|

|

Parts of this article (those related to images of new issuance of coins and banknotes (see zh:第五套人民币#第三版)) need to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2021) |

| 人民币 (Chinese)

RMB |

|

|---|---|

Renminbi banknotes |

|

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | CNY (numeric: 156) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Unit | yuán (元 / 圆) |

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency do(es) not have a morphological plural distinction. |

| Symbol | ¥ |

| Nickname | kuài (块) |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄10 | jiǎo (角) |

| 1⁄100 | fēn (分) |

| Nickname | |

| jiǎo (角) | máo (毛) |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | ¥1 RMB, ¥5 RMB, ¥10 RMB, ¥20 RMB, ¥50 RMB, ¥100 RMB |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | ¥0.1 RMB, ¥0.5 RMB, ¥1 RMB |

| Rarely used | ¥0.01 RMB, ¥0.02 RMB, ¥0.05 RMB |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 1948; 75 years ago |

| Replaced | Nationalist-issued yuan |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | People’s Bank of China |

| Website | www.pbc.gov.cn |

| Printer | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation |

| Website | www.cbpm.cn |

| Mint | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation |

| Website | www.cbpm.cn |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 2.5% (2017) |

| Source | [1] [2] |

| Method | CPI |

| Pegged with | Partially, to a basket of trade-weighted international currencies |

| Renminbi | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Renminbi» in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 人民币 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 人民幣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «People’s Currency» | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 圆 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圓 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «circle» (ie. a coin) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The renminbi (Chinese: 人民币; pinyin: Rénmínbì; lit. ‘People’s Currency’; symbol: ¥; ISO code: CNY; abbreviation: RMB) is the official currency of the People’s Republic of China[note 1]. It is the 5th most traded currency as of April 2022.[3]

The yuan (Chinese: 元 or simplified Chinese: 圆; traditional Chinese: 圓; pinyin: yuán) is the basic unit of the renminbi, but the word is also used to refer to the Chinese currency generally, especially in international contexts. One yuan is divided into 10 jiao (Chinese: 角; pinyin: jiǎo), and the jiao is further subdivided into 10 fen (Chinese: 分; pinyin: fēn). The renminbi is issued by the People’s Bank of China, the monetary authority of China.[4]

Valuation[edit]

Until 2005, the value of the renminbi was pegged to the US dollar. As China pursued its transition from central planning to a market economy and increased its participation in foreign trade, the renminbi was devalued to increase the competitiveness of Chinese industry. It has previously been claimed that the renminbi’s official exchange rate was undervalued by as much as 37.5% against its purchasing power parity.[5] However, more recently, appreciation actions by the Chinese government, as well as quantitative easing measures taken by the American Federal Reserve and other major central banks, have caused the renminbi to be within as little as 8% of its equilibrium value by the second half of 2012.[6] Since 2006, the renminbi exchange rate has been allowed to float in a narrow margin around a fixed base rate determined with reference to a basket of world currencies. The Chinese government has announced that it will gradually increase the flexibility of the exchange rate. As a result of the rapid internationalization of the renminbi, it became the world’s 8th most traded currency in 2013,[7] 5th by 2015,[8] but 6th in 2019.[9]

On 1 October 2016, the renminbi became the first emerging market currency to be included in the IMF’s special drawing rights basket, the basket of currencies used by the IMF as a reserve currency.[10]

| Current CNY exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

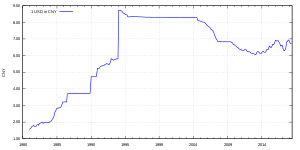

USD/CNY exchange rate 1981-2022

Terminology[edit]

| Chinese | pinyin | English | Literal translation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal currency name | 人民币 | rénmínbì | renminbi | «people’s currency» |

| Formal name for 1 unit | 元 or 圆 | yuán | yuan | «unit» |

| Formal name for 1⁄10 unit | 角 | jiǎo | jiao | «corner» |

| Formal name for 1⁄100 unit | 分 | fēn | fen | «fraction», «cent» |

| Colloquial name for 1 unit | 块 | kuài | kuai or quay[11] | «piece» |

| Colloquial name for 1⁄10 unit | 毛 | máo | mao | «feather» |

The ISO code for the renminbi is CNY, the PRC’s country code (CN) plus «Y» from «yuan».[12] Hong Kong markets that trade renminbi at free-floating rates use the unofficial code CNH. This is to distinguish the rates from those fixed by Chinese central banks on the mainland.[13] The abbreviation RMB is not an ISO code but is sometimes used like one by banks and financial institutions.

The currency symbol for the yuan unit is ¥, but when distinction from the Japanese yen is required RMB (e.g. RMB 10,000) or ¥ RMB (e.g. ¥10,000 RMB) is used. However, in written Chinese contexts, the Chinese character for yuan (Chinese: 元; lit. ‘beginning’) or, in formal contexts Chinese: 圆; lit. ’round’, usually follows the number in lieu of a currency symbol.

Renminbi is the name of the currency while yuan is the name of the primary unit of the renminbi. This is analogous to the distinction between «sterling» and «pound» when discussing the official currency of the United Kingdom.[12] Jiao and fen are also units of renminbi.

In everyday Mandarin, kuai (Chinese: 块; pinyin: kuài; lit. ‘piece’) is usually used when discussing money and «renminbi» or «yuan» are rarely heard.[12] Similarly, Mandarin speakers typically use mao (Chinese: 毛; pinyin: máo) instead of jiao.[12] For example, ¥8.74 might be read as 八块七毛四 (pinyin: bā kuài qī máo sì) in everyday conversation, but read 八元七角四分 (pinyin: bā yuán qī jiǎo sì fēn) formally.

Renminbi is sometimes referred to as the «redback», a play on «greenback», a slang term for the US dollar.[14]

History[edit]

China M2 money supply (red) vis-à-vis USA M2 money supply (blue)

The various currencies called yuan or dollar issued in mainland China as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and Singapore were all derived from the Spanish American silver dollar, which China imported in large quantities from Spanish America from the 16th to 20th centuries. The first locally minted silver dollar or yuan accepted all over Qing dynasty China (1644–1912) was the silver dragon dollar introduced in 1889. Various banknotes denominated in dollars or yuan were also introduced, which were convertible to silver dollars until 1935 when the silver standard was discontinued and the Chinese yuan was made fabi (法币; legal tender fiat currency).

The renminbi was introduced by the People’s Bank of China in December 1948, about a year before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. It was issued only in paper form at first, and replaced the various currencies circulating in the areas controlled by the Communists. One of the first tasks of the new government was to end the hyperinflation that had plagued China in the final years of the Kuomintang (KMT) era. That achieved, a revaluation occurred in 1955 at the rate of 1 new yuan = 10,000 old yuan.

As the Chinese Communist Party took control of ever larger territories in the latter part of the Chinese Civil War, its People’s Bank of China began to issue a unified currency in 1948 for use in Communist-controlled territories. Also denominated in yuan, this currency was identified by different names, including «People’s Bank of China banknotes» (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行钞票; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行鈔票; from November 1948), «New Currency» (simplified Chinese: 新币; traditional Chinese: 新幣; from December 1948), «People’s Bank of China notes» (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行券; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行券; from January 1949), «People’s Notes» (人民券, as an abbreviation of the last name), and finally «People’s Currency», or «renminbi«, from June 1949.[15]

Era of the planned economy[edit]

From 1949 until the late 1970s, the state fixed China’s exchange rate at a highly overvalued level as part of the country’s import-substitution strategy. During this time frame, the focus of the state’s central planning was to accelerate industrial development and reduce China’s dependence on imported manufactured goods. The overvaluation allowed the government to provide imported machinery and equipment to priority industries at a relatively lower domestic currency cost than otherwise would have been possible.

Transition to an equilibrium exchange rate[edit]

China’s transition by the mid-1990s to a system in which the value of its currency was determined by supply and demand in a foreign exchange market was a gradual process spanning 15 years that involved changes in the official exchange rate, the use of a dual exchange rate system, and the introduction and gradual expansion of markets for foreign exchange.

The most important move to a market-oriented exchange rate was an easing of controls on trade and other current account transactions, as occurred in several very early steps. In 1979, the State Council approved a system allowing exporters and their provincial and local government owners to retain a share of their foreign exchange earnings, referred to as foreign exchange quotas. At the same time, the government introduced measures to allow retention of part of the foreign exchange earnings from non-trade sources, such as overseas remittances, port fees paid by foreign vessels, and tourism.

As early as October 1980, exporting firms that retained foreign exchange above their own import needs were allowed to sell the excess through the state agency responsible for the management of China’s exchange controls and its foreign exchange reserves, the State Administration of Exchange Control. Beginning in the mid-1980s, the government sanctioned foreign exchange markets, known as swap centres, eventually in most large cities.

The government also gradually allowed market forces to take the dominant role by introducing an «internal settlement rate» of ¥2.8 to 1 US dollar which was a devaluation of almost 100%.

Foreign exchange certificates, 1980–1994[edit]

In the process of opening up China to external trade and tourism, transactions with foreign visitors between 1980 and 1994 were done primarily using Foreign exchange certificates (外汇券, waihuiquan) issued by the Bank of China.[16][17][18]

Foreign currencies were exchangeable for FECs and vice versa at the renminbi’s prevailing official rate which ranged from US$1 = ¥2.8 FEC to ¥5.5 FEC. The FEC was issued as banknotes from ¥0.1 to ¥100, and was officially at par with the renminbi. Tourists used FECs to pay for accommodation as well as tourist and luxury goods sold in Friendship Stores. However, given the non-availability of foreign exchange and Friendship Store goods to the general public, as well as the inability of tourists to use FECs at local businesses, an illegal black market developed for FECs where touts approached tourists outside hotels and offered over ¥1.50 RMB in exchange for ¥1 FEC. In 1994, as a result of foreign exchange management reforms approved by the 14th CPC Central Committee, the renminbi was officially devalued from US$1 = ¥5.5 to over ¥8, and the FEC was retired at ¥1 FEC = ¥1 RMB in favour of tourists directly using the renminbi.

Evolution of exchange policy since 1994[edit]

In November 1993, the Third Plenum of the Fourteenth CPC Central Committee approved a comprehensive reform strategy in which foreign exchange management reforms were highlighted as a key element for a market-oriented economy. A floating exchange rate regime and convertibility for renminbi were seen as the ultimate goal of the reform. Conditional convertibility under current account was achieved by allowing firms to surrender their foreign exchange earning from current account transactions and purchase foreign exchange as needed. Restrictions on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was also loosened and capital inflows to China surged.

Convertibility[edit]

During the era of the command economy, the value of the renminbi was set to unrealistic values in exchange with Western currency and severe currency exchange rules were put in place, hence the dual-track currency system from 1980 to 1994 with the renminbi usable only domestically, and with Foreign Exchange Certificates (FECs) used by foreign visitors.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, China worked to make the renminbi more convertible. Through the use of swap centres, the exchange rate was eventually brought to more realistic levels of above ¥8/US$1 in 1994 and the FEC was discontinued. It stayed above ¥8/$1 until 2005 when the renminbi’s peg to the dollar was loosened and it was allowed to appreciate.

As of 2013, the renminbi is convertible on current accounts but not capital accounts. The ultimate goal has been to make the renminbi fully convertible. However, partly in response to the Asian financial crisis in 1998, China has been concerned that the Chinese financial system would not be able to handle the potential rapid cross-border movements of hot money, and as a result, as of 2012, the currency trades within a narrow band specified by the Chinese central government.

Following the internationalization of the renminbi, on 30 November 2015, the IMF voted to designate the renminbi as one of several main world currencies, thus including it in the basket of special drawing rights. The renminbi became the first emerging market currency to be included in the IMF’s SDR basket on 1 October 2016.[10] The other main world currencies are the dollar, the euro, sterling, and the yen.[19]

Digital renminbi[edit]

In October 2019, China’s central bank, PBOC, announced that a digital reminbi is going to be released after years of preparation.[20] This version of the currency, also called DCEP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment),[21] can be “decoupled” from the banking system to give visiting tourists a taste of the nation’s burgeoning cashless society.[22] However, it is not based on cryptocurrency.[23] The announcement received a variety of responses: some believe it is more about domestic control and surveillance.[24] Some argue that the real barriers to internationalisation of the renminbi are China’s capital controls, which it has no plans to remove. Maximilian Kärnfelt, an expert at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, said that a digital renminbi «would not banish many of the problems holding the renminbi back from more use globally». He went on to say, «Much of China’s financial market is still not open to foreigners and property rights remain fragile.»[25]

The PBOC has filed more than 80 patents surrounding the integration of a digital currency system, choosing to embrace the blockchain technology. The patents reveal the extent of China’s digital currency plans. The patents, seen and verified by the Financial Times, include proposals related to the issuance and supply of a central bank digital currency, a system for interbank settlements that uses the currency, and the integration of digital currency wallets into existing retail bank accounts. Several of the 84 patents reviewed by the Financial Times indicate that China may plan to algorithmically adjust the supply of a central bank digital currency based on certain triggers, such as loan interest rates. Other patents are focused on building digital currency chip cards or digital currency wallets that banking consumers could potentially use, which would be linked directly to their bank accounts. The patent filings also point to the proposed ‘tokenomics’ being considered by the DCEP working group. Some patents show plans towards programmed inflation control mechanisms. While the majority of the patents are attributed to the PBOC’s Digital Currency Research Institute, some are attributed to state-owned corporations or subsidiaries of the Chinese central government.[26]

Uncovered by the Chamber of Digital Commerce (an American non-profit advocacy group), their contents shed light on Beijing’s mounting efforts to digitise the renminbi, which has sparked alarm in the West and spurred central bankers around the world to begin exploring similar projects.[26] Some commentators have said that the U.S., which has no current plans to issue a government-backed digital currency, risks falling behind China and risking its dominance in the global financial system.[27] Victor Shih, a China expert and professor at the University of California San Diego, said that merely introducing a digital currency «doesn’t solve the problem that some people holding renminbi offshore will want to sell that renminbi and exchange it for the dollar», as the dollar is considered to be a safer asset.[28] Eswar Prasad, an economics professor at Cornell University, said that the digital renminbi «will hardly put a dent in the dollar’s status as the dominant global reserve currency» due to the United States’ «economic dominance, deep and liquid capital markets, and still-robust institutional framework».[28][29] The U.S. dollar’s share as a reserve currency is above 60%, while that of the renminbi is about 2%.[28]

In April 2020, The Guardian reported that the digital currency e-RMB had been adopted into multiple cities’ monetary systems and «some government employees and public servants [will] receive their salaries in the digital currency from May. The Guardian quoted a China Daily report which stated «A sovereign digital currency provides a functional alternative to the dollar settlement system and blunts the impact of any sanctions or threats of exclusion both at a country and company level … It may also facilitate integration into globally traded currency markets with a reduced risk of politically inspired disruption.»[30] There are talks of testing out the digital renminbi in the upcoming Beijing Winter Olympics in 2022, but China’s overall timetable for rolling out the digital currency is unclear.[31]

Issuance[edit]

As of 2019, renminbi banknotes are available in denominations from ¥0.1, ¥0.5 (1 and 5 jiao), ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50 and ¥100. These denominations have been available since 1955, except for the ¥20 notes (added in 1999 with the fifth series) ¥50 and ¥100 notes (added in 1987 with the fourth series). Coins are available in denominations from ¥0.01 to ¥1 (¥0.01–1). Thus some denominations exist in both coins and banknotes. On rare occasions, larger yuan coin denominations such as ¥5 have been issued to commemorate events but use of these outside of collecting has never been widespread.

The denomination of each banknote is printed in simplified written Chinese. The numbers themselves are printed in financial[note 2] Chinese numeral characters, as well as Arabic numerals. The denomination and the words «People’s Bank of China» are also printed in Mongolian, Tibetan, Uyghur and Zhuang on the back of each banknote, in addition to the boldface Hanyu Pinyin «Zhongguo Renmin Yinhang» (without tones). The right front of the note has a tactile representation of the denomination in Chinese Braille starting from the fourth series. See corresponding section for detailed information.

The fen and jiao denominations have become increasingly unnecessary as prices have increased. Coins under ¥0.1 are used infrequently. Chinese retailers tend to avoid fractional values (such as ¥9.99), opting instead to round to the nearest yuan (such as ¥9 or ¥10).[32]

Coins[edit]

In 1953, aluminium ¥0.01, ¥0.02, and ¥0.05 coins began being struck for circulation, and were first introduced in 1955. These depict the national emblem on the obverse (front) and the name and denomination framed by wheat stalks on the reverse (back). In 1980, brass ¥0.1, ¥0.2, and ¥0.5 and cupro-nickel ¥1 coins were added, although the ¥0.1 and ¥0.2 were only produced until 1981, with the last ¥0.5 and ¥1 issued in 1985. All jiǎo coins depicted similar designs to the fēn coins while the yuán depicted the Great Wall of China.

In 1991, a new coinage was introduced, consisting of an aluminium ¥0.1, brass ¥0.5 and nickel-clad steel ¥1. These were smaller than the previous jiǎo and yuán coins and depicted flowers on the obverse and the national emblem on the reverse. Issuance of the aluminium ¥0.01 and ¥0.02 coins ceased in 1991, with that of the ¥0.05 halting in 1994. The small coins were still struck for annual uncirculated mint sets in limited quantities, and from the beginning of 2005, the ¥0.01 coin got a new lease on life by being issued again every year since then up to present.

New designs of the ¥0.1, ¥0.5 (now brass-plated steel), and ¥1 (nickel-plated steel) were again introduced in between 1999 and 2002. The ¥0.1 was significantly reduced in size, and in 2005 its composition was changed from aluminium to more durable nickel-plated steel. An updated version of these coins was announced in 2019. While the overall design is unchanged, all coins including the ¥0.5 are now of nickel-plated steel, and the ¥1 coin was reduced in size.[33][34]

The frequency of usage of coins varies between different parts of China, with coins typically being more popular in urban areas (with ¥0.5 and ¥1 coins used in vending machines), and small notes being more popular in rural areas. Older fēn and large jiǎo coins are uncommonly still seen in circulation, but are still valid in exchange.

Banknotes[edit]

As of 2020, there have been five series of renminbi banknotes issued by the People’s Republic of China:

- The first series of renminbi banknotes was issued on 1 December 1948, by the newly founded People’s Bank of China. It introduced notes in denominations of ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50, ¥100 and ¥1,000 yuan. Notes for ¥200, ¥500, ¥5,000 and ¥10,000 followed in 1949, with ¥50,000 notes added in 1950. A total of 62 different designs were issued. The notes were officially withdrawn on various dates between 1 April and 10 May 1955. The name «first series» was given retroactively in 1950, after work began to design a new series.[15]

- These first renminbi notes were printed with the words «People’s Bank of China», «Republic of China», and the denomination, written in Chinese characters by Dong Biwu.[35]

- The second series of renminbi banknotes was introduced on 1 March 1955 (but dated 1953). Each note has the words «People’s Bank of China» as well as the denomination in the Uyghur, Tibetan, Mongolian and Zhuang languages on the back, which has since appeared in each series of renminbi notes. The denominations available in banknotes were ¥0.01, ¥0.02, ¥0.05, ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥3, ¥5 and ¥10. Except for the three fen denominations and the ¥3 which were withdrawn, notes in these denominations continued to circulate. Good examples of this series have gained high status with banknote collectors.

- The third series of renminbi banknotes was introduced on 15 April 1962, though many denominations were dated 1960. New dates would be issued as stocks of older dates were gradually depleted. The sizes and design layout of the notes had changed but not the order of colours for each denomination. For the next two decades, the second and third series banknotes were used concurrently. The denominations were of ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5 and ¥10. The third series was phased out during the 1990s and then was recalled completely on 1 July 2000.

- The fourth series of renminbi banknotes was introduced between 1987 and 1997, although the banknotes were dated 1980, 1990, or 1996. They were withdrawn from circulation on 1 May 2019. Banknotes are available in denominations of ¥0.1, ¥0.2, ¥0.5, ¥1, ¥2, ¥5, ¥10, ¥50 and ¥100. Like previous issues, the colour designation for already existing denominations remained in effect. The second to fourth series of renminbi banknotes were designed by professors at the Central Academy of Art including Luo Gongliu and Zhou Lingzhao.

- The fifth series of renminbi banknotes and coins was progressively introduced from its introduction in 1999. This series also bears the issue years 2005 (all except ¥1), 2015 (¥100 only) and 2019 (¥1, ¥10, ¥20 and ¥50). As of 2019, it includes banknotes for ¥1, ¥5, ¥10, ¥20, ¥50 and ¥100. Significantly, the fifth series uses the portrait of Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong on all banknotes, in place of the various leaders, workers and representations of China’s ethnic groups which had been featured previously. During this series new security features were added, the ¥2 denomination was discontinued, the colour pattern for each note was changed and a new denomination of ¥20 was introduced for this series. A revised series of coins of ¥0.1, ¥0.5 and ¥1 and banknotes of ¥1, ¥10, ¥20 and ¥50 were issued for general circulation on 30 August 2019. The ¥5 banknote of the fifth series will be issued with new printing technology in a bid to reduce counterfeiting of Chinese currency, and will be issued for circulation in November 2020.

Commemorative issues of the renminbi banknotes[edit]

In 1999, a commemorative red ¥50 note was issued in honour of the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. This note features Chinese Communist Party chairman Mao Zedong on the front and various animals on the back.

An orange polymer note, commemorating the new millennium was issued in 2000 with a face value of ¥100. This features a dragon on the obverse and the reverse features the China Millennium monument (at the Center for Cultural and Scientific Fairs).

For the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a green ¥10 note was issued featuring the Bird’s Nest Stadium on the front with the back showing a classical Olympic discus thrower and various other athletes.

On 26 November 2015, the People’s Bank of China issued a blue ¥100 commemorative note to commemorate aerospace science and technology.[36][failed verification][37]

In commemoration of the 70th Anniversary of the issuance of the Renminbi, the People’s Bank of China issued 120 million ¥50 banknotes on 28 December 2018.

In commemoration of the 2022 Winter Olympics, the People’s Bank of China issued ¥20 commemorative banknotes in both paper and polymer in December 2021.

Use in ethnic minority regions of China[edit]

The second series of the renminbi had the most readable minority languages text, but no Zhuang text on it. Its issue of ¥0.1–0.5 even highlighted the Mongolian text.

The renminbi yuan has different names when used in ethnic minority regions of China.

- When used in Inner Mongolia and other Mongol autonomies, a yuan is called a tugreg (Mongolian: ᠲᠦᠭᠦᠷᠢᠭ᠌, төгрөг tügürig). However, when used in the republic of Mongolia, it is still named yuani (Mongolian: юань) to differentiate it from Mongolian tögrög (Mongolian: төгрөг). One Chinese tügürig (tugreg) is divided into 100 mönggü (Mongolian: ᠮᠥᠩᠭᠦ, мөнгө), one Chinese jiao is labeled «10 mönggü». In Mongolian, renminbi is called aradin jogos or arad-un jogos (Mongolian: ᠠᠷᠠᠳ ᠤᠨ ᠵᠣᠭᠣᠰ, ардын зоос arad-un ǰoγos).

- When used in Tibet and other Tibetan autonomies, a yuan is called a gor (Tibetan: སྒོར་, ZYPY: Gor). One gor is divided into 10 gorsur (Tibetan: སྒོར་ཟུར་, ZYPY: Gorsur) or 100 gar (Tibetan: སྐར་, ZYPY: gar). In Tibetan, renminbi is called mimangxogngü (Tibetan: མི་དམངས་ཤོག་དངུལ།, ZYPY: Mimang Xogngü) or mimang shog ngul.

- When used in the Uyghur autonomy region of Xinjiang, the renminbi is called Xelq puli (Uighur: خەلق پۇلى)

Production and minting[edit]

Renminbi currency production is carried out by a state owned corporation, China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation (CBPMC; 中国印钞造币总公司) headquartered in Beijing.[38] CBPMC uses several printing, engraving and minting facilities around the country to produce banknotes and coins for subsequent distribution. Banknote printing facilities are based in Beijing, Shanghai, Chengdu, Xi’an, Shijiazhuang, and Nanchang. Mints are located in Nanjing, Shanghai, and Shenyang. Also, high grade paper for the banknotes is produced at two facilities in Baoding and Kunshan. The Baoding facility is the largest facility in the world dedicated to developing banknote material according to its website.[39] In addition, the People’s Bank of China has its own printing technology research division that researches new techniques for creating banknotes and making counterfeiting more difficult.

Suggested future design[edit]

On 13 March 2006, some delegates to an advisory body at the National People’s Congress proposed to include Sun Yat-sen and Deng Xiaoping on the renminbi banknotes. However, the proposal was not adopted.[40]

Economics[edit]

Value[edit]

1 US dollar to renminbi, since 1981

For most of its early history, the renminbi was pegged to the U.S. dollar at ¥2.46 per dollar. During the 1970s, it was revalued until it reached ¥1.50 per dollar in 1980. When China’s economy gradually opened in the 1980s, the renminbi was devalued in order to improve the competitiveness of Chinese exports. Thus, the official exchange rate increased from ¥1.50 in 1980 to ¥8.62 by 1994 (the lowest rate on record). Improving current account balance during the latter half of the 1990s enabled the Chinese government to maintain a peg of ¥8.27 per US$1 from 1997 to 2005.

The renminbi reached a record high exchange value of ¥6.0395 to the US dollar on 14 January 2014.[42] Chinese leadership have been raising the yuan to tame inflation, a step U.S. officials have pushed for years to lower the massive trade deficit with China.[43] Strengthening the value of the renminbi also fits with the Chinese transition to a more consumer-led economic growth model.[44]

In 2015 the People’s Bank of China again devalued their country’s currency. As of 1 September 2015, the exchange rate for US$1 is ¥6.38.

Depegged from the US dollar[edit]

On 21 July 2005, the peg was finally lifted, which saw an immediate one-time renminbi revaluation to ¥8.11 per dollar.[45] The exchange rate against the euro stood at ¥10.07060 per euro.

However, the peg was reinstituted unofficially when the financial crisis hit: «Under intense pressure from Washington, China took small steps to allow its currency to strengthen for three years starting in July 2005. But China ‘re-pegged’ its currency to the dollar as the financial crisis intensified in July 2008.»[46]

On 19 June 2010, the People’s Bank of China released a statement simultaneously in Chinese and English claiming that they would «proceed further with reform of the renminbi exchange rate regime and increase the renminbi exchange rate flexibility».[47] The news was greeted with praise by world leaders including Barack Obama, Nicolas Sarkozy and Stephen Harper.[48] The PBoC maintained there would be no «large swings» in the currency. The renminbi rose to its highest level in five years and markets worldwide surged on Monday, 21 June following China’s announcement.[49]

In August 2015, Joseph Adinolfi, a reporter for MarketWatch, reported that China had re-pegged the renminbi. In his article, he narrated that «Weak trade data out of China, released over the weekend, weighed on the currencies of Australia and New Zealand on Monday. But the yuan didn’t budge. Indeed, the Chinese currency, also known as the renminbi, has been remarkably steady over the past month despite the huge selloff in China’s stock market and a spate of disappointing economic data. Market strategists, including Simon Derrick, chief currency strategist at BNY Mellon, and Marc Chandler, head currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman, said that is because China’s policy makers have effectively re-pegged the yuan. “When I look at the dollar-renminbi right now, that looks like a fixed exchange rate again. They’ve re-pegged it,” Chandler said.»[50]

Managed float[edit]

The renminbi has now moved to a managed floating exchange rate based on market supply and demand with reference to a basket of foreign currencies. In July 2005, the daily trading price of the US dollar against the renminbi in the inter-bank foreign exchange market was allowed to float within a narrow band of 0.3% around the central parity[51] published by the People’s Bank of China; in a later announcement published on 18 May 2007, the band was extended to 0.5%.[52] On 14 April 2012, the band was extended to 1.0%.[53] On 17 March 2014, the band was extended to 2%.[54] China has stated that the basket is dominated by the United States dollar, euro, Japanese yen and South Korean won, with a smaller proportion made up of sterling, Thai baht, roubles, Australian dollars, Canadian dollars and Singaporean dollars.[55]

On 10 April 2008, it traded at ¥6.9920 per US dollar, which was the first time in more than a decade that a dollar had bought less than ¥7,[56] and at ¥11.03630 per euro.

Beginning in January 2010, Chinese and non-Chinese citizens have an annual exchange limit of a maximum of US$50,000. Currency exchange will only proceed if the applicant appears in person at the relevant bank and presents their passport or Chinese ID. Currency exchange transactions are centrally registered. The maximum dollar withdrawal is $10,000 per day, the maximum purchase limit of US dollars is $500 per day. This stringent management of the currency leads to a bottled-up demand for exchange in both directions. It is viewed as a major tool to keep the currency peg, preventing inflows of «hot money».

A shift of Chinese reserves into the currencies of their other trading partners has caused these nations to shift more of their reserves into dollars, leading to no great change in the value of the renminbi against the dollar.[57]

Futures market[edit]

Renminbi futures are traded at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. The futures are cash-settled at the exchange rate published by the People’s Bank of China.[58]

Purchasing power parity[edit]

Scholarly studies suggest that the yuan is undervalued on the basis of purchasing power parity analysis. One 2011 study suggests a 37.5% undervaluation.[5]

- The World Bank estimated that, by purchasing power parity, one International dollar was equivalent to approximately ¥1.9 in 2004.[59]

- The International Monetary Fund estimated that, by purchasing power parity, one International dollar was equivalent to approximately ¥3.462 in 2006, ¥3.621 in 2007, ¥3.798 in 2008, ¥3.872 in 2009, ¥3.922 in 2010, ¥3.946 in 2011, ¥3.952 in 2012, ¥3.944 in 2013 and ¥3.937 in 2014.[60]

The People’s Bank of China lowered the renminbi’s daily fix to the US dollar by 1.9 per cent to ¥6.2298 on 11 August 2015. The People’s Bank of China again lowered the renminbi’s daily fix to the US dollar from ¥6.620 to ¥6.6375 after Brexit on 27 June 2016. It had not been this low since December 2010.

Internationalisation[edit]

Before 2009, the renminbi had little to no exposure in the international markets because of strict government controls by the central Chinese government that prohibited almost all export of the currency, or use of it in international transactions. Transactions between Chinese companies and a foreign entity were generally denominated in US dollars. With Chinese companies unable to hold US dollars and foreign companies unable to hold Chinese yuan, all transactions would go through the People’s Bank of China. Once the sum was paid by the foreign party in dollars, the central bank would pass the settlement in renminbi to the Chinese company at the state-controlled exchange rate.

In June 2009 the Chinese officials announced a pilot scheme where business and trade transactions were allowed between limited businesses in Guangdong province and Shanghai, and only counterparties in Hong Kong, Macau, and select ASEAN nations. Proving a success,[62] the program was further extended to 20 Chinese provinces and counterparties internationally in July 2010, and in September 2011 it was announced that the remaining 11 Chinese provinces would be included.

In steps intended to establish the renminbi as an international reserve currency, China has agreements with Russia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Japan, allowing trade with those countries to be settled directly in renminbi instead of requiring conversion to US dollars, with Australia and South Africa to follow soon.[63][64][65][66][67]

International reserve currency[edit]

Currency restrictions regarding renminbi-denominated bank deposits and financial products were greatly liberalised in July 2010.[68] In 2010 renminbi-denominated bonds were reported to have been purchased by Malaysia’s central bank[69] and that McDonald’s had issued renminbi denominated corporate bonds through Standard Chartered Bank of Hong Kong.[70] Such liberalisation allows the yuan to look more attractive as it can be held with higher return on investment yields, whereas previously that yield was virtually none. Nevertheless, some national banks such as Bank of Thailand (BOT) have expressed a serious concern about renminbi since BOT cannot substitute the deprecated US dollars in its US$200 billion foreign exchange reserves for renminbi as much as it wishes because:

- The Chinese government has not taken full responsibilities and commitments on economic affairs at global levels.

- The renminbi still has not become well-liquidated (fully convertible) yet.

- The Chinese government still lacks deep and wide vision about how to perform fund-raising to handle international loans at global levels.[71]

To meet IMF requirements, China gave up some of its tight control over the currency.[72]

Countries that are left-leaning in the political spectrum had already begun to use the renminbi as an alternative reserve currency to the United States dollar; the Central Bank of Chile reported in 2011 to have US$91 million worth of renminbi in reserves, and the president of the Central Bank of Venezuela, Nelson Merentes, made statements in favour of the renminbi following the announcement of reserve withdrawals from Europe and the United States.[73]

In Africa, the central banks of Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa either hold renminbi as a reserve currency or have taken steps to purchase bonds denominated in renminbi.[74] The «Report on the Internationalization of RMB in 2020», which was released by the People’s Bank of China in August 2020, said that renminbi’s function as international reserve currency has gradually emerged. In the first quarter 2020, the share of renminbi in global foreign exchange reserves rose to 2.02%, a record high. As of the end of 2019, the People’s Bank of China has set up renminbi clearing banks in 25 countries and regions outside of Mainland China, which has made the use of renminbi more secure and transaction costs have decreased.[75]

Use as a currency outside mainland China[edit]

The two special administrative regions, Hong Kong and Macau, have their own respective currencies, according to the «one country, two systems» principle and the basic laws of the two territories.[76][77] Therefore, the Hong Kong dollar and the Macanese pataca remain the legal tenders in the two territories, and the renminbi, although sometimes accepted, is not legal tender. Banks in Hong Kong allow people to maintain accounts in RMB.[78] Because of changes in legislation in July 2010, many banks around the world[79] are now slowly offering individuals the chance to hold deposits in Chinese renminbi.

The renminbi had a presence in Macau even before the 1999 return to the People’s Republic of China from Portugal. Banks in Macau can issue credit cards based on the renminbi, but not loans. Renminbi-based credit cards cannot be used in Macau’s casinos.[80]

The Republic of China, which governs Taiwan, believes wide usage of the renminbi would create an underground economy and undermine its sovereignty.[81] Tourists are allowed to bring in up to ¥20,000 when visiting Taiwan. These renminbi must be converted to Taiwanese currency at trial exchange sites in Matsu and Kinmen.[82] The Chen Shui-bian administration insisted that it would not allow full convertibility until the mainland signs a bilateral foreign exchange settlement agreement,[83] though president Ma Ying-jeou, who served from 2008 to 2016, sought to allow full convertibility as soon as possible.

The renminbi circulates[84] in some of China’s neighbors, such as Pakistan, Mongolia[85][86] and northern Thailand.[87] Cambodia welcomes the renminbi as an official currency and Laos and Myanmar allow it in border provinces such as Wa and Kokang and economic zones like Mandalay.[84] Though unofficial, Vietnam recognizes the exchange of the renminbi to the đồng.[84] In 2017 ¥215 billion was circulating in Indonesia. In 2018 a Bilateral Currency Swap Agreement was made by the Bank of Indonesia and the Bank of China which simplified business transactions, and in 2020 about 10% of Indonesia’s global trade was in renminbi.[88]

Since 2007, renminbi-nominated bonds have been issued outside mainland China; these are colloquially called «dim sum bonds». In April 2011, the first initial public offering denominated in renminbi occurred in Hong Kong, when the Chinese property investment trust Hui Xian REIT raised ¥10.48 billion ($1.6 billion) in its IPO. Beijing has allowed renminbi-denominated financial markets to develop in Hong Kong as part of the effort to internationalise the renminbi.[89] There is limited (under 1%) issuing of renminbi bonds in Indonesia.[88]

Other markets[edit]

Renminbi promotion at the China-CEEC 2017 summit

Since currency flows in and out of mainland China are still restricted, renminbi traded in off-shore markets, such as the Hong Kong market, can have a different value to renminbi traded on the mainland. The offshore RMB market is usually denoted as CNH, but there is another renminbi interbank and spot market in Taiwan for domestic trading known as CNT.

Other renminbi markets include the dollar-settled non-deliverable forward (NDF), and the trade-settlement exchange rate (CNT).[90][91]

Note that the two CNTs mentioned above are different from each other.

See also[edit]

- Digital renminbi

- Chinese lunar coins

- Economy of China

- List of Chinese cash coins by inscription

- List of renminbi exchange rates

- Tibetan coins and currency

Notes[edit]

- ^ excluding special administrative regions Hong Kong and Macau.

- ^ A set of numeral characters used traditionally in financial and accounting settings, not used in daily writing; see Chinese numerals#Standard numbers

- ^ The total sum is 200% because each currency trade always involves a currency pair; one currency is sold (e.g. US$) and another bought (€). Therefore each trade is counted twice, once under the sold currency ($) and once under the bought currency (€). The percentages above are the percent of trades involving that currency regardless of whether it is bought or sold, e.g. the US dollar is bought or sold in 88% of all trades, whereas the euro is bought or sold 32% of the time.

References[edit]

- ^ «CNY – Chinese Yuan Renminbi rates, news, and tools | Xe». Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ «Myanmar’s free-wheeling Wa state». 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ «Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2022» (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. 27 October 2022. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Article 2, «The People’s Bank of China Law of the People’s Republic of China». 27 December 2003. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007.

- ^ a b Lipman, Joshua Klein (April 2011). «Law of Yuan Price: Estimating Equilibrium of the Renminbi» (PDF). Michigan Journal of Business. 4 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Schneider, Howard (29 September 2012). «Some experts say China’s currency policy is not a danger to the U.S. economy». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ «RMB now 8th most traded currency in the world». Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. 8 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 November 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ «RMB breaks into the top five as a world payments currency». Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. 28 January 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ «RMB Tracker January 2020 – Slides». Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. 21 January 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ a b Solomon Teague (6 October 2016). «FX: RMB joins the SDR basket». Euromoney. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Randau, Henk R.; Medinskaya, Olga (10 November 2014). Chinese Business 2.0 | Internationalizing the RMB. ISBN 9783319076775. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Mulvey, Stephen (26 June 2010). «Why China’s currency has two names». BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019.

- ^ «China’s currency: the RMB, CNY, CNH…». Archived from the original on 18 April 2015.

- ^ Landry, David G.; Tang, Heiwai (16 September 2017). «Rise of the Redback: Internationalizing the Chinese Renminbi». The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ a b «中华人民共和国第一套人民币概述» [People’s Republic of China first RMB Overview]. China: Sina. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ «Banknotes • China • Heiko Otto». Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ «Provisional Regulations Of The Bank Of China Of Foreign Exchange Certificate». Asianlii.org. 19 March 1980. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ «Foreign Exchange Certificates Issued under Improved Forex Administration (1979–1989)». Bankofchina.com. 1 April 1980. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (30 November 2015). «China’s Renminbi Is Approved by I.M.F. as a Main World Currency». NY Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Tabeta, Shunsuke (31 December 2019). «China’s digital yuan takes shape with new encryption law». Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Authority, Hong Kong Monetary. «Hong Kong Monetary Authority – Hong Kong FinTech Week 2019». Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ «Digital yuan tsar gives green light for tourists to go cashless in China». South China Morning Post. 6 November 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ technology, Full Bio Follow Linkedin Rakesh Sharma is a writer with 8+ years of experience about the intersection between; investing, business Rakesh is an expert in; business; blockchain; Sharma, cryptocurrencies Learn about our editorial policies Rakesh. «Understanding China’s Digital Yuan». Investopedia. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ «China’s proposed digital currency more about policing than progress». Reuters. 1 November 2019. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Kynge, James; Yu, Sun (16 February 2021). «Virtual control: the agenda behind China’s new digital currency». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ a b Hannah Murphy; Yuan Yang (12 February 2020). «Patents reveal extent of China’s digital currency plans». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ «Is the US worried it is falling behind China’s digital currency?». South China Morning Post. 17 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Hui, Mary (10 September 2020). «The same problems plaguing the yuan will plague China’s digital currency». Quartz. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Prasad, Eswar (25 August 2020). «China’s Digital Currency Will Rise but Not Rule». Project Syndicate. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (28 April 2020). «China starts major trial of state-run digital currency». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ «What is China’s new digital currency all about?». Kitco News. 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Coldness Kwan (6 March 2007). «Do you get one fen change at Origus?». China Daily. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- ^ «New Chinese coins of 1 yuan, 0.5 yuan and 0.1 yuan – 2019New Chinese coins of 1 yuan, 0.5 yuan and 0.1 yuan – 2019». 30 April 2019. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ «China issues new edition of renminbi bills, coins – Xinhua | English.news.cn». Archived from the original on 31 August 2019.

- ^ «中国最早的一张人民币». Cjiyou.net. 22 October 2007. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ China new 100-yuan aerospace commemorative note reported for 26.11.2015 introduction Archived 18 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine BanknoteNews.com. 6 November 2015. Retrieved on 18 November 2015.

- ^ 中国人民银行公告〔2015〕第33号 Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine The People’s Bank of China (www.pbc.gov.cn). Retrieved on 18 November 2015.

- ^ 中国印钞造币总公司官网. www.cbpm.cn. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013.

- ^ 保定钞票纸厂. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

- ^ Quentin Sommerville (13 March 2006). «China mulls Mao banknote change». BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ «Triennial Central Bank Survey Foreign exchange turnover in April 2022» (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. 27 October 2022. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ «Profile of China’s Yuan – Characteristics and Economic Indicators». Binary Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Yahoo Finance, Dollar extends slide on views of low US rates Archived 3 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ «Is the Renminbi undervalued or overvalued?». CSIS China Power. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ «Public Announcement of the People’s Bank of China on Reforming the RMB Exchange Rate Regime». 21 July 2005. Archived from the original on 16 March 2007.

- ^ «‘Critically important’ that China move on currency: Geithner. Treasury chief says he shares Congress’ ire over dollar peg». 10 June 2010. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ Further reform of the RMB exchange rate regime and enhancing the RNM exchange rate flexibility Archived 3 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Phillips, Michael M.; Talley, Ian (21 June 2010). «Global Leaders Welcome China’s Yuan Plan». Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ «World stocks soar after Chinese move on yuan». Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Adinolfi, Joseph (10 August 2015). «China has effectively re-pegged the yuan». Market Watch. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ KWAN, C.H. «How China’s managed floating system under BBC rules actually works». RIETI. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ «Public Announcement of the People’s Bank of China on Enlarging the Floating Band of the RMB Trading Prices against the US Dollar in the Inter-bank Spot Foreign Exchange Market». 18 May 2007. Archived from the original on 16 March 2007.

- ^ «China to widen daily yuan band vs. dollar to 1%». 14 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013.

- ^ Wang, Wynne. «China’s Yuan Falls Further Against Dollar». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ «央行行长周小川在央行上海总部揭牌仪式上的讲话». 10 August 2005. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ David Barboza (10 April 2008). «Yuan Hits Milestone Against Dollar». New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ Frangos, Alex (16 September 2010). «Don’t Worry About China, Japan Will Finance U.S. Debt». The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ «Chinese Renminbi Futures» (PDF). CME Group. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ^ «World Bank: World Development Indicators 2006«. Archived from the original on 10 July 2010.

- ^ «World Economic Outlook Database, April 2009». IMF. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ «Quotes of the Day». Time. 24 November 2010. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ «The Use of RMB in International Transactions» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- ^ Barboza, David (11 February 2011). «In China, Tentative Steps Toward a Global Currency». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ «China, Japan to launch yuan-yen direct trading». Xinhuanet. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ «ANZ, Westpac to lead Chinese currency conversion». Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ «Designated Foreign Currencies – Central Bank of Sri Lanka» (PDF). Central Bank of Sri Lanka. 27 October 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ «Bank of China to serve as yuan clearing bank in S. Africa». Xinhua. 8 July 2015. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Cookson, Robert (28 July 2010). «China revs up renminbi expansion». The Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ Brown, Kevin; Cookson, Robert; Dyer, Geoff (19 September 2010). «Malaysian bond boost for renminbi». The Financial Times. Asia-Pacific. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ » McDonald’s RMB Corporate Bond Launched in HK» 19 August 2010 Xinhua Web Editor: Xu Leiying, accessed 7 October 2013

- ^ «ธปท.หาทางถ่วงน้ำหนักทุนสำรองหลังดอลลาร์สหรัฐผันผวน» [BOT. Weighted for the reserves after the US dollar volatility.]. MCOT. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (30 November 2015). «China’s Renminbi Is Approved by I.M.F. as a Main World Currency». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Laje, Diego (29 September 2011). «China’s yuan moving toward global currency?». CNN Business. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011.

- ^ «Chinese yuan penetrates African markets». African Renewal. August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ «《2020年人民币国际化报告》发布:人民币在全球外汇储备中占比创新高». Xinhua Net. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ «The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China». 4 April 1990. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

Article 18: National laws shall not be applied in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region except for those listed in Annex III to this Law.

- ^ «The Basic Law of the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China». 31 March 1993. Archived from the original on 5 March 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

Article 18: National laws shall not be applied in the Macao Special Administrative Region except for those listed in Annex m to this Law.

- ^ «Hong Kong banks to conduct personal renminbi business on trial basis». Hong Kong Monetary Authority. 18 November 2003. Archived from the original on 5 April 2005. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ «Bank of China New York Offers Renminbi Deposits». Archived from the original on 22 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ «Macao gets green light for RMB services». China Daily. 5 August 2004. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ «Regular Press Briefing of the Mainland Affairs Council». Mainland Affairs Council. 5 January 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ «CBC head urges immediate liberalization of reminbi conversion». Government Information Office, Taiwan. 26 December 2006. Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ «Taiwan prepares to allow renminbi exchange». Financial Times. 3 January 2007. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- ^ a b c «RMB increases its influence in neighbouring areas». People’s Daily. 17 February 2004. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ «人民幣在蒙古國被普遍使用». Ta Kung Pao (大公報). 6 May 2009.[dead link]

- ^ «Widely used in Mongolia». chinanewswrap.com. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012.

- ^ «Asian Monetary Cooperation: Perspective of RMB Asianalization» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat (31 July 2020). «The Internationalization of China’s Currency in Indonesia». The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ «Hong Kong’s first renminbi IPO raises $1.6bn». Financial Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Hui, Daniel; Bunning, Dominic (1 December 2010). «The offshore renminbi» (PDF). HSBC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ «The birth of a new currency». Treasury Today. May 2011. Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- Ansgar Belke, Christian Dreger und Georg Erber: Reduction of Global Trade Imbalances: Does China Have to Revalue Its Currency? In: Weekly Report. 6/2010, Nr. 30, 2010, ISSN 1860-3343, S. 222–229 (PDF-File; DIW Online Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine).

- Hai Xin (2012). The RMB Handbook: Trading, Investing and Hedging, Risk Books. ISBN 978-1906348816

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

- Cheung, Yin-Wong (2022). «The RMB in the Global Economy». Cambridge University Press.

External links[edit]

- Photographs of all Chinese currency and sound of pronunciation in Chinese

- Stephen Mulvey, Why China’s currency has two names – BBC News, 2010-06-26

- Historical and current banknotes of the People’s Republic of China (in English and German)

- Foreign exchange certificates (FEC) of the People’s Republic of China (in English and German)

|

|

Parts of this article (those related to images of new issuance of coins and banknotes (see zh:第五套人民币#第三版)) need to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2021) |

| 人民币 (Chinese)

RMB |

|

|---|---|

Renminbi banknotes |

|

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | CNY (numeric: 156) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Unit | yuán (元 / 圆) |

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency do(es) not have a morphological plural distinction. |

| Symbol | ¥ |

| Nickname | kuài (块) |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄10 | jiǎo (角) |

| 1⁄100 | fēn (分) |

| Nickname | |

| jiǎo (角) | máo (毛) |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | ¥1 RMB, ¥5 RMB, ¥10 RMB, ¥20 RMB, ¥50 RMB, ¥100 RMB |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | ¥0.1 RMB, ¥0.5 RMB, ¥1 RMB |

| Rarely used | ¥0.01 RMB, ¥0.02 RMB, ¥0.05 RMB |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 1948; 75 years ago |

| Replaced | Nationalist-issued yuan |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | People’s Bank of China |

| Website | www.pbc.gov.cn |

| Printer | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation |

| Website | www.cbpm.cn |

| Mint | China Banknote Printing and Minting Corporation |

| Website | www.cbpm.cn |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 2.5% (2017) |

| Source | [1] [2] |

| Method | CPI |

| Pegged with | Partially, to a basket of trade-weighted international currencies |

| Renminbi | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Renminbi» in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 人民币 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 人民幣 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «People’s Currency» | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yuan | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 圆 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 圓 (or 元) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «circle» (ie. a coin) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The renminbi (Chinese: 人民币; pinyin: Rénmínbì; lit. ‘People’s Currency’; symbol: ¥; ISO code: CNY; abbreviation: RMB) is the official currency of the People’s Republic of China[note 1]. It is the 5th most traded currency as of April 2022.[3]

The yuan (Chinese: 元 or simplified Chinese: 圆; traditional Chinese: 圓; pinyin: yuán) is the basic unit of the renminbi, but the word is also used to refer to the Chinese currency generally, especially in international contexts. One yuan is divided into 10 jiao (Chinese: 角; pinyin: jiǎo), and the jiao is further subdivided into 10 fen (Chinese: 分; pinyin: fēn). The renminbi is issued by the People’s Bank of China, the monetary authority of China.[4]

Valuation[edit]

Until 2005, the value of the renminbi was pegged to the US dollar. As China pursued its transition from central planning to a market economy and increased its participation in foreign trade, the renminbi was devalued to increase the competitiveness of Chinese industry. It has previously been claimed that the renminbi’s official exchange rate was undervalued by as much as 37.5% against its purchasing power parity.[5] However, more recently, appreciation actions by the Chinese government, as well as quantitative easing measures taken by the American Federal Reserve and other major central banks, have caused the renminbi to be within as little as 8% of its equilibrium value by the second half of 2012.[6] Since 2006, the renminbi exchange rate has been allowed to float in a narrow margin around a fixed base rate determined with reference to a basket of world currencies. The Chinese government has announced that it will gradually increase the flexibility of the exchange rate. As a result of the rapid internationalization of the renminbi, it became the world’s 8th most traded currency in 2013,[7] 5th by 2015,[8] but 6th in 2019.[9]

On 1 October 2016, the renminbi became the first emerging market currency to be included in the IMF’s special drawing rights basket, the basket of currencies used by the IMF as a reserve currency.[10]

| Current CNY exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR RUB |

USD/CNY exchange rate 1981-2022

Terminology[edit]

| Chinese | pinyin | English | Literal translation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal currency name | 人民币 | rénmínbì | renminbi | «people’s currency» |

| Formal name for 1 unit | 元 or 圆 | yuán | yuan | «unit» |

| Formal name for 1⁄10 unit | 角 | jiǎo | jiao | «corner» |

| Formal name for 1⁄100 unit | 分 | fēn | fen | «fraction», «cent» |

| Colloquial name for 1 unit | 块 | kuài | kuai or quay[11] | «piece» |

| Colloquial name for 1⁄10 unit | 毛 | máo | mao | «feather» |

The ISO code for the renminbi is CNY, the PRC’s country code (CN) plus «Y» from «yuan».[12] Hong Kong markets that trade renminbi at free-floating rates use the unofficial code CNH. This is to distinguish the rates from those fixed by Chinese central banks on the mainland.[13] The abbreviation RMB is not an ISO code but is sometimes used like one by banks and financial institutions.

The currency symbol for the yuan unit is ¥, but when distinction from the Japanese yen is required RMB (e.g. RMB 10,000) or ¥ RMB (e.g. ¥10,000 RMB) is used. However, in written Chinese contexts, the Chinese character for yuan (Chinese: 元; lit. ‘beginning’) or, in formal contexts Chinese: 圆; lit. ’round’, usually follows the number in lieu of a currency symbol.

Renminbi is the name of the currency while yuan is the name of the primary unit of the renminbi. This is analogous to the distinction between «sterling» and «pound» when discussing the official currency of the United Kingdom.[12] Jiao and fen are also units of renminbi.

In everyday Mandarin, kuai (Chinese: 块; pinyin: kuài; lit. ‘piece’) is usually used when discussing money and «renminbi» or «yuan» are rarely heard.[12] Similarly, Mandarin speakers typically use mao (Chinese: 毛; pinyin: máo) instead of jiao.[12] For example, ¥8.74 might be read as 八块七毛四 (pinyin: bā kuài qī máo sì) in everyday conversation, but read 八元七角四分 (pinyin: bā yuán qī jiǎo sì fēn) formally.

Renminbi is sometimes referred to as the «redback», a play on «greenback», a slang term for the US dollar.[14]

History[edit]

China M2 money supply (red) vis-à-vis USA M2 money supply (blue)

The various currencies called yuan or dollar issued in mainland China as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and Singapore were all derived from the Spanish American silver dollar, which China imported in large quantities from Spanish America from the 16th to 20th centuries. The first locally minted silver dollar or yuan accepted all over Qing dynasty China (1644–1912) was the silver dragon dollar introduced in 1889. Various banknotes denominated in dollars or yuan were also introduced, which were convertible to silver dollars until 1935 when the silver standard was discontinued and the Chinese yuan was made fabi (法币; legal tender fiat currency).

The renminbi was introduced by the People’s Bank of China in December 1948, about a year before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. It was issued only in paper form at first, and replaced the various currencies circulating in the areas controlled by the Communists. One of the first tasks of the new government was to end the hyperinflation that had plagued China in the final years of the Kuomintang (KMT) era. That achieved, a revaluation occurred in 1955 at the rate of 1 new yuan = 10,000 old yuan.

As the Chinese Communist Party took control of ever larger territories in the latter part of the Chinese Civil War, its People’s Bank of China began to issue a unified currency in 1948 for use in Communist-controlled territories. Also denominated in yuan, this currency was identified by different names, including «People’s Bank of China banknotes» (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行钞票; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行鈔票; from November 1948), «New Currency» (simplified Chinese: 新币; traditional Chinese: 新幣; from December 1948), «People’s Bank of China notes» (simplified Chinese: 中国人民银行券; traditional Chinese: 中國人民銀行券; from January 1949), «People’s Notes» (人民券, as an abbreviation of the last name), and finally «People’s Currency», or «renminbi«, from June 1949.[15]

Era of the planned economy[edit]

From 1949 until the late 1970s, the state fixed China’s exchange rate at a highly overvalued level as part of the country’s import-substitution strategy. During this time frame, the focus of the state’s central planning was to accelerate industrial development and reduce China’s dependence on imported manufactured goods. The overvaluation allowed the government to provide imported machinery and equipment to priority industries at a relatively lower domestic currency cost than otherwise would have been possible.

Transition to an equilibrium exchange rate[edit]

China’s transition by the mid-1990s to a system in which the value of its currency was determined by supply and demand in a foreign exchange market was a gradual process spanning 15 years that involved changes in the official exchange rate, the use of a dual exchange rate system, and the introduction and gradual expansion of markets for foreign exchange.

The most important move to a market-oriented exchange rate was an easing of controls on trade and other current account transactions, as occurred in several very early steps. In 1979, the State Council approved a system allowing exporters and their provincial and local government owners to retain a share of their foreign exchange earnings, referred to as foreign exchange quotas. At the same time, the government introduced measures to allow retention of part of the foreign exchange earnings from non-trade sources, such as overseas remittances, port fees paid by foreign vessels, and tourism.

As early as October 1980, exporting firms that retained foreign exchange above their own import needs were allowed to sell the excess through the state agency responsible for the management of China’s exchange controls and its foreign exchange reserves, the State Administration of Exchange Control. Beginning in the mid-1980s, the government sanctioned foreign exchange markets, known as swap centres, eventually in most large cities.

The government also gradually allowed market forces to take the dominant role by introducing an «internal settlement rate» of ¥2.8 to 1 US dollar which was a devaluation of almost 100%.

Foreign exchange certificates, 1980–1994[edit]

In the process of opening up China to external trade and tourism, transactions with foreign visitors between 1980 and 1994 were done primarily using Foreign exchange certificates (外汇券, waihuiquan) issued by the Bank of China.[16][17][18]

Foreign currencies were exchangeable for FECs and vice versa at the renminbi’s prevailing official rate which ranged from US$1 = ¥2.8 FEC to ¥5.5 FEC. The FEC was issued as banknotes from ¥0.1 to ¥100, and was officially at par with the renminbi. Tourists used FECs to pay for accommodation as well as tourist and luxury goods sold in Friendship Stores. However, given the non-availability of foreign exchange and Friendship Store goods to the general public, as well as the inability of tourists to use FECs at local businesses, an illegal black market developed for FECs where touts approached tourists outside hotels and offered over ¥1.50 RMB in exchange for ¥1 FEC. In 1994, as a result of foreign exchange management reforms approved by the 14th CPC Central Committee, the renminbi was officially devalued from US$1 = ¥5.5 to over ¥8, and the FEC was retired at ¥1 FEC = ¥1 RMB in favour of tourists directly using the renminbi.

Evolution of exchange policy since 1994[edit]

In November 1993, the Third Plenum of the Fourteenth CPC Central Committee approved a comprehensive reform strategy in which foreign exchange management reforms were highlighted as a key element for a market-oriented economy. A floating exchange rate regime and convertibility for renminbi were seen as the ultimate goal of the reform. Conditional convertibility under current account was achieved by allowing firms to surrender their foreign exchange earning from current account transactions and purchase foreign exchange as needed. Restrictions on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was also loosened and capital inflows to China surged.

Convertibility[edit]

During the era of the command economy, the value of the renminbi was set to unrealistic values in exchange with Western currency and severe currency exchange rules were put in place, hence the dual-track currency system from 1980 to 1994 with the renminbi usable only domestically, and with Foreign Exchange Certificates (FECs) used by foreign visitors.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, China worked to make the renminbi more convertible. Through the use of swap centres, the exchange rate was eventually brought to more realistic levels of above ¥8/US$1 in 1994 and the FEC was discontinued. It stayed above ¥8/$1 until 2005 when the renminbi’s peg to the dollar was loosened and it was allowed to appreciate.

As of 2013, the renminbi is convertible on current accounts but not capital accounts. The ultimate goal has been to make the renminbi fully convertible. However, partly in response to the Asian financial crisis in 1998, China has been concerned that the Chinese financial system would not be able to handle the potential rapid cross-border movements of hot money, and as a result, as of 2012, the currency trades within a narrow band specified by the Chinese central government.

Following the internationalization of the renminbi, on 30 November 2015, the IMF voted to designate the renminbi as one of several main world currencies, thus including it in the basket of special drawing rights. The renminbi became the first emerging market currency to be included in the IMF’s SDR basket on 1 October 2016.[10] The other main world currencies are the dollar, the euro, sterling, and the yen.[19]

Digital renminbi[edit]

In October 2019, China’s central bank, PBOC, announced that a digital reminbi is going to be released after years of preparation.[20] This version of the currency, also called DCEP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment),[21] can be “decoupled” from the banking system to give visiting tourists a taste of the nation’s burgeoning cashless society.[22] However, it is not based on cryptocurrency.[23] The announcement received a variety of responses: some believe it is more about domestic control and surveillance.[24] Some argue that the real barriers to internationalisation of the renminbi are China’s capital controls, which it has no plans to remove. Maximilian Kärnfelt, an expert at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, said that a digital renminbi «would not banish many of the problems holding the renminbi back from more use globally». He went on to say, «Much of China’s financial market is still not open to foreigners and property rights remain fragile.»[25]

The PBOC has filed more than 80 patents surrounding the integration of a digital currency system, choosing to embrace the blockchain technology. The patents reveal the extent of China’s digital currency plans. The patents, seen and verified by the Financial Times, include proposals related to the issuance and supply of a central bank digital currency, a system for interbank settlements that uses the currency, and the integration of digital currency wallets into existing retail bank accounts. Several of the 84 patents reviewed by the Financial Times indicate that China may plan to algorithmically adjust the supply of a central bank digital currency based on certain triggers, such as loan interest rates. Other patents are focused on building digital currency chip cards or digital currency wallets that banking consumers could potentially use, which would be linked directly to their bank accounts. The patent filings also point to the proposed ‘tokenomics’ being considered by the DCEP working group. Some patents show plans towards programmed inflation control mechanisms. While the majority of the patents are attributed to the PBOC’s Digital Currency Research Institute, some are attributed to state-owned corporations or subsidiaries of the Chinese central government.[26]

Uncovered by the Chamber of Digital Commerce (an American non-profit advocacy group), their contents shed light on Beijing’s mounting efforts to digitise the renminbi, which has sparked alarm in the West and spurred central bankers around the world to begin exploring similar projects.[26] Some commentators have said that the U.S., which has no current plans to issue a government-backed digital currency, risks falling behind China and risking its dominance in the global financial system.[27] Victor Shih, a China expert and professor at the University of California San Diego, said that merely introducing a digital currency «doesn’t solve the problem that some people holding renminbi offshore will want to sell that renminbi and exchange it for the dollar», as the dollar is considered to be a safer asset.[28] Eswar Prasad, an economics professor at Cornell University, said that the digital renminbi «will hardly put a dent in the dollar’s status as the dominant global reserve currency» due to the United States’ «economic dominance, deep and liquid capital markets, and still-robust institutional framework».[28][29] The U.S. dollar’s share as a reserve currency is above 60%, while that of the renminbi is about 2%.[28]