Правильное употребление (написание) карточных терминов: названий мастей и пр. часто представляет проблему. Как правильно: бубей или бубён? червовый или червонный? Предлагаем вашему вниманию две статьи на эту тему: Л.Н. Клоченко «Русский язык и карты» и Д.С. Лесного «О склонении названий карточных мастей».

Л.Н. Клоченко

РУССКИЙ ЯЗЫК И КАРТЫ

Эта статья является авторефератом одной из глав диссертации.

Грамматика мастей и названий карт – субстанция очень деликатная, а уж об орфоэпии и говорить не приходится. Такое впечатление, что игрокам всё равно – черви или червы, ведь от окончания масть не изменится и не станет козырной или козырнóй! Но пишущая братия (авторы книг по правилам карточных игр, редакторы журналов) забили тревогу.

На конференции любителей преферанса, проходившей в Москве 22 и 23 января 1996 года, был поставлен вопрос о нормах языка применительно к карточной лексике. Все согласились, что наиболее остро стоит проблема склонения мастей. Но вот что интересно: в карты в России играют уже более трёхсот лет, играют все слои населения – от уголовников до докторов наук. В творчестве всех русских писателей (за исключением, пожалуй, М.В. Ломоносова) присутствует тема карточной игры. Однако русская филологическая наука имеет всего три статьи, посвященные грамматике и этимологии карт. Первая статья В.В. Стасова опубликована в «Отчёте археологической комиссии за 1872 год». Статья посвящена исследованиям карточных рисунков и символики, а также этимологии. Сам автор так определяет задачи своей статьи: «Настоящие мои заметки имеют целью указать: откуда идут наши названия карточных мастей: черви, бубны, жлуди и вины». Как мы видим, автор описывает устаревшие на сегодняшний день названия трефовой и пиковой мастей.

А.И. Маркевич, автор интереснейшей статьи, опубликованной в 1904 году, уже самым названием «Отступления от грамматических правил в карточных играх» вступает в полемику со святая святых любого языка – грамматическими правилами и нормами. А.И. Маркевич пишет: «Ноне ухо играющего в карты грамотея ежесекундно оскорбляется теми антиграмматическими формами, которые он слышит из уст своих партнёров при склонении ими названий карт». К счастью, это высказывание на сегодняшний день практически устарело. Но что же считать правильной формой? Существуют ли нормы для данной лексико-семантической группы слов?

Многие карточные термины не занесены ни в один словарь. Можно ли считать нормой то, как говорят профессиональные картежники (в большинстве своем люди с техническим образованием), или то, что рекомендуют в словарях филологи, которые не умеют играть в карты (в основной своей массе). Может ли орфоэпический словарь под редакцией Р.И. Аванесова отразить все те нюансы, которые прекрасно чувствуют картежники?!

Но вернемся к статье Маркевича. Согласно правилам грамматики конца XIX – начала XX веков выражения «я снёс короля, я побил валета» считались неправильными, так как склонялись по одушевлённой парадигме (родительный и винительный падежи совпадают). По правилам, онёрные карты считались неодушевлёнными и, следовательно, должны были склонятся по неодушевлённой парадигме (совпадение именительного и винительного падежей). Правильная фраза должна была звучать так: «я снес король, я побил валет.» Но ведь ни один игрок ни тогда, ни сейчас не считает карты неодушевлёнными предметами. Вспомним рассказ Леонида Андреева «Большой шлем»: «Карты давно уже потеряли в их глазах значение бездушной материи, и каждая масть, а в масти каждая карта в отдельности, была строго индивидуальна и жила своей особенной жизнью. Масти были любимые и нелюбимые, счастливые и несчастливые. Карты комбинировались бесконечно разнообразно, и разнообразие это не поддавалось ни анализу, ни правилам, но было в то время закономерно. И в закономерности этой заключалась жизнь карт, особая от жизни игравших в них людей. Люди хотели и добивались от них своего, а карты делали своё, как будто они имели свою волю, свои вкусы, симпатии и капризы».

Обратимся еще к стихотворению Н.А. Некрасова «Чиновник»:

- Валетов, дам красивых, но холодных

- Пушил слегка, как все;

- Но никогда насчёт тузов и прочих карт почтенных

- Не говорил ни слова.

Как я уже говорила раньше, при склонении слова по одушевлённой парадигме совпадают родительный и винительный падежи. Особенно это важно при склонении слова ТУЗ. Самая старшая в большинстве игр карта, туз не является фигурой. Если валет, дама, король в общеупотребительной лексике в прямом значении обозначают людей определённого социального положения (поэтому-то и легко объяснить их склонение по одушевлённой парадигме в карточной лексике), то туз только в переносном значении (в общеупотребительной лексике) обозначает человека: «Что за тузы в Москве живут и умирают!» – Грибоедов «Горе от ума». Приведу лишь один яркий литературный пример правильного (по меркам начала XX века) употребления слова туз: «В зубах – цыгарка, примят картуз. В спину б надо бубновый туз». Все конечно узнали «Двенадцать» Александра Блока. А вот «неправильный» пример, взятый у Сергея Есенина:

- Ах, луна влезает через раму,

- Свет такой, хоть выколи глаза…

- Ставил я на пиковую даму,

- А сыграл бубнового туза.

В данных примерах словосочетание «бубновый туз» употреблено не в значении «туз бубновой масти», а в переносном – «красный ромб на спине арестантской верхней одежды».

Академическая грамматика русского языка 1980 года закрепила за названиями онёрных карт (кроме десятки) право склоняться по одушевлённой парадигме. Так что выражение Маркевича «антиграмматические нормы» по отношению к онёрным картам полностью устарело.

Теперь обратимся к очковым картам, к фоскам. Семёрка, пятерка, двойка – все эти существительные образовались от числительных – три очка, десять очков и так далее. Обратимся к толковому словарю под редакцией Д.Н. Ушакова. Я просмотрела все статьи о фосках. (Кстати, слово «фоска» словарь относит к карточному арго.) Все эти слова многозначны. Приведу лишь некоторые общие значения:

1) Цифра 2 (3, 5,

2) Название различных предметов, нумерованных этой цифрой – разговорное.

Практически все значения (за исключением сугубо конкретных, как, например, «школьная отметка») имеют пометку – разговорное или просторечное. Но интересующее нас значение «игральная карта, имеющая три (четыре, два) очка» не имеет никаких пометок, ограничивающих сферу употребления. Ещё нас интересует одна особенность фосок: склоняются они (в отличие от онёров) по неодушевлённой парадигме. Проверим: «Я снёс шестёрки», – фоска стоит в винительном падеже. Выражение «я снёс шестёрок» очень «режет ухо». Почему так произошло? Почему фоски и онёры различаются и на грамматическом уровне? Предоставим эти проблемы психолингвистике.

А теперь перейдём к самому сложному и проблематичному разделу карточной грамматики – к мастям. Думаю, что в рамках этой статьи нет смысла вдаваться в происхождение и появление названий мастей (современных). Существует очень много прекрасно обоснованных теорий, но ни одна из них не поможет объяснить грамматику.

Особую сложность представляют ЧЕРВИ… Вот что об этом пишет Маркевич:

Как известно, их (мастей) у нас четыре: червы, бубны, пики, трефы. Со склонением названия масти «червы» именно происходят довольно возмутительные операции из-за того, что смешиваются два слова: «червы» (именительный падеж единственного числа «черва») и «черви» (именительный падеж единственного числа «червь»). Считаю такое смешение черв с червями вовсе нежелательным, хотя нельзя не сознаться, что оно освещено не только бытовой, но и литературной практикой. Уже у Капниста в комедии «Ябеда» (1798) Проволов говорит, указывая на (по-видимому) запечатанные карты, что «…множество червей//В колодах сих давно свободы ждут своей…». Затем А.Я. >Булгаков

в 1825 году пишет брату: «Червей не распознаешь от пик». В академическом словаре вместо «червы» находится слово «черви», родительный падеж – червей. В словаре сказано, что слово «черви» употребляется лишь во множественном числе (приведём пример: я пошёл с червей), тогда как и ныне употребление слова «черва» очень обычно. Да и как иначе сказать: «У меня на руках была одна черва». Чтобы покончить с имеющимся у нас для данного вопроса материалом, напомню основанный на том же каламбуре, как и в комедии Капниста, известный рассказ о похоронах одного генерала. «Они великолепны: спереди идут духовные лица с крестами, (кресты – старое название треф), по бокам казаки с пиками, позади музыканты с бубнами, а посреди сам генерал с червями!»

А как же освещает этот вопрос современная лингвистическая наука и игровая практика? Заглянем в словарь русского литературного языка Академии наук СССР (1954). Там мы встретим ту же самую форму «черви», что и сто лет назад.

«Черви-ей и червы, черв, мн. (ед. прост. черва, ы, ж.)».

«Черви особенно часто приходили к Якову Ивановичу, а у Евпраксии Васильевны руки полны были пик». Л. Андреев «Большой шлем».

Орфоэпический словарь под редакцией Аванесова вторит Академическому: «черви, червей, червям и доп. червы, черв, червам». А вот толковый словарь русского языка под редакцией Д.Н. Ушакова на первое место ставит форму «червы»: «червы, черв, червам (червам простореч.), и черви, ей, ям, ед. прост. черва, ы, ж».

«Пролистав» словари, мы убедились, что лингвисты в большинстве своём не дают ту форму, к которой привыкли картёжники: «черва» везде считается просторечной (как и сто лет назад), а «червям» отдают преимущество. Почему же словари считают форму единственного числа просторечной? Название масти в единственном числе имеет два основных значения: Первое – собирательное, например: козырь – пика. Второе – единственная карта какой-либо масти, например: я пошел трефой. Я думаю, что все со мной согласятся в том, что употребление единственного числа в собирательном значении – действительно, просторечие. Мне кажется, что хотя бы в книгах этого быть не должно. Во втором же значении – форма единственного числа незаменима. (Если бы филологи и лексикографы играли в карты, то такой путаницы не возникло бы.)

Но вернёмся к нашему «червивому» вопросу. Просмотрим несколько современных учебников, написанных профессионалами. У меня такое чувство, что многие авторы, презрев все правила грамматики, выбирают ту словоформу, которая им удобна. Конечно, ни один современный игрок не скажет «черви». Очень хорошо написал об этом Николай Юрьевич Розалиев: «Согласитесь, что несколько двусмысленно звучит заявление о наличии у Вас «червей». Да и игра будет какая-то «червивая». Но уж коли принята форма «червы», то и падежные окончания нужно делать соответствующие парадигме». (См. конец статьи.)

В некоторых книгах мы встречаем удивительную вещь: автор даёт форму «червы», а затем у него проскальзывает форма родительного падежа – «червей» (вместо «черв»). Это я заметила в учебнике А.Г. Утяцкого «Преферанс от А до Я». «Младшей мастью по старшинству являются пики (п),….и наконец червы (ч)». И затем, в нарушение всех грамматических норм: «на любой руке можно назначить «7 червей» (вместо 7 черв). Игра Н.Ю. Розалиева никогда не будет «червивой»: «Карты игроков З и В нам пока не известны. З пошёл тузом черв».

Дмитрий Станиславович Лесной готовит к изданию учебник и в качестве вступительной статьи публикует «О склонении названий карточных мастей». Говоря о нашей «проблемной» масти, он справедливо указывает на одно затруднение: «Фонетически форма «черв» выглядит неблагозвучной – два твёрдых согласных звука просят какого-то окончания, особенно, если после них опять идут согласные: двух черв в прикупе». Я считаю, что эта проблема легко разрешима: форму «черв» можно легко заменить на прилагательное «червовый» – «червовый туз в прикупе», или на форму единственного числа в родительном падеже: «две червы в прикупе». И совсем не обязательно хвататься за форму «червей» как за спасательный круг.

Откуда же пошло смешение карточной масти и червяка? Думаю, что лучший ответ на этот вопрос даст этимологический словарь Н.М. Шанского (1971). Привожу полную словарную статью.

«Черви (карт. масть). По происхождению является формой множественного числа от несохранившегося чьрвъ – «красный» (ср.др-рус. чьрвъ – «красная краска», засвидетельствованное в памятниках), имеющего тот же корень, что и червь. Название дано по красному цвету рисунка на картах – червленый (багряный). Для понимания развития значения «червленый» следует иметь в виду, что из червей определённого вида добывалась краска красного цвета.

Мы подошли к образованию прилагательных. Как и раньше, обратимся к Маркевичу: «Укажу на ещё одну карточную неправильность: при образовании прилагательных от названий мастей у нас часто говорят: червовый туз, тогда как следует: червонный (т.е. красный), что имеется и в давней литературной практике; так в комедии князя Шаховского «Липецкие воды» (1815) в III действии явления I говорится: «Учтивее ввести товарища в ремиз, чем быть невежливым против червонной дамы». Здесь современники и Маркевич полностью «совпадают». Словарь Ушакова приводит очень интересное переносное значение словосочетания «червонный валет» (разговорное, устаревшее) – молодой человек из буржуазно-дворянского круга, ведущий праздную жизнь. «Червонный валет… существо, изнемогающее под бременем праздности и пьяной тоски, живущее со дня на день, лишённое всякой устойчивости для борьбы с жизнью и не признающее никаких жизненных задач, кроме удовлетворения минуты». М.Е. Салтыков-Щедрин.

Игроки против такого прилагательного имеют много возражений. Как известно, в колоде две красные масти: червы и бубны. Поэтому игроки конкретизируют значение «червонный» – либо бубновый, либо червовый.

Теперь перейдем к бубнам. Бубны являются семантической калькой с немецкого Schellen «бубны, бубенчики» (семантическая калька – это заимствование переносного значения слова). В России масть называли потому, что на картах изображались бубенцы. (Немецкое (устаревшее) название «шеллен» переводится как колокола.) В европейских странах значение этой масти многолико: бриллианты, плитки, квадраты, деньги. В отношении грамматики филологи единодушны: бубны, бубен, бубнами и бубен, бубнам.

Д.С. Лесной подошёл к этой проблеме с чисто практической точки зрения. По его версии, «неблагозвучное» и непривычное выражение «пошёл с бубён» можно сломать язык. Отсутствие в типографиях буквы «ё» и в результате чего совпадение формы «бубён» с музыкальным инструментом, только добавляет проблем. Я не вижу в этом ничего страшного, но раз уж подавляющее большинство игроков предпочитают говорить «бубей», то по старой нашей традиции примем мнение большинства за норму в разговорной речи. Но в книгах о картах необходимо оставить литературную форму. (Я почти уверена, что никто не спутает учебник по преферансу с музыкальной энциклопедией!)

Пики и трефы не вызывают затруднений с грамматической точки зрения. Такие «народные» формы как «пикенция, пикендрас, пикей, трефей, бубней» оставим для весёлых пословиц – и поговорок.

Подведём итоги. Уважаемые игроки! Уважаемые авторы карточных учебников! Давайте сохранять русский язык в классическом виде! Если очень уж тяжело в устной речи (эмоции, нервы, партнёр не тот попался), то хотя бы в письменной речи давайте соблюдать языковые нормы! И если не хотите расставаться с «червями и бубями», то лучше уж заменяйте их на письме прилагательными или (на худой конец) знаками!

Склонения названий мастей в единственном числе

|

Именительный |

пика |

трефа |

бубна |

черва |

|

Родительный |

пики |

трефы |

бубны |

червы |

|

Дательный |

пике |

трефе |

бубне |

черве |

|

Винительный |

пику |

трефу |

бубну |

черву |

|

Творительный |

пикой |

трефой |

бубной |

червой |

|

Предложный |

(о) пике |

(о) трефе |

(о) бубне |

(о) черве |

Склонения названий мастей во множественном числе

|

Именительный |

И. |

пики |

трефы |

бубны |

червы |

|

Родительный |

Р. |

пик |

треф |

бубен (ён) |

черв |

|

Дательный |

Д. |

пикам |

трефам |

бубнам |

червам |

|

Винительный |

В. |

пики |

трефы |

бубны |

червы |

|

Творительный |

Т. |

пиками |

трефами |

бубнами |

червами |

|

Предложный |

П. |

(о) пиках |

(о) трефах |

(о) бубнах |

(о) червах |

Прилагательные, образованные от названий мастей (единственное число)

- И. пиковый трефовый бубновый червовый

- Р. пикового трефового бубнового червового

- Д. пиковому трефовому бубновому червовому

- В. пикового трефового бубнового червового

- Т. пиковым трефовым бубновым червовым

- П. (о) пиковом (о) трефовом (о) бубновом (о) червовом

множественное число

- И. пиковые трефовые бубновые червовые

- Р. пиковых трефовых бубновых червовых

- Д. пиковым трефовым бубновым червовым

- В. пиковые трефовые бубновые червовые

- Т. пиковым трефовым бубновым червовым

- П. (о) пиковых (о) трефовых (о) бубновых (о) червовых

* * *

Д.С. Лесной

О СКЛОНЕНИИ НАЗВАНИЙ КАРТОЧНЫХ МАСТЕЙ

Серьёзные расхождения встречаются в названиях карточных мастей и образованных от них прилагательных при склонении по падежам. Как правильно сказать: червовый или червонный? Король бубновый или король бубен? Аможет быть, король бубён?

С одной стороны, есть классическая русская литература и все эти слова можно найти у Пушкина и Толстого, Тургенева и Некрасова, Гоголя и Достоевского. Но с другой стороны, существует современная языковая практика и чувство языка. Нет ли у Вас ощущения, что выражение без черв как-то режет ухо? Возможно, сегодня более привычно слышать червей, бубей… Сама фонетически форма черв кажется какой-то неблагозвучной – две твёрдых согласных просят окончания, особенно, если после них в следующем слове опять идут согласные: двух черв в прикупе. Авторы новейших книг на тему карт и карточных игр не обнаруживают единства взглядов на эту проблему, а может быть, не все обращают внимание на её существование.

Между тем, этот вопрос каким-то образом нужно решить, и существует, по крайней мере, две различные точки зрения. Николай Юрьевич Розалиев, автор серии книг “Карточные игры России”, высказал как-то опасение, что, будучи напечатано, просторечие становится нормой, узаконивает своё право на существование и что таким образом “насаждается низкий штиль”. Следовательно, авторы книг должны сверяться по источникам и употреблять исключительно нормативные лексические формы.

Другая точка зрения следующая: пишем-то мы для людей. Никто не хочет, чтобы читатель сломал себе язык (если будет читать вслух) о неблагозвучные или непривычные выражения: на руках не оказалось черв или пошёл с бубён. Особенно при отсутствии в большинстве изданий буквы “ё” как таковой, настаивать на норме бубён кажется странным – даже в словаре С.И. Ожегова (М., 1984) даётся нормативная форма бубён, а рядом пример: Король бубен. Вероятно, ошибка. А совпадение формы бубен с названием музыкального инструмента вносит в текст некоторую путаницу из-за того, что совпадают разные падежные формы: именительный падеж в названии инструмента и родительный в названии масти. И хотя этимологически эти слова близки и даже точно известно, что одно произошло от другого, некоторые люди находят такое совпадение затрудняющим поиск смысла текста.

Должен сразу признаться, что мои усилия «выяснить истину» не увенчались успехом. Само отсутствие ясности в этом вопросе, а также – согласия среди любителей карточных игр, «картописателей» и даже призванных на помощь филологических авторитетов (автор благодарит профессора В.И. Красных и аспирантку Л.Н. Клоченко за ценные советы и помощь в работе) – свидетельствует о том, что запрет карточных игр в нашей стране в течение длительного времени, их изгнание не только из жизни, но и из литературы и журналистики оставили свой след и в языке. Оказалось, что признанная норма в некоторых случаях устарела и стала архаизмом, а на общеупотребительной форме наклеен ярлык просторечия.

Что же делать?

Давайте попробуем для начала разобраться с нормой. Для этого у нас есть два надёжных источника: русская литература и справочные издания (словари). Поскольку названия чёрных мастей – пик и треф – особых разночтений в падежных формах не имеют (просторечные формы «пикями», «трефями», «пикей», «трефей» и т.д. практически не употребляются), сузим поле поиска до названий красных мастей.

Начнём по порядку. Бубны.

- «Сдавались, разминались новые карты, складывались бубны к бубнам…» (Толстой. Смерть Ивана Ильича).

- «– Вот тебе, Швохнев, бубновая дама!» (Гоголь. Игроки).

- «Если случится увидеть этак какого-нибудь бубнового короля или что-нибудь другое, то такое омерзение нападёт, что просто плюнешь.» (Гоголь. Ревизор).

- «Иногда при ударе карт по столу вырывались выражения: – А, была не была, не с чего, так с бубён!2 (Гоголь. Мёртвые души).

- «Они играли в вист с болваном, и нет слов на человеческом языке, чтобы выразить важность, с которой они сдавали, брали взятки, ходили с треф, ходили с бубён.» (Тургенев. Дым).

- «По рассказам, в его кабинете между разными картинами первых мастеров Европы висела в золотой рамке пятёрка бубён; повешена она была хозяином в знак признательности за то, что она рутировала ему в штос, который он когда-то метал на какой-то ярмарке и выиграл миллион». (Пыляев. Старое житьё).

- «– Ходи, ходи, бубны – козыри!..» (Леонов. Барсуки).

- «Положил я, как теперь помню, направо двойку бубён, налево короля пик и вымётываю середину, раз, два, три, пять, девять, вижу – заметалась карта, и про себя твержу: “Заметалась – в пользу банкомёта – известное игроцкое суеверие». (Куприн. C улицы).

- «У меня на бубнах: туз, король, дама, коронка сам-восемь, туз пик и одна, понимаете ли, одна маленькая червонка». (Чехов. Иванов).

- «У меня с прикупом образовалось восемь бубён… Капитан вдруг сказал: – А мы с этим прикупом наверняка бы сыграли пять». (Вересаев. Исполнение земли).

- «Брат Лев дал мне знать о тебе, о Баратынском, о холере… Наконец, и от тебя получил известие. Ты говоришь: худая вышла нам очередь. Вот! Да разве не видишь ты, что мечут нам чистый баламут; а мы ещё понтируем! Ни одной карты налево, а мы всё-таки лезем. – Поделом, если останемся голы как бубны». (Пушкин. Письмо Вяземскому от 5 ноября 1830 г. из Болдина).

В последнем примере Пушкин уподобляет проигравшегося дотла игрока всё-таки музыкальному инструменту, а не карточной масти, так как это бубен (барабан) совершенно лыс и гол – с его кожи вытравлены все волоски. Тот же смысл сравнения находим и у В.И. Даля: «Он проигрался, как бубен…».

В самом начале статьи мы коснулись родства двух этих слов – названия масти и музыкального инструмента. Чтобы окончательно внести ясность, добавим, что на старинных немецких картах, которые начали проникать в Россию через страны Восточной Европы в XVII веке, бубновая масть обозначалась изображением звонков – бубенчиков. В России XVII-XVIII в. эта масть называлась «звонки», «боти». По Фасмеру, название карточной масти бубны является калькой с немецкого Schellen – звонки, через чешск.: bubny. Очень редко в русском языке в XVIII веке употреблялось название этой масти, заимствованное из французского – «каро» (квадратный, четырёхугольный). О том, что именно немецкие карты, т.е. карты с немецкими мастями, появились в России независимо от французских карт и очень давно, свидетельствуют некоторые архаичные названия мастей, считающиеся просторечными: вины (виноградные листья на немецких картах соответствуют пиковой масти) и жлуди (трефовая масть на этих картах изображена в виде желудей). У П.А. Вяземского есть прекрасное стихотворение про карты, в котором к нашей теме относится, к сожалению, только первая строфа («к сожалению» – потому, что очень хочется привести его целиком, но приходится ограничивать себя рамками темы):

- В моей колоде по мастям

- Рассортированы все люди:

- Сдаю я жёлуди и жлуди,

- По вислоухим игрокам.

- Есть бубны – славны за горами;

- Вскрываю вины для друзей;

- Живоусопшими творцами

- Я вдоволь лакомлю червей;

(1827)

Как видно из приведённых литературных примеров, некоторая норма в склонениях названий мастей прослеживается. Но можно привести не менее длинный ряд, в котором употреблена другая форма:

- «Изредка произносит вполголоса: «…заходи, крести, вини, буби» (Куприн. Мелюзга).

Возможно, конечно, автор намеренно снижает лексику своих героев, стилизуя их речь под простонародную и т.д. Мы вернёмся к этому вопросу, когда рассмотрим ряд примеров употребления падежных форм слов черви (червы) и образованных от него прилагательных.

Черви (червы)

«Черви особенно часто приходили к Якову Ивановичу, а у Евпраксии Васильевны руки постоянно полны бывали пик, хотя она их очень не любила». (Леонид Андреев. Большой шлем).

- «Прекрасною твоей рукою Туза червонного вскрываешь. (Державин. На счастие).

- «…Тогда из рук его Давид (т.е. король пик, который на старинных французских картах изображался в виде библейского царя Давида.) на стол вступает, Которого злой хлап червонный поражает… (Майков. Игрок в ломбер).

- «Хозяйка хмурится в подобие погоде, Стальными спицами проворно шевеля, Иль на червонного гадает короля». (Пушкин. Стрекотунья белобока).

- «Кенигсек, поднявшись, чтобы взглянуть из-за спины Анны Ивановны в её карты, произносил сладко: “Мы опять червы». (Толстой А.Н. Пётр I).

- «Яков Иванович строго раскладывал карты и, вынимая червонную двойку, думал, что Николай Дмитриевич легкомысленный и неисправимый человек». (Леонид Андреев. Большой шлем).

- «Шарлотта: – Ну? Какая карта сверху? Пищик: – Туз червовый.» (Чехов. Вишнёвый сад.)

- «Штааль попросил карту и поставил сразу всё, что имел. По намеченному им плану игры надо было ставить на одну карту никак не более трети остающихся денег. Но он и не вспомнил о своём плане. «Будет девятка червей. Хочу, чтоб выпала девятка червей!» – сказал мысленно Штааль. Он в эту минуту был совершенно уверен, что девятка червей (к вопросу об авторской стилизации речи персонажей. Герой Алданова говорит «червей», а не «черв». Причём, к простонародью Штааля не отнесёшь. Но в следующей фразе, комментируя желание своего героя, автор сам употребляет ту же форму – «червей».) ему и достанется. Банкомёт равнодушно метал карты длинной белой рукой, в запылённой снизу, белоснежной наверху, кружевной манжете. Штааль открыл девятку бубён». (Алданов. Заговор).

- «– В трактирах прислуживали поголовно ярославцы… Шестёрки… их прозвание. – Почему «шестёрки»? – Потому, что служат тузам, королям, дамам… И всякий валет, даже червонный (червонный валет – символ мошенника) им приказывает, – объяснил мне старый половой Федотыч». (Гиляровский. Москва и москвичи).

У В. Брюсова, есть стихотворение «Дама треф»:

- Но зато вы – царица ночи,

- Ваша масть – чернее, чем тьма,

- И ваши подведённые очи

- Любовь рисовала сама.

- Вы вздыхать умеете сладко,

- Приникая к подушке вдвоём,

- И готовы являться украдкой,

- Едва попрошу я о том.

- Чего нам ещё ждать от дамы?

- Не довольно ль быть милой на миг?

- Ах, часто суровы, упорны, упрямы

- Дамы черв, бубён и пик!

- Не вздыхать же долгие годы

- У ног неприступных дев!

- И я из целой колоды

- Люблю только даму треф.

- «Червонный валет смотрит на своего собеседника как на «фофана». И вдруг мысль! Продать этому «фофану» присутственные казённые места». (Салтыков-Щедрин. Дети Москвы).

- «– И я, – подхватил Кудимов, загибая угол червонной семёрки (он понтировал в долг). – Пять рублей мазу». (Некрасов. Необыкновенный завтрак).

- «Можно очень самому обремизиться и остаться, как говорят специалисты, без трёх, а то и без пяти в червях (по правилам того времени, игра в червах была самой дорогой, в пиках – самой дешёвой. Поэтому-то на шести пиках нужно было обязательно вистовать)». (Стасюлевич. Письма Лескову).

- Случалось, что карты капризничали, и Яков Иванович не знал, куда деваться от пик, а Евпраксия Васильевна радовалась червям, назначала большие игры и ремизилась. (Леонид Андреев. Большой шлем).

- «Не забудьте, что в колоде один только туз червей, а не два». (Невежин. Сестра Нина).

- «…Когда он потерялся в соображениях, как выгоднее пустить в ход червонного туза или пиковую даму, или когда он, оставив меня в фофанах, ликовал». (Вовчок. Записки причетника).

У Марка Тарловского есть стихотворение «Игра», написанное в 1932 году.

- В пуху и в пере, как птенцы-гамаюныши,

- Сверкают убранством нескромные юноши.

- Четыре валета – а с ними четыре нам

- Грозят короля, соответствуя сиринам.

- Их манят к себе разномастные дамочки,

- Копая на щёчках лукавые ямочки.

- Их тоже четыре – квадрига бесстыжая –

- Брюнетка, шатенка, блондинка и рыжая.

- О зеркало карты! Мне тайна видна твоя:

- Вот корпус фигуры, расколотой надвое.

- Вот нежный живот, самому себе вторящий,

- Вот покерной знати козырное сборище,

- Вот пики, и трефы, и черви, и бубны и

- Трубные звуки, и столики клубные,

- И вот по дворам над помойными ямами,

- Играют мальчишки бросками упрямыми,

- И ямочки щёк и грудные прогалины

- На дамах семейных по-хамски засалены.

- Картёжник играет – не всё ли равно ему? –

- Ведь каждый художник рисует по-своему:

- Порой короля он, шаблоны варьируя,

- Заменит полковником, пьяным задирою,

- «Да будут, – он скажет, – четыре любовницы

- Не знатные дамы, а просто полковницы,

- Да служат им, – скажет, – четыре солдатика!

- Да здравствует новая наша тематика!»

- Усталый полковник сменяется дворником,

- Полковница – нянькой, солдат – беспризорником.

- Кривые столы в зеркалах отражаются,

- Свеча оплывает. Игра продолжается.

Как видим, действительно, «каждый художник рисует по-своему», и в литературе представлено всё многообразие форм: черви и червы, червей и черв, червовый и червонный. Возможно, не лишней будет маленькая справка о происхождении слова. В России XVIII века червовая масть называлась также «керы» (от французского «coeur» – сердце).

- «А кто этот преблагополучный трефовый король, который возмог пронзить сердце керовой дамы?» (Фонвизин. Бригадир).

Появившееся позже название черви (червы) восходит к «червлёный», «червонный» – красный, т.к. значки, обозначавшие масть, – сердца – были красного цвета. Считается, что в простонародной речи «червы» превратились в «черви». В литературных текстах и в обиходе встречаются различные производные формы, которые преимущественно имеют уменьшительно-ласкательный или даже пренебрежительный оттенок: «червоточина», «червонка», «червоночка» и др., означающие карту червовой масти, а также «черти» – по созвучию (в названиях других мастей так же имеются сходные уменьшительные формы: пики – пичка, пиковочка, пикушка, а в записной книжке Н.В. Гоголя: пикенция, пикендрас, пичура, пичук, пичурущух; трефы – трефушка, трефонка, трефоночка;бубны – бубновочка, бубнушечка, бубновка, бубёнка.)

- «У меня на бубнах: туз, король, дама, коронка сам-восемь, туз пик и одна, понимаете ли, одна маленькая червонка». (Чехов. Иванов).

Обратите внимание, что словообразование происходит как по ассоциации с прилагательным «червонный»(т.е. красный), так и с существительным «червь». В.И.Даль приводит некоторые местные названия червовой масти: жир (жиры – (устар.) диалектное (курское) название червонной масти в игральной карточной колоде. (Даль), копыта. Некоторые исследователи считают, что название «червы» появилось в результате прямого перевода немецкого rot – красный. Принцип прямого перевода названий и символов при заимствовании игры является очень распространённым. Например, в английском языке черва называется hearts – сердца, сердечки. Узбеки, говорящие по-русски, тоже называют эту масть «сердце», а бубны – «кирпич».

Чтобы не оставить в стороне устную традицию, приведём два анекдота и две поговорки

- Человека судят за убийство. Судья спрашивает: – Подсудимый, расскажите, как было дело. – Ну, как было дело… Слюнили мы пульку. Свидетель заказал 7 бубён. Я несу пичку, и покойничек – пичку, я трефу, и покойничек – трефу… – Ну так подсвечником его надо было, – горячо перебивает судья. – Я так и сделал, – смиренно вздыхает подсудимый.

- Хоронят преферансиста: он умер от инфаркта, когда получил четыре взятки на мизере. За гробом, чуть поодаль от родных, идут два его партнёра по преферансу, степенные пожилые благообразные люди. Сосредоточенно молчат, как и приличествует на похоронах. – А знаете, Пётр Иваныч, – вдруг прерывает молчание один из них, – если бы вы тогда пошли с бубей, то было бы ещё хуже…

- Кто играет шесть бубён, тот бывает нае…

- Хода нет – ходи с бубей (нет бубей – … бей).

Даю вам честное слово, я не подбирал ни анекдотов, ни пословиц с целью доказать правомерность употребления разных падежных форм. Добросовестность исследования легко проверить, т.к. мною выбраны все без исключения анекдоты, содержащие названия этих двух мастей, из статьи «Анекдоты игроцкие» в энциклопедии «Игорный Дом» 1994 года издания, а также все без исключения пословицы, в которых встречаются слова червы (черви) и бубны, из компьютерной программы «Марьяж» (версия 4.10).

На мой взгляд, достаточно характерно, что в приведённых источниках нормативная и разговорная формы встречаются в соотношении один к одному. Этот нечаянный статистический вывод является дополнительным аргументом в пользу решения, которое я хотел предложить: пусть имеют право на существование обе формы – нормативная и просторечная. А наши с Вами вкус и чувство языка подскажут, какую форму выбирать в каждом случае. Лет через 70 постоянного употребления этих слов в русской литературе – можно будет вернуться к данному вопросу, если в этом ещё будет необходимость.

Какие формы считать нормативными?

С.И. Ожегов. Словарь русского языка. М., 1984.

БУ’БНЫ, -бён, -бнáм, ед. (разг.) бýбна, -ы… Король бубен.|| прил. бубнувый, -ая, -ое.

ПИ’КИ, пик, -ам… Дама пик.|| прил. пúковый, -ая, -ое.

ТРЕ’ФЫ, треф, трéфам… Дама треф.|| прил. трефóвый, -ая, -ое.

ЧЕ’РВИ, -ей, -ям и (ЧЕ’РВЫ, черв, червам)… Король червей.|| прил. червóнный, -ая, -ое. Червонная дама.

Орфоэпический словарь русского языка. М., 1987.

бубны, -бён, -бнáм и бубен, бубнам || прил. бубновый, -ая, -ое.

пики, пик, пикам || прил. пúковый, -ая, -ое ! не рек. пикóвый.

трефы, треф, трéфам || прил. трéфовый, -ая, -ое и трефувый.

черви, червéй, червям и доп. червы, черв, чéрвам || прил. червóвый, -ая, -ое и червóнный, -ая, -ое.

«Словарь ударений для работников радио и телевидения» (М., 1985), «Словарь трудностей русского языка» (4-е издание. М., 1985), «Словарь русского языка» (в 4-х томах, изд. 3. М., 1985–1988) дают те же нормы.

Приведём таблицы падежных форм названий карточных мастей.

Таблица склонения названий мастей (множественное число)

|

Форма |

И |

Р |

Д |

В |

Т |

П |

|

Нормативная форма |

пики |

пик |

пикам |

пики |

пиками |

пиках |

|

Нормативная форма |

трефы |

треф |

трефам |

трефы |

трефами |

трефах |

|

Нормативная форма |

бубны |

бубен бубён |

бубнам |

бубны |

бубнами |

бубнах |

|

Разговорная форма |

буби |

бубей |

бубям |

буби |

бубями |

бубях |

|

Нормативная форма |

червы черви |

черв червей |

червам червям |

червы черви |

червами червями |

червах червях |

Таблица склонения названий мастей (единственное число) — (сама форма единственного числа для названия масти является в строгом смысле слова (по словарным источникам) разговорной. Допустимо использовать как метонимию для обозначения мелкой (или любой) карты данной масти: пошёл бубной (т.е. фоской или неважно какой).

|

Форма |

И |

Р |

Д |

В |

Т |

П |

|

Нормативная форма |

пика |

пики |

пике |

пику |

пикой |

пике |

|

Нормативная форма |

трефа |

трефы |

трефе |

трефу |

трефой |

трефе |

|

Нормативная форма |

бубна |

бубны |

бубне |

бубну |

бубной |

бубне |

|

Нормативная форма |

черва |

червы |

черве |

черву |

червой |

черве |

Таблица склонения прилагательных, образованных от названий мастей (множ. число)

|

Форма |

И |

Р |

Д |

В |

Т |

П |

|

Норма |

пиковые |

пиковых |

пиковым |

пиковые |

пиковыми |

пиковых |

|

Норма |

трефовые |

трефовых |

трефовым |

трефовые |

трефовыми |

трефовых |

|

Норма |

бубновые |

бубновых |

бубновым |

бубновые |

бубновыми |

бубновых |

|

Норма |

червовые червонные |

червовых червонных |

червовым червонным |

червовые червонные |

червовыми червонными |

червовых червонных |

Таблица склонения прилагательных, образованных от названий мастей (ед. число)

|

Форма |

И |

Р |

Д |

В |

Т |

П |

|

Норма |

пиковый |

пикового |

пиковому |

пикового |

пиковым |

пиковом |

|

Норма |

трефовый |

трефового |

трефовому |

трефового |

трефовым |

трефовом |

|

Норма |

бубновый |

бубнового |

бубновому |

бубнового |

бубновым |

бубновом |

|

Норма |

червовый червонный |

червового червонного |

червовому червонному |

червового червонного |

червовым червонным |

червовом червонном |

В заключение хотел бы указать на одну опасность, таящуюся в чрезмерно почтительном отношении к литературной норме. В языке каждой профессиональной группы есть слова и выражения, являющиеся профессионализмами. Например, бильярдист никогда не скажет сыграть шар, а скажет сыграть шара, хотя, по правилам русского языка, это неправильно. Тут дело в одушевлении бильярдистом этого самого шара. Форма винительного падежа для существительных мужского рода одушевлённых совпадает с формой родительного падежа, а для неодушевлённых – с именительным: стерегу дом, но вижу вора.

То же – со словом туз. Все говорят: надеюсь купить в прикупе туза, хотя литературная норма требует: купить туз. Про короля и валета (кстати, оба слова только что употреблены в винительном падеже, но форма совпадает с родительным) я уже не говорю – они как бы существа одушевлённые, на этих картах даже нарисованы люди. Но туз? Картёжники одушевили его тоже и очень давно. Я думаю, что в строчке «Он, правда, в туз из пистолета // В пяти саженях попадал» имеется в виду не карта (эка невидаль попасть в карту с восьми метров!), а очко, значок масти на карте. Потому что тот же автор написал: «Всякий пузастый мужчина напоминал ему туза» (А.С. Пушкин. «Пиковая дама»).

Если вы в книжке про бильярд

напишете сыграть шар, это будет признаком непрофессионализма. Говоря про карты, мы обязаны учитывать языковую практику игроков, если, конечно, хотим, чтобы они с уважением относились к нашему печатному слову.

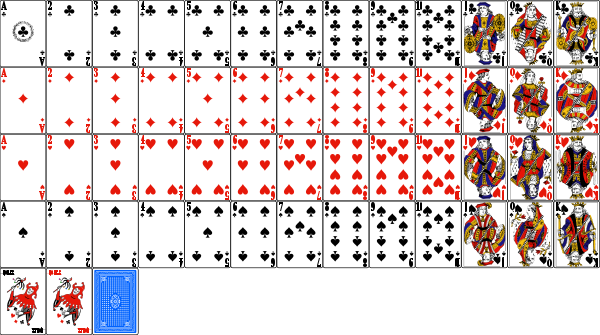

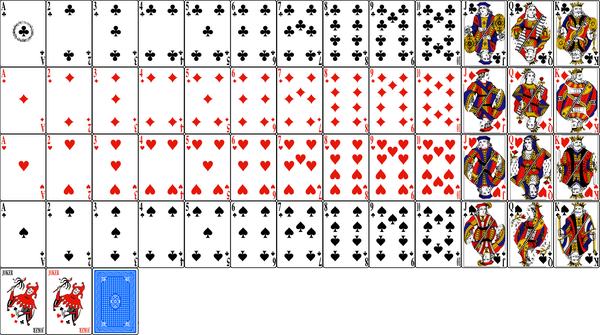

Колода игральных карт — это набор из 36 или 54 карт, предназначенных для карточных игр.

Стандартная колода из 54 карт

Содержание

- 1 Описание

- 1.1 Полная колода

- 1.2 Сокращённая колода

- 2 Варианты стандартной колоды

- 3 Другие виды колод

- 4 Масти

- 4.1 В других языках

- 4.1.1 Английские названия карт и мастей

- 4.1.2 Французские названия карт и мастей

- 4.1.3 Польские названия карт и мастей

- 4.1 В других языках

- 5 Значения

- 5.1 Все карты

- 5.2 Старшие карты

- 6 Ссылки

Описание

Карточные колоды бывают полные и сокращённые. Разделяют пластиковые и атласные (бумажные высокого качества).

Полная колода

Полная колода состоит из 54 карт: тузов, двоек, троек, четвёрок, пятёрок, шестёрок, семёрок, восьмёрок, девяток, десяток, вальтов, дам, королей и двух джокеров.

Полная колода подходит для всех карточных игр.

Сокращённая колода

Сокращённая колода насчитывает 36 карт. Минимальная карта — шестёрка. Джокеров в сокращённой колоде нет.

Сокращённая колода подходит для большинства карточных игр.

Варианты стандартной колоды

Стандартная колода состоит из 54 карт:

- 52 основные карты характеризуются одной из четырёх мастей (двух цветов) и одним из 13 достоинств.

- 2 специальные карты, так называемые джокеры, обычно различающиеся по рисунку.

Колода карт:

- 54 карты (максимальная колода, начинается с тузов до джокера)

- 52 карты (колода, начинается с двоек до туза),

- 48 карт (колода, начинается с троек до туза),

- 44 карты (средняя колода, начинается с четвёрок до туза),

- 40 карт (колода, начинается с пятёрок до туза),

- 36 карт (колода, начинается с шестёрок до туза),

- 32 карты (минимальная колода, начинается с семёрок до туза).

для игры в тысячу используется колода из 24 карт http://www.casinoobzor.ru/html/rules/pravila_igry_tysyacha_1000.php

Другие виды колод

В разных странах используют разные колоды. Самые известные:

- Итало-испанская колода

- Немецкая колода

- Стандартная колода

- Швейцарская колода

- Атласная колода

Масти

Названия мастей (литературным является только первое указанное):

-

- ♠ — пики (вины, вини)

- ♣ — трефы (крести, кресты, желуди, жыр)

- ♥ — червы (черви, жиры, любовные)

- ♦ — бубны (бубни, буби, звонки).

Карты пиковой и трефовой масти называются чёрными, а червовой и бубновой — красными.

В других языках

Английские названия карт и мастей

- Трефы — clubs

- Бубны — diamonds

- Червы — hearts

- Пики — spades

Достоинства:

- «В» = «J» — Jack

- «Д» = «Q» — Queen

- «К» = «K» — King

- «Т» = «A» — Ace

Карты младше десятки именуются по численному обозначению (two, three, .. ten), а также по прозвищам: двойка — «deuce», тройка — «trey».

Французские названия карт и мастей

- Трефы — trèfles

- Бубны — carreaux

- Червы — cœurs

- Пики — piques

Достоинства:

- «В» = «V» — Valet

- «Д» = «D» — Dame

- «К» = «R» — Roi

- «Т» = «A» — As

Польские названия карт и мастей

- Трефы — trefl, żołądź [трэфль, жо́ўоньдьжь]

- Бубны — karo, dzwonek [ка́ро, дзво́нэк]

- Червы — czerwień, kier [чэ́рвень, кер]

- Пики — pik, wino [пик, ви́но]

Достоинства:

- «В» = «J» — walet, Jopek [ва́лет, йо́пэк]

- «Д» = «Q» — dama [да́ма]

- «К» = «K» — król [круль]

- «Т» = «A» — As [ас]

Значения

Все карты

- Числовые (фоски) (9): двойка (обозначение 2), тройка, четвёрка, пятёрка, шестёрка, семёрка, восьмёрка, девятка, десятка.

- Картинки, бродвейные карты (фигуры или онёры, от англ. honour — честь) (3): валет (обозначение В или J — англ. Jack), дама (обозначение Д или Q — англ. Queen), король (обозначение К или K — англ. King), туз (обозначение Т или A — англ. Ace).

Принятый порядок (старшинство, последовательность) карт: туз (самая младшая карта), двойка, тройка, …, король, джокер. Во многих играх туз является самой старшей картой. В некоторых играх старшинство карт другое. Например, в немецкой колоде и итало-испанской колоде совершенно отсутствуют дамы, их место занимают «старшие валеты» или всадники. В карточной игре «Малые Тароки» присутствует колода являющаяся, по сути, полным набором Малых Арканов Таро, но с европейским обозначением мастей. Чуть ли не ежегодно на рынке появляются все новые колоды карт, в небольших деталях отличающиеся от классических, как по количеству онеров, так и по мастевому обозначению, количество мастей также может быть иным. Форма самих карт тоже может быть самой разнообразной: уже никого не удивят круглые и овальные игральные карты! Форма чаще всего просто приближена к симметричной, от равностороннего треугольника до амебоподобной.

Старшие карты

| № | Илл. | Имя | Описание и значение |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Джокер | На карте изображён шут — цветной или чёрно-белый. Самая сильная карта в колоде. |

| 2 |  |

Туз | На карте изображён один знак масти и две буквы «Т» |

| 3 |  |

Король (игральная) карта |

|

| 4 |  |

Дама | Каждая из дам изображена в красном платье и шали. В руках у них по цветку, а на голову надета корона. |

| 5 |  |

Валет | На каждого из валетов надеты рубашка и шапка. В руках они держат алебарды. |

Ссылки

- Всё о картах

Traditional Spanish suits – clubs, swords, cups and coins – are found in Mexico, Italy and parts of France as well as Spain

In playing cards, a suit is one of the categories into which the cards of a deck are divided. Most often, each card bears one of several pips (symbols) showing to which suit it belongs; the suit may alternatively or additionally be indicated by the color printed on the card. The rank for each card is determined by the number of pips on it, except on face cards. Ranking indicates which cards within a suit are better, higher or more valuable than others, whereas there is no order between the suits unless defined in the rules of a specific card game. In a single deck, there is exactly one card of any given rank in any given suit. A deck may include special cards that belong to no suit, often called jokers.

While English-speaking countries traditionally use cards with the French suits of Clubs, Spades, Hearts and Diamonds, many other countries have their own traditional suits. Much of central Europe uses German suited cards with suits of Acorns, Leaves, Hearts and Bells; Spain and parts of Italy and South America use Spanish suited cards with their suits of Swords, Batons, Cups and Coins; German Switzerland uses Swiss suited cards with Acorns, Shields, yellow Roses and Bells; and many parts of Italy use Italian suited cards which have the same suits but different patterns compared with Spanish suited cards. Asian countries such as China and Japan also have their own traditional suits. Tarot card packs have a set of distinct picture cards alongside the traditional four suits.

History[edit]

Modern Western playing cards are generally divided into two or three general suit-systems. The older Latin suits are subdivided into the Italian and Spanish suit-systems. The younger Germanic suits are subdivided into the German and Swiss suit-systems. The French suits are a derivative of the German suits but are generally considered a separate system.[1][2]

Origin and development of the Latin suits[edit]

| Italian[a] | Cups (Coppe) |

Coins (Denari) |

Clubs (Bastoni) |

Swords (Spade) |

| Spanish[b] | Cups (Copas) |

Coins (Oros) |

Clubs (Bastos) |

Swords (Espadas) |

The earliest card games were trick-taking games and the invention of suits increased the level of strategy and depth in these games. A card of one suit cannot beat a card from another regardless of its rank. The concept of suits predate playing cards and can be found in Chinese dice and domino games such as Tien Gow.

Chinese money-suited cards are believed to be the oldest ancestor to the Latin suit-system. The money-suit system is based on denominations of currency: Coins, Strings of Coins, Myriads of Strings (or of coins), and Tens of Myriads. Old Chinese coins had holes in the middle to allow them to be strung together. A string of coins could easily be misinterpreted as a stick to those unfamiliar with them.

By then the Islamic world had spread into Central Asia and had contacted China, and had adopted playing cards. The Muslims renamed the suit of myriads as cups; this may have been due to seeing a Chinese character for «myriad» (万) upside-down. The Chinese numeral character for Ten (十) on the Tens of Myriads suit may have inspired the Muslim suit of swords.[3] Another clue linking these Chinese, Muslim, and European cards are the ranking of certain suits. In many early Chinese games like Madiao, the suit of coins was in reverse order so that the lower ones beat the higher ones. In the Indo-Persian game of Ganjifa, half the suits were also inverted, including a suit of coins. This was also true for the European games of Tarot and Ombre. The inverting of suits had no purpose in terms of play but was an artifact from the earliest games.

These Turko-Arabic cards, called Kanjifa, used the suits coins, clubs, cups, and swords, but the clubs represented polo sticks; Europeans changed that suit, as polo was an obscure sport to them.

The Latin suits are coins, clubs, cups, and swords. They are the earliest suit-system in Europe, and were adopted from the cards imported from Mamluk Egypt and Moorish Granada in the 1370s.

There are four types of Latin suits: Italian, Spanish, Portuguese,[c] and an extinct archaic type.[4][5] The systems can be distinguished by the pips of their long suits: swords and clubs.

- Northern Italian swords are curved outward and the clubs appear to be batons. They intersect one another.

- Southern Italian and Spanish swords are straight, and the clubs appear to be knobbly cudgels. They do not cross each other (The common exception being the three of clubs).

- Portuguese pips are like the Spanish, but they intersect like Northern Italian ones. They sometimes have dragons on the aces.[6] This system lingers on only in the Tarocco Siciliano and the Unsun Karuta of Japan.

- The archaic system[d] is like the Northern Italian one, but the swords are curved inward so they touch each other without intersecting.[7][8]

- Minchiate (a game that used a 97-card deck) used a mixed system of Italian clubs and Portuguese swords.

Despite a long history of trade with China, Japan was not introduced to playing cards until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 1540s. Early locally made cards, Karuta, were very similar to Portuguese decks. Increasing restrictions by the Tokugawa shogunate on gambling, card playing, and general foreign influence, resulted in the Hanafuda card deck that today is used most often for fishing-type games. The role of rank and suit in organizing cards became switched, so the hanafuda deck has 12 suits, each representing a month of the year, and each suit has 4 cards, most often two normal, one Ribbon and one Special (though August, November and December each differ uniquely from this convention).

Invention of German and French suits[edit]

| Swiss-German[f] | Roses[g]

|

Bells[h]

|

Acorns[i]

|

Shields[j]

|

| German | Hearts[k]

|

Bells[l]

|

Acorns[m]

|

Leaves[n]

|

| French | Hearts

|

Tiles (Diamonds) |

Clovers (Clubs)[o] |

Pikes (Spades)[p] |

During the 15th-century, manufacturers in German speaking lands experimented with various new suit systems to replace the Latin suits. One early deck had five suits, the Latin ones with an extra suit of shields.[9] The Swiss-Germans developed their own suits of shields, roses, acorns, and bells around 1450.[10] Instead of roses and shields, the Germans settled with hearts and leaves around 1460. The French derived their suits of trèfles (clovers or clubs ♣), carreaux (tiles or diamonds ♦), cœurs (hearts ♥), and piques (pikes or spades ♠) from the German suits around 1480. French suits correspond closely with German suits with the exception of the tiles with the bells but there is one early French deck that had crescents instead of tiles. The English names for the French suits of clubs and spades may simply have been carried over from the older Latin suits.[11]

Tarot cards[edit]

Beginning around 1440 in northern Italy, some decks started to include an extra suit of (usually) 21 numbered cards known as trionfi or trumps, to play tarot card games.[12] Always included in tarot decks is one card, the Fool or Excuse, which may be part of the trump suit depending on the game or region. These cards do not have pips or face cards like the other suits. Most tarot decks used for games come with French suits but Italian suits are still used in Piedmont, Bologna, and pockets of Switzerland. A few Sicilian towns use the Portuguese-suited Tarocco Siciliano, the only deck of its kind left in Europe.

The esoteric use of Tarot packs emerged in France in the late 18th century, since when special packs intended for divination have been produced. These typically have the suits cups, pentacles (based on the suit of coins), wands (based on the suit of batons), and swords. The trump cards and Fool of traditional card playing packs were named the Major Arcana; the remaining cards, often embellished with occult images, were the Minor Arcana. Neither term is recognised by card players.[13][14]

Suits in games with traditional decks[edit]

Trumps[edit]

In a large and popular category of trick-taking games, one suit may be designated in each deal to be trump and all cards of the trump suit rank above all non-trump cards, and automatically prevail over them, losing only to a higher trump if one is played to the same trick.[15] Non-trump suits are called plain suits.[16]

Special suits[edit]

Some games treat one or more suits as being special or different from the others. A simple example is Spades, which uses spades as a permanent trump suit. A less simple example is Hearts, which is a kind of point trick game in which the object is to avoid taking tricks containing hearts. With typical rules for Hearts (rules vary slightly) the queen of spades and the two of clubs (sometimes also the jack of diamonds) have special effects, with the result that all four suits have different strategic value. Tarot decks have a dedicated trump suit.

Chosen suits[edit]

Games of the Karnöffel Group have between one and four chosen suits, sometimes called selected suits or, misleadingly, trump suits. The chosen suits are typified by having a disrupted ranking and cards with varying privileges which may range from full to none and which may depend on the order they are played to the trick. For example, chosen Sevens may be unbeatable when led, but otherwise worthless. In Swedish Bräus some cards are even unplayable. In games where the number of chosen suits is less than four, the others are called unchosen suits and usually rank in their natural order.

Ranking of suits[edit]

Whist-style rules generally preclude the necessity of determining which of two cards of different suits has higher rank, because a card played on a card of a different suit either automatically wins or automatically loses depending on whether the new card is a trump. However, some card games also need to define relative suit rank. An example of this is in auction games such as bridge, where if one player wishes to bid to make some number of heart tricks and another to make the same number of diamond tricks, there must be a mechanism to determine which takes precedence in the bidding order.

There is no standard order for the four suits and so there are differing conventions among games that need a suit hierarchy. Examples of suit order are (from highest to lowest):

- Bridge (for bidding and scoring) and occasionally poker: ♠, ♥, ♦, ♣.

- Preferans: ♥, ♦, ♣, ♠. Only used for bidding.

- Préférence: ♥, ♦, ♠, ♣ or

,

,

,

. Only used for bidding.

- Five Hundred: ♥, ♦, ♣, ♠ (for bidding and scoring)

- Ninety-nine: ♣, ♥, ♠, ♦ (supposedly mnemonic as they have respectively 3, 2, 1, 0 lobes; see article for how this scoring is used)

- Skat: ♣, ♠, ♥, ♦; or

,

,

,

(for bidding and to determine which Jack beats which in play)

- Cego: ♣, ♠, ♥, ♦ (for determining highest card in certain situations)

- Big Two: ♠, ♥, ♣, ♦

- Thirteen: ♥, ♦, ♣, ♠.

Pairing or ignoring suits[edit]

The pairing of suits is a vestigial remnant of Ganjifa, a game where half the suits were in reverse order, the lower cards beating the higher. In Ganjifa, progressive suits were called «strong» while inverted suits were called «weak». In Latin decks, the traditional division is between the long suits of swords and clubs and the round suits of cups and coins. This pairing can be seen in Ombre and Tarot card games. German and Swiss suits lack pairing but French suits maintained them and this can be seen in the game of Spoil Five.[17]

In some games, such as blackjack, suits are ignored. In other games, such as Canasta, only the color (red or black) is relevant. In yet others, such as bridge, each of the suit pairings are distinguished.

In contract bridge, there are three ways to divide four suits into pairs: by color, by rank and by shape resulting in six possible suit combinations.

- Color is used to denote the red suits (hearts and diamonds) and the black suits (spades and clubs).

- Rank is used to indicate the major (spades and hearts) versus minor (diamonds and clubs) suits.

- Shape is used to denote the pointed (diamonds and spades, which visually have a sharp point uppermost) versus rounded (hearts and clubs) suits. This is used in bridge as a mnemonic.

Four-color suits[edit]

Some decks, while using the French suits, give each suit a different color to make the suits more distinct from each other. In bridge, such decks are known as no-revoke decks, and the most common colors are black spades, red hearts, blue diamonds and green clubs, although in the past the diamond suit usually appeared in a golden yellow-orange. A pack occasionally used in Germany uses green spades (comparable to leaves), red hearts, yellow diamonds (comparable to bells) and black clubs (comparable to acorns). This is a compromise deck devised to allow players from East Germany (who used German suits) and West Germany (who adopted the French suits) to be comfortable with the same deck when playing tournament Skat after the German reunification.[18]

Other suited decks[edit]

Suited-and-ranked decks[edit]

A large number of games are based around a deck in which each card has a rank and a suit (usually represented by a color), and for each suit there is exactly one card having each rank, though in many cases the deck has various special cards as well. Examples include Mü und Mehr, Lost Cities, DUO, Sticheln, Rage, Schotten Totten, UNO, Phase 10, Oh-No!, Skip-Bo, Roodles, and Rook.

Other modern decks[edit]

Decks for some games are divided into suits, but otherwise bear little relation to traditional games. An example would be the board game Taj Mahal, in which each card has one of four background colors, the rule being that all the cards played by a single player in a single round must be the same color. The selection of cards in the deck of each color is approximately the same and the player’s choice of which color to use is guided by the contents of their particular hand.

In the trick-taking card game Flaschenteufel («The Bottle Imp»), all cards are part of a single sequence ranked from 1 to 37 but split into three suits depending on its rank. players must follow the suit led, but if they are void in that suit they may play a card of another suit and this can still win the trick if its rank is high enough. For this reason every card in the deck has a different number to prevent ties. A further strategic element is introduced since one suit contains mostly low-ranking cards and another, mostly high-ranking cards.

Whereas cards in a traditional deck have two classifications—suit and rank—and each combination is represented by one card, giving for example 4 suits × 13 ranks = 52 cards, each card in a Set deck has four classifications each into one of three categories, giving a total of 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 81 cards. Any one of these four classifications could be considered a suit, but this is not really enlightening in terms of the structure of the game.

Uses of playing card suit symbols[edit]

Card suit symbols occur in places outside card playing:

- The four suits were famously employed by the United States’ 101st Airborne Division during World War II to distinguish its four constituent regiments:

- Clubs (♣) identified the 327th Glider Infantry Regiment; currently worn by the 1st Brigade Combat Team.

- Diamonds (♦) identified the 501st PIR. 1st Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment is now part of the 4th Brigade (ABN), 25th Infantry Division in Alaska; the Diamond is currently used by the 101st Combat Aviation Brigade.

- Hearts (♥) identified the 502nd PIR;[19] currently worn by the 2nd Brigade Combat Team.

- Spades (♠) identified the 506th PIR; currently worn by the 4th Brigade Combat Team.

Character encodings[edit]

In computer and other digital media, suit symbols can be represented with character encoding, notably in the ISO and Unicode standards, or with Web standard (SGML’s named entity syntax):

| UTF code: | U+2660 (9824dec) | U+2665 (9829dec) | U+2666 (9830dec) | U+2663 (9827dec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol: | ♠ | ♥ | ♦ | ♣ |

| Name: | Black Spade Suit | Red Heart Suit | Red Diamond Suit | Black Club Suit |

| Entity: | ♠ | ♥ | ♦ | ♣ |

| UTF code: | U+2664 (9828dec) | U+2661 (9825dec) | U+2662 (9826dec) | U+2667 (9831dec) |

| Symbol: | ♤ | ♡ | ♢ | ♧ |

| Name: | White Spade Suit | White Heart Suit | White Diamond Suit | White Club Suit |

| UTF codes are expressed by the Unicode code point «U+hexadecimal number» syntax, and as subscript the respective decimal number. Symbols are expressed here as they are in the web browser’s HTML renderization. Name is the formal name adopted in the standard specifications. |

Unicode is the most frequently used encoding standard, and suits are in the Miscellaneous Symbols Block (2600–26FF) of the Unicode.

Metaphorical uses[edit]

In some card games the card suits have a dominance order, for example: club (lowest) — diamond — heart — spade (highest). That led to in spades being used to mean more than expected, in abundance, very much.[20]

In European games, the order is often different: diamond or bell (lowest) — heart — spade or leaf — club or acorn (highest). See, for example, the game of Bruus.

Other expressions drawn from bridge and similar games include strong suit (any area of personal strength) and to follow suit (to imitate another’s actions).

See also[edit]

- Hearts (card game)

- Spades (card game)

- Stripped deck

- Five-suit bridge

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sample pips come from the Venetian pattern

- ^ Sample pips come from the Castilian pattern

- ^ «Portuguese» is slightly misleading nomenclature. The suit system may have originated in Catalonia and spread out through the western Mediterranean before being replaced by the «Spanish» system. The association with Portugal comes from the fact that they continued to use it until completely going over to French suits at the beginning of the 20th century.

- ^ Probably associated with the Duchy of Ferrara and likely abandoned after the 15th century.

- ^ The French suit system is generally considered to be separate from the German and Swiss due to its different set of face cards. However, when comparing only the pips, it is German in origin.

- ^ There does not appear to be a single universal system of correspondences between Swiss-German and French suits. Cards combining the two suit systems are manufactured in different versions with different combinations of suits.

- ^ Swiss-German: Rosen

- ^ Swiss-German: Schellen

- ^ Swiss-German: Eichel

- ^ Swiss-German: Schilten

- ^ German: Herz (heart), Rot (red), Hungarian: Piros (red), Czech: Srdce (heart), Červené (red)

- ^ German: Schellen (bells), Hungarian: Tök (pumpkin), Czech: Kule (balls)

- ^ German: Eichel (acorn), Ecker (beechnut), Hungarian: Makk (acorn), Czech: Žaludy (acorns)

- ^ German: Laub (leaves), Grün (green), Gras (grass), Blatt (leaf) Hungarian: Zöld (green), Czech: Listy (leaves), Zelené (green)

- ^ The shape of the clubs symbol is believed to be an adaptation of the German suit of acorns. Clubs are also known as clovers, flowers and crosses. The French name for the suit is trèfles meaning clovers, the Italian name for the suit is fiori meaning flowers and the German name for the suit is Kreuz meaning cross.

- ^ In German-speaking countries the spade was the symbol associated with the blade of a spade. The English term spade originally did not refer to the tool but was derived from the Spanish word espada meaning sword from the Spanish suit. Those symbols were later changed to resemble the digging tool instead to avoid confusion. In German and Dutch the suit is alternatively named Schippen and schoppen respectively, meaning shovels.

References[edit]

- ^ Parlett, David (1990). The Oxford Guide to Card Games. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 27–34.

- ^ McLeod, John. Games classified by type of cards or tiles used at pagat.com. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Pollett, Andrea (2002). «Tuman, or the Ten Thousand Cups of the Mamluk Cards». The Playing-Card. 31 (1): 34–41.

- ^ Mann, Sylvia (1974). «A Suit-System Subdivided». The Playing-Card. 3 (1): 51.

- ^ McLeod, John. Games played with Latin suited cards at pagat.com. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ Wintle, Adam. Portuguese Playing Cards at the World of Playing Cards. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Dummett, Michael (1990–1991). «A Survey of ‘Archaic’ Italian Cards». The Playing-Card. 19 (2, 4): 43–51, 128–131.

- ^ Gjerde, Tor. Italian renaissance woodcut playing cards at old.no. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ Meyer, Huck. Liechtenstein’sches Spiel at trionfi.com. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Dummett, Michael (1980). The Game of Tarot. London: Duckworth. pp. 14–16.

- ^ Berry, John (1999). «French suits and English names». The Playing-Card. 28 (2): 84–89.

- ^ McLeod, John. Card Games: Tarot Games at pagat.com. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ Renée, Janina (2001). Tarot for a New Generation (First ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications. p. 5. ISBN 0738701602.

In the system that is most commonly used, these suits are designated as Wands, Swords, Cups, and Pentacles.

- ^ Smith, Caroline; Astrop, John (1999). The Elemental Tarot. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. p. 7. ISBN 0312241399.

The Minor Arcana comprises fifty-six cards divided into four suits, which in most decks are swords, wands, cups, and coins or pentacles.

- ^ McLeod, John. Mechanics of Card Games at pagat.com. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Parlett, David. The Language of Cards at David Parlett Gourmet Games. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ Leyden, Rudolf von; Dummett, Michael (1982). Ganjifa, The Playing Cards of India. London: Victoria and Albert Museum. pp. 52–53.

- ^ «Kartenbilder» (in German). deutscherskatverband.de. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Zaloga, Steven J (2007). US Airborne Divisions in the ETO 1944-45. Osprey Publishing. p. 58.

- ^ Martin, Gary. «‘In spades’ — the meaning and origin of this phrase». Retrieved 24 March 2017.

Traditional Spanish suits – clubs, swords, cups and coins – are found in Mexico, Italy and parts of France as well as Spain

In playing cards, a suit is one of the categories into which the cards of a deck are divided. Most often, each card bears one of several pips (symbols) showing to which suit it belongs; the suit may alternatively or additionally be indicated by the color printed on the card. The rank for each card is determined by the number of pips on it, except on face cards. Ranking indicates which cards within a suit are better, higher or more valuable than others, whereas there is no order between the suits unless defined in the rules of a specific card game. In a single deck, there is exactly one card of any given rank in any given suit. A deck may include special cards that belong to no suit, often called jokers.

While English-speaking countries traditionally use cards with the French suits of Clubs, Spades, Hearts and Diamonds, many other countries have their own traditional suits. Much of central Europe uses German suited cards with suits of Acorns, Leaves, Hearts and Bells; Spain and parts of Italy and South America use Spanish suited cards with their suits of Swords, Batons, Cups and Coins; German Switzerland uses Swiss suited cards with Acorns, Shields, yellow Roses and Bells; and many parts of Italy use Italian suited cards which have the same suits but different patterns compared with Spanish suited cards. Asian countries such as China and Japan also have their own traditional suits. Tarot card packs have a set of distinct picture cards alongside the traditional four suits.

History[edit]

Modern Western playing cards are generally divided into two or three general suit-systems. The older Latin suits are subdivided into the Italian and Spanish suit-systems. The younger Germanic suits are subdivided into the German and Swiss suit-systems. The French suits are a derivative of the German suits but are generally considered a separate system.[1][2]

Origin and development of the Latin suits[edit]

| Italian[a] | Cups (Coppe) |

Coins (Denari) |

Clubs (Bastoni) |

Swords (Spade) |

| Spanish[b] | Cups (Copas) |

Coins (Oros) |

Clubs (Bastos) |

Swords (Espadas) |

The earliest card games were trick-taking games and the invention of suits increased the level of strategy and depth in these games. A card of one suit cannot beat a card from another regardless of its rank. The concept of suits predate playing cards and can be found in Chinese dice and domino games such as Tien Gow.

Chinese money-suited cards are believed to be the oldest ancestor to the Latin suit-system. The money-suit system is based on denominations of currency: Coins, Strings of Coins, Myriads of Strings (or of coins), and Tens of Myriads. Old Chinese coins had holes in the middle to allow them to be strung together. A string of coins could easily be misinterpreted as a stick to those unfamiliar with them.

By then the Islamic world had spread into Central Asia and had contacted China, and had adopted playing cards. The Muslims renamed the suit of myriads as cups; this may have been due to seeing a Chinese character for «myriad» (万) upside-down. The Chinese numeral character for Ten (十) on the Tens of Myriads suit may have inspired the Muslim suit of swords.[3] Another clue linking these Chinese, Muslim, and European cards are the ranking of certain suits. In many early Chinese games like Madiao, the suit of coins was in reverse order so that the lower ones beat the higher ones. In the Indo-Persian game of Ganjifa, half the suits were also inverted, including a suit of coins. This was also true for the European games of Tarot and Ombre. The inverting of suits had no purpose in terms of play but was an artifact from the earliest games.

These Turko-Arabic cards, called Kanjifa, used the suits coins, clubs, cups, and swords, but the clubs represented polo sticks; Europeans changed that suit, as polo was an obscure sport to them.

The Latin suits are coins, clubs, cups, and swords. They are the earliest suit-system in Europe, and were adopted from the cards imported from Mamluk Egypt and Moorish Granada in the 1370s.

There are four types of Latin suits: Italian, Spanish, Portuguese,[c] and an extinct archaic type.[4][5] The systems can be distinguished by the pips of their long suits: swords and clubs.

- Northern Italian swords are curved outward and the clubs appear to be batons. They intersect one another.

- Southern Italian and Spanish swords are straight, and the clubs appear to be knobbly cudgels. They do not cross each other (The common exception being the three of clubs).

- Portuguese pips are like the Spanish, but they intersect like Northern Italian ones. They sometimes have dragons on the aces.[6] This system lingers on only in the Tarocco Siciliano and the Unsun Karuta of Japan.

- The archaic system[d] is like the Northern Italian one, but the swords are curved inward so they touch each other without intersecting.[7][8]

- Minchiate (a game that used a 97-card deck) used a mixed system of Italian clubs and Portuguese swords.

Despite a long history of trade with China, Japan was not introduced to playing cards until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 1540s. Early locally made cards, Karuta, were very similar to Portuguese decks. Increasing restrictions by the Tokugawa shogunate on gambling, card playing, and general foreign influence, resulted in the Hanafuda card deck that today is used most often for fishing-type games. The role of rank and suit in organizing cards became switched, so the hanafuda deck has 12 suits, each representing a month of the year, and each suit has 4 cards, most often two normal, one Ribbon and one Special (though August, November and December each differ uniquely from this convention).

Invention of German and French suits[edit]

| Swiss-German[f] | Roses[g]

|

Bells[h]

|

Acorns[i]

|

Shields[j]

|

| German | Hearts[k]

|

Bells[l]

|

Acorns[m]

|

Leaves[n]

|

| French | Hearts

|

Tiles (Diamonds) |

Clovers (Clubs)[o] |

Pikes (Spades)[p] |

During the 15th-century, manufacturers in German speaking lands experimented with various new suit systems to replace the Latin suits. One early deck had five suits, the Latin ones with an extra suit of shields.[9] The Swiss-Germans developed their own suits of shields, roses, acorns, and bells around 1450.[10] Instead of roses and shields, the Germans settled with hearts and leaves around 1460. The French derived their suits of trèfles (clovers or clubs ♣), carreaux (tiles or diamonds ♦), cœurs (hearts ♥), and piques (pikes or spades ♠) from the German suits around 1480. French suits correspond closely with German suits with the exception of the tiles with the bells but there is one early French deck that had crescents instead of tiles. The English names for the French suits of clubs and spades may simply have been carried over from the older Latin suits.[11]

Tarot cards[edit]

Beginning around 1440 in northern Italy, some decks started to include an extra suit of (usually) 21 numbered cards known as trionfi or trumps, to play tarot card games.[12] Always included in tarot decks is one card, the Fool or Excuse, which may be part of the trump suit depending on the game or region. These cards do not have pips or face cards like the other suits. Most tarot decks used for games come with French suits but Italian suits are still used in Piedmont, Bologna, and pockets of Switzerland. A few Sicilian towns use the Portuguese-suited Tarocco Siciliano, the only deck of its kind left in Europe.

The esoteric use of Tarot packs emerged in France in the late 18th century, since when special packs intended for divination have been produced. These typically have the suits cups, pentacles (based on the suit of coins), wands (based on the suit of batons), and swords. The trump cards and Fool of traditional card playing packs were named the Major Arcana; the remaining cards, often embellished with occult images, were the Minor Arcana. Neither term is recognised by card players.[13][14]

Suits in games with traditional decks[edit]

Trumps[edit]

In a large and popular category of trick-taking games, one suit may be designated in each deal to be trump and all cards of the trump suit rank above all non-trump cards, and automatically prevail over them, losing only to a higher trump if one is played to the same trick.[15] Non-trump suits are called plain suits.[16]

Special suits[edit]

Some games treat one or more suits as being special or different from the others. A simple example is Spades, which uses spades as a permanent trump suit. A less simple example is Hearts, which is a kind of point trick game in which the object is to avoid taking tricks containing hearts. With typical rules for Hearts (rules vary slightly) the queen of spades and the two of clubs (sometimes also the jack of diamonds) have special effects, with the result that all four suits have different strategic value. Tarot decks have a dedicated trump suit.

Chosen suits[edit]

Games of the Karnöffel Group have between one and four chosen suits, sometimes called selected suits or, misleadingly, trump suits. The chosen suits are typified by having a disrupted ranking and cards with varying privileges which may range from full to none and which may depend on the order they are played to the trick. For example, chosen Sevens may be unbeatable when led, but otherwise worthless. In Swedish Bräus some cards are even unplayable. In games where the number of chosen suits is less than four, the others are called unchosen suits and usually rank in their natural order.

Ranking of suits[edit]

Whist-style rules generally preclude the necessity of determining which of two cards of different suits has higher rank, because a card played on a card of a different suit either automatically wins or automatically loses depending on whether the new card is a trump. However, some card games also need to define relative suit rank. An example of this is in auction games such as bridge, where if one player wishes to bid to make some number of heart tricks and another to make the same number of diamond tricks, there must be a mechanism to determine which takes precedence in the bidding order.

There is no standard order for the four suits and so there are differing conventions among games that need a suit hierarchy. Examples of suit order are (from highest to lowest):

- Bridge (for bidding and scoring) and occasionally poker: ♠, ♥, ♦, ♣.

- Preferans: ♥, ♦, ♣, ♠. Only used for bidding.

- Préférence: ♥, ♦, ♠, ♣ or

,

,

,

. Only used for bidding.

- Five Hundred: ♥, ♦, ♣, ♠ (for bidding and scoring)

- Ninety-nine: ♣, ♥, ♠, ♦ (supposedly mnemonic as they have respectively 3, 2, 1, 0 lobes; see article for how this scoring is used)

- Skat: ♣, ♠, ♥, ♦; or

,

,

,

(for bidding and to determine which Jack beats which in play)

- Cego: ♣, ♠, ♥, ♦ (for determining highest card in certain situations)

- Big Two: ♠, ♥, ♣, ♦

- Thirteen: ♥, ♦, ♣, ♠.