На чтение 6 мин Просмотров 32.8к.

Содержание

- Немецкие письменные шрифты

- Австрийские письменные шрифты

- Какой письменный немецкий шрифт использовать?

Если вы уже освоили письменный шрифт немецких букв — можно перейти к изучению печатного варианта, чтобы ваше письмо было понятным не только вам.

Для чего это нужно?

- Во-первых, записывая слова рукой, мы подключаем к процессу обучения моторную память. Это ценный ресурс при изучении иностранного языка, его обязательно надо задействовать!

- Во-вторых, не для виртуальных же целей вы учите немецкий язык, а для реальной жизни. А в реальной жизни вам действительно может понадобиться заполнять какие-то формы, анкеты на немецком языке, возможно, писать от руки заявления и т. п.

Но — спросите вы, — разве недостаточно тех латинских букв, что мы знаем из математики или с уроков английского? Разве это не те же самые буквы?

И вы будете отчасти правы: конечно, это те же самые буквы, но, как и положено для самобытных культур, в немецком письменном шрифте встречаются некоторые особенности. И их полезно знать, чтобы столкнувшись, суметь прочитать написанное.

Отметим! А еще у многих людей почерк далек от школьной нормы, мягко говоря. И чтобы разбирать такого рода рукописные «шрифты», важно иметь свой собственный навык письма, эволюционировавший через разные ситуации — записывание в спешке, на клочках бумаги, в неудобных положениях, на школьной доске мелом или маркером и др.

Но самое главное — нужно четко представлять себе оригинал, который каждый пишуший от руки подвергает своим индивидуальным изменениям. Об этом оригинале далее и пойдет речь.

Немецкие письменные шрифты

В настоящий момент есть несколько письменных немецких шрифтов, которые используются для обучения в начальной школе, и, соответственно, применяются дальше в жизни. В одной Германии, например, действительны несколько «стандартов», принятых в разное время.

В одних Федеральных землях есть четкие предписания использовать определенный шрифт в начальной школе, в других полагаются на выбор учителя.

Латинский письменный шрифт (Lateinische Ausgangsschrift) был принят в ФРГ в 1953 году. Практически, он мало отличается от своего предшественника 1941 года, самое заметное — это нового вида заглавная буква S и новое скорописное написание букв X, x (из заглавной X также ушла горизонтальная черточка по центру), плюс упразднились «петельки» — в центре прописных букв E, R и в соединительных черточках (дугах) букв O, V, W и Ö.

В ГДР также были внесены корректировки в учебные программы для начальной школы, и в 1958 году был принят письменный шрифт Schreibschrift-Vorlage, который я здесь не показываю, поскольку он повторяет приведенный выше вариант почти один в один, за исключением следующих новшеств:

- новое скорописное написание строчной буквы t (см. в следующем шрифте)

- немного измененное написание буквы ß (см. в следующем шрифте)

- правая половина буквы X, x теперь немного отделялась от левой

- точки над i и j стали черточками, аналогично черточкам над умлаутами

- исчезла горизонтальная черта у заглавной Z

А через 10 лет, в 1968 году в той же ГДР, с целью облегчения обучения школьников письму, этот шрифт модифицировали дальше, кардинально упростив написание заглавных букв!

Примечание! Из строчных поменяли только x, остальное унаследовано от шрифта 1958 г. Еще раз обратите внимание на написание ß и t, а также на небольшие отличия в f и r по сравнению с написанием в «латинском» шрифте. В итоге, получилось следующее.

Школьный письменный шрифт (Schulausgangsschrift):

Полезно знать! В направлении упрощения пошли и в ФРГ, разработав свою версию подобного шрифта в 1969 году, которую так и назвали — «упрощенной». Инновацией и особенностью этого шрифта стало то, что все соединительные черточки вывели на один уровень, к верней «строчке» маленьких букв.

Упрощенный письменный шрифт (Vereinfachte Ausgangsschrift):

В целом, это не то же самое, что и «школьный» шрифт, приведенный выше, хотя и наблюдается некоторое стилистическое сходство. Кстати, точки над i, j сохранились, а штрихи над умлаутами, наоборот, стали больше похожи на точки. Обратите внимание на строчные буквы s, t, f, z (!), а также на ß.

Стоит упомянуть: еще один вариант, под основательным названием «базовый шрифт» (Grundschrift), все буквы которого, и строчные и прописные больше похожи на печатные, и пишутся они отдельно друг от друга.

Этот вариант, разработанный в 2011 году проходит апробацию в некоторых школах и, в случае принятия на национальном уровне, может заменить три вышеназванных шрифта.

Австрийские письменные шрифты

Для полноты картины приведу еще два варианта прописного немецкого алфавита, которые применяются в Австрии.

Оставлю их без комментариев, для самостоятельного сравнения с приведенными выше шрифтами, обратив ваше внимание лишь на пару особенностей — в шрифте 1969 года в строчных t и f перекладинка пишется одинаково (с «петелькой»). Другая особенность касается уже не собственно алфавита — написание цифры 9 отличается от той версии, к которой мы привыкли.

Австрийский школьный шрифт (Österreichische Schulschrift) 1969 г.:

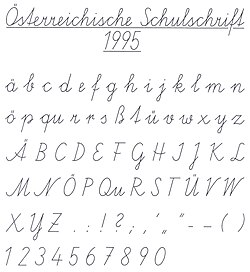

Австрийский школьный шрифт (Österreichische Schulschrift) 1995 г.:

Какой письменный немецкий шрифт использовать?

При таком разнообразии «стандартных» шрифтов, резонный вопрос — какому из них следовать на письме?

На этот вопрос нет однозначного ответа, но можно дать некоторые рекомендации:

- Если вы изучаете немецкий язык с целью применять его в конкретной стране, например, в Австрии, выбирайте между письманными образцами этой страны. В ином случае — выбирайте между германскими вариантами.

- Для самостоятельно изучающих немецкий язык в сознательном возрасте я бы порекомендовал «латинский» письменный шрифт. Это настоящая классика и традиционное немецкое письмо. Для взрослого человека не составит особого труда его освоить. Так или иначе, вы можете попробовать каждый из приведенныз вариантов и выбрать для себя тот, что вам больше понравится.

- Для детей, которые только-только учатся писать буквы, и важно научить их быстрее, можно выбирать между «школьным» и «упрощенным» шрифтами. Последнему, возможно, отдают большее предпочтение.

- Для изучающих язык в общеобразовательной школе этот вопрос особо не стоит, нужно следовать тому образцу, что дает (и требует соблюдать) учитель или учебник. Как правило, в наших школах это «латинский» письменный шрифт. Иногда — его ГДРовская модификация 1958 года, которую выдает то, как пишут строчную t.

Каковы должны быть итоги этого урока:

- Вы должны определиться с тем немецким шрифтом, которому вы будете следовать на письме. Попробуйте разные варианты и сделайте свой выбор.

- Вы должны научиться писать от руки все буквы алфавита, прописные и строчные. Повторите урок Немецкий алфавит, затем потренируйтесь в написании всех букв алфавита (по порядку) на память. При самопроверке внимательно сличайте каждый ваш штрих с образцом. Повторяйте этот пункт до тех пор, пока не допустите ни одной ошибки — ни в написании букв, ни в их порядке.

Полезно знать! В будущем, при выполнении письменных заданий, время от времени сравнивайте ваши записи с образцом шрифта, старайтесь ему следовать всегда (включая черновики), корректируйте свой почерк. Впрочем, об этом я буду вам напоминать.

Источник: http://www.sprechen.ru/2015/10/pismennyj-nemeckij-alfavit.html

German orthography is the orthography used in writing the German language, which is largely phonemic. However, it shows many instances of spellings that are historic or analogous to other spellings rather than phonemic. The pronunciation of almost every word can be derived from its spelling once the spelling rules are known, but the opposite is not generally the case.

Today, Standard High German orthography is regulated by the Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung (Council for German Orthography), composed of representatives from most German-speaking countries.

Alphabet[edit]

(Listen to a German speaker recite the alphabet in German)

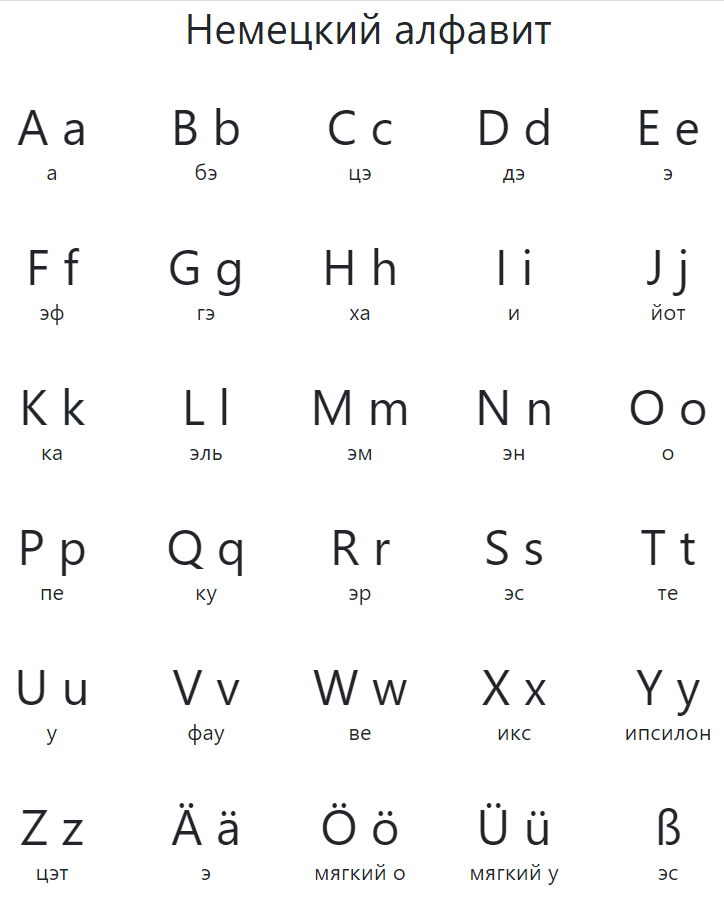

The modern German alphabet consists of the twenty-six letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet plus four special letters.

Basic alphabet[edit]

| Capital | Lowercase | Name[1] | Name (IPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0123456789 | 0123456789 | 0123456789 | /0123456789ː/ |

| –—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ | –—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ | –—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ | /–—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ː/ |

| A | a | A | /aː/ |

| B | b | Be | /beː/ |

| C | c | Ce | /t͡seː/ |

| D | d | De | /deː/ |

| E | e | E | /eː/ |

| F | f | Ef | /ɛf/ |

| G | g | Ge | /ɡeː/ |

| H | h | Ha | /haː/ |

| I | i | I | /iː/ |

| J | j | Jott1, Je2 | /jɔt/1

/jeː/2 |

| K | k | Ka | /kaː/ |

| L | l | El | /ɛl/ |

| M | m | Em | /ɛm/ |

| N | n | En | /ɛn/ |

| O | o | O | /oː/ |

| P | p | Pe | /peː/ |

| Q | q | Qu1, Que2 | /kuː/1

/kveː/2 |

| R | r | Er | /ɛʁ/ |

| S | s | Es | /ɛs/ |

| T | t | Te | /teː/ |

| U | u | U | /uː/ |

| V | v | Vau | /faʊ̯/ |

| W | w | We | /veː/ |

| X | x | Ix | /ɪks/ |

| Y | y | Ypsilon | /ˈʏpsilɔn/1

/ʏˈpsiːlɔn/2 |

| Z | z | Zett | /t͡sɛt/ |

1in Germany

2in Austria

Special letters[edit]

German has four special letters; three are vowels accented with an umlaut sign (⟨ä, ö, ü⟩) and one is derived from a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ (long s) and ⟨z⟩ (⟨ß⟩; called Eszett «ess-zed/zee» or scharfes S «sharp s»), all of which are officially considered distinct letters of the alphabet,[2] and have their own names separate from the letters they are based on.

(Listen to a German speaker naming these letters)

| Name (IPA) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ä | ä | /ɛː/ |

| Ö | ö | /øː/ |

| Ü | ü | /yː/ |

| ẞ | ß | Eszett: /ɛsˈt͡sɛt/ scharfes S: /ˈʃaʁfəs ɛs/ «sharp s» |

- Capital ẞ was declared an official letter of the German alphabet on 29 June 2017.[3] Previously represented as ⟨SS/SZ⟩.

- Historically, long s (ſ) was used as well, as in English and many other European languages.[4]

While the Council for German Orthography considers ⟨ä, ö, ü, ß⟩ distinct letters,[2] disagreement on how to categorize and count them has led to a dispute over the exact number of letters the German alphabet has, the number ranging between 26 (considering special letters as variants of ⟨a, o, u, s⟩) and 30 (counting all special letters separately).[5]

Use of special letters[edit]

Umlaut diacritic usage[edit]

The accented letters ⟨ä, ö, ü⟩ are used to indicate the presence of umlauts (fronting of back vowels). Before the introduction of the printing press, frontalization was indicated by placing an ⟨e⟩ after the back vowel to be modified, but German printers developed the space-saving typographical convention of replacing the full ⟨e⟩ with a small version placed above the vowel to be modified. In German Kurrent writing, the superscripted ⟨e⟩ was simplified to two vertical dashes (as the Kurrent ⟨e⟩ consists largely of two short vertical strokes), which have further been reduced to dots in both handwriting and German typesetting. Although the two dots of umlaut look like those in the diaeresis (trema), the two have different origins and functions.

When it is not possible to use the umlauts (for example, when using a restricted character set) the characters ⟨Ä, Ö, Ü, ä, ö, ü⟩ should be transcribed as ⟨Ae, Oe, Ue, ae, oe, ue⟩ respectively, following the earlier postvocalic-⟨e⟩ convention; simply using the base vowel (e.g. ⟨u⟩ instead of ⟨ü⟩) would be wrong and misleading. However, such transcription should be avoided if possible, especially with names. Names often exist in different variants, such as Müller and Mueller, and with such transcriptions in use one could not work out the correct spelling of the name.

Automatic back-transcribing is wrong not only for names. Consider, for example, das neue Buch («the new book»). This should never be changed to das neü Buch, as the second ⟨e⟩ is completely separate from the ⟨u⟩ and does not even belong in the same syllable; neue ([ˈnɔʏ.ə]) is neu (the root for «new») followed by ⟨e⟩, an inflection. The word ⟨neü⟩ does not exist in German.

Furthermore, in northern and western Germany, there are family names and place names in which ⟨e⟩ lengthens the preceding vowel (by acting as a Dehnungs-e), as in the former Dutch orthography, such as Straelen, which is pronounced with a long ⟨a⟩, not an ⟨ä⟩. Similar cases are Coesfeld and Bernkastel-Kues.

In proper names and ethnonyms, there may also appear a rare ⟨ë⟩ and ⟨ï⟩, which are not letters with an umlaut, but a diaeresis, used as in French and English to distinguish what could be a digraph, for example, ⟨ai⟩ in Karaïmen, ⟨eu⟩ in Alëuten, ⟨ie⟩ in Piëch, ⟨oe⟩ in von Loë and Hoëcker (although Hoëcker added the diaeresis himself), and ⟨ue⟩ in Niuë.[6] Occasionally, a diaeresis may be used in some well-known names, i.e.: Italiën[7] (usually written as Italien).

Swiss keyboards and typewriters do not allow easy input of uppercase letters with umlauts (nor ⟨ß⟩) because their positions are taken by the most frequent French diacritics. Uppercase umlauts were dropped because they are less common than lowercase ones (especially in Switzerland). Geographical names in particular are supposed to be written with ⟨a, o, u⟩ plus ⟨e⟩, except Österreich. The omission can cause some inconvenience, since the first letter of every noun is capitalized in German.

Unlike in Hungarian, the exact shape of the umlaut diacritics – especially when handwritten – is not important, because they are the only ones in the language (not counting the tittle on ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩). They will be understood whether they look like dots (⟨¨⟩), acute accents (⟨ ˝ ⟩) or vertical bars (⟨‖⟩). A horizontal bar (macron, ⟨¯⟩), a breve (⟨˘⟩), a tiny ⟨N⟩ or ⟨e⟩, a tilde (⟨˜⟩), and such variations are often used in stylized writing (e.g. logos). However, the breve – or the ring (⟨°⟩) – was traditionally used in some scripts to distinguish a ⟨u⟩ from an ⟨n⟩. In rare cases, the ⟨n⟩ was underlined. The breved ⟨u⟩ was common in some Kurrent-derived handwritings; it was mandatory in Sütterlin.

Sharp s[edit]

German label «Delicacy / red cabbage.» Left cap is with old orthography, right with new.

Eszett or scharfes S (⟨ß⟩) represents the “s” sound. The German spelling reform of 1996 somewhat reduced usage of this letter in Germany and Austria. It is not used in Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

As ⟨ß⟩ derives from a ligature of lowercase letters, it is exclusively used in the middle or at the end of a word. The proper transcription when it cannot be used is ⟨ss⟩ (⟨sz⟩ and ⟨SZ⟩ in earlier times). This transcription can give rise to ambiguities, albeit rarely; one such case is in Maßen «in moderation» vs. in Massen «en masse». In all-caps, ⟨ß⟩ is replaced by ⟨SS⟩ or, optionally, by the uppercase ⟨ß⟩.[8] The uppercase ⟨ß⟩ was included in Unicode 5.1 as U+1E9E in 2008. Since 2010 its use is mandatory in official documentation in Germany when writing geographical names in all-caps.[9] The option of using the uppercase ⟨ẞ⟩ in all-caps was officially added to the German orthography in 2017.[10]

Although nowadays substituted correctly only by ⟨ss⟩, the letter actually originates from a distinct ligature: long s with (round) z (⟨ſz/ſʒ⟩). Some people therefore prefer to substitute ⟨ß⟩ by ⟨sz⟩, as it can avoid possible ambiguities (as in the above Maßen vs Massen example).

Incorrect use of the ⟨ß⟩ letter is a common type of spelling error even among native German writers. The spelling reform of 1996 changed the rules concerning ⟨ß⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ (no forced replacement of ⟨ss⟩ to ⟨ß⟩ at word’s end). This required a change of habits and is often disregarded: some people even incorrectly assumed that the ⟨ß⟩ had been abolished completely. However, if the vowel preceding the ⟨s⟩ is long, the correct spelling remains ⟨ß⟩ (as in Straße). If the vowel is short, it becomes ⟨ss⟩, e.g. Ich denke, dass… «I think that…». This follows the general rule in German that a long vowel is followed by a single consonant, while a short vowel is followed by a double consonant.

This change towards the so-called Heyse spelling, however, introduced a new sort of spelling error, as the long/short pronunciation differs regionally. It was already mostly abolished in the late 19th century (and finally with the first unified German spelling of 1901) in favor of the Adelung spelling. Besides the long/short pronunciation issue, which can be attributed to dialect speaking (for instance, in the northern parts of Germany Spaß is typically pronounced short, i.e. Spass, whereas particularly in Bavaria elongated may occur as in Geschoss which is pronounced Geschoß in certain regions), Heyse spelling also introduces reading ambiguities that do not occur with Adelung spelling such as Prozessorientierung (Adelung: Prozeßorientierung) vs. Prozessorarchitektur (Adelung: Prozessorarchitektur). It is therefore recommended to insert hyphens where required for reading assistance, i.e. Prozessor-Architektur vs. Prozess-Orientierung.

Long s[edit]

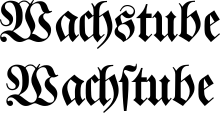

Wachstube and Wachſtube are distinguished in blackletter typesetting, though no longer in contemporary font styles.

In the Fraktur typeface and similar scripts, a long s (⟨ſ⟩) was used except in syllable endings (cf. Greek sigma) and sometimes it was historically used in antiqua fonts as well; but it went out of general use in the early 1940s along with the Fraktur typeface. An example where this convention would avoid ambiguity is Wachſtube (IPA: [ˈvax.ʃtuːbə]) «guardhouse», written ⟨Wachſtube/Wach-Stube⟩ and Wachstube (IPA: [ˈvaks.tuːbə]) «tube of wax», written ⟨Wachstube/Wachs-Tube⟩.

Sorting[edit]

There are three ways to deal with the umlauts in alphabetic sorting.

- Treat them like their base characters, as if the umlaut were not present (DIN 5007-1, section 6.1.1.4.1). This is the preferred method for dictionaries, where umlauted words (Füße «feet») should appear near their origin words (Fuß «foot»). In words which are the same except for one having an umlaut and one its base character (e.g. Müll vs. Mull), the word with the base character gets precedence.

- Decompose them (invisibly) to vowel plus ⟨e⟩ (DIN 5007-2, section 6.1.1.4.2). This is often preferred for personal and geographical names, wherein the characters are used unsystematically, as in German telephone directories (Müller, A.; Mueller, B.; Müller, C.).

- They are treated like extra letters either placed

- after their base letters (Austrian phone books have ⟨ä⟩ between ⟨az⟩ and ⟨b⟩ etc.) or

- at the end of the alphabet (as in Swedish or in extended ASCII).

Microsoft Windows in German versions offers the choice between the first two variants in its internationalisation settings.

A sort of combination of nos. 1 and 2 also exists, in use in a couple of lexica: The umlaut is sorted with the base character, but an ⟨ae, oe, ue⟩ in proper names is sorted with the umlaut if it is actually spoken that way (with the umlaut getting immediate precedence). A possible sequence of names then would be Mukovic; Muller; Müller; Mueller; Multmann in this order.

Eszett is sorted as though it were ⟨ss⟩. Occasionally it is treated as ⟨s⟩, but this is generally considered incorrect. Words distinguished only by ⟨ß⟩ vs. ⟨ss⟩ can only appear in the (presently used) Heyse writing and are even then rare and possibly dependent on local pronunciation, but if they appear, the word with ⟨ß⟩ gets precedence, and Geschoß (storey; South German pronunciation) would be sorted before Geschoss (projectile).

Accents in French loanwords are always ignored in collation.

In rare contexts (e.g. in older indices) ⟨sch⟩ (phonetic value equal to English ⟨sh⟩) and likewise ⟨st⟩ and ⟨ch⟩ are treated as single letters, but the vocalic digraphs ⟨ai, ei⟩ (historically ⟨ay, ey⟩), ⟨au, äu, eu⟩ and the historic ⟨ui, oi⟩ never are.

Personal names with special characters[edit]

German names containing umlauts (⟨ä, ö, ü⟩) and/or ⟨ß⟩ are spelled in the correct way in the non-machine-readable zone of the passport, but with ⟨AE, OE, UE⟩ and/or ⟨SS⟩ in the machine-readable zone, e.g. ⟨Müller⟩ becomes ⟨MUELLER⟩, ⟨Weiß⟩ becomes ⟨WEISS⟩, and ⟨Gößmann⟩ becomes ⟨GOESSMANN⟩. The transcription mentioned above is generally used for aircraft tickets et cetera, but sometimes (like in US visas) simple vowels are used (MULLER, GOSSMANN). As a result, passport, visa, and aircraft ticket may display different spellings of the same name. The three possible spelling variants of the same name (e.g. Müller/Mueller/Muller) in different documents sometimes lead to confusion, and the use of two different spellings within the same document may give persons unfamiliar with German orthography the impression that the document is a forgery.

Even before the introduction of the capital ⟨ẞ⟩, it was recommended to use the minuscule ⟨ß⟩ as a capital letter in family names in documents (e.g. HEINZ GROßE, today’s spelling: HEINZ GROẞE).

German naming law accepts umlauts and/or ⟨ß⟩ in family names as a reason for an official name change. Even a spelling change, e.g. from Müller to Mueller or from Weiß to Weiss is regarded as a name change.

Features of German spelling[edit]

Capitalization[edit]

A typical feature of German spelling is the general capitalization of nouns and of most nominalized words. In addition, capital letters are used: at the beginning of sentences (may be used after a colon, when the part of a sentence after the colon can be treated as a sentence); in the formal pronouns Sie ‘you’ and Ihr ‘your’ (optionally in other second-person pronouns in letters); in adjectives at the beginning of proper names (e. g. der Stille Ozean ‘the Pacific Ocean’); in adjectives with the suffix ‘-er’ from geographical names (e. g. Berliner); in adjectives with the suffix ‘-sch’ from proper names if written with the apostrophe before the suffix (e. g. Ohm’sches Gesetz ‘Ohm’s law’, also written ohmsches Gesetz).

Compound words[edit]

Compound words, including nouns, are written together, e.g. Haustür (Haus + Tür; «house door»), Tischlampe (Tisch + Lampe; «table lamp»), Kaltwasserhahn (Kalt + Wasser + Hahn; «cold water tap/faucet»). This can lead to long words: the longest word in regular use, Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften[11] («legal protection insurance companies»), consists of 39 letters.

Vowel length[edit]

Even though vowel length is phonemic in German, it is not consistently represented. However, there are different ways of identifying long vowels:

- A vowel in an open syllable (a free vowel) is long, for instance in ge-ben (‘to give’), sa-gen (‘to say’). The rule is unreliable in given names, cf. Oliver [ˈɔlivɐ].

- It is rare to see a bare i used to indicate a long vowel /iː/. Instead, the digraph ie is used, for instance in Liebe (‘love’), hier (‘here’). This use is a historical spelling based on the Middle High German diphthong /iə/ which was monophthongized in Early New High German. It has been generalized to words that etymologically never had that diphthong, for instance viel (‘much’), Friede (‘peace’) (Middle High German vil, vride). Occasionally – typically in word-final position – this digraph represents /iː.ə/ as in the plural noun Knie /kniː.ə/ (‘knees’) (cf. singular Knie /kniː/). In the words Viertel (viertel) /ˈfɪrtəl/ (‘quarter’), vierzehn /ˈfɪʁt͡seːn/ (‘fourteen’), vierzig /ˈfɪʁt͡sɪç/ (‘forty’), ie represents a short vowel, cf. vier /fiːɐ̯/ (‘four’). In Fraktur, where capital I and J are identical or near-identical

, the combinations Ie and Je are confusable; hence the combination Ie is not used at the start of a word, for example Igel (‘hedgehog’), Ire (‘Irishman’).

- A silent h indicates the vowel length in certain cases. That h derives from an old /x/ in some words, for instance sehen (‘to see’) zehn (‘ten’), but in other words it has no etymological justification, for instance gehen (‘to go’) or mahlen (‘to mill’). Occasionally a digraph can be redundantly followed by h, either due to analogy, such as sieht (‘sees’, from sehen) or etymology, such as Vieh (‘cattle’, MHG vihe), rauh (‘rough’, pre-1996 spelling, now written rau, MHG ruh).

- The letters a, e, o are doubled in a few words that have long vowels, for instance Saat (‘seed’), See (‘sea’/’lake’), Moor (‘moor’).

- A doubled consonant after a vowel indicates that the vowel is short, while a single consonant often indicates the vowel is long, e.g. Kamm (‘comb’) has a short vowel /kam/, while kam (‘came’) has a long vowel /kaːm/. Two consonants are not doubled: k, which is replaced by ck (until the spelling reform of 1996, however, ck was divided across a line break as k-k), and z, which is replaced by tz. In loanwords, kk (which may correspond with cc in the original spelling) and zz can occur.

- For different consonants and for sounds represented by more than one letter (ch and sch) after a vowel, no clear rule can be given, because they can appear after long vowels, yet are not redoubled if belonging to the same stem, e.g. Mond /moːnt/ ‘moon’, Hand /hant/ ‘hand’. On a stem boundary, reduplication usually takes place, e.g., nimm-t ‘takes’; however, in fixed, no longer productive derivatives, this too can be lost, e.g., Geschäft /ɡəˈʃɛft/ ‘business’ despite schaffen ‘to get something done’.

- ß indicates that the preceding vowel is long, e.g. Straße ‘street’ vs. a short vowel in Masse ‘mass’ or ‘host’/’lot’. In addition to that, texts written before the 1996 spelling reform also use ß at the ends of words and before consonants, e.g. naß ‘wet’ and mußte ‘had to’ (after the reform spelled nass and musste), so vowel length in these positions could not be detected by the ß, cf. Maß ‘measure’ and fußte ‘was based’ (after the reform still spelled Maß and fußte).

Double or triple consonants[edit]

Even though German does not have phonemic consonant length, there are many instances of doubled or even tripled consonants in the spelling. A single consonant following a checked vowel is doubled if another vowel follows, for instance immer ‘always’, lassen ‘let’. These consonants are analyzed as ambisyllabic because they constitute not only the syllable onset of the second syllable but also the syllable coda of the first syllable, which must not be empty because the syllable nucleus is a checked vowel.

By analogy, if a word has one form with a doubled consonant, all forms of that word are written with a doubled consonant, even if they do not fulfill the conditions for consonant doubling; for instance, rennen ‘to run’ → er rennt ‘he runs’; Küsse ‘kisses’ → Kuss ‘kiss’.

Doubled consonants can occur in composite words when the first part ends in the same consonant the second part starts with, e.g. in the word Schaffell (‘sheepskin’, composed of Schaf ‘sheep’ and Fell ‘skin, fur, pelt’).

Composite words can also have tripled letters. While this is usually a sign that the consonant is actually spoken long, it does not affect the pronunciation per se: the fff in Sauerstoffflasche (‘oxygen bottle’, composed of Sauerstoff ‘oxygen’ and Flasche ‘bottle’) is exactly as long as the ff in Schaffell. According to the spelling before 1996, the three consonants would be shortened before vowels, but retained before consonants and in hyphenation, so the word Schifffahrt (‘navigation, shipping’, composed of Schiff ‘ship’ and Fahrt ‘drive, trip, tour’) was then written Schiffahrt, whereas Sauerstoffflasche already had a triple fff. With the aforementioned change in ß spelling, even a new source of triple consonants sss, which in pre-1996 spelling could not occur as it was rendered ßs, was introduced, e. g. Mussspiel (‘compulsory round’ in certain card games, composed of muss ‘must’ and Spiel ‘game’).

Typical letters[edit]

- ei: This digraph represents the diphthong /aɪ̯/. The spelling goes back to the Middle High German pronunciation of that diphthong, which was [ei̯]. The spelling ai is found in only a very few native words (such as Saite ‘string’, Waise ‘orphan’) but is commonly used to romanize /aɪ̯/ in foreign loans from languages such as Chinese.

- eu: This digraph represents the diphthong [ɔʏ̯], which goes back to the Middle High German monophthong [yː] represented by iu. When the sound is created by umlaut of au [aʊ̯] (from MHG [uː]), it is spelled äu.

- ß: This letter alternates with ss. For more information, see above.

- st, sp: At the beginning of a stressed syllable, these digraphs are pronounced [ʃt, ʃp]. In the Middle Ages, the sibilant that was inherited from Proto-Germanic /s/ was pronounced as an alveolo-palatal consonant [ɕ] or [ʑ] unlike the voiceless alveolar sibilant /s/ that had developed in the High German consonant shift. In the Late Middle Ages, certain instances of [ɕ] merged with /s/, but others developed into [ʃ]. The change to [ʃ] was represented in certain spellings such as Schnee ‘snow’, Kirsche ‘cherry’ (Middle High German snê, kirse). The digraphs st, sp, however, remained unaltered.

- v: The letter v occurs only in a few native words and then, it represents /f/. That goes back to the 12th and 13th century, when prevocalic /f/ was voiced to [v]. The voicing was lost again in the late Middle Ages, but the v still remains in certain words such as in Vogel (compare Scandinavian fugl or English fowl) ‘bird’ (hence, the letter v is sometimes called Vogel-vau), viel ‘much’. For further information, see Pronunciation of v in German.

- w: The letter w represents the sound /v/. In the 17th century, the former sound [w] became [v], but the spelling remained the same. An analogous sound change had happened in late-antique Latin.

- z: The letter z represents the sound /t͡s/. The sound, a product of the High German consonant shift, has been written with z since Old High German in the 8th century.

Foreign words[edit]

For technical terms, the foreign spelling is often retained such as ph /f/ or y /yː/ in the word Physik (physics) of Greek origin. For some common affixes however, like -graphie or Photo-, it is allowed to use -grafie or Foto- instead.[12] Both Photographie and Fotografie are correct, but the mixed variants Fotographie or Photografie are not.[12]

For other foreign words, both the foreign spelling and a revised German spelling are correct such as Delphin / Delfin[13] or Portemonnaie / Portmonee, though in the latter case the revised one does not usually occur.[14]

For some words for which the Germanized form was common even before the reform of 1996, the foreign version is no longer allowed. A notable example is the word Foto, with the meaning “photograph”, which may no longer be spelled as Photo.[15] Other examples are Telephon (telephone) which was already Germanized as Telefon some decades ago or Bureau (office) which got replaced by the Germanized version Büro even earlier.

Except for the common sequences sch (/ʃ/), ch ([x] or [ç]) and ck (/k/) the letter c appears only in loanwords or in proper nouns. In many loanwords, including most words of Latin origin, the letter c pronounced (/k/) has been replaced by k. Alternatively, German words which come from Latin words with c before e, i, y, ae, oe are usually pronounced with (/ts/) and spelled with z. However, certain older spellings occasionally remain, mostly for decorative reasons, such as Circus instead of Zirkus.

The letter q in German appears only in the sequence qu (/kv/) except for loanwords such as Coq au vin or Qigong (the latter is also written Chigong).

The letter x (Ix, /ɪks/) occurs almost exclusively in loanwords such as Xylofon (xylophone) and names, e.g. Alexander and Xanthippe. Native German words now pronounced with a /ks/ sound are usually written using chs or (c)ks, as with Fuchs (fox). Some exceptions occur such as Hexe (witch), Nixe (mermaid), Axt (axe) and Xanten.

The letter y (Ypsilon, /ˈʏpsilɔn/) occurs almost exclusively in loanwords, especially words of Greek origin, but some such words (such as Typ) have become so common that they are no longer perceived as foreign. It used to be more common in earlier centuries, and traces of this earlier usage persist in proper names. It is used either as an alternative letter for i, for instance in Mayer / Meyer (a common family name that occurs also in the spellings Maier / Meier), or especially in the Southwest, as a representation of [iː] that goes back to an old IJ (digraph), for instance in Schwyz or Schnyder (an Alemannic variant of the name Schneider).[citation needed] Another notable exception is Bayern («Bavaria») and derived words like bayrisch («Bavarian»); this actually used to be spelt with an i until the King of Bavaria introduced the y as a sign of his philhellenism (his son would become King of Greece later).

In loan words from the French language, spelling and accents are usually preserved. For instance, café in the sense of «coffeehouse» is always written Café in German; accentless Cafe would be considered erroneous, and the word cannot be written Kaffee, which means «coffee». (Café is normally pronounced /kaˈfeː/; Kaffee is mostly pronounced /ˈkafe/ in Germany but /kaˈfeː/ in Austria.) Thus, German typewriters and computer keyboards offer two dead keys: one for the acute and grave accents and one for circumflex. Other letters occur less often such as ç in loan words from French or Portuguese, and ñ in loan words from Spanish.

A number of loanwords from French are spelled in a partially adapted way: Quarantäne /kaʁanˈtɛːnə/ (quarantine), Kommuniqué /kɔmyniˈkeː, kɔmuniˈkeː/ (communiqué), Ouvertüre /u.vɛʁˈtyː.ʁə/ (overture) from French quarantaine, communiqué, ouverture. In Switzerland, where French is one of the official languages, people are less prone to use adapted and especially partially adapted spellings of loanwords from French and more often use original spellings, e. g. Communiqué.

In one curious instance, the word Ski (meaning as in English) is pronounced as if it were Schi all over the German-speaking areas (reflecting its pronunciation in its source language Norwegian), but only written that way in Austria.[16]

Grapheme-to-phoneme correspondences[edit]

This section lists German letters and letter combinations, and how to pronounce them transliterated into the International Phonetic Alphabet. This is the pronunciation of Standard German. Note that the pronunciation of standard German varies slightly from region to region. In fact, it is possible to tell where most German speakers come from by their accent in standard German (not to be confused with the different German dialects).

Foreign words are usually pronounced approximately as they are in the original language.

Consonants[edit]

Double consonants are pronounced as single consonants, except in compound words.

| Grapheme(s) | Phoneme(s) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| b | otherwise | [b] or [b̥] | |

| syllable final | [p] | ||

| c | otherwise | [k] | Used in some loanwords and proper names. In many cases, the historically used letter c has been replaced by ⟨k⟩ or ⟨z⟩. |

| before ⟨ä, e, i(, ö)⟩ | [ts] | ||

| ch | after ⟨a, o, u⟩ | [x] | In Austro-Bavarian, especially in Austria, [ç] may always be substituted by [x]. Word-initial ⟨ch⟩ is used only in loanwords. In words of Ancient Greek origin, word-initial ⟨ch⟩ is pronounced [k] before ⟨a, o, l, r⟩ (with rare exceptions : Charisma, where both [k] and [ç] are possible); normally [ç] before ⟨e, i, y⟩ (but [k] in Southern Germany and Austria); [ç] before ⟨th⟩. In the word Orchester and in geographical names such as Chemnitz or Chur, ⟨ch⟩ is [k] (Chur is also sometimes pronounced with [x]). |

| after other vowels or consonants | [ç] | ||

| word-initially in words of Ancient Greek origin | [ç] or [k] | ||

| the suffix —chen | [ç] | ||

| In loanwords and foreign proper names | [tʃ], [ʃ] | ||

| chs | within a morpheme (e.g. Dachs [daks] «badger») | [ks] | |

| across a morpheme boundary (e.g. Dachs [daxs] «roof (gen.)») | [çs] or [xs] | ||

| ck | [k] | follows short vowels | |

| d | otherwise | [d] or [d̥] | |

| syllable final | [t] | ||

| dsch | [dʒ] or [tʃ] | used in loanwords and transliterations only. Words borrowed from English can alternatively retain the original ⟨j⟩ or ⟨g⟩. Many speakers pronounce ⟨dsch⟩ as [t͡ʃ] (= ⟨tsch⟩), because [dʒ] is not native to German. | |

| dt | [t] | Used in the word Stadt, in morpheme bounds (e. g. beredt, verwandt), and in some proper names. | |

| f | [f] | ||

| g | otherwise | [ɡ] or [ɡ̊] | [ʒ] before ⟨e, i⟩ in loanwords from French (as in Genie) |

| syllable final | [k] | ||

| when part of word-final -⟨ig⟩ | [ç] or [k] (Southern Germany) | ||

| h | before a vowel | [h] | |

| when lengthening a vowel | silent | ||

| j | [j] | [ʒ] in loanwords from French (as in Journalist [ʒʊʁnaˈlɪst], from French journaliste; note that -iste is Germanized to -ist, so the letter ⟨t⟩ remains pronounced) | |

| k | [k] | ||

| l | [l] | ||

| m | [m] | ||

| n | [n] | ||

| ng | usually | [ŋ] | |

| in compound words where the first element ends in ⟨n⟩ and the second element begins with ⟨g⟩ (-⟨n·g⟩-) | [nɡ] or [nɡ̊] | ||

| nk | [ŋk] | ||

| p | [p] | ||

| pf | [pf] | with some speakers [f] at the beginning of words (or at the beginning of compound words’ elements) | |

| ph | [f] | Used in words of Ancient Greek origin. | |

| qu | [kv] or [kw] (in a few regions) | ||

| r | [ʁ] before vowels, [ɐ] otherwise,

or [ɐ] after long vowels (except [aː]), [ʁ] otherwise |

[17] | |

| (Austro-Bavarian) | [r] or [ɾ] before vowels, [ɐ] otherwise | ||

| (Swiss Standard German) | [r] in all cases | ||

| rh | same as r | Used in words of Ancient Greek origin and in some proper names. | |

| s | before vowel (except after obstruents) | [z] or [z̥] | |

| before consonants, after obstruents, or when final | [s] | ||

| before ⟨p, t⟩ at the beginning of a word or syllable | [ʃ] | ||

| sch | otherwise | [ʃ] | |

| when part of the -chen diminutive of a word ending on ⟨s⟩, (e.g. Mäuschen «little mouse») | [sç] | ||

| ss | [s] | ||

| ß | [s] | ||

| t | [t] | Silent at the end of loanwords from French (although spelling may be otherwise Germanized: Debüt, Eklat, Kuvert, Porträt) | |

| th | [t] | Used in words of Ancient Greek origin and in some proper names. | |

| ti | otherwise | [ti] | Used in words of Latin origin. |

| in -⟨tion, tiär, tial, tiell⟩ | [tsɪ̯] | ||

| tsch | [tʃ] | ||

| tz | [ts] | follows short vowels | |

| tzsch | [tʃ] | Used in some proper names. | |

| v | otherwise | [f] | |

| in foreign borrowings not at the end of a word | [v] | ||

| w | [v] | ||

| x | [ks] | ||

| z | [ts] | ||

| zsch | [tʃ] | Used in some proper names. |

Vowels[edit]

| front | central | back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | ||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long |

| close | ([i] ⟨i⟩) | [iː] ⟨i, ie, ih, ieh⟩ | ([y] ⟨y⟩) | [yː] ⟨ü, üh, y⟩ | ([u] ⟨u⟩) | [uː] ⟨u, uh⟩ | |

| near-close | [ɪ] ⟨i⟩ | [ʏ] ⟨ ü, y⟩ | [ʊ] ⟨u⟩ | ||||

| close-mid | ([e] ⟨e⟩) | [eː] ⟨ä, äh, e, eh, ee⟩ | ([ø] ⟨ö⟩) | [øː] ⟨ö, öh⟩ | ([o] ⟨o⟩) | [oː] ⟨o, oh, oo⟩ | |

| mid | [ə] ⟨e⟩ | ||||||

| open-mid | [ɛ] ⟨ä, e⟩ | [ɛː] ⟨ä, äh⟩ | [œ] ⟨ö⟩ | [ɔ] ⟨o⟩ | |||

| near-open | [ɐ] -⟨er⟩ | ||||||

| open | [a] ⟨a⟩ | [aː] ⟨a, ah, aa⟩ |

Short vowels[edit]

Consonants are sometimes doubled in writing to indicate the preceding vowel is to be pronounced as a short vowel, mostly when the vowel is stressed. Most one-syllable words that end in a single consonant are pronounced with long vowels, but there are some exceptions such as an, das, es, in, mit, and von. The ⟨e⟩ in the ending —en is often silent, as in bitten «to ask, request». The ending —er is often pronounced [ɐ], but in some regions, people say [ʀ̩] or [r̩]. The ⟨e⟩ in the endings —el ([əl~l̩], e.g. Tunnel, Mörtel «mortar») and —em ([əm~m̩] in the dative case of adjectives, e.g. kleinem from klein «small») is pronounced short despite these endings have just a single consonant on the end, but this ⟨e⟩ is nearly always an unstressed syllable. The suffixes —in, —nis and the word endings —as, —is, —os, —us contain short unstressed vowels, but duplicate the final consonants in the plurals: Leserin «female reader» — Leserinnen «female readers», Kürbis «pumpkin» — Kürbisse «pumpkins».

- ⟨a⟩: [a] as in Wasser «water»

- ⟨ä⟩: [ɛ] as in Männer «men»

- ⟨e⟩: [ɛ] as in Bett «bed»; unstressed [ə] as in Ochse «ox»

- ⟨i⟩: [ɪ] as in Mittel «means»

- ⟨o⟩: [ɔ] as in kommen «to come»

- ⟨ö⟩: [œ] as in Göttin «goddess»

- ⟨u⟩: [ʊ] as in Mutter «mother»

- ⟨ü⟩: [ʏ] as in Müller «miller»

- ⟨y⟩: [ʏ] as in Dystrophie «dystrophy»

Long vowels[edit]

A vowel usually represents a long sound if the vowel in question occurs:

- as the final letter (except for ⟨e⟩)

- in any stressed open syllable as in Wagen «car»

- followed by a single consonant as in bot «offered»

- doubled as in Boot «boat»

- followed by an ⟨h⟩ as in Weh «pain»

Long vowels are generally pronounced with greater tenseness than short vowels.

The long vowels map as follows:

- ⟨a, ah, aa⟩: [aː]

- ⟨ä, äh⟩: [ɛː] or [eː]

- ⟨e, eh, ee⟩: [eː]

- ⟨i, ie, ih, ieh⟩: [iː]

- ⟨o, oh, oo⟩: [oː]

- ⟨ö, öh⟩: [øː]

- ⟨u, uh⟩: [uː]

- ⟨ü, üh⟩: [yː]

- ⟨y⟩: [yː]

Diphthongs[edit]

- ⟨au⟩: [aʊ]

- ⟨eu, äu⟩: [ɔʏ]

- ⟨ei, ai, ey, ay⟩: [aɪ]

Shortened long vowels

A pre-stress long vowel shortens:

- ⟨i⟩: [i]

- ⟨y⟩: [y]

- ⟨u⟩: [u]

- ⟨e⟩: [e]

- ⟨ö⟩: [ø]

- ⟨o⟩: [o]

Other vowels

- -⟨er⟩: /ər/, [ɐ]

- ⟨e⟩: [ə]

- ⟨ie⟩: [ɪ] (in the words: Viertel/viertel, vierzehn, vierzig)

Punctuation[edit]

The period (full stop) is used at the end of sentences, for abbreviations, and for ordinal numbers, such as der 1. for der erste (the first). The combination «abbreviation point+full stop at the end of a sentence» is simplified to a single point.

The comma is used between for enumerations (but the serial comma is not used), before adversative conjunctions, after vocative phrases, for clarifying words such as appositions, before and after infinitive and participle constructions, and between clauses in a sentence. A comma may link two independent clauses without a conjunction. The comma is not used before the direct speech; in this case, the colon is used. In some cases (e.g. infinitive phrases), using the comma is optional.

The exclamation mark and the question mark are used for exclamative and interrogative sentences. The exclamation mark may be used for addressing people in letters.

The semicolon is used for divisions of a sentence greater than that with the comma.

The colon is used before direct speech and quotes, after a generalizing word before enumerations (but not when the words das ist, das heißt, nämlich, zum Beispiel are inserted), before explanations and generalizations, and after words in questionnaires, timetables, etc. (e. g. Vater: Franz Müller).

The em dash is used for marking a sharp transition from one thought to another one, between remarks of a dialogue (as a quotation dash), between keywords in a review, between commands, for contrasting, for marking unexpected changes, for marking an unfinished direct speech, and sometimes instead of parentheses in parenthetical constructions.

The ellipsis is used for unfinished thoughts and incomplete citations.

The parenthesis are used for parenthetical information.

The square brackets are used instead of parentheses inside parentheses and for editor’s words inside quotations.

The quotation marks are written as »…« or „…“. They are used for direct speech, quotes, names of books, periodicals, films, etc., and for words in unusual meaning. Quotation inside a quotation is written in single quotation marks: ›…‹ or ‚…‘. If a quotation is followed by a period or a comma, it is placed outside the quotation marks.

The apostrophe is used for contracted forms (such as ’s for es) except forms with omitted final ⟨e⟩ (was sometimes used in this case in the past) and preposition+article contractions. It is also used for genitive of proper names ending in ⟨s, ß, x, z, ce⟩, but not if preceded by the definite article.

History of German orthography[edit]

Middle Ages[edit]

The oldest known German texts date back to the 8th century. They were written mainly in monasteries in different local dialects of Old High German. In these texts, ⟨z⟩ along with combinations such as ⟨tz, cz, zz, sz, zs⟩ was chosen to transcribe the sounds /ts/ and /s(ː)/, which is ultimately the origin of the modern German letters ⟨z, tz⟩ and ⟨ß⟩ (an old ⟨sz⟩ ligature). After the Carolingian Renaissance, however, during the reigns of the Ottonian and Salian dynasties in the 10th century and 11th century, German was rarely written, the literary language being almost exclusively Latin.

Notker the German is a notable exception in his period: not only are his German compositions of high stylistic value, but his orthography is also the first to follow a strictly coherent system.

Significant production of German texts only resumed during the reign of the Hohenstaufen dynasty (in the High Middle Ages). Around the year 1200, there was a tendency towards a standardized Middle High German language and spelling for the first time, based on the Franconian-Swabian language of the Hohenstaufen court. However, that language was used only in the epic poetry and minnesang lyric of the knight culture. These early tendencies of standardization ceased in the interregnum after the death of the last Hohenstaufen king in 1254. Certain features of today’s German orthography still date back to Middle High German: the use of the trigraph ⟨sch⟩ for /ʃ/ and the occasional use of ⟨v⟩ for /f/ because around the 12th and 13th century, the prevocalic /f/ was voiced.

In the following centuries, the only variety that showed a marked tendency to be used across regions was the Middle Low German of the Hanseatic League, based on the variety of Lübeck and used in many areas of northern Germany and indeed northern Europe in general.

Early modern period[edit]

By the 16th century, a new interregional standard developed on the basis of the East Central German and Austro-Bavarian varieties. This was influenced by several factors:

- Under the Habsburg dynasty, there was a strong tendency to a common language in the chancellery.

- Since Eastern Central Germany had been colonized only during the High and Late Middle Ages in the course of the Ostsiedlung by people from different regions of Germany, the varieties spoken were compromises of different dialects.

- Eastern Central Germany was culturally very important, being home to the universities of Erfurt and Leipzig and especially with the Luther Bible translation, which was considered exemplary.

- The invention of printing led to an increased production of books, and the printers were interested in using a common language to sell their books in an area as wide as possible.

Mid-16th century Counter-Reformation reintroduced Catholicism to Austria and Bavaria, prompting a rejection of the Lutheran language. Instead, a specific southern interregional language was used, based on the language of the Habsburg chancellery.

In northern Germany, the Lutheran East Central German replaced the Low German written language until the mid-17th century. In the early 18th century, the Lutheran standard was also introduced in the southern states and countries, Austria, Bavaria and Switzerland, due to the influence of northern German writers, grammarians such as Johann Christoph Gottsched or language cultivation societies such as the Fruitbearing Society.

19th century and early 20th century[edit]

(Becker, 1896)

(Falck-Lebahn, 1851)

(Smissen-Fraser, 1900)

(Schlomka, 1885)

Though, by the mid-18th century, one norm was generally established, there was no institutionalized standardization. Only with the introduction of compulsory education in late 18th and early 19th century was the spelling further standardized, though at first independently in each state because of the political fragmentation of Germany. Only the foundation of the German Empire in 1871 allowed for further standardization.

In 1876, the Prussian government instituted the First Orthographic Conference [de] to achieve a standardization for the entire German Empire. However, its results were rejected, notably by Prime Minister of Prussia Otto von Bismarck.

In 1880, Gymnasium director Konrad Duden published the Vollständiges Orthographisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache («Complete Orthographic Dictionary of the German Language»), known simply as the «Duden». In the same year, the Duden was declared to be authoritative in Prussia.[citation needed] Since Prussia was, by far, the largest state in the German Empire, its regulations also influenced spelling elsewhere, for instance, in 1894, when Switzerland recognized the Duden.[citation needed]

In 1901, the interior minister of the German Empire instituted the Second Orthographic Conference. It declared the Duden to be authoritative, with a few innovations. In 1902, its results were approved by the governments of the German Empire, Austria and Switzerland.

In 1944, the Nazi German government planned a reform of the orthography, but because of World War II, it was never implemented.

After 1902, German spelling was essentially decided de facto by the editors of the Duden dictionaries. After World War II, this tradition was followed with two different centers: Mannheim in West Germany and Leipzig in East Germany. By the early 1950s, a few other publishing houses had begun to attack the Duden monopoly in the West by putting out their own dictionaries, which did not always hold to the «official» spellings prescribed by Duden. In response, the Ministers of Culture of the federal states in West Germany officially declared the Duden spellings to be binding as of November 1955.

The Duden editors used their power cautiously because they considered their primary task to be the documentation of usage, not the creation of rules. At the same time, however, they found themselves forced to make finer and finer distinctions in the production of German spelling rules, and each new print run introduced a few reformed spellings.

German spelling reform of 1996[edit]

German spelling and punctuation was changed in 1996 (Reform der deutschen Rechtschreibung von 1996) with the intent to simplify German orthography, and thus to make the language easier to learn,[18] without substantially changing the rules familiar to users of the language. The rules of the new spelling concern correspondence between sounds and written letters (including rules for spelling loan words), capitalisation, joined and separate words, hyphenated spellings, punctuation, and hyphenation at the end of a line. Place names and family names were excluded from the reform.

The reform was adopted initially by Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein and Switzerland, and later by Luxembourg as well.

The new orthography is mandatory only in schools. A 1998 decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany confirmed that there is no law on the spelling people use in daily life, so they can use the old or the new spelling.[19] While the reform is not very popular in opinion polls, it has been adopted by all major dictionaries and the majority of publishing houses.

See also[edit]

- Binnen-I, a convention for gender-neutral language in German

- German braille

- Non-English usage of quotation marks

- German phonology

- Antiqua-Fraktur dispute

- Spelling

- Punctuation

- English spelling

- Dutch orthography

- Otto Basler

References[edit]

- ^ DIN 5009:2022-06, section 4.2 „Buchstaben“ (letters), table 1

- ^ a b Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2018, p. 15, section 0 [Vorbemerkungen] (1): «Die Umlautbuchstaben ä, ö, ü»; p. 29, § 25 E2: «der Buchstabe ß»; et passim.

- ^ Official rules of German spelling updated, Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung, 29 June 2017, retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ Andrew West (2006): «The Rules for Long S».

- ^ «Das deutsche Alphabet – Wie viele Buchstaben hat das ABC?» (in German). www.buchstabieralphabet.org. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

- ^ Die Erde: Haack Kleiner Atlas; VEB Hermann Haack geographisch-kartographische Anstalt, Gotha, 1982; pages: 97, 100, 153, 278

- ^ Italien: Straßenatlas 1:300.000 mit Ortsregister; Kunth Verlag GmbH & Co. KG 2016/2017; München; page: III

- ^ Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2018, p. 29, § 25 E3

- ^ (in German) Empfehlungen und Hinweise für die Schreibweise geographischer Namen, 5. Ausgabe 2010 Archived 2011-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in German) Rechtschreibrat führt neuen Buchstaben ein, Die Zeit, 29 June 2017, retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ (according to the Guinness Book of Records)

- ^ a b canoo.net: Spelling for «Photographie/Fotografie» 2011-03-13

- ^ canoo.net: Spelling for «Delphin/Delfin» 2011-03-13

- ^ canoo.net: Spelling for «Portemonnaie/Portmonee» 2011-03-13

- ^ canoo.net: Spelling for «Foto» 2011-03-13

- ^ Wortherkunft, Sprachliches

Das Wort Ski wurde im 19. Jahrhundert vom norwegischen ski ‚Scheit (gespaltenes Holz); Schneeschuh‘ entlehnt, das seinerseits von dem gleichbedeutenden altnordischen skíð abstammt und mit dem deutschen Wort Scheit urverwandt ist.[1]

Als Pluralform sind laut Duden Ski und Skier bzw. Schi und Schier üblich.[2] Die Aussprache ist vornehmlich wie „Schi“ (wie auch original im Norwegischen), lokal bzw. dialektal kommt sie auch als „Schki“ (etwa in Graubünden oder im Wallis) vor.

- ^ Preu, Otto; Stötzer, Ursula (1985). Sprecherziehung für Studenten pädagogischer Berufe (4th ed.). Berlin: Verlag Volk und Wissen, Volkseigener Verlag. p. 104.

- ^ Upward, Chris (1997). «Spelling Reform in German» (PDF). Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society. J21: 22–24, 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-05.

- ^ Bundesverfassungsgericht, Urteil vom 14. Juli 1998, Az.: 1 BvR 1640/97 (in German), Federal Constitutional Court, 14 July 1998.

External links[edit]

- Regeln und Wörterverzeichnis. Aktualisierte Fassung des amtlichen Regelwerks entsprechend den Empfehlungen des Rats für deutsche Rechtschreibung 2016 (PDF) (in German), Mannheim: Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung, 2018, p. § 25 E3, retrieved 2019-05-07

German orthography is the orthography used in writing the German language, which is largely phonemic. However, it shows many instances of spellings that are historic or analogous to other spellings rather than phonemic. The pronunciation of almost every word can be derived from its spelling once the spelling rules are known, but the opposite is not generally the case.

Today, Standard High German orthography is regulated by the Rat für deutsche Rechtschreibung (Council for German Orthography), composed of representatives from most German-speaking countries.

Alphabet[edit]

(Listen to a German speaker recite the alphabet in German)

The modern German alphabet consists of the twenty-six letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet plus four special letters.

Basic alphabet[edit]

| Capital | Lowercase | Name[1] | Name (IPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0123456789 | 0123456789 | 0123456789 | /0123456789ː/ |

| –—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ | –—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ | –—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ | /–—°′″≈≠≤≥±−×÷←→·§ː/ |

| A | a | A | /aː/ |

| B | b | Be | /beː/ |

| C | c | Ce | /t͡seː/ |

| D | d | De | /deː/ |

| E | e | E | /eː/ |

| F | f | Ef | /ɛf/ |

| G | g | Ge | /ɡeː/ |

| H | h | Ha | /haː/ |

| I | i | I | /iː/ |

| J | j | Jott1, Je2 | /jɔt/1

/jeː/2 |

| K | k | Ka | /kaː/ |

| L | l | El | /ɛl/ |

| M | m | Em | /ɛm/ |

| N | n | En | /ɛn/ |

| O | o | O | /oː/ |

| P | p | Pe | /peː/ |

| Q | q | Qu1, Que2 | /kuː/1

/kveː/2 |

| R | r | Er | /ɛʁ/ |

| S | s | Es | /ɛs/ |

| T | t | Te | /teː/ |

| U | u | U | /uː/ |

| V | v | Vau | /faʊ̯/ |

| W | w | We | /veː/ |

| X | x | Ix | /ɪks/ |

| Y | y | Ypsilon | /ˈʏpsilɔn/1

/ʏˈpsiːlɔn/2 |

| Z | z | Zett | /t͡sɛt/ |

1in Germany

2in Austria

Special letters[edit]

German has four special letters; three are vowels accented with an umlaut sign (⟨ä, ö, ü⟩) and one is derived from a ligature of ⟨ſ⟩ (long s) and ⟨z⟩ (⟨ß⟩; called Eszett «ess-zed/zee» or scharfes S «sharp s»), all of which are officially considered distinct letters of the alphabet,[2] and have their own names separate from the letters they are based on.

(Listen to a German speaker naming these letters)

| Name (IPA) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ä | ä | /ɛː/ |

| Ö | ö | /øː/ |

| Ü | ü | /yː/ |

| ẞ | ß | Eszett: /ɛsˈt͡sɛt/ scharfes S: /ˈʃaʁfəs ɛs/ «sharp s» |

- Capital ẞ was declared an official letter of the German alphabet on 29 June 2017.[3] Previously represented as ⟨SS/SZ⟩.

- Historically, long s (ſ) was used as well, as in English and many other European languages.[4]

While the Council for German Orthography considers ⟨ä, ö, ü, ß⟩ distinct letters,[2] disagreement on how to categorize and count them has led to a dispute over the exact number of letters the German alphabet has, the number ranging between 26 (considering special letters as variants of ⟨a, o, u, s⟩) and 30 (counting all special letters separately).[5]

Use of special letters[edit]

Umlaut diacritic usage[edit]

The accented letters ⟨ä, ö, ü⟩ are used to indicate the presence of umlauts (fronting of back vowels). Before the introduction of the printing press, frontalization was indicated by placing an ⟨e⟩ after the back vowel to be modified, but German printers developed the space-saving typographical convention of replacing the full ⟨e⟩ with a small version placed above the vowel to be modified. In German Kurrent writing, the superscripted ⟨e⟩ was simplified to two vertical dashes (as the Kurrent ⟨e⟩ consists largely of two short vertical strokes), which have further been reduced to dots in both handwriting and German typesetting. Although the two dots of umlaut look like those in the diaeresis (trema), the two have different origins and functions.

When it is not possible to use the umlauts (for example, when using a restricted character set) the characters ⟨Ä, Ö, Ü, ä, ö, ü⟩ should be transcribed as ⟨Ae, Oe, Ue, ae, oe, ue⟩ respectively, following the earlier postvocalic-⟨e⟩ convention; simply using the base vowel (e.g. ⟨u⟩ instead of ⟨ü⟩) would be wrong and misleading. However, such transcription should be avoided if possible, especially with names. Names often exist in different variants, such as Müller and Mueller, and with such transcriptions in use one could not work out the correct spelling of the name.

Automatic back-transcribing is wrong not only for names. Consider, for example, das neue Buch («the new book»). This should never be changed to das neü Buch, as the second ⟨e⟩ is completely separate from the ⟨u⟩ and does not even belong in the same syllable; neue ([ˈnɔʏ.ə]) is neu (the root for «new») followed by ⟨e⟩, an inflection. The word ⟨neü⟩ does not exist in German.

Furthermore, in northern and western Germany, there are family names and place names in which ⟨e⟩ lengthens the preceding vowel (by acting as a Dehnungs-e), as in the former Dutch orthography, such as Straelen, which is pronounced with a long ⟨a⟩, not an ⟨ä⟩. Similar cases are Coesfeld and Bernkastel-Kues.

In proper names and ethnonyms, there may also appear a rare ⟨ë⟩ and ⟨ï⟩, which are not letters with an umlaut, but a diaeresis, used as in French and English to distinguish what could be a digraph, for example, ⟨ai⟩ in Karaïmen, ⟨eu⟩ in Alëuten, ⟨ie⟩ in Piëch, ⟨oe⟩ in von Loë and Hoëcker (although Hoëcker added the diaeresis himself), and ⟨ue⟩ in Niuë.[6] Occasionally, a diaeresis may be used in some well-known names, i.e.: Italiën[7] (usually written as Italien).

Swiss keyboards and typewriters do not allow easy input of uppercase letters with umlauts (nor ⟨ß⟩) because their positions are taken by the most frequent French diacritics. Uppercase umlauts were dropped because they are less common than lowercase ones (especially in Switzerland). Geographical names in particular are supposed to be written with ⟨a, o, u⟩ plus ⟨e⟩, except Österreich. The omission can cause some inconvenience, since the first letter of every noun is capitalized in German.

Unlike in Hungarian, the exact shape of the umlaut diacritics – especially when handwritten – is not important, because they are the only ones in the language (not counting the tittle on ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩). They will be understood whether they look like dots (⟨¨⟩), acute accents (⟨ ˝ ⟩) or vertical bars (⟨‖⟩). A horizontal bar (macron, ⟨¯⟩), a breve (⟨˘⟩), a tiny ⟨N⟩ or ⟨e⟩, a tilde (⟨˜⟩), and such variations are often used in stylized writing (e.g. logos). However, the breve – or the ring (⟨°⟩) – was traditionally used in some scripts to distinguish a ⟨u⟩ from an ⟨n⟩. In rare cases, the ⟨n⟩ was underlined. The breved ⟨u⟩ was common in some Kurrent-derived handwritings; it was mandatory in Sütterlin.

Sharp s[edit]

German label «Delicacy / red cabbage.» Left cap is with old orthography, right with new.

Eszett or scharfes S (⟨ß⟩) represents the “s” sound. The German spelling reform of 1996 somewhat reduced usage of this letter in Germany and Austria. It is not used in Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

As ⟨ß⟩ derives from a ligature of lowercase letters, it is exclusively used in the middle or at the end of a word. The proper transcription when it cannot be used is ⟨ss⟩ (⟨sz⟩ and ⟨SZ⟩ in earlier times). This transcription can give rise to ambiguities, albeit rarely; one such case is in Maßen «in moderation» vs. in Massen «en masse». In all-caps, ⟨ß⟩ is replaced by ⟨SS⟩ or, optionally, by the uppercase ⟨ß⟩.[8] The uppercase ⟨ß⟩ was included in Unicode 5.1 as U+1E9E in 2008. Since 2010 its use is mandatory in official documentation in Germany when writing geographical names in all-caps.[9] The option of using the uppercase ⟨ẞ⟩ in all-caps was officially added to the German orthography in 2017.[10]

Although nowadays substituted correctly only by ⟨ss⟩, the letter actually originates from a distinct ligature: long s with (round) z (⟨ſz/ſʒ⟩). Some people therefore prefer to substitute ⟨ß⟩ by ⟨sz⟩, as it can avoid possible ambiguities (as in the above Maßen vs Massen example).

Incorrect use of the ⟨ß⟩ letter is a common type of spelling error even among native German writers. The spelling reform of 1996 changed the rules concerning ⟨ß⟩ and ⟨ss⟩ (no forced replacement of ⟨ss⟩ to ⟨ß⟩ at word’s end). This required a change of habits and is often disregarded: some people even incorrectly assumed that the ⟨ß⟩ had been abolished completely. However, if the vowel preceding the ⟨s⟩ is long, the correct spelling remains ⟨ß⟩ (as in Straße). If the vowel is short, it becomes ⟨ss⟩, e.g. Ich denke, dass… «I think that…». This follows the general rule in German that a long vowel is followed by a single consonant, while a short vowel is followed by a double consonant.

This change towards the so-called Heyse spelling, however, introduced a new sort of spelling error, as the long/short pronunciation differs regionally. It was already mostly abolished in the late 19th century (and finally with the first unified German spelling of 1901) in favor of the Adelung spelling. Besides the long/short pronunciation issue, which can be attributed to dialect speaking (for instance, in the northern parts of Germany Spaß is typically pronounced short, i.e. Spass, whereas particularly in Bavaria elongated may occur as in Geschoss which is pronounced Geschoß in certain regions), Heyse spelling also introduces reading ambiguities that do not occur with Adelung spelling such as Prozessorientierung (Adelung: Prozeßorientierung) vs. Prozessorarchitektur (Adelung: Prozessorarchitektur). It is therefore recommended to insert hyphens where required for reading assistance, i.e. Prozessor-Architektur vs. Prozess-Orientierung.

Long s[edit]

Wachstube and Wachſtube are distinguished in blackletter typesetting, though no longer in contemporary font styles.

In the Fraktur typeface and similar scripts, a long s (⟨ſ⟩) was used except in syllable endings (cf. Greek sigma) and sometimes it was historically used in antiqua fonts as well; but it went out of general use in the early 1940s along with the Fraktur typeface. An example where this convention would avoid ambiguity is Wachſtube (IPA: [ˈvax.ʃtuːbə]) «guardhouse», written ⟨Wachſtube/Wach-Stube⟩ and Wachstube (IPA: [ˈvaks.tuːbə]) «tube of wax», written ⟨Wachstube/Wachs-Tube⟩.

Sorting[edit]

There are three ways to deal with the umlauts in alphabetic sorting.

- Treat them like their base characters, as if the umlaut were not present (DIN 5007-1, section 6.1.1.4.1). This is the preferred method for dictionaries, where umlauted words (Füße «feet») should appear near their origin words (Fuß «foot»). In words which are the same except for one having an umlaut and one its base character (e.g. Müll vs. Mull), the word with the base character gets precedence.

- Decompose them (invisibly) to vowel plus ⟨e⟩ (DIN 5007-2, section 6.1.1.4.2). This is often preferred for personal and geographical names, wherein the characters are used unsystematically, as in German telephone directories (Müller, A.; Mueller, B.; Müller, C.).

- They are treated like extra letters either placed

- after their base letters (Austrian phone books have ⟨ä⟩ between ⟨az⟩ and ⟨b⟩ etc.) or

- at the end of the alphabet (as in Swedish or in extended ASCII).

Microsoft Windows in German versions offers the choice between the first two variants in its internationalisation settings.

A sort of combination of nos. 1 and 2 also exists, in use in a couple of lexica: The umlaut is sorted with the base character, but an ⟨ae, oe, ue⟩ in proper names is sorted with the umlaut if it is actually spoken that way (with the umlaut getting immediate precedence). A possible sequence of names then would be Mukovic; Muller; Müller; Mueller; Multmann in this order.

Eszett is sorted as though it were ⟨ss⟩. Occasionally it is treated as ⟨s⟩, but this is generally considered incorrect. Words distinguished only by ⟨ß⟩ vs. ⟨ss⟩ can only appear in the (presently used) Heyse writing and are even then rare and possibly dependent on local pronunciation, but if they appear, the word with ⟨ß⟩ gets precedence, and Geschoß (storey; South German pronunciation) would be sorted before Geschoss (projectile).

Accents in French loanwords are always ignored in collation.

In rare contexts (e.g. in older indices) ⟨sch⟩ (phonetic value equal to English ⟨sh⟩) and likewise ⟨st⟩ and ⟨ch⟩ are treated as single letters, but the vocalic digraphs ⟨ai, ei⟩ (historically ⟨ay, ey⟩), ⟨au, äu, eu⟩ and the historic ⟨ui, oi⟩ never are.

Personal names with special characters[edit]

German names containing umlauts (⟨ä, ö, ü⟩) and/or ⟨ß⟩ are spelled in the correct way in the non-machine-readable zone of the passport, but with ⟨AE, OE, UE⟩ and/or ⟨SS⟩ in the machine-readable zone, e.g. ⟨Müller⟩ becomes ⟨MUELLER⟩, ⟨Weiß⟩ becomes ⟨WEISS⟩, and ⟨Gößmann⟩ becomes ⟨GOESSMANN⟩. The transcription mentioned above is generally used for aircraft tickets et cetera, but sometimes (like in US visas) simple vowels are used (MULLER, GOSSMANN). As a result, passport, visa, and aircraft ticket may display different spellings of the same name. The three possible spelling variants of the same name (e.g. Müller/Mueller/Muller) in different documents sometimes lead to confusion, and the use of two different spellings within the same document may give persons unfamiliar with German orthography the impression that the document is a forgery.

Even before the introduction of the capital ⟨ẞ⟩, it was recommended to use the minuscule ⟨ß⟩ as a capital letter in family names in documents (e.g. HEINZ GROßE, today’s spelling: HEINZ GROẞE).

German naming law accepts umlauts and/or ⟨ß⟩ in family names as a reason for an official name change. Even a spelling change, e.g. from Müller to Mueller or from Weiß to Weiss is regarded as a name change.

Features of German spelling[edit]

Capitalization[edit]

A typical feature of German spelling is the general capitalization of nouns and of most nominalized words. In addition, capital letters are used: at the beginning of sentences (may be used after a colon, when the part of a sentence after the colon can be treated as a sentence); in the formal pronouns Sie ‘you’ and Ihr ‘your’ (optionally in other second-person pronouns in letters); in adjectives at the beginning of proper names (e. g. der Stille Ozean ‘the Pacific Ocean’); in adjectives with the suffix ‘-er’ from geographical names (e. g. Berliner); in adjectives with the suffix ‘-sch’ from proper names if written with the apostrophe before the suffix (e. g. Ohm’sches Gesetz ‘Ohm’s law’, also written ohmsches Gesetz).

Compound words[edit]

Compound words, including nouns, are written together, e.g. Haustür (Haus + Tür; «house door»), Tischlampe (Tisch + Lampe; «table lamp»), Kaltwasserhahn (Kalt + Wasser + Hahn; «cold water tap/faucet»). This can lead to long words: the longest word in regular use, Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften[11] («legal protection insurance companies»), consists of 39 letters.

Vowel length[edit]

Even though vowel length is phonemic in German, it is not consistently represented. However, there are different ways of identifying long vowels:

- A vowel in an open syllable (a free vowel) is long, for instance in ge-ben (‘to give’), sa-gen (‘to say’). The rule is unreliable in given names, cf. Oliver [ˈɔlivɐ].

- It is rare to see a bare i used to indicate a long vowel /iː/. Instead, the digraph ie is used, for instance in Liebe (‘love’), hier (‘here’). This use is a historical spelling based on the Middle High German diphthong /iə/ which was monophthongized in Early New High German. It has been generalized to words that etymologically never had that diphthong, for instance viel (‘much’), Friede (‘peace’) (Middle High German vil, vride). Occasionally – typically in word-final position – this digraph represents /iː.ə/ as in the plural noun Knie /kniː.ə/ (‘knees’) (cf. singular Knie /kniː/). In the words Viertel (viertel) /ˈfɪrtəl/ (‘quarter’), vierzehn /ˈfɪʁt͡seːn/ (‘fourteen’), vierzig /ˈfɪʁt͡sɪç/ (‘forty’), ie represents a short vowel, cf. vier /fiːɐ̯/ (‘four’). In Fraktur, where capital I and J are identical or near-identical

, the combinations Ie and Je are confusable; hence the combination Ie is not used at the start of a word, for example Igel (‘hedgehog’), Ire (‘Irishman’).

- A silent h indicates the vowel length in certain cases. That h derives from an old /x/ in some words, for instance sehen (‘to see’) zehn (‘ten’), but in other words it has no etymological justification, for instance gehen (‘to go’) or mahlen (‘to mill’). Occasionally a digraph can be redundantly followed by h, either due to analogy, such as sieht (‘sees’, from sehen) or etymology, such as Vieh (‘cattle’, MHG vihe), rauh (‘rough’, pre-1996 spelling, now written rau, MHG ruh).

- The letters a, e, o are doubled in a few words that have long vowels, for instance Saat (‘seed’), See (‘sea’/’lake’), Moor (‘moor’).

- A doubled consonant after a vowel indicates that the vowel is short, while a single consonant often indicates the vowel is long, e.g. Kamm (‘comb’) has a short vowel /kam/, while kam (‘came’) has a long vowel /kaːm/. Two consonants are not doubled: k, which is replaced by ck (until the spelling reform of 1996, however, ck was divided across a line break as k-k), and z, which is replaced by tz. In loanwords, kk (which may correspond with cc in the original spelling) and zz can occur.

- For different consonants and for sounds represented by more than one letter (ch and sch) after a vowel, no clear rule can be given, because they can appear after long vowels, yet are not redoubled if belonging to the same stem, e.g. Mond /moːnt/ ‘moon’, Hand /hant/ ‘hand’. On a stem boundary, reduplication usually takes place, e.g., nimm-t ‘takes’; however, in fixed, no longer productive derivatives, this too can be lost, e.g., Geschäft /ɡəˈʃɛft/ ‘business’ despite schaffen ‘to get something done’.

- ß indicates that the preceding vowel is long, e.g. Straße ‘street’ vs. a short vowel in Masse ‘mass’ or ‘host’/’lot’. In addition to that, texts written before the 1996 spelling reform also use ß at the ends of words and before consonants, e.g. naß ‘wet’ and mußte ‘had to’ (after the reform spelled nass and musste), so vowel length in these positions could not be detected by the ß, cf. Maß ‘measure’ and fußte ‘was based’ (after the reform still spelled Maß and fußte).

Double or triple consonants[edit]

Even though German does not have phonemic consonant length, there are many instances of doubled or even tripled consonants in the spelling. A single consonant following a checked vowel is doubled if another vowel follows, for instance immer ‘always’, lassen ‘let’. These consonants are analyzed as ambisyllabic because they constitute not only the syllable onset of the second syllable but also the syllable coda of the first syllable, which must not be empty because the syllable nucleus is a checked vowel.

By analogy, if a word has one form with a doubled consonant, all forms of that word are written with a doubled consonant, even if they do not fulfill the conditions for consonant doubling; for instance, rennen ‘to run’ → er rennt ‘he runs’; Küsse ‘kisses’ → Kuss ‘kiss’.

Doubled consonants can occur in composite words when the first part ends in the same consonant the second part starts with, e.g. in the word Schaffell (‘sheepskin’, composed of Schaf ‘sheep’ and Fell ‘skin, fur, pelt’).

Composite words can also have tripled letters. While this is usually a sign that the consonant is actually spoken long, it does not affect the pronunciation per se: the fff in Sauerstoffflasche (‘oxygen bottle’, composed of Sauerstoff ‘oxygen’ and Flasche ‘bottle’) is exactly as long as the ff in Schaffell. According to the spelling before 1996, the three consonants would be shortened before vowels, but retained before consonants and in hyphenation, so the word Schifffahrt (‘navigation, shipping’, composed of Schiff ‘ship’ and Fahrt ‘drive, trip, tour’) was then written Schiffahrt, whereas Sauerstoffflasche already had a triple fff. With the aforementioned change in ß spelling, even a new source of triple consonants sss, which in pre-1996 spelling could not occur as it was rendered ßs, was introduced, e. g. Mussspiel (‘compulsory round’ in certain card games, composed of muss ‘must’ and Spiel ‘game’).

Typical letters[edit]

- ei: This digraph represents the diphthong /aɪ̯/. The spelling goes back to the Middle High German pronunciation of that diphthong, which was [ei̯]. The spelling ai is found in only a very few native words (such as Saite ‘string’, Waise ‘orphan’) but is commonly used to romanize /aɪ̯/ in foreign loans from languages such as Chinese.

- eu: This digraph represents the diphthong [ɔʏ̯], which goes back to the Middle High German monophthong [yː] represented by iu. When the sound is created by umlaut of au [aʊ̯] (from MHG [uː]), it is spelled äu.

- ß: This letter alternates with ss. For more information, see above.

- st, sp: At the beginning of a stressed syllable, these digraphs are pronounced [ʃt, ʃp]. In the Middle Ages, the sibilant that was inherited from Proto-Germanic /s/ was pronounced as an alveolo-palatal consonant [ɕ] or [ʑ] unlike the voiceless alveolar sibilant /s/ that had developed in the High German consonant shift. In the Late Middle Ages, certain instances of [ɕ] merged with /s/, but others developed into [ʃ]. The change to [ʃ] was represented in certain spellings such as Schnee ‘snow’, Kirsche ‘cherry’ (Middle High German snê, kirse). The digraphs st, sp, however, remained unaltered.

- v: The letter v occurs only in a few native words and then, it represents /f/. That goes back to the 12th and 13th century, when prevocalic /f/ was voiced to [v]. The voicing was lost again in the late Middle Ages, but the v still remains in certain words such as in Vogel (compare Scandinavian fugl or English fowl) ‘bird’ (hence, the letter v is sometimes called Vogel-vau), viel ‘much’. For further information, see Pronunciation of v in German.

- w: The letter w represents the sound /v/. In the 17th century, the former sound [w] became [v], but the spelling remained the same. An analogous sound change had happened in late-antique Latin.

- z: The letter z represents the sound /t͡s/. The sound, a product of the High German consonant shift, has been written with z since Old High German in the 8th century.

Foreign words[edit]

For technical terms, the foreign spelling is often retained such as ph /f/ or y /yː/ in the word Physik (physics) of Greek origin. For some common affixes however, like -graphie or Photo-, it is allowed to use -grafie or Foto- instead.[12] Both Photographie and Fotografie are correct, but the mixed variants Fotographie or Photografie are not.[12]

For other foreign words, both the foreign spelling and a revised German spelling are correct such as Delphin / Delfin[13] or Portemonnaie / Portmonee, though in the latter case the revised one does not usually occur.[14]

For some words for which the Germanized form was common even before the reform of 1996, the foreign version is no longer allowed. A notable example is the word Foto, with the meaning “photograph”, which may no longer be spelled as Photo.[15] Other examples are Telephon (telephone) which was already Germanized as Telefon some decades ago or Bureau (office) which got replaced by the Germanized version Büro even earlier.