Как правильно пишется слово «менингит»

менинги́т

менинги́т, -а

Источник: Орфографический

академический ресурс «Академос» Института русского языка им. В.В. Виноградова РАН (словарная база

2020)

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: теза — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к слову «менингит»

Синонимы к слову «менингит»

Предложения со словом «менингит»

- Костный некроз достиг мозговой оболочки и привёл к смерти вследствие туберкулёзного менингита.

- При неблагоприятном течении гнойного лабиринтита может развиться лабиринтогенный гнойный менингит или абсцесс мозга.

- Перенесённый ею в детстве менингит дал тяжёлые осложнения на мозг.

- (все предложения)

Каким бывает «менингит»

Значение слова «менингит»

-

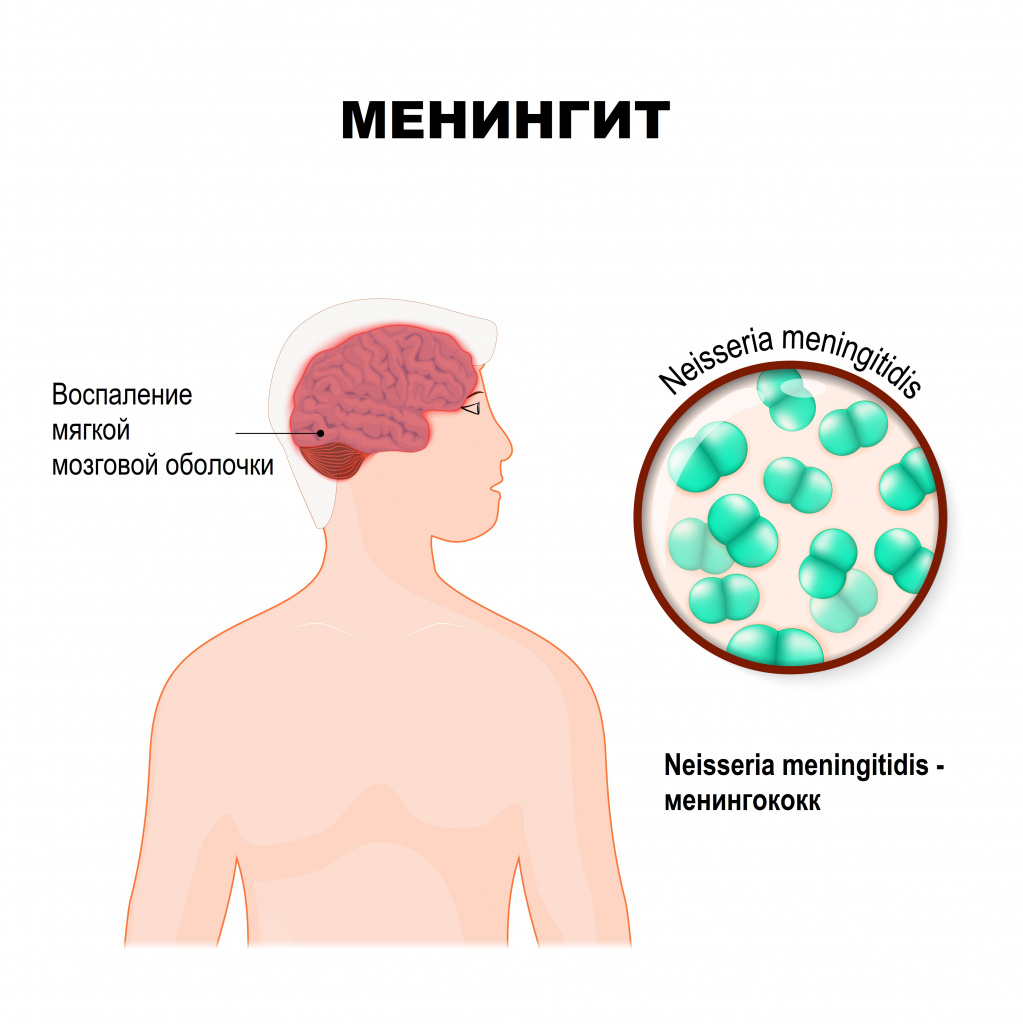

МЕНИНГИ́Т, -а, м. Воспаление оболочек головного и спинного мозга. (Малый академический словарь, МАС)

Все значения слова МЕНИНГИТ

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Русский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | менинги́т | менинги́ты |

| Р. | менинги́та | менинги́тов |

| Д. | менинги́ту | менинги́там |

| В. | менинги́т | менинги́ты |

| Тв. | менинги́том | менинги́тами |

| Пр. | менинги́те | менинги́тах |

ме—нин—ги́т

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -менинг-; суффикс: -ит [Тихонов, 1996].

Произношение[править]

- МФА: ед. ч. [mʲɪnʲɪnˈɡʲit], мн. ч. [mʲɪnʲɪnˈɡʲitɨ]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. воспаление оболочек головного мозга и спинного мозга ◆ Если цитоз превышает 600 в 1 мкл, то ликвор становится мутным, что, как правило, наблюдается при гнойных менингитах. А. В. Мазурин, И. М. Воронцов, «Пропедевтика детских болезней», 1985 г.

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

- —

Гиперонимы[править]

- воспаление; болезнь, заболевание

Гипонимы[править]

- лептоменингит, пахименингит

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология[править]

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Перевод[править]

| Список переводов | |

|

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Башкирский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Болгарский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Казахский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Киргизский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Осетинский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Таджикский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Татарский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

Якутский[править]

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства[править]

менингит

Существительное.

Корень: —.

Произношение[править]

Семантические свойства[править]

Значение[править]

- мед. менингит ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы[править]

Антонимы[править]

Гиперонимы[править]

Гипонимы[править]

Родственные слова[править]

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология[править]

От ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания[править]

Библиография[править]

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

| Meningitis | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Meninges of the central nervous system: dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, neurology |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, neck stiffness[1] |

| Complications | Deafness, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, cognitive deficits[2][3] |

| Causes | Viral, bacterial, other[4] |

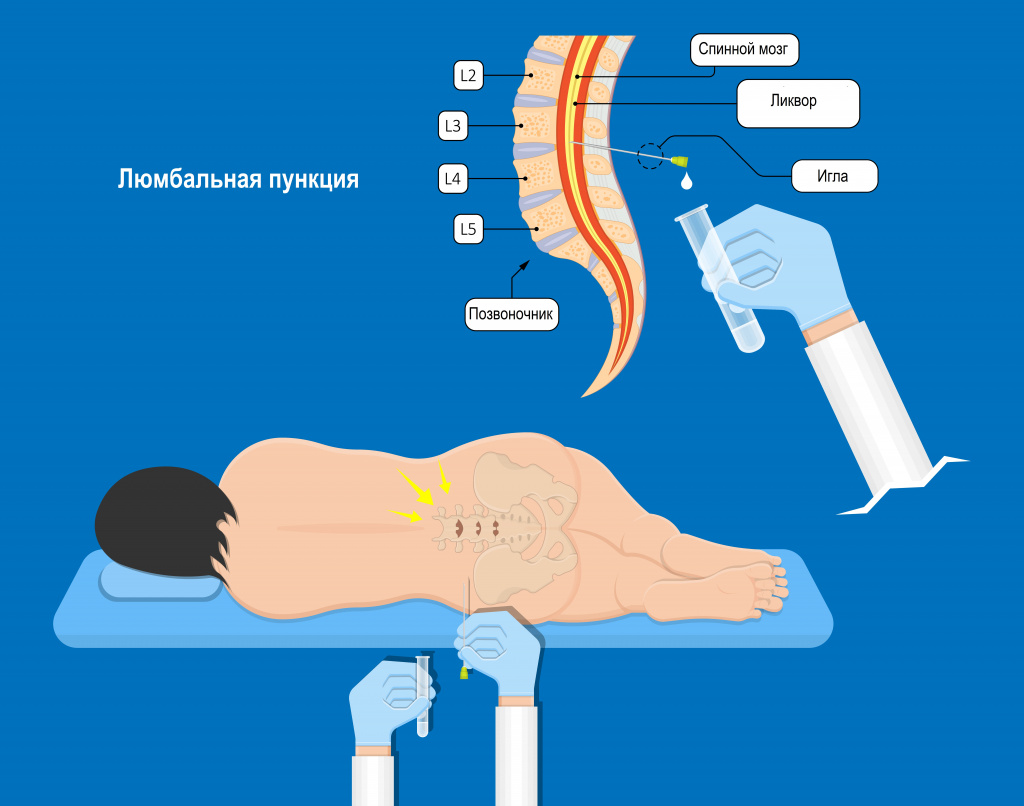

| Diagnostic method | Lumbar puncture[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Encephalitis, brain tumor, lupus, Lyme disease, seizures, neuroleptic malignant syndrome,[5] naegleriasis[6] |

| Prevention | Vaccination[2] |

| Medication | Antibiotics, antivirals, steroids[1][7][8] |

| Frequency | 7.7 million (2019)[9] |

| Deaths | 236,000 (2019)[9] |

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges.[10] The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness.[1] Other symptoms include confusion or altered consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light or loud noises.[1] Young children often exhibit only nonspecific symptoms, such as irritability, drowsiness, or poor feeding.[1] A non-blanching rash (a rash that does not fade when a glass is rolled over it) may also be present.[11]

The inflammation may be caused by infection with viruses, bacteria or other microorganisms. Non-infectious causes include malignancy (cancer), subarachnoid haemorrhage, chronic inflammatory disease (sarcoidosis) and certain drugs.[4] Meningitis can be life-threatening because of the inflammation’s proximity to the brain and spinal cord; therefore, the condition is classified as a medical emergency.[2][8] A lumbar puncture, in which a needle is inserted into the spinal canal to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), can diagnose or exclude meningitis.[1][8]

Some forms of meningitis are preventable by immunization with the meningococcal, mumps, pneumococcal, and Hib vaccines.[2] Giving antibiotics to people with significant exposure to certain types of meningitis may also be useful.[1] The first treatment in acute meningitis consists of promptly giving antibiotics and sometimes antiviral drugs.[1][7] Corticosteroids can also be used to prevent complications from excessive inflammation.[3][8] Meningitis can lead to serious long-term consequences such as deafness, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, or cognitive deficits, especially if not treated quickly.[2][3]

In 2019, meningitis was prevalent in about 7.7 million people worldwide.[9] This resulted in 236,000 deaths, down from 433,000 deaths in 1990.[9] With appropriate treatment, the risk of death in bacterial meningitis is less than 15%.[1] Outbreaks of bacterial meningitis occur between December and June each year in an area of sub-Saharan Africa known as the meningitis belt.[12] Smaller outbreaks may also occur in other areas of the world.[12] The word meningitis comes from the Greek μῆνιγξ meninx, «membrane», and the medical suffix -itis, «inflammation».[13][14]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Clinical features[edit]

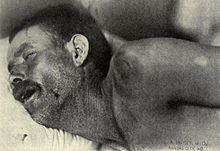

Neck stiffness, Texas meningitis epidemic of 1911–12

In adults, the most common symptom of meningitis is a severe headache, occurring in almost 90% of cases of bacterial meningitis, followed by neck stiffness (the inability to flex the neck forward passively due to increased neck muscle tone and stiffness).[15] The classic triad of diagnostic signs consists of neck stiffness, sudden high fever, and altered mental status; however, all three features are present in only 44–46% of bacterial meningitis cases.[15][16] If none of the three signs are present, acute meningitis is extremely unlikely.[16] Other signs commonly associated with meningitis include photophobia (intolerance to bright light) and phonophobia (intolerance to loud noises). Small children often do not exhibit the aforementioned symptoms, and may only be irritable and look unwell.[2] The fontanelle (the soft spot on the top of a baby’s head) can bulge in infants aged up to 6 months. Other features that distinguish meningitis from less severe illnesses in young children are leg pain, cold extremities, and an abnormal skin color.[17][18]

Nuchal rigidity occurs in 70% of bacterial meningitis in adults.[16] Other signs include the presence of positive Kernig’s sign or Brudziński sign. Kernig’s sign is assessed with the person lying supine, with the hip and knee flexed to 90 degrees. In a person with a positive Kernig’s sign, pain limits passive extension of the knee. A positive Brudzinski’s sign occurs when flexion of the neck causes involuntary flexion of the knee and hip. Although Kernig’s sign and Brudzinski’s sign are both commonly used to screen for meningitis, the sensitivity of these tests is limited.[16][19] They do, however, have very good specificity for meningitis: the signs rarely occur in other diseases.[16] Another test, known as the «jolt accentuation maneuver» helps determine whether meningitis is present in those reporting fever and headache. A person is asked to rapidly rotate the head horizontally; if this does not make the headache worse, meningitis is unlikely.[16]

Other problems can produce symptoms similar to those above, but from non-meningitic causes. This is called meningism or pseudomeningitis.[20]

Meningitis caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis (known as «meningococcal meningitis») can be differentiated from meningitis with other causes by a rapidly spreading petechial rash, which may precede other symptoms.[17] The rash consists of numerous small, irregular purple or red spots («petechiae») on the trunk, lower extremities, mucous membranes, conjunctiva, and (occasionally) the palms of the hands or soles of the feet. The rash is typically non-blanching; the redness does not disappear when pressed with a finger or a glass tumbler. Although this rash is not necessarily present in meningococcal meningitis, it is relatively specific for the disease; it does, however, occasionally occur in meningitis due to other bacteria.[2] Other clues on the cause of meningitis may be the skin signs of hand, foot and mouth disease and genital herpes, both of which are associated with various forms of viral meningitis.[21]

Early complications[edit]

Additional problems may occur in the early stage of the illness. These may require specific treatment, and sometimes indicate severe illness or worse prognosis. The infection may trigger sepsis, a systemic inflammatory response syndrome of falling blood pressure, fast heart rate, high or abnormally low temperature, and rapid breathing. Very low blood pressure may occur at an early stage, especially but not exclusively in meningococcal meningitis; this may lead to insufficient blood supply to other organs.[2] Disseminated intravascular coagulation, the excessive activation of blood clotting, may obstruct blood flow to organs and paradoxically increase the bleeding risk. Gangrene of limbs can occur in meningococcal disease.[2] Severe meningococcal and pneumococcal infections may result in hemorrhaging of the adrenal glands, leading to Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome, which is often fatal.[22]

The brain tissue may swell, pressure inside the skull may increase and the swollen brain may herniate through the skull base. This may be noticed by a decreasing level of consciousness, loss of the pupillary light reflex, and abnormal posturing.[3] The inflammation of the brain tissue may also obstruct the normal flow of CSF around the brain (hydrocephalus).[3] Seizures may occur for various reasons; in children, seizures are common in the early stages of meningitis (in 30% of cases) and do not necessarily indicate an underlying cause.[8] Seizures may result from increased pressure and from areas of inflammation in the brain tissue.[3] Focal seizures (seizures that involve one limb or part of the body), persistent seizures, late-onset seizures and those that are difficult to control with medication indicate a poorer long-term outcome.[2]

Inflammation of the meninges may lead to abnormalities of the cranial nerves, a group of nerves arising from the brain stem that supply the head and neck area and which control, among other functions, eye movement, facial muscles, and hearing.[2][16] Visual symptoms and hearing loss may persist after an episode of meningitis.[2] Inflammation of the brain (encephalitis) or its blood vessels (cerebral vasculitis), as well as the formation of blood clots in the veins (cerebral venous thrombosis), may all lead to weakness, loss of sensation, or abnormal movement or function of the part of the body supplied by the affected area of the brain.[2][3]

Causes[edit]

Meningitis is typically caused by an infection with microorganisms. Most infections are due to viruses,[16] with bacteria, fungi, and protozoa being the next most common causes.[4] It may also result from various non-infectious causes.[4] The term aseptic meningitis refers to cases of meningitis in which no bacterial infection can be demonstrated. This type of meningitis is usually caused by viruses, but it may be due to bacterial infection that has already been partially treated, when bacteria disappear from the meninges, or pathogens infect a space adjacent to the meninges (such as sinusitis). Endocarditis (an infection of the heart valves which spreads small clusters of bacteria through the bloodstream) may cause aseptic meningitis. Aseptic meningitis may also result from infection with spirochetes, a group of bacteria that includes Treponema pallidum (the cause of syphilis) and Borrelia burgdorferi (known for causing Lyme disease). Meningitis may be encountered in cerebral malaria (malaria infecting the brain) or amoebic meningitis, meningitis due to infection with amoebae such as Naegleria fowleri, contracted from freshwater sources.[4]

Bacterial[edit]

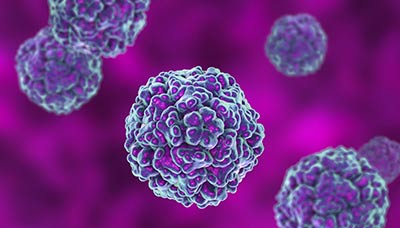

Streptococcus pneumoniae—a causative bacterium of meningitis (illustration).

The types of bacteria that cause bacterial meningitis vary according to the infected individual’s age group.

- In premature babies and newborns up to three months old, common causes are group B streptococci (subtypes III which normally inhabit the vagina and are mainly a cause during the first week of life) and bacteria that normally inhabit the digestive tract such as Escherichia coli (carrying the K1 antigen). Listeria monocytogenes (serotype IVb) can be contracted when consuming improperly prepared food such as dairy products, produce and deli meats,[23][24] and may cause meningitis in the newborn.[25]

- Older children are more commonly affected by Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (serotypes 6, 9, 14, 18 and 23) and those under five by Haemophilus influenzae type B (in countries that do not offer vaccination).[2][8]

- In adults, Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae together cause 80% of bacterial meningitis cases. Risk of infection with Listeria monocytogenes is increased in people over 50 years old.[3][8] The introduction of pneumococcal vaccine has lowered rates of pneumococcal meningitis in both children and adults.[26]

Recent skull trauma potentially allows nasal cavity bacteria to enter the meningeal space. Similarly, devices in the brain and meninges, such as cerebral shunts, extraventricular drains or Ommaya reservoirs, carry an increased risk of meningitis. In these cases, people are more likely to be infected with Staphylococci, Pseudomonas, and other Gram-negative bacteria.[8] These pathogens are also associated with meningitis in people with an impaired immune system.[2] An infection in the head and neck area, such as otitis media or mastoiditis, can lead to meningitis in a small proportion of people.[8] Recipients of cochlear implants for hearing loss are more at risk for pneumococcal meningitis.[27]

Tuberculous meningitis, which is meningitis caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is more common in people from countries in which tuberculosis is endemic, but is also encountered in people with immune problems, such as AIDS.[28]

Recurrent bacterial meningitis may be caused by persisting anatomical defects, either congenital or acquired, or by disorders of the immune system.[29] Anatomical defects allow continuity between the external environment and the nervous system. The most common cause of recurrent meningitis is a skull fracture,[29] particularly fractures that affect the base of the skull or extend towards the sinuses and petrous pyramids.[29] Approximately 59% of recurrent meningitis cases are due to such anatomical abnormalities, 36% are due to immune deficiencies (such as complement deficiency, which predisposes especially to recurrent meningococcal meningitis), and 5% are due to ongoing infections in areas adjacent to the meninges.[29]

Viral[edit]

Viruses that cause meningitis include enteroviruses, herpes simplex virus (generally type 2, which produces most genital sores; less commonly type 1), varicella zoster virus (known for causing chickenpox and shingles), mumps virus, HIV, LCMV,[21] Arboviruses (acquired from a mosquito or other insect), and the Influenza virus.[30] Mollaret’s meningitis is a chronic recurrent form of herpes meningitis; it is thought to be caused by herpes simplex virus type 2.[31]

Fungal[edit]

There are a number of risk factors for fungal meningitis, including the use of immunosuppressants (such as after organ transplantation), HIV/AIDS,[32] and the loss of immunity associated with aging.[33] It is uncommon in those with a normal immune system[34] but has occurred with medication contamination.[35] Symptom onset is typically more gradual, with headaches and fever being present for at least a couple of weeks before diagnosis.[33] The most common fungal meningitis is cryptococcal meningitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans.[36] In Africa, cryptococcal meningitis is now the most common cause of meningitis in multiple studies,[37][38] and it accounts for 20–25% of AIDS-related deaths in Africa.[39] Other less common fungal pathogens which can cause meningitis include: Coccidioides immitis, Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Candida species.[33]

Parasitic[edit]

A parasitic cause is often assumed when there is a predominance of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell) in the CSF. The most common parasites implicated are Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Gnathostoma spinigerum, Schistosoma, as well as the conditions cysticercosis, toxocariasis, baylisascariasis, paragonimiasis, and a number of rarer infections and noninfective conditions.[40]

Non-infectious[edit]

Meningitis may occur as the result of several non-infectious causes: spread of cancer to the meninges (malignant or neoplastic meningitis)[41] and certain drugs (mainly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics and intravenous immunoglobulins).[42] It may also be caused by several inflammatory conditions, such as sarcoidosis (which is then called neurosarcoidosis), connective tissue disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, and certain forms of vasculitis (inflammatory conditions of the blood vessel wall), such as Behçet’s disease.[4] Epidermoid cysts and dermoid cysts may cause meningitis by releasing irritant matter into the subarachnoid space.[4][29] Rarely, migraine may cause meningitis, but this diagnosis is usually only made when other causes have been eliminated.[4]

Mechanism[edit]

The meninges comprise three membranes that, together with the cerebrospinal fluid, enclose and protect the brain and spinal cord (the central nervous system). The pia mater is a delicate impermeable membrane that firmly adheres to the surface of the brain, following all the minor contours. The arachnoid mater (so named because of its spider-web-like appearance) is a loosely fitting sac on top of the pia mater. The subarachnoid space separates the arachnoid and pia mater membranes and is filled with cerebrospinal fluid. The outermost membrane, the dura mater, is a thick durable membrane, which is attached to both the arachnoid membrane and the skull.

In bacterial meningitis, bacteria reach the meninges by one of two main routes: through the bloodstream (hematogenous spread) or through direct contact between the meninges and either the nasal cavity or the skin. In most cases, meningitis follows invasion of the bloodstream by organisms that live on mucosal surfaces such as the nasal cavity. This is often in turn preceded by viral infections, which break down the normal barrier provided by the mucosal surfaces. Once bacteria have entered the bloodstream, they enter the subarachnoid space in places where the blood–brain barrier is vulnerable – such as the choroid plexus. Meningitis occurs in 25% of newborns with bloodstream infections due to group B streptococci; this phenomenon is much less common in adults.[2] Direct contamination of the cerebrospinal fluid may arise from indwelling devices, skull fractures, or infections of the nasopharynx or the nasal sinuses that have formed a tract with the subarachnoid space (see above); occasionally, congenital defects of the dura mater can be identified.[2]

The large-scale inflammation that occurs in the subarachnoid space during meningitis is not a direct result of bacterial infection but can rather largely be attributed to the response of the immune system to the entry of bacteria into the central nervous system. When components of the bacterial cell membrane are identified by the immune cells of the brain (astrocytes and microglia), they respond by releasing large amounts of cytokines, hormone-like mediators that recruit other immune cells and stimulate other tissues to participate in an immune response. The blood–brain barrier becomes more permeable, leading to «vasogenic» cerebral edema (swelling of the brain due to fluid leakage from blood vessels). Large numbers of white blood cells enter the CSF, causing inflammation of the meninges and leading to «interstitial» edema (swelling due to fluid between the cells). In addition, the walls of the blood vessels themselves become inflamed (cerebral vasculitis), which leads to decreased blood flow and a third type of edema, «cytotoxic» edema. The three forms of cerebral edema all lead to increased intracranial pressure; together with the lowered blood pressure often encountered in sepsis, this means that it is harder for blood to enter the brain; consequently brain cells are deprived of oxygen and undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death).[2]

It is recognized that administration of antibiotics may initially worsen the process outlined above, by increasing the amount of bacterial cell membrane products released through the destruction of bacteria. Particular treatments, such as the use of corticosteroids, are aimed at dampening the immune system’s response to this phenomenon.[2][3]

Diagnosis[edit]

| Type of meningitis | Glucose | Protein | Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute bacterial | low | high | PMNs, often > 300/mm³ |

| Acute viral | normal | normal or high | mononuclear, < 300/mm³ |

| Tuberculous | low | high | mononuclear and PMNs, < 300/mm³ |

| Fungal | low | high | < 300/mm³ |

| Malignant | low | high | usually mononuclear |

Diagnosing meningitis as promptly as possible can improve outcomes.[44] There is no specific sign or symptom that can diagnose meningitis and a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) to examine the cerebrospinal fluid is recommended for diagnosis.[44] Lumbar puncture is contraindicated if there is a mass in the brain (tumor or abscess) or the intracranial pressure (ICP) is elevated, as it may lead to brain herniation. If someone is at risk for either a mass or raised ICP (recent head injury, a known immune system problem, localizing neurological signs, or evidence on examination of a raised ICP), a CT or MRI scan is recommended prior to the lumbar puncture.[8][45][46] This applies in 45% of all adult cases.[3]

There are no physical tests that can rule out or determine if a person has meningitis.[47] The jolt accentuation test is not specific or sensitive enough to completely rule out meningitis.[47]

If someone is suspected of having meningitis, blood tests are performed for markers of inflammation (e.g. C-reactive protein, complete blood count), as well as blood cultures.[8][45] If a CT or MRI is required before LP, or if LP proves difficult, professional guidelines suggest that antibiotics should be administered first to prevent delay in treatment,[8] especially if this may be longer than 30 minutes.[45][46] Often, CT or MRI scans are performed at a later stage to assess for complications of meningitis.[2]

In severe forms of meningitis, monitoring of blood electrolytes may be important; for example, hyponatremia is common in bacterial meningitis.[48] The cause of hyponatremia, however, is controversial and may include dehydration, the inappropriate secretion of the antidiuretic hormone (SIADH), or overly aggressive intravenous fluid administration.[3][48]

Lumbar puncture[edit]

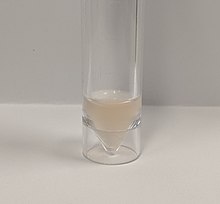

Cloudy CSF from a person with meningitis due to Streptococcus

Gram stain of meningococci from a culture showing Gram negative (pink) bacteria, often in pairs

A lumbar puncture is done by positioning the person, usually lying on the side, applying local anesthetic, and inserting a needle into the dural sac (a sac around the spinal cord) to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). When this has been achieved, the «opening pressure» of the CSF is measured using a manometer. The pressure is normally between 6 and 18 cm water (cmH2O);[49] in bacterial meningitis the pressure is usually elevated.[8][45] In cryptococcal meningitis, intracranial pressure is markedly elevated.[50] The initial appearance of the fluid may prove an indication of the nature of the infection: cloudy CSF indicates higher levels of protein, white and red blood cells and/or bacteria, and therefore may suggest bacterial meningitis.[8]

The CSF sample is examined for presence and types of white blood cells, red blood cells, protein content and glucose level.[8] Gram staining of the sample may demonstrate bacteria in bacterial meningitis, but absence of bacteria does not exclude bacterial meningitis as they are only seen in 60% of cases; this figure is reduced by a further 20% if antibiotics were administered before the sample was taken. Gram staining is also less reliable in particular infections such as listeriosis. Microbiological culture of the sample is more sensitive (it identifies the organism in 70–85% of cases) but results can take up to 48 hours to become available.[8] The type of white blood cell predominantly present (see table) indicates whether meningitis is bacterial (usually neutrophil-predominant) or viral (usually lymphocyte-predominant),[8] although at the beginning of the disease this is not always a reliable indicator. Less commonly, eosinophils predominate, suggesting parasitic or fungal etiology, among others.[40]

The concentration of glucose in CSF is normally above 40% of that in blood. In bacterial meningitis it is typically lower; the CSF glucose level is therefore divided by the blood glucose (CSF glucose to serum glucose ratio). A ratio ≤0.4 is indicative of bacterial meningitis;[49] in the newborn, glucose levels in CSF are normally higher, and a ratio below 0.6 (60%) is therefore considered abnormal.[8] High levels of lactate in CSF indicate a higher likelihood of bacterial meningitis, as does a higher white blood cell count.[49] If lactate levels are less than 35 mg/dl and the person has not previously received antibiotics then this may rule out bacterial meningitis.[51]

Various other specialized tests may be used to distinguish between different types of meningitis. A latex agglutination test may be positive in meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli and group B streptococci; its routine use is not encouraged as it rarely leads to changes in treatment, but it may be used if other tests are not diagnostic. Similarly, the limulus lysate test may be positive in meningitis caused by Gram-negative bacteria, but it is of limited use unless other tests have been unhelpful.[8] Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a technique used to amplify small traces of bacterial DNA in order to detect the presence of bacterial or viral DNA in cerebrospinal fluid; it is a highly sensitive and specific test since only trace amounts of the infecting agent’s DNA is required. It may identify bacteria in bacterial meningitis and may assist in distinguishing the various causes of viral meningitis (enterovirus, herpes simplex virus 2 and mumps in those not vaccinated for this).[21] Serology (identification of antibodies to viruses) may be useful in viral meningitis.[21] If tuberculous meningitis is suspected, the sample is processed for Ziehl–Neelsen stain, which has a low sensitivity, and tuberculosis culture, which takes a long time to process; PCR is being used increasingly.[28] Diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis can be made at low cost using an India ink stain of the CSF; however, testing for cryptococcal antigen in blood or CSF is more sensitive.[52][53]

A diagnostic and therapeutic difficulty is «partially treated meningitis», where there are meningitis symptoms after receiving antibiotics (such as for presumptive sinusitis). When this happens, CSF findings may resemble those of viral meningitis, but antibiotic treatment may need to be continued until there is definitive positive evidence of a viral cause (e.g. a positive enterovirus PCR).[21]

Postmortem[edit]

Histopathology of bacterial meningitis: autopsy case of a person with pneumococcal meningitis showing inflammatory infiltrates of the pia mater consisting of neutrophil granulocytes (inset, higher magnification).

Meningitis can be diagnosed after death has occurred. The findings from a post mortem are usually a widespread inflammation of the pia mater and arachnoid layers of the meninges. Neutrophil granulocytes tend to have migrated to the cerebrospinal fluid and the base of the brain, along with cranial nerves and the spinal cord, may be surrounded with pus – as may the meningeal vessels.[54]

Prevention[edit]

For some causes of meningitis, protection can be provided in the long term through vaccination, or in the short term with antibiotics. Some behavioral measures may also be effective.

Behavioral[edit]

Bacterial and viral meningitis are contagious, but neither is as contagious as the common cold or flu.[55] Both can be transmitted through droplets of respiratory secretions during close contact such as kissing, sneezing or coughing on someone,[55] but bacterial meningitis cannot be spread by only breathing the air where a person with meningitis has been. Viral meningitis is typically caused by enteroviruses, and is most commonly spread through fecal contamination.[55] The risk of infection can be decreased by changing the behavior that led to transmission.

Vaccination[edit]

Since the 1980s, many countries have included immunization against Haemophilus influenzae type B in their routine childhood vaccination schemes. This has practically eliminated this pathogen as a cause of meningitis in young children in those countries. In the countries in which the disease burden is highest, however, the vaccine is still too expensive.[56][57] Similarly, immunization against mumps has led to a sharp fall in the number of cases of mumps meningitis, which prior to vaccination occurred in 15% of all cases of mumps.[21]

Meningococcus vaccines exist against groups A, B, C, W135 and Y.[58][59][60] In countries where the vaccine for meningococcus group C was introduced, cases caused by this pathogen have decreased substantially.[56] A quadrivalent vaccine now exists, which combines four vaccines with the exception of B; immunization with this ACW135Y vaccine is now a visa requirement for taking part in Hajj.[61] Development of a vaccine against group B meningococci has proved much more difficult, as its surface proteins (which would normally be used to make a vaccine) only elicit a weak response from the immune system, or cross-react with normal human proteins.[56][58] Still, some countries (New Zealand, Cuba, Norway and Chile) have developed vaccines against local strains of group B meningococci; some have shown good results and are used in local immunization schedules.[58] Two new vaccines, both approved in 2014, are effective against a wider range of group B meningococci strains.[59][60] In Africa, until recently, the approach for prevention and control of meningococcal epidemics was based on early detection of the disease and emergency reactive mass vaccination of the at-risk population with bivalent A/C or trivalent A/C/W135 polysaccharide vaccines,[62] though the introduction of MenAfriVac (meningococcus group A vaccine) has demonstrated effectiveness in young people and has been described as a model for product development partnerships in resource-limited settings.[63][64]

Routine vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), which is active against seven common serotypes of this pathogen, significantly reduces the incidence of pneumococcal meningitis.[56][65] The pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, which covers 23 strains, is only administered to certain groups (e.g. those who have had a splenectomy, the surgical removal of the spleen); it does not elicit a significant immune response in all recipients, e.g. small children.[65] Childhood vaccination with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin has been reported to significantly reduce the rate of tuberculous meningitis, but its waning effectiveness in adulthood has prompted a search for a better vaccine.[56]

Antibiotics[edit]

Short-term antibiotic prophylaxis is another method of prevention, particularly of meningococcal meningitis. In cases of meningococcal meningitis, preventative treatment in close contacts with antibiotics (e.g. rifampicin, ciprofloxacin or ceftriaxone) can reduce their risk of contracting the condition, but does not protect against future infections.[45][66] Resistance to rifampicin has been noted to increase after use, which has caused some to recommend considering other agents.[66] While antibiotics are frequently used in an attempt to prevent meningitis in those with a basilar skull fracture there is not enough evidence to determine whether this is beneficial or harmful.[67] This applies to those with or without a CSF leak.[67]

Management[edit]

Meningitis is potentially life-threatening and has a high mortality rate if untreated;[8] delay in treatment has been associated with a poorer outcome.[3] Thus, treatment with wide-spectrum antibiotics should not be delayed while confirmatory tests are being conducted.[46] If meningococcal disease is suspected in primary care, guidelines recommend that benzylpenicillin be administered before transfer to hospital.[17] Intravenous fluids should be administered if hypotension (low blood pressure) or shock are present.[46] It is not clear whether intravenous fluid should be given routinely or whether this should be restricted.[68] Given that meningitis can cause a number of early severe complications, regular medical review is recommended to identify these complications early[46] and to admit the person to an intensive care unit if deemed necessary.[3]

Mechanical ventilation may be needed if the level of consciousness is very low, or if there is evidence of respiratory failure. If there are signs of raised intracranial pressure, measures to monitor the pressure may be taken; this would allow the optimization of the cerebral perfusion pressure and various treatments to decrease the intracranial pressure with medication (e.g. mannitol).[3] Seizures are treated with anticonvulsants.[3] Hydrocephalus (obstructed flow of CSF) may require insertion of a temporary or long-term drainage device, such as a cerebral shunt.[3] The osmotic therapy, glycerol, has an unclear effect on mortality but may decrease hearing problems.[69]

Bacterial meningitis[edit]

Antibiotics[edit]

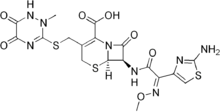

Structural formula of ceftriaxone, one of the third-generation cefalosporin antibiotics recommended for the initial treatment of bacterial meningitis.

Empiric antibiotics (treatment without exact diagnosis) should be started immediately, even before the results of the lumbar puncture and CSF analysis are known. The choice of initial treatment depends largely on the kind of bacteria that cause meningitis in a particular place and population. For instance, in the United Kingdom, empirical treatment consists of a third-generation cefalosporin such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone.[45][46] In the US, where resistance to cefalosporins is increasingly found in streptococci, addition of vancomycin to the initial treatment is recommended.[3][8][45] Chloramphenicol, either alone or in combination with ampicillin, however, appears to work equally well.[70]

Empirical therapy may be chosen on the basis of the person’s age, whether the infection was preceded by a head injury, whether the person has undergone recent neurosurgery and whether or not a cerebral shunt is present.[8] In young children and those over 50 years of age, as well as those who are immunocompromised, the addition of ampicillin is recommended to cover Listeria monocytogenes.[8][45] Once the Gram stain results become available, and the broad type of bacterial cause is known, it may be possible to change the antibiotics to those likely to deal with the presumed group of pathogens.[8] The results of the CSF culture generally take longer to become available (24–48 hours). Once they do, empiric therapy may be switched to specific antibiotic therapy targeted to the specific causative organism and its sensitivities to antibiotics.[8] For an antibiotic to be effective in meningitis it must not only be active against the pathogenic bacterium but also reach the meninges in adequate quantities; some antibiotics have inadequate penetrance and therefore have little use in meningitis. Most of the antibiotics used in meningitis have not been tested directly on people with meningitis in clinical trials. Rather, the relevant knowledge has mostly derived from laboratory studies in rabbits.[8] Tuberculous meningitis requires prolonged treatment with antibiotics. While tuberculosis of the lungs is typically treated for six months, those with tuberculous meningitis are typically treated for a year or longer.[28]

Fluid Therapy[edit]

Fluid given intravenously are an essential part of treatment of bacterial meningitis. There is no difference in terms of mortality or acute severe neurological complications in children given a maintenance regimen over restricted-fluid regimen, but evidence is in favor of the maintenance regimen in terms of emergence of chronic severe neurological complications.[71]

Steroids[edit]

Additional treatment with corticosteroids (usually dexamethasone) has shown some benefits, such as a reduction of hearing loss, and better short term neurological outcomes[72] in adolescents and adults from high-income countries with low rates of HIV.[73] Some research has found reduced rates of death[73] while other research has not.[72] They also appear to be beneficial in those with tuberculosis meningitis, at least in those who are HIV negative.[74]

Professional guidelines therefore recommend the commencement of dexamethasone or a similar corticosteroid just before the first dose of antibiotics is given, and continued for four days.[45][46] Given that most of the benefit of the treatment is confined to those with pneumococcal meningitis, some guidelines suggest that dexamethasone be discontinued if another cause for meningitis is identified.[8][45] The likely mechanism is suppression of overactive inflammation.[75]

Additional treatment with corticosteroids have a different role in children than in adults. Though the benefit of corticosteroids has been demonstrated in adults as well as in children from high-income countries, their use in children from low-income countries is not supported by the evidence; the reason for this discrepancy is not clear.[72] Even in high-income countries, the benefit of corticosteroids is only seen when they are given prior to the first dose of antibiotics, and is greatest in cases of H. influenzae meningitis,[8][76] the incidence of which has decreased dramatically since the introduction of the Hib vaccine. Thus, corticosteroids are recommended in the treatment of pediatric meningitis if the cause is H. influenzae, and only if given prior to the first dose of antibiotics; other uses are controversial.[8]

Adjuvant therapies[edit]

In addition to the primary therapy of antibiotics and corticosteroids, other adjuvant therapies are under development or are sometimes used to try and improve survival from bacterial meningitis and reduce the risk of neurological problems. Examples of adjuvant therapies that have been trialed include acetaminophen, immunoglobulin therapy, heparin, pentoxifyline, and a mononucleotide mixture with succinic acid.[77] It is not clear if any of these therapies are helpful or worsen outcomes in people with acute bacterial meningitis.[77]

Viral meningitis[edit]

Viral meningitis typically only requires supportive therapy; most viruses responsible for causing meningitis are not amenable to specific treatment. Viral meningitis tends to run a more benign course than bacterial meningitis. Herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus may respond to treatment with antiviral drugs such as aciclovir, but there are no clinical trials that have specifically addressed whether this treatment is effective.[21] Mild cases of viral meningitis can be treated at home with conservative measures such as fluid, bedrest, and analgesics.[78]

Fungal meningitis[edit]

Fungal meningitis, such as cryptococcal meningitis, is treated with long courses of high dose antifungals, such as amphotericin B and flucytosine.[52][79] Raised intracranial pressure is common in fungal meningitis, and frequent (ideally daily) lumbar punctures to relieve the pressure are recommended,[52] or alternatively a lumbar drain.[50]

Prognosis[edit]

Disability-adjusted life year for meningitis per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[80]

-

no data

-

<10

-

10–25

-

25–50

-

50–75

-

75–100

-

100–200

-

200–300

-

300–400

-

400–500

-

500–750

-

750–1000

-

>1000

Untreated, bacterial meningitis is almost always fatal. Viral meningitis, in contrast, tends to resolve spontaneously and is rarely fatal. With treatment, mortality (risk of death) from bacterial meningitis depends on the age of the person and the underlying cause. Of newborns, 20–30% may die from an episode of bacterial meningitis. This risk is much lower in older children, whose mortality is about 2%, but rises again to about 19–37% in adults.[2][3]

Risk of death is predicted by various factors apart from age, such as the pathogen and the time it takes for the pathogen to be cleared from the cerebrospinal fluid,[2] the severity of the generalized illness, a decreased level of consciousness or an abnormally low count of white blood cells in the CSF.[3] Meningitis caused by H. influenzae and meningococci has a better prognosis than cases caused by group B streptococci, coliforms and S. pneumoniae.[2] In adults, too, meningococcal meningitis has a lower mortality (3–7%) than pneumococcal disease.[3]

In children there are several potential disabilities which may result from damage to the nervous system, including sensorineural hearing loss, epilepsy, learning and behavioral difficulties, as well as decreased intelligence.[2] These occur in about 15% of survivors.[2] Some of the hearing loss may be reversible.[81] In adults, 66% of all cases emerge without disability. The main problems are deafness (in 14%) and cognitive impairment (in 10%).[3]

Tuberculous meningitis in children continues to be associated with a significant risk of death even with treatment (19%), and a significant proportion of the surviving children have ongoing neurological problems. Just over a third of all cases survives with no problems.[82]

Epidemiology[edit]

Demography of meningococcal meningitis.

meningitis belt

epidemic zones

sporadic cases only

Deaths from meningitis per million people in 2012

-

0–2

-

3-3

-

4–6

-

7–9

-

10–20

-

21–31

-

32–61

-

62–153

-

154–308

-

309–734

Although meningitis is a notifiable disease in many countries, the exact incidence rate is unknown.[21] In 2013 meningitis resulted in 303,000 deaths – down from 464,000 deaths in 1990.[83] In 2010 it was estimated that meningitis resulted in 420,000 deaths,[84] excluding cryptococcal meningitis.[39]

Bacterial meningitis occurs in about 3 people per 100,000 annually in Western countries. Population-wide studies have shown that viral meningitis is more common, at 10.9 per 100,000, and occurs more often in the summer. In Brazil, the rate of bacterial meningitis is higher, at 45.8 per 100,000 annually.[16] Sub-Saharan Africa has been plagued by large epidemics of meningococcal meningitis for over a century,[85] leading to it being labeled the «meningitis belt». Epidemics typically occur in the dry season (December to June), and an epidemic wave can last two to three years, dying out during the intervening rainy seasons.[86] Attack rates of 100–800 cases per 100,000 are encountered in this area,[87] which is poorly served by medical care. These cases are predominantly caused by meningococci.[16] The largest epidemic ever recorded in history swept across the entire region in 1996–1997, causing over 250,000 cases and 25,000 deaths.[88]

Meningococcal disease occurs in epidemics in areas where many people live together for the first time, such as army barracks during mobilization, university and college campuses[2] and the annual Hajj pilgrimage.[61] Although the pattern of epidemic cycles in Africa is not well understood, several factors have been associated with the development of epidemics in the meningitis belt. They include: medical conditions (immunological susceptibility of the population), demographic conditions (travel and large population displacements), socioeconomic conditions (overcrowding and poor living conditions), climatic conditions (drought and dust storms), and concurrent infections (acute respiratory infections).[87]

There are significant differences in the local distribution of causes for bacterial meningitis. For instance, while N. meningitides groups B and C cause most disease episodes in Europe, group A is found in Asia and continues to predominate in Africa, where it causes most of the major epidemics in the meningitis belt, accounting for about 80% to 85% of documented meningococcal meningitis cases.[87]

History[edit]

Some suggest that Hippocrates may have realized the existence of meningitis,[16] and it seems that meningism was known to pre-Renaissance physicians such as Avicenna.[89] The description of tuberculous meningitis, then called «dropsy in the brain», is often attributed to Edinburgh physician Sir Robert Whytt in a posthumous report that appeared in 1768, although the link with tuberculosis and its pathogen was not made until the next century.[89][90]

It appears that epidemic meningitis is a relatively recent phenomenon.[91] The first recorded major outbreak occurred in Geneva in 1805.[91][92] Several other epidemics in Europe and the United States were described shortly afterward, and the first report of an epidemic in Africa appeared in 1840. African epidemics became much more common in the 20th century, starting with a major epidemic sweeping Nigeria and Ghana in 1905–1908.[91]

The first report of bacterial infection underlying meningitis was by the Austrian bacteriologist Anton Weichselbaum, who in 1887 described the meningococcus.[93] Mortality from meningitis was very high (over 90%) in early reports. In 1906, antiserum was produced in horses; this was developed further by the American scientist Simon Flexner and markedly decreased mortality from meningococcal disease.[94][95] In 1944, penicillin was first reported to be effective in meningitis.[96] The introduction in the late 20th century of Haemophilus vaccines led to a marked fall in cases of meningitis associated with this pathogen,[57] and in 2002, evidence emerged that treatment with steroids could improve the prognosis of bacterial meningitis.[72][75][95] World Meningitis Day is observed on 24 April each year.[97]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «Bacterial Meningitis». CDC. 1 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Sáez-Llorens X, McCracken GH (June 2003). «Bacterial meningitis in children». Lancet. 361 (9375): 2139–48. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13693-8. PMID 12826449. S2CID 6226323.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u van de Beek D, de Gans J, Tunkel AR, Wijdicks EF (January 2006). «Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults». The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052116. PMID 16394301.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ginsberg L (March 2004). «Difficult and recurrent meningitis». Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 Suppl 1 (90001): i16–21. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.034272. PMC 1765649. PMID 14978146.

- ^ Ferri, Fred F. (2010). Ferri’s differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby. p. Chapter M. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (May 2008). «Primary amebic meningoencephalitis – Arizona, Florida, and Texas, 2007». MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (21): 573–27. PMID 18509301. Archived from the original on 2 April 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ a b «Viral Meningitis». CDC. 26 November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, Kaufman BA, Roos KL, Scheld WM, Whitley RJ (November 2004). «Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 39 (9): 1267–84. doi:10.1086/425368. PMID 15494903.

- ^ a b c d «Global Disease Burden 2019». Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ Putz, Katherine; Hayani, Karen; Zar, Fred Arthur (2013). «Meningitis». Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 40 (3): 707–726. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.06.001. PMID 23958365.

- ^ «NHS medical conditions meningitis». NHS. 20 October 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ a b «Meningococcal meningitis Fact sheet N°141». WHO. November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Mosby’s pocket dictionary of medicine, nursing & health professions (6th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier. 2010. p. traumatic meningitis. ISBN 978-0-323-06604-4. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ Liddell HG, Scott R (1940). «μῆνιγξ». A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b van de Beek D, de Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M (October 2004). «Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis» (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (18): 1849–59. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040845. PMID 15509818. S2CID 22287169. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Attia J, Hatala R, Cook DJ, Wong JG (July 1999). «The rational clinical examination. Does this adult patient have acute meningitis?». JAMA. 282 (2): 175–81. doi:10.1001/jama.282.2.175. PMID 10411200.

- ^ a b c Theilen U, Wilson L, Wilson G, Beattie JO, Qureshi S, Simpson D (June 2008). «Management of invasive meningococcal disease in children and young people: summary of SIGN guidelines». BMJ. 336 (7657): 1367–70. doi:10.1136/bmj.a129. PMC 2427067. PMID 18556318.

- ^ Management of invasive meningococcal disease in children and young people (PDF). Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). May 2008. ISBN 978-1-905813-31-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 July 2014.

- ^ Thomas KE, Hasbun R, Jekel J, Quagliarello VJ (July 2002). «The diagnostic accuracy of Kernig’s sign, Brudzinski’s sign, and nuchal rigidity in adults with suspected meningitis». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 35 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1086/340979. PMID 12060874.

- ^ «Meningitis». www.who.int. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Logan SA, MacMahon E (January 2008). «Viral meningitis». BMJ. 336 (7634): 36–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.39409.673657.AE. PMC 2174764. PMID 18174598.

- ^ Varon J, Chen K, Sternbach GL (1998). «Rupert Waterhouse and Carl Friderichsen: adrenal apoplexy». The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16 (4): 643–47. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00061-4. PMID 9696186.

- ^ «Meningitis | About Bacterial Meningitis Infection». cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 6 August 2019. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ «Prevent Listeria». cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 17 June 2019. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ «Listeria (Listeriosis)». cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 October 2015. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Hsu HE, Shutt KA, Moore MR, Beall BW, Bennett NM, Craig AS, Farley MM, Jorgensen JH, Lexau CA, Petit S, Reingold A, Schaffner W, Thomas A, Whitney CG, Harrison LH (January 2009). «Effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal meningitis». The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (3): 244–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0800836. PMC 4663990. PMID 19144940.

- ^ Wei BP, Robins-Browne RM, Shepherd RK, Clark GM, O’Leary SJ (January 2008). «Can we prevent cochlear implant recipients from developing pneumococcal meningitis?». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46 (1): e1–7. doi:10.1086/524083. PMID 18171202.

- ^ a b c Thwaites G, Chau TT, Mai NT, Drobniewski F, McAdam K, Farrar J (March 2000). «Tuberculous meningitis». Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 68 (3): 289–99. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.3.289. PMC 1736815. PMID 10675209.

- ^ a b c d e Tebruegge M, Curtis N (July 2008). «Epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of recurrent bacterial meningitis». Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (3): 519–37. doi:10.1128/CMR.00009-08. PMC 2493086. PMID 18625686.

- ^ «Meningitis | Viral». cdc.gov. 19 February 2019. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Shalabi M, Whitley RJ (November 2006). «Recurrent benign lymphocytic meningitis». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (9): 1194–97. doi:10.1086/508281. PMID 17029141.

- ^ Raman Sharma R (2010). «Fungal infections of the nervous system: current perspective and controversies in management». International Journal of Surgery. 8 (8): 591–601. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.07.293. PMID 20673817.

- ^ a b c Sirven JI, Malamut BL (2008). Clinical neurology of the older adult (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-7817-6947-1. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016.

- ^ Honda H, Warren DK (September 2009). «Central nervous system infections: meningitis and brain abscess». Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 23 (3): 609–23. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2009.04.009. PMID 19665086.

- ^ Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Patterson TF (June 2013). «Fungal infections associated with contaminated methylprednisolone injections». The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (26): 2495–500. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1212617. PMID 23083312.

- ^ Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE (1 January 2011). Essentials of clinical mycology (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4419-6639-1. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- ^ Durski KN, Kuntz KM, Yasukawa K, Virnig BA, Meya DB, Boulware DR (July 2013). «Cost-effective diagnostic checklists for meningitis in resource-limited settings». Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 63 (3): e101–08. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828e1e56. PMC 3683123. PMID 23466647.

- ^ Kauffman CA, Pappas PG, Sobel JD, Dismukes WE (1 January 2011). Essentials of clinical mycology (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4419-6639-1. Archived from the original on 16 May 2016.

- ^ a b Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM (February 2009). «Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS». AIDS. 23 (4): 525–30. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. PMID 19182676. S2CID 5735550.

- ^ a b Graeff-Teixeira C, da Silva AC, Yoshimura K (April 2009). «Update on eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and its clinical relevance». Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (2): 322–48, Table of Contents. doi:10.1128/CMR.00044-08. PMC 2668237. PMID 19366917.

- ^ Gleissner B, Chamberlain MC (May 2006). «Neoplastic meningitis». The Lancet. Neurology. 5 (5): 443–52. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70443-4. PMID 16632315. S2CID 21335554.

- ^ Moris G, Garcia-Monco JC (June 1999). «The challenge of drug-induced aseptic meningitis». Archives of Internal Medicine. 159 (11): 1185–94. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.11.1185. PMID 10371226.

- ^ Provan D, Krentz A (2005). Oxford Handbook of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856663-2.

- ^ a b Mount, Hillary R.; Boyle, Sean D. (1 September 2017). «Aseptic and Bacterial Meningitis: Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention». American Family Physician. 96 (5): 314–322. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 28925647. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chaudhuri A, Martinez-Martin P, Martin PM, Kennedy PG, Andrew Seaton R, Portegies P, Bojar M, Steiner I (July 2008). «EFNS guideline on the management of community-acquired bacterial meningitis: report of an EFNS Task Force on acute bacterial meningitis in older children and adults». European Journal of Neurology. 15 (7): 649–59. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02193.x. PMID 18582342. S2CID 12415715.

- ^ a b c d e f g Heyderman RS, Lambert HP, O’Sullivan I, Stuart JM, Taylor BL, Wall RA (February 2003). «Early management of suspected bacterial meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in adults» (PDF). The Journal of Infection. 46 (2): 75–77. doi:10.1053/jinf.2002.1110. PMID 12634067. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. – formal guideline at British Infection Society; UK Meningitis Research Trust (December 2004). «Early management of suspected meningitis and meningococcal septicaemia in immunocompetent adults». British Infection Society Guidelines. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ a b Iguchi, Masahiro; Noguchi, Yoshinori; Yamamoto, Shungo; Tanaka, Yuu; Tsujimoto, Hiraku (June 2020). «Diagnostic test accuracy of jolt accentuation for headache in acute meningitis in the emergency setting». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD012824. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012824.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7386453. PMID 32524581.

- ^ a b Maconochie IK, Bhaumik S (November 2016). «Fluid therapy for acute bacterial meningitis» (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD004786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004786.pub5. PMC 6464853. PMID 27813057. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

Careful management of fluid and electrolyte balance is also important in the treatment of meningitis… there are different opinions regarding the cause of hyponatraemia… if dehydration, rather than inappropriately increased antidiuresis… fluid restriction is open to question

- ^ a b c Straus SE, Thorpe KE, Holroyd-Leduc J (October 2006). «How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis?». JAMA. 296 (16): 2012–22. doi:10.1001/jama.296.16.2012. PMID 17062865.

- ^ a b Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, Harrison TS, Larsen RA, Lortholary O, Nguyen MH, Pappas PG, Powderly WG, Singh N, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC (February 2010). «Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america». Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (3): 291–322. doi:10.1086/649858. PMC 5826644. PMID 20047480. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012.

- ^ Sakushima K, Hayashino Y, Kawaguchi T, Jackson JL, Fukuhara S (April 2011). «Diagnostic accuracy of cerebrospinal fluid lactate for differentiating bacterial meningitis from aseptic meningitis: a meta-analysis». The Journal of Infection. 62 (4): 255–62. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2011.02.010. hdl:2115/48503. PMID 21382412. S2CID 206172763.

- ^ a b c Bicanic T, Harrison TS (2004). «Cryptococcal meningitis». British Medical Bulletin. 72 (1): 99–118. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh043. PMID 15838017.

- ^ Tenforde MW, Shapiro AE, Rouse B, Jarvis JN, Li T, Eshun-Wilson I, Ford N (July 2018). «Treatment for HIV‐associated cryptococcal meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (7): CD005647. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005647.pub3. PMC 6513250. PMID 30045416. CD005647.

- ^ Warrell DA, Farrar JJ, Crook DW (2003). «24.14.1 Bacterial meningitis». Oxford Textbook of Medicine Volume 3 (Fourth ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 1115–29. ISBN 978-0-19-852787-9.

- ^ a b c «CDC – Meningitis: Transmission». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 August 2009. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Segal S, Pollard AJ (2004). «Vaccines against bacterial meningitis». British Medical Bulletin. 72 (1): 65–81. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldh041. PMID 15802609.

- ^ a b Peltola H (April 2000). «Worldwide Haemophilus influenzae type b disease at the beginning of the 21st century: global analysis of the disease burden 25 years after the use of the polysaccharide vaccine and a decade after the advent of conjugates». Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 13 (2): 302–17. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.2.302-317.2000. PMC 100154. PMID 10756001.

- ^ a b c Harrison LH (January 2006). «Prospects for vaccine prevention of meningococcal infection». Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 19 (1): 142–64. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.1.142-164.2006. PMC 1360272. PMID 16418528.

- ^ a b Man, Diana. «A new MenB (meningococcal B) vaccine». Meningitis Research Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ a b FDA News Release (29 October 2014). «First vaccine approved by FDA to prevent serogroup B Meningococcal disease». FDA. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014.

- ^ a b Wilder-Smith A (October 2007). «Meningococcal vaccine in travelers». Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 20 (5): 454–60. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282a64700. PMID 17762777. S2CID 9411482.

- ^ World Health Organization (September 2000). «Detecting meningococcal meningitis epidemics in highly-endemic African countries». Weekly Epidemiological Record. 75 (38): 306–309. hdl:10665/231278. PMID 11045076.

- ^ Bishai DM, Champion C, Steele ME, Thompson L (June 2011). «Product development partnerships hit their stride: lessons from developing a meningitis vaccine for Africa». Health Affairs. 30 (6): 1058–64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0295. PMID 21653957.

- ^ Marc LaForce F, Ravenscroft N, Djingarey M, Viviani S (June 2009). «Epidemic meningitis due to Group A Neisseria meningitidis in the African meningitis belt: a persistent problem with an imminent solution». Vaccine. 27 Suppl 2: B13–19. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.062. PMID 19477559.

- ^ a b Weisfelt M, de Gans J, van der Poll T, van de Beek D (April 2006). «Pneumococcal meningitis in adults: new approaches to management and prevention». The Lancet. Neurology. 5 (4): 332–42. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70409-4. PMID 16545750. S2CID 19318114.

- ^ a b Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Fraser A, Gafter-Gvili A, Paul M, Leibovici L (October 2013). «Antibiotics for preventing meningococcal infections». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD004785. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004785.pub5. PMC 6698485. PMID 24163051.

- ^ a b Ratilal BO, Costa J, Pappamikail L, Sampaio C (April 2015). «Antibiotic prophylaxis for preventing meningitis in patients with basilar skull fractures». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD004884. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004884.pub4. PMID 25918919.

- ^ Maconochie IK, Bhaumik S (November 2016). «Fluid therapy for acute bacterial meningitis» (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD004786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004786.pub5. PMC 6464853. PMID 27813057. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Wall EC, Ajdukiewicz KM, Bergman H, Heyderman RS, Garner P (February 2018). «Osmotic therapies added to antibiotics for acute bacterial meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (2): CD008806. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008806.pub3. PMC 5815491. PMID 29405037.

- ^ Prasad K, Kumar A, Gupta PK, Singhal T (October 2007). Prasad K (ed.). «Third generation cephalosporins versus conventional antibiotics for treating acute bacterial meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (4): CD001832. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001832.pub3. PMC 8078560. PMID 17943757.

- ^ Maconochie, Ian K.; Bhaumik, Soumyadeep (4 November 2016). «Fluid therapy for acute bacterial meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD004786. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004786.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6464853. PMID 27813057.

- ^ a b c d Brouwer MC, McIntyre P, Prasad K, van de Beek D (September 2015). «Corticosteroids for acute bacterial meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9): CD004405. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004405.pub5. PMC 6491272. PMID 26362566.

- ^ a b Assiri AM, Alasmari FA, Zimmerman VA, Baddour LM, Erwin PJ, Tleyjeh IM (May 2009). «Corticosteroid administration and outcome of adolescents and adults with acute bacterial meningitis: a meta-analysis». Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 84 (5): 403–09. doi:10.4065/84.5.403. PMC 2676122. PMID 19411436.

- ^ Prasad K, Singh MB, Ryan H (April 2016). «Corticosteroids for managing tuberculous meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4): CD002244. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002244.pub4. PMC 4916936. PMID 27121755.

- ^ a b de Gans J, van de Beek D (November 2002). «Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis». The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (20): 1549–56. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021334. PMID 12432041. S2CID 72596402. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ McIntyre PB, Berkey CS, King SM, Schaad UB, Kilpi T, Kanra GY, Perez CM (September 1997). «Dexamethasone as adjunctive therapy in bacterial meningitis. A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials since 1988». JAMA. 278 (11): 925–31. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550110063038. PMID 9302246.

- ^ a b Fisher, Jane; Linder, Adam; Calevo, Maria Grazia; Bentzer, Peter (23 November 2021). «Non-corticosteroid adjuvant therapies for acute bacterial meningitis». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD013437. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013437.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8610076. PMID 34813078.

- ^ «Meningitis and Encephalitis Fact Sheet». National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). 11 December 2007. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR (2000). «Fungal meningitis». Seminars in Neurology. 20 (3): 307–22. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9394. PMID 11051295.

- ^ «Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002» (xls). World Health Organization (WHO). 2002. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

- ^ Richardson MP, Reid A, Tarlow MJ, Rudd PT (February 1997). «Hearing loss during bacterial meningitis». Archives of Disease in Childhood. 76 (2): 134–38. doi:10.1136/adc.76.2.134. PMC 1717058. PMID 9068303.

- ^ Chiang SS, Khan FA, Milstein MB, Tolman AW, Benedetti A, Starke JR, Becerra MC (October 2014). «Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis». The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 14 (10): 947–57. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70852-7. PMID 25108337.

- ^ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). «Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013». Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. (December 2012). «Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010». Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. S2CID 1541253. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ^ Lapeyssonnie L (1963). «Cerebrospinal Meningitis in Africa». Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 28 Suppl (Suppl): 1–114. PMC 2554630. PMID 14259333.

- ^ Greenwood B (1999). «Manson Lecture. Meningococcal meningitis in Africa». Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 93 (4): 341–53. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90106-2. PMID 10674069.

- ^ a b c World Health Organization (1998). Control of epidemic meningococcal disease, practical guidelines, 2nd edition, WHO/EMC/BA/98 (PDF). Vol. 3. pp. 1–83. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2013.

- ^ World Health Organization (August 2003). «Meningococcal meningitis : Overview». Weekly Epidemiological Record. 78 (33): 294–296. hdl:10665/232232. PMID 14509123.

- ^ a b Walker AE, Laws ER, Udvarhelyi GB (1998). «Infections and inflammatory involvement of the CNS». The Genesis of Neuroscience. Thieme. pp. 219–21. ISBN 978-1-879284-62-3. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Whytt R (1768). Observations on the Dropsy in the Brain. Edinburgh: J. Balfour.

- ^ a b c Greenwood B (June 2006). «Editorial: 100 years of epidemic meningitis in West Africa – has anything changed?». Tropical Medicine & International Health. 11 (6): 773–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01639.x. PMID 16771997. S2CID 28838510.

- ^ Vieusseux G (1806). «Mémoire sur le Maladie qui a regne à Génève au printemps de 1805». Journal de Médecine, de Chirurgie et de Pharmacologie (Bruxelles) (in French). 11: 50–53.

- ^ Weichselbaum A (1887). «Ueber die Aetiologie der akuten Meningitis cerebro-spinalis». Fortschrift der Medizin (in German). 5: 573–83.

- ^ Flexner S (May 1913). «The results of the serum treatment in thirteen hundred cases of epidemic meningitis». The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 17 (5): 553–76. doi:10.1084/jem.17.5.553. PMC 2125091. PMID 19867668.

- ^ a b Swartz MN (October 2004). «Bacterial meningitis – a view of the past 90 years». The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (18): 1826–28. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048246. PMID 15509815.

- ^ Rosenberg DH, Arling PA (1944). «Penicillin in the treatment of meningitis». Journal of the American Medical Association. 125 (15): 1011–17. doi:10.1001/jama.1944.02850330009002. reproduced in Rosenberg DH, Arling PA (April 1984). «Landmark article Aug 12, 1944: Penicillin in the treatment of meningitis. By D.H. Rosenberg and P.A.Arling». JAMA. 251 (14): 1870–76. doi:10.1001/jama.251.14.1870. PMID 6366279.

- ^ Meningitis Research Foundation. «Save the date for World Meningitis Day 2020 | Meningitis Research Foundation». www.meningitis.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meningitis.

- Meningitis at Curlie

- Meningitis Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

| Meningitis | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Meninges of the central nervous system: dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, neurology |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, neck stiffness[1] |

| Complications | Deafness, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, cognitive deficits[2][3] |

| Causes | Viral, bacterial, other[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Lumbar puncture[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Encephalitis, brain tumor, lupus, Lyme disease, seizures, neuroleptic malignant syndrome,[5] naegleriasis[6] |

| Prevention | Vaccination[2] |

| Medication | Antibiotics, antivirals, steroids[1][7][8] |

| Frequency | 7.7 million (2019)[9] |

| Deaths | 236,000 (2019)[9] |

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges.[10] The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness.[1] Other symptoms include confusion or altered consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate light or loud noises.[1] Young children often exhibit only nonspecific symptoms, such as irritability, drowsiness, or poor feeding.[1] A non-blanching rash (a rash that does not fade when a glass is rolled over it) may also be present.[11]

The inflammation may be caused by infection with viruses, bacteria or other microorganisms. Non-infectious causes include malignancy (cancer), subarachnoid haemorrhage, chronic inflammatory disease (sarcoidosis) and certain drugs.[4] Meningitis can be life-threatening because of the inflammation’s proximity to the brain and spinal cord; therefore, the condition is classified as a medical emergency.[2][8] A lumbar puncture, in which a needle is inserted into the spinal canal to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), can diagnose or exclude meningitis.[1][8]

Some forms of meningitis are preventable by immunization with the meningococcal, mumps, pneumococcal, and Hib vaccines.[2] Giving antibiotics to people with significant exposure to certain types of meningitis may also be useful.[1] The first treatment in acute meningitis consists of promptly giving antibiotics and sometimes antiviral drugs.[1][7] Corticosteroids can also be used to prevent complications from excessive inflammation.[3][8] Meningitis can lead to serious long-term consequences such as deafness, epilepsy, hydrocephalus, or cognitive deficits, especially if not treated quickly.[2][3]