В настоящее время известны три исторических варианта начертания букв грузинского алфавита, образующие три очень отличающиеся между собой группы шрифтов.

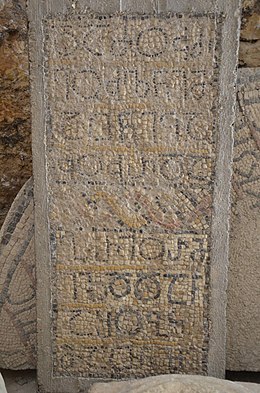

Заглавный грузинский шрифт «Асомтаврули» (в переводе ― «заглавные буквы»), называемый также «Хуцури» («Церковный»), или иногда «Мргловани» («Округлый»). Встречается в большом числе рукописей и надписей на стенах храмов, самая старая на территории Грузии ― конца V века в церкви в Болниси. За пределами Грузии, в монастырском комплексе св. Екатерины Синайской Горы в Египте, найдены тексты, датируемые несколькими десятилетиями ранее. Кроме того, в последние годы в Некреси (Кахетия) обнаружены надгробные стелы с надписями на «Асомтаврули«; их изучение только начинается.

Характерная особенность «Асомтаврули» ― каждая буква пишется отдельно от другой, буквы представляют собой композицию простейших геометрических фигур (отрезков прямых и дуг окружностей); все буквы пишутся между двумя линиями, в одну полосу (как заглавные латинские или русские). Направление письма ― строго слева направо.

В настоящее время шрифт «Асомтаврули«, помимо научноисторического, сохранил только религиозное и декоративное значение. Он используется при написании некоторых церковных текстов, а также для создания компьютерных логотипов и т.н. полиграфических «буквиц» с целью придания тексту особенной выразительности (подобно тому, как русские газеты сейчас используют отдельные литеры старославянского алфавита).

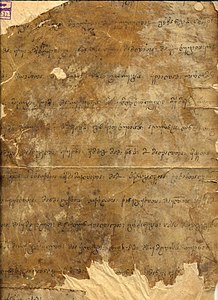

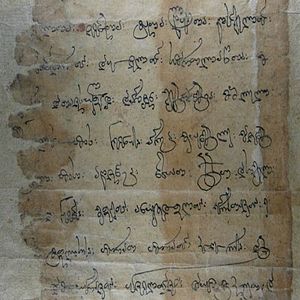

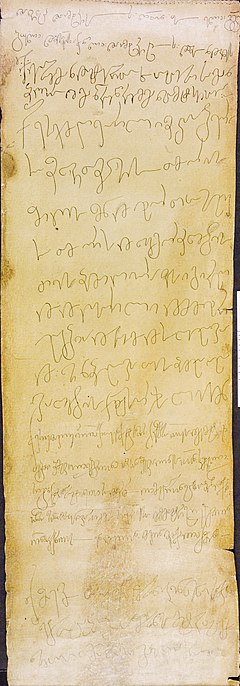

Шрифт церковной скорописи «Нусхури» (в переводе ― «для списков»). Встречается только в рукописях, начиная с VIII века и широко использовался для записи духовной литературы до XVIII века.

Будучи естественным графическим развитием «Асомтаврули«, предназначенным для быстрого письма с наклоненными угловатыми и лишенными геометрической гармонии буквами, написанными между четырьмя линиями (как строчные латинские или русские), «Нусхури» сохранил и фонетический состав, и последовательность букв, и даже в определенной степени графику «Асомтаврули», испытав при этом определенное развитие (в частности, расширившись литерой для фонемы «U»).

С исторической точки зрения, развитие шрифта «Нусхури» совпадает с эпохой арабского нашествия в Грузию, изгнания арабов и создания Единого Православного Грузинского Государства, что потребовало создания значительной по своему объему духовной литературы.

Интересной особенностью шрифта «Нусхури» является широкое употребление отдельных художественно выполненных литер шрифта «Асомтаврули» для обозначения заглавных букв в параграфах или абзацах текста (идея акад. Ак.Шанидзе фактически продолжила эту традицию). Кроме этого, шрифт «Нусхури» характеризует использование некоторых важных специальных литер, таких, как «титло» (сокращение для стандартных сочетаний литер, характерных для наиболее часто употребляемых слов), а также оригинальных знаков препинания, знаков цитирования и знаки схолий.

Другой уникальной особенностью алфавита «Нусхури«, встречающейся только в рукописях XXI веков, аналогично византийским рукописям того времени, является использование специальных знаков для отображения высоты музыкального тона при пении соответствующего текста. Семантика этих знаков, исследованная известным грузинским ученым Павле Ингороква, до настоящего времени не имеет бесспорной интерпретации. Изучение этих знаков пока еще далеко от завершения.

В настоящее время шрифт «Нусхури«, как и шрифт «Асомтаврули«, имеет только научно-историческое и религиозное значение, поскольку именно этим шрифтом записана подавляющая часть исторических памятников грузинской письменности, в первую очередь, духовного характера. Кроме того, сегодня на этом шрифте издается определенная часть церковной литературы, а его знание является обязательным для лиц достаточно высокого духовного сана.

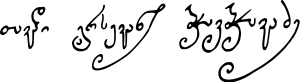

Шрифт гражданского письма «Мхедрули» (в переводе ― «рыцарское», то есть не церковное). Появляется в X веке (по некоторым данным ― даже раньше) как очень серьезная графическая модификация шрифта «Нусхури», связанная, вполне вероятно, с тем, что тесные культурные связи с арабском и персидском миром, которые были в ту эпоху безусловными культурными и политическими лидерами и на Ближнем Востоке, и в Европе, оказали значительное и всестороннее влияние на грузинский язык.

С социальной точки зрения, появление этого шрифта может быть интерпретировано, в отличие от шрифта «Нусхури«, не как средство расширения издания церковной литературы, а как своеобразное ментальное отражение интенсивных контактов военной, ремесленной и торговой части грузинского общества с окружающим тогда Грузию арабско-персидским миром.

Можно предположить, что светские грузины, которым, в отличие от лиц духовного сословия, приходилось все время писать по-арабски, поневоле стали придавать угловатым грузинским буквам «Нусхури» более мягкое, округлое очертание, связывать их изящными длинными изогнутыми соединительными дугами, вписывать их друг в друга и т.д. Это сходство является разительным в наиболее ранних источниках, постепенно ослабевая и к XVI-XVII векам сохраняясь лишь в самом общем образе.

Хотя грузинское письмо «Мхедрули» сохранило свое направление «слева направо», в отличие от принятого в арабском (и избравшем арабскую форму новом персидском) «справа налево», и в нем полностью сохранились гласные, сами грузинские буквы в этом шрифте претерпели значительное графическое изменение. Они выпрямились и удлинились, стали записываться в четыре линии, существенно изменились пропорции их отдельных элементов, появились связывающие элементы, переходящие в лигатуры (то есть объединенные или вписанные друг в друга буквы, примерно так, как как учат сейчас прописям в русских школах). Еще одно важное обстоятельство, которое роднит этот шрифт с арабско-персидским ― как было отмечено выше, в грузинском шрифте по сегодняшний день не имеется заглавных букв.

В результате появился новый, эстетически весьма совершенный и очень удобный для скорописи шрифт, который лишь очень отдаленно напоминает исходный «Асомтаврули» (в наше время потребовались значительные усилия ученых, чтобы строго доказать, что один произошел из другого); он постепенно вытеснил менее удобные при быстром письме шрифты «Асомтаврули» и «Нусхури«.

Шрифт «Мхедрули» практически не изменился до сегодняшнего дня, не считая того, что в конце XIX века наш известный общественный деятель Илья Чавчавадзе исключил из грузинской грамматики пять литер, обозначавших вышедшие к тому времени из употребления фонемы (то же самое сделал в 1918 году с русским языком Ленин). Заметим однако, что, в отличие от русского языка, указанные буквы продолжают употребляться для записи исторических текстов и текстов на диалектах грузинского языка, а также для записи текстов на близко родственных грузинскому языку сванском и мегрельском языках.

Другая серьезная модификация шрифта «Мхедрули» связана с деятельностью созданных, начиная с XVII века, в Италии и Австрии первых грузинских типографий, в результате чего перестали выписывать соединительные линии между буквами и стали изображать их по отдельности, как того требовала наборная техника (то же самое произошло и с латинскими, и с русскими буквами), хотя до этого весьма привлекательной стороной этого шрифта было широкое употребление связей между буквами, зачастую значительно изменяющих каноническое начертание каждой связываемой буквы. В результате настоящее время полиграфические шрифты, разработанные на основе «Мхедрули«, аналогично современным латинским и кириллическим шрифтам, не имеют лигатур, хотя элементы лигатурного письма изучаются на уроках родного языка грузинской средней школы, а лигатуры сохраняются в индивидуальном грузинском письме.

Понимание тех семантических потерь, которые возможны при механическом приравнивании выразительных средств трех исторических грузинских шрифтов, очень ясно видно у древних переписчиков грузинских церковных книг, которые всегда выбирали алфавит по согласованию со смыслом текста. В частности, многие тексты записаны с использованием двух и даже всех трех шрифтов.

Следует отметить еще одну новейшую тенденцию в развитии шрифта «Мхедрули«, которая близка к картине, наблюдающейся в современных латинских (и кириллических) шрифтах. Новые варианты шрифта «Мхедрули» имеют явную тенденцию к расширению средней полосы изображения буквы, очевидно, с целью облегчения визуального распознавания при быстром чтении значительных по объему текстов. Эта тенденция особенно ощущается в таких разработанных в середине XX века грузинских шрифтах, как «Григолия«.

| Georgian | |

|---|---|

damts’erloba «script» in Mkhedruli |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

AD 430[1] – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Uncertain, alphabetical order modelled on Greek

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Geor (240), Georgian (Mkhedruli and Mtavruli) – Georgian (Mkhedruli) Geok, 241 – Khutsuri (Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Georgian |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

| Living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage |

|

|

|

| Country | Georgia |

| Reference | 01205 |

| Region |

|

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2016 (11 session) |

The Georgian scripts are the three writing systems used to write the Georgian language: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. Although the systems differ in appearance, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order and are written horizontally from left to right. Of the three scripts, Mkhedruli, once the civilian royal script of the Kingdom of Georgia and mostly used for the royal charters, is now the standard script for modern Georgian and its related Kartvelian languages, whereas Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are used only by the Georgian Orthodox Church, in ceremonial religious texts and iconography.[2]

Georgian scripts are unique in their appearance and their exact origin has never been established; however, in strictly structural terms, their alphabetical order largely corresponds to the Greek alphabet, with the exception of letters denoting uniquely Georgian sounds, which are grouped at the end.[3][4] Originally consisting of 38 letters,[5] Georgian is presently written in a 33-letter alphabet, as five letters are obsolete. The number of Georgian letters used in other Kartvelian languages varies. Mingrelian uses 36: thirty-three that are current Georgian letters, one obsolete Georgian letter, and two additional letters specific to Mingrelian and Svan. Laz uses the same 33 current Georgian letters as Mingrelian plus that same obsolete letter and a letter borrowed from Greek for a total of 35. The fourth Kartvelian language, Svan, is not commonly written, but when it is, it uses Georgian letters as utilized in Mingrelian, with an additional obsolete Georgian letter and sometimes supplemented by diacritics for its many vowels.[2][6]

The «living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet» was granted the national status of intangible cultural heritage in Georgia in 2015[7] and inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.[8]

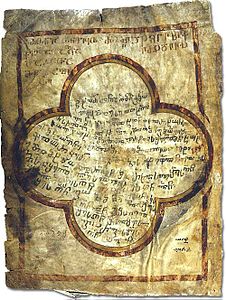

The three Georgian scripts: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, and Mkhedruli.

Origins[edit]

The origin of the Georgian script is poorly known, and no full agreement exists among Georgian and foreign scholars as to its date of creation, who designed the script, and the main influences on that process.

The first attested version of the script is Asomtavruli, which dates back to the 5th century; the other scripts were formed in the following centuries. Most scholars link the creation of the Georgian script to the process of Christianization of Iberia (not to be confused with the Iberian Peninsula), a core Georgian kingdom of Kartli.[9] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under King Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430,[9] contemporaneously with the Armenian alphabet.[10] It was first used for translation of the Bible and other Christian literature into Georgian, by monks in Georgia and Palestine.[4] Professor Levan Chilashvili’s dating of fragmented Asomtavruli inscriptions, discovered by him at the ruined town of Nekresi, in Georgia’s easternmost province of Kakheti, in the 1980s, to the 1st or 2nd century has not been accepted.[11]

A Georgian tradition first attested in the medieval chronicle Lives of the Kings of Kartli (ca. 800),[4] assigns a much earlier, pre-Christian origin to the Georgian alphabet, and names King Pharnavaz I (3rd century BC) as its inventor. This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaeological confirmation has been found.[4][12][13] Rapp considers the tradition to be an attempt by the Georgian Church to rebut the earlier tradition that the alphabet was invented by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots, and is a Georgian application of an Iranian model in which primordial kings are credited with the creation of basic social institutions.[14] Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze offers an alternative interpretation of the tradition, in the pre-Christian use of foreign scripts (alloglottography in the Aramaic alphabet) to write down Georgian texts.[15]

Another point of contention among scholars is the role played by Armenian clerics in that process. According to medieval Armenian sources and a number of scholars, Mesrop Mashtots, generally acknowledged as the creator of the Armenian alphabet, also created the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets. This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth-century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[16] and has been quoted by Donald Rayfield and James R. Russell,[17][18] but has been rejected by Georgian scholarship and some Western scholars who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation.[4] In his study on the history of the invention of the Armenian alphabet and the life of Mashtots, the Armenian linguist Hrachia Acharian strongly defended Koryun as a reliable source and rejected criticisms of his accounts on the invention of the Georgian script by Mashtots.[19] Acharian dated the invention to 408, four years after Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet (he dated the latter event to 404).[20] Some Western scholars quote Koryun’s claims without taking a stance on its validity[21][22] or concede that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.[4][13][23]

Another controversy regards the main influences at play in the Georgian alphabet, as scholars have debated whether it was inspired more by the Greek alphabet, or by Semitic alphabets such as Aramaic.[15] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.[3][4] Some scholars have also suggested certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers as a possible inspiration for particular letters.[24]

Asomtavruli[edit]

Asomtavruli (Georgian: ასომთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [ɑsɔmtʰɑvɾuli]) is the oldest Georgian script. The name Asomtavruli means «capital letters», from aso (ასო) «letter» and mtavari (მთავარი) «principal/head». It is also known as Mrgvlovani (Georgian: მრგვლოვანი) «rounded», from mrgvali (მრგვალი) «round», so named because of its round letter shapes. Despite its name, this «capital» script is unicameral.[25]

The oldest Asomtavruli inscriptions found so far date from the 5th century[26] and are Bir el Qutt[27] and the Bolnisi inscriptions.[28]

From the 9th century, Nuskhuri script started becoming dominant, and the role of Asomtavruli was reduced. However, epigraphic monuments of the 10th to 18th centuries continued to be written in Asomtavruli script. Asomtavruli in this later period became more decorative. In the majority of 9th-century Georgian manuscripts which were written in Nuskhuri script, Asomtavruli was used for titles and the first letters of chapters.[29] However, some manuscripts written completely in Asomtavruli can be found until the 11th century.[30]

Form of Asomtavruli letters[edit]

In early Asomtavruli, the letters are of equal height. Georgian historian and philologist Pavle Ingorokva believes that the direction of Asomtavruli, like that of Greek, was initially boustrophedon, though the direction of the earliest surviving texts is from left to the right.[31]

In most Asomtavruli letters, straight lines are horizontal or vertical and meet at right angles. The only letter with acute angles is Ⴟ (ჯ jani). There have been various attempts to explain this exception. Georgian linguist and art historian Helen Machavariani believes jani derives from a monogram of Christ, composed of the Ⴈ (ი ini) and Ⴕ (ქ kani).[32] According to Georgian scholar Ramaz Pataridze, the cross-like shape of letter jani indicates the end of the alphabet, and has the same function as the similarly shaped Phoenician letter taw (), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[33] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

From the 7th century, the forms of some letters began to change. The equal height of the letters was abandoned, with letters acquiring ascenders and descenders.[34][35]

| Ⴀ ani |

Ⴁ bani |

Ⴂ gani |

Ⴃ doni |

Ⴄ eni |

Ⴅ vini |

Ⴆ zeni |

Ⴡ he |

Ⴇ tani |

Ⴈ ini |

Ⴉ kʼani |

Ⴊ lasi |

Ⴋ mani |

Ⴌ nari |

Ⴢ hie |

Ⴍ oni |

Ⴎ pʼari |

Ⴏ zhani |

Ⴐ rae |

| Ⴑ sani |

Ⴒ tʼari |

Ⴣ vie |

ႭჃ Ⴓ uni |

Ⴔ pari |

Ⴕ kani |

Ⴖ ghani |

Ⴗ qʼari |

Ⴘ shini |

Ⴙ chini |

Ⴚ tsani |

Ⴛ dzili |

Ⴜ ts’ili |

Ⴝ ch’ari |

Ⴞ khani |

Ⴤ qari |

Ⴟ jani |

Ⴠ hae |

Ⴥ hoe |

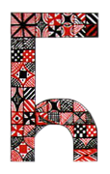

Asomtavruli illumination[edit]

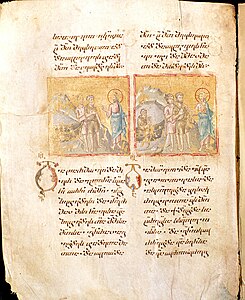

In Nuskhuri manuscripts, Asomtavruli are used for titles and illuminated capitals. The latter were used at the beginnings of paragraphs which started new sections of text. In the early stages of the development of Nuskhuri texts, Asomtavruli letters were not elaborate and were distinguished principally by size and sometimes by being written in cinnabar ink. Later, from the 10th century, the letters were illuminated. The style of Asomtavruli capitals can be used to identify the era of a text. For example, in the Georgian manuscripts of the Byzantine era, when the styles of the Byzantine Empire influenced Kingdom of Georgia, capitals were illuminated with images of birds and other animals.[36]

Decorative Asomtavruli capital letters, მ (m) and თ (t), 12–13th century.

From the 11th-century «limb-flowery», «limb-arrowy» and «limb-spotty» decorative forms of Asomtavruli are developed. The first two are found in 11th- and 12th-century monuments, whereas the third one is used until the 18th century.[37][38]

Importance was attached also to the colour of the ink itself.[39]

Asomtavruli letter დ (doni) is often written with decoration effects of fish and birds.[40]

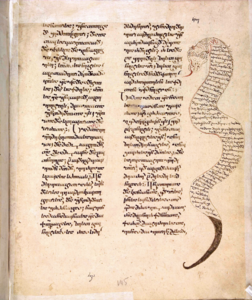

The «Curly» decorative form of Asomtavruli is also used where the letters are wattled or intermingled on each other, or the smaller letters are written inside other letters. It was mostly used for the headlines of the manuscripts or the books, although there are complete inscriptions which were written in the Asomtavruli «Curly» form only.[41]

The title of Gospel of Matthew in Asomtavruli «Curly» decorative form.

Handwriting of Asomtavruli[edit]

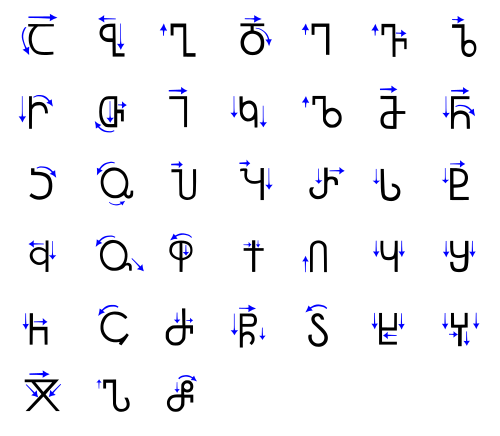

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Asomtavruli letter:[42]

Nuskhuri[edit]

Nuskhuri (Georgian: ნუსხური; Georgian pronunciation: [nusχuɾi]) is the second Georgian script. The name nuskhuri comes from nuskha (ნუსხა), meaning «inventory» or «schedule». Nuskhuri was soon augmented with Asomtavruli illuminated capitals in religious manuscripts. The combination is called Khutsuri (Georgian: ხუცური, «clerical», from khutsesi (ხუცესი «cleric»), and it was principally used in hagiography.[43]

Nuskhuri first appeared in the 9th century as a graphic variant of Asomtavruli.[9] The oldest inscription is found in the Ateni Sioni Church and dates to 835 AD.[44] The oldest surviving Nuskhuri manuscripts date to 864 AD.[45] Nuskhuri becomes dominant over Asomtavruli from the 10th century.[43]

Form of Nuskhuri letters[edit]

Nuskhuri letters vary in height, with ascenders and descenders, and are slanted to the right. Letters have an angular shape, with a noticeable tendency to simplify the shapes they had in Asomtavruli. This enabled faster writing of manuscripts.[46]

→

→

Asomtavruli letters ო (oni) and ჳ (vie). A ligature of these letters produced a new letter in Nuskhuri, უ uni.

| ⴀ ani |

ⴁ bani |

ⴂ gani |

ⴃ doni |

ⴄ eni |

ⴅ vini |

ⴆ zeni |

ⴡ he |

ⴇ tani |

ⴈ ini |

ⴉ kʼani |

ⴊ lasi |

ⴋ mani |

ⴌ nari |

ⴢ hie |

ⴍ oni |

ⴎ pʼari |

ⴏ zhani |

ⴐ rae |

| ⴑ sani |

ⴒ tʼari |

ⴣ vie |

ⴍⴣ ⴓ uni |

ⴔ pari |

ⴕ kani |

ⴖ ghani |

ⴗ qʼari |

ⴘ shini |

ⴙ chini |

ⴚ tsani |

ⴛ dzili |

ⴜ tsʼili |

ⴝ chʼari |

ⴞ khani |

ⴤ qari |

ⴟ jani |

ⴠ hae |

ⴥ hoe |

- Note: Without proper font support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Nuskhuri letters.

Handwriting of Nuskhuri[edit]

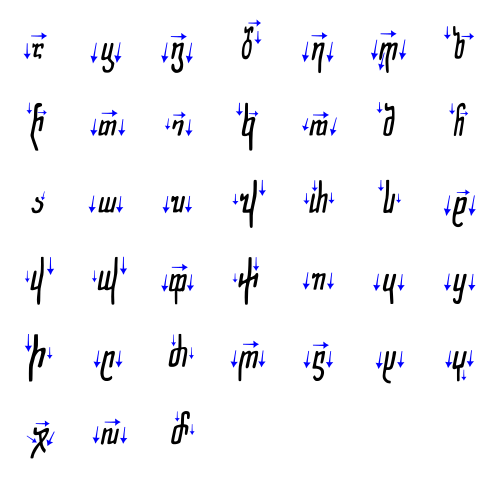

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Nuskhuri letter:[47]

Use of Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri today[edit]

Asomtavruli is used intensively in iconography, murals, and exterior design, especially in stone engravings.[48] Georgian linguist Akaki Shanidze made an attempt in the 1950s to introduce Asomtavruli into the Mkhedruli script as capital letters to begin sentences, as in the Latin script, but it did not catch on.[49] Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are officially used by the Georgian Orthodox Church alongside Mkhedruli. Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia called on people to use all three Georgian scripts.[50]

Mkhedruli[edit]

Mkhedruli (Georgian: მხედრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mχɛdɾuli]) is the third and current Georgian script. Mkhedruli, literally meaning «cavalry» or «military», derives from mkhedari (მხედარი) meaning «horseman», «knight», «warrior»[51] and «cavalier».[52]

Mkhedruli is bicameral, with capital letters that are called Mkhedruli Mtavruli (მხედრული მთავრული) or simply Mtavruli (მთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mtʰɑvɾuli]). Nowadays, Mkhedruli Mtavruli is only used in all-caps text in titles or to emphasize a word, though in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was occasionally used, as in Latin and Cyrillic scripts, to capitalize proper nouns or the first word of a sentence. Contemporary Georgian script does not recognize capital letters and their usage has become decorative.[53]

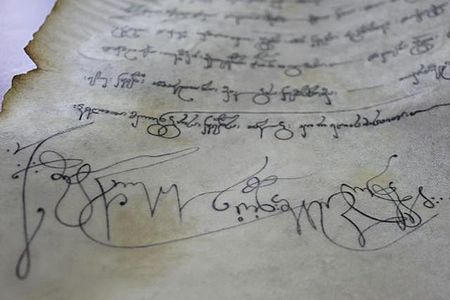

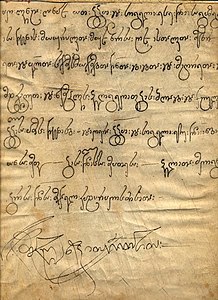

Mkhedruli first appears in the 10th century. The oldest Mkhedruli inscription is found in Ateni Sioni Church dating back to 982 AD. The second oldest Mkhedruli-written text is found in the 11th-century royal charters of King Bagrat IV of Georgia. Mkhedruli was mostly used then in the Kingdom of Georgia for the royal charters, historical documents, manuscripts and inscriptions.[54] Mkhedruli was used for non-religious purposes only and represented the «civil», «royal» and «secular» script.[55][56]

Mkhedruli became more and more dominant over the two other scripts, though Khutsuri (Nuskhuri with Asomtavruli) was used until the 19th century. Mkhedruli became the universal writing Georgian system outside of the Church in the 19th century with the establishment and development of printed Georgian fonts.[57]

Form of Mkhedruli letters[edit]

Mkhedruli inscriptions of the 10th and 11th centuries are characterized in rounding of angular shapes of Nuskhuri letters and making the complete outlines in all of its letters. Mkhedruli letters are written in the four-linear system, similar to Nuskhuri.

Mkhedruli becomes more round and free in writing. It breaks the strict frame of the previous two alphabets, Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli letters begin to get coupled and more free calligraphy develops.[58]

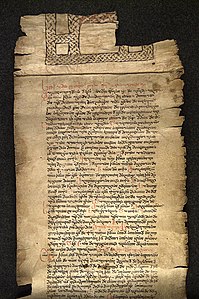

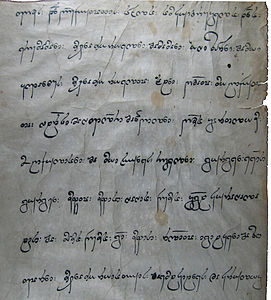

Example of one of the oldest Mkhedruli-written texts found in the royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, 11th century.

«Gurgen : King : of Kings : great-grandfather : of mine : Bagrat Curopalates»

Modern Georgian alphabet[edit]

The modern Georgian alphabet consists of 33 letters:

| ა ani |

ბ bani |

გ gani |

დ doni |

ე eni |

ვ vini |

ზ zeni |

თ tani |

ი ini |

კ k’ani |

ლ lasi |

| მ mani |

ნ nari |

ო oni |

პ p’ari |

ჟ zhani |

რ rae |

ს sani |

ტ t’ari |

უ uni |

ფ pari |

ქ kani |

| ღ ghani |

ყ q’ari |

შ shini |

ჩ chini |

ც tsani |

ძ dzili |

წ ts’ili |

ჭ ch’ari |

ხ khani |

ჯ jani |

ჰ hae |

Letters removed from the Georgian alphabet[edit]

The Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians, founded by Prince Ilia Chavchavadze in 1879, discarded five letters from the Georgian alphabet that had become redundant:[25]

| ჱ he |

ჲ hie |

ჳ vie |

ჴ qari |

ჵ hoe |

- ჱ (he) /eɪ/, Svan /eː/, sometimes called «ei«[59] or «e-merve» («eighth e«),[60] was equivalent to ეჲ ey, as in ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ kristʼey ‘Christ’.

- ჲ (hie) /je/, also called yota,[60] appeared instead of ი (ini) after a vowel, but came to have the same pronunciation as ი (ini) and was replaced by it. Thus, ქრისტჱ ~ ქრისტეჲ kristʼey «Christ» is now written ქრისტე kristʼe.

- ჳ (vie) /uɪ/, Svan /w/[60] came to be pronounced the same as ვი vi and was replaced by that sequence, as in სხჳსი > სხვისი skhvisi «others'».

- ჴ (qari, hari) /q⁽ʰ⁾/[60] came to be pronounced the same as ხ (khani), and was replaced by it. e.g. ჴელმწიფე qelmtsʼipe became ხელმწიფე khelmtsʼipe «sovereign».

- ჵ (hoe) /oː/[60] was used for the interjection hoi! and is now spelled ჰოი. Also used in Bats for the /ʕ/ or /ɦ/ sound.

All but ჵ (hoe) continue to be used in the Svan alphabet; ჲ (hie) is used in the Mingrelian and Laz alphabets as well, for the y-sound /j/. Several others were used for Abkhaz and Ossetian in the short time they were written in Mkhedruli script.

Letters added to other alphabets[edit]

Mkhedruli has been adapted to languages besides Georgian. Some of these alphabets retained letters obsolete in Georgian, while others required additional letters:

| ჶ fi |

ჷ shva |

ჸ elifi |

ჹ turned gani |

ჺ aini |

ჼ modifier letter nar |

ჽ aen |

ჾ hard sign |

ჿ labial sign |

- ჶ (fi «phi») is used in Laz and Svan, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2] It derives from the Greek letter Φ (phi).

- ჷ (shva «schwa»), also called yn, is used for the schwa sound in Svan and Mingrelian, and formerly in Ossetian and Abkhazian.[2]

- ჸ (elifi «alif») is used in for the glottal stop in Svan and Mingrelian.[2] It is a reversed ⟨ყ⟩ (q’ari).

- ჹ (turned gani) was once used for [ɢ] in evangelical literature in Dagestanian languages.[2]

- ჼ (modifier nar) is used in Bats. It nasalizes the preceding vowel.[61]

- ჺ (aini «ain») is occasionally used for [ʕ] in Bats.[2] It derives from the Arabic letter ⟨ع⟩ (ʿayn)

- ჽ (aen) was used in the Ossetian language when it was written in the Georgian script. It was pronounced [ə].[62]

- ჾ (hard sign) was used in Abkhaz for velarization of the preceding consonant.[63]

- ჿ (labial sign) was used in Abkhaz for labialization of the preceding consonant.[63]

Handwriting of Mkhedruli[edit]

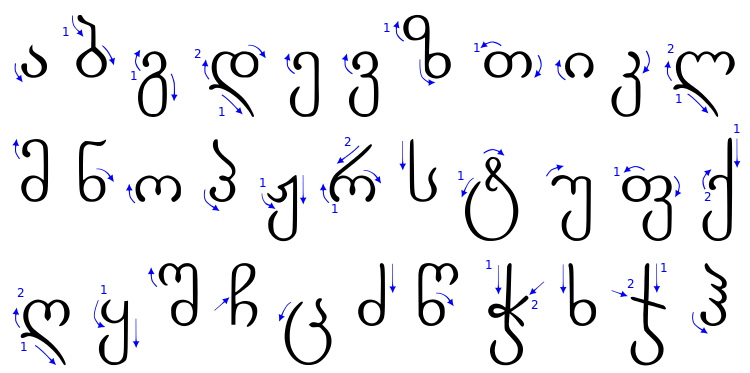

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Mkhedruli letter:[64][65][66]

ზ, ო, and ხ (zeni, oni, khani) are almost always written without the small tick at the end, while the handwritten form of ჯ (jani) often uses a vertical line, (sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter than in print.

- Only four letters are x-height, with neither ascenders nor descenders: ა, თ, ი, ო.

- Thirteen have ascenders, like b or d in English: ბ, ზ, მ, ნ, პ, რ, ს, შ, ჩ, ძ, წ, ხ, ჰ

- An equal number have descenders, like p or q in English: გ, დ, ე, ვ, კ, ლ, ჟ, ტ, უ, ფ, ღ, ყ, ც

- Three letters have both ascenders and descenders, like þ in Old English: ქ, ჭ, and (in handwriting) ჯ. წ has both ascender and descender in print, and sometimes in handwriting.

Variation[edit]

There is individual and stylistic variation in many of the letters. For example, the top circle of ზ (zeni) and the top stroke of რ (rae) may go in the other direction than shown in the chart (that is, counter-clockwise starting at 3 o’clock, and upwards – see the external-link section for videos of people writing).

Other common variants:

- გ (gani) may be written like ვ (vini) with a closed loop at the bottom.

- დ (doni) is frequently written with a simple loop at top,

.

- კ, ც, and ძ (k’ani, tsani, dzili) are generally written with straight, vertical lines at the top, so that for example ც (tsani) resembles a U with a dimple in the right side.

- ლ (lasi) is frequently written with a single arc,

. Even when all three are written, they’re generally not all the same size, as they are in print, but rather riding on one wide arc like two dimples in it.

- Rarely, ო (oni) is written as a right angle,

.

- რ (rae) is frequently written with one arc,

, like a Latin ⟨h⟩.

- ტ (t’ari) often has a small circle with a tail hanging into the bowl, rather than two small circles as in print, or as an O with a straight vertical line intersecting the top. It may also be rotated a bit clockwise, with the small circles further to the right and not as close to the top.

- წ (ts’ili) is generally written with a round bowl at the bottom,

. Another variation features a triangular bowl.

- ჭ (ch’ari) may be written without the hook at the top, and often with a completely straight vertical line.

- ჱ (he) may be written without the loop, like a conflation of ს and ჰ.

- ჯ (jani) is sometimes written so that it looks like a hooked version of the Latin «X»

Similar letters[edit]

Several letters are similar and may be confused at first, especially in handwriting.

- For ვ (vini) and კ (k’ani), the critical difference is whether the top is a full arc or a (more-or-less) vertical line.

- For ვ (vini) and გ (gani), it is whether the bottom is an open curve or closed (a loop). The same is true of უ (uni) and შ (shini); in handwriting, the tops may look the same. Similarly ს (sani) and ხ (khani).

- For კ (k’ani) and პ (p’ari), the crucial difference is whether the letter is written below or above x-height, and whether it’s written top-down or bottom-up.

- ძ (dzili) is written with a vertical top.

Ligatures, abbreviations and calligraphy[edit]

Asomtavruli is often highly stylized and writers readily formed ligatures, intertwined letters, and placed letters within letters or other such monograms.[67]

A ligature of the Asomtavruli initials of King Vakhtang I of Iberia, Ⴂ Ⴌ (გნ, GN)

A ligature of the Asomtavruli letters Ⴃ Ⴀ (და, da) «and»

Nuskhuri, like Asomtavruli, is also often highly stylized. Writers readily formed ligatures and abbreviations for nomina sacra, including diacritics called karagma, which resemble titla. Because writing materials such as vellum were scarce and therefore precious, abbreviating was a practical measure widespread in manuscripts and hagiography by the 11th century.[68]

A Nuskhuri abbreviation of რომელი (romeli) «which»

A Nuskhuri abbreviation of იესუ ქრისტე (iesu kriste) «Jesus Christ»

Mkhedruli, in the 11th to 17th centuries also came to employ digraphs to the point that they were obligatory, requiring adherence to a complex system.[69]

A Mkhedruli ligature of და (da) «and»

Typefaces[edit]

Georgian scripts come in only a single typeface, though word processors can apply automatic («fake»)[70] oblique and bold formatting to Georgian text. Traditionally, Asomtavruli was used for chapter or section titles, where Latin script might use bold or italic type.

Punctuation[edit]

In Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri punctuation, various combinations of dots were used as word dividers and to separate phrases, clauses, and paragraphs. In monumental inscriptions and manuscripts of 5th to 10th centuries, these were written as dashes, like −, = and =−. In the 10th century, clusters of one (·), two (:), three (჻) and six (჻჻) dots (later sometimes small circles) were introduced by Ephrem Mtsire to indicate increasing breaks in the text. One dot indicated a «minor stop» (presumably a simple word break), two dots marked or separated «special words», three dots for a «bigger stop» (such as the appositive name and title «the sovereign Alexander», below, or the title of the Gospel of Matthew, above), and six dots were to indicate the end of the sentence. Starting in the 11th century, marks resembling the apostrophe and comma came into use. An apostrophe was used to mark an interrogative word, and a comma appeared at the end of an interrogative sentence. From the 12th century on, these were replaced with the semicolon (the Greek question mark). In the 18th century, Patriarch Anton I of Georgia reformed the system again, with commas, single dots, and double dots used to mark «complete», «incomplete», and «final» sentences, respectively.[71] For the most part, Georgian today uses the punctuation as in international usage of the Latin script.[72]

Summary[edit]

This table lists the three scripts in parallel columns, including the letters that are now obsolete in all alphabets (shown with a blue background), obsolete in Georgian but still used in other alphabets (green background), or additional letters in languages other than Georgian (pink background). The «national» transliteration is the system used by the Georgian government, whereas «Laz» is the Latin Laz alphabet used in Turkey. The table also shows the traditional numeric values of the letters.[73]

| Letters | Unicode (mkhedruli) |

Name | IPA | Transcriptions | Numeric value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| asomtavruli | nuskhuri | mkhedruli | mtavruli | National | ISO 9984 | BGN | Laz | ||||

| Ⴀ | ⴀ | ა | Ა | U+10D0 | ani | /ɑ/, Svan /a, æ/ | A a | A a | A a | A a | 1 |

| Ⴁ | ⴁ | ბ | Ბ | U+10D1 | bani | /b/ | B b | B b | B b | B b | 2 |

| Ⴂ | ⴂ | გ | Გ | U+10D2 | gani | /ɡ/ | G g | G g | G g | G g | 3 |

| Ⴃ | ⴃ | დ | Დ | U+10D3 | doni | /d/ | D d | D d | D d | D d | 4 |

| Ⴄ | ⴄ | ე | Ე | U+10D4 | eni | /ɛ/ | E e | E e | E e | E e | 5 |

| Ⴅ | ⴅ | ვ | Ვ | U+10D5 | vini | /v/ | V v | V v | V v | V v | 6 |

| Ⴆ | ⴆ | ზ | Ზ | U+10D6 | zeni | /z/ | Z z | Z z | Z z | Z z | 7 |

| Ⴡ | ⴡ | ჱ | Ჱ | U+10F1 | he | /eɪ/, Svan /eː/ | — | Ē ē | Ey ey | — | 8 |

| Ⴇ | ⴇ | თ | Თ | U+10D7 | tani | /t⁽ʰ⁾/ | T t | Tʼ tʼ | Tʼ tʼ | T t | 9 |

| Ⴈ | ⴈ | ი | Ი | U+10D8 | ini | /i/ | I i | I i | I i | I i | 10 |

| Ⴉ | ⴉ | კ | Კ | U+10D9 | kʼani | /kʼ/ | Kʼ kʼ | K k | K k | Ǩ ǩ | 20 |

| Ⴊ | ⴊ | ლ | Ლ | U+10DA | lasi | /l/ | L l | L l | L l | L l | 30 |

| Ⴋ | ⴋ | მ | Მ | U+10DB | mani | /m/ | M m | M m | M m | M m | 40 |

| Ⴌ | ⴌ | ნ | Ნ | U+10DC | nari | /n/ | N n | N n | N n | N n | 50 |

| Ⴢ | ⴢ | ჲ | Ჲ | U+10F2 | hie | /je/, Mingrelian, Laz, & Svan /j/ | — | Y y | J j | Y y | 60 |

| Ⴍ | ⴍ | ო | Ო | U+10DD | oni | /ɔ/, Svan /ɔ, œ/ | O o | O o | O o | O o | 70 |

| Ⴎ | ⴎ | პ | Პ | U+10DE | pʼari | /pʼ/ | Pʼ pʼ | P p | P p | P̌ p̌ | 80 |

| Ⴏ | ⴏ | ჟ | Ჟ | U+10DF | zhani | /ʒ/ | Zh zh | Ž ž | Zh zh | J j | 90 |

| Ⴐ | ⴐ | რ | Რ | U+10E0 | rae | /r/ | R r | R r | R r | R r | 100 |

| Ⴑ | ⴑ | ს | Ს | U+10E1 | sani | /s/ | S s | S s | S s | S s | 200 |

| Ⴒ | ⴒ | ტ | Ტ | U+10E2 | tʼari | /tʼ/ | Tʼ tʼ | T t | T t | Ť t̆ | 300 |

| Ⴣ | ⴣ | ჳ | Ჳ | U+10F3 | vie | /uɪ/, Svan /w/ | — | W w | — | — | 400[74] |

| Ⴓ | ⴓ | უ | Უ | U+10E3 | uni | /u/, Svan /u, y/ | U u | U u | U u | U u | 400[74] |

| Ⴧ | ⴧ | ჷ | Ჷ | U+10F7 | yn, schva | Mingrelian & Svan /ə/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴔ | ⴔ | ფ | Ფ | U+10E4 | pari | /p⁽ʰ⁾/ | P p | Pʼ pʼ | Pʼ pʼ | P p | 500 |

| Ⴕ | ⴕ | ქ | Ქ | U+10E5 | kani | /k⁽ʰ⁾/ | K k | Kʼ kʼ | Kʼ kʼ | K k | 600 |

| Ⴖ | ⴖ | ღ | Ღ | U+10E6 | ghani | /ɣ/ | Gh gh | Ḡ ḡ | Gh gh | Ğ ğ | 700 |

| Ⴗ | ⴗ | ყ | Ყ | U+10E7 | qʼari | /qʼ/ | Qʼ qʼ | Q q | Q q | Q q | 800 |

| — | — | ჸ | Ჸ | U+10F8 | elif | Mingrelian & Svan /ʔ/ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴘ | ⴘ | შ | Შ | U+10E8 | shini | /ʃ/ | Sh sh | Š š | Sh sh | Ş ş | 900 |

| Ⴙ | ⴙ | ჩ | Ჩ | U+10E9 | chini | /tʃ⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ch ch | Čʼ čʼ | Chʼ chʼ | Ç ç | 1000 |

| Ⴚ | ⴚ | ც | Ც | U+10EA | tsani | /ts⁽ʰ⁾/ | Ts ts | Cʼ cʼ | Tsʼ tsʼ | Ʒ ʒ | 2000 |

| Ⴛ | ⴛ | ძ | Ძ | U+10EB | dzili | /dz/ | Dz dz | J j | Dz dz | Ž ž | 3000 |

| Ⴜ | ⴜ | წ | Წ | U+10EC | tsʼili | /tsʼ/ | Tsʼ tsʼ | C c | Ts ts | Ǯ ǯ | 4000 |

| Ⴝ | ⴝ | ჭ | Ჭ | U+10ED | chʼari | /tʃʼ/ | Chʼ chʼ | Č č | Ch ch | Ç̌ ç̌ | 5000 |

| Ⴞ | ⴞ | ხ | Ხ | U+10EE | khani | /χ/ | Kh kh | X x | Kh kh | X x | 6000 |

| Ⴤ | ⴤ | ჴ | Ჴ | U+10F4 | qari, hari | /q⁽ʰ⁾/ | — | H̱ ẖ | qʼ | — | 7000 |

| Ⴟ | ⴟ | ჯ | Ჯ | U+10EF | jani | /dʒ/ | J j | J̌ ǰ | J j | C c | 8000 |

| Ⴠ | ⴠ | ჰ | Ჰ | U+10F0 | hae | /h/ | H h | H h | H h | H h | 9000 |

| Ⴥ | ⴥ | ჵ | Ჵ | U+10F5 | hoe | /oː/, Bats /ʕ, ɦ/ | — | Ō ō | — | — | 10000 |

| — | — | ჶ | Ჶ | U+10F6 | fi | Laz /f/ | — | F f | — | F f | — |

| — | — | ჹ | Ჹ | U+10F9 | turned gani | Dagestanian languages /ɢ/ in evangelical literature[2] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჺ | Ჺ | U+10FA | aini | Bats /ʕ/[2] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჼ | — | U+10FC | modifier nar | Bats /◌̃/ nasalization of preceding vowel[61] | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ⴭ | ⴭ | ჽ | Ჽ | U+10FD | aen[63] | Ossetian /ə/[62] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჾ | Ჾ | U+10FE | hard sign[63] | Abkhaz velarization of preceding consonant[63] | — | — | — | — | — |

| — | — | ჿ | Ჿ | U+10FF | labial sign[63] | Abkhaz labialization of preceding consonant[63] | — | — | — | — | — |

Use for other non-Kartvelian languages[edit]

Ossetian text written in Mkhedruli script, from a book on Ossetian folklore published in South Ossetia in 1940. The non-Georgian letters ჶ [f] and ჷ [ə] can be seen.

Old Avar crosses with Avar inscriptions in Asomtavruli script.

- Ossetian language until the 1940s.[75]

- Abkhaz language until the 1940s.[76]

- Ingush language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[77]

- Chechen language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[78]

- Avar language (historically), later replaced in the 17th century by Arabic and by the Cyrillic script in modern times.[79][80]

- Turkish language and Azerbaijani language. A Turkish Gospel, dictionary, poems, medical book dating from the 18th century.[81]

- Persian language. The 18th-century Persian translation of the Arabic Gospel is kept at the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.

- Armenian language. In the Armenian community in Tbilisi, the Georgian script was occasionally used for writing Armenian in the 18th and 19th centuries, and some samples of this kind of texts are kept at the Georgian National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi.[82]

- Russian language. In the collections of the National Center of Manuscripts in Tbilisi there are also a few short poems in the Russian language written in Georgian script dating from the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

- Azerbaijani language. Used by Azeris in Georgia.[83]

- Other Northeast Caucasian languages. The Georgian script was used for writing North Caucasian and Dagestani languages in connection with Georgian missionary activities in the areas starting in the 18th century.[84]

Computing[edit]

The Georgian letter ⟨ღ⟩ (ghani) is often used as a love or heart symbol online.

The Georgian letter ⟨ლ⟩ (lasi) is sometimes used as a hand or fist in emoticons ( ex: ლ(╹◡╹ლ) ).

Unicode[edit]

The first Georgian script was included in Unicode Standard in October 1991 with the release of version 1.0. In creating the Georgian Unicode block, important roles were played by German Jost Gippert, a linguist of Kartvelian studies, and American-Irish linguist and script-encoder Michael Everson, who created the Georgian Unicode for the Macintosh systems.[85] Significant contributions were also made by Anton Dumbadze and Irakli Garibashvili[86] (not to be mistaken with the Prime Minister of Georgia Irakli Garibashvili).

Georgian Mkhedruli script received an official status for being Georgia’s internationalized domain name script for (.გე).[87]

Mtavruli letters were added in Unicode version 11.0 in June 2018.[88] They are capital letters with similar letterforms to Mkhedruli, but with descenders shifted above the baseline, with a wider central oval, and with the top slightly higher than the ascender height.[89][90][91] Before this addition, font creators included Mtavruli in various ways. Some fonts came in pairs, of which one had lowercase letters and the other uppercase; some Unicode fonts placed Mtavruli letterforms in the Asomtavruli range (U+10A0-U+10CF) or in the Private Use Area, and some ASCII-based ones mapped them to the ASCII capital letters.[53]

Blocks[edit]

Georgian characters are found in three Unicode blocks. The first block (U+10A0–U+10FF) is simply called Georgian. Mkhedruli (modern Georgian) occupies the U+10D0–U+10FF range (shown in the bottom half of the first table below) and Asomtavruli occupies the U+10A0–U+10CF range (shown in the top half of the same table). The second block is the Georgian Supplement (U+2D00–U+2D2F), and it contains Nuskhuri.[2] Mtavruli capitals are included in the Georgian Extended block (U+1C90–U+1CBF).

Mtavruli is defined as the upper case, but not title case, of Mkhedruli, and Asomtavruli as the upper case and title case of Nuskhuri.[92]

| Georgian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10Ax | Ⴀ | Ⴁ | Ⴂ | Ⴃ | Ⴄ | Ⴅ | Ⴆ | Ⴇ | Ⴈ | Ⴉ | Ⴊ | Ⴋ | Ⴌ | Ⴍ | Ⴎ | Ⴏ |

| U+10Bx | Ⴐ | Ⴑ | Ⴒ | Ⴓ | Ⴔ | Ⴕ | Ⴖ | Ⴗ | Ⴘ | Ⴙ | Ⴚ | Ⴛ | Ⴜ | Ⴝ | Ⴞ | Ⴟ |

| U+10Cx | Ⴠ | Ⴡ | Ⴢ | Ⴣ | Ⴤ | Ⴥ | Ⴧ | Ⴭ | ||||||||

| U+10Dx | ა | ბ | გ | დ | ე | ვ | ზ | თ | ი | კ | ლ | მ | ნ | ო | პ | ჟ |

| U+10Ex | რ | ს | ტ | უ | ფ | ქ | ღ | ყ | შ | ჩ | ც | ძ | წ | ჭ | ხ | ჯ |

| U+10Fx | ჰ | ჱ | ჲ | ჳ | ჴ | ჵ | ჶ | ჷ | ჸ | ჹ | ჺ | ჻ | ჼ | ჽ | ჾ | ჿ |

Notes

|

| Georgian Supplement[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+2D0x | ⴀ | ⴁ | ⴂ | ⴃ | ⴄ | ⴅ | ⴆ | ⴇ | ⴈ | ⴉ | ⴊ | ⴋ | ⴌ | ⴍ | ⴎ | ⴏ |

| U+2D1x | ⴐ | ⴑ | ⴒ | ⴓ | ⴔ | ⴕ | ⴖ | ⴗ | ⴘ | ⴙ | ⴚ | ⴛ | ⴜ | ⴝ | ⴞ | ⴟ |

| U+2D2x | ⴠ | ⴡ | ⴢ | ⴣ | ⴤ | ⴥ | ⴧ | ⴭ | ||||||||

Notes

|

| Georgian Extended[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1C9x | Ა | Ბ | Გ | Დ | Ე | Ვ | Ზ | Თ | Ი | Კ | Ლ | Მ | Ნ | Ო | Პ | Ჟ |

| U+1CAx | Რ | Ს | Ტ | Უ | Ფ | Ქ | Ღ | Ყ | Შ | Ჩ | Ც | Ძ | Წ | Ჭ | Ხ | Ჯ |

| U+1CBx | Ჰ | Ჱ | Ჲ | Ჳ | Ჴ | Ჵ | Ჶ | Ჷ | Ჸ | Ჹ | Ჺ | Ჽ | Ჾ | Ჿ | ||

Notes

|

Non-Unicode encodings[edit]

Mac OS Georgian is an unofficial[clarification needed] character encoding created by Michael Everson for Georgian on classic Mac OS. It is an extended ASCII encoding, using the 128 code points from 0x80 through 0xFF to represent the characters of the Asomtavruli and Mkhedruli scripts plus a number of widely-used symbols not included in 7-bit ASCII.[93]

Keyboard layouts[edit]

Below is the standard Georgian-language keyboard layout, the traditional layout of manual typewriters.

| “ „ |

1 ! |

2 ? |

3 № |

4 § |

5 % |

6 : |

7 . |

8 ; |

9 , |

0 / |

— _ |

+ = |

← Backspace |

| Tab key | ღ | ჯ | უ | კ | ე ჱ | ნ | გ | შ | წ | ზ | ხ ჴ | ც | ) ( |

| Caps lock | ფ ჶ | ძ | ვ ჳ | თ | ა | პ | რ | ო | ლ | დ | ჟ | Enter key ↵ |

| Shift key ↑ |

ჭ | ჩ | ყ | ს | მ | ი ჲ | ტ | ქ | ბ | ჰ ჵ | Shift key ↑ |

| Control key | Win key | Alt key | Space bar | AltGr key | Win key | Menu key | Control key | |

Gallery[edit]

Gallery of Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli scripts.

Gallery of Asomtavruli[edit]

-

Asomtavruli of the 6th and 7th centuries

-

-

Gallery of Nuskhuri[edit]

-

Nuskhuri of 8th to 10th centuries

-

Nuskhuri of Jruchi Gospels, 13th century

-

Nuskhuri of the 11th century

-

-

-

Nuskhuri by Nikrai, 12th century

Gallery of Mkhedruli[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Oldest found Georgian inscription so far. Exact date of introduction is unclear.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Unicode Standard, V. 6.3. U10A0, p. 3

- ^ a b Shanidze 2000, p. 444.

- ^ a b c d e f g Seibt, Werner. «The Creation of the Caucasian Alphabets as Phenomenon of Cultural History».

- ^ Machavariani 2011, p. 329.

- ^ Hüning, Vogl & Moliner 2012, p. 299.

- ^ «Georgian alphabet granted cultural heritage status». Agenda.ge. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ «Living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet». Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Hewitt 1995, p. 4.

- ^ West 2010, p. 230: Archaeological work in the last decade has confirmed that a Georgian alphabet did exist very early in Georgia’s history, with the first examples being dated from the fifth century C.E.

- ^ Rapp 2003, p. 19: footnote 43: «The date of the supposed grave marker is hopelessly circumstantial … I cannot support Chilashvili’s dubious hypothesis.»

- ^ Rayfield 2013.

- ^ a b Rapp 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Rapp 2006, p. 38.

- ^ a b Kemertelidze 1999, pp. 228-.

- ^ Koryun (1981). «The life of Mashtots». armenianhouse.org. Translated by Bedros Norehad. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ Rayfield 2013, p. 19: «The Georgian alphabet seems unlikely to have a pre-Christian origin, for the major archaeological monument of the 1st century 4IX the bilingual Armazi gravestone commemorating Serafua, daughter of the Georgian viceroy of Mtskheta, is inscribed in Greek and Aramaic only. It has been believed, and not only in Armenia, that all the Caucasian alphabets — Armenian, Georgian and Caucaso-Albanian — were invented in the 4th century by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots.<…> The Georgian chronicles The Life of Kartli – assert that a Georgian script was invented two centuries before Christ, an assertion unsupported by archaeology. There is a possibility that the Georgians, like many minor nations of the area, wrote in a foreign language — Persian, Aramaic, or Greek — and translated back as they read.»

- ^ Bowersock, Brown & Grabar 1999, p. 289: Alphabets. «Mastoc’ was a charismatic visionary who accomplished his task at a time when Armenia stood in danger of losing both its national identity, through partition, and its newly acquired Christian faith, through Sassanian pressure and reversion to paganism. By preaching in Armenian, he was able to undermine and co-opt the discourse founded in native tradition, and to create a counterweight against both Byzantine and Syriac cultural hegemony in the church. Mastoc’ also created the Georgian and Caucasian-Albanian alphabets, based on the Armenian model.»

- ^ Acharian, Hrachia (1984). Հայոց գրերը [The Armenian Script] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. p. 181.

«Կասկածել Կորյունի վրա՝ նշանակում է առհասարակ ուրանալ պատմությունը։» translation: «To doubt Koryun[‘s account] means to deny history itself.

- ^ Acharian, Hrachia (1984). Հայոց գրերը [The Armenian Script] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing. p. 391.

«408 … հնարում է վրաց գրերը»

- ^ Thomson 1996, pp. xxii–xxiii.

- ^ Rapp 2003, p. 450: «There is also the claim advanced by Koriwn in his saintly biography of Mashtoc’ (Mesrop) that the Georgian script had been invented at the direction of Mashtoc’. Yet it is within the realm of possibility that this tradition, repeated by many later Armenian historians, may not have been part of the original fifth-century text at all but added after 607. Significantly, all of the extant MSS containing The Life of Mashtoc* were copied centuries after the split. Consequently, scribal manipulation reflecting post-schism (especially anti-Georgian) attitudes potentially contaminates all MSS copied after that time. It is therefore conceivable, though not yet proven, that valuable information about Georgia transmitted by pre-schism Armenian texts was excised by later, post-schism individuals.»

- ^ Greppin 1981, pp. 449–456.

- ^ Haarmann 2012, p. 299.

- ^ a b Daniels 1996, p. 367.

- ^ Machavariani 2011, p. 177.

- ^ ქსე, ტ. 7, თბ., 1984, გვ. 651–652

- ^ შანიძე ა., ქართული საბჭოთა ენციკლოპედია, ტ. 2, გვ. 454–455, თბ., 1977 წელი

- ^ კ. დანელია, ზ. სარჯველაძე, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1997, გვ. 218–219

- ^ ე. მაჭავარიანი, მწიგნობრობაჲ ქართული, თბილისი, 1989

- ^ პ. ინგოროყვა, „შოთა რუსთაველი“, „მნათობი“, 1966, No. 3, გვ. 116

- ^ Machavariani 2011, pp. 121–122.

- ^ რ. პატარიძე, ქართული ასომთავრული, თბილისი, 1980, გვ. 151, 260–261

- ^ ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული დამწერლობათა-მცოდნეობა ანუ პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1949, 185–187

- ^ ე. მაჭავარიანი, ქართული ანბანი, თბილისი, 1977, გვ. 5–6

- ^ ელენე მაჭავარიანი, ენციკლოპედია „ქართული ენა“, თბილისი, 2008, გვ. 403–404

- ^ ვ. სილოგავა, ენციკლოპედია „ქართული ენა“, თბილისი, 2008, გვ. 269–271

- ^ ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული დამწერლობათა-მცოდნეობა ანუ პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1949, 124–126

- ^ Machavariani 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Machavariani 2011, p. 129.

- ^ ივ. ჯავახიშვილი, ქართული დამწერლობათა-მცოდნეობა ანუ პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1949, 127–128

- ^ Mchedlidze 2013, p. 105.

- ^ a b კ. დანელია, ზ. სარჯველაძე, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1997, გვ. 219

- ^ გ. აბრამიშვილი, ატენის სიონის უცნობი წარწერები, «მაცნე» (ისტ. და არქეოლოგ. სერია), 1976, No. c2, გვ. 170

- ^ კ. დანელია, ზ. სარჯველაძე, ქართული პალეოგრაფია, თბილისი, 1997, გვ. 218

- ^ ე. მაჭავარიანი, ქართული ანბანი, თბილისი, 1977

- ^ Mchedlidze 2013, p. 107.

- ^ «Lasha Kintsurashvili: About Georgian calligraphy». Archived from the original on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ Gillam 2003, p. 249.

- ^ (in Georgian) ილია მეორე ერს ქართული ენის დაცვისკენ კიდევ ერთხელ მოუწოდებს Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine საქინფორმ.გე

- ^ Nakanishi 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Allen & Gugushvili 1937, p. 324.

- ^ a b Everson, Michael; Gujejiani, Nika; Razmadze, Akaki (January 24, 2016). «Proposal for the addition of Georgian characters to the UCS» (PDF). Unicode Technical Committee Document Registry. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ ატენის სიონის უცნობი წარწერები, აბრამიშვილი, გვ. 170-1

- ^ Katzner & Miller 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Chambers Encyclopedia 1901, p. 165.

- ^ Putkaradze, T. (2006), «Development of the Georgian writing system», History of Georgian language, p. paragraph II, 2.1.5

- ^ მაჭავარიანი, თბილისი, 1977

- ^ Shanidze 1973, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d e Otar Jishkariani, Praise of the Alphabet, 1986, Tbilisi, p. 1

- ^ a b Ager, Simon (n.d.). «Bats alphabet, pronunciation and language». Omniglot. Archived from the original on 2018-08-03. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ a b Ager, Simon (n.d.). «Ossetian language, alphabet and pronunciation». omniglot.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Everson, Michael; Melkadze, Ninell; Pentzlin, Karl; Yevlampiev, Ilya (17 February 2010). «Proposal for encoding Georgian and Nuskhuri letters for Ossetian and Abkhaz» (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ Aronson 1990, pp. 21–25.

- ^ Paolini & Cholokashvili 1629.

- ^ Mchedlidze 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Ingorokva, Pavle ქართული დამწერლობის ძეგლები ანტიკური ხანისა (The monuments of ancient Georgian script) Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shanidze 2003.

- ^ შანიძე, 2003

- ^ Simonson, Mark (20 June 2005). «Fake vs. True Italics». Mark Simonson Studio. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- ^ Georgian Soviet Encyclopedia, V. 8, p. 231, Tbilisi, 1984

- ^ Gillam 2003, p. 252.

- ^ Aronson 1990, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b ჳ and უ have the same numeric value (400)

- ^ George 2009, p. 104.

- ^ The Abkhazians: A Handbook, George Hewitt, p. 171

- ^ Язык, история и культура вайнахов, И. Ю Алироев p.85, Чех-Инг. изд.-полигр. об-ние «Книга», 1990

- ^ Чеченский язык, И. Ю. Алироев, p.24, Академия, 1999

- ^ Грузинско-дагестанские языковые контакты, Маджид Шарипович Халилов p.29, Наука, 2004

- ^ История аварцев, М. Г Магомедов p.150, Дагестанский гос. университет, 2005

- ^ Enwall 2010, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Enwall 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Steffen, James (2013-10-31). The Cinema of Sergei Parajanov. University of Wisconsin Pres. ISBN 978-0-299-29653-7.

- ^ Enwall 2010, pp. 137–138.

- ^ უნიკოდში ქართულის ასახვის ისტორია (History of the Georgian Unicode) Archived 2014-03-09 at the Wayback Machine Georgian Unicode fonts by BPG-InfoTech

- ^ Font Contributors Acknowledgements Archived 2018-03-22 at the Wayback Machine Unicode

- ^ (in Georgian) საქართველოში საინტერნეტო მისამართები მხედრული ანბანით დაიწერება Archived 2016-01-22 at the Wayback Machine Rustavi 2

- ^ «Unicode 11.0.0». Unicode Consortium. June 5, 2018. Archived from the original on June 6, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ «Mtavruli for Perfect Bicameral Fonts». BPG Georgian Fonts. February 24, 2016. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ «The Unicode Standard, Version 11.0 — U110-1C90.pdf» (PDF). Unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-08. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

- ^ Everson, Michael; Gujejiani, Nika; Vakhtangishvili, Giorgi; Razmadze, Akaki (2017-06-24). «Action plan for the complete representation of Mtavruli characters» (PDF). Unicode Technical Committee Document Registry. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-15. Retrieved 2018-01-26.

- ^ «7: Europe-I: Modern and Liturgical Scripts» (PDF). The Unicode Standard Version 11.0 – Core Specification. Unicode Consortium. June 5, 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Everson, Michael (2002-02-20). «Mac OS Georgian to Unicode table». Evertype. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

Sources[edit]

- Allen, William Edward David; Gugushvili, A., eds. (1937). Georgica: A Journal of Georgian and Caucasian Studies (4–5): 324.

- Aronson, Howard Isaac (1990). Georgian: A Reading Grammar. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89357-207-5.

- Bowersock, Glen Warren; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- «Georgia». Chambers’s encyclopaedia; a dictionary of universal knowledge. Vol. 5. London: W. & R. Chambers. 1901.

- Daniels, Peter T. (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Enwall, Joakim (2010). «Turkish texts in Georgian script: Sociolinguistic and ethno-linguistic aspects». In Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (eds.). Turcology in Mainz. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-06113-1.

- George, Julie A. (2009). The Politics of Ethnic Separatism in Russia and Georgia. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-0-230-10232-3.

- Gillam, Richard (2003). Unicode Demystified: A Practical Programmer’s Guide to the Encoding Standard. Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 978-0-201-70052-7.

- Greppin, John A.C. (1981). «Some comments on the origin of the Georgian alphabet». Bazmavep (139): 449–456.*Haarmann, Harald (2012). «Ethnic Conflict and standardisation in the Caucasus». In Matthias Hüning; Ulrike Vogl; Olivier Moliner (eds.). Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-90-272-0055-6.

- Hewitt, B. G. (1995). Georgian: A Structural Reference Grammar. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-3802-3.

- Hüning, Matthias; Vogl, Ulrike; Moliner, Olivier (2012). Standard Languages and Multilingualism in European History. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-0055-6.

- Katzner, Kenneth; Miller, Kirk (2002). The Languages of the World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-53288-9.

- Kemertelidze, Nino (1999). «The Origin of Kartuli (Georgian) Writing (Alphabet)». In David Cram; Andrew R. Linn; Elke Nowak (eds.). History of Linguistics 1996. Vol. 1: Traditions in Linguistics Worldwide. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-8382-5.

- Machavariani, E. (2011). Georgian manuscripts. Tbilisi.

- Mchedlidze, T. (2013). The restored Georgian alphabet. Fulda, Germany.

- Nakanishi, Akira (1990). Writing Systems of the World. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-1654-0.

- Paolini, Stefano; Cholokashvili, Nikoloz (1629), Dittionario giorgiano e italiano, Rome: Palazzo di Propaganda Fide

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2003). Studies in medieval Georgian historiography: early texts and Eurasian contexts. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1318-9.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2006). «Recovering the Pre-National Caucasian Landscape». Mythical Landscapes then and Now: The Mystification: 13–52.

- Rapp, Stephen H. (2010). «Georgian Christianity». In Ken Parry (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9.

- Rayfield, Donald (2013). The Literature of Georgia: A History. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1163-5.

- Shanidze, Mzekala (2000). «Greek influence in Georgian linguistics». In Sylvain Auroux (ed.). History of the Language Sciences / Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaften / Histoire des sciences du language. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-019400-5.

- Shanidze, Akaki (2003), ქართული ენა [The Georgian Language] (in Georgian), Tbilisi, ISBN 978-1-4020-1440-6

- Shanidze, Akaki (1973). The Basics of the Georgian language grammar. Tbilisi.

- Thomson, Robert W. (1996). Rewriting Caucasian History: The Medieval Armenian Adaptation of the Georgian Chronicles : the Original Georgian Texts and the Armenian Adaptation. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826373-9.

- West, Barbara A. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

Further reading[edit]

- Barnaveli, T. Inscriptions of Ateni Sioni Tbilisi, 1977

- Gamkrelidze, T. Writing system and the old Georgian script Tbilisi, 1989

- Javakhishvili, I. Georgian palaeography Tbilisi, 1949

- Kilanawa, B. Georgian script in the writing systems Tbilisi, 1990

- Khurtsilava, B. The Georgian asomtavruli alphabet and its authors: Bakur and Gri Ormizd, Tbilisi, 2009

- Pataridze, R. Georgian Asomtavruli Tbilisi, 1980

- Shosted, Ryan K.; Chikovani, Vakhtang (2006), «Standard Georgian», Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (2): 255–264, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002659

External links[edit]

- Gallery of Mkhedruli, Omniglot page on Mkhedruli which shows some stylistic variations mentioned above

- Georgian alphabet animation on YouTube, produced by the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. Gives the sound of each letter, illustrates several fonts, and shows the stroke order of each letter.

- Learn Georgian Alphabet Now app Gives the name, pronunciation of each letter, and example words. Shows the stroke order of each letter. Permits drawing practice and has a quiz to learn the letters.

- Lasha Kintsurashvili and Levan Chaganava, submissions to the 2014 International Exhibition of Calligraphy

- Reference grammar of Georgian by Howard Aronson (SEELRC, Duke University)

- Georgian transliteration + Georgian virtual keyboard

- «Unicode Code Chart (10A0–10FF) for Georgian scripts» (PDF). (105 KB)

- «Transliteration of Georgian» (PDF). (105 KB)

| Georgian | |

|---|---|

damts’erloba «script» in Mkhedruli |

|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

|

Time period |

AD 430[1] – present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages |

|

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Uncertain, alphabetical order modelled on Greek

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Geor (240), Georgian (Mkhedruli and Mtavruli) – Georgian (Mkhedruli) Geok, 241 – Khutsuri (Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Georgian |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

| Living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage |

|

|

|

| Country | Georgia |

| Reference | 01205 |

| Region |

|

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2016 (11 session) |

The Georgian scripts are the three writing systems used to write the Georgian language: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri and Mkhedruli. Although the systems differ in appearance, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order and are written horizontally from left to right. Of the three scripts, Mkhedruli, once the civilian royal script of the Kingdom of Georgia and mostly used for the royal charters, is now the standard script for modern Georgian and its related Kartvelian languages, whereas Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are used only by the Georgian Orthodox Church, in ceremonial religious texts and iconography.[2]

Georgian scripts are unique in their appearance and their exact origin has never been established; however, in strictly structural terms, their alphabetical order largely corresponds to the Greek alphabet, with the exception of letters denoting uniquely Georgian sounds, which are grouped at the end.[3][4] Originally consisting of 38 letters,[5] Georgian is presently written in a 33-letter alphabet, as five letters are obsolete. The number of Georgian letters used in other Kartvelian languages varies. Mingrelian uses 36: thirty-three that are current Georgian letters, one obsolete Georgian letter, and two additional letters specific to Mingrelian and Svan. Laz uses the same 33 current Georgian letters as Mingrelian plus that same obsolete letter and a letter borrowed from Greek for a total of 35. The fourth Kartvelian language, Svan, is not commonly written, but when it is, it uses Georgian letters as utilized in Mingrelian, with an additional obsolete Georgian letter and sometimes supplemented by diacritics for its many vowels.[2][6]

The «living culture of three writing systems of the Georgian alphabet» was granted the national status of intangible cultural heritage in Georgia in 2015[7] and inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016.[8]

The three Georgian scripts: Asomtavruli, Nuskhuri, and Mkhedruli.

Origins[edit]

The origin of the Georgian script is poorly known, and no full agreement exists among Georgian and foreign scholars as to its date of creation, who designed the script, and the main influences on that process.

The first attested version of the script is Asomtavruli, which dates back to the 5th century; the other scripts were formed in the following centuries. Most scholars link the creation of the Georgian script to the process of Christianization of Iberia (not to be confused with the Iberian Peninsula), a core Georgian kingdom of Kartli.[9] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under King Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430,[9] contemporaneously with the Armenian alphabet.[10] It was first used for translation of the Bible and other Christian literature into Georgian, by monks in Georgia and Palestine.[4] Professor Levan Chilashvili’s dating of fragmented Asomtavruli inscriptions, discovered by him at the ruined town of Nekresi, in Georgia’s easternmost province of Kakheti, in the 1980s, to the 1st or 2nd century has not been accepted.[11]

A Georgian tradition first attested in the medieval chronicle Lives of the Kings of Kartli (ca. 800),[4] assigns a much earlier, pre-Christian origin to the Georgian alphabet, and names King Pharnavaz I (3rd century BC) as its inventor. This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaeological confirmation has been found.[4][12][13] Rapp considers the tradition to be an attempt by the Georgian Church to rebut the earlier tradition that the alphabet was invented by the Armenian scholar Mesrop Mashtots, and is a Georgian application of an Iranian model in which primordial kings are credited with the creation of basic social institutions.[14] Georgian linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze offers an alternative interpretation of the tradition, in the pre-Christian use of foreign scripts (alloglottography in the Aramaic alphabet) to write down Georgian texts.[15]

Another point of contention among scholars is the role played by Armenian clerics in that process. According to medieval Armenian sources and a number of scholars, Mesrop Mashtots, generally acknowledged as the creator of the Armenian alphabet, also created the Georgian and Caucasian Albanian alphabets. This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth-century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[16] and has been quoted by Donald Rayfield and James R. Russell,[17][18] but has been rejected by Georgian scholarship and some Western scholars who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation.[4] In his study on the history of the invention of the Armenian alphabet and the life of Mashtots, the Armenian linguist Hrachia Acharian strongly defended Koryun as a reliable source and rejected criticisms of his accounts on the invention of the Georgian script by Mashtots.[19] Acharian dated the invention to 408, four years after Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet (he dated the latter event to 404).[20] Some Western scholars quote Koryun’s claims without taking a stance on its validity[21][22] or concede that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.[4][13][23]

Another controversy regards the main influences at play in the Georgian alphabet, as scholars have debated whether it was inspired more by the Greek alphabet, or by Semitic alphabets such as Aramaic.[15] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.[3][4] Some scholars have also suggested certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers as a possible inspiration for particular letters.[24]

Asomtavruli[edit]

Asomtavruli (Georgian: ასომთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [ɑsɔmtʰɑvɾuli]) is the oldest Georgian script. The name Asomtavruli means «capital letters», from aso (ასო) «letter» and mtavari (მთავარი) «principal/head». It is also known as Mrgvlovani (Georgian: მრგვლოვანი) «rounded», from mrgvali (მრგვალი) «round», so named because of its round letter shapes. Despite its name, this «capital» script is unicameral.[25]

The oldest Asomtavruli inscriptions found so far date from the 5th century[26] and are Bir el Qutt[27] and the Bolnisi inscriptions.[28]

From the 9th century, Nuskhuri script started becoming dominant, and the role of Asomtavruli was reduced. However, epigraphic monuments of the 10th to 18th centuries continued to be written in Asomtavruli script. Asomtavruli in this later period became more decorative. In the majority of 9th-century Georgian manuscripts which were written in Nuskhuri script, Asomtavruli was used for titles and the first letters of chapters.[29] However, some manuscripts written completely in Asomtavruli can be found until the 11th century.[30]

Form of Asomtavruli letters[edit]

In early Asomtavruli, the letters are of equal height. Georgian historian and philologist Pavle Ingorokva believes that the direction of Asomtavruli, like that of Greek, was initially boustrophedon, though the direction of the earliest surviving texts is from left to the right.[31]

In most Asomtavruli letters, straight lines are horizontal or vertical and meet at right angles. The only letter with acute angles is Ⴟ (ჯ jani). There have been various attempts to explain this exception. Georgian linguist and art historian Helen Machavariani believes jani derives from a monogram of Christ, composed of the Ⴈ (ი ini) and Ⴕ (ქ kani).[32] According to Georgian scholar Ramaz Pataridze, the cross-like shape of letter jani indicates the end of the alphabet, and has the same function as the similarly shaped Phoenician letter taw (), Greek chi (Χ), and Latin X,[33] though these letters do not have that function in Phoenician, Greek, or Latin.

From the 7th century, the forms of some letters began to change. The equal height of the letters was abandoned, with letters acquiring ascenders and descenders.[34][35]

| Ⴀ ani |

Ⴁ bani |

Ⴂ gani |

Ⴃ doni |

Ⴄ eni |

Ⴅ vini |

Ⴆ zeni |

Ⴡ he |

Ⴇ tani |

Ⴈ ini |

Ⴉ kʼani |

Ⴊ lasi |

Ⴋ mani |

Ⴌ nari |

Ⴢ hie |

Ⴍ oni |

Ⴎ pʼari |

Ⴏ zhani |

Ⴐ rae |

| Ⴑ sani |

Ⴒ tʼari |

Ⴣ vie |

ႭჃ Ⴓ uni |

Ⴔ pari |

Ⴕ kani |

Ⴖ ghani |

Ⴗ qʼari |

Ⴘ shini |

Ⴙ chini |

Ⴚ tsani |

Ⴛ dzili |

Ⴜ ts’ili |

Ⴝ ch’ari |

Ⴞ khani |

Ⴤ qari |

Ⴟ jani |

Ⴠ hae |

Ⴥ hoe |

Asomtavruli illumination[edit]

In Nuskhuri manuscripts, Asomtavruli are used for titles and illuminated capitals. The latter were used at the beginnings of paragraphs which started new sections of text. In the early stages of the development of Nuskhuri texts, Asomtavruli letters were not elaborate and were distinguished principally by size and sometimes by being written in cinnabar ink. Later, from the 10th century, the letters were illuminated. The style of Asomtavruli capitals can be used to identify the era of a text. For example, in the Georgian manuscripts of the Byzantine era, when the styles of the Byzantine Empire influenced Kingdom of Georgia, capitals were illuminated with images of birds and other animals.[36]

Decorative Asomtavruli capital letters, მ (m) and თ (t), 12–13th century.

From the 11th-century «limb-flowery», «limb-arrowy» and «limb-spotty» decorative forms of Asomtavruli are developed. The first two are found in 11th- and 12th-century monuments, whereas the third one is used until the 18th century.[37][38]

Importance was attached also to the colour of the ink itself.[39]

Asomtavruli letter დ (doni) is often written with decoration effects of fish and birds.[40]

The «Curly» decorative form of Asomtavruli is also used where the letters are wattled or intermingled on each other, or the smaller letters are written inside other letters. It was mostly used for the headlines of the manuscripts or the books, although there are complete inscriptions which were written in the Asomtavruli «Curly» form only.[41]

The title of Gospel of Matthew in Asomtavruli «Curly» decorative form.

Handwriting of Asomtavruli[edit]

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Asomtavruli letter:[42]

Nuskhuri[edit]

Nuskhuri (Georgian: ნუსხური; Georgian pronunciation: [nusχuɾi]) is the second Georgian script. The name nuskhuri comes from nuskha (ნუსხა), meaning «inventory» or «schedule». Nuskhuri was soon augmented with Asomtavruli illuminated capitals in religious manuscripts. The combination is called Khutsuri (Georgian: ხუცური, «clerical», from khutsesi (ხუცესი «cleric»), and it was principally used in hagiography.[43]

Nuskhuri first appeared in the 9th century as a graphic variant of Asomtavruli.[9] The oldest inscription is found in the Ateni Sioni Church and dates to 835 AD.[44] The oldest surviving Nuskhuri manuscripts date to 864 AD.[45] Nuskhuri becomes dominant over Asomtavruli from the 10th century.[43]

Form of Nuskhuri letters[edit]

Nuskhuri letters vary in height, with ascenders and descenders, and are slanted to the right. Letters have an angular shape, with a noticeable tendency to simplify the shapes they had in Asomtavruli. This enabled faster writing of manuscripts.[46]

→

→

Asomtavruli letters ო (oni) and ჳ (vie). A ligature of these letters produced a new letter in Nuskhuri, უ uni.

| ⴀ ani |

ⴁ bani |

ⴂ gani |

ⴃ doni |

ⴄ eni |

ⴅ vini |

ⴆ zeni |

ⴡ he |

ⴇ tani |

ⴈ ini |

ⴉ kʼani |

ⴊ lasi |

ⴋ mani |

ⴌ nari |

ⴢ hie |

ⴍ oni |

ⴎ pʼari |

ⴏ zhani |

ⴐ rae |

| ⴑ sani |

ⴒ tʼari |

ⴣ vie |

ⴍⴣ ⴓ uni |

ⴔ pari |

ⴕ kani |

ⴖ ghani |

ⴗ qʼari |

ⴘ shini |

ⴙ chini |

ⴚ tsani |

ⴛ dzili |

ⴜ tsʼili |

ⴝ chʼari |

ⴞ khani |

ⴤ qari |

ⴟ jani |

ⴠ hae |

ⴥ hoe |

- Note: Without proper font support, you may see question marks, boxes or other symbols instead of Nuskhuri letters.

Handwriting of Nuskhuri[edit]

The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Nuskhuri letter:[47]

Use of Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri today[edit]

Asomtavruli is used intensively in iconography, murals, and exterior design, especially in stone engravings.[48] Georgian linguist Akaki Shanidze made an attempt in the 1950s to introduce Asomtavruli into the Mkhedruli script as capital letters to begin sentences, as in the Latin script, but it did not catch on.[49] Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri are officially used by the Georgian Orthodox Church alongside Mkhedruli. Patriarch Ilia II of Georgia called on people to use all three Georgian scripts.[50]

Mkhedruli[edit]

Mkhedruli (Georgian: მხედრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mχɛdɾuli]) is the third and current Georgian script. Mkhedruli, literally meaning «cavalry» or «military», derives from mkhedari (მხედარი) meaning «horseman», «knight», «warrior»[51] and «cavalier».[52]

Mkhedruli is bicameral, with capital letters that are called Mkhedruli Mtavruli (მხედრული მთავრული) or simply Mtavruli (მთავრული; Georgian pronunciation: [mtʰɑvɾuli]). Nowadays, Mkhedruli Mtavruli is only used in all-caps text in titles or to emphasize a word, though in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was occasionally used, as in Latin and Cyrillic scripts, to capitalize proper nouns or the first word of a sentence. Contemporary Georgian script does not recognize capital letters and their usage has become decorative.[53]

Mkhedruli first appears in the 10th century. The oldest Mkhedruli inscription is found in Ateni Sioni Church dating back to 982 AD. The second oldest Mkhedruli-written text is found in the 11th-century royal charters of King Bagrat IV of Georgia. Mkhedruli was mostly used then in the Kingdom of Georgia for the royal charters, historical documents, manuscripts and inscriptions.[54] Mkhedruli was used for non-religious purposes only and represented the «civil», «royal» and «secular» script.[55][56]

Mkhedruli became more and more dominant over the two other scripts, though Khutsuri (Nuskhuri with Asomtavruli) was used until the 19th century. Mkhedruli became the universal writing Georgian system outside of the Church in the 19th century with the establishment and development of printed Georgian fonts.[57]

Form of Mkhedruli letters[edit]

Mkhedruli inscriptions of the 10th and 11th centuries are characterized in rounding of angular shapes of Nuskhuri letters and making the complete outlines in all of its letters. Mkhedruli letters are written in the four-linear system, similar to Nuskhuri.

Mkhedruli becomes more round and free in writing. It breaks the strict frame of the previous two alphabets, Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri. Mkhedruli letters begin to get coupled and more free calligraphy develops.[58]

Example of one of the oldest Mkhedruli-written texts found in the royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, 11th century.

«Gurgen : King : of Kings : great-grandfather : of mine : Bagrat Curopalates»

Modern Georgian alphabet[edit]

The modern Georgian alphabet consists of 33 letters:

| ა ani |

ბ bani |

გ gani |

დ doni |

ე eni |

ვ vini |

ზ zeni |

თ tani |

ი ini |

კ k’ani |

ლ lasi |

| მ mani |

ნ nari |

ო oni |

პ p’ari |

ჟ zhani |

რ rae |

ს sani |

ტ t’ari |

უ uni |

ფ pari |

ქ kani |

| ღ ghani |

ყ q’ari |

შ shini |

ჩ chini |

ც tsani |

ძ dzili |

წ ts’ili |

ჭ ch’ari |

ხ khani |

ჯ jani |

ჰ hae |

Letters removed from the Georgian alphabet[edit]