойдут учебно-развлекательные видео и песенки на французском языке про буквы. Слушая песенку, ваш малыш и вы сами можете подпевать диктору, таким образом, осваивая алфавит и первые слова на французском языке.

Мы хотим предложить вам несколько вариантов, которые помогут вашему ребенку быстро выучить французский алфавит.

Здесь очень милый котенок поможет ребенку выучить буквы и повторить их за ним или вместе с ним. Включайте видео вашему малышу столько, сколько нужно! И да, у котенка прекрасное произношение!

Такие видео для детей можно как смотреть, так и просто слушать, изучая французский алфавит и язык в целом. Будьте рядом с вашим ребенком, чтобы в любой момент прийти ему на помощь и объяснить то, чего он не понял или не расслышал.

Несколько способов выучить алфавит

Если вы взрослый человек, то для вас выучить французский алфавит не составит особого труда: достаточно несколько раз прослушать его и повторить вслед за диктором, и voilà – вы его уже знаете! Главное – потренировать правильное произношение.

А вот с малышом дело обстоит иначе, ему потребуется ваша помощь и терпение.

- Во-первых, вы можете использовать те видео по алфавиту, которые мы предложили; найдите и другие ролики по теме алфавита.

- Во-вторых, сделайте процесс изучения букв французского языка креативным: нарисуйте каждую букву на отдельном листе бумаги. Рисуйте вместе с вашим малышом, сделайте каждую букву цветной, узорчатой и красочной.

- В-третьих, к каждой букве нарисуйте или подберите подходящую картинку, например: a – abeille, b – bâteau и т.д.

Теперь, повторив несколько раз алфавит целиком, показывайте ребенку каждую букву отдельно, а он пусть ее произносит. Через пять-шесть таких занятий ваш малыш полностью освоит французский алфавит и сможет рассказать его легко, свободно и без запинки!

Желаем вам удачи, друзья и до новых встреч!

French orthography encompasses the spelling and punctuation of the French language. It is based on a combination of phonemic and historical principles. The spelling of words is largely based on the pronunciation of Old French c. 1100–1200 AD, and has stayed more or less the same since then, despite enormous changes to the pronunciation of the language in the intervening years. Even in the late 17th century, with the publication of the first French dictionary by the Académie française, there were attempts to reform French orthography.

This has resulted in a complicated relationship between spelling and sound, especially for vowels; a multitude of silent letters; and many homophones—e.g., saint/sein/sain/seing/ceins/ceint (all pronounced [sɛ̃]) and sang/sans/cent (all pronounced [sɑ̃]). This is conspicuous in verbs: parles (you speak), parle (I speak) and parlent (they speak) all sound like [paʁl]. Later attempts to respell some words in accordance with their Latin etymologies further increased the number of silent letters (e.g., temps vs. older tans – compare English «tense», which reflects the original spelling – and vingt vs. older vint).

Nevertheless, there are rules governing French orthography which allow for a reasonable degree of accuracy when pronouncing French words from their written forms. The reverse operation, producing written forms from pronunciation, is much more ambiguous. The French alphabet uses a number of diacritics including the circumflex. A system of braille has been developed for people who are visually impaired.

Alphabet[edit]

The letters of the French alphabet, spoken in Standard French

The French alphabet is based on the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, uppercase and lowercase, with five diacritics and two orthographic ligatures.

-

Letter Name Name (IPA) Diacritics and ligatures A a /a/ Àà, Ââ, Ææ B bé /be/ C cé /se/ Çç D dé /de/ E e /ə/ Éé, Èè, Êê, Ëë F effe /ɛf/ G gé /ʒe/ H ache /aʃ/ I i /i/ Îî, Ïï J ji /ʒi/ K ka /ka/ L elle /ɛl/ M emme /ɛm/ N enne /ɛn/ O o /o/ Ôô, Œœ P pé /pe/ Q qu /ky/ R erre /ɛʁ/ S esse /ɛs/ T té /te/ U u /y/ Ùù, Ûû, Üü V vé /ve/ W double vé /dubləve/ X ixe /iks/ Y i grec /iɡʁɛk/ Ÿÿ Z zède /zɛd/

The letters ⟨w⟩ and ⟨k⟩ are rarely used except in loanwords and regional words. The phoneme /w/ sound is usually written ⟨ou⟩; the /k/ sound is usually written ⟨c⟩ anywhere but before ⟨e, i, y⟩, ⟨qu⟩ before ⟨e, i, y⟩, and sometimes ⟨que⟩ at the ends of words. However, ⟨k⟩ is common in the metric prefix kilo- (originally from Greek χίλια khilia «a thousand»): kilogramme, kilomètre, kilowatt, kilohertz, etc.

Diacritics[edit]

The usual diacritics are the acute (⟨´⟩, accent aigu), the grave (⟨`⟩, accent grave), the circumflex (⟨ˆ⟩, accent circonflexe), the diaeresis (⟨¨⟩, tréma), and the cedilla (⟨¸ ⟩, cédille). Diacritics have no effect on the primary alphabetical order.

- The acute accent or accent aigu (é), over e, indicates uniquely the sound /e/. An é in modern French is often used where a combination of e and a consonant, usually s, would have been used formerly: écouter < escouter.

- The grave accent or accent grave (à, è, ù), over a or u, is used primarily to distinguish homophones: à («to») vs. a («has»); ou («or») vs. où («where»; note that the letter ù is used only in this word). Over an e, indicates the sound /ɛ/ in positions where a plain e would be pronounced as /ə/ (schwa). Many verb conjugations contain regular alternations between è and e; for example, the accent mark in the present tense verb lève [lεv] distinguishes the vowel’s pronunciation from the schwa in the infinitive, lever [ləve].

- The circumflex or accent circonflexe (â, ê, î, ô, û), over a, e and o, indicates the sound /ɑ/, /ɛ/ and /o/, respectively, but the distinction a /a/ vs. â /ɑ/ tends to disappear in Parisian French, so they are both pronounced [a]. In Belgian French, ê is pronounced [ɛː]. Most often, it indicates the historical deletion of an adjacent letter (usually an s or a vowel): château < castel, fête < feste, sûr < seur, dîner < disner (in medieval manuscripts many letters were often written as diacritical marks: the circumflex for «s» and the tilde for «n» are examples). It has also come to be used to distinguish homophones: du («of the») vs. dû (past participle of devoir «to have to do something (pertaining to an act)»); however dû is in fact written thus because of a dropped e: deu (see Circumflex in French). Since the 1990 orthographic changes, the circumflex on most i‘s and u‘s may be dropped when it does not serve to distinguish homophones: chaîne becomes chaine but sûr (sure) does not change because it distinguishes the word from sur (on).

- The diaeresis or tréma (ë, ï, ü, ÿ), over e, i, u or y, indicates that a vowel is to be pronounced separately from the preceding one: naïve [naiv], Noël [nɔɛl].

- The combination of e with diaeresis following o (as in Noël) is nasalized in the regular way if followed by n (Samoëns [samwɛ̃], but note Citroën [sitʁoɛn])

- The combination of e with diaeresis following a is either pronounced [ɛ] (Raphaël, Israël [aɛ]) or not pronounced, leaving only the a (Staël [a]) and the a is nasalized in the regular way if aë is followed by n (Saint-Saëns [sɛ̃sɑ̃(s)])

- A diaeresis on y only occurs in some proper names and in modern editions of old French texts. Some proper names in which ÿ appears include Aÿ [a(j)i] (commune in Marne, now Aÿ-Champagne), Rue des Cloÿs [?] (alley in the 18th arrondissement of Paris), Croÿ [kʁwi] (family name and hotel on the Boulevard Raspail, Paris), Château du Feÿ [dyfei]? (near Joigny), Ghÿs [ɡi]? (name of Flemish origin spelt Ghijs where ij in handwriting looked like ÿ to French clerks), L’Haÿ-les-Roses [laj lɛ ʁoz] (commune between Paris and Orly airport), Pierre Louÿs [luis] (author), Moÿ-de-l’Aisne [mɔidəlɛn] (commune in Aisne and a family name), and Le Blanc de Nicolaÿ [nikɔlai] (an insurance company in eastern France).

- The diaeresis on u appears in the Biblical proper names Archélaüs [aʁʃelay]?, Capharnaüm [kafaʁnaɔm] (with the um pronounced [ɔm] as in words of Latin origin such as album, maximum, or chemical element names such as sodium, aluminium), Emmaüs [ɛmays], Ésaü [ezay], and Saül [sayl], as well as French names such as Haüy [aɥi].[WP-fr has as 3 syllables, [ayi]] Nevertheless, since the 1990 orthographic changes, the diaeresis in words containing guë (such as aiguë [eɡy] or ciguë [siɡy]) may be moved onto the u: aigüe, cigüe, and by analogy may be used in verbs such as j’argüe.

- In addition, words coming from German retain their umlaut (ä, ö and ü) if applicable but often use French pronunciation, such as Kärcher ([kεʁʃɛʁ] or [kaʁʃɛʁ], trademark of a pressure washer).

- The cedilla or cédille (ç), under c, indicates that it is pronounced /s/ rather than /k/. Thus je lance «I throw» (with c = [s] before e), je lançais «I was throwing» (c would be pronounced [k] before a without the cedilla). The cedilla is only used before the vowels a, o or u, for example, ça /sa/; it is never used before the vowels e, i, or y, since these three vowels always produce a soft /s/ sound (ce, ci, cycle).

The tilde diacritical mark ( ˜ ) above n is occasionally used in French for words and names of Spanish origin that have been incorporated into the language (e.g., El Niño). Like the other diacritics, the tilde has no impact on the primary alphabetical order.

Diacritics are often omitted on capital letters, mainly for technical reasons. It is widely believed that they are not required; however both the Académie française and the Office québécois de la langue française reject this usage and confirm that «in French, the accent has full orthographic value»,[1] except for acronyms but not for abbreviations (e.g., CEE, ALENA, but É.-U.).[2] Nevertheless, diacritics are often ignored in word games, including crosswords, Scrabble, and Des chiffres et des lettres.

Ligatures[edit]

The two ligatures œ and æ have orthographic value. For determining alphabetical order, these ligatures are treated like the sequences oe and ae.

Œ[edit]

(French: œ, e dans l’o, o-e entrelacé or o et e collés/liés) This ligature is a mandatory contraction of ⟨oe⟩ in certain words. Some of these are native French words, with the pronunciation /œ/ or /ø/, e.g., chœur «choir» /kœʁ/, cœur «heart» /kœʁ/, mœurs «moods (related to moral)» /mœʁ, mœʁs/, nœud «knot» /nø/, sœur «sister» /sœʁ/, œuf «egg» /œf/, œuvre «work (of art)» /œvʁ/, vœu «vow» /vø/. It usually appears in the combination œu; œil /œj/ «eye» is an exception. Many of these words were originally written with the digraph eu; the o in the ligature represents a sometimes artificial attempt to imitate the Latin spelling: Latin bovem > Old French buef/beuf > Modern French bœuf.

Œ is also used in words of Greek origin, as the Latin rendering of the Greek diphthong οι, e.g., cœlacanthe «coelacanth». These words used to be pronounced with the vowel /e/, but in recent years a spelling pronunciation with /ø/ has taken hold, e.g., œsophage /ezɔfaʒ/ or /øzɔfaʒ/, Œdipe /edip/ or /ødip/ etc. The pronunciation with /e/ is often seen to be more correct.

When œ is found after the letter c, the c can be pronounced /k/ in some cases (cœur), or /s/ in others (cœlacanthe).

The ligature œ is not used when both letters contribute different sounds. For example, when ⟨o⟩ is part of a prefix (coexister), or when ⟨e⟩ is part of a suffix (minoen), or in the word moelle and its derivatives.[3]

Æ[edit]

(French: æ, e dans l’a, a-e entrelacé or a, e collés/liés) This ligature is rare, appearing only in some words of Latin and Greek origin like tænia, ex æquo, cæcum, æthuse (as named dog’s parsley).[4] It generally represents the vowel /e/, like ⟨é⟩.

The sequence ⟨ae⟩ appears in loanwords where both sounds are heard, as in maestro and paella.[5]

Digraphs and trigraphs[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2008) |

French digraphs and trigraphs have both historical and phonological origins. In the first case, it is a vestige of the spelling in the word’s original language (usually Latin or Greek) maintained in modern French, for example, the use of ⟨ph⟩ in words like téléphone, ⟨th⟩ in words like théorème, or ⟨ch⟩ in chaotique. In the second case, a digraph is due to an archaic pronunciation, such as ⟨eu⟩, ⟨au⟩, ⟨oi⟩, ⟨ai⟩, and ⟨œu⟩, or is merely a convenient way to expand the twenty-six-letter alphabet to cover all relevant phonemes, as in ⟨ch⟩, ⟨on⟩, ⟨an⟩, ⟨ou⟩, ⟨un⟩, and ⟨in⟩. Some cases are a mixture of these or are used for purely pragmatic reasons, such as ⟨ge⟩ for /ʒ/ in il mangeait (‘he ate’), where the ⟨e⟩ serves to indicate a «soft» ⟨g⟩ inherent in the verb’s root, similar to the significance of a cedilla to ⟨c⟩.

Spelling to sound correspondences[edit]

Some exceptions apply to the rules governing the pronunciation of word-final consonants. See Liaison (French) for details.

Consonants and combinations of consonant letters

| Spelling | Major value (IPA) |

Examples of major value | Minor values (IPA) |

Examples of minor values | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -bs, -cs (in plural of words ending in silent ⟨b⟩ or ⟨c⟩), -ds, -fs (in œufs and bœufs, and plural words ending with silent -⟨f⟩), ‑gs, -ps, -ts | Ø | plombs, blancs, prends, œufs, cerfs, longs , draps, achats | ||||

| b, bb | elsewhere | /b/ | ballon, abbé | |||

| before a voiceless consonant | /p/ | absolu, observer, subtile | ||||

| finally | Ø | plomb, Colomb | /b/ | Jacob | ||

| ç | /s/ | ça, garçon, reçu | ||||

| c | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /s/ | cyclone , loquace, douce, ciel, ceux | |||

| initially/medially elsewhere | /k/ | cabas , crasse, cœur, sacré | /s/ (before æ and œ in scientific terms of Latin and Greek origin) | cæcum, cœlacanthe | /ɡ/ second | |

| finally | /k/ | lac, donc, parc | Ø | tabac, blanc, caoutchouc | /ɡ/ zinc | |

| cc | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ks/ | accès, accent | /s/ succion | ||

| elsewhere | /k/ | accord | ||||

| ch | /ʃ/ | chat , douche | /k/ (often in words of Greek origin[6]) | chaotique, chlore, varech | Ø yacht, almanach /tʃ/ check-list, strech, coach |

|

| -ct | /kt/ | direct , correct | Ø | respect, suspect, instinct, succinct | ||

| d, dd | elsewhere | /d/ | doux , adresse, addition | |||

| finally | Ø | pied , accord | /d/ | David, sud | ||

| f, ff | /f/ | fait , affoler, soif | Ø clef, cerf, nerf | |||

| g | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ʒ/ | gens , manger | /dʒ/ gin, management, adagio | ||

| initially/medially elsewhere | /ɡ/ | gain , glacier | ||||

| finally | Ø | joug, long, sang | /ɡ/ | erg, zigzag | ||

| gg | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ɡʒ/ | suggérer | |||

| elsewhere | /ɡ/ | aggraver | ||||

| gn | /ɲ/ | montagne , agneau, gnôle | /ɡn/ gnose, gnou | |||

| h | Ø | habite , hiver | /j/ (intervocalic, to some speakers, but Ø for most speakers) | Sahara | /h/ ahaner (also Ø or /j/), hit | |

| j | /ʒ/ | joue, jeter | /dʒ/ | jean, jazz | /j/ fjord /x/ jota, marijuana |

|

| k | /k/ | alkyler , kilomètre, bifteck | ||||

| l, ll | /l/ | lait , allier, il, royal, matériel | Ø (occasionally finally) | cul, fusil, saoul | Ø fils, aulne, aulx (see also -il) |

|

| m, mm | /m/ | mou , pomme | Ø automne, condamner | |||

| n, nn | /n/ | nouvel , panne | ||||

| ng (in loanwords) | /ŋ/ | parking , camping | ||||

| p, pp | elsewhere | /p/ | pain, appel | |||

| finally | Ø | coup, trop | /p/ | cap, cep | ||

| ph | /f/ | téléphone , photo | ||||

| pt | /pt/ | ptérodactyle, adapter , excepter, ptôse, concept | /t/ | baptême, compter, sept | Ø prompt (also pt | |

| q (see qu) | /k/ | coq , cinq, piqûre (in new orthography, piqure), Qatar | ||||

| r, rr | /ʁ/ | rat , barre | Ø monsieur, gars (see also -er) |

|||

| s | initially medially next to a consonant or after a nasal vowel |

/s/ | sacre , estime, penser, instituer | /z/ | Alsace, transat, transiter | |

| elsewhere between two vowels | /z/ | rose, paysage | /s/ | antisèche, parasol, vraisemblable | ||

| finally | Ø | dans , repas | /s/ | fils, sens (noun), os (singular), ours | ||

| sc | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /s/ | science | /ʃ/ fasciste (also /s/) | ||

| elsewhere | /sk/ | script | ||||

| sch | /ʃ/ | schlague , haschisch, esche | /sk/ | schizoïde, ischion, æschne | ||

| ss | /s/ | baisser, passer | ||||

| -st | /st/ | est (direction), ouest, podcast | Ø | est (verb), Jésus-Christ (also /st/), contest |

||

| t, tt | elsewhere | /t/ | tout , attente | /s/ | nation (see ti + vowel) | |

| finally | Ø | tant , raffut | /t/ | dot, brut, yaourt | ||

| tch | /t͡ʃ/ | tchat, match, Tchad | ||||

| th | /t/ | thème, thermique, aneth | Ø asthme, bizuth, goth /s/ thread |

|||

| v | /v/ | ville, vanne | ||||

| w | /w/ | kiwi , week-end (in new orthography, weekend), whisky | /v/ | wagon, schwa, interviewer | (see also aw, ew, ow) | |

| x | initially next to a voiceless consonant phonologically finally |

/ks/ | xylophone, expansion, connexe | /ɡz/ | xénophobie, Xavier | /k/ xhosa, xérès (also /ks/) |

| medially elsewhere | /ks/ | galaxie, maximum | /s/ /z/ /gz/ |

soixante, Bruxelles deuxième exigence |

||

| finally | Ø | paix , deux | /ks/ | index, pharynx | /s/ six, dix, coccyx | |

| xc | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ks/ | exciter | |||

| elsewhere | /ksk/ | excavation | ||||

| z | elsewhere | /z/ | zain , gazette | |||

| finally | Ø | chez | /z/ gaz, fez, merguez /s/ quartz |

Vowels and combinations of vowel letters

| Spelling | Major value (IPA) |

Examples of major value | Minor values (IPA) |

Examples of minor value | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, à | /a/ | patte, arable, là, déjà | /ɑ/ | araser, base, condamner | /ɔ/ yacht (also /o/) /o/ football /e/ lady |

|

| â | /ɑ/ | château, pâté | /a/ | dégât (also /ɑ/), parlâmes, liâtes, menât (simple past and imperfect subjunctive verb forms ending in -âmes, -âtes, and -ât) | ||

| aa | /a/ | graal, Baal, maastrichtois | /a.a/ | aa | ||

| æ | /e/ | ex-æquo, cæcum | ||||

| ae | /e/ | reggae | /a/ | groenendael, maelstrom, Portaels | /a.ɛ/ maestro /a.e/ paella |

|

| aë | /a.ɛ/ | Raphaël, Israël | /a/ Staël | |||

| ai | /ɛ/ (/e/) |

vrai, faite ai, aiguille, baisser, gai, quai |

/e/ | lançai, mangerai (future and simple past verb forms ending in -ai or -rai) | /ə/ faisan, faisons,[7] (and all other conjugated forms of faire which are spelt fais- and followed by a pronounced vowel) | |

| aî (in new orthography ⟨ai⟩) | /ɛː/ | maître, chaîne (in new orthography, maitre, chaine) | ||||

| aï | /a.i/ | naïf, haïr | /aj/ | aïe, aïeul, haïe, païen | ||

| aie | /ɛ/ | baie, monnaie | /ɛj/ | paie (also paye) | ||

| ao, aô | elsewhere | /a.ɔ/ | aorte, extraordinaire (also /ɔ/) | /a.o/ | baobab | /a/ faonne, paonneau /o/ Saône |

| phonologically finally | /a.o/ | cacao, chaos | /o/ curaçao | |||

| aou, aoû | /a.u/ | caoutchouc, aoûtien (in new orthography, aoutien), yaourt | /u/ | saoul, août (in new orthography, aout) | ||

| au | elsewhere | /o/ | haut, augure | |||

| before ⟨r⟩ | /ɔ/ | dinosaure, Aurélie, Laurent (also /o/) | ||||

| ay | elsewhere | /ɛj/ | ayons, essayer (also /ej/) | /aj/ | mayonnaise, papaye, ayoye | /ei/ pays (also /ɛi/) |

| finally | /ɛ/ | Gamay, margay, railway | /e/ okay | |||

| -aye | /ɛ.i/ | abbaye | /ɛj/ | paye | /ɛ/ La Haye /aj/ baye |

|

| e | elsewhere | /ə/ | repeser, genoux | /e/ revolver (in new orthography, révolver) | ||

| before multiple consonants, ⟨x⟩, or a final consonant (silent or pronounced) |

/ɛ/ | est, estival, voyelle, examiner, exécuter, quel, chalet | /ɛ, e/ /ə/ |

essence, effet, henné recherche, secrète, repli (before ch+vowel or 2 different consonants when the second one is l or r) |

/e/ mangez, (and any form of a verb in the second person plural that ends in -ez) assez /a/ femme, solennel, fréquemment, (and other adverbs ending in —emment)[8] /œ/ Gennevilliers (see also -er, -es) |

|

| in monosyllabic words before a silent consonant | /e/ | et, les, nez, clef | /ɛ/ es | |||

| finally in a position where it can be easily elided |

∅ | caisse, unique, acheter (also /ə/), franchement | /ə/ (finally in monosyllabic words) | que, de, je | ||

| é, ée | /e/ | clé, échapper, idée | /ɛ/ (in closed syllables) événement, céderai, vénerie (in new orthography, évènement, cèderai, vènerie) | |||

| è | /ɛ/ | relève, zèle | ||||

| ê | phonologically finally or in closed syllables | /ɛː/ | tête, crêpe, forêt, prêt | |||

| in open syllables | /ɛː, e/ | bêtise | ||||

| ea (except after ⟨g⟩) | /i/ | dealer, leader, speaker (in new orthography, dealeur, leadeur, speakeur) | ||||

| ee | /i/ | week-end (in new orthography, weekend), spleen | /e/ pedigree (also pédigré(e)) | |||

| eau | /o/ | eau, oiseaux | ||||

| ei | /ɛ/ | neige (also /ɛː/), reine (also /ɛː/), geisha (also /ɛj/) | ||||

| eî | /ɛː/ | reître (in new orthography, reitre) | ||||

| eoi | /wa/ | asseoir (in new orthography, assoir) | ||||

| eu | initially phonologically finally before /z/ |

/ø/ | Europe, heureux, peu, chanteuse | /y/ eu, eussions, (and any conjugated form of avoir spelt with eu-), gageure (in new orthography, gageüre) | ||

| elsewhere | /œ/ | beurre, jeune | /ø/ | feutre, neutre, pleuvoir | ||

| eû | /ø/ | jeûne | /y/ eûmes, eût, (and any conjugated forms of avoir spelt with eû-) | |||

| ey | before vowel | /ɛj/ | gouleyant, volleyer | |||

| finally | /ɛ/ | hockey, trolley | ||||

| i | elsewhere | /i/ | ici, proscrire | Ø business | ||

| before vowel | /j/ | fief, ionique, rien | /i/ (in compound words) | antioxydant | ||

| î | /i/ | gîte, épître (in new orthography, gitre, epitre) | ||||

| ï (initially or between vowels) | /j/ | ïambe (also iambe), aïeul, païen | /i/ ouïe | |||

| -ie | /i/ | régie, vie | ||||

| o | phonologically finally before /z/ |

/o/ | pro, mot, chose, déposes | /ɔ/ sosie | ||

| elsewhere | /ɔ/ | carotte, offre | /o/ | cyclone, fosse, tome | ||

| ô | /o/ | tôt, cône | /ɔ/ hôpital (also /o/) | |||

| œ | /œ/ | œil | /e/ /ɛ/ |

œsophage, fœtus œstrogène |

/ø/ lœss | |

| oe | /ɔ.e/ | coefficient | /wa, wɛ/ moelle, moellon, moelleux (also moëlle, moëllon, moëlleux) /ø/ foehn |

|||

| oê | /wa, wɛ/ | poêle | ||||

| oë | /ɔ.ɛ/ | Noël | /ɔ.e/ canoë, goëmon (also canoé, goémon) /wɛ/ foëne, Plancoët /wa/ Voëvre |

|||

| œu | phonologically finally | /ø/ | nœud, œufs, bœufs, vœu | |||

| elsewhere | /œ/ | sœur, cœur, œuf, bœuf | ||||

| oi, oie | /wa/ | roi, oiseau, foie, quoi (also /wɑ/ for these latter words) | /wɑ/ | bois, noix, poids, trois | /ɔ/ oignon (in new orthography, ognon) /ɔj/ séquoia /o.i/ autoimmuniser |

|

| oî | /wa, wɑ/ | croîs, Benoît | ||||

| oï | /ɔ.i/ | coït, astéroïde | /ɔj/ | troïka | ||

| oo | /ɔ.ɔ/ | coopération, oocyte, zoologie | /u/ | bazooka, cool, football | /ɔ/ alcool, Boskoop, rooibos /o/ spéculoos, mooré, zoo /w/ shampooing |

|

| ou, où | elsewhere | /u/ | ouvrir, sous, où | /o.y/ pseudouridimycine /aw/ out, knock-out |

||

| before vowel or h+vowel | /w/ | ouest, couiner, oui, souhait (also /u/) | ||||

| oû (in new orthography ⟨ou⟩) | /u/ | coût, goût (in new orthography, cout, gout) | ||||

| -oue | /u/ | roue | ||||

| oy | /waj/ | moyen, royaume | /wa, wɑ/ | Fourcroy | /ɔj/ oyez (and any conjugated form of ouïr spelt with oy-), goyave, cow-boy (in new orthography cowboy), ayoy /ɔ.i/ Moyse |

|

| u | elsewhere | /y/ | tu, juge | /u/ tofu, pudding /œ/ club, puzzle /i/ business /ɔ/ rhumerie (see also um) |

||

| before vowel | /ɥ/ | huit, tuer | /y/ | pollueur | /w/ cacahuète (also /ɥ/) | |

| û (in new orthography ⟨u⟩) | /y/ | sûr, flûte (in new orthography, flute) | ||||

| ue, uë | elsewhere | /ɥɛ/ | actuel, ruelle | /e/ /ɛ/ /ə/ /œ/ (see below) |

gué guerre que orgueil, cueillir |

|

| finally | /y/ | aiguë (in new orthography, aigüe), rue | Ø | clique | ||

| üe | finally | /y/ | aigüe | |||

| -ui, uï | /ɥi/ | linguistique, équilateral ambiguïté (in new orthography, ambigüité) | /i/ | équilibre | ||

| uy | /ɥij/ | bruyant, ennuyé, fuyons, Guyenne | /y.j/ | gruyère, thuya | /ɥi/ puy | |

| y | elsewhere | /i/ | cyclone, style | |||

| before vowel | /j/ | yeux, yole | /i/ | polyester, Libye | ||

| ÿ | (used only in proper nouns) | /i/ | L’Haÿ-les-Roses, Freÿr |

Combinations of vowel and consonant letters

| Spelling | Major value (IPA) |

Examples of major value | Minor values (IPA) |

Examples of minor value | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| am | before consonant | /ɑ̃/ | ambiance, lampe | /a/ damné | ||

| finally | /am/ | Vietnam, tam-tam, macadam | /ɑ̃/ Adam | |||

| an, aan | before consonant or finally | /ɑ̃/ | France, an, bilan, plan, afrikaans | /an/ | brahman, chaman, dan, gentleman, tennisman, naan | |

| aen, aën | before consonant or finally | /ɑ̃/ | Caen, Saint-Saëns | |||

| aim, ain | before consonant or finally | /ɛ̃/ | faim, saint, bains | |||

| aon | before consonant or finally | /ɑ̃/ | paon, faon | /a.ɔ̃/ | pharaon | |

| aw | /o/ | crawl, squaw, yawl | /ɑs/ in the 18th century and still traditional French approximation of Laws, the colloquial Scottish form of the economist John Law‘s name[9][10] | |||

| cqu | /k/ | acquit, acquéreur | ||||

| -cte | finally as feminine form of adjectives ending in silent ⟨ct⟩ (see above) | /t/ | succincte | |||

| em, en | before consonant or finally elsewhere | /ɑ̃/ | embaucher, vent | /ɛ̃/ | examen, ben, pensum, pentagone | /ɛn/ week-end (in new orthography, weekend), lichen /ɛm/ indemne, totem |

| before consonant or finally after ⟨é, i, y⟩ | /ɛ̃/ | européen, bien, doyen | /ɑ̃/ (before t or soft c) | patient, quotient, science, audience | ||

| eim, ein | before consonant or finally | /ɛ̃/ | plein, sein, Reims | |||

| -ent | 3rd person plural verb ending | Ø | parlent, finissaient | |||

| -er | /e/ | aller, transporter, premier | /ɛʁ/ | hiver, super, éther, fier, mer, enfer, Niger | /œʁ/ leader (also ɛʁ), speaker | |

| -es | Ø | Nantes, faites | /e/, /ɛ/ | les, des, ces, es | ||

| eun | before consonant or finally | /œ̃/ | jeun | |||

| ew | /ju/ | newton, steward (also iw) | /w/ chewing-gum | |||

| ge | before ⟨a, o, u⟩ | /ʒ/ | geai, mangea | |||

| gu | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ɡ/ | guerre, dingue | /ɡy, ɡɥ/ | arguër (in new orthography, argüer), aiguille, linguistique, ambiguïté (in new orthography, ambigüité) | |

| -il | after some vowels1 | /j/ | ail, conseil | |||

| not after vowel | /il/ | il, fil | /i/ | outil, fils, fusil | ||

| -ilh- | after ⟨u⟩[11] | /ij/ | Guilhem | |||

| after other vowels[11] | /j/ | Meilhac, Devieilhe | /l/ Devieilhe (some families don’t use the traditional pronunciation /j/ of ilh) | |||

| -ill- | after some vowels1 | /j/ | paille, nouille | |||

| not after vowel | /il/ | mille, million, billion, ville, villa, village, tranquille[12] | /ij/ | grillage, bille | ||

| im, in, în | before consonant or finally | /ɛ̃/ | importer, vin, vînt | /in/ sprint | ||

| oin, oën | before consonant or finally | /wɛ̃/ | besoin, point, Samoëns | |||

| om, on | before consonant or finally | /ɔ̃/ | ombre, bon | /ɔn/ canyon /ə/ monsieur /ɔ/ automne |

||

| ow | /o/ | cow-boy (also [aw]. In new orthography, cowboy), show | /u/ clown /o.w/ Koweït |

|||

| qu | /k/ | quand, pourquoi, loquace | /kɥ/ /kw/ |

équilatéral aquarium, loquace, quatuor |

/ky/ piqûre (in new orthography, piqure), qu | |

| ti + vowel | initially or after /s/ | /tj/ | bastion, gestionnaire, tiens, aquae-sextien | |||

| elsewhere | /sj/, /si/ | fonctionnaire, initiation, Croatie, haïtien | /tj/, /ti/ | the suffix -tié, all conjugated forms of verbs with a radical ending in -t (augmentions, partiez, etc.) or derived from tenir, and all nouns and past participles derived from such verbs and ending in -ie (sortie, divertie, etc.) |

||

| um, un | before consonant or finally | /œ̃/ | parfum, brun | /ɔm/ | album, maximum | /ɔ̃/ nuncupation, punch (in new orthography, ponch), secundo |

| ym, yn | before consonant or finally | /ɛ̃/ | sympa, syndrome | /im/ | gymnase, hymne |

- ^1 These combinations are pronounced /j/ after ⟨a, e, eu, œ, ou, ue⟩, all but the last of which are pronounced normally and are not influenced by the ⟨i⟩. For example, in rail, ⟨a⟩ is pronounced /a/; in mouiller, ⟨ou⟩ is pronounced /u/. ⟨ue⟩, however, which only occurs in such combinations after ⟨c⟩ and ⟨k⟩, is pronounced /œ/ as opposed to /ɥɛ/: orgueil, cueillir, accueil, etc. These combinations are never pronounced /j/ after ⟨o, u⟩ (except -⟨uill⟩-, which is /ɥij/: aiguille, juillet); in that case, the vowel + i combination as well as the ⟨l⟩s is pronounced normally, although as usual, the pronunciation of ⟨u⟩ after ⟨g⟩ and ⟨p⟩ is somewhat unpredictable: poil, huile, équilibre [ekilibʁ] but équilatéral [ekɥilateʁal], etc.

There are no longer silent k’s in French. They appeared in skunks, knock-out, knickerbockers and knickers, but from now onwards, the ⟨k⟩ is also pronounced. The only consonants always pronounced equally in French are now ⟨k⟩ and ⟨v⟩. Also, ⟨ei⟩ is always pronounced /ɛ/, even in leitmotiv.

Words from Greek[edit]

The spelling of French words of Greek origin is complicated by a number of digraphs which originated in the Latin transcriptions. The digraphs ⟨ph⟩, ⟨th⟩, and ⟨ch⟩ normally represent /f/, /t/, and /k/ in Greek loanwords, respectively; and the ligatures ⟨æ⟩ and ⟨œ⟩ in Greek loanwords represent the same vowel as ⟨é⟩ (/e/). Further, many words in the international scientific vocabulary were constructed in French from Greek roots and have kept their digraphs (e.g., stratosphère, photographie).

History[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

The Oaths of Strasbourg from 842 is the earliest text written in the early form of French called Romance or Gallo-Romance.

Roman[edit]

The Gaulish language of the inhabitants of Gaul disappeared progressively over the course of Roman rule as the Latin language began to replace it. Vulgar Latin, a generally lower register of Classical Latin spoken by the Roman soldiers, merchants and even patricians in quotidian speech, and adopted by the natives, evolved slowly, taking the forms of different spoken Roman vernaculars according to the region of the country.

Eventually the different forms of Vulgar Latin would evolve into three branches in the Gallo-Romance language sub-family, the langues d’oïl north of the Loire, the langues d’oc in the south, and the Franco-Provençal languages in part of the east.[13]

Old French[edit]

In the 9th century, the Romance vernaculars were already quite far from Latin. For example, to understand the Bible, written in Latin, footnotes were necessary. With consolidation of royal power, beginning in the 13th century, the Francien vernacular, the langue d’oil variety in usage then on the Île-de-France, brought it little by little to the other languages and evolved toward Classic French.

The languages found in the manuscripts dating from the 9th century to the 13th century form what is known as Old French or ancien français. These languages continued to evolve until, in the 14th century to the 16th century, Middle French (moyen français) emerged.[13]

Middle French[edit]

During the Middle French period (c. 1300–1600), modern spelling practices were largely established. This happened especially during the 16th century, under the influence of printers. The overall trend was towards continuity with Old French spelling, although some changes were made under the influence of changed pronunciation habits; for example, the Old French distinction between the diphthongs eu and ue was eliminated in favor of consistent eu,[a] as both diphthongs had come to be pronounced /ø/ or /œ/ (depending on the surrounding sounds). However, many other distinctions that had become equally superfluous were maintained, e.g. between s and soft c or between ai and ei. It is likely that etymology was the guiding factor here: the distinctions s/c and ai/ei reflect corresponding distinctions in the spelling of the underlying Latin words, whereas no such distinction exists in the case of eu/ue.

This period also saw the development of some explicitly etymological spellings, e.g. temps («time»), vingt («twenty») and poids («weight») (note that in many cases, the etymologizing was sloppy or occasionally completely incorrect; vingt reflects Latin viginti, with the g in the wrong place, and poids actually reflects Latin pensum, with no d at all; the spelling poids is due to an incorrect derivation from Latin pondus). The trend towards etymologizing sometimes produced absurd (and generally rejected) spellings such as sçapvoir for normal savoir («to know»), which attempted to combine Latin sapere («to be wise», the correct origin of savoir) with scire («to know»).

Classical French[edit]

Modern French spelling was codified in the late 17th century by the Académie française, based largely on previously established spelling conventions. Some reforms have occurred since then, but most have been fairly minor. The most significant changes have been:

- Adoption of j and v to represent consonants, in place of former i and u.

- Addition of a circumflex accent to reflect historical vowel length. During the Middle French period, a distinction developed between long and short vowels, with long vowels largely stemming from a lost /s/ before a consonant, as in même (cf. Spanish mismo), but sometimes from the coalescence of similar vowels, as in âge from earlier aage, eage (early Old French *edage < Vulgar Latin *aetaticum, cf. Spanish edad < aetate(m)). Prior to this, such words continued to be spelled historically (e.g. mesme and age). Ironically, by the time this convention was adopted in the 19th century, the former distinction between short and long vowels had largely disappeared in all but the most conservative pronunciations, with vowels automatically pronounced long or short depending on the phonological context (see French phonology).

- Use of ai in place of oi where pronounced /ɛ/ rather than /wa/. The most significant effect of this was to change the spelling of all imperfect verbs (formerly spelled -ois, -oit, -oient rather than -ais, -ait, -aient), as well as the name of the language, from françois to français.

Modern French[edit]

In October 1989, Michel Rocard, then-Prime Minister of France, established the High Council of the French Language (Conseil supérieur de la langue française) in Paris. He designated experts — among them linguists, representatives of the Académie française and lexicographers — to propose standardizing several points, a few of those points being:

- The uniting hyphen in all compound numerals

-

- i.e. trente-et-un

- The plural of compound words, the second element of which always takes the plural s

-

- For example un après-midi, des après-midis

- The circumflex accent ⟨ˆ⟩ disappears on all u’s and i’s except for words in which it is needed for differentiation

-

- As in coût (cost) → cout, abîme (abyss) → abime but sûr (sure) because of sur (on)

- The past participle of laisser followed by an infinitive verb is invariable (now works the same way as the verb faire)

-

- elle s’est laissée mourir → elle s’est laissé mourir

Quickly, the experts set to work. Their conclusions were submitted to Belgian and Québécois linguistic political organizations. They were likewise submitted to the Académie française, which endorsed them unanimously, saying:

«Current orthography remains that of usage, and the ‘recommendations’ of the High Council of the French language only enter into play with words that may be written in a different manner without being considered as incorrect or as faults.»[citation needed]

The changes were published in the Journal officiel de la République française in December 1990. At the time the proposed changes were considered to be suggestions. In 2016, schoolbooks in France began to use the newer recommended spellings, with instruction to teachers that both old and new spellings be deemed correct.[14]

Punctuation[edit]

In France and Belgium, the exclamation mark, question mark, semicolon, colon, percentage mark, currency symbols, hash, and guillemet all require a non-breaking space before and after the punctuation mark. Outside of France and Belgium, this rule is often ignored. Computer software may aid or hinder the application of this rule, depending on the degree of localisation, as it is marked differently from most other Western punctuation.

Hyphens[edit]

The hyphen in French has a particular use in geographic names that is not found in English.

Traditionally, the «specific» part of placenames, street names, and organization names are hyphenated (usually namesakes).[15][16]

For instance, la place de la Bataille-de-Stalingrad (Square of the Battle of Stalingrad [la bataille de Stalingrad]);

and l’université Blaise-Pascal (named after Blaise Pascal).

Likewise, Pas-de-Calais is actually a place on land; the real pas (“strait”) is le pas de Calais.

However, this rule is not uniformly observed in official names, e.g., either la Côte-d’Ivoire or la Côte d’Ivoire, but normally la Côte d’Azur has no hyphens.

The names of Montreal Metro stations are consistently hyphenated when suitable, but those of Paris Métro stations mostly ignore this rule. (For more examples, see Trait d’union)

See also[edit]

- Elision (French)

- French phonology

- French braille

- French manual alphabet

- Circumflex in French

- French heteronyms, words spelled the same but pronounced differently

Notes[edit]

- ^ Except in a few words such as accueil, where the ue spelling was necessary to retain the hard /k/ pronunciation of the c.

References[edit]

- ^ Académie française, accentuation Archived 2011-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Banque de dépannage linguistique — Accents sur les majuscules». 66.46.185.79. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ See wikt:fr:Catégorie:oe non ligaturé en français

- ^ Didier, Dominique. «La ligature æ». Monsu.desiderio.free.fr. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ wikt:fr:Catégorie:ae non ligaturé en français

- ^ See Ch (digraph)#French

- ^ «French Pronuncation: Vowel Sounds I -LanguageGuide». Languageguide.org. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ «French Pronuncation: Vowel Sounds II -LanguageGuide». Languageguide.org. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ «Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900/Law, John (1671-1729) — Wikisource, the free online library».

- ^ https://books.google.fi/books?id=vAFA8x953OMC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false , p. 487 to 506, especially p. 501

- ^ a b «Dictionnaire de l’Académie française».

- ^ «Is LL Pronounced Like an L or like a Y in French?». French.about.com. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ a b Translation of Évolution de la langue française du Ve au XVe siècle. See also Langue romane (French) and Romance languages (English).

- ^ «End of the circumflex? Changes in French spelling cause uproar». BBC News. 2016-02-05. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- ^ «Charte ortho-typographique du Journal officiel [Orthotypography Style Guide for the Journal Officiel]» (PDF). Légifrance (in French). 2016. p. 19.

On le met dans le nom donné à des voies (rue, place, pont…), une agglomération, un département… Exemples : boulevard Victor-Hugo, rue du Général-de-Gaulle, ville de Nogent-le-Rotrou.

Summary ranslation: «Hyphenate name in roadways (streets, squares, bridges), towns, départements«. See also «orthotypography». - ^ «Établissements d’enseignement ou organismes scolaires [Educational institutes or school-related bodies]». Banque de dépannage linguistique (in French).

Les parties d’un spécifique qui comporte plus d’un élément sont liées par un trait d’union […] Exemples : l’école Calixa-Lavallée, l’école John-F.-Kennedy

. Summary ranslation: «Multi-word «specifics» are hyphenated.».

Bibliography[edit]

- Fouché, Pierre (1956). Traité de prononciation française. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Tranel, Bernard (1987). The Sounds of French: An Introduction. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31510-7.

External links[edit]

- Alternate French spelling (in French)

- Recording of 3 different voices pronouncing the French alphabet

- French alphabet pronounced by a native speaker (Youtube)

French orthography encompasses the spelling and punctuation of the French language. It is based on a combination of phonemic and historical principles. The spelling of words is largely based on the pronunciation of Old French c. 1100–1200 AD, and has stayed more or less the same since then, despite enormous changes to the pronunciation of the language in the intervening years. Even in the late 17th century, with the publication of the first French dictionary by the Académie française, there were attempts to reform French orthography.

This has resulted in a complicated relationship between spelling and sound, especially for vowels; a multitude of silent letters; and many homophones—e.g., saint/sein/sain/seing/ceins/ceint (all pronounced [sɛ̃]) and sang/sans/cent (all pronounced [sɑ̃]). This is conspicuous in verbs: parles (you speak), parle (I speak) and parlent (they speak) all sound like [paʁl]. Later attempts to respell some words in accordance with their Latin etymologies further increased the number of silent letters (e.g., temps vs. older tans – compare English «tense», which reflects the original spelling – and vingt vs. older vint).

Nevertheless, there are rules governing French orthography which allow for a reasonable degree of accuracy when pronouncing French words from their written forms. The reverse operation, producing written forms from pronunciation, is much more ambiguous. The French alphabet uses a number of diacritics including the circumflex. A system of braille has been developed for people who are visually impaired.

Alphabet[edit]

The letters of the French alphabet, spoken in Standard French

The French alphabet is based on the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, uppercase and lowercase, with five diacritics and two orthographic ligatures.

-

Letter Name Name (IPA) Diacritics and ligatures A a /a/ Àà, Ââ, Ææ B bé /be/ C cé /se/ Çç D dé /de/ E e /ə/ Éé, Èè, Êê, Ëë F effe /ɛf/ G gé /ʒe/ H ache /aʃ/ I i /i/ Îî, Ïï J ji /ʒi/ K ka /ka/ L elle /ɛl/ M emme /ɛm/ N enne /ɛn/ O o /o/ Ôô, Œœ P pé /pe/ Q qu /ky/ R erre /ɛʁ/ S esse /ɛs/ T té /te/ U u /y/ Ùù, Ûû, Üü V vé /ve/ W double vé /dubləve/ X ixe /iks/ Y i grec /iɡʁɛk/ Ÿÿ Z zède /zɛd/

The letters ⟨w⟩ and ⟨k⟩ are rarely used except in loanwords and regional words. The phoneme /w/ sound is usually written ⟨ou⟩; the /k/ sound is usually written ⟨c⟩ anywhere but before ⟨e, i, y⟩, ⟨qu⟩ before ⟨e, i, y⟩, and sometimes ⟨que⟩ at the ends of words. However, ⟨k⟩ is common in the metric prefix kilo- (originally from Greek χίλια khilia «a thousand»): kilogramme, kilomètre, kilowatt, kilohertz, etc.

Diacritics[edit]

The usual diacritics are the acute (⟨´⟩, accent aigu), the grave (⟨`⟩, accent grave), the circumflex (⟨ˆ⟩, accent circonflexe), the diaeresis (⟨¨⟩, tréma), and the cedilla (⟨¸ ⟩, cédille). Diacritics have no effect on the primary alphabetical order.

- The acute accent or accent aigu (é), over e, indicates uniquely the sound /e/. An é in modern French is often used where a combination of e and a consonant, usually s, would have been used formerly: écouter < escouter.

- The grave accent or accent grave (à, è, ù), over a or u, is used primarily to distinguish homophones: à («to») vs. a («has»); ou («or») vs. où («where»; note that the letter ù is used only in this word). Over an e, indicates the sound /ɛ/ in positions where a plain e would be pronounced as /ə/ (schwa). Many verb conjugations contain regular alternations between è and e; for example, the accent mark in the present tense verb lève [lεv] distinguishes the vowel’s pronunciation from the schwa in the infinitive, lever [ləve].

- The circumflex or accent circonflexe (â, ê, î, ô, û), over a, e and o, indicates the sound /ɑ/, /ɛ/ and /o/, respectively, but the distinction a /a/ vs. â /ɑ/ tends to disappear in Parisian French, so they are both pronounced [a]. In Belgian French, ê is pronounced [ɛː]. Most often, it indicates the historical deletion of an adjacent letter (usually an s or a vowel): château < castel, fête < feste, sûr < seur, dîner < disner (in medieval manuscripts many letters were often written as diacritical marks: the circumflex for «s» and the tilde for «n» are examples). It has also come to be used to distinguish homophones: du («of the») vs. dû (past participle of devoir «to have to do something (pertaining to an act)»); however dû is in fact written thus because of a dropped e: deu (see Circumflex in French). Since the 1990 orthographic changes, the circumflex on most i‘s and u‘s may be dropped when it does not serve to distinguish homophones: chaîne becomes chaine but sûr (sure) does not change because it distinguishes the word from sur (on).

- The diaeresis or tréma (ë, ï, ü, ÿ), over e, i, u or y, indicates that a vowel is to be pronounced separately from the preceding one: naïve [naiv], Noël [nɔɛl].

- The combination of e with diaeresis following o (as in Noël) is nasalized in the regular way if followed by n (Samoëns [samwɛ̃], but note Citroën [sitʁoɛn])

- The combination of e with diaeresis following a is either pronounced [ɛ] (Raphaël, Israël [aɛ]) or not pronounced, leaving only the a (Staël [a]) and the a is nasalized in the regular way if aë is followed by n (Saint-Saëns [sɛ̃sɑ̃(s)])

- A diaeresis on y only occurs in some proper names and in modern editions of old French texts. Some proper names in which ÿ appears include Aÿ [a(j)i] (commune in Marne, now Aÿ-Champagne), Rue des Cloÿs [?] (alley in the 18th arrondissement of Paris), Croÿ [kʁwi] (family name and hotel on the Boulevard Raspail, Paris), Château du Feÿ [dyfei]? (near Joigny), Ghÿs [ɡi]? (name of Flemish origin spelt Ghijs where ij in handwriting looked like ÿ to French clerks), L’Haÿ-les-Roses [laj lɛ ʁoz] (commune between Paris and Orly airport), Pierre Louÿs [luis] (author), Moÿ-de-l’Aisne [mɔidəlɛn] (commune in Aisne and a family name), and Le Blanc de Nicolaÿ [nikɔlai] (an insurance company in eastern France).

- The diaeresis on u appears in the Biblical proper names Archélaüs [aʁʃelay]?, Capharnaüm [kafaʁnaɔm] (with the um pronounced [ɔm] as in words of Latin origin such as album, maximum, or chemical element names such as sodium, aluminium), Emmaüs [ɛmays], Ésaü [ezay], and Saül [sayl], as well as French names such as Haüy [aɥi].[WP-fr has as 3 syllables, [ayi]] Nevertheless, since the 1990 orthographic changes, the diaeresis in words containing guë (such as aiguë [eɡy] or ciguë [siɡy]) may be moved onto the u: aigüe, cigüe, and by analogy may be used in verbs such as j’argüe.

- In addition, words coming from German retain their umlaut (ä, ö and ü) if applicable but often use French pronunciation, such as Kärcher ([kεʁʃɛʁ] or [kaʁʃɛʁ], trademark of a pressure washer).

- The cedilla or cédille (ç), under c, indicates that it is pronounced /s/ rather than /k/. Thus je lance «I throw» (with c = [s] before e), je lançais «I was throwing» (c would be pronounced [k] before a without the cedilla). The cedilla is only used before the vowels a, o or u, for example, ça /sa/; it is never used before the vowels e, i, or y, since these three vowels always produce a soft /s/ sound (ce, ci, cycle).

The tilde diacritical mark ( ˜ ) above n is occasionally used in French for words and names of Spanish origin that have been incorporated into the language (e.g., El Niño). Like the other diacritics, the tilde has no impact on the primary alphabetical order.

Diacritics are often omitted on capital letters, mainly for technical reasons. It is widely believed that they are not required; however both the Académie française and the Office québécois de la langue française reject this usage and confirm that «in French, the accent has full orthographic value»,[1] except for acronyms but not for abbreviations (e.g., CEE, ALENA, but É.-U.).[2] Nevertheless, diacritics are often ignored in word games, including crosswords, Scrabble, and Des chiffres et des lettres.

Ligatures[edit]

The two ligatures œ and æ have orthographic value. For determining alphabetical order, these ligatures are treated like the sequences oe and ae.

Œ[edit]

(French: œ, e dans l’o, o-e entrelacé or o et e collés/liés) This ligature is a mandatory contraction of ⟨oe⟩ in certain words. Some of these are native French words, with the pronunciation /œ/ or /ø/, e.g., chœur «choir» /kœʁ/, cœur «heart» /kœʁ/, mœurs «moods (related to moral)» /mœʁ, mœʁs/, nœud «knot» /nø/, sœur «sister» /sœʁ/, œuf «egg» /œf/, œuvre «work (of art)» /œvʁ/, vœu «vow» /vø/. It usually appears in the combination œu; œil /œj/ «eye» is an exception. Many of these words were originally written with the digraph eu; the o in the ligature represents a sometimes artificial attempt to imitate the Latin spelling: Latin bovem > Old French buef/beuf > Modern French bœuf.

Œ is also used in words of Greek origin, as the Latin rendering of the Greek diphthong οι, e.g., cœlacanthe «coelacanth». These words used to be pronounced with the vowel /e/, but in recent years a spelling pronunciation with /ø/ has taken hold, e.g., œsophage /ezɔfaʒ/ or /øzɔfaʒ/, Œdipe /edip/ or /ødip/ etc. The pronunciation with /e/ is often seen to be more correct.

When œ is found after the letter c, the c can be pronounced /k/ in some cases (cœur), or /s/ in others (cœlacanthe).

The ligature œ is not used when both letters contribute different sounds. For example, when ⟨o⟩ is part of a prefix (coexister), or when ⟨e⟩ is part of a suffix (minoen), or in the word moelle and its derivatives.[3]

Æ[edit]

(French: æ, e dans l’a, a-e entrelacé or a, e collés/liés) This ligature is rare, appearing only in some words of Latin and Greek origin like tænia, ex æquo, cæcum, æthuse (as named dog’s parsley).[4] It generally represents the vowel /e/, like ⟨é⟩.

The sequence ⟨ae⟩ appears in loanwords where both sounds are heard, as in maestro and paella.[5]

Digraphs and trigraphs[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2008) |

French digraphs and trigraphs have both historical and phonological origins. In the first case, it is a vestige of the spelling in the word’s original language (usually Latin or Greek) maintained in modern French, for example, the use of ⟨ph⟩ in words like téléphone, ⟨th⟩ in words like théorème, or ⟨ch⟩ in chaotique. In the second case, a digraph is due to an archaic pronunciation, such as ⟨eu⟩, ⟨au⟩, ⟨oi⟩, ⟨ai⟩, and ⟨œu⟩, or is merely a convenient way to expand the twenty-six-letter alphabet to cover all relevant phonemes, as in ⟨ch⟩, ⟨on⟩, ⟨an⟩, ⟨ou⟩, ⟨un⟩, and ⟨in⟩. Some cases are a mixture of these or are used for purely pragmatic reasons, such as ⟨ge⟩ for /ʒ/ in il mangeait (‘he ate’), where the ⟨e⟩ serves to indicate a «soft» ⟨g⟩ inherent in the verb’s root, similar to the significance of a cedilla to ⟨c⟩.

Spelling to sound correspondences[edit]

Some exceptions apply to the rules governing the pronunciation of word-final consonants. See Liaison (French) for details.

Consonants and combinations of consonant letters

| Spelling | Major value (IPA) |

Examples of major value | Minor values (IPA) |

Examples of minor values | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -bs, -cs (in plural of words ending in silent ⟨b⟩ or ⟨c⟩), -ds, -fs (in œufs and bœufs, and plural words ending with silent -⟨f⟩), ‑gs, -ps, -ts | Ø | plombs, blancs, prends, œufs, cerfs, longs , draps, achats | ||||

| b, bb | elsewhere | /b/ | ballon, abbé | |||

| before a voiceless consonant | /p/ | absolu, observer, subtile | ||||

| finally | Ø | plomb, Colomb | /b/ | Jacob | ||

| ç | /s/ | ça, garçon, reçu | ||||

| c | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /s/ | cyclone , loquace, douce, ciel, ceux | |||

| initially/medially elsewhere | /k/ | cabas , crasse, cœur, sacré | /s/ (before æ and œ in scientific terms of Latin and Greek origin) | cæcum, cœlacanthe | /ɡ/ second | |

| finally | /k/ | lac, donc, parc | Ø | tabac, blanc, caoutchouc | /ɡ/ zinc | |

| cc | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ks/ | accès, accent | /s/ succion | ||

| elsewhere | /k/ | accord | ||||

| ch | /ʃ/ | chat , douche | /k/ (often in words of Greek origin[6]) | chaotique, chlore, varech | Ø yacht, almanach /tʃ/ check-list, strech, coach |

|

| -ct | /kt/ | direct , correct | Ø | respect, suspect, instinct, succinct | ||

| d, dd | elsewhere | /d/ | doux , adresse, addition | |||

| finally | Ø | pied , accord | /d/ | David, sud | ||

| f, ff | /f/ | fait , affoler, soif | Ø clef, cerf, nerf | |||

| g | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ʒ/ | gens , manger | /dʒ/ gin, management, adagio | ||

| initially/medially elsewhere | /ɡ/ | gain , glacier | ||||

| finally | Ø | joug, long, sang | /ɡ/ | erg, zigzag | ||

| gg | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ɡʒ/ | suggérer | |||

| elsewhere | /ɡ/ | aggraver | ||||

| gn | /ɲ/ | montagne , agneau, gnôle | /ɡn/ gnose, gnou | |||

| h | Ø | habite , hiver | /j/ (intervocalic, to some speakers, but Ø for most speakers) | Sahara | /h/ ahaner (also Ø or /j/), hit | |

| j | /ʒ/ | joue, jeter | /dʒ/ | jean, jazz | /j/ fjord /x/ jota, marijuana |

|

| k | /k/ | alkyler , kilomètre, bifteck | ||||

| l, ll | /l/ | lait , allier, il, royal, matériel | Ø (occasionally finally) | cul, fusil, saoul | Ø fils, aulne, aulx (see also -il) |

|

| m, mm | /m/ | mou , pomme | Ø automne, condamner | |||

| n, nn | /n/ | nouvel , panne | ||||

| ng (in loanwords) | /ŋ/ | parking , camping | ||||

| p, pp | elsewhere | /p/ | pain, appel | |||

| finally | Ø | coup, trop | /p/ | cap, cep | ||

| ph | /f/ | téléphone , photo | ||||

| pt | /pt/ | ptérodactyle, adapter , excepter, ptôse, concept | /t/ | baptême, compter, sept | Ø prompt (also pt | |

| q (see qu) | /k/ | coq , cinq, piqûre (in new orthography, piqure), Qatar | ||||

| r, rr | /ʁ/ | rat , barre | Ø monsieur, gars (see also -er) |

|||

| s | initially medially next to a consonant or after a nasal vowel |

/s/ | sacre , estime, penser, instituer | /z/ | Alsace, transat, transiter | |

| elsewhere between two vowels | /z/ | rose, paysage | /s/ | antisèche, parasol, vraisemblable | ||

| finally | Ø | dans , repas | /s/ | fils, sens (noun), os (singular), ours | ||

| sc | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /s/ | science | /ʃ/ fasciste (also /s/) | ||

| elsewhere | /sk/ | script | ||||

| sch | /ʃ/ | schlague , haschisch, esche | /sk/ | schizoïde, ischion, æschne | ||

| ss | /s/ | baisser, passer | ||||

| -st | /st/ | est (direction), ouest, podcast | Ø | est (verb), Jésus-Christ (also /st/), contest |

||

| t, tt | elsewhere | /t/ | tout , attente | /s/ | nation (see ti + vowel) | |

| finally | Ø | tant , raffut | /t/ | dot, brut, yaourt | ||

| tch | /t͡ʃ/ | tchat, match, Tchad | ||||

| th | /t/ | thème, thermique, aneth | Ø asthme, bizuth, goth /s/ thread |

|||

| v | /v/ | ville, vanne | ||||

| w | /w/ | kiwi , week-end (in new orthography, weekend), whisky | /v/ | wagon, schwa, interviewer | (see also aw, ew, ow) | |

| x | initially next to a voiceless consonant phonologically finally |

/ks/ | xylophone, expansion, connexe | /ɡz/ | xénophobie, Xavier | /k/ xhosa, xérès (also /ks/) |

| medially elsewhere | /ks/ | galaxie, maximum | /s/ /z/ /gz/ |

soixante, Bruxelles deuxième exigence |

||

| finally | Ø | paix , deux | /ks/ | index, pharynx | /s/ six, dix, coccyx | |

| xc | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ks/ | exciter | |||

| elsewhere | /ksk/ | excavation | ||||

| z | elsewhere | /z/ | zain , gazette | |||

| finally | Ø | chez | /z/ gaz, fez, merguez /s/ quartz |

Vowels and combinations of vowel letters

| Spelling | Major value (IPA) |

Examples of major value | Minor values (IPA) |

Examples of minor value | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a, à | /a/ | patte, arable, là, déjà | /ɑ/ | araser, base, condamner | /ɔ/ yacht (also /o/) /o/ football /e/ lady |

|

| â | /ɑ/ | château, pâté | /a/ | dégât (also /ɑ/), parlâmes, liâtes, menât (simple past and imperfect subjunctive verb forms ending in -âmes, -âtes, and -ât) | ||

| aa | /a/ | graal, Baal, maastrichtois | /a.a/ | aa | ||

| æ | /e/ | ex-æquo, cæcum | ||||

| ae | /e/ | reggae | /a/ | groenendael, maelstrom, Portaels | /a.ɛ/ maestro /a.e/ paella |

|

| aë | /a.ɛ/ | Raphaël, Israël | /a/ Staël | |||

| ai | /ɛ/ (/e/) |

vrai, faite ai, aiguille, baisser, gai, quai |

/e/ | lançai, mangerai (future and simple past verb forms ending in -ai or -rai) | /ə/ faisan, faisons,[7] (and all other conjugated forms of faire which are spelt fais- and followed by a pronounced vowel) | |

| aî (in new orthography ⟨ai⟩) | /ɛː/ | maître, chaîne (in new orthography, maitre, chaine) | ||||

| aï | /a.i/ | naïf, haïr | /aj/ | aïe, aïeul, haïe, païen | ||

| aie | /ɛ/ | baie, monnaie | /ɛj/ | paie (also paye) | ||

| ao, aô | elsewhere | /a.ɔ/ | aorte, extraordinaire (also /ɔ/) | /a.o/ | baobab | /a/ faonne, paonneau /o/ Saône |

| phonologically finally | /a.o/ | cacao, chaos | /o/ curaçao | |||

| aou, aoû | /a.u/ | caoutchouc, aoûtien (in new orthography, aoutien), yaourt | /u/ | saoul, août (in new orthography, aout) | ||

| au | elsewhere | /o/ | haut, augure | |||

| before ⟨r⟩ | /ɔ/ | dinosaure, Aurélie, Laurent (also /o/) | ||||

| ay | elsewhere | /ɛj/ | ayons, essayer (also /ej/) | /aj/ | mayonnaise, papaye, ayoye | /ei/ pays (also /ɛi/) |

| finally | /ɛ/ | Gamay, margay, railway | /e/ okay | |||

| -aye | /ɛ.i/ | abbaye | /ɛj/ | paye | /ɛ/ La Haye /aj/ baye |

|

| e | elsewhere | /ə/ | repeser, genoux | /e/ revolver (in new orthography, révolver) | ||

| before multiple consonants, ⟨x⟩, or a final consonant (silent or pronounced) |

/ɛ/ | est, estival, voyelle, examiner, exécuter, quel, chalet | /ɛ, e/ /ə/ |

essence, effet, henné recherche, secrète, repli (before ch+vowel or 2 different consonants when the second one is l or r) |

/e/ mangez, (and any form of a verb in the second person plural that ends in -ez) assez /a/ femme, solennel, fréquemment, (and other adverbs ending in —emment)[8] /œ/ Gennevilliers (see also -er, -es) |

|

| in monosyllabic words before a silent consonant | /e/ | et, les, nez, clef | /ɛ/ es | |||

| finally in a position where it can be easily elided |

∅ | caisse, unique, acheter (also /ə/), franchement | /ə/ (finally in monosyllabic words) | que, de, je | ||

| é, ée | /e/ | clé, échapper, idée | /ɛ/ (in closed syllables) événement, céderai, vénerie (in new orthography, évènement, cèderai, vènerie) | |||

| è | /ɛ/ | relève, zèle | ||||

| ê | phonologically finally or in closed syllables | /ɛː/ | tête, crêpe, forêt, prêt | |||

| in open syllables | /ɛː, e/ | bêtise | ||||

| ea (except after ⟨g⟩) | /i/ | dealer, leader, speaker (in new orthography, dealeur, leadeur, speakeur) | ||||

| ee | /i/ | week-end (in new orthography, weekend), spleen | /e/ pedigree (also pédigré(e)) | |||

| eau | /o/ | eau, oiseaux | ||||

| ei | /ɛ/ | neige (also /ɛː/), reine (also /ɛː/), geisha (also /ɛj/) | ||||

| eî | /ɛː/ | reître (in new orthography, reitre) | ||||

| eoi | /wa/ | asseoir (in new orthography, assoir) | ||||

| eu | initially phonologically finally before /z/ |

/ø/ | Europe, heureux, peu, chanteuse | /y/ eu, eussions, (and any conjugated form of avoir spelt with eu-), gageure (in new orthography, gageüre) | ||

| elsewhere | /œ/ | beurre, jeune | /ø/ | feutre, neutre, pleuvoir | ||

| eû | /ø/ | jeûne | /y/ eûmes, eût, (and any conjugated forms of avoir spelt with eû-) | |||

| ey | before vowel | /ɛj/ | gouleyant, volleyer | |||

| finally | /ɛ/ | hockey, trolley | ||||

| i | elsewhere | /i/ | ici, proscrire | Ø business | ||

| before vowel | /j/ | fief, ionique, rien | /i/ (in compound words) | antioxydant | ||

| î | /i/ | gîte, épître (in new orthography, gitre, epitre) | ||||

| ï (initially or between vowels) | /j/ | ïambe (also iambe), aïeul, païen | /i/ ouïe | |||

| -ie | /i/ | régie, vie | ||||

| o | phonologically finally before /z/ |

/o/ | pro, mot, chose, déposes | /ɔ/ sosie | ||

| elsewhere | /ɔ/ | carotte, offre | /o/ | cyclone, fosse, tome | ||

| ô | /o/ | tôt, cône | /ɔ/ hôpital (also /o/) | |||

| œ | /œ/ | œil | /e/ /ɛ/ |

œsophage, fœtus œstrogène |

/ø/ lœss | |

| oe | /ɔ.e/ | coefficient | /wa, wɛ/ moelle, moellon, moelleux (also moëlle, moëllon, moëlleux) /ø/ foehn |

|||

| oê | /wa, wɛ/ | poêle | ||||

| oë | /ɔ.ɛ/ | Noël | /ɔ.e/ canoë, goëmon (also canoé, goémon) /wɛ/ foëne, Plancoët /wa/ Voëvre |

|||

| œu | phonologically finally | /ø/ | nœud, œufs, bœufs, vœu | |||

| elsewhere | /œ/ | sœur, cœur, œuf, bœuf | ||||

| oi, oie | /wa/ | roi, oiseau, foie, quoi (also /wɑ/ for these latter words) | /wɑ/ | bois, noix, poids, trois | /ɔ/ oignon (in new orthography, ognon) /ɔj/ séquoia /o.i/ autoimmuniser |

|

| oî | /wa, wɑ/ | croîs, Benoît | ||||

| oï | /ɔ.i/ | coït, astéroïde | /ɔj/ | troïka | ||

| oo | /ɔ.ɔ/ | coopération, oocyte, zoologie | /u/ | bazooka, cool, football | /ɔ/ alcool, Boskoop, rooibos /o/ spéculoos, mooré, zoo /w/ shampooing |

|

| ou, où | elsewhere | /u/ | ouvrir, sous, où | /o.y/ pseudouridimycine /aw/ out, knock-out |

||

| before vowel or h+vowel | /w/ | ouest, couiner, oui, souhait (also /u/) | ||||

| oû (in new orthography ⟨ou⟩) | /u/ | coût, goût (in new orthography, cout, gout) | ||||

| -oue | /u/ | roue | ||||

| oy | /waj/ | moyen, royaume | /wa, wɑ/ | Fourcroy | /ɔj/ oyez (and any conjugated form of ouïr spelt with oy-), goyave, cow-boy (in new orthography cowboy), ayoy /ɔ.i/ Moyse |

|

| u | elsewhere | /y/ | tu, juge | /u/ tofu, pudding /œ/ club, puzzle /i/ business /ɔ/ rhumerie (see also um) |

||

| before vowel | /ɥ/ | huit, tuer | /y/ | pollueur | /w/ cacahuète (also /ɥ/) | |

| û (in new orthography ⟨u⟩) | /y/ | sûr, flûte (in new orthography, flute) | ||||

| ue, uë | elsewhere | /ɥɛ/ | actuel, ruelle | /e/ /ɛ/ /ə/ /œ/ (see below) |

gué guerre que orgueil, cueillir |

|

| finally | /y/ | aiguë (in new orthography, aigüe), rue | Ø | clique | ||

| üe | finally | /y/ | aigüe | |||

| -ui, uï | /ɥi/ | linguistique, équilateral ambiguïté (in new orthography, ambigüité) | /i/ | équilibre | ||

| uy | /ɥij/ | bruyant, ennuyé, fuyons, Guyenne | /y.j/ | gruyère, thuya | /ɥi/ puy | |

| y | elsewhere | /i/ | cyclone, style | |||

| before vowel | /j/ | yeux, yole | /i/ | polyester, Libye | ||

| ÿ | (used only in proper nouns) | /i/ | L’Haÿ-les-Roses, Freÿr |

Combinations of vowel and consonant letters

| Spelling | Major value (IPA) |

Examples of major value | Minor values (IPA) |

Examples of minor value | Exceptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| am | before consonant | /ɑ̃/ | ambiance, lampe | /a/ damné | ||

| finally | /am/ | Vietnam, tam-tam, macadam | /ɑ̃/ Adam | |||

| an, aan | before consonant or finally | /ɑ̃/ | France, an, bilan, plan, afrikaans | /an/ | brahman, chaman, dan, gentleman, tennisman, naan | |

| aen, aën | before consonant or finally | /ɑ̃/ | Caen, Saint-Saëns | |||

| aim, ain | before consonant or finally | /ɛ̃/ | faim, saint, bains | |||

| aon | before consonant or finally | /ɑ̃/ | paon, faon | /a.ɔ̃/ | pharaon | |

| aw | /o/ | crawl, squaw, yawl | /ɑs/ in the 18th century and still traditional French approximation of Laws, the colloquial Scottish form of the economist John Law‘s name[9][10] | |||

| cqu | /k/ | acquit, acquéreur | ||||

| -cte | finally as feminine form of adjectives ending in silent ⟨ct⟩ (see above) | /t/ | succincte | |||

| em, en | before consonant or finally elsewhere | /ɑ̃/ | embaucher, vent | /ɛ̃/ | examen, ben, pensum, pentagone | /ɛn/ week-end (in new orthography, weekend), lichen /ɛm/ indemne, totem |

| before consonant or finally after ⟨é, i, y⟩ | /ɛ̃/ | européen, bien, doyen | /ɑ̃/ (before t or soft c) | patient, quotient, science, audience | ||

| eim, ein | before consonant or finally | /ɛ̃/ | plein, sein, Reims | |||

| -ent | 3rd person plural verb ending | Ø | parlent, finissaient | |||

| -er | /e/ | aller, transporter, premier | /ɛʁ/ | hiver, super, éther, fier, mer, enfer, Niger | /œʁ/ leader (also ɛʁ), speaker | |

| -es | Ø | Nantes, faites | /e/, /ɛ/ | les, des, ces, es | ||

| eun | before consonant or finally | /œ̃/ | jeun | |||

| ew | /ju/ | newton, steward (also iw) | /w/ chewing-gum | |||

| ge | before ⟨a, o, u⟩ | /ʒ/ | geai, mangea | |||

| gu | before ⟨e, i, y⟩ | /ɡ/ | guerre, dingue | /ɡy, ɡɥ/ | arguër (in new orthography, argüer), aiguille, linguistique, ambiguïté (in new orthography, ambigüité) | |

| -il | after some vowels1 | /j/ | ail, conseil | |||

| not after vowel | /il/ | il, fil | /i/ | outil, fils, fusil | ||

| -ilh- | after ⟨u⟩[11] | /ij/ | Guilhem | |||

| after other vowels[11] | /j/ | Meilhac, Devieilhe | /l/ Devieilhe (some families don’t use the traditional pronunciation /j/ of ilh) | |||

| -ill- | after some vowels1 | /j/ | paille, nouille | |||

| not after vowel | /il/ | mille, million, billion, ville, villa, village, tranquille[12] | /ij/ | grillage, bille | ||