Так как сербский язык входит в группу славянских языков, то сербская грамматика довольно схожа с русской.

| Сербская азбука | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Кириллица | Латиница | Произношение | Транскрипция | ||

| А | а | А | а | а | сад |

| Б | б | B | b | б | банк |

| В | в | V | v | в | вопрос |

| Г | г | G | g | г | гараж |

| Д | д | D | d | д | дом |

| Ђ | ђ | Đ | đ | джь | мягкий звук,произносится как в буквосочетании «джя» |

| Е | е | E | e | э | это |

| Ж | ж | Ž | ž | ж | жарко |

| З | з | Z | z | з | зонт |

| И | и | I | i | и | имя |

| Ј | ј | J | j | й | йогурт |

| К | к | K | k | к | как |

| Л | л | L | l | л | ложка |

| Љ | љ | Lj | lj | ль | соль |

| М | м | M | m | м | май |

| Н | н | N | n | н | нож |

| Њ | њ | Nj | nj | нь | июнь |

| О | о | O | o | о | дом |

| П | п | P | p | п | пара |

| Р | р | R | r | р | рука |

| С | с | S | s | с | сом |

| Т | т | T | t | т | там |

| Ћ | ћ | Ć | ć | чь | чей |

| У | у | U | u | у | ухо |

| Ф | ф | F | f | ф | факт |

| Х | х | H | h | х | холм |

| Ц | ц | C | c | ц | царь |

| Ч | ч | Č | č | ч | более жёсткий чем в русском языке, произносится как «чэ» |

| Џ | џ | Dž | dž | дж | джаз |

| Ш | ш | Š | š | ш | шар |

Правила произношения в сербском языке

В сербском языке используются равноправно кириллица и латиница, причём правила правописания и произношения одинаковы для обоих шрифтов.

Произношение сербского языка основывается на фонетическом принципе: «Пиши так, как говоришь, и читай так, как написано».

Гласные

Все гласные в сербском языке надо произносить как соответствующие русские гласные под ударением, независимо от того, находятся ли они под ударением или нет. Это обозначает, что в сербском языке нет редукции безударных гласных. Разница между сербскими и русскими гласными состоит еще в том, что в звук «р» в некоторых случаях является гласным звуком и может быть под ударением. Ударение чаще всего находится на первом или втором слоге, и никогда не находится на последнем (за исключением некоторых слов иностранного происхождения). В транскрипции примеров слог под ударением выделен жирным шрифтом. В сербском языке существуют четыре различных типа ударения, которые здесь рассматриваться не будут.

Согласные

Согласно фонетическому принципу согласные произносятся так, как приведено в таблице сербской азбуки и всегда одинаково, в независимости от того перед какими гласным они находятся. Большинство из них произносятся одинаково или очень похоже на произношение соответствующих русских согласных, за исключением букв џ, ђ, ч, ћ, которые в русском языку не существуют. Џ произносится примерно как русское дж в слове джаз, а Ђ как джь. Ч произносится тверже русского ч, а Ћ мягче русского ч.

Примечание: В сербском языке существуют два варианта произношения — экавское и иекавское. Экавское встречается в большей части Сербии, иекавское в Черногории и некоторых районах Сербии. Разница заключается в том, что в экавице старославянская гласная «ѣ» перешла в «э», а в иекавице в «(и)йе». В этой статье будет рассмотрен экавский вариант как наиболее употребляемый в Сербии.

СУЩЕСТВИТЕЛЬНОЕ

В сербском языке три рода: мужской, женский и средний. В большинстве случаев род существительного можно определить на основании окончания. Как правило существительные мужского рода оканчиваются на согласную, женского рода на гласную -а, среднего рода на гласные -о или -е. Однако существует несколько существительных мужского рода, которые оканчиваются на букву -а, в то время как некоторые существительные женского рода оканчиваются на согласную. Существительные склоняются по падежам. В сербском языке семь падежей, т.е. кроме шести падежей, существующих в русском языке, существует еще звательный падеж.

Примеры склонений существительных

Единственное число

| Падеж | Мужской род | Женский род | Средний род |

|---|---|---|---|

| И | ученик | ученица | море |

| Р | ученика | ученице | мора |

| Д | ученику | ученици | мору |

| В | ученика | ученицу | море |

| З | учениче | ученице | море |

| Т | учеником | ученицом | морем |

| П | ученику | ученици | мору |

Множественное число

| Падеж | Мужской род | Женский род | Средний род |

|---|---|---|---|

| И | ученици | ученице | мора |

| Р | ученика | ученица | мора |

| Д | ученицима | ученицама | морима |

| В | ученике | ученице | мора |

| З | ученици | ученице | мора |

| Т | ученицима | ученицама | морима |

| П | ученицима | ученицама | морима |

ПРИЛАГАТЕЛЬНОЕ

Прилагательные, как и существительные, могут быть мужского, женского и среднего рода, при чём их род, число и падеж зависит от рода, числа и падежа существительных, которые прилагательные описывают. Здесь приведен пример склонения прилагательного леп (красивый).

Примеры склонений прилагательных

Единственное число

| Падеж | Мужской род | Женский род | Средний род |

|---|---|---|---|

| И | леп | лепа | лепо |

| Р | лепог | лепе | лепог |

| Д | лепом | лепој | лепом |

| В | леп (лепог) | лепу | лепо |

| З | лепи | лепа | лепо |

| Т | лепим | лепом | лепим |

| П | лепом | лепој | лепом |

Множественное число

| Падеж | Мужской род | Женский род | Средний род |

|---|---|---|---|

| И | лепи | лепе | лепи |

| Р | лепих | лепих | лепих |

| Д | лепим | лепим | лепим |

| В | лепе | лепе | лепе |

| З | лепи | лепе | лепе |

| Т | лепим | лепим | лепим |

| П | лепим | лепим | лепим |

МЕСТОИМЕНИЕ

Формы именительного падежа наиболее употребительных местоимений приведены в вводной части. Мы здесь приведем только склонение личных местоимений, так как притяжательные местоимения склоняются как прилагательные.

Склонение личных местоимений

Единственное число

| Падеж | 1-ое лицо | 2-ое лицо | 3-е лицо |

|---|---|---|---|

| И | ја | ти | он, она, оно |

| Р | мене/ме | тебе/те | њега/га, ње/је, њега/га |

| Д | мени/ми | теби/ти | њему/му, њој/јој, њега/га |

| В | мене/ме | тебе/те | њега/га, њу/ју, њега/га |

| З | — | ти | — |

| Т | (са) мном | тобом | њим, њој, њим |

| П | (о) мени | теби | њему, њој, њему |

Множественное число

| Падеж | 1-ое лицо | 2-ое лицо | 3-е лицо |

|---|---|---|---|

| И | ми | ви | они, оне, она |

| Р | нас | вас | њих/их |

| Д | нама/нам | вама/вам | њима/им |

| В | нас | вас | њих/их |

| З | — | ви | — |

| Т | нама | вама | њима |

| П | (о) нама | (о) вама | (о) њима |

ГЛАГОЛЫ

Обозначение лица местоимением в сербском языке не является необходимым, так как в окончаниях содержатся указания на лицо.

Неопределенная форма глаголов в сербском языке оканчивается на -ти или -ћи.

В сербском языке больше временных форм, чем в русском, но будет достаточно привести три основные формы настоящего, прошедшего и будущего времени, при чем:

Настоящее время образуется с помощью окончаний, а прошедшее и будущее время с помощью вспомогательных глаголов.

Прошедшее время образуется с помощью формы настоящего времени вспомогательного глагола бити (быть) и действительного причастия необходимого нам глагола. Действительное причастие образуется из основы глагола и окончаний:

в единственном числе

-о (мужской род),

-ла (женский род),

-ло (средний род);

во множественном числе

-ли (мужской род),

-ле (женский род),

-ла (средний род).

Будущее время образуется из краткой (безударной) формы настоящего времени вспомогательного глагола хтети (хотеть) и неопределенной формы необходимого нам глагола. Окончания, т.е. вспомогательные глаголы и окончания действительного причастия в примерах спряженияй выделены жирным шрифтом.

ПРИМЕРЫ НАСТОЯЩЕГО ВРЕМЕНИ

играти

(танцевать)

писати

(писать)

радити

(работать, делать)

пити

(пить)

Единственное число

1 л. играм

пишем

радим

пијем

2 л. играш

пишеш

радиш

пијеш

Множественное число

1 л. играмо

пишемо

радимо

пијемо

2 л. играте

пишете

радите

пијете

3 л. играју

пишу

раде

пију

ПРИМЕРЫ ПРОШЕДШЕГО ВРЕМЕНИ

волети (любить)

Единственное число

1 л. ја сам волео/-ла/-ло или волео/-ла/ло сам

2 л. ти си волео/-ла/-ло или волео/-ла/-ло си

3 л. он/она/оно је волео/ ла/-ло или волео/-ла/-ло је

Множественное число

1 л. ми смо волели/-ле/-ла или волели/-ле/-ла смо

2 л. ви сте волели/-ле/-ла или волели/-ле/-ла сте

3 л. они/оне/она су волели/-ле/-ла или волели/-ле/-ла су

ПРИМЕРЫ БУДУЩЕГО ВРЕМЕНИ

путовати (путешествовать)

Единственное число

1 л. ја ћу путовати или путоваћу

2 л. ти ћеш путовати или путоваћеш

3 л. он/она/оно ће путовати или путоваће

Множественное число

1 л. ми ћемо путовати или путоваћемо

2 л. ви ћете путовати или путоваћете

3 л. они/оне/она ће путовати или путоваће

Второй вариант использования и для прошедшего и для будущего времени применяется в случае, если не используются личные местоимения.

ЧИСЛИТЕЛЬНЫЕ

Количественные:

Порядковые:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Serbian alphabet» redirects here. For the Serbian Latin alphabet, see Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

| Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

Српска ћирилица |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

alphabet |

|

Time period |

9th century – present |

| Languages | Serbian |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs[1]

|

|

Child systems |

Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet Montenegrin Cyrillic alphabet Slavica alphabet [sh] |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrl (220), Cyrillic |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Cyrillic |

|

Unicode range |

subset of Cyrillic (U+0400…U+04FF) |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet (Serbian: Српска ћирилица / Srpska ćirilica, pronounced [sr̩̂pskaː tɕirǐlitsa]) is a variation of the Cyrillic script used to write the Serbian language, updated in 1818 by the Serbian philologist and linguist Vuk Karadžić. It is one of the two alphabets used to write modern standard Serbian, the other being Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

Karadžić based his alphabet on the previous Slavonic-Serbian script, following the principle of «write as you speak and read as it is written», removing obsolete letters and letters representing iotified vowels, introducing ⟨J⟩ from the Latin alphabet instead, and adding several consonant letters for sounds specific to Serbian phonology. During the same period, linguists led by Ljudevit Gaj adapted the Latin alphabet, in use in western South Slavic areas, using the same principles. As a result of this joint effort, Serbian Cyrillic and Gaj’s Latin alphabets for Serbian-Croatian have a complete one-to-one congruence, with the Latin digraphs Lj, Nj, and Dž counting as single letters.

Karadžić’s Cyrillic alphabet was officially adopted in the Principality of Serbia in 1868, and was in exclusive use in the country up to the interwar period. Both alphabets were official in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and later in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Due to the shared cultural area, Gaj’s Latin alphabet saw a gradual adoption in the Socialist Republic of Serbia since, and both scripts are used to write modern standard Serbian. In Serbia, Cyrillic is seen as being more traditional, and has the official status (designated in the constitution as the «official script», compared to Latin’s status of «script in official use» designated by a lower-level act, for national minorities). It is also an official script in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, along with Gaj’s Latin.

Official use[edit]

Serbian Cyrillic is in official use in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2] Although Bosnia «officially accept[s] both alphabets»,[2] the Latin script is almost always used in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[2] whereas Cyrillic is in everyday use in Republika Srpska.[2][3] The Serbian language in Croatia is officially recognized as a minority language; however, the use of Cyrillic in bilingual signs has sparked protests and vandalism.

Serbian Cyrillic is an important symbol of Serbian identity.[4] In Serbia, official documents are printed in Cyrillic only[5] even though, according to a 2014 survey, 47% of the Serbian population write in the Latin alphabet whereas 36% write in Cyrillic.[6]

Modern alphabet[edit]

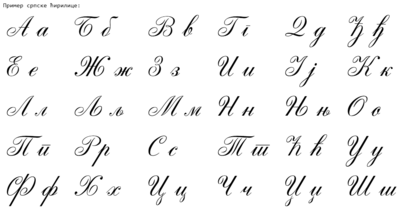

Example of typical cursive modern Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

Capital letters of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, along with the equivalent forms in the Serbian Latin alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) value for each letter. The letters do not have names, and consonants are normally pronounced as such when spelling is necessary (or followed by a short schwa, e.g. /fə/).:

|

|

Summary tables

| A | a | B | b | C | c | Č | č | Ć | ć | D | d | Dž | dž | Đ | đ | E | e | F | f | G | g | H | h | I | i | J | j | K | k |

| А | а | Б | б | Ц | ц | Ч | ч | Ћ | ћ | Д | д | Џ | џ | Ђ | ђ | Е | е | Ф | ф | Г | г | Х | х | И | и | Ј | ј | К | к |

| L | l | Lj | lj | M | m | N | n | Nj | nj | O | o | P | p | R | r | S | s | Š | š | T | t | U | u | V | v | Z | z | Ž | ž |

| Л | л | Љ | љ | М | м | Н | н | Њ | њ | О | о | П | п | Р | р | С | с | Ш | ш | Т | т | У | у | В | в | З | з | Ж | ж |

| А | а | Б | б | В | в | Г | г | Д | д | Ђ | ђ | Е | е | Ж | ж | З | з | И | и | Ј | ј | К | к | Л | л | Љ | љ | М | м |

| A | a | B | b | V | v | G | g | D | d | Đ | đ | E | e | Ž | ž | Z | z | I | i | J | j | K | k | L | l | Lj | lj | M | m |

| Н | н | Њ | њ | О | о | П | п | Р | р | С | с | Т | т | Ћ | ћ | У | у | Ф | ф | Х | х | Ц | ц | Ч | ч | Џ | џ | Ш | ш |

| N | n | Nj | nj | O | o | P | p | R | r | S | s | T | t | Ć | ć | U | u | F | f | H | h | C | c | Č | č | Dž | dž | Š | š |

Early history[edit]

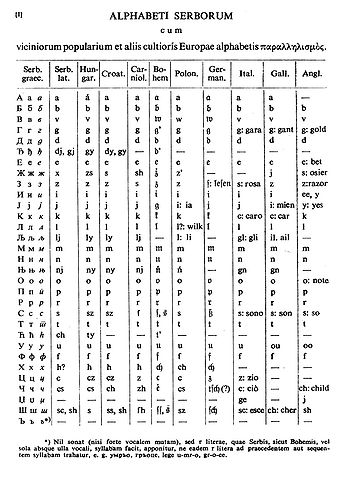

Serbian Cyrillic, from Comparative orthography of European languages. Source: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić «Srpske narodne pjesme» (Serbian folk poems), Vienna, 1841

Early Cyrillic[edit]

According to tradition, Glagolitic was invented by the Byzantine Christian missionaries and brothers Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 860s, amid the Christianization of the Slavs. Glagolitic alphabet appears to be older, predating the introduction of Christianity, only formalized by Cyril and expanded to cover non-Greek sounds. The Glagolitic alphabet was gradually superseded in later centuries by the Cyrillic script, developed around by Cyril’s disciples, perhaps at the Preslav Literary School at the end of the 9th century.[7]

The earliest form of Cyrillic was the ustav, based on Greek uncial script, augmented by ligatures and letters from the Glagolitic alphabet for consonants not found in Greek. There was no distinction between capital and lowercase letters. The standard language was based on the Slavic dialect of Thessaloniki.[7]

Medieval Serbian Cyrillic[edit]

Part of the Serbian literary heritage of the Middle Ages are works such as Miroslav Gospel, Vukan Gospels, St. Sava’s Nomocanon, Dušan’s Code, Munich Serbian Psalter, and others. The first printed book in Serbian was the Cetinje Octoechos (1494).

Karadžić’s reform[edit]

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić fled Serbia during the Serbian Revolution in 1813, to Vienna. There he met Jernej Kopitar, a linguist with interest in slavistics. Kopitar and Sava Mrkalj helped Vuk to reform Serbian and its orthography. He finalized the alphabet in 1818 with the Serbian Dictionary.

Karadžić reformed standard Serbian and standardised the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by following strict phonemic principles on the Johann Christoph Adelung’ model and Jan Hus’ Czech alphabet. Karadžić’s reforms of standard Serbian modernised it and distanced it from Serbian and Russian Church Slavonic, instead bringing it closer to common folk speech, specifically, to the dialect of Eastern Herzegovina which he spoke. Karadžić was, together with Đuro Daničić, the main Serbian signatory to the Vienna Literary Agreement of 1850 which, encouraged by Austrian authorities, laid the foundation for Serbian, various forms of which are used by Serbs in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia today. Karadžić also translated the New Testament into Serbian, which was published in 1868.

He wrote several books; Mala prostonarodna slaveno-serbska pesnarica and Pismenica serbskoga jezika in 1814, and two more in 1815 and 1818, all with the alphabet still in progress. In his letters from 1815-1818 he used: Ю, Я, Ы and Ѳ. In his 1815 song book he dropped the Ѣ.[8]

The alphabet was officially adopted in 1868, four years after his death.[9]

From the Old Slavic script Vuk retained these 24 letters:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

He added one Latin letter:

And 5 new ones:

| Ђ ђ | Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Џ џ |

He removed:

| Ѥ ѥ (је) | Ѣ, ѣ (јат) | І ї (и) | Ѵ ѵ (и) | Оу оу (у) | Ѡ ѡ (о) | Ѧ ѧ (мали јус) | Ѫ ѫ (велики јус) | Ы ы (јери, тврдо и) | |

| Ю ю (ју) | Ѿ ѿ (от) | Ѳ ѳ (т) | Ѕ ѕ (дз) | Щ щ (шт) | Ѯ ѯ (кс) | Ѱ ѱ (пс) | Ъ ъ (тврди полуглас) | Ь ь (меки полуглас) | Я я (ја) |

Modern history[edit]

Austria-Hungary[edit]

Orders issued on the 3 and 13 October 1914 banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, limiting it for use in religious instruction. A decree was passed on January 3, 1915, that banned Serbian Cyrillic completely from public use. An imperial order in October 25, 1915, banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, except «within the scope of Serbian Orthodox Church authorities».[10][11]

World War II[edit]

In 1941, the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia banned the use of Cyrillic,[12] having regulated it on 25 April 1941,[13] and in June 1941 began eliminating «Eastern» (Serbian) words from Croatian, and shut down Serbian schools.[14][15]

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was used as a basis for the Macedonian alphabet with the work of Krste Misirkov and Venko Markovski.

Yugoslavia[edit]

The Serbian Cyrillic script was one of the two official scripts used to write Serbo-Croatian in Yugoslavia since its establishment in 1918, the other being Gaj’s Latin alphabet (latinica).

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Serbian Cyrillic is no longer used in Croatia on national level, while in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro it remained an official script.[16]

Contemporary period[edit]

Under the Constitution of Serbia of 2006, Cyrillic script is the only one in official use.[17]

Special letters[edit]

The ligatures:

| Ђ ђ | Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Џ џ |

were developed specially for the Serbian alphabet.

- Karadžić based the letters ⟨Љ⟩ and ⟨Њ⟩ on a design by Serb linguist, grammarian, philologist, and poet Sava Mrkalj, known for his attempt to reform the Serbian language before, combining the letters ⟨Л⟩ (L) and ⟨Н⟩ (N) with the soft sign (Ь).

- Karadžić based ⟨Џ⟩ on letter «Gea» in the Old Serbian Cyrillic alphabet.[citation needed]

- ⟨Ћ⟩ was adopted by Karadžić to represent the voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate (IPA: /tɕ/). The letter was based on, but different in appearance to, the letter Djerv, which is the 12th letter of the Glagolitic alphabet; that letter had been used in written Serbian since the 12th century, to represent /ɡʲ/, /dʲ/ and /dʑ/.

- Karadžić adopted a design by Serbian poet, prose writer, polyglot, and Serbian Orthodox bishop Lukijan Mušicki for the letter ⟨Ђ⟩. It was based on the letter ⟨Ћ⟩, as adapted by Karadžić.

- ⟨Ј⟩ was adopted from the Latin alphabet, apparently in preference to ⟨Й⟩.

Differences from other Cyrillic alphabets[edit]

Alternate variants of lowercase Cyrillic letters: Б/б, Д/д, Г/г, И/и, П/п, Т/т, Ш/ш.

Default Russian (Eastern) forms on the left.

Alternate Bulgarian (Western) upright forms in the middle.

Alternate Serbian/Macedonian (Southern) italic forms on the right.

See also:

Serbian Cyrillic does not use several letters encountered in other Slavic Cyrillic alphabets. It does not use hard sign (ъ) and soft sign (ь), but the aforementioned soft-sign ligatures instead. It does not have Russian/Belarusian Э, Ukrainian/Belarusian І, the semi-vowels Й or Ў, nor the iotated letters Я (Russian/Bulgarian ya), Є (Ukrainian ye), Ї (yi), Ё (Russian yo) or Ю (yu), which are instead written as two separate letters: Ја, Је, Ји, Јо, Ју. Ј can also be used as a semi-vowel, in place of й. The letter Щ is not used. When necessary, it is transliterated as either ШЧ, ШЋ or ШТ.

Serbian italic and cursive forms of lowercase letters б, г, д, п, and т (Russian Cyrillic alphabet) differ from those used in other Cyrillic alphabets: б, г, д, п, and т (Serbian Cyrillic alphabet). The regular (upright) shapes are generally standardized among languages and there are no officially recognized variations.[18][19] That presents a challenge in Unicode modeling, as the glyphs differ only in italic versions, and historically non-italic letters have been used in the same code positions. Serbian professional typography uses fonts specially crafted for the language to overcome the problem, but texts printed from common computers contain East Slavic rather than Serbian italic glyphs. Cyrillic fonts from Adobe,[20] Microsoft (Windows Vista and later) and a few other font houses[citation needed] include the Serbian variations (both regular and italic).

If the underlying font and Web technology provides support, the proper glyphs can be obtained by marking the text with appropriate language codes. Thus, in non-italic mode:

<span lang="sr">бгдпт</span>, produces in Serbian language script: бгдпт, same (except for the shape of б) as<span lang="ru">бгдпт</span>, producing in Russian language script: бгдпт

whereas:

<span lang="sr" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>gives in Serbian language script: бгдпт, and<span lang="ru" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>produces in Russian language script: бгдпт.

Since Unicode unifies different glyphs in same characters,[21] font support must be present to display the correct variant. Programs like Mozilla Firefox, LibreOffice (currently[when?] under Linux only), and some others provide required OpenType support. Of course[why?], font families like Fira, Noto, Overpass, PT Fonts, Liberation, Gentium, Open Sans, Lato, IBM Plex Serif, Croscore fonts, GNU FreeFont, DejaVu, Ubuntu, Microsoft «C*» fonts from Windows Vista and above must be used.

Keyboard layout[edit]

The standard Serbian keyboard layout for personal computers is as follows:

See also[edit]

- Gaj’s Latin alphabet

- Yugoslav braille

- Yugoslav manual alphabet

- Romanization of Serbian

- Serbian calligraphy

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. «First Alphabet Found in Egypt», Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- ^ a b c d Ronelle Alexander (15 August 2006). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-299-21193-6.

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella (15 January 2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-55070-4.

In addition, today, neither Bosniaks nor Croats, but only Serbs use Cyrillic in Bosnia.

- ^ Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. 13 June 2013. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

- ^ «Ćeranje ćirilice iz Crne Gore». www.novosti.rs.

- ^ «Ivan Klajn: Ćirilica će postati arhaično pismo». B92.net.

- ^ a b Cubberley, Paul (1996) «The Slavic Alphabets». in Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright, eds. (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ^ The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, p. 387

- ^ Vek i po od smrti Vuka Karadžića (in Serbian), Radio-Television of Serbia, 7 February 2014

- ^ Andrej Mitrović, Serbia’s great war, 1914-1918 p.78-79. Purdue University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-55753-477-2, ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4

- ^ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia’s Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780195333435.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 312–. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- ^ Enver Redžić (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. Psychology Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0.

- ^ Alex J. Bellamy (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester University Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6502-6.

- ^ David M. Crowe (13 September 2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-317-98682-9.

- ^ Yugoslav Survey. Vol. 43. Jugoslavija Publishing House. 2002. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ Article 10 of the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (English version Archived 2011-03-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- ^ Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.

- ^ «Adobe Standard Cyrillic Font Specification — Technical Note #5013» (PDF). 18 February 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ^ «Unicode 8.0.0 ch.02 p.14-15» (PDF).

Sources[edit]

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). «Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries». Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Sir Duncan Wilson, The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, 1787-1864: literacy, literature and national independence in Serbia, p. 387. Clarendon Press, 1970. Google Books

External links[edit]

- Omniglot – Serbian and Croatian

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

«Serbian alphabet» redirects here. For the Serbian Latin alphabet, see Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

| Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

Српска ћирилица |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Script type |

alphabet |

|

Time period |

9th century – present |

| Languages | Serbian |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs[1]

|

|

Child systems |

Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet Montenegrin Cyrillic alphabet Slavica alphabet [sh] |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrl (220), Cyrillic |

| Unicode | |

|

Unicode alias |

Cyrillic |

|

Unicode range |

subset of Cyrillic (U+0400…U+04FF) |

| This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between [ ], / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters. |

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet (Serbian: Српска ћирилица / Srpska ćirilica, pronounced [sr̩̂pskaː tɕirǐlitsa]) is a variation of the Cyrillic script used to write the Serbian language, updated in 1818 by the Serbian philologist and linguist Vuk Karadžić. It is one of the two alphabets used to write modern standard Serbian, the other being Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

Karadžić based his alphabet on the previous Slavonic-Serbian script, following the principle of «write as you speak and read as it is written», removing obsolete letters and letters representing iotified vowels, introducing ⟨J⟩ from the Latin alphabet instead, and adding several consonant letters for sounds specific to Serbian phonology. During the same period, linguists led by Ljudevit Gaj adapted the Latin alphabet, in use in western South Slavic areas, using the same principles. As a result of this joint effort, Serbian Cyrillic and Gaj’s Latin alphabets for Serbian-Croatian have a complete one-to-one congruence, with the Latin digraphs Lj, Nj, and Dž counting as single letters.

Karadžić’s Cyrillic alphabet was officially adopted in the Principality of Serbia in 1868, and was in exclusive use in the country up to the interwar period. Both alphabets were official in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and later in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Due to the shared cultural area, Gaj’s Latin alphabet saw a gradual adoption in the Socialist Republic of Serbia since, and both scripts are used to write modern standard Serbian. In Serbia, Cyrillic is seen as being more traditional, and has the official status (designated in the constitution as the «official script», compared to Latin’s status of «script in official use» designated by a lower-level act, for national minorities). It is also an official script in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, along with Gaj’s Latin.

Official use[edit]

Serbian Cyrillic is in official use in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[2] Although Bosnia «officially accept[s] both alphabets»,[2] the Latin script is almost always used in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina,[2] whereas Cyrillic is in everyday use in Republika Srpska.[2][3] The Serbian language in Croatia is officially recognized as a minority language; however, the use of Cyrillic in bilingual signs has sparked protests and vandalism.

Serbian Cyrillic is an important symbol of Serbian identity.[4] In Serbia, official documents are printed in Cyrillic only[5] even though, according to a 2014 survey, 47% of the Serbian population write in the Latin alphabet whereas 36% write in Cyrillic.[6]

Modern alphabet[edit]

Example of typical cursive modern Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

Capital letters of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet

The following table provides the upper and lower case forms of the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet, along with the equivalent forms in the Serbian Latin alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) value for each letter. The letters do not have names, and consonants are normally pronounced as such when spelling is necessary (or followed by a short schwa, e.g. /fə/).:

|

|

Summary tables

| A | a | B | b | C | c | Č | č | Ć | ć | D | d | Dž | dž | Đ | đ | E | e | F | f | G | g | H | h | I | i | J | j | K | k |

| А | а | Б | б | Ц | ц | Ч | ч | Ћ | ћ | Д | д | Џ | џ | Ђ | ђ | Е | е | Ф | ф | Г | г | Х | х | И | и | Ј | ј | К | к |

| L | l | Lj | lj | M | m | N | n | Nj | nj | O | o | P | p | R | r | S | s | Š | š | T | t | U | u | V | v | Z | z | Ž | ž |

| Л | л | Љ | љ | М | м | Н | н | Њ | њ | О | о | П | п | Р | р | С | с | Ш | ш | Т | т | У | у | В | в | З | з | Ж | ж |

| А | а | Б | б | В | в | Г | г | Д | д | Ђ | ђ | Е | е | Ж | ж | З | з | И | и | Ј | ј | К | к | Л | л | Љ | љ | М | м |

| A | a | B | b | V | v | G | g | D | d | Đ | đ | E | e | Ž | ž | Z | z | I | i | J | j | K | k | L | l | Lj | lj | M | m |

| Н | н | Њ | њ | О | о | П | п | Р | р | С | с | Т | т | Ћ | ћ | У | у | Ф | ф | Х | х | Ц | ц | Ч | ч | Џ | џ | Ш | ш |

| N | n | Nj | nj | O | o | P | p | R | r | S | s | T | t | Ć | ć | U | u | F | f | H | h | C | c | Č | č | Dž | dž | Š | š |

Early history[edit]

Serbian Cyrillic, from Comparative orthography of European languages. Source: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić «Srpske narodne pjesme» (Serbian folk poems), Vienna, 1841

Early Cyrillic[edit]

According to tradition, Glagolitic was invented by the Byzantine Christian missionaries and brothers Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 860s, amid the Christianization of the Slavs. Glagolitic alphabet appears to be older, predating the introduction of Christianity, only formalized by Cyril and expanded to cover non-Greek sounds. The Glagolitic alphabet was gradually superseded in later centuries by the Cyrillic script, developed around by Cyril’s disciples, perhaps at the Preslav Literary School at the end of the 9th century.[7]

The earliest form of Cyrillic was the ustav, based on Greek uncial script, augmented by ligatures and letters from the Glagolitic alphabet for consonants not found in Greek. There was no distinction between capital and lowercase letters. The standard language was based on the Slavic dialect of Thessaloniki.[7]

Medieval Serbian Cyrillic[edit]

Part of the Serbian literary heritage of the Middle Ages are works such as Miroslav Gospel, Vukan Gospels, St. Sava’s Nomocanon, Dušan’s Code, Munich Serbian Psalter, and others. The first printed book in Serbian was the Cetinje Octoechos (1494).

Karadžić’s reform[edit]

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić fled Serbia during the Serbian Revolution in 1813, to Vienna. There he met Jernej Kopitar, a linguist with interest in slavistics. Kopitar and Sava Mrkalj helped Vuk to reform Serbian and its orthography. He finalized the alphabet in 1818 with the Serbian Dictionary.

Karadžić reformed standard Serbian and standardised the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by following strict phonemic principles on the Johann Christoph Adelung’ model and Jan Hus’ Czech alphabet. Karadžić’s reforms of standard Serbian modernised it and distanced it from Serbian and Russian Church Slavonic, instead bringing it closer to common folk speech, specifically, to the dialect of Eastern Herzegovina which he spoke. Karadžić was, together with Đuro Daničić, the main Serbian signatory to the Vienna Literary Agreement of 1850 which, encouraged by Austrian authorities, laid the foundation for Serbian, various forms of which are used by Serbs in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia today. Karadžić also translated the New Testament into Serbian, which was published in 1868.

He wrote several books; Mala prostonarodna slaveno-serbska pesnarica and Pismenica serbskoga jezika in 1814, and two more in 1815 and 1818, all with the alphabet still in progress. In his letters from 1815-1818 he used: Ю, Я, Ы and Ѳ. In his 1815 song book he dropped the Ѣ.[8]

The alphabet was officially adopted in 1868, four years after his death.[9]

From the Old Slavic script Vuk retained these 24 letters:

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ж ж | З з |

| И и | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о | П п | Р р |

| С с | Т т | У у | Ф ф | Х х | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш |

He added one Latin letter:

And 5 new ones:

| Ђ ђ | Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Џ џ |

He removed:

| Ѥ ѥ (је) | Ѣ, ѣ (јат) | І ї (и) | Ѵ ѵ (и) | Оу оу (у) | Ѡ ѡ (о) | Ѧ ѧ (мали јус) | Ѫ ѫ (велики јус) | Ы ы (јери, тврдо и) | |

| Ю ю (ју) | Ѿ ѿ (от) | Ѳ ѳ (т) | Ѕ ѕ (дз) | Щ щ (шт) | Ѯ ѯ (кс) | Ѱ ѱ (пс) | Ъ ъ (тврди полуглас) | Ь ь (меки полуглас) | Я я (ја) |

Modern history[edit]

Austria-Hungary[edit]

Orders issued on the 3 and 13 October 1914 banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, limiting it for use in religious instruction. A decree was passed on January 3, 1915, that banned Serbian Cyrillic completely from public use. An imperial order in October 25, 1915, banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, except «within the scope of Serbian Orthodox Church authorities».[10][11]

World War II[edit]

In 1941, the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia banned the use of Cyrillic,[12] having regulated it on 25 April 1941,[13] and in June 1941 began eliminating «Eastern» (Serbian) words from Croatian, and shut down Serbian schools.[14][15]

The Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was used as a basis for the Macedonian alphabet with the work of Krste Misirkov and Venko Markovski.

Yugoslavia[edit]

The Serbian Cyrillic script was one of the two official scripts used to write Serbo-Croatian in Yugoslavia since its establishment in 1918, the other being Gaj’s Latin alphabet (latinica).

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, Serbian Cyrillic is no longer used in Croatia on national level, while in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro it remained an official script.[16]

Contemporary period[edit]

Under the Constitution of Serbia of 2006, Cyrillic script is the only one in official use.[17]

Special letters[edit]

The ligatures:

| Ђ ђ | Љ љ | Њ њ | Ћ ћ | Џ џ |

were developed specially for the Serbian alphabet.

- Karadžić based the letters ⟨Љ⟩ and ⟨Њ⟩ on a design by Serb linguist, grammarian, philologist, and poet Sava Mrkalj, known for his attempt to reform the Serbian language before, combining the letters ⟨Л⟩ (L) and ⟨Н⟩ (N) with the soft sign (Ь).

- Karadžić based ⟨Џ⟩ on letter «Gea» in the Old Serbian Cyrillic alphabet.[citation needed]

- ⟨Ћ⟩ was adopted by Karadžić to represent the voiceless alveolo-palatal affricate (IPA: /tɕ/). The letter was based on, but different in appearance to, the letter Djerv, which is the 12th letter of the Glagolitic alphabet; that letter had been used in written Serbian since the 12th century, to represent /ɡʲ/, /dʲ/ and /dʑ/.

- Karadžić adopted a design by Serbian poet, prose writer, polyglot, and Serbian Orthodox bishop Lukijan Mušicki for the letter ⟨Ђ⟩. It was based on the letter ⟨Ћ⟩, as adapted by Karadžić.

- ⟨Ј⟩ was adopted from the Latin alphabet, apparently in preference to ⟨Й⟩.

Differences from other Cyrillic alphabets[edit]

Alternate variants of lowercase Cyrillic letters: Б/б, Д/д, Г/г, И/и, П/п, Т/т, Ш/ш.

Default Russian (Eastern) forms on the left.

Alternate Bulgarian (Western) upright forms in the middle.

Alternate Serbian/Macedonian (Southern) italic forms on the right.

See also:

Serbian Cyrillic does not use several letters encountered in other Slavic Cyrillic alphabets. It does not use hard sign (ъ) and soft sign (ь), but the aforementioned soft-sign ligatures instead. It does not have Russian/Belarusian Э, Ukrainian/Belarusian І, the semi-vowels Й or Ў, nor the iotated letters Я (Russian/Bulgarian ya), Є (Ukrainian ye), Ї (yi), Ё (Russian yo) or Ю (yu), which are instead written as two separate letters: Ја, Је, Ји, Јо, Ју. Ј can also be used as a semi-vowel, in place of й. The letter Щ is not used. When necessary, it is transliterated as either ШЧ, ШЋ or ШТ.

Serbian italic and cursive forms of lowercase letters б, г, д, п, and т (Russian Cyrillic alphabet) differ from those used in other Cyrillic alphabets: б, г, д, п, and т (Serbian Cyrillic alphabet). The regular (upright) shapes are generally standardized among languages and there are no officially recognized variations.[18][19] That presents a challenge in Unicode modeling, as the glyphs differ only in italic versions, and historically non-italic letters have been used in the same code positions. Serbian professional typography uses fonts specially crafted for the language to overcome the problem, but texts printed from common computers contain East Slavic rather than Serbian italic glyphs. Cyrillic fonts from Adobe,[20] Microsoft (Windows Vista and later) and a few other font houses[citation needed] include the Serbian variations (both regular and italic).

If the underlying font and Web technology provides support, the proper glyphs can be obtained by marking the text with appropriate language codes. Thus, in non-italic mode:

<span lang="sr">бгдпт</span>, produces in Serbian language script: бгдпт, same (except for the shape of б) as<span lang="ru">бгдпт</span>, producing in Russian language script: бгдпт

whereas:

<span lang="sr" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>gives in Serbian language script: бгдпт, and<span lang="ru" style="font-style: italic">бгдпт</span>produces in Russian language script: бгдпт.

Since Unicode unifies different glyphs in same characters,[21] font support must be present to display the correct variant. Programs like Mozilla Firefox, LibreOffice (currently[when?] under Linux only), and some others provide required OpenType support. Of course[why?], font families like Fira, Noto, Overpass, PT Fonts, Liberation, Gentium, Open Sans, Lato, IBM Plex Serif, Croscore fonts, GNU FreeFont, DejaVu, Ubuntu, Microsoft «C*» fonts from Windows Vista and above must be used.

Keyboard layout[edit]

The standard Serbian keyboard layout for personal computers is as follows:

See also[edit]

- Gaj’s Latin alphabet

- Yugoslav braille

- Yugoslav manual alphabet

- Romanization of Serbian

- Serbian calligraphy

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. «First Alphabet Found in Egypt», Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- ^ a b c d Ronelle Alexander (15 August 2006). Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a Grammar: With Sociolinguistic Commentary. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-299-21193-6.

- ^ Tomasz Kamusella (15 January 2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-55070-4.

In addition, today, neither Bosniaks nor Croats, but only Serbs use Cyrillic in Bosnia.

- ^ Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. 13 June 2013. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

- ^ «Ćeranje ćirilice iz Crne Gore». www.novosti.rs.

- ^ «Ivan Klajn: Ćirilica će postati arhaično pismo». B92.net.

- ^ a b Cubberley, Paul (1996) «The Slavic Alphabets». in Daniels, Peter T., and William Bright, eds. (1996). The World’s Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ^ The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, p. 387

- ^ Vek i po od smrti Vuka Karadžića (in Serbian), Radio-Television of Serbia, 7 February 2014

- ^ Andrej Mitrović, Serbia’s great war, 1914-1918 p.78-79. Purdue University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-55753-477-2, ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4

- ^ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia’s Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780195333435.

- ^ Sabrina P. Ramet (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. pp. 312–. ISBN 0-253-34656-8.

- ^ Enver Redžić (2005). Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Second World War. Psychology Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-7146-5625-0.

- ^ Alex J. Bellamy (2003). The Formation of Croatian National Identity: A Centuries-old Dream. Manchester University Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6502-6.

- ^ David M. Crowe (13 September 2013). Crimes of State Past and Present: Government-Sponsored Atrocities and International Legal Responses. Routledge. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-317-98682-9.

- ^ Yugoslav Survey. Vol. 43. Jugoslavija Publishing House. 2002. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ^ Article 10 of the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (English version Archived 2011-03-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Peshikan, Mitar; Jerković, Jovan; Pižurica, Mato (1994). Pravopis srpskoga jezika. Beograd: Matica Srpska. p. 42. ISBN 86-363-0296-X.

- ^ Pravopis na makedonskiot jazik (PDF). Skopje: Institut za makedonski jazik Krste Misirkov. 2017. p. 3. ISBN 978-608-220-042-2.

- ^ «Adobe Standard Cyrillic Font Specification — Technical Note #5013» (PDF). 18 February 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ^ «Unicode 8.0.0 ch.02 p.14-15» (PDF).

Sources[edit]

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). «Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries». Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Sir Duncan Wilson, The life and times of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, 1787-1864: literacy, literature and national independence in Serbia, p. 387. Clarendon Press, 1970. Google Books

External links[edit]

- Omniglot – Serbian and Croatian

Не нужно быть специалистом, чтобы правильно ответить на вопрос о том, какой язык в Сербии является официальным. Разумеется, сербский (он же сербохорватский). Однако такая уверенность может сыграть злую шутку с путешественником, который решит пообщаться с местным населением с помощью разговорника, и тем более с потенциальным мигрантом. А все потому, что Сербия — многонациональная страна, где изъясняются минимум на 14 языках. Кроме того, в государстве существуют регионы, в которых официальными признаны сразу несколько наречий.

Южнославянские наречия в Сербии

И действительно, население Сербии говорит на таком количестве наречий, что становится совершенно ясно, зачем нужен сербский язык: чтобы местные жители могли хоть как-то понимать друг друга, а также чтобы можно было оформлять документы по единому образцу. Помимо сербского, в стране распространены и другие южнославянские языки. В частности, выходцы из Южной и Восточной Европы, осевшие в Сербии, разговаривают на:

- болгарском;

- македонском;

- боснийском;

- хорватском;

- черногорском.

При этом македонский язык является наиболее непривычным для славян – так сложилось исторически, поскольку македонцы испытывали большое влияние со стороны турок, персов и других народов. А вот выучить сербский (сербохорватский) язык для выходца из любой страны СНГ обычно не составляет труда.

Немного о сербохорватском языке

Сербский или, как его часто (но не всегда) называют, сербскохорватский язык, безусловно, заслуживает наибольшего внимания. Ведь это уникальный язык, имеющий целых две «письменные» формы, а с точки зрения лексики представляющий собой совокупность диалектизмов. Строго говоря, сербскохорватский — это койне, то есть язык, выработанный для бытового общения людей, проживающих на территории одного государства. В ХХ веке на нем преимущественно изъяснялись:

- сербы;

- хорваты;

- черногорцы;

- боснийцы.

Сербскохорватский язык (к истории его возникновения мы еще вернемся) можно условно разделить на два: сербский (сербско-хорватский) и хорватский (хорватско-сербский). Между ними существует множество различий. Например, в сербском принято записывать заимствованные слова по принципу «как слышится, так и пишется», а вот в хорватском стараются сохранить оригинальное написание. Кстати, призванный сгладить эту разницу сербскохорватский считается отдельным языком ЮНЕСКО.

Как пишут сербы: латиницей или кириллицей

Как говорилось выше, сербскохорватскую речь можно перенести на бумагу двумя способами. Причем в первом случае нужно будет использовать сербскую кириллицу, которую называют «вуковица», а во втором — хорватскую латиницу (гаевицу). Стоит отметить, что кириллица-вуковица — скорее, национальный символ Сербии, нежели практичная азбука, так как сербы предпочитают писать латиницей. В то же время правительственные инициативы, направленные на популяризацию сербской кириллицы, вызывают недовольство хорватов.

Однако официальной азбукой Сербии все же является кириллица, которой местное население пользуется свыше тысячи лет. Кириллицей ведется делопроизводство, ее используют представители власти и оппозиции. Впрочем, веб-ресурсы Сербии, даже государственные, все чаще предоставляют юзерам право выбора между кириллицей и латиницей.

В чем сходство славянских языков

К счастью для иностранца, изучающего местные языки, все южнославянские наречия очень похожи, к тому же каждое из них имеет много общего со старославянским и церковнославянским языком. Именно эти языки активно использовались в первой половине второго тысячелетия жителями Киевской Руси. Поэтому в хорватском, боснийском и других языках сохранилось множество форм прошедшего времени. К примеру, если речь заходит о будущем, выходцы из Южной Европы говорят «хочу», а не «стану» (точно так принято строить предложения и в современном украинском языке).

В чем еще проявляется сходство между славянскими языками, используемыми в Сербии? Например, если говорить о том, насколько похожи сербский и болгарский языки, то перечислять элементы их сходства можно бесконечно. Так, в большинстве славянских языков ударение ставится свободно (только в польском оно всегда приходится на предпоследний слог). Кроме того, в украинском, как и в сербском, болгарском и македонском, есть звательный падеж. А вот польский и чешский по лексическому составу больше напоминают русский, нежели украинский (если речь идет о простых общеупотребительных словах).

Как складывался современный сербский язык

Так что же стало причиной тотальной языковой путаницы? Дело в том, что Сербия не всегда была самостоятельным государством: освободившаяся во второй половине XII в. от господства Византии страна в XV в. была завоевана Турцией, при этом часть ее отошла к Австрийской империи. В ХХ веке сербы участвовали во множестве войн и то завоевывали новые территории (в частности, некоторые области Македонии и Черногории), то теряли их. Естественно, завоеватели принесли свои языки на эти земли. К тому же распространению десятков наречий в Сербии способствовало ее географическое положение. Как известно, сербское государство граничит с несколькими странами:

- Венгрией;

- Румынией;

- Болгарией;

- Албанией;

- Черногорией;

- Боснией и Герцеговиной.

Что касается сербскохорватского языка, то до середины ХХ века он считался литературным (но не разговорным) в Республике Югославии. Его нормы были выработаны сербскими филологами и писателями и закреплены Венским соглашением в 1850 году. При этом лингвисты зафиксировали как особенности грамматики, так и уникальные слова в сербском языке, что позволяет им успешно пользоваться до настоящего времени. Именно поэтому сербский и хорватский не всегда выделяются в отдельные наречия. И хотя в 30-е годы минувшего столетия хорватские националисты предпринимали попытки создать ряд неологизмов, чтобы отделить-таки «свой» язык от сербского, однако придуманные ими слова в большинстве своем не прижились.

Прочие распространенные в Сербии языки

Как уже было отмечено, в Сербии живут носители множества наречий. Поэтому однозначно ответить, на каком языке говорят в Белграде, довольно сложно. Разумеется, большинство жителей столицы изъясняется на сербском, но они вполне могут говорить на одном из южнославянских языков, о которых мы упоминали, а также на:

- венгерском;

- румынском;

- словацком;

- албанском;

- паннонско-русинском;

- украинском;

- цыганском;

- чешском;

- буневачском.

При этом следует помнить о том, что сам по себе сербский (сербскохорватский) язык неоднороден: в его составе есть как минимум четыре диалекта, наиболее распространенным из которых, особенно на юге страны, является торлакское наречие.

Кроме того, именно на этом наречии изъясняются жители пограничных городов в Болгарии и Македонии.

В некоторых областях Сербии официально признанными являются сразу несколько наречий. Яркий пример тому – автономный край Воеводина, где официальными являются сразу шесть языков:

- сербский (не сербохорватский);

- словацкий;

- румынский;

- венгерский;

- хорватский;

- русинский.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A road sign in Serbia using Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. The towns are Šid (pronounced [ʃiːd]), Novi Sad and Belgrade.

The romanization of Serbian or latinization of Serbian is the representation of the Serbian language using Latin letters. Serbian is written in two alphabets, Serbian Cyrillic, a variation of the Cyrillic alphabet, and Gaj’s Latin, or latinica, a variation of the Latin alphabet. The Serbian language is an example of digraphia.

Main alphabets used in Europe around 1900:

Latin script: Antiqua variant

Gaj’s Latin alphabet is widely used in Serbia. The two are almost directly and completely interchangeable. Romanization can be done with no errors, but in some cases knowledge of Serbian is required to do proper transliteration from Latin back to Cyrillic. Standard Serbian uses both alphabets currently. A survey from 2014 showed that 47% of the Serbian population favors the Latin alphabet whereas 36% favors Cyrillic; the remaining 17% preferred neither.[1]

Use of romanization[edit]

Đuro Daničić added Đ instead of Dj in Croatian Academy 1882.

Serbo-Croatian was regarded as a single language since the 1850 Vienna Literary Agreement, to be written in two forms: one (Serb) in the adapted Serbian Cyrillic alphabet; the other (Croat) in the adapted Croatian Latin alphabet,[2] that is to say Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

The Latin alphabet was not initially taught in schools in Serbia when it became independent in the 19th century. After a series of efforts by Serbian writers Ljubomir Stojanović and Jovan Skerlić, it became part of the school curriculum after 1914.[3]

During World War I, Austria-Hungary banned the Cyrillic alphabet in Bosnia[4] and its use in occupied Serbia was banned in schools.[5] Cyrillic was banned in the Independent State of Croatia in World War II.[6] The government of socialist Yugoslavia made some initial effort to promote romanization, use of the Latin alphabet even in the Orthodox Serbian and Montenegrin parts of Yugoslavia, but met with resistance.[7] The use of latinica did however become more common among Serbian speakers.

In late 1980s, a number of articles had been published in Serbia about a danger of Cyrillic being fully replaced by Latin, thereby endangering what was deemed a Serbian national symbol.[8]

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, Gaj’s Latin alphabet remained in use in Bosnian and Croatian standards of Serbo-Croatian. Another standard of Serbo-Croatian, Montenegrin, uses a slightly modified version of it.

In 1993, the authorities of Republika Srpska under Radovan Karadžić and Momčilo Krajišnik decided to proclaim Ekavian and Serbian Cyrillic to be official in Republika Srpska, which was opposed both by native Bosnian Serb writers at the time and the general public, and that decision was rescinded in 1994.[9] Nevertheless, it was reinstated in a milder form in 1996, and today still the use of Serbian Latin is officially discouraged in Republika Srpska, in favor of Cyrillic.[10]

Article 10 of the Constitution of Serbia[11] adopted by a referendum in 2006 defined Cyrillic as the official script in Serbia, while Latin was given the status of «Script in official use».

Today Serbian is more likely to be romanized in Montenegro than in Serbia.[12] Exceptions to this include Serbian websites where use of Latin alphabet is often more convenient, and increasing use in tabloid and popular media such as Blic, Danas and Svet.[13] More established media, such as the formerly state-run Politika, and Radio Television of Serbia,[14] or foreign Google News,[15] Voice of Russia[16] and Facebook tend to use Cyrillic script.[17] Some websites offer the content in both scripts, using Cyrillic as the source and auto generating Romanized version.

In 2013 in Croatia there were massive protests against official Cyrillic signs on local government buildings in Vukovar.[18]

Romanization of names[edit]

Serbian place names[edit]

Serbian place names are consistently spelled in latinica using the mapping that exists between the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet and Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

Serbian personal names[edit]

Serbian personal names are usually romanized exactly the same way as place names. This is particularly the case with consonants which are common to other Slavic Latin alphabets — Č, Ć, Š, Ž, Dž and Đ.

A problem is presented by the letter Đ/đ that represents the affricate [dʑ] (the same sound written as <j> in most romanizations of Japanese, similar, though not identical to english <j> as in «Jam»), which is still sometimes represented by «Dj». The letter Đ was not part of the original Gaj’s alphabet, but was added by Đuro Daničić in the 19th century. A transcribed «Dj» is still sometimes encountered in rendering Serbian names into English (e.g. Novak Djokovic), though strictly Đ should be used (as in Croatian).

Foreign names[edit]

In Serbian, foreign names are phonetically transliterated into both Latin and Cyrillic, a change that does not happen in Croatian and Bosnian (also Latin). For example, in Serbian history books George Washington becomes Džordž Vašington or Џорџ Вашингтон, Winston Churchill becomes Vinston Čerčil or Винстон Черчил and Charles de Gaulle Šarl de Gol or Шарл де Гол.[19] This change also happens in some European languages that use the Latin alphabet such as Latvian. The name Catherine Ashton for instance gets transliterated into Ketrin Ešton or Кетрин Ештон in Serbian.

An exception to this are place names which are so well known as to have their own form (exonym): just as English has Vienna, Austria (and not German Wien, Österreich) so Croatian and romanization of Serbian have Beč, Austrija (Serbian Cyrillic: Беч, Аустрија).

Incomplete romanization[edit]

The incomplete romanization of Serbian is written using the English alphabet, also known as ASCII Serbian, by dropping diacritics. It is commonly used in SMS messages, comments on the Internet or e-mails, mainly because users do not have a Serbian keyboard installed. Serbian is a fully phonetic language with 30 sounds that can be represented with 30 Cyrillic letters, or with letters of 27 Gaj’s Latin alphabet and three digraphs («nj» for «њ», ”lj» for «љ», and «dž» for «џ»). In its ASCII form, the number of used letters drops down to 22, as the letters «q», «w», «x» and «y» are not used. This leads to some ambiguity due to homographs, however context is usually sufficient to clarify these issues.

Using incomplete romanization does not allow for easy transliteration back to Cyrillic without significant manual work. Google tried using a machine learning approach to solving this problem and developed an interactive text input tool that enables typing Serbian in ASCII and auto-converting to Cyrillic.[20] However, manual typing is still required with occasional disambiguation selection from the pop-up menu.

Tools for romanization[edit]

Serbian text can be converted from Cyrillic to Latin and vice versa automatically by computer. There are add-in tools available for Microsoft Word[21] and OpenOffice.org,[22] as well as command line tools for Linux, MacOS and Windows.

References[edit]

- ^ «Ivan Klajn: Ćirilica će postati arhaično pismo».

- ^ The World and Its Peoples 2009 — Page 1654 «Until modern times, Serbo-Croat was regarded as a single language, written in two forms: one (Serb) in the Cyrillic alphabet; the other (Croat) in …

- ^ Naimark, Norman M.; Case, Holly (2003). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0804745943. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ John Horne (16 March 2010). A Companion to World War I. John Wiley & Sons. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-4443-2364-1. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Serbia’s Great War 1914-1918. Purdue University Press. 2007. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Gregory R. Copley (1992). Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy. Copley & Associates. p. 17. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ The Social construction of written communication Bennett A. Rafoth, Donald L. Rubin — 1988 «Yugoslavian efforts to romanize Serbian (Kalogjera, 1985) and Chinese efforts to romanize Mandarin (De Francis, 1977b, 1984; Seybolt & Chiang, 1979) reveal that even authoritarian regimes may have to accept only limited success when the»

- ^ Bagdasarov, Artur (2018). «Ethnolinguistic policy in socialist Yugoslavia». Filologija. Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (71): 51. doi:10.21857/m8vqrtze29. ISSN 1848-8919. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Greenberg, Robert D. (2004). Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and Its Disintegration. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0191514551. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Greenberg, Robert D. (2004). Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and Its Disintegration. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0191514551. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ «Constitution Principles». Constitution of the Republic of Serbia. Government of Serbia. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ One thousand languages: living, endangered, and lost — Page 46 Peter Austin — 2008 «Croatian and Bosnian are written in the Latin alphabet; Serbian in both Serbia and Bosnia is written in the Cyrillic alphabet. Both scripts are used for Serbian in Montenegro.»

- ^ «Home». svet.rs.

- ^ «ТАНЈУГ | Новинска агенција».

- ^ https://news.google.com/[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ «Глас Русије». Archived from the original on 2013-04-24. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ Hitting the headlines in Europe: a country-by-country guide Page 166 Cathie Burton, Alun Drake — 2004 «The former state-run paper, Politika, which kept its retro style until very recently, using Serbian Cyrillic rather than the Latin alphabet, has been bought by a German company and is modernizing rapidly. There are a host of tabloids, ..»

- ^ Agence France-Presse, April 7, 2013 [1] Croatians protest against Cyrillic signs in Vukovar

- ^ Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a grammar: with sociolinguistic commentary — Page 3 Ronelle Alexander — 2006 -«… name in original Serbian (Cyrillic) Serbian (Latin) Croatian George Џорџ Džordž ; George Mary Мери Meri Mary ; Winston Churchill Винстон Черчил Vinston Čerčil Winston Churchill ; Charles de Gaulle Шарл де Гол Šarl de Gol Charles de Gaulle ;»

- ^ Google input tools for Serbian

- ^ Office 2003 Add-in: Latin and Cyrillic Transliteration

- ^ OOoTranslit add-on for OpenOffice

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A road sign in Serbia using Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. The towns are Šid (pronounced [ʃiːd]), Novi Sad and Belgrade.

The romanization of Serbian or latinization of Serbian is the representation of the Serbian language using Latin letters. Serbian is written in two alphabets, Serbian Cyrillic, a variation of the Cyrillic alphabet, and Gaj’s Latin, or latinica, a variation of the Latin alphabet. The Serbian language is an example of digraphia.

Main alphabets used in Europe around 1900:

Latin script: Antiqua variant

Gaj’s Latin alphabet is widely used in Serbia. The two are almost directly and completely interchangeable. Romanization can be done with no errors, but in some cases knowledge of Serbian is required to do proper transliteration from Latin back to Cyrillic. Standard Serbian uses both alphabets currently. A survey from 2014 showed that 47% of the Serbian population favors the Latin alphabet whereas 36% favors Cyrillic; the remaining 17% preferred neither.[1]

Use of romanization[edit]

Đuro Daničić added Đ instead of Dj in Croatian Academy 1882.

Serbo-Croatian was regarded as a single language since the 1850 Vienna Literary Agreement, to be written in two forms: one (Serb) in the adapted Serbian Cyrillic alphabet; the other (Croat) in the adapted Croatian Latin alphabet,[2] that is to say Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

The Latin alphabet was not initially taught in schools in Serbia when it became independent in the 19th century. After a series of efforts by Serbian writers Ljubomir Stojanović and Jovan Skerlić, it became part of the school curriculum after 1914.[3]

During World War I, Austria-Hungary banned the Cyrillic alphabet in Bosnia[4] and its use in occupied Serbia was banned in schools.[5] Cyrillic was banned in the Independent State of Croatia in World War II.[6] The government of socialist Yugoslavia made some initial effort to promote romanization, use of the Latin alphabet even in the Orthodox Serbian and Montenegrin parts of Yugoslavia, but met with resistance.[7] The use of latinica did however become more common among Serbian speakers.

In late 1980s, a number of articles had been published in Serbia about a danger of Cyrillic being fully replaced by Latin, thereby endangering what was deemed a Serbian national symbol.[8]

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, Gaj’s Latin alphabet remained in use in Bosnian and Croatian standards of Serbo-Croatian. Another standard of Serbo-Croatian, Montenegrin, uses a slightly modified version of it.

In 1993, the authorities of Republika Srpska under Radovan Karadžić and Momčilo Krajišnik decided to proclaim Ekavian and Serbian Cyrillic to be official in Republika Srpska, which was opposed both by native Bosnian Serb writers at the time and the general public, and that decision was rescinded in 1994.[9] Nevertheless, it was reinstated in a milder form in 1996, and today still the use of Serbian Latin is officially discouraged in Republika Srpska, in favor of Cyrillic.[10]

Article 10 of the Constitution of Serbia[11] adopted by a referendum in 2006 defined Cyrillic as the official script in Serbia, while Latin was given the status of «Script in official use».

Today Serbian is more likely to be romanized in Montenegro than in Serbia.[12] Exceptions to this include Serbian websites where use of Latin alphabet is often more convenient, and increasing use in tabloid and popular media such as Blic, Danas and Svet.[13] More established media, such as the formerly state-run Politika, and Radio Television of Serbia,[14] or foreign Google News,[15] Voice of Russia[16] and Facebook tend to use Cyrillic script.[17] Some websites offer the content in both scripts, using Cyrillic as the source and auto generating Romanized version.

In 2013 in Croatia there were massive protests against official Cyrillic signs on local government buildings in Vukovar.[18]

Romanization of names[edit]

Serbian place names[edit]

Serbian place names are consistently spelled in latinica using the mapping that exists between the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet and Gaj’s Latin alphabet.

Serbian personal names[edit]

Serbian personal names are usually romanized exactly the same way as place names. This is particularly the case with consonants which are common to other Slavic Latin alphabets — Č, Ć, Š, Ž, Dž and Đ.

A problem is presented by the letter Đ/đ that represents the affricate [dʑ] (the same sound written as <j> in most romanizations of Japanese, similar, though not identical to english <j> as in «Jam»), which is still sometimes represented by «Dj». The letter Đ was not part of the original Gaj’s alphabet, but was added by Đuro Daničić in the 19th century. A transcribed «Dj» is still sometimes encountered in rendering Serbian names into English (e.g. Novak Djokovic), though strictly Đ should be used (as in Croatian).

Foreign names[edit]

In Serbian, foreign names are phonetically transliterated into both Latin and Cyrillic, a change that does not happen in Croatian and Bosnian (also Latin). For example, in Serbian history books George Washington becomes Džordž Vašington or Џорџ Вашингтон, Winston Churchill becomes Vinston Čerčil or Винстон Черчил and Charles de Gaulle Šarl de Gol or Шарл де Гол.[19] This change also happens in some European languages that use the Latin alphabet such as Latvian. The name Catherine Ashton for instance gets transliterated into Ketrin Ešton or Кетрин Ештон in Serbian.

An exception to this are place names which are so well known as to have their own form (exonym): just as English has Vienna, Austria (and not German Wien, Österreich) so Croatian and romanization of Serbian have Beč, Austrija (Serbian Cyrillic: Беч, Аустрија).

Incomplete romanization[edit]

The incomplete romanization of Serbian is written using the English alphabet, also known as ASCII Serbian, by dropping diacritics. It is commonly used in SMS messages, comments on the Internet or e-mails, mainly because users do not have a Serbian keyboard installed. Serbian is a fully phonetic language with 30 sounds that can be represented with 30 Cyrillic letters, or with letters of 27 Gaj’s Latin alphabet and three digraphs («nj» for «њ», ”lj» for «љ», and «dž» for «џ»). In its ASCII form, the number of used letters drops down to 22, as the letters «q», «w», «x» and «y» are not used. This leads to some ambiguity due to homographs, however context is usually sufficient to clarify these issues.

Using incomplete romanization does not allow for easy transliteration back to Cyrillic without significant manual work. Google tried using a machine learning approach to solving this problem and developed an interactive text input tool that enables typing Serbian in ASCII and auto-converting to Cyrillic.[20] However, manual typing is still required with occasional disambiguation selection from the pop-up menu.

Tools for romanization[edit]

Serbian text can be converted from Cyrillic to Latin and vice versa automatically by computer. There are add-in tools available for Microsoft Word[21] and OpenOffice.org,[22] as well as command line tools for Linux, MacOS and Windows.

References[edit]

- ^ «Ivan Klajn: Ćirilica će postati arhaično pismo».

- ^ The World and Its Peoples 2009 — Page 1654 «Until modern times, Serbo-Croat was regarded as a single language, written in two forms: one (Serb) in the Cyrillic alphabet; the other (Croat) in …

- ^ Naimark, Norman M.; Case, Holly (2003). Yugoslavia and Its Historians: Understanding the Balkan Wars of the 1990s. Stanford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 0804745943. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ John Horne (16 March 2010). A Companion to World War I. John Wiley & Sons. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-4443-2364-1. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Serbia’s Great War 1914-1918. Purdue University Press. 2007. p. 231. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Gregory R. Copley (1992). Defense & Foreign Affairs Strategic Policy. Copley & Associates. p. 17. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ The Social construction of written communication Bennett A. Rafoth, Donald L. Rubin — 1988 «Yugoslavian efforts to romanize Serbian (Kalogjera, 1985) and Chinese efforts to romanize Mandarin (De Francis, 1977b, 1984; Seybolt & Chiang, 1979) reveal that even authoritarian regimes may have to accept only limited success when the»

- ^ Bagdasarov, Artur (2018). «Ethnolinguistic policy in socialist Yugoslavia». Filologija. Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (71): 51. doi:10.21857/m8vqrtze29. ISSN 1848-8919. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Greenberg, Robert D. (2004). Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and Its Disintegration. Oxford University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0191514551. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Greenberg, Robert D. (2004). Language and Identity in the Balkans: Serbo-Croatian and Its Disintegration. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0191514551. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ «Constitution Principles». Constitution of the Republic of Serbia. Government of Serbia. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ One thousand languages: living, endangered, and lost — Page 46 Peter Austin — 2008 «Croatian and Bosnian are written in the Latin alphabet; Serbian in both Serbia and Bosnia is written in the Cyrillic alphabet. Both scripts are used for Serbian in Montenegro.»

- ^ «Home». svet.rs.

- ^ «ТАНЈУГ | Новинска агенција».

- ^ https://news.google.com/[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ «Глас Русије». Archived from the original on 2013-04-24. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ^ Hitting the headlines in Europe: a country-by-country guide Page 166 Cathie Burton, Alun Drake — 2004 «The former state-run paper, Politika, which kept its retro style until very recently, using Serbian Cyrillic rather than the Latin alphabet, has been bought by a German company and is modernizing rapidly. There are a host of tabloids, ..»

- ^ Agence France-Presse, April 7, 2013 [1] Croatians protest against Cyrillic signs in Vukovar

- ^ Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, a grammar: with sociolinguistic commentary — Page 3 Ronelle Alexander — 2006 -«… name in original Serbian (Cyrillic) Serbian (Latin) Croatian George Џорџ Džordž ; George Mary Мери Meri Mary ; Winston Churchill Винстон Черчил Vinston Čerčil Winston Churchill ; Charles de Gaulle Шарл де Гол Šarl de Gol Charles de Gaulle ;»

- ^ Google input tools for Serbian

- ^ Office 2003 Add-in: Latin and Cyrillic Transliteration

- ^ OOoTranslit add-on for OpenOffice

| Сербская кириллица. | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Тип | Алфавит |

| Языки | сербохорватский. (кроме хорватского ) |

| Период времени | 1814 г. по настоящее время |

| Исходные системы | греческий алфавит (частично глаголица )

|

| Дочерние системы | Македонский. Черногорский |

| Направление | Слева направо |

| ISO 15924 | Cyrl, 220 |

| псевдоним Unicode | Кириллица |

| Unicode диапазон | подмножество кириллицы (U + 0400… U + 04F0) |

сербский кириллица (сербский : српска ћирилица / srpska ćirilica, произносится ) является адаптацией кириллицы для сербского языка, разработанной в 1818 году сербским лингвистом Вуком Караджичем. является одним из двух алфавитов, используемых для написания стандартных современных сербских, боснийских и черногорских, второй — латынь.

Караджич основал свой альп. habet на предыдущем сценарии «славяно-сербский », следуя принципу «пиши, как говоришь, и читай, как написано», удаляя устаревшие буквы и буквы, представляющие иотифицированные гласные, вводя Вместо этого J⟩ из латинского алфавита и добавление нескольких согласных букв для звуков, характерных для сербской фонологии. В тот же период хорватские лингвисты под руководством Людевита Гая адаптировали латинский алфавит, используемый в западных южнославянских регионах, используя те же принципы. В результате этих совместных усилий кириллица и латинский алфавиты для сербохорватского языка имеют полное взаимно-однозначное соответствие, при этом латинские диграфы Lj, Nj и Dž считаются отдельными буквами.

Кириллица Вука была официально принята в Сербии в 1868 году и использовалась исключительно в стране до межвоенного периода. Оба алфавита были официальными в Королевстве Югославия, а затем в Социалистической Федеративной Республике Югославии. Благодаря общему культурному пространству, латинский алфавит Гая постепенно получил распространение в Сербии, и оба алфавита используются для написания современных стандартных сербских, черногорских и боснийских языков; В хорватском языке используется только латинский алфавит. В Сербии кириллица считается более традиционной и имеет официальный статус (обозначенный в Конституции как «официальное письмо », по сравнению с латинским статусом «шрифта в официальном использовании», обозначенным нижним закон уровня, для национальных меньшинств). Это также официальный сценарий в Боснии и Герцеговине и Черногории, наряду с латынью.

Сербская кириллица была использована в качестве основы для македонского алфавита в трудах Криште Мисиркова и Венко Марковского.

Содержание

- 1 Официальное использование

- 2 Современный алфавит

- 3 Ранняя история

- 3.1 Ранняя кириллица

- 3.2 Средневековая сербская кириллица

- 4 Реформа Караджича

- 5 Современная история

- 5.1 Австро-Венгрия

- 5.2 Вторая мировая война

- 5.3 Югославия

- 5.4 Современный период

- 6 Специальные буквы

- 7 Отличия от других кириллических алфавитов

- 8 См. Также

- 9 Ссылки

- 9.1 Цитаты

- 9.2 Источники

- 10 Внешние ссылки

Официальное использование

Кириллица официально используется в Сербии, Черногории и Боснии и Герцеговине. Хотя боснийский язык «официально принимает [s] оба алфавита», латинский алфавит почти всегда используется в Федерации Боснии и Герцеговины, тогда как кириллица повседневно используется в Республике Сербской. сербский язык в Хорватии официально признан языком меньшинства, однако использование кириллицы в двуязычных знаках вызвало протесты и вандализм.

Кириллица является важным символом сербской идентичности. В Сербии официальные документы печатаются только на кириллице, хотя, согласно опросу 2014 года, 47% сербского населения пишут латиницей, а 36% пишут кириллицей.

Современный алфавит

В следующей таблице представлены заглавные и строчные формы сербской кириллицы, а также эквивалентные формы в сербском латинском алфавите и Значение международного фонетического алфавита (IPA) для каждой буквы:

|

|

Ранняя история

Ранняя кириллица

Согласно традиции, глаголицу изобрели византийские христианские миссионеры и братья Кирилл и Мефодий в 860-х годах, на фоне христианизации славян. Глаголица, по-видимому, старше, до появления христианства, формализована только Кириллом и расширена, чтобы охватить негреческие звуки. Кириллица была создана по приказу Бориса I из Болгарии учениками Кирилла, возможно, в Преславской литературной школе в 890-х гг.

Самой ранней формой кириллицы был устав, основанный на греческом унциале. письменность, дополненная лигатурами и буквами глаголического алфавита для согласных, не встречающихся в греческом языке. Не было различия между прописными и строчными буквами. Литературный славянский язык был основан на болгарском диалекте Салоник.

Средневековая сербская кириллица