- До 7 класса: Алгоритмика, Кодланд, Реботика.

- 8-11 класс: Умскул, Годограф, Знанио.

- Английский: Инглекс, Puzzle, Novakid.

- Взрослым: Skillbox, Нетология, Geekbrains, Яндекс, Otus, SkillFactory.

Как пишется: «Гонконг» или «Гонконк»?

Правила

В соответствии с орфографическими правилами русского языка слово «Гонконг» пишут с буквой «о» в первом слоге и согласным «г» в конце.

Правописание первого слога объясняется этимологией. Дословно название означает «Благоухающая гавань». Изначально рассматриваемое наименование относилось к одной из бухт острова Гонконг. Когда англичане захватили остров, назвали его Hong Kong. Через них название перешло и в остальные языки, в том числе и в русский. Сохраняем нормы первоисточника и запоминаем написание.

Чтобы проверить труднопроизносимый согласный в конце слова, необходимо поставить лексическую единицу в форму родительного падежа, чтобы после согласного стоял гласный звук: Гонконга – Гонконг.

Значение слова

Гонконг – специальный административный район Китая. С точки зрения морфологии, слово является неодушевлённым существительным мужского рода второго склонения, обозначает название географического объекта.

Примеры

- Во время визита в Китай обязательно стоит посетить Гонконг.

- Директору сообщили, что ему срочно нужно лететь в Гонконг.

- Чтобы вместе полететь в Гонконг, мы решили встретиться в Нью-Йорке.

- До 7 класса: Алгоритмика, Кодланд, Реботика.

- 8-11 класс: Умскул, Годограф, Знанио.

- Английский: Инглекс, Puzzle, Novakid.

- Взрослым: Skillbox, Нетология, Geekbrains, Яндекс, Otus, SkillFactory.

- Hong Kong — Гонконг, гонконгский

Родственные слова, либо редко употребляемые в данном значении

- Hong |ˈhɒŋ| — иностранное торговое предприятие в Китае, фактория

Правильное написание слова Гонконг:

Крутая NFT игра. Играй и зарабатывай!

Количество букв в слове: 7

Слово состоит из букв:

Г, О, Н, К, О, Н, Г

Правильный транслит слова: Гonkong

Написание с не правильной раскладкой клавиатуры: Гjyrjyu

Тест на правописание

Синонимы слова Гонконг

- Сянган

Специальный администрати́вный райо́н Гонко́нг (иер. трад. 香港特別行政區, упр. 香港特别行政区, англ. Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, кант. Хёнкон такпит ханчинкхёй?, пут. Сянган тэбе синчжэнцюй?), сокращённо Гонконг (иер. 香港, англ. Hong Kong, кант. Heūnggóng, Хёнкон?, пут. Сянга́н?) или Сянга́н — специальный административный район Китайской Народной Республики, один из ведущих финансовых центров Азии и мира.

Все значения слова «Гонконг»

-

Гонконг – это зона с пониженным налогообложением, отчасти офшор.

-

Гонконг был взят за несколько дней, Малайзия была разгромлена, а великая крепость – Сингапур – была полностью окружена и бесславно капитулировала.

-

Наконец, третья группа стран в качестве инструмента налоговой политики установила полное или частичное освобождение прироста капитала от налогообложения (Бельгия, Гонконг, Кипр, Люксембург, Мальта, Нидерланды, Сингапур и многие другие), что порождает проблемы классификации для отделения прироста капитала от обычной прибыли, учитывая важность налоговых последствий такой классификации.

- (все предложения)

- китайский город

- новые индустриальные страны

- японские острова

- пограничный переход

- колониальные владения

- (ещё синонимы…)

- гонг

- (ещё ассоциации…)

|

В настоящем руководстве отражены правила передачи по-русски гонконгских имён и названий, которых рекомендуется придерживаться в русской Википедии.

Если в отношении персоналии, объекта или явления, имеющих в своём имени или названии слова кантонского происхождения, в русскоязычных авторитетных источниках существует устойчивая традиция именования (в том числе латиницей — например, для названий организаций), следует придерживаться именно её. В отсутствие таковой применяются следующие рекомендации.

Основные принципы[править код]

За основу для транскрипции слова или названия берется принятое в Гонконге англоязычного написание. Его собственно английская часть транскрибируется согласно соответствующим правилам, а кантонская — записывается с помощью кантонско-русской практической транскрипции. В ряде источников (особенно, советского периода) гонконгские имена собственные транскрибируются с севернокитайского произношения по системе Палладия.

В начале статьи следует указывать альтернативные варианты транскрипции на русский и написание на английском с помощью шаблонов {{кантонский3}} и/или {{lang-en}}.

Топонимы и имена людей из Гуандуна транскрибируются только с помощью системы Палладия (кроме гуандунских артистов и лиц, эмигрировавших из этой провинции в Гонконг или за границу и записывающих свои имена по-английски с использованием кантонского произношения).

Географические названия[править код]

Несмотря на то, что на картах Роскартографии гонконгские топонимы перекладываются с севернокитайского (по системе Палладия), в статьях Википедии они транскрибируются с официального английского названия как более узнаваемого. Кантонская часть в их составе записывается при помощи кантонско-русской транскрипции, а севернокитайское произношение — указывается в транскрипционном шаблоне.

Слоги в кантонских и севернокитайских географических названиях (составных частях названий) пишутся слитно. Английская и кантонская части в рамках одного названия отделяются друг от друга дефисом (например, Yuen Long Town — Юньлон-Таун).

Административные единицы Гонконга (districts) обозначаются по-русски «округ». «Районами» называются устоявшиеся общеупотребительные названия частей города и населённых пунктов на территории Гонконга.

Имена людей[править код]

Для названия статьи следует выбирать наиболее распространенный и узнаваемый вариант. Чаще всего это английское имя и кантонская фамилия человека, например Энди Лау (иногда — только часть двухсложной фамилии: Кэрри Лам). При этом в названиях статей следует придерживаться обратного порядка (как для частичных псевдонимов) и ставить запятую после фамилии (Лау, Энди; Лам, Кэрри).

Для тёзок по фамилии и английскому имени, а также в случаях когда в источниках персоналия всегда именуется с использованием кантонского личного имени, такое имя следует добавлять в название статьи (в порядке «КантонскаяФамилия КантонскоеИмя, АнглийскоеИмя»: Люн Чу Вай, Тони). Кантонское личное имя также указывается в названии, если английское имя отсутствует или не употребляется (в этом случае запятая не ставится: Ли Ка-шинг). Если личное кантонское имя (в том числе, вместе с западным) последовательно употребляется в источниках на русском и других европейских языках в препозиции к фамилии, то статью рекомендуется именовать в порядке «КитайскаяФамилия, ЛичноеИмя» (Лён, И Кристи; Чан, Калок). В тексте статьи порядок слов в имени приводится согласно наиболее частому упоминанию в источниках: Тони Лён Кафай, но И Кристи Лён (в обоих случаях Лён — фамилия).

Склонение фамилии зависит от позиции кантонского личного имени. Если оно стоит после фамилии, то склоняется только его последний слог и, при наличии, английское имя, а фамилия не склоняется (с Тони Люн Чу Ваем). Если же кантонское имя стоит перед фамилией, то склоняются оба слова (с Калоком Чаном). Также склоняется отдельно употребляемая фамилия (с Чёном). Кантонские женские имена и мужские имена на «-а» не склоняются.

При использовании кантонско-русской транскрипции слоги в кантонском личном имени пишутся слитно.

Перед текстом статьи о персоналии рекомендуется ставить пометку, о том, что её фамилия является диалектным вариантом соответствующей китайской фамилии, используя шаблон {{диалектное китайское имя}}.

Кантонская фамилия Hui записывается согласно правилам транскрипции — «Хёй».

Некоторые кантонские фамилии уже устоялись в русском языке в передаче с английского, и в названиях статей рекомендуется использовать такие варианты. В частности, это:

- Вонг (иер. 王, 汪, 黃, кант.-рус. Вон, кит.-рус. Ван, Хуан; англ. Wong);

- Ли (иер. 李, кант.-рус. Лэй, кит.-рус. Ли; англ. Lee);

- Тонг (иер. 唐, кант.-рус. Тхон, кит.-рус. Тан; англ. Tong);

- Чан (иер. 陳, кант.-рус. Чхань, кит.-рус. Чэнь; англ. Chan);

- Цанг (иер. 曾, кант.-рус. Чан, кит.-рус. Цзэн; англ. Tsang; в том числе в целях различения с вышеприведённой «Чан»).

Фамилии Cheung (иер. 張, кант.-рус. Чён, кит.-рус. Чжан) и Leung (иер. 梁, кант.-рус. Лён, кит.-рус. Лян) у ряда известных гонконгских актёров чаще всего записываются по-русски как Чун и Люн (иногда Льюнг). Вместе с тем для новых персоналий, в отсутствие авторитетных источников на русском, рекомендуется приводить эти фамилии согласно кантонско-русской транскрипции.

Для персоналий, имена которых на английском языке приводятся в соответствии севернокитайской фонетикой (как правило это люди, переехавшие в Гонконг из материкового Китая во взрослом возрасте, для которых кантонский не является родным языком), следует использовать систему Палладия.

Дополнительные рекомендации[править код]

В целях пояснения сразу после первого упоминания предмета статьи можно поставить шаблон {{Кантонский2}} (ссылка на настоящее руководство).

С альтернативных вариантов транскрипции желательно создавать перенаправления.

При прочтении в русском тексте кантонских слов условное ударение ставится на последний слог (если гласный в нём представлен дифтонгом, то ударение ставится на основной гласный дифтонга[1]).

Получение записи слова в соответствии с кантонско-русской транскрипцией[править код]

Следует сначала узнать латинскую транскрипцию соответствующего кантонского слова по системе «ютпхин» (но не по официальной гонконгской романизации, поскольку она не имеет однозначного соответствия с кантонским произношением). Ютпхин часто приводятся внизу карточек в статьях английской Википедии и даётся для большинства китайских иероглифов в английском Викисловаре. Данную транскрипцию также можно получить, введя соответствующий иероглиф по этой ссылке. Затем запись на ютпхине следует переложить в кириллицу по таблице слогов.

См. также[править код]

- Англо-русская практическая транскрипция

- Кантонско-русская практическая транскрипция

- Транскрипционная система Палладия

- Википедия:Именование статей/Восточноазиатские имена

Примечания[править код]

- ↑ Такие дифтонги всегда содержат звук «у», при этом ударение всегда падает не на него, а на соседний гласный. Например, в слове «Аплэйчау» ударение ставится в слоге «Чау» на «а», поскольку «у» является неслоговым гласным.

Правила

В соответствии с орфографическими правилами русского языка слово «Гонконг» пишут с буквой «о» в первом слоге и согласным «г» в конце.

Правописание первого слога объясняется этимологией. Дословно название означает «Благоухающая гавань». Изначально рассматриваемое наименование относилось к одной из бухт острова Гонконг. Когда англичане захватили остров, назвали его Hong Kong. Через них название перешло и в остальные языки, в том числе и в русский. Сохраняем нормы первоисточника и запоминаем написание.

Чтобы проверить труднопроизносимый согласный в конце слова, необходимо поставить лексическую единицу в форму родительного падежа, чтобы после согласного стоял гласный звук: Гонконга – Гонконг.

Значение слова

Гонконг – специальный административный район Китая. С точки зрения морфологии, слово является неодушевлённым существительным мужского рода второго склонения, обозначает название географического объекта.

Примеры

- Во время визита в Китай обязательно стоит посетить Гонконг.

- Директору сообщили, что ему срочно нужно лететь в Гонконг.

- Чтобы вместе полететь в Гонконг, мы решили встретиться в Нью-Йорке.

|

Hong Kong |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Special administrative region |

||||

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China

|

||||

|

|

||||

Location of Hong Kong within China |

||||

| Sovereign state | China | |||

| British possession | 26 January 1841 | |||

| Treaty of Nanking | 29 August 1842 | |||

| Convention of Peking | 24 October 1860 | |||

| New Territories lease | 9 June 1898 | |||

| Imperial Japanese occupation | 25 December 1941 to 30 August 1945 | |||

| Sino-British Joint Declaration | 19 December 1984 | |||

| Handover to China | 1 July 1997 | |||

| Administrative centre | Tamar | |||

| Largest district by population |

Sha Tin | |||

| Official languages |

|

|||

|

Regional language |

Cantonese[a] | |||

|

Official scripts |

Traditional Chinese[b] English alphabet |

|||

| Ethnic groups

(2016) |

92.0% Chinese 2.5% Filipino 2.1% Indonesian 1.1% Indian 0.8% White 0.3% Nepalese 1.6% Others[6] |

|||

| Demonym(s) | Hongkonger | |||

| Government | Devolved executive-led government within a unitary one-party state[7] | |||

|

• Chief Executive |

John Lee | |||

|

• Chief Secretary |

Eric Chan | |||

|

• Council President |

Andrew Leung | |||

|

• Chief Justice |

Andrew Cheung | |||

| Legislature | Legislative Council | |||

| National representation | ||||

|

• National People’s Congress |

36 deputies | |||

|

• Chinese People’s |

203 delegates[8] | |||

| Area | ||||

|

• Total |

2,754.97[9] km2 (1,063.70 sq mi) (168th) | |||

|

• Water (%) |

59.70% (1644.79 km2; 635.05 sq mi)[9] |

|||

|

• Land |

1,110.18 km2 (428.64 sq mi)[9] |

|||

| Highest elevation

(Tai Mo Shan) |

957 m (3,140 ft) | |||

| Lowest elevation

(South China Sea) |

0 m (0 ft) | |||

| Population | ||||

|

• 2022 estimate |

||||

|

• 2021 census |

||||

|

• Density |

6,801[12]/km2 (17,614.5/sq mi) (4th) | |||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | |||

|

• Total |

||||

|

• Per capita |

||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | |||

|

• Total |

||||

|

• Per capita |

||||

| Gini (2016) | high |

|||

| HDI (2021) | very high · 4th |

|||

| Currency | Hong Kong dollar (HK$) (HKD) | |||

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (HKT) | |||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy yyyy年mm月dd日 |

|||

| Mains electricity | 220 V–50 Hz | |||

| Driving side | left[c] | |||

| Calling code | +852 | |||

| ISO 3166 code |

|

|||

| Internet TLD |

|

|||

| License plate prefixes | None for local vehicles, 粤Z for cross-boundary vehicles |

Hong Kong ( or ; Chinese: 香港, Cantonese: [hœ́ːŋ.kɔ̌ːŋ] (listen)), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR),[d] is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta in South China. With 7.5 million residents of various nationalities[e] in a 1,104-square-kilometre (426 sq mi) territory, Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated places in the world. Hong Kong is also a major global financial centre and one of the most developed cities in the world.

Hong Kong was established as a colony of the British Empire after the Qing Empire ceded Hong Kong Island from Xin’an County at the end of the First Opium War in 1841 then again in 1842.[18] The colony expanded to the Kowloon Peninsula in 1860 after the Second Opium War and was further extended when Britain obtained a 99-year lease of the New Territories in 1898.[19][20] British Hong Kong was occupied by Imperial Japan from 1941 to 1945 during World War II; British administration resumed after the surrender of Japan.[21] The whole territory was transferred to China in 1997.[22] As one of China’s two special administrative regions (the other being Macau), Hong Kong maintains separate governing and economic systems from that of mainland China under the principle of «one country, two systems».[23][f]

Originally a sparsely populated area of farming and fishing villages,[18][24] the territory has become one of the world’s most significant financial centres and commercial ports.[25] It is the world’s tenth-largest exporter and ninth-largest importer.[26][27] Hong Kong has a market economy characterised by a focus on services, low taxation and free trade; its currency, the Hong Kong dollar, is the eighth most traded currency in the world.[28] Hong Kong is home to the third-highest number of billionaires of any city in the world,[29] the second-highest number of billionaires of any city in Asia, and the largest concentration of ultra high-net-worth individuals of any city in the world.[30][31] Although the city has one of the highest per capita incomes in the world, severe income inequality exists among the population.[32] Most notably, housing in Hong Kong has been well-documented to experience a chronic persistent shortage; the extremely compact house sizes and the extremely high housing density are the effects of Hong Kong’s housing market being the least affordable and the most expensive housing market in the world.[33][34][35]

Hong Kong is a highly developed territory and ranks fourth on the UN Human Development Index.[36] The city has the largest number of skyscrapers of any city in the world, and its residents have some of the highest life expectancies in the world.[36] The dense space has led to a highly developed transportation network with public transport rates exceeding 90%.[38] Hong Kong is ranked 3rd in the Global Financial Centres Index.[39]

Etymology

| Hong Kong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Hong Kong» in Chinese characters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 香港 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | or Hèunggóng |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Fragrant Harbour»[40][41] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hong Kong Special Administrative Region | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 香港特別行政區 (香港特區) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 香港特别行政区 (香港特区) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | Hēunggóng Dahkbiht Hàhngjingkēui (Hēunggóng Dahkkēui) or Hèunggóng Dahkbiht Hàhngjingkēui (Hèunggóng Dahkkēui) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The name of the territory, first romanised as «He-Ong-Kong» in 1780,[42] originally referred to a small inlet located between Aberdeen Island and the southern coast of Hong Kong Island. Aberdeen was an initial point of contact between British sailors and local fishermen.[43] Although the source of the romanised name is unknown, it is generally believed to be an early phonetic rendering of the Cantonese (or Tanka Cantonese) phrase hēung góng. The name translates as «fragrant harbour» or «incense harbour».[40][41][44] «Fragrant» may refer to the sweet taste of the harbour’s freshwater influx from the Pearl River or to the odour from incense factories lining the coast of northern Kowloon. The incense was stored near Aberdeen Harbour for export before Victoria Harbour was developed.[44] Sir John Davis (the second colonial governor) offered an alternative origin; Davis said that the name derived from «Hoong-keang» («red torrent»), reflecting the colour of soil over which a waterfall on the island flowed.[45]

The simplified name Hong Kong was frequently used by 1810.[46] The name was also commonly written as the single word Hongkong until 1926, when the government officially adopted the two-word name.[47] Some corporations founded during the early colonial era still keep this name, including Hongkong Land, Hongkong Electric Company, Hongkong and Shanghai Hotels and the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC).[48][49]

History

Prehistory and Imperial China

Earliest known human traces in what is now Hong Kong are dated by some to 35,000 and 39,000 years ago during the Paleolithic period. The claim is based on an archaeological investigation in Wong Tei Tung, Sai Kung in 2003. The archaeological works revealed knapped stone tools from deposits that were dated using optical luminescence dating.[50]

During the Middle Neolithic period, about 6,000 years ago, the region had been widely occupied by humans.[51] Neolithic to Bronze Age Hong Kong settlers were semi-coastal people. Early inhabitants are believed to be Austronesians in the Middle Neolithic period and later the Yueh people.[51] As hinted by the archaeological works in Sha Ha, Sai Kung, rice cultivation had been introduced since Late Neolithic period.[52] Bronze Age Hong Kong featured coarse pottery, hard pottery, quartz and stone jewelry, as well as small bronze implements.[51]

The Qin dynasty incorporated the Hong Kong area into China for the first time in 214 BCE, after conquering the indigenous Baiyue.[53] The region was consolidated under the Nanyue kingdom (a predecessor state of Vietnam) after the Qin collapse[54] and recaptured by China after the Han conquest.[55] During the Mongol conquest of China in the 13th century, the Southern Song court was briefly located in modern-day Kowloon City (the Sung Wong Toi site) before its final defeat in the 1279 Battle of Yamen.[56] By the end of the Yuan dynasty, seven large families had settled in the region and owned most of the land. Settlers from nearby provinces migrated to Kowloon throughout the Ming dynasty.[57]

The earliest European visitor was Portuguese explorer Jorge Álvares, who arrived in 1513.[58][59] Portuguese merchants established a trading post called Tamão in Hong Kong waters and began regular trade with southern China. Although the traders were expelled after military clashes in the 1520s,[60] Portuguese-Chinese trade relations were re-established by 1549. Portugal acquired a permanent lease for Macau in 1557.[61]

After the Qing conquest, maritime trade was banned under the Haijin policies. From 1661 to 1683, the population of most of the area forming present day Hong Kong was cleared under the Great Clearance, turning the region into a wasteland.[62] The Kangxi Emperor lifted the maritime trade prohibition, allowing foreigners to enter Chinese ports in 1684.[63] Qing authorities established the Canton System in 1757 to regulate trade more strictly, restricting non-Russian ships to the port of Canton.[64] Although European demand for Chinese commodities like tea, silk, and porcelain was high, Chinese interest in European manufactured goods was insignificant, so that Chinese goods could only be bought with precious metals. To reduce the trade imbalance, the British sold large amounts of Indian opium to China. Faced with a drug crisis, Qing officials pursued ever more aggressive actions to halt the opium trade.[65]

British colony

In 1839, the Daoguang Emperor rejected proposals to legalise and tax opium and ordered imperial commissioner Lin Zexu to eradicate the opium trade. The commissioner destroyed opium stockpiles and halted all foreign trade,[66] triggering a British military response and the First Opium War. The Qing surrendered early in the war and ceded Hong Kong Island in the Convention of Chuenpi. British forces began controlling Hong Kong shortly after the signing of the convention, from 26 January 1841.[67] However, both countries were dissatisfied and did not ratify the agreement.[68] After more than a year of further hostilities, Hong Kong Island was formally ceded to the United Kingdom in the 1842 Treaty of Nanking.[69]

Administrative infrastructure was quickly built by early 1842, but piracy, disease, and hostile Qing policies initially prevented the government from attracting commerce. Conditions on the island improved during the Taiping Rebellion in the 1850s, when many Chinese refugees, including wealthy merchants, fled mainland turbulence and settled in the colony.[18] Further tensions between the British and Qing over the opium trade escalated into the Second Opium War. The Qing were again defeated and forced to give up Kowloon Peninsula and Stonecutters Island in the Convention of Peking.[19] By the end of this war, Hong Kong had evolved from a transient colonial outpost into a major entrepôt. Rapid economic improvement during the 1850s attracted foreign investment, as potential stakeholders became more confident in Hong Kong’s future.[70]

The colony was further expanded in 1898 when Britain obtained a 99-year lease of the New Territories.[20] The University of Hong Kong was established in 1911 as the territory’s first institution of higher education.[71] Kai Tak Airport began operation in 1924, and the colony avoided a prolonged economic downturn after the 1925–26 Canton–Hong Kong strike.[72][73] At the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Governor Geoffry Northcote declared Hong Kong a neutral zone to safeguard its status as a free port.[74] The colonial government prepared for a possible attack, evacuating all British women and children in 1940.[75] The Imperial Japanese Army attacked Hong Kong on 8 December 1941, the same morning as its attack on Pearl Harbor.[76] Hong Kong was occupied by Japan for almost four years before Britain resumed control on 30 August 1945.[77]

Its population rebounded quickly after the war, as skilled Chinese migrants fled from the Chinese Civil War and more refugees crossed the border when the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China in 1949.[78] Hong Kong became the first of the Four Asian Tiger economies to industrialise during the 1950s.[79] With a rapidly increasing population, the colonial government attempted reforms to improve infrastructure and public services. The public-housing estate programme, Independent Commission Against Corruption, and Mass Transit Railway were all established during the post-war decades to provide safer housing, integrity in the civil service, and more reliable transportation.[80][81]

Nevertheless, widespread public discontent resulted in multiple protests from the 1950s to 1980s, including pro-Republic of China and pro-Chinese Communist Party protests. In the 1967 Hong Kong riots, pro-PRC protestors clashed with the British colonial government. As many as 51 were killed and 802 were injured in the violence, including dozens killed by the Royal Hong Kong Police via beatings and shootings.[82]

Although the territory’s competitiveness in manufacturing gradually declined because of rising labour and property costs, it transitioned to a service-based economy. By the early 1990s, Hong Kong had established itself as a global financial centre and shipping hub.[83]

Chinese special administrative region

The colony faced an uncertain future as the end of the New Territories lease approached, and Governor Murray MacLehose raised the question of Hong Kong’s status with Deng Xiaoping in 1979.[84] Diplomatic negotiations with China resulted in the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, in which the United Kingdom agreed to transfer the colony in 1997 and China would guarantee Hong Kong’s economic and political systems for 50 years after the transfer.[85] The impending transfer triggered a wave of mass emigration as residents feared an erosion of civil rights, the rule of law, and quality of life.[86] Over half a million people left the territory during the peak migration period, from 1987 to 1996.[87] The Legislative Council became a fully elected legislature for the first time in 1995 and extensively expanded its functions and organisations throughout the last years of the colonial rule.[88] Hong Kong was transferred to China on 1 July 1997, after 156 years of British rule.[22]

Immediately after the transfer, Hong Kong was severely affected by several crises. The Hong Kong government was forced to use substantial foreign exchange reserves to maintain the Hong Kong dollar’s currency peg during the 1997 Asian financial crisis,[78] and the recovery from this was muted by an H5N1 avian-flu outbreak[89] and a housing surplus.[90] This was followed by the 2003 SARS epidemic, during which the territory experienced its most serious economic downturn.[91]

Political debates after the transfer of sovereignty have centred around the region’s democratic development and the Chinese central government’s adherence to the «one country, two systems» principle. After reversal of the last colonial era Legislative Council democratic reforms following the handover,[92] the regional government unsuccessfully attempted to enact national security legislation pursuant to Article 23 of the Basic Law.[93] The central government decision to implement nominee pre-screening before allowing chief executive elections triggered a series of protests in 2014 which became known as the Umbrella Revolution.[94] Discrepancies in the electoral registry and disqualification of elected legislators after the 2016 Legislative Council elections[95][96][97] and enforcement of national law in the West Kowloon high-speed railway station raised further concerns about the region’s autonomy.[98] In June 2019, mass protests erupted in response to a proposed extradition amendment bill permitting the extradition of fugitives to mainland China. The protests are the largest in Hong Kong’s history,[99] with organisers claiming to have attracted more than three million Hong Kong residents.

The Hong Kong regional government and Chinese central government responded to the protests with a number of administrative measures to quell dissent. In June 2020, the Legislative Council passed the National Anthem Ordinance, which criminalised «insults to the national anthem of China».[100] The Chinese central government meanwhile enacted the Hong Kong national security law to help quell protests in the region.[101] Nine months later, in March 2021, the Chinese central government introduced amendments to Hong Kong’s electoral system, which included the reduction of directly elected seats in the Legislative Council and the requirement that all candidates be vetted and approved by a Beijing-appointed Candidate Eligibility Review Committee.[102]

Government and politics

Hong Kong is a special administrative region of China, with executive, legislative, and judicial powers devolved from the national government.[103] The Sino-British Joint Declaration provided for economic and administrative continuity through the transfer of sovereignty,[85] resulting in an executive-led governing system largely inherited from the territory’s history as a British colony.[104] Under these terms and the «one country, two systems» principle, the Basic Law of Hong Kong is the regional constitution.[105] The regional government is composed of three branches:

- Executive: The Chief Executive is responsible for enforcing regional law,[104] can force reconsideration of legislation,[106] and appoints Executive Council members and principal officials.[107] Acting with the Executive Council, the Chief Executive-in-Council can propose new bills, issue subordinate legislation, and has authority to dissolve the legislature.[108] In states of emergency or public danger, the Chief Executive-in-Council is further empowered to enact any regulation necessary to restore public order.[109]

- Legislature: The unicameral Legislative Council enacts regional law, approves budgets, and has the power to impeach a sitting chief executive.[110]

- Judiciary: The Court of Final Appeal and lower courts interpret laws and overturn those inconsistent with the Basic Law.[111] Judges are appointed by the chief executive on the advice of a recommendation commission.[112]

The chief executive is the head of government and serves for a maximum of two five-year terms. The State Council (led by the Premier of China) appoints the chief executive after nomination by the Election Committee, which is composed of 1,200 business, community, and government leaders.[113][114][115]

The Legislative Council has 90 members, each serving a four-year term. Twenty are directly elected from geographical constituencies, thirty-five represent functional constituencies (FC), and forty are chosen by an election committee consisting of representatives appointed by the Chinese central government.[116] Thirty FC councillors are selected from limited electorates representing sectors of the economy or special interest groups,[117] and the remaining five members are nominated from sitting district council members and selected in region-wide double direct elections.[118] All popularly elected members are chosen by proportional representation. The 30 limited electorate functional constituencies fill their seats using first-past-the-post or instant-runoff voting.[117]

Twenty-two political parties had representatives elected to the Legislative Council in the 2016 election.[119] These parties have aligned themselves into three ideological groups: the pro-Beijing camp (the current government), the pro-democracy camp, and localist groups.[120] The Chinese Communist Party does not have an official political presence in Hong Kong, and its members do not run in local elections.[121] Hong Kong is represented in the National People’s Congress by 36 deputies chosen through an electoral college and 203 delegates in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference appointed by the central government.[8]

Chinese national law does not generally apply in the region, and Hong Kong is treated as a separate jurisdiction.[111] Its judicial system is based on common law, continuing the legal tradition established during British rule.[122] Local courts may refer to precedents set in English law and overseas jurisprudence.[123] However, mainland criminal procedure law applies to cases investigated by the Office for Safeguarding National Security of the CPG in the HKSAR.[124] Interpretative and amending power over the Basic Law and jurisdiction over acts of state lie with the central authority, making regional courts ultimately subordinate to the mainland’s socialist civil law system.[125] Decisions made by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress override any territorial judicial process.[126] Furthermore, in circumstances where the Standing Committee declares a state of emergency in Hong Kong, the State Council may enforce national law in the region.[127]

The territory’s jurisdictional independence is most apparent in its immigration and taxation policies. The Immigration Department issues passports for permanent residents which differ from those of the mainland or Macau,[128] and the region maintains a regulated border with the rest of the country. All travellers between Hong Kong and China and Macau must pass through border controls, regardless of nationality.[129] Mainland Chinese citizens do not have right of abode in Hong Kong and are subject to immigration controls.[130] Public finances are handled separately from the national government; taxes levied in Hong Kong do not fund the central authority.[131][132]

The Hong Kong Garrison of the People’s Liberation Army is responsible for the region’s defence.[133] Although the Chairman of the Central Military Commission is supreme commander of the armed forces,[134] the regional government may request assistance from the garrison.[135] Hong Kong residents are not required to perform military service, and current law has no provision for local enlistment, so its defence is composed entirely of non-Hongkongers.[136]

The central government and Ministry of Foreign Affairs handle diplomatic matters, but Hong Kong retains the ability to maintain separate economic and cultural relations with foreign nations.[137] The territory actively participates in the World Trade Organization, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, the International Olympic Committee, and many United Nations agencies.[138][139][140] The regional government maintains trade offices in Greater China and other nations.[141]

The imposition of Hong Kong national security law by the central government in Beijing in June 2020 resulted in the suspension of bilateral extradition treaties by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Finland, and Ireland.[142] The United States ended its preferential economic and trade treatment of Hong Kong in July 2020 because it was no longer able to distinguish Hong Kong as a separate entity from the People’s Republic of China.[142][143]

Administrative divisions

The territory is divided into 18 districts, each represented by a district council. These advise the government on local issues such as public facility provisioning, community programme maintenance, cultural promotion, and environmental policy. There are a total of 479 district council seats, 452 of which are directly elected.[144] Rural committee chairmen, representing outlying villages and towns, fill the 27 non-elected seats.[145]

Political reforms and sociopolitical issues

Hong Kong is governed by a hybrid regime that is not fully representative of the population. Legislative Council members elected by functional constituencies composed of professional and special interest groups are accountable to these narrow corporate electorates and not the general public. This electoral arrangement has guaranteed a pro-establishment majority in the legislature since the transfer of sovereignty. Similarly, the chief executive is selected by establishment politicians and corporate members of the Election Committee rather than directly elected.[146] Although universal suffrage for the chief executive and all Legislative Council elections are defined goals of Basic Law Articles 45 and 68,[147] the legislature is only partially directly elected, and the executive continues to be nominated by an unrepresentative body.[146] The government has been repeatedly petitioned to introduce direct elections for these positions.[148][149]

Ethnic minorities (except those of European ancestry) have marginal representation in government and often experience discrimination in housing, education, and employment.[150][151] Employment vacancies and public service appointments frequently have language requirements which minority job seekers do not meet, and language education resources remain inadequate for Chinese learners.[152][153] Foreign domestic helpers, predominantly women from the Philippines and Indonesia, have little protection under regional law. Although they live and work in Hong Kong, these workers are not treated as ordinary residents and do not have the right of abode in the territory.[154] Sex trafficking in Hong Kong is an issue. Local and foreign women and girls are often forced into prostitution in brothels, homes, and businesses in the city.[155][156][157][158]

The Joint Declaration guarantees the Basic Law of Hong Kong for 50 years after the transfer of sovereignty.[85] It does not specify how Hong Kong will be governed after 2047, and the central government’s role in determining the territory’s future system of government is the subject of political debate and speculation. Hong Kong’s political and judicial systems may be integrated with China’s at that time, or the territory may continue to be administered separately.[159][160] However, in response to large-scale protests in 2019 and 2020, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress passed the controversial Hong Kong national security law.[161] The law criminalises secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign elements and establishes the Office for Safeguarding National Security of the CPG in the HKSAR, an investigative office under Central People’s Government authority immune from HKSAR jurisdiction. Some of the aforementioned acts were previously considered protected speech under Hong Kong law.[124][162] The United Kingdom considers the law to be a serious violation of the Joint Declaration.[163] In October 2020, Hong Kong police arrested seven pro-democracy politicians over tussles with pro-Beijing politicians in the Legislative Council in May. They were charged with contempt and interfering with members of the council, while none of the pro-Beijing lawmakers were detained.[164] Annual commemorations of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre were also cancelled amidst fears of violating the national security law.[165] In March 2021, the Chinese central government unilaterally changed Hong Kong’s electoral system and established the Candidate Eligibility Review Committee, which would be tasked with screening and evaluating political candidates for their «patriotism».[102]

Geography

Areas of urban development and vegetation are visible in this satellite image.

Hong Kong is on China’s southern coast, 60 km (37 mi) east of Macau, on the east side of the mouth of the Pearl River estuary. It is surrounded by the South China Sea on all sides except the north, which neighbours the Guangdong city of Shenzhen along the Sham Chun River. The territory’s 1,110.18 km2 (428.64 sq mi)[166] area (2754.97 km2[166] if the maritime area is included) consists of Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, the New Territories, Lantau Island, and over 200 other islands. Of the total area, 1,073 km2 (414 sq mi) is land and 35 km2 (14 sq mi) is water.[36] The territory’s highest point is Tai Mo Shan, 957 metres (3,140 ft) above sea level.[167] Urban development is concentrated on the Kowloon Peninsula, Hong Kong Island, and in new towns throughout the New Territories.[168] Much of this is built on reclaimed land; 70 km2 (27 sq mi) (6% of the total land or about 25% of developed space in the territory) is reclaimed from the sea.[169]

Undeveloped terrain is hilly to mountainous, with very little flat land, and consists mostly of grassland, woodland, shrubland, or farmland.[170][171] About 40% of the remaining land area is country parks and nature reserves.[172] The territory has a diverse ecosystem; over 3,000 species of vascular plants occur in the region (300 of which are native to Hong Kong), and thousands of insect, avian, and marine species.[173][174]

Climate

Hong Kong has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa), characteristic of southern China, despite being located south of the Tropic of Cancer. Summers are long, hot and humid, with occasional showers and thunderstorms and warm air from the southwest. Typhoons occur most often then, sometimes resulting in floods or landslides. Winters are short, mild and usually sunny at the beginning, becoming cloudy towards February. Frequent cold fronts bring strong, cooling winds from the north and occasionally result in chilly weather. Autumn is the sunniest season, whilst spring is generally cloudy.[175] When there is snowfall, which is extremely rare, it is usually at high elevations. Hong Kong averages 1,709 hours of sunshine per year.[176] Historic temperature extremes at the Hong Kong Observatory are 36.6 °C (97.9 °F) on 22 August 2017 and 0.0 °C (32.0 °F) on 18 January 1893.[177] The highest and lowest recorded temperatures in all of Hong Kong are 39.0 °C (102 °F) at Wetland Park on 22 August 2017,[178] and −6.0 °C (21.2 °F) at Tai Mo Shan on 24 January 2016.[179] However, due to the humid nature of Hong Kong, the numbers don’t reflect the actual feelings of being outside in the X degree weather that is actually reported. 35C in Hong Kong feels way hotter than 35C in someplace dry like the United States.

| Climate data for Hong Kong (Hong Kong Observatory), normals 1991–2020,[g] extremes 1884–1939 and 1947–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.1 (97.0) |

36.6 (97.9) |

35.9 (96.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

36.3 (97.3) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

33.6 (92.5) |

34.1 (93.4) |

34.2 (93.6) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

25.1 (77.2) |

34.7 (94.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.8 (83.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.5 (86.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

26.3 (79.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 33.2 (1.31) |

38.9 (1.53) |

75.3 (2.96) |

153.0 (6.02) |

290.6 (11.44) |

491.5 (19.35) |

385.8 (15.19) |

453.2 (17.84) |

321.4 (12.65) |

120.3 (4.74) |

39.3 (1.55) |

28.8 (1.13) |

2,431.2 (95.72) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 5.70 | 7.97 | 10.50 | 11.37 | 15.37 | 19.33 | 18.43 | 17.50 | 14.90 | 7.83 | 5.70 | 5.30 | 139.90 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 79 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 78 | 73 | 72 | 70 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 145.8 | 101.7 | 100.0 | 113.2 | 138.8 | 144.3 | 197.3 | 182.1 | 174.4 | 197.8 | 172.3 | 161.6 | 1,829.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 43 | 32 | 27 | 30 | 34 | 36 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 55 | 52 | 48 | 41 |

| Source: Hong Kong Observatory[180][181][182] |

Architecture

Hong Kong has the world’s largest number of skyscrapers, with 482 towers taller than 150 metres (490 ft), and the third-largest number of high-rise buildings in the world.[183] The lack of available space restricted development to high-density residential tenements and commercial complexes packed closely together on buildable land.[184] Single-family detached homes are uncommon and generally only found in outlying areas.[185] The International Commerce Centre and Two International Finance Centre are the tallest buildings in Hong Kong and are among the tallest in the Asia-Pacific region.[186] Other distinctive buildings lining the Hong Kong Island skyline include the HSBC Main Building, the anemometer-topped triangular Central Plaza, the circular Hopewell Centre, and the sharp-edged Bank of China Tower.[187][188]

Demand for new construction has contributed to frequent demolition of older buildings, freeing space for modern high-rises.[189] However, many examples of European and Lingnan architecture are still found throughout the territory. Older government buildings are examples of colonial architecture. The 1846 Flagstaff House, the former residence of the commanding British military officer, is the oldest Western-style building in Hong Kong.[190] Some (including the Court of Final Appeal Building and the Hong Kong Observatory) retain their original function, and others have been adapted and reused; the Former Marine Police Headquarters was redeveloped into a commercial and retail complex,[191] and Béthanie (built in 1875 as a sanatorium) houses the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts.[192] The Tin Hau Temple, dedicated to the sea goddess Mazu (originally built in 1012 and rebuilt in 1266), is the territory’s oldest existing structure.[193] The Ping Shan Heritage Trail has architectural examples of several imperial Chinese dynasties, including the Tsui Sing Lau Pagoda (Hong Kong’s only remaining pagoda).[194]

Tong lau, mixed-use tenement buildings constructed during the colonial era, blended southern Chinese architectural styles with European influences. These were especially prolific during the immediate post-war period, when many were rapidly built to house large numbers of Chinese migrants.[195] Examples include Lui Seng Chun, the Blue House in Wan Chai, and the Shanghai Street shophouses in Mong Kok. Mass-produced public-housing estates, built since the 1960s, are mainly constructed in modernist style.[196]

City view of Kowloon, Hong Kong Island, and the Hong Kong skyline

Demographics

The Census and Statistics Department estimated Hong Kong’s population at 7,482,500 in mid-2019. The overwhelming majority (92%) is Han Chinese,[6] most of whom are Taishanese, Teochew, Hakka, and other Cantonese peoples.[197][198][199] The remaining 8% are non-ethnic Chinese minorities, primarily Filipinos, Indonesians, and South Asians.[6][200] However, most Filipinos and Indonesians in Hong Kong are short-term workers. According to a 2016 thematic report by the Hong Kong government, after excluding foreign domestic helpers, the real number of non-Chinese ethnic minorities in the city was 263,593, or 3.6% of Hong Kong’s population.[201] About half the population have some form of British nationality, a legacy of colonial rule; 3.4 million residents have British National (Overseas) status, and 260,000 British citizens live in the territory.[202] The vast majority also hold Chinese nationality, automatically granted to all ethnic Chinese residents at the transfer of sovereignty.[203] Headline population density exceeds 7,060 people/km2, and is the fourth-highest in the world.[204]

The predominant language is Cantonese, a variety of Chinese originating in Guangdong. It is spoken by 94.6% of the population, 88.9% as a first language and 5.7% as a second language.[3] Slightly over half the population (53.2%) speaks English, the other official language;[2] 4.3% are native speakers, and 48.9% speak English as a second language.[3] Code-switching, mixing English and Cantonese in informal conversation, is common among the bilingual population.[205] Post-handover governments have promoted Mandarin, which is currently about as prevalent as English; 48.6% of the population speak Mandarin, with 1.9% native speakers and 46.7% as a second language.[3] Traditional Chinese characters are used in writing, rather than the simplified characters used in the mainland.[206]

Among the religious population, the traditional «three teachings» of China, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, have the most adherents (20%), followed by Christianity (12%) and Islam (4%).[207] Followers of other religions, including Sikhism, Hinduism, and Judaism, generally originate from regions where their religion predominates.[207]

Life expectancy in Hong Kong was 82.38 years for males and 88.17 years for females in 2022, the highest in the world.[208] Cancer, pneumonia, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and accidents are the territory’s five leading causes of death.[209] The universal public healthcare system is funded by general-tax revenue, and treatment is highly subsidised; on average, 95% of healthcare costs are covered by the government.[210]

Income inequality has risen since the transfer of sovereignty, as the region’s ageing population has gradually added to the number of nonworking people.[211] Although median household income steadily increased during the decade to 2016, the wage gap remained high;[212] the 90th percentile of earners receive 41% of all income.[212] The city has the most billionaires per capita, with one billionaire per 109,657 people.[213] Despite government efforts to reduce the growing disparity,[214] median income for the top 10% of earners is 44 times that of the bottom 10%.[215][216]

Economy

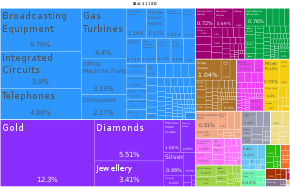

A proportional representation of Hong Kong exports, 2019

Hong Kong has a market economy focused on services, characterised by low taxation, minimal government market intervention, and an established international financial market.[217] It is the world’s 35th-largest economy, with a nominal GDP of approximately US$373 billion.[13] Hong Kong’s economy ranked at the top of the Heritage Foundation’s economic freedom index between 1995 and 2021.[218][219] However, Hong Kong was removed from the index by the Heritage Foundation in 2021, with the Foundation citing a «loss of political freedom and autonomy … [making Hong Kong] almost indistinguishable in many respects from other major Chinese commercial centers like Shanghai and Beijing».[220] The Hong Kong Stock Exchange is the seventh-largest in the world, with a market capitalisation of HK$30.4 trillion (US$3.87 trillion) as of December 2018.[221] Hong Kong is ranked as the 14th most innovative territory in the Global Innovation Index in 2022.[222] The city is sometimes referred to as «Silicon Harbor»,[223] a nickname derived from Silicon Valley in California. Hong Kong hosts several high tech and innovation companies,[224] including several multinational companies.[225][226]

Hong Kong is the tenth-largest trading entity in exports and imports (2017), trading more goods in value than its gross domestic product.[26][27] Over half of its cargo throughput consists of transshipments (goods travelling through Hong Kong). Products from mainland China account for about 40% of that traffic.[227] The city’s location allowed it to establish a transportation and logistics infrastructure which includes the world’s seventh-busiest container port[228] and the busiest airport for international cargo.[229] The territory’s largest export markets are mainland China and the United States.[36] Hong Kong is a key part of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.[230] It has little arable land and few natural resources, importing most of its food and raw materials. More than 90% of Hong Kong’s food is imported, including nearly all of its meat and rice.[231] Agricultural activity is 0.1% of GDP and consists of growing premium food and flower varieties.[232]

Although the territory had one of Asia’s largest manufacturing economies during the latter half of the colonial era, Hong Kong’s economy is now dominated by the service sector. The sector generates 92.7% of economic output, with the public sector accounting for about 10%.[233] Between 1961 and 1997 Hong Kong’s gross domestic product increased by a factor of 180, and per capita GDP increased by a factor of 87.[234][235] The territory’s GDP relative to mainland China’s peaked at 27% in 1993; it fell to less than 3% in 2017, as the mainland developed and liberalised its economy.[236] Economic and infrastructure integration with China has increased significantly since the 1978 start of market liberalisation on the mainland. Since resumption of cross-boundary train service in 1979, many rail and road links have been improved and constructed, facilitating trade between regions.[237][238] The Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement formalised a policy of free trade between the two areas, with each jurisdiction pledging to remove remaining obstacles to trade and cross-boundary investment.[239] A similar economic partnership with Macau details the liberalisation of trade between the special administrative regions.[240] Chinese companies have expanded their economic presence in the territory since the transfer of sovereignty. Mainland firms represent over half of the Hang Seng Index value, up from 5% in 1997.[241][242]

As the mainland liberalised its economy, Hong Kong’s shipping industry faced intense competition from other Chinese ports. Half of China’s trade goods were routed through Hong Kong in 1997, dropping to about 13% by 2015.[243] The territory’s minimal taxation, common law system, and civil service attract overseas corporations wishing to establish a presence in Asia.[243] The city has the second-highest number of corporate headquarters in the Asia-Pacific region.[244] Hong Kong is a gateway for foreign direct investment in China, giving investors open access to mainland Chinese markets through direct links with the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. The territory was the first market outside mainland China for renminbi-denominated bonds, and is one of the largest hubs for offshore renminbi trading.[245] In November 2020, Hong Kong’s Financial Services and the Treasury Bureau proposed a new law that will restrict cryptocurrency trading to professional investors only, leaving amateur traders (93% of Hong Kong’s trading population) out of the market.[246]

The government has had a passive role in the economy. Colonial governments had little industrial policy and implemented almost no trade controls. Under the doctrine of «positive non-interventionism», post-war administrations deliberately avoided the direct allocation of resources; active intervention was considered detrimental to economic growth.[247] While the economy transitioned to a service basis during the 1980s,[247] late colonial governments introduced interventionist policies. Post-handover administrations continued and expanded these programmes, including export-credit guarantees, a compulsory pension scheme, a minimum wage, anti-discrimination laws, and a state mortgage backer.[248]

Tourism is a major part of the economy, accounting for 5% of GDP.[191] In 2016, 26.6 million visitors contributed HK$258 billion (US$32.9 billion) to the territory, making Hong Kong the 14th most popular destination for international tourists. It is the most popular Chinese city for tourists, receiving over 70% more visitors than its closest competitor (Macau).[249] The city is ranked as one of the most expensive cities for expatriates.[250][251] However, since 2020, there has been a sharp decline in incoming visitors due to tight COVID-19 travel restrictions. Additionally, due to the closure of Russian airspace in 2022, multiple airlines decided to cease their operations in Hong Kong.[252] In an attempt to attract tourists back to Hong Kong, the Hong Kong government announced plans to give away 500,000 free airline tickets in 2023.[253]

Infrastructure

Transport

Hong Kong has a highly developed, sophisticated transport network. Over 90% of daily trips are made on public transport, the highest percentage in the world.[38] The Octopus card, a contactless smart payment card, is widely accepted on railways, buses and ferries, and can be used for payment in most retail stores.[254]

The Peak Tram, Hong Kong’s first public transport system, has provided funicular rail transport between Central and Victoria Peak since 1888.[255] The Central and Western District has an extensive system of escalators and moving pavements, including the Mid-Levels escalator (the world’s longest outdoor covered escalator system).[256] Hong Kong Tramways covers a portion of Hong Kong Island. The Mass Transit Railway (MTR) is an extensive passenger rail network, connecting 93 metro stations throughout the territory.[257] With a daily ridership of almost five million, the system serves 41% of all public transit passengers in the city[258] and has an on-time rate of 99.9%.[259] Cross-boundary train service to Shenzhen is offered by the East Rail line, and longer-distance inter-city trains to Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Beijing are operated from Hung Hom station.[260] Connecting service to the national high-speed rail system is provided at West Kowloon railway station.[261]

Although public transport systems handle most passenger traffic, there are over 500,000 private vehicles registered in Hong Kong.[262] Automobiles drive on the left (unlike in mainland China), because of historical influence of the British Empire.[263] Vehicle traffic is extremely congested in urban areas, exacerbated by limited space to expand roads and an increasing number of vehicles.[264] More than 18,000 taxicabs, easily identifiable by their bright colour, are licensed to carry riders in the territory.[265] Bus services operate more than 700 routes across the territory,[258] with smaller public light buses (also known as minibuses) serving areas standard buses do not reach as frequently or directly.[266] Highways, organised with the Hong Kong Strategic Route and Exit Number System, connect all major areas of the territory.[267] The Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge provides a direct route to the western side of the Pearl River estuary.[238]

Hong Kong International Airport is the territory’s primary airport. Over 100 airlines operate flights from the airport, including locally based Cathay Pacific (flag carrier), Hong Kong Airlines, low-cost airline HK Express and cargo airline Air Hong Kong.[268] It is the eighth-busiest airport by passenger traffic[269] pre-COVID and handles the most air-cargo traffic in the world.[270] Most private recreational aviation traffic flies through Shek Kong Airfield, under the supervision of the Hong Kong Aviation Club.[271]

The Star Ferry operates two lines across Victoria Harbour for its 53,000 daily passengers.[272] Ferries also serve outlying islands inaccessible by other means. Smaller kai-to boats serve the most remote coastal settlements.[273] Ferry travel to Macau and mainland China is also available.[274] Junks, once common in Hong Kong waters, are no longer widely available and are used privately and for tourism.[275]

The large size of the port gives Hong Kong the classification of Large-Port Metropolis.[276]

Utilities

Hong Kong generates most of its electricity locally.[277] The vast majority of this energy comes from fossil fuels, with 46% from coal and 47% from petroleum.[278] The rest is from other imports, including nuclear energy generated in mainland China.[279] Renewable sources account for a negligible amount of energy generated for the territory.[280] Small-scale wind-power sources have been developed,[277] and a small number of private homes and public buildings have installed solar panels.[281]

With few natural lakes and rivers, high population density, inaccessible groundwater sources, and extremely seasonal rainfall, the territory does not have a reliable source of freshwater. The Dongjiang River in Guangdong supplies 70% of the city’s water,[282] and the remaining demand is filled by harvesting rainwater.[283] Toilets in most built-up areas of the territory flush with seawater, greatly reducing freshwater use.[282]

Broadband Internet access is widely available, with 92.6% of households connected. Connections over fibre-optic infrastructure are increasingly prevalent,[284] contributing to the high regional average connection speed of 21.9 Mbit/s (the world’s fourth-fastest).[285] Mobile-phone use is ubiquitous;[286] there are more than 18 million mobile-phone accounts,[287] more than double the territory’s population.

Culture

Hong Kong is characterised as a hybrid of East and West. Traditional Chinese values emphasising family and education blend with Western ideals, including economic liberty and the rule of law.[288] Although the vast majority of the population is ethnically Chinese, Hong Kong has developed a distinct identity. The territory diverged from the mainland through its long period of colonial administration and a different pace of economic, social, and cultural development. Mainstream culture is derived from immigrants originating from various parts of China. This was influenced by British-style education, a separate political system, and the territory’s rapid development during the late 20th century.[289][290] Most migrants of that era fled poverty and war, reflected in the prevailing attitude toward wealth; Hongkongers tend to link self-image and decision-making to material benefits.[291][292] Residents’ sense of local identity has markedly increased post-handover: The majority of the population (52%) identifies as «Hongkongers», while 11% describe themselves as «Chinese». The remaining population purport mixed identities, 23% as «Hongkonger in China» and 12% as «Chinese in Hong Kong».[293]

Traditional Chinese family values, including family honour, filial piety, and a preference for sons, are prevalent.[294] Nuclear families are the most common households, although multi-generational and extended families are not unusual.[295] Spiritual concepts such as feng shui are observed; large-scale construction projects often hire consultants to ensure proper building positioning and layout. The degree of its adherence to feng shui is believed to determine the success of a business.[187] Bagua mirrors are regularly used to deflect evil spirits,[296] and buildings often lack floor numbers with a 4;[297] the number has a similar sound to the word for «die» in Cantonese.[298]

Cuisine

Food in Hong Kong is primarily based on Cantonese cuisine, despite the territory’s exposure to foreign influences and its residents’ varied origins. Rice is the staple food, and is usually served plain with other dishes.[299] Freshness of ingredients is emphasised. Poultry and seafood are commonly sold live at wet markets, and ingredients are used as quickly as possible.[300] There are five daily meals: breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea, dinner, and siu yeh.[301] Dim sum, as part of yum cha (brunch), is a dining-out tradition with family and friends. Dishes include congee, cha siu bao, siu yuk, egg tarts, and mango pudding. Local versions of Western food are served at cha chaan teng (Hong Kong-style cafes). Common cha chaan teng menu items include macaroni in soup, deep-fried French toast, and Hong Kong-style milk tea.[299]

Cinema

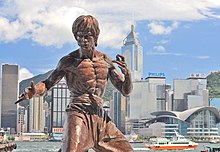

Statue of Bruce Lee on the Avenue of Stars, a tribute to the city’s film industry

Hong Kong developed into a filmmaking hub during the late 1940s as a wave of Shanghai filmmakers migrated to the territory, and these movie veterans helped build the colony’s entertainment industry over the next decade.[302] By the 1960s, the city was well known to overseas audiences through films such as The World of Suzie Wong.[303] When Bruce Lee’s The Way of the Dragon was released in 1972, local productions became popular outside Hong Kong. During the 1980s, films such as A Better Tomorrow, As Tears Go By, and Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain expanded global interest beyond martial arts films; locally made gangster films, romantic dramas, and supernatural fantasies became popular.[304] Hong Kong cinema continued to be internationally successful over the following decade with critically acclaimed dramas such as Farewell My Concubine, To Live, and Chungking Express. The city’s martial arts film roots are evident in the roles of the most prolific Hong Kong actors. Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, Jet Li, Chow Yun-fat, and Michelle Yeoh frequently play action-oriented roles in foreign films. Hong Kong films have also grown popular in oversea markets such as Japan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia, earning the city the moniker «Hollywood of the East».[305] At the height of the local movie industry in the early 1990s, over 400 films were produced each year; since then, industry momentum shifted to mainland China. The number of films produced annually has declined to about 60 in 2017.[306]

Music

Leslie Cheung (left) is considered a pioneering Cantopop artist, and Andy Lau has been an icon of Hong Kong music and film for several decades as a member of the Four Heavenly Kings.

Cantopop is a genre of Cantonese popular music which emerged in Hong Kong during the 1970s. Evolving from Shanghai-style shidaiqu, it is also influenced by Cantonese opera and Western pop.[307] Local media featured songs by artists such as Sam Hui, Anita Mui, Leslie Cheung, and Alan Tam; during the 1980s, exported films and shows exposed Cantopop to a global audience.[308] The genre’s popularity peaked in the 1990s, when the Four Heavenly Kings dominated Asian record charts.[309] Despite a general decline since late in the decade,[310] Cantopop remains dominant in Hong Kong; contemporary artists such as Eason Chan, Joey Yung, and Twins are popular in and beyond the territory.[311]

Western classical music has historically had a strong presence in Hong Kong and remains a large part of local musical education.[312] The publicly funded Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, the territory’s oldest professional symphony orchestra, frequently hosts musicians and conductors from overseas. The Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra, composed of classical Chinese instruments, is the leading Chinese ensemble and plays a significant role in promoting traditional music in the community.[313]

Hong Kong has never had a separate national anthem to the country that controlled it; its current official national anthem is therefore that of China, March of the Volunteers. The song Glory to Hong Kong has been used by protestors as an unofficial national anthem.[314][315]

Sport and recreation

Despite its small area, the territory is home to a variety of sports and recreational facilities. The city has hosted numerous major sporting events, including the 2009 East Asian Games, the 2008 Summer Olympics equestrian events, and the 2007 Premier League Asia Trophy.[316] The territory regularly hosts the Hong Kong Sevens, Hong Kong Marathon, Hong Kong Tennis Classic and Lunar New Year Cup, and hosted the inaugural AFC Asian Cup and the 1995 Dynasty Cup.[317][318]

Hong Kong represents itself separately from mainland China, with its own sports teams in international competitions.[316] The territory has participated in almost every Summer Olympics since 1952 and has earned nine medals. Lee Lai-shan won the territory’s first Olympic gold medal at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics,[319] and Cheung Ka Long won the second one in Tokyo 2020.[320] Hong Kong athletes have won 126 medals at the Paralympic Games and 17 at the Commonwealth Games. No longer part of the Commonwealth of Nations, the city’s last appearance in the latter was in 1994.[321]

Dragon boat races originated as a religious ceremony conducted during the annual Tuen Ng Festival. The race was revived as a modern sport as part of the Tourism Board’s efforts to promote Hong Kong’s image abroad. The first modern competition was organised in 1976, and overseas teams began competing in the first international race in 1993.[322]

The Hong Kong Jockey Club, the territory’s largest taxpayer,[323] has a monopoly on gambling and provides over 7% of government revenue.[324] Three forms of gambling are legal in Hong Kong: lotteries, horse racing, and football.[323]

Education

Education in Hong Kong is largely modelled after that of the United Kingdom, particularly the English system.[325] Children are required to attend school from age 6 until completion of secondary education, generally at age 18.[326][327] At the end of secondary schooling, all students take a public examination and awarded the Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education on successful completion.[328] Of residents aged 15 and older, 81% completed lower-secondary education, 66% graduated from an upper secondary school, 32% attended a non-degree tertiary program, and 24% earned a bachelor’s degree or higher.[329] Mandatory education has contributed to an adult literacy rate of 95.7%.[330] The literacy rate is lower than that of other developed economies because of the influx of refugees from mainland China during the post-war colonial era; much of the elderly population were not formally educated because of war and poverty.[331][332]

Comprehensive schools fall under three categories: public schools, which are government-run; subsidised schools, including government aid-and-grant schools; and private schools, often those run by religious organisations and that base admissions on academic merit. These schools are subject to the curriculum guidelines as provided by the Education Bureau. Private schools subsidised under the Direct Subsidy Scheme; international schools fall outside of this system and may elect to use differing curricula and teach using other languages.[327]

Medium of instruction

At primary and secondary school levels, the government maintains a policy of «mother tongue instruction»; most schools use Cantonese as the medium of instruction, with written education in both Chinese and English. Other languages being used as medium of instruction in non-international school education include English and Putonghua (Standard Mandarin Chinese). Secondary schools emphasise «bi-literacy and tri-lingualism», which has encouraged the proliferation of spoken Mandarin language education.[333]

English is the official medium of instruction and assessments for most university programmes in Hong Kong, although use of Cantonese is predominant in informal discussions among local students and local professors.[citation needed]

Tertiary education

Hong Kong has eleven universities. The University of Hong Kong (HKU) was founded as the city’s first institute of higher education during the early colonial period in 1911.[334] The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) was established in 1963 to fill the need for a university that taught using Chinese as its primary language of instruction.[335] Along with the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) established in 1991, these universities are consistently ranked among the top 50 or top 100 universities worldwide.[336][337][338] The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU)[339] and City University of Hong Kong (CityU), both granted university status in 1994, are consistently ranked among the top 100 or top 200 universities worldwide. [336][337][338] The Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) was granted university status in 1994 [340] and is a liberal arts institution. Lingnan University,[341] Education University of Hong Kong,[342] Hong Kong Metropolitan University (formerly Open University of Hong Kong),[343] Hong Kong Shue Yan University[344] and Hang Seng University of Hong Kong all attained full university status in subsequent years.

Media

TVB City, headquarters of Hong Kong’s first over-the-air television station

Most of the newsapapers in Hong Kong are written in Chinese but there are also a few English-language newspapers. The major one is the South China Morning Post, with The Standard serving as a business-oriented alternative. A variety of Chinese-language newspapers are published daily; the most prominent are Ming Pao and Oriental Daily News. Local publications are often politically affiliated, with pro-Beijing or pro-democracy sympathies. The central government has a print-media presence in the territory through the state-owned Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po.[345] Several international publications have regional operations in Hong Kong, including The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, The New York Times International Edition, USA Today, Yomiuri Shimbun, and The Nikkei.[346]

Three free-to-air television broadcasters operate in the territory; TVB, HKTVE, and Hong Kong Open TV air eight digital channels.[347] TVB, Hong Kong’s dominant television network, has an 80% viewer share.[348] Pay TV services operated by Cable TV Hong Kong and PCCW offer hundreds of additional channels and cater to a variety of audiences.[347] RTHK is the public broadcaster, providing seven radio channels and three television channels.[349] Ten non-domestic broadcasters air programming for the territory’s foreign population.[347] Access to media and information over the Internet is not subject to mainland Chinese regulations, including the Great Firewall, yet local control applies.[350]

See also

- Index of articles related to Hong Kong

- Outline of Hong Kong

Notes

- ^ a b No specific variety of Chinese is official in the territory. Residents predominantly speak Cantonese, the de facto regional standard.[1][2][3]

- ^ a b For all government use, documents written using Traditional Chinese characters are authoritative over ones inscribed with Simplified Chinese characters.[4] English shares equal status with Chinese in all official proceedings.[5]

- ^ Except for the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge Hong Kong Link Road, which drives on the right.[16]

- ^ Chinese: 中華人民共和國香港特別行政區; Cantonese Yale: Hēunggóng Dahkbiht Hàhngjingkēui

- ^ Hong Kong permanent residents can be of any nationality. A person without Chinese nationality who has entered Hong Kong with a valid travel document, has ordinarily resided there for a continuous period not less than seven years, and is permanently domiciled in the territory would be legally recognised as a Hongkonger.[17]

- ^ However, decisions made by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress override any territorial judicial process. Furthermore, the State Council may enforce national law in the region under specific circumstances.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data in Hong Kong from 1991 to 2020.

References

Citations

- ^ Leung 2016.

- ^ a b Official Languages Ordinance.

- ^ a b c d Population By-Census 2016, pp. 31, 51–52

- ^ Legislative Council Disclaimer and Copyright Notice

- ^ Use of Chinese in Court Proceedings 2011

- ^ a b c Population By-Census 2016, p. 46.

- ^ «China (People’s Republic of) 1982 (rev. 2004)». Constitute project. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ a b Cheung 2017.

- ^ a b c «Survey and Mapping Office – Circulars and Publications». Survey and Mapping Office. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ «Mid-year population for 2022» (Press release). Census and Statistics Department. 11 August 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ «Key statistics of the 2021 and 2011 Population Census» (PDF). census2021.gov.hk. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ «Main Tables – 2021 Population Census». census2021.gov.hk. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e «World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022». IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Household Income Distribution 2016, p. 7

- ^ «Human Development Report 2021/2022» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Technical Legislative Amendments on Traffic Arrangements for the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge 2017

- ^ Basic Law Chapter III Article 24.

- ^ a b c Carroll 2007, pp. 15–21.

- ^ a b Carroll 2007, pp. 21–24.