| Vietnamese alphabet

chữ Quốc ngữ |

|

|---|---|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

| Creator | Portuguese and Italian Jesuits[1][2][3][4] and Alexandre de Rhodes |

| Languages | Vietnamese, other indigenous languages of Vietnam |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

The Vietnamese alphabet (Vietnamese: chữ Quốc ngữ, lit. ‘script of the National language’) is the modern Latin writing script or writing system for Vietnamese. It uses the Latin script based on Romance languages[5] originally developed by Portuguese missionary Francisco de Pina (1585 – 1625).[1]

The Vietnamese alphabet contains 29 letters, including seven letters using four diacritics: ă, â/ê/ô, ơ/ư, đ. There are an additional five diacritics used to designate tone (as in à, á, ả, ã, and ạ). The complex vowel system and the large number of letters with diacritics, which can stack twice on the same letter (e.g. nhất meaning «first»), makes it easy to distinguish the Vietnamese orthography from other writing systems that use the Latin script.[6]

The Vietnamese system’s use of diacritics produces an accurate transcription for tones despite the limitations of the Roman alphabet. On the other hand, sound changes in the spoken language have led to different letters, digraphs and trigraphs now representing the same sounds.

Letter names and pronunciation[edit]

Vietnamese uses all the letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet except for f, j, w, and z. These letters are only used to write loanwords, languages of other ethnic groups in the country based on Vietnamese phonetics to differentiate the meanings or even Vietnamese dialects, for example: dz or z for southerner pronunciation of v in standard Vietnamese.

In total, there are 12 vowels (nguyên âm) and 17 consonants (phụ âm, literally «extra sound»).

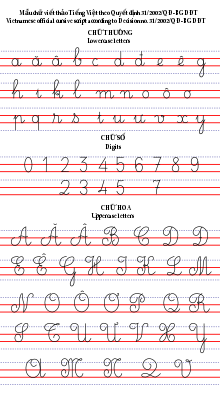

Handwritten Vietnamese alphabet

| Letter | Input keys | Name (when pronounced) |

IPA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TELEX | VNI | Northern | Southern | ||

| A a | a | /aː˧/ | /aː˧/ | ||

| Ă ă | AW

|

A8

|

á | /aː˧˥/ | /aː˧˥/ |

| Â â | AA

|

A6

|

ớ | /əː˧˥/ | /əː˧˥/ |

| B b | bê | /ɓe˧/ | /ɓe˧/ | ||

| C c | xê | /se˧/ | /se˧/ | ||

| D d | dê | /ze˧/ | /je˧/ | ||

| Đ đ | DD

|

D9

|

đê | /ɗe˧/ | /ɗe˧/ |

| E e | e | /ɛ˧/ | /ɛ˧/ | ||

| Ê ê | EE

|

E6

|

ê | /e˧/ | /e˧/ |

| G g | giê | /ʒe˧/ | /ʒe˧, ɹe˧/ | ||

| H h | hác | /ha:t˧˥/ | /hak˧˥/ | ||

| I i | i ngắn | /i˧ ŋan˧˥/ | /ɪi̯˧ ŋaŋ˧˥/[8] | ||

| K k | ca | /kaː˧/ | /kaː˧/ | ||

| L l | en lờ | /ɛn˧ ləː˨˩/ | /ɛŋ˧ ləː˨˩/ | ||

| M m | em mờ | /ɛm˧ məː˨˩/ | /ɛm˧ məː˨˩/ | ||

| N n | en nờ | /ɛn˧ nəː˨˩/ | /an˧ nəː˨˩/ | ||

| O o | o | /ɔ˧/ | /ɔ˧/ | ||

| Ô ô | OO

|

O6

|

ô | /o˧/ | /o˧/ |

| Ơ ơ | OW

|

O7

|

ơ | /əː˧/ | /əː˧/ |

| P p | pê | /pe˧/ | /pe˧/ | ||

| Q q | quy | /ku˧, kwi˧/ | /kwi˧/ | ||

| R r | e rờ | /ɛ˧ rəː˨˩/ | /ɛ˧ ɹəː˨˩/ | ||

| S s | ét sì | /ɛt˦˥ si˨˩/ | /ɛt˦˥, ə:t˦˥ (sə˨˩)/ | ||

| T t | tê | /te˧/ | /te˧/ | ||

| U u | u | /u˧/ | /ʊu̯˧/[8] | ||

| Ư ư | UW

|

U7

|

ư | /ɨ˧/ | /ɯ̽ɯ̯˧/[8] |

| V v | vê | /ve˧/ | /ve˧/ | ||

| X x | ích xì | /ik˦˥ si˨˩/ | /ɪ̈t˦˥ (si˨˩)/ | ||

| Y y | y dài | /i˧ zaːj˨˩/ | /ɪi̯˧ jaːj˨˩/[8] |

- Notes

- The vowels in the table are italicized.

- Pronouncing b as bê or bò and p as pê or pờ is to avoid confusion in some contexts, the same for s as sờ mạnh or sờ nặng (literally, «strong s» or «heavy s») and x as xờ nhẹ (literally, «light x»), i as i ngắn (literally, «short i») and y as y dài (literally, «long y»).

- Q and q is always followed by u in every word and phrase in Vietnamese, e.g. quần (trousers), quyến rũ (to attract), etc.

- The name i-cờ-rét for y is from the French name for the letter: i grec (Greek I),[9] referring to the letter’s origin from the Greek letter upsilon. The other obsolete French pronunciations include e (/ə:˧/) and u (/wi˧/).

- The Vietnamese alphabet does not contain the letters F (ép, ép-phờ), J (gi), W (u kép meaning «double u», vê kép, vê đúp meaning «double v») or Z (dét). However, these letters are often used for foreign loanwords or may be kept for foreign names.

- «Y» is most commonly treated as a vowel along with «i». «i» is «short /i˧/» and «y» is «long /i˧/«. «Y» can have tones as well as other vowels (ý, ỳ, ỹ, ỷ, ỵ) e.g. Mỹ (America). It may also act as a consonant (when used after â and a). It can sometimes be used to replace «i», e.g. «bánh mì» (bread) can also be written «bánh mỳ«.

- S and X are similar to each other in sound in Vietnamese and can sometimes replace each other e.g. sương xáo or sương sáo (grass jelly).

Consonants[edit]

The alphabet is largely derived from Portuguese with major influence from French, although the usage of gh and gi was borrowed from Italian (compare ghetto, Giuseppe) and that for c/k/qu from Greek and Latin (compare canis, kinesis, quō vādis), mirroring the English usage of these letters (compare cat, kite, queen).

| Grapheme | Word-initial (IPA) | Word-final | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern | Southern | Northern | Southern | ||

| B b | /ɓ/ | ||||

| C c | /k/ | /k̚/ | ⟨k⟩ is used instead when preceding ⟨i y e ê⟩. ⟨qu⟩ is used instead of ⟨co cu⟩ if a /w/ on-glide exists. Realized as [k͡p] in word-final position following rounded vowels ⟨u ô o⟩. |

||

| Ch ch | /tɕ/ | /c/ | /ʲk/ | /t̚/ | Multiple phonemic analyses of final ⟨ch⟩ have been proposed (main article). |

| D d | /z/ | /j/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨d⟩ represented /ð/. The distinction between ⟨d⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ is now purely etymological in most modern dialects. | ||

| Đ đ | /ɗ/ | ||||

| G g | /ɣ/ | ||||

| Gh gh | Spelling used ⟨gh⟩ instead of ⟨g⟩ before ⟨i e ê⟩, seemingly to follow the Italian convention. ⟨g⟩ is not allowed in these environments. | ||||

| Gi gi | /z/ | /j/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨gi⟩ represented /ʝ/. The distinction between ⟨d⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ is now purely etymological in most modern dialects. Realized as [ʑ] in Northern spelling pronunciation. Spelled ⟨g⟩ before another ⟨i⟩.[a] | ||

| H h | /h/ | ||||

| K k | /k/ | Spelling used instead of ⟨c⟩ before ⟨i y e ê⟩ to follow the European tradition. ⟨c⟩ is not allowed in these environments. | |||

| Kh kh | /x/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨kh⟩ was pronounced [kʰ] | |||

| L l | /l/ | ||||

| M m | /m/ | /m/ | |||

| N n | /n/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | In Southern Vietnamese, word-final ⟨n⟩ is realized as [ŋ] if not following ⟨i ê⟩. | |

| Ng ng | /ŋ/ | /ŋ/ | Realized as [ŋ͡m] in word-final position following rounded vowels ⟨u ô o⟩. | ||

| Ngh ngh | Spelling used instead of ⟨ng⟩ before ⟨i e ê⟩ in accordance with ⟨gh⟩. | ||||

| Nh nh | /ɲ/ | /ʲŋ/ | /n/ | Multiple phonemic analyses of final ⟨nh⟩ have been proposed (main article). | |

| P p | /p/ | Only occurs initially in loanwords. Some Vietnamese pronounce it as a «b» sound instead (as in Arabic). | |||

| Ph ph | /f/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨ph⟩ was pronounced [pʰ] | |||

| Qu qu | /kʷ/ | Spelling used in place of ⟨co cu⟩ if a /w/ on-glide exists. | |||

| R r | /z/ | /r/ | Variably pronounced as a fricative [ʐ], approximant [ɹ], flap [ɾ] or trill [r] in Southern speech. | ||

| S s | /s/ | /ʂ/ | Realized as [ʃ] in Northern spelling pronunciation. | ||

| T t | /t/ | /t̚/ | /k/ | In Southern Vietnamese, word-final ⟨t⟩ is realized as [k] if not following ⟨i ê⟩. | |

| Th th | /tʰ/ | ||||

| Tr tr | /tɕ/ | /ʈ/ | Realized as [tʃ] in Northern spelling pronunciation. | ||

| V v | /v/ | In Middle Vietnamese, it was represented by a b with flourish ⟨ Can be realized as [v] in Southern speech through spelling pronunciation and in loanwords. |

|||

| X x | /s/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨x⟩ was pronounced [ɕ]. |

- ^ This causes some ambiguity with the diphthong ia/iê, for example gia could be either gi+a [za ~ ja] or gi+ia [ziə̯ ~ jiə̯]. If there is a tone mark the ambiguity is resolved: giá is gi+á and gía is gi+ía.

Vowels[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

The correspondence between the orthography and pronunciation is somewhat complicated. In some cases, the same letter may represent several different sounds, and different letters may represent the same sound. This is because the orthography was designed centuries ago and the spoken language has changed, as shown in the chart directly above that contrasts the difference between Middle and Modern Vietnamese.

The letters y and i are mostly equivalent, and there is no concrete rule that says when to use one or the other, except in sequences like ay and uy (i.e. tay «arm, hand» is read as /tă̄j/ while tai «ear» is read as /tāj/). There have been attempts since the late 20th century to standardize the orthography by replacing all the vowel uses of y with i, the latest being a decision from the Vietnamese Ministry of Education in 1984. These efforts seem to have had limited effect. In textbooks published by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục («Publishing House of Education»), y is used to represent /i/ only in Sino-Vietnamese words that are written with one letter y alone (diacritics can still be added, as in ý, ỷ), at the beginning of a syllable when followed by ê (as in yếm, yết), after u and in the sequence ay; therefore such forms as *lý and *kỹ are not «standard», though they are much preferred elsewhere. Most people and the popular media continue to use the spelling that they are most accustomed to.

| Spelling | Sound |

|---|---|

| a | /a/ ([æ] in some dialects) except as below /ă/ in au /ăw/ and ay /ăj/ (but /a/ in ao /aw/ and ai /aj/) /ăj/ before syllable-final nh /ŋ/ and ch /k/, see Vietnamese phonology#Analysis of final ch, nh /ə̯/ in ưa /ɨə̯/, ia /iə̯/ and ya /iə̯/ /ə̯/ in ua except after q[note 1] |

| ă | /ă/ |

| â | /ə̆/ |

| e | /ɛ/ |

| ê | /e/ except as below /ə̆j/ before syllable-final nh /ŋ/ and ch /k/, see Vietnamese phonology#Analysis of final ch, nh /ə̯/ in iê /iə̯/ and yê /iə̯/ |

| i | /i/ except as below /j/ after any vowel letter |

| o | /ɔ/ except as below /ăw/ before ng and c[note 2] /w/ after any vowel letter (= after a or e) /w/ before any vowel letter except i (= before ă, a or e) |

| ô | /o/ except as below /ə̆w/ before ng and c except after a u that is not preceded by a q[note 3] /ə̯/ in uô except after q[note 4] |

| ơ | /ə/ except as below /ə̯/ in ươ /ɨə̯/ |

| u | /u/ except as below /w/ after q or any vowel letter /w/ before any vowel letter except a, ô and i Before a, ô and i: /w/ if preceded by q, /u/ otherwise |

| ư | /ɨ/ |

| y | /i/ except as below /j/ after any vowel letter except u (= after â and a) |

- ^ qua is pronounced /kwa/ except in quay, where it is pronounced /kwă/. When not preceded by q, ua is pronounced /uə̯/.

- ^ However, oong and ooc are pronounced /ɔŋ/ and /ɔk/.

- ^ uông and uôc are pronounced /uə̯ŋ/ and /uə̯k/ when not preceded by a q.

- ^ quô is pronounced /kwo/ except in quông and quôc, where it is pronounced /kwə̆w/. When not preceded by q, uô is pronounced /uə̯/.

The uses of the letters i and y to represent the phoneme /i/ can be categorized as «standard» (as used in textbooks published by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục) and «non-standard» as follows.

| Context | «Standard» | «Non-standard» |

|---|---|---|

| In one-lettered non-Sino-Vietnamese syllables | i (e.g.: i tờ, í ới, ì ạch, ỉ ôi, đi ị) | |

| In one-lettered Sino-Vietnamese syllables | y (e.g.: y học, ý kiến, ỷ lại) | |

| Syllable-initial, not followed by ê | i (e.g.: ỉa đái, im lặng, ích lợi, ỉu xìu) | |

| Syllable-initial, followed by ê | y (e.g.: yếu ớt, yếm dãi, yết hầu) | |

| After u | y (e.g.: uy lực, huy hoàng, khuya khoắt, tuyển mộ, khuyết tật, khuỷu tay, huýt sáo, khuynh hướng) | |

| After qu, not followed by ê, nh | y (e.g.: quý giá, quấn quýt) | i (e.g.: quí giá, quấn quít) |

| After qu, followed by ê, nh | y (e.g.: quyên góp, xảo quyệt, mừng quýnh, hoa quỳnh) | |

| After b, d, đ, r, x | i (e.g.: bịa đặt, diêm dúa, địch thủ, rủ rỉ, triều đại, xinh xắn) | |

| After g, not followed by a, ă, â, e, ê, o, ô, ơ, u, ư | i (e.g.: cái gì?, giữ gìn) | |

| After h, k, l, m, t, not followed by any letter, in non-Sino-Vietnamese syllables | i (e.g.: ti hí, kì cọ, lí nhí, mí mắt, tí xíu) | |

| After h, k, l, m, t, not followed by any letter, in Sino-Vietnamese syllables | i (e.g.: hi vọng, kì thú, lí luận, mĩ thuật, giờ Tí) | y (e.g.: hy vọng, kỳ thú, lý luận, mỹ thuật, giờ Tý) |

| After ch, gh, kh, nh, ph, th | i (e.g.: chíp hôi, ghi nhớ, ý nghĩa, khiêu khích, nhí nhố, phiến đá, buồn thiu) | |

| After n, s, v, not followed by any letter, in non-proper-noun syllables | i (e.g.: ni cô, si tình, vi khuẩn) | |

| After n, s, v, not followed by any letter, in proper nouns | i (e.g.: Ni, Thuỵ Sĩ, Vi) | y (e.g.: Ny, Thụy Sỹ, Vy) |

| After h, k, l, m, n, s, t, v, followed by a letter | i (e.g.: thương hiệu, kiên trì, bại liệt, ngôi miếu, nũng nịu, siêu đẳng, mẫn tiệp, được việc) | |

| In Vietnamese personal names, after a consonant | i | either i or y, depending on personal preference |

This «standard» set by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục is not definite. It is unknown why the literature books use Lí while the history books use Lý.

Spelling[edit]

Vowel nuclei[edit]

The table below matches the vowels of Hanoi Vietnamese (written in the IPA) and their respective orthographic symbols used in the writing system.

-

Front Central Back Sound Spelling Sound Spelling Sound Spelling Centering /iə̯/ iê/ia* /ɨə̯/ ươ/ưa* /uə̯/ uô/ua* Close /i/ i, y /ɨ/ ư /u/ u Close-mid/

Mid/e/ ê /ə/ ơ /o/ ô /ə̆/ â Open-mid/

Open/ɛ/ e /a/ a /ɔ/ o /ă/ ă

Notes:

- The vowel /i/ is:

- usually written i: /sǐˀ/ = sĩ (A suffix indicating profession, similar to the English suffix -er).

- sometimes written y after h, k, l, m, n, s, t, v, x: /mǐˀ/ = Mỹ (America)

- It is always written y when:

-

-

- preceded by an orthographic vowel: /xwīə̯n/ = khuyên ‘to advise’;

- at the beginning of a word derived from Chinese (written as i otherwise): /ʔīə̯w/ = yêu ‘to love’.

-

- The vowel /ɔ/ is written oo before c or ng (since o in that position represents /ăw/): /ʔɔ̌k/ = oóc ‘organ (musical)’; /kǐŋ kɔ̄ŋ/ = kính coong. This generally only occurs in recent loanwords or when representing dialectal pronunciation.

- Similarly, the vowel /o/ is written ôô before c or ng: /ʔōŋ/ = ôông (Nghệ An/Hà Tĩnh variant of ông /ʔə̆̄wŋ/). But unlike oo being frequently used in onomatopoeia, transcriptions from other languages and words «borrowed» from Nghệ An/Hà Tĩnh dialects (such as voọc), ôô seems to be used solely to convey the feel of the Nghệ An/Hà Tĩnh accents. In transcriptions, ô is preferred (e.g. các-tông ‘cardboard’, ắc-coóc-đê-ông ‘accordion’).

Diphthongs and triphthongs[edit]

-

Rising Vowels Rising-Falling Vowels Falling Vowels nucleus (V) /w/ on-glides /w/ + V + off-glide /j/ off-glides /w/ off-glides front e /wɛ/ oe/(q)ue* /wɛw/ oeo/(q)ueo* /ɛw/ eo ê /we/ uê /ew/ êu i /wi/ uy /wiw/ uyu /iw/ iu ia/iê/yê* /wiə̯/ uyê/uya* /iə̯w/ iêu/yêu* central a /wa/ oa/(q)ua* /waj/ oai/(q)uai, /waw/ oao/(q)uao* /aj/ ai /aw/ ao ă /wă/ oă/(q)uă* /wăj/ oay/(q)uay* /ăj/ ay /ăw/ au â /wə̆/ uâ /wə̆j/ uây /ə̆j/ ây /ə̆w/ âu ơ /wə/ uơ /əj/ ơi /əw/ ơu ư /ɨj/ ưi /ɨw/ ưu ưa/ươ* /ɨə̯j/ ươi /ɨə̯w/ ươu back o /ɔj/ oi ô /oj/ ôi u /uj/ ui ua/uô* /uə̯j/ uôi

Notes:

The glide /w/ is written:

- u after /k/ (spelled q in this instance)

- o in front of a, ă, or e except after q

- o following a and e

- u in all other cases; note that /ăw/ is written as au instead of *ău (cf. ao /aw/), and that /i/ is written as y after u

The off-glide /j/ is written as i except after â and ă, where it is written as y; note that /ăj/ is written as ay instead of *ăy (cf. ai /aj/) .

The diphthong /iə̯/ is written:

- ia at the end of a syllable: /mǐə̯/ = mía ‘sugar cane’

- iê before a consonant or off-glide: /mǐə̯ŋ/ = miếng ‘piece’; /sīə̯w/ = xiêu ‘to slope, slant’

- Note that the i of the diphthong changes to y after u:

- ya: /xwīə̯/ = khuya ‘late at night’

- yê: /xwīə̯n/ = khuyên ‘to advise’

- iê changes to yê at the beginning of a syllable (ia does not change):

- /īə̯n/ = yên ‘calm’; /ǐə̯w/ yếu’ ‘weak, feeble’

The diphthong /uə̯/ is written:

- ua at the end of a syllable: /mūə̯/ = mua ‘to buy’

- uô before a consonant or off-glide: /mūə̯n/ = muôn ‘ten thousand’; /sūə̯j/ = xuôi ‘down’

The diphthong /ɨə̯/ is written:

- ưa at the end of a syllable: /mɨ̄ə̯/ = mưa ‘to rain’

- ươ before a consonant or off-glide: /mɨ̄ə̯ŋ/ = mương ‘irrigation canal’; /tɨ̌ə̯j/ = tưới ‘to water, irrigate, sprinkle’

Tone marks[edit]

Vietnamese is a tonal language, so the meaning of each word depends on the pitch in which it is pronounced. Tones are marked in the IPA as suprasegmentals following the phonemic value. Some tones are also associated with a glottalization pattern.

There are six distinct tones in the standard northern dialect. The first one («level tone») is not marked and the other five are indicated by diacritics applied to the vowel part of the syllable. The tone names are chosen such that the name of each tone is spoken in the tone it identifies.

In the south, there is a merging of the hỏi and ngã tones, in effect leaving five tones.

| Order | Diacritic | Symbol | Input keys | Name | IPA diacritic | Vowels with diacritic | Unicode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TELEX | VNI | |||||||

| 1 | unmarked | N/A | Z*

|

0*

|

Ngang | mid level, ˧ | A/a, Ă/ă, Â/â, E/e, Ê/ê, I/i, O/o, Ô/ô, Ơ/ơ, U/u, Ư/ư, Y/y | |

| 2 | acute accent | á | S

|

1

|

Sắc | high rising, ˧˥ | Á/á, Ắ/ắ, Ấ/ấ, É/é, Ế/ế, Í/í, Ó/ó, Ố/ố, Ớ/ớ, Ú/ú, Ứ/ứ, Ý/ý | U+0341 or U+0301 |

| 3 | grave accent | à | F

|

2

|

Huyền | low falling, ˨˩ | À/à, Ằ/ằ, Ầ/ầ, È/è, Ề/ề, Ì/ì, Ò/ò, Ồ/ồ, Ờ/ờ, Ù/ù, Ừ/ừ, Ỳ/ỳ | U+0340 or U+0300 |

| 4 | hook above | ả | R

|

3

|

Hỏi | mid falling, ˧˩ (Northern); dipping, ˨˩˥ (Southern) | Ả/ả, Ẳ/ẳ, Ẩ/ẩ, Ẻ/ẻ, Ể/ể, Ỉ/ỉ, Ỏ/ỏ, Ổ/ổ, Ở/ở, Ủ/ủ, Ử/ử, Ỷ/ỷ | U+0309 |

| 5 | tilde | ã | X

|

4

|

Ngã | glottalized rising, ˧˥ˀ (Northern); slightly lengthened Dấu Hỏi tone (Southern) | Ã/ã, Ẵ/ẵ, Ẫ/ẫ, Ẽ/ẽ, Ễ/ễ, Ĩ/ĩ, Õ/õ, Ỗ/ỗ, Ỡ/ỡ, Ũ/ũ, Ữ/ữ, Ỹ/ỹ | U+0342 or U+0303 |

| 6 | dot below | ạ | J

|

5

|

Nặng | glottalized falling, ˧˨ˀ (Northern); low rising, ˩˧ (Southern) | Ạ/ạ, Ặ/ặ, Ậ/ậ, Ẹ/ẹ, Ệ/ệ, Ị/ị, Ọ/ọ, Ộ/ộ, Ợ/ợ, Ụ/ụ, Ự/ự, Ỵ/ỵ | U+0323 |

- * =

Z(in TELEX) and0(in VNI) keys are used to remove the mark. For example in TELEX,AS=> á, then pressZ=> a. - Unmarked vowels are pronounced with a level voice, in the middle of the speaking range.

- The grave accent indicates that the speaker should start somewhat low and drop slightly in tone, with the voice becoming increasingly breathy.

- The hook indicates in Northern Vietnamese that the speaker should start in the middle range and fall, but in Southern Vietnamese that the speaker should start somewhat low and fall, then rise (as when asking a question in English).

- In the North, a tilde indicates that the speaker should start mid, break off (with a glottal stop), then start again and rise like a question in tone. In the South, it is realized identically to the Hỏi tone.

- The acute accent indicates that the speaker should start mid and rise sharply in tone.

- The dot or cross signifies in Northern Vietnamese that the speaker starts low and fall lower in tone, with the voice becoming increasingly creaky and ending in a glottal stop.

In syllables where the vowel part consists of more than one vowel (such as diphthongs and triphthongs), the placement of the tone is still a matter of debate. Generally, there are two methodologies, an «old style» and a «new style». While the «old style» emphasizes aesthetics by placing the tone mark as close as possible to the center of the word (by placing the tone mark on the last vowel if an ending consonant part exists and on the next-to-last vowel if the ending consonant doesn’t exist, as in hóa, hủy), the «new style» emphasizes linguistic principles and tries to apply the tone mark on the main vowel (as in hoá, huỷ). In both styles, when one vowel already has a quality diacritic on it, the tone mark must be applied to it as well, regardless of where it appears in the syllable (thus thuế is acceptable while *thúê is not). In the case of the ươ diphthong, the mark is placed on the ơ. The u in qu is considered part of the consonant. Currently, the new style is usually used in textbooks published by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục, while most people still prefer the old style in casual uses. Among Overseas Vietnamese communities, the old style is predominant for all purposes.

In lexical ordering, differences in letters are treated as primary, differences in tone markings as secondary and differences in case as tertiary differences. (Letters include for instance A and Ă but not Ẳ. Older dictionaries also treated digraphs and trigraphs like CH and NGH as base letters.[10]) Ordering according to primary and secondary differences proceeds syllable by syllable. According to this principle, a dictionary lists tuân thủ before tuần chay because the secondary difference in the first syllable takes precedence over the primary difference in the second syllable.

Structure[edit]

In the past, syllables in multisyllabic words were concatenated with hyphens, but this practice has died out and hyphenation is now reserved for word-borrowings from other languages. A written syllable consists of at most three parts, in the following order from left to right:

- An optional beginning consonant part

- A required vowel syllable nucleus and the tone mark, if needed, applied above or below it

- An ending consonant part, can only be one of the following: c, ch, m, n, ng, nh, p, t, or nothing.[11]

History[edit]

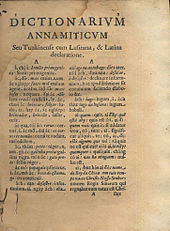

A page from Alexandre de Rhodes’ 1651 dictionary

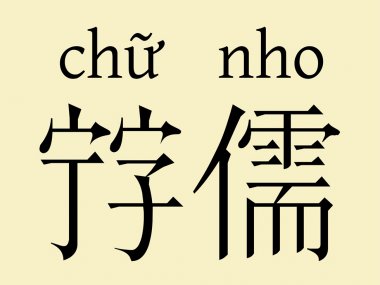

Since the beginning of the Chinese rule 111 BC, literature, government papers, scholarly works, and religious scripture were all written in classical Chinese (chữ Hán) while indigenous writing in chu han started around the ninth century.[12] Since the 12th century, several Vietnamese words started to be written in chữ Nôm, using variant Chinese characters, each of them representing one word. The system was based on chữ Hán, but was also supplemented with Vietnamese-invented characters (chữ thuần nôm, proper Nôm characters) to represent native Vietnamese words.

Creation of chữ Quốc ngữ[edit]

As early as 1620, with the work of Francisco de Pina, Portuguese and Italian Jesuit missionaries in Vietnam began using Latin script to transcribe the Vietnamese language as an assistance for learning the language.[1][3] The work was continued by the Avignonese Alexandre de Rhodes. Building on previous dictionaries by Gaspar do Amaral and Antonio Barbosa, Rhodes compiled the Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum, a Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary, which was later printed in Rome in 1651, using their spelling system.[1][13] These efforts led eventually to the development of the present Vietnamese alphabet. For 200 years, chữ Quốc ngữ was used within the Catholic community.[14][15]

Colonial period[edit]

In 1910, the French colonial administration enforced chữ Quốc ngữ.[16] The Latin alphabet then became a means to publish Vietnamese popular literature, which was disparaged as vulgar by the Chinese-educated imperial elites.[17] Historian Pamela A. Pears asserted that by instituting the Latin alphabet in Vietnam, the French cut the Vietnamese from their traditional Hán Nôm literature.[18] An important reason why Latin script became the standard writing system in Vietnam but not in Cambodia and Laos, which were both dominated by the French for a similar amount of time under the same colonial framework, had to do with the Nguyễn Emperors of Vietnam heavily promoting its usage.[19] According to the historian Liam Kelley in his 2016 work «Emperor Thành Thái’s Educational Revolution» neither the French nor the revolutionaries had enough power to spread the usage of chữ Quốc ngữ down to the village level.[19] It was by imperial decree in 1906 of Emperor Thành Thái, that parents could decide whether their children will follow a curriculum in Hán văn (漢文) or Nam âm (南音, «Southern sound», the contemporary Vietnamese name for chữ Quốc ngữ).[19] This decree was issued at the same time when other social changes, such as the cutting of long male hair, were occurring.[19] The main reason for the popularisation of the Latin alphabet in Vietnam/Đại Nam during the Nguyễn dynasty (the French protectorates of Annam and Tonkin) was because of the pioneering efforts by intellectuals from French Cochinchina combined with the progressive and scientific policies of the French government in French Indochina, that created the momentum for the usage of chữ Quốc ngữ to spread.[19]

From the first days it was recognized that the Chinese language was a barrier between us and the natives; the education provided by means of the hieroglyphic characters was completely beyond us; this writing makes possible only with difficulty transmitting to the population the diverse ideas which are necessary for them at the level of their new political and commercial situation. Consequently we are obliged to follow the traditions of our own system of education; it is the only one which can bring close to us the Annamites of the colony by inculcating in them the principles of European civilization and isolating them from the hostile influence of our neighbors.[20]

— In a letter dated January 15, 1866, Paulin Vial, Directeur du Cabinet du Gouverneur de la Cochinchine

Since the 1920s, the Vietnamese mostly use chữ Quốc ngữ, and new Vietnamese terms for new items or words are often calqued from Hán Nôm. Some French had originally planned to replace Vietnamese with French, but this never was a serious project, given the small number of French settlers compared with the native population. The French had to reluctantly accept the use of chữ Quốc ngữ to write Vietnamese since this writing system, created by Portuguese missionaries, is based on Portuguese orthography, not French.[21]

Mass education[edit]

Between 1907 and 1908, the short-lived Tonkin Free School promulgated chữ quốc ngữ and taught French language to the general population.

In 1917, the French system suppressed Vietnam’s Confucian examination system, viewed as an aristocratic system linked with the «ancient regime», thereby forcing Vietnamese elites to educate their offspring in the French language education system. Emperor Khải Định declared the traditional writing system abolished in 1918.[17]

While traditional nationalists favoured the Confucian examination system and the use of chữ Hán, Vietnamese revolutionaries, progressive nationalists, and pro-French elites viewed the French education system as a means to «liberate» the Vietnamese from old Chinese domination and the unsatisfactory «outdated» Confucian examination system, to democratize education and to help link Vietnamese to European philosophies.

The French colonial system then set up another educational system, teaching Vietnamese as a first language using chữ quốc ngữ in primary school and then the French language (taught in chữ quốc ngữ). Hundreds of thousands of textbooks for primary education began to be published in chữ quốc ngữ, with the unintentional result of turning the script into the popular medium for the expression for Vietnamese culture.[22]

Late 20th century to present[edit]

Typesetting and printing Vietnamese has been challenging due to its number of accents/diacritics.[23][24][25] Contemporary Vietnamese texts sometimes include words which have not been adapted to modern Vietnamese orthography, especially for documents written in Chữ Hán. The Vietnamese language itself has been likened to a system akin to «ruby characters» elsewhere in Asia. See Vietnamese language and computers for usage on computers and the internet.

Computing[edit]

Different ways in which tone marks can be presented on letters that already have diacritic e.g. (`) on letter ê when computerising Vietnamese.

The universal character set Unicode has full support for the Latin Vietnamese writing system, although it does not have a separate segment for it. The required characters that other languages use are scattered throughout the Basic Latin, Latin-1 Supplement, Latin Extended-A and Latin Extended-B blocks; those that remain (such as the letters with more than one diacritic) are placed in the Latin Extended Additional block. An ASCII-based writing convention, Vietnamese Quoted Readable and several byte-based encodings including VSCII (TCVN), VNI, VISCII and Windows-1258 were widely used before Unicode became popular. Most new documents now exclusively use the Unicode format UTF-8.

Unicode allows the user to choose between precomposed characters and combining characters in inputting Vietnamese. Because in the past some fonts implemented combining characters in a nonstandard way (see Verdana font), most people use precomposed characters when composing Vietnamese-language documents (except on Windows where Windows-1258 used combining characters).

Most keyboards on modern phone and computer operating systems, including iOS,[26] Android[27] and MacOS,[28] have now supported the Vietnamese language and direct input of diacritics by default. Previously, Vietnamese users had to manually install free softwares such as Unikey on computers or Laban Key on phones to type Vietnamese diacritics. These keyboards support input methods such as Telex, VNI, VIQR and its variants.

See also[edit]

- Portuguese orthography

- Special characters:

- Ă, Â, Đ, Ê, Ô, Ơ, Ư

- Dot (diacritic)

- Hook above

- Horn (diacritic)

- Historic Writing

- «Chữ Hán», classical Chinese written in Vietnam (Han characters)

- «Chữ Nôm», former script used to write Vietnamese using Han and Nom (invented characters) words

- Coding and Input Methods:

- Telex, the oldest standard input method for the Vietnamese alphabet on electronic devices.

- VNI, another input and encoding convention for Vietnamese alphabet.

- VIQR, another standard 7-bit input method for Vietnamese alphabet.

- VISCII, another standard 8-bit encoding for Vietnamese alphabet.

- Unicode, character encoding standard for most of the world’s writing systems

- Vietnamese Braille

- Vietnamese calligraphy

- Vietnamese phonology

- Francisco de Pina

- Alexandre de Rhodes

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Jacques, Roland (2002). Portuguese Pioneers of Vietnamese Linguistics Prior to 1650 – Pionniers Portugais de la Linguistique Vietnamienne Jusqu’en 1650 (in English and French). Bangkok, Thailand: Orchid Press. ISBN 974-8304-77-9.

- ^ Jacques, Roland (2004). «Bồ Đào Nha và công trình sáng chế chữ quốc ngữ: Phải chăng cần viết lại lịch sử?» Translated by Nguyễn Đăng Trúc. In Các nhà truyền giáo Bồ Đào Nha và thời kỳ đầu của Giáo hội Công giáo Việt Nam (Quyển 1) – Les missionnaires portugais et les débuts de l’Eglise catholique au Viêt-nam (Tome 1) (in Vietnamese & French). Reichstett, France: Định Hướng Tùng Thư. ISBN 2-912554-26-8.

- ^ a b Trần, Quốc Anh; Phạm, Thị Kiều Ly (October 2019). Từ Nước Mặn đến Roma: Những đóng góp của các giáo sĩ Dòng Tên trong quá trình La tinh hoá tiếng Việt ở thế kỷ 17. Conference 400 năm hình thành và phát triển chữ Quốc ngữ trong lịch sử loan báo Tin Mừng tại Việt Nam. Ho Chi Minh City: Ủy ban Văn hóa, Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Vietnam.

- ^ Tran (2022).

- ^ Haudricourt, André-Georges. 2010. «The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet.» Mon-Khmer Studies 39: 89–104. Translated from: Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1949. «L’origine Des Particularités de L’alphabet Vietnamien.» Dân Viêt-Nam 3: 61–68.

- ^ Jakob Rupert Friederichsen Opening Up Knowledge Production Through Participatory Research? Frankfurt 2009 [6.1 History of Science and Research in Vietnam] Page 126 «6.1.2 French colonial science in Vietnam: With the colonial era, deep changes took place in education, communication, and … French colonizers installed a modern European system of education to replace the literary and Confucianism-based model, they promoted a romanized Vietnamese script (Quốc Ngữ) to replace the Sino-Vietnamese characters (Hán Nôm)»

- ^ «Vietnam Alphabet». vietnamesetypography.

- ^ a b c d The close vowels /i, ɨ, u/ are diphthongized [ɪi̯, ɯ̽ɯ̯, ʊu̯].

- ^ «Do you know How to pronounce Igrec?». HowToPronounce.com. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

- ^ See for example Lê Bá Khanh; Lê Bá Kông (1998) [1975]. Vietnamese-English/English-Vietnamese Dictionary (7th ed.). New York City: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-87052-924-2.

- ^ «vietnamese Alphabet». Omniglot.com. 2014.

- ^ Kornicki 2017, p. 568.

- ^ Tran, Anh Q. (October 2018). «The Historiography of the Jesuits in Vietnam: 1615–1773 and 1957–2007». Jesuit Historiography Online. Brill.

- ^ Li 2020, p. 106.

- ^ Ostrowski, Brian Eugene (2010). «The Rise of Christian Nôm Literature in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Fusing European Content and Local Expression». In Wilcox, Wynn (ed.). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Ithaca, New York: SEAP Publications, Cornell university Press. pp. 23, 38. ISBN 9780877277828.

- ^ «Quoc-ngu | Vietnamese writing system». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ a b Nguyên Tùng, «Langues, écritures et littératures au Viêt-nam», Aséanie, Sciences humaines en Asie du Sud-Est, Vol. 2000/5, pp. 135-149.

- ^ Pamela A. Pears (2006). Remnants of Empire in Algeria and Vietnam: Women, Words and War. Lexington Books. p. 18. ISBN 0-7391-2022-0. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ a b c d e Nguyễn Quang Duy (12 September 2018). «Quốc ngữ và nỗ lực ‘thoát Hán’ của các vua nhà Nguyễn» (in Vietnamese). Người Việt Daily News. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Li 2020, p. 107.

- ^ Trần Bích San. «Thi cử và giáo dục Việt Nam dưới thời thuộc Pháp» (in Vietnamese). Note 3. «The French had to accept reluctantly the existence of chữ quốc ngữ. The propagation of chữ quốc ngữ in Cochinchina was, in fact, not without resistance [by French authority or pro-French Vietnamese elite] […] Chữ quốc ngữ was created by Portuguese missionaries according to the phonemic orthography of Portuguese language. The Vietnamese could not use chữ quốc ngữ to learn French script. The French would mispronounce chữ quốc ngữ in French orthography, particularly people’s names and place names. Thus, the French constantly disparaged chữ quốc ngữ because of its uselessness in helping with the propagation of French script.»

- ^ Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. pp. 127-128.

- ^ Wellisch, Hans H. (1978). The Conversion of Scripts, Its Nature, History, and Utilization. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-01620-5.

- ^ Language Monthly. Praetorius. 1987.

- ^ Sassoon, Rosemary (1995). The acquisition of a second writing system. Internet Archive. Oxford [England] : Intellect. ISBN 978-1-871516-43-2.

- ^ Anh, Hao (2021-09-21). «Hướng dẫn gõ tiếng Việt trên iOS 15 bằng tính năng lướt phím QuickPath». VietNamNet (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2022-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Set up Gboard on Android». Google Support. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ^ Phan, Kim Long. «UniKey in macOS and iOS». UniKey. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

Bibliography[edit]

- Gregerson, Kenneth J. (1969). A study of Middle Vietnamese phonology. Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoises, 44, 135–193. (Published version of the author’s MA thesis, University of Washington). (Reprinted 1981, Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics).

- Haudricourt, André-Georges (1949). «Origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien (English translation as: The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet)» (PDF). Dân Việt-Nam. 3: 61–68.

- Healy, Dana.(2003). Teach Yourself Vietnamese, Hodder Education, London.

- Kornicki, Peter (2017), «Sino-Vietnamese literature», in Li, Wai-yee; Denecke, Wiebke; Tian, Xiaofen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature (1000 BCE-900 CE), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 568–578, ISBN 978-0-199-35659-1

- Li, Yu (2020). The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-069906-7.

- Nguyen, Đang Liêm. (1970). Vietnamese pronunciation. PALI language texts: Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-462-X

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1955). Quốc-ngữ: The modern writing system in Vietnam. Washington, D. C.: Author.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (1992). «Vietnamese phonology and graphemic borrowings from Chinese: The Book of 3,000 Characters revisited». Mon-Khmer Studies. 20: 163–182.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1996). Vietnamese. In P. T. Daniels, & W. Bright (Eds.), The world’s writing systems, (pp. 691–699). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1997). Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 1-55619-733-0.

- Pham, Andrea Hoa. (2003). Vietnamese tone: A new analysis. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Routledge. (Published version of author’s 2001 PhD dissertation, University of Florida: Hoa, Pham. Vietnamese tone: Tone is not pitch). ISBN 0-415-96762-7.

- Pham, Thi Kieu Ly (2018). La grammatisation du vietnamien (1615–1919): histoire des grammaires et de l’écriture romanisée du vietnamien (PhD). Université Sorbonne Paris Cité.

- Sassoon, Rosemary (1995). The Acquisition of a Second Writing System (illustrated, reprint ed.). Intellect Books. ISBN 1871516439. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Thompson, Laurence E. (1991). A Vietnamese reference grammar. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1117-8. (Original work published 1965).

- Tran, Anh Q. (2022). «Catholicism and the Development of the Vietnamese Alphabet, 1620–1898». Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 9–37. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.9. S2CID 250513843.

- Wellisch, Hans H. (1978). The conversion of scripts, its nature, history and utilization. Information sciences series (illustrated ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0471016209. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Nguyen, A. M. (2006). Let’s learn the Vietnamese alphabet. Las Vegas: Viet Baby. ISBN 0-9776482-0-6

- Shih, Virginia Jing-yi. Quoc Ngu Revolution: A Weapon of Nationalism in Vietnam. 1991.

External links[edit]

Media related to Vietnamese writing at Wikimedia Commons

- Vietnamese Unicode FAQs

| Vietnamese alphabet

chữ Quốc ngữ |

|

|---|---|

| Script type |

Alphabet |

| Creator | Portuguese and Italian Jesuits[1][2][3][4] and Alexandre de Rhodes |

| Languages | Vietnamese, other indigenous languages of Vietnam |

| Related scripts | |

|

Parent systems |

Egyptian hieroglyphs

|

The Vietnamese alphabet (Vietnamese: chữ Quốc ngữ, lit. ‘script of the National language’) is the modern Latin writing script or writing system for Vietnamese. It uses the Latin script based on Romance languages[5] originally developed by Portuguese missionary Francisco de Pina (1585 – 1625).[1]

The Vietnamese alphabet contains 29 letters, including seven letters using four diacritics: ă, â/ê/ô, ơ/ư, đ. There are an additional five diacritics used to designate tone (as in à, á, ả, ã, and ạ). The complex vowel system and the large number of letters with diacritics, which can stack twice on the same letter (e.g. nhất meaning «first»), makes it easy to distinguish the Vietnamese orthography from other writing systems that use the Latin script.[6]

The Vietnamese system’s use of diacritics produces an accurate transcription for tones despite the limitations of the Roman alphabet. On the other hand, sound changes in the spoken language have led to different letters, digraphs and trigraphs now representing the same sounds.

Letter names and pronunciation[edit]

Vietnamese uses all the letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet except for f, j, w, and z. These letters are only used to write loanwords, languages of other ethnic groups in the country based on Vietnamese phonetics to differentiate the meanings or even Vietnamese dialects, for example: dz or z for southerner pronunciation of v in standard Vietnamese.

In total, there are 12 vowels (nguyên âm) and 17 consonants (phụ âm, literally «extra sound»).

Handwritten Vietnamese alphabet

| Letter | Input keys | Name (when pronounced) |

IPA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TELEX | VNI | Northern | Southern | ||

| A a | a | /aː˧/ | /aː˧/ | ||

| Ă ă | AW

|

A8

|

á | /aː˧˥/ | /aː˧˥/ |

| Â â | AA

|

A6

|

ớ | /əː˧˥/ | /əː˧˥/ |

| B b | bê | /ɓe˧/ | /ɓe˧/ | ||

| C c | xê | /se˧/ | /se˧/ | ||

| D d | dê | /ze˧/ | /je˧/ | ||

| Đ đ | DD

|

D9

|

đê | /ɗe˧/ | /ɗe˧/ |

| E e | e | /ɛ˧/ | /ɛ˧/ | ||

| Ê ê | EE

|

E6

|

ê | /e˧/ | /e˧/ |

| G g | giê | /ʒe˧/ | /ʒe˧, ɹe˧/ | ||

| H h | hác | /ha:t˧˥/ | /hak˧˥/ | ||

| I i | i ngắn | /i˧ ŋan˧˥/ | /ɪi̯˧ ŋaŋ˧˥/[8] | ||

| K k | ca | /kaː˧/ | /kaː˧/ | ||

| L l | en lờ | /ɛn˧ ləː˨˩/ | /ɛŋ˧ ləː˨˩/ | ||

| M m | em mờ | /ɛm˧ məː˨˩/ | /ɛm˧ məː˨˩/ | ||

| N n | en nờ | /ɛn˧ nəː˨˩/ | /an˧ nəː˨˩/ | ||

| O o | o | /ɔ˧/ | /ɔ˧/ | ||

| Ô ô | OO

|

O6

|

ô | /o˧/ | /o˧/ |

| Ơ ơ | OW

|

O7

|

ơ | /əː˧/ | /əː˧/ |

| P p | pê | /pe˧/ | /pe˧/ | ||

| Q q | quy | /ku˧, kwi˧/ | /kwi˧/ | ||

| R r | e rờ | /ɛ˧ rəː˨˩/ | /ɛ˧ ɹəː˨˩/ | ||

| S s | ét sì | /ɛt˦˥ si˨˩/ | /ɛt˦˥, ə:t˦˥ (sə˨˩)/ | ||

| T t | tê | /te˧/ | /te˧/ | ||

| U u | u | /u˧/ | /ʊu̯˧/[8] | ||

| Ư ư | UW

|

U7

|

ư | /ɨ˧/ | /ɯ̽ɯ̯˧/[8] |

| V v | vê | /ve˧/ | /ve˧/ | ||

| X x | ích xì | /ik˦˥ si˨˩/ | /ɪ̈t˦˥ (si˨˩)/ | ||

| Y y | y dài | /i˧ zaːj˨˩/ | /ɪi̯˧ jaːj˨˩/[8] |

- Notes

- The vowels in the table are italicized.

- Pronouncing b as bê or bò and p as pê or pờ is to avoid confusion in some contexts, the same for s as sờ mạnh or sờ nặng (literally, «strong s» or «heavy s») and x as xờ nhẹ (literally, «light x»), i as i ngắn (literally, «short i») and y as y dài (literally, «long y»).

- Q and q is always followed by u in every word and phrase in Vietnamese, e.g. quần (trousers), quyến rũ (to attract), etc.

- The name i-cờ-rét for y is from the French name for the letter: i grec (Greek I),[9] referring to the letter’s origin from the Greek letter upsilon. The other obsolete French pronunciations include e (/ə:˧/) and u (/wi˧/).

- The Vietnamese alphabet does not contain the letters F (ép, ép-phờ), J (gi), W (u kép meaning «double u», vê kép, vê đúp meaning «double v») or Z (dét). However, these letters are often used for foreign loanwords or may be kept for foreign names.

- «Y» is most commonly treated as a vowel along with «i». «i» is «short /i˧/» and «y» is «long /i˧/«. «Y» can have tones as well as other vowels (ý, ỳ, ỹ, ỷ, ỵ) e.g. Mỹ (America). It may also act as a consonant (when used after â and a). It can sometimes be used to replace «i», e.g. «bánh mì» (bread) can also be written «bánh mỳ«.

- S and X are similar to each other in sound in Vietnamese and can sometimes replace each other e.g. sương xáo or sương sáo (grass jelly).

Consonants[edit]

The alphabet is largely derived from Portuguese with major influence from French, although the usage of gh and gi was borrowed from Italian (compare ghetto, Giuseppe) and that for c/k/qu from Greek and Latin (compare canis, kinesis, quō vādis), mirroring the English usage of these letters (compare cat, kite, queen).

| Grapheme | Word-initial (IPA) | Word-final | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern | Southern | Northern | Southern | ||

| B b | /ɓ/ | ||||

| C c | /k/ | /k̚/ | ⟨k⟩ is used instead when preceding ⟨i y e ê⟩. ⟨qu⟩ is used instead of ⟨co cu⟩ if a /w/ on-glide exists. Realized as [k͡p] in word-final position following rounded vowels ⟨u ô o⟩. |

||

| Ch ch | /tɕ/ | /c/ | /ʲk/ | /t̚/ | Multiple phonemic analyses of final ⟨ch⟩ have been proposed (main article). |

| D d | /z/ | /j/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨d⟩ represented /ð/. The distinction between ⟨d⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ is now purely etymological in most modern dialects. | ||

| Đ đ | /ɗ/ | ||||

| G g | /ɣ/ | ||||

| Gh gh | Spelling used ⟨gh⟩ instead of ⟨g⟩ before ⟨i e ê⟩, seemingly to follow the Italian convention. ⟨g⟩ is not allowed in these environments. | ||||

| Gi gi | /z/ | /j/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨gi⟩ represented /ʝ/. The distinction between ⟨d⟩ and ⟨gi⟩ is now purely etymological in most modern dialects. Realized as [ʑ] in Northern spelling pronunciation. Spelled ⟨g⟩ before another ⟨i⟩.[a] | ||

| H h | /h/ | ||||

| K k | /k/ | Spelling used instead of ⟨c⟩ before ⟨i y e ê⟩ to follow the European tradition. ⟨c⟩ is not allowed in these environments. | |||

| Kh kh | /x/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨kh⟩ was pronounced [kʰ] | |||

| L l | /l/ | ||||

| M m | /m/ | /m/ | |||

| N n | /n/ | /n/ | /ŋ/ | In Southern Vietnamese, word-final ⟨n⟩ is realized as [ŋ] if not following ⟨i ê⟩. | |

| Ng ng | /ŋ/ | /ŋ/ | Realized as [ŋ͡m] in word-final position following rounded vowels ⟨u ô o⟩. | ||

| Ngh ngh | Spelling used instead of ⟨ng⟩ before ⟨i e ê⟩ in accordance with ⟨gh⟩. | ||||

| Nh nh | /ɲ/ | /ʲŋ/ | /n/ | Multiple phonemic analyses of final ⟨nh⟩ have been proposed (main article). | |

| P p | /p/ | Only occurs initially in loanwords. Some Vietnamese pronounce it as a «b» sound instead (as in Arabic). | |||

| Ph ph | /f/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨ph⟩ was pronounced [pʰ] | |||

| Qu qu | /kʷ/ | Spelling used in place of ⟨co cu⟩ if a /w/ on-glide exists. | |||

| R r | /z/ | /r/ | Variably pronounced as a fricative [ʐ], approximant [ɹ], flap [ɾ] or trill [r] in Southern speech. | ||

| S s | /s/ | /ʂ/ | Realized as [ʃ] in Northern spelling pronunciation. | ||

| T t | /t/ | /t̚/ | /k/ | In Southern Vietnamese, word-final ⟨t⟩ is realized as [k] if not following ⟨i ê⟩. | |

| Th th | /tʰ/ | ||||

| Tr tr | /tɕ/ | /ʈ/ | Realized as [tʃ] in Northern spelling pronunciation. | ||

| V v | /v/ | In Middle Vietnamese, it was represented by a b with flourish ⟨ Can be realized as [v] in Southern speech through spelling pronunciation and in loanwords. |

|||

| X x | /s/ | In Middle Vietnamese, ⟨x⟩ was pronounced [ɕ]. |

- ^ This causes some ambiguity with the diphthong ia/iê, for example gia could be either gi+a [za ~ ja] or gi+ia [ziə̯ ~ jiə̯]. If there is a tone mark the ambiguity is resolved: giá is gi+á and gía is gi+ía.

Vowels[edit]

Pronunciation[edit]

The correspondence between the orthography and pronunciation is somewhat complicated. In some cases, the same letter may represent several different sounds, and different letters may represent the same sound. This is because the orthography was designed centuries ago and the spoken language has changed, as shown in the chart directly above that contrasts the difference between Middle and Modern Vietnamese.

The letters y and i are mostly equivalent, and there is no concrete rule that says when to use one or the other, except in sequences like ay and uy (i.e. tay «arm, hand» is read as /tă̄j/ while tai «ear» is read as /tāj/). There have been attempts since the late 20th century to standardize the orthography by replacing all the vowel uses of y with i, the latest being a decision from the Vietnamese Ministry of Education in 1984. These efforts seem to have had limited effect. In textbooks published by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục («Publishing House of Education»), y is used to represent /i/ only in Sino-Vietnamese words that are written with one letter y alone (diacritics can still be added, as in ý, ỷ), at the beginning of a syllable when followed by ê (as in yếm, yết), after u and in the sequence ay; therefore such forms as *lý and *kỹ are not «standard», though they are much preferred elsewhere. Most people and the popular media continue to use the spelling that they are most accustomed to.

| Spelling | Sound |

|---|---|

| a | /a/ ([æ] in some dialects) except as below /ă/ in au /ăw/ and ay /ăj/ (but /a/ in ao /aw/ and ai /aj/) /ăj/ before syllable-final nh /ŋ/ and ch /k/, see Vietnamese phonology#Analysis of final ch, nh /ə̯/ in ưa /ɨə̯/, ia /iə̯/ and ya /iə̯/ /ə̯/ in ua except after q[note 1] |

| ă | /ă/ |

| â | /ə̆/ |

| e | /ɛ/ |

| ê | /e/ except as below /ə̆j/ before syllable-final nh /ŋ/ and ch /k/, see Vietnamese phonology#Analysis of final ch, nh /ə̯/ in iê /iə̯/ and yê /iə̯/ |

| i | /i/ except as below /j/ after any vowel letter |

| o | /ɔ/ except as below /ăw/ before ng and c[note 2] /w/ after any vowel letter (= after a or e) /w/ before any vowel letter except i (= before ă, a or e) |

| ô | /o/ except as below /ə̆w/ before ng and c except after a u that is not preceded by a q[note 3] /ə̯/ in uô except after q[note 4] |

| ơ | /ə/ except as below /ə̯/ in ươ /ɨə̯/ |

| u | /u/ except as below /w/ after q or any vowel letter /w/ before any vowel letter except a, ô and i Before a, ô and i: /w/ if preceded by q, /u/ otherwise |

| ư | /ɨ/ |

| y | /i/ except as below /j/ after any vowel letter except u (= after â and a) |

- ^ qua is pronounced /kwa/ except in quay, where it is pronounced /kwă/. When not preceded by q, ua is pronounced /uə̯/.

- ^ However, oong and ooc are pronounced /ɔŋ/ and /ɔk/.

- ^ uông and uôc are pronounced /uə̯ŋ/ and /uə̯k/ when not preceded by a q.

- ^ quô is pronounced /kwo/ except in quông and quôc, where it is pronounced /kwə̆w/. When not preceded by q, uô is pronounced /uə̯/.

The uses of the letters i and y to represent the phoneme /i/ can be categorized as «standard» (as used in textbooks published by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục) and «non-standard» as follows.

| Context | «Standard» | «Non-standard» |

|---|---|---|

| In one-lettered non-Sino-Vietnamese syllables | i (e.g.: i tờ, í ới, ì ạch, ỉ ôi, đi ị) | |

| In one-lettered Sino-Vietnamese syllables | y (e.g.: y học, ý kiến, ỷ lại) | |

| Syllable-initial, not followed by ê | i (e.g.: ỉa đái, im lặng, ích lợi, ỉu xìu) | |

| Syllable-initial, followed by ê | y (e.g.: yếu ớt, yếm dãi, yết hầu) | |

| After u | y (e.g.: uy lực, huy hoàng, khuya khoắt, tuyển mộ, khuyết tật, khuỷu tay, huýt sáo, khuynh hướng) | |

| After qu, not followed by ê, nh | y (e.g.: quý giá, quấn quýt) | i (e.g.: quí giá, quấn quít) |

| After qu, followed by ê, nh | y (e.g.: quyên góp, xảo quyệt, mừng quýnh, hoa quỳnh) | |

| After b, d, đ, r, x | i (e.g.: bịa đặt, diêm dúa, địch thủ, rủ rỉ, triều đại, xinh xắn) | |

| After g, not followed by a, ă, â, e, ê, o, ô, ơ, u, ư | i (e.g.: cái gì?, giữ gìn) | |

| After h, k, l, m, t, not followed by any letter, in non-Sino-Vietnamese syllables | i (e.g.: ti hí, kì cọ, lí nhí, mí mắt, tí xíu) | |

| After h, k, l, m, t, not followed by any letter, in Sino-Vietnamese syllables | i (e.g.: hi vọng, kì thú, lí luận, mĩ thuật, giờ Tí) | y (e.g.: hy vọng, kỳ thú, lý luận, mỹ thuật, giờ Tý) |

| After ch, gh, kh, nh, ph, th | i (e.g.: chíp hôi, ghi nhớ, ý nghĩa, khiêu khích, nhí nhố, phiến đá, buồn thiu) | |

| After n, s, v, not followed by any letter, in non-proper-noun syllables | i (e.g.: ni cô, si tình, vi khuẩn) | |

| After n, s, v, not followed by any letter, in proper nouns | i (e.g.: Ni, Thuỵ Sĩ, Vi) | y (e.g.: Ny, Thụy Sỹ, Vy) |

| After h, k, l, m, n, s, t, v, followed by a letter | i (e.g.: thương hiệu, kiên trì, bại liệt, ngôi miếu, nũng nịu, siêu đẳng, mẫn tiệp, được việc) | |

| In Vietnamese personal names, after a consonant | i | either i or y, depending on personal preference |

This «standard» set by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục is not definite. It is unknown why the literature books use Lí while the history books use Lý.

Spelling[edit]

Vowel nuclei[edit]

The table below matches the vowels of Hanoi Vietnamese (written in the IPA) and their respective orthographic symbols used in the writing system.

-

Front Central Back Sound Spelling Sound Spelling Sound Spelling Centering /iə̯/ iê/ia* /ɨə̯/ ươ/ưa* /uə̯/ uô/ua* Close /i/ i, y /ɨ/ ư /u/ u Close-mid/

Mid/e/ ê /ə/ ơ /o/ ô /ə̆/ â Open-mid/

Open/ɛ/ e /a/ a /ɔ/ o /ă/ ă

Notes:

- The vowel /i/ is:

- usually written i: /sǐˀ/ = sĩ (A suffix indicating profession, similar to the English suffix -er).

- sometimes written y after h, k, l, m, n, s, t, v, x: /mǐˀ/ = Mỹ (America)

- It is always written y when:

-

-

- preceded by an orthographic vowel: /xwīə̯n/ = khuyên ‘to advise’;

- at the beginning of a word derived from Chinese (written as i otherwise): /ʔīə̯w/ = yêu ‘to love’.

-

- The vowel /ɔ/ is written oo before c or ng (since o in that position represents /ăw/): /ʔɔ̌k/ = oóc ‘organ (musical)’; /kǐŋ kɔ̄ŋ/ = kính coong. This generally only occurs in recent loanwords or when representing dialectal pronunciation.

- Similarly, the vowel /o/ is written ôô before c or ng: /ʔōŋ/ = ôông (Nghệ An/Hà Tĩnh variant of ông /ʔə̆̄wŋ/). But unlike oo being frequently used in onomatopoeia, transcriptions from other languages and words «borrowed» from Nghệ An/Hà Tĩnh dialects (such as voọc), ôô seems to be used solely to convey the feel of the Nghệ An/Hà Tĩnh accents. In transcriptions, ô is preferred (e.g. các-tông ‘cardboard’, ắc-coóc-đê-ông ‘accordion’).

Diphthongs and triphthongs[edit]

-

Rising Vowels Rising-Falling Vowels Falling Vowels nucleus (V) /w/ on-glides /w/ + V + off-glide /j/ off-glides /w/ off-glides front e /wɛ/ oe/(q)ue* /wɛw/ oeo/(q)ueo* /ɛw/ eo ê /we/ uê /ew/ êu i /wi/ uy /wiw/ uyu /iw/ iu ia/iê/yê* /wiə̯/ uyê/uya* /iə̯w/ iêu/yêu* central a /wa/ oa/(q)ua* /waj/ oai/(q)uai, /waw/ oao/(q)uao* /aj/ ai /aw/ ao ă /wă/ oă/(q)uă* /wăj/ oay/(q)uay* /ăj/ ay /ăw/ au â /wə̆/ uâ /wə̆j/ uây /ə̆j/ ây /ə̆w/ âu ơ /wə/ uơ /əj/ ơi /əw/ ơu ư /ɨj/ ưi /ɨw/ ưu ưa/ươ* /ɨə̯j/ ươi /ɨə̯w/ ươu back o /ɔj/ oi ô /oj/ ôi u /uj/ ui ua/uô* /uə̯j/ uôi

Notes:

The glide /w/ is written:

- u after /k/ (spelled q in this instance)

- o in front of a, ă, or e except after q

- o following a and e

- u in all other cases; note that /ăw/ is written as au instead of *ău (cf. ao /aw/), and that /i/ is written as y after u

The off-glide /j/ is written as i except after â and ă, where it is written as y; note that /ăj/ is written as ay instead of *ăy (cf. ai /aj/) .

The diphthong /iə̯/ is written:

- ia at the end of a syllable: /mǐə̯/ = mía ‘sugar cane’

- iê before a consonant or off-glide: /mǐə̯ŋ/ = miếng ‘piece’; /sīə̯w/ = xiêu ‘to slope, slant’

- Note that the i of the diphthong changes to y after u:

- ya: /xwīə̯/ = khuya ‘late at night’

- yê: /xwīə̯n/ = khuyên ‘to advise’

- iê changes to yê at the beginning of a syllable (ia does not change):

- /īə̯n/ = yên ‘calm’; /ǐə̯w/ yếu’ ‘weak, feeble’

The diphthong /uə̯/ is written:

- ua at the end of a syllable: /mūə̯/ = mua ‘to buy’

- uô before a consonant or off-glide: /mūə̯n/ = muôn ‘ten thousand’; /sūə̯j/ = xuôi ‘down’

The diphthong /ɨə̯/ is written:

- ưa at the end of a syllable: /mɨ̄ə̯/ = mưa ‘to rain’

- ươ before a consonant or off-glide: /mɨ̄ə̯ŋ/ = mương ‘irrigation canal’; /tɨ̌ə̯j/ = tưới ‘to water, irrigate, sprinkle’

Tone marks[edit]

Vietnamese is a tonal language, so the meaning of each word depends on the pitch in which it is pronounced. Tones are marked in the IPA as suprasegmentals following the phonemic value. Some tones are also associated with a glottalization pattern.

There are six distinct tones in the standard northern dialect. The first one («level tone») is not marked and the other five are indicated by diacritics applied to the vowel part of the syllable. The tone names are chosen such that the name of each tone is spoken in the tone it identifies.

In the south, there is a merging of the hỏi and ngã tones, in effect leaving five tones.

| Order | Diacritic | Symbol | Input keys | Name | IPA diacritic | Vowels with diacritic | Unicode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TELEX | VNI | |||||||

| 1 | unmarked | N/A | Z*

|

0*

|

Ngang | mid level, ˧ | A/a, Ă/ă, Â/â, E/e, Ê/ê, I/i, O/o, Ô/ô, Ơ/ơ, U/u, Ư/ư, Y/y | |

| 2 | acute accent | á | S

|

1

|

Sắc | high rising, ˧˥ | Á/á, Ắ/ắ, Ấ/ấ, É/é, Ế/ế, Í/í, Ó/ó, Ố/ố, Ớ/ớ, Ú/ú, Ứ/ứ, Ý/ý | U+0341 or U+0301 |

| 3 | grave accent | à | F

|

2

|

Huyền | low falling, ˨˩ | À/à, Ằ/ằ, Ầ/ầ, È/è, Ề/ề, Ì/ì, Ò/ò, Ồ/ồ, Ờ/ờ, Ù/ù, Ừ/ừ, Ỳ/ỳ | U+0340 or U+0300 |

| 4 | hook above | ả | R

|

3

|

Hỏi | mid falling, ˧˩ (Northern); dipping, ˨˩˥ (Southern) | Ả/ả, Ẳ/ẳ, Ẩ/ẩ, Ẻ/ẻ, Ể/ể, Ỉ/ỉ, Ỏ/ỏ, Ổ/ổ, Ở/ở, Ủ/ủ, Ử/ử, Ỷ/ỷ | U+0309 |

| 5 | tilde | ã | X

|

4

|

Ngã | glottalized rising, ˧˥ˀ (Northern); slightly lengthened Dấu Hỏi tone (Southern) | Ã/ã, Ẵ/ẵ, Ẫ/ẫ, Ẽ/ẽ, Ễ/ễ, Ĩ/ĩ, Õ/õ, Ỗ/ỗ, Ỡ/ỡ, Ũ/ũ, Ữ/ữ, Ỹ/ỹ | U+0342 or U+0303 |

| 6 | dot below | ạ | J

|

5

|

Nặng | glottalized falling, ˧˨ˀ (Northern); low rising, ˩˧ (Southern) | Ạ/ạ, Ặ/ặ, Ậ/ậ, Ẹ/ẹ, Ệ/ệ, Ị/ị, Ọ/ọ, Ộ/ộ, Ợ/ợ, Ụ/ụ, Ự/ự, Ỵ/ỵ | U+0323 |

- * =

Z(in TELEX) and0(in VNI) keys are used to remove the mark. For example in TELEX,AS=> á, then pressZ=> a. - Unmarked vowels are pronounced with a level voice, in the middle of the speaking range.

- The grave accent indicates that the speaker should start somewhat low and drop slightly in tone, with the voice becoming increasingly breathy.

- The hook indicates in Northern Vietnamese that the speaker should start in the middle range and fall, but in Southern Vietnamese that the speaker should start somewhat low and fall, then rise (as when asking a question in English).

- In the North, a tilde indicates that the speaker should start mid, break off (with a glottal stop), then start again and rise like a question in tone. In the South, it is realized identically to the Hỏi tone.

- The acute accent indicates that the speaker should start mid and rise sharply in tone.

- The dot or cross signifies in Northern Vietnamese that the speaker starts low and fall lower in tone, with the voice becoming increasingly creaky and ending in a glottal stop.

In syllables where the vowel part consists of more than one vowel (such as diphthongs and triphthongs), the placement of the tone is still a matter of debate. Generally, there are two methodologies, an «old style» and a «new style». While the «old style» emphasizes aesthetics by placing the tone mark as close as possible to the center of the word (by placing the tone mark on the last vowel if an ending consonant part exists and on the next-to-last vowel if the ending consonant doesn’t exist, as in hóa, hủy), the «new style» emphasizes linguistic principles and tries to apply the tone mark on the main vowel (as in hoá, huỷ). In both styles, when one vowel already has a quality diacritic on it, the tone mark must be applied to it as well, regardless of where it appears in the syllable (thus thuế is acceptable while *thúê is not). In the case of the ươ diphthong, the mark is placed on the ơ. The u in qu is considered part of the consonant. Currently, the new style is usually used in textbooks published by Nhà Xuất bản Giáo dục, while most people still prefer the old style in casual uses. Among Overseas Vietnamese communities, the old style is predominant for all purposes.

In lexical ordering, differences in letters are treated as primary, differences in tone markings as secondary and differences in case as tertiary differences. (Letters include for instance A and Ă but not Ẳ. Older dictionaries also treated digraphs and trigraphs like CH and NGH as base letters.[10]) Ordering according to primary and secondary differences proceeds syllable by syllable. According to this principle, a dictionary lists tuân thủ before tuần chay because the secondary difference in the first syllable takes precedence over the primary difference in the second syllable.

Structure[edit]

In the past, syllables in multisyllabic words were concatenated with hyphens, but this practice has died out and hyphenation is now reserved for word-borrowings from other languages. A written syllable consists of at most three parts, in the following order from left to right:

- An optional beginning consonant part

- A required vowel syllable nucleus and the tone mark, if needed, applied above or below it

- An ending consonant part, can only be one of the following: c, ch, m, n, ng, nh, p, t, or nothing.[11]

History[edit]

A page from Alexandre de Rhodes’ 1651 dictionary

Since the beginning of the Chinese rule 111 BC, literature, government papers, scholarly works, and religious scripture were all written in classical Chinese (chữ Hán) while indigenous writing in chu han started around the ninth century.[12] Since the 12th century, several Vietnamese words started to be written in chữ Nôm, using variant Chinese characters, each of them representing one word. The system was based on chữ Hán, but was also supplemented with Vietnamese-invented characters (chữ thuần nôm, proper Nôm characters) to represent native Vietnamese words.

Creation of chữ Quốc ngữ[edit]

As early as 1620, with the work of Francisco de Pina, Portuguese and Italian Jesuit missionaries in Vietnam began using Latin script to transcribe the Vietnamese language as an assistance for learning the language.[1][3] The work was continued by the Avignonese Alexandre de Rhodes. Building on previous dictionaries by Gaspar do Amaral and Antonio Barbosa, Rhodes compiled the Dictionarium Annamiticum Lusitanum et Latinum, a Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary, which was later printed in Rome in 1651, using their spelling system.[1][13] These efforts led eventually to the development of the present Vietnamese alphabet. For 200 years, chữ Quốc ngữ was used within the Catholic community.[14][15]

Colonial period[edit]

In 1910, the French colonial administration enforced chữ Quốc ngữ.[16] The Latin alphabet then became a means to publish Vietnamese popular literature, which was disparaged as vulgar by the Chinese-educated imperial elites.[17] Historian Pamela A. Pears asserted that by instituting the Latin alphabet in Vietnam, the French cut the Vietnamese from their traditional Hán Nôm literature.[18] An important reason why Latin script became the standard writing system in Vietnam but not in Cambodia and Laos, which were both dominated by the French for a similar amount of time under the same colonial framework, had to do with the Nguyễn Emperors of Vietnam heavily promoting its usage.[19] According to the historian Liam Kelley in his 2016 work «Emperor Thành Thái’s Educational Revolution» neither the French nor the revolutionaries had enough power to spread the usage of chữ Quốc ngữ down to the village level.[19] It was by imperial decree in 1906 of Emperor Thành Thái, that parents could decide whether their children will follow a curriculum in Hán văn (漢文) or Nam âm (南音, «Southern sound», the contemporary Vietnamese name for chữ Quốc ngữ).[19] This decree was issued at the same time when other social changes, such as the cutting of long male hair, were occurring.[19] The main reason for the popularisation of the Latin alphabet in Vietnam/Đại Nam during the Nguyễn dynasty (the French protectorates of Annam and Tonkin) was because of the pioneering efforts by intellectuals from French Cochinchina combined with the progressive and scientific policies of the French government in French Indochina, that created the momentum for the usage of chữ Quốc ngữ to spread.[19]

From the first days it was recognized that the Chinese language was a barrier between us and the natives; the education provided by means of the hieroglyphic characters was completely beyond us; this writing makes possible only with difficulty transmitting to the population the diverse ideas which are necessary for them at the level of their new political and commercial situation. Consequently we are obliged to follow the traditions of our own system of education; it is the only one which can bring close to us the Annamites of the colony by inculcating in them the principles of European civilization and isolating them from the hostile influence of our neighbors.[20]

— In a letter dated January 15, 1866, Paulin Vial, Directeur du Cabinet du Gouverneur de la Cochinchine

Since the 1920s, the Vietnamese mostly use chữ Quốc ngữ, and new Vietnamese terms for new items or words are often calqued from Hán Nôm. Some French had originally planned to replace Vietnamese with French, but this never was a serious project, given the small number of French settlers compared with the native population. The French had to reluctantly accept the use of chữ Quốc ngữ to write Vietnamese since this writing system, created by Portuguese missionaries, is based on Portuguese orthography, not French.[21]

Mass education[edit]

Between 1907 and 1908, the short-lived Tonkin Free School promulgated chữ quốc ngữ and taught French language to the general population.

In 1917, the French system suppressed Vietnam’s Confucian examination system, viewed as an aristocratic system linked with the «ancient regime», thereby forcing Vietnamese elites to educate their offspring in the French language education system. Emperor Khải Định declared the traditional writing system abolished in 1918.[17]

While traditional nationalists favoured the Confucian examination system and the use of chữ Hán, Vietnamese revolutionaries, progressive nationalists, and pro-French elites viewed the French education system as a means to «liberate» the Vietnamese from old Chinese domination and the unsatisfactory «outdated» Confucian examination system, to democratize education and to help link Vietnamese to European philosophies.

The French colonial system then set up another educational system, teaching Vietnamese as a first language using chữ quốc ngữ in primary school and then the French language (taught in chữ quốc ngữ). Hundreds of thousands of textbooks for primary education began to be published in chữ quốc ngữ, with the unintentional result of turning the script into the popular medium for the expression for Vietnamese culture.[22]

Late 20th century to present[edit]

Typesetting and printing Vietnamese has been challenging due to its number of accents/diacritics.[23][24][25] Contemporary Vietnamese texts sometimes include words which have not been adapted to modern Vietnamese orthography, especially for documents written in Chữ Hán. The Vietnamese language itself has been likened to a system akin to «ruby characters» elsewhere in Asia. See Vietnamese language and computers for usage on computers and the internet.

Computing[edit]

Different ways in which tone marks can be presented on letters that already have diacritic e.g. (`) on letter ê when computerising Vietnamese.

The universal character set Unicode has full support for the Latin Vietnamese writing system, although it does not have a separate segment for it. The required characters that other languages use are scattered throughout the Basic Latin, Latin-1 Supplement, Latin Extended-A and Latin Extended-B blocks; those that remain (such as the letters with more than one diacritic) are placed in the Latin Extended Additional block. An ASCII-based writing convention, Vietnamese Quoted Readable and several byte-based encodings including VSCII (TCVN), VNI, VISCII and Windows-1258 were widely used before Unicode became popular. Most new documents now exclusively use the Unicode format UTF-8.

Unicode allows the user to choose between precomposed characters and combining characters in inputting Vietnamese. Because in the past some fonts implemented combining characters in a nonstandard way (see Verdana font), most people use precomposed characters when composing Vietnamese-language documents (except on Windows where Windows-1258 used combining characters).

Most keyboards on modern phone and computer operating systems, including iOS,[26] Android[27] and MacOS,[28] have now supported the Vietnamese language and direct input of diacritics by default. Previously, Vietnamese users had to manually install free softwares such as Unikey on computers or Laban Key on phones to type Vietnamese diacritics. These keyboards support input methods such as Telex, VNI, VIQR and its variants.

See also[edit]

- Portuguese orthography

- Special characters:

- Ă, Â, Đ, Ê, Ô, Ơ, Ư

- Dot (diacritic)

- Hook above

- Horn (diacritic)

- Historic Writing

- «Chữ Hán», classical Chinese written in Vietnam (Han characters)

- «Chữ Nôm», former script used to write Vietnamese using Han and Nom (invented characters) words

- Coding and Input Methods:

- Telex, the oldest standard input method for the Vietnamese alphabet on electronic devices.

- VNI, another input and encoding convention for Vietnamese alphabet.

- VIQR, another standard 7-bit input method for Vietnamese alphabet.

- VISCII, another standard 8-bit encoding for Vietnamese alphabet.

- Unicode, character encoding standard for most of the world’s writing systems

- Vietnamese Braille

- Vietnamese calligraphy

- Vietnamese phonology

- Francisco de Pina

- Alexandre de Rhodes

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Jacques, Roland (2002). Portuguese Pioneers of Vietnamese Linguistics Prior to 1650 – Pionniers Portugais de la Linguistique Vietnamienne Jusqu’en 1650 (in English and French). Bangkok, Thailand: Orchid Press. ISBN 974-8304-77-9.

- ^ Jacques, Roland (2004). «Bồ Đào Nha và công trình sáng chế chữ quốc ngữ: Phải chăng cần viết lại lịch sử?» Translated by Nguyễn Đăng Trúc. In Các nhà truyền giáo Bồ Đào Nha và thời kỳ đầu của Giáo hội Công giáo Việt Nam (Quyển 1) – Les missionnaires portugais et les débuts de l’Eglise catholique au Viêt-nam (Tome 1) (in Vietnamese & French). Reichstett, France: Định Hướng Tùng Thư. ISBN 2-912554-26-8.

- ^ a b Trần, Quốc Anh; Phạm, Thị Kiều Ly (October 2019). Từ Nước Mặn đến Roma: Những đóng góp của các giáo sĩ Dòng Tên trong quá trình La tinh hoá tiếng Việt ở thế kỷ 17. Conference 400 năm hình thành và phát triển chữ Quốc ngữ trong lịch sử loan báo Tin Mừng tại Việt Nam. Ho Chi Minh City: Ủy ban Văn hóa, Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Vietnam.

- ^ Tran (2022).

- ^ Haudricourt, André-Georges. 2010. «The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet.» Mon-Khmer Studies 39: 89–104. Translated from: Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1949. «L’origine Des Particularités de L’alphabet Vietnamien.» Dân Viêt-Nam 3: 61–68.

- ^ Jakob Rupert Friederichsen Opening Up Knowledge Production Through Participatory Research? Frankfurt 2009 [6.1 History of Science and Research in Vietnam] Page 126 «6.1.2 French colonial science in Vietnam: With the colonial era, deep changes took place in education, communication, and … French colonizers installed a modern European system of education to replace the literary and Confucianism-based model, they promoted a romanized Vietnamese script (Quốc Ngữ) to replace the Sino-Vietnamese characters (Hán Nôm)»

- ^ «Vietnam Alphabet». vietnamesetypography.

- ^ a b c d The close vowels /i, ɨ, u/ are diphthongized [ɪi̯, ɯ̽ɯ̯, ʊu̯].

- ^ «Do you know How to pronounce Igrec?». HowToPronounce.com. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

- ^ See for example Lê Bá Khanh; Lê Bá Kông (1998) [1975]. Vietnamese-English/English-Vietnamese Dictionary (7th ed.). New York City: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-87052-924-2.

- ^ «vietnamese Alphabet». Omniglot.com. 2014.

- ^ Kornicki 2017, p. 568.

- ^ Tran, Anh Q. (October 2018). «The Historiography of the Jesuits in Vietnam: 1615–1773 and 1957–2007». Jesuit Historiography Online. Brill.

- ^ Li 2020, p. 106.

- ^ Ostrowski, Brian Eugene (2010). «The Rise of Christian Nôm Literature in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam: Fusing European Content and Local Expression». In Wilcox, Wynn (ed.). Vietnam and the West: New Approaches. Ithaca, New York: SEAP Publications, Cornell university Press. pp. 23, 38. ISBN 9780877277828.

- ^ «Quoc-ngu | Vietnamese writing system». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ a b Nguyên Tùng, «Langues, écritures et littératures au Viêt-nam», Aséanie, Sciences humaines en Asie du Sud-Est, Vol. 2000/5, pp. 135-149.

- ^ Pamela A. Pears (2006). Remnants of Empire in Algeria and Vietnam: Women, Words and War. Lexington Books. p. 18. ISBN 0-7391-2022-0. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ^ a b c d e Nguyễn Quang Duy (12 September 2018). «Quốc ngữ và nỗ lực ‘thoát Hán’ của các vua nhà Nguyễn» (in Vietnamese). Người Việt Daily News. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Li 2020, p. 107.

- ^ Trần Bích San. «Thi cử và giáo dục Việt Nam dưới thời thuộc Pháp» (in Vietnamese). Note 3. «The French had to accept reluctantly the existence of chữ quốc ngữ. The propagation of chữ quốc ngữ in Cochinchina was, in fact, not without resistance [by French authority or pro-French Vietnamese elite] […] Chữ quốc ngữ was created by Portuguese missionaries according to the phonemic orthography of Portuguese language. The Vietnamese could not use chữ quốc ngữ to learn French script. The French would mispronounce chữ quốc ngữ in French orthography, particularly people’s names and place names. Thus, the French constantly disparaged chữ quốc ngữ because of its uselessness in helping with the propagation of French script.»

- ^ Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. pp. 127-128.

- ^ Wellisch, Hans H. (1978). The Conversion of Scripts, Its Nature, History, and Utilization. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-01620-5.

- ^ Language Monthly. Praetorius. 1987.

- ^ Sassoon, Rosemary (1995). The acquisition of a second writing system. Internet Archive. Oxford [England] : Intellect. ISBN 978-1-871516-43-2.

- ^ Anh, Hao (2021-09-21). «Hướng dẫn gõ tiếng Việt trên iOS 15 bằng tính năng lướt phím QuickPath». VietNamNet (in Vietnamese). Retrieved 2022-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Set up Gboard on Android». Google Support. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ^ Phan, Kim Long. «UniKey in macOS and iOS». UniKey. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

Bibliography[edit]

- Gregerson, Kenneth J. (1969). A study of Middle Vietnamese phonology. Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoises, 44, 135–193. (Published version of the author’s MA thesis, University of Washington). (Reprinted 1981, Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics).

- Haudricourt, André-Georges (1949). «Origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien (English translation as: The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet)» (PDF). Dân Việt-Nam. 3: 61–68.

- Healy, Dana.(2003). Teach Yourself Vietnamese, Hodder Education, London.

- Kornicki, Peter (2017), «Sino-Vietnamese literature», in Li, Wai-yee; Denecke, Wiebke; Tian, Xiaofen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature (1000 BCE-900 CE), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 568–578, ISBN 978-0-199-35659-1

- Li, Yu (2020). The Chinese Writing System in Asia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-069906-7.

- Nguyen, Đang Liêm. (1970). Vietnamese pronunciation. PALI language texts: Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-87022-462-X

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1955). Quốc-ngữ: The modern writing system in Vietnam. Washington, D. C.: Author.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà (1992). «Vietnamese phonology and graphemic borrowings from Chinese: The Book of 3,000 Characters revisited». Mon-Khmer Studies. 20: 163–182.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1996). Vietnamese. In P. T. Daniels, & W. Bright (Eds.), The world’s writing systems, (pp. 691–699). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- Nguyễn, Đình-Hoà. (1997). Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 1-55619-733-0.

- Pham, Andrea Hoa. (2003). Vietnamese tone: A new analysis. Outstanding dissertations in linguistics. New York: Routledge. (Published version of author’s 2001 PhD dissertation, University of Florida: Hoa, Pham. Vietnamese tone: Tone is not pitch). ISBN 0-415-96762-7.

- Pham, Thi Kieu Ly (2018). La grammatisation du vietnamien (1615–1919): histoire des grammaires et de l’écriture romanisée du vietnamien (PhD). Université Sorbonne Paris Cité.

- Sassoon, Rosemary (1995). The Acquisition of a Second Writing System (illustrated, reprint ed.). Intellect Books. ISBN 1871516439. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Thompson, Laurence E. (1991). A Vietnamese reference grammar. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1117-8. (Original work published 1965).

- Tran, Anh Q. (2022). «Catholicism and the Development of the Vietnamese Alphabet, 1620–1898». Journal of Vietnamese Studies. 17 (2–3): 9–37. doi:10.1525/vs.2022.17.2-3.9. S2CID 250513843.

- Wellisch, Hans H. (1978). The conversion of scripts, its nature, history and utilization. Information sciences series (illustrated ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0471016209. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Nguyen, A. M. (2006). Let’s learn the Vietnamese alphabet. Las Vegas: Viet Baby. ISBN 0-9776482-0-6

- Shih, Virginia Jing-yi. Quoc Ngu Revolution: A Weapon of Nationalism in Vietnam. 1991.

External links[edit]

Media related to Vietnamese writing at Wikimedia Commons

- Vietnamese Unicode FAQs

| Вьетнамский язык | |

|---|---|