|

al-Fārābī |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of al-Farabi in profile |

|

| Born | c. 870[1]

Faryāb in Khorāsān (modern day Afghanistan) or Fārāb (modern day Kazakhstan)[2] |

| Died | c. 950 (aged around 80)[1]

Damascus[3] |

| Other names | The Second Teacher[1] |

| Notable work | kitāb al-mūsīqī al-kabīr («Grand Book of Music»), ārā ahl al-madīna al-fāḍila («The Virtuous City»), kitāb iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm («Enumeration of the Sciences»), kitāb iḥṣāʾ al-īqā’āt («Classification of Rhythms»)[1] |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Islamic philosophy |

| School | Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism,[4] idealism[5] |

|

Main interests |

Metaphysics, political philosophy, law, logic, music, science, ethics, mysticism,[1] epistemology |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

Abū Naṣr Muḥammad al-Fārābī (Arabic: أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius;[7] (c. 870[1] – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)[3] was a renowned early Islamic philosopher and jurist who wrote in the fields of political philosophy, metaphysics, ethics and logic. He was also a scientist, cosmologist, mathematician, music theorist and physician.[8]

In Islamic philosophical tradition he was often called «the Second Teacher», following Aristotle who was known as «the First Teacher».[9] He is credited with preserving the original Greek texts during the Middle Ages via his commentaries and treatises, and influencing many prominent philosophers, such as Avicenna and Maimonides. Through his works, he became well-known in the West as well as the East.

Biography

The existing variations in the basic accounts of al-Farabi’s origins and pedigree indicate that they were not recorded during his lifetime or soon thereafter by anyone with concrete information, but were based on hearsay or guesses (as is the case with other contemporaries of al-Farabi). Little is known about his life. Early sources include an autobiographical passage where al-Farabi traces the history of logic and philosophy up to his time, and brief mentions by al-Mas’udi, Ibn al-Nadim and Ibn Hawqal. Sa’id al-Andalusi wrote a biography of al-Farabi. Arabic biographers of the 12th–13th centuries thus had few facts to hand, and used invented stories about his life.[2]

From incidental accounts it is known that he spent significant time (most of his life) in Baghdad with Syriac Christian scholars including the cleric Yuhanna ibn Haylan, Yahya ibn Adi, and Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Baghdadi. He later spent time in Damascus and in Egypt before returning to Damascus where he died in 950-1.[10]

His name was Abū Naṣr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Fārābī,[2] sometimes with the family surname al-Ṭarkhānī, i.e., the Turco-Mongolic element Ṭarkhān appears in a nisba.[2] His grandfather was not known among his contemporaries, but a name, Uzlag, or Awzalaḡ in Arabic suddenly appears later in the writings of Ibn Abī Uṣaibiʿa, and of his great-grandfather in those of Ibn Khallikan.[2]

His birthplace could have been any one of the many places in Central Asia- then known by the name of Khurasan. The name «parab/farab» is a Persian term for a locale that is irrigated by effluent springs or flows from a nearby river. Thus, there are many places that carry the name (or various evolutions of that hydrological/geological toponym) in that general area, such as Farab on the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) in modern Kazakhstan; Farab, an still-extant village in suburbs of the city of Chaharjuy/Amul (modern Türkmenabat) on the Oxus Amu Darya in Turkmenistan, on the Silk Road, connecting Merv to Bukhara, or Faryab in Greater Khorasan (modern day Afghanistan). The older Persian[2] Parab (in Hudud ul-‘alam) or Faryab (also Paryab), is a common Persian toponym meaning «lands irrigated by diversion of river water».[11][12] By the 13th century, Farab on the Jaxartes was known as Otrar.[13]

Background

Iranian stamp with al-Farabi’s imagined face

While Scholars largely agree that his ethnic background is not knowable,[2][14][15][16] Al-Farabi has also been described as being of either Persian or Turkic origin. Medieval Arab historian Ibn Abi Usaibia (died in 1270)—al-Farabi’s oldest biographer—mentions in his ʿUyūn that al-Farabi’s father was of Persian descent.[2][17] Al-Shahrazuri, who lived around 1288 and has written an early biography, also states that al-Farabi hailed from a Persian family.[18][19] According to Majid Fakhry, an Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, al-Farabi’s father «was an army captain of Persian extraction.«[20] A Persian origin has been stated by many other sources as well.[21] Dimitri Gutas notes that Farabi’s works contain references and glosses in Persian, Sogdian, and even Greek, but not Turkish.[2][22] Sogdian has also been suggested as his native language[23] and the language of the inhabitants of Farab.[24] Muhammad Javad Mashkoor argues for an Iranian-speaking Central Asian origin.[25] According to Christoph Baumer, he was probably a Sogdian.[26] According to Thérèse-Anne Druart, writing in 2020, «Scholars have disputed his ethnic origin. Some claimed he was Turkish but more recent research points to him being a Persian.»[27]

The oldest known reference to a Turkic origin is given by the medieval Persian historian Ibn Khallikan (died in 1282), who in his work Wafayat (completed in 669/1271) states that al-Farabi was born in the small village of Wasij near Farab (in what is today Otrar, Kazakhstan) of Turkic parents. Based on this account among others, some scholars say he is of Turkic origin.[28][29][30][31][32][33] Dimitri Gutas, an American Arabist of Greek origin, criticizes this, saying that Ibn Khallikan’s account is aimed at the earlier historical accounts by Ibn Abi Usaibia, and serves the purpose to «prove» a Turkic origin for al-Farabi, for instance by mentioning the additional nisba (surname) «al-Turk» (arab. «the Turk»)—a nisba al-Farabi never had.[2] However, Abu al-Fedā’, who copied Ibn Khallekan, corrected this and changed al-Torkī to the phrase «wa-kāna rajolan torkīyan», meaning «he was a Turkish man.»[2] In this regard, since works of such supposed Turks lack traces of Turkic nomadic culture, Oxford professor C.E. Bosworth notes that «great figures [such] as Farabi, Biruni, and ibn Sina have been attached by over enthusiastic Turkish scholars to their race».[34] R.N. Frye and Aydın Sayılı on the other hand assert, that Turks lived long before the Seljuks in Transoxiana during the Arab conquest in villages and these Turks had no nomadic life.[34]

Life and education

Al-Farabi spent almost his entire life in Baghdad. In the autobiographical passage preserved by Ibn Abī Uṣaibiʿa, al-Farabi stated that he had studied logic, medicine and sociology with Yuhanna bin Haylan up to and including Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, i.e., according to the order of the books studied in the curriculum, al-Farabi was claiming that he had studied Porphyry’s Eisagoge and Aristotle’s Categories, De Interpretatione, Prior and Posterior Analytics. His teacher, Yuhanna bin Haylan, was a Nestorian cleric. This period of study was probably in Baghdad, where al-Mas’udi records that Yuhanna died during the reign of al-Muqtadir (295-320/908-32). He was in Baghdad at least until the end of September 942, as recorded in notes in his Mabādeʾ ārāʾ ahl al-madīna al-fāżela. He finished the book in Damascus the following year (331), i.e., by September 943). He also studied in Tétouan, Morocco[35][unreliable source?] and lived and taught for some time in Aleppo. Al-Farabi later visited Egypt, finishing six sections summarizing the book Mabādeʾ in Egypt in 337/July 948 – June 949 when he returned to Syria, where he was supported by Sayf al-Dawla, the Hamdanid ruler. Al-Mas’udi, writing barely five years after the fact (955-6, the date of the composition of the Tanbīh), says that al-Farabi died in Damascus in Rajab 339 (between 14 December 950 and 12 January 951).[2]

Religious beliefs

Al-Farabi’s religious affiliation within Islam is disputed. While some historians identify him as Sunni,[36] some others assert he was Shia or influenced by Shia.

Najjar Fauzi argues that al-Farabi’s political philosophy was influenced by Shiite sects.[37] Giving a positive account, Nadia Maftouni describes shi’ite aspects of al-Farabi’s writings. As she put it, al-Farabi in his al-Millah, al-Siyasah al-Madaniyah, and Tahsil al-Sa’adah believes in a utopia governed by Prophet and his successors: the Imams.[38]

Works and contributions

Al-Farabi made contributions to the fields of logic, mathematics, music, philosophy, psychology, and education.

Alchemy

Al-Farabi wrote: The Necessity of the Art of the Elixir [39]

Logic

Though he was mainly an Aristotelian logician, he included a number of non-Aristotelian elements in his works. He discussed the topics of future contingents, the number and relation of the categories, the relation between logic and grammar, and non-Aristotelian forms of inference.[40] He is also credited with categorizing logic into two separate groups, the first being «idea» and the second being «proof».

Al-Farabi also considered the theories of conditional syllogisms and analogical inference, which were part of the Stoic tradition of logic rather than the Aristotelian.[41] Another addition al-Farabi made to the Aristotelian tradition was his introduction of the concept of «poetic syllogism» in a commentary on Aristotle’s Poetics.[42]

Music

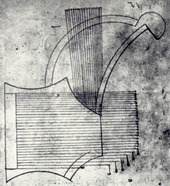

Drawing of a musical instrument, a shahrud, from al-Farabi’s Kitāb al-mūsīqā al-kabīr

Al-Farabi wrote a book on music titled Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir (Grand Book of Music). In it, he presents philosophical principles about music, its cosmic qualities, and its influences.

He also wrote a treatise on the Meanings of the Intellect, which dealt with music therapy and discussed the therapeutic effects of music on the soul.[43]

Philosophy

Gerard of Cremona’s Latin translation of Kitab ihsa’ al-‘ulum («Enumeration of the Sciences»)

As a philosopher, al-Farabi was a founder of his own school of early Islamic philosophy known as «Farabism» or «Alfarabism», though it was later overshadowed by Avicennism. Al-Farabi’s school of philosophy «breaks with the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle [… and …] moves from metaphysics to methodology, a move that anticipates modernity», and «at the level of philosophy, Farabi unites theory and practice [… and] in the sphere of the political he liberates practice from theory». His Neoplatonic theology is also more than just metaphysics as rhetoric. In his attempt to think through the nature of a First Cause, Farabi discovers the limits of human knowledge».[44]

Al-Farabi had great influence on science and philosophy for several centuries,[45] and was widely considered second only to Aristotle in knowledge (alluded to by his title of «the Second Teacher») in his time. His work, aimed at synthesis of philosophy and Sufism, paved the way for the work of Ibn Sina (Avicenna).[46]

Al-Farabi also wrote a commentary on Aristotle’s work, and one of his most notable works is Ara Ahl al-Madina al-Fadila (آراءُ اَهْلِ الْمَدینَةِ الْفاضِلَة / The Virtuous City) where he theorized an ideal state as in Plato’s The Republic.[47] Al-Farabi argued that religion rendered truth through symbols and persuasion, and, like Plato, saw it as the duty of the philosopher to provide guidance to the state. Al-Farabi incorporated the Platonic view, drawing a parallel from within the Islamic context, in that he regarded the ideal state to be ruled by the Prophet-Imam, instead of the philosopher-king envisaged by Plato. Al-Farabi argued that the ideal state was the city-state of Medina when it was governed by the prophet Muhammad as its head of state, as he was in direct communion with Allah whose law was revealed to him. In the absence of the Prophet-Imam, al-Farabi considered democracy as the closest to the ideal state, regarding the order of the Sunni Rashidun Caliphate as an example of such a republican order within early Muslim history. However, he also maintained that it was from democracy that imperfect states emerged, noting how the order of the early Islamic Caliphate of the Rashidun caliphs, which he viewed as republican, was later replaced by a form of government resembling a monarchy under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties.[48]

Physics

Al-Farabi wrote a short treatise «On Vacuum», where he thought about the nature of the existence of void.[47] His final conclusion was that air’s volume can expand to fill available space, and he suggested that the concept of perfect vacuum was incoherent.[47]

Psychology

Al-Farabi wrote Social Psychology and Principles of the Opinions of the Citizens of the Virtuous City (i.e. The Virtuous City), which were the first treatises to deal with social psychology. He stated that «an isolated individual could not achieve all the perfections by himself, without the aid of other individuals,» and that it is the «innate disposition of every human being to join another human being or other men in the labor he ought to perform.» He concluded that to «achieve what he can of that perfection, every man needs to stay in the neighborhood of others and associate with them.»[43]

In his treatise On the Cause of Dreams, which appeared as chapter 24 of his Principles of the Opinions of the Citizens of the Ideal City, he distinguished between dream interpretation and the nature and causes of dreams.[43]

Philosophical thought

Pages from a 17th-century manuscript of al-Farabi’s commentary on Aristotle’s metaphysics

Influences

The main influence on al-Farabi’s philosophy was the Aristotelian tradition of Alexandria. A prolific writer, he is credited with over one hundred works.[49] Amongst these are a number of prolegomena to philosophy, commentaries on important Aristotelian works (such as the Nicomachean Ethics) as well as his own works. His ideas are marked by their coherency, despite drawing together of many different philosophical disciplines and traditions. Some other significant influences on his work were the planetary model of Ptolemy and elements of Neo-Platonism,[50] particularly metaphysics and practical (or political) philosophy (which bears more resemblance to Plato’s Republic than Aristotle’s Politics).[51]

al-Farabi, Aristotle, Maimonides

In the handing down of Aristotle’s thought to the Christian west in the middle ages, al-Farabi played an essential part as appears in the translation of al-Farabi’s Commentary and Short Treatise on Aristotle’s de Interpretatione that F.W. Zimmermann published in 1981. Al-Farabi had a great influence on Maimonides, the most important Jewish thinker of the middle ages. Maimonides wrote in Arabic a Treatise on logic, the celebrated Maqala fi sina at al-mantiq, in a wonderfully concise way. The work treats of the essentials of Aristotelian logic in the light of comments made by the Persian philosophers: Avicenna and, above all, al-Farabi. Rémi Brague in his book devoted to the Treatise stresses the fact that al-Farabi is the only thinker mentioned therein.

Al-Farabi as well as Avicenna and Averroes have been recognized as Peripatetics (al-Mashsha’iyun) or rationalists (Estedlaliun) among Muslims.[52][53][54] However, he tried to gather the ideas of Plato and Aristotle in his book «The gathering of the ideas of the two philosophers».[55]

According to Reisman, his work was singularly directed towards the goal of simultaneously reviving and reinventing the Alexandrian philosophical tradition, to which his Christian teacher, Yuhanna bin Haylan belonged.[56] His success should be measured by the honorific title of «the second master» of philosophy (Aristotle being the first), by which he was known.[9][57] Reisman also says that he does not make any reference to the ideas of either al-Kindi or his contemporary, Abu Bakr al-Razi, which clearly indicates that he did not consider their approach to philosophy as a correct or viable one.[56]

Thought

Metaphysics and cosmology

In contrast to al-Kindi, who considered the subject of metaphysics to be God, al-Farabi believed that it was concerned primarily with being qua being (that is, being in and of itself), and this is related to God only to the extent that God is a principle of absolute being. Al-Kindi’s view was, however, a common misconception regarding Greek philosophy amongst Muslim intellectuals at the time, and it was for this reason that Avicenna remarked that he did not understand Aristotle’s Metaphysics properly until he had read a prolegomenon written by al-Farabi.[58]

Al-Farabi’s cosmology is essentially based upon three pillars: Aristotelian metaphysics of causation, highly developed Plotinian emanational cosmology and the Ptolemaic astronomy.[59] In his model, the universe is viewed as a number of concentric circles; the outermost sphere or «first heaven», the sphere of fixed stars, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and finally, the Moon. At the centre of these concentric circles is the sub-lunar realm which contains the material world.[60] Each of these circles represent the domain of the secondary intelligences (symbolized by the celestial bodies themselves), which act as causal intermediaries between the First Cause (in this case, God) and the material world. Furthermore these are said to have emanated from God, who is both their formal and efficient cause.

The process of emanation begins (metaphysically, not temporally) with the First Cause, whose principal activity is self-contemplation. And it is this intellectual activity that underlies its role in the creation of the universe. The First Cause, by thinking of itself, «overflows» and the incorporeal entity of the second intellect «emanates» from it. Like its predecessor, the second intellect also thinks about itself, and thereby brings its celestial sphere (in this case, the sphere of fixed stars) into being, but in addition to this it must also contemplate upon the First Cause, and this causes the «emanation» of the next intellect. The cascade of emanation continues until it reaches the tenth intellect, beneath which is the material world. And as each intellect must contemplate both itself and an increasing number of predecessors, each succeeding level of existence becomes more and more complex. This process is based upon necessity as opposed to will. In other words, God does not have a choice whether or not to create the universe, but by virtue of His own existence, He causes it to be. This view also suggests that the universe is eternal, and both of these points were criticized by al-Ghazzali in his attack on the philosophers.[61][62]

In his discussion of the First Cause (or God), al-Farabi relies heavily on negative theology. He says that it cannot be known by intellectual means, such as dialectical division or definition, because the terms used in these processes to define a thing constitute its substance. Therefore if one was to define the First Cause, each of the terms used would actually constitute a part of its substance and therefore behave as a cause for its existence, which is impossible as the First Cause is uncaused; it exists without being caused. Equally, he says it cannot be known according to genus and differentia, as its substance and existence are different from all others, and therefore it has no category to which it belongs. If this were the case, then it would not be the First Cause, because something would be prior in existence to it, which is also impossible. This would suggest that the more philosophically simple a thing is, the more perfect it is. And based on this observation, Reisman says it is possible to see the entire hierarchy of al-Farabi’s cosmology according to classification into genus and species. Each succeeding level in this structure has as its principal qualities multiplicity and deficiency, and it is this ever-increasing complexity that typifies the material world.[63]

Epistemology and eschatology

Human beings are unique in al-Farabi’s vision of the universe because they stand between two worlds: the «higher», immaterial world of the celestial intellects and universal intelligibles, and the «lower», material world of generation and decay; they inhabit a physical body, and so belong to the «lower» world, but they also have a rational capacity, which connects them to the «higher» realm. Each level of existence in al-Farabi’s cosmology is characterized by its movement towards perfection, which is to become like the First Cause, i.e. a perfect intellect. Human perfection (or «happiness»), then, is equated with constant intellection and contemplation.[64]

Al-Farabi divides intellect into four categories: potential, actual, acquired and the Agent. The first three are the different states of the human intellect and the fourth is the Tenth Intellect (the moon) in his emanational cosmology. The potential intellect represents the capacity to think, which is shared by all human beings, and the actual intellect is an intellect engaged in the act of thinking. By thinking, al-Farabi means abstracting universal intelligibles from the sensory forms of objects which have been apprehended and retained in the individual’s imagination.[65]

This motion from potentiality to actuality requires the Agent Intellect to act upon the retained sensory forms; just as the Sun illuminates the physical world to allow us to see, the Agent Intellect illuminates the world of intelligibles to allow us to think.[66] This illumination removes all accident (such as time, place, quality) and physicality from them, converting them into primary intelligibles, which are logical principles such as «the whole is greater than the part». The human intellect, by its act of intellection, passes from potentiality to actuality, and as it gradually comprehends these intelligibles, it is identified with them (as according to Aristotle, by knowing something, the intellect becomes like it).[67] Because the Agent Intellect knows all of the intelligibles, this means that when the human intellect knows all of them, it becomes associated with the Agent Intellect’s perfection and is known as the acquired Intellect.[68]

While this process seems mechanical, leaving little room for human choice or volition, Reisman says that al-Farabi is committed to human voluntarism.[67] This takes place when man, based on the knowledge he has acquired, decides whether to direct himself towards virtuous or unvirtuous activities, and thereby decides whether or not to seek true happiness. And it is by choosing what is ethical and contemplating about what constitutes the nature of ethics, that the actual intellect can become «like» the active intellect, thereby attaining perfection. It is only by this process that a human soul may survive death, and live on in the afterlife.[66][69]

According to al-Farabi, the afterlife is not the personal experience commonly conceived of by religious traditions such as Islam and Christianity. Any individual or distinguishing features of the soul are annihilated after the death of the body; only the rational faculty survives (and then, only if it has attained perfection), which becomes one with all other rational souls within the agent intellect and enters a realm of pure intelligence.[68] Henry Corbin compares this eschatology with that of the Ismaili Neo-Platonists, for whom this process initiated the next grand cycle of the universe.[70] However, Deborah Black mentions we have cause to be skeptical as to whether this was the mature and developed view of al-Farabi, as later thinkers such as Ibn Tufayl, Averroes and Ibn Bajjah would assert that he repudiated this view in his commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics, which has been lost to modern experts.[68]

Psychology, the soul and prophetic knowledge

In his treatment of the human soul, al-Farabi draws on a basic Aristotelian outline, which is informed by the commentaries of later Greek thinkers. He says it is composed of four faculties: The appetitive (the desire for, or aversion to an object of sense), the sensitive (the perception by the senses of corporeal substances), the imaginative (the faculty which retains images of sensible objects after they have been perceived, and then separates and combines them for a number of ends), and the rational, which is the faculty of intellection.[71] It is the last of these which is unique to human beings and distinguishes them from plants and animals. It is also the only part of the soul to survive the death of the body. Noticeably absent from these scheme are internal senses, such as common sense, which would be discussed by later philosophers such as Avicenna and Averroes.[72][73]

Special attention must be given to al-Farabi’s treatment of the soul’s imaginative faculty, which is essential to his interpretation of prophethood and prophetic knowledge. In addition to its ability to retain and manipulate sensible images of objects, he gives the imagination the function of imitation. By this he means the capacity to represent an object with an image other than its own. In other words, to imitate «x» is to imagine «x» by associating it with sensible qualities that do not describe its own appearance. This extends the representative ability of the imagination beyond sensible forms and to include temperaments, emotions, desires and even immaterial intelligibles or abstract universals, as happens when, for example, one associates «evil» with «darkness».[74][73] The Prophet, in addition to his own intellectual capacity, has a very strong imaginative faculty, which allows him to receive an overflow of intelligibles from the agent intellect (the tenth intellect in the emanational cosmology). These intelligibles are then associated with symbols and images, which allow him to communicate abstract truths in a way that can be understood by ordinary people. Therefore what makes prophetic knowledge unique is not its content, which is also accessible to philosophers through demonstration and intellection, but rather the form that it is given by the prophet’s imagination.[75][76]

Practical philosophy (ethics and politics)

The practical application of philosophy was a major concern expressed by al-Farabi in many of his works, and while the majority of his philosophical output has been influenced by Aristotelian thought, his practical philosophy was unmistakably based on that of Plato.[77] In a similar manner to Plato’s Republic, al-Farabi emphasized that philosophy was both a theoretical and practical discipline; labeling those philosophers who do not apply their erudition to practical pursuits as «futile philosophers». The ideal society, he wrote, is one directed towards the realization of «true happiness» (which can be taken to mean philosophical enlightenment) and as such, the ideal philosopher must hone all the necessary arts of rhetoric and poetics to communicate abstract truths to the ordinary people, as well as having achieved enlightenment himself.[78] Al-Farabi compared the philosopher’s role in relation to society with a physician in relation to the body; the body’s health is affected by the «balance of its humours» just as the city is determined by the moral habits of its people. The philosopher’s duty, he wrote, was to establish a «virtuous» society by healing the souls of the people, establishing justice and guiding them towards «true happiness».[79]

Of course, al-Farabi realized that such a society was rare and required a very specific set of historical circumstances to be realized, which means very few societies could ever attain this goal. He divided those «vicious» societies, which have fallen short of the ideal «virtuous» society, into three categories: ignorant, wicked and errant. Ignorant societies have, for whatever reason, failed to comprehend the purpose of human existence, and have supplanted the pursuit of happiness for another (inferior) goal, whether this be wealth, sensual gratification or power. Al-Farabi mentions «weeds» in the virtuous society: those people who try to undermine its progress towards the true human end.[80] The best known Arabic source for al-Farabi’s political philosophy is his work titled, Ara Ahl al-Madina al-fadila (The Virtuous City).

Whether or not al-Farabi actually intended to outline a political programme in his writings remains a matter of dispute amongst academics. Henry Corbin, who considers al-Farabi to be a crypto-Shi’ite, says that his ideas should be understood as a «prophetic philosophy» instead of being interpreted politically.[81] On the other hand, Charles Butterworth contends that nowhere in his work does al-Farabi speak of a prophet-legislator or revelation (even the word philosophy is scarcely mentioned), and the main discussion that takes place concerns the positions of «king» and «statesmen».[82] Occupying a middle position is David Reisman, who, like Corbin, believes that al-Farabi did not want to expound a political doctrine (although he does not go so far to attribute it to Islamic Gnosticism either). He argues that al-Farabi was using different types of society as examples, in the context of an ethical discussion, to show what effect correct or incorrect thinking could have.[83] Lastly, Joshua Parens argues that al-Farabi was slyly asserting that a pan-Islamic society could not be made, by using reason to show how many conditions (such as moral and deliberative virtue) would have to be met, thus leading the reader to conclude that humans are not fit for such a society.[84] Some other authors such as Mykhaylo Yakubovych argue that for al-Farabi, religion (milla) and philosophy (falsafa) constituted the same praxeological value (i.e. basis for amal al-fadhil—»virtuous deed»), while its epistemological level (ilm—»knowledge») was different.[85]

Modern Western Translations

- English

- Al-Farabi’s Commentary and Short Treatise on Aristotle’s De interpretatione, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Short Commentary on Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1963.

- Al-Farabi on the Perfect State, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

- Alfarabi, The Political Writings. Selected Aphorisms and Other Texts, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

- Alfarabi, The Political Writings, Volume II. «Political Regime» and «Summary of Plato’s Laws, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

- Alfarabi’s Philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, translated and with an introduction by Muhsin Mahdi, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001.

- Fusul al-Madani: Aphorisms of the Statesman Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961.

- «Al-Farabi’s Long Commentary on Aristotle’s Categoriae in Hebrew and Arabic», In Studies in Arabic and Islamic Culture, Vol. II, edited by Abrahamov, Binyamin. Ramat: Bar-Ilan University Press, 2006.

- Texts translated by D. M. Dunlop:

- «The Existence and Definition of Philosophy. From an Arabic text ascribed to al-Farabi», Iraq, 1951, pp. 76–93).

- «Al-Farabi’s Aphorisms of the Statesman», Iraq, 1952, pp. 93–117.

- «Al-Farabi’s Introductory Sections on Logic», The Islamic Quarterly, 1955, pp. 264–282.

- «Al-Farabi’s Eisagoge», The Islamic Quarterly, 1956, pp. 117–138.

- «Al-Farabi’s Introductory Risalah on Logic», The Islamic Quarterly, 1956, pp. 224–235.

- «Al-Farabi’s Paraphrase of the Categories of Aristotle [Part 1]», The Islamic Quarterly, 1957, pp. 168–197.

- «Al-Farabi’s Paraphrase of the Categories of Aristotle [Part 2]», The Islamic Quarterly, 1959, pp. 21–54.

- French

- Idées des habitants de la cité vertueuse. Translated by Karam, J. Chlala, A. Jaussen. 1949.

- Traité des opinions des habitants de la cité idéale. Translated by Tahani Sabri. Paris: J. Vrin, 1990.

- Le Livre du régime politique, introduction, traduction et commentaire de Philippe Vallat, Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 2012.

- Spanish

- Catálogo De Las Ciencias, Madrid: Imp. de Estanislao Maestre, 1932.

- La ciudad ideal. Translated by Manuel Alonso. Madrid: Tecnos, 1995.

- «Al-Farabi: Epístola sobre los sentidos del término intelecto», Revista Española de filosofía medieval, 2002, pp. 215–223.

- El camino de la felicidad, trad. R. Ramón Guerrero, Madrid: Ed. Trotta, 2002

- Obras filosóficas y políticas, trad. R. Ramón Guerrero, Madrid: Ed. Trotta, 2008.

- Las filosofías de Platón y Aristóteles. Con un Apéndice: Sumario de las Leyes de Platón. Prólogo y Tratado primero, traducción, introducción y notas de Rafael Ramón Guerrero, Madrid, Ápeiron Ediciones, 2017.

- Portuguese

- A cidade excelente. Translated by Miguel Attie Filho. São Paulo: Attie, 2019.

- German

- Der Musterstaat. Translated by Friedrich Dieterici. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1895.

Legacy

- A large Kazakh university KazNU, bears his name. There is also an Al-Farabi Library on the university grounds.

- Shymkent Pedagogical Institute of Culture named after al-Farabi (1967-1996).

- In many cities of Kazakhstan there are streets named after him.

- Monuments have been erected in the cities of Alma-Ata, Shymkent and Turkestan.

- In 1975, the 1100th anniversary of al-Farabi’s birth was celebrated on a large international scale in Moscow, Alma-Ata and Baghdad.[86]

- The main-belt asteroid 7057 Al-Fārābī was named in his honor.[87]

- In November 2021, a monument to al-Farabi was unveiled in Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan.[88]

See also

- List of modern-day Muslim scholars of Islam

- List of Muslim scientists

- Tenth Intellect in Ismailism

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Corbin 1993, pp. 158–165.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Gutas, Dimitri. «Fārābī i. Biography». Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c Dhanani 2007, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Fakhry 2002.

- ^ Laurence S. Moss, ed. (1996). Joseph A. Schumpeter: Historian of Economics: Perspectives on the History of Economic Thought. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9781134785308.

Ibn Khaldun drited away from Al-Farabi’s political idealism.

- ^ Brague, Rémi (1998). «Athens, Jerusalem, Mecca: Leo Strauss’s «Muslim» Understanding of Greek Philosophy». Poetics Today. 19 (2): 235–259. doi:10.2307/1773441. ISSN 0333-5372. JSTOR 1773441.

- ^ Alternative names and translations from Arabic include: Alfarabi, Farabi, Avenassar, and Abunaser.

- ^ Adamec, Ludwig W. (2009). Historical Dictionary of Islam. Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements. No. 95 (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-8108-6161-9.

- ^ a b López-Farjeat 2020.

- ^ Reisman 2005, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Daniel Balland, «Fāryāb» in Encyclopedia Iranica. excerpt: «Fāryāb (also Pāryāb), common Persian toponym meaning “lands irrigated by diversion of river water»

- ^ Dehkhoda Dictionary under «Parab» Archived 2011-10-03 at the Wayback Machine excerpt: «پاراب . (اِ مرکب ) زراعتی که به آب چشمه و کاریز ورودخانه و مانند آن کنند مَسقوی . آبی . مقابل دیم» (translation: «Lands irrigated by diversion of river water, springs and qanats.»)

- ^ Bosworth, Clifford E. «Otrār». Encyclopædia Iranica. Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Lessons with Texts by Alfarabi. «D. Gutas, «AlFarabi» in Barthaolomew’s World accessed Feb 18, 2010″. Bartholomew.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ^ Reisman 2005, p. 53.

- ^ F. Abiola Irele/Biodun Jeyifo, «Farabi», in The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Thought, Vol. 1, p. 379.

- ^ Ebn Abi Osaybea, Oyun al-anba fi tabaqat at-atebba, ed. A. Müller, Cairo, 1299/1882. وكان ابوه قائد جيش وهو فارسي المنتسب

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Mehdi Amin Razavi. «An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Vol. 1: From Zoroaster to Umar Khayyam», I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2007. Pg 134: «Ibn Nadim in his al-Fihrist, which is the first work to mention Farabi considers him to be of Persian origin, as does Muhammad Shahrazuri in his Tarikh al-hukama and Ibn Abi Usaybi’ah in his Tabaqat al-atibba. In contrast, Ibn Khallikan in his ‘»Wafayat al-‘ayan considers him to be of Turkish descent. In any case, he was born in Farab in Khurasan of that day around 257/870 in a climate of Persianate culture»

- ^ Arabic: و كان من سلاله فارس in J. Mashkur, Farab and Farabi, Tehran,1972. See also Dehkhoda Dictionary under the entry Farabi for the same exact Arabic quote.

- ^ Fakhry 2002, p. 157.

- ^ P.J. King, «One Hundred Philosophers: the life and work of the world’s greatest thinkers», chapter al-Fārābi, Zebra, 2006. pp 50: «Of Persian stock, al-Farabi (Alfarabius, AbuNaser) was born in Turkestan»

- Henry Thomas, Understanding the Great Philosophers, Doubleday, Published 1962

- T. J. De Boer, «The History of Philosophy in Islam», Forgotten Books, 2008. Excerpt page 98: «His father is said to have been a Persian General». ISBN 1-60506-697-4

- Sterling M. McMurrin, Religion, Reason, and Truth: Historical Essays in the Philosophy of Religion, University of Utah Press, 1982, ISBN 0-87480-203-2. page 40.

- Edited by Robert C. Solomon and Kathleen M. Higgins. (2003). From Africa to Zen : an invitation to world philosophy. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 163. ISBN 0-7425-1350-5 «al-Farabi (870–950), a Persian,»

- Thomas F. Glick. (1995). From Muslim fortress to Christian castle : social and cultural change in medieval Spain. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 170. ISBN 0-7190-3349-7 «It was thus that al-Farabi (c. 870–950), a Persian philosopher»

- The World’s Greatest Seers and Philosophers.. Gardners Books. 2005. pp. 41. ISBN 81-223-0824-4 «al-Farabi (also known as Abu al-Nasr al-Farabi) was born of Turkish parents in the small village of Wasij near Farab, Turkistan (now in Uzbekistan) in 870 AD. His parents were of Persian descent, but their ancestors had migrated to Turkistan.»

- Bryan Bunch with Alexander Hellemans. (2004). The history of science and technology : a browser’s guide to the great discoveries, inventions, and the people who made them, from the dawn of time to today. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 108. ISBN 0-618-22123-9 «Persian scholar al-Farabi»

- Olivier Roy, «The new Central Asia: the creation of nations», I.B.Tauris, 2000. 1860642799. pg 167: «Kazakhstan also annexes for the purpose of bank notes Al Farabi (870–950), the Muslim philosopher who was born in the south of present-day Kazakhstan but who presumably spoke Persian, particularly because in that era there were no Kazakhs in the region»

- Majid Khadduri; [foreword by R. K. Ramazani]. The Islamic conception of justice. Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, c1984.. pp. 84. ISBN 0-8018-6974-9 «Nasr al-Farabi was born in Farab (a small town in Transoxiana) in 259/870 to a family of mixed parentage — the father, who married a Turkish woman, is said to have been of Persian and Turkish descent — but both professed the Shi’l heterodox faith. He spoke Persian and Turkish fluently and learned the Arabic language before he went to Baghdad.

- Ḥannā Fākhūrī, Tārīkh al-fikr al-falsafī ʻinda al-ʻArab, al-Duqqī, al-Jīzah : al-Sharikah al-Miṣrīyah al-ʻĀlamīyah lil-Nashr, Lūnjmān, 2002.

- ’Ammar al-Talbi, al-Farabi, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, vol. XXIII, no. 1/2, Paris, 1993, p. 353-372

- David Deming,»Science and Technology in World History: The Ancient World and Classical Civilization», McFarland, 2010. pg 94: «Al-Farabi, known in Medieval Europe as Abunaser, was a Persian philosopher who sought to harmonize..»

- Philosophers: Abu Al-Nasr Al-Farabi Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine, Trinity College, 1995–2000

- ^ George Fadlo Hourani, Essays on Islamic Philosophy and Science, Suny press, 1975; Kiki Kennedy-Day, Books of Definition in Islamic Philosophy: The Limits of Words, Routledge, 2002, page 32.

- ^ Joshua Parens (2006). An Islamic philosophy of virtuous religions : introducing Alfarabi. Albany, NY: State Univ. of New York Press. pp. 3. ISBN 0-7914-6689-2 excerpt: «He was a native speaker of Turkic [sic] dialect, Soghdian.» [Note: Sogdian was an East Iranian language and not a Turkic dialect]

- ^ Joep Lameer, «Al-Fārābī and Aristotelian syllogistics: Greek theory and Islamic practice», E.J. Brill, 1994. ISBN 90-04-09884-4 pg 22: «..Islamic world of that time, an area whose inhabitants must have spoken Soghdian or maybe a Turkish dialect…»

- ^ مشكور، محمدجواد. “فاراب و فارابي“. دوره14، ش161 (اسفند 54): 15-20- . J. Mashkur, «Farabi and Farabi» in volume 14, No. 161, pp 15–12, Tehran,1972. [1] English translations of the arguments used by J. Mashkur can be found in: G. Lohraspi, «Some remarks on Farabi’s background»; a scholarly approach citing C.E. Bosworth, B. Lewis, R. Frye, D. Gutas, J. Mashkur and partial translation of J.Mashkur’s arguments: PDF. ولي فارابی فيلسوف تنها متعلق به ايران نبود بلكه

به عالم اسلام تعلق داشت و از بركت قرآن و دين محمد به اين مقام رسيد. از اينجهت هه دانشمندانی كه در اينجا گرد آمدهاند او را يك دانشمند مسلمان متعلق به عالم انسانيت ميدانند و كاری به تركی و فارسی و عربی بودن او ندارند. - ^ Baumer, Christoph (2016). The History of Central Asia The Age of Islam and the Mongols. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 9781838609405.

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (ca. 870–950) was a renowned philosopher and scientist with a keen interest in the theory of knowledge. Probably a Sogdian from the great merchant city of Farab, now called Otrar, in southern Kazakhstan

- ^ Druart 2021.

- ^ B.G. Gafurov, Central Asia:Pre-Historic to Pre-Modern Times, (Shipra Publications, 2005), 124; «Abu Nasr El-Farabi hailed from around ancient Farabi which was situated on the bank of Syr Daria and was the son of a Turk military commander«.

- ^ Will Durant, The Age of Faith, (Simon and Schuster, 1950), 253.

- ^ Nicholas Rescher, Al-Farabi’s Short Commentary on Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, University of Pittsburgh Pre, 1963, p.11, Online Edition.

- ^ Antony Black, The History of Islamic Political Thought: From the Prophet to the Present, Routledge, p. 61, Online Edition

- ^ James Hastings, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, Kessinger Publishing, Vol. 10, p.757, Online Edition

- ^ Edited by Ted Honderich. (1995). The Oxford companion to philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 269. ISBN 0-19-866132-0 «Of Turki origin, al-Farabi studied under Christian thinkers»

- Edited and translated by Norman Calder, Jawid Mojaddedi and Andrew Rippin. (2003). Classical Islam : a sourcebook of religious literature. New York: Routledge. pp. 170. ISBN 0-415-24032-8 «He was of Turkish origin, was born in Turkestan»

- Ian Richard Netton. (1999). Al-Fārābī and his school. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1064-7 «He appears to have been born into a military family of Turkish origin in the village of Wasil, Farab, in Turkestan»

- Edited by Henrietta Moore. (1996). The future of anthropological knowledge. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10786-5 «al-Farabi (873–950), a scholar of Turkish origin.»

- Diané Collinson and Robert Wilkinson. (1994). Thirty-Five Oriental Philosophers.. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-02935-6 «Al-Farabi is thought to be of Turkish origin. His family name suggests that he came from the vicinity of Farab in Transoxiana.»

- Fernand Braudel; translated by Richard Mayne. (1995). A history of civilizations. New York, N.Y.: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-012489-6 «Al-Farabi, born in 870, was of Turkish origin. He lived in Aleppo and died in 950 in Damascus»

- Jaroslav Krejčí; assisted by Anna Krejčová. (1990). Before the European challenge : the great civilizations of Asia and the Middle East. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 140. ISBN 0-7914-0168-5 «the Transoxanian Turk al-Farabi (d. circa 950)»

- Hamid Naseem. (2001). Muslim philosophy science and mysticism. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. pp. 78. ISBN 81-7625-230-1 «Al-Farabi, the first Turkish philosopher»

- Clifford Sawhney. The World’s Greatest Seers and Philosophers, 2005, p. 41

- Zainal Abidin Ahmad. Negara utama (Madinatuʾl fadilah) Teori kenegaraan dari sardjana Islam al Farabi. 1964, p. 19

- Haroon Khan Sherwani. Studies in Muslim Political Thought and Administration. 1945, p. 63

- Ian Richard Netton. Al-Farabi and His School, 1999, p. 5

- ^ a b C. Edmund Bosworth (15 May 2017). The Turks in the Early Islamic World. Taylor & Francis. p. 381. ISBN 978-1-351-88087-9.

- ^ Sadler, Anthony; Skarlatos, Alek; Stone, Spencer; Stern, Jeffrey E. (2016). The 15:17 to Paris: The True Story of a Terrorist, a Train, and Three American Heroes. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-61039-734-6.

- ^ Patrick J. Ryan SJ (10 October 2018), Amen, CUA Press, p. 101, ISBN 9780813231242

- ^ Najjar, Fauzi M. (1961). «Fārābī’s Political Philosophy and Shī’ism». Studia Islamica. XIV (14): 57–72. doi:10.2307/1595185. JSTOR 1595185.

- ^ Maftouni, Nadia (2013). «وجوه شیعی فلسفه فارابی» [Shi’ite Aspects of Farabi`s Philosophy]. Andishe-Novin-E-Dini (in Persian). 9 (33): 12. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Houtsma, M. Th (1993). E. J. Brill’s First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. ISBN 9789004097902.

- ^ History of logic: Arabic logic, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Feldman, Seymour (26 November 1964). «Rescher on Arabic Logic». The Journal of Philosophy. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. 61 (22): 726. doi:10.2307/2023632. ISSN 0022-362X. JSTOR 2023632.

Long, A. A.; D. N. Sedley (1987). The Hellenistic Philosophers. Vol 1: Translations of the principal sources with philosophical commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27556-3. - ^ Ludescher, Tanyss (February 1996). «The Islamic roots of the poetic syllogism». College Literature. Archived from the original on 2005-05-31. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ^ a b c Haque 2004, p. 363.

- ^ Netton, Ian Richard (2008). «Breaking with Athens: Al-Farabi as Founder, Applications of Political Theory By Christopher A. Colmo». Journal of Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. 19 (3): 397–8. doi:10.1093/jis/etn047. JSTOR 26200801.

- ^ Glick, Thomas F., Steven Livesey and Faith Wallis (2014). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-0415969307.

- ^ «Avicenna/Ibn Sina (CA. 980–1137)». The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ a b c McGinnis 2022.

- ^ Ronald Bontekoe, Mariėtta Tigranovna Stepaniants (1997), Justice and Democracy, University of Hawaii Press, p. 251, ISBN 0824819268

- ^ Black 1996, p. 178.

- ^ Motahhari, Mortaza, Becoming familiar with Islamic knowledge, V1, p:162

- ^ Reisman 2005, p. 52.

- ^ Motahhari, Morteza, Becoming familiar with Islamic knowledge, V1, p.166

اگر بخواهيم كلمه ای را به

كار بريم كه مفيد مفهوم روش فلسفی مشائين باشد بايد كلمه ( استدلالی ) را

به كار بريم . - ^ «Dictionary of Islamic Philosophical Terms». Muslimphilosophy.com. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ^ «Aristotelianism in Islamic philosophy». Muslimphilosophy.com. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

- ^ Motahhari, Mortaza, Becoming familiar with Islamic knowledge, V1, p.167

فارابی كتاب كوچك معروفی دارد به نام ( الجمع بين رأيی الحكيمين ) در

اين كتاب مسائل اختلافی اين دو فيلسوف طرح شده و كوشش شده كه به نحوی

اختلافات ميان اين دو حكيم از بين برود . - ^ a b Reisman 2005, p. 55-56.

- ^ Mahdi, Muhsin (1962). Alfarabi: Philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0801487161. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 188.

- ^ Reisman 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 189.

- ^ Reisman 2005, p. 57.

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 161.

- ^ Reisman 2005, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Reisman 2005, p. 61.

- ^ Madkour, Ibrahim (1963–1966). «Fārābī» (PDF). In Sharif, Mian M. (ed.). A History of Muslim Philosophy. With short accounts of other-disciplines and the modern renaissance in Muslim lands. Vol. I. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 450–468 (esp. p. 461). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-25.

- ^ a b Reisman 2005, p. 64.

- ^ a b Reisman 2005, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Black 1996, p. 186.

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 158.

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 165.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 184.

- ^ Reisman 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Black 2005, p. 313.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 185.

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 164.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 187.

- ^ Corbin 1993, p. 162.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 190.

- ^ Butterworth 2005, p. 278.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 191.

- ^ Corbin 1993, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Butterworth 2005, p. 276.

- ^ Reisman 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Joshua Parens, An Islamic Philosophy of Virtuous Religions: Introducing Alfarabi (New York: State University of New York Press, 2006), 2.

- ^ Mykhaylo Yakubovych. Al-Farabi’s Book of Religion. Ukrainian translation, introduction and comments / Ukrainian Religious Studies Bulletin, 2008, Vol. 47, P. 237.

- ^ «Аль-Фараби гордость не только нашего народа, но и всего исламского мира — Абсаттар Дербисали». www.inform.kz. 2020-01-29. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- ^ «7057 Al-Farabi (1990 QL2)». Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ^ «Monument to Al-Farabi unveiled in Nur-Sultan». www.inform.kz. 2021-11-30. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

Bibliography

- Black, Deborah L. (1996). «Fārābī». In Nasr, Seyyed Hossein; Leaman, Oliver (eds.). Routledge History of World Philosophies. Volume I: History of Islamic Philosophy. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 178–197. ISBN 978-0-415-05667-0.

- Black, Deborah L. (2005). «Psychology: Soul and Intellect». In Adamson, Peter S.; Taylor, Richard C. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 308–326. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521817439.015. ISBN 0-521-81743-9.

- Butterworth, Charles E. (2005). «Ethical and Political Philosophy». In Adamson, Peter S.; Taylor, Richard C. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 266–286. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521817439.013. ISBN 0-521-81743-9.

- Corbin, Henry (1993). History of Islamic Philosophy. Translated by Liadain Sherrard, with the assistance of Philip Sherrard. London: Kegan Paul International, in association with the Islamic Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7103-0416-2.

- Dhanani, Alnoor (2007). «Fārābī: Abū Naṣr». In Hockey, Thomas (ed.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Druart, Thérèse-Anne (December 21, 2021). «Farabi». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- Fakhry, Majid (2002). Fārābī, Founder of Islamic Neoplatonism: His Life, Works, and Influence. Great Islamic Thinkers. Oxford: Oneworld. ISBN 1-85168-302-X.

- Galston, Miriam (1990). Politics and Excellence: The Political Philosophy of Alfarabi. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07808-4.

- Guerrero, Rafael Ramón (2003). «Apuntes biográficos de Fârâbî según sus vidas árabes» (PDF). Anaquel de Estudios Árabes (in Spanish). XIV: 231–238.

- Gutas, Dimitri; Black, Deborah L.; Druart, Thérèse-Anne; Gutas, Dimitri; Sawa, George D.; Mahdi, Muhsin S. (January 24, 2012). Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). «Fārābī, Abū Naṣr. Table of Content: i. Biography. ii. Logic. iii. Metaphysics. iv. Fārābī and Greek Philosophy. v. Music. vi. Political Philosophy». Encuclopædia Iranica. Encuclopædia Iranica Foundation. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Haque, Amber (2004). «Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists» (PDF). Journal of Religion and Health. XLIII (4): 357–377. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z. JSTOR 27512819. S2CID 38740431.

- López-Farjeat, Luis Xavier (June 21, 2020). «Farabi’s Psychology and Epistemology». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- Marcinkowski, Christoph (2002). «A Biographical Note on Ibn Bājjah (Avempace) and an English Translation of his Annotations to Fārābī’s Isagoge». Iqbal Review. XLIII (2): 83–99.

- McGinnis, Jon (March 21, 2022). «Arabic and Islamic Natural Philosophy and Natural Science». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- Mahdi, Muhsin S.; Wright, Owen (1970–1980). «Fārābī, Abū Naṣr». In Gillispie, Charles C. (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. IV. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 523a–526b. ISBN 0-684-16962-2.

- Monteil, Jean-François (2004). «La transmission d’Aristote par les Arabes à la chrétienté occidentale: une trouvaille relative au De Interpretatione». Revista Española de Filosofía Medieval (in French). XI: 181–195. doi:10.21071/refime.v11i.9230.

- Rescher, Nicholas (1962). Fārābī: An Annotated Bibliography. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. OCLC 1857750.

- Reisman, David C. (2005). «Fārābī and the Philosophical Curriculum». In Adamson, Peter S.; Taylor, Richard C. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–71. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521817439.004. ISBN 0-521-81743-9.

- Touma, Habib Hassan (1996). The Music of the Arabs. New expanded edition. Translated by Laurie Schwartz. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

- Strauss, Leo (1936). «Eine vermisste Schrift Farabis» (PDF). Monatschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums (in German). LXXX (2): 96–106.

- Strauss, Leo (1945). «Fārābī’s Plato». Louis Ginzberg Jubilee Volume: On the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday. New York: American Academy for Jewish Research. pp. 357–393. OCLC 504266057.

- Strauss, Leo (2013). «Some Remarks on the Political Science of Maimonides and Farabi». In Green, Kenneth Hart (ed.). Leo Strauss on Maimonides: The Complete Writings. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 275–313. ISBN 978-0-226-77677-4.

- Strauss, Leo (1988). «How Fārābī Read Plato’s Laws». What Is Political Philosophy and Other Studies. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 134–154. ISBN 0-226-77713-8.

External links

Wikiquote has quotations related to Al-Farabi.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Al-Farabi.

- Wilfrid Hodges & Therese-Anne Druart. «Al-Farabi’s Philosophy of Logic and Language». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Nadja Germann. «Al-Farabi’s Philosophy of Society and Religion». In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Mahdi, Muhsin (2008) [1970–80]. «Al-Fārābī, Abū Naṣr Muḥammad Ibn Muḥammad Ibn Ṭarkhān Ibn Awzalagh». Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com.

- al-Farabi at Britannica

- Abu Nasr al-Farabi at muslimphilosophy.com

- Review (fr) of Rescher’s Al-Fârâbî : An Annotated Bibliography (Pitt. Univ. Press, 1962) at Persée.fr.*al-Fārābi—brief introduction by Peter J. King

- The Philosophy of Alfarabi and Its Influence on Medieval Thought (1947)

- al-madina al-fadila (The Virtuous City). German introduction with Arabic text.

- Article discussing Soghdian origin for Farabi PDF version[2]

- ALFARABI-Trinity College

- ALFARABI-Unesco

- Al Farabi

|

al-Fārābī |

|

|---|---|

Portrait of al-Farabi in profile |

|

| Born | c. 870[1]

Faryāb in Khorāsān (modern day Afghanistan) or Fārāb (modern day Kazakhstan)[2] |

| Died | c. 950 (aged around 80)[1]

Damascus[3] |

| Other names | The Second Teacher[1] |

| Notable work | kitāb al-mūsīqī al-kabīr («Grand Book of Music»), ārā ahl al-madīna al-fāḍila («The Virtuous City»), kitāb iḥṣāʾ al-ʿulūm («Enumeration of the Sciences»), kitāb iḥṣāʾ al-īqā’āt («Classification of Rhythms»)[1] |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Islamic philosophy |

| School | Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism,[4] idealism[5] |

|

Main interests |

Metaphysics, political philosophy, law, logic, music, science, ethics, mysticism,[1] epistemology |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

Abū Naṣr Muḥammad al-Fārābī (Arabic: أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius;[7] (c. 870[1] – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)[3] was a renowned early Islamic philosopher and jurist who wrote in the fields of political philosophy, metaphysics, ethics and logic. He was also a scientist, cosmologist, mathematician, music theorist and physician.[8]

In Islamic philosophical tradition he was often called «the Second Teacher», following Aristotle who was known as «the First Teacher».[9] He is credited with preserving the original Greek texts during the Middle Ages via his commentaries and treatises, and influencing many prominent philosophers, such as Avicenna and Maimonides. Through his works, he became well-known in the West as well as the East.

Biography

The existing variations in the basic accounts of al-Farabi’s origins and pedigree indicate that they were not recorded during his lifetime or soon thereafter by anyone with concrete information, but were based on hearsay or guesses (as is the case with other contemporaries of al-Farabi). Little is known about his life. Early sources include an autobiographical passage where al-Farabi traces the history of logic and philosophy up to his time, and brief mentions by al-Mas’udi, Ibn al-Nadim and Ibn Hawqal. Sa’id al-Andalusi wrote a biography of al-Farabi. Arabic biographers of the 12th–13th centuries thus had few facts to hand, and used invented stories about his life.[2]

From incidental accounts it is known that he spent significant time (most of his life) in Baghdad with Syriac Christian scholars including the cleric Yuhanna ibn Haylan, Yahya ibn Adi, and Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Baghdadi. He later spent time in Damascus and in Egypt before returning to Damascus where he died in 950-1.[10]

His name was Abū Naṣr Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Fārābī,[2] sometimes with the family surname al-Ṭarkhānī, i.e., the Turco-Mongolic element Ṭarkhān appears in a nisba.[2] His grandfather was not known among his contemporaries, but a name, Uzlag, or Awzalaḡ in Arabic suddenly appears later in the writings of Ibn Abī Uṣaibiʿa, and of his great-grandfather in those of Ibn Khallikan.[2]

His birthplace could have been any one of the many places in Central Asia- then known by the name of Khurasan. The name «parab/farab» is a Persian term for a locale that is irrigated by effluent springs or flows from a nearby river. Thus, there are many places that carry the name (or various evolutions of that hydrological/geological toponym) in that general area, such as Farab on the Jaxartes (Syr Darya) in modern Kazakhstan; Farab, an still-extant village in suburbs of the city of Chaharjuy/Amul (modern Türkmenabat) on the Oxus Amu Darya in Turkmenistan, on the Silk Road, connecting Merv to Bukhara, or Faryab in Greater Khorasan (modern day Afghanistan). The older Persian[2] Parab (in Hudud ul-‘alam) or Faryab (also Paryab), is a common Persian toponym meaning «lands irrigated by diversion of river water».[11][12] By the 13th century, Farab on the Jaxartes was known as Otrar.[13]

Background

Iranian stamp with al-Farabi’s imagined face

While Scholars largely agree that his ethnic background is not knowable,[2][14][15][16] Al-Farabi has also been described as being of either Persian or Turkic origin. Medieval Arab historian Ibn Abi Usaibia (died in 1270)—al-Farabi’s oldest biographer—mentions in his ʿUyūn that al-Farabi’s father was of Persian descent.[2][17] Al-Shahrazuri, who lived around 1288 and has written an early biography, also states that al-Farabi hailed from a Persian family.[18][19] According to Majid Fakhry, an Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at Georgetown University, al-Farabi’s father «was an army captain of Persian extraction.«[20] A Persian origin has been stated by many other sources as well.[21] Dimitri Gutas notes that Farabi’s works contain references and glosses in Persian, Sogdian, and even Greek, but not Turkish.[2][22] Sogdian has also been suggested as his native language[23] and the language of the inhabitants of Farab.[24] Muhammad Javad Mashkoor argues for an Iranian-speaking Central Asian origin.[25] According to Christoph Baumer, he was probably a Sogdian.[26] According to Thérèse-Anne Druart, writing in 2020, «Scholars have disputed his ethnic origin. Some claimed he was Turkish but more recent research points to him being a Persian.»[27]

The oldest known reference to a Turkic origin is given by the medieval Persian historian Ibn Khallikan (died in 1282), who in his work Wafayat (completed in 669/1271) states that al-Farabi was born in the small village of Wasij near Farab (in what is today Otrar, Kazakhstan) of Turkic parents. Based on this account among others, some scholars say he is of Turkic origin.[28][29][30][31][32][33] Dimitri Gutas, an American Arabist of Greek origin, criticizes this, saying that Ibn Khallikan’s account is aimed at the earlier historical accounts by Ibn Abi Usaibia, and serves the purpose to «prove» a Turkic origin for al-Farabi, for instance by mentioning the additional nisba (surname) «al-Turk» (arab. «the Turk»)—a nisba al-Farabi never had.[2] However, Abu al-Fedā’, who copied Ibn Khallekan, corrected this and changed al-Torkī to the phrase «wa-kāna rajolan torkīyan», meaning «he was a Turkish man.»[2] In this regard, since works of such supposed Turks lack traces of Turkic nomadic culture, Oxford professor C.E. Bosworth notes that «great figures [such] as Farabi, Biruni, and ibn Sina have been attached by over enthusiastic Turkish scholars to their race».[34] R.N. Frye and Aydın Sayılı on the other hand assert, that Turks lived long before the Seljuks in Transoxiana during the Arab conquest in villages and these Turks had no nomadic life.[34]

Life and education

Al-Farabi spent almost his entire life in Baghdad. In the autobiographical passage preserved by Ibn Abī Uṣaibiʿa, al-Farabi stated that he had studied logic, medicine and sociology with Yuhanna bin Haylan up to and including Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics, i.e., according to the order of the books studied in the curriculum, al-Farabi was claiming that he had studied Porphyry’s Eisagoge and Aristotle’s Categories, De Interpretatione, Prior and Posterior Analytics. His teacher, Yuhanna bin Haylan, was a Nestorian cleric. This period of study was probably in Baghdad, where al-Mas’udi records that Yuhanna died during the reign of al-Muqtadir (295-320/908-32). He was in Baghdad at least until the end of September 942, as recorded in notes in his Mabādeʾ ārāʾ ahl al-madīna al-fāżela. He finished the book in Damascus the following year (331), i.e., by September 943). He also studied in Tétouan, Morocco[35][unreliable source?] and lived and taught for some time in Aleppo. Al-Farabi later visited Egypt, finishing six sections summarizing the book Mabādeʾ in Egypt in 337/July 948 – June 949 when he returned to Syria, where he was supported by Sayf al-Dawla, the Hamdanid ruler. Al-Mas’udi, writing barely five years after the fact (955-6, the date of the composition of the Tanbīh), says that al-Farabi died in Damascus in Rajab 339 (between 14 December 950 and 12 January 951).[2]

Religious beliefs

Al-Farabi’s religious affiliation within Islam is disputed. While some historians identify him as Sunni,[36] some others assert he was Shia or influenced by Shia.

Najjar Fauzi argues that al-Farabi’s political philosophy was influenced by Shiite sects.[37] Giving a positive account, Nadia Maftouni describes shi’ite aspects of al-Farabi’s writings. As she put it, al-Farabi in his al-Millah, al-Siyasah al-Madaniyah, and Tahsil al-Sa’adah believes in a utopia governed by Prophet and his successors: the Imams.[38]

Works and contributions

Al-Farabi made contributions to the fields of logic, mathematics, music, philosophy, psychology, and education.

Alchemy

Al-Farabi wrote: The Necessity of the Art of the Elixir [39]

Logic

Though he was mainly an Aristotelian logician, he included a number of non-Aristotelian elements in his works. He discussed the topics of future contingents, the number and relation of the categories, the relation between logic and grammar, and non-Aristotelian forms of inference.[40] He is also credited with categorizing logic into two separate groups, the first being «idea» and the second being «proof».

Al-Farabi also considered the theories of conditional syllogisms and analogical inference, which were part of the Stoic tradition of logic rather than the Aristotelian.[41] Another addition al-Farabi made to the Aristotelian tradition was his introduction of the concept of «poetic syllogism» in a commentary on Aristotle’s Poetics.[42]

Music

Drawing of a musical instrument, a shahrud, from al-Farabi’s Kitāb al-mūsīqā al-kabīr

Al-Farabi wrote a book on music titled Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir (Grand Book of Music). In it, he presents philosophical principles about music, its cosmic qualities, and its influences.

He also wrote a treatise on the Meanings of the Intellect, which dealt with music therapy and discussed the therapeutic effects of music on the soul.[43]

Philosophy

Gerard of Cremona’s Latin translation of Kitab ihsa’ al-‘ulum («Enumeration of the Sciences»)

As a philosopher, al-Farabi was a founder of his own school of early Islamic philosophy known as «Farabism» or «Alfarabism», though it was later overshadowed by Avicennism. Al-Farabi’s school of philosophy «breaks with the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle [… and …] moves from metaphysics to methodology, a move that anticipates modernity», and «at the level of philosophy, Farabi unites theory and practice [… and] in the sphere of the political he liberates practice from theory». His Neoplatonic theology is also more than just metaphysics as rhetoric. In his attempt to think through the nature of a First Cause, Farabi discovers the limits of human knowledge».[44]

Al-Farabi had great influence on science and philosophy for several centuries,[45] and was widely considered second only to Aristotle in knowledge (alluded to by his title of «the Second Teacher») in his time. His work, aimed at synthesis of philosophy and Sufism, paved the way for the work of Ibn Sina (Avicenna).[46]

Al-Farabi also wrote a commentary on Aristotle’s work, and one of his most notable works is Ara Ahl al-Madina al-Fadila (آراءُ اَهْلِ الْمَدینَةِ الْفاضِلَة / The Virtuous City) where he theorized an ideal state as in Plato’s The Republic.[47] Al-Farabi argued that religion rendered truth through symbols and persuasion, and, like Plato, saw it as the duty of the philosopher to provide guidance to the state. Al-Farabi incorporated the Platonic view, drawing a parallel from within the Islamic context, in that he regarded the ideal state to be ruled by the Prophet-Imam, instead of the philosopher-king envisaged by Plato. Al-Farabi argued that the ideal state was the city-state of Medina when it was governed by the prophet Muhammad as its head of state, as he was in direct communion with Allah whose law was revealed to him. In the absence of the Prophet-Imam, al-Farabi considered democracy as the closest to the ideal state, regarding the order of the Sunni Rashidun Caliphate as an example of such a republican order within early Muslim history. However, he also maintained that it was from democracy that imperfect states emerged, noting how the order of the early Islamic Caliphate of the Rashidun caliphs, which he viewed as republican, was later replaced by a form of government resembling a monarchy under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties.[48]

Physics

Al-Farabi wrote a short treatise «On Vacuum», where he thought about the nature of the existence of void.[47] His final conclusion was that air’s volume can expand to fill available space, and he suggested that the concept of perfect vacuum was incoherent.[47]

Psychology

Al-Farabi wrote Social Psychology and Principles of the Opinions of the Citizens of the Virtuous City (i.e. The Virtuous City), which were the first treatises to deal with social psychology. He stated that «an isolated individual could not achieve all the perfections by himself, without the aid of other individuals,» and that it is the «innate disposition of every human being to join another human being or other men in the labor he ought to perform.» He concluded that to «achieve what he can of that perfection, every man needs to stay in the neighborhood of others and associate with them.»[43]

In his treatise On the Cause of Dreams, which appeared as chapter 24 of his Principles of the Opinions of the Citizens of the Ideal City, he distinguished between dream interpretation and the nature and causes of dreams.[43]

Philosophical thought

Pages from a 17th-century manuscript of al-Farabi’s commentary on Aristotle’s metaphysics

Influences

The main influence on al-Farabi’s philosophy was the Aristotelian tradition of Alexandria. A prolific writer, he is credited with over one hundred works.[49] Amongst these are a number of prolegomena to philosophy, commentaries on important Aristotelian works (such as the Nicomachean Ethics) as well as his own works. His ideas are marked by their coherency, despite drawing together of many different philosophical disciplines and traditions. Some other significant influences on his work were the planetary model of Ptolemy and elements of Neo-Platonism,[50] particularly metaphysics and practical (or political) philosophy (which bears more resemblance to Plato’s Republic than Aristotle’s Politics).[51]

al-Farabi, Aristotle, Maimonides

In the handing down of Aristotle’s thought to the Christian west in the middle ages, al-Farabi played an essential part as appears in the translation of al-Farabi’s Commentary and Short Treatise on Aristotle’s de Interpretatione that F.W. Zimmermann published in 1981. Al-Farabi had a great influence on Maimonides, the most important Jewish thinker of the middle ages. Maimonides wrote in Arabic a Treatise on logic, the celebrated Maqala fi sina at al-mantiq, in a wonderfully concise way. The work treats of the essentials of Aristotelian logic in the light of comments made by the Persian philosophers: Avicenna and, above all, al-Farabi. Rémi Brague in his book devoted to the Treatise stresses the fact that al-Farabi is the only thinker mentioned therein.

Al-Farabi as well as Avicenna and Averroes have been recognized as Peripatetics (al-Mashsha’iyun) or rationalists (Estedlaliun) among Muslims.[52][53][54] However, he tried to gather the ideas of Plato and Aristotle in his book «The gathering of the ideas of the two philosophers».[55]

According to Reisman, his work was singularly directed towards the goal of simultaneously reviving and reinventing the Alexandrian philosophical tradition, to which his Christian teacher, Yuhanna bin Haylan belonged.[56] His success should be measured by the honorific title of «the second master» of philosophy (Aristotle being the first), by which he was known.[9][57] Reisman also says that he does not make any reference to the ideas of either al-Kindi or his contemporary, Abu Bakr al-Razi, which clearly indicates that he did not consider their approach to philosophy as a correct or viable one.[56]

Thought

Metaphysics and cosmology

In contrast to al-Kindi, who considered the subject of metaphysics to be God, al-Farabi believed that it was concerned primarily with being qua being (that is, being in and of itself), and this is related to God only to the extent that God is a principle of absolute being. Al-Kindi’s view was, however, a common misconception regarding Greek philosophy amongst Muslim intellectuals at the time, and it was for this reason that Avicenna remarked that he did not understand Aristotle’s Metaphysics properly until he had read a prolegomenon written by al-Farabi.[58]

Al-Farabi’s cosmology is essentially based upon three pillars: Aristotelian metaphysics of causation, highly developed Plotinian emanational cosmology and the Ptolemaic astronomy.[59] In his model, the universe is viewed as a number of concentric circles; the outermost sphere or «first heaven», the sphere of fixed stars, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and finally, the Moon. At the centre of these concentric circles is the sub-lunar realm which contains the material world.[60] Each of these circles represent the domain of the secondary intelligences (symbolized by the celestial bodies themselves), which act as causal intermediaries between the First Cause (in this case, God) and the material world. Furthermore these are said to have emanated from God, who is both their formal and efficient cause.

The process of emanation begins (metaphysically, not temporally) with the First Cause, whose principal activity is self-contemplation. And it is this intellectual activity that underlies its role in the creation of the universe. The First Cause, by thinking of itself, «overflows» and the incorporeal entity of the second intellect «emanates» from it. Like its predecessor, the second intellect also thinks about itself, and thereby brings its celestial sphere (in this case, the sphere of fixed stars) into being, but in addition to this it must also contemplate upon the First Cause, and this causes the «emanation» of the next intellect. The cascade of emanation continues until it reaches the tenth intellect, beneath which is the material world. And as each intellect must contemplate both itself and an increasing number of predecessors, each succeeding level of existence becomes more and more complex. This process is based upon necessity as opposed to will. In other words, God does not have a choice whether or not to create the universe, but by virtue of His own existence, He causes it to be. This view also suggests that the universe is eternal, and both of these points were criticized by al-Ghazzali in his attack on the philosophers.[61][62]

In his discussion of the First Cause (or God), al-Farabi relies heavily on negative theology. He says that it cannot be known by intellectual means, such as dialectical division or definition, because the terms used in these processes to define a thing constitute its substance. Therefore if one was to define the First Cause, each of the terms used would actually constitute a part of its substance and therefore behave as a cause for its existence, which is impossible as the First Cause is uncaused; it exists without being caused. Equally, he says it cannot be known according to genus and differentia, as its substance and existence are different from all others, and therefore it has no category to which it belongs. If this were the case, then it would not be the First Cause, because something would be prior in existence to it, which is also impossible. This would suggest that the more philosophically simple a thing is, the more perfect it is. And based on this observation, Reisman says it is possible to see the entire hierarchy of al-Farabi’s cosmology according to classification into genus and species. Each succeeding level in this structure has as its principal qualities multiplicity and deficiency, and it is this ever-increasing complexity that typifies the material world.[63]

Epistemology and eschatology

Human beings are unique in al-Farabi’s vision of the universe because they stand between two worlds: the «higher», immaterial world of the celestial intellects and universal intelligibles, and the «lower», material world of generation and decay; they inhabit a physical body, and so belong to the «lower» world, but they also have a rational capacity, which connects them to the «higher» realm. Each level of existence in al-Farabi’s cosmology is characterized by its movement towards perfection, which is to become like the First Cause, i.e. a perfect intellect. Human perfection (or «happiness»), then, is equated with constant intellection and contemplation.[64]

Al-Farabi divides intellect into four categories: potential, actual, acquired and the Agent. The first three are the different states of the human intellect and the fourth is the Tenth Intellect (the moon) in his emanational cosmology. The potential intellect represents the capacity to think, which is shared by all human beings, and the actual intellect is an intellect engaged in the act of thinking. By thinking, al-Farabi means abstracting universal intelligibles from the sensory forms of objects which have been apprehended and retained in the individual’s imagination.[65]

This motion from potentiality to actuality requires the Agent Intellect to act upon the retained sensory forms; just as the Sun illuminates the physical world to allow us to see, the Agent Intellect illuminates the world of intelligibles to allow us to think.[66] This illumination removes all accident (such as time, place, quality) and physicality from them, converting them into primary intelligibles, which are logical principles such as «the whole is greater than the part». The human intellect, by its act of intellection, passes from potentiality to actuality, and as it gradually comprehends these intelligibles, it is identified with them (as according to Aristotle, by knowing something, the intellect becomes like it).[67] Because the Agent Intellect knows all of the intelligibles, this means that when the human intellect knows all of them, it becomes associated with the Agent Intellect’s perfection and is known as the acquired Intellect.[68]

While this process seems mechanical, leaving little room for human choice or volition, Reisman says that al-Farabi is committed to human voluntarism.[67] This takes place when man, based on the knowledge he has acquired, decides whether to direct himself towards virtuous or unvirtuous activities, and thereby decides whether or not to seek true happiness. And it is by choosing what is ethical and contemplating about what constitutes the nature of ethics, that the actual intellect can become «like» the active intellect, thereby attaining perfection. It is only by this process that a human soul may survive death, and live on in the afterlife.[66][69]