-

1

анубис

Русско-английский биологический словарь > анубис

-

2

Анубис

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Анубис

-

3

анубис

Новый русско-английский словарь > анубис

-

4

Анубис

Новый большой русско-английский словарь > Анубис

-

5

Анубис

Русско-английский синонимический словарь > Анубис

-

6

павиан анубис

Русско-английский биологический словарь > павиан анубис

-

7

павиан анубис

2.

RUS

павиан m анубис, догеровский павиан m

3.

ENG

anubis [olive, Doguera] baboon

DICTIONARY OF ANIMAL NAMES IN FIVE LANGUAGES > павиан анубис

-

8

(павиан) анубис

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > (павиан) анубис

-

9

павиан анубис

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > павиан анубис

-

10

павиан, догеровский

2.

RUS

павиан m анубис, догеровский павиан m

3.

ENG

anubis [olive, Doguera] baboon

DICTIONARY OF ANIMAL NAMES IN FIVE LANGUAGES > павиан, догеровский

-

11

2232

2.

RUS

павиан m анубис, догеровский павиан m

3.

ENG

anubis [olive, Doguera] baboon

DICTIONARY OF ANIMAL NAMES IN FIVE LANGUAGES > 2232

См. также в других словарях:

-

Анубис — (Anubis, Ανουβις). Египетское божество, сын Осириса и Изиды. Его изображали в виде человека с головой шакала (или собаки). Анубиса сопоставляют с греческим Гермесом. (Источник: «Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей». М.Корш. Санкт Петербург,… … Энциклопедия мифологии

-

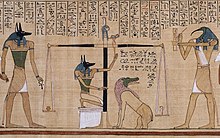

Анубис — извлекает сердце умершего, чтобы взвесить его на суде Осириса. Роспись гробницы. XIII в. до н. э. Анубис извлекает сердце умершего, чтобы взвесить его на суде Осириса. Роспись гробницы. XIII в. до н. э. Анубис () в мифах древних египтян… … Энциклопедический словарь «Всемирная история»

-

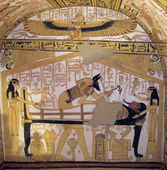

Анубис — Анубис. Деталь погребальной пелены. Сер. 2 в. Музей изобразительных искусств имени А.С. Пушкина. АНУБИС, в египетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых. Почитался в облике шакала. Анубис, завершающий мумификацию покойника . Древнеегипетская… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

АНУБИС — (древн. егип.). Древнеегипетское божество, сын Озириса, почитавшееся охранителем границ Египта и изображавшееся обыкновенно с собачьей головой. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. АНУБИС бог египетской… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

АНУБИС — АНУБИС, в египетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых. Почитался в облике шакала … Современная энциклопедия

-

АНУБИС — в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых, а также некрополей, погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Изображался в облике волка, шакала или человека с головой шакала … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

анубис — сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • бог (375) • покровитель (40) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Анубис — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Анубис (значения). Анубис в иероглифах … Википедия

-

Анубис — в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель мёртвых, а также некрополей, погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Изображался в облике волка, шакала или человека с головой шакала. * * * АНУБИС АНУБИС, в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель … Энциклопедический словарь

-

АНУБИС — древнеегипетский бог загробного мира. В ранний период развития египетской религии это шакалообразное божество, пожирающее умерших. Позже Анубис сохранил лишь отдельные черты, выдававшие его животное происхождение. Будучи богом некрополя Сиута… … Энциклопедия Кольера

-

АНУБИС (обезьяна) — АНУБИС (зеленый павиан; Papio anubis), вид обезьян рода павианов (см. ПАВИАНЫ). Немного крупнее гамадрила (см. ГАМАДРИЛ): масса его тела 25–30 кг, длина тела около 80 см, хвоста 50–60 см. Самки меньше самцов. Туловище анубисов более удлиненное,… … Энциклопедический словарь

Правильное написание слова анубис:

анубис

Крутая NFT игра. Играй и зарабатывай!

Количество букв в слове: 6

Слово состоит из букв:

А, Н, У, Б, И, С

Правильный транслит слова: anubis

Написание с не правильной раскладкой клавиатуры: fye,bc

Тест на правописание

Glosbe предназначен для предоставления услуг людям, а не интернет-роботам.

Вероятно, вы создали много запросов или другие факторы позволили Glosbe идентифицировать вас как робота и заблокировать доступ к данным.

Чтобы продолжить, подтвердите, что вы человек, решив CAPTCHA.

×òî òàêîå «ÀÍÓÁÈÑ»? Êàê ïðàâèëüíî ïèøåòñÿ äàííîå ñëîâî. Ïîíÿòèå è òðàêòîâêà.

ÀÍÓÁÈÑ

äðåâíååãèïåòñêèé áîã çàãðîáíîãî ìèðà.  ðàííèé ïåðèîä ðàçâèòèÿ åãèïåòñêîé ðåëèãèè ýòî — øàêàëîîáðàçíîå áîæåñòâî, ïîæèðàþùåå óìåðøèõ. Ïîçæå Àíóáèñ ñîõðàíèë ëèøü îòäåëüíûå ÷åðòû, âûäàâàâøèå åãî æèâîòíîå ïðîèñõîæäåíèå. Áóäó÷è áîãîì íåêðîïîëÿ Ñèóòà (Ëèêîïîëÿ), Àíóáèñ çàíèìàë ïîä÷èíåííîå ïîëîæåíèå ïî îòíîøåíèþ ê ãëàâíîìó áîãó ýòîãî ãîðîäà Óïóàòó («Îòêðûâàòåëþ ïóòè») — ñîëíå÷íîìó áîæåñòâó, èìåâøåìó îáëèê âîëêà. Ïîäîáíî Òîòó, Àíóáèñ áûë ïðîâîäíèêîì óìåðøèõ ïî Àìåíòè («Ïîòàåííîå ìåñòî», «Çàïàä») — òàê íàçûâàëàñü îáëàñòü çàãðîáíîãî ìèðà, ïðîéäÿ ÷åðåç êîòîðóþ äóøà ïîïàäàëà â ïàëàòó Îñèðèñà, è òàì ñîðîê äâà áîæåñòâåííûõ ñóäüè ðåøàëè, ïîñëàòü ëè åå íà «Ïîëÿ Èàëó» (áóêâàëüíî «Ïîëÿ Òðîñòíèêà» — èçîáèëüíàÿ ñòðàíà áëàæåííûõ) èëè æå ïðåäàòü ìó÷èòåëüíîé è îêîí÷àòåëüíîé ñìåðòè. Èç ñáîðíèêîâ çàêëèíàíèé, êîãäà-òî ñîñòàâëÿâøèõñÿ äëÿ ôàðàîíîâ V-VI äèíàñòèé, ïîçäíåå âûðîñëà Êíèãà ìåðòâûõ. Îäíà èç âåðñèé ýòîé êíèãè, âêëþ÷åííàÿ â ò.í. Ïàïèðóñ Àíè, ïðîëèâàåò ñâåò íà ðåëèãèîçíûå âåðîâàíèÿ åãèïòÿí, æèâøèõ âî âðåìÿ XVIII äèíàñòèè, è íà èõ ïðåäñòàâëåíèÿ î ïîòóñòîðîííåì ìèðå. Íà èëëþñòðàöèè ê 125 ãëàâå èçîáðàæåí ñàì Àíè, ñêëîíèâøèéñÿ â ïî÷òèòåëüíîì ïîêëîíå ïåðåä çàñåäàòåëÿìè Âåëèêîé ñóäåáíîé ïàëàòû, è åãî æåíà Òóòó.  óãëó çàëà óñòàíîâëåíû âåñû, çà ïðàâèëüíîñòüþ äåéñòâèÿ êîòîðûõ íàáëþäàåò øàêàëîãîëîâûé Àíóáèñ. Íà ëåâîé ÷àøå âåñîâ -ñåðäöå Àíè, íà ïðàâîé — ïåðî, ñèìâîëèçèðóþùåå Èñòèíó è ïðàâåäíîñòü ïîñòóïêîâ. Àíóáèñ, êîòîðîãî ãðåêè îòîæäåñòâëÿëè ñ Ãåðìåñîì, â åãèïåòñêèõ òåêñòàõ îáû÷íî ôèãóðèðóåò êàê ñûí Îñèðèñà. Íî åùå äî òîãî, êàê åãèïòÿíå ïðèçíàëè åãî ñûíîì öàðÿ çàãðîáíîãî ìèðà, îí ñ÷èòàëñÿ áîãîì óìåðøèõ, ïîýòîìó â ïîñëåäóþùèå ýïîõè åãî èçîáðàæàëè áðîäÿùèì ñðåäè ìîãèë â ïóñòûííûõ îêðåñòíîñòÿõ Ñèóòà.

ÀÍÓÁÈÑ —

â âåðîâàíèÿõ äðåâíèõ åãèïòÿí ïåðâîíà÷àëüíî áîã ñìåðòè â Òèíèòñêîì è Êèíîïîëüñêîì íîìàõ (îáë… Áîëüøàÿ Ñîâåòñêàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÀÍÓÁÈÑ — ÀÍÓÁÈÑ, â åãèïåòñêîé ìèôîëîãèè áîã — ïîêðîâèòåëü ìåðòâûõ. Ïî÷èòàëñÿ â îáëèêå øàêàëà. … Ñîâðåìåííàÿ ýíöèêëîïåäèÿ

ÀÍÓÁÈÑ — ÀÍÓÁÈÑ — â äðåâíååãèïåòñêîé ìèôîëîãèè áîã — ïîêðîâèòåëü ìåðòâûõ, à òàêæå íåêðîïîëåé, ïîãðåáàëüíûõ îá… Áîëüøîé ýíöèêëîïåäè÷åñêèé ñëîâàðü

Подробная информация о фамилии Анубис, а именно ее происхождение, история образования, суть фамилии, значение, перевод и склонение. Какая история происхождения фамилии Анубис? Откуда родом фамилия Анубис? Какой национальности человек с фамилией Анубис? Как правильно пишется фамилия Анубис? Верный перевод фамилии Анубис на английский язык и склонение по падежам. Полную характеристику фамилии Анубис и ее суть вы можете прочитать онлайн в этой статье совершенно бесплатно без регистрации.

Происхождение фамилии Анубис

Большинство фамилий, в том числе и фамилия Анубис, произошло от отчеств (по крестильному или мирскому имени одного из предков), прозвищ (по роду деятельности, месту происхождения или какой-то другой особенности предка) или других родовых имён.

История фамилии Анубис

В различных общественных слоях фамилии появились в разное время. История фамилии Анубис насчитывает несколько сотен лет. Первое упоминание фамилии Анубис встречается в XVIII—XIX веках, именно в это время на руси стали распространяться фамилии у служащих людей и у купечества. Поначалу только самое богатое — «именитое купечество» — удостаивалось чести получить фамилию Анубис. В это время начинают называться многочисленные боярские и дворянские роды. Именно на этот временной промежуток приходится появление знатных фамильных названий. Фамилия Анубис наследуется из поколения в поколение по мужской линии (или по женской).

Суть фамилии Анубис по буквам

Фамилия Анубис состоит из 6 букв. Фамилии из шести букв обычно принадлежат особам, в характере которых доминируют такие качества, как восторженность, граничащая с экзальтацией, и склонность к легкому эпатажу. Они уделяют много времени созданию собственного имиджа, используя все доступные средства для того, чтобы подчеркнуть свою оригинальность. Проанализировав значение каждой буквы в фамилии Анубис можно понять ее суть и скрытое значение.

Значение фамилии Анубис

Фамилия является основным элементом, связывающим человека со вселенной и окружающим миром. Она определяет его судьбу, основные черты характера и наиболее значимые события. Внутри фамилии Анубис скрывается опыт, накопленный предыдущими поколениями и предками. По нумерологии фамилии Анубис можно определить жизненный путь рода, семейное благополучие, достоинства, недостатки и характер носителя фамилии. Число фамилии Анубис в нумерологии — 5. Люди с фамилией Анубис — это свободолюбивые и целеустремленные люди, не терпящие контроля над собой. Они обладают врожденным талантом видеть суть вещей и разбираться в наиболее сложных и запутанных проблемах. Высшие силы наделили пятерок титанической работоспособностью, которая дает возможность реализации отчаянных проектов. Это бойцы, сражающиеся как своими недостатками, так и сложностями жизненного пути.

Они подвержены сомнениям, которые не могут быть развеяны более опытными коллегами. Весь опыт люди с фамилией Анубис накапливают самостоятельно и набивают немало шишек. Жизненные уроки помнят долго, чаще всего годами. Они быстро обучаются, вникают в новые проекты и привносят в них рациональное зерно.

Стремление к борьбе и сражениям проявляется у представителей фамилии Анубис с ранних лет. Они могут записываться в несколько спортивных секций и кружков по интересам, успевая при этом на всех направлениях. Со временем, выбирают для себя один вид деятельности и добиваются в нем совершенства. Природный оптимизм пятерок воспринимается со стороны как проявление ветренности, а потому им приходится доказывать свою состоятельность. На протяжении всего жизненного пути эти люди приковывают внимание и к ним предъявляются повышенные требования. Носителям фамилии Анубис нельзя оступаться: они тяжело переносят ошибки и часто замыкаются в себе.

Носители фамилии Анубис – не лучшие семьянины. Это душа компании, преданный друг, но не всегда – лучший муж или великолепная жена. Семейная жизнь у представителей фамилии Анубис на втором плане, а свое свободное время они посвящают хобби и любимой работе. При этом их любят дети, так как Анубис не пытается строить из себя взрослого человека. Люди с фамилией Анубис общаются с малышами на равных, а потому пробуждают в них чувство гордости и значимости. К сожалению, они склонны к увлечению противоположным полом: эта слабость может приводить к длительным романам и повторным бракам. Удержать в семье носителя фамилии Анубис сможет только сильный и уверенный в себе человек.

Носителям фамилии Анубис рекомендованы творческие профессии: они смогут добиться успеха в роли музыканта, художника, модельера или журналиста. Возможен успех в деловой сфере: но в этом случае им следует избегать рискованных операций. Врожденная склонность к психологии превращает пятерок в потенциальных психотерапевтов, социальных работников, преподавателей. Этим людям можно рекомендовать руководящие посты: при этом успех всего предприятия будет зависеть от правильно выбранной команды сотрудников.

К достоинствам фамилии Анубис можно отнести веселый нрав, оптимизм, открытость. Это щедрые люди, преданные друзья и верные партнеры. Несмотря на преследование ними выгоды, подвох и предательство с их стороны полностью исключены.

Как правильно пишется фамилия Анубис

В русском языке грамотным написанием этой фамилии является — Анубис. В английском языке фамилия Анубис может иметь следующий вариант написания — Anubis.

Склонение фамилии Анубис по падежам

| Падеж | Вопрос | Фамилия |

| Именительный | Кто? | Анубис |

| Родительный | Нет Кого? | Анубиса |

| Дательный | Рад Кому? | Анубису |

| Винительный | Вижу Кого? | Анубиса |

| Творительный | Доволен Кем? | Анубисом |

| Предложный | Думаю О ком? | Анубисе |

Видео про фамилию Анубис

Вы согласны с описанием фамилии Анубис, ее происхождением, историей образования, значением и изложенной сутью? Какую информацию о фамилии Анубис вы еще знаете? С какими известными и успешными людьми с фамилией Анубис вы знакомы? Будем рады обсудить фамилию Анубис более подробно с посетителями нашего сайта в комментариях.

Если вы нашли ошибку в описании фамилии, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Разбор слова «анубис»: для переноса, на слоги, по составу

Объяснение правил деление (разбивки) слова «анубис» на слоги для переноса.

Онлайн словарь Soosle.ru поможет: фонетический и морфологический разобрать слово «анубис» по составу, правильно делить на слоги по провилам русского языка, выделить части слова, поставить ударение, укажет значение, синонимы, антонимы и сочетаемость к слову «анубис».

Содержимое:

- 1 Слоги в слове «анубис» деление на слоги

- 2 Как перенести слово «анубис»

- 3 Синонимы слова «анубис»

- 4 Предложения со словом «анубис»

- 5 Значение слова «анубис»

- 6 Как правильно пишется слово «анубис»

Слоги в слове «анубис» деление на слоги

Количество слогов: 3

По слогам: а-ну-бис

Как перенести слово «анубис»

ану—бис

Синонимы слова «анубис»

Предложения со словом «анубис»

На колючих кустах раскачивалось, словно гамак, гнездо птицы анубис, а по берегам озёр, распуская по ветру крылья огненного цвета, целыми стаями бродили фламинго.

Жюль Верн, Дети капитана Гранта (адаптированный пересказ), 2015.

Анубис дал своим жрецам мудрость понимания смерти, и они смогли проникнуть в тайны запретного.

Владимир Андриенко, Книга тайн.

Когда это происходит, Анубис призывает своих детей обратно.

Значение слова «анубис»

Ану́бис (греч.), Инпу (др.-егип.) — божество Древнего Египта с головой шакала и телом человека, проводник умерших в загробный мир. В Старом царстве являлся покровителем некрополей и кладбищ, один из судей царства мёртвых, хранитель ядов и лекарств. В древнеегипетской мифологии — сын Осириса. (Википедия)

Как правильно пишется слово «анубис»

Правописание слова «анубис»

Орфография слова «анубис»

Правильно слово пишется:

Нумерация букв в слове

Номера букв в слове «анубис» в прямом и обратном порядке:

Анубис

- Анубис

- Ану́бис

в древнеегипетской мифологии бог — покровитель мёртвых, а также некрополей, погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Изображался в облике волка, шакала или человека с головой шакала.

* * *

АНУБИС

АНУ́БИС, в древнеегипетской мифологии бог — покровитель мертвых, а также некрополей (см. НЕКРОПОЛЬ (могильник)), погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования (см. БАЛЬЗАМИРОВАНИЕ). Изображался в облике волка, шакала, собаки или человека с головой этих животных. Древнейшее упоминание об Анубисе встречается в Книге пирамид (см. КНИГА МЕРТВЫХ) эпохи Древнего царства, где он ассоциировался исключительно с царскими захоронениями. Подобно другим богам древности, выполнял различные роли. Животные, в виде которых изображался Анубис — обитатели пустыни, то есть земель, пограничных со страной мертвых Дуатом (см. ДУАТ). Анубис прочно связан с черным цветом — цветом смерти, загробного мира и ночи. В Книге мертвых Анубис обычно изображается в сцене взвешивания сердца покойного.

В текстах пирамид Анубиса обычно называли четвертым сыном Ра (см. РА (в мифологии)). Позднее отцом Анубиса стал считаться Осирис (см. ОСИРИС), а матерью — Нефтида (см. НЕФТИДА). Как бог бальзамирования Анубис помогал сохранить тело Осириса. Дочерью Анубиса считалась Кебхут (см. КЕБХУТ). С возвышением почитания Осириса Анубис перешел на второстепенные позиции. Он часто ассоциировался с Упуатом (см. УПУАТ), другим богом в образе волка.

В эллинистическую эпоху Анубис был объединен греками с Гермесом (см. ГЕРМЕС) в синкретическом образе Германубиса. Этот бог как волшебник упоминается в римской литературе. В герметических текстах (см. ГЕРМЕТИЗМ (в философии)) также сохранялись упоминания о нем вплоть до эпохи Возрождения. Некоторые ученые видят черты Анубиса у святого Христофора и в средневековых рассказах о киноскефалах (людях с песьими головами).

Энциклопедический словарь.

2009.

Синонимы:

Полезное

Смотреть что такое «Анубис» в других словарях:

-

Анубис — (Anubis, Ανουβις). Египетское божество, сын Осириса и Изиды. Его изображали в виде человека с головой шакала (или собаки). Анубиса сопоставляют с греческим Гермесом. (Источник: «Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей». М.Корш. Санкт Петербург,… … Энциклопедия мифологии

-

Анубис — извлекает сердце умершего, чтобы взвесить его на суде Осириса. Роспись гробницы. XIII в. до н. э. Анубис извлекает сердце умершего, чтобы взвесить его на суде Осириса. Роспись гробницы. XIII в. до н. э. Анубис () в мифах древних египтян… … Энциклопедический словарь «Всемирная история»

-

Анубис — Анубис. Деталь погребальной пелены. Сер. 2 в. Музей изобразительных искусств имени А.С. Пушкина. АНУБИС, в египетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых. Почитался в облике шакала. Анубис, завершающий мумификацию покойника . Древнеегипетская… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

АНУБИС — (древн. егип.). Древнеегипетское божество, сын Озириса, почитавшееся охранителем границ Египта и изображавшееся обыкновенно с собачьей головой. Словарь иностранных слов, вошедших в состав русского языка. Чудинов А.Н., 1910. АНУБИС бог египетской… … Словарь иностранных слов русского языка

-

АНУБИС — АНУБИС, в египетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых. Почитался в облике шакала … Современная энциклопедия

-

АНУБИС — в древнеегипетской мифологии бог покровитель мертвых, а также некрополей, погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Изображался в облике волка, шакала или человека с головой шакала … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

анубис — сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • бог (375) • покровитель (40) Словарь синонимов ASIS. В.Н. Тришин. 2013 … Словарь синонимов

-

Анубис — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Анубис (значения). Анубис в иероглифах … Википедия

-

АНУБИС — древнеегипетский бог загробного мира. В ранний период развития египетской религии это шакалообразное божество, пожирающее умерших. Позже Анубис сохранил лишь отдельные черты, выдававшие его животное происхождение. Будучи богом некрополя Сиута… … Энциклопедия Кольера

-

АНУБИС (обезьяна) — АНУБИС (зеленый павиан; Papio anubis), вид обезьян рода павианов (см. ПАВИАНЫ). Немного крупнее гамадрила (см. ГАМАДРИЛ): масса его тела 25–30 кг, длина тела около 80 см, хвоста 50–60 см. Самки меньше самцов. Туловище анубисов более удлиненное,… … Энциклопедический словарь

Ударение в слове «Анубис»

анубис

Слово «анубис» правильно пишется как «анубис», с ударением на гласную — у (2-ой слог).

Оцени материал

7 голосов, оценка 4.714 из 5

Поставить ударение в другом слове

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Anubis | |

|---|---|

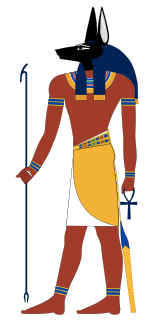

The Egyptian god Anubis (a modern rendition inspired by New Kingdom tomb paintings) |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Lycopolis, Cynopolis |

| Symbol | Mummy gauze, fetish, jackal, flail |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nepthys and Set, Osiris (Middle and New kingdom), or Ra (Old kingdom). |

| Siblings | Wepwawet |

| Consort | Anput, Nephthys[1] |

| Offspring | Kebechet |

| Greek equivalent | Hades or Hermes |

Anubis as a jackal perched atop a tomb, symbolizing his protection of the necropolis

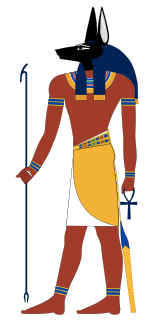

Anubis (;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις), also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian (Coptic: ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ, romanized: Anoup) is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the «Weighing of the Heart», in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon, however, no relevant myth involved him.[3]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brother Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[4] Anubis’ female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

«Anubis» is a Greek rendering of this god’s Egyptian name.[5][6] Before the Greeks arrived in Egypt, around the 7th century BC, the god was known as Anpu or Inpu. The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means «a royal child.» Inpu has a root to «inp», which means «to decay.» The god was also known as «First of the Westerners,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain,» «Ruler of the Nine Bows,» «The Dog who Swallows Millions,» «Master of Secrets,» «He Who is in the Place of Embalming,» and «Foremost of the Divine Booth.»[7] The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as «He Who Is upon His Mountain,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «Foremost of the Westerners,» and «He Who Is in the Place of Embalming.»[8]

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound signs inpw followed by a jackal[a] over a ḥtp sign:[10]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[10]

Anubis’ name jnpw was possibly pronounced [a.ˈna.pʰa(w)], based on Coptic Anoup and the Akkadian transcription 𒀀𒈾𒉺⟨a-na-pa⟩ in the name <ri-a-na-pa> «Reanapa» that appears in Amarna letter EA 315.[11][12] However, this transcription may also be interpreted as rˁ-nfr, a name similar to that of Prince Ranefer of the Fourth Dynasty.

History

In Egypt’s Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a «jackal» head and body.[13] A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[14] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[15] In the spirit of «fighting like with like,» a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because «a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation.»[16]

Anubis attending the mummy of the deceased.

Anubis receiving offerings, hieroglyph name in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara (Egypt)

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[17] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[18]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[19] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[20] Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra and Nephthys.[19] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris’s wife Isis:[21]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hart sees this story as an «attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon.»[20] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the «son of Isis.»[20] In Nubia, Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with the Greek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[23][24] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[25] The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means «city of dogs.» In Book XI of The Golden Ass by Apuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld.[26] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths «by the dog» (Greek: kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt», and «by the dog, the god of the Egyptians», both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

As jmy-wt (Imiut or the Imiut fetish) «He who is in the place of embalming», Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called ḫnty zḥ-nṯr «He who presides over the god’s booth», in which «booth» could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh’s burial chamber.[28][29]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[17] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris’s organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role. Khenty-Amentiu, which means «foremost of the westerners» and was also the name of a different canine funerary god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as tpy-ḏw.f (Tepy-djuef) «He who is upon his mountain» (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) and nb-t3-ḏsr (Neb-ta-djeser) «Lord of the sacred land», which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[28][29]

The Jumilhac papyrus recounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into a leopard. Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and he branded Set’s skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate the tombs of the dead.[31] Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis’ victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[34] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of «psychopomp», a Greek term meaning «guide of souls» that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role in Greek religion.[25] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

The «weighing of the heart,» from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth.

One of the roles of Anubis was as the «Guardian of the Scales.»[37] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma’at (or «truth»), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

This detailed scene, from the Papyrus of Hunefer (c. 1275 BCE), shows the scribe Hunefer’s heart being weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth by Anubis

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities in ancient Egyptian art.[3] He is depicted in royal tombs as early as the First Dynasty.[7] The god is typically treating a king’s corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Two Truths.[8] One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma’at’s white truth feather.[7]

In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40] Anubis’s distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41] It represented «the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification.»[41] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42] In the Middle Kingdom, Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in a chapel of Ramesses II in Abydos.[41][6]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nḫ3ḫ3 «flail» in the crook of his arm.[43] Another of Anubis’s attributes was the jmy-wt or imiut fetish, named for his role in embalming.[44] In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person’s mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[45]

-

Porable shrine of Anubis, exposition in Paris, from the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62)

-

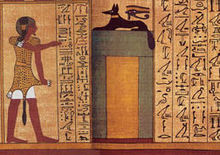

Isis, left, and Nephthys stand by as Anubis embalms the deceased, 13th century BC

-

The king with Anubis, from the tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[7] The Greeks linked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known as Hermanubis. Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[7]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god’s likeness when performing rituals.[7][8] His cult center was at Cynopolis in Upper Egypt but memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[7]

In popular culture

In popular and media culture, Anubis is often falsely portrayed as the sinister god of the dead. He gained popularity during the 20th and 21st centuries through books, video games, and movies where artists would give him evil powers and a dangerous army. Despite his nefarious reputation, his image is still the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and replicas of his statues and paintings remain popular.

See also

- Abatur, Mandaean uthra who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate

- Animal mummy#Miscellaneous animals

- Anput

- Anubias

- Bhairava

- Hades

Notes

- ^ The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of the golden jackal in older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as the African wolf, which was found to be more closely related to wolves and coyotes than to the jackal.[9] Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog’s head, not a jackal or wolf’s, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

References

- ^ a b Lévai, Jessica (2007). Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt. UMI.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^ a b Johnston 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Coulter & Turner 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b «Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis». Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Anubis». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Anubis». Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o’Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). «Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species». Current Biology. 25 (#16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Leprohon 1990, p. 164, citing Fischer 1968, p. 84 and Lapp 1986, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Conder 1894, p. 85.

- ^ «CDLI-Archival View». cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt); Freeman 1997, p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 («fighting like with like» and «by jackals and other wild dogs»).

- ^ a b Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Hart 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell, Price (2018). Ancient Egypt — Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Peacock 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^ «Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon». Babylon.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Riggs 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Hoerber 1963, p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^ E.g., Gorgias, 482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962, p. 318), or The Republic, 399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963, p. 268).

- ^ a b Hart 1986, pp. 23–24; Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

- ^ a b Vischak, Deborah (27 October 2014). Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107027602.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Armour 2001.

- ^ Zandee 1960, p. 255.

- ^ «The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis». touregypt.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Kinsley 1989, p. 178; Riggs 2005, p. 166 («The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era.»).

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127 and 166.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^ Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008, p. 155.

- ^ «Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart». British Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis». Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 22; Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b «Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis». Egyptianmyths.net. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001), Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), «Gorgias 482b», The Classical Journal, 57 (7): 318–19, JSTOR 3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.) (1894) [1893], The Tell Amarna Tablets (Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund by A.P. Watt, ISBN 978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008), The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Chronicle Books, ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968), Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt, London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002), «Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt» (PDF), Organon, 31 (31): 128–48, PMID 15017968, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), «The Socratic Oath ‘By the Dog’«, The Classical Journal, 58 (6): 268–69, JSTOR 3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5. (paperback).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986), Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen [The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, ISBN 978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), «The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period», The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 76: 163–64, doi:10.1177/030751339007600115, JSTOR 3822017, S2CID 192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000), «The Roman Period», in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960), Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions, Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005). The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Darengo Publications. ISBN 978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007). Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977). Anubis alexandrin et romain (in French). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04917-8.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anubis.

Look up Anubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Anubis | |

|---|---|

The Egyptian god Anubis (a modern rendition inspired by New Kingdom tomb paintings) |

|

| Name in hieroglyphs | |

| Major cult center | Lycopolis, Cynopolis |

| Symbol | Mummy gauze, fetish, jackal, flail |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Nepthys and Set, Osiris (Middle and New kingdom), or Ra (Old kingdom). |

| Siblings | Wepwawet |

| Consort | Anput, Nephthys[1] |

| Offspring | Kebechet |

| Greek equivalent | Hades or Hermes |

Anubis as a jackal perched atop a tomb, symbolizing his protection of the necropolis

Anubis (;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἄνουβις), also known as Inpu, Inpw, Jnpw, or Anpu in Ancient Egyptian (Coptic: ⲁⲛⲟⲩⲡ, romanized: Anoup) is the god of funerary rites, protector of graves, and guide to the underworld, in ancient Egyptian religion, usually depicted as a canine or a man with a canine head.

Like many ancient Egyptian deities, Anubis assumed different roles in various contexts. Depicted as a protector of graves as early as the First Dynasty (c. 3100 – c. 2890 BC), Anubis was also an embalmer. By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC) he was replaced by Osiris in his role as lord of the underworld. One of his prominent roles was as a god who ushered souls into the afterlife. He attended the weighing scale during the «Weighing of the Heart», in which it was determined whether a soul would be allowed to enter the realm of the dead. Anubis is one of the most frequently depicted and mentioned gods in the Egyptian pantheon, however, no relevant myth involved him.[3]

Anubis was depicted in black, a color that symbolized regeneration, life, the soil of the Nile River, and the discoloration of the corpse after embalming. Anubis is associated with his brother Wepwawet, another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog’s head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[4] Anubis’ female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

«Anubis» is a Greek rendering of this god’s Egyptian name.[5][6] Before the Greeks arrived in Egypt, around the 7th century BC, the god was known as Anpu or Inpu. The root of the name in ancient Egyptian language means «a royal child.» Inpu has a root to «inp», which means «to decay.» The god was also known as «First of the Westerners,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «He Who is Upon his Sacred Mountain,» «Ruler of the Nine Bows,» «The Dog who Swallows Millions,» «Master of Secrets,» «He Who is in the Place of Embalming,» and «Foremost of the Divine Booth.»[7] The positions that he had were also reflected in the titles he held such as «He Who Is upon His Mountain,» «Lord of the Sacred Land,» «Foremost of the Westerners,» and «He Who Is in the Place of Embalming.»[8]

In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound signs inpw followed by a jackal[a] over a ḥtp sign:[10]

A new form with the jackal on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[10]

Anubis’ name jnpw was possibly pronounced [a.ˈna.pʰa(w)], based on Coptic Anoup and the Akkadian transcription 𒀀𒈾𒉺⟨a-na-pa⟩ in the name <ri-a-na-pa> «Reanapa» that appears in Amarna letter EA 315.[11][12] However, this transcription may also be interpreted as rˁ-nfr, a name similar to that of Prince Ranefer of the Fourth Dynasty.

History

In Egypt’s Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a «jackal» head and body.[13] A jackal god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[14] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, jackals had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[15] In the spirit of «fighting like with like,» a jackal was chosen to protect the dead, because «a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation.»[16]

Anubis attending the mummy of the deceased.

Anubis receiving offerings, hieroglyph name in third column from left, 14th century BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara (Egypt)

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[17] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[18]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[19] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[20] Another tradition depicted him as the son of Ra and Nephthys.[19] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) reported a tradition that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris’s wife Isis:[21]

For when Isis found out that Osiris loved her sister and had relations with her in mistaking her sister for herself, and when she saw a proof of it in the form of a garland of clover that he had left to Nephthys – she was looking for a baby, because Nephthys abandoned it at once after it had been born for fear of Seth; and when Isis found the baby helped by the dogs which with great difficulties lead her there, she raised him and he became her guard and ally by the name of Anubis.

George Hart sees this story as an «attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon.»[20] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the «son of Isis.»[20] In Nubia, Anubis was seen as the husband of his mother Nephthys.[1]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with the Greek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[23][24] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[25] The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means «city of dogs.» In Book XI of The Golden Ass by Apuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egyptian animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called «Barker» by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld.[26] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths «by the dog» (Greek: kai me ton kuna), «by the dog of Egypt», and «by the dog, the god of the Egyptians», both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[27]

Roles

Embalmer

As jmy-wt (Imiut or the Imiut fetish) «He who is in the place of embalming», Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called ḫnty zḥ-nṯr «He who presides over the god’s booth», in which «booth» could refer either to the place where embalming was carried out or the pharaoh’s burial chamber.[28][29]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[17] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris’s organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Protector of tombs

Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role. Khenty-Amentiu, which means «foremost of the westerners» and was also the name of a different canine funerary god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as tpy-ḏw.f (Tepy-djuef) «He who is upon his mountain» (i.e. keeping guard over tombs from above) and nb-t3-ḏsr (Neb-ta-djeser) «Lord of the sacred land», which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[28][29]

The Jumilhac papyrus recounts another tale where Anubis protected the body of Osiris from Set. Set attempted to attack the body of Osiris by transforming himself into a leopard. Anubis stopped and subdued Set, however, and he branded Set’s skin with a hot iron rod. Anubis then flayed Set and wore his skin as a warning against evil-doers who would desecrate the tombs of the dead.[31] Priests who attended to the dead wore leopard skin in order to commemorate Anubis’ victory over Set. The legend of Anubis branding the hide of Set in leopard form was used to explain how the leopard got its spots.[32]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[33]

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[34] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[35] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of «psychopomp», a Greek term meaning «guide of souls» that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role in Greek religion.[25] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[36]

Weigher of hearts

The «weighing of the heart,» from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth.

One of the roles of Anubis was as the «Guardian of the Scales.»[37] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma’at (or «truth»), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[38][39]

Portrayal in art

This detailed scene, from the Papyrus of Hunefer (c. 1275 BCE), shows the scribe Hunefer’s heart being weighed on the scale of Maat against the feather of truth by Anubis

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented deities in ancient Egyptian art.[3] He is depicted in royal tombs as early as the First Dynasty.[7] The god is typically treating a king’s corpse, providing sovereign to mummification rituals and funerals, or standing with fellow gods at the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul in the Hall of Two Truths.[8] One of his most popular representations is of him, with the body of a man and the head of a jackal with pointed ears, standing or kneeling, holding a gold scale while a heart of the soul is being weighed against Ma’at’s white truth feather.[7]

In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black canine.[40] Anubis’s distinctive black color did not represent the animal, rather it had several symbolic meanings.[41] It represented «the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification.»[41] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians, black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[42] In the Middle Kingdom, Anubis was often portrayed as a man with the head of a jackal.[43] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in a chapel of Ramesses II in Abydos.[41][6]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nḫ3ḫ3 «flail» in the crook of his arm.[43] Another of Anubis’s attributes was the jmy-wt or imiut fetish, named for his role in embalming.[44] In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person’s mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt.[45]

-

Porable shrine of Anubis, exposition in Paris, from the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62)

-

Isis, left, and Nephthys stand by as Anubis embalms the deceased, 13th century BC

-

The king with Anubis, from the tomb of Horemheb; 1323-1295 BC; tempera on paper; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Anubis amulet; 664–30 BC; faience; height: 4.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Recumbent Anubis; 664–30 BC; limestone, originally painted black; height: 38.1 cm, length: 64 cm, width: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Statuette of Anubis; 332–30 BC; plastered and painted wood; 42.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Worship

Although he does not appear in many myths, he was extremely popular with Egyptians and those of other cultures.[7] The Greeks linked him to their god Hermes, the god who guided the dead to the afterlife. The pairing was later known as Hermanubis. Anubis was heavily worshipped because, despite modern beliefs, he gave the people hope. People marveled in the guarantee that their body would be respected at death, their soul would be protected and justly judged.[7]

Anubis had male priests who sported wood masks with the god’s likeness when performing rituals.[7][8] His cult center was at Cynopolis in Upper Egypt but memorials were built everywhere and he was universally revered in every part of the nation.[7]

In popular culture

In popular and media culture, Anubis is often falsely portrayed as the sinister god of the dead. He gained popularity during the 20th and 21st centuries through books, video games, and movies where artists would give him evil powers and a dangerous army. Despite his nefarious reputation, his image is still the most recognizable of the Egyptian gods and replicas of his statues and paintings remain popular.

See also

- Abatur, Mandaean uthra who weighs the souls of the dead to determine their fate

- Animal mummy#Miscellaneous animals

- Anput

- Anubias

- Bhairava

- Hades

Notes

- ^ The wild canine species in Egypt, long thought to have been a geographical variant of the golden jackal in older texts, was reclassified in 2015 as a separate species known as the African wolf, which was found to be more closely related to wolves and coyotes than to the jackal.[9] Nevertheless, ancient Greek texts about Anubis constantly refer to the deity as having a dog’s head, not a jackal or wolf’s, and there is still uncertainty as to what canid represents Anubis. Therefore the Name and History section uses the names the original sources used but in quotation marks.

References

- ^ a b Lévai, Jessica (2007). Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt. UMI.

- ^ Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 56

- ^ a b Johnston 2004, p. 579.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Coulter & Turner 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b «Gods and Religion in Ancient Egypt – Anubis». Archived from the original on 27 December 2002. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Anubis». World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ a b c «Anubis». Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; Johnson, Warren E.; o’Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). «Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species». Current Biology. 25 (#16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ a b Leprohon 1990, p. 164, citing Fischer 1968, p. 84 and Lapp 1986, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Conder 1894, p. 85.

- ^ «CDLI-Archival View». cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 (burials in shallow graves in Predynastic Egypt); Freeman 1997, p. 91 (rest of the information).

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 262 («fighting like with like» and «by jackals and other wild dogs»).

- ^ a b Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 166–67.

- ^ a b Hart 1986, p. 25.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Gryglewski 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Campbell, Price (2018). Ancient Egypt — Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-500-51984-4.

- ^ Peacock 2000, pp. 437–38 (Hellenistic kingdom).

- ^ «Hermanubis | English | Dictionary & Translation by Babylon». Babylon.com. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b Riggs 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Hoerber 1963, p. 269 (for Cerberus and Hades).

- ^ E.g., Gorgias, 482b (Blackwood, Crossett & Long 1962, p. 318), or The Republic, 399e, 567e, 592a (Hoerber 1963, p. 268).

- ^ a b Hart 1986, pp. 23–24; Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

- ^ a b Vischak, Deborah (27 October 2014). Community and Identity in Ancient Egypt: The Old Kingdom Cemetery at Qubbet el-Hawa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107027602.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 23.

- ^ Armour 2001.

- ^ Zandee 1960, p. 255.

- ^ «The Gods of Ancient Egypt – Anubis». touregypt.net. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Kinsley 1989, p. 178; Riggs 2005, p. 166 («The motif of Anubis, or less frequently Hathor, leading the deceased to the afterlife was well-established in Egyptian art and thought by the end of the pharaonic era.»).

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127 and 166.

- ^ Riggs 2005, pp. 127–28 and 166–67.

- ^ Faulkner, Andrews & Wasserman 2008, p. 155.

- ^ «Museum Explorer / Death in Ancient Egypt – Weighing the heart». British Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ «Gods of Ancient Egypt: Anubis». Britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Hart 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hart 1986, p. 22; Freeman 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b «Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Anubis». Egyptianmyths.net. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ^ Wilkinson 1999, p. 281.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, pp. 188–90.

Bibliography

- Armour, Robert A. (2001), Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt, Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press

- Blackwood, Russell; Crossett, John; Long, Herbert (1962), «Gorgias 482b», The Classical Journal, 57 (7): 318–19, JSTOR 3295283.

- Conder, Claude Reignier (trans.) (1894) [1893], The Tell Amarna Tablets (Second ed.), London: Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund by A.P. Watt, ISBN 978-1-4147-0156-1.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Jefferson (NC) and London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-0317-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O.; Andrews, Carol; Wasserman, James (2008), The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day, Chronicle Books, ISBN 978-0-8118-6489-3.

- Fischer, Henry George (1968), Dendera in the Third Millennium B. C., Down to the Theban Domination of Upper Egypt, London: J.J. Augustin.

- Freeman, Charles (1997), The Legacy of Ancient Egypt, New York: Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-816-03656-1.

- Gryglewski, Ryszard W. (2002), «Medical and Religious Aspects of Mummification in Ancient Egypt» (PDF), Organon, 31 (31): 128–48, PMID 15017968, archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Hart, George (1986), A Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 978-0-415-34495-1.

- Hoerber, Robert G. (1963), «The Socratic Oath ‘By the Dog’«, The Classical Journal, 58 (6): 268–69, JSTOR 3293989.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles (general ed.) (2004), Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01517-3.

- Kinsley, David (1989), The Goddesses’ Mirror: Visions of the Divine from East and West, Albany (NY): State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-88706-835-5. (paperback).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Lapp, Günther (1986), Die Opferformel des Alten Reiches: unter Berücksichtigung einiger späterer Formen [The offering formula of the Old Kingdom: considering a few later forms], Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, ISBN 978-3805308724.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (1990), «The Offering Formula in the First Intermediate Period», The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 76: 163–64, doi:10.1177/030751339007600115, JSTOR 3822017, S2CID 192258122.

- Peacock, David (2000), «The Roman Period», in Shaw, Ian (ed.), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Riggs, Christina (2005), The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003), The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05120-7.

- Wilkinson, Toby A. H. (1999), Early Dynastic Egypt, London: Routledge

- Zandee, Jan (1960), Death as an Enemy: According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions, Brill Archive, GGKEY:A7N6PJCAF5Q

Further reading

- Duquesne, Terence (2005). The Jackal Divinities of Egypt I. Darengo Publications. ISBN 978-1-871266-24-5.

- El-Sadeek, Wafaa; Abdel Razek, Sabah (2007). Anubis, Upwawet, and Other Deities: Personal Worship and Official Religion in Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-437-231-5.

- Grenier, J.-C. (1977). Anubis alexandrin et romain (in French). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04917-8.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anubis.

Look up Anubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Анубис

(Anubis, Ανουβις). Египетское божество, сын Осириса и Изиды. Его изображали в виде человека с головой шакала (или собаки). Анубиса сопоставляют с греческим Гермесом.

(Источник: «Краткий словарь мифологии и древностей». М.Корш. Санкт-Петербург, издание А. С. Суворина, 1894.)

АНУБИС

(греч.Άνουβις), Инпу (егип. inpw), в египетской мифологии бог — покровитель умерших; почитался в образе лежащего шакала чёрного цвета или дикой собаки Саб (или в виде человека с головой шакала или собаки). А.-Саб считался судьёй богов (по-египетски «саб» — «судья» писался со знаком шакала). Центром культа А. был город 17-го нома Каса (греч. Кинополь, «город собаки»), однако его почитание очень рано распространилось по всему Египту. В период Древнего царства А. считался богом мёртвых, его основные эпитеты «Хентиаменти», т. е. тот, кто впереди страны Запада (царства мёртвых), «владыка Расетау» (царства мёртвых), «стоящий впереди чертога богов». Согласно «Текстам пирамид», А. был главным богом в царстве мёртвых, он считал сердца умерших (в то время как Осирис главным образом олицетворял умершего фараона, который оживал подобно богу). Однако постепенно с конца 3-го тыс. до н. э. функции А. переходят к Осирису, которому присваиваются его эпитеты, а А. входит в круг богов, связанных с мистериями Осириса. Вместе с Исидой он ищет его тело, охраняет его от врагов, вместе с Тотом присутствует на суде Осириса.

А. играет значительную роль в погребальном ритуале, его имя упоминается во всей заупокойной египетской литературе, согласно которой одной из важнейших функций А. была подготовка тела покойного к бальзамированию и превращению его в мумию (эпитеты «ут» и «имиут» определяют А. как бога бальзамирования). А. приписывается возложение на мумию рук и превращение покойника с помощью магии в ах («просветлённого», «блаженного»), оживающего благодаря этому жесту; А.расставляет вокруг умершего в погребальной камере Гора детей и даёт каждому канопу с внутренностями покойного для их охраны. А. тесно связан с некрополем в Фивах, на печати которого изображался лежащий над девятью пленниками шакал. А. считался братом бога Баты, что отразилось в сказке о двух братьях. По Плутарху, А. был сыном Осириса и Нефтиды. Древние греки отождествляли А. с Гермесом.

р. и. Рубинштейн.

(Источник: «Мифы народов мира».)

Анубис

в египетской мифологии бог-покровитель умерших; почитался в образе лежащего шакала черного цвета или дикой собаки (или в виде человека с головой шакала или собаки). Анубис считался судьей богов. Центром культа Анубиса был город 17-го нома Каса (греческий Кинополь, «город собаки»), однако его почитание очень рано распространилось по всему Египту. В период Древнего царства Анубис считался богом мертвых, его основные эпитеты «Хентиаменти», т. е. тот, кто впереди страны Запада («царства мертвых»), «владыка Расетау» («царства мертвых»), «стоящий впереди чертога богов». Согласно «Текстам пирамид». Анубис был главным богом в царстве мертвых, он считал сердца умерших (в то время как Осирис главным образом олицетворял умершего фараона. который оживал подобно богу). С конца 3-го тысячелетия до н. э. функции Анубиса переходят к Осирису, которому присваивали его эпитеты. А Анубис входит в круг богов, связанных с мистериями Осириса. Вместе с Тотом присутствующем на суде Осириса. Одной из важнейших функций Анубиса была подготовка тела покойного к бальзамированию и превращению его в мумию. Анубису приписывалось возложение на мумию рук и превращение покойника с помощью магии в ах («просветленного», «блаженного»), оживающего благодаря этому жесту; Анубис расставлял вокруг умершего в погребальной камере Гора детей и дает каждому канопу с внутренностями покойного для их охраны. Анубис тесно связан с некрополем в Фивах, на печати которого изображен лежащий над девятью пленниками шакал. Анубис считался братом бога Баты. По Плутарху, Анубис был сыном Осириса и Нефтиды. Древние греки отождествляли Анубис с Гермесом.

© В. Д. Гладкий

(Источник: «Древнеегипетский словарь-справочник».)

АНУБИС

в египетской мифологии — покровитель мертвых. Он был сыном бога растительности Осириса и Нефтиды. Бог Сет хотел убить младенца, и Нефтиде пришлось спрятать ребенка в болотах дельты Нила. Верховная богиня Исида нашла малыша и вырастила его. Когда Сет убил Осириса, Анубис завернул тело своего бога-отца в ткани, которые пропитал придуманным им самим составом. Так появилась первая мумия. Поэтому Анубиса считают богом погребальных обрядов и бальзамирования. Анубис участвовал в суде над умершими и был провожатым мертвых в загробное царство. Изображали этого бога с головой шакала.

(Источник: «Словарь духов и богов германо-скандинавской, египетской, греческой, ирландской, японской мифологии, мифологий индейцев майя и ацтеков.»)

Анубис.

Анубис.

Деталь погребальной пелены.

Середина II в. н. э.

Москва.

Музей изобразительных искусств имени А. С. Пушкина.

Пелена мумии мужчины 1 век н.э.

Синонимы:

бог, покровитель