Программа лечения Врачи Цены Отзывы

Более двух тысяч лет человечество пытается разгадать все загадки этого тяжелого дерматоза, но до сих пор многое остается неизвестным. По статистике этим заболеванием страдает от 4 до 7 % населения, женщины и мужчины подвержены ему в равной степени. Первые признаки псориаза обычно появляются в период полового созревания и сопровождают человека всю последующую жизнь, то стихая и исчезая совсем, то усиливаясь.

Можно ли вылечить псориаз? Современная медицина многого достигла в лечении этого хронического дерматоза и способна обеспечить больному достойный уровень качества жизни.

Содержание

- Причины возникновения псориаза

- Аутоиммунная

- Генетическая

- Эндокринная

- Обменная

- Нейрогенная

- Инфекционная

- Признаки и симптомы псориаза

- Стадии псориаза

- Заразен ли псориаз

- Виды псориаза

- Простой (вульгарный, бляшечный)

- Локтевой

- Каплевидный

- Ладонно-подошвенный псориаз

- Псориаз ногтей

- Псориаз волосистой части головы

- Себорейный

- Псориаз на лице

- На половых органах

- Чем опасен псориаз и нужно ли его лечить

- Методы лечения псориаза

- Питание при псориазе

- Диета Пегано

- Медикаментозная терапия

- Наружное лечение псориаза

- Системное лечение псориаза

- Народные средства при псориазе

- Домашнее лечение псориаза

- Фототерапия

- Хирургический метод

- Питание при псориазе

- Помогут ли гормоны при псориазе?

- Методы восточной медицины при псориазе

- Санаторное лечение псориаза на море

- Профилактика псориаза

- Как быть с армией?

- Как вылечить псориаз навсегда?

Причины возникновения псориаза

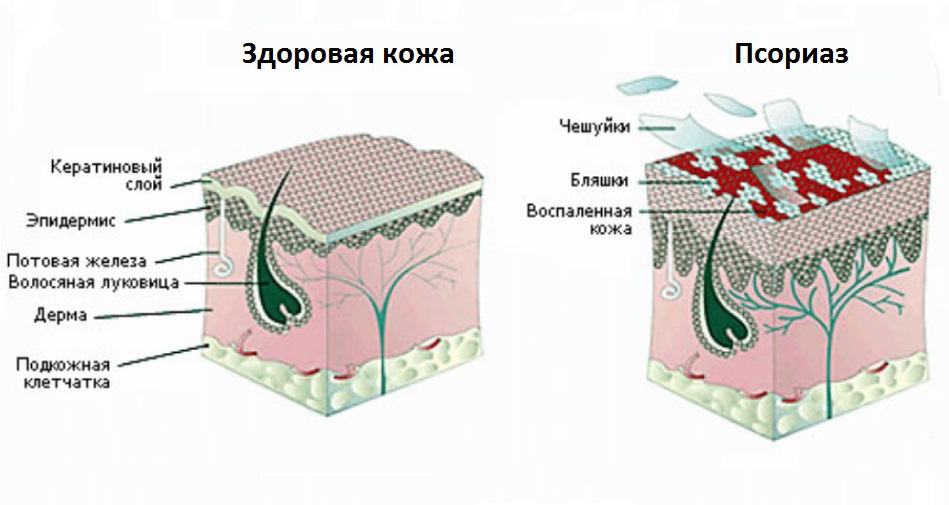

Псориаз – это хронический кожный воспалительный процесс, который современная медицина относит к аутоиммунным (связанным с аллергией на собственные ткани). Существует множество причин псориаза и факторов, предрасполагающих к развитию этого дерматоза, в связи с чем выдвинут ряд теорий его происхождения.

Аутоиммунная

Это основная теория, так как точно установлено, что иммунная система активно реагирует на некоторые виды воздействия на кожу. Кожные покровы людей, страдающих псориазом, очень чувствительны к механическим, физическим, химическим воздействиям. На такие воздействия реагируют не только клетки эпителия, но и вся иммунная система.

Нарушается клеточный иммунитет: соотношение между отдельными подвидами лимфоцитов, отвечающими за формирование нормального иммунного ответа. Так, при псориазе увеличивается число Т-лимфоцитов хелперов – помощников, регулирующих иммунитет, одновременно уменьшается число Т-лимфоцитов супрессоров, подавляющих чрезмерно сильную иммунную реакцию. Лимфоциты и некоторые другие клетки продуцируют цитокины – активные вещества, стимулирующие иммунный ответ. Страдает и гуморальный иммунитет, развивается дисбаланс антител (иммуноглобулинов) в сыворотке крови, появляются антитела к тканям организма больного.

Воспаление начинается на фоне активизации Т-лимфоцитов, но почему они активизируются, не установлено. В процессе исследования находится также вопрос о том, как подавить аутоиммунную реакцию, не навредив пациенту.

Обменная

Дисбаланс в обмене веществ оказывает значительное влияние на кожные покровы и иммунитет. У больных псориазом отмечается ускорение обмена веществ, появление большого количества токсичных свободных радикалов и других токсинов, поддерживающих воспалительную реакцию. Нарушается обмен веществ:

- белковый – ген предрасположенности CDSN стимулирует синтез белка корнеодесмосина, сенсибилизирующего (аллергизирующего) организм; снижается содержание в крови белков альбуминов и повышается содержание глобулинов; такое состояние называется диспротеинемией и еще более усиливает сенсибилизацию;

- жировой – в крови повышается содержание липидов и холестерина; употребление преимущественно растительной пищи и общее снижение калорийности суточного рациона способно снизить активность псориатического воспаления;

- углеводный – почти всегда нарушается;

- обмен витаминов и минералов – повышается содержание в коже витамина С, снижается содержание в крови витаминов С, А, В6, В12, железа, меди и цинка.

Инфекционная

Эта теория была актуальна вначале и в середине прошлого века. Возбудителями псориаза считали некоторые бактерии (стрептококки), грибы и вирусы. Эти теории не подтвердились. Но дерматологи отмечают, что любой острый инфекционный процесс или наличие постоянного очага инфекции способно провоцировать рецидивы. Особое место занимает вирусная теория. Последние исследования выявили влияние ретровирусов (РНК-содержащих вирусов – ВИЧ и др.) на генетический аппарат с формированием генов псориатической предрасположенности.

Генетическая

Предрасположенность к аутоиммунным реакциям передается по наследству. Если близкие человека страдают псориазом, то вероятность развития у него этой болезни многократно возрастает. Существуют гены предрасположенности к псориазу (локальные комплексы PSORS1 — PSORS9, особенно активен PSORS1, он содержит гены HLA-C, HLA-Cw6, CCHCR1 и CDSN, отвечающие за развитиеболезни). Гены оказывают воздействие на обмен веществ, иммунитет и развитие аутоиммунных процессов. Но наличие таких генов вовсе не гарантирует развитие болезни. Большое значение имеет воздействие провоцирующих факторов.

Нейрогенная

Затяжные стрессы, высокие нервно-психические нагрузки, нарушения со стороны вегетативной нервной системы (иннервирующей стенки кровеносных сосудов и внутренние органы) могут стать причиной развития псориаза, вызвав дисбаланс в эндокринной системе, нарушение обменных и иммунологических процессов.

Эндокринная

Эндокринные нарушения при псориазе встречаются часто и носят в основном роль провоцирующего фактора. Четкая связь между ними не доказана. Дерматологи отмечают, что у пациентов нередко выявляются нарушения функции щитовидной железы, надпочечников, гипофиза. Встречаются нарушения менструального цикла у женщин и половой функции у мужчин.

Симптомы псориаза

Основные симптомы псориаза – кожные высыпания. Но встречаются и другие признаки. Самые первые проявления появляются обычно в подростковом или в детском возрасте на фоне гормональных нарушений, вегето-сосудистой дистонии и затяжных стрессов.

Болезнь начинается с ощущения постоянной усталости, нарушения настроения. Характерны мелкие, возвышающиеся над поверхностью розоватые образования (папулы), припорошенные сверху белесоватым шелушением. Они окружены более ярким возвышающимся ободком.

Элементы сыпи разрастаются и соединяются в крупные бляшки причудливых форм. Основание папулы – воспалительный инфильтрат. По характеру сыпи псориаз делят на:

- точечный – элементы не более 1мм в диаметре;

- каплевидный – папулы-капельки размером до 2 мм;

- монетовидный – круглые папулы-монетки величиной до 5 мм.

Характерные особенности сыпи:

- стеариновое пятно – если поскоблить, поверхность папулы;

- терминальная пленка – тщательно очистив поверхность папулы от чешуек, увидим прозрачную пленочку;

- кровавая роса (феномен Ауспитца) – поскоблив пленку и нарушив ее целостность, увидим выступающие на поверхности мелкие кровавые капельки.

Стадии псориаза

Выделяют три стадии болезни:

- прогрессирующая – появляются первые элементы сыпи, их количество нарастает, захватываются все новые участки; высыпания появляются также при расчесывании зудящей кожи или воздействии на нее каких-то внешних раздражающих факторов (феномен Кебнера); в начальной стадия псориаза папулы начинают сливаться в крупные бляшки;

- стационарная – новых элементов нет, а те, что появились ранее, не регрессируют;

- регрессирующая – сыпь бледнеет основание ее становится менее плотным; постепенно сыпь регрессирует, процесс чаще начинается с центральной части, поэтому бляшки могут иметь образ колец; если бляшки при псориазе рассасываются от периферии к центру, то они просто постепенно уменьшаются в размере и вокруг них формируется белое кольцо – псевдоатрофический ободок Воронова; там, где была сыпь, остаются белые, лишенные пигмента участки– псориатическая лейкодерма.

Изредка на коже одновременно присутствуют папулы на всех трех стадиях развития. Выделяют также летнюю и зимнюю формы с преобладания обострений летом или зимой.

Заразен ли псориаз

Многочисленные исследования подтвердили, что это не заразное заболевание. Если инфекционные возбудители и принимают участие в его развитии, то только путем общего воздействия на обмен веществ, иммунитет и генетический аппарат.

Пациенты часто спрашивают:

Как передается псориаз?

От человека к человеку псориаз не передается.Передается ли псориаз по наследству?

Ответ вновь отрицательный, но существует наследственная предрасположенность в виде особенностей обмена веществ и функционирования иммунной системы, которая передается близким родственникам.

Виды псориаза

Характер высыпаний, их расположение, поражение других органов и систем при этом хроническом дерматозе могут быть разными. По данным признакам выделяют несколько видов болезни.

Простой (вульгарный, бляшечный)

Самый распространенный. Симптомами его являются папулы характерного ярко-розового цвета, покрытые белыми чешуйками. По течению бляшечный псориаз делят на следующие формы:

- легкую – если поражение захватывает не более 3% кожи; в прогрессирующей фазе папулы увеличиваются, но затем достаточно быстро подвергаются обратному развитию;

- средней тяжести – сыпь занимает от 3 до 10%; папулы крупные, сливаются в бляшки;

- тяжелую – поражение захватывает более 10%; высыпания многочисленные, сливаются, образуя самые разнообразные фигуры.

Протекает вульгарный псориаз в виде рецидивов, сменяющихся ремиссиями, но бывает также непрерывное течение.

Локтевой псориаз

Это одно из проявлений легкой формы бляшечного воспаления. Отличительной особенностью псориаза на локтях является постоянное присутствие одной или нескольких «дежурных» бляшек на разгибательной стороне локтевых суставов. Если эти элементы травмируются, начинается обострение.

Каплевидный псориаз

В развитии каплевидного псориаза большое значение имеет бактериальная (чаще всего стрептококковая) и вирусная инфекция. Встречается в детском возрасте. Воспаление начинается после перенесенной инфекции. Стрептококки выделяют токсины (антигены – вещества, чужеродные по отношению к организму человека), связывающиеся с белками тканей. К ним вырабатываются антитела и развивается аутоиммунное воспаление.

Начало острое. На коже конечностей (реже тела и лица) возникают мелкие красные папулки-слезки с шелушащейся поверхностью. При травмах в области высыпаний образуются небольшие эрозии и язвочки, увеличивается риск инфицирования.

Псориаз быстро принимает подострое и хроническое течение. Рецидивы сменяются ремиссиями, возможно самостоятельное выздоровление или переход во взрослую форму заболевания.

Ладонно-подошвенный псориаз

Развивается у тех, кто занимается физическим трудом, сопровождается сильным зудом и почти всегда дает осложнение на ногти. Выделяют подвиды:

- бляшечно-веерообразный – с крупными элементами на ладонных и подошвенных поверхностях, покрытыми белыми чешуйками, сливающимися в веерообразные бляшки; чаще встречается такой псориаз на руках;

- круговой – кольцевидные шелушащиеся элементы на ладонных и подошвенных поверхностях;

- мозолистый — характеризуется разрастанием грубого эпителия с формированием мозолей;

Отдельным подвидом является пустулезный псориаз на ладонях и подошвах Барбера. Участки под большими пальцами конечностей покрываются пузырьками и пустулами (с гнойным содержимым), появляется сильнейший зуд. Гнойники сливаются, потом присыхают, образуя корочки. В других местах на теле развиваются характерные псориатические элементы. Заболевание часто переходит на ногти.

Псориаз на ногах поддерживается и обостряется за счет варикозного расширения вен, в таком случае высыпания будут в основном в области голеней.

Псориаз ногтей

Поражение ногтей может быть, как самостоятельным, так и осложнением. Характерные симптомы:

- на ногтевой пластинке появляются мелкие ямочки разной глубины; аналогичные поражения ногтей встречаются при других дерматитах, но при псориатическом поражении они более глубокие и слегка болезненные при надавливании;

- самопроизвольное медленное безболезненное отделение ногтя (онихолизис);

- подногтевые кровоизлияния на ногтях ног, особенно, если больной носит тесную обувь;

- трахионихия – помутнение и неровности на ногтевой пластине; в середине ногтя формируется углубление и ноготь становится похожим на ложку (койлонихия).

Иногда поражается околоногтевой валик с переходом воспаления на другие ткани (псориатическая паронихия).

Псориаз волосистой части головы

Здесь болезнь протекает самостоятельно или как часть общего патологического процесса. Характерно мокнутие, образование корочек на части или на всей поверхности головы. Рост волос при этом не страдает: псориаз на голове не нарушает функцию корней волос. Но мокнутие создает угрозу присоединения инфекции с последующим поражением волосяных луковиц.

Протекает волнообразно, то затихая с исчезновением корок, то вновь обостряясь и сопровождается сильнейшим зудом, часто доводящим больных до невроза.

Себорейный псориаз

Себорея – это состояние, вызванное нарушением работы кожных желез, вырабатывающих сало. Вырабатывается вязкое сало, раздражающее кожу и способствующее развитию воспаления – дерматита.

Себорейный псориаз быстро распространяется на всю голову, покрывая ее в виде шапочки и сопровождаясь сильнейшим зудом. На заушных участках иногда развивается мокнутие и присоединяется инфекция. Покрытая перхотью и сплошными корочками голова иногда имеет вид псориатической короны.

Псориаз на лице

Обычно псориаз на лице локализуется в области носогубного треугольника, век, над бровями, на заушных участках. Слившиеся элементы сыпи образуют большие зоны покраснения и отека. Если имеется нарушение функционирования сальных желез, процесс часто сопровождается мокнутием, образованием корочек, увеличением риска присоединения инфекции.

Псориаз на половых органах

Это не изолированный процесс. Одновременно с поражением половых органов имеются характерные псориатические высыпания по всему телу, поэтому выявить заболевание бывает не сложно.

Псориаз на половом члене у мужчин и больших половых губах у женщин, а также на прилегающих к ним кожных участках, проявляется в виде овальных, слегка возвышающихся над кожей розовых шелушащихся папул. Зуда практически не бывает. Иногда процесс распространяется на слизистые оболочки и имеет вид вульвовагинита у женщин и баланопостита у мужчин.

Атипичные псориатические высыпания могут наблюдаться у полных людей в складках, расположенных рядом с половыми органами (паховых, межъягодичных). Здесь формируются участки интенсивного красного цвета с зеркальной поверхностью без признаков шелушения из-за постоянного мокнутия.

Чем опасен псориаз и нужно ли его лечить

Опасность в том, что псориаз может принять распространенную тяжелую форму, высыпания займут более 10% покровов. Такая стадия заболевания протекает тяжело, рецидивирует, элементы сыпи травмируются и мокнут, часто присоединяется инфекция. Только вовремя назначенное лечение псориаза может приостановить процесс его распространения.

Иногда заболевание осложняется воспалением в суставах с формированием псориатического полиартрита, на фоне которого может значительно нарушаться функция суставов.

На фоне системного аутоиммунного процесса, оказывающего значительное влияние на состояние больного часто развиваются другие аутоиммунные заболевания (ревматоидный артрит, некоторые типы артрозов, болезнь Крона и др.), а также тяжелая сердечно-сосудистая патология, болезни органов пищеварения, неврологические реакции.

Если не начать вовремя лечение псориаза, состояние больного резко осложнится и приведет к инвалидности.

Существует также такое осложнение, как псориатическая эритродермия, развивающаяся при неправильном или недостаточном лечении псориаза, а также при воздействии на воспаленную кожу различных раздражающих факторов. Кожные покровы приобретают ярко-розовую окраску с четким отграничением пораженных участков от здоровых, мелким и крупным пластинчатым шелушением. Такому больному требуется экстренная медицинская помощь.

Методы лечения

Аутоиммунное воспаление требует индивидуально подобранной комплексной терапии, изменения образа жизни, питания, исключения всех вредных привычек. Современной медициной предложены три основных принципа успешного лечения псориаза:

- строгое соблюдение алгоритмов проведения назначенной терапии;

- регулярное отслеживание эффективности проводимой терапии;

- своевременная коррекция назначенной терапии при ее недостаточной эффективности.

Питание при псориазе

Специальной диеты при псориазе нет, но питание имеет большое значение. Поэтому при назначении комплексного лечения обязательно даются рекомендации по питанию:

- выявлять повышенную чувствительность организма к отдельным продуктам и исключать их из рациона;

- отдавать предпочтение свежим овощам, некислым фруктам и ягодам, отварному и запеченному нежирному мясу, больше пить;

- что нельзя есть при псориазе:

- продукты, содержащие эфирные масла – лук, чеснок, редиску;

- напитки, содержащие кофеин (концентрированные чай, кофе), алкоголь;

- все соленее, кислое и сладкое, сдобное;

- продукты, способствующие сенсибилизации (аллергизации) организма –плоды оранжевого цвета, мед, орехи, какао, яйца;

- не употреблять жирное продукты животного происхождения.

Диета Пегано при псориазе

Эта диета была разработана американским врачом Джоном Пегано, но не нашла официального признания в медицине. Принцип построения диеты Пегано при псориазе связан с ощелачиванием организма путем подбора правильного рациона. По этому принципу все продукты делятся на:

- щелочеобразующие (две трети в суточном рационе) – некислые фруктово-ягодные смеси и соки, овощи (исключить вызывающие повышенное газообразование);

- кислотообразующие (треть рациона) – мясные, рыбные, молочные продукты, фасоль, горох, картофель, крупы, сладости и сдоба.

Больным рекомендуется пить минеральную воду без газа, питьевую воду до 1,5 л в сутки плюс другие выпиваемые жидкости (компоты, соки и др.)

Медикаментозная терапия

Лечение легкой формы псориаза проводится при помощи наружных лекарственных препаратов. Тяжелые и быстро прогрессирующие формы заболевания лечат преимущественно в условиях стационара с назначением лекарств общего (системного) действия.

Наружное лечение псориаза

Лекарство подбирает дерматолог. При вульгарном псориазе с сухими стягивающими бляшками подойдут мази, если развивается мокнутие (при себорейном), то используют кремы и лекарственные растворы. Для того, чтобы избежать резистентности (устойчивости) организма к определенному препарату, его со временем меняют.

В острой (прогрессирующей) стадии проводится следующая наружная терапия:

- средства, оказывающие размягчающее воздействие — борный вазелин, 2% салициловая мазь;

- эффективны негормональные мази от псориаза, содержащие активированный цинк-пиритионат (Скин-кап, Цинокап); они подавляют инфекцию и оказывают цитостатическое (подавляют разрастание тканей) действие;

- наружные средства, содержащие глюкокортикостероидные (ГКС) гормоны;

- мазь Дайвобет – комбинированное средство с кальципотриолом (аналогом витамина D3 ) и ГКС бетаметазоном; отлично подавляет воспалительный процесс;

Наружное лечение псориаза в стационарной стадии:

- мази, растворяющие чешуйки (кератолитические) и оказывающие противовоспалительное действие – 5% нафталановые, борно-нафталановые, дегтярно-нафталановые;

- кортикостероидные средства.

Наружное лечение псориаза в разрешающей стадии:

- те же кератолитические мази, но в более высокой концентрации: 10% дегтярно-нафталановые мази;

- мази на основе аналогов витамина Д3 (Кальципотриол, Псоркутан) – в течение 6 – 8 недель; подавляет воспалительный процесс и шелушения сыпи.

Для лечения ногтевого псориаза применяют специальные лаки (Бельведер), которые подавляют развитие патологического процесса. Околоногтевые фаланги рекомендуется обрабатывать увлажняющими гелями.

Системное лечение псориаза

- средства, снимающие воспаление и интоксикацию – хлористый кальций, тиосульфат натрия, унитиол в виде инъекций;

- таблетки от псориаза, подавляющие процессы пролиферации (размножения клеток эпителия) — цитостатики (Метотрексат), подавляющие активность иммунной системы (Циклоспорин А), аналоги витамина А (Ацитретин), кортикостероидные гормоны;

- биологические средства (устекинумаб — Стелара), содержащие человеческие моноклональные антитела класса IgG, воздействующие на определенные звенья воспаления путем подавления синтеза цитокинов; это очень эффективный современный препарат, который вводится в виде инъекций;

- витамины при псориазе способствуют восстановлению обмена веществ и ороговения клеток эпителия; врачи назначают витамины А, Е (Аевит), D3, группы В.

Народные средства при псориазе

Любое лечение псориаза, в том числе, с применением народных средств, может назначать только врач. Самостоятельное лечение может привести к обратному эффекту: распространению болезни.

В составе комплексной терапии могут быть использования следующие методы:

- солидол – продукт переработки технических масел; для приготовления мази нужно купить в аптеке медицинский солидол;

рецепт: в 0,5 кг солидола, добавить 50 г меда и половину упаковки детского крема; процедуры проводятся ежедневно; в аптеке можно приобрести готовые препараты на основе солидола Магнипсор, Унгветол и др. - сода пищевая – народное средство от псориаза, способствующее очищению от корочек, снимает зуд;

рецепт содовых аппликаций: взять 60 г соды, растворить в 0,5 л воды, намочить в растворе марлевую салфетку, сложить ее в несколько слоев и приложить к очагу поражения на 20 минут; после процедуры промокнуть кожу и нанести на нее любую смягчающую мазь; лечение псориаза содой проводят один раз в день; - мумие – обладает выраженным противовоспалительным действием, хорошо снимает зуд;

можно принимать внутрь 1 раз в день по 0,2 г в течение двух недель; наружная терапия проводится раствором мумие; его наносят на сухие зудящие бляшки дважды в день; лечение псориаза на голове проводят ополаскиванием кожи головы раствором мумие после мытья; - морская соль – хорошо снимает воспаление, зуд; ванны с морской солью:

взять 1 кг соли, развести в двух литрах воды и добавить в ванну; принимать ванну 15 минут, после чего смыть раствор под теплым душем, промокнуть тело полотенцем и нанести смягчающую мазь; лечение псориаза ваннами проводить не чаще двух раз в неделю; - глина – оказывает выраженное очищающее действие, адсорбируя на своей поверхности токсины, образовавшиеся в результате воспаления и неправильного обмена веществ; способствует подсушиванию, устранению корок и зуда;

взять можно любую глину, но лучше купить голубую глину в аптеке; кусочки глины нужно хорошо просушить, разбить молотком, развести водой и дать постоять несколько часов; полученную пластинообразную глину наложить на салфетку (до 3 см толщиной) и приложить к очагам воспаления на три часа; лечение псориаза глиной проводить через день.

Важно: лечение псориаза в домашних условиях народными средствами следует проводить с осторожностью и строго по назначению врача. Одному больному такое лечение поможет, а у другого может вызвать обострение и быстрое распространение воспаления. Поэтому, если на фоне проводимой терапии состояние больного ухудшилось, нужно немедленно прекратить ее и обратиться к врачу.

Домашнее лечение псориаза

При лечении псориаза в домашних условиях важно соблюдать рекомендации по питанию, вести здоровый образ жизни, исключить вредные привычки и четко выполнять все назначения дерматолога.

Как вылечить псориаз в домашних условиях? Некоторые пациенты стараются очиститься от токсинов и шлаков всевозможными нетрадиционными способами (клизмами и др.). Это может дать прямо противоположный результат: нарушится работа пищеварительного тракта и начнется обострение. Современная медицина признает очищение организма в виде правильного питания и избавления от вредных привычек.

Важно выполнять все назначения врача и обращать внимание на то, как действует назначенная терапия. Если она недостаточно эффективно, врач заменит лечение, добиваясь максимального лечебного эффекта.

Фототерапия

Лечение псориаза светом применяется давно и успешно. С этой целью используют ультрафиолетовое (УФ) излучение двух видов:

- средневолновое УФ излучение В – облучение проводится по методу избирательной (селективной) фототерапии, при которой облучаются пораженные участки кожи; на курс лечения достаточно 20 процедур с интервалами через день;

- длинноволновое УФ излучение А – это фотохимиотерапия или ПУВА-терапия; на тело пациента вначале воздействуют фотосенсибилизатором (его можно принимать внутрь или использовать наружно, в виде раствора), повышающим чувствительность кожи к УФ лучам; через 90 минут проводится облучение кожи длинноволновыми УФ лучами.

Хирургический метод

Хирургический метод лечения псориаза разработан доктором Мартыновым. Он заключается в укреплении баугиниевой заслонки – привратника, расположенного на границе тонкого и толстого кишечника.

В норме привратник пропускает пищу только в одном направлении: из тонкого кишечника в толстый. Но иногда заслонка не срабатывает и содержимое толстого кишечника забрасывается в тонкий. А так как в толстом кишечнике скапливается множество микроорганизмов, продуктов распада пищи, токсичных газов и т.д., организм страдает от интоксикации. Токсические вещества провоцируют развитие кожных нарушений.

После хирургического лечения псориаза у многих пациентов наступает стойкая ремиссия. Однако, следует понимать, что как и при любой полостной операции, есть риск развития тяжелых осложнений: инфицирования, кровотечения, осложнений от общей анестезии и т.д. Поэтому перед тем, как решиться на оперативное вмешательство, стоит обсудить с дерматологом, насколько этот метод лечения подойдет именно вам.

Помогут ли гормоны при псориазе?

Кортикостероидные гормоны широко используются в лечении псориаза. Они прекрасно устраняют отек, зуд, подавляют разрастание тканей. Но к гормонам быстро развивается привыкание и они дают серьезные побочные эффекты. Поэтому дерматологи применяют их с большой осторожностью, курсами и в сочетании с другими лекарствами, усиливающими их действие.

Одним из самых эффективных сочетаний является комбинация синтетического аналога витамина D3 кальципотриола и кортикостероида бетаметазона в препарате Дайвобет. Два активных действующих вещества взаимно усиливают действие друг друга и уменьшают побочные эффекты за счет уменьшения дозировок. Устойчивость организма к этому препарату практически не развивается при назначении его короткими повторяющимися курсами в течение года. Эта методика хорошо сочетается с системной терапией.

Часто встает вопрос о том, чем лечить псориаз на голове. Мазь Дайвобет прекрасно подойдет и для этих целей. Она способна поддерживать длительную ремиссию и предупреждать начало рецидивов. Дайвобет оценивается пациентами как стабилизирующий, поддерживающий ремиссию и предотвращающий наступление обострений препарат.

Методы восточной медицины при псориазе

Восточная медицина рассматривает аутоиммунное воспаление как нарушение нейроэндокринного баланса и иммунитета. Врачи нашей клиники воздействуют на определенные точки на теле (акупунктурные точки – АТ) больного для восстановления нарушенного баланса.

За долгие годы практики мы разработали уникальные методики лечения псориаза, сочитающие в себе проверенные техники востока и иновационные методы западной медицины:

Работаем с определенными зонами на коже (ступне или ладони), помогая организму побороть охватившую его болезнь. Метод снимает боль и напряжение, улучшает общее состояние.

Применяя индивидуально подобранные лекарственные травы и препараты из них, фитотерапевт помогает восстановить организм, ослабленный болезнью.

Прижигание разогретыми полынными сигарами — безболезненный метод, устраняющий болевой синдром, улучшающий метаболизм и кровообращение.

Суть плазмолифтинга заключается в том, что в проблемные места вводится плазма, обогащенная тромбоцитами. Тромбоциты приобретают регенеративную способность, когда их содержание в плазме становится в несколько раз выше нормы.

Врач иглотерапевт вводит на небольшую глубину стерильные иглы, индивидуально подбирая точки, связанные с внутренними системами организма пациента.

Прогреваем места расположения биологически активных точек с использованием безвредных для человека моксов — ароматических сигар.

Метод позволяет обойтись минимальными дозами лекарств, вводя их в известные специалисту области. Препарат моментально начинает воздействий на пораженную недугом зону.

PRP-терапия — новейший способ стимуляции восстановительных процессов. Применяется для восстановления функций различных органов после заболеваний и травм, в том числе, для лечения ран, восстановления функции опорно-двигательного аппарата.

Точки для лечения псориаза подбираются для каждого больного индивидуально после проведения врачом специальной диагностики по восточным методикам.

Если специалист действительно разбирается в восточных методах диагностики и лечения, то лечебный эффект устранит рецидивы на годы. Побочные эффекты отсутствуют! Эти методики широко применяются в нашей клинике, специалистами, имеющими всю необходимую подготовку по рефлексотерапии. После проведенного курса лечения псориаза обострений, как правило, не бывает долго, а регулярные профилактические курсы рефлексотерапии избавляют от рецидивов на многие годы и значительно улучшают качество жизни.

Санаторное лечение псориаза на море

Морские купания, солнечные ванны и грязи оказывают положительное воздействие на больных псориазом. При таком воздействии очищается кожа, она становится гладкой и здоровой. Пребывание больного псориазом в санатории на протяжении месяца способно избавить от рецидивов заболевания на полгода.

Санатории для больных псориазом есть на Черном и Азовском море. Более эффективным считается курортное лечение на Мертвом море. Метод подойдет больным в стационарной и регрессирующей стадиях. Острый воспалительный процесс (прогрессирующая стадия) является противопоказанием для такого лечения, так как прогрессирование может усилиться. Есть и такие больные, которым морские курорты противопоказаны, так как способствуют развитию обострений.

Профилактика псориаза

Профилактика обострений — это:

- подвижный образ жизни;

- диетическое питание;

- избавление от вредных привычек;

- правильный уход за кожей с подбором индивидуальных гигиенических средств;

- предупреждение травмирования кожи;

- привычка своевременно лечить все очаги инфекции;

- ограничение контактов с любыми кожными раздражителями;

- борьба с затяжными стрессами и высокими эмоциональными нагрузками;

- прием любых лекарственных препаратов нужно согласовывать с лечащим врачом;

- ношение просторной одежды из натуральных тканей;

- по возможности ежегодное санаторно-курортное лечение псориаза на море.

Заберут ли в армию с псориазом?

Берут ли в армию с псориазом? Этот вопрос интересует многих призывников. Распространенные, прогрессирующие и тяжелые формы этого аутоиммунного заболевания являются причиной освобождения от службы, независимо от того, заразен или нет псориаз для окружающих. В армию могут взять, если псориаз впервые начался и его удалось остановить. Но чаще таким призывникам дают заключение «Частично годен» и отправляют в запас. Заключение «Частично не годен» означает, что человек может быть призван на службу только в случае начала военных действий.

Как вылечить псориаз навсегда?

К сожалению, это невозможно, даже после длительной ремиссии может начаться очередное обострение. Об это следует помнить всегда и постоянно проводить профилактические процедуры.

Псориаз – тяжелая системная болезнь с преимущественным поражением кожных покровов и вовлечением в процесс множества других органов и систем. В большинстве случаев регулярная поддерживающая терапия по назначению грамотного специалиста позволяет взять под контроль распространение псориатического процесса и значительно улучшить качество жизни больного.

Специалисты нашей клиники проводят курсы лечения псориаза, как в активной фазе, так и во время ремиссии. Наше лечение отличается индивидуальным подходом и сочетанием лучших методик западной и восточной медицины. Такой подход позволяет больным забыть о рецидивах заболевания и побочных эффектах от лечения на долгие годы.

Оценка читателей

| Psoriasis | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Back and arms of a person with psoriasis | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Red (purple on darker skin), itchy, scaly patches of skin[3] |

| Complications | Psoriatic arthritis[4] |

| Usual onset | Adulthood[5] |

| Duration | Long term[4] |

| Causes | Genetic disease triggered by environmental factors[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[4] |

| Treatment | Steroid creams, vitamin D3 cream, ultraviolet light, Immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate[5] |

| Frequency | 79.7 million[6] / 2–4%[7] |

Psoriasis is a long-lasting, noncontagious[4] autoimmune disease characterized by raised areas of abnormal skin.[5] These areas are red, pink, or purple,[8] dry, itchy, and scaly.[3] Psoriasis varies in severity from small, localized patches to complete body coverage.[3] Injury to the skin can trigger psoriatic skin changes at that spot, which is known as the Koebner phenomenon.[9]

The five main types of psoriasis are plaque, guttate, inverse, pustular, and erythrodermic.[5] Plaque psoriasis, also known as psoriasis vulgaris, makes up about 90% of cases.[4] It typically presents as red patches with white scales on top.[4] Areas of the body most commonly affected are the back of the forearms, shins, navel area, and scalp.[4] Guttate psoriasis has drop-shaped lesions.[5] Pustular psoriasis presents as small, noninfectious, pus-filled blisters.[10] Inverse psoriasis forms red patches in skin folds.[5] Erythrodermic psoriasis occurs when the rash becomes very widespread, and can develop from any of the other types.[4] Fingernails and toenails are affected in most people with psoriasis at some point in time.[4] This may include pits in the nails or changes in nail color.[4]

Psoriasis is generally thought to be a genetic disease that is triggered by environmental factors.[3] If one twin has psoriasis, the other twin is three times more likely to be affected if the twins are identical than if they are nonidentical.[4] This suggests that genetic factors predispose to psoriasis.[4] Symptoms often worsen during winter and with certain medications, such as beta blockers or NSAIDs.[4] Infections and psychological stress can also play a role.[3][5] The underlying mechanism involves the immune system reacting to skin cells.[4] Diagnosis is typically based on the signs and symptoms.[4]

There is no known cure for psoriasis, but various treatments can help control the symptoms.[4] These treatments include steroid creams, vitamin D3 cream, ultraviolet light, immunosuppressive drugs, such as methotrexate, and biologic therapies targeting specific immunologic pathways.[5] About 75% of skin involvement improves with creams alone.[4] The disease affects 2–4% of the population.[7] Men and women are affected with equal frequency.[5] The disease may begin at any age, but typically starts in adulthood.[5] Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of psoriatic arthritis, lymphomas, cardiovascular disease, Crohn’s disease, and depression.[4] Psoriatic arthritis affects up to 30% of individuals with psoriasis.[10]

The word «psoriasis» is from Greek ψωρίασις, meaning «itching condition» or «being itchy»[11] from psora, «itch», and -iasis, «action, condition».

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Plaque psoriasis[edit]

Psoriatic plaque, showing a silvery center surrounded by a reddened border

Psoriasis vulgaris (also known as chronic stationary psoriasis or plaque-like psoriasis) is the most common form and affects 85–90% of people with psoriasis.[12] Plaque psoriasis typically appears as raised areas of inflamed skin covered with silvery-white, scaly skin. These areas are called plaques and are most commonly found on the elbows, knees, scalp, and back.[12][13]

-

Plaques of psoriasis

-

A person’s arm covered with plaque psoriasis

-

Psoriasis of the palms

Other forms[edit]

Additional types of psoriasis comprise about 10% of cases. They include pustular, inverse, napkin, guttate, oral, and seborrheic-like forms.[14]

Pustular psoriasis[edit]

Severe generalized pustular psoriasis

Pustular psoriasis appears as raised bumps filled with noninfectious pus (pustules).[15] The skin under and surrounding the pustules is red and tender.[16] Pustular psoriasis can either be localized or more widespread throughout the body. Two types of localized pustular psoriasis include psoriasis pustulosa palmoplantaris and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau; both forms are localized to the hands and feet.[17]

Inverse psoriasis[edit]

Inverse psoriasis (also known as flexural psoriasis) appears as smooth, inflamed patches of skin. The patches frequently affect skin folds, particularly around the genitals (between the thigh and groin), the armpits, in the skin folds of an overweight abdomen (known as panniculus), between the buttocks in the intergluteal cleft, and under the breasts in the inframammary fold. Heat, trauma, and infection are thought to play a role in the development of this atypical form of psoriasis.[18]

Napkin psoriasis[edit]

Napkin psoriasis is a subtype of psoriasis common in infants characterized by red papules with silver scale in the diaper area that may extend to the torso or limbs.[19] Napkin psoriasis is often misdiagnosed as napkin dermatitis (diaper rash).[20]

Guttate psoriasis[edit]

Guttate psoriasis is an inflammatory condition characterized by numerous small, scaly, red or pink, droplet-like lesions (papules). These numerous papules appear over large areas of the body, primarily the trunk, limbs, and scalp, but typically spares the palms and soles. Guttate psoriasis is often triggered by a streptococcal infection (oropharyngeal or perianal) and typically occurs 1-3 weeks post-infection. Guttate psoriasis is most commonly seen in children and young adults and diagnosis is typically made based on history and clinical exam findings.[21] Skin biopsy can also be performed which typically shows a psoriasiform reaction pattern characterized by epidermal hyperplasia and rate ridge prolongation. [22]

There is no firm evidence regarding best management for guttate psoriasis; however, first line therapy for mild guttate psoriasis typically includes topical corticosteroids.[23] [24]Phototherapy can be used for moderate or severe guttate psoriasis. Biologic treatments have not been well studied in the treatment of guttate psoriasis.[25]

Guttate psoriasis has a greater prognosis than plaque psoriasis and typically resolves within 1-3 weeks; however, up to 40% of patients with guttate psoriasis eventually convert to plaque psoriasis. [26][18]

Erythrodermic psoriasis[edit]

Psoriatic erythroderma (erythrodermic psoriasis) involves widespread inflammation and exfoliation of the skin over most of the body surface, often involving greater than 90% of the body surface area.[17] It may be accompanied by severe dryness, itching, swelling, and pain. It can develop from any type of psoriasis.[17] It is often the result of an exacerbation of unstable plaque psoriasis, particularly following the abrupt withdrawal of systemic glucocorticoids.[27] This form of psoriasis can be fatal as the extreme inflammation and exfoliation disrupt the body’s ability to regulate temperature and perform barrier functions.[28]

Mouth[edit]

Psoriasis in the mouth is very rare,[29] in contrast to lichen planus, another common papulosquamous disorder that commonly involves both the skin and mouth. When psoriasis involves the oral mucosa (the lining of the mouth), it may be asymptomatic,[29] but it may appear as white or grey-yellow plaques.[29] Fissured tongue is the most common finding in those with oral psoriasis and has been reported to occur in 6.5–20% of people with psoriasis affecting the skin. The microscopic appearance of oral mucosa affected by geographic tongue (migratory stomatitis) is very similar to the appearance of psoriasis.[30] However, modern studies have failed to demonstrate any link between the two conditions.[31]

Seborrheic-like psoriasis[edit]

Seborrheic-like psoriasis is a common form of psoriasis with clinical aspects of psoriasis and seborrheic dermatitis, and it may be difficult to distinguish from the latter. This form of psoriasis typically manifests as red plaques with greasy scales in areas of higher sebum production such as the scalp, forehead, skin folds next to the nose, the skin surrounding the mouth, skin on the chest above the sternum, and in skin folds.[19]

Psoriatic arthritis[edit]

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of chronic inflammatory arthritis that has a highly variable clinical presentation and frequently occurs in association with skin and nail psoriasis.[32][33] It typically involves painful inflammation of the joints and surrounding connective tissue, and can occur in any joint, but most commonly affects the joints of the fingers and toes. This can result in a sausage-shaped swelling of the fingers and toes known as dactylitis.[32] Psoriatic arthritis can also affect the hips, knees, spine (spondylitis), and sacroiliac joint (sacroiliitis).[34] About 30% of individuals with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis.[12] Skin manifestations of psoriasis tend to occur before arthritic manifestations in about 75% of cases.[33]

Nail changes[edit]

Psoriasis of a fingernail, with visible pitting

A photograph showing the effects of psoriasis on the toenails

Psoriasis can affect the nails and produces a variety of changes in the appearance of fingers and toenails. Nail psoriasis occurs in 40–45% of people with psoriasis affecting the skin, and has a lifetime incidence of 80–90% in those with psoriatic arthritis.[35] These changes include pitting of the nails (pinhead-sized depressions in the nail is seen in 70% with nail psoriasis), whitening of the nail, small areas of bleeding from capillaries under the nail, yellow-reddish discoloration of the nails known as the oil drop or salmon spots, dryness, thickening of the skin under the nail (subungual hyperkeratosis), loosening and separation of the nail (onycholysis), and crumbling of the nail.[35]

Medical signs[edit]

In addition to the appearance and distribution of the rash, specific medical signs may be used by medical practitioners to assist with diagnosis. These may include Auspitz’s sign (pinpoint bleeding when scale is removed), Koebner phenomenon (psoriatic skin lesions induced by trauma to the skin),[19] and itching and pain localized to papules and plaques.[18][19]

Causes[edit]

The cause of psoriasis is not fully understood, but many theories exist.

Genetics[edit]

Around one-third of people with psoriasis report a family history of the disease, and researchers have identified genetic loci associated with the condition. Identical twin studies suggest a 70% chance of a twin developing psoriasis if the other twin has the disorder. The risk is around 20% for nonidentical twins. These findings suggest both a genetic susceptibility and an environmental response in developing psoriasis.[36]

Psoriasis has a strong hereditary component, and many genes are associated with it, but how those genes work together is unclear. Most of the identified genes relate to the immune system, particularly the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and T cells. Genetic studies are valuable due to their ability to identify molecular mechanisms and pathways for further study and potential medication targets.[37]

Classic genome-wide linkage analysis has identified nine loci on different chromosomes associated with psoriasis. They are called psoriasis susceptibility 1 through 9 (PSORS1 through PSORS9). Within those loci are genes on pathways that lead to inflammation. Certain variations (mutations) of those genes are commonly found in psoriasis.[37] Genome-wide association scans have identified other genes that are altered to characteristic variants in psoriasis. Some of these genes express inflammatory signal proteins, which affect cells in the immune system that are also involved in psoriasis. Some of these genes are also involved in other autoimmune diseases.[37]

The major determinant is PSORS1, which probably accounts for 35–50% of psoriasis heritability.[38] It controls genes that affect the immune system or encode skin proteins that are overabundant with psoriasis. PSORS1 is located on chromosome 6 in the MHC, which controls important immune functions. Three genes in the PSORS1 locus have a strong association with psoriasis vulgaris: HLA-C variant HLA-Cw6,[39] which encodes an MHC class I protein; CCHCR1, variant WWC, which encodes a coiled coil protein overexpressed in psoriatic epidermis; and CDSN, variant allele 5, which encodes corneodesmosin, a protein expressed in the granular and cornified layers of the epidermis and upregulated in psoriasis.[37]

Two major immune system genes under investigation are interleukin-12 subunit beta (IL12B) on chromosome 5q, which expresses interleukin-12B; and IL23R on chromosome 1p, which expresses the interleukin-23 receptor, and is involved in T cell differentiation. Interleukin-23 receptor and IL12B have both been strongly linked with psoriasis.[39] T cells are involved in the inflammatory process that leads to psoriasis.[37] These genes are on the pathway that upregulate tumor necrosis factor-α and nuclear factor κB, two genes involved in inflammation.[37] The first gene directly linked to psoriasis was identified as the CARD14 gene located in the PSORS2 locus. A rare mutation in the gene encoding for the CARD14-regulated protein plus an environmental trigger was enough to cause plaque psoriasis (the most common form of psoriasis).[40][41]

Lifestyle[edit]

Conditions reported as worsening the disease include chronic infections, stress, and changes in season and climate.[39] Others factors that might worsen the condition include hot water, scratching psoriasis skin lesions, skin dryness, excessive alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and obesity.[39][42][43][44] The effects of stopping cigarette smoking or alcohol misuse have yet to be studied as of 2019.[44]

HIV[edit]

The rate of psoriasis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive (HIV) individuals is comparable to that of HIV-negative individuals, but psoriasis tends to be more severe in people infected with HIV.[45] A much higher rate of psoriatic arthritis occurs in HIV-positive individuals with psoriasis than in those without the infection.[45] The immune response in those infected with HIV is typically characterized by cellular signals from Th2 subset of CD4+ helper T cells,[46] whereas the immune response in psoriasis vulgaris is characterized by a pattern of cellular signals typical of Th1 subset of CD4+ helper T cells and Th17 helper T cells.[47][48] The diminished CD4+-T cell presence is thought to cause an overactivation of CD8+-T cells, which are responsible for the exacerbation of psoriasis in HIV-positive people. Psoriasis in those with HIV/AIDS is often severe and may be untreatable with conventional therapy.[49] In those with long-term, well-controlled psoriasis, new HIV infection can trigger a severe flare-up of psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis.[medical citation needed]

Microbes[edit]

Psoriasis has been described as occurring after strep throat, and may be worsened by skin or gut colonization with Staphylococcus aureus, Malassezia spp., and Candida albicans.[50] Guttate psoriasis often affects children and adolescents and can be triggered by a recent group A streptococcal infection (tonsillitis or pharyngitis).[17]

Medications[edit]

Drug-induced psoriasis may occur with beta blockers,[10] lithium,[10] antimalarial medications,[10] nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,[10] terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, captopril, glyburide, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor,[10] interleukins, interferons,[10] lipid-lowering medications,[14]: 197 and paradoxically TNF inhibitors such as infliximab or adalimumab.[51] Withdrawal of corticosteroids (topical steroid cream) can aggravate psoriasis due to the rebound effect.[52]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Psoriasis is characterized by an abnormally excessive and rapid growth of the epidermal layer of the skin.[53] Abnormal production of skin cells (especially during wound repair) and an overabundance of skin cells result from the sequence of pathological events in psoriasis.[16] The sequence of pathological events in psoriasis is thought to start with an initiation phase in which an event (skin trauma, infection, or drugs) leads to activation of the immune system and then the maintenance phase consisting of chronic progression of the disease.[37][17] Skin cells are replaced every 3–5 days in psoriasis rather than the usual 28–30 days.[54] These changes are believed to stem from the premature maturation of keratinocytes induced by an inflammatory cascade in the dermis involving dendritic cells, macrophages, and T cells (three subtypes of white blood cells).[12][45] These immune cells move from the dermis to the epidermis and secrete inflammatory chemical signals (cytokines) such as interleukin-36γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and interleukin-22.[37][55] These secreted inflammatory signals are believed to stimulate keratinocytes to proliferate.[37] One hypothesis is that psoriasis involves a defect in regulatory T cells, and in the regulatory cytokine interleukin-10.[37] The inflammatory cytokines found in psoriatic nails and joints (in the case of psoriatic arthritis) are similar to those of psoriatic skin lesions, suggesting a common inflammatory mechanism.[17]

Gene mutations of proteins involved in the skin’s ability to function as a barrier have been identified as markers of susceptibility for the development of psoriasis.[56][57]

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) released from dying cells acts as an inflammatory stimulus in psoriasis[58] and stimulates the receptors on certain dendritic cells, which in turn produce the cytokine interferon-α.[58] In response to these chemical messages from dendritic cells and T cells, keratinocytes also secrete cytokines such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α, which signal downstream inflammatory cells to arrive and stimulate additional inflammation.[37]

Dendritic cells bridge the innate immune system and adaptive immune system. They are increased in psoriatic lesions[53] and induce the proliferation of T cells and type 1 helper T cells (Th1). Targeted immunotherapy, as well as psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy, can reduce the number of dendritic cells and favors a Th2 cell cytokine secretion pattern over a Th1/Th17 cell cytokine profile.[37][47] Psoriatic T cells move from the dermis into the epidermis and secrete interferon-γ and interleukin-17.[59] Interleukin-23 is known to induce the production of interleukin-17 and interleukin-22.[53][59] Interleukin-22 works in combination with interleukin-17 to induce keratinocytes to secrete neutrophil-attracting cytokines.[59]

Diagnosis[edit]

Micrograph of psoriasis vulgaris. Confluent parakeratosis, psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia [(A), EH], hypogranulosis, and influx of numerous neutrophils in the corneal layer [(A), arrow]. (B) Transepidermal migration of neutrophils from the dermis to the corneal layer (arrows).[60]

A diagnosis of psoriasis is usually based on the appearance of the skin. Skin characteristics typical for psoriasis are scaly, erythematous plaques, papules, or patches of skin that may be painful and itch.[18] No special blood tests or diagnostic procedures are usually required to make the diagnosis.[16][61]

The differential diagnosis of psoriasis includes dermatological conditions similar in appearance such as discoid eczema, seborrheic eczema, pityriasis rosea (may be confused with guttate psoriasis), nail fungus (may be confused with nail psoriasis) or cutaneous T cell lymphoma (50% of individuals with this cancer are initially misdiagnosed with psoriasis).[52] Dermatologic manifestations of systemic illnesses such as the rash of secondary syphilis may also be confused with psoriasis.[52]

If the clinical diagnosis is uncertain, a skin biopsy or scraping may be performed to rule out other disorders and to confirm the diagnosis. Skin from a biopsy shows clubbed epidermal projections that interdigitate with dermis on microscopy. Epidermal thickening is another characteristic histologic finding of psoriasis lesions.[16][62] The stratum granulosum layer of the epidermis is often missing or significantly decreased in psoriatic lesions; the skin cells from the most superficial layer of skin are also abnormal as they never fully mature. Unlike their mature counterparts, these superficial cells keep their nuclei.[16] Inflammatory infiltrates can typically be seen on microscopy when examining skin tissue or joint tissue affected by psoriasis. Epidermal skin tissue affected by psoriatic inflammation often has many CD8+ T cells, while a predominance of CD4+ T cells makes up the inflammatory infiltrates of the dermal layer of skin and the joints.[16]

Classification[edit]

Morphological[edit]

| Psoriasis Type | ICD-10 Code |

|---|---|

| Psoriasis Vulgaris | L40.0 |

| Generalized pustular psoriasis | L40.1 |

| Acrodermatitis continua | L40.2 |

| Pustulosis palmaris et plantaris | L40.3 |

| Guttate psoriasis | L40.4 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | L40.50 |

| Psoriatic spondylitis | L40.53 |

| Inverse psoriasis | L40.8 |

Psoriasis is classified as a papulosquamous disorder and is most commonly subdivided into different categories based on histological characteristics.[3][10] Variants include plaque, pustular, guttate, and flexural psoriasis. Each form has a dedicated ICD-10 code.[63] Psoriasis can also be classified into nonpustular and pustular types.[64]

Pathogenetic[edit]

Another classification scheme considers genetic and demographic factors. Type 1 has a positive family history, starts before the age of 40, and is associated with the human leukocyte antigen, HLA-Cw6. Conversely, type 2 does not show a family history, presents after age 40, and is not associated with HLA-Cw6.[65] Type 1 accounts for about 75% of persons with psoriasis.[66]

The classification of psoriasis as an autoimmune disease has sparked considerable debate. Researchers have proposed differing descriptions of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis; some authors have classified them as autoimmune diseases[16][39][67] while others have classified them as distinct from autoimmune diseases and referred to them as immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.[37][68][69]

Severity[edit]

No consensus exists about how to classify the severity of psoriasis. Mild psoriasis has been defined as a percentage of body surface area (BSA)≤10, a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score ≤10, and a Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score ≤10.[70] Moderate to severe psoriasis was defined by the same group as BSA >10 or PASI score >10 and a DLQI score >10.[70]

The DLQI is a 10-question tool used to measure the impact of several dermatologic diseases on daily functioning. The DLQI score ranges from 0 (minimal impairment) to 30 (maximal impairment) and is calculated with each answer being assigned 0–3 points with higher scores indicating greater social or occupational impairment.[71]

The PASI is the most widely used measurement tool for psoriasis. It assesses the severity of lesions and the area affected and combines these two factors into a single score from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).[72] Nevertheless, the PASI can be too unwieldy to use outside of research settings, which has led to attempts to simplify the index for clinical use.[73]

Management[edit]

Schematic of psoriasis treatment ladder

While no cure is available for psoriasis,[52] many treatment options exist. Topical agents are typically used for mild disease, phototherapy for moderate disease, and systemic agents for severe disease.[74] There is no evidence to support the effectiveness of conventional topical and systemic drugs, biological therapy, or phototherapy for acute guttate psoriasis or an acute guttate flare of chronic psoriasis.[75]

Topical agents[edit]

Topical corticosteroid preparations are the most effective agents when used continuously for eight weeks; retinoids and coal tar were found to be of limited benefit and may be no better than placebo.[76] Greater benefit has been observed with very potent corticosteroids when compared to potent corticosteroids.

Vitamin D analogues such as paricalcitol are superior to placebo. Combination therapy with vitamin D and a corticosteroid are superior to either treatment alone and vitamin D is superior to coal tar for chronic plaque psoriasis.[77]

For psoriasis of the scalp, a 2016 review found dual therapy (vitamin D analogues and topical corticosteroids) or corticosteroid monotherapy to be more effective and safer than topical vitamin D analogues alone.[78] Due to their similar safety profiles and minimal benefit of dual therapy over monotherapy, corticosteroid monotherapy appears to be an acceptable treatment for short-term treatment.[78]

Moisturizers and emollients such as mineral oil, petroleum jelly, calcipotriol, and decubal (an oil-in-water emollient) were found to increase the clearance of psoriatic plaques. Some emollients have been shown to be even more effective at clearing psoriatic plaques when combined with phototherapy.[79] Certain emollients, though, have no impact on psoriasis plaque clearance or may even decrease the clearance achieved with phototherapy, e.g. the emollient salicylic acid is structurally similar to para-aminobenzoic acid, commonly found in sunscreen, and is known to interfere with phototherapy in psoriasis. Coconut oil, when used as an emollient in psoriasis, has been found to decrease plaque clearance with phototherapy.[79] Medicated creams and ointments applied directly to psoriatic plaques can help reduce inflammation, remove built-up scale, reduce skin turnover, and clear affected skin of plaques. Ointment and creams containing coal tar, dithranol, corticosteroids (i.e. desoximetasone), fluocinonide, vitamin D3 analogues (for example, calcipotriol), and retinoids are routinely used. (The use of the finger tip unit may be helpful in guiding how much topical treatment to use.)[42][80]

Vitamin D analogues may be useful with steroids; steroids alone have a higher rate of side effects.[77] Vitamin D analogues may allow less steroids to be used.[81]

Another topical therapy used to treat psoriasis is a form of balneotherapy, which involves daily baths in the Dead Sea. This is usually done for four weeks with the benefit attributed to sun exposure and specifically UVB light. This is cost-effective and it has been propagated as an effective way to treat psoriasis without medication.[82] Decreases of PASI scores greater than 75% and remission for several months have commonly been observed.[82] Side effects may be mild such as itchiness, folliculitis, sunburn, poikiloderma, and a theoretical risk of nonmelanoma cancer or melanoma has been suggested.[82] Some studies indicate no increased risk of melanoma in the long term.[83] Data are inconclusive with respect to nonmelanoma skin cancer risk, but support the idea that the therapy is associated with an increased risk of benign forms of sun-induced skin damage such as, but not limited to, actinic elastosis or liver spots.[83] Dead Sea balneotherapy is also effective for psoriatic arthritis.[83] Tentative evidence indicates that balneophototherapy, a combination of salt bathes and exposure to ultraviolet B-light (UVB), in chronic plaque psoriasis is better than UVB alone.[84]

UV phototherapy[edit]

Phototherapy in the form of sunlight has long been used for psoriasis.[74] UVB wavelengths of 311–313 nanometers are most effective, and special lamps have been developed for this application.[74] The exposure time should be controlled to avoid overexposure and burning of the skin. The UVB lamps should have a timer that turns off the lamp when the time ends. The amount of light used is determined by a person’s skin type.[74] Increased rates of cancer from treatment appear to be small.[74] Narrowband UVB therapy has been demonstrated to have similar efficacy to psoralen and ultraviolet A phototherapy (PUVA).[85] A 2013 meta-analysis found no difference in efficacy between NB-UVB and PUVA in the treatment of psoriasis, but NB-UVB is usually more convenient.[86]

One of the problems with clinical phototherapy is the difficulty many people have gaining access to a facility. Indoor tanning resources are almost ubiquitous today and could be considered as a means for people to get UV exposure when dermatologist-provided phototherapy is not available. Indoor tanning is already used by many people as a treatment for psoriasis; one indoor facility reported that 50% of its clients were using the center for psoriasis treatment; another reported 36% were doing the same thing. However, a concern with the use of commercial tanning is that tanning beds that primarily emit UVA might not effectively treat psoriasis. One study found that plaque psoriasis is responsive to erythemogenic doses of either UVA or UVB, as exposure to either can cause dissipation of psoriatic plaques. It does require more energy to reach erythemogenic dosing with UVA.[87]

UV light therapies all have risks; tanning beds are no exception, being listed by the World Health Organization as carcinogens.[88] Exposure to UV light is known to increase the risks of melanoma and squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas; younger people with psoriasis, particularly those under age 35, are at increased risk from melanoma from UV light treatment. A review of studies recommends that people who are susceptible to skin cancers exercise caution when using UV light therapy as a treatment.[87]

A major mechanism of NB-UVB is the induction of DNA damage in the form of pyrimidine dimers. This type of phototherapy is useful in the treatment of psoriasis because the formation of these dimers interferes with the cell cycle and stops it. The interruption of the cell cycle induced by NB-UVB opposes the characteristic rapid division of skin cells seen in psoriasis.[85] The activity of many types of immune cells found in the skin is also effectively suppressed by NB-UVB phototherapy treatments.[89] The most common short-term side effect of this form of phototherapy is redness of the skin; less common side effects of NB-UVB phototherapy are itching and blistering of the treated skin, irritation of the eyes in the form of conjunctival inflammation or inflammation of the cornea, or cold sores due to reactivation of the herpes simplex virus in the skin surrounding the lips. Eye protection is usually given during phototherapy treatments.[85]

PUVA combines the oral or topical administration of psoralen with exposure to ultraviolet A (UVA) light. The mechanism of action of PUVA is unknown, but probably involves activation of psoralen by UVA light, which inhibits the abnormally rapid production of the cells in psoriatic skin. There are multiple mechanisms of action associated with PUVA, including effects on the skin’s immune system. PUVA is associated with nausea, headache, fatigue, burning, and itching. Long-term treatment is associated with squamous cell carcinoma (but not with melanoma).[43][90] A combination therapy for moderate to severe psoriasis using PUVA plus acitretin resulted in benefit, but acitretin use has been associated with birth defects and liver damage.[91]

Systemic agents[edit]

Psoriasis resistant to topical treatment and phototherapy may be treated with systemic therapies including medications by mouth or injectable treatments.[92] People undergoing systemic treatment must have regular blood and liver function tests to check for medication toxicities.[92] Pregnancy must be avoided for most of these treatments. The majority of people experience a recurrence of psoriasis after systemic treatment is discontinued.

Non-biologic systemic treatments frequently used for psoriasis include methotrexate, ciclosporin, hydroxycarbamide, fumarates such as dimethyl fumarate, and retinoids.[93] Methotrexate and ciclosporin are medications that suppress the immune system; retinoids are synthetic forms of vitamin A. These agents are also regarded as first-line treatments for psoriatic erythroderma.[27] Oral corticosteroids should not be used as they can severely flare psoriasis upon their discontinuation.[94]

Biologics are manufactured proteins that interrupt the immune process involved in psoriasis. Unlike generalized immunosuppressive medical therapies such as methotrexate, biologics target specific aspects of the immune system contributing to psoriasis.[93] These medications are generally well-tolerated, and limited long-term outcome data have demonstrated biologics to be safe for long-term use in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.[93][95] However, due to their immunosuppressive actions, biologics have been associated with a small increase in the risk for infection.[93]

Guidelines regard biologics as third-line treatment for plaque psoriasis following inadequate response to topical treatment, phototherapy, and non-biologic systemic treatments.[95] The safety of biologics during pregnancy has not been assessed. European guidelines recommend avoiding biologics if a pregnancy is planned; anti-TNF therapies such as infliximab are not recommended for use in chronic carriers of the hepatitis B virus or individuals infected with HIV.[93]

Several monoclonal antibodies target cytokines, the molecules that cells use to send inflammatory signals to each other. TNF-α is one of the main executor inflammatory cytokines. Four monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol) and one recombinant TNF-α decoy receptor, etanercept, have been developed to inhibit TNF-α signaling. Additional monoclonal antibodies, such as ixekizumab,[96] have been developed against pro-inflammatory cytokines[97] and inhibit the inflammatory pathway at a different point than the anti-TNF-α antibodies.[37] IL-12 and IL-23 share a common domain, p40, which is the target of the FDA-approved ustekinumab.[39] In 2017 the US FDA approved guselkumab for plaque psoriasis.[98] There have been few studies of the efficacy of anti-TNF medications for psoriasis in children. One randomized control study suggested that 12 weeks of etanercept treatment reduced the extent of psoriasis in children with no lasting adverse effects.[99]

Two medications that target T cells are efalizumab and alefacept. Efalizumab is a monoclonal antibody that specifically targets the CD11a subunit of LFA-1.[93] It also blocks the adhesion molecules on the endothelial cells that line blood vessels, which attract T cells. Efalizumab was voluntarily withdrawn from the European market in February 2009, and from the U.S. market in June 2009, by the manufacturer due to the medication’s association with cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.[93] Alefacept also blocks the molecules that dendritic cells use to communicate with T cells and even causes natural killer cells to kill T cells as a way of controlling inflammation.[37] Apremilast may also be used.[12]

Individuals with psoriasis may develop neutralizing antibodies against monoclonal antibodies. Neutralization occurs when an antidrug antibody prevents a monoclonal antibody such as infliximab from binding antigen in a laboratory test. Specifically, neutralization occurs when the anti-drug antibody binds to infliximab’s antigen binding site instead of TNF-α. When infliximab no longer binds tumor necrosis factor alpha, it no longer decreases inflammation, and psoriasis may worsen. Neutralizing antibodies have not been reported against etanercept, a biologic medication that is a fusion protein composed of two TNF-α receptors. The lack of neutralizing antibodies against etanercept is probably secondary to the innate presence of the TNF-α receptor, and the development of immune tolerance.[100]

There is strong evidence to indicate that infliximab, bimekizumab, ixekizumab, and risankizumab are the most effective biologics for treating moderate to severe cases of psoriasis.[101]

There is also some evidence to support use of secukinumab, brodalumab, guselkumab, certolizumab, and ustekinumab.[102] [101]In general, anti-IL17, anti-IL12/23, anti-IL23, and anti-TNF alpha biologics were found to be more effective than traditional systemic treatments.[101] The immunologic pathways of psoriasis involve Th9, Th17, Th1 lymphocytes, and IL-22. The aforementioned biologic agents hinder different aspects of these pathways.[citation needed]

Another treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis is fumaric acid esters (FAE) which may be similar in effectiveness to methotrexate.[103]

It has been theorized that antistreptococcal medications may improve guttate and chronic plaque psoriasis; however, the limited studies do not show that antibiotics are effective.[104]

Surgery[edit]

Limited evidence suggests removal of the tonsils may benefit people with chronic plaque psoriasis, guttate psoriasis, and palmoplantar pustulosis.[105][106]

Diet[edit]

Uncontrolled studies have suggested that individuals with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis may benefit from a diet supplemented with fish oil rich in eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).[107] A low-calorie diet appears to reduce the severity of psoriasis.[44] Diet recommendations include consumption of cold water fish (preferably wild fish, not farmed) such as salmon, herring, and mackerel; extra virgin olive oil; legumes; vegetables; fruits; and whole grains; and avoid consumption of alcohol, red meat, and dairy products (due to their saturated fat). The effect of consumption of caffeine (including coffee, black tea, mate, and dark chocolate) remains to be determined.[108]

Many patients report improvements after consuming less tobacco, caffeine, sugar, nightshades (tomatoes, eggplant, peppers, paprika and white potatoes) and taking probiotics and oral Vitamin D.[109]

There is a higher rate of celiac disease among people with psoriasis.[108][110] When adopting a gluten-free diet, disease severity generally decreases in people with celiac disease and those with anti-gliadin antibodies.[107][111][112]

Prognosis[edit]

Most people with psoriasis experience nothing more than mild skin lesions that can be treated effectively with topical therapies.[76]

Psoriasis is known to hurt the quality of life of both the affected person and the individual’s family members.[39] Depending on the severity and location of outbreaks, individuals may experience significant physical discomfort and some disability. Itching and pain can interfere with basic functions, such as self-care and sleep.[54] Participation in sporting activities, certain occupations, and caring for family members can become difficult activities for those with plaques located on their hands and feet.[54] Plaques on the scalp can be particularly embarrassing, as flaky plaque in the hair can be mistaken for dandruff.[113]

Individuals with psoriasis may feel self-conscious about their appearance and have a poor self-image that stems from fear of public rejection and psychosexual concerns. Psoriasis has been associated with low self-esteem and depression is more common among those with the condition.[3] People with psoriasis often feel prejudiced against due to the commonly held incorrect belief that psoriasis is contagious.[54] Psychological distress can lead to significant depression and social isolation; a high rate of thoughts about suicide has been associated with psoriasis.[20] Many tools exist to measure the quality of life of people with psoriasis and other dermatological disorders. Clinical research has indicated individuals often experience a diminished quality of life.[114] Children with psoriasis may encounter bullying.[115]

Several conditions are associated with psoriasis. These occur more frequently in older people. Nearly half of individuals with psoriasis over the age of 65 have at least three comorbidities (concurrent conditions), and two-thirds have at least two comorbidities.[116]

Cardiovascular disease[edit]

Psoriasis has been associated with obesity[3] and several other cardiovascular and metabolic disturbances. The number of new cases per year of diabetes is 27% higher in people affected by psoriasis than in those without the condition.[117] Severe psoriasis may be even more strongly associated with the development of diabetes than mild psoriasis.[117] Younger people with psoriasis may also be at increased risk for developing diabetes.[116][118] Individuals with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis have a slightly higher risk of heart disease and heart attacks when compared to the general population. Cardiovascular disease risk appeared to be correlated with the severity of psoriasis and its duration. There is no strong evidence to suggest that psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of death from cardiovascular events. Methotrexate may provide a degree of protection for the heart.[43][116]

The odds of having hypertension are 1.58 times ( i.e. 58%) higher in people with psoriasis than those without the condition; these odds are even higher with severe cases of psoriasis. A similar association was noted in people who have psoriatic arthritis—the odds of having hypertension were found to be 2.07 times ( i.e. 107%) greater when compared to odds of the general population. The link between psoriasis and hypertension is not currently[when?] understood. Mechanisms hypothesized to be involved in this relationship include the following: dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin system, elevated levels of endothelin 1 in the blood, and increased oxidative stress.[118][119] The number of new cases of the heart rhythm abnormality atrial fibrillation is 1.31 times ( i.e. 31%) higher in people with mild psoriasis and 1.63 times ( i.e. 63%) higher in people with severe psoriasis.[120] There may be a slightly increased risk of stroke associated with psoriasis, especially in severe cases.[43][121] Treating high levels of cholesterol with statins has been associated with decreased psoriasis severity, as measured by PASI score, and has also been associated with improvements in other cardiovascular disease risk factors such as markers of inflammation.[122] These cardioprotective effects are attributed to ability of statins to improve blood lipid profile and because of their anti-inflammatory effects. Statin use in those with psoriasis and hyperlipidemia was associated with decreased levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and TNFα as well as decreased activity of the immune protein LFA-1.[122] Compared to individuals without psoriasis, those affected by psoriasis are more likely to satisfy the criteria for metabolic syndrome.[16][120]

Other diseases[edit]

The rates of Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are increased when compared with the general population, by a factor of 3.8 and 7.5 respectively.[3] People with psoriasis also have a higher risk of celiac disease.[108][112] Few studies have evaluated the association of multiple sclerosis with psoriasis, and the relationship has been questioned.[3][123] Psoriasis has been associated with a 16% increase in overall relative risk for non-skin cancer, thought to be attributed to systemic therapy, particularly methotrexate.[43] People treated with long term systemic therapy for psoriasis have a 52% increased risk cancers of the lung and bronchus, a 205% increase in the risk of developing cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract, a 31% increase in the risk of developing cancers of the urinary tract, a 90% increase in the risk of developing liver cancer, and a 46% increase in the risk of developing pancreatic cancer.[43] The risk for development of non-melanoma skin cancers is also increased. Psoriasis increases the risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the skin by 431% and increases the risk of basal cell carcinoma by 100%.[43] There is no increased risk of melanoma associated with psoriasis.[43] People with psoriasis have a higher risk of developing cancer.[124]

Epidemiology[edit]

Psoriasis is estimated to affect 2–4% of the population of the western world.[7] The rate of psoriasis varies according to age, region and ethnicity; a combination of environmental and genetic factors is thought to be responsible for these differences.[7] It can occur at any age, although it most commonly appears for the first time between the ages of 15 and 25 years. Approximately one third of people with psoriasis report being diagnosed before age 20.[125] Psoriasis affects both sexes equally.[65]

Psoriasis affects about 6.7 million Americans and occurs more frequently in adults.[5]

Psoriasis is about five times more common in people of European descent than in people of Asian descent.[126]

People with inflammatory bowel disease such as Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis are at an increased risk of developing psoriasis.[51] Psoriasis is more common in countries farther from the equator.[51] Persons of white European ancestry are more likely to have psoriasis and the condition is relatively uncommon in African Americans and extremely uncommon in Native Americans.[52]

History[edit]