Запишись на урок и обсуди эту тему с нами!

할 수 있다고 믿으면, 이미 반은 이룬 것이다

Стоит поверить в свои силы – и вот, вы уже на полпути к цели.

(корейская пословица)

Боитесь приниматься за изучение корейского? Или, наоборот, хотите поскорее начать, но не знаете, с какой стороны к нему подступиться?

Мы подскажем, как быстро выучить корейский язык (только имейте в виду – это не значит: «молниеносно» ;), поможем приблизиться к пониманию того, как правильно произносятся звуки, выучим необходимые корейские буквы и потренируемся в их начертании.

В этой статье разберёмся, как быстро выучить корейский алфавит самостоятельно.

Для начала взглянем на то, как он вообще выглядит.

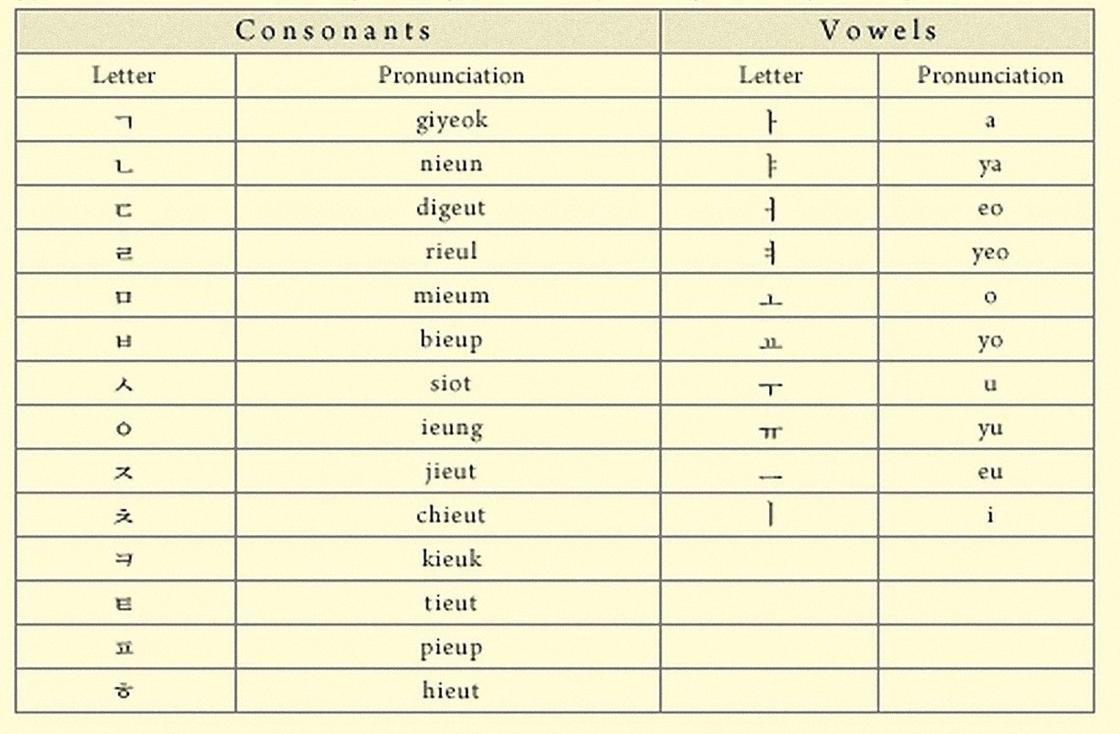

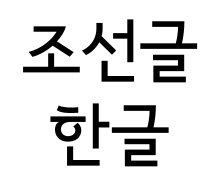

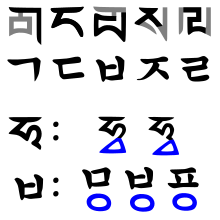

Сама система называется хангыль (한글), что в переводе с древнего означает «великая письменность», а с современного – «корейская письменность».

Буквы корейского алфавита называются чамо (자모), то есть «мать», что показывает: это – основа языка.

Начнём с простых гласных букв:

|

№

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

ㅣ |

«и» |

Базовая гласная. |

|

2 |

ㅡ |

«ы» |

Базовая гласная. |

|

3 |

ㅏ |

«а» |

Звучит более открыто, чем русский звук «а». |

|

4 |

ㅑ |

«я» |

|

|

5 |

ㅓ |

«о» |

Нечто среднее между русскими «о» и «э». |

|

6 |

ㅕ |

«ё» |

Среднее между «ё» и «э». |

|

7 |

ㅗ |

«о» |

Среднее между «у» и «о». |

|

8 |

ㅛ |

«ё» |

Среднее между «ю» и «ё». |

|

9 |

ㅜ |

«у» |

|

|

10 |

ㅠ |

«ю» |

Также, существуют ещё так называемые сложные гласные.

Не торопитесь пугаться – на письме они составлены из простых, с которыми мы уже познакомились. Вы легко запомните их тоже.

|

№

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

ㅐ |

«э» |

|

|

2 |

ㅔ |

«е» |

|

|

3 |

ㅒ |

«йэ» |

|

|

4 |

ㅖ |

«йе» |

|

|

5 |

ㅚ |

«вэ» |

|

|

6 |

ㅟ |

«ви» |

|

|

7 |

ㅘ |

«ва» |

|

|

8 |

ㅝ |

«во» |

|

|

9 |

ㅙ |

«вэ» |

|

|

10 |

ㅞ |

«ве» |

|

|

11 |

ㅢ |

«ый»/ «и» |

В начале слова читается «ый». В конце слова – «и». |

Переходим к согласным звукам и, точно так же, вначале знакомимся с простыми:

|

№

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

ㄱ |

«киёк» |

В начале/конце слова, на стыке двух согласных – читается, как «к». После звонкого согласного, между двумя гласными – как «г». |

|

2 |

ㄴ |

«ниын» |

Читается как «н». |

|

3 |

ㄷ |

«тигыт» |

В начале/конце слова, на стыке двух согласных – читается, как «т». После звонкого согласного, между двумя гласными – как «д». |

|

4 |

ㄹ |

«риыль» |

В начале слова/между двумя согласными – читается как «р». В конце слова, перед согласным – как «ль». |

|

5 |

ㅁ |

«миым» |

Читается как «м». |

|

6 |

ㅂ |

«пиып» |

В начале/конце слова, на стыке двух глухих согласных – читается, как «п». После звонкого согласного, между двумя гласными – как «б». |

|

7 |

ㅅ |

«сиот» |

Перед йотированными гласными («и», «ё», «ю», «я») читается «шепеляво» – нечто среднее между «сь» и «щ». |

|

8 |

ㅇ |

«иын» |

Читается «в нос» (похоже на “ng” в английском). В начале слога – не читается вообще. |

|

9 |

ㅈ |

«чиыт» |

В начале/конце слова, на стыке двух глухих согласных – читается как «ч». После звонкого согласного/между двумя гласными – мягко: «дж». |

|

10 |

ㅎ |

«хиыт» |

Слабо: «х». |

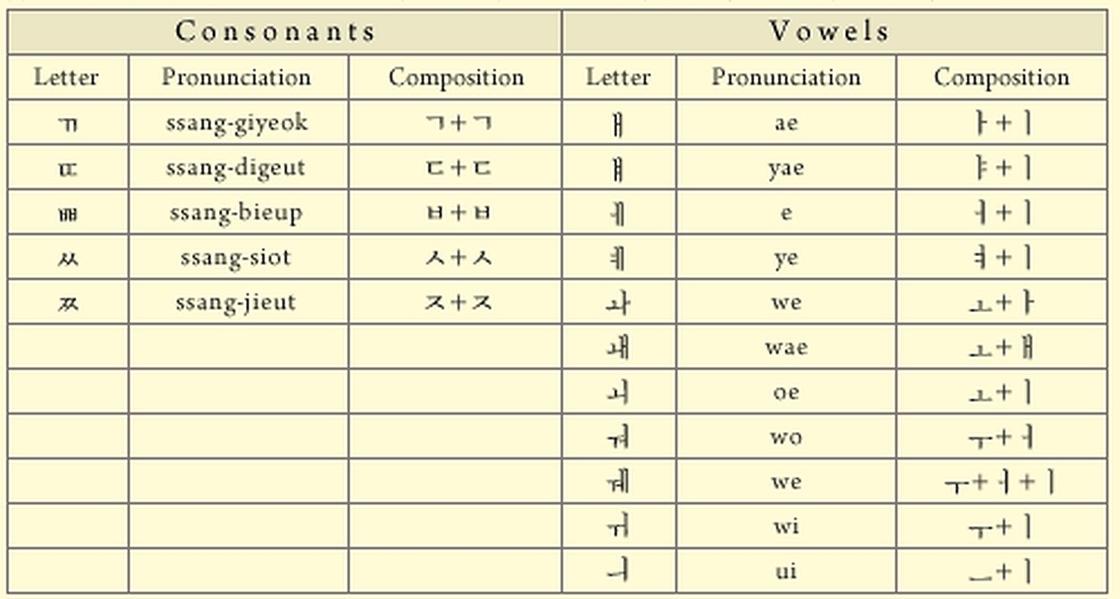

Оставшиеся («сложные») согласные составляют две группы: придыхательные и сдвоенные.

Есть четыре «придыхательных»…

|

№

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

ㅋ |

«кхиёк» |

Читается: «к». В транскрипции – «кх». |

|

2 |

ㅌ |

«тхиыт» |

Читается: «т». В транскрипции – «тх». |

|

3 |

ㅍ |

«пхиып» |

Читается: «п». В транскрипции – «пх». |

|

4 |

ㅊ |

«чхиыт» |

Читается: «ч». В транскрипции – «чх». |

…и пять «глоттализованных» (сдвоенных) согласных.

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

ㄲ |

«ссанъ-киёк» |

Произносится: «кк». |

|

2 |

ㄸ |

«ссанъ-тигыт» |

Произносится: «тт». |

|

3 |

ㅃ |

«ссанъ-пиып» |

Произносится: «пп». |

|

4 |

ㅆ |

«ссанъ-сиот» |

Произносится: «сс». |

|

5 |

ㅉ |

«ссанъ-чиыт» |

Произносится: «чч». |

Сколько букв в корейском алфавите?

Всего можно насчитать 51 чамо. Из них именно буквами являются 24 чамо («простые» гласные + «простые» и «придыхательные» согласные). Остальные 27 составляют «сдвоенные» согласные + 11 диграфов и 11 дифтонгов.

Как всё это выучить и поскорее запомнить?

Для начала – сконцентрируйтесь на 24 чамо, которые составляют основную структуру алфавита.

Во-первых, постарайтесь воспользоваться знакомыми вам мнемотехниками, которые помогают лучше запоминать любую другую информацию. Вспомните, например, как в школе вам легче всего было учить стихи или запоминать математические формулы? Самое время обратиться к этим приёмам ещё раз.

Во-вторых, постройте ассоциативные ряды: мысленно свяжите изображение буквы с её отдельным звучанием. Затем, когда будете уверены в том, что связка прочно укрепилась в сознании, свяжите её с особыми правилами произношения в различных частях слова (если таковые есть).

В-третьих, не пытайтесь выучить всё сразу и не торопитесь – при таком подходе вы едва ли сэкономите больше времени. Оцените все имеющиеся у вас знаки (визуально или мысленно – как вам удобно) и постарайтесь разбить их на несколько блоков (например, на 6 – по 4 знака). Заучивайте буквы постепенно, группами.

Когда управитесь с основными чамо – переходите к изучению гласных, согласных и дифтонгов. Их можно группировать и запоминать по той же схеме.

Как писать корейские буквы?

Считается, что это чуть ли не единственный оригинальный алфавит на всей территории Дальнего востока. Он сильнее других напоминает нам системы знаков, к которым привыкли на Западе. Тем не менее, есть несколько моментов в корейской письменности, которые стоит учесть.

Во-первых, всё, что мы пишем, должно быть всегда направлено слева направо и сверху вниз. Ни в коем случае не наоборот!

Во-вторых, выберите удобные прописи, чтобы отточить написание иероглифов и «набить» руку. Важно регулярно тренироваться, прописывая минимум по паре строчек для каждой буквы. Помните, что записи от руки всегда запоминаются намного лучше – ещё один способ быстро и естественно запомнить все необходимые символы.

В-третьих, не забудьте отдельно потренировать такие прописи, как «кагяпхё». Они содержат особые связки гласных с согласными, которые будет полезно научиться бегло писать.

Правда, удивительный язык? И очень красивые иероглифы, которые интересно было бы уметь читать и красиво писать (пусть поначалу не так, как это делают профессиональные мастера каллиграфии).

Однако определённых успехов достичь определённо можно, отправившись на курсы корейского.

Если вдруг вам не с кем оставить ребёнка, пока вы сами будете постигать тайны языка, то почему бы не организовать обучение детей? Затем можно будет отправиться в путешествие по Корее всей семьёй! И чувствовать себя там свободно и расковано в общении с местными жителями

| Korean alphabet

한글 / 조선글 |

|

|---|---|

«Chosŏn’gŭl» (top) and «Hangul» (bottom) |

|

| Script type | Featural

alphabet |

| Creator | Sejong of Joseon |

|

Time period |

1443–present |

| Direction | Hangul is usually written horizontally, from left to right and classically from right to left. It is also written vertically, from top to bottom and from right to left. |

| Languages | Korean and Jejuan (standard); Cia-Cia (limited use) |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hang (286), Hangul (Hangŭl, Hangeul) Jamo (for the jamo subset) |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Hangul |

|

Unicode range |

|

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

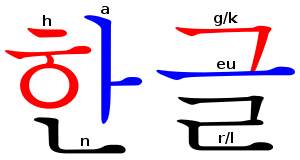

The Korean alphabet, known as Hangul[a] ( HAHN-gool[1]) in South Korea and Chosŏn’gŭl in North Korea, is the modern official writing system for the Korean language.[2][3][4] The letters for the five basic consonants reflect the shape of the speech organs used to pronounce them, and they are systematically modified to indicate phonetic features; similarly, the vowel letters are systematically modified for related sounds, making Hangul a featural writing system.[5][6][7] It has been described as a syllabic alphabet as it combines the features of alphabetic and syllabic writing systems, although it is not necessarily an abugida.[6][8]

Hangul was created in 1443 CE by King Sejong the Great in an attempt to increase literacy by serving as a complement (or alternative) to the logographic Sino-Korean Hanja, which had been used by Koreans as its primary script to write the Korean language since as early as the Gojoseon period (spanning more than a thousand years and ending around 108 BCE), along with the usage of Classical Chinese.[9][10] As a result, Hangul was initially denounced and disparaged by the Korean educated class. The script became known as eonmun («vernacular writing», 언문, 諺文) and became the primary Korean script only in the decades after Korea’s independence from Japan in the mid-20th century.[11]

Modern Hangul orthography uses 24 basic letters: 14 consonant letters[b] and 10 vowel letters.[c] There are also 27 complex letters that are formed by combining the basic letters: 5 tense consonant letters,[d] 11 complex consonant letters,[e] and 11 complex vowel letters.[f] Four basic letters in the original alphabet are no longer used: 1 vowel letter[g] and 3 consonant letters.[h] Korean letters are written in syllabic blocks with the alphabetic letters arranged in two dimensions. For example, the Korean word for «honeybee» (kkulbeol) is written as 꿀벌, not ㄲㅜㄹㅂㅓㄹ.[12] The syllables begin with a consonant letter, then a vowel letter, and then potentially another consonant letter called a batchim (Korean: 받침). If the syllable begins with a vowel sound, the consonant ㅇ (ng) acts as a silent placeholder. However, when ㅇ starts a sentence or is placed after a long pause, it marks a glottal stop.

Syllables may begin with basic or tense consonants but not complex ones. The vowel can be basic or complex, and the second consonant can be basic, complex or a limited number of tense consonants. How the syllable is structured depends if the baseline of the vowel symbol is horizontal or vertical. If the baseline is vertical, the first consonant and vowel are written above the second consonant (if present), but all components are written individually from top to bottom in the case of a horizontal baseline.[12]

As in traditional Chinese and Japanese writing, as well as many other texts in East Asia, Korean texts were traditionally written top to bottom, right to left, as is occasionally still the way for stylistic purposes. However, Korean is now typically written from left to right with spaces between words serving as dividers, unlike in Japanese and Chinese.[7] Hangul is the official writing system throughout Korea, both North and South. It is a co-official writing system in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture and Changbai Korean Autonomous County in Jilin Province, China. Hangul has also seen limited use in the Cia-Cia language.

Names[edit]

Official names[edit]

| Korean name (North Korea) | |

| Chosŏn’gŭl |

조선글 |

|---|---|

| Hancha |

朝鮮㐎 |

| Revised Romanization | Joseon(-)geul |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chosŏn’gŭl |

| IPA | Korean pronunciation: [tso.sɔn.ɡɯl] |

| Korean name (South Korea) | |

| Hangul |

한글 |

|---|---|

| Hanja |

韓㐎 |

| Revised Romanization | Han(-)geul |

| McCune–Reischauer | Han’gŭl[13] |

| IPA | Korean pronunciation: [ha(ː)n.ɡɯl] |

The word «Hangul», written in the Korean alphabet

The Korean alphabet was originally named Hunminjeong’eum (훈민정음) by King Sejong the Great in 1443.[10] Hunminjeong’eum (훈민정음) is also the document that explained logic and science behind the script in 1446.

The name hangeul (한글) was coined by Korean linguist Ju Si-gyeong in 1912. The name combines the ancient Korean word han (한), meaning great, and geul (글), meaning script. The word han is used to refer to Korea in general, so the name also means Korean script.[14] It has been romanized in multiple ways:

- Hangeul or han-geul in the Revised Romanization of Korean, which the South Korean government uses in English publications and encourages for all purposes.

- Han’gŭl in the McCune–Reischauer system, is often capitalized and rendered without the diacritics when used as an English word, Hangul, as it appears in many English dictionaries.

- hān kul in the Yale romanization, a system recommended for technical linguistic studies.

North Koreans call the alphabet Chosŏn’gŭl (조선글), after Chosŏn, the North Korean name for Korea.[15] A variant of the McCune–Reischauer system is used there for romanization.

Other names[edit]

Until the mid-20th century, the Korean elite preferred to write using Chinese characters called Hanja. They referred to Hanja as jinseo (진서/真書) meaning true letters. Some accounts say the elite referred to the Korean alphabet derisively as ‘amkeul (암클) meaning women’s script, and ‘ahaetgeul (아햇글) meaning children’s script, though there is no written evidence of this.[16]

Supporters of the Korean alphabet referred to it as jeong’eum (정음/正音) meaning correct pronunciation, gungmun (국문/國文) meaning national script, and eonmun (언문/諺文) meaning vernacular script.[16]

History[edit]

Creation[edit]

Koreans primarily wrote using Classical Chinese alongside native phonetic writing systems that predate Hangul by hundreds of years, including Idu script, Hyangchal, Gugyeol and Gakpil.[17][18][19][20] However, many lower class uneducated Koreans were illiterate due to the difficulty of learning the Korean and Chinese languages, as well as the large number of Chinese characters that are used.[21] To promote literacy among the common people, the fourth king of the Joseon dynasty, Sejong the Great, personally created and promulgated a new alphabet.[3][21][22] Although it is widely assumed that King Sejong ordered the Hall of Worthies to invent Hangul, contemporary records such as the Veritable Records of King Sejong and Jeong Inji’s preface to the Hunminjeongeum Haerye emphasize that he invented it himself.[23]

The Korean alphabet was designed so that people with little education could learn to read and write. A popular saying about the alphabet is, «A wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; even a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days.»[24]

A page from the Hunminjeong’eum Eonhae. The Hangul-only column, third from the left (나랏말ᄊᆞ미), has pitch-accent diacritics to the left of the syllable blocks.

The project was completed in late December 1443 or January 1444, and described in 1446 in a document titled Hunminjeong’eum (The Proper Sounds for the Education of the People), after which the alphabet itself was originally named.[16] The publication date of the Hunminjeongeum, October 9, became Hangul Day in South Korea. Its North Korean equivalent, Chosŏn’gŭl Day, is on January 15.

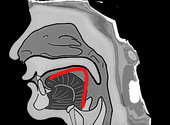

Another document published in 1446 and titled Hunminjeong’eum Haerye (Hunminjeong’eum Explanation and Examples) was discovered in 1940. This document explains that the design of the consonant letters is based on articulatory phonetics and the design of the vowel letters is based on the principles of yin and yang and vowel harmony.[citation needed]

Opposition[edit]

The Korean alphabet faced opposition in the 1440s by the literary elite, including Choe Manri and other Korean Confucian scholars. They believed Hanja was the only legitimate writing system. They also saw the circulation of the Korean alphabet as a threat to their status.[21] However, the Korean alphabet entered popular culture as King Sejong had intended, used especially by women and writers of popular fiction.[25]

King Yeonsangun banned the study and publication of the Korean alphabet in 1504, after a document criticizing the king was published.[26] Similarly, King Jungjong abolished the Ministry of Eonmun, a governmental institution related to Hangul research, in 1506.[27]

Revival[edit]

The late 16th century, however, saw a revival of the Korean alphabet as gasa and sijo poetry flourished. In the 17th century, the Korean alphabet novels became a major genre.[28] However, the use of the Korean alphabet had gone without orthographical standardization for so long that spelling had become quite irregular.[25]

Songangasa, a collection of poems by Jeong Cheol, printed in 1768.

In 1796, the Dutch scholar Isaac Titsingh became the first person to bring a book written in Korean to the Western world. His collection of books included the Japanese book, Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu (An Illustrated Description of Three Countries) by Hayashi Shihei.[29] This book, which was published in 1785, described the Joseon Kingdom[30] and the Korean alphabet.[31] In 1832, the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland supported the posthumous abridged publication of Titsingh’s French translation.[32]

Thanks to growing Korean nationalism, the Gabo Reformists’ push, and Western missionaries’ promotion of the Korean alphabet in schools and literature,[33] the Hangul Korean alphabet was adopted in official documents for the first time in 1894.[26] Elementary school texts began using the Korean alphabet in 1895, and Tongnip Sinmun, established in 1896, was the first newspaper printed in both Korean and English.[34]

Reforms and suppression under Japanese rule[edit]

After the Japanese annexation, which occurred in 1910, Japanese was made the official language of Korea. However, the Korean alphabet was still taught in Korean-established schools built after the annexation and Korean was written in a mixed Hanja-Hangul script, where most lexical roots were written in Hanja and grammatical forms in the Korean alphabet. Japan banned earlier Korean literature from public schooling, which became mandatory for children.[35]

The orthography of the Korean alphabet was partially standardized in 1912, when the vowel arae-a (ㆍ)—which has now disappeared from Korean—was restricted to Sino-Korean roots: the emphatic consonants were standardized to ㅺ, ㅼ, ㅽ, ㅆ, ㅾ and final consonants restricted to ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄹ, ㅁ, ㅂ, ㅅ, ㅇ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ. Long vowels were marked by a diacritic dot to the left of the syllable, but this was dropped in 1921.[25]

A second colonial reform occurred in 1930. The arae-a was abolished: the emphatic consonants were changed to ㄲ, ㄸ, ㅃ, ㅆ, ㅉ and more final consonants ㄷ, ㅈ, ㅌ, ㅊ, ㅍ, ㄲ, ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅄ were allowed, making the orthography more morphophonemic. The double consonant ㅆ was written alone (without a vowel) when it occurred between nouns, and the nominative particle 가 was introduced after vowels, replacing 이.[25]

Ju Si-gyeong, the linguist who had coined the term Hangul to replace Eonmun or Vulgar Script in 1912, established the Korean Language Research Society (later renamed the Hangul Society), which further reformed orthography with Standardized System of Hangul in 1933. The principal change was to make the Korean alphabet as morphophonemically practical as possible given the existing letters.[25] A system for transliterating foreign orthographies was published in 1940.

Japan banned the Korean language from schools and public offices in 1938 and excluded Korean courses from the elementary education in 1941 as part of a policy of cultural genocide.[36][37]

Further reforms[edit]

The definitive modern Korean alphabet orthography was published in 1946, just after Korean independence from Japanese rule. In 1948, North Korea attempted to make the script perfectly morphophonemic through the addition of new letters, and in 1953, Syngman Rhee in South Korea attempted to simplify the orthography by returning to the colonial orthography of 1921, but both reforms were abandoned after only a few years.[25]

Both North Korea and South Korea have used the Korean alphabet or mixed script as their official writing system, with ever-decreasing use of Hanja especially in the North.

In South Korea[edit]

Beginning in the 1970s, Hanja began to experience a gradual decline in commercial or unofficial writing in the South due to government intervention, with some South Korean newspapers now only using Hanja as abbreviations or disambiguation of homonyms. However, as Korean documents, history, literature and records throughout its history until the contemporary period were written primarily in Literary Chinese using Hanja as its primary script, a good working knowledge of Chinese characters especially in the academia is still important for anyone who wishes to interpret and study older texts from Korea, or anyone who wishes to read scholarly texts in the humanities.[38]

A high proficiency in Hanja is also useful for understanding the etymology of Sino-Korean words as well as to enlarge one’s Korean vocabulary.[38]

In North Korea[edit]

North Korea instated Hangul as its exclusive writing system in 1949 on the orders of Kim Il-sung of the Workers’ Party of Korea, and officially banned the use of Hanja.[39]

Non-Korean languages[edit]

Systems that employed Hangul letters with modified rules were attempted by linguists such as Hsu Tsao-te [zh] and Ang Ui-jin to transcribe Taiwanese Hokkien, a Sinitic language, but the usage of Chinese characters ultimately ended up being the most practical solution and was endorsed by the Ministry of Education (Taiwan).[40][41][42]

The Hunminjeong’eum Society in Seoul attempted to spread the use of Hangul to unwritten languages of Asia.[43] In 2009, it was unofficially adopted by the town of Baubau, in Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia, to write the Cia-Cia language.[44][45][46][47]

A number of Indonesian Cia-Cia speakers who visited Seoul generated large media attention in South Korea, and they were greeted on their arrival by Oh Se-hoon, the mayor of Seoul.[48] However, it was confirmed in October 2012 that the attempts to disseminate the use of the Korean alphabet in Indonesia ultimately failed.[49]

Letters[edit]

Korean alphabet letters and pronunciation

Letters in the Korean alphabet are called jamo (자모). There are 19 consonants (자음) and 21 vowels (모음) used in the modern alphabet. They were first named in Hunmongjahoe, a hanja textbook written by Choe Sejin.

In typography design and in IME automata, the letters that make up a block are called jaso (자소).

Consonants[edit]

The shape of tongue when pronouncing ㄱ (g)

The shape of tongue when pronouncing ㄴ (n)

The shape of teeth and tongue when pronouncing ㅅ (s)

ㅇ (ng) is similar to the throat hole.

ㅁ (m) is similar to a closed mouth.

The chart below shows all 19 consonants in South Korean alphabetic order with Revised Romanization equivalents for each letter and pronunciation in IPA (see Korean phonology for more).

| Hangul | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Romanization | g | kk | n | d | tt | r | m | b | pp | s | ss | ‘ [i] | j | jj | ch | k | t | p | h |

| IPA | /k/ | /k͈/ | /n/ | /t/ | /t͈/ | /ɾ/ | /m/ | /p/ | /p͈/ | /s/ | /s͈/ | silent | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͈͡ɕ͈/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /kʰ/ | /tʰ/ | /pʰ/ | /h/ | |

| Final | Romanization | k | k | n | t | – | l | m | p | – | t | t | ng | t | – | t | k | t | p | t |

| g | kk | n | d | l | m | b | s | ss | ng | j | ch | k | t | p | h | |||||

| IPA | /k̚/ | /n/ | /t̚/ | – | /ɭ/ | /m/ | /p̚/ | – | /t̚/ | /ŋ/ | /t̚/ | – | /t̚/ | /k̚/ | /t̚/ | /p̚/ | /t̚/ |

ㅇ is silent syllable-initially and is used as a placeholder when the syllable starts with a vowel. ㄸ, ㅃ, and ㅉ are never used syllable-finally.

Consonants are broadly categorized into either obstruents (sounds produced when airflow either completely stops (i.e., a plosive consonant) or passes through a narrow opening (i.e., a fricative)) or sonorants (sounds produced when air flows out with little to no obstruction through the mouth, nose, or both).[50] The chart below lists the Korean consonants by their respective categories and subcategories.

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo-palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstruent | Stop (plosive) | Lax | p (ㅂ) | t (ㄷ) | k (ㄱ) | ||

| Tense | p͈ (ㅃ) | t͈ (ㄸ) | k͈ (ㄲ) | ||||

| Aspirated | pʰ (ㅍ) | tʰ (ㅌ) | kʰ (ㅋ) | ||||

| Fricative | Lax | s (ㅅ) | h (ㅎ) | ||||

| Tense | s͈ (ㅆ) | ||||||

| Affricate | Lax | t͡ɕ (ㅈ) | |||||

| Tense | t͈͡ɕ͈ (ㅉ) | ||||||

| Aspirated | t͡ɕʰ (ㅊ) | ||||||

| Sonorant | Nasal | m (ㅁ) | n (ㄴ) | ŋ (ㅇ) | |||

| Liquid (lateral approximant) | l (ㄹ) |

All Korean obstruents are voiceless in that the larynx does not vibrate when producing those sounds and are further distinguished by degree of aspiration and tenseness. The tensed consonants are produced by constricting the vocal chords while heavily aspirated consonants (such as the Korean ㅍ, /pʰ/) are produced by opening them.[50]

Korean sonorants are voiced.

Consonant assimilation[edit]

The pronunciation of a syllable-final consonant (which may already differ from its syllable-initial sound) may be affected by the following letter, and vice-versa. The table below describes these assimilation rules. Spaces are left blank when no modification is made to the normal syllable-final sound.

| Preceding syllable block’s final letter-sound | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㄱ

(k) |

ㄲ

(k) |

ㄴ

(n) |

ㄷ

(t) |

ㄹ

(l) |

ㅁ

(m) |

ㅂ

(p) |

ㅅ

(t) |

ㅆ

(t) |

ㅇ

(ng) |

ㅈ

(t) |

ㅊ

(t) |

ㅋ

(k) |

ㅌ

(t) |

ㅍ

(p) |

ㅎ

(t) |

||

| Subsequent syllable block’s initial letter | ㄱ(g) | k+k | n+g | t+g | l+g | m+g | b+g | t+g | — | t+g | t+g | t+g | p+g | h+k | |||

| ㄴ(n) | ng+n | n+n | l+n | m+n | m+n | t+n | n+t | t+n | t+n | t+n | p+n | h+n | |||||

| ㄷ(d) | k+d | n+d | t+t | l+d | m+d | p+d | t+t | t+t | t+t | t+t | k+d | t+t | p+d | h+t | |||

| ㄹ(r) | g+n | n+n | l+l | m+n | m+n | — | ng+n | r | |||||||||

| ㅁ(m) | g+m | n+m | t+m | l+m | m+m | m+m | t+m | — | ng+m | t+m | t+m | k+d | t+m | p+m | h+m | ||

| ㅂ(b) | g+b | p+p | t+b | — | |||||||||||||

| ㅅ (s) | ss+s | ||||||||||||||||

| ㅇ(∅) | g | kk+h | n | t | r | m | p | s | ss | ng+h | t+ch | t+ch | k+h | t+ch | p+h | h | |

| ㅈ(j) | t+ch | ||||||||||||||||

| ㅎ(h) | k | kk+h | n+h | t | r/

l+h |

m+h | p | t | — | t+ch | t+ch | k | t | p | — |

Consonant assimilation occurs as a result of intervocalic voicing. When surrounded by vowels or sonorant consonants such as ㅁ or ㄴ, a stop will take on the characteristics of its surrounding sound. Since plain stops (like ㄱ /k/) are produced with relaxed vocal chords that are not tensed, they are more likely to be affected by surrounding voiced sounds (which are produced by vocal chords that are vibrating).[50]

Below are examples of how lax consonants (ㅂ /p/, ㄷ /t/, ㅈ /t͡ɕ/, ㄱ /k/) change due to location in a word. Letters in bolded interface show intervocalic weakening, or the softening of the lax consonants to their sonorous counterparts.[50]

ㅂ

- 밥 [pap̚] – ‘rice’

- 보리밥 [poɾibap̚] – ‘barley mixed with rice’

ㄷ

- 다 [ta] – ‘all’

- 맏 [mat̚] – ‘oldest’

- 맏아들 [madadɯɭ] – ‘oldest son’

ㅈ

- 죽 [t͡ɕuk] – ‘porridge’

- 콩죽 [kʰoŋd͡ʑuk̚] – ‘bean porridge’

ㄱ

- 공 [koŋ] – ‘ball’

- 새 공 [sɛgoŋ] – ‘new ball’

The consonants ㄹ and ㅎ also experience weakening. The liquid ㄹ, when in an intervocalic position, will be weakened to a [ɾ]. For example, the final ㄹ in the word 말 ([maɭ], ‘word’) changes when followed by the subject marker 이 (ㅇ being a sonorant consonant), and changes to a [ɾ] to become [maɾi].

ㅎ /h/ is very weak and is usually deleted in Korean words, as seen in words like 괜찮아요 /kwɛnt͡ɕʰanhajo/ [kwɛnt͡ɕʰanajo]. However, instead of being completely deleted, it leaves remnants by devoicing the following sound or by acting as a glottal stop.[50]

Lax consonants are tensed when following other obstruents due to the fact that the first obstruent’s articulation is not released. Tensing can be seen in words like 입구 (‘entrance’) /ipku/ which is pronounced as [ip̚k͈u].

Consonants in the Korean alphabet can be combined into one of 11 consonant clusters, which always appear in the final position in a syllable block. They are: ㄳ, ㄵ, ㄶ, ㄺ, ㄻ, ㄼ, ㄽ, ㄾ, ㄿ, ㅀ, and ㅄ.

| Consonant cluster combinations

(e.g. [in isolation] 닭 dag; [preceding another syllable block] 없다 – eop-ta, 앉아 an-ja) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preceding syllable block’s final letter* | ㄳ

(gs) |

ㄵ

(nj) |

ㄶ

(nh) |

ㄺ

(lg) |

ㄻ

(lm) |

ㄼ

(lb) |

ㄽ

(ls) |

ㄾ

(lṭ) |

ㄿ

(lp̣) |

ㅀ

(lh) |

ㅄ

(ps) |

|

| (pronunciation in isolation) | g | nj | nh | g | m | b | s | ṭ | p̣ | h | p | |

| Subsequent block’s initial letter** | ㅇ(∅) | g+s | n+j | l+h | l+g | l+m | l+b | l+s | l+ṭ | l+p̣ | l+h | p+s |

| ㄷ(d) | g+t | nj+d/

nt+ch |

n+t | g+d | m+d | b+d | l+t | l+ṭ | p̣+d | l+t | p+t |

In cases where consonant clusters are followed by words beginning with ㅇ or ㄷ, the consonant cluster is resyllabified through a phonological phenomenon called liaison. In words where the first consonant of the consonant cluster is ㅂ,ㄱ, or ㄴ (the stop consonants), articulation stops and the second consonant cannot be pronounced without releasing the articulation of the first once. Hence, in words like 값 /kaps/ (‘price’), the ㅅ cannot be articulated and the word is thus pronounced as [kap̚]. The second consonant is usually revived when followed by a word with initial ㅇ (값이 → [kap̚.si]. Other examples include 삶 (/salm/ [sam], ‘life’). The ㄹ in the final consonant cluster is generally lost in pronunciation, however when followed by the subject marker 이, the ㄹ is revived and the ㅁ takes the place of the blank consonant ㅇ. Thus, 삶이 is pronounced as [sal.mi].

Vowels[edit]

The chart below shows the 21 vowels used in the modern Korean alphabet in South Korean alphabetic order with Revised Romanization equivalents for each letter and pronunciation in IPA (see Korean phonology for more).

| Hangul | ㅏ | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revised Romanization | a | ae | ya | yae | eo | e | yeo | ye | o | wa | wae | oe | yo | u | wo | we | wi | yu | eu | ui/

yi |

i |

| IPA | /a/ | /ɛ/ | /ja/ | /jɛ/ | /ʌ/ | /e/ | /jʌ/ | /je/ | /o/ | /wa/ | /wɛ/ | /ø/ ~ [we] | /jo/ | /u/ | /wʌ/ | /we/ | /y/ ~ [ɥi] | /ju/ | /ɯ/ | /ɰi/ | /i/ |

The vowels are generally separated into two categories: monophthongs and diphthongs. Monophthongs are produced with a single articulatory movement (hence the prefix mono), while diphthongs feature an articulatory change. Diphthongs have two constituents: a glide (or a semivowel) and a monophthong. There is some disagreement about exactly how many vowels are considered Korean’s monophthongs; the largest inventory features ten, while some scholars have proposed eight or nine.[who?] This divergence reveals two issues: whether Korean has two front rounded vowels (i.e. /ø/ and /y/); and, secondly, whether Korean has three levels of front vowels in terms of vowel height (i.e. whether /e/ and /ɛ/ are distinctive).[51] Actual phonological studies done by studying formant data show that current speakers of Standard Korean do not differentiate between the vowels ㅔ and ㅐ in pronunciation.[52]

Alphabetic order[edit]

Alphabetic order in the Korean alphabet is called the ganada order, (가나다순) after the first three letters of the alphabet. The alphabetical order of the Korean alphabet does not mix consonants and vowels. Rather, first are velar consonants, then coronals, labials, sibilants, etc. The vowels come after the consonants.[53]

The collation order of Korean in Unicode is based on the South Korean order.

Historical orders[edit]

The order from the Hunminjeongeum in 1446 was:[54]

- ㄱ ㄲ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㄸ ㅌ ㄴ ㅂ ㅃ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅅ ㅆ ㆆ ㅎ ㆅ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ

- ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ

This is the basis of the modern alphabetic orders. It was before the development of the Korean tense consonants and the double letters that represent them, and before the conflation of the letters ㅇ (null) and ㆁ (ng). Thus, when the North Korean and South Korean governments implemented full use of the Korean alphabet, they ordered these letters differently, with North Korea placing new letters at the end of the alphabet and South Korea grouping similar letters together.[55][56]

North Korean order[edit]

The new double letters are placed at the end of the consonants, just before the null ㅇ, so as not to alter the traditional order of the rest of the alphabet.

- ㄱ ㄴ ㄷ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅅ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㄸ ㅃ ㅆ ㅉ

- ㅏ ㅑ ㅓ ㅕ ㅗ ㅛ ㅜ ㅠ ㅡ ㅣ ㅐ ㅒ ㅔ ㅖ ㅚ ㅟ ㅢ ㅘ ㅝ ㅙ ㅞ

All digraphs and trigraphs, including the old diphthongs ㅐ and ㅔ, are placed after the simple vowels, again maintaining Choe’s alphabetic order.

The order of the final letters (받침) is:

- (none) ㄱ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㄲ ㅆ

(None means there is no final letter.)

Unlike when it is initial, this ㅇ is pronounced, as the nasal ㅇ ng, which occurs only as a final in the modern language. The double letters are placed to the very end, as in the initial order, but the combined consonants are ordered immediately after their first element.[55]

South Korean order[edit]

In the Southern order, double letters are placed immediately after their single counterparts:

ㄱ ㄲ ㄴ ㄷ ㄸ ㄹ ㅁ ㅂ ㅃ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

ㅏ ㅐ ㅑ ㅒ ㅓ ㅔ ㅕ ㅖ ㅗ ㅘ ㅙ ㅚ ㅛ ㅜ ㅝ ㅞ ㅟ ㅠ ㅡ ㅢ ㅣ

The modern monophthongal vowels come first, with the derived forms interspersed according to their form: i is added first, then iotized, then iotized with added i. Diphthongs beginning with w are ordered according to their spelling, as ㅗ or ㅜ plus a second vowel, not as separate digraphs.

The order of the final letters is:

(none) ㄱ ㄲ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅄ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ

Every syllable begins with a consonant (or the silent ㅇ) that is followed by a vowel (e.g. ㄷ + ㅏ = 다). Some syllables such as 달 and 닭 have a final consonant or final consonant cluster (받침). Then, 399 combinations are possible for two-letter syllables and 10,773 possible combinations for syllables with more than two letters (27 possible final endings), for a total of 11,172 possible combinations of Korean alphabet letters to form syllables.[55]

The sort order including archaic Hangul letters defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1 is:[57]

- Initial consonants: ᄀ, ᄁ, ᅚ, ᄂ, ᄓ, ᄔ, ᄕ, ᄖ, ᅛ, ᅜ, ᅝ, ᄃ, ᄗ, ᄄ, ᅞ, ꥠ, ꥡ, ꥢ, ꥣ, ᄅ, ꥤ, ꥥ, ᄘ, ꥦ, ꥧ, ᄙ, ꥨ, ꥩ, ꥪ, ꥫ, ꥬ, ꥭ, ꥮ, ᄚ, ᄛ, ᄆ, ꥯ, ꥰ, ᄜ, ꥱ, ᄝ, ᄇ, ᄞ, ᄟ, ᄠ, ᄈ, ᄡ, ᄢ, ᄣ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ꥲ, ᄧ, ᄨ, ꥳ, ᄩ, ᄪ, ꥴ, ᄫ, ᄬ, ᄉ, ᄭ, ᄮ, ᄯ, ᄰ, ᄱ, ᄲ, ᄳ, ᄊ, ꥵ, ᄴ, ᄵ, ᄶ, ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ, ᄺ, ᄻ, ᄼ, ᄽ, ᄾ, ᄿ, ᅀ, ᄋ, ᅁ, ᅂ, ꥶ, ᅃ, ᅄ, ᅅ, ᅆ, ᅇ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ꥷ, ᅌ, ᄌ, ᅍ, ᄍ, ꥸ, ᅎ, ᅏ, ᅐ, ᅑ, ᄎ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅔ, ᅕ, ᄏ, ᄐ, ꥹ, ᄑ, ᅖ, ꥺ, ᅗ, ᄒ, ꥻ, ᅘ, ᅙ, ꥼ, (filler;

U+115F) - Medial vowels: (filler;

U+1160), ᅡ, ᅶ, ᅷ, ᆣ, ᅢ, ᅣ, ᅸ, ᅹ, ᆤ, ᅤ, ᅥ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅦ, ᅧ, ᆥ, ᅽ, ᅾ, ᅨ, ᅩ, ᅪ, ᅫ, ᆦ, ᆧ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ힰ, ᆁ, ᆂ, ힱ, ᆃ, ᅬ, ᅭ, ힲ, ힳ, ᆄ, ᆅ, ힴ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ᆈ, ᅮ, ᆉ, ᆊ, ᅯ, ᆋ, ᅰ, ힵ, ᆌ, ᆍ, ᅱ, ힶ, ᅲ, ᆎ, ힷ, ᆏ, ᆐ, ᆑ, ᆒ, ힸ, ᆓ, ᆔ, ᅳ, ힹ, ힺ, ힻ, ힼ, ᆕ, ᆖ, ᅴ, ᆗ, ᅵ, ᆘ, ᆙ, ힽ, ힾ, ힿ, ퟀ, ᆚ, ퟁ, ퟂ, ᆛ, ퟃ, ᆜ, ퟄ, ᆝ, ᆞ, ퟅ, ᆟ, ퟆ, ᆠ, ᆡ, ᆢ - Final consonants: (none), ᆨ, ᆩ, ᇺ, ᇃ, ᇻ, ᆪ, ᇄ, ᇼ, ᇽ, ᇾ, ᆫ, ᇅ, ᇿ, ᇆ, ퟋ, ᇇ, ᇈ, ᆬ, ퟌ, ᇉ, ᆭ, ᆮ, ᇊ, ퟍ, ퟎ, ᇋ, ퟏ, ퟐ, ퟑ, ퟒ, ퟓ, ퟔ, ᆯ, ᆰ, ퟕ, ᇌ, ퟖ, ᇍ, ᇎ, ᇏ, ᇐ, ퟗ, ᆱ, ᇑ, ᇒ, ퟘ, ᆲ, ퟙ, ᇓ, ퟚ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᆳ, ᇖ, ᇗ, ퟛ, ᇘ, ᆴ, ᆵ, ᆶ, ᇙ, ퟜ, ퟝ, ᆷ, ᇚ, ퟞ, ퟟ, ᇛ, ퟠ, ᇜ, ퟡ, ᇝ, ᇞ, ᇟ, ퟢ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ᇢ, ᆸ, ퟣ, ᇣ, ퟤ, ퟥ, ퟦ, ᆹ, ퟧ, ퟨ, ퟩ, ᇤ, ᇥ, ᇦ, ᆺ, ᇧ, ᇨ, ᇩ, ퟪ, ᇪ, ퟫ, ᆻ, ퟬ, ퟭ, ퟮ, ퟯ, ퟰ, ퟱ, ퟲ, ᇫ, ퟳ, ퟴ, ᆼ, ᇰ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ퟵ, ᇱ, ᇲ, ᇮ, ᇯ, ퟶ, ᆽ, ퟷ, ퟸ, ퟹ, ᆾ, ᆿ, ᇀ, ᇁ, ᇳ, ퟺ, ퟻ, ᇴ, ᇂ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ, ᇹ

-

Sort order of Hangul consonants defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1

-

Sort order of Hangul vowels defined in the South Korean national standard KS X 1026-1

Letter names[edit]

names of the Korean consonant letters (South Korean)

names of the Korean vowel letters

Letters in the Korean alphabet were named by Korean linguist Choe Sejin in 1527. South Korea uses Choe’s traditional names, most of which follow the format of letter + i + eu + letter. Choe described these names by listing Hanja characters with similar pronunciations. However, as the syllables 윽 euk, 읃 eut, and 읏 eut did not occur in Hanja, Choe gave those letters the modified names 기역 giyeok, 디귿 digeut, and 시옷 siot, using Hanja that did not fit the pattern (for 기역) or native Korean syllables (for 디귿 and 시옷).[58]

Originally, Choe gave ㅈ, ㅊ, ㅋ, ㅌ, ㅍ, and ㅎ the irregular one-syllable names of ji, chi, ḳi, ṭi, p̣i, and hi, because they should not be used as final consonants, as specified in Hunminjeongeum. However, after establishment of the new orthography in 1933, which let all consonants be used as finals, the names changed to the present forms.

In North Korea[edit]

The chart below shows names used in North Korea for consonants in the Korean alphabet. The letters are arranged in North Korean alphabetic order, and the letter names are romanised with the McCune–Reischauer system, which is widely used in North Korea. The tense consonants are described with the word 된 toen meaning hard.

| Consonant | ㄱ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅅ | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㄲ | ㄸ | ㅃ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅉ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 기윽 | 니은 | 디읃 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 시읏 | 지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 | 된기윽 | 된디읃 | 된비읍 | 된시읏 | 이응 | 된지읒 |

| McCR | kiŭk | niŭn | diŭt | riŭl | miŭm | piŭp | siŭt | jiŭt | chiŭt | ḳiŭk | ṭiŭt | p̣iŭp | hiŭt | toen’giŭk | toendiŭt | toenbiŭp | toensiŭt | ‘iŭng | toenjiŭt |

In North Korea, an alternative way to refer to a consonant is letter + ŭ (ㅡ), for example, gŭ (그) for the letter ㄱ, and ssŭ (쓰) for the letter ㅆ.

As in South Korea, the names of vowels in the Korean alphabet are the same as the sound of each vowel.

In South Korea[edit]

The chart below shows names used in South Korea for consonants of the Korean alphabet. The letters are arranged in the South Korean alphabetic order, and the letter names are romanised in the Revised Romanization system, which is the official romanization system of South Korea. The tense consonants are described with the word 쌍 ssang meaning double.

| Consonant | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name (Hangul) | 기역 | 쌍기역 | 니은 | 디귿 | 쌍디귿 | 리을 | 미음 | 비읍 | 쌍비읍 | 시옷 | 쌍시옷 | 이응 | 지읒 | 쌍지읒 | 치읓 | 키읔 | 티읕 | 피읖 | 히읗 |

| Name (romanised) | gi-yeok | ssang-giyeok | ni-eun | digeut | ssang-digeut | ri-eul | mi-eum | bi-eup | ssang-bi-eup | si-ot (shi-ot) | ssang-si-ot (ssang-shi-ot) | ‘i-eung | ji-eut | ssang-ji-eut | chi-eut | ḳi-euk | ṭi-eut | p̣i-eup | hi-eut |

Stroke order[edit]

Letters in the Korean alphabet have adopted certain rules of Chinese calligraphy, although ㅇ and ㅎ use a circle, which is not used in printed Chinese characters.[59][60]

-

ㄱ (giyeok 기역)

-

ㄴ (nieun 니은)

-

ㄷ (digeut 디귿)

-

ㄹ (rieul 리을)

-

ㅁ (mieum 미음)

-

ㅂ (bieup 비읍)

-

ㅅ (siot 시옷)

-

ㅇ (ieung 이응)

-

ㅈ (jieut 지읒)

-

ㅊ (chieut 치읓)

-

ㅋ (ḳieuk 키읔)

-

ㅌ (ṭieut 티읕)

-

ㅍ (p̣ieup 피읖)

-

ㅎ (hieuh 히읗)

-

ㅏ (a)

-

ㅐ (ae)

-

ㅓ (eo)

-

ㅔ (e)

-

ㅗ (o)

-

ㅜ (u)

-

ㅡ (eu)

For the iotized vowels, which are not shown, the short stroke is simply doubled.

Letter design[edit]

Scripts typically transcribe languages at the level of morphemes (logographic scripts like Hanja), of syllables (syllabaries like kana), of segments (alphabetic scripts like the Latin script used to write English and many other languages), or, on occasion, of distinctive features. The Korean alphabet incorporates aspects of the latter three, grouping sounds into syllables, using distinct symbols for segments, and in some cases using distinct strokes to indicate distinctive features such as place of articulation (labial, coronal, velar, or glottal) and manner of articulation (plosive, nasal, sibilant, aspiration) for consonants, and iotization (a preceding i-sound), harmonic class and i-mutation for vowels.

For instance, the consonant ㅌ ṭ [tʰ] is composed of three strokes, each one meaningful: the top stroke indicates ㅌ is a plosive, like ㆆ ʔ, ㄱ g, ㄷ d, ㅈ j, which have the same stroke (the last is an affricate, a plosive–fricative sequence); the middle stroke indicates that ㅌ is aspirated, like ㅎ h, ㅋ ḳ, ㅊ ch, which also have this stroke; and the bottom stroke indicates that ㅌ is alveolar, like ㄴ n, ㄷ d, and ㄹ l. (It is said to represent the shape of the tongue when pronouncing coronal consonants, though this is not certain.) Two obsolete consonants, ㆁ and ㅱ, have dual pronunciations, and appear to be composed of two elements corresponding to these two pronunciations: [ŋ]~silence for ㆁ and [m]~[w] for ㅱ.

With vowel letters, a short stroke connected to the main line of the letter indicates that this is one of the vowels that can be iotized; this stroke is then doubled when the vowel is iotized. The position of the stroke indicates which harmonic class the vowel belongs to, light (top or right) or dark (bottom or left). In the modern alphabet, an additional vertical stroke indicates i mutation, deriving ㅐ [ɛ], ㅚ [ø], and ㅟ [y] from ㅏ [a], ㅗ [o], and ㅜ [u]. However, this is not part of the intentional design of the script, but rather a natural development from what were originally diphthongs ending in the vowel ㅣ [i]. Indeed, in many Korean dialects,[citation needed] including the standard dialect of Seoul, some of these may still be diphthongs. For example, in the Seoul dialect, ㅚ may alternatively be pronounced [we̞], and ㅟ [ɥi]. Note: ㅔ [e] as a morpheme is ㅓ combined with ㅣ as a vertical stroke. As a phoneme, its sound is not by i mutation of ㅓ [ʌ].

Beside the letters, the Korean alphabet originally employed diacritic marks to indicate pitch accent. A syllable with a high pitch (거성) was marked with a dot (〮) to the left of it (when writing vertically); a syllable with a rising pitch (상성) was marked with a double dot, like a colon (〯). These are no longer used, as modern Seoul Korean has lost tonality. Vowel length has also been neutralized in Modern Korean[61] and is no longer written.

Consonant design[edit]

The consonant letters fall into five homorganic groups, each with a basic shape, and one or more letters derived from this shape by means of additional strokes. In the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye account, the basic shapes iconically represent the articulations the tongue, palate, teeth, and throat take when making these sounds.

| Simple | Aspirated | Tense | |

|---|---|---|---|

| velar | ㄱ | ㅋ | ㄲ |

| fricatives | ㅅ | ㅆ | |

| palatal | ㅈ | ㅊ | ㅉ |

| coronal | ㄷ | ㅌ | ㄸ |

| bilabial | ㅂ | ㅍ | ㅃ |

- Velar consonants (아음, 牙音 a’eum «molar sounds»)

- ㄱ g [k], ㅋ ḳ [kʰ]

- Basic shape: ㄱ is a side view of the back of the tongue raised toward the velum (soft palate). (For illustration, access the external link below.) ㅋ is derived from ㄱ with a stroke for the burst of aspiration.

- Sibilant consonants (fricative or palatal) (치음, 齒音 chieum «dental sounds»):

- ㅅ s [s], ㅈ j [tɕ], ㅊ ch [tɕʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅅ was originally shaped like a wedge ∧, without the serif on top. It represents a side view of the teeth.[citation needed] The line topping ㅈ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The stroke topping ㅊ represents an additional burst of aspiration.

- Coronal consonants (설음, 舌音 seoreum «lingual sounds»):

- ㄴ n [n], ㄷ d [t], ㅌ ṭ [tʰ], ㄹ r [ɾ, ɭ]

- Basic shape: ㄴ is a side view of the tip of the tongue raised toward the alveolar ridge (gum ridge). The letters derived from ㄴ are pronounced with the same basic articulation. The line topping ㄷ represents firm contact with the roof of the mouth. The middle stroke of ㅌ represents the burst of aspiration. The top of ㄹ represents a flap of the tongue.

- Bilabial consonants (순음, 唇音 suneum «labial sounds»):

- ㅁ m [m], ㅂ b [p], ㅍ p̣ [pʰ]

- Basic shape: ㅁ represents the outline of the lips in contact with each other. The top of ㅂ represents the release burst of the b. The top stroke of ㅍ is for the burst of aspiration.

- Dorsal consonants (후음, 喉音 hueum «throat sounds»):

- ㅇ ‘/ng [ŋ], ㅎ h [h]

- Basic shape: ㅇ is an outline of the throat. Originally ㅇ was two letters, a simple circle for silence (null consonant), and a circle topped by a vertical line, ㆁ, for the nasal ng. A now obsolete letter, ㆆ, represented a glottal stop, which is pronounced in the throat and had closure represented by the top line, like ㄱㄷㅈ. Derived from ㆆ is ㅎ, in which the extra stroke represents a burst of aspiration.

Vowel design[edit]

A diagram showing the derivation of vowels in the Korean alphabet.

Vowel letters are based on three elements:

- A horizontal line representing the flat Earth, the essence of yin.

- A point for the Sun in the heavens, the essence of yang. (This becomes a short stroke when written with a brush.)

- A vertical line for the upright Human, the neutral mediator between the Heaven and Earth.

Short strokes (dots in the earliest documents) were added to these three basic elements to derive the vowel letter:

Simple vowels[edit]

- Horizontal letters: these are mid-high back vowels.

- bright ㅗ o

- dark ㅜ u

- dark ㅡ eu (ŭ)

- Vertical letters: these were once low vowels.

- bright ㅏ a

- dark ㅓ eo (ŏ)

- bright ㆍ

- neutral ㅣ i

Compound vowels[edit]

The Korean alphabet does not have a letter for w sound. Since an o or u before an a or eo became a [w] sound, and [w] occurred nowhere else, [w] could always be analyzed as a phonemic o or u, and no letter for [w] was needed. However, vowel harmony is observed: dark ㅜ u with dark ㅓ eo for ㅝ wo; bright ㅗ o with bright ㅏ a for ㅘ wa:

- ㅘ wa = ㅗ o + ㅏ a

- ㅝ wo = ㅜ u + ㅓ eo

- ㅙ wae = ㅗ o + ㅐ ae

- ㅞ we = ㅜ u + ㅔ e

The compound vowels ending in ㅣ i were originally diphthongs. However, several have since evolved into pure vowels:

- ㅐ ae = ㅏ a + ㅣ i (pronounced [ɛ])

- ㅔ e = ㅓ eo + ㅣ i (pronounced [e])

- ㅙ wae = ㅘ wa + ㅣ i

- ㅚ oe = ㅗ o + ㅣ i (formerly pronounced [ø], see Korean phonology)

- ㅞ we = ㅝ wo + ㅣ i

- ㅟ wi = ㅜ u + ㅣ i (formerly pronounced [y], see Korean phonology)

- ㅢ ui = ㅡ eu + ㅣ i

Iotized vowels[edit]

There is no letter for y. Instead, this sound is indicated by doubling the stroke attached to the baseline of the vowel letter. Of the seven basic vowels, four could be preceded by a y sound, and these four were written as a dot next to a line. (Through the influence of Chinese calligraphy, the dots soon became connected to the line: ㅓㅏㅜㅗ.) A preceding y sound, called iotization, was indicated by doubling this dot: ㅕㅑㅠㅛ yeo, ya, yu, yo. The three vowels that could not be iotized were written with a single stroke: ㅡㆍㅣ eu, (arae a), i.

| Simple | Iotized |

|---|---|

| ㅏ | ㅑ |

| ㅓ | ㅕ |

| ㅗ | ㅛ |

| ㅜ | ㅠ |

| ㅡ | |

| ㅣ |

The simple iotized vowels are:

- ㅑ ya from ㅏ a

- ㅕ yeo from ㅓ eo

- ㅛ yo from ㅗ o

- ㅠ yu from ㅜ u

There are also two iotized diphthongs:

- ㅒ yae from ㅐ ae

- ㅖ ye from ㅔ e

The Korean language of the 15th century had vowel harmony to a greater extent than it does today. Vowels in grammatical morphemes changed according to their environment, falling into groups that «harmonized» with each other. This affected the morphology of the language, and Korean phonology described it in terms of yin and yang: If a root word had yang (‘bright’) vowels, then most suffixes attached to it also had to have yang vowels; conversely, if the root had yin (‘dark’) vowels, the suffixes had to be yin as well. There was a third harmonic group called mediating (neutral in Western terminology) that could coexist with either yin or yang vowels.

The Korean neutral vowel was ㅣ i. The yin vowels were ㅡㅜㅓ eu, u, eo; the dots are in the yin directions of down and left. The yang vowels were ㆍㅗㅏ ə, o, a, with the dots in the yang directions of up and right. The Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye states that the shapes of the non-dotted letters ㅡㆍㅣ were chosen to represent the concepts of yin, yang, and mediation: Earth, Heaven, and Human. (The letter ㆍ ə is now obsolete except in the Jeju language.)

The third parameter in designing the vowel letters was choosing ㅡ as the graphic base of ㅜ and ㅗ, and ㅣ as the graphic base of ㅓ and ㅏ. A full understanding of what these horizontal and vertical groups had in common would require knowing the exact sound values these vowels had in the 15th century.

The uncertainty is primarily with the three letters ㆍㅓㅏ. Some linguists reconstruct these as *a, *ɤ, *e, respectively; others as *ə, *e, *a. A third reconstruction is to make them all middle vowels as *ʌ, *ɤ, *a.[62] With the third reconstruction, Middle Korean vowels actually line up in a vowel harmony pattern, albeit with only one front vowel and four middle vowels:

| ㅣ *i | ㅡ *ɯ | ㅜ *u |

| ㅓ *ɤ | ||

| ㆍ *ʌ | ㅗ *o | |

| ㅏ *a |

However, the horizontal letters ㅡㅜㅗ eu, u, o do all appear to have been mid to high back vowels, [*ɯ, *u, *o], and thus to have formed a coherent group phonetically in every reconstruction.

Traditional account[edit]

The traditionally accepted account[j][63][unreliable source?] on the design of the letters is that the vowels are derived from various combinations of the following three components: ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ. Here, ㆍ symbolically stands for the (sun in) heaven, ㅡ stands for the (flat) earth, and ㅣ stands for an (upright) human. The original sequence of the Korean vowels, as stated in Hunminjeongeum, listed these three vowels first, followed by various combinations. Thus, the original order of the vowels was: ㆍ ㅡ ㅣ ㅗ ㅏ ㅜ ㅓ ㅛ ㅑ ㅠ ㅕ. Note that two positive vowels (ㅗ ㅏ) including one ㆍ are followed by two negative vowels including one ㆍ, then by two positive vowels each including two of ㆍ, and then by two negative vowels each including two of ㆍ.

The same theory provides the most simple explanation of the shapes of the consonants as an approximation of the shapes of the most representative organ needed to form that sound. The original order of the consonants in Hunminjeong’eum was: ㄱ ㅋ ㆁ ㄷ ㅌ ㄴ ㅂ ㅍ ㅁ ㅈ ㅊ ㅅ ㆆ ㅎ ㅇ ㄹ ㅿ.

- ㄱ representing the [k] sound geometrically describes its tongue back raised.

- ㅋ representing the [kʰ] sound is derived from ㄱ by adding another stroke.

- ㆁ representing the [ŋ] sound may have been derived from ㅇ by addition of a stroke.

- ㄷ representing the [t] sound is derived from ㄴ by adding a stroke.

- ㅌ representing the [tʰ] sound is derived from ㄷ by adding another stroke.

- ㄴ representing the [n] sound geometrically describes a tongue making contact with an upper palate.

- ㅂ representing the [p] sound is derived from ㅁ by adding a stroke.

- ㅍ representing the [pʰ] sound is a variant of ㅂ by adding another stroke.

- ㅁ representing the [m] sound geometrically describes a closed mouth.

- ㅈ representing the [t͡ɕ] sound is derived from ㅅ by adding a stroke.

- ㅊ representing the [t͡ɕʰ] sound is derived from ㅈ by adding another stroke.

- ㅅ representing the [s] sound geometrically describes the sharp teeth.[citation needed]

- ㆆ representing the [ʔ] sound is derived from ㅇ by adding a stroke.

- ㅎ representing the [h] sound is derived from ㆆ by adding another stroke.

- ㅇ representing the absence of a consonant geometrically describes the throat.

- ㄹ representing the [ɾ] and [ɭ] sounds geometrically describes the bending tongue.

- ㅿ representing a weak ㅅ sound describes the sharp teeth, but has a different origin than ㅅ.[clarification needed]

Ledyard’s theory of consonant design[edit]

A close-up of the inscription on the statue of King Sejong above. It reads Sejong Daewang 세종대왕 and illustrates the forms of the letters originally promulgated by Sejong. Note the dots on the vowels, the geometric symmetry of s and j in the first two syllables, the asymmetrical lip at the top-left of the d in the third, and the distinction between initial and final ieung in the last.

(Top) ‘Phags-pa letters [k, t, p, s, l], and their supposed Korean derivatives [k, t, p, t͡ɕ, l]. Note the lip on both ‘Phags-pa [t] and the Korean alphabet ㄷ.

(Bottom) Derivation of ‘Phags-pa w, v, f from variants of the letter [h] (left) plus a subscript [w], and analogous composition of the Korean alphabet w, v, f from variants of the basic letter [p] plus a circle.

Although the Hunminjeong’eum Haerye explains the design of the consonantal letters in terms of articulatory phonetics, as a purely innovative creation, several theories suggest which external sources may have inspired or influenced King Sejong’s creation. Professor Gari Ledyard of Columbia University studied possible connections between Hangul and the Mongol ‘Phags-pa script of the Yuan dynasty. He, however, also believed that the role of ‘Phags-pa script in the creation of the Korean alphabet was quite limited, stating it should not be assumed that Hangul was derived from ‘Phags-pa script based on his theory:

It should be clear to any reader that in the total picture, that [‘Phags-pa script’s] role was quite limited … Nothing would disturb me more, after this study is published, than to discover in a work on the history of writing a statement like the following: «According to recent investigations, the Korean alphabet was derived from the Mongol’s phags-pa script.»[64]

Ledyard posits that five of the Korean letters have shapes inspired by ‘Phags-pa; a sixth basic letter, the null initial ㅇ, was invented by Sejong. The rest of the letters were derived internally from these six, essentially as described in the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye. However, the five borrowed consonants were not the graphically simplest letters considered basic by the Hunmin Jeong-eum Haerye, but instead the consonants basic to Chinese phonology: ㄱ, ㄷ, ㅂ, ㅈ, and ㄹ.[citation needed]

The Hunmin Jeong-eum states that King Sejong adapted the 古篆 (gojeon, Gǔ Seal Script) in creating the Korean alphabet. The 古篆 has never been identified. The primary meaning of 古 gǔ is old (Old Seal Script), frustrating philologists because the Korean alphabet bears no functional similarity to Chinese 篆字 zhuànzì seal scripts. However, Ledyard believes 古 gǔ may be a pun on 蒙古 Měnggǔ «Mongol,» and that 古篆 is an abbreviation of 蒙古篆字 «Mongol Seal Script,» that is, the formal variant of the ‘Phags-pa alphabet written to look like the Chinese seal script. There were ‘Phags-pa manuscripts in the Korean palace library, including some in the seal-script form, and several of Sejong’s ministers knew the script well. If this was the case, Sejong’s evasion on the Mongol connection can be understood in light of Korea’s relationship with Ming China after the fall of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and of the literati’s contempt for the Mongols.[citation needed]

According to Ledyard, the five borrowed letters were graphically simplified, which allowed for consonant clusters and left room to add a stroke to derive the aspirate plosives, ㅋㅌㅍㅊ. But in contrast to the traditional account, the non-plosives (ㆁ ㄴ ㅁ ㅅ) were derived by removing the top of the basic letters. He points out that while it is easy to derive ㅁ from ㅂ by removing the top, it is not clear how to derive ㅂ from ㅁ in the traditional account, since the shape of ㅂ is not analogous to those of the other plosives.[citation needed]

The explanation of the letter ng also differs from the traditional account. Many Chinese words began with ng, but by King Sejong’s day, initial ng was either silent or pronounced [ŋ] in China, and was silent when these words were borrowed into Korean. Also, the expected shape of ng (the short vertical line left by removing the top stroke of ㄱ) would have looked almost identical to the vowel ㅣ [i]. Sejong’s solution solved both problems: The vertical stroke left from ㄱ was added to the null symbol ㅇ to create ㆁ (a circle with a vertical line on top), iconically capturing both the pronunciation [ŋ] in the middle or end of a word, and the usual silence at the beginning. (The graphic distinction between null ㅇ and ng ㆁ was eventually lost.)

Another letter composed of two elements to represent two regional pronunciations was ㅱ, which transcribed the Chinese initial 微. This represented either m or w in various Chinese dialects, and was composed of ㅁ [m] plus ㅇ (from ‘Phags-pa [w]). In ‘Phags-pa, a loop under a letter represented w after vowels, and Ledyard hypothesized that this became the loop at the bottom of ㅱ. In ‘Phags-pa the Chinese initial 微 is also transcribed as a compound with w, but in its case the w is placed under an h. Actually, the Chinese consonant series 微非敷 w, v, f is transcribed in ‘Phags-pa by the addition of a w under three graphic variants of the letter for h, and the Korean alphabet parallels this convention by adding the w loop to the labial series ㅁㅂㅍ m, b, p, producing now-obsolete ㅱㅸㆄ w, v, f. (Phonetic values in Korean are uncertain, as these consonants were only used to transcribe Chinese.)

As a final piece of evidence, Ledyard notes that most of the borrowed Korean letters were simple geometric shapes, at least originally, but that ㄷ d [t] always had a small lip protruding from the upper left corner, just as the ‘Phags-pa ꡊ d [t] did. This lip can be traced back to the Tibetan letter ད d.[citation needed]

There is also the argument that the original theory, which stated the Hangul consonants to have been derived from the shape of the speaker’s lips and tongue during the pronunciation of the consonants (initially, at least), slightly strains credulity.[65]

Hangul supremacy theory[edit]

Hangul supremacy or Hangul scientific supremacy is the claim that the Hangul alphabet is the simplest and most logical writing system in the world.[66]

Proponents of the claim believe Hangul is the most scientific writing system because its characters are based on the shapes of the parts of the human body used to enunciate.[citation needed] For example, the first alphabet, ㄱ, is shaped like the root of the tongue blocking the throat and makes a sound between /k/ and /g/ in English. They also believe that Hangul was designed to be simple to learn, containing only 28 characters in its alphabet with simplistic rules.[citation needed]

Harvard professor Edwin Reischauer, a Japanologist, regarded Hangul as a highly logical system of writing.

Edwin O. Reischauer and John K. Fairbank of Harvard University wrote that «Hangul is perhaps the most scientific system of writing in general use in any country.»[67]

Former professor of Leiden University Frits Vos stated that King Sejong «invented the world’s best alphabet,» adding, «It is clear that the Korean alphabet is not only simple and logical, but has, moreover, been constructed in a purely scientific way.»[68]

Obsolete letters[edit]

Hankido [H.N-GI-DO], a martial art, using the obsolete vowel arae-a (top)

Numerous obsolete Korean letters and sequences are no longer used in Korean. Some of these letters were only used to represent the sounds of Chinese rime tables. Some of the Korean sounds represented by these obsolete letters still exist in dialects.

| 13 obsolete consonants

(IPA) |

Soft consonants | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ᄛ | ㅱ | ㅸ | ᄼ | ᄾ | ㅿ | ㆁ | ㅇ | ᅎ | ᅐ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ㆄ | ㆆ | |

| /ɾ/ | first:/ɱ/

last:/w/ |

/β/ | /s/ | /ɕ/ | /z/ | /ŋ/ | /∅/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕ/ | /t͡sʰ/ | /t͡ɕʰ/ | /f/ | /ʔ/ | |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | 微(미)

/ɱ/ |

非(비)

/f/ |

心(심)

/s/ |

審(심)

/ɕ/ |

日

(ᅀᅵᇙ>일) |

final position: 業 /ŋ/ | initial position:

欲 /∅/ |

精(정)

/t͡s/ |

照(조)

/t͡ɕ/ |

淸(청)

/t͡sʰ/ |

穿(천)

/t͡ɕʰ/ |

敷(부)

/fʰ/ |

挹(읍)

/ʔ/ |

|

| Toneme | falling | mid to falling | mid to falling | mid | mid to falling | dipping/ mid | mid | mid to falling | mid (aspirated) | high

(aspirated) |

mid to falling

(aspirated) |

high/mid | ||

| Remark | lenis voiceless dental affricate/ voiced dental affricate | lenis voiceless retroflex affricate/ voiced retroflex affricate | aspirated /t͡s/ | aspirated /t͡ɕ/ | glottal stop | |||||||||

| Equivalents | Standard Chinese Pinyin: 子 z [tsɨ]; English: z in zoo or zebra; strong z in English zip | identical to the initial position of ng in Cantonese | German pf | «읗» = «euh» in pronunciation |

| 10 obsolete double consonants

(IPA) |

Hard consonants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ㅥ | ᄙ | ㅹ | ᄽ | ᄿ | ᅇ | ᇮ | ᅏ | ᅑ | ㆅ | |

| /nː/ | /v/ | /sˁ/ | /ɕˁ/ | /j/ | /ŋː/ | /t͡s/ | /t͡ɕˁ/ | /hˁ/ | ||

| Middle Chinese | hn/nn | hl/ll | bh, bhh | sh | zh | hngw/gh or gr | hng | dz, ds | dzh | hh or xh |

| Identified Chinese Character (Hanzi) | 邪(사)

/z/ |

禪(선)

/ʑ/ |

從(종)

/d͡z/ |

牀(상)

/d͡ʑ/ |

洪(홍)

/ɦ/ |

|||||

| Remark | aspirated | aspirated | unaspirated fortis voiceless dental affricate | unaspirated fortis voiceless retroflex affricate | guttural |

- 66 obsolete clusters of two consonants: ᇃ, ᄓ /ng/ (like English think), ㅦ /nd/ (as English Monday), ᄖ, ㅧ /ns/ (as English Pennsylvania), ㅨ, ᇉ /tʰ/ (as ㅌ; nt in the language Esperanto), ᄗ /dg/ (similar to ㄲ; equivalent to the word 밖 in Korean), ᇋ /dr/ (like English in drive), ᄘ /ɭ/ (similar to French Belle), ㅪ, ㅬ /lz/ (similar to English lisp but without the vowel), ᇘ, ㅭ /t͡ɬ/ (tl or ll; as in Nahuatl), ᇚ /ṃ/ (mh or mg, mm in English hammer, Middle Korean: pronounced as 목 mog with the ㄱ in the word almost silent), ᇛ, ㅮ, ㅯ (similar to ㅂ in Korean 없다), ㅰ, ᇠ, ᇡ, ㅲ, ᄟ, ㅳ bd (assimilated later into ㄸ), ᇣ, ㅶ bj (assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄨ /bj/ (similar to 비추 in Korean verb 비추다 bit-chu-da but without the vowel), ㅷ, ᄪ, ᇥ /ph/ (pha similar to Korean word 돌입하지 dol ip-haji), ㅺ sk (assimilated later into ㄲ; English: pick), ㅻ sn (assimilated later into nn in English annal), ㅼ sd (initial position; assimilated later into ㄸ), ᄰ, ᄱ sm (assimilated later into nm), ㅽ sb (initial position; similar sound to ㅃ), ᄵ, ㅾ assimilated later into ㅉ), ᄷ, ᄸ, ᄹ /θ/, ᄺ/ɸ/, ᄻ, ᅁ, ᅂ /ð/, ᅃ, ᅄ /v/, ᅅ (assimilated later into ㅿ; English z), ᅆ, ᅈ, ᅉ, ᅊ, ᅋ, ᇬ, ᇭ, ㆂ, ㆃ, ᇯ, ᅍ, ᅒ, ᅓ, ᅖ, ᇵ, ᇶ, ᇷ, ᇸ

- 17 obsolete clusters of three consonants: ᇄ, ㅩ /rgs/ (similar to «rx» in English name Marx), ᇏ, ᇑ /lmg/ (similar to English Pullman), ᇒ, ㅫ, ᇔ, ᇕ, ᇖ, ᇞ, ㅴ, ㅵ, ᄤ, ᄥ, ᄦ, ᄳ, ᄴ

| 1 obsolete vowel

(IPA) |

Extremely soft vowel |

|---|---|

| ㆍ | |

| /ʌ/

(also commonly found in the Jeju language: /ɒ/, closely similar to vowel:ㅓeo) |

|

| Letter name | 아래아 (arae-a) |

| Remarks | formerly the base vowel ㅡ eu in the early development of hangeul when it was considered vowelless, later development into different base vowels for clarification; acts also as a mark that indicates the consonant is pronounced on its own, e.g. s-va-ha → ᄉᆞᄫᅡ 하 |

| Toneme | low |

- 44 obsolete diphthongs and vowel sequences: ᆜ (/j/ or /jɯ/ or /jɤ/, yeu or ehyu); closest similarity to ㅢ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆜ /gj/),ᆝ (/jɒ/; closest similarity to ㅛ,ㅑ, ㅠ, ㅕ, when follow by ㄱ on initial position, pronunciation does not produce any difference: ᄀᆝ /gj/), ᆢ(/j/; closest similarity to ㅢ, see former example inᆝ (/j/), ᅷ (/au̯/; Icelandic Á, aw/ow in English allow), ᅸ (/jau̯/; yao or iao; Chinese diphthong iao), ᅹ, ᅺ, ᅻ, ᅼ, ᅽ /ōu/ (紬 ㅊᅽ, ch-ieou; like Chinese: chōu), ᅾ, ᅿ, ᆀ, ᆁ, ᆂ (/w/, wo or wh, hw), ᆃ /ow/ (English window), ㆇ, ㆈ, ᆆ, ᆇ, ㆉ (/jø/; yue), ᆉ /wʌ/ or /oɐ/ (pronounced like u’a, in English suave), ᆊ, ᆋ, ᆌ, ᆍ (wu in English would), ᆎ /juə/ or /yua/ (like Chinese: 元 yuán), ᆏ /ū/ (like Chinese: 軍 jūn), ᆐ, ㆊ /ué/ jujə (ɥe; like Chinese: 瘸 qué), ㆋ jujəj (ɥej; iyye), ᆓ, ㆌ /jü/ or /juj/ (/jy/ or ɥi; yu.i; like German Jürgen), ᆕ, ᆖ (the same as ᆜ in pronunciation, since there is no distinction due to it extreme similarity in pronunciation), ᆗ ɰju (ehyu or eyyu; like English news), ᆘ, ᆙ /ià/ (like Chinese: 墊 diàn), ᆚ, ᆛ, ᆟ, ᆠ (/ʔu/), ㆎ (ʌj; oi or oy, similar to English boy).

In the original Korean alphabet system, double letters were used to represent Chinese voiced (濁音) consonants, which survive in the Shanghainese slack consonants and were not used for Korean words. It was only later that a similar convention was used to represent the modern tense (faucalized) consonants of Korean.

The sibilant (dental) consonants were modified to represent the two series of Chinese sibilants, alveolar and retroflex, a round vs. sharp distinction (analogous to s vs sh) which was never made in Korean, and was even being lost from southern Chinese. The alveolar letters had longer left stems, while retroflexes had longer right stems:

| 5 Place of Articulation (오음, 五音) in Chinese Rime Table | Tenuis 전청 (全淸) |

Aspirate 차청 (次淸) |

Voiced 전탁 (全濁) |

Sonorant 차탁 (次濁) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sibilants 치음 (齒音) |

치두음 (齒頭音) «tooth-head» |

ᅎ 精(정) /t͡s/ |

ᅔ 淸(청) /t͡sʰ/ |

ᅏ 從(종) /d͡z/ |

|

| ᄼ 心(심) /s/ |

ᄽ 邪(사) /z/ |

||||

| 정치음 (正齒音) «true front-tooth» |

ᅐ 照(조) /t͡ɕ/ |

ᅕ 穿(천) /t͡ɕʰ/ |

ᅑ 牀(상) /d͡ʑ/ |

||

| ᄾ 審(심) /ɕ/ |

ᄿ 禪(선) /ʑ/ |

||||

| Coronals 설음 (舌音) |

설상음 (舌上音) «tongue up» |

ᅐ 知(지) /ʈ/ |

ᅕ 徹(철) /ʈʰ/ |

ᅑ

澄(징) /ɖ/ |

ㄴ 娘(낭) /ɳ/ |

Most common[edit]

- ㆍ ə (in Modern Korean called arae-a 아래아 «lower a«): Presumably pronounced [ʌ], similar to modern ㅓ (eo). It is written as a dot, positioned beneath the consonant. The arae-a is not entirely obsolete, as it can be found in various brand names, and in the Jeju language, where it is pronounced [ɒ]. The ə formed a medial of its own, or was found in the diphthong ㆎ əy, written with the dot under the consonant and ㅣ (i) to its right, in the same fashion as ㅚ or ㅢ.

- ㅿ z (bansiot 반시옷 «half s«, banchieum 반치음): An unusual sound, perhaps IPA [ʝ̃] (a nasalized palatal fricative). Modern Korean words previously spelled with ㅿ substitute ㅅ or ㅇ.

- ㆆ ʔ (yeorinhieut 여린히읗 «light hieut» or doenieung 된이응 «strong ieung»): A glottal stop, lighter than ㅎ and harsher than ㅇ.

- ㆁ ŋ (yedieung 옛이응) “old ieung” : The original letter for [ŋ]; now conflated with ㅇ ieung. (With some computer fonts such as Arial Unicode MS, yesieung is shown as a flattened version of ieung, but the correct form is with a long peak, longer than what one would see on a serif version of ieung.)

- ㅸ β (gabyeounbieup 가벼운비읍, sungyeongeumbieup 순경음비읍): IPA [f]. This letter appears to be a digraph of bieup and ieung, but it may be more complicated than that—the circle appears to be only coincidentally similar to ieung. There were three other, less-common letters for sounds in this section of the Chinese rime tables, ㅱ w ([w] or [m]), ㆄ f, and ㅹ ff [v̤]. It operates slightly like a following h in the Latin alphabet (one may think of these letters as bh, mh, ph, and pph respectively). Koreans do not distinguish these sounds now, if they ever did, conflating the fricatives with the corresponding plosives.

New Korean Orthography[edit]

The words 놉니다, 흘렀다, 깨달으니, 지어, 고와, 왕, 가져서 written in New Orthography.

To make the Korean alphabet a better morphophonological fit to the Korean language, North Korea introduced six new letters, which were published in the New Orthography for the Korean Language and used officially from 1948 to 1954.[69]

Two obsolete letters were restored: ⟨ㅿ⟩ (리읃), which was used to indicate an alternation in pronunciation between initial /l/ and final /d/;

and ⟨ㆆ⟩ (히으), which was only pronounced between vowels.

Two modifications of the letter ㄹ were introduced, one which is silent finally, and one which doubled between vowels. A hybrid ㅂ-ㅜ letter was introduced for words that alternated between those two sounds (that is, a /b/, which became /w/ before a vowel).

Finally, a vowel ⟨1⟩ was introduced for variable iotation.

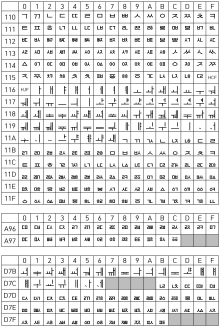

Unicode[edit]

Hangul jamo characters in Unicode

Hangul Compatibility Jamo block in Unicode

Hangul Jamo (U+1100–U+11FF) and Hangul Compatibility Jamo (U+3130–U+318F) blocks were added to the Unicode Standard in June 1993 with the release of version 1.1. A separate Hangul Syllables block (not shown below due to its length) contains pre-composed syllable block characters, which were first added at the same time, although they were relocated to their present locations in July 1996 with the release of version 2.0.[70]

Hangul Jamo Extended-A (U+A960–U+A97F) and Hangul Jamo Extended-B (U+D7B0–U+D7FF) blocks were added to the Unicode Standard in October 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

| Hangul Jamo[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+110x | ᄀ | ᄁ | ᄂ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ |

| U+111x | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | ᄓ | ᄔ | ᄕ | ᄖ | ᄗ | ᄘ | ᄙ | ᄚ | ᄛ | ᄜ | ᄝ | ᄞ | ᄟ |

| U+112x | ᄠ | ᄡ | ᄢ | ᄣ | ᄤ | ᄥ | ᄦ | ᄧ | ᄨ | ᄩ | ᄪ | ᄫ | ᄬ | ᄭ | ᄮ | ᄯ |

| U+113x | ᄰ | ᄱ | ᄲ | ᄳ | ᄴ | ᄵ | ᄶ | ᄷ | ᄸ | ᄹ | ᄺ | ᄻ | ᄼ | ᄽ | ᄾ | ᄿ |

| U+114x | ᅀ | ᅁ | ᅂ | ᅃ | ᅄ | ᅅ | ᅆ | ᅇ | ᅈ | ᅉ | ᅊ | ᅋ | ᅌ | ᅍ | ᅎ | ᅏ |

| U+115x | ᅐ | ᅑ | ᅒ | ᅓ | ᅔ | ᅕ | ᅖ | ᅗ | ᅘ | ᅙ | ᅚ | ᅛ | ᅜ | ᅝ | ᅞ | HC F |

| U+116x | HJ F |

ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ᅩ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ |

| U+117x | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | ᅶ | ᅷ | ᅸ | ᅹ | ᅺ | ᅻ | ᅼ | ᅽ | ᅾ | ᅿ |

| U+118x | ᆀ | ᆁ | ᆂ | ᆃ | ᆄ | ᆅ | ᆆ | ᆇ | ᆈ | ᆉ | ᆊ | ᆋ | ᆌ | ᆍ | ᆎ | ᆏ |

| U+119x | ᆐ | ᆑ | ᆒ | ᆓ | ᆔ | ᆕ | ᆖ | ᆗ | ᆘ | ᆙ | ᆚ | ᆛ | ᆜ | ᆝ | ᆞ | ᆟ |

| U+11Ax | ᆠ | ᆡ | ᆢ | ᆣ | ᆤ | ᆥ | ᆦ | ᆧ | ᆨ | ᆩ | ᆪ | ᆫ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᆮ | ᆯ |

| U+11Bx | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ | ᆶ | ᆷ | ᆸ | ᆹ | ᆺ | ᆻ | ᆼ | ᆽ | ᆾ | ᆿ |

| U+11Cx | ᇀ | ᇁ | ᇂ | ᇃ | ᇄ | ᇅ | ᇆ | ᇇ | ᇈ | ᇉ | ᇊ | ᇋ | ᇌ | ᇍ | ᇎ | ᇏ |

| U+11Dx | ᇐ | ᇑ | ᇒ | ᇓ | ᇔ | ᇕ | ᇖ | ᇗ | ᇘ | ᇙ | ᇚ | ᇛ | ᇜ | ᇝ | ᇞ | ᇟ |

| U+11Ex | ᇠ | ᇡ | ᇢ | ᇣ | ᇤ | ᇥ | ᇦ | ᇧ | ᇨ | ᇩ | ᇪ | ᇫ | ᇬ | ᇭ | ᇮ | ᇯ |

| U+11Fx | ᇰ | ᇱ | ᇲ | ᇳ | ᇴ | ᇵ | ᇶ | ᇷ | ᇸ | ᇹ | ᇺ | ᇻ | ᇼ | ᇽ | ᇾ | ᇿ |

Notes

|

| Hangul Jamo Extended-A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+A96x | ꥠ | ꥡ | ꥢ | ꥣ | ꥤ | ꥥ | ꥦ | ꥧ | ꥨ | ꥩ | ꥪ | ꥫ | ꥬ | ꥭ | ꥮ | ꥯ |

| U+A97x | ꥰ | ꥱ | ꥲ | ꥳ | ꥴ | ꥵ | ꥶ | ꥷ | ꥸ | ꥹ | ꥺ | ꥻ | ꥼ | |||

Notes

|

| Hangul Jamo Extended-B[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+D7Bx | ힰ | ힱ | ힲ | ힳ | ힴ | ힵ | ힶ | ힷ | ힸ | ힹ | ힺ | ힻ | ힼ | ힽ | ힾ | ힿ |

| U+D7Cx | ퟀ | ퟁ | ퟂ | ퟃ | ퟄ | ퟅ | ퟆ | ퟋ | ퟌ | ퟍ | ퟎ | ퟏ | ||||

| U+D7Dx | ퟐ | ퟑ | ퟒ | ퟓ | ퟔ | ퟕ | ퟖ | ퟗ | ퟘ | ퟙ | ퟚ | ퟛ | ퟜ | ퟝ | ퟞ | ퟟ |

| U+D7Ex | ퟠ | ퟡ | ퟢ | ퟣ | ퟤ | ퟥ | ퟦ | ퟧ | ퟨ | ퟩ | ퟪ | ퟫ | ퟬ | ퟭ | ퟮ | ퟯ |

| U+D7Fx | ퟰ | ퟱ | ퟲ | ퟳ | ퟴ | ퟵ | ퟶ | ퟷ | ퟸ | ퟹ | ퟺ | ퟻ | ||||

Notes

|

| Hangul Compatibility Jamo[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+313x | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄳ | ㄴ | ㄵ | ㄶ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㄺ | ㄻ | ㄼ | ㄽ | ㄾ | ㄿ | |

| U+314x | ㅀ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅄ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ | ㅏ |

| U+315x | ㅐ | ㅑ | ㅒ | ㅓ | ㅔ | ㅕ | ㅖ | ㅗ | ㅘ | ㅙ | ㅚ | ㅛ | ㅜ | ㅝ | ㅞ | ㅟ |

| U+316x | ㅠ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅣ | HF | ㅥ | ㅦ | ㅧ | ㅨ | ㅩ | ㅪ | ㅫ | ㅬ | ㅭ | ㅮ | ㅯ |

| U+317x | ㅰ | ㅱ | ㅲ | ㅳ | ㅴ | ㅵ | ㅶ | ㅷ | ㅸ | ㅹ | ㅺ | ㅻ | ㅼ | ㅽ | ㅾ | ㅿ |

| U+318x | ㆀ | ㆁ | ㆂ | ㆃ | ㆄ | ㆅ | ㆆ | ㆇ | ㆈ | ㆉ | ㆊ | ㆋ | ㆌ | ㆍ | ㆎ | |

Notes

|

Enclosed Hangul characters in Unicode

Parenthesised (U+3200–U+321E) and circled (U+3260–U+327E) Hangul compatibility characters are in the Enclosed CJK Letters and Months block:

| Hangul subset of Enclosed CJK Letters and Months[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+320x | ㈀ | ㈁ | ㈂ | ㈃ | ㈄ | ㈅ | ㈆ | ㈇ | ㈈ | ㈉ | ㈊ | ㈋ | ㈌ | ㈍ | ㈎ | ㈏ |

| U+321x | ㈐ | ㈑ | ㈒ | ㈓ | ㈔ | ㈕ | ㈖ | ㈗ | ㈘ | ㈙ | ㈚ | ㈛ | ㈜ | ㈝ | ㈞ | |

| … | (U+3220–U+325F omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| U+326x | ㉠ | ㉡ | ㉢ | ㉣ | ㉤ | ㉥ | ㉦ | ㉧ | ㉨ | ㉩ | ㉪ | ㉫ | ㉬ | ㉭ | ㉮ | ㉯ |

| U+327x | ㉰ | ㉱ | ㉲ | ㉳ | ㉴ | ㉵ | ㉶ | ㉷ | ㉸ | ㉹ | ㉺ | ㉻ | ㉼ | ㉽ | ㉾ | |

| … | (U+3280–U+32FF omitted) | |||||||||||||||

Notes

|

Halfwidth Hangul jamo characters in Unicode

Half-width Hangul compatibility characters (U+FFA0–U+FFDC) are in the Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms block:

| Hangul subset of Halfwidth and Fullwidth Forms[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) |

||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| … | (U+FF00–U+FF9F omitted) | |||||||||||||||

| U+FFAx | HW HF |

ᄀ | ᄁ | ᆪ | ᄂ | ᆬ | ᆭ | ᄃ | ᄄ | ᄅ | ᆰ | ᆱ | ᆲ | ᆳ | ᆴ | ᆵ |

| U+FFBx | ᄚ | ᄆ | ᄇ | ᄈ | ᄡ | ᄉ | ᄊ | ᄋ | ᄌ | ᄍ | ᄎ | ᄏ | ᄐ | ᄑ | ᄒ | |

| U+FFCx | ᅡ | ᅢ | ᅣ | ᅤ | ᅥ | ᅦ | ᅧ | ᅨ | ᅩ | ᅪ | ᅫ | ᅬ | ||||

| U+FFDx | ᅭ | ᅮ | ᅯ | ᅰ | ᅱ | ᅲ | ᅳ | ᅴ | ᅵ | |||||||

| … | (U+FFE0–U+FFEF omitted) | |||||||||||||||

Notes

|

The Korean alphabet in other Unicode blocks:

- Tone marks for Middle Korean[71][72][73] are in the CJK Symbols and Punctuation block: 〮 (

U+302E), 〯 (U+302F) - 11,172 precomposed syllables in the Korean alphabet make up the Hangul Syllables block (

U+AC00–U+D7A3)

Morpho-syllabic blocks[edit]

Except for a few grammatical morphemes prior to the twentieth century, no letter stands alone to represent elements of the Korean language. Instead, letters are grouped into syllabic or morphemic blocks of at least two and often three: a consonant or a doubled consonant called the initial (초성, 初聲 choseong syllable onset), a vowel or diphthong called the medial (중성, 中聲 jungseong syllable nucleus), and, optionally, a consonant or consonant cluster at the end of the syllable, called the final (종성, 終聲 jongseong syllable coda). When a syllable has no actual initial consonant, the null initial ㅇ ieung is used as a placeholder. (In the modern Korean alphabet, placeholders are not used for the final position.) Thus, a block contains a minimum of two letters, an initial and a medial. Although the Korean alphabet had historically been organized into syllables, in the modern orthography it is first organized into morphemes, and only secondarily into syllables within those morphemes, with the exception that single-consonant morphemes may not be written alone.

The sets of initial and final consonants are not the same. For instance, ㅇ ng only occurs in final position, while the doubled letters that can occur in final position are limited to ㅆ ss and ㄲ kk.

Not including obsolete letters, 11,172 blocks are possible in the Korean alphabet.[74]

Letter placement within a block[edit]

The placement or stacking of letters in the block follows set patterns based on the shape of the medial.

Consonant and vowel sequences such as ㅄ bs, ㅝ wo, or obsolete ㅵ bsd, ㆋ üye are written left to right.

Vowels (medials) are written under the initial consonant, to the right, or wrap around the initial from bottom to right, depending on their shape: If the vowel has a horizontal axis like ㅡ eu, then it is written under the initial; if it has a vertical axis like ㅣ i, then it is written to the right of the initial; and if it combines both orientations, like ㅢ ui, then it wraps around the initial from the bottom to the right:

A final consonant, if present, is always written at the bottom, under the vowel. This is called 받침 batchim «supporting floor»:

A complex final is written left to right:

|

|

|

Blocks are always written in phonetic order, initial-medial-final. Therefore:

- Syllables with a horizontal medial are written downward: 읍 eup;

- Syllables with a vertical medial and simple final are written clockwise: 쌍 ssang;

- Syllables with a wrapping medial switch direction (down-right-down): 된 doen;

- Syllables with a complex final are written left to right at the bottom: 밟 balp.

Block shape[edit]