For the moth known as «Chinese character», see Cilix glaucata. For the Chinese philosopher often known as «Hanzi», see Han Fei. For the primary literary work attributed to said philosopher, see Han Feizi.

Unless otherwise specified, Chinese text in this article is presented as simplified Chinese or traditional Chinese, pinyin. If the simplified and traditional characters are the same, they are written only once.

| Chinese characters | |

|---|---|

| Script type |

Logographic |

|

Time period |

13th century BC to present |

| Direction | Left-to-right (modern) Top-to-bottom, columns right-to-left (traditional) |

| Languages | Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Ryukyuan, Vietnamese, Zhuang, Miao, etc. |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Oracle bone script

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hani (500), Han (Hanzi, Kanji, Hanja) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Han |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

| Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

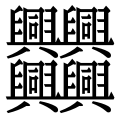

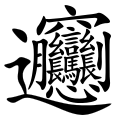

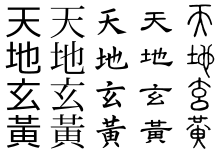

Hanzi (Chinese character) in traditional (left) and simplified form (right) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Han characters» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | chữ Hán chữ Nho Hán tự |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 𡨸漢 𡨸儒 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thai | อักษรจีน | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Zhuang | 𭨡倱[1] Sawgun |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 한자 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 漢字 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | かんじ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khmer | តួអក្សរចិន |

Chinese characters (traditional Chinese: 漢字; simplified Chinese: 汉字; pinyin: hànzì; Wade–Giles: han4 tzŭ4; Jyutping: hon3 zi6; lit. ‘Han characters’) are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese.[2][3] In addition, they have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as kanji. Chinese characters in South Korea, which are known as hanja, retain significant use in Korean academia to study its documents, history, literature and records. Vietnam once used the chữ Hán and developed chữ Nôm to write Vietnamese before turning to a romanized alphabet. Chinese characters are the oldest continuously used system of writing in the world.[4] By virtue of their widespread current use throughout East Asia and Southeast Asia, as well as their profound historic use throughout the Sinosphere, Chinese characters are among the most widely adopted writing systems in the world by number of users.

The total number of Chinese characters ever to appear in a dictionary is in the tens of thousands, though most are graphic variants, were used historically and passed out of use, or are of a specialized nature. A college graduate who is literate in written Chinese knows between three and four thousand characters, though more are required for specialized fields.[5] In Japan, 2,136 are taught through secondary school (the Jōyō kanji); hundreds more are in everyday use. Due to separate simplifications of characters in Japan and in China, the kanji used in Japan today has some differences from Chinese simplified characters in several respects. There are various national standard lists of characters, forms, and pronunciations. Simplified forms of certain characters are used in mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia; traditional characters are used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, and, to some extent, in South Korea. In Japan, common characters are often written in post-Tōyō kanji simplified forms, while uncommon characters are written in Japanese traditional forms. During the 1970s, Singapore had also briefly enacted its own simplification campaign, but eventually streamlined its simplification to be uniform with mainland China.

In modern Chinese, most words are compounds written with two or more characters.[6] Unlike alphabetic writing systems, in which the unit character roughly corresponds to one phoneme, the Chinese writing system associates each logogram with an entire syllable, and thus may be compared in some aspects to a syllabary. A character almost always corresponds to a single syllable that is also a morpheme.[7] However, there are a few exceptions to this general correspondence, including bisyllabic morphemes (written with two characters), bimorphemic syllables (written with two characters) and cases where a single character represents a polysyllabic word or phrase.[8]

Modern Chinese has many homophones; thus the same spoken syllable may be represented by one of many characters, depending on meaning. A particular character may also have a range of meanings, or sometimes quite distinct meanings, which might have different pronunciations. Cognates in the several varieties of Chinese are generally written with the same character. In other languages, most significantly in modern Japanese and sometimes in Korean, characters are used to represent Chinese loanwords or to represent native words independent of the Chinese pronunciation (e.g., kun’yomi in Japanese). Some characters retained their phonetic elements based on their pronunciation in a historical variety of Chinese from which they were acquired. These foreign adaptations of Chinese pronunciation are known as Sino-Xenic pronunciations and have been useful in the reconstruction of Middle Chinese.

Function[edit]

When the script was first used in the late 2nd millennium BC, words of Old Chinese were generally monosyllabic, and each character denoted a single word.[9] Increasing numbers of polysyllabic words have entered the language from the Western Zhou period to the present day. It is estimated that about 25–30% of the vocabulary of classic texts from the Warring States period was polysyllabic, though these words were used far less commonly than monosyllables, which accounted for 80–90% of occurrences in these texts.[10]

The process has accelerated over the centuries as phonetic change has increased the number of homophones.[11]

It has been estimated that over two thirds of the 3,000 most common words in modern Standard Chinese are polysyllables, the vast majority of those being disyllables.[12]

The most common process has been to form compounds of existing words, written with the characters of the constituent words. Words have also been created by adding affixes, reduplication, and borrowing from other languages.[13]

Polysyllabic words are generally written with one character per syllable.[14][a]

In most cases, the character denotes a morpheme descended from an Old Chinese word.[15]

Many characters have multiple readings, with instances denoting different morphemes, sometimes with different pronunciations. In modern Standard Chinese, one fifth of the 2,400 most common characters have multiple pronunciations.

For the 500 most common characters, the proportion rises to 30%.[16]

Often these readings are similar in sound and related in meaning. In the Old Chinese period, affixes could be added to a word to form a new word, which was often written with the same character. In many cases, the pronunciations diverged due to subsequent sound change. For example, many additional readings have the Middle Chinese departing tone, the major source of the 4th tone in modern Standard Chinese. Scholars now believe that this tone is the reflex of an Old Chinese *-s suffix, with a range of semantic functions.[17]

For example,

- 传/傳 has readings OC *drjon > MC drjwen’ > Mod. chuán ‘to transmit’ and *drjons > drjwenH > zhuàn ‘a record’.[18] (Middle Chinese forms are given in Baxter’s transcription, in which H denotes the departing tone.)

- 磨 has readings *maj > ma > mó ‘to grind’ and *majs > maH > mò ‘grindstone’.[18]

- 宿 has readings *sjuk > sjuwk > sù ‘to stay overnight’ and *sjuks > sjuwH > xiù ‘celestial «mansion»‘.[19]

- 说/説 has readings *hljot > sywet > shuō ‘speak’ and *hljots > sywejH > shuì ‘exhort’.[20]

Another common alternation is between voiced and voiceless initials (though the voicing distinction has disappeared on most modern varieties).

This is believed to reflect an ancient prefix, but scholars disagree on whether the voiced or voiceless form is the original root.

For example,

- 见/見 has readings *kens > kenH > jiàn ‘to see’ and *gens > henH > xiàn ‘to appear’.[21]

- 败/敗 has readings *prats > pæjH > bài ‘to defeat’ and *brats > bæjH > bài ‘to be defeated’.[21] (In this case, the pronunciations have converged in Standard Chinese, but not in some other varieties.)

- 折 has readings *tjat > tsyet > zhé ‘to bend’ and *djat > dzyet > shé ‘to break by bending’.[22]

Principles of formation[edit]

Excerpt from a 1436 primer on Chinese characters

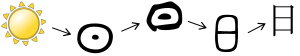

Chinese characters represent words of the language using several strategies. A few characters, including some of the most commonly used, were originally pictograms, which depicted the objects denoted, or ideograms, in which meaning was expressed iconically. The vast majority were written using the rebus principle, in which a character for a similarly sounding word was either borrowed or more commonly extended with a disambiguating semantic marker to form a phono-semantic compound character.[23]

The traditional six-fold classification (liùshū 六书 / 六書 «six writings») was first described by the scholar Xu Shen in the postface of his dictionary Shuowen Jiezi in 100 AD.[24]

While this analysis is sometimes problematic and arguably fails to reflect the complete nature of the Chinese writing system, it has been perpetuated by its long history and pervasive use.

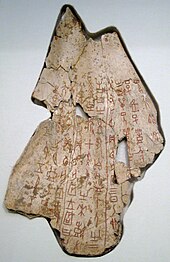

Pictograms[edit]

- 象形字 xiàngxíngzì

Pictograms are highly stylized and simplified pictures of material objects. Examples of pictograms include 日 rì for «sun», 月 yuè for «moon», and 木 mù for «tree» or «wood». Xu Shen placed approximately 4% of characters in this category.

Though few in number and expressing literal objects, pictograms and ideograms are nonetheless the basis on which all the more complex characters such as associative compound characters (会意字/會意字) and phono-semantic characters (形声字/形聲字) are formed.

Over time pictograms were increasingly standardized, simplified, and stylized to make them easier to write. Furthermore, the same Kangxi radical character element can be used to depict different objects.

Thus, the image depicted by most pictograms is not often immediately evident. For example, 口 may indicate the mouth, a window as in 高 which depicts a tall building as a symbol of the idea of «tall» or the lip of a vessel as in 富 a wine jar under a roof as symbol of wealth. That is, pictograms extended from literal objects to take on symbolic or metaphoric meanings; sometimes even displacing the use of the character as a literal term, or creating ambiguity, which was resolved through character determinants, more commonly but less accurately known as «radicals» i.e. concept keys in the phono-semantic characters.

Simple ideograms[edit]

- 指事字 zhǐshìzì

Also called simple indicatives, this small category contains characters that are direct iconic illustrations. Examples include 上 shàng «up» and 下 xià «down», originally a dot above and below a line. Indicative characters are symbols for abstract concepts which could not be depicted literally but nonetheless can be expressed as a visual symbol e.g. convex 凸, concave 凹, flat-and-level 平.

Compound ideographs[edit]

- 会意字 / 會意字 huìyìzì

Also translated as logical aggregates or associative idea characters, these characters have been interpreted as combining two or more pictographic or ideographic characters to suggest a third meaning. The canonical example is 明 bright. 明 is the association of the two brightest objects in the sky the sun 日 and moon 月, brought together to express the idea of «bright». It is canonical because the term 明白 in Chinese (lit. «bright white») means «to understand, understand». Adding the abbreviated radical for grass, cao 艹 above the character, ming, changes it to meng 萌, which means to sprout or bud, alluding to the heliotropic behavior of plant life. Other commonly cited examples include 休 «rest» (composed of the pictograms 人 «person» and 木 «tree») and 好 «good» (composed of 女 «woman» and 子 «child»).

Xu Shen placed approximately 13% of characters in this category, but many of his examples are now believed to be phono-semantic compounds whose origin has been obscured by subsequent changes in their form.[25] Peter Boodberg and William Boltz go so far as to deny that any of the compound characters devised in ancient times were of this type, maintaining that now-lost «secondary readings» are responsible for the apparent absence of phonetic indicators,[26] but their arguments have been rejected by other scholars.[27]

In contrast, associative compound characters are common among characters coined in Japan. Also, a few characters coined in China in modern times, such as 鉑 platinum, «white metal» (see Chemical elements in East Asian languages) belong to this category.

Rebus[edit]

- 假借字 jiǎjièzì

Also called borrowings or phonetic loan characters, the rebus category covers cases where an existing character is used to represent an unrelated word with similar or identical pronunciation; sometimes the old meaning is then lost completely, as with characters such as 自 zì, which has lost its original meaning of «nose» completely and exclusively means «oneself», or 萬 wàn, which originally meant «scorpion» but is now used only in the sense of «ten thousand».

Rebus was pivotal in the history of writing in China insofar as it represented the stage at which logographic writing could become purely phonetic (phonographic). Chinese characters used purely for their sound values are attested in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period manuscripts, in which zhi 氏 was used to write shi 是 and vice versa, just lines apart; the same happened with shao 勺 for Zhao 趙, with the characters in question being homophonous or nearly homophonous at the time.[28]

Phonetical usage for foreign words[edit]

Chinese characters are used rebus-like and exclusively for their phonetic value when transcribing words of foreign origin, such as ancient Buddhist terms or modern foreign names. For example, the word for the country «Romania» is 罗马尼亚/羅馬尼亞 (Luó Mǎ Ní Yà), in which the Chinese characters are only used for their sounds and do not provide any meaning.[29] This usage is similar to that of the Japanese Katakana and Hiragana, although the Kanas use a special set of simplified forms of Chinese characters, in order to advertise their value as purely phonetic symbols. The same rebus principle for names in particular has also been used in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Maya glyphs.[30] In the Chinese usage, in a few instances, the characters used for pronunciation might be carefully chosen in order to connote a specific meaning, as regularly happens for brand names: Coca-Cola is translated phonetically as 可口可乐/可口可樂 (Kěkǒu Kělè), but the characters were carefully selected so as to have the additional meaning of «Delicious and Enjoyable». A more literal translation would be «the Mouth can be happy», and the phrase in Chinese is technically grammatically sound.[29][30]

Phono-semantic compounds[edit]

- 形声字 / 形聲字 Mandarin: xíngshēngzì

Structures of compounds, with red marked positions of radicals

Semantic-phonetic compounds or pictophonetic compounds are by far the most numerous characters. These characters are composed of at least two parts. The semantic component suggests the general meaning of the compound character. The phonetic component suggests the pronunciation of the compound character. In most cases the semantic indicator is also the 部首 radical under which the character is listed in dictionaries. In some rare examples phono-semantic characters may also convey pictorial content. Each Chinese character is an attempt to combine sound, image, and idea in a mutually reinforcing fashion.

Examples of phono-semantic characters include 河 hé «river», 湖 hú «lake», 流 liú «stream», 沖 chōng «surge», 滑 huá «slippery». All these characters have on the left a radical of three short strokes (氵), which is a reduced form of the character 水 shuǐ meaning «water», indicating that the character has a semantic connection with water. The right-hand side in each case is a phonetic indicator- for instance: 胡 hú has a very similar pronunciation to 湖 and 可 kě has a similar (though somewhat different) pronunciation to 河. For example, in the case of 沖 chōng (Old Chinese *ɡ-ljuŋ[31]) «surge», the phonetic indicator is 中 zhōng (Old Chinese *k-ljuŋ[32]), which by itself means «middle». In this case it can be seen that the pronunciation of the character is slightly different from that of its phonetic indicator; the effect of historical sound change means that the composition of such characters can sometimes seem arbitrary today.

In general, phonetic components do not determine the exact pronunciation of a character, but only give a clue as to its pronunciation. While some characters take the exact pronunciation of their phonetic component, others take only the initial or final sounds.[33] In fact, some characters’ pronunciations may not correspond to the pronunciations of their phonetic parts at all, which is sometimes the case with characters after having undergone simplification. The 8 characters in the following table all take 也 for their phonetic part, however, as it is readily apparent, none of them take the pronunciation of 也, which is yě (Old Chinese *lajʔ). As the table below shows, the sound changes that have taken place since the Shang/Zhou period when most of these characters were created can be dramatic, to the point of not providing any useful hint of the modern pronunciation.

| Character | Semantic part | Phonetic part | Mandarin (pinyin) |

Cantonese (jyutping) |

Japanese (romaji) |

Middle Chinese |

Old Chinese (Baxter–Sagart) |

meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 也 | (originally a pictograph of a vulva)[35] | none | yě | jaa5 | ya | jiaX | *lajʔ | grammatical particle; also |

| 池 | 水(氵)water | 也 | chí | ci4 | chi | ɖje | *Cə.lraj | pool |

| 馳 / 驰 | 马 / 馬 horse | 也 | chí | ci4 | chi | ɖje | *lraj | gallop |

| 弛 | 弓 bow (bend) | 也 | chí (Mainland and Taiwan) shǐ (Taiwan) |

ci4 | chi, shi | ɕjeX | *l̥ajʔ | loosen, relax |

| 施 | 㫃 flag | 也 | shī | si1 | se, shi | ɕje | *l̥aj | spread, set up, use |

| 地 | 土 earth | 也 | dì | dei6 | ji, chi | dijH | *lˤej-s | ground, earth |

| de, di | — | — | — | adverbial particle in Mandarin | ||||

| 他 | 人 (亻)person | 也 | tā | taa1 | ta | tʰa | *l̥ˤaj | he, other |

| 她 | 女 female | 也 | — | — | — | she | ||

| 拖 | 手 (扌)hand | 㐌 | tuō | to1 | ta, da | tʰaH | *l̥ˤaj | drag |

Xu Shen (c. 100 AD) placed approximately 82% of characters into this category, while in the Kangxi Dictionary (1716 AD) the number is closer to 90%, due to the extremely productive use of this technique to extend the Chinese vocabulary.[citation needed] The chữ Nôm characters of Vietnam were created using this principle.

This method is used to form new characters, for example 钚 / 鈈 bù («plutonium») is the metal radical 金 jīn plus the phonetic component 不 bù, described in Chinese as «不 gives sound, 金 gives meaning». Many Chinese names of the chemical elements and many other chemistry-related characters were formed this way. In fact, it is possible to tell from a Chinese periodic table at a glance which elements are metal (金), solid nonmetal (石, «stone»), liquid (氵), or gas (气) at standard temperature and pressure.

Occasionally a bisyllabic word is written with two characters that contain the same radical, as in 蝴蝶 húdié «butterfly», where both characters have the insect radical 虫. A notable example is pipa (a Chinese lute, also a fruit, the loquat, of similar shape) – originally written as 批把 with the hand radical (扌), referring to the down and up strokes when playing this instrument, which was then changed to 枇杷 (tree radical 木), which is still used for the fruit, while the character was changed to 琵琶 when referring to the instrument (radical 玨).[36] In other cases a compound word may coincidentally share a radical without this being meaningful.

Derivative cognates[edit]

- 转注字 / 轉注字 zhuǎnzhùzì

The smallest category of characters is also the least understood.[37] In the postface to the Shuowen Jiezi, Xu Shen gave as an example the characters 考 kǎo «to verify» and 老 lǎo «old», which had similar Old Chinese pronunciations (*khuʔ and *C-ruʔ respectively[38]) and may once have been the same word, meaning «elderly person», but became lexicalized into two separate words. The term does not appear in the body of the dictionary, and is often omitted from modern systems.[39]

History[edit]

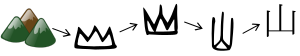

Comparative evolution from pictograms to abstract shapes, in cuneiform, Egyptian and Chinese characters

Legendary origins[edit]

According to traditional legend, Chinese characters were invented by Cangjie, a figure said to have been a scribe to the legendary Yellow Emperor during the 27th century BC. Inspired by his study of the animals of the world, the landscape of the earth and the stars in the sky, Cangjie is said to have invented symbols called zì (字) – the first Chinese characters. The legend relates that on the day the characters were created, grain rained down from the sky and that night the people heard ghosts wailing and demons crying because the human beings could no longer be cheated.[40]

Early sign use[edit]

In recent decades, a series of inscribed graphs and pictures have been found at Neolithic sites in China, including Jiahu (c. 6500 BC), Dadiwan and Damaidi from the 6th millennium BC, and Banpo (5th millennium BC). Often these finds are accompanied by media reports that push back the purported beginnings of Chinese writing by thousands of years.[41][42] However, because these marks occur singly without any implied context and are made crudely, Qiu Xigui concluded that «we do not have any basis for stating that these constituted writing nor is there reason to conclude that they were ancestral to Shang dynasty Chinese characters.»[43] They do however demonstrate a history of sign use in the Yellow River valley during the Neolithic through to the Shang period.[42]

Oracle bone script[edit]

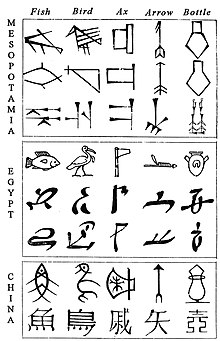

Ox scapula with oracle bone inscription

The earliest confirmed evidence of the Chinese script yet discovered is the body of inscriptions carved on bronze vessels and oracle bones from the late Shang dynasty (c. 1250–1050 BC).[44][45] The earliest of these is dated to around 1200 BC.[46][47] In 1899, pieces of these bones were being sold as «dragon bones» for medicinal purposes, when scholars identified the symbols on them as Chinese writing. By 1928, the source of the bones had been traced to a village near Anyang in Henan Province, which was excavated by the Academia Sinica between 1928 and 1937. Over 150,000 fragments have been found.[44]

Oracle bone inscriptions are records of divinations performed in communication with royal ancestral spirits.[44] The shortest are only a few characters long, while the longest are 30 to 40 characters in length. The Shang king would communicate with his ancestors on topics relating to the royal family, military success, weather forecasting, ritual sacrifices, and related topics by means of scapulimancy, and the answers would be recorded on the divination material itself.[44]

The oracle bone script is a well-developed writing system,[48][49] suggesting that the Chinese script’s origins may lie earlier than the late second millennium BC.[50] Although these divinatory inscriptions are the earliest surviving evidence of ancient Chinese writing, it is widely believed that writing was used for many other non-official purposes, but that the materials upon which non-divinatory writing was done – likely wood and bamboo – were less durable than bone and shell and have since decayed away.[50]

Bronze Age: parallel script forms and gradual evolution[edit]

The Shi Qiang pan, a bronze ritual basin dated to around 900 BC. Long inscriptions on the surface describe the deeds and virtues of the first seven Zhou kings.

The traditional picture of an orderly series of scripts, each one invented suddenly and then completely displacing the previous one, has been conclusively demonstrated to be fiction by the archaeological finds and scholarly research of the later 20th and early 21st centuries.[51] Gradual evolution and the coexistence of two or more scripts was more often the case. As early as the Shang dynasty, oracle bone script coexisted as a simplified form alongside the normal script of bamboo books (preserved in typical bronze inscriptions), as well as the extra-elaborate pictorial forms (often clan emblems) found on many bronzes.

Based on studies of these bronze inscriptions, it is clear that, from the Shang dynasty writing to that of the Western Zhou and early Eastern Zhou, the mainstream script evolved in a slow, unbroken fashion, until assuming the form that is now known as seal script in the late Eastern Zhou in the state of Qin, without any clear line of division.[52][53] Meanwhile, other scripts had evolved, especially in the eastern and southern areas during the late Zhou dynasty, including regional forms, such as the gǔwén («ancient forms») of the eastern Warring States preserved as variant forms in the Han dynasty character dictionary Shuowen Jiezi, as well as decorative forms such as bird and insect scripts.

Unification: seal script, vulgar writing, and proto-clerical[edit]

Seal script, which had evolved slowly in the state of Qin during the Eastern Zhou dynasty, became standardized and adopted as the formal script for all of China in the Qin dynasty (leading to a popular misconception that it was invented at that time), and was still widely used for decorative engraving and seals (name chops, or signets) in the Han dynasty period. However, despite the Qin script standardization, more than one script remained in use at the time. For example, a little-known, rectilinear and roughly executed kind of common (vulgar) writing had for centuries coexisted with the more formal seal script in the Qin state, and the popularity of this vulgar writing grew as the use of writing itself became more widespread.[54] By the Warring States period, an immature form of clerical script called «early clerical» or «proto-clerical» had already developed in the state of Qin[55] based upon this vulgar writing, and with influence from seal script as well.[56] The coexistence of the three scripts – small seal, vulgar and proto-clerical, with the latter evolving gradually in the Qin to early Han dynasties into clerical script – runs counter to the traditional belief that the Qin dynasty had one script only, and that clerical script was suddenly invented in the early Han dynasty from the small seal script.

Han dynasty[edit]

Proto-clerical evolving to clerical[edit]

Proto-clerical script, which had emerged by the time of the Warring States period from vulgar Qin writing, matured gradually, and by the early Western Han period, it was little different from that of the Qin.[57] Recently discovered bamboo slips show the script becoming mature clerical script by the middle-to-late reign of Emperor Wu of the Western Han,[58] who ruled from 141 to 87 BC.

Clerical and clerical cursive[edit]

Contrary to the popular belief of there being only one script per period, there were in fact multiple scripts in use during the Han period.[59] Although mature clerical script, also called 八分 (bāfēn)[60] script, was dominant at that time, an early type of cursive script was also in use by the Han by at least as early as 24 BC (during the very late Western Han period),[b] incorporating cursive forms popular at the time, well as many elements from the vulgar writing of the Warring State of Qin.[61] By around the time of the Eastern Jin dynasty, this Han cursive became known as 章草 zhāngcǎo (also known as 隶草 / 隸草 lìcǎo today), or in English sometimes clerical cursive, ancient cursive, or draft cursive. Some believe that the name, based on 章 zhāng meaning «orderly», arose because the script was a more orderly form[62] of cursive than the modern form, which emerged during the Eastern Jin dynasty and is still in use today, called 今草 jīncǎo or «modern cursive».[63]

Neo-clerical[edit]

Around the mid-Eastern Han period,[62] a simplified and easier-to-write form of clerical script appeared, which Qiu terms «neo-clerical» (新隶体 / 新隸體, xīnlìtǐ).[64] By the late Eastern Han, this had become the dominant daily script,[62] although the formal, mature bāfēn (八分) clerical script remained in use for formal works such as engraved stelae.[62] Qiu describes this neo-clerical script as a transition between clerical and regular script,[62] and it remained in use through the Cao Wei and Jin dynasties.[65]

Semi-cursive[edit]

By the late Eastern Han period, an early form of semi-cursive script appeared,[64] developing out of a cursively written form of neo-clerical script[c] and simple cursive.[66] This semi-cursive script was traditionally attributed to Liu Desheng c. 147–188 AD,[65][d] although such attributions refer to early masters of a script rather than to their actual inventors, since the scripts generally evolved into being over time. Qiu gives examples of early semi-cursive script, showing that it had popular origins rather than being purely Liu’s invention.[67]

Wei to Jin period[edit]

Regular script[edit]

Regular script has been attributed to Zhong Yao (c. 151–230 AD), during the period at the end of the Han dynasty in the state of Cao Wei. Zhong Yao has been called the «father of regular script». However, some scholars[68] postulate that one person alone could not have developed a new script which was universally adopted, but could only have been a contributor to its gradual formation. The earliest surviving pieces written in regular script are copies of Zhong Yao’s works, including at least one copied by Wang Xizhi. This new script, which is the dominant modern Chinese script, developed out of a neatly written form of early semi-cursive, with addition of the pause (顿/頓 dùn) technique to end horizontal strokes, plus heavy tails on strokes which are written to the downward-right diagonal.[69] Thus, early regular script emerged from a neat, formal form of semi-cursive, which had itself emerged from neo-clerical (a simplified, convenient form of clerical script). It then matured further in the Eastern Jin dynasty in the hands of the «Sage of Calligraphy», Wang Xizhi, and his son Wang Xianzhi. It was not, however, in widespread use at that time, and most writers continued using neo-clerical, or a somewhat semi-cursive form of it, for daily writing,[69] while the conservative bafen clerical script remained in use on some stelae, alongside some semi-cursive, but primarily neo-clerical.[70]

Modern cursive[edit]

Meanwhile, modern cursive script slowly emerged from the clerical cursive (zhāngcǎo) script during the Cao Wei to Jin period, under the influence of both semi-cursive and the newly emerged regular script.[71] Cursive was formalized in the hands of a few master calligraphers, the most famous and influential of whom was Wang Xizhi.[e]

Dominance and maturation of regular script[edit]

It was not until the Northern and Southern dynasties that regular script rose to dominant status.[72] During that period, regular script continued evolving stylistically, reaching full maturity in the early Tang dynasty. Some call the writing of the early Tang calligrapher Ouyang Xun (557–641) the first mature regular script. After this point, although developments in the art of calligraphy and in character simplification still lay ahead, there were no more major stages of evolution for the mainstream script.

Modern history[edit]

Although most simplified Chinese characters in use today are the result of the works moderated by the government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the 1950s and 60s, the use of some of these forms predates the PRC’s formation in 1949. Caoshu, cursive written text, was the inspiration of some simplified characters, and for others, some are attested as early as the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) as either vulgar variants or original characters.

The first batch of Simplified Characters introduced in 1935 consisted of 324 characters.

One of the earliest proponents of character simplification was Lufei Kui, who proposed in 1909 that simplified characters should be used in education. In the years following the May Fourth Movement in 1919, many anti-imperialist Chinese intellectuals sought ways to modernise China as quickly as possible. Traditional culture and values such as Confucianism were challenged and subsequently blamed for their problems. Soon, people in the Movement started to cite the traditional Chinese writing system as an obstacle in modernising China and therefore proposed that a reform be initiated. It was suggested that the Chinese writing system should be either simplified or completely abolished. Lu Xun, a renowned Chinese author in the 20th century, stated that, «If Chinese characters are not destroyed, then China will die» (漢字不滅,中國必亡). Recent commentators have claimed that Chinese characters were blamed for the economic problems in China during that time.[73]

In the 1930s and 1940s, discussions on character simplification took place within the Kuomintang government, and a large number of the intelligentsia maintained that character simplification would help boost literacy in China.[74] In 1935, 324 simplified characters collected by Qian Xuantong were officially introduced as the table of first batch of simplified characters, but they were suspended in 1936 due to fierce opposition within the party.

The People’s Republic of China issued its first round of official character simplifications in two documents, the first in 1956 and the second in 1964. In the 1950s and 1960s, while confusion about simplified characters was still rampant, transitional characters that mixed simplified parts with yet-to-be simplified parts of characters together appeared briefly, then disappeared.

«Han unification» was an effort by the authors of Unicode and the Universal Character Set to map multiple character sets of the so-called CJK languages (Chinese/Japanese/Korean) into a single set of unified characters and was completed for the purposes of Unicode in 1991 (Unicode 1.0).

Apart from Chinese ones, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese normative medium of record-keeping, written historical narratives and official communication are in adaptations and variations of Chinese script.[75]

Adaptation to other languages[edit]

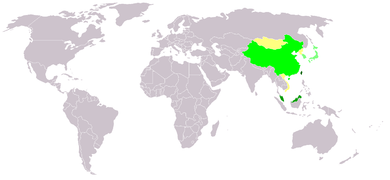

Current (dark and medium green) and former extension (light green) of the use of Chinese characters

Countries and regions using Chinese characters as a writing system:

Dark Green: Traditional Chinese used officially (Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau)

Green: Simplified Chinese used officially but traditional form is also used in publishing (Singapore, Malaysia)[76]

Light Green: Simplified Chinese used officially, traditional form in daily use is uncommon (China, Kokang, and Wa State of Myanmar)

Cyan: Chinese characters are used in parallel with other scripts in respective native languages (South Korea, Japan)

Yellow: Chinese characters were once used officially, but this is now obsolete (Mongolia, North Korea, Vietnam)

The Chinese script spread to Korea together with Buddhism from the 2nd century BC to 5th century AD (hanja).[77] This was adopted for recording the Japanese language from the 5th century AD.[f]

Chinese characters were first used in Vietnam during the millennium of Chinese rule starting in 111 BC. They were used to write Classical Chinese and adapted around the 13th century to create the chữ Nôm script to write Vietnamese.

Currently, the only non-Chinese language outside of China that regularly uses the Chinese script is Japanese. Vietnam abandoned its use in the early 20th century in favour of a Latin-based script, and Korea in the late 20th century in favour of its homegrown hangul script. Since the education of Chinese characters is not mandatory in South Korea,[78] the usage of Chinese character is rapidly disappearing.

Japanese[edit]

Chinese characters adapted to write Japanese words are known as kanji. Chinese words borrowed into Japanese could be written with Chinese characters, while native Japanese words could also be written using the character(s) for a Chinese word of similar meaning. Most kanji have both the native (and often multi-syllabic) Japanese pronunciation, known as kun’yomi, and the (mono-syllabic) Chinese-based pronunciation, known as on’yomi. For example, the native Japanese word katana is written as 刀 in kanji, which uses the native pronunciation since the word is native to Japanese, while the Chinese loanword nihontō (meaning «Japanese sword») is written as 日本刀, which uses the Chinese-based pronunciation. While nowadays loanwords from non-Sinosphere languages are usually just written in katakana, one of the two syllabary systems of Japanese, loanwords that were borrowed into Japanese before the Meiji Period were typically written with Chinese characters whose on’yomi had the same pronunciation as the loanword itself, words like Amerika (kanji: 亜米利加, katakana: アメリカ, meaning: America), karuta (kanji: 歌留多, 加留多, katakana: カルタ, meaning: card, letter), and tenpura (kanji: 天婦羅, 天麩羅, katakana: テンプラ, meaning: tempura), although the meanings of the characters used often had no relation to the words themselves. Only some of the old kanji spellings are in common use, like kan (缶, meaning: can). Kanji that are used to only represent the sounds of a word are called ateji (当て字).

Because Chinese words have been borrowed from varying dialects at different times, a single character may have several on’yomi in Japanese.[79]

Written Japanese also includes a pair of syllabaries known as kana, derived by simplifying Chinese characters selected to represent syllables of Japanese.

The syllabaries differ because they sometimes selected different characters for a syllable, and because they used different strategies to reduce these characters for easy writing: the angular katakana were obtained by selecting a part of each character, while hiragana were derived from the cursive forms of whole characters.[80]

Modern Japanese writing uses a composite system, using kanji for word stems, hiragana for inflectional endings and grammatical words, and katakana to transcribe non-Chinese loanwords as well as serve as a method to emphasize native words (similar to how italics are used in Latin-script languages).[81]

Korean[edit]

Throughout most of Korean history as early as the Gojoseon period up until the Joseon Dynasty, Literary Chinese was the dominant form of written communication. Although the Korean alphabet hangul was created in 1443, it did not come into widespread official use until the late 19th and early 20th century.[82][83]

Even today, much of the vocabulary, especially in the realms of science and sociology, comes directly from Chinese. However, due to the lack of tones in Modern Standard Korean, as the words were imported from Chinese, many dissimilar characters and syllables took on identical pronunciations, and subsequently identical spelling in hangul.[citation needed] Chinese characters are sometimes used to this day for either clarification in a practical manner, or to give a distinguished appearance, as knowledge of Chinese characters is considered by many Koreans a high class attribute and an indispensable part of a classical education. It is also observed that the preference for Chinese characters is treated as being culturally Confucian.[83]

In Korea, hanja have become a politically contentious issue, with some Koreans urging a «purification» of the national language and culture by totally abandoning their use. These individuals encourage the exclusive use of the native hangul alphabet throughout Korean society and the end to Hanja education in public schools. Other Koreans support the revival of Hanja in everyday usage, like in the 1970s and 80s.[84] In South Korea, educational policy on characters has swung back and forth, often swayed by education ministers’ personal opinions. At present, middle and high school students (grades 7 to 12) are taught 1,800 characters,[84] albeit with the principal focus on recognition, with the aim of achieving newspaper literacy.[83] Hanja retains its prominence, especially in Korean academia, as the vast majority of Korean documents, history, literature and records (such as the Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty, among others) were written in Literary Chinese using Hanja as its primary script. Therefore, a good working knowledge of Chinese characters is still important for anyone who wishes to interpret and study older texts from Korea, or anyone who wishes to read scholarly texts in the humanities. Hanja is also useful for understanding the etymology of Sino-Korean vocabulary.[85]

There is a clear trend toward the exclusive use of hangul in day-to-day South Korean society. Hanja are still used to some extent, particularly in newspapers, weddings, place names and calligraphy (although it is nowhere near the extent of kanji use in day-to-day Japanese society). Hanja is also extensively used in situations where ambiguity must be avoided, such as academic papers, high-level corporate reports, government documents, and newspapers; this is due to the large number of homonyms that have resulted from extensive borrowing of Chinese words.[86] Characters convey meaning visually, while alphabets convey guidance to pronunciation, which in turn hints at meaning. As an example, in Korean dictionaries, the phonetic entry for 기사 gisa yields more than 30 different entries. In the past, this ambiguity had been efficiently resolved by parenthetically displaying the associated hanja. While hanja is sometimes used for Sino-Korean vocabulary, native Korean words are rarely, if ever, written in hanja.

When learning how to write hanja, students are taught to memorize the native Korean pronunciation for the hanja’s meaning and the Sino-Korean pronunciations (the pronunciation based on the Chinese pronunciation of the characters) for each hanja respectively so that students know what the syllable and meaning is for a particular hanja. For example, the name for the hanja 水 is 물 수 (mul-su) in which 물 (mul) is the native Korean pronunciation for «water», while 수 (su) is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of the character. The naming of hanja is similar to if «water» were named «water-aqua», «horse-equus», or «gold-aurum» based on a hybridization of both the English and the Latin names. Other examples include 사람 인 (saram-in) for 人 «person/people», 큰 대 (keun-dae) for 大 «big/large//great», 작을 소 (jakeul-so) for 小 «small/little», 아래 하 (arae-ha) for 下 «underneath/below/low», 아비 부 (abi-bu) for 父 «father», and 나라이름 한 (naraireum-han) for 韓 «Han/Korea».[87]

North Korea[edit]

In North Korea, the hanja system was once completely banned since June 1949 due to fears of collapsed containment of the country; during the 1950s, Kim Il Sung had condemned all sorts of foreign languages (even the then-newly proposed New Korean Orthography). The ban continued into the 21st century. However, a textbook for university history departments containing 3,323 distinct characters was published in 1971. In the 1990s, school children were still expected to learn 2,000 characters (more than in South Korea or Japan).[88]

After Kim Jong Il, the second ruler of North Korea, died in December 2011, his successor Kim Jong Un began mandating the use of Hanja as a source of definition for the Korean language. Currently, it is said that North Korea teaches around 3,000 Hanja characters to North Korean students, and in some cases, the characters appear within advertisements and newspapers. However, it is also said that the authorities implore students not to use the characters in public.[89] Due to North Korea’s strict isolationism, accurate reports about hanja use in North Korea are hard to obtain.

Okinawan[edit]

Chinese characters are thought to have been first introduced to the Ryukyu Islands in 1265 by a Japanese Buddhist monk.[90] After the Okinawan kingdoms became tributaries of Ming China, especially the Ryukyu Kingdom, Classical Chinese was used in court documents, but hiragana was mostly used for popular writing and poetry. After Ryukyu became a vassal of Japan’s Satsuma Domain, Chinese characters became more popular, as well as the use of Kanbun. In modern Okinawan, which is labeled as a Japanese dialect by the Japanese government, katakana and hiragana are mostly used to write Okinawan, but Chinese characters are still used.

Vietnamese[edit]

The first two lines of the classic Vietnamese epic poem The Tale of Kieu, written in the Nôm script and the modern Vietnamese alphabet. Chinese characters representing Sino-Vietnamese words are shown in green, characters borrowed for similar-sounding native Vietnamese words in purple, and invented characters in brown.

In Vietnam, Chinese characters (called Chữ Hán, chữ Nho, or Hán tự in Vietnamese) are now limited to ceremonial uses, but they were once in widespread use. Until the early 20th century, Literary Chinese was used in Vietnam for all official and scholarly writing.

The oldest writing Chinese materials found in Vietnam is an epigraphy dated 618, erected by local Sui dynasty officials in Thanh Hoa.[91] Around the 13th century, a script called chữ Nôm was developed to record folk literature in the Vietnamese language. Similar to Zhuang Sawndip, the Nom script (demotic script) and its characters formed by fusing phonetic and semantic values of Chinese characters that resemble Vietnamese syllables.[92] This process resulted in a highly complex system that was never mastered by more than 5% of the population.[93] The oldest writing Vietnamese chữ Nôm script written along with Chinese is a Buddhist inscription, dated 1209.[92] In total, about 20,000 Chinese and Vietnamese epigraphy rubbings throughout Indochina were collected by the École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) library in Hanoi before 1945.[94]

The oldest surviving extant manuscript in Vietnam is a late 15th-century bilingual Buddhist sutra Phật thuyết đại báo phụ mẫu ân trọng kinh, which is currently kept by the EFEO. The manuscript features Chinese texts in larger characters, and Vietnamese translation in smaller characters in Old Vietnamese.[95] Every Sino-Vietnamese book in Vietnam after the Phật thuyết are dated either from 17th century to 20th century, and most are hand-written/copied works, only few are printed texts. The Institute of Hán-Nôm Studies’s library in Hanoi had collected and kept 4,808 Sino-Vietnamese manuscripts in total by 1987.[96]

During French colonization in the late 19th and early 20th century, Literary Chinese fell out of use and chữ Nôm was gradually replaced with the Latin-based Vietnamese alphabet.[97][98] Currently this alphabet is the main script in Vietnam, but Chinese characters and chữ Nôm are still used in some activities connected with Vietnamese traditional culture (e.g. calligraphy).

Other languages[edit]

Several minority languages of south and southwest China were formerly written with scripts based on Hanzi but also including many locally created characters.

The most extensive is the sawndip script for the Zhuang language of Guangxi which is still used to this day.

Other languages written with such scripts include Miao, Yao, Bouyei, Mulam, Kam, Bai, and Hani.[99] All these languages are now officially written using Latin-based scripts, while Chinese characters are still used for the Mulam language.[citation needed] Even today for Zhuang, according to survey, the traditional sawndip script has twice as many users as the official Latin script.[100]

The foreign dynasties that ruled northern China between the 10th and 13th centuries developed scripts that were inspired by Hanzi but did not use them directly: the Khitan large script, Khitan small script, Tangut script, and Jurchen script.

Other scripts in China that borrowed or adapted a few Chinese characters but are otherwise distinct include Geba script, Sui script, Yi script, and the Lisu syllabary.[99]

Transcription of foreign languages[edit]

Along with Persian and Arabic, Chinese characters were also used as a foreign script to write the Mongolian language, where characters were used to phonetically transcribe Mongolian sounds. Most notably, the only surviving copies of The Secret History of the Mongols were written in such a manner; the Chinese characters 忙豁侖紐察 脫[卜]察安 (nowadays pronounced «Mánghuōlún niǔchá tuō[bo]chá’ān» in Chinese) is the rendering of Mongγol-un niγuca tobčiyan, the title in Mongolian.

Hanzi was also used to phonetically transcribe the Manchu language in the Qing dynasty.

According to the Rev. John Gulick: «The inhabitants of other Asiatic nations, who have had occasion to represent the words of their several languages by Chinese characters, have as a rule used unaspirated characters for the sounds, g, d, b. The Muslims from Arabia and Persia have followed this method … The Mongols, Manchu, and Japanese also constantly select unaspirated characters to represent the sounds g, d, b, and j of their languages. These surrounding Asiatic nations, in writing Chinese words in their own alphabets, have uniformly used g, d, b, etc., to represent the unaspirated sounds.»[101]

Simplification[edit]

Chinese character simplification is the overall reduction of the number of strokes in the regular script of a set of Chinese characters.

Asia[edit]

China[edit]

The use of traditional Chinese characters versus simplified Chinese characters varies greatly, and can depend on both the local customs and the medium. Before the official reform, character simplifications were not officially sanctioned and generally adopted vulgar variants and idiosyncratic substitutions. Orthodox variants were mandatory in printed works, while the (unofficial) simplified characters would be used in everyday writing or quick notes. Since the 1950s, and especially with the publication of the 1964 list, the People’s Republic of China has officially adopted simplified Chinese characters for use in mainland China, while Hong Kong, Macau, and the Republic of China (Taiwan) were not affected by the reform. There is no absolute rule for using either system, and often it is determined by what the target audience understands, as well as the upbringing of the writer.

Although most often associated with the People’s Republic of China, character simplification predates the 1949 communist victory. Caoshu, cursive written text, are what inspired some simplified characters, and for others, some were already in use in print text, albeit not for most formal works. In the period of Republican China, discussions on character simplification took place within the Kuomintang government and the intelligentsia, in an effort to greatly reduce functional illiteracy among adults, which was a major concern at the time. Indeed, this desire by the Kuomintang to simplify the Chinese writing system (inherited and implemented by the Chinese Communist Party after its subsequent abandonment) also nursed aspirations of some for the adoption of a phonetic script based on the Latin script, and spawned such inventions as the Gwoyeu Romatzyh.

The People’s Republic of China issued its first round of official character simplifications in two documents, the first in 1956 and the second in 1964. A second round of character simplifications (known as erjian, or «second-round simplified characters») was promulgated in 1977. It was poorly received, and in 1986 the authorities rescinded the second round completely, while making six revisions to the 1964 list, including the restoration of three traditional characters that had been simplified: 叠 dié, 覆 fù, 像 xiàng.

As opposed to the second round, a majority of simplified characters in the first round were drawn from conventional abbreviated forms, or ancient forms.[102] For example, the orthodox character 來 lái («come») was written as 来 in the clerical script (隶书 / 隸書, lìshū) of the Han dynasty. This clerical form uses one fewer stroke, and was thus adopted as a simplified form. The character 雲 yún («cloud») was written with the structure 云 in the oracle bone script of the Shang dynasty, and had remained in use later as a phonetic loan in the meaning of «to say» while the 雨 radical was added a semantic indicator to disambiguate the two. Simplified Chinese merges them instead.

Japan[edit]

In the years after World War II, the Japanese government also instituted a series of orthographic reforms. Some characters were given simplified forms called shinjitai (新字体, lit. «new character forms»); the older forms were then labelled the kyūjitai (旧字体, lit. «old character forms»). The number of characters in common use was restricted, and formal lists of characters to be learned during each grade of school were established, first the 1850-character tōyō kanji (当用漢字) list in 1945, the 1945-character jōyō kanji (常用漢字) list in 1981, and a 2136-character reformed version of the jōyō kanji in 2010. Many variant forms of characters and obscure alternatives for common characters were officially discouraged. This was done with the goal of facilitating learning for children and simplifying kanji use in literature and periodicals. These are common guidelines, hence many characters outside these standards are still widely known and commonly used, especially those used for personal and place names (for the latter, see jinmeiyō kanji),[citation needed] as well as for some common words such as «dragon» (竜/龍, tatsu) in which both old and new forms of the character are both acceptable and widely known amongst native Japanese speakers.

Singapore[edit]

Singapore underwent three successive rounds of character simplification. These resulted in some simplifications that differed from those used in mainland China.

The first round, consisting of 498 Simplified characters from 502 Traditional characters, was promulgated by the Ministry of Education in 1969. The second round, consisting of 2287 Simplified characters, was promulgated in 1974. The second set contained 49 differences from the Mainland China system; those were removed in the final round in 1976.

In 1993, Singapore adopted the six revisions made by Mainland China in 1986. However, unlike in mainland China where personal names may only be registered using simplified characters, parents have the option of registering their children’s names in traditional characters in Singapore.[103]

It ultimately adopted the reforms of the People’s Republic of China in their entirety as official, and has implemented them in the educational system. However, unlike in China, personal names may still be registered in traditional characters.

Malaysia[edit]

Malaysia started teaching a set of simplified characters at schools in 1981, which were also completely identical to the Mainland China simplifications. Chinese newspapers in Malaysia are published in either set of characters, typically with the headlines in traditional Chinese while the body is in simplified Chinese.

Although in both countries the use of simplified characters is universal among the younger Chinese generation, a large majority of the older Chinese literate generation still use the traditional characters. Chinese shop signs are also generally written in traditional characters.

Philippines[edit]

In the Philippines, most Chinese schools and businesses still use the traditional characters and bopomofo, owing from influence from the Republic of China (Taiwan) due to the shared Hokkien heritage. Recently, however, more Chinese schools now use both simplified characters and pinyin. Since most readers of Chinese newspapers in the Philippines belong to the older generation, they are still published largely using traditional characters.

North America[edit]

Canada & United States[edit]

Public and private Chinese signage in the United States and Canada most often use traditional characters.[104] There is some effort to get municipal governments to implement more simplified character signage due to recent immigration from mainland China.[105] Most community newspapers printed in North America are also printed in traditional characters.

Comparisons of traditional Chinese, simplified Chinese, and Japanese[edit]

The following is a comparison of Chinese characters in the Standard Form of National Characters, a common traditional Chinese standard used in Taiwan; the Table of General Standard Chinese Characters, the standard for Mainland Chinese jiantizi (simplified); and the jōyō kanji, the standard for Japanese kanji. Generally, the jōyō kanji are more similar to fantizi (traditional) than jiantizi are to fantizi. «Simplified» refers to having significant differences from the Taiwan standard, not necessarily being a newly created character or a newly performed substitution. The characters in the Hong Kong standard and the Kangxi Dictionary are also known as «Traditional», but are not shown.

| Chinese | Japanese | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Simplified | ||

| Simplified in mainland China only, not Japan (Some radicals were simplified) |

|||

| 電 | 电 | 電 | electricity |

| 買 | 买 | 買 | buy |

| 車 | 车 | 車 | car, vehicle |

| 紅 | 红 | 紅 | red |

| 無 | 无 | 無 | nothing |

| 東 | 东 | 東 | east |

| 馬 | 马 | 馬 | horse |

| 風 | 风 | 風 | wind |

| 愛 | 爱 | 愛 | love |

| 時 | 时 | 時 | time |

| 鳥 | 鸟 | 鳥 | bird |

| 島 | 岛 | 島 | island |

| 語 | 语 | 語 | language, word |

| 頭 | 头 | 頭 | head |

| 魚 | 鱼 | 魚 | fish |

| 園 | 园 | 園 | garden |

| 長 | 长 | 長 | long, grow |

| 紙 | 纸 | 紙 | paper |

| 書 | 书 | 書 | book, document |

| 見 | 见 | 見 | watch, see |

| 響 | 响 | 響 | echo, sound |

| Simplified in Japan, not Mainland China (In some cases this represents the adoption of different variants as standard) |

|||

| 假 | 假 | 仮 | false, day off, borrow |

| 佛 | 佛 | 仏 | Buddha |

| 德 | 德 | 徳 | moral, virtue |

| 拜 | 拜 | 拝 | kowtow, pray to, worship |

| 黑 | 黑 | 黒 | black |

| 冰 | 冰 | 氷 | ice |

| 兔 | 兔 | 兎 | rabbit |

| 妒 | 妒 | 妬 | jealousy |

| 每 | 每 | 毎 | every |

| 壤 | 壤 | 壌 | soil |

| 步 | 步 | 歩 | step |

| 巢 | 巢 | 巣 | nest |

| 惠 | 惠 | 恵 | grace |

| 莓 | 莓 | 苺 | strawberry |

| Simplified differently in Mainland China and Japan | |||

| 圓 | 圆 | 円 | circle |

| 聽 | 听 | 聴 | listen |

| 實 | 实 | 実 | real |

| 證 | 证 | 証 | certificate, proof |

| 龍 | 龙 | 竜 | dragon |

| 賣 | 卖 | 売 | sell |

| 龜 | 龟 | 亀 | turtle, tortoise |

| 藝 | 艺 | 芸 | art, arts |

| 戰 | 战 | 戦 | fight, war |

| 繩 | 绳 | 縄 | rope, criterion |

| 繪 | 绘 | 絵 | picture, painting |

| 鐵 | 铁 | 鉄 | iron, metal |

| 圖 | 图 | 図 | picture, diagram |

| 團 | 团 | 団 | group, regiment |

| 圍 | 围 | 囲 | to surround |

| 轉 | 转 | 転 | turn |

| 廣 | 广 | 広 | wide, broad |

| 惡 | 恶 | 悪 | bad, evil, hate |

| 豐 | 丰 | 豊 | abundant |

| 腦 | 脑 | 脳 | brain |

| 雜 | 杂 | 雑 | miscellaneous |

| 壓 | 压 | 圧 | pressure, compression |

| 雞/鷄 | 鸡 | 鶏 | chicken |

| 總 | 总 | 総 | overall |

| 價 | 价 | 価 | price |

| 樂 | 乐 | 楽 | fun, music |

| 歸 | 归 | 帰 | return, revert |

| 氣 | 气 | 気 | air |

| 廳 | 厅 | 庁 | hall, office |

| 發 | 发 | 発 | emit, send |

| 澀 | 涩 | 渋 | astringent |

| 勞 | 劳 | 労 | labour |

| 劍 | 剑 | 剣 | sword |

| 歲 | 岁 | 歳 | age, years |

| 權 | 权 | 権 | authority, right |

| 燒 | 烧 | 焼 | burn |

| 贊 | 赞 | 賛 | praise |

| 兩 | 两 | 両 | two, both |

| 譯 | 译 | 訳 | translate |

| 觀 | 观 | 観 | look, watch |

| 營 | 营 | 営 | camp, battalion |

| 處 | 处 | 処 | processing |

| 齒 | 齿 | 歯 | teeth |

| 驛 | 驿 | 駅 | station |

| 櫻 | 樱 | 桜 | cherry |

| 產 | 产 | 産 | production |

| 藥 | 药 | 薬 | medicine |

| 嚴 | 严 | 厳 | strict, severe |

| 讀 | 读 | 読 | read |

| 顏 | 颜 | 顔 | face |

| 關 | 关 | 関 | concern, involve, relation |

| 顯 | 显 | 顕 | prominent, to show |

| Simplified (almost) identically in Mainland China and Japan | |||

| 畫 | 画 | 画 | picture |

| 聲 | 声 | 声 | sound, voice |

| 學 | 学 | 学 | learn |

| 體 | 体 | 体 | body |

| 點 | 点 | 点 | dot, point |

| 麥 | 麦 | 麦 | wheat |

| 蟲 | 虫 | 虫 | insect |

| 舊 | 旧 | 旧 | old, bygone, past |

| 會 | 会 | 会 | be able to, meeting |

| 萬 | 万 | 万 | ten-thousand |

| 盜 | 盗 | 盗 | thief, steal |

| 寶 | 宝 | 宝 | treasure |

| 國 | 国 | 国 | country |

| 醫 | 医 | 医 | medicine |

| 雙 | 双 | 双 | pair |

| 晝 | 昼 | 昼 | noon, day |

| 觸 | 触 | 触 | contact |

| 來 | 来 | 来 | come |

| 黃 | 黄 | 黄 | yellow |

| 區 | 区 | 区 | ward, district |

Written styles[edit]

There are numerous styles, or scripts, in which Chinese characters can be written, deriving from various calligraphic and historical models. Most of these originated in China and are now common, with minor variations, in all countries where Chinese characters are used.

The Shang dynasty oracle bone script and the Zhou dynasty scripts found on Chinese bronze inscriptions are no longer used; the oldest script that is still in use today is the seal script (篆書(篆书), zhuànshū). It evolved organically out of the Spring and Autumn period Zhou script, and was adopted in a standardized form under the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang. The seal script, as the name suggests, is now used only in artistic seals. Few people are still able to read it effortlessly today, although the art of carving a traditional seal in the script remains alive; some calligraphers also work in this style.

Scripts that are still used regularly are the «clerical script» (隸書(隶书), lìshū) of the Qin dynasty to the Han dynasty, the weibei (魏碑, wèibēi), the «regular script» (楷書(楷书), kǎishū), which is used mostly for printing, and the «semi-cursive script» (行書(行书), xíngshū), used mostly for handwriting.

The cursive script (草書(草书), cǎoshū, literally «grass script») is used informally. The basic character shapes are suggested, rather than explicitly realized, and the abbreviations are sometimes extreme. Despite being cursive to the point where individual strokes are no longer differentiable and the characters often illegible to the untrained eye, this script (also known as draft) is highly revered for the beauty and freedom that it embodies. Some of the simplified Chinese characters adopted by the People’s Republic of China, and some simplified characters used in Japan, are derived from the cursive script. The Japanese hiragana script is also derived from this script.

There also exist scripts created outside China, such as the Japanese Edomoji styles; these have tended to remain restricted to their countries of origin, rather than spreading to other countries like the Chinese scripts.

Calligraphy[edit]

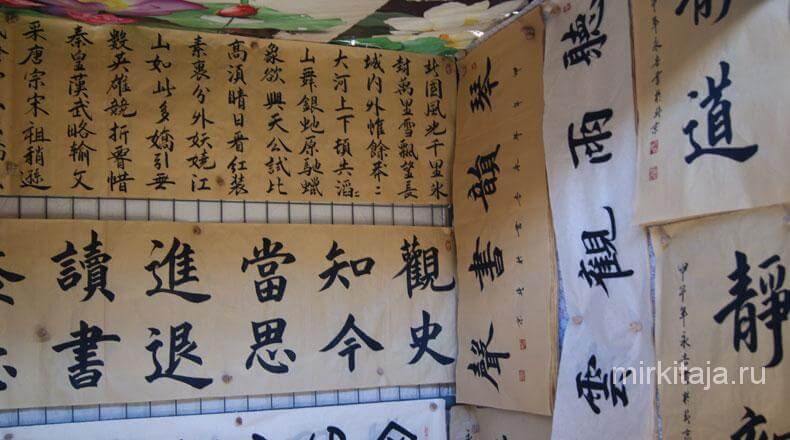

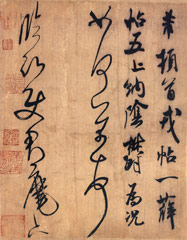

Chinese calligraphy of mixed styles written by Song dynasty (1051–1108 AD) poet Mifu. For centuries, the Chinese literati were expected to master the art of calligraphy.

The art of writing Chinese characters is called Chinese calligraphy. It is usually done with ink brushes. In ancient China, Chinese calligraphy is one of the Four Arts of the Chinese Scholars. There is a minimalist set of rules of Chinese calligraphy. Every character from the Chinese scripts is built into a uniform shape by means of assigning it a geometric area in which the character must occur. Each character has a set number of brushstrokes; none must be added or taken away from the character to enhance it visually, lest the meaning be lost. Finally, strict regularity is not required, meaning the strokes may be accentuated for dramatic effect of individual style. Calligraphy was the means by which scholars could mark their thoughts and teachings for immortality, and as such, represent some of the most precious treasures that can be found from ancient China.

Typography and design[edit]

Three major families of typefaces are used in Chinese typography:

- Ming or Song

- Sans-serif

- Regular script

Ming and sans-serif are the most popular in body text and are based on regular script for Chinese characters akin to Western serif and sans-serif typefaces, respectively. Regular script typefaces emulate regular script.

The Song typeface (宋体 / 宋體, sòngtǐ) is known as the Ming typeface (明朝, minchō) in Japan, and it is also somewhat more commonly known as the Ming typeface (明体 / 明體, míngtǐ) than the Song typeface in Taiwan and Hong Kong. The names of these styles come from the Song and Ming dynasties, when block printing flourished in China.

Sans-serif typefaces, called black typeface (黑体 / 黑體, hēitǐ) in Chinese and Gothic typeface (ゴシック体) in Japanese, are characterized by simple lines of even thickness for each stroke, akin to sans-serif styles such as Arial and Helvetica in Western typography.

Regular script typefaces are also commonly used, but not as common as Ming or sans-serif typefaces for body text. Regular script typefaces are often used to teach students Chinese characters, and often aim to match the standard forms of the region where they are meant to be used. Most typefaces in the Song dynasty were regular script typefaces which resembled a particular person’s handwriting (e.g. the handwriting of Ouyang Xun, Yan Zhenqing, or Liu Gongquan), while most modern regular script typefaces tend toward anonymity and regularity.

Variants[edit]

Variants of the Chinese character for guī ‘turtle’, collected c. 1800 from printed sources. The one at left is the traditional form used today in Taiwan and Hong Kong, 龜, though 龜 may look slightly different, or even like the second variant from the left, depending on your font (see Wiktionary). The modern simplified forms used in China, 龟, and in Japan, 亀, are most similar to the variant in the middle of the bottom row, though neither is identical. A few more closely resemble the modern simplified form of the character for diàn ‘lightning’, 电.

Five of the 30 variant characters found in the preface of the Imperial (Kangxi) Dictionary which are not found in the dictionary itself. They are 為 (爲) wèi «due to», 此 cǐ «this», 所 suǒ «place», 能 néng «be able to», 兼 jiān «concurrently». (Although the form of 為 is not very different, and in fact is used today in Japan, the radical 爪 has been obliterated.) Another variant from the preface, 来 for 來 lái «to come», also not listed in the dictionary, has been adopted as the standard in Mainland China and Japan.

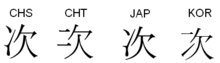

The character 次 in Simplified and Traditional Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. If you have an appropriate font installed, you can see the corresponding character in Vietnamese:

次

.

Just as Roman letters have a characteristic shape (lower-case letters mostly occupying the x-height, with ascenders or descenders on some letters), Chinese characters occupy a more or less square area in which the components of every character are written to fit in order to maintain a uniform size and shape, especially with small printed characters in Ming and sans-serif styles. Because of this, beginners often practise writing on squared graph paper, and the Chinese sometimes use the term «Square-Block Characters» (方块字 / 方塊字, fāngkuàizì), sometimes translated as tetragraph,[106] in reference to Chinese characters.

Despite standardization, some nonstandard forms are commonly used, especially in handwriting. In older sources, even authoritative ones, variant characters are commonplace. For example, in the preface to the Imperial Dictionary, there are 30 variant characters which are not found in the dictionary itself.[107] A few of these are reproduced at right.

Regional standards[edit]

The nature of Chinese characters makes it very easy to produce allographs (variants) for many characters, and there have been many efforts at orthographical standardization throughout history. In recent times, the widespread usage of the characters in several nations has prevented any particular system becoming universally adopted and the standard form of many Chinese characters thus varies in different regions.

Mainland China adopted simplified Chinese characters in 1956. They are also used in Singapore and Malaysia. Traditional Chinese characters are used in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Postwar Japan has used its own less drastically simplified characters, Shinjitai, since 1946, while South Korea has limited its use of Chinese characters, and Vietnam and North Korea have completely abolished their use in favour of Vietnamese alphabet and Hangul, respectively.

The standard character forms of each region are described in:

- The List of Commonly Used Characters in Modern Chinese for Mainland China.

- The List of Graphemes of Commonly-Used Chinese Characters for Hong Kong.

- The three lists of the Standard Form of National Characters for Taiwan.

- The list of Jōyō kanji for Japan.

- The Han-Han Dae Sajeon (de facto) for Korea.

In addition to strictness in character size and shape, Chinese characters are written with very precise rules. The most important rules regard the strokes employed, stroke placement, and stroke order. Just as each region that uses Chinese characters has standardized character forms, each also has standardized stroke orders, with each standard being different. Most characters can be written with just one correct stroke order, though some words also have many valid stroke orders, which may occasionally result in different stroke counts. Some characters are also written with different stroke orders due to character simplification.

Polysyllabic morphemes[edit]

Chinese characters are primarily morphosyllabic, meaning that most Chinese morphemes are monosyllabic and are written with a single character, though in modern Chinese most words are disyllabic and dimorphemic, consisting of two syllables, each of which is a morpheme. In modern Chinese 10% of morphemes only occur as part of a given compound. However, a few morphemes are disyllabic, some of them dating back to Classical Chinese.[108] Excluding foreign loan words, these are typically words for plants and small animals. They are usually written with a pair of phono-semantic compound characters sharing a common radical. Examples are 蝴蝶 húdié «butterfly» and 珊瑚 shānhú «coral». Note that the 蝴 hú of húdié and the 瑚 hú of shānhú have the same phonetic, 胡, but different radicals («insect» and «jade», respectively). Neither exists as an independent morpheme except as a poetic abbreviation of the disyllabic word.

Polysyllabic characters[edit]

In certain cases compound words and set phrases may be contracted into single characters. Some of these can be considered logograms, where characters represent whole words rather than syllable-morphemes, though these are generally instead considered ligatures or abbreviations (similar to scribal abbreviations, such as & for «et»), and as non-standard. These do see use, particularly in handwriting or decoration, but also in some cases in print. In Chinese, these ligatures are called héwén (合文), héshū (合书, 合書) or hétǐzì (合体字, 合體字), and in the special case of combining two characters, these are known as «two-syllable Chinese characters» (双音节汉字, 雙音節漢字).

A commonly seen example is the Double Happiness symbol 囍, formed as a ligature of 喜喜 and referred to by its disyllabic name (simplified Chinese: 双喜; traditional Chinese: 雙喜; pinyin: shuāngxǐ). In handwriting, numbers are very frequently squeezed into one space or combined – common ligatures include 廿 niàn, «twenty», normally read as 二十 èrshí, 卅 sà, «thirty», normally read as 三十 sānshí, and 卌 xì «forty», normally read as 四十 «sìshí». Calendars often use numeral ligatures in order to save space; for example, the «21st of March» can be read as 三月廿一.[8]

Modern examples particularly include Chinese characters for SI units. In Chinese these units are disyllabic and standardly written with two characters, as 厘米 límǐ «centimeter» (厘 centi-, 米 meter) or 千瓦 qiānwǎ «kilowatt». However, in the 19th century these were often written via compound characters, pronounced disyllabically, such as 瓩 for 千瓦 or 糎 for 厘米 – some of these characters were also used in Japan, where they were pronounced with borrowed European readings instead. These have now fallen out of general use, but are occasionally seen. Less systematic examples include 圕 túshūguǎn «library», a contraction of 圖書館 (simplified: 图书馆).[109][110] Since polysyllabic characters are often non-standard, they are often excluded in character dictionaries.

The use of such contractions is as old as Chinese characters themselves, and they have frequently been found in religious or ritual use. In the Oracle Bone script, personal names, ritual items, and even phrases such as 受又(祐) shòu yòu «receive blessings» are commonly contracted into single characters. A dramatic example is that in medieval manuscripts 菩薩 púsà «bodhisattva» (simplified: 菩萨) is sometimes written with a single character formed of a 2×2 grid of four 十 (derived from the grass radical over two 十).[8] However, for the sake of consistency and standardization, the CCP seeks to limit the use of such polysyllabic characters in public writing to ensure that every character only has one syllable.[111]

Conversely, with the fusion of the diminutive -er suffix in Mandarin, some monosyllabic words may even be written with two characters, as in 花儿, 花兒 huār «flower», which was formerly disyllabic.

In most other languages that use the Chinese family of scripts, notably Korean, Vietnamese, and Zhuang, Chinese characters are typically monosyllabic, but in Japanese a single character is generally used to represent a borrowed monosyllabic Chinese morpheme (the on’yomi), a polysyllabic native Japanese morpheme (the kun’yomi), or even (in rare cases) a foreign loanword. These uses are completely standard and unexceptional.

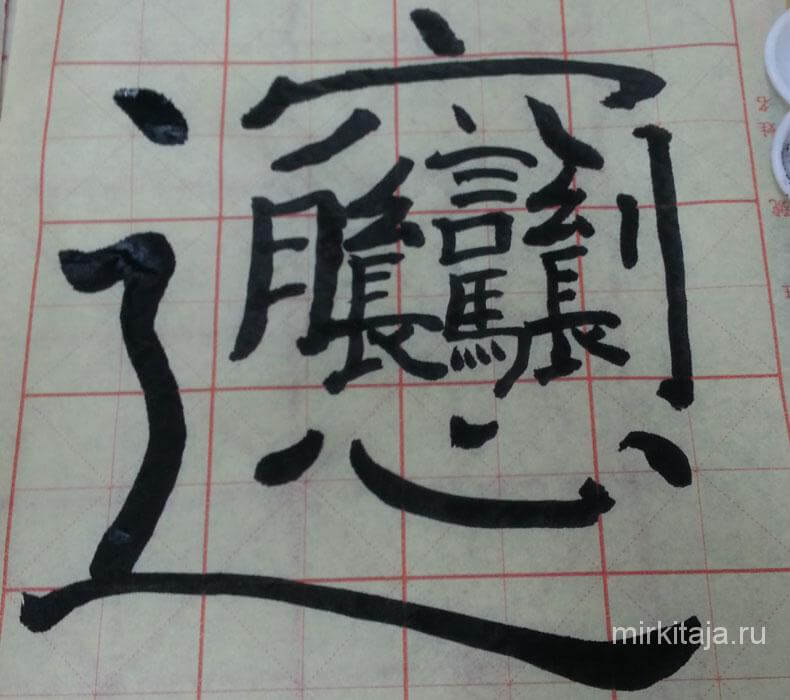

Rare and complex characters[edit]

Often a character not commonly used (a «rare» or «variant» character) will appear in a personal or place name in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese (see Chinese name, Japanese name, Korean name, and Vietnamese name, respectively). This has caused problems as many computer encoding systems include only the most common characters and exclude the less often used characters. This is especially a problem for personal names which often contain rare or classical, antiquated characters.

One man who has encountered this problem is Taiwanese politician Yu Shyi-kun, due to the rarity of the last character (堃; pinyin: kūn) in his name. Newspapers have dealt with this problem in varying ways, including using software to combine two existing, similar characters, including a picture of the character, or, especially as is the case with Yu Shyi-kun, substituting a homophone for the rare character in the hope that the reader would be able to make the correct inference. Taiwanese political posters, movie posters etc. will often add the bopomofo phonetic symbols next to such a character. Japanese newspapers may render such names and words in katakana instead, and it is accepted practice for people to write names for which they are unsure of the correct kanji in katakana instead.[citation needed]

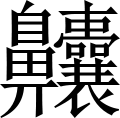

There are also some extremely complex characters which have understandably become rather rare. According to Joël Bellassen (1989), the most complex Chinese character is /𪚥 (U+2A6A5) zhé

listen (help·info), meaning «verbose» and containing 64 strokes; this character fell from use around the 5th century. It might be argued, however, that while containing the most strokes, it is not necessarily the most complex character (in terms of difficulty), as it requires writing the same 16-stroke character 龍 lóng (lit. «dragon») four times in the space for one. Another 64-stroke character is

/𠔻 (U+2053B) zhèng composed of 興 xīng/xìng (lit. «flourish») four times.